etc. Fall 2022 Carving Wood into Stone Treasures of the Redwood: Celebrating 275 Years

The Magazine of The Redwood Library & Athenæum

Dear Friends,

This special issue of etc. has two aims, both tied to our 275th anniversary we are celebrating this year, a point in the Redwood’s history unthinkable without you our members and benefactors—thank you.

The first is to revisit the history and meaning of our flagship building, the nation’s first purpose-built library and think space, a structure laden with as much symbolic as historical value. For architecture—the best kind—doesn’t just serve the prosaic, albeit important, function of sheltering, in this case, originally, the most important book collection in the American Colonies. It also contains and makes visible the history and values dear to its patrons and designers and, perhaps even more significant, activates said same in the tangible terms of civic engagement. In this way, Newport’s maritime traditions informed the choice of wood as the primary material of the Redwood’s construction, just as the balanced openness of its Palladian design, illuminated by a trio of oversized windows, accorded directly with its purpose as a civic commons conceived to produce knowledge.

The issue’s second aim is to give a glimpse of the treasures contained within, a trove born of gifts and acquisitions that reflects the Redwood’s enduring dual role as Newport’s intellectual center and municipal archive. Serving as the current anniversary exhibition’s abbreviated catalog, the magazine’s back half hews to the show’s lay-out, designed as a tour through some of the Redwood’s principal Special Collections areas: the ‘long’ eighteenth century, early modern architecture and decorative arts, and the history of Newport and Rhode Island. These subject areas confirm the Redwood as the abiding nexus of research for the range of constituents—tourists to scholars—who have forever been drawn to the richness of Newport’s historic built environment and its near 400-year history.

It is therefore with much gratitude that I invite all of you, our devoted members, supporters, and staff—and with all of our predecessors in mind—to join me in drawing satisfaction from our communal work in perpetuating this incredible institution. Thank you and see you soon in Newport at the Redwood.

CONTENTS

2 Carving Wood into Stone

Caroline Culp

7 Treasures of the Redwood: Celebrating 275 Years

28 Exhibitions at the Redwood

etc.

Fall 2022 | Vol. IIl, 2

redwoodlibrary.org

Editorial Director

Benedict Leca, Ph.D.

Editor Patricia Barry Pettit

Editor’s Assistant Julia Boron Design

Pam Rogers Design

Benedict Leca, Ph.D. Executive Director

Mission

Statement

Founded in 1747 on the Enlightenment ideals of intellectual pursuit and civic engagement, and committed to lifelong, interdisciplinary learning, the Redwood Library & Athenæum generates knowledge in the humanities for the benefit of the widest possible audience with “nothing in view but the good of mankind.”

Redwood Library & Athenæum Board of Directors 2021-2022

R. Daniel Prentiss, Esq., President

Frank Ray, Vice President

Daniel Benson, Secretary

M. Holt Massey, Treasurer

Marvin Abney

Josiah Bunting III

Michelle Drum

Jacalyn Egan

Edwin G. Fischer, M.D.*

Michael Gewirz

John D. Harris II

Elizabeth Leatherman

Aida Neary Waring Partridge

Janet A. Pell

Earl A. Powell III

Jeffrey Siegal

*Honorary Board Member

chartered 1747

Redwood Library & Athenæum 50 Bellevue Avenue Newport, Rhode Island 02840 401.847.0292

This issue has been generously supported by a grant from the Herman H. Rose Civic, Cultural and Media Access Fund at the Rhode Island Foundation, a charitable community trust serving the people of Rhode Island.

Reprint of any content herein must bear following credit line: Originally Published in etc., The Magazine of the Redwood Library & Athenæum Fall 2022

Cover: Man with Dog in Front of Redwood Library c.1875-1885.

Photographer unknown

The Redwood Library & Athenæum’s commitment to environmental responsibility includes utilizing paper products manufactured through sustainable forest practices and using low VOC inks and solvents.

redwoodlibrary.org 1

WELCOME

redwood@redwoodlibrary.org @redwoodlibrary @theredwoodlibrary @RedwoodLibrary

redwoodlibrary.org 1

Carving Wood into Stone: Peter Harrison and the Redwood Library

by Caroline Culp

In 1750, when James Birket of Antigua traveled to the harbor city of Newport in the British colony of Rhode Island, he was surprised to find an ochre-colored Grecian temple rising above the city’s ordinary clapboard buildings (fig. 1). “They have here a very handsome Library built upon the hill above the Town,” Birket wrote, a building with a particularly pleasing view down to the waterfront from its front portico. 1

Peter Harrison, the first professional architect in America, designed the Neo-Palladian building between 1747 and 1748 to house The Redwood Library Company’s collection of “Classiks, History, Divinity and Morality, Physick, Law, Natural History, Mathematics &.”2 Set on a raised base with stairs ascending to its main and only room, this was a structure set quite literally above the noise of Newport’s busy harbor in its own American Acropolis and on a lawn of absorbed quiet. The building’s façade was made in the image of an ancient temple popularized by Andrea Palladio, that vastly influential architect of the Italian Renaissance. It was intended to be a temple of knowledge and learning—an externalized expression of the Redwood Library Company’s mission of moral and intellectual inquiry.

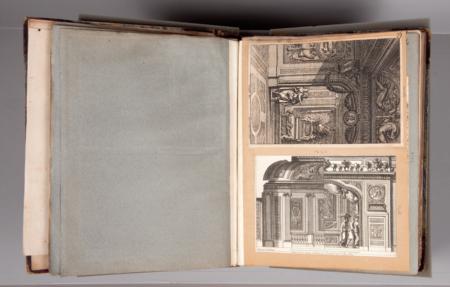

Harrison fashioned his Newport temple-front after an engraving in Edward Hoppus’s 1735 translation of Andrea Palladio’s Architecture, In Four Books (fig. 2). Mechanically reproduced engraved images allowed architectural designs and the fashions they contained to travel, extending the anatomy of style to international horizons. Craftsmen like Harrison conversant in the visual language of twodimensional engraved designs translated Hoppus’s image into a three-dimensional building in real space. The architect probably looked to the strictures of Palladio when deciding on the temple design for the library at Newport (though we will never know for

sure, since Harrison’s loyalist sympathies drove a New Haven mob to burn his house, library, and drawing collection after his death in 1775).

According to Palladio, a temple’s heightened perspective and raised dais should allow “the Minds of all [to] be excited and inflam’d to Diligence and Industry” in the space of the building—an appropriate aim for one of the first public libraries in the colonies.3 But Harrison’s inspirations were not limited to the pattern books of the age—his design surely had material precedents as well. In London, Harrison adopted the tropes of contemporary Palladian forms. St. Paul’s Church at Covent Garden, designed by Inigo Jones after Palladio, is the seventeenth-century counterpart to Harrison’s library (fig. 4). On the east end of the building facing the piazza, the tawny, smoothly finished ashlar with four Tuscan columns support an unadorned projecting pediment—static, reposeful, and geometric, it is much like the edifice of the Redwood Library.

But unlike this English church made of stone, the exterior of Harrison’s Redwood Library was carved and painted wood—made to look like blocks of limestone or granite. Large pine panels make up the façade. Each panel is about six feet square. The pine planks were

Figure 2, Edward Hoppus, Design of a classical building, Headpiece to Book IV, in Andrea Palladio’s four books delineated and revised, 1735. (Redwood Library Special Collections)

2 etc. Fall 2022

Figure 1, Pierre Eugène Du Simitière, Redwood Library, Newport, R.I., 1767, watercolor and pencil on paper, courtesy The Library Company of Philadelphia.

first smoothed, then carved to look like beveled stone, and finally painted with an ochre-colored pigment containing sand (fig. 5). Locally prolific, pine was an inexpensive solution to the problem of costly and hard-to-quarry blocks of limestone or granite. Harrison’s rusticated façade was a crafty sleight of hand so inventive it set off a fad for the carved and painted pine planks in Newport and across the colonies. (The grand expansion of George Washington’s Mount Vernon, completed in 1759, uses the same faux-stone planks.) The material enigma of the building’s siding fooled the eye in an alchemic deception—wood, carved and painted, became stone. And the deception was a convincing one. In 1774 Patrick M’Robert described the city’s buildings as “pretty good, some of stone, and some of brick, and some of wood.”4

The city’s buildings were constructed of wood, with some made of brick—but none of stone. This means M’Robert and other eighteenth-century visitors likely assumed the five or more structures employing the wooden rustication pioneered by Harrison were, in fact, made of stone. 5

Scholars have long explained Harrison’s masquerading façade as being “built of wood for economy’s sake.”6 But the deviation in expense between the Redwood Library’s book collection and the structure built to house it was enormous: the books cost twice the amount of the building. And although wood was the most accessible building material in the region, the two other public buildings designed by Peter Harrison in Newport during the middle decades of the eighteenth century were made of brick. The Touro Synagogue (completed 1763) and the Old Brick Market (completed 1772), both prominent examples of Neo-Palladian design, were also publicly funded buildings and surely under strict budgets, but were still constructed of brick. So why was the Redwood Library—a structure made to protect books constantly at risk of destruction by flames—made of such a flammable material as wood?

What if wood was not a solution to the problem of budgetary constraint or the inaccessibility of stone, but rather a medium of choice, an expression of provinciality, local sourcing, and pride in local craftsmanship? The region’s forests had long been the source

material for the structures that transformed the landscape from rural to urban. Wood defined the city’s sculpted spaces. Post-medieval Jacobean homes (built of wood) were small and compact by design, more easily heated (by wood fires) during the brutal New England winters. These homes, simple by European standards, were no more than variants of Vitruvius’s primitive wooden hut—the structure believed by that father of Roman architecture and his followers to be the theological origin of all built structures thereafter.

Considered in this light, Harrison’s Library becomes an admixture of primitivism and classicism. A conflation of the wooden hut and the ancient temple, this first Neo-Palladian temple-fronted structure in the Americas followed the origins of architecture back to its genesis in Antiquity, linking America’s new and developing body politic with the virtue and lineage of Greek republicanism. This constructive vision was much like the republican vision colonists were then developing for their new country. In matters of politics—and architecture—they referred to age-old problems not in submission to some metropolitan authority or in deference to the wisdom of the ages. Rather, colonists developed their own belief systems based on their experiences in the American landscape. By inheriting cultural values, ideas, attitudes, and assumptions with a critical eye, Americans updated past traditions rather than simply importing them. This innovative, rational vision is exemplified in Harrison’s invention of wooden rustication and its popularization in the colonies.

Born in York, England in 1716, by 1747 Peter Harrison was well versed in wooden designs and constructions, manipulating its material values to achieve his own ends. According to one of his biographers, Harrison trained under the architect William Etty of York.7 But the downturn in England’s economy during the 1730s forced the ambitious but impecunious Peter Harrison and his older brother Joseph to seek advancement at sea. Trained in navigation, charting, and seamanship as a crewmember on his brother’s ship, by the time the architect reached Newport harbor in 1739, he was given command of his own ship. 8 A year later, under the auspices

redwoodlibrary.org 3

Figure 3, The Redwood Library and Athenaeum, designed by Peter Harrison, Newport, Rhode Island, 1747-50.

Figure 4, Saint Paul’s Church at Covent Garden, London, designed by Inigo Jones circa 1630, completed 1633.

Figure 5, Detail of Harrison’s wooden rustication: pine planks carved, painted and sanded to look like stone.

of the Cheapside merchant Joseph Leathley, Harrison was sent to Providence, where a ship was being built for the London merchant. “You’l oblige me,” states an introductory letter from Leathley to the Rhode Island shipyard, “to follow [Peter Harrison’s] Directions in all respects concerning her. Allso the Carver. Capt. Harrison you’l find to be an Ingenious young commander in regard to finishing and adorning a vessel.” 9

So Peter Harrison, a skilled wood carver and captain, built and finished the Leathley of American timber as early as 1740. At the time, ships’ decks would have been painted an ochre color to disguise their age. Camouflaging wooden construction with ochre paint—the same strategy employed on the Redwood Library—was a process of creative masking Harrison would later copy. Ships connoted motion, travel, trade, and exchange in voyages over the Atlantic. Their holds would have carried the architectural pattern books Harrison used to design the Redwood Library. Ships were the vehicles that diffused Neo-Palladianism to the colonies and beyond.

Thus the ships Harrison constructed and commanded were the direct precursors to the design plan he produced for the Redwood Library. With its four columns like masts and its two side wing offices spreading out like great sails, the Library connoted the symbolic and metaphorical form of a ship sailing between two continents. Holding books on topics ranging from Pococke’s 1745 Description of the East to Templeman’s Survey of the Globe and Molls’ Maps, the Library, like a ship, transferred knowledge between old world and new. Transcending the space it contained by embodying the cartographies and geographies of the globe, the Library’s material of American pine became less of an enigma and more of a signifier of place. It is also quite possible—if not probable—that some amount of the Redwood Library’s original timber was made of repurposed ship beams. Americans at Newport reused discarded ship masts for the inner columns of Colony House, completed in 1739-41, a few years before the erection of the Redwood Library several blocks away. (fig. 6).

Marine architecture in fact seems to have inspired more than one land-bound building in Newport. The timbered ceiling of the foursquare Great Friends Meeting House, one of the largest structures in the city during the first half of the eighteenth century, looked uncannily like an inverted ship’s hull (fig. 7). The roof with its rising cupola connected Quaker worshipers to higher spheres of existence with defining verticality, inspiring the “centering down” that helped silent worshippers find the “Inner Light” of god. Like the Redwood Library, the meetinghouse was originally a single, square, room; it was made of local wood, finished, and painted; and it sat on an open expanse of land, separated from adjoining buildings. Harrison, born a Quaker, would have been familiar with the interior of the meetinghouse, just as he was familiar with the sight of an incomplete ship’s frame on the ways. Maritime iconology on land was, therefore, primarily invested in wooden structures, and Newport’s dependence on the Atlantic for trade, subsistence, and connection instilled every part of the local landscape with an oceanic significance.

As a sea captain, Harrison would also have been familiar with the science of navigation, ship handling, plotting, and the use of charts—skills which in turn required a knowledge of design and draftsmanship. Using the stars as a navigational field, eighteenthcentury course-plotting turned vision skyward, an orientation that paralleled the elevating sense of the Redwood Library’s hilltop prospect.

The Librar y’s pyramidal pediment surmounting its square base seems to both diffuse and amplify the vertical, upward force of the building’s façade, an effect seemingly doubled by its uniquely rusticated exterior. Inside the original one-room structure, vision was extended horizontally. On the back wall, a set of three arched Palladian windows looked onto a cultivated landscape and let in light to read by (fig. 8). Their east-facing prospect constructed an ordered vision of Nature. These controlled viewpoints symbolized the vision of enlightened minds who studied in the library. But these interior focal points may have done something more than frame a pleasing bucolic view: their orientation defined a ceremonial use for the building.

According to the founding laws of the Redwood Library Company, all members were bound “to assemble and meet together on the last Wednesday in September in every year” in the “forenoon.”10 Marking the end of the harvest year when the weather began to turn cold, the late September date fell precisely at the autumn equinox, the day when the sun’s path follows the celestial equator, rising directly east and setting directly west. In the morning of the equinox, the company’s annual meeting would have been illuminated by the morning sun coursing through the temple’s east-facing arched windows, giving ritualized form to the acts of enlightenment the building performed.

Presumably, this heliocentric iconology was not accidental. Library members would have been familiar with celestial patterns,

4 etc. Fall 2022

Figure 6, Discarded ship masts reused in the interior columns of the Colony House (completed 1739-41).

taking up the enlightenment banner of astronomical practice. The Company’s original book collection included both Keill’s Introduction to Astronomy and Gregory’s Elements of Astronomy. These were part of an original donation by the wealthy Newport merchant Abraham Redwood for the purposes of “propagating virtue, knowledge, and useful learning.”11 The first shipment of books from London included some 1,338 volumes, including books on astronomy but also theology, law, heraldry and English lineage, classics by Homer, Cicero, Euclid, and Pliny, gardeners’ dictionaries and handbooks of surgery, a history of the Council of Trent, a large collection of maps, treatises on navigation and carpentry, as well as books on classical architecture like Isaac Ware’s translation of Andrea Palladio’s Four Books of Architecture from 1737. Harrison may have wanted to create a stone-fronted temple after reading Palladio, who spoke of Rome, Temples, and rustication in the same breath. His Four Books of Architecture illustrate rustic stone walls referencing the Temple of Augustus. So, in an act of visual magic appropriate to a temple, Harrison made wood chimerical—with a painted covering, it was transfigured into something it was not.

The profusion of woodworkers, furniture makers, and skilled craftsmen in eighteenthcentury Newport provides another dimension of explanation for Harrison’s beveled wood planking on the façade of the Redwood Library. Like the castaway Robinson Crusoe, a novel long in Harrison’s personal library, the architect found himself awash on the provincial Rhode Island with only his understanding of design, familiarity with local materials, and problemsolving capabilities to guide his fashioning of London’s NeoPalladian architecture in the American colonies.12 The novel, first published in 1719, is symptomatic of the larger currents in a world bombarded with increasing globalism—an interest in seafaring adventure, maritime industry, and entrepreneurial creativity. But it was the sense of industrious problem solving which inspired eighteenth-century men such as Harrison to find new ways to unravel old problems.

James Gibbs’s A Book of Architecture, also in Harrison’s library, offered some advice to those craftsmen in want of source materials.

“It is not the Bulk of a Fabrick, the Richness and quality of the Materials, the Multiplicity of Lines, nor the Gaudiness of the Finishing, that gives Beauty or Grandeur to a Building,” Gibbs wrote, “but the Proportion of the Parts to one another and the Whole, whether entirely plain, or encircled with a few Ornaments properly disposed.”13 The material of construction of a Palladian building, it would seem, did not matter as much for the articulation of proper neoclassicism as proportion, balance, and symmetry. Wood, though thought to be inferior to stone, had the power to encapsulate some fission of the age and some sense of the place that any other material would not.

The Redwood Library’s façade thus embodies a certain kind of neoclassical vision—a hopeful, entrepreneurial impulse that connected Newport to an increasingly dynamic and international world. This world, with ships at its vital center, was dominated by an eager mercantilism—the same force that founded the Redwood Library Company in 1747. Abraham Redwood “bestow[ed] five hundred pounds sterling to be laid out in a collection of useful books suitable for a Public Library,” a book collection for “propagating virtue, knowledge, and useful learning.” The Company’s founding Charter granted the society the power, by law, to tax; to “give, grant, let, sell, or assign the same lands, tenements, hereditaments, goods, and chattels;” to sue, and be sued, and to “defend and be defend against” in any court of law.14 The Company was founded as a body with the power of a mercantile guild, invested with the legal and financial rights endowed in the republican contract between citizen and ruler.

The Company of the Redwood Library was a literary society modeled off the foundational ideals of colonial charters—it was made to be a government in miniature. The voting body of the society, who could “limit and appoint their trust and authority,” regulated the positions of the Directors, a treasurer, librarian, and secretary. Laws were enacted to admit new members and “to do all the things concerning the government, estates, goods, lands, and revenues, and also all the business and affairs” of the Company.

In its foundational contract, then, The Company of the Redwood Library was invested with a certain degree of economic, legal, and intellectual symmetry, propagating the ethos of knowledge and the power of learning in language that was fundamentally classical in nature. The Company needed a building to match these foundations. Its façade should be classical in design—the exterior making public the kind of inner order and symmetry founded in the structured outline of the society’s contract. The architectural plan for the Redwood Library was, therefore, not only in line with the order of the society it served: it also became an icon for a blossoming culture of republicanism in the decades leading up to the Revolution.

Harrison’s Neo-Palladian design for the Redwood Library, then, was a harbinger of the impacts revolutionary ideals of republicanism would have on the architectural style employed to represent a newfound body politic. A certain spirit of invention and enterprise influenced his vision for the Newport Library: this was an upward vision that also looked forward. And the architect’s alchemical problem solving—his invention of wood rustication imitating stone—was a symptom of a much larger paradigm shift in the cultural thinking of Americans. Harrison’s introduction of Palladianism into the visual nomenclature of the colonies became a

redwoodlibrary.org 5

Figure 7, The Great Friends Meeting House, Newport, Rhode Island. The original building was opened in 1699. Courtesy the Newport Historical Society

The Company of the Redwood Library was a literary society modeled off the foundational ideals of colonial charters—it was made to be a government in miniature.

foundation in the construction of fields as diverse as mercantilism, politics, and architectural design. Symbolic of formational new plans for a republic based on classical designs, Harrison’s beveled wood paneling was a solution to the problem of reinterpreting old forms in a new world.

1 C.M. Andrews, ed., Some Cursory Remarks made by James Birket in his Voyage to North America, 1750-51 (New Haven, 1916), 30.

2 For a complete account of the Library’s original book collection, see Marcus A. McCorison, The 1764 Catalogue of the Redwood Library Company At Newport, Rhode Island (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1965).

3 Andrea Palladio, Andrea Palladio’s Architecture, In Four Books Containing a Dissertation On the Five Orders & Ye Most Necessary Observations Relating to All Kinds of Building. ... The Whole Containing 226 Folio Copper Plates Carefully Revis’d and Redelineated by Edwd. Hoppus (London: printed for & sold by the proprietor & engraver, Benjamin Cole, 1735), 186-87. For Palladio, a temple should be erected “in the highest places,” and “in the most noble and most populous Parts of the City, as distant as possible from unseemly or scandalous Places, and adjoining to beautiful Squares, or other open Places, where several Streets meet. So too, “the Floor of the Temple must be elevated above the Level of the other Edifice, as much as possibly can be; so that the Ascent will consist of divers Steps, which sets off the Majesty of a Church, and begets greater Devotion.”

4 Patrick M’Robert and Carl Bridenbaugh, A Tour Through Part of the Northern Provinces of America: Being a Series of Letters Wrote On the Spot, In the Years 1774 & 1775; to Which Are Annex’d, Tables, Shewing the Roads, the Value of Coins, Rates of Stages, &c. (Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1935), 13.

5 Two extant examples of buildings with rusticated wood facades in Newport include the Buliod-Perry House and the Vernon House.

6 James L. Yarnall, Newport Through Its Architecture: A History of Styles From Postmedieval to Postmodern (Newport, RI: Salve Regina University Press in association with University Press of New England, Hanover and London, 2005), 19.

7 John Fitzhugh Millar, The Buildings of Peter Harrison: Cataloguing the Work of the First Global Architect, 1716-1775 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2014), 10.

8 John Banister, Newport merchant, “immediately gave him the Command of a Ship…[and] Sent him home with Such Recommendations to his Principle owner that he directed me to Sett up a Larger vessel, about 300 Tons. And this Mr. Peter came over to Command her.” Banister letter book, 1739, as quoted in Bridenbaugh, Peter Harrison, 10.

9 Banister letter book, 1739, as quoted in Bridenbaugh, Peter Harrison 11.

10 Ezra Stiles, Laws of the Redwood-Library Company (Newport, RI: Samuel Hall, 1765), 32.

11 Charter of the Redwood Library Company: Granted A.D. 1747 (Newport, RI: Rousmaniere & Barber, 1816).

12 “Peter Harrison’s Library (1775 inventory),” in Bridenbaugh, Peter Harrison, 164-167.

13 James Gibbs, A Book of Architecture: Containing Designs of Buildings and Ornaments (London, 1728), i-ii.

14 Charter of the Redwood Library Company: Granted A.D. 1747 (Newport, RI: Rousmaniere & Barber, 1816).

Caroline Culp is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Art History at Vassar College. She is a scholar of American art and recently completed her doctoral dissertation on the colonial American portraitist John Singleton Copley (1738-1815) at Stanford University.

6 etc. Fall 2022

Figure 8, The rear façade of the Redwood Library’s original structure, which originally faced east onto a grassy, tree-lined expanse, was shifted piecemeal in a nineteenth-century expansion. The three Palladian windows flanked by recessed Ionic columns now face south.

Treasures of the Redwood : Celebrating 275 Years

Conceived to service Southern New England as the third touchstone center of Colonial learning alongside Harvard and Yale, the Redwood Library—and later Athenaeum (1836)—has for all times embodied Newporters’ aspirations to make theirs a city of culture as well as of commerce and leisure. From the beginning therefore, with its initial book collection comprised of shareholder collections and concerted acquisitions, the Redwood’s holdings were shaped by individuals at the same time that they in turn shaped a distinct profile for the city. As described by one period source, the Library “rendered the inhabitants of Newport, if not a learned, yet a better read, and inquisitive people, than any other town in the British colonies.”

The resulting collections thus reflect both individual tastes and a sort of aggregate autobiography of the city itself. And while one might imagine that a ‘treasure house’ constituted over 275 years by a multitude of donors—some famous and many unknown— might yield a disparate group of oddities, certain distinct areas of excellence have coalesced naturally. Beginning with the supremely rare documentation of the early Library itself, the Redwood holds a singular but coherent—and still expanding—inventory: masterpiece Colonial portraits, signal volumes of the French Rococo, the rarest published materials of early modern decorative arts and architecture, and the life’s work of Newport portraitist Charles Bird King.

But more than an expression of Newport’s enduring devotion to learning and refinement, or its fondness for aesthetic pleasure and evocative beauty, the character of this unique assemblage reinscribes the Redwood’s eternal commitment to civic engagement—as a municipal resource for cultural enrichment with no greater objective than “the good of mankind.”

Manuscript

Map of the City and Harbor of Newport, August 9, 1758 Ezra Stiles (1727-1795)

Meeting Minutes of the Company of the Redwood Library, 1747-1848. First Meeting of the Company of the Redwood Library, 1747.

From the Redwood Library Archives

“At a meeting of the Company of the Redwood Library, in the Council Chamber at Newport, the last Wednesday of September, 1747. This being the first meeting of the Company since their Incorporation, the Charter was publicly read. It is agreed by the Company that the Directors shall be eight in number and any five of them constitute a quorum. This day being the anniversary for electing Directors, etc., according to the Company’s Charter, the following gentlemen were chosen to the respective offices ascribed to their names: Directors for the Year Ensuing:

Abraham Redwood, Esq.

The Rev. Mr. Honyman

The Rev. Mr. Callender

Mr. Henry Collins

Edward Scott, Esq.

Samuel Wickham, Esq.

Capt. John Tillinghast

Peter Bours, Esq.

Capt. Joseph Jacob – Treasurer

Edward Scott, Esq.- Librarian

Thomas Ward – Secretary

The Company agree to meet again the 7th of October at 3 o’clock afternoon.”

redwoodlibrary.org 7

Catalog Photos: Hansen Photography

A Catalogue of the Books belonging to the Company of the Redwood Library in Newport on Rhode Island A.D. 1750. Manuscript Catalog of the Redwood Library, 1750-1764.

From the Redwood Library Archives “Books bought in London by John Thomlinson, Esq. with the Five Hundred Pounds Sterling given by Abraham Redwood, Esq. to the Company of the Redwood Library.” When the Redwood Library was chartered in 1747, Abraham Redwood donated five hundred pounds sterling for the purchase of “a collection of useful books suitable for a Public Library.” The Directors prepared a list of titles in 1748 and sent John Thomlinson to London to act as their agent in purchasing the collection. He returned with 751 titles, documented in this manuscript catalog and ordered by size. The titles in the Original Collection include works on history, geography, medicine, religion, the arts, the classics, cider making and even beekeeping.

Receipt Book of the Company of the Redwood Library, 1757. Receipt Book beginning April 21, 1757.

From the Redwood Library Archives

“I PROMISE to pay to Ezra Stiles or his Order, the Sum of Fifty Pounds for Value received. Nevertheless, if within four Weeks from the Date hereof, I return undefaced to the said Ezra a Book belonging to the REDWOOD LIBRARY COMPANY, entituled, Prideaux’ Connexion V. 1 Folio, which I have borrowed of him, this Bill is to be void. WITNESS my Hand, the 21st Day of April A.D. 1757. [NAME REMOVED]”

At a meeting of the Company of the Redwood Library held on March 15, 1750, the Directors presented the Body of Laws they had drawn up for the governing of the library. These laws included the rule that “any member may borrow any one, and but one book at one time, and for one month, or less… giving a note to the Librarian to the value of the book fixed in the Catalogue as security for its being returned in the same good condition.” When borrowers returned the books to the library, or paid the required fee for its damage, the librarian tore their names out of the receipt book.

8 etc. Fall 2022

Self-Portrait at 24 (1778)

Gilbert Stuart (American, 1755-1828)

Oil paint on canvas

Bequest of Louisa Lee Waterhouse

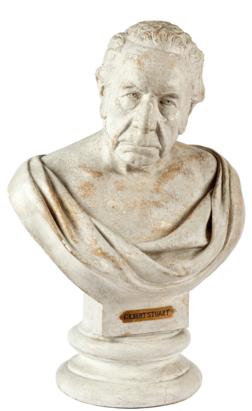

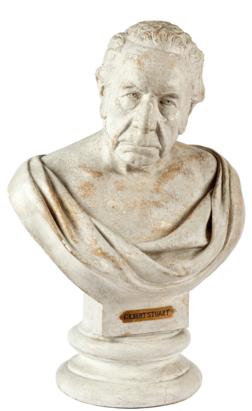

Gilbert Stuart (1825) John Henri Isaac Browere (American, 1792-1834)

Plaster Gift of David King

redwoodlibrary.org 9

John Banister (c. 1775)

Gilbert Stuart (American, 1755-1828)

Oil paint on canvas Gift of David Melville

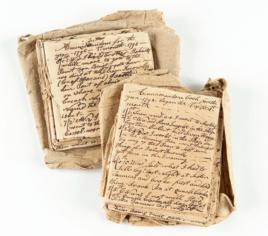

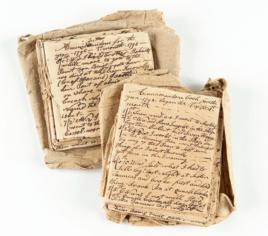

Nailer Tom’s Diary (1778-1840)

Thomas Benjamin Hazard (1756-1845)

Thomas Benjamin “Nailer Tom” Hazard was the son of Benjamin Hazard and Mehitable Redwood, daughter of Abraham Redwood. His diaries contain references to over 6100 people, including a mention of General George Washington in his 1781 visit to Newport.

Christian Banister and Son (c. 1774-1775)

Gilbert Stuart (American, 1755-1828)

Oil paint on canvas Gift of David Melville

Card Table (c. 1760)

Attributed to John Townsend (American, 1732-1809) Mahogany, pine, and maple Gift of Ellen Townsend

10 etc. Fall 2022

A Compleat Treatise on Perspective, in Theory and Practice; on the True Principles of Dr. Brook Taylor. Made Clear, in Theory, by Various Moveable Schemes, and Diagrams… 2 vol.; text & plates Thomas Malton (1726-1807). (London: Printed for the author, 1776)

Gift of Jane Stuart

Inscription on front pastedown: “This book was purchased by Gilbert Stuart, for his daughter, Miss Jane Stuart, as the best book on this subject at that time.”

William Claggett, Tall Case Clock (ca. 1740)

Tombstone dial with a moon phase disk in the arch and four subsidiary dials in the corners. The movement chimes the quarter hours on six bells. The dial indicates an extraordinary, ten functions: the hour, minute, second, day of the week, phase of the moon, date of the lunar month, date of the month, month of the year with the number of days in each, hour of high tide, and a switch to silence the bells.

A pine case with japanned surface. It seems that there were no active japanners in Newport at the time that this clock was produced, so Claggett turned to skilled Boston craftsmen for a clock case made in the latest fashion for his client. Only a few eighteenth century American clock cases survive with their original japanned surfaces. The combination of original japanned case and complicated, quarter chiming movement elevate this clock to the apex of early American clockmaking.

History of early ownership with John Stanton (1730-1782) of Newport. Descended in the Stanton family to Reverend, Samuel Gavitt Babcock (1851-1938). Purchased by the Redwood Library & Athenæum in 1948.

redwoodlibrary.org 11

Palladianism in Early America: the Architecture of Freedom

It was perceptions of Greco-Roman Republicanism prevailing in the Colonies that drew the Founders to Palladianism, the architectural style inspired by the designs of Renaissance Venetian architect Andrea Palladio (1508-1580). Benjamin Franklin, speaking in general terms, evoked this exact politically-infused parallel: “Government is aptly compared to architecture; if the superstructure is too heavy for the foundation the building totters.” Thomas Jefferson, for his part, referred to Palladio as “a god,” going on to design Monticello and the University of Virginia under his influence while channeling the Redwood’s front facade.

And so it was no accident that the Redwood’s Original Collection contained Isaac Ware’s translation of Palladio’s Four Books of Architecture, especially since Redwood architect Peter Harrison’s own book collection contained multiple volumes treating Palladian architecture. Palladianism’s characteristic balanced and ordered designs thus came to signify both a greater openness and social stability, at the same time that they formed actual spaces—like the Redwood Library—for public assembly and free expression.

Benjamin Franklin (c. 1778)

Jean Antoine Houdon (French, 1741-1828)

Tinted plaster

Gift of Mr. & Mrs. Verner Z. Reed

12 etc. Fall 2022

Thomas Jefferson (n.d.) Charles Bird King (American, 1785-1862) Oil paint on panel Bequest of Charles Bird King

Books and significant authors—and patrons—played a preponderant role in the creation and diffusion of the purified British Palladian style that predominated in the American colonies. Beginning with Colen Campbell’s Vitruvius Brittanicus (1715-1725), which codified the British variant in England, an entire industry of Palladian books made their way to America and into libraries such as Redwood architect Peter Harrison’s and the Redwood’s own Original Collection.

The collection inc ludes a presentation copy—gifted to the poet Alexander Pope by the Earl of Burlington, the “architect earl” who spearheaded the eighteenth-century Palladian revival in Britain—of Isaac Ware’s edition of the designs of seventeenthcentury architect Inigo Jones, the pivotal figure who first brought knowledge of Palladio’s architecture to Britain. A sumptuous example of Edward Hoppus’s hugely influential translation of Palladio’s Architecture in Four Books is a book owned by Redwood architect Peter Harrison, who derived the Library’s façade directly from it.

If Palladio’s designs could be issued in sumptuous volumes or, as the Ware book, as privately printed collector’s editions, many were more humble productions of more practical usage.

The First Book of Architecture by Andrea Palladio. Andrea Palladio (1508-1580). Translated by Godfrey Richards. Designs by Pierre Le Muet (1591-1669). (London: Printed for H. Tracy, 1721).

Purchase funded by Marion Oates Charles

The Mirror of Architecture: or The Ground-Rules of the Art of Building, Exactly Laid Down by Vincent Scamozzi, Master-Builder of Venice…

Vincenzo Scamozzi (1548-1616), Joachim Schuym, W. Fisher (translator), and John Brown, Philomath. (London: W. Fisher, 1676).

The Ground-Rules of Architecture Collected from the Best Authors and Examples by that Learned and Ingenious Gentleman Sir Henry Wotton…

Sir Henry Wotton (1568-1639). (London: W. Fisher, 1670).

The Mirror of Architecture & The Ground-Rules of Architecture are bound together

Purchased with funds given by the B.H. Breslauer Foundation

redwoodlibrary.org 13

Designs of Inigo Jones and Others. Isaac Ware (d. 1766) and P. Fourdrinier (engravings, fl. 1720-1760) Designs by Inigo Jones (1573-1652), William Kent (1685-1748), and Burlington, Richard Boyle, Earl of (1694-1753). (London: I. Ware, 1735). Formerly owned by Alexander Pope (16881744).

Gift of Guy F. Cary; Cynthia Cary Collection Inscription on leaf: “A. Pope. Given me by the Earl of Burlington”

14 etc. Fall 2022

The Greenough Collection of Early Modern Illustrated Books:

The seed of the Greenough Collection can be traced back to the Francophile New York Beaux-Arts architect Whitney Warren (1864-1943), who amassed a fine collection of significant French early modern illustrated books. The collection was passed on to, and enriched by, his daughter Charlotte Warren Greenough (1885-1957)—herself a bibliophile Board member of the Redwood Library—and in turn to her own daughter Beatrice Goelet Greenough (1908-1984), who bequeathed it to the Redwood in 1961. Numbering over two hundred titles, the collection features a slew of rare festival and illustrated books, with a particular strength in works from the French eighteenth century.

Charlotte Warren Greenough (c. 1902)

Paul César Helleu (French, 1859-1927) Dry point etching Gift of Beatrice Greenough

par... Gabriel Huquier.

Gabriel Huquier (1695-1772) after Gilles-Marie Oppenord (1672-1742). (Paris: Chez Huquier, ca. 1748-1751). Gift of Beatrice Greenough

Large folios composed of high art prints came to their full flower as highly fashionable items around 1700 in France. Aimed at an international network of noble and moneyed connoisseurs, these monumental works, and a slew of smaller-sized variations, satisfied a vogue for ornament prints, at the same time that they promulgated French taste and France itself as the period’s predominant country in the realm of printmaking.

Presented here are two of the most important books by the two greatest exponents of the French Rococo style, the signature organic motifs of which had an enduring influence that remains to this day. At left is an exceptionally preserved example of Gille-Marie Oppenord’s posthumous opus, which documented his adaptations of Italian Baroque elements to major architectural commissions in Regency Paris. Below is a rare compilation of suites of ornament prints by Jacques de Lajoüe. The plate shown exemplifies Lajoüe’s blend of the fantastic and the mystical: here the lightly delineated triangle surrounded by rays of light presumably references the Eye of Providence or Freemasonry.

Livre de Buffets

Gabriel Huquier (16951772) after Jacques de Lajoüe (1686-1761). (Paris: Chez Huquier, ca.1750).

Gift of Beatrice Greenough

redwoodlibrary.org 15

Oeuvres de Gille Marie Oppenord Contenant Différents Fragments d’Architecture et d’Ornements…

Il Mondo Festeggiante: Balletto a Cavallo, Fatto nel Teatro Congiunto al Palazzo de Sereniss… Attributed to Alessandro Carducci & Alessandro Segni (original prose), Giovanni Andrew Moniglia (verses, 16241700), Stefano della Bella (engravings, 16101664). Florence: Nella Stamperia di S.A.S., 1661 Gift of Beatrice Greenough

Battaglia Navale Rapp. in Arno per le Nozze del Sermo Principe di Tosc. lan: 1608.

Andromède Tragédie, Représentée avec les Machines sur le Théâtre Royal de Bourbon.

Pierre Corneille (1606-1684). Engravings by François Chauveau (1620-1676) after Giacomo Torelli (1608-1678). (Paris: ca. 1650). Gift of Beatrice Greenough

Engravings by Remigio Gallina (ca.1582-130) after designs of Giulio Parigi, Lodovico Cardi & Jacopo Ligoza. (Florence: ca. 1608). Gift of Beatrice Greenough

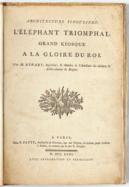

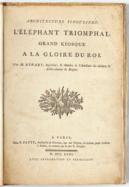

Architecture Singuliere: L’Éléphant Triomphal. Grand Kiosque à la Gloire du Roi…

Charles François Ribart. (Paris: Chez P. Patte, architecte & graveur, 1758).

Originating in Renaissance Italy, and combining music, costume, theater, as well as painting and engineering, festivals were ephemeral staged-managed projections of power well served by the permanence and greater diffusion of the illustrated book.

Carducci’s account—illustrated by Stefano della Bella— is of Cosimo III’s 1661 marriage to Marguerite Luisa d’Orleans in the Boboli gardens, which took the form of an equestrian pageant. At the upper right is a book produced by the painter Lodovico Cardi (Cigoli) illustrated the mock naval battles on the Arno river enacted in celebration of Cosimo Il de’Medici 1608 wedding. Directly above is an example of a sub-category of festival books: those depicting Royal theatre, in this case Pierre Corneille’s Andromède The book is especially significant for the six engravings by Chauveau depicting the elaborate, machine-driven set designs by Giacomo Torelli. At right is Pierre Patte’s publication of Ribart’s extravagant 1748 project in honor of Louis XV showing a gigantic elephant containing decorated rooms, conceived to be placed at the top of the elevated hill of the Étoile, where the Arc de Triomphe now stands.

Gift of Beatrice Greenough

16 etc. Fall 2022

Contes et Nouvelles en Vers, 2 vol. Jean de La Fontaine (1621-1695). (Amsterdam: 1764). Purchased as a supplement to the Greenough Collection

It could be said that no period or country was ever more preoccupied with books and imagery than eighteenth-century France, where the so-called ‘Republic of Letters’ reflected the searching explorations of the Enlightenment while ushering in the frenetic pace, variety, and merchandizing of today’s publishing landscape.

The books presented reflect the era’s wide range of subjects, formats, and intent: The architect Blondel’s famous treatise aimed to inculcate his view of the ideal Louis XV-style chateau to wealthy consumers, exemplified in the rare publisher’s boards; A rare scrapbook of 21 plates after Fragonard epitomizes the titillating gallantry so prized by aesthetes; the rare Amsterdam edition of Jean de la Fontaine’s Tales and Novelties, with masterpiece illustrations engraved by the great Charles-Dominique Eisen, is a work widely held to be one of the finest illustrated books of the period. The highly sought-after Le Mire edition of Montesquieu’s The Temple of Gnide is another summit of French book illustration featuring Eisen. Proof that fine art illustrations could effectively lend themselves to the more serious purpose of reportage and propaganda is an editioned collection of sixteen engravings by N. Ponce and F. Godefroy detailing the war of American independence.

De la Distribution des Maisons de Plaisance, et de la Decoration des Edifices en General…

[Volumes 1 & 2]

Jacques-François Blondel (1705-1774).

(Paris: Chez Charles-Antoine Jombert Libraire du Roy, 1737-1738).

Gift of Beatrice Greenough

redwoodlibrary.org 17

Contes de La Fontaine, Suite. Scrapbook of 21 plates. after Jean Honoré Fragonard (1762-1806). Gift of Beatrice Greenough

Collection d’Estampes Representant les Evénements de la Guerre, pour la Liberté de l’Amerique Septentrionale. Nicolas Ponce (1746-1831). (Paris: Chez F. Godefroy et Chez N. Ponce, 1784).

Gift of Beatrice Greenough

Le Temple de Gnide avec Figures Gravées par N. Le Mire… Noel Le Mire (1724-1801) after designs by Charles Eisen (1720-1778). (Paris: Chez Le Mire, graveur, 1772).

Purchased as a supplement to the Greenough Collection

18 etc. Fall 2022

The Cary Collection of Ornament and Pattern Books:

Gathered by the socialite Cynthia Roche Cary (1884-1966) with the assistance of her husband Guy Fairfax Cary (1879-1950), and bequeathed to the Redwood by Guy Fairfax Cary, Jr. (1923-2004), the Cary collection gathers together a world-class assemblage of English and Continental books, pamphlets, and engraving suites devoted to furniture, decoration, and ornament from the late-fifteenth to the mid-nineteenth century. It forms one of the high points of the Redwood’s holdings, containing many unique materials, as well as rarities that haven’t appeared on the market since the early twentiethcentury, and which are only now held in major institutional collections.

Comparatively early ornament books such as those shown below emerged at the intersection of artisanal engraving and the nascent modern book trade that came to full flower in the eighteenth century.

Robert Pricke, for example, the author of the extremely rare first volumes at left and center, trained as an engraver before becoming a bookseller supplying architects and craftsmen with Continental prints and books. His books thus tend towards decorative presentation. But their real impact was as conduits for the mannerist aesthetic then favored by English builders and craftsmen. Likewise, Simon Gribelin, below at right, one of the very greatest illustrators of the period, aimed his books at watchmakers and silversmiths, and the superb quality of his designs betray his own skills as a known engraver of watchcases, plate, and decorative salvers.

redwoodlibrary.org 19

Cynthia Roche Cary ca. 1920

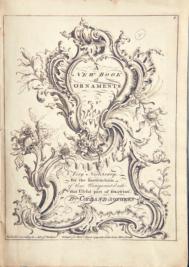

A New Book of Ornaments with Twelve Leaves. Consisting of Chimneys, Sconces, Tables, Spandle Pannels, Spring Clock Cases, & Stands… Matthias Lock and Henry Copland. (London: Publish’d according to act of Parliamt., 1752).

Gift of Guy F. Cary; Cynthia Cary Collection

Eighteenth-century England was a high point of ornament and pattern book production, spurred by a growing public of print collectors and bibliophiles, an expanding category of craftsmen that relied on their utility to service upwardly mobile consumers, and fed by a nascent modern publishing industry that supplied them all with a profusion of prints, suites of designs and instructive books.

The volumes presented here offer a selection of examples that make clear their role in the international transmission of styles— notably by taste-making collectors—as well as the adaptability of their usage, given that most were used by a wide range of architects, designers, furniture makers, carvers and decorative craftsmen.

A rare pamphlet epitomizes the British anxiety over proper training for native craftsmen—through drawing—to better rival the French, at a time when the English were readily absorbing the French rococo style. Also shown are the most ambitious publications by Matthias Lock, a master carver affiliated with Thomas Chippendale, who was the first Englishman to publish designs in the rococo style. The extremely rare book of Chinese designs by Matthias Darly capitalized on the fashion for the exotic to present itself as a useful source to supply architects with “the graceful addition of ornament.”

Prints produced by Lock and their distinctive sketch-like etching style placed the works in the realm of print collecting. The supremely rare New Book of Designs.. by Benedetto Pastorini, known in only two examples, betrays a movement away from French exuberance towards a more classicizing idiom redolent of antique grotesques.

A Drawing Book of Ornament. Matthias Lock. (London: 1743).

A New Book of Ornaments Henry Copland. (London: Copland, 1746).

A Drawing Book of Ornament & A New Book of Ornaments are bound together

Gift of Guy F. Cary; Cynthia Cary Collection

20 etc. Fall 2022

A New Book of Ornaments for Looking Glass Frames, Chimney Pieces &c. In the Chinese Taste… Matthias Lock. (London: Printed for Robt. Sayer, between 1755 and 1774).

Gift of Guy F. Cary; Cynthia Cary Collection

A New Book of Ornaments: Very Necessary for the Instruction of Those Unacquainted with that Useful Part of Drawing

Henry Copland. (London: Publish’d according to act of Parliamt. printed for Robt. Sayer, ca. 1750).

Gift of Guy F. Cary; Cynthia Cary Collection

A New Book of Designs for Girandoles and Glass Frames in the Present Taste.

Benedetto Pastorini (1746-after 1804). (London: I. Taylor, 1775).

Purchased as a supplement to the Cynthia Cary Collection

redwoodlibrary.org 21

Pattern and ornament books were perceived differently by their varied users. Whether aesthetic objects aimed at collectors, utilitarian repertories of models for craftsmen, or vehicles of artistic expression for a range of designers, they nonetheless for all times contained an element of commercial promotion. This

increased with the rising popular consumerism beginning in the late eighteenth century.

The examples shown here betray the fluid divide between art book and trade catalog that could be contained in a single volume.

A Sample Book of English Fancy-Chair Decoration (ca. 1800)

Gift of Guy F. Cary; Cynthia Cary Collection

Heytsebury Bills for Furniture & Receipts from 1782 to 1787 (London: firm of Ince & Mayhew, 1782-1787)

Gift of Guy F. Cary; Cynthia Cary Collection

22 etc. Fall 2022

Motifs

de Décoration Moderne: Reproduction des carton et poncis de Charles Polisch Peintre-Decorateur

Charles Claesen after Charles Polisch. (Paris: C. Claesen, 1886).

Purchased as a supplement to the Cynthia Cary Collection

Maquette Drawing for Interior Decoration (ca. 1875) Charles Polisch (French)

redwoodlibrary.org 23

24 etc. Fall 2022

Maquette Drawing for Interior Decoration (ca. 1875) Charles Polisch (French)

Charles Bird King: Portraitist and Benefactor

Few can claim a closer relationship to the Redwood than Newport portraitist Charles Bird King (1785-1862), who all his life found intellectual sustenance at the Library. This intellectual debt is acknowledged below the self-portrait at right: “Attributing much of his success in life to an early taste in Literature and Art, cultivated within the walls of this Library.”

King became among the most highly regarded portraitists of the Federal period. John Quincy Adams, writing in 1819, declared

King “..one of the best Portrait Painters in this country.” The selfportrait below exemplifies King’s portrait style: spare details, muted colors, and piercing characterizations.

King repaid the Redwood with “successive donations,” which not only enriched the Library, but also spurred a reshaping of its premises. It was because of King’s donations that Library Directors undertook to build the Delivery Room addition in 1875, the first art gallery in Rhode Island.

Self-Portrait at 70 (c. 1856)

Charles Bird King (American, 1785-1862)

Oil paint on canvas Bequest of Charles Bird King

Self-Portrait at 30 (c. 1815)

Charles Bird King (American, 1785-1862)

Oil paint on canvas

Bequest of Charles Bird King

redwoodlibrary.org 25

The Scrapbooks

of Charles Bird King (ca. 1810-1862)

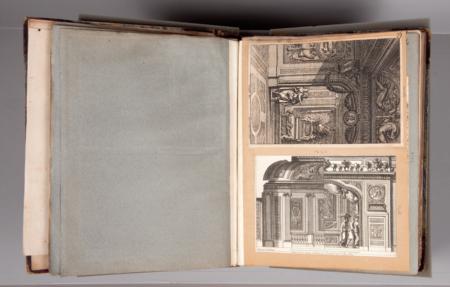

Consisting of seventeen volumes of engravings of various sizes, from large quarto to folio, King’s scrapbooks include more than 1,100 prints and a handful of drawings. The scrapbooks represent a lifetime of collecting, comprising a huge variety of images which served as models and memory aids. It is for this reason that the scrapbooks are roughly arranged in subject orders such as landscapes or figures.

The variety—and relative value—of the prints vary wildly: mannerist prints, classical buildings or Dutch tavern scenes etc. Likewise, the albums contain examples of many graphic techniques: etchings, line engravings, lithographs. Among this mass are pieces by some of the greatest printmakers in art history: etchings by Rembrandt; a woodcut by Dürer, and the counterproof by Jean-Honoré Fragonard.

26 etc. Fall 2022

Italianate Landscape (1761)

Jean-Honoré Fragonard (French, 1732-1806)

From one of the scrapbooks of Charles Bird King Red chalk

Gift of Charles Bird King

Perhaps the most unexpected work found in King’s scrapbooks is this red chalk counterproof depicting an Italianate villa by Frenchman Jean-Honoré Fragonard. Counterproofs are made by moistening a chalk drawing and covering it with a blank sheet, the whole then run through a press to produce a mirror image (counterproof). The Redwood’s piece relates directly to a series of red chalk drawings depicting an Italian villa and garden Fragonard made in 1761, as he passed through the Veneto on his way back to Paris from Rome. We can only speculate if King recognized it as a Fragonard: it is nestled among a profusion of architectural images and landscape views. Certainly, King appreciated its subtle tonalities and evocative scenery enough to have mounted it in his album. According to Marjorie B. Cohn and Eunice Williams it is “completely unprecedented in a print compilation made in America prior to the civil war.”

redwoodlibrary.org 27

EXHIBITIONS AT THE REDWOOD

COMING SOON

Treasures of the Redwood: Celebrating 275 Years

In celebration of its 275th year, this exhibition brings forth a rich selection of some of the Redwood’s unparalleled holdings, gathered over nearly three centuries of collecting and donations. Starting with rare, annotated works from the Original Collection, to a range of eighteenth-century materials, such as the famous Stiles map, period portraits and sculptures, manuscripts, furniture and artifacts. Also featured are supremely rare works from the Cary collection of pattern and decorative art books, as well as the private notebooks of American portraitist Charles Bird King, a cache of rare French decorative drawings, and a range of books only known in a single copy from the Redwood.

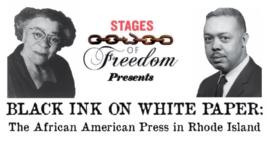

Showing now through March 5, 2023 Van Alen Gallery

“Black Ink on White Paper: The African American Press in Rhode Island” The Black Press in Rhode Island is a remarkable, yet virtually unknown history. In 1857 we find Alexander P. Niger, an accomplished typesetter, in the Providence print shop of A. C. Greene. In 1860, the first African American newspaper, Rev. George W. Hamblin’s L’Overture, begins publication. In 1906, John Carter Minkins becomes the nation’s first Black editor of an all-white newspaper, the NewsDemocrat, starting what will become a seventy-year career in Rhode Island media. In 1950, the Providence Journal hires its first Black reporter, James N. Rhea, who remains for thirty-three challenging years, writing on the plight of African Americans locally and nationally, and winning a Pulitzer for doing so. 1968 through 2018 is the longest stretch of Black publications in the state, with six different newspapers coming and going, and for the most part creating a continuous pipeline of information for and about the Black community.

Opening October 28, 2022 Rovensky Room

Funded by Herman H. Rose Media Access Fund and the Rhode Island Council for the Humanities

28 etc. Fall 2022

Back cover graphic: Fleming + Company

Join us in Honoring the Past and Celebrating the Future Become a Redwood Member redwoodlibrary.org/membership Tel: 401.847.0292 x 115

Nailer Tom’s Diary (1778-1840) Thomas Benjamin Hazard (1756-1845)

Photo: Kevin Dacey

Nailer Tom’s Diary (1778-1840) Thomas Benjamin Hazard (1756-1845)

Photo: Kevin Dacey

4 etc. Summer 2022 www.redwoodlibrary.org

From Redwood Library & Athenæum charter, 1747

Nailer Tom’s Diary (1778-1840) Thomas Benjamin Hazard (1756-1845)

Photo: Kevin Dacey

Nailer Tom’s Diary (1778-1840) Thomas Benjamin Hazard (1756-1845)

Photo: Kevin Dacey