VarietiesofReligious(Non)Affiliation

APrimerforMentalHealthPractitionersonthe “SpiritualbutNotReligious” andthe “Nones”

DavidSaunders,MD,PhD,*MichaelNorko,MD,MA,†‡ BrianFallon,MD,MPH,§JamesPhillips,MD,† JeniferNields,MD,† SalmanMajeed,MD,||JosephMerlino,MD,MPA,¶andFayezEl-Gabalawi,MD#

Abstract: Givenchangingdemographicsofreligiosityandspirituality,thisarticleaimstohelpcliniciansunderstandcontemporarytrendsinpatientreligious andspiritualorientation.Itfirstidentifiesanddescribestheevolvingvarieties ofreligio-spiritualorientationandaffiliation,asidentifiedinsurveystudies.Particularattentionisgiventotheexaminationofthosewhoidentifyasspiritualbut notreligious(SBNR)andNone(i.e.,noreligiousaffiliation),whichisimportant tomentalhealthpracticebecausemanypatientsnowidentifyasSBNRorNone. Next,empiricaldataareconsidered,includingwhattheliteraturerevealsregarding mentalhealthoutcomesandSBNRsandNones.Weconcludewithasummary ofthemainpointsandfiverecommendationsthatmentalhealthpractitioners andresearchersneedtoconsiderregardingthisincreasinglylargeportionof thepopulation.

KeyWords: Religion,spirituality,spiritualbutnotreligious,Nones (JNervMentDis 2020;208:424 430)

TwosegmentsoftheAmericanreligiouslandscapeareundergoing precipitousgrowth: “Nones,” orthereligiouslyunaffiliated,and the “spiritualbutnotreligious.” Asof2019,Nonesrepresent23.1% oftheAmericanpopulation anorderofmagnitudeincreasefrom the1950s,andupfrom22.8%only2yearsago(Jenkins,2019).The spiritualbutnotreligious(SBNR)accountfor27%oftheUSpopulation,analmost150%increasefrom2012,despitenotexistingasa categoryoforientationinthe1950s(LipkaandGecewicz,2017).The followingarticleconcernsthesetwopartiallyoverlappingsubgroups withintheAmericanreligiouslandscape,thatis,thereligiouspractices andbeliefsendorsedbyresidentsoftheUnitedStates.

“None” refers,quitesimply,tothecheckingofaboxbyasurvey respondent—“None”—inresponsetothequestion, “Whatisyourpresentreligion,ifany?” (PewResearchCenter,2015).Thisgrouphascollectivelycometobereferredtoasthe “Nones.” Whilemorethanathird ofNonesidentifyas “spiritual” (Drescher,2012),theirdefiningfeature isneverthelessnonaffiliationwithreligiousinstitutions(seeFig.1). SlightlymoredifficulttodefinearetheSBNR.Althoughthe termsspiritualityandreligiosityoncereferredtomorecloselyrelated phenomena,theyhavebecomeincreasinglydistinctduetoanynumber

*YaleChildStudyCenter; † DepartmentofPsychiatry,YaleSchoolofMedicine, NewHaven; ‡CTDepartmentofMentalHealthandAddictionServices,Hartford, Connecticut;§ColumbiaUniversityDepartmentofPsychiatry,NewYork,New York;||PennStateHersheyMedicalCenter,DepartmentofPsychiatry,Hershey, Pennsylvania;¶StateUniversityofNewYork-DownstateDepartmentofPsychiatry andBehavioralSciences,Brooklyn,NewYork;and#DepartmentofPsychiatry andHumanBehavior,ThomasJeffersonUniversity,Philadelphia,Pennsylvania.

SendreprintrequeststoDavidSaunders,MD,PhD,160TheodoreFremdAve, AptA8,Rye,NY10580.E mail:david.saunders@yale.edu.

AllauthorsaremembersofthePsychiatryandReligionCommitteeoftheGroupfor theAdvancementofPsychiatry,whichhasapprovedsubmissionofthis manuscriptasaGAPproduct.

Copyright©2020WoltersKluwerHealth,Inc.Allrightsreserved.

ISSN:0022-3018/20/20805 0424 DOI:10.1097/NMD.0000000000001141

ofpolitical,religious,andculturalforces(Fuller,2001;Mercadante, 2014).Onesequelaoftheuntetheringofreligiosityandspiritualityis thebirthofthisnewtermonthespectrumofreligio-spiritualorientation,SBNR(Ammerman,2013;Fuller,2001;Kenneson,2015; Mercadante,2014;SaucierandSkrzypińska,2006).Interestingly,almosttwo-thirdsofpeoplewhoidentifyasSBNRstillacknowledgea religiousaffiliation(boxCinFig.1),Protestantinabouthalfofthose individuals,andCatholicinaboutonequarter(LipkaandGecewicz, 2017;PewResearchCenter,2012).Theliteraturedoesnothelpclarify thissurveyfinding.

Thequestionaddressedinthisarticleiswhymentalhealthpractitionersshouldcareaboutthedemographicsandreligiouspracticesof SBNRsandNones.Theansweristhreefold.First,thedataclearlyindicatethatmanyofourpatientswillidentifyaseitherNonesorSBNRs. Thereare57.5millionNonesand68.1millionSBNRsinAmerica 23.1%and27%oftheUSadultpopulation,respectively(Lipkaand Gecewicz,2017),withsomeidentifyingasbothaNoneandanSBNR (boxC′ inFig.1),andothersidentifyingasoneortheother(Nonein boxA′ andSBNRinboxCinFig.1).Second,SBNRsandNones aredrawnfromallsexes,ageranges,ethnicities,income-ranges,and multiplepoliticalorientations(PewResearchCenter,2012).Regardlessofpracticelocationorpopulation,cliniciansarethereforebound toencounterNonesandSBNRsinmentalhealthpractice.Third,surveysindicatethatmanyindividuals theexactpercentagedependson theclinicalcontext wouldprefertohavespiritualityand/orreligiosityconsideredintheircare(McCordetal.,2004).Unfortunately,dataindicatethatmostdoctorsneverinquireaboutpatients'religiosity/ spiritualityoronlyrarelydoso(Curlinetal.,2006).Whetherviaaninformalspiritualassessmentorbyusingarangeofestablishedformal methodsforconductingassessmentsofreligio-spiritualorientation (SaguilandPhelps,2012),suchastheFICASpiritualHistoryTool (PuchalskiandRomer,2000)andtheHOPEQuestions(Anandarajah andHight,2001),knowingaboutpatients'supports,beliefsystems,and helpfulpractices,includingwhethertheyidentifyasaNoneoranSBNR, canhelpaclinicianbetterunderstandthem,howtheymanagetheirlives, andaidintimesofcrisiswhenthey mightneedremindersaboutusing theirreligiousorspiritualsupports.Giventhatreligious/spiritualorientationhasbeenshowntoimpactmentalillnessandwell-being(Dein etal.,2012;Gonçalvesetal.,2015;Koenig,2015,2012;Unterrainer etal.,2014;WeberandPargament,2014),itmakesgoodsenseformentalhealthpractitionerstopayattentiontomentalhealthconsiderationsin thisgrowingsegmentofthepopulation,acasethatwearguethroughout thecourseofthearticle.

Unfortunately,althoughanextensivebodyofresearchoffersinsightintotheeffectsofconventionalreligiosityand/orspiritualityon mentalwell-being(Deinetal.,2012;Koenig,2015,2012;Unterrainer etal.,2014;WeberandPargament,2014),littlehasbeenwrittenabout thementalhealthofSBNRsorNones,arapidlyexpandingsegmentof thepopulation.Toaddressthisshortcoming,theobjectivesofthearticle arefivefold:firstandforemost,tooffercliniciansanuancedandup-todateunderstandingontrendsinreligiosityandspiritualityinthegeneral

FIGURE1. Varietiesofreligio-spiritualorientationandaffiliation.NonesconsistofA′ throughD′.TheSBNRpopulationconsistsofboxesCandC′ Surveydataindicatethattwo-thirdsoftheSBNRpopulationreportsareligiousaffiliation(boxC),whereastheotherone-third(boxC′)reportsno religiousaffiliation(i.e.,arebothNoneandSBNR),whichmayseemcounterintuitive.Intuitively,thepopulationsinA,B′,andD′ shouldbenegligible comparedwithA′,B,andD,respectively(e.g.,individualswhodescribethemselvesasnotreligiousandnotspiritualwouldnotbeexpectedtoreporta religiousaffiliation).Ofnote,thesizesoftheboxesdonotrepresentthetruesizeofthepopulationtheycategorize.Thisfigurecanbeviewedonlinein coloratwww.jonmd.com.

populationand,byextension,ourpatients;totracethedevelopmentof SBNRsandNonesinAmericanreligioushistorysoastooffercliniciansthehistoricalbackdrop;toexaminehowthetermsforreligiospiritualorientationhavebeenusedandoperationalizedinclinical andresearchsettings;toreviewempiricaldatasothatcliniciansmay assesstheevidencebase;andtoarguethatcliniciansandresearchers alikeoughttopaygreaterattentiontothisgrowingsegmentofthe populationbecausedoingsowillultimatelybenefitourpatients.

VARIETIESOFRELIGIO-SPIRITUALORIENTATION

Achallengeconfrontinganydiscussionofthesubtypesof religio-spiritualorientationisdefiningfivecriticalterms:religious, spiritual,SBNR,neitherspiritualnorreligious,andNone.Thereneverthelessexistmoreorlessauthoritativedefinitionsthatareinstructive, someofwhicharebrieflyreviewedhere.

Definitionsof “religious” rangewidely(Zinnbaueretal.,1997) from “asystemofbeliefsinadivineorsuperhumanpower,andpracticesofworshiporotherritualsdirectedtowardsuchapower” (Argyle andBeit-Hallahmi,1975,p1)toWilliamJames' “thefeelings,acts, andexperiencesofindividualmenintheirsolitude,sofarastheyapprehendthemselvestostandinrelationtowhatevertheymayconsider thedivine” (James,1902,p31).ThenotedscholarofreligionMarkC. Taylordefinesreligionasfollows:

“

anemergent,complex,adaptivenetworkofmyths,symbols, andritualsthat,ontheonehand,figureschemataoffeeling, thinking,andactinginwaysthatlendlifemeaningandpurpose and,ontheother,disrupt,dislocate,anddisfigureeverystabilizingstructure” (Taylor,2007,p12)

Othersdefinereligiositybydifferentiatingitfromspirituality,arguing thatreligioninvolvestwothingsthatspiritualitydoesnot.Forexample, accordingtoHillandcolleagues,theydifferin “themeansandmethods ( e.g.,ritualsorprescribedbehaviors)ofthesearchforthesacredthat receivevalidationandsupportfromwithinanidentifiablegroup ” (Hilletal.,2000,p68).Second,religionmayinclude “thesearch fornon-sacredgoals(suchassocialidentity,affiliation,health,wellness) inacontextthathasasitsprimarygoalthefacilitationofthesearchfor thesacred” (Hilletal.,2000,p68).Theparticularsaside,clearly,there isnosingledefinitionofwhatitmeanstobe “religious,” andperhapsit

isbettertothinkofreligionasaliving,breathing,andevolving,culturally boundsubject.

Spiritualityhasasimilarlywiderangeofdefinitionsandcan meanmanydifferentthingsatonce.Despitethisdiversity,severalmultidisciplinaryeffortshaveproducedconsensusdefinitionsofspirituality (Nolanetal.,2011;Norko,2018;Puchalskietal.,2009,2014).These definitionsfocusonmeaning,purpose,andconnectedness,withsome advocatingtheinclusionofanindividual'srelationshipwiththetranscendent.TheInternationalConsensusConferenceonImprovingthe SpiritualDimensionofWholePersonCarearrivedatthisdefinition: “Spiritualityisadynamicandintrinsicaspectofhumanitythrough whichpersonsseekultimatemeaning,purpose,andtranscendence, andexperiencerelationshiptoself,family,others,community,society, nature,andthesignificantorsacred.Spiritualityisexpressedthrough beliefs,values,traditions,andpractices” (Puchalskietal.,2014,p46)

Liketheterm “religious,”“spirituality” isdifficulttodefineinaprecise manner,despitetheworkofconsensusconferences,complicatingits operationalizationintoempiricalresearchsettings.Furtherconfounding matters,manydefinitionsofspiritualityspuriouslyequateitwithmentalhealth,asKoenig(2008)notes.Inotherwords,someresearchon spiritualityandmentalhealthissimplytautologicalbecauseofthesignificantoverlapinthewaytheseconstructs spiritualityontheone hand,andmentalhealthontheother aremeasured.Importantdifferencesbetweenmentalhealthandspiritualitywillbecapturedbyavalid definitionofspirituality,specificallywithregardtophenomenalike meaning,transcendence,andrelationshiptothesacred,tonameafew (Koenig,2008).

Giventhedifficultyinherentindefiningreligiousandspiritual,it wouldfollow,then,that “SBNR” isalsodifficulttodefine,andindeed, aconsensusdefinitionofSBNRhasnotbeenachieved.Nevertheless, SBNRshaveattractedtheattentionofthepopularpress(Barrie-Anthony, 2014;King,2016),physicians(Kingetal.,2013),legalscholars (Miller,2016),andofcoursereligiousstudiesscholars(Fuller, 2001;Mercadante,2014).ThereissomesensethattheSBNRidentifier isoftenrhetoricalatitscore,rather thanrepresentativeofatrueorientation(Mercadante,2014,p6).Manyargue “ithassomethingtodowith dissatisfactionwithorganizedreligion” (Chaves,2011)althougheven” organizedreligion” maynothaveaclearmeaning(Ammerman,2013). Complicatingmatters,manySBNRsstillidentifywithareligion,so someareNoneswhileothersarenot.Inanycase,acollectiveinability

Copyright © 2020 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

todefineandoperationalizeSBNRisnotwithoutconsequences,especiallyformentalhealthresearchersseekingtostudySBNRs.

Nones,ontheotherhand,areaclearlydefinedandidentified group:peoplewhoanswerasurveyquestionabouttheirreligiousaffiliationbysayingtheyhave “none” (PewResearchCenter,2012).AlthoughscholarsofreligionintheUnitedStateshavebeenreferringto thisgroupofpeopleasNonessincethe1960s(PewResearchCenter, 2012),referencetothetermhasrecentlybecomemorewidespread,perhapsasthenumberofindividualswhoidentifyasNonecontinuesto grow.(Ofnote,Nonesaredistinctfromthe “neitherspiritualnor religious”—thosewhoidentifywithneitherspiritualitynorreligiosity. Thislattergroupwillnotbediscussedfurther,butthereadershould beawarethatthe “neitherspiritualnorreligious” aredistinctfrom Noneswhoaredefinedbynonaffiliationwithreligion;seeFig.1.)

AnAmericanReligiousHistoryPerspective

SBNRsandNonesarerelativelynewtermsinAmericanreligious history,complicatingattemptstotracetheiroriginsanddevelopment. Sufficeittosay,however,thatwhiletheysharesomedemographic overlap(seenextsection),theyhaveuniquehistories.RegardingSBNRs, weareunabletoidentifyanorigindatefortheterm.Thatsaid,modern AmericanreligioustheoristsoftenciteWilliamJames' VarietiesofReligiousExperience (James,1902)asseminaltothedevelopmentofthe SBNRinAmerica(Fuller,2001).Jamesneverusedthetermspiritual, letaloneSBNR,butratherdiscussedvalencesoftheterm “religious” inwaysthatforeshadowedthenotionof “spirituality” today.Asaharbingerofthecontemporaryspiritualityversusreligiositydistinctionsto come,hesaysofreligion: “theword…cannotstandforanysingleprincipleoressence,butisratheracollectivename Letusnotfallimmediatelyintoaone-sidedviewofoursubject,butletusratheradmitfreely attheoutsetthatwemayverylikelyfindnooneessence,butmanycharacterswhichmayalternatelybeequallyimportantinreligion” (James, 1902,p26).Hecontinues: “wearestruckbyonegreatpartitionwhich dividesthereligiousfield.Ontheonesideofitliesinstitutional,onthe otherpersonalreligion” (James,1902,p28).Hispublicversuspersonal distinctioncapturesonesignificantdifferentiationofreligiosityfrom spirituality.Interestingly,James'ownreligiousorientationmayhave alsopresagedthedevelopmentoftheSBNRs,withonescholararguing, “Ifanyoneindividualhaseverpersonifiedwhatitmeanstobe ‘spiritualbutnotreligious,’ itwasWilliamJames” (Fuller,2001).

RegardingNonesinparticular,Galluppolls,whichbegancollecting informationonreligious(non-)identityin1948,showthatonly2%of Americanssaidthattheyhadnoreligiousidentityduringthatdecade (Newport,2010).Althoughthesepollsdidnotdirectlymeasurethe numberofNonesinthemannerthatcontemporaryPewResearchsurveysdo(withthequestion “Whatisyourpresentreligion,ifany?”), itmaybesafetoassumethatthepercentageofNonesin1948was thesameasorclosetotheGallupfigureof2%.Againstthisbackdrop, thegrowthofNonesbeganalongperiodofgrowththatmirroredthe declineinparticipationinorganizedreligiousinstitutions.Thelate 1960sand1970switnessedculturalupheaval,characterizedbyavirulentoppositiontomanydominantculturalinstitutions,includinginstitutionalizedreligion(Mercadante,2014,p24).Bythelate1970s,the numberofNoneshadmorethanquadrupled,to9%(Newport,2010). Predictably,acounterrevolutionintheformofaconservativeevangelicalrevivalensuedinthe1980sand1990s.Thisdevelopmentisoften conceivedofasareactiontomoraldeteriorationsomefelthadoccurred inthe1960sand1970s,reflectingapendulumswingbacktowardtraditionalreligiousinstitutions(Mercadante,2014),presumablyhalting, foraperiod,thedramaticriseinNones.Later,asevangelicalismbecamemorewidespread,however,anequalandoppositegrowthinthe populationofNonestookplaceacrossthe1990sand2000s,cementing thealmost70-yeardevelopmentoftheNones.By2012,surveysshowed that20%oftheUSpopulationwasunaffiliatedwithanyorganized

religion,withsomebelievingthatthis estimateisactuallylow,owingto overreportingofchurchattendance(Hadawayetal.,1993;Mercadante, 2014;Newport,2010).Theevidenceisclearthatthepopulationof Noneshasincreaseddramaticallyfromthepeakofreligiousinstitution affiliationinthe1940sand1950s.

DEMOGRAPHICSOFSBNRSANDNONES

SurveydatacollectedbythePewResearchCenter'sForumon ReligionandPublicLiferevealsanumberoftrendsinthesepopulations(Mercadante,2014,p2;alldatapresentedinthissectionare drawnfromthe2014PewReligiousLandscapesurvey,withamargin oferrorof±0.6%forthefullsampleof35,071).Morethanoneinfive AmericanadultsidentifiesasaNone,representingapproximately 57.5millionindividuals.Onethirdofadultsunder30identifiesasa None.Thisfigureisgreaterthanthenumberof “mainline” Protestants intheUnitedStates.Interestingly,approximatelytwo-thirdsofthem stillbelieveinGod(68%)andmorethanoneinfiveprayeveryday (21%).OftheNones,37%(21.2million)identifyasSBNR,representing 8.4%oftheUSpopulation(boxC′ inFig.1).Thisfigurerepresentsmore thanthenumberofAmericanswhoidentifyasMormon,Buddhist,Jewish,Muslim,orHinducombined,andonlyslightlylessthanthetotal numberofthosewhoidentifyasWhiteEvangelical.Conversely,63% ofNonesarenotSBNR,mostofwhomarepresumptively “neitherreligiousnorspiritual” (boxA′ inFig.1),withasmallpercentageofthem,at leastintheory,identifyingaseitherreligiousalone(boxB′),orreligious andspiritual(boxD′).Itisnotclear,however,howbeliefinGodand dailyprayeraredistributedamongthesesubgroups.

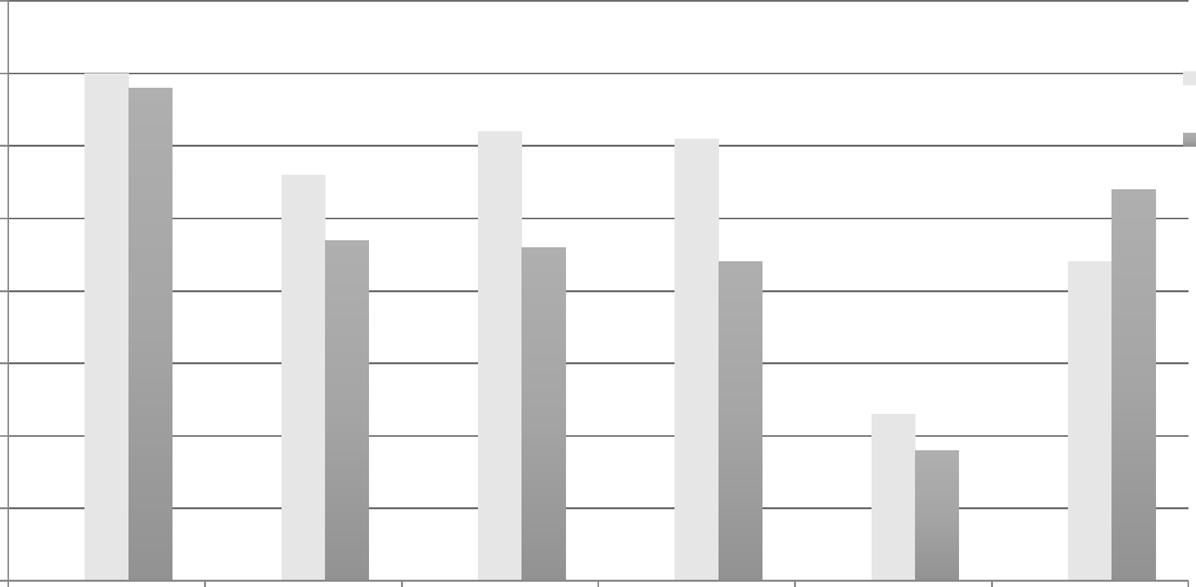

DemographicdataaredisplayedinFigure2.Overall,while SBNRsandNonesrepresentdistinctreligio-spiritualorientations,their demographicsareneverthelessverysimilar.Furthermore,theyboth differconsiderablyfromthereligious.Specifically,intermsofsex, politicalaffiliation,education,andmaritalstatus,SBNRsandNones areverysimilartoeachother,anddivergefromthereligious.Menconstitute56%ofbothSBNRsandNones,butonly47%ofthereligious. SBNRsandNonesbothidentifyasDemocrat/leaningDemocrattwice asfrequentlyasRepublican/leaningRepublican(62%Democrat vs.31% Republican),whereasreligiouspersonsidentifywitheitherpartyinapproximatelyequalproportions(48%Republican/leaningRepublican vs 46%Democrat/leaningDemocrat).SBNRsandNonesaremoreeducated(definedasattendingsomecollegeormore)thanthereligious, with65%,61%,and44%,respectively,attendingatleastsomecollege. Finally,marriageratesareapproximately40%forbothSBNRsand Nones,incomparisonto54%forthosewhoidentifyasreligious.The onlysignificantdemographicdifferencebetweenNonesandSBNRs emergesintermsofage,asalargershareofNonesisdrawnfromthe 18to29demographic(35%)thanSBNRsorthereligiouslyaffiliated (23%and18%,respectively).

AnalysisofthereligiouspracticesandbeliefsofNonesand SBNRsrevealsinterestingand,attimes,surprisingfindings.Forexample,severalmetricsofreligiouspracticeandbeliefsuggestthatSBNRs aremoresimilartothereligiousthantheyaretoNones,consistentwith thefindingthattwo-thirdsofthemreportareligiousaffiliation,asnoted previously.Specifically,SBNRsattendchurchorworship with19% attendingatleastweeklyand53%attendingatleastonceyearly thoughatlesserfrequencythanthosewhoidentifyasreligious(52% and87%,respectively).Ontheotherhand,only5%ofNonesattend serviceweekly,and27%atleastyearly.Furthermore,SBNRsconsider religiontobeimportant,despitethefactthattheydonotconsider themselvesreligious,as63%findreligiontobeeitherveryorsomewhatimportant.Althoughsignificantlylessthanthereligious,98%of whomfindreligiontobeeithersomewhatorveryimportant,SBNRs considerreligiontobeimportantalmosttwiceasfrequentlyasNones, only33%ofwhombelievethatreligionissomewhatorveryimportant.

©2020WoltersKluwerHealth,Inc.Allrightsreserved.

Copyright © 2020 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

FIGURE2.

DemographicsofNones,SBNRs,andtheReligious.Thisfiguredisplaysthepercentageof “Nones” (thosewhoidentifywithnoreligion), “SBNRs” (spiritualbutnotreligious),andreligiouspersonsacrossanumberofdemographicvariables,includingethnicity,sex,politicalaffiliation, education,age,andrelationshipstatus.DataaredrawnfromthePewResearchCenter(2015).Thisfigurecanbeviewedonlineincoloratwww.jonmd.com.

Finally,almostallSBNRsandreligiouspersonsbelieveinGod(92% and99%,respectively),whereasonly68%ofNonesbelieveinGod.

Insum,thedemographicsofNonesandSBNRsareessentially identical,butdiffermarkedlyfromthereligious.NonesandSBNRs aremoremale,white,wealthy,andDemocrat.

SBNRsandNonesdiffer,however,inthatSBNRsareslightly younger,slightlybettereducated,andmorelikelymarried.Inthesemetrics,however,theNonesandSBNRsaremoresimilartoeachotherthan tothereligious.Ontheotherhand,SBNRsappearmoresimilartothe religiousthantotheNonesintermsofattendingworship,findingreligiontobeimportant,andendorsingbeliefinGod.

MENTALHEALTHACROSSTHERELIGIO-SPIRITUAL ORIENTATIONSPECTRUM

Religiosity,Spirituality,andMentalHealth

Therelationshipbetweenreligion/spiritualityandmentalhealth hasbeenwell-documentedinanumberofreviewarticles(Deinetal., 2012;Gonçalvesetal.,2015;Koenig,2015,2012;Unterraineretal., 2014;WeberandPargament,2014).Thespecificeffectsofreligiosity andspirituality(asidefromSBNRsandNones)onthevariousmental healthoutcomes,includingmagnitudeoftheeffect,arebeyondthe scopeofthisarticle.Wethereforereferthereadertotheabovereviews, whichcollectivelysuggestthatreligionand/orspiritualityarecorrelated withpositivementalhealthoutcomesacrossavarietyofclinicaland nonclinicalpopulations,includingschizophrenia,depression,substance use,andteenagedelinquency(citedinDeinetal.,2012);anxiety(cited inGonçalvesetal.,2015);andsuicide, maritalinstability,personality traits,parentandchildwell-being(citedinKoenig,2012).Furthermore, positivementalstatesandtraitsarepositivelycorrelatedwithreligiosity and/orspirituality,includingwell-being,meaningandpurpose,hope, optimism,andself-esteem(citedinKoenig,2015);positivereligious coping,communityandsupport,andpositivebelief(citedinWeber andPargament,2014);andsubjectivewell-being(citedinUnterrainer etal.,2014).Despitethelargebodyofevidenceforapositivecorrelationbetweenreligiosityandspiritualityonmentalhealth,however, somestudieshavesuggestedthatreligiosityandspiritualitycanhave adverseeffectsonmentalhealthoutcomesaswell,includingthose citedinWeberandPargament(2014),aswellastherecentworkof Peteet(2019).Nevertheless,thebulkoftheevidencesuggeststhat religiosityand/orspiritualityap peartobecorrelatedwithanumber

ofpositivementalhealthoutcomes,withasmallerbodyofevidence suggestingotherwise.

Critically,however,moremethodologicallyrigorousmethods thatareconsistentacrosstheliteratureneedtobeemployedbeforedefinitiveconclusionsshouldbedrawn.Forexample,theabilityofresearcherstostudytheimpactofreligionand/orspiritualityonmental healthishamperedbytheaforementioneddifficultyindefiningwhat itmeanstobereligiousorspiritual.Indeed,alloftheabovereviews employslightlydifferentdefiniti onsforreligiosityandspirituality becausethey,inturn,relyonthevarieddefinitionsemployedbytheresearcherstheycite.Inadditiontoaheterogeneousdistributionofterms, manyofthetermsemployedarenonspecificandvague(orotherwise problematic)andthereforedifficulttointerpret(Deinetal.,2012). Furthermore,themagnitudesoftheoutcomesthatostensiblybenefit fromreligiosityandspiritualityarereportedinconsistently,ifthey arereportedatall.Asaresult,itisdifficultand/ormethodologically unreliabletoquantitativelysummarizethedata,asinacriterionstandard meta-analyses(twonotablemeta-analysesnotwithstandingbyGonçalves etal.,2015,andSmithetal.,2003).Withoutsuchdata,themagnitude oftheeffectofreligiosityand/orspiritualityisimpossibletoestimate. Assuch,mostreviewsareeitherqualitativeorsystematicreviews, andthereforelessreliable.

Independentoftheseparticulars,thecoremethodologicalquandarytroublingthefield andthecentralbarriertomethodologicalrigor andconsistency isperhapsbestarticulatedbyKoenig,whoelegantly writes: “…humanemotionsandbehaviorarenonlinearandcomplex andareadaptivephenomena.Classicalreductionistlinearstatistical methodsusedinthevastmajorityofstudies(onreligiosityand/or spirituality)maynotbethebestforarealunderstanding” (Koenig, 2015,pp25 26).

SBNRs,Nones,andMentalHealth

greaterspiritualitythanreligiosity andtherefore,beinganSBNR wouldpredictincreasesindepression,separatefromtheoveralllevel ofreligiosityandspirituality.Indeed,thatiswhattheirstudyfound. Overallspiritualityplusreligiositydidnotpredictdepression.Greater spiritualitythanreligiosity,however,predictedincreasesindepressive symptoms,aswellasriskformajordepressivedisorder(Vittengl,2018).

Kingandcolleaguesexaminedtheassociationbetweenspiritualityorreligiosityandpsychiatricsymptomsanddiagnosesamong 7403participantsinthethirdNationalPsychiatricMorbidityStudy inEngland.Theyconcludedthat “peoplewithaspiritualunderstanding intheabsenceofareligiousframeworkappeartohavetheworstmental health,” includingincreasesingeneralizedanxietydisorder,phobias, neuroticdisorders,substanceusedisorders,anduseofpsychotropic medications(Kingetal.,2013,p71).Inanearlierarticle,Kingetal. suggestthatthisphenomenonmayrepresent “vulnerablepeople whoareseekingexistentialmeaningfortheirlives” (Kingetal.,2006, p161).Regardlessofthemechanismbywhichitoccurs,thesetwostudiesseemtosuggestthatspiritualityintheabsenceofreligiosityconfersa greaterriskformentalillness.

Giventhepaucityofresearchonmentalhealthoutcomesof thosewhoself-identifyasaNone,onemaybetemptedtodrawconclusionsabouttheirmentalhealthfromstudiesinvestigatingthosewho identifyasreligiousanddrawingtheinverseconclusionaboutbeing nonreligious.Forexample,tworeviewarticlesfoundthatcertainmeasuresofreligiositywerecorrelatedwithadecreaseinanxietyanddepressivesymptoms(Shreve-NeigerandEdelstein,2004;Smithetal., 2003).Itisnotreasonabletoconcludefromsuchdata,however,that beingaNoneconferstheopposite,namely,anincreaseinanxietyand depression;suchaconclusionisinherentlyflawed,becausetheoriginalauthorswerenotseekingtounderstandtheeffectofnoreligious affiliation.Furthercomplicatingmatters,allsuchstudiesaresubject tothemethodologicalandconceptuallimitationsdiscussedpreviously. SpecificdataonthementalhealthoftheNonesarevirtuallynonexistent.Kingetal.(2013)note,however,thatthosewhoareneither religiousnorspiritual acloseapproximationofNones havebetter mentalhealththanthosewhoareSBNR.Still,thedearthofdataon Nonesleavesresearchseekingtounderstandtheimpactofreligious nonaffiliationonmentalhealthseverelywanting.

Insum,theliteratureonSBNRsandNonesandmentalhealth outcomesisnotwelldeveloped.Toaddressthepaucityofdataonthe mentalhealthofthisgrowingsegmentofthepopulation,more,and better,researchisneeded.

FUTUREDIRECTIONS

Atleastsixobjectivescanbedescribedformentalhealthresearchersandcliniciansseekingtobetterunderstandthementalhealth ofNonesandSBNRsand,mostimportantly,addressthem:collect epidemiologicdata,considerinternationalperspectives,achievesemanticandoperationalconsistency,collaborateacrossdisciplines,seek objectivemeasures,andtalkaboutspirituality/religiositywithpatients. Collectingepidemiologicdataisperhapsthemostimportant,andattainable,objective,assuchdatawillhelpcliniciansunderstandtrends inreligiosity/spiritualityinpatients.ThePewResearchCenter,which conductscomprehensivesurveysonreligionintheUnitedStates,would beasensibleorganizationtoconductsuchresearch(PewResearch Center,2012).ThePewReligiousLandscapeStudyhasprovidedinvaluabledataonthegrowthofNonesandSBNRsinAmerica,collectingusefuldemographicinformationontopicsrangingfromageandsexto politicalaffiliationandreligious practice.However,theindicesmental healthpractitionersareconcernedwithpertaintomentalhealthandwellness.Whatisneededisanunderstandingoftheratesofmentalillnessin NonesandSBNRsincomparisontothereligious.Perhapstappinginto surveysfromtheCentersforDiseaseControl,whichconductsthe NationalHealthInterviewSurveyandtheNationalHealthand

NutritionExaminationSurvey,wouldbeausefulwaytostudymental healthoutcomesinSBNRsandNones.Furthermore,becausebeing anSBNRorNonemayimpactdifferentindicesofmentalillnessincontradictoryways(i.e.,conferalowerriskofdepressionbuthigherriskof anxiety),surveysmustbecomprehensive,investigatingawiderangeof psychiatricdisorders,includinganxiety,mood,psychotic,andsubstanceusedisorders.Thatsaid,thesedataalonewillnotprovide causalinformation.Rather,longitudinalorprospectiveresearchdesigns,inlieuofsimplecross-sectionalresearch,arerequiredtotestpotentialcausallinksandmechanismsofaction.Withoutsuchdata,and longitudinalresearchdesigns,thereislittlehopeforunderstandingthe relationshipbetweenSBNRs,Nones,andmentalhealth.

Second,consideringcategoriesofreligiosity/nonreligiosity/ spirituality aswellasmentalhealthandillness fromaninternational perspectivemayprovideahigh-yieldopportunitytoelucidatethe specificeffectsofreligionorspirituality,becauseitwouldallowresearcherstoidentifyandcontrolforthenonspecificeffectsofAmerican cultureonmentalhealththatarenoteasilyseparatedfromreligious considerationsproper,andmanypatientsseeninclinicalpracticehave internationalorigins.Inaddition,giventhatthereligio-spiritualorientationspectrumvarieswidelyfromcountrytocountry,asdoconceptions andmanifestationsofmentalhealth,itisimportanttounderstandhow beingaNoneinaBuddhistcountry(e.g.,Myanmar)isdifferentfrom beingaNoneinaMuslimcountry( e.g. ,SaudiArabia),andwhether orhowmentalhealth,howeveritisconceived,isaffected.Internationalresearchintroducesahostofcomplicatingfactors(language, forone),butthisshouldnotdissuaderesearchersfromtryinggiven theostensiblebenefits.

Third,fordecades,researchershavecalledforpreciseandconsistentdefinitionsandoperationalizationofrelevantterms,including religious,spiritual,SBNR,orNone.Butconsistently,thefieldhasstruggledtoachievesemanticandoperationalconsistency.Onegrouphasrecentlybeenabletoidentify,throughpsychometricanalysis,specificand precisecomponentswithinaglobalmeasureofreligiosity/spirituality, providinganavenueforsubsequentstudyofSBNRs(McClintock etal.,2019,2016).TheyconductedExploratoryFactorAnalyseson asampleof5512individuals(andsubsequentConfirmatoryFactor Analysisonadifferentpool)toderivecommonunderlyingdimensions ofspirituality,identifyingfiveinvariantfactorsacrossthreedifferent countries:love,unifyinginterconnectedness,altruism,contemplative practice,andspiritualreflection.Althoughthisparticularanalysisdid notexamineSBNRsinparticular,orteaseapartmore “religious ” factorsfrom “spiritual” factors,researchlikethis,whichdeconstructs globalmeasuresofreligiosityandspirituality,canallowresearchers whostudySBNRstoassesstherelationshipbetweenSBNR-hood andmentalhealthwithgreaterprecisionandgranularity.

Fourth,tryingtounderstandthementalhealthofNonesand SBNRsrequiresaninterdisciplinaryapproach,aboveandbeyonddefiningreligiosity,spirituality,orSBNR.StudiesaimedatamorecompleteunderstandingofSBNRswillrangefromneurosciencetopublic health,fromtheclinictothecommunity,andfromafirst-tothirdpersonperspective.Itisimportantthatmentalhealthcliniciansare involvedintheresearch.Theirpersonalinteractionswithpatients whoidentifyasNonesorSBNRsprovidecriticalinformationforresearchers.Onlytheycanprovidethefirst-personperspectivethatresearchersneed.Inaddition,publichealthresearcherswithexpertisein investigatingmentalhealthandwell-beinginlargepopulationsareneeded. Demographerswithexperiencesurveyinglargepopulationsoughttobe involved.Sociologistsandanthropologistswouldprovideinsightintothe roleofcultureandsocietalfactorsinthehistoryanddevelopmentof SBNRsandNones.Experimentalpsychologists,cognitiveneuroscientists, geneticists,andbiologistsneedtofocusspecificallyonobjectivemeasures ofmentalhealth.Scholarsfromthefieldsofphilosophy,religiousstudies, theology,andlinguisticsmayhelpdefineandrefineresearchers'understandingofwhatitmeanstobeanSBNRoraNone.Altogether,for

©2020WoltersKluwerHealth,Inc.Allrightsreserved.

Copyright © 2020 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

clinicianstotrulyunderstandthereligio-spiritualorientationsoftheir patients,interdisciplinaryworkofthissortneedstobedone.

Fifth,andperhapsmostambitiously,investigatorsneedtodevelopobjectiveassessmentsofspiritual,religious,andSBNRgroups ofindividuals.Self-reportandbehaviormeasuresarehelpfulandinteresting,butmoreispossible.Thefieldwouldbenefitfromneuroimagingstudiesthatexplorestructuralandfunctionalunderpinningsof thesereligio-spiritualorientations.TherearenopublishedneuroimagingfindingsonSBNRsorNones.Oneresearchgrouprecentlyreported onneuroanatomicalcorrelatesofreligiosity/spiritualityanddepression, butspiritualityandreligiositywerenotdifferentiated(Milleretal., 2014).Studiessuchasthese,ifdoneonSBNRs,canhelpelucidate themechanismsbywhichvarietiesofreligio-spiritualorientation confertheirvariousbenefitsoradverseeffects.Employingobjective measuresofreligio-spiritualorientation,thefieldmustpursueways ofassessingitsimpactonmentalhealth.

Finally,andmostimportantly,cliniciansneedtoreneweffortsto inquireaboutpatients'religiousandspiritualorientation.Asdiscussed previously,thedatashowthatmillionsofAmericansidentifyasSBNR orNone,butfewclinicianseveninquireaboutreligionand/orspirituality.Toneglectinquiryintospiritualandreligiousmattersinpatients' liveswillultimatelyharmthem.Afrankandopendiscussionofone's spiritualityandreligiositycanpositivelyimpactaclinician'sencounter withapatientinmyriadways.Byinquiringaboutapatient'sspirituality and/orreligiosity perhapsdiscoveringthattheyareSBNRandascertainingwhy,whateverthereasonmaybe one'sdiagnosticformulation,therapeuticapproach,orpharmacologicchoicesmaybeaffected. Consider,forexample,a22-year-oldpatientwhopresentswithsymptoms ofmajordepressivedisorder.HewasraisedinaconservativeCatholic family(oranalternativesociallyconservativetradition),butdecidedto leavehischurchbecausehisbestfriendidentifiesasahomosexualand hestrugglestoreconcilethatfactwiththeformalteachingofhisparish, whichteachesthathomosexualityisasin.Havingleftthechurch,he nowidentifiesas “spiritualbutnotreligious.” Perhapspsychotherapy couldbefocusedonthetransitionfromCatholicismtobeinganSBNR, andwhatthe “conversion,” asitwere,meansforhisemotional,moral, ethical,political,and/orculturalidentityandexperience.Perhapsone wouldbelesslikelytoprescribemedication,atleastuntiltheissue couldbediscussedingreaterdetail.Orratherthandiagnosingapatient withmajordepressivedisorder,perhapsadjustmentdisorderismore appropriate.Ontheotherhand,anotherpatientcouldeasilybenefitfrom thetransitiontobeingSBNR.Perhapsalong-timepatienttreatedforanxietywhohasalwaysidentifiedas,say,adevoutMuslim,decidestoformallyleavethatreligionandnowidentifiesasanSBNR,thenbecomes graduallylessbesetbydebilitatinganxiety.Inbothcases,inquiryintoa patient'sspiritualidentityhasthepotentialtochange,forthebetter,a clinician'sformulationandtreatmentapproach.ThepointisnottosingleoutCatholicismorIslam,butrathertoillustratethatdiscussionofapatient's spiritualorreligiousidentitycanserveacriticalroleinclinicalcare.

CONCLUSIONS

Attheturnofthe20thCentury,WilliamJamespublishedthe VarietiesofReligiousExperience,aground-breakingworkinthephenomenologyofreligion.Now,almost120yearslater,itistimetoconsider theimpactofthevarietiesofreligious(non)affiliationonmentalhealth.

SBNRsandNonesarearapidlygrowingsegmentofthereligiospirituallandscapeintheUnitedStates.SBNRsnowcomprise7.5%of thepopulation,orapproximately17millionindividuals,andNones comprise20%ofthepopulation,orabout46millionpeople.Weknow howSBNRsandNonesdifferdemographicallyfromtheaveragereligiousperson.Althoughagreatdealofresearchhasbeenconducted ontheroleofreligiosityand/orspiritualityonmentalhealth,thesame cannotbesaidforSBNRsandNones.Theresearchagendaidentified previouslywouldhelpmitigatethatdeficiency.

©2020WoltersKluwerHealth,Inc.Allrightsreserved.

Withwhatwealreadyknowabouttheemergenceandprevalence ofindividualswhoidentifyasSBNRorNone,itisalsoclearthatmentalhealthcliniciansmustexpandtheirresponsetosuchindividualsin clinicalpractice.Pastassumptionsaboutthemeaningofreligionor spiritualityinpeople'slivesarenolongervalid.Theabsenceofreligiousaffiliationrevealslittleabouthowandwhereanindividualfinds meaningandpurpose,orthenatureorintensityoftheirspiritualpursuits.Itmayevenmeanthatthepersonhassomesenseofaffiliation withmultiplereligiousgroups,just noneinparticular.Worse,itmayindicatepasttraumainareligiouscontext.Perhapsthemostimportantresearch,then,beginsattheclinician-patientlevelwithsensitiveand curiousexploration,asindicated,ofeachpatient'sspiritualandreligious experiencesandneeds,regardlessoftheinitialaffiliationornonaffiliation response.Pendingfurtherresearchonmentalhealthoutcomesamong SBNRsandNones,cliniciansshouldconducttheirownidiographic analysisofwhatthesedesignationsmeanforindividualpatients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

TheauthorswouldliketothanktheGroupfortheAdvancementof Psychiatryfortheirendorsementofthismanuscript.Theywouldliketo officiallyacknowledgemembersofthepublicationcommittee,includingDavidAdler,MaryBarber,JackDrescher,andCarolNadelson.

DISCLOSURES

Theauthorshavenoconflictsofinterestorsourcesoffunding todisclose.

REFERENCES

AmmermanNT(2013)Spiritualbutnotreligious?Beyondbinary. JSciStudyRelig 52:258 278.

AnandarajahG,HightE(2001)Spiritualityandmedicalpractice:UsingtheHOPE questionsasapracticaltoolforspiritualassessment. AmFamPhysician.63: 81 88.

ArgyleM,Beit-HallahmiB(1975) Thesocialpsychologyofreligion.London: Routledge&K.Paul.

Barrie-AnthonyS(2014) “SpiritualbutNotReligious”:ARising,MisunderstoodVotingBloc-TheAtlantic. Atl.Availableat:https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/ archive/2014/01/spiritual-but-not-religious-a-rising-misunderstood-voting-bloc/ 283000/.AccessedAugust15,2017.

ChavesM(2011) Americanreligion:Contemporarytrends.Princeton,NJ:Princeton UniversityPress.

CurlinFA,ChinMH,SellergrenSA,RoachCJ,LantosJD(2006)Theassociationof physicians'religiouscharacteristicswiththeirattitudesandself-reportedbehaviorsregardingreligionandspiritualityintheclinicalencounter. MedCare.44:446 453.

DeinS,CookCCH,KoenigH(2012)Religion,spirituality,andmentalhealth. JNerv MentDis.200:852 855.

DrescherE(2012)Doesrecordnumberofreligious “Nones” MeanDeclineofReligiosity? ReligDispatches.Availableat:https://religiondispatches.org/does-record-numberof-religious-nones-mean-decline-of-religiosity/.AccessedFebruary3,2020.

FullerRC(2001) Spiritual,butnotreligious:Understandingunchurchedamerica Oxford,UnitedKingdom:OxfordUniversityPress.

GonçalvesJP,LucchettiG,MenezesPR,ValladaH(2015)Religiousandspiritual interventionsinmentalhealthcare:Asystematicreviewandmeta-analysisof randomizedcontrolledclinicaltrials. PsycholMed.45:2937 2949.

HadawayCK,MarlerPL,ChavesM(1993)WhatthepollsDon'tshow:Acloserlook atU.S.churchattendance. AmSociolRev.58:741 752.

HillPC,PargamentKI,HoodRW,McCulloughMEJr.,SwyersJP,LarsonDB, ZinnbauerBJ(2000)Conceptualizingreligionandspirituality:Pointsofcommonality,pointsofdeparture. JTheorySocBehav.30:51 77.

JamesW(1902) Thevarietiesofreligiousexperience.Mineola,NY:DoverPublications.

Copyright © 2020 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

JenkinsJ(2019)'Nones'nowasbigasevangelicals,CatholicsintheUS-Religion NewsService. ReligNewsServ.Availableat:https://religionnews.com/2019/03/21/ nones-now-as-big-as-evangelicals-catholics-in-the-us/.AccessedAugust16,2019.

KennesonPD(2015)What'sinaname?Abriefintroductiontothe “spiritualbutnot religious.” Liturgy.30:3 13.

KingBJ(2016)Chimpanzees:Spiritualbutnotreligious. Atl.Availableat:https:// www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2016/03/chimpanzee-spirituality/475731/. AccessedAugust15,2017.

KingM,MarstonL,McManusS,BrughaT,MeltzerH,BebbingtonP(2013)Religion,spiritualityandmentalhealth:ResultsfromanationalstudyofEnglish households. BrJPsychiatry.202:68 73.

KingM,WeichS,NazrooJ,BlizardB(2006)Religion,mentalhealthandethnicity. EMPIRIC AnationalsurveyofEngland. JMentHeal.15:153 162.

KoenigHG(2008)Concernsaboutmeasuring “spirituality” inresearch. JNervMent Dis.196:349 355.

KoenigHG(2012)Religion,spirituality,andhealth:Theresearchandclinicalimplications. ISRNPsychiatry.2012:1 33.

KoenigHG(2015)Religion,spirituality,andhealth:Areviewandupdate. AdvMind BodyMed.29:19 26.

LipkaM,GecewiczC(2017)MoreAmericansnowsaythey'respiritualbutnotreligious|PewResearchCenter. PewResCent .Availableat:https://www. pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/09/06/more-americans-now-say-theyre-spiritualbut-not-religious/.AccessedAugust16,2019.

McClintockCH,AndersonM,SvobC,WickramaratneP,NeugebauerR,MillerL, WeissmanMM(2019)Multidimensionalunderstandingofreligiosity/spirituality: Relationshiptomajordepressionandfamilialrisk. PsycholMed.49:2379 2388.

McClintockCH,LauE,MillerL(2016)Phenotypicdimensionsofspirituality:ImplicationsformentalhealthinChina,India,andtheUnitedStates. FrontPsychol 7:1600.

McCordG,GilchristVJ,GrossmanSD,KingBD,McCormickKE,OprandiAM, SchropSL,SeliusBA,SmuckerDO,WeldyDL,AmornM,CarterMA,Deak AJ,HefzyH,SrivastavaM(2004)Discussingspiritualitywithpatients:Arational andethicalapproach. AnnFamMed.2:356 361.

MercadanteL(2014) Beliefswithoutborders:Insidethemindsofthespiritualbutnot religious.NewYork:OxfordUniversityPress.

MillerC(2016) “Spiritualbutnotreligious”:Rethinkingthelegaldefinitionofreligion. VaLawRev.102:833 895.

MillerL,BansalR,WickramaratneP,HaoX,TenkeCE,WeissmanMM,PetersonBS (2014)Neuroanatomicalcorrelatesofreligiosityandspirituality:Astudyinadults athighandlowfamilialriskfordepression. JAMAPsychiatry.71:128 135.

NewportF(2010)InU.S.,increasingnumberhavenoreligiousidentity. Gallup Availableat:http://news.gallup.com/poll/128276/increasing-number-no-religiousidentity.aspx.AccessedFebruary26,2018.

NolanS,SaltmarshP,LegetC(2011)Spiritualcareinpalliativecare:Workingtowards anEAPCtaskforce. EurJPalliatCare.18:86 89.

NorkoMA(2018)Whatistruth?Thespiritualquestofforensicpsychiatry. JAmAcad PsychiatryLaw.46:10 22.

PeteetJR(2019)Approachingreligiouslyreinforcedmentalhealthstigma:Aconceptualframework. PsychiatrServ.70:846 848.

PewResearchCenter(2012) “ Nones ” ontheRise:One-in-FiveAdultsHaveNo ReligiousAffiliation.Availableat:https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/ uploads/sites/7/2012/10/NonesOnTheRise-full.pdf.AccessedAugust 15,2018.

PewResearchCenter(2015)America’sChangingReligiousLandscape:Christians DeclineSharplyasShareofPopulation;UnaffiliatedandOtherFaithsContinue toGrow.Availableat:https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/ 2012/10/NonesOnTheRise-full.pdf.AccessedSeptember12,2018.

PuchalskiC,FerrellB,ViraniR,Otis-GreenS,BairdP,BullJ,ChochinovH,Handzo G,Nelson-BeckerH,Prince-PaulM,PuglieseK,SulmasyD(2009)Improving thequalityofspiritualcareasadimensionofpalliativecare:Thereportoftheconsensusconference. JPalliatMed.12:885 904.

PuchalskiC,RomerAL(2000)Takingaspiritualhistoryallowsclinicianstounderstandpatientsmorefully. JPalliatMed.3:129 137.

PuchalskiCM,VitilloR,HullSK,RellerN(2014)Improvingthespiritualdimension ofwholepersoncare:Reachingnationalandinternationalconsensus. JPalliat Med.17:642 656.

SaguilA,PhelpsK(2012)Thespiritualassessment. AmFamPhysician.86: 546 550.

SaucierG,SkrzypińskaK(2006)Spiritualbutnotreligious?Evidencefortwoindependentdispositions. JPers.74:1257 1292.

Shreve-NeigerAK,EdelsteinBA(2004)Religionandanxiety:Acriticalreviewofthe literature. ClinPsycholRev.24:379 397.

SmithTB,McCulloughME,PollJ(2003)Religiousnessanddepression:Evidencefor amaineffectandthemoderatinginfluenceofstressfullifeevents. PsycholBull 129:614 636.

TaylorMC(2007) AfterGod.Chicago:UniversityofChicagoPress.

UnterrainerHF,LewisAJ,FinkA(2014)Religious/spiritualwell-being,personality andmentalhealth:Areviewofresultsandconceptualissues. JReligHealth.53: 382 392.

VittenglJR(2018)Alonelysearch?:Riskfordepressionwhenspiritualityexceeds religiosity. JNervMentDis.206:386 389.

WeberSR,PargamentKI(2014)Theroleofreligionandspiritualityinmentalhealth. CurrOpinPsychiatry.27:358 363.

ZinnbauerBJ,PargamentKI,ColeB,RyeMS,ButterEM,BelavichTG,HippKM, ScottAB,KadarJL(1997)Religionandspirituality:Unfuzzyingthefuzzy. JSciStudyRelig.36:549 564.

©2020WoltersKluwerHealth,Inc.Allrightsreserved.