The Bridge

Welcome

Welcome to Issue 4 of ‘The Bridge’, Gesher School’s learning journal for schools and teachers with the ambition to explore beyond traditional schooling to expand the range of learning opportunities for children and young people who learn differently.

In this issue we will be addressing this concept through the following themes: the importance–for children and their learning–of positive relationships and a sense of belonging in school. Inside you will find: articles exploring learner-led conferences, which promote agency, belonging and caring, and approaches to assessment that enhance learner engagement and self-esteem; and materials to support learning environments in which learners feel valued and positive relationships thrive.

All articles and materials are contributed by members of the Gesher School community and by educators around the world whose practice inspires us.

Over the previous three issues, readership of ‘The Bridge’ has grown to around 1,000 in print and roughly 10,000 online. If you are reading this online, you can sign up here to receive a free print copy along with Gesher School’s regular newsletter. And if you’d like to contribute or learn more you can contact the team at thebridge@gesherschool.com

The Bridge is organised into three sections:

- ‘Rethinking Education’ explores progressive and interesting practice relevant to all schools.

- ‘Teaching and Learning’ for Neurodiverse Children focuses on strategies and approaches that help to meet all pupils’ needs.

- ‘Resources for Teachers’ shares materials for use in project-based learning and related professional development, including tried and tested Project Cards from Gesher School and elsewhere.

In this issue, Resources for Teachers includes Project Cards from High Tech High in San Diego, from Great Denham School in Bedfordshire and from Gesher.

Also in this issue we remember the remarkable life and contribution of David Price OBE, who passed away in 2024, and to whom hundreds of schools and thousands of teachers—including here at Gesher School— owe a huge debt of thanks.

We hope you enjoy ‘The Bridge’ Issue 4. Thanks so much for your continued interest.

The Bridge Editorial Team

Four Shifts to Drive Real Change

David Jackson

Assessment Practices That Lead to Deeper Learning

Kim Wynne, Kelly Sanders, and Carolyn Fink

What If...A National ‘Open School’ Became a Reality for Every Young Learner?

Dr Fiona Aubrey-Smith

Student-led Conferences at XP School Doncaster

Andy Sprakes

David Price OBE: A Legacy for Young Lives

Valerie Hannon

A Fireside Chat with Pani Matsangos: Headteacher, Westside AP School, London

The Relevance of Therapeutic Approaches for All Schools

Zahra Axinn

Finding Beauty in Uniqueness: A Reflection

Loni Bergqvist

Relationships, Belonging and a Network of Joy Polly Ross

What Do We Mean by ‘Belonging’?

Belonging: A Staff Workshop Activity

Student-Led Conference: Model Agenda

Randy Scherer

Assessment for Deeper Learning: A teacher discussion group CPD resource

Kim Wynne, Kelly Sanders, and Carolyn Fink

Project Cards

Gesher School, High Tech Elementary North County/High Tech High North County, High Tech High, Great Denham School

Question from a Reader

Bradley Conway

Editorial

Editorial Team: Zahra Axinn, Loni Bergqvist, Ali Durban, David Jackson, Julie Temperley

Designers: Zahra Axinn & Danny Cazzato

Photo Credits: Zahra Axinn, Danny Cazzato, Jeremy Coleman, Holly Edwards, Leah Wright

Proof Reader: Tania Mason

Special Thanks to: Emily Bacon, Bradley Conway, Tamaryn Yartu

“Education

means teaching a child to be curious, to wonder, to reflect, to enquire. The child who asks becomes a partner in the learning process, an active recipient. To ask is to grow.”

- Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks zt”l

Four Shifts to Drive Real Change

David Jackson

This article explores insights from the Institute of Public Policy Research (IPPR), which, in its 2023 report ‘Out of Kilter’, proposes four shifts, which together encapsulate the fundamental changes needed to rethink education.

Introduction

Conversations about rethinking education often centre on a long list of issues that need to be addressed, for instance funding, or school buildings, or teacher recruitment and retention, or admissions and so on….

But if you believe that all young people have the right to an education that builds their selfesteem and efficacy; that recognises and values their unique talents; that helps them to form meaningful relationships and sets them up for fulfilling progression pathways from school, then addressing these ‘nuts and bolts’ issues, while necessary, is woefully insufficient.

Education is in need of a transformational vision. Schools do a great job in the circumstances, but the system is broken and the model of schooling out of date.

There is no worse example of this than SEND provision. However, the fault lines in SEND are just one component of the system’s challenges. SEND is not the problem, it is the symptom of a more allembracing set of issues.

Four Shifts That Could Transform Education

I listened recently to a presentation discussing the

findings from a 2023 report called ‘Out of Kilter’ by the Institute of Public Policy Research. Not heard about it? There’s a surprise! The report was the result of a massive consultation exercise and proposed some very significant changes with huge potential, but it was released to a largely indifferent policy audience.

At the heart of ‘Out of Kilter’ sit four proposed shifts, which IPPR identify as necessary to create an education system that unlocks the potential of all young people, enabling them to thrive. If these 4 shifts resonate with you, that is unsurprising, since ‘Out of Kilter’ draws on the findings of a major consultation with young people,

parents and employers.

“Education is in need of a transformational vision. Schools do a great job in the circumstances, but the system is broken and the model of schooling out of date.”

Rethinking Education First Requires Rethinking Assessment

The order in which the four shifts feature is also important. The first shift, from a system narrowly focused on attainment to one that values a wider set of goals, is the ‘crucial cog’; the magic key that will unlock all others.

To question the current system is to be accused of undermining standards – ‘standards’ as a synonym for approaches developed many decades ago to sift and sort society, with assessment approaches that condemn 40%+ of young people to leave school feeling that they have failed, rather than that all can succeed.

Until the UK has an assessment system that is able to reward and recognise the diverse aptitudes, talents and passions of all young learners; one that values learning and achievement other than academic subject knowledge; one that recognises the wider interests and passions pursued by all young people, both within school and out of school, we will have a system that maintains the status quo and fails too many.

‘Out of Kilter’ was authored by Harry Quilter-Pinner, Efua Poku-Amanfo, Loic Menzies and Jamie O’Halloran, September 2023, published by the Institute for Public Policy Research and supported by Big Change and the Paul Hamlyn Foundation. The full report can be accessed here: Out of kilter: How to rebalance our school system to work for people, economy and society | IPPR.

David Jackson has been a teacher, a headteacher, a founding director at the National College for School Leadership and, for the last 15 years, has supported educational innovation projects in the UK and internationally. He is a member of the editorial team for The Bridge

Professional Prompts

1.

To what extent does your school’s assessment system “reward and recognise the diverse aptitudes, talents and passions of all young learners”?

Do pupils feel that the school recognises their culture, beliefs, wider interests and passions pursued within school and externally”?

What might need to change for this to happen and for every learner to feel that their beliefs, culture, ideology, talents and interests are affirmed?

“What if we could see assessment as a way to recognise every child’s talents and brilliance?

What if our assessment practices were as aspirational as our vision for high-quality teaching and learning?”

Assessment Practices That Lead to Deeper Learning

Kim Wynne, Kelly Sanders, and Carolyn Fink

This article argues for a strengths-based approach to assessment that empowers learners and promotes Deeper Learning. The authors share practical advice and materials that draw on their experiences in Farmington Public Schools, Connecticut, USA.

These days, it seems we have a growing vision of classrooms as places for active, engaging, and purposeful learning. So much is written about the need for students to develop as creators, producers, and collaborators focused on meaningful tasks, rather than completing worksheets or listening to long lectures.

Why, then, is it more challenging to imagine assessment as equally engaging and studentcentered? Why do we tend to think of assessment in more traditional ways such as scoring, sorting, and assigning marks that put students into categories of achievement?

What if we could see assessment as a way to recognise every child’s talents and brilliance? What if our assessment practices were as aspirational as our vision for high-quality teaching and learning?

We three so-called writers work in Farmington, Connecticut, where we have been focused on transforming our teaching and learning practices to meet the needs of next-generation learners for over a decade. Our Vision of the Global Citizen (VoGC), featured in the last edition of The Bridge, articulates the skills and dispositions we believe will equip students to navigate and contribute to our rapidly changing world. Our Framework for Teaching and Learning describes the five principles of high-quality instruction necessary for achieving the VoGC.

Our instructional improvement efforts have been influenced by the work of Harvard professor Jal Mehta, whose vision for a “new grammar of schooling” calls for students to move beyond a surface-level understanding of a topic or discipline and instead to delve deeper into underlying concepts and questions. He describes this kind of thinking as Deeper Learning – a phrase that has taken hold in the US.

As we defined and contextualised “Deeper

Learning” for ourselves, we organised our thinking around three essential principles. We believe that student-centered Deeper Learning experiences happen:

1. When classroom communities are characterised by high trust relationships

2. When teachers hold high expectations for every student, and

3. When there is evidence of high engagement in the tasks students are working on.

We believe that we can apply those same principles to assessment practice.

Instead of assessment OF learning (assigning a score or level), let’s think about Assessment FOR learning (empowering students to recognise their strengths and areas for growth and become more empowered, aware, and self-directed as learners).

When we think about assessment not as judgment but as one of the many opportunities for students to learn, we see the relationship between teacher and student differently. Assessment is no longer a singular experience at the end of a unit or a score assigned by the teacher. Instead, it can become a process of self-reflection in which students evaluate their own skills in light of pre-established targets. In this way, the process leverages the high trust relationship between teacher and student and provides every learner the opportunity to better understand their own strengths and areas for growth.

Take a closer look at what the teacher and student might be doing when these three principles are applied in classrooms (Table 1.) Many of the bullets included in this table come directly from our Vision of the Global Citizen and Framework for Teaching and Learning, which

demonstrates our desire to transform assessment as central to the learning process. Although we have yet to fully realise all of these attributes in daily practice, the “look-fors” in the “We see students…” column helps us collect evidence of progress and identify our next level of work.

If you are wondering how this might actually play out in a classroom, or during a lesson, take a look in the ‘Resources for Teachers’ section of this issue of ‘The Bridge’, where you will find three scenarios, one for each of:

- Primary (ages 5 - 9);

- Middle (ages 10 - 14); and

- High school (ages 15 - 18).

Elements of Deeper Learning

High Trust

We hope you might find it useful to explore these in discussion groups to identify evidence that supports Deeper Learning practices in your school.

High Expectations

When teachers.... We see students....

•Design learning experiences with a strengths-based approach, avoiding deficit thinking.

•Establish and monitor norms that support productive feedback and critique.

•Anticipate challenges or misconceptions by designing differentiated responsive instruction.

•Learn about studentsʼ family and cultural backgrounds to maximise opportunities to amplify connectedness to the curriculum.

•Use learning targets to describe content standards and learner expectations achievable by all with flexible pacing.

•Build learnersʼ understanding of success using rubrics, examples, and models of beautiful work.

High Engagment

•Consider the diversity of interests, experiences, cultures and other identity-rich factors as opportunities to develop authentic tasks that have meaning to students.

•Offer multiple and varied ways of demonstrating mastery.

•Engage students in practice, rehearsal, and critique protocols to refine knowledge and skills.

•Assess their own personal strengths and needs.

•Build effective personalised habits of work and study.

•Seek teacher and/or peer support as needed.

•View learning as an interactive process.

•Know themselves as learners and make good choices about what, when,and how they want to learn.

•Describe the attributes of success and reflect on their own related strengths.

•Use models, rubrics, and feedback to evaluate and improve their work.

•Learn from successes and failures by engaging in feedback and self-assessment protocols.

•Ask questions to clarify expectations, learning targets, and available resources.

•Develop stamina, focus and confidence as a result of overcoming challenges.

•Attend to accuracy and reason with evidence.

•Persist in overcoming obstacles to reach their goals.

1.

In your school, how are students regularly “assessing” one another’s work to develop self-assessment skills and constructive feedback? What tools and processes are being used?

What mindsets about education and school need to change in order to see students driving conversations about assessment?

Do they regularly “assess” one another’s work to develop these self-assessment skills? What key skills and mindsets are you developing through self-assessment that would benefit them later in life?

What If…A National ‘Open School’ Became a Reality for Every Young Learner?

Dr Fiona Aubrey-Smith

This article is a little different. Its focus is not on changes to existing school practices. It is about establishing a very different model of learning which, international evidence shows, can be much more accessible for some groups of learners who find the learning conventions of school difficult.

This might include many of those currently long-term absent; or some SEND students with needs not well met in mainstream; or those with physical difficulties, or anxiety challenges. Put simply, the Open University transformed learning for literally thousands of learners whose personal and/or learning needs were better met by its approaches and flexibilities.

Highly successful Open Schools exist around the world, working in harmony with and adding value to the mainstream system. On the theme of Reimagining School, here is food for thought.

The article sets out a vision for The Open School highlighting how, as with The Open University, its establishment could address many of the challenges and opportunities that exist in education by adding possibilities and value for all learners, without disrupting or competing with existing schools.

What if…

We can do so much better for our young people, can’t we? As Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer said recently, education needs to be reformed so that “children have more control of their future”. Although actually, shouldn’t we go one step further and give children more control of what they do today, not just a future that sits on an unspecified horizon?

What if… every young person – whatever their background or location – had access to vocational, recreational, creative, competitive and aspirational learning?

What if… we removed that arbitrary separation between curriculum and extra-curricular?

What if… we intelligently used contemporary technologies to make learning more personalised, more accessible, more connected, and more

“What if…every young person—whatever their background or location—had access to vocational, recreational, creative, competitive and aspirational learning?”

relevant to the world that young people actually live in?

If as adults, we embrace the benefits of on-demand, personalised, anywhere/anytime tools that help us with our tasks and priorities, why would we prevent young people from safely utilising those same tools?

What if… young people’s aspirations (not just our targets for them), were mapped to opportunities, coached, and nurtured through properly joined-up provision?

What if… the curriculum and qualification pathways available to young people could break free from the shackles of location, of teacher capacity, of time and local socioeconomics?

If a child attends a small school or a school that is not yet thriving, why would we accept that their subject and qualification options will be much narrower than a child in a neighbouring school? What if… the career pathways for our teaching workforce were not constrained by the structures of time, place and imagination?

If we have an inspirational physics teacher in one school and a vacancy in another, why would we accept the inequality that creates for the children involved rather than use technology to connect the two together?

You know the saying that “it takes a village to educate a child”? Well, what if… we removed some of the unnecessary barriers and empowered young people to access the wide range of support networks that already exist – within, and beyond their physical or ‘home’ school.

A Clear Vision to Meet This Ambition

In their 2020 article in The Guardian, Tim Brighouse and Bob Moon spoke about the life-changing impact The Open University has had for adults – democratising access to learning through structured anytime/anywhere provision, and meaningful student/tutor relationships.

However, when the idea of The Open University was originally proposed, it wasn’t welcomed by people whose identities were tied to traditional models. It took time, but The Open University has since helped to revolutionise the very idea of what ‘going to university’ can mean.

So imagine what impact an Open School could have for children and young people who struggle with traditional school, or cannot attend for a range of reasons, or for those who are eager to study something not offered by their home school.

What might an Open School be like?

An Open School would have learners of all ages at its core but would be especially targeted towards school-age children. It could function both online and in person through a regionally coordinated structure. Materials would be available 24/7.

Learners would belong to a cohort with a teacher/ mentor, but also join wider large-scale learning sessions exploring big ideas and interest-led

discussion groups with pupils from elsewhere.

The Open School would not replace but would complement existing schools. It would have a parallel, interlinked school programme meaning school-based learners could draw on components, but The Open School offer would also be more extensive and varied, providing learning opportunities not widely available in mainstream schools.

It would draw in businesses, community and cultural organisations, providing a blend of learning experiences and building programmes around learners’ personal interests, aptitudes, passions and ambitions, supported by teachers who will point youngsters that they know well in the right directions for their individual learning programme.

Adapted from Tim Brighouse and Mick Waters (2022) About Our Schools: Improving on Previous Best Crown House Publishing.

From Vision to Reality

Over the last few years, a growing group of influential education leaders have been working hard in the background to make The Open School aspiration into a reality. Voices across the sector have fed into discussions and design thinking which has touched upon funding and operational models, governance and accountability, partnerships and communications. We are incredibly excited that seven regional pathfinder projects are about to be launched, which will build further momentum for this work.

Together, we can make this happen.

Together, we can give back control to the young people whose lives we are all ultimately here to serve.

Named in 2024 as one of the Top 5 Visionary Women in Education, Dr Fiona Aubrey-Smith is an award-winning teacher, leader and academic with a passion for supporting those who work with children and young people. As Founder of PedTech and Director of One Life Learning, Fiona works closely with schools and trusts, professional learning providers and EdTech companies. She is also an Associate Lecturer, PhD supervisor and Consultant Researcher at a number of universities, and sits on the board of a number of multi-academy and charitable trusts.

Professional Prompts

How might an Open School result in wider changes in the education system? This article is future-focused, so the prompts below are designed for conversation with colleagues:

Does the idea of an Open School make sense to you? Why or why not?

If a ‘regional hub’ of an Open School existed in your area, which of your students do you think might benefit? How? Why?

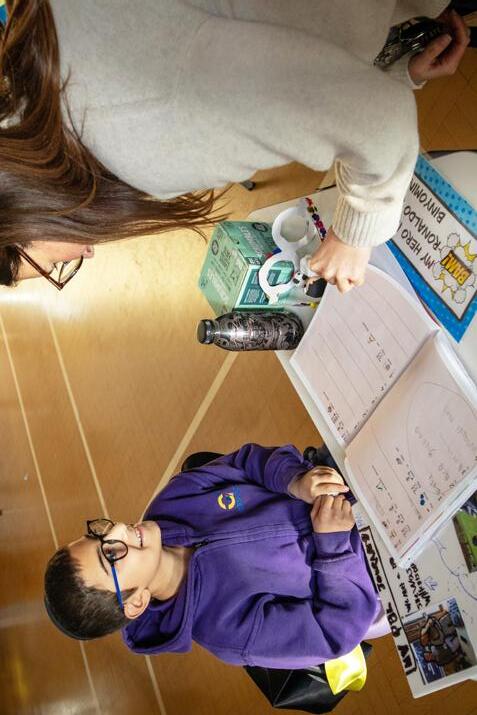

Student-led Conferences at XP School Doncaster

Andy Sprakes

This article is about what happens when learners are given space and support to share their learning journey with their family and their teachers. Student-Led Conferences privilege learner voice and agency and are an inspiring alternative to traditional parents’ evenings.

‘A thing of beauty is a joy forever.’ John Keats

It is ten years since we opened XP School in Doncaster and currently, I’m writing a book that collates some of the highlights of our first decade.

The book is already filled with student work such as field guides, published books, student-scripted films, videos, beautiful artwork and music. At the heart of this work lies student growth and character: every time a student creates work that matters, when it is drafted and redrafted to ensure high quality, when the work connects with the world and has agency, there is something enduring about the impact.

Young people and the world around them are never quite the same after they are published authors, artists who have displayed their work in a public gallery, or poets who have ‘slammed’ in the local Arts Centre.

Young people are never quite the same after hearing and representing the stories of asylum seekers, organising climate conferences, and writing scientific reports that directly tackle the issue of flooding in their district.

This is work that makes a difference to the student who becomes an agent for positive social change and the wider community that benefits from this service.

When you empower young people to do good for the world, they rarely disappoint.

One of the areas that I haven’t written about yet, and I suppose this is a good place to start to gather my thoughts, is how by having high expectations for our young people we empower them still further.

“When you empower young people to do good for the world, they rarely disappoint.”

For example, at XP, we do not run conventional parent consultation evenings, where parents arrive, meet a teacher, and are given information about their son or daughter that is determined by the adult. We wanted our kids to lead their own learning, so we introduced Student-Led Conferences, taking the simple but highly effective idea from Expeditionary Learning Schools.

What do Student-Led Conferences look like?

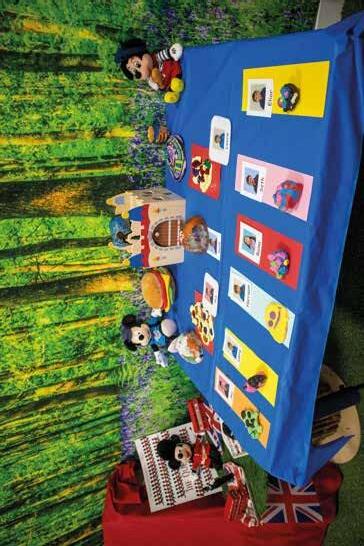

At least once a year across our schools, primary and secondary, students lead a conference expressly for their families and teachers. In these conferences, each student shares their portfolio of work and discusses their progress in terms of their academic learning targets, their developing Habits of Work and Learning (HoWLs) and the products they have created.

Students facilitate their conferences from start to finish.

Student-Led Conferences put students in charge of sharing information about their progress with their families. Students learn to advocate for themselves; they reflect upon and provide evidence for their progress; they are able to be explicit about the support they request going forward from teachers and parents. The structure builds students’ sense of responsibility and accountability for their own learning, as well as intentionally developing their leadership skills and confidence.

Student-Led Conferences also greatly enhance family engagement with learning that takes place at school. The conference structure builds family members’ interest and understanding in what has been happening in school and strengthens relationships between students, family members and staff.

The impact of Student-Led Conferences is profound. To watch and listen to students articulate their learning, their mastery of specific learning targets and places they have struggled, and their sense of who they are through the work they are producing is both humbling and uplifting.

It is a ritual and rite that is transformative, full of joy and beautiful–and as Keats said, the memory lasts forever.

Andy Sprakes is the Principal and Co-Founder of XP School in Doncaster.

“Student-Led Conferences also greatly enhance family engagement with learning that takes place at school.”

Professional Prompts

1.

As a parent of a school age child (or imagine that you are) how might you respond to attending a Student-Led Conference at consultation evening? What might you like and not like?

In discussion with one or more colleagues, list the points you can think of in favour of Student-Led Conferences and those against. Which side wins?

In the Resources for Teachers section of this edition there is a protocol or guide designed to support teachers with Student-Led Conferences. It has been contributed by Randy Scherer from High Tech High in San Diego. Discuss this with other teachers and see if you can find a place to try it out in your school.

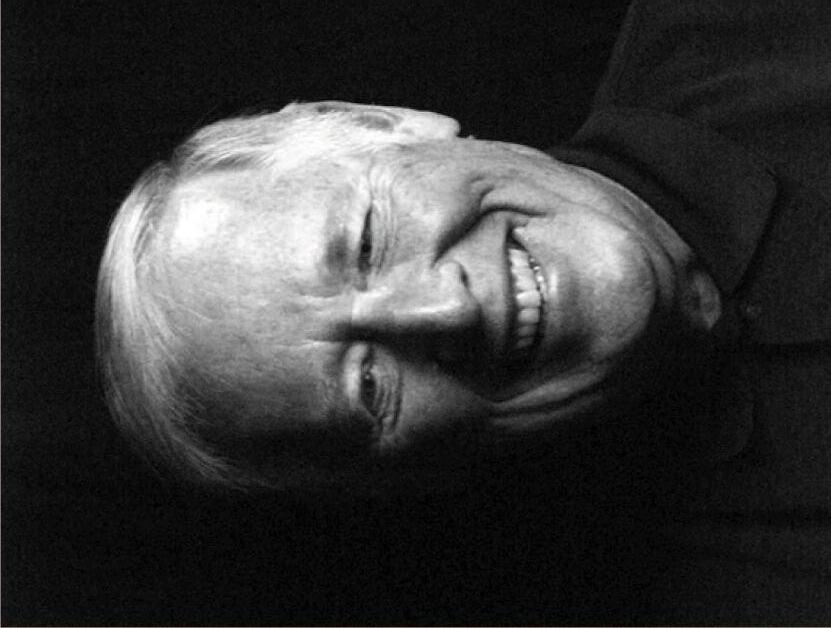

David Price OBE: A Legacy for Young Lives

Valerie Hannon

Paying tribute to an inspirational leader.

There are some features of learning that are a part of Gesher School’s DNA.

One is the way in which learning happens and is assessed–in and out of the classroom, within and beyond the school and connected to realworld activities, projects and themes. A second is an emphasis on wellbeing, therapeutic support, independent skills development, and self-advocacy.

Learning at Gesher builds from the strengths and passions of young people, enhances self-esteem and efficacy, equips them to relate well to others and provides the purpose and ambition for fulfilment and success in life.

There are many strands of thinking and practice that have led to this end, but an important one is the work of David Price OBE, who died in May. David was a highly unusual individual, in terms of the breadth of his interest and influence; and the unconventional route he took to achieving them.

David left school early and made a living playing the pubs and clubs of the Northeast where he was born. A natural and gifted musician, he was largely (though not wholly) self-taught. When a contract with a music company got cancelled (by Sharon Osborne!!) he decided to give formal education a go; so he took a degree and began teaching in community arts settings.

David understood deeply the barriers that many people encounter to becoming successful learners, and he set out to overcome them. This began with a seminal innovation programme for the Paul Hamlyn Foundation, Musical Futures, which leveraged the power of making music in groups and of young people’s love of popular music. The pedagogy he developed (driven by interest and passion, pulling on learners’ strengths) led to many young people moving towards formal music training and qualification. But above and beyond this outcome, it resulted in joyful learning and empowerment. Musical Futures lives on, in this country and many parts of the world.

At the Innovation Unit of that period, we were seeking a platform and framework for working with schools on a new model of engaging pedagogy. David helped us morph Musical Futures into

Learning Futures which took some of the insights and ideas it had developed (together with those of several other thinkers and practitioners) and applied them to the way we design learning in all classrooms. A major focus was on how to make learning deeply engaging. Hundreds of schools were involved across England, and their work lives on in strands and tributaries that will never be traced.

From these beginnings, substantial work was done on codifying what good project-based learning looked like – David was the author of a series of publications and resources on this entitled REAL projects. He also authored books on related themes: OPEN - How we’ll work, live and learn in the future, and The Power of Us developed his ideas and illustrated how they were working in practice in many different settings. In systems around the world where the conditions were more conducive to a project-based learning approach, David was much in demand. His great sorrow was that it was so tough for teachers to embrace the approach in the English context.

Nevertheless, enterprising teachers, leaders and entrepreneurs saw possibilities – the “gaps in the hedge” as Tim Brighouse used to call them. Thus the School Design Lab was born as a way of

translating high-level principles into workable strategies that could be realised in English education. Out of this came the principles set out at the top of this article: the Gesher DNA.

As I reflect on David’s life, I think of the many children and young people, and indeed teachers, who will unknowingly have benefitted from the work that David Price did. It is a joy that schools like Gesher demonstrate that an approach that puts children at the centre – whatever their assumed capabilities and backgrounds – can flourish, and be a bridge to a different future.

Valerie Hannon is a global thought leader, inspiring systems to re-think what ‘success’ will mean in the C 21st, and the implications for education. The co-founder of both Innovation Unit and of the Global Education Leaders Partnership, Valerie is a radical voice for change, whilst grounded in a deep understanding of how education systems currently work.

Formerly a secondary teacher, researcher and Director of Education for Derbyshire County Council; then an adviser in the UK Department for Education (DfE), she now works independently to support change programmes across the world.

TEACHING AND LEARNING WITH NEURODIVERSE CHILDREN

A Fireside Chat with Pani Matsangos: Headteacher, Westside AP School, London

This conversation with Pani was held with Zahra Axinn and David Jackson of The Bridge Editorial Team. Only Pani’s responses are attributed.This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Thanks for joining us, Pani. Ali Durban from Gesher visited Westside recently and was impressed, which led to this follow-up for The Bridge

Pani: I know The Bridge; it’s a lovely publication.

Let’s start by hearing about Westside School.

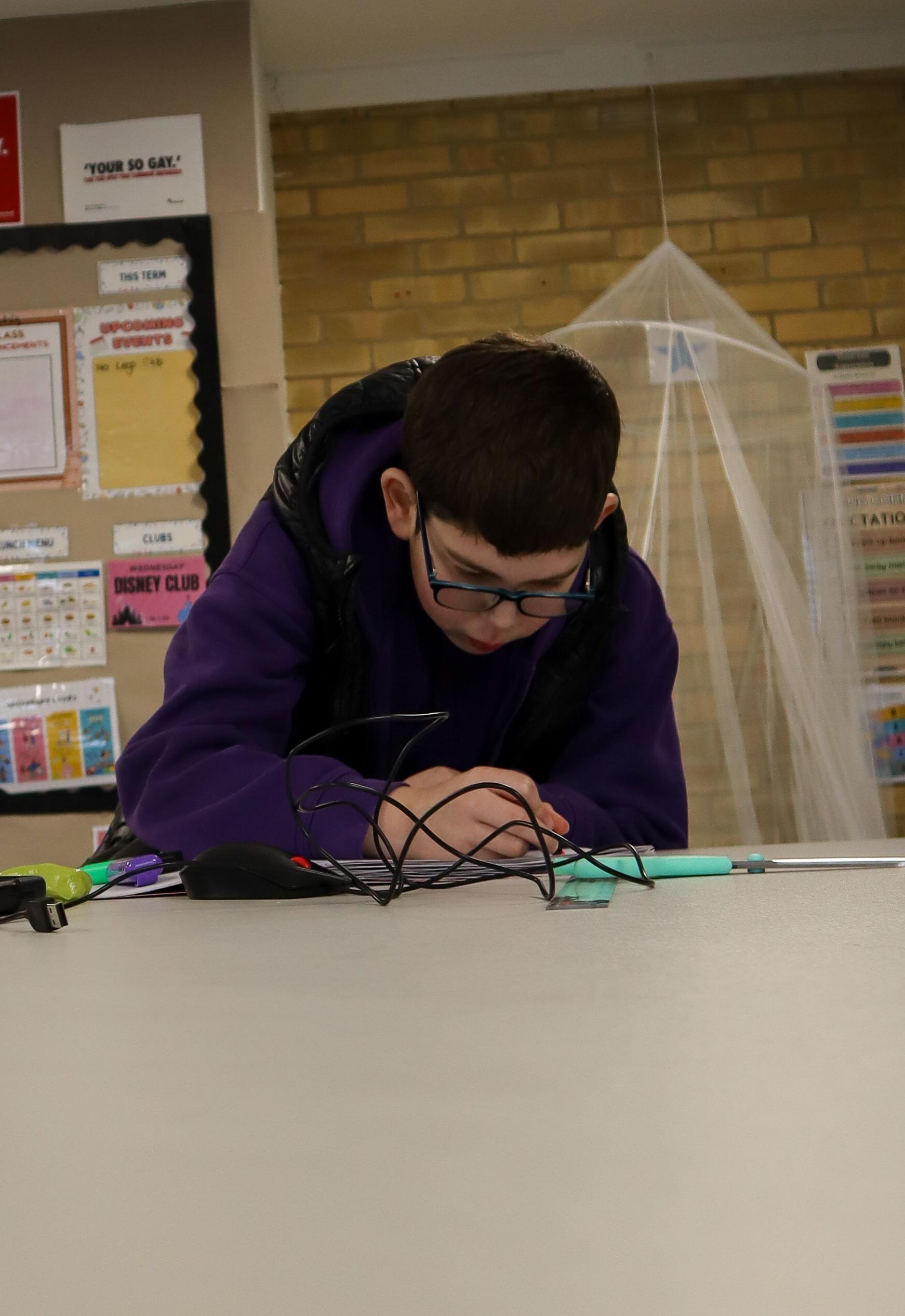

Pani: Westside is an Alternative Provision (AP) school for secondary-aged children who have been excluded or are struggling in mainstream settings due to social, emotional and mental health challenges. We offer a tailored education for up to 70 students, currently at 55, delivering Key Stage 3 curriculum and GCSEs for Years 10 and 11.

Number one on our list really is engagement: first wanting to be in school, and slowly scaffolding the support that they need in order to get to remain in lessons, to engage in lessons, and to partake in a full school life, which also involves a lot of sport, art and culture at the same time, and broadening the notion of success beyond the academic. That’s really important to the children we work with. There has to be opportunity to win as often as possible, in as broad as possible a sense.

And the last thing I’ll say is about identity. The children who join us haven’t identified as students that can succeed at school, and we really need to flip that and to transform their sense of self. In this way we have tangible impact on the way in which they work and the way in which they engage with staff and achieve some sort of success.

Sounds like a unique approach. Gesher focuses on learner engagement too. How do you achieve that while teaching a GCSE curriculum?

Pani: The hook is about adaptive teaching techniques to keep students engaged. For example, we integrate game design into lessons, like weekly

revision sessions for Year 11. They work in teams, moving through stations that test their knowledge. Collaborative learning is a core focus, especially with students’ social and emotional development. Additionally, we have Progress Leaders (PLs) who support students by understanding their individual needs and tailoring learning strategies accordingly.

Tell us more about the role of Progress Leaders.

Pani: They focus on enabling each child to become as self-sufficient in their learning as possible. It’s a coaching model. PLs act as coaches, guiding students toward autonomy in their learning. They are assigned to specific classes and work with each student throughout the day, building up data on their progress. This model moves away from the traditional teaching assistant role, instead fostering independence through continuous support and observation.

How do Progress Leaders assess where each student is on the journey to autonomy?

Pani: They gather and record data from daily observations, looking for patterns in behaviour and learning which can inform next steps. This helps them identify when a child is dysregulated and making impulsive decisions or choosing unwisely. We use this information to tailor support and determine the next steps for each student.

Is the teaching just subject-specific, or do you incorporate integrated learning? Do teachers collaborate in planning?

Pani: We do both. For Year 11, we’ve integrated collaborative planning across subjects, like English, Maths, and Science, to engage students in cross-curricular activities. For younger students, particularly Years 8 and 9, we focus on personal

development lessons that address their social and emotional needs. We also have a strong culture of collaboration among teachers and PLs to meet each child’s needs.

You’ve mentioned building trust-based relationships with students. How does that shape your school culture?

Pani: Trust is fundamental. We understand that disruptive behaviour often stems from unmet emotional needs, so staff work to build empathy with students. This strengthens relationships and creates a supportive environment. We believe in a long-term approach–lessons are just one part of helping students grow and develop.

Could you elaborate on your definition of inclusion?

Our definition of inclusion underpins everything. We look at inclusion in a three-tiered way.

I. The first is inclusion within the school – making sure that each child is able to feel included in the school, via adaptive teaching, strong relationships, and having a broad notion of success outside the academic and strong parental relationships, so that they realise that school is for them.

II. The second is functional inclusion outside school – how they communicate with people, how they have the confidence to try things out, how they regulate themselves in tricky situations. It might be going to a museum. It might be going to a sporting activity outside school. We explore what inclusion means outside Westside School.

III. Finally, we’re working hard on the third, longer-term inclusion beyond Westside. This is inclusion in an impact sense. Are they able to use their voice to articulate their needs, and to effect some sort of positive change, beyond 16 and beyond Westside.

Your personal story seems to connect with the work you do. What led you to alternative provision?

Pani: Professionally, I saw mainstream education failing to address the needs of marginalised students. I wanted to better understand those children. We know that the numbers are huge, almost 10,000 exclusions last year.

On a personal level, I have a sibling who was a child who struggled tremendously at school, and eventually, a few years ago, that became a really difficult circumstance. He became a rough sleeper, and he had significant mental health issues. When he passed away, I started to think. Regarding

his autism, from a young age he didn’t have the support that he needed, and you can see how things compound negatively. Needs are not met over the years. With the right interventions early on, I think there’s a great deal that can be done to support young people who think differently or have had adverse child experiences. I think you can unlock a lot of positivity and a lot of potential just by thinking differently about the way in which we work. And so that was important for me to join AP and to work in a way in which we’re working now at Westside.

Thanks for sharing, Pani. Do we need more quality AP provision or for mainstream schools to better meet the needs of all children?

Pani: We need both. Some students thrive in smaller settings, which allow for more tailored support. While mainstream schools can’t always offer that level of attention, they could benefit from adopting the inclusive strategies we use in APs, especially around data-driven decision-making to better understanding the underlying factors inhibiting a young person’s social and emotional growth and development. This is of course a lifelong journey and applies to us as adults.

Our journal, The Bridge, was established as a way of seeking to share the practices evolving at Gesher and other interesting schools – like yours. Is Westside an island of excellence or is there also a mission to influence others?

Pani: I think there’s definitely a mission – hence this interview. There’s a national need to rethink how we approach education for students who don’t fit the traditional model. It’s just a really tragic story ultimately that we have this sort of pipeline to prison scenario. The accountability measures of mainstream schools often fail to meet the needs of these children, leading to exclusion. And there’s also the issue of low expectations. We talk a lot about expectations in schools and there is this idea that children should be sitting behind a desk compliant and quiet and working really hard. And, for me, that’s also low expectations in some ways, because high expectations should be about developing independence, developing, understanding of self and working with others and, and wanting to be curious about things and not having that sort of drummed out of you.

What is your success rate, and how do you measure success?

Pani: Of course, we’re not universally successful. It’s a dynamic process. Success isn’t guaranteed, and the challenges evolve. But we remain

adaptive, constantly evaluating each student’s journey. We focus on success in school as the first step—if a student can engage in learning and feel included, that’s a meaningful measure of success.

Are there any final thoughts you’d like to share?

Pani: Absolutely, yes. The core purpose of education should be about fostering curiosity, independence, and emotional intelligence. We need to shift the conversation about what education is for, and stop focusing as much on compliance and linear models for learning, accepting that learning is a complex and messy endeavour! Each person in school, or connected to the school, whether it’s someone in our HR team or the canteen, or a visiting speaker or external mentor is someone that could make a difference to that young person’s life. That’s something that we’re trying to create here, because why not? We ALL have a part to play in raising our children.

Thank you very much indeed, Pani.

Pani Matsangos is the Headteacher at Westside School, an Ofsted Outstanding Alternative Provision (AP) school serving pupils across London. With almost 20 years of experience in mainstream education, he is deeply committed to supporting children with special educational needs, mental health challenges, and difficult home circumstances. Drawing from both formal training and personal experience–having managed his own SEN and a complex upbringing–Pani champions inclusive education. He ensures pupils access a high-quality traditional curriculum enriched by arts, sports, and culture, broadening the definition of success so every student can thrive, both academically and through diverse, life-enriching opportunities.

The Relevance of Therapeutic Approaches for All Schools

Zahra Axinn

This article captures learning from a range of therapeutic approaches used in Gesher School. In a series of interviews, therapists working in the school suggest small changes to practice and learning environments that will make a big difference to learners, and that can be safely and inexpensively implemented in mainstream schools.

At Gesher School, being a “therapeutic school” is not just a philosophy or frame of mind, it is a feature of our everyday lives. We recognise the importance of therapy for equipping children for future challenges by allowing them to develop their resilience, self-esteem, and compassion, so we embed therapy into teaching and learning throughout the school. Therapists work alongside teachers and really get to know students in session, in the classroom, and in other settings.

We are very fortunate, of course, to have therapists and therapy assistants working alongside our teachers and teaching assistants, a feature that we realise not all schools will be able to replicate. However, there are some approaches we use that can be safely applied in any school without a huge investment in specialist materials or training.

For this article, I spoke with our Head of Therapies and Speech and Language Therapist Victoria Rutter, our Art Psychologist Hollie Smedley, and our Deputy Head/Drama Therapist Chris Gurney in three separate conversations about their perspectives on the impact of therapy at Gesher and beyond. The following is an adaptation of their advice.

Invest in therapeutic approaches that benefit the most children.

If financial constraints make it tough to invest, focus on a small number of approaches that will benefit the most children, such as language or vocabulary skills, or sensory circuits where students can learn skills for self-regulation. Games that help build up necessary listening abilities and activities targeting gross motor skills can also be widely beneficial.

“We recognise the importance of therapy for equipping children for future challenges by allowing them to develop their resilience, selfesteem, and compassion, so we embed therapy into teaching and learning throughout the school. ”

Little and often is best.

Regular practice of these skills, little by little and often–even five minutes a day–can offer more benefits than one weekly half-hour session. Pick a priority or two per term–i.e. play skills, listening attention, vocabulary, or social skills for example –and look for online resources, factoring in what’s age-appropriate.

Create moments of calm.

Brain breaks and yogic breathing during lessons or PE classes can be a great strategy. Also, it’s often an idea to give learners an option to step away and calm themselves by going to a reading corner or other separate space in the classroom. Offer children ways to indicate their mood or ask for help via small visuals on a desk, for example

by flipping a colour-coded card.

Never underestimate the importance of being seen and heard.

Children exhibit poor behaviour when they have trouble expressing their needs. Any behaviour is ultimately a form of communication. Acknowledging a child and recognising that they’re asking for help is important, even if you can’t yet figure out what they need. Let them know that you see and hear them.

Introduce micro-breaks and manage transitions.

Some children struggle to notice when they’re hungry or need the toilet, so it’s important to have regular breaks built into the timetable. At Gesher School we have a low arousal environment that allows children to relax, regulate and reflect between transitions. Children who have experienced chaotic environments and tend to be on high alert often find a quiet space useful to adjust and calm.

Expand opportunities to experience success and build self-esteem.

We notice that children with additional needs who come into Gesher School from mainstream schools exhibit negative self-talk, where they tell themselves that they can’t do something, or that things won’t work. We think this comes from comparing themselves unfavourably to peers, and that once they begin learning with other children who have similar or varied difficulties, they don’t feel so alone in their struggles. The tools provided by art and art therapy, for instance encouraging children with sensory issues to draw using an iPad, also seem to help build self-esteem. For those who struggle with academic subjects, art can be brought into the learning environment to help reduce difficulties.

Grow trust through consistent interactions.

At Gesher, we employ the PACE approach in our interactions with children, where PACE stands for playfulness, acceptance, curiosity, and empathy. Trust can be built through consistent interactions which in turn help to grow strong relationships between children and adults. Children thrive when they have the chance to engage with an adult who offers them space to express themselves as a whole person. They can be seen and valued in ways they haven’t experienced before rather than being dismissed or infantilised.

TEACHING

“Children thrive when they have the chance to engage with an adult who offers them space to express themselves as a whole person. They can be seen and valued in ways they haven’t experienced before rather than being dismissed or infantilised”

Find your community.

Reach out to other teachers and schools, or to community groups, to talk about how you can best support children. Simple examples are:

- Place2Be is a children’s mental health charity with over 30 years’ experience working with pupils, families and staff in UK schools

- Schools in Mind supports primary and secondary schools in mental health and well-being and SEND.

Many schools have established links with community organisations or faith groups. Gesher, for example, as a Jewish faith school, is able to access the Partnership for Jewish Schools’ wellbeing programme, ‘Heads Up Kids’, which was designed by drama therapists.

Make the most of specialists.

If you do have access to therapists, lean into support from them and ask for their advice on the best strategies for your setting.

You can find out more about the role of therapy at Gesher School here or by contacting us at thebridge@gesherschool.com

Zahra Axinn is Content Manager at Gesher School. She has worked in education communications for over five years. Her areas of expertise include writing and editing copy, social media management, video and audio editing, design collaboration, and brand strategy. She earned a dual-degree MA in Visual & Critical Studies and MFA in Creative Writing from California College of the Arts, as well as a BA in English Literature and Theater & Performance Studies from Stanford University. Zahra is a member of The Bridge editorial team.

TEACHING AND LEARNING WITH NEURODIVERSE CHILDREN

Professional Prompts

1. 2. 3.

Many mainstream schools do not have dedicated therapy expertise or therapy policies outside their SEND unit or department. What is your school’s therapy policy? Is there a strategy whereby you might access and incorporate therapeutic expertise in your school?

Which of the ideas in this article hold the most potential for use in your school? How might you introduce them?

What strategies and approaches can help support students who are disregulated or who cannot engage in their learning? What are some factors which contribute to students being disregulated?

TEACHING AND LEARNING WITH NEURODIVERSE CHILDREN

Finding Beauty in Uniqueness: A Reflection

Loni Bergqvist

This little vase has changed my world.

Most normal vases are meant to hold a bunch of flowers. A bouquet with flowers that look good together, and complement each other in colour and shape.

Our schools are a lot like traditional vases: serving bunches of kids that are pretty much the same.

But this vase?

It was a fancy designer gift from our kitchen company as an apology for a cabinet door that took a whole year to be installed. When I opened the box, I thought it was a toothbrush holder.

This little vase has changed my world.

Small holes, a place for each individual stem.

The vase itself is not revolutionary.

But I’ve noticed a beautiful thing when I go into our garden and pick plants to fill it. I’m not looking for the huge volume of flowers anymore.

I’m looking for the individual flowers

The unknown weed alongside the house that looks like a green version of wheat.

The daisy in the back next to the trampoline.

A couple of sprigs of lavender that my new plants could spare.

A barely opened pink flower that still needs time.

And a few random weeds with splashes of purple and yellow.

My trips to the garden are now focused on seeing the beauty and uniqueness in everything sprouting from the ground. Not because it needs to fit together, but because now it has a place to stand alone.

Surprisingly, no matter what combination of flowers I choose, they all look stunning together.

Our schools need to be this.

Our kids are the wheat, daisies, lavender, unopened pink-flower and random collection of weeds.

Look, we can’t wait for the system to design this for us. The larger system will likely forever be stuck in the big-normal-vase thinking.

Those who know me will know my solution is Project-Based Learning. It’s something we have the possibility to do every day in our classrooms... if we have the courage to do something different.

What vase will you fill today?

TEACHING AND LEARNING WITH NEURODIVERSE CHILDREN

Loni was (and always will be) a teacher. She became a Project-Based Learning ‘convert’ when she started attending night school in Leadership at the High Tech High Graduate School of Education. Loni left her school to teach at High Tech High, knowing one day her mission would be to bring Project-Based Learning to students who needed it the most; the ones who were in traditional schools. Since 2014, Loni has been working with schools around the world to re-imagine education. She is the founder of Imagine If

Professional Prompts

1. 2. The central metaphor in Loni’s piece has a lot of impact. How can we change our school to allow all student to thrive? At Gesher School, one of our maxims is “every younge person profoundly well known—and knowing that they are known”.

Think of your own students. How does your school recognise and show the skills, abilities, beliefs and interests of each child? How might you re-think your teaching to make a place for each one of them?

TEACHING AND LEARNING WITH NEURODIVERSE CHILDREN

Relationships, Belonging and a Network of Joy

Polly Ross

This is a story about a boy, his teacher, a wooden tree and a school full of love and learning. It reminds us that learning can and does happen anywhere and any way in a school when the culture is right.

Our School

Shefford Lower School is a large lower school in Central Bedfordshire with a significant SEND register. We don’t believe in an approach to SEND in which learners should either be in a specialist environment or a mainstream school. So, we have adapted our learning environment and teacherstudent relationships to support a wholly inclusive mainstream specialist environment accessible to all young learners in our community.

We further believe that progress can take many different forms and that all children have an entitlement to leave us with every step, however small, recognised, captured and celebrated.

One example of this belief evolved almost by accident.

When I was young, my mother gave me a wooden Christmas tree. When I became a headteacher, with an office, I brought it into school where each December it was displayed, decorated and lit. By last summer it was looking tired and I kept reminding myself to throw it away.

Peter’s story (not his real name)

Peter is a young learner who receives a high level of adult support due to his complex needs. These include a significant speech delay, autism, social communication needs and self-care needs.

One day Peter came in because his Teaching Assistant wanted to mention something to me. As he waited, Peter saw the tree gathering dust on the top of a cupboard and gestured that he would like to see it. I had no idea that this would be the beginning of something magical!

Peter decorated this sad little tree, and then

We further believe that progress can take many different forms and that all children have an entitlement to leave us with every step, however small, recognised, captured and celebrated.

returned the next day, then each day, several times a day, beginning to talk as he did it, presenting it joyously to me and showing it to everyone along his way as he proudly walked it around the school en route to show his teacher.

He had found something in the school which brought him (and many others) joy. This tree was subsequently to become a powerful tool in his speech and language development. The creativity flowed and anything and everything became a potential decoration, from a kitchen spoon to

We realised, of course, that this had also been an exercise in relationships and belonging.

flowers from the forest, bringing warmth and amusement to all.

After this had been going on for a month or two, someone suggested keeping the tree in Peter’s classroom as I may sometimes be in meetings,. This was until we realised that walking down to my office and saying hello was an important part of it!

The ritual continued. Peter’s confidence grew and his speech and language seemed to be coming on until one day he came in and said: “Hello Mrs Ross. Can I have the tree please?” A clearly enunciated sentence!

Reciprocal Joy

I started to take photos of this tree my mother had bought me and sent one to her to let her know it was not only still going strong but, in fact, supporting a child with additional needs to thoroughly enjoy his experience of school. My mother responded, telling me how beautiful it was, and so it continued. He would decorate a tree, show it to all around the school who would smile, share it with me and it would also make my mother’s day!

Just before his annual review I sent all the photos to his teaching assistant to share with his family at the meeting, following which she sent this reply:

Oh Polly, thank you for these pictures, they are really great. I will print them off for his review next week. He makes my day and fills it with joy every day–whether it’s through watching him carefully decorating his (your) beloved tree, some work he has done, learning he has remembered, or new

vocabulary he has said to me. :) Thank you for always being so supportive and welcoming when we come to see you. Helen

Educational Reflections

We realised, of course, that this had also been an exercise in relationships and belonging; Peter’s relationship with the TA and the pride she took in working with him and watching him grow. This, allied to the knowledge she developed about his interests through safe talk, had supported him to be successful. It has also facilitated relationships with other pupils and adults – and with me through his friendly visit each day.

This story is also about joy, which all learning should bring: the joy Peter brought to those around him in walking his tree through school; or that his TA gets from working creatively alongside him and making a difference; or that he brought to my office and many a meeting held there – and even the joy he brought to the lady, a retired art teacher, who had once given her daughter a small wooden tree.

Polly Ross is Headteacher at Shefford Lower School in Bedfordshire.

Peter’s Trees.

Professional Prompts

In the ‘Welcome’ editorial, we said that relationships and belonging would be two of the sub-themes of this issue. How does Polly Ross’s piece illustrate these themes?

2.

What are ways that students’ beliefs, interests and passions can be incorporated into the school context?

How can school leaders be more engaged and connected to students on a regular basis?

What Do We Mean by ‘Belonging’?

Belonging is a theme that runs through this issue of The Bridge. Teachers know that a sense of belonging is really important to children’s learning but do we really have a shared understanding of what is required of us as educators to create belonging classrooms and schools, where learners and learning can flourish?

Informed by articles in the previous two sections, the draft model which follows is offered as a point of reflection and discussion. It is designed to enable teachers, individually or in groups, to form for ourselves a richer picture of what a school that emphasises belonging might involve.

In this ‘Resources for Teachers’ section, you are invited not just to reflect on the model, but to edit it (hence draft) to make it useful in your context. We have suggested some group discussion questions and activities that might be used in staff workshops to surface strengths and areas for development in your school’s receptiveness to ‘belonging’.

“As human beings, one of the most essential needs we have is the need to belong. When that sense of belonging is there, children throw themselves into the learning environment and when that sense of belonging is not there, children will alienate, they will marginalise, they will step back.” - Dr. Linda DarlingHammond, President and CEO of the Learning Policy Institute in Building a Belonging Classroom, Edutopia

Belonging: A Staff Workshop Activity

In the introduction to this activity, the model for helping us to think about belonging in school was proposed. It suggests four features that together might contribute or comprise feelings of belonging for young people in school.

Belonging

Obviously, belonging links to inclusion or inclusivity, but it is more than that. Inclusion is something that the school does; it’s about school policies and practices. In contrast, belonging describes how a young person feels towards or within the school culture and community and the relational dynamics s/he experiences.

This discussion activity is a vehicle for teachers to engage together on the subject of belonging–what it is and how well you feel your school fosters feelings of belonging for all young people.

Activity One

In groups discuss the model. What does it make you: Think? Feel? Wonder about?

Is there anything you would change? Based on your experience, what would you take out and replace or re-word? What would you add? Why?

Do you think each feature is equally important? Is there an order? Redraw the model using the size of the features to indicate relative importance.

Think of some learners in your context. How might the model help you to explore and better understand their experience of school? What questions does this raise for you?

If there are multiple groups, facilitate an opportunity to share insights and ideas to arrive

at a version of the model that feels right for your school.

Activity Two

In groups (the same or different) discuss each of the features in your updated version of the model. What do you do well and how? What do you do less well and why? Give yourselves marks out of 10 for each feature.

Share and discuss your scores. Where is there strong agreement? What can you learn from the differences?

Agree a score for each feature for the whole school.

Activity Three

Take the two lowest-rated features and, in groups, discuss what action(s) would need to be taken to improve these scores.

If there are multiple groups, split the two features being discussed to make the best use of time.

Ask each group to share their suggested actions. Ideally someone (in advance) might be delegated to take ownership of the suggested actions so that the people taking part can see that their insights and ideas matter.

Student-Led Conference: Model Agenda

In Section 1, XP School, Doncaster contributed an article on student-led conferences as a transformative approach to facilitating learner agency, improved relationships and a sense of ownership and belonging. This guide or protocol, printed by permission, featured in High Tech High’s Unboxed journal (September 2024).

Student-Led Conference: A High Tech High Guide

Student-Led Conferences (SLCs) flip traditional parent-teacher conferences to put students in charge of an important conversation about their experience in school. All students deserve the opportunity to reflect on their life at school with adults who care about them. Families and teachers can form strong networks of support when they build relationships together and hear about learning experiences directly from students. SLCs empower students to develop a range of skills and mindsets that foster a growing sense of responsibility, healthy communication, and leadership.

Who attends: The student, at least one significant adult such as a family member, and at least one teacher.

Time commitment: 15 to 30 minutes per conference.

What to bring: The student, with the teacher’s support, brings work samples from each of their classes and extracurriculars, including drafts, final products, photos, and more. The work is selected by the student to reflect appropriately the breadth of their current school experience and learning, and encourage a conversation that goes deeply into how school is going for them, including successes and challenges. Curating a portfolio is an excellent step in preparation, and supports the conversation.

Sample agenda:

Introductions: Begin the conversation by having each person introduce themselves and their relationship to the student.

Why? SLCs facilitate a web of support for a student, and it is essential that each person understands who the others are, and their support connections to the student.

Appreciations and Celebrations–Opening: Each

participant shares at least one specific aspect of the student’s experience in school or their personality that they appreciate and want to celebrate.

Why? By beginning the conversation with appreciations and celebrations, we create a welcoming space in which students are open to feedback and embraced as members in good standing of the learning community.

Student Strengths

The student shares areas of experience in school in which they are proud of their efforts, progress, or accomplishments. Ground this conversation in work samples from each area of the student’s work in school, and value all of them equally: expertise, effort, and growth.

Why? By beginning with strengths, we identify areas where the student has a good foundation to build upon. All students bring strengths to the classroom; validating strengths is essential to building relationships that facilitate learning. Sometimes adults surprise students by noticing strengths that they may not have identified yet on their own.

Areas for Growth

The student shares areas of their school experience that they identified as good opportunities for growth. This could reflect their effort, progress, or future accomplishments. Continue to ground this conversation in work samples from each area of the student’s experience in school.

Why? Students learn to take ownership of their education through understanding how addressing areas for growth with the support of caring adults will help them accomplish their goals.

Randy Scherer

adults and asks questions they may have to the adults.

Why? Up until now, it is possible that this is a student-led presentation. By intentionally shifting to questions, we ensure that the group has a conversation.

Goals Setting

The student shares goals and the next steps they will take to accomplish them. Help students identify “SMART” goals: goals that are specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and timebound.

The student identifies next steps for the adults in the room to help support them through their experience in school.

Why? By having students articulate their goals, they practice numerous skills of self-efficacy and develop important habits to lead their own learning.

Appreciations and Celebrations–Closing

Each participant shares at least one aspect of the student’s presentation, or their personality

manifested, that they appreciate and want to celebrate as a strength to build on.

Why? By ending the conversation with appreciations and celebrations, we communicate to the student that we value what they shared in their conference, and that we see numerous strengths that they can use as they take the next steps in their education.

Suggested questions for the panel of educators and significant adults:

What did you learn from that? Tell us more!

Looking ahead, what are you most excited about and why?

What are you most proud of from your experience in school so far?

What new learning goals do you have for yourself?

What would you like to learn next?

For the student to ask their panel:

What do you appreciate most about the work that I’ve shared with you?

What advice do you have for me?

How can you help me accomplish, achieve, learn…?

Assessment for Deeper Learning: A teacher discussion group CPD resource

Kim Wynne, Kelly Sanders, and Carolyn Fink

This Resource for Teachers applies the principles of Deeper Learning to assessment. It demonstrates how assessment practices can be transformed to build trust, raise expectations and promote engagement – our three core principles for Deeper Learning.

We have created three scenarios designed to be used as discussion tools by groups of teachers. We have tried to make them age-appropriate so that they will have relevance for both primary and secondary schools in the UK. After each scenario there is an italicised paragraph that ‘unpicks’ what is going on. As a tool, you can use it with that section and discuss both the scenario and the analysis. Or, you might want to have your own discussion before reading the italicised paragraph –and then discuss both the scenario and the analysis together. Your call!

Primary Level (aged 5 to 9):

It’s reading time in Mr. Wilson’s first grade classroom. Zach enters the classroom from his decoding intervention with Mrs. Swanson. He sees his classmates are arranging themselves in partner groups in different spaces around the room. He spots his partner, Mikaela, grabs his book box, and settles down next to her. Earlier in the week, students had the opportunity to study short videos of other first graders reading aloud. From there, the class created a criteria chart of effective reading. They noticed things like ‘read all the words correctly,’ ‘fluent reading,’ and ‘know how to solve tricky words using the letters and sounds.’ Now it’s time for them to apply the co-created strategies to their own work with their partners. Zach asks Mikaela if he can go first. He pulls out his book about trains, which is a favorite topic for Zach. Mikaela asks: “What goal are you working on?” “I’m working with Mr. Wilson and Mrs. Swanson on reading all the way through words. Can you watch me and put tallies on my goal tracker when you see me doing that?” Zach will share his progress with his teachers later in the day.

In this scenario, Zach is drawing on a trusted relationship with a peer to get real-time feedback on how frequently he is using the targeted strategy, reading all the way through words. As his partner tracks his progress and gives feedback, Zach naturally adjusts his reading behaviours. In the process he also develops a deeper understanding of himself as a reader, enhancing his sense of agency in his own learning.

Middle Level (aged 10-14): There is an excited hum in Mrs. Kay’s class as her fifth graders come back from recess. They have just finished a unit on animal adaptations and biomimicry in which they explored how the form of animals’ bodies supports their adaptation and survival in the wild. During the unit, students completed independent research on animal adaptations, engaged in experiments in which they explored different adaptations, and created informational books on a chosen animal.

As a final project, they worked in collaborative groups to explore biomimicry, or the creation of new inventions inspired by the form, structures, or adaptations of animals. Working collaboratively, Cora and her group developed an idea for a crab-inspired, ocean-walking robot whose hinged legs provide stability, helping it to deftly navigate the ocean floor when investigating environmental accidents or to help in search and rescue missions. Following the engineering and design process, her team made iterative models of their invention, seeking feedback and making revisions as they went. Ultimately, they built a prototype and tested their invention. This afternoon, they will analyse their work from this unit of study in preparation for mid-year Student-Led Conferences with their families when students present their progress and next steps in academic achievement and VOGC skill development.

“Scientists, as we wrap up this unit and prepare for our Student-Led Conferences, it’s the perfect time to reflect on and document your growth using the VoGC skills and dispositions,” says Mrs. Kay. “You’ve gathered all your artefacts. Your task is to

analyse and evaluate your own work, including your assessments and checks for understanding from across the unit, using the descriptors in the VoGC. Make sure to tag and document your artefacts, noting how your work matches the VoGC.” Mrs. Kay approaches Cora’s work area and asks how it’s going. “I’m looking back at the engineering model we developed for the ocean-walking robot and thinking about myself as an Engaged Collaborator.” Mrs. Kay nods and says, “What evidence are you finding in your group’s work?” “Right here in our notes from our first meetings,” she says. Cora explains that the process of designing the model was challenging, because her group mates had many conflicting ideas in the beginning. “This work shows that I am an Engaged Collaborator because, at first, no one could agree on how to design our robot. Everyone had different ideas and they got upset when other people challenged them. These notes here show how I helped to take the best parts of everyone’s ideas and help us come up with something good. I learned that I am good at finding a compromise and helping other people feel good about our work. I can’t wait to show my family this evidence and talk about how I’m doing on the VoGC dispositions.”

In this scenario, Cora and her classmates are learning how to use products of their work during a unit to demonstrate not only how they meet unit standards, but also their development of skills and dispositions necessary for lifelong learning and success. Mrs. Kay designs assessment tasks to help them analyse and unpack their individual growth within the context of their collaborative group work. She conveys the importance of this work by having them identify and articulate specific examples of where they see themselves developing these skills and dispositions that they can track in their personal learning portfolios. The Student-Led Conferences offer an authentic purpose for both understanding and advocating for themselves as learners.

High School Level (aged 15-18):

Jahmal, a senior at Farmington High School, thinks about his upcoming meeting with his Capstone advisor as he walks into school on a chilly winter morning. All FHS students complete an Aspire course or Capstone experience based on an area of interest in order to demonstrate mastery of the VoGC. Capstone is an independent inquiry project that includes research, field work, engagement with an outside expert, and some form of service to the community. “Hey, Ms. Wilton,” Jahmal says as he enters her room. “I’ve been working on my digital portfolio.” “Great,” says Ms. Wilton. “I know you are in the middle of

conducting research on how executive functioning impacts learning in young children, right?” “Yup,” he answers. He shares that he’s also had several meetings with his outside expert, a second grade teacher at a nearby school where he will intern after winter break. “When I put together what I’ve learned from the research, my conversations with Mrs. Doyle, and the observations I’ve done in her class, I see how important executive functioning and self-regulation skills are for success in school and in life. No wonder it’s an interest for me,” he laughs. Ms. Wilton asks Jahmal how he is demonstrating mastery of the VoGC in his digital portfolio. “Well, researching my topic has helped me strengthen my skills as an Empowered Learner, especially in organisation.” Jahmal shows Ms. Wilton how he’s using the tools she suggested: a daily task sheet to organise his research and a note taker to document his conversations with his mentor teacher. “I’m most proud of my work as a Disciplined Thinker, because I’m applying all that I’ve learned from this experience to actually create something that will help others.” “This is impressive, Jahmal,” Ms. Wilton says. “What have you been thinking about for your service project?” He shares a website he’s started to create for parents and teachers. “It will have resources for developing executive functioning and self-regulation skills for young kids. I’ve found a lot of strategies that I think will be useful. They also would have helped me as a kid.” They go on to discuss the improvement in his fall semester grades. “Any idea why?” asks Ms. Wilton. “Definitely. I’m more excited about learning because of this project. I’ve increased my ability to focus in class and be organised. I also hand in assignments on time.” Jahmal smiles. “I’m taking the SAT test this weekend. I think I can increase my score with my improved focus and attention to detail.”

In this scenario, Jahmal not only knows himself well as a learner, but he understands his insight can be used to make decisions about his future and for making contributions to his community. He recognises that his areas of challenge are opportunities for growth. While working independently on a topic of personal interest, he is improving his academic achievement, demonstrating important life skills, and contributing to his community. Ms. Wilton acts as facilitator and coach, providing him with encouragement, tools, and just-right support through carefully posed questions that help him reflect on his progress toward achieving his goals.

We recognise that some of the more traditional forms of assessment, like national tests, are a reality in our current educational systems and therefore tell one part of a student’s academic

story. But as educators, we can support our students in telling a fuller, more complete story of who they are and what they know and can do by giving them increased agency and ownership.

When students tell their own stories, they believe they are trusted to make wise choices, they internalise high expectations for themselves, and they seek engaging experiences as lifelong learners – the three principles of Deeper Learning.

When we create high trust cultures, with high expectations for all students, and highly engaging learning experiences, we help our students understand that standardized test scores and summative assessments are just data points within a larger body of collected information. Zach, Cora, and Jahmal know this. They used these data, along with the pursuit of personal interests and information about themselves as learners, to

recognize both their unique strengths and areas for growth. This is what we want for all students. By shifting our assessment practices, our students will experience deeper learning and get to know themselves as learners and humans who can then go out into the world ready to make an impact.