All At Sea

Geoff Duffield1

A Personal Response to Brexit, Identity and Memory

David

Cameron, Prime Minister, March 2013.“I hope this will enable The Conservative Party to stop banging on about Europe.”

“The day after we vote to leave, we hold all the cards and we can choose the path we want. It’s also important to realise that while we calmly take our time to change the law, the one thing that will not change is our ability to trade freely with Europe.”

“I do not think it would be right for me to try to be the captain that steers our country to its next destination”.

David Cameron, Prime Minister, June 24th, 2016.

“Brexit means Brexit.”

Theresa May, Prime Minister, July 2016.

Helen (Newlyn), Adam (Newlyn), Michael (Dover), Katie (Dover), Paul (Shoreham), Ellie (Shoreham), Deborah (Holyhead), Will (Holyhead) Stuart (Ramsgate), Katie (Ramsgate), Jamie (Brightlingsea), Emma (Brightlingsea), et al. July- September 2022

“I didn’t really know what I was voting for.”

“For my group of friends, Brexit feels like a cloud constantly, hanging above us; the new reality that you can’t quite escape but wish that you could. Perhaps because of the limit it places on your hopes for the future or your daydreams about it.”

Trish, Penzance , August 2022.

“I’m clear people voted for us to leave. We will leave and will leave on 29 March 2019.”

Theresa May, Prime Minister, November 2018

“February 24, 2019: “We still have it within our grasp to leave the Europan Union with a deal on 29 March”.

Theresa May , Prime Minister February 201

“MPs have been unable to agree on a way to implement the UK’s withdrawal. As a result we will now not leave on time with a deal on the 29th March”.

Theresa May, Prime Minister, March 2019

“I was too young to vote. My Mum voted to stay, and my Dad voted Brexit. It’s difficult to talk about it with friends now, isn’t it…what do they think? It’s depressing in the way it has caused division. Because it provokes such strong emotions… it creates a wariness lurking overhead.”

Jessica , Margate, June 2022

“It is, and will always remain, a matter of deep regret to me that I have not been able to deliver Brexit.”

“We will deliver Brexit.”

Theresa May, Prime Minister, Resignation speech, 24th May 2019.

“Leaving would cause business uncertainty, while embroiling the Government for years in a fiddly process of negotiating new arrangements, so diverting energy from the real problems - low skills, low social mobility, low investment - that have nothing to do with Europe”.

“If we Vote Leave, we can take back control of our borders and our money. We can take back control of £350m a week. We can take back control of immigration. By 2020, we can give the NHS a £100 million per week cash injection, and we can ensure that the wealthy interests that have rigged the EU rules in their favour at last pay their fair share”.

“There will be no border down The Irish Sea – over my dead body.”

Boris Johnson, Prime Minister, August 2020.

“I wanted to make an image of the border in The Irish Sea because it somehow contemplation was broken when my phone pinged. It was a notification informing a UK company to an Irish one. That’s when I made this image”.

Geoff Duffield, September 2022

because it somehow represents the mirage that Brexit is. My on-deck notification informing me that my service provider had changed from

“We feel nothing but sorrow. They lied. We voted to leave but we didn’t really know what we were voting for. We thought it would help Penzance and the local fishing industry but that hasn’t happened. There’s still empty shelves in Aldi and now we’ve got sewage discharging straight onto this beach. Where are the politicians now?”

Dewi and Elys, Wherry Town, August 2022

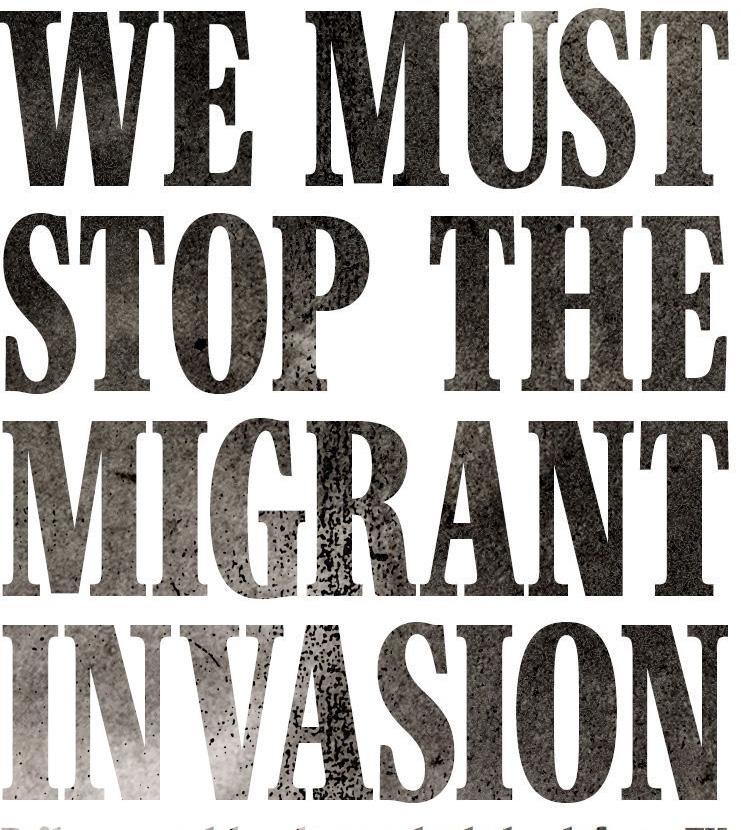

“We will stop European Union migrants from treating Britain as their own country”.

‘I’m from Hayes in Middlesex. I moved to Dover four years ago. You wouldn’t recognise Hayes now, compared to how it was when I was growing-up there. I voted leave. We need to control our borders and immigration, but right now I’m feeling abandoned by the politicians”.

Deborah, Dover, August 2022.

“When will people wake the f**k up? We were led like lambs to the slaughter. We were told that we would have £350 million more for the NHS, and that’s what really prompted me to say leave. I would change my mind now”.

Richard, Holyhead, September 2022

“The key is that we’ve got our fish back. They’re British fish and they’re better and happier fish for it”.

Rees Mogg , Leader of The House of Commons, January 2021

“Brexit was my first vote. All my family, and everyone I know, voted to leave because we were told that we’d get bigger quotas and that we’d take back control of our waters. My Dad runs a boat, and he won’t talk about Brexit anymore. There’s too much anger. They lied to us, didn’t they?”

Andy, son of a fishing boat owner,Newlyn, August 2022

A guy came along – not a local - before the vote. Half the town gathered on the quay to hear him. He promised us unicorns and rainbows…that we’d get our fishing grounds back. Well, that hasn’t happened, there’s fewer boats going out because the EU workers have gone, and the politicians have disappeared and left us in limbo.”

Clemo, Newline Chandlery, Newlyn Harbour, August 2022

“I hoped and believed that our friends in the EU would not necessarily want to apply the Northern Ireland protocol in quite the way that they have”.

Boris Johnson, Prime Minister, May 2022

“You won’t find a single soul within twenty miles of the border who voted to leave. We all knew what Brexit could mean… the end of peace. When I was a kid, this town was full of fear. Look at how beautiful it is now. Boris ignored us, and now we’re in this mess.”

Liam, Warrenpoint, Newry, Northern Ireland, September 2022

126

“We have a Remainer’s Brexit.”

David

Davis, ex-Brexit Secretary , June 2022.“I’m not sure if it’s ever going to be clear whether it has succeeded or failed. I’m not sure we’ll ever get the kind of economic evidence one way or another”.

David Frost, ex-UK Chief Brexit Negotiator, June 2022“We should have stayed in The Single Market.”Lord

In the making of All At Sea, I’ve spoken with and listened to almost two hundred people in the UK who, in 2016, voted to leave the European Union (the EU).

Last summer, I walked 280 kilometres around six Leave-voting locations to explore how people are feeling about things now, six years down the line. In this sense, my work is a moment-in-time piece, a snapshot of a seemingly endless Brexit narrative.

With each iteration of the Brexit story, the previous incarnation feels as though it is lost beneath the waves, and since that narrative is largely owned by pro-Brexit politicians, I wanted to record how feelings were running in the summer of 2022, before that memory too was lost.

By juxtaposing the pro-Brexit headlines from the national press as events unfolded, from the referendum campaign leading up to the 23rd June 2016 vote, until the final demise of Boris Johnson’s premiership in September 2022, with images made along the coastline of those areas most likely to have voted to leave the EU, I wanted to explore the gap between the rhetoric and the reality. How, for example, do people feel about the politicians’ promises made then, compared to their own experiences now? This is not just about documentation, but also about holding the politicians to account. I hope that this work is one of the many which, when aggregated, can lead to change, or at least provide another perspective that wasn’t influenced by those in power. I’ve seen a complicit British tabloid press feeding into the Leave narrative to influence the outcome of both the referendum, and the story since, and I’ve intertwined their role into my work.

The conversations I had were with people in towns on the edge of Brexit Britain: Brightlingsea, Ramsgate, Dover, Shoreham-by-Sea, Newlyn, Holyhead : towns that, when you join the dots, create a line that not only traces a route along our coastline, but which also delineates our border with the EU.

It’s clear that people voted to leave for two chief reasons, one emotional and predominantly the motivator for older people (entwined in identity and memory), the other practical, and the biggest driver for younger people.

The most important motivation for older people to vote Leave, based on my conversations with them, was an overwhelming sense of nostalgia. There was a collective sentimental longing for, and memory of, the past and their youth : a ‘gentler’ Britain, with respect for the institutions, the Queen, and each other, a simpler life, a ‘whiter’ society...a unified identity of an homogenous Britain, the spirit of The Second World War (even though most people I talked with weren’t born then), when Britain had more influence in the world. Immigration was more often than not spontaneously mentioned as a factor, though not overtly, with the two most common refrains about their town or birthplace being “you wouldn’t recognise the place now” or “it’s changed”. Remembering their younger selves in itself was a motivator...they were happier then, with fewer responsibilities. This was at a time in their lives before the UK joined what was then the European Economic Community (in 1973), so they believed

that the changed Britain of today, and a less happy life, must be the result of Britain’s membership of the EU. They saw it as cause and effect. It was a neat, simple equation into which those advocating Leave played.

The motivation for people to vote Leave for those under 40, was less about the past, and more about the future, specifically about how leaving would improve their job prospects and income. (To acknowledge the socio-economic status of most of these people, few had been to university, and most were on low incomes). A clear example of this is the community of Newlyn in Cornwall, home to England’s largest fishing fleet. Just about everyone in that community earns their living directly or indirectly from fishing. They voted Leave for two practical reasons : bigger fishing quotas and ‘taking back control of British waters’. Nostalgia played second fiddle to their income. Given that my research was carried out at the time of the cost-of-living-crisis, these feelings were running high.

A common characteristic of both young and old Leavers that I listened to was their insularity. Generally, they weren’t considering the pros and cons of the referendum in terms of wider society, but rather they focussed on how it would affect them and their families. Not one of the two hundred asked me what I thought about Brexit. Maybe they were fearful of disagreement? Or was it lack of curiosity? The very act of casting their vote in the referendum could also be seen as an example of indifference since the overwhelming chorus was : “I didn’t really know what I was voting for.” This insularity struck me as ironic, given that most of the conversations took place on a promenade or on a beach, looking outward. It’s as though the sea onto which we gazed was less a passage to the wider world for them, and more about confirming that we are an island, and that this was the border.

Brexit was a political deed....the practical act of leaving the EU. As we’ve been told many times by politicians, ‘Brexit is done’. And it is, in as much as we left the EU on 31st January 2020. So why is it still part of our everyday lexicon, influencing so much of our political and personal lives? The answer, again from the perspective of the people I have spoken with, can be summarised in one word : division. Arguably, Brexit has caused the deepest, the most emphatic, and the longest-lasting divide across the country since The English Civil War. It has created two camps : Leavers and Remainers. It has split the so-called union of the UK, with England and Wales voting to Leave, and Scotland and Northern Ireland to Remain. It has pitted old against young, cities against old industrial towns and the countryside, the educated against the less educated. There was persecution leading up to the referendum (an increase in racist attacks, the murder of Jo Cox) and long after the event as Brexiteers continue to use the Remainer moniker as an insult.

However, perhaps more significant than this, and again this was a theme in my conversations, is that it has caused irrevocable splits between family and friends. I’m not sure that anyone foresaw the broken personal relationships that Brexit has caused in practice. Even amongst the young, years after the vote, there is a reluctance to discuss Brexit for fear that it will create tensions. Others talked about permanently fractured friendships. Within families, everyone knows who voted which way - people are psychologically-mapping their most personal relationships in order to avoid conflict.

The Leave campaign remains very active (with secretive funding).The Tufton Street network of right-wing think tanks works at the heart of the UK government, and the

“European Research Group” (ERG), a secretive caucus of Conservative MPs remains “the most influential research group in recent political history.” (The Financial Times, December 2020). Indeed, the current Home Secretary is a member of this group, which has Brexit as its single focus. Somewhat incredibly, I feel, is that the ERG is funded by taxpayers’ money. Brexiteers continue to demonise those who want a closer working relationship with the EU (the latter being the majority of the population, according to Statista, October 2022) accusing them of being unpatriotic and undemocratic for any attempt to do so.

More widely, this division is apparent in established media : those who continue to beat the Brexit drum (The Mail, The Express, The Sun, The Telegraph, The Spectator, and GB News), and those who decry Brexit (The Guardian, Channel 4 News, The Independent, The New Statesman).

The division is played out even more viscerally on social media, and on Twitter in particular. Brexit hashtags still trend every day on Twitter, with individuals interacting with each other in real time. Twitter has the benefit of the user being able to hear from politicians first-hand, without the filter of a media owner. However, it is open to incredible abuse by vested interests who choose feed this division for political gain.

One outcome of the post-Brexit period and this division has been silence, practically an omertà, across the BBC. The corporation continues to report on, for example, lack of staffing levels in the NHS and the hospitality sector, without ever explaining the underlying symptoms (200,000 EU nationals have left the UK since 2016 : Bloomberg). Nigel Farage has been on the BBC’s Question Time thirty five times during and since the Brexit period, more than any other politician. Richard Sharp, the BBC’s Chair is a donor to The Conservative Party....these are indicative of a much wider, insidious web of influence of political ideologues who have Brexit as their emblem, a cause to be “cherished” (Liz Truss, August 2022). The fact that Brexit has caused a 4% reduction in the UK’s annual gross domestic product (Office For Budget Responsibility) is rarely mentioned by the BBC in its economic analysis, including in its daily news analysis of the current economic crisis. This, when that 4% equates to £108 billion at a time when the government is attempting to find just £65 billion to balance the books. Not talking about Brexit feels like a conscious defensive measure to preserve it.

If that is some context for my project, the reality of this psychodrama for those that I talked to is evident. Brexit is still with us, but it is hidden, for reasons of selfpreservation. As the vicar for Brightlingsea, the Reverend Caroline Beckett, said to me as she described the division in her own community: “the people who voted Leave are hurting, and the people who voted Remain are too angry to talk”.

This silence and division was a principal reason for my project....Brexit doesn’t go away because it’s not discussed. I wanted to get people to talk to me about how they were feeling now, partly as a matter of record to document it, partly out of curiosity, and partly because I think it might help. If we can’t discuss this schism that hangs over us, how will it ever be healed?

This leads to my methodology. My images have three strands : seascapes, portraits of Leave leaders, and the graphic text images that represent what was said by politicians, the media, and the people with whom I spoke. I wouldn’t go as far to say

that my images take second place to my conversations, but it is true to say that the conversations with these people who voted Leave directed my image-making. My seascapes are metaphorical and autobiographical, reflecting both the turbulence and shifting narrative of Brexit, and also representing my emotions, because I feel allat-sea as a result of Brexit, and so do many of the people with whom I talked. I also feel that this description encapsulates Britain’s political turmoil of 2022, as we move onto our third Prime Minister in four months. The politicians’ quotes, and images come from research through books and the internet, and the quotes from the people I talked with are verbatim.

The fact that Brexit is still a raw topic has influenced the way in which I talk to people. I walked, and approached random strangers as they worked, or walked along the coast, the promenade or the shoreline. Brexit always comes at the end of any conversation.

I approach people and engage them on their own terms….they might be mending a fishing net, gazing out to sea, walking their dog, working in a shop, or having a conversation among themselves. I have a set routine of showing my Falmouth University Student Card, letting them know that I’m making images of the place in question, and then talk to them about whatever it is they’re doing. Generally, people were only too happy to talk, taking pride in their work or their town, and happy to voice their opinion. This general chat accounted for most of the conversation. It helps that I’m an older white male….in their eyes, I’m part of their tribe. It also helps that I’m comfortable talking to people as I can develop the conversation and, after at least twenty minutes, I would segue into Brexit. The longest conversation I’ve had with someone purely on Brexit is thirty minutes, the briefest was when a fisherman clammed up completely and walked off. Generally, people will talk about it for three or four minutes. Brexit is not a gateway to a long conversation among Leavers. Hesitancy, wariness and anger (directed towards the politicians) are the usual responses.

I’ve described All At Sea as a personal response to Brexit, identity and memory. Although most of the text in this work represents others’ views, the act of making this work in the first place was deeply personal. It began as therapy, and as an attempt at understanding in response to the shattering of an ideal. It has resulted in a compassion for those who believed the politicians, and a hardening of both my European identity, and the contempt in which I hold those who advocate Brexit. Being by the sea, and on the sea, has been something of a balm to the latter.

If there is one final takeaway for me from this project, and I hope that this is not simply optimism on my part, it is that the people I spoke with appear to be acknowledging that Brexit has not given them what they were told it would give them. Unfortunately, over the months that I’ve been talking with people, things have got worse for them, especially financially. They’re more reflective about the causes for this. Yes, the war in Ukraine is one factor, but their general dissatisfaction is causing them to consider other factors, Brexit included. I wouldn’t say that the tide has turned yet, but it may be just possible that we’re approaching high water.

Brexit: The Un-Civil War.

An interview with the photographer, Geoff Duffield, about ‘All At Sea’. By Anna Melville-James.

“When I was seven my grandmother told me that she had never left England. She said that she had once gone to the White Cliffs of Dover though and seen France, and even at that age I thought that was incredible — this sense of curiosity about a mysterious place you could see ‘just across there’ but would never visit. That has stuck with me.

My own European identity is strongly pinned around the war and the part my parents played – my father a pilot in the RAF, my mother a nurse - in fighting against fascism. And on a contemporary note, I spent a year in France, Spain and Italy when I was 20 that gave me a basic understanding that our issues are universal — so I could never buy into the foreigner-as-stranger argument. I remember putting European as my nationality on the 1981 census.

That night in 2016 when the results were announced it felt like my identity had been ripped out of me. I still feel that. And I was looking for someone to blame when I went into this project.

But I was also trying to avoid the ‘cancel culture’ approach, to let people talk for themselves, to root it in understanding — and aware, too, this project was in many ways therapy for me. A colleague said to me, “You’re obviously angry about this. Why aren’t you sharing that?” But when you shout at people that they’re wrong they just double down.

In 2021, I collaborated with Brightlingsea on the Essex coast, visiting over seven months, and getting to know the community, many of whom voted Leave. Stopping to talk to people, I often wouldn’t need to ask, “Why did you vote for Brexit?” I’d say, “Do you live around here?” and they’d say, “I moved here from Ramsgate”, then drop their voice and say, “it’s changed so much”. That meant there were people of colour there now.

I also got real understanding around how many people believed what they were told. A lot of people literally believed that £350m a week would be going to the NHS. The chandler on Newlyn Harbour told me that half the town turned up on the quay in 2016, to hear a guy, who wasn’t local, talk about Brexit: “He promised us unicorns and rainbows,” he said. “We thought, ‘well, probably not all of it will happen, but a lot of it will’”.

I’ve talked to close-on 200 people who voted Leave in the past 20 months and have never once been asked what my view is, which is interesting and indicative of what I find in Leave areas. Many are quite insular through a combination of their geography and history and often the people I talk to are not that inquisitive. I can’t think of another issue where people would just stop asking questions.

The omerta around the whole thing now is part of my response. BBC News will refer to COVID and NHS staff shortages, but not to the 22,000 EU nationals that have left the

service since the vote.

I had naively, despite what history tells us, assumed that progress was this simple upward line. The idea of being part of Europe and of something bigger was one of a greater good for me, a set of values that comes from my upbringing. The referendum result was a shattering of idealism — and of certainty. I wondered if we – I - had become complacent about progress. The real injustice though was that we were told so many lies and the tolerance of that is shocking — or maybe people just feel helpless? One thing that has changed is that people are starting to hurt and to examine why in their own lives. Straightaway, they distance themselves — they acknowledge Brexit, although it’s someone else’s fault.

I’ve moved to a place now where I’m essentially holding politicians and the media to account, not by saying ‘you lied’, but ‘this is what you said’. Using politicians’ words on record, talking about Brexit’s ‘sunlit uplands’ is a reminder that what was promised has not materialised. I want to carry on the conversation, so it doesn’t get assimilated and hidden from view, and continue to ask, ‘where are the benefits of Brexit and who has them?’

Brexit was a mirage based on emotion. And an emotion is very hard to argue against. Everyone I speak to seems to say: ‘we didn’t really know what we were voting for’. That’s such a big decision made without any real information — and as a result it wasn’t ever defined. Once you’ve done that, you’ve handed everything to the people in power”.