Reclaiming Sitio San Roque

The Filipino Urban Poor’s Diminishing Rights to the City as a Result of Profit-driven Gentrification

Francille Raven Castro

Cover image by the author using images from Google Earth

Francille Raven Castro

Cover image by the author using images from Google Earth

The Filipino Urban Poor’s Diminishing Rights to the City as a Result of Profit-driven Gentrification

Francille Raven Castro

Cover image by the author using images from Google Earth

Francille Raven Castro

Cover image by the author using images from Google Earth

Francille Raven Castro 200124706

University of Sheffield

School of Architecture

ARC322 Special Study

Word count: 4680

I would like to thank my tutor, Tanzil Shafique, for his guidance and support throughout this study. Thank you also to Redento Recio and the Save San Roque Alliance for their enthusiasm and hospitality towards my curiosity.

‘The world is being constructed, quite literally, in ways that adversely affect how we regard politics and who we recognize as fellow citizens’ thus, making Architecture and Urbanism powerful lenses from which social inequalities could be investigated. Through the integration of spatial analysis alongside the exploration of underlying political and sociological notions, the study of Sitio San Roque’s recent progressions will inaugurate.

This remote study will be facilitated by a profusion of published and online resources including a range of academic writings, personal blogs, interviews, newspaper articles, etc in order to accommodate varied personal and outsider narratives and perceptions about the community. Additionally, Google Earth satellite images and data will be utilised in the spatial analysis and creation of diagrams of the informal settlement site. The writing will therefore draw a synthesis between collective arguments and the mapping of spatial evidence as a way to investigate the spatially rich district of Sitio San Roque.

Translation:

“Isang ugat, isang dugo Pare-parehong Pilipino Mga tadhanang magkapatid Isang panata, isang bandila”

There is a lot of pride in calling myself a Filipino citizen. From the inconceivable allure of the country’s natural landscape to the vibrant customs and traditions communities practice in their daily lives – there is a lot to be proud of. There are however a number of hostile realities that continue to permeate through the Filipino society. In the nation’s quest to achieve a ‘global city’ status, its most important constituent is somehow overlooked – the Filipino people. Residing in the Philippines would mean an awareness of the socio-economic state of the country’s financial metropolis, including the struggles people face within its spatial parameters. The urban poor who are often branded as barriers who jeopardise developments towards a ‘bright’ future, have just as many rights to the city as affluent individuals driven by a profit surplus agenda.

The quest for globalisation in the Global South entails extreme ramifications for the urban poor which subsequently demonstrates their diminishing rights to the city. The Philippines is of course, no exemption to this phenomenon. As these developments progress at an ever-accelerating rate, it has resulted in the aggravation of poverty within the country. Sitio San Roque is a prime example of an informal settlement community in the country that experience persistent threats of their homes being taken away from them without ample compensation. The uncertainty of where they would go after eviction is also a reoccurring apprehensive notion for the residents. The entire system of eviction and post-eviction procedures has shown the utilisation of unethical means for the sake of commodifying the nation’s land. My study aims to investigate the extent public-private partnerships would go in order to convert these areas into profitable districts, particularly through their eviction ploys and post-eviction schemes that have direct and oppressive consequences towards the residents. The extent, or rather the limitations, of the integration of the urban poor in the development of cities will also be examined. Discernibly, this surfaces the question of whether the whole eviction and displacement cycle should be characterised as a form of urban cleansing that rejects the image of poverty in the quest to paint a picture of modernity.

02 Introducing Sitio San Roque

“Ang ding-ding ng bahay namin ay pinagtagpi-tagping yero Sa gabi ay sobrang init na tumutunaw ng yelo…

Gamit lang panggatong na inanod lamang sa istero Na nagsisilibing kusina sa umaga’y aming banyo”

– Upuan, Gloc-9

Translation:

“The walls of our house are metal sheets patched together It is very warm at night that it could melt ice… Using firewood that has drifted away from the canal In the kitchen that serves as our bathroom in the morning”

Sitio San Roque is a 29.1-hectre self-built urban poor community situated in Quezon City’s North Triangle on publicly owned land overseen by the National Housing Authority (NHA). Speaking from a historical viewpoint, the site was deployed as a relocation area for surrendering anti-Japanese Filipino soldiers post World War II. Alongside these soldiers, poor migrants from rural areas of the country also evolved the area into a prosperous community that grow and manufacture various produce for personal consumption and selling. The trading business within the community expanded by the late 1990s albeit the substandard condition of the site and tangible structures it sits on.

Like many other informal settlements, the community is situated in close proximity to urban industries that enable residents to access various livelihood opportunities. Its spatial ingress to both the formal and informal sectors of the city relatively stabilises the residents’ income generation, typically through untenured employment. The steady trade of cheap goods and services operating in the Sitio alongside the resourceful spatial adaptation and progression of their homes facilitate the urban poor’s continued survival in the neoliberal city and subsequently, the country. This is only possible through the residents’ collective and incremental efforts, or as Filipinos would describe as ‘diskarte’ (strategy).

It can also be deducted that the protraction of informal settlements has become the most effective system that accommodates rapid population growth and housing issues within the country. As the fabrication of homes within these communities are relatively cheap and easy to build, simply utilising reclaimed materials alongside the Filipino value of ‘bayanihan’ (mutual cooperation), it has continued to provide homes to the Filipino poor. However, over the last decade and a half, Sitio San Roque’s existence has been under persistent threat from state-sponsored gentrification that prioritises profit surplus through the commodification of the land their homes sit on.

5

Figure 5: Sitio San Roque Material Sketch Analysis by Author.

Figure 5: Sitio San Roque Material Sketch Analysis by Author.

Translation:

“The rich will only get richer, if they greedy and indifferent”

“Ang mayaman ay lalong yayaman, kung sakim at walang pakialam”

6

Prior to the demolition that occurred in 2010, Sitio San Roque was home to around 9,000 families. The Sitio’s precarious times began in August 2009 when the NHA and private developers, Ayala Land Inc. (ALI), entered a joint venture agreement to develop North Triangle into a mixed-use complex, formally known as the Quezon City Business District Project (QCCBD). This JVA was implemented despite limited consultations with the Sitio’s residents, hence illustrating their continuous exclusion from urban developments within the city. A consequence of the JVA was the transferal of all NHA’s rights on the project area to ALI. Additionally, NHA was also responsible in making sure the site was secure against ‘unlawful’ occupancy or situations that might cause delays in the project’s development and consequently, the clearing of informal settler families. Furthermore, NHA is also to hold ALI free of accountability whereby damage resulting from the clearing process was to occur. These consensuses legibly highlight the advantages ALI has in the partnership; not only are they exempted in dealing with Sitio San Roque’s residents throughout the eviction and relocation process, their reputation is also almost guaranteed to remain untouched as all the responsibility will be accounted for by the state. This goes to show the indifference many private developers and planners have towards the urban poor in developing countries as they fixate on the commodification of public land.

The project involves the construction of shopping malls, office spaces and residential compounds that somehow ‘requires’ the erasure of all embodiments of informality. This is an illustration of neoliberal urban planning that revolves around an economic agenda in an attempt to construct a globally competitive city in addition to attracting investments. ALI ironically claims that their mission is to ‘enrich the lives of more Filipinos’ as they seemingly operate under social responsibility. However, the scope of who they consider as fellow citizens could be questioned as their projects continue to cater only to middle and upper-class citizens. As public spaces become increasingly private, the notion of purifying the city emerges. Thus, there is a resulting segregation from hyper-realised concepts of home and public space. This system is evidently further amplified and sustained by the state through the establishment and use of neoliberal policies.

Moreover, according to a 2010 report from the Department of Interior and Local Government (DILG), there is already an extensive housing backlog making current housing supplies for relocation schemes insufficient. This has taken the interest of private developers such as ALI who the state views as partners in solving the metropolis’ housing problem. Pragmatically speaking, the construction of housing for informal settlers has ordinarily become a profitable pursuit for private developers. Through this neoliberal alliance, housing concessions are therefore constrained by the lucrativeness of the gentrification project. Additionally, these developments also result in the rise of land and housing values, making the city even more inaccessible to people with low and insecure incomes. Urban poverty has therefore worsened as a consequence of this accelerated rate of globalisation. At present, it seems to be that existing and future housing demands are not being resolved effectively; instead, current urban planning schemes appear to only concern the masking of urban poverty as opposed to finding viable solutions

8

Enhancing Land, Enriching Lives, and Caring for the Environment | Ayala Land 2022 Corporate Video, online video recording, YouTube, 27 April 2022, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VrjEWvmRY5o> [accessed 27 January 2023].

9 Susan Bickford, ‘Constructing Inequality City Spaces and the Architecture of Citizenship’, Political Theory, 20.3 (2000), 355-376 (pp. 356-371).

10 Myra Mabilin, ‘Forced evictions, off-city relocation and resistance: Ramifications of neo-liberal policies towards the Philippine urban poor’, in Claiming the City Civil Society Mobilisation by the Urban Poor, ed. Heidi Moksnes and Mia Melin (Uppsala: Hallvigs, 2014), pp. 133-137.

11 Koki Seki, Ethnographies of Development and Globalization in the Philippines: Emergent Socialities and the Governing of Precarity (London: Routledge, 2020).

Figure 6: Ayala Malls Vertis North.

“Kayong malaon nang iginupo ng dahas Magkaisa’t labanan ang pang-aapi Kahit na libong buhay man ang masawi”

During the early stages of the neoliberal alliance between the state and private developers, the method of eviction they employed can be described as rapid and forceful. This was subsequently faced with strong opposition by Sitio San Roque residents. On the 23rd of September 2010, the residents came together to construct a barricade in the adjacent highway resulting in the immobilisation of traffic. Around 700 members of the demolition team came alongside 500 policemen and 300 SWAT members. This large group tasked with the eviction and forceful demolition of homes were eventually forced to retreat due to the residents’ strong resolve and solidarity that day. One resident stated that the phenomenon offered a sense of joy or contentment as they felt that they ‘won in that battle’. Arguably, that day can be considered a success due to changes in the way eviction is now implemented.

The community barricade that occurred in September 2010 was a consequential event that led to a shift in the process of eviction performed by the state and developers. To illustrate, the then President Benigno Aquino declared a moratorium on forced evictions as a consequence of the barricade. In place of the prompt aggressive methods previously used, eviction of the Sitio’s residents now occurs incrementally. This method utilises a somewhat manipulative process that leads to ‘voluntary’ evacuations. Residents who own properties in the settlement are offered compensation in addition to relocation into public housing given that they ‘demolish their house, remove all the materials and vacate the site’. The residents are essentially coerced into leaving their homes as those who hold out are threatened with the possibility of not receiving any compensation. ‘Pocket-sized’ demolitions are also being utilised through the excuse of various legal rationales such as road widening projects and public transport infrastructure construction. Although large-scale forceful demolitions are no longer deployed, the resulting state tactics are still well within the unethical spectrum as the eviction process utilises power play through the persistent surveillance and intimidation of residents.

It is also worth noting that only around 2000 out of the 6000 households remaining in the Sitio qualify for relocation schemes which require proof of long-term residence and house ownership. As social housing provision remains scarce, this has resulted in the segregation of long-term ‘owners’ and those viewed as having less/limited rights to social housing. Furthermore, the unity amongst community-based organisations has become fragmented as they struggle to negotiate with the state, regarding compensations and relocation sites. This fragmentation of community concord is further amplified by the NHA as they only give consideration to organisations that are open to relocation. Meanwhile, organisations resisting eviction are disregarded and given no chance to negotiate.

These incremental micro-practices have colossal consequences within community relationships and interactions. As Redento Recio and Kim Dovey state in their article about Metro Manila’s neoliberal urban development, ‘the empty patches of concrete flooring and sense of dereliction diminish the hopes of those who remain’. The visible expansion of sparseness within Sitio San Roque’s land does diminish the residents’ resolve to continue fighting for their homes. Whilst these incremental evictions appear to operate in a quiet manner, it still extrudes the perception of the neoliberal alliance’s violent intrusion.

Figure 10: Resident Demolishing their Home.

Figure 10: Resident Demolishing their Home.

05 Post Eviction Measures

“Hukay, luha’y magpapatunay

Na kahit hindi makulay, kailangang magbigay-pugay

Sa kung sino ang lamang, mga bitukang halang

At kung wala kang alam ay yumuko ka na lang”

– Hari ng Tondo, Gloc-9

Translation: “Grave, tears are proof That even when there’s no colour, you have to give way To who is better, intestines lay across And if you don’t know anything just bow your head”

19

In cases where the partnership was successful in securing land from Sitio San Roque, several measures to prevent re-encroachment were implemented. A pragmatic method they used was the fencing of vacant sites; these were also floodlit to heighten the level of ‘protection’ at night. Additionally, a large team of security guarding the settlement 24 hours a day were tasked to avert residents from attempting any new construction and repairs alongside the confiscation of their construction materials. Lookout towers were even built for the guards around the sitio’s perimeter for surveillance over the whole community. Ironically, many of these guards and other labourers working for ALI are people who live in the Sitio and other informal settlement communities. This phenomenon illustrates the heavy reliance of private and formal sectors on the manual labour provided by the urban poor. Nonetheless, these rigorous preventative measures indicate the alliance’s strong resolve to remove informal settler families within the city’s core. This implies that they are either oblivious or indifferent towards the importance of this marginalised group in the operation and sustenance of the metropolis they are purportedly enhancing.

Arguably, these practices performed by the state and private developers can be described as demeaning as it reveals their perception of the Sitio’s residents. The exertion of guards within the community involves this concept of unwanted intrusion which essentially encroaches on the residents’ privacy as they go about their daily lives. Numerous residents were vocal about their frustration regarding this as they protested outside the NHA’s building demanding that they ‘pull out the guards’ from their community. Furthermore, the whole system also embodies a degree of criminalisation of residents within their own homes – a place that is supposed to provide oneself with comfort and security. The level of sensitivity the state and developers have towards the residents could be questioned as they continue to utilise devious procedures that contribute to the fragmentation of the community and mistreatment of individuals.

06 The Discriminatory Nature of Off-City Relocation

– Quote from a mural in Sitio San Roque

Translation: “Service for the people, don’t turn it into a business”

“Serbisyo sa tao, huwag gawing negosyo”

Reasonably, being able to call a place ‘home’ suggests that one feels a level of comfort, contentment and familiarity whilst residing there. Being coerced into leaving that place entails difficulties that affect a person immensely – from their daily micro practices all the way to the course of their future. This therefore highlights the extensive potency of relocation schemes on the lives of Sitio San Roque’s residents as they navigate the new ‘home’ provided by the state and private developers. This encompasses the locality of the site, quality of the houses themselves, as well as community relationships post relocation.

According to a 2022 report by the Save San Roque Alliance, a local grassroot organisation, 6 out of 7 social housing projects for the Sitio’s residents are off-city. The singular in-city relocation site accommodates another San Roque grassroot organisation after negotiations with the NHA and ALI. In other words, the vast majority are located in provinces outside Metro Manila where the way of life is completely different from what the residents are accustomed to. Figure 14 shows a map of Metro Manila and surrounding provinces that pinpoints these relocation sites in relation to Sitio San Roque. To investigate the calibre of off-city relocation schemes, Towerville in Barangay (district) Gaya Gaya, San Jose Del Monte, Bulacan will be focalised.

Off-city relocation schemes have been collectively met with dissatisfaction by the residents due to various reasons. The locality of the site plays a huge role in the residents’ opposition. As these new houses are situated in provinces, access to various livelihood opportunities is significantly lower than Metro Manila. Many relocated residents in Towerville have expressed their frustration regarding this predicament. One resident stated that his income has declined to roughly half of what he was earning in the city due to the lack of job prospects for manual labourers like himself. An alternative solution that some residents deploy is travelling back into Metro Manila for work. However, this proves to be counterproductive as transportation can be costly and laborious. Considering that a large percentage of the Sitio’s residents rely on untenured manual labour as a mode of employment, relocation to urban fringes with minimal provision for these types of jobs visibly engenders financial difficulties. This subsequently makes life in the relocation site unsustainable which essentially exacerbates the already existing problem of nationwide poverty. Zaldy C. Collado and Noella May-i G. Orozco in their study of the urban poor’s resettlement experiences, mentions that there have been recommendations for changes in policies to ‘include social impact assessment and the restoration of income and livelihood’. These key deviations come with the objective of alleviating the condition of relocated residents. Arguments such as these are crucial especially when branding the relocation schemes as long-term housing for the urban poor. At present, the lack of attentiveness regarding the viability of these social housing projects for the specific demographic of Informal Settler Families (ISFs) renders the whole system futile.

Another concern regarding the location of the housing is the lack of social and utility service provisions on or near the site. The scarceness of hospitals, schools and markets denotes its remote location which subsequently illustrates the challenging lives relocated residents are having to endure. Towerville residents who took part in the study by Collado and Orozco mentioned that due to the extensive distance of these facilities, they are having to spend more on transport than necessary. They also disclosed that the lone health centre within the community is only visited by a doctor once a week. On top of that, there is also a shortage of medication supply. Concerning the topic of safety and security, researchers have discovered the absence of street lighting within the community. This would visibly contribute to making the place feel unsafe and potentially encourage the prevalence of crime within the area. Moreover, the level of potential risk is heightened by the site’s distant location from police services.

There are also concerns regarding the standard of the housing provision. A lot of Towerville residents recall having no access to electricity and water when they first moved in. Installing electricity would sometimes mean having to wait several months or even a few years, making the houses practically inhabitable in the early stages of relocation. Additionally, obtaining water involves having to fetch it from outside as it is not readily available within the building. Regarding the actual structure itself, reports of its substandard construction is common. For instance, residents recounted cracks on walls and floors denoting its defective condition. Furthermore, the sizing of the houses does not cater to a range of ISFs as some claim that the houses are not spacious enough for their whole family. This implies the likelihood that the houses were built to maximise the quantity rather than offering quality and flexibility to a wide range of ISFs which is ultimately more beneficial. Evidently, NHA is reported to have around 61,000 units across the country, however only 9,000 units are inhabited which illustrates the unsuccessful nature of current social housing schemes. This correspondingly feeds into the reoccurring notion of the government’s neoliberal agenda that fails to implement feasible solutions to urban poverty due its profit fixation.

30

The effects of off-city relocation schemes are not bounded by tangible elements, social relationships within and beyond the community are also influenced. In the context of Towerville, the allocation of houses aligns with the relocated residents’ place of origin. This means that residents from Sitio San Roque would have been assigned to neighbouring houses. Arguably, this decision would facilitate the conservation of the sense of community that the Sitio’s residents would already have prior to relocation. However, when investigating the whole context of Barangay Gaya Gaya, the relocation site appears to be situated in its fringes, away from the original residents of the district. This has instigated a sense of animosity from the original residents towards relocated residents as they are isolated from the existing community in the place they have been relocated to.

Arguably, current government policies on social housing provision are ‘discriminatory by nature’ as stated by Myra Mabilin in her article about forced evictions and off-city relocation. Given that essential facilities are absent within and near the houses, which arguably were practically enforced upon the residents, is discriminatory in all its rights. Additionally, all the other realities in Towerville mentioned earlier, once again echo the lack of careful planning for relocated communities as they are proven to be deprived of the bare necessities every person is entitled to. The current system of housing provision in the country discernibly only benefits the private real estate sector all whilst treating the Sitio’s residents as an afterthought throughout the whole gentrification scheme. Understandably, the futile nature of off-city relocation schemes results in the residents’ return to the city; whether that may be back in Sitio San Roque, other existing informal settlements and feasibly the establishment of new ones. This subsequently reveals the never-ending cycle of urban poverty that is stimulated by current government policies and neoliberal urban planning systems.

07 Alternative Solutions?

“Alam natin ang tama, ‘bat ‘di natin ginagawa?

Paulit-ulit na lang na ito ang bagong simula Simula ng simula bakit walang natatapos?

Atras abante lagi, pudpod na swelas ng sapatos”

– Dapat Tama, Gloc-9

Translation:

“We know what’s right, why don’t we do it? We keep repeating this new beginning We keep beginning why don’t we finish? Back and forth always, the shoe soles are now worn out”

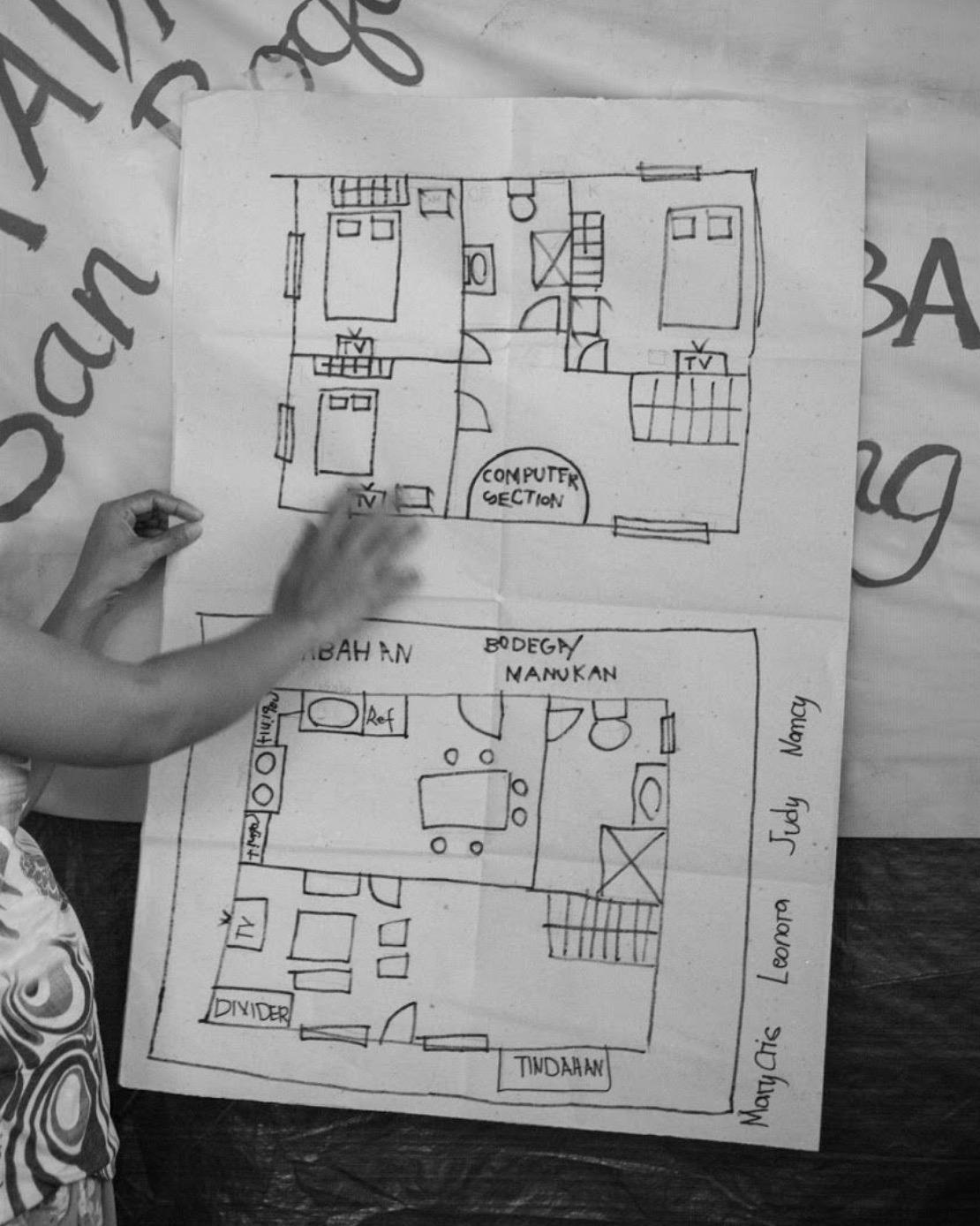

Due to the ineffective nature of off-city relocation and its apparent negative impacts on Sitio San Roque’s relocated residents, a push for other housing solutions is surfacing. The most ideal option would be the implementation of on-site upgrading which the Save San Roque Alliance alongside the Sitio’s residents, represented by Kalipunan ng Damayang Mahihirap (KADAMAY), are proposing through their Community Development Plan (CDP). This utilises participatory architecture and urban planning in order to develop Sitio San Roque in a manner that responds to the residents’ needs and wants effectively. The process involves numerous workshops, beginning by informing residents about current challenges regarding their community to ‘dream house workshops’ where they were tasked to design and plan their desired houses. Design conclusions such as the suitability of medium rise buildings and the integration of communal facilities were deducted through the steady involvement of the residents in the CDP process. The thoroughness and range of these workshops undoubtedly result in an accurate understanding of what social housing provisions for the Sitio’s residents should be. As stated by the Save San Roque Alliance, ‘affordable on-site housing development has the least adverse effect on the socio-economic situation of the urban poor’, therefore its beneficial effects on the Sitio’s residents should not be disregarded by the state and developers alike.

Alternatively, due to the supposed ‘difficulty’ the state is facing regarding the implementation of on-site upgrading, proposals for in-city relocation are being negotiated. Although this route is not as ideal as on-site upgrading, it comes with the assurance of minimal disruption to livelihood prospects for the Sitio’s residents. By remaining within the Metro Manila’s spatial parameters, residents are still able to access the same or similar types of jobs that they performed whilst residing in Sitio San Roque. Objectively, this would be a more appropriate option to off-city relocation which downright disrupts the residents’ livelihood prospects.

Figure 17: Dream House Workshop.

Figure 18: Counter-mapping Workshop.

Figure 17: Dream House Workshop.

Figure 18: Counter-mapping Workshop.

08 Acknowledging Political Design Responsibilities - A Call for Action

–

“As

Translation:

Architecture and Urbanism simultaneously play crucial roles in the progression of cities. Designing places with a strong political agenda as its foundation ensures the development of inclusive environments that do not discriminate the most vulnerable members of society. By conducting this study, gaps and limitations within architecture and urban planning alongside government policies, are outlined. Fundamentally, Sitio San Roque’s residents should be recognised as rightful members of the city whose only request is to be integrated and respected in the urban progression of Metro Manila. Once this is acknowledged by the state, developers, and designers all together, the city will proceed in a positive direction that does not perpetuate disparaging social divisions.

Perceivably, the development of cities requires a more thorough investigation and focus on the current needs of its population. The capitalistic character of built environment practices testifies to the inadequacy in addressing the most important societal issues. In Sitio San Roque’s case, prioritising the construction of business-oriented buildings over the integration of affordable housing for the urban poor, who arguably are the backbone of the city, will eventually emerge as a fruitless endeavour.

The emerging focus and re-education around working with communities is also an important prospect for the construction industry. Andrea Fitrianto in her article about the role of architects in communities argues that ‘Architecture education is more accustomed to a top-down delivery system’ that essentially lacks an approach to working with local communities. This therefore highlights the importance of unlearning old ineffective structures in order to underpin people focused design. Participatory planning, when undertaken properly, becomes a powerful tool in alleviating a developing nation’s issues. These would require the consistent involvement of the local community to nurture the sense of ownership that makes a place prosperous. However, there is still the unfortunate circumstance of professionals reverting to isolation in their studio after gathering data from the community. This becomes devoid of stances and possibilities that can only be achieved through steady community participation.

Current and future challenges developing nations’ face cannot be detached from the Architecture and Urbanism profession. The services professionals offer must be enhanced through various standpoints ranging from contextually responsive technical solutions to locally grounded design methods and programming. This ultimately poses an exciting and urgent challenge for the built environment profession to reform the old practice of seclusion by becoming more aware and engaged with a place’s people and ethos.

Abesamis, Felix D., ‘Squatter-Slum Clearance and Resettlement Programs in the Philippines.’, NEDA Journal of Development, 19.1 (2020), 35-69

Arcilla, Chester Antonino, ‘Disrupting Gentrification: From Barricades and Housing Occupations to an Insurgent Urban Subaltern History in a Southern City’, A Radical Journal of Geography, 0.0 (2022), 1-24

Ayala Land, Enhancing Land, Enriching Lives, and Caring for the Environment | Ayala Land 2022 Corporate Video, online video recording, YouTube, 27 April 2022, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VrjEWvmRY5o> [accessed 27 January 2023]

Bamboo, ‘Tatsulok’, We Stand Alone Together, [download track], (Spotify, 28 December 2022)

Bickford, Susan, ‘Constructing Inequality City Spaces and the Architecture of Citizenship’, Political Theory, 20.3 (2000), 355-376

Collado, Zaldy C. and Noella May-i Orozco, ‘From displacement to resettlement: how current policies shape eviction narratives among urban poor in the Philippines’, Housing, Care and Support, 23.2 (2020), 49-63

Cunanan, Kaloy M., ‘Slum-fit? Or, Where is the Place of the Filipino Urban Poor in the Philippine City?’, An International Journal for Critical Geographies, 19.1 (2020), 35-69

Fitrianto, Andrea, ‘Securing local ownership, and the architect’s dilemma’, in Claiming the City Civil Society Mobilisation by the Urban Poor, ed. Heidi Moksnes and Mia Melin (Uppsala: Hallvigs, 2014), pp. 95-102

Gloc-9, ‘Dapat Tama’, Dapat Tama, [download track], (YouTube, 28 December 2022)

Gloc-9, ‘Hari ng Tondo’, MKNM (Mga Kwento Ng Makata), [download track], (Spotify, 28 December 2022)

Gloc-9, ‘Upuan’, Matrikula, [download track], (Spotify, 28 December 2022)

GMA News, Mga taga-Sitio San Roque, nagbarikada at nakasagupa ang mga pulis, online video recording, YouTube 2 July 2013, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eXw5iPSM6Og> [accessed 28 December 2022]

GMA News, Mga taga-Sitio San Roque sa Brgy. North Triangle sa QC, magbabarikada sa EDSA vs demolisyon, YouTube 1 October 2012, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pTGfoFiJ_yM> [accessed 28 December 2022]

Guerrero, Sylvia H., ‘Staying where the action is: relocation within the city.’, Philippine Sociological Review, 25.1/2 (1977), 51-56

Mabilin, Myra, ‘Forced evictions, off-city relocation and resistance: Ramifications of neo-liberal policies towards the Philippine urban poor’, in Claiming the City Civil Society Mobilisation by the Urban Poor, ed. Heidi Moksnes and Mia Melin (Uppsala: Hallvigs, 2014), pp. 133-137

Ortega, Arnisson Andre C., ‘Manila’s metropolitan landscape of gentrification: Global urban development, accumulation by dispossession & neoliberal warfare against informality.’, Geoforum, 70 (2016), 35-50

Quijano, Ilang-Ilang, Puso ng Lungsod (Heart of the City), documentary, Cinemata, 9 March 2022, <https://cinemata.org/view?m=CVCqO9mr4> [accessed 10 February 2023]

Recio, Redento B. and Kim Dovey, ‘Forced Eviction by Another Name: Neoliberal Urban Development in Manila’, Planning Theory and Practice, 22.5 (2021), 806-812 Rivermaya, ‘Isang Bandila’, Isang Ugat, Isang Dugo, [download track], (Spotify, 28 December 2022)

Rosebud, ‘Pabahay: Assessment and Perception of Housing Beneficiaries on National Housing Authority (NHA)’s Resettlement Project in Towerville, Brgy. Gaya-gay, San Jose del Monte, Bulacan’, (2016) <https://politicssocietyngovt.wordpress. com/2016/05/27/pabahay/> [accessed 10 February 2023]

Save San Roque Alliance, Moving towards ‘Housing For All’: A 2022 Report on Housing Eligibility (Census Status, Occupancy Type, and Evidence of Residence) in Sitio San Roque, North Triangle, Quezon City, pp. 1-10

Save San Roque Alliance, Sitio San Roque Development Plan: An alternative housing solution initiated by Kadamay-San Roque, pp. 1-15

Seki, Koki, Ethnographies of Development and Globalization in the Philippines: Emergent Socialities and the Governing of Precarity (London: Routledge, 2020)

Starte, Julius, Jerson Pesebre, Reynold Cantero, Rodil Cantero, Sadath Cantero, and Myrna S. Cuntapay, ‘Problems Encountered By The Informal Settlers in Sitio San Roque Brgy. Bagong Pag-Asa, Quezon City.’, Ascenders Asia Singapore-Bestlink College of the Philippines Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, 1.1 (2019)

Vera, Rody, ‘Manggagawa’, [download track], (YouTube, 28 December 2022)

Figure 1: Castro, Francille Raven, Sitio San Roque Homes, 2023, Digital Collage

Figure 2: Castro, Francille Raven, My Filipino Upbringing, 2023, Digital Sketch

Figure 3: Castro, Francille Raven, Map Locating Sitio San Roque, 2023, Digital Infographic

Figure 4: Castro, Francille Raven, Sitio San Roque’s Work Force, 2023, Digital Sketch

Figure 5: Castro, Francille Raven, Sitio San Roque Material Sketch Analysis, 2023, Digital Infographic

Figure 6: Ayala Land, Ayala Malls Vertis North, digital photograph, 2019 <https://www.ayalaland.com.ph/estates/vertis-north/> [accessed 10 March 2023]

Figure 7: Ayala Land, Seda Vertis North, digital photograph, 2019 <https://www.ayalaland.com.ph/estates/vertis-north/> [accessed 10 March 2023]

Figure 8: Castro, Francille Raven, Enriching Lives?, 2023, Digital Collage

Figure 9: Quijano, Ilang-Ilang, Puso ng Lungsod (Heart of the City), documentary, Cinemata, 9 March 2022, <https://cinemata.org/view?m=CVCqO9mr4> [accessed 10 February 2023]

Figure 10: Quijano, Ilang-Ilang, Puso ng Lungsod (Heart of the City), documentary, Cinemata, 9 March 2022, <https://cinemata.org/view?m=CVCqO9mr4> [accessed 10 February 2023]

Figure 11: Ellao, Janess Ann J., Lorna Conception: “This used to be my house.”, Bulatlat, 27 January 2014 <https://www.bulatlat.com/2014/01/27/north-triangle-residents-lose-homes-to-demolition-decry-overkill/> [accessed 10 February 2023]

Figure 12: Google, Bagong Pag-asa, Google Earth, <https://earth.google.co.uk> [accessed 10 March 2023]

Figure 13: Recio, Redento B. and Kim Dovey, ‘Houses are incrementally demolished and then fenced to prevent re-encroachment, digital photograph, ‘Forced Eviction by Another Name: Neoliberal Urban Development in Manila’, Planning Theory and Practice, 22.5 (2021), 806-812

Figure 14: Castro, Francille Raven, Map Locating Relocation Sites, 2023, Digital Infographic

Figure 15: Castro, Francille Raven, Towerville Housing Sketch Analysis, 2023, Digital Infographic

Figure 16: Castro, Francille Raven, Diagram Showing the Eviction Cycle, 2023, Digital Infographic

Figure 17: Save San Roque Alliance, ‘Dream House Workshop’, digital photograph, Sitio San Roque Development Plan: An alternative housing solution initiated by Kadamay-San Roque, pp. 1-15

Figure 18: Tinig Maralita, ‘Counter-mapping Workshop’, digital photograph, <https://tinigmaralita.com/> [accessed 10 March 2023]

Figure 19: Save San Roque Alliance, ‘CDP Validation Workshop’, digital photograph, Sitio San Roque Development Plan: An alternative housing solution initiated by Kadamay-San Roque, pp. 1-15

Figure 20: Castro, Francille Raven, Working with the Community, 2023, Digital Collage