— Laura T., Fort Worth

— Laura T., Fort Worth

46 Hold the Mole Burgers, barbecue, and steak? They’re everywhere. But only Texas can claim Tex-Mex. In Fort Worth, the cuisine is as big in the culture as steers. Plate me, andale.

By Malcolm Mayhew

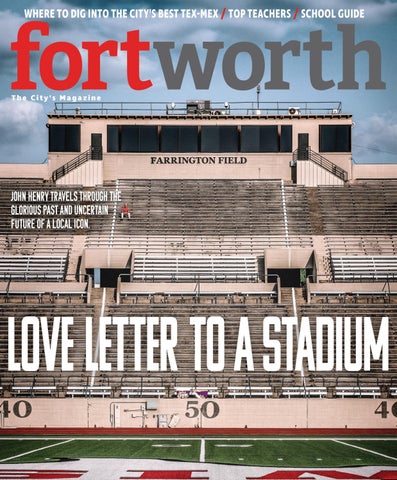

36 Save It, and They Will Come Farrington Field isn’t just a stadium. It’s part of the soul of Fort Worth, a place that connects us all regardless of neighborhood, race, creed, or socioeconomic status. Its future is up in the air. For John Henry, it’s personal.

By John Henry

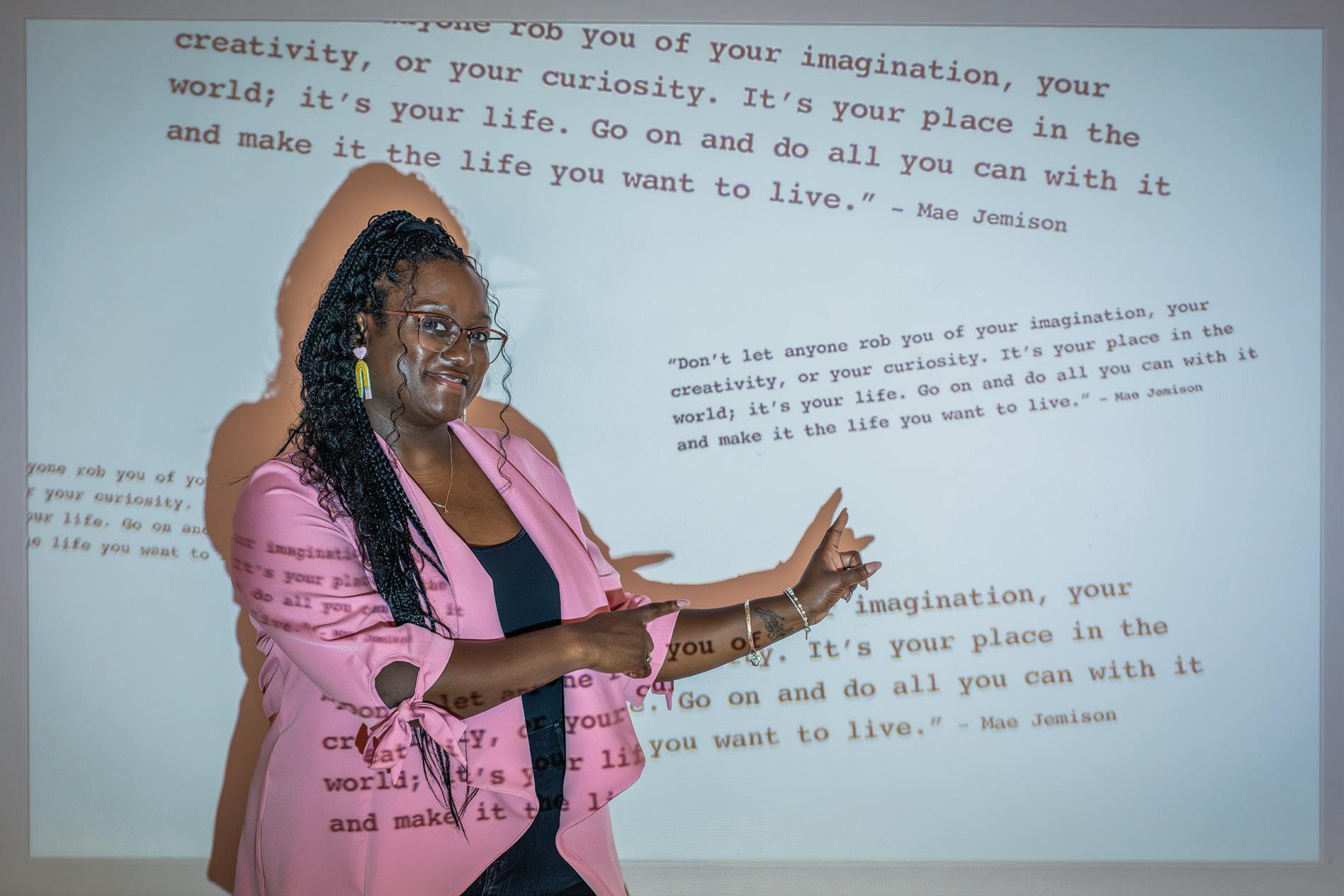

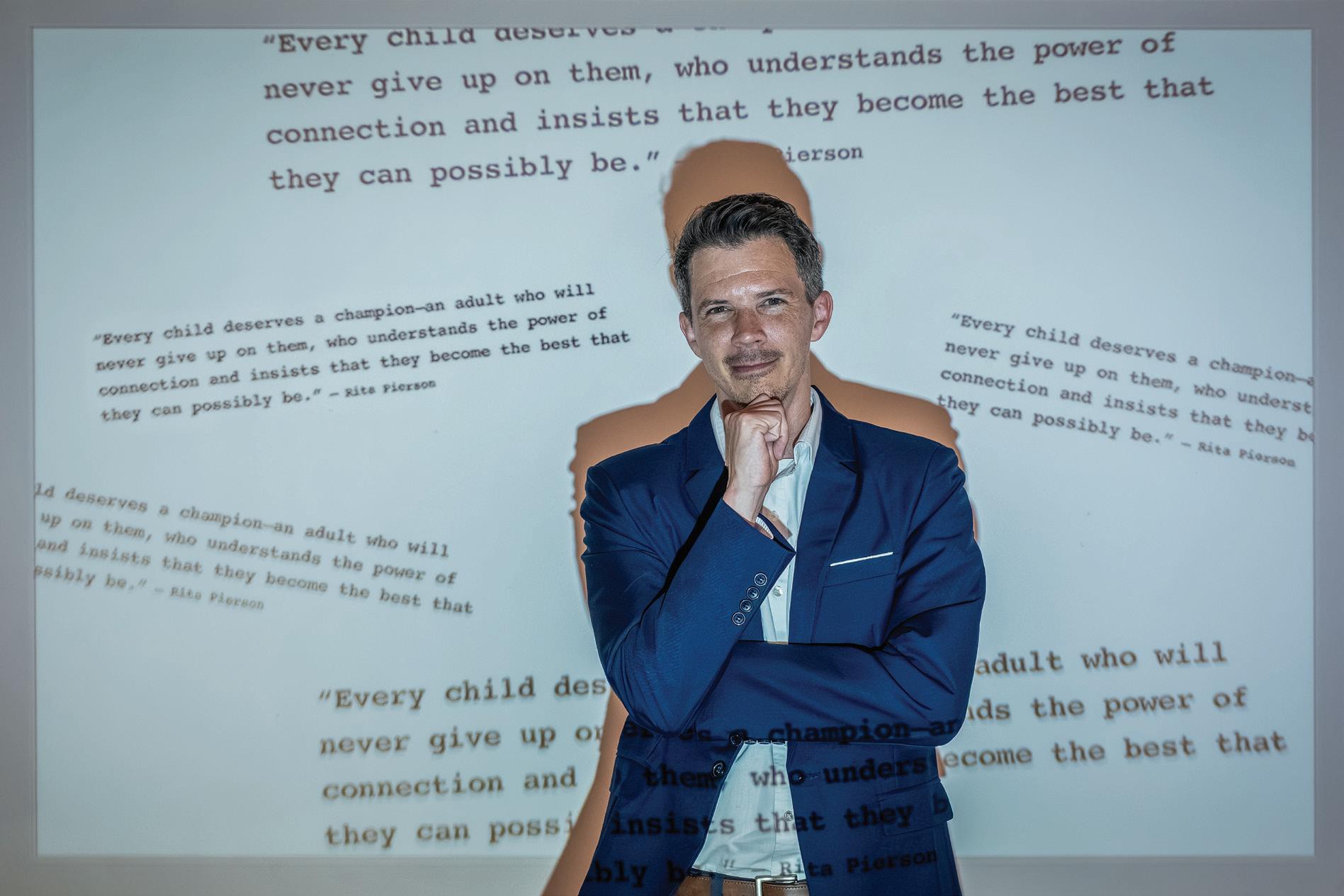

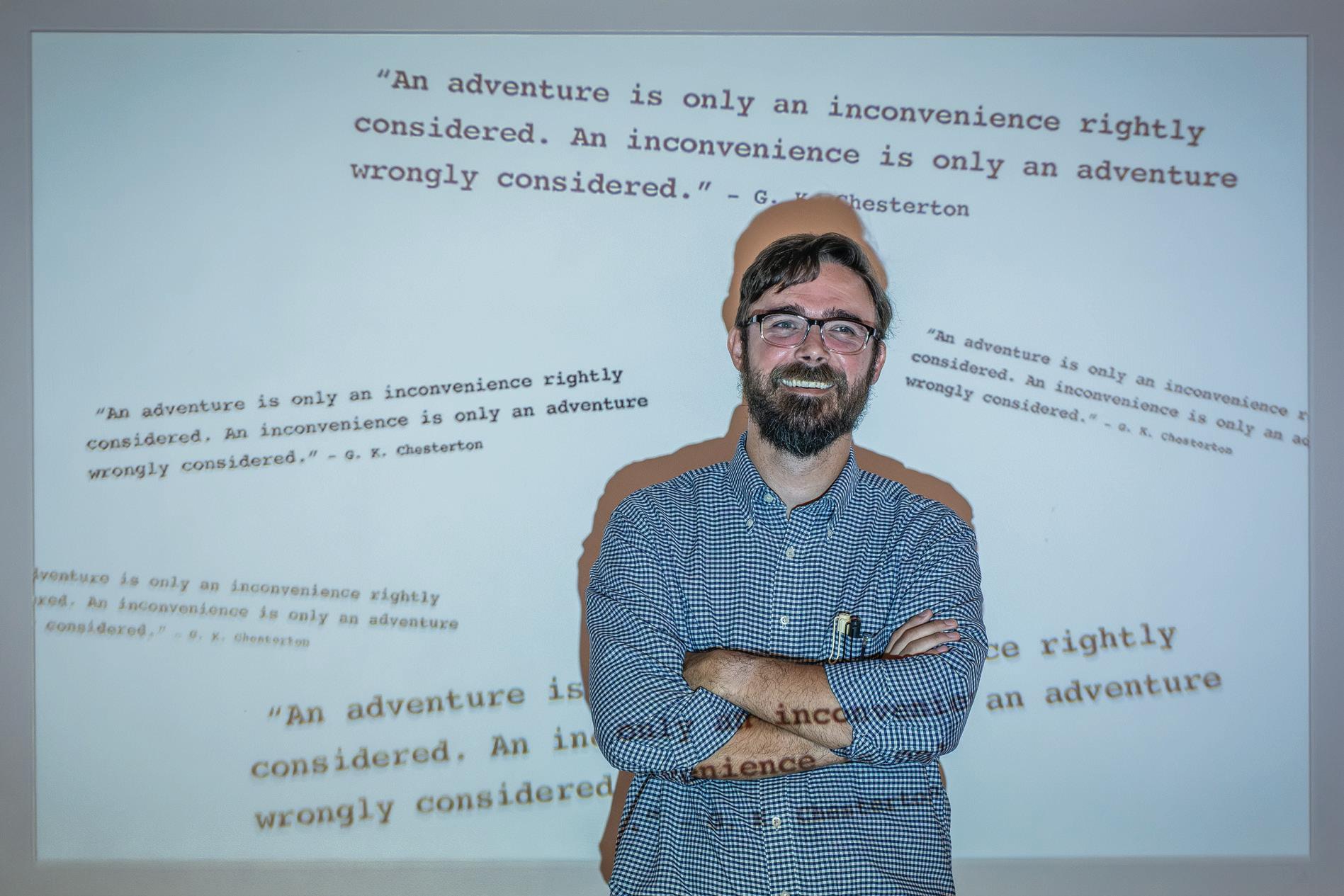

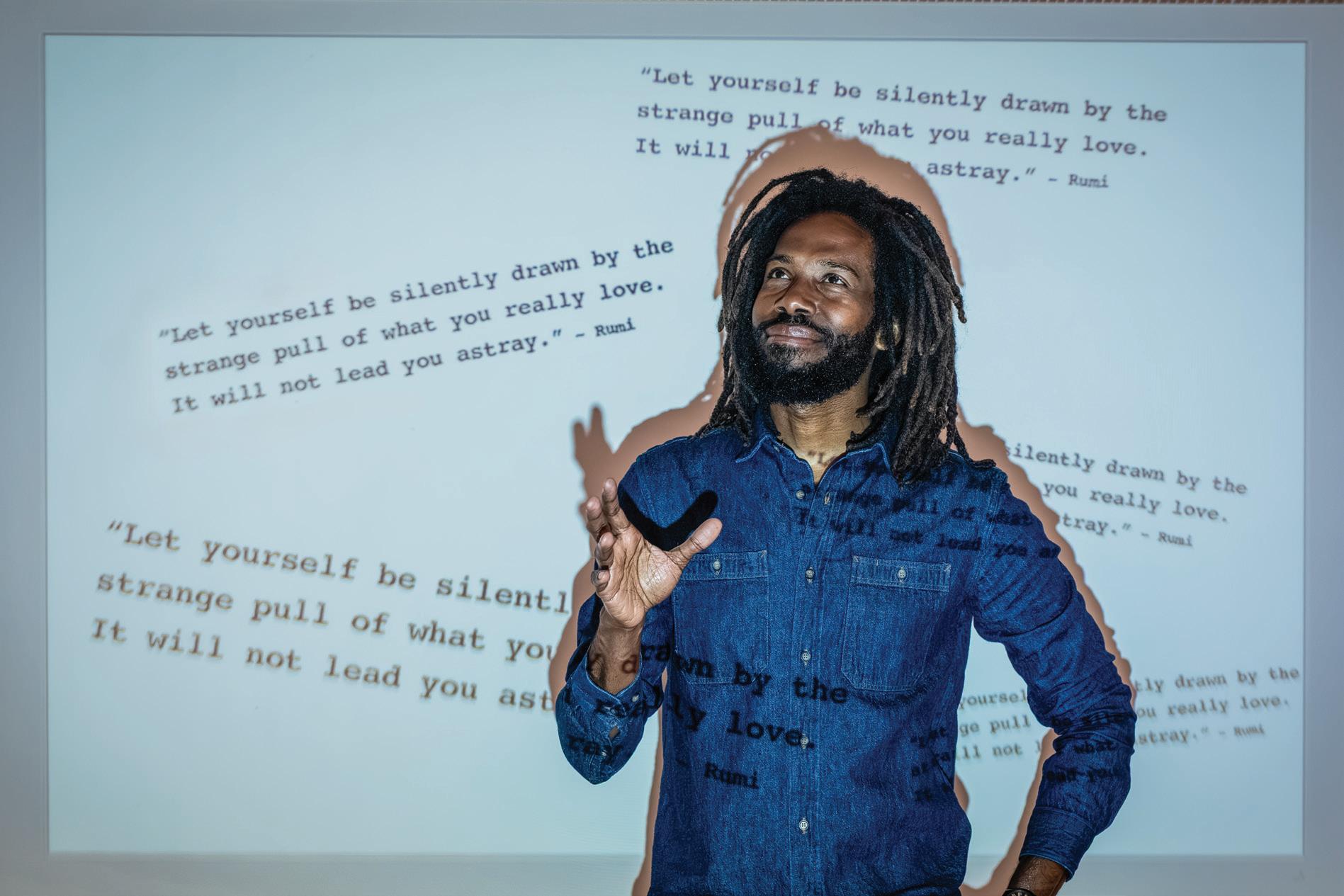

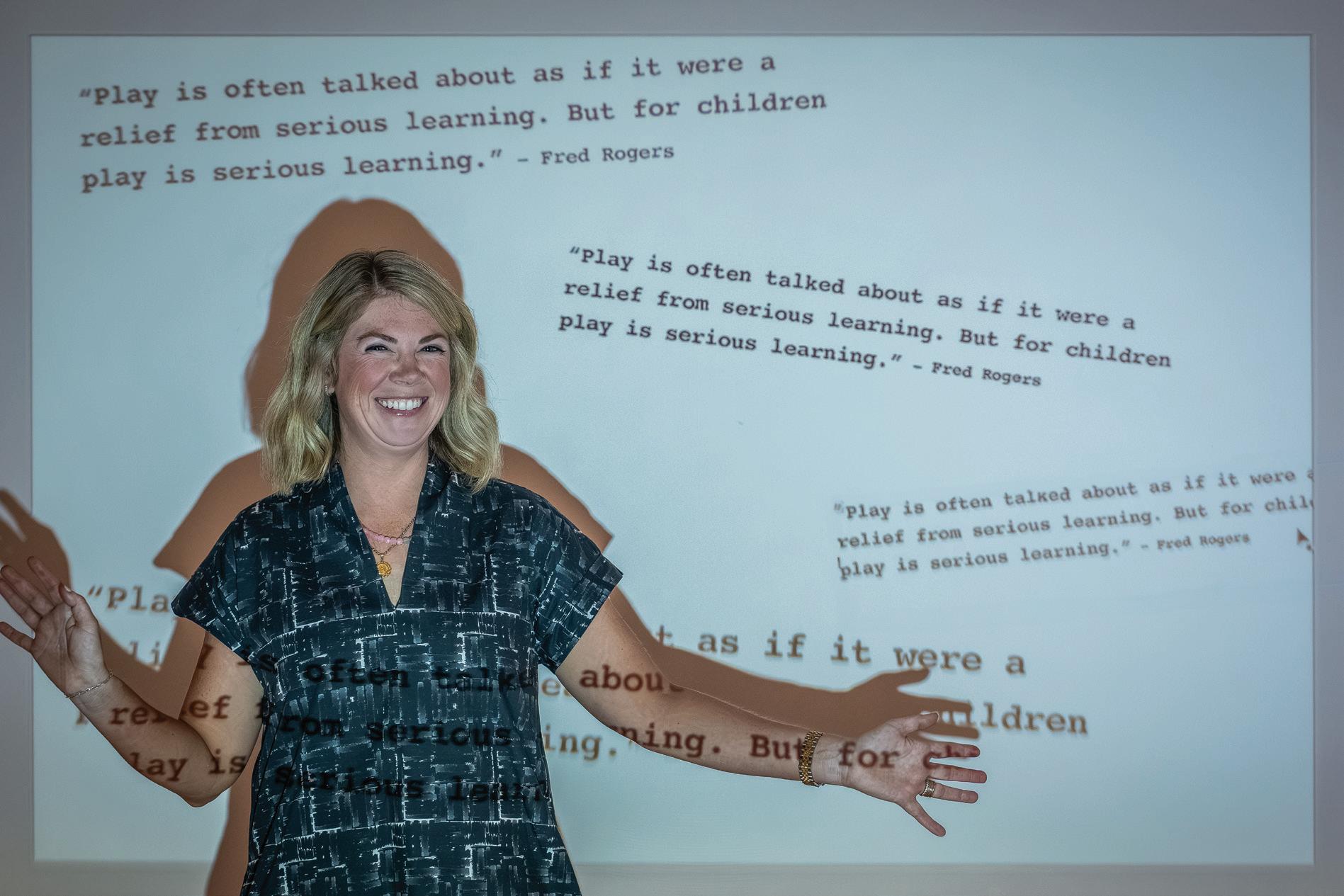

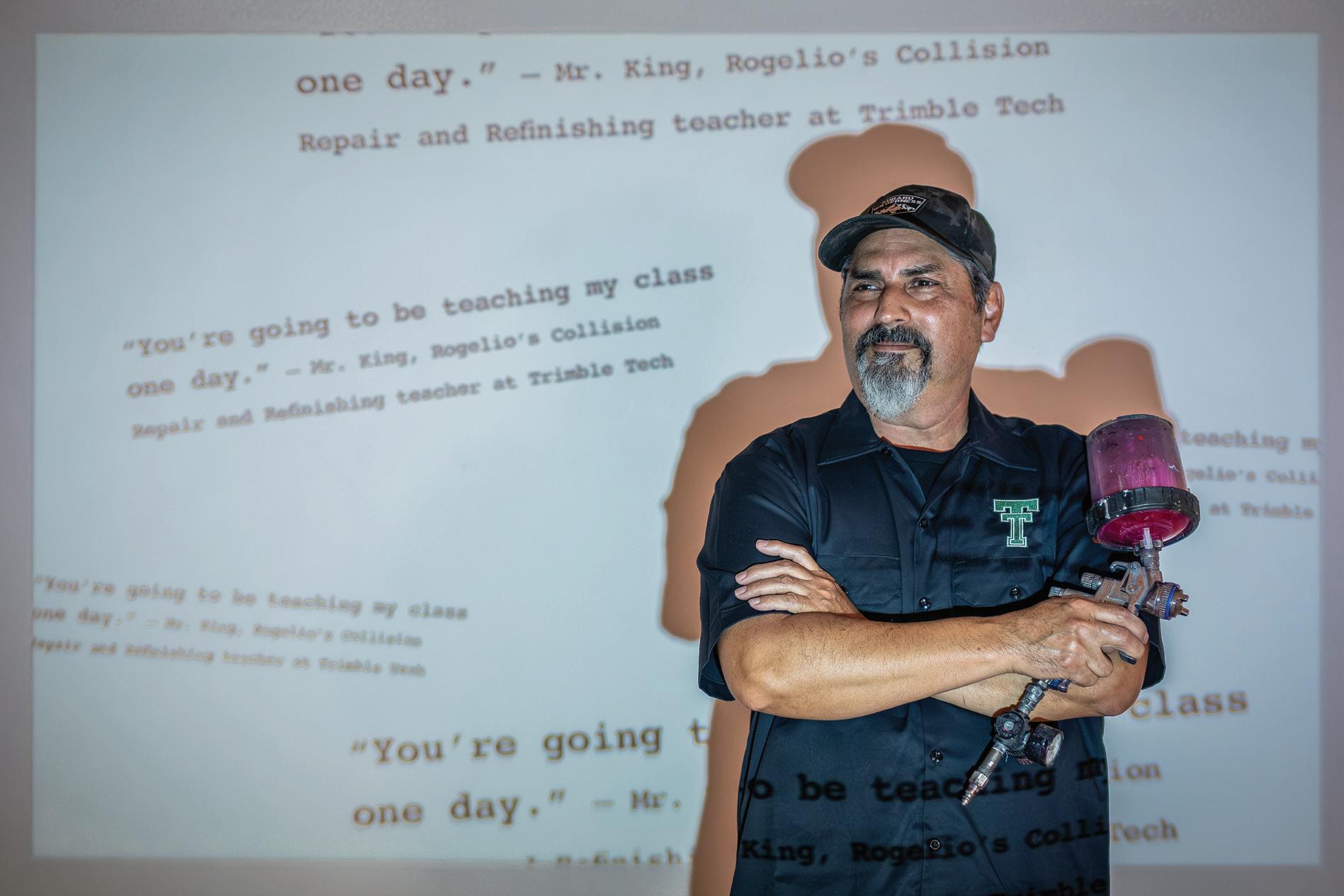

Every success story starts with a great teacher. These 10 teachers inspire, lead, and shape the future, one student at a time.

By Brian Kendall

14 City Dweller

Fort Worth citizens rally to the side of devastated Kerr County, pitching in with financial resources, boots on the ground, and prayer.

20 Calendar

Save the dates for “The Book of Mormon” and Pat Green and Randy Rogers at Billy Bob’s.

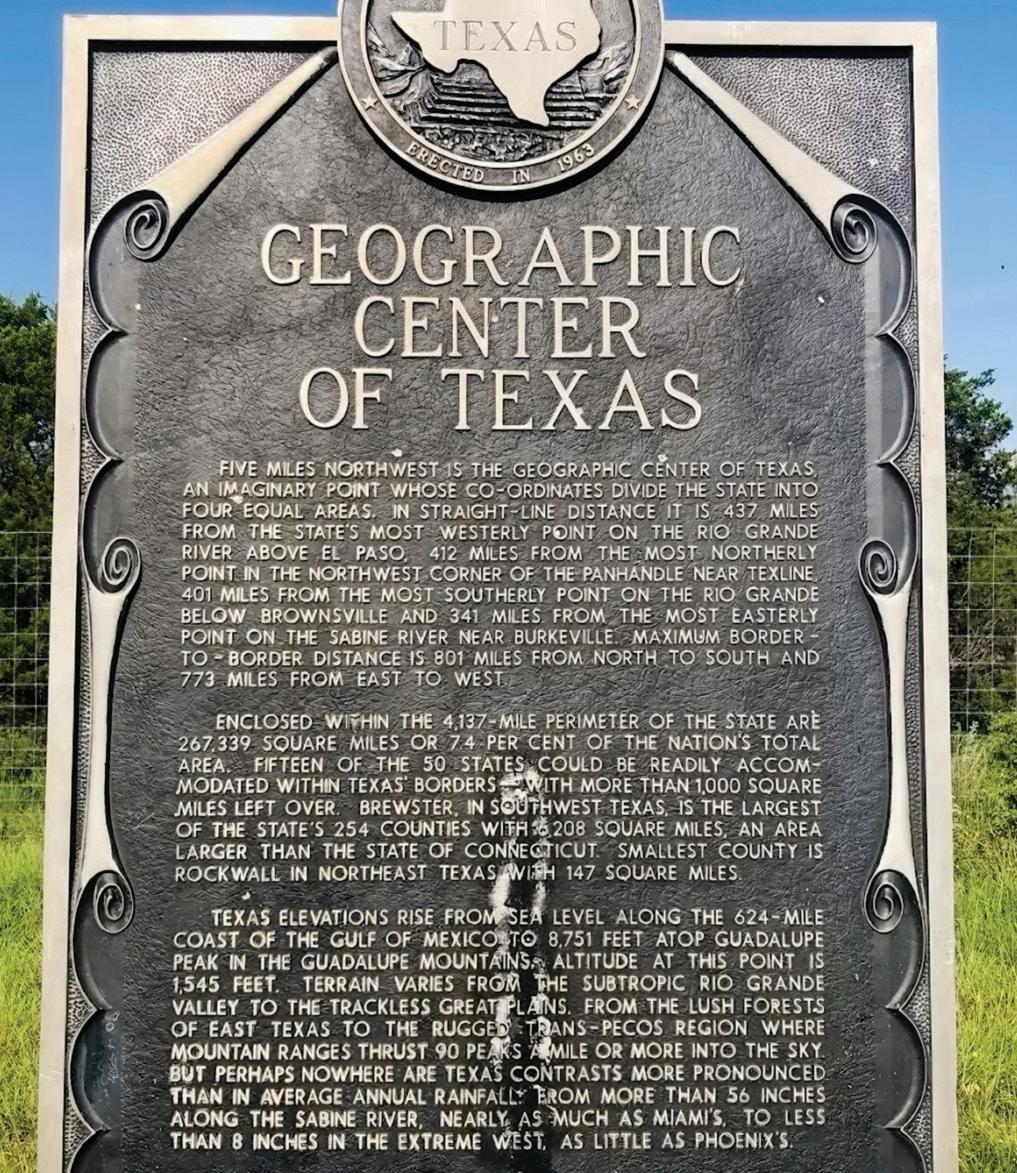

22 State Lines Brady, Texas: pop. 4,965.

26 Cowhand Culture

Little Richard’s show in Fort Worth in 1956 went off without a hitch, despite a high-profile mishap in Amarillo. A firsthand account.

32 The Reverie

One guy gets a taste of filmmaking in Fort Worth as an extra, err, background artist.

82 Dining

Here’s your table talk: Updates for the everhungry Fort Worth foodie community.

WE COMPOUND:

» Weight Loss Injections

» Ophthalmic Sterile Solutions

» Hormone Replacement Therapies

» Pediatric Medications

» Dermatological Preparations

» ED And Women’s Health Treatments

» Veterinary Medications

The best find of my yearslong pursuit of everything related to Farrington Field is Evan Farrington. He is the grandson of stadium namesake E.S. Farrington, the Fort Worth athletic director and visionary who was the driving force for building the historic facility on the corner of University Drive and Lancaster Avenue.

Evan and his wife, Melaine, have become good friends over the years. I found Evan about 15 years ago on a standard Google search. We discovered we had much in common. Barbecue and beer, margaritas and Tex-Mex, sports, faith tradition, and an appreciation and love for history and heritage — specifically how those things align with the preservation of Farrington Field.

We’ve spent untold hours discussing the possibilities of what could be for this civic treasure.

On a broader spectrum is the discussion about old places. Old places matter not just because they’re old, but because they’re ours. They carry the fingerprints of those who came before us: the dreams of E.S. Farrington, the creativity of the architects and the craftsmen who constructed it, of teachers and coaches. The handiwork of artist Evaline Sellors on the west side façade is her bestknown work.

As important are the relationships forged there both as teammates and competitors.

Earl Campbell and Mike Renfro became close friends as teammates of the NFL’s Houston Oilers, but they first met as combatants at Farrington Field in a high school football playoff game.

Farrington Field is a place where four generations have gathered. Where they made memories. Where they fell in love. Where they won and lost. Where they showed up. Where they grew up.

Nothing can replicate that.

Preservation isn’t nostalgia. It’s stewardship. It’s understanding that cities, like people, have souls. That soul lives in the spaces we inherit, not just the ones we

invent, and the people who came before us.

In that way, Farrington Field, and buildings like it, are our identity. You can’t just simply toss it to the ash heap without significant cultural loss.

The past, present, and future are interconnected.

Fort Worth is a city built on great neighborhoods and rich in historic character — from its pioneer roots and cattle drives to the Stockyards, railroads, oil boom, and aviation legacy. As a matter of public policy, the city recognizes that identifying, preserving, and celebrating these cultural resources is essential to supporting Fort Worth’s economic vitality, cultural identity, educational value, and overall public good, particularly as we surge past one million people.

Naturally, we can’t save them all. As Jerre Tracy, the executive director of Historic Fort Worth Inc., said to me, money is at the heart of all preservation projects. Sometimes it’s simply not there, and difficult decisions have to be made.

But the next time someone tells you a building or stadium is a “dump,” the next logical question is, “How do we fix that? Can we fix it? Is it worth keeping?”

More often than not, the answer is yes. Cities aren’t great because of what they build. They’re great because of what they choose to keep.

John Henry CONTRIBUTING EDITOR

Olaf Growald snapped this shot early in the morning at Farrington Field with Henry, our FortWorth Inc.editor who scribed the cover story, hanging out in the empty stands.

CORRECTIONS? COMMENTS? CONCERNS?

Send to executive editor Brian Kendall at bkendall@fwtexas.com.

NEXT MONTH

Women Who Forward Fort Worth

Cowgirls of the Chisholm Trail

TCU Kickoff Preview

Texas Rattlers

Tell us about a teacher who inspired you or had a positive impact on your life.

My third-grade teacher, Mrs. Cooper. Scatterbrained, cluttered, and incredibly creative, I’ve never related to a teacher more. Can’t tell you what I learned that year beyond gaining a better understanding and confidence in who I am, which is a hell of a thing.

Certainly one would be Dr. Camilo Martinez, a professor of history at Texas Tech, who reminded us of the most important reason we were there: “One day, in the middle of the night, you’ll get a phone call. Your kid is in jail. You happened to sit next to the sheriff in history class 25 years ago.”

I’ve got two shout-outs for my high school English teachers, Mrs. Hilbert and Mrs. Williams. I was a rebellious kid, but they looked past all that and helped me find a passion for writing. And now, here I am.

My business teacher at Abilene High School, Mrs. Billie Gray, taught more than just shorthand and typing — she gave me the tools to support myself through college and inspired me to follow in her footsteps and become a business teacher myself.

owner/publisher hal a. brown

president mike waldum

EDITORIAL

executive editor brian kendall

contributing editor john henry

digital editor stephen montoya

contributing writers malcolm mayhew, michael h. price, shilo urban

copy editor sharon casseday

editorial intern maddy clark

ART

creative director craig sylva

senior art director spray gleaves

contributing ad designer jonathon won

ADVERTISING

advertising account supervisors

gina burns-wigginton x150

marion c. knight x135

account executive tammy denapoli x141 territory manager, fort worth inc. rita hale x133

senior production manager

michelle mcghee x116

MARKETING

director of digital robby kyser director of marketing grace behr events and promotions director victoria albrecht

project manager kaitlyn lisenby events and promotion interns

keely garcia, stella todd

CORPORATE

chief financial officer charles newton

founding publisher mark hulme

CONTACT US

main line 817.560.6111

subscriptions 817.766.5550 fwmagsubscriptions@omeda.com

My high school art teacher was no slouch; he taught me figure proportion and perspective. But the one that started the real creativity bug was my sixth-grade teacher, Mr. Black. He approached every lesson with a twist, using art and storytelling to enhance each assignment — from history to world economics — it made us absorb every lecture.

Recently, a teacher that made a lasting impression on me was Mr. Scotty Miller at Burleson High School. He was my son’s teacher last year for his construction class. My son was going through a rough time, and over the Christmas break, Mr. Miller took time to call and check in on him. Mr. Miller’s class was the only class my son actually enjoyed going to.

One of the most incredible teachers I’ve ever known is my mom; her students called her Ms. K. She taught high school English and was known for her strict grading standards. She would deduct 25 points — or even give a zero — for certain grammatical mistakes on a paper. At the time, I thought it was a bit harsh, but she believed that by setting high expectations, her students would develop strong writing skills and be better prepared for college.

DIGITAL EDITION:

The virtual editions of both current and previous issues are available on our website. Flip through the pages to read more about the great city of Fort Worth by visiting fwtx.com.

©2025 Panther City Media Group, LP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher.

FortWorthMagazine(ISSN 1536-8939) is published monthly by Panther City Media Group, LP, 6777 Camp Bowie Blvd., Suite 130, Fort Worth, TX 76116. Periodicals Postage Paid at Fort Worth, Texas. POSTMASTER: Send change of address notices and undeliverable copies to Panther City Media Group, PO Box 213, Lincolnshire, IL 60069. Volume 28, Number 8, August 2025. Basic

Subscription price: $21.95 per year. Single copy price: $4.99

817.570.9401

PAT GREEN Fort Worth jumped to the aid of a devastated Kerr County with financial resources and boots on the ground. Pat Green, who lost his brother, sister-in-law, and their family in the tragedy, assembled musicians for a $1 million fundraiser.

WHAT WE’RE WRITING ABOUT THIS MONTH:

On page 20 Things to do in August. On page 22 Brady is the GOAT of world championship barbecue goat cookoffs — we hope you followed that. On page 26 Little Richard played without incident in Fort Worth in 1956, despite a notable dustup on the way while in Amarillo. On page 32 Fort Worth’s burgeoning film industry comes with lots of “extras.”

by Stephen Montoya

It’s been difficult to find the words to illustrate such a tragedy — none seem adequate.

The entirety of Texas — and beyond — has been in a state of shellshock since the early hours of July 4, when hard rain caused the Guadalupe River to rise to never-before-seen levels in Kerr County. The river reached a record-breaking crest in Hunt, rising 26 feet in 45 minutes, and surged through homes, cabins, and campgrounds. Ten million pounds of water flowed every second — 1,000 times faster than normal and comparable to the rush of water one would experience at the drop of Niagara Falls.

Stories from survivors paint a particularly harrowing scene — desperate clinging to large floating objects the only recourse for those who made it

out alive. But many didn’t. And many are still missing.

At press, the death toll has reached 135 — a number we would have collectively described as unfathomable on July 3. Among those who lost their lives include 27 young girls, teenage counselors, and staff of Camp Mystic, an all-girls Christian summer camp. Still photographs of their ravaged lodging — mud-covered purple and pink comforters and stuffed animals strewn about destroyed bunk beds — put a heartbreaking and indelible face to the incomprehensible scale of the tragedy.

Questions as to how and why this happened will linger for some time; the why question will likely never go away.

Very few Texans escaped this event unscathed; you likely know someone or know someone who knows some-

one whose life has been forever altered since July 4. Grief-stricken Texas country legend and Fort Worth local Pat Green lost his younger brother John, John’s wife Julia, and their two sons — Green’s nephews.

Fort Worth, whether through donations, creative ideas, or boots on the ground, has stepped up to lend a helping hand.

In fact, before the floodwaters had even receded, Fort Worth was mobilizing. Seventeen members of the Fort Worth Fire Department — including divers and elite swift-water rescue personnel — were deployed to Kerr County, where they assisted in the search for survivors and recovering the bodies of those who had died.

At the same time, grassroots efforts began to blossom. Corrigan Camp, a girl who had attended Camp Mystic just two weeks earlier, and her brother, Cannon, set up a lemonade and cookie stand in their Fort Worth neighborhood. Their fundraiser benefited both Camp Mystic and a nearby boys’ camp that suffered flood damage, transforming personal grief into support.

“It makes me feel very sad for the people that were at Camp Mystic,” Corrigan told Fox 4 News. “Everyone should help, and they’re being very generous to help us.”

Local restaurants pitched in, too. La Bistro Italian Grill, a family-owned establishment in Hurst, pledged 100% of food and beverage sales that ran from July 7 through 10 to flood relief. The restaurant owner posted on Facebook, “I may not have the power to change what happened, but I do have the power to feed people.”

Chef Jon Bonnell, a stalwart of Fort Worth’s culinary scene, committed 10% of sales from his restaurants (Bonnell’s, Waters, Jon’s Grille, and Buffalo Bros) from July 7 to 11 to vetted relief efforts. And bartender Hannah Rucas donated all tips from a night’s shift at Bush League Bar & Grill, raising $1,300 to aid Hill Country communities.

Fort Worth’s celebrity chef, Tim Love, used his clout to launch “Hats with Heart,” a limited-edition cap

Designers, Builders, and Home Owners agree, The Jarrell Company is the trusted name in appliances, plumbing, lighting, and decorative hardware solutions. To book your complimentary one-on-one design consultation or to locate a show room near you, scan the QR Code:

fundraiser for flood recovery (available at shoptimlove.com). Proceeds benefit grief counseling through M2G Ventures’ Mental Health Initiative and disaster relief meals provided by José Andrés’ World Central Kitchen. “This isn’t just about money,” Love said. “It’s about showing up. Texas is a big place, but in moments like these, we become one tight-knit community.”

Meanwhile, donation stations accepting canned goods, diapers, pet food, and school supplies were established throughout the Stockyards, including Hotel Drover, H3 Ranch, and 97 West Kitchen & Bar.

Not turning a blind eye to our furry friends, Humane Society of North Texas has played a vital role in animal rescue efforts. Partnering with Wings of Rescue, a national nonprofit specializing in emergency animal airlifts, HSNT has assisted in the evacuation over 200 dogs and cats from shelters overwhelmed by the flood, freeing up critical space at shelters in affected counties. HSNT then coordinated medical treatment and adoption placements for many of the evacuated pets across North Texas.

Fort Worth country musician Josh Weathers raised nearly $500,000 to aid flood victims after an impulsive four-hour livestream, where he played a slew of Texas country favorites, and silent auction that featured brisket, guided hunts, and weekend getaways.

Transforming his tragic loss of family members into public purpose, Pat Green hosted a benefit concert from Globe Life Field on July 16, which featured fellow country stars Miranda Lambert, Dierks Bentley, Jon Pardi, Casey Donahew, and Joe Nichols. The event — streamed free on YouTube and Givebutter — raised over $1 million for families affected by the disaster.

As part of that effort, Fort Worthbased EECU Community Foundation presented a gift of $50,000 to The Pat Green Foundation.

“This is the only way I know how to help,” Green said. “We all look after each other in this big place.”

Frank Kent Motor Co., one of Texas’ longest-standing family-owned automotive dealerships with nearly a century of history, is being sold, marking the end of an era for a family that has been synonymous with Fort Worth’s automotive industry for generations.

The company founded by Frank Kent in 1935 has reached an agreement to sell its dealerships — Frank Kent Cadillac Fort Worth and Frank Kent Cadillac Arlington — to Autobahn Fort Worth, Frank Kent co-owner Will Churchill confirmed in July.

The deal is contingent on manufacturer approval, but pending that, the transaction is expected to close in October, Churchill said.

Autobahn will keep the brand name, something critical to Churchill and his sister Corrie, who have co-owned the dealership since the death of their mother, Wendy Kent Churchill, in 2005. Staff is not expected to change, Churchill said.

“Their culture aligns with ours. They’re in a growth stage. They’re Fort Worth,” said Churchill, the great-grandson of the founder. “It gives all of our young people an opportunity to grow. It gives us an opportunity to ensure the Frank Kent brand will be around for a 100th anniversary.”

Autobahn Fort Worth, a 45-yearold luxury car dealership owned by Fort Worth investor Robert Bass, is preparing to relocate. The dealership currently operates from 3000 White Settlement Road, where it sells and services premium brands like BMW, Porsche, Land Rover, Volvo, Volkswagen, and Mini.

Facing space constraints and looming redevelopment plans in the area, the company has secured a new home on a nearly 75-acre site

off Oakmont Boulevard in southwest Fort Worth, near Chisholm Trail Parkway. The new dealership campus, on land owned by Clearfork developer Cassco, is scheduled to break ground this summer and open by December 2026.

The Frank Kent dealerships will remain at their current sites, Churchill said.

“Really, it’s almost just pulling Corrie and me out and inserting Autobahn,” Churchill said.

The Frank Kent legacy is deeply rooted in Fort Worth. You can’t talk about Fort Worth’s automotive history without mentioning the name.

Frank D. Kent came to Fort Worth in 1927 as a used-car salesman. In 1930, he became a junior partner in the Webb-Kent Buick franchises after purchasing Earl North’s interest in Webb North Buick. Five years later, in 1935, he launched his own venture — the Frank Kent Motor Company — representing Ford and Lincoln Mercury.

In 1939, Kent relocated his growing dealership from West 7th Street to a prominent new facility at Main and Lancaster, a bustling intersection in the heart of downtown Fort Worth. Then in 1953, he made a bold pivot: Kent secured the prestigious Cadillac franchise and relinquished the Ford line, aligning his brand with the pinnacle of American automotive luxury in a move that would define the dealership’s identity for generations.

As chairman, Kent, along with then-President John Luddington, relocated the dealership to the Benbrook Traffic Circle

At the time of his death in 1987, his granddaughter, Wendy Kent Churchill, estimated that he had sold 31,000 Cadillacs in the 34 years.

by John Henry

Business leaders, public servants, longtime friends, and four generations of family gathered in First United Methodist Church in downtown Fort Worth last month to bid farewell to Jon Brumley, the pioneering entrepreneurial giant and civic leader whose influence shaped Texas business, education, and community life for more than half a century. Brumley died July 3. He was 86.

In a eulogy delivered by close friend Billy Rosenthal, Brumley was remembered for the quality he considered most essential: attitude. Rosenthal read a favorite reflection Brumley often passed out to colleagues and friends, a piece by Charles Swindoll that emphasized that life is 10% what happens to us and 90% how we respond.

We cannot change our past. We cannot change the fact that people will act in a certain way. We cannot change the inevitable. The only thing we can do is play the one string we have, and that is our attitude. Brumley, Rosenthal said, believed attitude could make or break a company, a church, or a home.

“Just remember Jon,” Rosenthal said. “He led with his heart. He loved every morning, and he always wanted more and better for each of us — whether it

was family, business, or community.”

Brumley’s professional legacy left a deep, lasting imprint on the oil and gas industry. He helped launch and lead a series of successful companies, including Cross Timbers Oil Company — later XTO Energy — with Steve Palko and Bob Simpson, and Encore Acquisition Company, which he co-founded with his son Jonny. The two were named Forbes Entrepreneurs of the Year in 2005.

Brumley set a record for public listings by any individual on the New York Stock Exchange.

But Brumley’s influence went far beyond business. In the early 1980s, he was tapped to chair a citizen commission to address the failures of school desegregation and busing in Fort Worth. He approached the task, family, friends, and stakeholders said, not with ideology but with humility, riding buses with concerned parents and ultimately delivering a set of reforms that won praise from across the political and racial spectrum. A federal judge called it the finest citizen commission ever brought before his court.

Later, as chairman of the Texas State Board of Education — appointed by Texas Gov. Mark White — Brumley implemented statewide academic reforms, including the controversial but lasting “no pass, no play” rule. It was in that role he met Rebecca Dawson Canning, the board’s vice chair and, later, his wife. They married after their terms ended.

Together, the Brumleys built Red Oak Ranch in East Texas, a place of family reunions, wildflower picnics, and campstyle weekends for grandkids. They also established the Red Oak Foundation, which has given away nearly 900,000 books to support early childhood literacy in Fort Worth.

Born in Pampa in 1939, Ira Jon Brumley was the youngest of three sons born to Raymond and Florence Brumley. He graduated from the University of Texas and later earned an MBA from the Wharton School.

Jon Brumley, a great life of Fort Worth.

A smattering of things you might’ve missed

1. Fort Worth Police’s Next Big Cheese: The City Manager’s office tells us the finalists for the city’s police chief are Interim Chief Robert Alldredge; former Dallas Chief Eddie Garcia; Vernon Hale, assistant chief of Prince George County in Maryland; and Emada Tingirides, deputy chief in Los Angeles. Garcia appears to be the leader in the clubhouse.

2. No … Kidding, Sherlock: Texas Gov. Greg Abbott signs a resolution declaring Fort Worth the Aviation and Defense Capital of Texas. Texas already knew that but carry on.

3. AllianceHollywood: Taylor Sheridan’s Bosque Ranch Productions secures roughly 450,000 square feet inside Hillwood’s 27,000-acre AllianceTexas masterplanned community — for what else? Visual storytelling, of course.

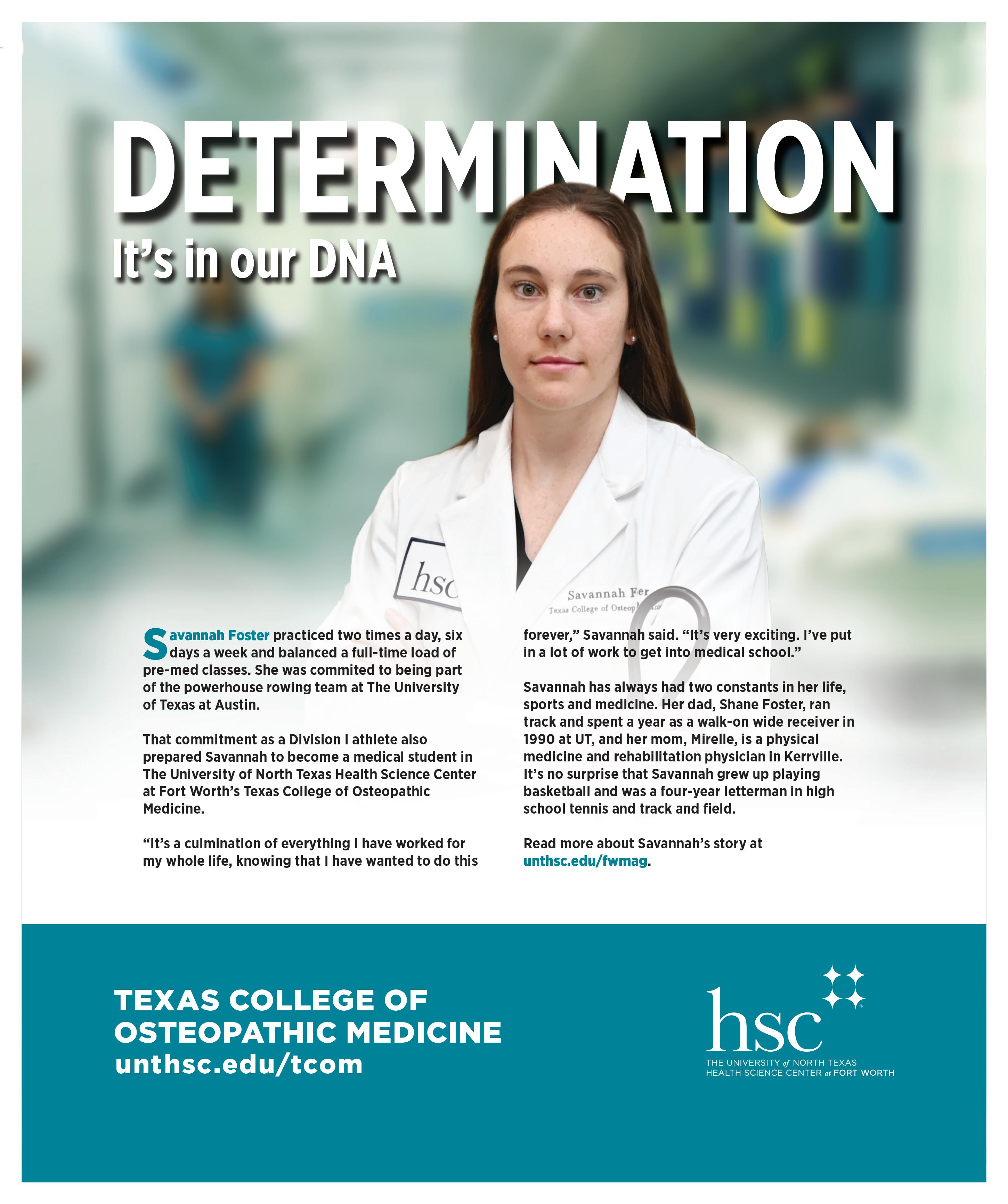

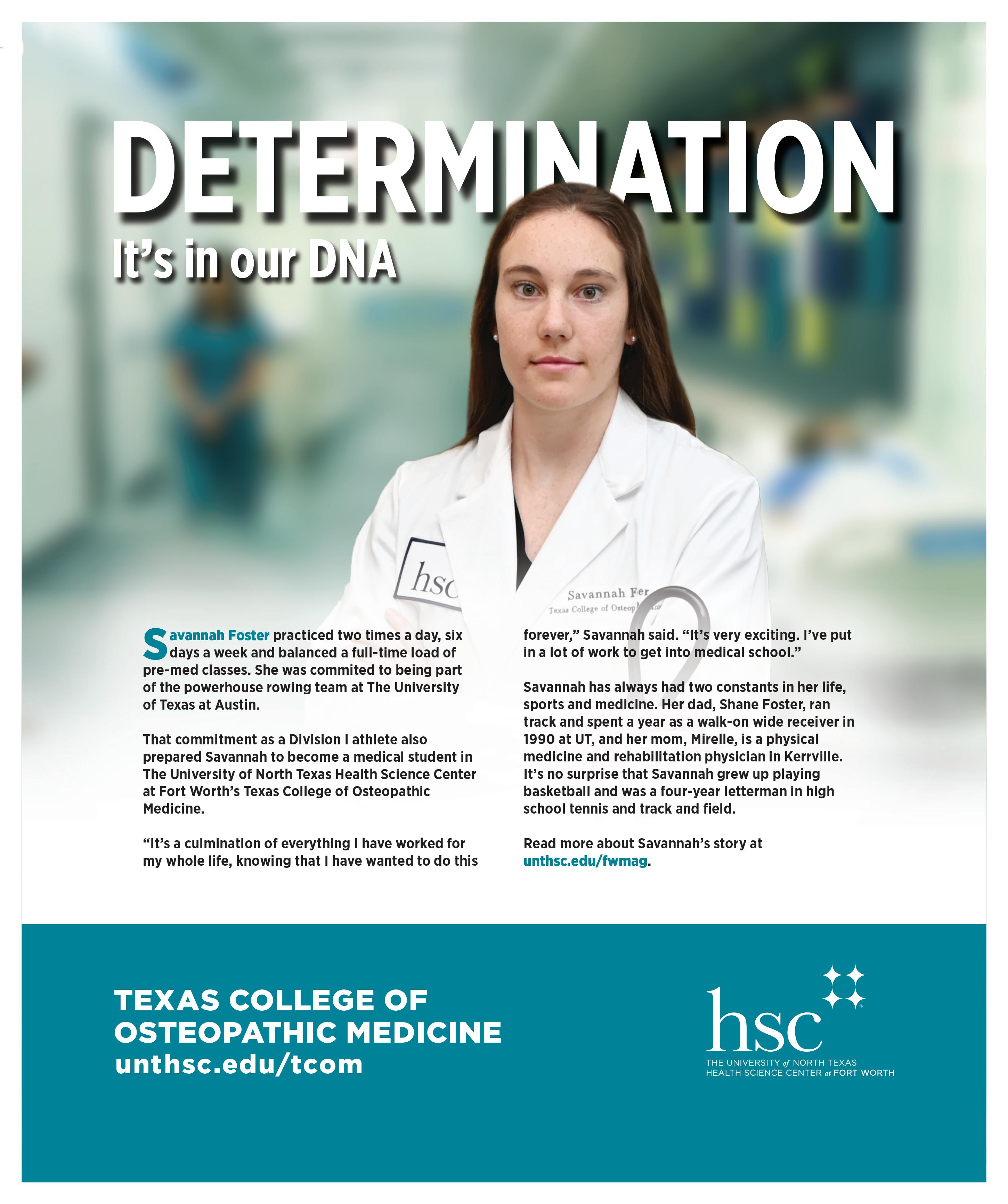

4. Name Dropping: The University of North Texas Health Science Center at Fort Worth is now UNT Health Fort Worth, a rebrand that emphasizes its Fort Worth roots and its growing role as a hub for health care education, research, and community service.

5. Fort Worth — The Big Apple: MP Materials will supply Apple with rare earth magnets manufactured at its Fort Worth facility as part of a $500 million deal. The magnets will be produced using 100% recycled materials, making Fort Worth a central player in the development of a sustainable, domestic supply chain for critical components used in smartphones, computers, wearables, and other electronics.

6. United in Compassion: The United Way of Tarrant County, along with Near Southside Inc., and other partners raises more than $100,000 for the more than 800 residents displaced by a fire at The Cooper apartment complex.

7. What Are They Smoking?

Something called “Lawnstarter” recently published its rankings of America’s best barbecue cities. Fort Worth came in at No. 79. Bold choice for a list pretending to know barbecue. Tell us you know nothing about barbecue without telling us.

8. Hopping to Class: TCU has a parking problem. The campus rookies — that is, freshmen — might not be “allowed to bring a car to campus” in the fall. The issue: The school is in the midst of building a new residence hall and parking garage. There’s no room. Entrepreneurs are busy making spaces.

by Maddy Clark

‘The Lightning Thief: The Percy Jackson Musical’

Based on Rick Riordan’s bestselling teen novel, this performance features an original score that follows the story of a young demigod as he learns to navigate unforeseen challenges and attempts to prevent war with the gods before it’s too late.

Casa Mañana casamanana.org

8-10

‘The Book of Mormon’

Winner of nine Tonys and proclaimed “the best musical of the century” by The New York Times, “The Book of Mormon” follows the journey of two Latterday Saints missionaries as they spread the “Good Word” far from any comforts of home.

Bass Performance Hall basshall.com

14-Sept. 6

‘The Last Five Years’

With Nick Jonas playing the lead earlier this year, this 20-year-old musical about the end of a relationship finally received its Broadway debut. More importantly, the heartbreaking musical will get its Cowtown debut in August with the players at Circle Theatre.

Circle Theatre circletheatre.com

15

Randy Rogers and Pat Green

Six weeks after the devastating Texas floods, Lone Star State country legends Randy Rogers and Pat Green — who lost four family members in the disaster — play the World’s Largest Honky Tonk for a special, one-time only acoustic performance.

Billy Bob’s Texas billybobstexas.com

16-Nov. 2

David-Jeremiah: The Fire This Time

Spotlighting the Dallasbased conceptual artist, David-Jeremiah, this carefully curated installation features 28 works crafted on wood that tower over 10 feet and encircle the viewer.

The Modern themodern.org

23

Stars of the Symphony

28

Shinedown w/BUSH

Multiplatinum band Shinedown and “Glycerine”-crooning BUSH swing by Dickies Arena for the penultimate performance of their 24-date summer tour. Special guest Morgan Wade, who recently notched a hit with “Wilder Days,” will open the proceedings.

Dickies Arena dickiesarena.com

Aug. 16

Though best known for her Grammy Award-winning “Redneck Woman,” released over 20 years ago, Gretchen Wilson has stayed busy with six releases and numerous collaborations over the ensuing two decades.

Billy Bob’s Texas | billybobstexas.com

Showcasing the aweinspiring talent of the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra, “Stars of the Symphony” is a series of repertoire pieces spotlighting individual members of the city’s orchestra.

Bass Performance Hall basshall.com

A Solitary Man: The Music of Neil Diamond

One of the most prolific and successful singersongwriters of the ’60s and ’70s, the stars of Reid Cabaret Theater will have the arduous task of fitting all of Neil Diamond’s hits in a brisk 90-minute set. Reid Cabaret Theater at Casa Mañana casamanana.org

28-31

The USA Weightlifting North American Open Series

Following a successful competition in 2024, USA Weightlifting’s Open Series returns to the Fort Worth Convention Center, where over 1,200 athletes will lift very heavy things for a chance to earn a spot at the North American Open Finals in December. Fort Worth Convention Center usaweightlifting.org

S i n c e 1 9 5 2 , F o r t W o r t h B i l l i a r d s h a s b e e n t h e g

LEARN MORE

r e m i u m g a m e r o o m e s s e n t i a l s . F r o m p o o l t a b l e s & c u e s t o s h u f f l e b o a r d , f o o s b a l l , a i r h o c k e y , d a r t s , a n d a r c a d e

s p a c e W e a l s o o f f e r e x p e r t s e r v i c e s , i n - h o u s e c u e r e p a i r , a n d e x c l u s i v e d i s c o u n t s f o r i n t e r i o r d e s i g n e r s .

V i s i t u s t o d a y a n d d i s c o v e r w h y w e ’ v e b e e n a t r u s t e d n a m e

i n N o r t h T e x a s g a m e r o o m s f o r o v e r 7 0 y e a r s .

V i s i t O u r S h o w r o o m

3 9 7 0 W V i c k e r y B l v d

F o r t W o r t h , T X 7 6 1 0 7

8 1 7 - 3 7 7 - 1 0 0 4

s a l e s @ f o r t w o r t h b i l l i a r d s c o m

f t w o r t h b i l l i a r d s

f w b i l l i a r d s

by Shilo Urban

Population: 4,965

Every Labor Day weekend, more than 200 teams from across America and beyond gather in Brady to try for the prize at the World Championship BBQ Goat Cookoff. Thousands of fans flood the rural hamlet, which is easy to find: It’s smack in the geographical heart of Texas, on the northwestern edge of the Hill Country. Barbecue smokers line the banks of Brady Creek as kids cavort in bounce houses and

craftspeople sell their wares. The festival has been around since 1974, and these days over 5,000 pounds of goat are smoked, sauced, and served each year.

Before Brady became known for goats, cattle ruled the scene. After frontier settlement impeded the easterly Chisholm Trail, the Western Trail opened in 1874 and rumbled right through Brady. The cattle drives

roughly followed today’s Highway 283, which runs north from the city. Brady’s ranches, railroads, and cotton fields tell a familiar story of small-town Texas — until World War II prompted the construction of Curtis Field airport three miles away. A primary flight school for the U.S. Army Air Forces, it’s estimated that 10,000 pilots trained at the facility during the war. They practiced in the skies above their enemies: Just a few miles away was Camp Brady, a prisoner-of-war camp with over a thousand German inmates. Most were from Gen. Rommel’s Afrika Korps, and many were SS or Gestapo. The POW camp is long gone, but you can see the guard shack at Brady’s Heart of Texas Historical Museum, along with Curtis Field’s 1940s wooden control tower.

If you’re interested in World War II history, be sure to visit the courthouse square and see the 8-foot statue of hometown hero James Earl Rudder. Rudder commanded one of D-Day’s most heroic feats during the invasion of Normandy, the perilous Pointe du Hoc assault. The 33-yearold and his Army Rangers stormed the beach and then used ropes and ladders to scale the Pointe, a sheer 110-foot cliff, to seize the German artillery battery on top. Despite constant enemy fire, multiple counterattacks, and a devastating 50% casualty rate — the Americans cap -

tured the position. After the war, Rudder returned home to Brady and served as mayor before becoming the president of Texas A&M University in 1959. His statue stands ready in combat uniform, and a bottle hidden inside holds sand from Normandy Beach.

Brady is no longer filled with soldiers but with the sounds of traditional country music, and it’s largely thanks to one man: Tracy Wilcox. The longtime radio DJ runs the local record label, booking company, and Heart of Texas Country Music Museum. You can’t miss the museum; Jim Reeves’ blue-and-white tour bus is parked out front. Inside the building, you’ll find the best collection of country music memorabilia this side of Nashville, from vintage instruments to rhinestone-studded stage costumes. See artifacts from 100-plus country musicians like Loretta Lynn, Patsy Cline, Ernest Tubb, and Ray Price. Wilcox also masterminds Brady’s two annual country music festivals, including the upcoming Heart of Texas Honky Tonk Fest on August 20 to 23.

Whether you’re two-stepping at a music show or eating your fill of barbecue goat, Brady gives you plenty of reasons to kick up your heels, loosen your belt, and give a friendly nod to this throwback Texas town.

Savor: The first train that ever rolled into Brady came from Fort Worth, and the town’s old Santa Fe depot is now its newest eatery, Big Easy Station. Burgers at the popular watering hole have fun toppings like pepperoni, fried banana peppers, and caramelized onions. Fried catfish is the fan favorite at Boondocks, a local mainstay with housemade ranch and complimentary pinto beans. For breakfast, Mexico City Café makes a mean plate of migas and a wide variety of omelets and burritos. Wine lovers will want to check out Dotson-Cervantes, a vineyard and winery outside of town owned by a former Oakland Raiders lineman and his wife.

Shop: Are you shopping for a taxidermied raccoon, a vintage trench bugle, or a whimsical necklace made of dentures? You’re in luck. D&J’s Good Ole Days Antiques & Oddities isn’t just a shop — it’s an adventure. From half-burnt doll heads to tumbleweed sculptures and crusty Victorian books, this off-the-wall store specializes in the quirky and uncommon. Browse prosthetic eyeballs and skeleton keys or pick up a retro cattle brand for your collection. All the oddball treasures are well organized and thoughtfully curated, and the clever, humorous staging may keep you looking longer than you planned.

Enjoy: Deer season is big news in Brady. Hunters travel from far and wide to try and bag a buck on the large ranches and leases that surround the town. It’s been a hunting hotspot since before the McCulloch County Jail was built in 1910; the three-story, red-brick structure has the foreboding appearance of a medieval castle. Today it houses the Heart of Texas Historical Museum, where you can see the old iron cells, a hangman’s noose, and 500 model airplane engines. If you have time, catch a movie at the Palace Theater, which was built in 1927 and restored in 2017.

Snooze: Bonnie and Clyde hid out at the TruCountry Inn on more than one occasion. Built in 1923,

its themed suites (cowboys and country musicians) feature original windows and carved wooden doors — and in one case, a bullet hole. Country singer Heather Miles restored the landmark building in 2020. For something a bit more modern, try short-term rentals on Airbnb or Vrbo like 4th Street House, a colorful blue bungalow with a backyard fire pit and hot tub. The Gates Guest House nearby is a freshly renovated 1950s cottage with a sparkling white kitchen, and the Heart of Texas House has a fenced-in yard for your pooch.

How to Get There: For the shortest and easiest route, drive south from Fort Worth on US-377, which leads all the way to Brady. You’ll pass through Granbury, Stephenville, and Comanche along the way. The entire trip is about 190 miles and takes just over three hours.

by Michael H. Price

How Little Richard’s Amarillo bust nearly flummoxed his Fort Worth début

Little Richard Penniman, the piano-pounding blues-belter from Georgia, was riding high on the rock ’n’ roll charts — “Tutti Frutti,” “Long, Tall Sally,” those radical reinventions of the conventionally accepted idea of a pop-tune hit — when Fort Worth beckoned with a booking at the Will Rogers Memorial Auditorium.

Richard’s barnstorming tour of July-August 1956 ranged from New Orleans’ Labor Union Hall to the Soldiers & Sailors Memorial Auditorium in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Nor did Little

Richard’s anchoring label, Los Angeles-based Specialty Records, neglect the provinces: Amarillo and Lubbock provided concert stops en route to Fort Worth.

Amarillo nearly jinxed the deal. Specialty Records’ founder, Art Rupe, prized emotional fervor over formal musicianship. Rupe had given Little Richard the liberty to be his own raw-edged self, challenging a segregated musical marketplace to accept an essentially Black rhythm-andblues style without dilution. Before

“Tutti Frutti” had splashed in 1955, Little Richard was still laboring under archaic typecasting as a “race records” artist at a larger but less adventurous corporate label, RCA Victor.

That transformative recording of “Tutti Frutti,” its erotic essence tempered by a chant of seemingly nonsensical syllables, would thrust Little Richard (1932-2020) into the emerging, cautiously integrated idiom called rock ’n’ roll. The singer-pianist became a kinsman of the agreeably mixed likes of Elvis Presley, Fats Domino, Chuck Berry, and Carl Perkins. The announcement of an Aug. 25 appearance in Fort Worth saw a surge in local retail sales of Little Richard’s records; the show became a standing-room sellout.

The snag occurred on Aug. 23, 1956, at Amarillo. Could have been worse, and almost was. Cooler heads prevailed, however, as a result of some fast thinking (make-nice peacekeeping, that is) by Little Richard and his road manager-chauffeur, Aubrey Prince. The Lubbock and Fort Worth engagements went on as planned — not to give away too much, y’know. The conspicuous arrests had included Richard, Prince, and the instrumental accompanists — a scant eight citizens, but nonetheless a full-band lineup in the small-ensemble music-making economy of the period.

I revisited the scene of that municipal embarrassment a few years ago.

The site of Little Richard’s disturbing-the-peace bust stands now as a ghostly West Side landmark of Old Amarillo called the Nat Ballroom — still sturdy, although its festive atmosphere has long since succumbed to the gloom of a ragtag antiques mall. The site is the San Jacinto neighborhood, an off-downtown enclave that has adapted its once-prosperous mercantile foundations to a tourist-bait vibe, stemming from its ties to a historic pre-Interstate System highway known as Route 66. (Yes, the inspiration of Bobby Troup’s famous song of that title; rhymes with “get your kicks.”)

The Nat’s immense dance floor,

nowadays, seems cramped and mazelike when partitioned into vendors’ booths. The once-ornate, acoustically bright bandstand has been crammed with trinkets and furnishings that resemble nothing so much as thriftstore merchandise with forbidding price tags. In recent times, a halfhearted attempt to decorate the stage with musical instruments, attached to human-scale mannequins in musician-like attire, seemed a feeble wax-museum echo of the Nat’s heyday. The place scarcely resembles its jive-jumping state of the night

when my Uncle Grady L. Wilson and I had watched Little Richard and his band stir a mixed crowd to a frenzy (the happy and benevolent sort) and then get themselves arrested in the process.

Now, my Uncle Grady managed Amarillo’s downtown movie theaters and made a sideline of booking traveling entertainers for the Black-neighborhood nightclubs. Grady was the first picture-show boss within Dallas-based Interstate Theater Circuit to remove the barriers of segregated moviegoing. The Interstate brass cast a cautious gaze at Grady’s policy-busting experiment, given the geographical isolation of Amarillo. But Interstate applied such desegregation companywide when an increase in paid admissions became evident. Grady made no secret of his integrationist politics. He would be the only one among my blood-kin elders to vote the Kennedy ticket for 1960, and he entrusted his dental care to one

Dr. Richard W. Jones, a fellow combat veteran of World War II who also held forth as president of Amarillo’s branch of the NAACP. No pretensions of fashionably liberal superciliousness for this uncle of mine; he merely made the choices that suited his interests, and so there.

On that pivotal date of Aug. 23, 1956, when I was 8 years old, Grady invited me to attend Little Richard’s pivotal show at Amarillo’s Nat Ballroom. The cavernous, balconied dancehall had thrived for decades on customarily white-folks patronage, showcasing since the 1930s-1940s such monumental big-band personalities as Glenn Miller, Bob Wills, and Jimmie Lunceford.

By 1956, the inflated post-WWII economy had deflated the traveling big-band attractions to a procession of small but emphatic combos, ranging from jazz to country-western to the stirrings of rock ’n’ roll. On this occasion, the headliner was Little Richard Penniman, a profoundly Black rock ’n’ roll star, born of amen-corner gospel and barrelhouse R&B. The crowd was salt-and-pepper — anybody could buy tickets — and the promoters had made none of the standard provisions for segregated seating. The adjoining Alamo Bar offered Schlitzes and Lone Stars in chilled cans, along with soft drink setups.

Little Richard’s program, frantic and thrilling, ended prematurely in an impulsive and awkwardly timed police raid that resulted in several arrests on intended charges of miscegenation — a misdemeanor rap, calculated to divide and conquer by sheer dehumanizing force of humiliation — for a number of mixed-color couples on the dance floor. The centerpiece was a public-nuisance bust for Little Richard, who had provided the provocation for such unbridled merriment. My uncle had sensed the raid before it could begin and edged us toward an exit, but not before we had witnessed a measure of the misadventure.

The entertainer’s face, accompanied by a headline reading, “Hepcat Hand-

cuffed,” adorned the next morning’s Daily News. The photograph captured a fleetingly somber expression on the face of the usually ebullient Little Richard, as if conforming to the naturally grim face of a Potter County deputy sheriff named John Brown. Depending upon which edition a subscriber might have received, the photo appeared variously upon Page 1 (the “bulldog” edition, printed around 1 a.m. for the Panhandle-at-large readership), or on an interior page of the “four-star,” or late-morning press run.

Now, the Globe-News Company’s resident publisher, S.B. Whittenburg, exercised a standing policy that no Black individual’s face should appear upon Page 1 of any given day’s editions, unless associated with a provocative or urgent story. But Whittenburg also knew better than to enforce that rule when its exception might help to sell a few thousand additional copies. As my father ranted over breakfast about the disgrace thus visited upon our town and the pernicious influence of this newfangled anti-music, I kept mum. The official account, from where I sat, allowed as how Uncle Grady and I had attended a double-bill feature at one of his theaters. I had studied up accordingly on the films’ promotional kit. And, yes, that pairing of “The Werewolf” and “Earth vs. the Flying Saucers” had been a sure-enough humdinger, embellished for good measure with a “Popeye” cartoon.

On a visit in 2018 to Amarillo, I dropped in on the life-support remains of the Nat Ballroom, just to see if any disembodied spirits might be stirring. While working as a musician during high school and college, I had booked my white-boy soul band into the Nat on occasion, and I had covered the property’s erratic fortunes during the 1970s as a reporter and editor with the Daily News & Globe-Times.

On this stopover of times more recent, I encountered a stranger near the cluttered former bandstand: The

woman looked to be about 85 years of age. She had a story to tell.

“I was dancing up a storm, here — right here — when all that happened, y’know,” she said by way of an almost-introduction.

“Here when all what happened?” I said.

“Why, when Little Richard got busted for stripping off his shirt,” she said. “It was in the newspaper.”

“No kidding? I was right here, too, when it happened.”

“Wouldn’t you have been a little too young for such rowdy nightlife?” she demanded in a matronly, scolding tone.

“I was a guest of an uncle. He was in show business.”

“Oh. Then you remember.”

“Looks as though we both remember,” I said.

Another source, too young to possess first-hand impressions but capable of turning up surviving primary sources, had surfaced in 1999: Karen D. Smith, a new-generation reporter for Amarillo’s since-conjoined Globe-News papers, located a long-retired law enforcer who had helped to railroad the raid and found him willing to talk. Smith’s retrospective report tells the story like this:

request to temper the performance, as if expecting Perry Como or Pat Boone to materialize in his place. The entertainer resumed his act to welcoming applause — and cranked the tensions a notch by removing his shirt. At least the show ended on a crowd-pleasing high note, even if the authorities had stopped the music with a full-band shutdown.

Karen D. Smith’s account of 1999 continues: “In Justice of the Peace C.W. Carder’s courtroom the next morning, the group paid a collective $76 in fines after pleading guilty to a disturbing-the-peace charge. The other charges were dropped.

“The singer and the manager, Aubrey Prince, said they only pleaded guilty because they had a Lubbock performance that night.” The Lubbock and Fort Worth engagements proceeded without incident, although

major-label, mass-audience attraction, better suited to Amarillo’s Municipal Auditorium, and Fats Domino would at length play the Nat Ballroom without complications.

Smith’s story continues: “Amarillo’s audience didn’t wow Little Richard, anyway. ‘It’s the quietest dance I ever played,’ the artist told the Globe-Times.”

In the on-the-spot newspaper coverage of 1956, the singer’s appraisal seemed at odds with an accompanying story by another Globe staffer named Loyal Gould: “The cats jumped last night,” wrote Gould, affecting a condescending teenage vocabulary. “In fact, they rocked way out..., then rolled away their inhibitions with the help of Little Richard and his orchestra.” At 29, Gould was a year away from joining the Associated Press, where he would become a prominent international correspondent en route to an extended career as a professor of journalism.

“Liquor agents and other authorities raided the singer’s crowded concert at the Nat Ballroom after spotting several minors milling outside the hall, holding alcoholic beverage bottles.

“Lawman Wayne Bagley, assistant district attorney at the time, and his wife were returning from dinner out with [liquor agent] W.C. Brewer and his wife when Brewer ... stopped to check the situation out. Other liquor agents arrived, as well, Bagley said.

“‘Next thing I knew, they came carting Little Richard out,’ Bagley said. ‘They filed on him for some lewd conduct on stage... That was before he got to be so well-known.’”

During an intermission, Bagley and Brewer’s improvised fun-police squad had approached Little Richard with a

neither city’s newspapers-of-record appear to have assigned any critics to appraise the performances. Localized arts-and-entertainment coverage of the day confined itself as a rule to hometown symphony orchestras and Little Theatre amateurism. Not to mention that the 1950s’ nearest equivalent to formal or even consistent rock-music journalism amounted to blathering fan-magazine drivel.

“‘Really, what happened is that [the authorities] told them not to come back,’” Bagley told Karen Smith. The reporter added as an aside: “The performers said they didn’t want to return to Amarillo, anyway, and Prince ventured that the situation would threaten other concert dates he had arranged here for Nat “King” Cole and Fats Domino.” The road manager seems to have been bluffing, here: Nat Cole was a

“In the stratospheric twilight of the Nat Ballroom,” Gould’s report continued, “some 400 teenagers and a few old-timers in their 20s bopped to the rhythms of three weaving saxophonists, two steel guitarists (sic), a drummer, and a pianist.” (The reporter probably meant electric guitars. Little Richard’s lineup used no steel guitars, which symbolized C&W-style music.)

“Fellows with ducktail haircuts and turned-up collars, girls with tight skirts, went through sundry gyrations, contortions, and deep knee bends. They looked like Halloween goblins in a puppet show,” added Gould.

“And they really flipped when Little Richard, wearing a Mediterranean-blue suit, white shirt, and brown suede shoes, delivered the three songs which have brought him close to the top of the rock ’n’ roll hierarchy.

“The songs: ‘Tutti Frutti,’ ‘Slippin’ an’ Slidin,’ and ‘Long, Tall Sally.’

“‘It’s just the beat,’ Little Richard said. ‘It really gets you, man.’”

Summer sips and Quince trips.

by John Henry

Presumably, if you follow along with the goings-on of Paramount pop culture, you’ve heard of the new genre of television called “Taylor Sheridan” and his newest — at least new to me — hit “Landman.”

His audiences are — to borrow a phrase — hog wild about it.

Well, it was on this particular show that I received my entry into The Industry — my Hollywood debut. Actually, the first rule of The Industry is that one is not an “extra.” He is a “background artist.”

I don’t expect anyone to treat me any differently with my newfound status as an actor. I put my pants on one leg at a time, just like everyone else.

The lasting impression? Demi Moore has still got it. She has defied the burdens of Father Time. And, no, I don’t care how she’s done it.

Demi Moore — and Andy Garcia — was as close to Hollywood glamour as I got while shooting this dinner scene in downtown Fort Worth. (Producers and viewers alike need not worry about any spoilers because I didn’t know what the hell was going on. In fact, to that point, I’d never seen the show.)

The experience for us background artists was more akin to Burk Burnett moving cattle from the Red River to the railhead to, well, the Railhead. A young point rider at the front leading this herd of 150-200 promising actors, with swing, flank, and drag riders turning and keeping the stragglers in line.

It’s a difficult job these guys have dealing with all these Hollywood personalities.

There are a lot of “nos” you have to learn before you get on set. No talking

— to each other or to Demi Moore. No looking at the camera — it’s a mortal sin that destroys the soul’s grace and severs one’s relationship with God. Don’t even think about snapping a photograph or selfie. That’ll get you run off the premises and blacklisted faster than you can say “communist sympathizer.”

And whatever you do, don’t clink your silverware during the dinner scene. Even the slightest noise gets picked up by the sound team’s ultrasensitive mics. To the audio crew, your fork is a jackhammer.

There’s also no complaining about your whiskey on the rocks being water and food coloring. It’s a special kind of buzzkill, especially after waiting all day for the big moment of lights, camera, action. Oh, and, yes, if you have any aversion to waiting, this hustle in the gig economy is not for you.

Being on-set, though, is a fun experience, getting a firsthand look at how productions work. It’s kind of film school without the outrageous tuition. And I’ve been able to tell everyone in town I’m a star in “Landman.” And unless there’s some sort of AI at play, they literally can’t shoot these scenes, especially a dinner scene, without the extras.

Yet, there was something far bigger at play. All the reasons for Fort Worth and Texas saying “yes” to the film industry were on full display for this rookie.

Keep trickling on down, Ronald Reagan and Arthur Laffer.

The thought of what just this particular day cost these industry executives was staggering. And that

money creeps into local coffers. The local economy feels it. Over the past nine years, the film industry in Fort Worth has generated somewhere in the neighborhood of $800 million in economic impact. Local vendors and equipment companies, the hospitality and catering businesses, and hotels all reap the benefits of increased business. Estimates of job creation are eye-opening, a reported more than 20,000 locals — like me — put to work through the film industry.

This is all expected to ramp up with the Legislature passing a bill authorizing an increase in incentives for film production in Texas. The governor is expected to sign it. The bill authorizes the depositing of $300 million in an incentive fund every two years until 2035. A lack of incentives had been keeping production companies out of Texas.

Sheridan, Matthew McConaughey, Woody Harrelson, and Dennis Quaid all testified in favor of the bill. Texas’ great lure for the industry is its varied topography. You can get just about any kind of setting in Texas. The low cost of living, too.

“One of my great frustrations was that I wrote ‘Hell or High Water,’ and they filmed the darn thing in New Mexico,” Sheridan told legislators. “My love story to Texas was shot west of where it should have been shot.”

So, too, was the case for “You Gotta Believe,” the story of Fort Worth’s West Side Little League World Series team. Much of that was shot in Canada.

“There are tons of Texans who live in California and New York, all over the globe, who are pursuing their careers, because those opportunities weren’t here in Texas,” said Grant Wood, cofounder of Media for Texas, who spoke to the Texas Tribune. “We have essentially been subsidizing the workforce of these other states.”

My career in film is likely a one-anddone, unless, of course, they need a leading man for Demi Moore.

Fort Worth, on the other hand, is a long way from being done.

Despite its storied history and iconic status, the future of Farrington Field, where generations of Fort Worthians have gathered for decades to enjoy America’s game, is in limbo. And for John Henry, it’s personal.

I’ll be the first to admit that as a lover and student of history, my historic sense sometimes sweeps me away to another time and place, where the past feels as vivid as the present. It’s not so much getting lost in my imagination as it is being transported to another time and place. Call it a sixth sense. Who needs Doc Brown?

And so, it was at Farrington Field, the art deco classic on the near West Side, many years ago as I sat perched high atop the stadium in the press box — spartan by any measure compared to today’s modern suites of gawdawful Suburbia, Texas — awaiting kickoff of a high school football game, one of several dozen I’ve written about over the years at the historic grounds, which sit at the corner of University Drive and Lancaster Avenue.

I looked to the southeast as the open-top car pulled into the entrance of the stadium. Its driver navigated past the visiting team locker rooms and down the concrete ramp onto the track.

Its occupants — one of the most brilliant and able, albeit controversial, men of his age, and his wife and their young son — waved to cheering onlookers. When the car stopped, they got out and walked to a podium set up on the south side of the field.

The weather on this Saturday morning in June was tolerable. Threatening rain clouds dispersed, evidence, I heard one man say, that the weatherman was a Republican. Surely, the skies would have opened on the reviled President Truman, the “accidental tyrant and patron saint of containment.”

Gen. Douglas MacArthur came to demonstrate a clear distinction between himself and his archnemesis, President Truman. In doing so, he’d fire off a number of figurative Howitzer shells at the commander-in-chief. Texas would be crucial to his presidential campaign the next year in 1952.

shifts, he said, were eroding national confidence, weakening moral purpose, and throttling the energies that had made the country great.

“Make America great again,” I thought. What a novel idea. Breaking new political ground in 1952.

“It has been a rare privilege for me to travel during the past four days through the heart of Texas and observe with my own eyes the almost miraculous progress which has been made in the development of your great state. I have found here a vast reservoir of spiritual and material strength which fills me with a sense of confidence in the future of our nation. It confirms my faith that with such resources none can excel us in peaceful progress nor safely challenge us to the tragedy of war.”

I snapped out of my trance as the public address announcer asked us to stand for the national anthem, but an epiphany had occurred. This place — Farrington Field — had through the years become something far bigger than football or track.

For eight warm days in July 1949, thousands assembled in Farrington Field to commemorate Fort Worth’s 100th birthday. “Fiestacade” told the history of Fort Worth in 20 episodes in a show produced by the John B. Rogers Company of Fostoria, Ohio. (Ohio? Get a rope.)

The narrative began with the early days of Native Americans and closing with a prediction that future greatness would “never rob the city of its friendly Western spirit.”

The spectacle closed with a stirring demonstration of the city’s dominance as an aviation center after World War II and the establishment of Convair’s “Bomber Plant” that we know today as Lockheed Martin.

High-powered Army searchlights crossed the sky and caught a B-36 Peacemaker circling overhead. The big bomber made two low passes across the field in the path of lights.

MacArthur warned of a dangerous “drift” in American life — a drift away from truth, from high moral standards, and from the foundational principles that shaped the American tradition. He spoke of a drift away from individual initiative and personal incentive, caused by growing dependence on government and creeping socialism. He lamented the drift downward in the purchasing power of the dollar, increasingly subject to political manipulation. At the same time, he saw a drift upward in public spending and bureaucracy, which threatened to turn citizens into servants of the state. Together, these

Farrington Field is the binding thread in the story of Fort Worth in the last 100 years. Everybody born or raised here between the ages 16 and 100 — hell, older than 100, if, God willing, they are still with us — shares a connection to the place. It is the place that binds us, regardless of the dividing lines of age, ethnicity, gender, and neighborhood. Everybody has a memory there whether as a player, track athlete, cheerleader, dance team, the band, a homecoming game or date, or some mischief teenagers have become famous for — like, for example, Paschal rascals 40 years ago breaking into the stadium to bleach “Heights Bites” at midfield.

(The city’s law enforcement authorities caught wind of the incursion and led a chase of the vandals, who beat a path south down University into Trinity Park. But I digress. You didn’t come here for this.)

From that particular Friday night forward, Farrington Field became my fixation and fascination. I was Captain Ahab; Farrington was my whale — minus the self-destruction. Or maybe I was Hinckley and it was Jodie Foster, without the long stay at St. Elizabeths.

My all-consuming interest sent me off to research whatever I could find. I began to write about it. Whenever I was there, I looked upon the stadium like an artist studying his muse. It was love, there was no confusing it. And then, boom — the news dropped. The Fort Worth school district, without adequate resources to maintain it, much less upgrade it, planned to put an aging facility that no longer served its needs on the market.

Not to mention that the public entities undoubtedly saw the upside in the possibility of one of the most valuable pieces of property in town going on the tax rolls.

Though disputes remain over

and others

My stomach turned as if I’d downed a lipful of Copenhagen. Suffice to say, I took that news the way one does after stubbing a toe on the biggest, meanest, ill-willed doorframe in town. No! No! No!

You can’t just discard Farrington Field like a used Whataburger wrapper. The stadium is an icon in the Cultural District, a poetic reminder that fulfillment includes healthy in body, mind, and spirit. Mens sana in corpore sano: “A healthy mind in a healthy body.”

There is much learning yet to be done here. For a city with a grand history, it is essential for preservation. Places like Farrington Field — its charm, character, history, and architecture — distinguish Fort Worth from the likes of Allen, Frisco, and Plano.

Has a name better encapsulated a town quite like Plano? The city fathers nailed that one.

Its football heroes have included two future NFL Hall of Famers — Yale Lary and Earl Campbell — and NFL standouts, including Elijah Alexander, Victor Bailey, Blake Brockermeyer, Marcus Buckley, Raymond Clayborn, Henry Ford, Doug Hart, Greg Hawthorne, Sherrill Headrick, Joe Don Looney, Mike Renfro, A’Shawn Robinson, Frank Ryan, Jim Shofner, Tylan Wallace, Darrent Williams, and Tariq Woolen. Certainly, I’m missing someone, such as the notable kickers — Tony Franklin and Uwe von Schamann. The others who turned heads in college also began here, with guys like Carlos Francis, Turner Gill, James Gray, Terry Pierce, Roy Lee Rambo, and Roland Sales.

And, of course, the literally thousands upon thousands of others who have suited up there, stars and role players alike.

The Masonic Home Mighty Mites’ feats at Farrington have been retold in literature and Hollywood. They had two NFLers, too, in Hardy Brown and Dewitt Coulter.

And who could forget Arlington Heights star Harry Moreland, who, according to Dan Jenkins, said of Bob Lilly at TCU: “If I were as big as Lilly, I would charge people $10 a day to live.”

A sign in the home locker room greets every player who takes a step onto the field: “Since 1938, thousands of athletes and coaches have made the walk down this tunnel into historic Farrington Field. You just became a part of HISTORY.”

There is no doubting the neglect the stadium has sustained over the years. The school district spends much of its budget simply trying to keep the school doors open, and books and laptops, or whatever they’re using these days to supplement learning the three R’s.

For the preservationists, however, white knights have appeared, as if Commissioner Gordon 911’d Batman. The heroes of Historic Fort Worth Inc. — notably Jerre Tracy, the executive director — have worked tirelessly to save the stadium. Through Historic Fort Worth’s advocacy, as well as the grandson of the namesake, Farrington Field earned its rightful place in the National Register of Historic Places.

That doesn’t protect it from demolition. Only the school district — the owner of the property — or city or city manager can make that decree. It doesn’t appear to be forthcoming.

The National Register designation, though, appears to have turned on a light switch. Voters turned down a more than $105 million bond proposal to build three 5,000-seat stadium complexes.

And now the city is taking positive steps toward preservation. It’s more like a giant leap.

In June, the City Council voted to approve a Tax Increment Financing district — better known by its shorthand, a TIF — that will allocate $55 million of collected tax revenue to renovate and upgrade Farrington Field. The TIF’s main purpose is to fix notorious stormwater issues and make road improvements. Those are keeping developers away.

However, it now looks possible to redevelop and preserve the stadium for high school sports and who knows what else — a youth sports destination, maybe? High school playoffs? Destination football games between a Texas team and one from another state? Nolan Catholic plays in the “Catholic Bowl” with five other teams. Why not on occasion play that at a refurbished Farrington Field?

The breakthrough has gotten us preservationists out of our funk.

“Preservation is always about money,” Tracy says. “You can talk about it, but it’ll still fall down if you can’t find the money. We have hope! We have a shot.

“The National Register nomination really turned the game around. It woke people up. People are seeing and understanding that what you already have built in your city is an asset.”

In Why Old Places Matter: How Historic Places Affect Our Identity and Well-Being, Thompson Mayes argues that preservation isn’t about nostalgia — it’s about using the past and the built environment to deepen our present and shape a meaningful future. His essays push back against the emphasis on placemaking through new development, instead advocating for “place-sustaining,” which values longevity, memory, and the ways our surroundings influence identity, well-being, and our collective sense of a shared future.

Preservation is about the kids.

Shortly after the vote to approve the tax district, two renderings of what a future Farrington Field could look like with development on its north and south ends suddenly appeared on social media channels.

No one, including the city, seems to know where they came from. With AI capabilities, it could have come from anybody with a smart phone.

In the early 1960s, the Dallas Texans played exhibition games at Farrington against the Denver Broncos, and owner Lamar Hunt even brought his team back as the Kansas City Chiefs for “Fort Worth’s Third Annual Football Classic” in 1964 against Denver. One of those games featured the first overtime game in the AFL.

But finding a good solution for preservationists and ambitious developers will require the same kind of vision of the stadium’s founder.

We look to be on the right path.

It was a brisk November morning in 1937 when Coach Herman Clark of Fort Worth’s North Side High School made his way down the linoleum-floored hallway to the office of his boss.

Clark, always one to think of his boys first, had a modest list of necessities in mind for the coming gridiron season. Stepping into the office, he doffed his hat respectfully, then cleared his throat.

“We could use a few supplies,” he began.

“A pair of cleats or two, some shoestrings … maybe a little rubbing alcohol and cotton. The usual.”

Across the desk, E.S. Farrington — his former coach and now the athletic director — broke into a wide grin that gave Clark pause.

“You’ll get your supplies,” Farrington said, pausing for effect, “and more than that. We’re getting a new

Of the emerging preservation strategy building for

really turned the game around. It woke people up. People are seeing and understanding that what you already have built in your city is an asset.”

stadium.”

Clark blinked.

Not just any field, but a bona fide stadium, a showpiece for the city’s high school athletes. The district had at last come to terms with the city on 38 acres at the corner of University and Lancaster — $7,600 sealed the deal. To Clark, it might as well have been Christmas morning.

Farrington had spent 10 years working to get to this point. And it was worth every inch of blood, sweat, and tears.

“It’s for my boys,” he remarked then.

The final bill to build Farrington came to about $400,000 in 1939.

“He was a broad shouldered, stocky young man,” is how a Star-Telegram reporter described Evan Stanley Farrington. “He had a ready smile, a quiet air of efficiency. And as soon as the Steers went out to work on their old rocky field west of the old school, the boys discovered at once that he knew his football.”

Evan Stanley Farrington was a young man of 30 when he arrived in Fort Worth to become the head football coach at North Side. Born in Lewisville, he had lettered at Baylor in football, was a regular on the theater stage and the senior class president of 1913. After graduation, he moved to Grapevine where he was principal and then superintendent of schools for the 1914-15 school year.

“I aspired to build up the schools to the highest standard, to place them second to none in the country. Encourage your children in their schoolwork and watch their growth and development with careful interest. See that they observe proper hours for study and then see that they do study.”

He left education to work in private industry, but his calling, he discovered, was teaching and education. And his new home was the North Side of Fort Worth.

His connection to the city was through his wife, Sidney King, the niece of John P. King, the “Candy King” of Fort Worth. They had met when both were teachers in Grapevine. She taught in primary grades and left when her husband became superintendent. They married at Magnolia Avenue Christian Church in Fort Worth.

Farrington coached two seasons at North Side before moving into athletics administration and making history. Both were led by Herman Clark, the quarterback of those teams.

Evaline Sellors, a pioneering figure in Fort Worth’s arts scene, is best remembered for her bas-relief sculptures at Farrington Field, her most recognized and enduring works. Commissioned in 1938, the two 8 1/2-foot art deco figures on the stadium’s west side façade embody the strength and athletic spirit of youth, and they stand as a testament to her influence in shaping the city’s public art.

Beyond Farrington Field, Sellors left a legacy of works that became part of Fort Worth’s visual fabric. She created the sculpted finials for the Fragrant Garden at the Fort Worth Botanic Garden, the life-size figure of a young girl titled The Song at the Child Study Center, and stainedglass windows for Beth-El Congregation’s chapel and Grace First Presbyterian Church in Weatherford. Her public commissions also included a bronze bust of Al Hayne, the hero of the 1890 Texas Spring Palace fire, and a new grave marker for Fort Worth founder Maj. Ripley A. Arnold.

Her work, both classical and modern in tone, reflected a commitment to community and accessibility. Today, her sculptures are held in permanent collections across Texas, a lasting reminder of her contributions to Fort Worth’s cultural landscape.

Twice, though, under Farrington the Steers won the city championship. In 1921, they beat Masonic Home 38-14 to claim

the title. In those two years, North Side also twice beat Central — now Paschal. In 1922, the victory over Central was for the city championship.

North Side’s 1922 team was in reality making a run for a state title until it was derailed by Cleburne through what I’ll just simply call the tactics of a sore loser.

The Steers had defeated Cleburne that season, but the Yellow Jackets coach, Fred Erney, filed a protest with the State Interscholastic League, alleging that Clark and teammate Walter Holland had been paid to play baseball the summer before. (Cleburne, by the way, had been co-state champions two years before with Houston Heights after a championship game that ended in a 0-0 tie.)

“An effort is being made to prove Clark was paid for playing baseball with Gainesville last summer,” Farrington said at the time. Holland, as it turned out, had also played baseball, in Waco.

Both players, the coach said, indeed did play baseball and were paid, but only for their expenses, “which is legitimate.” In other words, legal, according to the rules of the State Interscholastic League.

The State Interscholastic League ultimately sustained Cleburne’s protest, taking away the Steers’ victory and allowing Cleburne to move on in the playoffs. The outcome was the only blemish on the Steers’ record that season.

Farrington remained steadfast in his defense of his players.

Farrington left for athletics administration, becoming the Fort Worth athletic director.

Back in a trance, I watched him tell a newspaper reporter about his grand vision of a football stadium and track.

“Think of this. West Lancaster will run right by the stadium when the new bridge is built over the Trinity. TCU and south side traffic can move over Burleson Street [now University Drive], through Forest and Trinity parks, directly to the stadium. North Side people can drive straight to the stadium from the north on Burleson Street. Arlington Heights folks have a straight shot down El Campo. Poly comes in over Lancaster, and Riversiders use Belknap and West Seventh.”

As athletic director, Farrington quickly earned a reputation for running a tight, financially sound athletic operation. By 1932, Fort Worth’s school sports programs — aside from coaches’ salaries — cost nothing to the taxpayers. In a city of 165,000 residents, some 33,000 students,

both Black and white, participated in athletics. Game attendance generated real economic momentum for the city’s athletic programs.

By the mid-1930s, crowds were swelling. In 1934 alone, Paschal and Poly drew more than 16,000 paying fans to LaGrave Field for their game. Farrington had reason to believe that Fort Worth needed its own dedicated stadium. He could point to a surge in paid attendance at LaGrave and Wortham Field over four consecutive years: 51,745 in 1932; 54,940 in 1933; 78,476 in 1934; and 72,994 in 1935. Low ticket prices — 25 cents for general admission and 50 cents for reserved seating — helped fuel the surge, making games accessible and popular, to the point that marquee matchups were pushing existing venues past capacity.

With numbers on his side, Farrington set about advancing his vision for a new stadium. He shifted from rallying athletic support to lobbying political allies — among them Fort Worth’s power broker Amon G. Carter Sr. Carter’s influence helped secure federal Works Progress Administration funding and persuade the city to sell a tract of land east of the Fiesta Grounds, which Carter had promoted as part of Fort Worth’s own centennial celebration.

The stadium was the gathering place for one of the last century’s hottest political hot potatoes. Gen. Douglas MacArthur, at the end of a ticker-tape parade thrown for him after being fired by President Truman, addressed 7,500 at the stadium, a far cry from the estimated 150,000 who showed for the parade. It was the precursor to a hopedfor triumphant presidential campaign in 1952, which ultimately fizzled.

Blueprints were completed and made public on Nov. 9, 1937. Plans called for 10,000 seats on each side of a north-south gridiron, with open ends to the oval. To maximize capacity between the 20-yard lines, the central sections would rise 54 rows high, arranged in semicircles to provide optimal sightlines. A complete lighting system was included for night games.

The financing came together through a combination of $160,000 in WPA support for labor and materials, $90,000 in revenue bonds, and roughly $82,000 from the school district.

The stadium was designed by architects Arthur George King and Everett Lee Frazior Sr., with oversight from Preston M. Geren Sr. It featured advanced overhead lighting and 70-foot columns that framed the west entrance.

The city agreed to sell the land with one condition: It must be used for school district athletic purposes. The property had originally been donated to

the city for public benefit, and if its use ever changed, ownership would revert back to the city.

Precedent has been set on any past deed restrictions with a Tarrant County District court ruling in 2008 that restrictions mandated by the Van Zandt Land Co. to be unenforceable because there was no longer a Van Zandt Land Co., which disbanded in 1947.

A city official told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram in 2020 that the city and school district had an agreement to split the net proceeds of 1.7 acres surround the stadium in the event of a sale.

“From the city’s perspective, there is nothing in the agreement that would prohibit Fort Worth ISD from selling Farrington Field,” the city official said.

At any rate, by 1937, Fort Worth was on the cusp of having athletic facilities to rival any in the nation. For Farrington, it was a longpursued goal finally taking shape.

E.S. Farrington never saw the completion of his prized legacy project.

Farrington had a heart attack and died at his home on Waits Avenue in 1937. He had been watching an I.M. Terrell football game, a team “he has done much to help and encourage,” when he was stricken with what felt like a knot the size of a fist in his stomach near the heart. He was able to drive home, but a doctor was “hastily summoned.”

He was 46.

“Fort Worth and Texas have lost one of the finest men in athletics,” said TCU coach Dutch Meyer. “It is a real blow.”

His very last words he spoke were about the stadium. He discussed it with the doctor. Farrington and his wife are buried in Greenwood Cemetery.

Wrote Amos Melton of the StarTelegram: “We wish to be among the first to suggest that the new field, when and if completed, be named for the man who made it possible. ‘Farrington Stadium’ should stand for many decades as a tribute to one of Texas’ greatest schoolmen. Every football game, every track event, every function in the new plant should be held in affectionate memory of a real man.”

The very first part of my Far-

The stadium “needs to be upgraded and improved,” says Evan Farrington, but “it could be a really cool sports venue with some vision. People just need to have a little vision. Just love it a little.”

rington Field fixation was a Google of the name “Evan S. Farrington.”

Sure enough, Evan S. Farrington III came into view. He lived near Austin. I called a number provided.

That began a close friendship between us — Farrington Field serving as yet another bind between people, though we’ve discovered many other common interests. Evan, an attorney, and his wife Melaine have since moved to Fort Worth.

He spoke to the City Council in June in favor of the new tax district, as did Jerre Tracy, the executive director of Historic Fort Worth Inc. Evan more recently has begun to carry around a copy of his presentation to the Texas Historical Commission. He passed out copies to the City Council.

Evan’s father, Evan S. Farrington Jr., who went by Stanley, was part of the ceremonious groundbreaking festivities in 1937 as a 10-year-old. In 1939, for the dedication ceremonies — young Stanley made the ceremonial first kick. It’s an event that makes son Evan chuckle.

“Dad was not an athlete,” says Evan. “It skipped a generation. Of course, when you’re the athletic director’s son, you got to be an athlete, but he just wasn’t. He said he practiced for that kick for three months. And when it came time, he was in front of the whole city and he kicked it 15 yards. He said he felt like Charlie Brown. He kind of turned around and walked off.”

Amarillo beat Paschal 31-13 in the first game.

Stanley Farrington, who went to Paschal and then both TCU and Texas, later had a long career in medicine. He was also the recipient of a Bronze Star with valor as a medic during the Korean War.

Father and young son — Stanley and Evan — were in attendance at Farrington Field for Arlington Heights’ playoff game against Tyler John Tyler, featuring Earl Campbell in 1973.

“We lived in East Texas, and my dad loved Earl Campbell,” Evan recalls.

“There was no ESPN or internet, nobody really knew outside the city who the really good players around the state or nation were,” said Mike Renfro, Heights’ star. “We started to hear about Earl Campbell about two weeks before the playoffs.

“I like to tell this story, that [Heights’ coach] Merlin [Priddy] was so nervous about what we’d see on film that he wouldn’t even show us