WHERE ART + DESIGN MEET

52 ND ANNUAL CONFERENCE

BERLIN, GERMANY

15–18 MAY, 2024

52 ND ANNUAL CONFERENCE

15–18 MAY, 2024

GAS BOARD OF DIRECTORS 2023-2024

President Michael Saroka

Vice President Nadania Idriss

Treasurer John Moran

Secretary Lisa Zerkowitz

Ben Cobb

Mika Drozdowska

Percy Echols II

Eric Goldschmidt

Frederik Rombach

Debra Ruzinsky

Kimberly Thomas

Sunny Wang

Martha Zackin

Jocelyn Chan Student Representative

Leia Guo Student Representative

GAS 2024 BERLIN CONFERENCE SITE COMMITTEE

Eric Goldschmidt

Nadania Idriss

Chris Leeuw

Jay Macdonell

Viviane Stroede

Brandi Clark, Executive Director

Amanda Crans, Communications Manager

Jennifer Hand, Conference + Events Manager

Marja Huhta, Digital + Design Assistant

KCJ Swedzinski, Operations Assistant

Julie Thompson, Development Manager

Robin Babb, GASnews Editor*

Mike Berger, Conference Photographer*

Sarah Kulfan, Journal Graphic Designer*

Cathy Noble-Jackson, Bookkeeper*

*Contract employee

Published by: GLASS ART SOCIETY

700 NW 42nd St #101 Seattle, WA 98107 USA glassart.org

Editor: Amanda Crans

Graphic Designer: Sarah Kulfan

Photographers: Mike Berger, Amanda Crans, Leia Guo

Copyright © 2024 by Glass Art Society ISSN 0278-9426

No part of this publication may be reprinted or otherwise reproduced in any form without the written permission of Glass Art Society. The opinions expressed and text written in the GAS Journal are those of the annual conference presenters and do not necessarily reflect the beliefs of Glass Art Society, its Board of Directors, or staff. Copies of this GAS Journal may be ordered for a fee from glassart.org

For information about the Glass Art Society, visit glassart.org or email us at info@glassart.org

Cover image

Death of the frog, by Chuchen Song.

All permission for photographic reproduction is the responsibility of the author. Unless otherwise noted, the photographs were submitted by the artist. Dimensions, when available, are usually given in inches or feet as height x width x depth.

Dear Conference Attendees,

As President of the Glass Art Society, it was my distinct pleasure to extend a warm and enthusiastic welcome to each of you as we gathered in Berlin for this year's conference. Our return to Europe marked a significant and much-anticipated occasion, the first since our memorable conference in Murano in 2018.

Over the past few years, we have witnessed a remarkable growth in our European membership, a testament to the vibrant and expanding global interest in glass as both a medium and an art form. It is truly heartening to see our community flourish, welcoming members from all corners of the world. This diversity not only enriches our organization, but also strengthens our shared commitment to advancing the field of glass art.

This year's conference theme, "Where Art and Design Meet," could not have been more fitting. It reflects our focus on exploring the dynamic intersection between art and design, and the profound relationship that exists between artists and designers. Our conference serves as a unique platform for this exploration, providing a space where different perspectives, techniques, and mindsets converge. It is in these meetings and intersections that we find the opportunity to create something truly extraordinary, something that transcends what any one of us could achieve in isolation.

As we came together in Berlin, we embraced the spirit of collaboration and innovation that defines our community. We engaged in meaningful dialogue, shared our knowledge and experiences, and celebrated the boundless possibilities of glass as a medium of artistic expression. This conference not only inspired us, but also fortified the bonds that unite us as artists, designers, and enthusiasts of glass art.

Thank you for being an essential part of our community and for joining us in Berlin. Together, we will continue to push the boundaries of glass art and design, fostering a future that shines even brighter with the contributions of our talented and passionate members.

Warm regards,

Michael Saroka

Michael Saroka President, Glass Art Society

The Site Committee was thrilled to welcome the Glass Art Society to Germany’s capital! Berlin has been and continues to be a glassy city. In the 17th century, an alchemist named Johann von Löwenstern-Kunckel came to Berlin, where he developed gold-ruby glass and penned Ars Vitraria Experimentalis (Perfect Glassmaker’s Art). In the 20th century, the Stralauer Glaswerke produced glass bottles until 1997. The site is now an apartment complex that sits on Glasbläserallee, a delightful nod to its history. Fourteen years later, in 2011, a small group of international artists–and enthusiasts–opened Berlin Glas and a decade later, three of our former students founded their own studio.

As Berlin was reunified in the 1990s the city became an epicenter for both art and design. In 2006, UNESCO named Berlin a City of Design. Today there are around 600 museums and galleries and an estimated 7,000 artists and designers in Berlin! Among them is one of the most internationally recognized design studios: Bocci. In 2021, they partnered with Philipp Solf to open Wilhelm Hallen, a former iron foundry and one of the most sought-after venues for art shows and events. We are grateful to Bocci for donating the use of Wilhelm Hallen for the conference.

Berlin Glas is located in a former schnapps factory composed of unique, historic buildings with varying architectural styles. Along with our neighbors (Monopol Berlin and Bard College Berlin), we have built a community of artists, designers, and craftspersons. Enthusiastic about the Glass Art Society conference, our neighbors let us use whichever space we needed for the conference. Our community continues to grow from a shared love for the craft and through our support of each other.

Nadania Idriss

Site Committee Chair + GAS Vice President

The Glass Art Society honored Beth Hylen with a Lifetime Membership Award at the Annual GAS Conference in Berlin, Germany.

A member since 1989, Beth’s dedication to GAS has manifested in years of volunteering at conferences, strutting the runway in six Glass Fashion Shows, leading the charge on creating the GAS archives at the Rakow Library, and being a key member of the GAS History Project conducting oral history interviews. We were able to interview Beth about her connection to GAS and what it means to be honored in this way.

GAS: How have you been involved with GAS over the years?

Beth: My first Glass Art Society conference was in 1979, coinciding with the New Glass: a Worldwide Survey exhibit in Corning. As a CMoG staff member, I was invited to attend lectures, demos and even the party (with Marvin Lipofsky and Pat Oleszko entertaining us). I was able to meet artists whose work I admired, and became a huge fan of Studio Glass! I gave my first lecture at the 1984 Corning GAS conference.

By 1989, I had become a point person for questions from artists at the Rakow Library and had started taking glassblowing classes in NYC (there were no teaching studios in Corning then). I joined GAS and loved attending the conference in Toronto. Since then, I’ve only missed four conferences, and I’ve been in all but one GAS fashion show!

Much of my involvement in GAS is behind the scenes, for example, I was a resource for GAS staff, particularly for Alice Rooney, when she spent six months in Corning preparing to move the office from Corning to Seattle. For years I maintained the list of glass educational schools and programs; publications; and organizations.

I was involved in establishing the Glass Art Society archive at the Rakow Research Library. I co-led a “Workshop for Educators,” at the Glass Art Society, Corning, June 2016, with Bill Warmus and Shane Fero. Our goal was to provide a place for curators, glass historians, critics and others with interest in the historical aspects of glass to meet.

I’ve written articles for the GAS Journal and GASnews. I indexed the first twenty years of the GAS Journal as well. I was an active participant in planning elements of GAS conferences in Corning, beginning in 1990. I even had a one-person exhibition at the ARTS Council on Market Street during a Corning conference.

Sally Prasch and I compiled a “History of the Glass Art Society – 50 Year Celebration,” Timeline and exhibit for the GAS Conference, Tacoma, WA in 2022. I am co-chair of the GAS History Committee and I am currently part of a team volunteering to inventory the GAS archives at the Rakow Library.

GAS: What does it mean to be honored with a GAS Lifetime Membership Award?

Beth: Over the years, the Glass Art Society has offered me so many wonderful opportunities to make meaningful connections and personal friendships. I have especially loved interviewing some of the top glass artists with the GAS History Committee; connecting artists with information they needed; and wearing my own creations in Laura Donefer’s Glass Fashion Shows. I cherish my memories of GAS Conferences in Corning and across the globe. I view the list of GAS Lifetime Members with awe – I am honored and grateful that you have chosen me to join them. Thank you for recognizing my contributions to GAS.

What is your fondest

Beth: Laura Donefer’s Glass Fashion Shows are a highlight! I love transforming from quiet librarian to glassy diva strutting the stage in my own glass creations.

I remember the first time I came out on stage in a glass dress, to a chorus of “That’s Beth!” from one group and from the other “That’s the Librarian!” (perhaps in disbelief). It’s no surprise any more – I still love the energy of the crowd and the performance.

And I’ll never forget gliding through Murano on a BOAT, in my glass-encrusted Commedia del Arte dress, waving to GAS friends who crowded the sidewalks along the canal and locals who waved back from upper story apartments.

Thanks so much Laura!

GAS: You’ve been a key figure in preserving GAS’s history. Why is this so important to you and what is your favorite thing you’ve learned through your research?

Beth: To me, it is important to preserve the voices of the members who created and continue to build our society –they have contributed extensively/significantly to contemporary glass. We have a rich history, and have evolved so much since the early conferences at Penland. Each of us have stories to tell and I love capturing these unique viewpoints in our oral histories.

Little things add up: at every conference, I chat with each Glass Market exhibitor to ask for catalogs, price lists, postcards, and ephemera—and cart loads of paper home with me. The Rakow Library now has a wonderful research collection of studio glass trade catalogs and educational brochures thanks to their generosity.

GAS: What do you see as the value of GAS?

Beth: I’ve explored wonderful places at GAS conferences across the globe. Watching demos, listening to and participating in lectures, touring studios, galleries, and factories – I learn so much!

Most of all, when I think of GAS, I think of all the people I’ve come to know. Each year I meet new people and renew friendships. I believe relationships like these bring together makers of all types of glass, collectors, teachers, and vendors to foster community and understanding.

Also, volunteering for GAS lets me give back to an organization that has offered so much to me.

To help GAS continue to grow and change, I encourage you to volunteer. You don’t have to be on the Board to make a contribution. Often, it’s the little things that count most. Take the time to sit with someone new at a demo or lecture, help them feel welcome. You could also assist our History Committee preserve memories of GAS by helping with oral histories. Connect with the wonderful GAS staff members – ask how your skills might help them.

Danke schön!

An artist, researcher, and writer, Beth Hylen spent over 40 years as a reference librarian at the Rakow Library at the Corning Museum of Glass where she was involved in more than 40,000 research inquiries and projects about glass. Beth is currently helping survey the GAS archives at the Rakow Library, which she helped found with a request to GAS and the board for materials in 2000. Assisted by Sally Prasch, Beth was instrumental in developing the 50th anniversary GAS timeline that was presented at the Tacoma 2022 conference. In addition to her work as a librarian and historian, Beth is a talented glassmaker in her own right, dedicating her career to flameworking and has spent much time researching the history of flameworking.

Each year, GAS awards three promising young artists the Saxe Emerging Artist Award. Funded by Dorothy and the late George Saxe, this award recognizes emerging talent in the glass community. The 2024 Saxe Emerging Artist Award was juried by:

• Mikkel Elming, director of Glas – Museum of Glass Art in Ebeltoft, Denmark

• Dr. Jörg Garbrecht, director of The Alexander TutsekStiftung

• Luisa Restrepo, independent artist

Out of more than 30 nominated artists, Priscilla Kar Yee Lo, Sadhbh Mowlds, and Abegael Uffelman were selected to receive the 2024 Saxe Emerging Artist Award because of their fresh and unique approaches to working with glass.

Priscilla Kar Yee Lo

Growing up as a Chinese immigrant taught Priscilla success equated to assimilation and stability. After years as a healthcare worker where she experienced the blunt reality of intersectionality of race and gender, she felt disheartened and turned to artist endeavors to find a voice and explore her identity as a minority. She was drawn to glass for its duality, constantly existing in a state of fragility and permanency. She has a Bachelors in Craft and Design from Sheridan College, and her Master of Fine Arts from Illinois State University. Priscilla is currently the Resident Artist at Rochester Institute of Technology.

Kar Yee Lo’s work highlights the astute way in which our inherent patriarchal society has affected the Asian female position within its structure and how it maintains control through cultural and social expectations and normalized gender roles. She employs visual language containing artifacts of patriarchy from her childhood that have since become pop culture icons. The symbolism of these images is far removed from their original medium and their patriarchal foundation, making them easy to manipulate and go undetected while subtly reinforcing social norms and binary systems.

Top: Priscilla Kar Yee Lo. Middle: Evolution: The Theory of “The Asian Mystique.” Mould blown glass, digitally enhanced plaster. 5.5” x 4.5” x 12” (each, 8 shown), 2019. Photo by Katarina Kaneff. Bottom: My Little GroomMe playset, Gilded Memories: Interactive Series. Kiln formed glass, bronze, human hair, mix media. 6” x 4.5” x 6”, 2020. Photo by B. Fortuné.

The globalization of the iconic Hello Kitty character has an undeniable relationship with the maintenance and propagation of the controlling images of Asian females in the West. Hello Kitty is a recurring image in Kar Yee Lo’s work because she is a universally recognizable icon in pop culture that dictates Asian female identity. This is characterized by cuteness, meekness, submissiveness, and a playfulness that can be interpreted as provocative, blurring the line between innocence, vulnerability, infantilization, and sexuality. Stereotypes are not false, rather they are an arrested representation of a changing reality. By employing pop culture icons rooted in systemic patriarchy to highlight the intersectionality of being a minority female, Kar Yee Lo hopes to advance this changing reality. She views this as an act of defiance, taking back a symbol of oppression to create a counter narrative that serves to empower Asian females. Ultimately, she views her work as a nostalgic and whimsical, yet mischievous way of documenting where women, particularly immigrant women, are placed within a societally prescribed racial framework.

Kar Yee Lo hopes to initiate discourse about this reality to validate our collective experiences and raise awareness of the continual existence of these issues.

Sadhbh Mowlds

Sadhbh Mowlds is a visual artist who was born and raised in Dublin. After receiving her BA from the National College of Art and Design, Ireland (2014), she moved to Germany where she worked as a freelance glassblower out of Berlin Glas. In 2019 she moved to the U.S, where she received her MFA from Southern Illinois University Carbondale (2022). Recent residencies include the RHA (Dublin, IE), WheatonArts (NJ) and STARworks (NC). Mowlds has participated in numerous international exhibitions, showing throughout Europe and the USA. Her work is included in the permanent collections of Kunstsammulungen Coburg, Germany and the Museum of American Glass, NJ.

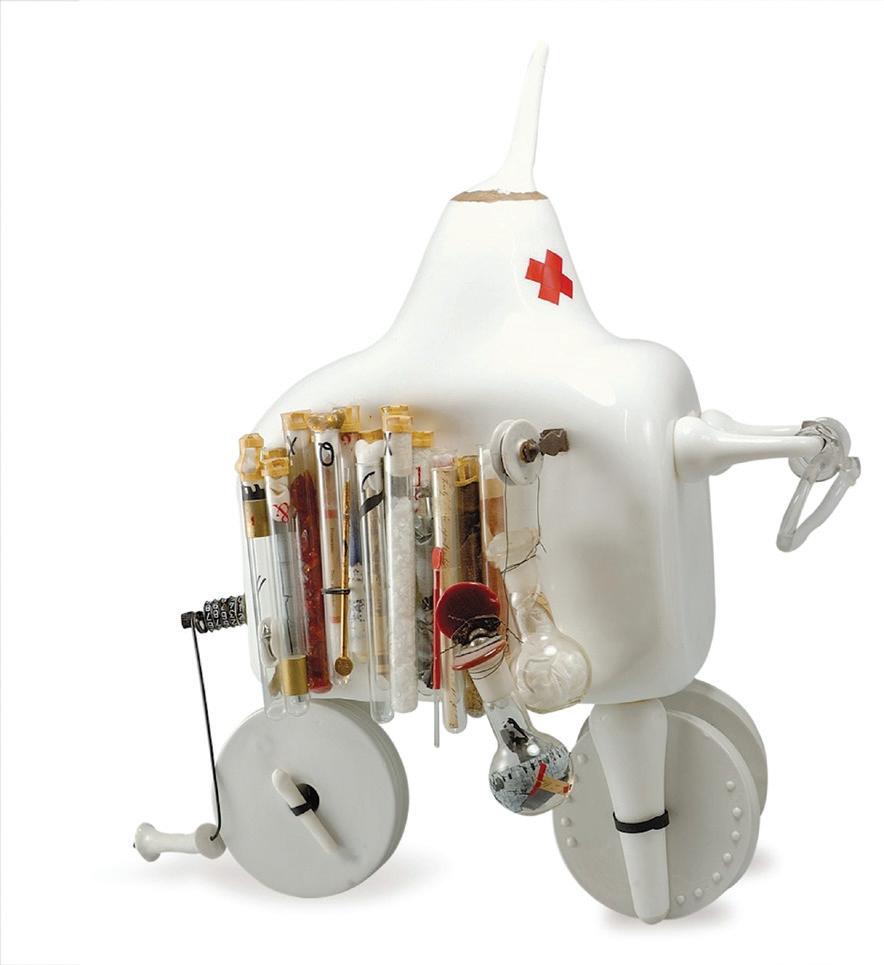

Existing in the realm of the uncanny, Mowlds’ work strad-

dles the line between hyper-realism and surrealism to create absurd yet recognisable realities that challenge prevalent and destructive social constructs. Her fixation on the human ability to contemplate is at the core of her pursuit, which reveals the absurdity of the beliefs, behaviours and perceptions of our species. As she often approaches these themes through the lens of her own frustration and vulnerability as a woman, Mowlds explores the phenomenon of consciousness and what it is to be self-aware.

Using the body as an emissary, she probes the delicate boundary between our internal and external self, describing the impact societal perceptions of gender roles, value systems and class divides have on our suffering consciousness. This investigation culminates in bizarre, bodily sculptures that emphasise the restrictive bond we have with our flesh and the social situations that come along with it. Existentialist theories, such that of De Beauvoir and Sartre, resonate with Mowlds’ own musings about identity and societal behaviour, fueling the manifestation of her work and providing solace in

an upturned, modern society. As a sculptor, material usage and skill-based processes become integral to her practice, in which Mowlds sculpts by hand each wrinkle, crease and pore of the skin we are confined within. Working in an array of materials, most notably silicone and glass, Mowlds creates grotesquely life-like work that begs the viewer's contemplation, while initiating difficult, but critical, conversations.

Abegael Uffelman earned her Bachelor of Fine Arts from Tyler School of Art, Temple University in 2019. Her work has been featured and awarded at Bullseye Glass Transitions in Kiln-Glass Exhibition, where she earned first place in the emerging artist category, and the Glass Art Society International Student Exhibition in 2019. Uffelman has been a Visiting Artist at Tyler School of Art and Worcester Center for Craft. In 2023, she completed the Better Together Residency at Pilchuck Glass School. Currently, Uffelman is the

Program Coordinator and an instructor at glass non-profit, Foci Minnesota Center for Glass Art in Minneapolis, MN.

As a glass and mixed media conceptual artist I relate the physical qualities of my work to societal disparities. I analyze concepts of social interaction, politics, identity, and memory through creating physical objects and installations that others can relate to. Through glass and mixed media objects and installations, I blur, distort, and obscure information; curating how people view these topics.

I strive to understand the relationships and connections between others, both intimate and fleeting. Growing up as a transracial, Asian adoptee in a White family has impacted my life in a profound way. My work is a comment on situations my family and I have faced in American society-from personal reflection into adoption records to racial microaggressions.

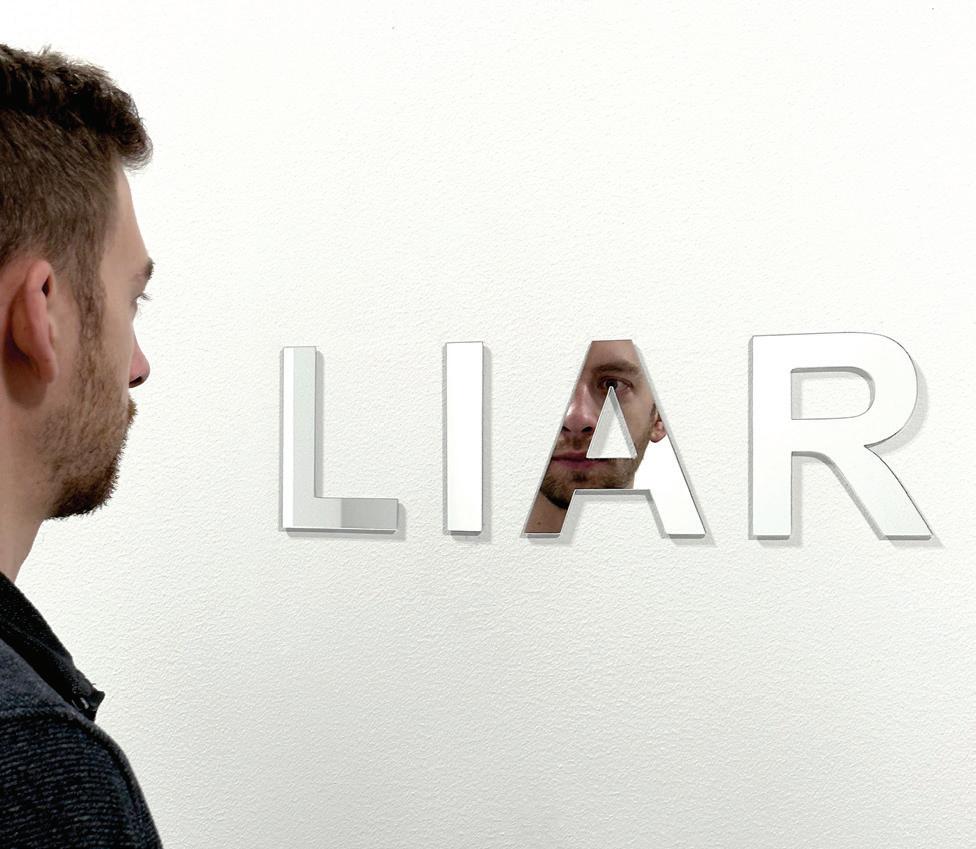

Top left: Always, with Wings Edition (Maxi, CrimsonTide, MoonTime), My Little GroomMe line, Priscilla Kar Lee Yo. Kiln formed glass, gold, human hair. 6” x 4” x 7” each, 2022. Photo by B. Fortuné. Right: The Wait, Sadhbh Mowlds. Blown glass; mirror; silicone; human hair; foam. Glass-blowing/ Sculpting/ Mold-making/ Silicone Casting. H15” x D16” x W10.” Year: 2023. Photo Credit: artist’s image. Bottom left: was it a lie, Abegael Uffelman. Sheet Glass, Mirror, Paint. Cold Application. 26”x32.” Photo by Abegael Uffelman.

My work spans several topics, recently including the act of lying as a result of experiencing grief and loss. Lies are abundant, inevitable, inescapable,routine, even expected and desired. Infinite. From young to old, perpetrators and victims of lies include every single person in existence. Mirroring the stages of grief, over time I learned to accept what lies are and their function in society. From personal impact to societal expectation and political governance, lies are reality and they are a version of truth.

This work is personal, but it extends a universal welcome to those who have felt the pain of loss, or been hurt by systems of power, angered by our status quo. And if they don’t personally, deeply connect, they tell a story, a step towards understanding.

This year’s exhibitions featured a truly global array of work that showcased techniques from the entire spectrum of glassmaking techniques and wonderfully represented the conference’s theme, Where Art + Design Meet. We received 158 entries from 40 countries: Australia, Austria, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, China, Colombia, Croatia, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Hungary, Iceland, India, Iran, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Mexico, Morocco, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Republic of Korea, Russia, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Türkiye, United Kingdom, United States, and Wales. View our 2024 exhibitions online through April 2025.

View online at glassart.org/evolution-2024

FIRST PLACE

Brooklyn Roots, Boricua Branches: After Dos Corazones by Noemi Nieves-Hoblin

Noemi Nieves-Hoblin (United States), “Brooklyn Roots, Boricua Branches: After Dos Corazones,” stained glass, 2023. 15 x 15 x 1”.

SECOND PLACE

Particles of Freedom by Xiaozhe Huang

Xiaozhe Huang (China/Italy), “Particles of freedom,” lampworked Murano glass, sterling silver, 2023. 4.2 x 3 x 1.5 cm.

THIRD PLACE

Let’s meet in a better times by Julia Ciułek

Julia Ciułek (Poland), “Let’s meet in a better times,” blown glass, plastic water pump, 2022. 40 x 45 x 15 cm.

View online at glassart.org/connection-2024

FIRST PLACE

Towel Rack by Narrae Kang

Narrae Kang (Republic of Korea), “Towel Rack,” cold worked and engraved glass, window frame, brass, 2023. Photo credit: Gun Ha Park. 111.7 x 59.3 x 3 cm.

SECOND PLACE

Boolean Sweep by Joshua Kerley and Guy Marshall Brown

Joshua Kerley + Guy Marshall Brown (United Kingdom), “Boolean Sweep,” kilncast glass foam, 2024. 40 x 24 x 24 cm.

THIRD PLACE

Flying Bird with Seven Lenses by Kirsti Taiviola

Kristi Taiviola (Finland), “Flying Bird with Seven Lenses,” blown glass, light, mixed media, 2023. 2.5 x 2.5 x 2.5 m..

View online at glassart.org/trace-2024

FIRST PLACE

Midden by Karen Browning and Jon Lewis

Karen Browning + Jon Lewis (United Kingdom), “Midden,” B&O Beovision 1 television - glass, copper aluminium, plastic, resin, steel, hot cast, kiln cast, and machined, 2024. 120 x 9 x 165 cm.

SECOND PLACE (4-WAY TIE)

Golden Tree Paperweight by Lynden Over and Christine Robb

Lynden Over + Christine Robb (New Zealand), “Golden Tree Paperweight,” hot-sculpted glass, 2023. 17 x 11 x 11 cm.

SECOND PLACE (4-WAY TIE)

Architectural Panel by Balázs Telegdi

Balázs Telegdi (Hungary), “Architectural Panel,” vitreographed glass, glass threads, float glass, aluminum, silicone, 2023. Photo credit: Anett Demeter. 1200 x 750 x 9 mm per panel.

SECOND PLACE (4-WAY TIE)

Thames Glass by Lulu Harrison

Lulu Harrison (United Kingdom), “Thames Glass,” mold-blown sand, wood ash, shells, flux, 2022. Photo credit: Ben Turner. 26 x 33 x 10 cm.

SECOND PLACE (4-WAY TIE)

DAILY DOSE by Marta Ramírez

Marta Ramírez (Colombia), “DAILY DOSE,” flameworked and cold worked borosilicate glass, 2023. 11 x 4 x 4”.

By Phillip Murray Bandura

In this article, I reflect on my lecture titled “Is Glass Queer? Or Is It Just Me?.” I delve into my experience delivering the lecture and the insights I gained from it. The lecture explored the intersection of glass art, queer identity, and queer theory, and examined how glass, as a medium, embodies queer qualities and how the Studio Glass Movement exhibits queer characteristics as well.

Introduction

The event began with a warm introduction by Michael Saroka, the current president of the Glass Art Society (GAS). Michael highlighted my educational background, noting that I earned my MFA from the Alberta University of the Arts in 2022, where I studied under Natali Rodrigues. He mentioned my role as a founding member of the Calgary-based Canadian glassblowing collective Bee Kingdom, which operated from 2005 to 2020. He also noted that Elton John has collect-

ed one of my artworks. I had to correct him when I started the lecture as Elton had collected four of my artworks. This correction provided me the chance to give Michael a lighthearted ribbing to start, setting the tone for a cheeky and humorous presentation.

During my lecture, I brought a disco ball and a bubble maker to set the mood, though I never explained their presence. In hindsight, this omission added a layer of queerness to the talk itself. The unexpected effect of the bubble maker, creating a mountain of bubbles that queerly wiggled and waltzed in front of the stage as I spoke, further contributed to the whimsical and unconventional atmosphere, reinforcing the theme of queerness in both the medium of glass and the lecture experience.

I also failed to mention that the disco ball and bubble maker were donated to Berlin Glass e.V. to proliferate their use in glass hot shops. If you would like me to come to your institu-

tion to give this lecture, you will also get a disco ball and bubble maker!

When encountering the word “queer,” interpretations vary widely based on personal experiences. As a 42-year-old gay man who identifies as queer and grew up in a middle-class home in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, my perspective is shaped by these contexts. Historically, “queer” has had multiple connotations. According to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), the term has been in use since the 1500s to denote something strange, odd, peculiar, or of questionable character. By the early 1900s, it evolved into a derogatory term for homosexuals. In recent decades, however, the LGBTQ+ community has reclaimed “queer” as a term of empowerment, celebrating gender diversity and inclusion, and it is now frequently used in gender studies and queer theory1

In my lecture, I utilized “queer” in both its historical sense of being strange or odd, its contemporary usage within the LGBTQ+ community, and finally, the liberal arts academic context of queer theory. I view “queer” as a symbol of infinite possibilities, this is mirrored in the queer approach the Studio Glass Movement takes to its exploration of the artistic possibilities of glass.

The central questions of my lecture involved some wordplay: “Is glass queer? Or is it just me?” Here, I explored three facets. First, I affirmed my own queer identity and how it relates to my approach to glass as an art form. I began my glass education at the Alberta College of Art and Design from 2001–2005 under Norman Faulkman, who initiated the glass program there in the mid-1970s. The program is characterized by an

open, exploratory approach to glass. I have seen this approach mirrored in many other Studio Glass Movement institutions. This open-ended exploration of glass paralleled my personal journey of self acceptance to come out as gay, and then as queer, thus making glass an inspiration in my self-discovery.

Sara Ahmed’s concept of “queer use” from her book What’s the Use?: On the Uses of Use? was instrumental in this development. Ahmed defines “queer use” as improper use, repurposing things or ideas in ways they were not originally intended2 The Studio Glass Movement, with its emphasis on exploring the potential of glass, consistently engages in such “queer use.”

Dr. Jane Cook’s work further elucidates the queer nature of glass, specifically in their lecture “Glass is a Verb, and So Are You”3. Dr. Jane Cook explains how glass is an amorphous solid, meaning glass is inherently disorganized at the molecular level, which is counterintuitive and thus queer.

Isobel Armstrong’s “Victorian Glassworlds: Glass Culture and the Imagination 1830-1880” explores how glass has radically transformed our world4. Glass has expanded human understanding of the macro and micro worlds through inventions like the telescope and microscope. The omnipresence of reflections in mirrors and windows in modern cities has also altered self-perception, promoting a broader, more inclusive sense of identity—an inherently queer characteristic.

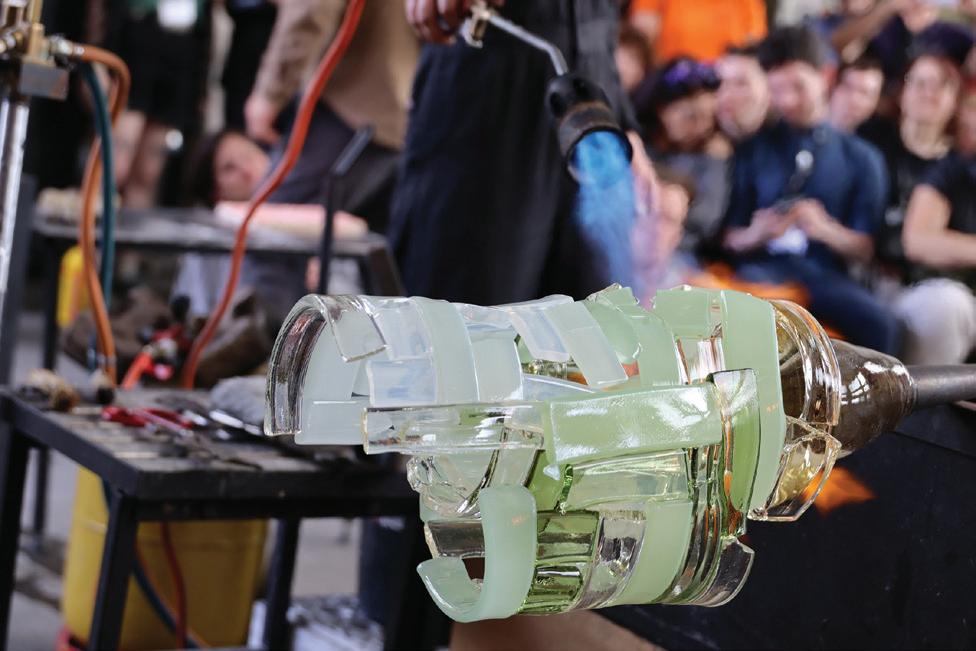

The performative aspect of glassblowing within the studio glass movement further exemplifies its queerness. Studios worldwide, such as the Museum of Glass in Tacoma, the Corning Museum of Glass, and the Glass Furnace in Turkey, feature auditorium-style seating for glassblowing demonstrations and performances. Portable glass studios and those on cruise ships also highlight the performative, and thus queer, nature of glass art and how it is made.

After visiting many glass studios over the years I noticed many studios had a disco ball. During my time at Pilchuck Glass School from 2003 to 2011, a disco ball often adorned the studio, facilitating dance parties. The disco ball was one that Karen Willenbrink-Johnsen brought to the school, and it underscores the glass community’s love for celebration and performance, akin to the drag community’s spirit. The connec-

1 “Queer, Adj.1 Meanings, Etymology and More | Oxford English Dictionary,” n.d. https://www.oed.com/dictionary/queer_adj1.

2 Ahmed, Sara. “Conclusion: Queer Use.” In What’s the Use? On the Uses of Use, 197–229. Duke University Press Books, 2019.

3 Cook, Jane. “Glass Is a Verb, and so Are You by Jane Cook.” Knowledge Stream, n.d. https://www.knowledgestream.org/presentations/bon-bon-chemistry-chocolate.

4 Armstrong, Isobel. Victorian Glassworlds: Glass Culture and the Imagination 1830-1880. OUP Oxford, 2008.

5 Issuu. “2023 GAS Journal Detroit,” November 3, 2023. https://issuu.com/glassartsociety/docs/2023_gas_journal.

tion between the glass and drag community is profound. You can look at “Laura Donefer’s Glass Fashion Show” that first happened in 1989 as part of the joint conference between GAS and the Glass Art Association of Canada in Toronto, Canada to see one of the spectacular connections the Studio Glass Movement has with the drag community5

Just as the glass community has various teaching institutions worldwide that revolve around mentorship and learning by demonstration, the drag community comprises houses and groups where drag mothers mentor their drag children. For my master’s thesis, I asked Norman Faulkner if he would be my queer glass drag mother, to which he agreed, and I was ecstatic.

Julia Bryan-Wilson’s “Fray: Art and Textile Politics,” particularly the chapter on queer hand making, introduced me to the Cockettes, a drag performance group6. The Cockettes’ DIY ethos resonates with the countercultural beginnings of institutions like Pilchuck Glass School, emphasizing a playful irreverence similar to what I learned from people like Norm

Faulkner, Stephen Paul Day, and at institutions such as BildWerk Frauenau in Germany and Pilchuck Glass School.

Concluding my lecture, I reflected on my own work and its queer qualities. My art embodies a camp sense of humour, heavily influenced by a Canadian perspective. Susan Sontag’s “Notes on Camp”7 and John Waters’ work informed my understanding of camp, which is evident in my community’s piece “Shiny Shit.”

“Shiny Shit” refers to the blobs of glass created when learning to blow glass. While these blobs might seem trivial to the untrained eye, they represent a journey and experience to a glassblower. During my thesis exhibition, I stayed in the gallery for two weeks, inviting visitors to adopt a “Shiny Shit” with adoption fees based on weight. I would tell people, “I have more shit than I can handle, and my shit could become your shit.”

This work finds humour in adversity, drawing on my experiences as a queer man. I aim to make people laugh at life’s struggles, finding levity in difficult times. The communal experience of the COVID-19 pandemic reinforced the importance of seeing positives amidst challenges. “Shiny Shit” serves as a reminder that even in the face of adversity, there is beauty and humour to be found.

The work is inclusive, recognizing that everyone faces struggles and has the capacity to find joy. “Shiny Shit” makes a meaningful keepsake or gift, embodying the complexities of our relationships and experiences.

The queerness of glass is multifaceted, encompassing its scientific properties, societal impact, performative nature, and connection to the drag community. Through my work, I celebrate these queer qualities, using humour and camp to navigate and reflect on my own identity and experiences.

I believe that an open approach to the material of glass inherently embodies queerness. This openness has fostered a glass community that embodies many queer qualities. Just as glass is queer, so am I. I hope that recognizing and embracing the queer qualities in glass can inspire glass enthusiasts and everyone to accept and celebrate the diverse differences that make our world so rich and vibrant.

6 Bryan-Wilson, Julia. “Queer Handmaking.” In Fray: Art and Textile Politics, 39–105. University of Chicago Press, 2017.

7 Sontag, Susan. Notes on Camp. Penguin UK, 2018.

By Fatma Ciftci

While the term "Mesopotamian" is used in the caption of this photo, the artifact itself originates from the 8th century. The term Mesopotamia was used to refer to a particular geographical region that played a significant role in the early history of glass. This method is part of the cultural heritage of Islamic lands.

Paste luster is a decorative technique using metal salts, coloring oxides, and carrier materials on glass surfaces. It creates shimmering pearlescent images by creating a reducing atmosphere in a kiln at the glass's transformation temperature. This creates a thin metallic layer, known as "luster," which produces a pearlescent effect in natural light.1

The paste luster technique on glass surfaces has declined in use over time, while its use on glazed ceramic surfaces continues to advance. Previous research focused on investigating the presence of genuine gold in artifacts where scientists examined

Figure 1. 753-755, Egypt-Abbasids 8th century AD (Cairo Museum of Islamic Art, 2023, https://www.miaegypt.org)

metallic nanoparticles on the surface to understand their visual appearance. Materials used to produce luster remain unchanged, with copper, iron, and silver nanoparticles found on metallic layers. So far, we have found one article where the researchers attempted to apply this technique to glass.

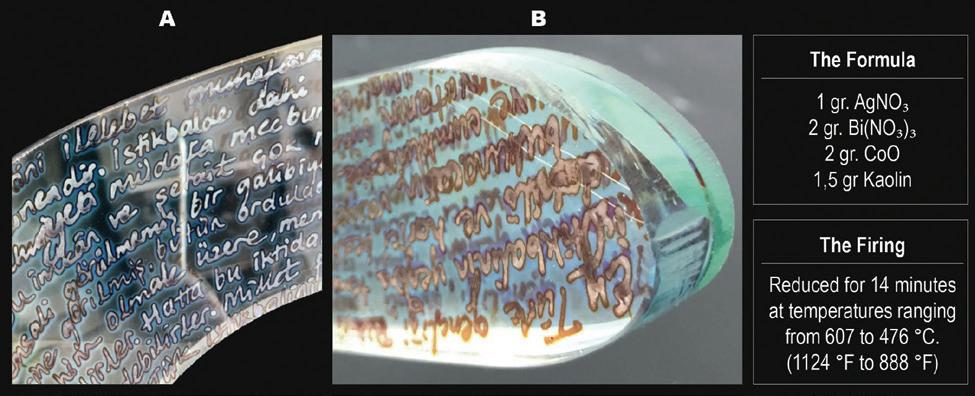

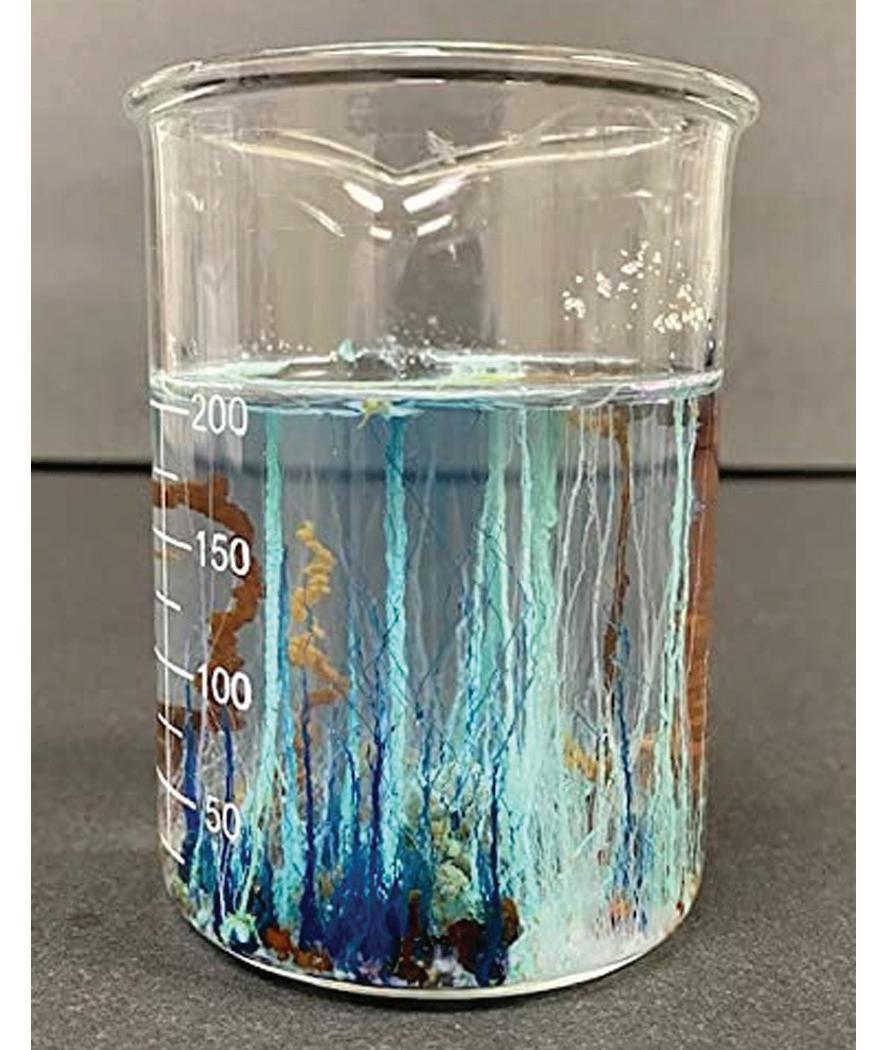

The objective of this study is to create our own formulas by building upon formulas that have been utilized since the 8th century. The formulas created in our experiments were derived from an 8th century manuscript, Kitab al Durra Al Maknuna, authored by Jabir Ibn Hayyan. New formulas are applied to glass surfaces with various structures.

Figure 1 displays the earliest known example of a glass piece decorated with luster paste. The origin of luster paste on glass is debated, with some suggesting it was first used in Basra2 during the 8th century or Kasr-ul-Hayr al-Sharqi, a Syrian palace city under Umayyad caliph Hisham Abd al-Malik3, both within the Abbasid-era geographical scope.

Formulas: The manuscript contains formulas containing hazardous substances like mercury and arsenic, which have been eliminated. We aim to minimize potential damage to raw materials. Some formulas use obsolete weight units, while others use modern weight units. We have chosen to use one type of weight unit for all formulas.

Glass: We conducted our experiments on alkali-silica glasses, including both window glass and pre-manufactured glassware.

Kiln and Reducing Atmosphere: The paste luster decorations applied on glass were subjected to firing in a reducing environment using an 80-liter ceramic kiln fueled with a mixture of LPG (70% butane and 30% propane gas). We utilized gas to generate a reducing atmosphere.

1 Çiftçi, Fatma. 2024. “Cam Yüzeylerde Macun Lüsteri Araştırmaları”. PhD diss., Dokuz Eylul University.

2 Neu Keramik, 1992

3 Al-Hassan, Y. 2009. “An Eighth Century Arabic Treatise on the Colouring of Glass: Kitab Al-Durra Al-Maknuna (The Book of Hidden Pearl) of Jabir Ibn Hayyan (c.721-c.815)” Arabic Sciences and Philosophy 19, 121-156. DOI:10.1017/S0957423909000605

An oxygen probe was used to calculate the atmosphere within a kiln, indicating the minimum oxygen concentration and corresponding temperature. This was crucial for determining the duration required to achieve the desired color under reducing variables, as it quantifies the oxygen concentration in the atmosphere.

The firing technique in a reducing environment can be briefly described as the combustion process that takes place when oxygen ions are reduced in an environment lacking sufficient oxygen.4 To achieve luster effects, it is essential to ensure ion exchange in a reducing atmosphere at the conversion temperature of the glass (viscosity 103-8) after the paste mixture is applied to the glass surface. The expression “duration of reducing atmosphere” in the text corresponds to the lowest oxygen level that the oxygen probe shows as 1,0 λ on the screen.5

An experiment was conducted to determine the softening temperature of window glass, based on the manufacturer's information. The glass was exposed to temperatures ranging from 600-700°C without any hold. The results showed that the glass did not bend at 600°C, moved downwards at 630°C, bent at 650°C, and broke free at 700°C after 27 millimeters of bending.

Calcination removes crystalline water, lowers melting point, and reduces molecular weight of raw materials, making it sufficient for carrier raw materials to maintain ion exchange in a reducing atmosphere. The carrier raw materials utilized in this study had calcination at a temperature of 900°C.

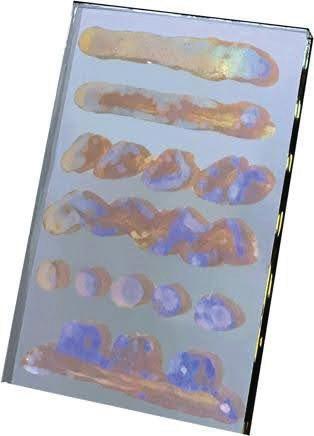

Table 1 demonstrates the alteration made to the luster paste formula by modifying the carrier raw material. The formulas and variable carrier raw materials as shown in Table 1. In variant A, 1.5 grams of kaolin were added, in variant B, an equivalent amount of Sal-ammoniac was added, and in variant C, the same quantity of red clay was used as the carrier raw material. All the samples were fired in the same kiln, during which the oxygen content reached its minimum level for a duration of 6 minutes, within a temperature range of 650 to 482 degrees Celsius. So far, ceramists who work with luster have categorized ingredients as colorant and carrier

raw materials. However, as a result, we observed that each of the outcomes exhibited a distinct color. When combined with coloring raw materials, they changed luster color and display a coloring effect. Cobalt oxide, a raw material used for coloring, has the ability to act as both a carrier and a coloring agent due to its formation at high temperatures. Iron oxide, also having coloring properties, can be used as both a colorant and carrier. It is not possible to precisely define the raw materials

Kaolin Sal ammoniac Red Clay A B C

Carrier Raw Material:

Kaolin 1,5 gr

Carrier Raw Material: Sal-ammoniac 1,5 gr

Coloring Raw Materials of the Formula

Coloring Raw Materials Amount (gr)

AgNO3 1 Fe2SO4 2 CuNO2 2

as either colorants or carriers, as this distinction depends on the specific conditions.

Figure 2 shows that window glass with higher iron content, like A and B, and glassware with lower iron content, like C and D, have different colors. Both types were painted with the same luster formula and fired in the same kiln. It was subjected to a reducing atmosphere for a duration of 14 minutes, with temperatures ranging from 607 to 476 °C (1124 °F to 888 °F). As a result, the luster color of glass varies based

on its composition, with glassware resulting in a platinum hue (Fig.1,C,D) and window glass a reddish tint (Fig.1,A,B).

Ion exchange and luster effects occur at the transformation temperature of glass (538-677 °C) after passing the thermal shock range (440-505 °C). Annealing cannot be done later due to luster formation reversing in an oxidizing atmosphere. Annealing temperature is close to the luster's fixed temperature, and temperature cannot be raised again because the atmosphere does not have any oxygen left for burning. This method cannot remove thickness-related stresses. Nevertheless, all of the samples remained unbroken. Figure 4 shows the stress on the glass in the polariscope. Figure 3 shows the glass before (A) and after (B) firing, illustrating the stress level within the glass. Distinct and sudden color shifts suggest increased stress in glass, while no tension or stress exists between the material and formula.

The process of ion exchange in a kiln is essential for achieving specific colors. This is because the formulas containing iron compounds need to interact with copper Compounds, and careful attention must be given to the interaction between these formulas in order to obtain the desired color.

To prevent a smoky appearance on glass surfaces in a kiln atmosphere, oxygen is introduced during the cooling process at 400-480 C.

A paste luster is effective when its consistency is watery enough for dip pen writing, achieved by combining vinegar, water, and propylene glycol (Figure 4).

The optimal temperature range for atomic mobility depends on the ionization capacity of the paste formula and glass atoms, with close synchronization between them for desired luster. The paste luster should be maintained at an optimal

temperature, and for sharp lines, the heat should be synchronized with the glass transformation point.

Glass thickness of 1 cm contains higher stress than a glass thickness of 4 mm due to the inability to create a controlled cooling program after annealing due to the reducing atmosphere in the gas furnace.

Resources

Al-Hassan, Y. 2009. “An Eighth Century Arabic Treatise on the Colouring of Glass: Kitab Al-Durra Al-Maknuna (The Book of Hidden Pearl) of Jabir Ibn Hayyan (c.721-c.815)” Arabic Sciences and Philosophy 19, 121-156. DOI:10.1017/S0957423909000605 Çiftçi, Fatma. 2024. “Cam Yüzeylerde Macun Lüsteri Araştırmaları”. PhD diss., Dokuz Eylul University.

Cairo Museum of Islamic Art, 2023, https://www.miaegypt.org

Neu Keramik.1992.s.370

Tanaka, Y. (. (2007). Ion Exchange Membranes Fundamentals and Applications. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

By John Erwin Dillard

On October 7th, 2023 I became witness to what would become the darkest event to unfold in my lifetime. I had been working on my lecture Why Glassblowing is Irrelevant for two months. In those two months and beyond I received multiple communications about the title of my lecture being “offensive.”

My then graduate advisor came to me and said she had received criticism that my lecture deeply offended one or more people. At the time, the lecture and its title were not yet public. Colleagues told me I should change the title, because no one would come. I was advised against presenting such a controversial opinion. I was asked by a trusted mentor if I “was doing this to hurt other people’s feelings.” It went so far that there was a period I believed the lecture would be censored.

Seven more months went by, and the conflict only escalated. A global dissention was taking place around me. The earth started to move in a different way. The world grew quieter. Outbreaks of divisive antagonism proliferated all around. A pestilence of rage, censorship, and prejudice gently blanketed

the earth. Yet, my proposition on glassblowing was still considered offensive.

For these reasons, I knew giving this lecture was even more important. As an academic, I would never waste the saliva to personally attack any individual. It is my occupation to question systems of power. Scholarship, for me, is about the search for freedom. Academia is a place where we may challenge the structures that hold others in bondage. These opportunities are a bastion which hold humanity up against total disorder. The disorder, subjugation, and systems of oppressive power do not exist separately. Glassblowing does not exist in a magical vacuum where we melt sand and sing kumbaya.

In terms of the scale in which human life exists, glassblowing is irrelevant. However, it is what we can do with glassblowing that matters. When glassblowing can become a mechanism to dismantle the white supremacist capitalist patriarchy then it will truly matter. In my lecture I described why, how, and if this is possible. I believe it is.

Henceforth, I allocate the remainder of this entry to author bell hooks, a revolutionary American author who defined white supremacist capitalist patriarchy. I believe it should be her own words which you come to understand what it is I’ve said.

bell hooks, CULTURAL CRITISICM & TRANSFORMATION, 1997

“I began to use the phrase in my work “white supremacist capitalist patriarchy” because I wanted to have some language that would actually remind us continually of the interlocking systems of domination that define our reality and not to just have one thing be like, you know, gender is the important issue, race is the important issue, but for me the use of that particular jargonistic phrase was a way, a sort of short cut way of saying all of these things actually are functioning simultaneously at all times in our lives and that if I really want to understand what's happening to me, right now at this moment in my life, as a black female of a certain age group, I won't be able to understand it if I'm only looking through the lens of race. I won't be able to understand it if I'm only looking through the lens of gender. I won't be able to understand it if I'm only looking at how white people see me.

when we use the term white supremacy it doesn't just evoke white people, it evokes a political world that we can all frame ourselves in relationship to.

And I think that I was able to do that because I grew up, again, in racial apartheid, where there was a color caste system. So that obviously I knew that through my own experiential reality, you know, that it wasn't just what white people do to black people that was wounding and damaging to our lives, I knew that when we went over to my grandmother's house, who looked white, who lived in a white neighborhood, and she called my sister, Blackie, because she was dark and her hair was nappy and my sister would sit in a corner and cry or not want to go over there. I knew that there is some system here that is hurting this little girl, that is not directly, the direct hit from the white person. And white supremacy was that term that allowed one to acknowledge our collusion with the forces of racism and imperialism.”

To me an important break through, I felt, in my work and that of others was the call to use the term white supremacy, over racism because racism in and of itself did not really allow for a discourse of colonization and decolonization, the recognition of the internalized racism within people of color and it was always in a sense keeping things at the level at which whiteness and white people remained at the center of the discussion. In my classroom I might say to students that you know that

Radical ideology will always offend hegemonic systems of power. When power is consolidated it is the best interest of supremacist to silence us. Offensiveness can be our power. May bell hooks rest in power. May her words guide us into seeing new and better possibilities for our world. Every day we are able to search for those possibilities is a gift. I am eternally grateful to have had the opportunity and privilege to share these thoughts.

By Ryan Kuhns

Computer Aided Design has always been a part of my glassblowing process. Whether it be multimedia adornments or custom tools, CAD plays an integral part in my finished products.

My journey with CAD began in jewelry design, however, at present, I am predominantly a flameworker and freelance CAD designer. After double majoring in Metals/Jewelry/ CAD-CAM and Glassblowing, I couldn’t leave either world behind. In the past I've worked as a jewelry designer and have experience in the hot shop as well. Throughout the years I have more or less combined those aspects into my work melding elements of each discipline. I’ve learned my creativity and skill in design is best expressed through CAD as a tool to “get things on paper.”

Some of the ways in which I have used CAD include designing and printing adornments for lampworked glass pieces, designing molds for lampworking, resin castings, and tools, as well as design and layout.

One of the first ways in which I combined CAD and 3-D printing with glass as a professional artist is with adornments. At the time I was working at a jeweler doing custom engagement jewelry and remounting projects. I was strongly influenced by this work and used the aspects of my jewelry designs to create the adornments I was adding to my glass. As you can tell, the jewelry influence is strong with these. It challenged me to design and print in a way that allowed both stone setting and attachment to borosilicate glass. For this, I used CAD to design the adornments, printed them on a SLA machine, and electroformed them onto the glass.

When I first started this body of work, desktop 3-D printers were just emerging and my process was much different and sometimes required outsourcing. However, as the technology progressed, it became easier to use these tools in house to incorporate printing with my body of work. I began printing in my studio using a Form1, which is a desktop stereolithography printer. The reason I chose SLA printers with a laser and resin vat is because the build lines are very minimal, and with electroforming, they would be invisible once electroformed over. This process was used for specific designs that were electroformed individually as well as electroformed onto glass. I ultimately used this printer for making reliefs for other mold, jewelry, and sculpture projects. It has been a part of a variety of different styles of work I’ve produced.

Eventually I wanted to move on from some of my multimedia work and to streamline my process. This takes us into the tools and molds aspect of my work. I wanted to use my skill in CAD and my love of using molds with glassblowing. There is some overlap here with my molds and electroforming work, however once I got my two-part machine running, I stopped with the adorned components and mostly stopped electroforming as well. I reflected back on when I was in college and used blow molds to create lighting pieces. I used traditional methods then, but became set on incorporating my newer skills with borosilicate molds. There is something meditative in using molds to create a whole piece out of many multiples. I missed that work and wanted to bring it to the torch.

I started with basic truncated designs to create triangular, square, pentagonal, and hexagonal borosilicate tubing while simultaneously working on a two-part mold system. I am drawn to geometric shapes in glass for several reasons. First, due to glass’s natural desire to be round, using blow molds to create glass that has sharp edges is both visually appealing and rewarding to accomplish. Secondly, I draw inspiration from designs in architecture and architectural elements. Using straight lines, shapes and multiple elements to create larger pieces is rewarding.

At this point, I had established a studio set up that included

Clockwise from left: Kuhns Presence of exposure, photo credit Tim Malone, “Presence of Exposure” 2009, Soft glass, rope, 4x4x20 foot

Kuhns solo electroform “hand pipe with electroformed set stones” 2012, borosilicate glass, photopolymer resin, copper, cubic zirconia 4.5x1.5x2 inch

Kuhns solo travelers and explorer, photo credit Scott Southern, “Geo travelers and explorer set” 2020, Borosilicate glass, 2x2x3, 4x3x6 inch

not only the SLA printer but FDM printers as well, broadening my printing abilities for what would ultimately be cast for the mold machine. Both my one- and two-part molds were designed in CAD and printed on either my FDM or SLA machine, molded, and cast in bronze.

I designed the two-part mold machine in CAD and tested several versions by laser cutting MDF board to test its functionality. Once I was satisfied I had it water jet cut out of ¼ inch steel. The machine operates using a foot pedal and pneumatic cylinder. This exact machine is the same one I've used since 2017. The shapes I’ve designed for this two-part mold are used to blow a variety of different borosilicate pipe designs.

Recently, I have been able to utilize both the progression of my skill set and the progression of technology in designing, printing, and casting. My most recent project brought me to

design and manufacture a four-part mold machine in house. I have significantly less limitations in design and production with a four-part mold versus the two-part mold.

The design limitations of two-part molds had me struggling and I felt a bit stuck so about a year ago I became determined to resolve the issue. With the amount of trial-and-error I knew was in store I went to my computer knowing I had to think outside the box. Ultimately I decided to use only the tools and processes I have at hand with the addition of some readily-available components.

I am thrilled to have completed the new machine. It took countless design hours and hundreds of hours on my print farm but keeping it in house helped me have a lot of control over the outcome and allowed for small tweaks to be made consistently, creating a clean and refined machine. Moving forward, this machine and the production of new molds will give me the opportunity to create the unique borosilicate glass designs I imagine, and maybe even get me back in the hot shop.

By Daniel Kvesić, Bokart Glass

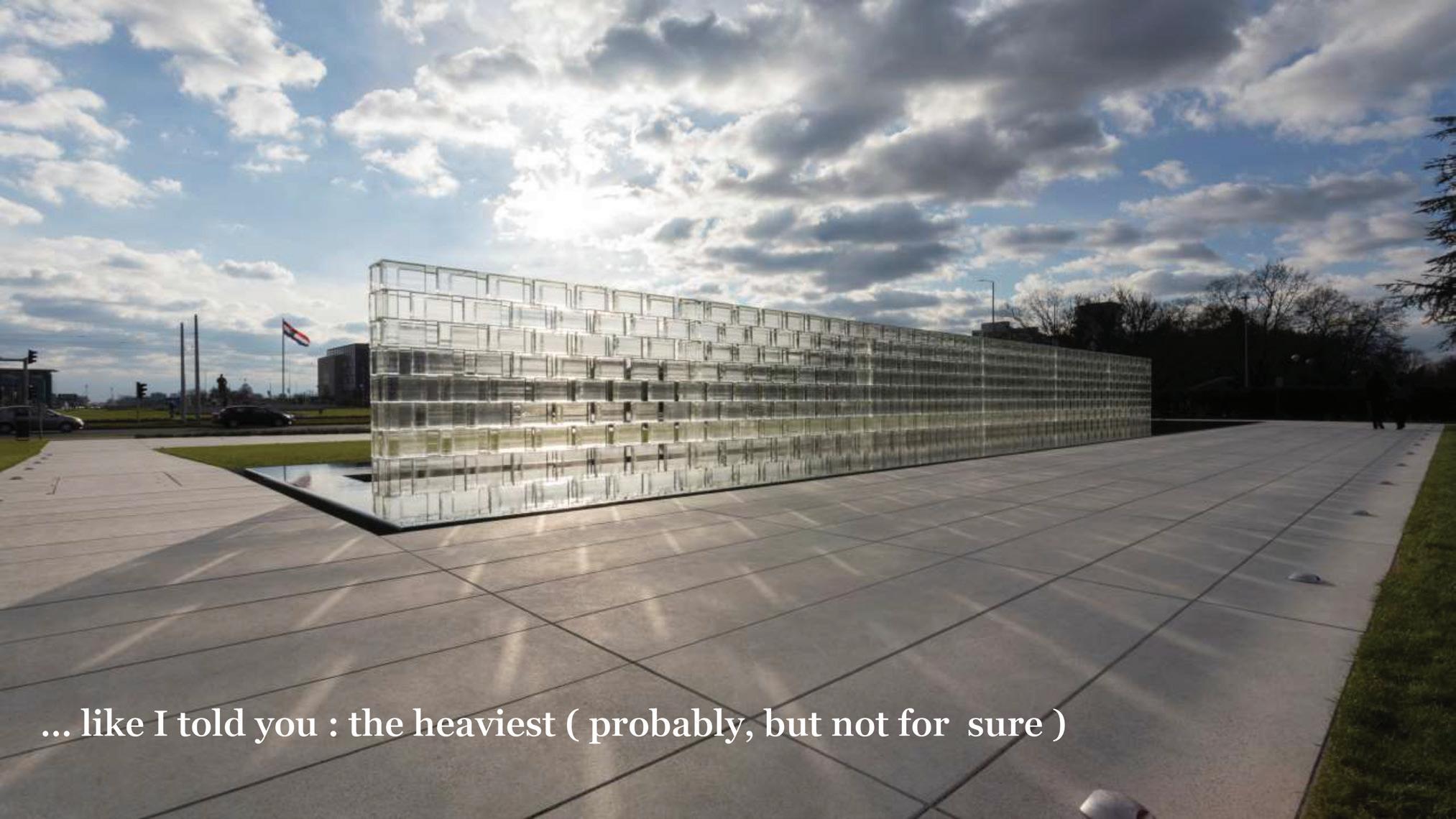

To be involved in building a monument to your homeland, in your town, and to build the biggest glass wall ever was challenging. Croatia is a relatively new democratic country, although we have been here for centuries. The country was founded after the bloody war that swept through the former Yugoslavia and transformed the region into new flags and banners. Croatia has exited the war with scars and war memories, and a call went out to create a national monument that acknowledged the history that defined our nation, the present, and the future. Monuments have always been a reminder to the victory of freedom and the obstacles that needed to be conquered for that victory.

Where did the inspiration come from and why did we need to build this long wall? During the war, common people searched for people who were missing. To express their anger and to demonstrate their fight against oppression, they started to build a wall of bricks with names of missing people on it in front of the UN office in Zagreb. In the end, that wall was made out of the solid bricks and was 47 meters long. The wall became a symbol of fighting for freedom and praying for peace.

Many years later that wall served as inspiration for a monument

to represent a past and proud nation that stood its ground in crucial moments of one nation.

The architect Nenad Fabijanic, a most respected professor at the Academy in Croatia, became a leader on the monument project and asked us, along with the artist Jeronim Tisljar, to create a glass wall that was 47 meters long and 3 meters high. The initial idea was to create a wall of hollow glass bricks, but the request was that the wall needs to be transparent, solid, translucent, and built with the highest optical-quality glass that can be found.

That first task was difficult enough since the project was approved just at the end of 2019 and the COVID-19 pandemic shut down production. The European market could not provide us with any quality producer that could provide the glass before lockdowns began and with all the restrictions placed, so we had to look further from the EU zone. Before choosing the glass and style of assembling, we looked at similar projects such as Crystal House Netherlands, Atocha Memorial Spain, and Qwalala monument in Greenland where various glass blocks and assembling techniques were used. All

these projects had different styles and problems, but none of them were meant to be this long and this heavy.

Our biggest issue was to find a super stable solid and super transparent glass. In the end, we decided to use a borosilicate glass block that was mold-blown to be 45 x 35 x 7 cm. The only producer available was in China, which had the ability at that time to produce and deliver solid blocks. We sent all the details, they replied and made beautiful samples that we tested to hold three tons. The next most difficult task was to find the best silicone to hold everything in place. As we have seen in other case studies, the silicone must be very solid, but very flexible and durable, so that means a type of hybrid silicone with extra transparency. After testing, we chose the Soudal Crystal Fix-all Hybrid Adhesive Super Transparent sealant that was UV stable, mold resistant, and very solid after various tests were made.

Since the wall is 47 meters long, it needed to be perfectly straight and wind resistant, and most of all, stress free from potential earth movements. Zagreb lies on unstable ground that commonly experiences earthquakes, the base of the monument needed to be specially constructed with a chamber underneath the glass that will act as a shock absorber. Underneath the glass, there is a chamber with steel pillars that are placed strategically for shock absorption and can support the 45 ton weight of the glass. These pillars are adjustable so they gave us an ability to align the perfect straight line for the glass base. This glass was then placed in a stainless steel structure, an U – shaped profile with 10 mm thickness that has specific screws that can allow us to adjust the alignment and have lighting integrated under the glass. This stainless steel structure is crucial since it serves as a barrier for the glass to protect from frost and water. The steel can shrink and cause problems, and that is why the steel was seven mm wider and the glass was separated with two-component Soudal All Fix Sealant that is much stronger as the Crystal All Fix.

Once the base was created, we started to build the structure, one line on top of each other with crucial elements like corners that were built with two blocks that were cut under 45 degrees, polished and glued in the workshop and each five meters on the structure, another block was placed that connects two lines of the walls. These two parts are basically the ones that are holding the line and providing stability. Additionally, once the bricks were built, we added small crystal plastic bumpers that allowed us to adjust the wall in lines. It was built during winter, so we had to build a heated tent that held the temperature at about 25 Celsius degrees and the humidity was not a bigger issue since it was built during November, December and January.

The biggest issue was the COVID-19 pandemic and constant delays, but we had to move constantly in order to get the wall up. After around 60 days, the wall reached three meters in height, and it was time to strengthen the wall with stainless steel cables placed in between the glass bricks that will hold the structure against the wind, which proved to be the biggest problem for this long wall. These cables need to be adjusted every couple of years, and they provide final stability to the structure and ensure it is safe.

For the final test of stability, there were several unfortunate events; two earthquakes, one that was 5.6 on the Richter Scale and later that year near Zagreb that was a 6.4. The wall stood without any damage because of the steel pillars that absorbed the shock and the silicone that allowed structure to move. In 2023, a hurricane with strong north wind hit, but the steel cables did its job and held the wall.

The wall now proudly stands at the entrance of Zagreb city, providing a very special place for everyone to pay their respects to the fallen ones, a place to hold its breath for the country and liberty that it gave us. More than everything, it gives a clear view of the future that can show the new generation a bright way forward.

By Silvia Levenson

Art must make itself a magnifying glass laid on the everyday outside , what the naked eye tends to scroll over without stopping. Italo Calvino *

I feel in between different realities: between Latin America and Europe, between the contemporary art world and the glass world, between concepts and process, thinking and making.

Even more, I stand between a society that is struggling to change and my desires for justice.

Through my work, I try to express the urgent need to reconcile ethics and aesthetics. However, I am not the only one who feels pain in the face of injustice and violence. Maybe my ability to inhabit this world is based on the capacity of processing feelings of frustration, sadness, and anger through my sculptures and installations. In other words, through my work, I seek to communicate my consciousness.

I was surprised when someone would call me a "glass artist" because it seemed absurd to me to define someone only by

the material they use to do her artwork but I can understand that sometimes people need to apply labels.

Honestly now I don't care at all how I'm defined because that's not what bothers me. People can apply the labels they want: I can be a craftswoman or an artivist, an artist, or a maker. I really don't care because all my energy is put into making my sculptures and installations that refer to conflict zones. And for me conflict zones can be the home, a country, my body, or borders.

I remember when I first came into contact with the world of glass in 1994 during a residency at Bullseye. Since I did not live in Murano and did not blow glass, I was not part of the glass community in Italy. My first impression was that they seemed very strange to me because they were only talking about glass and I said to myself: I don't want to get so odd! But here I am happy and proud to be part of this beautiful community of such determined people who after thousands of years still try to tame glass.

I began exhibiting my work made in glass in 1994, and through all these years I have developed work very related to our society: the desaparecidos during the Argentinean dictatorship, childhood abuse, violence against women, and postcolonialist policies in the world.

I was born in Argentina in 1957 and emigrated to Italy under the military dictatorship. Those years between 1976 and 1983 during which 30,000 Argentines disappeared changed my life and the lives of most Argentines.

I was 23 years old when I arrived in Italy as an immigrant with two small children: 4-year-old Natalia and 11-month-old Emiliano and no money.

In the past, I felt uncomfortable talking about my autobiographical experience; whenever someone mentioned it, I would reply that as an artist, I was just exploring reality. Underlying that my work did not fall into the category of art therapy. It was only in 2000 in New York when I met Louise Bourgeois in one of her Sunday Salons at her Chelsea home that I was able to override the pain. This event changed me profoundly; I learned to talk about my work without erasing my personal experience.

Between 2014 and 2022, I developed a traveling exhibition called Missing Identity concerning the 500 children born during the mothers' captivity and given in illegal adoptions by the Argentine military. The exhibition started in a former concentration camp (ex Esma) in Argentina and went around the world from Buenos Aires to La Plata, Montevideo, Washington, D.C., Portland (OR), Barcelona, Paris, Riga, Santo Domingo, and Munich. The exhibition included 133 glass baby clothes representing children who are now adults and have recovered their identities, thanks to the work of the indefatigable Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo.

In these 30 years, I have created installations, sculptures and videos aimed at dissolving borders: physical and psychological borders and I have used glass to see what is happening around me. I love the ambiguity of glass. Like all materials used in art, glass is not neutral. We use it to protect ourselves in our homes through doors and windows. We use glass to preserve food and we trust it so much that we place it over our mouths to drink. But somewhere in our brains we know that it can break and hurt us.

For this reason, it is the perfect material for investigating human relationships. For me, it is like a magnifying lens that creates some distance from the conflict that allows me to observe and say out loud what is not normally said.

I know that we can hardly change the world with art, but we can certainly change the gaze of the beholder. Personally, as an artist, I cannot look the other way when I read that 50,000 women are killed worldwide each year as a result of femicide. So, I made several pieces, videos and actions about this topic.

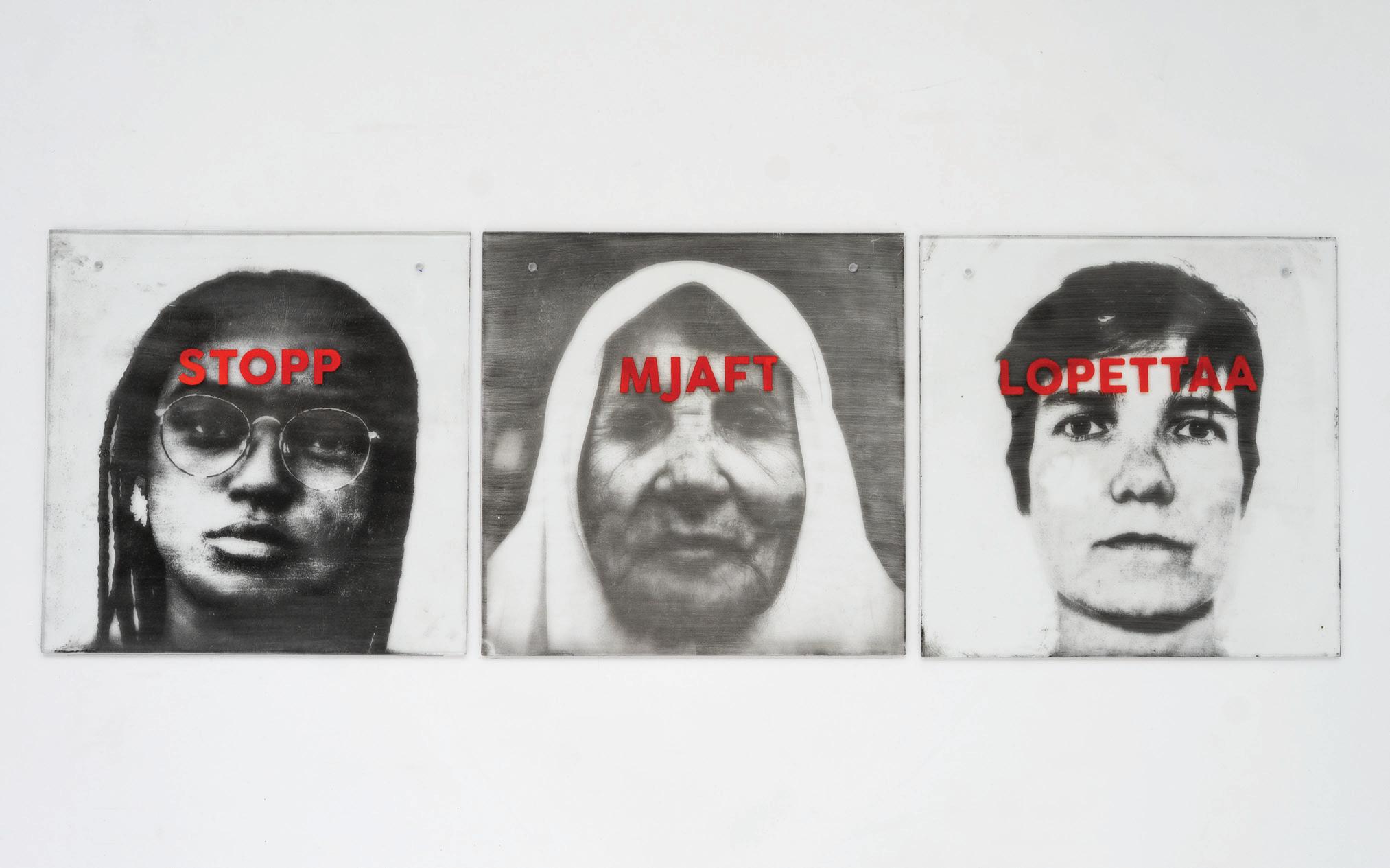

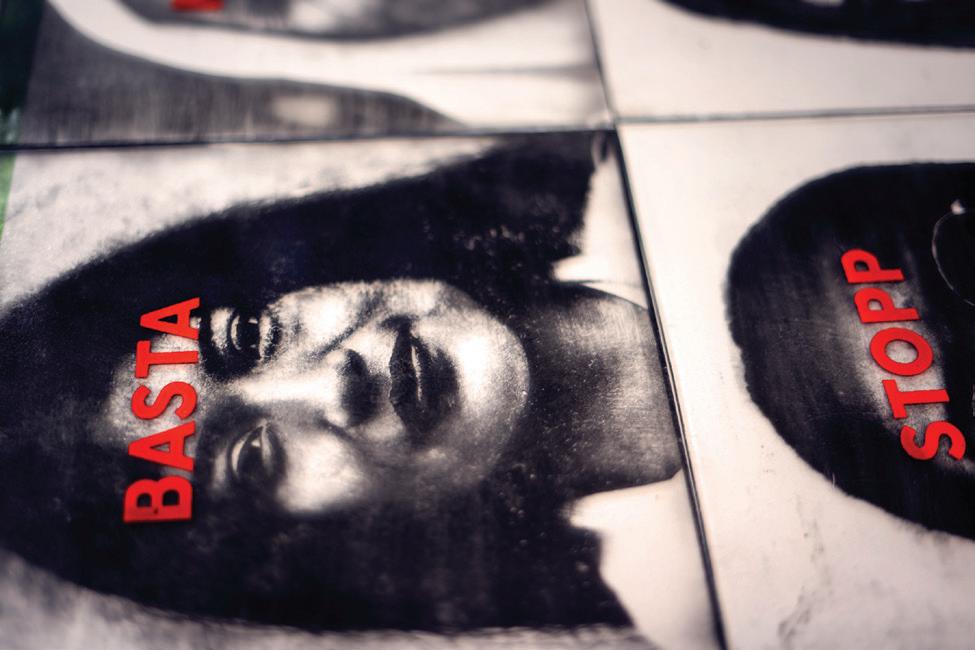

For example, “Digo basta” ( I say Enough) is a form of indictment against gender-based violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on several studies from different countries around the world, incidents of domestic violence increased in response to lockdown orders. During the pandemic, I encouraged women around the world to send me "selfies" on social media. Once I received the files, I turned them into negatives that I printed on glass using an ancient photographic technique.

Successively I wrote the word "enough" in many languages. Although I didn't get to know most of the women involved in the project, printing their images and having their faces appear on glass was a great experience. Nevertheless, with some of these women, I was able to exchange messages and thoughts: creating a meaningful connection. Finally I showed this installation in the Argentinian Embassy in Washington, D.C.

The transparency and fragility of glass combined with a photographic technique have allowed me to create works that not only capture images, but also capture deep stories and emotions. I'm always excited to share my vision with others.

I think that as an artist I am creating something like a bridge where the viewer can enter my world and together we can imagine one other world.

*"A Spectator's Autobiography,”Italo Calvino. 1980

By Alison Lowry

Since my graduation in 2009, the dress has been a powerful symbol and metaphor in my work. My fascination with the dress as an art form began with the desire to explore themes of identity, memory, and history. The dress, as a symbol, carries layers of meaning—it is at once intimate and public, a marker of personal identity, and a reflection of societal norms. By recreating dresses in glass, I have been able to explore themes in a way that is both visually striking and conceptually rich.

In 2019, this approach culminated in the exhibition (A)Dressing our hidden truths at the National Museum of Ireland. This project was never intended as a form of art activism, but rather as a bridge through which survivors could tell their own truths to a wider audience. It was extremely important to research the subject matter thoroughly, and so, it is on the shoulders of the many academics that work within this field, and the survivors who told me their stories, that this work rests, and to whom I am greatly indebted.

(A)Dressing our hidden truths

Ireland has had a long and complex history regarding the institutionalization of its people. In the 50 years after the partition

of Ireland in 1922, the Saorstát or ‘Free State’ incarcerated approximately one of every hundred of its citizens1 in institutions funded by the State, and run largely by religious orders. These industrial schools, mother and baby homes, Magdalene laundries, and psychiatric hospitals were interconnected and codependent on each other, described by James Smith as an ‘architecture of containment.’2

In 2012, an amateur historian named Catherine Corless from Tuam, County Galway, wrote an essay called ‘The Home’ in The Historical Journal of Tuam. In it, she laid out years of research into the Bon Secours Mother and Baby Home—a secretive and closed institution housed in an old Victorian workhouse that operated between 1925 and 1961. In Ireland, mother and baby institutions were places where women and girls, pregnant outside of wedlock, could birth their babies and have them adopted in secret, as being an unmarried mother in Ireland was regarded as a mortal sin.

Catherine discovered the death certificates of 796 children and babies that had lived at the home, but could not locate the corresponding burial certificates. In her essay, she surmised that the missing children’s bodies could have been ‘buried’ in the warren of disconnected tunnels that would have originally led to the old workhouse’s septic tank. The allegation that the Bon Secours Sisters would have buried the remains of babies in this underground tank was initially ignored and then ridiculed in Ireland. In 2017, Dan Barry wrote about it in The New York Times, titled ‘Ireland wanted to forget. But the dead don’t always stay buried.’3 As the world was now watching, Ireland suddenly had to take Catherine’s claim seriously.

1 O’Donnell, Ian. & O’Sullivan, Eoin. Coercive Confinement in Post- Independence Ireland. Manchester University Press, 2007

2 Smith, James. Ireland’s Magdalen laundries and the Nation’s Architecture of Containment. Notre Dame Press, 2007

3 Barry, Dan. “Ireland wanted to Forget. But the dead don’t always stay buried”. New York Times, 28th October 2017 https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/10/28/world/europe/tuam-ireland-babies-children.html

(A)Dress, 2017

In 2015, I was preparing for a solo show at the Millennium Court Arts Centre in Northern Ireland. I had called the show (A)Dress, and was using clothing as a construct to investigate things that we don’t like to discuss in polite society. Like the rest of Ireland, I was horrified on hearing Catherine’s claims. Speaking with Catherine Corless, she told me about growing up in Tuam as a child. She remembered the ‘home babies’ as they were known in her school. The children would arrive late and leave early—limiting their interaction with the others, they were poorly dressed, thin, and dirty. The other children were discouraged from speaking with them or making friends.

An installation work entitled, Home Babies, memorialized the children. Nine sand-cast pâte de verre christening robes hung like shadows in a dark room, invoking the place the children, still, to this day lie. Wall-mounted were nine glass baptismal records, based on an original furnished by Catherine herself, the glass ‘paper’ crumpled as if discarded, the details missing. A soundscape quietly intoned the names of the 796 missing— presumed dead—children.

A collaborative video work with performance artist Jayne Cherry, called 35 I Can’ts, drew on Jayne’s personal experience of being a victim of domestic violence in her previous marriage. In consultation with Women’s Aid, we flipped the fairy tale Cinderella on its head. In heavy, custom-made cast glass ‘slippers’, Jayne takes 35 steps—each uncertain step illustrating how hard it can be to leave an abusive partnership. Tentatively balancing with long glass rods in her hands and wearing a ‘fog’ for a headdress, Jayne dragged her glass slippers across the ground, thus demonstrating the statistic, ‘On average it takes a woman to be assaulted on average 35 times before she will phone the police.’4

Another collective work was A New Skin. Referencing the impact of childhood sexual abuse, this was a personal work for me, and one that I found incredibly hard to resolve. Working with the Irish leather worker Úna Burke, we created a female ‘suit of armour’, positioning a breakable glass casing within the medieval suits worn into battle. This transparent shell reminded

me of how exposed and fragile I felt walking into court to give evidence during my rape trial.

The exhibition was opened in August 2017 by Dr. Audrey Whitty, then Deputy Director and Head of Collections and Learning at the National Museum of Ireland. Subsequently, she began making enquiries about displaying the work at the National Museum, at Collins Barracks in Dublin. In October 2018, I heard that the museum had agreed to the exhibition and the opening was set for March 2019.

It was decided viewers would encounter the exhibition via a chronological timeline. The Magdalene laundries were the first form of women-centered institutions in Ireland, followed by the industrial schools, then the mother and baby ‘homes’, then ‘contemporary’ issues faced by women. Addressing the incoherent nature of the multiple rooms, the whole space was painted a dark grey and the windows blacked out. Ensuring survivors' voices were central, recorded interviews interspersed the space and could be accessed via monophones. Interpretive panels would be mounted, communicating the museum's ‘voice of authority.’ The art objects needed to be explanatory, accessible, and direct. I did not want artistic ambiguity. My aim was to force the viewer to have an emotional encounter upon experiencing the exhibit.

The Irish Magdalene Laundry system operated a harsh and brutal regime. Women and girls were regarded as ‘penitents’ and were incarcerated to ‘atone for their sins.’ Working in silence, unless praying; there was no pay; awful food and limited medical provision; long hours were worked, and inmates

4 Jaffe, Peter, Wolfe, David, Telford, Anne, and Austin, Gary. “The impact of police charges in incidents of wife abuse”. Journal of Family Violence, no. 1 (1986): 37-49

were never told when they might be allowed to leave. Records from the many Irish institutions are still privately held by the religious congregations. Access is only granted when the latest Commission of Enquiry forces them to hand them over—albeit temporarily.

It was important to make the link between the fiscal and the religious, as these were extremely profitable organizations. I represented the forced labour of the estimated 10,000 women and girls that worked in the Magdalene laundries (since Irish Independence) by producing 10,000 paper dolls, laser-cut from reproduced £5 notes. They spill, uncontained from Church offertory bags. The particular note used had the face of Catherine McAuley, founder of the Sisters of Mercy Convent in 1831, whose congregation ran several industrial schools and Magdalene laundries in Ireland.

Considering the museum's duty of care towards their staff, a briefing day was held prior to the exhibition opening. A parental advisory notice was positioned at the entrance of the exhibition and signposting to counselling organizations was displayed at the end of the exhibition beside visitors' books where we encouraged comments and thoughts.

The day before the official launch, survivors and survivor groups were invited to come and see the work privately. The exhibition was opened by Minister Katherine Zappone on 26th March 2019. It was framed by the museum as ‘an artistic response to the legacy of Ireland’s Mother and Baby Homes and the Magdalene Laundries.’5

The exhibition featured in major Irish news outlets. Melissa Stern from Hyperallergic. com described the exhibition as being, ‘delicate yet hardedged, sensitive yet unflinching, deeply personal and yet universal, this show is most worthy of the stories it tells’.6 Initially, the exhibition was to run until summer 2019, but it has since been acquired for the national collection and can still be viewed today.

Art can fill the void created when we struggle to accept the actions of our own state, congregations, and, crucially, of ourselves as a society. However, any forms of memorialization can be problematic and controversial when the most basic principles of transitional justice are not followed by the state.

Artists have a duty of care to make sure that the ‘survivor voice’ is central to any work that they do. Exclusion of the survivors' voice, only to be filled by the artist’s, amounts to more suppression and marginalization of the victim/survivor.

As Nathalie Sebanne writes: ‘there has been a strong desire on the part of the Irish State, and perhaps also on the part of society in general, to move on. Thus, after decades of silencing and invisibilization, the nation has now seemingly ‘built a monument to Amnesia.’7

(A)Dressing our hidden truths is only one small part in a chain of artistic interventions that have attempted a form of memorialization. The ‘never again’ imperative as instigated by Holocaust remembrance and its attempt to prevent future horrific suffering means memorial museums, and museums that tackle contentious issues can act, as Paul Williams writes, ‘as surrogate homes for debates that would otherwise be placeless.’8 And while truth-telling commissions and academic reports allow historical re-examination, we still need physical sites that render the ‘othered’ narrative and can offer public space that allows us to feel the vulnerability and pain of our fellow human beings while fundamentally connecting with our own, and where the art object becomes the conduit through which transformation can take place.

5 Alison Lowry: (A)Dressing our hidden truths, exhibition brochure, ed. Audrey Whitty. National Museum of Ireland, 2019