11 minute read

October Monthly Luncheon Associate Professor Nicola Reavley

October 2020 Monthly Luncheon Review

Associate Professor Nicola Reavley

Advertisement

Associate Professor Nicola Reavley spoke on the topic of Mental Health Literacy and Stigma at our online October Monthly Luncheon on Wednesday, 7th October, held in Mental Illness Awareness Week and in the lead up to World Mental Health Day, 10th October 2020. Associate Professor Reavley is from the Centre for Mental Health at Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, The University of Melbourne. Associate Professor Reavley began her presentation by introducing herself as having grown up in the south of England, attending Bristol University and working in Belgium and Japan before visiting Australia in 1994 – a year with Paul Keating as Prime Minister (Bill Clinton was President of the United States), the West Coast Eagles winning the grand final, and the films The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert and Muriel’s Wedding being released. She loved Australia so much that she stayed. All her research career has been in this country. One of her first jobs was to write a book about vitamins and nutrition called Vitamins Etc: The Complete Guide to Vitamins and Minerals published by Bookman, Melbourne. She then went on to undertake a PhD in complementary medicine and cancer (working with the Gawler Institute established by cancer survivor, Ian Gawler) and entitled Evaluation of the effects of a psychosocial intervention on mood, coping and quality of life in cancer patients, before starting work at The University of Melbourne in 2007 and shifting her research focus more fully to mental health in 2009. The structure for the remainder of the presentation was around three statements which she put to the audience with True, False and Partly True response options: 1. Australians know a lot more about mental health than they did 25 years ago. 2. Stigma and discrimination towards people with mental health problems are much lower than they used to be. 3. Media reporting has an impact on attitudes to people with mental health problems.

Understanding of Mental Health

In addressing the first statement on the understanding by Australians of mental health, Associate Professor Reavley mentioned her research collaboration with Professor Tony Jorm who coined the term ‘Mental Health Literacy’ in a now-oft-cited 1997 publication (Jorm, A.F., Korten, A.E., Jacomb, P.A., Christensen, H., Rodgers, B. and Pollitt, P. “Mental health literacy”: a survey of the public’s ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Med J Aust; 166 (4):182), defining this term as ‘the knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders which aid their recognition, management or prevention’. Professor Jorm has also been instrumental in promoting the funding of mental health research through the Australian Rotary Health Fund.

Mental Health Literacy comprises the following domains:

• knowledge about how to prevent mental disorders; • knowledge of causes and risk factors; • recognition of when a disorder is developing; • knowledge of, and beliefs about, self-help strategies; • knowledge of, and beliefs about, help-seeking options and treatments; and • first aid skills to support others (Professor

Jorm and his wife Betty Kitchener AM having pioneered Mental Health First Aid programs). It is important to understand these domains when looking at treatment gaps in mental health. According to the World Health Organisation, 50 per cent of people with mental disorders in high income countries, like Australia, receive no treatment. In low to middle income countries, 85 per cent receive no treatment. These significant treatment gaps might relate to structural (e.g., availability of health services) and/or individual (e.g., knowledge and belief) factors. In the 1990s much funding and focus was being placed on health services and upskilling in, particularly, the primary health care sector. There was little understanding and focus on the individual factors. Professor Jorm thus undertook the first National Mental Health Literacy Survey in 1995 with questions on each of the above domains. Vignettes were provided for different mental health conditions as defined in DSMIV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition). One vignette, for example, was of John, a 30-year-old with clinical depression. Another was of Mary, a 24-yearold with psychosis in schizophrenia. Survey participants were asked: ‘What, if anything, do you think is wrong?’ The results in 1995 indicated that less than 40 per cent of the population correctly labelled John has having depression and that only about 25 per cent labelled Mary as having schizophrenia. In terms of the best source of help, just over 40 per cent suggested that John see a doctor while less than 30 per cent of the population suggested same (or to see a psychiatrist) for Mary. Given these and other results suggesting poor mental health literacy, the recommendations stemming from this research thus included the need to focus mental health literacy training on members of the general public, as well as on health professionals. These recommendations were thence translated into policy actions in the Fourth National Mental Health Plan. Supported by the Federal government and each Australian state and territory. Beyond Blue was also established. Though the initial focus of this not-for-profit in 2000 was on depression – raising awareness and reducing stigma – Beyond Blue has since added anxiety conditions (in 2011) and suicide prevention (not all suicides stemming from depression). With these significant investments, the question is thus ‘Have things changed?’ Associate Professor Reavley’s answer to that was a cautious ‘yes’. She pointed to a 2012 publication in the British Journal of Psychiatry (200(5):419-425) entitled Public recognition of mental disorders and beliefs about treatment: changes in Australia over 16 years with herself and Professor Jorm as authors; and explained that similar surveys to that in 1995 were repeated in 2003-4 and then in 2011 to determine whether recognition of mental disorders and beliefs about treatment had changed. Though the results showed improved recognition of depression and more positive ratings for a range of interventions, including help from mental health professionals and antidepressants, there was still potential for mental health literacy gains in the areas of recognition and treatment beliefs for mental disorders, particularly for schizophrenia. Associate Professor Reavley also gave an encouraging answer to the question of whether beliefs and knowledge translate into action; and pointed to further research demonstrating the mirroring of help seeking intentions with increases in service use; the parallels between greater mental health literacy and greater disclosure of experiences and of receiving treatment; the predictions of actions taken following expression of first aid intentions and beliefs; and the improvements to the quality of help given to a person at risk of suicide through mental health training.

Stigma and discrimination

In addressing the next major statement regarding stigma and discrimination towards people with mental health problems, Associate Professor

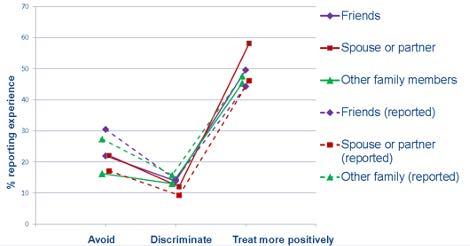

Reavley spoke to national surveys of stigmatising attitudes, using scales on ‘personal and perceived stigma’ and ‘desire for social distance’, undertaken in 2003-4 (household survey) and 2011 (CATI – computer-assisted telephone interviewing). The domains in the personal and perceived stigma scale include those that regard people with certain mental disorders as ‘dangerous’, ‘weaknot-sick’, ‘to be avoided’ and ‘for employment or to be voted for’. The ‘desire for social distance’ scale asks questions related to likelihood of social interactions with those who have mental disorders, such as how they would feel about living next door, being friends, working closely, marrying into the family, etc. The results demonstrated a ‘mixed bag’ of changes in stigmatising attitudes between 20034 and 2011. While there was very little change for the majority of domains, positively, a higher percentage of the population would be willing to work with someone who had depression, and regarded depression as a real illness. Though a higher percentage were willing to work with or have someone with schizophrenia marry into their family, there was a jump (10 per cent) in those who considered this condition as dangerous and a rise also in those who would not want to live next door to someone with schizophrenia. In summary, thus, there appeared to have been less progress in reducing stigma towards people with lower prevalence mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and psychosis (of other origin). A further national survey was undertaken in 2014 with the aim to capture both negative (avoidance, discrimination) and positive treatment experiences of those with and without mental illness (identified using a screening scale – the 12-month Kessler 6 scale – and questions about diagnoses). Questions on stigmatisation included those on whether friends/workmates/ relatives, etc. had avoided them or discriminated against them in other ways, as well as those on whether these same people treated them more positively because of these problems. There were also questions about what they had observed by way of stigmatisation or positive treatment in others with mental illness. An example of the results from this 2014 survey is shown in the following graph which suggests that positive treatment, both from the personally experienced and observed perspective, was more common than avoidance or discrimination by friends and family, and that the reported personal experiences mirrored the reported observations of how people with mental illness were treated.

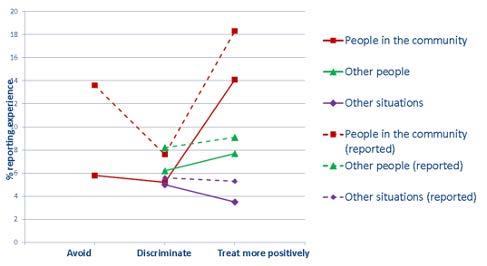

2014 Mental Health stigmatisation and discrimination survey results. Solid lines reflect personal, while dotted lines reflect observed, experiences. As shown in the following graphs, the results in workplace and education settings were similar. However, there were higher levels of discrimination and a lower percentage of positive treatments experienced and observed in these settings, particularly for those with mental illness who were looking for work.

2014 Mental Health stigmatisation and discrimination survey results. Solid lines reflect personal, while dotted lines reflect observed, experiences.

When asked to give examples of negative experiences, the most common from family and friends was the reducing and cutting of contact, followed by being dismissive, lacking understanding, teasing or verbally abusing and judging. In the workplace, examples included being fired or made redundant, being given changed responsibilities, being dismissive, lacking understanding and being teased/bullied. GPs were reported as the most common health professional to give negative experiences (4.5 per cent to 9.1 per cent of respondents). The most common experience was reported as ‘diagnostic overshadowing’ whereby the health professional would ‘see’ predominantly the mental health disorder rather than other health issues.

Examples of positive treatment by family and friends included maintaining and increasing contact, checking in on them, trying to cheer them up and other forms of less specific support. In the workplace, examples included nonspecific support or help, being allowed to take time off, have the pressure reduced and making allowances and talking/listening. Encouragingly, GPs were the most common health professional to give positive treatment experiences (17.5 per cent to 36.2 per cent). In summary, the findings indicated that positive treatment experiences were more common than avoidance or discrimination (except when looking for work), friends and family were more likely to avoid than to discriminate, and symptom severity, together with a diagnosis of psychotic or eating disorders, predicted experiences of both avoidance and discrimination but not positive treatment.

Impact of media

In addressing the third statement about the impact of media on attitudes to people with mental health problems, Associate Professor Reavley spoke to the research being undertaken by her PhD student, Anna Ross, on the relationships between media exposure and beliefs about dangerousness; and showed news articles with such headlines as ‘woman ‘floridly psychotic’ when she killed her mother’, ‘Vic mental health crisis means more murder’ and ‘gunman had history of mental illness’. Data to evaluate this media relationship was gathered also in the 2014 discrimination survey using vignettes like those used in the 1995 survey. The results differed according to the mental health problem. Recall of media reports and having felt afraid of someone were associated with beliefs about the dangerousness of those with schizophrenia but not of those with depression or anxiety. Knowing someone with a mental health problem and having a higher level of education were associated with less belief in the dangerousness of people with either mental health condition. Recommendations stemming from this research have been included in Mindframe guidelines on media reporting of severe mental illness in the context of violence and crime so that stigma is reduced and so that help-seeking behaviour is promoted. Managed by Everymind, Mindframe is a national program, funded by the Australian

Government’s Department of Health under the National Suicide Prevention Leadership and Support Program, supporting safe media reporting, portrayal and communication about suicide, mental ill-health and alcohol and other drugs.

Conclusions

Concluding her presentation, Associate Professor Reavley acknowledged that progress on mental health literacy over the last two decades, appeared to have been made for higher prevalence conditions, such as depression and anxiety, and that there was room for improvement for less prevalent conditions, such as schizophrenia. To inform the Fifth National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Plan, she was thus consulting with people of lived experience of less prevalent or less understood mental illness types as provided in Priority Area 6 for government to take action to reduce the stigma and discrimination experienced by people with mental illness that is poorly understood in the community. Interviews have been also with mental health advocates, employers, health and other professionals with the aim of gaining consensus about the specific actions to be implemented under this Priority Area 6. The following gives a summary of these recommendations gained from the analysis of these interviews: