BERNARD PALISSY A TRIBUTE TO

French lead-glazed earthenware 1580-1650

French lead-glazed earthenware 1580-1650

French lead-glazed earthenware 1580-1650

This publication would not have been possible without the continuous support of William Iselin, Stephen Wright - London - and Nadège Fray Laigroz - Paris - for their immense contribution to the research and texts. I'm much obliged to Nathalie Atwood, Deputy Archivist at the Rothschild Archive, London, for her assistance.

I would also like to express my gratitude to Michel Vandermeersch for his benevolence, and to Sophie Hasaerts for coordinating this project.

Bernard Palissy (c.1510-1590) remains one of the most enigmatic and fascinating figures of the French Renaissance.

A true Renaissance man, he was at once a potter, scientist, writer and engineer. Palissy is best known for his exquisite « rustic ware » (‘rustiques figulines’ as he termed them) - ceramic pieces adorned with lifelike casts of plants, shells, and animals, which he achieved through an innovative moulding technique.

Despite his artistic genius, his life was marked by struggle and hardship. He spent years obsessively experimenting with glazes and firing techniques, often at great personal cost. Legend has it that, in his desperate pursuit of the perfect formula, he burned his own furniture to feed the kiln. This mythical scene was painted by Alexandre-Évariste Fragonard in 1829. His devotion to his craft, however, did not shield him from the religious turmoil of the time. As a Huguenot, Palissy was eventually imprisoned and perished in the Bastille, leaving behind both a legacy of artistic brilliance and an aura of mystery.

Centuries later, Palissy’s story takes an unexpected turn. In the second half of the 20th Century archaeologists, researchers and curators started to realise that most of the ceramics in museums and private collections were not by Bernard Palissy, but by anonymous French potters of the late 16th - early 17th Century.

In the late 1980s, when construction crews excavated and laid the foundations for the renovations of the Louvre Museum in the Tuileries gardens, they unearthed a remarkable cache of ceramic fragments, broken moulds, discarded test pieces, and shards of Palissy-style works. It was soon revealed that they had stumbled upon the very workshop where Palissy had conducted his passionate experiments. This extraordinary find reshaped our understanding of his œuvre. With the help of modern technology, scholars meticulously analysed the fragments and realised that the number of Palissy works was shockingly small, barely a dozen pieces worldwide. Most of the intricate, nature-inspired ceramics long attributed to Bernard Palissy, and which for centuries had contributed to his fame, were in fact masterpieces of anonymous French late Renaissance potters.

In the 19th and early 20th Centuries, prominent collectors enthusiastically acquired what they believed at the time to be Bernard Palissy ceramics. Baron Alphonse de Rothschild (1827-1905) and his younger brother, Baron Gustave de Rothschild (1829-1911), Alphonse’s son, Baron Edouard de Rothschild (1868-1949), Prince Pierre Soltykoff (c. 1801-1889) and the collector-dealer, Frédéric Spitzer (1815-1890) all constituted important groups of what is now known as lead-glazed earthenware ceramics. They feature prominently in their cabinets of Renaissance wonders alongside Limoges enamels, Venetian glass and precious hardstones and rock crystal, a reflection of their immense wealth and impeccable taste. Many of the works in this catalogue can trace their provenance back to these seminal collectors and especially Alphonse de Rothschild whose vast collection had an entire catalogue devoted to it.

This 1856 painting by Arthur Henri Roberts of Alexandre-Charles Sauvageot (1781-1860) perfectly conveys the importance of these wares for 19th Century connoisseurs. Sauvageot was a musician and one of the most admired collectors of the day who donated to the Louvre just before his death his eclectic group of no less than 1,424 works of art and books. Sauvageot’s post-Palissy ceramics form the core of the Louvre’s holdings in this area and are an important source of early documented pieces.

20th Century research transforms this narrative surrounding Palissy’s legacy. No longer the sole creator of an entire genre so dear to the Romantic notions of these early collectors, Palissy emerges instead as the founder of an artistic movement, inspiring a lineage of craftsmen whose names have been lost to history. The image of the lone genius struggling in his atelier is replaced by a vision of a vibrant, yet anonymous, collective.

This publication presents some of these masterpieces, giving due credit to the forgotten hands that shaped them, and illuminates the ongoing fascination with the art of Bernard Palissy and those that came after him.

Plate 18 from Frédéric Spitzer’s 1893 auction catalogue showing his collection of ‘

French lead-glazed earthenware 1580-1650

A French lead-glazed earthenware 'Rustiques figulines' oval dish, probably Fontainebleau or Paris, by the Maître du dragon, late 16th – early 17th century

Width: 52 cm. (20 ½ in.) • Depth: 41.5 cm. (16 ¼ in.) • Height: 7 cm. (2 ¾ in.)

waves reserved with five fish, the border with frogs, insects, crayfish, a coiled grass snake, a dragonfly, a lizard, among leaves, ferns, shells and fossils, the underside marbleised with srreaky mottled blue and maroon glaze.

Collection of Alain Moatti

L.N. Amico, Bernard Palissy: in search of earthly paradise, New York, 1996, pp. 128-129.

I. Perrin, Les techniques céramiques de Bernard Palissy, 2 vols., Villeneuve d’Ascq, 2000, p. 253, p. 313, no. 48, and pp. 346-347, nos. 77-78.

C. Viennet, Bernard Palissy et ses suiveurs du XVIe siècle à nos jours: Hymne à la nature, Dijon, 2010, p. 119.

J-C. Plaziat, ‘L’identification des moulages des coquilles fossiles et des organismes actuels des rustiques figulines : un apport naturaliste à la caractérisation des ateliers successifs de Palissy et de ses émules’, Technè, no. 47 (2019), pp. 108-111, figs. 15-18.

Bernard Palissy’s immediate followers have not to date been identified through documentary evidence. However, certain distinct hands have been discerned based on characteristic mouldings or other stylistic analysis. This dish belongs to a small group with nearly identical rims including a small ‘dragon’ motif. Leonard Amico in 1996 coined the nickname ‘Griffin Master’ for works including this characteristic mould (op. cit., p. 128). Isabelle Perrin in 2000 set out a corpus of dishes including some without the dragon but clearly by the same potter, dating them all to the late 16th or early 17th Century (op. cit., p. 253). In his 2019 article analysing the fossil and shell moulds on the rims, Jean-Claude Plaziat regarded the creature as more like a dragon than a winged griffin and so re-named this anonymous artist the Maître du dragon (op. cit., p. 108).

As Amico remarked, the rims of these dishes come from common moulds which were then attached to basins made separately and with different features (op. cit., p. 128). Most of these basins are centred on undulating snakes. One such dish has been in the Louvre since 1856 as part of the Sauvageot donation (OA 1361). Another is at Écouen but recorded in the De Sommerard collection since at least 1847. Plaziat’s archival discovery of a late 17th Century drawing matching exactly the Écouen dish has proved beyond any reasonable doubt that the Maître du dragon worked in the period shortly following the lifetime of Bernard Palissy himself.

Étienne de Faye (1670-1750), drawing of a 'Rustiques figulines' dish (dragon highlighted top right) in Description d’un cabinet et d’un médaillier Bibliothèques d’Amiens-Métropole (MS 400 E, pl. 301) Reproduced in Plaziat, op. cit., fig. 18

Dishes like this one with a central circular arrangement of shells are rarer. Perrin located only two others (op. cit., nos. 7778), and overlooked a third, all in American museums. The one illustrated here is in the collections of the Toledo Museum of Art, with the others in the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore (48.1345) and the Art Institute of Chicago (1965.127).

The Maître du dragon uses great finesse and often employs various tools and fabrics to enhance the details of life-castings (Viennet, op. cit., p. 119). Here the scales of the large fish are made more textural through cross-hatching.

FRENCH LEAD-GLAZED EARTHENWARE 1580-1650

A French lead-glazed earthenware gondola cup, probably Fontainebleau or Paris, circa 1600-1650

Height: 8.5 cm. (3 ¼ in.) • Width: 11 cm. (4 ¼ in.) • Length: 19 cm. (7 ½ in.)

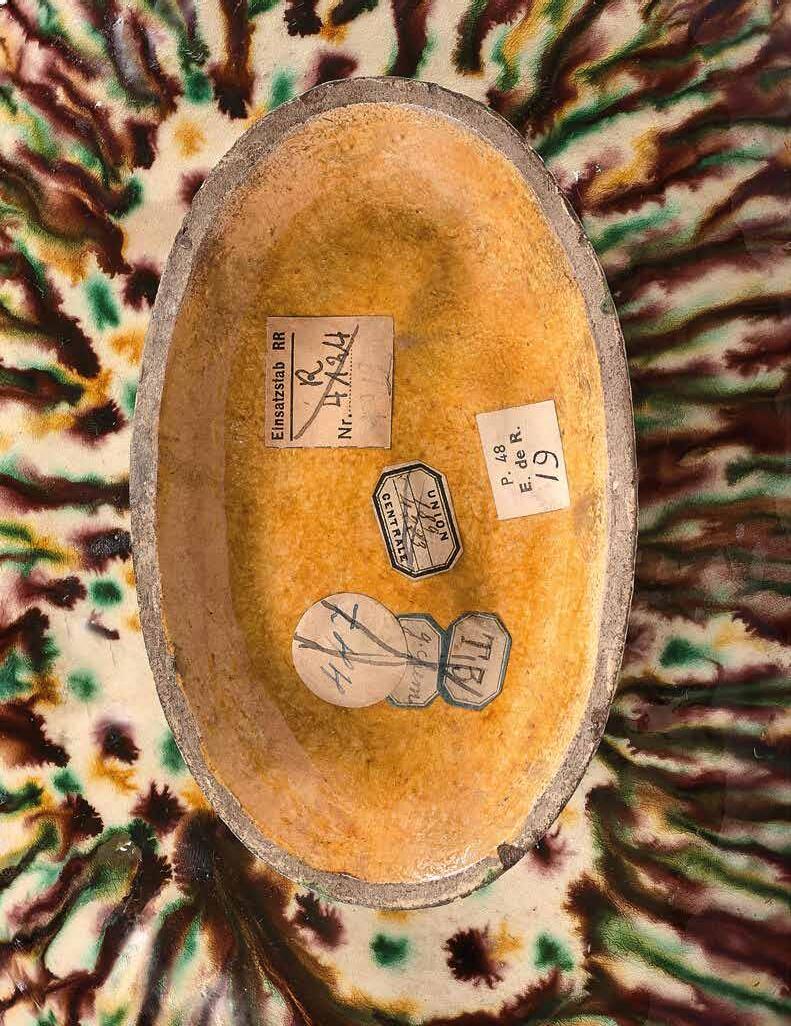

Of oval form, the scroll handle flanked by two wings, moulded with the figures of Mars and Venus in an embrace, accompanied by a putto holding a breastplate on a blue ground, the underside marbleised in blue, green and manganese and with labels inscribed P. 48 /E. de R./ for Édouard de Rothschild and another inscribed Einsatzstab R nr. 4173.

Baron Alphonse de Rothschild (1827-1905)

Baron Edouard de Rothschild (1868-1949)

Confiscated from the above by the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg following the Nazi occupation of Paris in May 1940 (ERR no. R 4173)

Recovered by the Monuments Fine Arts and Archives Section and transferred to the Munich Central Collecting Point (MCCP no. 340/8)

Returned to France on 9 January 1946 and restituted to the Rothschild family

Baron Guy de Rothschild (1909-2007), Hôtel Lambert, Paris, and by descent

Exhibited

Exposition Rétrospective de l’Art français des origines à 1800, Exposition Universelle, Paris, 1900, no. 923 (one of two « saucières ovales »).

Literature

Collection de Mr. Le baron Alphonse de Rothschild, circa 1890, (n.d.), vol. II, pl. 55.

H. Roujon, E. Molinier and F. Marcou, Catalogue officiel illustré de l’Exposition rétrospective de l’art français des origines jusqu’à 1800, Exposition Universelle, Paris, 1900, p. 274, no. 923.

G. de Rothschild and S. Grandjean, Bernard Palissy et son école, Paris, 1952, no. XXXVII, pl. 36.

J. Bergeret, ‘Les Suites de Palissy, une vaisselle d’apparat et une vision du monde’, in Les céramiques du Pré-d’Auge. 800 ans de production, exh. cat., Lisieux, Musée d’art et d’histoire, 3 Jul – 30 Sep 2004, Lisieux, 2004, p. 111.

A. Sauzay, H. Delange, C. Delange and C. Borneman, Monographie de l’œuvre de Bernard Palissy suivie d’un choix de ses continuateurs ou imitateurs, Paris: Lemercier, 1862, pl. 44, pl. 45, pl. 46 and pl. 47.

A. Darcel and A. Basilewsky, Collection Basilewsky, catalogue raisonné, Paris, 1874, p. 173, no. 465.

A. MacGregor, Tradescant’s Rarities; Essays on the Foundation of the Ashmolean Museum, 1683, With a Catalogue of the Surviving Early Collections, Oxford, 1983, pp. 275-276.

I. Perrin, Les techniques céramiques de Bernard Palissy, 2 vols., Villeneuve d’Ascq, 2000, I, p. 61.

Several different types of gondola cup containing mythological relief figures are known. Four were illustrated in 1862 when Lemercier published colour lithographs1, although this particular type was not included. It appears to be the rarest model; indeed this example – then still in Rothschild ownership – was the only one cited by the catalogue authors of the major 2004 exhibition in Lisieux on post-Palissy ceramics2.

Only one other example is known: now in the Hermitage, it formerly belonged to the important 19th Century Parisian collection of the Russian diplomat, comte Alexander Basilewsky3.

gondola cup

The Ashmolean Museum in Oxford has two similar gondola cups, both decorated with a couple embracing – in this case, Bacchus and Ceres.

These examples are of particular interest for dating this form. They are recoded since 1656, making them the earliest documented pieces of post-Palissy ceramic4. They were given to Oxford by Elias Ashmole (1617-1692), who donated his collection to the museum that bears his name in 1691. Ashmole himself had acquired the collection after the death of John Tradescant, Jr. and his wife. On the latter's death in 1662, the Tradescant collection was displayed in their family home in south London's Lambeth district, bringing together the curiosities collected in the first half of the 17th Century not only by John Jr. (1608-1662), but also by his father of the same name, John Tradescant (circa 1570-1638). In the collection catalogue published in 1656, these French ceramics are described as "Variety of China dishes", providing a terminus ante quem for this form of dish. They may have been acquired by John Tradescant, Sr. in the early decades of the 17th Century, when he travelled in France for the Earl of Salisbury, and later for the Duke of Buckingham5.

gondola cups

A French lead-glazed earthenware oval footed dish depicting the Nymph of Fontainebleau, Manerbe or Pré-d’Auge (Normandy), Maître au pied ocre workshop, circa 1600-1650

Length: 28.3 cm. (11 ¼ in.) • Depth: 22.5 cm. (8 ¾ in.) • Height: 6 cm. (2 ¼ in.)

The centre decorated in relief with a nude nymph seated on the ground, resting her left arm on a large overturned amphora from which flows a stream of water, attended by two hounds, the edge with radiating rays and foliage, the underside marbleised in yellow, green and purple and the inside of the foot glazed in ochre, and with printed labels for the Union central exhibition in 1865 with number 189/4223, P. 48 /E. de R./19 for Edouard de Rothschild, Einsatzstab R nr. 4124, G. Chem, T.B. and with number 447.

Provenance

Probably Prince Pierre Soltykoff collection, his sale; Paris, Hôtel Drouot, Me Pillet, 8 April-1 May 1861, lot 538

Baron Alphonse de Rothschild (1827-1905)

Baron Edouard de Rothschild (1868-1949)

Confiscated from the above by the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg following the Nazi occupation of France in May 1940 (ERR no. R 4124)

Recovered by the Monuments Fine Arts and Archives Section and transferred to the Munich Central Collecting Point (MCCP no. 113/7)

Returned to France on 9 January 1946 and restituted to the Rothschild family

Baron Guy de Rothschild (1909-2007), Hôtel Lambert, Paris, and by descent

Exhibited

Paris, Palais de l’Industrie, Union Centrale des Beaux-Arts Appliqués à l’Industrie, Musée Rétrospectif, 1865, p. 85, no. 857.

Collection de Mr. Le baron Alphonse de Rothschild, circa 1890, (n.d.), vol. II, pl. 18.

G. de Rothschild and S. Grandjean, Bernard Palissy et son école, Paris, 1952, no. XVI, pl. 10.

A.V.B. Norman¸ Wallace Collection, Catalogue of Ceramics, Pottery, Maiolica, Faïence, Stoneware, London, 1976, pp. 323-325, no. C168.

A. Gibbon, Céramiques de Bernard Palissy, Paris, 1986, p. 119, no. 85.

L.N. Amico, Bernard Palissy: in search of earthly paradise, Paris and New York, 1996, p. 39, figs. 29-30.

I. Perrin, Les techniques céramiques de Bernard Palissy, 2 vols., Villeneuve d’Ascq, 2000, I, p. 213, no. 10 and pp. 243-248.

D. Dufournier and D. Thiron, ‘Le site de la Bosqueterie et la famille Vattier au Pré-d’Auge’, in 800 ans de production céramique dans le Pays d’Auge, exh. cat., Lisieux, Musée d’art et d’histoire, 3 Jul – 30 Sep 2004, Lisieux, 2004, p. 28, nos. 13a-b.

D. Dufournier and D. Thiron, ‘Les carreaux de pavement faïencés augerons dits « pavés de Lisieux » ou « pavés Joachim »’, in 800 ans de production céramique dans le Pays d’Auge, op. cit., pp. 58-66, esp. p. 64 and p. 66, no. 133.

J. Bergeret, ‘Les Suites de Palissy, une vaisselle d’apparat et une vision du monde’, in 800 ans de production céramique dans le Pays d’Auge, op. cit., p. 82, p. 91, no. 177.

The MaItre au pied ocre

Some post-Palissy ceramics share a distinctive mottled glaze on the reverse, with fused green, ochre and purple lines and dots intermingled on a whitish ground. Blue tones are completely absent. The underside of the foot is glazed a uniform ochre. The finely cut rim and moulding are often adorned with daisies, the glaze is applied thinly in a range of colours and the mottled finish gives an impression of speckling. The ochre-coloured foot is the origin of the name Isabelle Perrin gave to this group of works, ‘céramiques du Maître au pied ocre’ (Master of the ochre foot). By comparing the mottled glaze on their reverses with that of floor tiles produced in the region, Perrin concludes that these pieces, all of a “très grande finesse”, were probably made near Lisieux.1

Glazed terracotta paving tiles from the Château d’Hénauville (near Rouen), Pré-d'Auge, 17th Century Ecouen, Musée national de la Renaissance (E.CL. 13264)

A similar single tile, Pré-d'Auge, 17th Century 7 x 5 x 9 cm.; thickness 2.5 cm Lisieux, Musée d'art et d'histoire (F13-03)

Excavations carried out at the Bosqueterie site in 2004 uncovered fragments of two bowls whose feet are not ochre-coloured, but whose reverses bear a very similar mottled glaze, confirming the resemblance to pieces produced in the Pré-d'Auge2.

Two pierced footed dishes, Pré-d'Auge, Bosqueterie workshop, late 16th / 17th Century Height: 6.5 and 6 to 7.5 cm.; diameter: 24 cm. (each) Lisieux, Musée d'art et d'histoire (FA-19 and FA-20)

The scene on this dish is based on a print begun by the Parisian engraver Pierre Milan and finished several years later in 1554 by his assistant, René Boyvin. It derives from a fresco by Rosso Fiorentino in the Galerie François 1er in Fontainebleau3. The subject refers to the origin of the Château’s name: a hound, Bleau, held dear by King Louis IX is said to have discovered a spring during a hunt in the old forest of Brière, which then took the name of the "Fontaine de Bleau".

Milan and René Boyvin, after Rosso Fiorentino

A dish of this model was in the Prince Soltykoff collection sold in Paris, 8 April – 1 May 1861, lot 538, bought by Mannheim for 511 francs.

Alphonse de Rothschild is recorded as the buyer of a number of Italian maiolica works in this sale through the dealer Charles Mannheim, making it very likely that this dish comes from the Soltykoff collection. It was certainly in Alphonse’s possession by 1865, when he exhibited it under no. 857 at that year’s Paris Exposition at the Palais de l'industrie.

A very similar ochre-footed dish which once formed part of the Sauvageot collection is in the Louvre4. Another in the Musée départemental des Antiquités in Rouen was selected for inclusion in the major 2004 exhibition in post-Palissy ceramics at Lisieux5. A third ochre-footed dish, although with a different border, is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (inv. 53.225.66).

A dish with the same scene but an entirely different border is in the Wallace Collection. The underside of the Wallace dish also differs from this one and those cited above6. A specific production centre for the Nymph of Fontainebleau model has yet to be identified and it seems likely that the mould was available in more than one location.

A French lead-glazed earthenware oval dish depicting the Garden of Pomona, Probably Fontainebleau or Paris, circa 1600-1650

The deep dish moulded with a figure of Pomona or ‘la Belle Jardinière’ after Maerten de Vos, seated near a vase beneath a tree, holding a bouquet and a palm, a manor house and formal gardens in the background, the underside marbleised in blue, green and manganese and with a printed label from the Union central exhibition in 1865 with number 189/4210, and printed labels inscribed A. de R. N° for Alphonse de Rothschild, P. 48 /E. de R./33 for Edouard de Rothschild, Einsatzstab R nr. 4130 and labels inscribed T.3 and with number 431.

Length: 34 cm. (13 ½ in.)

• Depth: 27.5 cm. (10 ¾ in.)

• Height: 5.5 cm. (2 ¼ in.)

Baron Alphonse de Rothschild (1827-1905)

Baron Edouard de Rothschild (1868-1949)

Confiscated from the above by the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg following the Nazi occupation of France in May 1940 (ERR no. R 4130)

Recovered by the Monuments Fine Arts and Archives Section from the Altaussee salt mines, Austria, and transferred to the Munich Central Collecting Point, 18 June 1945 (MCCP no. 116/3)

Returned to France on 9 January 1946 and restituted to the Rothschild family

Baron Guy de Rothschild (1909-2007), Hôtel Lambert, Paris, and by descent

Exhibited

Paris, Palais de l’Industrie, Union Centrale des Beaux-Arts Appliqués à l’Industrie, Musée Rétrospectif, 1865, p. 85, no. 851.

Collection de Mr. Le baron Alphonse de Rothschild, circa 1890, (n.d.), vol. II, pl. 32.

G. de Rothschild and S. Grandjean, Bernard Palissy et son école, Paris, 1952, no. XXI, pl. 24.

A. Sauzay, H. Delange, C. Delange and C. Borneman, Monographie de l’œuvre de Bernard Palissy suivie d’un choix de ses continuateurs ou imitateurs, Paris: Lemercier, 1862, pl. 52.

H. Roujon, E. Molinier and F. Marcou, Catalogue officiel illustré de l’Exposition rétrospective de l’art français des origines jusqu’à 1800, Exposition Universelle, Paris, 1900, p. 274, no. 932.

A. Gibbon, Céramiques de Bernard Palissy, 1986, p. 117, no. 81.

L.N. Amico, Bernard Palissy: in search of earthly paradise, Paris and New York, 1996, p. 183, fig. 166.

I. Perrin, Les techniques céramiques de Bernard Palissy, 2 vols., Villeneuve d’Ascq, 2000, I, p. 217, no. 25.

J. Bergeret, ‘Les Suites de Palissy, une vaisselle d’apparat et une vision du monde’, in Les céramiques du Pré-d’Auge. 800 ans de production, exh. cat., Lisieux, Musée d’art et d’histoire, 3 Jul – 30 Sep 2004, Lisieux, 2004, p. 92, no. 180.

The scene on this dish is based on an engraving by Philip Galle (1537-1612) after a composition by Maerten de Vos (1532-1603). Titled in Latin ‘Ver’ (Spring), it shows Pomona, the Roman goddess of fruits, with all her gardening equipment. Pomona was associated more generally with orchards and gardens during the Renaissance. In time this depiction became identified as ‘la Belle Jardinière’.

This scene obviously found lasting favour on glazed earthenware as it was frequently repeated1. Several institutions have examples of this dish, some collected as far back as the early 19th Century.

A review of these dishes reveals varying degrees of crispness of modelling, a measure of the amount of repeated use of and consequent wear to the same moulds. The design and condition of this dish’s rim suggests that it comes from one of the least used moulds, making it amongst the best defined of all known examples. The majority of these dishes can be divided into two groups based on their rim designs. The first group, with this rim, is much rarer; indeed, the only other know example is the one in the Louvre acquired in 1856 as part of the Sauvageot collection2.

The second rim type is more commonly found, including:

Another dish in the Louvre from the 1856 Sauvageot donation, here illustrated.

One in the Dutuit bequest at the Petit Palais in Paris (ODUT1148), included in the major 2004 Lisieux exhibition on post-Palissy ceramics3. When still in the Dutuit collection in the 19th Century, a lithograph of this dish was published by Lemercier in 18624.

One in the Victoria & Albert Museum from the 1910 Salting Bequest (inv. C.2304-1910).

One in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (inv. 53.225.60)

A very worn one in the Musée national de la Renaissance at Ecouen (inv. E. CL. 2961)5.

Finally, isolated other examples with different rims exist6.

This dish was in the possession of Alphonse de Rothschild since at least 1865, when he exhibited it under no. 851 at that year’s Paris Exposition at the Palais de l’Industrie.

A French lead-glazed earthenware pierced footed dish, Manerbe or Pré-d'Auge (Normandy), Maître au pied ocre workshop, circa 1600-1650

Diameter: 30 cm. (11 ¾ in.) • Height: 7.5 cm. (3 in.)

Of circular form with an everted rim, pierced and moulded with a geometric openwork pattern of flowerheads among scrolls below a border of stiff leaves and flowers, supported by a domed foot, the underside marbleised in green, ochre and purple and with printed labels inscribed A. de R. N° for Alphonse de Rothschild and P. 48 /E. de R./ 28 for Edouard de Rothschild, and label inscribed G. Chem.

Baron Alphonse de Rothschild (1827-1905)

Baron Edouard de Rothschild (1868-1949)

Confiscated from the above by the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg following the Nazi occupation of France in May 1940 (ERR nos. R 4112 or R 4114)

Recovered by the Monuments Fine Arts and Archives Section from the Altaussee salt mines, Austria, and transferred to the Munich Central Collecting Point, 18 June 1945 (MCCP nos. 116/1 or 113/3)

Returned to France on 9 January 1946 and restituted to the Rothschild family Baron Guy de Rothschild (1909-2007), Hôtel Lambert, Paris, and by descent

Literature

Collection de Mr. Le baron Alphonse de Rothschild, circa 1890, (n.d.), vol. II, pl. 45.

G. de Rothschild and S. Grandjean, Bernard Palissy et son école, Paris, 1952, no. XIV, pl. 9.

G. de Rothschild, Bernard Palissy, Paris, 1956, cover image.

I. Perrin, Les techniques céramiques de Bernard Palissy, 2 vols., Villeneuve d’Ascq, 2000, I, pp. 243-248.

Comparative Literature

B. Christman, A. Heuer and J. Castaing, ‘Palissy ceramics in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art’, Technè, no. 20 (2004), pp. 92-95.

D. Dufournier and D. Thiron, ‘Le site de la Bosqueterie et la famille Vattier au Pré-d’Auge’, in 800 ans de production céramique dans le Pays d’Auge, exh. cat., Lisieux, Musée d’art et d’histoire, 3 Jul – 30 Sep 2004, Lisieux, 2004, p. 28, nos. 13a-b.

D. Dufournier and D. Thiron, ‘Les carreaux de pavement faïencés augerons dits « pavés de Lisieux » ou « pavés Joachim »’, in 800 ans de production céramique dans le Pays d’Auge, op. cit., pp. 58-66, esp. p. 64 and p. 66, no. 133.

J. Bergeret, ‘Les Suites de Palissy, une vaisselle d’apparat et une vision du monde’, in 800 ans de production céramique dans le Pays d’Auge, op. cit., pp. 82-86 and p. 94, no. 186.

C. Viennet, Bernard Palissy et ses suiveurs du XVIe siècle à nos jours, Paris, 2010, pp. 101-103.

Some post-Palissy ceramics share a distinctive mottled glaze on the reverse, with fused green, ochre and purple lines and dots intermingled on a whitish ground. Blue tones are completely absent. The underside of the foot is glazed a uniform ochre. The finely cut rim and moulding are often adorned with daisies, the glaze is applied thinly in a range of colours and the mottled finish gives an impression of speckling. The ochre-coloured foot is the origin of the name Isabelle Perrin gave to this group of works, 'céramiques du Maître au pied ocre' (Master of the ochre foot). By comparing the mottled glaze on their reverses with that of floor tiles produced in the region, Perrin concludes that these pieces, all of a “très grande finesse”, were probably made near Lisieux1. ^

Glazed terracotta paving tiles from the Château d’Hénauville (near Rouen) Pré-d’Auge, 17th Century. Ecouen, Musée national de la Renaissance (E.CL. 13264)

A similar single tile, Pré-d’Auge, 17th Century

7 x 5 x 9 cm.; thickness 2.5 cm. Lisieux, Musée d’art et d’histoire (F13-03)

Two pierced footed dishes, Pré-d’Auge, Bosqueterie workshop, late 16th / 17th Century

Height: 6.5 and 6 to 7.5 cm.; diameter: 24 cm. (each) Lisieux, Musée d’art et d’histoire (FA-19 and FA-20)

Excavations carried out at the Bosqueterie site in 2004 uncovered fragments of two bowls whose feet are not ochre-coloured, but whose reverses bear a very similar mottled glaze, confirming the resemblance to pieces produced in the Pré-d'Auge2.

Perrin knew of the present dish through its publication in the 1952 Rothschild collection catalogue and includes it in her corpus of works by the Maître au pied ocre alongside the following examples in major museums3:

One with variations to its colouring in the Musée national de Céramique at Sèvres4, which Perrin has shown entered the collections there in 1827. This early provenance ensures that the Maître au pied ocre was not a 19th Century Palissy imitator.

Lead-glazed earthenware pierced footed dish, Manerbe or Pré-d'Auge, Maître au pied ocre workshop

Sèvres, Musée national de Céramique (MNC1041)

An identically coloured one in the Dutuit bequest at the Petit Palais in Paris. The dish’s reverse has not been photographed but is confirmed as having an ochre foot5 [I].

Another in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York [II].

A smaller version of this dish with a differently decorated reverse is in the Cleveland Museum of Art6. In 2004, this dish was analysed using X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRF) and an Ion Beam accelerator. The results led the study’s authors to conclude that this dish was amongst the earliest in their collection, dating to the late 16th Century, thus providing a possible dating for this group [III].

I. Lead-glazed earthenware pierced footed dish Manerbe or Pré-d’Auge, Maître au pied ocre workshop Paris, Petit Palais (ODUT1528)

II. Lead-glazed earthenware pierced footed dish Manerbe or Pré-d’Auge, Maître au pied ocre workshop New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art (53.225.46)

III. Lead-glazed earthenware pierced footed dish Cleveland Museum of Art (1986.56)

A lead-glazed earthenware oval plate depicting the Sacrifice of Isaac, probably Fontainebleau or Paris, circa 1610

Length: 31.5 cm. (12 ½ in.)

• Width: 26.5 cm. (10 ½ in.)

• Height: 5 cm. (2 in.)

Obverse with Abraham’s Sacrifice of Isaac, the rim moulded with gadroons with a brown ground and white and green highlights, the underside marbleised in blue and manganese and with labels printed 601 and inscribed in pencil Vente Soltykoff, printed F. 6., inscribed 2eme inv 1685 (or 1635(?)), and painted inscriptions (twice) AD 974.250.1.

Provenance

Collection of Prince Peter Soltykoff, Paris; his sale, Paris, 8 April 1861 sqq., p. 156, lot 601, sold for 180 to Guillard Collection of the Société Industrielle de Mulhouse for over a century up to the present day

Literature

J. Webb, Report on the collection of Prince Soltykoff, [London], [1860], pp. 1-5.

A. Darcel, ‘La Collection Soltykoff’, in Gazette des BeauxArts, tom. X (Jun., 1861), p. 303.

I. Perrin, Les techniques céramiques de Bernard Palissy, 2 vols., Villeneuve d'Ascq, 2000, p. 228, no. 64.

B. Christman, A. Heuer and J. Castaing, ‘Palissy ceramics in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art’, Technè, no. 20 (2004), pp. 92-95, esp. 92-93.

J. Bergeret, 'Les Suites de Palissy, une vaisselle d’apparat et une vision du monde', in Les céramiques du Pré-d'Auge. 800 ans de production, exh. cat., Lisieux, Musée d'art et d'histoire, 3 Jul – 30 Sep 2004, Lisieux, 2004, p. 82, p. 89, no. 167.

A. Bouquillon, J. Castaing, F. Barbe, T. Crépin-Leblond, L. Tilliard, S.R. Paine, B. Christman and A.H. Heuer, ‘French decorative ceramics mass-produced during and after the 17th Century: chemical analyses of the glazes’, Archaeometry, vol. 60, issue 5 (Mar., 2018), pp. 1-20, esp. p. 4, fig. 2b.

This composition was included in Isabelle Perin’s summary catalogue of post-Palissy figurative works under no. 641. No exact source has been identified. Amongst the 16th Century engravers working at Fontainebleau, Jean Mignon and Jacques Androuet Du Cerceau both treated the subject. Whilst their prints contain key elements in common with this plate such as the goat and brazier, there are enough differences to indicate the potters were working from a more recent, perhaps derivative, source2.

Obviously popular, the model was repeated many times, judging by the number of surviving examples in various formats. Amongst the known oval plates, the closest to this one, with identical rim designs and similarly jaspered reverses, are:

A plate at the Cleveland Museum of Art3 [I].

Another in the Louvre which employs a different colour scheme for the rim. It has an early 19th Century provenance, having been bought from the Revoil collections in 1828 [II].

One more at Ecouen, again with a different coloured rim, whose architectural background and other details are less clearly defined [III].

Recent chemical and X-ray spectroscopy analysis performed on the Cleveland and Louvre plates has demonstrated not only that they were “probably produced in the 17th Century” but that “significant differences” suggests production in “different workshops, each having different but related glaze chemistries”5. Noting overarching similarities in the results with those for dishes depicting the family of Henri IV (see cat. pp.96-101) the authors of the study proposed a dating of around 1610 (the year of the king’s death) for the Sacrifice of Isaac plates6.

The collections of Prince Peter Soltykoff and the Société Industrielle de Mulhouse

The Russian émigré, Prince Peter Soltykoff (circa 18011889), amassed over the course of two decades in Paris one of the greatest collectors of medieval and Renaissance objets d’art of the era. In 1860, the London dealer John Webb attempted to broker its entire sale to the South Kensington Museum, writing in his report “they are the finest objects selected from every fine collection that has been purchased during the last forty years”7. Soltykoff’s collection was prepared for public sale by the critic, arts administrator and later director of the Musée de Cluny, Alfred Darcel, who provided a lengthy summary spread across several issues of the Gazette des Beaux-Arts in 1861. Like nearly all the Palissy pieces in the collection, this dish was not individually mentioned by Darcel, who explained that the size of the collection alone was enough to signal its importance (« cent trente pièces… de Bernard Palissy… suffit seul pour montrer l’importance de cette division [de la collection] »).8

The names of buyers in the BnF’s scanned copy of the Soltykoff sale catalogue include many of the most eminent collectors and dealers of the day on both sides of the English Channel. The best-known amongst them –Rothschild, Durlacher, Webb, Basilewsky, Seillière, Spitzer, Lowengard and Beurdeley – are cited repeatedly throughout the sale. ‘Guillard’ by contrast only appears as a named buyer in the sections selling Palissy, Italian Maiolica and Italian glass. He bought 14 other pieces aside from this dish, which suggests he was either an agent acting on behalf of a collector, or a smaller, specialist dealer who has left no other trace.

Founded in 1826, the Société Industrielle de Mulhouse initially concentrated its interventions in economic and scientific fields. But as education and culture rapidly emerged as essential development issues for the territory, its collections grew to span the natural sciences and fine arts, some of which are considered prestigious in their fields. Thousands of unique works remain today, many deposited in the cultural institutions of the territory such as the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Mulhouse (over 500 works) and the Musée historique de Mulhouse (10% of the collection there).

A French lead-glazed earthenware oval plate depicting the Beheading of St John the Baptist, probably Fontainebleau or Paris, 17th Century

Length: 26.2 cm. (10 ¼ in.) • Width: 20.5 cm. (8 in.) • Height: 5 cm. (2 in.)

The rim moulded with gadroons with a blue ground and white highlights, the underside marbleised in blue and manganese and with labels inscribed No 10791-39000(?) and painted inscriptions AD 974.249.1 and 914(?)172.

Provenance

Collection of the Société Industrielle de Mulhouse for over a century up to the present day

Literature

A. Sauzay, H. Delange, C. Delange and C. Borneman, Monographie de l’œuvre de Bernard Palissy suivie d’un choix de ses continuateurs ou imitateurs, Paris: Lemercier, 1862, pl. 82.

A. Gibbon, Céramiques de Bernard Palissy, Paris, 1986, pp. 9495, no. 59.

I. Perrin, Les techniques céramiques de Bernard Palissy, 2 vols., Villeneuve d’Ascq, 2000, I, pp. 233-234, nos. 81-82.

J. Bergeret, ‘Les Suites de Palissy, une vaisselle d’apparat et une vision du monde’, in Les céramiques du Pré-d’Auge. 800 ans de production, exh. cat., Lisieux, Musée d’art et d’histoire, 3 Jul – 30 Sep 2004, Lisieux, 2004, p. 88, no. 165.

Two versions of this composition exist. One has a scene of Herod’s banquet taking place in the background, whereas the other – the model to which this dish belongs – shows simply two grilled windows1. Production of either version must have been limited as both exist in only a small number of examples (see below). No printed source for either variant of the composition has so far been identified.

An example of this particular model was included amongst the colour lithographs published in 1862 by Lemercier.

‘Décollation de St. Jean, collection de Mr. D'Yvon’ (Sauzay et al., op. cit., pl. 82)

Only three other known dishes do not show Herod’s banquet in the background, all coloured differently to this one:

One in the Louvre with an early 19th Century provenance, having been acquired in 1825 with the Durand collection.

A second in the Musée national Adrien Debouché in Limoges since 1866.

A third virtually identical to the Limoges dish in a private Paris collection when illustrated by Gibbon in 19862.

Lead-glazed earthenware dish

Lead-glazed earthenware dish

Limoges, Musée national Adrien Dubouché (ADL 7586)

The collections of the Société Industrielle de Mulhouse

Founded in 1826, the Société initially concentrated its interventions in economic and scientific fields. As education and culture rapidly emerged as essential development issues for the territory, its collections grew to span the natural sciences and fine arts, some of which are considered prestigious in their fields. Thousands of unique works remain today, many deposited in the cultural institutions of the territory such as the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Mulhouse (over 500 works) and the Musée historique de Mulhouse (10% of the collection there).

A French lead-glazed earthenware gondola cup, probably Fontainebleau or Paris, circa 1600-1650

Height: 8.5 cm. (3 ¼ in.) • Width: 11.5 cm. (4 ½ in.) • Length: 20.5 cm. (8 in.)

Of oval form edged with shell ornaments, moulded with a reclining allegorical female figure of Spring, a flowering cornucopia in her right arm, surrounded by water and reeds, on a blue ground, the underside glazed in grey with a printed label inscribed Einsatzstab R nr. 4172

Baron Alphonse de Rothschild (1827-1905)

Baron Edouard de Rothschild (1868-1949)

Confiscated from the above by the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg following the Nazi occupation of France in May 1940 (ERR no. R 4172)

Recovered by the Monuments Fine Arts and Archives Section from the Altaussee salt mines, Austria, and transferred to the Munich Central Collecting Point, 23 June 1946 (MCCP no. 340/7)

Returned to France on 9 January 1946 and restituted to the Rothschild family

Baron Guy de Rothschild (1909-2007), Hôtel Lambert, Paris, and by descent

Exhibited

Exposition Rétrospective de l’Art français des origines à 1800, Exposition Universelle, Paris, 1900, no. 923 (one of two « saucières ovales »).

Collection de Mr. Le baron Alphonse de Rothschild, circa 1890, (n.d.), vol. II, pl. 55.

H. Roujon, E. Molinier and F. Marcou, Catalogue officiel illustré de l’Exposition rétrospective de l’art français des origines jusqu’à 1800, Exposition Universelle, Paris, 1900, p. 274, no. 923.

G. de Rothschild and S. Grandjean, Bernard Palissy et son école, Paris, 1952, no. XXXVIII, pl. 36.

Comparative Literature

A. Sauzay, H. Delange, C. Delange and C. Borneman, Monographie de l'œuvre de Bernard Palissy suivie d'un choix de ses continuateurs ou imitateurs, Paris: Lemercier, 1862, pl. 44 and pl. 45.

A. MacGregor, Tradescant's Rarities; Essays on the Foundation of the Ashmolean Museum, 1683, With a Catalogue of the Surviving Early Collections, Oxford, 1983, pp. 275-276.

J. McNab, Seventeenth-Century French Ceramic Art, New York, 1987, p. 4, fig. 1, p. 6, p. 36, no. 1.

I. Perrin, Les techniques céramiques de Bernard Palissy, 2 vols., Villeneuve d'Ascq, 2000, I, p. 61, p. 222, no. 40 and p. 227, no. 61.

J. Bergeret, 'Les Suites de Palissy, une vaisselle d’apparat et une vision du monde', in Les céramiques du Pré-d'Auge. 800 ans de production, exh. cat., Lisieux, Musée d'art et d'histoire, 3 Jul – 30 Sep 2004, Lisieux, 2004, p. 91, no. 175 and p. 111. C. Viennet, Bernard Palissy et ses suiveurs du XVIe siècle à nos jours: hymne à la nature, Dijon, 2010, pp. 80-81.

This form exists in two basic variations, both of which were known in 1862 when Lemercier published colour lithographs1 [I and II].

‘Saucière, collection de M. Dutuit à Rouen’ (Sauzay et al., op. cit., pl. 45)

‘Saucière, collection d’Andrew Fountaine Esqe., Narford Hall, Angleterre’ (Sauzay et al., op. cit., pl. 44)

This cup belongs to the model with a female figure adorned with a pearl necklace, holding a single cornucopia under her right arm and sitting up slightly with her head resting on a shell at the end of the cup. Isabelle Perrin included this in her summary catalogue of figural works under no. 612.

Two cups of this single cornucopia model have plain grey glazed undersides like this one:

One in the Metropolitan Museum of Art3.

One in the 1910 Salting Bequest at the Victoria & Albert Museum.

earthenware gondola cup London, Victoria & Albert Museum (C.2310-1910).

Three further cups all in Paris museums are of the same pearl necklace model, but have jasper glazed undersides4:

Lead-glazed earthenware gondola cup, before 1656 Oxford, Ashmolean Museum (AN1685.B.584)

One in the Petit Palais acquired with the Dutuit collection and formerly in the Soltykoff collection5.

One in the Louvre acquired by donation in 1856 from the Sauvageot collection.

Another there in the 1922 Salomon de Rothschild bequest with a replacement foot which tips the head of the cup downwards.

The second model illustrated by Lemercier, fractionally smaller, has the figure more completely submerged within the cup, holding a cornucopia under each arm and without a necklace [II]. She has been identified variously as the goddess of the harvest Ceres or as an allegory of Abundance6.

This model is of particular significance for dating these wares. A version in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford was part of the bequest of Elias Ashmole (16171692), who donated his collection to the museum that bears his name in 1691. Ashmole himself had acquired the collection after the death of John Tradescant, Jr. and his wife. On the latter's death in 1662, the Tradescant collection was displayed in their family home in

south London's Lambeth district, bringing together the curiosities collected in the first half of the 17th Century not only by John Jr. (1608-1662), but also by his father of the same name, John Tradescant (circa 1570-1638). In the collection catalogue published in 1656, these French ceramics are described as "Variety of China dishes", providing a terminus ante quem for this form of dish. They may have been acquired by John Tradescant, Sr. in the early decades of the 17th Century, when he travelled in France for the Earl of Salisbury, and later for the Duke of Buckingham7.

A French lead-glazed earthenware tankard, probably Fontainebleau or Paris, late 16th / early 17th Century

Height: 28.5 cm. (11 ¼ in.) • Width including handle: 17.5 cm. (7 in.)

With relief decoration of Bacchic scenes and village festivals in three medallions with a pale blue ground and draped faces in three medallions with a blue ground, the shoulder decorated with flowers, the cylindrical neck with a blue ground, the lid pewter, the underside with printed labels inscribed A. de R. for Alphonse de Rothschild, P. 48 E. de R. 83 for Edouard de Rothschild, Einsatzstab R nr. 4150 and labels with numbers 1307 A de R and 457.

Baron Alphonse de Rothschild (1827-1905)

Baron Edouard de Rothschild (1868-1949)

Confiscated from the above by the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg following the Nazi occupation of France in May 1940 (ERR no. R 4150)

Recovered by the Monuments Fine Arts and Archives Section from the Altaussee salt mines, Austria, and transferred to the Munich Central Collecting Point, 18 June 1945 (MCCP no. 337/5)

Returned to France on 9 January 1946 and restituted to the Rothschild family

Baron Guy de Rothschild (1909-2007), Hôtel Lambert, Paris, and by descent

Literature

Collection de Mr. Le baron Alphonse de Rothschild, circa 1890, (n.d.), vol. II, pl. 38.

A. Sauzay, H. Delange, C. Delange and C. Borneman, Monographie de l’oeuvre de Bernard Palissy suivie d’un choix de ses continuateurs ou imitateurs, Paris: Lemercier, 1862, pl. 25 and pl. 42.

Collection de Mr. Le baron Alphonse de Rothschild, circa 1890, (n.d.), vol. II, pl. 40.

G. de Rothschild and S. Grandjean, Bernard Palissy et son école, Paris, 1952, no. XXXII, pl. 33.

I. Perrin, Les techniques céramiques de Bernard Palissy, 2 vols., Villeneuve d’Ascq, 2000, I, p, 219, no. 32 and p. 220, no. 34.

tankards with pewter lids

French earthenware tankards are extremely rare; only one other is known, also from Alphonse de Rothschild’s collection1, illustrated in the series of lithographs published by Lemercier in 1862. As with this tankard, its body is decorated with greyblue ground relief medallions, although here they have been polychromed, and represent allegories of Water, Earth and Air after the celebrated French pewterer, François Briot (15501615). Isabelle Perrin included it as the sole known example of the form in her summary catalogue of post-Palissy figural works, as she was unaware of the existence of this one.2

French Renaissance glazed ceramic vessels decorated with the same grey-blue ground relief medallions are also a rarity. Only two other examples, both hanap form ewers, share the same blue ground and thick brown borders to the medallions seen on this tankard.

One in the Louvre (inv. MR 2339) entered the collections there as early as 1850 when it was bought at the collection sale of Edmé Unité Jacquot-Préaux. This early provenance makes it very unlikely to be a 19th Century imitation. It was subsequently illustrated by Lemercier in 18623. The Louvre example’s medallions, like this one, are uncoloured, and represent the three theological virtues, Faith, Hope and Charity. Perrin included the Louvre ewer in her catalogue under model no. 32.4

The second example – unknown to Perrin – with identical but coloured medallions, was once again in the collections of Alphonse de Rothschild. It was selected for inclusion in the 1952 Rothschild catalogue, where the authors remarked on the rarity of the relief medallions.5

The three medallions on this tankard all appear to be unique and as yet sources for them in other media are untraced. United by a theme of Bacchanalian revelry, they depict a chaotic scene of inebriated peasants, a drunken Hercules riding a lion, and a debauched Silenus.

Lead-glazed earthenware hanap-form ewer. Paris, Musée du Louvre (MR 2339)

Lead-glazed earthenware hanap-form ewer (Rothschild and Grandjean, op. cit., pl. 33)

A French lead-glazed earthenware ewer, probably Fontainebleau or Paris, late 16th – early 17th Century

Height: 21 cm. (8 ¼ in.) • Width including handle: 18.5 cm. (7 ¼ in.)

Of octagonal form, the upper register decorated in relief with women each holding a palm and a bird, the lower register with women each holding a cornucopia, framed by foliate scrollwork on a grey ground, the upper terminal of the handle as a dolphin's head, the inside of the foot and ewer with a green glaze, the underside with printed labels inscribed A. de R. 1308 for Alphonse de Rothschild, P. 48 /E. de R./ 48 for Edouard de Rothschild, Einsatzstab R nr. 4140 and a label with number 456.

Baron Alphonse de Rothschild (1827-1905) Baron Edouard de Rothschild (1868-1949)

Confiscated from the above by the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg following the Nazi occupation of France in May 1940 (ERR no. R 4140)

Recovered by the Monuments Fine Arts and Archives Section from the Altaussee salt mines, Austria, and transferred to the Munich Central Collecting Point, 18 June 1945 (MCCP no. 104/1)

Returned to France on 9 January 1946 and restituted to the Rothschild family

Baron Guy de Rothschild (1909-2007), Hôtel Lambert, Paris, and by descent

LITERATURE

Collection de Mr. Le baron Alphonse de Rothschild, circa 1890, (n.d.), vol. II, pl. 36.

G. de Rothschild and S. Grandjean, Bernard Palissy et son école, Paris, 1952, no. XXXIII, pl. 34.

A. MacGregor, Tradescant's Rarities; Essays on the Foundation of the Ashmolean Museum, 1683, With a Catalogue of the Surviving Early Collections, Oxford, 1983, pp. 275-276.

This model is extremely rare. The only other known octagonal form ewer is the smaller one, jaspered all over and otherwise undecorated, at the ceramics museum in Limoges and catalogued there as attributed to Bernard Palissy, 16th Century. The overall shape and relief decoration point to pewter or silver prototypes for this model. The faceted body is found on a pewter example in the Victoria & Albert Museum.

Elements of the relief decoration relate to other ceramic works securely dated pre-1650. The female figures holding cornucopia framed with scrolls and volutes in the lower register are strongly reminiscent of those lying in gondola cups produced by the immediate successors to Palissy. Three of these gondola cups are in the collections of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford with a recorded provenance as far back as 1656.1

Lead-glazed earthenware ewer Limoges, Musée national Adrien Dubouché (ADL7598)

French pewter ewer, ca. 1600 London, V&A (M.47-1971)

Elements of the relief decoration relate to other ceramic works securely dated pre-1650. The female figures holding cornucopia framed with scrolls and volutes in the lower register are strongly reminiscent of those lying in gondola cups produced by the immediate successors to Palissy. Three of these gondola cups are in the collections of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford with a recorded provenance as far back as 1656.

A French lead-glazed earthenware oval dish depicting the Family of Henri IV, Probably Fontainebleau or Paris, circa 1610.

Length: 33.5 cm. (13 ¼ in.) • Width: 27.5 cm. (10 ¾ in.) • Height: 6 cm. (2 ¼ in.)

Obverse with Henri IV and his family based on an engraving by Léonard Gauthier, the rim with a brown ground highlighted with fleurons in compartments framed by falling piastres on a blue ground, the underside marbleised in blue and manganese.

A. Du Sommerard, Les arts au moyen âge : en ce qui concernent principalement le Palais romain de Paris, l’Hôtel de Cluny, issue de ses ruines, et les objets d’art de la collection classée dans cet hôtel, Paris, 1838-1846, vol. 3, chap. XVI: Les Arts au Moyen Age, pl. V.

A. Sauzay, H. Delange, C. Delange and C. Borneman, Monographie de l'œuvre de Bernard Palissy suivie d'un choix de ses continuateurs ou imitateurs, Paris: Lermercier, 1862, pl. 76.

A. Bouquillon, J. Castaing, F. Barbe, T. Crépin-Leblond, L. Tilliard, S.R. Paine, B. Christman and A.H. Heuer, ‘French decorative ceramics mass-produced during and after the 17th Century: chemical analyses of the glazes’, Archaeometry, vol. 60, issue 5 (Mar., 2018), pp. 1-20.

This dish was intended to celebrate the union of the royal family around the dauphin. Seated in the centre is Henri IV, the first French sovereign of the Bourbon branch of the Capetian dynasty (r. 1589-1610). His wife, Marie de’ Medici sits next to him on the same bench and two children are represented in the foreground. The youngest, resting on the knees of his governess and offering his hand to the king is the dauphin, Louis (born in 1601), the future Louis XIII. The second, older child, who stands before the king is probably César de Vendôme, Henri’s son with his former mistress Gabrielle d’Estrées, born seven years earlier in 1594 and legitimized the following year. Four great lords surround the royal family in various attitudes.

The dish’s decoration is inspired by a famous engraving by Léonard Gaultier (1561-1635) after a painting by François Quesnel, dated 1602 and published by Jean Leclerc in Paris. The engraving, like this ceramic dish, belonged to an official propaganda policy aimed at strengthening the foundations of the monarchy. The king is presented as a good father alongside his two sons, one the legitimate heir to the crown, the other formerly illegitimate but kept close by. This is the only overtly political scene known in post-Palissy ceramics.

Perhaps due to this political function, numerous models illustrating the subject were reproduced in important 19th Century publications and are inventoried in French museums. A similar dish was engraved by Théophile Fragonard to illustrate Du Sommerard’s groundbreaking series of publications on the art of the ‘middle ages’ which spanned the years 1838-1846. Another belonging to Prince Ladislas Czartoryski was included amongst the colour lithographs published by Lemercier in 1862.

Variations in rim design, quality of the modelling and colour scheme exist, suggestive of the popularity of the model and the possibility of several production centres.

This has been confirmed by the technical analysis of three of these comparable dishes published in the Archaeometry journal in 2018 (Bouquillon et al., op. cit.). The study’s authors state that the dish in the Louvre (inv. OA 1351) “was most probably produced around 1610, the year of the king’s death” (p. 16), whereas significant differences in the pigments of the ones at Lisieux (inv.m.86.1.4) and Sèvres (inv. MNC 6016) suggest “different workshops, each having different but related glaze chemistries” (p. 12).

A French lead-glazed earthenware oval dish depicting the Washing of the Feet, probably Fontainebleau or Paris, circa 1600-1650

Length: 37.5 cm. (14 ¾ in.) • Width: 27 cm. (10 ½ in.) • Height: 5.5 cm. (2 ¼ in.)

Obverse with Christ washing the feet of the twelve Apostles, the rim with a brown ground and white highlights moulded with gadroons and foliage, the underside marbleised in blue, ochre and manganese.

I. Perrin, Les techniques céramiques de Bernard Palissy, 2 vols., Villeneuve d’Ascq, 2000, I, p. 234, no. 83.

The model for the ceramic composition is probably of Bellifontain or Flemish origin. An engraving by Adriaen Collaert after Maerten de Vos, an example of which is at the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent, presents compositional similarities with the representation on the dish.

A. Collaert after M. de Vos, Washing of the Feet, from the series Vita, passio et Resvrrectio Iesv Christi, circa 1598-1618 Engraving Ghent, Museum of Fine Arts. (2014-LZ-28)

Religious themes played an important role in the production of Palissy and his followers during a period when Protestantism evolved. The themes chosen are often linked to redemption and martyrdom, reflections of the restless spirit and the feeling of persecution that inhabited Bernard Palissy, and his great knowledge of holy texts. The ceramicist also played a major role in the creation of the Calvinist church in Saintes. However, the theme of the Washing of the Feet, although found on certain models of the same shape, is quite unusual (Perrin, op. cit., no. 83.)

Lead-glazed earthenware dish

Paris, Musée du Louvre (OA 1327)

Lead-glazed earthenware dish

Écouen, Musée national de la Renaissance (E.Cl. 1125)

Lead-glazed earthenware dish

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art (53.225.30)

Two models with simlar decoration are in the Louvre (invs. OA 1327 and MR 2306). Unlike this dish, the one in the Louvre illustrated here has a blue-ground rim with slight additions of green. However, the same gadroon and fleuron motifs adorn the rim and its edge.

On a technical level, the colours on the Louvre model have bled out and blend in several places into the decoration, a characteristic perhaps more evocative of the production of Pré-d’Auge or Manerbe.

Those at Écouen and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York are stylistically closer, notably in the use of colours, even if both again have bluepainted rims and green dominates the central decoration in the New York version.

Two French lead-glazed earthenware oval dishes with Allegories of Spring and Summer, probably Fontainebleau or Paris, circa 1600-1650

Length: 27.7 cm. (11 in.) • Width: 22.5 cm. (8 ¾ in.) • Height: 4 cm. (1 ½ in.)

Obverses with allegories of Spring in the form of a draped young man holding a bouquet of flowers and a crown of flowers, and Summer in the form of a man holding a sheaf of wheat and a billhook. Rims with a brown (Spring) or blue (Summer) ground and white highlights moulded with gadroons and foliage. The undersides of both marbleised in blue and manganese.

A. Gibbon, Céramiques de Bernard Palissy, Paris, 1986, pp. 74-75, nos. 44-45.

Part of the allegorical repertoire of post-Palissy production, these two dishes belong to a series of four models representing the allegories of the Seasons, the remaining two representing Autumn and Winter.

Each season depicts a single, central character enriched with small surrounding details and attributes that give meaning to the iconography: a floral wreath, bouquet and basket of flowers for Spring; a wheatsheaf and basket of summer fruits for Summer; harvested produce and buckets of grapes for Autumn; an old man leaning on his staff in an arid landscape for Winter. This simple and balanced décor lends the works an immediate clarity.

These representations are perhaps borrowed from Flemish engravings such as those by Maerten de Vos (1532-1603). At the same time, these allegories recall carved reliefs on the facades of Parisian private mansions of the second half of the 16th and early 17th Centuries (e.g. Hôtel de Sully, Hôtel Carnavalet).

Lead-glazed earthenware dish with an Allegory of Spring Paris, Musée du Louvre (MR 2308 ; N 176)

A comparable model representing Spring is in the Louvre. In this example, a tree in the background completes the composition on the left and a cloud has been added to the upper part, no doubt for the sake of visual balance. The same flower motifs on the ground are found from one work to another. A model of Summer in the Metropolitan Museum of Art again presents the element of the tree in the decoration, as does the one formerly in the Al Thani collections at the Hôtel Lambert and the version in Écouen. The example in the ceramics museum in Limoges is more comparable in several respects to this dish.

Lead-glazed earthenware dishes with an Allegory of Summer:

A French lead-glazed earthenware footed bowl depicting Perseus and Andromeda, probably Fontainebleau or Paris, circa 1600-1650

Diameter: 25.3 cm. (10 in.) Height: 5 cm. (2 in.)

Obverse with Perseus delivering Andromeda, the edge with a plain blue ground, the underside marbleised in blue and manganese.

A. Sauzay, H. Delange, C. Delange and C. Borneman, Monographie de l'œuvre de Bernard Palissy suivie d'un choix de ses continuateurs ou imitateurs, Paris: Lemercier, 1862, pl. 69.

G. de Rothschild and S. Grandjean, Bernard Palissy et son école, Paris, 1952, no. XXII, pl. 25.

L’Ecole de Fontainebleau, exh. cat., Paris, Grand Palais, 17 Oct 1972 – 15 Jan 1973, Paris, 1972, p. 434, no. 604 and p. 441, no. 624.

I. Weber, Deutsche, niederländische und französische Renaissance Plaketten 1500-1650, vol. I, Munich, 1975, p. 315, no. 730.

I. Perrin, Les techniques céramiques de Bernard Palissy, 2 vols., Villeneuve d'Ascq, 2000, I, p. 225, no. 52 and p. 242. Les céramiques du Pré-d'Auge. 800 ans de production, exh. cat., Lisieux, Musée de Lisieux, 3 Jul – 30 Sep 2004, pp. 87-88, no. 163.

This is one of the most widespread narrative works among French earthenware of the period. Numerous important 19th Century sales contained examples, and today several are found in museum collections (see below for a resume).

The compositional source identified by scholars is a bronze plaquette known in two examples. One in the Rijksmuseum is dated 1572 and is attributed to the Nuremberg goldsmith Hans Jamnitzer (1539-1603). Another, of lesser quality, is in the Louvre (Ecole de Fontainebleau, op. cit., no. 604; Weber, op. cit., no. 730). Both these plaquettes are considerably smaller than the ceramic production, indicating an adaptation of scale in the ceramicist’s workshop. Isabelle Perrin emphasises this as further evidence that the Perseus and Andromeda bowls postdate the activity of Bernard Palissy, who is known to have only taken moulds directly from goldsmiths’ work (Perrin, loc. cit.).

Bronze plaquette depicting Perseus and Andromeda Attributed to Hans Jamnitzer, dated 1572. Dia. 14.5 cm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum (BK-NM-9656)

Bronze plaquette depicting Perseus and Andromeda German or French(?), ca. 1572. Dia. 13.1 cm. Paris, Musée du Louvre (OA 9192)

The Perseus and Andromeda story is part of the mythological repertoire, inspired in particular by Ovid’s Metamorphoses which the followers of Palissy and the School of Fontainebleau artists used extensively. Andromeda’s nudity contrasts with the dress of the surrounding characters, suggesting a certain eroticism, characteristic of the Bellifontain style. At the same time, there are points of comparison with a more restrained Flemish mannerism. The Perseus and Andromeda dated 1611 by the Utrecht painter Joachim Wtewael in the Louvre features an analogous arrangement of the principal characters and a similar dragon.

A Perseus and Andromeda composition within a ribbed and mottled-glaze edge was included amongst the lithographs published by Lemercier in 1862.

Another, more similar one, with a plain blue border along with a mottled violet and blue underside, was in the collection of Alphonse de Rothschild (Rothschild and Grandjean, op. cit., no. XXII, pl. 25) and sold recently at Christie’s Paris, 21 November 2023, lot 427.

Several comparable models attributable to the Fontainebleau workshop are held in museums in France and abroad. Amongst the closest are those at Sèvres and Écouen.

A pair of French lead-glazed earthenware footed bowls decorated with masks and foliage, Manerbe or Pré-d'Auge (Normandy), circa 1600-1650

Diameter: 23.5 cm. (9 ¼ in.) • Height: 5.5 cm. (2 ¼ in.)

Polychrome, green, blue, turquoise, yellow, purple and manganese ceramic bowl on pedestal, decorated with alternating smiling and grimacing masks and foliage around a central dished reserve, the underside marbleised in blue, green and manganese.

One bowl with a 19th Century label on the underside inscribed Bernard Palissy | acheté à Joinville avec | deux autres. plus beau que ceux du Louvre et du Musée | de Cluny. Estimé environ | 160 francs. 1858. | N°16.

Sold Beaussant-Lefèvre, Paris, 10 June 2009, lot 100 Collection of Alain Moatti

A. Sauzay, H. Delange, C. Delange and C. Borneman, Monographie de l'œuvre de Bernard Palissy suivie d'un choix de ses continuateurs ou imitateurs, Paris: Lemercier, 1862, pl. 32. J. Bergeret, 'Les Suites de Palissy, une vaisselle d’apparat et une vision du monde', in Les céramiques du Pré-d'Auge. 800 ans de production, exh. cat., Lisieux, Musée d'art et d'histoire, 3 Jul – 30 Sep 2004, Lisieux, 2004, pp. 94-95, no. 188.

This version with a central well is much rarer than the more commonplace model found in numerous museum collections which have a foliate rosette in the middle. Its rarity is confirmed by the fact that Lemercier could not find an example to include amongst the lithographs published in 1862, instead illustrating one with a central rosette from the Sauvageot Collection in the Louvre [I].

Only two other examples of this exact model are known: one donated by Sir Augustus Wollaston Franks to the British Museum in 1883 [II], and one sold from the Estate of Eugene V. Thaw, Christie’s New York, 30 October 2018, lot 366 [III]. Both appear to be identical in all respects, except for the glazing of their reserves which is monochrome as opposed to the polychrome jasper effect achieved here.

I. ‘Plat a mascarons. Musée du Louvre. Collection Sauvageot’ Sauzay et al., op. cit., pl. 32

II. Lead-glazed earthenware footed bowl London, British Museum (1883,1019.15)

III. Lead-glazed earthenware footed bowl (Source: Christie’s)

This composition has always been popular with collectors and examples are now in many major museums. The visual evidence suggests they were potted in more than one production centre. A comparison of the marbling on the reverse and colour of the underside of the foot provides certain clues: those with streaky blue, green and manganese colours like these ones have generally been ascribed to the Normandy kilns of the Pré-d'Auge area.

A possible print source was suggested when a bowl of this type was included in the important Pré-d'Auge ceramics exhibition in Lisieux in 2004 (Bergeret, op. cit., no. 188). The idea of a décor radiating from a central point resembles certain compositions by the influential designer Jacques Androuet du Cerceau (1510-1585). One of these so-called fonds de coupes engravings – intended for the undersides or covers of cups in ceramics or gilt or enamelled metal – features masks and could easily have influenced the maker of these footed bowls.

A French lead-glazed earthenware triangular salt-cellar, probably Fontainebleau or Paris, circa 1600-1650

Height: 12 cm. (4 ¾ in.) • Width of base: 14 cm. (5 ½ in.)

The underside with pale manganese glaze and a printed label inscribed COLLECTION | SPITZER | 1893 and another inscribed in ink no. 98 Coll. Stein

Collection of Charles Stein, Paris; his sale, Paris, 10-14 May 1886, 2nd day (11 May), lot 98 (one of two)

Collection of Frédéric Spitzer (1815-1890), Paris; his sale, Paris, 17 April – 16 June 1893, 15th day (16 May), vol. I, p. 111, lot 638 or 639 (both ill. pl. XVIII)

Sold Cambi, Genoa, 11 December 2018, lot 54 (one of two)

Collection of Alain Moatti

E. Molinier and F. Spitzer, La collection Spitzer : Antiquité, MoyenAge, Renaissance, 2 vols., Macon, 1890, I, p. 246, no. 49 or 50. Résumé du catalogue des objets d'art et de haute curiosité... composant l'importante et précieuse collection Spitzer, Paris, 1893, p. 69.

A. Sauzay, H. Delange, C. Delange and C. Borneman, Monographie de l'œuvre de Bernard Palissy suivie d'un choix de ses continuateurs ou imitateurs, Paris: Lemercier, 1862, pl. 60. G. de Rothschild and S. Grandjean, Bernard Palissy et son école, Paris, 1952, no. XXXIV, pl. 35.

Post-Palissy salts of this form are extremely rare. The triangular base section is known primarily through three other examples, all in the Louvre. In all three cases, the finished work is presented as a socle with no salt pan above it. Of the Louvre examples, only one also has the three lions atop the platform like this one [I]. In the museum’s collections since 1828, it is also shown without a salt pan in the colour lithographs published by Lemercier in 1862 [II].

I. Lead-glazed earthenware triangular socle Paris, Musée du Louvre (MRR 114 ; N 241)

II. The same socle illustrated in Sauzay et al., op. cit., pl. 60

Two larger and more elaborate square salts were formerly in the collection of Alphonse de Rothschild, one illustrated in Rothschild and Grandjean, op. cit., pl. 35.

This salt passed through two important 19th Century Parisian collections, those of Charles Stein and Frédéric Spitzer. Spitzer’s mansion near the Arc de Triomphe, though inaccessible to the general public, was nevertheless renowned as ‘Le musée Spitzer’. Serving as a cross between a residence and a gallery, members of high society were drawn there to view and buy from an extraordinary wealth of medieval and Renaissance works of art. Spitzer finally published his collection in 1890, and following his death in 1893 it was sold in an auction lasting three months. Accompanying the sale catalogue was an Atlas-size volume of photographic reproductions, with one plate entirely devoted to and illustrating 40 separate ‘Faïences de Palissy’. This title betrays the misguided contemporary belief in the legend of Bernard Palissy: modern scholarship has disproved his direct authorship of most French Renaissance lead-glazed earthenware ceramics. This salt appears amongst the illustrations as either lot 638 or 639. Both sold for the same price, 980 francs each (Résumé, op. cit., p. 70).

Two French lead-glazed earthenware small bowls Probably Fontainebleau or Paris, circa 1600-1650

13.5 cm. (5 ¼ in.) • Height: 3.5 cm. (1 ½ in.)

Decorated with waved borders of eight masks surrounding central reserves depicting birds eating from a bouquet of vegetables and fruit, one underside marbleised in manganese with touches of blue and green, the other predominantly in blue with manganese streaks.

Sold Cambi, Genoa, 11 December 2018, lot 53

Collection of Alain Moatti

These are the only known examples of this diminutive model. They appear to be a smaller scale variation of the footed bowls adorned with six masks (see cat. pp.126-135) but here centred on a trompe l’oeil effect of birds pecking at pea pods and fruit.

A French lead-glazed earthenware ewer, probably Fontainebleau or Paris late 16th – early 17th Century

Of round form, decorated in two registers with vertical bands of foliage divided by ribbing in tones of blue, green and yellow. The handle formed as a winged bird and spout decorated with a female mask. The inside of the ewer marbleised in blue, green and manganese, the underside marbleised in blue and manganese with printed labels numbered 123 and G | K. 8. inscribed in red ink M 8, and painted inscription 123AR.

Height: 19 cm. (7 ½ in.) • Width including handle: 18 cm. (7 in.)

PROVENANCE

Baron Gustave de Rothschild (1829-1911), 23 avenue Marigny, Paris

Baron Robert de Rothschild (1880-1946)

Sold Pierre Bergé et Associés, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, 21 December 2009, lot 210 Collection of Alain Moatti

G. de Rothschild and S. Grandjean, Bernard Palissy et son école, Paris, 1952, no. XXXI, pl. 32.

A. Gibbon, Céramiques de Bernard Palissy, Paris, 1986, p. 42.

Like a related covered and spouted ewer in the Louvre with similar bands of foliate relief decoration, this piece is inspired by contemporary silver and pewter works of art. The Louvre ewer is catalogued as Saintonge – Bernard Palissy’s birthplace – circa 1600- 1650.

This ewer’s form is particularly rare, with only three others known:

One formerly in the Alphonse de Rothschild Collection which most clearly resembles it in design and glazing (Rothschild and Grandjean, op. cit., no. XXXI).

One in the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, close in form to the preceding one but of markedly inferior quality. The imprecise modelling and sloppy glazing would likely imply this is a later version when the mould had become worn.

One in a private collection, illustrated by Gibbon in 1986 with a later replacement metal handle.

earthenware ewer (Rothschild and Grandjean, op. cit., no. XXXI)

The labels and markings on the underside of the ewer correspond to entries in Rothschild archives papers. The ewer appears in the post-mortem inventory of Gustave de Rothschild (1829-1911) drawn up in 1912 where it is listed as inventory number 163 and described as “Hanap, ancienne faïence de Palissy, (M8), estimé cent cinquante francs”. The ‘M8’ reference matches that inked in red on the label on the ewer’s underside.

Inventaire après le décès de Monsieur le Baron Gustave de Rothschild, Hôtel Avenue Marigny, no. 23, 26 April 1912.

It further appears in the papers of Gustave’s son, Robert de Rothschild (18801946), in undated documents dealing with the division of his collection into 4 ‘lots’ to be selected at random by his children. It appears in ‘Lot A’ as object number 123 where the description for inventory number 163 is repeated. The ‘123’ matches that painted on the ewer’s underside.

A French lead-glazed earthenware oval dish depictinG

The ceramics in this catalogue all are between 400 and 450 years old and have general wear and tear associated with objects of this age. This consists primarily of chips and abrasions to the surface of the relief decoration and the extremities such as rims and feet. In some cases, these minor damages will have been restored, in others they are visible in the photographs. As with Italian majolica from this period, more significant condition issues are commonplace. These are described below for each piece.

Old restored break through rim and body of one side of dish.

1. MARS AND VENUS GONDOLA CUP

Overall good condition with small firing cracks to the body of Mars.

2. NYMPH OF FONTAINEBLEAU OVAL DISH

A restored clean break runs through the rim and behind the nymph’s left shoulder. Five foliage tips restored.

3. GARDEN OF POMONA OVAL DISH

A restored crack to the border at 12 o’clock. Restored chips to the rim, foot and relief decoration.

4.PIERCED DISH

Overall good condition.

5. SACRIFICE OF ISAAC OVAL DISH

Overall good condition.

6. SAINT JOHN THE BAPTIST OVAL DISH

Overall good condition.

7. SPRING GONDOLA CUP

Overall good condition.

8. TANKARD

Overall good condition. Small chips to handle and foot.

9. OCTAGONAL EWER

Overall good condition.

10. HENRI IV OVAL DISH

A restored section of the border with an extended crack at 11 o’clock. Chip to the underside of the rim.

11. WASHING OF THE FEET OVAL DISH

Overall good condition.

12. TWO OVAL DISHES: THE SEASONS

Spring: broken in three pieces and re-glued. Summer: broken in two pieces and re-glued.

13. PERSEUS AND ANDROMEDA DISH

Overall good condition with two small firing cracks.

14. PAIR OF BOWLS WITH MASKS

Overall good condition. Each foot with a later drilled suspension hole.

15. TRIANGULAR SALT CELLAR

Tip of one angle restored. Chips to one side of foot.

16. TWO DISHES WITH MASKS

Overall good condition. Restored chips to the edge and foot.

17. EWER

A restored star crack and associated crack to side of base. Chip to the upper edge.

2. A French post-Palissy lead-glazed earthenware oval footed dish depicting the Nymph of Fontainebleau, Manerbe or Pré-d'Auge (Normandy), Maître au pied ocre workshop, circa 1600-1650 (p.34)

1 Perrin, op. cit., p. 245, Dufournier and Thiron, ‘Les carreaux de pavement...’, op. cit., p. 64 and p. 66, no. 133, and also see Bergeret, op. cit., p. 82.

2 Dufournier and Thiron, ‘Le site de la Bosqueterie...’, op. cit., nos. 13a-b.

3 Amico, op. cit., p. 39, figs. 29-30.

4 Gibbon, op. cit., no. 85 and Amico, op. cit., fig. 29.

5 Bergeret, op. cit., no. 177.

6 Norman, op. cit., no. C168. Perrin in her summary catalogue of figural post-Palissy works excluded this dish from the group attributed to the Maître au pied ocre workshop (op. cit., no. 10 and pp. 246-248).

3. A French post-Palissy lead-glazed earthenware oval dish depicting the Garden of Pomona, probably Fontainebleau or Paris, circa 1600-1650 (p.42)

1 Perrin, op. cit., no. 25.

2 Amico, op. cit., fig. 166.

3 Bergeret, op. cit., no. 180.

4 Sauzay et al., op. cit., pl. 52.

5 Perrin, op. cit., p. 217, no. 25.

6 These include one in the Louvre acquired in 1825 as part of the Durand collection (inv. MR 2304; Gibbon, op. cit., no. 81), and one in the V&A acquired in 1860 (inv. 7170-1860).

4.A French post-Palissy lead-glazed earthenware pierced footed dish, Manerbe or Pré-d'Auge (Normandy), Maître au pied ocre workshop, circa 1600-1650

1 Perrin, op. cit., p. 245, Dufournier and Thiron, ‘Les carreaux de pavement...’, op. cit., p. 64 and p. 66, no. 133, and also see Bergeret, op. cit., p. 82.

2 Dufournier and Thiron, ‘Le site de la Bosqueterie...’, op. cit., nos. 13a-b.

3 Perrin, op. cit., pp. 247-248.

4 Viennet, op. cit., pp. 101-103.

5 Bergeret, op. cit., no. 186.

6 Christman et al., op. cit., pp. 93-95.

5. A French post-Palissy lead-glazed earthenware oval plate depicting the Sacrifice of Isaac, probably Fontainebleau or Paris, circa 1610

1 Perrin, op. cit., p. 228.

2 Bergeret, op. cit., p. 82.

3 Christman et al., op. cit., pp. 92-93.

4 Bouquillon et al., op. cit., p. 5, table 1.

5 Ibid., pp. 7-10, table 2 and p. 12.

6 Ibid., p. 16.

7 Webb, op. cit., p. 1.

6. A French post-Palissy lead-glazed earthenware oval plate depicting the Beheading of St John the Baptist, probably Fontainebleau or Paris, 17th Century

1 Perrin, op. cit., nos. 81 and 82 respectively.

2 Gibbon, op. cit., no. 59.

3 Bergeret, op. cit., no 165.

7. A French post-Palissy lead-glazed earthenware gondola cup, probably Fontainebleau or Paris, circa 16001650

1 Sauzay et al., op. cit., pls. 44-45.

2 Perrin, op. cit., p. 227.

3 McNab, op. cit., no. 1.

4 Additionally, a simplified half-scale variation is known through a second cup at the V&A (inv. C.677-1909).

5 Bergeret, op. cit., no. 175.

6 Perrin, op. cit., no. 40 and Bergeret, op. cit., p. 111. As well as the important Ashmolean example hereby described in detail, others are at the Musée National de Céramique at Sèvres (ibid., and Viennet, op. cit., pp. 80-81), and the State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, formerly in the Basilewsky collection (inv. Ф-444).

7 MacGregor, op. cit., pp. 275-276.

8. A French post-Palissy lead-glazed earthenware tankard, probably Fontainebleau or Paris, late 16th / early 17th Century

1 Collection de... Alphonse de Rothschild 1890, op. cit., pl. 40.

2 Perrin, op. cit., no. 34.

3 Sauzay, op. cit., pl. 42.

4 Perrin, op. cit., p. 219.

5 Rothschild and Grandjean, op. cit., no. XXXII.

9. A French post-Palissy lead-glazed earthenware ewer, probably Fontainebleau or Paris, late 16th – early 17th Century

1 MacGregor, op. cit., pp. 275-276.

A. Sauzay, H. Delange, C. Delange and C. Borneman, Monographie de l'œuvre de Bernard Palissy suivie d'un choix de ses continuateurs ou imitateurs, Paris: Lemercier, 1862.

Collection de Mr. Le baron Alphonse de Rothschild (1827-1905), [circa 1890], vol. II.

E. Molinier and F. Spitzer, La collection Spitzer: Antiquité, Moyen-Age, Renaissance, 2 vols., Paris, 1890.