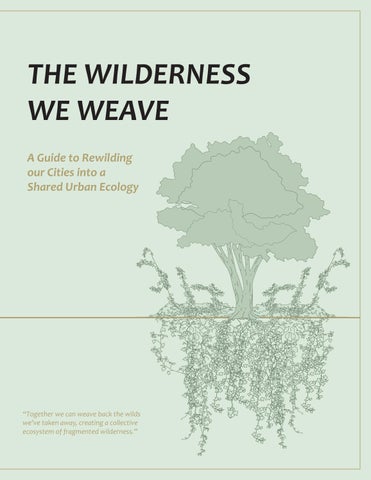

THE WILDERNESS WE WEAVE

A Guide to Rewilding our Cities into a Shared Urban Ecology

“Together we can weave back the wilds we’ve taken away, creating a collective ecosystem of fragmented wilderness.”

“Together we can weave back the wilds we’ve taken away, creating a collective ecosystem of fragmented wilderness.”

As our cities expand, we push back the wilderness and split it into separated fragments of “greenspace”.

Instead of isolating the wild into this disconnected archipelligo, urban rewilding weaves the wilderness back into the city one yard, sidewalk, or vacant lot at a time.

By restoring native plants and habitats, we rebuild the living relationships that connect people, wildlife, and place.

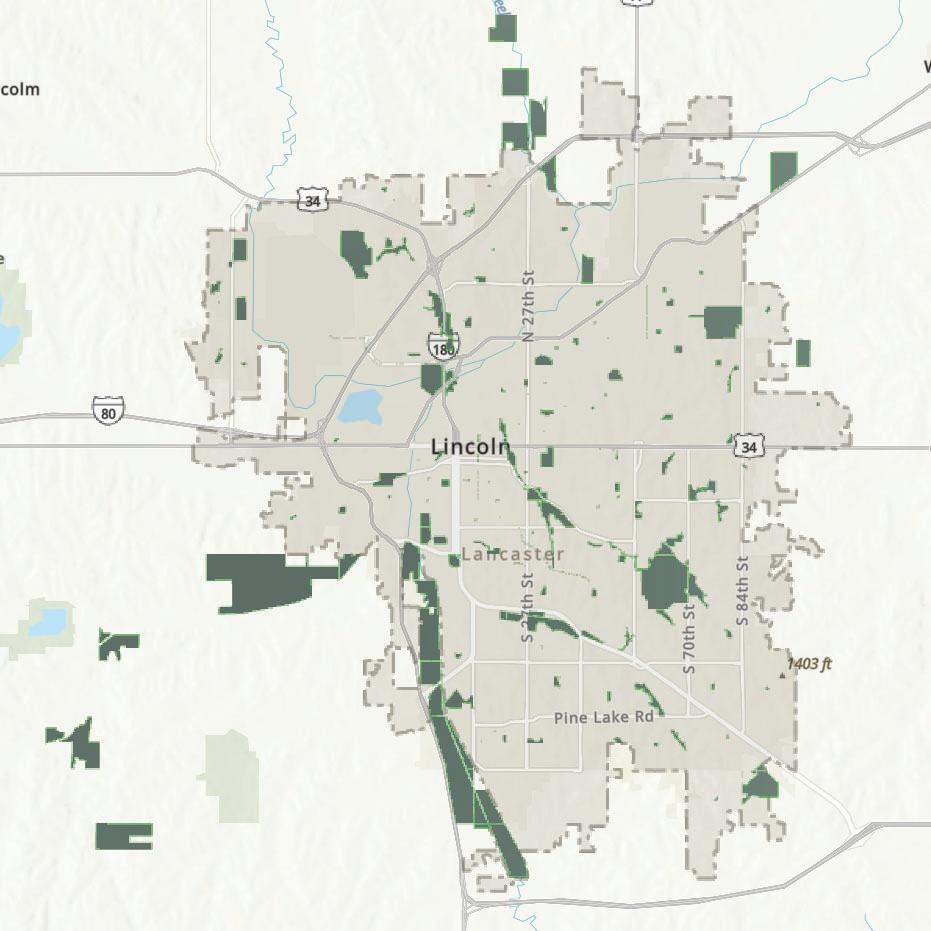

Fragmented greenspaces in Lincoln, NE

Each small patch becomes part of a larger ecological quilt, stitched together through everyday acts of care.

So, how can we do this?

The Miyawaki Method is a way to grow small forests that are fast, dense, and full of life. It works by planting diverse species of native trees and shrubs close together, helping them grow quickly and support each other — just like in a natural forest. These mini-forests grow much faster and healthier than traditional plantings, often reaching full maturity in just 10 to 20 years instead of 100.

Today, the method is being used all over the world to rewild dense urban areas, from urban lots in Europe to schoolyards in Asia. It brings back shade, birds, insects, and healthy soil in places where nature has been pushed out. We’re using it in this guide because it works — turning even the smallest patch of land into something wild, resilient, and full of hope.

50+ ft | Grows above the canopy, disperses seeds and provides habitat for larger birds

The method has been applied across the world since its conception, and is still being used today! Here are a few examples of some ways the method has been used to rewild urban spaces:

Main entry pathway to

implementing a Miyawaki-style reforestation.

This guidebook has broken down a resarch-driven approach to a multi-scalar Miyawaki-based strategy, designed for anyone to be able to contribute to the collective effort of rewilding our cities.

Seen through this tree-lifecycle framework are five simplified phases of rewilding, through which anyone can become a steward of their wild city!

Soil Building + Site Prep

Intention + Site Selection

Community + Continuity

Early Care + Stewardship

Forest

“Every forest begins with a single seed, an act of intention.”

The first step in rewilding is setting your intention and choosing a site that fits your vision. Do you want to create a native garden in your yard? Transform a public plant bed into a pollinator haven? Reimagine that neglected lot down the street? No matter the size or scope, rewilding can start small and grow big!

To help you begin, we’ve outlined three common site types you might find in your city, each with ideas for how it could be rewilded. These examples are just starting points — let them guide your thinking, not limit it. They each include a small selection of plants available at local nurseries/retailers.

Some spaces can be rewilded solo. Others may call for a team. Larger public spaces often require collaboration with neighbors, city staff, or local organizations. But remember: every wild space starts with someone willing to plant the first seed. In later sections, we’ll show you how to invite others into the process and build a collective effort.

IDENTIFY YOUR SITE!

Jot down some notes about your potential site, and guess which scale it might be!

Which of the three scales?:

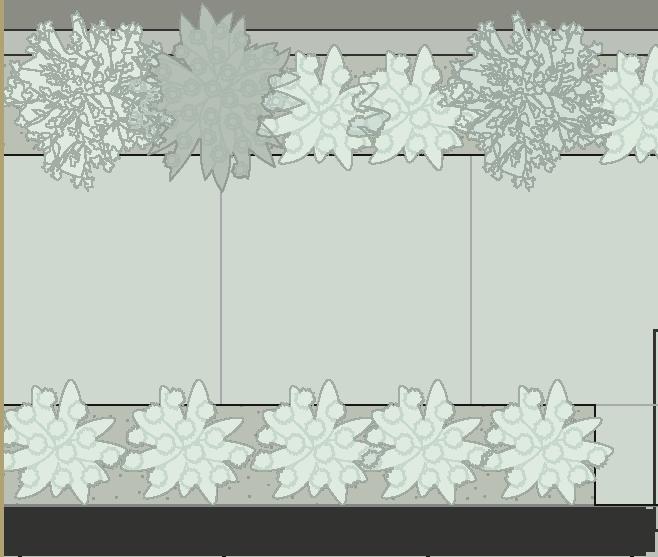

URBAN BOX (Microgarden)

URBAN EDGE (Garden)

URBAN LOT (Miniforest)

Even the smallest patch can become a pocket of the wild.

Black-Eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta)

Drought-tolerant, pollinator-friendly

Purple Coneflower (Echinacea purpurea)

Supports butterflies and bees

Little Bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium)

Compact native grass

Prairie Dropseed (Sporobolus heterolepis)

Soft texture, fragrant seed heads

Wild Bergamot (Monarda fistulosa)

Attracts hummingbirds, bees, butterflies

Microgardens are perfect for those working with very limited space — sidewalk bump-outs, planter boxes, curbside strips, or even large pots.

These spaces might be small, but when planted densely with the right native species, they can still support pollinators, boost soil health, and bring moments of wild beauty into the urban fabric.

Microgardens are the easiest way to begin rewilding and are perfect for individuals looking to make a difference on their own or dip their toes into a larger effort.

The edge is where transformation begins.

Butterfly Milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa)

Bright orange blooms, host plant for monarchs

Serviceberry (Amelanchier alnifolia)

Small shrub/tree with berries for birds

Leadplant (Amorpha canescens)

Drought-tolerant nitrogen fixer, attracts pollinators

New Jersey Tea (Ceanothus americanus)

Low-growing shrub, loved by birds and butterflies

False Indigo-Bush (Amorpha fruticosa)

Adaptable shrub, thrives in edge conditions

Edge gardens grow in the in-between spaces side yards, fences, and street frontages. These o en-overlooked strips can become vital habitat corridors, linking green pockets across the city. With na ve plants and though ul care, they support pollinators, improve soil, and so en the built environment.

Their visibility also makes them powerful tools for educa on, sparking curiosity and conversa on among neighbors. Whether at the edge of a home, business, or parking lot, these gardens prove that rewilding can happen anywhere.

A forest can begin in a single season. With the right roots, and the right hands.

Eastern Redbud (Cercis canadensis)

Spring-flowering understory tree, great for pollinators

Chokecherry (Prunus virginiana)

Hardy native shrub, offers fruit for wildlife

Serviceberry (Amelanchier alnifolia)

Works at both garden and forest scales, multi-use

Buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis)

Wet-tolerant shrub, blooms attract a range of insects

Leadplant (Amorpha canescens)

Useful as a forest edge stabilizer and pollinator magnet

Miniforests are densely planted native woodlands built using the Miyawaki Method. They thrive in small urban lots (vacant land, schoolyards, or neglected corners of parks) and grow into vibrant ecosystems in just a few years.

Though they require more effort, they give more back: shade, stormwater control, wildlife habitat, and long-term resilience. These forests grow best with a team, making them perfect for community action and collective care.

Now that you’ve chosen your site, it’s time to start imagining. Use this page to sketch out a rough layout of your rewilding vision. Don’t worry about precision, this is just planting the seed: Quick, simple, intuitive.

Think about the plants you might use, the shapes your space could take, and how people or wildlife might move through it. This is your first glimpse of what your wild patch could become.

“Roots reach under the earth, creating the foundation for growth.”

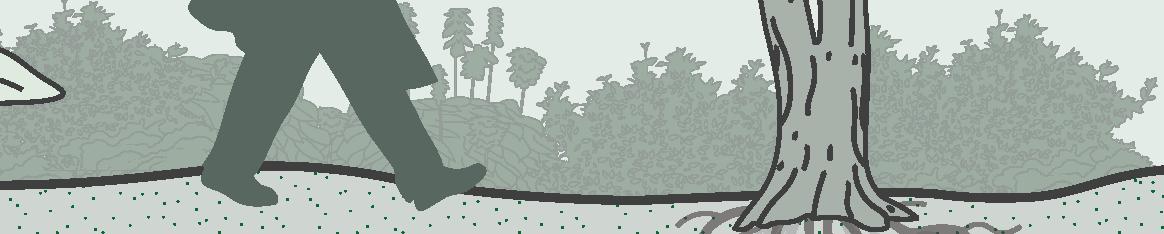

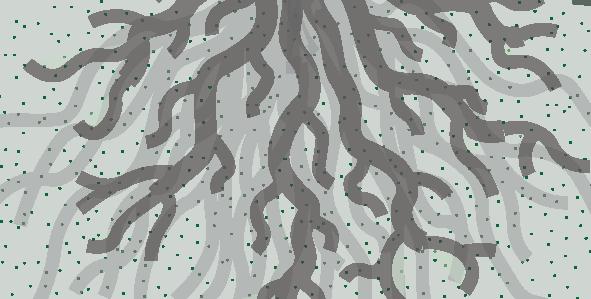

The health of a forest begins underground. Soil isn’t just where plants grow — it’s a living system that holds water, breathes air, and supports billions of tiny organisms. In cities, this system is often broken. Years of compaction, construction, and turf grass leave soil hard, dry, and stripped of life.

That’s why rewilding begins here: by loosening the ground and feeding it with organic matter. Compost and mulch mimic the forest floor, adding nutrients and kickstarting microbial life. Even a little bit of local soil can introduce native fungi and bacteria, tiny partners that help plants thrive.

Start by clearing away turf or invasive growth. Loosen the soil with a shovel or garden fork. Then add layers: compost, straw, leaf litter, and a splash of local soil if you can find it. Let the site rest for a week or two if time allows. You’re not just planting into dirt — you’re rebuilding an underground ecosystem.

Spade or shovel

Garden fork or broadfork

Wheelbarrow or buckets

Rake Gloves

Compost / straw / leaf matter

Hose or watering can

GROW YOUR GARDEN

Remove anything that may be in the way of your soonto-be Miyawaki garden

Atop the soil, layer straw, then compost or manure, then leaves to rejuvinate the soil

Stir up the topsoil with a garden fork or shovel, break it down so it can absorb new nutrients

4 | LET IT REST

Week 1: Settle

Week 2: Microbes activate Week 3: Ready to plant

“A sapling alone is small, but collectively, forms the birth of an entire ecosystem.”

Whether you’re planting a full mini-forest, a pocket garden, or a single sidewalk box, this phase brings your space to life. The goal isn’t just to install plants, but to create a self-supporting, diverse, and resilient plant community.

We take inspiration from the Miyawaki Method and other naturalistic planting approaches. That means planting densely, mixing species generously, and embracing irregularity. Instead of neat rows, imagine how plants grow in a wild meadow or forest edge — layered, interwoven, and full of surprise.

The more diversity and structure you include, the better your rewilded patch will function. Plants support one another underground and above, creating shade, trapping moisture, and building soil over time. A single shoot may feel small, but many together become an ecosystem.

Plant densely

For Microgardens

For Gardens

~1 plant per square foot

~2–3 plants per square foot

For Miniforests ~3 trees/shrubs per 10 square feet

Mix species types

Don’t plant all of one kind together — scatter and mingle

Layer your planting, Combine:

Tall trees or grasses (for canopy or structure)

Shrubs and subshrubs

Groundcovers and forbs

Think like a forest, even at small scales. Cluster for function, not for looks. Let nature’s messiness guide you.

Black-Eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta)

Purple Coneflower (Echinacea purpurea)

Little Bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium)

Prairie Dropseed (Sporobolus heterolepis)

Wild Bergamot (Monarda fistulosa)

Drought-tolerant, pollinator-friendly

110

A hardy perennial with large, daisylike pink to purple flowers. Attracts pollinators.

Ornamental grass with blue-green stems turning mahogany-red in fall.

Fine-textured grass with a pleasant fragrance; provides cover for small wildlife.

Attracts hummingbirds, bees, butterflies

Showy Goldenrod (Solidago speciosa)

Joe Pye Weed (Eutrochium purpureum)

Salvia azurea (Blue Sage)

Sideoats Grama (Bouteloua curtipendula)

Leadplant (Amorpha canescens)

Tall, clump-forming plant with bright yellow flowers. Supports pollinators.

Tall plant with mauve or pink-purple flowers; thrives in moist, well-drained soils.

Tall, slender plant with sky-blue flowers; attracts bees and butterflies.

Grass with distinctive seed spikes; provides food and shelter for birds and butterflies.

Shrub with purple flower spikes; fixes nitrogen and supports pollinators.

Butterfly Milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa)

Bright orange blooms, host plant for monarchs

615

Alumroot (Heuchera richardsonii)

Low-growing plant with small flowers; attracts pollinators and adds ground cover.

Aromatic Aster (Symphyotrichum oblongifolium)

Dotted Blazing Star (Liatris punctata)

False Indigo-Bush (Amorpha fruticosa)

Late-blooming with lavenderblue flowers; supports migrating butterflies.

716

Tall spikes of purple flowers; attracts butterflies and bees.

Blue, lupine-like flowers; fixes nitrogen in the soil, enhancing fertility.

Blue Grama (Bouteloua gracilis)

Eastern Bluestar (Amsonia tabernaemontana)

Pagoda Dogwood (Cornus alternifolia) 817

Bur Oak (Quercus macrocarpa)

Wild Plum (Prunus americana) 918

Eastern Redbud (Cercis canadensis)

Large, long-lived tree; supports a wide range of wildlife.

Small tree with pink spring blossoms; provides early nectar for pollinators.

Missouri Evening Primrose (Oenothera macrocarpa)

Gray Dogwood (Cornus racemosa) 1924

American Hazelnut (Corylus americana)

Buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis)

Multi-stemmed shrub producing edible nuts; attracts wildlife.

Shrub with spherical white flowers; thrives in moist soils and supports pollinators.

Multi-stemmed shrub or small tree producing white flowers and edible berries.

Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis)

Ninebark (Physocarpus opulifolius)

Short grass with eyelash-like seed heads; drought-tolerant and supports wildlife.

Blue, star-shaped flowers in spring; provides fall foliage color.

Large, yellow flowers that open in the evening; tolerates drought and poor soils.

Small understory tree with layered branching and white spring flowers. Tolerant of partial shade and adaptable to clay soils.

Suckering shrub or small tree with fragrant white blooms and edible fruits. Excellent for wildlife habitat.

Dense, thicket-forming shrub with white flower clusters and white berries. Provides cover and food for birds.

Medium-sized tree tolerant of urban conditions, clay soils, and drought. Hosts a wide range of caterpillars and birds.

Hardy shrub with exfoliating bark and small white flower clusters. Supports pollinators and has strong visual texture for forest understories.

With these plants in mind, the next step is to revisit the plans we drew up earlier and map out exactly where each of these plants should go!

Planning out the planting strategy before gathering all the materials ensures that the physical planting is a breeze!

“This is where the wild takes hold, but still needs your hand.”

Once planted, your rewilded patch enters its first season of growth. Like any young ecosystem it needs attention, which means water, weeding, and patience. This is the phase where roots deepen, shoots stretch, and the landscape begins to shift.

In the first 1–2 years, your role is to help the plants establish. That might mean watering during dry spells, pulling back aggressive weeds, or observing how species are taking hold. Over time, maintenance will decrease as the system becomes more self-sustaining. But early care makes all the difference, this is how your patch goes from planted to thriving. We reccommend creating your own Care Calendar outlining how you plan to steward!

Water deeply once a week (if no rain)

Remove invasive weeds before they spread

Observe which plants are thriving (don’t worry if some grow slowly)

Reapply mulch if the soil is exposed

Replant any major gaps if needed

Reduce watering (only during dry spells)

Let natural succession begin (volunteers, wildflowers, groundcover spread)

Start stepping back — your role is shifting from gardener to observer

JUNE

Water weekly after planting

Mulch or leaf-litter if needed

Watch for signs of early weeds

JULY

Deep watering every 5-7 days (if no rain)

Remove fast-growing weeds

Let things look a little messy, its natural

AUGUST

SEPTEMBER

No care needed — let the ground rest

Some stalks and seedheads can be left standing for wildlife, but some foliage should be cleared before snowfall

OCTOBER

NOVEMBER

Minimal watering unless extremely dry

Replant if any plants didn’t take

Observe changes and note what thrived

A single patch of wild can ripple outward. Once your forest, garden, or box is established, the next phase is sharing it — inviting others in, exchanging care, and planting new seeds in new places. Just as trees form networks underground, your act of rewilding becomes part of a larger web.

Whether you start a conversation with a neighbor, host a planting day, or leave a tiny sign for a passerby, this phase is about connection. Rewilding isn’t only about ecology, it’s also about culture. The canopy isn’t the end of growth, but the beginning of shade, shelter, and shared life.

Invite neighbors to help tend or visit your site

Host a planting event or info table (e.g. Lowe’s, library, school)

Create a social media post to share what you’ve made

Create your own guide and share it online

Observe how your space changes year to year

Track wildlife visits, note patterns

Leave a forest journal or message for future stewards

Add signage to brand the movement

**Printable sign on next spread**

“What

gives energy to the forest -- to a community of trees -- is the community of humans infusing it with their own energy”

-- Broomforest