Dairy Grist

Dear Friends,

Spring greetings to dairy producers across the Prairies and in the West. We trust that crops are in, forages are growing well and milk production is high. We do pray for our friends in Alberta where a smaller snow pack and lack of rain is resulting in early and substantial forest fires. We pray for rain to quell the fires and allow for high yield and high quality crops and forages.

We are pleased to provide you with this quarter’s Dairy Grist that includes two great articles by Jeff Keunen, Ruminant Nutritionist and Stephanie Murphy, Dairy Specialist, surrounding early calve nutrition. In study after study, regardless of the species, neonate and early life nutrition has been shown to impact the lifetime performance of the animal. This is why colostrum volume and quality and early dry matter intake for calves is so important. We hope that the two related articles will provide you with some insights, tips and tricks to further improve the growth and development of your future lactating herd.

It seems that no matter where milk, meat and eggs are produced in the world, there are growing challenges with animal diseases that have significant impacts on herd health and productivity. Whether ASF, PED or Strep Zoo in swine, High path AI in poultry, or foot and mouth in numerous species, including ruminants as well as Mannheimia haemolytica, producers of all types will need to continue to work closely with their veterinarians on prevention with vaccine protocols as well as both traditional and novel treatments. We are pleased to provide an article by guest writer, Robyn Elgie DVM, who discusses the details surrounding this emerging form of pneumonia. Additionally, producers will need to consider heightening bio-security and hygiene protocols in their operations while taking a very good “second look” at the cleanliness and quality of the water they provide their animals each day. Animals consume 2-3x the amount of water that they do feedstuffs but water is often the most overlooked nutrient. With the recent addition of six water and hygiene experts at Farmers Depot, across Canada, consider having one of them visit your operation to see how they can assist in improving herd health, performance and feed efficiency together with your dairy feed specialist.

Sincerely,

Ian Ross, President & CEO, GVF group of companies

PNEUMONIA IN DAIRY COWS: WHAT IS OLD IS NEW AGAIN

by: ROBYN ELGIE, DVM Kirkton Veterinary ClinicOver the past few years, there is a growing incidence of severe pneumonia outbreaks in dairy herds across Ontario and other parts of Canada. From a veterinarian’s perspective, the most troubling aspect of these outbreaks has been the speed and unpredictability with which it begins. During these sudden outbreaks it is possible to lose up to 5% of the herd and have 30% or more of the animals treated, all within the span of 1 week. Surprisingly, the implicating pathogen found in these herd outbreaks is not new. In fact, it can be found in almost all healthy cattle and is a well-known pathogen associated with pneumonia in feedlot cattle (1). The pathogen is known as Mannheimia haemolytica

Over the past three years, our practice has encountered 10 presumed and 7 confirmed cases of Mannheimia haemolytica herd outbreaks. This article is based on the collective clinical experiences of our veterinarians as well as discussions with veterinarians from other parts of Ontario and Canada.

What is Mannheimia haemolytica?

Mannheimia haemolytica is a bacterial pathogen that can be found in the nasal passages and larynx of clinically health cattle. Mannheimia,

along with a few other bacterial pathogens, commonly live in the upper respiratory tract in low numbers. However, once a stressful event occurs it is able to rapidly reproduce into a large population and travel to the lower part of the respiratory tract (1). In the lungs, Mannheimia bacteria release a substance called leukotoxin which is designed to kill white blood cells (2). Under normal conditions white blood cells are able to consume and destroy bacterial cells like Mannheimia. When Mannheimia increases in number suddenly, the leukotoxin it releases can quickly eliminate the white blood cell supply, overwhelming the immune system (2). Once this occurs, Mannheimia bacteria can cause severe irreversible lung damage. Mannheimia haemolytica is one of the main bacterial pathogens in the Bovine Respiratory disease complex which is commonly associated with calves shortly after transport and arrival to a feedlot. Until recently, Mannheimia has not been associated as a common cause of pneumonia in dairy cattle.

There are 4 things that make Mannheimia 1960 “outbreaks” in particularly devastating in dairy herds:

1. The apparent unpredictability of when an outbreak will occur.

2. The high number of affected animals within the herd.

3. The speed at which the animals become clinically sick and die.

4. Affected animals do not always look like a cow with pneumonia.

Risk Factors

Our clinic gathered farm level treatment records and Dairy Comp

herd level data from 3 herds that had recent outbreaks of Mannheimia haemolytica within a 21-day period of one another. While outbreaks do appear to be unpredictable and likely multi-factorial (3), there were some commonalities among these herds that may be considered risk factors.

1) Vaccine Protocol and Compliance

Classically, Mannheimia haemolytica is an opportunistic pathogen that will increase in number soon after a stressful event such as viral pneumonia (1). A well designed and executed modified-live vaccine (MLV) protocol can reduce the risk of viral pneumonia and abortion. In dairy herds this has been the main focus of vaccine programs. Until recently, Mannheimia haemolytica pneumonia was not identified as a major pathogen in Ontario dairy herds. As a result, most veterinarians recommended viral only vaccines. The theory was prevention of viral pneumonia would reduce the risk of a less likely bacterial pneumonia outbreak.

The effectiveness of a well-designed vaccine program is limited by compliance to the protocol. To achieve adequate protection using a 5-way Modified-Live vaccine, every animal needs to receive a proper primary series as a calf/heifer and a booster dose every 12 months after the primary series is completed. There are killed vaccines available that will provide immunity for the same viruses however they require more frequent booster doses.

Protocol compliance is dependent on accuracy. Every time an animal receives a dose there are 4 areas where error can occur. The correct cow, the correct product at the correct dose and the correct timing of administration are all variables where compliance can suffer. For example, a cow is bred and confirmed pregnant late in lactation so her calving interval will be greater than 12 months. This means the recommended time between her previous dose and the next dose of vaccine will exceed 12 months. Therefore, her previous dose may not be effective and theoretically she would need a primary series again to be 100% protected.

It is also important to note that vaccine handling, storage and proper administration route are also very important factors to achieve effective protection.

2) Ventilation

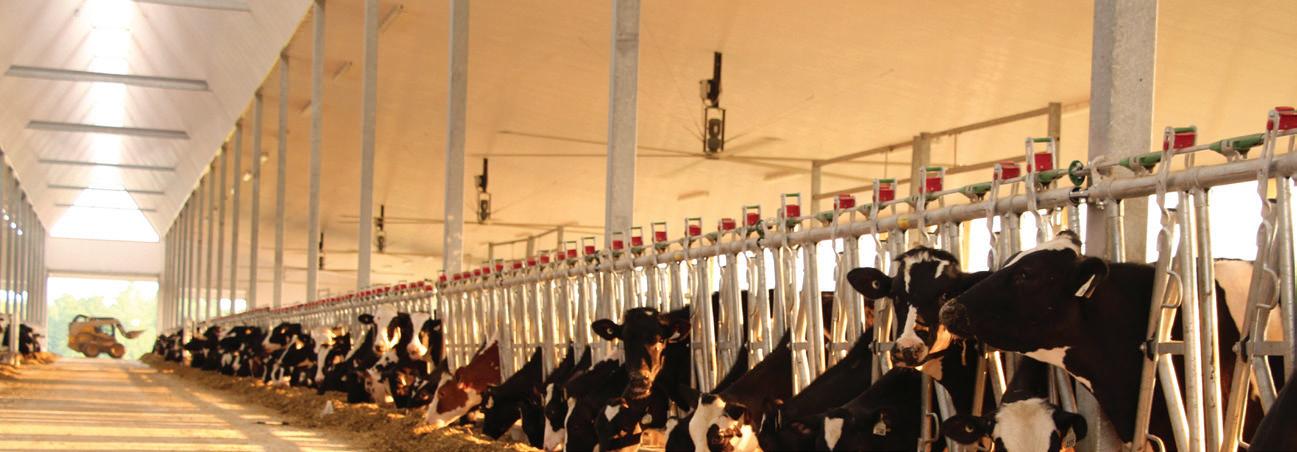

In lactating animals, we often think of ventilation primarily as cow cooling. However, ventilation is actually defined as bringing fresh air in and removing stale air at an adequate rate. Naturally ventilated barns are designed to achieve 4 air exchanges an hour during the winter when the side curtains are almost closed. This is achieved by the differences in air temperature between the outside and inside air.

Natural ventilation does not work in the same way when the outside temperature is more moderate. During these times we rely on open curtains and fans to move air. When there is extreme humidity with low natural air movement, less fresh air will come into the barn. Therefore, the fans can only push or move stale air.

During warmer weather, the curtains may be raised to reduce sunlight into the barn leaving less space for stale air to exit and for fresh air to enter the building. The type of fan can also make a difference. High volume, low speed fans create “dead spots” of air between fans. This type of fan moves air in a multi-directional manner, therefore it does not move stale air away from the cows.

3) Herd Health Status (Closed or Open)

The risk of bringing in a novel disease is significantly increased if animals are brought in from multiple other sources or, from somewhere where they would have been exposed to animals from other herds. Even if the vaccine protocol is well designed and the compliance is excellent, there is still opportunity for novel diseases to enter the herd. Even diseases that cause only mild sickness can be enough of a stressor to trigger Mannheimia haemolytica proliferation (3)

Taking animals off farm and then re-entering is also a risk but can be controlled by isolation, quarantine and booster vaccination of those animals.

It is very important to point out that although the above 3 factors increase the risk of a Mannheimia haemolytica outbreak, limiting or controlling all three does not guarantee immunity from a Mannheimia outbreak. We hypothesize that the unpredictable nature of the outbreaks we have encountered is likely due to a “perfect storm” of factors that coincide to cause an abnormal physiologic stress on the herd.

These coinciding factors can be difficult to prove in retrospect. In many cases, a proportion of these inciting factors may be invisible to our observation but may include sudden feed and weather changes, bedding type, season or other herd level health stressors. We have also seen cases where the herd was struggling with pink eye or mild viral exposure such as coronavirus which can cause dysentery or mild respiratory infection which is often evidenced by tearing around the eyes.

With regards to seasonality, our clinic has experienced a herd outbreak in every season on the calendar. There is a tendency to see more cases during the classic pneumonia season of the fall, however, there have been clusters of herd outbreaks in the winter and summer months as well.

At the cow level, our practice has not seen a stage of lactation or lactation number represented more than another overall. There does appear to be an increased risk in high production herds. We have seen it in both lactating and dry cows, with lactating cows being the most common. Other clinics in Ontario have experienced higher representation in fresh cows.

Rarely are heifers younger than those found in the close up group affected. In multiple cases, groups of differing pregnancy status or lactation were housed within nose to nose contact of the pen experiencing an outbreak and did not demonstrate any clinical signs consistent with Mannheimia haemolytica. This demonstrates that Mannheimia haemolytica is not contagious from animal to animal but requires a stressor within the animal, or a group of animals, to trigger the disease process.

Prevention and Control

In Ontario dairy herds, many calf vaccine protocols have incorporated intranasal vaccines which include Mannheimia haemolytica however, it has not been common to include it in the vaccine protocols for the lactating herd. Fortunately, there are a number of options that include Mannheimia haemolytica as part of a combination or on its own in both injectable and intranasal forms. Our current clinic principle outlines each animal should receive at least 2 doses annually of a vaccine with Mannheimia haemolytica as one of the components. The selection of vaccine and timing of administration is herd specific depending on management and facilities as well as known risk factors. It is best to consult with your herd veterinarian to tailor the protocol to your herd.

What to do in the Face of an Outbreak

1)

Take Samples for Confirmation – Post Mortem animals that have died

In our experience, a farm will lose an animal unexpectedly proceeding the outbreak. This often occurs around 1 week before the majority of the cases appear. This does not mean that every animal that dies unexpectedly may be the beginning of an outbreak, but it is important to discuss with your herd veterinarian to determine whether a post mortem would be beneficial for any sudden deaths. Certainly, if morbidity and mortality have increased in adult animals in a short period of time this would be warranted.

2) Intranasal Vaccination

Due to the speed in which animals transition from clinically healthy to very sick, action needs to be taken immediately to reduce mortality and morbidity. This is almost always before results from the lab are available. Administration of intranasal vaccines in the affected group and any other groups that may be potentially affected are the most effective and quickest way to boost immunity in the face of an outbreak. Injectable options are also available but have a slower immune response. They can be used as an alternative when restraint for intranasal administration is

unsafe.

Herd level supportive measures can also include increasing the amount of chopped straw in the ration temporarily and bicarbonate freely available.

3) Treat Animals Immediately When Detected

Mannheimia haemolytica pneumonia often presents with very subtle clinical signs in the early stages. Producers who have experienced these outbreaks report a change in attitude is the first sign a cow will typically demonstrate. Clinically affected animals do not always have apparent increased expiratory effort or audible increase in lung sounds. Using tools like milk temperature, milk yield and rumination as well as walking the pens and observing the animals every 4-6 hours can help detect animals in the early stage of disease.

Mannheimia haemolytica progresses clinically very quickly. Antibiotics and anti-inflammatories can have successful cure rates but must be given early in the disease process to reduce morbidity and mortality. It is not uncommon to have up to a third of the affected group treated over the course of 1-2 weeks.

Depending on antibiotic selection and the number of animals treated within the lactating herd there should be clear communication with the client about the possibility of antibiotic residues and appropriate testing and withdrawals.

Take Home Messages

1. Mannheimia haemolytica is a normal upper respiratory bacterial inhabitant of cattle that can cause sudden and severe pneumonia.

2. An outbreak is often triggered by undetected stressful event(s) in a group of animals, up to one third of the herd can be affected.

3. Herd level intranasal vaccination as well as early detection and treatment of affected individuals will significantly reduce morbidity and mortality during an outbreak.

4. Reducing known risk factors as well as effective implementation of a regular vaccine protocol can considerably reduce the risk of an outbreak.

References

1. Radostits, O., Gay, C., Hinchcliff, K., Constable, P. (2007). Veterinary Medicine (10th Ed). Saunders Ltd.

2. Campbell, J. (2022). Merck Veterinary Manual. Merck & Co., Inc. Rahway, NJ, USA.

3. Caswell, J. and Gordon, J. (2020, November). Mannheimia in Dairy Cows, [Conference presentation] OABP Annual Fall Meeting Online Webinar.

Tony Bergsma

Jesse

One thing that we need to remember is that while whole milk/milk replacer is the biggest source of nutrition to the calf and the amount fed will primarily determine their growth rate until weaning. However, we also need to get them onto calf starter as soon as possible to develop the rumen. In the beginning, calves only receive liquid nutrients which bypass the reticulum and the rumen through the closed esophageal groove, sending the liquid nutrients to the omasum and abomasum where they are quickly digested. By feeding only liquid feeds we are not allowing for the growth of the rumen or the reticulum which is needed for when they start to consume forages. Therefore, it is very important that within the first week of a calf’s life we introduce dry feeds whether that be a prepared calf starter or an on farm calf TMR mix. The dry feeds are moving through the esophagus into the rumen where digestion begins and rumen papillae growth results from volatile fatty acids produced from the starch and sugars in the calf starter/TMR. Remember to always have clean fresh free choice water available to your calves. Research shows a 45% increase in calf starter consumption when water is available. Selecting the right species and implementing good agronomy practices are critical to successfully producing winter cereal forage.

We want to ensure the calf starter is of high quality, has no dust or mold and is palatable to the calves, anything less will decrease their intakes. Ideally, we want the calves to be consuming 1kg per day of calf starter by 8 weeks of age or approximately 3.5kg of TMR. It is important to keep the dry feed fresh, it should be a daily routine to give the leftover/old dry feed to the older calves and provide fresh dry feed to the young calves. If we were to stop the liquid nutrients before the rumen is completely developed the calves will not grow and may even lose body weight for a couple of weeks until the rumen has been developed. This is key as you want your calves to have a fully developed rumen to continue growing. Research shows that keeping calves on milk/milk replacers for 10 weeks provides better growth of the calf, and this would be recommended for all calves to achieve superior growth.

| MB

| AB

OUR ON-FARM HYGIENE SPECIALISTS have been trained to help support livestock producers in reaching hygiene and water sanitation goals that result in improved animal health and reduce the use of antibiotics.

CALF MANAGEMENT/GROWTH

AB

| AB

It is important to make sure that the amount of grain/TMR your calves are being fed is known. With the help of your nutritionist weigh how much grain/TMR each age group of calves is eating and ensure that it is adequate to reach their maximum growth potential. Consistency for calves is so important, consistent in amount being fed, time being fed, and quality of feeds for example.

While feed is very important to achieve adequate growth, the housing environment of the calf is just as much so. Keeping calves out of drafts and wet environments is important to maintain a healthy calf and prevent sickness. Calves should have a deep bed to be able to make a nest and stay warm. A good way to check if the bedding is dry is to do a knee test, simply kneel down for 20 seconds and if your knees are damp or cold, there needs to be more fresh bedding added. In group housing environments,

group calves according to size will allow for optimum growth and less competition at the feed bunk. If calves can be moved through the heifer program as a group to eliminate a stressor of introducing new calves to one another, that will help to keep them performing well.

In closing keeping the calf program consistent with high quality milk/ milk replacer, good quality dry feeds and a dry, draft free environment calves will perform well.

FACTORS AFFECTING COLOSTRUM YIELD

by: JEFF KEUNEN Ruminant Nutritionist, Grand Valley Fortifiers, Nutrition Direct

Every year in late fall and through the winter months we inevitably hear from a handful of producers concerned with low colostrum yields on their most recent cows that have calved. Reasons for low colostrum yields in cows has been poorly studied and on most farms the problem tends to resolve itself with some small tweaks to the dry cow ration. Recently, a study done by researchers at Cornell University in New York, attempted to summarize the environmental and nutritional factors that influence the quality and quantity of colostrum. We will summarize the key takeaways from that study below.

Monthly colostrum yields for the study are summarized in Figure 1. The median (range) colostrum yield was 4.1 (0.1-38.6) kg for primiparous and 5.0 kg (0.1-43.8) kg for multiparous cows. Average colostrum quality (Brix %) was 24.6 and 25.7 for primiparous and multiparous cows, respectively.

with Brix % (as mentioned above) with the lower colostrum levels having the higher Brix % across parities.

Heat & Humidity Index (THI 7 d before calving): Cows that calved in periods of more cold weather (THI <40.2 & THI 40.3-50.1) had lower levels of colostrum than cows that calved in more moderate temperatures (THI 50.2-60.0 & THI 60.1-69.2). Cows that calved with a THI higher than 69.2 gave the most colostrum. This would confirm the bias that we see lower levels of colostrum in our colder months.

Light Intensity: Cows with greater light intensity in the last 14 days of the dry period had higher volumes of colostrum compared to those animals with lower levels.

There are pen level factors that also affect the amount of colostrum yield. They are summarized below:

Starch (% of DM) : Diets with dietary starch levels in their close-up pens greater than 18.5% lead to cows giving more colostrum than diets lower in starch.

peNDF (% of DM): Diets with more physically effective NDF (peNDF) >27.1% lead to cows giving more colostrum than those diets with lower levels of peNDF (<27.0%).

Crude Protein (% of DM): Diets that were below 13.5% or greater than 15.5% had lower levels of colostrum when compared to diets that were between 13.5-15.5%. (peNDF) >27.1% lead to cow

DCAD (mEq/100g): Negative DCAD diets are commonly fed to mitigate the risk of milk fever in our fresh cows. The goal for most negative DCAD diets is to achieve a dietary DCAD of -10. In this study, diets that were higher in DCAD (> -8.0) had the most colostrum compared to diets that had achieved a more negative balance (-8.0 - ≤-16.0). ha

BHB ≥1.2 mmol/L (%): The study looked at the percentage of fresh cows that had a BHB measure of ≥1.2 mmol at 3-14 days after calving. Herds with > 10% of cows with a BHB reading ≥1.2 mmol had higher colostrum yields than those herds with < 10% of cows measuring higher BHB levels.

Figure 1. Box and whisker plot of monthly colostrum yield (kg) from 5,700 primiparous and 12,553 multiparous Holstein cows from 18 NY farms

When looking at the results of the study on an individual animal basis here are the factors that affect colostrum yield.

Brix %: Higher Brix % leads to a lower colostrum yield, suggesting a dilution effect as volume increases the amount of total IgGs stays the same, thus leading to a lower Brix % reading.

Calf Sex: Cows having females had lower colostrum volume than those with male calves, while cows having twins had the highest volume of colostrum.

Dry Period Length: Cows with shorter dry periods (<47 days(d)) had lowest amounts of colostrum, cows with more normal dry periods (47-67 d) were in the middle, while cows with longer dry periods (>67 d) had the highest yield.

Previous Lactation Milk Yield: Cows with more than 13,090 kg (305 ME) in the previous lactation had more colostrum at calving compared to those cows that were below this amount of milk.

Gestation Length: The shorter the gestation length the lower the colostrum yield, with cows carrying calf (283-293 d) giving more colostrum than cows with 274-282 d. Both groups yielded more than cows with a gestation length of less than 273 d.

Stillbirth: Cows with a calf born alive give more colostrum than cows with a stillborn calf.

Previous Lactation Length: Longer lactation length is associated with higher colostrum yields. Cows with a lactation longer than 344 d had higher amounts of colostrum than cows with a shorter lactation.

Parity: Cows in parity #2 had the highest volume of colostrum when compared to cows in 3+ parity. Of note, the volume of colostrum did link

As you can see, there are many factors that can influence the volume of colostrum in a given cow at a given time of year. Both colostrum yield and Brix % are associated with cow, farm management, nutritional and prepartum environmental factors. It is important to remember the volumes that are to be expected from your cows, as this study showed a median 4.05.0 kg on more than 18,000 cows. If you are experiencing a period of lower colostrum yields, assessing these nutritional and management factors on your farm, and making any necessary adjustments should help alleviate the issue.