BEYOND boundaries

GIRL UP UAE GIRL UP UAE

The Editor’snote

Welcome to the second edition of Womanalogy! In this edition, we push boundaries on beauty and feminism. Our magazine is a catalyst for breaking these beauty standards in a world where unrealistic beauty standards take a toll on people’s minds. Feminism is the belief in all genders' social, economic, and political equality. Most feminists agree on five basic principles—working to increase equality, expanding human choice, eliminating gender stratification, ending sexual violence, and promoting sexual freedom.

Each article in this magazine discovers each principle of feminism in depth. We celebrate women who discovered beauty in feminine relationships. We challenge the questions society often imposes on women and we question society for its mistakes. Feminism has been rooted in society for centuries. Discover feminist movements across continents in this edition of Womanalogy.

We strive to challenge societal norms while creating a safe and inclusive space for our readers. In this edition, we hope to shed light on stories that align with these feminist principles and leave it to our readers to decide whether our so-called progressive society is really on its path to respect and equality for all. Feminism is not just a concept, it is a dynamic movement that requires collective effort. At Girl Up UAE, each effort is aimed at creating a better world that's safe and inclusive for everyone and we believe our magazine will contribute to the vision we root for.

No movement can take force without communication. So we urge you, our readers, to now take the stage and share your thoughts and opinions. We encourage you to take these pieces beyond the boundaries of these pages.

JaanakiSanker EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

What Is and What Could Be.

There's a border after which I see the sun. There's a cliff after which I see the colours of the horizon. There's a mist after which I see the twinkling stars.

There's a fence after which I see the blooming fields.

Yet chained by the colossal might of the demons, My feet don't find their chosen destination. It isn't that I don't have any chance of escape...

But the chances are blocked by my own vile thoughts.

The sweet smell of the free air seeps into my side of the world, It tempts me, makes me want to fly to that land. The melodies of the colorful minstrels twirl into my lifeless ears, They call to me, make me want to dance my life out to their tunes.

But each yearning of mine is placed under scrutiny. My wish to walk out of my darkened world is criticized with unearthly passion. It's strange, though, how my captivity is in equal ill repute.

I'm even heckled for not having the courage to run to my own freedom.

The feel of the warm meadows haunts my dreams. My skin tingles, imagining the touch of the soft grass. My delusions construct a sweet taste of ripe fruit in my tongue. It's all made up, I know, but that's my only resort

The hypocrisy of scrutiny over my state and desire is unnerving. But I've been made to grow used to the storm clouds.

I've been made to dry my tears and make my eyes void of emotion. There's no depth in my heart for its warmth has dried up.

Such is the state of mine in distress... The tale of a girl who is placed in the middle of rock solid boundaries. A fragile glass doll who has no right to see, The world that awaits for her to thrive.

There's a whole lot of things she can do within the boundaries. But she is still under the leash of silent commands. So she prances around under the haze, And smiles lifelessly, awaiting to be let out of her cage.

-Trisha Sayani

-Trisha Sayani

A R T I C L E S

INTERSECTIONAL IDENTITIES: BREAKINGTHEBOUNDSOF BEAUTYISM

The myth of beauty has haunted women for decades, echoing ghostly pursuits of unattainable perfection, mirrored in its perceptionthroughmedia.Thiselusivestandard, crafted by societal norms and media representations, casts a shadow over women's self-perceptionandworth,perpetuatingacycle of comparison and dissatisfaction. Despite efforts to redefine beauty and promote inclusivity,therelentlesspressuretoconformto narrow ideals persists, creating a relentless pursuitthatleavesmanyfeelinginadequateand unseen.

In the realm of beauty, an industry that generated $528.59billion worldwideinrevenue and sales, beauty exists objectively, and universallyforoneandall.Womenmuststriveto exhibit the highest of their potential objective beauty so long as they can fit into a predeterminedsetofrulesandobligations.The storyiscarvedinstone,itcannotaccommodate nor portray the immensely diverse range of beauty within the world nor pleasure itself beyonditscongenitalculturalclassics.

BEAUTYISM

Beautyism,thoughnotcoinedinthedictionary, isatermthatreferstotheassumptionthat one's outward appearance prevails their knowledge, morals, or mannerisms.Thebiascanmanifest itself in many forms such as hiring practices, promotions, social interactions, and media representation, where individuals who are perceivedasmorephysicallyattractiveareoften favored.

The concept of Beautyism has a long deeprooted history in societal perceptions and culturalnorms.Inancientcivilizations,suchas ancient Greece, beauty was often associated with proportion, symmetry, youthfulness, and ‘inner virtue’. In ancient China, beauty was associated with ideals such as small feet and delicate features, often achieved through painful and harmful practices such as foot binding. During the Renaissance period in Europe, beauty ideals shifted to emphasize naturalbeautyandthehumanform,celebrated through artists and scholars who redefined thesestandardsthroughtheirworks.Despitea dramatic shift in beauty standards and practices from the past, and a large jump in forward-thinking, the concept of beautyism remainsanacceptedprincipleandpractice.

Inthemodernera,feminismaimstoelucidatethe biases within beautyism and its lack of various characters within its pages. Intersectional feminism acknowledges that beauty standards are not one-size-fits-all and recognizes the intersecting factors of race, class, gender, and other identities that shape how beauty is perceivedandexperienced.

For women of color, the pressure to conform to eurocentric beauty standards is in the name of escaping benchmarks tied to ‘appearing’ as thoughyoubelongtoamarginalizedcommunity.

Intersectional feminism seeks to challenge these norms by promoting inclusivity and celebrating diversity. It calls for representation that reflects the full spectrum of beauty, including women of all races, sizes, ages, and abilities. This includes advocating for more diverse and inclusive media representation, as well as challenging harmful beauty practices such as whitening creams and restrictivebeautyideals.

Tess Holliday,

American model

'I have to wear fast fashion, I can't be as ethical because plus-size fashion is not there yet'

By centering the voices and experiences of marginalized women, intersectional feminism seeks to create a more inclusive and empowering vision of beauty. It encourages women to embrace their unique beauty and reject societal pressures to conform to narrow standards. Ultimately, it is through collective action and a commitment to intersectional feminism that we can break the bounds of beautyism and create a world where every woman feels valued and seen, beyond boundaries. It is time to break the bounds of traditionally celebrated beauty norms through theembracingofself-loveandinclusivity!

"I'mfindingbeautyfromwithin.Itdoesn't matterhowthinorhowprettyorwhatever. IfIdon'tfeelit,I'mnotgoingtoseeitinmyself. Sothat'swhatI'mfocusingonnow."

DemiLovato,Americansingerandsong-writer

A R T I C L E

2

BURNING SUGAR

BURNING SUGAR

I see Avni Doshi for the first time on a warm February afternoon in 2023. She is giving a talk on the craft of writing women at the Emirates Airline Festival of Literature, the premier literary gathering in the UAE and–according to the website–in the Middle East. Her co-panelist is Tishani Doshi(unrelatedinblood,verymuchrelatedinspirit).

A few minutes later, the two Doshi's emerge onto stage. Avni's speech immediately captures my attention. Seeing a role model in person is always tinged with surreality. You watch as a set of vague, loosely connected impressions crystallize into something more solid and tactile. Plus, as a devoted reader of her debut novel, Burnt Sugar, I was familiar with her brilliance. Still, there is something mesmerizing about witnessing her in person. All her words are carefully enunciated and her thoughts carefully considered. There is something regal about the rhythm of her speech, somethingmeasuredandmeditative,asthoughshehasjustemergedfromthe Puneashramsthatfeatureheavilyinhernovel.

Doshi is longlisted for the prestigious Booker Prize in early 2020 for her debut novel, Burnt Sugar. Though she does not go on to win the Booker, earning a place on the shortlist a few months later catapults her into literary fame. The months in between the longlist and winner announcement are filled with a flurry of media appearances. Anyone who has read or watched any of these interviews will be familiar with the arc of Doshi's writing career: she began writing the book in earnest in 2013 when she won a literary prize for a stillrough manuscript. Yet the book would not be published until 2020. In the seven years in between, Doshi moved from India back to the US where she grew up, undertook a fellowship at the University of East Anglia, got married and ultimately moved to Dubai. It is here that she did the bulk of her “serious writing”. Eight drafts later, Doshi landed a publisher in India where the book wasinitiallypublishedunderthetitle, Girl in White Cotton.

The book opens with the now-famous line: “I would be lying if I said my mother’s misery has never given me pleasure.” It follows the mother-daughter duo, Tara and Antara, as Antara, an artist in her 30s, must now become a caretaker for her aging mother shortly after she receives her dementia diagnosis. The emotional debris of their past lurks like a phantom on the edges oftheplot:atumultuousdivorce,astintatanashram,atrailofloveaffairs.

The imprint of this legacy still reverberates today. After the founding of the UAE in 1971, scores of South Asians–Indians and Pakistanis, Sri Lankans and Bangladeshis–would continue to come to the region and plant roots here. As these generations of migrants mature and come into their own, they represent latent literary talent–unharvested, yet fertile, territory for literary exploration: notions of belonging and alienation, of home and hybridity, of permanence and impermanence. It is particularly interesting to see this migrant experience inflected through gender. What does it mean to navigate as a woman the currents of culture and custom, faith and fashion, nationality (or the lack thereof) at the crossroads of two regions–South Asia and the Middle East–where each of these questionsissymbolicinitsownway?

And it is women like Doshi who may be leading this wave; though she grew up in the US, Doshi has spoken of the “intergenerational connection to this city” that many–including her husband who grew up in Dubai share–and of how Dubai became home to much of her “serious writing”. Indeed, I can’t help but see in Doshi’s own personal history of writing Burnt Sugar– criss-crossing from Mumbai to New York and Dubai–echoes of the region’s larger history as a cradle of cosmopolitanism.SowhilethediasporaexperienceintheWesthasproducedsuch reams of fiction from literary giants like the Indian-American Jhumpa Lahiri and Fatima Farheen Mirza, the decades to come may witness something similar–yet uniquelypowerful–intheGulf.

“DOSHI’S RISE IS EMBLEMATIC OF A STEADILY GROWING WAVE OF LITERARY VOICES EMERGING FROM THE UAE WHO, IN DOSHI’S OWN WORDS, ARE LEVERAGING “DUBAI AS A BASE FOR THEIR CREATIVE WORK”.”

The book is stunningly subversive and brazen in its bitterness. Doshi’s characters, Tara and Antara, dabble in resentment and regret, unburdened with the weight of sainthood, peeled free of perfection. Yet Doshi doesn't flinch from probing the dark recesses of these relationships. Instead, she does away entirely with the tropes of the saintly mother and the sacrificial daughter. In a world that glorifies motherhood as a joyful enterprise, Burnt Sugar asks what happens when something sweet and sappy,likesugar,degeneratesintosomethingsour.

But as much as the content of her book merits attention, I am equally struck by the symbolism of Doshi's success. Perhaps most remarkably, Doshi’s rise is emblematic of a steadily growing wave of literary voices emerging from the UAE who,inDoshi’sownwords,areleveraging“Dubaiasabasefortheircreativework”.

Over the last two decades, the global discourse on literary representation has expanded. Calls for writers to challenge the traditionally male/white/upperclass/orientalist gaze and write authentically about their own experiences have grown. This discourse has also found home in the MENA region where writers–often female writers like Susan Abulhawa and Adania Shibli–are gaining increasing recognition as they reclaim narratives about the region, some even writing in Arabic and embracing translation as a midwife of meaning. However, the MENA region encompasses many countries, and those countries encompass many communities, and one of the overlooked communities in the Gulf region are South Asian ‘expats’ orimmigrants.

Allow here a brief history trip: South Asians have called the UAE, and Gulf region, homeforcenturies.BeforethefoundingoftheUAEin1971,theGulfwasrenowned as a trading partner connecting the Indian Ocean to the east and Arabia and Mesopotamia to the west. Every winter, between September and April, dhows would set off from the Gulf coast and venture to the Indian coast where they would trade goods like silk and spices, wait for the winds to turn, and then venture back with said goods. As a result, the Gulf became a mosaic of ethnically diverse merchants and traders: Arabs and Indians, Africans and Iranians intermingling for centuries.

A R T I C L E

3

CONTINENTAL DRIFT: FEMINISTMOVEMENTS ACROSSCONTINENTS

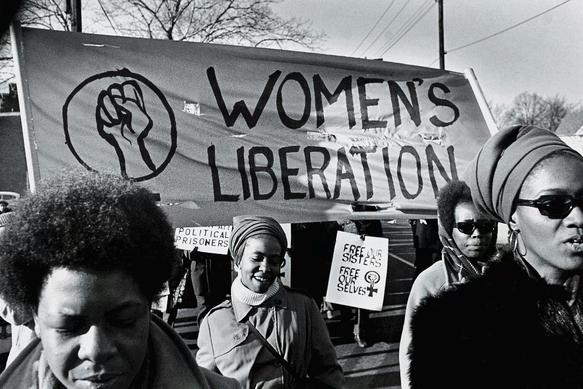

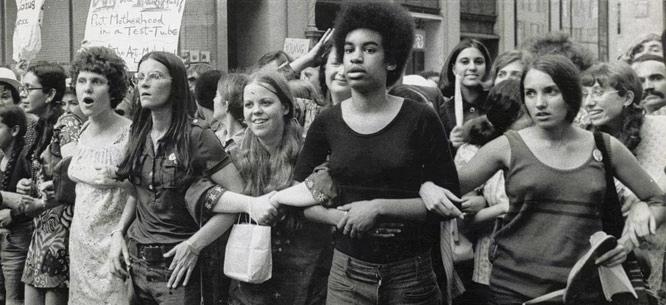

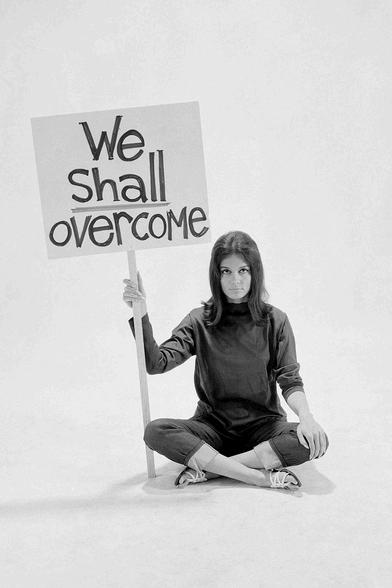

Feminismisatapestryofideologies,histories,andexperienceswoventogetherwith bleeding and bruised hands by the women who came generations past. With Women'sHistoryMonthpassingbeforeus,weasfeministsreflectonthevastpastof the feminist movement across the globe. From the suffragettes to the birth of intersectionality in a society where women are the architects, we explore the tempestuousnatureoffeministmovementsacrosstheglobe.

Northern America: Thefeministmovementbeganinthe19thcentury,intheSeneca Fallsconventionin1848,andstartedthefirstwaveoffeminisminNorthernAmerica, focusingonwomen'ssuffrage(righttovote),coinedbySusanB.Anthony,Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Sojourner Truth, whose activism was instrumental in women gaining the right to vote. This convention adopted the Declaration of Sentiments, whichcalledforwomen’srights,includingtherighttovote.

Organizations such as the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) were formed to advocateforwomen’ssuffrageatthestate and national levels. This was quickly alternatedasthesuffragemovementsplit initspursuitofliberation.

The NWSA, under leadership by Anthony and Stanton, strategized federal amendments to grant suffrage, while the AWSA, under Lucy Stone’s leadership, focusedonstate-by-statecampaigns.Afterdecadesofstruggleandactivism,the19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution granted women the right to vote in 1920. This wasamajorwinforthesuffragettemovement.

ThesuffragettemovementinCanadagainedtractioninthe19thcentury,ledbyEmily Stowe and Henrietta Muir Edwards. Organizations like the Dominion Women’s Enfranchisement Association and the Canadian Women’s Suffrage Association were formed to advocate suffrage at federal and provincial levels. Canadian women achieved partial suffrage at the federal level in 1918. Shortly after this in 1920, full suffragewasgranted,allowingwomeninthecountrytovoteforthefirsttime.

The suffragette movement in Mexico gained momentum in the early 20th century, heavily influenced by The Mexican Revolution and growing feminist movements in the rest of the continent. Women played active roles, allowing them to advocate for women's rights, which was achieved when women were given the right to vote in federalelectionsin1953.

South

America: Characterizedbyastrongcommitmenttoequalityandwomen’s rights,thesemovementshavebeeninfluencedbytheSuffragemovementsofthelate 19thcenturyandstrugglesagainstauthoritarianregimesincountriessuchasBrazil andChile.Inthe1970sand1980s,themedia,theCatholicChurch,andmanypolitical partiesnegativelyportrayedfeminists,callingthemselfish,andanti-male,causing divisionsincommunities,andmakingithardtobelievethatastrongfeminist movementcoulddevelopinLatinAmerica.Howeverfollowingthesurgeoffemale mobilizationinothercountries,asecondwaveoffeminismwasborn.

Women in America fought for their rights, brought on by the overriding of war and revolution. The fierce grip of foreign affairs had bonded communities of those pushed by the power of revolution, bringing on empowerment from new social movements. TheMontelimarEncuentromarkedthefirsttimethatCentralAmericanfeministshad ever tried to work together. It took place in Montelimar, Nicaragua, in July 1981, and brought together feminist activists from across the region. It was a space for women to discuss and debate issues related to gender equality, women's rights, and feminism in Latin America. It was a pivotal moment in the development of Latin American feminist thought and activism and helped strengthen feminist organizations and movements.

Asia: FeministideasinAsiawereinfluencedbyWesternmovementsandthespreadof ideasthroughcolonizationandglobalization.Womenwerebeginningtoadvocatefor aworldbroadenoughfortheeverydaymanandwomanincountrieslikeChina,India, etc., representing goals of societal structural change for the values bestowed on the everydaywoman.

These movements were often intertwined with both Nationalist and Independence movements, contriving liberation and women's rights. Sarojini Naidu in India was paving roads for suffrage, whilst Qui Jin in China attacked repressive regimes as traditionalism through her prolific pieces of writing, mirrored in Iranian activist Shirin Ebadi’s legal activism through her representation of legal clients who have faced gender-based discrimination as well as her international advocacy in conferencesandforumsonwomen'srights.

Asian women took to many different forums to express advocacy for different issues in repressive societies dressed in the values of traditionalism. This became increasingly apparent in movements like The Chipko Movement in India, highlighting women's roles in environmental activism by preventing deforestation, and The Comfort Women Movement in South Korea, advocating for justice for the "comfort women," the women forced into sexual slavery by the JapanesemilitaryduringWorldWarII,and networks like The Women's Coalition of Japan that collaborate to promote women'srightsandgenderequality.

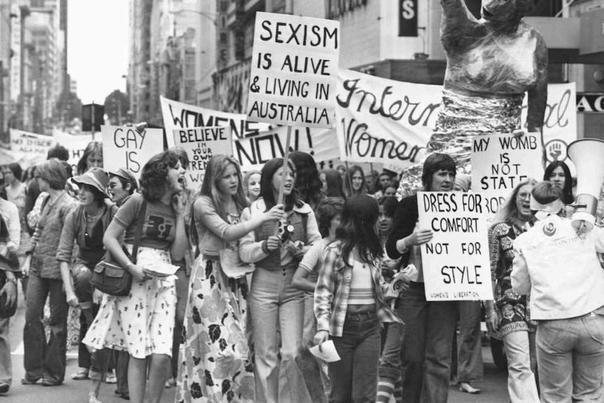

Australia: The early wave of feminism can be traced back to the early 19th century when women began to question patriarchal values and reform whatitmeanttobeawoman.

This first wave saw the fight for women's suffrage in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. South Australia wasthefirstcolonytograntwomenthe right to vote and stand for election in 1894.TheCommonwealthFranchiseAct in 1902 granted only white women the righttovoteinfederalelections.

However, this brought on the interwar period, which saw a resurgence of feminist ideals with women advocating for issues like equal pay, access to education, and political representation. The second wave paved the way for movements like the Women'sLiberationMovement(WLM)duringthelate1960sandearly19780s. Characterized by its focus on issues like gender equality, reproductive rights, and ending discrimination and violence against women, the WLM was decentralized, with groups forming in cities and towns across Australia to campaign for women's rights and social change. It played a significant role in raising awareness about women's issuesinAustraliaandadvocatingforlegalandsocialreformstoimprovethestatusof womeninsociety.

Europe: Early feminism can be traced back to the books of Mary Wollstonecraft and Olympe de Gouges when she began to argue for women's rights and gender equality. Wollstonecraft's seminal work, "A Vindication of the Rights of Woman" (1792), is one of the earliest works of feminist philosophy. The first wave of feminism in Europe emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, focusing primarily on women's suffrage. Women in countries such as Britain, France, and Germany organized and campaigned for the right to vote, creating iconic and crucial movements.

The Suffragettes campaigned for women's right to vote in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Led by Emmeline Pankhurst, it used militant tactics and acts of civil disobedience, to draw attention to its cause. This was instrumental in securing the right to vote for women in the UK with the Representation of the People Act 1918, which granted voting rights to women over the age of 30 who met certain property qualifications.

Securing Suffrage brought on the ‘interwar’ period for feminism in Europe, seeing a continuation of feminist activism in Europe, with women's rights organizations advocating for a wide range of issues including reproductive rights, access to education and employment, and legal reform. The Women's International League for Peace and Freedom, founded in 1915, was one of the key organizations of this period, leadingtothesecondwaveofthemovement,characterizedbyadvocacyonequalpay, reproductiverights,etc.

Africa: Feminist ideas and movements have existed in Africa for centuries, as women's resistance to colonialism, slavery, and patriarchal norms. Many African countries experienced a resurgence of feminist activism that otherwise ended in the colonial era, where women played major roles that laid the clockwork for later feministmovementstotakeplace.

Women's organizations and movements emerged to advocate for gender equality leadingtoeventsliketheAbaWomen'sRiotsof1929inNigeria.

Also known as the Women's War, it was primarily led by the Igbo group, and held in theprominentcityofAbaanditssurroundingneighbors.

The immediate trigger for the protests was the introduction of a new system of taxation by British colonial administrators, which was particularly burdensome and unfairtowomen,Authoritiesimposedindirectrulethroughwarrantchiefs,whooften abused their power and imposed harsh measures on the local population. Women organized themselves into groups, and employed various tactics like protests, and demonstrations, to voice their grievances and demand that the taxes be revoked and thewarrantchiefsberemoved.

The protests quickly spread to southeastern Nigeria, involving tens of thousands of women who used traditional methods of communication, such as drumming and singing, to mobilize and coordinate their actions. The colonial authorities underestimated the intensity of the protests but eventually responded with force. Theysenttroopstosuppresstheriots,resultinginseveraldeathsandinjuries.

Despite the violent suppression of the protests, the Aba Women's Riots had a lasting impact on Nigerian society. They exposed the injustices of colonial rule and exploitationofthelocalpopulation.

Feminist movements have played a crucial role in shaping societies and advocating for gender equality and women's rights across different continents. From the suffragette movement in Europe to the Aba Women's Riots in Africa, feminist activismhaschallengedpatriarchalnorms,foughtforpoliticalandsocialreforms,and empoweredwomentodemandjusticeandequality.

While each continent has its unique history and challenges, one single thread unites these movements; determine. Determination of past women who have fought for theirplaceinunacceptingsocietiesthroughanumberofpublicforumsandpiecesof media, paving the way for various feminist ideals to take place and the global mobilizationofwomenacrosstheseas.

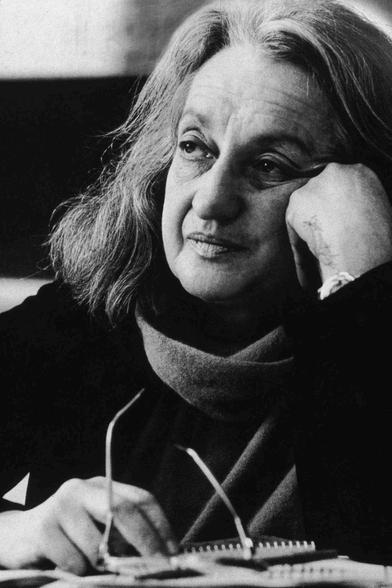

Major Feminists - Barbara Walters, Betty Friedan, Gloria Steinem (left to right)

Major Feminists - Barbara Walters, Betty Friedan, Gloria Steinem (left to right)

A R T I C L E

4

The crowd is not always right

Many people today see the Nirbhayacaseasthecatalystfor feminist action in India. The IndianMeToothatprecededthe allegationsagainstWeinsteinby nearly half a decade caused majorsocialanddejurechanges is what our generation considers to be the landmark social justice event in Indian history.Unfortunately,Nirbhaya was only part of a gruesome cycle of periodic events that forced Justitia to turn the wheelsofjustice.FromHathras being a sad imitation of Nirbhaya, incomparably lower outrage thanNirbhayaduetocovid,and sadly,socialregression;asimilar case in India did manage to create change, even though it cameatthecostofeverypillar of the justice, from the local magistrate to the Supreme court, failing a minor victim of rape,goingsofarastopainther

herbrotherGama,workingasa maidatNunshi’shousehold. fell in love with her employer’s nephew Alok, and married him soon after. Gama however, had an issue with the otherwise consensualunion,duetowhich AlokandMathuraeloped.Gama registeredacomplainatDesiganj polide station, citing Adivasi PersonalLaws,grantingthestate the right to investigate the marriage without any further

latrine, sexually violated her, dragged her to a veranda and raped her. Another officer, Tukaram,, forcefully assaulted mathura with his hands, and failed to rape her due to his extremeintoxication.

An unanswered scream from wastaken,andshewasdeclared to be “habituated to sexual intercourse”. This gave the sessionscourtjudgejustification to declare that Mathura was “a shocking liar” and that her testimony was “riddled with falsehood and improbabilities”, with the improbability being that she was raped, despite semen being found on her pyjamasandGanpat’scloths.

Shockingly the evidence on Ganpat’s cloths was delacred to be “nightly discharge” and the onesonMathura’stobeanother man’s “given her proclivities to the act”. The final opinion was that Mathura falsified an accusationofrapeasshecould notbaretoadmittoNunshiand her ‘lover’(a very casual delegitimisation of Adivasi weddingcustoms)Alokthatshe had willingly ‘surrendered’ her body to a police constable, and wishedtosound‘virtuous’when theoccurrenceofsexualactivity wasdiscovered.

The two rapists were acquitted in the sessions court, and the case ascended to the Bombay highcourt,whichfinallygranted justice to Mathura, or so it seemed. The High court’s opinion compedium was that fearful submission to sexual advances, given the power dynamic between the two stakeholders,didnotamountto consent. However this victory was short-lived, as the appeal session in the Supreme court, baffling and infuriatingly, overturned the High court’s ruling, with the justification being that Mathura’s testimony had been altered, with her during a single statement confusingthetwomen,withthe court unwilling to accept her advocate’s corrections, which arguedthatthedarknessofthe room and the lack of previous aquaitance between the victim and accused were sufficient grounds for errors of that margin.

Theenforcersvictimisedher,the lus invaded her further, and upholderdeniedhervictimhood entirely.

There are a multitude of issues present with the case at hand, starting from the fact that Gama’s complaint was valid at all.Thelawatthetime,allowed for a relative’s objection to a marriage,onlyfromthewoman’s side,onitsown,tobeimportant

in return for financial services, which he would generate anyways as his stock role in society.Thisviewhighlightswhy Gama felt he had a right to objecttothemarriage,andwhy thelawtooksuchobjectionsso seriously.Theywere’tdefending Mathuraquaperson,ratherthey exerting influence on her qua Gama’spossession.

AlargerissueinMathura’sstory isthe“twofingertest”.Inplace ofreliableindicatorsofrapeand sexual assualt, such as DNA/forensic assessment, rape was determined by “virginity

So we see all three pillars of justicefailMathura.

speakstowhattheinstitutionof marriage served as, a contact between familial entities where the bartered property was womenandsocialfiat.Marriages make a lot more sense when viewed as a coerced quid pro quo arrangements. The man received sexual gratification, a familystructureanddaycare,

Thetwofingertestspecificallyis the process of inserting two fingers into the vagina and checking for is the hymen is brokenandtotestthe“laxityof the vagina”. Often a woman declared to be “habituated to sex”wouldhavethislabelused against her during the legal battle to prove her victimhood. It is already dystopian that sexual activity is considered as an indicator to probability of victimisation, but to assess this inthesamemannerinwhichthe victim was violated only compoundstheissue.

Two finger tests are a consequence of upholding hirarchy.Thereisaverysimple explanation as to why the systemevolvedtobethewayit was, and for many, still is. The constructionofsocietyhasbeen off the backs of individuals in hierarchy. It is not a simplistic dual structure like Marx’s class duality, or anything resembling thepyramid-esqueJatisystem.

Identity is multi-dimensional, with each attribute heavily dependant on the dominating culture the individual is participating in. To simplify, ‘noblemen’(noble as in class, not moral attribution) have dominated society, and the plunderedbottomhasbeenthe femalepeasantry.Aperspective of inherent owner ship does welltoexplainwhywesaw19th century society upholding the values it did, its because each ‘higher’classessentiallyowned theother.Allgearsworkinthe system, its about which gear teethbearthemajorityofload.

It is hard to point at any individualandexplainwhythey hold stock privilege, but bring inacomparisonoftheirlower, and we already see the differences. Mathura’s testimony didn’t ‘stand up’ to Ganpat’s not just because she wasawoman,butbecauseshe wasanAdivasi,poororphan.A girlthatfromGanpat’sposition inthehierarchy,itbelowhimin every,singleway,andis

destined to remain there. A position of no upward mobility servesasaspecialcase,sincethat positionbearsnothreattothose above it. In society the rich can makeacaseforkeepingthepoor appeased,butforsocietytokeep women appeased was a much harder pill to swallow, because until now, the measure of hierarchical strength, physicality, made sure that women had no upwardmobility.Thegradualshift toamore‘intellectual’measureof hierarchical strength has left an interesting predicament for society.NowthatwomenDOhave hierarchical mobility, it is autonomy they seek, and they have the power to disrupt the order,andhencetheirautonomy is bound via sexual shaming. Mathura being denied autonomy during the case of her marriage yetexclusivelybeinggranteditin asserting her as a sexual deviant poses as obvious paradox. A woman that cannot consent to marriage could consent to begin sexually used, is clearly paradoxical,untilyoulookatthe asymetry between the two. A marriage as a quid pro quo falls apart when the woman participates in it as the trading party, rather than the trading good, hence her autonomy here was revoked. A man taking advantage of a woman’s lack of autonomy needs deniability, hence that autonomy is granted. The ultimate way in which to uphold this badaid on the institution’s cracks was/is sexists practiseslikethetwofingertest.

ThedemonisationofMathurawas not wasted. Her story and the subsequent protests it generated lead to custodial rape being enshrinedinlaw,itwasthefirst

major case that generated rape awareness, lead to the eventual abolition of two finger tests and sexual history as weighted evidence in cases, as well as specifically called attention to howrapecomplainantsareoften re-victimised in the pursuit of justice.IfNirbhayawasacasethat showed the success of what status, competency and premepted response to public outrage does to the justice systems, then Mathura is what a lackofallthosewouldbringforth. Mathura’sstoryandtheeventual outrage it generated was also a show of what populist politics in the judicial wing of governance candoforgood.Itcametoshow that a scoeity can come together to recognise injustice, and with enoughpeople,fixtheissue.

The Mathura story, regardless of all this, leaves a bad taste in my mouth.Itshatteredmyhopeinde jure reform, and whether we reallyshouldhaveasetofranked deliverersofjustice,sinceconflict between is historically resolved via the people, and the people aren’talwaysright.

"Justbecausethecrowddisapproves of something, that does not necessarily make it wrong. Just because the crowd approves of something,thatdoesnot necessarilymakeitright."

~Pericles (Thucydides)

Women march in New Delhi in 1980 to demand that the Indian Supreme Court reconsider the case of Mathura Activist Seema Sakhare stands with Mathura, left, at an anti-rape rally after the Indian Supreme Court ruling.