The Redwood Library & Athen um is a member of the Museum Travel Alliance (MTA), a consortium of museums whose patrons and supporters are passionate about cultural travel. MTA offers affiliated museums and cultural institutions access to select travel opportunities led by renowned curators and scholars.

Join the MTA and the Redwood Library & Athen um on journeys that awaken new insights into art and culture. Visit UNESCO World Heritage Sites, enjoy exclusive events, see private collections, and travel on elegant chartered ships and luxury trains.

Consider one of these extraordinary trips:

Belgium & Holland: Brussels & Bruges to Amsterdam Aboard Magnifique III

May 17 to 26, 2026 with Jennifer Dasal, Lecturer

English Elegance: Art, Estates & Spas of Cheltenham & Bath

May 31 to June 9, 2026 with Alice W. Iglehart, Lecturer

Monet in Normandy & Paris: Impressionist Painting Retreat on the Seine Aboard AmaDante

June 12 to 20, 2026 with Jennifer Dasal, Lecturer

Sicily & Malta: Catania to Palermo Aboard Sea Cloud II

October 1 to 9, 2026 with Rika Burnham, Lecturer

MUSEUM TRAVEL ALLIANCE

260 West 39th Street, 17th Floor New York NY 10018 USA

+1 212-324-1893 | trips@museumtravelalliance.com

Explore more trips at www.museumtravelalliance.com/trips/

Dear members, shareholders, friends and supporters,

It is always a pleasure to welcome you to another issue of our magazine, which gives me occasion to communicate my gratitude for your support on behalf of the board and sta . In this sesquicentennial year, a moment in our nation’s history which should have us re ect on the shared citizenship that binds us, I would also underline my gratitude for your interest and participation in all that we are, in Newport and beyond.

Participation is civic engagement, with voting its most fundamental expression. It is also a concerted e ort to take part in and enrich Newport’s cultural life for the bene t of all of its citizens. is was the original impetus for the founding of the Redwood, just as it is for this iteration of our magazine—a ‘Newport Special issue.’ Very helpful to those of us in the culture sector, Newport is an inexhaustible well of historical insight. Indeed, the three articles contained herein touch on four centuries of our city’s history, showing us that Newport has for all times—as both source and site—incited countless notable interventions that render it a place like no other.

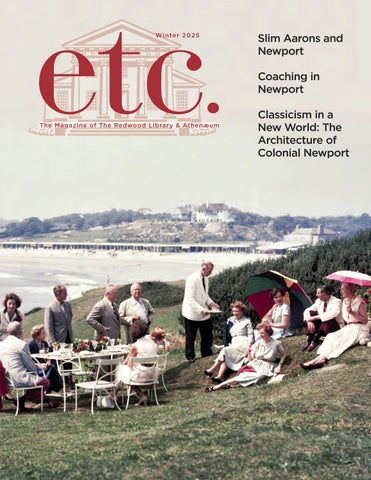

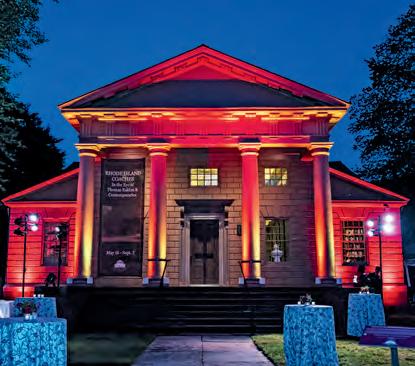

e lead article, imaged on the cover, cements in hard copy our hit Summer 2024 show devoted to the indelible pictures of photographer Slim Aarons, a visual record of a mythical Newport of sea, sun, and leisure now seemingly so distant from our present turbulence. e second piece, authored by the incomparable Paul Miller, also evokes days of bygone leisure, here in the realm of coaching. In it we learn of the historical context that undergirds this strand of the sporting life, the traditions of which endure to this day. Finally, the architectural historian John Tschirch reminds us that Newport was always a center of learned style. From the earliest days of the city’s grand public architecture—exempli ed in Trinity Church and the Redwood itself—Newporters understood that buildings mean, and that Greco-Roman classicism was the exact language for their lofty aspirations.

With all of this in mind, and with so much forthcoming to celebrate Newport and its role in our nation’s rich history, it is always worthwhile to take stock of our good fortune to be living and working in this very special city, surrounded by its many remarkable natural attributes and cultural institutions. For those of you further a eld, may reading this special issue have a ‘transportative’ e ect, or better yet, may it spur you to make a return visit to Newport and the Redwood in 2026.

Winter 2025 | Vol. V, 1 redwoodlibrary.org

Editorial Director

Benedict Leca, Ph.D. Design

Pam Rogers Design

Benedict Leca, Ph.D. Executive Director

Mission Statement

Founded in 1747 on the Enlightenment ideals of intellectual pursuit and civic engagement, and committed to lifelong, interdisciplinary learning, the Redwood Library & Athenæum generates knowledge in the humanities for the benefit of the widest possible audience with “nothing in view but the good of mankind.”

Redwood Library & Athenæum Board of Directors 2025-2026

Daniel Benson, President

Michelle Drum, Secretary

John D. Harris II, Vice President M. Holt Massey, Treasurer

Elisabeth Clark

Maura Cullen

Edwin G. Fischer, M.D.*

Michael Gewirz

Leslie Godridge

John Rovensky Grace

William Guenther

Edward W. Kane*

Adam Keefe

Elizabeth Leatherman

Waring Partridge

R. Daniel Prentiss*

Andy Ridall

Je rey Siegal

Robin Warren

*Emeritus Director

chartered 1747

Redwood Library & Athenæum

50 Bellevue Avenue Newport, Rhode Island 02840

401.847.0292

redwood@redwoodlibrary.org

@theredwoodlibrary

@RedwoodLibrary

@redwoodlibrary

Reprint of any content herein must bear following credit line: Originally Published in etc., The Magazine of the Redwood Library & Athenæum Winter 2025

Cover:

Slim Aarons, Luncheon at Plaisance, the James Becks estate, 1953 © Slim Aarons / Getty Images.

The Redwood Library & Athenæum’s commitment to environmental responsibility includes utilizing paper products manufactured through sustainable forest practices and using low VOC inks and solvents.

by Shawn Waldron

Following the exhibition Slim Aarons: Newport Days, a look at his photographic journey from combat to castle and the growing market for Slim Aarons works nearly twenty years following his death.

The photographer George “Slim” Aarons (1916–2006) is hailed as the quintessential chronicler of 20th-century American society and the international leisure class. Born in the tenements of New York’s Lower East Side and later raised by extended family in New Hampshire, Aarons enlisted in the U.S. Army in the spring of 1939 aiming to learn the photography trade. Hitler’s invasion of Poland in the fall thrust Aarons from the darkroom to the front lines as a staff photographer for Yank magazine, a weekly magazine distributed to active-duty soldiers throughout the war. He spent years covering the front lines

in North Africa and Italy and experienced the brutalities of war firsthand, including a close call with a Nazi bomb that earned him a Purple Heart. The violence and chaos left a deep scar that shaped his future in photography. In his own words, “The war was over; I was eager to put all of that misery behind me.”

In 1974, Slim wrote, “With its history, traditions, and Old World atmosphere, there is no resort in America that comes close to Newport.”

Back in the States by December 1944, Aarons continued working for Yank1 but covering domestic stories. He soon began crisscrossing the country photographing Main Streets from Providence to Des Moines and even spent ten days traveling up the Missouri and Ohio Rivers aboard the country’s last operating steamship. This new phase marked the beginning of five decades on the road (and sea and sky). Following his honorable discharge in August 1945 he connected with an army buddy, the Pulitzer Prize-winning comic

illustrator Bill Maudlin. The two men followed Horace Greeley’s advice and headed West in search of work.

Another army connection—one of Slim’s great professional skills was networking—introduced him to the actress Jean Howard. The fomer Ziegfiled dancer turned MGM contract player was one half of a Hollywood power couple with agent to the stars Charles Feldman. Howard was also an enthusiastic amateur photographer who took an immediate liking to Slim. She introduced him to Beverly Hills society and Hollywood A-listers; in return he gave tips on photography and tagged along on a few shoots as her practice developed. The two remained friendly, and years later Howard was named godmother to Slim’s daughter Mary.

Over the years Aarons developed a simple philosophy: photograph attractive people doing attractive things in attractive places.

Slim sold a California story to Look magazine in 1946 which led to assignments from Holiday. The Look editors chose to include a portrait of the fledgling photographer on the contents page and described him as, “brash, likeable…and one of the most fabulous GIs of the war.” Slim’s first trip to Hollywood proved valuable for its connections and photographic education—the legendary Hollywood portraitist Clarence Sinclair Bull taught him about the importance of glamour and MGM chief Louis B. Mayer gifted him a simple rule of thumb: The women must be beautiful, the men handsome.

Aarons spent the next two years bouncing between the coasts chasing assignments. In the fall of 1947, Life offered him an East

Coast assignment covering the Glidden Tour of Automobiles. It was his first for the magazine; Aarons, as did most of the American public, considered Life to be the pinnacle of magazine journalism. Slim joined the group near Mount Washington, New Hampshire and rode along as it made its way south through New England to Newport. He photographed the antique cars, drivers wearing period clothes, and sites along the way capped off with a grand parade through the streets of Newport. The tour’s closing awards dinner was held at the Viking Hotel, steps away from the Redwood. Life’ s editors ultimately decided not to run the story, so the negatives were returned and filed away for safe keeping.2 Nearly seventy-five years later, the negatives were extracted from the archive and, in the summer of 2024, made their public debut at the Redwood as the opening images in the original exhibition Slim Aarons: Newport Days.

Although Aaron’s first assignment for Life was never published, it established a relationship with the magazine that would change the trajectory of his life. After a handful of published assignments on the West Coast Life offered Slim the opportunity to become part of the small team tasked with reopening the magazine’s Rome bureau. Slim jumped at the chance and in the fall of 1948 settled into a modest room in the Excelsior Hotel. Of this time, Slim wrote, “The hotel had special rates for actors, newspapermen, and courtesans. The reasons were obvious, the manager told me: actors and actresses decorated the lobby; newsmen might be working on

a book (remember Grand Hotel?), and beautiful courtesans always demanded the biggest and best suites from their current lovers.”3

Rome was a bustling hub of postwar activity filled with Hollywood stars, political figures, and high society. Hollywood productions arrived in the city following the reopening of the Cinecittà studios. Aarons photographed Orson Welles productions, Anna Magnani at home, Louis and Lucille Armstrong along with the nuptial celebrations of Tyrone Power and Linda Christian, dubbed the “Wedding of the Century”. He befriended the actor Joseph Cotton and had his heart broken following a brief affair with Joan Fontaine. In the first big scoop of his career, Lucky Luciano, the exiled gangster (and fellow Excelsior Hotel resident), invited Slim to join him in his forced return to Sicily. The Eternal City, with its potent mix of grand palaces and ancient ruins, became, in his own words, “a wonderful place to begin my quest for the beautiful and the elegant.”4 There was no looking back.

freelance life was still an endless hustle for magazine assignments and commercial work. That year, Life changed his career in a different way when he met Lorita Dewart, an assistant in the Life photo department. Lorita, a Boston native and graduate of The Mary C. Wheeler School and Briarcliff, had moved to New York to pursue her dream job at Life. As Lorita told me, Slim was immediately smitten but she needed a little convincing. The young couple became engaged on a weekend visit to Newport and married in 1951. Rita became Slim’s muse, model, travel partner, and sometimes assistant. She can often be seen dressed in red, providing a brilliant pop of color.

By 1950, Aarons was back in New York living in a small midtown apartment. His reputation was solidifying, but the

Over the years Aarons developed a simple philosophy: photograph attractive people doing attractive things in attractive places. This mantra led him to some of the world’s most glamorous and exclusive locations—Palm Beach, Palm Springs, Gstaad, Rome, London, Capri, Cannes, and, one of his personal favorites, Newport. In 1974, Slim wrote, “With its history, traditions, and Old World atmosphere, there is no resort in America that comes close to Newport.”5

The city’s allure as an elite summer destination was immortalized by Slim’s lens during five separate assignments between 1947 and 1987. Collectively his photographs highlight Newport’s gilded cottages, tennis at the famed Newport Casino, water sports at Bailey’s Beach, the city’s deep connection to sailing and the sea, and the personalities that bring them to life. In The Last Resorts, social historian Cleveland Amory famously called Newport the Queen of Resorts, praising its blend of history, architecture, and social traditions. Slim’s photographs reinforced Amory’s argument and played a critical role in ensuring the city and its residents’ place in the visual lexicon of American society.

Mark Getty personally acquired Slim’s archive for Getty Images in 1997. The company was still fledgling, just two years old, and was keen to build up its library of photography. Getty turned up at Slim’s 1782 farmhouse in Westchester County on a rainy morning unsure of exactly what the photographer had tucked away in his attic. The two men, both well over six feet tall, climbed the rickety pull-down

stairs and stood amongst the hundreds of stacked boxes. Five decades of non-stop shooting had produced 750,000 frames— only a fraction of which had ever been seen by the public. The sheer volume was staggering, and the list of locations, venues, and personalities was unparalleled. The two men shook hands and within a year the archive was shipped to the company’s archive outside of London, where it remains today.

Print sales were not part of Slim’s lifetime practice, mostly for practical reasons such as time, money and demand. As a committed freelancer, Slim’s professional life was an endless loop of travel, shooting, editing, submission, securing new assignments, and repeating the cycle. He preferred spending his limited free time indulged in one of his favorite activities—cutting his ample suburban lawn with a hand mower—over toiling in the darkroom. Journalism was what mattered. Beyond that, the market for fine art photography was miniscule and undeveloped for most of Slim’s active years. What little interest that did exist was centered on black and white prints. The acceptance of color photography as a legitimate art form was

slow to develop even as exhibitions such as the groundbreaking show of William Eggleston’s work at the Museum of Modern Art in 1976 helped to alter perceptions. Editorial and advertising work such as Slim’s was viewed and classified as commercial work that sat largely outside the purview of museums, galleries, and thereby, collectors.

His legacy as a chronicler of high society and celebrity remains unmatched, and his work is celebrated not only for its artistry but also for its role in shaping 20th century visual culture.

The shift began when London gallerist Michael Hoppen recognized the inherent fine art value of Slim’s work and came calling in the 1990s. While today there is a robust global market for Slim’s prints, the change hardly occurred overnight—remember Mark Getty’s reason for buying the archive in 1997 was copyright and intellectual property, not fine art and property value. Since then, however, the art world and collectors have come around to recognize Aarons’s oeuvre as a historically significant and aesthetically rich body of work. Slim Aarons limited editions prints are now sold in galleries on six continents. As the market for his work has expanded, so too has their value: in October 2024, a limited edition print of Poolside Glamour fetched $63,000 at Christie’s Fall Photography auction, easily surpassing the previous high of $40,300 set in 2022.

Slim Aarons’s photographs continue to captivate audiences with their timeless elegance, offering unfettered access to a world of beauty, leisure, and privilege. His legacy as a chronicler of high society and celebrity remains unmatched, and his work is celebrated

not only for its artistry but also for its role in shaping 20th century visual culture. From the beautiful people to the glamorous resorts such as Newport, his images serve double purpose as historical documents and pieces of art. The work is a testament to a unique moment in time—one that continues to inspire young audiences and evoke nostalgia for the golden age of leisure and elegance.

Shawn Waldron is Getty Images Curator of Exhibitions and manager of the Slim Aarons archive. He is the author of Slim Aarons: Style (Abrams, 2021) and Slim Aarons: The Essential Collection (Abrams, 2023).

1Yank began including domestic stories as the war wound down and the enlisted men turned their attention towards returning home. The magazine published its final issue in December 1945.

2The Life darkroom staff labeled the negatives folder as belonging to “George Ahrens.”

3Aarons, Slim. Once Upon A Time. Abrams, 2003.

4Ibid

5Aarons, Slim. A Wonderful Time. Harper & Row, 1974.

by Paul Miller

Two generations have now grown up in Newport to the pageantry and horsemanship of the triennial Coaching Weekend as part of the accustomed summer schedule. Most spectators have a notion of the event as being tied to the city’s Gilded Age past but as to how generally remains unclear. On the occasion, this year, of the one hundred fiftieth anniversary of the 1875 founding of The Coaching Club of America, it is time to acknowledge and celebrate those ties.

The Coaching Club was founded in New York by DeLancey Astor Kane (1844-1915) and William Jay (1841-1915), New York sportsmen and members of the Newport summer colony. DeLancey Kane was born at his family’s estate Beach-Cliffe on Bath Road (now Memorial Boulevard) and Col. Jay was the brother-in-law of Hermann Oelrichs of Rosecliff on Bellevue Avenue. Their aim was to encourage “four-in-hand” driving in America, a sport inspired by the nostalgic tradition of late 18th-and early 19th-century British mail coaches renowned for the efficient skill and punctuality of their drivers. Driving road coaches modeled after the earlier mail coaches for sport became a pastime of English aristocrats in the 1840s. Coaching was transformed from a public service into a test of skill

for affluent sportsmen able to handle a private coach and a team of four horses with reins held in one hand. American gentlemen spending time abroad took up the practice and, once back in America, invited English trainers to provide driving instruction to a growing coterie of enthusiasts. Purpose-built road coaches were initially imported from London, including Olden Times for Jay and the celebrated Tally-Ho for Kane.

By 1876, New York carriage maker Brewster & Company began production of regulation road coaches based on the Tally-Ho for the Coaching Club’s growing membership, which attracted numerous Newport summer residents. Appropriate vehicles to choose from included the heavy road coach, capable of carrying multiple passengers at 2,866 pounds and the lighter, more elegant, park drag at 2,249 pounds. Given the weight, sturdy horse breeds were needed to pull the load, generally Hackneys or Morgans. Rules and traditions were quickly adopted by the Club relating to equipage, livery and protocol. These efforts resulted in an elegant display, and made of the Club’s Spring and Fall Fifth Avenue parades a highlight of the social calendar. Newport evolved as a center of the Club’s summer activities with popular August meets commencing in 1878 and drawing such

Newport evolved as a center of the Club’s summer activities with popular August meets commencing in 1878 and drawing such resident participants as Isaac Bell Jr., August Belmont and sons, James Gordon Bennett, Harold Brown, Theodore Havemeyer, Ogden Mills, William Watts Sherman, William K. Vanderbilt and George Peabody Wetmore.

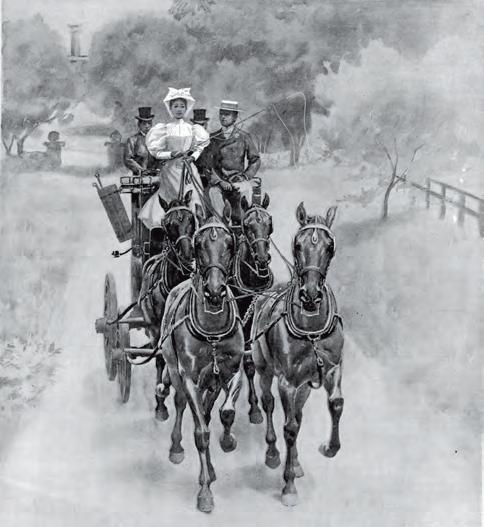

resident participants as Isaac Bell Jr., August Belmont and sons, James Gordon Bennett, Harold Brown, Theodore Havemeyer, Ogden Mills, William Watts Sherman, William K. Vanderbilt and George Peabody Wetmore. (Illustration 1.)

Members’ coaches were shipped to Newport via the Fall River Line for seasonal use. For an organized coaching meet, the road coaches or park drags would convene along Narragansett Avenue east. The coaches would arrive around noon for a prompt 12:30 departure, precedence was accorded to senior members of the Club. Other coaches were positioned by order of arrival. The owner-driver, referred to as the “whip”, was elegantly attired, wearing a long coat in Coaching Club colors with brass buttons, silk top hat, driving gloves and shielded by a monogrammed driving apron. He would

be seated on the top front box seat, flanked, generally, by his wife carrying a nosegay of flowers matching those decorating the fourin-hand horse team. Up to eight passengers could be accommodated behind them together with a liveried groom and a guard whose duties including sounding the coaching horn. The interior of the coach was reserved for servants and provisions for al fresco dining. Most frequently, the coaches would make a short trot to Bateman’s Hotel on Ocean Avenue at Brenton Point. (Illustration 2.) There, the coaches were drawn up in parade formation and guests moved on to decorated tables set up under tents on the lawn. Luncheon followed with the Casino Orchestra playing for dancing. The parade then re-formed and moved on to the nearby Polo Grounds to watch a match before disbanding. Alternate popular runs included

3. The Annual Coaching Parade at Newport - The Start from Narragansett Avenue

As drawn by Mac F. Klepper for Harper’s Weekly, August, 1892 Collection of the Redwood Library & Athenæum

excursions to The Glen in Portsmouth, Belmont Farm at Hanging Rock and Ward McAllister’s Bayside Farm in Middletown. In August, 1892, eighteen coaches, the largest number ever in line in America, participated in the Newport meet; the line stretched from Bellevue & Narragansett Avenues to the Pinard Cottages at the corner of Annandale Road. (Illustration 3.)

Driving a coach on a public road between pre-arranged points, according to a fixed time-table that allowed for changes of horse teams, was the ultimate test of the whip’s skill. Public coaching excursions began in 1876 when DeLancey Kane ran the TallyHo on a seasonal basis, with subscription passengers, from the Brunswick Hotel in New York to Pelham, NY. Whip Fairman Rogers, of Philadelphia and Fairholme on Ruggles Avenue, challenged the Club to undertake more arduous, cross-country excursions, resulting in a round-trip New York to Philadelphia run on May 4-7, 1878. (Illustration 4.) The practice expanded and continued annually. A Newport Casino to Tiverton, RI public route, with the coach Aquidneck, was put on by W.R. Travers and H.R.A. Carey in 1892. In the following generation, Alfred G, Vanderbilt of Oakland Farm, Portsmouth, would considerably expand these runs in New York, Newport and abroad, operating in England, between 1908 and 1914, a London to Brighton route, with his coach Venture. In 1909,

the Club’s final long-distance trip before World War I was the three-day, 205-mile drive from New York to Newport and Oakland Farm

Driving a coach on a public road between pre-arranged points, according to a fixed time-table that allowed for changes of horse teams, was the ultimate test of the whip’s skill.

Newport-New York Club members with part-time residences abroad founded the Reunion Road Club in Paris in 1893, participating in the Paris-Trouville meets. While in New York, a Ladies Fourin-Hand Driving Club was formed in 1901 as a counterpart to the Coaching Club for women who took an interest in driving. (Illustration 5.) The First World War and increased automobile congestion diminished interest in the practicality of Coaching. The Interwar years, however, witnessed a short resurgence of the sport. In the 1920s and ‘30s, renewed interest in coaching was led, locally, by Gov. William H. Vanderbilt, son of Alfred, and his cousin Muriel Vanderbilt Phelps, before fading almost completely after World War II. Nevertheless, as Newport “whip” O.H.P. Belmont predicted: “No sport which requires the perfection of skill and dash and the exercise of nerve will ever be abandoned by Americans”. Coaching in Newport was reborn in 1968 through the initiative of the Carriage Association of America and its then president, J. Cecil Ferguson of Greene, RI, with the support of fellow whips James K. Robinson of Westchester, PA, John M. Seabrook of Woodstown, NJ, Chauncey D. Stillman of Amenia, New York and George A. “Frolic” Weymouth of

Illustration 4. The Fairman Rogers Four-in-Hand, Fairmont Park, Philadelphia, 1879-80, oil on canvas by Thomas Eakins (American, 1844-1916) Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of William Alexander Dick, 1930-105-1

Chadds Ford, PA. Their passion for the sport was infectious and the enthusiasm generated by the initial August 9-11 exhibition and parade led to the creation of a triennial Weekend of Coaching. Visiting “whips” and vintage coaches again maneuver the routes of yore under the auspices of the Coaching Club of America and The Preservation Society of Newport County.

Paul F. Miller is Curator Emeritus of the Preservation Society of Newport County and currently serves as Director of the Clouds Hill House Museum in Warwick, RI.

Illustration 5. Coaching at Newport, Lady Whip at the reins of a four-in-hand coach

As drawn by Max F. Klepper for Harper’s Weekly, August 1895 Collection of the Redwood Library & Athenæum

by John R. Tschirch, Architectural Historian

at the height of its prosperity, and just as the town would decline economically as a result of the War for Independence. Note the detailed list of all public buildings and houses of worship.

raise up Newport’s buildings. In each case, the private dwellings and houses of worship demonstrate an adaptability to local climate and materials, and a degree of freedom in proportion, scale, and overall composition. By 1712, the minutes of the colonial assembly declared the city to be “the admiration of all.” Civic pride already manifested itself in the physical environment, a projection of an ancient classicism in a new setting.

How did a 2,000 year Greco-Roman architectural tradition make its way across a 3,000 mile ocean to settle in what British colonists perceived as a New World? It is a story of cultural aspiration and design adaptation. The result in Newport, Rhode Island was the creation of a city propagating the virtues of enlightenment and practicing the vices of empire in architectural form. As architecture was not an established profession in the colonial period, it remained to the gentleman amateur and the local carpenter to conceive of and

Upon its founding in 1639, Newport developed into a cosmopolitan seaport, spurred on by the Rhode Island colony’s founding principle, and later codified in a charter, granting freedom of conscience, with a population comprised of a variety of Protestant sects, the Society of Friends, and Sephardic Jews. By 1640, the clearly established urban plan consisted of two main streets, Thames along the harbor with space for attendant wharves of the merchant oligarchy, and Spring Street running along the base of today’s Historic Hill district. The area of present-day Washington Square

evolved from a spring site into a triangular area terminating to the west in Long Wharf, established in 1680 by a group of proprietors, a true corporate undertaking to create the ideal access point for large ships. Easton’s Point, donated to the Society of Friends in the 1680s by Nicholas Easton, was laid out in a classic grid pattern by Samuel Easton in 1725. These areas formed the basic template of the city’s colonial districts. Noticeable were the lack of grand buildings in the cityscape. Commerce dominated in this seaport linked to the trading networks of the ever expanding British Empire. Great architecture, when it began to arise in the 1700s, inserted itself where space allowed.

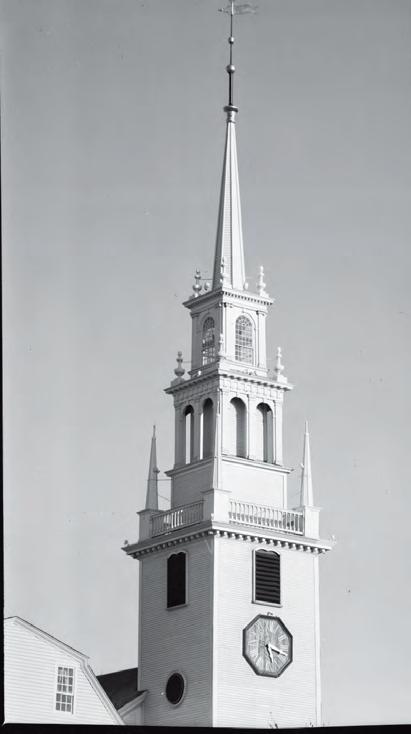

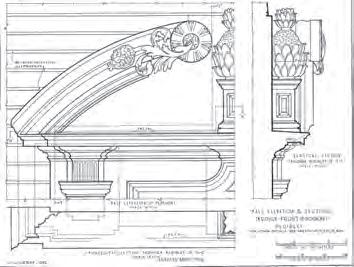

Many 17th-century buildings in Newport, and throughout the British colonies in North America, were more Medieval than classical. The Great Friend’s Meeting House (1699) is of half-timbered construction, a direct heir to the craft traditions of England. By the 1700s, classicism made its entry on the scene. During the first half of the 18th century, a lush, bold, baroque-inspired approach to design prevailed, while a restrained classicism appeared by mid-century, prompted by the fashion for Palladian architecture transmitted through pattern books. Among the earliest large scale works is Trinity Church (1726) by Richard Munday, who excelled at extravagantly carved detail. The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, based in England, produced a book of designs in order to establish a uniform church type for Anglican houses of worship across the empire. In accordance with Anglican practice and modeled on the galleried hall churches of London by Sir Christoper Wren and James Gibbs, Trinity Church is markedly simple on street level, while its steeple is an original concoction of classical pilasters, arches, and obelisks. In

addition to these classical forms, bolection mouldings are used for door and window frames and for the interior galleries and pulpit. Curved and raised from the wall surfaces, these mouldings lend a sculptural baroque quality, and are a testament to the skill of the woodworker. And here is the critical point: wood was the primary artistic medium of the colonial era. Architecture and furniture, practical in use and ideal for the display of wealth and aesthetic discretion, were the wood carver’s domain.

Trinity Church and the Colony House became models, inspiring the forms and adornments of houses grand and modest, built by carpenters whose names are largely unknown, but whose skill interpreted the pediments, bolection mouldings, and overall forms of Munday’s works.

Munday’s Colony House (1741), placed at the eastern edge of present-day Washington Square, created a grand visual terminus since it aligned with Long Wharf. A visitor disembarking from ship had a clear view to the building marked by a broken carved pediment with a gilded pineapple, a symbol of hospitality and wealth, of voyages to far off places with a return of riches. The pineapple is also a mark of the connection with the Caribbean and the trade in enslaved Africans, here at the very visual heart of Newport. Made of brick with brownstone used for the window surrounds, quoins at the corners, and the front steps, the structure cost a fortune as lime mortar and brownstone had to be imported from outside of Rhode Island. The result is a building representing political power and mercantile wealth.

Trinity Church and the Colony House became models, inspiring the forms and adornments of houses grand and modest, built by carpenters whose names are largely unknown, but whose skill interpreted the pediments, bolection mouldings, and overall forms of Munday’s works. The Nichols-Wanton-Hunter House (1747, and expanded in the mid-1750s) sports a lush pineapple pediment. The Dr. David King House on Pelham Street contains

Nichols-Wanton-Hunter House. Intersecting cornices, layered Corinthian-style pilasters and bolection mouldings for wall panels. Photo

of the Preservation Society of Newport County.

King

25

Street. A simply rendered triangular pediment and flat surfaced pilasters.

William James Stillman.

The curved pediment supported on scrolled brackets is a dramatic example of early to mid-18th century Newport carving. Courtesy of the

a simplified version of a curved broken pediment. Depending upon one’s economic means, a house in Newport could feature an elaborate door surround supported by pilasters (half-columns) with fluting at extra expense or in a more affordable unadorned manner. These entry ways illustrate the adaptability of the classical language of design, from simple to complex arrangements.

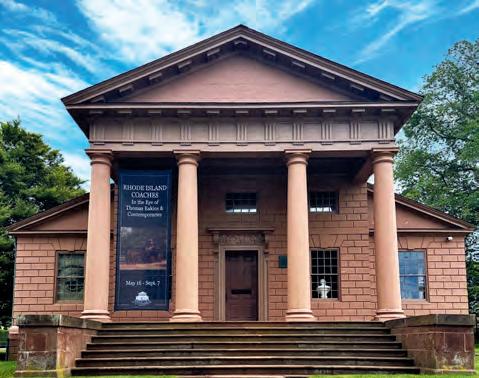

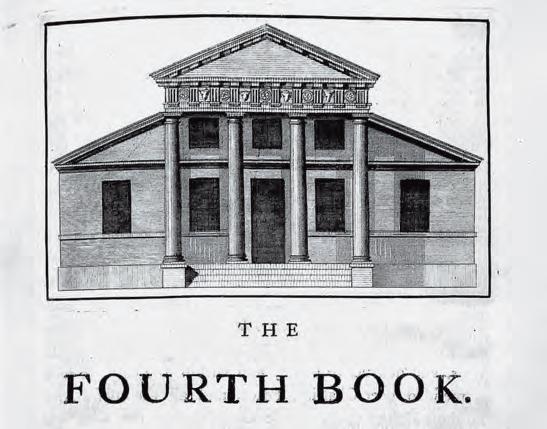

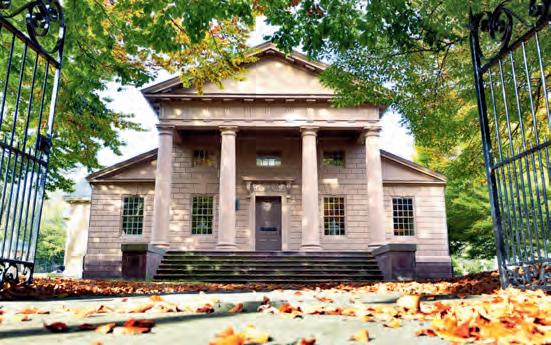

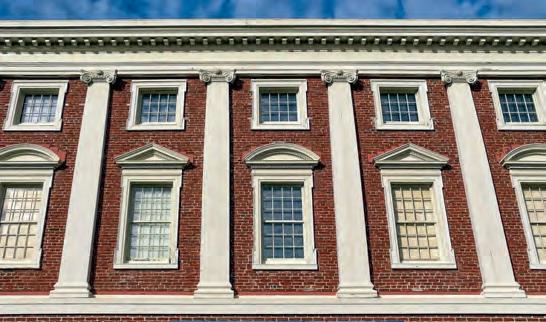

By the mid-1700s, a new spirit infused the design world, and it declared itself with the Redwood Library and Athenaæm (1747). Aided by a fine collection of pattern books, Peter Harrison devised the Roman Doric temple front in wood for the group of divines, merchants, and men-of-letters who had first gathered in the 1730s as the Society of the Propagation of Knowledge and Virtue Through a Free Conversation. This philosophical and literary group evolved into the the Redwood Library Company, which promoted in its mission to “propagate virtue, knowledge and useful learning with nothing in view but the good of mankind.” This principle is the spirit of the Enlightenment at its very core. At the same time, wealth produced by the Triangular Trade in human enslavement was the stark economic foundation of this organization, where enlightened thought and imperial realities intersected, a trait not specific to the Redwood Library alone, but permeating colonial life. These two contrasting traits also expressed themselves in a home for books. Born of the book, the Redwood Library is based on a temple structure in Edward Hoppus’s 1739 edited version of Andrea Palladio’s Il Quattro Libri dell’ Architeturra, or The Four Books of Architecture, (1570). No baroque flourishes in broken pediments and high relief bolection mouldings characterize Harrison’s library. If theatricality presented itself in Richard Munday’s buildings, serenity prevailed in Harrison’s designs. Forms are pristine, carefully framed, and the wood siding is rusticated to appear as stone, the preferred material for fine building in England. Local craftsmen quickly adopted these details for houses, among them the remodeling of the Vernon House (remodeled in the 1760s) on Clarke Street and the Buliod-Perry House (ca. 1750) on Touro Street.

Peter Harrison’s practice of architecture demonstrates that classicism is not simply the process of applying Greco-Roman

Courtesy

Nichols-Wanton-Hunter House. Detail of pediment. HABS drawing. A product of the earlier half of the 18th century, this door pediment demonstrates the baroque richness and high relief carving of the period, in contrast to the work at the Vernon House later in the century.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The Buliod-Perry House. Rusticated wood with beveled edges meant to resemble stone was a labor intensive craft. This building is another example of the classicism of the Redwood Library influencing Newport’s domestic architecture.

of the Newport Restoration Foundation.

William James Stillman. Touro Synagogue. Photo, 1774. Renowned as the photographer of the Parthenon, the Acropolis and ancient sites throughout Greece, William James Stillman was commissioned by architect Charles Follen McKim to record Newport’s 18th century buildings and objects of interest. Photo Courtesy of the Newport Historical Society.

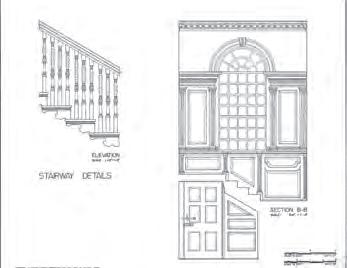

Detail. Brick Market. The alternating triangular and segmental pediments and the pilasters are rendered in exact proportions and rest relatively flat against the surface of the brick façade in contrast to the high relief details of early 18th century Newport buildings.

Washington Square. Photo, 1965. The two faces of Newport’s 18th century classicism in two landmarks that have stood the test of time: The Baroque richness of the Colony House rises above 20th century traffic; a detail of the Brick Market, its restrained Palladianinspired pilasters rest nobly as constant classical landmarks in a changing cityscape of utility wires and neon signs.

What survives as Newport’s artistic heritage from the colonial age is a lesson in cultural aspiration and technical adaptation. From the Parthenon atop the Acropolis in Athens to Redwood Library and Athenæum set upon a high point of land originally with views to Newport harbor, classicism has proved an enduring aesthetic.

columns to a cube. He proved that the classical idiom is an adaptable system, beginning with proportion and purity of form as a foundation and utilizing ornamental detail only to enhance, not to dominate. In this he was a disciple of the Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio, whose country villas in and around Vicenza and churches in nearby Venice are founded on basic geometries of square, rectangle, and circle. This simplicity is what made Palladio so attractive to English builders, who then brought this to their colonies overseas. One could build in an august manner on a budget and with limited technologies, creating a square that one added ornament if and when needed.

Two buildings assert the flexibility of the classical manner in Newport: Brick Market (1762) and Touro Synagogue (1763). In 1760, the proprietors of Long Wharf gifted land at to the city for a commercial center and Harrison created a Palladian palace as the triumphant symbol of maritime trade. The arcaded first floor provided open space for trading a variety of commodities; the second and third levels are marked by Ionic pilasters and windows with alternating triangular and curved pediments, a formula derived from Palladio’s designs and its English interpretations, such as Somerset House (ca. 1625) and the terraced houses of Covent Garden (1637), both by Inigo Jones, who introduced Palladian principles to England. Touro Synagogue is the most inventive of all of Newport’s colonial era buildings, due in great part to the fact that Jewish communities largely worshiped in private to avoid persecution so there were few models to consult. The great synagogue in Amsterdam did offer a template of basic features, which Harrison would draw upon in plans that addressed the need for a galleried space with a raised bimah in the center for the reading of the Torah, a storage cabinet for the holy texts, and the back wall facing east in the direction of Jerusalem. Other than these requirements, Harrison was left to devise an appropriate scheme. He produced a perfect cube of absolute exterior simplicity. Only four Ionic columns and three arches topped by a triangular pediment comprise the entrance porch. The interior is composed of twelve columns on two levels, representing the twelve tribes of Israel. Balusters for the railings are taken from Palladio’s churches, and the cabinet for the Torah with the frame for the ten commandments above is based on Georgian fireplace compositions. Something entirely unprecedented emerged from an innovative combination of historic precedents.

One site in Newport, a place of eternal rest, speaks to GrecoRoman influences of another sort; the imposition of classicism not only on buildings, but on a people. God’s Little Acre, a parcel in the Common Burying Ground, contains the gravestones of enslaved and free Africans and African Americans. One artist, Pompe Stevens, carved his name into the stone he created for his brother, Cuff Gibbs. With an arched top and scrolls on the sides, the marker is evidence of his skill and his time as an enslaved worker in the

stone cutting shop of the Stevens family on Thames Street. Pompe combined classical detail and created an image of his wife, Phillis, and son, who had both died in childbirth, in African dress for their grave marker. Not only the stones themselves but the names on them speak of classical precedence, for other grave markers bear the names of Cesar, Cato, and Hercules, all summoning up ancient Roman generals, senators, orators and gods. Just as in their buildings, colonial Newporters projected their classical will upon the enslaved. Among the earliest and intact signed, work of art produced by African Americans, these stones sit quietly, witnesses to a classical age in a New World, where the enlightened ideas of classicism and the realities of an empire of commerce coincided and co-existed.

What survives as Newport’s artistic heritage from the colonial age is a lesson in cultural aspiration and technical adaptation. From the Parthenon atop the Acropolis in Athens to the Redwood Library and Athenæum set upon a high point of land originally with views to Newport harbor, classicism has proved an enduring aesthetic. It has been a journey through time, cultures and artistic interpretations, all linked by the classical language of design, encapsulating hopes, desires, and the mix of dreams and realities.

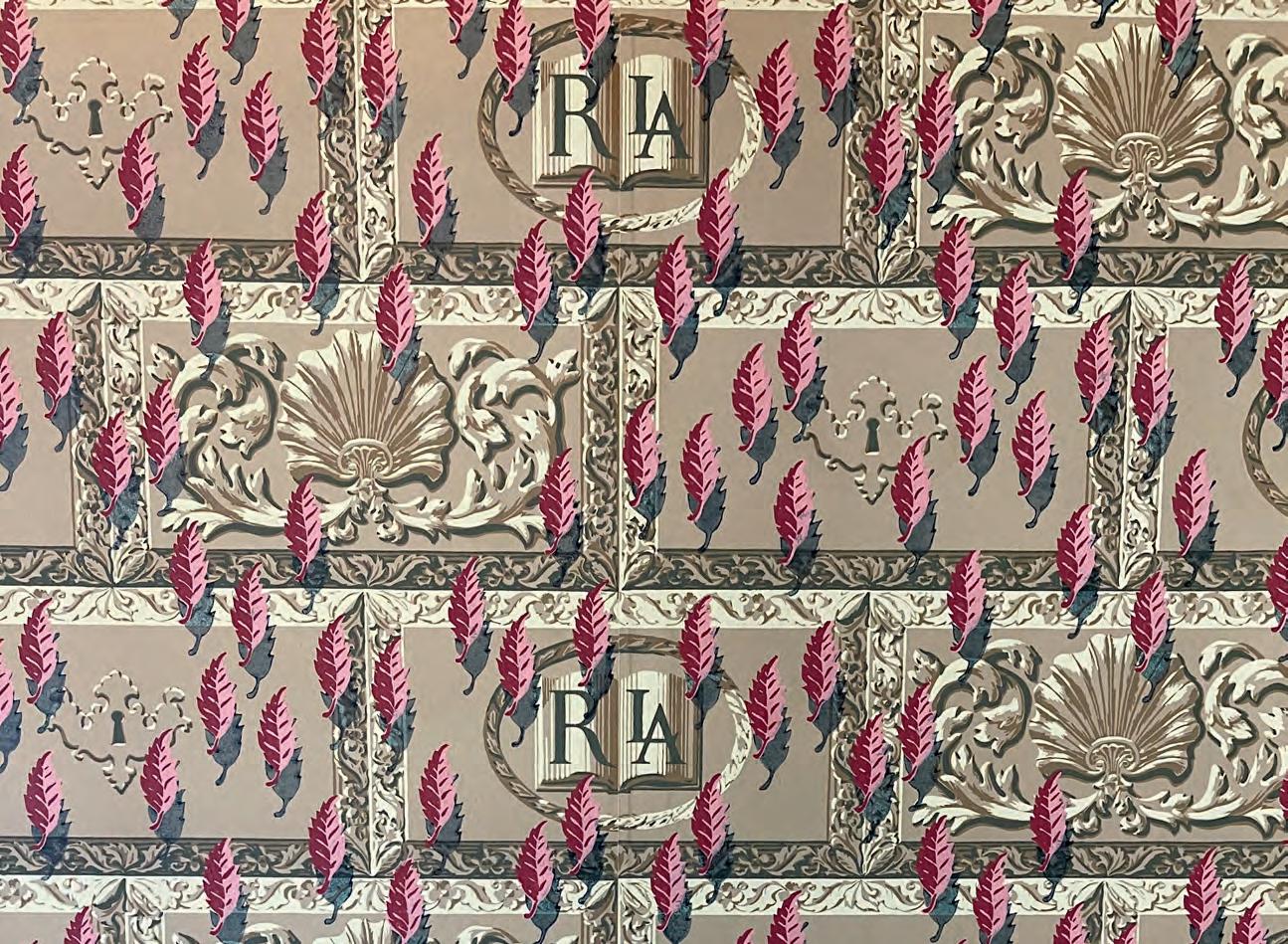

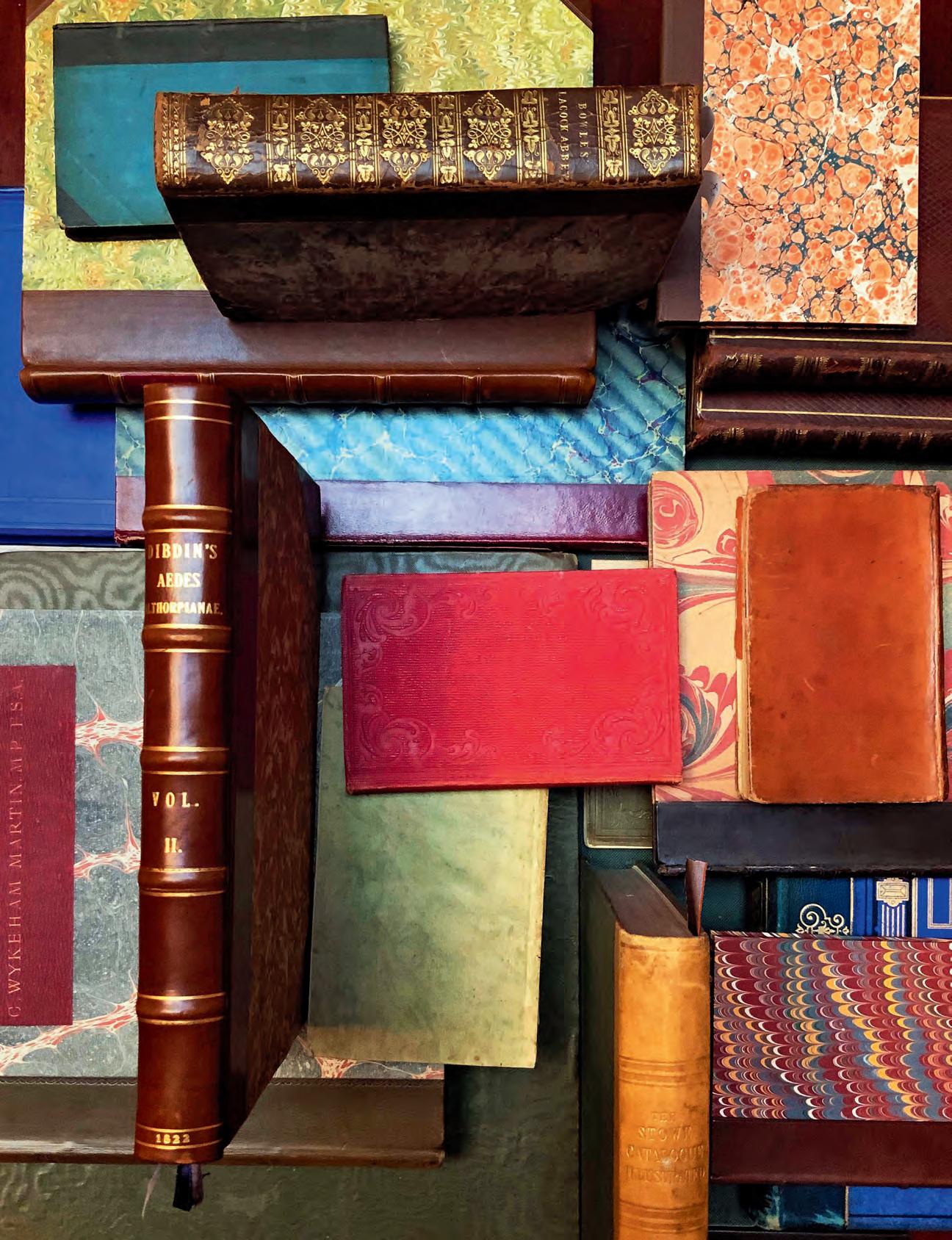

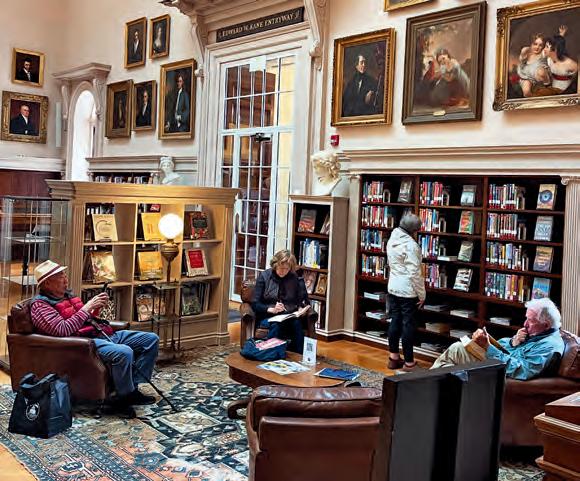

A project engineered by the Redwood Contemporary Arts Initiative (RCAI), graphic master Andrew Raftery has created a custom, block-printed Redwood Library wallpaper now permanently installed in the vestibule. Winner of this year's prestigious Abbey Mural Prize from the National Academy of Design, the wallpaper is a monumental contemporary print made by hand-carving Redwood speci c motifs into wooden blocks, in this way re-inscribing the Library as a center for the study of decorative arts, while gesturing to Newport's longstanding place as a city of artists and makers.