Thecoverartforthisissueisinspiredbyitsthreeorganizingthemes.Featuringacollection ofhandswhichtogetherformtheoutlineofthephysicallandof“NorthAmerica”,thepiece speakstothearbitrarynatureofbordersandchallengesthedisconnectionbetweenland andculturewhichbordersoftencreate.ThehandsarealsointendedtohonourIndigenous lifewaysandknowledgethroughrepresentingtheinseparableandindivisiblerelationship betweenlandandpeople(asapartofland),andrecognitionoflandasaliveratherthanas resource.Thehandsthemselvesalsoseektoreflectthephysicalgeographyofthelandina waydi!erentthanintraditionalmaps:knucklesfortheRockies,flatpalmsfortheplains, andacuppedhandforHudsonBay.

TheJournalofUndergraduateGeography

Volume10(2025)

ManagingEditor

JaneYearwood

Editors-in-Chief

JaniceWalder

Youjia(Avila)Zhang

EditorialBoard

SnehaBansal

TaliaFrockt

MuznaMian

MargadSukhbaatar

IsabelThompson

LeilaVessey

VanessaWiltshire

Contributors

AnnaAngelIzemengia

NiamhEllwood

NatalieHeiChingChan

SandraGlozshtein

PolinaGorn

EmmanuelPasternak

LukaPilasanovic

JaniceWalder

VanessaWiltshire

KaedanYu

SpecialThanksTo

ProfessorPaulHess

TheTorontoUndergraduateGeographySociety(TUGS)

Editors’Notes

JaniceWalder,JaneYearwood,andYoujia(Avila)Zhang

DemonizationandDispossession:Anti-IndigenousSpiritualNarrativesin 17thCenturyVirginia

TourismandtheColonialImaginary:IndigenousDispossessioninMuskoka

Land,Sovereignty,andFrontier:HowtheLouisianaPurchaseCatalyzed ManifestDestinyandIndigenousDispossession

TheImpactsofRiver/LakeIceontheCanadianArctic KaedanYu

TheSvalbardGlobalSeedVault:A‘Noah’sArk,’orSomethingMore Sinister?

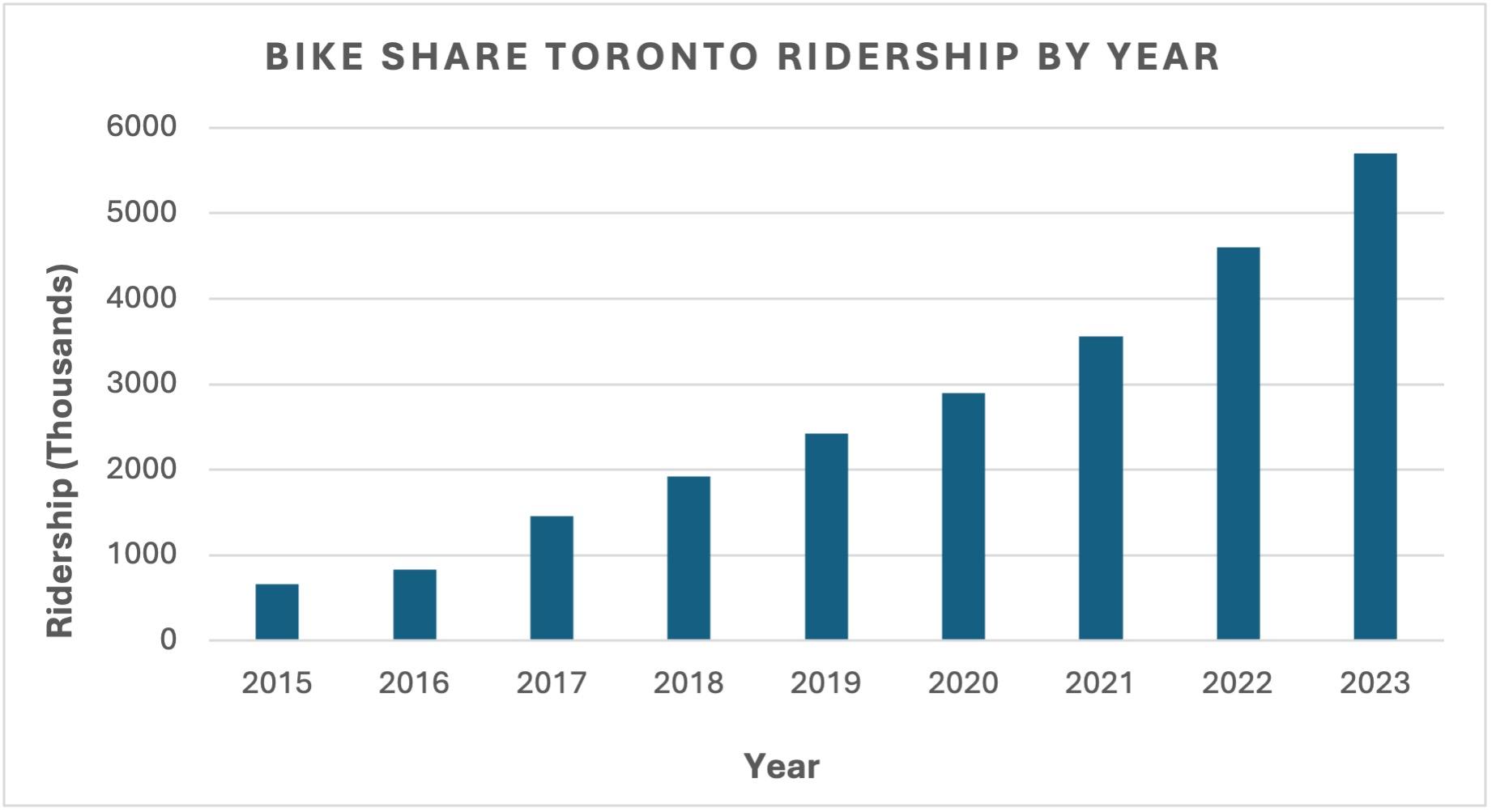

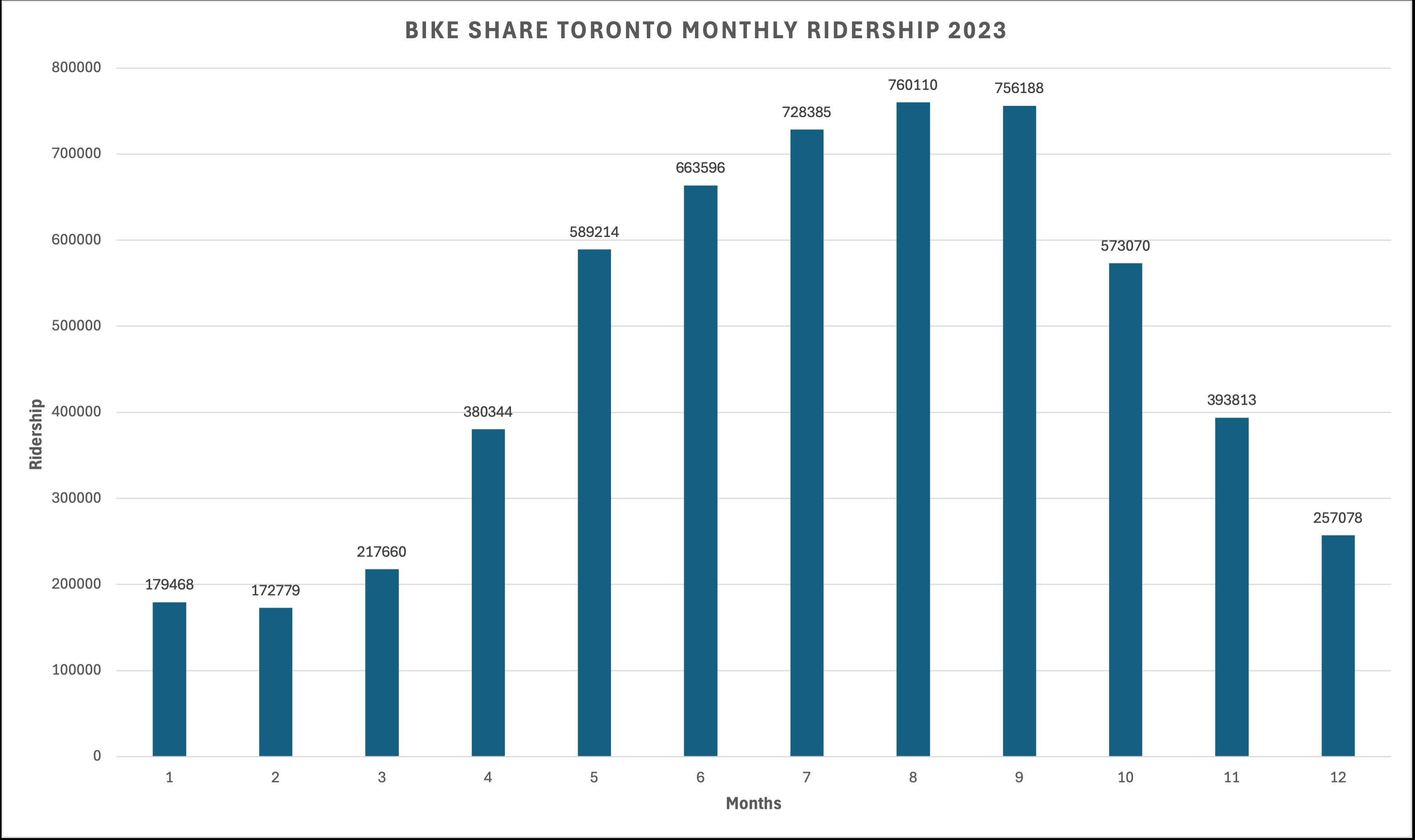

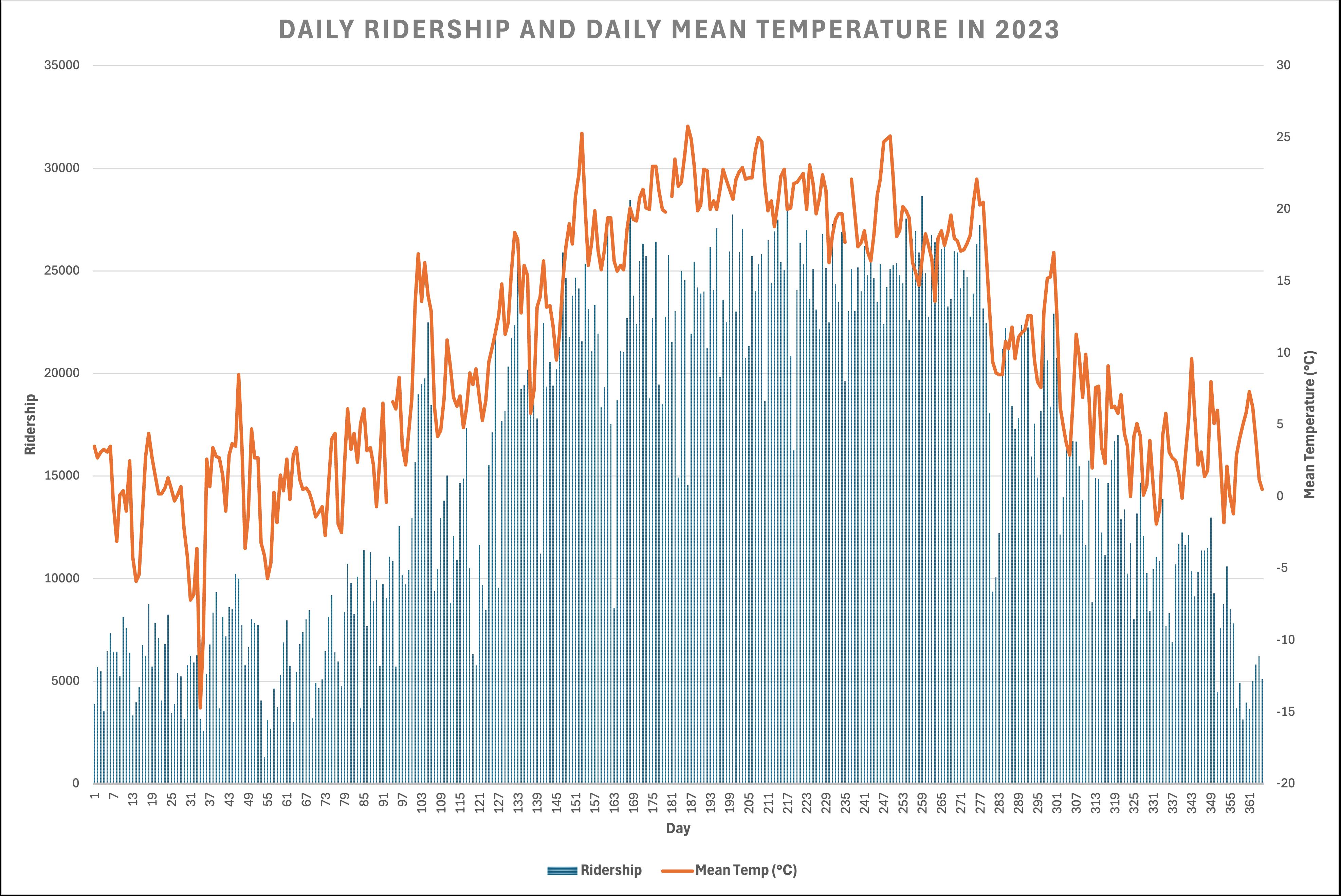

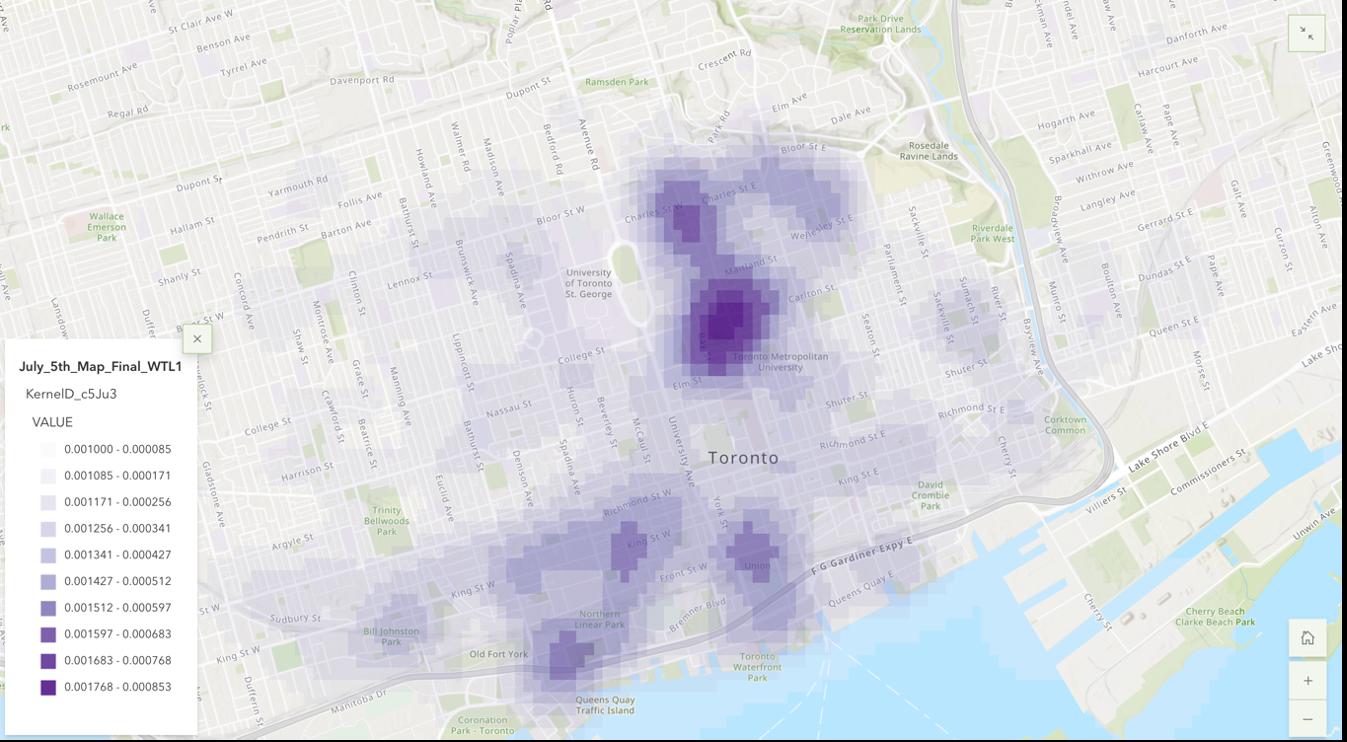

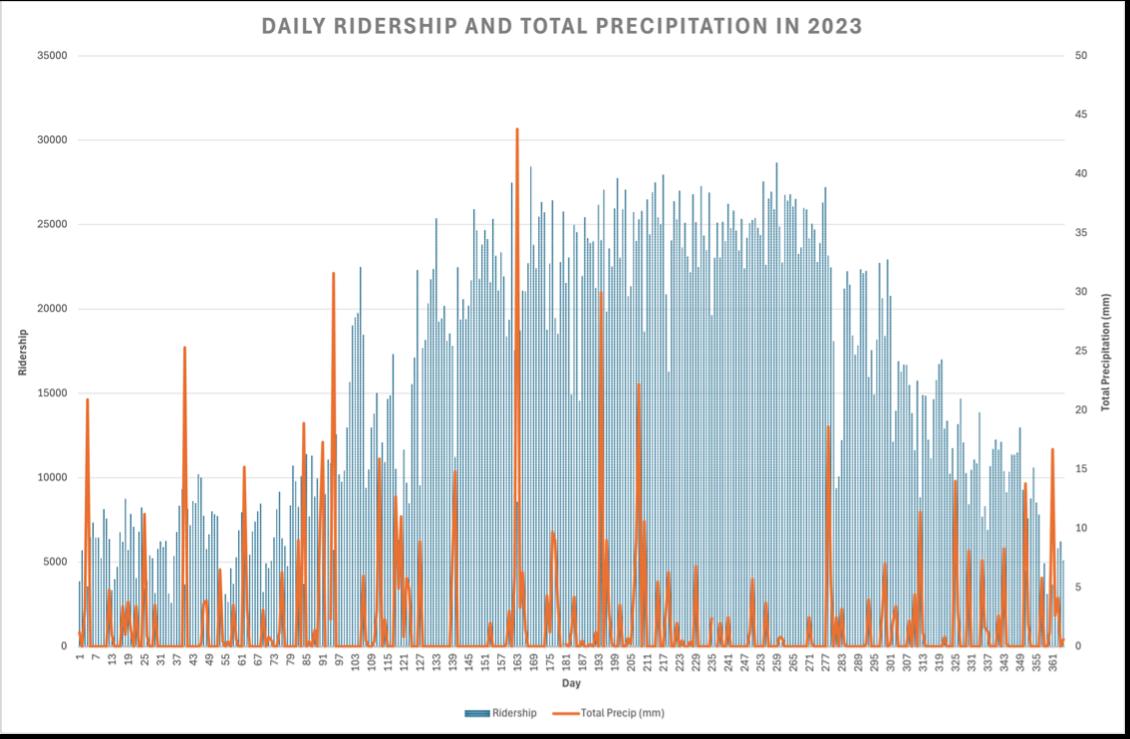

Bikes,Weather,andtheCity:AStudyofToronto’sBikeShareRidership Patterns

WhyThereAreNoFeralCatsinT¨urkiye:CaseStudyofIstanbul

PolinaGorn

APrisonWithoutWalls:TheGeographyofTimeandtheImmobilization ofBlackMen

AnnaAngelIzemengia 85

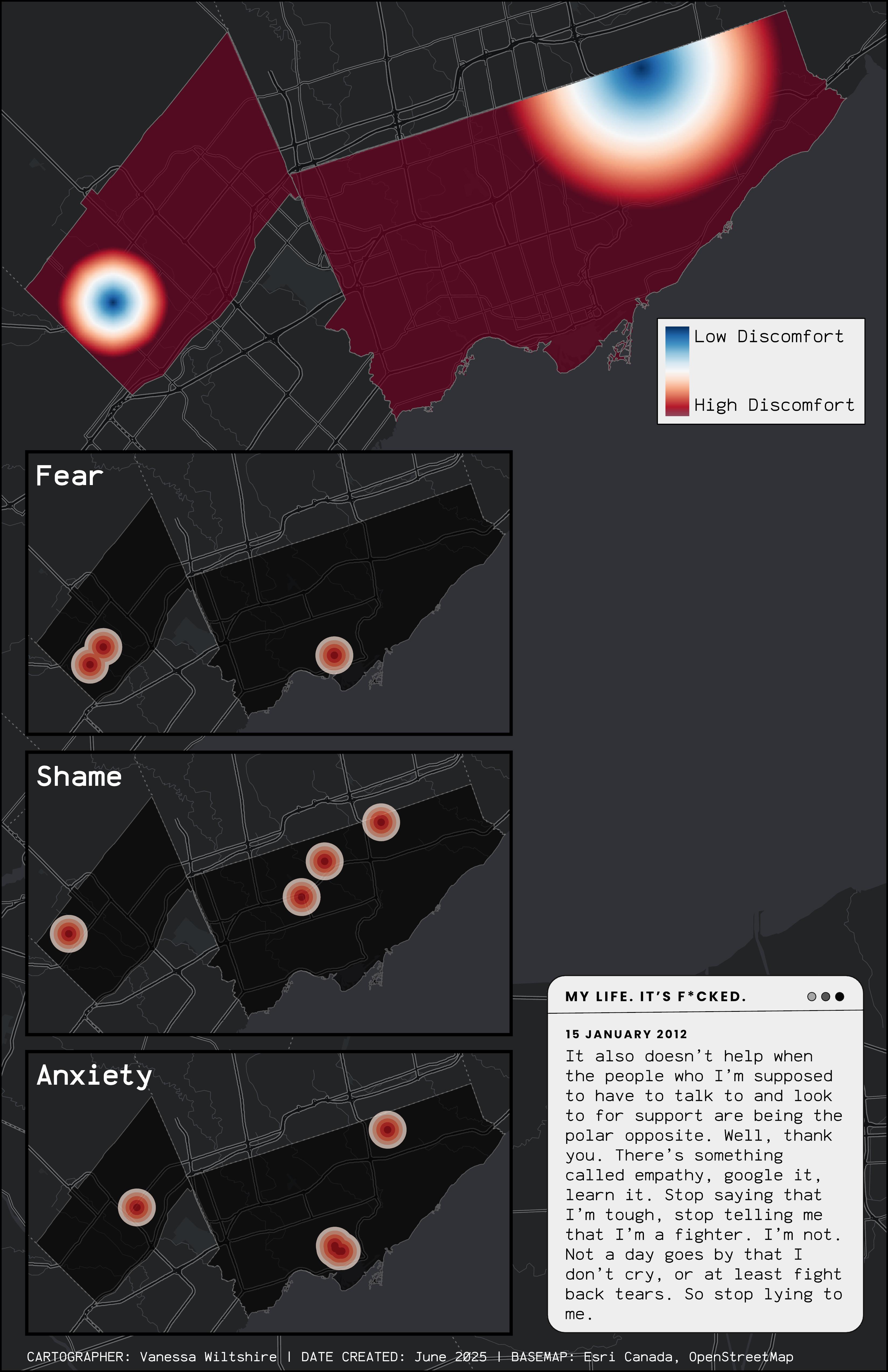

NavigatingMisogynoirThroughEmotionalandEmbodiedKnowledge

VanessaWiltshire

TheEditorialBoardisproudtopresentthetenthvolumeof Landmarks:JournalofUndergraduateGeography.Thisyear’sissueemergesintheshadowofmountingglobalprecarity: theviolentdisplacementofPalestiniansinGaza;sweepingbillsacrossCanada,including BillC-5andC-2;massdeportationsacrosstheborder;escalatingclimatecrises;andthe riseofauthoritarianisminmanycornersoftheworld.Inthefaceofthesecompounding crises,geographyo!erstoolsnotonlytotracesystemsofpowerbuttoenvisionalternatives. Geographyo!ersalensthroughwhichtoimaginetheworldotherwise.

Thisyear’scontributionscoalescearoundthreeinterrelatedthemes:“Indigenous‘North America’”,“ThinkingwithLandscape,”and“MovingthroughtheCity”.Acrossthisvolume’spages,authorsinterrogatelandrights,landscapes,andmobilitytoo!ernewmapsof understandingthatarerootedinjustice,resistance,andhope.

ThreearticlesinthissectionchallengethecolonialconstructionsofIndigenouslandsas spirituallyvacant,legallytransferable,andeconomicallyripeforexploitation.Oneexamines how17th-centuryEnglishcolonistsinVirginiausedreligiousrhetorictoportrayIndigenous spiritualpracticesasdemonic,fuellinganarrativethatlegitimizedviolentexpansion.Another traceshowtheriseofMuskoka’stourismindustry—alandscapefamiliartomanyOntarians—transformedAnishinaabeghomelandsintosettlerplaygrounds,framedasuntouched despitelonghistoriesofmigrationandstewardship.AthirdreadstheLouisianaPurchase notmerelyasalanddeal,butasalegalandideologicalactthatenabledManifestDestinyby erasingIndigenousgovernancefromthegeopoliticalrecord.Together,thesepiecesshowhow settlernarrativesworknotonlytoseizelandbutalsotoattempttooverwritetheworlds alreadypresent.

Thissectionexamineshowhumansocietiesshapeandareshapedbytheenvironmentsthey inhabit.OnearticleanalyzesriverandlakeicedynamicsintheCanadianArcticinthe contextofworseningclimatechangeandanthropogenicpressures.Anotherinterrogatesthe GlobalSeedVaultinSvalbardasanimaginarygeography:lessavaultofsalvationandmore atechnocraticmonumenttohighmodernism.AthirdrevisitsIreland’sbogs,exploringhow theseecologieshavebeenracialized,romanticized,andrenderedprofitablethroughcolonial histories.Together,thesearticlesunsettletheviewoflandscapesaspassiveorahistorical

andinsteadtracehowpower,memory,andideologyareembeddedinlanditself.

Thisfinalsectionexploreshowurbanmovement,bothhumanandmore-than-human,is shapedbyinfrastructure:howitisallowed,controlled,limited,expanded,communal,and individual.OnearticleexaminesToronto’sBikeSharesystem,showinghowdi!erentfactors ofweather,geography,andaccessa!ectpatternsofmobility.Anotherfollowsthestreetlife offeralcatsinIstanbultochallengeassumptionsofdomesticationandcohabitation.And twopiecesreflectonhowrace,gender,andincarcerationlimitorimmobilizethemovement ofBlackbodiesacrossspaceandtime,throughpersonalreflectionandhistoricalanalysis.

Wehopethisissuechallenges,provokes,andinspires,andthatitreflectsthecommitment, creativity,andcourageofundergraduategeographersattheUniversityofToronto.

Workingonthisissuehasbeenadeeplycollaborativeandrewardingprocess.AsCo-Editors andManagingEditor,wearegratefulfortheintellectualgenerosityshownbyourediting teamandfortheauthorswhoentrusteduswiththeirwork.Specialthankstoourfaculty advisor,ProfessorPaulHess,andtheTorontoUndergraduateGeographySociety(TUGS) fortheirongoingsupport.Andmostimportantly,thankstotheDepartmentofGeography andPlanningattheUniversityofToronto,whichmadethisjournalpossible.

Sincerely,

JaniceWalder,JaneYearwood,andYoujia(Avila)Zhang (Alphabeticalbysurname)

EmmanuelPasternak

ThedemonizationofIndigenousbeliefsystemsbyEnglishcolonistsin17th-centuryVirginia wasakeydrivingforcebehindtheprocessesofIndigenousdispossessionanddislocation. ThisarticleexplorescolonialmethodsofdispossessioninVirginia,focusingonhowAngloSaxonreligiousstructuresinteractedwithIndigenousspiritualitytocreatenarrativesthat servedastoolsoflandseizureandculturalerasure.Byconsideringbothprimarysources fromtheaccountsofVirginiancolonialforcesandsecondarysourcestocontextualizethe historicalcircumstancesofcolonialproceedings,thisarticlearguesthatEnglishcolonists framedIndigenousspiritualityas‘immoral’and‘satanic’,fuelingthewidespreaddisplacement ofNortheastWoodlandtribes.ThesenarrativesbecameacentralfeatureofEnglishcolonial ideology,enablingsettlerexpansionandreducingIndigenouspeopleto‘satanicsavages’or ‘helpless’subjectsinneedofChristianguidance.Thearticlealsoinvitesreflectiononhowsuch narratives,whicharerootedinEnglishcolonialthought,continuetoinformourpresent-day understandingofreligionandspirituality,ultimatelyactingasmechanismsofdispossession.

Keywords: colonialism,dispossession,demonization,spirituality,religion,Anglo-Saxon, ColonyofVirginia,NortheastWoodlands,PowhatanConfederacy

ThedemonizationofIndigenousbeliefsystemswasusedasatoolofdispossessionin 17th-centuryVirginia.Throughnarratives thatframedIndigenousspiritualityasinferiororsatanic,Englishcolonistsreinforced Anglo-SaxonChristiansuperiority,justifyingandpropellingaviolentcolonialexpansion.Theanti-Indigenoussentimentthat developedinthecolonyfueledthestrategiesofphysicalviolenceandreligiousas-

similationthatguidedEnglishcolonialefforts(Hixson,2013).Thesestrategieswere soonextrapolatedascolonialsettlements expandedacrosstheeasterncoastline,makingVirginiaalaboratoryforanti-Indigenous colonialthought(Hixson,2013).Colonial accountsdescribedasatanicmysticismassociatedwithIndigenousspiritualpractices, acommonperceptionamongstcolonistsin theregion(Beverley,1855).Asearlyas 1610,colonialwritingsenshrinedtheseideas,

withprominentcolonialfiguresclaiming thattight-knitconnectionsexistedbetween IndigenouscommunitiesandtheChristian devil(Beverley,1855).

ThispaperexaminesthecontextofAngloIndigenousrelationsintheBritishcolony ofVirginia,exploringthedispossessionof Indigenouslandandviolenceperpetrated againstIndigenouscommunitiestobuilda historicalunderstandingoftheseprocesses. ItwillthenfocusondescriptorsofIndigenousspiritualpracticesfromcolonialaccountstoidentifyrhetoricalpatternsincolonialdiscourse.Thesenarrativesarefurther analyzedinrelationtothejustificationpracticesofEnglishcolonistsinVirginia,highlightingthecentralroleofreligiousframing inthebroaderstrategytodisplaceIndigenouspeoplesfromtheirlandintheNortheastWoodlands.

Incontemporarygeographicconversations surroundingthehistoricaltrendsinIndigenousdispossession,itisessentialtocontinue toconsiderhownarrativesbuiltintothe foundationofcolonialsocietiesshapeour understandingsofIndigenouscommunities’ historicalandcurrentrelationshiptotheir lands.Fromthere,theseconsiderationscan determinepathwaystowardreconciliation. WithinthehistoryoftheColonyofVirginia, thedispossessionprocesswasconsistentlyvi-

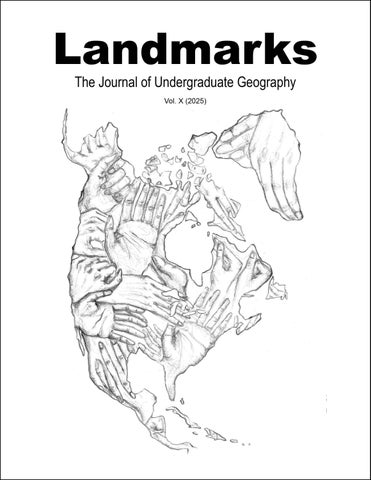

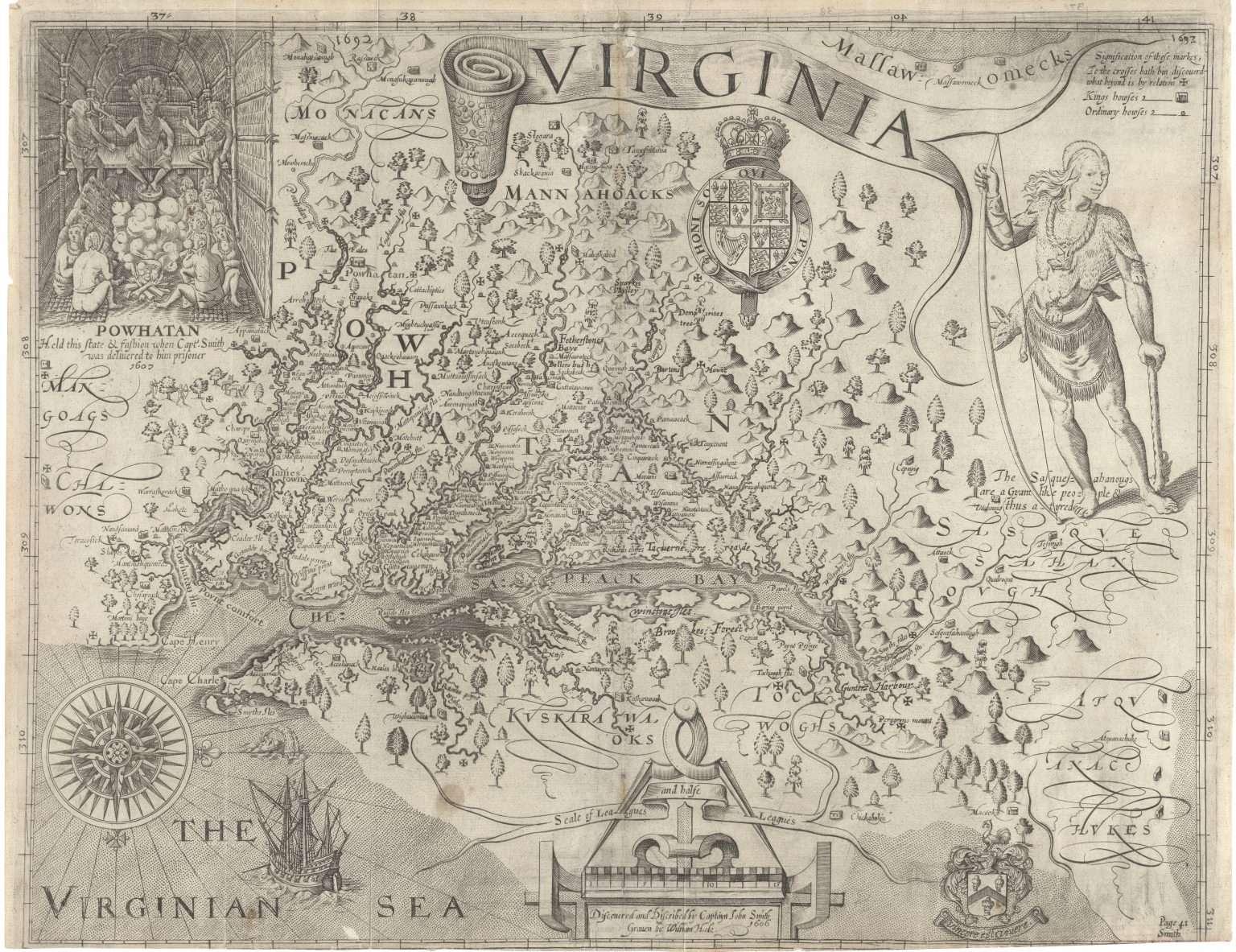

olent.TacticssuchasattacksonIndigenous infrastructurewereusedtoassertastate ofEnglishpoliticalandculturaldominance. ColonialactionwascloselytiedtothedemonizationofIndigenousspiritualbeliefsystems,utilizingtheideathatIndigenoussocietypossessedanultimatemoralshortcomingtojustifyandpropelEnglishaggression.InPeoplefromtheUnknownWorld, WalterHixson(2013)writesaboutAngloIndigenousrelationshipsinVirginia,noting thatIndigenousgroupswithintheNortheastWoodlands—mostfallingunderthe PowhatanConfederacy,whichencompassed over30Indigenoustribes—providedEnglish populationswithcrucialfoodandsupport duringtheearlycolonialperiod.Captain JohnSmith’s1606MapoftheChesapeake region(Figure1)illustratestheprominence ofthePowhatan,withhisgeologicrecords demonstratingtheirpoliticalandterritorial significanceinthearea.AsEnglishpopulationsgrewdependentonassistancefrom Indigenouspeoples,thispowerimbalance sparkedresentmentandhostilityagainstIndigenouspopulations,inlargepartdueto theirviewofIndigenousspiritualotherness andtheircolonialcategorizationas“heathens,”devoidofwhattheyconsidereda properoradequatespiritualsystem(Hixson,2013,p.30).

Figure1.A17th-centurycolonial“MapofVirginia,” designedbyEnglishCaptainJohnSmithin1606 andpublishedinLondonin1624,highlightsthe presenceoftheIndigenousPowhatanConfederacy intheChesapeakeRegion.

The1606settlementofJamestownwas oneofNorthAmerica’sfirstlong-termEnglishcolonialventures,wherecolonistscompiledlegalchartersthatdevelopedinto foundationalelementsofcolonialsocieties (Howard,2007).Shortlyafter,in1609,the firstAnglo-PowhatanWarbrokeout,duringwhichEnglishcolonistsattackedIndigenoushomesandcropfields(Hixon,2013). SuchattacksdestabilizedIndigenouspopulations,promptingretaliatione!orts,includingorganizedresistanceledbyOpechancanoughofthePowhatanConfederacyin both1622and1644(Hixson,2013).In 1676,NathanielBacon,aprominentplantationowner,launchedattacksonIndigenouspopulatedareasacrossVirginia,characterizingIndigenousgroupsas“delinquents”as hebelievedthattheBritishCrownwas showingtoomuchfavourtowardsIndigenoustribesovermattersoflanddisputes (Hixson,2013,p.31).Bythispoint,In-

digenouspeopleswithintheVirginiacolony hadalreadysu!eredsignificantlossesof landandpopulationthroughoutthe17th centuryduetoarmedconflictandtheonslaughtofdiseasebroughtonbyEnglish colonials.Still,Bacon’sRebellionsought todiminishIndigenousinfluenceandpresenceinVirginia(Hixson,2013).Thisact ofviolenceshowcaseshowthecolonization ofIndigenousspaceshouldbehistorically analyzed,notonlythroughstatepolicybut alsothroughcivil-leddispossessionmeasures. NealSalisbury(2003),inhisarticle,EmbracingAmbiguity:NativePeoplesandChristianityinSeventeenth-CenturyNorthAmerica,explainshowsignificantactsofviolence againstIndigenouspeoplesresultedintheir forcedmigrationanddisplacement,allowing Englishcoloniststosecureanupperhand inAnglo-Indigenousdisputesandbeginto establishingcolonialinfrastructureandculturalinstitutionsinVirginia.

Itisimportanttonotethatthedispossession ofIndigenouspeopleinVirginiainvolvednot justphysicalviolenceandforcedmovement butalsotheattemptederasureofIndigenouscultureandsocietalsystems.Inan analysisofthegoalsofEnglishcolonistsin Virginia,Nash(1979)explainsthattheEnglishsoughttoconvertIndigenouspeople toChristianity,whichwaspositedbythe EnglishCrownasanactofliberation,based onthebeliefthatIndigenouspeoplewere inastateofmiseryduetotheirspirituality. DrivenbyanideologicalviewofIndigenous

peoplesaslackingaChristianGod,thishistoryofAnglo-Indigenousrelationsinthe 17thcenturyandgeneralanti-Indigenous rhetoriccontextualizesthestrategiesofcolonialdispossessionemployedascolonistsattemptedtoimposetheirsocietalstructures ontoIndigenousterritories.

Colonialrhetoricalstrategiesdemonstrate thatAnglo-Saxonreligiousandculturalsuperiorityplayedacentralroleinjustifying thedispossessionofIndigenouspeoplesin Virginia.Inhisbook,TheHistoryofVirginia,RobertBeverley(1855)illuminates therhetoricusedamongstcoloniststodescribeIndigenouspopulations.Whilethe bookwasinitiallypublishedinLondonin 1705,aversionwasrepublishedbyJ.W.Randolphin1855,basedonBeverley’saccounts of17th-centuryAnglo-Indigenousrelations. LouisB.Wright(1944),inhisexamination ofBeverley’shistoricalwork,highlightsthe popularityofBeverley’sHistory,especially atthebeginningofthe18thcentury,dueto itsengagingwritingstyleanddetailedaccountsofcoloniallifeandIndigenoussociety. InrecountinganencounterwithanIndigenousmanwhomhehadmetduringhistravelsthroughoutthecolony,Beverleystates thathetoldthemanthat,tohisknowledge, Indigenouspeopleworshipthe“devil,”(Beverley,1855,p.170)andfurtherquestioned themanonwhythatis).Thisencounter

shedslightonBeverley’sthoughtsonIndigenousspirituality,withBeverleyposinghis commentasanexchangeofbeliefs,asopposedtoacalculatedculturalattack.While Beverleywasattimessympathetictowards topicsrelatedtoIndigenouslife,theassociationshedrewwithSatanismandIndigenous peopleswerenonethelesspresent(Wright, 1944).Thishighlightstheregion’sstandard colonialrhetoric.WhileBeverley’shistorical accountsoftenaimedawayfromconstant attacksonIndigenousbeliefstructures,with atruerinterestingainingsocialknowledge ofIndigenouscustoms,hisunderlyingassumptionsofsatanicIndigenousassociation areinfusedinhisscholarlyinquiriesand presentedasafact.

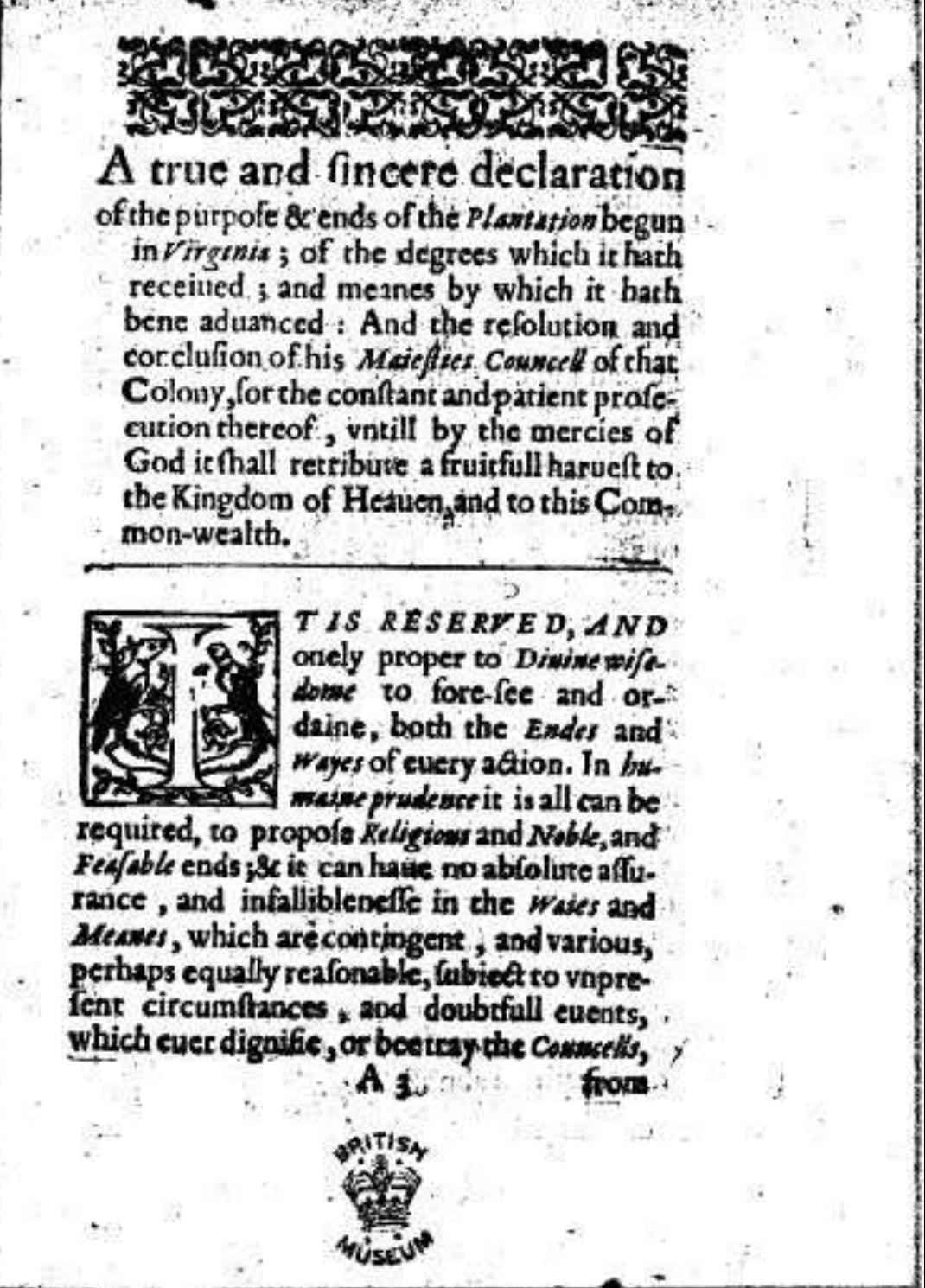

TheBritishcrownreinforcedthenarrativeofIndigenouspeoplesasconnected totheChristianDevil,developinginto awidespreadsentimentamongBritish colonists,whichdroveIndigenouslanddispossessioninVirginia.Atthestartofthe 17thcentury,thegovernorsandcouncillors ofthecolonypublishedATrueandSincereDeclarationofthePurposeandends oftheplantationbeguninVirginia(1610). TheyclaimedthatIndigenouspeopleneeded Christianitytosavethemfromthegraspof theDevil,contributingtothenarrativeof Indigenousspiritualityassatanic(Colony ofVirginia,1610)(Figure2).Aprominent aspectofdispossessionisidentifiedinthis narrative,asitnotonlycontributestothe generaldemonizationofIndigenoustribesin

theVirginiacolonybutalsotothepractice ofEnglish-ledattemptstodissolveIndigenousculturalidentity.Byreconstructing IndigenoussocietyaroundtheChristianreligion,colonistssoughttoestablishanAngloSaxonclaimtotheland,showcasinghow tacticsofdispossessionandIndigenousdisplacementwerealsoenactedatacultural scale.

Figure2.Anexcerptfromthefirsttwopagesof“A trueandsinceredeclarationofthepurpose&ends ofthePlantationbeguninVirginia,”publishedin 1610.

Anti-IndigenousrhetoricbasedonthespiritualbeliefsystemsofIndigenoustribesin theNortheasternWoodlandsishistorically observedonbothcivilandsystemiclevels.Englishcolonizersemployedinaccurate andhostiledescriptionsofIndigenousspiritualpracticeastoolstojustifydispossession. PhoebeDufrene(1991)examinestheactualitiesofIndigenous,specificallyPowhatan, beliefsandspirituallife.Sheexplainshow thetribesofthePowhatanConfederacyreg-

ularlyengagedinritualsofartandmusic,suchasceremoniesthathighlightedthe deeplyinterconnectednatureofIndigenous lifewiththenaturalworld.Artoftenshaped spiritualexpressionforPowhatancommunities,whoengagedinpracticessuchassculptingandweaving(Dufrene,1991).

Incontrast,Europeansheldbeliefsaligned withtheChurchofEngland,whichemphasizedtheworshipofasingularentity.

G.W.Bernard(1990)highlightsthefactors shapingtheChurchofEngland,whichwas centralinformingcolonialreligiousstructuresamongstVirginiansettlers.Whileinternaldivisionswerefrequentintheideologicalalignmentsanddirectionofthe church,EnglishChristiansbelievedinone god(Bernard,1990).Atthestartofthe 17thcentury,manyemphasizedtheconcept ofPredestination,claimingthattheirGod wouldselectonlysomemenwhocouldbe sparedfrometernaldamnationwhilethe restwouldsu!er(Bernard,1990).ThroughoutperiodsofreligiousunrestoverthedirectionofChristianthought,theconcepts ofasingularhighpower,damnation,and thedevilwereprevalentanddefiningfor colonialstrainsofChristianity.

MarkCharles(2016)acknowledgestheDoctrineofDiscovery,acolonialtoolconstructedinthe15thcenturythatemphasizedEuropeanstandardsofa“civilized” societyandopposedIndigenouswaysoflife. Charles(2016)relatesthisdoctrinedirectly tocolonialprojectsinAmerica,explaining

thedoctrine’sbasisforjustifyingChristian superiority.Thedoctrineguidedcoloniststo Virginia,andthesoon-establishedEnglish narrativessurroundingIndigenouspeoples as“enemiesofChrist”allowedcoloniststo enactdispossessionprocesses,buildingupon idealsofinherentChristianrightswithin newlands(Charles,2016,p.149).While Charlesmakesitclearthatmuchcolonial justificationrestsupontheDoctrineofDiscovery,theutilizationofdemonizingnarratives,entanglingIndigenouspeoplewiththe ChristianDevil,positionsIndigenouspeopleasnotonlyinferiorduetotheirlackof Christianity,butalsoasdirectlyopposedto thevaluesoftheEnglish.

ChristiansettlersframedIndigenouspeoples as“ignorant”tojustifytheforcefulimpositionofAnglo-Saxoncolonialprojectson Indigenousland(ColonyofVirginia,1610, p.2).Apaternalnarrativewasprominent amongcolonialforces.TheBritishcrown notonlyshamedIndigenousspiritualityover afabricatedassociationwiththeDevil,but alsourgedcoloniststoaidIndigenouspopulationsinescapingthe“[arms]ofthe[Devil]” andastateof“invincibleignorance”(Colony ofVirginia,1610,p.2).Thecombination ofpaternalismanddemonizationcreateda formulaofIndigenousdispossessioninVirginia,whichjustifiedviolenceasawayof displacingIndigenouspeoples,asseenin theAnglo-PowhatanWarandBacon’sRebellion.Thisprocesssoughttodissolveany culturaltieswhichIndigenouspeopleheldto

theareathroughconversiontoChristianity.

In17th-centuryVirginia,Englishcolonial processesofdispossessionprofoundlydisruptedthelives,lands,andbeliefsystems ofNortheastWoodlandstribes.Colonialists usednarrativeswhichfocusedonpresentingIndigenousspiritualpracticesasbeingin closerelationwithEnglishnotionsofsatanic ritual.Adualstrategycombiningphysical violencewithculturalerasureformedacohesivesystemofdispossessionaimedatboth removingIndigenouspresenceanderadicatingtheirspiritualworldviews.

Byrecognizingtacticsofdemonization,this researchfurtherallowsscholarstoaddress howsystemicinequalitiesfacingIndigenous groupsincontemporaryNorthAmericacan beconnectedbacktothesecolonialfoundations.Furtherresearchmayconsiderthe Indigenouspopulation’spositionininvoluntaryservitudeinVirginiaduringtheperiod ofplantationfarming,examininghowtherelationshipbetweenIndigenouspeoplesand landdispossessionevolvedduringthisprocess.

Bernard,G.W.(1990).TheChurchofEnglandc.1529–c.1642. History,75 (244), (pp.183–206).

Beverley,R.(1855).Concerningthereligion, worship,andsuperstitiouscustomsof theindians.In TheHistoryofVirginia (pp.152–172).J.W.Randolph. ColonyofVirginia.(1610). Atrueand sinceredeclarationofthepurposeand endsoftheplantationbeguninVirginia. London.

Charles,M.(2016).TheDoctrineofDiscovery,War,andtheMythofAmerica. Leaven,24 (3),(pp.148–154).

Dufrene,P.(1991).Contemporary PowhatanArtandCulture:ItsLink withTraditionandImplicationsforthe Future. AlgonquianPapers-Archive,22, (pp.125-136).

Howard,A.E.D.(2007).TheBridgeat Jamestown:TheVirginiaCharterof 1606andConstitutionalismintheModernWorld. UniversityofRichmondLaw

Review,42 (1),(pp.9–36).

Hixson,W.L.(2013).“Peoplefromthe UnknownWorld”:TheColonialEncounterandtheAccelerationofViolence. In AmericanSettlerColonialism (pp. 23–44).PalgraveMacmillan.

Nash,G.B.(1979).PerspectivesontheHistoryofSeventeenth-CenturyMissionary ActivityinColonialAmerica.In Terrae Incognitae,(pp.19–27).

Salisbury,N.(2003).EmbracingAmbiguity:NativePeoplesandChristianity inSeventeenth-CenturyNorthAmerica. Ethnohistory,50 (2),(pp.247–259).

Smith,J.(1624).MapofVirginia,17th century,DiscoveredandDiscribed(sic) byCaptaynJohnSmith1606Gravenby WilliamHole. TheGenerallHistorieof Virginia,NewEngland,andtheSummer Isles. map,London.

Wright,L.B.(1944).Beverley’sHistory... ofVirginia(1705):ANeglectedClassic. TheWilliamandMaryQuarterly,1 (1), (pp.49–64).

Indigenous“NorthAmerica”

SandraGlozshtein

TourisminMuskoka,Ontarioisconsideredinthisresearchreportasacasestudyfor Indigenousdispossessionandtheproductionofacolonialidentityrelatedtorace,nature, andproperty.Twoprimarysources—an1899mapandchartoftheMuskokalakesanda 1909advertisementforMuskokatourism—areanalyzedtointerprethowthetourismindustry wasco-producedwithIndigenousdispossessionandEuropeancolonialimposition.Thisreport findsthattheMuskokaLakestourismindustryperpetuatedEuropeancolonialismthroughthree mainavenues:theerasureofAnishinaabegpresenceintheregion,theexploitationofnature, andtheuseandpromotionofthe“civilizedversuswild”colonialnarrative.Additionally,the inventionoftherailwayandthetelegraphescalatedcolonialexpansiononthecontinentatan unprecedentedpace,providingafoundationfromwhichtourismcouldemerge.Settlerssawin tourismanopportunitytoprofitfromthelandscapeinspiteofitsconditionsasinhospitable toagriculture.Atthestartofthe20thcentury,seasonaltourismgaveMuskokaitscurrent demographics,landscape,andplaceinpublicconsciousness.

Keywords: Muskoka,colonization,tourism,nature,wilderness,cartography

ThecolonizationofNorthAmericaunfolded throughfrontierexpansionintoterritories Europeansimaginedasuntamedwilderness. DespitesustainedresistancefromIndigenouspeoples,manyoftheirlandsandresourceswereappropriated,aprocessfurther acceleratedbytechnologicaldevelopments, suchasthetelegraphandrailwaysystem (Blackhawk,2023;Jasen,1995).Whilesettlercolonizationadvancedthroughmaterial violence,itwasalsorootedinpsychological

andculturalnarrativesthathelpedjustify domination.Apowerfulexampleofthis dynamicistheemergenceofthetourism industryinMuskoka,Canada,cultivated throughsettlers’romanticizationof“unfamiliar”landsandracializedportrayalsof Indigenouspeoplesas“wild”(Watson,2017; Grandin,2019,p.117).Settlerscommodifiedthelakesandforeststhaturbanization hadnotyettouched,transformingtheidea ofan“authentic”Indigenouslandscapeinto aconsumableproductforEuropeantourists.

Thispaperarguesthat,bytheearly20th century,Europeancolonialismpersistedin Muskokathroughthreeprincipleforces:the erasureofIndigenouspresence,theexploitationofnatureforEuropeanprofit,andthe reinforcementofthe“civilizedversuswild” colonialbinary.Todemonstratethis,I drawontwoprimarysources:a1899map andchartoftheMuskokalakes(Figure 1),anda1909tourismadvertisementfor LakeRosseau(Figure2).Together,these sourcesconstructasettler-orientedvisionof MuskokadesignedtoattractEuropeanvisitorsandrevealculturalmarkersdeeplyentrenchedincolonialnarratives—illustrating theentanglementofcapitalismandcolonialismintheregion.

DispossessioninCanadaconsistedofthe coercedremovalofIndigenouspeoplesfrom theirterritoriestoenableEuropeansettlement(Daschuk,2013).Thedispossession andattemptedgenocideofIndigenouspeopleswereenactedmateriallythroughEuropeandiseases,bladesandguns(Merbs, 1992).Thisviolencewasunderpinnedby theliethatthelandwasunoccupiedbeforeEuropeanarrival,aconcepttermed “terranullius”(Joseph,2016).Europeans believedthatmuchofthelandwasbeing “wasted”,andwhicheverpartswereclearly usedbyIndigenouspeoplesweredeemed notuptoa“civilized”standard(Harris, 2004,“ThePowertoDispossess”section, para.7).Indigenouslandswereremapped

andre-envisionedforsettleruse,withIndigenouspeoplesbeingforciblyconfinedto smallplotsoflandcalledreserves,which werelegallymanagedbyEuropeans(Harris, 2004).Throughsystemsofaccounting,colonialadministratorsrecordedandregulated consequencestoIndigenouspeople’sbehaviours.Forexample,BritishColumbia’s reservecommissionersdocumentedwhich familiessentchildrentoresidentialschools orhowmuch“cultivable”landbelonged toanIndigenousband(Harris,2004,“The ManagementofDispossession”section,para. 5).

Inthelatenineteenthcentury,theimpositionoftelegraphandrailwaysystems onthelandscapeenabledtransportation andcommunicationacrossvastdistances (Cowen,2020,“Empire’sInfrastructure”section,paras.5,9-10).Thiscreatedanationalcommercialnetworkandstrengthened colonialadministrativepracticesandsettlerexpansion(Harris,2004,“TheManagementofDispossession”section,para. 6;Cowen,2020,“Empire’sInfrastructure” section,para.9).AstheCanadianPacificRailwayexpandedintotheMuskokaregion,newsettlementsdisplacedIndigenous communities(Watson,2022).Bythemidnineteenthcentury,thisdisplacementparticularlya!ectedtheAnishinaabeg,followed byasmallernumberofMohawkfamilies beginningin1881(Jenness,1935;Watson, 2014).

Figure1.MapoftheMuskokaLakes,including LakesRosseau,JosephandMuskoka.Cottagepropertiesarelisted,andthereisapastedadvertisement forsuppliesfromMichieandCompany.

Thesedevelopments—settlerdisplacement, seasonallandusedisruption,andrailwayexpansion—arevisuallyreflectedinhistorical cartography.Onesuchartifactisan1899 mapandchartoftheMuskokaLakes,which embedsbothsettlerinfrastructureandcommercialadvertising.Atthebottomofthe Muskokamap(Figure1),alistoftelegraph andexpresso”cessignalsthisinfrastructuretransformationandMuskoka’sgrowing integrationintocolonialtransportationnetworks.

Asshownonthetoprightofthemap,anadvertisementfromaToronto-basedgroceryestablishmenta”rmsthereachofurbancommercialnetworks,whilearegistrationstamp

atthebottommostconfirmsthemap’sofficialentryintoanOttawao”ce.These elementsdocumentMuskoka’splaceina nationalinfrastructurethatfurthermaterializedEuropeanimperialism(Cowen,2020). Themapnotonlychartedgeographybut alsoencodedsettlerclaims,infrastructure, andcommerce,visuallyreinforcingcolonial occupationandtheerasureofIndigenous presence.

Figure2.PrintedadvertisementfortheRoyal MuskokaHotel,PublicDomain.

WhilethemapdocumentsthephysicalembeddingofsettlerinfrastructureinMuskoka, promotionalmaterialsfromthesameperiodreflecttheideologicalsellingoftheregiontourbanelites.Thesecondprimary source—anadvertisementfortheRoyal MuskokaHotel(Figure2)—framesLake Rosseauasbothluxuriousandeasilyaccessiblebyrail.Itemphasizesa“magnificenttrainserviceonthreelines,”reinforcing theconnectionbetweentourism,infrastructure,andthecommodificationofIndigenous lands.

RailwaycompaniesportrayedMuskokaas deceptivelyclosetomanymajorcitiestoattracttourists(Kuhlberg,2022,p.105).Industrialization,particularlytheconstruction ofrailroadsandtelegraphlines,wasviewed asanextensionoftheEuropean“civilizing”projectacrossthecontinent.Oncethis projectreachedMuskokainthe19thcentury, theAnishinaabegresistedandnavigatedincreasinglimitationsontheirmigrationsand lifeways(Watson,2022,pp.55-63).InWild Things,oneoftheearliestbooksexamining theimperialandculturalcontextofOntario’stourism,Jasen(1995)commentsthat “...aseriesofmajorlandsurrendershad largelyremovedthisandadjacentregions fromOjibwaycontrol,preparingtheway forimmigrantsandtourists,”(p.117).By 1850,Indigenouscommunitiesintheregion werelargelyconfinedtoreserves(Watson, 2022,p.63).Soonafterthat,thegovernmentlimitedtheiraccesstofisheriesnear thereservesbyplacingrestrictionsonIndigenousfishingrightsundertheguiseofa “civilizingmission”(Watson,2022,pp.6364),whilesimultaneouslyestablishingalicensingsystemtobroadensettler-controlled commercialfishing.

ThefirstplotsoflandinMuskokawere madeavailabletosettlersin1859,following townshipsurveysandtheconstructionof theMuskokaRoad(Watson,2017,p.201).

Tosurvivethesettlereconomy,theAnishinaabegbegansellingtheircraftsorworking astouristandhuntingguides,drawingon

theirextensiveknowledgeoftheland(Watson,2022,p.6).Asenvironmentalhistorian Watson(2022)statesinMakingMuskoka, “Whereassettlersemployedtheiracquired knowledgeoftheShieldtoaligntheirrural identitywiththeseasonalcycleoftourism, theAnishinaabegrepurposedtheirknowledgeinthecontextoftourism.”ThisgeographicfamiliarityhelpedIndigenousguides directsettlerswhilefinanciallysupporting themselvesandtheirfamilies.

Yet,MichieandCompany’sadvertisement ontheMuskokamap(Figure1)invitesenquiriesfrompotentialvisitorsandclaims expertiseinoutfitting“Camping,Fishing, andShootingparties,”basedon“64yearsin business.”Thispromotionalcopyomitsany referencetoIndigenousguidanceof“surveyors,settlers,andtourists”(Jasen,1995,p. 118).Nordoesitacknowledgewherelater settlerguides—whoultimatelyreplacedIndigenousonesbythe21stcentury—obtained theirknowledge(LawsonCousineau,2017, para.13;Watson,2022,p.168).Theseerasuresarepartofthebroaderterranullius mentalitythatdeemedthecontinentvacant andripeforsettlement.

Similarly,Indigenouspresenceisabsent fromtheMuskokamap(Figure1),which includesanindextosummercottageslisted underEuropeannames.AssigningEuropeanownershipovertraditionallyAnishinaabegterritoriesdeniesrecognitionoftheir forcedremoval.Indigenousplace-namesfor thelakesarealsoreplaced,suchasthecase

of“LakeJoseph”,whichwasrenamedafterEuropeansettlerJosephDennis(Mason, 1957).Thisshowcasesthecolonialpracticeofassertinghumandominationovernatureandtheindividualisticclaimingofland. Muskoka’s“ColonizationRoad”,pavedin the1860sandjustnorthofthemap’scuto!, furtherexemplifieshowcartographyandrenamingservedastoolsofsettlerpowerto eraseIndigenouspresence(MuskokaAreaIndigenousLeadershipTable,2025;Kuhlberg, 2022,p.104;LawsonCousineau,2017, para.7).Throughtheseacts,Europeans subordinatedbothIndigenousagencyand thenaturallandscapetotheirdesiredreorganizationoftheappropriatedland.

ThephilosophythatnatureshouldbedominatedandexploitedforthebenefitofEuropeansettlersurvivalwascentraltothe economythatdevelopedinMuskoka’searly settlements.Incontrast,asAnishinaabeauthorCaryMiller(2010)explains,anAnishinaabegcosmologyattributesequalagency andlife-forcetohumans,plants,andanimals.Historically,thetraditionalsubsistencepracticesoftheAnishinaabegin Muskokaweretiedtoseasonalpatterns (Watson,2014,pp.142-143).Theycyclicallymigratedbetweendi!erentlocations thatprovidedsustenanceandresourcesfor tradeanddailylife(Allen,2002).According toWatson’s(2014)dissertationonMuskoka between1850and1920,theeconomicandsocialactivitiesofIndigenousgroupswerenot

alwaysenvironmentallyneutral.Still,the MuskokaWatershedCouncil(2012)reports thattheoverallimpactofIndigenousland usewasminimallydestabilizing(pp.10, 16).TheAnishinaabegpeoplescoordinated band-a”liatedhuntinggroundsthat“[structured]amoresustainableaccesstoscarce resources”(Watson,2022,pp.53–55).This generationalsystemenableda“balanced” reproductionofresources,inwhichfishand gamewouldreplenishpredictably(Thoms, 2004,p.68).Altogether,Indigenouspeoplesintheregionmaintainedaneutralor evenbeneficialrelationshipwiththeenvironment.

TheprogressionofEuropeansettlements, however,dramaticallytransformedtheimpactofhumansonMuskoka’secosystems. Capitalismdirectedthegrowthoftheresourceextractionindustrythatbecameintegraltotheeventualtourismindustry (MuskokaWatershedCouncil,2012,pp. 10-15).InNorthAmerica,capitalismcoevolvedwiththedispossessionofIndigenous landandtheimportofenslavedlabourto produceprofitforEuropeancolonists(Dorriesetal.,2022,paras.7-9).Labourwasunderpaidandlandwasextractedtomaximize wealthforslave-ownersandcapitalists(Robbinsetal.,2014,p.101).Overtime,this accumulationofcapitalbyaselectfewreinforcedaneconomiclogicofcompetitionand individualism,wheresurvivalisinseparable fromfinancialstability,theimpoverishment ofnatureandracializedothers.

Muskoka’sthin,acidicsoilslimitedsettlers’ attemptstoestablishagriculturallivelihoodsfollowingthefirstsettlementsin1859 (Watson,2017,pp.269,274).Manyfamiliesabandonedtheregionuponfailureto makethelandproductivethroughfarming (Watson,2017,p.275).Eventually,settlersdiscoveredthattheprofitpotentialof Muskoka’slandscapelaymoreintheforests andtheirappealtotourists.Theimageryof vacationinginwilderness—farfromeverydayurbanlife—establishedwhatJasencalls a“wildernessholiday”(Jasen,1995,p.116). Thoughsomehouseholdscontinuedfarming, manyturnedtosummertourismandlogging forgreaterincome(Watson,2017,p.281). LoggingpracticesledtofurtherdisplacementofIndigenouscommunities(Watson, 2014,p.191),andtheresultingdebrispollutedwaterways.Theeventualdepletionof theforesthabitatrenderedloggingnolonger fruitful(MuskokaWatershedCouncil,2012, p.16;Watson,2017,p.273).

TheadvertisementfortheRoyalMuskoka Hotel(Figure2)describestheregionas “Lakesofbluesetwithislesofemerald”. Thiscomparisonofnaturalfeaturestogemstonesrevealsthatnature’sappealwasincreasinglyaestheticizedandcommodified tosignalluxury.Thevery“islesofemerald”referencedwerethesameforestsbeing overexploitedbyloggers(Kuhlberg,2022,p. 101).Soprizedwasthecultivatedillusionof untouchedwildernessthatsettlersresisted naturalecologicalprocessesthatthreatened it(Kuhlberg,2022).WhenthenativehemlocklooperbugfeastedonMuskoka’spine needlesandturnedothersbrownin1929, settlerslobbiedtheOntariogovernmentto indiscriminately“carpetbomb”theforest withtoxicpesticides(Kuhlberg,2022,p. 101).Accompanyingthatwasthetoxic wastefromthetanningindustrythatgrew togetherwithlogging,whichspreadtoxins intoriversandfurtherdegradedtheforests (Watson,2022,p.126).Touristambitions hadevenledtoriverdammingandlake draininginpursuitofacharmingcottage landscape(Kuhlberg,2022,p.130).Despite theseharmfulpractices,Muskoka’sreputationasapristinenaturaldestinationpersisted—maintainedthroughaestheticcurationandenvironmentalerasure(Kuhlberg, 2022.p.112).

TheMuskokamap(Figure1)reinforces theseextractivepatterns.Itshowsthesectioningo! oflandforsummerlotsandcottageproperties,emphasizingprivatization andcompetitionforresources.Onthetop rightoftheMuskokaLakesmap(Figure1), theheadofadeerisdrawninfrontofagun, sword,andoar—symbolsthatgesturetothe leisureactivitiesmarketedtosettlers,includingshootingparties.Thesevisualsreflect thecolonialworldviewthatpositionednatureasinferiorandconsumable.Asaresult, overfishingandoverhuntingwereconsidered acceptablerecreationalpractices,regardless ofenvironmentaldamage(Jasen,1995,pp. 147-148).Moreover,settlersdeniedrespon-

sibilityfordecreasesin“fishandgame”, oftenblamingthisonIndigenouspeoples, whosefishingmethodswereviewedasmore e!ectiveandthusdeemed“‘lazy’and‘unsportsmanlike’”(Jasen,1995,p.148;Blair, 2008,ascitedinWatson,2022,p.64).This racializedscapegoatingjustifiednewlaws thatrequiredIndigenouspeoplestoobtain leasesandlicensesfromtheCrowntoaccesstheirtraditionalfoodsources(Watson, 2014,pp.166).TheseexploitativepatternsdemonstratehowMuskoka’senvironmentwasnotincidentaltocolonization—it wasacentralfeatureofthesettlereconomy, whereinnatureitselfbecamearesourceto beconsumedandmarketed.

Thecommunionwithnatureembeddedin Indigenouslifewayswasreinterpretedbysettlersthroughacoloniallensthatportrayed Indigenouspeopleasbiologically“closerto nature”andhence“savage”andinferior(NiigaaniinMacNeill,2022;Grandin,2019,p. 118).Thesenotionsjustifiedtheviolence andsubjugationfoundationaltosettlerexpansion(Grandin,2019,p.118).Thepresenceofboththeswordandgunonthe1899 Muskokamap(Figure1)areproductsofthe normalizationofviolencethatwasinherent inthecolonialfrontier.

The“savage”colonialnarrativealsocontributedtoMuskoka’s“exotic”appealfor settlers:asJasen(1995)describes,“Tourists enjoyedbelievingthatherewasatrue

primevalwilderness,notfarfromcivilization butveryrealnonetheless...[Indigenous guides’]utilitylaynotonlyintheirpracticalexpertisebutalsointheirimaginative appeal”(p.119).Theterm‘exotic’relies onthepowertopositionwhiteEuropean cultureascentralandnormative,whilecastingIndigenouspeoplesastheoppositional unfamiliar‘Other’.Throughthisdynamic, Indigenouslandswerereimaginedassitesof wonder—openforobservation,consumption, andcontrolbyEuropeansettlers.Muskoka wasmarketedasalocationwheresettlers couldexperiencewildernesswithoutrelinquishingtheirauthorityoverit.

By1909,oneoftheprominenthospitality businessesonLakeRosseauwastheRoyal MuskokaHotel,alargewhitestructureamid theforestandfeaturedinthevintageadvertisement(Figure2).Thechoiceofthe nameof“Royal”invokedassociationswith Britishmonarchy,appealingtoitssettler audience’saspirationstowardclassandcivility.Inthisfashion,itechoedbroader imperialarchitecturalstylessuchasthose ondisplayatthe1893World’sColumbian ExpositioninChicago,where“TheWhite City”symbolizedthetriumphofWestern modernity(RudwickMeier,1965,p.354). ThechiefdesignerofTheWhiteCitywould laterbecomethecityplannerofBaguio—a colonialadministrativecentreinthePhilippines—followingAmerica’soccupationin 1898(Cody,2003,p.22).InFigure2, theRoyalHotel’sclassicalformcontrasts

againstthesupposedprimitivenessofthe surroundingnature,championingtheimageryofwilderness.Apromotionalbrochure publishedbytheGrandTrunkRailway (GTR)andMuskokaNavigationCompany insisted“Muskokaisnofakesummerresort” (GTRMuskokaNavigationCo.,1895,as citedinJasen,1995,p.116),exemplifying howtheindustryadvertisedan“outdoors” thatwasconvenientforurbansettlers.

Moreover,theadvertisement(Figure2)also conveysthistensionthroughvisualrepresentation.Awhitemanispicturedina white-collareddressshirtandtie,asopposedtoblue-collar(manuallabour)uniforms.Itimaginesanactivitywherethe whitesettlerscouldmaintaintheirseparationfromnature,theirpristinedress-shirt drydespitebeingonthewater.Inthisway, Muskokatourism’spromotionofa‘civilized’ engagementwithnature—clean,elevated, andaesthetic—therebysustainedthecolonialnarrativeofwhitedominanceoverland andpeople.

Asdemonstrated,thetwoprimarysources drawnuponinthispaper,includinga 1899mapandchartoftheMuskokalakes anda1909tourismadvertisementfor LakeRosseau,helpexhibithowMuskoka’s tourismindustryemergedfromandsustainedaprocessofEuropeansettlercolonialism.Itdidsothroughthreemainavenues: theerasureofAnishinaabegpresenceinthe

region,theexploitationofnature,andthe useandpromotionofthecivilizedversus wildnarrative.

OnceitbecameclearthatMuskoka’senvironmentwasnotconduciveto“capitalaccumulatingfarms”,settlersinsteaddevelopedthetourismindustry(Watson,2017, p.263).Buildingonearliersettlerpracticesofremapping,renaming,andresource extraction,thetourismindustryfurthersuppressedIndigenoushistoryandspatialrelationships.Throughpromotionalimagery andselectivestorytelling,settlerslaidclaim notonlytothelandbuttotheknowledge ofit—recastingIndigenouslandsassettler leisurespaces.Asthevisualmaterialsshow, thecolonialtourismindustryreliedontransformingviolenceanddisplacementintomarketabletranquility,obscuringtherealcost ofsettlementthroughidyllicscenesandromanticizedwilderness.

Muskoka’spast,then,isnotsimplyone ofsceniclandscapesandsummerretreats, butofdeeplyentangledcolonialrelations—relationsthatcontinuetoshapehow land,nature,andindigeneityareperceived today.

Allen,W.A.(2002)Wa-nant-git-che-ang: CanoeroutetoLakeHuronthrough SouthernAlgonquia. OntarioArchaeology,73,38.

Blackhawk,N.(2023). Therediscoveryof America:NativepeoplesandtheunmakingofU.S.history. YaleUniversity Press.

Cody,J.W.(2003). ExportingAmerican architecture,1870-2000. Routledge.

Cowen,D.(2020).Followingtheinfrastructuresofempire:Notesoncities,settler colonialism,andmethod. UrbanGeography,41 (4),469–486.

Daschuk,J.W.(2013). ClearingthePlains: Disease,politicsofstarvation,andthe lossofAboriginallife. Universityof ReginaPress.

Dorries,H.,Hugill,D.,Tomiak,J.(2022). Racialcapitalismandtheproductionof settlercolonialcities. Geoforum,132, 263–270.

Grandin,G.(2019). Theendofthemyth: Fromthefrontiertotheborderwall inthemindofAmerica. Metropolitan Books,HenryHoltandCompany. Harris,C.(2004).Howdidcolonialismdispossess?Commentsfromanedgeof empire. AnnalsoftheAssociationof AmericanGeographers,94 (1),165–182.

Jasen,P.(1995). Wildthings:nature,culture,andtourisminOntario,1790-1914. UniversityofTorontoPress.

Jenness,D.,NationalMuseumofCanada, issuingbody.(1935). TheOjibwaIndiansofParryIsland:Theirsocialand religiouslife. CanadaDept.ofMines, NationalMuseumofCanada.

Kuhlberg,M.(2022). Killingbugsforbusinessandbeauty:Canada’saerialwar againstforestpests,1913-1930. UniversityofTorontoPress.

Lawson,S.,Cousineau,B.(2017). The AnishinaabegatLakeofBays. Ontario HeritageTrust.

Mason,D.H.C.(1957). Muskoka:Thefirst Islanders. Herald-GazettePress.

Marshall,G.W.(1899).“Mapchartof theMuskokaLakes”.Scale1:47,520, S/409/Muskoka/[1899],Maps,plansand charts,LibraryandArchivesCanada.

Merbs,C.F.(1992).Anewworldofinfectiousdisease. AmericanJournalof PhysicalAnthropology,35 (S15),3–42. Miller,C.(2010). Ogimaag:Anishinaabeg leadership,1760-1845. UniversityofNebraskaPress.

Muskoka.(1909,July). TheCanadianMagazine,3 (33),59.Canadiana.

MuskokaAreaIndigenousLeadershipTa-

ble.(2025,March19). MAILT. Engagemuskoka.

MuskokaWatershedCouncil.(2012,May 11). Muskoka’sBiodiversity:UnderstandingourPasttoProtectourFuture.

Niigaaniin,M.,MacNeill,T.(2022).Indigenouscultureandnaturerelatedness: Resultsfromacollaborativestudy. EnvironmentalDevelopment,44,100753-.

Robbins,P.,Hintz,J.,Moore,S.A.(2014). Environmentandsociety:Acriticalintroduction (Secondedition.).JohnWiley Sons.

Rudwick,E.M.,Meier,A.(1965).Black Maninthe“WhiteCity”:Negroesand theColumbianExposition,1893. Phylon,26 (4),354–361.

Segalen,V.,Fish,S.,Jameson,F.(2020). Essayonexoticism:Anaestheticsof diversity.In EssayonExoticism (pp. 11–70).DukeUniversityPress.

Thoms,J.M.(2004). Ojibwafishing grounds:historyofOntariofisherieslaw, science,andthesportsmen’schallengeto Aboriginaltreatyrights,1650-1900 [Doctoraldissertation,UniversityofBritish Columbia].UBCLibraryOpenCollections.

Watson,A.(2014). PoorSoilsand RichFolks:HouseholdEconomiesand SustainabilityinMuskoka,1850-1920 [Doctoraldissertation,YorkUniversity]. YorkSpace.

Watson,A.(2017).PioneeringaRuralIdentityontheCanadianShield:Tourism, HouseholdEconomies,andPoorSoils inMuskoka,Ontario,1870–1900. The CanadianHistoricalReview,98 (2), 261–293.

Watson,A.(2022). MakingMuskoka: Tourism,ruralidentity,andsustainability,1870-1920. UBCPress.

TheLouisianaPurchaseof1803wasmorethanalandacquisition:itwasatransformative eventthatreshapedU.S.territorialexpansionandIndigenoussovereignty.Thispaperexamines howthePurchaseinstitutionalizedlegalframeworks,suchastheDoctrineofDiscovery, legitimizingsettlercolonialismandlayingthefoundationforManifestDestiny.Byanalyzing theLouisianaPurchaseTreatyandGratiot’s1837mapalongsidesecondarysources,thisstudy highlightshowterritorialexpansionwasframedasbothinevitableanddivinelysanctioned. Thetreaty’slanguageignoredIndigenousgovernance,reinforcingthenotionofterranullius andenablingtheU.S.tojustifydisplacement.France’sweaksovereigntyovertheMissouri watershedfurtherunderscoresthePurchase’slegalambiguities,asIndigenousnationslike theOsageandSiouxmaintainedcontroloftheselands.Additionally,thefortificationof thefrontier,facilitatedbyU.S.militaryinstallations,exemplifiedhowManifestDestinywas realizedthroughmilitarizationanddispossession.Economicandculturalerasurefollowed,as Indigenouscommunitieswerecoercedintolandcessionsandsubjectedtoassimilationpolicies. Ultimately,theLouisianaPurchasecatalyzedU.S.westwardexpansionwhileentrenching systemicIndigenousdispossession,alegacythatcontinuestoshapehistoricalnarrativesand contemporarydiscussionsonlandsovereignty.

Keywords: LouisianaPurchase,ManifestDestiny,Indigenousdispossession,settlercolonialism,DoctrineofDiscovery,terranullius,treaties,Indigenousresistance

TheLouisianaPurchaseof1803wasamonumentalterritorialacquisitionthatdoubled theUnitedStates’ssizeandcatalyzedits westwardexpansionacrossthecontinent. Morethanalanddeal,itrepresentedalegalandideologicalshiftthatestablishedthe necessarymechanismsfordispossessingIndigenousnations.Atitscore,acquisition embeddedprinciplesliketheDoctrineof DiscoveryintoU.S.policyandsetthestage forManifestDestiny,reframingU.S.territorialexpansionasinevitableanddivinely sanctioned.

TheLouisianaPurchasenotonlyfacilitatedterritorialgrowthbutalsoperpetuatedthesystemicdispossessionandcultural erasureofIndigenouspeoples.Usingthe LouisianaPurchaseTreaty(1803)andGratiot’sMap(1837)asprimarysources,alongsideabreadthofsecondarysources,this essayexaminesthelegalambiguitiesand sovereigntyimplicationsoftheLouisiana Purchase;exploresitsimpactontheevolutionoftheideologicalframeworkofManifest Destiny;andanalyzesthepolitical,cultural, andfinancialimpactsithadonIndigenous Nationswithinthecededterritory.

TheDoctrineofDiscoverywasalegal andreligiousdoctrineoriginatingfroma seriesof15th-centurypapalbulls,which permittedChristianEuropeanpowersto claimsovereigntyoverlandsinhabitedby non-Christians(AssemblyofFirstNations, 2018).InthecontextofNorthAmerica,itprovidedthefoundationallegaland moraljustificationforcolonialexpansion andthedisregardofIndigenoussovereignty. Closelytiedtothiswastheconceptofterra nullius—aLatintermmeaning“nobody’s land”—whichpresumedthatlandnotcultivatedorclaimedaccordingtoEuropean normscouldbeseized,evenwhenlonginhabitedbyIndigenouspeoples(Assemblyof FirstNations,2018).

Figure1.FirstpageofLouisianaPurchaseTreaty. From TreatybetweentheUnitedStatesofAmericaandtheFrenchRepubliccedingtheprovince ofLouisianatotheUnitedStates,byU.S.Senate, 1803.

TheLouisianaPurchaseTreaty,asshownin Figure1above,reliedontheDoctrineofDiscovery,legitimizingEuropeansovereignty overunoccupiedorunusedIndigenouslands. ArticleIoftheLouisianaPurchaseTreaty codifiedthesettler-colonialassumptionthat imperialpowerscouldunilaterallytransfer Indigenousland.TheTreatystatesthat FrancecededtotheUnitedStates“thesaid territorywithallitsrightsandappurtenancesasfullyandinthesamemanner astheyhavebeenacquiredbytheFrench Republic,”(LouisianaPurchaseTreaty1803,

ArticleI)erasingIndigenoussovereigntyand legitimizingthetransferoflandFrancenever trulygoverned(LouisianaPurchaseTreaty, 1803).Thislegalmaneuverrestedonthe DoctrineofDiscovery,whichtreatedIndigenousnationsasmereoccupantswithout title,allowingsettlergovernmentstoabsorbterritorythroughimperialnegotiation (Miller,2011).France’ssaleofthelandto theUnitedStatesignoredthecontinuedpoliticalcontrolexercisedbynationssuchas theOsageandPawnee,enablingtheU.S. toclaimtheselandswithoutnegotiationor consent.

TheLouisianaPurchaseTreatyframesthe territoryasanobjectofimperialpossession,absentofIndigenousgovernance.ArticleIdescribesLouisianaas“theColony orProvinceofLouisianawiththesame extentthatitnowhasinthehandsof Spain,andthatithadwhenFrancepossessedit,”aformulationthatdefineslegitimacysolelyintermsofEuropeancontrol (LouisianaPurchaseTreaty,1803).ThislanguageomitsIndigenouspresenceentirely, reinforcingtheDoctrineofDiscovery’snotionthatonlyChristianEuropeanpowers couldexercisesovereignty.Italignswith theideaofterranullius,suggestingtheland waslegallyemptyandavailablefortransfer, despitethecontinuedpresenceandgovernanceofIndigenousnations(Miller,2011). ByfailingtoacknowledgeIndigenousclaims, theTreatylegallyjustifiedU.S.occupation andexpansionwhilerhetoricallyerasingIndigenouslife.

ContestingSovereignty:France, theU.S.,andIndigenousNations France’slackofdefactosovereigntyover theMissouriwatershedunderminesthelegallegitimacyoftheLouisianaPurchaseand U.S.claimstoIndigenouslands.Indigenous nations,notablytheOmaha,Sioux,and Osage,maintainedpoliticalandterritorial controlovertheselandsthroughcomplex tradenetworksandalliances(McNeil,2019). McNeil(2019)highlightshowFrance’snominalclaimstotheseterritorieswereneversolidifiedthroughgovernanceorenforcement. ThissituatestheU.S.acquisitionoftheterritoryasmoresymbolicthanpractical.

TheU.S.,however,usedtheTreatyasjustificationtoasserttheirterritorialambitions overIndigenouslands,ignoringtheactual sovereigntyofnationsliketheOsage,who resistedtheseclaims(Kastor,2008).This misrepresentationofterritorialsovereignty revealshowtheU.S.exploitedlegalambiguitiestolegitimizeitsexpansionistambitions (Kastor,2008).

ThomasJe!ersonframedtheLouisianaPurchaseascentraltohisvisionofan“Empire ofLiberty,”thatexpandingitsterritorywas integraltothesurvivaloftheburgeoning UnitedStates(Frentzos&Antonio,2015; LouisianaPurchaseTreaty,1803).Je!erson

treatedthelandacquisitionasamoralimperative,emphasizingtheroleofthisexpansioninspreadingdemocracyandsafeguardingAmericanideals(Frentzos&Antonio, 2015;LouisianaPurchaseTreaty,1803).

ThelegallanguageoftheTreatymirroredJe!erson’sdisregardforIndigenous politicalrealitybydefiningthepopulation oftheLouisianaTerritoryinvagueand settler-centricterms.ArticleIIIdeclares that“theinhabitantsofthecededterritory shallbeincorporatedintheUnionofthe UnitedStates...totheenjoymentofall theserights,advantagesandimmunities” (LouisianaPurchaseTreaty,1803).While theclausemayappearinclusive,itfailsto distinguishamongthediversepeoplesliving intheregion,e!ectivelycollapsingIndigenoussovereigntyintoagenericcategoryof “inhabitants.”ThisrhetoricalflatteningreinforcedJe!erson’sbeliefinexpansionas amoralandnationalimperative,ignoring Indigenouspoliticalsystemsandultimately justifyingtheirexclusionfromtherights promisedtofutureU.S.citizens(Frentzos &Antonio,2015;Richter,2003).

ManifestDestinyemergedfromideological rootsintheDoctrineofDiscoveryandwas facilitatedbytheLouisianaPurchase.Pratt (1927)describesManifestDestinyasthebeliefthattheU.S.wasdestinedbyProvidence toexpandacrossthecontinent,spreading libertyanddemocracy.ThisideologyprovidedamoraljustificationforthedispossessionofIndigenouspeoples,presenting

expansionbyanymeans,includingviolence, asnecessaryforthefulfillmentofAmerica’s destiny.

TheLouisianaPurchasewasaprecursorto thisdoctrine,establishingaframeworkfor viewingterritorialexpansionasintegralto nationalidentity.Byinstitutionalizingconceptsliketerranullius,theU.S.setaprecedentforfuturepoliciesprioritizingsettler claimsoverIndigenoussovereignty(Miller, 2011).Thephysicalacquisitionoflandby theTreatyprovidedthegeopoliticalmeans forManifestDestinytounfold.Withthe LouisianaPurchaseeliminatingthepolitical walltheU.S.facedtoitswestbefore1803, theU.S.couldexpandwestward,developing asanationbothcoloniallyandideologically. Thisvastterritorialgaindoubledthesize oftheUnitedStatesandcreatedthegeographicfoundationforexpansionistpolicies toflourish(Frentzos&Antonio,2015).The newlyacquiredlandsbecamethestagefor ManifestDestiny,enablingthemovement ofsettlerswestwardandcementingthebeliefthattheU.S.wasdestinedtospanthe continent.

ExpansionbyForce:Forts, Frontiers,andGratiot’sMap

Gratiot’s1837map(seeFigure2)illustrates howManifestDestinycreatedmilitaristic projectsoutofterritorialacquisitions,highlightingtheroleofexpansionistideologies inshapingU.S.policy.Themapdepictsa networkofU.S.forts,includingFortGibson

inpresent-dayOklahomaandFortLeavenworthinKansas,strategicallyplacedto protectnewsettlersandassertU.S.control overoccupiedIndigenousterritories(Gratiot,1837).Thesefortsservednotonlyas literalmilitaryinstallations,butalsoassymbolsofU.S.powerprojectionintheregion, showingtheUnitedStates’commitmentto westwardexpansionanditsmilitaristicattitudetowardstheIndigenouspeoplesalready ontheland.

Figure2.Mapshowingmilitaryinstallmentsacross theLouisianaTerritory.From Illustratingtheplan ofthedefencesoftheWestern&NorthWestern Frontier,byC.Gratiot,1837.

Fortsweremilitaryinstallationsandsafe spacesforcommerce,governance,andcommunication(McNeil,2019).Theywerenecessarytocreatethestableenvironments neededforpermanentandrobustsettlementsincontestedregionsliketheGreat PlainsandMissouriRiverBasin(McNeil, 2019).ThesettlerdevelopmentssystematicallyreducedIndigenousautonomyby cuttingo! mobilityandaccesstoresources whilealsocreatinglegitimacy—intheeyes ofWesternpowers—fortheUnitedStates’ territorialclaims(McNeil,2019).

Gratiot’smapalsohighlightstheweaponizationofcartographywithinthesettlercolonialprocess.AsRichter(2003)notes, theuseofcartographytominimizeorerase thetruenatureofIndigenouspresenceinthe territoryallowedsettlerstoreimaginethe frontierasawildernessripeforcultivation andsettlement.ByvisuallyassertingU.S. militarydominanceandunderratingIndige-

TheforwardpositioningofmilitaryinstallmentsacrossthefrontiershowstheU.S.’s deliberatestrategytoconsolidateterritorial claimsthrougharmedpresence.Theforts, LeavenworthandGibson,servedasstaginggroundsforexpansionsintoIndigenous lands,reinforcingtheperceptionofIndigenousnationsasobstaclestosettlercolonialismandU.S.expansionistprogress(Gratiot,1837;McNeil,2019).Theseaggressive powerprojectionsexemplifythemilitaristic qualitiesofManifestDestiny.Thedivine righttoexpandbyanymeansnecessarylogicallyvalidatestheuseofforcetoeliminate obstacles,includingIndigenouspeoples,to achieveU.S.goals.

nouspresence,themapencapsulatedthe intersectionofideological,infrastructural, andmilitarystrategiesemployedtofulfill ManifestDestiny.

TheLouisianaPurchasedisguisedsystemic financialexploitation.Indigenousnations wereforcedtocedetheirlandsunderunfair conditions(Lee2017).Lee(2017)calculatesthattheU.S.compensatedIndigenous nationswithapproximately $2.6billion(adjustedforinflation)forlandcessions.He arguesthattheseagreementswereoftennegotiatedundercoercivecircumstances(Lee, 2017).

Anexampleofthiscoercioncanbeseen withtheOsage,whowerepressuredinto cedinglargeswathsoflandintheMissouri RiverBasinatmerefractionsoftheirvalue (McNeil,2019).ThisdisadvantagedtheOsage,asthecompensationtheyreceivedwas insu”cienttosustaintheircommunitiesand didnotreflectthevastvalueofthelands theywereforcedtocede,whichwerequickly absorbedintosettleragriculturalexpansion. The1808TreatyofFortClarkexemplifies theseinequitablearrangements,forcingthe Osagetorelinquishover52millionacresundertermsthat,asmentionedbefore,heavilyfavouredtheU.S.government(McNeil, 2019).

Thesecoercedlandcessionsmarkeda broadershiftinsovereigntywithinthe

Louisianaterritory.TheOsage,who hadmaintainedautonomyintheMissouri RiverBasinthroughalliancesandmilitary strengthduringSpanishandFrenchcolonial possession,couldnotsuccessfullyfacetheencroachmentfromU.S.militaryactions,such astheestablishmentofFortOsagein1817 (McNeil,2019).TheconsolidationofU.S. controlintheregionnormalizedIndigenous dispossessionandsetthestageforpolicies liketheIndianRemovalAct(Richter,2003).

TheLouisianaPurchasesupportedcultural erasurebyframingIndigenousnationsas inferiorthroughpoliciesandlegallanguage, whichsupportedthedismantlingoftheir societalstructures.ManifestDestinyprovidedtheidealframeworkforthesee!orts, utilizingdiscriminatoryrhetoricandgeneral‘othering’toportrayIndigenousculturesasincompatibleandhostiletosettler progressandWesternsociety.ThisperspectiveunderpinnedpoliciestargetingIndigenoustraditions,language,religion,andgovernance,attemptingtosystematicallyerase theiridentity.Missionaryschools,mainly utilizedamongtheSiouxandPawneenations,werethedrivingmachinesforthis erasure.Inthe1820s,missionaryschools enforcedChristianityandEuro-American customsonIndigenouschildrenwhileforbiddingtheirnativelanguagesandcustoms entirely(Richter,2003).Pawneechildren wereremovedfromtheirfamiliesandco-

ercedintorenouncingtheirspiritualbeliefs andculturalpractices(Miller,2011).

WhilemuchfocuswasplacedonIndigenous youth,religiousconversioncampaignsextendedtoentirecommunitiesasawayof dismantlingtraditionalstructures.Among theSioux,missionariespromotedChristian convertsasleaders,underminingtraditional governancepracticesandsocialcohesion (Richter,2003).Thisweakeningofcultural autonomylefttheSiouxlessabletoresist settlerencroachment(Richter,2003).Simultaneously,settlernarrativesreframed theGreatPlainsasa“virginwilderness,” disregardingthedeeprelationshipsIndigenousnationshadcultivatedwiththeland forcenturies(Richter,2003).Byportraying thelandasuninhabitedandripeforsettlement,theseaccountsmarginalizedIndigenouspeoplesandjustifiedtheirexclusion fromtheexpandingsettlersociety.Like theaforementionedmissionarycampaigns, thesenarrativesalignedwithManifestDestinyideas,entrenchingsettlercolonialism andreinforcingcoercedassimilationasatool ofexpansion(Miller,2011;Richter,2003).

TheLouisianaPurchasewasaterritorialacquisitionandafoundationalmomentinU.S. settlercolonialism.ThroughtheLouisiana PurchaseTreaty,theUnitedStatesappropriatedIndigenoussovereigntybyregardingvastterritoriesasterranullius,legitimizedbytheDoctrineofDiscovery.The

legalframeworkintheTreatyitselfallowed theassertionofU.S.claimsintoIndigenous territory.Theideologicalandgeopolitical groundworklaidbythePurchasebecame centraltothedevelopmentofManifestDestiny,apillarofU.S.settlercolonialism.Gratiot’s1837mapexemplifieshowtheseideologiestranslatedintomilitarizede!orts onthefrontier,withfortsmanifestingU.S. powerprojectionandenablingsettlements toforminoccupiedIndigenouslands.Finally,theLouisianaPurchaseinstitutionalizedsystemicdispossessionandcultural erasurethroughinequitabletreatiesandassimilationpolicies,coercivelypushingIndigenouscommunitieso! oftheirlandsand attackingtheiridentity.Thisfoundational momentinU.S.expansionhasleftalegacy ofdisplacementandculturallossforIndigenouspeoples.

AssemblyofFirstNations.(2018). DismantlingtheDoctrineofDiscovery.

Frentzos,C.G,Antonio,A.S.(2015). The RoutledgehandbookofAmericanmilitary anddiplomatichistory:theColonialPeriodto1877 (1sted.).Routledge.

Gratiot,C.(1837). Illustratingtheplanof thedefencesoftheWesternNorthWesternFrontier.

Kastor,P.J.(2008). TheNation’sCrucible. YaleUniversityPress.

Lee,R.(2017).AccountingforConquest: ThePriceoftheLouisianaPurchaseof IndianCountry. TheJournalofAmericanHistory(Bloomington,Ind.),103(4), 921–942.

McNeil,K.(2019).TheLouisianaPurchase: IndianandAmericanSovereigntyinthe

MissouriWatershed. TheWesternHistoricalQuarterly,50 (1),17–42.

Miller,R.J.(2011). AmericanIndians, theDoctrineofDiscovery,andManifest Destiny.WyomingLawReview,11 (2), 329–349.

NationalArchivesandRecordsAdministration.(1803,April30). Treaty betweentheUnitedStatesofAmericaandtheFrenchRepubliccedingthe provinceofLouisianatotheUnited States [Treatydocument].General RecordsoftheUnitedStatesGovernment,RecordGroup11.

Pratt,J.W.(1927).TheOriginof“ManifestDestiny.” TheAmericanHistorical Review,32 (4),795–798.

Richter,D.K.(2003).FacingEastfrom IndianCountry.In HarvardUniversity PresseBooks.HarvardUniversityPress.

TheImpactsofRiver/LakeIceontheCanadianArctic

KaedanYu

ThispaperprovidesananalysisoflakeandrivericeintheCanadianArctic.Theformation andnaturalcyclesofthisicecontextualizesitsimportancetotheregionanditsinhabitants. AchangingclimatedisruptsthedelicatebalanceoftheArcticcryosphere,especiallyasArctic amplificationexacerbatesthee!ectsofwarming.Lakeandrivericeissubjecttoearlier melting,andlaterfreezing,withanoverallshorterdurationobservedeachsubsequentwinter inmanyareas.Thispaperexplorestheroleoflakeandrivericeinsupportingbothecosystems andhumansintheArctic,andhowitsessentialfunctionisbeingjeopardized,leadingto profoundimpactsontheclimateandhabitability.Itconcludesthatbothadaptationand mitigationstrategiesarenecessarytosupportthefuturesofIndigenousandotherArctic communities,aswellastheregion’swildlifeandthenaturalenvironment.

Keywords: lakeandriverice,freshwaterice,CanadianArctic,climatechange,Indigenous communities,mining

TheFormationofRiverandLake

IceintheCanadianArctic

Canadaisthecountrywiththemostlakesin theentireworld,with879,900lakesintotal (WorldPopulationReview,2024).Given thatmanyoftheselakesfreezeoverinthe winter,freshwatericehasasignificantimpactontheCanadiancryosphere.Justas important,riversflowingintotheArctic Oceanrepresentover10%ofglobalriver discharge,despitethisoceanonlycomprising1%oftheglobaloceanvolume(Aagaard andCarmack,1989;McClellandetal.,2012). Riverandlakeiceareuniquecryospheric features,astheyarealmostexclusivelycom-

posedoffreshwater,asopposedtosalinesea ice(Bringetal.,2016).Freshwatericeis extremelyrelevantintheCanadiancontext, asmostCanadianlakeandriversystems haveseasonalicecover(Bringetal.,2016). ThoughlakeandrivericeismainlyassociatedwiththeArcticduetoitscoldertemperaturesandseaice,eventheGreatLakes freezeoverannually(UnitedStatesEnvironmentalProtectionAgency,2024).However, therearedrasticseasonaldi!erencesinhow muchofthelakefreezes,varyingbetween ¡20%to¿90%icecoverasseeninFigure 1(UnitedStatesEnvironmentalProtection Agency,2024).

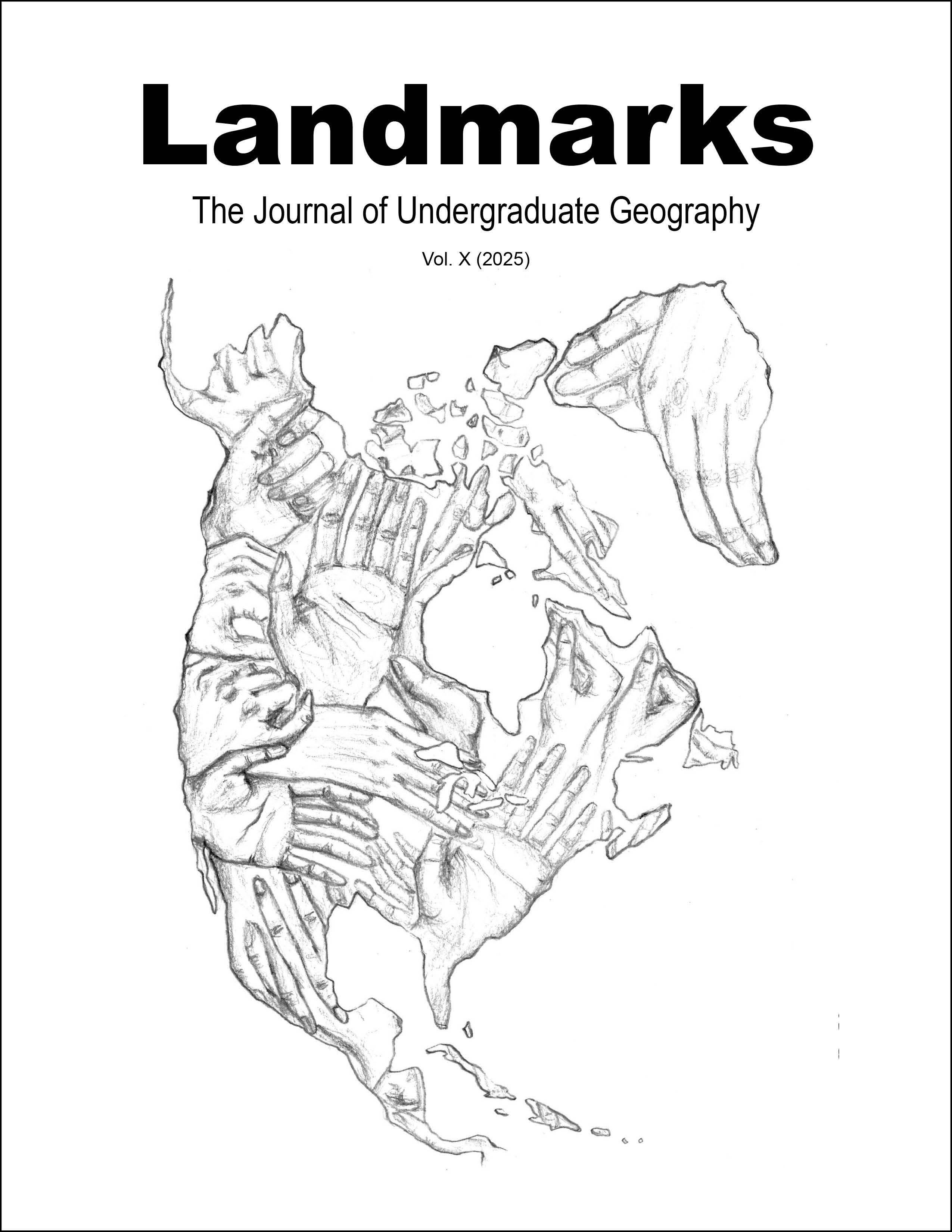

Figure1.AmapoftheArcticshowingtheboundariesofareaswithicecoverbythenumberofdays peryear.FromBatesBilello,1966.

Datafrom1966indicatesNorthernCanada waterwayshavingbeenunnavigablefor180 daysoftheyear,whilenearlytheentiretyof CanadaandalargeproportionoftheUSA wasunnavigablefor100daysoftheyear (BatesBilello,1966).Thenumberofunnavigabledayshassincedecreaseddueto climaticwarming(InuitTapiriitKanatami, 2018).However,thisopensupeconomic opportunitiesinNortherncoldwaterports, increasingseafaringaccessalongwaterways (InuitTapiriitKanatami,2018).Multiple riversflowintotheArcticocean,notably theMackenzieandLena,whichhavesprawlingdeltasharbouringecologiesandcommunities,deeplytiedtopatternsofriverice (L¨utjenetal.,2024;MarshPiper,2024). Smalllakesaremorecommonlysubjectto freezing,astheyonlytakeacoupleofweeks tofreezeover(Bringetal.,2016).Larger

lakes,ontheotherhand,cantakemonths, ormaynotevenfreezeovercompletely,especiallyinthecaseoftheGreatLakesand Canada’sothermassivelakes(Bringetal., 2016).Rivers,ontheotherhand,freezelater oninthecolderseasonsandbreakupearlier,leadingtoashorteroveralltimefrozen comparedtolakes,butalsogreatlydi!ering basedonthelength/sizeoftheriver(Bring etal.,2016).Thereasonsforthisaredue tothewayinwhichriverandlakeiceforms andmeltsannually.

Anannualcyclecomprisingthreecomponentsdefinesfreshwaterice:freeze-up, growth,andbreak-up(Bringetal.,2016). However,duetothelargeinfluenceofclimateandotherexternalfactorsapartfrom thehydrologicalsystem,theamountand thicknessoficeoneachwaterbodydi!ers drasticallyeachseason.Theformationof thistypeoficeoccursdi!erentlydepending onifitformsoveracalmbodyofwater (usuallylakes),oraturbulentbody(usually rivers)(Bringetal.,2016).Forcalmwater bodies,iceisformedwhenthesurfacewater coolsto4°C(thetemperatureatwhichwateristhemostdense)whichresultsinthat watersinking,andbringingupcolderwater fromdeeperareas(Bringetal.,2016).This wateristoocoldtocontinuethiscirculation, thereforeitremainsatthesurfaceandcools belowfreezingpoint,icingover(Bringet al.,2016).Intermsofmoreturbulentwaterbodies,waterisconstantlymixingandis generallyshallower,sothewatercoolsatthe

sameratethroughout(Bringetal.,2016).

Inthiscase,thefreeze-upoccurswhentypes oficeparticlescalledfrazilbuilduponce thewaterreaches0°C(Bringetal.,2016).

Theicegrowthstageisespeciallynotable forturbulentwaters,astheiceaccumulates acrossthewidthoftheriver,beforegrowing downwards(i.e.stretchingdeeper)(Bring etal.,2016).Thebuild-upandgrowthis greatlyinfluencedbyexternalvariablessuch aswindandsnowcoverontopoftheice, specificallythedensityofthesnow(Bring etal.,2016).RivericebreakupisasignificantspringeventinNorthernCanada,as icejamsoftenoccurduetotheinfluxof waterthroughsnowmeltandruno!,unique torivers(Bringetal.,2016).Thisresults infloodswhicharefarmoreimpactfulthan summerflooding(Bringetal.,2016).

Overlyingsnowhasuniqueimpactsonlake ice,includingcausingthespatialandtemporalvariabilityoficethicknessandpresence oficeacrossasinglelakethroughtheinsulatingcharacteristicsofsnow(Brown,2024). Notalllakeiceisthesame:thedi!erent typeshavedi!erentimpactsonthemicroclimateofthelake,andareimpactedbyoverlyingsnowindi!erentways.Blackiceappearsclear,andhasicecrystalswhichgrow downwardtothebottomofthelakeina columnarfashion(Brown,2024).Itsgrowth isslowedbysnowcoverduetothesnow’s insulatinge!ects(Brown,2024).Whiteice istranslucent,andisformedfromslushrefreezingfromtheweightofoverlyingsnow

(Brown,2024).Whiteicehasaloweralbedo (50%ofblackice),asthebubblesandice crystals,whichcomefromthewaytheice isformed,refractslightintoitself(Brown, 2024).Multi-yearicealsodrasticallya!ects lakeconditions,preventingwaterfrommixingastheiceshieldsitfromthewindyear round(Brown,2024).Theuniquelightconditionsfromconstanticecoveralsocreates auniqueecosystemoflakespecies(Brown, 2024).

Theimpactsofriverandlakeicecandirectlybeseenonsurroundingenvironments, andviceversa.InNorthernQu´ebec,around 10%ofriverdischargecanbeattributed tosnowfalldepressingtheice,pushingout morewaterduetotheincreasedpressure (Bringetal.,2016).Theiceisbeneficial inmanywaysforecosystems,servingfunctionssuchasprotectingfishfromlandpredators,whilemitigatingcoolinge!ectsbyinsulatingtheunderlyingwater(Bringetal., 2016).Forhumans,theiceactuallyopens upawholemodeoftransportation:winter andiceroads(Bringetal.,2016).Winter roadsaremorecommon,astheyareroads whichrunoverlakes,rivers,andlandinterchangeably,whileiceroadsarepredominantlyoverbodiesofwater(Barrette,2015). TheNorthwestTerritoriesisthehubofwinterandiceroads,withtheirroadsystem nearlydoublingeachwinter(Prowse,2009).

Theterritoryharboursthelongesticeroad intheworld:theTibbitttoContwoytowinterroad,seeninFigure2(NorthSlaveIce Roads,n.d.).

Figure2.FromTibbitttoContwoytoWinterRoad [Photograph],byJointVentureTibbitttoContwoytoWinterRoad,n.d. JVTCWRwebsite.

The600km-longroadis85%frozenlakes and15%portageoverland,andisoperated byseveralminingcompanies(Bringetal., 2016;BurgundyDiamondMinesLtd,2023). Itmustberebuilteveryyearbyfloodingcertainareastoensuresafeicethickness(BurgundyDiamondMinesLtd,2023).Thefact thelongestwinterroadisaprivateroadfor theminingindustryindicatestheArctic’s economicimportance,andhowfreshwater iceisessentialtothisindustry.WhilewinterroadsareessentialfortheArcticmining industry,theyalsoserveasavitallifelinefor IndigenouscommunitiesintheArcticduring wintermonths,allowingforthetransportof essentialservicesandsupplies(Indigenous ServicesCanada,2024).Thatsaid,more generally,theactivitiesofminingcompanies areofteninconflictwiththoseofIndigenous communities,withtheneedsandrightsof

communitiesbeinginfringedupon,asminingcanputthetraditionalwayoflifeof Indigenouscommunitiesatrisk.Oneunfortunatelycommonexampleisintheleaching ofmercuryintoculturally-significantwaterways,leadingtothecommunitiesbeingunabletosafelyfish,andseverethreatsto humanhealthandsafety(IsumaTV,2010). Inanotherexample,miningvesselsoften dumpballastwaterintotheArcticOcean tomakeroomforores,whichcanincrease invasivespeciesintheregion,disturbingthe ecosystembalancewhichInuitrelyonfor food(InuitTapiriitKanatami,2018).Overall,itisclearthatlakeandrivericeisvital toNortherncommunitiesandindustriesin theCanadianArctic,asdireconsequences wouldbefeltbytheregionwithanabsence ofthisice.

TheArcticfacesanexacerbatedclimatecrisis,knownasArcticamplification(Serreze &Barry,2011).TheArcticiswarming atapacetwotofourtimesasfastasthe restoftheworld(Bringetal.,2016).This ispartiallyduetopositivefeedbackloops, suchaswhenrisingtemperaturesfromclimatechangemeltice,exposemoreopen water,andlowertheoverallalbedointhe area,causingmoreenergytobeabsorbed andthushighertemperatures(Bringetal., 2016).Cryosphericfeatureslikelakeand riverice,therefore,areimperativetounderstandingourchangingclimate(Bringetal.,

2016).MultiplefactorsintheArcticcompoundtoexacerbatethee!ectsofglobal warmingoncryosphericsystemslikerivers andlakes(Brown,2024).Forexample,climatechangecausesacceleratedsnowmelt, whichfloodsrivers,whilerisingtemperaturessimultaneouslyspeedupicebreakup inrivers,allcoalescingintogreater,warmer waterinputintolakes(Brown,2024).Due toanincreasedfrequencyanddurationof winterwarmspellsasaconsequenceofclimatechange,riverandlakeiceisfreezing significantlylaterintheyearandbreaking upearlier(Bringetal.,2016).Thismeans thereisalongeropenwaterseason,when icedoesnotexistforaslongandhasless timetobuildup.

Warmertemperatures,especiallyintheArctic,generallyresultinriver/lakeicefreezing lateronintheseasoninNorthAmerica; however,thisvariesgreatlyseasonallyand regionally(Brown&Duguay,2022).Arctic icebreakupalreadyoccurredtwoweeksearlieronaveragefrom1846-1945,andcould occur15-35daysearlierbytheendofthe century(Bringetal.,2016).Thoughclimate changehasresultedinmoreicebreakup thanfreezingoverthepastcentury,the lastthirtyyearshasseenmoresignificant changesinfreeze-up,happening1.6days earlierperdecade(Bringetal.,2016).The issueisalsofurtherexacerbatedinhigher latitudes,withlakesintheHighArcticlosingicecoveratarateover4.5timesfaster thantherateoflakesinSouthernCanada (Bringetal.,2016).Thisbeingsaid,atrend towardsthereductionoficecoverinthe GreatLakesisstilloccurring,withLake Superiorbeinghitespeciallyhardasthe furthestNorth,largest,anddeepestofthe group(UnitedStatesEnvironmentalProtectionAgency,2024).

Thisreductionintheamountofoveralllake andrivericeintheCanadianArcticdue towarmingtemperatureswillhaveother detrimentale!ectsontheclimate.Tobegin, therewillbeagreaterreleaseinamountsof greenhousegasesintotheatmosphere,becauseriverandlakeicesequesterscarbon andmethane(Bringetal.,2016).Thisreleaseofgasescontributestothepositive feedbackloopofclimatechange,whichis keytoArcticamplification(Serreze&Barry, 2011).Further,reductioninicewilllimit theice’sabilitiestoenableheatstorage andwilldampenthestabilizatione!ects inregardstoevaporationandsensibleheat whichfreshwatericemaintains(Bringetal., 2016).Evaporativee!ectsarealreadycausinglakestobecomesalineorcompletelydry out;smallerlakesareespeciallysusceptible (Bringetal.,2016).Thelackoflakeice alsocausesgreatermixingoflakewater,as iceservesasashieldfromwind,somixingcausesextremeimpactsonthechemistryoflakewater(Cavaliereetal.,2021). Theconstanttumultfromwindalsolimits theamountoflightthatpenetrateslakewater,reducingtheactivityofvitalprimary producerslikephytoplankton(Cavaliereet

al.,2021).However,climatechangecanincreaseproductivityinlakeecosystems:for example,increasedtemperaturesandsolar radiationyieldgreateramountsofzooplankton(Cavaliereetal.,2021).Thishasa bottom-uptrophiccascadee!ect,allowing otherorganismsintheecosystemtothrive (Cavaliereetal.,2021).Climatechangeis alsocausingmoreextremeseasonalvariation (Bringetal.,2016).Theincreaseinsealevel iscausingfloodingfurtherupstreamfrom thebreak-upofriverice,disruptingecosystemsandimpactingcommunities,notably intheMackenzieRiverDelta(Bringetal., 2016).Ontheotherhand,lessicecanresult inlessdramaticbreak-ups,whichdriesout basinsandimpactsentireecosystems(Bring etal.,2016).

Themeltingoflakeandrivericenotonly hasdrastice!ectsonecosystemsandthe environment,butalsoonhumancommunities.Justlikethenaturalenvironment, thereisaspectrumofpositiveandnegative e!ectsofclimatechangefordi!erentgroups intheCanadianArctic.ManyNorthern communitiesareestablishedattheconfluenceofrivers,orwhenriversflowintolakes; areaswhichareespeciallyatriskforice jams(Bringetal.,2016).Whenthesejams break,acatastrophicinfluxofwaterengulfs downstreamcommunities(UnitedStatesEnvironmentalProtectionAgency,2024).Ice jamfloodsareprominentintheNorthwest

TerritoriesalongtheMackenzieRiverand itstributaries,particularlytheLiardRiver (EnvironmentandClimateChangeCanada, 2010).FortLiardandHayRiveraretwo notableicejamflood-pronecommunities intheNorthwestTerritories,astheirrespectiveriversarefedbyglaciersofthe RockyMountains,whichexperienceacceleratedmeltingduetoclimatechange,seenin Figure3(EnvironmentandClimateChange Canada,2010).

Figure3. FloodingofK´at!l’odeecheFirstNation homesatHayRiver. From Whywasthisyear’sHay Riverfloodsobad? [Photograph],byO.Williams, 2022, CabinRadio.

Dynamicrivericebreak-upscouldalso threatenhydroelectricfacilities,avitalenergysupplyforsomecommunities,anda revenuesourceforthegovernmentandcompanies(Bringetal.,2016).AsCanada’s Arctichasanactiveindustry,companies willalsofacechallengesindealingwiththe e!ectsofclimatechangeonlakeandriverice. Thisiceisessentialforthecontinuedsafeuse ofwinterroadsintheNorthwestTerritories, whichisbeingjeopardizedbyunpredictable andshorterwinters,andwarmertemper-

aturesmeltingvitalice(KleanIndustries, 2024).Companiesandproducerswhorely onwinterroadsforthetransportofgoods willloseaccesstostretchesofroad,and willneedtodomoremaintenanceonwinter roads(Bringetal.,2016).Inthewordsof thedirectoroftheTibbitttoContwoyto WinterRoad:“Iftherewasnowinterroad, therewouldbenodiamondmines”(Blake, 2022).InManitobaalone,winterroadscost thefederalgovernment $4.5millionannually, anumberwhichisonlyincreasing(Klean Industries,2024).Thealternativetomaintenanceisreplacingwinterroadswithall seasonroads,whichisestimatedtocostthe NorthwestTerritories $2billionover20years (KleanIndustries,2024).Itispredictedthat halfofCanada’siceroadswillbeunusable by2050,andeventuallynonewillbeby2080 (KleanIndustries,2024).

Theclosureofwinterroadsdoesnotonly impactindustryandthetownscentered aroundthesemines,butthemanyIndigenouscommunitieswhichrelyonthemfor goods(KleanIndustries,2024).Freshproducecanbeupto175%moreexpensivefor communitiesrelyingonwinterroads,exacerbatingthefoodinsecuritycrisisforArcticIndigenouscommunities(KleanIndustries,2024).Icefishingisimportantinmany NorthernIndigenouscultures,beingaprimaryfoodsourceformany,meaningicemelt couldfurtherexacerbateissuesoffoodinsecurityandjeopardizeacentralaspectofIndigenoustradition(IsumaTV,2010).Other

Canadianswhopartakeinrecreationalactivitiesonice,suchasskatingoricefishing,will seetheseactivitiesbeimpactedbymelting lake/riverice(UnitedStatesEnvironmental ProtectionAgency,2024).

Thoughclimatechangeyieldsanuncertain futureforCanada’sArctic,therearestrategiestocurbclimatechange’simpactson lakeandriverice.TraditionalIndigenous knowledgemustbecentraltoanysolutions, especiallythoseproposedbygovernment institutionsandcorporations(VogelBullock,2020).Ashasbeendemonstrated,in notmeaningfullyengagingIndigenoustraditionalknowledge,adaptationisinhibited (Fordetal.,2015).Anexampleofapositive andcollaborativeadaptatione!ortledby Indigenouspeopleswasthe2016relocation ofanadministrativecentreintheNorthwest TerritoriesfromAklaviktoInuvik(Bring etal.,2016).Inuvikisfurthernorth,away fromthefloodingwhichishappeningfurtherupstreamontheMackenzieRiverdue toclimatechange(Bringetal.,2016).Institutionalbarrierswhichpreventsuchactions fromtakingplacemustbechallenged.As ofnow,therehavebeennosuccessfulrelocationsofcommunities,despitecallsfrom Indigenousgovernmentstodoso(Fordet al.,2015).

Whilerelocationisapotentiallastresort, governmentfundsshouldbeprimarilyallo-

catedtodisasterpreventionandmitigation ratherthanrebuilding,whichisthecurrentfocus(Fordetal.,2015).Duetothe impactofclimatechangeonwinterroads, investmentinotherformsoftransportation shouldbeconsidered,suchaswaterways leadingintotheNorthwestPassage,which isopeningupduetothemeltingofsea ice(InuitTapiriitKanatami,2018).The passagecouldeconomicallysupportNortherncommunitiesaswellasfurthergrowing industry(InuitTapiriitKanatami,2018). SomeIndigenouspeoplesacknowledgethe importanceofshipping,andhowthepassage willimproveaccesstogoodsformanycommunities(InuitTapiriitKanatami,2018). Cheaperthanplanetransport,moreregular shippingwouldlowerfoodcostsforcommunities(InuitTapiriitKanatami,2018).LookingtotheNorthwestpassageisanimportant adaptatione!orttoconsider,especiallyfor communities.Thatsaid,mitigatione!orts shouldbeprioritizedasiceroadsarestillimperativeforindustrieslikediamondmining (Blake,2022).

Riverandlakeiceareimportantcryospheric featuresinCanada’sArctic.Theexacerbatede!ectofclimatechangebyArcticamplificationiscausingreducedfreshwaterice cover,whichdirectlyimpactscommunities andcompanieswhorelyonvitaliceroadsas aconnectiontotherestofCanada.Inthe Arctic’srapidlychanginglandscape,climate changehasuniquee!ectsonriverandlake ice,whichinturnhasimplicationsforkey Arcticgroups.Negativeimpactsmustbe urgentlyaddressed,utilizingthesolutions presented,andinconsultationwithIndigenousinhabitants.

Newtechnologymustbeusedtomonitor lakeandriverice,sothatcommunitiescan predictandprepareforthefuture.However,thesetechnologiesareoftenexpensive, sofundingfromdi!erentlevelsofgovernmentisrequired(Brown,2024).Lakeand rivericeisextremelydi”culttomonitor, asitisoftenremoteandconstantlychangingovershortperiodsoftime,andbylocation(sometimesevenwithinthesamelake) (Brown,2024).Cameraimageryshould keepbeingusedfortimelapsesasitissimpleandinexpensive,thoughitisunsuitableforextremelyremotelocations(Brown, 2024).Manualmeasurementisalsoanoption—althoughthisrequiresalargerteam, itcanprovidemoreaccurateresultsforice thickness(Brown,2024).Relativelynew technologysuchastheShallowWaterIce Profiler(SWIP)isanotheroption.Though somewhatexpensive,itisextremelye”cient andlowmaintenance,andhascontributed todevelopmentsinunderstandingoffrazilin riverice,andslushandthermalice(Brown, 2024;Buermansetal.,2011).Itise!ectiveinmeasuringlakeandriverice,though multipleSWIPsmaybeneededasdatacan beinaccuratefromasingleinstrumentas oneSWIPonlycapturesdataforasingular pointofthewaterbody(Brown,2024).

Aagaard,K.,Carmack,E.C.(1989). TheroleofseaiceandotherfreshwaterintheArcticcirculation. Journal ofGeophysicalResearchAtmospheres, 94 (C10),14485–14498.

Bates,R.E.,Bilello,M.A.(1966).Defining theColdRegionsoftheNorthernHemisphere,10.USArmyCorpsofEngineers, ColdRegionsResearchandEngineering Laboratory,Hanover,NewHampshire, TechnicalReport178.

Barrette,P.D.(2015).AreviewofguidelinesoniceroadsinCanada:Determinationofbearingcapacity.In National ResearchCouncil.

Blake,E.(2022,November17). Limitedtransportationinfrastructurefacing threatsintheNorth. CBC.

Bring,A.,Fedorova,I.,Dibike,Y.,Hinzman, L.,M˚ard,J.,Mernild,S.H.,Prowse, T.,Semenova,O.,Stuefer,S.L.,Woo, M.(2016).Arcticterrestrialhydrology:Asynthesisofprocesses,regional e!ects,andresearchchallenges. Journal ofGeophysicalResearchBiogeosciences, 121 (3),621–649.

Brown,L.C.(2024).GGR308–Week8 –ArcticHydrology[PowerpointSlides]. Quercus.

Brown,L.C.,Duguay,C.R.(2022)Lake Ice.ArcticReportCard2022.

Buermans,J.,Fissel,D.B.,Kanwar,A. (2011). SevenYearsofSWIPSMeasurements,ApplicationsandDevelopment: Where,HowandWhatCantheTechnologyDoforUs. ASLEnvironmental SciencesInc. BurgundyDiamondMinesLtd.(2023). The TibbitttoContwoytoWinterRoad,an essentialtransportationlifelineforEkati DiamondMine.

Cavaliere,E.,Fournier,I.B.,Hazukov´a,V., Rue,G.P.,Sadro,S.,Berger,S.A.,Cotner,J.B.,Dugan,H.A.,Hampton,S. E.,Lottig,N.R.,McMeans,B.C.,Ozersky,T.,Powers,S.M.,Rautio,M., O’Reilly,C.M.(2021).TheLakeIce ContinuumConcept:Influenceofwinter conditionsonenergyandecosystemdynamics. JournalofGeophysicalResearch Biogeosciences,126 (11). EnvironmentandClimateChangeCanada. (2010,December2). Flooding:Northwestterritories.GovernmentofCanada.

Ford,J.D.,McDowell,G.,Pearce,T. (2015).Theadaptationchallengeinthe Arctic. NatureClimateChange,5 (12), 1046–1053.

IndigenousServicesCanada.(2024,November28). FirstNations,Canadaand Manitobacometogethertoimprovewinterroads. GovernmentofCanada.

InuitTapiriitKanatami.(2018).Nilliajut2:InuitPerspectivesontheNorthwestPassage.InK.Kelley(Ed.),S. HillZ.Nungak(Trans.), InuitTapiriit Kanatami(ITK).

IsumaTV.(2010,February11). Inuit KnowledgeandClimateChange.

JVTC.(2018). TibbitttoContwoyto. TibbitttoContwoytoWinterRoad.

KleanIndustries.(2024,March12). UnpredictablewintersputnorthernCanada’s vitaliceroadsatrisk.

L¨utjen,M.,Overduin,P.P.,Juhls,B.,Boike, J.,Morgenstern,A.,Meyer,H.(2024). DriversofwintericeformationonArctic waterbodiesintheLenaDelta,Siberia. ArcticAntarcticandAlpineResearch, 56 (1).

Marsh,J.,Piper,L.(2023).Mackenzie River. TheCanadianEncyclopedia.

McClelland,J.W.,D´ery,S.J.,Peterson,B. J.,Holmes,R.M.,Wood,E.F.(2006). Apan-arcticevaluationofchangesin riverdischargeduringthelatterhalfof the20thcentury. GeophysicalResearch

Letters,33 (6).