After the Door Closes When Art Comes Alive Beyond Opening Hours

by Soojin Jinnie Kang / Editorial Coordinator

In New York, art often finds people before people find art. On a recent Friday evening at MoMA, during its free UNIQLO Friday Nights, a friend of mine, someone who knew little about Ruth Asawa, joined simply because it was a convenient place to meet after work. She came for conversation and atmosphere and left captivated by A Retrospective, quietly moved by Asawa’s wire sculptures, lingering long after the pop-up talk had ended. What began as casual evening entertainment unexpectedly became a moment of artistic discovery. This is the power of after-hours museum engagement. People enter without intention and leave with resonance.

As someone who grew up in the performing arts, I have often found that the most powerful artistic experiences do not always happen under perfect lighting or during the final curtain call. I remember sitting quietly during ballet rehearsals, listening to the subtle rhythm of dancers’ feet aligning with the floor, the breath between movements, the soft cue of a director before a sequence. These moments, stripped of costume, spotlight and applause, felt raw and deeply intimate. They revealed a different kind of beauty. Not the polished product but the living process behind it. What struck me recently is that museums, which do not traditionally have rehearsal moments, have begun to generate similar experiences through after-hours programming. It is not the spectacle but the encounter that matters.

Unlike traditional daytime visits, these evening programs remove expectation. The museum feels less like a place of instruction and more like a social space, a blend of gathering and reflection. Visitors may arrive with friends, drawn by music, a brief talk or simply because admission is free to New Yorkers. Yet in the softened atmosphere they begin to notice details. The shadow of a looped wire in Asawa’s work. The repetition of form. The intimacy of materials shaped by hand. They listen not because they came to learn but because curiosity arrives quietly.

MoMA’s pop-up conversations, often held within the exhibition, offer enough insight to open the work without directing it. The tone is informal and responsive. What starts as something to do on a Friday evening often becomes a reason to return alone. In New York, art does not wait to be pursued. It interrupts.

Across the Atlantic, London explores this idea

through a more choreographed lens. During the Frieze London art fair this past October, the National Gallery hosted a special edition of its program Unexpected Views. Approximately 800 invited guests filled the galleries after closing hours, but admission was limited to selected artists, patrons and major supporters. Eight contemporary artists and curators led ten minute sessions, each positioned in front of a different masterpiece. Participants moved from one conversation to the next almost like an artistic speed

dating sequence. Rather than offering conclusions, these exchanges unfolded as live reflections shaped by months of dialogue and research. Standing in dialogue with works that have survived centuries, the immediacy of the conversation felt surprisingly modern. The energy was not loud but concentrated, like stepping into a rehearsal room where ideas are still becoming something.

If New York’s approach is improvisational and socially driven, London’s is refined and intentionally inward. Yet both pursue the same idea. Museum engagement does not have to occur within official hours or under formal structures. Some of the most meaningful encounters happen when the institution relaxes and curiosity is allowed to lead.

Increasingly, museums recognize that visitors

may arrive for reasons unrelated to art and stay because of it. People come for companionship, for pause, for the rhythm of the evening. They remain because something unexpected meets them.

Perhaps the most powerful artistic experiences do not emerge when the lights are brightest, but when the room softens. After the door closes, the gallery shifts. People do not only look at art. They meet it. They may not arrive searching, but often, that is precisely when art finds them.

About Principia

Principia is a Monthly Publication on Art, Policy, and Cultural Economy, advancing critical discourse and shaping the cultural agenda of our time. It serves as a leading forum for ideas that define the role of culture in society and the economy.

Editor’s Note

As the Editor-in-Chief, I offer this issue with gratitude to the many artists, institutions, thinkers and unscripted audiences who shaped the year we are now concluding. 2025 reminded us that art does not wait for grand openings or prepared minds. It reveals itself in rehearsal rooms, on city streets, in restored museums and through technologies we are still learning to understand. What we encounter today will define the cultural questions of tomorrow.

This December issue traces that idea through five perspectives—five ways in which art moved beyond the act of display and into everyday life, public memory, national identity, technological authorship and civic space. Rather than surveying trends, we explore how these encounters reshaped the way art works on us and within us. Thank you for sharing this year of discoveries with us. PRINCIPIA remains committed to treating art not as a final statement, but as a process that shapes public life, civic imagination and the ways we see one another. May we continue to meet art unexpectedly—and allow it to change how we move through the world.

by JunHwan Chang / Editor-in-Chief

The Frick Collection Reopens A Turning Point in New York’s Museum History

by Editorial Team

The Frick Collection reopened its Fifth Avenue building on April 17, 2025, after a fiveyear renovation that marks a significant moment not only for the institution itself but for the broader landscape of New York’s museum history. Known for its intimate atmosphere rather than encyclopedic scale, the Frick has long offered a distinctive encounter with European Old Master paintings, presented within the domestic architecture of Henry Clay Frick’s former residence.

Established by an industrial magnate whose wealth was generated through late-nineteenth-century steel and coke industries, the house was converted into a museum in 1935, reflecting the rise of American collectors seeking cultural legitimacy through European art. Unlike the Metropolitan Museum of Art and other large institutions on Museum Mile, the Frick’s identity has been grounded in the idea of the house-museum, a hybrid space where masterpieces are encountered in rooms that once belonged to private life.

The latest renovation expands this dual character rather than erasing it. Designed by Selldorf Architects, the project opens previously private sec-

ond-floor quarters to the public for the first time, enlarges exhibition areas by roughly thirty percent, and adds a new auditorium, conservation facilities, and improved accessibility. These changes modernize the museum without transforming it into a neutral white cube, preserving the domestic tone that has shaped its contemplative experience.

As a result, the reopening repositions the Frick within New York’s cultural infrastructure, strengthening its role not simply as a preserved relic of elite taste but as an evolving public institution. The opening of former living spaces offers a symbolic shift in visibility: what was once personal and exclusionary is now reframed as shared cultural property.

Yet this transition also highlights the paradox inherent in museums built from private wealth, where the legacies of accumulation become aesthetic heritage. Rather than resolving this contradiction, the renovated Frick acknowledges it by expanding access while maintaining the architectural intimacy that historic house-museums inevitably carry.

For museums and galleries elsewhere, especially those navigating the balance between historical identity and contemporary relevance, the Frick’s

transformation demonstrates that institutional evolution need not erase a building’s past but can reinterpret it. In this sense, the reopening offers a productive model for redefining the relationship between collections, architecture, and public engagement, suggesting that democratization in museums may occur not through radical transparency or formal neutrality, but through an honest negotiation between origin and present.

As museums renegotiate the meaning of public access in the shadow of private histories, it becomes clear that the act of exhibiting is never neutral: it carries the authority to define what a culture remembers, values, and projects outward. This question of representation becomes even more striking when the museum is not only a public institution but a national monument, where heritage is mobilized to shape collective identity. With this in mind, the next essay turns to the opening of the Grand Egyptian Museum—an institution where archaeology, nationhood and global spectatorship converge on an unprecedented scale.

Grand Egyptian Museum A Nation Steps onto Its Own Stage After Twenty Years

by Editorial Team

Each September, New York’s Asia Week returns with the composure of a ritual that has learned to speak in the language of influence. Seventeen galleries and six auction houses converge across the Upper East Side, not merely to exhibit art but to synchronize perception — to convert culture into capital and visibility into diplomacy. The event’s quiet rhythm conceals a sophisticated negotiation: artworks are not only traded, they are translated into systems of trust, interpretation, and power.

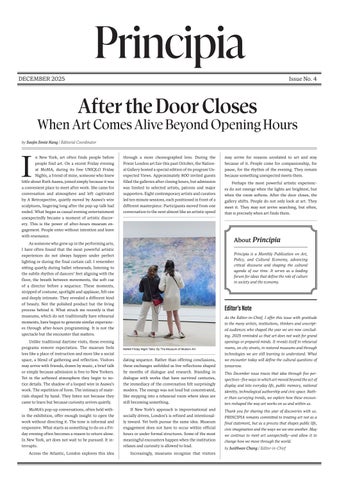

Twenty years of anticipation finally ended on November 1, 2025, when the Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM) opened its doors just beyond the shadows of the Giza Pyramids. Floodlights washed over the building’s massive façade as diplomats, archaeologists, cultural ministers, and international press stepped onto a newly built arrival platform connected to the desert highway. The scene resembled a state ceremony more than a museum opening. “This is not an institution,” one Egyptian official remarked to journalists. “It is our declaration.” Egypt was not merely unveiling a collection; it was announcing its authorship of a world civilization.

Claiming to be the largest museum in the world dedicated to a single ancient culture, the GEM houses more than 50,000 objects, including the complete funerary assemblage of Tutankhamun. Visitors encountering these artifacts together for the

first time experience a rare, almost overwhelming sense of wholeness. A young curator described the moment with quiet pride: “People have studied Tutankhamun their entire lives without ever seeing his story in one place. Now the narrative breathes.” What scholars once pieced together through fragments scattered across museums is now experienced as a unified arc.

The museum’s long gestation echoes Egypt’s own political turbulence. Dates of completion appeared and faded across the years—2011, 2018, 2020, 2022—each delay shaped by revolution, economic pressure, and the Covid-19 pandemic. The opening ceremony bore the weight of this history. Drone displays lit the desert sky, LED screens projected cinematic renderings of pharaonic iconography, and a live orchestra performed beside the colossal Ramesses II, now serving as the museum’s de facto guardian. The message was unmistakable: ancient Egypt is not frozen in the past; it is a national asset with a future.

Inside, the design strategy is meticulous, monumental, and deeply intentional. Galleries stretch into wide dramatic vistas, corridors lead into immersive chronological sequences, and architectural framing elevates even the smallest objects into symbols of civilizational memory. Yet theatricality brings its own complications. “The risk of spectacle,” a visiting European archaeologist

noted, “is that visitors forget history is uncertain. Here, everything feels too sure.” Where immersion succeeds, nuance sometimes recedes.

Beyond galleries, the institution reveals another layer of strategy. The GEM includes high-tech conservation labs, but also vast commercial areas, corporate lounges, and event spaces designed to attract global tourism and international funding. Heritage is preserved and performed, but also monetized. The pyramids once represented a system of ancient labor producing divine power for pharaohs; the GEM now represents a system of modern investment producing cultural authority for the nation. Egypt is not only protecting its past—it is leveraging it.

This complexity is precisely what makes the museum significant. Mega-museums in the 21st century are no longer passive guardians of history; they are strategic cultural actors. The GEM stands as both archaeological achievement and diplomatic instrument. Its success will depend on whether it can balance spectacle with scholarship and economic momentum with intellectual honesty. In a world where nations increasingly shape identity through heritage, Egypt now stands at the forefront, narrating civilization from within rather than being narrated by others.

From New York’s newly reopened Frick Collection, which transformed a private mansion into public authority, to Cairo’s colossal new institution asserting national authorship, museums today do more than display culture—they negotiate it. They tell the world not only what to remember, but who holds the right to define memory itself.

Art + Tech: When Museums Become Innovation

Labs, Not Just Galleries

by Editorial Team

In 2025, the most influential museum initiatives were not defined by blockbuster exhibitions, but by unexpected alliances with technology. When LG announced the LG Guggenheim Art & Technology Initiative, followed by a multi-year partnership with The National Gallery in London and growing collaborations with digital art platforms like ArtLumen, it signaled a shift that is no longer experimental. Museums are moving into the tech sector, and tech companies are entering culture not as sponsors, but as co-producers.

The LG Guggenheim partnership is built around a decisive principle: technology is not a service to art, but a medium of authorship. At the Guggenheim, LG does not simply install displays or support exhibitions; it helps commission works that would not exist without its research in robotics, AI imaging, and advanced display engineering. One curator involved in early conversations described the collaboration as “R&D repurposed into cultural capital.” The company’s proprietary technology becomes part of the artist’s toolset — as essential as clay, film, or oil paint once were.

In London, The National Gallery is following a parallel trajectory. Here, technology is not only a means of production but a method of interpretation. Using LG’s imaging systems and AI-driven analysis tools, conservation scientists are conducting microscopic reconstructions of masterpieces to study pigment decay, composition

layers, and historical lighting conditions. This work affects future exhibition design and conservation policy, prompting one museum scientist to remark: “The most radical thing technology does is not change how we display art, but how we protect it.” Suddenly, corporate technology is shaping museum decisionmaking at the policy level.

Meanwhile, smaller platforms like ArtLumen are testing a different model: distributed authorship. Unlike Guggenheim or the National Gallery, which integrate tech on the institutional level, ArtLumen invites engineers, coders, and data artists into shared studio environments with museums and galleries. Instead of funding art after its creation, these platforms develop work at the prototyping stage. This reverses a century-old pattern where industry sponsored culture only at the final exhibition moment. Here, software engineers are not donors; they are collaborators.

These three approaches reveal the emergence of a new ecosystem. In the 1990s, digital art was peripheral, economically weak, and marketambivalent. In 2025, the value proposition has reversed. Museums increasingly depend on private sector innovation to conserve works, attract audiences, expand global reach, and commission art that exceeds analog limitations. Corporate R&D has become part of the cultural infrastructure.

Yet this shift also raises difficult questions. Who owns works created with proprietary technology?

What happens to cultural preservation if a piece requires a corporation’s hardware or software decades later? Can a museum conserve a digital sculpture if the required operating system no longer exists? As one digital artist recently noted, “Without open access, a work can die the moment a company upgrades its platform.”

This is where policy — not creativity — becomes the true frontier of art and technology. Museums must now negotiate intellectual property agreements, archive source code, maintain outdated systems, and create conservation contracts that treat hardware as part of the art. Tech companies, in turn, must decide whether their cultural value lies in invention alone or in ethical stewardship of artworks that rely on their innovation.

The lesson of 2025 is clear: art and technology no longer meet at the moment of presentation. They meet during research, creation, legal negotiation and long-term preservation. The museum is evolving from a venue of display into a laboratory of development. And as the boundary between creative authorship and corporate innovation dissolves, the future of culture will depend less on who funds art and more on who engineers it — and who guarantees its survival.

Public Art as Urban Policy

Larry Bell at Madison Square Park

by Editorial Team

The geography of art is changing—quietly, yet irreversibly. For more than half a century, the art world revolved around a familiar constellation: New York for the market, London for the sale, Paris for the myth, and Hong Kong for the gateway to Asia. But that orbit is shifting. The gravity that once held firm in the North Atlantic has begun to drift south and east, toward the desert skylines of Dubai, Abu Dhabi, and Doha. This new axis—the Gulf Triangle—is no longer a footnote to global art. It is becoming the map itself.

Public art in 2025 is no longer a question of aesthetic access; it is a question of civic infrastructure. When Madison Square Park Conservancy commissioned Larry Bell for a site-specific installation this fall, the work entered not just the cultural landscape of New York, but its legal, ecological and social grid. In a city where open space is a scarce commodity and park usage is governed by municipal policy, any artwork placed in public green space inherently asks: who is the park for, and under what conditions can culture occupy it?

Madison Square Park sits within one of the densest commercial districts in the United States. According to NYC’s Department of Parks and Recreation, over 60% of its daily users are not leisure visitors but “circulatory users”—commuters, office workers and dog-walkers passing through on default routines. When a sculpture interrupts circulation, it doesn’t simply appear; it reorganizes behavior. Bell’s work—a series of reflective, tinted glass structures— created new pedestrian routes, slowed traffic, and transformed a pass-through zone into an intentional gathering site. In urban design terms, this was a temporary reallocation of public space, where art functioned as urban planning without the language of planning.

The installation also demonstrates the ecological tension built into New York parks policy. Any intervention in a public garden requires negotiation with horticultural management, soil protection requirements and seasonal shade mapping. Bell’s reflective sculptures altered sunlight distribution across grass plots and tree roots, requiring the park’s horticulture team to adjust irrigation and ground coverage. Public art here was not just a cultural decision but a landscaping one. One park official phrased it succinctly: “Art changes microclimates.”

Economically, the project underscores a growing shift in funding models. While museum partnerships often rely on corporate sponsorship, public parks rely on hybrid governance: a mix of municipal oversight and private philanthropy. Madison Square Park Conservancy operates as a non-profit steward of public land, negotiating between community use and cultural programming. Bell’s work therefore exists within an economic model distinct from traditional art institutions. It is not owned by the city, yet

it affects public property. It is financed privately, yet regulated publicly. It is accessible to all, but maintained by donors. This hybrid status complicates the notion of public value.

Bell’s installation also revised audience demographics. Surveys conducted by the park’s programming department showed a 38% increase in first-time visitors from boroughs outside Manhattan during the exhibition period. The majority cited “being outdoors” as their principal motive—not viewing contemporary art. This aligns with broader cultural data: in public space, art often serves as a secondary driver that activates civic engagement as much as cultural engagement. People may come for fresh air, lunch breaks or playground access, yet they leave having encountered art unintentionally. Here, the artwork does not ask for devotion; it benefits from distraction.

The significance of Bell’s project ultimately lies in its policy implications. If public art reshapes movement, environment and resource allocation within parks, then commissioning sculpture becomes a form of urban governance. Future projects will require public agencies to draft clearer frameworks for soil impact, circulation equity, shade disruption, and maintenance logistics. As artworks become part of the city’s physical ecosystem, the relevant questions

shift from “What does this mean?” to “What does this do?” and “Who bears responsibility for its consequences?”

Madison Square Park has long blended landscape and culture, but Bell’s installation affirms a new reality: in dense cities, public art is not a decorative addition. It is a functional intervention into civic life. It operates as planning, impacts ecology and shapes public behavior. Whether a visitor recognizes Larry Bell’s legacy or simply pauses to look at their own reflection within tinted glass, they are participating in a system where art influences the very structure of everyday urban experience. In this context, aesthetic judgment becomes inseparable from public policy. What we place in the park is a decision about how we choose to share the city.

Cities as Emotional Landscapes Miguel Ángel Iglesias on Color, Structure, and the Quiet Drama of Urban Life

Q: You grew up visiting the Louvre, surrounded by dramatic Romantic paintings. Do you think our emotional life today has moved from nature into the city?

M: Yes. Our strongest emotions now take place not in storms or mountains, but in crowded stations, towers, and anonymous streets. A skyscraper can hold the same tension as a violent wave, shaped by human ambition instead of nature. The city is where we confront desire, exhaustion, conflict, and hope today. Urban life has become our emotional landscape.

Q: Your cities resemble real places, yet remain nameless. Why remove identity?

M: A nameless city belongs to everyone. When I remove landmarks or signs, I replace geography with memory, allowing many cultures to recognize themselves in the same structure. The anonymity reflects globalization, but also mirrors my own shifting identity formed between Paris, Barcelona, New York, and Asia. The city becomes less literal, and more human.

Q: You eliminate windows, cars, and other narrative elements. What remains after removing them?

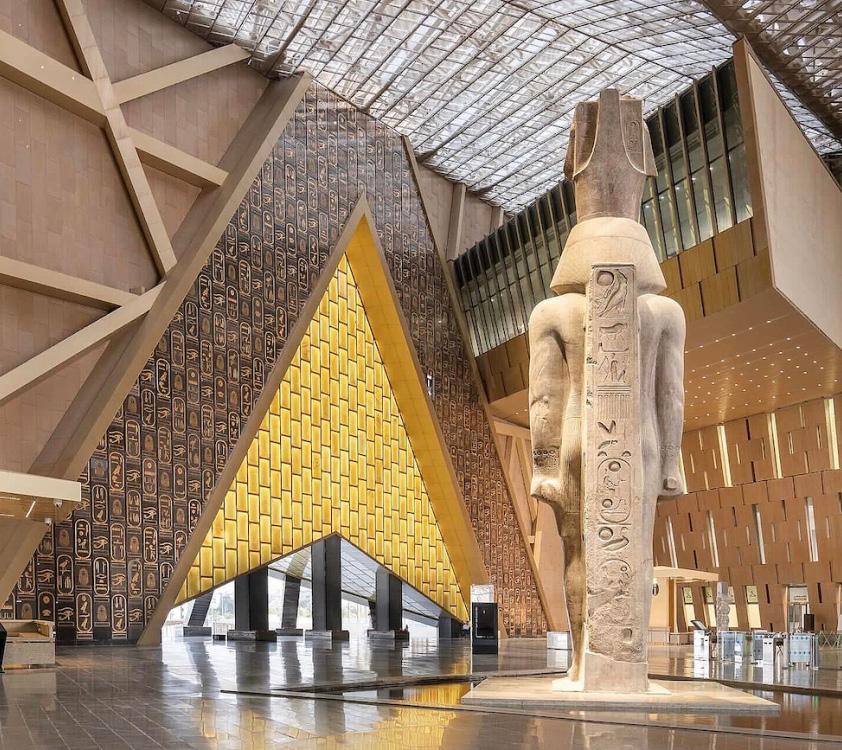

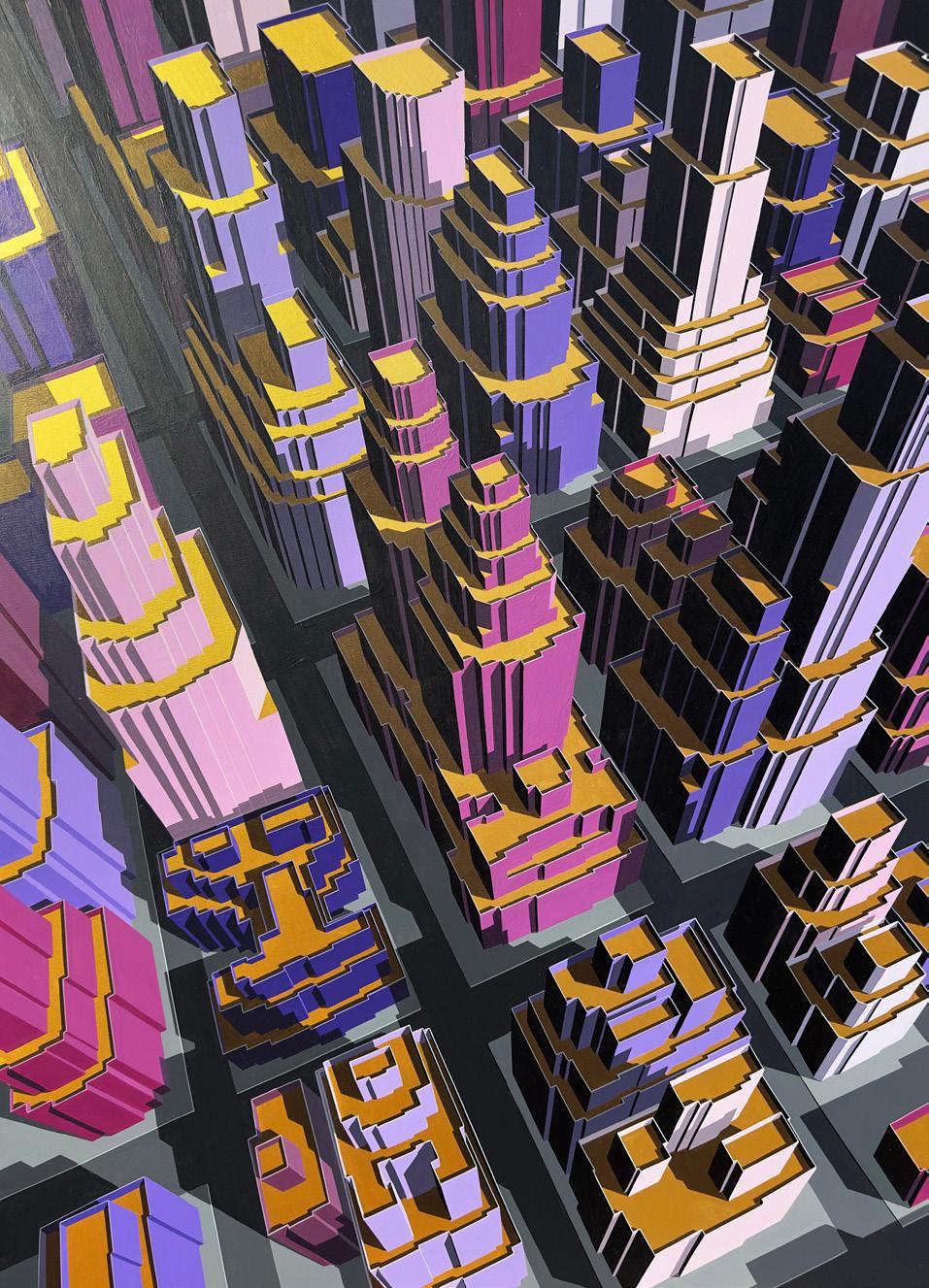

Miguel Ángel Iglesias paints cities not as locations, but as emotional structures. Stripping away windows, cars, and signage, he reveals the essence of urban life through rhythm, volume, and light. His cityscapes resemble familiar skylines yet remain anonymous, allowing viewers to recognize a shared, global experience rather than a single geography. Viewed from above, his works treat the city as a living organism shaped by coexistence and collective memory. In recent works, Iglesias has shifted toward subtler palettes and even black-and-white compositions, exposing the bones of structure without the temperature of color. Whether vibrant or restrained, his paintings propose not the city we inherit, but the one we hope to build.

a psychological space rather than a descriptive one. I am more interested in how a place feels than how it looks. Removing the anecdote reveals the essence and forces the viewer to confront their own interpretation of urban life.

Q: You’ve said color only becomes itself through other colors. Is painting for you a study of coexistence?

M: Exactly. A single color has no meaning until it meets another—it finds identity through contrast, balance, or tension. People work the same way; we discover who we are through others. Painting becomes a quiet reflection on interdependence, where identity is built not alone but in relation.

Q: Your perspective is always from above. Is that distance emotional?

M: It’s not emotional distance—it’s empathy from a wider view. From above, I see how millions of lives coexist like one living organism, layered with beauty and contradiction. I’m not escaping the city; I’m trying to understand its full pulse at once, without losing the whole to the detail. The elevated view lets me embrace rather than isolate.

Q: You said you stopped painting “the sad city” and began painting “the city you want to see.” Why?

M: Because painting should not only mirror reality — it should propose another one. Instead of repeating cynicism, I choose to construct possibility through color. Hope becomes a tool, not a distraction. I paint the city as it could be, rather than the city we inherit without questioning it.

Q: Do you think color is today’s equivalent of the Romantic “sublime”?

M: Yes. Color carries the intensity that nature once delivered in storms and mountains. It overwhelms, vibrates, and destabilizes our perception just as the sublime once did. Through color, the emotional shock comes not from nature anymore, but from the power of perception itself.

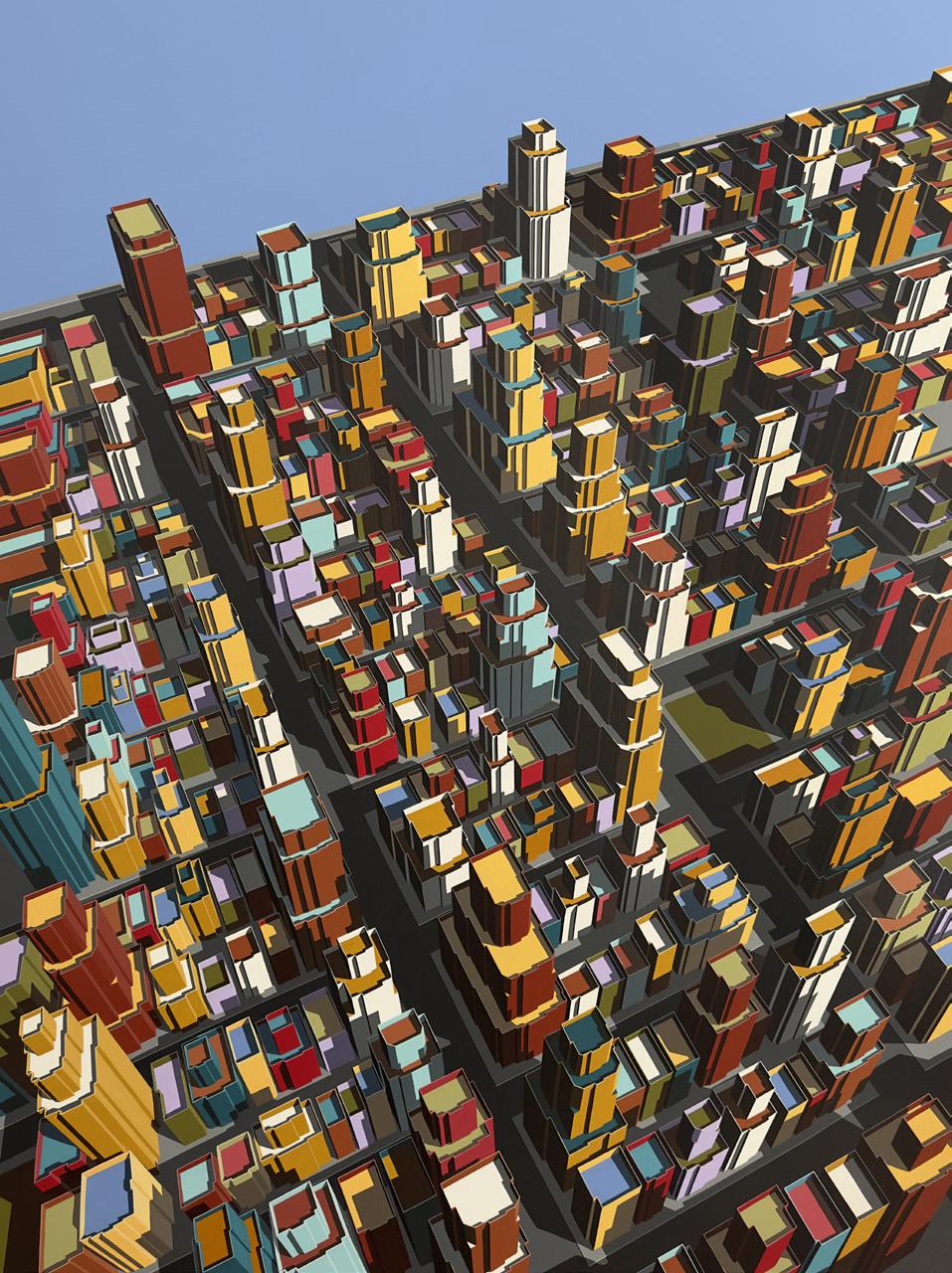

Q: Recently, you introduced a black-and-white New York series, and your palette overall has become more subtle. Why this shift toward restraint?

M: I think restraint reveals clarity. Black and white exposes the bones of the city—its density, pressure, and structure—without the emotional temperature of color. My recent palette has become subtler because I no longer need intensity to create impact; tension can also appear in quiet tones. When color whispers instead of shouts, it invites a deeper kind of attention.

Q: Your work shows shifts in palette, structure, and even perspective. What does artistic evolution mean to you?

M: Evolution is not change for novelty—it’s alignment between feeling and expression. With time, I need fewer gestures to express more meaning. I remove what is loud and keep what is essential. Growth is the slow ability to be honest, and to accept that clarity can come through simplification. The work becomes quieter, but more precise.

Structure, Anonymity, and the Emotional Architecture of Global Cities

by David Castillo i Buïls

WRITTEN BY - David Castillo i Buïls

David Castillo i Buïls (b. 1961) is a Catalan poet, novelist, and influential literary critic from Barcelona, whose career bridges underground counterculture and mainstream literary acclaim. Emerging from the radical poetic movements of the 1970s,

he gained recognition through both rigorous criticism and award-winning creative works, including the Carles Riba Poetry Prize for Game Over (1998) and the Crexells Prize for the novel El cel de l’infern (1999). A defining cultural voice in contemporary Catalonia, Castillo has shaped public literary discourse as editor of Avui’s cultural supplement, founder and director of Barcelona’s Poetry Week, and lecturer at the Autonomous University of Barcelona. His writing—spanning biographies, poetry, and fiction—reveals a commitment to artistic dissent, urban memory, and the dialogue between popular culture and literary tradition.

Miguel Ángel Iglesias paints the city at the threshold where memory becomes structure. His work refuses the conventions of urban representation—no windows to peek into, no signage to decode, no traffic to mark time. By removing these narrative signals, Iglesias does not simplify the city; he intensifies it. What remains is a condensed organism made of volume, pressure, and repetition, where architecture is no longer background but the very condition of human life. His paintings are not “views of cities,” but concentrations of what the city does to us—how it orders, compresses, overwhelms, or silently carries us.

To Iglesias, the aerial perspective is not a factual vantage point, but a moral one. Distance becomes the only way to approach the collective—without collapsing back into individual anecdote. Seen from above, urban life resembles a nervous system, a tangle of functions and contradictions that cannot be understood from the sidewalk. If traditional landscape painting once located the sublime in storms and mountain ranges, Iglesias relocates it into stacked buildings that hold millions of private narratives at once. His canvases ask: What does it mean to exist together, while remaining strangers? By offering no individual figure, he paints a society without protagonists.

Color enters this structure not as decoration but as emotional weather. Iglesias often describes color as relational, gaining identity only when confronted with other tones. This logic mirrors the city’s social condition: one does not become oneself alone, but through the friction of difference. In his work, color is not merely applied—it negotiates. A red becomes more assertive next to blue; a violet loses authority near Naples yellow; neutrality is nearly impossible. Color, like community, forms meaning through coexistence. In this sense, Iglesias’s paintings are not just visual spaces but ethical proposals—models for how identity might exist without isolation.

Recently, the artist has moved toward a subtler palette, even adopting black-and-white compositions in his New York series. This restraint is not a withdrawal, but a sharpening. Without chromatic heat, structure is exposed without anesthesia—the bones of density, the weight of accumulation, the geometry of routine. In black and white, the city loses seduction and reveals its control. Yet Iglesias does

not criticize this architecture; he listens to it. By limiting the palette, he enters a quieter negotiation with form, allowing tension to rise from rhythm instead of chromatic conflict. The quieter the tone, the more precisely the city speaks.

In these recent works, Iglesias no longer paints the city he sees, but the city he chooses to imagine. This shift is not an escape from reality, but a recalibration of it. His practice aligns with a fundamental question: If painting is not criticism, can it be construction? Rather than mirror the cynicism of contemporary urban life, his work proposes subtle alternatives—spaces built from clarity, empathy, and disciplined restraint. He replaces spectacle with structure, noise with attention, description with inquiry. His cities do not document what we already know; they invite us to reconsider what we have come to accept.

Ultimately, Iglesias’s artistic evolution suggests that to paint the city is to confront the ethics of living within it. Every reduction, every muted tone, every erased detail becomes a gesture of responsibility: an insistence that meaning requires focus, that clarity demands discipline, and that beauty is not a luxury but a form of attention. In this sense, Iglesias’s canvases do not merely depict global urban life—they test it. They ask whether a city built from memory, relation, and restraint can offer a model for how we might inhabit one another more thoughtfully. His paintings refuse spectacle, yet they expand our capacity to see.

Stillness Before the Next Beginning

As 2026 Nears, Art Learns to Breathe Again

by Jungeun Janis Park / Senior Editor

As the year comes to a close, the art world enters a brief and necessary stillness.

The final lights of the galleries dim, public rhythms loosen, and the many openings and unveilings that defined the year settle into a quiet that feels almost architectural. In this pause—before the next cycle begins—art regains its breath.

This year reminded us that the life of art extends far beyond the moment of display. It lives after hours, in softened galleries where a single work reveals new depth; in institutions reopening after years of renovation, reshaping their civic identity; and in museums stepping forward after decades of construction to reclaim cultural narrative. These shifts reveal that art’s endurance lies in its capacity for continual reinterpretation.

2025 also showed how profoundly our senses are expanding. Technology is no longer an auxiliary tool but a medium through which museums study,

preserve, and imagine. AI reassembles lost pigments and forms, digital infrastructures move artworks across borders, and hybrid studios blur the lines between engineer and artist. Yet one principle holds: technology does not replace human perception—it extends the distance that perception can travel. Within that expanded field, art becomes more—not less—human.

Across cities, parks, and public squares, art reframed how we inhabit space.

Sculptures redirected pedestrian flows; installations reshaped urban ecosystems; and artists rendered cities as emotional rather than physical landscapes. Art no longer exists only to be seen—it becomes something collectively negotiated, lived, and felt.

And yet, at year’s end, we return to quiet. This stillness is not an ending but a threshold. A moment in which institutions reassess their responsibilities,

technology is asked to serve meaning rather than momentum, and the emotional life of cities becomes part of cultural memory.

In this brief pause, art rediscovers its pulse.

As 2026 approaches, art is not asked to grow louder or faster.

It is asked to deepen— to look with greater clarity, to listen with more intention, to expand with integrity.

It is asked to imagine a future where heritage and innovation move not in opposition, but in continuity.

Art is reborn not in spectacle, but in the quiet intervals where we learn to feel the world again.

As we cross into 2026, we witness art awakening— newly attentive, newly expansive, and newly alive.

Principia

JunHwan Chang / Editor-in-Chief

Jungeun Janis Park / Senior Editor

Soojin Jinnie Kang / Editorial Coordinator

YoonKyung Hailey Cho / Graphic Designer