ADR INSTITUTE Co-Hosted by: Georgia Office of Dispute Resolution State Bar of Georgia Dispute Resolution Section EST. 1993 29TH ANNUAL ADR INSTITUTE O F F I C I A L C O N F E R E N C E P R O G R A M FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 18, 2022 GEORGIA TECH HOTEL & CONFERENCE CENTER 800 SPRING STREET NW, ATLANTA, GA 30308

COPYRIGHT © 2022 BY THE GEORGIA OFFICE OF DISPUTE RESOLUTION (GODR). ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. NO PART OF THIS PUBLICATION MAY BE REPRODUCED OR REPRINTED, ELECTRONICALLY PUBLISHED, STORED IN A RETRIEVAL SYSTEM, TRANSMITTED, DISTRIBUTED, OR OTHERWISE, WITHOUT THE PRIOR WRITTEN PERMISSION OF GODR.

THIS PROGRAM AND ITS MATERIALS HEREIN DO NOT CONSTITUTE LEGAL ADVICE. THE OPINIONS OF PRESENTERS AND PROGRAM MATERIALS ARE NOT NECESSARILY THAT OF THE GEORGIA OFFICE OF DISPUTE RESOLUTION, THE SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA COMMISSION ON DISPUTE RESOLUTION, OR AFFILIATES; THESE ENTITIES DO NOT ASSUME ANY LIABILITY FOR INCORRECT INFORMATION OR ASSOCIATED DAMAGES OR LOSS.

ALL INFORMATION PROVIDED IS CURRENT AS OF NOVEMBER 1, 2022.

COPYRIGHT © 2022 BY THE GEORGIA OFFICE OF DISPUTE RESOLUTION

29THANNUALADRINSTITUTE

1

WELCOME TO THE 29TH ANNUAL ADR INSTITUTE

Welcome to the 29th Annual ADR Institute, co-sponsored by the Supreme Court of Georgia Commission on Dispute Resolution and Dispute Resolution Section of the State Bar of Georgia. For almost three decades, the ADR Institute has been the premiere dispute resolution conference in Georgia, drawing a variety of professional disciplines and featuring both local and national speakers. It has and remains our goal to provide our attendees with quality speakers, informative content, and concrete takeaways which you may implement into your practice.

We are delighted and honored to have nearly 500 attendees for this event. We appreciate those who were able to be here with us in person and are grateful that those who were unable to be with us who are watching the livestream.

The success of any conference depends on the people behind the scenes, and the ADR Institute is no different. There are many individuals who have contributed to the planning and execution of this event, and we would like to take this opportunity to give special recognition to a few:

• Ms. Erika Birg, Dispute Resolution Chair

• Ms. Carole Collier; Ms. Kriste Pope; Ms. Kristy King; and Mr. Herbert Gordon, Judicial Council/Administrative Office of the Courts

• ADR Planning Committee

• FourthParty, Diamond Sponsor

• University of Georgia School of Law Certificate in ADR, Diamond Sponsor

• And an extra special thank you to GODR Deputy Director, Ms. Karlie Sahs, who has served as the crucial person and driving force in organizing this event.

Please mark your calendars for November 17, 2023, as we are planning an extra special conference to celebrate our 30th Anniversary. In the meantime, please let us know how we can be of service to you.

Kindest Regards, Tracy B. Johnson Executive Director

Georgia Office of Dispute Resolution

PREFACE

29THANNUALADRINSTITUTE NOVEMBER 18, 2022 GEORGIA TECH HOTEL AND CONFERENCE CENTER

2

THANK YOU TO OUR DIAMOND SPONSORS

SPONSORS

29THANNUALADRINSTITUTE NOVEMBER 18, 2022 GEORGIA TECH HOTEL AND CONFERENCE CENTER 3

4

5

LAW.UGA.EDU/ADR To learn more, please visit or adrcert@uga.edu Faculty Director, Alternative Dispute Resolution Certificate 6

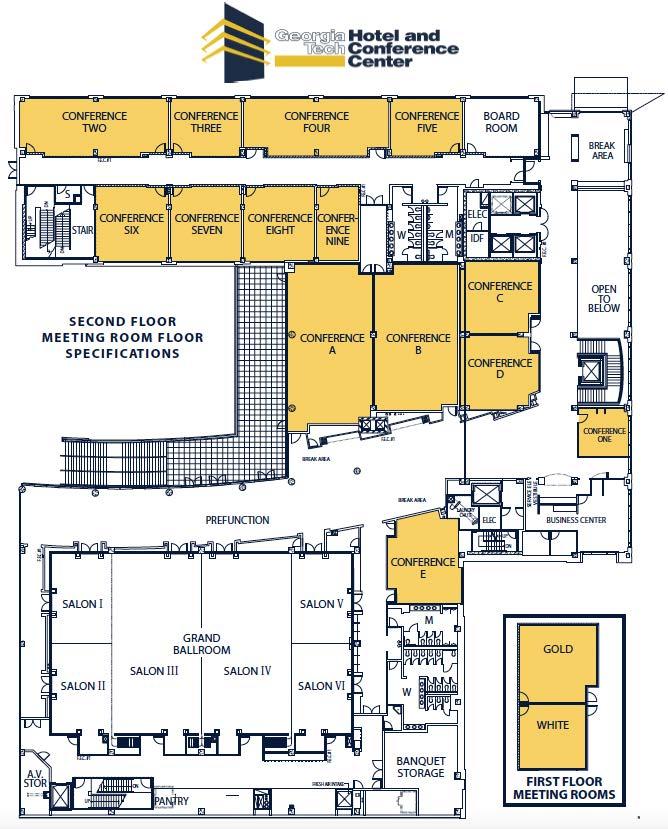

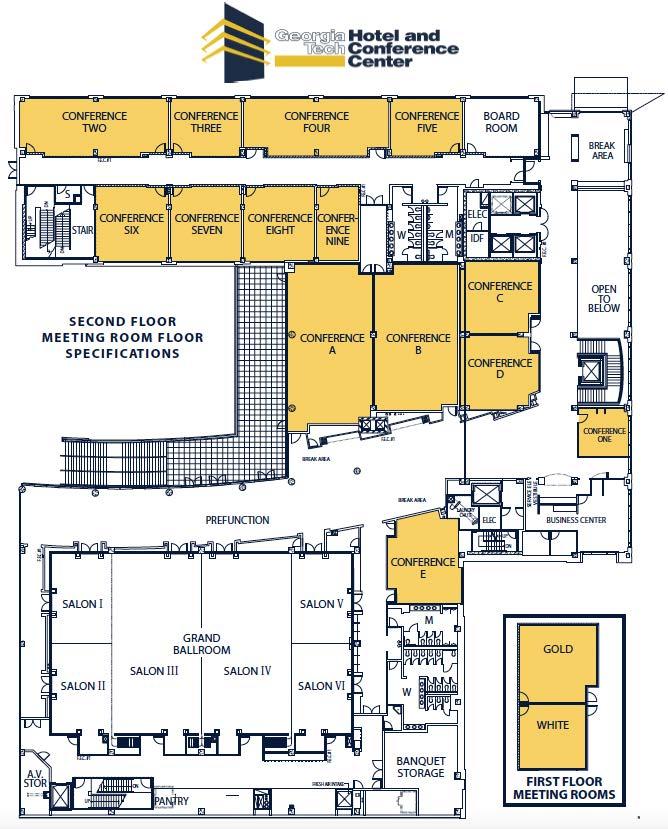

VENUE INFORMATION

GEORGIA TECH HOTEL & CONFERENCE CENTER

800 Spring Street NW, Atlanta, GA 30308

CONFERENCE SPACE

The conference space is on the second floor. There will be many GODR Event signs posted throughout to help you navigate.

To access the conference space through the front lobby, take the stairs or elevator up one floor. Both the stairs and elevator to the second floor are located to the right, just beyond the front desk.

To access the conference space through the parking garage, park on or take the parking garage elevator to floor 2. Enter the “Global Learning Center”, then make a right and go through the double doors.

The registration table will be set up outside of the Grand Ballroom. You may check in on Thursday evening at the pre-event reception or on Friday morning, beginning at 7:30 AM.

Track I sessions will be held in the Grand Ballroom (Salons I-IV)

Track II sessions will be held in Conference Room A

The Georgia Courts Registrar will be onsite to assist with neutral registration renewal (not required) in Salons V-VI.

A floor map of the conference space has been provided to you in this conference program.

29THANNUALADRINSTITUTE NOVEMBER 18, 2022 GEORGIA TECH HOTEL AND CONFERENCE CENTER

7

VENUE INFORMATION

GEORGIA TECH HOTEL & CONFERENCE CENTER

800 Spring Street NW, Atlanta, GA 30308

PARKING

Covered (garage) parking is attached to the Conference Center. The walkway from the garage to the lobby (outside) is also covered.

Parking is included all day for the conference (Friday, 11/18. Validation stickers will be including in name badges, which can be picked up at the registration table outside of the Grand Ballroom.

Parking is NOT included during the reception (Thursday, 11/17. The estimated cost for 2 hours is about $10.

If you are lodging at the hotel, overnight parking is not included with your stay. You may park overnight for $21/night.

29THANNUALADRINSTITUTE NOVEMBER 18, 2022 GEORGIA TECH HOTEL AND CONFERENCE CENTER

8

29THANNUALADRINSTITUTE NOVEMBER 18, 2022 GEORGIA TECH HOTEL AND CONFERENCE CENTER 9

INVITES YOU TO A PRE-CONFERENCE RECEPTION StateDisputeBar Resolution Section Dress code: Business Casual GA TECH CONFERENCE CENTER: BALLROOM FOYER 6 TO 8 PM NOVEMBER THURSDAY 2023 17 10

AGENDA APPROVED CLE HOURS: 6 GENERAL CLE HOURS + 1 ETHICS + 1 TRIAL + 1 PROFESSIONALISM START END TRACKI BALLROOM LIVESTREAMED+RECORDED TRACKII CONFERENCEROOMA NOTLIVESTREAMED/RECORDED 7:30AM 8:30AM Registration&Breakfast 8:30AM 8:45AM WELCOMEANDPROGRAMOVERVIEW JusticeJohnJ.Ellington withTracyB.Johnson&ErikaBirg,Esq. AwardPresentation:HaroldG.ClarkeAward BALLROOM 8:45AM 9:45AM VerbalAtemi–ATechniqueforCreativeDisruption:Part1 StephenKotev BALLROOM 9:45AM 9:55AM BREAK 9:55AM 10:55AM VerbalAtemi–ATechniquefor CreativeDisruption:Part2 StephenKotev BALLROOM InTheirShoes KyleeElliott,GCFV CONFERENCEROOMA 10:55AM 11:05AM BREAK 11:05AM 12:05PM PracticalCybersecurity:AHow-toGuide BenLuke,JC/AOC BALLROOM 12:05AM 1:00PM LUNCH SponsorPresentations: FourthParty&UGAADRCertificateProgram ADR INSTITUTE AGENDA PAGE 1 OF 2 Thank you to our sponsors 11

AGENDA APPROVED CLE HOURS: 6 GENERAL CLE HOURS + 1 ETHICS + 1 TRIAL + 1 PROFESSIONALISM

TRACKII CONFERENCEROOMA

PracticalTipsfortheMediatorandAdvocate

RecentDevelopments inArbitration-2022

BREAK

ShowMe...EthicalSafeguards! Host:Dr.TimothyHedeen,Ph.D BALLROOM

RAFFLE&Closing BALLROOM ADR INSTITUTE AGENDA PAGE 1 OF 2 Thank you to our sponsors 12

START END TRACKI BALLROOM LIVESTREAMED+RECORDED

NOTLIVESTREAMED/RECORDED 1:00PM 2:00PM CulturalConsiderationsandLanguageBarriers:

Panelists: JusticeCarlaWongMcMillian;JanaEdmondson-Cooper,Esq.; andMichaelEshman,Esq. Moderator: DouglasJ.Witten,Esq. BALLROOM 2:00PM 2:10PM BREAK 2:10PM 3:10PM ResolvingConflictin ComplexFamilyLawIssues Panelists: AndyFlink;HannibalHeredia,Esq.; ChristinaScott,J.D.; andDawnSmith,Esq. Moderator: TheHon.RebeccaCrumrineRieder BALLROOM

JohnAllgood,Esq.,FordHarrison & ShelbyGrubbs,Esq.,GrubbsADRLLC CONFERENCEROOMA 3:10PM 3:20PM

3:20PM 4:20PM

12:05AM 1:00PM

PREFACE

Forward Sponsors Venue Information Pre-event Reception Information Program Agenda

I.VERBAL ATEMI - PARTS 1 & 2

Session Information Speaker Biography Materials

II.IN

THEIR SHOES

Session Information Speaker Biography Materials

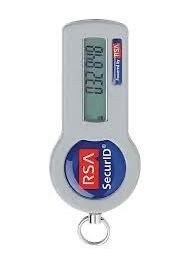

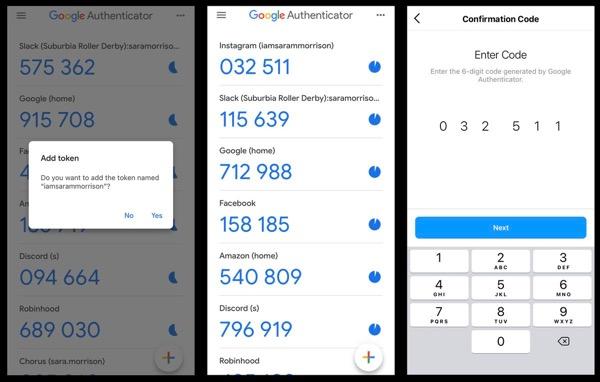

III.CYBERSECURITY

Session Information Speaker Biography Materials

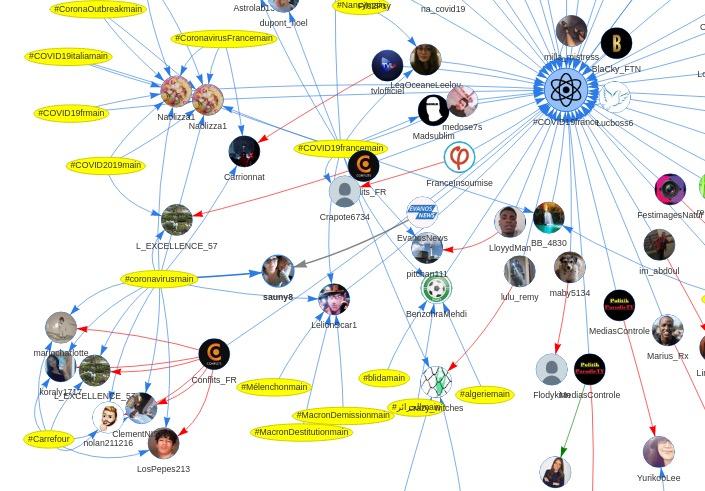

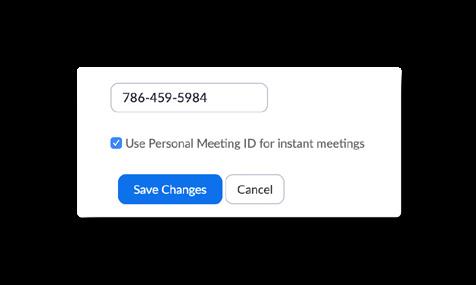

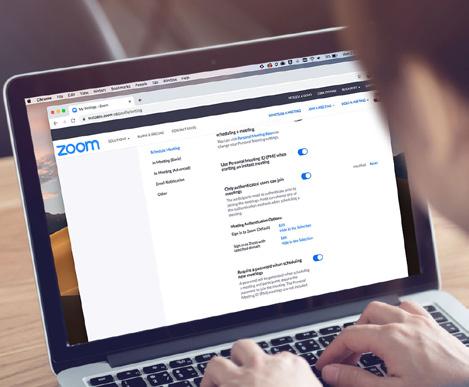

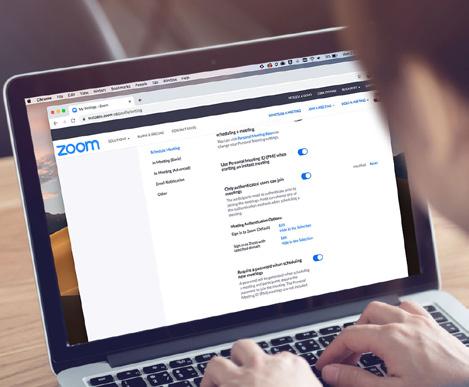

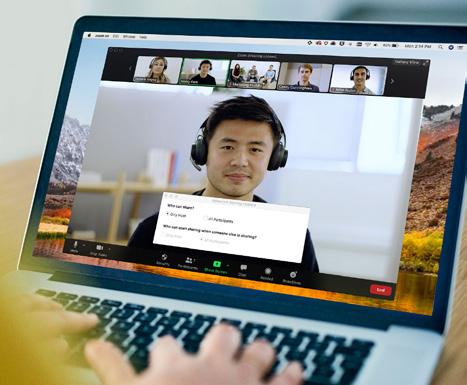

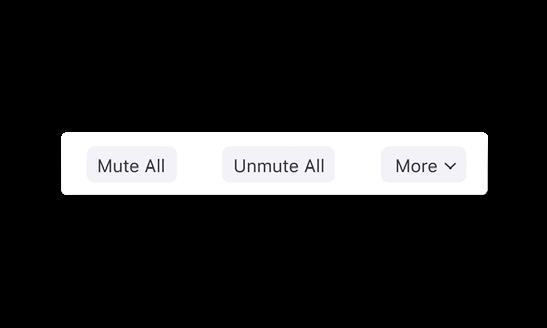

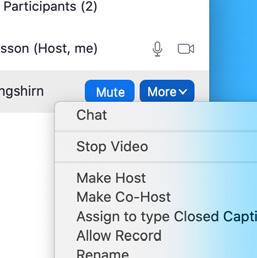

Bonus: Best Practices for Securing Your Zoom Meetings

TABLE

OF CONTENTS

2 3 7 10 11 15 16 17 29 30 32 79 80 81 91

29THANNUALADRINSTITUTE NOVEMBER 18, 2022 GEORGIA TECH HOTEL AND CONFERENCE CENTER 13

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CONSIDERATIONS Session Information Speaker Biographies Panel Materials Committee on Interpreters Materials Professionalism Materials 103 104 112 125 135 140 141 148 169 170 173 192 193 195

FAMILY LAW Session Information Speaker Biographies Materials

IN ARB - '22 Session Information Speaker Biographies Materials VII.ETHICAL SAFEGUARDS Session Information Speaker Biography Materials 29THANNUALADRINSTITUTE NOVEMBER 18, 2022 GEORGIA TECH HOTEL AND CONFERENCE CENTER POSTFACE GA Commission on Dispute Resolution ADR-Related Statutes & Legislation (Georgia) 225 226 228 14

IV.CULTURAL

V.COMPLEX

VI.DEVELOPMENTS

VERBAL ATEMIPARTS 1 & 2

VERBAL ATEMI - A TECHNIQUE FOR CREATIVE DISRUPTION

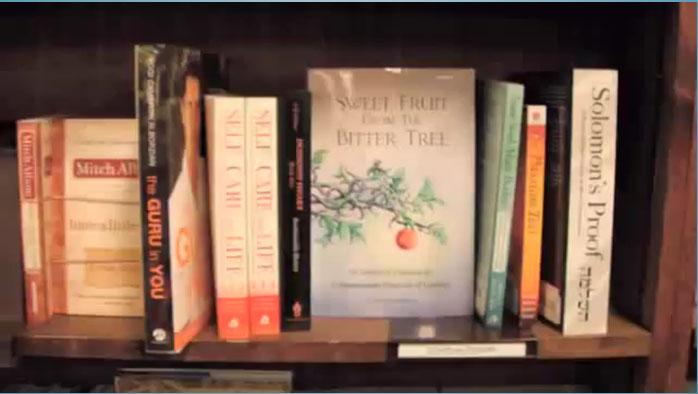

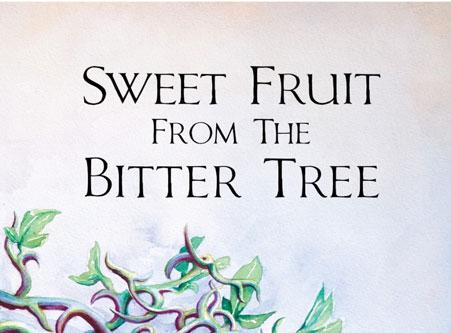

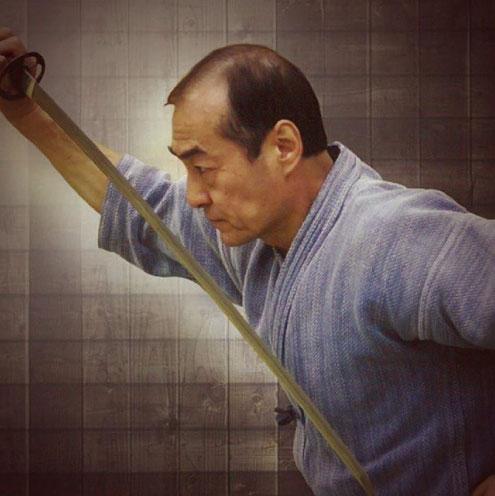

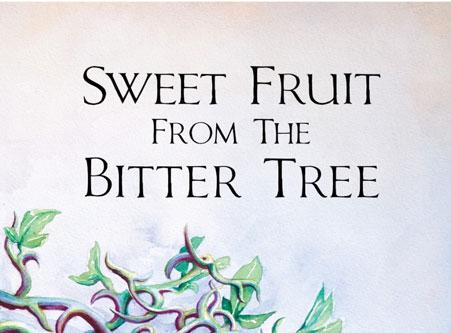

Contained within the Japanese martial art of Aikido, Atemi is a strike used to unbalance or disrupt a pattern of intent. This workshop will explore the concept of verbal Atemi through stories taken from the conflict resolution text, Sweet Fruit from the Bitter Tree: 61 Stories of Creative & Compassionate Ways out of Conflict by Mark Andreas. Join Aikido black belt and seasoned conflict resolver Stephen Kotev as he explores how to apply verbal Atemi to high-conflict situations. The idea of verbal Atemi will be introduced during the plenary session. Part 2 will continue to explore the concept of verbal Atemi as well as how to apply it during high-conflict situations such as mediation during a dynamic breakout session.

Presented by: Stephen Kotev

In-person attendees can join Verbal Atemi in the ballroom. Both sessions will be livestreamed to virtual attendees.

29THANNUALADRINSTITUTE NOVEMBER 18, 2022 GEORGIA TECH HOTEL AND CONFERENCE CENTER PART 1 - 8:45 AM TO 9:45 AM PART 2 - 9:55 AM TO 10:55 AM 1 CLE HOUR FOR EACH SESSION

15

Stephen Kotev

www.StephenKotev.com

Sought out for his insight and innovative ways of tackling difficult disputes, Stephen is one of the few practitioners that sits at the nexus of embodiment, leadership coaching and conflict resolution and is known for his practical, engaging and highly interactive teaching style informed by his study of Aikido, Embodied Peacemaking, Men’s Work, Brazilian Jiu Jitsu, Somatic Abolitionism and mytho somatic explorations.

Based in Washington, D.C., Stephen works as a conflict resolution consultant offering leadership coaching, mediation, negotiation and facilitation services, training and embodiment education to private and government clients. He has extensive experience resolving workplace disputes ranging from team interventions to pre complaint/pre litigation mediation. He holds a Masters degree from George Mason University’s School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution and certificates in leadership coaching and conflict coaching from Georgetown University and Dr. Tricia Jones of Conflict Coaching Matters LLC.

He specializes in training conflict resolvers on how to maintain their calm in high conflict situations and teaches graduate and undergraduate courses on this topic as an Adjunct Professor George Mason University’s School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution. He is the Chair of the Association for Conflict Resolution Taskforce on Safety in ADR and holds rank in the Japanese martial art of Aikido and Brazilian Jiu Jitsu.

Stephen has conducted trainings for international and national audiences from the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Qatar, Germany, Northern Ireland, Ireland, Canada and across the continental United States and can be reached at www.StephenKotev.com

16

VERBAL ATEMI A TECHNIQUE FOR CREATIVE DISRUPTION

Conflict Resolution Consultant offering mediation, negotiation, leadership & conflict coaching, facilitation services, training and somatic education

11/1/2022

Presented by Stephen Kotev www.StephenKotev.com

© Stephen Kotev 2022

17

Masters in Conflict Analysis and Resolution from George Mason University’s School of Conflict Analysis and Resolution

Certified

Chair

Black

11/1/2022

instructor of Being in Movement® Embodied Peacemaking

of the ACR Taskforce on Safety in ADR

© Stephen Kotev 2022 Stephen Kotev All Rights Reserved 2022 18

Belt in Aikido and Purple Belt in Brazilian Jiu Jitsu

OBJECTIVES:

To provide you with a different way of looking at confrontation/engagement To talk about an untapped resource in the Japanese martial art of Aikido To provide powerful examples of creative disruptions of high conflict situations ©

GETTING TO KNOW YOU

• What would you like to learn today/what caught your attention?

• Please also share, What do you do – And how long have you been doing it for ©

WHEN WAS THE LAST TIME YOU DID SOMETHING TOTALLY UNEXPECTED DURING A DIFFICULT CONVERSATION OR MEETING? • Take a moment to reflect • Then find a partner and share your experience and how others were impacted by this action ©

11/1/2022

2022

Stephen Kotev

2022

Stephen Kotev

19

Stephen Kotev 2022

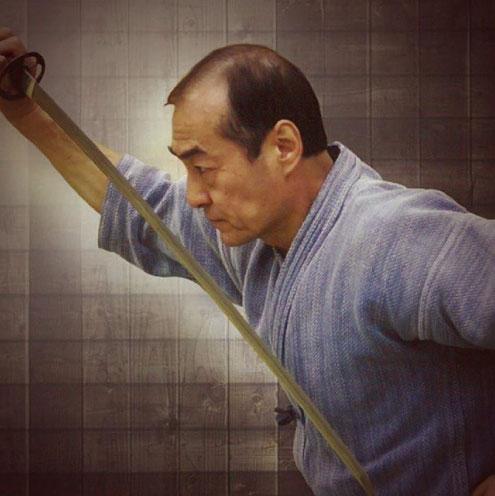

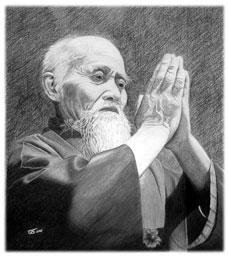

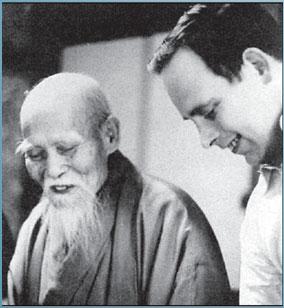

A deeply spiritual man, Ueshiba strove to meld his spirituality with his martial practice.

He created Aikido as a way to transform the notion of warrior: from that of destroyer to protector.

11/1/2022

Stephen Kotev 2022, image courtesy of Aikiweb

©

Image

of Aikido Journal © Stephen Kotev 2022

Morihei Ueshiba Founder of Aikido

courtesy

Image courtesy of Aikiweb.com © Stephen Kotev 2022 20

ATEMI

11/1/2022

© Stephen Kotev 2022 “YOUR

© Stephen Kotev 2022 © Stephen Kotev 2022 21

A strike meant to unbalance and surprise NOT injure the attacker

SHOES UNTIED”

VERBAL ATEMI

11/1/2022

2022

2022 YOU

22

A creative technique used to disrupt a pattern of intent through unexpected and unorthodox means

© Stephen Kotev

© Stephen Kotev

WENT WHERE?...

11/1/2022

2022 + +

© Stephen Kotev

23

GOOD COUNSEL FROM UNCLE IROH

CAN YOU THINK OF ANY OTHER EXAMPLES WHERE YOU DID SOMETHING UNEXPECTED THAT DISRUPTED OR DEESCALATED THE CONFLICT?

“Moving through the gaps in your mind.”

11/1/2022

VERBAL JIU JITSU -SIFU TIM TACKETT

Stephen Kotev 2022

©

© Stephen Kotev 2022 24

Tetsuzan Kuroda Sensei

HILL, WASHINGTON DC JUNE 16, 2007

11/1/2022

CAPITOL

© Stephen Kotev 2022, Image Wikimedia Commons © Stephen Kotev

2022

“You have to hit them with love.”

© Stephen Kotev 2022 25

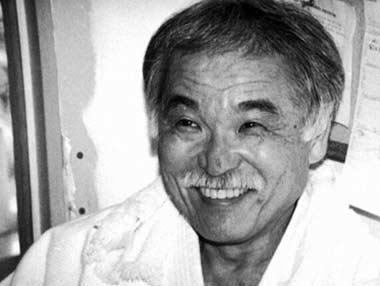

Clyde

Takeguchi Sensei

11/1/2022

YOUR GOAL IS TO CONNECT TO THE BEST VERSION OF THE OTHER PERSON THAT YOU CAN ACCESS

© Stephen Kotev 2022

© Stephen Kotev 2022, Image Wikimedia Commons 26

OPENING PRESENTS BY DAVID CLARK

A SOFT ANSWER

BY TERRY DOBSON

BY TERRY DOBSON

QUESTIONS?

11/1/2022

© Stephen Kotev 2022

Stephen Kotev All Rights Reserved 2022 27

WHAT IS ONE SIMPLE THING THAT YOU TOOK AWAY FROM TODAY THAT YOU CAN USE TOMORROW?

VERBAL ATEMI A TECHNIQUE FOR CREATIVE DISRUPTION

Presented by Stephen Kotev Stephen@StephenKotev.com

Presented by Stephen Kotev Stephen@StephenKotev.com

11/1/2022

28

© Stephen Kotev 2022

IN THEIR SHOES

IN THEIR SHOES

Every year in Georgia, more than 40,000 victims report experiencing domestic violence. ADR professionals encounter these victims every day, but many struggle to understand the barriers victims face and the choices they make. This interactive workshop, presented by Kylee Elliott, will feature an activity to help participants understand the limited options available to victims. This session will conclude with a discussion of how ADR professionals may be part of a coordinated community response supporting survivors in their journey towards a life free from domestic violence.

Presented by: Kylee Elliott

29THANNUALADRINSTITUTE NOVEMBER 18, 2022 GEORGIA TECH HOTEL AND CONFERENCE CENTER

29

9:55 AM TO 10:55 AM 1 CLE HOUR In-person attendees can join In Their Shoes in Conference Room A . This session will NOT be livestreamed to virtual attendees.

Kylee Elliott

Support Survivors of Murder Suicide Project Coordinator Georgia Commission on Family Violence 2 MLK Drive, Suite 470, East Tower, Atlanta, GA 30334 Direct: 404 615 3267 Fax: 470 745 0497 kylee.elliott@dcs.ga.gov gcfv.georgia.gov

Kylee Elliott is the Support Survivors of Murder Suicide Project Coordinator for the Georgia Commission on Family Violence. In that capacity she both individually supports survivors that have lost loved ones to murder suicide by walking alongside them as they navigate the myriad of legal, emotional, and social challenges present after such a tragedy. She develops, promotes, and guides community driven programs that enhance and build local services for survivors of murder suicide across the state of Georgia, and she created and leads the Georgia Murder Suicide Response Network which consists of a statewide network of licensed mental health clinicians trained in providing grief support to survivors of violent loss using the Restorative Retelling model of clinical support.

Prior to her current role Kylee worked for nearly a decade at a community based domestic violence and sexual assault center directing and managing their legal advocacy program. During her tenure the Cobb County Temporary Protection Order office was recognized by many in the legal community as one of the busiest and most progressive TPO advocacy departments in the state of Georgia.

Kylee has served on the Family Violence Intervention Program (FVIP) Rules Committee for the State of Georgia and has been qualified as an expert witness in family violence. She is the current chair of the Georgia TPO Forum, is a member of

30

the National Homicide Roundtable and the Georgia Suicide Stakeholder Task Force.

Kylee is the former chair of both the Cobb County Domestic Violence Task Force and the Fatality Review Committee.

Kylee regularly provides training and technical support both nationally and locally on issues related to family violence, murder suicide response, safety planning and stalking victimization. Kylee is a Certified Professional Trainer on Stalking Victimization by SPARC, a QPR Suicide Prevention Gatekeeper Instructor, and a a Georgia Women’s Policy Institute Fellow (2020 2021).

Kylee received bachelor’s degrees in both Criminal Justice and English from the University of Georgia and prior to becoming a victim advocate she worked in the legal field as a paralegal and also had an extensive career in the non profit organization field as a fundraising, development and operations director.

31

GeorgiaCommission onFamilyViolence

Whoweare:

●GCFVwascreatedin1992bythestatelegislaturetodevelopa comprehensivestateplanforendingfamilyviolenceinGeorgia

WhatourProjectsare:

●FamilyViolenceFatalityReview

●SupportforSurvivorsofMurder-Suicide

●FamilyViolenceInterventionProgram

●FamilyViolenceTaskForces

●LawEnforcementEducationProgram

WhatwedoinGeorgia:

●Trackdomesticviolence-relatedfatalities

●Studyandevaluateneedsandservicesrelatingtofamily violence

●Evaluateandmonitortheadequacyandeffectivenessofexisting familyviolencelaws

●Initiateandcoordinatethedevelopmentoffamilyviolence legislation

●HosttheAnnualFamilyViolenceConference

●MonitorandcertifyFamilyViolenceInterventionPrograms

●Developmodelsforcommunitytaskforcesonfamilyviolence

●ProvidetrainingtoLawEnforcementonFamilyViolence

Nationally

1in4womenwillexperiencedomesticviolenceduringtheirlifetime. Morethan3womenaremurderedbytheirhusbandsorboyfriendseveryday.

53womenareshottodeathbyacurrentorformerboyfriend orhusbandeverymonth.

Victimsofdomesticviolence:85%women,15%men

Alleconomicgroups,races,religions,sexualorientations,professions,age,etc.

InTheirShoes 11/18/22 NikiLemeshka,GCFV InTheirShoes ThisprojectwassupportedbysubgrantnumberW21-8-013,awardedbythestateadministeringofficefortheSTOPFormulaGrantProgram.Theopinions, findings,conclusions,andrecommendationsexpressedinthispublication/program/exhibitionarethoseoftheauthor(s)anddonotnecessarilyreflectthe viewsofthestateortheU.S.DepartmentofJustice,OfficeonViolenceAgainstWomen.

gcfv.georgia.gov

Howprevalentis domesticviolence?

11,541 NumberofExParteTemporaryProtective Orders(TPOs)IssuedinGeorgiain2020 +76% IncreaseinFamilyViolenceMurder-Suicide FatalitiesinGeorgiafrom2020to2021 HowPrevalentisFamilyViolenceinGeorgia? 212 KnownFamilyViolenceFatalitiesinGeorgia in2021 42,635 NumberofReportedFamilyViolence IncidentsinGeorgiain2021 Whatisdomesticviolence? 1 2 3 4 5 6 32

CycleofViolence

DomesticViolence

Apatternofbehaviors usedtogainor maintainpowerand controloveran intimatepartner.

Physicalandsexual violence,threatsand intimidation, emotionalabuseand economicdeprivation.

InTheirShoes 11/18/22 NikiLemeshka,GCFV

Notallviolentrelationshipsmirrorthiscycle. Manipulation Whydoesshestay? Leavingisa process. Leavingis dangerous. Victimsstayand/orreturnin ordertosurvive. Activity 7 8 9 10 11 12 33

LethalityIndicators:Changeinrelationshipstatus

Whatcanyourprograms dotohelp?

Whatcanyourprogramsdotohelp?

Utilizethescreeningandreinforceitsimportancetothesafetyofall particpants.

Listenandbelievevictims.Benonjudgmental. Askaboutsafedecisions.

“Whatyouaredescribingisconcerningandcommon.” “Youdonotdeservetobeabused.” “Doesthisplanmakeyoufeelmoreorlesssafe?”

Whatcanyourprogramsdotohelp?

Knowtheservicesinyourareaandmakeawarmreferral!

“Advocatesatthedomesticviolenceprogramcantalktoyou aboutyouroptionsandhelpyousafetyplan.”

Sharetheseconfidentialhotlines: 1(800)33-HAVEN(Georgia) 1(800)799-SAFE(National)

Whereisthebuyin?

Systemsinvolvementcanalso leadtoburnoutorthe appearanceofapathyonthepart ofthevictim.

Remember,mediationisjustone ofalargersetofstressorsthat oftenenvelopvictimsaftera familyviolenceincident.

InTheirShoes 11/18/22 NikiLemeshka,GCFV

•24-hourcrisisline •Safe,confidentialshelteraccessibletovictims24/7 Linkswithcommunityagencies •Children'sservices Emotionalsupport •Communityeducationservices •Legalandsocialserviceadvocacy Householdestablishmentassistance •Followupservices Parentingsupportandeducation AllCertifiedDVProgramsProvide Supervise d Exchange/ Visitation Filesfor Divorce FamilyCourt Hearing FinalDivorce Hearing Mediation Interviews byEvaluator Custody Awarded Child Support Established Custody Hearing Temporary Custody Praxis–RuralTechnicalAssistanceonViolenceAgainstWomen

13 14 15 16 17 18 34

InTheirShoes 11/18/22 NikiLemeshka,GCFV Advocacy Program Landlord/HRA Notified WarningGiven EvictionHearing SheriffEvicts 911 Cal Squads Investigat e ArrestNoArrest Arrest Report Non-Arrest Report Jail Arraignment Hearing NoContact Order Conditions ofRelease Pre-Trial/ Hearing TrialSentencingMonitoring /Probation FilesOFP Seeks Shelter ExParte Granted Sheriff Serves Respondent ExParte Denied JudgeReviews Civil Court Hearing InitialIntervention UnitContacted ChildProtection Screening CPInvestigation ChildWelfare Assessment Child Maltreatment Assessment LawEnforcement Notified Risk Assessment ServicePlan SafetyPlan CPCase Mgmt CDAssessment Psych/MentalHealth ParentingEducation Visitation Individual/FamilyTherapy DVClasses Emergency Placement EPC Hearing Safety Assessment CHIPSCOURT CourtOversees andSanctionsPlan ChildPlacement OFP Granted OFP Denied Reliefs Granted OFP Filed Supervised Exchange/Vi sitation Filesfor Divorce FamilyCourt Hearing FinalDivorce Hearing Mediation Interviews byEvaluator Custody Awarded Child Support Established Custody Hearing Temporary Custody Praxis–RuralTechnicalAssistanceonViolenceAgainstWomen Abuser accountability andvictim safetygohand inhand! Accountability andsafetyare twosidesof thesamecoin! Whatcanyourprogramsdotohelp? Knowthedifferencebetweenangermanagementissuesand domesticviolence. Includeabuserinterventioninsettlements. “FamilyViolenceInterventionProgramisrecommendedfor peoplewhohaveusedabusivetacticsintheirrelationships.” FVIPInformationisavailableat: https://gcfv.georgia.gov/family-violence-intervention-programs FamilyViolenceInterventionPrograms(FVIP) ●Designedtorehabilitatefamily violenceoffendersbyholding themaccountableand prioritizingvictimsafety ●FVIPAddresses: Powerandcontrol Beliefsandsocialcontext Effectsofviolenceandabuse ●24-weekpsycho-educational classes ●Focusonaccountabilityand nonviolenceoversaving relationships ●Notconfidential ●Centeredonvictimsafety ●Referralsourcesareupdated uponparticipant’scompletion ortermination FVIPandAngerManagementarenotInterchangable FamilyViolenceInterventionProgram ●Powerandcontrol ●CommunityPsychology ●Target:thoseinarelationshipwith individual ●ProgramsareStateCertifiedand Monitored ●VictimsContactedthroughDVVictim Liaison ●Noconfidentiality AngerManagement ●Impulsecontrol ●ClinicalPsychology ●Target:anyone ●Nostatecertificationand monitoring ●Nocontactwithvictims ●Maybeconfidential ThankYou! NikiLemeshka ProgramManager Niki.Lemeshka@dcs.ga.gov (470)270-4125 ContactGCFV: gcfv.georgia.gov Georgiafatalityreview.com (404)657-3412 19 20 21 22 23 24 35

Family Violence: Georgia Statistics

a pattern of abusive behavior in any relationship that is used by one partner to gain or maintain power and control over another intimate partner.¹

Known family violence-related fatalities in Georgia totaled 1,493; a 57% increase from 2012-2021.² 212

Known family violencerelated fatalities in Georgia in 2021.²

There were 42,031 family violence incidents reported to law enforcement in 2020.³

In 2020, 69% of victims in family violence incidents reported to law enforcement were female and 31% were male.³

In 2021, there were 114,640 crisis calls to Georgia's certified family violence and sexual assault agencies, a 20% increase from 2020 crisis calls.⁴

There were 27,894 family violence and stalking Temporary Protective Orders (TPOs) issued in 2020.⁵

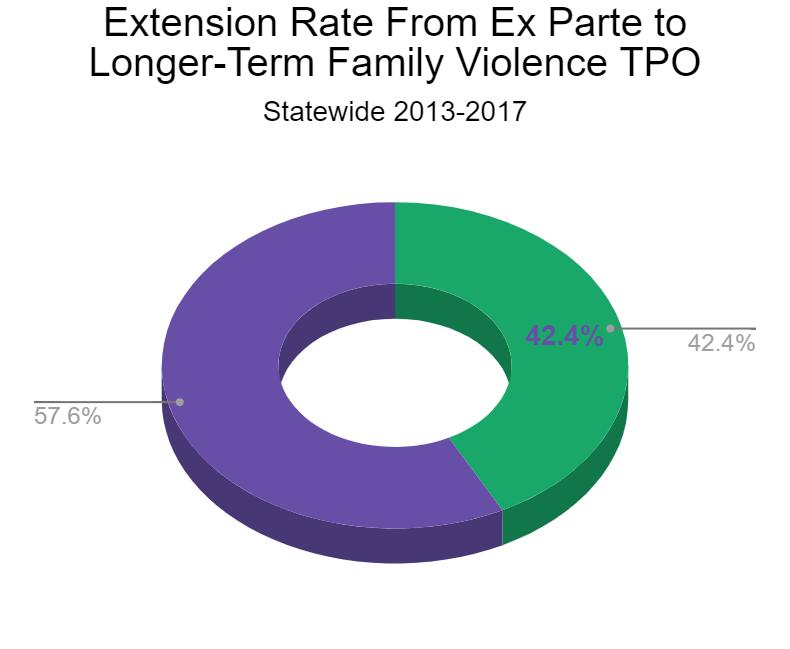

In 2020, the overall "extension rate," or the rate at which Ex Parte (emergency) TPOs were extended into a longer-term TPO (6-month, 12-month, 3-year), was 39%.⁵

There was a 49% increase in family violence-related fatalities from 2020 to 2021.²

In 2021, firearms were the cause of death in 85% of all family violence-related fatalities.²

49%

85% 39%

114,640

27,894 42,031

69%

FAMILY VIOLENCE is

1,493

1-800-33-HAVEN (VOICE/TTY & SPANISH) CALL THE TOLL-FREE, 24-HOUR HOTLINE FOR CONFIDENTIAL HELP AND RESOURCES.

1,381

THE

HOTLINE 855-812-1001

DEAF

(HOTLINE@ADWAS.ORG) CONTACT THE 24-HOUR HOTLINE FOR CONFIDENTIAL HELP AND RESOURCES. 36

Other 31%

Family violence-related murder-suicide fatalities increased 76% from 2020 to 2021.²

Gender in Murder-Suicide Incidents

95% (40)

Weapons in Murder-Suicide Fatalities

murder-suicide

NationalStatistics

by a female.²

by a male and 5% (2) were

A firearm was the cause of death in 94% of all family violence-related murder-suicide fatalities in 2021.²

Over their lifetime, 1 in 5 of women and 1 in 7 men experience severe physical violence by an intimate partner.⁶

Over their lifetime, 1 in 3 (31%) women and 1 in 6 (16%) men have been stalked by an intimate partner placing them in fear for their own life or the lives of those close to them.⁶

Half of women seen in emergency departments report a history of abuse, and approximately 40% of those killed by their abuser sought help in the 2 years before the fatal incident.⁷

The presence of a gun in domestic violence situations increases the risk of homicide by 500%.⁸

41% of sexual and gender minority high school students and 10.5% of heterosexual students, report experiencing physical and/or sexual dating violence.⁹

Lowry, R. (2020). Interpersonal violence victimization among high school students — youthriskbehaviorsurvey,UnitedStates,2019.MMWRSupplements,69(1),28–37.https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su6901a4

This project was supported by subgrant numbers W21-8-012 and W21-8-013, awarded by the state administering office for the Office on Violence Against Women, U.S. Department of Justice’s STOP Formula Grant Program. The opinions, findings, conclusions, and recommendations expressed in this publication/program/exhibition are those of theauthor(s)anddonotnecessarilyreflecttheviewsofthestateortheU.S.DepartmentofJustice.. REVISEDJUNE2022

10.5% 41% 31%16%

In 2021,

of family violence-related

incidents were perpetrated

perpetrated

1. Office of Violence Against Women (2012). http://www.ovw.usdoj.gov/domviolence.htm, 2. Georgia Family Violence Fatality Review Project (2022), 3. Georgia Crime InformationCenter(2021).PersonalCommunication., 4.CriminalJusticeCoordinatingCouncil(2022).PersonalCommunication.,5.GeorgiaProtectiveOrderRegistry, Personal Communication., 6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, (2022). https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/index.html, 7. Huecker MR, King KC, Jordan GA, et al. Domestic Violence. [Updated 2021 Aug 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499891/ 8. Bureau of Justice Statistics (2013). https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/ipvav9311.pdf, 9. Basile, K. C., Clayton, H. B., DeGue, S., Gilford, J. W., Vagi, K. J., Suarez, N. A., Zwald, M. L., &

37

02 Lethality Indicators

2018 | 15TH ANNUAL REPORT

38

One of the key questions Fatality Review Teams (FRTs) sought to answer during the review process was, “What lethality indicators were present in this case?” The answers to this question were uncovered in police reports, court filings and during interviews with the family and friends of the deceased. In nearly every reviewed case, multiple lethality indicators were present.

Unfortunately, due to gaps in information sharing, training and communication among service providers, rarely did anyone who was in a position to help the victim have a complete grasp on the danger the victim was in. Moreover, victims and those closest to them were also not able to connect the dots between the perpetrator’s behaviors and what it meant for the safety of the victim. During interviews, several family members shared with FRTs that, while they knew something was not right, they never imagined their loved one would be killed. Victims who survived their abusers’ attempts to kill them and who were interviewed by the Project indicated a similar sense of their level of danger. While they were scared of what the perpetrator could do, they did not fathom they were in mortal danger — especially at the hands of someone they loved and who professed to love them.

Though all domestic violence cases involve some risk of serious or fatal injury, there are some situations which stand out as more dangerous. Homicide prediction is not an exact science. However, several factors have emerged from research and should be considered benchmarks for increased likelihood of lethal violence.

Georgia is not alone in the study of domestic violence-related deaths. The Project joins 40 other states nationwide whose active FRTs contribute to the study of lethality indicators in abusive relationships (National Domestic Violence Fatality Review Initiative, 2018). Working alongside the research of Jacquelyn Campbell, Evan Stark, T.K. Logan, Neil Websdale and many more, the fatality review process generates data and analyzes trends regarding cases which ended in lethal incidents of abuse. The commonalities within the incidents, also known as lethality indicators, include:

+ history of physical and/or non-physical domestic violence

+ increasing severity or frequency of abusive incidents

+ looming accountability related to criminal charges or civil matters

+ stalking

+ use of strangulation

+ presence of a firearm

+ previous suicide threats or attempts

+ co-occurring depression

+ co-occurring drug or alcohol abuse

+ prior threats to kill, or threats which involve weapons

+ threats to take, harm or kill the victim’s children

+ abuse during pregnancy

+ harm to pets

+ diagnosis of a serious or terminal illness

+ anticipated loss of financial security or job loss

+ possessiveness over victim or severe/morbid jealousy

+ change in relationship status

The wide range of lethality indicators and the ebb-and-flow, in terms of both victim safety and relationship status which accompany abusive intimate relationships, necessitate ongoing safety planning and risk assessment for victims of domestic violence. Steps taken to move away from an abusive relationship should be contemplated and navigated with the assistance of a trained professional who is well-versed in risk assessment and safety planning with victims.

To identify high-risk victims and provide appropriate intervention, professionals conducting risk assessments must consider the comprehensive combination of the victim’s experiences and known risk factors. Given the complexity of the issues in intimate partner violence, generating a list of factors comprehensive enough to encompass all of the issues identified in fatal abuse is nearly impossible. And while we cannot predict what will happen over the course of an abusive relationship nor how it will end, assisting victims in understanding the potential risk their abusive partner poses to their safety is paramount.

8

LETHALITY INDICATORS | 02 39

HISTORY OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE

Without question, past behaviors remain the most accurate indicators of future risk. For that reason, a prior history of domestic violence remains a red flag for potential lethality in abusive relationships. Perpetrators are known to employ a wide variety of techniques in their attempts to maintain power and control over victims. When some types of abuse are present in the history of the relationship, there is a higher association with lethal violence.

In 91 percent of cases reviewed by the Project, there was a known history of physical and/or non-physical domestic violence between the victim and perpetrator prior to the fatal incident. National research has yielded similar findings, showing at least two-thirds of women killed by an abusive partner were battered prior to a fatal incident (Campbell, 2017). A perpetrator’s use of violence in his past relationships may also be tied to potential risk for current or future victims. In 26 percent of cases reviewed by the Project, the perpetrator was known to have been abusive to at least one prior partner.

Victims in cases reviewed by the Project experienced physical abuse which included being hit or slapped in the face or body, being grabbed by the neck, handcuffed to a bed, kicked, pinned down, having a gun pulled on them or held to their head, having a bullet shot into a surface next to them, having their hair pulled,

being pushed down stairs or into a wall, being spit on, and having their teeth knocked out. In 21 percent of cases reviewed by the Project, the abuser was known to perpetrate sexual violence in the relationship. Documented injuries to victims, as noted in police incident reports, included bruises, cuts and contusions, head injuries, busted lips, bloody noses, broken bones, neck injuries due to strangulation, red marks on shoulders, burning caused by a foreign substance, and stab wounds.

INCREASING SEVERITY OR FREQUENCY OF ABUSIVE INCIDENTS

One of the most commonly identified characteristics for increased risk of lethal violence is an uptick in the frequency or severity of abusive incidents. The shift can be sudden and may be accompanied by an increase in serious injuries to the victim. Perpetrators were known to have inflicted serious injury on their victim in 25 percent of the cases reviewed by the Project.

Often when law enforcement responds to abuse, however, there is no significant physical indicator signaling the severity of violence in the relationship. In 75 percent of reviewed cases there was contact with law enforcement about abuse at some point prior to the homicide, in only 23 percent of those incidents was a visible injury documented when law enforcement responded to a domestic violence incident involving the parties.

2018 | 15TH ANNUAL REPORT

02 | LETHALITY INDICATORS HISTORY OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE AGAINST VICTIM

Known Lethality Indicators in Reviewed Cases (2004–2018) DOCUMENTED INJURIES AT LAW ENFORCEMENT CONTACT When Law Enforcement Contacted About Abuse in Reviewed Cases (2004–2018) 9% 91% No Known History of DV Known History of DV 77% 5% No Visible Injuries 18% Visible Injuries, Minor Visible Injuries, Major 40

Perpetrator’s

RATES OF CONTACT WITH CRIMINAL JUSTICE AGENCIES AND COURTS

By Victim and Perpetrator in Reviewed Cases (2004–2018)

PERPETRATOR VICTIM

Law Enforcement

Prosecutor

Magistrate Court

Superior Court

Probation Civil Court/ Juvenile Court

State Court Parole Municipal Court

LOOMING ACCOUNTABILITY RELATED TO CRIMINAL CHARGES OR CIVIL MATTERS

Often accompanying the increased frequency or severity of abuse within the relationship, increasing contact with civil and criminal justice systems is an indicator of elevated risk of lethal violence. In reviewed cases, a startling 83 percent of perpetrators were in contact with law enforcement officers in the five years leading up to the fatal incident of abuse.

In a national study researching risk of intimate partner homicide, victims of completed or attempted femicide experienced abuse by a partner who had been arrested for domestic violence in 27 percent of cases (Campbell, 2017). Further, 48 percent of perpetrators in reviewed cases were known to have a violent criminal history. Details of police contacts about abuse were known in 69 percent of reviewed cases. In those cases, 254 incidents of abuse were reported, of which 199 calls (78 percent) had known outcomes. Roughly

half of those incidents (98 incidents, 49 percent) resulted in an arrest. For more information on criminal justice outcomes in reviewed cases view related data on page 68.

Both victims and perpetrators in reviewed cases were also likely to have engaged in the civil court system, usually through the Temporary Protective Order (TPO), divorce or child support processes. In reviewed cases, 24 percent of victims had previously obtained a TPO against the perpetrator. Thirteen percent of victims had a TPO in place at the time of the fatal incident. TPOs are a highly useful tool for victims seeking safety from abuse, but the multi-step process of obtaining a TPO may lead to an escalation in threatening or violent behavior by the perpetrator. It is imperative all victims of domestic violence seeking relief from the courts be referred to a domestic violence advocate who can explore the potential risks associated with filing a TPO, conduct risk assessment and safety planning, and offer additional resources and support.

10

50

30%

33%

21%

23%

79% 0%

50 100 100 83% 40% 55%

40%

40% 11% 38%

36%

22% 2% 10% 6% 8% 0%

LETHALITY INDICATORS | 02

41

STALKING

The term “stalking” most commonly refers to a course of conduct directed at a specific person that would cause a reasonable person to feel fear. This course of conduct, or pattern of behaviors, often includes the following acts by the perpetrator: placing the victim under surveillance; sending unwanted gifts or messages; damaging the victim’s property; making threats to harm the victim, their loved ones, or their property; and harassing the victim privately or in public. Stalking behaviors were known to be present in 58 percent of all cases reviewed by the Project. Our research supports other research nationwide, indicating intimate partner stalkers are the most dangerous type of stalker and stalking is a risk factor for homicide (Mohandie et al., 2006; McFarlane et al., 1999).

Intimate Partner Stalking was the focus of the 2017 Georgia Domestic Violence Fatality Review Project Annual Report. That report covers the tactics used by intimate partner stalkers in-depth and identifies ways to address communities’ response to the issue. The 2017 report can be downloaded from GeorgiaFatalityReview.com/reports/report/2017-report. This issue is also briefly explored on page 40.

USE OF STRANGULATION

Use of strangulation both indicates an increase in the severity of abuse as well as a higher risk of lethal violence (Campbell, 2017). One study found the likelihood of becoming a homicide victim increased sevenfold for women who had been strangled by their partner (Glass et al., 2008). Non-fatal strangulation assault often leaves no visible injuries. This fact simultaneously reduces the likelihood an abuser will be held accountable for the act, and serves as notice to the victim he is willing and able to kill her.

In circumstances where the victim has been strangled to the point of loss of consciousness on multiple occasions, the lethality risk is substantially higher (Campbell, 2017). Non-fatal strangulation was known to have occurred prior to the lethal incident in 23 percent of cases reviewed by the Project. It should be noted, however, that Project data is primarily sourced from open records of reported abuse by the victim; given this, and considering the victim was deceased and unable to tell us if they had experienced strangulation assault prior to their death, this percentage is likely to be an undercount.

USE OF STRANGULATION

2018 | 15TH ANNUAL REPORT 02 | LETHALITY INDICATORS

RELATIONSHIP

STALKING BEHAVIORS IN THE

Perpetrator’s Known Lethality Indicators in Reviewed Cases (2004–2018)

42% No Known History of Stalking 58% Known History of Stalking 77% No Known History of Strangulation 23% Known History of Strangulation 42

Perpetrator’s Known Lethality Indicators in Reviewed Cases (2004–2018)

PRESENCE OF A FIREARM

Outnumbering all other means combined, firearms were the leading cause of death for victims in cases reviewed by the Project. The presence of a firearm in domestic violence situations increases the risk of homicide, regardless of who owns the gun. This issue is explored more in depth on page 23.

PREVIOUS SUICIDE THREATS OR ATTEMPTS

The strong connection between suicide and domestic violence homicide risk is made apparent when evaluating the indicators which overlap both issues. Abusers who are at increased risk of perpetrating a domestic violence-related homicide or murder-suicide often have: symptoms of depression; a history of prior suicide threats or attempts; a history of substance abuse; experiences of a recent medical crisis, financial issues, loss of a loved one, or relationship changes; access to a firearm; and/or looming accountability for their behavior, such as an impending arrest or a court case.

In a national study on the risk of intimate partner homicide, female victims who were killed experienced abuse by a male partner who had threatened or attempted suicide 39 percent of the time (Campbell, 2017). Georgia research yields identical data: 39 percent of the Project’s reviewed cases are classified as attempted or completed murder-suicides. Further demonstrating the risk a suicide crisis poses to victims of intimate partner violence, perpetrators in Project-reviewed cases were known to have known to have threatened or attempted suicide prior to the fatal incident in 37 percent of cases.

The homicide-suicide connection was the focus of the 2016 Georgia Domestic Violence Fatality Review Project Annual Report. This report includes information and recommendations for how to address the intersection of suicide and domestic violence to reduce the likelihood of a murder-suicide incident. The 2016 Annual Report can be downloaded from GeorgiaFatalityReview. com/reports/report/2016-report. This issue is also explored on page 37.

12 LETHALITY INDICATORS | 02

59% 0% 25 50 75 100 Firearm 23% Stabbing 9% Strangulation, Hanging, or Asphyxiation 7% Blunt Force 1% Run Over by Car 1% Multiple Traumatic Injuries VICTIM CAUSE OF DEATH in Reviewed Cases (2004–2018) SUICIDE THREATS OR ATTEMPTS BY PERPETRATOR Perpetrator’s Known Lethality Indicators in Reviewed Cases (2004–2018) 63% 37% No Known History of Suicide Threats or Attempts Known History of Suicide Threats or Attempts 43

PERPETRATOR’S

HISTORY OF DEPRESSION

Perpetrator’s Known Lethality Indicators in Reviewed Cases (2004–2018)

PERPETRATOR’S HISTORY OF ALCOHOL OR DRUG ABUSE

CO-OCCURRING DEPRESSION

Though not all depressed people will experience a suicide crisis, the two are often linked. In 34 percent of cases reviewed by the Project, the perpetrator was known to be depressed prior to the fatal incident. Like with many of the lethality indicators, there is help for abusers experiencing symptoms of depression which could mitigate the risk of a lethal incident. Sadly, perpetrators in reviewed cases were known to be in contact with a mental health provider sometime in the five years prior to the lethal incident in only 24 percent of cases.

CO-OCCURRING DRUG OR ALCOHOL ABUSE

Substance abuse issues are often mistaken as the root of intimate partner violence, but we must be clear: Substance abuse and domestic violence often coexist in relationships, but substance abuse is not the cause of abuse. Many individuals who abuse substances never abuse their partner and, conversely, many who abuse their partner never abuse alcohol or drugs.

Perpetrator’s Known Lethality Indicators in Reviewed Cases (2004–2018)

Perpetrator’s

The cause of abuse is rooted in power and control, not the use of alcohol or drugs, but substance abuse is connected to increased risk of lethal violence. Alcohol and drug abuse were present in 52 percent of the Project’s cases prior to the fatal incident and Project data falls closely in line with other research. In a national study on the risk of intimate partner homicide, victims of completed or attempted femicide experienced abuse by a partner who was drunk every day in 42 percent of cases (Campbell, 2017). Increased alcohol abuse may also be part of an overall deterioration of the perpetrator’s personal circumstances including neglect of hygiene, depression, lack of sleep and job loss. Any combination of these factors is a cause for concern for victim safety.

Just as with depression, there is help for perpetrators who abuse drugs and alcohol. Although just 7 percent of perpetrators in reviewed cases were known to be in contact with a substance abuse treatment provider in the five years prior to the fatal incident, addressing substance abuse issues in addition to the domestic violence is paramount to reduce risk. This issue is explored more in depth on page 37.

2018 | 15TH ANNUAL REPORT 02 | LETHALITY INDICATORS

34% No

Known History

Depression 48% 52% No

66%

Known History of Depression

of

Known History of Alcohol or Drug Abuse Known History of Alcohol or Drug Abuse

History of Alcohol and Drug Abuse

44

While we cannot predict what will happen over the course of an abusive relationship nor how it will end, assisting victims in understanding the potential risk their abusive partner poses to their safety is paramount.

PRIOR THREATS TO KILL OR THREATS WITH WEAPONS

Abusers do not have to use physical force against a victim to be dangerous; threatening to kill the victim, especially with a weapon, can increase lethality. Making threats to kill the victim is a common tactic used by abusers to obtain or maintain power and control in the relationship. This tactic should also be considered a clear indicator of increased risk for potential lethal violence. In incidents reviewed by the Project, perpetrators were known to have made prior threats to kill the victim in 55 percent of circumstances.

Threats to cause harm to the victim using a weapon were also very common, with victims experiencing these threats in 38 percent of cases reviewed by the Project. While firearms pose a particularly significant threat to intimate partners, threats to use weapons of any type should be seen as a risk factor for potentially lethal violence. In cases reviewed by the Project, the perpetrator had previously harmed the victim with a weapon in 12 percent of cases.

THREATS TO/ABUSE OF VICTIM’S CHILDREN

Abusers often do not limit their violence to the intimate partner. Research has indicated it is not uncommon, in cases which

ended in fatal violence, for the abuser to have made threats to take, harm or kill children, as he demonstrated to the victim his willingness to use more severe violence (Zeoli, 2018b). In 45 percent of the Project’s cases, the perpetrator and victim shared at least one minor child. Project data also revealed that, while threats to cause harm to a child is an often-used tactic to manipulate or control the victim, in many circumstances the abuser had been known to escalate to child abuse. In 26 percent of reviewed cases, the perpetrator had been abusive to a child prior to the homicide. National research reveals a similar trend with abusers threatening to harm the children in 19 percent of cases studied (Zeoli, 2018b). One study showed perpetrators made threats to harm the children 19 percent of the time (Zeoli, 2018b), and killed children during the incident in 19 percent of intimate partner homicides studied (Campbell, 2017).

You can read more about the impact of domestic violence on children in the 2015 Georgia Domestic Violence Fatality Review Project Annual Report, available for download at GeorgiaFatalityReview.com.

THREATS TO FAMILY AND FRIENDS OF THE VICTIM

In 12 percent of reviewed cases, someone other than an intimate partner was killed in the fatal incident. This includes children of the intimate partner, new dating partners, family members

THREATS TO KILL VICTIM MADE BY PERPETRATOR

Perpetrator’s Known Lethality Indicators in Reviewed Cases (2004–2018)

PERPETRATOR MADE THREATS TO HARM VICTIM WITH A WEAPON

Perpetrator’s Known Lethality Indicators in Reviewed Cases (2004–2018)

14 LETHALITY INDICATORS | 02

62% 38% No Known History of Threats to Harm Victim with a Weapon Known History of Threats to Harm Victim

a Weapon

with

45% 55% No Known Threats to Kill Victim Known Threats to Kill Victim 45

CHILD ABUSE PERPETRATION

Perpetrator’s Known Lethality Indicators in Reviewed Cases (2004–2018)

THREATS TO KILL CHILDREN, FAMILY, AND/OR FRIENDS MADE BY PERPETRATOR

Perpetrator’s Known Lethality Indicators in Reviewed Cases (2004–2018)

16%

Known Threats to Kill Children, Family, and/or Friends

Known History of Child Abuse 84%

No Known History of Child Abuse

and bystanders. Often, children and other people close to the victim are targeted because they are with the intimate partner victim at the time of the fatal attack. Other times, the perpetrator intends to cause additional anguish to the intimate partner victim by harming her loved ones. That said, threats to kill family, friends or children of the victim should be seen as an indicator of potentially lethal violence.

Threats to kill family or friends of the victim were present in 16 percent of reviewed cases. National research reveals even more dire findings, with 34 percent of abusers who perpetrated lethal violence having made threats to kill victims’ families prior to the incident (Zeoli, 2018b).

ABUSE DURING PREGNANCY

In a national study on risk of intimate partner homicide, victims of completed or attempted femicide experienced beatings by their partner during pregnancy in 36 percent of cases (Campbell, 2017). The same study found 3 percent of femicide cases involved a victim who was killed while pregnant.

Research on women who died during their pregnancy or first year postpartum found the leading cause of death was homicide and the current or former intimate partner was the perpetrator in 55 percent of those deaths (Campbell, 2017).

Because it is not uncommon for victims at high risk for lethal violence to be abused during their pregnancy, additional screening for abuse and referrals for supportive services for pregnant women are encouraged. Pregnant women are regularly in contact with medical personnel. In fact, studies

show 40–47 percent of homicide victims were in contact with health care professionals in the year prior to their deaths (Campbell, 2017). Routine appointments, such as Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) screenings, provide a good point of entry for domestic violence assessments. Six percent of victims in cases reviewed by the Project were receiving WIC just before or at the time of the homicide.

HARM TO PETS

When animals in a home are abused or neglected, it is a warning sign others in the household may not be safe. A correlation between animal abuse and family violence has been well established, with studies identifying 71–85 percent of victims in domestic violence shelters report their abusers also threatened, harmed or killed the family pets (American Humane Association, 2016; Humane Society of the United States, 2008). Indeed, pet abuse is an effective tool batterers use to terrorize victims and keep them silent about their abuse.

Pet abuse — including tactics such as threats or physical harm to a pet, killing pets, deprivation of pets, and financial abuse impeding the obtaining of veterinary care — often functions to discourage victims from leaving the relationship, for fear the abuser will harm or release the pet if they take steps towards independence. Pets were used to manipulate all the victims interviewed for a recent Georgia study, regardless of the abuser’s reported affinity for the pet (Johnson, 2018). Concern for a beloved companion animal’s welfare prevents or delays 50–100 percent of victims from escaping domestic abuse

2018 | 15TH ANNUAL REPORT

74% 26%

No Known Threats to Kill Children, Family, and/or Friends 02 | LETHALITY INDICATORS 46

(Carlisle-Frank et al., 2004; Johnson, 2018). For victims who flee the relationship, pets left behind may be used as a tool of retaliation against a victim, as a way to coerce her return to the relationship, or as a way to intimidate the victim and children against testifying in court.

While Project data on pet abuse is limited, demand for domestic violence services for Georgia pets is on the rise. Ahimsa House, a Georgia nonprofit organization dedicated to helping human and animal victims of domestic violence reach safety together, has provided more than 84,000 nights of safe shelter for pets in need (M. Rasnick, personal communication, August 17, 2018). During 2017, Ahimsa House saw a 28 percent increase in demand for services over the prior year and received 24 times the number of calls as in 2007, the year the program expanded its reach statewide (Rasnick, 2018). To learn more about services to animal victims of domestic violence in Georgia, visit AhimsaHouse.org.

DIAGNOSIS OF A SERIOUS OR TERMINAL ILLNESS

Loss of physical health is a detriment to the mental health of any person, but for abusers already struggling to maintain a level of control in their family life, the diagnosis of a serious or terminal illness may amp up the risk to an intimate partner victim. The abuser may contemplate the victim’s future without him, which may trigger extreme jealousy. He may view the financial circumstances which often accompany a medical crisis as insurmountable, or may experience the onset of depressive symptoms or suicidal ideations, both of which put him in a position of increased risk to himself, the victim and others.

As is the case with victims experiencing abuse during pregnancy, the medical community is uniquely situated to screen domestic violence perpetrators experiencing a medical crisis and connect them with appropriate, supportive crisis and family violence intervention. In cases reviewed by the Project, during the five years leading up to the fatal incident, perpetrators were known to be in contact with a private physician in 19 percent of cases and made contact with a hospital in 20 percent of cases.

ANTICIPATED LOSS OF FINANCIAL SECURITY OR JOB LOSS

The anticipated loss of a person’s financial security, often in the form of a job loss, is detrimental to the dynamics of any home. In circumstances where abuse is present, the additional pressures associated with financial hardship can be dangerous. Financial success is a measure of power in American life, and

for abusers who struggle to obtain or maintain power and control in their relationships, loss of financial power may open up additional sources for relationship turmoil. In reviewed cases, 41 percent of perpetrators were employed full-time when they killed the victim. Seven percent were employed part-time and 25 percent of perpetrators were unemployed at the time of the lethal incident. For more information on the employment of perpetrators and victims in reviewed cases, consult the data included on page 62.

Although there are supportive community and government services to assist families experiencing financial crisis, it appears they were underutilized in cases reviewed by the Project. For example, only 8 percent of victims and 3 percent of perpetrators were receiving Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), also known as food stamps, prior to the lethal incident of abuse.

POSSESSIVENESS OVER VICTIM OR SEVERE/MORBID JEALOUSY

In a national study on risk of intimate partner homicide, victims of completed or attempted femicide experienced abuse by a partner who controlled all of their activities in 60 percent of cases (Campbell, 2017). The same study revealed that of abusers in those cases, 79 percent were violently jealous, making statements such as “If I can’t have you, no one can.” Georgia’s Project data supports the national findings that severe possessiveness of the victim and intense jealousy are precursors to potentially lethal abuse. In cases reviewed by the Project, perpetrators who went on to kill the victim were known to express attitudes of ownership over the victim 26 percent of the time.

Perpetrators of fatal abuse are also known to exhibit what researcher Neil Websdale refers to as “morbid jealousy.” Discussed in his book, Understanding Domestic Homicide, Websdale’s research reveals almost half of male perpetrators of intimate partner homicide displayed obsessive-possessive beliefs about their partners or former partners (Websdale, 1999).

Often growing from the perpetrator’s jealousy about the partner’s real or perceived affairs with other men, it is not uncommon for an abuser to socially or geographically isolate the victim. In roughly one-third of cases reviewed by the Project, the victim was isolated by the perpetrator prior to the homicide. In more than half of the cases reviewed by the Project, perpetrators were known to have exhibited monitoring and controlling behaviors towards the victim they later killed.

16 LETHALITY INDICATORS | 02

47

ATTITUDES OF OWNERSHIP OF VICTIM IN RELATIONSHIP

Perpetrator’s Known Lethality Indicators in Reviewed Cases (2004–2018)

MONITORING AND CONTROLLING BEHAVIOR IN RELATIONSHIP

Perpetrator’s Known Lethality Indicators in Reviewed Cases (2004–2018) 74%

Known History of Attitudes of Ownership of Victim

No Known History of Attitudes of Ownership of Victim

ISOLATION OF THE VICTIM IN RELATIONSHIP

Perpetrator’s Known Lethality Indicators in Reviewed Cases (2004–2018)

Known History of Isolation

No Known History of Isolation

Known History of Monitoring and Controlling Behavior

No Known History of Monitoring and Controlling Behavior

Monitoring and controlling behaviors are often a part of a pattern of stalking behaviors within the relationship, but also point to unhealthy levels of jealousy or possessiveness which can, in turn, indicate an increased level of fatal risk in an abusive relationship.

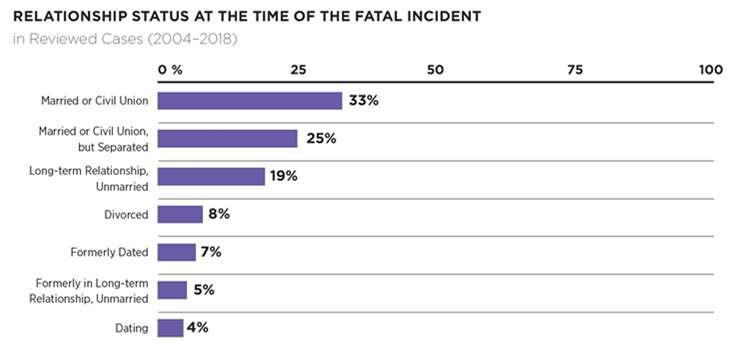

CHANGES IN RELATIONSHIP STATUS

Fatality reviews revealed that simply leaving an abusive relationship does not always lead to safety. Despite this, the public discourse around the issue of intimate partner violence often revolves around the question, “Why doesn’t she just leave?” In addition to relaying a sentiment of victim blame, that question fails to account for the serious risk facing victims who

decide to flee an abusive relationship.

Although studies show victims who leave an abusive relationship do eventually become more safe, statistically speaking, the risk of lethal violence actually increases for victims at the three-month and one-year mark after leaving the relationship (Campbell, 2017). Victims are at the highest risk of being killed by their abusive partners when they separate from them; both rates of, and severity of, physical abuse increase during periods of separation and divorce (Zeoli et al., 2013).

The majority of fatal incidents reviewed by the Project involved current or former intimate partners who were in a long-

2018 | 15TH ANNUAL REPORT

02 | LETHALITY INDICATORS

26%

68% 32%

44% 56%

48

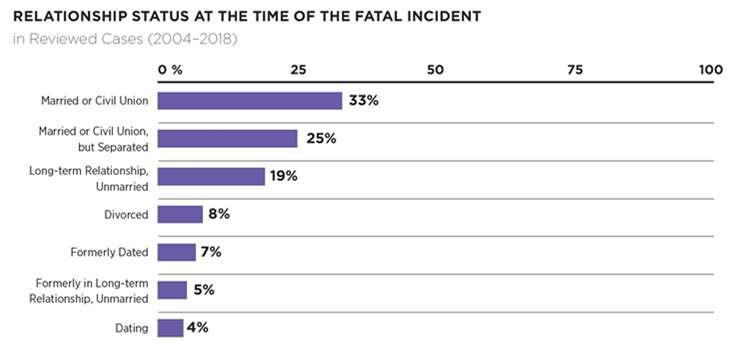

RELATIONSHIP STATUS AT THE

TIME OF THE FATAL INCIDENT in Reviewed Cases (2004–2018)

Married or Civil Union

Married or Civil Union, but Separated 19% Long-term Relationship, Unmarried 8% Divorced 7% Formerly Dated 5% Formerly in Long-term Relationship, Unmarried 4% Dating

standing relationship. In just under half of reviewed cases, the relationship had ended or the couple had separated. However, this data does not accurately relay the anecdotal information which has been revealed through the fatality review process: that almost all victims were contemplating leaving the relationship or taking steps to do so.

A victim’s steps to gain independence may signal to the perpetrator that he is losing control over the victim. Some examples of steps taken by victims in reviewed cases included accepting a new job, increasing social activities, saving money, and changing locks on doors. In some cases, victims had an unspoken desire to leave the relationship and were in the early planning stages of assessing resources and options available to

them. All steps towards independence and separating, even less obvious steps, can trigger an increase in the severity of the abuse.

Understanding the risk factors which signal an increased risk for serious injury or death for domestic violence victims is imperative. Not only does it shape the services and interventions provided for victims and perpetrators, but it can help inform safety plans for victims. Beyond that, communities intent on addressing the problem of domestic violence are most effective when they consider these risk factors as they develop strategic initiatives to combat abuse.

18 LETHALITY INDICATORS | 02

33%

0% 25 50 75 100

25%

49

FAMILY VIOLENCE STATISTICS AND TRENDS IN

THE STATE OF GEORGIA 2013-2017

PUBLISHED JUNE 2020 50

ABOUT THIS REPORT

The coordinated community response to family violence in Georgia is continually evolving and improving. As stakeholders move toward evidence based decision making, the need for reliable data about the problem of family violence grows. The Georgia Commission on Family Violence (GCFV) recognizes the need for accurate and current information on how this prevalent and pressing issue is impacting Georgians. This report represents a key step forward in the State’s capacity to enable a strategic response to family violence.

Family violence in Georgia persists amid silence. Open discussion about the scope of the problem within our communities is an important step to enhance systems’ performance by preventing violence, intervening with people who are abusive, enhancing community connections and support, providing equitable access to resources, and ensuring effective responses with the goal of ending family violence in Georgia.

The data contained in this report represent only reported or known incidents of family violence in Georgia and should be considered an undercount of the true number of incidents statewide. Many abusive relationships are never known to the criminal or civil justice systems, and many services provided to victims and offenders are done under protection of confidentiality.

With the support of other state agencies including the Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI) and the Criminal Justice Coordinating Council, GCFV seeks to act as a clearinghouse for statewide data pertaining to the problem of family violence in Georgia. As we develop our data sharing partnerships, we hope to also grow the capacity of our reporting on this issue and the coordinated community response to family violence in Georgia.

ABOUT GCFV

The Georgia Commission on Family Violence is a state agency created by the Georgia General Assembly in 1992 to develop a comprehensive state plan for ending family violence in Georgia. The mission of GCFV is to provide leadership to end family violence by promoting safety, ensuring accountability, and improving justice for generations to come.

Charged with the study and evaluation of needs, priorities, programs, policies, and accessibility of services relating to family violence in Georgia, GCFV is led by 37 appointed Commissioners and a staff of eight. GCFV is administratively attached to the Georgia Department of Community Supervision (DCS).

1 51

GCFV carries out our statutory duties through the following projects:

Public Awareness and Education GCFV provides training statewide on family violence and related issues, such as building safer communities, protocol development, and ensuring a coordinated community response to relationship violence.

Statewide Annual Conference GCFV’s Annual Family Violence Conference provides an opportunity for more than 600 participants to receive training by state and national experts on best practices addressing family and domestic violence.

Family Violence Intervention Programs (FVIPs) GCFV and DCS establish standards for FVIPs in Georgia and provide training, certification, and monitoring of FVIP facilitators and programs. Certified FVIPs are designed to rehabilitate family violence offenders and are charged with prioritizing victim safety and participant accountability.

Community Task Forces GCFV works throughout the state to help create and support task forces made up of citizen volunteers working to end family violence in their communities.

Domestic Violence Fatality Review - GCFV compiles statistics and studies trends unique to family violence-related deaths in Georgia and works with communities to conduct in depth case reviews and to implement recommendations for systematic change.

Support for Survivors of Murder Suicide GCFV provides support, resources, and referrals to survivors of family violence related murder suicide incidents occurring in Georgia, as well as provides training, technical assistance, and resources to communities responding to murder suicide incidents.

Legislative Advocacy GCFV has been instrumental in creating laws which enhance safety for victims of family violence and their children, and increase accountability for family violence offenders.

Research GCFV conducts ongoing research on a range of issues related to family violence and periodically disseminates the findings to policymakers and the general public.

For more information, visit gcfv.georgia.gov.

2 52

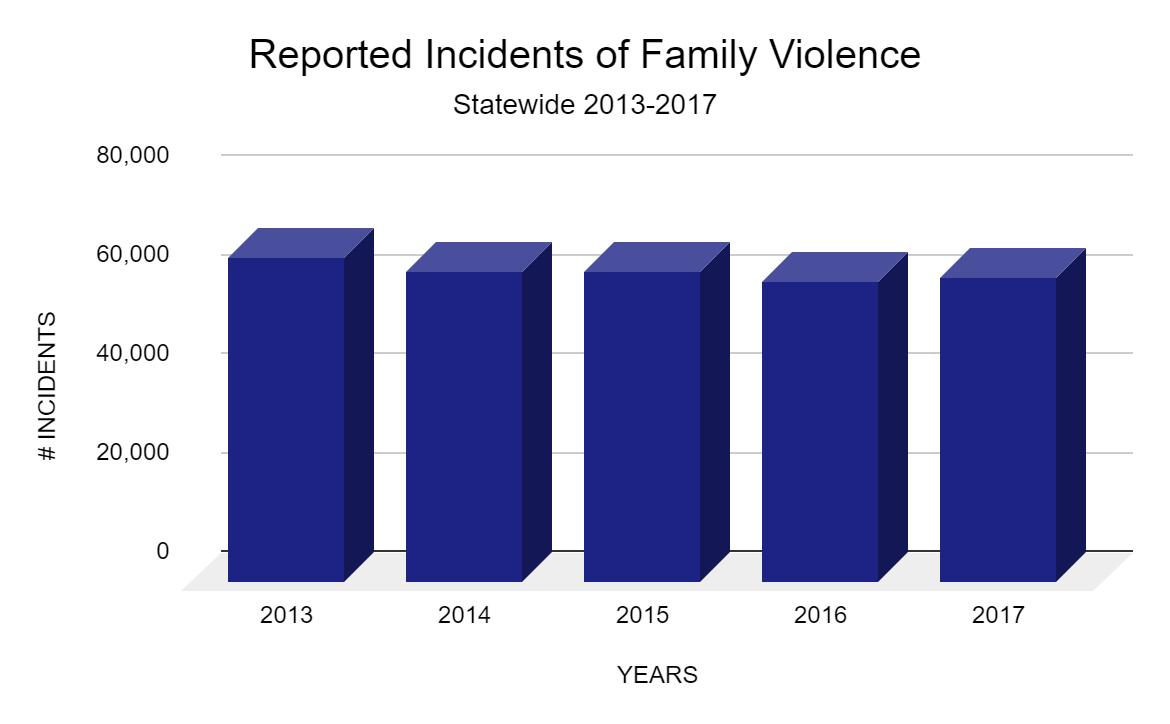

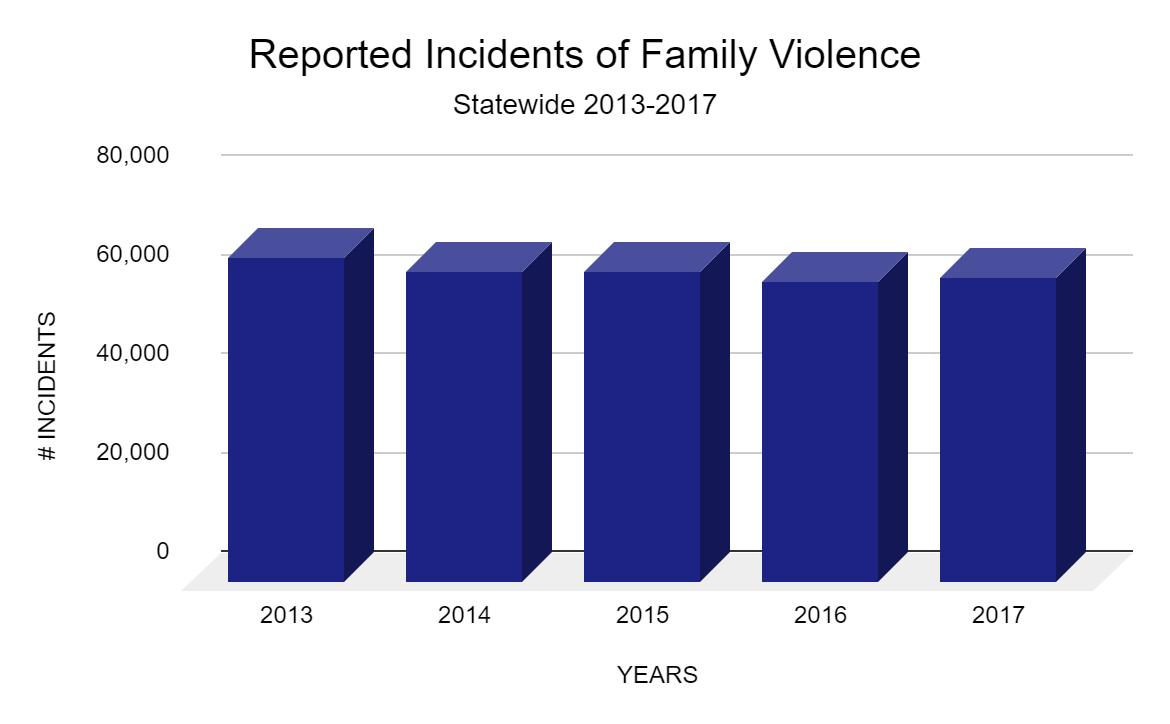

Over thecourseofthe five year reportingperiod,therateof familyviolence incidents reported to lawenforcementfell 6%. There were 311,975 family violence incidentsreported in Georgia,2013 2017

YEARS # INCIDENTS 2013 65,201 2014 62,659 2015 62,358 2016 60,451 2017 61,306

Relationship of Parties in Reported Incidents of Family Violence

Georgia’s familyviolence incidentreportincludesmultiplefields with theoptionforanofficerto select “other.” The definitionof“other”hasnotbeenproperlydefined,andthecontentsofthiscatch allcategory withinthedata are otherwiseunspecified Clarifying theselection criteria forthecategory“other” is an areaforimprovementwithinthedata. This is particularlytruegiventhattheresponse“other” was selected72.4% ofthetimeas it pertainstotherelationshipoftheparties involvedin a familyviolence incident

State of Georgia (2013-2017)

Reported Incidents of Family Violence RELATIONSHI P TOTAL INVOLVED Present Spouse 70,450 Former Spouse 11,853 Parent 24,010 Child 33,261 Step Parent 3,826 Step-Child 2,759 Foster Parent 301 Foster Child 432 Live in Same Household 11,050 Other 415,177

3

53

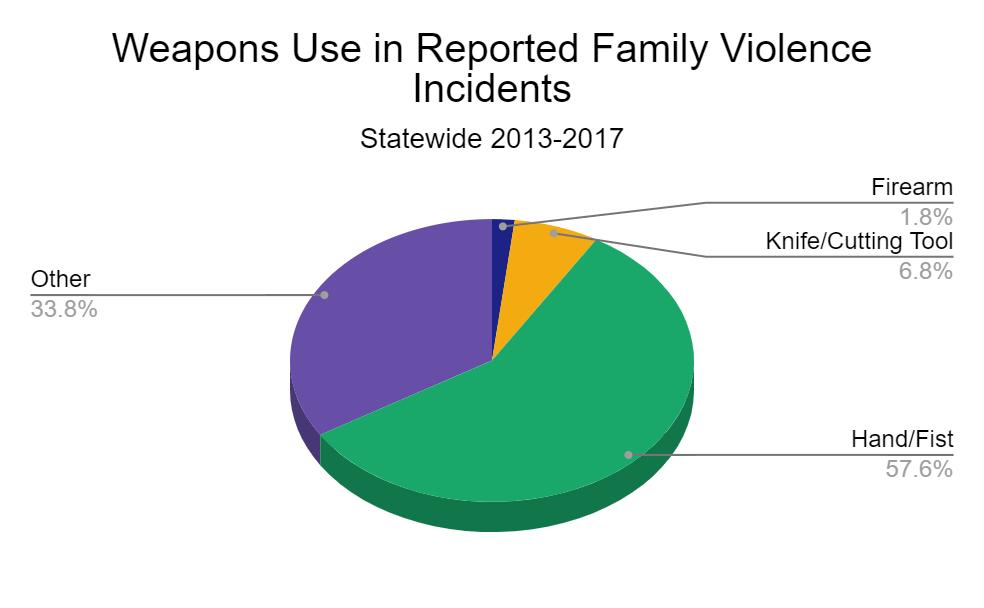

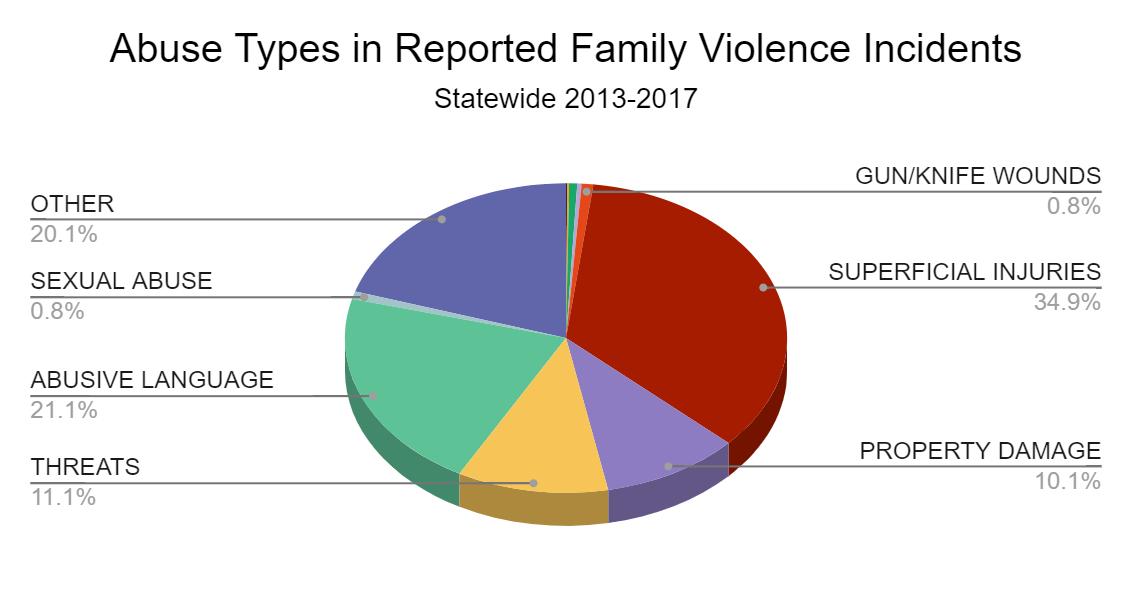

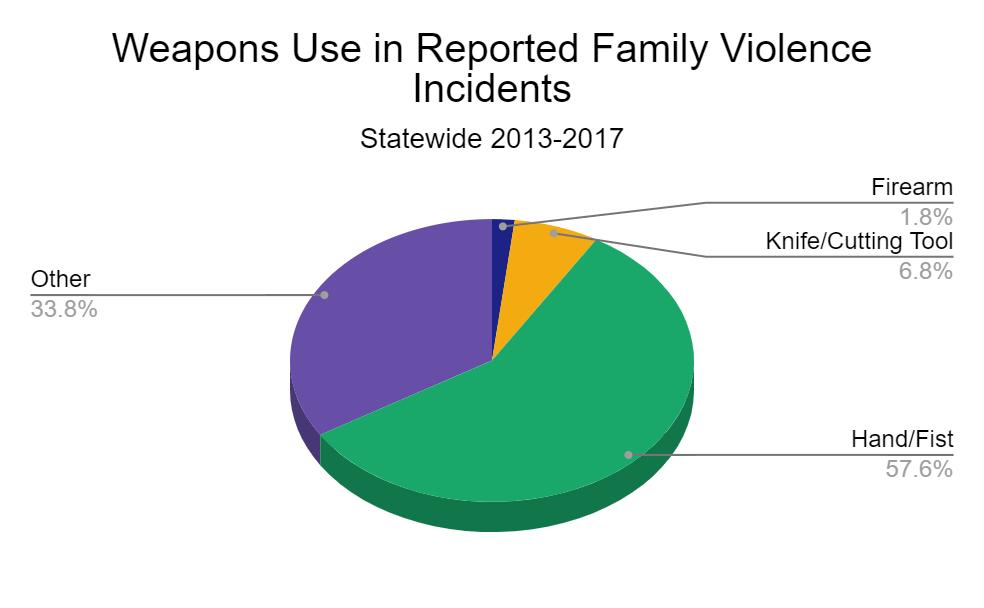

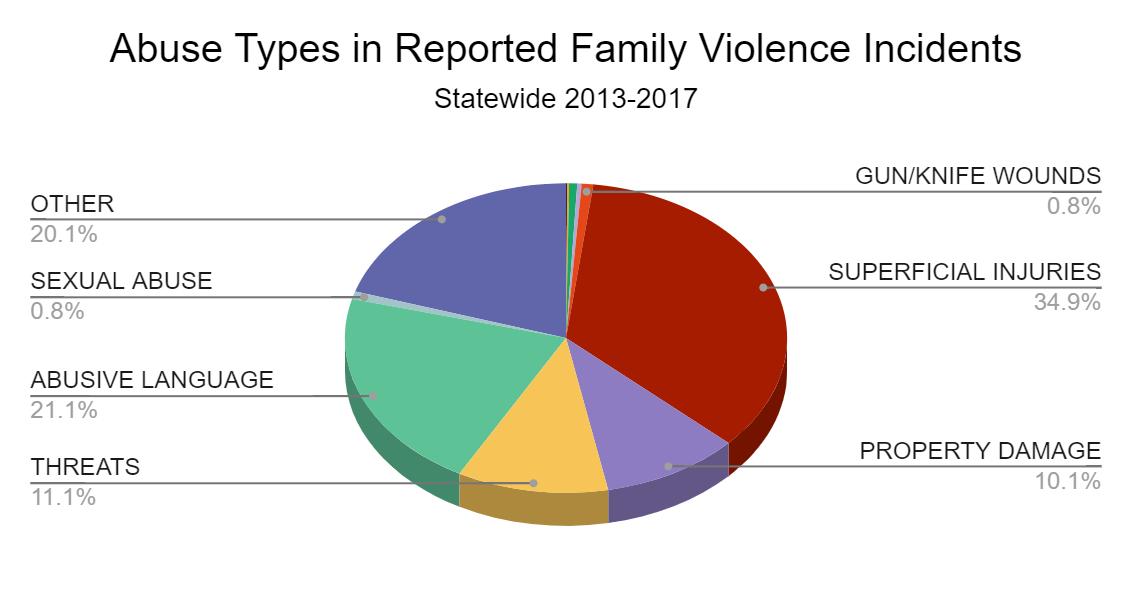

Weapons Use in Reported Family Violence Incidents WEAPON TOTAL Hand/Fist 179,54 5 Knife/ Cutting Tool 21,318 Firearm 5,616 Other 105,49 6 Abuse Types in Reported Family Violence Incidents ABUSE TYPE # INCIDENTS Superficial Injuries 154,843 Abusive Language 93,523 Threats 49,072 Property Damage 44,763 Gun/Knife Wounds 3,757 Sexual Abuse 3,572 Temporary Disability 2,606 Broken Bone 1,431 Permanent Physical Injury 650 Fatal Injury 359 Other 89,375 4 Publicawarenesscampaignsoftenhighlightthe physical aspects of family violence,oftenfeaturingblack eyes andbruises. This imageof the issue ignoresmany more prevalentaspectsof familyviolence Duringthe five-yearreportingperiod, more thanthreequarters (77.2%) oftheincidents involved either no injuriestothe victim (abusivelanguage21.1%, threats11.1%, propertydamage10.1%) or superficialinjuries

fists are

54

(34.9%). Abusers’handsand

the weaponof choicein themajority (57.6%) ofallreportedfamily violence incidents Weaponsuse patterns vary significantlybetween non fatalandfatalincidents (See page12for more information.) State of Georgia (2013-2017)

State of Georgia (2013-2017)

in

Incidents of Family Violence

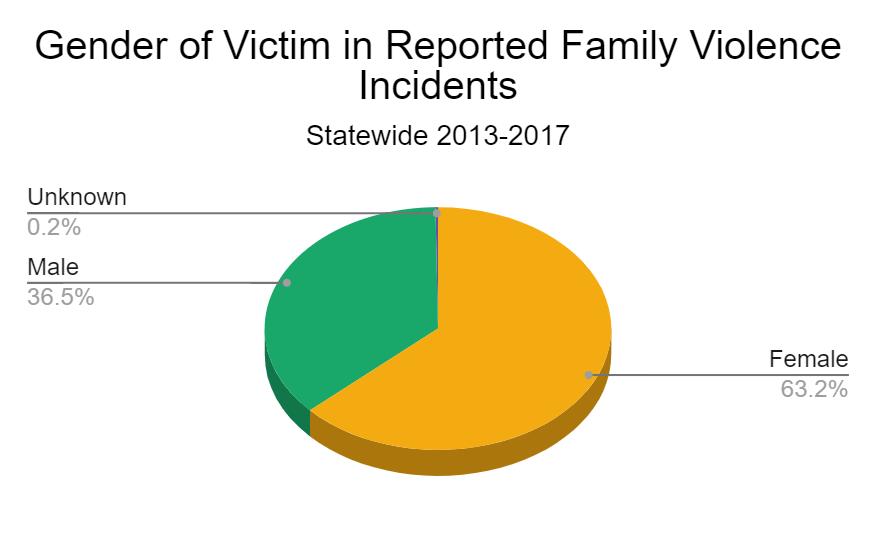

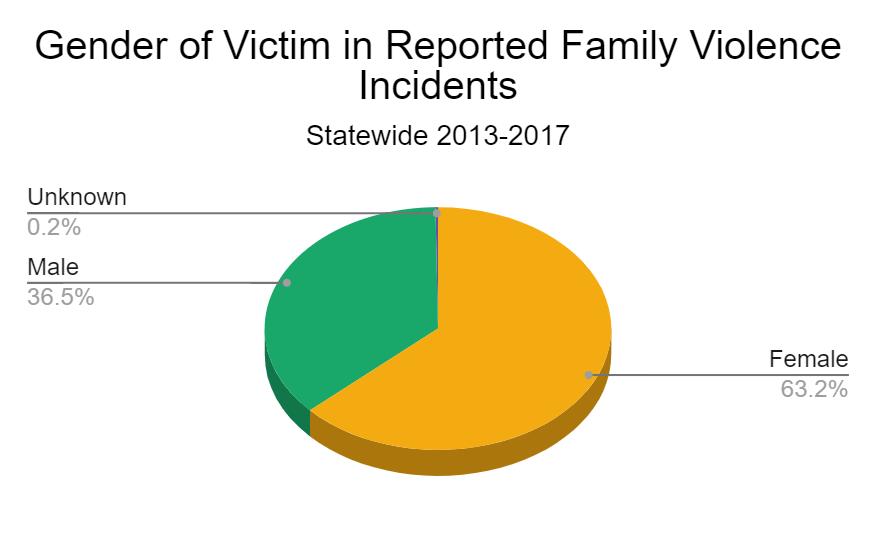

Georgia’sdefinitionof family violence,andthereforethe familyviolence incidentdatacontained in thisreport, includesintimatepartner violence along with incidents involving otherrelationshipsincludingparent/childand roommates,butouroveralltrend fallsinline with nationalresearch which hasrevealedthat victims ofintimatepartner violence aredisproportionately female¹andoffenders are disproportionatelymale Footnote references are available on page 17.

Gender of Offender and Victim

Reported

GENDER # OFFENDERS # VICTIMS Female 108,792 205,687 Male 184,111 118,909 Unknown 8,942 752

5

55

State of Georgia (2013-2017)

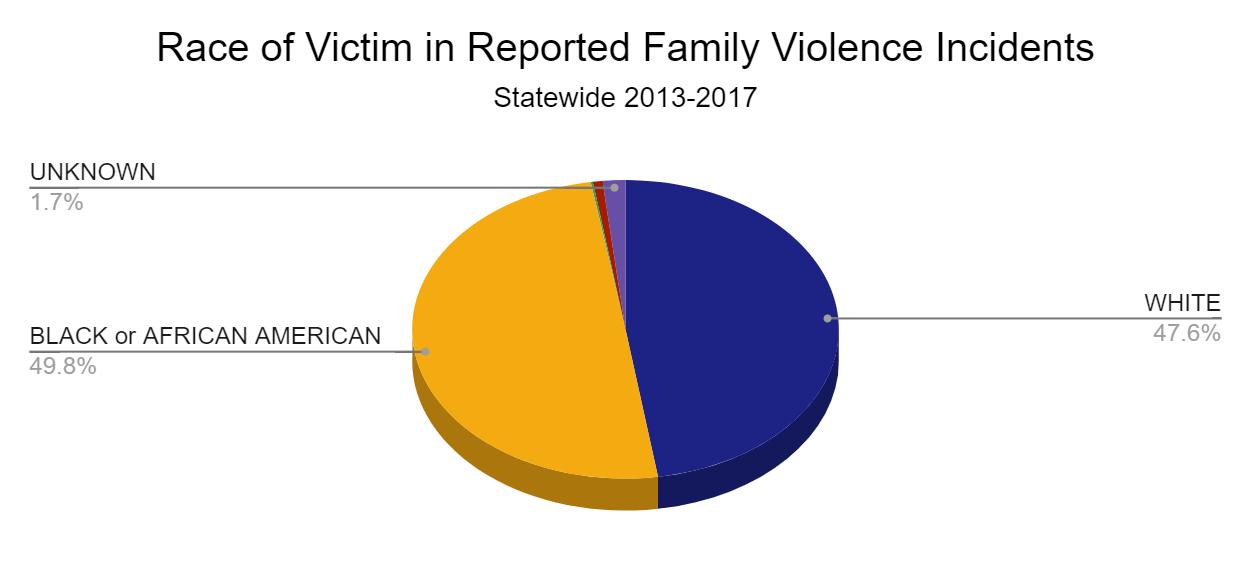

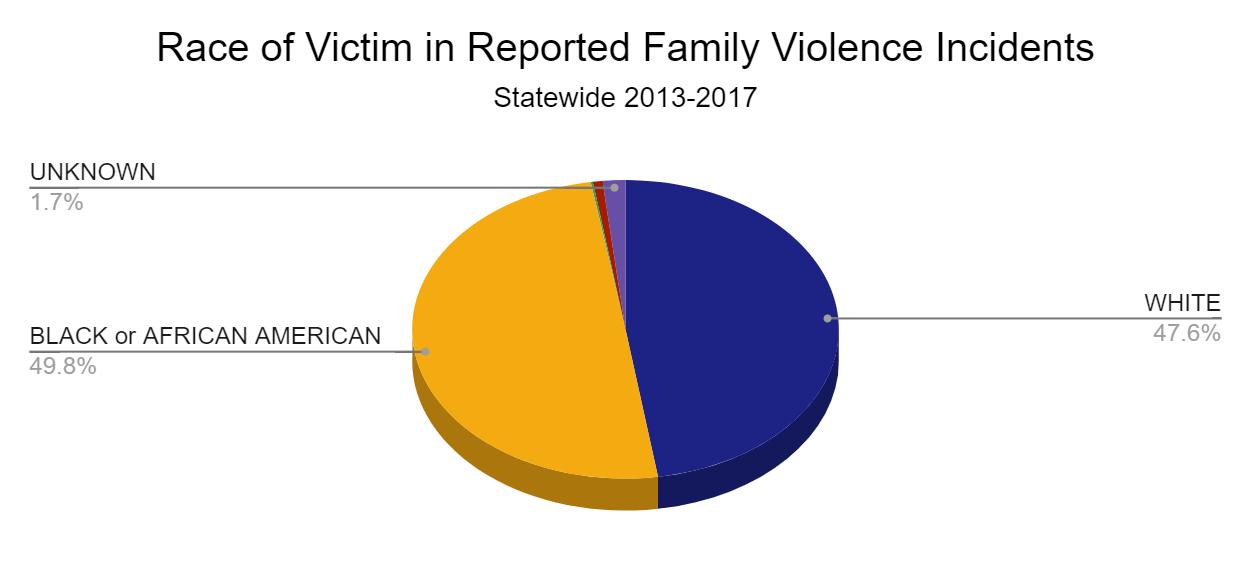

Race of Offender and Victim in Reported Incidents of Family Violence

RACE

# OFFENDERS

American Indian or Alaska Native 408 Asian 2,225 Black or African American 163,743 White 141,297 Unknown 14,057

RACE # VICTIMS

Race in Population of Georgia

Researchontheintersectionof race andintimatepartner violenceis limited,butGeorgia’s victim datashowthat Black women are victimized athigher ratesthantheirpeersofdifferent racialbackgrounds Thisfinding isinline with nationalresearch aboutthedisparateimpactsof abuseon Black communities.²

6

American Indian or Alaska Native 480 Asian 2,372 Black or African American 162,731 White 155,294 Unknown 5,632 56

State of Georgia (2013-2017)

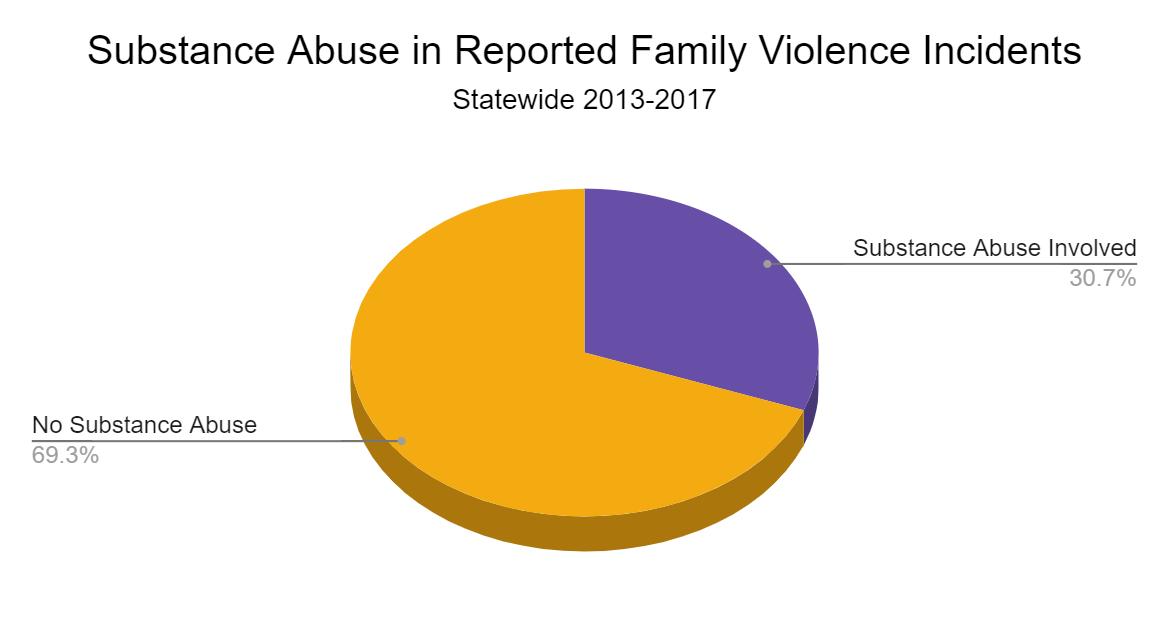

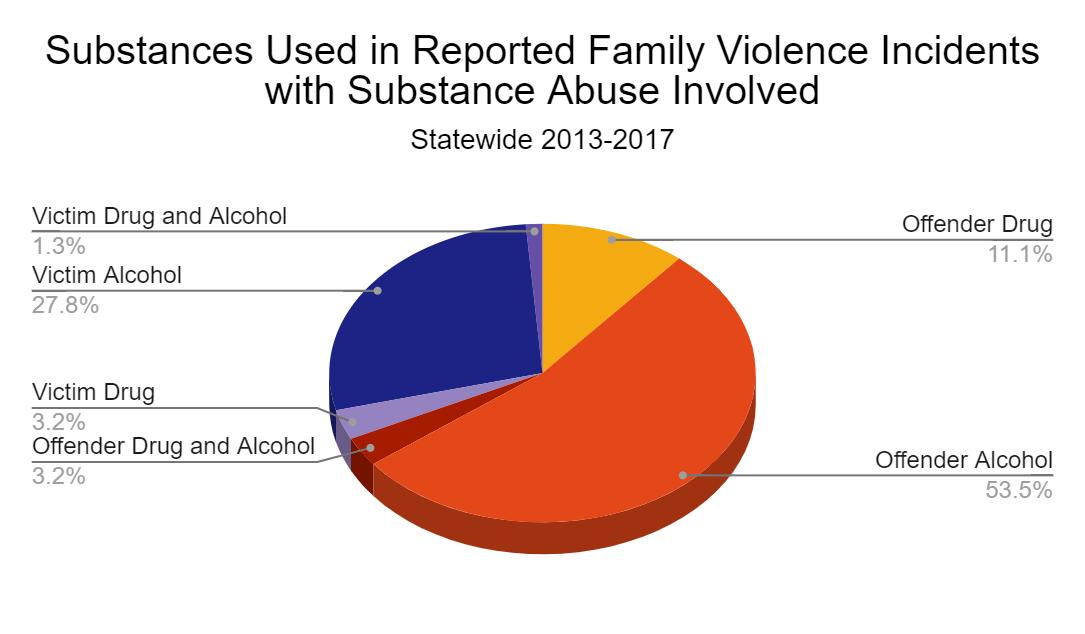

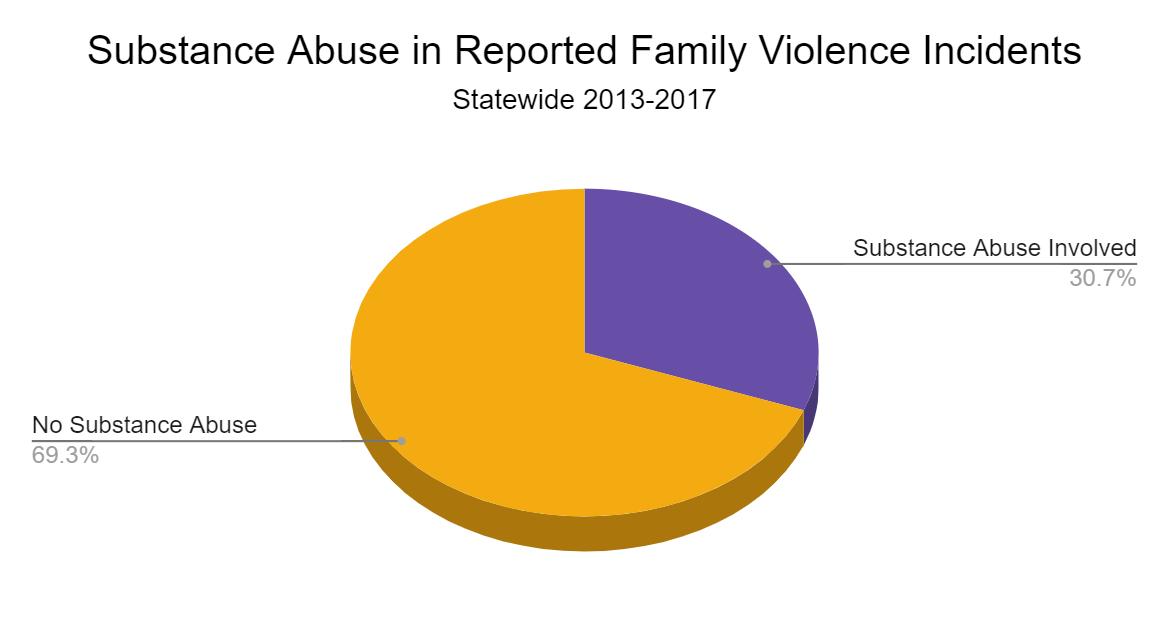

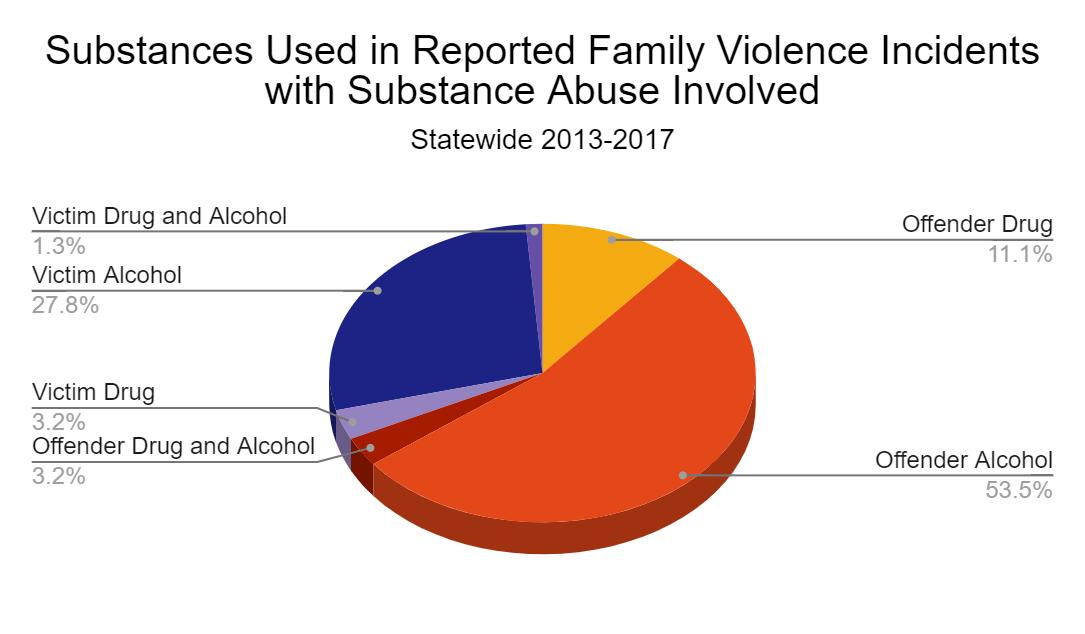

Substance Abuse in Reported Incidents of Family Violence

SUBSTANCE ABUSE # INCIDENTS

Offender Drug 10,619

Offender Alcohol 51,270

Offender Drug and Alcohol 3,039

Victim Drug 3,109

Victim Alcohol 26,599

Victim Drug and Alcohol 1,206

Offender Substance Abuse (Total) 64,928

Victim Substance Abuse (Total) 30,914

While the co occurrenceofsubstanceabuseandintimate partnerviolence is common, we mustbe aware thatone issue doesnotcausetheother. Infact, less than a third (30.7%) of familyviolence incidents in Georgia involve alcoholor drug use Of thosethatdo, itis theabuserthat is undertheinfluence67.8% ofthetime. Given that, Georgia’sdata may supportnationalresearchthat shows abuse is more likely tooccur if theoffender is underthe influenceofalcohol³ordrugs.⁴

7

57

State of Georgia (2013-2017)

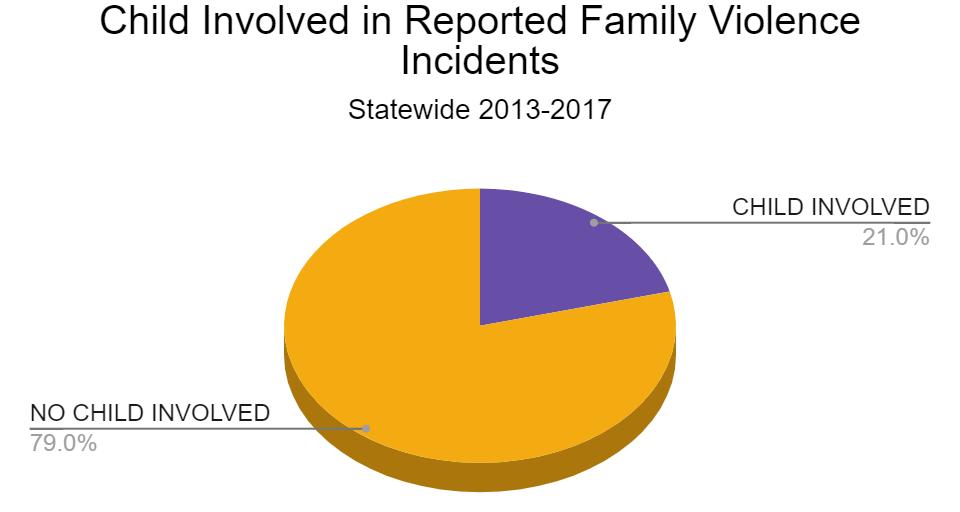

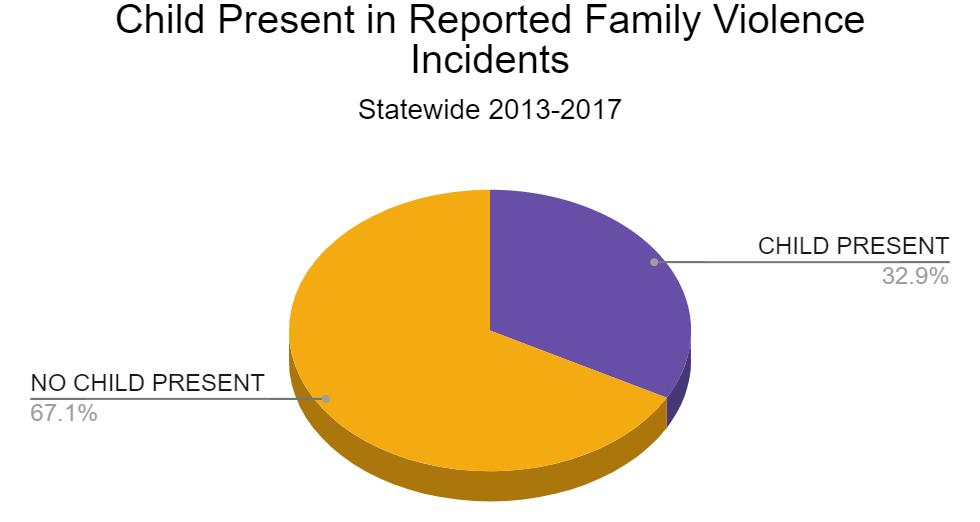

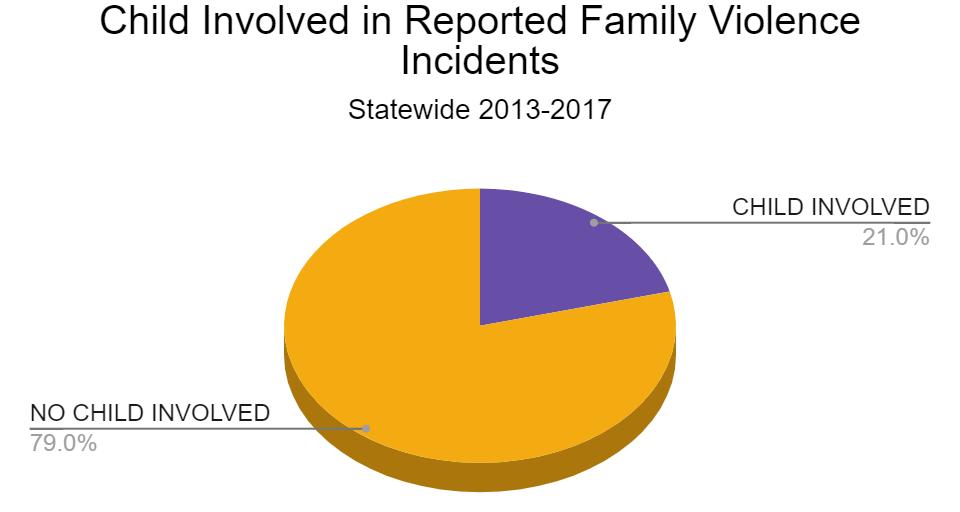

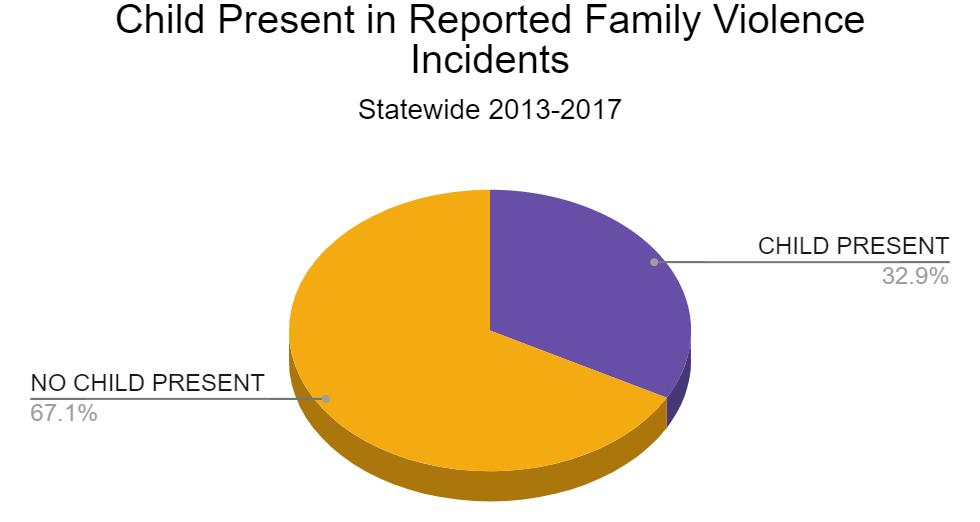

Child(ren) Involved or Present in Reported Family Violence Incidents

CHILD(REN) INVOLVED # INCIDENTS

CHILD(REN) PRESENT # INCIDENTS

Child(ren) Present 102,704 No Child(ren) Involved 246,526 No Child(ren) Present 209,271

Child(ren) Involved 65,449

For children,theimpactofexposuretointimatepartnerviolence is long-lastingand significant.⁵ Unfortunately,thefullextentoftheirexposuretoGeorgia familyviolence incidentscannot be accurately measuredusingthe law enforcementreporting systems in placeduringthe five year reportingperiod Georgiaplanstoaddressthis issue underitstransitiontothe NIBRS reportingsystem in 2018. NOTE: The dataincludeddonotreflectthenumberofchildrenexposed,ratherthedatareflectthenumberof reportedincidentswhereoneor more children were presentor involved

8

58

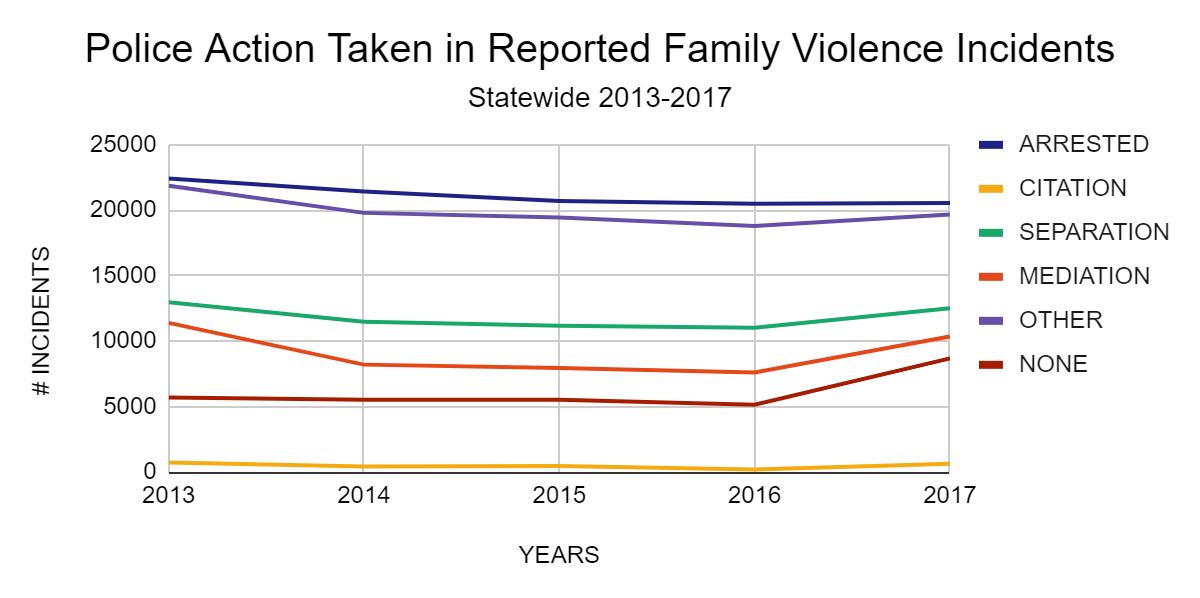

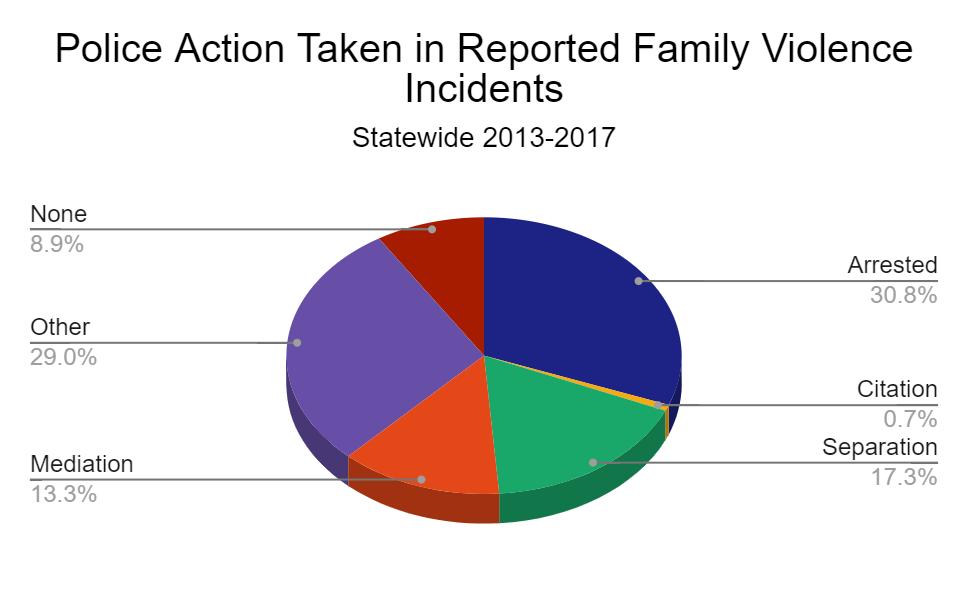

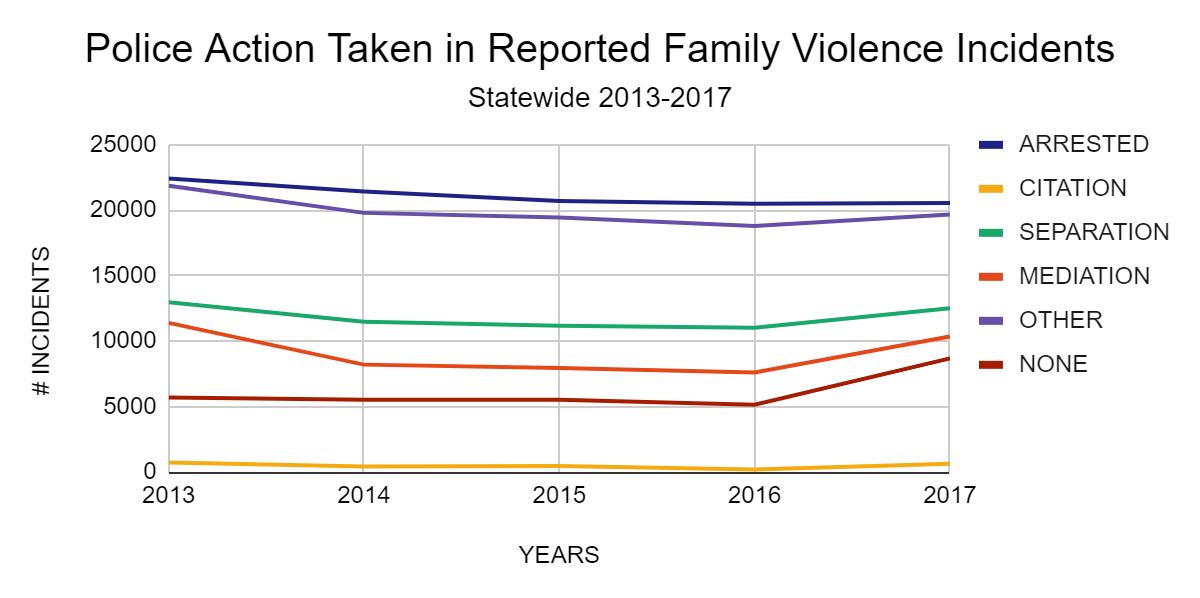

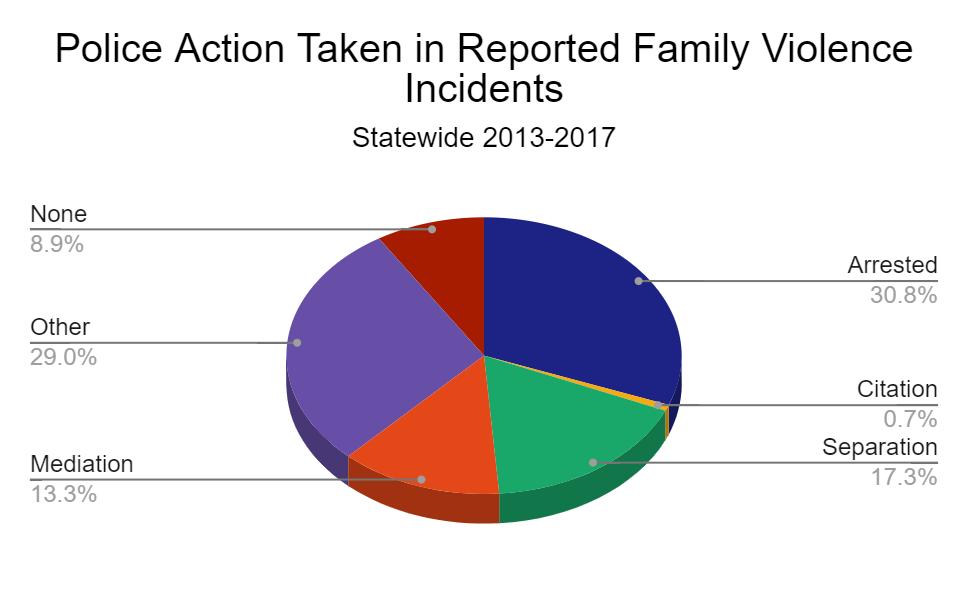

Police Action Taken in Family Violence Incidents

Georgiaofficers are not mandatedtomakean arrest infamily violenceincidents ⁶ Moreover,thestatute clearly allows officersto arrest oneparty,even if bothpartieshaveused violence. Appropriately identifyingthe primary physical aggressorandchargingthatperson is themosteffectiveintervention in familyviolence incidents While GBI’s dataon police actiontaken infamilyviolence incidentsdoindicate that arrest is themostfrequently occurring outcome,arrestsrepresentonly30.8% ofreported police responses This meansthat in more than two thirdsofresponses,preference was given to a different outcome And,when we examinetheseresponses by year, thetrendsshow a decrease (-8.5%) in the rateof arrest. Even more disconcerting,therehasbeen a significantrise (+52.2%) in therateofreports inwhich “none” (no actiontaken) was the officer’s reportedresponse

9

Arrested Citation Mediation None Separation Other

POLICE ACTION TAKEN

59

TOTAL 105,630 2,469 45,519 30,610 59,196 99,600 State of Georgia (2013-2017)

State of Georgia (2013-2017)

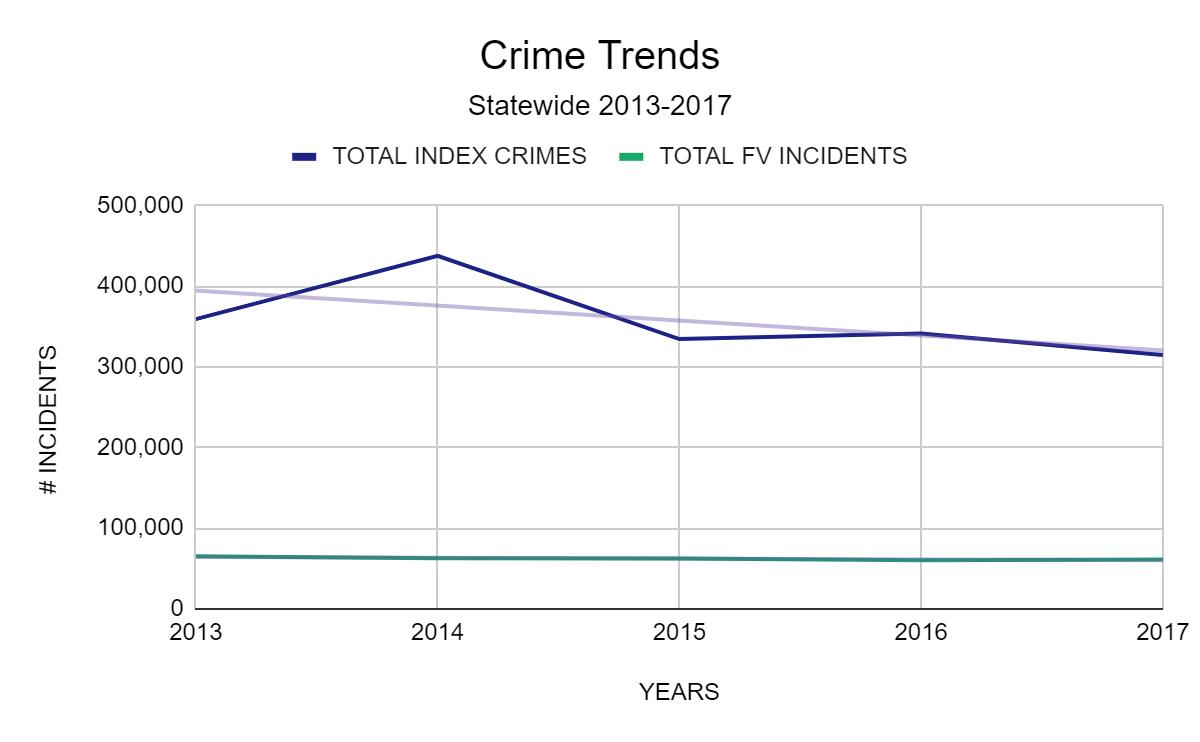

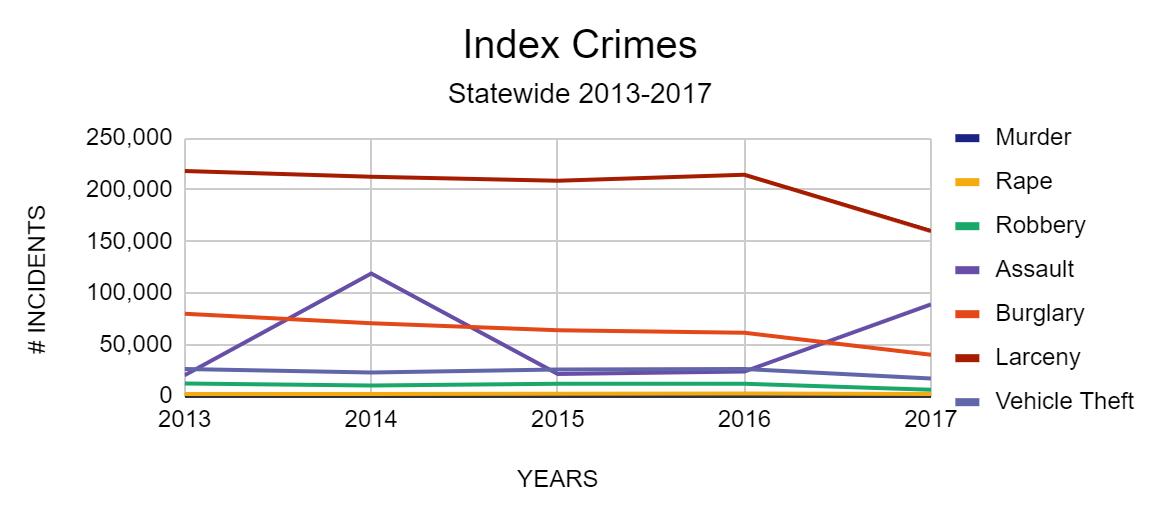

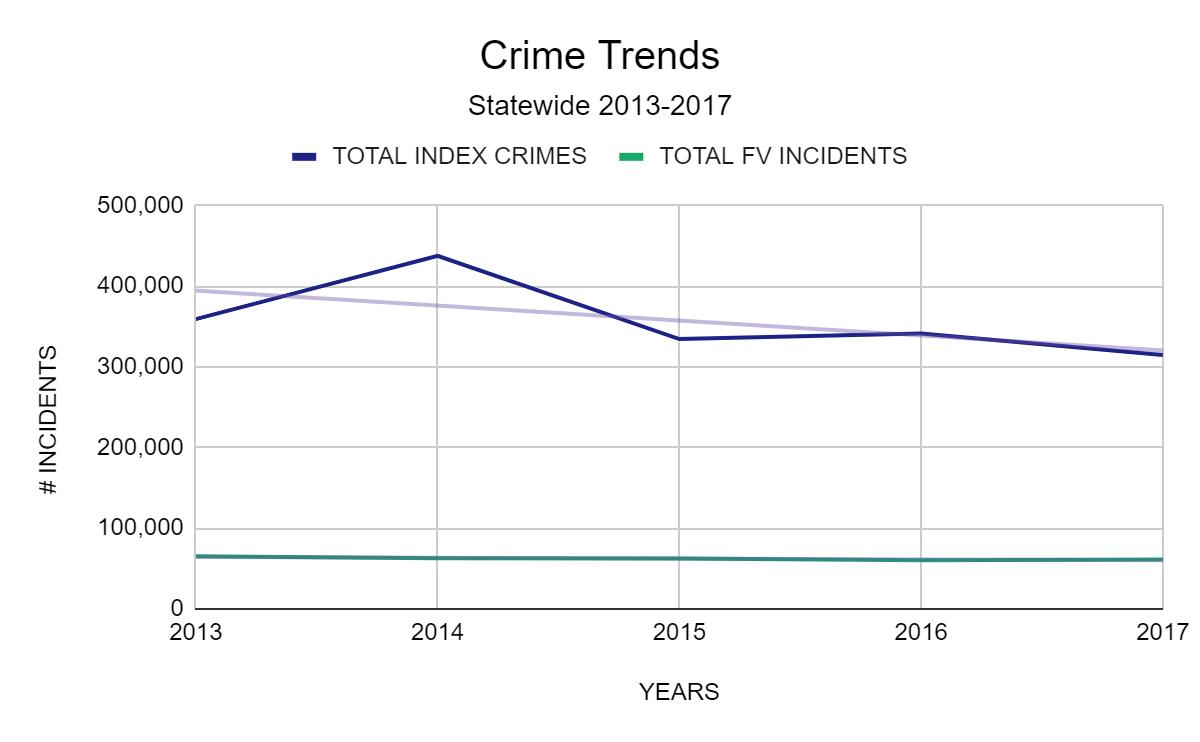

Crime Trends

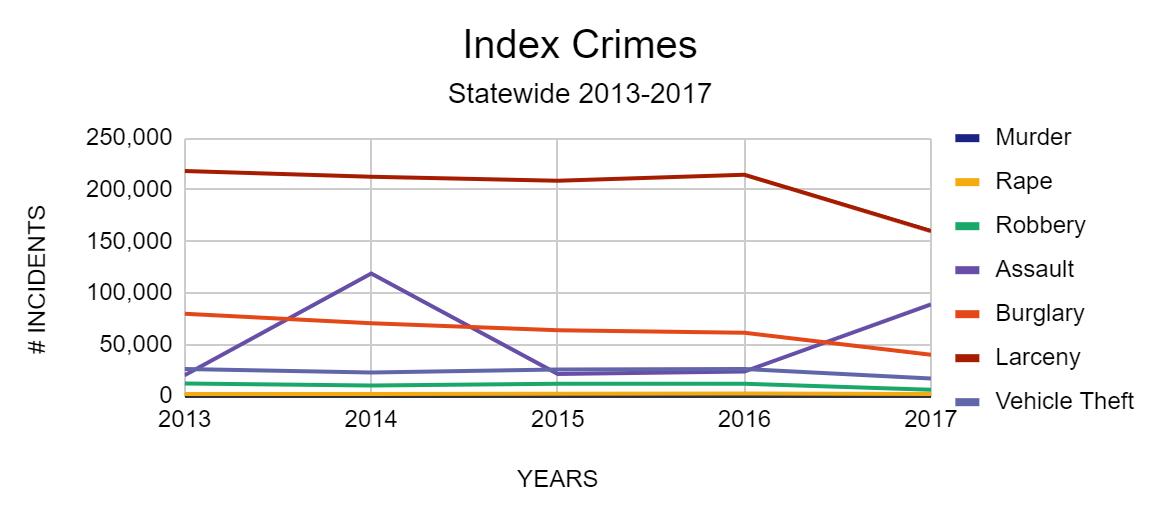

Index crimes, includingassault,burglary,larceny,murder,rape, robbery,and vehicle theft, are usedasanindicatoroftherateof violent crimes nationally. InGeorgia,index crime data are generated from uniform crime reports (UCR) completed by law enforcementofficers Thesereports are also thesourceof family violence incidentinformationstatewide. Many familyviolence incidents also qualify as index crimes Despitesomeduplication giventhatoverlap,comparingthetrendlinesofindex crimes and familyviolence incidentsprovidesgreat insight intoourstate’s efforttoreduce violentcrime. InGeorgia,bothindex crimes and familyviolence incidents were onthedeclineduringthe five year reportingperiod. However, index crimes fell12%, while family violence incidents were reducedatonlyhalfthatrate (-6%).

YEARS

TOTAL INDEX CRIMES

TOTAL FV INCIDENTS

2013 359,297 65,201 2014 437,566 62,659 2015 334,508 62,358 2016 341,254 60,451 2017 314,776 61,306

10

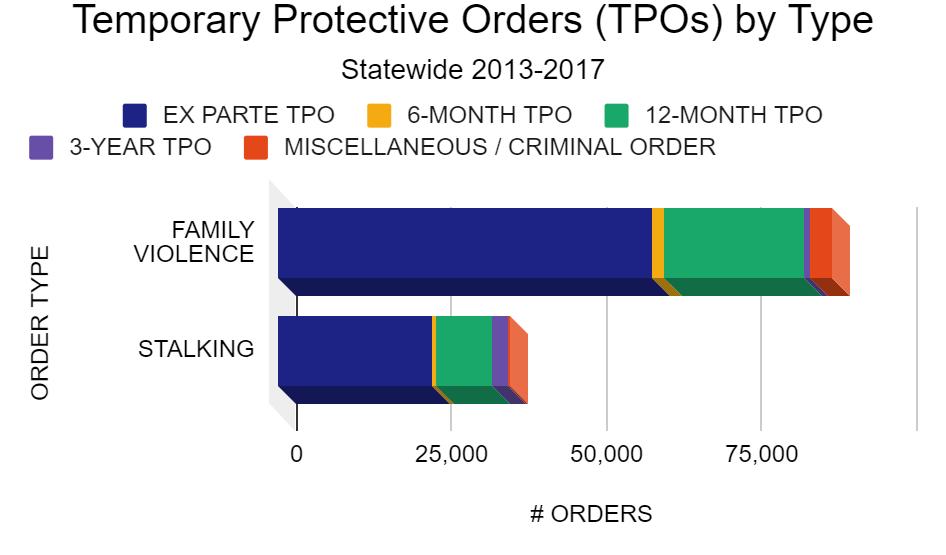

60

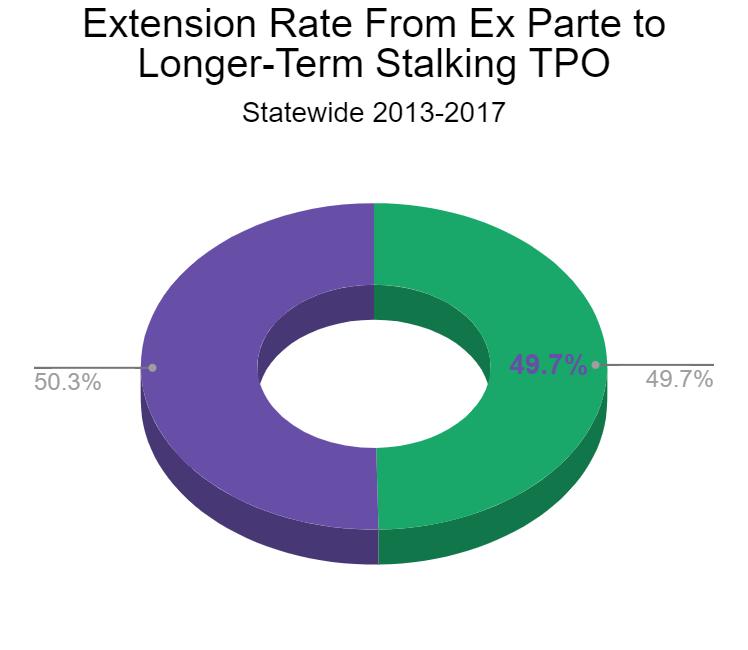

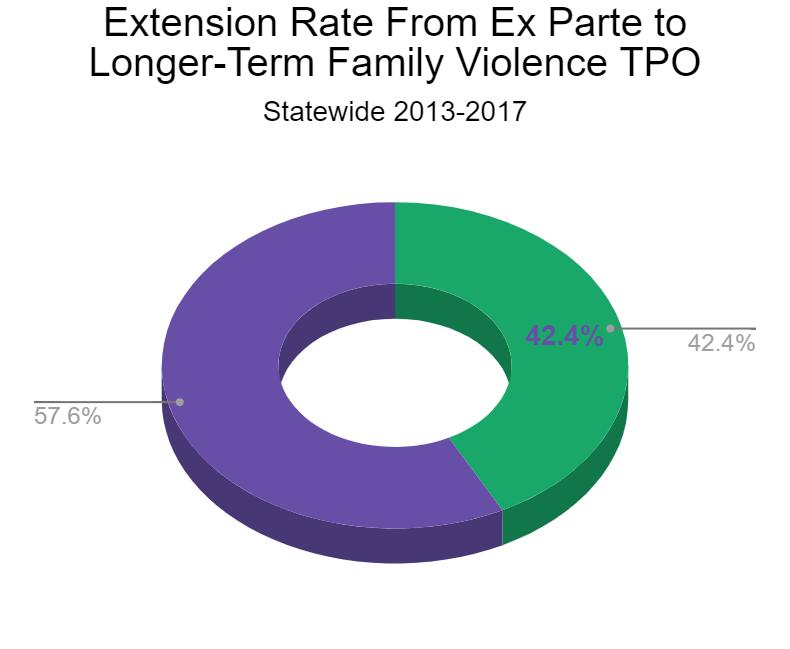

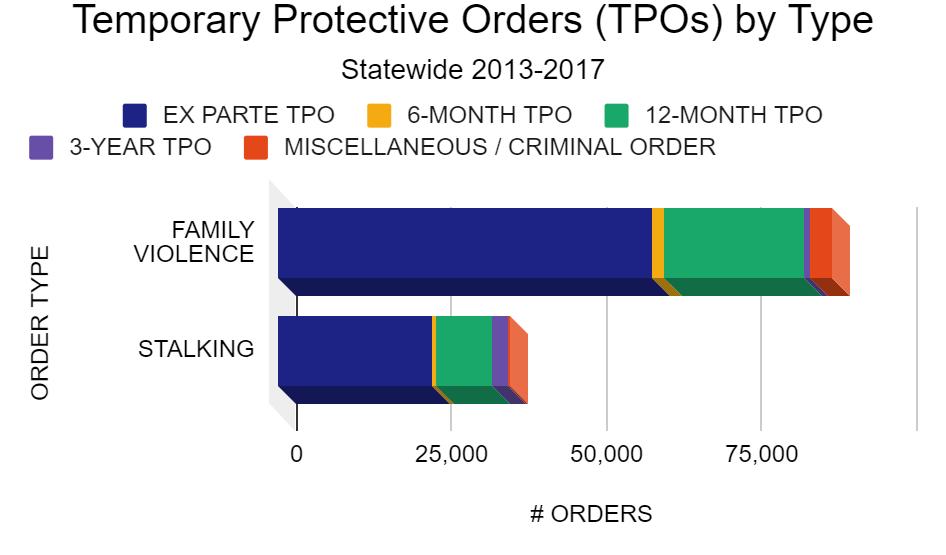

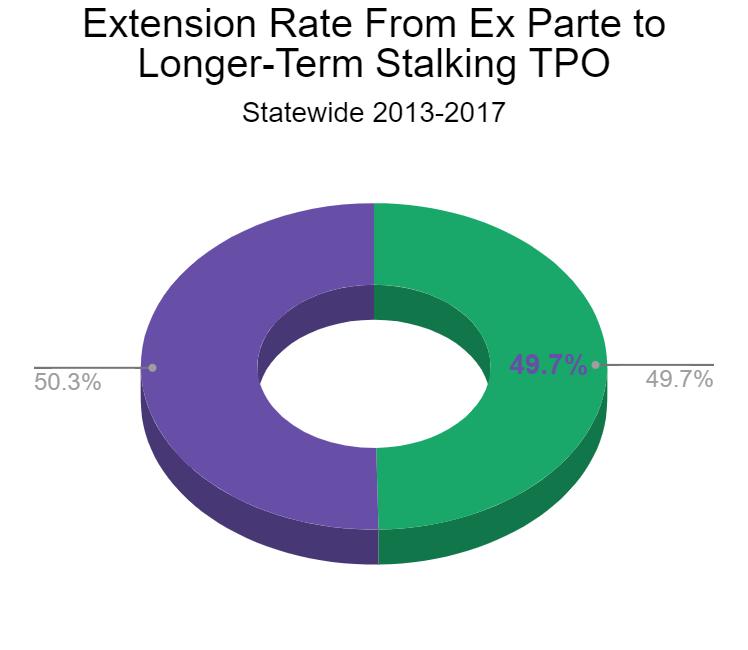

ORDER TYPE EX PARTE TPO 6-MONTH TPO 12 MONTH TPO 3-YEAR TPO MISCELLANEOU S / CRIMINAL ORDER TOTAL TPOs (ALL TYPES) FAMILY VIOLENCE 60,219 1,968 22,557 994 3,452 89,190 STALKING 24,595 802 8,991 2,431 394 37,213 Temporary Protective Orders (TPOs) by Type 57.6% 50.3% TemporaryProtective Orders(TPOs)are an effectivetoolfor victim safety. Research shows themajority of victims reporttheir TPO endedthe violence ⁷ Inmanycases,thelongertheprotectiveperiod,the bettertheoutcomes Between2013and2017, 126,403 familyviolence and stalking TPOs were issued statewide. InGeorgia,theoverall“extensionrate,” or therateat which anemergency (Ex Parte) TPO is extendedinto a longer term (6-Month,12 Month, 3-Year) order, is 55.5%. The “extensionrate” is 7.3% higherfor stalking casesthanfor familyviolence cases Inboth types, the“extensionrate” is impacted by judicial discretion,failuretolegally serve noticeoftheproceedingtotheabuser, lack oflegal representation,and victim decisionsastohoworwhethertoproceed with a follow uphearing 11 Extended Not Extended Not Extended Extended State of Georgia (2013-2017) 61

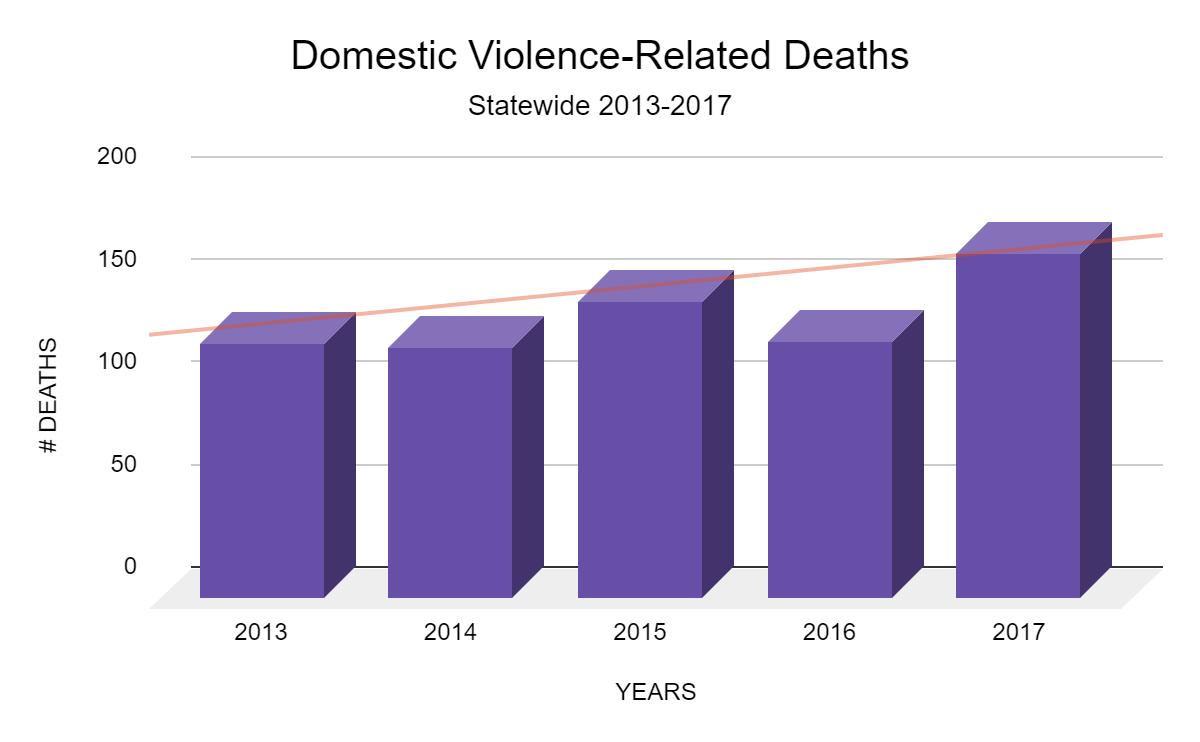

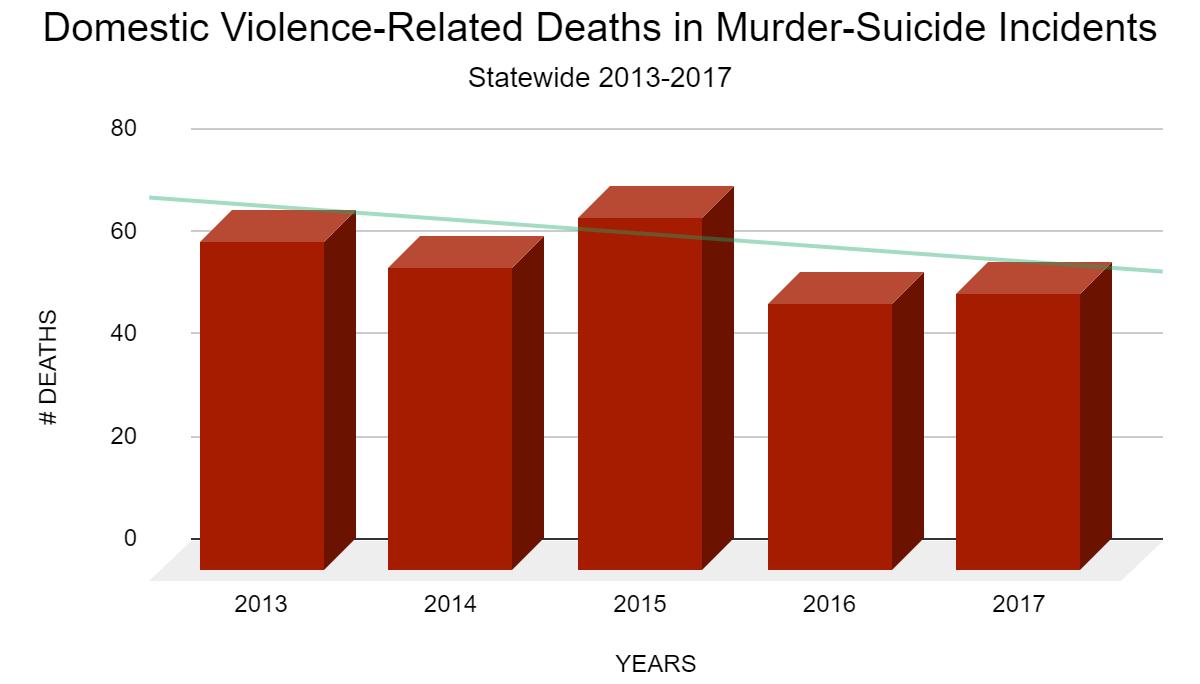

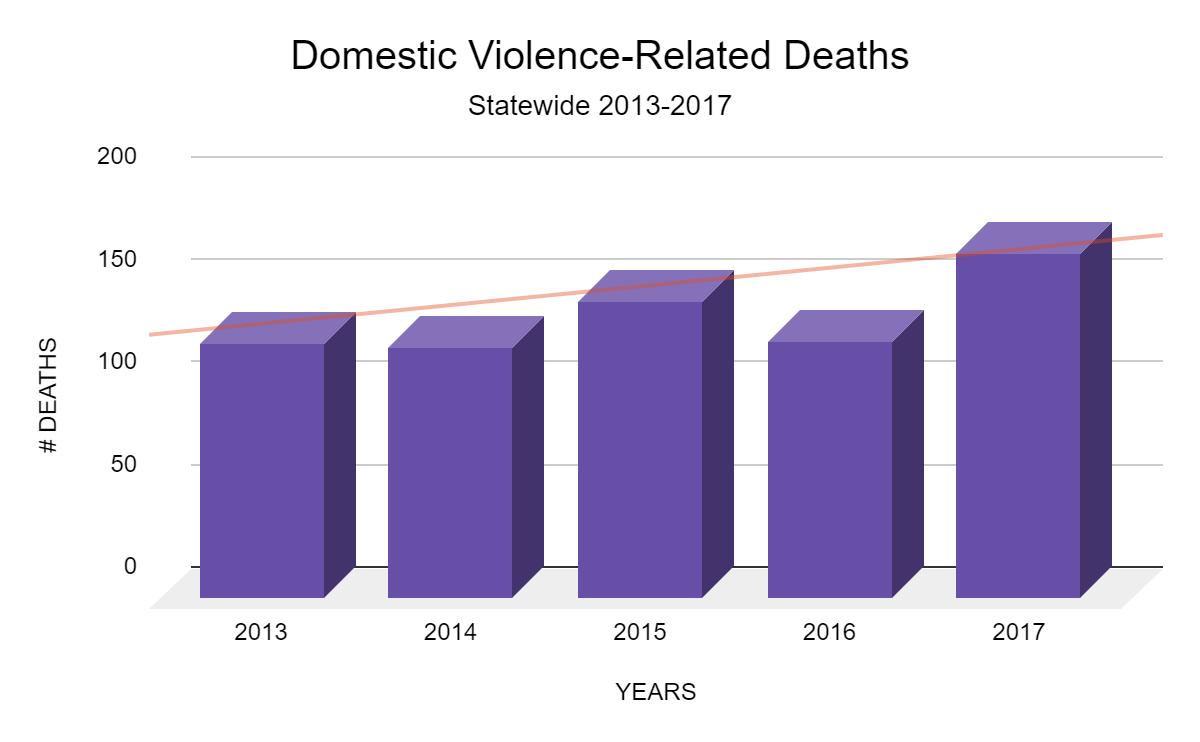

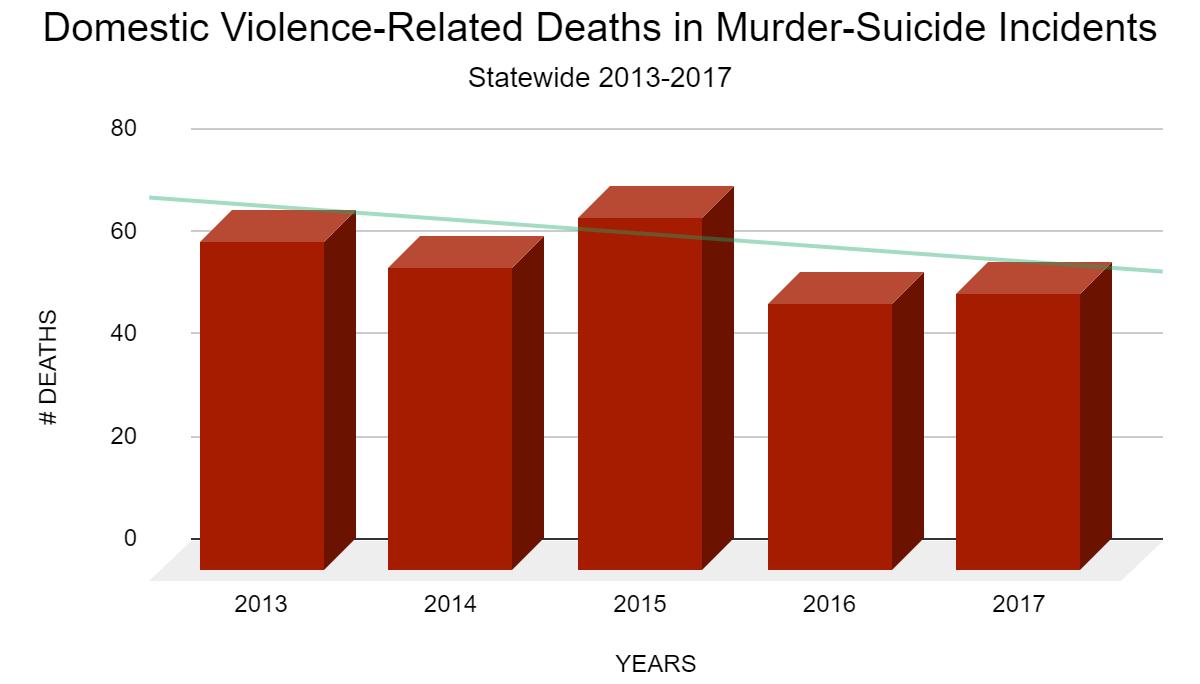

Domestic Violence-Related Deaths YEARS 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 # Fatal Incidents 89 93 100 97 136 # Victim Deaths 70 80 85 70 95 # Perpetrator Deaths 44 32 35 33 45 # Bystander Deaths 10 10 25 22 28 # Deaths Resulting From Incidents 124 122 145 125 168 Murder-Suicide Incidents YEARS 201 3 201 4 201 5 201 6 201 7 # Completed Murder Suicide Incidents 27 24 26 20 24 # Attempted Murder Suicide Incidents 6 8 7 6 7 # Deaths Resulting From Incidents 64 59 69 52 54 The homicide-suicide connection in lethalincidentsofdomestic violence hasbeen well establishedand represents a prevalentproblem in Georgia.⁸ Murder suicides represent30% offatalincidentsofdomestic violence statewide,butaccountfor44% ofalldomestic violence relateddeaths Theirdisproportionate weightwithinstatewidedeaths,hashighlighted a needforcollaborationbetweendomestic violence and mentalhealthstakeholders. 12 State of Georgia (2013-2017) 62

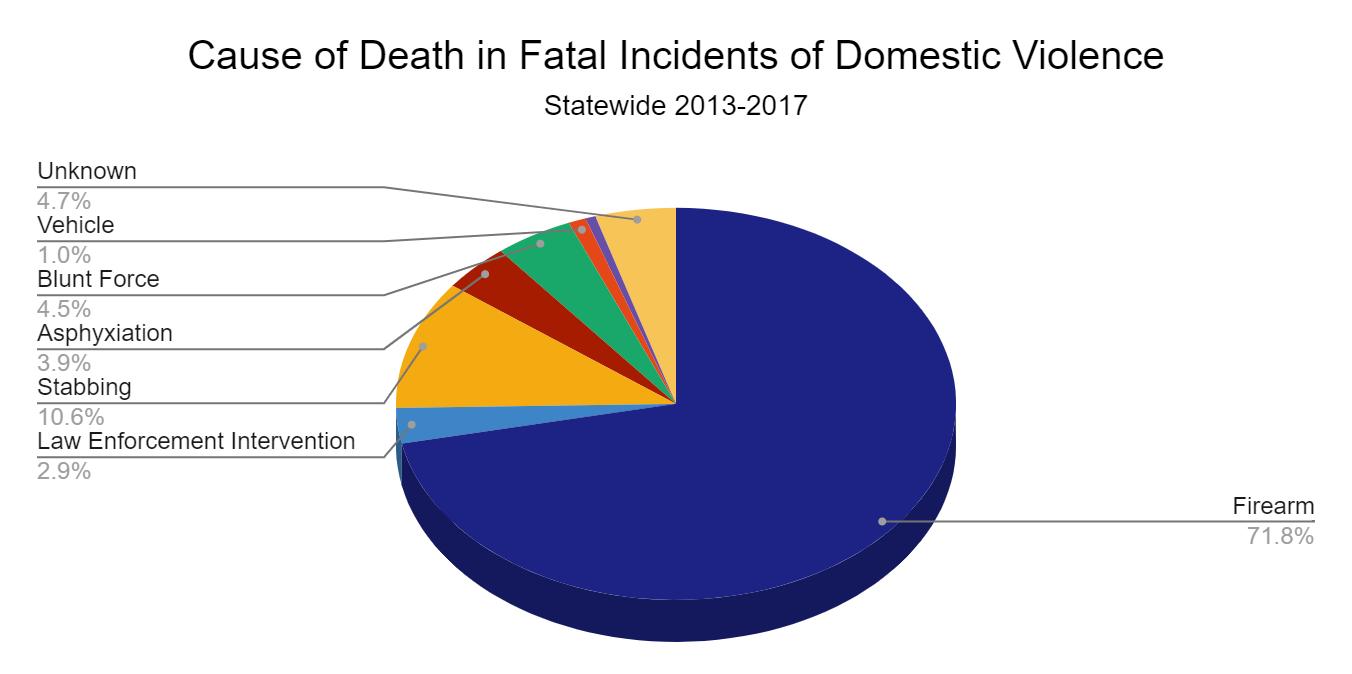

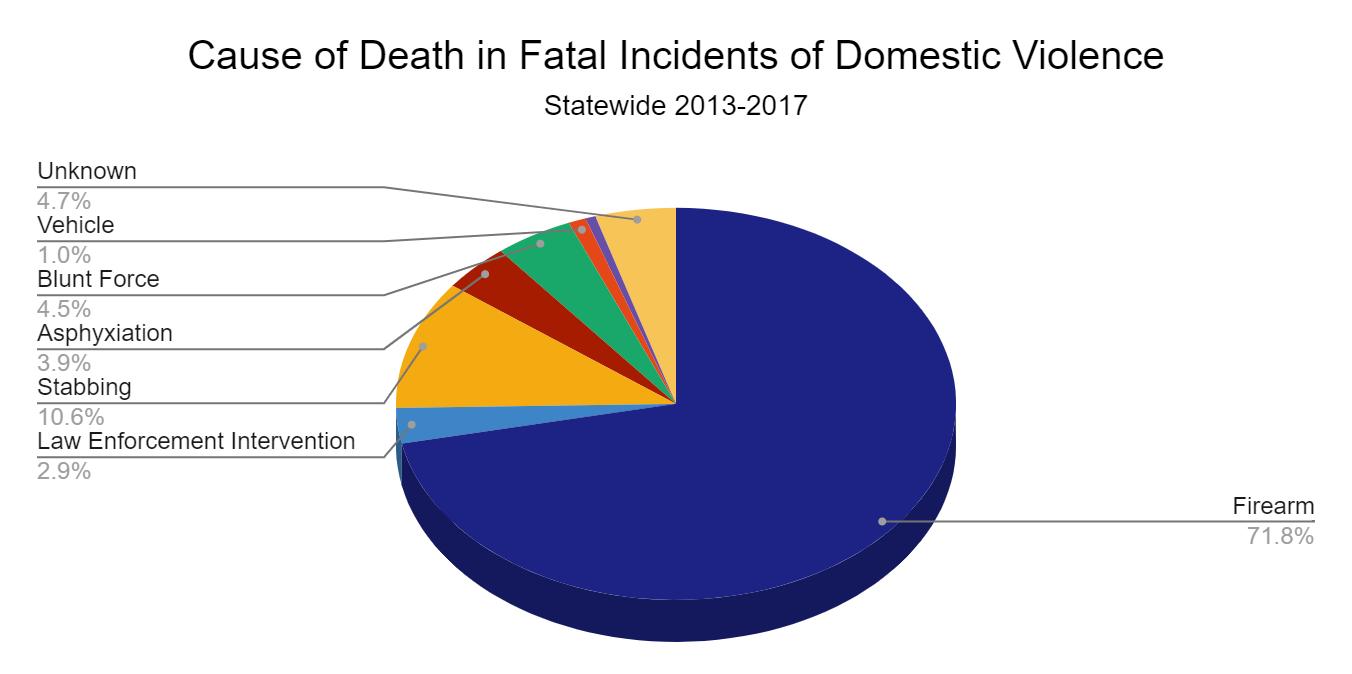

State of Georgia (2013-2017)

Firearms were theleadingcauseofdeath in fatal incidentsofdomestic violence duringthe fiveyear reportingperiod,accountingforthree quartersofallknowndomestic violence deaths statewide [71.8% firearm, 2.9% lawenforcement intervention (firearm)] The highrateof firearms use in fatalincidentsofabuse isin sharpcontrast totheirpresence in only 1.8% ofreported family violence incidentsstatewide,allowingthe conclusion thatwhen firearmsare present in a familyviolence incident,the risk of a fatalincident is increasedexponentially This findinghasbeen consistentlynoted locally⁹ and in national research, which reveals a 500% increase in the risk of homicide whenanabuserhas access to a firearm.

NOTE: In some circumstancesmultiple causes are attributedto a singledeath. Given that,thetotalnumbersreflectedforeachcauseof death, may be inexcess ofthenumbersof statewidedeathsoccurring in a givenyear.

YEARS 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 Firearm 91 80 116 89 117 Stabbing 7 22 11 16 17 Blunt Force 8 4 5 3 11 Asphyxiation 2 7 5 5 8 Law Enforcement Intervention (Firearm) 6 1 5 3 5 Vehicle 0 2 0 5 0 Other 0 0 0 2 2 Unknown 10 6 3 2 11

13

¹⁰

Cause of Death in Domestic Violence-Related Deaths 63

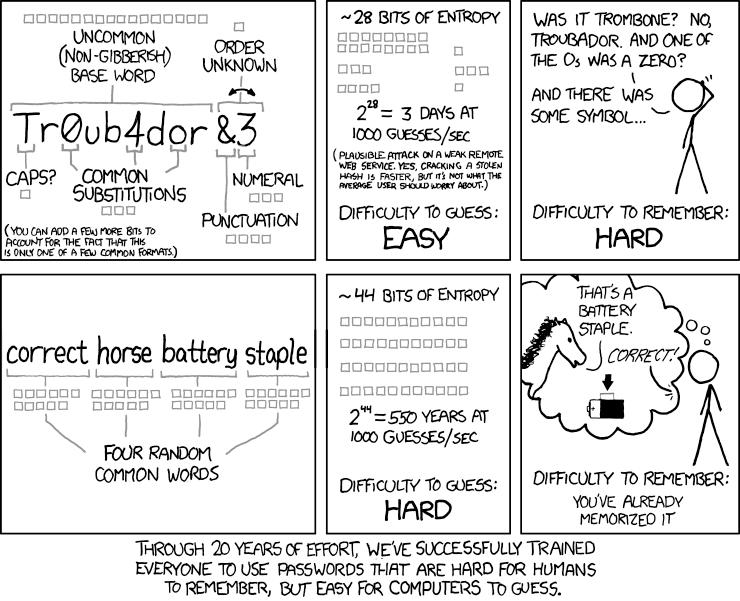

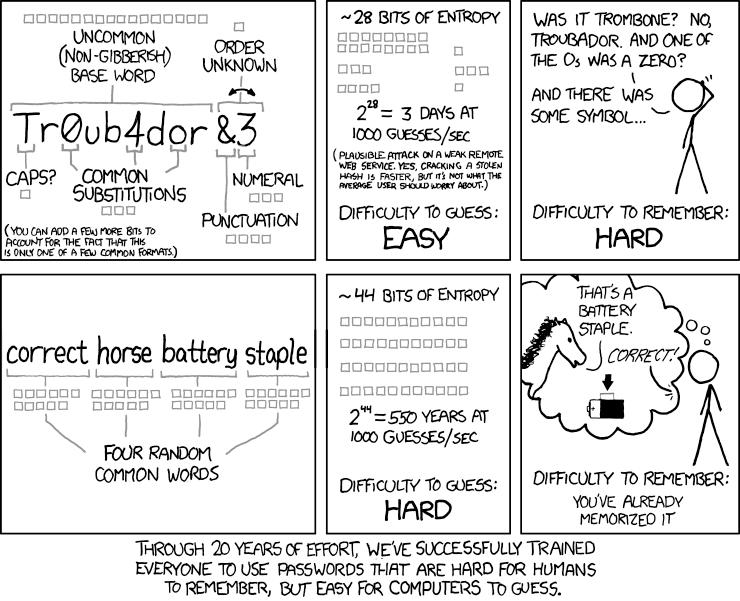

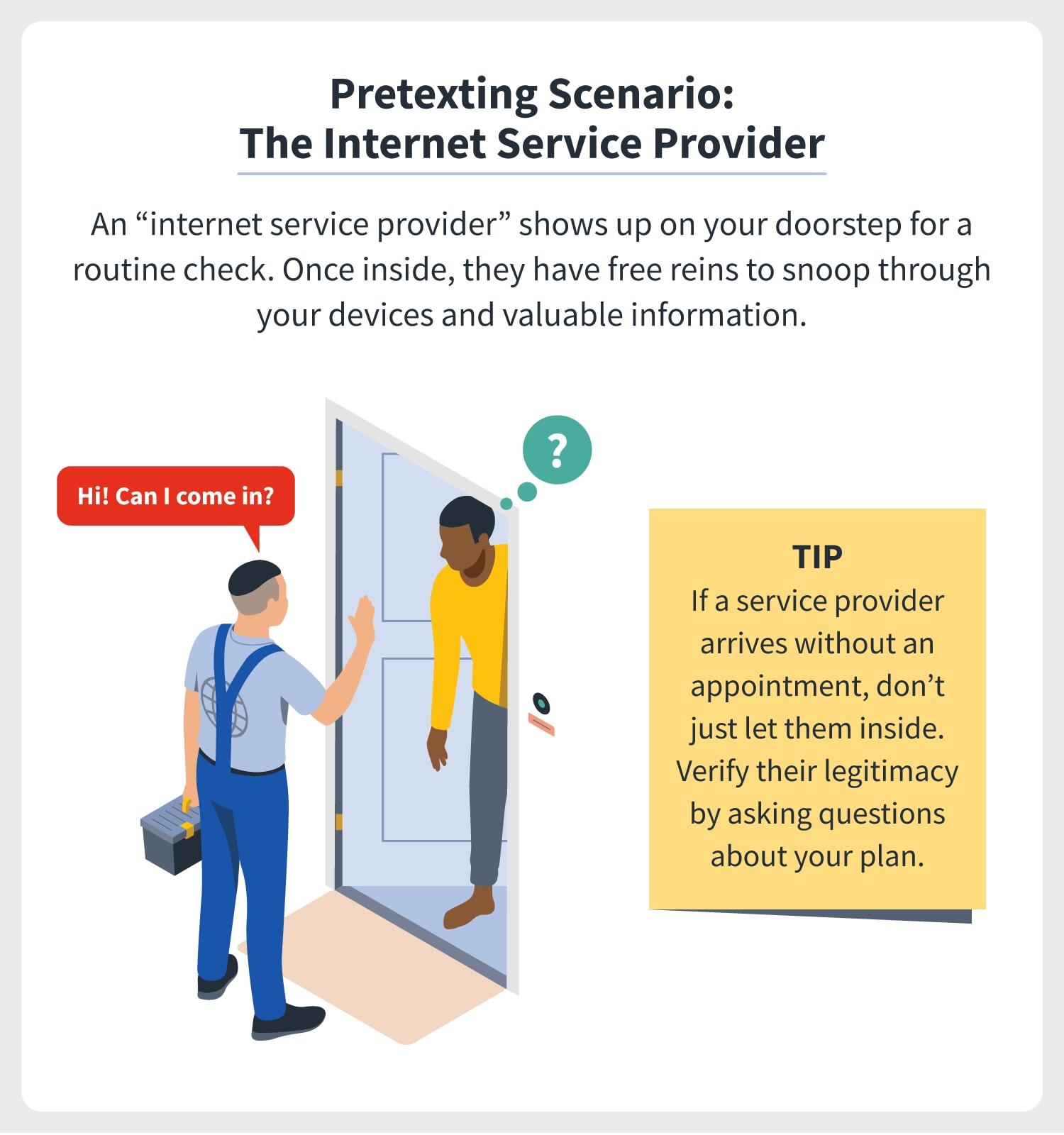

HOW TO USE THIS REPORT