Differential Equations Computing and Modeling 5th Edition Edwards

Full download link at: https://testbankpack.com/p/solution-manualfor-differential-equations-computing-and-modeling-5th-edition-byedwards-isbn-0321816250-9780321816252/

CHAPTER 4

INTRODUCTION TO SYSTEMS OF DIFFERENTIAL EQUATIONS

This chapter bridges the gap between the treatment of a single differential equation in Chapters 1-3 and the comprehensive treatment of linear and nonlinear systems in Chapters 5-6. It also is designed to offer some flexibility in the treatment of linear systems, depending on the background in linear algebra that students are assumed to have Sections 4.1 and 4.2 can stand alone as a very brief introduction to linear systems without the use of linear algebra and matrices. The final Section 4.3 of this chapter extends to systems the numerical approximation techniques of Chapter 2.

SECTION 4.1

FIRST-ORDER SYSTEMS AND APPLICATIONS

system:

16. Let x1 = x

Equivalent system:

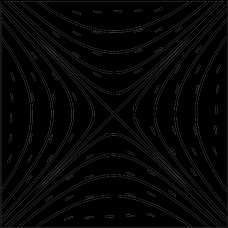

17. The computation x = y = x yields the single linear second-order equation x + x = 0 with characteristic equation r2 + 1 = 0 and general solution x (t) = Acost + B sin t Then the original first equation y = x gives y (t) = B cost Asin t The figure shows a direction field and typical solution curves (obviously circles?) for the given system.

Problem 17

18. The computation x = y = x yields the single linear second-order equation x x = 0

with characteristic equation r2 1 = 0 and general solution x (t) = Aet + Be t . Then the original first equation y = x gives y (t) = Aet Be t . The figure shows a direction field and some typical solution curves of this system. It appears that the typical solution curve is a branch of a hyperbola.

19. Thecomputation x = 2y = 4x yields the single linear second-order equation

x + 4x = 0 with characteristic equation r2 + 4 = 0 and general solution

x (t) = Acos2t + B sin2t Then the original first equation y = 1 x gives 2

y (t) = B cos2t + Asin2t . Finally, the condition x (0) = 1 implies that A = 1, and then the condition y (0) = 0 gives B = 0. Hence the desired particular solution is given by

x (t) = cos2t, y (t) = sin2t .

The figure shows a direction field and some typical circular solution curves for the given system.

Problem 19

Problem 20

20. Thecomputation x = 10y = 100x yields the single linear second-order equation

x +100x = 0 with characteristic equation r2 +100 = 0 and general solution

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education, Inc.

x (t) = Acos10t + B sin10t . Then the original first equation y = 1 10 x gives

y (t) = B cos10t Asin10t . Finally, the condition x (0) = 3 implies that A = 3, and then the condition y (0) = 4 gives B = 4 Hence the desired particular solution is given by

x (t) = 3cos10t + 4sin10t, y (t) = 4cos10t 3sin10t .

The typical solution curve is a circle, as the figure suggests.

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education, Inc.

21. Thecomputation x = 1 y = 4x 2 yields the single linear second-order equation

x + 4x = 0 with characteristic equation r2 + 4 = 0 and general solution

x (t) = Acos2t + B sin2t . Then the original first equation y = 2x gives

y (t) = 4B cos2t 4 Asin2t . The figure shows a direction field and some typical elliptical solution curves.

Problem 21

Problem 22

22. Thecomputation x = 8y = 16x yields the single linear second-order equation

x +16x = 0 with characteristic equation r2 + 16 = 0 and general solution

x (t) = Acos4t + B sin4t . Then the original first equation y = 1 x gives 8

y t = B cos 4t A sin 4t . The typical solution curve is an ellipse. The figure shows a 2 2 direction field and some typical solution curves.

23. Thecomputation x = y = 6x y = 6x x yields the single linear second-order equation

x + x 6x = 0 with characteristic equation r2 + r 6 = 0, characteristic roots r = 3 and 2, and general solution x (t) = Ae 3t + Be2t . Then the original first equation y = x gives y (t) = 3Ae 3t + 2Be2t . Finally, the initial conditions

x (0) = A + B = 1, y (0) = 3A + 2B = 2 implythat A = 0 and B = 1, so the desired particular solution is given by

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education, Inc.

The figure shows a direction field and some typical solution curves.

Problem 23

24. Thecomputation x

Problem 24

yields the single linear second-order equation x + 7x + 10

= 0 with characteristic equation r2 + 7r +10 = 0, characteristic roots r = 2 and 5, and general solution

Be 5t . Then the original first equation y = x gives y (t) =

Finally, the initial conditions

implythat

particular solution is given by

It appears that the typical solution curve is tangent to the straight line shows a direction field and some typical solution curves.

25. Thecomputation x = y =

= 2x The figure

yields the single linear second-order equation x 4x + 13x = 0 with characteristic equation r2 4r +13 = 0 and characteristic roots r = 2 3i ; hence the general solution is

Acos3t + Bsin3t) The initial condition x (0) = 0 thengives A = 0 , so

Be

t sin3t . Then the original first

Copyright

equation y = x gives y (t) = e2t (3B cos3t + 2B sin3t) . Finally, the initial condition

y (0) = 3 gives B = 1, so the desired particular solution is given by

.

The figure shows a direction field and some typical solution curves.

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education, Inc.

Problem 25

26. Thecomputation x = y = 9x + 6y = 9x + 6x yields the single linear second-order equation x 6x + 9x = 0 with characteristic equation r2 6r + 9 = 0 and repeated characteristic root r = 3,3, so its general solution is given by x (t) = ( A + Bt)e3t Then the original first equation y = x gives y (t) = (3A + B + 3Bt) e3t . It appears that the typical solution curve is tangent to the straight line and some typical solution curves. y = 3x . The figure shows a direction field

27. (a) Substituting the general solution found in Problem 17 we get

or x2 + y2 = C2 , the equation of a circle of radius C = .

(b) Substituting the general solution found in Problem 18, we get

=

AB , the equation of a hyperbola.

28. (a) Substituting the general solution found in Problem 19 we get x2 + y2 = ( Acos2t

2

or x2 + y2 = C2 , the equation of a circle of radius C = .

(b) Substituting the general solution found in Problem 21 we get

16x2 + y2 = 16( Acos2t + Bsin2t)2 + (4Bcos2t 4Asin2t)2

= 16( A2 + B2 )(cos2 2t + sin2 2t)

= 16( A2 + B2 ),

or 16x2 + y2 = C2 , the equation of an ellipse with semi-axes 1 and 4.

29. When we solve Equations (20) and (21) in the text for e t and e2t we get 2x y = 3Ae t and x + y = 3Be2t Hence (2x y)2 (x + y) = (

Ae t )2 3Be2t = 27A2B = C .

Clearly y = 2x or y = x if C = 0, and expansion gives the equation

4x3 3xy2 + y3 = C .

30. Looking at Fig. 4.1.11 in the text, we see that the first spring is stretched by x1, the second spring is stretched by x2 x1 , and the third spring is compressed by x2 . Hence Newton's second law gives m1

31. Looking at Fig. 4.1.12 in the text, we see that

We get the desired equations when we multiply each of these equations by L T and set k = mL T

32. The concentration of salt in tank i is ci = x

Copyright © 2015 Pearson Education, Inc. A2 + B2

for i = 1,2,3,… and each inflow-outflow

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

only to point to some of the symptoms which, individually considered, are found in other disorders, and may therefore be misinterpreted. The chief of these is vertigo, which, as already stated, being associated with nausea, and even vomiting, is not infrequently confounded with stomachic vertigo, while the opposite error is also, though less frequently, fallen into. The chief differential points are—that stomachic vertigo is relieved by vomiting, and anæmic vertigo is not; that the former is rather episodical, the latter more continuous; that in the free intervals of the former, while there may be some dulness, there is not the lethargy found with anæmia; that the headache with the former is either over the eyes or occipital, and most intense after the passage of a vertiginous seizure, while anæmic headache is verticalar or general, and not subject to marked momentary changes. It is unnecessary to indicate here the positive evidences of gastric disorder which are always discoverable in persons suffering from stomachic vertigo; but it is also to be borne in mind that such disorder is frequently associated with the conditions underlying general and cerebral anæmia, particularly in the prodromal period of some pulmonary troubles.

There are a number of organic affections of the brain which are in their early periods associated with symptoms which are in a superficial way like those of cerebral anæmia. As a rule, focal or other pathognomonic signs are present which render the exclusion of a purely nutritive disorder easy; but with some tumors, as is generally admitted, these signs may be absent. It is not difficult to understand why a tumor not destructive to important brain-centres, nor growing sufficiently rapid to produce brain-pressure, yet rapidly enough to compress the blood-channels, may produce symptoms like those of simple cerebral anæmia. It is claimed that with such a tumor the symptoms are aggravated on the patient's lying down, while in simple anæmia they are ameliorated.34 The latter proposition holds good as a general rule; as to the former, I have some doubts. Not even the ophthalmoscope, although of unquestionable value in ascertaining the nature of so many organic conditions of the brain and its appendages, can be absolutely relied on in this field. Until quite recently, optic neuritis, if associated with cerebral symptoms,

was regarded as satisfactory proof that the latter depended on organic disease; but within the year it has been shown by Juler35 that it may occur in simple cerebral anæmia, and both the latter and the associated condition of the optic nerve be recovered from.

34 The increased flow of blood to the brain in anæmia is not always momentarily remedial: if, for example, the patient stoop down, he flushes more easily than a normal person, and suffers more than the latter The same is observed with regard to stimulants.

35 British Medical Journal, Jan. 30, 1886. In the case reported suppression of the catamenia is spoken of, as well as the fact that treatment was directed to the menstrual disturbance. It is not evident from the brief report at my disposal whether the suspension of the menstrual flow was symptomatic of general anæmia or of a local disturbance. Optic neuritis has been recorded as having been present in a large number of cases with no other assignable cause than a uterine disorder As previously stated, Hirschberg and Litten found choked disc under like circumstances.

The claim of Hammond and Vance that ordinary anæmia of the brain may be recognized through the ophthalmoscope is almost unanimously disputed by experienced ophthalmoscopists, nor is it unreservedly endorsed by any authority of weight among neurologists. That there may be color-differences to indicate anæmia is, however, not impossible; and the fact that a concentric limitation of the visual field sometimes occurs should not be forgotten. It is distinguished from that found with organic diseases by its variability through the day and in different positions of the body.

TREATMENT.—Chronic as well as acute cerebral anæmia, dependent on general anæmia, usually requires no other medicinal treatment than that rendered necessary by the general anæmic state of which it is a part. This has been discussed at length in the third volume of this work: it remains to speak of certain special precautions and procedures rendered necessary by the nervous symptoms predominating in such cases. As the insufficiently nourished brain is not capable of exertion, mental as well as physical rest is naturally indicated. And this not only for the reason that it is necessary to avoid functional exhaustion, but also because the anæmic brain

when overstrained furnishes a favorable soil for the development of morbid fears, imperative impulses, and imperative conceptions. This fact does not seem to have been noticed by most writers. The mind of the anæmic person is as peculiarly sensitive to psychical influences as the anæmic visual and auditory centres are to light and sound; and in a considerable proportion of cases of this kind the origin of the morbid idea has been traced to the period of convalescence from exhausting diseases. The prominent position which masturbation occupies among the causes of cerebral anæmia perhaps explains its frequent etiological relationship to imperative conceptions and impulsive insanity.

Although the radical and rational treatment of cerebral anæmia is covered by the treatment of the general anæmia, there are certain special symptoms which call for palliative measures. Most of these, such as the vertigo, the optic and aural phenomena, improve, as stated, on assuming the horizontal position. The headache if very intense will yield to one of three drugs: nitrite of amyl, cannabis indica, or morphine. I am not able to furnish other than approximative indications for the use of remedies differing so widely in their physiological action. Where the cerebral anæmia and facial pallor are disproportionately great in relation to the general anæmia, and we have reason to suppose the existence of irritative spasm of the cerebral blood-vessels—a condition with which the cephalalgia is often of great severity—nitrite of amyl acts as wonderfully as it does in the analogous condition of syncope.36 Where palpitations are complained of, and exist to such a degree as to produce or aggravate existing insomnia, small doses of morphine will act very well, due precautions being taken to reduce the disturbance of the visceral functions to a minimum, and to prevent the formation of a drug habit by keeping the patient in ignorance of the nature of the remedy. When trance-like conditions and melancholic depression are in the foreground, cannabis indica with or without morphia will have the best temporary effect: it is often directly remedial to the cephalalgia. Chloral and the bromides are positively contraindicated, and untold harm is done by their routine administration in nervous headache and insomnia, irrespective of their origin. Nor are

hypnotics, aside from those previously mentioned, to be recommended; the disadvantages of their administration are not counterbalanced by the advantages.37 Frequently, in constitutional syphilis, insomnia resembling and probably identical with the insomnia of cerebral anæmia will call for special treatment. In such cases the iodides, if then being administered, should be suspended, and if the luetic manifestations urgently require active measures, they should be restricted to the use of mercury in small and frequent dosage, while the vegetable alteratives may be administered if the state of the stomach permit.

36 There are disturbances in the early phases of cerebral syphilis, whose exact pathological character is not yet ascertained, which so closely resemble the condition here described that without a knowledge of the syphilitic history, and misled by the frequently coexisting general anæmia, it is regarded as simple cerebral anæmia. Under such circumstances, as also with the cerebral anæmia of old age, amyl nitrite should not be employed.

37 Urethran and paraldehyde have failed in my hands with anæmic persons.

Among the measures applicable to the treatment of general anæmia there are three which require special consideration when the cerebral symptoms are in the foreground: these are alcoholic stimulants, the cold pack, and massage. It is a remarkable and characteristic feature of cerebral anæmia that alcoholic stimulants, although indicated, are not well borne38—at least not in such quantities as healthy persons can and do take without any appreciable effect. I therefore order them—usually in the shape of Hungarian extract wines,39 South Side madeira, or California angelica—to be given at first in such small quantities as cannot affect the cerebral circulation unpleasantly, and then gradually have the quantity increased as tolerated. In fact, both with regard to the solid nourishment and the stimulating or nourishing fluids and restorative drugs the division-of-labor principle is well worth following. The cerebral anæmic is not in a position to take much exercise, his somatic functions are more or less stagnant, and bulky meals are therefore not well borne. Small quantities of food,

pleasingly varied in character and frequently administered, will accomplish the purpose of the physician much better.

38 Hammond, who classes many disorders under the head of cerebral anæmia which the majority of neurologists regard as of a different character, has offered a very happy explanation. He says, “Now, it must be recollected that the brains of anæmic persons are in very much the same condition as the eyes of those who have for a long time been shut out from their natural stimulus, light. When the full blaze of day is allowed to fall upon them retinal pain is produced, the pupils are contracted, and the lids close involuntarily. The light must be admitted in a diffused form, and gradually, till the eye becomes accustomed to the excitation. So it is with the use of alcohol in some cases of cerebral anæmia. The quantity must be small at first and administered in a highly diluted form, though it may be frequently repeated.”

39 Such as Meneszer Aszu; there is no genuine tokay wine imported to this country, as far as I am able to learn.

The cold pack, strongly recommended by some in general anæmia, is not, in my opinion, beneficial in cases where the nervous phenomena are in the foreground, particularly in elderly persons. Gentle massage, on the other hand, has the happiest effects in this very class of cases.

Of late years my attention has been repeatedly directed to cerebral anæmia of peculiar localization due to malarial poisoning. It has been noted by others that temporary aphasia and other evidences of spasm of the cortical arteries may occur as equivalents or sequelæ of a malarial attack. I have seen an analogous case in which hemianopsia and hemianæsthesia occurred under like circumstances, and were recovered from. Whether more permanent lesions, in the way of pigmentary embolism or progressing vascular disease, causing thrombotic or other forms of softening, may develop after such focal symptoms is a matter of conjecture, but I have observed two fatal cases in which the premonitory symptoms resembled those of one which recovered, and in which these were preceded by signs of a more general cerebral anæmia, and in one case had been mistaken for the uncomplicated form of that disorder. Where a type is observable in the exacerbation of the vertigo,

headache, tinnitus, and lethargy of cerebral anæmia, particularly if numbness, tingling, or other signs of cortical malnutrition are noted in focal distribution, a careful search for evidences of malarial poisoning should be made; and if such be discovered the most energetic antimalarial treatment instituted. It is in such cases that arsenic is of special benefit.

The treatment of syncope properly belongs to this article. Where the signs of returning animation do not immediately follow the assumption of the recumbent position, the nitrite of amyl, ammonia, or small quantities of ether should be exhibited for inhalation. The action of the former is peculiarly rapid and gratifying, though the patient on recovery may suffer from fulness and pain in the head as after-effects of its administration. The customary giving of stimulants by the mouth is to be deprecated. Even when the patient is sufficiently conscious to be able to swallow, he is usually nauseated, and, as he is extremely susceptible to strong odors or tastes in his then condition, this nausea is aggravated by them. By far the greater number of fainting persons recover spontaneously or have their recovery accelerated by such simple measures as cold affusion, which, by causing a reflex inspiration, excites the circulatory forces to a more normal action. Rarely will the electric brush be necessary, but in all cases where surgical operations of such a nature as to render the development of a grave form of cerebral anæmia a possibility are to be performed, a powerful battery and clysters of hot vinegar, as well as the apparatus for transfusion, should be provided, so as to be within reach at a moment's notice.

Inflammation of the Brain.

Before the introduction of accurate methods of examining the diseased brain the term inflammatory softening was used in a much wider sense than it is to-day. Most of the disorders ascribed to inflammatory irritation by writers of the period of Andral and Rush are to-day recognized as regressive, and in great part passive, results of

necrotic destruction through embolic or thrombic closure of afferent blood-channels. Two forms of inflammation are universally recognized. One manifests itself in slow vascular and connectivetissue changes and in an indurating inflammation. There are two varieties of it: the first of these, which is associated with furibund vaso-motor explosions and regressive metamorphosis of the functional brain-elements, is known from its typical association with grave motor and mental enfeeblement as paretic dementia or dementia paralytica. The second, which is focal in the distribution of the affected brain-areas, is known as sclerosis. The former is treated of in a separate article; the latter is considered in connection with the spinal affections which either resemble it in histological character or complicate its course. The second form of cerebral inflammation is marked by the formation of the ordinary fluid products of acute inflammation in other organs of the body; this is the suppurative form, usually spoken of as abscess of the brain.

In addition to these two generally recognized inflammatory affections there are a number of rare diseases which are regarded by excellent authority as also of that character The vaguely-used term acute encephalitis has been recently reapplied with distinct limitations to an acute affection of children by Strümpell. This disease is usually of acute onset, infants under the sixth year of age being suddenly, and in the midst of apparently previous good health sometimes, attacked by fever, vomiting, and convulsions.40 Occasionally coma follows, which may last for several days, perhaps interrupted from time to time by recurring convulsions or delirium. The convalescence from this condition is rapid, and in some cases is complete; in others paralysis remains behind in the hemiplegic form. The paralysis is usually greater in the arm than in the leg; in extreme cases it involves the corresponding side of the face, and, as the paralyzed parts are arrested or perverted in growth, considerable deformity, even extending to asymmetry of the skull, may ensue. The deformity is aggravated by contractures. Usually there is some atrophy of the muscles, but in one case I found actual hypertrophy41 of some groups, probably in association with the hemiathetoid movements.

40 As in my case of infantile encephalitis followed by athetoid symptoms (Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases).

41 This was followed by atrophy. There are never any qualitative electrical changes.

The sequelæ of acute infantile encephalitis present us with the most interesting forms of post-paralytic disturbances of muscular equilibrium. Hemichorea and hemiathetosis, as well as peculiar associated movements and hemicontracture, are found in their highest development with this class of cases. Occasionally epileptiform symptoms are noted,42 and in others true epilepsy is developed. It is under such circumstances that imbecility is apt to be a companion symptom or result; and this imbecility is prominently noted in the moral sphere.

42 Which in one case of my own disappeared spontaneously.

The grave set of symptoms briefly detailed here are attributed by Strümpell43 to an acute encephalitis, analogous, in his opinion, to the acute poliomyelitis of children. Its frequent occurrence after measles and scarlatina, as well as the fact that Ross44 in a carefully-studied case arrived at the opinion that the disease was an embolo-necrotic result of endocarditis, would lead to the conclusion that it is a focal affection, probably due to the transportation of infectious elements to the brain through the blood-vessels. Its occurrence in children in the midst of apparent health45 is consistent with the fact that rheumatism and an attendant slight endocarditis frequently pass unrecognized in infancy. It is supposed that a diffuse form of inflammatory nonsuppurative softening exists by some of the Germans, but the proof advanced in favor of this view is not conclusive.

43 As a surmise, for up to his writing no reliable autopsies had been made.

44 Brain, October, 1883.

45 McNutt (American Journal of Medical Sciences, January, 1885) cites Strümpell as attributing the theory of an inflammatory affection, which is analogous to poliomyelitis in its suddenness and nature, to Benedict, and refers to p. 349 of Strümpell's textbook

under the erroneous date of 1864. This work was published in 1883-84, and the theory is advanced by Strümpell as his own. It is only a synonym, hemiplegia spastica infantile, that is attributed to Benedict.

A number of rare forms of interstitial encephalitis have been described. In one, elaborately studied by Danillo, an inflammatory hypertrophy of the cortex, involving the parenchyma as well as the connective and vascular structures, was found in a limited area of the motor province of the right hemisphere. There had been crossed epileptiform convulsions during life.46

46 Bulletin de la Société de Biologie, 1883, p. 238.

There is some question among pathologists as to the recognition of Virchow's encephalitis of the new-born. Certainly a part of Virchow's material was derived from the imperfect study of a condition of infantile brain-development which, as Jastrowitz showed, is physiological, and on which Flechsig based his important researches of tract-development. More recent studies, however, demonstrate that there is a form of miliary encephalitis in new-born children due to septic causes, such as, for example, suppuration of the umbilical cord. The demonstration by Zenker of the occurrence of metastatic parasitic emboli in cases of aphthous stomatitis, and by Letzerich of a diphtheritic micrococcus invasion in the brain of his own child, show that the subject of early infantile encephalitis merits renewed consideration.47

47 The attempt of Jacusiel to revive Virchow's encephalitis of the new-born (Berliner klinische Wochenschrift, 1883, No. 7) under the title of interstitial encephalitis does not seem to have met with encouragement, for, besides Jastrowitz, Henoch and Hirschberg opposed this view in the discussion.

Strictly speaking, the reactive changes which occur in the brainsubstance bordering on tumors, hemorrhagic and softened foci, belong to the domain of encephalitis; but as they are considered in conjunction with the graver lesions to which they are secondary both in occurrence and importance, it is not necessary to more than refer to them here.

Abscess of the Brain.

As indicated in the last article, there formerly existed much confusion in the minds of pathologists regarding the terms softening and abscess of the brain. As long as softening was regarded as an inflammation, so long was abscess of the brain regarded as a suppurative form of softening. Aside from the fact that there is some resemblance in mechanical consistency between a spot of ordinary softening and one of inflammatory softening, there is no essential similarity of the two conditions. True softening is to-day regarded as the result of a death of brain-tissue produced by interference with the blood-supply; it is therefore a passive process. Inflammatory softening, of which abscess is a form, is due to an irritant, usually of an infectious nature. It is to the results of such irritation that the term suppurative encephalitis should be limited.

MORBID ANATOMY.—In all well-established inflammatory brain troubles the active part is taken by the blood-vessels and connective tissue; the ganglionic elements undergo secondary, usually regressive or necrotic, changes. The brain, considered as a parenchymatous organ, is not disposed to react readily in the way of suppurative inflammation unless some septic elements are added to the inflammatory irritant. Foreign bodies, such as knitting-needles, bullets, and slate-pencils, have been found encapsulated in this organ or projecting into it from the surrounding bony shell without encapsulation and without any evidences of inflammatory change. As a rule, a foreign body which enters the brain under aseptic conditions will, if the subject survive sufficiently long, be found to have made its way to the deepest part of the brain, in obedience to the law of gravity, and through an area of so-called inflammatory red softening which appears to precede it and facilitate the movement downward. This form of softening derives its color from the colored elements of the blood, which either escape from the vessels in consequence of the direct action of the traumatic agent; secondly, in consequence of vascular rupture from the reduced resistance of the

perivascular tissue in consequence of inflammatory œdema and infiltration; or, thirdly, in obedience to the general laws governing simple inflammation.

A cerebral abscess may present itself to the pathological anatomist in one of three phases—the formative, the crude, and the encapsulated. In the first it is not dissimilar to a focus of yellow softening, being, like the latter, a diffuse softened area varying from almost microscopical dimensions to the size of a walnut, and of a distinctly yellow tinge. Microscopic examination, however, shows a profound difference. In pure yellow softening there are no pus-cells; in the suppurative encephalitic foci they are very numerous, and congregated around the vessels and in the parenchyma in groups. The crude abscess is the form usually found in cases rapidly running to a fatal termination. Here there is an irregular cavity in the brain, usually the white central substance of the cerebrum or cerebellum, formed by its eroded and pulpy tissue; it is filled with yellow, greenish, and more rarely brownish pus. In the most furibund cases broken-down brain-detritus may be found in the shape of whitish or reddish flocculi, but in slowly-formed abscesses the contents are free from such admixture, and thus the third phase is produced, known as the encapsulated abscess. The cavity of the abscess becomes more regular, usually spheroid or ovoid; the pus is less fluid, more tenacious, and slightly transparent; and the walls are formed by a pseudo-membrane48 which is contributed by the sclerosing brainsubstance, which merges gradually into the outlying normal tissue. I have seen one acute cerebral abscess from ear disease which might be appropriately designated as hemorrhagic; the contents were almost chocolate-colored; on closer inspection it was found that they were true pus, mingled with a large number of red blood-discs and some small flocculi of softened brain-substance. This hemorrhagic admixture was not due to the erosion of any large vessel, for the abscess had ruptured into the lateral ventricle at that part where it was most purely purulent. In a case of tubercular meningitis, Mollenhauer in my laboratory found an abscess in the white axis of the precentral gyrus, with a distinct purulent infiltration following the line of one of the long cortical vessels. The abscess was not

encapsulated, the surrounding white substance exhibited an injected halo, and the consistency of the contents was that of mucoid material.

48 There is considerable dispute as to the real nature of the tissue encapsulating cerebral abscesses. It is known, through the careful observations of R. Meyer, Goll, Lebert, Schott, and Huguenin, that the capsule may form in from seven to ten weeks in the majority of cases, about eight weeks being the presumable time, and that at first the so-called capsule of Lallemand does not deserve the name, being a mucoid lining of the wall. At about the fiftieth day, according to Huguenin, this lining becomes a delicate membrane composed of young cells and a layer of spindle-shaped connective elements.

In cases where the symptoms accompanying the abscess during life had been very severe it is not rare to find intense vascular injection of the parts near the abscess, and it is not unlikely that the reddish or chocolate color of the contents of some acutely developed abscesses is due to blood admixture derived from the rupture of vessels in this congested vicinity. Sometimes the entire segment of the brain in which the abscess is situated, or the whole brain, is congested or œdematous. In a few cases meningitis with lymphoid and purulent exudation has been found to accompany abscesses that had not ruptured. It is impossible to say whether in this case there was any relation between the focal and the meningeal inflammation, as both may have been due to a common primary cause.49 In such cases, usually secondary to ear disease, thrombosis of the lateral sinus may be found on the same side. Where rupture of an abscess occurs, if the patient have survived this accident long enough—for it is usually fatal in a few minutes or hours —meningitis will be found in its most malignant form. A rupture into the lateral and other ventricles has been noted in a few cases.50

49 Otitis media purulenta in the two cases of this kind I examined.

50 In one, observed together with E. G. Messemer, intense injection of the endymal lining, with capillary extravasations, demonstrated the irritant properties of the discharged contents.

Some rare forms of abscess have been related in the various journals and archives which have less interest as objects of clinical study than as curiosities of medical literature. Thus, Chiari51 found the cavity of a cerebral abscess filled with air, a communication with the nose having become established by its rupture and discharge.

51 Zeitschrift für Heilkunde, 1884, v p. 383. In this remarkable rase the abscess, situated in the frontal lobe, had perforated in two directions—one outward into the ethmoidal cells, the other inward into the ventricles, so that the ventricles had also become filled with air. This event precipitated a fatal apoplectiform seizure.

The contents of a cerebral abscess usually develop a peculiarly fetid odor. It has been claimed that this odor is particularly marked in cases where the abscess was due to some necrotic process in the neighborhood of the brain-cavity. The only special odor developed by cerebral abscesses, as a rule, is identical with that of putrid brainsubstance, and it must therefore depend upon the presence of braindetritus in the contents of the abscess or upon the rapid post-mortem decomposition of the neighboring brain-substance.

In two cases of miliary abscess which, as far as an imperfect examination showed, depended on an invasion of micro-organisms, an odor was noticed by me which was of so specific a character that on cutting open the second brain it instantly suggested that of the first case, examined six years previous, although up to that moment I had not yet determined the nature of the lesion.52

52 Owing to the lack of proper methods of demonstrating micro-organisms, the first case whose clinical history was known was imperfectly studied; of the second case, accidentally found in a brain obtained for anatomical purposes, the examination is not yet completed.

That form of abscess which, from its situation in or immediately beneath the surface, has latterly aroused so much interest from its important relations to localizations is usually metastatic, and directly connected with disease of the overlying structures, notably the cranial walls. In this case the membranes are nearly always involved. The dura shows a necrotic perforation resembling that

found with internal perforation of a mastoid or tympanic abscess.

The pia is thickened and covered with a tough fibro-purulent exudation; occasionally the dura and leptomeninges are fused into a continuous mass of the consistency of leather through the agglutinating exudation. The abscess is usually found open, and it is not yet determined whether it begins as a surface erosion, and, bursting through the cortex, spreads rapidly on reaching the white substance, or not. The white substance is much more vulnerable to the assault of suppurative inflammation than the gray, and not infrequently the superficial part of the cortex may appear in its normal contiguity with the pia, but undermined by the cavity of the abscess, which has destroyed the subcortical tissue. Possibly the infecting agent, as in some cases of ear disease, makes its way to the brain-tissue through the vascular connections, which, however sparse at the convexity of the brain, still exist.

CLINICAL HISTORY.—The symptoms of a cerebral abscess depend on its location, size, and rapidity of formation. There are certain parts of the brain, particularly near the apex of the temporal lobe and in the centre of the cerebellar hemisphere, where a moderately large abscess may produce no special symptoms leading us to suspect its presence. There are other localities where the suppurative focus53 indicates its presence, and nearly its precise location and extent, by the irritative focal symptoms which mark its development and by the elimination of important functions which follows its maturation. It is also in accordance with the general law governing the influence of new formations on the cerebral functions that an acutely produced abscess will mark its presence by more pronounced symptoms than one of slow, insidious development. Indeed, there are found abscesses in the brain, even of fair dimensions, that are called latent because their existence could not have been suspected from any indication during life, while many others of equal size are latent at some time in their history.

53 Practically, our knowledge of localization of functions in the human brain begins with the observation by Hitzig of a traumatic abscess in a wounded French prisoner at Nancy named Joseph Masseau. The year of the publication of this interesting case

constitutes an epoch in advancing biological knowledge, which will be remembered when even the mighty historical events in which Hitzig's patient played the part of an insignificant unit shall have become obsolete. This, the first case in the human subject where a reliable observation was made was an unusually pure one; the abscess involved the facial-hypoglossal cortical field (Archiv für Psychiatrie, iii. p. 231).

An acute cerebral abscess is ushered in by severe, deep, and dull headache, which is rarely piercing, but often of a pulsating character. The pain is sometimes localized, but the subjective localization does not correspond to the actual site of the morbid focus.54 It is often accompanied by vertigo or by a tendency to dig the head into the pillow or to grind it against the wall. With this there is more or less delirium, usually of the same character as that which accompanies acute simple meningitis. As the delirium increases the slight rise in temperature which often occurs in the beginning undergoes an increase; finally coma develops, and the patient dies either in this state or in violent convulsions. The case may run its course in this way in a few days, but usually one to three weeks intervene between the initial symptoms and death.

54 Although Ross seems to be of a contrary opinion, it is the exception for the pain to correspond in location to the abscess.

Between the rapid and violent course of acute cerebral abscess detailed, and the insidious course of those which as latent abscesses may exist for many years without producing any noticeable symptoms whatever, there is every connecting link as to suddenness and slowness of onset, severity and mildness of symptoms, and rapidity and slowness of development and progress. It is the encapsulated abscesses which are properly spoken of as chronic, and which may even constitute an exception to the almost uniform fatality of the suppurative affections of the brain. Thus, the symptoms marking their development may correspond to those of an acute abscess, but coma does not supervene, temporary recovery ensues, and the patient leaves the hospital or returns to his vocation. But all this time he appears cachectic, and there will be found, on accurate observation, pathological variations of the temperature and

pulse. The appetite is poor; the bowels are usually constipated; there are frequent chilly sensations and horripilations, and a general malaise. This condition slowly passes away in the few cases which recover; in others relapses occur, usually of progressing severity, and terminate life. The period during which the symptoms of the abscess are latent may be regarded as corresponding to the latent period which sometimes intervenes between an injury and the development of the symptoms of acute abscess, and which, according to Lebert, may comprise several weeks or months. In other words, the morbid process may be regarded all this time as progressing under the mask of a remission. It is this latent period which it is of the highest importance for the diagnostician to recognize. There is usually headache, which is continuous and does not change in character, though it may be aggravated in paroxysms. Usually the temperature rises with these paroxysms, and if they continue increasing in severity they may culminate in epileptic convulsions.

Many of the symptoms of cerebral abscess—prominently those attending the rapidly-developed forms and the exacerbations of the chronic form—are due to cerebral compression. It is the pulse and pupils, above all, that are influenced by this factor.

In an affection having so many different modes of origin as cerebral abscess, and occupying such a wide range of possible relations to the cerebral mechanism, it is natural that there should exist many different clinical types. So far as the question of the diagnosis of localized cerebral abscesses is concerned, I would refer to the article dealing with cerebral localization, in order to avoid repetition. With regard to the etiological types, they will be discussed with the respective causal factors.

ETIOLOGY.—Abscess of the brain is so frequently found to be due to metastatic or other infectious causes that it is to be regarded as highly improbable that it is ever of idiopathic occurrence. The most frequent associated conditions are—suppurative inflammation in neighboring structures, such as the tympanic cavity, the mastoid

cells, the nasal cavity, or inflammation or injury of any part of the cranium and scalp. The connection of these structures with the brain through lymphatic and vascular channels is so intimate that the transmission of a pyogenic inflammatory process from the former to the latter is not difficult to understand. But disease of far distant organs, such as gangrene of the lung, and general affections, such as typhoid fever, occasionally figure among the causes of cerebral abscess, particularly of the miliary variety.

Among the commonest causes of cerebral abscesses are those which the surgeon encounters. The injury may be apparently slight and limited to the soft parts, or the bone may be merely grazed. Gunshot wounds are particularly apt to be followed by a cerebral abscess; and it has been noted that those which granulate feebly, whose base is formed by a grayish, dirty, and fetid material, are most apt to lead to this ominous complication. The symptoms do not usually develop immediately, and after the surgeon is led to indulge in the hope that danger is past, proper reaction sets in, healthy granulations develop—nay, the wound may close and be undergoing cicatrization—then the patient complains of feeling faint or drowsy, and with or without this premonition he has convulsive movements of one side, sometimes involving both extremities and the corresponding side of the face. Consciousness is usually preserved, but the spells recur, and the patient is noted to be absent-minded during and after the convulsive seizure. On some later day he is noticed to become pale, as in the initial stage of a true epileptic seizure; total abolition of consciousness follows, and the clonic spasms, affecting the same limbs and muscles involved in the first seizures, now recur with redoubled violence. After such an attack more or less paresis is observed in the muscles previously convulsed. A number of such seizures may occur, or a fatal issue terminate any one of them. Not infrequently the field of the involved muscles increases with each fit. Thus the thumb or a few fingers may be the first to show clonic spasm; in the next fits, the entire arm; in succeeding ones, the leg and face may follow suit. In such a case the periphery first to be convulsed is the first to become paralyzed, thus showing that where the disease began as an irritative lesion the

cortex is now destroyed, and that around the destructive focus as a centre the zone of irritation is spreading excentrically, first to irritate and then to destroy seriatim the functions of the various cortical fields in their order. According to the teachings laid down in the article on Localization, the order of invasion and extension, as well as the nature, of the focal symptoms will vary. Finally, the attacks become more severe and of longer duration; the patient does not recover in the intervals, but complains of nausea, pain, confusion, and head-pressure. He is noted to be dull, his temperature is slightly raised (100° F.), and the speech may be affected. Several attacks may occur in a day, each leaving the patient more and more crippled as to motility and mind. He is delirious and drowsy at intervals; his temperature may rise after an attack from one to four degrees, usually remaining near 103°–104° F. in the evening; and, coma developing, death occurs, the convulsion or paralytic phenomena continuing at intervals during the moribund period, and the temperature and pulse sometimes running up rapidly toward the last. On examining the parts, it is found that the bone is necrotic at the point of injury, usually only in its outer table, but sometimes in its entire thickness. In exceptional cases the normal continuity of the entire table is not interrupted to all appearances, and a small eroded spot on the inner table is found bathed in pus, or a detached necrotic fragment may be found in the latter. Corresponding to the purulent focus on the inner table the dura mater is detached, discolored, and perforated in one or more places with irregular rents or holes which have a greenish or blackish border. An abscess is found in that part of the brain which corresponds to this opening. There is no question that it was caused by direct infection from the necrotic spot.

Cases have been noted,55 apparently of idiopathic origin, in which a sudden paralysis of a few fingers was the first symptom produced by the development of a cerebral abscess. In a few days such a paralysis extends to the other fingers and to the forearm. Occasionally no convulsive phenomena are noted, or choreic movements indicate, in their place, that the cortical field is irritated. Such cases usually run a rapidly fatal course.

55 Arthur E. W. Fox, Brain, July, 1885.

The most frequent cause of cerebral abscess in civil practice is suppurative inflammation of the middle ear. It may be safely asserted that the person suffering from this affection is at no time free from the danger of a cerebral abscess, a purulent meningitis, or a phlebitic thrombosis of the sinuses. Cases are on record where the aural trouble had become chronic, and even quiescent, for a period of thirty years, and at that late date led to abscess with a fatal termination. Of 6 cases of this character in my experience, 4 of which were verified by anatomical examination, not one but had occurred at least four years after the commencement of the ear trouble, and 1 happened in a man aged fifty-four who had contracted the latter affection in childhood. In 2 there was in addition diffuse purulent meningitis, limited on the convexity to the side where the abscess was situated.56 In 4 the abscess was in the temporal lobe, 1 of them having in addition an abscess in the cerebellar hemisphere of the same side; in a fifth the abscess was in the deep white substance of the cerebral hemisphere, opening into the lateral ventricle, and in the sixth it was in one cerebellar hemisphere alone.

56 One of these was seen during life by J. R. Pooley; the other was a paretic dement at the New York City Pauper Asylum.

The course of this class of abscesses is usually obscure: focal symptoms are not commonly present, and the constitutional and local symptoms usually appear as a gradual outgrowth from the aural troubles. Thus there is at first usually little fever, vertigo, and chilliness, but considerable tinnitus, and sometimes pain in the ear. Occasionally local signs of a septic metastasis of the otitis, such as œdema over the mastoid or painful tumefaction of the cervical glands, are visible. The pain previously referred to the region of the ear now becomes general; commonly—even where the abscess is in the temporal lobe—it becomes progressively aggravated in the frontal and sometimes in the nuchal region, and under an increase of the febrile phenomena death may exceptionally occur without further complication. Even large abscesses in one half of the cerebellum

occur without producing Ménière's symptom—a fact which leads to the suspicion that the purulent deposit must have been of slow and gradual development. In one case distinct symptoms indicating an affection of the subcortical auditory tract were observed. As a rule, this class of abscesses are accompanied toward the close by active general symptoms—convulsions, coma, narrowing and impaired light-reaction of the pupils. Delirium, when a prominent symptom from the beginning, indicates the probable association of meningitis with the abscess.57 Occasionally severe pain, rigor, high temperature, and paralysis may be absent even with rapidlydeveloped abscess from otitis.58

57 The same is probably true of oculo-motor paralysis, which Ross (loc. cit., vol. ii. p. 735) refers to uncomplicated abscess.

58 This was the case with an abscess containing five ounces of pus recorded by C. S. Kilham at the Sheffield Medical Society (British Medical Journal, February 13, 1886).

As illustrating what was stated about the non-correspondence of the pain and the location of the abscess, it may be stated that notwithstanding this large abscess was in the temporal lobe, what pain was present was in the forehead.