BLUEPRINTS IN SOUND

Welcome to the 2025 Great Lakes Chamber Music Festival!

Each June, our community of artists and audiences comes together to explore the boundless world of chamber music. This year’s theme, Blueprints in Sound, invites us to discover the foundations and frameworks that shape music across centuries. From the architectural beauty of classical forms to bold contemporary designs, we examine how composers build sonic worlds—and how performers bring them to life.

I am thrilled to collaborate with the extraordinary musicians and composers who join us this season. Their artistry and imagination breathe new energy into each performance, turning every concert into a shared journey of discovery.

Thank you for being part of this Festival. Whether you are a long-time supporter or joining us for the first time, your presence helps create the vibrant spirit that

ARTISTIC DIRECTOR

Paul Watkins

ARTISTIC DIRECTOR EMERITUS

James Tocco

SHOUSE INSTITUTE DIRECTOR

Philip Setzer

CHAIRS

Virginia & Michael Geheb, Board Chairs

Marguerite Munson Lentz

Janelle McCammon & Raymond Rosenfeld

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Kathleen Block

Nicole Braddock

Cathleen Corken

Christine Goerke

Robert D. Heuer

Judith Greenstone Miller

Gail & Ira Mondry

Bridget & Michael Morin

Frederick Morsches & Kareem George

Sandi & Claude Reitelman

Randolph Schein

Lauren Smith

Jill & Steven Stone

Rev. Msgr. Anthony Tocco

Michael Turala

Gwen & S. Evan Weiner

EX-OFFICIO MEMBERS

Fr. Mark Brauer

Rev. Edwin Estevez

Mitchell Garcia

Cantor Rachel Gottlieb Kalmowitz

Rabbi Mark Miller

Maury Okun

TRUSTEE ADVISORY COMMITTEE

Cecilia Benner

Linda & Maurice Binkow

Cindy & Harold Daitch

Lillian Dean

Nathalie Doucet

Afa Dworkin

Adrienne & Herschel Fink

Jackie Paige-Fischer & David Fischer

Barbara & Paul Goodman

Barbara Heller

Fay B. Herman

William Hulsker & Aris Urbanes

Rayna Kogan

Yuki Mack

Martha Pleiss

Kristin Ross

Franziska Schoenfeld

Marc A. Schwartz

Josette Silver

Isabel & Lawrence Smith

Kimberley & Victor Talia

James Tocco

Beverly & Barry Williams

ARTOPS STAFF

Administration

Maury Okun, President & CEO

Jennifer Laredo Watkins, Director of Artistic Planning

Community Engagement

Jainelle Robinson, PR/Community Engagement Officer

Development

Jocelyn Conselva, Director of Development

Allison Prost, Development Associate

Allison Wamser, Patron Engagement Associate

Muse Ye, Institutional Giving Manager

Marketing

Bridget Favre, Director of Marketing

Layla Blahnik-Thoune, Multimedia Marketing Associate

Lauren Cichocki, Marketing Associate

Olivia Donnel, Marketing Associate

Shelby Alexander, Marketing Intern

Since late 2016, Virginia and Michael Geheb have led the Festival with vision, generosity, and dedication. Their leadership has guided a period of growth, artistic excellence, and community connection. We are deeply grateful for their years of service as Board Co-chairs.

Please join us in welcoming our new Board Co-chairs: Cathleen Corken, Marguerite Munson Lentz, and Gwen Weiner.

Operations

Nolan Cardenas, Artistic Operations Manager

Lane Warren, Operations Associate

Alexander Lee, Operations Intern

Finance

Triet Huynh, Controller

Phuong Huynh, Finance Assistant

Client Liaison

Lulu Fall, Cabaret 313 Executive Director

FOUNDING MEMBERS

Wendy & Howard Allenberg

Kathleen & Joseph Antonini

Toni & Corrado Bartoli

Margaret & William Beauregard

Nancy & Lee Browning

Nancy & Christopher Chaput

Julie & Peter Cummings

Aviva & Dean Friedman

Patricia & Robert Galacz

Rose & Joseph Genovesi

Elizabeth & James Graham

Susan & Graham Hartrick

Linda & Arnold Jacob

Rosemary Joliat

Penni & Larry LaBute

Emma & Michael Minasian

Beverly & Thomas Moore

Dolores & Michael Mutchler

Nancy & James Olin

Helen & Leo Peterson

Marianne & Alan Schwartz

Leslie Slatkin

Sandra & William Slowey

Wilda C. Tiffany

Rev. Msgr. Anthony Tocco

Debbie & John Tocco

Georgia & Gerald Valente

Thelma & Ganesh Vattyham

Nancy & Robert Vlasic

Gwen & S. Evan Weiner

Barbara & Gary Welsh

THANK YOU TO OUR SPONSORS AND FUNDERS OF

Phillip & Elizabeth Filmer Memorial Charitable Trust

Mary Thompson Foundation

Wilda C. Tiffany Trust

Maxine and Stuart Frankel Foundation

Burton A. Zipser & Sandra D. Zipser Foundation

The Great Lakes Chamber Music Festival celebrates and advances its art form through extraordinary performance, collaboration, and education, inspiring diverse audiences to share in the intimate dialogue that is unique to chamber music.

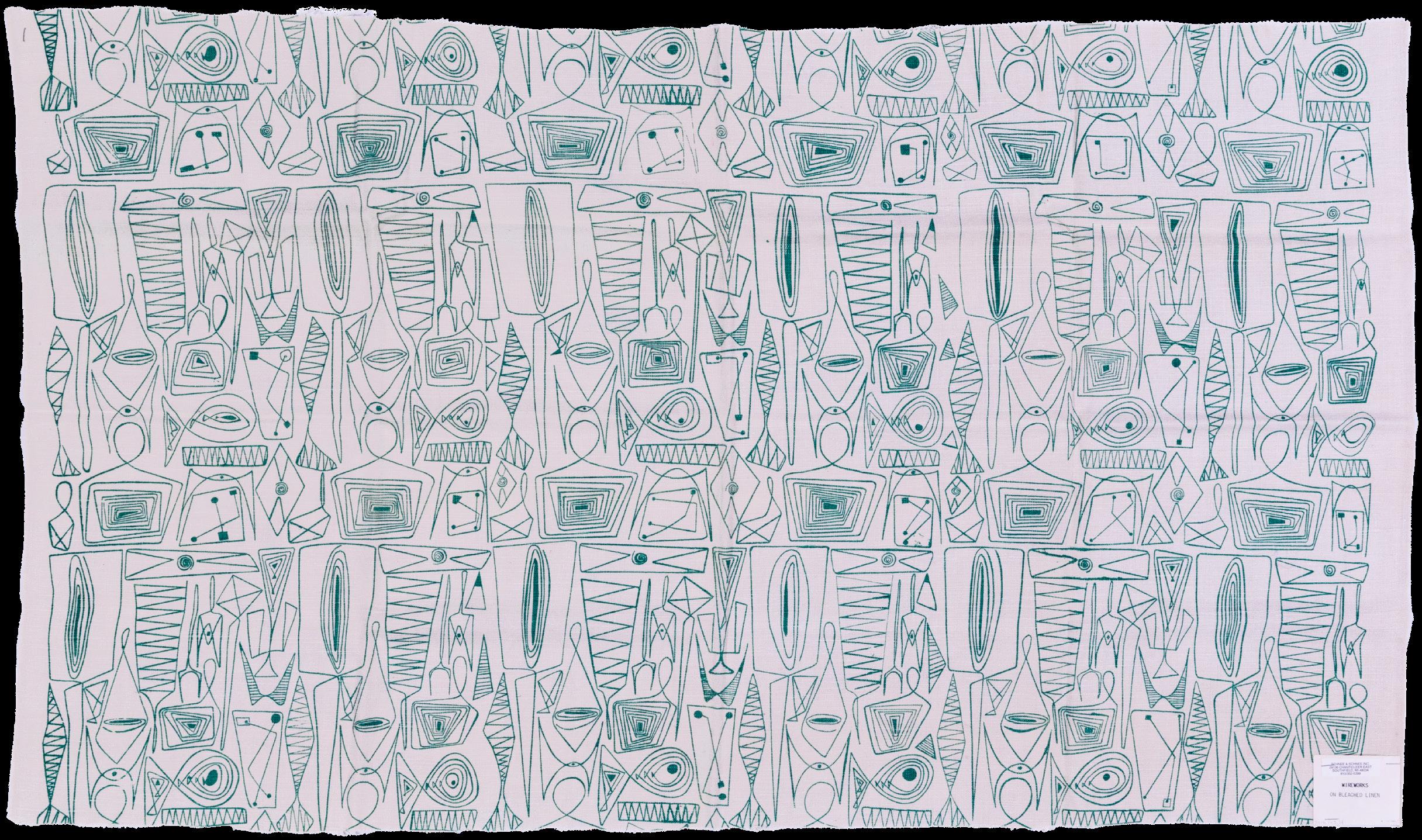

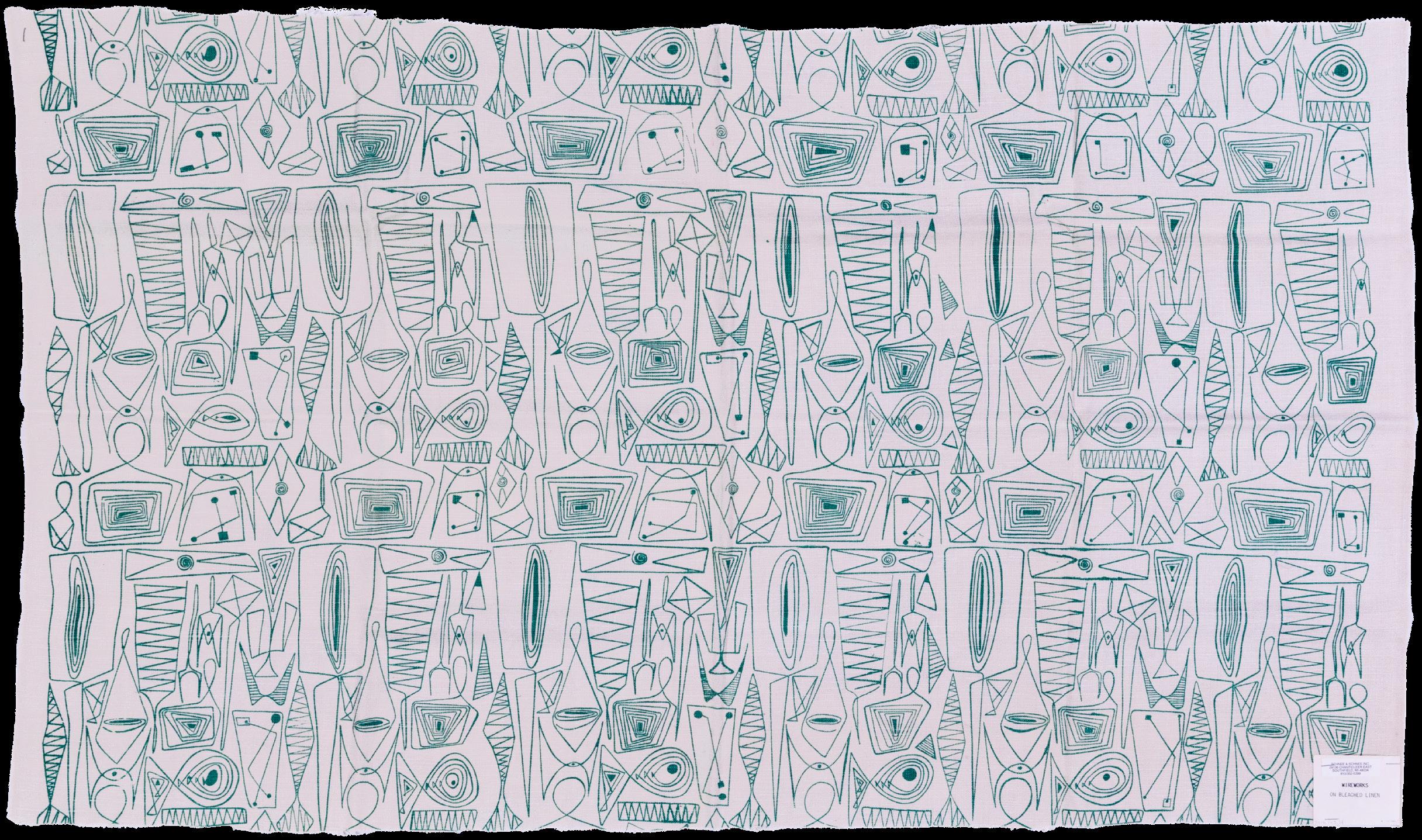

Pioneering designer Ruth Adler Schnee was trained in architecture and first began designing textiles when her architectural projects demanded a more modern aesthetic. This need launched her career in textile design. Both natural and man-made environments inspire her work. This textile on our program cover, Wireworks, was inspired by the fireplace tools she encountered during a trip to the studio of renowned sculptor Alexander Calder.

Ruth and her husband Ed were founding members of the Festival’s board. In many respects, they personified the Festival’s aspirations. The Schnees lived at the crossroads of creativity and practicality. They understood art. They understood business. And they understood the relationship between the two.

This season’s theme, Blueprints in Sound, honors the interweaving of music, architecture, and design. We celebrate the Schnees’ impact in the world of design and how they are so deeply embedded into the fabric of our event’s character. Ruth’s art is both visionary and pragmatic, a duality that the Festival still strives for in every decision that it makes.

This season, as we explore music as an architectural art form, we celebrate the life and legacy of Ruth Adler Schnee. Just as she left an indelible mark on the world of design, her impact on this Festival will forever be etched in our history.

Wireworks

Fabric Swatch Designed by Ruth Adler Schnee, 1950, Courtesy of The Henry Ford

SUNDAY, JUNE 8 | 5 PM

Seligman Performing Arts Center

Sponsored by David Nathanson

PROGRAM

— CONCERT INTRODUCTION BY SEAN SHEPHERD —

Sean Shepherd Latticework for violin and cello (world premiere) (b. 1979)

Josefowicz, Watkins

Benjamin Britten Six Metamorphoses after Ovid, Op. 49 (1913–76)

Pan

Phaeton

Niobe

Bacchus

Narcissus

Arethusa

Kinmonth

Joseph Haydn Cello Concerto in C major, Hob. VIIb:1 (1732–1809)

Moderato

Adagio

Allegro molto

Watkins, Scott, Detroit Chamber Winds & Strings, The Dolphins Quartet, The Paddington Trio, Trio Dolce

ARTISTS

GLORIA CHIEN, piano

LEILA JOSEFOWICZ, violin

PHILIP SETZER, violin

CHE-YEN CHEN, viola

DILLON SCOTT, viola, Sphinx apprentice

EDWARD ARRON, cello

PAUL WATKINS, cello

ALEXANDER KINMONTH, oboe

DETROIT CHAMBER WINDS & STRINGS THE DOLPHINS QUARTET, Shouse ensemble

MEMBERS OF THE PADDINGTON TRIO, Shouse ensemble

MEMBERS OF TRIO DOLCE, Shouse ensemble

— INTERMISSION —

Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Quartet No. 1 in E-flat major, Op. 16 (1770–1827)

Adagio assai

Allegro con spirito

Theme and variations: Cantabile

Chien, Setzer, Chen, Arron

OPENING NIGHT DINNER

Seligman Performing Arts Center, Octagon Room Sponsored by Honigman LLP

Join the artists for our Opening Night Dinner after the performance to kick off the 2025 Festival, featuring a live auction and wine pull. Catered by Plum Market.

Call (248) 559-2097 for more information. Donation to attend is $100 per person.

PERFORMANCE SPONSORS

Haydn Cello Concerto | Linda & Maurice Binkow

There is a rare little word for all this. Its coinage lies buried in a dense architectural treatise (the first of its kind, really), drafted at the behest of Caesar Augustus. In his De architectura, the Roman architect Vitruvius partitions the field of design into three constituent arenas: ichnography, orthography, and scenography. The first—and, for today, the only one that really matters—he takes from ichnos, Greek for print, and defines it as “the representation on a plane of the groundplan of the work, drawn by rule and compasses.” Ichnography, he terms modestly, is the art of the blueprint

The word will remain an oddity until 1712, when Gottfried Leibniz picks it up while writing to the theologian Bartholomew Des Bosses: “the difference between the appearance of a body for us and for God is the difference between scenography and ichnography,” by which he means we see the world from a fixed singularity, in perspective, while God sees ichnography’s plurality: infinite, geometric, omnidirectional. Fast forward, and Michel Serres will read Leibniz reading Vitruvius in his Genesis, and take both men to the following conclusion: “Once more, what is the ichnography? It is the ensemble of possible profiles, the sum of horizons. Ichnography is what is possible, or knowable, or producible, it is the phenomenological well-spring, the pit. It is the complete chain of metamorphoses of the sea god Proteus, it is Proteus himself.”

Serres’s point, mutatis mutandis, will be ours as well: that the privilege of the blueprint is to treat space as absolutely logical and generatively legible under the sign of geometry’s lines, angles, grids, points, figures. The privilege of ichnography, in other words, is an inherent formalism. And so: Blueprints in Sound, our 2025 theme, gives name to both a musical thematics as much as to an intellectual project. In the space of these program notes, we will read, time and again, for form, for the fragile contingencies and the shapes of impasses between structure and material that are always already becoming otherwise.

The four works on our opening concert each problematize the blueprint in opposing and revealing ways. Sean Shepherd has long had a predilection for intricate exactitude. His music’s sonic fragility—hazy, hovering harmonies in endless permutation, glinting textures half-bathed in sun—is borne out on a structure watertight in its unfolding: he has a rigorous bent for proportion, for calculation. Tonight’s Latticework takes, as the title suggests, the cross-hatched pattern as an organizing principle: the invisible structure suggesting material possibilities is that particular interlaced shape. But it is also a curious foundation for labor. This is lattice work: there is exertion and effort in bringing such a detailed shape to audibility. We might, then, sense as though the music itself obeyed a strange obligation to exertion, as if the violin’s material were contractually drawn in these diagonals and hatchings, working to hang its body across so delicate a structure.

Where Shepherd takes an abstract geometric principle and unspools from it a narrative of sound’s material transformation, Benjamin Britten moves in the opposite direction: human narratives become abstract designs for musical transformation. (Note already the overlap with Serres: Protean metamorphoses are always a question of extreme form.) Six stories from the Metamorphoses serve as governing paradigms, but the idea was never that the music would somehow wordlessly “tell the story” of Phaeton, who rode upon the chariot of the sun, or Niobe, who transforms from her grief into a mountain. Instead, the change in state undergone by Ovid’s characters suggest only a form. The final phrase of Niobe, for instance—after nearly a whole page of hilly ascents and descents, an expanding field of arches scaling up towards the mountainous—reads senza espressivo—without expression. The transformation has turned melody from a subjective, pining utterance into pure abstracted harmony: the transformation, after all, was to reprieve her of human expression.

Both Haydn and Beethoven, meanwhile, in different ways, problematize fidelity to the blueprint. Haydn’s first cello concerto is strict as strict can be: three movements, each a meticulous sonata form. The use of sonata was, at the time, eminently modern: it is only just coming into fashion as a major formal discovery, a means for organizing transformation along logical lines. But where Haydn is obedient—his blueprint matches the building absolutely (Mozart will start the trend of breaking those rules)—Beethoven runs rampant, his sonatas a series of fake-outs and excessive ornament. Not to mention he’s twice removed from his ichnography: the Piano Quartet is itself a recasting of his previous Piano Quintet with winds, itself modeled on Mozart’s quintet with the same instrumentation and key. And while the revisionist sutures are expertly covered up, one can still hear in the material an older sensibility and a windy intention: the very first gesture betrays a music once meant to be played on a horn.

There is another ichnographic reading. Louis Marin, too, knew Vitruvius, though his conclusions were more somber: “The outline on the ground at the surface level is nothing but the trace that would be left by the building if it were to be destroyed by time, by the violence of meteors or men… [ichnography] is its ruin.” Leading Eugenie Brinkema, who reads the whole lot of these commentators in her treatise on formalism, to conclude: “Ichnography… names a giving of form that contains every undoing of form: what is there as what is already ravaged.”

These notes will always be the ruins and ravages of the music they address, whose vitality is only in the present of their instantiation. Read, certainly, but more importantly: listen © 2025 Ty Bouque

One Note at a Time, the Festival’s Capital Campaign, aims to provide long-term support for Festival activities, with emphasis on artistic and operational excellence, as well as education and engagement.

For three decades, the Great Lakes Chamber Music Festival has thrived at the intersection of intimate friendships and world-class artistic dialogue. Inspired by great artists, great music, and great friends, the Festival has earned its reputation as a forward-thinking and effective institution.

Our extended family of artists, audience, board, and staff share a passion for us to grow, to expand our reach, and embed ourselves more deeply in the cultural fabric of our community. We must continue to evolve, taking pride in our success while not resting on our laurels.

The world has changed dramatically since our birth in the early 1990s. Our opportunity is to leverage our experience and the good will that we have amassed to anticipate, respond to, and thrive in the new environment in which we find ourselves. One Note at a Time foresees a future of exceptional music-making and community engagement as we move forward with open eyes and ears, positioning the Festival for thirty more years of great chamber music.

To date, One Note at a Time has raised approximately $500,000 in cash and pledges toward its $1 million goal. For more information or to participate, contact Jocelyn (Zelasko) Conselva at jocelyn@art-ops.org.

TUESDAY, JUNE 10 | 7 PM

Kirk in the Hills

Sponsored by Marguerite Munson Lentz & David Lentz

PROGRAM

Claude Debussy Sonata in G minor for violin and piano, L. 140 (1862–1918)

Allegro vivo

Intermède: Fantasque et léger

Finale: Très animé

Josefowicz, Chien

Steve Reich Music for Pieces of Wood (b. 1936) Third Coast Percussion

— INTERMISSION —

Johann Sebastian Bach Goldberg Variations, BWV 988 (1685–1750) Frautschi, Chen, Arron arr. Dmitry Sitkovetsky

A tension: truss means two things, torn by competing forces.

ARTISTS

GLORIA CHIEN, piano

JENNIFER FRAUTSCHI, violin

LEILA JOSEFOWICZ, violin

CHE-YEN CHEN, viola

EDWARD ARRON, cello

THIRD COAST PERCUSSION

SEAN CONNORS

ROBERT DILLON

PETER MARTIN

DAVID SKIDMORE

The architectural definition has, from the seventeenth century on, signaled a form of beaming, most often wooden, used to brace bridges or buildings. The classic truss is five-beamed, a square bisected into triangles. Triangles are simple but eminently sturdy; you can understand the allure. A truss, according to Engineering Mechanics, “consists of two-force members only, where the members are organized so that the assemblage as a whole behaves as a single object.” It is said that such a rigorous definition allows the truss to take any shape, so long as its connections remain stable. Stable and five and any shape will be important later.

The earlier sense hews closer to etymology. From the Latin torquere, “to twist,” itself from the Proto-Indo-European*terkw- (a root truss shares with torque and torsion but also torture and contort), the 13th-century verb form meant “to load, load up, pack up in a bundle” (relying on the sense of what is wrapped or twisted ‘round). The main residue English has retained of that particular understanding is the phrase trussed up, most often heard around November holidays, referring to what is tightly bound with rope or some such thing.

The conflict at the core of this concert, then, is between a rigid, often planar architectural force, a geometric structure whose job is to hold forever firm, and the twist, what wraps, ensconces, flexes, binds, folds but never along straight lines. A (wooden) truss cannot by definition submit to twisting force, but to truss is precisely what is twisted all around. What both definitions share, however—albeit to opposite ends—is an impulse to stay or bring together. The forces that hold a trussed bird in place restrict its movement into gastro-aesthetic form; the forces of wood that stabilize a bridge lend it rigorous fortitude: trusses, by twist or tightest frame, hold firm.

The Debussy Sonata in G minor for violin and piano is, by the repertoire’s standard, an odd little piece precisely for being so little. At half the length of the Kreutzer, it strikes a diminutive stance among a much beefier canon generally more prone to exhaustive virtuosity. Written as one of an unfinished cycle of six sonatas for instruments, one can understand the brevity: colorectal cancer had given the composer less than a year to live.

PERFORMANCE SPONSORS

Bach Goldberg Variations | Gail & Ira Mondry

But short is hardly simple. The work is a tightrope, the consequence of an unusually equalized distribution of responsibility (an assemblage, that is, behaving as a single object): the and in the title matters. The music is unusually reactive to itself, binding the two instruments by an invisible string whose elasticity forces them into exposed dependency. Attend to how they catch each other at a hair’s breadth, how they hem each other in here but breathe expansion to the other there, how when one holds the other inevitably torques but how the result is always two as one. In such a confined space, all formal activity is intensely, almost erotically charged: both are vulnerable in their reliance on the other for the security of the work they build together: trust/trussed.

The premiere in May of 1917—with Gaston Poulet and the composer at the piano—would be Debussy’s last performance. He died shortly after, despite numerous attempts at invasive intervention. (A third, archaic definition, from the 1650s: truss, a surgical appliance to support a rupture.)

The implicit materiality of violin and piano—tensile wooden objects brought to audibility—is literalized in Steve Reich. Written in 1973—only a year after Clapping Music (and with the identical rhythm appearing in the second entrance)— Music for Pieces of Wood is a clamorous thing. Five interlocking parts, none of them entirely virtuosic on their own, combine into a dramatic showcase of coordination and endurance. It is percussion quintessence: pure rhythm as music.

But where Debussy’s magic is a breathtaking array of color, the magic of Music for Pieces of Wood is achieved by perfect homogeneity. Because all five players share identical sets of wood, each new layer becomes immediately enfolded in the whole, resulting in a perceptual trick: the experienced pulse of the music appears to change with stunning variety, without the ongoing music changing even a bit. Sameness is never heard the same. There’s something hypnotic about so many cycles all hammered to the beam: five vectors, none exceptionally ornamental but unflappably secure, behaving as a single object, structurally sound in whatever shape they take.

And there is, perhaps, no single work of architectural bondage more immaculate than the Goldberg Variations. Written at the request of a Count Kaiserling who suffered from frequent bouts of insomnia, the Variations—Bach’s first and only foray into a form he otherwise deemed too limiting—were intended as comfort for the sleepless ear, and named for Kaiserling’s staff musician, Johann Gottleib Goldberg, whose responsibility it was to keep the Count entertained in his wee hour wakings. Bach had originally resisted the variation form for what he perceived as its harmonic limitation: for an experimental harmonist, the threat of enchainment to a single set of chords for well-nigh an hour was unthinkable. But it is precisely that limitation that makes Goldberg so satisfying a puzzle to decode. The work takes a richly decorated aria and, treating it as sheer material, explodes it into thirty permutations, each an exercise in formal innovation and technical prowess. There are dances and overtures, toccatas and fugues, even a series of canons every third variation that each time increase the interval between voices. Third, of course, for Bach’s Protestant devotion to the trinity, but also because triangles are simple yet eminently sturdy.

(After all, is it not said that a rigorous definition allows the truss to take any shape, so long as its connections remain stable?)

A formal exercise, then: how many ways can you twist around an impossibly stable frame? © 2025 Ty Bouque

WEDNESDAY, JUNE 11 | 7 PM

Birmingham Unitarian Church

Sponsored by Nancy Duffy in memory of William Duffy

PROGRAM

— CONCERT INTRODUCTION BY DANIEL SCHNEE —

W. A. Mozart

Piano Quartet No. 1 in G minor, K. 478 (1756–91) Allegro

Andante

Rondo (Allegro)

Preucil, The Paddington Trio

Dillon Scott A Moment in Time

Scott

The Dolphins Quartet Tales from the Great Lakes (world premiere) The Dolphins Quartet

— INTERMISSION —

Johannes Brahms

Piano Trio No. 1 in B major, Op. 8 (1833–97)

Allegro con brio

Scherzo: Allegro molto

Adagio

Finale: Allegro

Trio Dolce

JAMES PREUCIL, viola, member of The Dolphins Quartet

DILLON SCOTT, viola, Sphinx apprentice

THE DOLPHINS QUARTET, Shouse ensemble

THE PADDINGTON TRIO, Shouse ensemble

TRIO DOLCE, Shouse ensemble

The Dolphins spend each summer at music festivals, where our contrasting personalities invite constant adventure. From quirky people to breathtaking nature, inspiration for music is everywhere. We often improvise together—no rules, just free-flowing, musical conversation. These sessions spark many of our compositions, sometimes yielding fully formed themes or entire sections that make it into our final work.

Tales From the Great Lakes is a 23-minute rhapsody capturing stories from our time at GLCMF in June 2024. It begins with “Aerial Overview,” a theme portraying a sweeping view of the lakes—expansive yet emotional. This motif meanders throughout the piece, threading the movements together. As the perspective narrows, we see locals and eventually, four musicians playing frisbee in a field. That “Frisbee Field” music, taken straight from an improvisation, returns 3 times in various forms throughout the piece, the frisbee’s flight being portrayed by a playful auxiliary instrument. Next is “Phil’s Waltz,” commemorating how violinist Philip Setzer mistook wasabi for guacamole and enthusiastically ate a full scoop at the opening dinner. A cheerful waltz is interrupted by insidious ponticello bowing, evoking the spicy surprise. After a short interlude, we recall a frightening misadventure at the Canadian border after mistakenly arriving a day early for a concert. Through miscommunications, our violinist Luke was suspected of passport fraud. We illustrate the ensuing interrogation with sliding glissandi lines mimicking the tense dialogue. But nothing matched the terror of our encounter with Sand-Hill cranes. Led by a tip from our host Randy Schein, we searched for and found these large, sharp-beaked birds—only for them to chase us. One voice at a time joins the chase, layered with eerie textures that mimic the cranes’ calls. The piece closes with a calm, nostalgic reflection on our unforgettable time around the Great Lakes. –The Dolphins

In our opening concert, we covered the first of Vitruvius’s three arenas of architectural design. The first, ichnography, the art of the blueprint, lends this year’s festival its thrust. Tonight we turn to the second in the series. Orthography is, at least according to De architectura, “the elevation of the front, slightly shadowed, and shewing the forms of the intended building,” which is today an outdated understanding. Virtuvius got to his definition by an imaginative etymologic pirouette: with orthos meaning correct and graphein meaning writing, he took orthography to mean the first sketch of a design in which the building is drafted in relief and with some sense of its optical reality. (Today we now call this orthographic projection.) Ground plans, after all, are hardly indicative of elevation and scale, of how the building will actually look. Nowadays, of course, orthography takes its etymology literally and refers to the conventional spelling systems of a given language (correctly/written); as a field of study, however, it retains Vitruvius’s interest in first glimpses: how a written language first comes into relief.

No matter how we read for the orthographic, whether by language or architectural projection, we turn up a curious throughline tonight. We’ll tease out both in time. But the real unifier here is not what is being played but by whom: the Shouse ensembles, young emerging musicians from around the country, take turns showcasing their interpretive gifts. The real magic tonight, in other words, is what orthography always promises, only this time viewed through living bodies: in young musicians whose groundwork has been laid, one glimpses, in the elevation and scale of their musicality, the future professionals they will one day become.

Not to mention that two works by the players themselves are also on display. Both Dillon Scott and The Dolphins mix composition and improvisation with their performance practice, a healthy activity for any creative. The expansion of a musician’s toolkit can only ever serve them well: sensibility is clarified as it crosses medial boundaries. In both works tonight, the priority is on musical moments: it is in Scott’s title, and in the Dolphins’s characteristic miniature captures of their surroundings. Music here is a capture technique for preserving the aura of life’s unrepeatable flickers.

Now linguistic orthography attends with great detail to—among many other things—the historical moments in which speech enters into writing, when sound first fixes on the paper as a series of recognizable signs, malleable in their order but firm in their signification. Scott and the Dolphins, we might say, are after something of the same moment: this music speaks to the instant when a feeling in an environment crystallizes into something knowable and transmittable: tonight we hear feelings at the moment they becomes legible. Where orthography will tell you the codification of language permits its breakage and extravagant free play, the musical memorialization of these precious moments in time too turns them plastic and tactile, allowing both Scott and the quartet free reign to continue to return to such special memories and splash in their emotional depths. On the architectural side of things, I want to return to Vitruvius and draw out a curious little phrase: slightly shadowed, he says, a characteristic essential to orthography. The relief of space is achieved above all by varying shades of light, themselves a trick of artificial and artistic means.

The Adagio from Brahms’s first Piano Trio is a thing of wonder—the whole trio is, really, but the adagio more than most. It takes a bizarre form, a kind of permanent hovering and rotating in place, alternating between piano and strings. It is a movement which goes nowhere and does nothing. The beauty of the thing—in some ways anticipating more pointed experiments by modern composers—emerges instead in the gradations of light and shadow that every harmony, every texture, every rhythm drawn here in so slow and plaintive a pace, cast upon the whole. The movement’s sectional structure is clarified not by immense contrasts in material but by slowly revealed gradations in how they are shaded: it teaches you to hear its small differences. And when, by the end, the piano begins to walk in tiny steps over the arch of the string chorale, one is not sure whether the light is fading or rising, so enfolded have we become in its many hollows, corners, and rays.

And Mozart—it is no great leap of criticism to point out that he’s an architect first. But you find him at his most attentive when he has to get from one place to another. (He gets this from Bach and passes it down through German lineage; the music of Helmut Lachenmann, the last living inheritor of that legacy, is founded on that principle.) In some ways, Mozart’s dazzling melodies are just blank shapes, lovely and precious and wonderful to the ear but themselves only building blocks. They’re the blueprint. Where Mozart really heats up is when he takes those pure shapes and begins to morph them into an architecture of change. The first movement of the First Piano Quartet is a masterclass in these transformational shadings. Titled in G minor but refusing to stay put, the movement flirts endlessly with its relative major as a means of both destabilizing the home key while making it all the more visceral and fearsome. This constant zig-zag between the major and the minor is played out in a host of transitional gestures—sometimes sequences, sometimes sudden drops, here slow reimaginings, there rapid flight—which are nothing more or less than orthography itself. Mozart, having drawn the geometric blueprint with each pure melody, begins to shade until the architecture begins to rise. He turns the figure to another side, shading as he goes; he rotates again, elevating here. Until at last—in the final minute, the long series of harmonies unable to decide which way to tile—the complete diagram appears like a magical vision before vanishing. It is in these passages of material on their way to becoming otherwise that one can hear Mozart’s architectural pencil hardest at work. © 2025 Ty Bouque

THURSDAY, JUNE 12 | 7 PM

Kirk in the Hills

Sponsored by Plante Moran

PROGRAM

— PRE-CONCERT TALK WITH JOAN TOWER AT 6:40 PM —

Franz Schubert String Trio in B-flat major, D. 471 (1797–1828) Allegro

Andante sostenuto

Setzer, Neubauer, Arron

Joan Tower To Sing or Dance (premiere) (b. 1938) Frautschi, Third Coast Percussion

To Sing or Dance was commissioned by the Great Lakes Chamber Music Festival, Chamber Music Northwest and Emerald City Music.

ARTISTS

GLORIA CHIEN, piano

JENNIFER FRAUTSCHI, violin

LEILA JOSEFOWICZ, violin

PHILIP SETZER, violin

PAUL NEUBAUER, viola

EDWARD ARRON, cello

PAUL WATKINS, cello

THIRD COAST PERCUSSION

SEAN CONNORS

ROBERT DILLON

PETER MARTIN

DAVID SKIDMORE

— INTERMISSION —

Dmitri Shostakovich

Piano Trio No. 2 in E minor, Op. 67 (1906–75)

Andante - Moderato

Allegro con brio

Largo

Allegretto - Adagio

Chien, Josefowicz, Watkins

When I spent some time with the wonderful composer Arvo Pärt, we had a discussion about the origins of music. He felt music came from the voice (or singing) and I had a different idea that it came from the drum (or dancing). Basically, this difference of opinion reflects a longtime split between composers who write mostly for the voice (Pärt, Verdi, Puccini, Wagner, etc.) and those that compose mostly for instruments (me, Beethoven, Brahms, Tchaikovsky, etc.)

When I was asked to write a piece for violin and percussion, that difference became immediately apparent-how to have these two very different instruments in the same space -living fairly comfortably together.

What I discovered was that the pitched percussion (vibraphones, glockenspiels, and crotales) were an easier match to join the violin. So right at the beginning, when the percussion starts alone, there is a dialogue between non-pitched and pitched percussion, which eventually invites the violin in to join the discussion.

And eventually the violin starts picking up on some of the rhythms of the percussion as another interaction.

Occasionally, I gave solo space to both the violin and the percussion group to let them develop forward into their individual and special DNAs without having to adapt to the other one.

I want to thank the Maxine and Stuart Frankel Foundation for helping commission this piece. — Joan Tower

PERFORMANCE SPONSORS

Tower To Sing or Dance | Maxine & Stuart Frankel Foundation

Texture is about the particular way things feel; etymology, then, might be thought of as a kind of exercise in historical textures, the way sounds accrue intuitive feeling in the fabric knit by language and the world. Reading across etymology is a way of seeing how texture connects the most unlikely of cohabitants.

One word, then, but three definitions.

Tract is spatial in its first sense: 1) tract, from the Latin trahere, draw, pull: an endless swath of ground. In early 19th century England, however, a bastard derivation of the word tractate (meaning treatise), its root in the Latin tractatus, made tract into a nickname for 2) a short pamphlet on a single subject, the kind passed around by religious fanatics or political hawkers in the streets at Charing Cross. Much earlier (and much less frequently) Roman Catholicism borrowed the Medieval Latin phrase tractus cantus to mean, in the liturgy at least, 3) a drawn-out song. Apt that so protracted a series of definitions can be given for a word whose root means drawn, pulled.

Begin with the shortest of the three, short not by designed concision but by poor attention. Schubert never really had it in him to finish his grand plans, and today the String Trio is missing its last two movements: they’re not lost, he just never wrote them. All we have is the brief first and some twenty-off bars of a sketch for number two. (Schubert had, in fall of 1816, just left his stifling academic post, fled his overcrowded family home, and moved in with Franz Schober, a rather handsome poet with a wide circle of well-to-do artistic friends; there was much to be distracted by.)

This is our short pamphlet on a single subject. The String Trio in B-flat major—or what we have of it—packs into its little space an exceptionally convincing argument: the difference between the arpeggio and the scale. The whole flux of the movement is generated by a tension between competing patterns of motion. Often arpeggios ladder upwards, they’re already in the second bar of the melody. Scales, meanwhile, tumble down, and they pick up pace as they do so until all three strings are scattering in bursts of stepwise descent. And they play to musicians’ strengths (in the same way a religious pamphlet might tap innate morality): what string player has not spent their life practicing three octave scales and arpeggios? So while there are melodies and harmonies between, the entire movement of the trio can be understood as one composer’s intellectual excursus into the varying attractions, directions, and devotions of these two most elemental musical objects.

Joan Tower’s entire career is, to some extent, a long, drawn-out song, but not in that Wagnerian endliche Melodie sense. Tower’s art is to draw song out of earthen materials, to summon and bewitch the natural world to pour forth in sudden lyricism. Her usual recourse to natural metaphors in her titles—attendees of last year’s festival will remember particularly stony music— are overt references to the beginnings of her sonic imagination: her harmonies and sounds mirror phenomena and colors from the wild. This year’s new work, however—co-commissioned by the Great Lakes Chamber Music Festival—harkens toward the arrival: To Sing or Dance is where Tower’s music is always headed: to make the earth sing; to make the sky dance.

A geographical tract is of indefinite extent: it is never given just how far it can stretch. The Shostakovich Piano Trio No. 2 is a work of grief, and as such, faces off against that endless swath of world-without-you that those who’ve lost know all too well. The death of Ivan Sollertinsky, closer friend to Shostakovich than anyone, interrupted the composition of its first movement. He was 41. In the wake of the news, the composer cried out: “it seems to me that I will never be able to compose another note again.” Writing paused accordingly, while grief set in. Work resumed later in the fall, by which time the trio was already dedicated to Ivan.

Though the first movement preceded the precipitous loss, the first notes set an unbearably open space, fragile, hovering— only to fill it in with the Russian folk verve that its composer had originally intended the work contain. It’s not until the second movement—properly written in grief’s wake—that mourning as a spatial phenomenon takes real hold. The immense, unbearable duration between piano attacks gives the key: it is the time of waiting, the stretch of infinite that unfurls without end, that will be the rest of this work’s concern.

Grief always takes the form of a duration. Viewers of Michael Haneke’s cult film Funny Games will remember that the most violent episode of grief involves no camera or physical motion at all: it is a still tableau, the longest in the film. Only the light moves: grief is an illumined duration.

So too in Shostakovich: the two movements written in death’s wake do not go on. There is no catharsis or solution. They do not move. They sit and observe as pain floods like light. In the second: the endless cycle of overlapping melodies, too much emotion to hear clearly, vision wet from mourning. In the third: the unendurable string insistence, the same rhythm hammered out again and again, ceaseless and violent, thick walls of sound whose pressure only gives way to pressure. And the ending: continuous cadence that will not close, refusal to end, inability to stop.

The contradiction: a tract which is intractable, impossible to bear. © 2025 Ty Bouque

FRIDAY, JUNE 13 | 7 PM

Wasserman Projects

Sponsored by Fay Herman

TIME PIECES: THE NEW CLASSICAL

Danny Clay “Teeth” from Playbook (2016) (b. 1989)

Third Coast Percussion “Niagara” from Paddle to the Sea (2016)

Clarice Assad “The Hero” from Archetypes (2019/2020) (b. 1978)

arr. Third Coast Percussion

Jlin “Obscure” from Perspective (2020) (b. 1987)

Philip Glass Metamorphosis No. 1 (1988/1999/2020) (b. 1937)

arr. Third Coast Percussion

— INTERMISSION —

Jlin Please Be Still (2024)

Jessie Montgomery Lady Justice/Black Justice, The Song (2024) (b. 1981)

Tigran Hamasyan Sonata for Percussion (2024) (b. 1987)

1. Memories from Childhood

2. Hymn

3. 23 for TCP

20 Years of Impact and Resonance

Since 2005, Third Coast Percussion has forged a unique path in the musical landscape with virtuosic, energetic performances that celebrate the extraordinary depth and breadth of musical possibilities in the world of percussion. This performance marks the passing of time, both in the diverse approaches to rhythm revealed in each work, and in celebrating the 20-year history of championing this music. The program features works that highlight some important moments of this journey, points to different facets of the organization’s work, and shares exciting new pieces commissioned to celebrate this landmark occasion.

THIRD COAST PERCUSSION

SEAN CONNORS

ROBERT DILLON

PETER MARTIN

DAVID SKIDMORE

ABOUT TASTING NOTES

Tasting Notes concerts offer a relaxed concert format with a curated tasting of wine and cheese.

Playbook was created by composer and educator Danny Clay as part of Third Coast Percussion’s Currents Creative Partnership, an education and mentorship program that provides an opportunity to compose for TCP through a highly collaborative process, for music creators who are early in their careers or are exploring a new artistic direction. Playbook was inspired by musical games that Clay uses with students of different ages, and like all works in the Currents Creative Partnership, was composed through multiple workshops with TCP during the compositional process. Three years later, Danny Clay worked with TCP again to develop a massive education and community performance piece entitled The Bell Ringers. (“Teeth” duration: 6 minutes)

“Niagara” from Paddle to the Sea was one of the pieces Third Coast Percussion performed as part of its NPR Tiny Desk Concert in 2018, a bucket-list performance for any musician. It is a small excerpt of a larger project, Paddle to the Sea, which was one of Third Coast Percussion’s first collaboratively composed works, written together by the four members of the quartet. While pieces written by ensemble members have always been a special part of the TCPs repertoire, co-composing as a group only began about 10 years into the ensemble’s history. Third Coast’s multi-media program Paddle to the Sea, based on the children’s film and book of the same name, was the quartet’s first touring project to feature a collaboratively composed work, and was a staple of the ensemble’s repertoire for years. The film tells the story of a small wooden figure in a canoe, that makes a long journey from the Great Lakes out to the Atlantic Ocean and beyond. Paddle also encounters danger in his journey, as in this passage, when he goes over Niagara Falls. (duration: 3 minutes)

The album of TCP’s Archetypes project with Clarice and Sérgio Assad earned the quartet its first GRAMMY nomination as composers (Best Contemporary Classical Composition), and one of its six nominations as performers to date (Best Chamber Music/Small Ensemble Performance). The twelve movements of this suite are each inspired by a universal character concept that appears in stories and myths across cultures, such as the jester, the ruler, the creator, or the caregiver. Each of the performers chose certain archetypes that sparked their imaginations, with Clarice and Sérgio each composing four of the movements, and each member of Third Coast Percussion composing one. With Clarice’s blessing, TCP arranged her composition “The Hero” from this project for percussion quartet alone, as an additional opportunity to share this bold music with audiences. It has now become a common repertoire piece for percussion ensembles at universities and conservatories. (duration: 4 minutes) Jlin’s seven-moment work for TCP, Perspective, was named a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Music. This music also featured prominently in the “Metamorphosis” touring program with Movement Art Is, which TCP brought to Carnegie Hall, as well as other TCP projects, and was recorded on another GRAMMY-nominated album, Perspectives, alongside Philip Glass’s Metamorphosis No. 1 and works by Danny Elfman and Flutronix. The collaborative process for creating Perspective marked an important development in TCP’s work commissioning music from creators of many different genres; after exploring and sampling instruments from TCP’s vast collection of percussion sounds at their studio in Chicago, Jlin created an electronic audio version of each of the work’s seven movements using these samples and other sounds from her own library. The members of Third Coast Percussion then set about notating this music and determining how to realize these pieces in live performance. Jlin named her piece Perspective as a reference to this unique collaborative process: “When I give an ensemble a piece, I don’t want to hear them play it back exactly as I wrote it. I want to hear it from another perspective.” (“Obscure” duration: 5 minutes)

Metamorphosis No. 1 is one of many works by iconic composer Philip Glass that TCP has arranged over the years. This particular piece was part of an important TCP project, “Metamorphosis,” which was a collaboration with Movement Art Is (choreographers Lil Buck and Jon Boogz) and which TCP performed at its Carnegie Hall debut in 2023. TCP’s performance of Metamorphosis No. 1 was also featured as part of “Philip Glass: Three Cities,” a video performance series celebrating Glass’s 85th birthday in 2022. As part of the ensemble’s ongoing relationship with the influential composer, Third Coast Percussion also commissioned Glass’s first work for percussion ensemble, Perpetulum, in 2018. (duration: 10 minutes)

To celebrate Third Coast Percussion’s 20th Anniversary, the quartet is undertaking collaborations with some of its musical heroes as well as favorite partners from past projects, including three works on this program: TCP approached Jlin to compose another work for the occasion, this time adding another layer to the musical chain, by asking her to create a new work that would be a remix or reworking of music by another composer that inspires her. Please Be Still reimagines materials from “Kyrie Elieson” from J.S. Bach’s Mass in B Minor. A lover of Bach’s music since childhood, Jlin focused in on Bach’s rhythmic vocabulary. The creative process with TCP was an extension of the collaboration that yielded Perspective. (duration: 6 minutes)

Third Coast Percussion built an artistic kinship with composer Jessie Montgomery during her time as Composer-in-Residence for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, arranging some of her existing music and serving as a sort of “percussion laboratory” as she composed her first percussion ensemble piece, Study No. 1. Her new work, commissioned for TCP’s 20th Anniversary, Lady Justice/Black Justice, The Song expands the techniques she developed in Study No. 1, particularly methods of continued on page 18

continued from page 17

pitch-bending metal and drum sounds. This new work is inspired by the artwork of Ori G. Carino and his painting “Black Justice” (2020-2022), which is a rendering of a Romanesque statue of the symbolic sword- and scale-bearing figure of Lady Justice, depicted as a Black woman. The image is airbrushed upon several layers of silk, stretched in staggered alignment across a life-sized canvas to create a holographic effect that reveals the figure’s timelessness and multiple hues. The image is staggering, aspirational, and technically virtuosic. (duration: 12 minutes)

Pianist and composer Tigran Hamasyan has long been a musician that the members of Third Coast Percussion have admired and appreciated. While he has built a career as a performer of his own music — known to his fans as a sort of prog rock version of the modern jazz musician — his work seems a natural choice for composing for a contemporary percussion ensemble. Within an extremely complex rhythmic landscape exists compelling counterpoint, and expressive melodic lines that transcend the mathematics of their complex metric skeletons. His Sonata for Percussion is very classical in some ways, with three distinct movements that echo the classical sonata (fast-slow-fast), lilting dance feels, arpeggiated harmonies, and ornamented melodies. Hamasyan’s distinct voice is present throughout, with the moments of hard-grooving energy or ghostly lyricism winding their way through an asymmetrical rhythmic jigsaw puzzle. The outer movements both explore different subdivisions of 23-beat rhythmic cycles, while the middle movement is in a (relatively) tame seven. (duration: 22 minutes)

Please Be Still was commissioned by Third Coast Percussion for its 20th Anniversary, with support by Carnegie Hall, the Zell Family Foundation, and the Robert and Isabelle Bass Foundation.

Lady Justice/Black Justice, The Song was commissioned by Third Coast Percussion for its 20th Anniversary, with support from the Zell Family Foundation, Carnegie Hall, Hancher Auditorium at the University of Iowa, Stanford Live, Stanford University, The Robert and Isabelle Bass Foundation, and Third Coast Percussion’s New Works Fund.

Tigran Hamasyan’s Sonata for Percussion was commissioned by Third Coast Percussion for its 20th Anniversary, with support from Elizabeth and Justus Schlichting and the Zell Family Foundation. – Third Coast Percussion Discovery Beauty, History,

Come visit the Park West Museum for a complimentary tour and receive $500 off any purchase of art made on site.

days a week. Visit us today.

Monday-Saturday: 10am-6pm, Sunday: 11am-5pm

JEFF OSAER, MBA, CRPC VP, FINANCIAL ADVISOR

services offered through Cadaret, Grant & Co, Inc., an SEC Registered Investment Advisor and member FINRA/SIPC. Cadaret Grant Management are separate entities. The information in this email is confidential and is intended solely for the addressee. If you are not addressee and have received this email in error, please reply to the sender to inform them of this fact. We cannot accept trade orders through letters, email, or fax messages should be confirmed by calling 248.297.6600. This email service may not be monitored every day, or after Information to consider when your representative changes firms: http://www.finra.org/industry/broker-recruitment-notice WEALTH ADVISORY BENEFITS

Take control of your financial future, starting today. With 15 years of experience helping families build and preserve lasting wealth, your first step is simple—call me for a complimentary introductory conversation.

Discover Precision in Wealth Management with Jeff at Spartan Wealth Management.

Investing involves risk, including loss of principal.

Securities and advisory services offered through Cadaret, Grant & Co, Inc., an SEC Registered Investment Advisor and member FINRA/SIPC. Cadaret Grant and Spartan Wealth Management are separate entities. The information in this email is confidential and is intended solely for the addressee. If you are not the intended addressee and have received this email in error, please reply to the sender to inform them of this fact. We cannot accept trade orders through email. Important letters, email, or fax messages should be confirmed by calling 248.297.6600. This email service may not be monitored every day, or after normal business hours. Information to consider when your representative changes firms: http://www.finra.org/industry/broker-recruitment-notice

( 248 ) 297-6600 www.SpartanWealth.com Jeff.Osaer@Spartanwealth.com

FRIDAY, JUNE 13 | 7:30 PM

Kerrytown Concert House

Sponsored by Pearl Planning

TICKET INFORMATION

To learn more or purchase tickets, please visit kerrytownconcerthouse.com or contact Kerrytown Concert House at (734) 769-2999.

Joseph Haydn Piano Trio No. 25 in E minor, Op. 57, No. 2,

Hob. XV:12 (1732–1809)

Allegro moderato

Andante

Rondo: Presto

Trio Dolce

Johann Sebastian Bach Sonata in G major for Viola da Gamba and Harpsichord, BWV 1027 (played on cello and piano) (1685–1750)

Adagio

Allegro ma non tanto

Andante

Allegro moderato

Arron, Tang

— INTERMISSION —

Dmitri Shostakovich Piano Quintet in G minor, Op. 57 (1906–75)

Prelude: Lento - Poco più mosso - Lento

Fugue: Adagio

Scherzo: Allegretto

Intermezzo: Lento

Finale: Allegretto

Setzer, Scott, The Paddington Trio

STEPHANIE TANG, piano, member of the Paddington Trio

PHILIP SETZER, violin

DILLON SCOTT, viola, Sphinx apprentice

EDWARD ARRON, cello

THE PADDINGTON TRIO, Shouse ensemble

TRIO DOLCE, Shouse ensemble

Tomorrow’s is the program titled Cornerstone, but tonight is the closest to a linchpin. The three composers on offer tonight are ferociously canon-bound, all, by different means but with no less sincerity, foundational to what came in their wake. Bach and Haydn are intuitive choices for the edifice of this thing we call classical music, although it is Shostakovich that tonight appears in his most canonized robes. And it is on such sedimented historical assurances we purchase a mode of listening tonight. This program, which shares no real thematic except good classical music, becomes an exercise in a brief material history. Tonight we use the assumption of good to ask more probing questions about how economic conditions encode themselves in scores, how creativity adapts to market forces, and how the establishment of canons themselves in turn become new conditions for creativity. Much ink has been spilled about the timeline of Bach’s viola da gamba sonatas. For many years, the best musicological guesses placed them somewhere during his years in Köthen, where the court cellist Christian Ferdinand Abel (also a gifted gambist) was presumed as dedicatee. Abel, who was also behind the six suites for cello that have so impacted our musical world, seemed an obvious choice for a less-than-obvious score. And indeed that may still have been the case, but revisions to the timeline came on the discovery of the Trio Sonata for Two Flutes and Basso Continuo, identical in every way but itself bearing equal evidence of having been arranged from something else. That first instrumentation remains lost. And so the revised date and placement put the Sonata newly in Leipzig somewhere in the 1730s. There, Bach was serving as music director for a series of professional chamber music recitals—not unlike the one in which you’re currently sitting—at which a work demanding this technical proficiency would have been perfectly acceptable. In Köthen, where more amateur musicians (excepting Abel) were employed, it would have stuck out as an extreme and indulgent ask.

We tend to treat Bach now as holy, pure music flowing from the fount. But the Sonata in G major for Viola da Gamba and Harpsichord is evidence of the working conditions of professional musicians in the 18th century and, as a result, betrays how the valuation of genius has changed our perception of the notion of work of art with time. This sonata is a copy of a copy; Bach is recycling old material to get a job done. Today we hear it with ears entrained by nostalgia and social cachet and so gasp at divine inspiration; the reality was of a father who, to pay bills, rewrote an old ditty for an instrument on the cusp of archaism because he was asked. The glorious art part was our making, not his.

Haydn more clearly troubles the compositional economy. Tonight’s is the 25th installment in what would ultimately be 45 piano trios—a staggering number of works in a single genre. To that end, number 25 isn’t particularly remarkable, at least not any more so than the rest of the piano trios, or the rest of Haydn for that matter, who is himself generally remarkable. It is a good work but not groundbreaking—Mozart’s K.542 piano trios, written the same year, are the ones credited with actually redrawing the rules of the genre—and as such its listening is eminently pleasurable without being shattering. Such is the consequence of financial arrangements available to composers at the time: Haydn wrote the 25th while still music director at the wealthy house of Esterházy, where his responsibility was to provide continuous freshness. In such an isolated and continuous job, one can understand why simplicity and similarity became second nature.

But dig a little deeper, and the work turns up encoded histories otherwise invisible to the ear. The educational economy for performers in Haydn’s day was exceptionally stratified. Virtuoso pianists were in abundance, but the skills in string departments left much to be desired. Haydn can be here spotted writing to his players. The piano part (particularly crisp, having been written for the 18th century pianoforte’s less resonant attack) bears much of the musical brunt, with the violin tracing out its prominent lines and the cello supporting in the bass. Occasionally—as in the shuddering interjections in the third-movement rondo—the strings provide texture more than timbre, but on the whole they play relatively within the lines. Social priorities—the keyboard as the age’s most respectable instrument, worthy of lifelong study—embed themselves silently but certainly.

The circumstances of the Shostakovich Piano Quintet, meanwhile, bear witness to an age in which the canon of classical music is itself an active force in the compositional economy. Shostakovich was commissioned by a string quartet called the Beethoven Quartet to write a work in which, old-style, the composer could play the piano. History is, already, pregnant here. The result is a work of chamber music in homage to the very history of its form. The quintet practically bleeds reference— the very opening is a prelude and fugue with a knowing nod to Bach, while later, the intermezzo will quote Bach directly, alongside Purcell and Grieg. Much of its arresting thrill for the modern listener is in catching all the echoes of eras past as they refract through Shostakovich’s eye. The audible weight of history is by 1940 measurable as its own value system and paid out as such: the work won Shostakovich the Stalin Prize and 100,000 rubles, often cited as the highest cash award ever given for a work of chamber music.

All of which is to say that the historical edifice we treat as unshakable is itself only the product of a series of happenstances, intuitions, accidents, and invisible social forces well outside the “genius” of the creator. This thing we treat as canon and absolutely fixed could have, a hundredthousand times before, turned out to be any other way. Too often we assume the music we love has always had value, forgetting the fragile and temperamental conditions of material histories through which that value was purchased and renewed over time. We cannot take the preciousness of our classical cathedral for granted: that worth was accrued by circumstances and pressures well beyond the scale of what you or I can ever fully know.

© 2025 Ty Bouque

SATURDAY, JUNE 14 | 7 PM

St. Hugo of the Hills

Sponsored by the Wilda C. Tiffany Trust

PROGRAM

— PRE-CONCERT TALK WITH JAMES O’DONNELL AT 6:40 PM —

Huw Watkins Pièce d’orgue (b. 1976) O’Donnell

George Frideric Handel Organ Concerto No. 5, Op. 7 (HWV 310) (1685–1759)

Allegro ma non troppo, e staccato

Andante larghetto, e staccato (Basso ostinato)

Menuet

Gavotte

O’Donnell, Detroit Chamber Winds & Strings, Shouse Strings, Watkins

Hannah Kendall Tuxedo: Crown; Sun King (b. 1984) Henderson

— INTERMISSION —

Camille Saint-Saëns Violin Sonata No. 1 in D minor, Op. 75 (1835–1921)

Allegro agitato

Adagio

Allegretto moderato

Allegro molto

Frautschi, Vonsattel

Francis Poulenc Organ Concerto in G minor, Op. 36 (1899–1963) Andante

Allegro giocoso

Subito andante moderato

Tempo allegro, molto agitato

Très calme: Lent

Tempo de l’allegro initial

Tempo d’introduction: Largo

O’Donnell, Detroit Chamber Winds & Strings, Shouse Strings, Watkins

PROGRAM NOTES

ARTISTS

JAMES O’DONNELL, organ

GILLES VONSATTEL, piano

JENNIFER FRAUTSCHI, violin

LUKE HENDERSON, violin, member of The Dolphins Quartet

DETROIT CHAMBER WINDS & STRINGS

THE DOLPHINS QUARTET, Shouse ensemble

MEMBERS OF THE PADDINGTON TRIO, Shouse ensemble

MEMBERS OF TRIO DOLCE, Shouse ensemble

DILLON SCOTT, viola, Sphinx apprentice

PAUL WATKINS, conductor

There is a reverence verging on mania endowed upon the cornerstone. Its sacred affection has nothing to do with its structural support or the quality of materials or even its scale. It is, rather, the first site at which the blueprint becomes a reality, and it is from the position of the cornerstone that the remainder of the structure will be mapped. Its placement, then, is a kind of

PERFORMANCE SPONSORS

Poulenc Organ Concerto | David Nathanson

key: the position of all form can be traced back to the calculations of that single moment. Tonight we will be looking at small building blocks upon which a whole has been built. They’re not always easy to spot, but composers inevitably engrave their cornerstones with a certain quantity of hands-on love that helps them to stand out.

The twin organ concertos on tonight’s program deserve to be discussed in tandem, for that instrument is (at least logistically speaking) what draws this program together.

Poulenc’s is a study in—the cornerstone, an idea as opposed to an object—what we might call gear changes. The notion of stark contrast as both architecture and drama pervades this concerto, a project over which Poulenc toiled for several years. (He wanted both to fulfill the desire of its commissioner—Winaretta Singer, heiress to the Singer sewing fortune and a lesbian socialite of high taste—for a work she, a decent but amateur organist could play, and his own desire for a work of towering artistic achievement. Ultimately he sided with the latter.) Everything—from dynamics to harmonies to density to range—is calculated to sit adjacent to its polar opposite. It is a work which strives at every possible moment to maneuver extremes without sacrificing coherence. (How else can one explain the shock of the quiet ending in the fourth and fifth movements, or the almost abrasive difference in harmonies that modulate across the second?) What is irreconcilable in extremis becomes the project of the concerto, resulting in a work always on the edge of its seat: it can—no, will, desires to—change on a dime.

Handel’s cornerstone, meanwhile—and this is a bit of an odd reading—was himself. Tonight’s Organ Concerto is built on an eclectic hodgepodge of themes borrowed from elsewhere in his catalogue, from trio sonatas and earlier works in the same genre. (He’s effectively credited with inaugurating the organ concerto as a form.) Accordingly, long sections of the work remain only sparingly notated because Handel—an organist by training (he studied with an organist in Halle, whose oldschool ways were where Handel learned his dazzling fluency in fugues, canons, and counterpoint)—would have improvised the solos. The concerto was one meant to build itself around Handel’s creative mind, a kind of amalgamation of his life and work. (Familiar listeners will, however, spot a not-so-oblique reference to Pachelbel in the second movement.)

Historical curio: Handel’s concerto was published posthumously in a set of six concertos, transcribed in part from barrel organs made by his assistant containing themes and sections of each. These little music-box-like captures allowed later editors to compile these works, once believed to be lost.

And music boxes return as the cornerstone for Hannah Kendall, this week in the role of festival Composer in Residence. Since 2020, the British composer has been accumulating a series of works titled Tuxedo, after the Jean-Michel Basquiat behemoth of the same name. Basquiat’s drawing is immense, fifteen sections of street-art inspired blocks of white text on a black background (the colors inverted from his usual), all of them littered with diagrams and graphics and stacked in columns, topped, at last, with his signature crown. Kendall describes seeing the work in person at New York’s Guggenheim, sitting for two hours in breathless awe before its scale and density. It would be easy, in some ways, to read Tuxedo’s cornerstone as Basquiat himself.

But look closer. In Kendall’s account, Basquiat’s Tuxedo—and the sprawling history of black heritage, resistance, and art contained within it—was Basquiat’s attempt at something “bigger than you and I and it.” Accordingly, Kendall’s series never strives to capture the whole: so gargantuan an undertaking can only really be experienced in snippets and small fragments, glimpses that leave completion to the work of the imagination. Tuxedo: Crown; Sun King continues Kendall’s fascination with small objects of musical-adjacency. Here, a collection of music-boxes—our actual cornerstone—played in overlapping cycles blur the sound field, creating a kind of thick shimmer through which the violin must push to inscribe its rebellious body. The music box as a kind of imperfect memory, an object of hazy nostalgia whose accumulation becomes a kind of dangerous wash, gives the piece its emotional thrust: how the beautiful boxes, through which we interact with our past, often fail to accommodate nostalgia’s violence.

Saint-Saëns’s cornerstone, meanwhile, is not a chord or a key or an object but a texture which encodes a relationship. The cornerstone of the Violin Sonata—written in the Frenchman’s fifties, only a few months before work began on the Carnival of the Animals —is homophony, or unison playing between the two instruments. Reconciliation and togetherness is where the entire Sonata begins, and it is what it’s destined towards, a white-hot blur of unison playing at the very end that crashes into a cadence. Across the work—though especially in the slow movement, where the violin’s hovering line provides static points of reference—the piano chases after the soloist, desperate to reinstate perfect unison if only for an instant. The erotics of touching—of moving in absolute tandem, knowing the other’s every step, thinking two-as-one, when you reach for my hand at the same time I do yours—are at all times what this sonata desires.

Desire is curiously inscribed across all four works tonight. Cornerstones, after all, tilt towards the future: from this here point in time and space, one can just begin to envision how the building might come to feel. It is the point where the abstract touches the real—holy indeed. © 2025 Ty Bouque

SUNDAY, JUNE 15 | 2 PM

Detroit Institute of the Arts, Rivera Court

Sponsored by Barbara Heller

Michi Wiancko Fantasia for Tomorrow (b. 1976) Kennedy, Neubauer

Hannah Kendall Vera for string trio and clarinet (b. 1984) Walters, Kennedy, Scott, Watkins

Maurice Ravel Piano Trio in A minor (1875–1937) Modéré Pantoum. Assez vif Passacaille. Très large Final. Animé

The Paddington Trio

ADMISSION INFORMATION

Event is included with museum admission. Visit dia.org or call the Detroit Institute of Arts at (313) 833-7900 for details.

KIMBERLY KALOYANIDES KENNEDY, violin

PAUL NEUBAUER, viola DILLON SCOTT, viola, Sphinx apprentice

PAUL WATKINS, cello

JACK WALTERS, clarinet

THE PADDINGTON TRIO, Shouse ensemble

The melodic and harmonic material in this piece was generated through a 12‐tone row. In the first instance, the ‘white notes’ (as on the piano) were removed from the series in order and the opening playful section is based on these notes only. These pitches, but in retrograde, also form the basis of the clarinet line when it first enters. The remaining notes of the prime row are introduced for the first time in the following ‘still’ section and as these pitches inflect the harmony in‐turn, a much heavier and darker effect is created. Each instrument is then given a solo before coming back together for a calmer replay of the opening. — Hannah Kendall | January 2008

The most fundamental principle of design and form: an attention not to what is there but to what is not. Music is often colloquially understood (though there’s something much deeper behind the impulse) as an art of density: phrases like pitch space indicate a loose acoustic architecture, while textural thickness or harmonic richness signify gradations of saturation. And silence, of course—Cage proposed it most succinctly—is the absence that gives access to such a presence as constitutively identifiable at all: the empty space at the beginning and end and in-between movements of the work are as much a part of the music as the notes. But this afternoon we’re listening not to silence, but to absence or emptiness from within the notes themselves. Think of the music like a series of large rooms and hallways: while we could certainly marvel at the intricacies of their layout, at their ornamental sconces and odd nooks and curious choices of material, we’d be better off to listen for the empty space which the notes carve out: all the empty space these rooms so elegantly enclose.

Hannah Kendall, who this week serves as the festival’s Composer in Residence, has relied on that oldest of modern techniques, the twelve-tone row, to generate the scaffold of Vera’s pitch world: in other words, there’s a compositional apparatus governing which notes get used in which order. But the result is hardly so calculatedly cryptic: with the row as base material, the form of this quartet relies on a gradual process of removal and reintroduction that could not be clearer. At the start, one hears only the “white notes” (as on the piano), maintaining the row’s original order but leaving out all the interceding “black notes.” (Yesterday, we heard about Kendall’s engagement with Basquiat, and in particular in a work which inverted that artist’s usual arrangement of black-on-white, attending to his color schemes as symbolic of racial relations: color symbolism plays a likewise role in Kendall’s imagination.) As the missing notes are introduced, the texture appears to slack, weighted

down by new impasses and harmonic thicknesses that recolor how we hear the opening. One by one, those missing pitches are removed again, but now we can no longer hear the plain “white” material as whole: something from the middle has been taken away, leaving a shadowy void behind it. (N.B. In classical painting, negative space is also referred to as white space.) Ravel, meanwhile, is often cited as the master orchestrator, with a hand for textural magic tricks that never come at the expense of clarity. The same is no less true in the Piano Trio: one can hear, in the armory of drastic color choices, an orchestral composer’s sensibility.

The secret—if there can be said to be one—to Ravel’s hand is in the maintenance of distance. Think back—though Ravel would hate us doing so, its success was his biggest regret—to the first two solos at the opening of Bolero. The low flute against the snare is practically a hollow mold, the strings almost nothing in their plucking beneath it. The clarinet picks up in the identical register of the flute, only the strings have risen to fill a small portion of the space around the solo, slowly but surely fleshing the harmony, slightly higher, slightly closer. It is the same thing again, only marginally more sketched, but already we can hear the trajectory beginning to erect its journey towards the inevitable crash. All it took was a small change in space between.

So too in the trio. The opening octaves between strings hold something like austerity in place, though later they’ll chase each other at the tail. The piano starts mid-register and close at hand, but by the third movement is so far in the basement that it rumbles rather than rings. Overwhelmingly, the voicing Ravel will prefer by default puts the strings at outer limits and the piano somewhere filling out the middle—an ecstasy of independence and architectural care—but then all three will enter the same room (as in the screaming trills at the work’s end) and the ecstasy ramps up. But in any of the infinite gauzy colors we hear across the work, what is actually being heard is an extreme attention to empty space.

(Another story goes that Ravel, in preparing sketches for the trio, quipped: “My Trio is finished. I only need the themes for it.” The harmonic progression and formal designs—pulled from an uncanny mixture of personal sensibility and inherited models for a classic instrumentation—were built in advance. Which is to say that the “negative space” of abstract harmony was conceived of first: the music came later, drawn thin around the empty air while leaving it untouched.)

And Michi Wiancko’s Fantasia for Tomorrow encodes its empty space right there in the title. Tomorrow is always an unknown quantity, a void around which we decorate today in hopes that it arrives with something like beauty. This work, then, might be read as a fantasia for what is here only as a kernel, what will soon be but is not yet. Where Ravel and Kendall both rely on strictly musical parameters in the articulation of negative space, Wiancko’s is more abstract and contemplative. This music—in its deep reliance on connection between players and shared command of musical time (it was written in homage to Wiancko’s mother, a violinist and violist and her earliest duo partner)—holds open a space for the unspoken and the hopeful, a beam of white light around which this ever-changing material congeals.

This afternoon, music itself is after what Jankélévitch called the ineffable, an articulation of something that is not there and cannot be named. All we can do is dance around it, which is, after all, what architecture is: a dance at the peripheries of nothing. © 2025 Ty Bouque

TUESDAY, JUNE 17 | 7 PM

Temple Beth El

Sponsored by Beverly Baker & Dr. Edward Treisman

PROGRAM

Hannah Kendall Network Bed for Piano Quartet (b. 1984) Huang, Trio Dolce

Frank Bridge

Cello Sonata in D minor, H. 125 (1897–1941)

Allegro ben moderato

Adagio ma non troppo

Watkins, Vonsattel

— INTERMISSION —

Antonín Dvořák Piano Quintet No. 2 in A major, Op. 81 (1841–1904) Allegro ma non tanto

Dumka: Andante con moto

Scherzo: Molto vivace, poco tranquillo

Finale: Allegro

Barnatan, The Dolphins Quartet

ARTISTS

INON BARNATAN, piano

GILLES VONSATTEL, piano

HSIN-YUN HUANG, viola

PAUL WATKINS, cello

THE DOLPHINS QUARTET, shouse ensemble

TRIO DOLCE, shouse ensemble

Network Bed is inspired by my artist friend Katriona Beales’ sunken black-velvet bed installation of the same name, which was exhibited as part of her ‘Are We All Addicts Now?’ series at Furtherfield Gallery (2017), made in response to her interest in digital culture and online behavioural addictions. More specifically, Network Bed recreated Katriona’s experience of a prolonged period of insomnia both fuelled and soothed by her nocturnal online habits. My musical depiction of the work aims to encapsulate the conflicting hyper-stimulating, yet sometimes calming, sensations of delving into, and becoming lost in the online world. A fluid glass sculpture with an embedded screen showing projections of moths was housed within the structure, and I was particularly drawn to this feature, in the same way that the moths themselves seemed compulsively attracted to the screen’s light. A repetitive single-note phrase, dispersed with grace notes, is immediately presented as a main motif in the piano’s right hand, and returns throughout the piece to represent this. Indeed, grace notes and pizzicato strings feature heavily to recreate the flitting of moths’ wings; particularly adding to the restless and distracted nature of the opening sections. This transitions into a highly-punctuated moment, with inflections of the more driving material to come in the piano, to emulate the piercing and bright glow of the screen, in addition to the generally high tessitura of the piece overall. A contrasting sultry cello solo is introduced to capture the seductive aspect of being drawn into the digital sphere, before eventually culminating with propulsion and tense forward momentum, which is finally released with the return of the initial repeating single-note motif.

— Hannah Kendall

Tonight we return to that most fundamental of musical and architectural materials, the formal device par excellence: we return to lines. And we return to lines by way of the woman whose visual imagination and material dexterity gave the Great Lakes Festival such a prerogative to think this year about form and structure; one of her textiles lends the title for this concert. Ruth Adler Schnee’s Strata Echo looks, if we have music on the brain (and its title certainly suggests sound), like a cross-section of a wave form. Computer-generated spectral imaging of sound turns up likewise piles of bandwidths, lines of varying thicknesses and curves meant to visually replicate the acoustic fluctuations of frequencies as they move through air. The miracle of Strata

Echo, however, on closer inspection, is that Adler Schnee’s lines don’t only flow, like a flat spectrogram, left to right, up and down. In small jets of energy, her bands of color—always two, giving each vector its “echo” pair below it—begin to weave in 3D space as well, trading between foreground and background as they cross the z-axis. The visual dimension on the one hand reiterates what is happening in the physical material: strands (in this case cotton and wool) are being woven artfully together.

Hannah Kendall’s Network Bed could not be more apt for such an environment. The work relies a meticulous series of hand-offs to ensure that one member of the quartet is at any given time holding fast to a single note, around which the other three dance in jolting rhythms that echo and rebound in tiny bursts. Like the Adler Schnee, Kendall’s title says much indeed: “Network Bed” calls to mind the anatomical term for the criss-crossing network of vessels bringing blood to various organs in a body. That highly complicated lacing, called a “capillary bed,” works as a decentralized system along which blood flows in all directions to connect distant physical regions with their animating heart. And Kendall, too, connects distant emotional arenas by complex maneuvers of line and space. Kendall’s quartet is the most literal on tonight’s program, erecting horizons (strata) that serve as a kind of fixed spatial reference against which the mirage of 3D space flashes in and out of sight.