We are thrilled to present to you the fifth issue of Common Home, Georgetown’s magazine on environment and sustainability from the Earth Commons Institute (ECo).

In this issue, we dive deep into issues surrounding the ocean. We talk to Elizabeth Hogan (SFS ‘97) about some of the biggest problems plaguing marine wildlife, as well as her experience in the field as a marine conservation scientist. Farther out to sea, we examine the fascinating oddity of rafting species—floating ecosystems which have been found growing on dead trees, debris, and even plastic in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

We highlight stories where the resources of the ocean—and of the land—are managed sustainably while also meeting the vital needs of communities. Candice Powers (CAS ‘22) illustrates the wealth of environmental benefits of certain marine food systems, such as māra mataitai—an approach to mariculture traditionally practiced by Māori communities emphasizing reciprocity between humans and the ecosystem. Alannah Nathan (SFS ‘24) covers innovative technological solutions emerging in the private sector to grow food more efficiently and sustainably. Shelby Gresch (SFS ‘22) reflects on urban farming—a growing practice in cities like DC—and how the Georgetown Hoya Harvest Garden may contribute to our local community.

Lastly, this issue also aims to spotlight underrepresented voices and issues in the environment, especially regarding Indigenous perspectives and the right to access resources. Sadie Morris (SFS ‘22) highlights the significance of the Klamath River dam removal for the Yurok, Hupa, Klamath, and Kurok communities. Green Commons Award recipient Anya Wahal travels to Arizona, where farmers are struggling amidst the state’s water crisis.

Gillian Meyers (SFS ‘23) analyzes the durability of corporate-Indigenous partnerships and their interests in protecting people, profits, and the planet.

We are excited to share with you an issue that features the most Georgetown student voices yet. We would also like to give a special thank you to our esteemed guest writers within and beyond Georgetown. We are delighted to share your voices with our readers.

Sincerely,

Maya Alcantara, Marion Cassidy, Deena Eichhorn, Alannah Nathan, Maya Snyder, and Nishitha Vivek Students at Georgetown University

With support from Katryn Bowe and Sadie Morris (SFS ‘22)

To Conserve Biodiversity, We Must Stop Chasing Ghosts and Start Making Plans

By Peter P. Marra, Director of The Earth CommonsEcosystems Afloat: The ecosystems growing on our plastic waste

By Dr. Rebecca Helm, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies at Georgetown University & Georgetown Earth Commons AffiliateDismantling Dams for Decolonization

By Sadie Morris, SFS ‘22 & Environmental Educator, Farmer, and WriterDrought-Stricken, Arizona Farmers Face a Bleak Growing Season

By Anya Wahal, SFS ‘23 & Green Commons Award RecipientReinventing the Food System Through Private Investment: Two companies in the growing landscape of food and AgTech

By Alannah Nathan, SFS ‘24 & Common Home EditorPeople, Profits, and Planet: Can Mutually Beneficial Corporate-Indigenous Partnerships Protect all Three?

By Gillian Meyers, SFS ‘23A Win for the Environment: How Brazil’s new president has the chance to steer the country back to the future

By Olivia Ainbinder & Climate and Sustainability ConsultantFrontiers of Mariculture Series

By Candice Powers, COL’22 & Maine Aquaculture Pioneers Program Intern• Changing our minds, stomachs, and planet: The mission to make kelp mainstream

• Kelp is on the way: How one scientist is using seaweed and oysters to save our coastal waters and communities

• Stewardship of Our Oceans Should Belong to the First Nations People

Under Jamaican Sea: Turning seaweed into carbon credits at Kee Farms

Nicholas Kee, CEO and co-founder of Kee Farms, interviewed by Nishitha Vivek, MS ‘23 & Common Home Editor

Invasive Insects: Examining the Spread of The Cabbage White Butterfly

By Maya Snyder, SFS ‘24 & Common Home EditorHello Hoya Harvest: Reflecting on Georgetown’s role in Urban Agriculture

By Shelby Gresch, COL ‘22 Fellow& Post-Baccalaureate

at the Earth Commons

Climate Change and Curriculum: Georgetown’s Core Pathways Initiative at Five Years

By Sarah Craig, SFS ‘23 & Assistant at The Red House at Georgetown University

Alumni Spotlights:

• Elizabeth Hogan, SFS ‘97 & Program Director at National Geographic

• Miguel CuUnjing, MBA ‘15 & Associate Director of North America

The Breakdown: Electric Vehicles

By Ryan Levandowski, GULC ‘20 & Institute Associate at Georgetown Climate Center

Marion Cassidy is a Senior in the college studying History and Art History. She is from Brooklyn, NY and is passionate about the intersection of sustainability and the arts.

Alannah is a Junior in the Walsh School of Foreign Service, pursuing a degree in Global Business. Alannah has a strong interest in the energy transition and the private sector’s role in pursuing sustainable development, including sustainable business and investment. She is from Brooklyn, NY.

Maya is a Junior in the Walsh School of Foreign Service, majoring in Science, Technology, & International Affairs with a focus in Energy & Environment and minoring in Chinese. In her free time, she enjoys hiking and reading. She is from San Diego, California.

Maya Snyder

Marion Cassidy

Alannah Nathan

Maya Snyder

Marion Cassidy

Alannah Nathan

Deena Eichhorn

Deena is a Junior in the College of Arts and Sciences studying Justice and Peace studies, Government, and Spanish. She is from Wichita, Kansas, and loves to cook.

Maya Alcantara

Maya is a graduate student in the McDonough School of Business and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences studying Environment and Sustainability Management. Her favorite pastimes are journaling and painting. She is from Rancho Cucamonga, CA.

Nishitha Vivek

Nishitha is a Master's in Management (STEM) Graduate Student at McDonough School of Business, graduating in May 2023. She completed her undergraduate at SRM University in Chennai, India.

Policy debates around climate change and biodiversity loss both suffer from the same misconceptions: that vague, non-binding agreements and a focus on a few, charismatic species—think polar bears—will spur the international community to act in such a way that life on earth can continue as we know it.

But just as we can’t fight climate change exclusively via lastditch efforts and give up when we fail to reach certain targets— like 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming—we can’t fight biodiversity loss by acting only when species’ populations dwindle to only a few individuals and then pouring all our energy into resurrecting others that are already gone.

In biodiversity conservation as in climate action, seeing the forest for the trees means acting before the forest is reduced to a single tree. That means taking real action now by passing legislation like the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act, revamping existing international treaties, and investing in the research that is required to inform proactive conservation.

Too often, we’ve lavished attention on species like the Whooping Crane and the Kākāpō, which were brought back from the brink of extinction by expensive, decades-long interventions only when it was nearly too late.

We’ve also spent too much time and energy holding out hope for lost species, like the Ivory-billed Woodpecker, a wonderful but almost certainly extinct species that continues to capture imaginations and headlines, but which ultimately distracts us from taking steps to protect other fantastic creatures that still exist.

Just last week, the IPCC—the UN’s climate panel—released its annual climate change report, which provides an update to the signatories of the Paris Agreement about the science of climate change and where the world stands on its goals.

Like the Paris Agreement in 2015, the COP15 UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) agreed to in Montreal last December was widely regarded as a pivotal, consequential moment for the future of Earth’s biodiversity. But the agreement that emerged from the conference (which the U.S. is not even party to) was a report lofty in concept but unenforceable in practice.

CBD countries “pledged” to protect 30 percent of natural areas on the earth by 2030. As laudable as this sounds, it is intangible and unenforceable. None of the 20 biodiversity targets the CBD agreed to 10 years ago were achieved, leaving us with nothing but unbounded (and ungrounded) hope that this time countries will act.

Left out of the CBD negotiations were specific science-based measures to prevent future species extinctions by addressing specific causes of population declines. Meanwhile, more than 70 bird species in the U.S. alone are considered to be at tipping points that put them at risk of being listed under the Endangered Species Act.

Thinking about our children’s future, we can—and should— focus on achievable and impactful species conservation by using tangible, existing opportunities and mechanisms.

The United States has an opportunity to lead by example and pass landmark legislation through the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act, which would dedicate 1.3 billion dollars for statelevel conservation and 97.5 million to tribal nations to recover

and sustain fish and wildlife populations on reservations. This is low-hanging fruit, and legislation that must pass in the next session of Congress.

Another opportunity: the United States is party to the Convention on Nature Protection and Wildlife Preservation in the Western Hemisphere, a visionary instrument put in place in 1942 that calls for protecting species from extinction, establishing protected areas, regulating international trade in wildlife, taking special measures for migratory birds, and encouraging the need for international co-operation in scientific research.

Revitalizing that convention could focus hemispheric cooperation on the most urgent threats to our shared wildlife—threats we must address now if we want to avoid more species becoming ghosts in the binoculars of a passionate few. But we need to act fast.

Now is the time to recover the populations of miraculous birds like the whimbrel, mountain plover and evening grosbeak while we can still enjoy them in their natural habitats. We must lead by prioritizing conservation measures specifically tailored for each of these 70 species and others like them before they are formally listed.

Our new understanding of migratory science can pinpoint exactly where to act for each species, whether to prioritize the protection of critical habitats; the removal and reduction of threats from invasive species, including outdoor house cats; the reduction of chemical exposures from pesticides like neonicotinoids; or the design of wildlife-friendlier cities on migration routes.

Funding more research can inform conservation efforts for other species across the tree of life.

If we do not move from vague non-binding pledges and scattershot approaches to habitat conservation toward discrete, science-based conservation efforts, the natural world will continue to vanish before our eyes, leaving us with an impoverished world populated only by the ghosts of our own making.

By Dr. Rebecca Helm, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, Earth Commons, Georgetown University

By Dr. Rebecca Helm, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, Earth Commons, Georgetown University

What if we told you that there are entire ecosystems on the ocean surface that live on our plastic waste?

When Ben Lecompt swam from California to Hawai’i through the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, he saw something he didn’t expect: life. “Every time I saw plastic debris floating, there was life all around it,” Mr. Lecomte told the New York Times.

As scientists who study high-seas ecosystems, my colleagues and I collaborated with Mr. Lecompt to understand the mysterious ecology of the ocean’s surface. Through our work, we learn that the story of plastic debris in the oceans isn’t as clear as it seems on the surface.

We discovered that floating life might be concentrated by the same physical forces, such as currents and wind, that concentrate plastics. These animals do not depend on plastic and may live peaceably beside our debris. But a key piece of the puzzle is still missing: Mr. Lecompt also found many species living directly on plastic debris.

Why did Mr. Lecompt find a vast amount of life in the Garbage Patch? The answer may lie in an unexpected place: forests.

Before industrial-scale damming and deforestation, large amounts of natural floating wood entered the ocean every year. In fact, there are some species that only live in the open ocean on floating wood. Let me say that again: there are species of animals that have only been found on floating dead trees drifting thousands of miles from shore!

The tragic 2011 Japanese tsunami proved that wood could last years in the open ocean and carry life with it. Animals that call floating debris home are known as rafters, and their natural habitat may be dramatically shrinking. Rafting species are found naturally on driftwood, where they attach themselves and spend years riding on waves.

Now, widespread deforestation and river damming have dramatically decreased the amount of natural wood that enters the ocean. Scientists estimate that, at a minimum, there are 300,000 cubic meters (m3) of large woody pieces entering the ocean each year. In contrast, before humans started altering the environment, at least 70 million m3 of wood objects entered the ocean each year. For rafters, that reduces their living space by over 99%.

If the wood is largely gone, where will the rafting ecosystem go?

Rafting species that can live on buoyant objects are now developing ecosystems on the floating plastics in the ocean. One study found 95 rafting species living on floating plastic in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

However, rafting animals are not the only species living around plastic. Floating objects also attract fish.

On a swim through the Garbage Patch, Mr. Lecompt once saw a school of curious fish beneath him. “They were leading me back to what had become their house,” he said of the plastic they now lived around.

The fishing industry has noticed this tendency, too. Tuna fisheries now intentionally release between 47,000–105,000 large floating objects into the ocean every year, many of which are made out of plastic. These objects, called “fish aggregating devices” (or FADs), attract large open-ocean fish, especially tuna. Once enough fish gather around a FAD, a fishing boat surrounds the FAD with a purse-like net to collect the island of life. If you’ve eaten tuna recently, there is a chance you have eaten a fish collected with a FAD.

The tendency of tuna and other open-ocean fish to gather around floating objects hints at what may have been a oncegreat ecosystem floating at the ocean’s surface. The massive reduction in oceanic wood and the global increase in plastic have undoubtedly changed the open ocean. While plastic may be a far more dangerous material than wood, it is undeniably a home for some animals.

Recently, we have seen a big public push to “save our oceans” by cleaning up plastic in the open ocean using large nets or other remote devices. While images of marine life tangled in plastic are heartbreaking, the rush by some companies to clean up plastic from the open ocean may be premature because we know very little about the impacts of plastic in the open ocean, and even less about the ecosystems now growing on our waste.

Though little is known, we cannot ignore the role the rafting ecosystem, now displaced onto plastic, may play in the health of our oceans. We cannot disregard the unknown historical damage that logging and damming may have inflicted upon the ocean’s surface.

As scientists and citizens, we must address the negative impacts of plastic, but we can and should also examine the role that plastic may play in keeping the rafting ecosystem afloat. After all, deforestation and damming will certainly not stop anytime soon, and the amount of floating plastic debris entering the ocean will inevitably continue to grow. We must understand the role of the rafting ecosystem and floating debris in our ocean health in order to protect the ocean’s future.

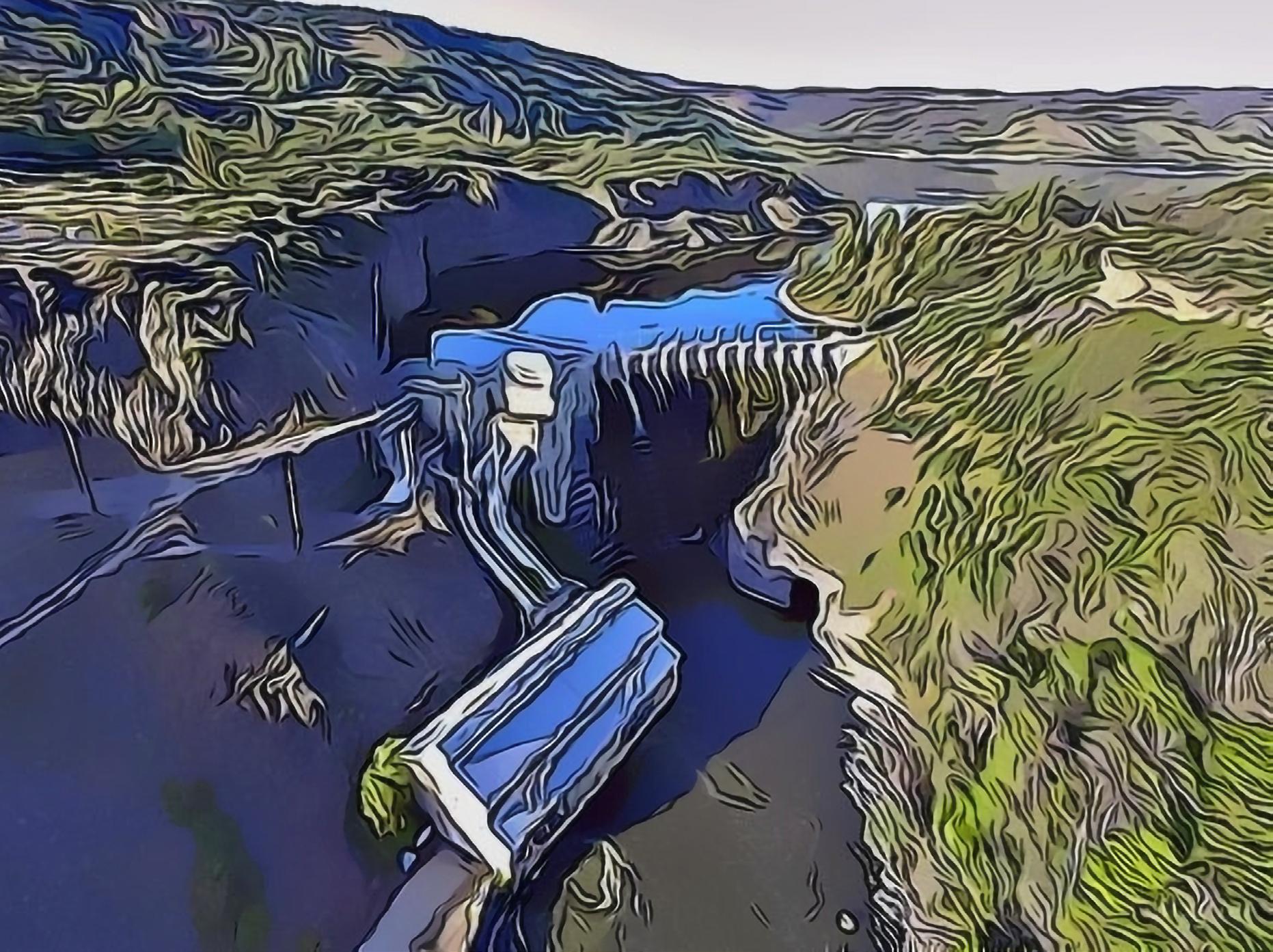

In November of 2022 the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission gave final approval to begin the removal of four dams on the lower Klamath, an area straddling the Oregon-California border. After two decades of tireless struggle by Indigenous communities to undam 400 miles of river and salmon habitat, the final plan includes nearly 200 projects ranging from fish habitat and flow restoration to the actual removal of the dams.

The first dam on the lower Klamath will be removed the summer of 2023 with the complete removal of the first dam by early 2024.

The project is already historically unparalleled in scope, but the victory’s implications run deeper than returning the land to its more natural state. It is a direct rebuke of the colonizing forces that have directed the course of U.S. history and in particular US relations with Indigenous nations since the original British colonization.

To understand the full meaning of the Klamath dam removal, it is helpful to examine the relationship between colonization and water infrastructure projects as well as the motives of the Indigenous peoples leading the “un-damming” movement.

Colonization occurs at both the material and symbolic levels. When the English, Spanish, and French colonized the present-day United States they brought with them certain ideas that underpinned their justification for colonization and implemented cultural colonization of the original peoples of the Americas. Namely, colonizers instilled a dualistic perspective of nature in which nature and humans are pitted against one another and humans must subjugate nature.

Theorists like Val Plumwood root the paradigm in the “technological capacities to direct events in the material environment,” indicating the direct link between the ability to control the environment and emerging worldviews. When colonizers arrived on the shores of the present-day United States, they equated the original peoples with the natural environment: “The inhabitants of untamed, or even unacceptable wildernesses, deserts, and swamps are thrown rhetorically into the class of needing domination or ‘civilizing influences.’” Thus, colonization, displacement, and even mass murder of Indigenous peoples were justified by colonizers in the same breath in which they justified the “taming” of their new natural environment.

Control over water was and continues to be an important aspect of domination in colonizer relations. Since water is both essential for life and fundamentally finite, it plays a particular role in social relations as an impetus for the development of social practices and relationships in order to regulate water access within a community.

Environmental anthropologist Veronica Strang elucidates the relationship between water and society further: “The link between water and power is an expression of material relations. No exercise of power is possible unless it can be expressed in material form, in this instance through the physical control of water bodies or the capacity to determine (from whatever distance) whose interests will benefit from the flow of water.”

Dams as regulators of water flow and access to water are key manifestations of material control over water. It should come as little surprise then that dams have played a unique and prominent role in colonization.

In the United States, the majority of dam projects fall under the purview of the Bureau of Reclamation which was established in 1902 under the Department of the Interior. Uncoincidentally, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (and its various precursors) is also housed in the Department–a material embodiment of the continued naturalization of Native bodies in the U.S..

Jane Griffith is a communications scholar who focuses on settler colonialism. She conducted an analysis of the magazine published by the Bureau of Reclamation from 1907 to 1983 in order to explicate the connection between infrastructure projects–particularly dams–and the continuation of U.S. colonizing practices. Her use of written narrative further underscores the connection between material and symbolic forms of colonization, as she writes: “[I] demonstrate how dams are built with more than engineering equipment—their tools also include narratives, language, rhetoric, and image that recast Indigenous waterways for settler audiences.” In language parallel to earlier justifications for the occupation of Indigenous land, the Bureau “painted land in the West as arid and otherwise useless without Reclamation, ‘a desert solitude’ home only to ‘sand and cactus desolation,” and ‘infertile, nonirrigable, seeped or otherwise unproductive.’”

The Bureau even utilized “before and after” reclamation spreads, so “readers could view water unfold over time from original water source to white settlement” with Native stewardship but one step in a march towards modernization.

In actuality, what the Bureau painted as “reclamation” was occupation funded by theft of Indigenous lands. Beth Rose Middleton, Chair of Native American Studies at U.C. Davis, explains that “Federal water projects in the American West

were funded by the seizure and sale of Indian lands to non-Indians” by order of the 1901 Reclamation Act. In the same way in which the Dawes Act had allowed the partitioning of Native land into parcels for sale to settlers, the Reclamation Act sold unceded Native land in order to provide areas for water infrastructure projects that “tamed” the wild, arid lands of the West.

As a result, Indigenous peoples are at the forefront of resistance to dams globally in opposition to colonization.

While the U.S. led the way in 21st-century major infrastructure projects, the rest of the world readily followed suit. By 2003, $2 trillion dollars globally had been spent on dam construction and geophysicists believe “The world’s dams have shifted so much weight that…they have slightly altered the speed of the earth’s rotation, the title of its axis, and the shape of its gravitational field.” At the height of the neoliberal hegemonic heyday in the late 1980s and 90s, the World Bank and International Monetary Fund regularly pursued water infrastructure projects across the Global South as a means of implementing capitalistic economic models. These incursions became a rallying point for Indigenous groups who readily classified dam project schematics as a new form of colonization for the modern age.

Dam construction slowed down in 1997 after Indigenous resistance prompted the World Commission on Dams that supported Indigenous claims that dam profits did not clearly

outweigh the environmental and social costs of dams. Nonetheless, construction in the Global South continues at a slower pace–and Indigenous resistance continues.

In the U.S. context, Indigenous response to dam construction in the 21st century was largely quashed by overwhelming government suppression; nonetheless, Indigenous resistance has found renewed expression in the openings created by the post-industrial nature of U.S. capitalist society. As Western science catches up with Indigenous understandings of water relations, Indigenous people are leading an un-damming movement as a way of “(re)activating water as an agent of decolonization, as well as the very terrain of struggle over which the meaning and configuration of power is determined.”

The Klamath River dam removal project is the embodiment of how the removal of dams operates as a decolonizer on both the material and symbolic levels.

Four Native American tribes – the Yurok, Hupa, Klamath, and Kurok – are the original and present-day inhabitants of the Klamath Basin where 6 dams currently control the flow of the river. Each of their cultures has a unique relationship with the surrounding waterways and in particular with the salmon who populated the rivers before the dams. For example, the Yurok Tribe embeds their cultural practices in the lifecycle of the salmon which they view as their kin. As anadromous fish,

salmon complete a multi-year lifecycle in which they breed in the freshwater rivers, travel downstream to the ocean and eventually return to rivers where they hatched in order to lay their own eggs. The Yurok Tribe accompanies the salmon during their return home and roots their value system of sharing and care around what provides for the health of the salmon.

Dams have devastated the salmon life cycle because they have altered the temperature of the water in the rivers, allowed the proliferation of diseases, and literally blocked the return of salmon to their nesting grounds. Since the installation of dams, humans have tried to manage the salmon populations–which are now on the Endangered Species list–by building hatcheries and fish ladders, but efforts have proved unable to restore or even sustain population levels.

The Yurok, Hupa, and Kurok tribes have sued multiple times in court, claiming “the dams were hurting the river, the fish and its culture.” In 2002, “60,000 [salmon] died after the Bush Administration limited water releases for fish in favor of agricultural water deliveries.” The incident galvanized the four Indigenous tribes to band together and demand that the dams be removed entirely.

The effort to remove the dam is happening at both the material and symbolic levels. As Yurok Tribe chair Joseph James relates, “‘This dam removal is more than just a concrete project coming down, it’s a new day and new era for California tribes…we are connected with our hearts and prayers to these creeks, lands, animals, and our way of life will thrive with these dams being out.’” James references both the symbolic connection between the Yurok cosmological relationship to the river–his heart connection to the river– and the material ability for the Tribe to practice their traditions. Frankie Myers, vice-chairman of the Yurok Tribe is even more direct: “For the Yurok, Myers says the dams are seen as ‘monuments to colonialism’ and compares them to statues of Confederate generals. ‘These dams are statues of the war that we fought here on the Klamath River. And these statues destroy our river, the landscape, our culture. We have to deal with them every single day.’”

Emboldened by the stakes of their actions, Tribal leaders and allies went on to lead a series of attacks on PacifiCorp, the company in charge of operating the dams. On one front, the tribes participated in direct action; for instance, in 2004, a group picketed at Scottish Power (a parent company of PacifiCorp) company’s annual shareholders meeting, and in 2007, tribal members embarked on a caravan from California to Nebraska to protest outside an additional parent company. On another front, the tribes took the company to court using the federal licensing renewal process which brought both the state and federal governments to the table.

An initial agreement was reached in 2010 to decommission four of the dams but quickly was bounced between different lawsuits and eventually different presidential administrations. Nonetheless, the tribes have persisted and in 2020 a new agreement was reached between the tribe, state governments, and PacifiCorp, cutting out the federal government entirely. The 2022 Federal Energy Regulatory Commission ruling was the final piece needed before removal could begin.

The Indigenous victory in the Klamath River Basin is a major boon to a movement sweeping the U.S.. One thousand seven hundred dams have been removed in the U.S. overall and 69 in 2020 alone. Elizabeth Grossman, who has documented the undamming movement across the U.S., identifies how the movement positions itself in opposition to the colonized, capitalist norm: “Reconsidering the use of our rivers means examining our priorities as a nation. It forces us to rethink our patterns of consumption and growth and may well be key to reclaiming a vital part of America’s future.”

The future is exactly what Indigenous leaders within the movement are looking to: Indigenous leadership pointedly rejects that Indigenous ways are those of the past, meant to be dammed over by modern means of environmental control. Rather, un-damming demonstrates that Indigenous ways of relating to water are actually a living lesson, “a glimpse of an alternative form of sovereignty.”

Un-damming should not be viewed as a regression to a time before the “civilizing” force of colonization but rather an embrace of an alternative, decolonized way of being. Like Franz Fanon reminds us, “No, there is no question of a return to Nature. It is simply a very concrete question of not dragging men towards mutilation, of not imposing upon the brain rhythms which very quickly obliterate it and wreck it.”

When Indigenous peoples today tear down dams, they are not only freeing the waters and living creatures caged behind dams but breaking the cultural trap of the colonized mindset.

Sadie Morris graduated from Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service in 2022 with a bachelor’s in Culture and Politics. She continues to engage in issues of the environment, water, and the West as a farmer in Montana. She is a former editor of Common Home.

By Anya Wahal, SFS ‘23 & Green Commons Award Recipient

By Anya Wahal, SFS ‘23 & Green Commons Award Recipient

Drenched in sweat and scorched by the 110°F Arizona heat, I made my way towards Caywood Farms, a fifth-generation farm run by Nancy Caywood.

Nancy and other farmers have struggled to recoup their businesses from Arizona’s record-setting drought. Farming had been her family’s livelihood since they first moved to the West decades ago. As I sought to understand and amplify her story, she shared her distant hopes for a more water-abundant future and financial struggles - which have inevitably accompanied our state-wide drought.

Cotton, a water-intensive crop, helped Nancy’s family fulfill their ‘American Dream.’ From an environmental perspective, building a business dependent on the crop is at extreme odds with the state’s sustainable development goals. And while Nancy expressed a desire to implement more water conscious practices, she did not have the resources to do so, even on a smaller scale. In the midst of our interview, Nancy gazed forlornly at a patch of life on her fields: cotton, in a midst of cracked, brown, dirt.

Experiences like those of Nancy have spread like wildfire across Arizona. But despite the overwhelming news coverage of the Colorado River water shortages, the human impact of Arizona’s water policies on its most affected group—farmers— is often missing from the discourse.

Due to severe drought, farmers are experiencing unprecedented financial hardships and letting their fields lie fallow. In fact, according to Steve Miller, Supervisor for Pinal County, one of the hardest hit counties in the state, 60% of agricultural land could be fallowed because of the Colorado River water shortages. Still, the voices of farmers are consistently being lost amid competing narratives surrounding water in the Southwest. At the same time, farmers suffer from a disconnect between the implementation and intent of water policies. While policymakers may intend for policies to positively impact farmers and ranchers, these same policies, such as those on water taxes and surface water management, have sometimes undermined the interests of those exact communities.

To better understand these challenges, I returned to my home state of Arizona this past summer to film a mini-documentary

from farmers’ perspectives on how water shortages are impacting their lives and livelihoods. With the support of the Earth Commons and Mortara Center for International Studies, I spent months interviewing and filming farmers with the goal of understanding and amplifying their stories. What I learned transformed my thinking on what policies might be necessary to tackle environmental crises in Arizona and around the world.

My conversations changed my view of Arizona’s water challenges in three key ways.

First, conversations among policymakers and farmers surrounding agriculture and development must be reframed to encapsulate a greater understanding of the nuanced perspectives of all stakeholders. Currently, the dialogue orients farmers against developers, and vice versa, reflective of an “us versus them mentality.” Although conversations with farmers did reveal some resentment against unqualified development, opinions tended to be more nuanced in practice.

In fact, as one farmer I spoke with put it, “I’m not against development. I’m just against how they’re going about it… [They just want to] build the cheapest house possible.” Focusing on who is angered by development and why they are angry about it sheds crucial light on how to build a more sustainable and inclusive path forward.

In the West, we often throw around the phrase “whiskey is for drinking, water is for fighting,” when discussing water shortages. This phrase encapsulates the conflict: water, because of its scarcity, is too often the source of great tension, but collaboration is still possible.

Second, the existence of Phoenix and other large cities must be acknowledged to create policies that effectively support sustainable development in desert cities. In response to water shortages, progressive environmentalists in Arizona have often made arguments that a large city like Phoenix should never have existed since Arizona is a desert. However, this point is moot, because Phoenix does exist. Phoenix is one of the fastest growing cities in the country and a hub for business and development. Accepting that Phoenix and other cities in Arizona will continue to grow is a crucial step in ensuring they do so

sustainably. For instance, investing in improved wastewater and groundwater management, engaging in dialogue between other Colorado River basin states and Mexico, and considering the possibility of water augmentation through desalination may be instrumental to policymakers as they craft future water policy.

Third, many reasonable citizens and policymakers are demanding that farmers make their businesses more sustainable. However, demanding this change without providing the necessary support would lead to less-than-ideal outcomes. Such demands can make farmers out to be the villains, when the blame often lies with policymakers as well.

In a field visit I conducted, one farmer mentioned that she wanted to diversify to more sustainable crops, but simply didn’t have the necessary financial resources or labor. When I asked if government grants existed to make this change, she said that they didn’t, and any help that was offered by nonprofits wasn’t nearly enough to cover the costs. This sentiment was widespread amongst the 25 farmers I spoke with, most of whom were actively considering new ways to conserve water in their businesses.

If Arizona policymakers aim to maintain agricultural traditions, support farming businesses, and create new development,

they must make a more conscious effort to include farmers’ perspectives. Only then might we see policies produce their intended effects and policymakers make reasonable demands of farmers and ranchers disproportionately affected by water shortages.

These lessons I learned from studying my state’s water crisis are not applicable to only Arizona. Just as farmers in the West are poorly treated in the environmental discourse, so too are coal miners in Appalachia and oil field workers in Texas. As an environmental advocate, I too yearn for sweeping environmental policy changes to conserve our country’s precious resources and build resilience strategies in the wake of the climate crisis. But I also know that true progress can only be sustainable if it is inclusive of those left behind.

Arizona farmers need monetary aid to change their growing practices; sustainability on a larger scale sometimes means supporting existing ways of life. To shift away from conflict and towards genuine progress, we need to create a policy discourse that reflects the interests of all communities affected by environmental crises.

Meeting the increased demand for food in the face of mounting environmental threats and climatic shifts requires nothing short of a complete transformation in how we produce and consume food globally. Public sector reforms are vital, but private sector solutions such as those at Smallhold and Hippo Harvest are a new and important avenue to tackle this crisis.

Currently, 35% of all greenhouse gas emissions trace back to our food system, primarily a result of industrial farming practices, mass livestock, rice production, fertilizer use, and food waste.

Solutions from the private sector play an important role in bringing to market new technologies, products, and behaviors. However, such solutions aren’t cheap, nor are they risk-free. The high cost of new agricultural production technologies and infrastructure such as vertical farming, digitalization, genetic engineering, and fermentation—known as “AgTech”—can only reach economically viable scale with the backing of investors willing to generously fund businesses and take on significant risks.

The good news? One class of investors—venture capitalists (VCs)–are currently pouring record amounts of money into AgTech. In 2020, VCs invested a total of $3.3 billion across 422 deals. By 2021, the total invested capital rose to $5 billion across 440 funding deals.

Venture capital investment comes in all shapes and sizes and with various strategic aims. Venture capitalists (VCs) are private equity investors that provide capital to privately-held companies in exchange for a stake in the company (equity). They invest when the companies are rather early, provide guidance alongside their financial investment, and then sell their stake once the company has grown.

Within venture capital (and other asset classes), some investors identify as “impact investors.” They seek financial return and creating a positive, measurable impact in the world, so they only invest in companies that provide a product or service that improves the environment or society. This subset of venture capital funds are accountable to their investors for delivering positive impact, just as they are in meeting financial returns.

In order to create such impact, they might make investments that financially driven investors might overlook; perhaps they have a higher degree of risk, cater to an underserved market, or require a more patient timeline.

Beyond this small space of self-designated “impact investors” are other venture capital firms that also invest in companies that improve the environment, but they are not driven to do so because of such impact. Rather, they simply see a compelling business opportunity. Investors into such funds are often finance-first, choosing between such a fund and other equally-lucrative opportunities, agnostic of impact.

Although their motivations are different from impact investors, in practice, capital from the entire spectrum is critical to get environmentally-innovative companies off the ground.

One particular VC firm, Energy Impact Partners (EIP), invests in companies and entrepreneurs leading the transition to a sustainable energy future. EIP has invested in companies decarbonizing utilities, industrial infrastructure, and

steelmaking; developing carbon capture and sequestration and battery storage systems; building digital environmental, social, and corporate governance products and solutions; renting electric vehicles (EVs); amongst others. Recently, EIP has expanded its investment portfolio to firms in AgTech.

Within the growing landscape of food and AgTech investment, we sat down with two founders of EIP-backed ventures: Andrew Carter, the co-founder and CEO of Smallhold, and Eitan Marder-Eppstein, the CEO and founder of Hippo Harvest.

Specialty mushrooms have recently taken the U.S. by storm and Smallhold, a Brooklyn-based start-up founded in 2017, is leading the way.

Smallhold grows and sells specialty varieties of mushrooms to over 500 retailers across the United States, including Whole Foods and Erewhon. Each of Smallhold’s varieties of

mushrooms are grown in climate-controlled environments across New York, Texas, and Los Angeles. Not only does Smallhold seek to bring to market a higher quality product, but Smallhold’s mission is also rooted in sustainability.

“The vast majority of our customers are within 100 miles of our farms,” says Carter. The benefit of localized production is twofold: a smaller carbon impact and a higher quality product. “We also really try to limit the packaging plastic we use. If you check us out in stores it's mostly just cardboard which is recyclable and compostable at home.” Moreover, in a recent lifecycle assessment, Smallhold found that their carbon footprint is 30% lower than other mushroom growers with publicly available data. The farms’ carbon and water footprints are a tiny fraction of those in the meat production industry.

Smallhold began by developing and patenting technologies that allow for optimal conditions to grow mushrooms anywhere and everywhere, from the heart of Brooklyn, NY, to a Texas macrofarm and even a hotel bar. Smallhold’s mushrooms are grown on waste streams from timber—most of which would have likely gone straight to landfills. All of Smallhold’s waste goes to large-scale compost and bioremediation projects.

Currently, mushrooms make up just a small fraction of the American diet. In the U.S., the annual per capita mushroom consumption is estimated between two and four pounds. In China, Japan, and Korea, those numbers are far higher. Chinese mushroom consumption is estimated closer to 20 to 30 pounds per person per year. While American consumption may not reach levels on par with East Asia anytime soon, even a doubling or tripling of consumption would create a significant market opportunity, particularly as demand for non-meat products increases.

“I think it's important for people to eat less meat,” says Carter, “so, if people aren't eating mushrooms now, they will be in the future, especially if they're trying to lead a more sustainable lifestyle.”

Since its launch, Smallhold has been backed by private investors. In 2021, it received Series A investment from multiple investors, including Energy Impact Partners.

When asked why Smallhold chose EIP, Carter noted: “I tried to focus on people who have a thesis around indoor agriculture. EIP has historically been focused on decarbonization and clean energy,” explains Carter. “But food is energy. We don't use nearly as much energy as, for instance, an indoor

vertical farm, but we still have to be thoughtful about where the energy comes from” he notes. “We have to be thoughtful about whether we can find the right kinds of partners to not only provide us the right kinds of energy, but also the real estate to do things. We’ve focused on transportation routes, for example.”

For Carter’s investors, sustainability metrics are equally as important as revenue and profitability: “It’s refreshing to be in board meetings with people who care that much about sustainability,” says Carter. “When your investors don't care, and you're weighing out the difference between a compostable recyclable cardboard box— which is inherently more expensive than Styrofoam—that's a different kind of conversation if your shareholders aren't aligned with your company. It's a lot easier when we care and our investors are aligned with that.”

Smallhold’s future looks bright. It recently launched in Los Angeles and plans to expand to regions across the U.S., building out a national brand with local production. Smallhold is focused on building more facilities, working on producing more mushroom varieties, and increasing the efficiency of their farms and supply chains.

“I think that we're in a moment with mushrooms that has never existed before. Smallhold’s definitely positioned in a really interesting way to take advantage,” says Carter.

Record-breaking floods in eastern Kentucky. Temperatures surpassing 110 Fahrenheit in California. Shrinking lakes in Arizona and Utah. All of these climate change-fueled natural disasters have had devastating effects on U.S. agriculture. In fact, the frequency of billion-dollar climate-based agriculture disasters in the United States has more than doubled since 2015, a trend expected to increase as climate change disasters persist and intensify.

The impacts of climate change—including droughts, floods, and extreme temperatures—on food security in the U.S. warrant new models of food production—and may even call for entirely moving away from traditional food production systems on outdoor fields.

Hippo Harvest, a controlled environment agriculture (CEA) company, takes CEA a step further and employs machine learning, robots, and artificial intelligence (AI) to grow vegetables sustainably in greenhouse environments.

Controlled environmental agriculture (CEA) includes a variety of technology-based solutions to farming. CEA ranges from simple greenhouses to full indoor and vertical farms with fully automated systems, including controlled lighting, irrigation, and ventilation.

Utilized for decades as a way to grow food in harsh climates and extend growing seasons, CEA is now being looked at as a strategy to adapt to increasingly unpredictable weather.

With CEA, farmers are far less at the mercy of the weather to grow their food. Moreover, on an acre of land, CEA farmers can produce a yield 11 times larger than traditional outdoor field farmers.

“What we're trying to do is improve the unit economic profile and build greenhouses that are cost-competitive with outdoor organic farming in fields,” says Eitan Marder-Eppstein, the founder and CEO of Hippo. “If you [we] can accomplish that, it will become a catalyst for the transition from outdoor production to controlled environment agriculture.”

While greenhouses are still not cost-competitive with outdoor organic agriculture, decreasing prices have created a growing consumer base. Additionally, as climate-related disasters intensify, the cost of outdoor production will increase while the cost of CEA continues to decrease.

Machine learning and AI allow for Hippo Harvest to constantly improve their production yield and lower costs, creating a flywheel effect: As they achieve more scale, they accumulate more data on optimal growing conditions, leading to more insights, lower costs, and, in turn, more scale.

“We're moving away from a linear model of agriculture, where you do research and development (R&D) in a university or in a research greenhouse, then you do your field trial, and you learn from that and get your insights, then your improvements, and then you deploy them, and then you scale them,”

notes Marder-Eppstein. With Hippo’s systems, production is constantly fine-tuned and adjusted to create the conditions for an optimal yield.

In the summer of 2020, Hippo raised an initial seed round of funding and built their first proof-of-concept greenhouse, roughly 6,000 square feet, in Half Moon Bay, California. In a six-month period, Hippo doubled its yields. Energy Impact Partners (EIP)—along with Amazon—has since invested in Hippo’s Series A round, allowing Hippo to expand production.

Hippo Harvest now has a 150,000-square-foot facility, about three and a half acres.

“The next two years will be about replication for us,” says Eitan-Eppstein. “Assuming that we hit our unit economic target, then it'll be like, “Ok, can we do this in a few different environments? How do we start getting to scale? How do we shift production to this modality and give consumers a choice where they don't have to decide on price.”

While both the public and the private sectors are vital to the transformation of the global food system, private-backed companies like Smallhold and Hippo Harvest are exciting examples of the private sector already at work in transforming the agricultural industry toward sustainability.

Dotted along highways crisscrossing the country, scattered among towns and nestled into buzzing urban intersections, Shell’s cheerful yellow logo is a familiar sight for most Americans. Many even sought it out after BP’s disastrous 2010 oil spill.

Yet Shell’s record is equally stained: since the 1990s, it has relentlessly pushed into Ogoniland, a lush corner of the Niger Delta as rich in gnarled mangroves and teeming rainforests as it is in oil. Though Shell’s exploitation has faced unwavering pushback from the Indigenous Ogoni people since it began, Shell has continued extracting oil, paying Nigerian soldiers to torture, assault, and murder innocent Indigenous people who got in the way.

Oil prospecting subdivided and contaminated native territory, forcing the Ogoni people into smaller and smaller pieces of land that are now overcrowded and underfunded. Though Shell has yet to atone for its long-standing mistreatment of people and environmental destruction, over a decade of relentless litigation finally pushed Shell to settle with the widows of murdered tribal leaders in 2009 for $15.5 million. However, no amount of funding can restore the land and the lives

upended by Shell’s extraction, raising a fundamental question: how can businesses justify the cost-benefit analysis of a project when there are human lives in play?

Settlement agreements–like that of Shell with the Ogoni people–are a result of Indigenous struggle for international recognition of the harm caused to their land and livelihood by natural resource exploitation. In recent years, the Indigenous rights movement has gained strength and scope. Contemporary Indigenous protests often aim to damage business' reputations as easily accessed reserves run dry leaving remote tribal land the main target for exploitation.

By widely sharing the impacts of corporate abuses, Indigenous peoples have enlarged the reputational and legal risks of exploiting Indigenous land. This was the case with the 2007 UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples which explicitly requires the Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) of Indigenous groups before extraction can occur. Corporations have also become incentivized to build positive, healthy relationships with Indigenous communities resulting in use agreements between corporations and Indigenous tribes.

Corporate interactions with Indigenous communities are usually evaluated by the environmental and social aspects of the ESG (environmental social governance) framework.

In the case of Shell’s impact on Ogoni land, both environmental and social factors are at play. There is both the environmental poisoning of Ogoni forest and waterways as well as the impact of Shell-funded murders of several tribal leaders who played significant roles in their communities.

In order to consider how Shell might move forward with creating an ESG agreement that would mitigate its harm to the Ogoni people, it is useful to examine other agreements reached between corporations and Indigenous peoples.

The partnership between the Black River tribe and Tembec, a Canadian forestry company, is an example of one such positive relationship between an Indigenous community and a powerful corporation. Black River, a tribe of roughly 750 people living near Winnipeg, might seem outnumbered against Tembec, an industrial giant employing 10,000 people. Yet the two have founded a valuable partnership. The Black River tribe contribute sustainable forest management practices based on traditional knowledge, while Tembec provides courses on modern forestry to increase tribe members’ skills and employability.

Tembec succeeded because it achieved what other corporations overlook: inclusive communication. Its Regional Advisory Committees allow community members––including Indigenous people––to directly discuss their needs with Tembec representatives. In addition, Tembec works with Manitoba Model Forest, a nonprofit that brings together tribal communities, scientists and natural resource specialists, industry, and government to establish common values related to sustainable forest development.

By listening to (and acting on) Indigenous peoples’ needs, Tembec and the Black River tribe created a mutually beneficial relationship that improved the earning potential of both parties, while profiting from natural resources sustainably. Developing a positive relationship between the Indigenous tribe and the foestry company through ESG principles proved to help mitigate the reputational and legal risks to the company’s bottom line.

Other companies can achieve similar partnerships by following three guiding practices: gaining Indigenous consent for exploitation, understanding the business case for ESG, and drawing on cross-sectoral knowledge.

First, multinational corporations must obtain Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) for any activities undertaken in Indigenous territory, characterized by inclusive dialogue, transparent goals, and accurate communications. Even though the right to consent is guaranteed by the UN, corporations must

increase funding and support for internal departments that manage their social relationships with tribes. In addition, external ethics review boards, context-specific training, and shareholder engagement can all help avoid unethical behavior.

Companies should formalize processes for gaining consent wherever possible and draw on outside support–such as the First Peoples Worldwide, a coalition of North American tribes–to ensure their practices are beneficial for all parties involved. This organization facilitates FPIC by enabling dialogue between Indigenous people and representatives of extractive industries. In addition, FPW funds the translation of documents into native languages to ensure that Indigenous communities’ consent is always informed.

Secondly, businesses must examine the financial case for ESG agreements. In actuality, businesses are measured predominantly using balance sheets rather than the ESG framework so business needs incentives to prioritize ESG initiatives. The First Peoples Worldwide’s 2014 Indigenous Rights Risk Report found that companies with lower social risks had higher returns than those with exploitative community relationships. And a positive impact on the environment can also drive better performance: sustainability is now viewed as a core element of large corporations’ strategies, and multinationals have already lost millions from failing to address climate-related risks.

Third, cross-sectoral research and collaboration should drive business decisions. While the Manitoba-Tembec partnership model of sustainable harvesting is an exciting indication of the the kinds of beneficial cross-sectoral work that can be done, research on the relationship between corporations and Indigenous groups is thin. This is due in large part to the way in which Indigenous knowledge has long been undervalued by Western science. If corporations can incorporate stewardship methods perfected by Indigenous groups over centuries, as well as cultural and spiritual practices that prohibit pollution and degradation, they can align with both the environmental and social criterion of the ESG framework, to the benefit of all parties involved.

Until Shell and similar companies change their behaviors, ESG principles remain a thin veneer for a continued pattern of exploitation. Yet, companies can drive real change by backing their words with genuine action: they can establish relationships with Indigenous communities built on trust, consent, and clear communication. In doing so, they may just unlock the ability to simultaneously safeguard people, profits, and the planet.

Like the US elections of 2020, the 2022 presidential election in Brazil was decisive in determining whether the world can achieve a zero-carbon future. Brazil is one of the greatest greenhouse gas global emitters, representing 4% of the world's emissions. It is also home to the Amazon, the largest tropical forest on the planet, which stores an enormous amount of carbon and contributes to the regulation of the global climate. In other words, a lot was at stake.

In the hands of an authoritarian president, Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil was on the road to potential collapse. During his presidential term from 2019 to 2022, Bolsonaro denied science, attacked minorities, and neglected critical issues. His term was characterized by ineffective COVID-19 policies, weak environmental protection laws, and disregard for Indigenous peoples.

Bolsonaro attacked and dismantled environmental institutions. His government allocated insufficient public resources

to critical environmental departments, persecuted civil servants, excluded members of civil society from important decision-making spaces, and nominated individuals openly against the environmental agenda to public offices, such as the Minister of Environment.

In addition, Bolsonaro neglected to care for Indigenous peoples, as shown by the recently discovered humanitarian crisis in the Yanomami Indigenous lands, which revealed serious health problems in the Indigenous population, such as malnutrition, malaria, and respiratory diseases.

During his four-year term, his government loosened standards on previously established environmental regulation, which had been part of a globally recognized framework of Brazilian environmental policies. A report from the Talanoa Institute identified over 800 regulations from the Bolsonaro era that contributed to this dismantling process. Four hundred and seventy two of these changes require immediate revision to avoid more severe environmental consequences. Some of these regulations altered the way in which environmental infractions were investigated and punished, cut off resources for important funds, and revised policies protecting forests and Native peoples.

After Bolsonaro took office, there was a significant rise in harmful activities in the forests, including a recorded 60% increase in deforestation.

Consequently, after Bolsonaro took office, there was a significant rise in harmful activities in the forests, including a recorded 60% increase in deforestation.

Ultimately, Brazil’s voters chose to elect former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who previously governed Brazil from 2003 to 2011. The recent election was close, and Lula won by a difference of just over 2 million votes.

Lula was a president who, unlike Bolsonaro, placed Brazil as a protagonist in the international arena for fighting deforestation. During Lula’s first terms, his administration implemented a series of positive environmental policies. Led by Marina Silva, the Minister of the Environment, they focused on strengthening environmental monitoring and control policies, expanding protected areas and indigenous lands, and establishing public funds to finance climate and sustainability projects. Several laws and policies were created for setting environmental quality standards and protecting Brazilian biomes as well.

With Lula and Marina Silva, the fight against one of Brazil’s worst climate foes– deforestation– was treated at the highest level of the federal government’s political agenda. With the implementation of these policies, deforestation fell by 83% between 2004 and 2012 and Brazilian emissions decreased as well.

Furthermore, during Lula’s government– and later during that of his successor, Dilma Rousseff– Brazil became a signatory of important international climate agreements. In 2009, Brazil was recognized worldwide for having been a pioneer for its National Climate Change Policy. It internalized the voluntary goal, which it assumed before developing countries had to establish targets under the Climate Change Convention, to reduce 80% of deforestation in the Amazon by 2020.

This was unfulfilled by Bolsonaro. The rate of deforestation in 2020 was three times higher than the established target, putting the country even further away from its goals of the Paris Agreement and its NDC to reduce GHG emissions by 37% by 2025 and 43% by 2030.

In contrast, Lula poses as a leader who takes seriously the global issues faced by Brazil. As the newly elected president, in his emblematic speech at COP27, he promised to achieve zero deforestation not only in the Amazon, but also in other critical Brazilian biomes, strengthening environmental monitoring and control institutions, as well as imposing strict laws regarding illegal activities in the forest.

So far, in his first month as president, Lula and his new Ministers– which include Marina Silva again as Minister of the Environment and Sonia Guajajara, an Indigenous woman, as the newly created Minister of Indigenous Peoples–have already revoked 58 of Bolsonaro’s regulation changes, as identified by Talanoa. In addition, he promised to treat climate change as a priority in his government and proposed the city of Belém, on the Amazon, as a Brazilian candidate to host COP30.

Lula has the solutions available to meet Brazil’s commitments and the potential to once again become a prestigious leader in the fight against climate change. He has in his hands a unique opportunity for combining Brazil’s previously successful policies with new solutions, reversing Bolsonaro's recent trail of destruction and steering Brazil back to the future.

Olivia Ainbinder is a lawyer and a climate and sustainability consultant. She has previously worked at the Talanoa Institute, a climate policy think tank based in Brazil.

The 2022 presidential election in Brazil was decisive in determining whether the world can achieve a zero-carbon future.

“Lula and his new Ministers have already revoked 58 of Bolsonaro’s regulation changes.”

By Candice Powers, COL’22 & Maine

By Candice Powers, COL’22 & Maine

This is a part of a three part series on mariculture in the United States.

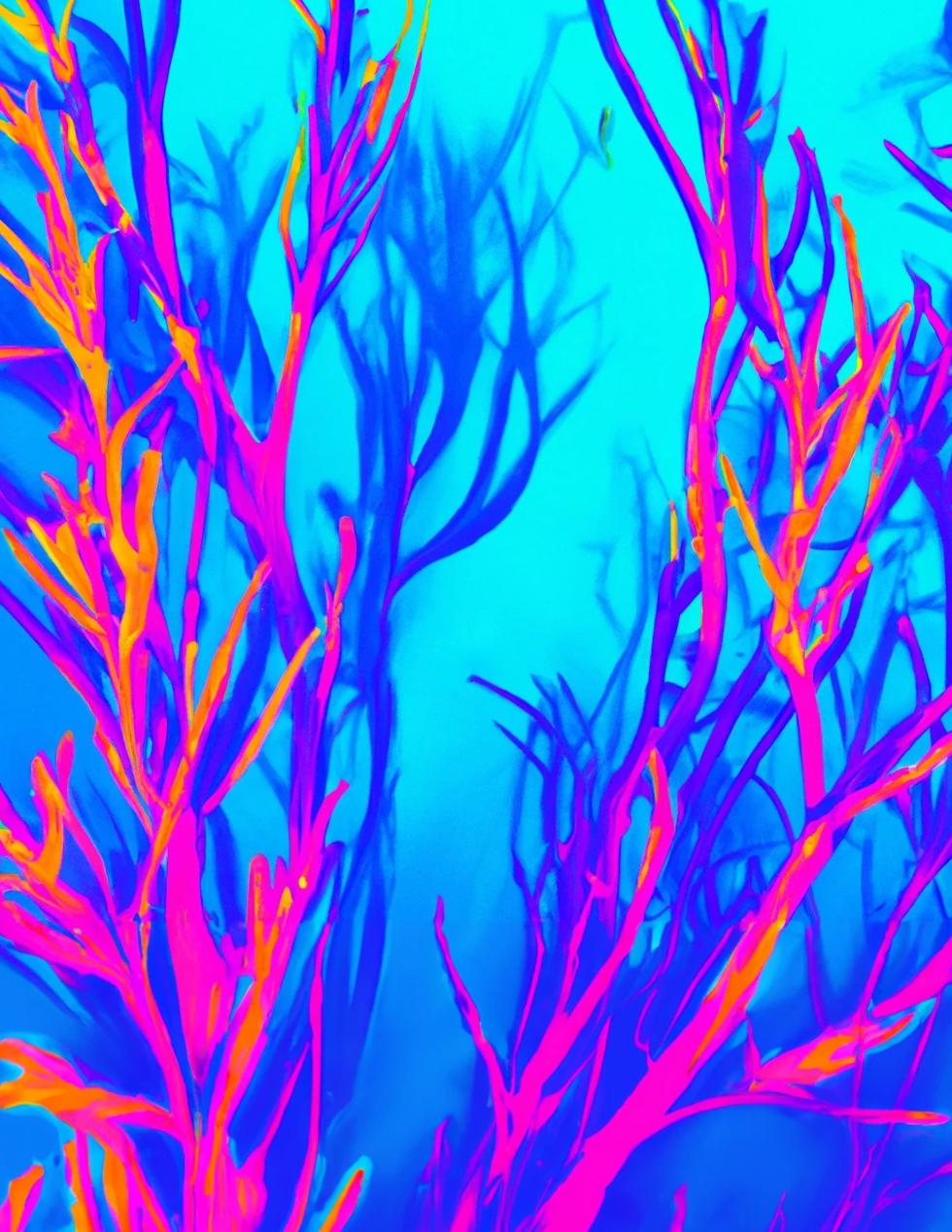

The ocean waves lapping the shoreline of Machiasport, a sleepy town of fewer than 1,000 people situated along the coast of Downeast Maine, is a soothing sight. If you look beyond the jagged coastline, vibrant buoys bob in synchrony, unsuspiciously supporting a sea crop that flourishes just feet below the surface: kelp.

This ocean farm belongs to Morgan-Lea Fogg, a Machiasport local who is now the resident farmer and Director of Impact & Special Projects for AKUA, a kelp foods company founded in 2019.

AKUA is one of many similar kelp-centered enterprises that have sprung up in recent years as seaweed grown in the United States has taken a front seat in aquaculture ventures. In Maine alone, farmed seaweed harvests grew from 15,000 pounds in 2015 to over 325,000 pounds in 2019. And more and more businesses within the growing industry are hatching innovative ways to normalize this nutritious, environmentally-restorative sea vegetable.

Ocean-based kelp farming has emerged as not only one of the most sustainable methods of aquaculture, but an actively restorative one. Contrary to its land-dwelling relatives, kelp requires no freshwater, no pesticides, and no arable land to

flourish. This maintenance-free system actively protects the surrounding ecosystem from the hazards of ocean acidification (OA) by soaking up dissolved carbon dioxide for use in photosynthesis, thereby restoring pH to healthy levels. Kelp can also help prevent harmful algal blooms (HABs) by absorbing anthropogenic inputs of nitrogen and phosphorus–nutrients that stimulate the toxic proliferation of algae– to feed itself.

U.S. investment in this method of regenerative ocean farming (ROF) has grown substantially in the past decade as people have sought to supplant the tradition of purchasing seaweed products from China and Indonesia. With imports accounting for over 95% of edible seaweed products available in the U.S., there is plenty of room for homegrown farmers to take over. Such a switch would also eliminate the monetary and emissions costs of cross-continent transportation. Farmers such as Fogg are therefore “[creating] nutritious, delicious kelp-based products that support ocean farmers and fight climate change.”

Currently, Maine and Alaska are farming the majority of domestic seaweed biomass, but regenerative ocean farming is quickly expanding throughout New England and the West Coast. Researchers project U.S.-farmed seaweed harvests will quadruple by 2035. Expansion of the kelp farming industry creates and diversifies coastal jobs, provides healthy seafood from local sources, and buffers marine wildlife from the impacts of OA and HABs. So, what's left to do?

Sell this seaweed all along the seashore.

“Kelp is making a new name for itself by flaunting its applicability and nutrition.”

Finally growing out of the boutique, US-grown seaweed market in 2019, kelp is making a new name for itself by flaunting its applicability and nutrition. Kelp is a versatile food that can be kept fresh, frozen, dried, or ground into an array of products, from noodles to seasoning. This salty sea veggie is packed with potassium, magnesium, fiber, essential fatty acids (omega-3’s), high quality proteins, and vitamins A, B, C, E, and K. A single ⅓ cup serving of kelp can satisfy your daily iodine requirements– a mineral that is essential for regulating metabolism, among other important bodily processes.

commercially sold kelp burger. Since their launch, AKUA has tripled their purchasing volume and garnered more capacity for food research and development, adding pasta, ground “meat,” and a kelp “krab” cake to their list of creations. “We’re on a mission to make kelp mainstream,” says Boyd Myers.

And they’re not alone. Back in Maine, Atlantic Sea Farms (ASF) is making waves with their award-winning kelpbased kimchi, fresh seaweed salad, and smoothie-ready frozen kelp cubes. ASF even boasts high-profile partners such as Sweetgreen and Daily Harvest. Alaska’s Barnacle Foods is creating a line of salsa made from bull kelp that packs an umami punch. Eat More Kelp (Long Island, NY), Seagrove Kelp Co. (Alaska), and Blue Evolution (Pacific Coast) are also hopping on the regenerative seaweed farming boat. Excitingly, more than eighty percent of domestic seaweed production growth through 2035 is projected to be stimulated by value-added edible products.

The U.S. non-profit Greenwave is leading the charge to establish more regenerative ocean farming (ROF) operations and is now directing a market innovation program that helps open up new business channels for these ROF farmers. AKUA is just one of the companies that Greenwave is partnering with to develop desirable kelp commodities.

Courtney Boyd Myers, the co-founder of AKUA, launched her first product, kelp jerky, in 2019 upon learning about the vast environmental, economic, and health benefits of kelp farming. Their new headline product which propelled the company to the national stage is the world’s first

The benefits of kelp are being explored beyond the human market, creating an even larger demand for biomass. One surprising candidate: cows. There are about 3 billion ruminant, plant-eating animals on the planet, including cows, sheep and goats, that burp methane as part of their digestive process. Methane has almost 30 times the short-term, heat-trapping power as carbon dioxide, making it an especially potent greenhouse gas. According to the EPA, domestic livestock in the U.S. contributes 36% of

“U.S.-farmed seaweed harvests will quadruple by 2035.”

anthropogenic emissions, and in California alone, 1.8 million dairy cows together emit the CO2 equivalent of 2.5 million cars each year. In some environmentalists' perfect world, the entire planet would be vegan. However, this tactic ignores the 1.3 billion people that partially or entirely depend on the livestock industry as a vital source of income, the cultural implications, and the world’s dependency on animal-based protein.

Through kelp driven innovation, perhaps we do not have to condemn livestock production outright. Researchers at James Cook University in Australia explored the ancient Greek and Icelandic practice of raising cattle by the ocean on kelpbased diets to explore how kelp-based diets for cattle can reduce methane emissions. The team tested over 20 species of seaweed in cow’s diets and came up with one clear climatefriendly winner: Asparagopsis taxiformis

Whereas some species reduced methane emissions by 50% when comprising up to 20% of the feed, A. taxiformis reduced methane production by 99% when only taking up 2% of the diet.

Kinley and his team realized that bromoform–a molecule found in A. taxiformis –disrupts an enzyme used by

methane-producing gut bacteria in the course of digestion. In addition to solving an environmental problem, seaweed feeds also help farmers save on cattle cuisine: by minimizing energy waste in animal digestion (~15% of feed expenses are lost in methane emissions) the livestock can grow and produce more milk while requiring less sustenance.

Many growers and foodies originally projected that kelp will take over as “the new kale” and come to dominate the plates of health-minded consumers. Despite this enthusiasm, kelp still needs all (I’m looking at you, cows) of our curiosity and support to reach an economy of scale in which such nutrient-rich, climate-friendly creations can compete with other GMO, lab-grown, and resource-intensive food alternatives on the market today.

The bottom line, says Myers: “If we can move people’s stomachs, we can move their minds to be conscious of the impact of their decisions around food and in other parts of their life.” The next time you visit the grocery store, go out to eat, or talk to a friend, try to make a choice that will actively help our farmers, our seas, and our planet.

Kelp requires no freshwater, no pesticides, and no arable land to flourish

This is a part of a three part series on mariculture in the United States.

For Michael Doall, the salty waters surrounding Long Island have long harbored promises for exploration and entertainment. Growing up along the coast, Doall spent countless days fishing, surfing, and swimming at the beach, partly because his mother let him skip school on especially lovely spring afternoons. “From birth, one of my passions has been the ocean,” Doall says, a lasting enthusiasm that ultimately led to his career in regenerative aquaculture and shellfish restoration. While his days of skipping class to bum it at the beach may be over, you can still find Doall in the bays of Long Island, dedicating hours to researching and restoring the marine organisms that provide innumerable benefits to the ecosystem he calls home.

When Doall began studying marine biology, regenerative aquaculture—the farming of marine species in open waters to bolster habitat quality—was far from common in the U.S. However, having always had gardens growing up, Doall found that the field of ocean aquaculture brought together his passions for the ocean and cultivation.

Doall was first exposed to regenerative aquaculture 20 years ago when The Nature Conservancy started a hard-shell clam and oyster restoration program in Long Island’s Great South Bay and reached out to Doall for his analytic expertise. Bivalves, such as clams and oysters, are essential to ocean ecosystems. They suck up excess nutrients and sediment from waterways, improving water quality and preventing harmful algal blooms. At The Nature Conservancy, Doall grew shellfish in cages across the bay to study how different marine environments would support these species.

There, he realized how much he enjoyed growing the oysters and rebuilding marine ecosystems, so he dove deeper into open-water aquaculture by establishing some of the first oyster

restoration projects in New York Harbor (NYH). While first working at these sites, he aimed to use oysters solely for environmental purposes—the harbor’s pollution meant organisms wouldn’t be safe for consumption. Later, however, he had “the epiphany that oysters do the same thing in an aquaculture setting as they do in nature.” By growing oysters for human consumption, these filter feeders would naturally improve water quality by consuming excess nutrients while providing a sustainable source of fresh seafood.

Inspired, in 2008 Doall started his own oyster farm: Montauk Shellfish Company. He took a lot of pride in being an oyster farmer, stating that “one of the most important activities you can do is to grow food and feed your community.” And that’s exactly what he did. Doall was on the cusp of an “oyster renaissance” and would soon witness Montauk take off beyond his expectations.

Doall would next discover the missing piece to make his project sustainable: kelp. During his time as an oyster farmer, Doall visited Maine where he learned from the first U.S. kelp farmers that by diversifying his crop to include kelp, which has an opposite growing season to oysters, he could complement his shellfish operation (kelp in the winter, shellfish in the summer).

The relationship between kelp and oysters would later inspire Doall’s research. After selling his farm in 2017, Doall still considers himself a farmer in his current role as Associate Director for Bivalve Restoration and Aquaculture at Stony Brook University. Doall combined his experience in cultivating both oysters and kelp in his new role to create a marine-cleaning superteam to counteract eutrophication that has long plagued Long Island.

“Doall developed a specialized technique for growing kelp in the shallow coastal waters of Long Island.”01 Ocean farmer Michael Doall manages a kelp rope in the waters off Long Island, New York

Like oysters, kelp sucks excess nitrogen out of the water, helping to keep our oceans clean. Kelp also captures carbon dioxide from the water column as it photosynthesizes. Harvesting the kelp then removes carbon from the ocean, making the seaweed an important tool for combating harmful ocean acidification. Unfortunately, Long Island does not yet allow kelp farming due to a decade-long battle surrounding permits. Nonetheless, Doall has been able to implement research projects over the last four years dedicated to bringing the benefits of kelp to the area.

Through one such research project, Doall developed a specialized technique for growing kelp in the shallow coastal waters of Long Island, as opposed to traditional kelp farming done in much deeper waters. He was impressively able to grow 12-foot-long kelp fronds in only two feet of water. This compact feat can help not only shallow-water ocean farmers, but also other species residing in shallow bays, where poor water flow otherwise means poor water quality.

The nutrient-extraction capabilities of kelp are especially important in Long Island. As Doall says of his hometown, “Long Islanders love their lawns and golf courses.” He tells me about the truckloads of fertilizer that are brought in during the warmer months, dumping nitrogen all across the island. A farmer at heart, Doall envisions growing forests of kelp along the coast to absorb the nitrogen runoff from shore. Once harvested, this kelp can be developed into nitrogen-rich fertilizer packed with other micronutrients and biostimulants that can be used throughout the community. It would be a closed nitrogen loop, lowering the demand for imported fertilizer and delivering environmental and economic benefits to the island. Doall plans to explore such a system’s feasibility this summer through garden studies on kelp-based fertilizer’s benefits.

Along Doall’s journey to restore his local ecosystem, he encountered a variety of challenges. Despite support from large environmental groups such as the Nature Conservancy

and Pew Charitable Trust, regenerative aquaculture must compete with a variety of stakeholders on the water. Recreational boaters, commercial fishermen, and even windsurfers have opposed Doall’s projects.

“In the end, all these groups recognize the value of regenerative farming, but a lot of people don’t want it in an area where they’re doing something,” he says. There is also a so-called “social carrying capacity” for aquaculture: as soon as over ~5% of the coastline is occupied by ocean farmers, “people start freaking out” and are quick to complain about the oyster farms visible from their backyard. Nevertheless, Doall has found that a healthy, bustling ocean can unify disparate marine interests.

At the end of the day, Doall believes in his mission to support ocean farming and rebuild shellfish populations in his home waters. While he knows these nature-based projects are not the only climate solutions, the benefits of regenerative aquaculture and shellfish restoration cannot be ignored. Aquaculture projects secure jobs and income while nutrient bio-extraction revitalizes the ecosystem, a win-win for coastal economies and environments. Moreover, because of overfishing and marine habitat degradation, fishing communities that have long relied on the ocean for their sense of identity are losing their cultural ties. Luckily, according to Doall, “regenerative aquaculture is a way to bring that cultural identity back…so there's a win-win-win.”

You will always find Doall working away in the waters of Long Island, happy as a clam, because, “When do you plant a victory flag? Never.” The fight for climate-resilient solutions never stops, but local, restorative projects such as Doall’s continue to provide hope for a greener future.

“A farmer at heart, Doall envisions growing forests of kelp along the coast to absorb the nitrogen runoff from shore.”

The recent attention on advancements in mariculture is exciting for environmentalists and ocean activists. But for Jen Rose Smith and her fellow dAXunhyuu (Eyak people), seaweed has always been a treasured tool as well as a tasty treat. The Eyak peoples have developed an array of uses for kelp, from using specially prepared kelp as an anti-crack finish for canoes to pressing it into blocks for later consumption. It is an important reminder that mariculture is not a new development but rather part of a long history. While this knowledge has persisted in the community, centuries of imperialism and colonialism have intentionally disrupted traditional Indigenous activities.