Where science MEETS ART

Mapping cancer cell diversity with AI

Engineering immunity to fight disease

Welcome

Dear Garvan family,

Welcome to this special issue of Breakthrough, where we celebrate the fusion of two worlds that are deeply transformative: science and art.

At Garvan, our mission centres on discovery, as we lead the biomedical studies that translate into meaningful impact for the community. As well as being a data-driven endeavour, this is an intensely creative one. Our Art of Discovery exhibition, launched during National Science Week, is a celebration of both aspects. By reimagining research images as visual art, the exhibition invited visitors to see the beauty and complexity of science.

Science and art share more than you might think. Both demand curiosity and a willingness to challenge the status quo. Together, they inspire us to look closer, think differently and imagine new possibilities.

Inside this issue, you’ll learn more about our multi-faceted approach to cancer – from dormant cells that drive relapse, to a revolutionary AI tool that reveals tumour complexity and new insights on treatment resistance. You’ll also discover our research into enhancing newborn screening for immune disorders, and how we’re repurposing bacterial defence systems to correct these life- threatening genetic conditions.

These stories represent what makes Garvan special: brilliant people asking important questions, supported by people like you who share our belief that understanding leads to better treatments.

Thank you for standing alongside us in this vital work.

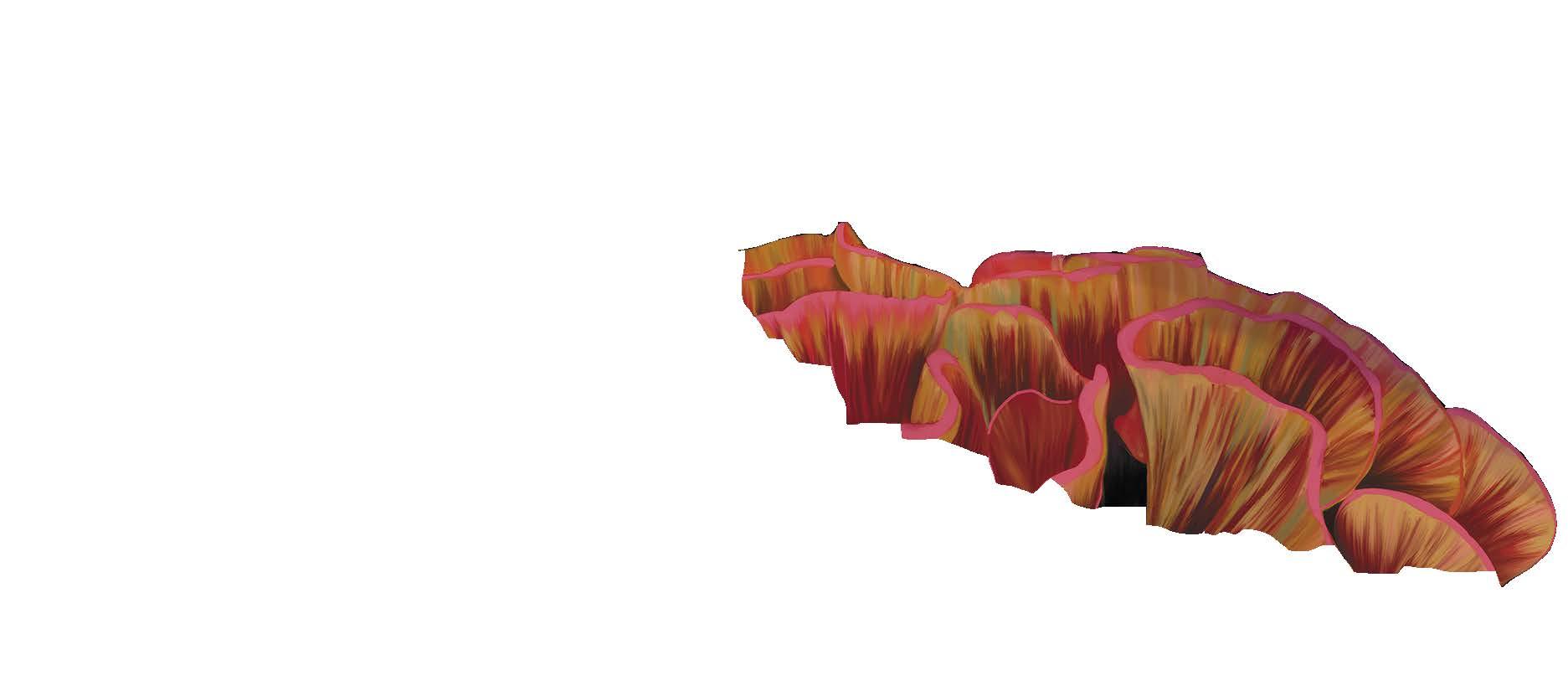

Cover image: Blossom – Winner of Garvan’s 2025 Art of Discovery People’s Choice Award. In this digital painting, the brain is reimagined as a blooming flower, illustrating adaptive neural development through stochastic interactions.

Credit: Xochitl Diaz

Engineering immunity

What if the body’s own defences could be turned into medicine? Antibodies – the proteins that recognise and block harmful invaders – are nature’s precision tools. Scientists can adapt these molecules, known as biologics, into therapies designed to stop disease in its tracks.

For Dr Rachel Galimidi, this potential became personal while growing up during the HIV crisis. Determined to understand how viruses evade immunity, she chose science over medicine – a decision that set her on a career path with global impact.

After completing her PhD, Rachel spent the next decade in biotech and startups before joining Garvan. Now leading two Programs, she explores how antibodies can be adapted as precise therapies for autoimmune disease, cancer and infectious disease.

Professor Benjamin Kile Executive Director

“The exciting thing about biologics is that you can test and refine ideas quickly, with the potential to help someone directly,” she explains. With her team, she aims to foster a culture where translation is built in from the start, bringing discoveries closer to the clinic.

Dr Rachel Galimidi

Stopping cancer relapse

Solving one of the most urgent challenges in breast cancer.

Each year more than 21,000 Australians will be diagnosed with breast cancer and around 3,300 will pass away from the disease. For some of these people, breast cancer cells can disseminate from the primary tumour and hide dormant in the body, most commonly in the bone, reawakening years or even decades later to cause therapy-resistant metastases. Around 15% of people will experience a relapse of their breast cancer within 10 years, and this return can be life threatening.

Now, an ambitious research program led by Garvan, called AllClear, will focus on these disseminated breast cancer cells –‘seeds’ of relapse – with the longterm goal of halving breast cancer deaths.

AllClear will use cutting-edge tools to isolate and study these ‘seeds’, refine tools to predict who is most at risk of relapse, and develop and test targeted therapies to eliminate these cells, before they reawaken and cause metastatic breast cancer. Understanding and tackling cancer cell dormancy has the potential to transform clinical management of breast cancer, improve patient outcomes and significantly reduce deaths.

This is a really exciting time in breast cancer research. We have the skill set, we have the technology, and we have a diverse group of experts coming together, all centered around this one question. Finding these seeds of relapse and eliminating them.

Associate Professor Christine Chaffer, Principal Investigator of AllClear

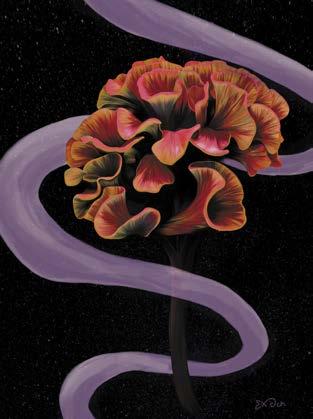

AllClear is enabled by Garvan’s strategic collaboration with St Vincent’s Hospital Sydney and UNSW Sydney and is a collaboration of nearly 60 researchers across seven leading research institutes and organisations. This includes Breast Cancer Trials, the University of Sydney, the University of Newcastle, together with world-renowned international partners including Yale and Washington University, and 11 hospitals across NSW.

This research is supported by the National Breast Cancer Foundation Visit garvan.org.au/allclear

L-R: Mary-Anne Young, Dr John Lock, Professor Frances Boyle, Professor Benjamin Kile, Associate Professor Christine Chaffer, Professor Peter Croucher

Tending to the future

From propagation to petri dishes, Greg’s support is helping science take root.

Each Wednesday Greg can be found elbow-deep in potting mix at the Royal Botanic Gardens of Sydney, where he clocks up 500 volunteer hours a year propagating and selling plants with a group he co-leads.

A lifelong horticultural scientist, he spent decades researching, developing and commercialising plants. But recently, another type of science has captured his attention.

“I started hearing about the Garvan Institute and the work they do from a close friend, who’s a longtime Garvan donor,” Greg says. “Then I started donating too because it’s an organisation that’s just extraordinary.”

He was drawn not only to the science, but to the people behind it. “I’ve been on a public tour of Garvan and I’m in awe of the competence and the complex science that goes on there,” he says. “I came away with this feeling of ‘Wow.’”

A year into his support, Greg decided to go a step further and become a Partner for the Future, pledging a gift to Garvan in his Will.

It’s money I want to see go to an institution like Garvan, rather than spending it on things,” he says. “I don’t need it all, so I’m happy to give some away.

This gift took on added significance after the death of Greg’s longtime colleague, Bill. “For 30 years, I worked with Bill. He was my boss, but also a great mate,” Greg says.

“He passed away last year from a blood clot. But he also had retinitis pigmentosa, an inherited eye disorder.”

Greg didn’t know Garvan was studying the condition. But after Bill’s death, he was touched to learn a memorial fund had been established, supporting the work of Associate Professor Owen Siggs in identifying the disorder’s genetic causes and developing targeted treatments.

Still, Greg’s support for Garvan isn’t limited to any one disease. “I’d like to see breakthroughs in all manner of debilitating illnesses,” he says. “And I’d like to see people in chronic pain due to unknown causes get answers and treatments.”

Just as he’s spent a lifetime nurturing growth from the ground up, Greg is now helping cultivate the conditions for breakthroughs to flourish. Like any good gardener, he knows the most meaningful things take time and, while they might not sprout in your lifetime, you plant the seed anyway.

Greg, Partner for the Future

Nature’s precision tools for better medicine

How Garvan researchers are harnessing immune targeting systems from bacteria and mammals to develop better therapies.

Over millions of years, life forms have evolved remarkable systems to protect themselves from threats like infectious disease. At Garvan, the Immune Biotherapies Program is turning these natural mechanisms into new therapies for difficult-totreat conditions.

“Nature has already created incredibly precise molecular targeting systems,” says Professor Robert Brink, who leads the program, which brings together multiple labs across Garvan. “We’re taking inspiration from two of these systems – CRISPR from bacteria and antibodies from mammals – and adapting them to create therapies that can identify specific targets with extraordinary accuracy.”

The bacterial CRISPR system functions like molecular scissors, allowing researchers to find and edit specific DNA sequences. Meanwhile, the immune systems of mammals produce antibodies capable of distinguishing between molecules that differ by less than 1% from the body’s own tissues. Both systems offer great precision in targeting disease.

For children born with genetic immune deficiencies, the team is developing virus-like particles that deliver CRISPR components directly to bone marrow stem cells. This approach repairs the genetic mutations at their source without requiring bone marrow transplants or lifelong immunosuppressive drugs.

The researchers are also addressing rare inflammatory conditions like MVK deficiency, caused by defects in

how cells attach fatty acids to proteins.

By understanding this cellular pathway, they’ve created diagnostic tools and are developing two treatment approaches: a pill containing the missing fatty acid and a genetic correction using CRISPR technology.

We’re essentially adapting nature’s precision tools to create therapies that were unimaginable just a decade ago. For example, this approach could dramatically improve vaccine effectiveness while reducing the doses needed – a critical advantage for responding quickly to future pandemics.

The program is even tackling food allergies. Some people develop dangerous allergic reactions to mammalian meat after tick bites – a condition called alpha-gal syndrome. Garvan researchers have identified the specific antibodies responsible and modified them to block rather than trigger the allergic response.

Through collaborations with clinicians, research networks and industry partners, the Immune Biotherapies Program is translating these biological innovations into practical treatments – showing how nature’s defence mechanisms can become powerful tools for human health.

CRISPR

• Acts like molecular scissors to find and edit specific DNA sequences

• Used to repair genetic mutations at their source

• Function as molecular detectives that identify and tag harmful invaders

• Used to target specific disease-causing molecules without affecting healthy tissues Antibodies

Professor Robert Brink

Professor Robert Brink

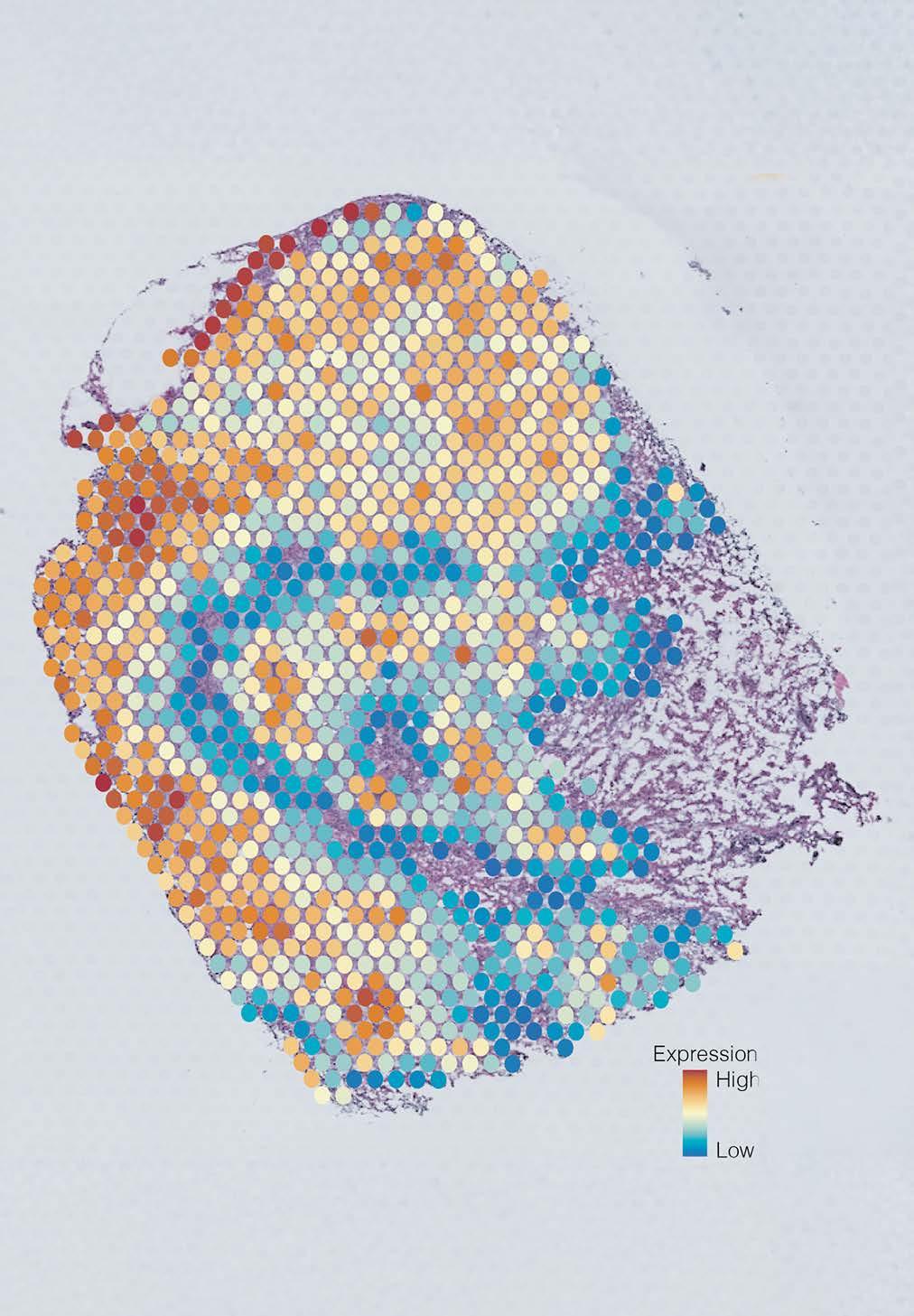

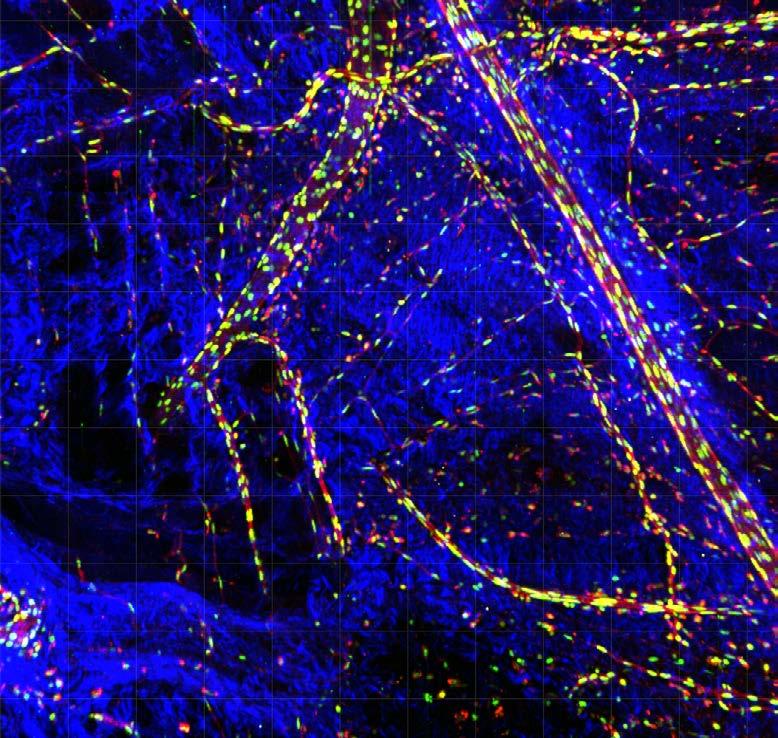

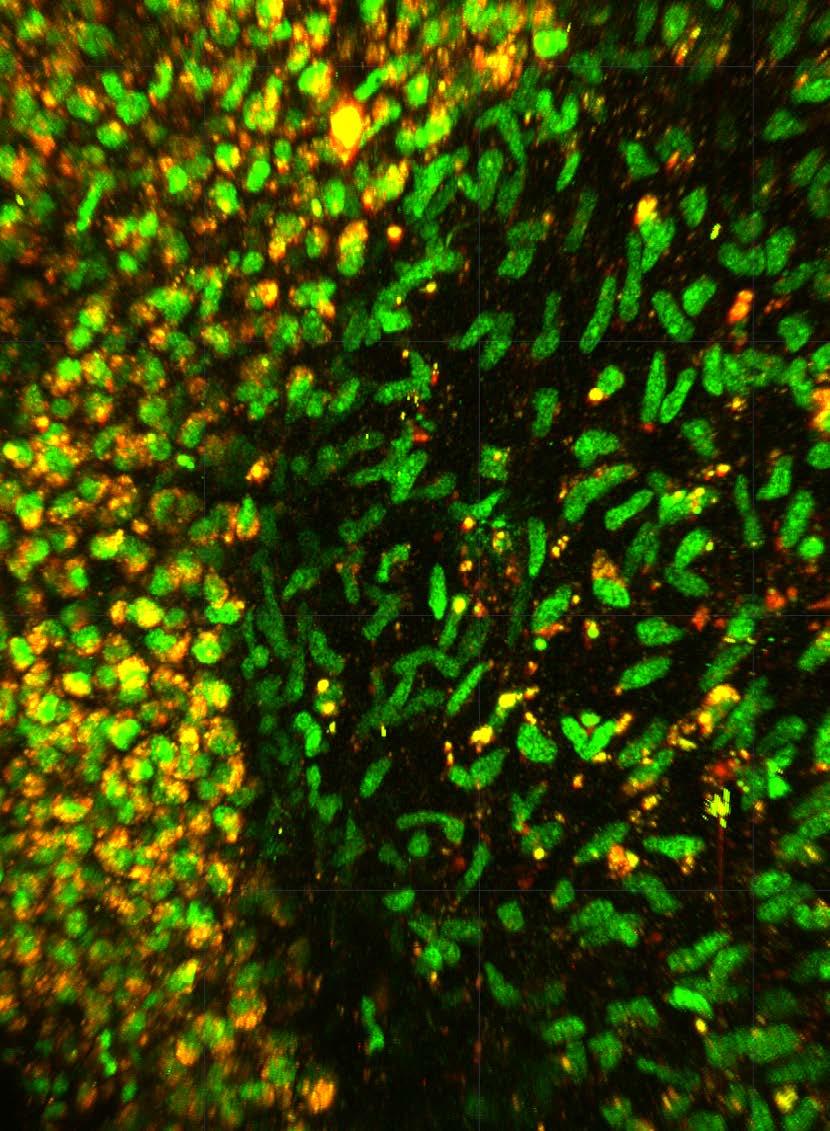

How do cancer cells differ from their neighbours?

The AI tool revolutionising our understanding of cancer cell behaviour.

Image: Tumour cross section showing five cell groups, each coloured differently based on gene expression.

A multinational team of researchers, co-led by Garvan, has developed a new AI tool to better describe the behaviour of individual cells within tumours, opening doors to more targeted cancer therapies. The findings were published in the prestigious journal Cancer Discovery.

Tumours aren’t made up of just one cell type –they’re a mix of different cells that grow and respond to treatment in different ways. This diversity, or heterogeneity, makes cancer harder to treat.

“Heterogeneity is a problem because we treat tumours as if they’re made up of the same cell type. This means we give one therapy that kills most cells in the tumour by targeting a particular mechanism. But not all cells may share that mechanism. So, while the patient may have an initial response, the remaining cells can grow and the cancer comes back,” says Associate Professor Christine Chaffer, co-senior author of the study and Co-Director of the Cancer Plasticity and Dormancy Program at Garvan.

In a bid to better understand this cell diversity, scientists worldwide have harnessed the recent explosion of technologies that generate data at the single-cell level. However, the challenge now lies in analysing the ensuing masses of data to provide meaningful insights into cancer cell behaviour and, in turn, to develop new cancer therapies.

Enter AAnet, a powerful new AI tool developed by the research team that can uncover patterns in gene expression within individual cells in a tumour and then match them to biological pathways used by each cell. This represents an unprecedented level of detail of how cancer cells behave.

Focusing on preclinical models and human samples of breast cancers, the team used AAnet to derive five different breast cancer cell groups – or ‘archetypes’ –each with distinct gene expression profiles, reflecting differences in cell biology and behaviour.

Associate Professor Chaffer says the development of AAnet opens doors for a paradigm shift in cancer therapies.

Currently the choice of cancer treatment for a patient is based on the organ the cancer came from such as breast, lung or prostate and any molecular markers it may exhibit. But this assumes that all cells in that cancer are the same.

Now we have a tool to characterise the heterogeneity of a patient’s tumour and really understand what each group of cells is doing at a biological level.

With AAnet, we now hope to improve the design of therapies that we know will target each of those different groups through their biological pathways,” says Associate Professor Chaffer.

Co-senior author of the study and Chief Scientific Officer, Professor Sarah Kummerfeld adds: We envision a future where doctors combine this AI analysis with traditional cancer diagnoses to develop more personalised treatments that target all cell types within a person’s unique tumour. These results represent a true melding of cutting-edge technology and biology that can improve patient care.

Professor Sarah Kummerfeld

Associate Professor Christine Chaffer

Professor Sarah Kummerfeld

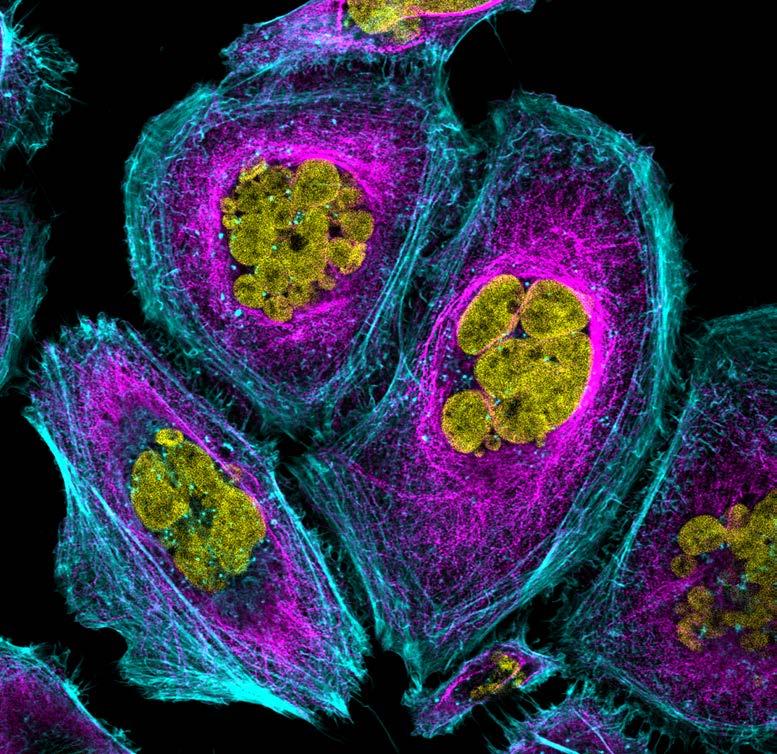

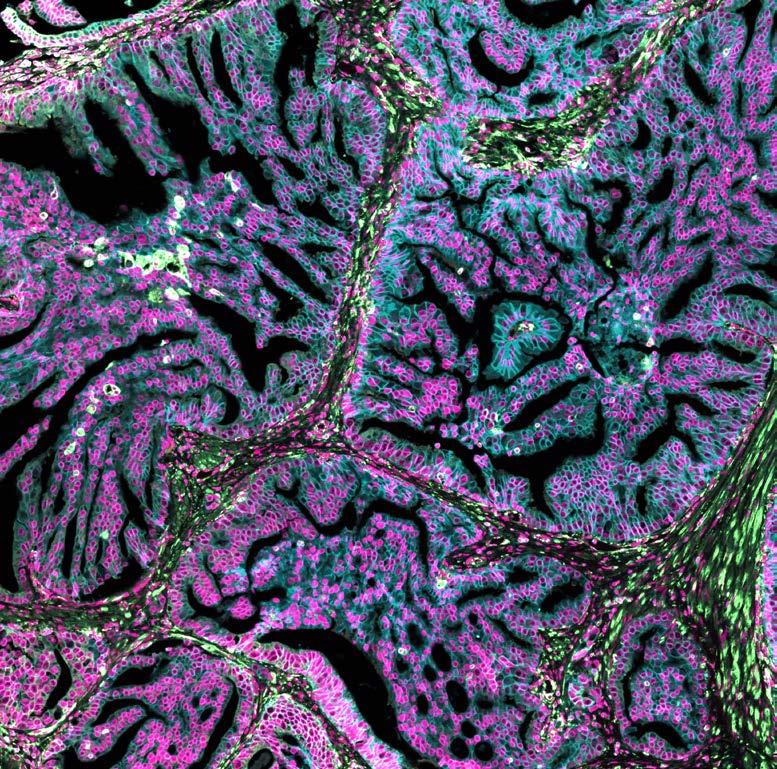

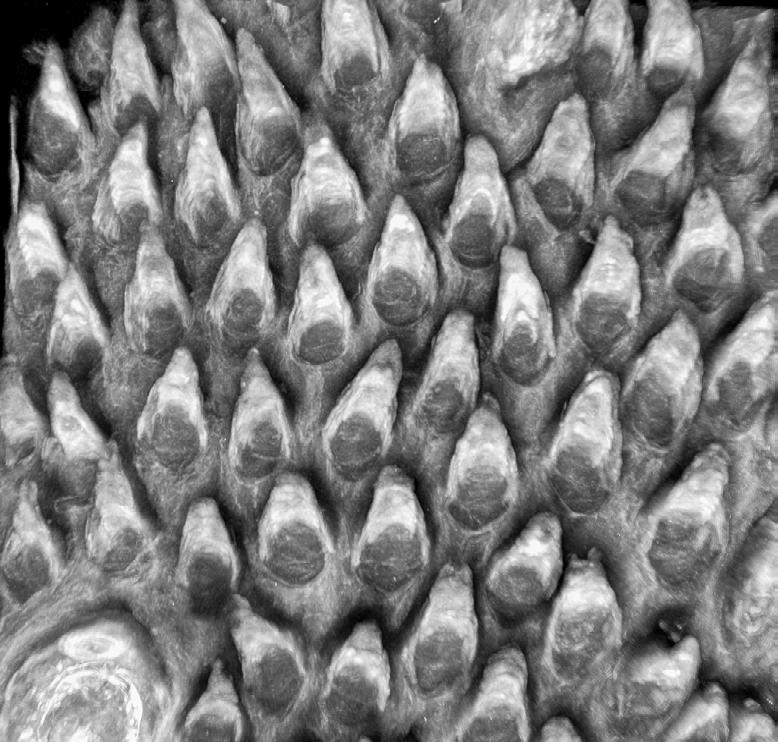

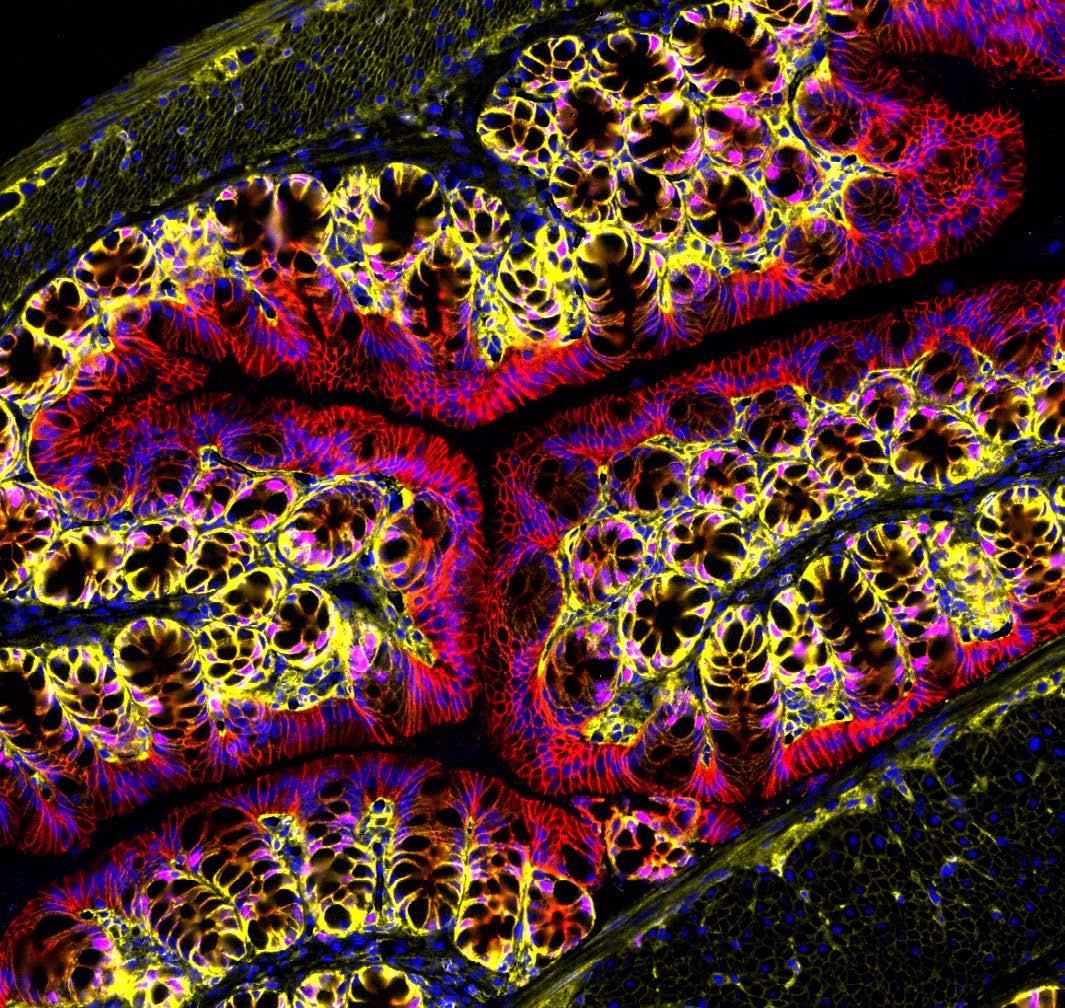

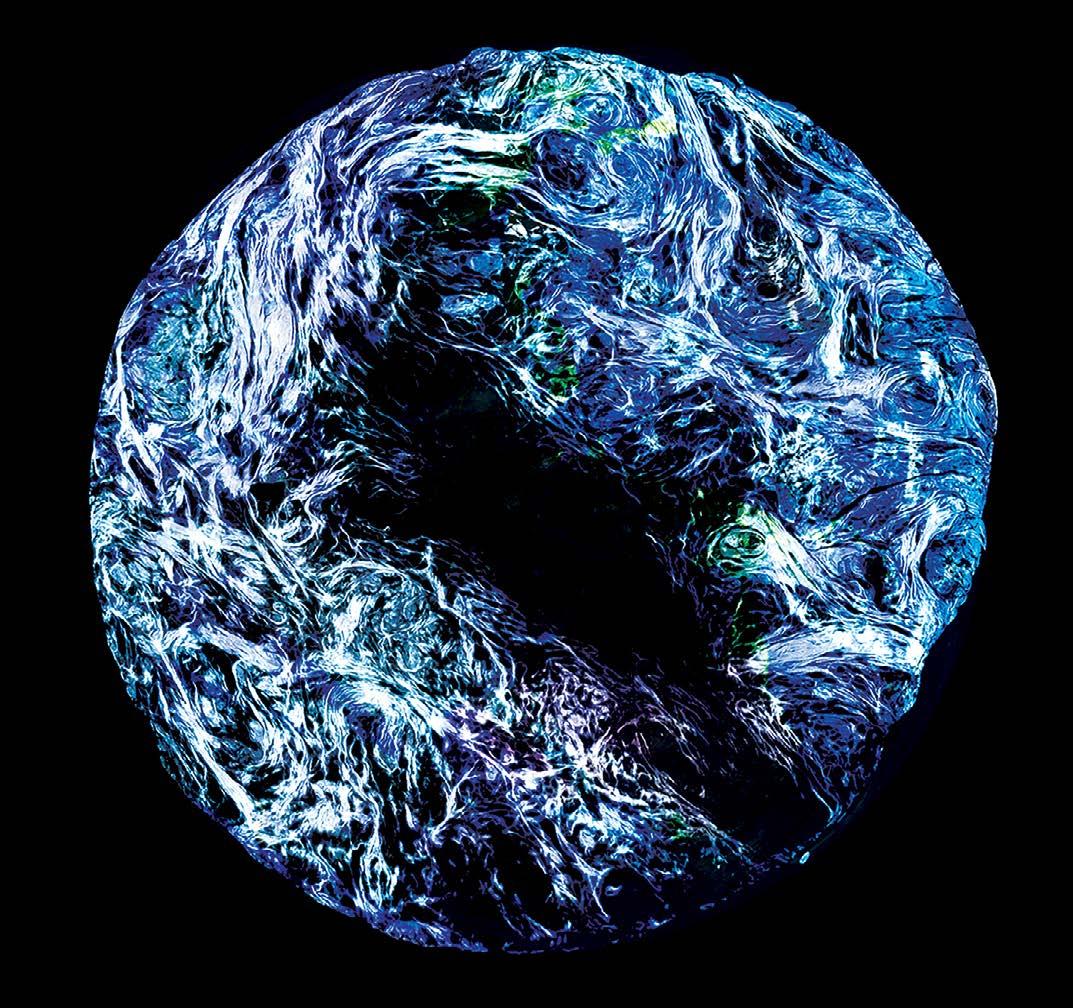

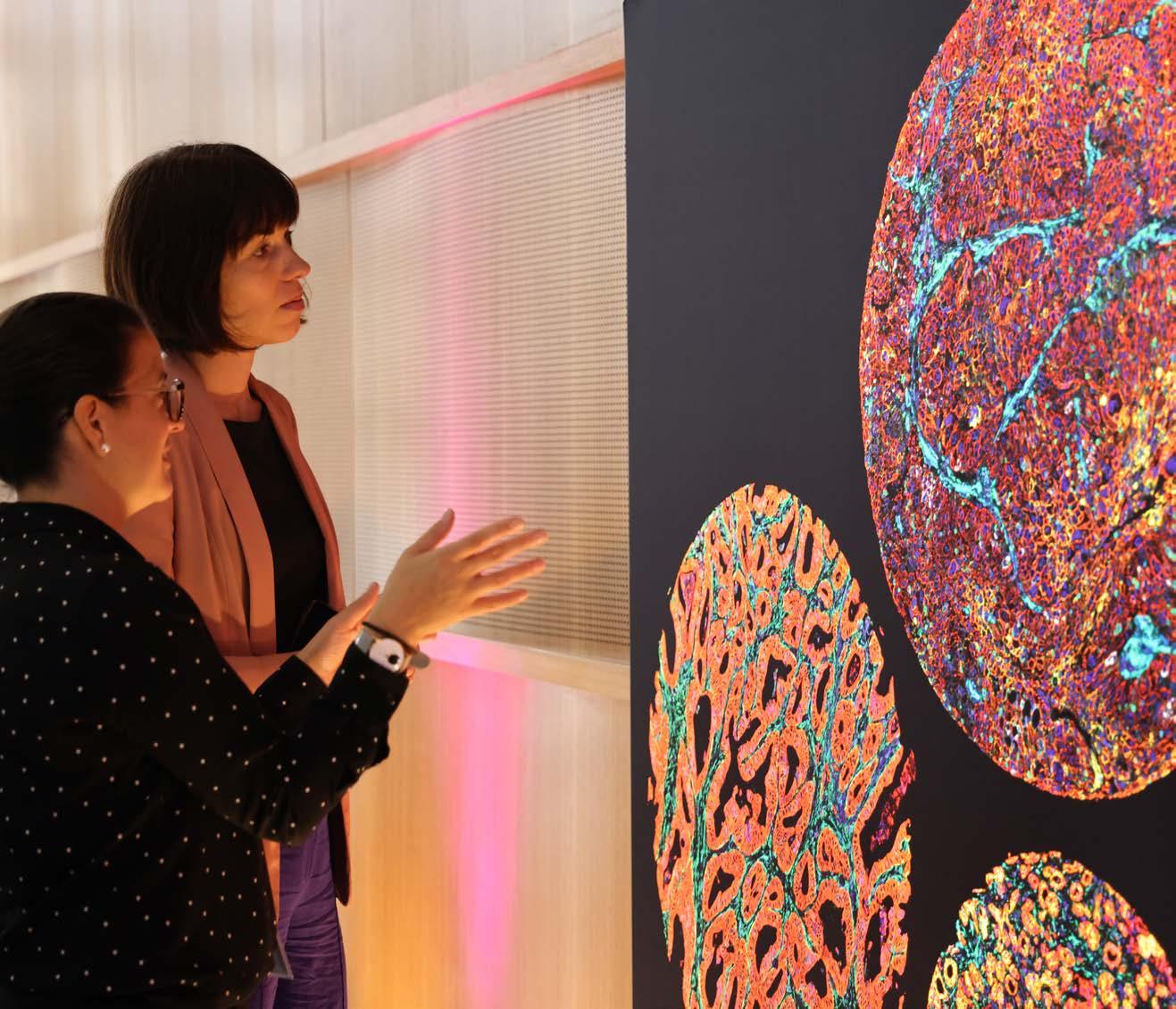

Seeing science in a new light

Garvan’s exhibition transformed research images into striking visual art.

Our Art of Discovery exhibition brought science to life in August, giving visitors a fresh look at Garvan research as part of National Science Week. More than 400 people came through our Darlinghurst doors to explore the illuminated lightboxes displaying visuals from our immunology, cancer and genomics labs – each image offering a window into the intricate patterns that underlie health and disease.

The winning entry, “Warhol’s Lymph Node” by Holly Ahel and Dr Gabriela Segal, used DNA barcoding to highlight 18 different proteins within a lymph node, showing the intricate inner architecture of these immune hubs. Runner-up “Blossom” by

Xochitl Diaz, as featured on the front cover, reimagined the brain as a flowering neural network – a vision that captured your hearts as the People’s Choice Award winner. Our sold-out Discovery After Dark event offered after-hours access to the exhibition and featured six researchers debating whether data or art better helps us understand the world.

“These images serve as both research tools and artworks,” said Abbey Roberts, Public Engagement Officer. “They show the creative thinking behind scientific discovery.”

We look forward to sharing the beauty and significance of this research with even more of you in 2026.

Garvan’s Discovery after Dark event

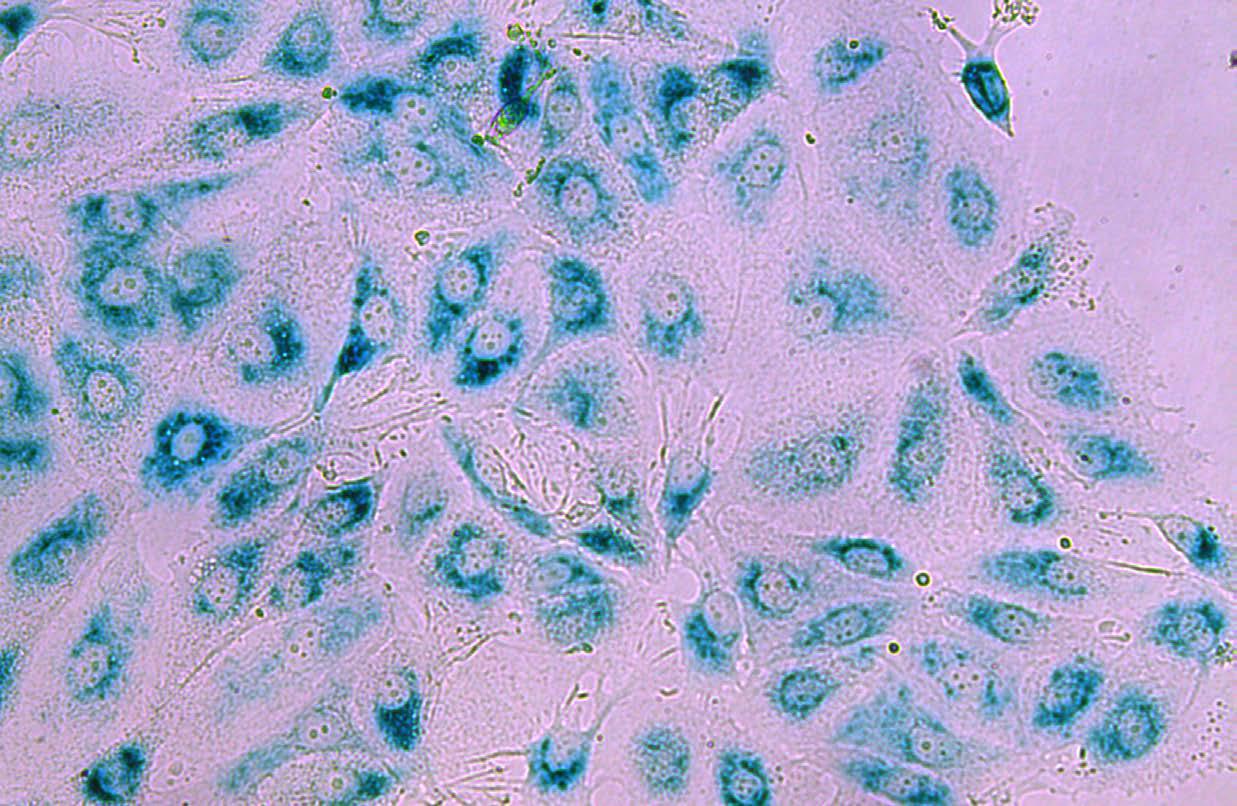

Why do cancer treatments stop working?

A critical discovery about how breast cancers resist a common treatment could lead to better treatment approaches to avoid recurrence.

When cancer patients hear their treatment is no longer effective, it’s devastating news. Drug resistance – when cancer cells adapt to survive treatments that once worked – remains one of medicine’s most challenging puzzles. For people with recurring cancer, options narrow while hope diminishes.

Garvan researchers have uncovered a cellular mechanism that may explain this treatment resistance in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer, which

accounts for about 70% of all breast cancer cases. While this type often has better outcomes than others, it still causes over 2000 deaths yearly in Australia, with most of these due to recurrence after initially successful treatment.

The Caldon Lab’s recent study focuses on the JNK pathway – a cellular signalling system that helps cells respond to stress.

“Think of the JNK pathway as a cellular alarm system,” says Associate Professor Liz Caldon, who led the research.

When functioning properly, it helps cancer treatments trigger cell death. But when this system is underactive, cancer cells can survive treatments that should eliminate them.

Interestingly, previous research has shown that overactivation of this same pathway can also promote cancer growth in certain contexts – highlighting the delicate balance needed for effective treatment.

Using comprehensive genetic screening, the researchers identified which genes influence treatment resistance. “We found that breast cancer cells where we knocked out the JNK pathway don’t respond well to our current combination therapy – specifically CDK4/6 inhibitors combined with hormone-blocking treatments,” says Associate Professor Caldon. “These cells no longer receive the message to stop growing or die, even when damaged with therapy.”

This finding helps explain why some people initially respond to treatment but later develop resistance: cancer cells with lower JNK activity may survive the initial therapy and eventually lead to recurrence with a more resistant form of the disease.

“Too much and too little JNK activity can be problematic – in the context of response to endocrine therapy and CDK4/6 inhibitors, loss of the pathway is clearly

Associate Professor Liz Caldon (left) and Dr Sarah Alexandrou (right)

Associate Professor Liz Caldon

detrimental to treatment effectiveness by driving resistance,” says Dr Sarah Alexandrou, the study’s first author.

“The ultimate goal is to be able to test a patient’s tumour for JNK activity before treatment, allowing doctors to select the most effective therapy for each individual,” says Associate Professor Caldon. For those with low JNK activity, the team is now working to identify alternative treatments that might be more effective.

Visit garvan.org.au/news/er-resistance

Can we improve early detection of immune disorders?

New Garvan study aims to enhance newborn screening by identifying more genetic immune conditions sooner.

The Genomic Evaluation of Newborn Immune Errors (GENIE) study is recruiting Australian families to help improve early detection of genetic immune disorders.

Led by Dr Isabelle Bosi in Garvan’s Siggs Lab, the research focuses on inborn errors of immunity – over 500 genetic conditions that can cause increased infections, inflammation and autoimmunity.

While current newborn screening detects some severe genetic immune disorders, most immune disorders remain undiagnosed until symptoms appear.

“Many individuals and families live through a ‘diagnostic odyssey’, trying to get answers to their symptoms. This not only generates worry but affects overall health and quality of life as possible treatments are also delayed,” says Dr Bosi.

The team will investigate whether combining traditional heel prick tests with whole genome sequencing and other advanced technologies could identify more immune disorders at birth. Associate Professor Owen Siggs, Snow Fellow and co-Director of Garvan’s Genomics and Inherited Disease Program, notes “the sooner we can diagnose people, the sooner we can offer treatment, and help them live longer and healthier lives.”

Families interested in participating can find more information on Garvan’s GENIE webpage.

Visit garvan.org.au/genie

Breast cancer cells under the microscope

Associate Professor Caldon’s research is supported by Mostyn Family Foundation and Tour de Cure.

The diagnostic odyssey

Bev has lived most of her life in a body she doesn’t fully understand.

It began in her late twenties with persistent pins and needles in her legs, followed by headaches, brain fog, fatigue and clumsiness. At times her speech slurs, or words tumble out that she doesn’t intend to say. But despite decades of seeking answers, a diagnosis has remained elusive.

Now 70, Bev has spent years moving between clinics, collecting test results and specialists’ notes. Doctors initially suspected multiple sclerosis, but when they couldn’t find clear evidence, she was again left without answers.

Bev is not alone in her search. More than two million Australians live with a rare disease, and many face the same exhausting ‘diagnostic odyssey’ in pursuit of a diagnosis. It’s cases like these Garvan’s Genomics of Rare Disease Registry was created to solve. Led by Associate Professors Jodie Ingles and Owen Siggs, the initiative aims to identify the genetic causes of rare conditions.

“Right now, there isn’t a national, coordinated approach to rare disease care or research, which makes things really tough for patients,” says Associate Professor Siggs. “It can be hard for them to find out about or get access to the latest research or clinical trials.

And it goes both ways – researchers also struggle to connect with the right patients. That’s where the Registry comes in.”

For Bev, this effort represents hope. Clinically, her MRI scans and symptoms suggest a leukodystrophy – a rare neurological disorder that erodes the brain and spinal cord’s protective white matter. But without a molecular diagnosis pinpointing the gene involved, leukodystrophy can’t be confirmed.

If her unknown condition is genetic, Bev also knows that her children could also be affected. “I just want to find out what it is so my kids can get treatment,” she says.

I’ve waited my whole life for an answer. I don’t want my children waiting too.

That’s where the Registry can make a difference. By offering genetic testing with sequencing tools often unavailable in standard clinical care, researchers can help uncover the genetic cause behind a disease – a crucial step toward diagnosis. It also connects patients with advocacy groups and builds a community around isolating conditions.

For Bev, that knowledge alone has eased a burden she has carried for decades. “I’ve waited my whole life for an answer,” she says. “It’s just so beautiful to know that we’ve got other people helping us carry this mental load now.”

Bev

Eureka Prize for genomic computing innovation

Garvan scientist honoured for making complex DNA analysis simpler and more accessible.

Dr Hasindu Gamaarachchi, a visiting scientist in Garvan’s Deveson Lab, has been awarded the 2025 Macquarie University Eureka Prize for Outstanding Early Career Researcher.

Dr Gamaarachchi’s work focuses on computational methods that dramatically reduce the processing power needed for genomic analysis – the complex task of interpreting vast amounts of data produced by DNA sequencing.

His innovations enable analysis on standard computers and even portable devices, making this powerful technology accessible beyond specialised research centres.

One notable achievement was developing a smartphone app capable of analysing the complete SARS-CoV-2 virus genome.

The Eureka Prizes are Australia’s most prominent science awards, recognising excellence in research, innovation, leadership and science communication.

Jewellery with purpose

Since 2016, Paspaley has shown unwavering support for Garvan’s cancer research. They generously contribute 20% of the proceeds from each Kimberley bracelet sale. The collection combines hand-selected Australian South Sea Pearls with regional, aromatic sandalwood for a wearable, timeless style.

To give a gift that means more this holiday, please visit: garvan.org.au/paspaley

Dr Hasindu Gamaarachchi

New mechanism found to supercharge the immune system against cancers

A Garvan study, led by Associate Professor Megan Barnet and Professor Chris Goodnow, has uncovered a novel mechanism that may explain why some people with cancer respond remarkably well to immunotherapy while others don’t. The discovery could pave the way for more personalised and effective immunotherapy treatments against a range of cancers.

The research uncovered that less active versions of a gene called NOD2, in combination with radiotherapy or immunotherapy, may help supercharge the immune system’s ability to attack cancer.

Immunotherapy has emerged as one of the most significant advances in cancer treatment in recent decades. It works by recruiting the body’s own immune system to recognise and eliminate cancer cells. But not everyone responds equally, with some experiencing strong immune activation, while others experiencing no effect.

One widely used cancer immunotherapy is called antiPD1, part of a family of treatments called checkpoint inhibitors. Normally, cancer evades elimination by the immune system by putting a break on the action of immune cells. Checkpoint inhibitors release this brake, allowing the immune system to see and destroy cancer cells. Anti PD-1 therapy is now commonly used for treating many cancers, including lung, skin, blood and gastro-intestinal cancers.

Anti-PD1 therapy has become part of standard treatment for many cancers. But only a minority of people experience a really significant benefit, and we don’t completely understand why.

Associate Professor Megan Barnet

Professor Chris Goodnow and Associate Professor Megan Barnet

To understand why some people respond well to anti-PD1 and others don’t, Garvan researchers studied a group of people with advanced lung cancer who responded exceptionally well to this therapy. They found that they were more than twice as likely as the general population to have less active versions of the gene NOD2, in combination with an autoimmune-type reaction caused by the immunotherapy. The team then looked at a range of cancers and found that those who had less active variants of NOD2 showed a better response to the therapy.

“We believe that for those people undergoing anti-PD1 therapy and experiencing an autoimmune-like response to the treatment, having less active NOD2 gives the immune system an additional nudge to attack and eliminate cancer cells. This is exciting as it suggests that the action of immunotherapies could be boosted through several complementary pathways,” says Professor Goodnow.

These findings are important because they help us understand the role of the patient as well as the cancer in responding to immune therapy. Less active versions of the immune regulator gene NOD2 are often found in people with Crohn’s disease, an autoinflammatory condition of the gut. This was the first time that the gene has been identified as playing a role in anti-cancer response to immunotherapy,” says Associate Professor Barnet.

The team is now investigating ‘exceptional responders’ – both people who respond very well or very poorly to treatment – across a variety of cancers and therapies, with the aim of better predicting therapeutic responses to deliver a more personalised approach to cancer treatment.