Sun, Sea Cables, and GriT

The song of wade, remixed

A Girtonian’s bet on renewables A long-standing Chaucer manuscript mystery solved

This sport could change your life

How a Girton alumna is transforming sporting opportunities for young people

A Girtonian’s bet on renewables A long-standing Chaucer manuscript mystery solved

How a Girton alumna is transforming sporting opportunities for young people

Three goals, one enabler: a transformative new courts project

We extend our sincere thanks to the many Girtonians, Fellows, colleagues, and friends whose contributions, insights, and support helped shape this edition.

Let me open this inaugural edition of The Girtonian with heartfelt thanks and appreciation for our alumni. Three years in, I’m deeply conscious of just how extraordinary this community is. The stories you share, the ideas you champion, and the work you lead – all speak to the enduring spirit of courage and generosity that defines Girton.

In this issue, we celebrate alumni who are breaking new ground in medicine, law, public policy, climate, and sport; who are leading organisations, creating companies, and advancing positive change in their communities; and who, in countless quiet ways, make the world kinder, fairer, and more hopeful. I never cease to be inspired by what Girtonians achieve – whether on the world stage or closer to home.

Back here in College, the rhythm of the new academic year has begun in earnest: Freshers settling in; returning students rekindling friendships and diving back into study; Fellows moving from research to teaching; and alumni visiting their old haunts to delight in not only what has changed, but also – what hasn’t. The College hums with energy, ideas, and purpose.

Girton has always been about connection – across generations, disciplines, and distances. This magazine is one more thread in that web, carrying stories of our shared past and our collective future. I hope you will enjoy reading about the adventures, achievements, and discoveries of fellow Girtonians, and that you will feel proud – as I do – of the College’s growing global community and its impact.

Wherever life has taken you, please know that you remain part of Girton’s story. And if you haven’t visited for a while, I warmly invite you to come back – to walk the grounds, enjoy dinner in Hall, and feel once more the spark that first brought you here.

My warmest wishes,

Dr Elisabeth Kendall The Mistress of Girton College

Dear Girtonians,

One year into this role, I have had the privilege of meeting many of you – in College, online, and around the world. Each conversation has left me inspired and energised and reminded of the quiet strength and purpose that define our community.

This inaugural magazine offers a moment to pause and take stock. It captures the character of a College that honours its radical past while shaping an even bolder future.

You will meet Girtonians across the decades who embody Girton’s founding ethos – questioning assumptions, sharing knowledge freely, and turning principle into practical progress worldwide.

You will also read about the Girton Skills Programme – now expanded to help our students learn and lead with confidence – and about Fellows whose work continues to break new ground and make a difference far beyond our walls.

In the same spirit, our community of more than 12,000 Girtonians, our G-Force, is increasingly active: mentoring, opening doors, and sharing expertise where it matters most.

Alongside this, the new courts project signals the next chapter in Girton’s evolution, and will create beautiful, sustainable spaces for study, conversation, and collaboration.

Thank you for the pride and purpose you continue to bring to Girton. I look forward to seeing you soon – in Cambridge and beyond – and to hearing your thoughts on what comes next.

With warmest wishes,

‘Miss Marple’ of the IP World — Honouring the

Magdalena Douleva Fellow and Director of Development

The Relentless Pursuit of Perfection

Adam Kenyon

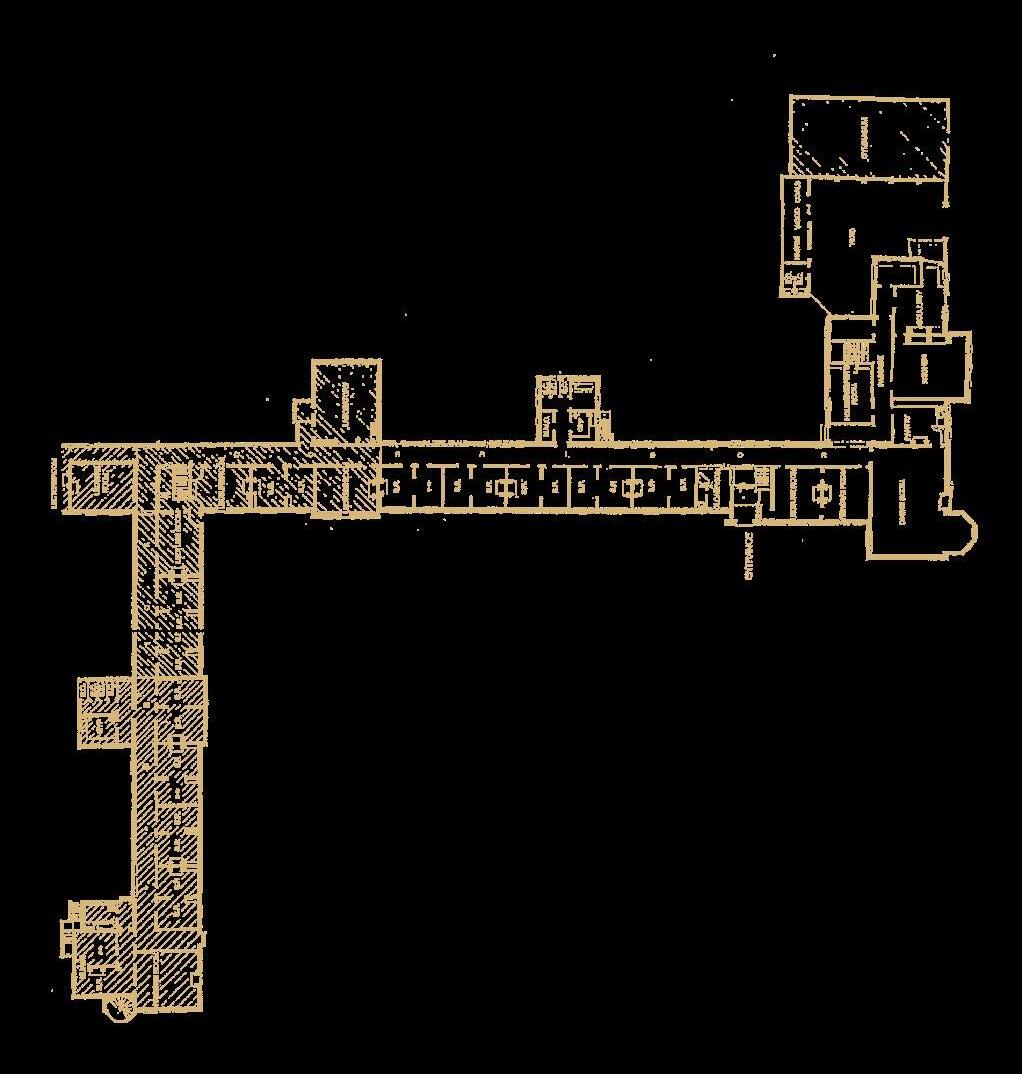

Sun, Sea Cables, and Grit: A Girtonian’s Bet on Renewables

Mark Budd

From Architecture to Fashion — Shaping a Family Legacy into a Global Icon

Kristina Blahnik

This Sport Could Change Your Life

Lottie Birdsall-Strong

The Stem-Cell Code

Antonia Vogt

Tradition meets Transformation — Navigating the Challenges of the Global Wine Industry Waves of Change: Inside the Podcast Boom and What Comes Next

Like Google Maps, but for the Human Brain

Dr John Tadross

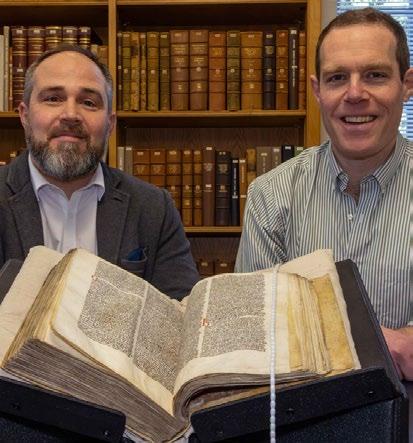

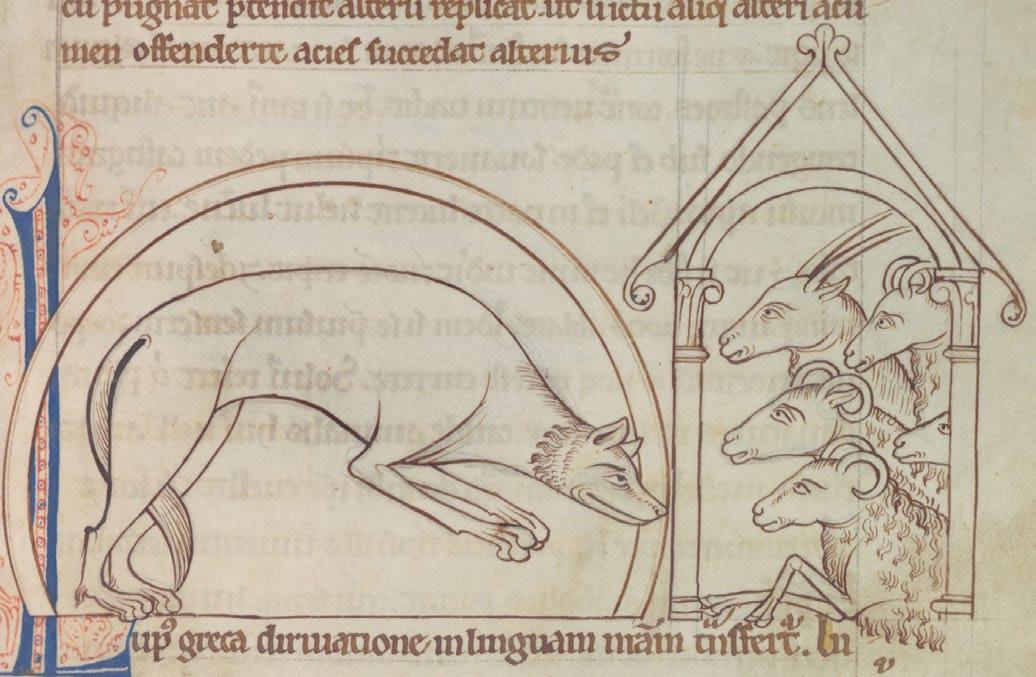

The Song of Wade, Remixed

Dr James Wade and Dr Seb Falk

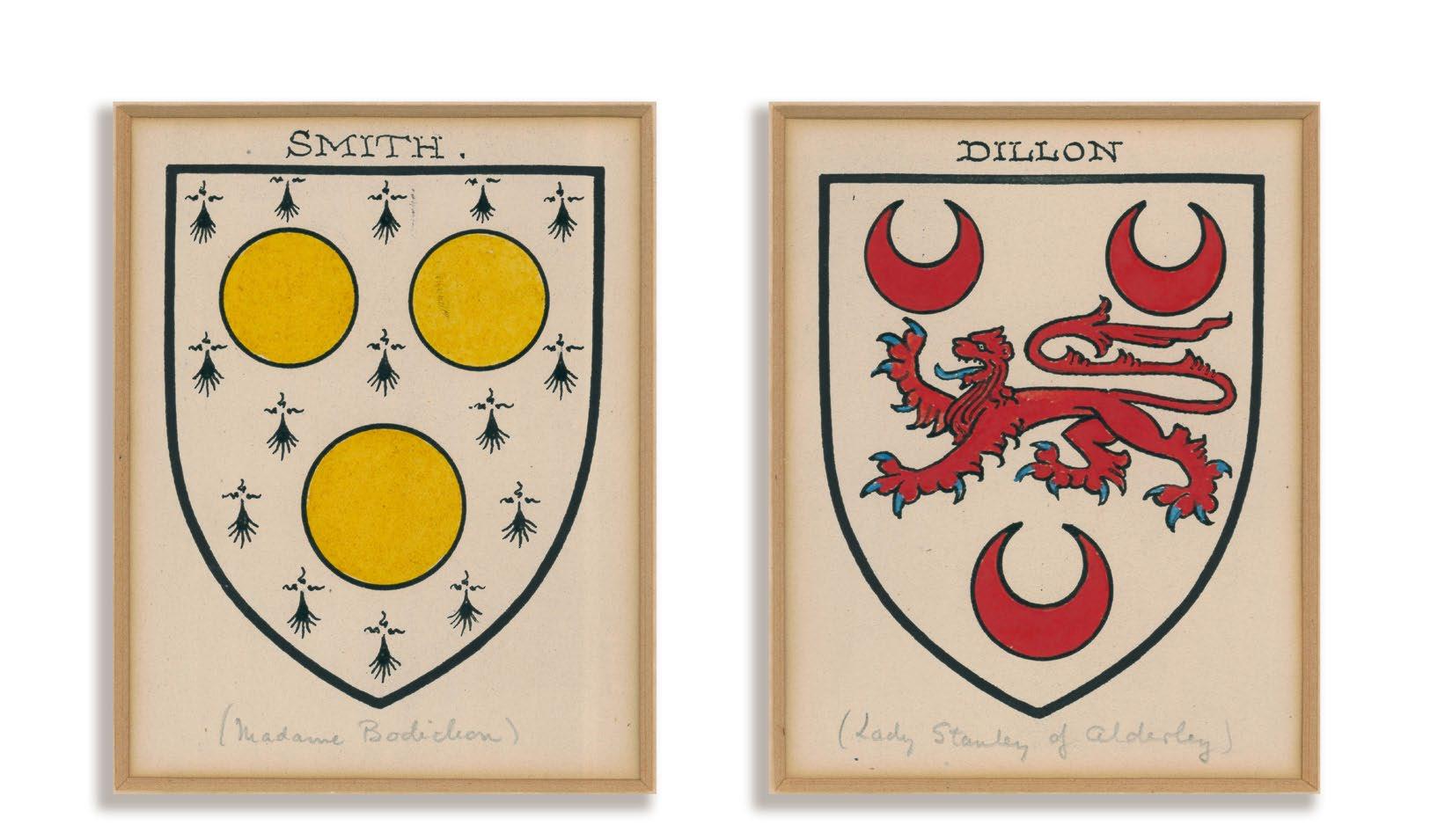

Art and Culture at Girton

Jazzing up the Cambridge Music Scene Girton Jazz/ Tim Boniface Rituals of Discovery

Akeelah Bertram

Can You Answer These Exam Questions?

Pots of Colour — Girton in Your Garden

Girton Couples

A Year in Poetry at Girton

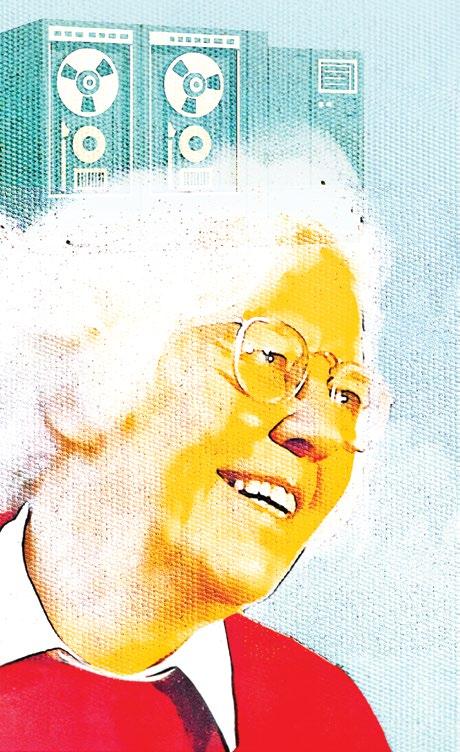

When Karen Spärck Jones arrived at Girton College in the early 1950s, her ambitions were already radical. She would go on to pioneer the field of natural language processing and shape the future of artificial intelligence. Now, almost seventy years later, her legacy is opening doors for the next generation of AI researchers.

So how does a history student from Huddersfield end up shaping how machines understand language?

The humanities mind behind machine intelligence

Spärck Jones came to Girton to study History in 1953, but Cambridge’s flexible Tripos system allowed her to shift course in her third year to Moral Sciences (then the term for Philosophy). This academic pivot would be the first of many. After graduating, she briefly taught in schools before deciding it wasn’t for her. Encouraged by Roger Needham, one of the early pioneers of computer science at Cambridge (and Spärck Jones’s future husband), she joined the Cambridge Language Research Unit (CLRU) in 1958.

It was an unconventional route into computing. CLRU itself was an unconventional lab – unofficial, interdisciplinary, and led by philosopher Margaret Masterman. In an era when computers were used almost exclusively for number crunching, Spärck Jones was already imagining something far more human: machines that could understand and process language.

Spärck Jones believed that computing should not be the domain of mathematicians alone. Her focus was on non-numerical computing: finding ways for machines to process the ambiguity, synonymy, and subtlety of human language. At CLRU, she worked on methods for grouping words by meaning – a task that sounds almost mundane today but was radical at the time.

Her 1964 PhD thesis, Synonymy and Semantic Classification, was initially met with scepticism by examiners. And yet, the very ideas she explored in that thesis became foundational to the search engine technologies we now take for granted. She later developed the TF-IDF model – a mathematical way of ranking the relevance of words in documents – which remains central to how search engines like Google determine what information matters most.

Spärck Jones showed that nuance and meaning could be modelled. She turned language into something machines could learn from, and in doing so, she laid the groundwork for today’s natural language processing systems, including AI models like ChatGPT.

“Computing is too important to be left to men”

Spärck Jones did not just challenge the limitations of technology – she also challenged the culture surrounding it. In a field dominated by men, she often found herself the only woman in the room. But she wasn’t there to play along quietly. She was known for her forthright views on women and academia, summed up by her most quoted line: “Computing is too important to be left to men.”

It’s a phrase that has become emblematic of her vision of inclusive computing. It was not about tokenism – it was about bringing different perspectives into the design of the systems that shape our lives. And it’s this vision that continues to inspire change in the sector.

This year, the University of Cambridge – in partnership with the UK Government’s Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT) – launched the Spärck AI Scholarships, named in her honour. The scholarships will support Master’s-level students from underrepresented groups to pursue postgraduate studies in AI and related fields, with wraparound support including mentoring, work experience, and communitybuilding opportunities.

The goal? To open up the AI sector to voices and talent who might otherwise be shut out. To fund not just academic study but pathways into meaningful careers

in AI. And to embed the inclusive, interdisciplinary spirit that Spärck Jones embodied.

As Professor Anna Korhonen, Director of the new UKRI AI Centre for Doctoral Training in Machine Learning for Language, explains:

“This isn’t just about financial access. It’s about building a community of future AI leaders who think deeply about the human contexts of their work.”

It’s a fitting tribute to a woman who refused to stay in a lane, who moved between disciplines, who challenged structures, and who believed that computing needed philosophy just as much as it needed code.

In 1948, a few years prior to Spärck Jones’ arrival, the University had finally voted to award full degrees to its female scholars. As Spärck Jones later reflected, “It was a privilege to come to Cambridge; you didn’t mess around.”

As we look ahead to an AI-powered future, it’s worth remembering that some of its most powerful ideas began not in Silicon Valley, but with the work of a Girtonian who asked a simple but revolutionary question:

What if computers could understand us?

Launched in June 2025, the Spärck AI Scholarships are a major new initiative to support the next generation of global AI leaders. Named in honour of Girton alumna and computer science pioneer Professor Karen Spärck Jones, the programme will support 100 outstanding students over four years with fully funded master’s study, a living stipend, and priority placements with leading UK AI organisations. Cambridge is proud to be a founding partner, helping to champion academic excellence, leadership, and diversity in AI. The first scholars will begin their studies in 2026–27.

Joan Robinson: Girton’s

radical economist and her enduring legacy

The purpose of studying economics is not to acquire a set of ready-made answers to economic questions, but to learn how to avoid being deceived by economists.”

Joan Robinson never did things by the book. As one of the most original economic thinkers of the 20th century she refused to play by the rules – neither of the discipline, nor of the institutions to which she belonged.

Today, she is remembered as a trailblazer of the Cambridge School of Economics, but at Girton, she remains something more: a symbol of what it means to challenge orthodoxy with brilliance, courage, and conviction.

She never received a Nobel Prize. Yet among economists, she is often remembered as “the greatest Nobel Prize winner that never was”. Her contributions were vast, her politics – radical, and her influence – undeniable.

When Robinson – then Joan Maurice – arrived at Girton in 1922, Cambridge was still refusing to grant degrees to women. She graduated in economics in 1925 but left without a degree – a “great disappointment”, she later said.

After marrying economist Austin Robinson in 1926 and spending time in India, she returned to Cambridge determined to make her mark, but her progression through academia was slow. Despite her growing reputation, it wasn’t until 1965 – more than 30 years after her first appointment to a lectureship – that she was promoted Professor of Economics. Many believed her husband’s position in the same department delayed her promotion. At the time, opportunities for married women and female scholars at the University were limited. But figures like Robinson would force the change.

Praise was often tinged with condescension. One colleague, Gottfried Haberler, described her work as “much too clever for a woman”. Robinson rejected the label “woman economist” – she simply wanted to be known as an economist but her presence at the top of the field was revolutionary. She opened doors, not with slogans, but with substance.

In 1933, Robinson published The Economics of Imperfect Competition – a direct challenge to the prevailing free-market theories of Alfred Marshall. She introduced the concept of monopsony, showing how dominant employers could hold wages below what workers were worth. She used it to explain the wage gap between men and women – and the theory became widely accepted. Nearly a century later, the US Supreme Court would cite it in a landmark labour case.

She was also a key member of the Cambridge Circus, a group of young economists who helped shape Keynes’s ‘General Theory’. Keynes shared drafts with her, and she responded with critiques. Their collaboration helped turn Keynesianism into a global force.

In The Accumulation of Capital (1956), Robinson again challenged orthodox economic thinking by reframing capital and income distribution as political, not merely technical, questions. This was a pivotal move – shifting the debate from abstract models to the real-world dynamics of power that shape economic outcomes. She later called for a “spring cleaning” of the discipline, clearing out the dogmas that no longer addressed real-world problems. Economics, she believed, must be grounded in history, ethics, and human experience – not just elegant mathematics. In other words, for Robinson, economics was truly a political science, not just a

technical science rooted in calculations and theories of economic equilibrium.

Robinson was never afraid of controversy. She engaged seriously with Marx’s work, explored planned economies, and visited Mao’s China and even North Korea. Her commitment to humanity and the human state meant that she believed economics should confront suffering, not ignore it.

Many of the questions she explored remain highly relevant today. Discussions about market concentration, the persistence of income disparities, and the limitations of growth-focused policy reflect themes she had examined decades earlier. Her caution against an over-reliance on mathematical modelling now resonates broadly within the field.

“Joan Robinson reminds us that economics serves people, not dogma: a Girtonian who opened doors, unsettled received wisdom, and championed courage, realism, and historical understanding. Her spirit continues to shape our work and community.” notes Dr Andonis Ragusis, Joan Robinson Fellow in Heterodox Economics at Girton College.

Robinson was not successful in changing ideologies in her lifetime. Her attempts to bridge, reconcile and “spring clean” the separation between neoclassical and classical economics weren’t embraced. But imagine if Robinson’s ideas had exerted a stronger influence on economics after the Second World War. Her views on wages and market structures pointed in a different direction, and while we will never know what would have happened, they still offer a fresh way of looking at the economy today.

Robinson lived her beliefs. A strict vegetarian, she famously slept in an unheated hut in her garden, walking barefoot to breakfast each morning. She once described herself as “simple-minded” – not out of modesty, but because it let her see things clearly, and act. Professor Maria Cristina Marcuzzo – in a lecture for the Girton Economics Society – begged to differ: “I don’t think Joan Robinson was simple minded, she was intellectually daring.”

Girton celebrates her with an economics society, a fellowship, and a workshop series that bear her name, but her greatest legacy may be her example: of what it means to challenge from within – to belong to an institution but also to reshape it.

Honouring the life and legacy of Sheila Lesley (1950 Natural Sciences)

Sheila Lesley’s interest in inventions was first sparked by a childhood glimpse of John Logie Baird, the inventor of television, walking across the golf course in Bude. What followed was a pre-university job as an analytical chemist, where she first came across patents. From there, her path was clear.

Lesley joined Forrester Ketley & Co (now Forresters IP) in London and qualified as a Chartered Patent Agent in 1958. She was just the third woman ever to qualify, and the first in nearly three decades. By 1983, she was joint Senior Partner. In a profession dominated by men, Lesley was not only a pioneer, but also a driving force in opening up opportunities for others. One colleague recalled that under her leadership, Forresters employed more women trainees than any other UK patent firm at the time.

Lesley’s expertise in trade mark law earned her Fellowship of The Chartered Institute of Trade Mark Attorneys (CITMA), which she would later go on to lead as the first woman President in 1981. Her impact was recognised nationally when she was awarded an OBE in 1988 for services to patents and trade marks.

More than a legal powerhouse, Lesley was a true character, known for her signature hats (and gloves), and her sharp, inquisitive mind. Her occasional nickname, ‘Miss Marple’, wasn’t just about style; it reflected her relentless pursuit of accuracy. She never settled for superficial answers and encouraged others to think deeply and critically.

Once she retired, Samphire Island in the Blackwater Estuary, Essex became Lesley’s new frontier – a place to explore history and ecology. She joined the Essex Wildlife Trust, became a Freeman of the City of London, chaired a school governing body, and supported the RNLI. She was also an active member of Soroptimist International of Southend-on-Sea & District.

Lesley embodied inclusive excellence, intellectual curiosity, and critical thinking; values that remain at the heart of Girton’s mission. She passed away in 2019, but her impact endures in the many professionals she mentored and the barriers she helped dismantle. Her legacy also lives on through her extraordinary generosity to the College. Thanks to her gift, Girton now supports a Law Fellowship, a Postgraduate Studentship in Law, and the Law and Innovation Fund – all of which bear her name.

Sheila Lesley didn’t just make history. She has created a legacy here at Girton that will support and inspire scholars for generations to come.

The Sheila Lesley Law and Innovation Fund empowers excellence in legal education by supporting research, practice, and public engagement in law and related fields. As part of achieving this ambition each year, it awards grants to undergraduate Law students, enabling them to pursue academic internships that offer hands-on experience and deepen their understanding of the law.

In summer 2024, Hadeal Abdelatti (2022 Law) seized this opportunity and interned with The Woods Foundation in Alabama, the United States. The Foundation is a nonprofit tackling injustice in the state’s criminal justice system, especially wrongful convictions, medical negligence, and harsh sentencing.

Immersed in real casework, Abdelatti gained firsthand insight into the complexities of legal advocacy and joined sessions with leading lawyers, politicians, and activists – helping to drive change in justice reform.

After completing the internship, Abdelatti authored the report “Hopelessness is the Enemy of Justice”, drawing its title from Bryan Stevenson’s powerful statement and paying tribute to Stevenson’s pioneering work in Alabama.

Abdelatti’s internship laid the groundwork for a successful application to the Human Rights Project at Bard College, NY, where she has now taken up a prestigious Anthony Lester Fellowship. These fellowships support practical work in human rights and the rule of law. Mere months after graduating, Abdelatti is already making strides toward a career as a barrister and is dedicated to amplifying the voices of those pushed to society’s margins.

When one Girton student signed up for a data support drop-in, part of the Girton Skills Programme, they weren’t sure what to expect.

“The Girton Skills Programme has been one of the most valuable academic experiences I’ve had –especially the data and programming sessions,” they later reflected. “The facilitator’s expertise was immediately evident, but what truly set it apart was their ability to break complex concepts into clear, manageable steps. They were patient and encouraging.”

Now in its third year, the Girton Skills Programme (GSP) is becoming part of the fabric of College life. Designed to complement formal teaching and supervision, it helps students develop both academic skills and the wider capabilities needed to thrive at Cambridge and beyond.

A programme of unusual breadth

GSP combines academic support, wellbeing initiatives, and career development. No other Cambridge College has brought these strands together in quite this way. In 2024–25, it offered 55 open sessions, along with regular drop-ins, and one-to-one support. Around 148 students took part, and the programme recorded 470 engagements.

“It has been wonderful to see our students grow in confidence. Ensuring that they can put into practice their newfound and developing skills is of benefit not just to them individually, but also to the wider community at Girton and beyond.”, Dr Stuart Davis, Deputy Senior Tutor for Teaching and Learning reflects on the Programme.

55 open sessions in 2024/25 – 148 students, 470 engagements

c. 30 students supported by the Data & Programming drop-ins

10 academic internships in 2025 (6 STEM, 4 Arts & Humanities) from 15 proposals; 52 students and 104 applications

100+ one-toone life-coaching sessions delivered Girton among top five Colleges for engagement with the University Careers Service

c. 300 alumni and c.170 students joined the Girton Careers Network on LinkedIn 18 students reached 100+ participation credits; 17 Personal Development Grants awarded

The academic strand ranges from Freshers’ Induction workshops on essay-writing and time-management to postgraduate sessions on publishing papers and supervising undergraduates. The new Data and Programming support quickly proved popular, with about 30 students drawing on help with Python and R, statistical modelling, and data visualisation.

The Academic Internship Scheme has also taken root, with the second cohort of students taking part over the summer of 2025, working on projects that range from Girton’s role in wartime codebreaking to the College’s Roman and Anglo-Saxon cemetery. Feedback has highlighted the value to both students and Fellows:

“This initiative is a true win-win-win: I gain a motivated, hard-working student to support a key Whittle Laboratory project; the intern builds handson experience in a dynamic research environment while completing their engineering placement; and the College sees students who are more deeply engaged with their subject – carrying that engagement into stronger academic performance in the second half of their degree,”, says Dr Sam Grimshaw, Engineering Fellow.

The wellbeing strand is based on positive psychology and aims to help students build resilience as well as balance. This year’s programme included workshops on managing stress and anxiety, relationships, and perfectionism, alongside practical sessions such as financial wellbeing.

Life coaching sessions, introduced last year, continue to be in high demand: more than 100 one-to-one sessions took place during 2024–25. Students described the coaching as “insightful” and “helpful in making real changes”. And new initiatives – swimming lessons, neurodiversity workshops, and gardening activities –were particularly well received.

Careers provision has been another area of growth. Girton students are now the fifth most engaged with the University Careers Service. Highlights this year included one-to-one CV clinics, alumni talks, and the pilot of a 1:1 Careers Coaching Scheme offered by an alumna. A new Finalists’ Day provided practical support — from professional headshots to alumni panels and advice on personal branding.

The launch of the Girton Careers Network on LinkedIn has also been a milestone, with c. 300 alumni and 170 students joining within the first few weeks. It promises to be a valuable resource for mentoring, networking, and opportunities.

Continuing to evolve, the Girton Skills Programme is already enriching student experience in measurable ways – from increased confidence to closer connections between students and alumni.

For those who take part, it is more than a support programme: it is a way of making the most of their time at Cambridge. As one student ambassador put it, “It was so nice to reassure new students that there was support for all their worries – especially since I remember how overwhelming it was for me.”

With a 12,000+ strong alumni community spanning almost every career stage and sector worldwide, Girton offers an extraordinary resource for students taking their first steps into work – bringing realworld insight and warm introductions.

Launched on LinkedIn in 2024-25, the Girton College Careers Network has already attracted hundreds of Girtonians. It connects students with alumni to share expertise and experience. With almost every industry represented – from finance to film, start-ups to the civil service – the Network helps students explore a wide range of paths, ask smart questions, and gain practical insight into what’s possible.

Join the Network today

The Girton Skills Programme exemplifies Girton’s commitment to giving our students not just the best possible education, but also the skills and confidence to use it well.

Our support doesn’t stop online. At the first ever Finalists’ Day, alumni returned to College to share guidance on moving from university to professional life. Some of the most popular sessions included:

• Creating Your Professional Brand with Jane Hamilton (1989 Social and Political Sciences) –including actionable tips students could implement immediately.

• From Idea to Impact with Rohit Pothukuchi (2021 Finance) and Shambhawi Shambhawi (2018 Chemical Engineering) – honest insights into startups and turning ideas into impact.

• Life After Girton panel – Rachael Richards (Hedley, 1997 History), Dom McGough (2014 Mathematics), and Emily Kell (2011 English) –shared practical tactics for job-hunting, navigating early-career challenges, and building momentum. Students left with clear next steps, and the confidence to take them.

Della Banerji (Unwin, 1986 Modern and Medieval Languages) offers personalised one-to-one coaching that makes a tangible difference. Sessions help students clarify ambitions, sharpen in-demand skills, and build practical, achievable plans. It’s a focused space for reflection and strategy, empowering students to move forward with purpose – whether exploring options or preparing for specific opportunities.

As Della puts it, “The transition from student life to the world of work is increasingly challenging because of the number of potential options and the emergence of new technologies. A coaching setting creates a safe environment in which to brainstorm new ideas about life after College. It frequently leads to tangible outcomes, sometimes in unexpected ways. The students on the programme really do commit themselves to the process.”

Throughout the year, we run lively subject- and sectorspecific events with alumni – one of the most powerful ways to energise and empower our students. These sessions bring the world of work into the heart of the Girton experience: from Law and Finance panels to Q&As with Classics and MML alumni, showcasing how these subjects lead to diverse careers – from independent theatre to combating organised crime, from marketing and communications to leading figures in law. Each gathering helps students explore pathways, ask questions, build networks, and grow in confidence. The participation of alumni adds authenticity and relatability, and their experiences show students that success is achievable, and that they are part of a lifelong community – a community that inspires and supports one another well beyond graduation.

In summer 2024, thanks to the generous support of Chris Rokos, Girton launched the Rokos Summer Academic Internship Programme. Our inaugural cohort of six outstanding Rokos Interns – undertook full-time, paid academic internships –gaining hands-on experience at the cutting edge of research while contributing to impactful projects across multiple scientific disciplines.

• Biological Sciences: Investigated protein content in wheat, advancing research with the potential to improve agricultural practices and food security.

• Physical Sciences: Contributed to the development of the Cambridge University Whittle Laboratory Aerodynamic Probe Calibration Facility, a significant step forward for aerodynamics research.

• Environmental & Wildlife Studies: Mapped human–wildlife interactions in Nepal, generating critical data to inform regional conservation efforts.

• Palaeoecology: Explored the comparative palaeoecology of the Jurassic Kimmeridge Clay, yielding fresh insight into ancient ecosystems.

In October 2024, the Rokos Interns presented their findings to an audience including the benefactor, Fellows, and students at Girton. The event celebrated their achievements and showcased the programme’s tangible outcomes.

On the strength of year one, the College is expanding the programme to include humanities projects – further enriching the Girton experience and enabling more students to engage in meaningful research across a wider range of academic fields.

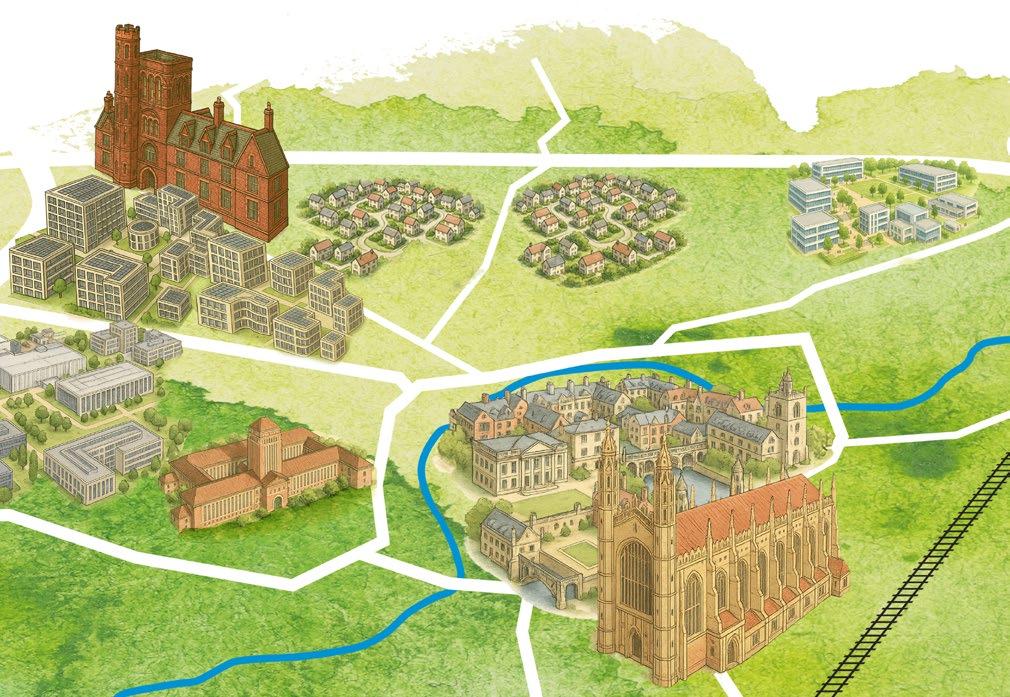

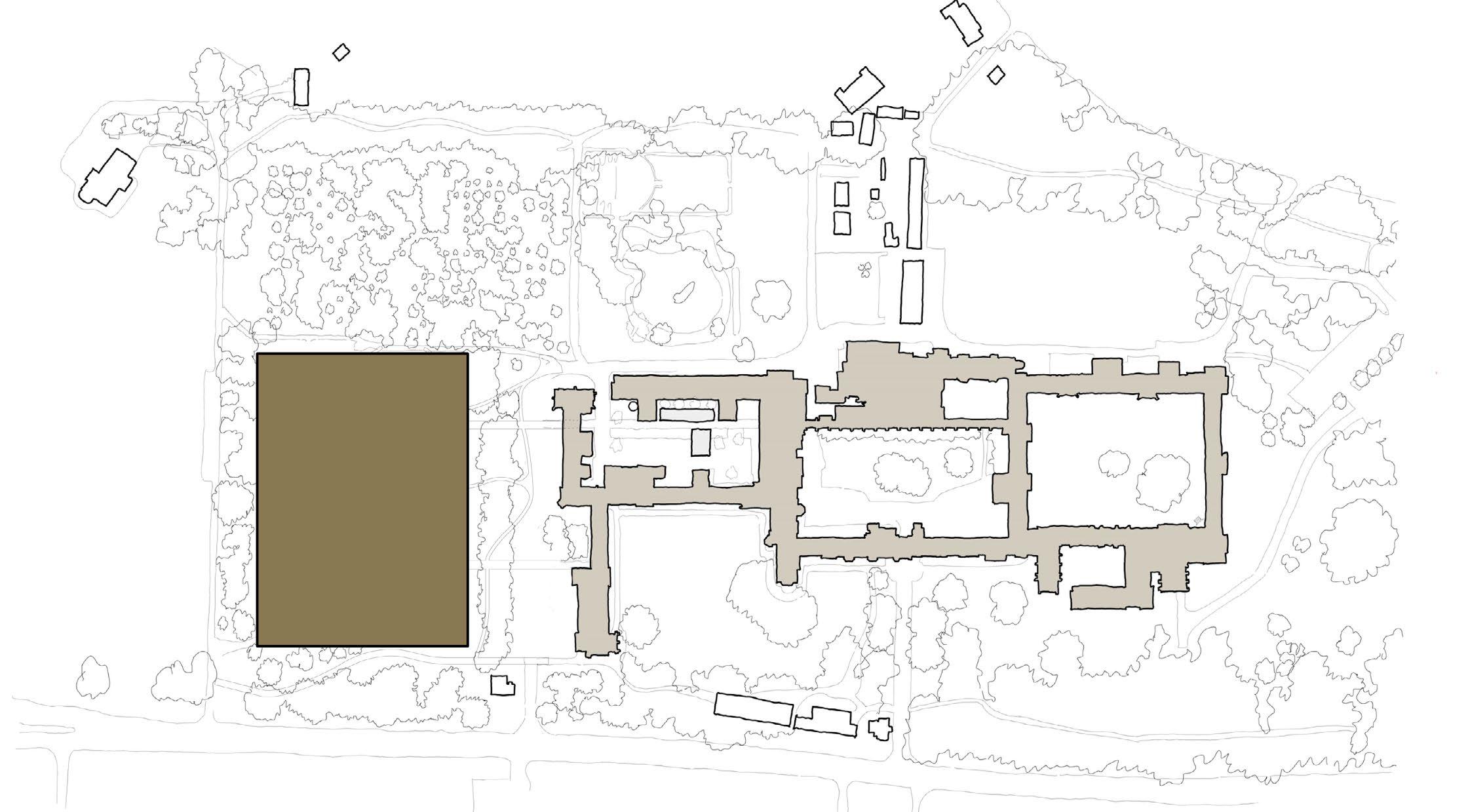

Behind postcard Cambridge – spires, punts, chapels, and choirs – is an ever-evolving kaleidoscope of medieval cloisters, nineteenth-century brickwork, post-war concrete, modern research parks, and futuristic laboratories, all chronicling the evolution of one of the most important centres of knowledge and learning in the world.

Girton has long been set slightly apart from the medieval heart of Cambridge. Founded in 1869, the College occupies generous grounds – courtyards, orchards, and fields that give it a distinct rhythm – and that space now gives Girton a real advantage as the University’s estate strategy unfolds. The plans for West Cambridge and Eddington are shifting the city’s campus horizon westwards. For Girton, that shift is an opportunity to bring more of college life onto our main site and to play a more active role in the life of the University and the city.

The University’s Reshaping Our Estate programme – a new, twenty-year masterplan – seeks to manage growth while conserving heritage and sets three clear objectives: better use of space, improved connectivity between sites, and a commitment to reach net zero by 2048.

“Our duty today is to ensure that the University can continue to maintain and develop the physical spaces that will allow us to deliver world-leading education and groundbreaking discoveries for generations to come” said Professor Deborah Prentice, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cambridge, at the launch of the programme.

The estate is being considered in three broad zones –Cambridge West, Cambridge Centre, and Cambridge South – and the University proposes a connective strategy it calls the “Golden Web”. Enhanced by wayfinding and transport nodes in collaboration with local authorities, the Golden Web will link sites, buildings, colleges, historic centres, and other key elements of the city through a more welcoming and biodiverse infrastructure that promotes connection and wellbeing.

“We need an estate that enables collaboration, connecting people across different disciplines. We need an estate that is efficient and sustainable” continued Professor Prentice.

At a city level, Cambridge is preparing for a substantial transformation. A new c. 80,000 sq ft innovation hub is at the centre of a wider growth strategy intended to expand the city’s research and commercial capacity over the next quarter of a century. The scheme – with support from the University, major developers, and tech investors – aims to deepen links between discovery and commerce.

At the same time, the Greater Cambridge plan to 2041 steers development towards brownfield land and seeks to protect green-belt and village identities, while transport, water, and services remain limits on expansion. If these practical challenges can be met through coordinated public and private investment, the strategy could offer a model for regionally led economic renewal.

Demographic changes add weight to the case for development: between 2011 and 2021 Cambridge’s population rose from about 123,900 to roughly 145,700 – a 17.6% increase, nearly three times the national average – while South Cambridgeshire grew by 8.9% over the same period.

Cambridge West and Eddington are important elements of this vision and offer a unique opportunity to deliver expansion at a scale that is sufficiently large.

Cambridge features prominently in government plans announced in early 2025 to go “further and faster” in kick-starting economic growth across the UK. The government has set out a strategy to unlock the potential of the Oxford–Cambridge Growth Corridor by accelerating the expansion of UK science and technology. The plan recognises the University of Cambridge as one of the world’s most intense clusters for science and technology and stresses its capacity to build on the roughly £30 billion it already contributes to the national economy.

Cambridge’s proposal for a new large-scale innovation hub to attract global investment and foster a community that catalyses innovation is endorsed by the government.

Modelled on projects such as The Engine in Cambridge, MA, LabCentral in Boston, and Station F in Paris, the proposed hub is intended as a place to accelerate the translation of leading research into new companies. The package also includes substantial investment in transport and infrastructure across Cambridge and the wider Oxford–Cambridge corridor, together with measures to secure water supplies and deliver homes and community facilities: schools, fitness and leisure provision, and the office and laboratory space that a growing knowledge economy will require.

West Cambridge is being recast not simply as another research park but as a visible, people-focused innovation district on a site of roughly 66 hectares that already hosts much of the University’s engineering and physical-sciences activity.

Planners envisage a substantial uplift in employment on the site (the workforce is modelled to grow from about 4,000 today to some 15,000 by 2041), and the campus is already attracting major capital projects: donorbacked facilities, such as the Ray Dolby Centre, and test-bed infrastructure, including a solar farm.

The approved scheme makes room for wildlife, softens noise, and shapes public life around green, landscapeled areas. The carefully curated open green spaces, leisure facilities, and public places complement the vibrant West Hub and University Sports Centre offering.

The so-called “green spine” and a programme of pedestrian and cycle upgrades (photovoltaic canopies atop cycle sheds, rain gardens, and new active-travel corridors) are intended to make walking and cycling the default. Similarly, the shared amenity hub, combining café, restaurant and retail, is an exploration into how campus facilities can serve the wider community alongside employees and students.

Eddington was conceived as a mixed-use district of housing (including some affordable units), a primary school, shops, and an innovation campus. Built in phases since 2017, it is intended as a place where students, academics, and local residents live and work. Since 2017, Girton has been operating Swirles Court in Eddington, providing 325 student rooms close to our main site.

The University’s third-round proposals in 2025 envisage up to 3,800 additional homes, bringing the Eddington total to roughly 5,650 when added to the c. 1,850 already delivered or under construction. The plans set out two- to six-storey residential blocks (with select landmarks having up to eight storeys), significant public spaces, and more than 100,000 sq m of employment floorspace.

Around 79% of current trips to and from Eddington are by walking, cycling, or public transport, and the brief retains a strong emphasis on active travel. A large proportion of the new housing is intended to serve University-affiliated staff or key workers.

However, the complementarity between West Cambridge (research capacity) and Eddington (homes and services) will only function with adequate infrastructure in place: coordinated transport upgrades, reliable water and energy capacity, careful flood-risk management, and sensible sequencing that ensures demand does not outstrip supply.

Together, the planned investments could knit research, homes, and public life into a resilient and greener chapter for Cambridge. All this bodes well for Girton. The continued expansion means we find ourselves at the heart of modern Cambridge and can make the most of our strengths: our space and our open, inclusive ethos.

The new courts programme – our plans to develop the College site – is therefore both an exercise in making Girton more contiguous and a deliberate repositioning: bringing more undergraduate and postgraduate life onto a single site and creating spaces that can host conferences and performances as well as day-to-day academic and outreach activities.

As James Anderson, our Bursar, puts it: “The new courts are a bold statement of Girton’s self-confidence and 21st-century ambition.”

The award-winning architectural vision created by Gort Scott speaks to that dual purpose. The new buildings have been designed to respond in a sympathetic and imaginative way to the College’s iconic Waterhouse buildings while using beautiful and sustainable contemporary materials. This is a practical marriage of heritage and efficiency: a new construction that respects tradition while improving thermal performance and reducing running costs.

Equally explicit is our emphasis on wellbeing. Landscaped spaces, accessible rooms and other amenities are designed to foster informal encounters and encourage stronger interdisciplinary exchanges among students and Fellows.

“Unlike the medieval heart of the city, Girton is directly accessible by road, benefits from on-site parking and can be secured or temporarily cordoned off for large events, making it easier to host conferences and public gatherings” the Bursar continues.

Having completed our Strategy Refresh in 2025, and as we look to the future with renewed purpose, we are excited by the opportunity to play an even more active role in the life of the University and the city by doing what we do best: challenging convention and creating opportunity. Watch this space.

Sources Full list of sources available at www.girton.cam.ac.uk/girtonian2025

Girton Strategy Refresh 2025-2027

– three goals and one enabler: a transformative new courts project

In 1869, Girton College challenged the very foundations of higher education. At a time when society insisted that women belonged at home, rather than in lecture halls, Girton stood resolute and declared: “Watch us.”

The early Girtonians were turned away. They persisted. Girton happened because they decided the future should arrive sooner. That spirit has never really left us; it simply changes its shape with the times.

“The new courts will be the crucible in which scholarly and creative sparks fly, turning our academic ambition into impact and keeping Girton bold, influential, and ready for the future.”

Earlier this year we paused, took a clear-eyed look at the world, and asked a simple question: what would those early Girtonians do now? So much has shifted around us – how students learn, how researchers collaborate, how ideas find audiences, how communities meet.

Rather than write a long wish list, we chose to focus. We refreshed our strategy to concentrate on the things that will make the biggest difference: welcoming and nurturing talent from every background, enabling teaching and research to flourish, and connecting Girton thinking with the world beyond our College.

All three goals call for something very tangible: space. Space for people to live on the main site, to bump into each other, to rehearse, to debate, to record, to share. This is why the new courts project matters.

The most significant single building development at Girton since our foundation in 1869, the new courts will advance our core missions of learning and research and drive our global impact and relevance.

As our Mistress, Dr Elisabeth Kendall, puts it “The new courts will be the crucible in which scholarly and creative sparks fly, turning our academic ambition into impact and keeping Girton bold, influential, and ready for the future.”

Girton has always been at the forefront of creating opportunity. Today’s barriers may take different forms – financial, social, or cultural – but they still prevent far too many talented students from achieving their full potential.

This is why we are intensifying our commitment to “inclusive excellence.” Continuing to uphold the highest academic standards, we are widening access by offering targeted support, such as bursaries, scholarships, and the Girton Skills Programme, to ensure every student can succeed.

Additionally, every undergraduate will benefit from international exposure because stepping outside one’s comfort zone broadens the mind in ways no textbook can.

Professor Toni Williams, Senior Tutor, reflects: “‘Inclusive excellence’ is about belonging and achievement. It requires spaces reflecting the world’s diversity and dynamism. Through challenge, encouragement, and care, we empower every student, whatever their background, to flourish and excel – both academically and personally.”

We are also expanding opportunities in sport, music, the arts, and volunteering, so that all our students have the chance to discover their spark and nurture their passion. It is easier to push boundaries and engage creatively when immersed in multiple modes of learning.

Girton thrives because our Fellows are not just outstanding scholars, but also creative thinkers who are deeply committed to their students. We seek to attract and retain the brightest minds – to mentor the next generation of trailblazers and to drive research that contributes to society.

To achieve this, we are investing in our Fellows – offering competitive salaries, strong research support, and the freedom to work across disciplinary boundaries. We are providing them with an environment that stirs the imagination and propels discovery.

Also, we will not keep our achievements hidden. We will share Girton’s insights with the wider world – through greater media

Goal 3: confined to historic cloisters – that it can empower anyone with a desire to learn.

Rooted in a community of more than 12,000 Girtonians and linked to c. 300,000 Cambridge alumni, our impact extends beyond the College – Fellows pushing at the frontiers of knowledge; alumni shaping change and ideas across industries and communities worldwide, from creating opportunity and empowering women to driving climate action.

Girton already convenes global conversations; with enhanced resources and platforms, we will expand their frequency, ambition, and reach, taking our knowledge far beyond Cambridge.

Girton is poised for the most significant physical transformation since its foundation. The new courts project – already recognised for its award-winning design – will do more than extend our estate. It will give concrete expression to what the College stands for in the 21st century: inclusive excellence, scholarship with real-world reach, and a community that draws strength from its diversity.

Set around two sustainably landscaped courtyards, the development will create c. 100 new en-suite rooms for students, Fellows and visitors – welcoming and well-planned spaces that keep more Girtonians living, learning and collaborating on the main site.

Alongside these, a modern, state-of-the-art auditorium (see cover) offers a crisp acoustic, refined design, and the versatility to host chamber music, contemporary performance, major debates and keynote lectures.

The new courts will be built for the way in which knowledge is created and shared today and in the future. Flexible teaching rooms support supervisions, seminars and workshops; configurable spaces invite conversations and spark fresh thinking. A media suite enables recording, broadcasting and streaming – so research and big ideas can travel, and students can learn to present their work with confidence.

In the words of Elena Buermann, JCR President, “Girton students are already an especially close-knit community, and the new facilities will make it even easier for us to come together and enjoy every aspect of College life –whether sport, music, or studying.”

When this strategy and the new buildings come together, you will notice more students living and learning on the main site. You will hear more music and debate coming from rooms that are used from morning to night. You will see undergraduates, postgraduates and Fellows sharing space as a matter of course rather than only exceptionally. You will find visiting scholars and partners welcomed into a place that feels ready for them. You will experience simple, everyday benefits: comfortable rooms, quieter corridors, and inviting green spaces, all supported by energy-efficient design.

“The new courts will be transformative in realising Girton’s intellectual ambitions – a centre for scholarly debate and exchange, and a refined venue for the performing arts – shaping knowledge and culture” said Dr. James Wade, Vice-Mistress.

“…everything that is good for body, soul, and spirit”

We are careful stewards of a remarkable setting – 50 acres of orchards, wetlands, wildflower meadows, and beehives – where the seasons are visible, and thinking can slow and deepen.

True to Emily Davies’ vision, wellbeing and sustainability are at the heart of the new courts. The design targets high energy performance and improves biodiversity. Daylight and fresh air matter; so do materials that age well and paths that encourage both chance encounters and quiet exploration. We are committed to sustainability in practice as well as promise, and the new courts project is a big step on Girton’s path towards

carbon neutrality

by 2048.

Join us

The Girton story has always been about moving from principle to practice. Girtonians before us imagined a College that would change what was possible. Girtonians after us will inherit what we choose to build. The new strategy gives us direction, and the new courts give us the means to realise our ambitions. The rest, as ever, depends on what we do next – together.

Formula 1 is a huge global sport with a fanbase of 827 million worldwide. It’s also a thrilling combination of human performance, science, data and experimentation, as Atlassian Williams’ Head of Aerodynamics Adam Kenyon explains.

A lap time that secures pole position by a nose. A smooth and effective pit stop. A lightning-quick reaction to avoid a hazard or overtake a rival.

Sometimes, that’s down to the drivers: athletes who captivate crowds with their blend of experience, talent, instinct, and fearlessness. But more often, those milliseconds are the result of months and years of work behind the scenes.

As Scottish Formula 1 (F1) legend David Coulthard once said: “The driver is the primary focus of attention, but it’s the thousand-plus team members who create the opportunity to win”.

So, what is it like to be part of one of those teams, united by what Coulthard once called “the relentless pursuit of perfection”?

Adam Kenyon knows. The Girton alumnus (2000 Engineering) has worked in F1 for nearly two decades and has been part of winning teams at Red Bull Racing and MercedesAMG Petronas. In April 2024 he was unveiled as Head of Aerodynamics at Atlassian Williams Racing.

“At its core, F1 is a combination of athlete and engineering”, he says. “It’s a balance of theory and testing, as well as a willingness to take risks and give something a go.”

“Innovation is key to being at the front in F1, and you’re not going to do that by playing it safe.”

Kenyon remembers watching F1 on TV with his dad and brother growing up, but being part of the sport wasn’t necessarily a childhood dream. He was interested in sciences at school and found aeroplanes intriguing. So when he discovered aerodynamics, it seemed like a good fit.

He studied Engineering before pursuing a PhD in Aerodynamics. He

then took a role at an engineering consultancy but found himself craving something more exhilarating and fast-paced. And, well, it doesn’t get much more fast-paced than where he went next.

“I remember my first day in F1 at Red Bull. Just walking in the door and thinking, ‘wow’.

“One of the amazing things about Cambridge is that you were surrounded by so many talented people, and F1 is similar. You can build off one another and learn from each other.”

“A team doesn’t feel like this vast organisation. Even if you’re just starting, you can feel that sense of camaraderie. You can learn from the most experienced people in the industry.”

Aerodynamics is a key factor in the success of any F1 team. Teams work tirelessly to adjust their designs to optimise how air flows around their car. This can impact how it corners, its speed, and how challenging it is to drive.

“We work on virtually the whole design cycle of components”, says Kenyon. “We’re involved in the Computer Aided Design, the idea generation, the simulation side of things. We test our theories in Computational Fluid Dynamics and select the most promising ideas. Then we manufacture parts and prepare them for testing.

“We have a wind tunnel on site which we use for experimental testing, and we compare our results against what we thought would happen. And then we measure performance on the track and get driver feedback.”

No two weeks are the same in an F1 team. The car that starts the first race of the year is not the same as the one on the grid for the last one. In fact, teams are often juggling two concurrent car programmes: the one they’re using this year, and the one they’re developing to meet next year’s rules and standards.

“We release a car at the start of the year, but we’re constantly upgrading it to stay ahead. You can really see performance changing, as teams bring in upgrades.

“Typically, we’ll be running multiple programmes in the wind tunnel and in Computational Fluid Dynamics. And we’ll be analysing how the car performs on the track on a weekby-week basis. That will include speaking to the drivers about any weaknesses and sensitivities in the car, and how it matches up to the competition.”

Williams is synonymous with F1 legends such as Nigel Mansell, Damon Hill and Jacques Villeneuve, but it’s building a new identity as it looks to return to the front of the grid. It’s a challenge that Kenyon relishes.

“We’re looking to build a culture and develop a tight-knit team from back to front that will help us succeed.

“One thing that’s been really great over the last couple of years is that there’s this focus on long-term sustainable performance. We’re not trying to make quick fixes. We’re empowered to speak up when there’s a better way of doing things, even if it impacts the short term.

“We’re creating a culture where people aren’t afraid of failure, and we’re pushing the boundaries and trying to learn as quickly as we can.”

A lot has changed since Kenyon’s first role in F1. Regulations such as the “Cost Cap” have been brought in, to level the playing field by limiting how much teams can spend

on their car. Plans to achieve net zero in F1 by 2030 are ongoing. One big difference he notes is the sheer amount of data that today’s teams work with.

“In my time in F1, the level of detail to which we develop has increased significantly and is supported by vast amounts of data.

“In terms of aerodynamics, as the air flow becomes more complex, the importance of small details increases. I believe that leveraging data science and improving our simulation capabilities are – and will continue to be – key to competitiveness.”

Kenyon is glad to see teams today investing in initiatives and programmes that offer opportunities to talented young people from many different backgrounds. As a team with big ambitions, Williams is offering various routes into the industry on its website at careers.williamsf1.com, including apprenticeships, graduate roles, and the Komatsu Williams Engineering Academy.

What would Kenyon say to someone looking for somewhere to learn, grow and build an exciting career?

“There’s a clarity of purpose in F1 teams that’s very special. I don’t know many other industries that offer anything similar. It’s fast-paced, cutting-edge, and people work hard to solve complex problems to very short timescales.

“It’s got a relentlessness to it that doesn’t suit everyone, and that relentlessness can be addictive. You unlock some performance, and you want to start finding more and more.

“If you want to be in an environment where you’re constantly trying to do things better, Formula 1 is a great place to be.”

What is life in an F1 team like for someone who’s just starting their career?

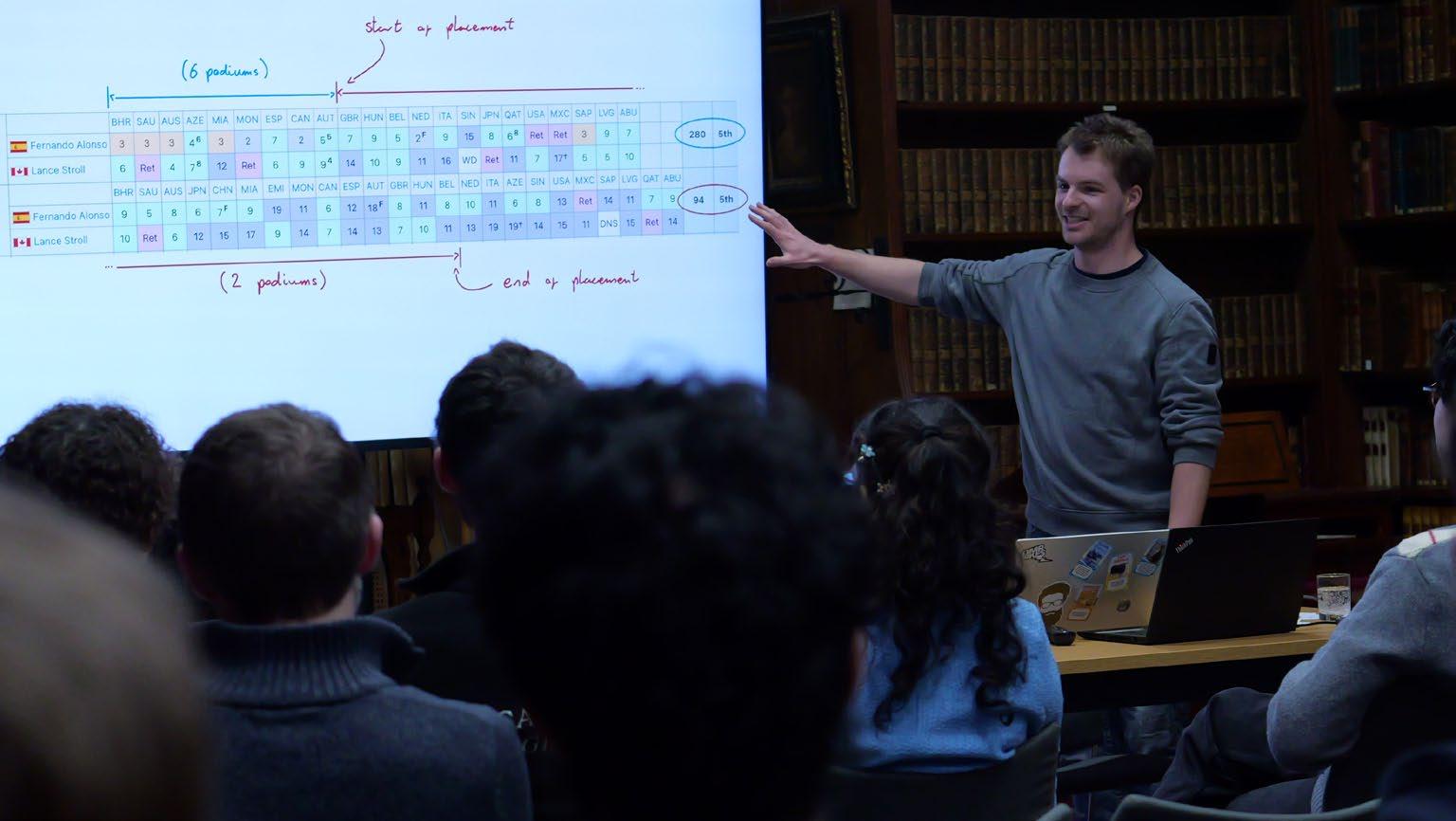

Thomas Lack joined the Aston Martin F1 team as a Graduate Aero Performance Engineer, soon after graduating from Cambridge (2019 Mathematics).

“A lot of things appealed to me”, he says. “The fast-paced environment, the chance to apply mathematics, and the quick feedback, much of it visible each time the cars take to the track.”

Lack works in Aero Performance, helping to analyse and correlate results from the track, wind tunnel, Computational Fluid Dynamics, simulation and more.

“I focus on the modelling aspect of aero performance, applying techniques from statistics and machine learning to build mathematical representations of the patterns we observe in the data. These models not only enhance our physical understanding of aerodynamic behaviour but also improve the accuracy of our predictions, supporting better decision-making and development strategies.

“My work is most often a mix of problem solving, coding and writing reports, but no two days are quite the same.

“After a race weekend, for example, I might need to turn around a quick piece of analysis or write a Python script, all while balancing the longerterm projects. I am always mindful that there could be someone in each of the other nine teams (soon ten) doing a similar job, so the challenge is to make sure I do it the best.”

Lack drew on his science and mathematics background to secure the role. However, he notes that an

F1 team is a mix of people with a range of different skills, working together “toward a shared goal”.

“One of the biggest reasons I wanted to go into F1 was the chance to be part of a team. I have been lucky to play violin in orchestras since school, and that experience gave me an appreciation for how rewarding it is to contribute to something bigger than yourself.”

While Lack didn’t grow up glued to F1 races, he started watching properly in 2021 and soon found himself trying to predict race strategies from his sofa.

“My dad used to watch F1 by himself, but since 2021 it has become something we enjoy together. After I joined Aston Martin in 2023, my mum and brother also started watching. It’s rare for us all to sit down to the same thing on TV, so F1 has brought us together as a family in that way.

“And of course, being part of an F1 team makes for an interesting conversation point when someone asks, ‘What do you do

Girton has always led from the front – opening doors, challenging conventions, and backing ideas that change the world. By remembering the College in your Will, you help ensure that Girton’s future is just as pioneering as its past.

Your gift can:

• Open doors for brilliant students from every background.

• Spark discovery through world-class research and innovation.

• Sustain Girton by helping to protect and evolve our extraordinary estate. No matter the size, your gift makes a measurable difference.

Your legacy. Girton’s future. Our shared story.

Learn more at www.girton.cam.ac.uk/legacy or contact Emma Cornwall on e.cornwall@girton.cam.ac.uk | +44 (0) 1223 338 901

By Mark Walsh (1997 English)

You’ve probably heard some version of this thought experiment: How much of the Sahara Desert would need to be covered with solar panels to power Europe? It’s usually accompanied by a picture of some tantalisingly minuscule strip of uninhabited nowhere, and a lament: Why doesn’t someone just do it?

The punchline: This is why we can’t save the planet. Useless humans.

Mark Budd (1994 Mathematics) has heard the argument. Unlike most, however, he might be on the verge of doing something about it.

It was 2020, and Budd was looking for a new challenge. An old friend approached him, Budd recalls, and said, “Let me talk you through my idea, and you can tell me if I’m crazy –I listened to him, and I said, ‘You’re crazy.’” But the friend – Simon Morrish – was very serious. Morrish, a British entrepreneur, made his fortune in environmental services

and has since pushed green initiatives in energy generation and transport.

As Budd listened, the idea began to sound less crazy. Less crazy, but still fiendishly difficult. “You’ve actually got huge barriers to this,” Budd says. “Securing land. Securing connection agreements. Getting the permits for the transit countries.”

There was also the challenge of navigating the intermittent nature of solar power generation and other renewables – such as wind – which means finding solutions to battery storage problems. And then there is the need to develop heavy-duty cables to transfer the power thousands of miles. Daunting.

catastrophe had driven down costs and ramped up motivation among governments. “When he went through the numbers, it slowly became less crazy,” Budd says. “I thought, let’s go for it. Let’s see if we can change the world.”

The concept that Budd has been helping to guide could generate electricity in Africa for transmission to Europe and help meet a significant share of the demand of a major European country – “the largest renewable-energy project outside of China.”

“I thought, let’s go for it. Let’s see if we can change the world.”

But Morrish persisted and when he once again approached Budd to join the project, baptised Xlinks, the equation had changed. Feasibility studies had been conducted, and a swath of the Moroccan desert identified as a suitable location. Similarly, the march of technology and the desperation to avoid climate

There’s a certain irony in a son of the North Midlands’ coalfields helping to lead the charge away from fossil fuels. Budd grew up in Sutton-inAshfield; his mother was a machinist, and his father was a miner before also working in a textiles factory. Budd was an only child, and it was a tight-knit, happy family. A working-class community where people grafted hard. But also, one with narrow horizons, and not one where academic excellence was usually expected.

Even Budd finds it difficult to say what drove him. “When I start things, I like to finish them,” he says. “And that lends itself well to a school environment, right?” He shrugs. “I was hard-working, I was disciplined. I was able to do well in all my subjects…” He shrugs again, “I was lucky.”

Another sign of an academic mind: “I loved puzzles. I did puzzles, and puzzles and puzzles, and I enjoyed solving maths problems, which are, really, just puzzles in a different form.”

He was also a talented sportsman, and, perhaps, that insulated him from the insults that might have come his way for being good at school. “I think if I’d have been academic and not sporty, things would have been quite different,” he admits.

Budd was so good at football, in fact, that he was taken on by his local professional team, Mansfield Town, at 16.

But as he continued to sail through school, a wrenching question loomed: What would be the best bet for his future: university or football? “That was the first time we had a family conversation about it,” Budd says. “It was Mansfield Town, not Manchester United. I kind of knew I wasn’t good enough to be real top level. I didn’t quite have

that cockiness or that confidence that the best footballers need.”

He also had options. Storming through his Mathematics, Chemistry and Physics A-levels, Cambridge came into view. A teacher took him to an open day, and something clicked.

“When you’re from my part of the world, you’re not used to beauty,” he says. “Even the most generous person would not describe Sutton or Mansfield as pretty or attractive in any way, and then you’re in Cambridge, and it’s just, wow. Wouldn’t it be incredible to live here and study here?”

Fortunately, back at his comprehensive school, which had no particularly strong history of sending students to university, let alone Oxbridge, Budd found an old box, with a yellowing brochure – and a description of Girton. It looked ideal – a mix of sexes, plenty of state-school students, beautiful buildings.

“At the interview at Girton, I had to explain to them that I’d taught myself. I think they probably saw that as a sign of someone who was really determined. And that probably counted in my favour.” He pauses. “One of the reasons I’m so fond of Girton is that other Colleges in the University wouldn’t have taken that chance. Whereas Girton were like, ‘Let’s have a punt.’”

“One of the reasons I’m so fond of Girton is that other Colleges in the University wouldn’t have taken that chance.

Whereas Girton were like, ‘let’s have a punt.”’

There was still a problem, though. Budd’s school didn’t offer Further Maths as an A-Level. He had to teach himself over the summer.

The memory of what came next puts a bit of steel in Budd’s eye. He had to catch up. Quickly. “My knowledge of maths was exhausted within that first week,” he explains. After his first term, he was pretty much bottom of the class. But the work ethic instilled by his parents – plus a belief that he could make up the gap –pushed him on. Between playing football – he would win three Blues –and adapting to university life, Budd played hard and worked even harder. Every year, his results improved; every year, he moved up the list of his peers. He finished with a First.

“It was instructive,” Budd says ruefully. “It pushed me to my boundary. After doing that and getting through to the other side, I always knew that I had more gas in the tank, if I needed it. So, when I had hard times in the future, I knew I’d been through something pretty tough before, and that’s been incredibly useful in my career.”

After Cambridge, where he not only excelled academically but also met his wife-to-be, fellow Girtonian Naomi Hill, Budd worked in banking briefly before joining the management consultant McKinsey. He went on to gain an MBA at Stanford in 2002 and later moved into private equity with a company called TDR Capital, working for more than a decade on several projects to turn around faltering businesses, including the leisure chain David Lloyd.

At this point, Budd had built a successful track record but was ready for something a little different. That was when Morrish approached him.

Xlinks has recruited other industry “big hitters”. “We’ve got some of the best people,” Budd says, citing fellow board members Sir Dave Lewis, a former CEO of Tesco; Sir Ian Davis, a former Rolls Royce

chairman; and Paddy Padmanathan, a leading name in solar generation. The project aims to have all the structures in place – planning, permits, agreements, site licences, procurement – for an investor to come in with the funds to build everything. “We will do everything apart from physically going and putting the wind turbines, solar panels and batteries in place and connecting things up,” Budd says. “If we were working at corporate time scales, this would take 15 years, but we’ve been going incredibly quickly.”

with the National Grid. Procurement processes had been completed. The project was set to come online at the start of the next decade.

“This could transform how the world thinks about electrical grids. Which would be a legacy for anyone, right?”

Electricity would travel almost 4,000 kilometres through undersea cables protected by insulation, lead and steel, with very little transmission loss. If built, it would be the largest such interconnector, able to power 7 million homes for 20 hours a day at half the cost of nuclear in half the time (smaller subsea networks already tie the UK to nearby European states).

As a rule, such large-scale infrastructure projects rely on governmental support, and Xlinks is one of a wave of projects that reflect Europe’s interest in clean energy generated in North Africa, and in exploring whether importing power made in ideal conditions beats domestic production on cost.

Naturally, the UK was considered as the flagship destination. The Moroccan government had granted land the size of Greater London and an export licence. The undersea route was charted. A landing site in the UK had been secured, and there was a connection agreement

However, in June 2025, British government officials announced that the UK was stepping back from the £25bn Xlinks project and instead was pivoting to other initiatives seen as less risky and focused on developing domestic clean power generation. Xlinks’ high-profile nature led to various other European, Middle Eastern and African governments expressing interest, and several alternative projects are now underway.

“This could transform how the world thinks about electrical grids and the energy transition,” Budd says. “Which would be a legacy for anyone, right?”

By Pippa Considine (1985 Law and English)

Kristina (Hulsebus) Blahnik (1992 Architecture) visited Girton recently, the first time she’d returned since graduating with a degree in Architecture in 1995. She took her children to see “the magnificent building” where she’d spent her three undergraduate years. “I’m very proud to be a Girtonian and to be a Cambridge alumna. I still to this day pinch myself that I went to Cambridge.”

She now runs the family business, set up by her uncle Manolo Blahnik and famous for his signature, crafted shoes, known by shoe “cognoscenti” as Manolos.

Kristina Blahnik is dynamic. It’s not only her career that has taken on a new shape, and the flow of ideas that have helped to breathe more life into the Blahnik brand, she is alive to the people, thoughts and designs around her. When we meet

on Zoom, she looks impeccable and her conversation is enthusiastic, exploring memories and making connections between university and where she is now.

Between Girton and joining her uncle’s business in 2009, she worked in the world of architecture and, with her ex-husband, established a practice. She became CEO of Manolo Blahnik in 2013. At the helm, she has seen the business grow – from six employees at its headquarters in London, to more than 250 worldwide, and from two stores, to more than 20 around the world.

“When I reflect on what it is about Girton that helped me on my journey, it was probably the people, the friendships, the support that we gave each other,” she says. “Girton has its own community – more so than any other College – because of its special location.” She remembers her two years at Wolfson Court and the small corridors with six rooms or so on each, describing them as “micro-communities.”

Her time at Girton gave her the

chance to find out about much more than Architecture. “What was so wonderful about Cambridge and Girton was the variety of subjects. You start that whole journey of curiosity that goes beyond your own subject.” She remembers one good friend who was studying Law, which felt to Blahnik “like an alien world.”

The friend introduced her to the Law Library, and she found herself engrossed in law texts.

Blahnik’s curiosity and energy also led her to spend time on the river and the Ely ice rink. In her second year, rowing for the College, she was asked to trial for the University. She recognised that she would not have time to both study and row at that level. But she didn’t want to give up the idea of competing for Cambridge.

“I thought to myself, ‘Okay, I want to get a Blue, but I don’t want to have to do eight hours a day rowing.’”

Her strategy was to find something a little more obscure, and she lit on ice hockey, where there was only one practice on the ice rink in Ely each week, with other fitness

training in Cambridge. “I’d been a goalie in lacrosse; I’d been a goalie in hockey. For some miraculous reason, no one else wanted to be goalie, so I went into the first team.” And voila, a Half Blue.

Before Girton, she says, she always felt like an outsider. “I’m half German, half Spanish. I moved to England when I was six. I didn’t know the system.” She had thought about a degree in Economics, and perhaps following her father into banking, but that changed in sixth form.

Her school was building a theatre. Alongside studying for Mathematics, Economics, Art and German A-levels, she became responsible for designing and building the set for the theatre’s first play. She was inspired by the process of construction and the realisation that she had an unusual combination of academic strengths, “logic and creativity that I needed to bring together. And Architecture landed, it felt right.”

Her decision to apply to Girton was, amongst other factors, influenced by the red bricks of the College, “such a beautiful building.” In her first year she had a room on one of the towers. “I had the most fantastic windows – on two sides – and curved because of the turrets.”

“Academia was valuable, not just for doing an exam, getting a result, but how it can feed your view on the world. That, in itself, was formative. It gave me the confidence to go out into the world and think about my view, adding my personality.”

At work, she has launched many initiatives with her own twist, both creative and thinking about the impact on society. “One of the big pillars of our company is the next generation,” she says. One example is working with the British Fashion Council on its national Fashion and Business Saturday Clubs, for 13- to 16-year-olds. “It’s about opening the doors to the world of fashion for young people and often disadvantaged people, so they can think ‘I could do that.’ Having faces, people, and voices that they can recognise to give them confidence.”

without appreciating the history of an art.”

Her uncle’s motto is “without tradition we are nothing”, a phrase he heard from the Italian film director Luchino Visconti in 1970 during a dinner party conversation. It’s a belief that his niece shares. “You can’t create in a vacuum. You have to have references,” she says. “So having been educated in the history of architecture was one of the best foundations I could have had as an architect and, equally, for what I’m doing now, because those are the foundations of our creative manifesto as a brand, as a company.”

“It’s dangerous to become a creative without appreciating the history of an art.”

She muses that while Cambridge undoubtedly gave her confidence, it “maybe set me up perfectly for what I’m doing now. Although probably not in a linear way.” The academic discipline chimes with her tenet that tradition must be respected. “Architecture at Cambridge encompassed the history of Architecture,” she says. “I think it’s dangerous to become a creative

Blahnik grew up in a household focused on her uncle’s coveted shoes, with her mother running the business as managing director. She describes summer breaks working in the shop and using rooms over the shop to study and unwind after school. “As a young child, I used to go up to the small office above the shop and do my homework while watching cartoons on a little black-and-white TV.

“I grew up in that world and have a natural, intrinsic passion for it.”

“I’d been a goalie in lacrosse, I’d been a goalie in hockey. For some miraculous reason, no one else wanted to be goalie, so I went into the first team.”

Her move to work at Manolo Blahnik in 2009, while demanding, saw her surrounded by the familiar. And the discipline of architecture underpinned her switch of career in a practical sense, as well as her knowledge and appreciation of history and tradition. “As an architect, you need to visualise what something physically looks like in the future. Then you need to retro plan how you’re going to get to it from where you are today: through words, through drawings, through a narrative. I think that’s a skill that I’ve used. Being able to build the journey so that you bring everyone with you along it.”

Blahnik talks about having an unusual balance of left and right brain, a blend that lends itself to running a creative business. She has taken part in Insights Discovery, based on work by Carl Jung that uses four colour quadrants to analyse personality. “My lead colour is yellow, which is creative, followed by red, which is directive. So, I have quite an odd combination.”

“My favourite colour is red,” she adds, “probably inspired by the red bricks of Girton.”

Girton alumna Lottie Birdsall-Strong (2013 Multi-Disciplinary Gender Studies) is on a mission to give every young person the opportunity to fall in love with sport

England were on the verge of crashing out to Italy, just one step away from the Euro 2025 final..

Then came the cross that caused chaos. The parry from the goalkeeper. And the low, confident finish from 19-year-old Michelle Agyemang which gave England a dramatic, last-minute lifeline.

A few days later, the Lionesses lifted the trophy to become backto-back champions. All over the country, millions celebrated a resilient, inspiring team that never, ever, think it’s all over.

Moments like that have power. They are recreated hundreds of times on playgrounds and pitches and gardens. They inspire young people to play, and dream.

The key is to ensure that every child who wants to play can do so to the best of their ability, regardless of gender or background. This is where people like Lottie Birdsall-Strong come in.

“I often describe sports as the ultimate Trojan horse. It’s an incredible vehicle to add value to people’s lives.”

Lottie Birdsall-Strong is the Head of Youth Strategy at the England & Wales Cricket Board (ECB). As part of her wide-ranging role, covering investment, impact and participation, she is responsible for work that ensures over half a million young people per year play cricket.

The former Girton student has devoted her career to sport. She has been a strategist at the Football Association (FA) and a councillor at the Lawn Tennis Association (LTA) and is currently a member of the Board of Trustees at Manchester United Foundation.

“I often describe sports as the ultimate Trojan horse”, says Lottie. “It’s an incredible vehicle to add value to people’s lives.

“Not everyone has to love it, but what I can’t stand is the idea that there are people who don’t have the opportunity to discover if they love it – either as a player, a fan, or someone who might want to work in the industry. Opportunity and potential. That’s what gets me out of bed.”

And fortunately, according to Lottie, there are already promising signs in girls’ football. Since 2020, at Manchester United Foundation, there has been a 208% increase in female attendances at football sessions across Greater Manchester. “At Manchester United Girls’ Academy, which is managed by the Foundation, our vision is to have the most successful talent

programme in the country, with the aim of developing first-team and international players.”

While more than 16 million people watched England’s 2025 final win against Spain, Lottie knows as well as anyone how far the sport has come for women and girls in the UK. “I started playing football when I was about four or five. At times, I had to hide my ponytail under a baseball cap to pretend I was a boy, otherwise I wouldn’t have been allowed to join in some of the matches in my local park. My friends even gave me a boy’s name to complete the disguise.

“You’d get a lot of other kids telling you that girls couldn’t play football. But my family couldn’t have been more supportive in every single way, and it develops a resilience around doing what makes you happy.”

She grew up in an Arsenalsupporting family, playing in Highbury Fields, in the shadow of the team’s old Highbury stadium. It was there that she was spotted and invited for a trial at Arsenal’s Centre of Excellence.

“Football developed a real sense of teamwork in me, and I learned how to make something stronger than the sum of its parts, to trust in people, and value different strengths. That’s as valuable in the boardroom, as it is on the pitch.”

After ten years at Arsenal, she secured a scholarship to play

football in the USA in North Carolina. There she discovered the impact of legislation such as Title IX, which requires schools receiving state funds to give equal opportunities to all students, regardless of gender. She decided to explore how measures like this around the world stimulated the growth of women and girls’ sport – what worked where, what didn’t, and why – a quest that took her to the corridors of Girton College, University of Cambridge.

“I realised there was so much potential to do more, and I wanted to be part of figuring out how to do that. Girton is such a special place. It inspired a relentless curiosity in me, and a confidence to connect with other people.”

investment and impact in sport. On top of that, she has helped shape the growth of tennis with the LTA, as well as Manchester United Foundation’s drive to improve female football participation.

“I’m a big believer in data and insight, and I enjoy working with it. But really, I like talking to people and understanding challenges, whether they’re strategic, financial or social.

“There are so many things one sport can learn from another, even if they’re not trying to do the exact same thing.”