Holocaust Remembered # COMBATING ANTISEMITISM

Here are a few ways to support “Combating Antisemitism.” The flag pin expresses the close friendship between the United States of America and Israel. The round pin illustrates the “Stand Up to Hate” campaign from the Kraft Foundation to Combat Antisemitism. The square blue pin represents the television campaign of # �� # StandUpToJewishHate from the Kraft Foundation. See pg. 3.

MAY 1, 2024 | VOL. 11 Supplement created and paid for by the SOUTH CAROLINA COUNCIL ON THE HOLOCAUST

We Must Continue to Tell the Story

Despite my fervent prayers, 2024 has not turned out to be “peace on earth, especially in the middle east.” For the first time in my life, I silently thanked G-d that my parents, Jadzia and Ben Stern (obm) were not here to see the terrorist attack in Israel on October 7, 2023.

As Holocaust Survivors, they were strong supporters of this country and the people and country of Israel, the safe haven for all Jews all over the world. Had there been an Israel in 1938 or 1939, millions of Jews would still be here. Families would have flourished and the times would have changed. But alas, that is not so. The terrorist attack in Israel was the impetus for thousands of American college students and young people to blame Israel for the attack and then try to perpetuate the memes and chants: from the River to the Sea! I believe most of these young people were protesting and shouting about a history and a geography that they knew nothing about. Many were unable to explain the meaning of the chant, point to the borders of Israel or explain the complex history of the British mandate, the Balfour Declaration signed during WWI on November 2, 1917. This mandate was supported by European countries and US President Woodrow Wilson. This mandate

was then relinquished in 1947 and in May 1948, Israel became a state and a home for Jews all over the world. For the past 76 years there have been multiple attempts for a two state solution, all rejected by the Palestinian Authority. Remember, there are 22 Arab/ Muslim countries in the world, and only one Jewish country/state. World Jewry is only .2% of the population. In the United States, only 2.4% of the population is Jewish. The theme of “Combating Antisemitism” was decided upon in the summer of 2023. I felt that there were too many acts of antisemitism to ignore. However, after the October massacre, the antisemitism seen and heard soared over 400% than previously. Why is there so much hatred of the Jews? We know it has existed for centuries, exacerbated by the Soviets at the turn of the 20th century through the publication of “Protocols of the Elders of Zion.” In 1903 this story was fabricated detailing a Jewish plot for global domination. It continues to be published and apparently believed by many. Conspiracy theories have always swirled around the purported activities of the Jews: blood libels,

banking practices, world control, and even the Covid virus.

The 2024 Holocaust Remembered is the 11th edition published. It has been the most difficult for me to clearly define. I had naively felt that by teaching the Lessons of the Holocaust such as prevention of bigotry, hatred, racism, etc and educating our middle and high school students that evil can exist if we are not mindful, empathetic or open to differences. I felt we that we could educate one by one, family by family, and community by community. I am still reeling from the events of the fall and the continued antisemitic rhetoric and attacks. This edition will discuss recognizing and combating antisemitism. I am not ready to abandon the need for further education. I am steadfast in my desire to continue to teach our students, teachers, and community about the Holocaust. Every Survivor and Liberator has a story to tell. Novelist, Richard Powers, once stated: “The best arguments in the world won’t change a person’s mind. The only thing that can do that is a good story.” Our Survivors and Liberators and their families can certainly tell their factual and compelling good stories. n

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Statement on the Attack on Israel, October 8, 2023:

The USHMM is outraged by Hamas’s unconscionable attach on Israel, killing hundreds and targeting Israeli citizens for kidnapping, including a Holocaust survivor, according to the US Department of State.

Museum Chair Stuart E. Eizenstadt said, “These vile acts by this terrorist organization must be universally condemned and all hostages immediately released. Our prayers are with all Israelis, including the many Holocaust survivors who helped build the State of Israel, where they could finally live in the freedom and security they deserved after centuries of persecution, and ultimately genocide.”

A nonpartisan federal educational institution, the USHMM is America’s national memorial to the victims of the Holocaust, dedicated to ensuring the permanence of the Holocaust memory, understanding the relevance. Through the power of Holocaust history, the Museum challenges leaders and individuals worldwide to think critically about their role in society and to confront antisemitism and other forms of hate, prevent genocide, and promote human dignity.

IHRA Definition of Antisemitism accepted by 43 countries adopted on May 26, 2016 in Bucharest:

“Antisemitism is a certain perception of Jews, which may be expressed as hatred toward Jews. Rhetorical and physical manifestations of antisemitism are directed toward Jewish or nonJewish individuals and/or their property, toward Jewish community institutions and religious facilities.”

What is the Holocaust?

As defined in 1979 by President Jimmy Carter’s Commission on the Holocaust:

“The Holocaust was the systematic bureaucratic annihilation of 6 million Jews by the Nazis and their collaborators as a central act of state during the Second World War. It was a crime unique in the annals of human history, different not only in the quantity of violence—the sheer numbers killed—but in its manner and purpose as a mass criminal enterprise organized by the state against defenseless civilian populations. The decision to kill every Jew everywhere in Europe: the definition of Jew as target for death transcended all boundaries …

The concept of annihilation of an entire people, as distinguished from their subjugation, was unprecedented; never before in human history had genocide been an all-pervasive government

policy unaffected by territorial or economic advantage and unchecked by moral or religious constraints …

The Holocaust was not simply a throwback to medieval torture or archaic barbarism, but a thoroughly modern expression of bureaucratic organization, industrial management, scientific achievement, and technological sophistication. The entire apparatus of the German bureaucracy was marshalled in the service of the extermination process …

The Holocaust stands as a tragedy for Europe, for Western Civilization, and for all the world. We must remember the facts of the Holocaust, and work to understand these facts.”

2 HOLOCAUST REMEMBERED 2024 | Supplement created and paid for by the SOUTH CAROLINA COUNCIL ON THE HOLOCAUST | scholocaustcouncil.org

Lilly S. Filler, MD, Chair of the South Council on the Holocaust, Editor of Holocaust Remembered, daughter of Holocaust survivors

Photos of Israeli hostages held in Gaza.

Stand Together Stronger

Almost 80 years ago the world promised, “never again.” Never again would Jewish families need to hide in the face of evil attempting to eradicate them. Never again would the world stay silent at the rise of Jewish hate, and all hate. Never again would the world allow history to repeat itself.

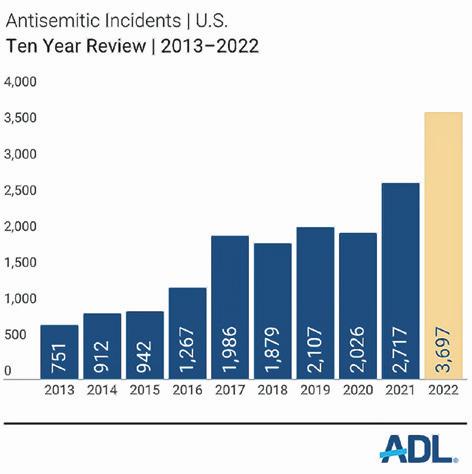

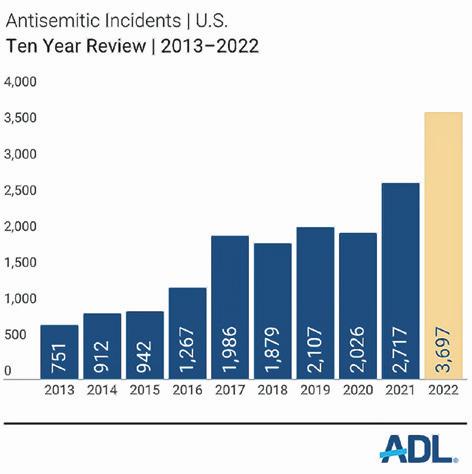

But today, Jewish hate is rising to unprecedented levels. We have watched in horror at the rise around the world and within the United States — with data from the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) showing a 388% increase in antisemitic incidents in America in the fall of 2023 compared to the fall of 2022.

With hate, comes violence and we have seen it manifest itself in more ways than one — in ways that have brought divisiveness and ugliness to communities across our nation. I have been laser focused on fighting that exact hate — which is like nothing I have ever seen before. That’s why I originally started the Foundation to Combat Antisemitism (FCAS) in 2019. I looked around at the fracture and divide and I felt like this country, which I still believe is the greatest country in the world, was beginning to look a lot like Germany in the late 1930s. We need to ensure it does not look like the 1940s.

Robert Kraft, Chairman and CEO of the Kraft Group and Founder of the Foundation to Combat Antisemitism.

Robert Kraft, Chairman and CEO of the Kraft Group and Founder of the Foundation to Combat Antisemitism.

To do so, our work at FCAS is focused on humanity. There are a lot of entities focused on fighting Jewish hate, but so many of them are either too academic or too adversarial. We create content that highlights the human pain associated with Jewish hate and hate of all forms. We build empathy. These insights powered our multimedia campaign running this year to move people who do not know or do not care towards action, generating over 5.6 billion impressions, and

establishing the Blue Square as a symbol that individuals can wear and share to show support. Our mission is to fight the hate that feeds senseless violence and discrimination against the Jewish people by changing hearts and minds through powerful messaging and partnerships.

We rely on extensive data to drive our mission. Through our Command Center we monitor conversations about antisemitism across 300 million online data sources including public social media, traditional media, websites, blogs, forums, and more. The information is then used to monitor trends in conversations and to develop actionable insights that impact our work. Through our social media channels,

newsletter, and partner organization we unpack online conversations happening in real time and act as a thought leader to drive conversations on important issues.

The Stand Up to Jewish Hate campaign has been among the largest US campaigns to combat Jewish hate utilizing television, social media, billboards, and partner organizations. In just nine weeks, the campaign delivered dramatic increases in awareness, empathy, and behavioral changes, especially among people who indicated previous apathy to the issue as part of a selected cohort to test and survey.

And it is clear that now more than ever, there is so much more work to do.

The Blue Square serves as a symbol of unity and solidarity — an easy way for all Americans to show their commitment to standing with the Jewish community and standing up to all hate.

And since the campaign has rolled out, it has appealed to the goodness and decency of countless people who want to fight hate, regardless of if they are Jewish or not.

People want to stand with us to fight hate against Jews; against people of color; against Asian Americans; against anyone who is different.

Hate is infectious. We need to stand with our brothers and sisters, arm in arm, to stop its spread.

Incorporating the Blue Square, posting and sharing it, and working together to spread the message will turn this effort into a far-reaching movement. Visit FCAS.ORG to learn more about how you can help and to support our cause.

Let’s fight this hate and stand together stronger — so we can ensure that the world keeps its promise of “never again.” n

3 HOLOCAUST REMEMBERED 2024 | Supplement created and paid for by the SOUTH CAROLINA COUNCIL ON THE HOLOCAUST | scholocaustcouncil.org

Robert Kraft and Meek Mill during the 2023 March of the Living through Auschwitz-Birkenau.

The First Documented Account of Antisemitism

The Alexandrian Pogrom 38 CE is the first account of antisemitism by a historian that is both horrifying and revealing of what was to come. It is horrifying because of the graphic depiction of the atrocities that Jews had to endure during the pogrom. It is instructive because it already lays out all elements of antisemitism that history has witnessed ever since.

What happened in Alexandria some two thousand years ago has all the markings of modern discrimination against, prejudice and hostility toward Jews. The Alexandrian Pogrom was not the first manifestation of Anti-Judaism. Hatred, enmity, or violence against the people of Israel are on full display already in the Hebrew Bible as well as in the New Testament to a lesser degree.

Philo of Alexandria (around 20 BCE to 50 CE) was a Hellenistic Jewish writer, historian, and philosopher who lived in Egypt during the time of Roman occupation. His account of the Alexandrian Pogrom is not only supported by other sources but also includes important philosophical and political reflections about violence against Jews during times of peace. First, Philo provides an impartial account of what led to the violence against the Alexandrian Jewish community. But then he turns more compassionate describing in detail what happened during and after the days of violence. He clearly identifies himself as a surviving member of the Jewish community in Alexandria. His essay is so important because it is an eyewitness account by a member of the Jewish community. Other writers would refer to the pogrom as riots or suggesting that the violence was incited by Jewish radicals.

Not so Philo: he unmistakably identifies an unsubstantiated aversion against Jews that already existed and was increasing within the Hellenistic (Greek) population of

Alexandria. He also calls out Aegypti Aulus Avilius Flaccus, governor of Alexandria and Egypt, as a reckless and appalling opportunist. Flaccus allowed frequent and growing assaults against the Jewish population. He had hoped to gain political influence for letting antisemitic behavior go rampant in the city. He sided with an unhappy mob and allowed the Greeks in the city to blame Jews for any type of misfortune.

What is more, Philo’s description reminds today’s readers how lingering antisemitism will eventually burst into the open: Flaccus began by curtailing equal treatment of Jews in front of the courts; then he restricted freedom of speech and revoked their citizenship. What came next is all too familiar to the modern reader of “Flaccus,” the title of Philo’s essay. Vandalism of synagogues followed, images of Hellenistic deities were displayed

in Jewish temples, houses of worship, and Jewish institutions were damaged or destroyed, the hostility toward Jewish customs and rituals became unbearable so much so that it deterred Jews to display their faith and identity publicly. Jewish homes were searched, weapons confiscated, and finally open violence and bodily harm against Jews ensued. The perpetrators indiscriminately began to kill those who dared to show themselves in the streets: young children, women, elders, religious or cultural leaders alike.

Philo also describes how the entire Jewish population was crammed into the smallest quarter of the city, effectively creating a ghetto. Private houses and shops were plundered and thus the livelihood of many was destroyed. Being Jewish himself, Philo was especially horrified that the bodies of those murdered were desecrated and burnt, denying the victims’ families to perform proper rites and burials. It left him speechless that even the living were burnt alive in the streets: “But so excessive were the sufferings of our people that anyone who spoke of it would be at a loss for adequate terms to express the magnitude of cruelty, so unprecedented that the actions of conquerors in war would seem kind in comparison.” The following weeks and months after the pogrom gave no reprieve to the Jewish population in Alexandria. The violence continued, but now the mob rule shifted to prosecution by the government of Flaccus. Jewish leaders and representatives of the senate became part of a gruesome show in the theater that included humiliation and torture. Eventually, the emperor in Rome became aware of the rampant mistreatment and massacre of Jews. Because of his disregard for their lives and rights that he should have guaranteed to protect as Rome’s prime representative, Flaccus was eventually recalled, and justice prevailed, as Philo pronounced.

But Philo was seriously concerned about the more long-term, more dire consequences of the pogrom. He prompts his readers to think about Jewish residents elsewhere in Egypt and beyond: “This was an attack against them all.” Philo recognized that violence against innocent inhabitants of Alexandria was a serious violation of peace, and even though Flaccus had to pay for his crimes, the antisemitism in Alexandria set a precedent for the future. Philo proved to be right. Only a decade after his death, the survivors of the Jewish community decided to leave for good after yet another pogrom in 66 CE. The last ancient synagogue in Alexandria was destroyed in 117. The Jewish population recovered only in the 6th century.

The first Alexandrian Pogrom is a harrowing lesson in antisemitism. Allowing prejudice against Jews, in fact against anyone considered to be the other, must be met with education and justice. Philo understood that bad behavior by a few cannot be ignored by officials: “Why did Flaccus show no indignation? Why did he not arrest them? Why did he not chastise them for their presumptuous evils-peaking? No, these are clear proofs that Flaccus was a party to the defamation.” n

4 HOLOCAUST REMEMBERED 2024 | Supplement created and paid for by the SOUTH CAROLINA COUNCIL ON THE HOLOCAUST | scholocaustcouncil.org

Philo of Alexandria. André Thevet (1502-1509): Les vrais pourtraits et vies des hommes illustres grecz, latins et payens (1584) / Wikipedia

Johannes Schmidt, PhD, Professor of German at Clemson University, member of SCCH

The Great Synagogue of Alexandria existed from 250 BCE to 38 CE. The medieval synagogue EliyahuHanavi Synagogue was replaced in 1850 by a synagogue that to this day one of the largest in the Middle East. / Wikipedia

The Pittsburgh Synagogue Shooting, Five Years Later

On October 27, 2018, a lone gunman opened fire on three congregations that met at the Tree of Life building in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The building sits in the heart of Squirrel Hill, one of the last remaining urban Jewish neighborhoods in the United States.

On that Fall day, surrounded by the splendor of autumn leaves, Robert Bowers killed eleven beloved community members as they met for Saturday morning Shabbat services.

The Tree of Life is a sprawling structure, composed of three buildings, constructed in different eras. The interior is maze-like, with half-flights of stairs, mezzanines, two sanctuaries, including the Pervin chappel, where Tree of Life congregants met that morning, and two additional spaces, where Dor Hadash and New Light congregations met.

Bowers made his way from room to room, up and down staircases and hallways, murdering members of all three congregations. In the end, he was cornered by law enforcement in a small classroom that had the Hebrew alphabet and elementary language lessons taped to the wall along with children’s versions of the 10 commandments.

Dr. Lauren Bairnsfather, CEO of Anne Frank Center USA, formerly Executive Director of the Holocaust Center of Pittsburgh, early leader in the effort to rebuild Tree of Life

Thou Shalt Not Kill.

In the days and weeks that followed the shooting, the Pittsburgh Jewish community witnessed something that is particularly rare — an outpouring of support came forth from every neighborhood in the city, and from surrounding communities. Inside Pittsburgh, Wasi Mohammad, then leader of the Islamic Center of Pittsburgh, raised funds to pay for the victims’ funerals. Zach Banner, formerly of the Pittsburgh Steelers, has described the way that day changed his life, and he continues to speak out against antisemitism and the importance of unity. The Jewish

Federation of Greater Pittsburgh organized a vigil to take place October 28 with leaders from across faiths and denominations. The slogan “Stronger than Hate” appeared on lawn signs, in doorways, on t-shirts, and on yarmulkes.

At the Holocaust Center of Pittsburgh, where I was serving as Executive Director, we had other plans on October 27 and 28, 2018. We had been working since January with the Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center on a plan to bring a Holocaust survivor along with a new technology — New Dimensions in Testimony — to Pittsburgh for a public event and for several field trips. On the morning of October 27, Magda Brown, of blessed memory, and her daughter Rochelle Brown Rainey were sitting at O’Hare Airport in Chicago waiting to board their flight to Pittsburgh.

That morning, I was at home, preparing to host friends for brunch. I received a message from a friend in Atlanta: “active shooter at Tree of Life.” “Tree of Life in Pittsburgh?!” I responded. My phone rang — as it would for days on end. The first call came from my younger sister — “WHERE ARE YOU?!” She asked with great urgency. “I am home,” I said. “I am at home.” It was reasonable to imagine that I would have been at Tree of Life. Holocaust survivors invited me to come to services on Saturday mornings, and I often accepted.

At 11:00 or so, I received a call from Rochelle. “I see what’s happening in Pittsburgh. Is that where mom is speaking tomorrow?” I confirmed that it was. “Mom doesn’t know what’s happening,” Rochelle said, “but I have to tell her before we get on the plane.” I replied “I don’t know what is going to happen here, and I will understand if you don’t come. But I hope you will.” Several moments later Rochelle called back, “Mom said now it’s more important than ever, Let’s go!”

The afternoon of October 27 saw me at the Pittsburgh airport, picking up Magda and Rochelle, not knowing that they would be exactly what we needed to get through the weekend and to face our lives after the shooting. Magda spoke to a packed house

at Chatham University on October 28. On October 29, she spoke to two school groups. We debuted the New Dimensions experience — where the audience can ask questions of a “hologram” of a Holocaust survivor. Every question was about the shooting, so Magda quickly took the microphone to answer questions in real life.

Since October 27, 2018, and especially since her passing in July of 2020, I can always hear Magda whispering in my ear, “Let’s go!” It is a reminder to be brave and that love is stronger than hate.

In November of 2018, Rabbi Jeffrey Myers of Tree of Life approached me and asked if we would consider moving the Holocaust Center of Pittsburgh into the Tree of Life building. So began a friendship that has only grown stronger as the hate that we saw that morning five years ago metastasizes. Six months after the Pittsburgh synagogue shooting, a member of Chabad of Poway, California, was killed during services. At a Walmart in El Paso,Texas, and at Tops Supermarket in Buffalo, minority communities across the United States were attacked because of a common ideology among White Nationalists that sprouts from antisemitic roots.

In August 2023, nearly five years after the Pittsburgh synagogue shooting, Robert Bowers was convicted of the 63 counts against him, including hate crime charges, and sentenced to death.

On October 7, 2023, Hamas entered Southern Israel, killed 1400 civilians and kidnapped

an unknown number, thought to be around 220 individuals. Hostages include babies, young people who had been celebrating at a music festival, and several Holocaust survivors, among others. At the time of writing four hostages have been released. As the news broke about the attack, around the world many people questioned the numbers, blamed Israel for the attack, and publicly supported Hamas. Public support for Hamas quickly morphed into attacks on Jews around the world and protests on college campuses across the United States. A pattern we have known throughout history repeats itself — one manifestation of antisemitism is blaming Jews for our own misfortunes, including the Nazi-perpetrated genocide of the Jews known as the Holocaust.

The Holocaust Center of Pittsburgh and the Tree of Life congregation worked through the first year of the pandemic to begin the process of rebuilding. Our work led to the founding of Tree of Life Incorporated, an organization that will bring about the transformation of the site into a “national center for change,” featuring a museum, memorial, and synagogue, along with national education programs and events.

This is but one contribution to the struggle to end antisemitism around the world. This endeavor takes all of us coming together as the Pittsburgh region did in the days and weeks after our greatest tragedy. I invite you to join the effort. n

5 HOLOCAUST REMEMBERED 2024 | Supplement created and paid for by the SOUTH CAROLINA COUNCIL ON THE HOLOCAUST | scholocaustcouncil.org

President Donald J. Trump and First Lady Melania Trump Travel to Pittsburgh to the Tree of Life memorial. Official White House Photo by Andrea Hanks

Teaching Against Antisemitism

Antisemitism is resurgent. Its presence reaches widely and the anxieties and worries it causes are everywhere. Recent statistics on antisemitic incidents, property damage, and violent attacks are all up. Reports from the Anti-Defamation League paint a particularly sad picture — especially if we focus on the world of social media.

A rise in antisemitic statements, outbursts, and even violence should not come as a shock to anyone aware of current events or following the political climate we all live in today. We know antisemitism rises with the tides of division as sure as the sun in the east. That connection between wider social issues and hatred of Jews is important to drive home in college classes focused on teaching about these issues. So too, however is the influence of current events around the world.

After the murderous Hamas attacks of October 7, this only grew more critical as individuals and groups in American society reacted to renewed war in Gaza with criticism of Israel and, sometimes, of Jews generally. This has been particularly visible on the campuses of many American universities and in the streets of some cities at home and abroad.

Chad S.A. Gibbs, Assistant Professor and Director of the Zucker/ Goldberg Center for Holocaust Studies at the College of Charleston, teaching courses on the Holocaust, antisemitism

Chad S.A. Gibbs, Assistant Professor and Director of the Zucker/ Goldberg Center for Holocaust Studies at the College of Charleston, teaching courses on the Holocaust, antisemitism

A collision of superheated condemnation of Israel’s military response and America’s own political environment makes for a particularly dangerous perfect storm. The relevance of courses on antisemitism is all around us.

In my role at the College of Charleston, I have never been asked whether we should teach about this problem, the question is instead how should we teach about antisemitism at the college level? How do we shape this teaching to the present?

How do we help students understand how to discuss and critique Israel without straying

into antisemitism? And, in thinking about our present environment, how can we effectively teach about the dangers of antisemitic thought in an era of conspiracy theories and arguments over basic fact?

I believe the answers to these questions are rooted in a direct confrontation with the connections between antisemitic lies and conspiracy beliefs. The troubles of the present political and social debates make it an absolute necessity to take on both at once.

I approach these issues in a class called “A History of Lies: Anti-Jewish and Antisemitic Tropes.” Instead of a 2,000-year-long (or more) straight line history, “A History of Lies” focuses on one trope, or lie, about Jews per week. A trope is a common phrase, metaphor, or belief. In the context of antisemitism, these are normally age-old lies about some supposedly universal Jewish trait. A trait that is almost always bad, though it can still be dangerous when it is positive, but essentializing.

The topics of weeks in this course include the blood libel, so-called Judeo-Bolshevism, the Protocols, allegations of divided loyalties, neo-Nazism and the far right, leftwing antisemitism, and Holocaust denial. In each, we take on the content of the lie and the context in which it emerges and reemerges. Reemergence as a factor in antisemitic belief cannot be overstated. Antisemites are not original people. The lie that worked 200 years ago will do just fine again tomorrow. Antisemitic beliefs, in this way, fit on a bookshelf of bad ideas — always sitting there and ready for return, revival, and reuse. These days, we can see that even in ideas that seem too medieval for recurrence in a modern context. Take for, example, QAnon conspiracy theories that include child murder and the use of blood taken from the innocent young by hidden powerful elites. What is this if not a rehashing and recasting of the ancient blood libel?

Phyllis Goldstein’s book A Convenient Hatred explains so much about the process and motivations of antisemitic thought in its

title alone. By taking apart each lie and the moments of its occurrence and recurrence, this class also underscores the importance of context and the uses of antisemitic ideas for their holders. The convenience of anti-Jewish hatred is often the whole point.

Moment of economic downturn? Blame Jews in business. Fears of foreign powers and others at home? Blame the supposedly divided loyalties of Jews as a people present in more than one place. In a time like the present — with Israel at war and the subject of criticism — Jews here and abroad are frequently accused of this sort of divided loyalty or of unblinking support for the Israeli state. The cycle goes on and on as much as each hatred remains on the bookshelf of antisemitic ideas ready as ever for its next use in its next opportune moment.

Education, awareness, and vigilance are the only things shown to counter

such trends in antisemitism. Time and time again, studies reveal our best path to a less hateful world leads through classes and other learning opportunities that teach who Jews really are and reveal the corrupt and hateful foundations of anti-Jewish hate. As always, I hope my class contributes to this knowledge and education for non-Jews while it simultaneously reassures and prepares my Jewish students. n

6 HOLOCAUST REMEMBERED 2024 | Supplement created and paid for by the SOUTH CAROLINA COUNCIL ON THE HOLOCAUST | scholocaustcouncil.org

Re-examining Holocaust Education After the Hamas Massacre

Now, Holocaust education must return to what it should have always included — a call to safeguard the lives, well-being, and future of Jews in the world and, first and foremost, in their ancestral homeland.

The murderous attack by thousands of Hamas terrorists on the Israeli border that triggered the Gaza War has leveled the thin fence between civilization and barbarism, and with it many conceptions and misconceptions, military doctrines, and national security policies. It did not take long for Israelis and, instantaneously, for Jews around the world, to place what we were witnessing in context — not that of the most recent Israeli-Palestinian conflicts, but rather, Nazi Germany’s war against European Jewry.

While placing the Hamas assault in the context of the Holocaust might seem detached and anachronistic, a deeper dive into its nature clearly illustrates why the traditional framework of Middle East carnage lacks viability. The unprecedented nature of the violence on civilian men, women, and children, the brutality of the killers, the sense of helplessness experienced by Israelis, the targeting of innocent human beings for the sole crime of being Jewish — these are more aligned with a part of Hitler’s Final Solution than they are as another episode in Israel’s endless war with Hamas.

Dr. Shay Pilnik, Director of the Emil and Jenny Fish Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Yeshiva University in NY.

Dr. Shay Pilnik, Director of the Emil and Jenny Fish Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Yeshiva University in NY.

In ordinary times, linking current events with the chronology and events of the Holocaust is what good educators do not do. In Holocaust education, we insist on the imperative to teach about it as a singular event, to explain, using photographs, history, literature, diaries, and testimonies, that Auschwitz was another planet, that the destruction of European Jewry was sui

generis — not compared or equated with what came before or after.

But these are not ordinary times. Now, we find ourselves confronted by scenes of graphic carnage — sickeningly familiar and now visible instantly — as they happen. Now savagery is projected before our wide-open eyes on Telegram, Instagram, X, and Tik-Tok. These murderous scenes make many of those captured in old black-and-white Holocaust photographs pale in comparison. They break the veneer of civilization that has for decades led us to believe that we would never again confront such unbridled sadism. When the question is not “how many” but “how” and “what have they done,” we realize that we are witnessing attacks and rampages that meet and far exceed the Nazis and their collaborators in cruelty.

Yoav Galant, Israel’s Minister of Defense, promised that the IDF response will reverberate in the minds of our enemies for generations to come. The Israeli government’s massive and strong reaction is where, fortunately, comparisons with the Holocaust end. We have a national homeland, and our enemies know that a high price will be paid by those whose life mission is to shed innocent Jewish blood. Yet the Hamas attack, and not only Israel’s response to it, will affect the way Jews read their own history and understand their place in the world. Holocaust education can no longer be what it has evolved into.

For some time now, general education about the Holocaust has moved from the story of the Jews and the scourge of antisemitism to a general concern for human

rights, a vehicle for teaching about the necessity to treat all humans with respect and dignity, and the noble call to stand up to racism, violence, and genocide wherever they occur. Holocaust education has often become, for a variety of reasons, a universal touchstone for peace and justice. Today, though, the utility of this grand civil, lofty, and quasi-pacifist lesson must be called into question. As Jews today find themselves confronting the reality that a pogrom on a scale hitherto reserved for Hitler’s followers can happen here and now, education on the Holocaust must undergo a transformation if it is to remain viable.

The stance of relative tranquility from which we have viewed the Holocaust has shifted. It can no longer be divorced from its original and crucial Jewish context. It can no longer be merely a historical overview of facts and statistics, assessed by the requirement to name and spell correctly the death camps. It can no longer be merely a sequence of gray images from the past that become a universal gold standard of evil, of man’s inhumanity to man, of victims and perpetrators, with no mention of Jews or the racial antisemitism that helped to make the Holocaust possible. Today, such universalist packaging has become impossible to defend.

Now, Holocaust education — in museum tours, in classroom instruction, in state mandates, in survivor and secondgeneration testimonies, in films–must return to what it should have always included — a call to safeguard the lives, well-being, and future of Jews in the world and, first and foremost, in their ancestral homeland. Holocaust education that deviates from this call, morally questionable yesterday, must today be declared dead. Holocaust education must be life-affirming for world Jewry, for the Jews and for all peace-loving citizens of Israel, and, of course, for all those still wishing to embrace humanity and condemn and reject antisemitism in this terrifying new world. n

Originally published in Jewish Journal, Nov. 1, 2023. Reprinted with permission.

7 HOLOCAUST REMEMBERED 2024 | Supplement created and paid for by the SOUTH CAROLINA COUNCIL ON THE HOLOCAUST | scholocaustcouncil.org

Alexander Vorontsov/Keystone/Hulton/Archive/Getty Images

Antisemitism on Both Sides of the Atlantic: Differences of Degree

In December 2021, Dutch politician Thierry Baudet, founder and leader of the far-right Forum for Democracy party, faced criminal charges for “having created a breeding ground for antisemitism.” The court found him guilty of inciting hatred and ordered him to delete several social media posts within 24 hours or be fined 25,000 euros for every day that they remained online. In a series of Twitter posts the month before, Baudet had linked the Dutch government’s strict Covid-19 restrictions to the Holocaust, comparing those who were unvaccinated to innocent victims of Nazi genocidal violence.

In the wake of the pandemic, government regulations restricted access to certain public places to prevent contagion, a measure that disproportionally affected unvaccinated citizens like Baudet. It was, he fumed, an infringement of their civil rights. The unvaccinated were like European Jews, targeted and victimized by a dictatorial regime.

The court disagreed. “The comparison is flawed and you have spoken unnecessarily offensively and unlawfully of survivors of the Holocaust.”

While Baudet enjoyed freedom of expression, the judge decreed that these liberties were not limitless and still contained responsibility toward his fellow man. By making false comparisons, he had “contributed to a climate that fueled the fire of antisemitism,” an offense that demanded intervention. He was to remove the venomous social media posts and banned from reposting any images that linked the coronavirus to the Holocaust.

Baudet’s offense was egregious for a number of reasons. First, he tapped into old, persistent antisemitic tropes that are

gaining new popularity on modern media platforms. He coupled Jews to disease, a falsehood with roots in the Middle Ages, when Christians blamed Jews for causing the bubonic plague and other misunderstood illnesses. Lacking scientific knowledge and filled with distrust toward the Jewish Other, locals habitually accused Jews of poisoning water wells or using “demonic” power to undermine the Christian majority. A global coronavirus pandemic — lethal, destabilizing, invisible and initially perplexing — produced swift finger-pointing to a minority already associated historically with disease.

Second, Baudet had the audacity to equate Dutch government measures implemented to protect citizens with the Nazi state’s intent to annihilate. Temporary limits to public spaces for the unvaccinated — i.e., for people who deliberately chose to say no to a vaccine — somehow equaled the relentless violence inflicted on Europe’s Jews, whose lives were permanently lost and who had had no choice at all. Being barred from a local pub, the court reminded Baudet, was not quite the same thing as being systematically persecuted by a genocidal regime that aimed to erase your existence, history, and culture. To those already predisposed to crying foul the distinction didn’t matter. The ruling only strengthened convictions among Baudet’s supporters that their spokesperson was a victim.

Lastly, the politician’s insinuations were alarming because they so clearly revealed the power and influence of social media, where antisemitism spreads like wildfire

Only weeks after Baudet received his ruling in court, in January 2022, hundreds of residents in Florida woke up to find flyers on their lawns, carefully folded into ziplock bags, falsely claiming that the public health response to Covid-19 was orchestrated by Jews.

and is rarely countered or proven false. Combine the possibility of anonymity and the lightning speed in which information is (re)posted with already existing prejudice and falsehoods, and you have a platform that is nearly impossible to monitor or contain, especially in times of crisis. Baudet was a public figure with no shame, but he’s the mouthpiece for countless others who spew hatred in online forums that receive no court ruling. During Baudet’s hearing, one of his Twitter followers posted a photo of the gates of Auschwitz captioned “QRcode macht frei.” The damage had already been done. The real epidemic is antisemitism, mutating, thriving, and adapting to new circumstances. We have yet to find a vaccine that lasts.

Holland is not an exception, of course, but the Baudet case is perhaps surprising to American readers because of the country’s often hailed reputation for tolerance. The Dutch have long prided themselves on this virtue, yet these days they cannot deny that the rise in anti-Jewish sentiments and spikes in antisemitic incidents are as much palpable in “hospitable little Holland” (as one nineteenth-century observer labeled the place) as elsewhere.

Only weeks after Baudet received his ruling in court, in January 2022, hundreds of residents in Florida woke up to find flyers on their lawns, carefully folded into ziplock bags, falsely claiming that the public health response to Covid-19 was orchestrated by Jews. Portraying an image of the Star of David, the flyer listed top government health

8 HOLOCAUST REMEMBERED 2024 | Supplement created and paid for by the SOUTH CAROLINA COUNCIL ON THE HOLOCAUST | scholocaustcouncil.org

Saskia Coenen Snyder, Professor of Modern Jewish History at USC, Director, Jewish Studies Program

Dutch politician Thierry Baudet, founder and leader of the far-right Forum for Democracy party was found guilty of inciting hatred for comparing Dutch government Covid restrictions to the Holocaust.

officials, pharmaceutical company leaders, and heads of investment management firms, all of whom were allegedly Jewish, raking in profits from the global pandemic. Similar to the Dutch case, the message associated Jews with disease, but there were also blatant allegations of conspiracy theories, Jewish power and control. “We couldn’t believe it,” exclaimed a local resident, “here in 2022, here in Surfside. This is absolutely hideous.” People may have been “used to hearing these types of stories back 50 years ago, back 60 years ago,” he stated, but not these days. Equivalent antisemitic flyers appeared in driveways in Wisconsin, Colorado, Maryland, California, and Texas. They have reappeared, including in South Carolina, after the recent attacks by Hamas plunged Israel into war.

Whether in America or Europe, whether in a Twitter feed or a ziplock bag, the content of antisemitic propaganda is often the same, recycling age-old myths into contemporary manifestations, tailored to only the latest crisis. Despite different histories and legacies, both places have, in the past twenty years, seen hatred escalate into assault and shootings — Pittsburgh is an alarming example. Anti-Jewish prejudice is not limited to the extreme Right but exists in politically Leftist circles as well. The two continents also share similarities in responses. Antisemitic incidents are typically followed by widespread public outcries and condemnation, by Jews and non-Jews alike. Local law enforcement agencies initiate investigations, anti-defamation leagues take action, and courts rulings penalize the likes of Baudet. Newspapers publish stories and report the latest sobering data on hate crimes. Many organizations, governments, and universities in Europe and America are actively working to promote tolerance, education, and interfaith dialogue to counteract the spread of hatred and bigotry. Governments on both sides of the Atlantic have allocated resources and passed legislation to combat anti-Jewish prejudice and violence, from the American Antisemitism Awareness Act to the Dutch Werkplan Antisemitismebestrijding 2022-2025, a strategic plan to coordinate a multi-pronged approach to the persistent problem. These efforts are laudable and necessary. Yet it is sometimes discouraging to realize that while we’ve been able to send human beings to the moon, we remain unsuccessful in eradicating the false idea that Jews are dangerous people responsible for all the ills in this world. But we have to press on. I take some comfort in the fact that, together with my energetic university colleagues, I educate students so they

A

better understand the history of racism, the conditions in which bigotry thrives, and the lethal consequences if we don’t fight it. Our Jewish Studies Program invites speakers to campus. We support the ADL and other

organizations that take action. I teach my son to be kind and open-minded, and to speak up when he sees injustice. Perhaps all these small individual steps, combined with larger, institutional initiatives, will make

a difference. But given the recent surge in antisemitism due to a new and ongoing war in Israel and Gaza, it is clear that there’s a long and difficult road ahead. n

9 HOLOCAUST REMEMBERED 2024 | Supplement created and paid for by the SOUTH CAROLINA COUNCIL ON THE HOLOCAUST | scholocaustcouncil.org

flyer distributed to Florida residents in 2022. Similar flyers have been distributed across the country.

“One

of the worst things is hatred and prejudice...” Survivor Harry Schneider

Harry Schneider was just two years old when the Nazis invaded Poland in 1939 to begin World War II. His father, who was serving in the Polish army at the time, returned home to their small Jewish town (shtetl) of Lomzy. He had witnessed the atrocities committed by the Germans in other towns and told the family they had to flee. Their goal was to get to Russia where Harry’s mother’s brother lived, but since Russia was allied with Germany, they were not allowed to enter the country. So they escaped to the forests.

Harry, his parents, Gedalia and Gital, a cousin who lived with them, Baruch Feldman, and another aunt, uncle, Misha and Melvin, were among some 300,000 Jews who fled Poland between 1939 and 1941 to escape the German onslaught. Not all of Harry’s family fled. His grandmother, Tauba, was too old. Another uncle, Moshe, wanted to stay in Poland with his family.

For two years, the family was on the run in the forest, sleeping in makeshift huts, scrounging for food and struggling to survive. Often they met up with other Jews also on the run. The entire time, they were hunted by Germans. Harry’s aunt was killed in one of the German raids.

In 1941, the Germans broke the treaty and invaded Russia. The family was then able to go to Brest-Litovsk, where they lived with another aunt and uncle and their children for six to nine months. While there, Harry’s sister Henya, was born. As Germany continued to invade further east, their lives were uprooted again.

Harry’s father was drafted into the Russian army. The rest of the family was put on a train and deported to an area in the Ural Mountains near Siberia, where they were placed with a woman whose husband was fighting on the western front. Harry was able to go to kindergarten. His mother was able to get a job at the railroad station.

all the Jews in their hometown were taken to the forest and massacred. As Harry got older, he began to understand what happened and to think about what his family lost, although they didn’t talk about it. He realized he didn’t have grandparents, uncles, nieces, or nephews. He was very bitter for a long time.

Food was strictly rationed. Harry remembers standing in long lines in the freezing cold with a bucket to get milk for his little sister. Often he and his cousin, who was 10 years older, went to nearby farms and stole whatever food they could find, mostly digging up potatoes that had been buried deep in the snow. Despite the harsh conditions, they remained safe until the war ended in 1945.

After the war, they went back to Poland to try to find their family. They were placed in a Displaced Person’s (DP) camp, where Harry’s father eventually found them. Their family home was destroyed. Although the war was over, Poland was still dangerous for Jews. There were anti-Jewish riots. Jews were killed.

The Schneiders went to Austria, where they stayed in a DP camp for a few years before moving to Washington, PA, near Pittsburgh, in 1951. In the DP camp, Harry’s name was changed from his Polish name, Hersz Sznaijder. His parents became Gertrude and George.

The Jewish community in Washington, PA, assisted their resettlement. Harry was 13 and didn’t speak any English, although he spoke several other languages. He said it was pretty rough, but he studied many hours after school with the help of a dedicated teacher. Harry, his parents and sister, one uncle and a cousin are the only family members who survived the Holocaust. They later learned that in 1942,

Harry met and married his wife, Patti while in Wheeling, PA. Harry was in college and was a BBYO counselor. Harry and Patti have two children and four grandchildren. Harry had studied accounting and economics in college, and ultimately became involved with the Import/export business. He traveled extensively and then opened his own business, Galaxy International, with a partner. He retired, moved to Florida and then came to Charleston to be closer to one of their children.

Since moving to Charleston a few years ago, Harry has shared his experience in the Holocaust with thousands of students and groups in the community. In addition, Harry shared his experience on a video, produced by his grandson, Josh Rogers. “On the Run: One Man’s Struggle for Survival,” can be found on YouTube.

“I now tell young people there was a Holocaust and it can happen again. One of the worst things is hatred and prejudice. I impress upon them that each one of them can do a lot of good by being a good person.” n

10 HOLOCAUST REMEMBERED 2024 | Supplement created and paid for by the SOUTH CAROLINA COUNCIL ON THE HOLOCAUST | scholocaustcouncil.org

Harry Schneider

Eileen Chepenik, member of SCCH

Harry Schneider at left next to his mother Gertrude, center, with his father George and younger sister Henya at right, in Washington, PA.

Harry Schneider at around 10 years old, in a Displaced Persons (DP) camp in Austria.

“Once Upon a Time….” The Story of Survivor Lewis Laszlo Rosinger

Adistinguished silver-haired man in a light blue suit and tie sits in front of a camera. An unseen interviewer (judging by the voice, a young woman) is in the room with him. The camera starts rolling, the interviewer begins to ask her questions. These questions are deliberate and part of the plan to draw out of the interviewee everything he can recall about his past. A past that goes back a few decades, to when he was but a boy of 13, in 1941 Hungary. The man’s name is Laszlo Rosinger. He is a Holocaust survivor.

Imagine, for a moment, that you were asked to retell your life story: Would it be easy to pick just the right threads, which could better than others give a sense of the whole? Would you leave something out — perhaps to protect some people, or not to offend the memory of family members? Would you try to make yourself the hero of the story at all costs, or would you admit to having been, sometimes, a bit of a villain too? Retelling one’s own life story is never easy. Our memories are irrevocably flawed, our sense of the facts changes as time progresses, as we age, as our subconscious raises barriers between us and days long gone in order to shelter us from the pain of remembering. And all this is especially true when the memories in question are rooted in trauma, near-death experiences, fraught with horror and sorrow. It can’t have been easy for Laszlo Rosinger to have been interviewed that day. At times, he is visibly pained by what he is being asked to remember. Most of all, what one notices, is the difficulty he experiences in relating the whole story in chronological order, as a coherent narrative. This is because life is not a book: history rarely follows the sane logic of novels. What could a 13-year-old boy know and understand of the European disaster unfolding around him from 1939 to 1945?

F.K. Schoeman, Professor of English and Jewish Studies, University of South Carolina, member of SCCH

F.K. Schoeman, Professor of English and Jewish Studies, University of South Carolina, member of SCCH

This is how his story begins: Once upon a time, in Szakoly, a small village in eastern Hungary, there lived a tiny Jewish community. Laszlo was born there in 1928. His father, Miklos, a butcher by trade, was also a horse and stock breeder. His mother, Erzebet, was a fashion designer and a fantastically creative woman. Her love for life and beautiful things exuded from everything she did — including the way she ate (Laszlo tells us she was a tremendous gourmet) and the delicious pastries she baked, particularly her epic Dobos Torte (a traditional Hungarian layered sponge cake filled with chocolate buttercream).

There were healthy, fun, adorable siblings too: József, Éva, and Lili.

Then, guided by the interviewer, Laszlo Rosinger is forced to remember what happened once the war began. What happened, he tells us, is that everything he knew, his life, the people he loved and who loved him — whom he has just vividly described for us, the places he cherished, were all taken away from him, were all destroyed.

At first, the Jews in his little village suffered confiscations, persecutions, restrictions, assaults, thefts: slowly but surely, they were deprived of everything. Religious practice was impossible: the Hungarian police and the local bullies harassed Jews on their way to shul, interrupted the services, vandalized the synagogues — with or without Jews inside. There was no kosher food to be found: Laszlo Rosinger remembers how, in order to kosherize the meats, the rabbi and the shochet (ritual butcher) had to hide and work at night.

As the war was already raging in the rest of Europe, Laszlo (only 13 at the time, and newly bar mitzva’ed) took a train to the capital, Budapest. Maybe there was work and food there? Maybe he could be of help to those left behind?

No one could have guessed that while indeed the decision of leaving Szakoly would turn out to be salvific for Laszlo, it also meant that he’d never see his family again.

The Hungarian government was in the hands of the Fascists, and they opposed no resistance to the Gestapo’s plan to exterminate the entire Jewish population of Hungary, after Germany occupied the country in the spring of 1944.

The Jewish community of Szakoly was captured and deported. Among them, Laszlo Rosinger’s family as well: his father was murdered in Mauthausen, his mother and the two girls (Éva 10, Lili 4) were murdered upon arrival at Auschwitz; no one knows what happened to József, or where he was transported. He was never heard from again.

Laszlo was left all alone in the world: only the charity of people provided food from time to time; he had no change of clothes; he slept wherever he found a place to stay; occasionally he found an odd job here and there. He would have never made it without the solidarity of other human beings caught in the same infernal tragedy. For example, a friend of his dad, named Laszlo Kokràk, did all he could to feed, protect, and hide the child while in Budapest. He even stole money from his own boss’ cash register to give to young Laszlo. At some point, Kokràk put the kid up in the apartment of a woman who turned out to be an enthusiast Hitlerian, and as soon as he found out, he told Laszlo to run away from that place and the kid’s desperate wanderings began again.

No matter how careful he tried to be, one day Laszlo Rosinger was finally caught. The Hungarian police and the Gestapo arrested him and sent him to a camp. He took advantage of the general confusion at the train station and, driven by a mixture of utmost courage, despair and the recklessness of youth, he managed to escape.

Laszlo Rosinger’s brushes with death are too numerous to be recounted.

By the time the war ended, he was hungry, feeble, without a penny and no home to return to. He got in touch with the only relative he could think of: an uncle who had emigrated to the United Stated before the war and lived in Virginia. This uncle wrote back and convinced him to give up, at least for the moment, his dream of emigrating to Palestine and, instead, to join him in America. As it turns out, his new life here was off to a bitter start, as this uncle’s family wasn’t too happy to see Laszlo arrive: they made him feel unwelcome and treated him unkindly. He left them, worked his way through a college degree, and eventually became a successful man, with a prosperous family of his own. He married and moved to South Carolina. While his dream of emigrating to Israel didn’t materialize, one of his two sons, Michael, lives in the Jewish country and, at the time of the interview, was serving as a liaison officer for the United Nation in Israel.

Life gave Laszlo Rosinger a chance to repay in part his father’s friend, Laszlo Kokràk, for his good deeds towards him during the war. In 1956, when the Russian tanks moved into Hungary to suppress the nation’s rebellion against its Soviet puppet government, Kokràk had fled to Austria, but his sister was trapped back home: Laszlo Rosinger set the wheels in motion to get her the necessary papers to leave Hungary, he sponsored her and helped her find a job in North Carolina. At least one thread of this tragic story came full circle.

IIn the end, Laszlo Rosinger was able to rebuild a life after surviving the horrors of the Holocaust, and he prospered in South Carolina. But the scars never healed. He admits to having become a bitter man. He has never forgotten the past. He wants others to know it too. He fears a world where antisemitism is rampant: he calls this undying hate of Jews “a mental disease.”

We hear the voice of the off-camera interviewer thank him, sincerely moved by the story she has just heard and recorded for posterity. We do the same and pledge, also in Laszlo Rosinger’s honor, to help the memory of what happened live on. n

11 HOLOCAUST REMEMBERED 2024 | Supplement created and paid for by the SOUTH CAROLINA COUNCIL ON THE HOLOCAUST | scholocaustcouncil.org

Lewis Laszlo Rosinger in a 1991 interview.

Varieties of Antisemitism

Aterrible — and terribly prescient article appeared in the New York Times, presaging the ultimate number of Holocaust victims: it read, “127,000 Jews have been killed and 6,000,000 are in peril.” From what we know about the Holocaust, and how the mass killing of Jewish communities began upon Hitler’s betrayal of his alliance with Stalin and the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union (known as Operation Barbarossa) in June, 1942, we could expect such an article to have appeared in July or August 1942. But this article was published on September 8, 1919, before the Nazis even existed.

The numbers were not correct, but the violence against Jews in the form of pogroms in Central and Eastern Europe during this period certainly was, although those atrocities are generally eclipsed in our memory by the Holocaust. Nevertheless, this violence was typically an expression of centuries-old, religiously motivated antisemitism.

The lands of pogroms would prove fertile territory for the Holocaust, even if the particular variant of antisemitism motivating Nazi hate was of a new character. Nazi ideology was not religious, but was often quite hostile to religious institutions. What was new in the Nazi ideology? They had adopted a racial view of the world, but not one that used exactly the “Black and White” race categories familiar to Americans. The Nazis certainly regarded people of African descent as inferior, but also many groups who might be regarded as white in the U.S. today, including (European) Jews and anyone with Slavic heritage, whether Polish, Ukrainian, Russian, and so on. Racial mixing was banned between the imaginary category of Aryan with real Jews, Slavs, and people of African and Asian descent.

For the Nazis, racism was another weapon for their antisemitic arsenal. They wedded their racial thinking to a warped Social Darwinism, a kill or be killed mentality applied at the collective racial level. Logically, antisemitism would seem to be a form of religious prejudice because it targets Jews and Judaism is a religion. But such reasoning applies logic to what is a most illogical hatred. In the U.S. context where most Jews of European descent are perceived to be white, it is difficult to understand that antisemitism stems more today from racial thinking than religious intolerance. The fact that Anne Frank could be perceived as white in the US today and yet was targeted for elimination — and killed — for her supposed race in Europe shows how incoherent the whole concept of race is across cultures.

It is important to be clear here: race was the idea that some groups of people are inherently better than others, and scientific advancement has made clear there is no basis in reality for this idea. Race (in this sense) is a biological fiction. In fact, in Germany today, the word race is never used in mainstream society — only racism. There are no subspecies of human beings, and there is only one race, the human race. We continue to use the word “race” today in American English, but its meaning has changed, and most Americans — except for some extremists — reject its original hierarchical meaning.

In turn, “racial thinking” refers to judging people on the basis of physical characteristics (real or imagined!) beyond their control; in racial thinking, it doesn’t matter what we do or what we believe — others define us by categories they impose on us. That’s why even Jews who converted to Christianity were still murdered by the Nazis in death

One of the the Yellow Stars that Jews were forced to wear in the Netherlands during the Nazi occupation. “Jood” is the Dutch spelling of “Jew”. From the Anne Frank Center at the University of South Carolina.

camps: in their racial worldview, the Nazis felt that Jewish people’s (imaginary) racial identity remained unchanged even if they changed their beliefs or faiths. In Mein Kampf, Hitler asserted this view concisely: the big lie, he claimed, was that Jews are a religion, and not a race.

Whether motivated by religious intolerance, racial hatred, or other motivation, antisemitism is consistent only in its target, the Jewish people. Antisemitism is difficult to combat with facts, reasoning or logic precisely because it has many motivations and no requirement to be consistent or coherent. Indeed, Hitler maintained that both the capitalists and the communists were expressions of Jewish conspiracy, nevermind that these categories of people have scant common ground.

Jewish identity includes religion, of course, but not only religion. Jewish identity

is as diverse as the societies in which Jews live, and how they understand themselves may align only partially with how the rest of society sees them. Americans, in general, see Jewish identity primarily in terms of a religious category. The Nazis advanced a racial conception of Jewish identity. In Russian, whether in the Russian empire or Soviet Union, Jewish identity was understood as a national identity and appears in passports as such, in parallel with Lithuanian, Ukrainian, and other peoples under their dominion. In colloquial English, nation is a synonym for country, but for understanding European history, it is best to think of the nation as a group of people who identify with one another culturally and linguistically, i.e., the French, and nationalism as the movement for each group to have a country of its own.

12 HOLOCAUST REMEMBERED 2024 | Supplement created and paid for by the SOUTH CAROLINA COUNCIL ON THE HOLOCAUST | scholocaustcouncil.org

Doyle Stevick, PhD, Executive Director of the Anne Frank Center at USC, Associate Professor at USC, School of Education

As the First World War loomed, Europe remained a continent of empires, each of which spanned many peoples (and hence, languages and cultures). Within those empires over the preceding half century, many national movements blossomed among peoples wanting countries of their own.

For Jews in particular, facing pogroms and desiring security, there were a few leading possibilities, including emigration (especially to the United States), an independent state for Jews in Europe, or Zionism, the desire to establish a Jewish state in Palestine. After the war, the dissolution of empires — Russian, Ottoman, German and Austro-Hungarian — resulted in new states for the Finns, Estonians, Latvians, Lithuanians, Hungarians, Austrians, Poles, with the Czechs and Slovaks combined in one country. In other words, most groups with at least a million members got their own countries; the exceptions were the Jews or Roma/Sinti (pejoratively called Gypsies), and we know who was most vulnerable when they were trapped between Hitler and Stalin. As American immigration restrictions after WWI took emigration off the table, and the newly consolidated European borders made a European Jewish state increasingly unlikely, Zionism remained a plausible future.

The foundation in Israel in 1948, so often associated with the end of the Holocaust just three years earlier, has much longer and deeper roots. The antisemitism of Hamas, however, shares a vitriol and its target with other variants of antisemitism, and is fueled in part by the displacement of Palestinians that occurred with the founding of Israel, but also by a millenarian and apocalyptic character that must be reckoned with.

While issues such as the Hamas attacks, the war in Gaza, and the ongoing Israeli/ Palestinian conflict are beyond my expertise, the lens of the current crisis, however, has made some aspects of the Nazi era

particularly salient for me in the present. The particular motivations of a Hamas may differ from other historic expressions of antisemitism, but their eliminationist rhetoric echoes painfully in the present. Which aspects of Holocaust history are most salient to one trying to follow developments in the wake of the 10/7 attacks? Two points in particular stick with me personally. First, most Nazi perpetrators outside of the highest ranks hoped themselves to

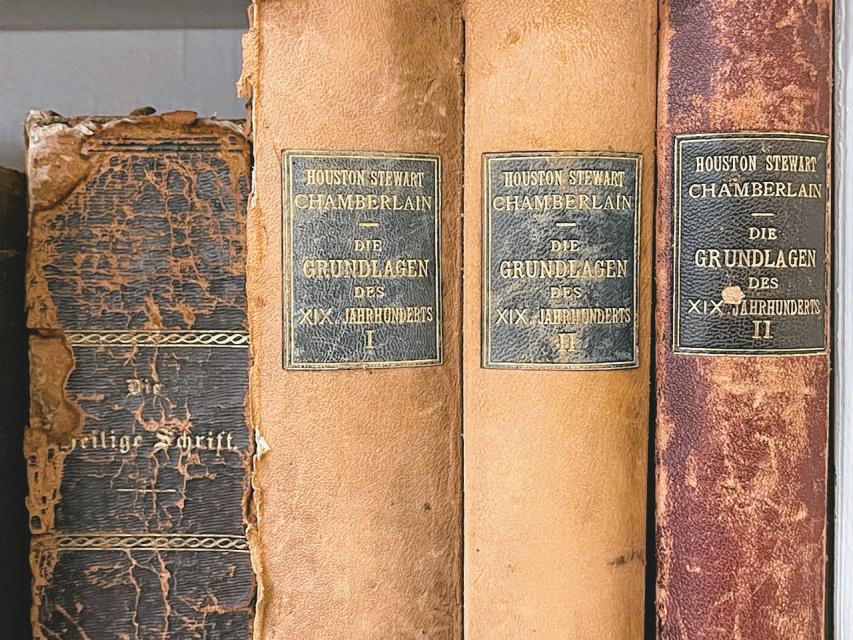

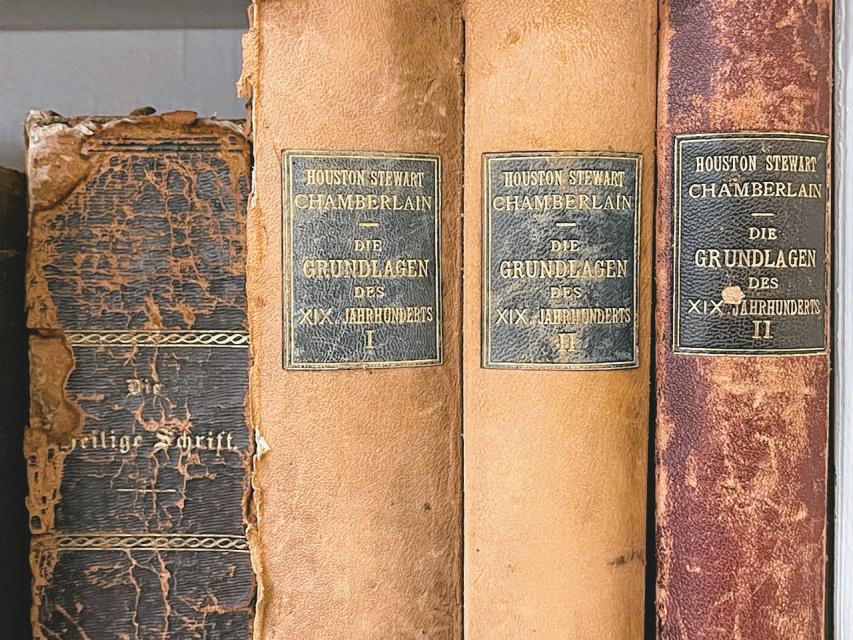

Houston Steward

Chamberlain’s 1899 work, the “Foundations of the 19th Century,” laid out a racial vision of history, imagining “Aryans” as the source of all progress and arrayed against Jews and people of African or Asian descent. His bizarre fantasies included the belief that Jews strove to create a Europe with “only a single people of pure race, the Jews, all the rest would be a herd of pseudo-Hebraic mestizos.”

live, and did what they could to conceal their crimes and their participation. Few were such committed ideologues that they welcomed the opportunity to die for the cause of killing as many Jews as possible. In the Hamas attacks, we saw thousands of terrorists who seemed happy to die and were motivated to kill as many Jewish people — and frankly, anyone in Israel at all — as they could. Further, they did not hope to hide their crimes, but wore GoPro

cameras and hoped to broadcast their crimes as extensively as possible, even livestreaming on victims’ accounts. This particular expression of antisemitism, where thousands seem happy to die in order to kill as many Jews as possible — is simply terrifying, and should, in my view, be confronted explicitly by anyone proposing plans for the short-term and long-term for the peoples of Israel, Gaza and the West Bank. n

Thomas Dixon Jr. celebrated the Confederacy and the rise of the KKK in his 1904 book, The Clansman, which was adapted by D.W. Griffith into the film “Birth of a Nation.” The film was screened at the White House by Dixon’s close friend, Woodrow Wilson. A striking feature of this book is that it already in 1904 frames its topic as a glorious chapter ‘in the history of the Aryan Race.’ In the early years of the 20th Century, the Aryan racial ideal had not yet fully fused with the antisemitism later adopted by the Nazis. In fact, despite his profound racism, Dixon seemed to have at least a grudging admiration for the Jewish people, writing "The Jewish race Is the most persistent, powerful, commercially successful race that the world has ever produced.” Still, his apparent admiration features a racial conception of Jewish identity and stereotypical and even conspiratorial views of Jewish wealth and influence.

13 HOLOCAUST REMEMBERED 2024 | Supplement created and paid for by the SOUTH CAROLINA COUNCIL ON THE HOLOCAUST | scholocaustcouncil.org

The Anne Frank Center represents the hiding place where Anne Frank, her family, the Van Pels family and dentist Fritz Pfeffer spent 761 days in hiding before being captured by the Nazis and their accomplices.

Witness to the Massacre at Gardelegen Liberator Dr. Allen C. Wise

Allen Carson Wise was born on August 17, 1918, in Saluda, South Carolina, the son of Dr. Oscar Patrick Wise and Allie Witt Wise. Allen graduated from Saluda High School in 1935 and Newberry College in Newberry, SC, in 1939. He got a medical degree in 1943 at the Medical College of South Carolina in Charleston, SC, (now known as MUSC).

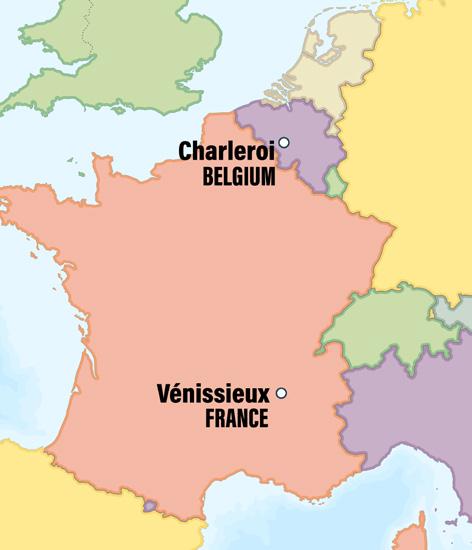

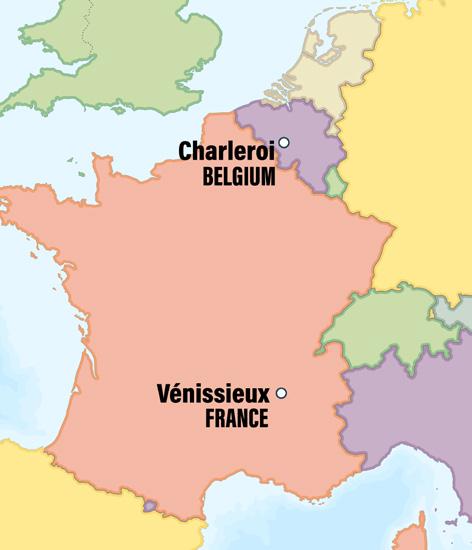

During WWII he was called to active duty in February 1944 and sent to the Medical Field Service School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. He was later stationed at Camp Swift, Texas, where he joined the 2nd Batallion, 405th Battery of the 102nd Infantry Division, as one of its medical doctors. The 102nd entered combat in September 1944 and thereafter engaged the German Army in France — and

later in the Netherlands, the Rhineland and other parts of central Germany. In late March and early April of 1945, as Allied military forces were moving toward and into Nazi Germany from the West — and as Russian military forces started pushing toward and into Germany from the East, the German SS ( “Schutzstaffel”) started the process of evacuating prisoners from concentration camps located in or near combat areas and relocating them to the interior of the Third Reich. On April 3 and 4, 1945, approximately 4,000 prisoners (the majority of whom were Christian and from Poland) were evacuated from the Dora-Mittelbau Concentration Camp, a subcamp of Buchenwald located near the city of Nordhausen in central Germany. The evacuation was by train and by foot. The inmates who were

forced to leave on foot and who could not keep up during their forced march were shot and killed by their guards. Because of air raid damage to rail lines, those who were aboard trains had to dismount several days later near Gardelegen — a town located midway between Hanover and Berlin. On April 13, 1945, with the assistance of local civilians, over 1,000 of those inmates were taken by the SS to a large barn on the outskirts of town,

where they were forced inside. The doors were barricaded and gasolinesoaked straw was set afire.

1016 of those inmates were burned alive by the fire and/ or suffocated from smoke. As the fire spread, some prisoners tried to escape by digging under the walls of the barn. A few escaped — but most who tried were shot and killed by the guards. The next day the SS and local civilians returned to the barn to dispose of the bodies and cover up their massacre and crime. However, the arrival of the 102nd Infantry Division that day prevented their plans from being completed. Shortly after the 102nd’s arrival, Dr. Wise and others were ordered to the barn to investigate the incident and report their findings. In an August 29, 1991, interview with the South Carolina ETV Network in Columbia, SC, Dr.

14 HOLOCAUST REMEMBERED 2024 | Supplement created and paid for by the SOUTH CAROLINA COUNCIL ON THE HOLOCAUST | scholocaustcouncil.org

US Troops inspecting the barn at Gardelegen in April 1945. More than one thousand inmates were barricaded in the barn and burned alive by Nazi troups.

Joe Wachter, member of SCCH, attorney, Myrtle Beach

Dr. Allen C. Wise described the scene he witnessed at Gardelegen in a 1991 interview.

Wise described, in part, the investigation and what he witnessed:

“….[The] barn [was] sitting on a hill. [Inside that barn [were] found a large number of people — people who were obviously prisoners of some sort or another, some of whom had on the striped prison unform — some didn’t. And they had been burned to death inside that barn…This barn was approximately 100 feet long and fifty feet wide. I don’t know how they got a thousand of ‘em in there, but that’s what it turned out to be…[I]t was just a horrible scene and just beyond my I can’t describe it, and it’s not the kind of thing that I cared about watching or looking at.”

On April 21, 1945, the 102nd’s commander, Major General Frank A. Keating, ordered men from the Town of Gardelegen to give the murdered prisoners a proper burial. During the next several days, 430 bodies were recovered from the barn and another 586 bodies were exhumed from trenches near the barn. Each recovered body was then placed in an individual grave. On April 25, 1945, the 102nd held a ceremony to honor the dead and erected a memorial tablet to the victims which read, in part, that the citizens of Gardelegen were charged with the responsibility that: “…(the) graves are forever kept as green as the memory of those unfortunates will be kept in the hearts of freedom-loving men everywhere.”

During World War II, Dr. Wise was awarded a number of accommodations and medals, including the Combat Medics Badge, a Bronze Star and two Battle Stars. He was discharged from military service in 1946. In 1947, he returned to Saluda to take over his father’s medical practice and thereafter practiced medicine there for almost 40 years.

Among his many accomplishments, he was active member of the Mt. Pleasant Lutheran Church and the Lion’s Club — and he was a founder of the Saluda County Historical Society. Dr. Wise passed away on July 21, 2007, at the age of 88. n

The author would like to express appreciation and thanks to one of Dr. Wise’s children, Suzanne Wise, and Annie Meade Hendrix of the Saluda County Historical Society for providing some of the information and/or photos for this article.

15 HOLOCAUST REMEMBERED 2024 | Supplement created and paid for by the SOUTH CAROLINA COUNCIL ON THE HOLOCAUST | scholocaustcouncil.org

Charred remains of inmates killed at the barn at Gardelegen.

German citizens were ordered to help bury the dead at Gardelegen by Major Gen. Frank A. Keating.

Above: Gardelegen Military Cemetery sign erected in April, 1945 by Major General Frank A. Keating, Commander 102nd Infantry Division. Below: the cemetary as it is seen today.

Dr. Allen C. Wise was awarded a Bronze Star and other medals and commodations during World War II.

“I witnessed man’s

inhumanity to man.”

Liberator Claude Hipp

Claude Hipp came forward and consented to be interviewed about his time in WWII and as a Holocaust Liberator. This narrative came from the visual testimonies given in the early 1990’s through a joint project of SC ETV and the SC Council on the Holocaust. Hipp was born in Cross Hill, SC in 1923 and graduated from Greenwood High School. He attended Clemson College, (now Clemson University) but at the end of his Clemson junior year, he and others volunteered to go into active service.

As Claude states,” the US Government, very obligingly, let us in to be privates.” Claude was assigned to the infantry and sent to Officer Candidate School. He graduated in the summer of 1944 and was assigned to the

89th infantry at Fort Butner, North Carolina, a training camp. He was sent overseas to France in January, 1945. His division landed in the port of Le Havre, France in the winter. After the Battle of the Bulge , the 89th infantry was among the first in the US Army to have crossed the Rhine River in the early morning. This division of the US Army continued to fight “as if they were going to Berlin”, however, they never arrived as they were being held back by orders. The Russians overtook Berlin.

Claude Hipp and his division (10,00015,000 soldiers) were mainly combat troops, assigned into units (100-250 soldiers) called

Armored Third Army. General Patton formed combat teams, a certain number of infantrymen in a battalion (300-12,00 soldiers) along with a platoon of four tanks. According to Hipp, they were to march fast and far so they could seize the initiative from the Germans. Our soldiers successfully travelled for hundreds of miles in a very short time.

Eventually, Gotha, a German town, was found as the division (10,000-15,000 soldiers) moved forward. Hipp’s regiment went into a work camp that had been run by the

German SS (Schutzstaffel) outside of a small town called Ordruf. This work camp (also a concentration camp) was later called Stalag Nord-Ohrdruf. The Germans used hundreds of workers as slave labor from all over Europe, especially Eastern Europe. Claude Hipp and others discovered an American flier, who was shot down. The workers were forced to work in a munitions plant and held in a wired compound. The compound of several acres was filled with hundreds of dead bodies. Hipp said “It was a sight I had never seen before and hope to never see again in my life. It impressed me so greatly that I am telling you about it now. Otherwise, I would rather be quiet because it brings a lot of sadness to me and to know what man can do to man.”

Hipp then continued about a Clemson Professor, John Lane. “Dr. Lane talked about ‘man’s inhumanity to man.’ I never really realized what it meant until I found this area and we marched through, The Camp Ohrdruf.” n

16 HOLOCAUST REMEMBERED 2024 | Supplement created and paid for by the SOUTH CAROLINA COUNCIL ON THE HOLOCAUST | scholocaustcouncil.org

Margaret Walden, member of SCCH, retired SC educator

Claude Hipp in a 1991 interview.

The 3rd Armored Division’s shoulder sleeve insignia, active 1941–1945 and 1947–1992.

Ordruf camp in Gotha, Germany, which was liberated by Claude Hipp’s Army division.

• Gotha, Germany

He recognized the essential humanity of all people.

Chiune Sugihara