Winter

i am searching for you in every sentence, every song.

i look for you in candlelight

Hoping the flame will burn the strands of hair you last touched. burn the fingers you last held.

blister these lips you last put against yours — so soft, you said — so gentle, I said but it still burns

I listen for your laugh while I wait for the train. I yearn for you in every conversation I have waiting to hear that slight lisp of yours or the giggle that escapes mid-sentence anytime you try to say something funny even though the sound would bring me to bite my tongue swallow it whole like a well-dressed oyster. and while the blood is pouring out of my mouth I’d smile because i found you. finally the weeks spent waiting for even a whisper were not for naught

And then, with my chin raised dripping in burgundy, maroon, crimson I’d walk toward the platform edge. Almost home.

Here I am Where I am

Moon dust feels like talcum powder

I think to myself as I lay on my moon lawn and I stare up at the sky which is no longer space because now it is much closer

And the stars still look like stars

But they shine much brighter now

Even though they are still light years away

I decide to go inside my space dome because it feels like dinner time

Even though there is no concept of day and night on the moon

I enter my space home which is made of chrome and other-worldly materials and I greet my alien wife

Her name is something astronomical like Zenon or Mimlex, or Sylvie

And I love her so much

And we sit down at our Kitchen table and eat space food like dehydrated ice cream, and moon rocks

And me and my wife have this beautiful human-alien baby

Who looks like a normal baby but the more she grows the more she glows

So we’re eating our dinner and I look at my beautiful alien wife and we marvel at our odd yet magnificent baby

And I am so happy here on the moon in our moon palace

But I can’t help but imagine what life on the sun is like

And as I lay on the surface of the sun I laugh at how unaffected by the heat I am now that I’ve settled into life on this hot ball of rock

I stare off into the bright orange sky, which is only orange because I assume it is on fire

And I think to myself “I should go in for dinner”

Even though there is no concept of day and night on the sun

So I go into my fire resistant home and I take off my sunglasses that I wear all of the time because I’m only human after all

And then I kiss my fiery sun husband hello

And we eat a dinner full of scolding hot spicy food because there is nothing cold to eat on the sun

And although I love my hot husband and the passion in which he speaks to me and the flame the sun kindles in our hearts

And although I love being tan and wearing sunglasses at all times

I can’t help but imagine what life must be like on earth

And as I lay on the grass in my backyard

I let the strands tickle my skin and it feels exactly like how I remember it always being

And I am itchy but warm

But not too warm

And I can hear the birds singing to each other sweetly

And cars honking rudely

And dogs barking at other dogs wishing they were together to howl in unison

And the sun is setting and the moon is showing her skin

So it seems like I should go inside to eat dinner

And I go inside and I make penne pasta with tomato sauce and I eat it while listening to all the people I love talk about their days

And they ask me how mine went

I tell them it was long but not unenjoyable

And we laugh

And not much else happens

But I am not full of fire

Or surrounded by darkness

So I am simply happy to be here

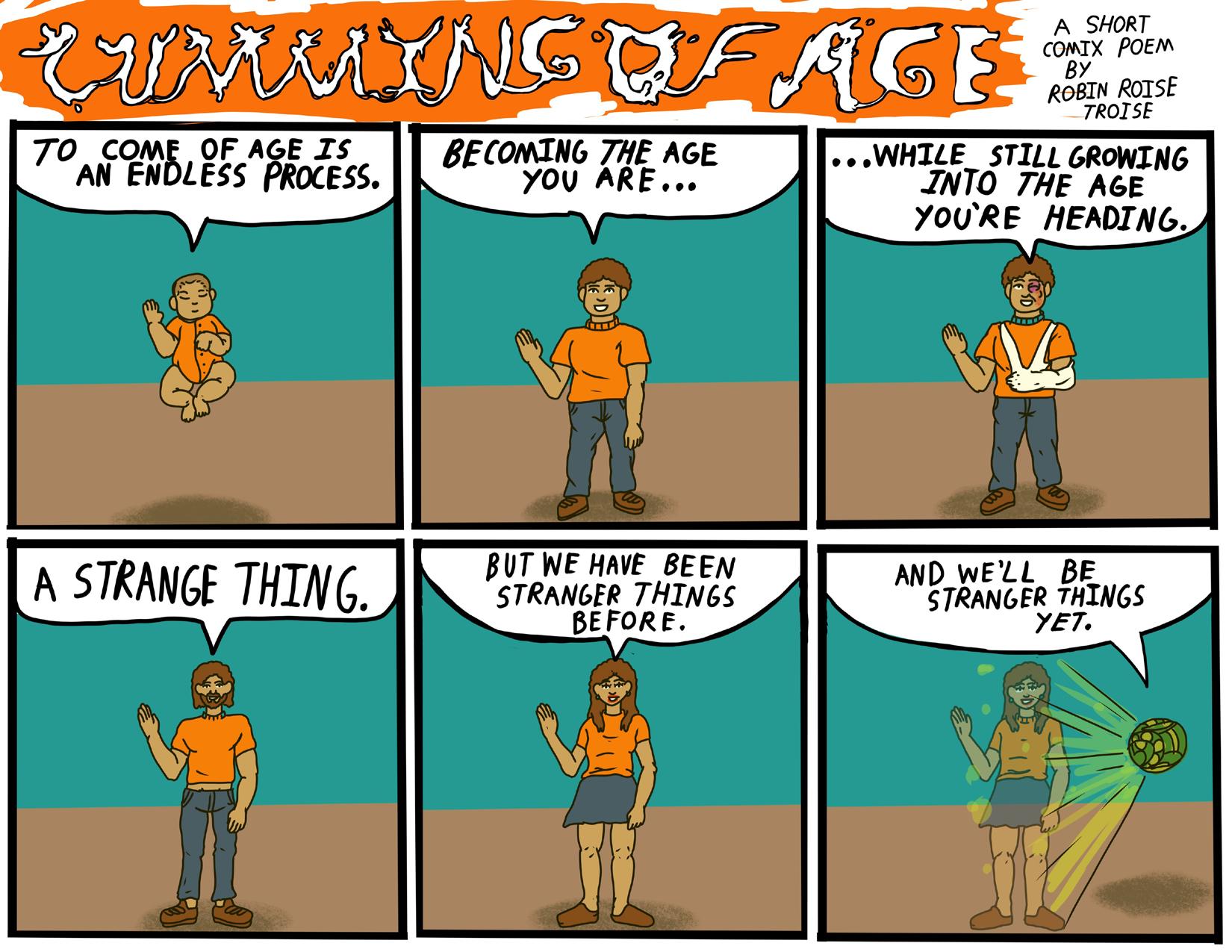

Catie KoblandYour Age Now

If I was your age now, why I’d kiss a boy like you

Like me?

Yep, like you, if your chocolate eyes invite me to.

I’d kiss your supple lips Sweet caress with fingertips Why, If I were your age now, all the things that I would do.

Well, what more then? Tell me more!

If I was your age now, I would murder in a dress

And once the pigs are summoned greet them sweetly to confess But of course they’d never take me with my lashes long and low For I’d quickly then convince them to pretermit what they know.

And how?

And how!

No, but how?

Don’t you know? All dishonest men are privy to the selves they never show!

Oh, I do know.

I thought so. We all know!

Gay Hero

I wonder if I could be a gay hero. If Americans, young and old, Could ever look up to me As the pillar of aspiration. I get out of my car, On the side of the street of my simplicity, And they look on with wonder, And try to capture my essence But settle for just my image. My walk is a style, My hair a trend;

Shirtless pictures cover the fronts of magazines, With headlines of praise and gratitude. No one knows exactly what I did, But everyone agrees it was enough. I wonder, does it matter, and could I? Look up to myself—I mean.

Not My Face

I look into the mirror... and I see you not me that face will never be me no matter how hard I try the gaze of another stuns and I have to look away

As long as there are mirrors I will never be free from that face that stares back at me

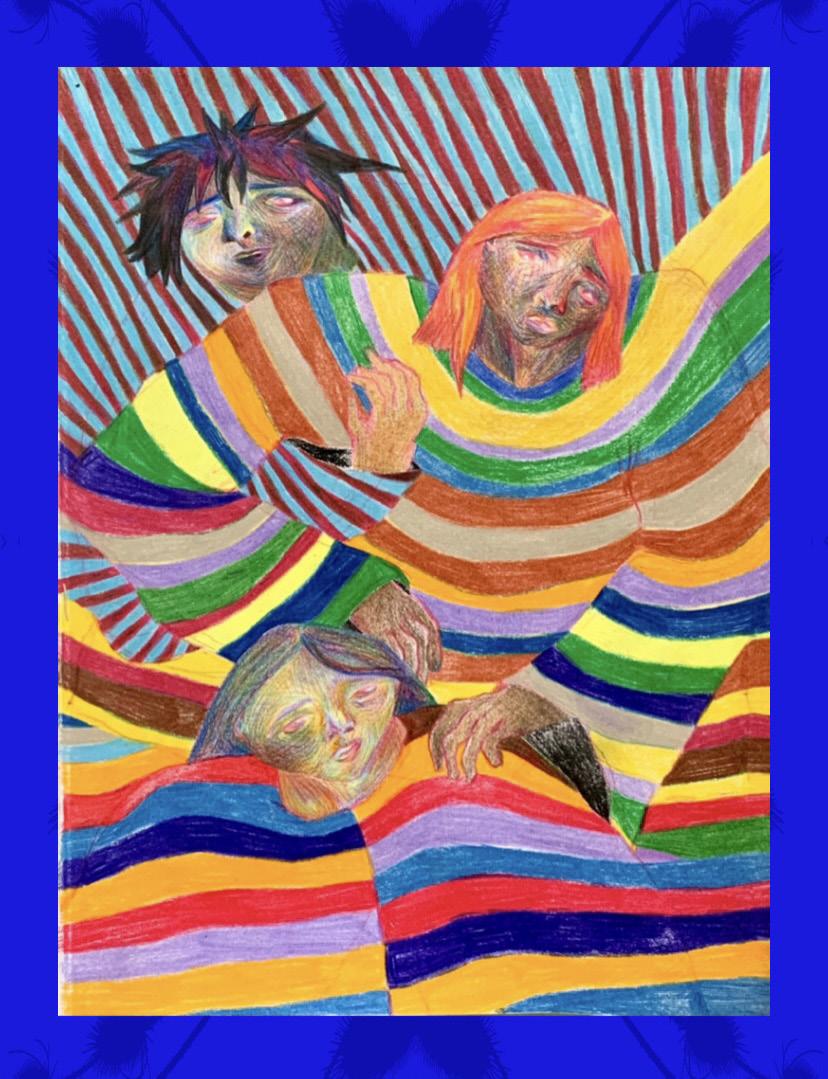

Identity See Supportive Community

I Seek And Have Found

Jrenby / IG: @rabenfedercraft (top)

Alex Low (bottom)

Jrenby / IG: @rabenfedercraft

Jrenby / IG: @rabenfedercraft

Fake Friends Interview: Reality in the American Theatre

Amaal Saifudeen and Isaiah Brooks conduct an interview with two of the founding members of Fake Friends, Michael Breslin and Patrick Foley. Fake Friends- the Pulitzer Prize Finalist in Drama is a theatre company based in Brooklyn known for their striking productions Circle Jerk, This American Wife. Michael and Patrick sit down with GrassRoots and discuss art, Ratatouille the Tik-Tok Musical, Queer Coming of Age, and everything else in between. Breslin is in the final stretch of completing their Phd studies. Meanwhile, Foley concluded a successful run of Thomas Bradshaw’s The Seagull/ Woodstock NY by The New Group– starring opposite the most delightful doll: Hari Nef.

Amaal: We wanted to ask you about your beginnings as collaborators together! How did you two find each other?

Patrick: Do you wanna do it Michael, or should I?

Michael: You start and then I’ll sort of like, potpourri it with character.

Patrick: So Michael and I both met at an institution that was formally called the Y*l* School of Dr*m*. We were backstage at a friend’s play that we were both working on and we were talking… We realized that we both had these twin obsessions, which was like the downtown theater scene of the early aughts and um, Real Housewives.

Michael: The early aughts?

Patrick: Wasn’t… wouldn’t you say–

Michael: Like– I feel like our obsessions were more 1970s.

Patrick: I mean–

Michael: I think it was 1970s through the early aughts. Maybe we can meet in the middle.

Patrick: Like, 1970s filtered through early aughts– our understanding of the 1970s at least.

Amaal: And what specifically from the 1970s was the draw for you?

Michael: Well, okay, so to get real I think we were interested in the lineage of like, queer theater from Charles Ludlam and all of his collaborators– he worked with Andy Warhol– and then the performance artists that were also coming out of that same era or responding to that era. Patrick studied with Karen Finley– who obviously is still alive and working– but they come out of that lineage.

And we were interested in these artists who use their own autobiographies in different ways in performance. So either to like–create a confessional text or to create a completely scripted play. But always sort of using the self in that way.

Amaal: And what did you see that was missing from the American theatre that made you feel that these seventies theatre influences needed to come back?

Patrick: I think when we met, the specific context is really relevant. We met in school and there was a dominant taste of that institution that veered more towards the well-made play and how that wellmade play can be sort of reinterpreted naturalistically for the 21st century. I think Michael and I were sort of hungry for a different, queer, more complex lens on the human experience. So our first show that we made was This American Wife, which was kind of a mashup of the influences that Michael is talking about– particularly, the kind of solo performers like Karen Finley– a mashup of those sensibilities with the world of reality television. That play came out of a desire to create a hyper queer space in this institution that we felt paid lip service to queer art, but didn’t actually let that art influence the curriculum.

Michael: Yeah, I think like MFA programs in general and BFA programs and the hyper professionalization of the industry, like, we are a hundred percent products of that. So it’s not like we’re saying like, oh, it sucks. We went through the programs, so like we’re not above it, but it’s– it’s interesting

to see how the institutionalization of theater training has impacted, like, the kinds of plays that are coming out of professional theaters in the United States. Certain methods are taught and valued in those schools and an interdisciplinary approach is like, not really one that was like part of the Yale curriculum.

So the idea of an actor and a dramaturg making a show together was actually, um, really confusing to most people at school. And the first time that we performed it, people didn’t quite know what to make of it. Which was interesting.

IB: Patrick, how do you view the modernization of queer art in relation to both queer culture and cancel culture? How much of the media do you think is facilitated by queer audiences and aesthetics?

Patrick: Where my mind immediately goes is to… One of the first seeds for making our show Circle Jerk was this article about queer Republicans, um, in the New York Times.

And this lineage of queer performance being entwined with a kind of outre, avant-garde, boundary pushing, almost aggression. Sort of asking like, “What is happening in dominant society? It does not reflect me and so I’m gonna almost push past it.” There’s a politician in this Times article who basically says that the lineage of queer transgression can only really be found on the alt-right because so much of modern society sort of claims to have embraced queer culture. So that kind of transgressive behavior is kind of more difficult within, um, within “normal” institutions. So, uh, anyway, a major inquiry of, or a jumping off point, for Circle Jerk was just asking if, you know, gay people can still be transgressive without being on the alt-right.

. Michael: Yeah, I mean, I think the history of queer theater from the late sixties through the present, like, has always been in conversation with a quotational style or a referential style– using pop culture texts as found text in constructing both narrative driven plays and monologues or performance. What’s really interesting to us

and what we found in creating Circle Jerk together and with our company was that some of those early ridiculous plays almost read like a string of memes or a TikTok feed in the way that the internet functions on the appropriation of everything.

Like, like TikTok specifically is like an app that is mostly functioning on appropriation of sounds, memes, dances, et cetera. So I think there’s an interesting intersection there too, in addition to what Patrick is saying about sort of offending normative culture. I think there’s also this thing of citation and quoting that is a part of gay culture broadly, but it’s definitely a part of the internet too.

IB: How do all of the influences that you recognize– whether it be from childhood/ growing up or within your disciplinary studies as a theater artist– influence what “queer coming of age” means to you?

Michael: It’s such an interesting question and it’s an interesting framework– this idea of coming of age. I was recommended this book on queer childhood and it has been making me think about how there is no single coming of age moment in our lives.

I think something that we need as artists–as queer artists– is a total commitment to not being grown up and sort of having a childlike mind in order to access the creativity and the ability to create new, strange forms of things I associate with childlike freedom.

Patrick: I mean, it’s such a funny coming of age. Makes me think of like.. middle school and adolescence. Like, we’re working on a project right now about that age group and as a part of the process of working on that show I hacked into my live journal from that time period– which still exists– and, and it’s like spooky, you know? It is all at once affirming and scary to see the seeds of who I am now way back there and see questions that I have now… also there.

And, and so then I sort of wonder, “Is there really an arc there? Or, or am I still… at the same intellectual level as I was when I was 13.” Who’s to say?

Michael: Patrick was reading The New Yorker at age 11, as evidenced by this live journal.

Patrick: I did get my parents to get me a subscription to the New Yorker, I think, because I was just like, “I wanna move to New York and it’s in the title of this magazine.” But I didn’t really read it. I just sort of read the film reviews. But all to say, like, there’s something inherent in adolescence, at least in my experience, you know, there’s something to that experience, which is like– the trying on of different identities? Locating yourself in different stories, in a kind of like rapid fire way, as a means by which to figure out, “Who am I?” and, “How did these things resonate to me?”

And I think there’s something to the, um, fluidity of identity in that age group, in that time period, that feels exciting and also sort of mirrors the creative process, right? Like we inoculate ourselves with these worlds when we’re working on these shows and then we move to something else. So I think there’s something about that, I don’t know what the word is, but that kind of like freedom and that looseness with identity that feels sort of daring in this day and age. And I don’t mean that in an incredibly explicitly political way, but I do think so many of us are in creative fields to try to expand our experience of the world and to do that in a moment in time where we’re all sort of hyper-labeled is such an interesting task.

Michael: Yeah. It’s like this horrible, horrible tension of being alive right now is that, you know, as a queer person or as anyone: is that on one hand there is this horrible system of having to label yourself at every minute of your life according to a set of, like, neoliberal identity markers. But then there’s also the horrible lived reality of trans people and queer children, across the country, suffering like horrendous laws and religious persecution like, like horrible shit. So it’s like both of those things at the same time, I think it puts the contemporary, queer consciousness in this really crazy state of conflict. Because you’re like, “I want to be more than just my identity.” But I also see that just the basic fact of many people’s

identity in different states or different regions is literally a question of life and death. So it’s like: where do you fall in that?

Amaal: Yeah, totally. I think with what you’ve just talked about, a lot of younger queer people are finding their queer coming of age and this community fully online. It’s also a weird balance of there being so many dangers to it. As quickly as you can find a community online is as quick as someone else can be to ruin your day.

IB:This segways into my next question regarding the relationship between queer folk and reality TV. Our [queer] people have actively supported the cultures within unscripted television for years, especially meeting in such spaces as online forums. Patrick, what do you think the reason is?

Patrick: (laughs) Um, well, I mean, we’re two queer people who are obsessed with reality TV. I think that what is so exciting to me about unscripted content and reality TV is that I feel that it asks me as a viewer to be a more active listener and a more analytical engaged viewer because there is no suspension of disbelief. And in actuality I’m watching to see where the seams of performance and production and artifice are. At least that’s how I feel with The Real Housewives. And I feel there’s a clear straight line that is drawn between that kind of active viewing and the kind of hyper vigilance that most queer people of any identity sort of have. To grow up cultivating–to either move themselves to become more like the dominant culture or to sort of seek out community in spaces like this. It is this kind of like, “What’s happening here? What drag are you wearing?”

Michael: I was just listening to this podcast the other day about Tila Tequila and her trajectory from like MySpace star, to reality star, to this far right white supremacist, queen of the AltRight girl. Um, which is just weird that we haven’t sort of… actually Patrick, we need to get the life rights of Tila Tequila.

Patrick: She was like the “first bisexual person on television.” (Patrick used air quotes here.)

Michael: Yes. She was like– it was like this huge thing. Her show was a dating show–like a gay dating show– cuz there were like half men contestants and half women. And then she would sort of like… figure out which one she liked better! Anyway– I think we just have to say her name here because it’s really important that Tila Tequila gets spoken into the archive. But I also think that reality television– like, I think Patrick and I are always interested in conflict and in paradox. And I think as much as reality TV can be liberatory for many queer viewers and past members like Brandi Glanville on Real Housewives as a queer woman… I think it also– especially the Housewives–participates in a much longer lineage of, like, misogyny and the fetishization of hyper-feminine rich white women. And I think for a different community– like, rich black women with Atlanta and Potomac, et cetera. But from my standpoint, it’s like this fetishization of the beautiful white blonde woman from the standpoint of the gay male.

And I think our show, This American Wife, tries to get at that conflict that it’s not just liberatory and it’s not just horrible like it’s… it just is many things at the same time. And like, the gay projection onto the cis woman is an interesting phenomenon.

Michael: And that, that all began with Tila Tequila.

IB: You both have experience investigating the hybrid of live and virtual performance. I guess we all have been forced to acknowledge and adapt to diverse presentations of what “theatre” is and can be. What are some of the silver linings of developing work in a virtual space?

Michael: I think it’s… yeah, we’re at this interesting point now where like– we don’t know if we’ll continue to do exactly the same thing that we’ve done– but we’re looking for different versions of, of representing the internet in different forms like TV and theatre and like: what new modes can we discover? We never wanna find ourselves doing a project that’s like a different version of something we’ve already done.

Patrick: Yeah. And to sort of bring it back

to the beginning of the conversation: our work together has always included cameras and projections and screens. Michael and I, we had our sort of seventies/earliest aughts bit at the beginning of the show, but that kind of lineage of the Wooster Group in the seventies working with screens and projectors through like… there was a group called Radio Hole that I saw in like 2010 that was calling cues from iPhones strapped to their wrists. There’s a lineage of incorporating technology in kind of homespun ways in those theatre circles. To, you know, draw attention to the alienation of the human experience or what have you. So that lineage of operating within screened, projected technology is one that we see our work as hopefully being a part of. And in, in 2018 with everything.. 2019? Jesus, my years, why am I, why am I putting everything in 2018?

Michael: Because time is festive.

Patrick: Thank you.

Michael: It’s horizontal.

Patrick: But, with the pandemic we sort of were like– you know, Circle Jerk had been developed pre-pandemic and a lot of what wound up being in the show, even design-wise had already been decided on pre-pandemic with David Bengali, our video designer. And so it felt like an intuitive leap to bring Circle Jerk into a live streamed format.

And then that format enabled us to do even more experiments with our show This American Wife– which was live streamed from a McMansion in Great Neck, Long Island. Um, and then we worked on this show called Ratatouille, which was less of a live stream and more of just an uploaded video.

Isaiah & Amaal: (applauding)

Patrick: Thank you.

Michael: Um, yeah. Yeah. You know, we can talk about the queerness of that rat.

Patrick: Just so you know, there was, um, there’s a much more explicit, there was a

much more explicitly queer script that was edited.

Michael: Wait, really?

Patrick: Mike. You don’t remember this? I don’t wanna, I don’t wanna say anything that could get us in trouble-

Michael: With D*sn*y?

Patrick: With D*sn*y or with someone else. But that script as delivered to the director and performer was much queerer than the one that we got a video of.

Michael: The rat was meant to be much gayer, let’s just say that.

Patrick: And let’s just say that queer erasure is not always at the hands of straight people. Okay.

Michael: Exactly.

Patrick: Representation matters until it doesn’t.

Michael: (laughs) Well, there’s only so far it can go.

But the amazing thing about the internet is like– literally we wouldn’t be having this conversation with you. We found a whole new audience of people to respond to our work and to be in community with and that would never have happened if we were just in like… a theater with 60 seats and did, you know, 25 shows or whatever we were gonna do.

So that’s the really interesting thing to continue to explore. Like, our upcoming show that we’re working on now and we’re doing a workshop of is a fully musicalbased project with original songs. And it’s like– the video streaming online is probably not gonna be a part of it– but the music and digital music and online music might be a new way to have the work be online, even if it’s not like the show itself. So it’s like all the different ways that theatre can live in a digital space that we’re interested in.

IB: Absolutely, absolutely excited… I’m still thinking about, sorry, I’m still thinking about

the rat. Honestly…

Michael: Just think about it all! He’s obsessed with those hats.

IB: Now that you said it, I’m literally thinking about like...

Michael: He likes to pull that guy’s hair.

Patrick: It’s dom-sub. It’s giving fem top fall.

Amaal: There’s a bit of humiliation kink in there too.

Michael: Yeah, and there’s something that I had never heard of until grad school with–there’s definitely like a trans species thing going on.

Amaal: Yeah. Oh, a hundred percent.

Michael: I didn’t know that animal studies was like a very large, um, area of critical thought, but it is.

Amaal: Yeah. I think he’s like– rat is a trans man in the way that he’s a rat and wants to be a man.

Michael: Thank you. Thank you for saying that.

Amaal: Like– that’s like one plus one in my head.

Michael: Have you read the Jack Halberstam book The Queer Art of Failure?

Amaal: No.

Michael: Oh my God. You guys have to read it. You’ll love it. But he does all these close readings of like, Chicken Run and other animated films. You should read it.

Amaal: Yeah, definitely. I mean, getting into this conversation today, I was thinking about like, The Babadook, and how that became a thing for a hot second too– and there’s just been like so many weird phases of the internet just picking an amorphous thing and being like, you’re, you’re actually one of us.

Michael: Yeah. You’re a king now. Yeah.

Patrick: When Circle Jerk first came out, so much of the response to it was like, about how “hyper referential” it is, which Michael and I, you know... it’s intentional. In my experience at least, that’s just how queer people talk! In these meme-like quips of references constantly. And I mean that’s how Michael and I are, that’s how our friend Jakeem and I are– we have a quasi impulsive thing where we say “Portugal!” all the time when we’re with each other because it’s a reference to, like, a vacation clip from The Real Housewives of Potomac.

You know there’s something about this, like, compulsive referencing of queer culture that speaks to– to bring it back to adolescence–to that adolescent feeling of not belonging, of not having community, of not having understanding with people. And so now that we’re, like, in our thirties and we have the internet and we have this abundance–

Michael: (shushing patrick)

Patrick:I know. Sorry. Oh, reveal. We’re in our th*rt**s.

Michael: No, we’re not.

Patrick: We can’t go into that right now because... yeah. But anyways… Anyway, It’s almost this thing that’s like, when I’m with other queer people where I’m like, “Oh, like what about that? What about that? What about that?,” and it’s like creating an abundant, an overabundant, feeling of belonging with this shared language.

Michael: I think the fundamental thing about quotation or reference or whatever– is like an obscuring of reality or originality. So like, by quoting something at someone, you are like, repurposing another thing that was original at some point.

And that’s when straight people start to flip out cause they’re like, “Wait, like are you being real? Are you being– I can’t tell if you’re being serious or not.” And it’s like–that sounds like a you problem. Because I honestly dunno the answer to that question.

Amaal: That was the thing that was so

wonderful to watch about both of those pieces and specifically Circle Jerk– I’d never seen queer theater that engaged with our language that way and like… I don’t wanna read a play about a gay person dying for the millionth time in a row. I don’t know…Like to see something that SO isn’t for straight people to watch.

Michael: Someone said to me a few years ago that like, Circle Jerk is a play about being gay. But This American Wife is like, from the standpoint of gayness. Cause it’s like actually, in many ways, way more twisted and humiliating. I love both of our babies, but those are just the difference between them.

Amaal: Yeah. That’s so, so visible in both of those pieces. So really to like, bring it all together. We just wanted to ask what brings you joy both right now and what’s sort of always brought you specifically queer joy.

Patrick: Do you have something, Michael?

Michael: Um, my answer is I’ve become obsessed with going to the opera, which I guess is a very queer thing that I’ve just never fully been embedded in, though I did go when I was like five years old to Hansel and Gretel at the Met Opera, but like I didn’t really come back to it until recently and I’m very, very obsessed.

I think it’s so beautiful and it feels like so much more fun than theatre to like, go to the opera cause the seats are nicer, people are dressed up, and it’s actually a very queer, expansive space– like you can dress however you want. You’re actually encouraged to dress sort of fabulously. So, um, the opera and then also Vanderpump Rules is really bringing me a lot of queer joy.

Patrick Um, I really like watching– this is not new– but I really like watching home tours on YouTube of luxury homes. And um, you know, I think I sort of– in my brain– sort of pretend that I’m like a wealthy white woman who is like “Oh, I have this much to spend, or I have this much to spend.” I have nothing to spend.

And there’s like one couple from England

who does these– they’re real estate agents– and they do these home tours together where one is holding the camera and one is speaking for the first half and then they switch. But the one behind the camera talks back to the one giving the tour in a way that is… incredibly sexual. Not explicitly sexual, but the dynamic is like “Oh yeah, babe. That’s right. What about the window? Yeah, it’s a great window” and it, like, hits all my buttons, you know: it’s aesthetically pleasing and erotically charged and British. So that gives me a lot of joy.

Michael: That is so you.

Isaiah: Is that so Patrick?

Michael: That’s SO Patrick. It’s actually really sweet. Even though it’s like, so deranged.

Isaiah You have me with the tension– and British people definitely raise the bar for me– and like, luxury.

Thank you both so much for doing this interview. Hopefully we’ll run into each other again!

Amaal: It was so wonderful to see you both again. It means a lot to be able to talk to you more about the work that you’ve created.

Patrick Thank you!

Michael: Thank you, thank you, thank you. It was so fun.

Patrick: Thank you, and I’m on a new journey of trying to become a stoner, so if you have any resources for me… uh, yeah.

These Slurs Are Not Mine

I’m afraid to say

tranny -- because

I don’t know if I am one. Do I count am I

faggot -- enough

Who can tell me that which someone might-- know In three years I’ll have wondered if I’m faking it longer than I ever Knew

strawberry wedding cake pickleback shot that I am a girl

who likes boys. But that word just above me feels like dead squirrel tail corroding in my maybe throat. /tranny --/

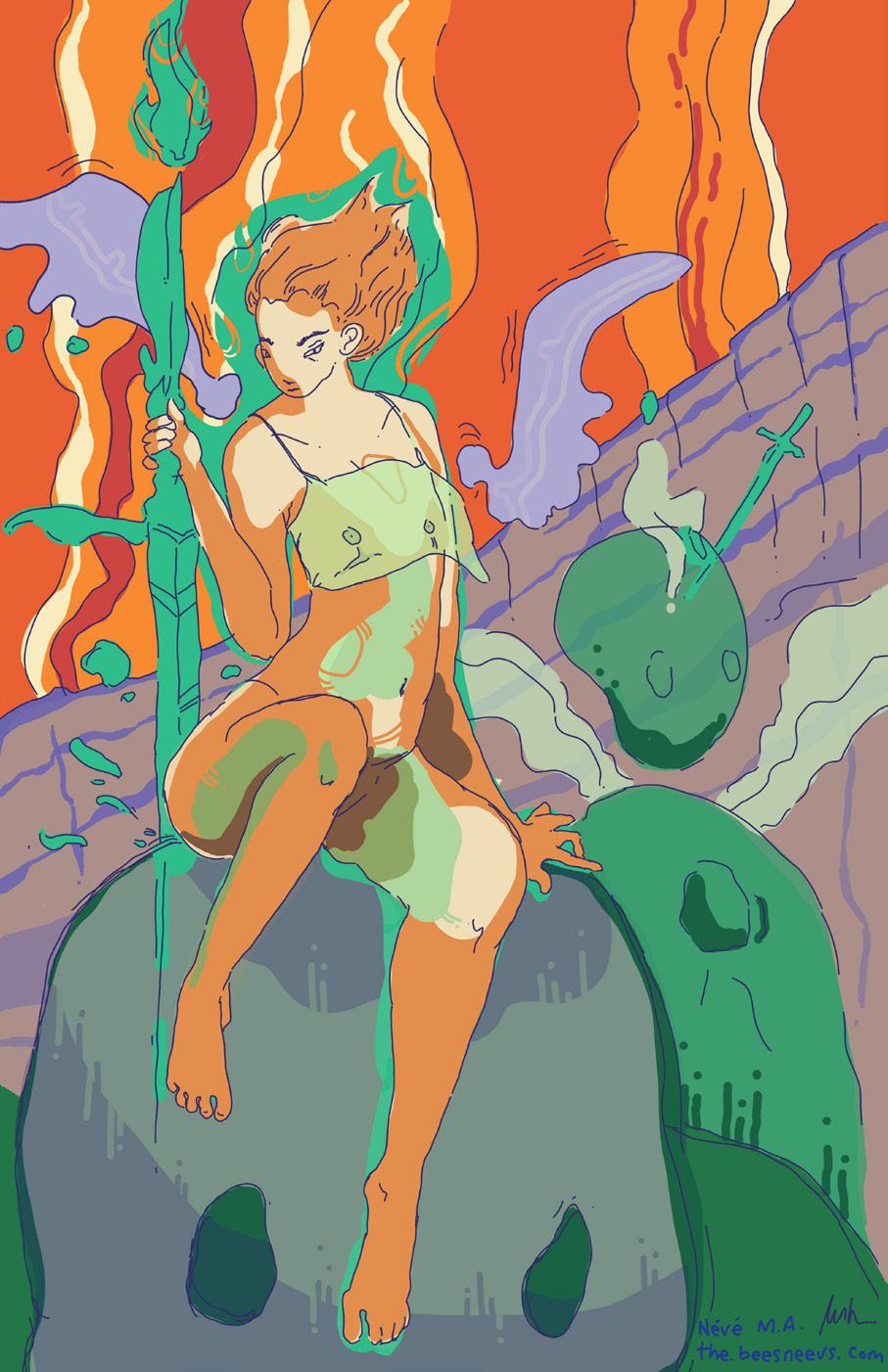

Neve Monroe-Anderson / twitter: @neevspoilsbees, website: the.beesneevs.com (top) Elian JRF Wiseblatt

one last thing

I had a dream last night that you kissed me full on the mouth. we were in a room with pink wallpaper, a room where everybody gets what they want. I was someone other than myself, someone stronger, a girl with a gun in a briefcase. you, on the other hand, were exactly yourself. your hair was grown out just the way I like it. you touched the soft place behind my ear where I like to be kissed.

I’m afraid to stop running, I spoke into your hand, a secret.

you don’t have to stop, you said, you just have to change direction. there was water pouring through the cracks in the doorway, Titanic-style. there wasn’t much time. why did this take so long? I asked you, and the water was pooling at my ankles. the same reason the end of the world is taking so long, you said. we’re all afraid to collapse ourselves and become something new.

gasoline.

skirting around potholes, screaming along with Janis our voices meld into cacophony. staring at the quarry dead in the eye, you joust with every bit of horsepower, wondering if it will jolt me.

what we’d give to give our time to strangers. to disappear into the mirrored minds of others, disco ball, perceptions & sticky shoes before running.

“Feelin’ good was good enough for me” tangled limbs, sitting on jackets in the cool wet ground just to be around each other, of tripping on curbsides, hangnails, back porch sacred, rotted temple. worrying if we smell like smoke.

time being wasted by a guy explaining something I already know but am too polite to interrupt. let them have their moments. tamp down, remember the sweet taste of cups to lips to hips shaking in the dingy tiled kitchen.

my colored glasses cut me when I realize how I didn’t realize back then. hands you held, faces you scream in as we ran through library halls, leaping over cellophane walls, thudding chests, coughing, bleary. it’s all bleary, it’s not even the truth, is it? but it felt good, good enough. & so it happened. & so it goes.

these days

no, i never wrote about the joy but these days i can’t help it. these days

i catch myself dancing when i picture your face and i savor the taste when i say your name and yes, these days i smile. no, i never knew softness but these days i melt into a stillness, a warmth that smells like you and

no, i never knew wonder, magic, or faith but these days it’s safe to believe in something because these days i’m held. and no, i never made love and these days it floats, it’s unencumbered by every other thing and you feel like god and we feel like us and

yes, these days i laugh at selves of youth in days of old who never thought it possible to be beautiful and happy at once. and yes, i found my finally and yes, these days i’m home.