DOCTOR OF DIFFUSION

BY MIKE LEVINE

BY MIKE LEVINE

On the Cover: For the past half a decade, Dr. Peter D’Antonio has largely lived behind the scenes in pro audio, but the top studio designers in the world certainly know him, and this year, the bass-playing scientist celebrates the 40th anniversary of his company, RPG, will give a special presentation at the AES Show, and has been awarded a prestigious Sabine Medal by the Acoustical Society of America ‘for contributions to the theory, design, and application of acoustic diffusers.’

BY TOM KENNY

BY TOM KENNY

FOLLOW US twitter.com/Mix_Magazine facebook/MixMagazine instagram/mixonlineig

CONTENT

VP/Content Creation Anthony Savona

Content Directors Tom Kenny, thomas.kenny@futurenet.com

Clive Young, clive.young@futurenet.com

Senior Content Producer Steve Harvey, sharvey.prosound@gmail.com

Content Manager Anthony Savona, anthony.savona@futurenet.com

Technology Editor, Studio Mike Levine, techeditormike@gmail.com

Technology Editor, Live Steve La Cerra, stevelacerra@verizon.net

Contributors: Craig Anderton, Barbara Schultz, Barry Rudolph, Robyn Flans, Rob Tavaglione, Jennifer Walden, Tamara Starr

Production Manager Nicole Schilling

Group Art Director Nicole Cobban

Design Directors Lisa McIntosh, Cliff Newman and Will Shum

ADVERTISING SALES

Managing Vice President of Sales, B2B Tech Adam Goldstein, adam.goldstein@futurenet.com, 212-378-0465

Janis Crowley, janis.crowley@futurenet.com

Debbie Rosenthal, debbie.rosenthal@futurenet.com

Zahra Majma, zahra.majma@futurenet.com

SUBSCRIBER CUSTOMER SERVICE

To subscribe, change your address, or check on your current account status, go to mixonline.com and click on About Us, email futureplc@computerfulfillment.com, call 888-266-5828, or write P.O. Box 8518, Lowell, MA 01853.

LICENSING/REPRINTS/PERMISSIONS

Mix is available for licensing.

Contact the Licensing team to discuss partnership opportunities. Head of Print Licensing: Rachel Shaw, licensing@futurenet.com

MANAGEMENT

SVP Wealth, B2B and Events Sarah Rees

Managing Director, B2B Tech & Entertainment Brands Carmel King

Managing Vice President of Sales, B2B Tech Adam Goldstein

Head of Production US & UK Mark Constance

Head of Design Rodney Dive

FUTURE US, INC.

Future US LLC, 130 West 42nd Street, 7th Floor, New York, NY 10036

England

Wales. Registered office: Quay House, The Ambury, Bath BA1 1UA. All information contained in this publication is for information only and is, as far as we are aware, correct at the time of going to press. Future cannot accept any responsibility for errors or inaccuracies in such information. You are advised to contact manufacturers and retailers directly with regard to the price of products/services referred to in this publication. Apps and websites mentioned in this publication are not under our control. We are not responsible for their contents or any other changes or updates to them. This magazine is fully independent and not affiliated in any way with the companies mentioned herein.

If you submit material to us, you warrant that you own the material and/or have the necessary rights/ permissions to supply the material and you automatically grant Future and its licensees a licence to publish your submission in whole or in part in any/all issues and/or editions of publications, in any format published worldwide and on associated websites, social media channels and associated products. Any material you submit is sent at your own risk and, although every care is taken, neither Future nor its employees, agents, subcontractors or licensees shall be liable for loss or damage. We assume all unsolicited material is for publication unless otherwise stated, and reserve the right to edit, amend, adapt all submissions.

We are committed to only using magazine paper which is derived from responsibly managed, certified forestry and chlorine-free manufacture. The paper in this magazine was sourced and produced from sustainable managed forests, conforming to strict environmental and socioeconomic standards.

Zach Edey is 7-foot, 5-inches tall and plays basketball for Purdue University. He’s a center, obviously, the reigning NCAA Player of the Year, and he passed up tens of millions of NBA dollars this past summer to return for his senior year. He let it be known that he wants to win a national championship, and that he’s still having fun. A Toronto native, he credits much of his success to the fact that he played a wide range of sports throughout childhood, especially hockey. Even at that height, and he’s always been the tallest person wherever he goes, he didn’t start playing basketball until age 15.

Tony Gonzalez is in the NFL Hall of Fame, considered by many to be the greatest tight end ever. In the mid-1990s at UC Berkeley, he was an All-American football player and a starting power forward on the Cal basketball team. More than once, he talked about how years of crashing the boards, calculating the angles of the ball bouncing off the rim while simultaneously jumping and twisting his body to grab a rebound, made him better at catching passes and running down the field while people were trying to knock him down. He considered himself an athlete first.

Let’s switch from sports to music. Producer/engineer Jacquire King has been known to credit much of his studio success (Kings of Leon, Norah Jones, many others), and really his studio approach, to the 10 years he spent at the start of his career as the house mixer at Slim’s, the late, legendary San Francisco club owned by Boz Scaggs. You have to make creative decisions fast when you’re mixing live, I remember him telling me, especially with a new band every night. And you don’t have the luxury of fixing a bad channel or waiting for someone to bring you a replacement outboard limiter. But, he says, the experience was fundamental in shaping how he works and who he is today.

If Zach Edey had been born in the United States instead of Canada (or had different parents), it’s not likely he would have played much hockey as a child; more likely, he would have been handed a basketball by age 4 and been sent to elite camps year-round, with home-schooling in between. If Tony Gonzalez had been born 15 years later, there’s no way he would have been allowed to play two major college sports. And if Jacquire King had been born a digital native, with his primary audio education and production skills revolving around his laptop, I doubt…well, Jacquire would still be a Grammy-winning engineer, but I doubt he would have stayed at Slim’s the full 10 years,

While it isn’t all that unusual for a football player to hit the basketball court, or a live sound mixer to work in the studio, the world as a whole is sliding into an age of specialization. Every parent knows this, longing for

the days of old when a “kid could just be a kid,” while at the same time enrolling their sixth-grader in SAT prep courses, or insisting that there’s not enough time in the week for karate classes at the rec center when their fourth-grader is preparing for a career in dance. I was outraged when public schools started to eliminate music programs. Now I’m mortified as I watch public universities across the country start to cut back, and in some cases eliminate, liberal arts programs.

Each and every person you run into is about so much more than “what they do.” Every background is unique, and every personality is built up over years and influenced by so many others. That’s one of the things I love most about the pro audio industry: The people are so damned interesting.

I remember back in the late-1990s, when the AES Show came to San Francisco, the Mix editorial team decided to publish a Vanity Fair-style feature, with full-page photos and very little text, to profile some of the great local audio personalities. We sent Steve Jennings out with a camera to shoot the great producer David Rubinson in full meditative pose, with legs crossed and palms up, atop Mt. Tamalpais. Skywalker Sound engineer Leslie Ann Jones is a foodie, so she posed in front of her backyard barbecue as she grilled lamb chops. There were a dozen others, but the point is, we wanted them all outside of the studio. We wanted a glimpse into who else they were.

I think it’s fantastic that Oscar-winning sound designer Mark Mangini plays a mean guitar and that the great Walter Murch spent years in his spare time researching and trying to solve Bode’s Law, a mathematical equation related to orbital bodies in space. I wouldn’t want to order the wine if Russ Berger were at the table; he knows too much! And I can hear the excitement in the voice of my buddy Evan Baake, who runs Power Station New England, when he’s about to head out for a weekend of fly fishing.

In this very issue, we find out that Dr. Peter D’Antonio is a scientist who brought his academic and research background in crystallography into the study of acoustics and studio design. He also plays bass. And he still records and plays gigs.

Everything we do informs everything else we do, and it’s up to us to understand that afternoons spent preparing a gourmet meal or mornings spent birdwatching is not time wasted outside of the studio. It’s all part of what each of us brings to the party.

Tom Kenny, Co-Editor

In early June, it was quietly announced that the Association Solutions division of MCI USA, a global engagement and marketing agency, would be taking on the Audio Engineering Society as its newest full-service association management client. Monica EvansLombe, CAE, was named Executive Director.

“The Audio Engineering Society’s partnership with MCI USA will help us meet the changing needs of our members and supporters as we move into the next phase of our 75-year history,” said Bruce Olson, President, AES. “I am very excited about the new opportunities for sustaining, improving and growing our Society.”

Founded in the United States in 1948, AES is the only professional society devoted exclusively to audio technology and is now an international organization that includes 10,000-plus members, 90-plus AES professional sections and more than 120 student section around the world, providing members opportunities for professional

networking, education and career growth.

Evans-Lombe brings to the AES 20 years of experience providing associations with organizational management, membership and client services. She will lead a team of professionals to provide sales, education, events, marketing, IT, accounting and support services.

“MCI USA is proud to welcome the Audio Engineering Society as a full-service management partner,” said Carrie Hartin, President, Association Solutions, MCI USA. “With Monica EvansLombe serving as Executive Director, we have an outstanding team in place to provide AES with a customized suite of services tailored to deliver maximum impact in key areas.” ■

In late August, YouTube Music published a set of three fundamental AI music principles and launched the YouTube Music AI Incubator, initially partnering with artists, songwriters and producers from Universal Music Group.

YouTube’s CEO, Neal Mohan, shared the platform’s AI music principles and his vision for how the framework will enhance creative expression while also protecting artists on the platform:

“Principle 1: AI is here, and we will embrace it responsibly together with our music partners. As generative AI unlocks ambitious new forms

of creativity, YouTube and our partners across the music industry agree to build on our long collaborative history and responsibly embrace this rapidly advancing field.

“Principle 2: AI is ushering in a new age of creative expression, but it must include appropriate protections and unlock opportunities for music partners who decide to participate.

“Principle 3: We’ve built an industry-leading trust and safety organization and content policies. We will scale those to meet the challenges of AI. Generative AI systems may amplify current challenges like trademark and copyright abuse, misinformation, spam and more. But AI can also be used to identify this sort of content, and we’ll continue to invest in the AI-powered technology that helps us protect our community of viewers, creators, artists and songwriters.”

YouTube’s AI Music Incubator program will reportedly bring together numerous artists, songwriters and producers to help inform YouTube’s approach to generative AI in music. The incubator will kick off with a genre-spanning cohort of creatives from Universal Music Group that includes Anitta, Björn Ulvaeus, d4vd, Don Was, Juanes, Louis Bell, Max Richter, Rodney Jerkins, Rosanne Cash, Ryan Tedder, Yo Gotti and the Estate of Frank Sinatra, among others. ■

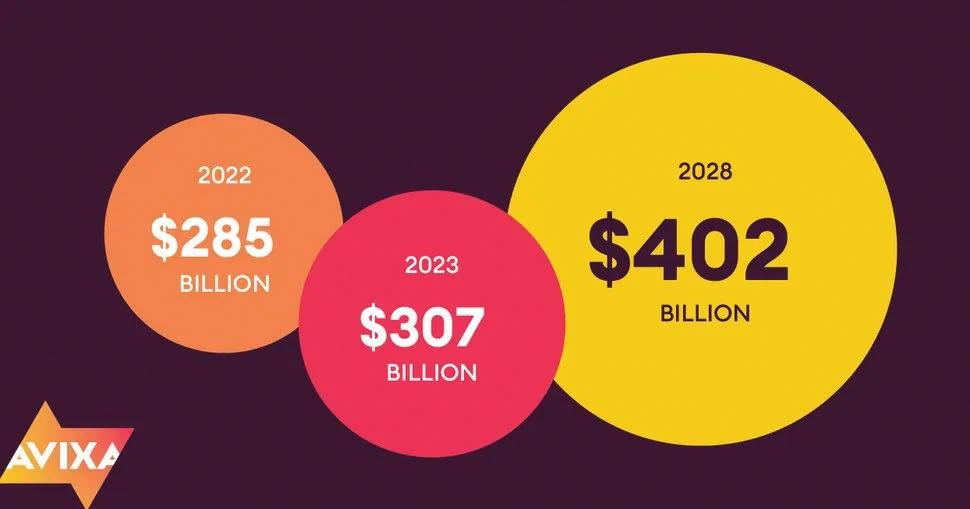

The Pro AV industry is forecast to add nearly $100 billion in revenue over the next five years, reaching $402 billion in 2028, according to AVIXA’s 2023 Industry Outlook and Trends Analysis (IOTA). With pandemic recovery largely in the past, the industry is poised for growth through 2028, even as year-over-year percentages slowly decline.

AVIXA’s report presents analysis about the size of the Pro AV industry with global, regional and vertical perspectives, outlining product trends, solution categories and vertical markets.

Sean Wargo, vice president of market intelligence at AVIXA, noted that the forecast “shows a return to a rate of growth that would have been considered more normal before the pandemic. However, looking below the surface, one can still see a varied landscape of opportunity. Immersive experiences across the venue and events market is a particular one to watch.”

Pro AV revenue will grow from $307 billion in 2023 to $402 billion in 2028—a 5.6% compound annual growth rate. The near term shows a mix of demand growth and deflation as supply issues improve. While 2022 did slightly better than initially expected, this came at the cost of 2023 growth because recovery was pulled forward from 2023 into 2022. On net, 2023 revenue totals reflect offsetting impacts of elevated demand and deflation in some core categories.

APAC economies are experiencing higher growth each year, contributing to its position as the largest region for Pro AV spending. Most notable is the return of live events, reviving the rental and staging market. Digital signage is expanding faster in APAC, with a 7.2% growth rate as the consumer base grows.

The Americas were stronger in 2022 as inperson surged back but are expected to see lower 2023 growth. The return to in-person is a mixed story in the Americas. On the corporate side, U.S. companies have settled into a hybrid mode, driving less growth in conferencing solutions

for offices. Though Pro AV is seeing the tail end of the growth from return to in-person, the venues and events industry is now spending in the region, leading growth. While the rise of software is a global phenomenon, it is the most pronounced in the Americas, where growth is nearly 12%.

EMEA experienced the lowest growth in 2022 due to the Russia/Ukraine War. Inflation is higher, and so is propping up growth slightly in 2023. EMEA is an events-based market, more than the rest of the world. The live events market is fully benefiting from audience return in EMEA, growing by 7.69%. Though overall growth is lower in the region, many core segments relating

to events are seeing higher growth in EMEA. Sustainable energy is also a source for Pro AV spending growth.

Corporate remains the largest revenue source of Pro AV revenue, but more growth comes from media/entertainment and venues. These top markets remain dominated by spending on back-end technology. Across many parts of the globe, investments are being made to transition to sustainable sources of energy and to improve grids. This also trickles down into the AV industry, most often in the form of control rooms for monitoring. While not a huge market for AV, it is one to watch for upside as the toplevel investments increase. ■

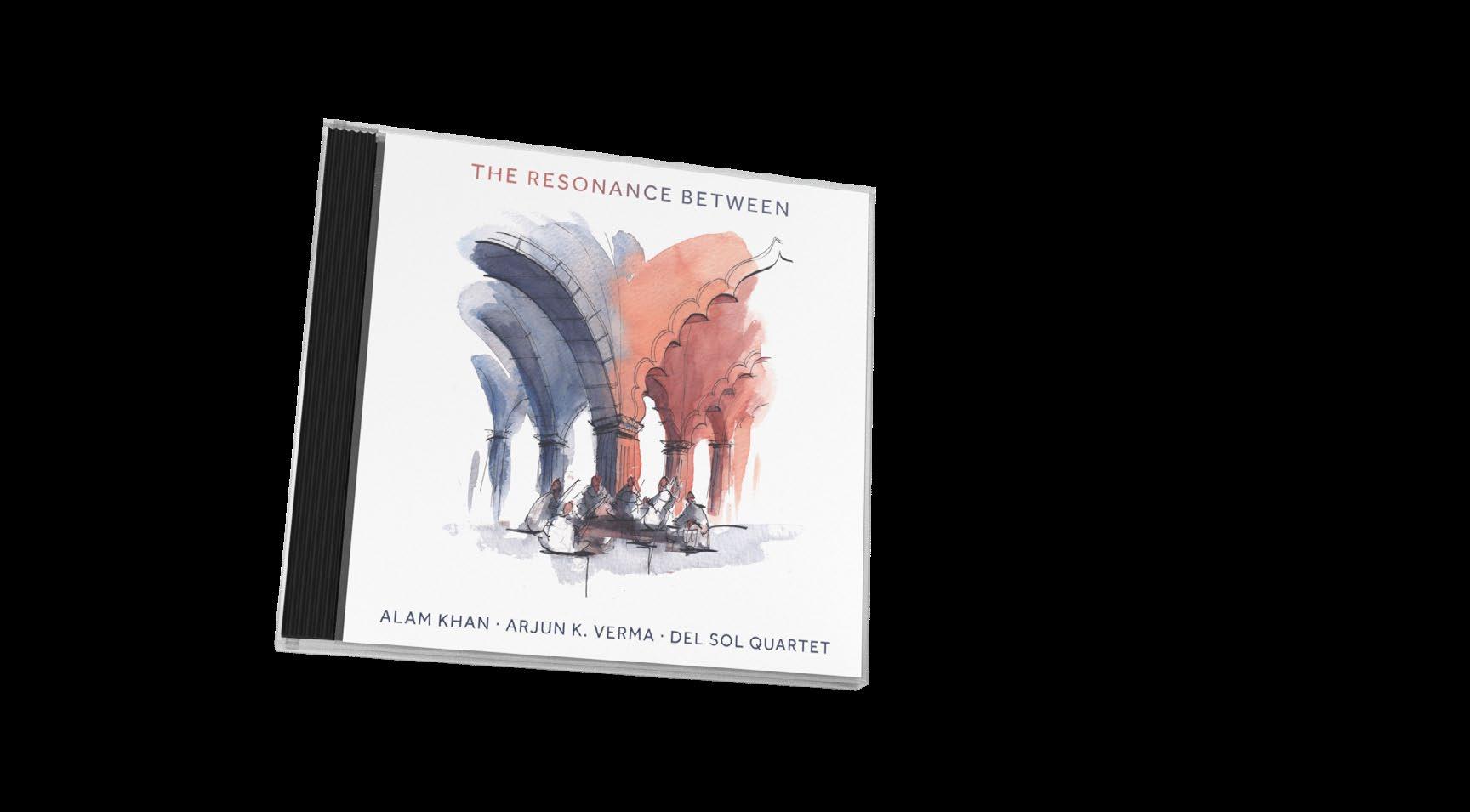

In music, as in life, two seemingly opposing perceptions can often be true. We have all listened to the outcome of a project that sounds so magnificently seamless, flowing in an almost simplistic sonic bliss, while at the same we are aware of the unparalleled complexity of its conception, performance and production.

So it was with The Resonance Between, a courageous, innovative, cross-cultural collaboration between Alam Khan, Arjun K. Verma and Del Sol Quartet.

Talks among the artists began back in 2018, followed by a submission for a Bay Area Creative Work Fund Grant on the basis of their multi-

cultural and mixed race background, along with the rich musical lineages that would form the foundation for a groundbreaking collaboration between Western and Indian musical traditions. They received the grant, which required a public performance, but when Covid struck, the collaborators decided to fulfill their obligation by pivoting from the stage to the studio.

Alam Khan, a sarod player, is steeped in the true ancestry of Indian music In the early 1900s, his grandfather, Allauddin Khan, established the Maihar band, which was largely made

up of orphans who had been displaced from Bangladesh. He taught the children the tradition of Indian ragas, and at the same time trained his son, Ali Akbar Khan, on the sarod, and Ravi Shankar on the sitar. The late Ali Akbar Khan carried on the tradition, starting the Ali Akbar College in San Rafael, Calif., where Alam Khan today teaches advanced instrumental classes.

Even with that background, The Resonance Between, Khan says, is actually more classical than some of the other projects he has done recently.

“It took me a long time to get to that place I was a purist for many years, and about 15 years ago, I began to choose collaborations with some artists

I really respected,” he explains, noting the 2011 Tedeschi Trucks album, Revelator, which won a Grammy for Best Blues Album.

Verma says Khan is like a big brother, as they first met when he was just eight years old; his own father, the notable sitarist Roop Verma, was a student of Khan’s father in India in the ’60s. Verma’s father began teaching his son the sitar; later, Verma became a student at Khan’s father’s school. It seemed only logical that the two younger musicians would come together for a thoughtful integration of Western harmony and raga.

“We’re both mixed race,” Khan points out. “There’s an Indian classical world, there’s a Western world. Where’s our world? It’s somewhere in between—so speaking from that world between worlds, if you will, when we were young, there were not a lot of people to look up to who were mixed race. I’d like to be a voice for that as I get older. There are a lot more people who are being born today mixed race.”

Khan, the project’s primary artist/composer, is more of the “big picture” person, while Verma tends to be more detailed. For this project, they brought in Jack Perla to arrange the MIDI compositions and flesh them out as parts for Del Sol Quartet, which would soon join the two.

Engineer Neil Godbole, owner and operator of Airship Laboratories in the San Francisco Bay Area, began working with Indian instrumentation in 2015. He has collaborated with Khan and Verma on their various solo records, and was

tapped to engineer, produce, mix and master The Resonance Between, with much of the actual communication taking place over Audiomovers and Zoom.

To get started, Khan and Verma sent Godbole rough demos, with their parts recorded at home and including mocked-up MIDI strings. The intent was to first establish a clear identity and consistency of sound, as the sitar can tend to overpower the sarod.

They then started looking for a quartet that would be able to handle just temperament and just intonation, which was extremely important in order for the Western instrumentation to accommodate the tuning style of traditional classical Indian music. For Godbole, one of the major accomplishments of the work was to produce a record entirely in just temperament.

“Indian classical instruments have an overtone sequence because they have resonant strings, so when you hit a note, extra strings ring out in sympathetic vibration,” the engineer explains. “Melodyne has a few modes for pitch correction, namely monophonic or polyphonic. In polyphonic mode, Melodyne breaks up the audio information into its various tones and resonances, so separate aspects of the polyphony of a sound source can be edited—like a chord into its constituents. Because these instruments have some competing overtones, we wanted to be able to adjust the overtones, but not necessarily the normal fundamental polyphony. There is a drawer in Melodyne where pitches much higher up are usually grayed out and not adjustable. We found we can make Melodyne show us these extra overtones that normally aren’t part of the detection/correction process, and just lower the volume, or adjust the pitch, of these.

“This is especially useful for Indian classical instruments that have Chikari (resonant/ sympathetic strings), which can ring out quite loudly. This allowed us to get control of these resonant strings and allow them to play well with the quartet without dominating them— yet still keep the fundamental tones of the instruments intact.”

Del Sol tracked in two blocks of three days each, eight to ten hours a day, at Airship while Khan and Verma patched in through Zoom to view Godbole’s remote desktop along with a video feed into the live room. Audiomovers was used

to shuttle near-real-time, high-resolution audio. Most of the string quartet was recorded through Godbole’s Cranesong Spiders.

“The Cranesong really lets me tweak the harmonic profile, as well as record it very clearly,” he explains. “I have 16 channels of Cranesong, and a lot of times, especially when I’m recording a quartet, I just want them all to be the same kind of preamp profile so that I can then tweak them individually, but then have them all be of a similar coloration.”

The quartet was actually split into “dB layers” so the team could record the lower and upper octaves separately. “We actually had eight layers of strings,” Godbole says “It’s a technique people use so you’re not forcing the instrument especially in just temperament, where you require a retune to try to make the massive octave switches mid-composition, midplay. We just recorded them in two-layer passes. I wanted the second layer and first layer to blend together and sound like one quartet playing together, so I used impulse response on both of them so I could marry the sound of the room with the sound of the playing.”

After Del Sol recorded, Khan and Verma rerecorded their parts so they could create more realistic interplay. Godbole also had them send

files of the ambient sound of their room so he could add that into the mix.

Khan recorded all his parts at home on Ableton, with an Apogee Duet interface and an AKG C-414 mic on the front end. Verma also recorded to Ableton, through a UA Apollo Twin X interface and his go-to home studio mic, an Earthworks QTC-1. “What I love about it is I would record with it and think that the highs were brightened, which is always something I look at because the sitar is already a bright instrument,” Verma says. “A lot of condensers over-brighten it the typical U87 makes it sound way too metallic. With this mic, I notice that it sounds like it’s brighter, but it’s not actually brighter; it just has better detail and impulse response, so you get better representation of the higher frequencies. For the warmth, I use a simple AKG 319B.”

The tablas were recorded at the end. Khan and Verma chose three young tabla players, one local and two who recorded their parts in India.

Then Godbole began to mix. The gear he used during the pandemic included Neve 5059 summing mixer. His path for mixing was to sum through the 5059, then through

a Cranesong HEDD, where he used general settings for saturation, and back in. “Everything else is in the box; I normally set both the Neve and the HEDD before the session so it becomes the glue and the overall sound that all the tracks are getting, and then I mix into that,” Godbole explains, adding that he didn’t want to create an overly processed sound; he wanted it to feel like everyone was together in the room.

“Western instruments and quartets have been playing together for a long time, but then you add sitar and sarod to it, and it makes everything

progression of music, who is talking, what is it trying to lead me to? When everyone is talking at the same time, it’s like a bunch of people at a house party trying to tell me their viewpoints; they don’t come across as much Maybe in this particular house party there were a few really cool viewpoints, so how do we organize them? My job was to realize that my job was in the nature of the transient responses. I had to figure out how to get which instrument to shine by emphasizing the transient nature coming through a given instrument.”

In the end, Godbole says, he hopes that the dissection of the process of this ambitious undertaking does not diminish the heart and soul of the intention, the performance and the

Khan doesn’t seem concerned. He is pleased with the outcome. He feels it is something different. He knows it won’t appeal to everyone, but he hopes listeners will open their hearts He believes his father would approve of “at least some of it,” he says with a laugh. “At least I hope so. I think he would say, ‘Mmmm, good,’ and give us a head

Todd Hooge, owner of Sonic Forest Studios in British Columbia, is all-in on Dolby Atmos, building a facility and putting his studio together with the assistance of Dolby engineers, who helped him with acoustical advice and technology selections.

“Investing in Atmos is no small thing,” Hooge says, citing both equipment costs and the necessary renovations to his home. He predicated his new 7.1.4 mix facility—opened in January 2021 at his home on five acres near Victoria on Vancouver Island—on the continued momentum of the immersive Dolby Atmos format in cinema, gaming, music and other media genres, he says.

“Before I did it, I wanted to make sure that was the way the market was trending,” he says. “I didn’t just read the pro-audio magazines, but also the financial papers and magazines. I wanted to be absolutely sure this was the way to go, the thing to do. Like any major life decision, I wanted to do my homework.”

The studio’s Dante infrastructure is enabled by Focusrite Red and RedNet devices, including a Red 16Line 64-in/64-out Thunderbolt 3 and Pro Tools | HD-compatible audio interface. “This is the main interface for the entire rig, and the hub for all the Atmos,” he explains. “It’s my digital patch bay, and through it, I can reach any other device in all seven recording-enabled rooms of the house.”

Three RedNet HD32R 32-channel HD Dante network bridges support the immersive system’s 128 objects. “I work in Pro Tools HDX 2, and without the HD32R, I would have fewer channels; I wanted to max the system from the start,” Hooge says. A RedNet 5 Pro Tools HD bridge provides access to an older Pro Tools rig.

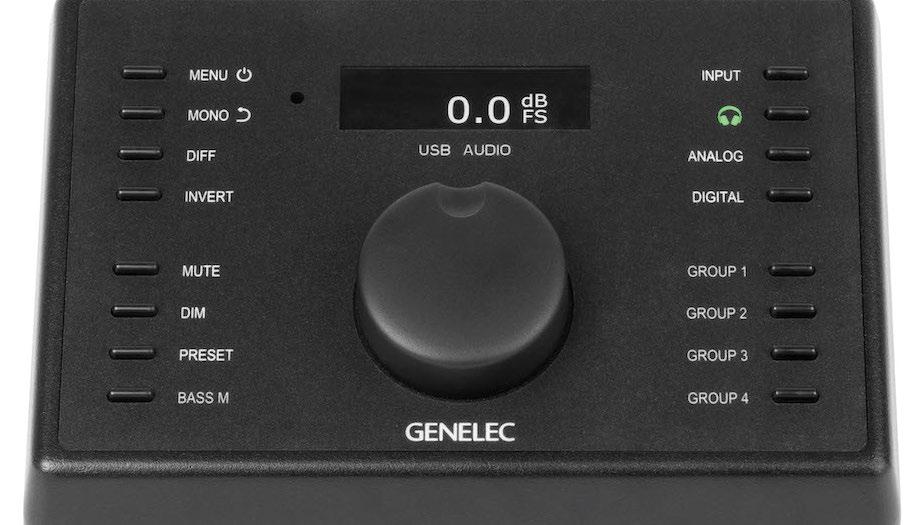

“I can’t do without it,” Hooge says of his RedNet R1 desktop remote monitor controller. “I have a Yamaha RX-A8A Atmos receiver, and with the R1, I can instantly switch it to capture immersive audio, such as Apple Spatial sound, in the wild. Also, the R1 has power over Ethernet, so it doesn’t need external power.”

Hooge can place his pair of RedNet X2P 2x2 Dante audio interfaces anywhere there is a Cat6 jack, noting: “I can use it as a headphone mixing device, put a singer in one of the rooms and record remotely, because it has two mic pres on it.” n

Times change, but the need for a good time never does—which is why Slightly Stoopid’s fans come out every year to let loose to some deep grooves. The band got its first record deal in the early Nineties while still in high school (and was signed by Sublime frontman Bradley Nowell, no less), so the group has grown up with its audience—and that audience has grown. These days, Slightly Stoopid fills amphitheaters across the country, like it did this year on the Summertime 2023 tour, bringing its unique mix of punk, reggae, dub, hip-hop and blues to sold-out crowds in venues like Colorado’s Red Rocks Amphitheater

and New Jersey’s PNC Arts Center.

Helping bring those good vibes to the fans at each stop was FOH engineer James “Jwiz” Wisner. While his audio background includes time in the studio with Nas, Shakira, Justin Timberlake, Toots and the Maytals and others, for the last 16 years, Wisner’s worked with Slightly Stoopid on records and the road, seeing the group’s dedication and work ethic take it to new heights. “It’s definitely been a growing process; this was the biggest tour we’ve done thus far, but they’ve been doing 5,000-7,000-seat amphitheaters across the country for easily the last 10 years,” said Wisner.

For this year’s journey, the tour brought along a passel of gear provided by Gainsville, Fla.-based Vivid Sky Productions, including a sizable PK Sound Trinity Black robotic PA system. Hearing about Vivid Sky’s newly acquired system from a friend, Wisner first tried a Trinity PA at a demo in Las Vegas earlier this year. “I did a virtual playback with some of our live show and mixed it on a system they had set up in a racetrack. From that, I was convinced that it was the next step up in audio quality from what we were using. With the PK rig, it’s incredible how defined the clarity is; for instance, you really hear that I’m adding distortion on the vocal because it’s so

clear in the mix. The PK rig can be revealing and for me, I enjoy that you hear stuff that normally would get lost.”

As a result, this year’s tour went out with a system flexible enough to handle a variety of different-sized venues. “We have 32 Trinity Blacks, 24 T10s and 24 T218 subs,” said Drew White, PA Systems Tech, “so sometimes it’ll be 16 Trinity Blacks per side on the main hang, but if we have to fly them further downstage, we’ll do 12 Trinity Blacks over four T10s to angle down. They are powered boxes; they all have amplifiers in them, and they also are controlled and powered by PK cells on the ground.” The “robotics” aspect of the speakers allows users to hang an array straight, and then configure and remotely adjust the array’s directivity mechanically from 60 to 120 degrees, both symmetrically and asymmetrically, using industrial linear actuators.

Out at the FOH position, Wisner oversaw an Avid S6L 32-D console, marshalling around 60 inputs from the stage. Most effects put to use were either the desk’s onboard offerings or a selection of McDSP plug-ins like FutzBox, used for distortion on fan faves like “Devil’s Door.”

Given his work with the group in the studio—he recorded, mixed, produced and mastered the group’s Top of the World album in collaboration with the band—Wisner has an ear for honing the Slightly Stoopid sound. “It definitely helps give me the path of what the sound is, and how to recreate the album experience live,” he said.

Of course, given his history mixing the group in concert, perhaps it’s inevitable that the live

approach would come into play when recording, particularly given the band’s reputation as a touring act: “My approach—and something that works great with them—is recording everything as live as possible and not compartmentalizing anything too much in the production process. I think that live feel and sound in the studio is very much portrayed on the albums, which in turn is in the show—so I don’t know which one leads the other, but it definitely provides the overall vibe and feel.”

Keeping that vibe very much in the present during a show, the group typically used a click but there were no pre-recorded tracks. Hand in hand with that, the group had a general set list, but expanded it when necessary, Wisner explained: “Some of the core elements are the same throughout the summer—there are a few audibles, but for the most part, it’s the same set with a few changes here and there. However, we did two nights at Red Rocks where I mixed 50-something songs in all. The first night was more like the summer tour set, but the second night, they played the Closer to the Sun album from start to finish and then added some songs at the end.”

The result was a mix that kept Wisner listening and thinking on his feet throughout the entire show: “I’m mixing on the fly but using a lot of function keys and events so everything has a trigger and a place and I don’t have to page around to get to anything. That gives me a lot on one page to play with, whether it’s turning on and sending something to a delay or something else.”

Capturing the musical mélange on-stage was a varied group of microphones, with vocals heard via Shure Axient Digital handhelds and Beta 57s used for guitars. The drum kit was outfitted with an AKG D112 floating inside the kick with a Shure Beta 91A outside it; a Shure SM57 on the snare and Sennheiser e604s on the tom-toms. “We use Heil PR 30Bs on the horns; we like those a lot and they sound really good,” Wisner added.

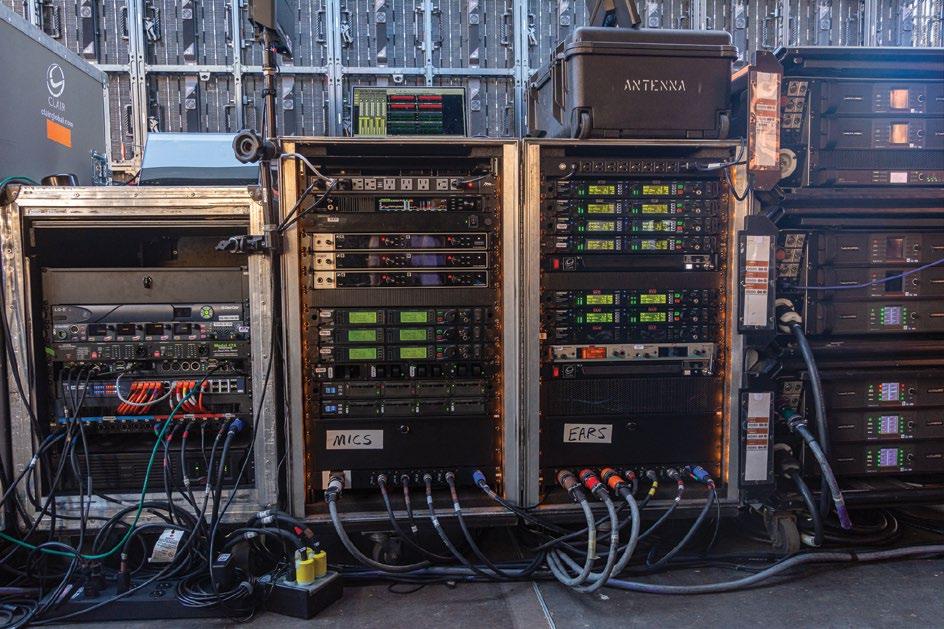

Over in monitorworld, engineer Jess Chapman tackled the mixes nightly on a DiGiCo Quantum5 console. Most of the band wore JH Audio and Ultimate Ears in-ear monitors, but not everyone had them in all the time. As a result, the tour also carried a sidefill rig—two or three L-Acoustics ARCs on top of two SB28 subs—strong enough to be a full-on PA. “We ended up where we have lots of ears and wireless going on, but we also have a stage that’s 115 dB sometimes,” said Wisner with a chuckle. “That can get interesting for the mix when I’ve got a vocal mic that’s got just as much guitar and snare drum as it does vocals!”

The summer tour ended in September, but the band plays the Reggae Rise Up festival in Las Vegas this month and wraps up the year in December with its ninth-annual destination event, Closer to the Sun 2023, taking place in Mexico over four days. Still, for Wisner, the highlight of the year may have been back in July when the tour hit San Diego. “We played Petco Park, where the Padres play,” he grinned. “It was 20,000-plus people in the band’s hometown baseball stadium—pretty incredible!” ■

New York, NY—Prog metal maestros Dream Theater have never done anything halfway, which is why when they founded their own touring festival this year—Dreamsonic—they brought along support acts Devin Townsend and Animals As Leaders, and presented it all to audiences through a brand-new L-Acoustics L Series system. Provided by PRG, along with all the other audio production, the production marked the first North American tour to carry L-Acoustics’ new flagship PA.

Dreamsonic was the first tour to carry L2 and L2D enclosures since PRG was one of a handful of pilot-phase production providers globally. Steve Thom, system engineer on Dreamsonic, found that local crews “want to know what we’re carrying, and I get to say, ‘Have I got a surprise for you! Everybody is very intrigued about the new technology.”

The L Series is comprised of two elements that are designed to work together or on their own, with the L2 above and L2D below. For comparison to previous L-Acoustics systems, one L2 or L2D element provides the same contour as four K2 elements in a format that is reportedly 46% smaller and 40% lighter.

“Depending on the size of the venue, we’ll do either two or three L2 over an L2D,” said Thom. “The largest we’ve done is three L2 on top of an L2D. We don’t have to set 16 inter-cabinet angles and eight jumpers as with a conventional line array; we only have four elements to connect, instead of 16, without sacrificing any output.”

When it came to powering the new system, the production had on-hand a LA7.16 high-resolution touring amplified controller, which supports L2 and L2D with 16 channels of amplification and processing, based in a new LA-RAK III touring rack offering 48 channels of amplification in a Milan AVB-ready package, with more than 60,000 watts of power in 9U. Thom noted, “Everything you need is integrated into a single amplifier, so you don’t need multiple amps, and the multipin connector on the back takes any guesswork out of the process.”

Thom noted, “Compared to a conventional line source that will most likely have one group of FIR filters dedicated to four compression drivers, each group of FIR filters on the L Series is dedicated to each individual compression driver in the line, providing increased resolution,” he says. “Also, the transition from component to component is incredibly precise, so there’s no gap in coverage, and the system’s tight directivity really helps clean up the sound on stage.”

Out in front of the system, Dream Theater front-of-house engineer Michael “Ace” Baker said he’d noticed that audiences liked the tour’s

sound, as did, intriguingly, the bandmembers’ wives: “They’re all musicians, too, and they knew something was up with the sound right away. They could clearly and distinctly hear greater definition of each instrument.” ■

Currently out on her first extended tour in nearly a decade, Natalie Merchant has been bringing her mellow, insistent folk pop to the masses once again in support of her latest album, Keep Your Courage. Backed by piano, drums, bass, guitar, a backup singer and a string quartet, the singer/songwriter finished a second U.S. leg in September and will hit Europe this month to share selections from across her solo career and the occasional tune from her previous group, 10,000 Maniacs.

In keeping with the bespoke nature of her music, the tour’s sound is equally self-contained, with mixing duties provided by FOH engineer George Cowan and monitor engineer Dave Cook. “Both of us go back a pretty long way with Natalie,” said Cowan. “We both met her in recording studios—Dave worked at Dreamland Studios in the 1980s and I worked at Bearsville Studios, all in upstate New York.” Cook befriended the singer while assistant engineering on 10,000 Maniacs’ 1989 album, Blind Man’s Zoo, during the recording of which Cowan became acquainted with the group (“My wife was catering the food,” Cowan explained). A few years later, the band’s 1993 MTV Unplugged album and then Merchant’s 5x-platinum solo debut, 1995’s Tigerlily, were tackled at Bearsville. “I was on another project,” said Cowan, “but I would meet Natalie in the in the hallway, say hello and subsequently got to know her. Fastforward a few years, she was doing Lilith Fair in 1998 and they were looking for a front-of-house engineer; somebody brought my name into the discussion, and she nodded approval because she knew me.”

Cook began mixing Merchant’s monitors 12 years ago on a tour behind 2010’s Leave Your Sleep, but both engineers keep busy in recording and live sound, as Cook owns Area 52 Studios in Saugerties, New York and Cowan has his own mixing facility.

While the current tour has been using local or house PAs, the two engineers have opted to bring along gear they own, much of it—such as the mics—culled from their own studios. The audio

path starts onstage with Midas DL32 mic pres leading into Cook’s Behringer Wing monitor desk where pre levels are set, and then signal heads out to FOH via Dante networking.

“I’m using an old Yamaha DM2000 mixer as a control surface, which people sometimes make fun of because it’s an older desk,” said Cowan. “The audio gets to me, then it’s going

through Universal Audio plug-ins and then out to the house. I have three Apollo units racked up for plug-ins and reverbs, with 24 paths to and from via Lightpipe. I have the UA Capitol Chambers plug-in for vocal reverb, which sounds beautiful; Little Labs IBP Phase Alignment plugin, which helps line up the phase response of the bass microphone and DI; various Lexicons for

drum reverb; LA-3As, LA-2As, and I put everything through a Studer A-800 plug-in so I get to bring back a little analog tape wonk to the whole picture.”

Tackling monitor mixes on the Behringer Wing desk, Cook uses onboard emulations of dbx 160s and a LA-3A on vocals, as well as the company’s take on a SSL Bus compressor for mastering the musicians’ in-ears. “We have a couple of sidefills, and Natalie will keep a couple of downstage wedges as insurance, too, but the stage volume is very quiet,” said Cook. “Everyone has brand-new Ultimate Ears custom molds, and Natalie and the background singer are both on Sennheiser ewG4 wireless for their in-ears. Everyone else has Behringer P16 personal mixers, where I’m sending a combination of direct outs and pre-mixed stems so they can dial in what they need themselves. There was a learning curve during rehearsals, but everyone’s settled in and loves it.” Miking for the stage includes Sennheiser Digital 6000 wireless with a Neumann KK 205 capsule for Merchant’s vocal, while the string quartet is captured via DPA d:vote 4099s.

Throughout the tour, audiences have warmly welcomed Merchant back after such a long absence from the road. Cook cited stops in Portland, St. Louis and Washington, D.C.’s Kennedy Center as particularly memorable shows, but arguably the highlight for the crew may have been the unusual hospitality of the St. Augustine Amphitheater; he explained, laughing, “We all got to hold a threefoot alligator they brought in from a local alligator farm!” ■

For 15 years, Outside Lands has been one of the Bay Area’s premiere music events—and this year’s edition, held August 11-13, was no exception. The three-day event in Golden Gate Park featured music on eight stages with performances by more than 100 acts, including Kendrick Lamar, Foo Fighters, Odesza and Megan Thee Stallion.

Once again, UltraSound, LLC and McCune Audio provided sound for 225,000 music fans in attendance, using Meyer Sound solutions on stages throughout the festival, including Panther linear array loudspeakers for the Lands End main stage.

Outside Lands may be in a natural setting, but it’s surrounded by a dense urban environment.

“The big sound challenge here is to keep things aimed down to the ground where the people are and not let it get too far into the air,” said Bob McCarthy, Meyer Sound’s director of system optimization. “What we’ve done is

use a three-part approach: We start with the main stage, then we hit delays, and then we hit delays again. This allowed me to get the mains aimed down more because they have to throw a shorter distance. The second set of delays, which are almost as powerful as the mains, restart the process from a nice, high position and aim down again. We finish it with a small system to end the system peacefully. The result is a betterquality experience for the audience from front to back and a better-quality experience for the neighborhood.”

The Lands End stage featured 14 80-degree Panther-L over four 110-degree Panther-W loudspeakers per side, supplemented by Meyer Sound 1100-LFC low-frequency control

A cornerstone of the New York City indie scene, Yeah Yeah Yeahs have been touring the U.S. behind last year’s Cool It Down album. Along for the ride has been a tour package from Nashville-based Worley Sound that is overseen nightly by engineers Daniel Good (FOH) and Nahuel Gutierrez (monitors).

The pair are each mixing on Allen & Heath dLive S5000 surfaces, with DM0 MixRacks handling 128 channels of 96 kHz input processing. For I/O, various DX168 expanders are distributed on the stage. A SuperMADI card is used, allowing for a multichannel broadcast feed when needed, as well as a 128-channel Waves card for multitrack recording and playback.

At front of house, Good uses dLive’s display output to set up a live RTA on an external monitor. “It’s cool to have that without having Smaart, to see how things are translating.” He also makes use of the console’s ABCD input feature, which allows a user to swap the input source of a mic channel using a user-defined SoftKey, noting, “Karen will jump mics sometimes; I need to be ready to swap from wired mics to wireless instantly and in pitch black, so I can do that now with a single button push.”

At monitors, Gutierrez shared, “We basically mix everything in the box, the DYN8 dynamic EQ is fantastic, as well as all the onboard FX and parallel compression options.” He also pointed to the dLive’s new Source

For the second year, UltraSound provided

elements deployed in gradient cardioid arrays behind each main array and across the front of the stage and Lyon linear line array loudspeakers serving as side hangs. Two primary delay towers combined wide- and narrow-coverage Panther loudspeakers, with Meyer Sound Leopard compact linear line array loudspeakers powering four secondary delay towers, VIP fills, and ancillary areas. ■

Expander plug-in: “That’s becoming a really good tool to clean mixes. I have it inserted on cymbals, vocals, and a couple of the open mics that are not used frequently to eliminate background noise.”

For creating distorted vocals on certain songs, Gutierrez employs the Dual Stage Valve preamp emulation. “It’s probably one of the best vocal distortions I’ve heard,” he remarked. “We’ve tried pedals and a few other solutions, but nothing sounded right until we found this emulation.” ■

Today, anybody from anywhere in the world can pick up their phone, download an app or visit a site, enter a few numbers, wait a few minutes for a recommendation, click on a package of acoustic materials, and a week later, once the packages arrive and the panels, cylinders and clouds are placed on the walls and in the corners, their personal studio immediately sounds better.

Results, of course, will vary depending on the quality of the app, the amount of data entered, the boundary limits of the space, materials in the walls, floor and ceiling, speaker location, whether there is follow-up measurement included, and dozens of other factors. Still, the simple fact that the sound and performance in a personal space can be dramatically improved by entering a set of data points is remarkable.

This didn’t just happen overnight, or because some kid in Silicon Valley had an idea. It’s all possible because of science. Real science. Decades of theory, test and measurement by a relatively small number of individuals at universities, in laboratories and at home. Dr. Peter D’Antonio is one of those individuals—but he’s also a scientist who plays bass guitar. His name is not always included when conversations turn to the great studios of the world and those who designed them, but when the top studio designers get together, D’Antonio has a seat at the head of the table—though his humble nature and sociable personality would likely force him to get up and move down near the middle, among his friends.

celebration of his original company, a highly anticipated AES Paper presentation later this month, and the honor of receiving the prestigious Wallace Clement Sabine Medal from the Acoustical Society of America for “contributions to the theory, design and application of acoustic diffusers.”

It’s been quite a ride. D’Antonio never planned to study acoustics or become the world’s leading expert in diffusion, or what he sometimes calls “the scattering of sound.”

life behind. Then in 1970, he lost his wife in an accident.

To deal with the loss, D’Antonio says, he slowly began to bring music back into his life, hooking up with a next-door neighbor to jam and write. They built a rudimentary, single-room studio in his house and dubbed it Underground Sound. The songs got better, the playing got better, but the recording quality was noticeably lacking. In the early 1980s, D’Antonio proposed building a better studio, one with a separate control room and proper isolation. At the time, he was still working at the lab and had zero knowledge of acoustics— studio, architectural or otherwise—but he was a scientist, he could figure it out. And that’s where we begin this month’s special Mix Interview.

So this lifetime spent in acoustics all began because you wanted better recordings? There were some good studios out there in 1983.

Over the past 40 years, following the establishment of RPG Diffusor Systems in December 1983 and through his ongoing collaborations with the world’s top studio designers, D’Antonio, as much as any single person in professional audio, has helped to shape the look, feel and performance of the modern recording studio.

This year, D’Antonio is earning his just recognition, with a 40-year anniversary

Born and raised in a middle-class, working-man Italian neighborhood of Brooklyn, his interest in music was nurtured by his mother and uncle, both outstanding vocalists, he says. He played in bands in high school, gigging through the summers at the Long Beach Resort, developing an early fondness for harmonies and doo-wop.

Then, admittedly having never really applied himself in school, he went to college, majoring in physical chemistry at nearby St. John’s, followed by a graduate degree in infrared spectroscopy, with a minor emphasis in crystallography, A professor recommended him for a job at the Naval Research Laboratory, and in 1968 he moved to Washington, D.C., leaving his musical

I had a typical two-story, suburban neighborhood home with a sub-basement that would work as a studio, but I had absolutely no idea how to build one. I hadn’t thought about acoustics for one second of my life before that. How do we even soundproof this room? I went through the literature, like all scientists do, and found you have to float the room and all that good stuff. Then we spent about two years on the construction, the AC, the plumbing, the air conditioning, the wiring—everything by ourselves.

The problem was there was no control room. For a lot of studios at that time, the speakers were still hanging from chains and the rooms were not symmetrical, which you need for an effective soundstage. I had seen a booth at another studio, and that’s when I thought, “Well, how do we design a control room?” I went to the literature, and there was absolutely nothing. All I could find was articles on how so-and-so had a hit record and used this kind of speaker, and

then everybody copied that design.

Then I came across an article by Don and Carolyn Davis and it actually sounded scientific, talking about the principles of Live End Dead End. They were using a device that I had never heard of, developed by Richard Heyser, called time delay spectrometry. Richard worked at Jet Propulsion Laboratory and he was a brilliant guy who was interested in audio. He would measure loudspeakers for audio magazines, and he developed this hardware that originally had about 15 pieces of gear with wires and everything. Then Crown built it into what was called the TEF Analyzer.

Anyway, I built a room and I implemented Live End Dead End. I put some pressure on the wall in the front, and I had a bare back wall, but when I listened to the room, it was very disappointing. The interference between those strong specular reflections and the direct sound was severe.

What did you do?

I decided to take the approach of, “What if I just came down from Mars? What would I do?” So I started researching concert hall design. There’s an important aspect of a concert hall in that you have the direct sound, and then there’s a period of time, which is called the initial time delay, before the reflections come in from the side walls. I say side walls because in the early concert hall designs, the ceiling was a lot higher than the width of the room, so the first reflections that came into the room came from the side, but because the speed of sound is finite, it takes time to go from the stage to the side wall to the audience—this initial time delay. How in the hell can I get an initial time delay in a small room when there is no time delay between the sidewalls and the speaker?

That’s when I came up with this idea of a temporal and spatial reflection free zone, where

I splayed the sidewalls out so that the reflections from the loudspeakers hit the sidewalls and went to the back of the room. It didn’t come to the listening position. Then I also slanted the ceiling vertically at an angle so that those reflections would go to the back of the room. That has become the signature of all control rooms to this day—but now that sound is going to bounce back and cause problems at the listening position. How do I constructively control that real-world dance? The answer was diffusion.

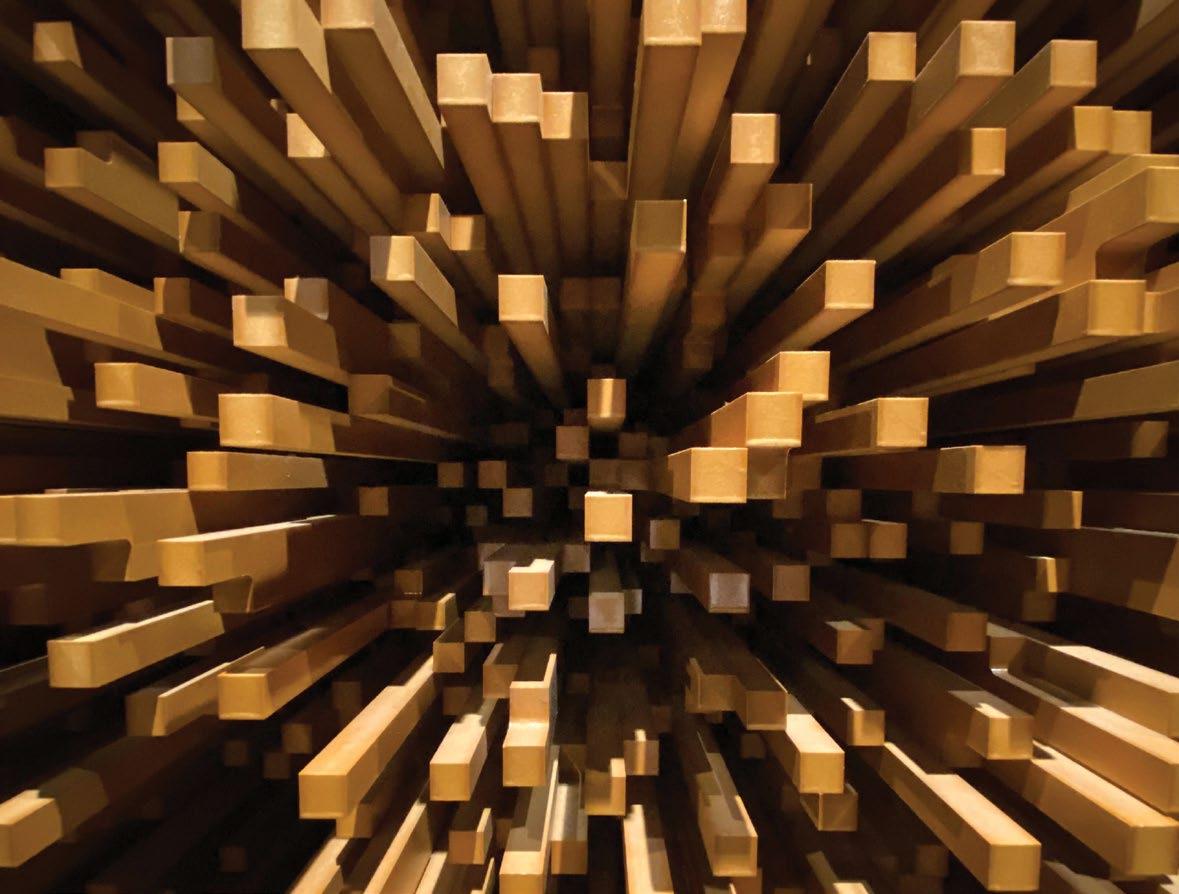

So the back wall of the studio in your basement is what led to RPG Diffusor Systems? [Laughs] You could look at it that way. During my research, I came across an article by Manfred Schroeder in Physics Today’s October 1980 issue. It described reflection phase grating (RPG) diffusors that were capable of uniformly scattering sound, and I realized that these diffusors were 2-dimensional periodic versions of the 3-dimensional periodic crystal lattices I had been studying as a diffraction physicist at the Naval Research Lab, using x-ray crystallography. That led me to further research and my first acoustical presentation at the 74th AES Studio Design Session C in October of 1983 in New York. To my surprise, Manfred Schroeder presented the leadoff presentation.

Anyway, because these diffusors scattered the sound and because the reflection was not in one direction, all of the energy in that reflection was now distributed to all of the reflections. So the sound that came back to the mixing position was attenuated, but the sound remained in the room, The room remained ambient.

I needed to control those reflections to create the reflection free zone. I realized that the diffusor in the back of the room was sending sound out over a semicircle in the back of the room, and a lot of the sound was hitting the sidewalls, so I made the sidewalls reflective and they reflected the sound back to the listener at 55 degrees, so when you go into a room that has reflections diffused on the rear wall, you get a sense of envelopment. I didn’t realize it at the time, but we had created what’s called passive surround. That’s when the high-end audio community became really interested in diffusion.

Do you mean studio owners, studio designers, other acousticians?

Don Davis was at my AES presentation, and

after the meeting, he introduced himself, saying that he taught acoustics and that he and his wife Carolyn had these traveling roadshows around the country. He invited me to their next meeting in Dallas, the first on LEDE, and asked that I bring my diffusors. I thought, “Okay, this is great”—but I didn’t have any.

We built two—and they were big. We shipped them to Dallas for the Syn-Aud-Con event, where they had a TEF Analyzer. That was the first measurement of the time response of these units. As we measured, I thought, “Wow! That’s what they should do!” What intrigued me was that we could actually see on the screen all of the reflective sound—when it arrived, what level it was. I thought this was fantastic. Bob Todrank was there, and Don Davis. They basically befriended me and introduced me to the world of acoustics.

Bob owned Valley Audio in Nashville at the time and he said, “You know, I got this job for the Oak Ridge Boys in Hendersonville, and I like what you’re talking about. You want to collaborate with me?” I said, sure, though at the time, I really couldn’t manufacture anything. I basically provided him with plans, and in 1984, the Oak Ridge Boys’ studio was the first commercial project to incorporate RPG Diffusors. The next Syn-Aud-Con meeting was held there, and that’s where I met Russ Berger. The first studio he did with RPGs was called the Dallas Sound Labs; we put a whole array of 4311s in there, and that became a really successful room. I also met Neil Grant at that Oak Ridge Boys event—later, I would do Peter Gabriel’s Real World Studios with Harris Grant in the UK, and Neil became probably my closest friend.

By the time of Real World, we did, but at the start, they were all custom to a project. The first units that I built were four feet wide and about two feet deep, and included 43 wells with a oneinch width. I called them the 4311 and started building them in my home.

For these diffusers, all you need is a rigid surface, so I wound up using plywood because it had to have multiple layers and it worked. The biggest problem was I had to divide the wells, and they had varying depth; they were like waveguides, but you have to prevent the wells from interfering with one another. You have to put these dividers that went from the face of the unit to the back of the unit and separated the wells—at each well, the sound

had a different time. That’s really what that constructive interference is, what creates the diffusion. In theory, the dividers should have been infinitely thin, so I decided to use metal.

I found a local vendor of sheet aluminum, and my oven handled the annealing. I was manufacturing in my carport, which I eventually

converted to a garage.

Reflection phase grating was different. It wasn’t the first form of diffusion—you had columns, balustrades, coffered ceilings, all kinds of surfaces that scattered sounds. What made reflection phase grating unique was that it was not dependent on the angle of incidence. It was invariant to the angle of incidence and invariant to the frequency, to a certain extent. I did a lot of research, and I had to modify the design of the diffusers over the years because the original RPG was essentially like a midrange speaker. I eventually developed a high-frequency diffuser, a mid-frequency diffuser and a low-end diffuser, but they all incorporated the RPG form.

We were awarded a patent in 1987 for the QRD 734, which became the first commercially

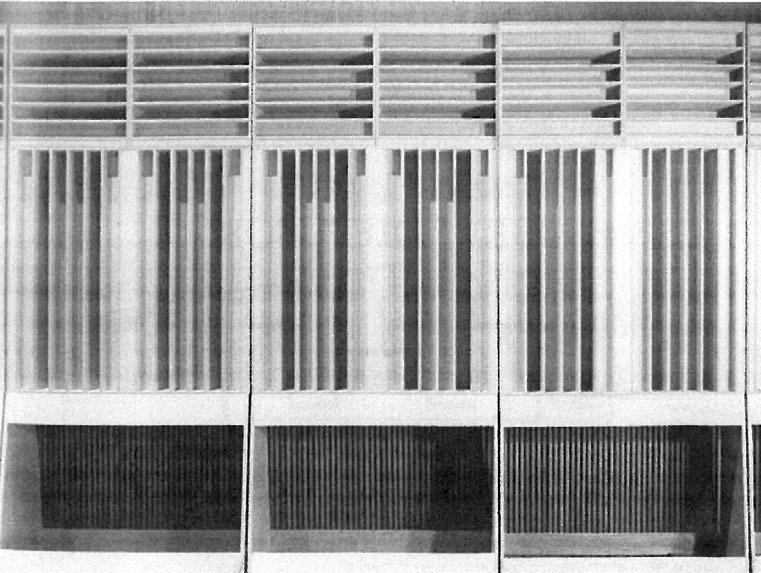

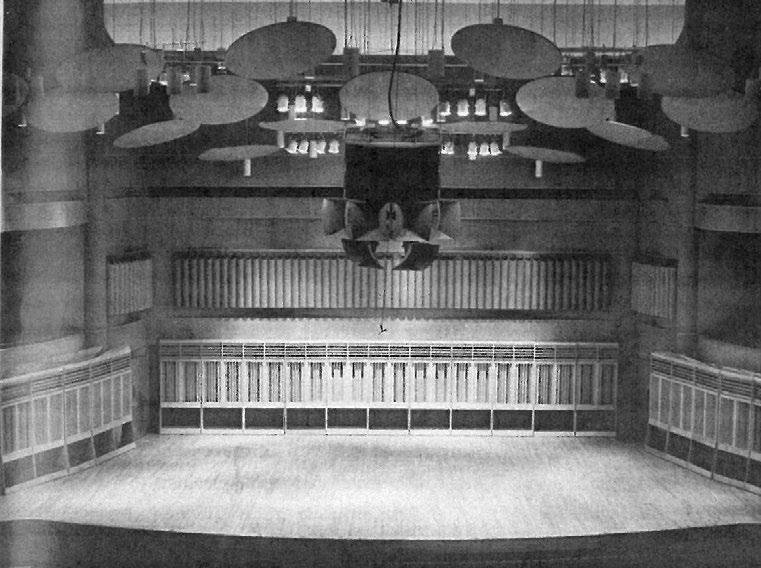

I had met Jack Renner, one of the founders of Telarc Records, and he did a lot of classical recording. He would be recording a symphony orchestra and they were monitoring in the green room or in a closet or hallway. I would send him some of our products just so they could hear what and how they were recording on the concert stage. Then one day, I get this call from Meyerhoff Symphony Hall, home of the Baltimore Philharmonic, saying, “You guys are down here sometimes and some of your boxes found their way on stage, and the musicians are saying they can finally hear one another. They just love these things. They put them all over the stage.” I said, “Well, that’s interesting.”

When I went to the Meyerhoff and looked at the stage, I said, “Well, I think I know what the problem is.” Acousticians are very, very protective of the projects that they design, and I’m a consultant and didn’t really know these people, though I got to know them very well later on. I told them that the theater wanted me to take some measurements and improve the stage acoustics. They ended up okay with it, as long as I didn’t touch their work.

I took my test machine, and I rented an omnidirectional loudspeaker and placed it around different locations on the stage to simulate the different instruments—say, first violins, cello,

etcetera, and I put the microphone in different places. I didn’t know anything about a symphony orchestra playing with different instruments. I sat in the different locations, starting with the basses. I realized from the analysis of the data that, for example, when the percussion hit the snare drum, it would reflect off these massive sidewalls. They had these large doors, entry doors, where they brought different instruments and things onto the stage. So what the conductor was hearing was the reflection off the sidewalls, and it was almost as loud as the direct sound. He essentially had no idea where the direct sound was coming from.

I thought, ‘Okay, we have to diffuse those sidewalls’ and then the rear wall was just flat, so we needed to get some diffusion there. We used whatever we had, if I remember, with aluminum dividers, and then on the side walls, we put a plexiglass cavity because there is a large area

on the side of the stage for people to look at the orchestra. I wanted to reflect the sound of the violins from this plexiglass reflector over to the middle of the orchestra. We put diffusors on the back wall and put in these plexiglass reflectors— and I wrote a paper about it.

Previously, I made up a questionnaire and gave it to musicians at the Meyerhoff before we implemented the change. Then they filled it out again after we implemented the change and there was close to a 100 percent average improvement in the perceptive qualities. I guess the chronology of RPG is that we went from studios to broadcast video to high-end audio, and then to performance venues. Later, we ended up doing the back wall of Carnegie Hall.

That conductor, by the way, was David Zinman, a very famous conductor. He gave me the best compliment when he said that I “had made coming to work a joy.”

PHOTO: Courtesy of Peter D’Antonio PHOTO: Courtesy of Peter D’Antoniodeveloped and available sound diffusor.

And then everything flowed smoothly and here we are 40 years later!

[Laughs] Well, we did have a few products now, but I had been doing a lot of theoretical predictions, and as RPG continued to grow, I really felt the urgency to verify all of that experimentally, for a variety of reasons. First, scientists like to verify things, but also I wanted to eventually develop a diffusion coefficient that could be used alongside the absorption coefficient. I needed to develop an experimental method to measure and document their performance so they could be specified by acousticians and added to the acoustical palette.

I began a systematic program of experimental measurements, using the TEF analyzer, beginning in large sports facilities, then my son’s high school gymnasium. When we wore out our welcome, we developed a new scale-model measurement system called a Goniometer, which was another example of how my experience in crystallography led to a development in acoustics. This research eventually led to the current ISO 17497-2 diffusion coefficient measurement standard published in 2012.

Right after I developed my capability to measure a polar response, I got a call from the editor of the Journal of the Acoustical Society of America asking me to referee a paper by a guy named Trevor Cox, a recent graduate on the topic, I read it, and I thought, “Oh my God. This is like an incredible freakin’ paper. Unbelievably creative. What Trevor did was he wrote a

boundary element code. He was using a different theory than my simulations, noting that because the wavelength of a sound is a million times bigger than the wavelength of electromagnetic radiation, which is what I was using—x-rays as I did in crystallography. You have to use a different theory called wave theory, basically solving what is called the wave equation.

Without diving into the science, this relationship with Trevor eventually led to the co-authorship of three reference books on acoustics, development of software that would eventually lead to a virtual goniometer and the formation of NIRO and REDI Acoustics, and, of course, the co-efficient, which now allows us to predict the performance of a future space as accurately as we could measure it.

We haven’t even talked about Real World, Hit Factory, Blackbird Studio C, Jungle City, the just-opened Rue Boyer in Paris, or any of the hundreds of projects you’ve contributed to. I’ve been very fortunate in my life, working with such talented and creative designers. Don Davis, Bob Todrank, Chips Davis, Steve Blake, Neil Grant, John Storyk, Russ Berger, Doug Jones,

Steve Langstaff, Neil Muncy, Lennert Nilsson, Bob Richards, Bob Skye, Martin Pilchner, Chris Pelonis, and most recently, Wes Lachot—I’ve learned from all of them, and I consider them all friends to this day.

You just turned 81, and you’re celebrating 40 years of RPG. You got a late start! But it doesn’t seem like you’re slowing down all that much.

Well, I sold RPG Diffusor Systems in 2016, and then in 2017, I launched a new entity known as RPG Acoustical Systems to manufacture the products designed prior by RPG Diffusor Systems and begin research and development into new areas. We added the Acoustical Research Center with a 285 cubic-meter rev room, a new Goniometer and a seven-ton, 25-foot-long long impedance tube. We invite any and all to join the ARC Associates Alliance and share the facility.

But if I were to look back, I’m most proud of the fact that we now know how to design, predict, optimize, measure, characterize and standardize the performance of scattering surfaces. While there is still much to do, there is a general consensus in the architectural acoustics community that a solid theoretical and experimental foundation has been laid, that diffuser performance can now be quantified and standardized, and that diffusers can now be integrated into contemporary architecture, taking their rightful place along with absorbers and reflectors in the acoustical palette. The future holds exciting possibilities, and we’re looking forward to the next 40 years! ■

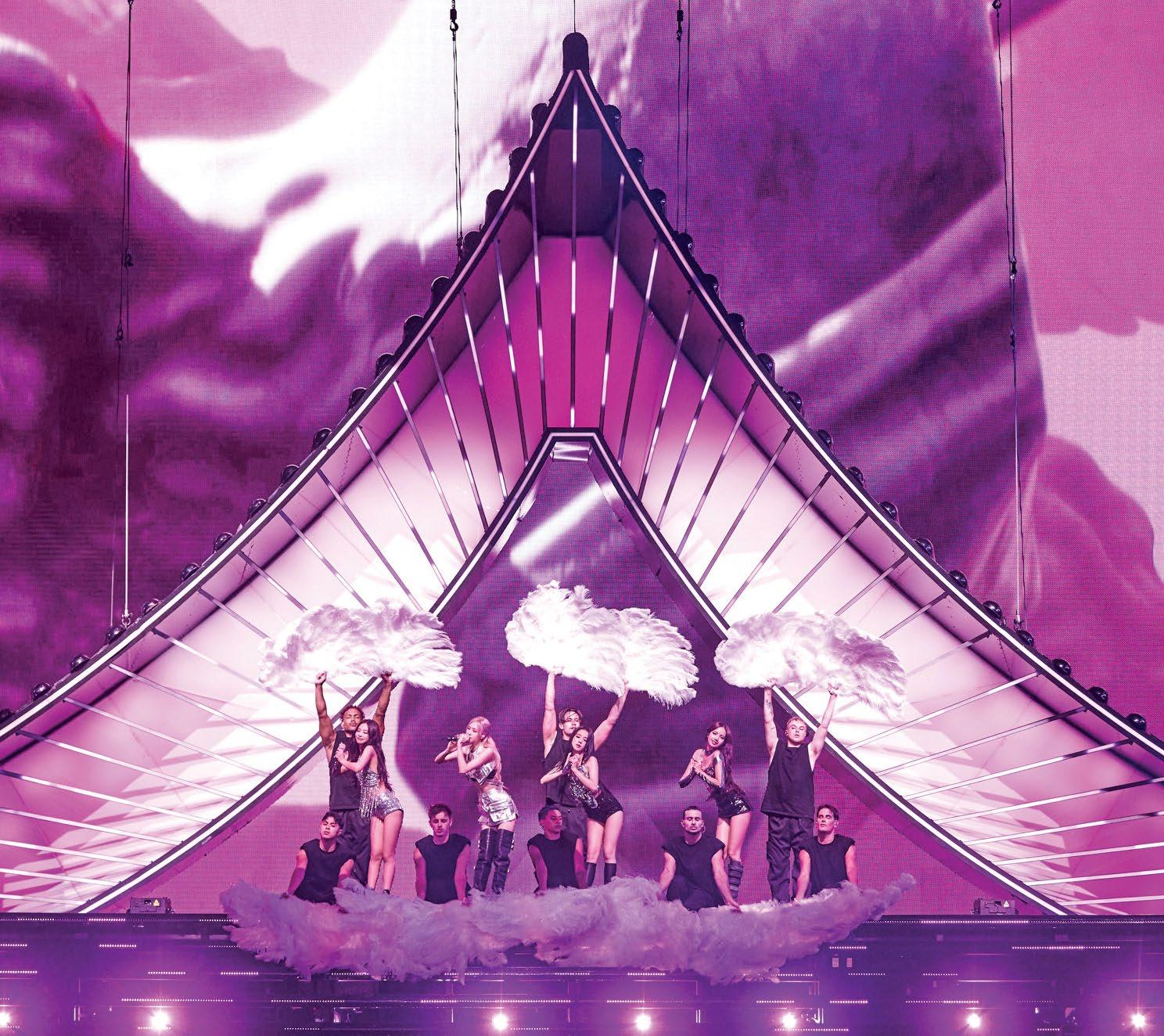

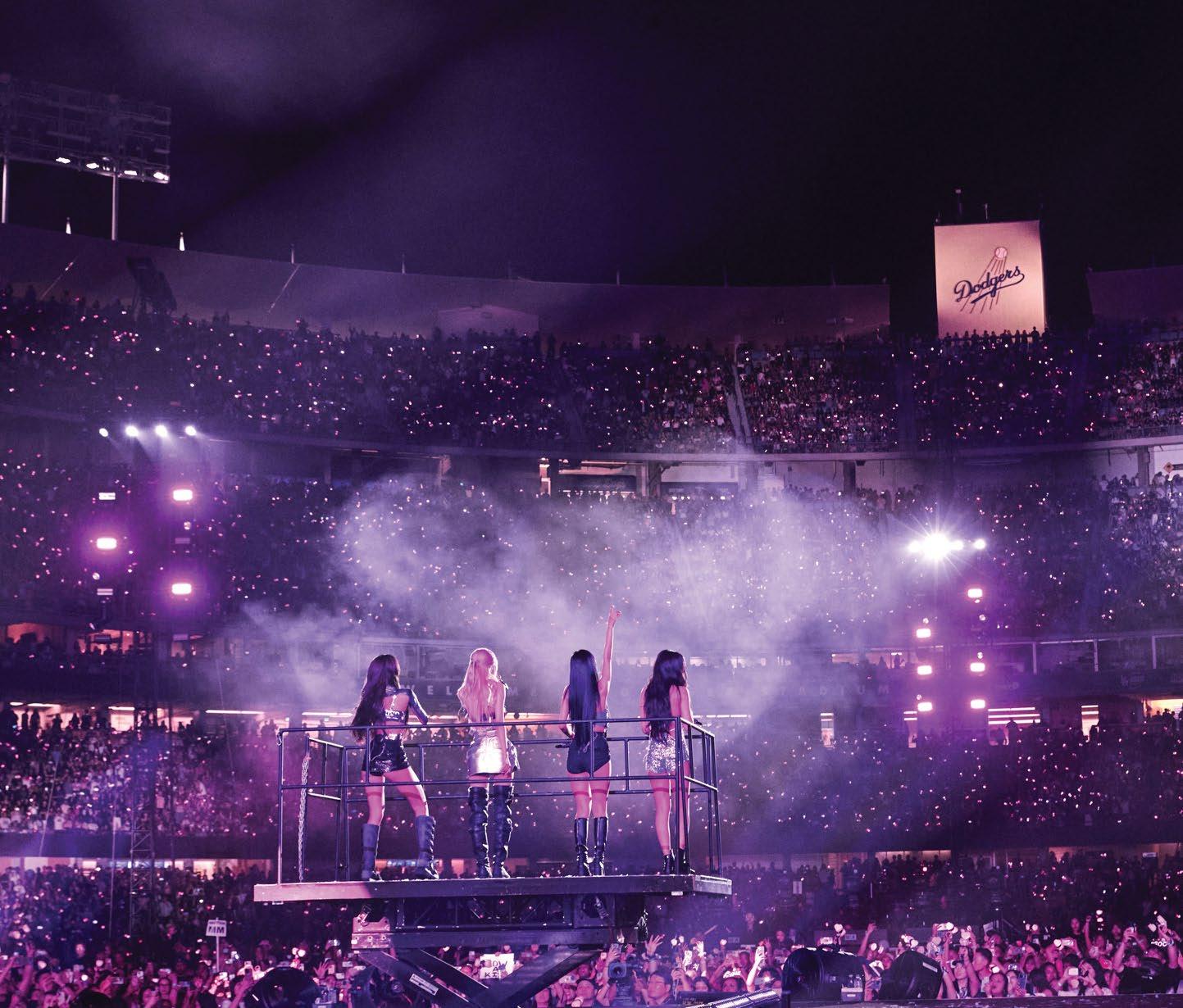

South Korean K-pop artists Blackpink smashed yet another record, becoming the highest-earning girl group for a single tour, according to Touring Data, which tracks box office receipts. Over the two months ending in late August, the group raked in nearly $75 million from 26 performances, pushing the Spice Girls into second place, ahead of TLC and Destiny’s Child. And the Born Pink World Tour, Blackpink’s second global jaunt, still had months to go.

Part of South Korea’s YG Entertainment management stable, the group—Jennie, Jisoo,

Rosé and Lisa—have been rewriting the history books almost since dropping their first single in late 2016. In addition to breaking one chart record after another, they were the first female K-pop group recognized by the RIAA to win a VMA and to appear on the cover of Billboard. They currently have four songs in YouTube’s Billion Views Club.

On the road, they were the first Asian act and the first all-female group to headline Coachella, in 2023. On August 11 and 12, with four shows left on the tour itinerary, 100,000 fans packed into MetLife Stadium in East Rutherford, N.J.,

making Blackpink only the third female act to sell out back-to-back shows at the venue, following Beyoncé (July 2023) and Taylor Swift (May 2023).

Reportedly just 10 percent of the K-pop audience lives in South Korea, with the other 90 percent distributed worldwide.

It’s no surprise, then, that the Born Pink Tour, which kicked off in October 2022 in Seoul, South Korea, was quite the international affair, visiting 22 countries across four continents and bringing together YG Entertainment, U.K. visual production company Ceremony London, an all-American

In K-pop, it’s not unusual for studio production and live sound to be tightly integrated. “I’ve done K-pop tours where the studio engineer who mixed the record is on one side of the console mixing the tracks and stems, and the live guy will be mixing the vocals,” Clair Global’s Alex Kociper said, “but Kim does it all himself.”

“I try to minimize the distance between the recording and the live performance,” Kim elaborated. To faithfully reproduce the sound of the record in a live setting, he said, he will listen to the source tracks— the instruments and the effects—to understand how they were produced in the studio. “I ask the studio engineer how they processed everything so that I can apply that to the live sound.”

Digging into the music and the way it was created has been a valuable learning experience, he said. Ultimately, it’s his job to translate those studio tracks to the live arena, taking input from all the stakeholders. “I have to express what the artist wants and understand what the artist management company and the production wants. They know how the sound from their artists should be, and I have to meet that expectation.”

That’s harder than some people might think, Kim said, “but it’s necessary for this type of music.”

band and music director, and Lititz, Penn.-based sound production company Clair Global. By the time the Blackpink juggernaut rolled into the 56,000-capacity Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles on August 26, the group was on its second pass through the U.S., the tour now renamed Born Pink Encore, with only a Seoul finale left to play. During soundcheck, FOH engineer YoungIl Kim, with Clair Global’s Jae J. Song translating, took time out to explain his hybrid analog/ digital mixing philosophy. Kim, who established his own live sound company, Tristar Audio, in South Korea in 2006, has worked with a long list of K-pop artists, including BTS, 2NE1, Big Bang, TXT, Enhyphen, Le Sserafim and Treasure.

For Blackpink’s tour, he said, “I was looking for digital gear with an analog taste.” Concerned about latency, he chose to minimize his use of plug-ins, instead combining an Avid S6L-32D desk with a double-wide rack of analog toneshaping tools. His research into converters to interface between the desk and rack led him to RME’s M-32 Pro, for its clarity and performance, he said. To achieve the coloration that he wants on a song-by-song basis, he inserted either AMS Neve 33609N, Cranesong STC-8 or API 2500 compressors across his outputs or on specific channels, such as for the rhythm section.

Further processing options included devices from Manley, Bricasti and others, while a Waves Soundgrid server provided whatever plug-ins he chose to use.

While testing converters, Kim noticed a general difference in latencies between the AES and MADI feeds into the converter versus the analog signal and opted for MADI. “He told me you should A/B the analog and AES outputs of the console, any console, to the MADI outputs, and you’ll hear a difference,” confirmed Clair Global system engineer Alex Kociper.

Seung Ho Ryu, also mixing on an Avid S6L32D at the monitor position, generated 28 mixes from 64 inputs, not including talkback, for the four principals, 16 dancers, five band members and crew who listened via Shure PSM 1000 and Sennheiser G3 IEM systems. A dozen Clair CM14 wedges and two 18-inch subs provided additional stage coverage.

The four singers favor a Sennheiser Digital 6000 system with custom pink SKM 6000 handhelds topped with MM 445 dynamic capsules. For dance numbers, three of the women switched to Shure WBH54 headset mics with URD4+ receivers, the fourth using a Crown CM311-A head-worn mic. Kim prefers the sound of the Crown, he said, but the headsets were too heavy for three of the women when they danced.

The only major audio challenge on the

tour was in Thailand, Ryu recalled, where a cell phone provider, responding to dropout reports, sent a booster van to the venue minutes before the show started. Unfortunately, he said, with cell phones there operating between 600 MHz and 700 MHz—prime wireless audio real estate—they were unable to use the headsets that night.

For his part, Kociper had his own set of tools

likes Cohesion; he’s familiar with it, and he knows what he wants out of it,” Kociper said. “It’s all Lab.gruppen PLM amps with integrated Lake processing. I have [Lake] LM 44s [DSP speaker management units] at front-of-house to take his drive lines, AES from the console, and use that to distribute the Dante primary transmission with an analog backup.”

modules flown as main left and right hangs, with two wing arrays and, where extra seating required it, outfill, plus three delay towers. Eight CO-10 modules provided frontfill.

Kim observed that Cohesion arrays are lightweight, flexible, offer good curvature capabilities and generate plenty of low end with a wide overall frequency response. However, K-pop, like EDM and hip-hop, needs some serious low-frequency extension, Kociper noted. “We have 40 Clair CP-218 subs on the ground and 12 in the air. That’s more than half a truck of subs. All the songs have that big 808 [kick drum] drop, so you need the impact. There’s so much headroom left, and Kim’s not hitting them super-hard, so it’s clean. The CP-218 is very efficient.”

Overall, he reported, “It’s loud—108, 109 dB, A-weighted; 130 dB, C-weighted, because of all

The gear is older than you! [Except for the Pro Tools],” exclaims the website for Southern Grooves, Matt Ross-Spang’s stylish new recording studio in Memphis, Tenn. It’s not just the equipment that’s vintage, either. The Grammy-winning producer, engineer and mixer is very much an enthusiast of MidCentury Modern style, and it shows. Step into the studio and you’re transported back to the 1950s and ’60s, when facilities like Sun Studios and Sam Phillips Recording—two spots where Ross-Spang spent years working—first opened for business. Heck, he even lives in a 1957 ranch house.

“I’ve gotten to work in so many amazing places over the years,” says Ross-Spang, who has always gravitated toward studios of a certain age, such as Nashville’s RCA Studio A and F.A.M.E. in nearby Sheffield, Ala. He had been dreaming of opening his own room for years, building a mental mood board of each studio’s features that he wanted to incorporate. There was a common thread, he realized: “The rooms are made for a bunch of people to record together. You can hear each other and everything’s balanced, even without headphones. I feel like that’s a lost art in today’s studios.”

In 2021, Ross-Spang found a 3,000 squarefoot space on the second floor of Crosstown Concourse, a 1920s, multi-story, former Sears warehouse that has been transformed into a vertical mixed-use urban village. In consultation

with acoustician Steve Durr of Durr Acoustics and studio designer Ken Capton of Solar Two Studios, he set to work building the studio of his dreams.

“I knew I didn’t want acoustic tile,” Ross-Spang says, opting instead for the burlap-and-wood design favored by such iconic Memphis facilities as Stax Records and Ardent Studios. “I also knew I wanted an angled ceiling, because Sam Phillips did that at Sun and Phillips Recording. I’ve always loved that look and sound.”

At his previous workplaces, he would use the lobbies as an echo chamber or a drum room. “You can hear those on a lot of records I’ve done,” he notes. “I purposely had this lounge [in the new facility] be reflective and bouncy, and I have a long hallway, so I can put guitar or drums at one end. All these rooms are wired for sound— and we have an echo chamber, as well.” As things turned out, the three-foot support columns in the space dictated the perfect control room layout, measuring 23 feet by 20 feet. “It’s a little bit bigger than I would have planned, but now I love it. It’s just the right size.” The live room is 35 by 32 feet. One iso booth was sufficient, he decided.

His first paying client was Memphis band Lucero; working on their third album together, they had started at Phillips Recording before moving to Southern Grooves.

“We loved the way it sounded here so much that we redid a lot of the stuff we had already done,” Ross-Spang says. “Part of that was that Phillips has a lot of carpet, so the drums were a little bit livelier in my space, and I have a vintage seven-foot Baldwin, so we also got a little bit better low end on the piano sound here.”

Other recent projects have included Iron and Wine and Elvis Presley. Through industry contacts, Ross-Spang hooked up with Sony’s Legacy Recordings some time ago and has remixed several Elvis reissues. The latest, Aloha From Hawaii via Satellite, is a box set commemorating the 50th anniversary of the first full-length concert to be transmitted worldwide by satellite, in January 1973. “I was able to automate the EQ to really pull out the strings and the piano in certain sections,” he says, noting that the technology wasn’t available to engineers at the time. “I’m really proud of the new Aloha From Hawaii release because I feel like we really got some of those elements out in the mix better.”

Beginning in the mid-1960s in Memphis, Welton Jetton, with business partner Steve Sage, assembled parts made by Spectra Sonics in Utah into mixing desks that they sold under the Auditronics brand to a good number of highprofile customers, including Stax and Ardent. “They were very popular consoles, especially in Memphis,” Ross-Spang confirms, “but they’re

Producer/engineer’s new Memphis studio reflects a taste for mid-century-modern style and vintage analog sound.

By

Photography: Cody Fletcher

really hard to find.”

Undeterred, he had long kept an eye on the Internet, and about 10 years ago spotted an all-discrete model made before Auditronics substituted its own op amp designs. The owner, Warren Parker, a Canadian broadcast and recording engineer, had purchased it in 1969, driving to Memphis to pick it up. Ross-Spang spoke with Parker, and they hit it off—but when he told Parker he wanted to buy the board, “He goes, ‘I’m not gonna ship it,’” Ross-Spang recalls. “My heart sank. Then he says, ‘I’d love to see Memphis again.’ He drove down and dropped it off—a mile from where it was built!”

With limited space available at Sun, the console sat in Ross-Spang’s house for a time, but he was able to install it when he rented the B room at Phillips Recording. “I loved it so much that I had a sidecar built; we jokingly called it the Swamp Rat,” he laughs. “I would pull channels out of the console and take them with me when I went to Nashville or Muscle Shoals to record. Now it’s the centerpiece in my control room.”

The new control room also features a pair of soffited Ocean Way Audio main monitors and numerous tape machines. “My favorite format for a long time has been 8-track,” he states unequivocally. Indeed, Ross-Spang has an unfortunate history of buying a one-inch eight-track machine, selling it, regretting it, and buying another: “I had a Scully 280 that I sold to Mark Ronson. I had a Studer A800 one-inch eight-track, which I loved; I sold that to Dave Cobb. Then I found this amazing, clean, oneinch eight-track MCI. The thing I love about it is that it’s got pots on the front of the machine, so you can take it out of cal and really hit something hard or turn it down.

“I was excited to find the Ampex two-inch 16-track; to me, it’s the ultimate format. I never really need more than 16 tracks, and the MM1200 just sounds amazing. I bought it from my hero, Dan Penn. There’s a guy at RTZ Audio, Bob Starr, who makes replacement power supplies and tape tension mod replacement cards that make it a little bit more stable.

“From my Sun days, I’ve got an Ampex 350, the ultimate slap-back machine, and an Ampex AG350 two-track, which is a weird germanium one. It’s what they used at Stax and has a sound like no other machine.