Justice Across Generations

We are delighted to present the third issue of Common Home, the magazine on all things environment and sustainability from the Earth Commons at Georgetown.

A key focus of the Earth Commons this year has been intergenerational justice, so our pages examine how environmental issues shape the children of today and tomorrow. From the Georgetown Collaborative on Global Children’s Issues, Emily Prest and Dr. Joan Lombardi deftly cast light on the acute health burden children bear, and call for political action on their behalf. Casting our gaze to expectant parents, playwright Melissa-Kelly Franklin’s perspective on family planning in the age of climate change grants us another angle to view intergenerational justice, contextualized by our editor Sadie Morris. In our coverage of Voices of the Environment, a program put on by the Earth Commons, we also listen to youth perspectives shared at COAL + ICE this spring at the Kennedy Center.

During the Spring semester, the Earth Commons held an art showcase to complement our work on intergenerational justice. We share art from the six awardees; and a special congratulations to Isabella Callagy and Victoria Smith for first place in the traditional and freeform categories, respectively.

So too, do we consider justice across species. What are the legal rights of an animal or tree? Does nature itself deserve recourse when devastated by oil companies? With Dr. Hope Babcock’s guidance, we delve into the legal status of nature and reflect on its importance in a world increasingly hostile to nature.

We examine a broad selection of transnational environmental concerns, from Elsa Barron’s work on the security concerns posed by climate-conflict in Syria, Ethiopia, and Ukraine; to climate refugees fleeing increasingly severe natural disasters. We dive deep into a multidisciplinary analysis of the energy transition with David Bailey, who offers a thorough telling of the war in Ukraine and its consequences in the global energy landscape.

We would also like to extend our utmost gratitude to Georgetown faculty, Dr. Christopher Pyke, Dr. John McNeill, as well as Jan Menafee at the Red House at Georgetown, who all contributed greatly to articles in this issue.

Sincerely,

The Common Home Editorial Board Sadie Morris, Marion Cassidy, Mark Agard, Alannah Nathan, and Maya Snyder Undergraduates at Georgetown UniversityLetter from the Editors

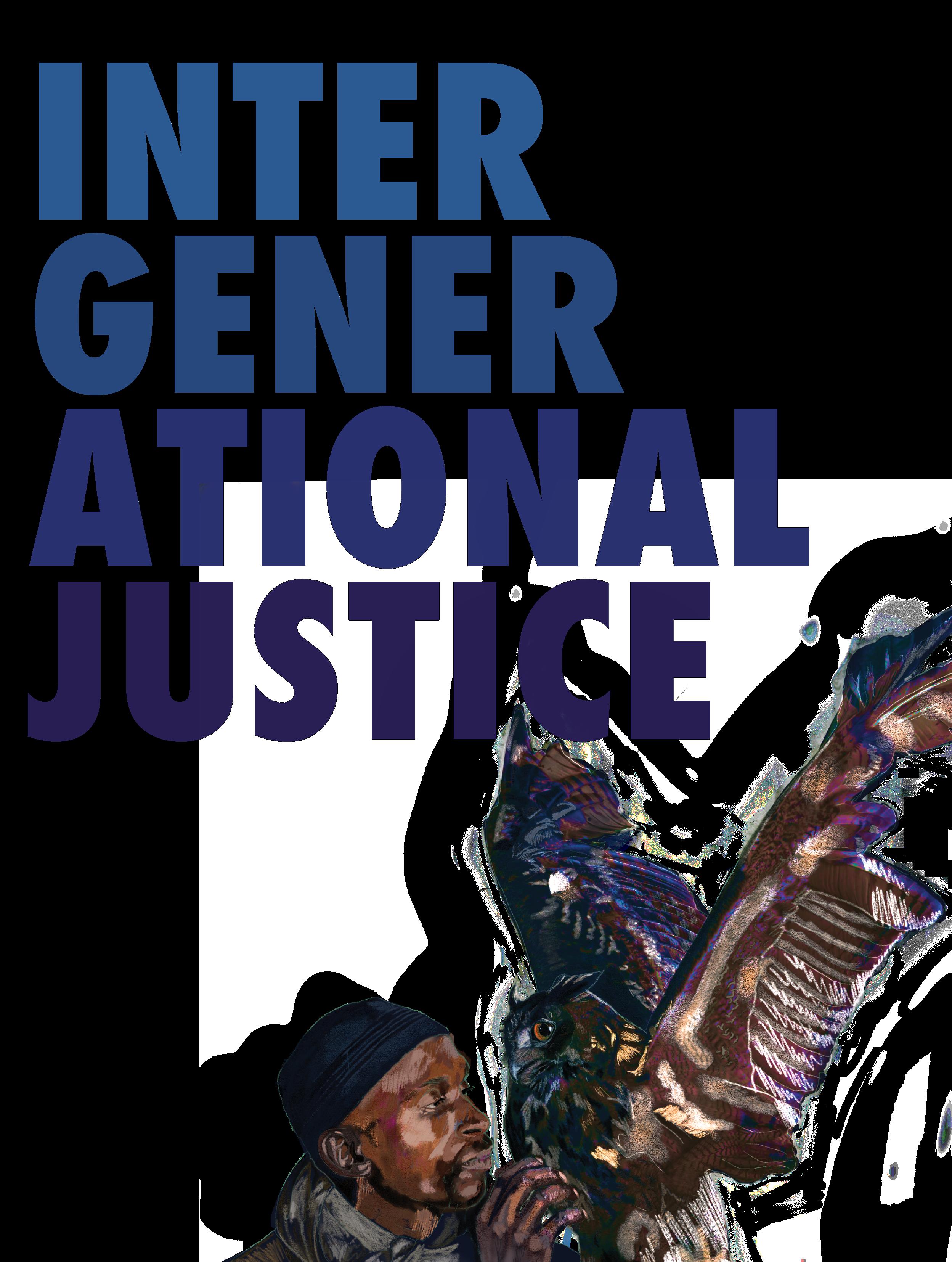

Voices on the Environment: Intergenerational Justice

Earth Day with Earth Commons: Bird Brother Rodney Stotts and more

We Hear You: A Climate Archive on a Global Stage

By Justine Bowe, Marion Cassidy, C’23 and Alannah Nathan, SFS ‘24

By Justine Bowe, Marion Cassidy, C’23 and Alannah Nathan, SFS ‘24

Common Home Arts Showcase: Georgetown Students

Awarded in First Annual Juried Event

The Black Side of the River: Race, Language, and Belonging in Washington D.C. by Jessica Grieser

Review by Jan Menafee, Program Specialist for Environment, Justice, and Education at the Georgetown Red House at Georgetown

Once There Were Wolves by Charlotte McConaghy

Review by Maya Snyder, SFS ‘24

Fueling Mexico: Energy and Environment, 1850-1950 by German Vergara

ByMarion Cassidy, C’23 with awardees Isabella Callagy, C‘23; Dany Garza Mendoza, MSFS ‘23; Peris Lopez, SFS ‘23, Victoria Smith C’22; Shelby Gresch C’22, and Alexandra Bowman C’22

To Plan a Family: Children, Hope, and the Climate Crisis

By Sadie Morris, SFS ’22 with playwright Melissa-Kelly FranklinSafeguarding the Future Generation: Climate Action on Behalf of Children’s Health

Review by Professor John McNeill, Edmund. A. Walsh School of Foreign Service & Department of History at Georgetown

Statehood Denied: the Burden on the Environment and DC’s Minority Residents

By Sadie Morris, SFS ‘22Climate Migration: the Change We Aren’t Talking About

By Malina Brannen, C‘23 By Emily Prest, GSAS ‘23with Joan

Lombardi, Senior Fellow, Georgetown Collaborative on Global Children’s IssuesDoes Nature Have Rights?

When Tensions Simmer, Too: Climate-Conflict Crossovers in Syria, Ethiopia, and Ukraine

ByElsa Barron, Program Assistant at the Center for Climate and Security

BySadie Morris, SFS’22 with Hope Babcock, Professor at Georgetown Law & Director of the Institute for Public Representation

Ingredients of a Sustained Research Program

Consequences on the Global Energy Transition in the Wake of Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine by Professor David Bailey, Edmund. A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown & Senior Advisor, Climate Leadership Council

By Robert Groves,Provost and Gerard J. Campbell, S.J. Professor in the Math and Statistics Department and Sociology Department at Georgetown

The Devil and Gaia: Film Reviews of the DC Environmental Film Festival

By Maya Snyder, SFS ‘24and

The Problem with Recycling

By Alexa Boglitz, C ‘24 Alannah Nathan, SFS ‘24Cover Art “Childrens Vulnerability to Climate Risks”

by Alisa SingerThe Energy Transition Calls on All of Us: Overcoming Education Silos at Georgetown and Beyond

ByChiara

Pappalardo,Doctor of Juridical Science Candidate & International Economic Law Fellow at Georgetown Law

Reimagining Cities: the Future of Urban Planning

Professor Christopher Pyke, Urban & Regional Planning Program at the Georgetown School of Continuing Studies with Mark Agard, SFS ‘23

Alannah Nathan

Junior in Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service studying Global Business with a minor in French. Her interests in the environment space include the energy transition, climate economics, and sustainable economic development. Born and raised in Seattle, WA, she now calls Brooklyn, NY, home.

Marion Cassidy

Marion Cassidy is as Senior in the college studying History and Art History with a minor in Theater and Performance Studies. She is from Brooklyn, NY and is passionate about the intersection of sustainability and the arts.

Sadie Morris: Originally from Northern California, Sadie graduated in May of 2022 from Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service studying Culture and Politics with a focus on political economy and the environment.

Maya Snyder: Junior at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service, majoring in Science, Technology, & International Affairs and minoring in English. Originally from San Diego, California.

Mark Agard: Mark is a Senior at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service, majoring in Science, Technology, & International Affairs with a minor in French and Environmental Studies. His hometown is Vancouver, Washington.

Voices on the Environment is a multi-year event series at the intersection of science, the humanities and the arts with the environment at its core.

This year’s theme, “intergenerational justice,” focuses on the duties that present generations have towards future ones. The series links environmental journalism, literary writing, activist performance, and critical approaches to climate change, among other channels.

Through the lens of justice between generations, climate change raises particularly pressing issues. Which risks should people living today be allowed to impose on future generations? How could available natural resources be used without

threatening the sustainable functioning of the planet’s ecosystems? We are confronted with the urgent ethical issue of how to balance the rights of future generations with those of today.

Collaborators include the Earth Commons, the Georgetown Humanities Initiative, the Lab for Global Performance & Politics, the Office of Student Equity & Inclusion, and the Office of Sustainability.

How might Georgetown’s sustainability plan align with Indigenous philosophy? The Office of Sustainability explored this question with Georgetown Professor Shelbi Nawhilet Meissner, who specializes in American Indian and indigenous

philosophy, particularly as it relates to language, knowledge systems, and power.

The discussion explored how the sustainability plan might center indigenous philosophy, and steps forward for future relationships with the university, the environment, and the community.

Bird Brother: Dialogue with a Bird Expert & Environmentalist

Earth Commons hosted Rodney Stotts, a master falconer and a licensed raptor specialist and – to the great appreciation of the attendees – several of his raptors. With mouths agape, Georgetown students gazed into the dark eyes of a peregrine falcon, XYZ perched on their extended arms, talons holding their muscular bodies steady.

While Mr. Stotts’ raptor demonstration was a once-in-a-lifetime event, the participants learned falconry does not only impart awe; it’s a powerful force for positive change.

Conservation is a key driver for Mr. Stotts, who infused the community event at Georgetown with deep knowledge and discussion of his recent book. Falconry can strengthen raptor populations and keep the population healthy, he shared.

D.C. is home to numerous species of birds of prey, from the falcon family (Peregrine falcon and American Kestrel) to the hawks (such as the Cooper’s hawk, red-tailed hawk), harriers, kites, and our national bird, the bald eagle, but most DC residents are unfamiliar and disconnected from the species. As Mr. Stotts bringsbringing people face-to-face with raptors, he builds a bridge to caring, and conserving, the special birds.

Mr. Stotts is as passionate about contributing to his human community, particularly in mentoring youth in Southeast Washington D.C., as he is about strengthening the raptor communities. Mr. Stotts (who is fondly called the Bird Brother”) was drawn to falconry because it is a conservation pursuit that could cut across barriers of color, socioeconomic levels, and ethnicities. As he discussed with Dr. Adanna J. Johnson, Associate Vice President for Student Equity and Inclusion, Mr. Stotts sees a powerful connection between endangered species of all kinds and local youth who navigate survival in stressed communities.

He founded his organization Rodney’s Raptors to channel the excitement of holding a raptor into transformative opportunities for youth. The D.C. based group creates interactive and educational programming that connect young people to the environment and their community. Through Rodney’s Raptors, Mr. Stotts turns what could be a fleeting moment into a long term impact; “Falconry can help build character, compassion and caring. Its importance is immeasurable. It changes lives.”

A land acknowledgement, as the event helped inform students, is a written statement that recognizes and respects that Indigenous Peoples are traditional stewards of a particular land. Georgetown’s Shelbi Nawhilet Meissner asked student-generated interview questions on the topic to Hayden King, Executive Director of the Yellowhead Institute and Advisor to the Dean of Arts on Indigenous Education at X University. The conversation explored what land acknowledgements mean in today’s political climate and how or if they can be improved.

The two experts in Indigenous thought addressed the philosophy and practice of land acknowledgement today. They investigated the diverse meanings of “acknowledgement.” The word carries multiple definitions; on the one hand, a statement of truth that is legally binding; on the other, merely a gesture, which may be empty.

The practice of land acknowledgements – and acknowledgement more broadly – might deepen material practices of repair, restoration, and responsibility towards the land and its rightful inhabitants. How might that relationship deepen?

The Earth Commons, Dramaten (The Royal Dramatic Theatre of Sweden), The Embassy of Sweden in Washington, DC, and The Laboratory for Global Performance and Politics launched We Hear You—A Climate Archive, co-conceived by Earth Commons Artist in Residence Caitlin Nasema Cassidy and Jacob Hirdwall.

Inspired by Greta Thunberg’s urgent question “Can you hear me?,” this project sought to amplify—and to record for future generations—the ways that today’s young people are experiencing changes in the fundamental forces of the earth. We Hear

You—A Climate Archive included a two-year series of curated international performance and the launch of a digital platform for global climate storytelling. In addition to these public programs, the project also involved curricular engagement with students at Georgetown University.

The performance series officially launched with an evening of climate storytelling on Friday, March 18 at the COAL + ICE exhibition presented by the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts and Asia Society. An ensemble of DC-area youth artists and activists presented an original performance

weaving their own experiences with the words of Greta Thunberg.

Following its launch in DC, We Hear You—A Climate Archive is commissioning 77 additional stories from young people around the world. These commissions will inform the launch of a digital platform for global climate storytelling, as well as a multi-year international curated performance series, culminating in a performance at Dramaten directed by Jacob Hirdwall.

We Hear You—A Climate Archive opened the United Nations Stockholm+50 June 1 plenary at Stockholm University. The performance featured Razmus Nyström and Melinda Kinnaman from The Royal Dramatic Theatre of Sweden with text by Greta Thunberg, Lilli Hokama, and Jacob Hirdwall and direction by Jacob Hirdwall.

“We need stories about what we love and stand to lose,” says Cassidy. “In this time of global crises, I know I need stories that deliver joy, that offer me ways to root in wisdom and move forward in hope. We Hear You—A Climate Archive is asking: How can we hear the young folx—the artists and activists doing the work of imagining more liveable futures? What can we learn from them—from one another?”

We Hear You—A Climate Archive grows from the performance We Hear You—Greta Thunbergs Tal, originally presented at Sweden’s Royal Dramatic Theatre in Stockholm on January 31, 2020. Staged by Jacob Hirdwall and Ada Berger, this performance drew on the texts of Greta’s speeches collected in No One Is Too Small To Make a Difference (Penguin, 2019).

Reflections from attendees

I hadn’t realized how much I need to be thinking about climate change. The only time I typically see the word climate change is in a meme or an existential-crisis joke so it was really moving to hear young people talk about 1) that there’s hope 2) that we need to do something about it. My favorite moments were the ones where the performers were talking about their hometowns and what parts of nature were most important to them. It put me back into my childhood and my backyard. They spoke about there being pieces of nature and specific memories that held a place in their heart. They carry them with them amidst all the negative talk about climate change and the demise of the world. I really relate to that.” –– Maddie Gaeta, COL ‘22

“Hearing the five youth voices and their different perspectives was very engaging. They did a good job tying it into Greta Thunberg’s speech. I really enjoyed how each performer incorporated a sense of place and home that they brought to the stage and their roles and really highlighted the universal nature of the climate crisis.” –– Jack Healy, SFS ‘23

“Two themes especially resonated with me: what the activists felt was their “call” to activism (which so varied) and what the role calls of them. Being an activist, I learned, is telling the truth. The activists were fighting for something, rather than against it; this repositioned what I think of activism. They expressed how taxing and scary it is to be in this space, and deal with pain from hundreds of miles away. While it is so inspiring to hear them, they felt at times they never felt like they were doing enough. Our fellow editor at Common Home – Sadie Morris – just wrote about this last issue, so hit home on a few fronts.

The setting drove these sentiments home for me. The performance was in a tent on the lawn/patio of the Kennedy Center. It was so much better than being in a typical theater with no access to windows, fresh air, etc. To be able to hear birds, alongside motor boats on the Potomac emphasized the duality of our natural world as one that is beautiful but also one that we are constantly invading and changing. Listening to the activists speak while hearing planes above and being reminded of the fuel used in travel was certainly self-reflective and something tricky for me to reconcile.”-

Marion Cassidy, Common Home Editor

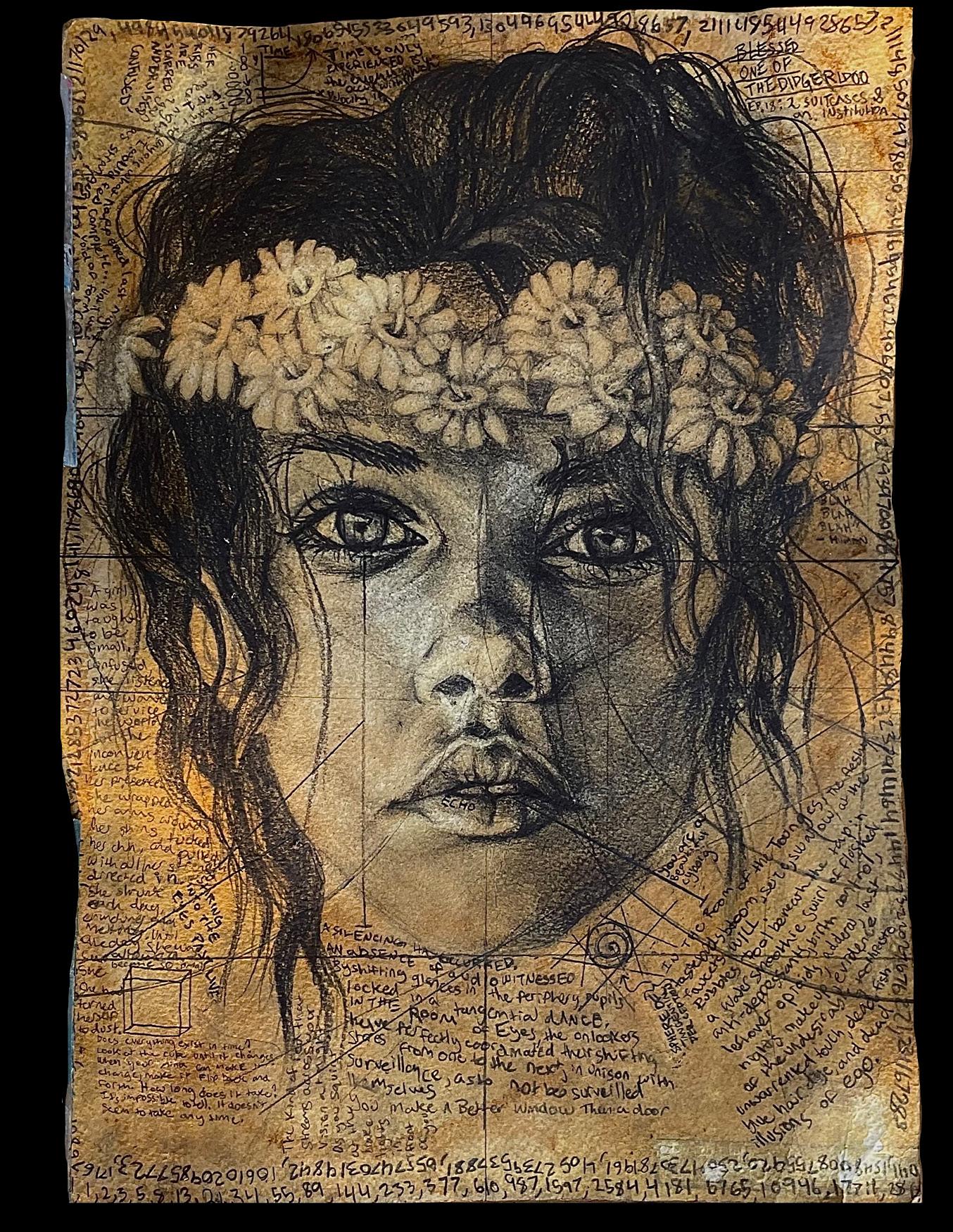

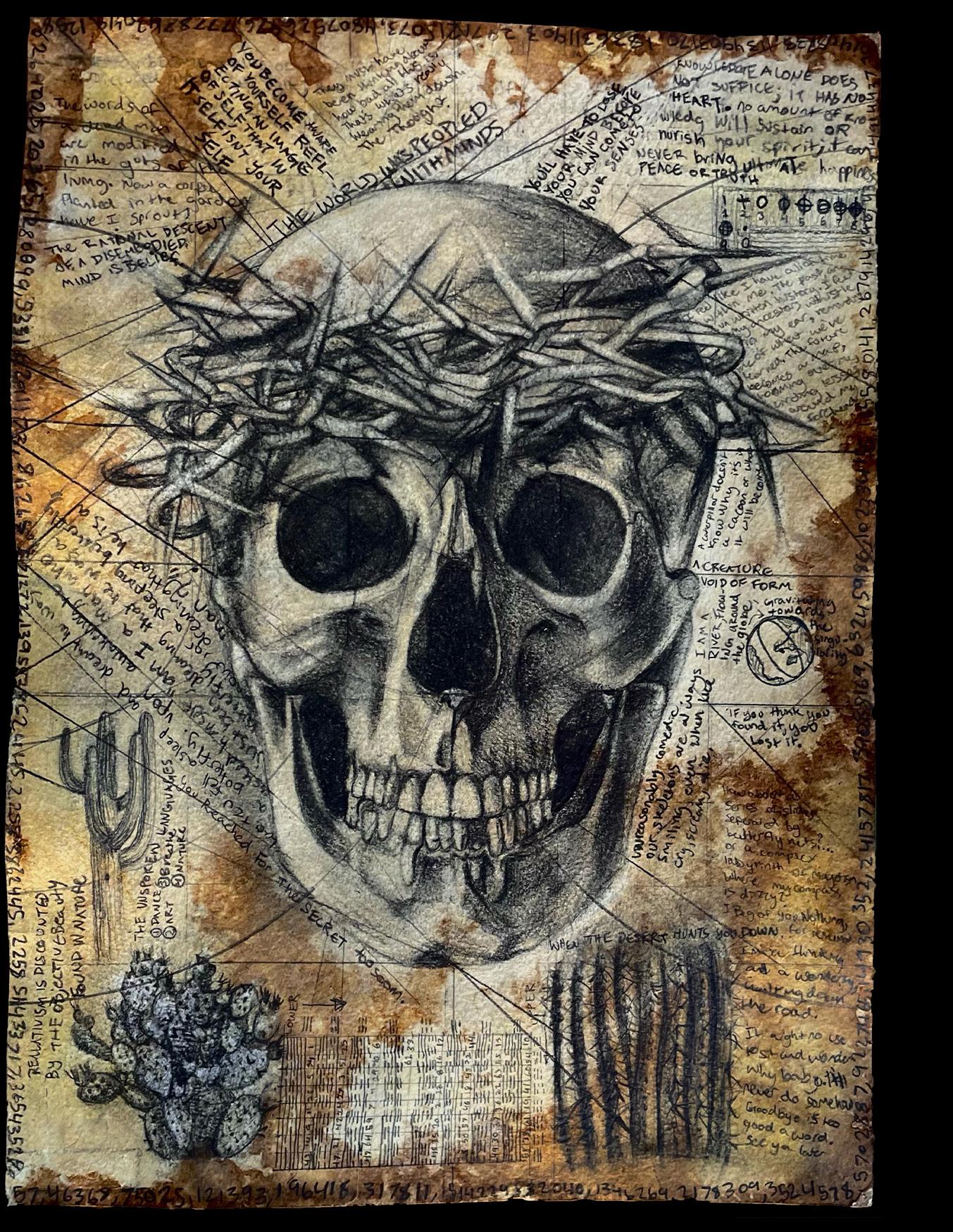

In 2022, the Earth Commons and its signature Common Home magazine welcomed the Georgetown community to express their feelings in a changing world, infuse environment and sustainability thinking throughout the university, and showcase the diversity of talents and perspectives in the community by submitting to the Common Home Arts Showcase.

Theme. The year’s inaugural theme, in conjunction with the institute’s collaborative “Voices on the Environment” series, was “Intergenerational Justice.” Top submissions link the theme of intergenerational justice with the environment through highly original, compelling artwork that conveys a strong message and sparks discussion about the environment and our relationship to it. “Intergenerational justice,” focuses on the duties that present generations have towards future ones. Climate change raises particularly pressing issues, such as which risks those living today are allowed to impose on future generations and how available natural resources can be used without threatening the sustainable functioning of the planet’s ecosystems.

The showcase featured 2 categories, the first, “Traditional,” includes graphic/studio arts, such as photographs, paintings, and digital drawings); the second, Freeform, includes written and multimedia arts, such as poems, videos, audio and filmed performances.

“A Black Future” by Dany Garza Mendoza (opposite)—Traditional Category Dany Garza Mendoza (MSFS Candidate ’23) earned second place in the “Traditional” category for her painting. “My piece is called ‘A Black Future,’ and it’s inspired by the Deepwater Horizon BP oil spill in April of 2010,” writes the painter. “The artwork is meant as a warning: a visual representation of the

devastating effects that humans have had on our planet, and the potential future if we continue with the status quo.

“Holding On” by Isabella Callagy (above) —Traditional Category Isabella Callagy (C’23), won first place in the “Traditional” category for her painting, “Holding On” (oil on canvas). The painter wrote of the piece; “it resonates with the dangers posed by climate change around us today, most notably water in our world. The piece places importance on hands trying to grasp onto water, only further connecting the impact of humans on climate change. The piece recognizes that climate change disrupts our world and dangerously affects humans in many parts of the world. This composition ties together art, healing, nature, and disaster. As human beings, it is our duty, especially my generation, to protect our planet and those around us; every small handful of clean water is vital to the survival of children, adults, and the older generation in our world. As a result, water is life.”

Second place, Freeform category

The planterbed flowers are bolder than I

Or perhaps just more naive

Undressing and sharing their color with the pale spring sky

Unafraid of another freeze

Unaware the seasons aren’t dependable anymore

Still

I smile down and greet them

Like the old friends that they are

Forsythia, daffodil, hyacinth

The chosen ones I learned from the nursery

And planted with my dad

I wonder where they grow wild

Anywhere?

The crocus and bluebell and buttercup

Are less ruly

They dance in the yard and play hide and seek

In the woods of Rock Creek Park

All delights.

The environmentalist to nihilist pipeline

Scares me. Better to not see

The magnolia bravely let her guard down

And rejoice until I remember

That urban trees live shorter lives

Than their wild relatives

It is risky to root for the underdog

I think gardens are beautiful

But will I feel that we lost if they’re all we have left?

Probably.

Perhaps the caged tree is a sacrifice

Perhaps the picture of resilience

Who am I to say

I don’t plan to bring children into such an uncertain world

But if I did

I would want to introduce them to the bluebells

So they could learn

To bloom on their own terms.

“The Humans Are Destroying Earth For Us” by Alexandra Bowman (righ)—Freeform Category. T he third place submission in the “Freeform” category is “The Humans Are Destroying Earth For Us” by Alexandra Bowman (C’22), digital media, 2021. An accomplished illustrator, Bowman often explores climate issues in her vivid digital cartoons. The illustration was originally created for Our Daily Planet.

“Female Faces of Change” by Victoria Smith (right)— Freeform Category. T he first place submission for the “Freeform” category is a collage by Victoria Smith (C’22) that features black and white photographs, pen and ink, and faux flowers. The collage depicts women who have been instrumental in environmental advocacy, including Eunice Newton Foote, a scientist and feminist whose research in the 1800s predicted the impact of greenhouse gases. “Foote was a pioneer in the environmental and women’s rights world,” Smith notes, “so I wanted to connect her to women in the present day as this journey is all connected with many different branches for people to take,” she wrote. “Many more women to come will be part of this intergenerational journey for climate justice.”

“The Self Through Time” by Peris Lopez (following pages)— Traditional Category. Peris Lopez (SFS ‘23) earned third place in the “Traditional” category with this diptych drawing created on paper soaked in water, dirt creosote, mesquite leaves, and other desert plants. Peris explained “this work begins with the paper, soaked in a mix of water, dirt, creosote, mesquite leaves, and other desert plants. After toning the paper with life grown from my home in Tucson, Arizona, my family’s home for at least the past 6 generations, I started drawing. The drawing was inspired by the eternal cycle of time, from death to rebirth. This diptych drawing brings human life and death together with the other lifeforms sustaining us to depict the beauty that exists in the patterns of our natural world. ”

By Sadie Morris, SFS ’22 & Common Home Editor

By Sadie Morris, SFS ’22 & Common Home Editor

Like the Cold War generations worried about the ethics of bringing children into a world of nuclear threats, young people today are asking serious questions about having children in a future shaped by the climate crisis

As each new IPCC report warns of humanity’s quickening descent into disaster, celebrities, politicians, and everyday people have publicly discussed whether it is ethical to have children. In 2020, the Morning Consult found that 25% of childless adults were factoring climate change into their reproductive decision to not have children, and 33% of 20- to 45-year-old adults cited climate change as a reason they had or expected to have fewer children than they considered ideal.

The data is clear that population size drives resource consumption and climate-driven hardships are exponentially increasing. But how should those prospects weigh into the profoundly personal decision of having children?

Professional ethicists offer guidance through the lens of morality and philosophy, but they reach vastly different conclusions. In the extreme, anti-natalist philosophers unequivocally find

life on a dying planet a nonstarter for childbirth. The Voluntary Human Extinction movement, for example, believes people should voluntarily “cease to breed” to improve “crowded conditions and resource shortages.”

Other philosophers question how many children it is ethical for a family to have by weighing the environmental impact per child born. In the 2016 book One Child: Do We Have a Right to More? philosopher Sarah Conly argued that “the foreseeable harm from population growth seems to make unlimited procreation too dangerous to be something that can be protected as a right.”

Climate change and sustainability researchers Seth Wynes and Kimberly Nicholas evaluated hundreds of lifestyle scenarios to reduce one’s carbon footprint. Having one fewer child was the single most impactful action, at 58 tons per carbon dioxide equivalent. The scale was striking, at 24 times greater carbon impact than living car-free and 72 times that of eating a plant based diet.

Yet, four years later Nicholas reversed her claim in her book

Rehearsal of the playUnder the Sky We Make: How to Be Human in a Warming World. She argued that given the timeline on which climate action needs to take place, the decision to have kids is really not that consequential. If someone wants to, they should go for it. Talk about an existential crisis: In her take, even one’s biggest, most personal life decisions have no impact.

Nicholas’ flip-flop speaks to the limitations of what an ethicist or data scientist can say about having children. Academics can point to the facts on either side of the argument but they fail to speak to the core underlying question of whether to have children: Do you have hope for a better world?

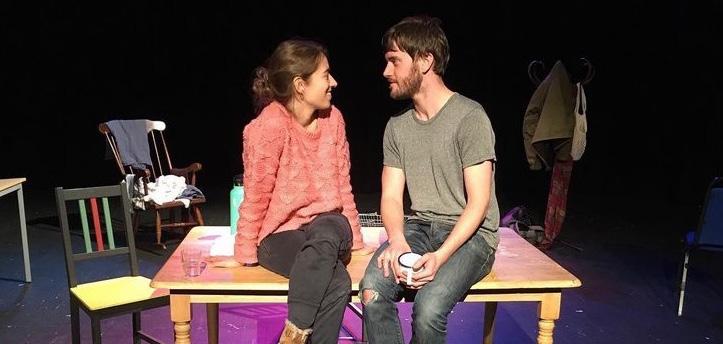

When it comes to amorphous questions like hope, art can often take us where philosophy falls short. Common Home reached out to writer Melissa-Kelly Franklin, whose play We’ll Dance on the Ash of the Apocalypse harnesses the power of art to tackle these morally-fraught issues.

The play is set in the unspecified future where the climate emergency (as it is often called in Franklin’s home country of Australia) has displaced millions. Disruptions wrack food chains, medical access, and the basic fabric of society. On a stripped-down set, a young activist couple learns that one of them is pregnant and they must decide whether to give birth.

When Franklin began writing in 2018, she foresaw a future that echoed historical movements; on the horizon, the rise of climate protests and concurrent authoritarian government that closed universities, museums, theaters–“places where people gather to share ideas.” Ironically, as she wrote, mass climate movements arose globally–Sunrise Movement in the U.S., Extinction Rebellion in the U.K., among others–but a global pandemic cracked down on protests before governments did, closing for two years the communal spaces of sharing and protesting.

As she saw her original themes play out in real life–and worked with the lead actress who actually became pregnant–she began to see her play as less about protest and more about “hope, defiant hope, and clinging on to that hope. Not a vain hope that someone somewhere is going to do something about it, but hope that’s going to give us the energy to keep fighting for the future that we all want to secure for each other.”

The play was partially born out of conversations with Franklin’s partner, a scientist. They were frustrated with “how it was quite difficult to emotionally engage people in these scientific questions and the thought of, what would it take in a storytelling capacity to emotionally engage people?” They concluded: “Think about the ultimate symbol of the future, which is children.”

Franklin entwines the couple’s decision with other issues in the not-too-distant-future world. This effort at intersectionality nuances both the characters’ decisions and the audience’s

experience of imagining the future in a “visceral, emotionally raw way.” Franklin sought to “incorporate how the climate emergency is going to impact all of us to varying degrees based on race, gender and where we are geographically in the world. I felt that it was really important to explore how the climate emergency might impact women uniquely, compared to men, particularly when it comes to women’s health and access to reproductive health care.”

At the same time, Franklin intentionally left the play devoid of defining details like character and location names, so that it could be adapted anywhere in the world. The playwright worries “about the carbon footprint, taking the theater piece internationally and touring;” so, the current ambiguity leaves open the door for “other versions and different interpretations that could be translated,” anywhere in the world. The Icelandic version is already in the works.

As Franklin brings the play out into the world, she has found that people “recognize themselves in these characters and recognize the conversations that these characters are having.” The reception inspires her. “That so many people experience these anxieties and feelings makes me feel less alone. That brings some sort of kind of comfort in solidarity.” This ultimately is the hope that Franklin has for her play–and what she has begun to see come to fruition. “I’m hoping that if we can come together as communities through sharing these conversations and ideas with other people in our lives, that may lead to making decisions about what one can do on a personal level. It’s as the young woman says in the play, ‘it’s not just about doing all this on a huge global scale; it’s also about doing what I can in my little patch. I might not be able to stop the ice caps melting, but I can help make my corner better, greener, happier.’”

But, what does the play offer for those in the audience still wondering whether it is ethical to have children? Ultimately, Franklin says, “I don’t think the play seeks to answer that question. But I think thinking about what the future might look like for anyone who comes after us is a really important one. I see the exploration of family planning in the play as a symbol for the future, and kind of a broader conversation about the legacy that we’re going to leave.”

As I consider the existential threat that climate change poses to mine and future generations, I am left with the words of the male protagonist echoing in my head: “Yes, fear keeps us alive, it makes us run; but without hope, it’s a paralytic. Hope gives us something to run to.”

Melissa-Kelly Franklin is a writer and director based in London and Sydney. She has received international recognition for her independent film and theater. We’ll Dance on the Ash of the Apocalypse is currently being performed in London at the Come What May festival.

Children bear the most severe threat that climate change poses to humanity. The children of today and tomorrow are inheriting a world riddled with poverty, food and water insecurity, illness and environmental degradation–all of which climate change will further intensify.

Children often find themselves in vulnerable positions wherein–on a physical level–their bodies are not as resilient to environmental stressors like adults, and–on a political level–they lack the agency and political influence to successfully advocate for combating climate change and ensuring a decent future for themselves.

Climate change can increase a child’s exposure to allergens, extreme heat, insect-borne disease and contaminated water, creating greater risk to the developing child by threatening sickness or death. Further, undernutrition is likely to be the leading cause of child mortality resulting from climate change.

Children growing up in developing nations are even more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. These countries are the least responsible for the volume of legacy global greenhouse gas emissions yet find themselves more vulnerable to the negative effects of climate change. The children of low-and middle-income countries will have to face greater “damage to health and human capital, land, cultural heritage, indigenous and local knowledge, and biodiversity as a result of climate change.”

Some effects of climate change are already being felt across children today.

• In 2019, 80 million people–30-34 million of which were children–were displaced due to conflict, climate change, and natural disaster.

• It is also estimated that at least 33 million people–16 million of which are children–in East and Southern Africa are at emergency levels of food insecurity due to climate change.

• The circumstances surrounding our changing climate are not at the fault of children, yet in a survey of 10,000 children and young people across the globe, over 50% of respondents reported the emotion of “guilty” in association with climate change.

• The stressors of climate change are evident and climate anxiety is prevalent across our children, causing acute psychological distress.

We are faced with a critical threshold; if we manage to stay at 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, we could avoid the more severe and intense climate impacts that 2 degrees Celsius would deliver. To do so, carbon dioxide emissions need to be reduced by 45% by 2030 and reach net zero emissions by 2050.

The fate of our world is contingent upon how well policymakers–alongside citizens and business–across the globe respond to this irrefutable science.

While much work needs to be done, some steps are being taken to raise awareness on the impacts on children.

• In 2021, the United Nations Child Rights Committee ruled that “emitting states are responsible for the negative impact of the emissions originating in their territory on the rights of children–even those children who may be located abroad.”

• Efforts to include the climate crisis within educational settings and academic curricula are also making headway. Summits, such as the Glasgow Climate Education Summit, are being organized to better brief policymakers and researchers on how to thoughtfully address and incorporate climate into meaningful conversations.

• Some of our world leaders have also pledged to consider children more carefully in climate change discussion. In 2019 and the 25th United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change of Parties, 28 member states signed the “Declaration on Children, Youth and Climate Action,” pledging to “accelerate inclusive, child and youth-centered climate policies and action at national and global levels.”

• In the United States, detrimental environmental impacts associated with children’s health were emphasized on a federal level via President Bill Clinton’s Executive Order on the Protection of Children from Environmental Health Risks and Safety Risks. Under this Executive Order, all federal agencies are required “to assign a high priority to addressing health and safety risks to children, coordinate research priorities on children’s health, and ensure that their standards take into account special risks to children.”

Further in 1997, the Environmental Protection Agency’s Office of Children’s Health Protection was established, armed with the goal “to ensure that all EPA actions and programs address the unique vulnerabilities of children.”

Children have also been taking a stand, fighting for their rights by protesting and starting youth-led organizations aimed towards tackling the climate crisis.

• In Zambia and Zimbabwe, adolescent girls produced a research paper analyzing the impact that climate change has on a girls’ education, to which they found that floods, shifting rainfall patterns and recurring drought will likely result in increased school dropouts and early and forced childhood marriages in the region.

• In the Caribbean, young women and girls are being mentored on the intersections between climate change, youth advocacy and the global feminist agenda, and what that means for their respective communities.

• Internationally, through groups like Fridays for our Futures, Zero Hour, and Extinction Rebellion Youth, children have organized protests and increased accessibility to the climate movement to make their voices more widely heard while calling on governments to take greater action.

Children will unfairly have to manage and adapt to a world ravaged by runaway climate change. They should not have to pay the price of our costly, selfish, and unsustainable habits that have forced the most adverse effects of climate change upon unwilling and unsuspecting future generations.

When it comes to climate awareness and advocacy, the voices of our children should not be dismissed, but rather amplified. These children have traded their naivety as our world falls victim to a changing climate, trying to fill the gap that policymakers across the globe are failing to properly address. Protecting them is, at the most basic level, a moral obligation–and one we are falling short at fulfilling.

Emily Prest is a second year Master’s student at the Environmental Metrology and Policy (EMAP) Program at Georgetown’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, and a Student Fellow at the Georgetown Collaborative on Children’s Issues.

Joan Lombardi is a senior scholar at the Center for Child and Human Development and was the Deputy Assistant Secretary, Early Childhood Development, at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. She is a Senior Fellow at the Georgetown Collaborative on Children’s Issues

By Sadie Morris, SFS’22 & Common Home Editor

By Sadie Morris, SFS’22 & Common Home Editor

With Hope Babcock, Professor of Law and Director of the Institute for Public Representation at Georgetown

With Hope Babcock, Professor of Law and Director of the Institute for Public Representation at Georgetown

Looking out on a sea of sleepy-eyed first-year law students in his University of Southern California property class, Professor Christopher Stone posed the question for which he would become famous, mostly just to keep his students’ foreheads from hitting the desks: Should trees have legal standing?

This was a revelatory question because in the U.S. an entity must be able to prove standing in order to bring a lawsuit. It’s historically reserved for humans and the human-adjacent, not trees. Standing is a legal doctrine adapted from English common law and enshrined in Article III of the U.S. Constitution.

A party may only bring a lawsuit if they demonstrate that they personally have suffered actual or threatened injury that can be traced to an action by the opponent party. When it comes to cases involving threats to natural features (such as trees), litigants (humans) traditionally must prove some connection between themselves and the threatened resource.

For example, if someone wanted to stop the dredging of a

wetland by applying the Endangered Species Act, they would have to demonstrate that harming the wetland ecosystem would affect their own quality of life, such as through losing enjoyment of the land. This connection can be hard to prove.

While irreparable harm to a natural phenomenon is usually scientifically demonstrable or even visible to the naked eye, it often requires imagination, and turns of logic, for a litigant to place their own detrimental impact at the center.

Even as environmental lawyers rejoiced at the passage of major legislation–such as the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, and the Endangered Species Act– in the 1970s, , their actual efforts have continuously been stymied by the failure to prove standing; environmental cases are consistently thrown out of court before the merits of the case are even heard.

To avoid this legal dead end, Professor Stone argued that instead of trying to finesse a way for humans to prove standing on behalf of nature, nature itself should be recognized as an entity that could bring cases. After all, the actual injury to nature is able to be proven scientifically and is often visible to the naked eye.

Traditionalists argue that opening the door to “inanimate objects” such as rivers, wetlands, and trees, would open the doors of the court for anything to walk through (though not literally of course). Moreover, a view of nature that imbues natural beings with legal standing would represent a dramatic reconceptualization of the relationship between humans and nature. Such a view would put the two on an even footing. Lawyers unprepared to see such a radical transformation within one of the most conservative institutions in the United States argue that the proper venue for such arguments is within the political realm of the legislative branch.

In fact, the more far-reaching cultural question of personhood for nature has been a political and social question central to Indigenous struggles for decades. Legal battles around standing have played out only a few times in U.S. courts: namely, in the 1972 Sierra Club v. Morton suit that skyrocketed Stone’s question and later article to fame, the 2005 case involving the Little Mahoning Creek in Pennsylvania, and most recently a Florida suit to protect Lake Mary Jane.

However, Indigenous Nations in the U.S. and globally have begun a struggle for the more encompassing, transformative

legal idea often shorthanded the Rights of Nature. The Earth Law Center describes the idea as “a holistic worldview in which human beings and natural entities are interdependent and connected beings, [which] recognizes that Nature has a value in herself…[it] is promoting a shift in our collective consciousness of our relationship with Nature, and transforming the ethics, values and beliefs that underlie our legal, governance and economic systems.”

Indigenous tribes in Ecuador lead the way in 2008 when they instigated the first national movement to amend the constitution to include a recognition of the rights of nature. They succeeded. The new Ecuadorian constitution recognizes the rights of Pachamama (a term for Mother Earth used by the Indigenous peoples of the Andes) including the right “to exist and to maintain and regenerate its cycles, structure, functions and evolutionary processes” as well as the “precautionary rule” meant to protect natural resources even when it is not one hundred percent clear the impact on the environment.

This sweeping step has inspired other nations to follow suit. Panama legally recognized the rights of nature this year and Chile is currently redrafting its constitution with a new article for nature’s rights. In 2017, New Zealand, which relies on a

common law legal system like the U.S., recognized personhood for the Whanganui River in a landmark move collaborating with Indigenous tribes to establish guardianship for the river.

In the U.S., Indigenous groups have largely worked within the national legal system but recently have embraced the Rights of Nature movement to enshrine in law their traditional Indigenous conceptions of the human-nature relationship. In Minnesota, the Ojibwe tribe is suing on behalf of the rights of Manoomin, a species of wild rice that is threatened by the Line 3 pipeline.

Inspired by the tribe’s efforts, in 2019 the Yurok Tribe in Northern California adopted a resolution recognizing the rights of the Klamath River. And in Seattle, the Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe is suing the city over its hydroelectric dams on behalf of salmon.

Nonetheless, while the struggle for a more comprehensive re-evaluation of the status of nature in the legal system is underway, the question of standing for natural beings remains a potential way to use the current legal system to better protect the environment where human voices fall short.

~~~~~~~

In the year of the fiftieth anniversary of Stone’s seminal article, Common Home student editor Sadie Morris sat down with Georgetown Law professor Hope Babcock to talk about the impact, implications, and future of Stone’s question. The conversation soon wove into one about the future of environmental litigation at large.

Common Home: Here we are fifty years from Stone’s 1972 article, Should Trees Have Standing? What are your initial thoughts about his piece at this point in time?

Hope Babcock: Despite its great promise, very little has happened with Stone’s article. It has not been cited often by law professors, let alone by courts. In spite of the excitement we all felt when it came out, nothing has happened. The question I am currently exploring in my new piece for the anniversary of Stone’s article is why has this line of thought stalled?

CH: It’s interesting to hear you so unequivocally say that little has happened with Stone’s piece in the U.S. even as the international Rights of Nature movement has picked up steam. What makes the U.S. different?

HB:The idea that a tree could go to court and demonstrate it has been injured has been a nonstarter for a lot of folks. It seems to me that the barrier in the United States, for reasons that I am now exploring, is much higher than in other countries. So you find that yes, the idea has more viability outside of the United States, although it is not unchallenged.

CH: Even though the current ethos in the U.S. regarding nature is likely to make a constitutionally enshrined version of the Rights of Nature impossible, you have suggested in the past that there are other extensions of rights to non-humans already in U.S. law that provide apt parallels. Can you elaborate on that?

HB: Yes, in the U.S. we have given inanimate objects, namely corporations, rights. So I said, coming from an environmental perspective, well, of course, we’re so business-oriented that if corporations are trying to get into court and there is this obstacle of standing, the courts will quickly climb over it. But when it comes to animals or trees or whatever, they aren’t willing to do it, even though the door opens up the minute you say non-humans can get rights. The concern had been the courts wouldn’t want to open the door at all, but they opened the door. But I think the courts fear that if it’s outside of that now sphere of injury, they will lose control and the courts will

be swamped with cases. I say the same rules would apply to an animal as applies to a corporation.

The question is the capacity to stand up in court and whether the court will allow representatives of guardians to speak and they do, again, in the case of corporations. Why is it so hard to do on behalf of a noncommercial interest? A tree, a fish, a wolf, etc? Why can a corporation go to court? But a whale can’t go to court? Corporations can’t speak. Whales can’t speak. Corporations can’t think well, so they’re also dependent on a guardian.

As you alluded to, there are some countries that have given rights to nature in their constitutions. Would we ever do that? No. Why? Well, it gives too much power to nonbusiness interests. And, if I want to think as a proceduralist or a law professor, it gives an open invitation to all kinds of abuse, which means the courts are going to have to work really, really hard to keep a lot of stuff out of their chambers or out of their office, or

their courtrooms.

It is interesting to compare the environmental situation to what happened during the civil rights movement because there was a sense that with the new civil rights legislation, every Dick, Harry, or Jane could bring a claim, suddenly, on an amorphous showing of discrimination. But somehow, we kept charging ahead on that one. In the environmental area, nobody’s charging. That’s what bothers me. Because obviously, there is a parallel between civil rights and the environment in terms of the resistance to them. It was a hard slog, you know. But even then, the civil rights litigation had the Constitution on their side–it just had to be fleshed out in court–but we do not have that in the environmental area.

CH: You have written that an economic interest can be used to make the case for personhood; that is one of the factors supporting personhood for corporations. How is that

challenging in environmental cases? How is that changing as more and more ways to put an economic value on the environment are developed?

HB: It’s on my list of things to look at more deeply. I think that the world has not changed sufficiently to the point that an entity that doesn’t have an economic number attached to it can actually stand in court. Alternatively, you can say, I can put an economic value on the whale. So why is it any different from a ship? I keep coming back to, even though I don’t want to, the courts’ fear of environmental cases. They don’t want to get into an area of knowledge that the courts are unfamiliar with like scientific numbers. And there is the potential to be swamped.

You’d have to think of some way of having, I think, good standards for guardians. You shouldn’t be able to walk into court and say, “Well, I’m a friend of this whale, and therefore I want to file a suit.” It would require some greater showing. As a safeguard, as I say, the injuries would have to be capable of monetization. But even then, at some level, why do we have to know the worth of a whale in order to bring an injunction action to prevent something from happening to the whale–what difference does the value of the whale make? At the end of the day, there’s no reason a court cannot control the flow of requests.

CH: People thought the courts would receive far more environmental cases after major environmental legislation in the 1970s allowed for citizens’ suits on behalf of nature, but that didn’t happen. Why not?

HB: Yeah, it’s interesting. Why aren’t the doors swinging open? I don’t know the answer. I mean, there’s a wonderful thing about being a law professor I discovered, as opposed to just a practicing lawyer: I don’t have to have the answers, I just have to ask good questions.

I haven’t brought a case for a while, but even in the 70s, you were still working overtime to persuade the court that yes, there was an injury, let alone get over the other jurisdictional barriers. And my sense is that these barriers are worse in the environmental area, maybe because of the scientific stuff, maybe because of lack of familiarity, maybe because of the commercial countervailing interest, I don’t know. But it’s harder to make an argument today on behalf of the environment than actually, it was a while ago, which seems so ridiculous given how far we’ve come. You can get really, really discouraged in this business because you think, okay, I know it’s a big rock, I’m trying to get up a steep grade, but if I keep my shoulder to it, eventually we’re going to make it. I don’t feel that way. I feel that not so much that the steep slope has gotten steeper, but that it has to do with the courts themselves. The courts simply do not want these cases, enough for them to stop them. Because they are time-consuming. They are difficult. They require the judge and their clerks to bury themselves in arcane, complex scientific stuff. If I were a judge, from an

efficiency standpoint, I would ask is it worth it?

CH: Are there other reasons for this amount of pushback to environmental cases?

HB: To some extent, it is the impact on industry that environmental cases threaten. Environmental litigants should pick their cases carefully because they want the impact to force companies to make changes in their practices. But, historically, very few cases have actually had that impact on companies. Most companies survive and are able to pay whatever fines they incur. But, there is still a threat of monetary impact on industry. There’s also the effect on the public. Prices may go up and may affect them as well. You can’t complain about an industry disposing of some horrible chemical if you know that the public is disposing of a variation of that same horrible chemical down their drain. So it’s really hard stuff. I’m glad I didn’t think these thoughts when I started out–I probably never would have done it.

CH: Some people claim that the courts are right to limit the environmental cases that they take because many of the questions coming before them belong in the realm of the legislature. What do you think?

HB: If you’re looking to Congress for heroism, forget it. Sure, the president can issue an executive order but then a new president comes in and issues another executive order that counteracts the first one. So it’s really got to be a long-term change, and Congress is the only entity other than a court that can make a long-term change. So if the courts hang back saying, “Well, this really is more a matter for the legislative branch,” then nothing’s going to move. The barriers that Stone was speaking to in his 1972 article are still there. If anything, they are deeper, wider, higher. So the fix, the idea of granting an entity, a nonhuman entity, the right to go to court, or the ability to go to court is still incredibly important. If anything, you might argue it is more important today than ever.

But, it’s a catch-22. You can’t bring the cases that would demonstrate the popular concern that might lead to legislative change. And even if you’re successful in filing a case, and get beyond the motion to dismiss, you still have to frame it in a way that removes it from the rights of nature framework and into a quite standard realm of which the courts are comfortable. And that means you’re doing this forever. You can’t say I am speaking for the trees. Because they have no right to be in court.

CH: On top of all that, the cases you are most familiar with are in the footsteps of the major environmental legislation of the 1970s which focuses on pollutants, endangered species, etc. What about climate change litigation where the claims are often even more amorphous?

HB: I have not been a fan of climate change litigation. I think it is extremely difficult to prosecute, and along the way, you lose a lot of ground. The only way you win is incremental. If you win on climate change, you win big. But if you don’t win on climate change, you have to be careful you don’t lose big. Litigants must know how to choose cases. One of the criteria for us was obviously the likelihood of success. Now you can also bring cases where the likelihood of success was lower but then the flip side of that was that the loss would not be that big. My sense is that there is less litigation today than before. Maybe that is because when I was litigating, the doors were wide open. What remains are really the hard, hard cases. They take a lot of time to bring and a lot of investment.

CH: Given everything we have talked about, what do you think about the future of environmental litigation? Are you hopeful?

HB: I don’t think we ever really give up or else we wouldn’t be in this line of work. Hopeful? I’m really disappointed that

things haven’t moved, especially given the physical evidence of human impact on the planet. I think many of us have been doing this for so long, seeing so many defeats, that many of us are paralyzed. Maybe what we need is for the next generation to come in, who doesn’t know squat, and say “What the hell, let’s go for it. It’s bad. How much worse can we make it?”

Hope Babcock is an environmental and natural resources law professor at Georgetown University. From 1981-1991, she served as deputy general counsel to the National Audubon Society as well as their Director of Audubon’s Public Lands and Water Program from 1981-87. She was also a member of the Standing Committee on Environmental Law of the American Bar Association and served on the Clinton-Gore Transition Team. You can find her 2016 article on Stone’s 1972 article here. Her updated reflection in the Southern California Law Review is forthcoming.

One of my deep pleasures is to interact with a large set of research-active faculty, each of whom is pushing the edges of developments in their fields. Of course, the scholarship and research tools that they use are highly variable across fields. The culture of research also varies – some work in teams, some work by themselves. The gestation periods for research projects also vary, from months to years. In watching and talking to such scholars there seem to be, however, some common elements of their day-to-day lives.

Time management – many have very well-defined schedules of their weeks, with designated periods for different types of research-related work. Reading and idea generation can be scattered throughout the day in bits (letting the brain do its

synthesis magic over time), but writing seems to be best done in large blocks. A common daily regimen seems to be waking up early (before the rest of the household) and in the quiet of the morning, carving out a few hours of solitary writing.

Collecting and documenting new ideas – many of the most productive have integrated their teaching and research. Some even claim that their best research ideas have come from trying to answer a question from a student. The most generative questions appear to be those not based on the traditional conceptual framework of the field. The reaction cited is often “I never thought of it that way before.” Followed by, “Why haven’t I thought of it that way before?” The best among us have some way to document these ideas, creating idea lists for the next

projects they might mount.

Working on multiple tasks concurrently – A common feature appears to be that the person is always working on multiple research projects. They are often in different stages of maturation. When the researcher finds they are running out of energy on one project, they switch to another, then return to the first with new perspectives. It seems to be a useful tool to avoid completely blocked progress.

Pushing an idea in successive stages – Many of the faculty have invented ways to try out big research ideas in little pieces. They may use an essay to sketch the ideas of a book; they may publish the seeds of an idea in a lower ranked journal just to articulate a disciplined presentation of the idea. If reactions to the small step are positive, the next step may be a bigger chunk of the work.

Knowing when an idea isn’t ready – The best researchers come up with more ideas than they can ever pursue. Success comes both from devoting time on the ideas with greatest promise and avoiding spending time on ideas that, upon reflection, don’t have merit. The best among us seem to have ways of rejecting unworkable ideas very quickly. Some seek out interaction with

colleagues, seeking active critique.

Importing approaches from other fields – It was interesting to learn that how many of our most productive colleagues are reading the research literatures outside their fields. They seek the importation of concepts or methods used in other domains to their own. Often that innovation permits new perspectives on old problems and new insights unlocked with methods formerly not used in the field.

Using other minds – Importing new ideas from other fields is quite compatible with collaborations across boundaries. The boldest of our colleagues seek out experts in other fields as partners in new research, often producing breakthroughs in creativity.

Nurturing critical readers of one’s work – Very, very few among us can produce perfect writing in one iteration. One of the surprises to students is the number of drafts that most research products require on their way to completion. So, the most precious resource a scholar can have is a colleague willing to critically (but constructively) evaluate early drafts. For such relationship to be sustainable, however, most often there is a reciprocation. You read my work; I read your work. Even better, when the two scholars are collaboratively producing the research product, there is an organic other-person evaluation. That is, in fact, one of the pleasures of collaborative work.

Persevering with good ideas even in the face of failure – Many of our colleagues have stories about failures in early attempts at some project (e.g., failure to convince anyone of its merits and losing support; inability to implement the methods proposed). Some of the stories cite coming back to a failed idea years later and succeeding in the project. The scholar’s life often experiences more failures than successes. It is the unrivaled sweetness of the successes that make us forget the failures. Thus, resilience and tolerance of deferred gratification are personal traits of the best scholars.

Robert Groves is a Social Statistician, who studies the Impact of Social Cognitive and Behavioral Influences on the quality of Statistical Information. Among his many publications, he received the 2011 AAPOR Book Award for his co-authored book, Survey Nonresponse. Groves serves on the National Research Council Committee on National Statistics, Pew Research Center Board, the National Science Board, and the Federal Economic Statistics Advisory Committee, and is an elected member of the US National Academy of Sciences, of the National Academy of Medicine, of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and of the International Statistical Institute.. He served as the Director of the US Census Bureau between 2009-2012.

Post originally appeared on The Provost’s Blog, March 2022

The DC Environmental Film Festival aims to educate, inspire, and incite environmental action through the power of film. This year marks its thirtieth anniversary. Our editors at Common Home reviewed two of this year’s featured films: Going Circular and Devil Put Coal in the Ground

Directed by David Hutchinson & Lucas Sabean; 2022 Winner of DCEFF Audience Award for Best Feature Film

“If coal was the future of the country, and it was so good for this state, why is Boone Country one of the poorest in the nation?” asks Lisa Henderson, a West Virginian mother. For decades, the U.S. has capitalized off the energy-abundant and environmentally-destructive fossil fuel, coal. The communities that mine the coal, however, often see little of its benefits and all of its costs. Told from the personal stories of West

Virginians, Devil Put Coal in the Ground documents the rise of Big Coal corporations and the devastation of Appalachian mining communities.

For many families in West Virginia, coal has been a part of their lives for generations. However, today’s coal mining communities look very different than they did thirty years ago. The film depicts the thriving coal mining communities in the years before the 1970s, the peak of union membership.

A turning point came in the early 1990s when large coal corporations like Massey Energy grew in power and restricted union activity. They soon cut wages. Families that were previously financially stable began to struggle. Many community members left in search of better opportunities.

The town became almost unrecognizable. “It’s eerie because it feels almost like an atomic bomb went off,” said Henderson of

the drastic changes in her hometown. “Once it had life. Now it’s gone.”

As large coal companies continued to dominate the West Virginian coal industry, environmental conditions rapidly deteriorated. To remove larger quantities of coal more quickly and cheaply, coal corporations turned to more invasive techniques. Mountaintop removal–where explosives blow apart mountain ridgelines–became an increasingly popular method of coal mining. Appalachia’s distinctive landscape was changed forever.

Coal has had serious effects on West Virginians’ health. Parents and other residents began raising concerns when children attending an elementary school a mere 400 yards from a Massey Energy subsidiary coal processing plant began exhibiting health problems.

At one point, the film followed Paula Jean Swearengin, a West Virginian politician, driving through a residential neighborhood as she pointed out house after house that belonged to someone who had cancer. While driving through these “unexplainable cancer clusters,” she expressed her despair for so much loss in her community. “To lose my daddy at fifty-two, that’s not fair. To see my neighbor’s children get cancer, that’s not fair,” Swearengin said. “My biggest fear is that one of my children will get cancer. This isn’t worth it.”

The film also exposes ties between the coal industry and the opioid epidemic that is ravaging the state. The coal industry and Big Pharma are symbiotic, asserts Bob Kincaid, an activist and local West Virginian. He adds, “Beyond this physical world of devastation is internal, spiritual, psychological devastation–and they come from the same place.”

However, opposition to coal companies remains controversial in West Virginia. In a community eager to attract jobs and rebuild the economy, corporations are given friendly treatment and health concerns are swept under the rug. Moreover, because of coal’s long history in Appalachia, coal remains central to many people’s identity. And yet Lisa Henderson notes, “There’s a difference between being a friend of a coal miner, and a friend of coal.”

Devil Put Coal in the Ground captures West Virginians’ anger, frustration, and sadness as they witness the environmental and emotional devastation of their community. At the same time, the film paints a powerful picture of resilience, showcasing members of the community who continue to fight for their children, their mountains, their home.

Directed by Nigel Walk and Richard Dale

In 1972, James Lovelock proposed that all systems–living and

nonliving–are connected in one vast, self-regulating system. His big idea–The Gaia Theory–asserts that every living organism plays a role in defining and maintaining the conditions for life on earth. Today, in the wake of unhinged consumer culture, unquestioned economic assumptions, and a perceived distance between humanity and nature, humans have knocked that system perfectly balanced system out of balance. In our quest for modernity, we’ve forgotten that we’re part of the Earth system, not separate from it.

Going Circular, directed by two-time Emmy nominees Nigel Walk and Richard Dale, imagines and plots a circular economy future in which humans work with nature, rather than against it.

Today’s 21st century economy is linear: We follow a “takemake-dispose” step-by-step plan. We extract materials from the ground, produce single-use goods, distribute the goods around the globe, then consume them, with little thought of where they come from or where they’ll go post-use. Our model of consumption is in complete contrast with nature’s natural system of renewal. In nature, the waste of one system is the energy of the next system. There is no such thing as waste.

The promises of a circular economy are extensive. What if we widely adopted biomimicry, the practice of using nature as a model for human inventions? As the film notes, “The truth is, natural organisms have managed to do everything we want to do without guzzling fossil fuels, polluting the planet or mortgaging the future.” For example, one company, spotLESS Materials, uses sprayable coatings that repel liquid and bacteria by using materials inspired by the same physics as the Nepenthes pitcher plant.

What if we harnessed the potential of 3-D printing to reduce waste–both in our homes and factories? For example, Ford and HP have collaborated to create a printer that recycles waste into automotive parts.

The questions abound: What if we rethought our food systems in a way that deliberately ensured zero-waste? Or used fabrics that could be used and reused over and over?

A circular economy could reduce 90% of wasted materials. Today, the economy is only about 8.6% circular. Doubling our circularity would cut CO2 emissions by 39% by 2030. Moreover, the circular economy could result in $4.5 trillion in economic growth.

In the words of James Lovelock, “We live on a live planet that can respond to the change we make, either by canceling the changes or by canceling us.” We are at a critical turning point in which we must change the way in which we live, starting with the way in which we consume.

As children, most of us saw and heard the phrase “Reduce, Reuse, Recycle!” The “three R’s” were an attempt to bring awareness to our environmental impact, highlighting our (over) consumption of nearly everything. Unfortunately, the most popular of the three words is the least effective: recycling.

When most people talk about recycling, they only consider plastic and paper materials. After finishing a milk jug or receiving a graded essay, we instinctively throw it into the blue container with the three arrows making a circle, assuming it will, indeed, get recycled.

However, recycling is not as successful as we think it is. In 2017, the U.S. generated 267.8 million tons of municipal solid

waste, yet only 94.2 million tons were recycled or composted–including only 8 percent of all plastics. Within the plastics family, small objects like straws and utensils are not recycled. They are too small and often too contaminated with food to be reused. Moreover, certain types of plastic like PVC (polyvinyl chloride) simply cannot be recycled.

Even for PET plastic bottles, the most common plastic, the recycling rate is only 30% in the U.S. Furthermore, recycling is an expensive process, meaning that there is often not an economic incentive for companies to recycle it and it is easier to send the product to the landfill.

The focus should shift from recycling to the first two R’s:

reduce and reuse. We can examine the efficacy of the three R’s on Georgetown’s campus as a case study. During the months of to-go eating from Leo’s (the Georgetown dining hall), paper bags could be seen overflowing from all trash cans in the dining tents and common rooms. Most of the time the use of the bags was unnecessary. These bags were usually used only once, for a few yards from point A to point B. Once discarded, these bags contributed to our planet’s already overflowing landfills if thrown in the trash and, if thrown in the recycling, required an immense amount of energy to recycle them. More effective alternatives would have been to either limit distributed bags (“Reduce”), or to repurpose the bags after their initial use (“Reuse”).

This issue exists in the fashion industry on an even larger scale. Fast fashion produces 20% of the global water waste and 10% of global carbon emissions, and the industry is only expected to increase in the following years. Fast fashion’s short-lived trends exacerbate these problems. For example, cow print was in very high demand a couple months ago only to quickly lose popularity, pushing consumers to acquire more items to keep up with the break-neck speed of fashion trends.

As the harmful practices of fast fashion become more prevalent, consumers are becoming increasingly cognizant of the brands from which they shop. People often debate the ethics of buying from a source utilizing underpaid child labor, the environmental sustainability of the brand, and the limited size ranges in trendy stores. More retail companies are responding

to consumers’ increased scrutiny by beginning to brand themselves as environmentally friendly, and some have taken genuine steps to reduce the resource footprint of garments.

But such steps largely miss the point; the more sustainable option is to simply produce and consume fewer clothes. Overconsumption of fashion is a global phenomenon. We are constantly producing more fabric, putting a toll on both our environmental resources for clothing production and our landfills for clothing waste.

While recycling clothing is possible, most people do not take the steps to recycle their clothing. In fact, recycling rates for all textiles in the U.S. is only about 15%. Instead, most people send their clothes to the garbage or the thrift store. However, even shopping at thrift stores–which has often been seen as the more sustainable option–has its problems, as it may increase the prices for people who actually need to shop there.

Of course, the world’s environmental problems do not all come down to the average consumer’s habits, and no one expects the average consumer to buy strictly necessary or only sustainably-made goods. However, simply being more conscious of the things we buy is an important step forward and something everyone can partake in. So, in the phrase “Reduce, Reuse, Recycle,” let’s start focusing on the first two more.

How we relate to spaces depends on the stories that we believe about them.

Telling a story about a space is like casting a spell, with the power to speak into existence a place of beauty and belonging.

These are the lessons that I learned from reading The Black Side of the River : Race, Language, and Belonging in Washington D.C. by Dr.

Jessica Grieser.Dr. Grieser is a socio-linguist who looks at African American English (AAE) as an expression of intersections between race, place, and social class. For Black Side of the River, she draws on ten years of interviews with dozens of Black residents of Anacostia, a historically Black neighborhood in Washington, D.C., to explore how language is a primary means that residents claim and preserve their neighborhood as a Black space.

Black Side of the River begins beautifully with an excerpt from an early Langston Hughes poem, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers.” With this framing, Dr. Grieser describes how Black souls, including her own, have “grown deep like the rivers.” Now I will never forget that “when Black people cross rivers, it matters.” Memorable lines like these, along with the printed interviews and socio-linguistic analysis, all fit into the book’s testimony to the power of stories and the Black sides of rivers everywhere.

In fact, while reading Black Side of the River, I noted all of the ways that Dr. Grieser and her interviewees inspired me to reimagine language: as a communal glue, as an ecological restorer, as a historical library, as a line of defense, as a connector and a creator, as a description and a prescription, as a map

of relationships and a compass guiding us home, and as the universal invitation to listen closer. Dr. Grieser has done so by listening to the Black side of the river.

Her book felt like a gift as my own memories with rivers came flooding back to me while reading. And that brought me to my freshman year at Georgetown when I first encountered the Anacostia River, and unfortunately, learned the subtly poisonous stories told about Wards 7 and 8.

For a fun field trip, my proseminar professor organized an Anacostia River boat tour. None of us had ventured farther than Capitol Hill into D.C.; soon, the tour flipped our perspective of the city upside down. We arrived at the dock not knowing what to expect, standing back with arms crossed across our vests during the on-land introduction. Then one by one, we awkwardly extended our legs out over the dock and into the boat. With everyone secured in seats and life vests, the guide motored us off into the river and began to tell one of its stories:

The Anacostia is named for the people who first belonged here, the Nacotchtank. The river cradled their communities for centuries, along with the Potomac, until colonizers displaced the people and repurposed the rivers. They not only became routes for trade and human trafficking, but also became the boundaries through which North and South, rich and poor, and Black and White would be established.

But the Anacostia’s path diverged from the Potomac’s when city leaders allowed the military and industry to pollute the river, and therefore pollute the Black residents who relied on it. Decades of wasting the river transformed

it from a place for swimming, fishing, and communing with each other and nature into a vehicle for corporate profits and environmental racism. Decades of damage done by the polluters has left these communities’ relationships with the river scarred, which has contributed to the negative effects of poverty and urban blight in Wards 7 and 8.

As a first-semester freshman, that class field trip introduced me to D.C. as a place of complex, often unjust, historical, and ongoing relationships among different people and their environments. What was less obvious to me, though more insidious, were the ways in which I unknowingly absorbed this narrative of the Black communities of Wards 7 and 8 as being damaged and in need of saving.

It’s the single, misleading, story of many places and peoples that I mistook for the full reality of the Black side of the river.

It’s the stereotype that I heard reinforced in most Georgetown classrooms and campus spaces–in the rare instances when Wards 7 and Ward 8 were brought up at all.

It’s the unique form of division and environmental pollution, hidden in the words we speak.

This is what makes Dr. Grieser’s book so important. By

listening to the lived experiences of Black residents of Anacostia, she models a form of research and public discourse that centers the agency, desires, identities, and needs of a local community amid persistent urban change.

Although rivers often divide one community from another, they can also bring people together.

The Black Side of the River allowed me to see how the Anacostia River that separates Wards 7 and 8 from the rest of D.C. also protects them as undeniably proud Black places. On the Eastern side of the river, through every word spoken, Anacostia residents reclaim their neighborhood as a worthy place, rich in Black history and culture, natural beauty, and possibility. By casting their home in these ways, residents not only undermine the frequent stereotyping and commodification of their community but also envision futures where the relationships between Black people and our ecosystems can flourish.

This is what it means for Black people to be inextricable from the places we live. This is what it means to honor our stories as a starting point to protecting and healing the bodies of water and land that we depend on. Through such rigorous research and intentional framing, Dr. Grieser compels every reader of The Black Side of the River to remember and respect this form of communal power.

Once There Were Wolves tells the heartwarming tale of wolves’ return to the Scottish Highlands. It’s also a dark and nail-biting murder mystery.

Author Charlotte McConaghy breaks the standard mold of environmental writing. Her use of language pushes the reader to empathize with nature. She immerses her readers in a perspective from nature. The novel’s protagonist Inti has mirror-touch synesthesia. “My brain recreates the sensory experiences of living creatures, of all people and even sometimes animals; if I see it I feel it, and for just a moment I am them, we are one and their pain or pleasure is my own,” Inti says.