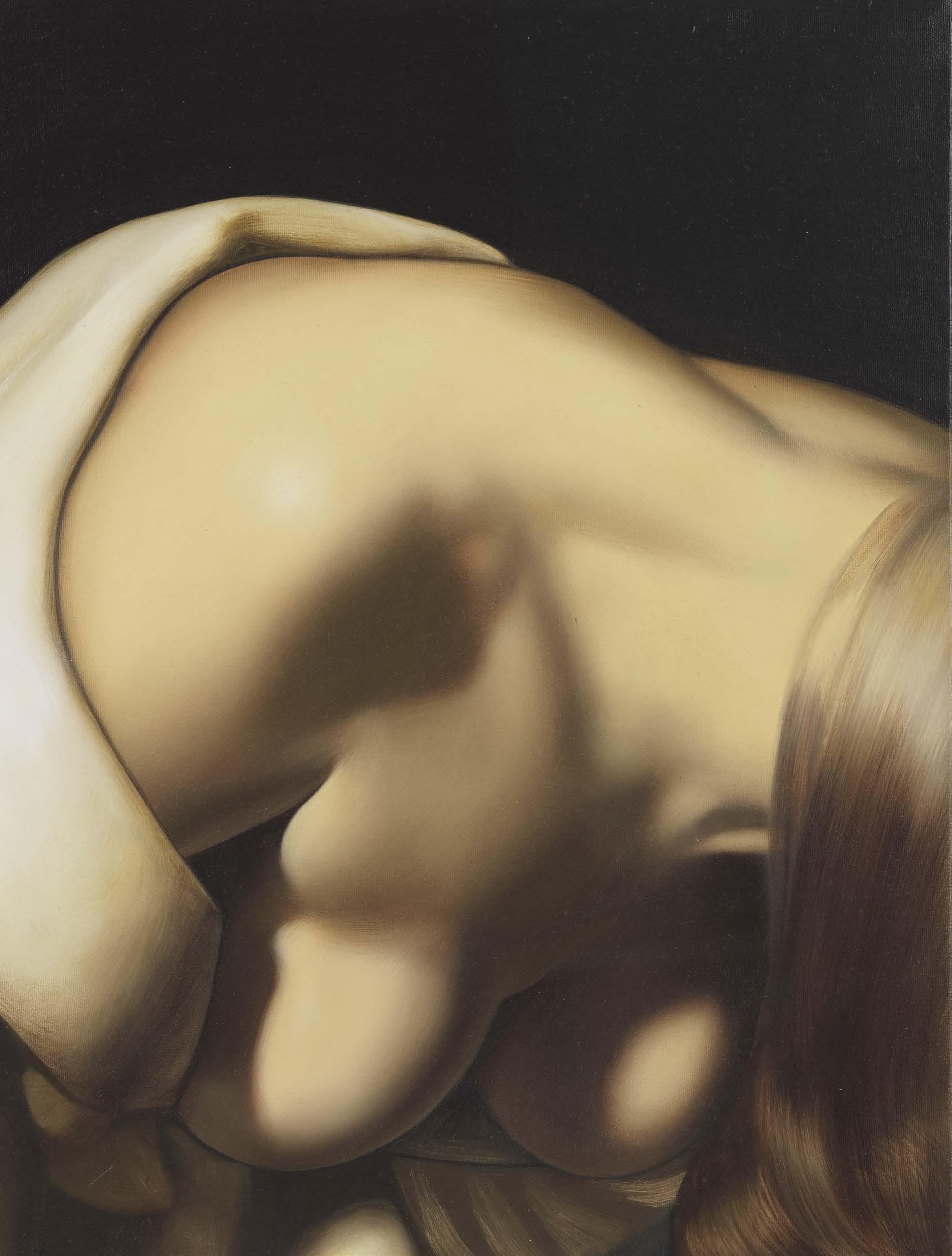

Figurative painting takes a lead role in this issue, starting with a remarkable cover by Anna Weyant. In her accompanying text, novelist Emma Cline discusses how Weyant’s precisely rendered scenes often allude to something sinister just beneath the surface.

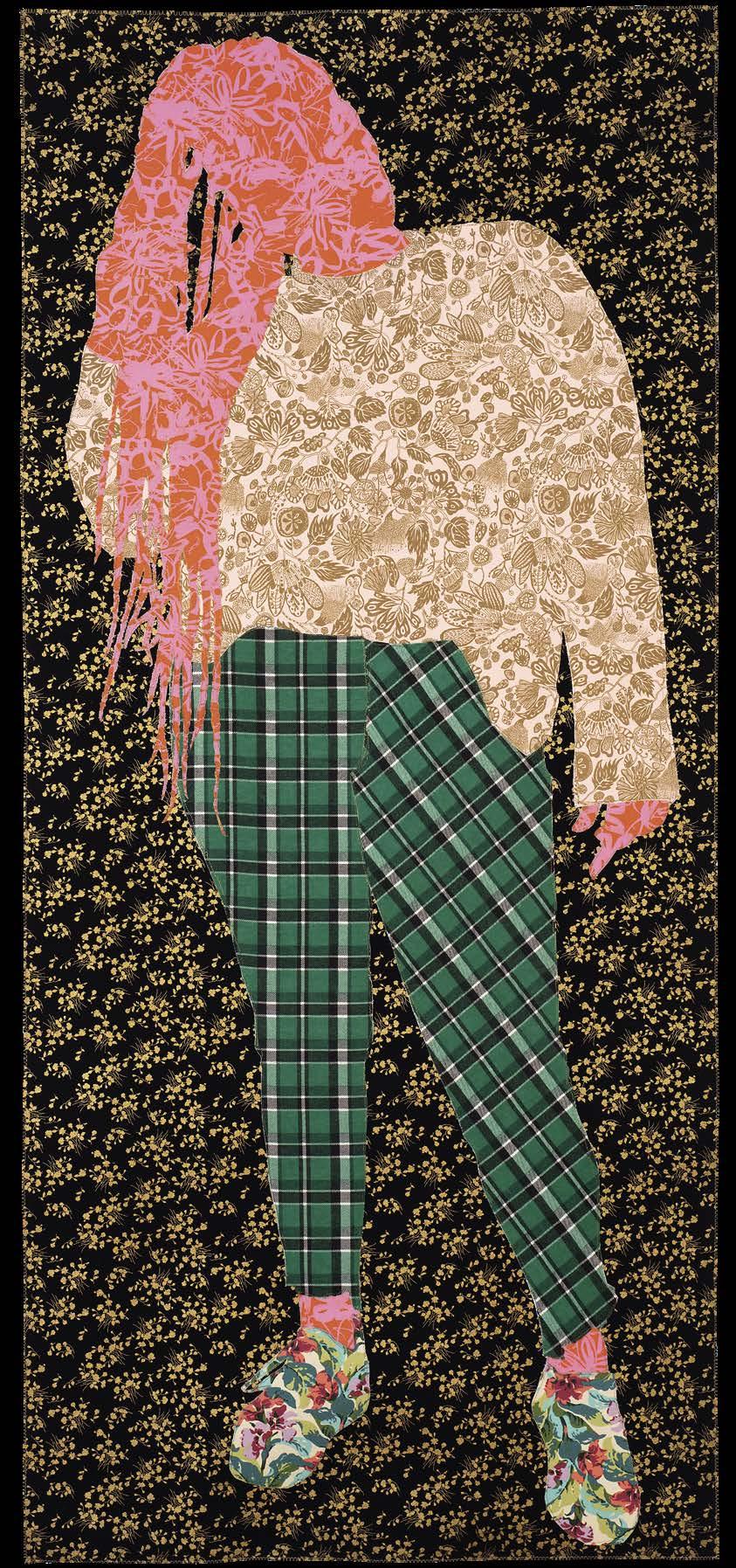

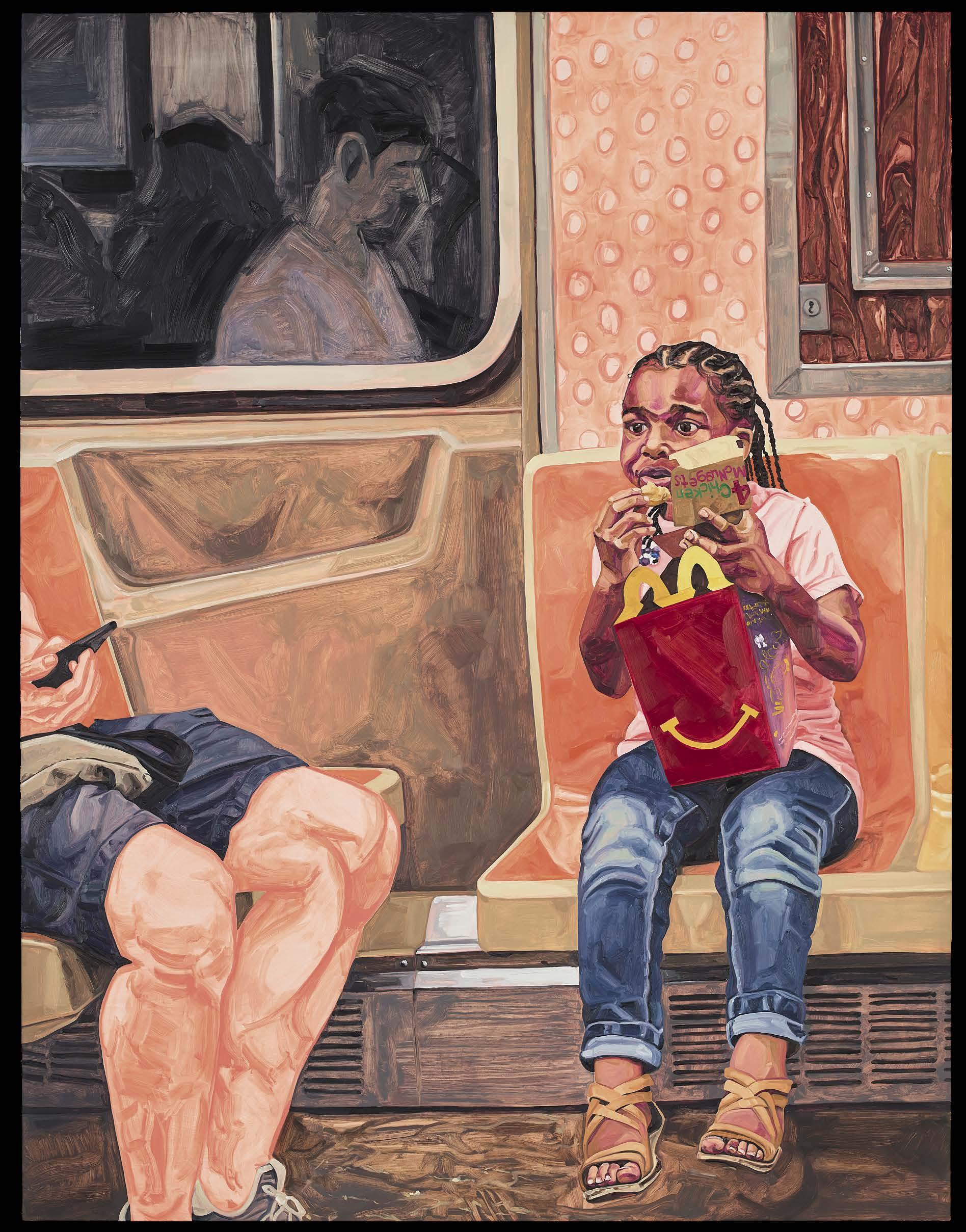

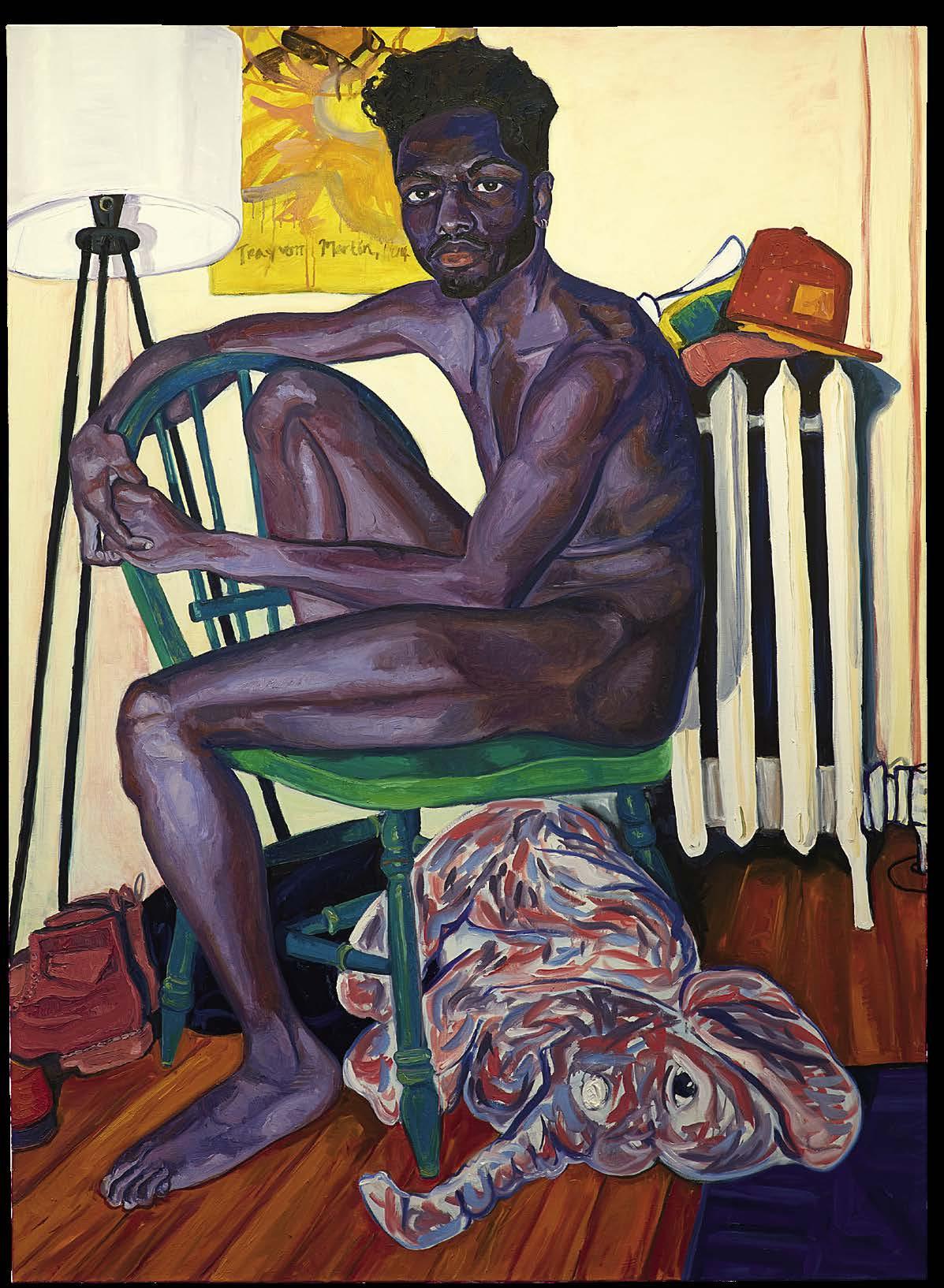

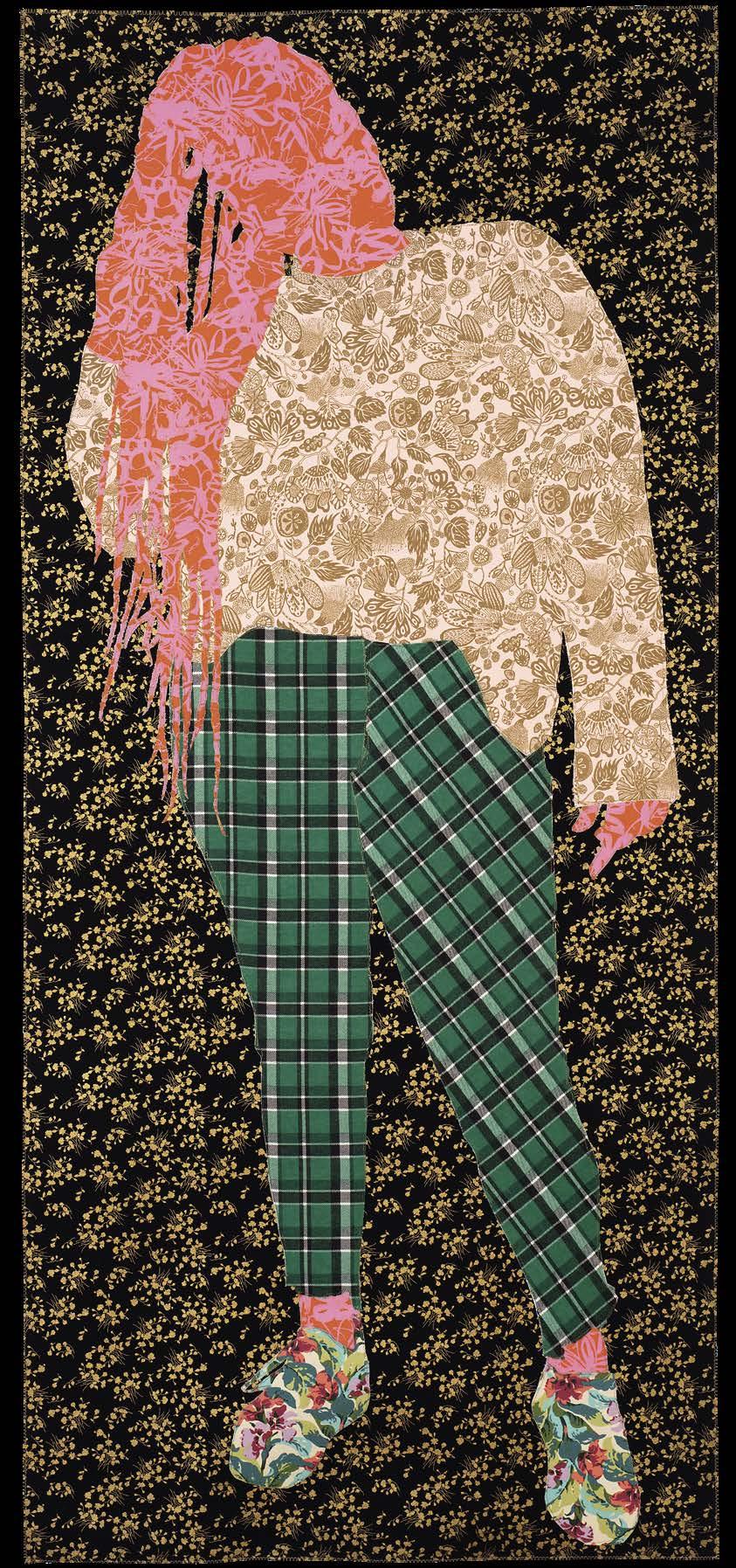

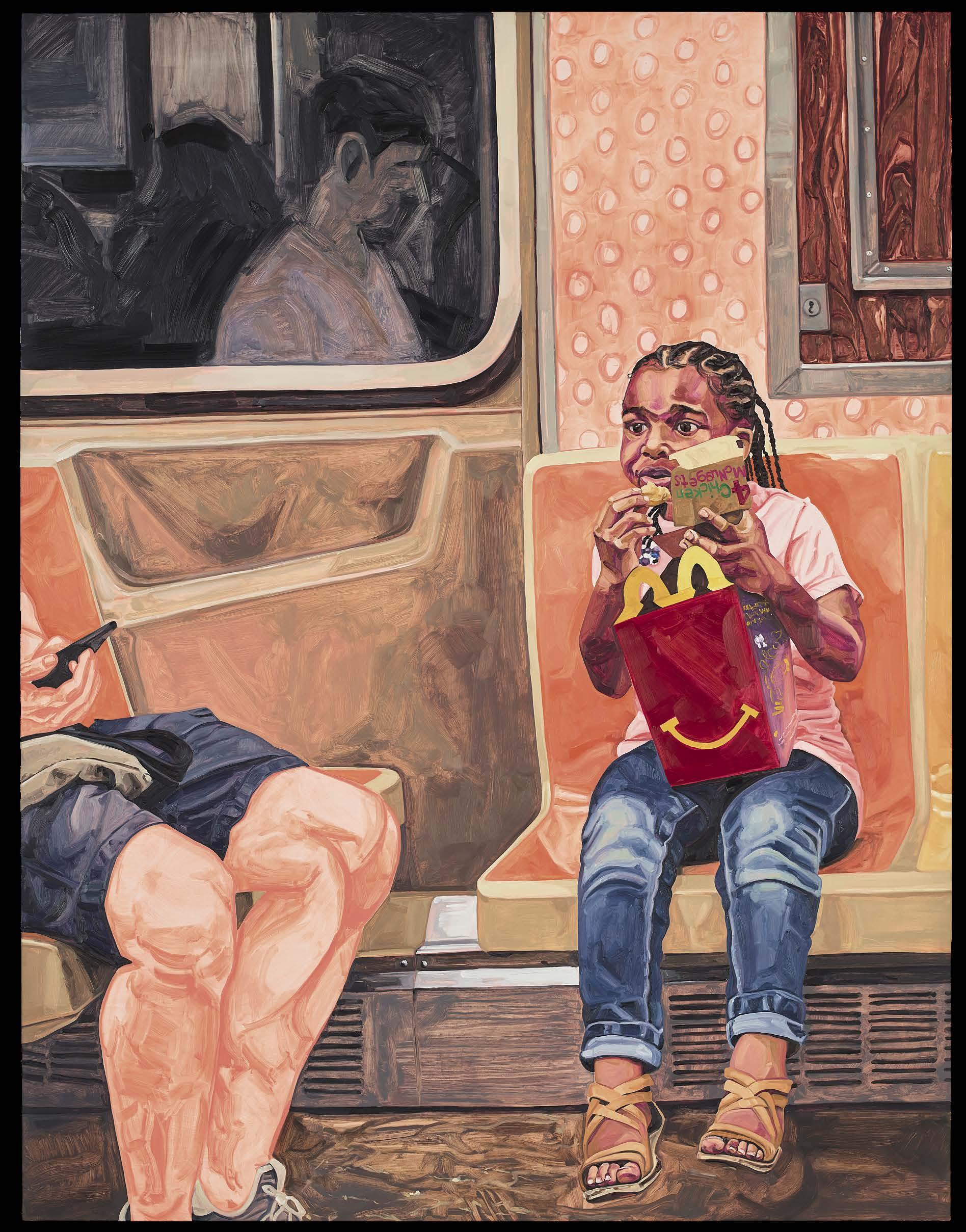

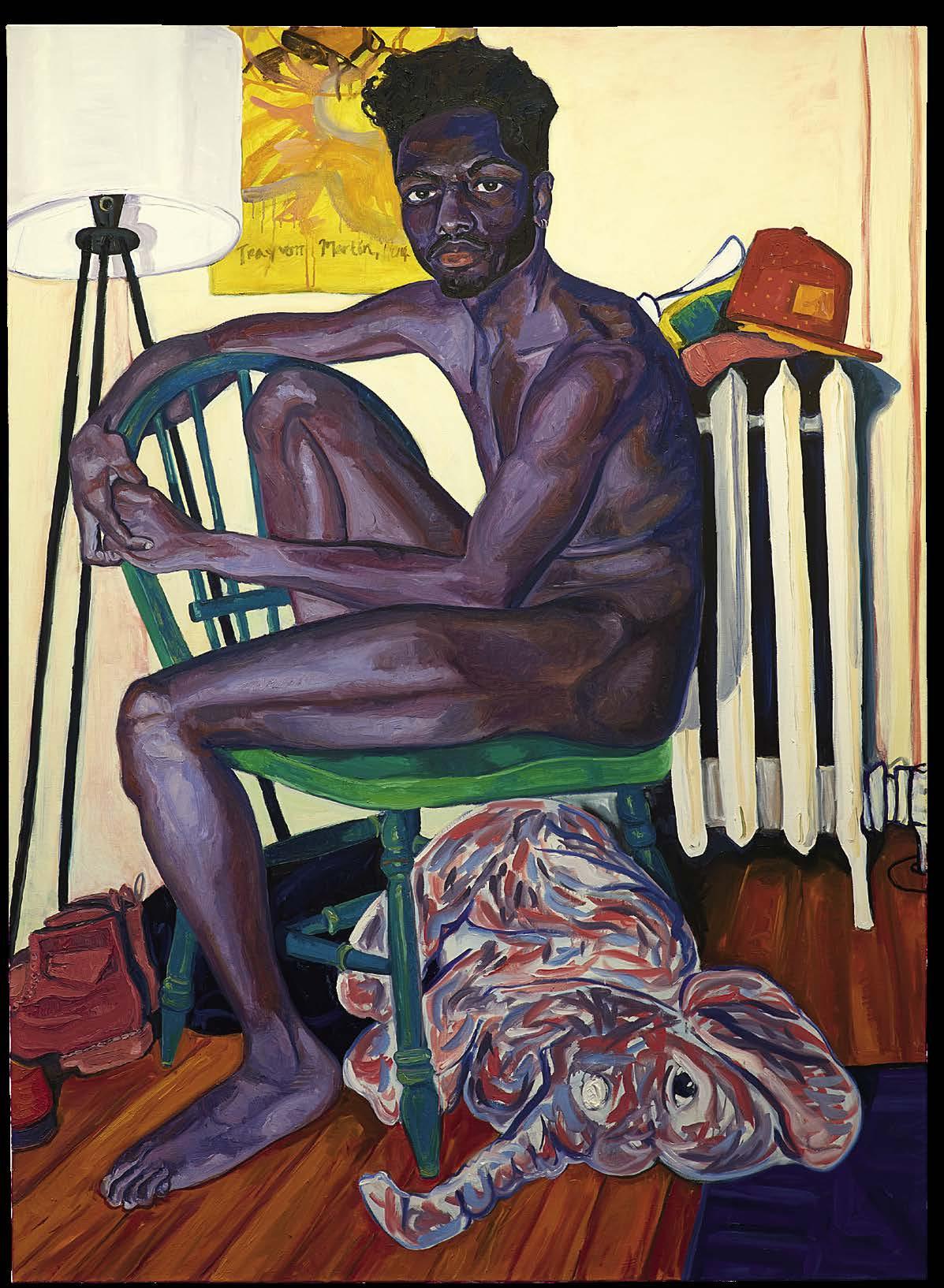

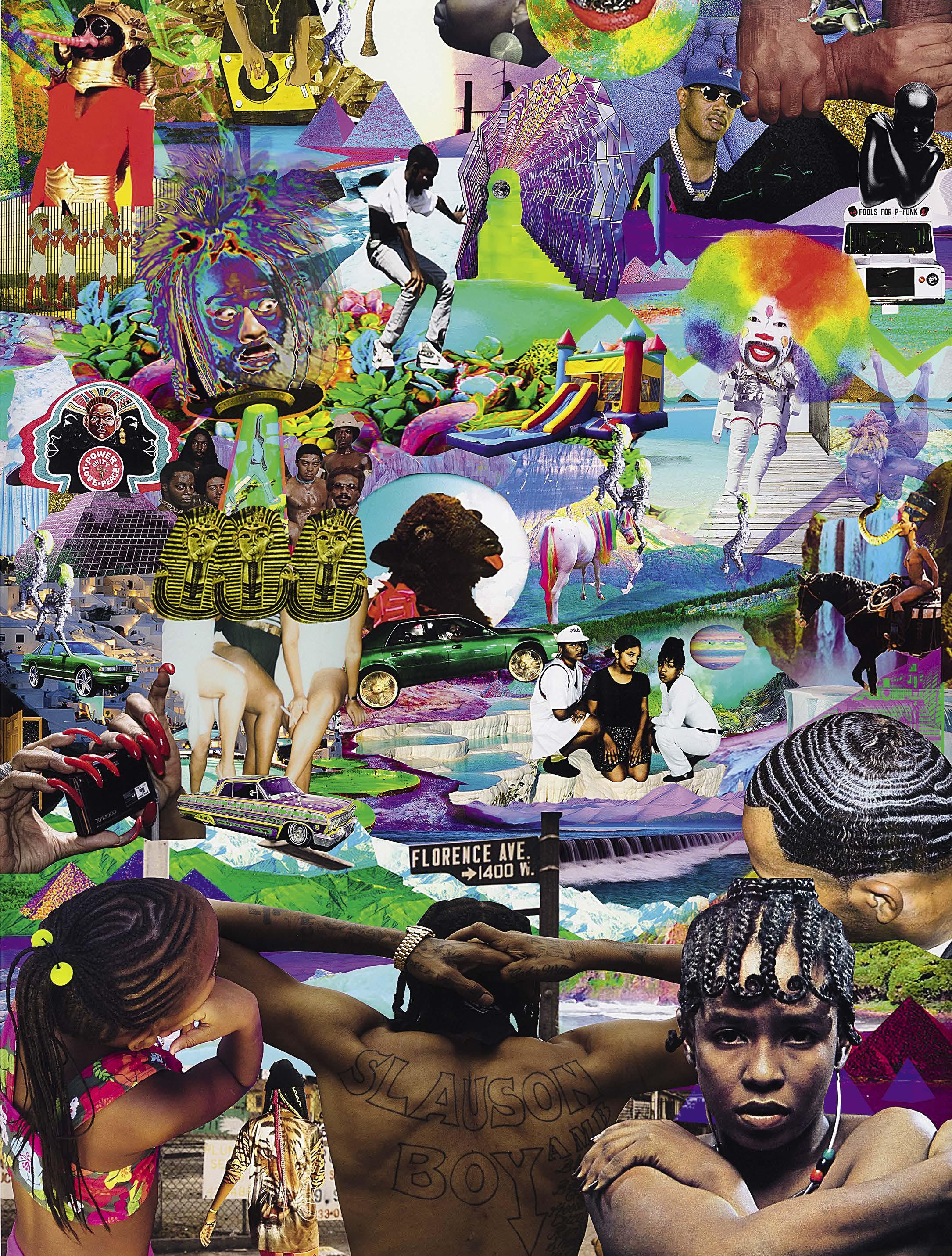

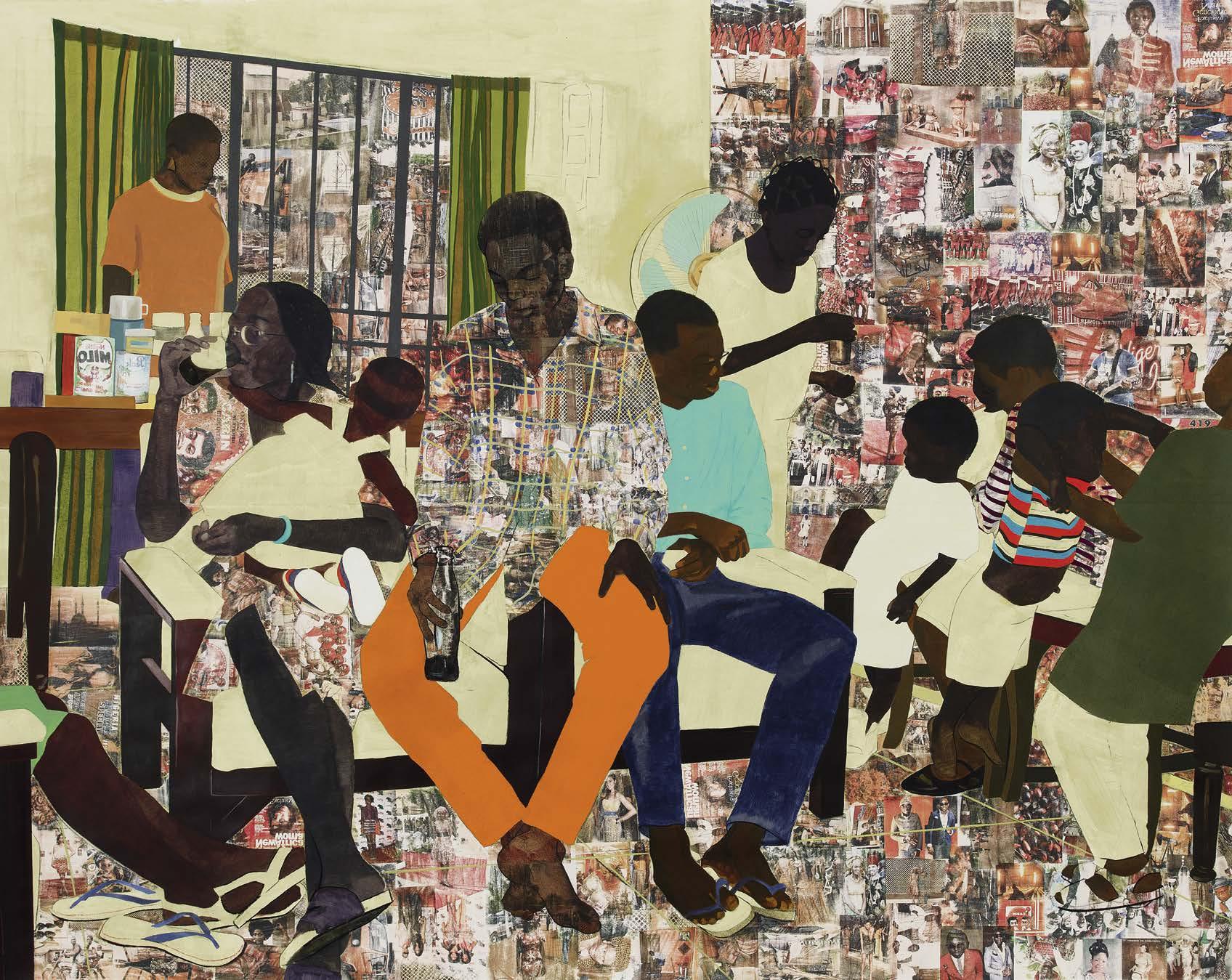

We invited Roxane Gay to guest-edit a special section in this issue’s pages. The essays she has brought together focus on some of today’s leading Black female artists who are working within and against the tradition of figuration.

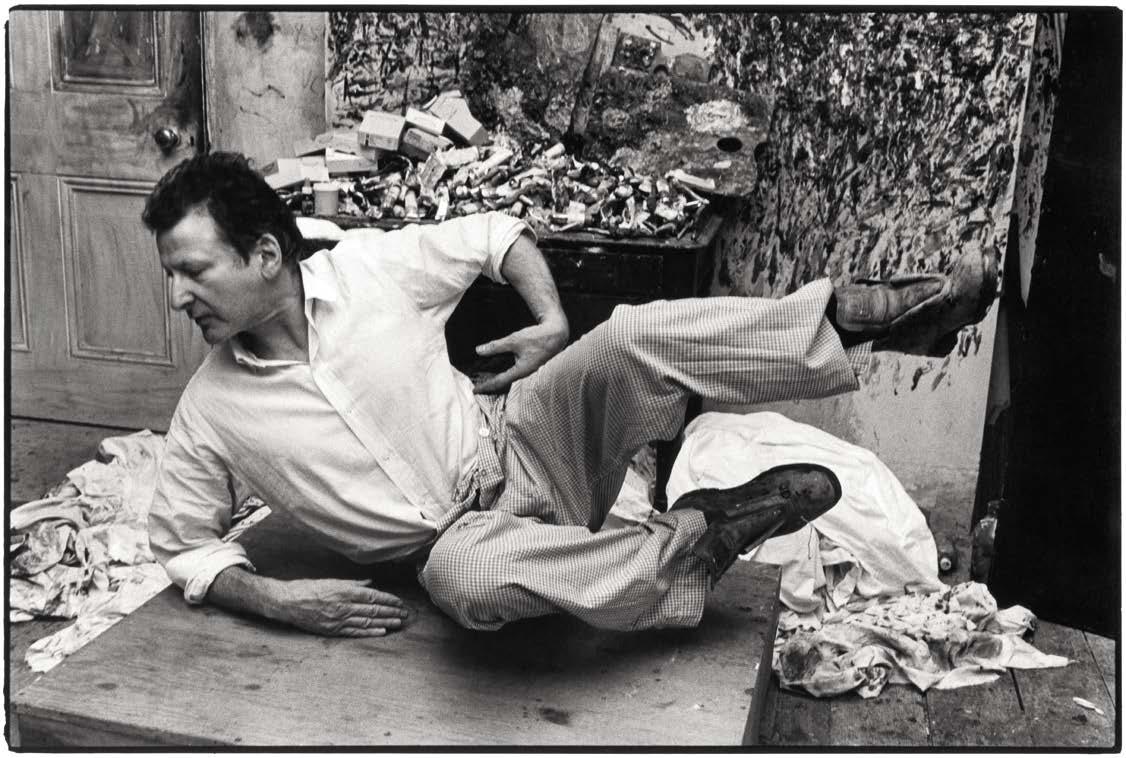

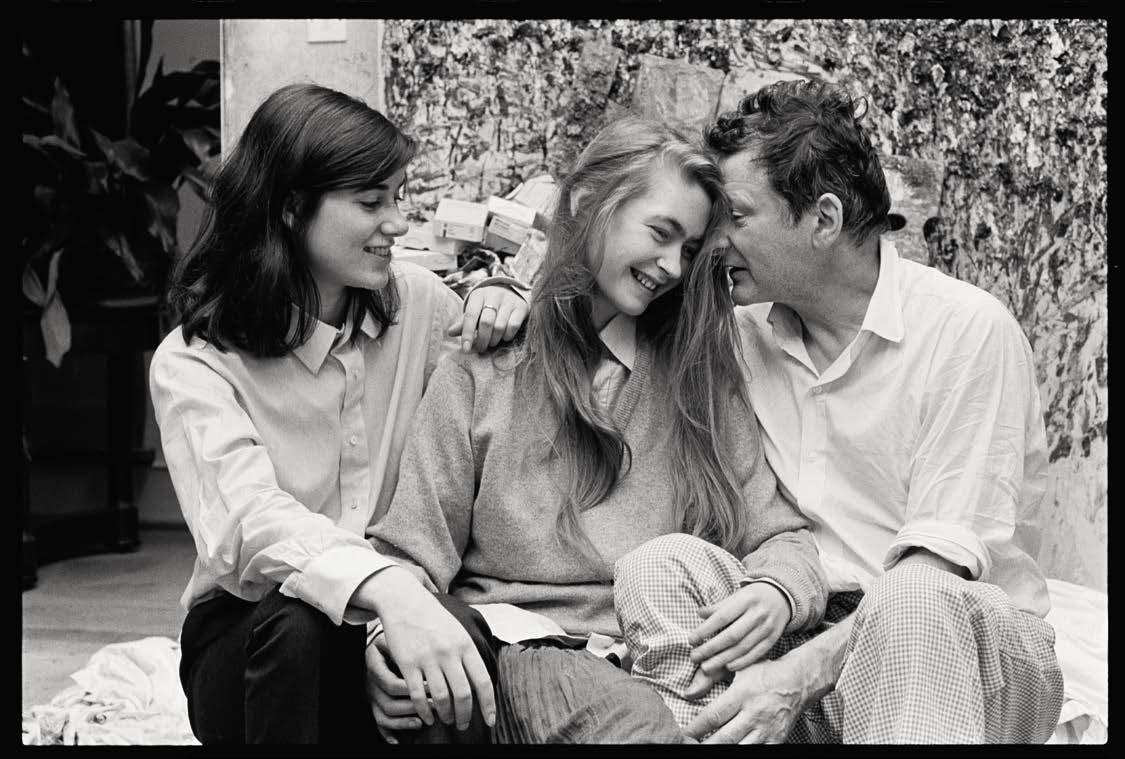

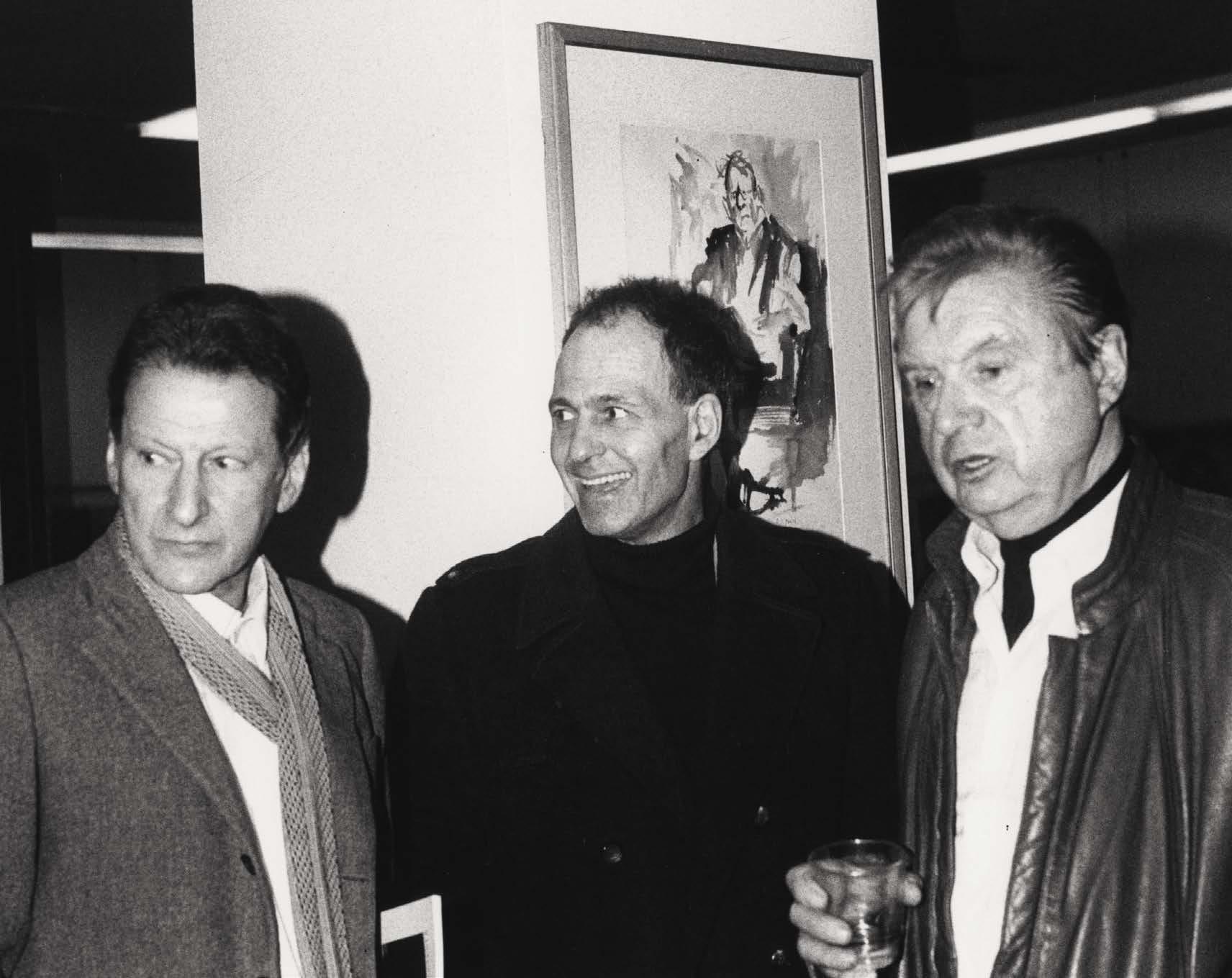

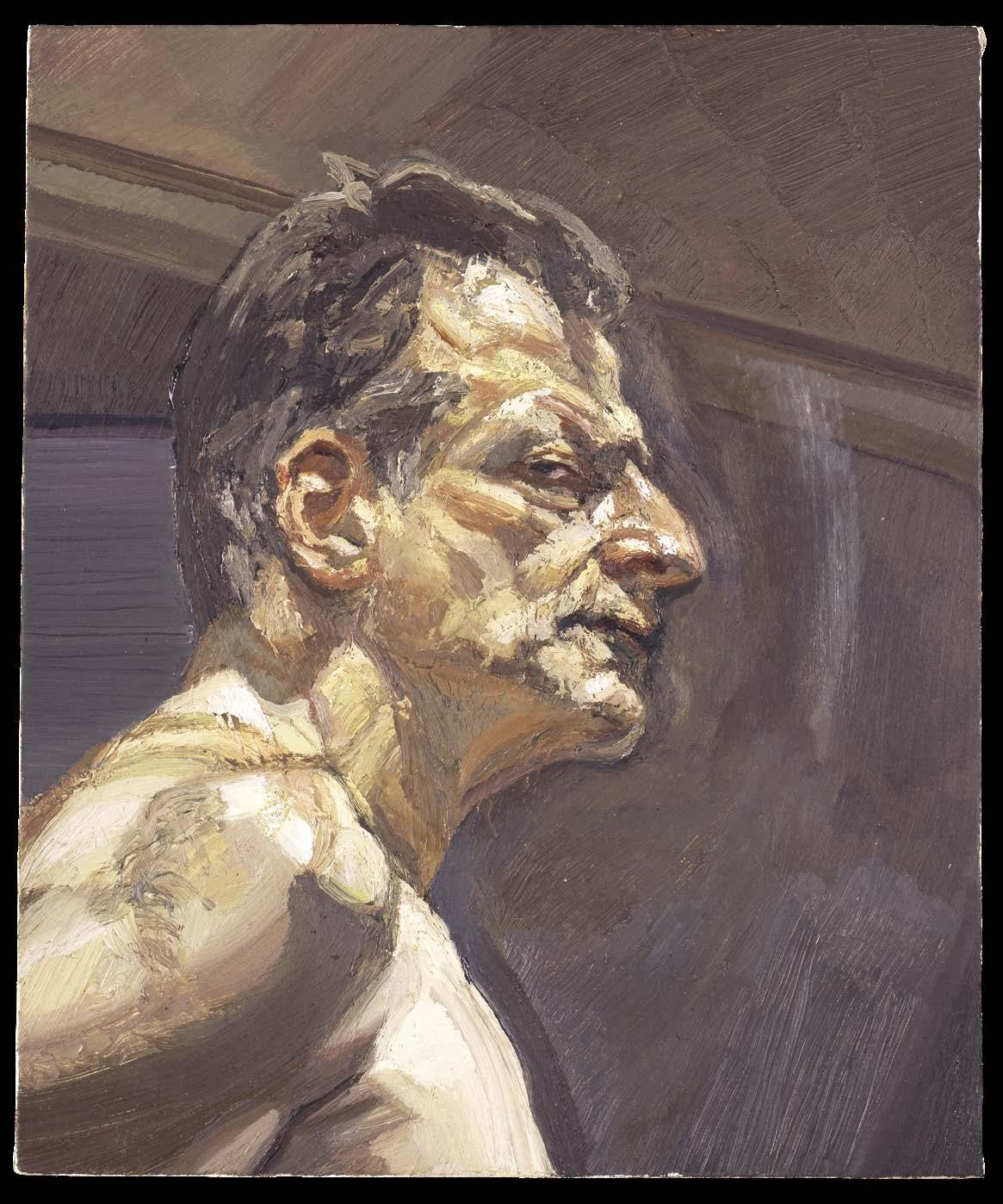

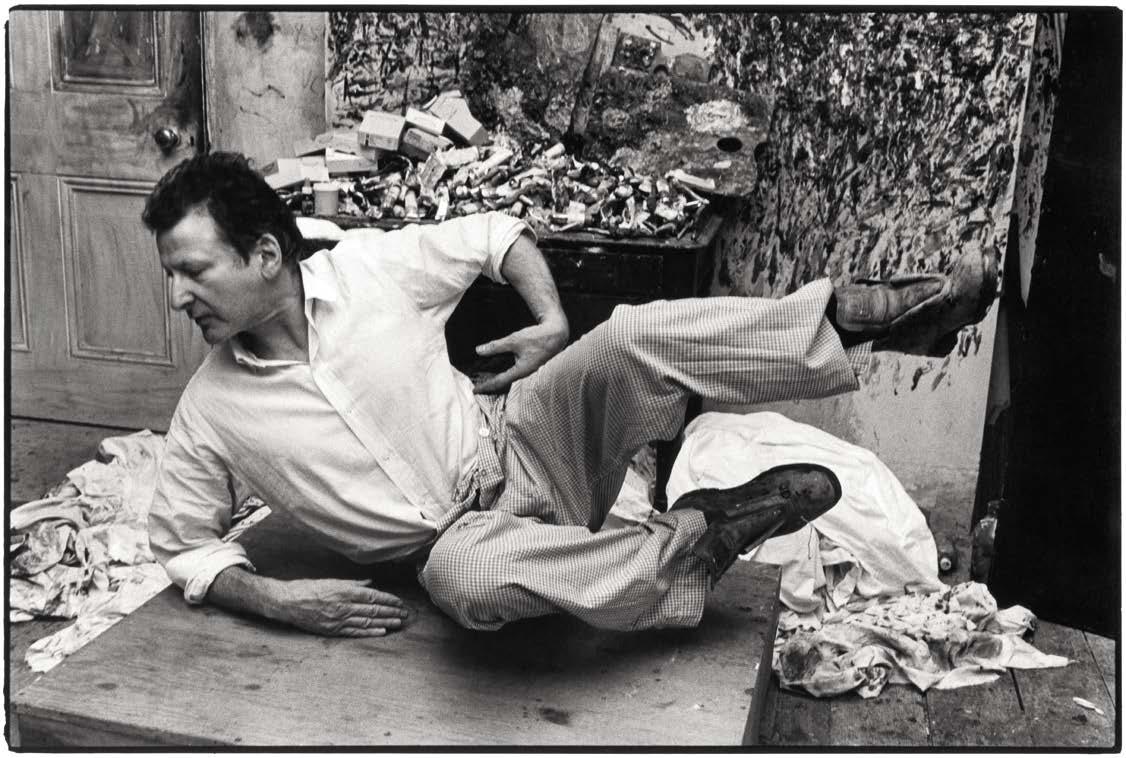

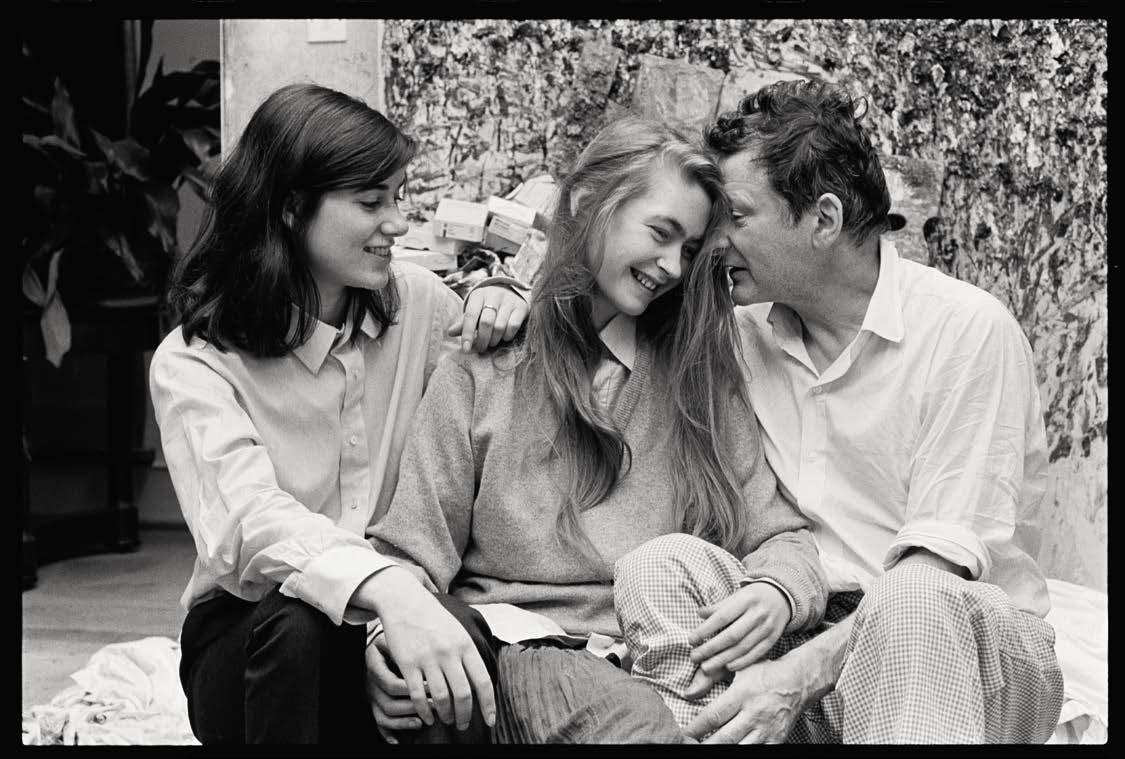

It is a thrill to read Frank Auerbach talking with Richard Calvocoressi about his friendships with Michael Andrews, Francis Bacon, and Lucian Freud. The interconnected lives and practices of those legendary artists were often photographed by Bruce Bernard, whose documentation of and participation in the London group is considered in a companion article by the painter Virginia Verran.

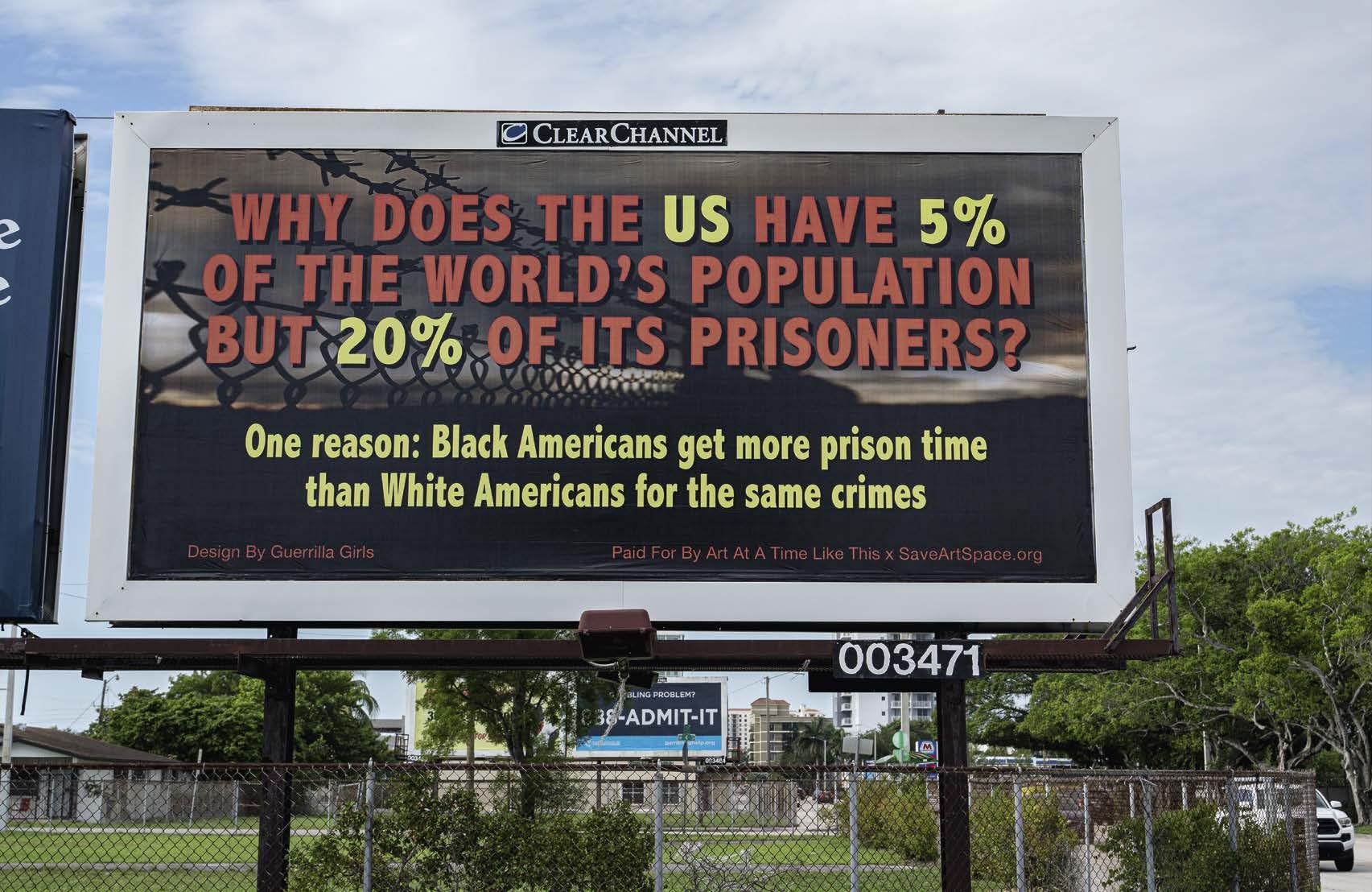

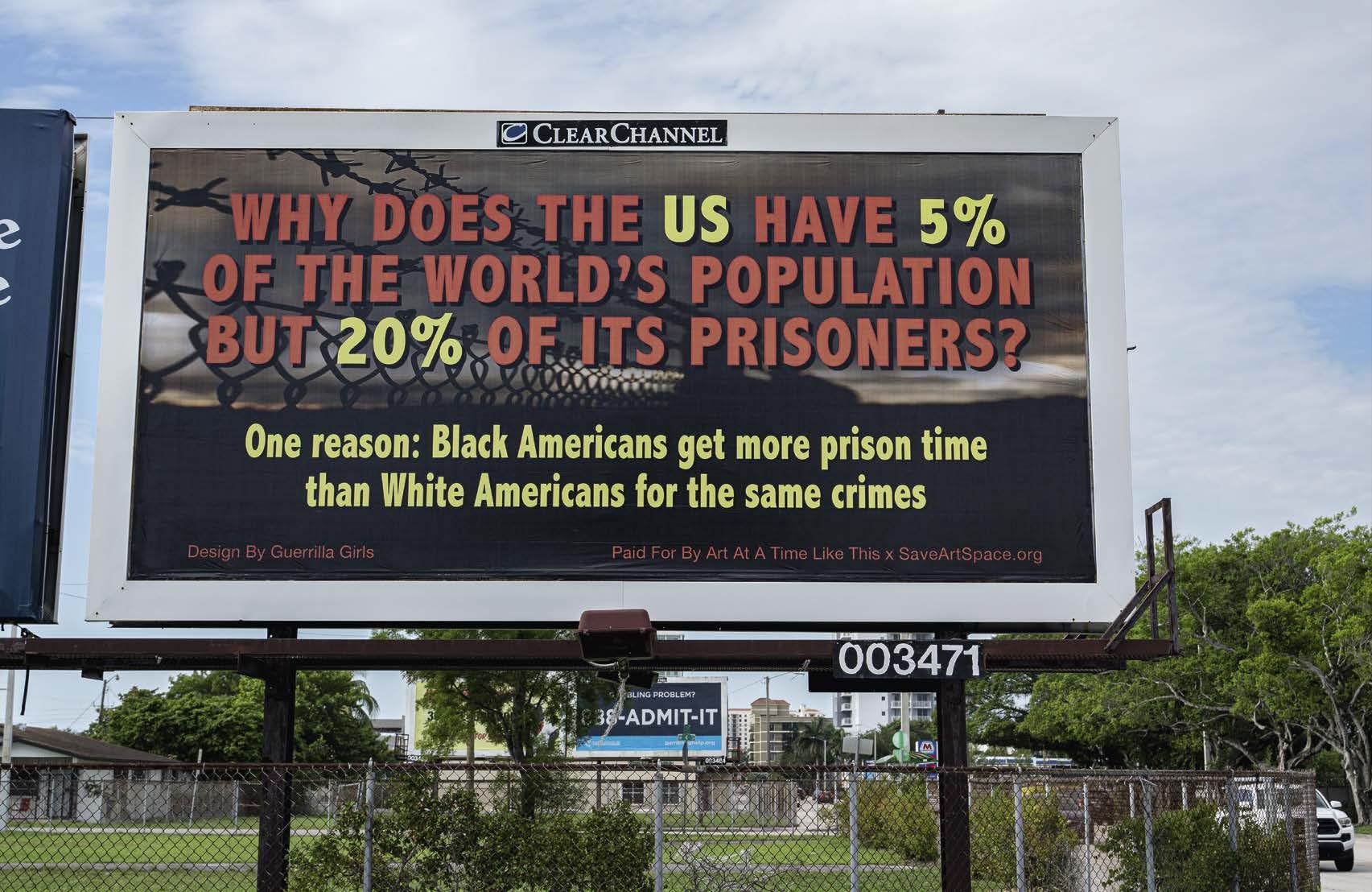

Our Building a Legacy column spotlights the Andy Warhol Foundation, exploring its navigation of philanthropic pursuits, licensing opportunities, intellectual property, and more. Our Bigger Picture series focuses on artists and organizations making a stand against mass incarceration in the United States. The final installment of a ghoulish love story by Venita Blackburn, which we have published in each issue over this past year, brings her fiction contribution to a dynamic conclusion.

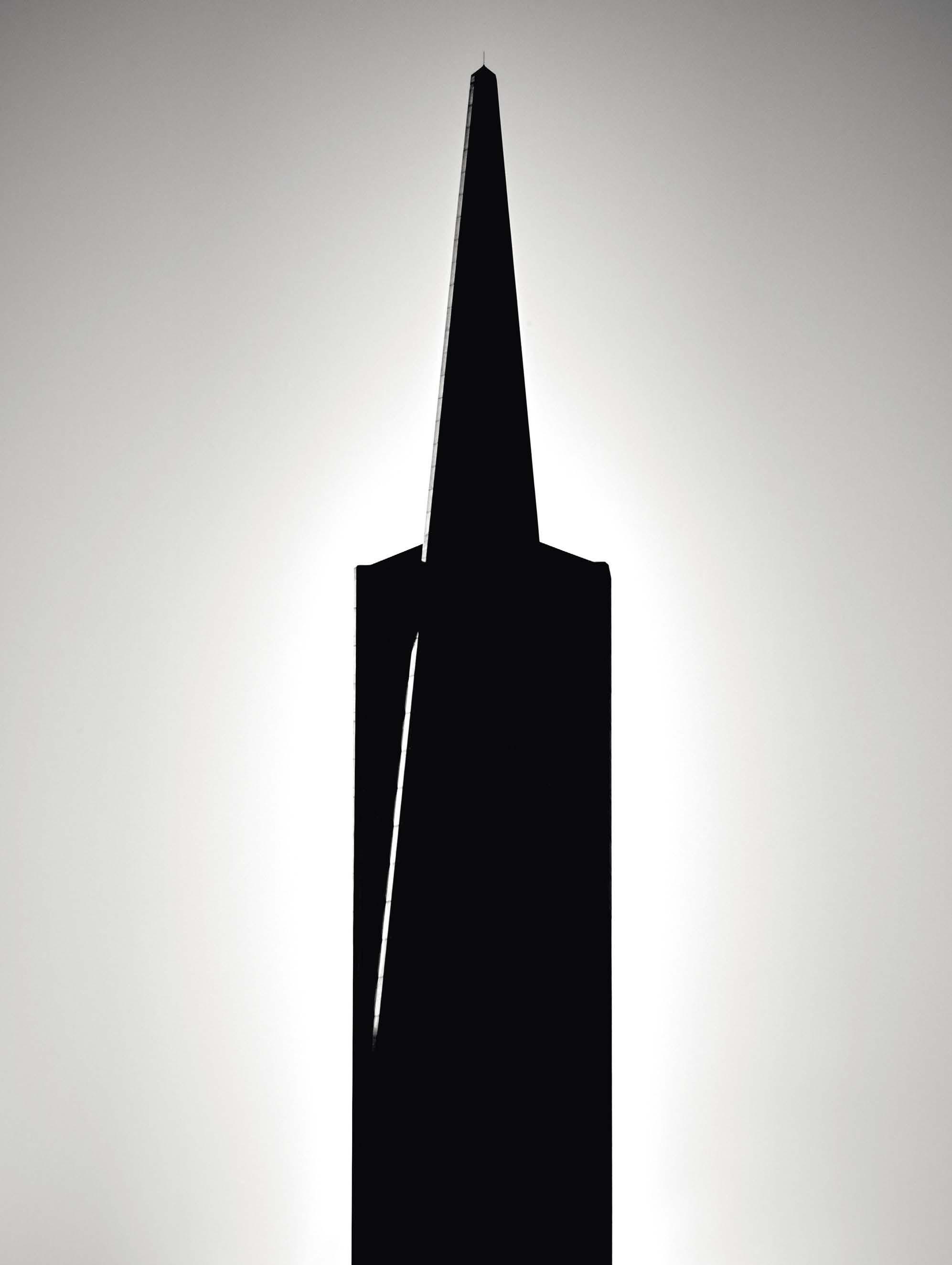

A recently published monograph on the work of Walter De Maria promises to bring the entirety of his career into singular focus. We speak with the editors of that volume about the discoveries they made in their research and about an extraordinary exhibition at the Menil Collection in Houston. Presenting De Maria’s early works, the show allows us insight into the lesser-known but foundational building blocks of his practice.

Our Game Changer column focuses on the gallerist, patron, and curator Virginia Dwan, whose early and long support of a vital generation of artists proved critical in cementing their legacy. She played a role in helping them to realize their milestone achievements throughout her unparalleled life and career.

McDonald, Editor-in-chief

Alison

Walter De Maria: The Object, the Action, the Aesthetic Feeling

The definitive monograph on the work of Walter De Maria is being released this fall. To celebrate this momentous occasion, Elizabeth Childress and Michael Childress of the Walter De Maria Archive talk to Gagosian senior director Kara Vander Weg about the origins of the publication and the revelations brought to light in its creation.

54

Hans Ulrich Obrist’s Questionnaire: Anselm Kiefer

The fourth installment of the series.

56

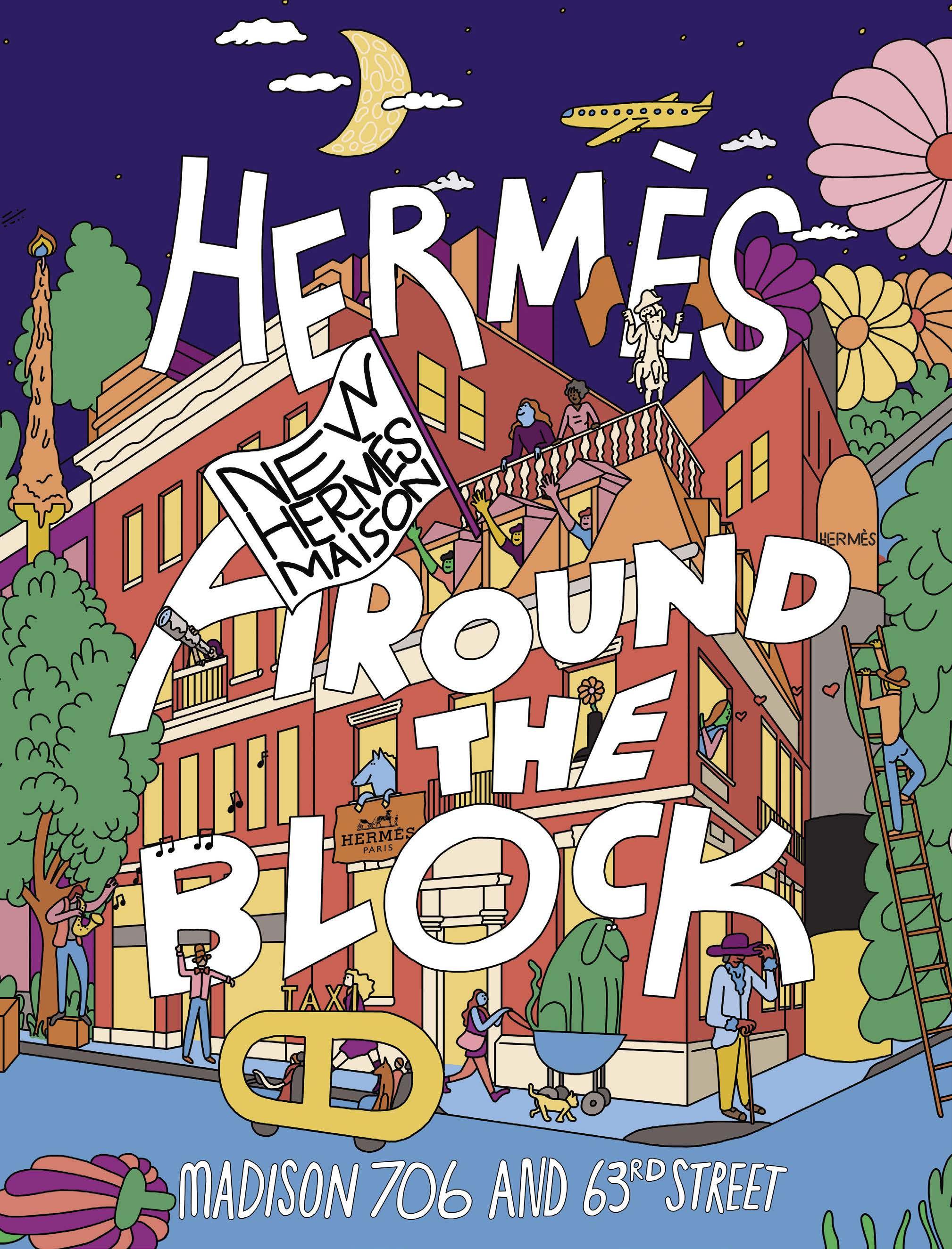

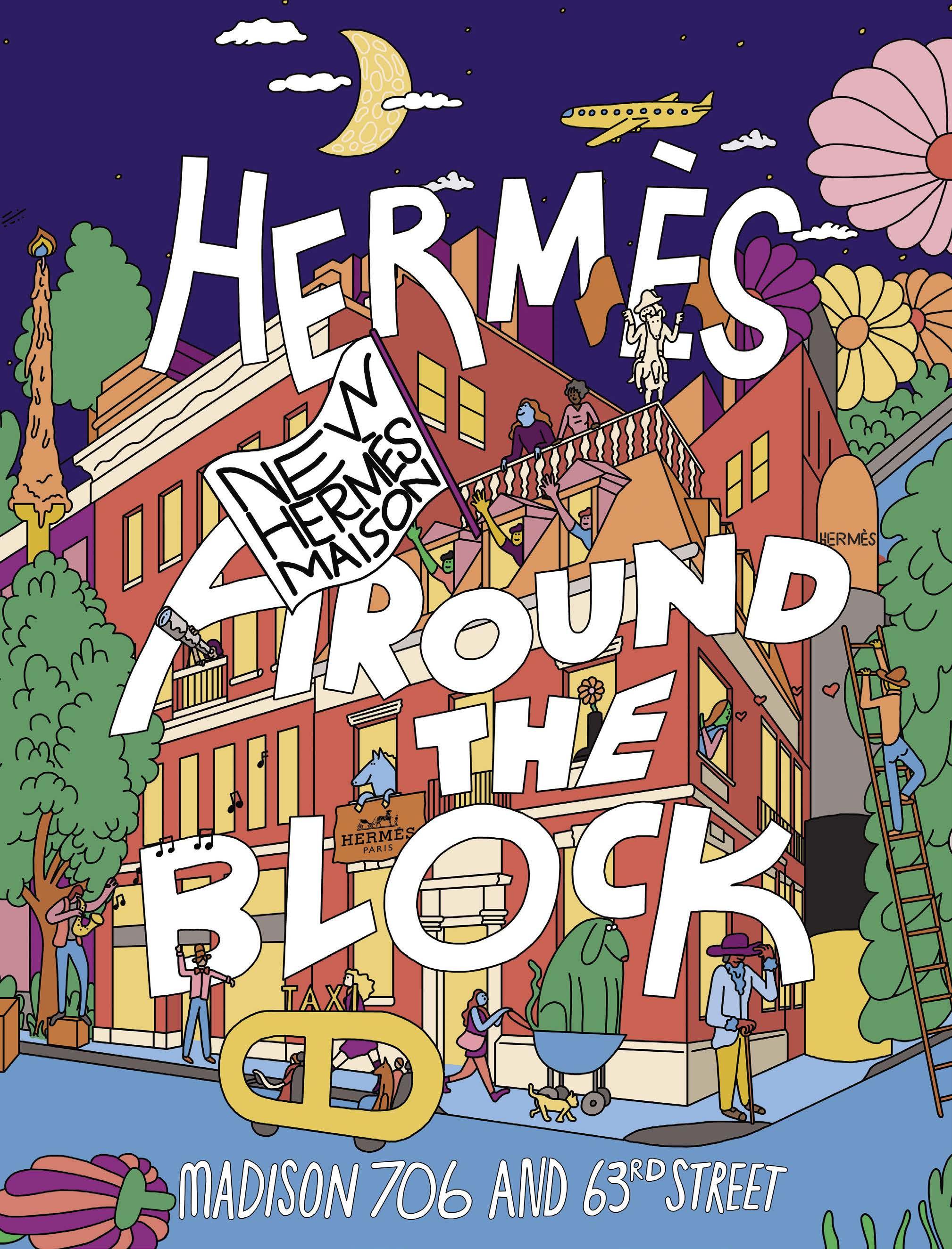

Fashion and Art, Part 12: PierreAlexis Dumas

Pierre-Alexis Dumas, the artistic director for Hermès, speaks with the curator Abby Bangser about the central role of the house’s art collection in their creative process.

60

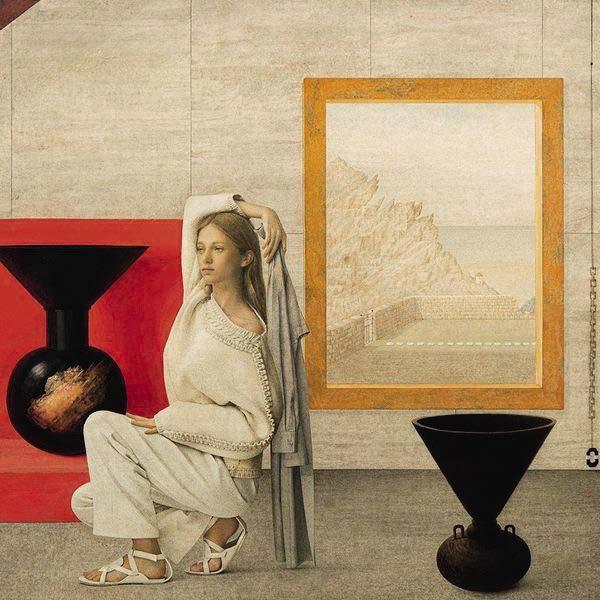

Anna Weyant: Baby, It Ain’t Over Till It’s Over

Novelist Emma Cline traces the boundaries between terror and hilarity in Anna Weyant’s new paintings.

68

The Celestial Cinema of Gregory Markopoulos

Raymond Foye reports on the Temenos, the screening of Gregory Markopoulos’s film Eniaios in Lyssarea, Greece, in the summer of 2022.

76

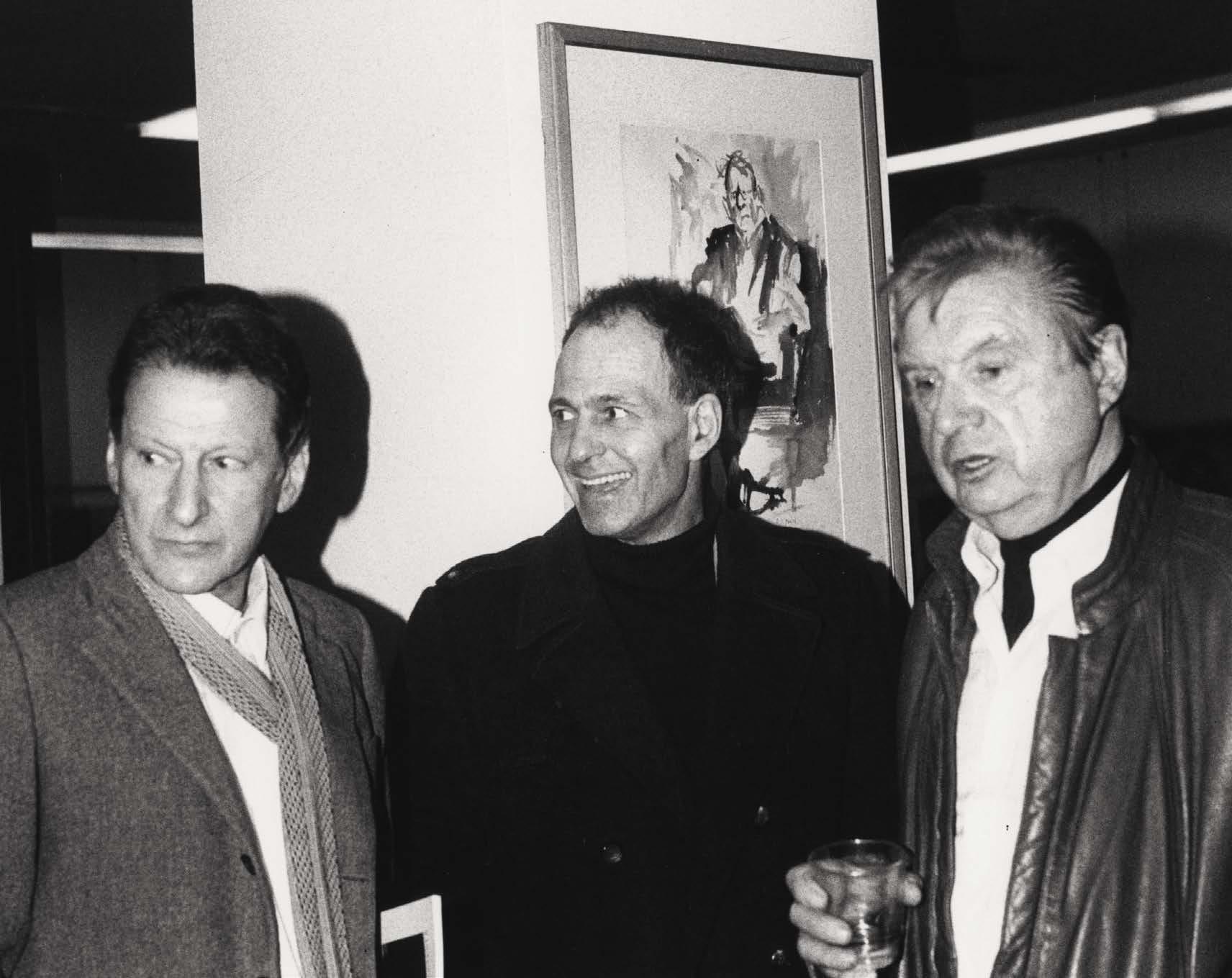

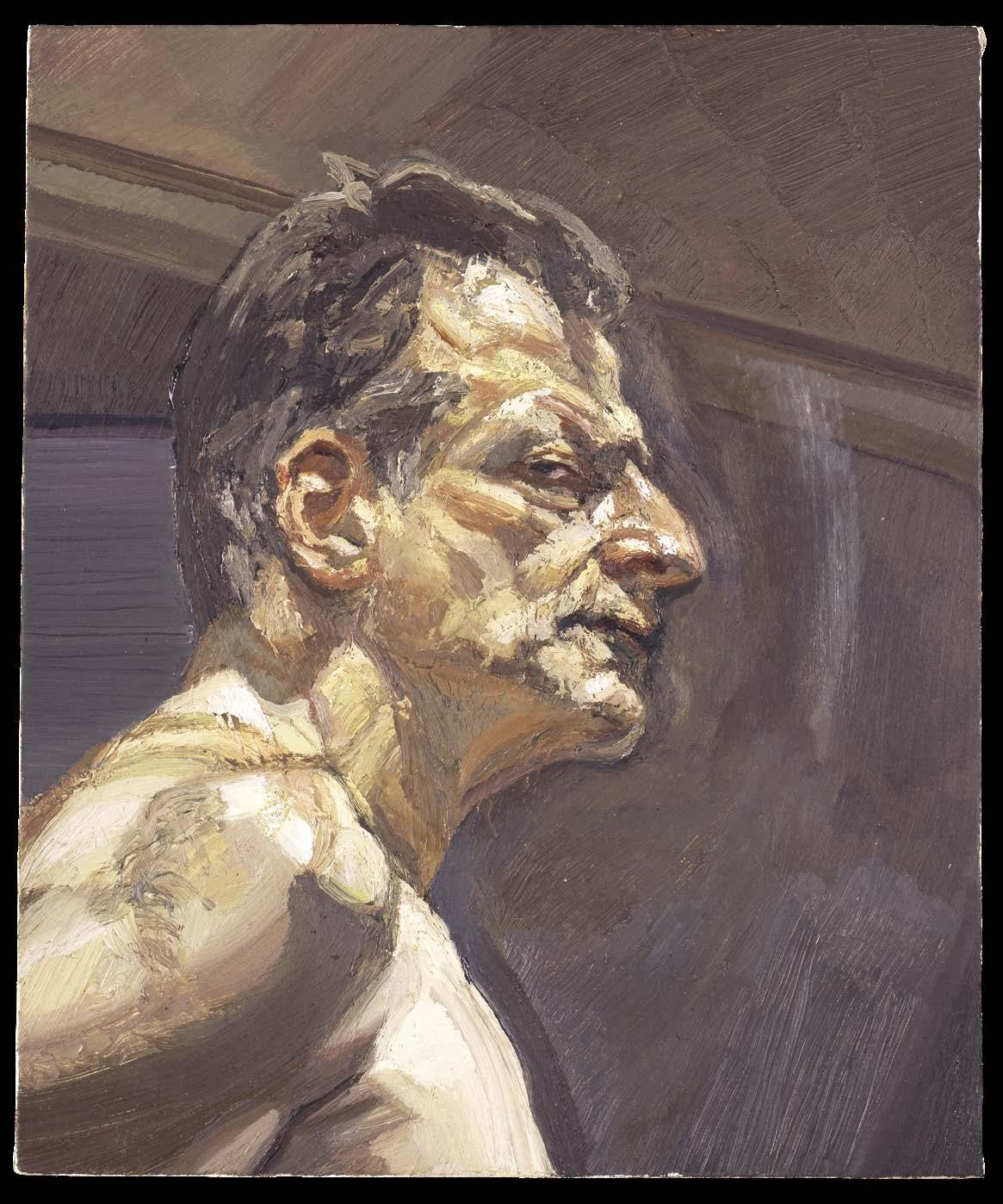

Frank Auerbach: Artist Friends

In this candid interview with Richard Calvocoressi, the painter Frank Auerbach reminisces on his friendships with Michael Andrews, Francis Bacon, and Lucian Freud.

88

Bruce Bernard: Portraits of Friends

Virginia Verran details the photographer’s friendships with the London painters.

94

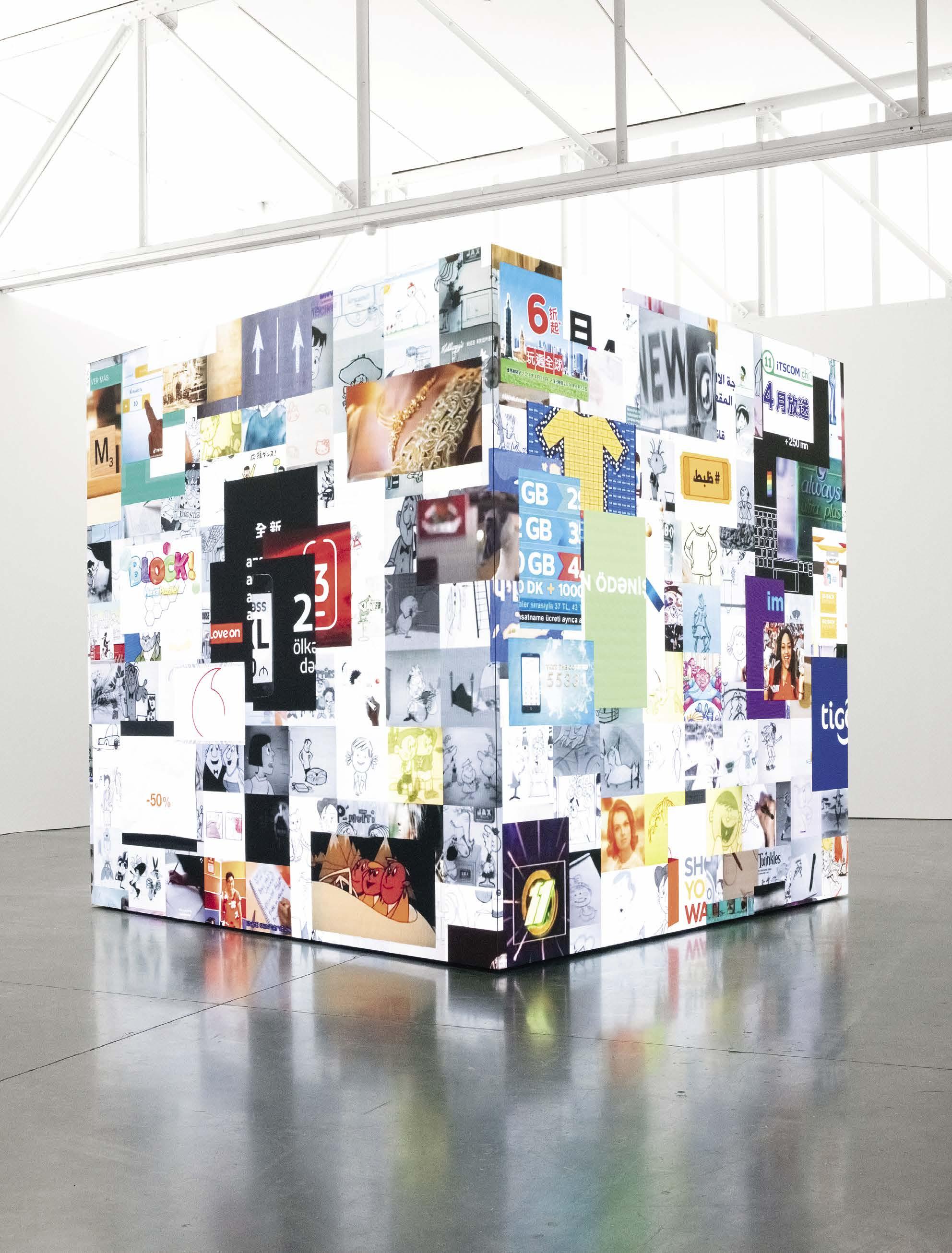

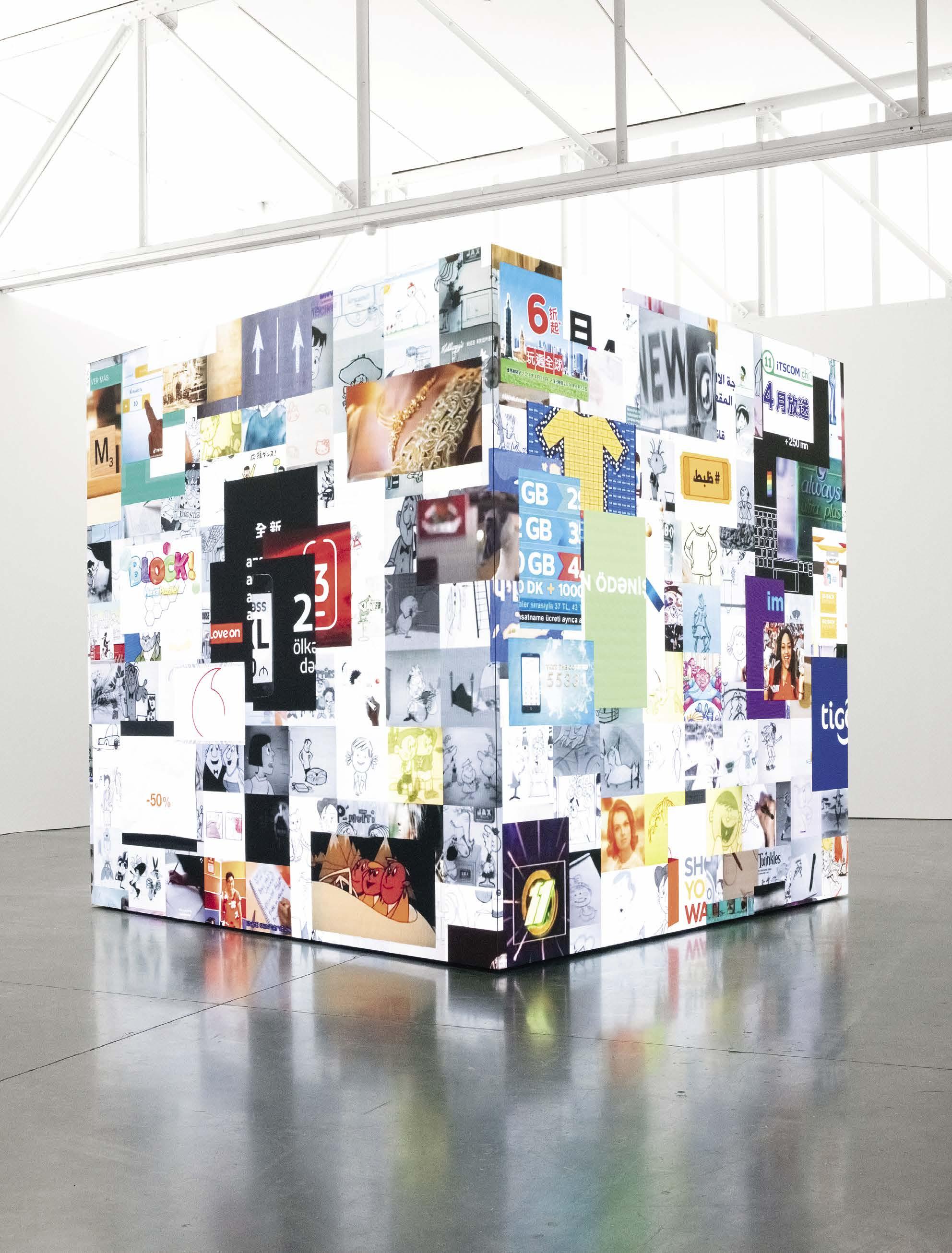

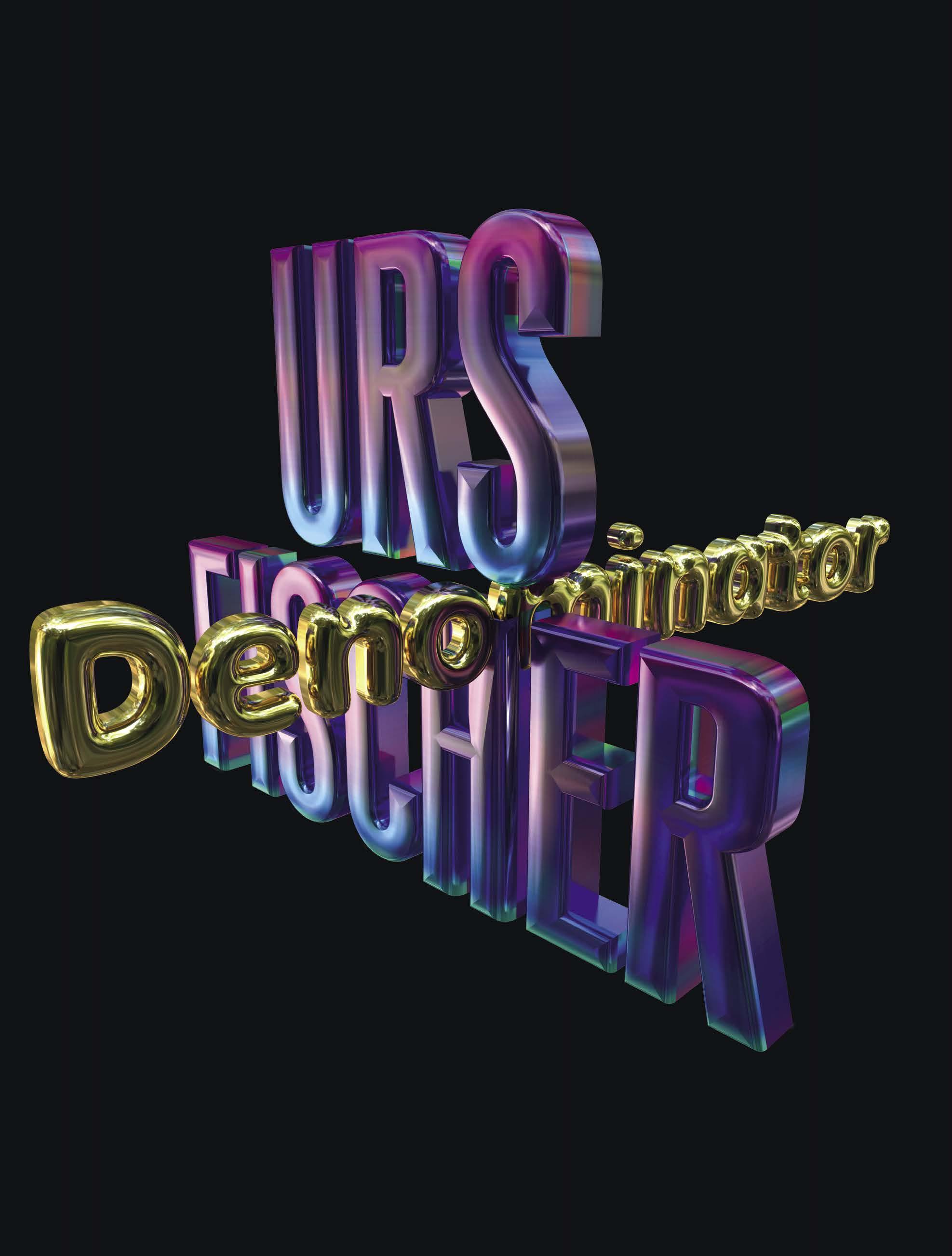

Urs Fischer: Denominator

Urs Fischer sits down with his friend the author and artist Eric Sanders to address the perfect viewer, the effects of marketing, and the limits of human understanding.

102

Bigger Picture: Artists against Mass Incarceration

Salomé Gómez-Upegui reports on cultural organizations and artists standing up against mass incarceration in the United States.

106

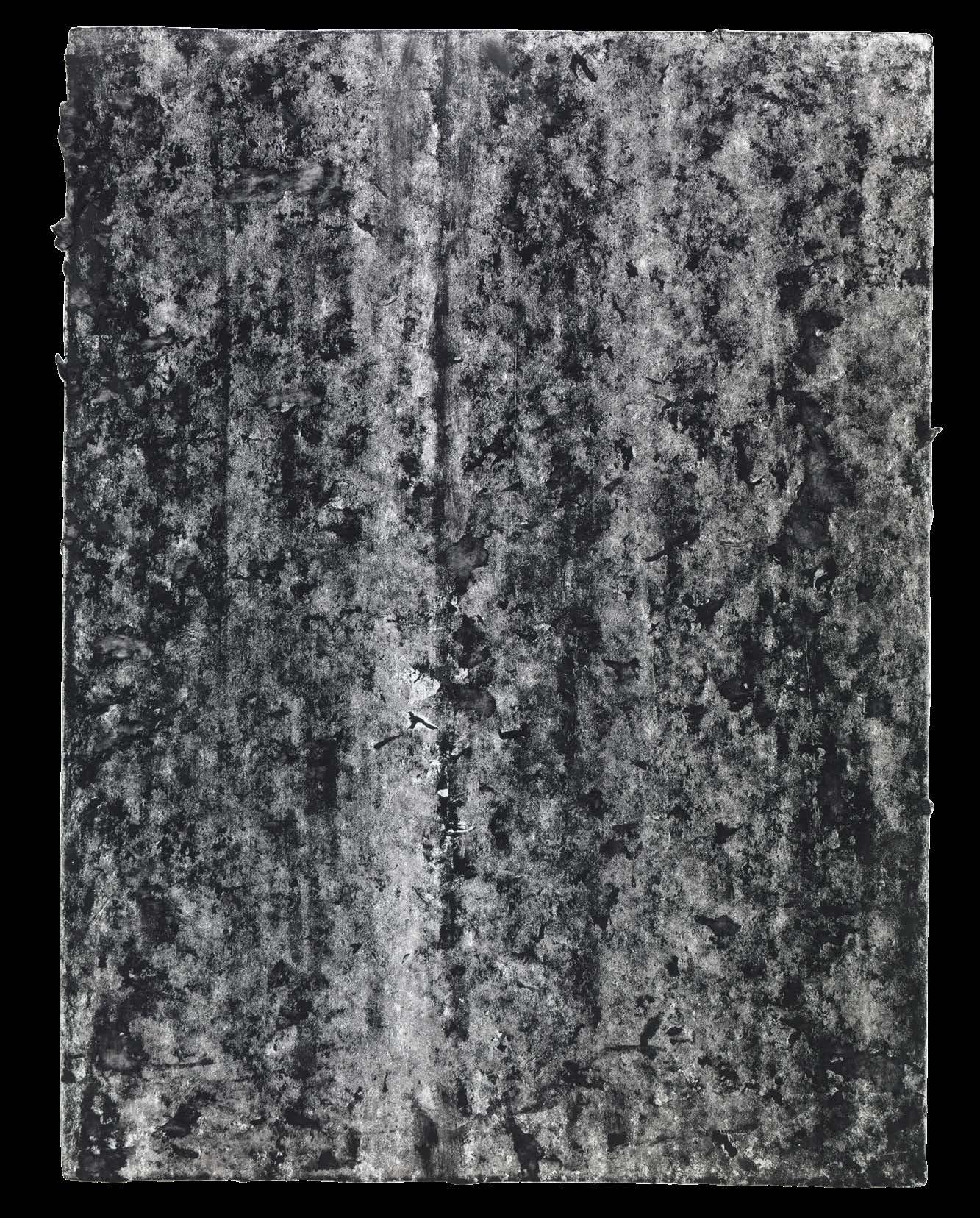

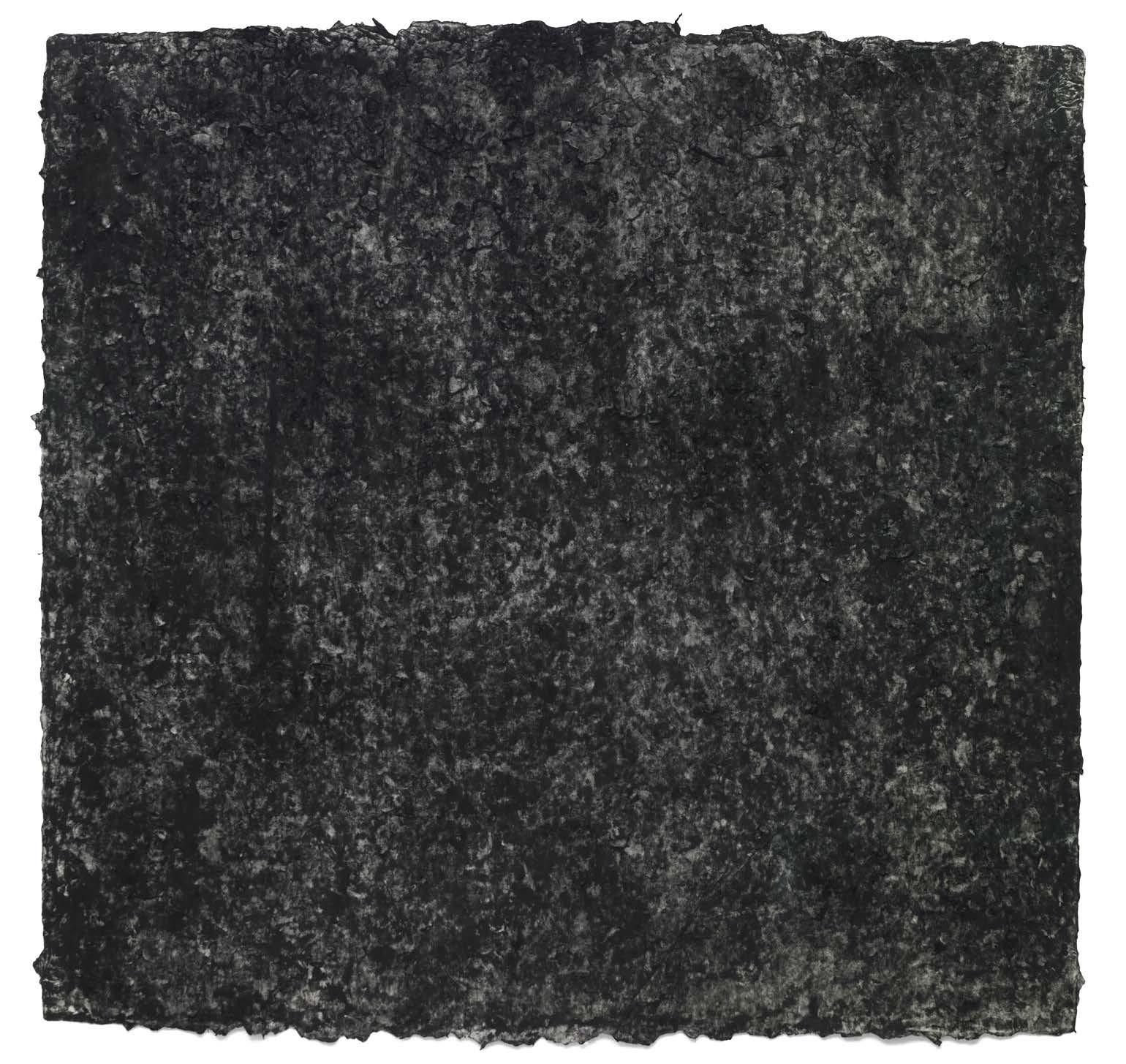

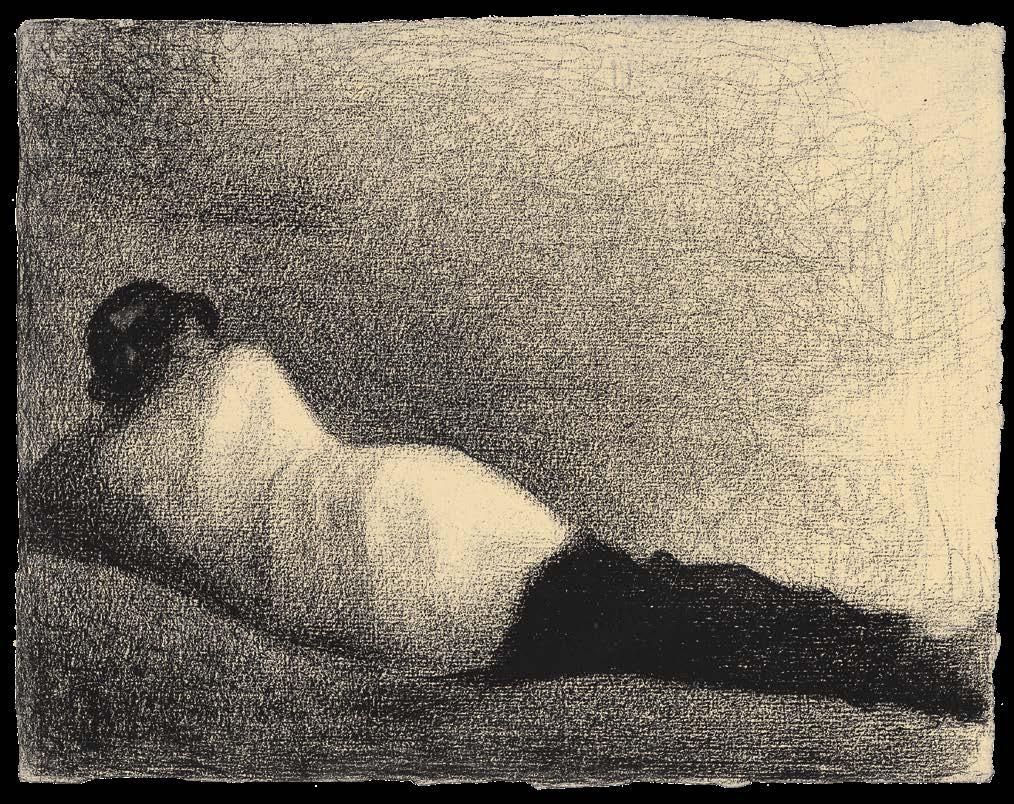

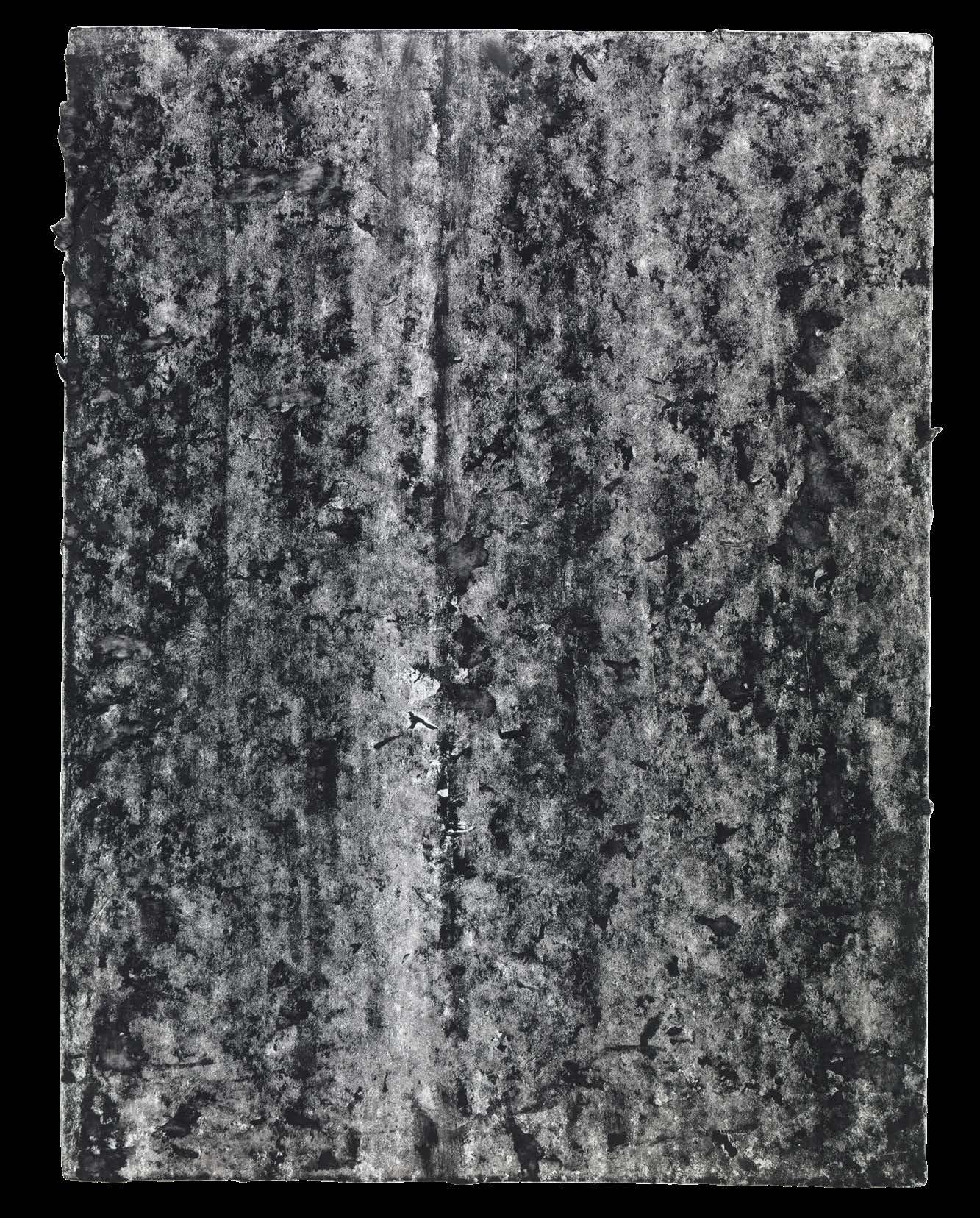

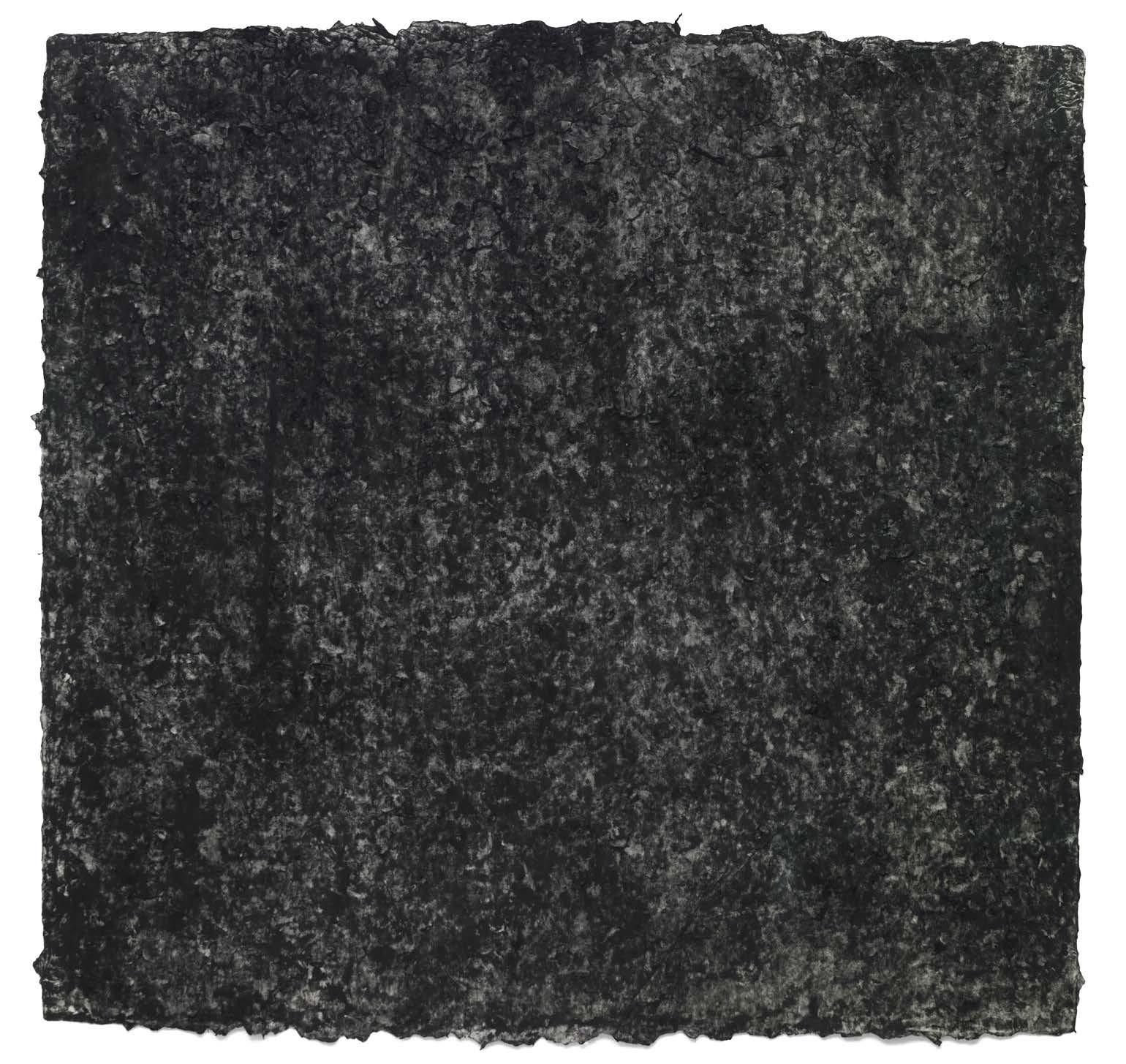

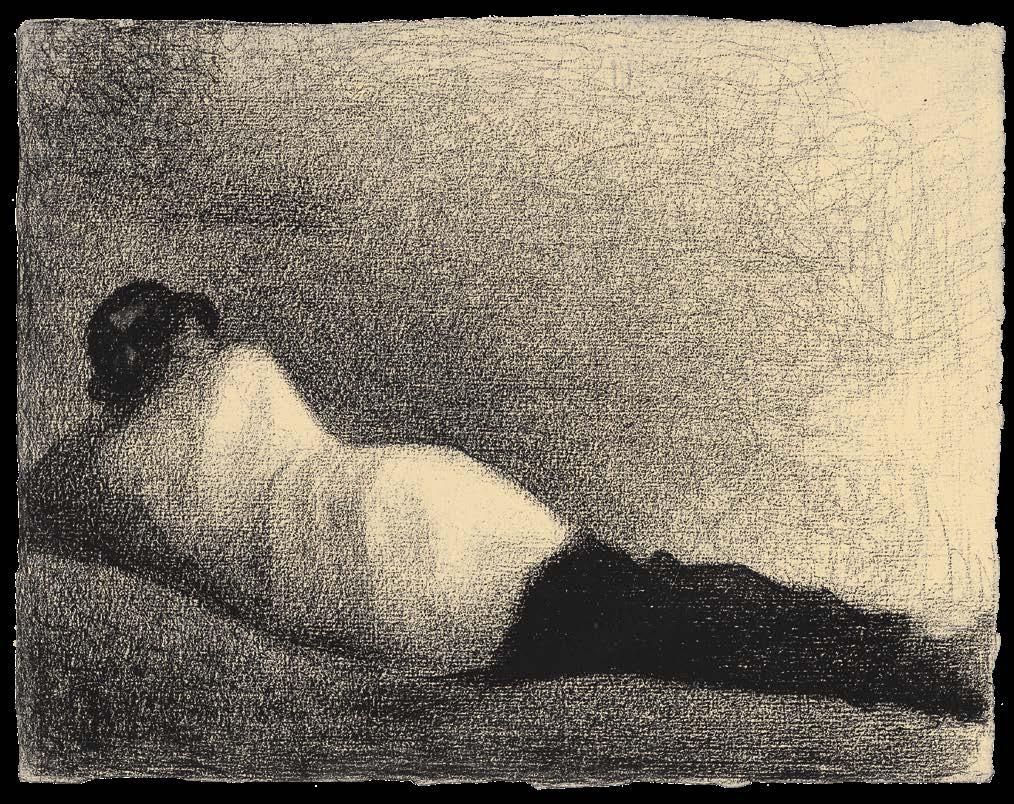

Serra/Seurat: Drawings

Cocurated by Lucía Agirre and Judith Benhamou, the Bilbao exhibition Serra/Seurat: Dibujos puts drawings by Georges Seurat and Richard Serra into dialogue. A Spanish-language catalogue was produced for the show, featuring texts by both curators; the Quarterly is pleased to debut the English translations of these texts.

114

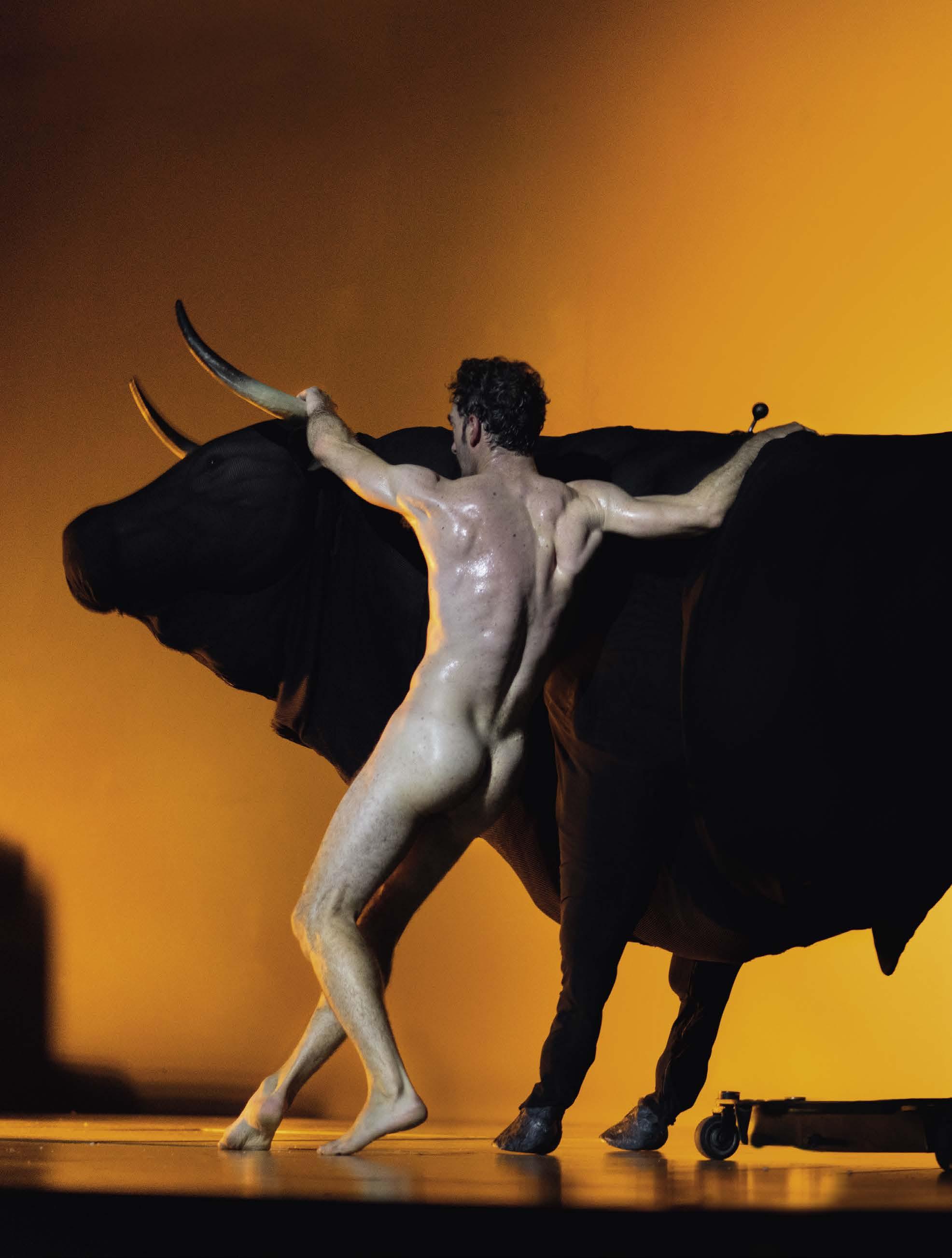

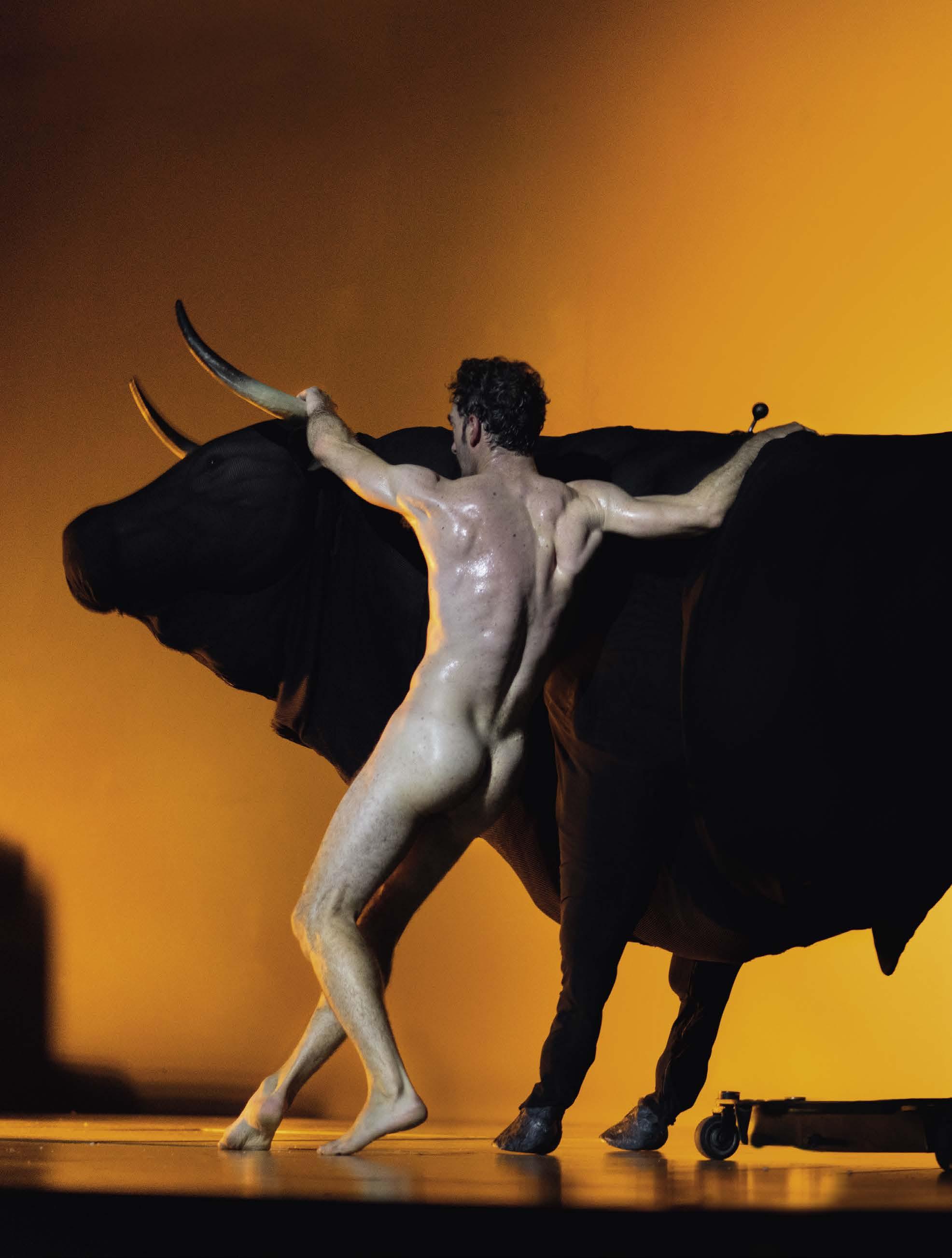

Myths and Monsters

Mike Stinavage visits Dimitris Papaioannou in Athens as he closes one world tour and opens another.

120

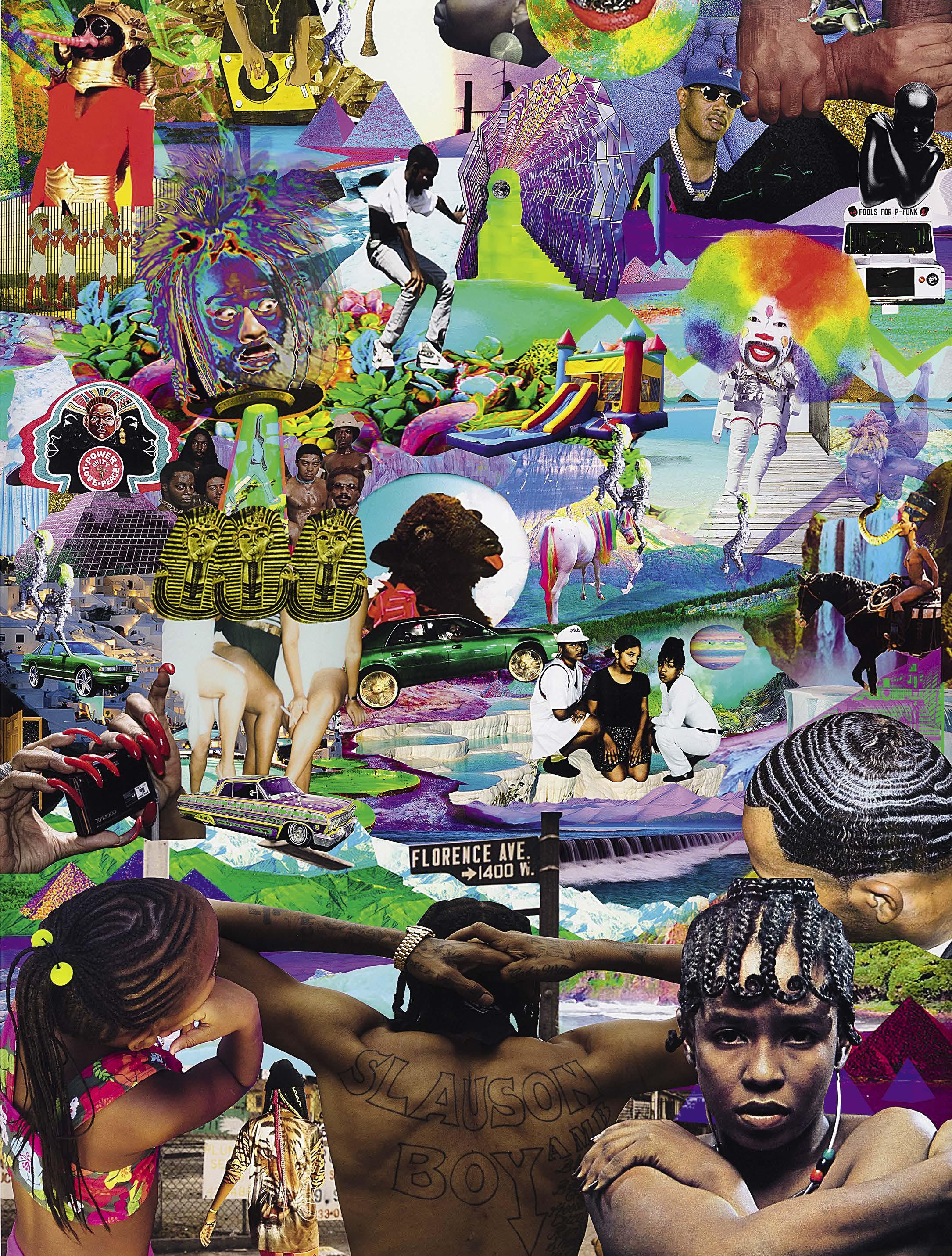

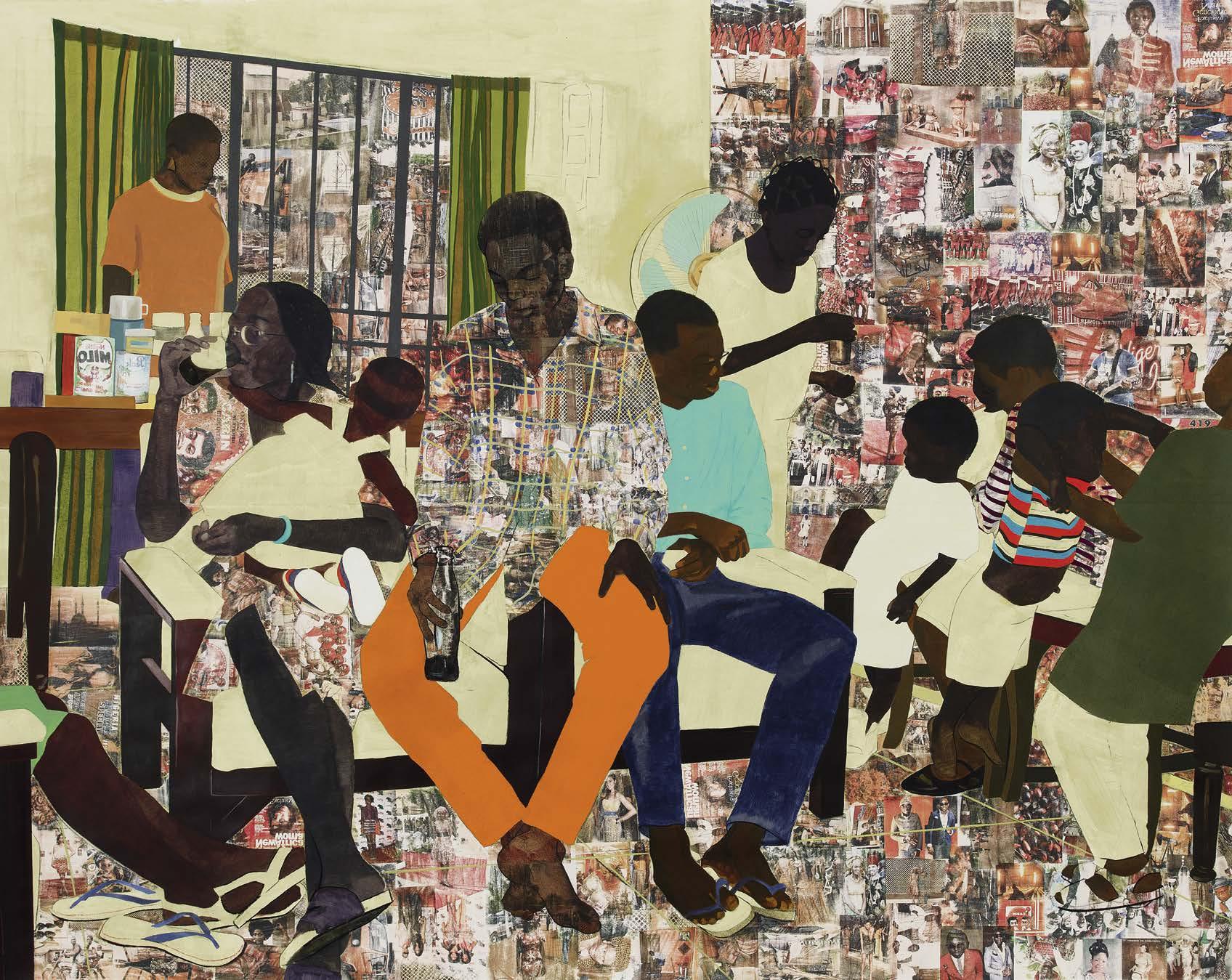

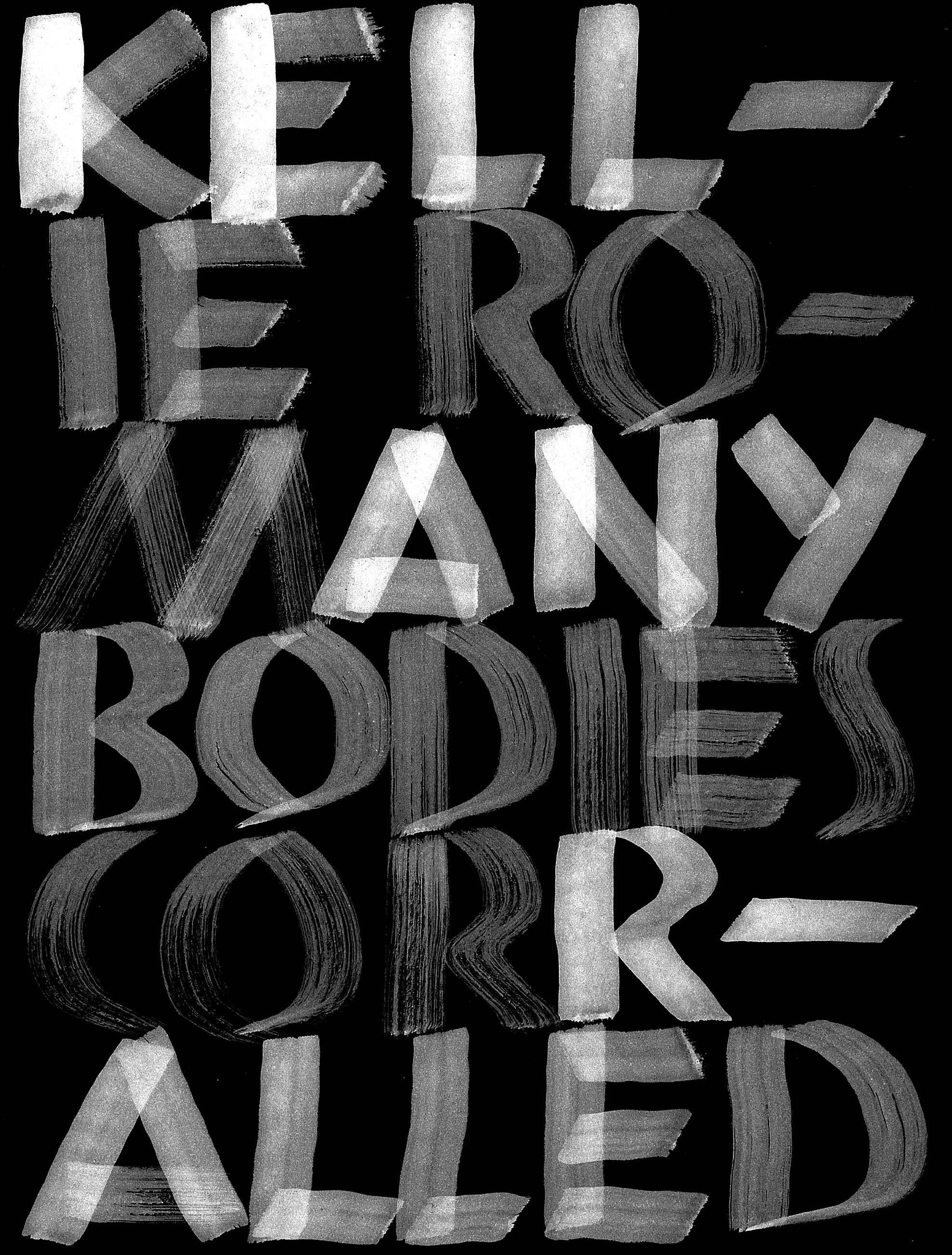

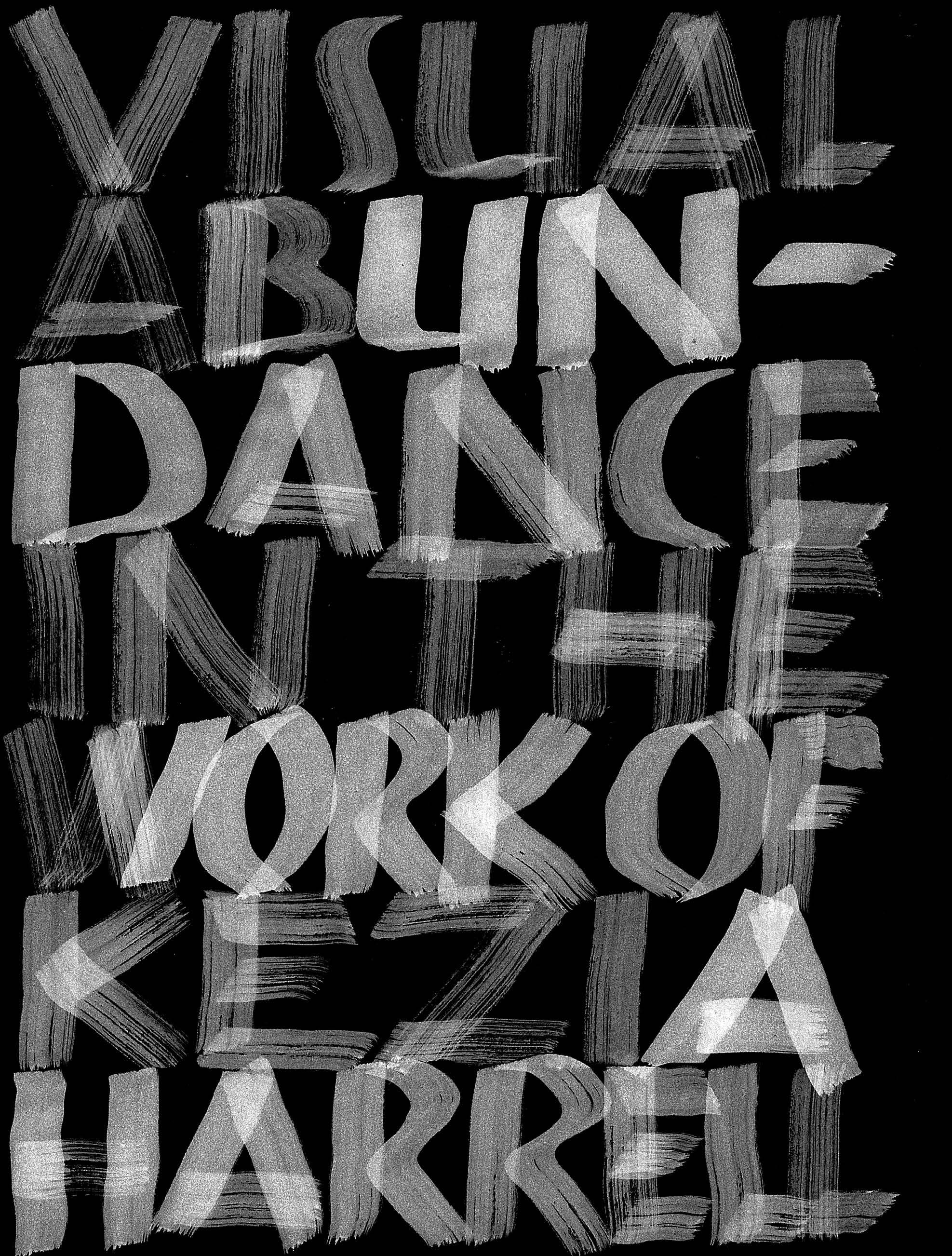

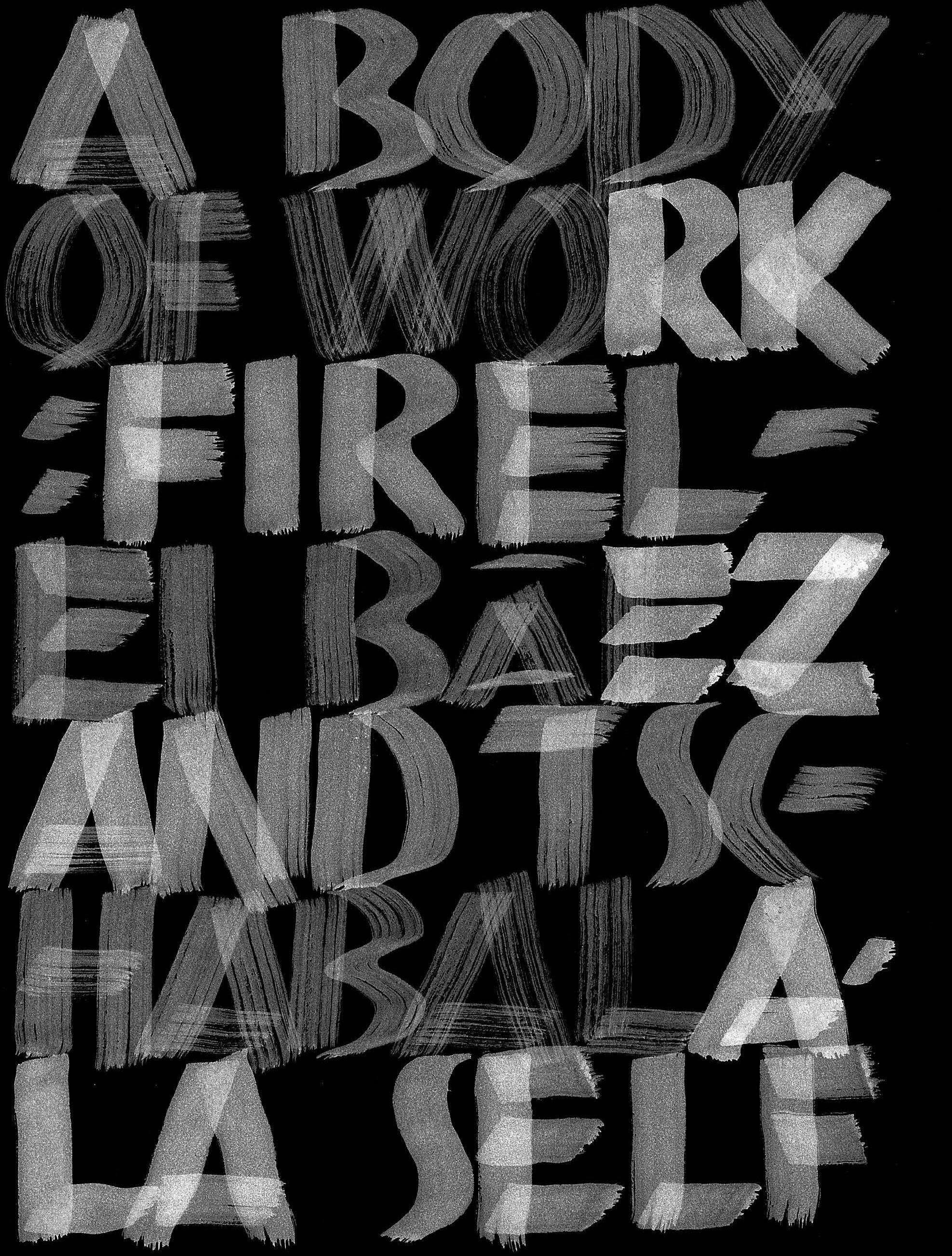

Roxane Gay: Black to Black

A special section guest-edited by Roxane Gay.

156

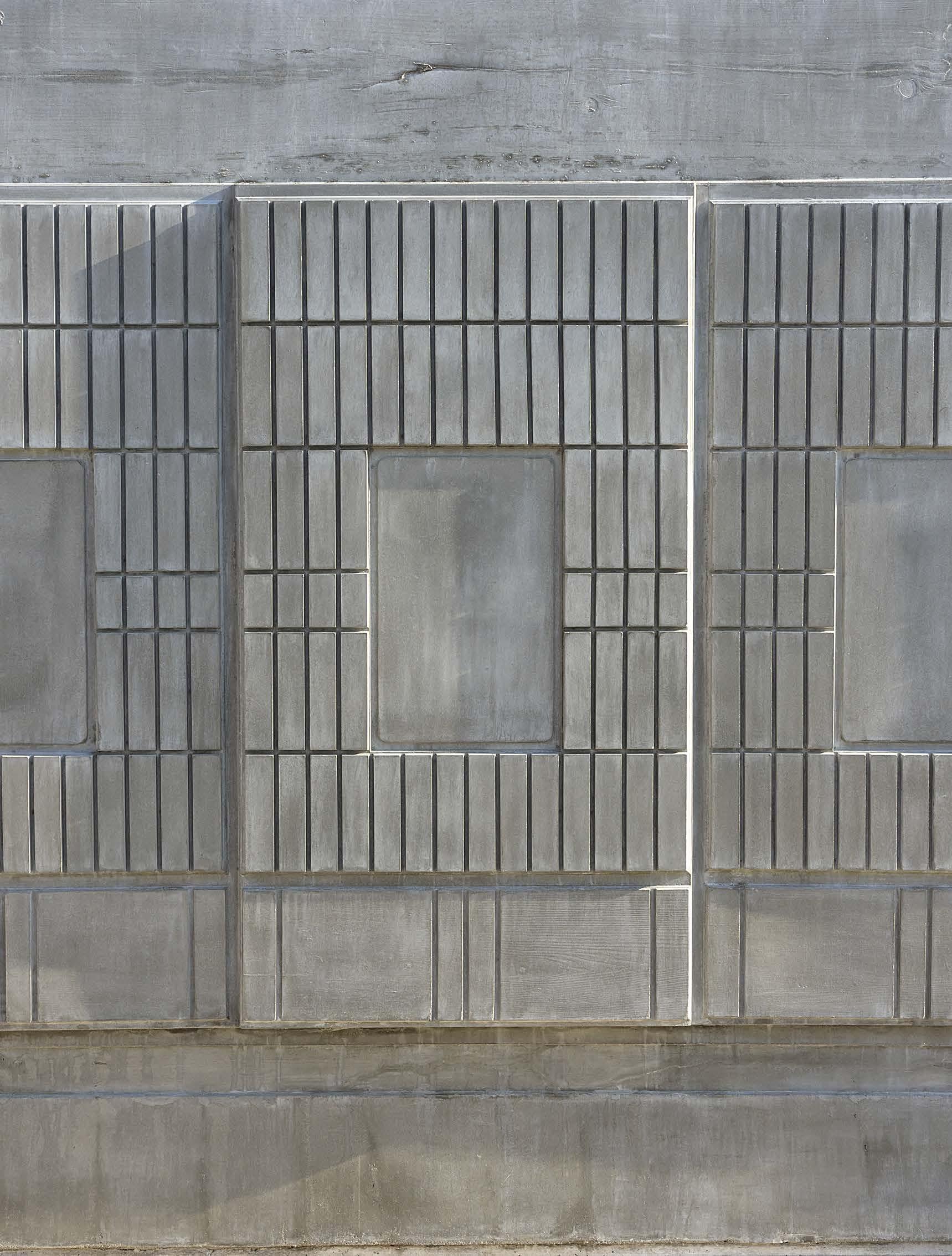

Rachel Whiteread: Shy Sculpture

For the unveiling of her latest Shy Sculpture in Kunisaki, Japan, Rachel Whiteread joins curator and art historian Fumio Nanjo for a conversation about this ongoing series.

162 Memoirs of a Poltergeist, Part Four

The fourth and final installment of a short story by Venita Blackburn.

NXTHVN: Curatorial Visions

Jamillah Hinson and Marissa Del Toro, the most recent curatorial fellows of Titus Kaphar’s nonprofit community arts hub NXTHVN, address their curatorial praxes.

Building a Legacy: The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts

For this installment of Building a Legacy, the Quarterly ’s Alison McDonald meets with Michael Dayton Hermann, the director of licensing, marketing, and sales at the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, to discuss questions around intellectual property and licensing.

176

Screen Time: A Conversation with Andrei Pesic

In conversation with Ashley Overbeek, scholar Andrei Pesic traces the art-historical roots of the NFT market to the Paris Salons. Along the way, they discuss questions of authenticity, value, and ownership.

182

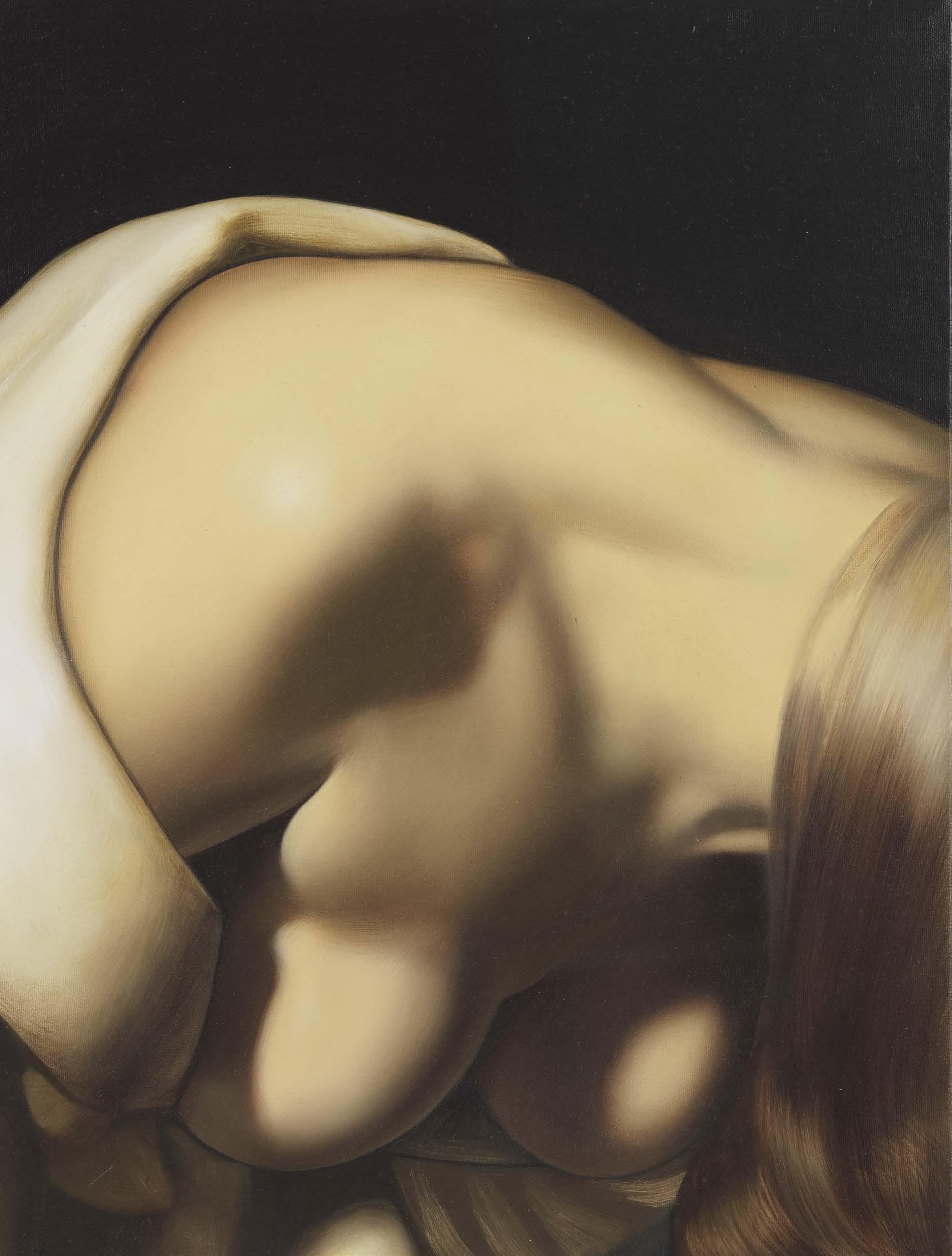

The Actual Picture: On Karin Kneffel’s Painting

Ulrich Wilmes takes note of the radical break in the painter’s new series of portraits.

202

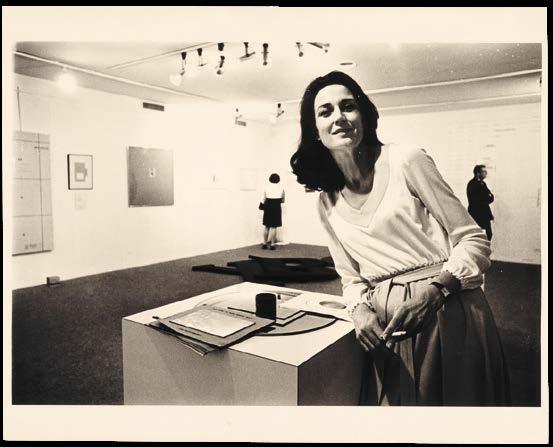

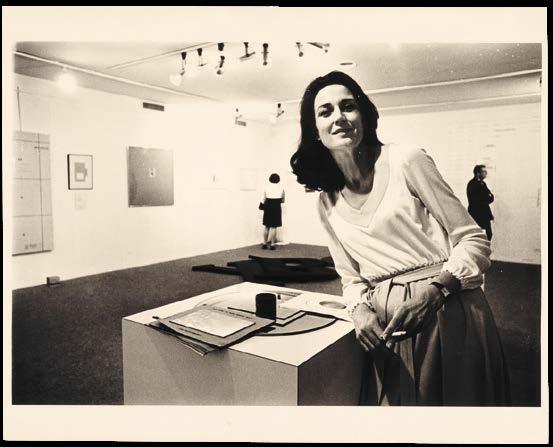

Game Changer: Virginia Dwan

Charles Stuckey reflects on the unparalleled life and career of the gallerist, patron, and curator Virginia Dwan, enumerating key moments from a lifetime dedicated to artists and their visions.

TABLE OF CONTENTS WINTER

Front cover: Anna Weyant, Two Eileens , 2022, oil on canvas, 60 ⅛ × 48 ⅛ inches (152.7 x 122.2 cm) © Anna Weyant. Photo: Rob McKeever

44

168

174

2022

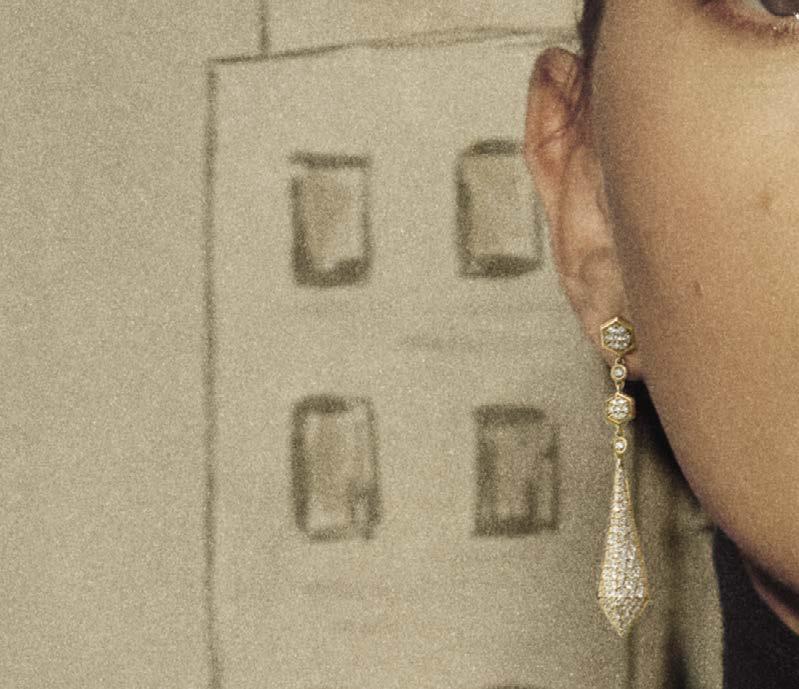

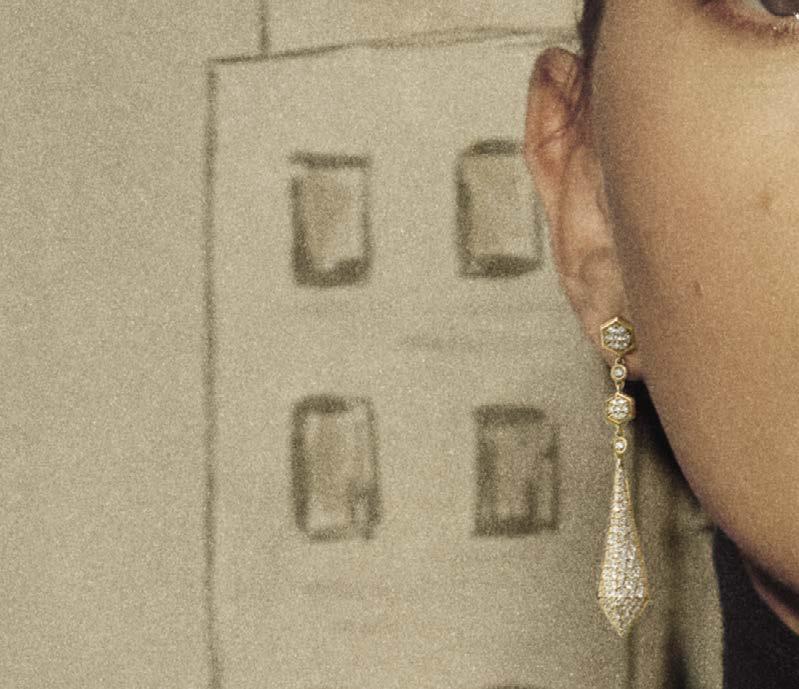

1932 COLLECTION

THE STARS ALIGNED

In 1932, Gabrielle Chanel created BIJOUX DE DIAMANTS, t he first high jewelr y collection in history. Inspired by t he allure of t he stars, it was designed to be worn freely in a brand-new way. Mademoiselle t hen turned her concept of jewelr y in motion — par t of her vision for women — into a manifesto .

In 2022, C HANEL High Jewelr y celebrates t his celestial revolution wit h t he launch of t he 1932 COLLECTION , based on t he perpetual motion of t he stars and tailored to t he natural movements of t he body In t he same spirit, C HANEL asked an aut hor known for his reflections on movement to write a manifesto for t he new collection.

After winding around from the nape of the neck, the string of diamonds suddenly bursts into a shooting star, trailed by a cascade of sparks leading to a sapphire that ts perfectly into the negative space of a crescent moon of diamonds. A fragmented nimbus then explodes around a profusion of carats pulsating at the neckline. A line of precious stones rises and falls with the rhythm of the breath, trapping the gaze in their bewitching depths. Beneath this blue eclipse, a string of cr ystals leads the eye toward the heart, where a diamond sun blazes, its early-morning rays oscillating and sparkling with the wearer ’ s movements. In this theater of precious stones, celestial bodies undulate on the skin’s “Milky Way,” sketching new landscapes each time the head moves or tilts. Like the necklace, the collection is a series of celestial bodies journeying across the skin and enhancing each movement of the body as the planets travel past twinkling stars. e beauty of the world lies in this radiance. e glow of the stones is tangible, sculpted into the diamond, itself becoming a jewel, liberated, as if the aura could be removed and worn as a brooch. What was a parure has become a jewel, a stone cut in stone, made even more precious by what has been removed from it. From the depths of the Earth to the Cosmos, there is little light, but it sometimes burns beneath the eyelids in insistent lines. e gems begin to dance within us: diamonds, blue diamonds, rubies, yellow diamonds, sapphires and rings running along the ngers, orbiting, spilling their brilliance over the hand. Bracelets and diamonds give way to a streaking comet on the skin, a virtuoso play of light and the ever-changing gestures of a woman who is suddenly the center of the universe.

Hugo Lindenberg

chanel .c om *WHITE GOLD WITH A THIN LA YER OF RHODIUM PL A TING FOR CO LO R © 2022 C HANEL ® , Inc. THE NEW 1932 COLLECTION CELEBRATES THE 90TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE BIJOUX DE DIAMANTS COLLECTION, CREATED IN 1932 BY G ABRIELLE CHANEL . TRANSFORMABLE ALLURE CÉLESTE NEC KL ACE IN 18K WHITE GOLD* AND DIAMONDS, WITH A 55.55-C ARAT OVAL-CUT SAPPHIRE.

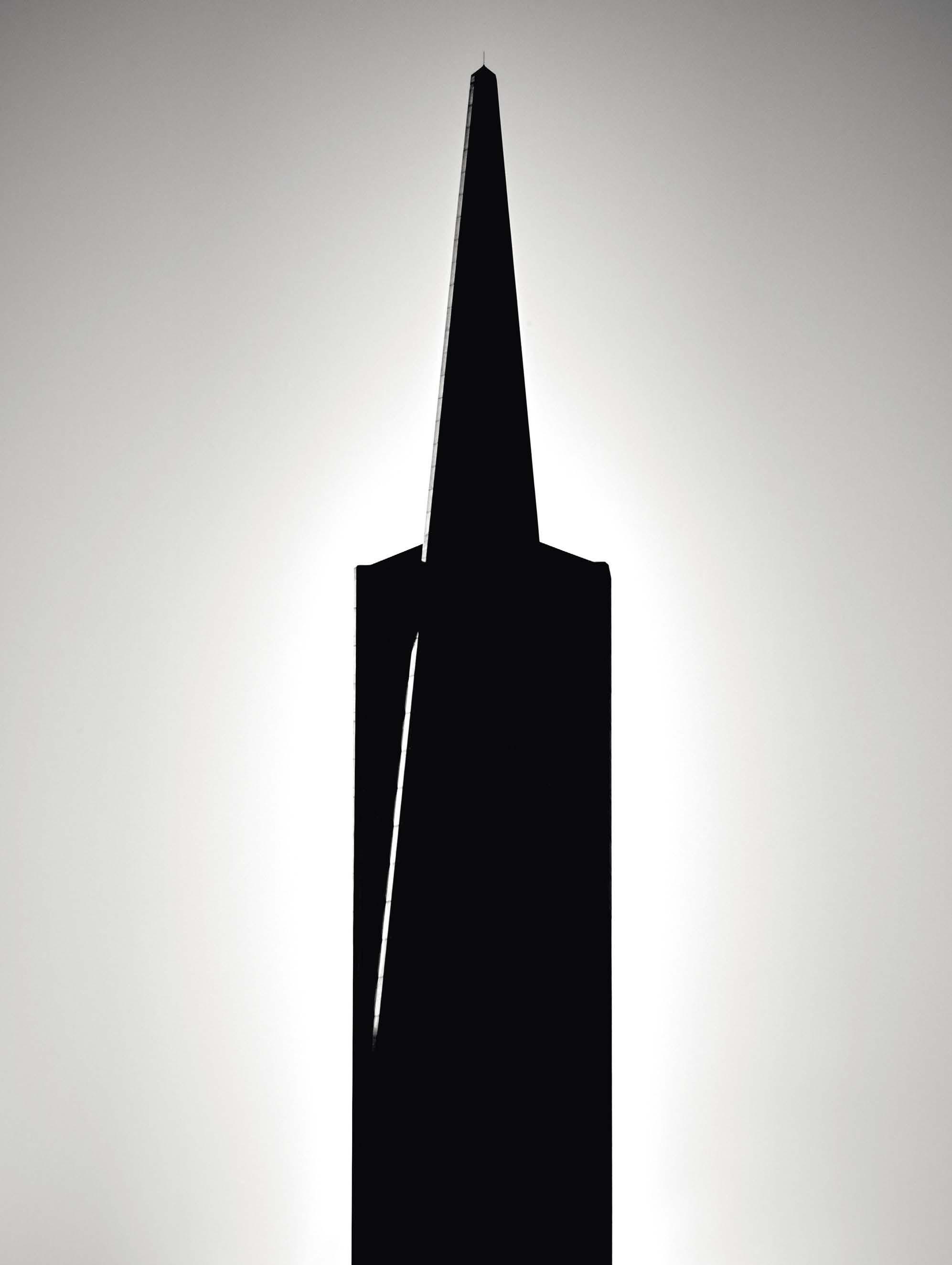

JOURNE Y BE YOND TIME

di or .c om 80 0 92 9 .d io r ( 3 467 )

LA ROSE DIOR COL LEC TION

Ye llow gold, pi nk gold, wh ite gold and diamonds

CARLYL

E C O LLE CT IO N

da vid yurman.com

Actr ess Kathr yn Ne wton photogra phed by Christian Högsted t

Actr ess Kathr yn Ne wton photogra phed by Christian Högsted t

SA IN TGE RMAI N S OF A, P HO TO GRAP HE D BY P AO L O R OV ER SI

Alison

Wyatt

Contributors

Lucía Agirre Frank Auerbach

Abby Bangser

Judith Benhamou Venita Blackburn

Richard Calvocoressi

Jordan Casteel

Elizabeth Childress Michael Childress Emma Cline

Michael Dayton Hermann Marissa Del Toro Pierre-Alexis Dumas Urs Fischer

Raymond Foye Roxane Gay Salomé Gómez-Upegui

Jeff Henrikson

Jamillah Hinson

Randa Jarrar

Ladi’Sasha Jones

Anselm Kiefer

Alison McDonald

Fumio Nanjo Brooke C. Obie Hans Ulrich Obrist

Ashley Overbeek Andrei Pesic

Amber J. Phillips

Calida Rawles

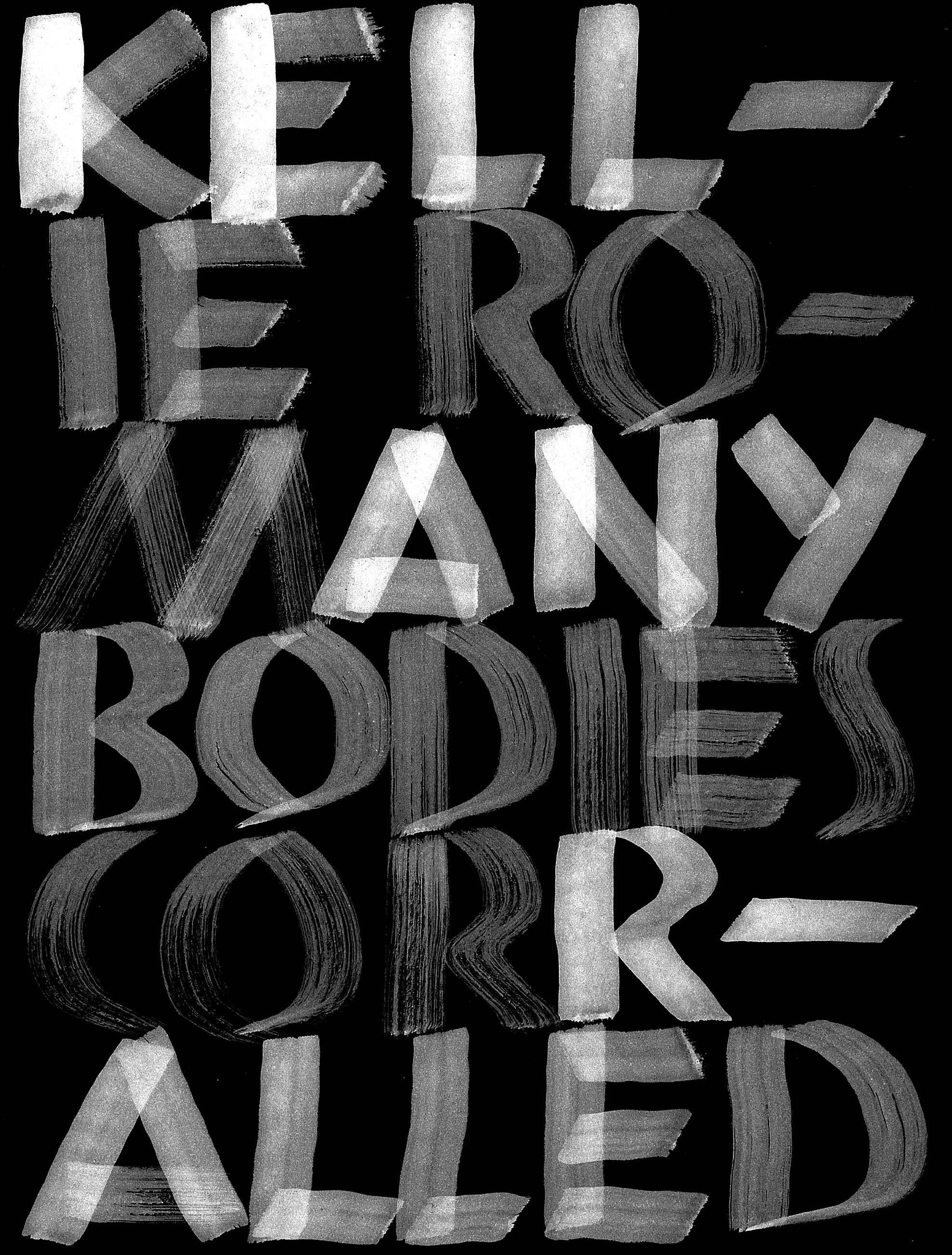

Kellie Romany

Eric Sanders

Ashley Stewart Mike Stinavage Charles Stuckey

Kara Vander Weg Virginia Verran Rachel Whiteread Ulrich Wilmes

Thanks Karrie Adamany

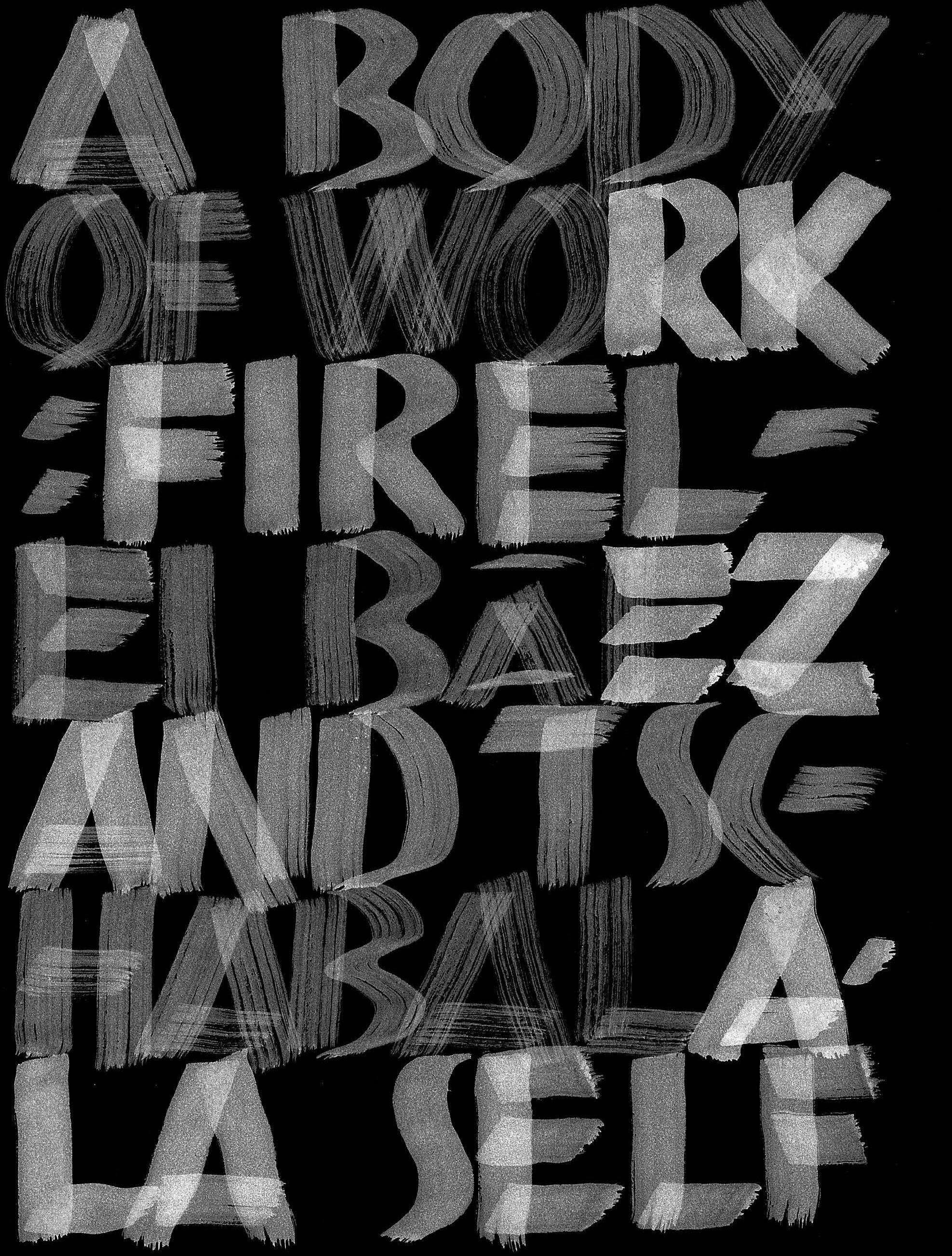

Richard Alwyn Fisher Julia Arena Jin Auh Firelei Báez Priya Bhatnagar Martha Blakey Kalia Brooks Michael Carl Michael Cary

Serena Cattaneo Adorno Claudia Chow Alice Chung

Vittoria Ciaraldi Cristina Colomar Emily Cooper John Dennis Andrew Fabricant

Mark Francis Hallie Freer

Brett Garde

Jonathan Germaine Lauren Gioia

Darlina Goldak

Lauren Halsey

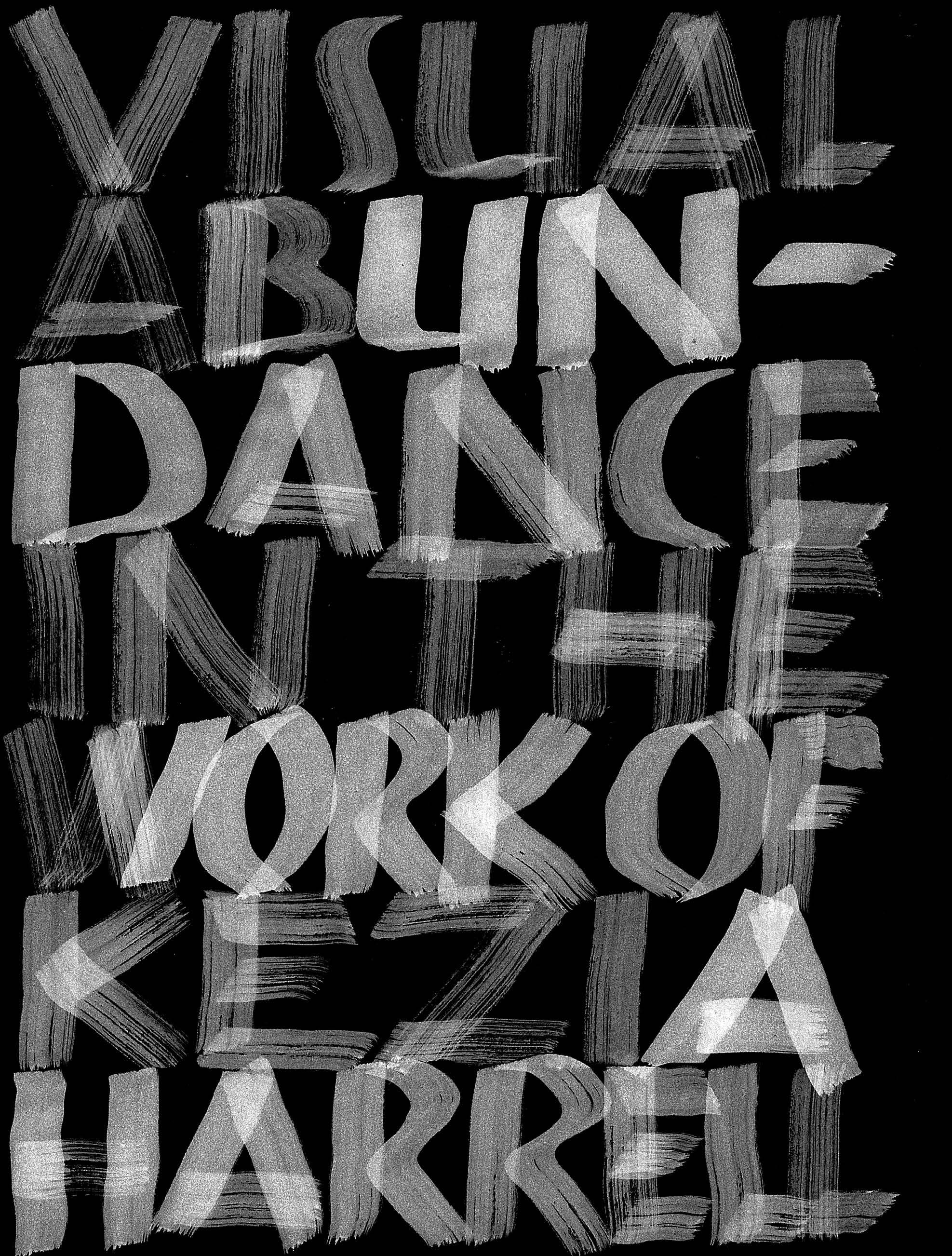

Kezia Harrell

Delphine Huisinga Alejandro Jassan Sarah Jones

Titus Kaphar

Karin Kneffel

Jennifer Knox White Linda Levinson Tyler Logan Lauren Mahony Kelly McDaniel Quinn Rob McKeever Trina McKeever Olivia Mull

Louise Neri Kathy Paciello

Dimitris Papaioannou Mark Recker Ian Rubinstein

Antwaun Sargent

Tschabalala Self Richard Serra Isabel Shorney Diallo Simon-Ponte Micol Spinazzi

Jessica Steele Chandler Sterling Sofia Strazzabosco

Gio Swaby Harry Thorne

Jess Topping

Andie Trainer

Lisa Turvey Louis Vaccara

Timothée Viale

Mark Webber

Ketter Weissman

Anna Weyant

Lilias Wigan

Eva Wildes

27

Gagosian Quarterly, Winter 2022

Editor-in-chief

McDonald Managing Editor

Allgeier Editor, Online and Print Gillian Jakab Text Editor David Frankel Executive Editor Derek Blasberg Digital and Video Production Assistant Alanis Santiago-Rodriguez Design Director Paul Neale Design Alexander Ecob Graphic Thought Facility Website Wolfram Wiedner Studio Cover Anna Weyant Founder Larry Gagosian Published by Gagosian Media Publisher Jorge Garcia Associate Publisher, Lifestyle Priya Nat For Advertising and Sponsorship Inquiries Advertising@gagosian.com Distribution David Renard Distributed by Magazine Heaven Distribution Manager Alexandra Samaras Prepress DL Imaging Printed by Pureprint Group

Opposite page: Urs Fischer, Denominator, 2020–22, database, algorithms, and LED cube, 141 ¾ × 141 ¾ × 141 ¾ inches (360 × 360 × 360 cm), edition of 2 + 1 AP © Urs Fischer.

Photo: Tom Powel

Imaging

Virginia Verran

Virginia Verran is a painter based in London, England, whose work implies large atmospheric space incorporating small graphic details. She has exhibited and been celebrated internationally and has taught at leading institutions, including the Chelsea College of Art and Design. She represents the Bruce Bernard Estate.

Photo: Dafyyd Jones

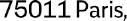

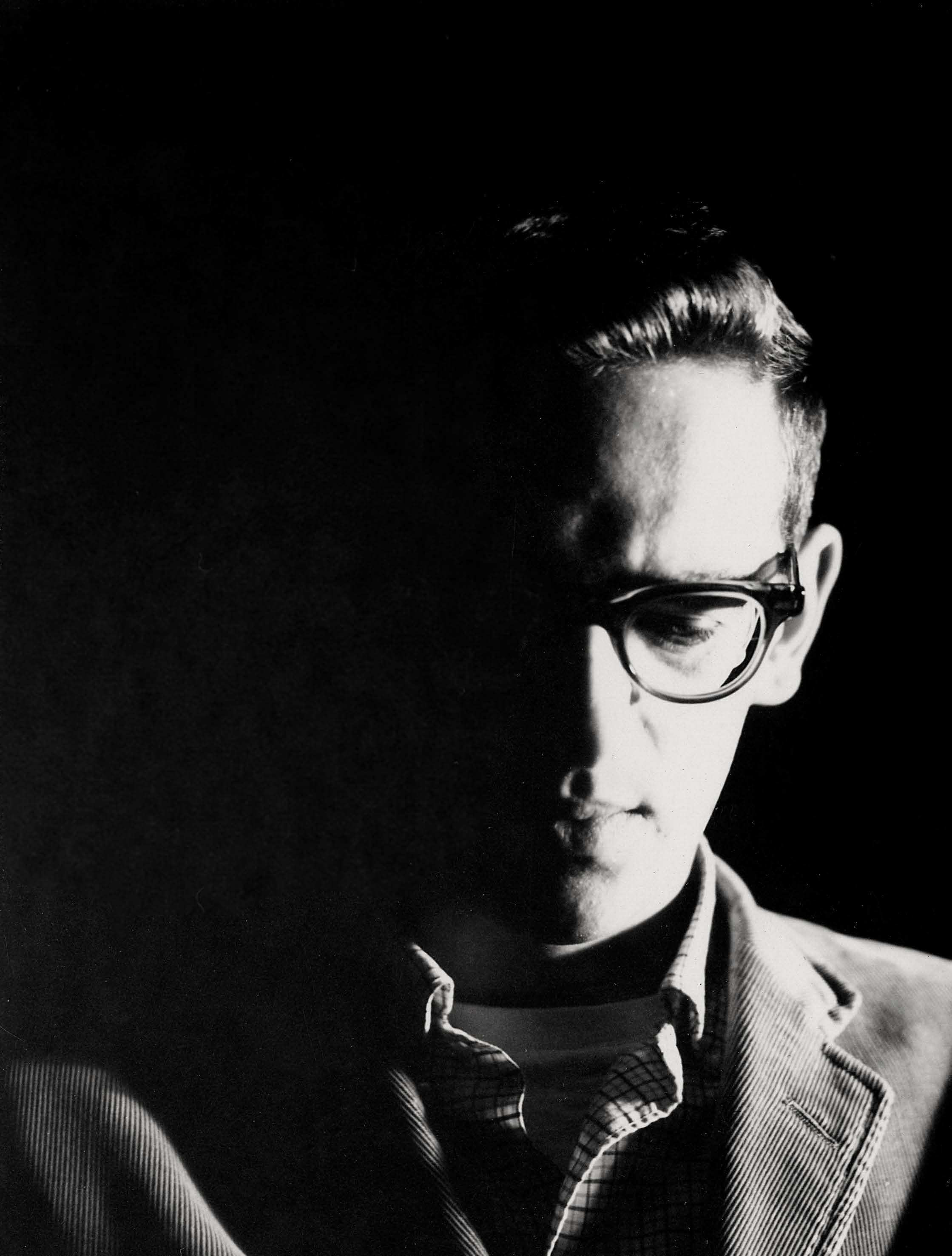

Frank Auerbach

One of Britain’s preeminent postwar painters, Frank Auerbach was born in Berlin, Germany, in 1931. Arriving in England as a Jewish refugee in 1939, he attended St Martin’s School of Art, London, and studied with David Bomberg in night classes at Borough Polytechnic. He then studied at the Royal College of Art and has remained in London ever since. His first exhibition was held at London’s Beaux Arts Gallery in 1956; since then his works have been collected widely.

Photo: © David Dawson/All rights reserved, 2022/Bridgeman Images

Richard Calvocoressi

Richard Calvocoressi is a scholar and art historian. He has served as a curator at Tate, London, as director of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, and as director of the Henry Moore Foundation. He joined Gagosian in 2015.

Rachel Whiteread

In Rachel Whiteread’s sculptures and drawings, everyday settings, objects, and surfaces transform into ghostly replicas that are eerily familiar. Through her use of the casting process, her subject matter—ranging from beds, tables, and boxes to water towers and entire houses—is freed from practical use, suggesting a new permanence, imbued with memory.

Photo: Dan Kitwood/Getty Images

Jeff Henrikson

Jeff Henrikson is a New York City–based photographer whose work focuses on portraiture and revolves around the eclectic worlds of art, fashion, and music. He has contributed to many publications including W, Vogue , L’Uomo Vogue , and A Magazine

Curated By Photo: Daniel Arnold

30 CONTRIBUTORS

Roxane Gay

Roxane Gay’s writing appears in The Best American Mystery Stories 2014, The Best American Short Stories 2012 , Best Sex Writing 2012 , A Public Space , McSweeney’s , Tin House , Oxford American , American Short Fiction , Virginia Quarterly Review, and many other publications. She is a contributing opinion writer for the New York Times . She is the author of the books Ayiti , An Untamed State , the New York Time s–bestselling Bad Feminist , the nationally bestselling Difficult Women , and the New York Times –bestselling Hunger. She is also the author of World of Wakanda for Marvel. She has several books forthcoming and is at work on television and film projects. She also produces a newsletter, The Audacity, and a podcast, The Roxane Gay Agenda

Jordan Casteel

Jordan Casteel received her BA in studio art from Agnes Scott College, Decatur, and her MFA in painting and printmaking from the Yale School of Art, New Haven (2014). In 2020, Casteel presented a solo exhibition, Within Reach , at the New Museum, New York, accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue. Other recent solo exhibitions include Jordan Casteel: Returning the Gaze , presented at the Denver Art Museum in 2019 and at the Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University in 2019–20. Casteel is the recipient of a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship (2021). She lives and works in New York.

Ladi’Sasha Jones

Ladi’Sasha Jones is a writer and curator from Harlem, New York. Her research-based practice explores Black cultural and spatial histories through text, design, and public programming. She is currently a PhD student in architecture at Princeton University.

Calida Rawles

The paintings of Calida Rawles merge hyperrealism with poetic abstraction. Ranging from buoyant and ebullient to submerged and mysterious, her recent work uses water as a vital, organic, multifaceted material: Black bodies float in exquisitely rendered submarine landscapes of bubbles, ripples, refracted light, and expanses of blue. For Rawles, water signifies both physical and spiritual healing as well as historical trauma and racial exclusion. Photo: Glen Wilson, courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin

Brooke C. Obie

Brooke C. Obie is a screenwriter for TV and film, the award-winning author of the Black-revolution novel Book of Addis: Cradled Embers , and an awardwinning film journalist. She is the editor-in-chief of Will Packer Media’s Black-women’s lifestyle site xoNecole.

In 2019, she was named to the Root 100 Most Influential African Americans in the media category.

Amber J. Phillips

Amber J. Phillips is a storyteller, filmmaker, and creative director. She creates world-building narratives using warm visuals and vulnerable performances through the lens of a fat Black queer femme auntie from the Midwest. Phillips recently released her first short film, Abundance , which was a 2021 BlackStar Film Festival selection and won the audience award for Best Short Narrative.

31

Anselm Kiefer

Anselm Kiefer’s monumental body of work represents a microcosm of collective memory, visually encapsulating a broad range of cultural, literary, and philosophical allusions as well as symbols from religion, mysticism, mythology, history, and poetry. Photo: Peter Rigaud c/o Shotview Syndication

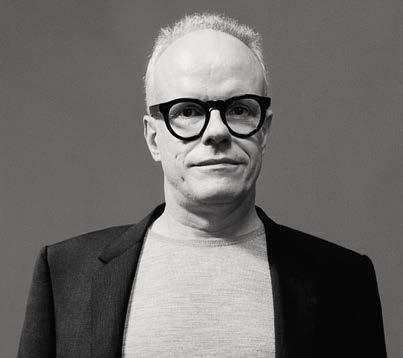

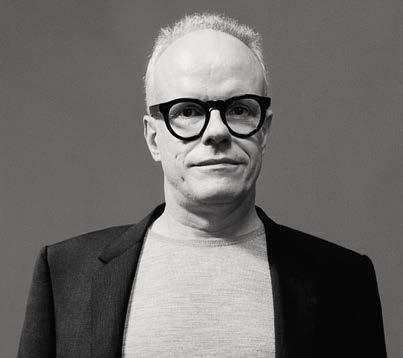

Hans Ulrich Obrist

Hans Ulrich Obrist is artistic director of the Serpentine Galleries, London. He was previously curator ats the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. Since his first show, World Soup (The Kitchen Show) in St. Gallen, Switzerland, in 1991, he has curated more than 300 exhibitions. Photo: Tyler Mitchell

Emma Cline

Emma Cline is the author of The Girls (2016) and of the story collection Daddy (2020). Cline was the winner of the Plimpton Prize and was named one of Granta ’s Best Young American Novelists. The Girls was an international bestseller and was a finalist for a National Book Critics Circle Award, the First Novel Prize, and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize.

Randa Jarrar

Randa Jarrar is the author of three books, most recently Love Is an Ex-Country. She is a performer and professor and lives in Los Angeles.

Urs Fischer

Urs Fischer mines the potential of materials, from clay, steel, and paint to bread, dirt, and produce, to create works that disorient and bewilder. Through scale distortions, illusion, and the juxtaposition of common objects, his sculptures, paintings, photographs, and largescale installations explore themes of perception and representation while maintaining a witty irreverence.

Photo: Robert Banat

Eric Sanders

Eric Sanders is a Los Angeles–based writer and artist.

32

©MIKE PERRY

Kellie Romany

Kellie Romany is an abstract painter interested in bodily representation, materiality, and the history of the painting process. Using a color palette of skin tones, Romany creates objects that act as catalysts for discussion of human connections, race, and the systems surrounding these themes. She has exhibited both nationally and internationally, including shows at the High Museum of Art, the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, and the DePaul Art Museum. Photo: Perry Haselden

Elizabeth Childress

Elizabeth Childress is the director of the Walter De Maria Archive. She was De Maria’s archivist and studio manager from 1979 until his death, in 2013. She is the coauthor and editor of Walter De Maria: The Object, The Action, The Aesthetic Feeling (2022).

Ulrich Wilmes

Ulrich Wilmes is a curator, editor, and writer. Previously deputy director of the Museum Ludwig, Cologne, and chief curator at the Haus der Kunst, Munich, he has published numerous books and articles on contemporary art.

Michael Childress

Michael Childress is an artist based in Northampton, Massachusetts. He began working with the Estate of Walter De Maria in 2013 and helped to establish the Walter De Maria Archive. He is the coauthor and coeditor of Walter De Maria: The Object, The Action, The Aesthetic Feeling (2022).

Venita Blackburn

Venita Blackburn’s writing has appeared in thenewyorker.com, Harper’s , Ploughshares , McSweeney’s , The Paris Review, and other publications. The winner of the Prairie Schooner book prize in fiction for her collected stories, Black Jesus and Other Superheroes , in 2017, she is the founder of the literary nonprofit Live, Write (livewriteworkshop. com), which provides free creativewriting workshops for communities of color. Blackburn’s second collection of stories, How to Wrestle a Girl , was published in the fall of 2021. She is an assistant professor of creative writing at California State University, Fresno.

Michael Dayton Hermann

In addition to being director of licensing, marketing, and sales at the Andy Warhol Foundation, Michael Dayton Hermann is a multidisciplinary artist and the author of Warhol on Basquiat and Andy Warhol: Love, Sex, and Desire . In his role at the Warhol Foundation, he has developed numerous high-profile Warhol projects.

34

35

Jamillah Hinson

Jamillah Hinson is an independent curator and arts programmer. With a focus on historical and contemporary Black cultural and artistic traditions as they present themselves through experimental sound, film and photography, and performance, her practice engages various methods of storytelling and centers artistic and community narratives. Hinson has realized exhibitions and developed programming with the Center for Afrofuturist Studies, the Art Institute of Chicago, LATITUDE Chicago, Intuit: The Center for Intuitive & Outsider Art, and the Reva and David Logan Center for the Arts, among other independent art and cultural spaces.

Ashley Stewart

Ashley Stewart joined Gagosian as a director in 2019 and is based in New York. She manages a number of the gallery’s artists, including Nathaniel Mary Quinn, Titus Kaphar, and Stanley Whitney. She was previously the director of sales at Salon 94, where she oversaw the sales team and worked directly with a number of artists.

Marissa Del Toro

Marissa Del Toro is an independent curator and art historian of contemporary and modern art of the Americas (primarily Latin America and the United States). Currently based in New York, she was a 2021–22 curatorial fellow at NXTVHN in New Haven, Connecticut. In both her professional and her personal life, she continues to work for the promotion and advocacy of diverse narratives in art.

Salomé Gómez-Upegui

Salomé Gómez-Upegui is a Colombian-American writer and creative consultant based in Miami. She writes about art, gender, social justice, and climate for a wide range of publications, and is the author of the book Feminista Por Accidente (2021).

Abby Bangser

Abby Bangser is founder and creative director of the exhibition platform Object & Thing. She is a former Artistic Director of Frieze Art Fairs and was the founding head of the Americas Foundation of the Serpentine Galleries. She has worked for nonprofit arts institutions in New York and Los Angeles including the Dia Art Foundation, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

Ashley Overbeek

Ashley Overbeek is the director of strategic initiatives at Gagosian. She has been collecting NFTs since early 2019 and is a cohost on Wednesday Wonders, a weekly Twitter space where she interviews leading crypto artists.

40

Lucía Agirre

Lucía Agirre is a curator at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao. She joined the museum in 2000 and has been involved in both the organizational and the curatorial aspects of the art program, curating temporary exhibitions and presentations from the permanent collection. She has also conducted research on the museum’s artistic holdings, collaborating with international artists, curators, and institutions.

Mike Stinavage

Mike Stinavage is a writer and waste specialist from Michigan. He holds a masters degree in political science from CUNY Graduate Center. As a Fulbright and Martin Kriesberg fellow, he researched the politics of waste management and wrote his second collection of short stories in Pamplona, Spain. His writings can be found in Slate , the Brooklyn Rail , the Riverdale Press , and more.

Judith Benhamou

Judith Benhamou is an art critic and exhibition curator. She has been writing about art and the market for the past thirty years in the French daily newspaper Les Échos . She has created a website, Judith Benhamou Reports (https://judithbenhamouhuet. com/), dedicated to international art news and notable for its video interviews. The exhibitions she has curated include Ai Weiwei Fan-Tan (2018) at the Mucem, Marseille, and Mapplethorpe—Rodin (2014), at the Musée Rodin, Paris.

Charles Stuckey

Charles Stuckey is a widely published independent scholar who has served as curator in major US museums including the Art Institute of Chicago. He has worked on highly acclaimed retrospectives of Paul Gauguin, Claude Monet, and others.

Raymond Foye

Raymond Foye is a writer, publisher, and curator currently based in Woodstock, New York. In 2020 he received an American Book Award from the Before Columbus Foundation for his editing of The Collected Poems of Bob Kaufman for City Lights. He is a consulting editor with the Brooklyn Rail Photo: Amy Grantham

Andrei Pesic

Andrei Pesic is a cultural and intellectual historian of early modern France, with special interests in the arts and economic thought.

42

43

THE OBJECT, THE ACTION, THE AESTHETIC FEELING

The definitive monograph on the work of Walter De Maria is being released this fall. To celebrate this momentous occasion, Elizabeth Childress and Michael Childress of the Walter De Maria Archive talk to Gagosian senior director Kara Vander Weg about the origins of the publication and the revelations brought to light in its creation.

ELIZABETH CHILDRESS I first met Walter at The Light ning Field [1977] in 1978; I was there with my boy friend, John Cliett, to photograph lightning storms over the field. We were good friends with Robert Fosdick and his wife, Helen Winkler, one of the founders of the Dia Art Foundation. They were working closely with Walter at The Lightning Field , developing a program for visiting the sculpture. Dia was a huge supporter of Walter and his work at the time, providing spaces and funds for major projects but also providing artists with assistants and archi vists. They really did so much to make it possible for Walter to make his work, which was often quite complex to create, install, and maintain.

Anyway, we became a bit of a family. By the end of that summer, after leaving The Lightning Field , Walter asked me to be his assistant and help him organize his studio in SoHo. Then I was approached by Heiner Friedrich, the German art dealer who founded Dia in 1974 with Philippa de Menil and Helen. Heiner thought that it would be great if John and I could work on more photographs of The Light ning Field . We went back in the summer of 1979, and when I returned to New York, Heiner set me up with an office in part of the New York Earth Room [1977] gallery and I started working with Walter on a reg ular basis. This primarily entailed establishing an archive and working with him on his new projects. Eventually we moved over to his building at 421 East Sixth Street in Manhattan and over the years I con tinued to work with him on many projects, until he had a stroke in 2013.

KVW And your work has continued, because after his death, you were responsible for archiving the

entire studio.

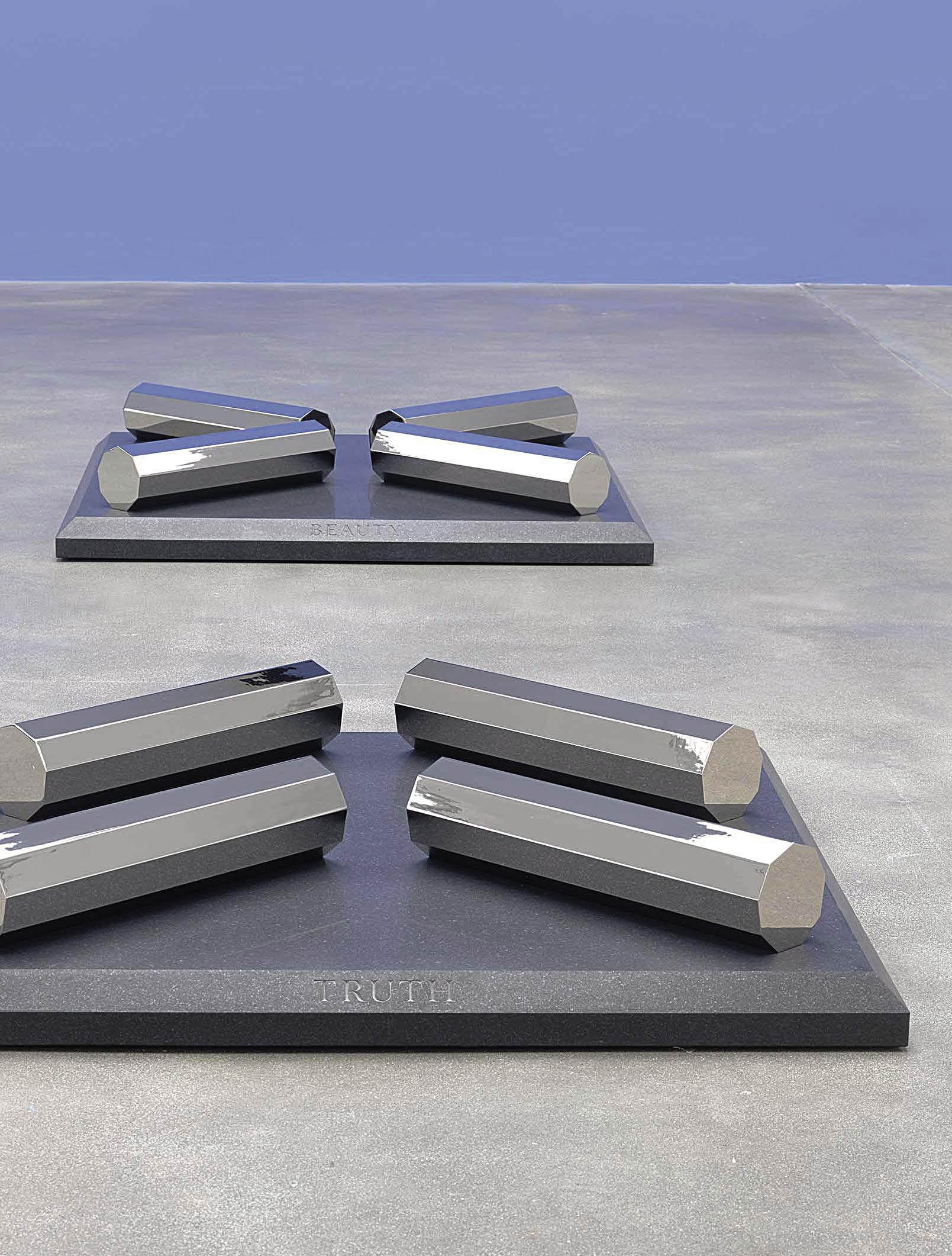

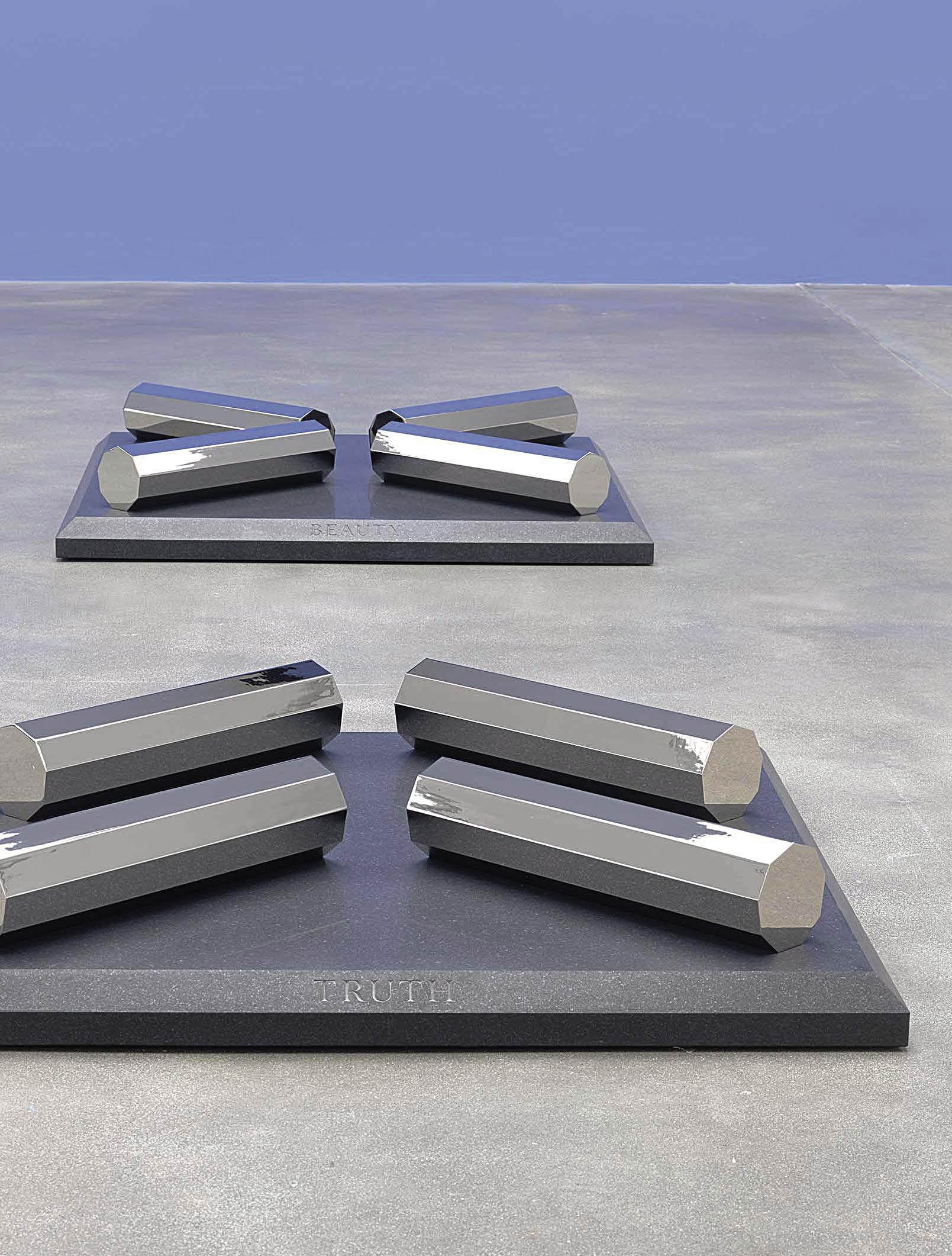

EC Yes. Because Walter died quite suddenly, none of us were prepared. Walter had work that was not completed. He had an enormous building full of art that we had to inventory. He had worked, for nearly thirty years, on the Truth/Beauty series [1990–2016], and we were able to complete that with the support of his family and the gallery. That was huge. The gallery, in addition to Dia, was really important to Walter, particularly toward the end of his life. And after he died, you and the gallery were so supportive—it made the whole process so much more structured. And you worked closely with Walter’s family to make a plan, and that was ideal, because Walter never established a foundation.

KVW Larry Gagosian began working with Wal ter in 1989, and from the very beginning he saw the importance of the work. Over the years, he saw that, as is often the case with artists, consistent sup port makes a big difference in terms of their careers and legacy, so whenever he could he would sup port Walter in that way and allow him some lee way. It was Walter’s exhibition that inaugurated the Thompson Street gallery that Larry operated with Leo Castelli.

MICHAEL CHILDRESS And during our research we dis covered that after his first show with Larry, Walter never showed with another private dealer again. He had plenty of institutional recognition and exhibi tions, of course, but his only gallery representation after that moment was through Gagosian.

KVW And then there were the New York shows we worked on together in 2007: 13, 14, 15 Meter Rows [1985], on Twenty-Fourth Street, and A Computer Which Will Solve Every Problem in the World/3–12 Polygon [1984], on Twenty-First, which belonged

46

KARA VANDER WEG Elizabeth, when did you first meet Walter De Maria?

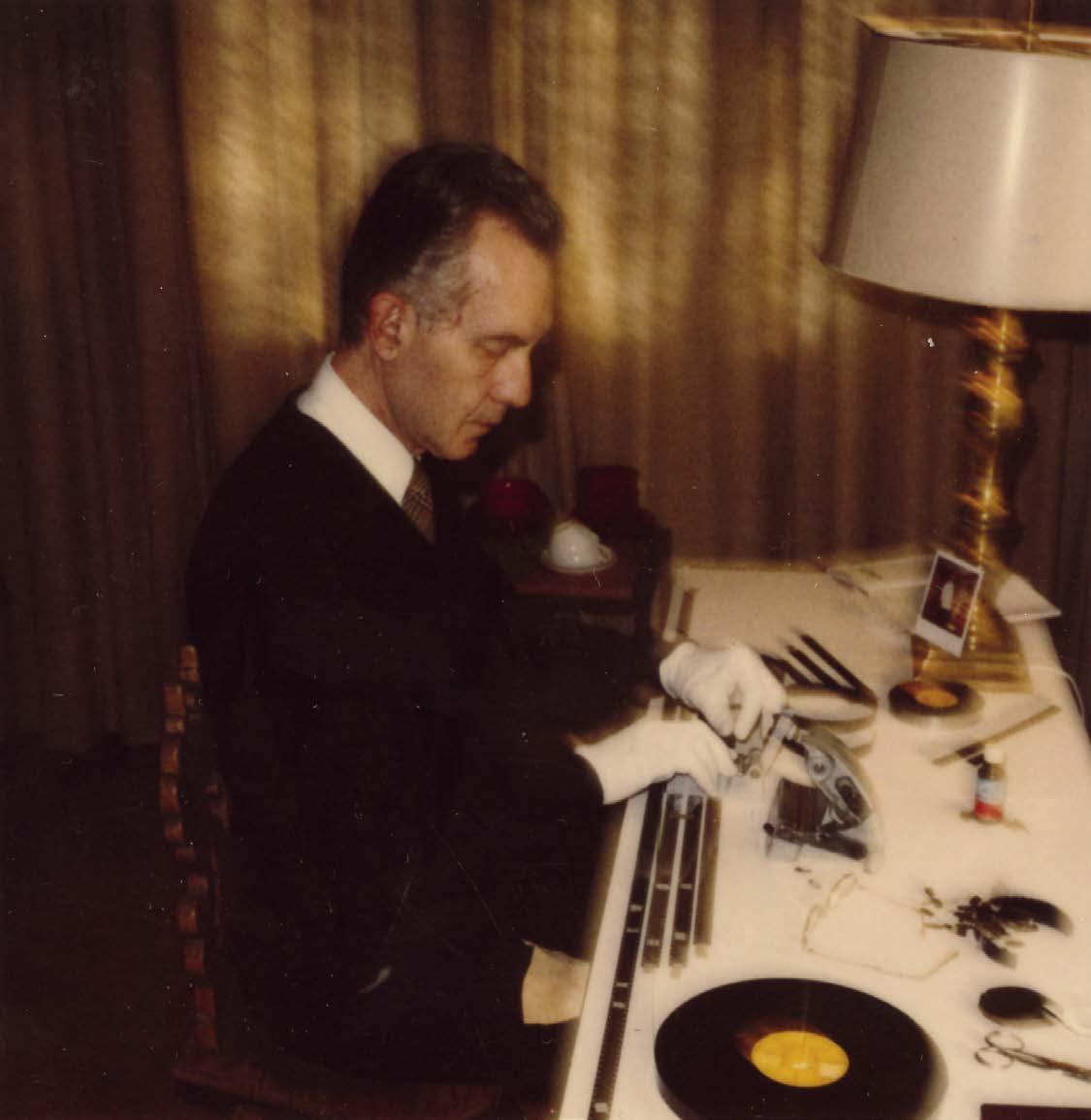

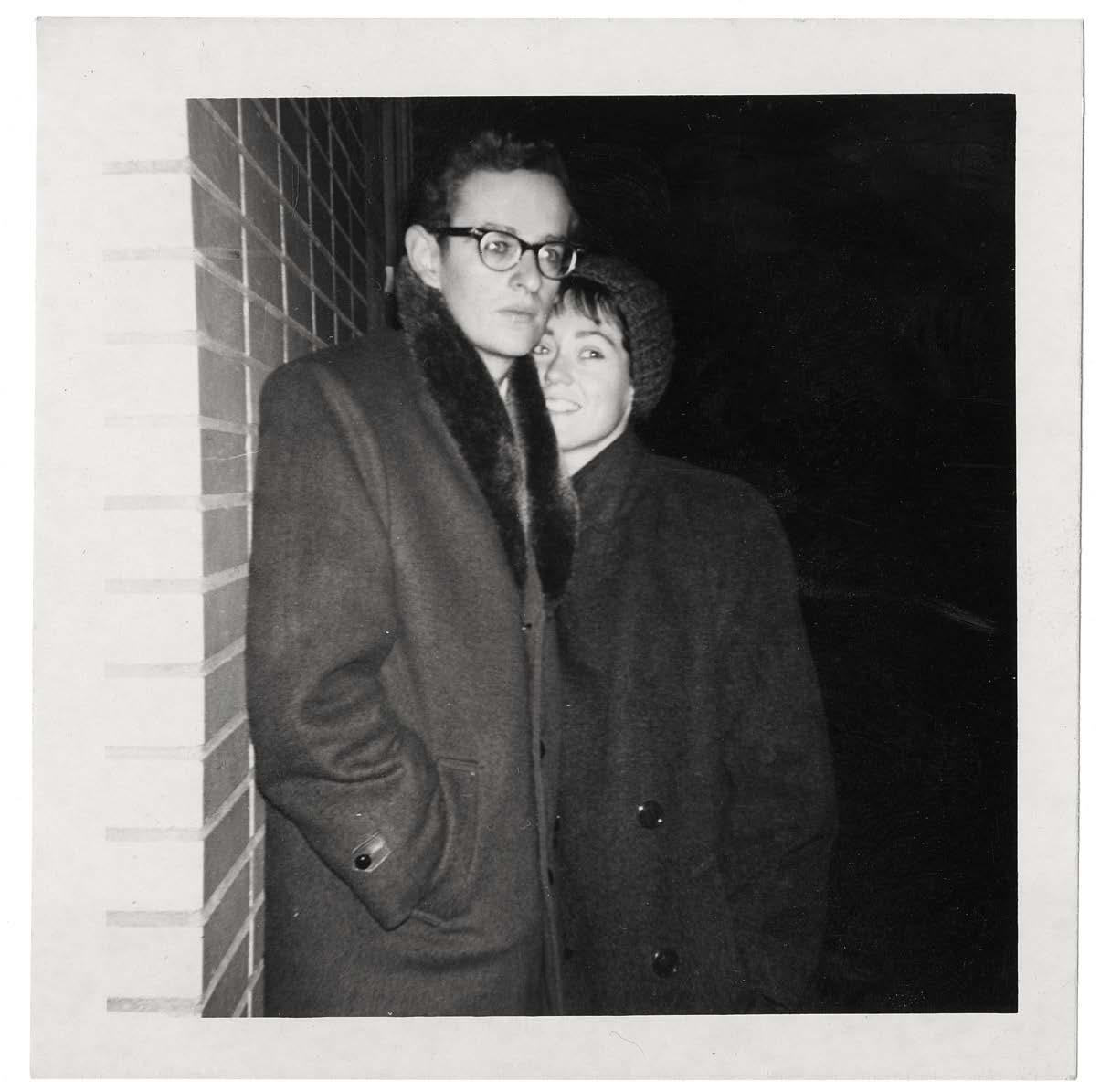

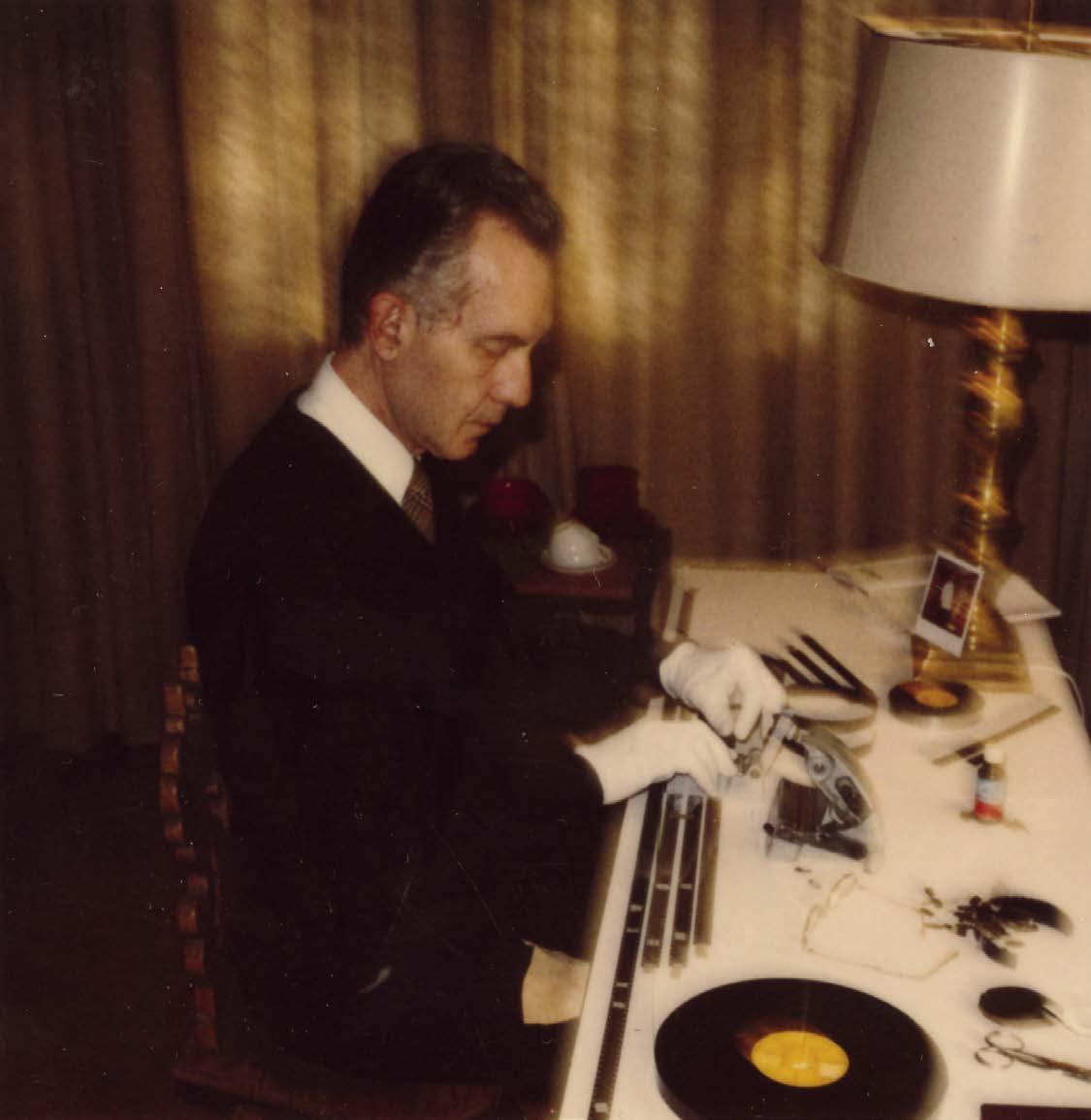

Previous spread: Walter De Maria, 1961. Photo: George Maciunas

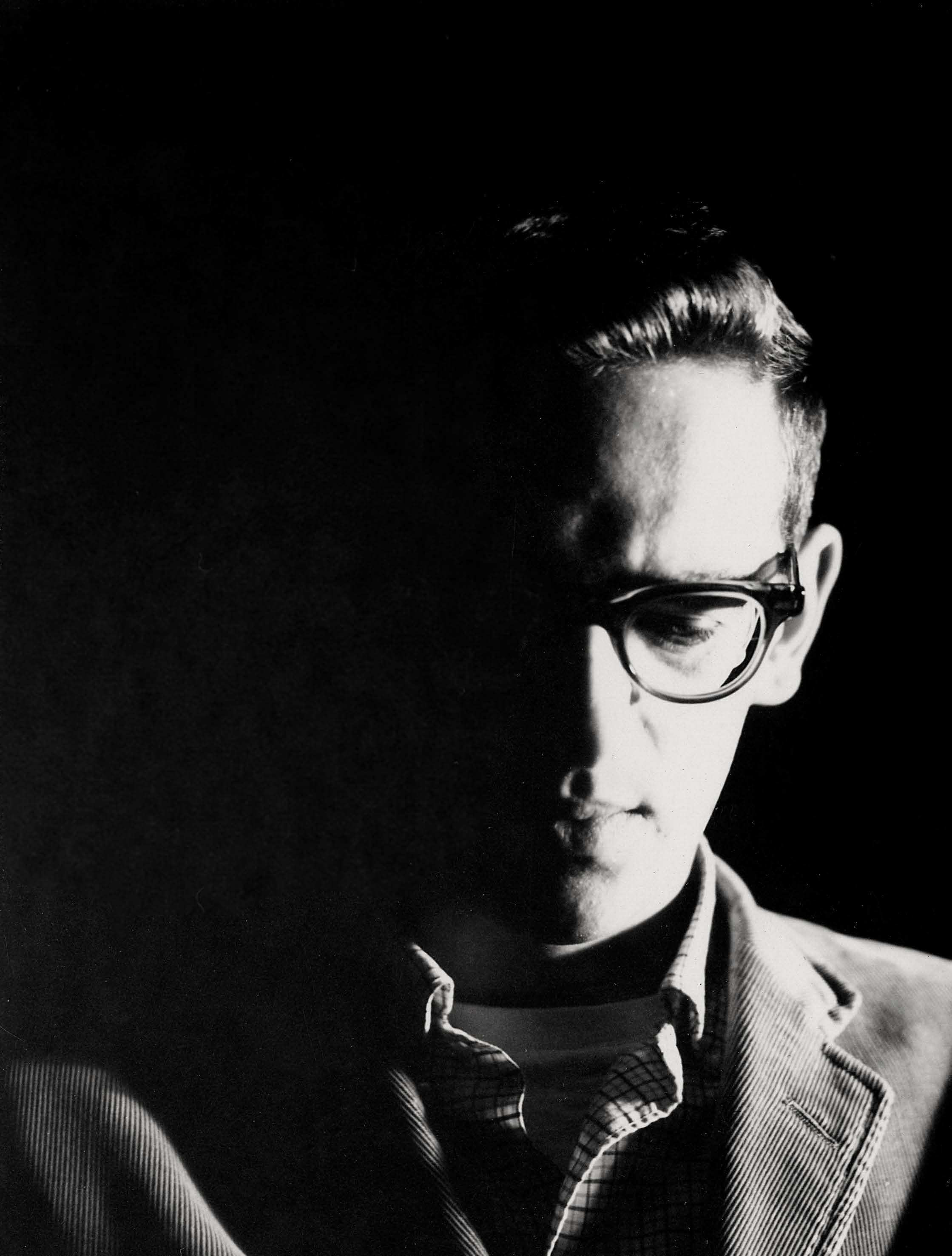

This page: Walter De Maria and his wife, Susanna, in New York, c. 1961. Photo: courtesy Walter De Maria Archive

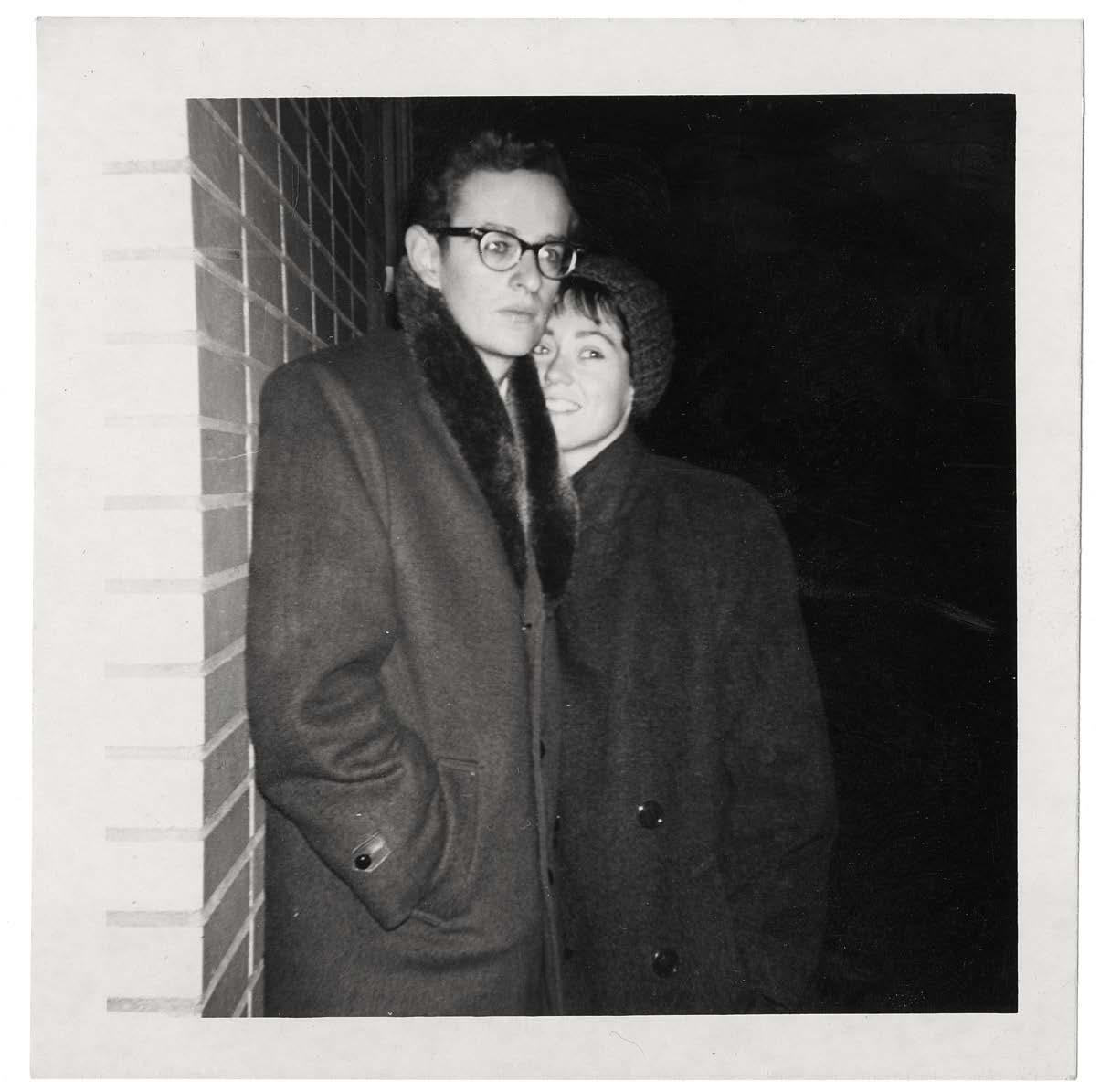

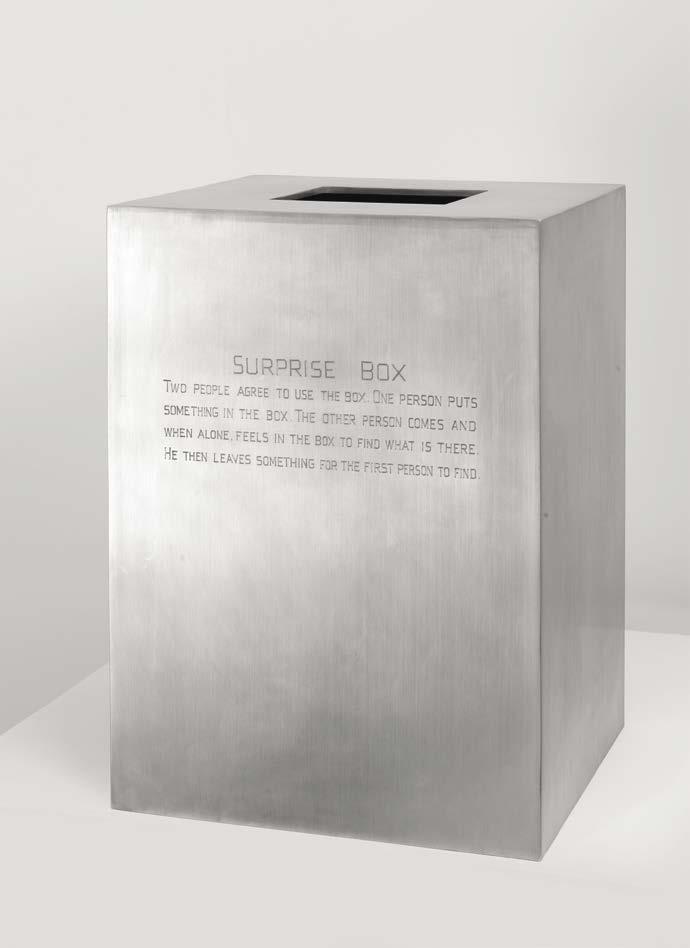

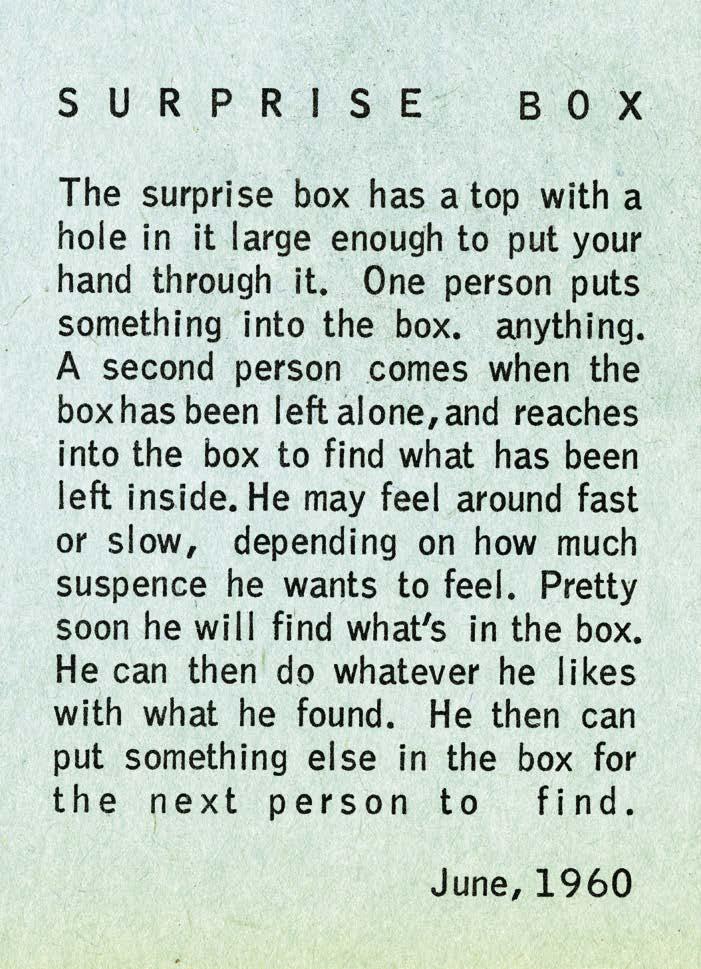

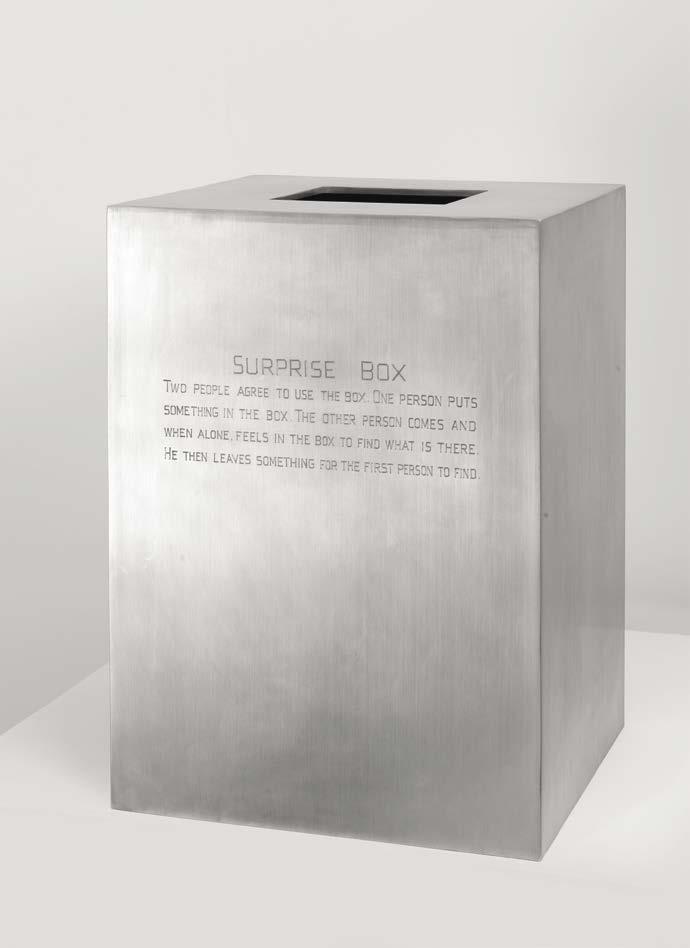

47 SURPRISE BOX Left: First published in An Anthology of Chance Operations , ed. La Monte Young and Jackson Mac Low (New York: Young/Mac Low, 1963) Right: Susanna De Maria interacting with Surprise Box (1961) in De Maria’s Bond Street studio, New York, c. 1963. Photo: courtesy Walter De Maria Archive Left: Walter De Maria, Surprise Box, 1961, wood and paint, box: 19 × 13 × 13 inches (48.3 × 33 × 33 cm), painted pedestal: 35 × 9 ¼ × 7 ¾ inches (88.9 × 23.5 × 19.7 cm), The Menil Collection, Houston. Photo: Rob McKeever Right: Walter De Maria, Surprise Box, 1965, aluminum, 19 × 13 ½ × 13 ¾ inches (48.3 × 34.1 × 34.8 cm), Private collection, New York. Photo: Rob McKeever Two people agree to use the box. One person puts something in the box. The other person comes and when alone, feels in the box to find what is there. He then leaves something for the first person to find. De Maria developed his idea for Surprise Box in a text dated June 1960.

to the Museum Boijmans van Beuningen in Rot terdam. We borrowed it back from the museum because it was important for Walter to show those two objects together and to have that circle com pleted, so to speak.

EC When did you first meet Walter, Kara?

KVW I first met Walter in 2005, a year after I started working for Gagosian. Larry told me to call Walter De Maria and see if he wants to do anything in any of our spaces. And I think I called for about, I don’t know, a couple of months, and he would just hang up—the phone would ring and then he would hang up [laughs ].

EC [laughs ] What? No.

KVW He thought I was a real estate agent trying to sell the building. Eventually I sent a fax saying, I’ve always admired your work. I love the Earth Room , I love the Broken Kilometer [1979]—both of those installations are meaningful to me. Then he called me up and said, “Hello, this is Walter De Maria” [laughs ]. So that was my introduction to Walter.

EC It would always take Walter a little bit of time to feel comfortable and trust people. But you were one of those people whom, eventually, he really did.

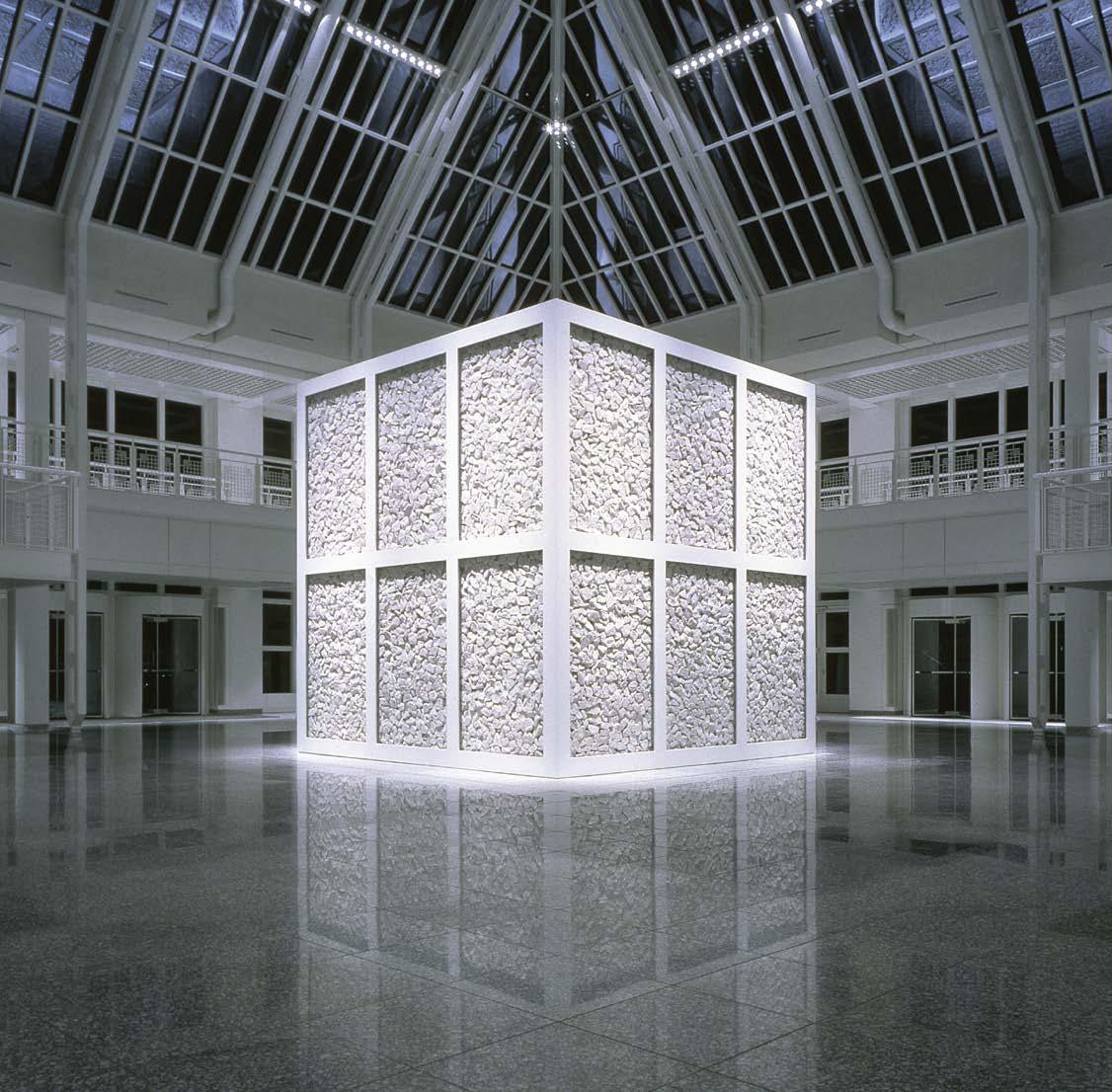

KVW Well, I appreciate that trust. That for me was why it was important to try to make a book about his life and work. It deserves such a publication and I think it’s crucial in terms of memorializing that material and informing people going forward; there’s a paucity of information on Walter’s work out there. Additionally, because we’re able to coincide with the exhibition taking place at the Menil Collec tion in Houston, which includes so much of Walter’s early work [Walter De Maria: Boxes for Meaningless Work , October 29, 2022–April 23, 2023], the timing feels particularly appropriate.

Michael, maybe you could talk about how you become involved with Walter’s work, and

specifically about all the great work you’ve been doing on the monograph and the archive.

MC I grew up knowing him, but only on the phone, really. But when he had to prepare the sec ond floor for the Bel Air installation at the Menil Collection in 2011–12, I came by the studio and worked with him going through a lot of the mate rial that was being stored there on the second floor, and moved it up to the fourth floor in preparation for the restoration turning the second floor into a gallery space. It was fortunate that we had that time together because two or three years later, when Walter died, I came down to go through that mate rial that I’d only just moved, and to figure out what it was that we had just gone through. Later we began the process of analyzing and initiating the database project, with the goal of eventually producing the monograph.

KVW And can you describe what the database pro ject is?

MC Everything was well organized in its phys ical form, but after the move, we realized that we needed to have a digital system with which to access the material. When we were looking for a database, we found a system that was specifically focused on making a catalogue raisonné. From there, we started entering the data from the office, setting up a base that we could use to make the book.

KVW Were there any surprises in the book that arose as you were putting this material together?

EC The most extraordinary moment was when we first created a timeline. We had images for each of Walter’s works, with the dates, and we laid them out according to their chronology on side-byside panels across three long tables. I had never viewed his work from that perspective before; when you’re working in it, you’re not thinking about the timeline. Seeing the evolution of his career, and

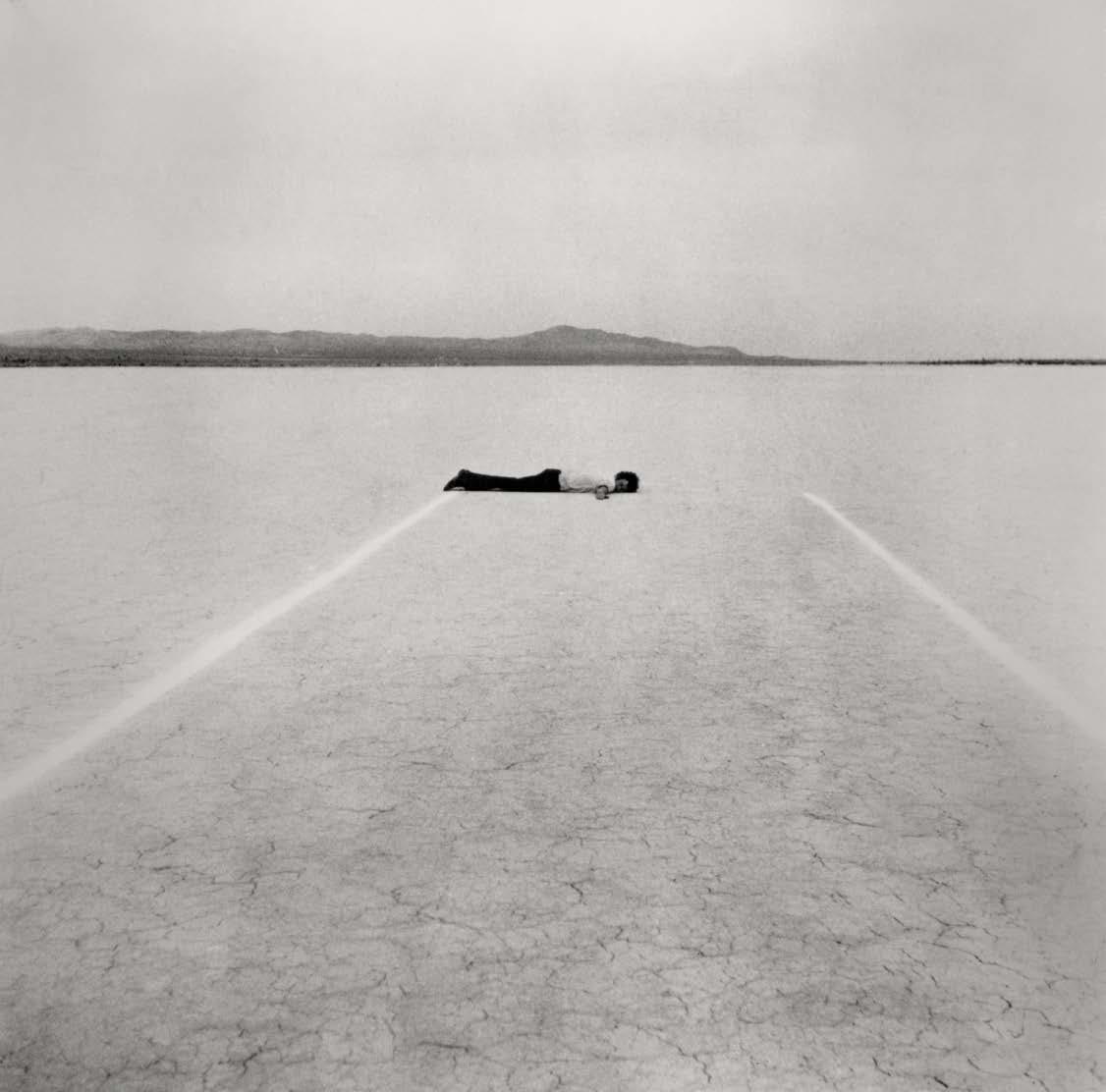

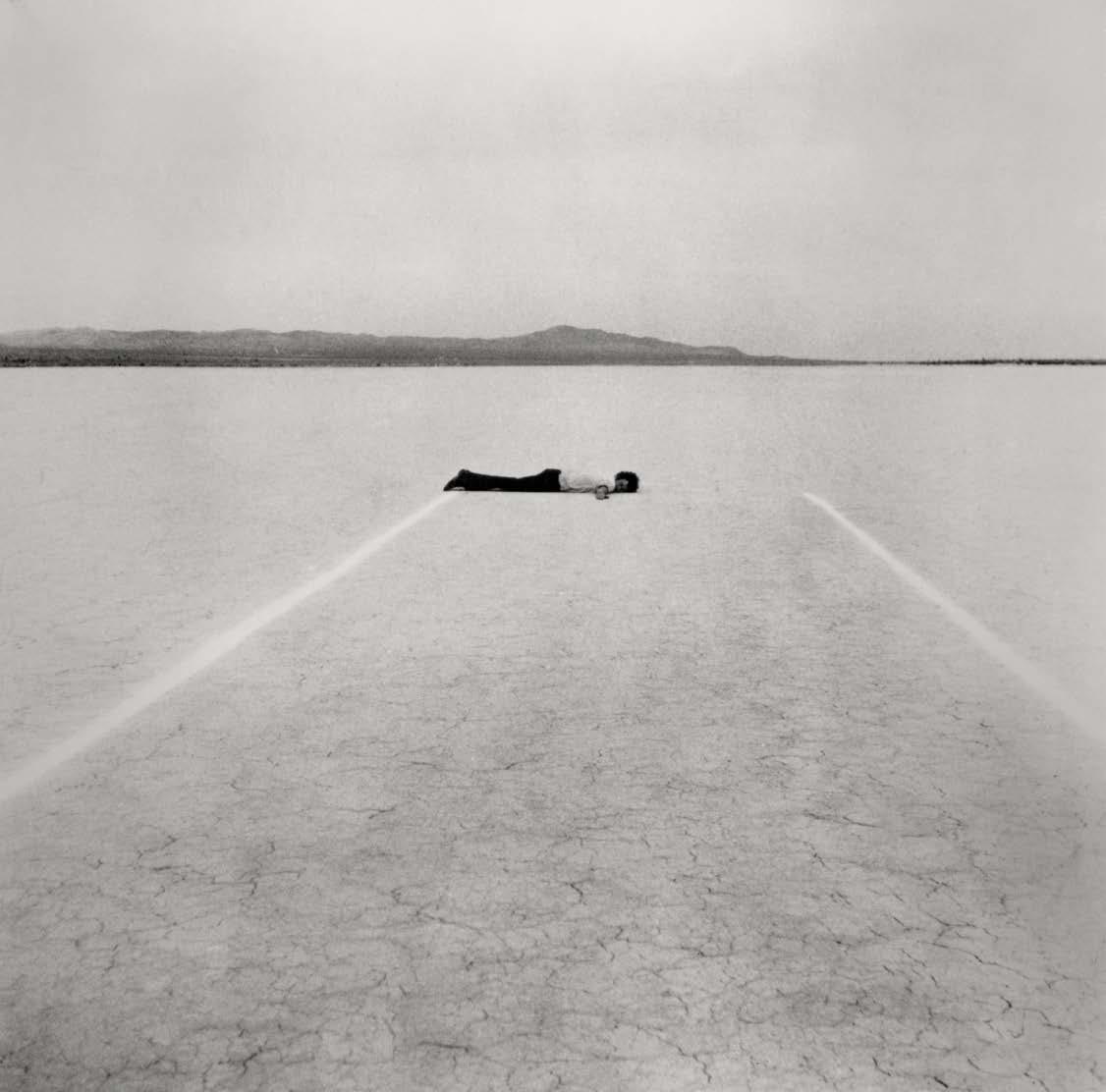

This page: View of Walter De Maria lying on the desert floor touching one chalk line of Mile Long Drawing (1968). Photo: courtesy Walter De Maria Archive

Opposite: Walter De Maria, Truth / Beauty, 1990–2016, solid stainless steel and granite, 14 sculptures in 7 sets, each sculpture: 7 ½ × 42 1⁄8 × 42 1⁄8 inches (19 × 107 × 107 cm).

Installation view, Walter De Maria , Gagosian, Britannia Street, London, May 26–July 30, 2016. Photo: Mike Bruce

48

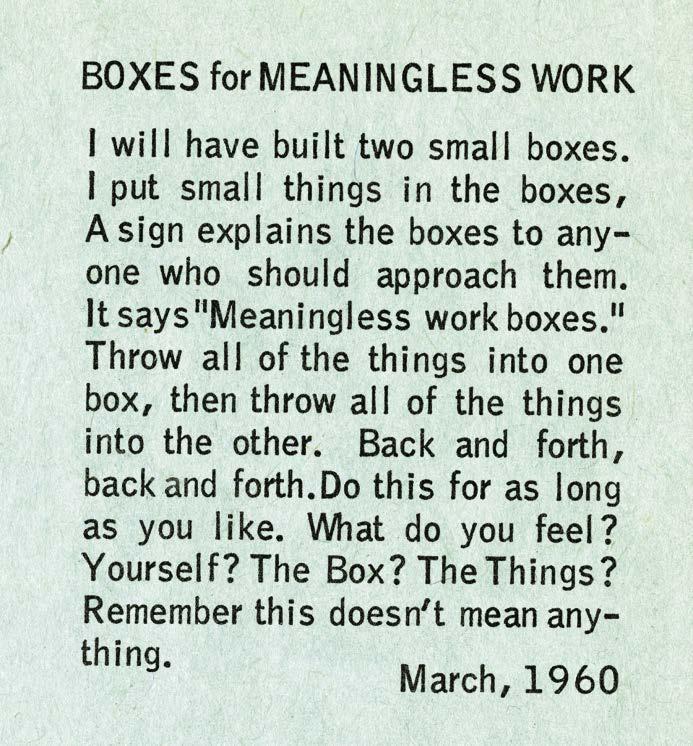

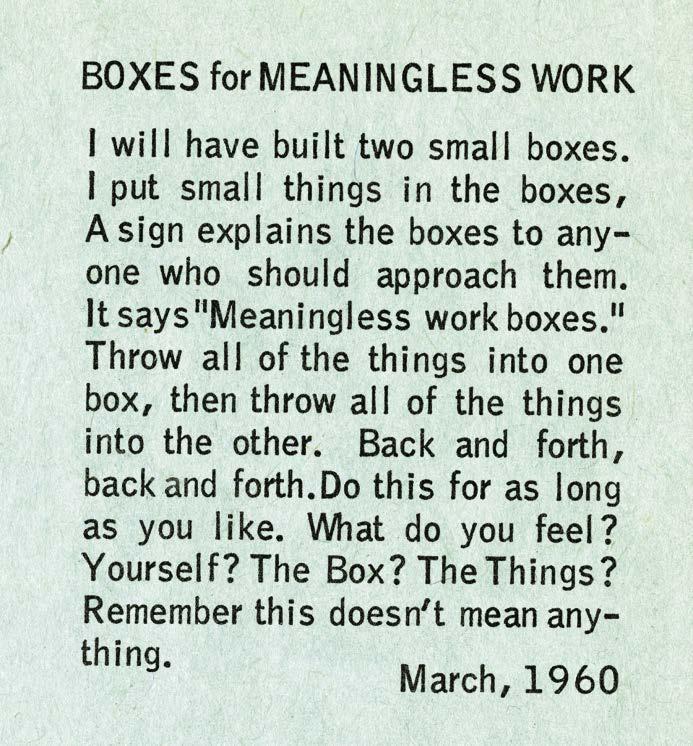

BOXES FOR MEANINGLESS WORK

Walter

Below:

50

De Maria developed his idea for Boxes for Meaningless Work in a series of texts and drawings he made prior to moving to New York City in October 1960. The original inscription was “Transfer things from one box to the next box, back and forth, back and forth, etc. Be aware that what you are doing is meaningless.”

Above:

First published in A n Anthology of Chance Operations , ed. La Monte Young and Jackson Mac Low (New York: Young/Mac Low, 1963)

Above:

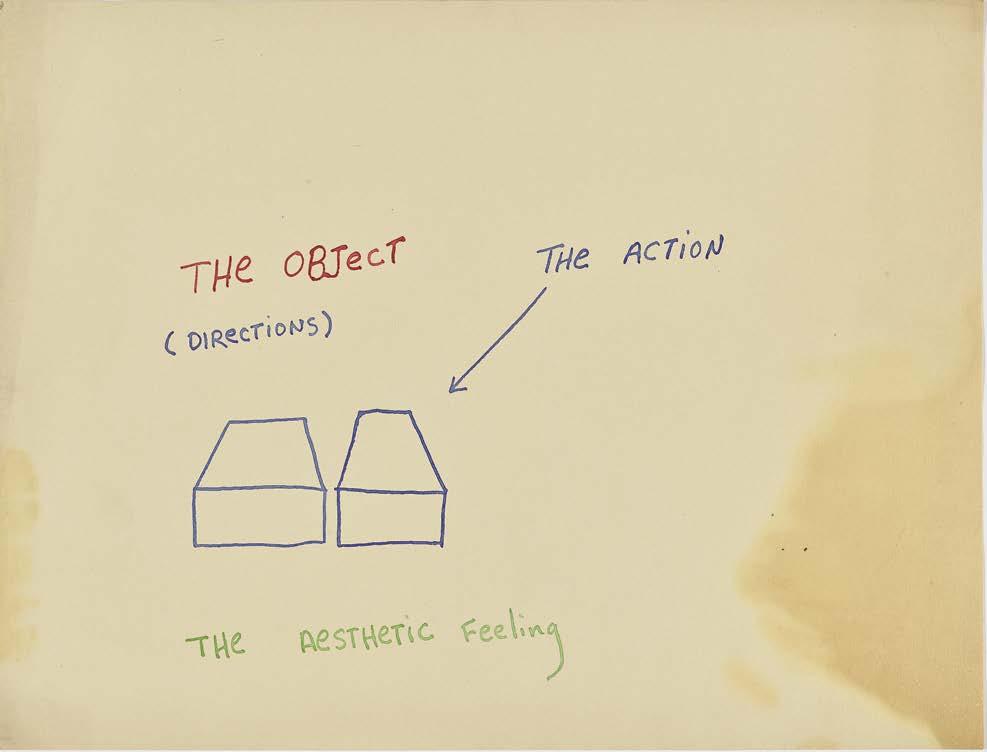

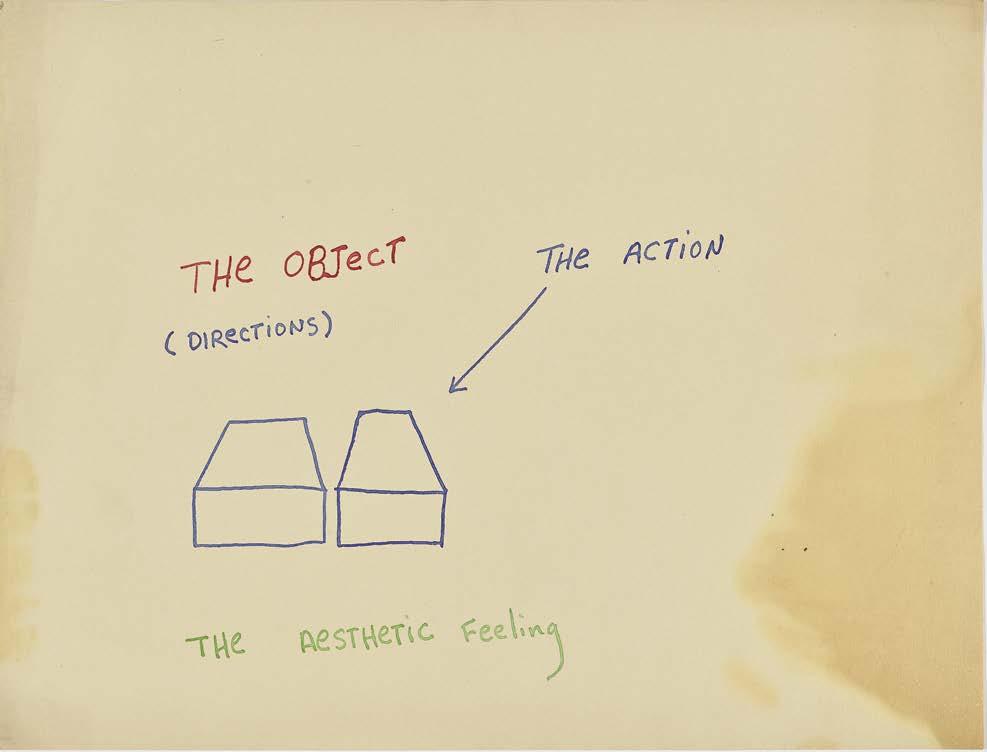

Walter De Maria, Untitled [The Object, the Action, the Aesthetic Feeling], c. 1960–61, ink on paper, 8 ½ × 11 inches (21.6 × 27.9 cm). The Menil Collection, Houston, Purchased with funds provided by

Louisa

Stude

Sarofim. Photo: Paul

Hester

Walter De Maria, Boxes for Meaningless Work , 1961, wood, each box: 9 5 ⁄8 × 18 × 13 ¼ inches (24.4 × 45.7 × 33.5 cm), base: 4 1 8 × 48 × 24 inches (10.5 × 121.9 × 61 cm), The Menil Collection, Houston.

Photo: Rob McKeever

recognizing early moments that foreshadowed later major works, was something of a revelation. And that carries through into the finished monograph.

Also, all of Michael’s work with the drawings and studies provided so much more information about Walter’s process, especially in the early 1960s.

MC Picking up on these arcs in Walter’s work, being able to see the echoes of his early work in later projects—that’s something that wasn’t possible before.

KVW I love looking at some of those early drawings and seeing, as you were saying, the early ideas that he was developing, even the early iterations of The Lightning Field . And I love seeing Walter’s hand in these works, because when I knew him, the work had been developed to the point where it was all so well-produced, milled—it was perfect. But with these drawings and studies you really get a sense of the person behind the work.

EC And his sense of humor!

KVW Oh God, yes.

MC The drawing that we always use as an exam ple is Untitled [Large Ball in Small Room ] [c. 1959–62]: to know that he was thinking about that in ref erence to Michelangelo’s David , all delineated on

the same page, was revelatory. His interest in art and architecture from the very beginning opens new ways for experiencing the work. Also, the essays in the monograph, by Donna De Salvo, Michael Govan, Christine Mehring, and Lars Nit tve, all elucidate different aspects of his work.

KVW He had such an interest in current events, which I experienced in my conversations with him between 2004 and 2013. He would bring up events that he had seen on television, sporting events, that sort of thing. But in those early drawings, where he writes about the death of JFK or the Cuban mis sile crisis, you realize that all these artworks, all these steel sculptures that appear to be straightfor ward abstract geometric forms, have all this content behind them in some way.

EC He was a history major.

KVW That was really the topic of every conversation.

EC I think we must have had subscriptions to about twenty-five magazines. Walter read everything.

KVW Another part of the book that will be a discov ery for people is the chronology, written by Dagny Corcoran but of course the two of you were editing, supplying illustrations, and connecting her with the

right people. It was a delicate dance to give a com prehensive overview without violating Walter’s pri vacy, which he valued very much. Many decisions were required about what was applicable to Walter the man versus Walter the artist. For me, the infor mation about the music he made, his participation in early Happenings and performances, his early family life, his friends and acquaintances—this was incredible information and often quite unexpected.

MC Absolutely, that’s not what his reputation was. Walter was not known for being out and about and traveling a lot, but when you read this chronology, it subverts all those misunderstandings.

KVW Do each of you have a favorite part of the book? Or a project that piqued your interest in a different way when you were working on it for the book, as opposed to looking at it in real life?

MC Speaking further about the echoes or themes that we can now pick up on because of the chron ological order, or just having all his work in one place, we can see new relationships arising between artworks. For example, The Arch [1964] was the first time Walter really engaged with architecture or with an environmental installation. You see here that his “box” has increased in scale to the point

51

Walter De Maria framed by

The Arch (1964) in Walker Street studio, 1964. Photo: courtesy Walter De Maria Archive

where you’re no longer reaching into it, as you are with Surprise Box [1961], but actually entering and ultimately passing through it. This type of form, the corridor or passageway, is also related to his Walls in the Desert proposal [1961–64] and the Mile Long Drawing [1968]. Even his channel sculptures, such as Instrument for La Monte Young [1965–66] or Cross [1965–66], can be looked at as formally related to the passageway.

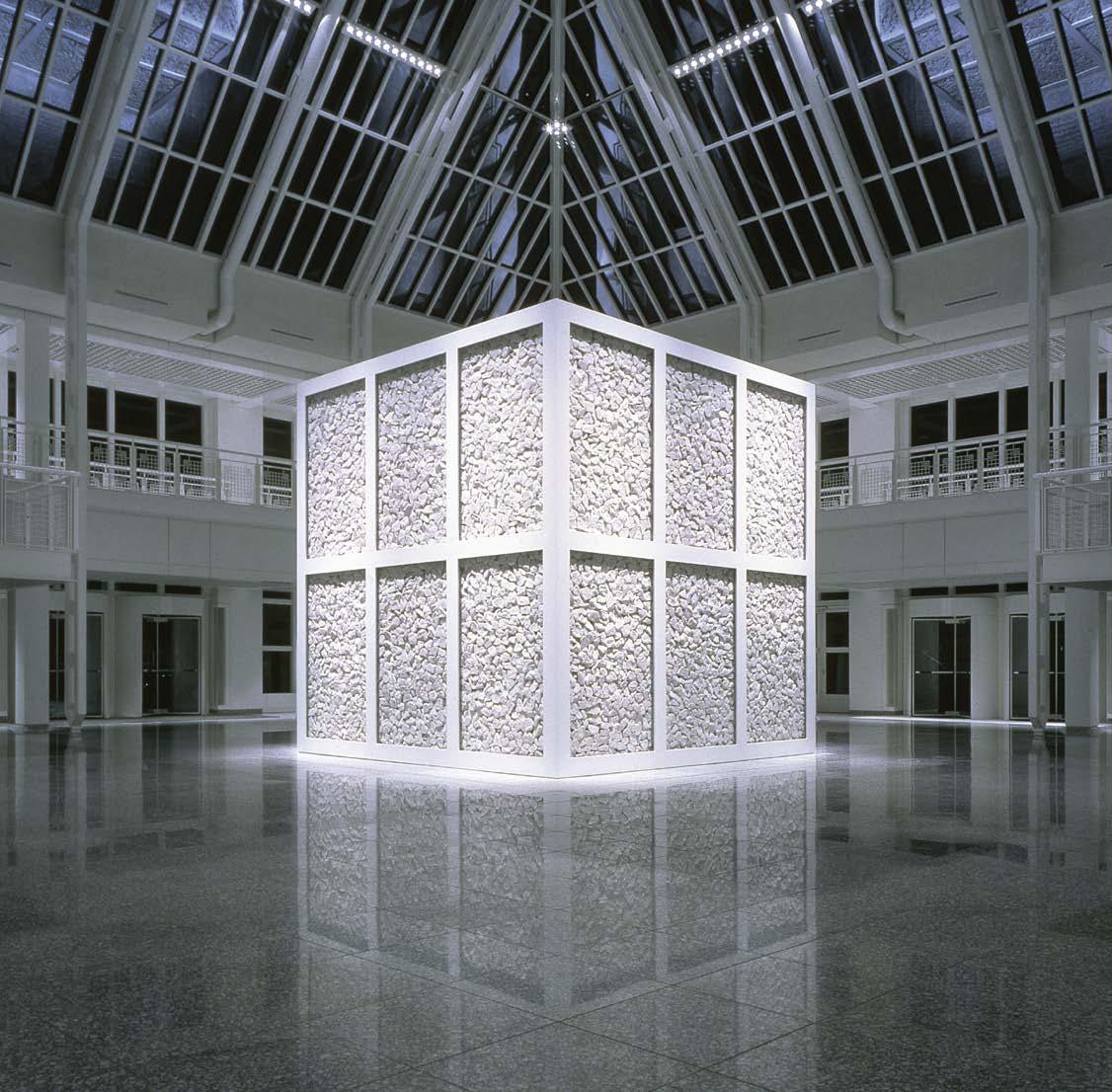

In addition to these thematic relationships, a deeper understanding of the work is achieved when looking at the development of Walter’s sin gular ideas over time. Many people know of The New York Earth Room as a permanent installation in SoHo, but they may not know that this was the third earth room that Walter made. Or that he later took the concept even further with 5 Continent Sculp ture [1989], using white rocks sourced from mines around the world, a work relating back to his Three Continent Project proposal [1967–69].

KVW Well, I hope the Menil exhibition and this book will generate more conversation, more ideas, more books, more museum exhibitions.

EC I think that’s exactly what will happen. When we had to document many of these early works, I realized how little I knew about that period in his career, so we had to go back over and over again to make sure all of our facts were correct. Walter rarely spoke about his earlier work, so most people don’t know about it, even those who know the later work quite well.

KVW Now that you’ve done this, may I ask what resources you had available?

EC The first time I ever went to Walter’s studio, in 1978, he had this two-room setup—essentially an enormous loft, where he lived on one side and worked on the other. There was a series of about ten tables constructed out of four-by-eight sheets of

plywood and sawhorses, and on each one of those tables there were piles of paper. That was Walter’s office [laughs ].

KVW That sounds very artistlike.

EC Nothing was organized. So I started putting things in boxes and asking him about each piece of paper.

KVW So forty years later, when you’re writing descriptions for the early artworks, you could go back to these boxes, find correspondence or— EC Exactly. And we were also able to access infor mation from different European archives—one of them in particular was hugely helpful for informa tion about the never realized 99-Sided Circle [1977], they made scans of everything they had in their files. So now, in the book, you can see some of these unrealized projects that Walter initiated when he was much younger, like the Three Continent Project , and understand what his intent was.

MC We were fortunate that most of Walter’s work is owned by public institutions. A huge part of the initial phase was reaching out to all known owners and sending them the fact sheets that we had pro duced with the database and having them verify a lot of that information for accuracy.

KVW Well, I have to say, your work has made a huge difference in making available this incredible his torical resource that you used to compile the mon ograph and that will be in the archive for the future. Do you think differently about Walter after working on this book?

MC For me as a young artist, the opportunity to read through the notes and works on paper that he was working on at my age, essentially, was extremely rewarding. He was really going through and developing his ideas, but also encouraging himself to stay true to his vision in a way that I have found quite inspiring.

This page: Walter De Maria, 5 Continent Sculpture (cube installation), 1989, white stones, painted steel frame, and plexiglass windows, overall dimensions: 16 feet 4 7 8 inches × 16 feet 4 7⁄8 inches × 16 feet 4 7⁄8 inches (500 × 500 × 500 cm), volume: 163.49 cubic yards (125 cu. m), weight of stones: 400,000 lb. (18,1437 kg). Installation, MercedesBenz Group AG International Administration Building, Möhringen, Germany, Collection Mercedes-Benz Group AG, Möhringen, Germany. Photo: Dieter Leistner

Opposite: Walter De Maria, Time / Timeless / No Time: The 3-45 Series , 2004, Indian Green granite, mahogany, Manetti 23 ¾-kt red gold leaf, and cement, sphere: 86 ¾ inches (220 cm) diameter, sphere weight: 34,000 lb. (15,422 kg), twenty-seven gilded wood sculptures, each overall: 52 ¾ × 34 7 8 × 10 ¾ inches (134 × 88.6 × 27.1 cm), twenty-seven 3-sided rods, each: 50 × 6 ¾ × 5 ¾ inches (127 × 17 × 14.6 cm), twenty-seven 4-sided rods, each: 50 × 5 × 5 inches (127 × 12.7 × 12.7 cm), twenty-seven 5-sided rods, each: 50 × 6 ½ × 6 1⁄8 inches (127 × 16.5 × 15.6 cm), twenty-seven cement pedestals, each: 5 1⁄8 × 39 3 8 × 14 inches (13 × 100 × 38 cm), gallery: 32 feet 9 ¾ inches × 32 feet 9 ¾ inches × 78 feet 8 7 8 inches (10 × 10 × 24 m), commissioned by Soichiro and Nobuko Fukutake for Chichu Art Museum, Naoshima, Japan. Photo: Naoya Hatakeyama

Artwork © Estate of Walter De Maria

52

Hans Ulrich Obrist’s Questionnaire

Anselm Kiefer

54

In this ongoing series, curator has devised a set of thirty-seven questions that invite artists, authors, musicians, and other visionaries to address key elements of their lives and creative practices. Respondents are invited to make a selection from the larger questionnaire and to reply in as many or as few words as they desire. For the fourth installment, we are honored to present the artist

.

4. What is harmony?

A: I mistrust harmony. Harmony can be the opposite of truth, which according to the “coincidentia oppositorum” is, in essence, untruth.

9. What keeps you coming back to the studio?

A: I never leave it.

13. The future is . . . ?

A: We all create from memory, without which nothing new can emerge. As Andrea Emo stated, “The new arises out of us, ourselves the future if we can relinquish it.”

6. What is your unrealized project?

A: The masterpiece.

10. Who do you admire most in history?

A: Alexander the Great.

14. Do you write poems?

A: No, but the poems of great poets, some of which I have learned by heart, accompany me, they are in me. For me they are like buoys in the sea—without them I am lost.

26. Who or what would you have liked to have been?

A: A woman.

27. What was your biggest mistake?

A: To leave Germany—a mistake that, in the end, was fruitful for me and my work.

32. What is your favorite book?

A: At the moment, “Finnegans Wake.”

31. What music are you listening to?

A: Hildegard of Bingen.

55

Hans Ulrich Obrist

Anselm Kiefer

Pierre-Alexis Dumas, the artistic director for Hermès, speaks with the curator Abby Bangser about the central role of the house’s art collection in its creative process.

ART PART 10:

56 FASHION AND

PIERREALEXIS DUMAS

Abby Bangser: I’ve been looking at the plans for your new location in New York and I noticed that the Hermès art collec tion is at the core of the architecture and design choices in the store. How have you related to the art col lection during your career?

Pierre-Alexis Dumas: Well, first, I always say that the store is more than a store; it’s a house that functions as a deep expression of what Hermès is about. This is true of all Hermès locations, and this new house in New York truly exem plifies that perspec tive. The art collection is key to this.

I’ve always had a personal interest in the visual arts—I studied art his tory at Brown—and in my work at Hermès, I’ve pushed the idea of pairing the work that we do with the art on the wall. This dialogue goes into everything, from our printing process to our designs, stores, and offices.

Hermès was founded in 1837 by my ancestor Thierry Hermès, a skilled craftsman who made horse harnesses. Through his success in this enter prise, he was able to acquire his own workshop and produce the harnesses for carriage-making companies in Paris. In the nineteenth century, Paris was full of carriages, so the demand wasn’t insignificant. Thierry’s son, CharlesÉmile Hermès, started the idea of extending the craft. Their clients were rid ers and Charles-Émile convinced his father that they should also make sad dles and that they should have a store where they could sell directly to their clients.

It’s interesting to see how each generation alters the family history. Crucially for this story, Thierry’s grandson Émile Hermès changed trajec tory in a remarkable way. Émile was a compulsive collector. He started col lecting at the age of twelve, and with an unusual object, I’d say: an umbrella, which he bought because he was fascinated by the mechanism and the way it was made. He was from a family of craftsmen so maybe this isn’t so sur prising. From there, he bought whatever he could afford, which meant not much, or what wouldn’t interest other people. He started to buy everything he could that related to the tradition of the horse. This was the period of the industrial revolution—did he have an intuition that that tradition would van ish? Did he sense that it was going to fade away? Maybe, because something dramatic did happen, which was World War I. At the time, Émile was run ning Hermès with his older brother, Adolphe, so it was called Hermès Brothers. And at the end of the war, Adolphe told Émile, “We have to sell the busi ness. Our clients now have automobiles. Our busi ness is dead.” And Émile told his brother, “You’re selling, I’m buying.” And he bought his brother’s shares and found himself the owner of Hermès. He gathered his craftsmen and said, “What can you do with your hands that will be relevant to our cli ents, since they don’t have horses anymore?” The shift was immediate: they started to equip their cli ents to travel in automobiles with luggage, hand bags, clothing. Émile created the brand called Her mès Sport. For a man born in 1871, he was very modern, and he met immediate success.

With that success, whenever he could he would buy art. Now, in his generation, he could have bought Les Demoiselles d’Avignon in 1907 or something, which would have been wonderful,

but that wasn’t his culture: he was a man of the nineteenth century. He was probably melancholic in a way, and he managed to turn that into something positive by being creative and accumulating all these objects that were rem nants of the past he had known. That was the origin of his fabulous collec tion, and with each successive generation we’ve continued to buy works that we think he would have appreciated.

AB: I’ve read about Émile’s legendary office, where the collection is primar ily kept—I must come to Paris to see it. That mixing of times and that nonhi erarchical approach, bringing different materials and media together, is a great interest of mine and I think it’s exactly how art and design should be appreciated. When we separate it so much, as we tend to do in museums, we lose the sense of how it’s meant to operate in the world and how it was created in an artist’s studio.

PAD: Exactly, and this is what propels the collection forward. It’s really all about curiosity and serendipity, allowing your mind to make nonrational connections. That is the essential foundation for the emergence of a cre ative idea.

AB: As I understand it, there are multiple collections. You’ve spoken about Emile’s; what are the others?

PAD: We have the Émile Hermès collection, which is all these objects we buy related to equestrian culture, but they are not Hermès objects. Then we have a second collection that we call the Conservatoire des Créations Her mès , the Hermès creations collection. We started collecting our own pro duction in the 1980s. This was begun by my father, who, when he became a young chairman, in 1978, realized we had very few items from our own past.

He even placed an ad in the national newspapers asking people who had old Hermès products they wanted to get rid of to contact Hermès. That’s how we started the Conservatoire. Today we have over 35,000 items and have managed to go all the way back to 1860.

Then there’s a third collection. I wanted to introduce a contemporary element into these collections, not to be focused only on either the nine teenth century or our own work. More specifically, I wanted to find a medium that wouldn’t clash too much with all the drawings and paintings we already owned, and I thought of photography as a good alternative that could coexist harmoniously with the older collections. This was the origin of the Hermès Photo Fund, and we’ve been buying since 2008. Presently we have more than 1,300 photos.

Previous spread: The Émile Hermès Museum, Paris. Photo: Nathalie Baetens, courtesy Hermès This page, above: Pierre-Alexis Dumas. Photo: Julien Oppenheim

This page, below: The exterior of Maison Hermès on Madison Avenue. Photo: Kevin Scott Opposite, above: Artwork by Cassandre, Émile Hermès Collection

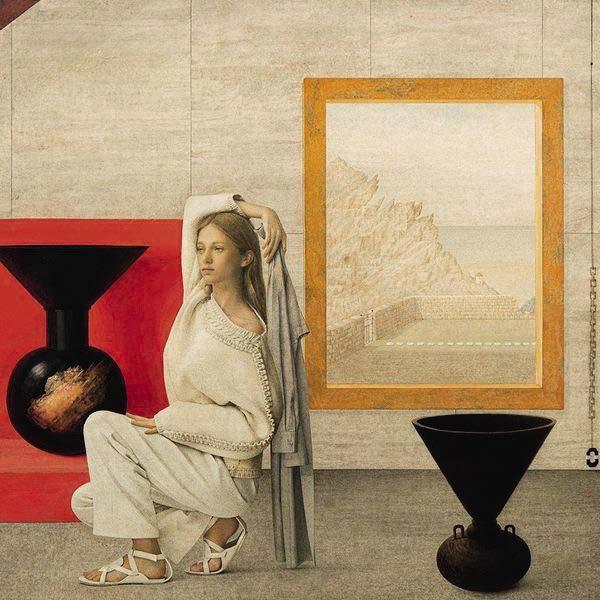

Opposite, below: Graham Little, Untitled (two vases), 2020, gouache on paper, Hermès Collection of Contemporary Art

58

These three collections are represented in every one of our stores. For a special store like Madison Avenue, I wanted a big statement, so I worked on this unique staircase design. I thought, This is my exhibition space to celebrate serendipity and curiosity and our own culture, which is a visual culture and also a symbolic culture around all the values you associate with horses and horse-riding and traveling: journeys, journeys of the mind and also of the soul.

AB: Could you tell me more about the works that you’ve cho sen for the central staircase?

PAD: One of my favorite items is a miniature carriage made as a toy for children in the nineteenth century. It is functional and would have been pulled by a pony or a goat. Fascinatingly, it’s an exact replica of a one-person taxi dating back to 1840—what was once called a cabriolet, which is where the English word “cab” comes from. And in Paris and London the cabriolets were yellow and black.

AB: Incredible. Perfect for New York City.

PAD: Exactly, and it links back to the question of heritage. My father used to tell me that you can’t create without memory. I can’t see how you can devise the future if you don’t know your history, if you’re not inspired by the past, so that you can go beyond your heritage but also nourish your mind with it. When ever we’re short on ideas, we go back to the collections. We just wander and let serendipity happen. But the purpose of art is to invent, to stimulate the mind to project ourselves into the future, to go further. The pieces I chose are all related to the interactions between North American culture and Paris culture. There are all these invisible threads.

Before the staircase, we have two beautiful small gouaches made by the French artist Cassandre in the 1930s as covers for Harper’s Bazaar. My grandfather bought them because Cassandre also designed for Hermès. They’re a really great example of collaboration between a French artist and an Amer ican magazine, and they come back to life in the Hermès store in New York. These are small touches that I think are moving.

Another piece that I’m thrilled to be showing is a work by the New York–based painter and graphic designer Elaine

Lustig Cohen. The American team introduced me to her, I went to her home in the city and we had a long, incredible conversation. She was in her late eighties at the time, a very elegant, sharp woman with an incredibly intense eye. While there, I fell in love with a beautiful abstract painting, and she allowed us to reproduce the colors in a collection we were working on. And now we’re able to put that very same work on display.

AB: It’s brilliant to bring this all together around the staircase. If we look at the boutique as a whole, are there other areas that you see as quintessen tial to the overriding concepts of Hermès?

PAD: First, the fundamental element of that building is natural light. The reason for the staircase is that at the top of the building is a glass dome, which allows light to travel down through the staircase to the ground floor. The idea is natural light has to penetrate as deep as possible because light is life. Light is the beginning of everything.

Second, our ever present inspiration at Hermès is nature. It is nature that gives us the materials; we merely transform what is given. Entering on the ground floor on Madison and 63rd, you’re somewhere geometrical by virtue of the architecture: already as you walk in, you see the geometry in the stonework, the floor, and the vertical elements. But it’s already more humane and warmer because of the materials. And as you walk up, the whole idea is that at the top of the building you have a garden and you have light. The whole architecture of the building gradually becomes more organic, with more curves, and the walls literally open, and in the recesses of the walls, as if in the bark of a tree, you’ll see a bag.

AB: I’m sure the window displays will be a visual treat for people walking past the store, as they always are at Hermès.

PAD: The window showcase is an integral part of the Hermès story, from Émile Hermès to the incredible work of Annie Beaumel and Leïla Menchari in the twentieth century, and on to the present, where we continue to col laborate with creators from a variety of disciplines. I’ve met important art ists who have told me that they remember seeing the Hermès windows as a kid with their mother or grandmother, and dreaming and feeling strong emotions that they cannot forget. For a long time, my biggest fear was that people didn’t dare to push open the door, thinking, This is not for me, this is not my world. I don’t expect people to come in and buy everything, or even buy at all; I expect people to come in and enjoy and open their eyes. I hope we’re contributing to enriching the cultural life of New York City. New York is a city about retail, like it or not, so better make that a fun and exciting experi ence. If you told me I couldn’t go into an art gallery because it’s not my world and I’m not going to buy a painting—No, no, no. Go into the gallery and look at the art, even if you can’t afford to buy it.

59

ANNA WEYANT:

BABY, IT AIN’T OVER

Novelist Emma Cline traces the boundaries between terror and hilarity in Anna Weyant’s new paintings.

TILL IT’S OVER

The paintings of Anna Weyant evoke a certain airless time of day: 5 p.m., the house still, the air going stale, the silver starting to cast off reflections from the lights. Composure with tension build ing underneath, an edge, like someone clearing their throat in a silent room. There is the quality of waiting, as in the opening scenes of a fairy tale—a girl, in prim clothes, about to be acted on by forces beyond her understanding, the normal rules of the universe tinted with a dream logic.

I was sitting at a long table with a lot of nice things on it , begins a short story by Alexandra Kleeman called “Fairy Tale.”

My mother and father were sitting next to each other on the long side of the table, and a man I didn’t recognize at all was sitting next to them. I sat across on the other end, alone.

I was looking at all of the things and trying to notice connections between them. Why this table, why now? . . .

It was then that I noticed none of the others seated

at the table were looking at the table or its con tents. They were all looking at me. . . .

You were announcing your engagement, said my father helpfully.

To who? I asked. . . .

To us, they said. All of you? I said.

No, only me, said the man in the button-up shirt, whom I did not recognize. . . .

Who am I engaged to? I asked.

To me, he said, no longer looking satisfied.

The young woman finds herself playing a part in a story that has lost all connection to reality. In this world that she doesn’t recognize, her fate is out of her hands. Even her mother and father are no help—they are part of the confusion, no longer reliable. What surreal logic propels her forward?

I think of Anna Weyant as a great teller of fairy tales. And girlhood is a kind of fairy tale, one in which your existence, even your body, can become distorted and unreal in sudden and even violent ways. As in a fairy tale, women are often subject to forces beyond their control: the strange dance

of passivity and power that they experience, cast in the starring role of the story while simultane ously defanged, made into dollhouse dwellers, figures arranged in the scene by hands outside the frame. And, as in the great gothic fairy tales, there is, in Weyant’s paintings, a sinister elegance: the Dutch-master black of her backgrounds, the expertly rendered silver candlesticks and unbe lievably lovely roses, the salmon-pink balloons and the figures done in narcotic marzipan smoothness. But Weyant’s universe never stops at that polished surface—the work is deeper than that, much deeper and much darker and very, very funny. There is always another element cutting through the static, an added bite—a fearless mordancy and a bracing wit that feel entirely contemporary and entirely her own.

In Weyant’s telling, the valence of the fairy tale takes on a savage and brilliant edge: the tropes are distorted, slyly rearranged, made more uncanny or hilariously deflated. A young woman flops out of a many-tiered birthday cake, her hair a flag of bored surrender. A gleaming revolver is now beribboned, a weapon made into a lovely little gift or even a

63

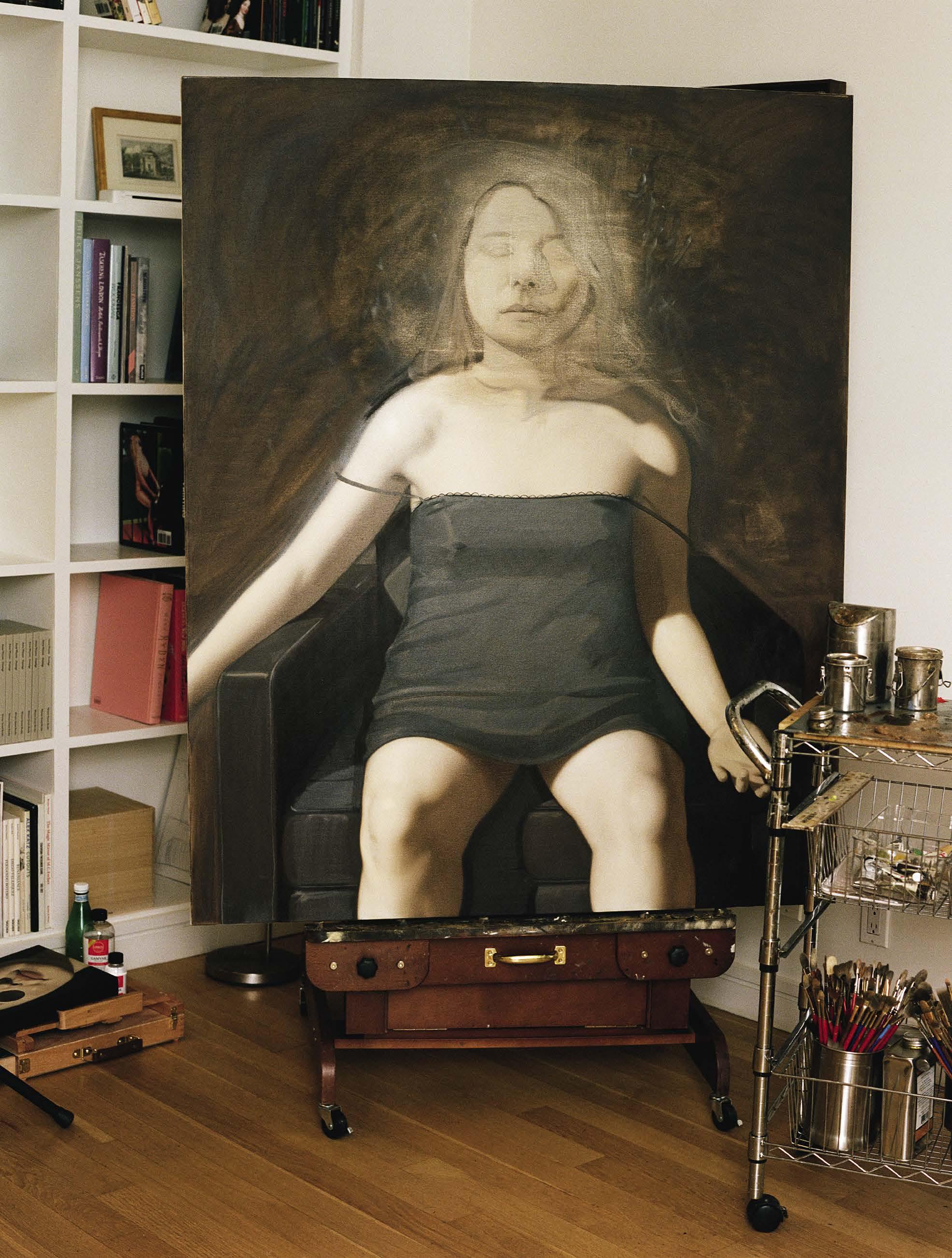

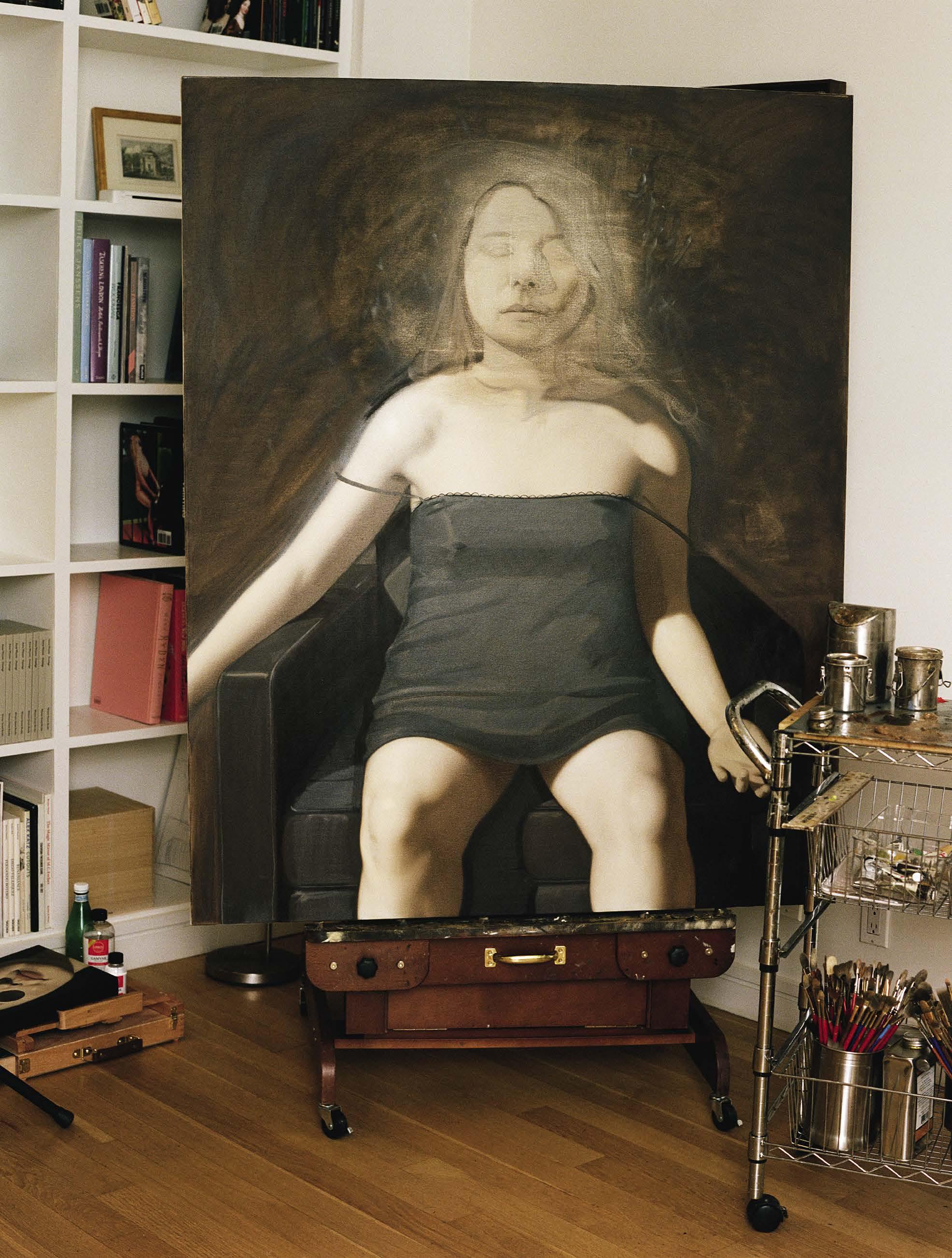

Previous spread: Anna Weyant in her studio, New York, 2022. Photo: Jeff Henrikson Opposite: Anna Weyant, Head , 2020 (detail), oil on canvas, 24 × 20 1⁄8 inches (61 × 51.1 cm) © Anna Weyant. Photo: Rob McKeever This page: Anna Weyant’s studio, New York, 2022. Photo: Jeff Henrikson

kind of acerbic invitation. A pair of wine glasses meet in a crashing “Cheers,” both glasses shattered into jagged teeth—social encounters as minor-key battle. A woman engages in what at first seems to be convivial conversation; then her smile becomes more of a grimace, a jackal’s bark. Her hand, bound in gauze, rests politely on the table, an injury that you suspect will go unexplained.

There was a book of Hans Christian Andersen fairy tales that fascinated me as a child. I still have the copy I grew up reading—a clothbound Jun ior Library edition with jewel-toned illustrations by Arthur Szyk. Even though I read them obses sively, the stories gave me a queasy feeling. They were frightening in a way that I couldn’t yet under stand, and the horror was doubled by the illustra tions, baroque images of girls and women in trou ble. One illustration obsessed me more than the others, accompanying the story “A Girl Who Trod on a Loaf.” It’s a weird little tale in which a girl’s vanity (protecting her new shoes from the mud at the expense of a loaf of bread meant for a hungry family) results in her doom (instantly banished to a terrible underworld). The illustration in my book

shows a blonde, droopy-eyed Szyk girl in a red furtrimmed coat, trapped in a massive spider’s web, surrounded by all manner of creatures who mean to do her harm—gape-mouthed dragons and fear some bats and an enormous rocky toad. “Great, fat, sprawling spiders spun webs of a thousand years round and round their feet,” the caption reads. A thousand years! Doom! Yet the girl’s expression is only mildly concerned. There’s something in the way her eyebrows are raised, a weary resignation in her features, that seems almost to say, Ok, great, fat spiders, hideous beasts, a thousand years—so what?

The women in Weyant’s paintings navigate their uneasy surroundings with that same cool know ingness, a gimlet-eyed awareness that inures them to the vagaries of this fairy-tale world. These are not the passive heroines of fairy tales, asleep for 100 years—if a Weyant subject slept for 100 years, it would be because she was bored, withdrawing from society in Bartleby-like protest: I would pre fer not to

If the subjects at first appear strangely calm, even under duress, on second glance their remove starts to look like a choice, an exhausted opting-out

64

This spread: Anna Weyant’s studio, New York, 2022. Photos: Jeff Henrikson

66

or a calculated pose, a weaponized strategy formed as an illogical response to a ridiculous world. These strategies can result in their own form of violence, too: a young woman with a bow around her ponytail, taking the innocent, enthusiastic pose of a cheerleader, is—you realize—standing on brutal tiptoe, her body balanced on a young woman’s cheek. Do both of these women have the same face? The brutality is turned inward, acted out on another version of the self. As in a horror story, the call is coming from inside the house. Or from inside yourself. Even so, the expressions on these faces are placid, amused. The woman grins happily as her cheek is ground down by the cheerleader. None of this, their faces seem to say, is entirely unexpected. Even when a Wey ant subject is screaming, the scream seems hilar iously mellow, self-aware, an echo of an echo of terror.

In Weyant’s recent paintings, these ripples of otherworldliness and the uncanny appear in more overt ways, breaching their formerly polite bounds. It’s exciting to see these parts of her work

Opposite: Anna Weyant,

This page:

intensify, torquing her visual universe with new energy. Weyant’s bone-white roses, unsettlingly perfect, are now joined by flat fake daisies, like the gag flowers on a clown’s lapel that might sud denly blast you with water. The elements of artifice are foregrounded, made visible. In another paint ing, a cartoon face distorts the features of a beau tiful young woman, like a startling rude blurt into this composed world. Something hidden makes itself known. So much is controlled; then Weyant ruptures the control with psychological precision, exposing what spills out of us even when we try to keep the boundaries maintained.

In a still life of polished silver, the reflections in the surface of the pots and pans aren’t just innoc uous flashes of light and dark—we see a shadowy, sinister figure creeping in the background, a knife raised in their hand in Norman Bates fashion. The polish reveals the poison. But is the danger real?

Or is the violence cartoonish, just juvenile haunt ed-house antics?

Weyant plays with doubling: a woman in a silk slip dress smiles in a satisfied, internal way, her

eyes closed. Then she is twinned, only the twinned version glances down to the side with mild disdain or regret, like that moment of pause after you’ve said too much at a party. In a single painting, Wey ant toggles between these two selves, the pleased self and the self that polices that pleasure, doesn’t appear to quite trust it.

There’s something very funny, too, about the discomfort in an Anna Weyant painting. It’s a pres surized, antic hilarity, the tension between the lovely, prim surface and what’s underneath, threat ening to breach that surface—like the queasy and awful thrill of trying not to laugh at an inappropri ate time. Needing to laugh, but knowing you abso lutely cannot laugh—humor teetering on the knife’s edge of horror, like the balance Weyant so expertly strikes. A thousand years bound in a spider’s web, a woman en pointe on your cheek, a figure with a knife creeping up behind you: horrifying? Maybe. Maybe also kind of funny. And maybe that medi ation between humor and horror is a truer kind of fairy tale, a fairy tale that crystallizes this moment brilliantly, as only Anna Weyant can.

67

Sophie, 2022, oil on canvas, 113 × 76 ¾ inches (287 × 194.9 cm) © Anna Weyant. Photo: Rob McKeever

Anna Weyant, A Disaster, Such a Catastrophe, 2022, 36 ¼ × 48 1⁄8 inches (92.1 × 122.2 cm) © Anna Weyant. Photo: Rob McKeever

CELESTIAL CINEMA OF

THE

MARKOPOULOS

GREGORY

Raymond Foye reports on the Temenos, the screening of Gregory Markopoulos’s film Eniaios in Lyssarea, Greece, in the summer of 2022. Addressing the mythological and mystical nature of Markopoulos’s singular cinematic production, Foye traces the developments in the filmmaker’s life that led to this influential work.

Time is the moving image of eternity. —Plato, Timaeus , c. 360 bce

In June 2022, approximately 150 people gath ered in the heart of ancient Greece for one of the stranger rituals in the world of cinema: two week ends of screenings devoted to the epic work Eni aios , an eighty-hour 16mm film created by Greg ory J. Markopoulos. This legendary independent filmmaker’s official filmography comprises more than forty films created between 1940 and 1976, followed by his final film, Eniaios , completed in 1991—the year before his death—which largely consists of a radical reedit of many of these ear lier films, plus later footage that does not appear elsewhere. ( Eniaios means “uniqueness” or “unity.”) The filmmaker himself never saw the finished work projected; short of funds and ter minally ill, he only had time to edit the film and put it on the shelf, leaving an immense number of

practical details to be realized by his life partner, the filmmaker Robert Beavers. The relationship of Markopoulos and Beavers is in itself one of the more affecting accounts of artistic collaboration in our time, making the screenings—an event called the Temenos—a true union of spirits. 1

For Markopoulos, “filmmaker” meant many things: scientist, sorcerer, physician. At the Temenos, all these roles are in play. Joseph Campbell once said that myths are public dreams and dreams are private myths; Markopou los’s films function like a communicating ves sel between these two states. He saw life through

the framework of the Greek myths, which to him were expressions of psychic states, the “universe of fluid force,” as Ezra Pound called it. 2 Markopou los created his own myth and then inhabited it.

Eniaios is a work of endurance on the part of both filmmaker and audience. Since 2004, reels of Eniaios have been premiered at long week ends of screenings that last three to five hours per night.3 To see the entire cycle as it is currently presented—only at four-year intervals—would take twenty-eight years. 4 Since 2004, all of the reels screened have been premieres. This is not about the popular but, in Markopoulos’s words, about the search for the “single perfect Spectator.”5 Aside from the barest of over views, I will not attempt to review these films in any conventional sense. Highly abstract in concep tion and execution, they exist well beyond words. I would rather inspire lov ers of cinema to make this pilgrimage of discovery themselves.

“ Temenos ” in Greek means “holy grove,” a place apart. The location is a field in a natural amphi theater near Lyssarea, in the region of Arcadia, home of the great god Pan and a place rightly synonymous throughout centuries with idyllic natural beauty. The censorship of Markopou los’s film The Illiac Passion (1964–67) in Athens in 1980, because of nudity, led him and Beavers to start search ing for an appropriate site for his films. Staying with an uncle in Markopoulos’s ancestral village of Lys sarea, they began screen ing their films annually in this setting from 1980 to 1986. After a hiatus due to Markopoulos’s illness and

70

Previous spread: Temenos, Lyssarea, Greece, 2022. Photo: Linda Levinson

Above: Gregory Markopoulos, Psyche , 1947, 16mm film, color, sound, 24 min. © The Estate of Gregory J. Markopoulos. Courtesy Temenos Archive

Temenos, Lyssarea, Greece, c. 1980s. Photo: Giorgios Zikoyannis

© The Estate of Gregory J. Markopoulos. Courtesy Temenos Archive

death, the screenings resumed, in 2004, 2008, 2016, and 2022. The Temenos proper—which is to say, the screening of the late masterwork Eniaios is usually held only once every four years.

The Temenos offers a refreshing lack of distrac tions: the guesthouse where I stayed had no Inter net, but did have a balcony with a view of a beauti ful fruit and vegetable garden tended daily by an elderly couple. Sheep roamed freely through the town and the local café was open until 3 a.m., or whenever the last patrons decided to go home. There is something in the DNA of Greeks to welcome travelers from afar, and the cordial ity of the locals continues to this day.

In the early 1970s Markopoulos withdrew his work from circulation, one of many peremptory acts that defined his career. (He similarly demanded that P. Adams Sitney remove the chapter about him from the author’s classic study Visionary Film , of 1974; Sit ney obliged.) 6 Lyssarea is now the only place where one can see his epic, and for those who love inde pendent film, attendance is as close as it comes to the Muslim hajj, a pilgrim age de rigeur at least once in one’s life. Markopoulos took the adage “If you build it, they will come” to the extreme. Carrying an idea to its farthest point, regard less of practicalities or cost, was what he excelled at. This is about as absolute as art gets.

Crucial models for the Temenos were the sacred sites of ancient Greece described as healing centers in the travel writ ings of Pausanias, from the second century ce. Attend ees stay in local guest houses and in the early evening are bussed to the village of Lyssarea, from which they then hike by foot for thirty minutes as night falls. (Arrangements are made for the physically challenged.) The amphi theater commands a pan orama 100 miles around, and every sound, no matter how small, seems to carry. The films are silent save for the insects, frogs, and owls who contribute an ambi ent soundtrack. The nat ural setting establishes a remarkable relationship between the screen and its environs: the boundary where the film ends and

the cosmos begins is blurred. The silent atten tion among the audience is a meditation in itself, and the soul of the place soon becomes palpa ble. To call the experience immersive is an under statement. This was made clear on the third night this year, when heavy rains necessitated a move indoors into an old schoolhouse, and the spacious ness was lost.

Through the combined forces of art and nature, Markopoulos created something akin to

an environmental sculpture, highly conceptual. One thinks of The Lightning Field of Walter De Maria (1977), a place of latent power and potenti ality, where meaning is revealed not only in the event but in the waiting. This quality of abiding constitutes an important part of the experience. Attendance means just that: readiness, anticipa tion, awareness. It is a formula that carries over into the films, which are largely composed of clus ters of frames, often as few as three or four (so that

71

Gregory Markopoulos filming Swain , 1950 © The Estate of Gregory J. Markopoulos. Courtesy Temenos Archive

they take up less than a second on-screen), sepa rated by longer stretches of clear and black leader. To look away even for a second is to miss some thing important.

Addressing the small gathering in the vil lage square one evening, Beavers described Markopoulos’s montage technique, involving elaborate numerical notations on pieces of paper that were discarded after the editing. In his writ ings Markopoulos describes this as a “musi cal-mathematical structure,” and it creates an overall abstract framework into which images are placed as minimal units. Spontaneity was also a factor: edits were improvised until the very last

moment. In Markopoulos’s focus on single frames, one senses him working on a quantum level, and the absoluteness of his vision is both stunning and forbidding—it is as if one were inside a perplexing philosophical theorem. In his essay “Element of the Void” (1972), the filmmaker took this infini tesimal focus one step further, speculating about the uncaptured images that existed between the twenty-four frames per second that the camera caught, escaped images he calls “the winged con science of total reality.”7

Many of the reels premiered at the Temenos in 2022 displayed Markopoulos the master of the film portrait, in which, he said, “the personalities

photographed . . . released their true selves.” 8 Subjects included Peggy Guggen heim, Jasper Johns, Shirley Clarke, Jonas Mekas, Mar guerite Maeght, and David Hockney. Other sections of Eniaios focus on nature, architecture, and sacred spaces: the “Divinity of a Place,” in the filmmaker’s words. 9 Like Pound (who also had to leave his home land to realize his true self), Markopoulos composed a sprawling personal epic built from fragments of memory—a lost paradise where form and formless ness are locked in perpet ual struggle.

I have brought the great ball of crystal; who can lift it? Can you enter the great acorn of light?

—Ezra Pound, Canto CXVI , 1969

The ancient Greek phi losopher Markopoulos was most drawn to was Par menides, a pre-Socratic who left his teachings in the form of poems, exploring the dialectics of light and darkness and the nature of being. For Parmenides, “Light/Fire” and “Night” were the opposite poles of the cosmos, and this duality seems to constitute the psy chic energy of the Temenos. The writings from the last decade of Markopoulos’s life are poems and hymns that invoke the elements of his cinema: Light, Silence, Eros, Cosmos, Intuition, Image. These writings are distributed to attendees of the Temenos in beau tifully printed oversized folios bearing the symbol of the event: a grasshopper, emblem of ancient Athens.

Markopoulos was an expert cinematographer, and he seems to have absorbed most of the history of cinema. As a student at the University of South ern California, Los Angeles, he attended lectures by Josef von Sternberg, and his first film, Psy che (1947), was made concurrently with Kenneth Anger’s Fireworks (1947) and Curtis Harrington’s Fragment of Seeking (1946)—three cornerstones of American homoerotic cinema made by acquaint ances in close proximity. Shortly after, a disas trous experience attempting to make a movie within the Hollywood industry set Markopou los on a path of total independence. His encoun ters in the 1950s with Jean Cocteau in Paris and with Maya Deren in New York encouraged

72

David Hockney in Gregory Markopoulos’s

Genius , 1970, 16mm film, color, silent, 60 min.

© The Estate of Gregory J. Markopoulos. Courtesy Temenos Archive

further explorations into the heart of dream, myth, and trance—Markopou los’s personal intensity is such that his images seem to always exist in the dead center of the psy che. Throughout the 1950s and ’60s, Markopou los explored homosexu ality to a far deeper and more serious degree than any other filmmaker I can think of, in a way quite devoid of the often self-deprecating camp of Andy Warhol or Jack Smith.

From the start, Markopoulos eschewed cine matic conventions such as fades and dissolves in favor of single frames, rapid cuts, and in-camera superimpositions. The plastic nature of film, its physical fact, supplanted illusion. Many of the inno vations credited to the French New Wave may rightly have originated with Markopoulos, who had spent time in Paris in the 1950s. (Jean-Luc Godard asked Markopou los to sponsor his visa for his first lecture tour of America.)