PRESERVING, SHARING, AND CELEBRATING AMERICA’S CULTURAL LEGACY

THE GARDEN CONSERVANCY

#GardenPreservation

Copyright © 2020 The Garden Conservancy, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

#OpenDays25: A Quarter Century of America’s Gardeners and Their Gardens

ISBN: 978-0-578-68500-7

Gardens—Gardeners—Garden Visiting—United States

Published and distributed by The Garden Conservancy, P.O. Box 608, Garrison, NY 10524 www.gardenconservancy.org

The Garden Conservancy is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization incorporated in New York State.

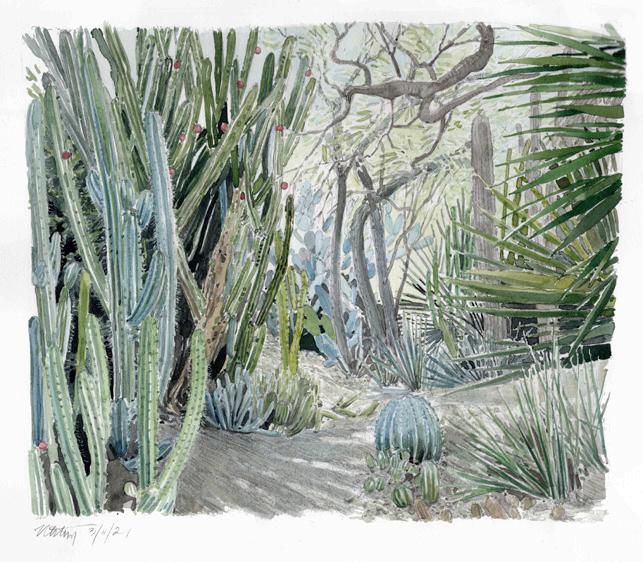

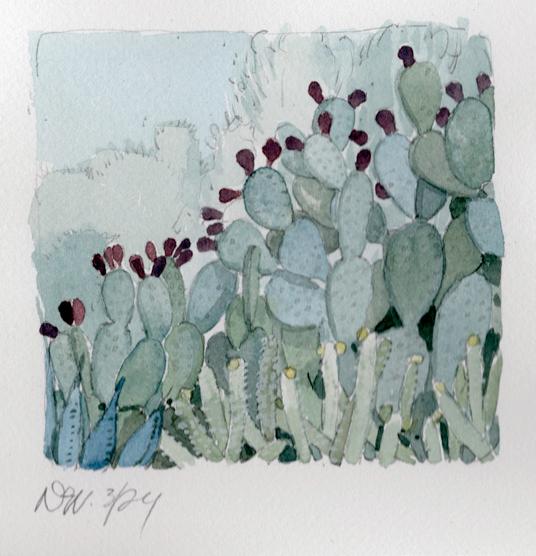

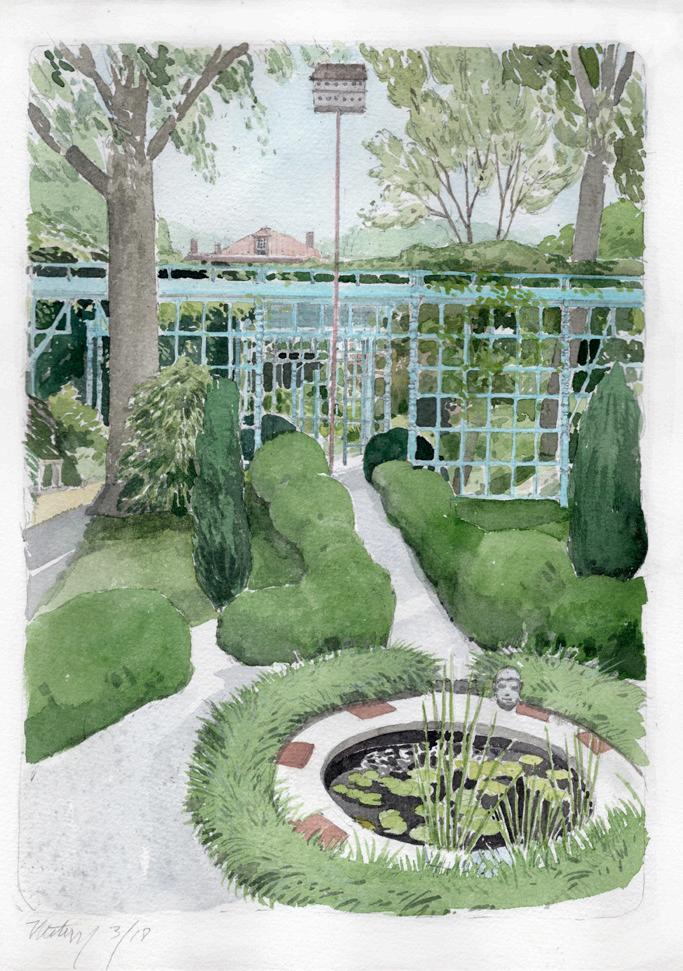

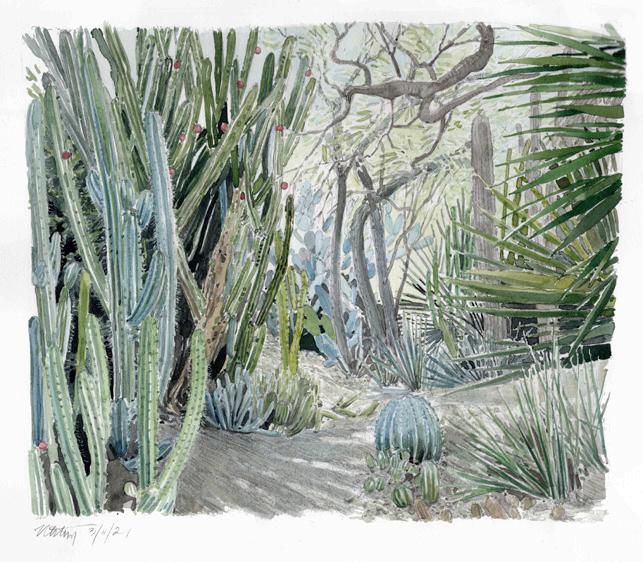

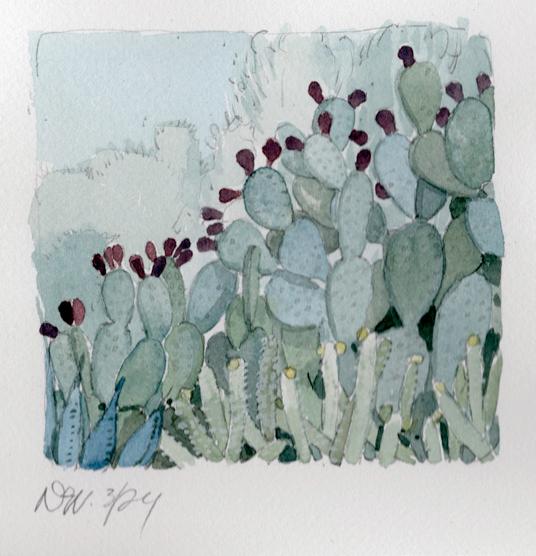

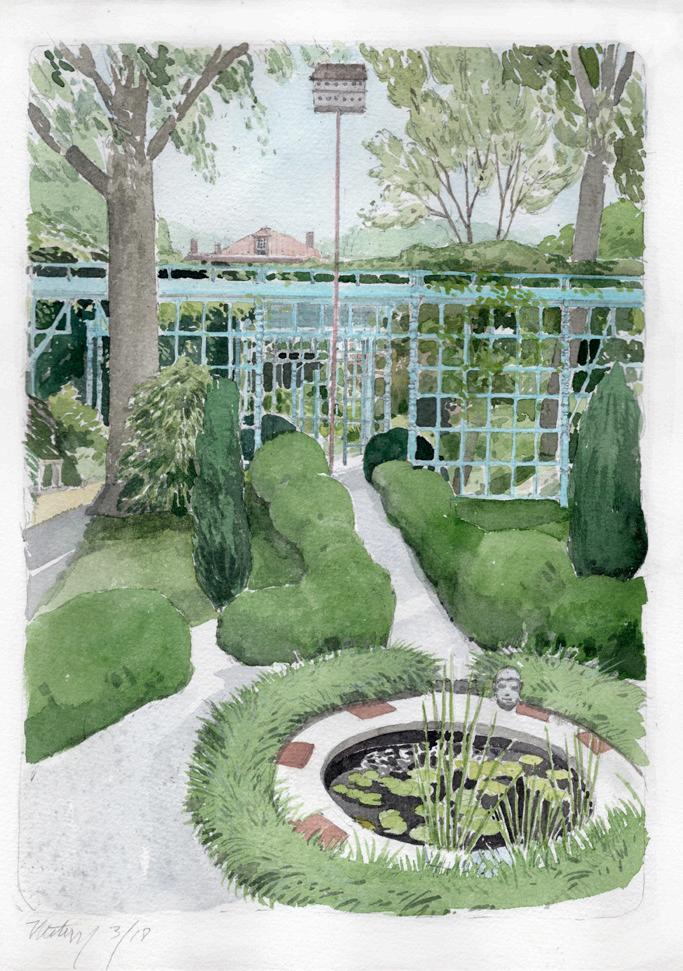

Botanical artwork by Marian McEvoy

Photography credits:

Christine Ashburn Photography: Pages 3, 10, 15, 18, 21, 26, 29, 32, 37, 41, 48, 51, 52, and 56

Erica Berger: Page 45

Brian Jones: Pages 9, 12 16, 23, 25, 30, 35, 43, 46, 55, and 58

John Storey: Page 38

Editing and project management by Garden Conservancy communications staff members George Shakespear, Lori Moss, and Stephanie Werskey, in partnership with the Public Programs and Education team, including Patrick MacRae, Kate H. Kerin, Christopher Gow, and Rani Long.

Design by Kat Nemec, studiokatinc.com

Printing by Recycled Paper Printing, Inc., in Waltham, Massachusetts

THE GARDEN CONSERVANCY STAFF

James Brayton Hall

President and Chief Executive Officer

Donna Mortensen

Chief Operating Officer

Bridget Connors

Director of Membership & Annual Giving

Pamela Governale

Director of Preservation

Patrick MacRae

Director of Public Programs & Education

Sarah Parker Director of Development

George Shakespear

Director of Communications

Pruda Vingoe

Executive Assistant to the President

Kyle Beach

Events Coordinator

Arie Bram

Database Manager

Claire Briguglio

Development Associate

Christopher Gow

Open Days Program Manager

Katherine H. Kerin

Special Programs & New Region Coordinator, Open Days

Rani Long

Open Days Program Associate

Lorraine Mahon Fellows Tours Coordinator

Lori Moss

Associate Director of Communications

Cara Schaffer

Administrative Coordinator

Anne Welles

Associate Director of Preservation

Stephanie Werskey

Communications Manager

Elaine Zanck

Business Manager

Contents Preservation as a Tool for Discovery, by James Brayton Hall x Why Are We Preserving?, by Pamela Governale ................................................ x PERSPECTIVES ON PRESERVATION Tomas L. Woltz x Brent Leggs and Lawana Holland-Moore........................................................... x Shaun Spencer-Hester x Barbara and Rick Romeo .................................................................................... x Judith B. Tankard x Lucinda Brockway ............................................................................................... x Donnamarie Barnes x Walter Hood .......................................................................................................... x PRESERVATION IN ACTION Alcatraz x The Ruth Bancroft Garden .................................................................................. x Blithewood Garden x Chase Garden ...................................................................................................... x The Elizabeth Lawrence Garden x John P. Humes Japanese Stroll Garden ............................................................. x The Gardens at Palmdale x The John Fairey Garden ...................................................................................... x With Special Thanks x

4 P PRESERVING, SHARING, AND CELEBRATING AMERICA’S CULTURAL LEGACY

What Are We Preserving?

Gardens in one way or another have always been an expression of our values, culture, and the enduring connection we have to the land. They are portraits of place, imagination, and infinite opportunities; sometimes capturing wildness, always capturing our spirit. In their public iteration, gardens are community resources—sharing intangible heritage and engaging diverse perspectives. When we preserve a garden, we are preserving something essential to what it means to be human.

If there was ever a turning point for gardens in our lifetime, it has been the past year and a half. Across the country and throughout the world, there has been a collective awakening and collective need to connect with nature and to be in gardens. We know intuitively, nature is a great source of stress relief. It is where we originated. The pandemic has revealed just how important gardens are to us.

As playwright Lorraine Hansberry observed, “This is one of the glories of man, the inventiveness of the human mind and the human spirit: whenever life doesn’t seem to give an answer, we create one.”

Historically, and certainly during this pandemic, public gardens and home gardens alike have been the answer for many of us, providing joy and solace, refuge and inspiration, connection with the past and present, and dreams of the future. In 2020, our garden partners from coast-to-coast saw an increase in visitation, in some cases by more than 300%! We have seen a blossoming of victory and community gardens, home veggie gardens and immersion into the wilderness, as we have sought out meaningful ways to experience the garden.

For more than 30 years, the Garden Conservancy has been championing gardens and broadening the preservation narrative. Each season has brought new learnings and insights that have inspired our evolving methods for protecting and stewarding these ephemeral cultural journeys. It is through this expanding lens that we view each garden as a whole system. Preserving a garden is the stewardship of botanical diversity, design intent, and architecture. It is also gives voice to important stories, seen and unseen. Preserving a garden fosters its growth into a viable and transformative resource, ensuring that it will last into the future. Our challenge is to identify and articulate what is most essential to a garden’s purpose and to use that as the catalyst for treatment and planning.

I was captivated by gardens early on, growing vegetables at home and exploring magical, historic, and woodland gardens. It was a summer job gardening at the John P. Humes

Japanese Stroll Garden when I was a teen that ignited in me a passion for gardens that would be enduring. At the time, I didn’t know these places existed as a result of purposeful, careful preservation efforts

Preservation is a process, and as with all things that are important, it takes time. “Gardening is the slowest of the performing arts,” observed cultural landscape historian Mac Griswold. We would argue, even more so is preservation!

Our strategic, multidisciplinary approach to preserving gardens weaves together the practical and the intangible. We facilitate on-the-ground restoration of historic gardens and also document gardens, capturing their history and spirit through film, photography, interviews, and archives filled with plans and maps. We hold conservation easements that permanently protect “conservation values”—the most significant features of gardens, such as their plant collections, design, hardscape, or vistas. We advocate for gardens at risk, taking a public stand to raise awareness and encourage action. And, as preservation is not possible without education, we engage the community and provide professional education to garden leaders, board members, and staff, and provide mentorship and resources as well.

Preservation is also not possible without community. It is driven by an intricate web of relationships, united in understanding the “why” of gardens, gardens as cultural legacy, and the importance of preserving them. We are grateful to our community, who share our mission to ensure these important places will be lasting and connect generations over time. As a department of dedicated preservationists, we enthusiastically manifest this mission.

In the following pages, you will hear from many of our friends: leading voices in preservation, landscape architecture, garden history, conservation, and documentation. Their essays are followed by case studies featuring a number of the Garden Conservancy’s partners. They all reveal the garden as a cultural bridge, a site for scientific study and ecological conservation, a path to equity and social justice, a catalyst for design innovation and stimulus for spiritual expansion. It is the stories interwoven through these gardens that reveal what we are really preserving: the human spirit.

Pamela Governale Director of Preservation

P PRESERVING, SHARING, AND CELEBRATING AMERICA’S CULTURAL LEGACY 5

6 P PRESERVING, SHARING, AND CELEBRATING AMERICA’S CULTURAL LEGACY

Preservation as a Tool for Discovery

I am the first to admit that gardens exist in multiple realities. We read about gardens, plan them out on graph paper, drool over them in glossy publications, remember them from our childhood, even imagine them in our dreams. Many of my favorite (sometimes even heated) conversations with friends and colleagues are about gardens. Increasingly, as our culture seems ever more seduced by new technologies, we are introduced to gardens near and far by both amateurs and professionals aided by cellphones, video cameras, or even drones. All of these are good ways to think about, honor, and celebrate gardens.

But none of these activities can ever compare with visiting a garden.

While recently re-reading Andrea Wulf’s excellent book Founding Gardeners: The Revolutionary Generation, Nature, and the Shaping of the American Nation, I was reminded that it was in Wulf’s writing that I first learned that Thomas Jefferson, on an unsuccessful trade mission to London, had left the city on April 2, 1786, to join, as Wulf tells us, “hordes of tourists who traveled the length and breadth of the country to visit England’s landscape gardens.” Visiting gardens and identifying notable gardens as worthy destinations are fine (and ancient) traditions. Included in the seven wonders of the ancient world, along with the pyramids, were the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. Unlike the pyramids, the.

Twenty-five years ago, the Garden Conservancy began partnering with gardeners in New York and Connecticut to open their private gardens and welcome other garden enthusiasts on an “Open Day.” A national garden visiting program was born. Long before the advent of the “pop-up” event, these carefully scheduled visiting opportunities made a private garden almost public, but just for one day. It was, in all honesty, a rather improbable proposition. Its success is a testament to the passion and generosity of gardeners. One of the things that I love best treasure hunt or a festival; if it rains, or if you have a conflict that day, you’re out of luck until next year…. or maybe not! Some gardens return year after year, and others close the gates. Like gardens themselves in which a rose may bloom beautifully.

A defining characteristic that all gardens share is that they are a creation of human beings. In one way or another, someone has drawn a conceptual line around that special “moment” in the wider landscape that is the “garden.” Irrespective of how we endeavor to blur the line between the man-made and the natural, gardens always delight us precisely because they are “artifice.” They often tell us as much (if not more) about the gardeners who created them as they do about the plants, trees, etc., that first draw our attention. This commemorative book introduces you to some of those gardeners and their stories.

The Garden Conservancy recently reaffirmed that the Open Days program is central to our mission. We will continue to work hard to offer opportunities to visit private gardens, hear from experts, see and explore parts of public gardens that are rarely accessible, to learn about garden history and I am delighted to mark this important milestone in the Garden Conservancy’s beloved Open Days program with this beautiful publication, the culmination of a year’s efforts to explore and celebrate the gardens and the people who have made Open Days possible. In the process, we hope we have also captured, in the portraits that follow, the spirit of the program. The book has come together with a great deal of excitement, Beautiful drawings from our good friend, artist, and aesthete Marian McEvoy, whose lovely hillside garden overlooks the Hudson River, grace the cover and pages of this book. Inspired by gardens she has visited around the world, Marian creates gardens on paper, using pen and ink, and also in delightful collages of pressed flowers and leaves the world, Marian creates gardens on paper, using pen and ink, and also in delightful collages of pressed flowers and leaves..

Photographers Brian Jones and Christine Ashburn traveled across the country last year to capture intimate portraits of passionate volunteers who open their own gardens and search out new gardens for our Open Days visitors t

Great credit and thanks also go to our communications and Open Days staff members, who created this important commemorative book based on an idea that I proposed barely twelve months ago. Graphic designer Kat Nemec embraced the idea of the project, working tirelessly and with great good humor to lend her careful and joyous aesthetics to the finished product.

I would be remiss were I to ignore that, as I write this, our world has changed radically. We are celebrating 25 years of the joy of visiting gardens at the very moment that a global pandemic prevents us from doing just that. However, it is the essence of gardens that they remind us of the passage of time and of the promise of a seasonal rebirth. I write these words with every confidence that not only will we return soon to the wonderful adventure and discovery that is an Open Day, but that gardens, and gardening, will show us the way to a brighter and healthier future.

Come join us in the garden!

James Brayton Hall President and CEO

P PRESERVING, SHARING, AND CELEBRATING AMERICA’S CULTURAL LEGACY 7

8 P PRESERVING, SHARING, AND CELEBRATING AMERICA’S CULTURAL LEGACY

P PRESERVING, SHARING, AND CELEBRATING AMERICA’S CULTURAL LEGACY 9 Perspectives

on Preservation

A Users Guide to Preservation: One Contemporary Designer’s Perspective on History

By Thomas L. Woltz

I propose that a possible definition of landscape design could be the process of shaping the human experience in nature through the creation of form and space infused with narrative intent. This simple definition captures the universal human instinct to influence and configure our environment and to tell stories. For me, the process of design begins with endeavoring to see land and nature with deep clarity and to ask the land its own history before attempting to write the next chapter. This is why, as a contemporary landscape architect, I firmly believe in the importance of garden and landscape preservation as an essential resource – knowing our past in order to responsibly design our future. I will assert from the start that there is no blank slate, no tabula rasa, no “empty land” in the Anthropocene Landscape. Every site is filled with underlying ecological processes and cultural history, often erased or occluded over time, and the most authentic contemporary design instincts are rooted in an understanding of the continuum of culture and ecology. Without assiduous garden preservation and conservation, we lose entire chapters of self-awareness and knowledge of the human condition in relationship to the complexity of nature.

To begin a design is to enter into a personal dialogue, a partnership with the natural and cultural processes that shape land. Having designed projects over twenty-five years on several continents, I am convinced of the importance of learning the unique geology, soils, climate, plant communities,

and hydrology of every site. Mapping the geologic evolution of a landscape from pre-historic time to today reveals the origin of landforms, sources of mineral deposits, and hydrodynamics, and helps one decipher the unique conditions that exist today. In sites around the world, understanding this deep “lineage” of land offers clues to the resulting cultural responses to these natural assets. The migratory patterns of wildlife, the settlement patterns of First Nations Peoples, insights into the motivations for Colonial Expansion, agriculture, the enslavement of humans, the rise of Industrialization, and essential factors shaping the modern city all find themselves rooted to some aspect of the ecologies that have shaped the landscape over time. I think of this as a continuum of ecology and culture, where a pre-existing ecosystem attracts a human response which then alters that ecosystem. The altered ecosystem then exerts changes to the culture, which in turn, reshapes the environment, and so on in perpetuity. A continuum of unstoppable flows.

History is one of the most valuable resources in the initiation of a design, but as one works to understand a site’s true history, one must be mindful of the lenses of the narrators of the past. Who told what story and why, and from what vantage point? Quite often, we discover dark and uncomfortable history in landscapes, the traces of which have been intentionally erased to serve a more convenient narrative by those who have the privilege to tell the story. Historic maps, deeds, tax

10 P

PRESERVING,

SHARING, AND CELEBRATING AMERICA’S CULTURAL LEGACY

Above We now understand better than ever that gardens are much more than just beautiful places. In an increasingly fragmented world, our gardens are places that celebrate the natural world and where we have an opportunity to help heal the damage done to the planet. Scientific understanding of the environment, soil ecology, hydrology, and the complexity of nature has grown by leaps and bounds. Gardening practices increasingly reflect our

records, and even insurance maps are helpful clues to the biography of a site that gain color and texture when augmented with oral histories and personal letters. Learning the many layers of human experience on the landscape evokes the richness of context and leads to authentic inspiration for designed interventions. The resources for this research are essential to understanding our cultures and offer a strong argument for the preservation and conservation of landscapes and their associated documentation. Archivists, librarians, gardeners, and historians are an essential coterie diligently tending the documentation of our existence. Initiation of design without this process of environmental and cultural research feels tantamount to trespassing, in my mind. With the body of research in progress, my attention turns to the land itself. Whether the commission is for a botanic garden, arboretum, farm, preserve, park, or urban square, the next step is to experience the site itself. Sensing and documenting the flows of energy in a landscape along with absorbing the topographic features are essential steps in knowing the site. In many cases the formal structure of a landscape design, the parti, emerges from observing the existing landform and bringing those forms into a coherent design relationship. Outcrops, mounds, ridges, and plateaus inspire the geometry of both path and place in the landscape. Groves, woodlands, meadows, and discernible plant communities reveal soil and moisture conditions and inspire a horticultural design response in harmony with the ecological context. This development of essential form is an exercise rooted in the application of all senses: sight, smell, sound, touch, and even taste, as the minerals in soils tell us so much information. This approach of seeing form as emerging from a site stands in direct opposition to the frequent application of pattern or alien forms in a landscape that is ill-suited to accept them. In contrast, this approach builds on long-standing theories of the human response to certain archetypal landscapes that offer prospect and refuge, and earth forms including theater, mound, grove, and allée.

Often, we incorporate discovered artifacts of human occupation that offer intriguing elements of inspiration for designed form. Historic occupation can be read through persistent traces such as roadbeds, abandoned rail lines, foundations, ruins, stone walls, fence lines, trenches, and terracing. Plant communities also reveal clues to past land management practices: forests of a singular species age can indicate the date of the last cutting; intense, invasive plant pressure might reflect the abandonment of former grazing land; the presence of a particular species could point toward historical settlement patterns. These remnants can offer the opportunity to hold hands with history by engaging with the actual artifact or plant community of the site’s past. We embrace the disruptions to an idealized form that artifacts and historic traces provide in contemporary design and see our work as just the most recent layer of the evolution of the site in a dialogue with both past and future.

At this point in the design process, we have become familiar with the land’s particular history and ecologies, land forms have been identified, and unique artifacts have been discovered. Here the contemporary programming of the design project begins to find its place within a site. New uses and patterns are adapted to the site’s narratives and conditions in ways that offer compelling tensions between past and present, continuity and disruption, and adaptation and preservation, providing context and depth to new interventions. This is a design philosophy that becomes difficult to classify into common stylistic categories, trends, or fashions.

A design philosophy free of stylistics and so tailored to a given landscape that the resultant forms cannot be replicated elsewhere… rather than imposing a vision disconnected from what the land itself reveals, we have the honor of adding the next chapter to the fascinating continuum of culture and ecology.

To illustrate the design process I have outlined, I would like to share elements of projects we have designed that rely on landscape history and preservation to inspire new landscapes and engage people in deep narratives of the contexts in which they operate.

COCKRILL SPRING, CENTENNIAL PARK, NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE

When engaged by Metro Parks Department of Nashville, Tennessee, to construct new program elements within the boundary of historic Centennial Park, we suggested a period of historic research that might expand the Park’s stated “period of significance” of only six months, during the 1897 Centennial Exposition of Tennessee. We suggested that it was worth knowing what the site had been prior to the Exposition. What groups of Native Americans might have occupied the region and what was the footprint of Colonial Expansion? The research process led us on a fascinating journey into the ecological and cultural history of Nashville in general and Centennial Park specifically.

We learned that the park had originally belonged to Anne Cockrill, the first colonial woman west of the Appalachian Mountains to own free title and deed of land, and a pioneer with the Donaldson Party that founded Nashville along the Cumberland River in 1797. Through letters from the early nineteenth century, we learned that a spring on her farm, then known as Cockrill Spring, was renowned for its water quality and for its location at the terminus of the heavily trafficked Natchez Trace.

After three major outbreaks of cholera in the nineteenth century, Nashville enclosed many of its urban streams and creeks in brick galleries to prevent the spread of the waterborne disease. What if Cockrill Spring still surged below the Park? What if we could daylight this ancient water flowing for thousands of years and bring it back to the people of 21st-century Nashville in this public landscape setting? Through investigation into historic sanitation maps, photographs, and oral accounts, we closed in on what might be the location of the spring, and began exploration of the piping and subterranean waterways beneath the park. With

P PRESERVING, SHARING, AND CELEBRATING AMERICA’S CULTURAL LEGACY 11

great excitement, the original limestone wellhead was hit about 6 feet below the surface and a surge of fresh cold water came to the light of day for the first time in a century. The resulting landscape design was a simple terrace built of local limestone that holds a basin in which the original wellhead stone is submerged. The water flows up through the basin and into a limestone channel of water that meanders through a meadow of native Tennessee shrubs and perennials, evocative of the plants Anne Cockrill would have seen on this site in 1789. Today, thousands of annual visitors learn the story of this pioneer woman, her role establishing the first frontier school, and the historic connection to the Natchez Trace. Children and adults splash in the cool fresh water of the ancient spring that has supplied drinking water to passing humans from the Woodland Era of Native Peoples to the modern citizens of Nashville.

The millions of gallons of water produced by the spring annually, previously piped to the sewage treatment plant, are now captured into cisterns and a lake. The abundant spring water is used to irrigate the contemporary park, dramatically reducing the park’s consumption of potable City water. In the case of Cockrill Springs, we see proactive historic landscape research uncovering and preserving unique histories of a site, that in turn inspired authentic new amenities that contribute to improved long-term sustainability of the park and its water usage. The comingling of ecology and culture that had been erased was brought back to light through creativity and a research-based design process.

BOK TOWER GARDENS, LAKE WALES, FLORIDA

Tasked with doubling the size of the public landscape at the famous Bok Tower Gardens, we recognized the first step was to study the dialogue between the founder, Edward Bok, and his designer, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., to understand the original vision and how the expansion could best harmonize with that vision. The original design brief envisaged by Bok in 1921 was to create a bell tower at the highest point on the Lake Wales Ridge, nearly 300 feet above sea level, surrounded by meandering paths, a reflecting pool, and col-

lections of native trees and shrubs designed to attract native wildlife. From the start, the garden was created as a public landscape, intended to immerse people in nature and inspire gratitude. Over many years of dialogue and evolution, that native plant mandate was occluded by exotic and tropical introductions that were not native to the region but that were now well established, spectacular, and beloved nearly a century later. We concurred with the garden directors that rather than didactically restoring the original concept, we would apply that vision to the many new gardens while making careful insertions in the existing gardens that would allow universal accessibility for the first time.

One important observation was that the original spatial sequence of the Olmsted project had been entirely lost, given the location of a visitor’s center and parking lot within eyeshot of the tower. We learned that many visitors entirely missed the experience of hide-and-reveal of the tower, the topographic drama, and the sinuous paths curving along carefully calibrated geometries through groves of oaks, palms, azaleas, and camelias. The brief our firm received was to expand the gardens to regain more of the original concept of wildlife stewardship and native ecosystems, so we worked to use those gardens to seamlessly convey the visitor to the origin point of the Olmsted landscape. It was like writing the seamless prequel to a novel by another author and was an exciting exercise in harmonic thought and posthumously “collaborative design.”

With our new gardens completed in 2016, the visitor arrives to a massive elliptical green, scaled to the greater landscape, and dotted with iconic longleaf pines. This central green serves as an intuitive guide to the distributed experience of newly built native landscapes radiating outward. The visitor winds through pollinator gardens, bog and pond gardens, oak hammocks, and a wiregrass palmetto meadow that is the rare habitat of gopher tortoises. To order these experiences we used the spiral curve geometry for the path design, a signature of the Olmsted firm. The large geometric forms of ellipse and axial relationships is augmented by meandering secondary paths, offering both a sense of orientation in a vast landscape and immersion in the distinct ecologies

12 P

PRESERVING, SHARING, AND CELEBRATING AMERICA’S CULTURAL LEGACY

Above We now understand better than ever that gardens are much more than just beautiful places. In an increasingly fragmented world, our gardens are places that celebrate the natural world and where we have an opportunity to help heal the damage done to the planet. Scientific understanding of the environment, soil ecology, hydrology, and the complexity of nature has grown by leaps and bounds. Gardening practices increasingly reflect our

we were establishing from zero. The circulation seamlessly delivers the visitor to the starting point of the Olmsted, Jr. designed sequential approach to the tower. To mark this important location, we relocated a large stone marker that served the purpose of a cornerstone for the garden upon opening in 1929.

There were other exciting gardens included in this design that further expanded the contemporary appeal to audiences of all ages. A vegetable garden, outdoor cooking and teaching facility, and a children’s garden inspired by the habitats of animals native to the Lake Wales ecosystem. Children can develop an empathetic relationship to animals by crawling through a Gopher Tortoise tunnel, occupying a giant globe spider nest, and playing in sand surrounded by a installation referencing Indigo Snakes. In summary, the contemporary landscape interventions made in this historic garden work to increase relevance to issues of climate resilience, food security and biodiversity, while preserving the historic experience and artfully inserting universal accessibility into the nearly century old gardens of Bok Tower.

NAVAL CEMETERY LANDSCAPE, BROOKLYN, NEW YORK

The Naval Cemetery Landscape is an example of a site whose cultural history was entirely erased from the land and from memory, from which historical research was uncovered to create a meditative and immersive garden experience in New York City. The original Naval Yard Hospital was built in 1895 and by the very nature of hospitals, included a site for burial of the dead. Over the coming century the cemetery accumulated an estimated two thousand bodies, many of which remained unidentified. In 1926, nearly one thousand bodies were exhumed and reinterred in Cypress Hills National Cemetery, and the Navy installed recreational ball fields on the site. The bodies, and their memory, were erased until the property was given to the Brooklyn Greenway Initiative, who hired our firm in 2010 to design a park for repose and contemplation along their eighteen-mile bike lane.

Through our research we learned that prior to being a hospital, the site was home to Wallabout Creek, a meandering coastal wetland and stream complex. Early maps show the sinuous nature of the water body making its way to the bay through land behind the hospital that was later filled to expand the cemetery. We also learned about the thriving agricultural communities here in the nineteenth century, managed by European immigrant communities and focused on the production of cherries and other stone fruits. Given these ecological and cultural histories of the site, and the likelihood

of further remains on site, regrading or disturbing the soil at any significant depth was considered off limits.

So how do you memorialize the history of the site and create a thriving park for repose and meditation along in the shadow of the Brooklyn Queens Expressway? The narrative for the park and the resulting design scheme drew from the diverse factors contained in the land to create a cohesive experience for the user, allowing them to see a layered past and a resilient future at once. The narrative is rooted in an embrace of the collective human condition of death and life, celebrated through the establishment of a rich meadow of pollinator-attracting plants drawing an abundance of life into the site. This meadow ecology is installed by scraping away existing invasive vegetation but not tilling or excavating the soil. To move people through the meadow while respecting the ground plane that once held human remains, we designed an elevated boardwalk that meanders, like Wallabout Creek once did, as a wooden river through a sea of native grasses and perennials reminding people of the fecundity of life and the cycle of death. A circular grove of cherry trees inspired meditation and recalls the historic orchards. A bench installed by NatureSacred Foundation, a major funder of the project, holds an all-weather journal where people write their most private reflections on the mental and physical benefits of the space. The entries in this book are amongst the most moving and gratifying results of my professional career.

Each of these examples describes a contemporary landscape that resulted from a research-based process reliant on the discoveries history can offer us. Our human history is embedded in the soil beneath our feet and we must attune our instincts and attention to listen carefully. I hope that what I have shared here supports an impassioned argument for the preservation of landscapes and their histories, so that future generations may come to see the Earth that we tend as a continuum of flows, a thrilling dance of culture and ecology.

Thomas Woltz is the owner of Nelson Byrd Woltz Landscape Architects in Charlottesville, VA, and New York City. He was named the Design Innovator of the Year by the Wall Street Journal Magazine in 2013 and a member of the American Society of Landscape Architects Council of Fellows.

P PRESERVING, SHARING, AND CELEBRATING AMERICA’S CULTURAL LEGACY 13

Above We now understand better than ever that gardens are much more than just beautiful places. In an increasingly fragmented world, our gardens are places that celebrate the natural world and where we have an opportunity to help heal the damage done to the planet. Scientific understanding of the environment, soil ecology, hydrology, and the complexity of nature has grown by leaps and bounds. Gardening practices increasingly reflect our appreciation that actions we take on our plots of land have an observable impact on the health of the environment. As the gardening public becomes more informed, our gardens in turn have become vital sanctuaries for birds, pollinators, and native plant species and we are better

14 P PRESERVING, SHARING, AND CELEBRATING

AMERICA’S CULTURAL LEGACY

Preserving Traces and Remnants of a Gardening Past

By Brent Leggs and Lawana Holland-Moore

African Americans have always gardened.

Our cultural identity was once inextricably tied to soil, to earth, to designing and manicuring agricultural landscapes stamped with the marks we made upon them. Blackness was born in the South to feed and sustain a nation’s thirst for power and independence. It manifested in the form of Black hands and bodies forced to toil in the land. Black hands coaxed seeds reaching for sunlight, and as the seeds bloomed into colorful new life, so did our ancestors’ creativity and innovation. You will find traces and remnants of this cultural memory in unexpected ways and places.

Our memories are real and personal. Memories of Kentucky and being six years-old in grandmother’s lush garden with towering and haunting sunflowers. In another moment and garden, the smell of Dad’s organic herb, pepper, and tomato blossoms, which mesmerized honey bee and person alike. Memory travels north where rosebushes cultivate deeper admiration of a beloved relative lost. Then, a flash of great-great uncle’s smile while at family land in Virginia where magnificent cherry, apple, and walnut trees planted by ancestors over 100 years ago still bear fruit for their descendants and dark, sweet, muscadine grapes grow plump on their vine. These places and stories might not be historic, but the legacies they represent contain profound value and signify countless other examples of this nature and heritage relationship. As professionals working in the historic preservation field for some time, we have found that the recognition and preservation of historic African American places is often linked to legacies and memories such as these.

Through the work that we do at the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund, a program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, we preserve and protect American legacies—landscapes and buildings that tell overlooked stories of a culture fundamental to the nation itself. Too often, the historic imprint of Black people has been rendered invisible in urban and rural communities, but that is not to say important Black sites have been totally ignored. To be sure, significant sites associated with African American history are formally recognized and serve as permanent reminders about our ancestors and their journey in America.

For instance, God’s Little Acre, an African American Colonial-era cemetery in Newport, RI; public parks such as Stuart Nelson Park in Paducah, KY; and private ones, like the three-acre park currently being designed at the John and Alice Coltrane home in Dix Hills, NY, will showcase what happens when creativity and nature harmonize. In Chicago, the Sweet Water Foundation has reactivated and transformed once vacant city blocks into The Commonwealth—a community gathering space and campus embodying the concept of “regenerative community development.” The Commonwealth creates employment and educational opportunities to learn more about urban agriculture and includes a two-acre community garden that nourishes more than 200 residents

a week. In Bishopville, SC, a 400-plant topiary garden showcases the artistry and creativity of its African American creator, Pearl Fryar. All of these places exemplify how African American spaces—whether commemorative, public, or personal—are important to our shared past, present, and future, compelling us to reflect upon what more those spaces can be.

We must think about and redefine what it means to garden and who contributes to it. Whether it’s an individual nurturing lush houseplants in an urban apartment, communities coming together in neighborhood gardens, or a family taking pride in well-tended flowerbeds and carefully trimmed shrubbery, gardens and the land connect us to a part of our culture and nature that passes forward memory and traditions. Agricultural gardening, especially, represents a through-line spanning centuries of tangible and intangible heritage. Cultural heritage sites that bring forward this African American narrative serve a crucial role in telling the country’s overlooked garden history. These are connections to our past, and it is our responsibility to ensure that those sites—and the natural elements and landscapes that are so intrinsically a part of them—are celebrated for generations to come, so all Americans can share in their inspiration and joy.

P PRESERVING,

AND CELEBRATING AMERICA’S CULTURAL LEGACY 15

SHARING,

Nothing is more beautiful than the loveliness of woods before sunrise.

—George Washington Carver

Brent Leggs is the Executive Director and Lawana Holland-Moore is the Program Officer of the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund.

I am here.

By Shaun Spencer-Hester

Gardens are created from dreams and I am here following three generations of visionaries and gardeners.

I was born and lived in San Bernardino, CA, until age 10. My backyard, near Route 66, had palms, sandy beaches, and bordered the San Bernardino National Forest. Dad and Mom retire from the United States Army Air Force at Norton Air Force Base and are busy with eight children and new careers. Dad made chore time, fun time. We sweep the neighborhood curbs, clean out the garage, or, better yet, clean up and treasure hunt in the palm-lined alley. As Dad kept law and order, I escape into the alley jungle and imagine thrilling adventures of survival in the urban jungle. I scout for natural and man-made artifacts, sweep the alley white free of debris. Pre-siesta, I treat myself to sun-warmed pomegranate juice squeezed directly into my mouth.

In 1934, dad realized his dream to fly and became a pilot at the Coffee School of Aviation, where Cornelius Coffee offered flight lessons for Blacks at the Harlem Airport in Chicago.

Two years earlier Oscar DePriest, the Black Chicago congressional representative, visited my grandfather Edward (Pop), a businessman and postal worker with an artist’s eye and a love of architectural recycling. These finds were later upcycled into garden structures and a writer’s cottage named “EDANKRAAL,” a haven for my grandmother Anne Spencer (Dranny), his beloved wife and American poet, librarian, and avid gardener.

The Spencers’ mecca hosted the leading Black voices of the time. James Weldon Johnson, W.E.B. Dubois, Booker T. Washington, Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, Marion Anderson, Thurgood Marshall, Dr.

16 P PRESERVING,

AND CELEBRATING

SHARING,

AMERICA’S CULTURAL LEGACY

Photo: David Lapage Shaun

Martin Luther King, and George Washington Carver were among many others who came to talk about cultural issues, race relations, politics, poetry, education, landscapes, and gardening. Family cookouts and parties and weddings, including mine, continued in the garden.

Two events in 1938 brought further changes to Blacks in aviation: Charles Lindbergh published an article in Readers Digest calling flying “a tool specifically shaped for Western Hands,” and the formation in Chicago, Illinois, of the National Airmen’s Association (NAA). Shortly thereafter approximately twenty Negro Flyers produced an air show viewed by twenty-five thousand spectators at Chicago’s Harlem Airport.

Dad and his friend Dale White could not be stopped. Supported by the NAA and the Chicago Defender, they rented an airplane for a goodwill tour of ten cities to demonstrate the dream to Americans that Negros Can Fly.

The tenth city on the tour was Washington, DC. There, in an underground tunnel, the flyers met Senator Harry S. Truman, who kept his promise to put through legislation ensuring that Negro flyers would be trained along with whites under the Civilian Pilot Training Program.

Dad said, “When I am flying is when I feel the freest!” He touched the sky while Dranny touched the garden soil.

Dad’s dream, and the dream of the Challengers Air Pilots Association, National Airmen’s Association, and the Tuskegee Airmen came true in 1941, when the segregated branch of the US Army Corps offered training to African Americans to become pilots and mechanics. Dad and mom were assigned to Moton Field [in Tuskegee, GA] for the training program of the Black air personnel.

My cultural landscape changes when we move to Michigan.

Dad’s Tuskegee buddies, including Highland Park mayor Robert Blackwell, Wardell Polk, and Godfrey Franklin, joined forces to rebuild cities burned out after the 1967 Detroit riots. Coleman Young, former Tuskegee Airman and then mayor of Detroit, joined them.

For the first time, I attend a predominantly black school. I am too young to participate in news or social movements, but keep up with the music coming out of Motown. I walk up McLean to Woodward Avenue for gallons of milk from Ivanhoe Grocery, take the bus uptown to S.S. Kresge and eat lunch with mom at the counter. On the way to Belle Isle, I cruise by the Monument to Joe Lewis and escape to the McGregor Library check out the books. I become fascinated with the architecture and culture of my Black heritage.

At age fifteen, Dad and Mom declared yet another landscape change, this time south to Lynchburg, where at least four generations of our Black and white ancestors inhabited the lush fertile land of Virginia and where my paternal grandparents were the first in their generation to be born free of slavery. Pop died in 1964 and Dranny in 1975, two years later their beloved home and garden became the nonprofit Anne Spencer House and Garden Museum.

I did not expect to become the museum’s overseer in 2008, when I return to Lynchburg, but find my path there followed by many volunteers devoted to preserving her legacy, including family, residents, and the Friends of Anne Spencer, who all contributed to the listing on the National Register as a Virginia Historic Landmark. In 2020, Anne Spencer was honored with a Voices of Harlem Forever U.S. Postal Stamp. Anne Spencer’s dreams and visions are thus still alive,

Earth, I thank you

making room for our own, in this serene and historic public space. Noted authors and scholars are adding volumes to her legacy, even inspiring my own non-fiction family history book, which is in progress.

The diverse cultures and landscapes of California, Michigan, and Virginia are all part of my feeling, seeing, smelling, and touching. Reflecting on these sensory impressions helps me understand and incubate my own dreams and visions.

Since 1977, the Anne Spencer House and Garden has attracted visitors from 23 countries and now averages five thousand visitors per year. It is the only known intact house museum and restored garden of an African American in the United States.

In 1983, the Hillside Garden Club unveil their first restoration of Anne Spencer’s garden and receive two Commonwealth Awards for their ongoing preservation work. The club restore, maintain, and volunteer in the public garden 38 years later. Edankraal, 25’ x 45’ is divided into four rooms; the rose, cottage, arbor, and water garden are open seven days a week sunrise to sunset. We want you to come to keep the shrine alive; we want families, schools, businesses, and neighbors to come and share their own stories and visions in this fertile garden.

P PRESERVING,

CULTURAL LEGACY 17

SHARING, AND CELEBRATING AMERICA’S

Shaun Spencer-Hester is the executive director and board treasurer of the Anne Spencer House and Garden Museum in Lynchburg, VA.

Photo: Susan Saandholland

By Anne Spencer

Earth, I thank you for the pleasure of your language

You’ve had a hard time bringing it to me from the ground to grunt thru the noun

To all the way feeling seeing smelling touching —awareness

I am here!

Interview with Barbara and Rick Romeo, Stewards of Rocky Hills

The finest gardens in the world will wither and slowly transmogrify into a grotesque semblance of what was—until Nature recovers completely what was hers. Decades, if not generations of effort, can and will be lost. Fortunately, in the case of a garden, loss can be avoided if the right people and the right measures are in place.

Rocky Hills is a garden well known and loved by friends of the Garden Conservancy. Lovingly tended for decades by its equally regarded owner, Henriette Granville Suhr, and her husband, William, the garden sits in Westchester County, NY, north of New York City. It was a living, layered, multi-dimensional representation of a mid-twentieth century design ethic. Sometimes gardens age better than people. We all get to a point in life where things we used to do become difficult and complicated. When that happens, the “What’s next for this place?” question gets asked about the spaces we create. So it was with Henriette.

The Garden Conservancy, dedicated fans of Rocky Hills, and the parks department of Westchester County were not about to let this work of horticultural art be lost. A conservation easement, one of the Conservancy’s signature preservation tools, was arranged to protect the property and its future. The easement was transferred from the Conservancy to the Westchester Land Trust after Henriette’s passing, and a short time later, the property, with the easement in place, was sold to Barbara and Rick Romeo, long-time friends of Rocky Hills and nearby homeowners.

For many years the Romeos had volunteered at Rocky Hills to help Henriette manage Garden Conservancy Open Days. Now they have owned the property for more than four years and are actively involved in garden preservation and garden stewardship. Garden Conservancy President James Brayton Hall and Director of Preservation Pamela Governale spoke with the Romeos about stepping into a property with a long history, and with legal restrictions that impose certain responsibilities.

How did you come to be involved with Rocky Hills?

Barbara Rormeo: We’d lived down the street for 30 years. I was walking by one day and she was standing at the gate. She waved to me and I waved back. She invited me in.

I just thought it was so stunning. It was like a fairyland in here. It was spring; the forget-me-nots were all over the place and the azaleas were just opening. To me, it was incredibly beautiful. There is something about this place with so much depth and texture.

I was invited to be on the board of the Friends of Rocky Hills when the garden was headed toward becoming a Westchester County park. We aimed at preparing it to become a public garden. During the garden’s Open Days, 200 to 300 people would come through at times, talking about what they got out of seeing a garden like this and the ideas that they were taking home with them. It was just a wonderful, wonderful introduction to the garden.

Rick Romeo: The garden became so loved and so well-regarded by so many people that there was some sense of relief while it was in a “pre-park” situation. Henriette was in her 90s when the county had to back out of that idea. Then there was a lot of concern until her death at age 98: what’s going to

happen with Rocky Hills without the cushion of a large institution, a county organization, to keep it as a park. What’s going to happen to the garden? It’s not everybody’s cup of tea to come into a preexisting garden with a conservation easement that inhibits one’s freedom to do whatever you want to do. It is not a typical thing to handle [a property] with a view toward preserving, maintaining, and continuing.

Speaking of easements… what have you learned about conservation easements that you wish you knew before purchasing the property?

BR: The easement is held by the Westchester Land Trust and they have been absolutely wonderful to work with. They come out once a year and they have given us some good tips. We understood that we would never be able to divide the property. The Land Trust also has to be very careful about the watershed; water flows through this garden and into a public reservoir. That’s their second priority. Number three is removing invasive plants as much as possible. And number four was not to cut new paths through the area. We walked into ownership with eyes wide open. We knew exactly what was expected.

RR: A lot of people might view an easement as a burden or a restriction. I view it as consistent with what we would have done here anyway. It’s kind of a guide, rather than an enormous burden that I might feel constrained by. An easement may bother people in the abstract, but, as a practical matter for us, and in terms of the way we approach this place, it’s seamless.

The easement requires a minimum number of opportunities for the public to experience Rocky Hills. How has that worked out?

BR: We participate in the Conservancy’s Open Days program. When we opened for our first Open Day, it rained from all day. The people who came were hardy gardeners, many of them Master Gardeners themselves, and had wonderful questions. We loved doing it; what a nice group. They identified some things for me that I did not know and I tagged along to hear their observations and got a little better educated.

What have your biggest challenges been?

BR: It’s very, very different and it’s pretty daunting to take over somebody’s 60-plus year old garden, one that’s been beautifully planted by people who had a very creative way of planting, and of looking at plants and at design.

RR: A whole lot of gardening that has nothing to do with plants. Structural things, especially when dealing with an

18 P PRESERVING, SHARING, AND CELEBRATING AMERICA’S CULTURAL LEGACY

older garden. Fencing, for example. They call it “deer fencing” because it’s supposed to keep the deer out. Well, in the last couple of weeks we’ve had a number of incidents where they figured out ways to either jump over or squirm under it. An extensive sprinkler system is now old; when you turn it on in the springtime after winter, there are geysers here and there. A lot of non-plant maintenance is needed to preserve infrastructure, which leads to preserving plants because you don’t want the deer to eat them and you want plants to be irrigated.

BR: One plant challenge is dealing with invasive plants. Another is “native versus non-native,” which we could debate for the next three hours. Invasives are sometimes a problem with plants that were purposely planted here 20 or 30 years ago. There are barberries (Berberis) down in the woods, which we’ve been removing. An even bigger problem is burning bush (Euonymus), which were once planted and maintained, but now are all over this place. They are beautiful, but I spent last summer digging them out of the fern garden, digging them out of the perennial garden, digging them out of the woods. 2021 is the year; we’re just getting them out of here. There’s no halfway with them. And then there are pachysandras, English ivy, and vinca all over. We’re going to replace some of these aggressive non-natives with native plants. Henriette was aiming in that direction when she was still here and that’s important to us.

How are you handling the design of the garden, its look and feel?

BR: Another challenge of being an owner maintaining this property is that the color palette was meant to span the aesthetic between the manicured landscape and the naturalistic. There was a naturalistic bent; for the most part, there are no straight lines here. It definitely wanders. you have to pick your spots because there’s certainly a lot to do without trying to create new places to work on.

RR: We also wound up moving lots of things around. Some plants were meant to be small, but they have grown quite large and overwhelming.

BR: Everything Henriette planted, she wanted to look full immediately, especially when it was going to be a park and garden groups were coming through. With our prior land, our idea was that you put something in and we’d wait. Henriette couldn’t do that. She would put in what she considered to be dwarf plants. But in fact, they had nothing to do with dwarf plants! Her idea was that, in a year or two, you pull them up and move them somewhere else. She really wanted the garden to always look full and ready. So, yes, we’ve moved a lot of plants around.

Now that you know this garden so intimately, what do you consider its most important elements?

BR: There are a lot of structural elements to the trees and plants. It’s not just about flowers; it’s about the whole look of the place. When you’re looking out, you’re see a palette of

color, but I also went out and took black and white pictures of the garden because I love the interplay of so many of the plantings. It’s all about the ones that aren’t just unusual, but lend shape to the landscape and take your eye places that you really want to go.

RR: There is such a splash here in spring. No question, prime time here is May into early June. We are here in the summertime, so we have invested in having that splash of color continue into summer and early fall.

BR: Watching the seasons change is wonderful. We came back in March and the winter aconites were everywhere— seas of yellow flowers as soon as the snow melted a bit. And then you roll on to the spring bulbs, forget-me–nots and the azaleas. It’s one thing after another to the point where I walk out the door only to rush back and tell Rick, “Look! This just opened. Look at these. These have just come.” It is an unfolding that goes on. The fall is just gorgeous. There are so many trees here that turn color. I like the Camperdown elm (Ulmus glabra ‘Camperdownii’) in the front better in the winter because you see incredible shapes that are usually hidden under the leaves. I have a friend who is an artist down the street and I have asked her to sketch it for me.

What makes you happiest here in this garden?

BR: Walking out every single day and seeing something different. Constant change, seeing something new spring up. I grow a lot from seed. I love doing that. Rick and I also love the vegetable garden. Just being outside every day. It is a healthy lifestyle and I think it is good for you. Even on rainy days, we are still out here doing things.

Any advice to others, in conclusion?

BR: To me, it’s all about keeping the spirit of Rocky Hills and its past. We knew the garden. I mean, you think you know it until you actually own it, but we did know what we were walking into. If someone had taken over without having known the garden and wanted to continue it, the learning curve might have been steep. Make sure you really, truly understand, that you know what the spirit of the place is BUT, if you have the spirit to do it, for heaven’s sake, do it!

You do have to pick your spot. Mother Nature is going to do things. You know you’re going to have storms, perhaps more and more. You’re going to see insect invasions and fungus and things like that. And we do have climate change happening. So you have to pick your battles to some extent.

I also want to thank the Garden Conservancy immensely for its help, for your documentation of the garden and for the historical information you gave us. Because of you and Henriette we have a history of everything, everything she bought, including all the tree peonies, and we know when they were bought, where they were from, and all their names. It’s been a huge help.

P PRESERVING, SHARING, AND CELEBRATING AMERICA’S CULTURAL LEGACY 19

Above We now understand better than ever that gardens are much more than just beautiful places. In an increasingly fragmented world, our gardens are places that celebrate the natural world and where we have an opportunity to help heal the damage done to the planet. Scientific understanding of

An Accidental Preservationist

By Judith B. Tankard

As a young art historian, I was well aware of preservation issues with paintings, sculpture, objects, buildings, and monuments, but gardens—no! It wasn’t until the 1980s when I was in hot pursuit of Arts & Crafts architects such as Edwin Lutyens that I stumbled on some sorry examples of Jekyll gardens that happened to be part of the grounds. Overgrown trees and shrubs, pitiful flower borders, missing ornament, and modern-day water features were the name of the game. It wasn’t until the publication of books on historic gardens and monographs on Sissinghurst, Hidcote, and Great Dixter that I realized there was another layer called historic gardens. After that initial fire was lit, I’ve never looked back. Over the years I’ve had an opportunity to observe good and bad preservation attempts based on varying levels of expertise, willingness of the owners, and—most crucial—approaches to maintenance. The Garden Conservancy’s advisory role on preservation methodology for significant gardens as well as alerts by the Cultural Landscape Foundation for public spaces at risk have been invaluable in saving and managing important properties. Detailed cultural landscape reports have aided enormously in broadening our understanding of significant places that otherwise would be ignored.

While gaining expertise in the careers of landscape architects such as Ellen Shipman and Beatrix Farrand, I discovered that many of their gardens had disappeared, victims of readaptation or lethargy. Fortunately, the tables have turned in recent years and more sites are being rediscovered and resurrected. What has been consistently excellent is the quality and depth of research, in part thanks to the designers’ archives. The landmark restorations of the Beatrix Farrand Garden at Bellefield, as well as Eolia, the Harkness Estate, were greatly facilitated by landscape architects trained in research pro-

cedures. Detailed planting plans, archival photographs, and correspondence brought a surfeit of information that had to be evaluated in terms of modern-day usage as public properties. In most cases, the installation and maintenance steps were done by trained volunteers, but only after crucial funding was raised. These are the good stories. There are also the cases where research and installation were impeccably completed, but the project failed due to lack of understanding the intricacies of maintenance. In their day, Shipman’s gardens, for example, were unusually maintenance-intensive, necessitating a plant replacement schedule that most budgets would not allow. One thinks of the tragic story of Beatrix Farrand at the end of her life having to close down Reef Point due to the lack of a fully trained gardener who could carry on her meticulous work.

When the National Park Service undertook the restoration of the small parterre garden at the Longfellow House in Cambridge, designed by Martha Brookes Hutchinson in the early 1900s and revitalized by Ellen Shipman twenty years later, there were many challenges to face: a detailed history of the site necessitated archaeological digs, replacement of built features, and the search for substitutions for Shipman’s plant palette, most of which had long gone out of cultivation. Consideration for modern-day pests, irrigation issues, and foot traffic all figured in to the highly praised rehabilitation privately funded by a friends’ group who collaborated with the park service. Following along similar lines, a friends’ group has recently initiated a partial replanting of Shipman’s once-magnificent gardens at Chatham Manor (now Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park) in Fredericksburg, VA. The grandaddy of them all are the gardens and grounds at the Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site in Cornish, NH. All three properties, plus others, reflect solid research and rigorous maintenance.

In the case of institutions, such as Harvard University’s Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, DC, it goes without saying that research, routine maintenance, and plant replacements reflect the high level of a professionally trained staff. However, the case is rarely so with private gardens that have seen significant changes over time, as wings are added to the original house, swimming pools dropped in, and plantings simplified. When property transfers to new owners, the gardens generally suffer or are irretrievably lost. The outcome is generally doomed due to unavoidable changes to the landscape, uneducated owners, lack of rigorous research, questionable maintenance, and limited budgets. Exceptions, of course, include knowledgeable owner-gardeners who revitalize rather than obliterate.

There are a several stories for outstanding public gardens that have been rediscovered through research or recovered from disasters. The most famous is Longue Vue House and Gardens in New Orleans, former home of philanthropists Edith and Edgar Stern. Designed by Ellen Shipman in the 1930s, the gardens were open to the public in 1968 during Edith’s lifetime, but it took several major hurricanes to put the aging

20 P PRESERVING,

SHARING, AND CELEBRATING AMERICA’S CULTURAL LEGACY

Above We now understand better than ever that gardens are much more than just beautiful places. In an increasingly fragmented world, our gardens are places that celebrate the natural world and where we have an opportunity to help heal the damage done to the planet. Scientific understanding of

gardens in perspective. After Katrina’s destruction in 2005, several groups, led by the Garden Conservancy, stepped in to assess the damage and commission a history of the grounds in order to implement an informed recovery and maintenance plan. Today the gardens are one of Shipman’s finest achievements.

It took a book, rather than a storm to resurrect a slumbering Shipman garden in Jacksonville, Florida, designed in the early 1930s, but long forgotten in the tangle of overgrown shrubs. Shortly after the publication of my book on Shipman in 1996, a garden advisory committee member spotted the name “Cummer” in the client list and promptly found plans in Shipman’s archive at Cornell. Fortunately, the bones of the garden lay undisturbed for decades, so the committee set to work to bring it back to life. A full-scale restoration was quickly spearheaded, but not before running into problems with some of the plants indicated on the plans. The committee learned that it’s one thing to plant-by-plan, but another to find substitutes that are better performing. It was a miraculous discovery, but just after completing the restoration, Hurricane Irma severely damaged the waterfront garden. The museum acted quickly to repair the damage and replant. In recent years, a number of Farrand gardens have undergone restoration, but a little-known one in Maine deserves mention. While much is known about the demise of Farrand’s long-time home and garden at Reef Point, few people know about Garland Farm, where she spent the last three years of her life. Now the headquarters of the Beatrix Farrand Society, Garland Farm was once the home of her long-time caretakers at Reef Point. It was here that she designed her last garden—for herself—consisting of a sunny flower terrace at the back of the house and a small entrance garden shaded by her favorite trees and shrubs that she brought with her from Reef Point. Although no plans have been found for the terrace garden, vintage color photos were useful for the

Maine Master Gardeners volunteer team. A cultural landscape report unearthed information for a multi-year restoration strategy that included plant propagation and locating missing garden ornaments. Attention has now turned to the entrance garden for which a few sketches have been located. Thanks to the volunteers who maintain this important garden, visitors from around the world can now glimpse one of Farrand’s most personal gardens.

On a more personal level, in 2002 I had the pleasure of collaborating with landscape architect Norma E. Williams on documenting Greenwood Gardens, a preservation project of the Garden Conservancy in Short Hills, NJ. The slumbering garden had Arts and Crafts teahouses, pergolas, trellises, and grottos filled with Rookwood tiles, as well as water features, including an Italianate cascade that turned out to be the work of a little-known architect, William Whetten Renwick. Eighty years later, the original 1920s gardens were slumbering, the Art Deco-style house had been replaced, and a newer layer of plantings had been installed in the 1960s. The ambitious, multi-year restoration of built features and plantings has now come to fruition.

P PRESERVING,

AND CELEBRATING AMERICA’S CULTURAL LEGACY 21

SHARING,

An art historian specializing in landscape history, Judith B Tankard is the author of books on Beatrix Farrand, Ellen Shipman, and Gertrude Jekyll, among others. She is a longtime Fellow of the Garden Conservancy and organizes the Martha’s Vineyard Open Day. Photo: Jennifer Packard

Preserving Gardens that Spring from the Soul

By Lucinda Brockway

By Lucinda Brockway

Nestled into the Berkshire hills not far from the Garden Conservancy headquarters, Naumkeag is one of America’s cultural treasures and one of its most renowned Massachusetts gardens. Here, creators Fletcher Steele and Mabel Choate believed that garden making was a fine art, and pushed the limits of color, line, form, and horticulture as they molded their masterpiece. As biographer Robin Karson wrote, “Fletcher Steele made gardens as playgrounds for people’s imaginations.” Certainly, Naumkeag reflected this lavish garden theater: from the moon gated wall of the Chinese Temple garden to the birch bedecked Blue Steps, the magnificent views of the Stockbridge mountains offered a dramatic backdrop to Steele’s stage. Sometimes the magic of a garden, however, is not evident to everyone. When The Trustees was approached to accept Naumkeag as a bequest, one member of the Standing Committee vehemently argued against its acceptance, writing, “It isn’t an old house, it isn’t a beautiful house, and it has one of the most horrendous gardens in the Commonwealth… I really can’t see why The Trustees should take over this white elephant of a house.”

Many years later, long after Naumkeag did, in fact, come to The Trustees, retired president Gordon Abbott, Jr. wrote a history of the organization that included our foray into garden preservation. “Preserving gardens,” he wrote, “presents a special set of problems. Landscape gardens such as those at Naumkeag… derive their character from their design. Given sufficient funds, technical knowledge, labor, and, of course, an understanding of the original design concept and an appreciation for its subtleties, they can be maintained

with relative ease.” After having recently restored Naumkeag’s gardens, I might question the “relative ease” part of his statement as we continue to polish this masterpiece and determine the tools necessary to guide stewardship decisions in the future.

As we continue to steward Naumkeag, we are also challenged to rejuvenate two very personal gardens in North Andover and Beverly, MA, where historic records have been uncovered only after hours of diligent research, and the personal development of the gardens had to be understood and translated to master planners and organizational leaders. Abbot recognized these two gardens and their specific challenges as he wrote, “But it is the personal gardens such as those at Long Hill and the Stevens-Coolidge Place, whose poetic charm has come from the special interests, tastes, and sensibilities of an individual, which present the greatest challenge. For these are characteristics which spring from the soul and are not easy to institutionalize.” Certainly, this is the challenge of garden preservation: how to understand, guide, and institutionalize “gardens that spring from the soul” so that their inherent genius of people and place can continue to inspire under the umbrella of their legacy.

Each time the Garden Conservancy accepts a conservation easement on a garden property, they are pledging to ensure the easement’s preservation goals are maintained—in perpetuity. Part of shouldering that responsibility involves establishing a relationship with the garden owner (either a nonprofit organization or a private individual) and creating resources ”

22 P

PRESERVING, SHARING, AND CELEBRATING AMERICA’S CULTURAL LEGACY

Above: Long Hill, Beverly, MA Photo: Terri Unger Photography

Right: Stevens-Coolidge House & Garden, North Andover, MA Photo: Coco McCabe

for stewardship of the garden, such as management plans and records that document the garden’s special qualities or its “conservation values.” This is much like the suite of documents we at the Trustees of Reservations are developing to inform site stewardship and protect core features at garden properties that we manage.

Each time we establish a garden preservation easement, staff build documents that guide its long-term management, a suite of documents we are developing to inform site stewardship and protect core features. Managing change is foundational to garden preservation. Gardens are dynamic and very personal heritage sites, filled with plants at various stages of youth, maturation, and decay. To preserve and protect what makes each unique, guiding documents must clarify how much change is acceptable. They must accurately defend features or plant collections sacred to the core spirit of the garden. Most importantly, they anticipate where, how, and at what pace, change will occur. As gardens transition from private to public spaces, they adapt to welcome and accommodate visitors, provide parking, ticketing systems, visitor services, staff workspaces, and appropriate interpretation and programming. Most of all, each needs a sound business plan and suitable financial support to operate and maintain the garden. Opening the doors to the public requires more funding, and more site changes, than supporting a private garden. Yet every generous gardener wants to share and engage their garden with the community. As they should, for each garden, when done well, offers an inspiration and refuge unlike any other cultural resource.

In 2014, The Trustees looked to the English National Trust as a model for our management tools. We established Statements of Significance. We tested Spirit of Place statements. We created baseline standards and a work order system for capital expenses. We approved a Living Collections Policy for the curation of plant collections. Today, we are testing Guiding Principles documents that describe each garden area, state its management intent, and frame the style, type, and intent of plantings while allowing individual horticulturists some freedom in horticultural selections that allow the gardens (and the horticulturists) to thrive. In almost all cases, we have inherited a garden that has matured into a unique work

of art. That maturation, however, means that existing plants are reaching their viable life span, particularly in New England, so the curation of the plant collections at each site is becoming our most critical planning need. While welcoming repeat visitation, we have also had to recognize the impact of people on a place and build awareness of site capacity and seasonal pacing of visitation to protect property resources while maximizing their public enjoyment 365 days a year.

As the nation’s oldest, statewide, conservation and historic preservation organization, the 120 properties of Massachusetts’ Trustees of Reservations are united by Charles Eliot’s bold idea of protecting exceptional places of historic, natural, and scenic value for the public enjoyment. Today, we are striving to create public gardens where curated horticultural collections thrive in beautifully preserved settings and welcome all visitors. Unique legacy gardens and creative new garden design is often signature to our public gardens. Interpretation and programming are focused on horticulture, botany, garden techniques, historic legacy, and new garden spaces that spring from that legacy. This work has leveraged our public gardens from relative obscurity to a major pillar of our current strategic plan. More than a preservation success, they connect spirit and mind with the personal touch of each creator. With the right guiding documents, preservation easements, and financial plans in place, they can each become playgrounds for the imagination.

P PRESERVING, SHARING, AND CELEBRATING AMERICA’S CULTURAL LEGACY 23

Lucinda Brockway is the Program Director for Cultural Resources at the Trustees of Reservations, where she is responsible for 112 properties and 25,000 acres of Massachusetts cultural landscape.

Above We now understand better than ever that gardens are much more than just beautiful places. In an increasingly fragmented world, our gardens are places that celebrate the natural world and where we have an opportunity to help heal the damage done to the planet. Scientific understanding of the environment, soil ecology, hydrology, and the complexity of nature has grown by leaps and bounds. Gardening practices increasingly reflect our appreciation that actions we take on our plots of land have an observable impact on the health of the environment. As the gardening public becomes more informed, our gardens in turn have become vital sanctuaries for birds, pollinators, and native plant species and we are better equipped to make a positive difference.

24 P PRESERVING, SHARING, AND CELEBRATING

CULTURAL LEGACY

AMERICA’S

Landscape and Memory at Sylvester Manor

By Donnamarie Barnes

As you enter the long drive at Sylvester Manor, the outside world drifts away and you are surrounded by the sounds and silence of the forest. Senses are heightened with the sway of the trees in the wind and the smell of the woods and the water. A feeling of “story” is present often without knowing anything about the place. This is a place of history and memory whose essence has been held by the land itself over the centuries and through generations.

Sylvester Manor on Shelter Island in New York is considered to be the most intact Northern plantation remnant. The island is the ancestral home of the Indigenous Manhansett people, who called it Manhansack-aha-quash- awamock, “Island Sheltered by Islands,” in the waters now known as Eastern Long Island’s Peconic Bay. The English claimed the territory for the king in 1638 and, in 1651, Shelter Island was purchased with 1,600 pounds of turbinado sugar by four English partners, including brothers Constant and Nathaniel Sylvester, to serve as a Provisioning Plantation for their sugar operations on the West Indies island of Barbados.

Far from the sugarcane killing fields, they brought to Shelter Island enslaved African men, women, and children to perform the labors of clearing and farming the land, raising livestock, harvesting timber for barrel staves to transport foodstuffs, sugar, and molasses, and tending the Sylvester house and family. For 368 years, property ownership passed through eleven generations of Sylvester descendants, until Sylvester Manor Educational Farm was established in 2009 and the land donated in 2014 to the nonprofit organization. Now comprising 235 acres, a Georgian-style Manor House built in 1737, outbuildings, and a working farm, Sylvester Manor Educational Farm’s mission is to preserve, cultivate, and share the history of Sylvester Manor.