Featured Interviews: Fashion Program

University Spotlights

Sylwia Nazzal: Looking to the Past, Changing the Future

South Asian Motifs: Resistance in Times of Rising Turmoil

Being so Fur Real: The Cultural Politics of Furs in Fashion

Featured Interviews: Fashion Program

University Spotlights

Sylwia Nazzal: Looking to the Past, Changing the Future

South Asian Motifs: Resistance in Times of Rising Turmoil

Being so Fur Real: The Cultural Politics of Furs in Fashion

If this year at GWFBA has proven anything, it’s that we are more than just a student organization. We are a center for change, a catalyst for creativity, and a channel for impact—especially at the intersection of fashion, business, and now, culture.

When I joined FBA in the fall of my sophomore year, I never imagined I’d be in the position I am today. As a general body member, I could see the organization’s untapped potential to do something truly unique on GW’s campus. As Vice President of Graphic Design during my junior year, I saw that potential transform into passion as we brought GEORGE to life on a much larger scale. And now as President in my final year, I’ve watched that passion spread across our entire organization—felt in every conversation, every collaboration, and every member.

This year has demanded a tremendous amount of time, effort, and sacrifice, in a way that has fundamentally changed me. But I would do it all over again to see this project come to life once more. I genuinely don’t know where I’d be without the community FBA has given me, and I am still in awe of the growth it’s experienced since its inception in 2018. It’s been a space of personal growth—as a student, as a leader, and as a friend—and for that, I am endlessly grateful.

I truly believe this issue is not only the pinnacle of what we can achieve professionally, but a reflection of who we are as a community. GEORGE VII stands for more than any issue before it—honoring the cultures, colors, and identities that make our world what it is today. Over the past year, our team has worked tirelessly, in partnership with student organizations across campus, to bring this vision to life.

To my Vice President Nneoma—thank you for your strength, strife, and service.

To our e-board—thank you for believing in this vision and sacrificing so much to make it real.

To every member—thank you for contributing to this magazine in every way, both big and small.

And to every reader—I hope you are just as inspired, challenged, and impacted by the creation of this magazine as

Welcome to the seventh edition of GEORGE! This issue holds a very special place in my heart and has given me one of the most rewarding experiences of my young life thus far. As it was my final year being Editor-in-Chief, I wanted to create a theme completely unlike anything that FBA had ever done before. I had bored of recycling the same topics and wanted to challenge writers to explore areas of the fashion zeitgeist that go beyond the usual mainstream trends and designers. I asked myself: What other fashion communities can we highlight that are often overlooked?

This desire for something fresh, coupled with the current anti-diversity climate of Trump’s America, sparked the perfect idea: Decentering Eurocentrism. With this theme, I gave my writers full reign to write about any topic they wanted, as long as it did not adhere to Eurocentric fashion standards. Their response was nothing short of enthusiastic, and they completely exceeded my expectations. I am incredibly proud and honored to have worked with such a talented team of writers and I’m thrilled with this body of work we collectively worked together to create. Now more than ever, it’s crucial to champion diversity in all aspects, especially in fashion.

I’d like to give a special shoutout not only to my amazing writers but also to the creative team and all of E-board, who went above and beyond to transform this vision from a loose concept into a fully realized, published piece of editorial work. Their behind-thescenes effort deserves all the recognition.

Another special shoutout is deserved for our general members and outside enthusiasts who volunteered their time and energy to contribute to GEORGE and help bring these articles to life. Photographers, models, graphic designers, makeup artists, those who lent us clothing, and so many more. I see you and I thank you!

I hope you all take the time to read and appreciate these pieces thoroughly. This magazine is the culmination of months of hard work that deserves every reader’s full and undivided attention. Take the time to learn something new, reflect on your own thinking, or discover something unexpected.

I am truly so happy and fulfilled that I am ending my time in FBA on such a fantastic note and I truly hope you all enjoy what we have to offer. *Cue tears—sad, but mostly happy*

Editor-in-Chief, GEORGE Nneoma Iloeje

Managing Editor, GEORGE Adyant Patnaik

Editor-in-Chief, After Hours

Noah Edelman

Design Team

Hung Nguyen

Isabel Humphrey

Kelly Rahimi

Coco Kim

Jasmine Sacks

Photo and Video Team

Sarah Strausberg

Rachel Schwartz

Tony Boyd Sam Penzone

President Ethan Valliath

Vice President Nneoma Iloeje

Multimedia

Ethan Fernandes

Social Media

Amari Sharma

Modeling

Grace Lane

Events

Keja Ferguson

Orli Rose

Business Outreach

Ava Zohn

Treasurer and Secretary Fayre Li

Podcast

Madeline Ng

Kyla Robinson

Ariana Ceinos

Zakir Zurga

Philippe Tchokokam

Zoe Luce

Declan Kelly

Adyant Patnaik

Carly Cavanaugh

Nick Patterson

Disha Goyal

Maddie Keiser

Sam Penzone

Kiki Baumgartner

Charlotte Brodbeck

Alexandra Ennabi

Sarah Gross

Sofia Giannetto

Krithika Krishnan

Megan Krueger

Lily Legere

Alex Marootian

Adyant Patnaik

Keira Peters

Ava Privratsky

Victoria Smajlaj

Rita Stein

Eliza Thorn

Molly Wolf

Amelia Achmad

Hibah Ahmed

Hien An

Genieve Anokye

Simrin Arora

Adi Bahal

Alexa Balian

Alex Batzar

Uma Bondada

Lauren Brandt

Giacomo Brosco

Alexa Brown

Ana Bursac

Noelle Cardi

Matteo Chang

Marcus (MJ) Childs

Ainsley Cobb

Sofía Corral Kindlund

Jack Couser

Reva Dalmia

Caroline Demetrakas

Nazira Djor

Quinn Dolan

Priyanka Dubey

Luke Fernandez de los Muros

Vittoria Ferrari

Sasha Fishilevich

Kyla Freeman

Ava Gilder

Lucas Golluber

Ariana Gonzalez

Elias Gray

Elizabeth Hajosy

Callie Hoffman

Lara Jasaitis

Katia Jebejian

Chandler Johnson

Alex Johnson

Neda Joulapour

Jordan Juliano

Michael Kaplan-Nolan

Maddie Keiser

Isabella Kelly

Chanel Kenney

Aaryan Khanna

Coco Kim

Joshua Kim

Alexa Kieltyka

Natalie Kozhemiakin

Chaewon Lee

Faith Lee

Abigail Levack

Audrey Lorence

Danielle Lucero

Hema Mangat

Rebecca Marsalese

Nathalia Martinez

Lucas Matuszewski

Audrey McDaniel

Lucy McKay

Anna Mennuti

Leah Meyerson

Lina Moini

Siena Morgenthal

Ethan Mpanju

Zay Naeem

Parnia Nasrullah

Nina Necek

Paige Nelson

Kennedy Nga

Sophie O’Connell

Hadassah Olakanpo

Sophia Oppenheim

Naz Ozkaya

Samriddhi Patankar

Noah Pavlov

Dre Pedemonte

Kiera Peters

Deepti Pillai

Benjamin Preceruti

Renee Purcait

Arjun Rajan

Noah Roberson

Joie Ruble

Eliza Rzhevskaya

Jasmine Sacks

Shashank Salgam

Eva Sarder

Lily Saunders

Mukul Seem

Jeremiah Serrano

Leila Shahidi

Violet Sheehan

Janice Shin

Crosslin Silcott

Lily Silverman

Victoria Sim

Suzanne Slovak

Sonali Sood

Rita Stein

Justin Stern

Ava Stewart

Sophia Tamburrino

Ginger Taurek

Megan Taylor

Florence Tian

Anna Tracy

Samie Travis

Abby Turner

Francesca Fiona Umali

Aanya Usmani

Kuren Vandyoussefi

Jade Vann

Isa Vasseva

Beatrix Verstegen

Arizona Weinstein

Gabriel Wright

Seiji Wright

Jenna Xavier

Kaitlin Yang

Christine Yoo

by Megan Krueger

Ebubechukwu Udeh

Shot by Sarah Strausberg

The convention hall in Bamako, Mali is a collage of colors: lilac, scarlet, lime, and fuchsia. Models glide down the catwalk, accompanied by a score courtesy of musicians hailing from all over the West African region. The true focus of the evening, however, is on the eye-catching garments being showcased on the runway. The oneof-a-kind designs, from tailored suits to experimental haute couture, all have one thing in common: they are created entirely from bazin.

This is Festi’Bazin, a festival dedicated to this special textile. In Mali, bazin isn’t just fabric. It’s a symbol of identity, history, and artistry celebrated not only for its beauty, but also for its role in shaping lives and livelihoods.

“West African traditional wear is bazin,” Fatoumata Diaby, founder of a

commercial bazin business in Bamako, tells journalist Mel Bailey.

Diaby’s family has dyed and sold bazin since 1968, so she knows first-hand the cultural significance the fabric possesses. Malians will spend nearly every special day in their lives wearing it, including marriages, baptisms, and holidays like Eid al-Adha and Ramadan. This popularity has allowed bazin to become not only an important cultural symbol, but also an economic staple in the country.

To understand why this fabric holds such prominence, we must journey back to its origins and the evolution of its craft. Bazin originated in England and was widely used in the 1700s to make clothing, curtains, pillows, and tapestries. The textile arrived in Mali around a century later, leading to the

creation of an entire industry oriented around its production and importation. Well-known bazin sectors have also popped up in neighboring countries like Senegal and Ghana, but to this day, Mali’s bazin industry remains the most famous.

Bazin, simply put, is a heavy, hand-dyed, polished cotton, typically made from cotton fiber or from a mix of cotton and satin. It is also called damask, which means that when it is woven, different yarn is used in the vertical warp and horizontal weft directions. Bazin is also classified as a brocade because a raised design is woven into the fabric. The quality of the cotton threads used determines which bazin variety the fabric is classified as. Premium bazin is the highest in quality, made with extremely fine cotton, resulting in increased vibrancy and shine.

Monyennement Riche is considered a mid-grade option, as it is typically made from cheaper cotton than premium varieties. Finally, Moins Riche is of the lowest quality but is also a quarter of the premium price, which allows people on a tighter budget to also have access to the beautiful fabric.

Despite Mali’s fame for its bazin sector, bazin is typically not woven within the country but is imported from places like Germany, India, Austria, and China. Once it arrives in Mali, it passes through the hands of countless workers including dyers, beaters, shippers, tailors, tinters, and boutique owners before being purchased by customers, many of whom travel to cities like Bamako specifically for the textile. Bazin is a timeconsuming product to create, as its transformation from a plain white fabric into a shimmering masterpiece involves meticulous dyeing and hours of careful finishing. The fabric is plunged into dye baths to give it its characteristic vivid color. It may also be knotted before being dipped in pigment, creating ornate patterns such as diamonds and spirals.

Dyed bazin is washed in cold water to seal its color before being soaked in a starch solution and rubbed with wax to increase its stiffness. After drying in the sun, the bazin is hammered with a wooden mallet called a finigochila, which brings out the fabric’s iconic luster. One finigochila can weigh up to 35 pounds and is glazed with wax before being used to beat the bazin. This part of the process can take up to three hours in order to achieve the preferred level of shine. Finally, the bazin will be sold, or perhaps sent to tailors and designers who create stunning garments from the fabric.

As can be expected, the popularity of bazin has led to a push for cheaper workarounds to create the fabric faster. Natural dyes may be abandoned in favor of harsher chemicals, many of which can be harmful to dyers who may work without protection. Their skin is often stained due to long exposure to the dyes, which, during times of high demand, may be up to twelve hours. Bazin beaters also work extremely long hours, and often for little pay. Still, the

industry continues to remain popular, given how easy it is to enter. No school is required, and anyone is allowed to train in order to pick up traditional techniques that have been passed down for generations.

“I watched for three weeks before they let me start,” Bailey quotes Gigi Koné, who works as a bazin beater in Bamako. “That was two years ago.”

Issoufou Soumalia Mouleye, an economics professor at a business school in Bamako, has also observed the job opportunities the bazin industry provides.

“The bazin sector is actually a booming sector for people who are familiar with bazin, and its impact on the Malian economy is real,” he agrees in a documentary for Reuters. “It’s a positive impact when you realize that the group of essential actors from the informal sector make their livings in making Malian bazin.”

Many people in the bazin sector hope that the Malian government will continue to recognize the importance of bazin to the economy. When artisans began hand-dying the imported cloth, the sale value of bazin went up by 40%. The next step for the industry could be creating the fabric itself. Although Mali is one of the top producers of cotton in all of Africa, the bazin itself continues to be imported. The creation of cotton factories in Mali itself could allow the industry to continue to grow and create even more jobs.

“It is not likely to happen in one or two years, or even 10 years,” admits Aminata Bocoum, founder of Mali’s famous Festi’Bazin, in an interview with Reuters, “but it will happen at some point. We

already have the added value—if we have the factory, we’ll have the whole production chain.”

In fact, Bocoum created Festi’Bazin specifically to highlight how bazin can bring positive change to the lives of Malians, and to West Africa as a whole. The event is held in Bamako every October to showcase the fabric and features clothing by designers from not only Mali, but also Senegal, Niger, and Morocco. Historically, bazin has been worn as a status symbol and indicator of wealth, but Festi’Bazin allows it to be celebrated as a cultural unifier. The festival pays tribute to the many hard-working people responsible for the bazin industry’s existence through design exhibitions and workshops demonstrating bazin’s complex dyeing process. Festi’Bazin aims to connect craftsmanship to contemporary fashion while emphasizing the economic importance of bazin. Alongside the clothing, attendees are treated to music and dance performances, as well as Malian cuisine. Festi’Bazin is a celebration of bazin, but it is also a celebration of Mali’s cultural landscape itself, demonstrating how the two—bazin and Malian culture—are intrinsically linked.

From the textile markets in Bamako’s industrial center to festive celebrations like Festi’Bazin, it is obvious how deeply woven one shining fabric is into the cultural identity of Mali. The crafting of bazin is a practice that dates back centuries, and the bazin industry in Mali seeks to keep this tradition alive for many centuries to come by continuing to expand and innovate within its production. Bazin is more than just a fabric, or even a tradition. It is a bridge between Mali’s past and aspirations for the future, where innovation meets heritage, and artistry drives economic transformation.

Courtesy of Awale Biz, Lakroz, Mel Bailey, UK Entry, and Reuters.

Bazin is more than just a fabric, or even a tradition. It is a bridge between Mali’s past and aspirations for the future, where innovation meets heritage, and artistry drives economic transformation.

by Ava Privratsky

Precious metals like gold and silver have held a meaningful place in fashion for centuries. The alluring materials have a timeless enduring appeal and have been ascribed many intricate meanings by human societies, solidifying their importance in our cultures and practices of physical adornment.

From jewelry to clothing, gold, and silver have been universally used to adorn and enhance fashion and beauty, as well as demonstrate status and eliteness in society. Gold is typically valued for its elegance and versatility, with its warm shine and resistance to tarnish. Silver is appreciated in more of a contemporary view, with its sleek, cool look and hypoallergenic quality. However, these conceptualizations of the metals only scratch the surface of their deeper meaning. The significance of gold and silver in fashion is much more nuanced when analyzing their complex and diverse history.

The use of gold and silver in fashion and adornment has deep historical roots, originating in South and East Asia and Africa and moving westward over time as groups migrated across the world. While the significance of metals across cultures shares many similar themes, diverse applications have made their use unique to each tradition, culture, and continent. Exploring the origins of precious metals in fashion reveals the starting point of these meanings, from which the varying modern meanings and uses of gold and silver then unfold.

South and East Asian and African societies were the first to incorporate metals into adornment. Over 3000 years ago, the first man-made metallic fibers were created with silver and gold, manipulating and incorporating metal alloys into clothing fabrics. Gold and silver wire were beaten thin and drawn into a fine thread-like substance, which was then used to decorate garments or blended into cotton or silk to create lamé fabric.

The workmanship and cost required of this process made these fibers a statement of luxury, power, and wealth.

The metallic fabrics were superior structurally and visually, with their strong, conductive properties and lustrous, eye-catching appearance. They were initially incorporated into clothing through embellished elements on garments, headdresses, scarves, and belts. Singaporean societies specifically used these metallic threads to embroider their clothing, also incorporating precious gemstones into the designs to complete the look.

The incorporation of precious metals in clothing techniques mirrored the existing traditions and meanings held by gold and silver jewelry. The oldest recorded African, Middle Eastern, Asian, and Indian jewelry traditions feature the use of gold and silver beaded jewelry, cuffs and bracelets, hoops and dangling earrings, pendants and charms, chains, shoulder and hair ornaments, anklets, rings, and more. Owning and wearing these items was also a sign of wealth, power, and sophistication in such societies.

Indian societies specifically have always used gold jewelry as an intrinsic part of their culture. While gold was initially just valued as an investment for wealth, it eventually became associated with good fortune. Wearable gold was therefore a must-have adornment, with importance set on the craftsmanship, detail, and meaning behind the pieces as they were bought and passed down through generations.

Gold historically symbolizes eternity, often worn by and buried with the societal elite because of its high value and resistance to decay. Silver has also been historically highly valued, symbolizing wisdom, luck, and protection against evil.

The historical comparison of silver and gold is quite interesting. Societies valued the metals differently for their religious, cultural, and fiscal significance. These opinions changed with time and accessibility, too. For example, in ancient Egypt - one of the most well-recorded

societies that prominently used precious metals - there was a shift in preference from silver to gold over time, allegedly due to resource availability.

Ancient Egyptian society was one of the first on record to value gold as a symbol of wealth, power, and status. It was considered the metal of the gods and was used in jewelry and garments to adorn the upper class. Mesopotamian societies in modern-day Turkey, however, preferred silver, extracting it from lead to create currency, small statues, and rings.

Records of various African, Middle Eastern, and Asian societies also depict royalty and elite members of society wearing metallic jewelry and clothing embellished with gold. These

Fast forward to a more modern day, the world (and its gold and silver production) became industrialized in the 19th and 20th centuries. Metallic jewelry and fabric became more accessible, but not at the expense of their original connotations.

occurrences were over 500 years before similar behaviors were adopted in Grecian and Roman European societies. Silver was also often highly regarded in these societies, and was used to make jewelry, accessories, and ceremonial objects.

From this starting point, the ideologies and values surrounding precious metals further developed. The metals solidified their prominent place in fashion through their adornment of royalty and the social elite, becoming important in reinforcing social and religious hierarchy, status, political influence, and the concept of an idyllic life.

As fashion technology advanced into the 1930s and 40s, metallic fabrics started to incorporate plastic fibers, creating imitation gold and silver materials that were stronger and more versatile. Metallic gowns and accessories were fashionably adopted in Hollywood, heavily worn and endorsed by celebrities whose influence further solidified the societal value of such metals. Gold and silver clothing was

a symbol of superiority, glamour, and sophistication in modern American society, much resembling its historical roots in non-eurocentric cultures.

Since then, metallic elements have consistently appeared in important fashion and cultural moments. In the fashion movements of the late 20th century, metals began to be used in a more provocative fashion, with subcultures using jewelry in new ways to create trends that went against the existing norms. For example, larger and edgier silver jewelry pieces were used in punk rock and alternative styles in the 1980s. In a similar vein, large decorative gold brooches were also popularized in the 80s, providing a bold contrast to create a statement in one’s look. While these two trends may seem completely different, their underlying purpose of using precious metals to stand out and demonstrate meaning through style is one and the same.

Today, gold and silver clothing and jewelry seem to be more of a laidback element in our collective fashion portfolio as a global society. Gold and silver have become much more available and affordable resources, and faux materials make identical copies of true metallic materials in clothing and jewelry.

While fine jewelry is still considered a sign of luxury and opulence, the metals have been incorporated more casually into our everyday wear. From delicate, dainty jewelry and accessories to bold metallic statement pieces, street fashion around the world differs based on personal preferences and cultural trends. Groups and individuals often still display their preferences between the two metals, or, more modernly, have opted to mix metals for a fresh look.

As for metallic clothing, metallic threads, embroidery, and fabrics have been popularized, along with metallic

embellishments like sequins, beads, foil, chainmail, and more.

Reflecting on modern uses of silver and gold, it is fascinating to look back at the cultures and history that shape current trends and behaviors. Making note of the history of these precious metals helps us recognize the broad and international cultural background that led to their aesthetic value in today’s contemporary fashion. All of the metallic fashion trends we see today can be traced back to important cultural origins rooted in both vanity and value, encapsulating a rich niche in fashion history.

The consistent presence of silver and gold in fashion proves the universal allure of metals in human society, solidifying their existence as a timeless element in fashion. Contemporary uses are influenced by diverse traditions, renewing old trends and ideologies in ways that fit the development of today’s society. Modern use of gold and silver may seem Westernized,

commercialized, and generalized at face value, but their significance and intrinsic value are a strong nod to how past social and cultural values have grown and changed into what they are today.

By examining the history of the precious metals and what they represent both in the past and present, one main thing is certain - gold and silver certainly make a statement in fashion, shining brilliantly despite the wear time.

Courtesy of Harper’s Bazaar, Antique Jewelry University, Ragya Jewels, FIT Newsroom, Science Direct

by Lily Legere

In the highly competitive world of art and fashion, Jean-Yves Kouassi and Gaston Ouedraogo take an unconventional approach. Through their brand, Djainin, they aim to make a noncompetitive, collaborative space for creators and designers, where they can express their appreciation for West African culture and streetwear. Kouassi, with little experience but lots of passion for the fashion industry, founded his brand in 2022, drawing inspiration from the vibrant nature of Ivorian street style. His brand aimed to represent the rich culture and history of Côte d’Ivoire, which, despite the turbulent conditions of surrounding West African countries, found itself persisting and thriving in a post-independence golden age. After pouring countless hours into his passion project, he recognized the need for support in growing his vision. Kouassi partnered with codesigner Gaston Ouedraogo, forming a formidable creative team.

“Our clothes are real pieces of history in our eyes. It’s the alignment of our two creative minds that creates the magic,” Kouassi told Dola in a 2024 interview—a platform that sells products by African designers and publishes blogs showcasing their stories.

Djainin’s inaugural collection centered on a crucial figure: Marie Thérèse Houphouët-Boigny, Côte d’Ivoire’s first First Lady. A fashion icon and pillar of poise and grace, Houphouët-Boigny represented what the brand aimed to encompass. She is a source of pride for many Ivorians, with her monumental contributions to health, wellness, and education for countless children across the continent. The line’s tribute to Houphët-Boigny, using screen printing and sun drying techniques, featured repeating patterns of her iconic portrait across various denim pieces. This distinctive design gained recognition, catapulting Djainin into the public

eye, and securing its place in Abidjan Fashion Week.

With “New Future” as its mantra, Djainin’s historically appreciative, yet modern style fits in seamlessly with the first-ever Abidjan Fashion Week’s core vision. Held in October 2024, the event featured Djainin’s models on the runway, but its purpose extended beyond showcasing fashion. At its core, the event aimed to unite designers nationwide to breathe new life into Côte d’Ivoire’s fashion industry.

“It’s a crossroads where talent, passion, and commitment meet to celebrate not only aesthetics but also the ideas, voices, and cultures that shape our industry,” explained Georgette Griffit, cofounder of Abidjan Fashion Week, in an interview with Africa News Agency about the event.

Beyond the event, Djainin continues this synergistic mission through its studio, Blu Lab. This space’s minimalistic design displays clothing in a museumlike fashion, drawing attention to the true artistry and beauty of each garment. Though originally opened by Djainin’s codesigners, Blu Lab is home to a myriad of Ivorian-based brands including Free the Youth, Mayeti, and Bana Bana. The appeal does not end here; beyond becoming a collaborative space for designers, Blu Lab opens its doors for workshops, talks, and exhibitions. It’s a space where people are encouraged to learn.

In March 2024, Djainin released its second line: Akan Roots and Sawfish. This collection draws inspiration from the vibrant textiles common in Akan culture–a matrilineal tradition on Africa’s west coast characterized by a shared religion, language, and society–and represents resilience and strength through the sign of the sawfish. Once again, Kouassi and Ouedraogo

flawlessly combined their unique and futuristic vision with thoughtful homage to their country’s rich history. They continue to push the boundaries of fashion as they expand their scope and pursue their mission of teaching others to embrace their diverse and introspective styles.

Courtesy of Djainin, InStyle, Nataal, The Dola, and Africa News Agency

by Keira Peters

The Maasai people of East Africa are often recognized worldwide for their distinctive dress and traditional jumping dances, but this surface-level familiarity can overshadow their complex and sophisticated culture. With a population of over one million across Kenya and Tanzania, the Maasai are a seminomadic ethnic group whose rich traditions extend far beyond the common tourist snapshots.

The Maasai are a Nilotic ethnic group residing in East Africa, namely in Kenya and Tanzania. In Maasai society, clothing and adornment serve as a sophisticated social language. Each piece of jewelry, choice of fabric, and style of dress communicates specific information about an individual’s place within the community - from their age and marital status to their social standing and role. This intricate visual communication system reflects the depth and complexity of Maasai cultural traditions that have evolved over generations.

Young boys in the Maasai tribe wear clothes tied over one shoulder, typically in a single color. Starting around age 6, the boys carry wooden sticks called fimbos, which serve as both fighting and walking sticks. Before adolescence, the clothing remains similar for these

boys. The fimbos grow longer to accommodate their increasing height, and their sandals are usually crafted from recycled rubber tires.

When a boy reaches adolescence, he undergoes the circumcision ritual known as the Emorata ceremony. This marks the transition from boyhood to manhood. Upon preparation to become a warrior, young men wear black cloaks and ostrich feather headdresses. They also paint symbols on their faces using white soil. The color black signifies unity and prepares them for the struggles they will face. After transitioning into a warrior, known as the Morani, men wear two pieces of

cloth, predominantly red. One piece is draped around the shoulders, while the other crosses over the right shoulder and is secured with a belt around the waist.

The elders of the Maasai tribe wear two to three pieces of cloth. These garments are a darker shade of red, with one piece wrapped around the waist and another draped across the right shoulder. The shuka, a cloth with a checkerboard pattern, can also be draped over the shoulders for warmth.

The role of women within Maasai culture is similarly defined through dress, adornment, and additional layers of clothing. Young girls, up to

three or four, wear a single piece of clothing tied at the right shoulder. A shuka can also be wrapped around the shoulders to protect them from the cold. This garment is similar to what young Maasai boys wear. Teenage girls wear two pieces of clothing. One is worn around the waist and fastened with a belt, while the other is draped around the right shoulder. These garments are typically red and blue. In Maasai culture, red symbolizes bravery, unity, and blood, while blue represents the sacred, holy, energy, and the sky.

Like many other cultures, the Maasai have traditional attire for weddings. Brides wear a red or orange dress

adorned with shimmering metal embellishments to create intricate patterns. The jewelry, primarily white, is crafted by the bride’s mother. The colors and patterns of the beads often represent the bride’s family and clan. The pregnancy status of a woman is also reflected in Maasai clothing. Pregnant women wear garments in red, yellow, green, purple, and white, with hints of black. A red shuka is wrapped around the woman’s body to protect the baby and provide strength to the woman during her pregnancy.

Elders wear simpler clothing, usually in red, blue, or purple. Their shukas and beadwork tend to be more elaborate, often accompanied by headdresses and staff decorations. These items symbolize the wisdom, experience, and authority of the elders.

While clothing plays a significant role, beaded jewelry holds deep cultural significance in Maasai culture, particularly for women. The art of making jewelry is passed down from mothers to daughters. More elaborate jewelry indicates greater wealth and age. Jewelry is often presented during ceremonies and rites of passage and given to visiting tourists as a sign of gratitude and respect. This sale of Maasai materials provides an important source of income for the Maasai communities, as they sell their products to visitors and expand the reach of their culture.

GEORGE Editor-in-Chief, Nneoma Iloeje, recounts her time with the Maasai people during her vacation to Tanzania this past summer. “They are incredibly welcoming. During my trip, I had the chance to purchase a beautiful, oneof-a-kind beaded necklace, a hallmark of their craftsmanship. It was truly an unforgettable experience.”

The colors of the beads carry symbolic meanings: red represents bravery and unity; orange represents hospitality; yellow represents fertility and growth; green is associated with health and the land; blue represents energy and sustenance from the sky; and black reflects the people and the struggles

they endure.

The emphasis on beadwork and patterns has not remained static. Maasai traditional wear has also evolved with modern influences. Maasai designers now incorporate shuka patterns into various clothing items and accessories. This fusion highlights their culture while embracing contemporary lifestyles.

The Maasai’s sophisticated system of dress and adornment represents generations of cultural knowledge, serving both practical and social purposes in their communities. Their clothing and jewelry aren’t simply decorative - they’re a living language that communicates personal histories, family ties, and social responsibilities. Understanding this deeper significance helps challenge superficial stereotypes and reveals the Maasai’s enduring influence as one of East Africa’s most prominent indigenous cultures.

Courtesy of 100 Humanitarians International and personal testimonies from the Masaai people located in Tanzania

How does the diversity within your organization shape its creative vision and encourage forms of selfexpression? Can you share a recent fashion project that was influenced by this diversity?

“At Vanderbilt Fashion Week (VFW), the diversity within our team forms the foundation of our creative vision. The 2025 team is comprised of 45 talented and passionate individuals, each bringing unique perspectives shaped by their diverse majors, cultural backgrounds, and campus involvement. These members are divided into seven specialized teams—Advertising, Photography & Film, Corporate Sponsorship, Events & Sustainability, Modeling, Beauty, and Styling & Garments—based on their unique skill sets. This structure allows for fresh ideas, innovative solutions, and a collaborative energy that makes our environment both inclusive and forward-thinking. By celebrating individuality and promoting nonconformity, we create a space where every member feels empowered to share their story and explore their creative potential. This diversity defines our community, drives authenticity, and shapes the creative vision behind our events.

A great representation of this was the 2024 Future of Fashion Show, a highlight of VFW 2024. The show featured 15 global designers and a diverse cast of 48 student models, reflecting a wide range of sizes, races, and heights. This inclusivity was central to the show’s success and left a lasting impression on our audience. My partner, Logan Gaskin, and VFW 2025’s Producer captures this beautifully:”

One of the most inspiring aspects of Vanderbilt Fashion Week (VFW) is its organic celebration of diversity. When recruiting for VFW, we don’t seek out a specific ‘type’ of person or idea; instead,

Hi, my name is Kiki Baumgartner, and I am a sophomore in GWFBA. I interviewed students from six renowned universities with highly respected fashion programs: NYU, Yale, Northeastern, Stanford, Vanderbilt, and the University of South Carolina. The purpose of these interviews was not to compare and contrast the fashion at these schools but to understand how the individuals within these institutions shape their program’s creative vision and foster a level of global cultural inclusivity through their projects.

These interviewees, whom you will get to know throughout the GEORGE Magazine, are incredible writers who help readers develop an appreciation for fashion beyond the surface level. Their work demonstrates how garments inspired by cultures from around the world can interconnect and introduce society to diverse backgrounds.

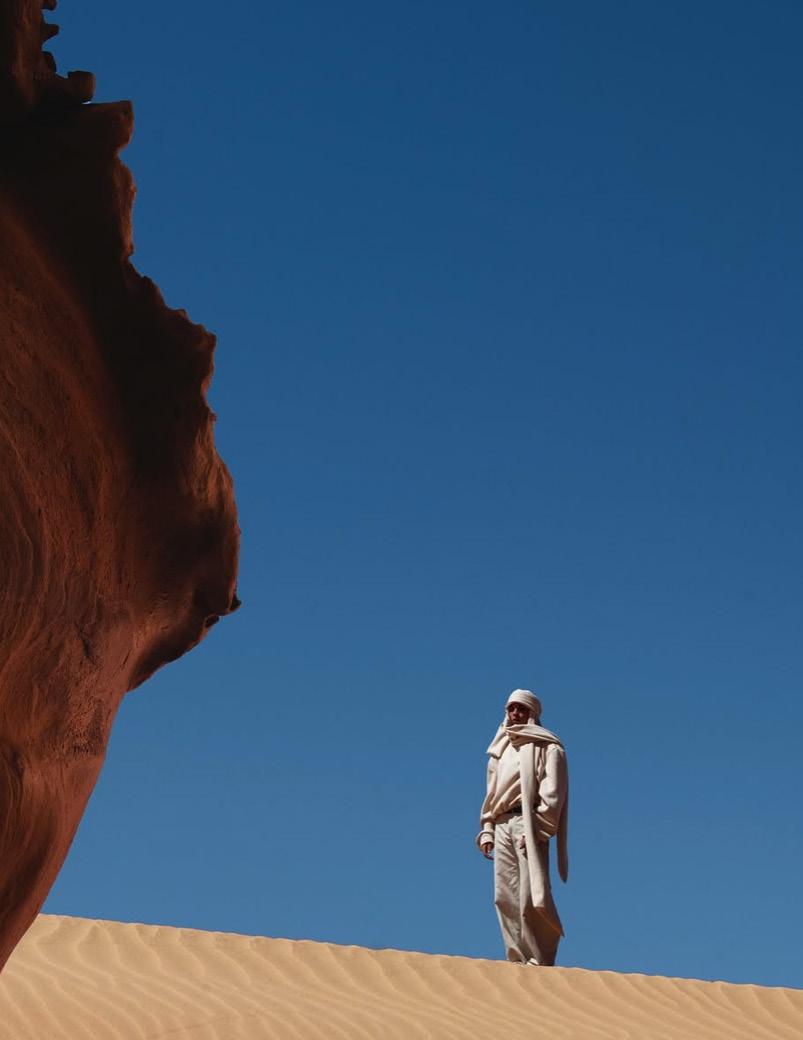

Shot by Ethan Valliath

what emerges is a beautifully woven creative vision, with each individual contributing something unique to the team. Together, we form a vibrant quilt of creatives from all facets of fashion, each adding a piece of themselves to the organization.

A clear example of this is the models featured in the 2024 Future of Fashion Show. At VFW, we recruit models based on two key criteria: coachability and

confidence. This approach naturally fosters diversity, with our models representing a wide range of sizes, races, and heights. Fashion is for everyone, and showcasing a diverse set of models is essential to reflect this truth.

As a tall, Black, plus-size woman, I understand the profound impact of not seeing yourself represented on runways. This personal experience motivated me, as the Modeling Team Lead last year, to ensure that no one in the audience felt excluded. After the show, I heard countless attendees comment on how the diversity of our models was unlike anything they had seen before and how deeply it resonated with them. VFW remains committed to fostering this inclusivity and will continue to celebrate diversity in all future fashion shows.

Do you think fashion as a whole promotes global inclusion and helps educate people about different cultures and backgrounds? Have you observed a recent trend toward cultural fusion in clothing and designs?

“Fashion is a reflection of culture, and it often serves as a bridge between identities, communities, and traditions. When approached with intentionality,

fashion can be an excellent medium for educating people about different cultures and fostering global inclusion. However, it’s crucial for designers and consumers to engage with cultural references thoughtfully. Incorporating elements of a culture into clothing and designs should come with acknowledgment, respect, and a desire to celebrate the artistry and heritage of that culture, rather than appropriating or rebranding it without credit.

Recently, there has been a trend toward cultural fusion in fashion, where designers draw inspiration from diverse cultural legacies to create something new and exciting. When done respectfully, this fusion has the power to highlight the beauty of multiculturalism and share stories of ancestry and heritage, offering a sense of belonging and connection to wearers and audiences alike.

Logan Gaskin, VFW 2025’s Producer, emphasizes the importance of representation in fashion as a tool for inclusion:

Fashion is a pure form of connection—a visual medium that doesn’t need language to convey its message. It has the power to celebrate the legacies of different cultures and highlight their stories on a global stage. But with this power comes responsibility: designers must craft with intentionality and respect to ensure that fashion fosters connection rather than division.

At its best, fashion is more than a visual statement; it’s a tool for storytelling and cross-cultural dialogue. By celebrating diversity and promoting awareness, fashion can bring people together from opposite corners of the world and serve as a platform for shared understanding and appreciation.”

Who is your favorite fashion designer, and where are they from/where do they get their inspiration from?

“My favorite fashion designer at the moment is Daniel Roseberry, who hails from Plano, Texas. I’m captivated by his work as the Artistic Director at Schiaparelli. His vivid, imaginative, and surrealist designs leave a lasting

impression, pushing the boundaries of creativity and craftsmanship.

I also admire how he navigated his career and unconventional journey in the fashion industry—his role at Schiaparelli was only his second job in fashion, following a decade of invaluable experience at Thom Browne. It’s fascinating that despite not speaking French, he communicates with the Schiaparelli team through his drawings, which showcases his exceptional ability to express ideas visually. This beautifully demonstrates that fashion is a visual medium that transcends language, relying purely on creativity and connection to bring ideas to life.”

Fashion predictions for 2025: Sophia believes there will be a greater “shift towards sustainable fashion” in 2025 as more people become aware of the harmful effects of fast fashion. She cautions against participating in the “culture of overconsumption” promoted by the media, which contributes to “over 13 million tons of global textile waste annually.” Instead, she advocates for thrifting and supporting brands that “prioritize eco-friendly materials, innovative production methods, and ethical labor practices,” emphasizing these choices as essential for the “longevity” and “creativity” of the future.

Sophia Arnold is a junior from Indiana majoring in Psychology and minoring in Human and Organizational Development—fields that allow her to connect her academics with her “extracurricular exploration of how fashion can serve as a powerful tool for identity, community, and inclusivity.” She serves as the Director of Vanderbilt Fashion Week (VFW), which was founded by Lauren Parker in 2022. VFW is a sustainable fashion week where Sophia leads “45 talented individuals to create innovative, sustainable, and community-focused fashion events,” embedding global designers into Nashville’s community to promote “collaboration and inclusivity.”

Sophia’s interest in fashion was ignited by a combination of her admiration for the “creative processes” in Project Runway and the constraints her boarding school uniform placed on her self-expression. While her boarding school did not fully allow her to immerse herself in her love of fashion, she appreciates the skills she developed there, which have contributed to her success in her leadership role for VFW. After graduating from high school, Sophia embraced the opportunities on campus to transform her previous constraints into ways to find her “identity through fashion.” She values comfort and sustainable clothing, helping her to “align [her] external appearance with [her] internal sense of self.”

Sophia further explored her relationship with fashion when she joined the Beauty Team of Vanderbilt Fashion Week as a freshman, foreshadowing her roles as the Beauty Team Lead in 2023 and CoDirector of VFW with Matti Angelides in 2024. Their 2024 Future of Fashion show “featured 15 global designers, a diverse cast of 48 student models, and 200 attendees.” Sophia deeply values her involvement with VFW, stating that it “has not only deepened [her] passion for fashion but has also shown [her] how it can connect people, build community, and inspire sustainable practices.”

by Charlotte

Mainstream media often centers on Eurocentric wedding fashion, overshadowing the rich diversity of traditional wedding attire from cultures around the world. Upon typing the phrase “wedding attire” into Google, thousands of images portraying white, flowy dresses and slick, black tuxedos flood one’s screen. Yet, the stunning beauty of Japanese kimonos, Indian lehengas, Chinese Qun Kwas, Ethiopian Habesha kemis, and handmade garments from Indigenous tribes are nowhere to be found. These vibrant, culturally significant garments deserve as much recognition and celebration as their Western counterparts. By shifting focus from “normative” Western wedding fashion to the diversity of wedding attire across a multitude of cultures, we can restructure the narrow-minded definition of what wedding fashion looks like.

At traditional Japanese weddings, brides often wear a variety of exquisite kimonos, each with its own unique beauty and significance. Among these, one of the most iconic bridal garments is the Shiromuku (translating to “pure white”), a stunning all-white kimono made from luxurious silk. The Shiromuku is known for its simplicity and elegance, with intricate embroidered accents that add depth and beauty to the fabric. While traditionally pure white to symbolize purity and new beginnings, some brides choose to personalize their Shiromuku by incorporating subtle hints of color, such as soft shades of pink or red, to reflect their style and add a touch of warmth to the otherwise serene look. Another popular choice for the traditional Japanese bride is the Irouchikake kimono, a stunningly colorful and patterned garment. The eyecatching hues of the Iro-uchikake are created using the ancient art of Yuzen dyeing, a meticulous technique that involves the application of rice paste to fabric before dyeing.

Top to Bottom:

According to Japan Dream Wedding, “The Iro-uchikake was originally the formal attire for wives of samurais in the Muromachi period…they gradually came to be preferred by rich merchants and aristocrats during the Edo period and are now one of the most popular styles of traditional dress…”

Kimonos also hold great ancestral value in Japanese culture as many are passed down across generations. These garments are a beautiful blend of art, history, and sentimental value. The

grooms’ outfits, though less detailed, incorporate traditional elements of kimono attire as well. The groom wears a black haori, a formal kimono jacket, paired with a silk cord known as a haorihimo. Other accessories include an obi (belt), zori shoes, and a fan. An heirloom crest serves as the finishing touch to the outfit—piecing it all together.

At traditional Indian weddings, brides typically don elaborate garments like lehengas or sarees. A lehenga consists of a long, embellished skirt

paired with a matching blouse (choli) and a decorative scarf (dupatta). Alternatively, the saree is a long piece of fabric, elegantly draped around the body. Both outfits are made from luxurious fabrics like silk and adorned with intricate embroidery, beads, and sequins, representing the rich cultural heritage and beauty of the occasion.

Courtesy of @tokiyajapan 2002 17th St NW Washington, DC 20009

As Crystal View states, “Unlike Western weddings, you won’t see an Indian bride wearing white as it symbolizes mourning.”

The significance of color in Indian bridal attire goes beyond aesthetics, carrying deep cultural and symbolic meaning. Red draws connections to the astrological significance of Mars, which promotes fertility, good fortune, and prosperity in marriage. Other colors that the bride may wear include yellow, pink, brown, gold, and orange. Beyond attire, intricate traditions enhance the bridal look. Before a wedding ceremony, henna is often applied to the feet and hands,

symbolizing good luck and positive spirits. Gold jewelry serves as the focal point of the bride’s adornments, with elaborate combinations of necklaces, earrings, bangles, and Maang tikkas— an ornament worn on the forehead— completing the ensemble.

The groom’s attire is similarly rooted in tradition, typically consisting of either a Bandhgala suit or a Sherwani. The Bandhgala, a structured, collared jacket typically paired with tailored trousers, is also known as the Jodhpuri suit—so named because, as Brides explains, it “was born in the princely state of Jodhpur in the 19th century.” Meanwhile, the Sherwani, a long,

buttoned coat, is traditionally worn with fitted churidar trousers, creating a regal and sophisticated look. To complete the look, grooms decorate themselves with carefully selected accessories. The groom’s accessories include Sarpechs or Kilangis— decorative ornaments embellished with a mixture of feathers and diamonds—placed on turbans. Over the years, grooms have taken a more active role in curating their wedding attire. As Brides notes, “It’s a myth that the groom is limited by choice in comparison to [the] bride. There are various modern takes on traditional Indian wear available now…grooms themselves have honed their fashion

sensibilities, no longer afraid to step out of the mold for their celebrations.”

In Ethiopia, traditional brides commonly choose to opt for dresses known as Habesha kemis. These are long dresses, handwoven from pieces of cotton sewn together. Oftentimes, kemis have personalized details on them—called Tibeb—that are woven on with threads. For Shewa styles of kemis, these details are typically embroidered on the waist, cuffs, or bottom of dresses. For Gondar styles, however, the embroidery is visible on the bottom back of the dress. Given that kemis are made by hand it can take up to three weeks to finish one. Women also typically add Netelas to complete the look, which are a type of scarf that also has Tibeb on the outer rims to pair with the kemis. The Tibeb can be more simplistic with one color or can feature a range of different colors and patterns. A majority of women wear two Netelas, draping them over their head and shoulders.

When it comes to grooms, they typically wear traditional Ethiopian suits, common for formal events. The elements of these suits include long-sleeved jackets, matching pants, and knee-length shirts. Made from chiffon, the suits are both light and elegant, while the undershirts often feature a Mandarin, band, or Nehru collar. To add the final touch to their wedding ensemble, grooms may accessorize with additional Neteles or Kutas, which are types of scarves.

This rich diversity in wedding attire highlights the unique cultural expressions found across the globe. While this article touches upon only some of the many forms of wedding fashions across the world, it is crucial that we expand our knowledge in order to challenge our conventional perspectives. By expanding our view to encompass wedding traditions from diverse cultures, we can shed light on the beauty and artistry of wedding fashion beyond the Western scope, reshaping our stringent definition of it.

Courtesy of The Knot, Brides, Lin and Jirsa, Mohi, Japan Dream Wedding, IKEHIKO Japan, Crystal View, and Kyoto Kimono

How does the diversity within your organization shape its creative vision and encourage forms of selfexpression? Can you share a recent fashion project that was influenced by this diversity?

“Diversity in our organization shapes creative vision because everybody has their own unique upbringing and everyone thinks in different ways. Because of that, people tend to develop their own personal style and their individual ways of viewing fashion. When you have an environment where there are so many different ideas and inspirations being bounced around, it really maximizes the creative vision of the community as a whole. Each year, we host a completely studentrun spring fashion show, and diversity plays a huge part in this event because it brings variety. Although there are common themes in each subsection of the show (our shows are formatted with a common theme that has four subsections relating to it), committee members will have their own way of viewing the theme; models have their own ideas of what their walk or pose should look like, stylists have their own visions of how their outfits represent the theme, and more. Because of this variety, the show becomes extremely interesting because you never know what’s coming next.”

Who is your favorite fashion designer, and where are they from/where do they get their inspiration from?

“Rei Kawakubo, founder of Comme des Garcons, was one of the first people that I discovered when getting into Japanese fashion and I love her work because of the way that she experiments with shapes in her designs.”

Fashion Predictions for 2025: Yuan has not been following trends recently, but is hopeful that his basketball shoes will start reemerging because they are “very important to [his] relationship with fashion.”

Do you think fashion as a whole promotes global inclusion and helps educate people about different cultures and backgrounds? Have you observed a recent trend toward cultural fusion in clothing and designs?

“I think that fashion promotes global inclusion when creativity is being used to its max, since the fashion scene as a whole tends to generally have a spotlight more on cultures in America, Western Europe, and Japan. When creativity is being used to the

max, though, you get to see insanely cool outfits such as Mongolia’s 2024 Olympics uniform. This allows people to become more educated about different cultures and backgrounds as well, since they get to see how amazing every culture can be.”

Shot by Kevin Theodat @stateofother

Yuan is a junior from New Jersey majoring in Computer Engineering at Northeastern University. He is also the vice president of The Fashion Society at Northeastern.

Yuan’s interest in fashion was sparked by the music and art his brother introduced him to, particularly rappers from the early 2010s. This influence inspired his love for “skate culture” and streetwear, paving the way for his future passion “for all areas of fashion.”

Fashion brands, styles, and trends from the West are often highlighted in mainstream media, saturating our feeds and newsletters with these influences. Fashion weeks showcase “new” and “trending” elements like intricate embroidery; elaborate, vibrant colors; dazzling fabrics, and unique, diverse patterns. Yet, many so-called new Western trends are anything but new. They originate from the longstanding traditions of various non-Western cultures. The West continuously draws inspiration from these influences, often without recognition. So, who is the notso-secret muse behind Western fashion?

Western fashion has been shaped by a multitude of cultural influences, with elements from Asia, Africa, and the Middle East making bold statements in modern style. Textiles such as India’s cotton, China’s silk, and Middle Eastern brocades form the foundation of fashion. Traditional patterns, including India’s paisley, Japan’s floral motifs, and Africa’s geometric designs, continue to inspire designers today. Silhouettes like Middle Eastern kaftans, India’s A-line neckline, and Japan’s kimonostyle wrap dress have seamlessly been integrated into Western wardrobes. Accessories also reflect this influence, with Africa’s beaded necklaces, the Middle East’s hamsa hand and evil eye jewelry, and India’s ornate headdresses all making an impact. The list of non-Western traditions shaping contemporary style is endless. In fact, many of these elements have become part of everyday trends. Recently, hand chains and chima skirts, both rooted in Asian culture, have gained popularity. Hand chains, originating in India but also significant in the Middle East, have become a staple accessory, while the flowing, high-waisted chima skirt, which comes from Korean culture, is making waves in fashion. When looking closely, it’s clear that much of today’s apparel and its designs can be traced back to non-Western origins, showing just how deeply these influences are woven into modern fashion.

A notable example comes from the 1970s, a time when Chinese influence on Western fashion was particularly

by Rita Stein

prominent. After decades of separation, China began opening its doors to the West with a relaxed foreign policy and a growing emphasis on diplomatic relations. This newly found access to Chinese culture and fashion intrigued the West. This fascination was evident with the Mao suit, a tunic featuring a high collar, four (sometimes five) symmetrical pockets, five buttons, and a boxy, utilitarian silhouette, which made its way into the pages of Vogue in 1973. There are actually quite a few more Vogue issues showcasing the impact Chinese culture had at this time! The Qipao, a form-fitting, elegant dress complete with beautiful embroidery and alluring side slits made a striking impression as well. This period of influence, often referred to as “Chinoiserie”, dates back to the 17th century. While the term itself is neutral and refers to Chinese inspiration, it is also linked to the era of colonialism and cultural appropriation, with elements taken out of their original context. Chinese culture was exoticized and romanticized, with colonizers creating stereotypes that inaccurately represented the culture. This occurred largely due to the lack of accurate information available when the term “Chinoiserie” was coined, leading people to rely on secondhand accounts of “the East.” This led to depictions that were rooted in fantasy rather than reality, with design elements featuring whimsical patterns detached from their true origins and context.

This wave of interest in Chinese fashion during the 1970s highlights a broader issue about how cultures are borrowed, often without proper acknowledgment.

This raises the question: When does inspiration become appropriation? It is important to acknowledge the distinct differences between appreciation and appropriation. As previously mentioned, during periods of colonization, the West often failed to give credit where it was due, resulting in a significant lack of understanding of cultural significance. Nowadays, brands continue to profit from nonWestern elements while neglecting to acknowledge their true origins. This is how cultural appropriation, rather than appreciation, is perpetuated in the fashion industry. On the other hand, appreciation means showing respect, giving credit, and involving partnership. When incorporating elements of another culture into your work, it is important to not only understand but also actively seek to learn about the history and context behind what you’re drawing inspiration from. Being able to know the background of the incorporated elements shows that you hold genuine respect towards the traditions, values, and history of the said culture and are taking the time to recognize the pieces you are integrating, rather than just taking it for surface level, aesthetic means. Additionally, partnership and collaboration have the power to bridge and unite communities and bring positive awareness to certain cultures, not to mention the potential economic benefits it may have for certain communities.

While non-Western influence in Western fashion has a troubling history rooted in colonialism, recent shifts driven by globalization and the evolving presence of the digital world have fostered more positive change. Though globalization has its cons, it has also allowed for a greater exchange of diverse fashion traditions, giving underrepresented cultures a platform to share their unique styles with a global audience. That is a beautiful thing! When this cultural fusion meets fashion, it encourages and celebrates diversity. Especially considering the digital revolution over the past few decades, designers, influencers, and consumers can now exchange ideas and showcase their artistry, ultimately

influencing the cross-cultural trends we see more prominently today.

Social media, online marketplaces, and fashion blogs are great mediums that facilitate this. Platforms such as Instagram and TikTok are extremely powerful tools where one can make a post that can go viral, reaching thousands, if not millions, of people on a global scale. These platforms enable direct communication between creators and consumers, allowing individuals to bypass once-existing limitations. Fashion, once limited to the traditional print media, has been liberated by this social media flux, eradicating the boundaries that once limited its reach.

Non-Western influence is not a trend that seems to come and go but rather a fundamental element woven through the fabric of Western fashion’s evolution. The history clearly reveals the undeniable power and impact the non-West has. The increasing interconnectedness of the world, fueled by the digital revolution, gives way to exciting possibilities for the future of fashion where we can share and pay tribute to our cultures. Through genuine appreciation and openness, we can move towards a world of vibrant, diverse, and innovative styles, while still honoring the sources they come from. It is important to give credit where it is due so we can celebrate one another and our unique cultures. As we explore the future of fashion, let us be reminded that it is a shared future, one where our diverse cultures have the power to shape and foster a global fashion landscape built on mutual appreciation and ever-evolving style.

Courtesy of LinkedIn, ResearchGate, and Psychology Today

An

Interview

by

Alex Marootian and Ethan Valliath

Sylwia Nazzal and her brand, Nazzal Studio, are a testament to the magnetic pull of Palestinian art and culture. With the release of her debut collection—and her college senior thesis—Nazzal quickly gained international recognition for her work, which fuses Palestinian tradition, politics, and avant-garde aesthetics. Since this interview in October 2024, she has won the Fashion Trust Arabia’s Best Debut Talent award, received major press coverage from outlets like Vogue and Dazed, and seen her designs worn by celebrities like Saint Levant, marking a remarkably successful year. In this conversation, Nazzal reflects on her Palestinian identity, the political nature of her designs, and the importance of embracing one’s own culture. Her work offers a singular perspective on the Palestinian struggle, capturing both its pain and beauty. Thank you to Sylwia for her time—we’re excited to see what’s next for Nazzal Studio.

Alex: Where did you grow up and when did you start becoming interested in fashion?

Sylwia: I was born and raised in Amman, Jordan. My family is Palestinian and immigrated to Jordan where I was born and raised. To be honest, I always wanted to go into a creative field and I didn’t necessarily know fashion would be the one. I kind of switched every year or two from interior design, architecture, acting, and arts. I was always playing around with the idea of creativity. And then at the last minute, I was like, you know what? I’ll do fashion. I actually started in fashion business and then I switched after the first week of university to fashion design because, I don’t know, I think I realized somewhere in that moment that I couldn’t continue the rest of my university years in business. I needed to go full out and I had no idea about sewing or anything like that. I was kind of just spontaneous and once I started sewing, I realized, you know, I’m actually kind of good at this and I do love doing this and I could see myself doing this for the rest of my life.

Alex: How do you think your Palestinian heritage has affected your creative output?

Sylwia: It’s a bit of a story because in university I didn’t even know I wanted to go into political fashion or art in general. [During] COVID, I regained this love for my culture. There were moments of me as a teenager despising a bit of my culture and my heritage, and then, in 2020 and COVID, it flipped completely. I became obsessed with my culture and heritage and literally couldn’t even imagine the way I felt before or why I was feeling those things. When I started university, I was just creating art, but inherently it was all political and I didn’t realize it yet. And then, there was a project that we had to do in our first year about using our traditional garments, mixing [them] with different designers, and finding a way to create something new. So I was looking into the thawb and I actually took a tent apart, re-patterned it with a different fabric, and re-stitched it into a jacket. [It was] a whole sculpture piece.

That project really shaped me, because it made me realize how much I wanted to talk about my culture and how I view it. Even the fact that I was talking about refugees and trying to represent that in some way through fashion…it really sparked something for me.

So I always knew my senior thesis collection definitely had to be about Palestine and my culture. I spent years thinking about it and wanting to do it. I made the collection in Paris—I studied fashion design in Paris and graduated before October 7th—and [it was a] full collection about Palestine and Palestinian resistance. It was not taken well by my school. I received a lot of intense backlash from everyone: administration, colleagues, classmates. It was bad. I [still] managed to graduate, but looking for a job was difficult with the portfolio of politics I had. And then on top of that, October 7th hit and all of a sudden anyone who opened my portfolio was even more afraid than they were before. So I decided that by December if I [didn’t] have a job, I was going to start my own brand and just create some ethical art. I had always thought this would happen in a couple of years, but I

decided to go down this path because I happened to post something on October 7th about my collection and it went viral. I had no idea what October 7th was or what it was going to be, but it went viral [anyway].

That kind of sparked this ‘wow’ moment. I received so much backlash for the past few years, especially working on this collection that, to my surprise, it had actually been so well received. It opened up a door for me to say maybe it’s not time for me to work for anyone. Maybe I’m supposed to show the things I’ve been working on to the world and show the world what a Middle Eastern Arab creative can do and the spaces that I can infiltrate. I started thinking about it more and then by the time it was March this year I was like I need to go full out. That’s how I got more into the political side.

Ethan: How do you see Jordan and Amman itself reflected in your clothes? Do you find inspiration from what the average person in Jordan wears and do you get inspired from the local creative and cultural scene?

Sylwia: I like seeing how people view our culture because it’s like, ‘Oh, you’re presenting the things we’re used to in a way that’s showcased beautifully.’ I think that in general, it’s inspiring, but I think I get more inspired by, for example, seeing a man in a dishdasha—a type of long dress—on the street and he’s wearing a suit jacket on top paired with an agal [with a] keffiyeh falling into the jacket. Seeing that alone, a man in a traditional dress with a blazer, is so Western. And then another traditional piece on top of the keffiyeh tying into everything— that alone, to me, is so inspiring. I think for me, that’s the fashion sense I would actually take away from the upand-coming scene and actually put more into the everyday dress of how we try to westernize ourselves or use contemporary garments in traditional dress. I love seeing that. So yeah, I think that’s my perspective.

Alex: Tell me about your experience at Parsons Paris, besides what happened with your senior thesis. What was it like going to school? Were you able to explore your Arab identity in Paris, or did you feel stifled in exploring that?

Sylwia: I think it had a fun effect on me where at first I was like, ‘Wow, I’m seeing what fashion looks like in a capital, versus being in the Middle East.’ It was so different—this is not how our lifestyle is at all. We don’t have many big creatives to look up to, except for a select few who were more focused on political and social change. So I think it was such a fun playground for me at first, but then it very quickly switched to me feeling like I needed to hold on even tighter to my identity and my culture. I wanted to represent my culture even more because there was such a lack and I think it pushed me to want it more.

Alex: Let’s get into your senior thesis. What were the overarching ideas you were hoping to communicate?

Sylwia: I think I just wanted to showcase what was happening

in the world, and I wanted to do it in a way that reflected how I view my culture. I think the concept behind it is, I think I target the West a lot. I like to say that I’m speaking the enemy’s language, but I’m also speaking a language that they haven’t infiltrated yet. I’m using a language that I can communicate through, one they understand—fashion, which has been heavily influenced by the West. But then at the same time, it’s a language I don’t think they’ve yet learned to combat.

So I think this was a huge approach for me. One thing I really enjoyed—or rather, the idea of it—was seeing how people react to a giant puffer jacket. At first, they might think, ‘Wow, this is a really cool shape,’ or whatever they feel. If they’re intrigued, they’ll look deeper, and when they do, they’ll see the reference photo of something really brutal and horrific. That completely changes the conversation they’re having with themselves in their heads. It brings up the conversation about Palestine through imagery and symbolism, focusing more on social impact than being [overt or in-your-face]. I think a lot of the time we see the keffiyeh prints or tatreez, which is embroidery, and it’s almost become fashionable. I don’t like that. So I wanted to take a step back and take a new approach, showcasing how to focus your voice, mind, and thoughts on Palestine by using a design you wouldn’t expect to be associated [with it]. But actually, the image it’s compared to is so brutal that it forces you to have that conversation with yourself. I think that’s the core of the collection and how I wanted it to be presented, though there are many details beyond that.”

Alex: That was kind of my next question, you make references to Palestinian culture and traditional Palestinian dress, but like you said, also very specific visual referencing of Palestinian oppression and violence against Palestinians. What was your

journey for finding those references and the transformation of these images and raw emotions into your work?

Sylwia: Yeah, I love that you’re asking me actually because the research took years. I started a year before the collection—2020, 2021—looking at all these images and not realizing [that] they would become references. By 2022, I spent four to five months researching Palestine, which was very difficult. Nowadays I think there’s a lot more accessibility, but then, it was really hard to find things online. I actually found a lot more in books and libraries and things like that. Funny enough, I even found a Chinese book about Palestinian traditional dress that ended up giving me so much information. Then, I took one of my first solo trips to Palestine in 2022.

reasons if that makes sense.

Alex: It seems like a lot of the pieces feature a subversion of Western garments and fabrics, as you mentioned with the giant puffer coat.

How do you think that interplay happens between mainstream Western items of clothing and your Palestinian heritage?

I was speaking to as many people as I could meet, and they showed me a lot of their images that they wanted to share with me for my work. I got a lot of references offbook if that makes sense. [It was] either me taking a photo, people showing me images that they wanted me to see, or books that weren’t able to be sold that I was able to receive. It was very special for me because I felt a deeper connection to my culture, more than I had ever felt before. I spent my whole life knowing I’m Palestinian and hearing from my family how my culture and my heritage [are] important, but I think experiencing it alone and connecting with it and creating a relationship that’s not tied to what I was raised with changed a lot of my collection for me. It made me want to create something so much bigger than myself and dedicate my life and my career to something without selfish

Do you see yourself as subverting these garments with the usage of nonWestern silhouettes, imagery, and visual references or references to oppression?

Sylwia: I think something that’s sad is, especially here in the Middle East, a majority of the time we’re looking to the West for something we think is superior. Even whiteness is considered superior because we’re all viewing things through the Western gaze. Even the puffer jackets I use—though clearly Western garments— carry a deeper meaning. I reference them because of the image of a boy being detained and dragged by his puffer jacket. For me, it’s about the contrast between modernity, represented by these contemporary garments, and tradition. I see resistance in two forms: one is preserving tradition through traditional silhouettes, and the other is resisting occupation by blending the modern with the traditional. It’s about finding a balance between contemporary and traditional garments, a balance that I think a lot of people Westernize, but in some sense, can still be rooted in the East.

Alex: Take me through the development of the coin dress and coin hoodie. How is it constructed and what do you hope to communicate with it?

Sylwia: The concept behind it was to use traditional coins to adorn headpieces and scarves. Essentially, these coins are believed to protect against the evil eye and symbolize wealth, beauty, and protection. I think in a lot of traditional weddings, you’ll see these coins used on garments as both a symbol of beauty and as a form of protection. I originally had the idea

of creating a hijab hoodie with a flat, no-neck shape that mimics the look of a hijab when worn. At first, I thought about adding coins to the border of the hoodie, but while I was thinking about this concept, I was like, ‘That just doesn’t sound like it’s impactful. It just sounds like I’m throwing it on for the sake of tradition.’ And I decided to just go crazy and cover the whole thing with coins. Then it turned into, ‘Maybe I should make it a skirt as well.’ These two pieces combined to create a full Arab silhouette. When I shared the concept with refugee women in Jordan, they were very excited. I think my favorite thing was getting their support for it and

respecting how I was creating my work. It took about 4 or 5 months to create all the coin pieces, but we had no idea how heavy it was going to be. We started with the hoodie, which was fine. 32 kg, but wearable. But then with the added skirt, it became 40 kg. I ended up having to stitch a leather harness to the skirt to hold it up. To stitch it, I needed two people carrying the skirt on the machine. It was a challenge, but[ it turned out to be a] beautiful piece.

Ethan: I find it so interesting how you’re talking about fashion in a modern

sense, especially in terms of the Arab culture and inverting how people incorporate that into fashion today. Do you feel that the way you represent your work—balancing modernity and tradition, not rejecting either but creating a tangible relationship between both—makes it inherently political, especially in the Arab world? Do you feel like that lends itself to being specifically political because of that vision, or is that open to a larger cultural interpretation in the Arab context?

Sylwia: I think this is an interesting topic, because, for example, I’ve noticed some Palestinian designers don’t like

that they are inherently political. Not because they want to be, but because they’re Palestinian and with that, it is associated with politics. I know I’ve experienced telling someone I’m Palestinian and seeing their reaction and me just realizing, you know, this is just my heritage it’s not political in this moment right now. I am political, but this is just where I’m from. So I think in this sense, it can be hard for some young creatives who don’t want their life revolving around politics. Especially [for] Palestinians living in Palestine, creating a brand from there may not always involve constantly sharing or focusing on their everyday political reality. But inherently, their existence as Palestinians living under occupation makes their work political.

So that is one aspect of it. I don’t think Paris or embroidery is political, [but] I think the keffiyeh is. The keffiyeh garnered a lot of solidarity with Palestine and wearing it is largely associated with it. If you are using [it], you are 100% being political. Let’s say even for my pieces, I know I want them to be political. I know I want them to make a statement and I know I want them to also be traditional because

at least for me, resistance is both tradition and these horrific moments. I [personally] don’t think you can talk about Palestine without bringing up the genocide at the same time.

Alex: How do you see trauma and oppression and intergenerational pain specifically as part of your work? Do you feel a responsibility to depict that pain through your clothes? What do you hope to convey with those ideas? Also, I guess getting back into the idea of politics, do you see that pain and that trauma as inherently political, or is there a way to divorce it, and give respect to just the things people have gone through?