DYLAN LEWIS

HOMAGE TO LÖWENMENSCH

A PRIVATE EXHIBITION OF RECENT SCULPTURE BY KINDLY HOSTED BY

THE SCHUMANN FAMILY

A sculpture that particularly evokes the narratives of Dylan Lewis’s art is a circular composition of three male figures which the artist produced after viewing one of the oldest figurative sculptures ever discovered.

The Löwenmensch (Lion-man) was found in the Hohlenstein-Stadel cave not too far from Munich, Germany. Carved from mammoth ivory, the fantastical animal/human hybrid - referred to as a ‘therianthrope’ – stands 31 centimetres tall and features a cave lion’s head and front legs (serving as arms), with a human male torso and legs. While we can only speculate on what the hybrid figure may have meant to those who carved it, the Löwenmensch represents the earliest unequivocal evidence of symbolic thinking in the human archaeological record. This ability set us on a vastly different path from our primate ancestors.

Inspired, Dylan made sketches of the sculpture and visited the cave in which it was found, near the Swabian Alb in southern Germany. While reflecting on the 40,000-year span since the figure was carved, he felt acutely aware that this sculpture held meaning for both his own life, as well as the trajectory of humankind. Consequently, Dylan produced his sculpture in homage to the Löwenmensch. Similar to its Palaeolithic predecessor, the innermost figure has a human body with a cave lion head. Above it, a human figure wearing a lion skull mask merges into a final figure that is entirely unadorned human.

The lion-headed figure in Dylan’s composition represents the early stagesof consciousness as we began to separate from our animal origins. The central shamanistic figure wearing a lion skull mask suggests a time when - although separated from our primal origins - the symbol of the animal remained powerful to hunter-gatherer and early agricultural societies closely attuned to the rhythms of nature. The uppermost figure, fully human, represents the ascent of modern human society. It is striking that this figure’s posture resembles classical depictions of Prometheus, who, in Greek mythology, angered the gods and endured eternal punishment for gifting fire to humanity. The myth could be interpreted as an allegory for human progress, fire is not just about warmth and light, but also represents knowledge, technology and civilisation. Prometheus’s punishment, therefore, suggests the suffering, alienation and violence which can arise when our pursuit of these advancements relentlessly veers into hubris.

For Dylan Lewis, this juxtaposition points to a fraught dichotomy in the human experience. The sculpture’s circular composition visualises a journey from the emergence of symbolic thinking towards the modern condition. As we strive to embrace technology and progress, Dylan suggests, we find ourselves partially blinded by its brilliance. We are simultaneously pulled back and downward by the weight of the history from which we strove to emancipate ourselves, but are also propelled by it. Yuval Noah Harari puts this well in his book Sapiens when he says, “We have Palaeolithic emotions, medieval institutions and godlike technology.”

In an evolutionary timeline, the modern condition is very recent and most of our behaviours and biology were deeply encoded to deal with a very different world. This apparent mismatch could explain many of the seemingly unresolvable paradoxes of the modern human condition. From the artist’s point of view, while it is helpful to attempt to rise above these encoded imperatives, it is even more important to understand and come to terms with these forces at play within our individual biology and psyche, as well as the wider social milieu. They are formative parts of ourselves and will not be ignored. It is said that what you don’t let come to you, will come at you.

(Top) Dylan sketching at the Hohlenstein-Stadel cave at the southern rim of the Lonetal in the Swabian Jura in Germany.

Photographs by Christian Rode

A small mammoth Ivory statue called the Löwenmensch was discovered here in 1939. Dated at approximately 40,000 years old, this sculpture of a human figure with a lion’s head is one of the most ancient figurative sculptures ever discovered.

(Above right) Replica of the Löwenmensch sculpture

(Above left) Dylan working on the original clay sculpture “Homage to Löwenmensch” in his studio.

(Top) Dylan sketching at the Hohlenstein-Stadel cave at the southern rim of the Lonetal in the Swabian Jura in Germany.

Photographs by Christian Rode

A small mammoth Ivory statue called the Löwenmensch was discovered here in 1939. Dated at approximately 40,000 years old, this sculpture of a human figure with a lion’s head is one of the most ancient figurative sculptures ever discovered.

(Above right) Replica of the Löwenmensch sculpture

(Above left) Dylan working on the original clay sculpture “Homage to Löwenmensch” in his studio.

Homage to Löwenmensch P012, Giclée print on Hahnemühle etching paper, edition of 45 100 x 70 cm

Homage to Löwenmensch P012, Giclée print on Hahnemühle etching paper, edition of 45 100 x 70 cm

There is often tension within Dylan Lewis’s sculptures of being torn between opposite states. The Beast with Two Backs sculptures reflect the process of finding harmony within that. They are about reconnecting with the chthonic, embracing self-acceptance, and recognising the vital parts of ourselves that have been painfully locked away. More than any other of Dylan’s works, these sculptures represent an image of libido, of life force. The joy of genuine intimate connection is made all the more meaningful when one has known the pain of isolation. These evocative masculine and feminine figures emerging from three muscular animal legs are perhaps the purest representation of the idea of the Red Gods within the artist’s work.

There is an erotic exuberance to these sculptures precisely because they reflect the bliss of individuation. The works metaphorically convey a transcendent sense of wholeness. They depict balance and consolidation: the masculine and feminine are depicted on a plane of mutually consenting desire and participation. Through the fusing of human and animalistic elements, these sculptures speak to restoring a balance between the rational and the wildly instinctual.

“Our sensual and sexual natures are central to an ‘authentic animal state’,” Dylan observes. “When we shame it, we shame the very core of our being. I was raised in a religious tradition that strongly emphasised sexual regulation. Sexual pleasure, of all pleasures, was singled out as something to be particularly afraid of. Attempting to reconcile sex as natural joy and at the same time, dirty dangerous urge, mired me in decades of shame. Ultimately, a deeper understanding of human origins gave me a genuinely helpful view of this paradox. The battle was not a result of ‘God’ or the ‘Devil’ or my Fallen Nature. It was simply a struggle to reconcile impulses, adapted over millennia of years, to the social and moral constraints of an increasingly complex human society.”

Significantly, the animalistic legs of these works bear no relation to the lithe elegance of the big cats, and instead, recall other animal sculptures such as Dylan’s buffalo works. For him, the buffaloes represented wildness in a vastly different way from the cats. As opposed to solitude, sensuality, and stealth, the buffaloes stood as relentless forces of strength and danger that would not be ignored. Instead of quietly moving in the shadows, they were primal creatures of the earth, covered in mud. This reflects the intensity of the emotional terrain channelled by these sculptures.

To speak of returning to the earth - to the chthonic - is really to speak about the idea of embodiment. By this, we mean the quality of physically being present within our bodies. Certainly, in Western traditions and within the context of many organised religious practices, we are encouraged to view the mind and body as separate things. We are told to ignore our actual lived experience and to rather dwell in a world of abstract ideals and perpetual judgements. As Barnaby B. Barratt asserts in his book Liberating Eros, “The source of our capacity for the experience of love, freedom, and joy, is to be found within the lived experience of our body.” The Beast with Two Backs sculptures are, therefore, very much an expression of this sense of embodiment.

Over time and through various phases, Dylan has similarly made peace with authentically expressing his subjectivity in his work. “The sculptures of the Beast with Two Backs series are a powerful exploration of the sensual, the sexual, and the erotic instinct. My earlier work explored sensuality in a more covert way through the animal form, but over time the expression has become increasingly human, to the point now that the sexual and erotic references are no longer hidden.”

Beast with Two Backs XI Maquette I

S-H 28 d, bronze, edition of 12 99 x 48 x 46 cm

Beast with Two Backs XI Maquette I

S-H 28 d, bronze, edition of 12 99 x 48 x 46 cm

Dylan surrounded by his Monumental “Beast with Two Backs” series

Dylan surrounded by his Monumental “Beast with Two Backs” series

Beast with Two Backs II Maquette I

S-H 26 c, bronze, edition of 12 54 x 20 x 56 cm

Beast with Two Backs II Maquette I

S-H 26 c, bronze, edition of 12 54 x 20 x 56 cm

Beast with Two Backs IV Maquette II S-H 30 c, bronze, edition of 12 67 x 36 x 70 cm

Beast with Two Backs IV Maquette II S-H 30 c, bronze, edition of 12 67 x 36 x 70 cm

Beast with Two Backs IV Life Size I

S-H 30 e, epoxy composite resin

Beast with Two Backs IV Life Size I

S-H 30 e, epoxy composite resin

Beast with Two Backs Miniature S-H 30 f, bronze, edition of 100 17 x 11 x 17 cm

Beast with Two Backs Miniature S-H 30 f, bronze, edition of 100 17 x 11 x 17 cm

Beast with Two Backs I Maquette I S-H 21 e, bronze, edition of 12 97 x 50 x 87 cm

Beast with Two Backs I Maquette I S-H 21 e, bronze, edition of 12 97 x 50 x 87 cm

With the Spoor series, Dylan Lewis hones in on the textural quality of his sculptures while eschewing their figurative components. The result is a series of wall-mounted relief works that leap between the realms of painting, sculpture, and printmaking. Dylan’s other works involve careful navigation between several steps before completion. The Spoor works allow for immediate, intuitive interaction with the clay panels. Bypassing intentionality, the Spoor works are a vessel for raw, unfiltered emotion and a testament to corporeal experience.

Without any explicit subject matter, the panels tend towards abstraction. At the same time though, the imprints that remain of the artist’s actions speak to an element of intense performativity and physical action. Some are ambiguously marked, while others testify to a continuous circular motion of footprints. Some convey violence and turmoil with their deep slashes and feral ‘claw’ marks. Others are powerfully serene and calming. What is key is the element of traces, mark-making as an assertion of presence.

This is where the title of the series becomes significant. In the wild, spoor are traces left behind by animals that indicate their presence and actions in a particular area and can be used for tracking and surveying. These include distinctive animal tracks, scents, broken foliage, and drag marks. Because these works require Dylan to act spontaneously and interpret later, in a sense they are traces of the artist’s unconscious, his instinctual self.

“Tracking was an essential part of our ancestral past,” Dylan observes. “The literal wilderness can be an incredibly dangerous place if you don’t understand the hidden threats, as well as the sources of sustenance and shelter. We searched for patterns and looked for similarities, in order to understand our environment. This meant our survival, we searched for meaning in a vast, impersonal, violent, nurturing and paradoxical universe.

“In a process like psychotherapy, we track the ‘beast’ that has wounded us, trying to get sight of it, doubling back on it as it ambushes us. Sometimes the tracks are clear, sometimes they are obscured and difficult to follow. Often, we lose them entirely and pick them up again at a later stage. At first, the tracks are simply an indication that something has happened. Over time, a skilled tracker will be able to read the life, movement, habits, and character of the animal in the marks left behind.”

In a much broader sense, there is something particularly primal in the compulsion to leave markings and handprints behind. Handprints or reverse handprints – which are silhouettes created by placing the hand on a rocky surface and blowing pigmentation around it – are ubiquitous in rock art. They can be found in a multitude of locations and time periods across the world, often appearing alongside animal or geometric imagery.

While we will most likely never know the original intentions behind these, what is important is the human desire to intentionally leave an imprint, to assert the validity of one’s existence to the world, and to leave behind a symbolic image that can hold broader meaning. For Dylan Lewis, the tendency towards similar means of mark-making - despite vastly different contexts - points to something akin to genetic memory, or what Jung called the ‘collective unconscious’ in humanity. A desire to survive the experience of being human, to intentionally express one’s embodiment through leaving a hand- or footprint.

SPOOR XIII

A013, Fibre reinforced acrylic plaster, edition of 8 182 x 8 x 128 cm

SPOOR XIII

A013, Fibre reinforced acrylic plaster, edition of 8 182 x 8 x 128 cm

SPOOR XIV

A014, Fibre reinforced acrylic plaster, edition of 8 241 x 10 x 134 cm

SPOOR XVIII

A018, Fibre reinforced acrylic plaster, edition of 8 126 x 8 x 81 cm

SPOOR XIV

A014, Fibre reinforced acrylic plaster, edition of 8 241 x 10 x 134 cm

SPOOR XVIII

A018, Fibre reinforced acrylic plaster, edition of 8 126 x 8 x 81 cm

The untamed ‘wilderness within’

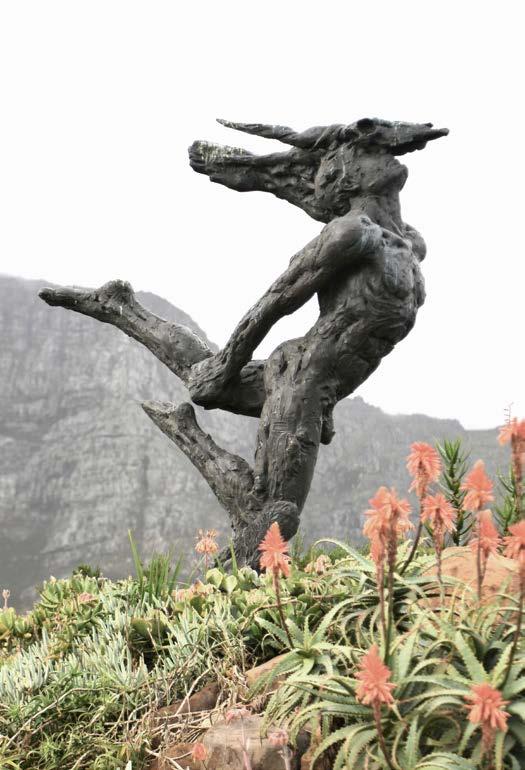

Dylan Lewis’s Shamanic figures mark the point where the artist moved beyond animal forms to explore metaphor and emotion through the human figure. Formally, the works encompass isolated naked male and female figures, often with their faces hidden behind animal skulls. Some of these figures incorporate hybrid human/animal traits in the form of horns, wings, and talons, which have strong mythic and archetypal connotations.

“My art explores the notion of an untamed, authentic ‘wilderness within’, the burning point between tameness and wildness, between the Devil and God, between human and animal that is both paradox and crucifixion,” Dylan observes. “This wild place has nothing to do with human savagery born of fear and a consequent desire to control and dominate others. Instead, it is a true wild authenticity arising out of self-love and non-judgement, a place where I can roam free and leave others be.”

It is important to stress that this is not art as shamanism, Dylan is not positioning his art practice within a shamanic tradition. Rather, he is interested in how the historical role of shamans as arbiters between worlds can serve as a metaphor for our own personal grappling with our external relationships and internal states. For Dylan, they represent both the history of mankind’s increasing sophistication and the corresponding move away from the animal and, within the context of his work, a move away from the pure metaphor of the animal to one of the tensions of the human condition.

The animal skulls in these works serve an important metaphorical role. Worn by Dylan’s male figures, the skulls of lion, waterbuck, gemsbok, and eland each symbolise a particular energy. The skull masks both conceal and reveal something of the identity of the wearer, signifying a ritualistic engagement with authentic life. The question arises: “What kind of life or death do I choose for myself, both at certain moments and over the full span of my life?”

“Human history teaches that engaging with authenticity often ends in death,” Dylan observes. “There are countless stories of political, religious, and scientific martyrs who have died at the hands of their families, communities, and nations because they chose to resolutely follow their internal truth. Today, this death is still literal for some but for most, it seems to be symbolic. Perhaps a relationship, an ideal, or a career has to die to make way for the new life coming through. To me, the necessary life of the tamed path has to do with service, self-sacrifice, and finding meaning within community, all of which seem to be important to the psyche. The death we may meet on this path is the possibility that we live out that which others expect of us to such an extent that our own authentic life dies within us.”

“The cave you fear to enter holds the treasure you seek,” is a quotation ascribed to mythologist Joseph Campbell, which suggests that the parts of ourselves that we don’t want to confront are the parts we need to make peace with in order to achieve self-acceptance. Dylan’s masked Shamanic figures alternate between visualising the internal suffering that comes from shunning our authentic nature, and beckoning the viewer to go on an inward journey to acknowledge what lies within the cave they fear.

Male Trans-Figure XVII S344, bronze, edition of 8 229 x 75 x 214 cm

Trans-Figure XXIV Miniature S431, bronze, edition of 100 12 x 9 x 15 cm

Male Trans-Figure I Miniature S449, bronze, edition of 100 15 x 8 x 19 cm

Trans-Figure XXIV Miniature S431, bronze, edition of 100 12 x 9 x 15 cm

Male Trans-Figure I Miniature S449, bronze, edition of 100 15 x 8 x 19 cm

Male Trans-Figure VII Maquette S467, bronze, edition of 15 72 x 23 x 35 cm

Male Trans-Figure VII Maquette S467, bronze, edition of 15 72 x 23 x 35 cm

Trans-Figure XXXI Maquette S359, bronze, edition of 12 53 x 29 x 37 cm

Trans-Figure XXXI Maquette S359, bronze, edition of 12 53 x 29 x 37 cm

Male Trans-Figure XVII Maquette S343, bronze, edition of 12 78 x 26 x 75 cm

Male Trans-Figure XVIII Maquette S465, bronze, edition of 15 74 x 31 x 40 cm

Male Trans-Figure XVII Maquette S343, bronze, edition of 12 78 x 26 x 75 cm

Male Trans-Figure XVIII Maquette S465, bronze, edition of 15 74 x 31 x 40 cm

In the poem On Freedom, Kahlil Gibran explores the multifaceted nature of freedom. In Gibran’s view, any true freedom requires us to be able to acknowledge and consolidate our interdependence on others willingly. If we don’t, the fear and doubt in our relationships with others will always serve as additional chains that constrain us, and we cannot ever be truly free.

For Dylan Lewis, intimate relationships are at the very core of this human dilemma. While his earlier sculptures grappled with intense inner tensions relating to self-acceptance or a yearning to recalibrate, they did so primarily as individuals alone, either in isolation or solitude. Lewis’s Interrelation series takes these ideas a step further by shifting the focus to intertwined human figures. Along with this comes a direct grappling with the emotions that were originally projected onto landscape and animal forms.

The works reflect this openness visually in that these are purely masculine and feminine human figures. The animalistic traits - skulls, wings, claws, and horns – which once concealed parts of them are gone. Instead, they are presented unabashed, their nakedness expressing raw, unrestrained emotion. Lewis has reached a point in his artistic journey of being able to channel intense emotion directly into the works, even if he remains ill at ease with the experience of them outside of their sculptural vessels. “As I grow older, I am trying to live more courageously and openly and, in this sense, my sculptures are ahead of me,” the artist reflects.

Much of the power of these works comes from Dylan’s astute ability to embed emotion within the physicality of his figures. There is a concentrated energy captured in their body language and muscular tension which communicates so much about their inner battles, and how these affect their relationships to their corresponding pairs. It is a richly empathetic body of work; we know these feelings deeply within our bodies.

The emotions shift substantially across these sculptural sketches. In some, there is an intimate stillness, in others a wild eroticism. Others depict grief and power struggles. Often, there is an underlying sense of longing, attempting to relate to or connect with others while preserving one’s own authenticity. Intrinsically, there is the sense that within personal relationships, love and cruelty can unintentionally be two sides of the same coin, both sustaining and subjugating.

The figures in these sculptures are perpetually pulled between agony and ecstasy. Embracing, fighting, grieving, struggling, they channel both the freedom and burden of intimate connection. These are the innumerable micro-conflicts that permeate our relationships with others and ourselves.

“The beauty and terror of the human condition is hard enough to bear when it is a step removed from us,” Dylan asserts. “However, in intimate relationships, the same forces are at play but the difference is that this is where we are truly the most vulnerable, so the horror and beauty of the world is magnified. When love fails, we are confronted with the raw existential pain of loss, of aloneness, of not being able to meet the most fundamental human needs of connection and acceptance. If our intimate relationships are intact, we can stand against the world ‘out there’, but what do we do when our nature brings us into opposition with those closest, those we love? How do I express my desires, my true nature, and still get support from group, tribe, without being ostracised and thrown out?”

Dylan working on Monumental Interrelation IX in his studio.

Photograph by Stella Olivier

Dylan working on Monumental Interrelation IX in his studio.

Photograph by Stella Olivier

Interrelation Miniature S-H 13 d, bronze, edition of 100 17 x 7 x 12 cm

Interrelation Miniature S-H 22 d, bronze, edition of 100 13 x 11 x 17 cm

Interrelation VII Maquette I S-H 20 b, bronze, edition of 25 30 x 13 x 15 cm

Interrelation Miniature S-H 13 d, bronze, edition of 100 17 x 7 x 12 cm

Interrelation Miniature S-H 22 d, bronze, edition of 100 13 x 11 x 17 cm

Interrelation VII Maquette I S-H 20 b, bronze, edition of 25 30 x 13 x 15 cm

Interrelation XIII Maquette II

S-H 36 c, epoxy composite resin

Interrelation XIII Maquette II

S-H 36 c, epoxy composite resin

Interrelation V Maquette I S-H 15 b, bronze, edition of 25 32 x 15 x 24 cm

Torso III

P003, Giclée print on Hahnemühle etching paper, edition of 75 64 x 92 cm

Torso I

P001, Giclée print on Hahnemühle etching paper, edition of 75 64 x 92 cm

Interrelation V Maquette I S-H 15 b, bronze, edition of 25 32 x 15 x 24 cm

Torso III

P003, Giclée print on Hahnemühle etching paper, edition of 75 64 x 92 cm

Torso I

P001, Giclée print on Hahnemühle etching paper, edition of 75 64 x 92 cm

Dylan sculpting in his studio with Monumental Interrelation XIII in the background

Dylan sculpting in his studio with Monumental Interrelation XIII in the background

The fields of genetic research, palaeoarchaeology, and evolutionary psychology are increasingly unearthing just how strongly most contemporary human behaviour is ingrained in the distant past. In Dylan Lewis’s view, reconnection with the deeply rooted knowledge of our ancestral past holds the key to moving beyond the perplexities of the present. “It seems like past generations are contained within our body and psyche,” he explains. “In evolution, you layer additional features on top of old features. Every one of our physical features and behaviours can be traced to some point in our evolution and all of that continues to live, breathe, divide and metabolise within us.”

Carl Jung believed that the ‘collective unconscious’ constitutes a facet of the human psyche shared universally among all individuals. These elements, deeply embedded in the human mind, manifest as universal experiences, symbols, and archetypes that span various cultures and societies. They find their expression in myths, dreams, symbols, and cultural narratives, compounding like layers of sedimentary rock.

Dylan Lewis’s Trance busts intentionally speak to this visual metaphor through the rock formations which rise out of the figures. In a sense, the sculptures appear to have undergone fossilisation and have become stone. Dylan seems to be invoking the idea of the collective unconscious through this, of something akin to genetic memory, something ancient but fundamental, rooted in nature, that has steadfastly endured. We can think here too of the giant Moai stone sculptures that punctuate Easter Island’s barren landscape, believed to be ceremonial conduits for speaking to the gods above.

The pieces in this series create a compelling contrast by combining more traditional academic human busts with the intricate interplay of conflicting emotions emanating from within them. The Trance busts could be seen as a sort of paleoethological excavation for Dylan. They mark a symbolic locating of artefacts which speak to the deep-rooted origins of our modern behaviour within the layers of our behavioural evolution.

“The difficult challenge is to make sense of, understand and interpret all the different voices and impulses at play in our psyche,” Dylan proposes. “To trace them back to their origins as best we can, to understand what they are asking of us, to separate out the deck of cards we have been dealt including genes and epigenetics, behavioural biochemistry, cultural forces, early family dynamics, evolutionary psychology, and finally the more esoteric forces like body memory and collective unconscious. It is not surprising that Auden said, ‘We are lived by powers we pretend to understand.’”

Trance II Maquette S-H 77 (5), epoxy composite resin

Trance III Maquette I epoxy composite resin

Trance III Maquette I epoxy composite resin

Trance Miniature S-H 77 (5a), bronze, edition of 100 22 x 8 x 8 cm

Trance Miniature S-H 77 (2a), bronze, edition of 100 21 x 9 x 7 cm

Trance Miniature S-H 77 (1a), bronze, edition of 100 21 x 10 x 10 cm

Trance Miniature S-H 77 (5a), bronze, edition of 100 22 x 8 x 8 cm

Trance Miniature S-H 77 (2a), bronze, edition of 100 21 x 9 x 7 cm

Trance Miniature S-H 77 (1a), bronze, edition of 100 21 x 10 x 10 cm

Trance II Maquette S-H 77 (5), bronze, edition of 8 124 x 48 x 60 cm

Trance II Maquette S-H 77 (5), bronze, edition of 8 124 x 48 x 60 cm

Unquestionably one of the most striking images that Dylan Lewis has produced, the maelstrom of Vortex continues to grow in scale and complexity. Beginning life as a sculptural sketch rendered in bas-relief, the swirling mass of human figures has expanded into increasingly monumental incarnations and smaller maquette interpretations. Each version is never an exact reproduction, Dylan allows the work to intuitively evolve as he reflects on, and responds to, the ideas that the rich imagery carries.

Vortex marks the next step in the evolution of Dylan’s work with human figures, bringing together themes and ideas from across these works, and beyond. It speaks to the idea that while each person carries their own personal heavens and hells, we are all caught up in the greater irreconcilable riptides of the human experience. Figures claw and writhe. There is pain. There is intense joy. There is alienation. There is connection. There is tumult. That recurring theme in Dylan’s work – the tension between wildness and tameness – returns through the contrast between the frenetic figurative imagery and the beauty of the circular composition.

Within the first iteration, the circular tide of the Vortex’s figures is contained within a broader square shape. This brings to mind the metaphorical conundrum of the ‘squaring of the circle’. Taking its name from a perpetually elusive Greek mathematics problem, the idea has extended beyond its mathematical origins to refer to any endeavour or situation where someone is attempting to reconcile two opposing or incompatible ideas, goals, or principles. This is precisely Dylan’s point about the seeming impossibility of aligning personal authenticity and freedom with the expectations and wishes of social and intimate relationships.

As with the idea of squaring the circle, Dylan Lewis’s Vortex becomes about striving to achieve harmony through consolidating rationality with passions. It depicts the emotional battle of attempting to transcend the alienation of unchecked Logos – damaging religious, governmental, or societal constructs that seek to rationalise through fear and shame – and reconnect with the boundless instinctual life force of Eros. The initial iterations of the Vortex circled a central pair of Interrelation figures, their bodies seemingly forming an infinity symbol, the line that never ends. Dylan’s point is that even if this harmony is achieved, if the circle is squared, the resulting stability is inevitably temporary and we will soon have to be realigned once more.

Because of this formal tension, the Vortex feels like a threshold between two worlds, an idea that becomes compounded in the later, larger incarnations of the piece. Here Dylan omits the central figures, leaving a void behind. This absence shifts the reading of the piece substantially. What felt like a whirlwind extending recursively suddenly resembles a cave mouth. Once more, the figures transform into a living geology, evoking the undulating contours of cave walls, reminiscent of ancient rock visages.

As the work expands to a monumental scale, it becomes an immersive space that completely envelopes the viewer in concentric compositions. From this perspective, it is no longer a whirlwind but a grotto. The animal sculptures return, coexisting with the human forms. For the viewer, there is the sense that the threshold is now between a space of rich symbolism and the world outside.

Chthonios I Monumental I

S-H 83 (3), epoxy composite resin

Dylan in his studio with Monumental Vortex III in the foreground

Dylan in his studio with Monumental Vortex III in the foreground

Dylan Lewis is a South African artist who has emerged as one of the foremost figures in contemporary figurative sculpture. Lewis’s work features in private collections throughout the UK, Continental Europe, the United States and Australia, and he is one of only a handful of living artists to have had solo auctions of his sculpture with Christie’s in London. Lewis’s primary inspiration is wilderness. At one level his bronze sculptures celebrate the power and movement of Africa’s life forms; at another the textures he creates speak of the continent’s primeval, rugged landscapes and their ancient rhythms. He works intensively from life, filling books with sketches, notes and drawings. By referring to these in the solitude of his studio, he is able to reproduce the subject’s physical form while exploring their more abstract, deeper meaning. Dylan was born in 1964 and raised in an artistic family in South Africa. His father was an accomplished sculptor, his mother and his grandmother were painters, and his two great-grandfathers were an architect and cabinet-maker, respectively. Lewis initially followed in the family tradition, beginning his career as a painter (studying under Ryno Swart), but later turned to sculpture. Widely recognised as one of the world’s foremost sculptors of the animal form, he initially focused on the big cats. In recent years, he has used the human figure to explore our relationship with our inner wilderness.

Monumental Lion Torso Fragment S362, epoxy composite resin

Photograph by Gerda Genis

Catalogue photography by Hayden Phipps Text by Tim Leibbrandt

Monumental Lion Torso Fragment S362, epoxy composite resin

Photograph by Gerda Genis

Catalogue photography by Hayden Phipps Text by Tim Leibbrandt