Designed with a cushion core that stays soft under pressure.

20–26 OCTOBER

It’s now been a few editions since we reintroduced Fashion Journal in print and it’s nice to see a clear identity forming, separate from what you see online. Our print publication is a home for creativity that isn’t limited by the confines of a clicky headline or social media hook. With fewer restrictions, it’s called for us to find our feet and quietly experiment to see what sticks.

The beauty of this process is that each edition of Fashion Journal is an evolution of the last. It’s our goal that each time you pick up a copy, you’re met with new ideas, new inspiration and new voices.

This issue is a fun one, as in the same vein, we celebrate the nonconformists among us: the party girl who turned her love of underground music into a career, the dissenters who made brow-plucking a form of quiet rebellion, the artists who didn’t wait for big-label backing to take their shot, the free spirits who prefer to holiday in the nude.

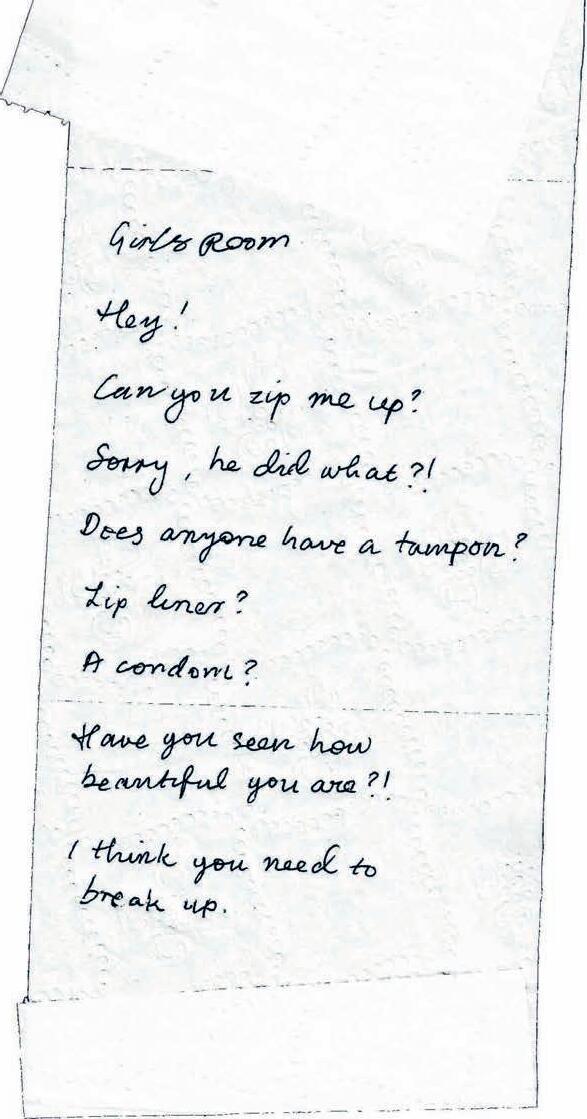

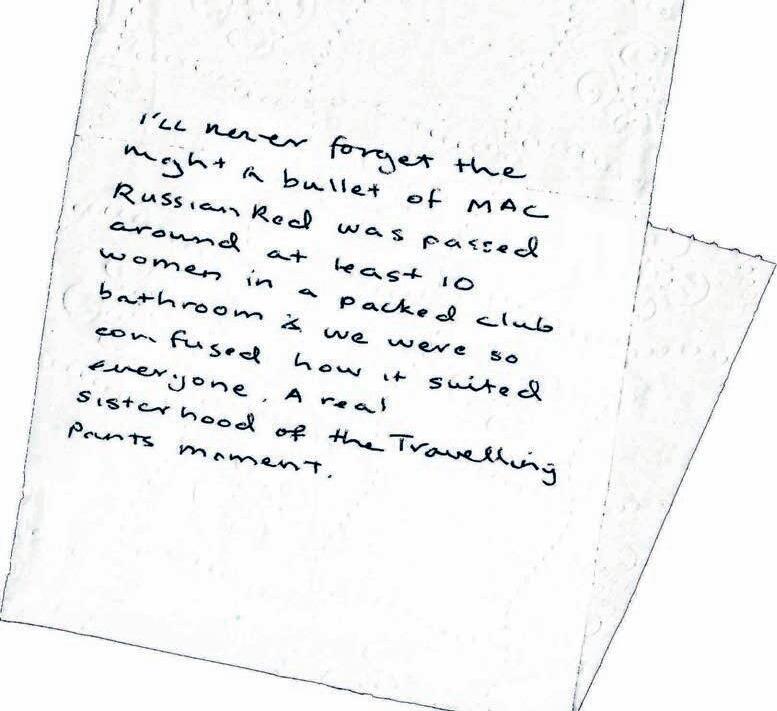

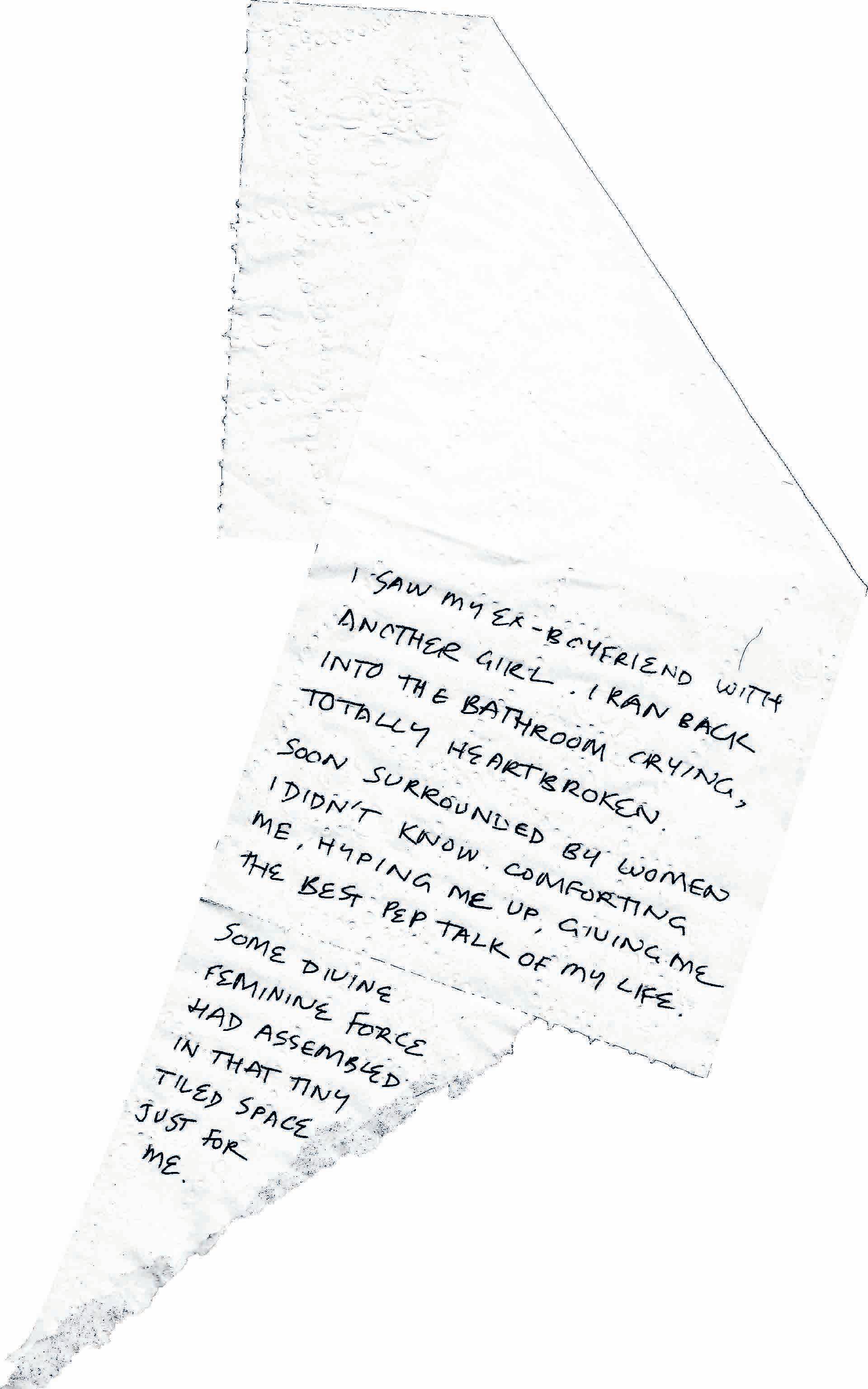

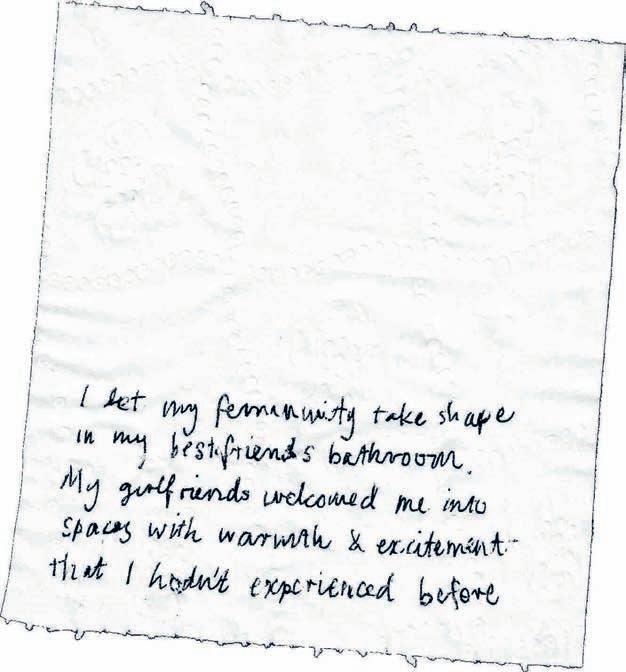

We also celebrate what unites us, like the friendships we form in nightclub bathrooms with strangers, or the vulnerability of a life lived online. I hope this issue serves as a reminder to carve your own path without waiting for permission, but also to recognise the goodness in what we all share.

You’ll see these themes represented in the fashion across our pages, too. We’ve embraced the designers whose work is more art than apparel, alongside the dearly beloved labels that continue to dress us each day.

While we’ve worked with some longtime collaborators, we’ve also welcomed new friends into the fold, including those whose careers are just starting but whose creativity is second to none.

The timing is impeccable, as we prepare ourselves for Melbourne Fashion Week in just a few weeks. Many of the contributors behind this edition are also involved in its production, working behind the scenes to bring the event to life. We’ve been a media partner for some time now, and know how beautifully it celebrates the spectrum of the country’s fashion talent, from graduates to industry stalwarts. In the same way, we’ve tried to embrace a full spectrum of Australian design.

We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the many lands on which this edition was made, and pay our respects to Elders past and present.

We’re so thankful to have you with us as we step into this next chapter.

Giulia Brugliera Managing Editor

Managing Editor

Giulia Brugliera

Features Editor

Lara Daly

Assistant Editor

Daisy Henry

Designer

Kelly Lim

–

Distribution

and Accounts

Frances Thompson

Managing Director

Kris Furst

Founder

Rob Furst

Contributors

Shamillar Manhika, Madeleine Ryan, Simone Esterhuizen, Constance McDonald, Julie Mrozinski, Robyn Daly, Hannah Nikkelson, Yasmine Sharaf, Maryel Sousa, Saige Coleman, Annemieke Ytsma, Jess Grindell, Tarek Kourhani, Juanita Page, Corin Corcoran, Jordan Gogos, Lucinda Houghton, Aleks Markovic, Jordan Drysdale, Enrico Kasjan, Stuart Walford, Valentina Barrios, Caroline Caroline, Julie Provis, Kaitlyn Bošnjak, Kirk Rinon, Steph Penderson, Monica Morales, Koby DulacDaley, Gina Yates, Jemma Barclay, Britt Murphy, Sophia Stamellos, Maggie Wu, Devaura, Gazal, Maddy Jane, Daniel Mizzi, Em Crowe, Monica Dragut, Ned Quail, Anthony Tchourilov, Alexcea Apostolakis, Sofia Perica, Parth Rahatekar, Izzy Wight

Cover photographer Kaitlyn Bošnjak

Zara wears IORDANES SPYRIDON GOGOS X BILLIE RONIS dress, ROMANCE WAS BORN shirt, MAISON ESSENTIELE skirt (worn as headscarf), HEAVEN BY MARC JACOBS necklace from P.A.M. STORE

Fashion Journal is free and distributed to hundreds of locations around Melbourne and Sydney that we hope you frequent and stumble upon. To enquire about having Fashion Journal distributed at your business, please email distribution@furstmedia.com.au

Enquiries, thoughts and ideas submissions@fashionjournal.com.au

For advertising, content or commercial partnerships please email advertise@fashionjournal.com.au

Advertising and Partnerships Manager Molly Griffin

Branded Content and Production Coordinator Holly Villagra

Fashion Journal is printed in Australia on ECF Elemental and PEFC certified paper manufactured by an ISO9001 certified mill. Our paper is certified and audited as coming from sustainably managed forests meeting PEFC’s internationally recognised sustainability benchmarks.

We acknowledge the Wurundjeri Woiworung and Bunurong people of the Kulin Nation as the traditional custodians of the lands on which we largely live and work. We recognise that sovereignty was never ceded and pay respect to Elders past and present.

Visit us at fashionjournal.com.au

Join us at @fashionjournalmagazine

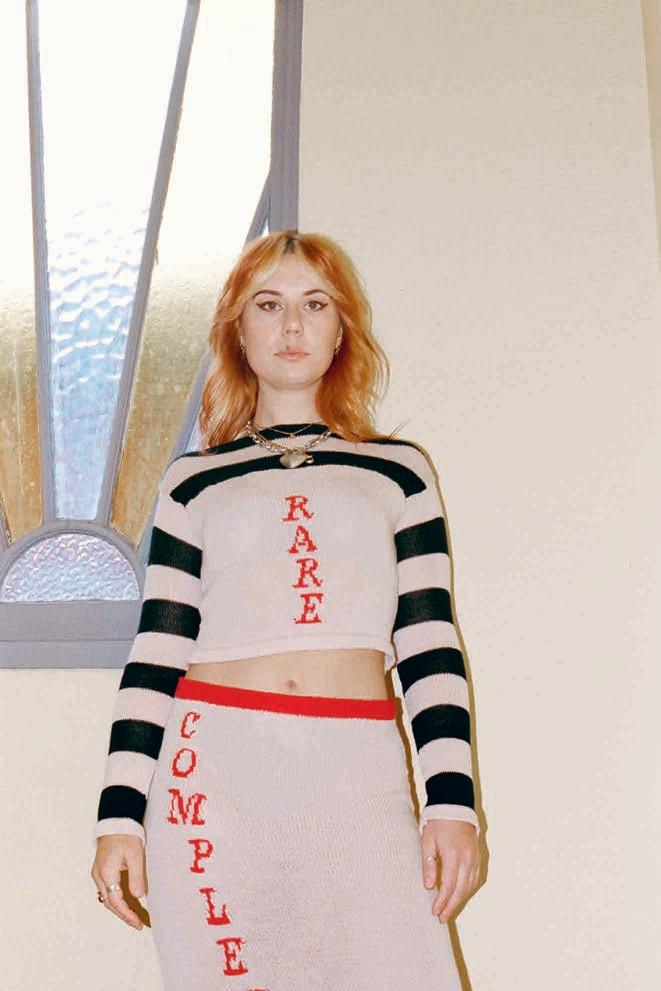

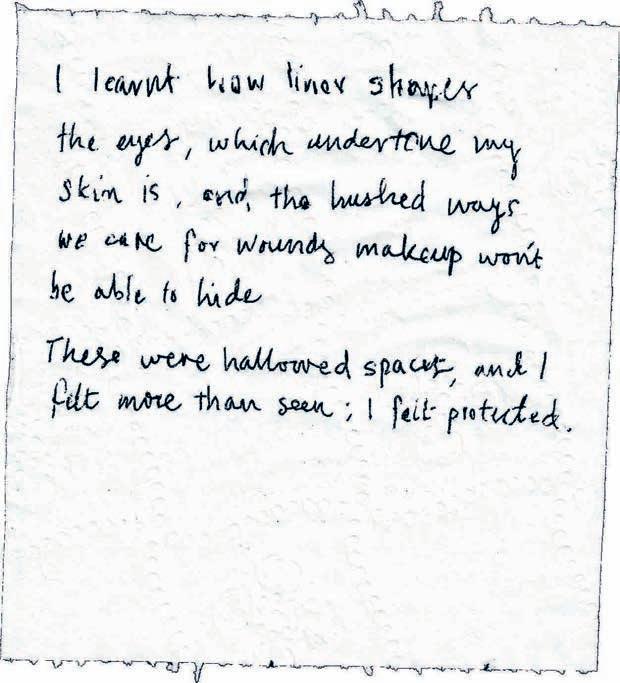

One of the most challenging aspects of creative work is the grey zone in which it exists. The work will never quite be ‘complete’ but at some point, you need to either wrap or risk overengineering the outcome. So how exactly do the contributors of this issue know when to call it?

On a shoot, I don’t know that there’s ever really a moment when the brushes go down and I call it as being ‘finished’. I’ll want to finesse and perfect all day! But when I’m really happy with the skin and the work I’ve done, I’ll usually do an ‘artist squint’ and scan the face, looking for things I’ve missed, then step back for a broader view. Then, if no one’s looking (we’re usually pushed for time), I’ll take a quick, sneaky pic, which is also great to zoom in on for a final check.

McDonald, Photographer and writer

I read my writing aloud and record it, then take it for a walk with headphones and a notebook ready for any last-minute fixes. If it survives the walk test, it’s ready to (hopefully) seduce, perplex and entertain.

I don’t have a ‘routine’ as such or something superstitious I do before calling something finished. Before stepping in front of the camera, I throw myself into it right away so I don’t overthink. When I take shooting too seriously, it always shows in the photos, and I sometimes think the best photos are the ones that go with the flow.

Everything is a continuation. Nothing starts and finishes. But yes, there are moments and rituals along the way that mark the sacred: the lighting of a candle, a sigh of relief, cheers-ing drinks, crying, floating in the sea, eating dark chocolate, lying with an animal, dancing, laughing, spritzing face mist or perfume, being held. But rather than demarcating an ‘end’ or the idea of something being ‘complete’, these moments and rituals elevate what is. They wrap holiness around the everyday. I do them as often as I can.

I’m always doing a billion things and trying not to run late, so when I finish something, I just hope that it’s finished as best as it can be, and I move on to the next thing quickly.

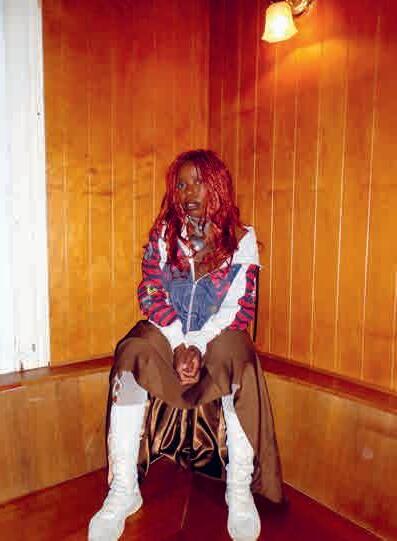

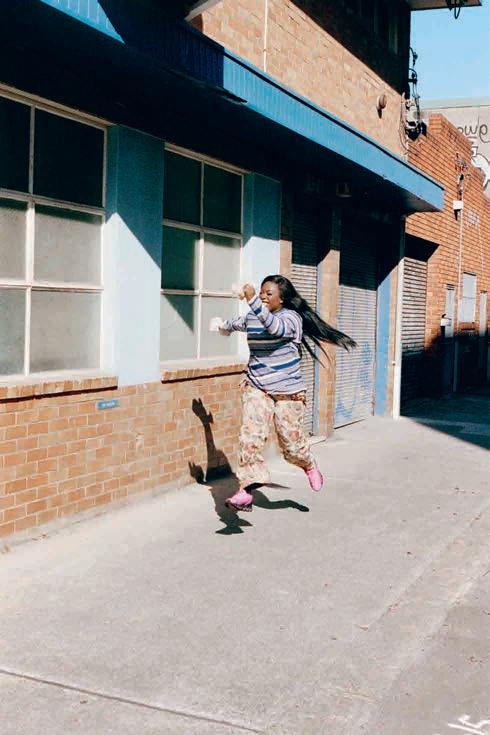

Stylist Shamillar Manhika is obsessed with colour, community and craftsmanship, just like us. “Getting dressed is my way of romanticising life, one outfit at a time,” she says. “Now I’m exploring how to fold my African heritage into my work, blending bold textiles, ancestral stories and traditions that feel nostalgic, yet new.” Upon request, she shares what she’s been wearing, watching and reading lately.

I’m currently living in my ‘The Rioter’ hoodie from Briar Will. I love how she plays with colour and creates illusions by printing vintage clothes onto new garments. I’ve also been eyeing Kahe’s ‘This Is My Boot 2’, a stunning leather boot that transforms into a wedged mule. Its designer, Kacy, is the queen of multifunctionality. Then there’s Bizarre Lingerie, making flattering, sultry lace lingerie that’s made to live outside the bedroom.

Naarm’s Inner North and West are unmatched. Footscray on a Thursday afternoon is my favourite, with African aunties in head wraps and Asian uncles dripping casual swag. It’s effortless, alive and never trying too hard.

Nū is an Ethiopian artist based in Naarm and her album Technifro-185 is pure magic. Imagine live coding with angel vocals. She’s also my sisi (sister), so I got to hear her talent before the world did.

The last book that really stayed with me was The House in the Cerulean Sea by TJ Klune. It’s a whimsical tale of family, love and embracing what makes us different. Perfect for anyone craving an escape that leaves you beautifully wrecked long after.

After nearly a decade off social media, writer Madeleine Ryan logs back in and confronts the seductive chaos of the algorithm.

WORDS

BY MADELEINE RYAN COLLAGE BY SIMONE ESTERHUIZEN

Ijoined Instagram for the first time this year. I’d deleted MySpace in 2010, Facebook in 2014 and LinkedIn in 2016.

They brought out the worst in me. I had a harrowing moment while curating a Facebook album after a friend’s suitably photogenic ‘derelict’-themed birthday party, when it occurred to me that I was putting more creative energy into a photo album than into my actual life. I wanted a life I was proud of before I had a Facebook photo album I was proud of.

So, almost a decade had passed when I found myself sitting at the kitchen table arguing with my partner about how I’d never be on social media ever again, because ‘Why would I invite that spiralling vortex of sorcery into my life right now? Clearly, I don’t need it. Clearly, I’ve created things without it. Clearly, I have friends without it. Clearly, I exist without it.’ Then, head in my hands, I realised that I was still scared of it. After so many years, I still feared what social media might ‘do’ to me.

I’d also grown accustomed to the envious and admiring looks on people’s faces when I said I didn’t have it. They made me feel more noble and more pure than everyone else, and I finally saw this was just as much, if not more, insidious than anything social media could throw at me.

And I wanted to put what I’d supposedly learnt about myself ‘offline’ to the test. As the American spiritual teacher Ram Dass said, “If you think you’re enlightened, go and spend a week with your family”. Well, maybe, ‘if you think you’re enlightened, go on social media and follow everyone you’ve ever met’ is equally applicable.

I didn’t sleep for two days after signing up to Instagram. Watching the algorithm guess at what I might or might not like became enthralling. A stalker following my every move, obsessed with me, desperately wanting my attention and trying everything to get it: Sleeping Beauty memes, candid snaps of Rosie Huntington-Whiteley in Jason Statham’s lap, reels of Audrey Hepburn weeping, Shalom Harlow twirling down John Galliano’s 1993 runway. Oscar Wilde quotes about the moon, serums for glass skin, moody stills from Le Beau Mariage, Brittany Murphy with a finger to her lips. The living and the dead. Past, present and future.

It made me aware of how well humanity is doing. I had no idea. It’s a miracle we’re still functioning at all with this beast in our lives now. Social media exemplifies the axiom ‘where attention goes, energy flows’ because our passions, fears, insecurities and obsessions shape it. Whatever we linger on, hover over or click, we get more of.

simply magnifies it. Once we give it permission to enter our mental, emotional, virtual and actual space, it can only be blamed for so much. We are responsible for what it shows us and for where it leads.

A few weeks after joining, I was at a Magdalena Bay concert on the St Kilda Beach foreshore. It was a warm, late summer night. Luna Park’s Ferris wheel shimmered and spun. I swayed with the crowd, hypnotised by ‘Image’, when a bright phone screen was thrust before my eyes with Instagram’s search page open, cursor blinking. I turned and a guy with spiky hair and tiny glasses, who’d been fist-pumping alongside me, leaned in. “Love your vibe,” he said, pushing the phone screen closer, inviting me to find myself. I smiled.

“This is so weird, I just joined.”

“Well, fair warning, my page is pretty skanky.”

“I actually posted my first naked pic today.”

“Omg it’s so freeing, isn’t it?”

It is. Deciding what to do with the blank canvas of a profile page is exciting. Ah, a page of one’s own! A wide open space to ask the big questions: Who am I? Who do I want to be? How do I want to be seen? What do I care about? Is this personal? Or is this business? What’s private? And what’s public? If something happens and it doesn’t go online, did it happen at all?

Watching myself – and everyone else – play out these dilemmas is humbling, because we don’t have any DNA to help us out. Our ancestors have got nothing. We’re the first to play this billions-strong communal game, so of course it’s crazy and childlike and ridiculous and upsetting. It’s the big bang and we’re living it.

Some people are yelling and screaming while others are lurking, opting for anonymity. Some people are hustling while others are colour-coordinating their bookshelves and dumping baby photos. There are atrocities alongside string bikinis. It’s an endless stream, a ‘monkey mind’, a city that never sleeps, a Las Vegas we can hold.

Social media is scary and overwhelming, but there’s also a vulnerability that I hadn’t expected. People always talk about how toxic and addictive it is, but the desire to be seen and heard is innocent. Wanting to feel valued and connected to others is primal. Self-expression, dreaming of more, seeking inspiration –

The problem is when I, say, go to Instagram looking for an escape and I end up right where I started: wanting an escape. It’s just that instead of sitting and staring out a window, or lying on the grass, feeling my feelings and thinking my thoughts, fully experiencing awkwardness, existential angst, FOMO, boredom or whatever, I’m eyeballs deep in cat memes and quotes from writers writing better than me, and babes rocking bods better than mine, and images of unspeakable horrors that I can’t un-see and, my god, I’ve gotten exactly what I deserved, because if I can’t sit with myself, I’ll never be able to stand social media.

I’ve already deleted the app. I access it through my web browser and this seems to keep the beast contained somehow, in a cage, where it belongs. But it’s powerful to have it. Living with social media is like living with a narcissist: it can teach us a lot, and make us stronger, just as it can undermine and crush us.

After signing up, as I was spiralling, people I hadn’t thought about in years flooded into my awareness: high school friends, exlovers, extended family, crushes, uni mates, frenemies, old bosses. It reminded me of how social media interferes with the process of letting go, which was another reason why I deleted it in the first place. When I was done with a person, place or identity, I wanted it gone. However, I’ve subsequently discovered that nothing and no one ever really ‘leaves’ us. Everything we encounter becomes a part of who we are.

Then I saw a ghost. He was the brother of one of my oldest and dearest friends. He struggled with addiction and recovered before working in the recovery space and becoming a beacon of hope for many. He died suddenly in 2015. Hundreds turned up to his funeral. Yet there he was, on Instagram, with a handful of followers and three posts on his profile, the last a film photograph of New York City’s skyline from 2013. A virtual tombstone he had unwittingly created for himself. Yet we’re all creating them. Together, we’re staring into the virtual abyss.

Our social media profiles are going to outlive us. And while I don’t want to look back on life and think, ‘Wow, I spent way too much time on there’. I also don’t want to look back and think, ‘Wow, I was way too scared of social media,’ because it’s one of our lifetime’s most inexplicable and cataclysmic offerings. Our words, images and sounds are going to die in its arms. For better or worse, it will come to define us, individually and collectively, across time and space. With each post, we dance with eternity.

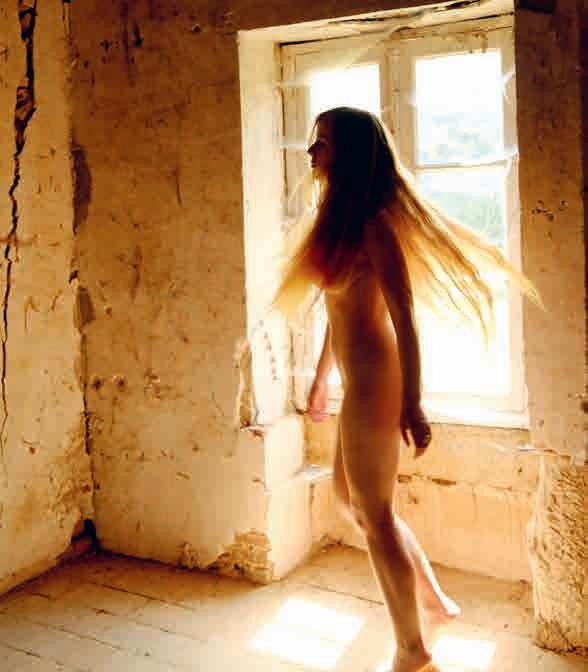

Nothing prepared me for living completely naked in a medieval village in Spain for a month with a conspiracy theorist who thinks chemtrails make you gay and a guy who drinks his own piss mixed with mandarin juice.

McDonald

There’s a Spanish medieval village, built a thousand years ago, off the grid with intermittent and limited power. Wells have dried up (I started drinking my pasta water, feeling too guilty to tip it down the sink) and there’s a fourkilometre driveway with no town at the end of it, just a road. No internet. No alcohol allowed, no clothes, no washing machine. I love to make rules for myself and I told myself I would spend a month there, naked.

Before we go any further, let me save you from the social faux pas you will want to commit: calling this place a ‘nudist colony’. That phrase died in the ’60s. This is a naturist community.

The naturists’ thesis is simple: bodies are just bodies. But can a body actually be ‘just a body’? I wondered this, as I removed my op shop Laura Ashley dress in the apartment that would be mine for the next month. The only mirror was bathroom-mounted and brochure-sized, decorated with a constellation of toothpaste spatter.

The population of the village swells to 100 in summer and dwindles to around 20 permanent residents in winter. Every day, I’d mop my floor. I’d watch the sun move across my medieval stone walls. I learnt the goats’ individual personalities. When it was windy and therefore a spot of electricity was being generated, I’d run back to my apartment and plug my phone in to charge.

I quickly found the two people in the village who spoke English. These two men became my mildly problematic lifelines.

One was a conspiracy theorist who believed that chemtrails make you gay. I’d go to his house in the morning and we’d listen to Leonard Cohen’s album Ten New Songs on repeat while building furniture. He’d launch into these elaborate theories about government mind control while measuring wood planks. He’d tut and point at the sky with his screwdriver. “Look at the chemtrails.” I’d nod and hand him another screw. We built a table and a wardrobe together. I drilled into bathroom tiles for the first time, he listened to my suggestions of where to put up mirrors and shelves, and we did it there and then, clocking up many hours on the drill.

In exchange, he’d cook for me. Breakfast was eggs and one shaving of precious jamón serrano, bought in Barcelona, seemingly a million miles away from where we were. Salty miso soup was our working pick-me-up, and, if he believed we needed it, a couple of squares of milk chocolate. Most dinners were vegetable-rich paella. On site, a small shop sold fruit and vegetables delivered by farmers in neighbouring towns every few days. So, yes, I shopped in the nude!

The second English-speaking man was a self-described archetype of Christ who claimed to have seen a UFO from his window in the village. We would walk for hours around the

“Never put your bare bum on communal furniture without a towel barrier.”

150-hectare property, every time in a different direction. We went to the Witch’s Square, the two churches and fed the goats, all in the nude, of course. These walks became my education in alternative living philosophy. He’d speak about rejecting materialism while stepping carefully around goat shit.

We would end at his apartment, which was even more off the grid than mine, with no power or running water. One time, he poured me a tea, handed me two mandarins and disappeared around the side of his apartment. I could hear him peeing into a receptacle. When he came back, he told me he collects his urine so he can drink it with freshly squeezed mandarin juice. When I asked why, he launched into a long-lasting monologue about the healing properties of urine, how it’s sterile and full of nutrients, how it connects him to his body’s natural cycles. He promised me that only his mug contained his urine. I sipped what I hoped was just tea.

When you remove clothes, you remove a layer of social performance. Conversations in the village quickly traversed beyond weather-talk and nude-talk. Without the signals of fashion, status or even basic coverage, people seemed to speak more directly. These weren’t profound conversations because we were naked, they were honest because we couldn’t hide. When you can’t conceal your body, you stop trying to conceal your thoughts.

The conspiracy theorist and I would debate politics while naked and sweaty from building furniture. The Christ-archetype would explain his spiritual theories while we walked naked through olive groves, his gestures completely uninhibited. And, as bizarre as both of these men were, I knew them and I loved them.

by Julie Mrozinski

A guide to getting started

I’m sure you’ll agree that nude swims are superior to textile-clad ones. Maybe you’ll even agree that walking around the house with nothing on during a truly alone summer weekend, AC on, beats even the loosest pyjamas. Snorkelling is also better in the nude. What about playing cards? Or soft-boiling an egg with a perfect yolk that drips onto your nipple? Do you want to find out? Let me hold your hand through this.

I recommend starting with nude beaches. Go on a weekday if possible (it will be quieter) and keep your bikini bottoms on until you feel ready. Nobody’s keeping score. If the thought of outdoor nudity feels like a stretch, seek out a friend and an onsen or hammam. The structured environment might soothe you.

If outdoors, sunscreen everything. Your butt crack, the underside of your boobs, between your toes, SPF50 minimum, reapply every two hours, yes, set a timer. Bring a friend or make one quickly, because you’re going to need help. The first time you get naked in front of strangers, you may be convinced that everyone’s staring at and judging you. Don’t fret: they’re probably too busy worrying about their sunscreen schedule.

Keep your phone in your bag. If you absolutely must take photos (I get it!), make it obvious they’re of yourself or your consenting friends only.

Expect to see everything: stretch marks, surgical scars, cellulite, missing limbs, medical devices, tampon strings. Yup, that is my naturist menstrual product of choice but damn, free bleeding in the sea is something I beg you to experience.

The naturist’s towel is like their rosary. Some people personalise theirs with their name or pick a jaundice yellow that’s unmistakably their own. Learn from me and never put your bare bum on communal furniture without a towel barrier. This is a golden rule.

The heart of it

What I learnt in Spain is that these places aren’t just about nudity: they’re experiments in intentional living. The nudity, it turns out, is often just the most visible part of a much broader rejection of social conventions.

In Spain, the handyman designed his work schedule so that he would reluctantly leave nude living for exactly one week each month, scheduling back-to-back jobs in Barcelona from 5am until 11pm, crashing on friends’ couches between appointments. Seven days of city life would earn him enough money to cover food and electricity for the remaining three weeks back at the village. Money is just money, he told me. (Urine is just urine? Okay, I never quite got on board with that.)

In the village, I watched the sunset every single day. I had conversations that lasted days, the whole month, we’re not even finished. I helped build things with my hands. I learnt that my body, when not constantly managed and modified and hidden, actually feels like home.

I see you there, too. Biting into plums, juice dripping down your chin, jumping into the nearest river to clean yourself up. Your UE Boom plays Sibylle Baier’s first and only folk album, and sweat pools in your belly button. Drizzling extra virgin olive oil pressed from the thousand-year-old trees you lean against to read a book in one sitting. Pouring water onto the parched, hot pavers and them steaming ‘thank you’. Everything is better in the nude.

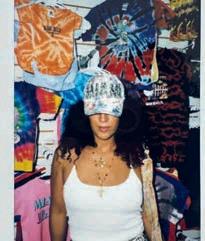

It took us a minute to figure out what, exactly, Yasmine Sharaf does for a living. In short: she throws parties. But the longer version is a story of relentless hustle, burnout and a career reset that led her to create what she saw was missing from Melbourne’s nightlife.

WORDS BY LARA DALY PHOTOGRAPHY BY ASSIGNMENT STUDIO

Yasmine Sharaf fell in love with the underground music scene the way many of us did – through teenage parties. “When I was 19, I went to a house show pool party in South Yarra. It was insane. It was like Skins but with rock bands. I thought, ‘Wow, this must be what cool parties are like,’ and then nothing that fun ever happened again,” she says.

That night must have sparked something in her. Whether she knows it or not, the Naarm-based music curator, radio presenter, event producer and DJ has been chasing (and recreating) that same chaotic magic ever since.

Hi Yasmine! In your own words, tell me what it is you ‘do’?

Hi! I’m a music curator, radio presenter, event producer and founder of Cease and Desist, a live music event project and weekly radio show on 3RRR. Through this project, I’ve put on over 50 live music events, toured international artists, and collaborated with a huge range of incredible labels, festivals and institutions.

How did you get your start in the music industry?

Like most people, I started as a fan. I didn’t know many people until I started getting into live music photography in my teens. Taking photos was a great way to meet people in bands, and many of my formative relationships in the industry started around then. When I turned 18,

I started bartending in venues and landed my first booking job.

At the same time, I was studying a Bachelor of Arts, but it hadn’t occurred to me that you could study underground music in an academic setting until I came across Sarah Thornton’s Club Cultures, an incredible book on subculture and the underground raves of the ’90s. I transferred over to Cultural Studies and started focusing on ethnomusicology straight away.

I was also working at an amazing independent record store called Lulu’s. The store was run almost like a creative collective and I learnt so much from everyone there. When it came time to write a thesis, I chose to write it about Lulu’s and the role of physical space in musical communities.

I never expected academia or music to lead to any ‘real’ jobs, but I ended up landing a role as a music coordinator, and after that contract wrapped, I started as head programmer for a music venue, before moving to Cease and Desist fulltime in 2019.

What led you to start Cease and Desist?

The slightly longer answer is that the project started as a record label, but I pivoted to doing events because I quickly realised that my strong suits were not in running a record label…

The main impetus for starting my own thing was kind of just being burnt out from my job. I was running a two-level music venue, [putting on] like eight gigs a week, and I got really burnt out. I ended up leaving and I was like, ‘Well, it’s still

something I enjoy. If I just do something on my own once a month, that’s surely going to be easier than doing eight a week’.

What was the vision for your early events? What did you want to do differently?

I kind of took on the idea of ‘the promoter’, in the nightclub sense of the word, and moved that into live music. I hadn’t really seen anyone do that before… to regularly curate lineups but change venues each time, from pubs to clubs to community halls.

Post-Covid, I felt like everyone separated into their own little music subcultures and sub-scenes: the punk bands were playing with the punks, the club people were playing with club people.

I’ve always said, if you’ve got the skaters and the fashion crew, and the art scenes there, alongside other music people, that’s the real melting pot that makes gigs really special. So I wanted to create more musically diverse, more culturally diverse gigs. And I felt like that wasn’t really popping off at the time.

How has the project evolved? Can you tell me about a memorable gig?

It didn’t really explode into what it is now until our first big day festival in Russian House [a historical venue in the middle of Fitzroy], in 2023. From there, it really took off. I began doing a lot of longform gigs, day parties and almost little micro festivals.

Earlier this year, I co-hosted a boat party with London-based DJ, Flo Dill.

I don’t think we really thought through the magnitude of throwing a boat party until we saw the line of 200 people waiting to board. It was truly a wild scene…

At one point, someone was spraying the crowd with the smoke machine, while the boat was whizzing around Port Phillip Bay. There’s something about a boat that makes people lose their inhibitions.

What are three tangible things you absolutely need to put on a great live show?

A diverse group of people, a good smoking area and a loud PA.

What about three intangible things?

If you have those three things, usually the intangible magic follows.

You pour a lot of energy into creating memorable events for the community. What are the best parts and what are the downsides?

The best gigs I’ve ever put on have been with collective help from the community. There’s a beautiful exchange of knowledge that happens when working with different people, and that’s by far the best thing about the music industry – you get to work with a huge range of people.

At the same time, burnout is very real in the nightlife economy, as well as exploitation. You shouldn’t let anyone exploit your love for community or leverage it to justify not paying you. It can be really tricky.

Of course, we all need to show up for community – get out there and support more gigs. But if it always feels like a chore, maybe you haven’t found the right space for you. Love should be the motivator, not guilt.

It’s also a great way to meet people off the dating apps, if that's what you're doing.

Oh my gosh, totally. No, like, go to a gig. At least you’ll know that you have something in common before you even talk to each other. And then usually, your friends will both be there, so it’s a good vetting process because someone will let you know if that’s not a person to talk to.

Very true. What would surprise people the most about what you do?

How DIY it is! Even when I’ve worked on larger projects. Sometimes you get to do glamorous things and meet your heroes, but at the same time, you’re often waking up early to lug a PA across town or emptying bins at the end of the night. That’s show business!

As the ‘sober curious’ movement grows, the way we catch up with friends is changing. Exploring the people and brands at the forefront of this shift, writer Maryel Sousa finds that forgoing alcohol doesn’t mean missing out; it makes way for a new social rhythm.

When I lived in New York, I loved nothing more than meeting up with friends for a drink. My housemates and I would depart our Bushwick apartment once the sun had set and hop on a J train bound for our favourite dive bar in the Lower East Side. We’d cosy up in the corner, mixed drinks in hand, anticipating the night’s newest side character –a gallery owner to schmooze, a magazine editor to flirt with or a band manager to cover the next round.

Then, one day, something in me changed. Maybe it was the ‘hangxiety’ or the mounting pressure that every night had to be as spectacular as the last, but drinking just lost its appeal.

Becoming (mostly) sober in my early twenties wasn’t easy. For a long time, I felt like I’d fallen out of step with an established social rhythm. When I didn’t drink, people treated me like a strange anomaly.

My experience isn’t unusual. Sobriety and sober-adjacent lifestyles have been stigmatised for a long time, particularly in Australia. “Drinking is a massive part of social culture here and it can be difficult to remove yourself from that,” says Naomi Kilmany, a Naarm-based creator and disability advocate who’s practised alcohol sobriety for three years. “The challenge of choosing to be sober in any form is struggling with peer pressure or a fear of missing out.”

However, attitudes are changing. According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, the proportion of drinking-aged young people abstaining from alcohol increased from 13 per cent to 23 per cent between 2007 and 2023. While the reasons vary, many cite mental health, chronic illness, a desire for deeper connections and the unrelenting cost-of-living crisis as the catalysts for pivoting to something softer.

As the non-alcoholic drink aisle expands, other savvy businesses are acting on this shift. One such brand is made by Fressko, a Melbourne-based business known for its sleek reusable drinkwear. It’s just released its 20oz ‘Venti Tumbler’, specifically designed to hold the drinks you’d tend to seek out in favour of alcohol, like bubble tea or iced matcha. Made with a leak-proof flat top lid and titanium straw, the design makes it easy for people to catch up on the go, without the pressure to head to a bar.

Although some young Australians are choosing to forego alcohol entirely, others have adopted a more flexible attitude. The ‘sober curious’ movement encourages people to be intentional about if, when and how much they drink. As this spectrum of sobriety becomes more normalised, a new question arises: Without alcohol, what can adult friendships look like?

It’s not uncommon for certain friends to disappear when you ditch the booze. When Saskia Waterman co-founded Melbourne’s Sober Social Club, she hypothesised that decentering alcohol in social interactions could lead to deeper connections. At the club’s

first intimate dinner party for the sober-curious, Saskia noticed guests were arriving ready to connect with others in earnest, without a haze of alcohol obscuring their personalities. She soon realised that alcohol had caused her to overestimate the depth of her own relationships.

“I realised some friendships were built almost entirely around drinking,” she says, “I have fewer friends now, but the friendships I do have are stronger, and so are my boundaries.”

In Naomi’s experience, alcohol could often hinder the depth and vulnerability of her conversations, especially when it was used as a form of escapism. Replacing alcohol-fuelled evenings with softer, more intimate hangouts helped her fill the gaps once occupied by bars and clubs. Now, she opts for Sunday park strolls, dry dinner parties and window shopping with an iced matchafilled Fressko tumbler in hand.

On paper, these activities might lack the magic spontaneity of a rowdy night out, but in practice, they’re keeping the soul of friendship alive.

“I think spending quality time doing wholesome or even mundane activities can really strengthen friendships,” says Naomi. “It’s really special when you can spend extended periods with someone where alcohol doesn’t have to be involved to enjoy each other’s company.”

Sober-ish lifestyles can keep your social battery from maxing out, too. Saskia recalls the hangxiety after late-night wines with friends, waking up the next morning unable to remember the details or worrying she had overshared – a problem she hasn’t had after sober catch-ups.

“I love finding ways into creative conversations, debates, brainstorming and learning from my friends. When I meet friends for coffee or lunch, there’s always an interesting way into those kinds of conversations. I feel more like myself, more thoughtful in conversation and really clear-headed afterwards. And I always leave these activities feeling really joyful,” she says.

A lot has changed since I went sober-ish five years ago. The sober curious movement is reshaping our relationships with alcohol, ourselves and each other, becoming more widely accepted as people realise its benefits. Our friendships are adapting to richer interactions that move at a slower, more sustainable social rhythm. Turning down a drink doesn’t mean you’ll lose your seat at the table.

So, is the soft social life here to stay? I’d like to think so. “Some people already say the shift towards sobriety was temporary but from where I’m standing, that’s not the case,” says Saskia, “I know more people now who don’t drink regularly. There’s a balance in living sober-ish, or even just trying to.”

au.madebyfressko.com

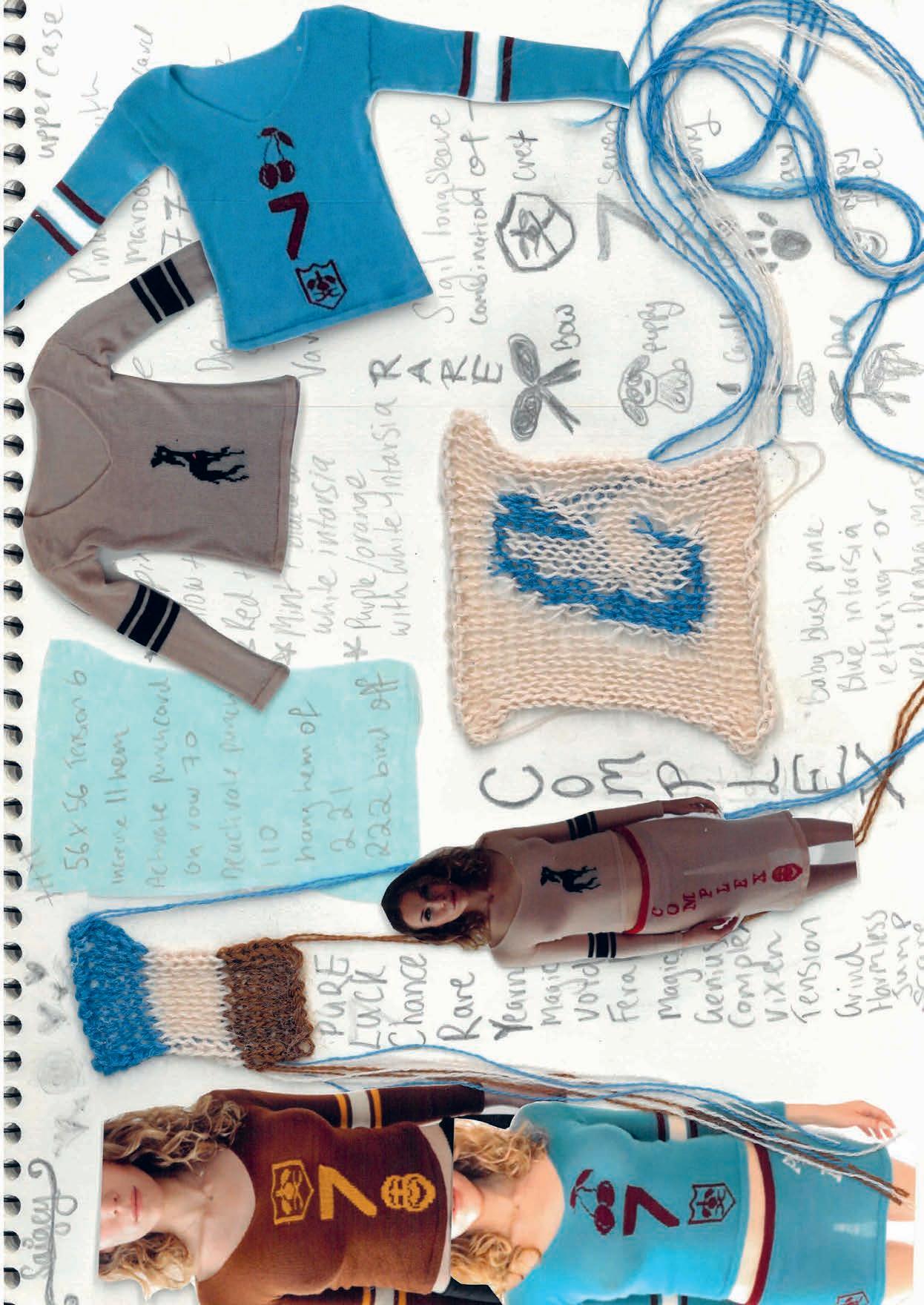

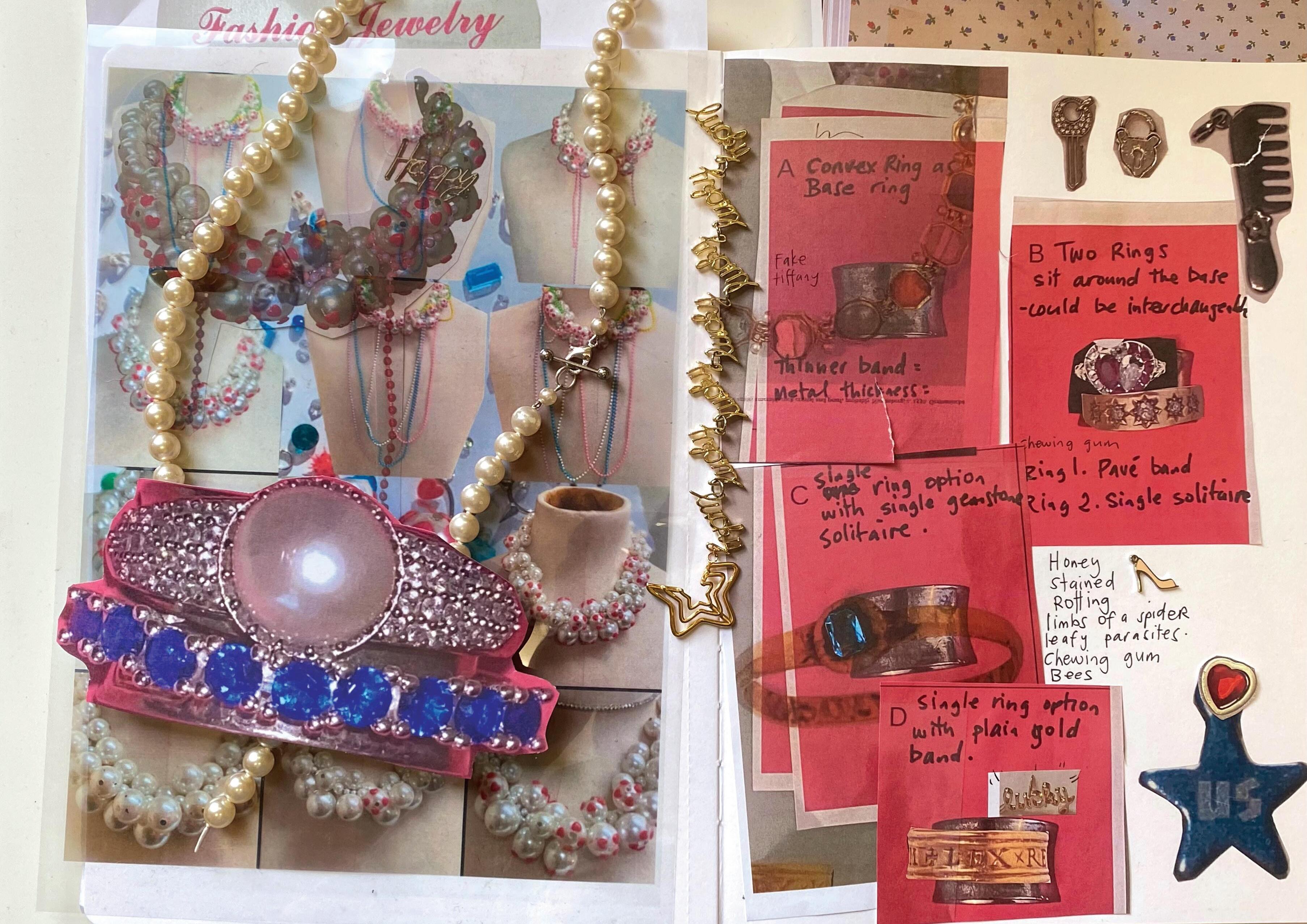

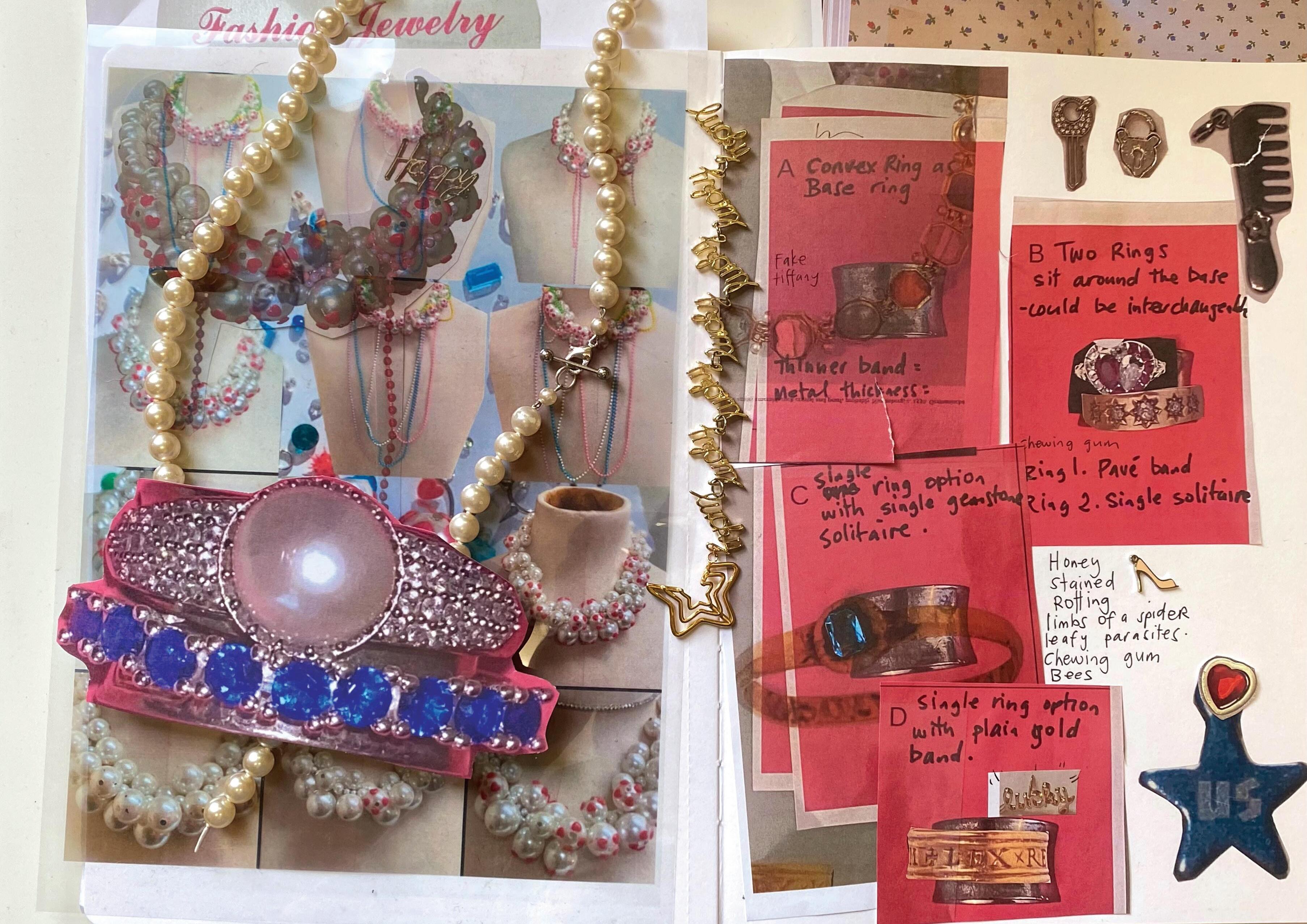

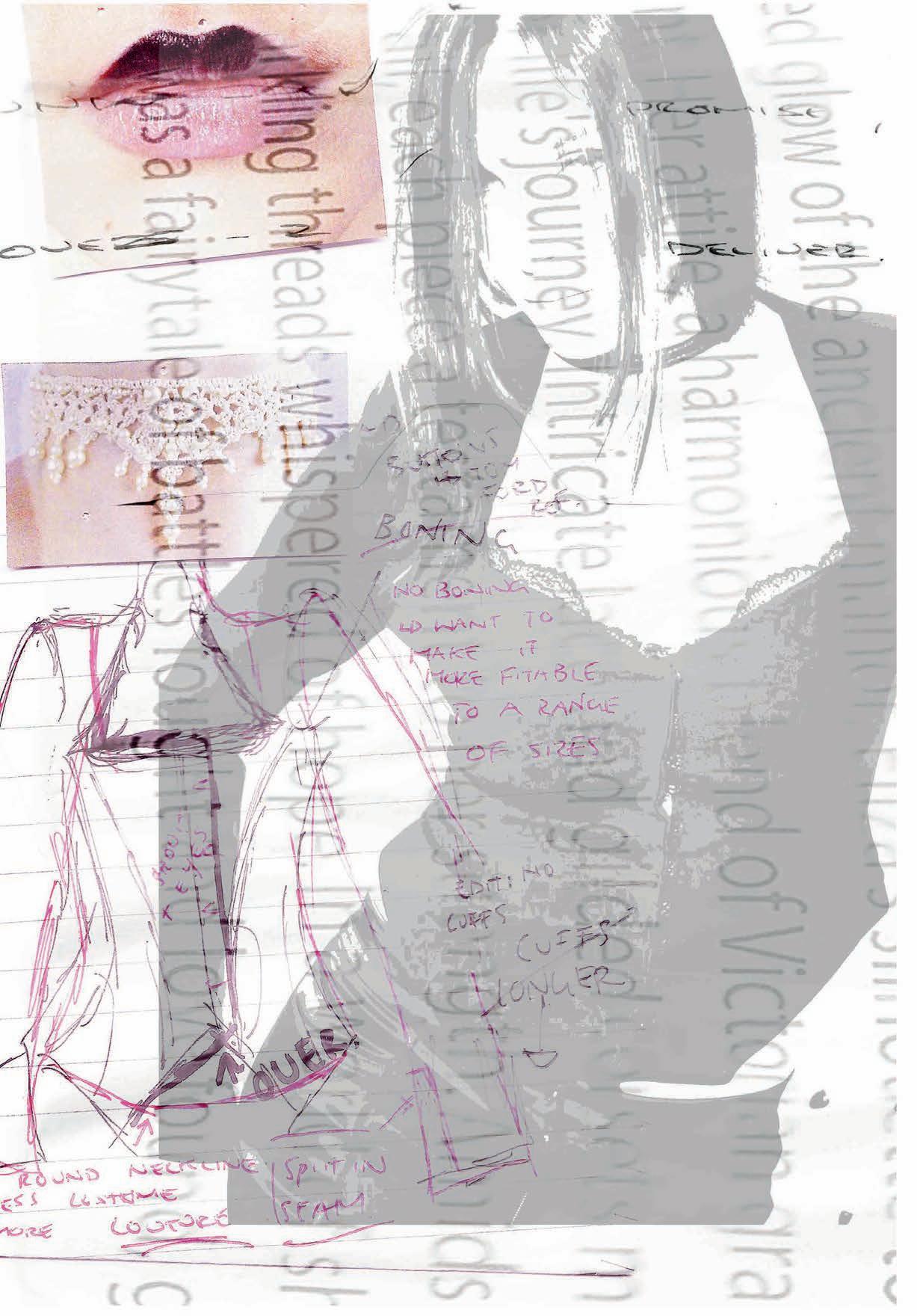

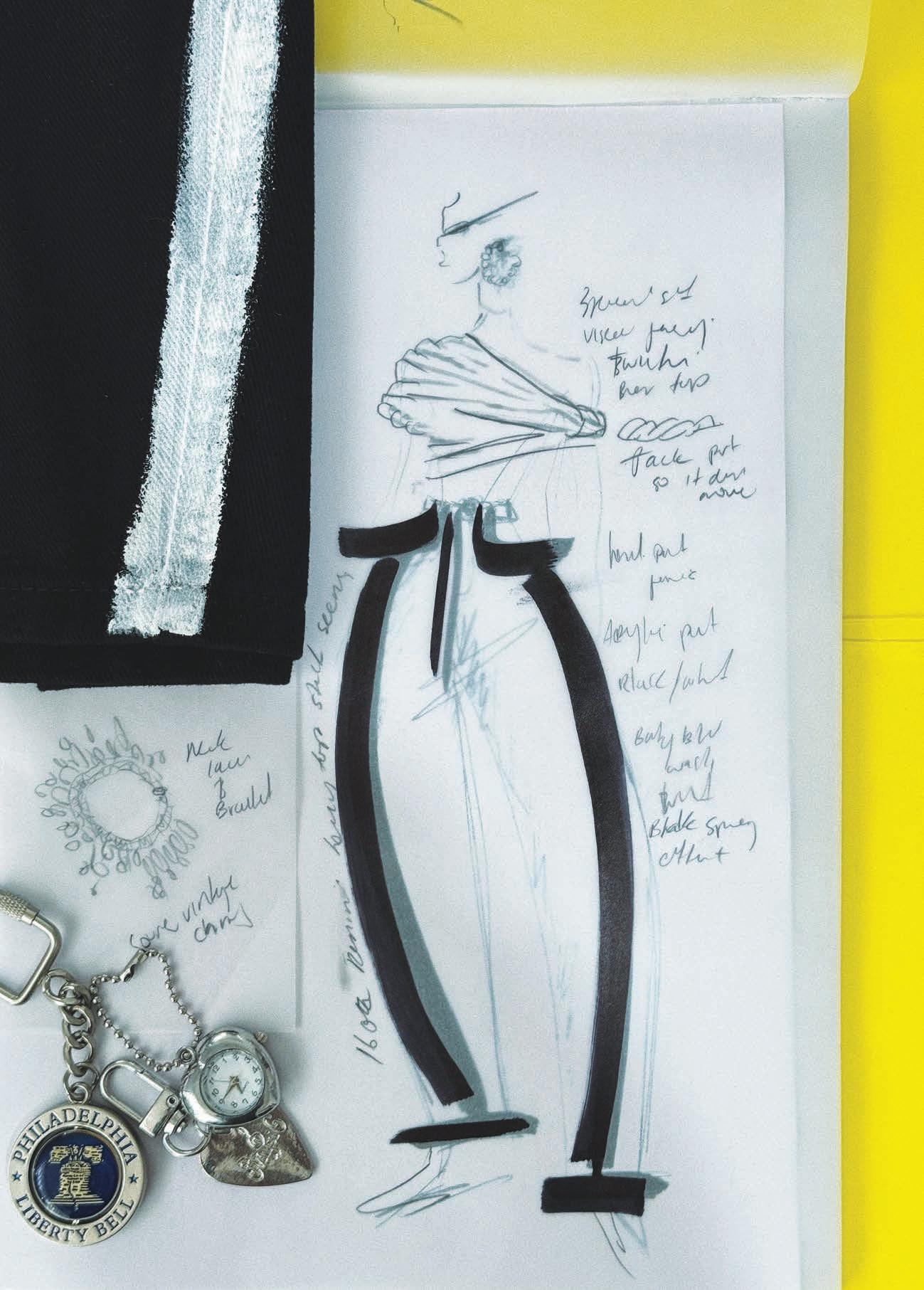

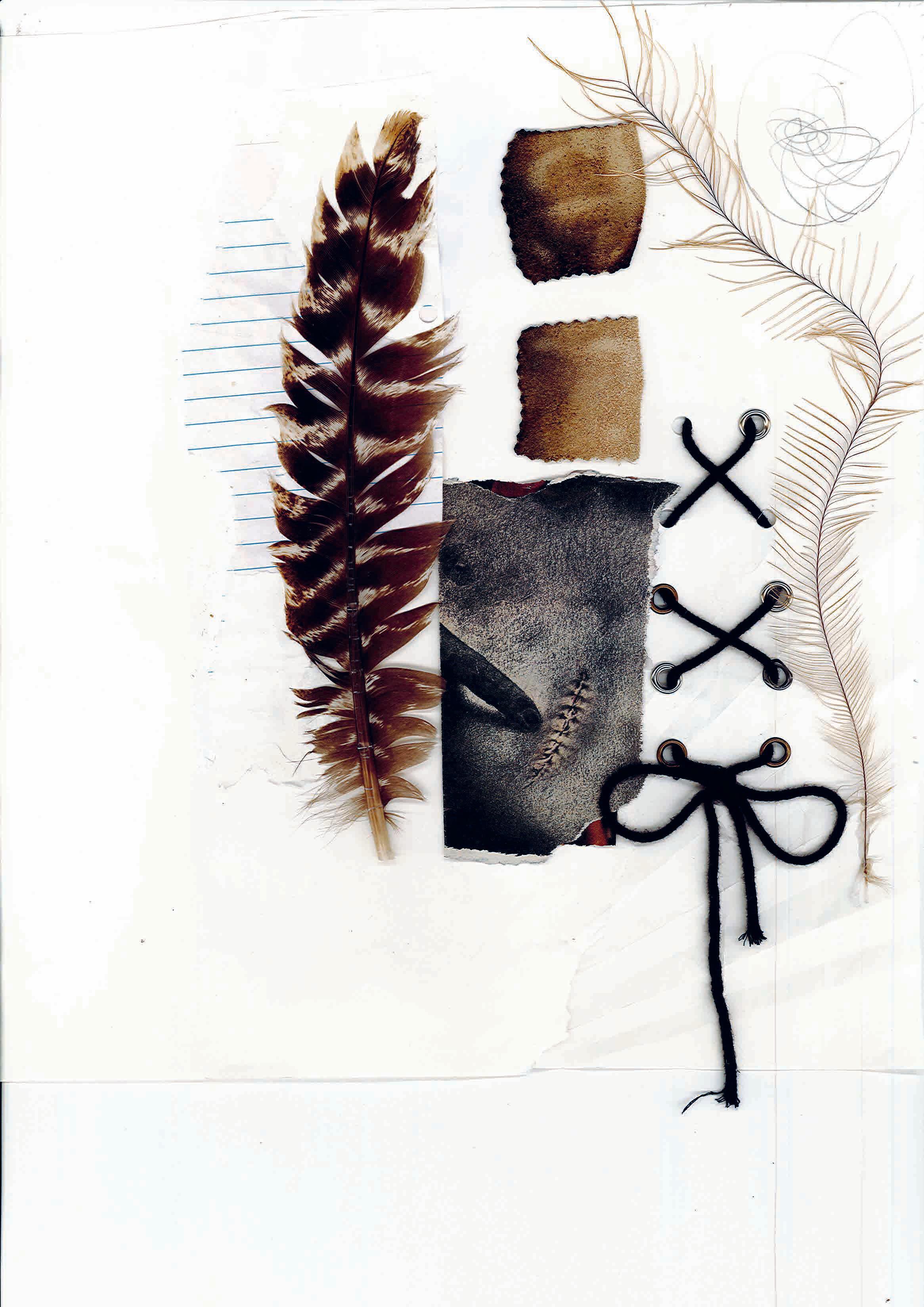

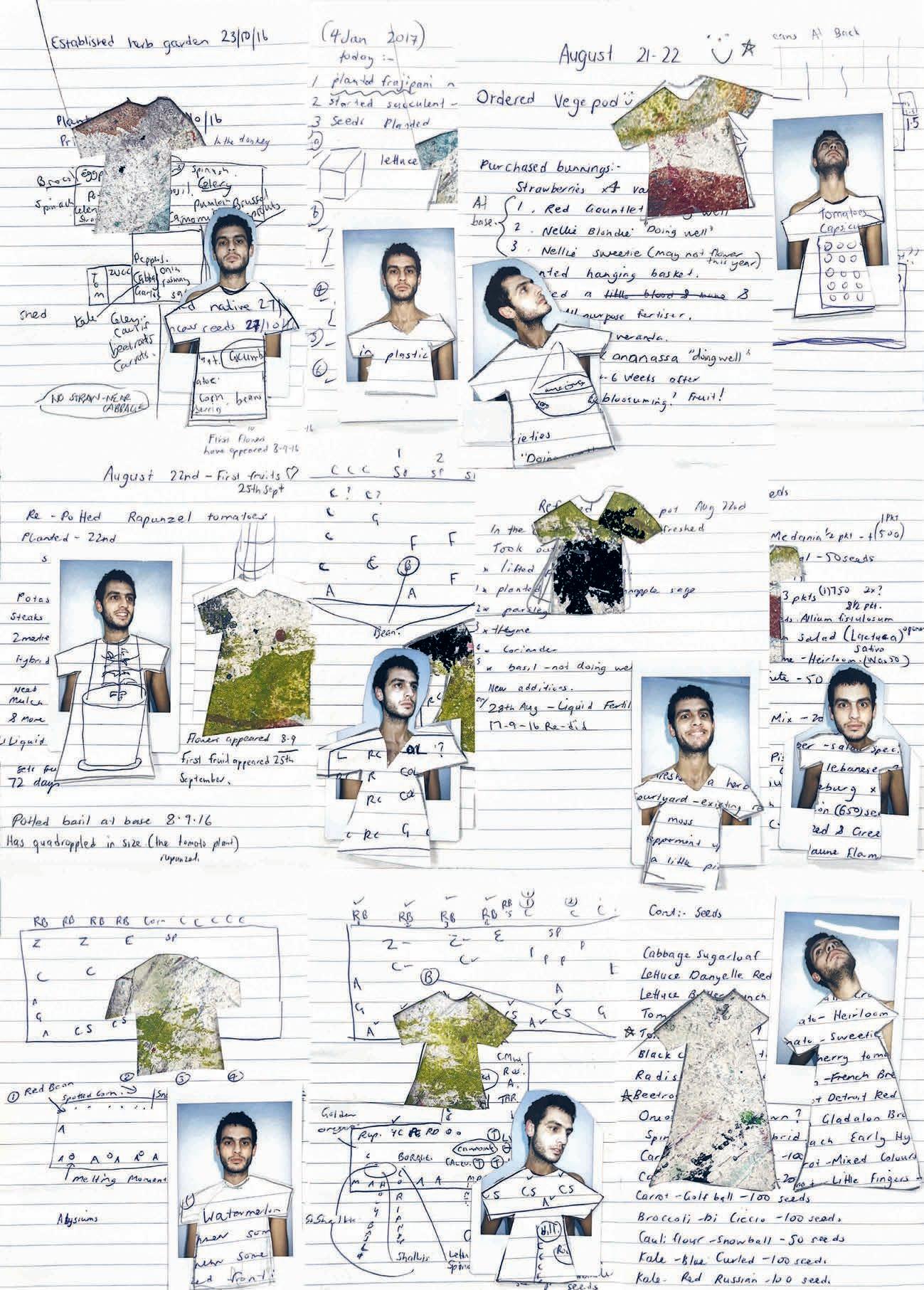

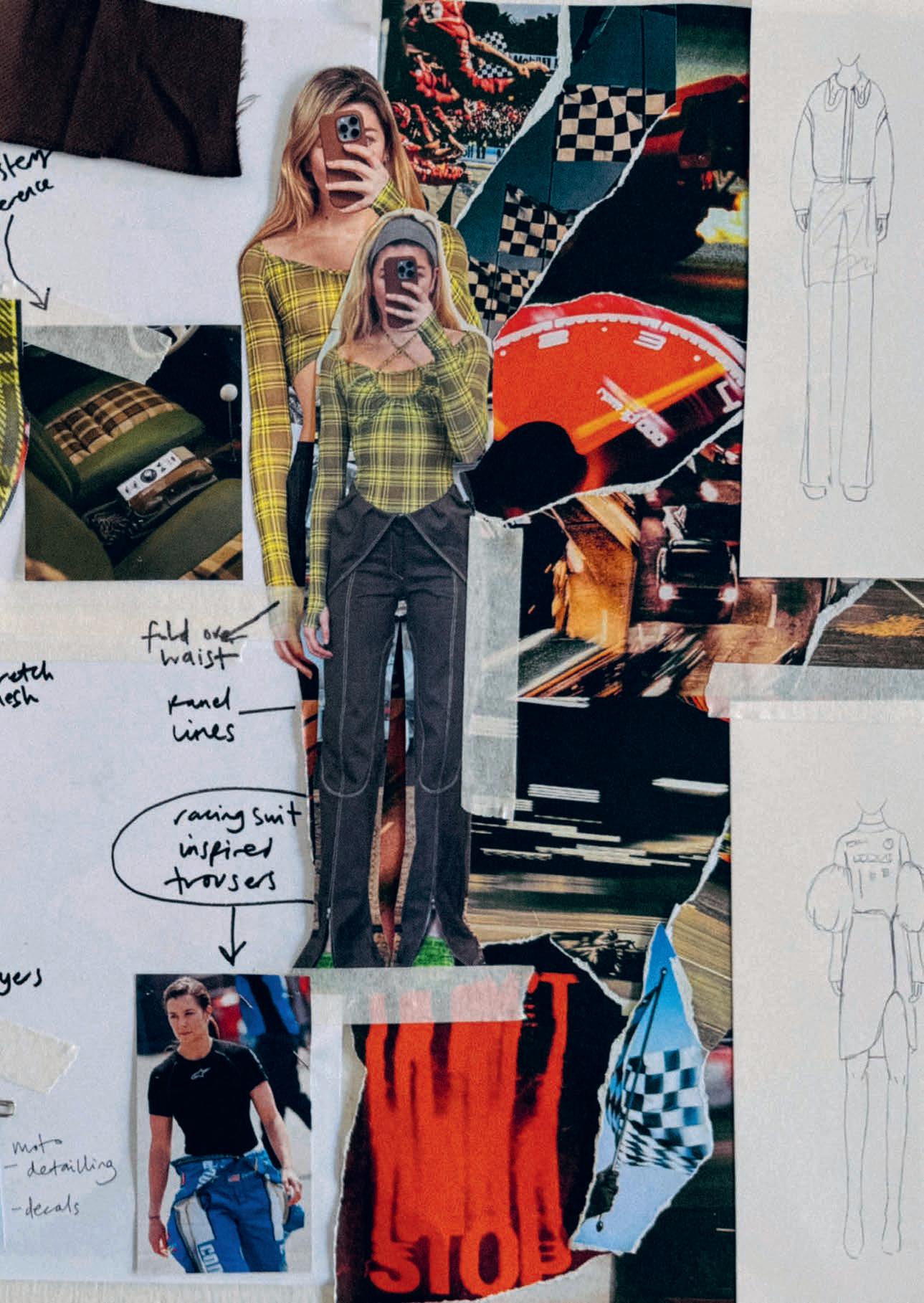

A peek into the ideation stages of a designer’s work can show a surprising set of influences. Early moodboards often include photos of architecture, automotive design, stills from old films, photos of pets, shreds of fabric, letters from loved ones, travel souvenirs and even trash, all of which shape what eventually materialises. These collages offer a window into the designer’s mind, a place to snoop while we wait for what they create next.

THIS PAGE

PHOTOGRAPHER Kaitlyn Bošnjak

PHOTOGRAPHER’S ASSISTANT Kirk Rinon

DIGITAL ASSISTANT Steph Pederson

STYLIST Monica Morales

STYLIST’S ASSISTANT Koby Dulac-Daley

HAIR Gina Yates using Shark Beauty

MAKEUP Jemma Barclay

MODEL Zara Wong at Chadwick Models

RAMP TRAMP TRAMP STAMP dress and pants, ALIX HIGGINS skirt, MANOLO BLAHNIK shoes from EVOllA, GANNI bag, POPPY LISSIMAN sunglasses, DINOSAUR DESIGNS bangles and rings, stylist’s own earrings

ALIX HIGGINS shirt, ROMANCE WAS BORN skirt, MAISON ESSENTIELE lace pants, CONICHIWA BONJOUR cap from MAILLOT, PUCCI bangle from DEPOP DINOSAUR DESIGNS rings, HEAVEN BY MARC JACOBS earrings from KOT-J

OPPOSITE PAGE SAINT LAURENT shirt, SONG FOR THE MUTE pants, MAISON ESSENTIELE belt AMISS shoes, LE SPECS glasses

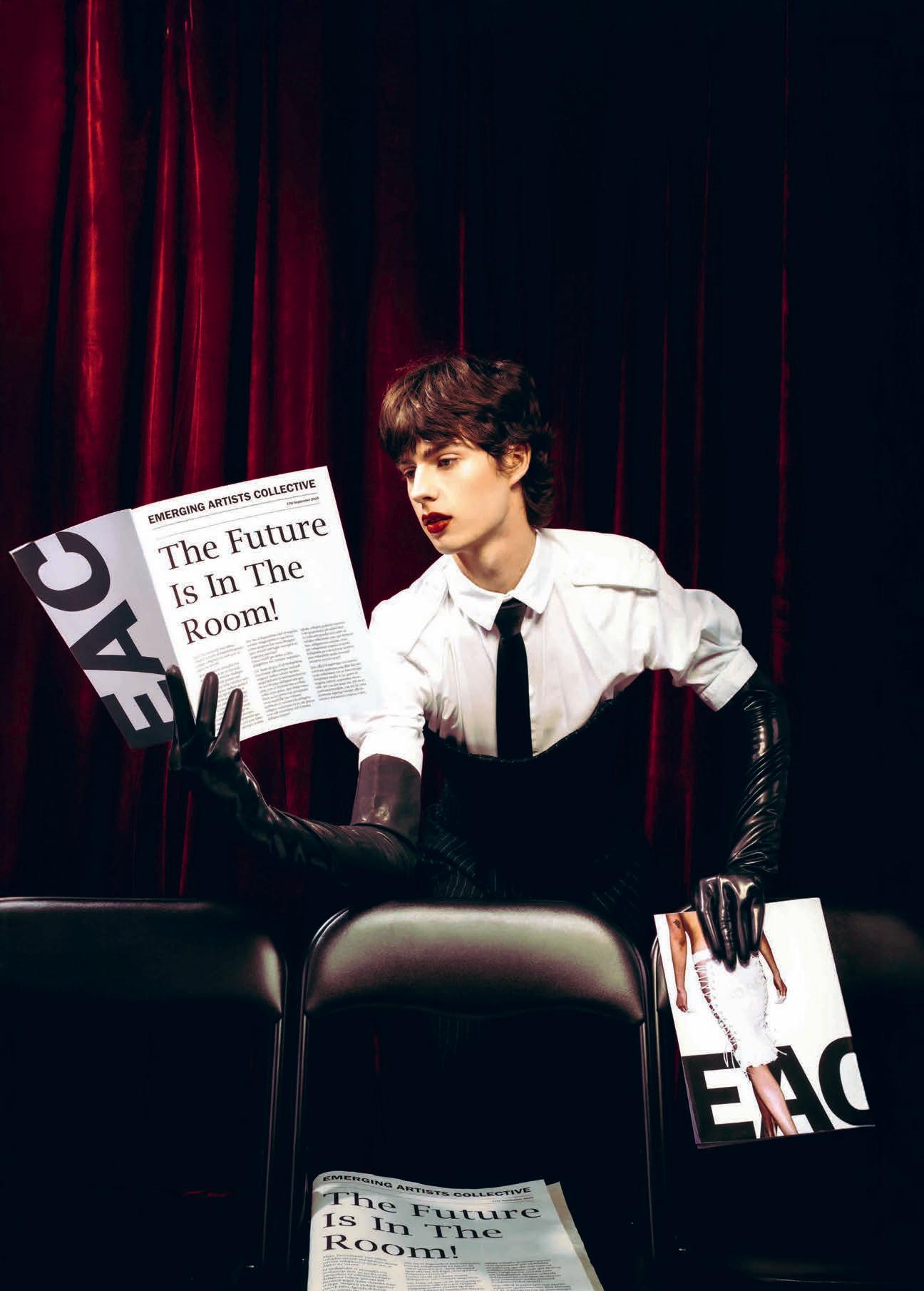

From self-producing EPs to directing their own music videos, a new wave of female musicians is proving you don’t need industry backing to make an impact. Fashion Journal’s Assistant Editor Daisy Henry meets three artists who are rewriting the rules, building careers on their own terms.

WORDS BY DAISY HENRY

To be an indie musician today is to be go, go, go. It’s a tightly packed schedule stacked with release dates, live shows, tour logistics, dragging gear from place to place, interviews, photoshoots, lastminute meetings and, of course, actually finding time to write and record music.

It’s years of adding hyphens to your resume: singer, songwriter, instrumentalist, producer, performer, content creator, creative director. “It’s overwhelming but at the same time, the usual,” says Madeleine Jane Woolley, a singer-songwriter who performs under the name Maddy Jane.

I’ve lined up interviews with three Australian musicians, each having entered the industry through entirely different doors, to get a temperature check on the current landscape for independent artists. Between closing venues, vanishing festivals and an increasing need to master social media algorithms, I’m curious: How exactly does one forge a career in an industry notorious for its financial instability? And perhaps more importantly, how do you keep hold of the reins without selling your soul (or your masters)?

A foot in the door

Hailing from Tasmania’s Bruny Island (“an even more isolated island off the island, off the island”), Maddy Jane has the atypical experience of having worked

with a record label early in her career before stepping out on her own.

After an early single, ‘Drown it Out’, earned her a Falls Festival slot and recognition as Triple J Unearthed’s Artist of the Week, industry attention snowballed. First came a manager, then a booking agent and soon after, a deal with a record label. But when her debut album, Not All Bad or Good, came out in the early stages of the 2020 lockdowns, momentum came to a standstill.

“We had spent all that time prepping the album and went, ‘Okay, do we just still release it?’ We had no idea how long any of this was going to go on,” she reflects. Unable to tour, Maddy Jane moved back to Bruny Island to write, and when she eventually returned to Sydney, she and her label parted ways. “I had to relook at everything and work out how I was even going to do it.” ‘It’ being her music career, on her own.

As it turns out, stripping everything back suited her. “I had nothing, so I started writing more songs and it was coming out of me. Maybe not relying on anyone or having anyone to rely on [made me realise] it’s completely up to me, so either make it happen or sit here and feel sorry for yourself.”

When it came time to release her next batch of music, “independent was the only way”. She took creative control, forming a small team that could help bring her vision for her latest EP, Clear as Mud Pt. 1, to life.

Similarly, for Sydney-based musicians Deborah Amenawon and Alessandra Gazal, who go by the stage names Devaura and Gazal respectively, being independent hasn’t meant going it entirely alone. Instead it’s led to signing with teams that let them call the shots creatively and retain ownership of their work.

Gazal’s early exposure to music largely involved Arabic or orchestral music drifting through her childhood home. After high school, she taught herself to write, produce and record music, eventually racking up nearly 400 demos in a Sydney studio.

Initially, she was determined to make it as an artist on her own. But after connecting with recording company, AWAL (‘Artists without a Label’), she was able to negotiate a distribution deal, leading to the recent release of her debut EP, Gods Into Frauds. Unlike a traditional record contract, the deal has allowed her to maintain full control and creative license of her work, while AWAL distributes her music.

“As an artist, you second-guess yourself so often, so [having] people back your music – and it doesn’t even need to be monetary, just hearing people fuck with it – is really encouraging,” she says.

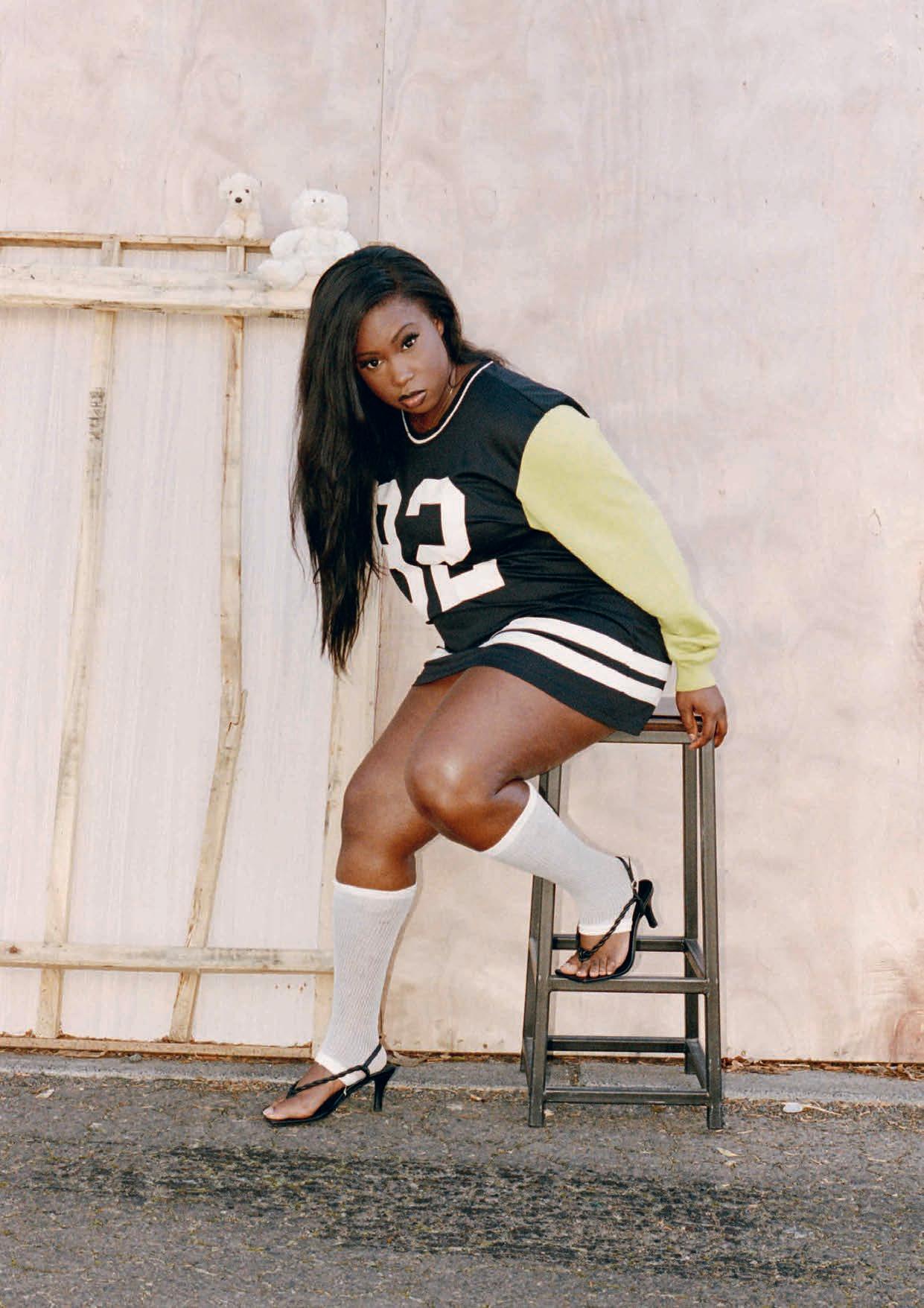

For hip-hop and R&B singer Devaura, a career in music didn’t seriously enter the picture until she went to see Yawdoesitall at the Vanguard in Newtown.

“It was the first time I saw an Aussie artist live… but also an artist who was black in Australia. And I just couldn’t get enough of it,” she remembers.

Devaura is currently signed to Offbeat Collective, an artist-run and community-driven label. “The creative process is very sacred to me,” she says. “[It] will be the one thing that I will fight tooth and nail for. And I’m so glad I don’t have to.”

Ahead of the release of her debut EP, Vol.1 Learning in Public, her team invited her into every step of the process, from producing to negotiating contracts. “They let me be an active learner,” she tells me. “[They gave] me the confidence to be able to say no and to say yes, even when it might not make sense from a financial perspective.”

The push and pull

Being an indie artist involves wrestling with a constant tension. There’s more creative freedom, sure, but there’s often a financial sacrifice. “The main thing is money and exposure. You can have all the creative control but maybe not have the money to actually create,” says Maddy Jane.

Plus, doing it yourself inevitably means… you’re doing a lot of it yourself. “You’ve got to be so passionate about it because it’s so much work,” Gazal adds. From writing to creating moodboards and visuals, to maintaining relationships with third-party streaming platforms, there’s a lion’s share of work that goes on behind the scenes, even if you have others supporting you.

Then there’s the expectation that artists are prolific on social media, making the most of TikTok’s algorithms. “You can have all your ideas and your opinions and strategies, but there’s no guarantee [it’ll work],” Maddy Jane tells me. The unpredictable nature of the algorithms means that even the most lo-fi videos can take off and go viral.

“TikTok’s the lottery,” Gazal agrees. Her mentality? “Chuck yourself in the lotto as many times as you want. See what happens.”

Exposure and momentum, whether from social media, touring or accolades, are key drivers in finding success as an indie artist. But what’s often glossed over is how these external markers can complicate a musician’s trajectory.

Maddy Jane has learnt from experience that even when opportunities arise that feel like a breakthrough, it’s best to view them as a stepping stone, not a golden ticket. She’s supported major acts like Harry Styles and the Red Hot Chilli Peppers, and notes that while these moments lead to visibility, they don’t always translate to long-term success. When she supported the RHCP in Tasmania, the audience was pretty eager for the headliner to take the stage. But for Styles’ fans, attitudes were different. “Harry Styles fans were like, ‘Oh, Harry chose you. We love you.”

For Devaura, the pressure to build momentum is dwarfed by an even greater pressure to keep it going. Over the past year alone, she’s racked up a long list of major achievements: winning the Best Emerging Artist award at SXSW Sydney and the Triple J Unearthed’s Laneway Competition, performing at Party in the Paddock and Dark Mofo in Tasmania, and releasing her debut EP. And she’s already put the finishing touches on a follow-up, If You Don’t Laugh, You’ll Cry, slated for release later this year.

“It’s still a little ‘pinch me’,” she says. “I’m still a little confused as to why everybody is interested… And I think there’s a big part of me that just wants to be worthy of it.”

So, what’s missing?

For emerging artists in Australia, there’s always going to be a pull to chase opportunities overseas. Maddy Jane, Gazal and Devaura all agree that in order to build their careers on home soil, there needs to be more local incentives, more funding of the arts, and a stronger infrastructure.

At the most grassroots level, the solution might mean listeners need to start showing up more. Devaura suggests tapping into community radio (think Sydney’s FBi or Melbourne’s Triple R), following musicians you like online and, if you have the means, going to see live music and buying merch.

For these artists, putting on live shows (and seeing people show up) is a key element to sustaining their love for what they do. “What a privilege it is to have anybody spend even a dollar [to see us],” Devaura says. “Even if it’s a free event, they spent their time and energy to be there in that space.”

“It’s all about connection, right?” Maddy adds. “If you can actually connect with people... that’s the most fulfilling thing.”

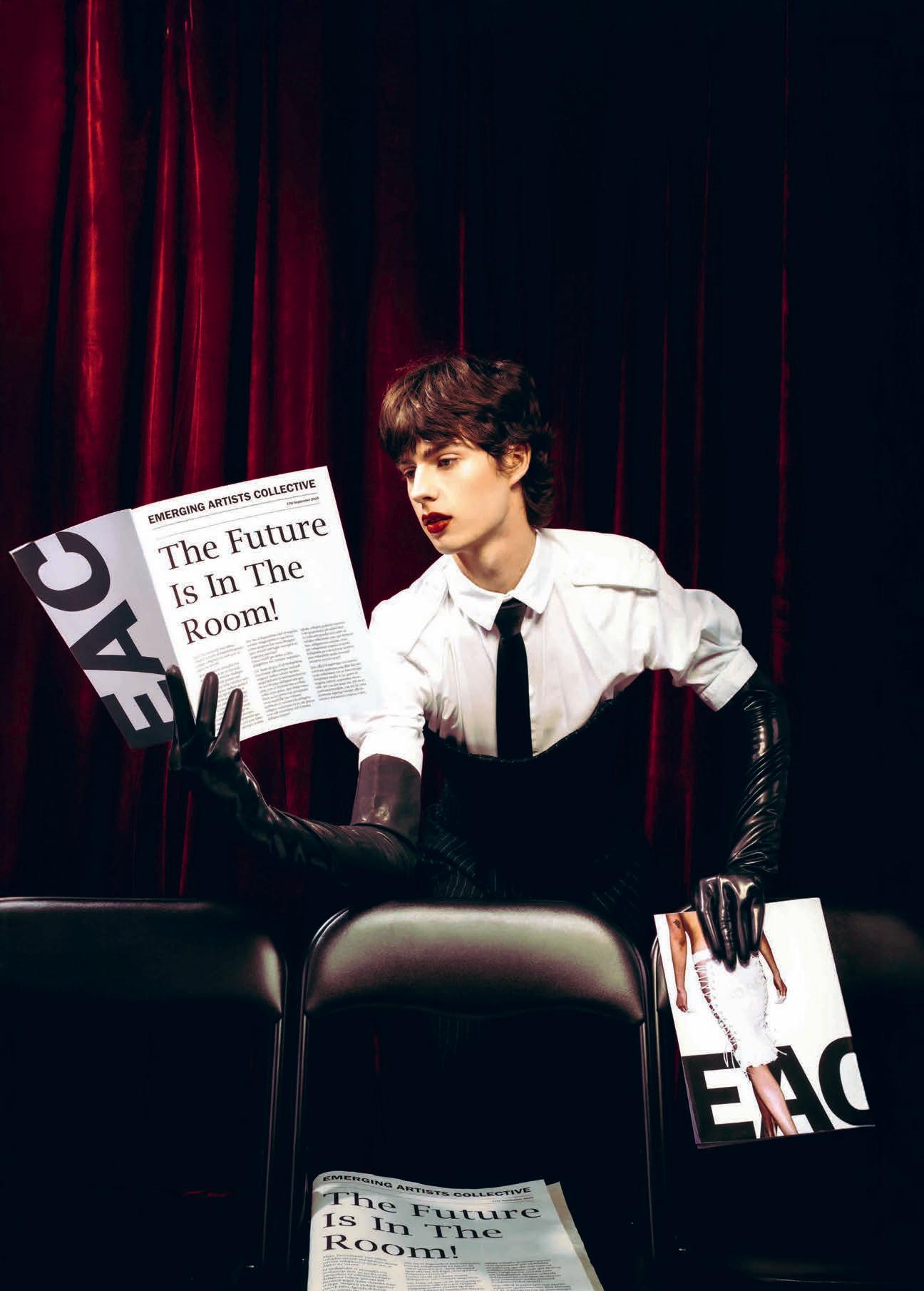

CREATIVE DIRECTOR AND PRODUCER Daniel Mizzi PHOTOGRAPHER Em Crowe

PHOTOGRAPHER’S ASSISTANT Monica Dragut STYLIST Ned Quail PROP GRAPHIC DESIGNER Anthony Tchourilov MODELS Claudia Viant-Berg and Mala Hedley at Alt-Cast

TOP TO BOTTOM CLAUDIA

WEARS

CAKEY

DINOSAUR DESIGNS bangles

MALA WEARS KARLAIDLAW top and bag, CANDY’S LINGERIE tights, TONY BIANCO shoes

Where have our eyebrows gone? Writer Izzy Wight traces how skinny arches became a counter-culture icon.

When Aotearoa-based hairdresser Victoria Clare

was in high school, she had an important realisation. After arriving at class with her natural arches overdrawn “at least two centimetres thick”, she learnt just how divisive eyebrows can be. “The boys in particular hated them,” she explains. “I thought, ‘Wow, this makes people emotional. I can really annoy people with the way I do my makeup.’”

That was in 2012 – Victoria’s peak Tumblr era. From there, she continued to push boundaries with her brows: bleaching them, shaving them off and pencilling them back on in shades of black, hot pink and lurid green. It was, and continues to be, her little act of transgression, a subversive statement that attracts those who ‘get it’ and repels those who don’t.

Over a decade later, skinny (or entirely absent) brows have become the look du jour in the world of alternative celebrity style icons. Gabbriette, Amelia Gray, Julia Fox and FKA Twigs are all poster girls for dramatically thin or bleached-off arches, while Doja Cat has sported a range of experimental eyebrows since shaving hers off on Instagram Live in 2022. I’d be remiss not to mention Riri here, who was a step ahead of the It Girls, sporting pencil-thin brows on the cover of British in 2018, drawn on by then-emerging makeup artist, Isamaya Ffrench.

In reality, the act itself is anticlimactic. It’s as simple as the swipe of a razor, a thimble of bleach or one dedicated half-hour with a mirror and a good pair of tweezers. If eyebrows frame the face, removing them leaves a blank canvas – one to fill with angry, slanted lines; thin, rounded arches; colourful squiggles; forehead-touching eyeshadow; or perhaps most daringly, nothing at all.

At the same time, we’re seeing a growing shift towards conservatism on social media. With the rise of tradwives, Ozempic and trends such as ‘quiet luxury’, the pendulum seems to be swinging back to more traditional beauty standards. Subtlety is back in a big way, and can be seen in the number of women posting about removing their tattoos, dissolving their filler and forgoing heavy makeup and unnatural hair colours in favour of a more widely palatable look.

For those looking to signal their counterculture status, this move towards ‘natural’ beauty only makes a statement eyebrow (or lack thereof) more appealing. “Eyebrows are used by so many subcultures to push away and separate out from the mainstream,” says James Dobson, a New Zealand-based designer and one-half of Beauty Benders, a social media duo that highlights subversive beauty on Instagram. “They’re such a powerful way to redefine and reshape the face.”

On a mission to ‘degender makeup’, James and his Beauty Benders co-founder, Andre Sv, encourage their followers to experiment with looks that exist outside of the gender binary. “I have bleached my brows numerous times – mostly because, having hooded eyes, it gives you so much more room to play with eye makeup,” James says.

The duo takes cues from drag, goth and punk subcultures, where traditionally, natural eyebrows are glued down, plucked into oblivion or shaved off entirely to expand the surface area for makeup. From there, a blank forehead can bend to all eyebrow whims – like the menacing 90-degree angles of Pink Flamingos actor and ‘queen of filth’, Divine; the straight, tapered lines of postpunk icon Siouxsie Sioux; or the lifted, hyperfeminine arches of RuPaul’s Drag Race alumni, Violet Chachki and Trixie Mattel.

sexuality. Modelled after stars like Clara Bow and Josephine Baker, bobs were sharp, skirts were shorter and eyebrows were micro-fine. It was a rejection of the buttoned-up beauty standards of wartime, marking a moment in which thin eyebrows became distinctly political.

Fast forward to ’60s Southern California, and a kindred beauty movement was developing among young MexicanAmerican women. Now known as ‘chola’ style, it’s a look that often combines baggy menswear and distinctly feminine makeup – like low-slung Dickies and a plaid shirt paired with dramatic cut-crease eyeshadow and barely-there, sharply arched eyebrows.

It’s a style we might associate with the ’90s but its roots extend back much further. “[It] stems from the Pacheco era,” explains San Jose-based digital creator, Winnonah Sarah, referring to a period during World War II when young women – known as pachucas – used makeup and clothing as a way to revolt against White America’s notions of femininity.

“Thin brows always have and always will represent non-conformity.”

“Both drag and goth are about reimagining and engineering the architecture of the face to transform yourself... even the most micro adjustment can make a dramatic statement,” James explains. “In saying that, both are still referencing historical precedents. Goth owes a lot to the pencil-thin brows of the ’20s, and a shaved brow goes right back to Ancient Egypt.”

It’s true, humans have been using eyebrows as a form of self-expression and communication for centuries. In Ancient Egypt, brows were dramatic, often emphasised with kohl or shaved off entirely to mark a period of mourning. During Elizabethan times, eyebrows and hairlines of the upper class were heavily plucked, made to accentuate their high, smooth foreheads and signal their nobility.

In the post-war 1920s, beauty became a means of liberation. Women began to break away from previous traditional ideas of class and gender in favour of opulence, glamour and overt

Loved for her old-school beauty tutorials on TikTok, Winnonah’s makeup pays homage to her mum, a “tough yet elegant” Chicana woman who also wore dramatic winged liner, white eyeshadow and heavily plucked, pencil-thin brows.

“My cousins plucked my brows off at age 13 and taught me how to heat up the liner pencil so it goes on smooth and dark. They also taught me how to trim my feathered hair, which I still maintain today as well.”

Now a mother herself, Winnonah tells me that while parts of her look have changed, one element has remained consistent: her thin eyebrows. “How else can I showcase my cool whiteshadowed lids? Thick brows would take away from the true artistry of the perfect wing and shadow lines. Thin brows always have and always will represent non-conformity.”

In reality, these patches of hair hold as much or as little cultural subtext as you allow. Thin arches aren’t always an act of defiance, just like thicker brows aren’t a sign of political apathy. But in a time where beauty standards are swinging back toward subtlety, it might just be a skinny brow – or lack thereof – that speaks the loudest.

A collation of some of Fashion Journal’s favourite local labels whose sizes extend beyond a 16. Circle those you love, highlight for future reference, even cut them out and stick them to your fridge.

REPRESENTATION FROM RUBY!

Representing Aotearoa, Ruby doesn’t just carry an inclusive size range (4 to 20, to be exact). It shows what its clothes look like on a range of DIFFERENT BODIES!!! The brand also offers custom sizing on most styles, at no extra cost.

DYSPNEA IS SPARKLES GALORE Hand-beaded in Bali by an allwomen team. Sparkly, sheer and size-inclusive. Matching sets. Booty shorts. Cat suits. Thank you.

☆☆ 1800-APRÈS-STUDIO ☆☆

ISO a plaid dress? Or a striped top? What about a matching set of napkins? CALL APRÈS STUDIO NOW FOR CLOTHING AVAILABLE IN SIZES XXS TO 4XL.

SOME PANTS PLEASE, KARLA

Just a girl, seeking one pair of Karlaidlaw made-in-Melbourne Circus Pants, please. And a pair of Spider Pants. And maybe the North ones, too.

WE ♥ LOVE ♥ ELK Melbourne label since 2004, high ethical standards, colour and prints for all occasions, handmade leather and ready-to-wear, sizes 6 to 20.

ARE YOU A RAMP TRAMP?

A size range that varies from an XS to 4XL??? Sydney designer Niamh Galea has answered the call. The brand’s focus on ‘fit flexible’ sizing means many styles can be adjusted as your body fluctuates. We’ll take a Yummy Mummy hoodie and a pair of trackpants to match.

WEAR YOUR VALUES

Clothing the Gaps is merch with a message, in sizes XS to 7XL. Choose between ‘Mob Only’ or ‘Ally Friendly’ pieces and let your clothes spark a conversation.

★★ GAGA FOR GARY ★★

PSA, Gary Bigeni hand-paints the artful prints in his collections, offering sizes 6 to 20! Now THIS is dopamine dressing!

SAVED BY SANCT

Sanct creates pieces to pair seamlessly with your wardrobe, all ethically made in Melbourne. Hard-wearing denim, crisp cotton shirts and transeasonal merino knits. Sizes 8 to 30, or custom-made to your body.

SQUINT AND YOU’LL MISS IT

Handmade in Melbourne, up to a size 30, for the girly girls who like a ruffle, oversized collar and a bow <3 <3

SUPER KUWAII

Fun prints, colour blocking and all the basics. ICONIC local label Kuwaii offers a curated selection for bodies up to a size 24. Intelligent design! Quality fabrics!

♥ WE LOVE KOWTOW ♥

Born in Aotearoa and loved here in Australia. Kowtow makes plasticfree pieces to last, designed to stay in your wardrobe long-term until you’re ready to recycle them back to the brand’s design room.

CALL NOW!!

DK ACTIVE

Get moving!!! Activewear and leisurewear from sizes 6 to 24, made with organic and recycled materials wherever possible.

HELLO HOMIE

On a mission to support young people affected by hardship, Homie still won’t compromise on design. A unique range of streetwear in sizes XS to 3XL.

CALLING KATHARINA LOU

Hello? Hello? A message for Katharina Lou, we love all that you do. Enquire now for the cutest styles made from deadstock fabrics, in sizes XS to 4XL.

★ E NOLAN ★

More than made-to-order!!! This tailor’s offering is steadily growing, with a ready-to-wear line in sizes 4 to 24. The BEST shirts you’ll find, hands down. Not to mention the gorgeous Italian-made footwear, with inclusive sizing up to an EU 44

HOLY OBUS

PROUDLY MADE IN MELBOURNE. Vibrant styles up to a size 20, dress yourself from head to toe in Obus. Playing with colour, shape and texture since 2000!

HERE TO WORK

Sük Workwear has hard-wearing pieces in sizes 4 to 30!!! For all bodies, designed by women. Call now for a heavy-duty 310 gsm 100% Fairtrade cotton drill and flattering features. Pants made for bums and thighs! Cinched waists! Pleats! Suitable for:

• Chefs

• Tradies

• Doctors and nurses

• Anyone with style

VARIETY! VARIETY!

READ ALL ABOUT IT!

If you’ve got the morning to yourself, take the 86 tram down Melbourne’s Gertrude Street. Walk into the doors of a little shop called Variety Hour and exhale. You’ve made it. The clothing is colourful, the prints are hand-painted and sizes go up to a 3XL. You’re here, finally, and it’s wonderful.

WAKEY WAKEY CAKEY

A refreshing project by shoemaker Matea Glušćevič, this time in apparel!! Expect the unexpected. Cakey Sportsman’s playful, sculptural designs come in both ready-to-wear and madeto-order styles, up to a size 24.

IN GOOD FORM

Form and Fold, we <3 you. Swimwear for D+ cups, up to a size 20, in sleek designs. Founded by two clever women who were sick of buying and tying oversized swimwear to fit their busts. A firm favourite of Fashion Journal!

☆☆ FANCY A DIP? ☆☆

Seek out swimwear made from recycled fabrics by Camp Cove Swim in fun prints for summer!

RAQ APPAREL

Swimwear in sizes 8 to 20 for busts up to a J cup. Fun prints like leopard or a simple black, full or cheeky coverage, and low, low prices!!!

MORNING OATS!!

Sheer lace for layering. A masterclass in ruching, fit and flare. Dress up with Oats the Label NOW. All pieces made-to-order or find select stock at Error404 in Fitzroy North, Melbourne.

♥LOVE♥ ♥LOCLAIRE♥

From sharp tailoring to ultrafeminine draping and girlie details like flower and heart cut-outs, NZ label Loclaire is for the modern woman! Made-to-order apparel up to a size 18 (with custom sizing available at no extra cost), your dream piece is a few weeks away.

MY FAVOURITE COLOUR

Surprise, surprise, surprise! Perple designs are a little unexpected! All made in Melbourne with lots of deadstock fabric, so little goes to waste. Our long-time love.

★ RACHEL MILLS 4 YOU ★ Understated but elevated. The building blocks of your wardrobe, made with love in Tāmaki Makaurau, Aotearoa. Organic cotton and merino, and the sexiest swimwear. No excess! No guesses! ALL MADE ONDEMAND, WITHIN SEVEN DAYS.

☆☆ HARA DREAMSCAPES

☆☆ Hara the Label: Designing soft, dreamy, naturally-dyed bamboo loungewear and underwear that all bodies can make a home in.

HOPELESSLY DEVOTED TO HOPELESS LINGERIE

Designed, cut and sewn in-house to minimise waste! Ethically made from sizes XXS to 5XL, with the option to customise to any body! Worn by Madonna! Beyoncé! Britney!

OH HI, LÉ BUNS Underwear made ethically without compromising on design. Browse sizes 6 to 24 now. Not just to stay hidden, look to Lé Buns for swim and apparel essentials too!!

NALA HAS YOUR BACK AND YOUR BUM Nala has done the impossible. It’s made sexy bras that are comfortable enough to sleep in!!!!! Cup sizes go up to a K and bands to a 26. See how everything fits on real, unedited bodies and boobs.

GEL CUMULUS™ 16