by Michael Edwards

Michael Edwards

Dedicated to Guy Robert (1926 – 2012) and Edmond Roudnitska (1905 – 1996), and to the many readers who urged me to continue the Perfume Legends saga.

Henry Ford famously declared that history was bunk: an interesting, if somewhat controversial, statement. But if one ignores perfumes’ history, how can one anticipate the future?

New fragrances rarely spring from nowhere. So often, they take inspiration from the past.

Yet perfumery’s heritage is gradually disappearing. So many iconic fragrances have been tampered with, often beyond recognition.

Behind every great fragrance there is a great story. But today that story is often overwritten by IFRA regulations or marketing strategies. Think of the Mona Lisa repainted without her enigmatic smile. History reinvented.

Perfume is my profession and my passion. I have always been intrigued by how the great fragrances came about. But, apart from Edmond Roudnitska’s insightful Le Parfum, I could find no books in which perfumers spoke of their work.

Fortunately, throughout my career, I have had the chance to meet many perfumers while updating my annual Fragrances of the World reference guides. To my surprise and delight, most were willing to discuss their work and fragrant creations.

Two master perfumers, in particular, opened doors for me: Guy Robert (Madame Rochas, Calèche, Dioressence) and Edmond Roudnitska (Femme, Diorissimo, Eau Sauvage). In all, I interviewed some 160 perfumers, bottle designers, Houses’ executives and couturiers. I asked them all to name the French perfumes they regarded as true icons.

Gradually the definition of a legend evolved: an accord so innovative that it inspired other compositions; an impact so profound that it shaped a new trend; and an appeal likely to transcend the whims of fashion.

I was determined to let the creators speak for themselves. The quotes in this book are their actual words. Each had the opportunity to check my drafts.

Perfume Legends, published in 1996, was the result.

For the first time, perfumers spoke openly of their work and the sources of their inspiration.

Today, perfumers are celebrities. The book has acquired cult status, resold on eBay and Amazon for extraordinary prices.

Readers encouraged me to update the Legends saga. I hesitated only because I was pushed to the hilt evaluating as many as 2,700 new fragrances each year for the Fragrances of the World database and reference guide.

But I continued to research and interview because the Perfume Legends project is my legacy, a perfume museum whose exhibits are historically accurate and their narratives factually correct.

The updated Perfume Legends II adds eight new treasures to the museum’s collection. Most of the original legends have been extensively revised as well, with the addition of new material.

Now I shall turn to the next project, American Legends. No one has written in detail about the evolution of American fragrances. I shall enjoy the challenge.

Michael Edwards

Paris, 2019

Michael Edwards’s book represents a truly praiseworthy effort to help people better appreciate the great perfumes of this century. The result of many years of painstaking research, there is no other book like it.

Michael Edwards has asked me to write this foreword because, having begun my career in 1926, I am the last perfumer with first-hand knowledge of the great perfumers and their work.

In the first chapter, Michael Edwards makes a thorough examination of the birth of modern perfumery. Houbigant’s Fougère Royale in 1882 – an accord of oakmoss, coumarin and, later, amyl salicylate – was the first milestone, followed seven years later by Aimé Guerlain’s Jicky, in which for the first time a perfume was dominated by the essence of sandalwood. Although quite heady for its time, it was nothing next to what would become Samsara one hundred years later. Jicky flowered a century after the horrors of the 1789 Terror, so it was not without sadness that amidst the great to-do surrounding the Bicentenary of the French Revolution in 1989, I heard no celebration for Jicky’s hundredth birthday.

Following in the footstep of Aimé, Jacques Guerlain was to achieve great success, notably with L’Heure Bleue in 1912, Mitsouko in 1919 and Shalimar in 1925, all of which are still popular today. Jacques Guerlain’s most modern composition was probably Vol de Nuit, which was not given the full appreciation it merited, either from the public or from the House.

The story of the early days of the career of François Coty and the rapid development of his business are described with great accuracy and in great detail. The major milestones of his brilliant career were La Rose Jacqueminot, Ambre Antique, L’Or and the most especially L’Origan in 1905 and Chypre in 1917. Coty brought perfume to the world. Neither Fougeraie au Crépuscule, La Jacée nor Muguet des Bois – a magnificent synthesis of flowers launched after Coty’s death –achieved the success that the beauty of their composition deserved.

The story of the Chanel perfumes, especially that of N° 5, has excited so much malicious gossip that truth and fiction, or rather legend, have become closely entwined. What is not in doubt, however, is the talent and taste of Ernest Beaux, nor his temperament which allowed no one the privilege of telling him what to do. His best composition was not N° 5, which has always been cleverly promoted, but rather the magnificent Bois des Iles of which Chanel has never taken full advantage. Beaux also created a good Gardénia and a fine Cuir de Russie for Chanel, and an excellent Soir de Paris for Bourjois.

If in this foreword I have looked only at the first chapters, dealing with the dawn of modern perfumery, it is so that the reader need no longer be deprived of the pleasure of learning about the other illustrious people who have a place in the world of contemporary perfume. They –beyond any doubt – are treated with the full honour that they deserve.

Edmond Roudnitska Cabris, February 1996

Opium revolutionised perfumery. The perfect synergy of its scent, name, bottle, pricing and advertising changed forever the presentation and marketing of prestige perfumes. Opium brought oriental fragrances back into vogue, and opened the door for the explosion of floral oriental notes in the 1980s. Ironically, the perfume was conceived and born over the protests of its foster parents. Yet had it not been for the determination of a number of people who believed in Yves Saint Laurent’s controversial vision, Opium might never have seen the light of day.

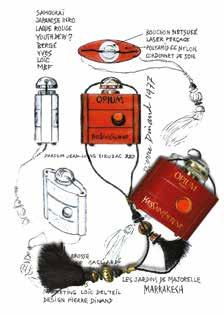

The saga began quietly. “We started thinking about Opium late in 1972,” says former marketing director Loïc Delteil. “For eighteen months or so, we bounced various ideas around with M. Saint Laurent. I sensed there was a desire amongst women for a new kind of oriental fragrance, rich and tenacious. Not only was it a fragrance category that had been ignored for years, but it also meshed perfectly with M. Saint Laurent’s vision of a perfume which evoked the Orient. Pierre Dinand’s bottle, though, was the trigger that inspired M. Saint Laurent to name it Opium.”

Hélène Rochas first introduced Dinand to Saint Laurent shortly after the young couturier left Christian Dior. Their association was fruitful. Dinand designed the bottles Y (1964), Rive Gauche (1969), Pour Homme (1971), and Eau Libre (1974). “Yves had just returned from a trip to Japan and China when I met him and his partner, Pierre Bergé, to talk

about the project. ‘I’d like something oriental,’ he told me as we discussed possible bottle designs. The direction intrigued me because I shared his taste for the Orient. I had once spent eighteen months studying at the Royal School of Fine Arts in Cambodia. At that point, the working name for the fragrance was Ichi, a Japanese word that means Number 1, but Yves imagined a bottle with pompoms more in the oriental style of Napoleon III.”

Orientalism had long fascinated Saint Laurent. “It’s the old world which gives us modernity,” he said.

“Orientalism in Europe began around 1820 in France. It was at its maximum creative level around 1919. Bakst, the Ballets Russes, Nijinsky, jazz, Josephine Baker in Paris, Picasso and Matisse are all part of the modern development of orientalism. Even today, everything that is modern in music, colour, art has as its base the orientalism of Europe.” 1

Dinand probed deeper. “What do you see when you think of the Orient?” he asked Saint Laurent. “Flowers of fire,” replied the designer, “like when you take LSD.’ ‘Sorry,’ I told him, I don’t take LSD.’ ‘If you want to see what I mean,’ he said, ‘close your eyes, push on your eyeballs, and you will see the flowers of fire.’ ”

“He was right,” says Dinand. “I saw an explosion of yellow and red and blue. And so the red and gold flowers of fire on the Opium box were Yves’ imaginative idea. I absorbed his words and symbols: the orientalism of Napoleon III, pompoms, Japan, China, red, purple, gold, flowers of fire, and trans-

Yves Saint Laurent: creative sketch on vellum paper “Yves imagined a bottle with pompoms more in the oriental style of Napoleon III.”

lated his perceptions into a number of bottle options.”

Dinand proposed three designs to Delteil. “The first, a Napoleonic bottle looked too Victorian, and we dismissed it immediately,” says Delteil. “The second proposal looked like a Chinese screen, while the third was the inro design. Although it had been developed originally for Kenzo, who had refused it, the shape interested us.”

Dinand was convinced that the most appropriate symbol was an oriental objet d’art. “I had already worked for Kenzo on a stylised version of the ancient inro which the Japanese samurai used to hang on their belts,” he says. “The inros were small wooden boxes containing several drawers in which were kept spices, medicinal herbs, salt and opium for soothing the pain of wounds. The inro drawers were secured by a cord, which was pulled through a small sculptured ball, a netsuke, on the top of the box, representing a person or animal. The inros were quite ornate, and often inlaid with mother-of-pearl and ivory. Although Kenzo had turned down my proposal, I was convinced that the idea was good. The more I thought about it, the more perfectly it seemed to fit Yves’ requirements. So I decide to show him my wooden inro bottle with a netsuke cap.”

The opium trademark? What was this all about? ‘It’s for the new Saint Laurent fragrance,’ they said. And that was how Charles of the Ritz and Squibb learnt of Opium.”

At the time, Saint Laurent and Bergé’s relationship with Charles of the Ritz was not good. “They did not feel that the U.S. company had their interests at heart,” says Miller. “We had allowed the French team to operate fairly independently because we also had some very major problems in other areas. Besides, Loïc Delteil clearly knew what he was talking about. It was he who identified an opportunity for a strong, longlasting French fragrance, and it was he who decided to target the fragrance against Guerlain’s Shalimar (1925). Working with Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Dinand, Loïc did all the preliminary work on fragrance profiles and packaging designs.”

Bergé invited Dinand to present his work in Marrakech at the house he shared with Saint Laurent. “I showed my model to Yves, who immediately recognised an inro and its netsuke. His reaction was enthusiastic. ‘I love it,’ he said. ‘That’s where the samurai keep their medicine and their opium pellets,’ he exclaimed. ‘Opium ... Opium? Oh, that would be a fantastic name.’ I had written the name Ichi on the bottle in gold. Yves loathed the name. ‘We’ll call it Opium!’ he said.”

The trademark Opium was owned by Pinot. “I introduced myself as the European manager of Charles of the Ritz, the American company that owned the perfume rights to Yves Saint Laurent, and bought the name for only 1,200 francs,” says Delteil.

By some oversight, Charles of the Ritz was not advised of the purchase. Robert Miller had just been made president of the international division when an item in the French financial statements caught his eye. “I queried it and was told that it related to the purchase of the trademark from Pinot. ‘What trademark?’ I asked. ‘The Opium trademark!’ they said.

Saint Laurent’s choice of name bemused the conservative Squibb Corporation, which at the time owned both E. R. Squibb & Sons, the pharmaceutical giant, and Charles of the Ritz, which in turn owned Parfums Yves Saint Laurent. “Frankly, I don’t think they took it too seriously because the project was still in its early stage of development,” says Miller. “No one asked me to approach Saint Laurent to change the name and I certainly had no intention of doing so. It was not until early 1976 that the name became an issue. At the suggestion of Dick Furlaud, Squibb’s chairman, the new president of Charles of the Ritz asked the US marketing group responsible for Parfums Yves Saint Laurent to begin planning for Opium’s introduction. It was only then that objections were raised that ultimately brought panic to the executive suite.”

“Squibb’s senior managers reacted with horror to the implications of Opium,” says Larry Appel, former U.S. marketing vice president of Parfums Yves Saint Laurent “But they overlooked the fact that Saint Laurent had the authority to make the name legitimate. Only Saint Laurent could have come up with a fragrance called Opium. Only Saint Laurent’s name had the power to turn Opium into a fashion statement, and make it respectable. He was the most avant-garde designer of the time. His reputation was at its peak.”

Saint Laurent was born in 1936 in Oran, Algeria. When he was only eleven, he saw a superb production of Molière’s The School for Wives, with sets

“I showed my model to Yves, who immediately recognised an inro and its netsuke. ‘That’s where the samurai keep their medicine and their opium pellets,’ he exclaimed. ‘Opium ... Opium?’”

and costumes by Christian Bérard. It made such an impression that he spent most of his spare time designing miniature sets and costumes. On finishing high school, Saint Laurent furthered his studies in Paris at the haute couture school run by the Chambre syndicale de la couture parisienne. Within six months, he won first prize in an International Wool Secretariat contest which brought him to the attention of Michel de Brunhoff, editor of French Vogue. Looking through Saint Laurent’s portfolio, he was astounded at the similarity between the young man’s designs and those planned by Christian Dior for his upcoming A-line collection. He introduced the two and Saint Laurent was immediately hired as an assistant. “Working with Christian Dior was, for me, a miracle,” said Saint Laurent. “I had an endless admiration for him. He was a prodigal master and taught me the roots of my art.”

It was against this background that Squibb struggled to come to grips with Saint Laurent’s vision of perfume. “I express my point of view through the creation of the scent just as I would in a collection,” the designer told Vogue editor-at-large André Léon Talley. “Opium does not have the same echo for me as perhaps it may have for those who associate it only as a drug. It is the beginning of all that is seductive. I wanted a perfume for the Empress of China. I started with that name in mind, and it was the only name I wanted. After Y (1964), I wanted a lush, heavy, indolent fragrance. I wanted Opium to be captivating, and it’s a fragrance which evokes all the things I lovethe refined Orient, imperial China, exoticism.” 2

In October 1957, Dior died suddenly and Saint Laurent was named his successor. At the age of only twenty-one, he had become head of the world’s largest couture House. His first collection was classic Dior. His next four collections won praise for their “effective combination of youthfulness and beauty”, but his autumn/winter 1960 collection was a disaster. Inspired by street fashion, he presented a downmarket melange of motorcycle jackets and turtle-neck sweaters. It was his last collection for the House. Shortly after he was called up for military service, Dior announced that Saint Laurent had been replaced by Marc Bohan.

On January 29, 1962, Saint Laurent struck back, opening his own House in partnership with Pierre Bergé. Finance came from Atlanta businessman J. Mack Robinson, who later sold eighty percent of his shares to Charles of the Ritz.

Saint Laurent’s first collection was a triumph. Life magazine said that he had produced “the best suit collection since Chanel.” His second was praised as “a glittering tour de force” by U.S. Vogue

In 1971, Harper’s Bazaar dubbed Saint Laurent “the greatest fashion designer in the world”. By 1976, his reputation was cemented. Even the New York Times gave his Ballets Russes collection front page coverage. “A revolutionary collection, which will change the course of world fashion,” read the headline.

Saint Laurent put his heart, mind and soul into Opium: “Opium was his creation, and he went through hell to put it together,” says Appel. “Creation never came easily to him. It was an agonising process for him. His work drained him. That was why Bob Miller tried to convey the message to Squibb, ‘YSL is serious. He is not advocating drugs. Opium is a fashion statement.’ It did not cut any ice. Most of our colleagues at Squibb really didn’t get it. So I was given the task of finding another name. I asked everyone I knew for ideas, from advertising agencies to freelance copywriters and journalists - even my gardener, who had a way with words. I remember that the name Black Orchid captured Squibb’s imagination for a while, but nothing of worth really surfaced. Meanwhile, Saint Laurent continued to say, ‘It’s Opium or nothing.’

“The whole idea scared Squibb. The only executive who understood what we were talking about was the chairman, Richard Furlaud. He was a very sophisticated, bright and sensitive man who had been educated in France and spoke French fluently. He understood the wider world. Without his perception, Opium would have been dead in the water, but the man who deserves the credit for pushing Opium was Bob Miller. I remember attending a high-level meeting at which objections were raised yet again about the drug implication of the name. Miller’s reply was simple: ‘I’ll put my job on the line that this is going to be an important project and that it’s going to be successful, and that it will not embarrass the company - and all you people in this room are witnesses!’ It was a bold move by a brave man who was convinced Saint Laurent was right.”

Miller personally took charge of the project towards the end of 1975. “It was a difficult time because Yves was out of commission,” he says. “There were rumours around Paris that he had a drug problem or had suffered a nervous breakdown. It was also about that time that Loïc ran into some problems with Yves’ inner circle. They felt that he was preempting Saint Laurent’s decisions and made him persona non grata. Reluctantly, I became the contact, even though I spoke little French at the time.”

Delteil agrees that it was a difficult period: “Everything was coming to a head, and there were so many details to be finalised. I resigned three times,

but came back because Opium was my life, my passion. I was lucky to find Chantal Roos, who had assisted Coty’s communications manager. Chantal took over the project at its most interesting stage and became the go-between.”

Roos joined the team at the beginning of 1976.

“I remember that all there was at that point was the name Opium, a wooden mock-up of the inro bottle, and a number of fragrances under evaluation,” says Roos. “The name Opium did not disconcert me; I found it intriguing. As a young product manager, I didn’t care what people might say because M. Saint Laurent had chosen a name which put the world at my feet.”

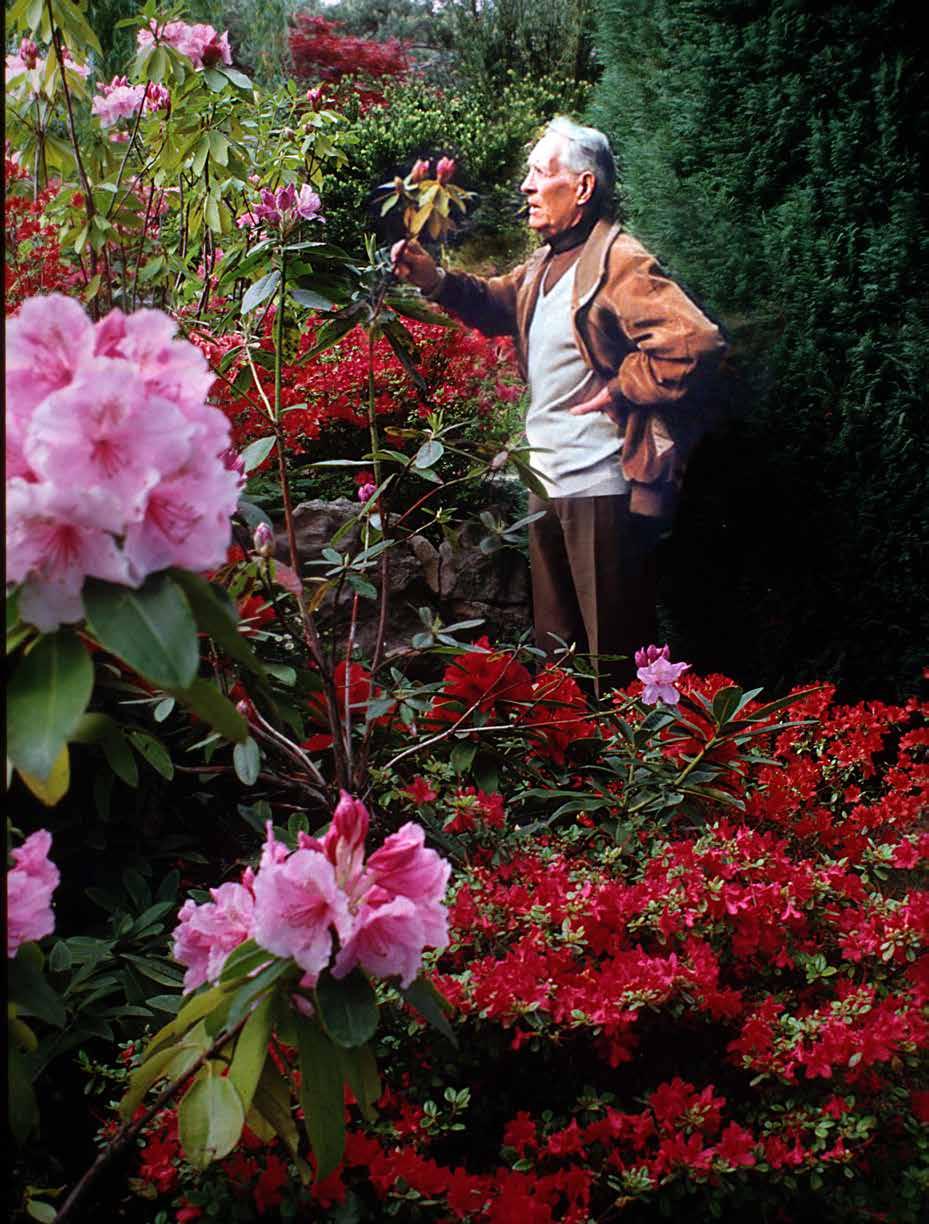

Created by Jean-Louis Sieuzac (below), Raymond Chaillan and Françoise Marin of Roure Bertrand Dupont, now incorporated into Givaudan

From the start, Delteil had intended Opium to be YSL’s first international fragrance. “We imagined a perfume that would create its own revolution ... and shock the United States,” he says. “The direction of the first brief went like this: when a woman is young and wants to have fun, she goes to a disco. She needs a perfume for the night out, a perfume that will let her dream of escaping into another world. To me, that implied a heady perfume, an oriental such as Shalimar. That feeling became a conviction when M. Saint Laurent decided on the name Opium.”

Although Charles of the Ritz was careful to leave the direction of the project in French hands, they decided to collaborate on the fragrance development. “We had to make sure the fragrance suited both sides of the Atlantic,” says Richard Loniewski, then vice president of fragrance product development at Charles of the Ritz. In Paris, Delteil and Roos briefed a number of laboratories, including Roure Bertrand Dupont, which had already composed the four earlier Saint Laurent fragrances. His brief was specific: an oriental capable of competing against Shalimar. “I know that Mrs Lauder felt Opium was a softer version of Youth-Dew (1953) but I had no idea at that time what Youth-Dew was!” declares Roos. “For a young French product manager, the best fragrances in the world are

Guerlain. That’s why we tested the perfumes against Shalimar.”

In New York, Loniewski headed the search. “The Opium profile called for a fragrance that would impart a sense of ‘modernity, elegance, sophistication, glamour and fashion’,” he recalls. “We wanted something modern with a strong, elegant personality. We wanted something really original, so we told the fragrance suppliers to submit something avantgarde. We looked at Shalimar and Youth-Dew, both of which were very popular in the States at the time, and thought of modernising them by adding fruity notes, and some aldehydes to give the accord more fusion.”

Loniewski gave the profile to five laboratories. “We weren’t happy with the first round of submissions, so we decided to work most closely with Roure, not just because their French perfumers were developing submissions for Chantal, but also because they had had such a long and close relationship with Saint Laurent, having created Y (1964), Rive Gauche (1969) and Pour Homme (1971).”

Youth-Dew may not have inspired Roos, but it did influence Roure’s perfumers. “Roure’s vice-president, Alvin ‘Bud’ Lindsay, had worked at IFF, which created Youth-Dew,” says Dinand. “Lindsay knew Youth-Dew well, and he

encouraged Roure’s perfumers to use it as a target when they were creating Opium.”

Perfumer Raymond Chaillan

A Roure submission finally won the brief. “Opium was created by the ‘school of Roure’, and a number of perfumers contributed to it,” says Jean Amic, former president of Roure. Jean-Louis Sieuzac, Raymond Chaillan and Françoise Marin all contributed a piece to the puzzle. “Few perfumes today are the sole work of one perfumer,” Amic continues. “In the old days, it was different. Perfumers worked on their own. Now, it’s a team effort. One perfumer may have the idea, while another may be very good at finishing or balancing the fragrance. In a company like Roure, there is a reservoir of formulae, so perfumers start with an advantage.”

The basic accord which evolved into Opium took its starting point from two fragrances: Youth-Dew (1953) and You’re the Fire, a soft oriental created by Roure in 1973. In turn, You’re the Fire may be traced through Shocking (1937), another Roure composition, to Tabu (1932), both created by Roure’s great perfumer, Jean Carles. “It was not by coincidence that Opium was created at Roure, because it evolved from the patchouli/carnation accord of my father’s

Tabu,” says Marcel Carles, former director of Roure’s perfumery school. Jean-Louis Sieuzac, who later created Oscar de la Renta (1978) and Dune (1991), finished the work. “The brief was to create an original perfume, in the direction of Shalimar, but totally modern,” he says. “We had emerged from the vogue for green, rather dry floral chypres like Calandre (1969), No 19 (1971) and Rive Gauche (1969). There was an unconscious desire for voluptuousness. Opium started as a spicy floral, full of tiny carnations and little marigolds, to which we added an oriental dimension, because China was the theme of Yves Saint Laurent’s couture collection at the time. The oriental facet of Opium represents only some ten per cent of the overall formula but creates fifty per cent of the effect.

‘Opium, a sensual, heady and mysterious perfume, is an oriental blend which combines fragrant wood, pungent spices and the softest flowers with myrrh.’

Yves Saint Laurent

“It is the interpretation of the Chinese spirit which makes Opium so interesting. The originality of Opium lies in its combination of a spicy floral bouquet with a very special fresh note and a warm base. The harmony of the three elements makes it original. The trick was to assemble notes which are totally opposite, and to find a way to make them love each other. That’s where Opium is so clever.” Head notes Aldehydic spicy

Aldehydes, tangerine, plum, pepper, oriander, lemon, bergamot

notes

Clove buds, jasmine, cinnamon, rose, lily of the valley, ylang-ylang, peach, myrrh

Benzoin, vanilla, patchouli, opopanax, cedar, sandalwood, labdanum, cistus, castoreum, musk

In the United States, Loniewski tested Sieuzac’s Opium and two other submissions against Chloé (1975). “One was a soft oriental like Opium, but closer to Youth-Dew (1953), while the other was a chypre in the direction of Coriandre (1973),” he says. “We tested all three against Chloé because it was walking off the shelves at the time. The chypre got very good scores. The fragrance we now know as Opium finished a little bit behind, although it scored highly on lasting power and diffusion. In reviewing the results, we all came to the conclusion that Opium had to be an oriental. Most women would not know the difference between an oriental and a chypre, but the fact remains that an oriental has a deeper, spicier, fuller note than a chypre. The fragrance for Opium had to fit the whole picture and smell rich, mysterious and elegant.”

Opium was also the first French prestige fragrance to lift its concentration to levels previously unheard of in France. “Historically, French eaux de toilette had concentrations of only four to six per

cent.” says Loniewski. “American fragrances, by contrast, were much stronger. Chloé eau de toilette and Charlie concentrated cologne, for example, were around eighteen to twenty per cent. French women were prepared to top up their fragrance every four or five hours, but Americans felt differently. ‘One spray and I’m done for the day,” they declared. In essence, Estée Lauder had persuaded American women that fragrance should last and last and last. Her Youth-Dew started life as a bath oil with a level of more than seventy per cent perfume. She was the first to fragrance eaux de parfum at a level even higher than that of most concentrated perfumes. Against such competition, we had no choice but to make Opium stronger. That was why we perfumed the eau de toilette at nineteen per cent, and the perfume at around thirty per cent. Ironically, French women loved it just as much. Here at last was a fragrance with a lot of punch which lasted and lasted. They welcomed it as another great innovation from Yves Saint Laurent.”

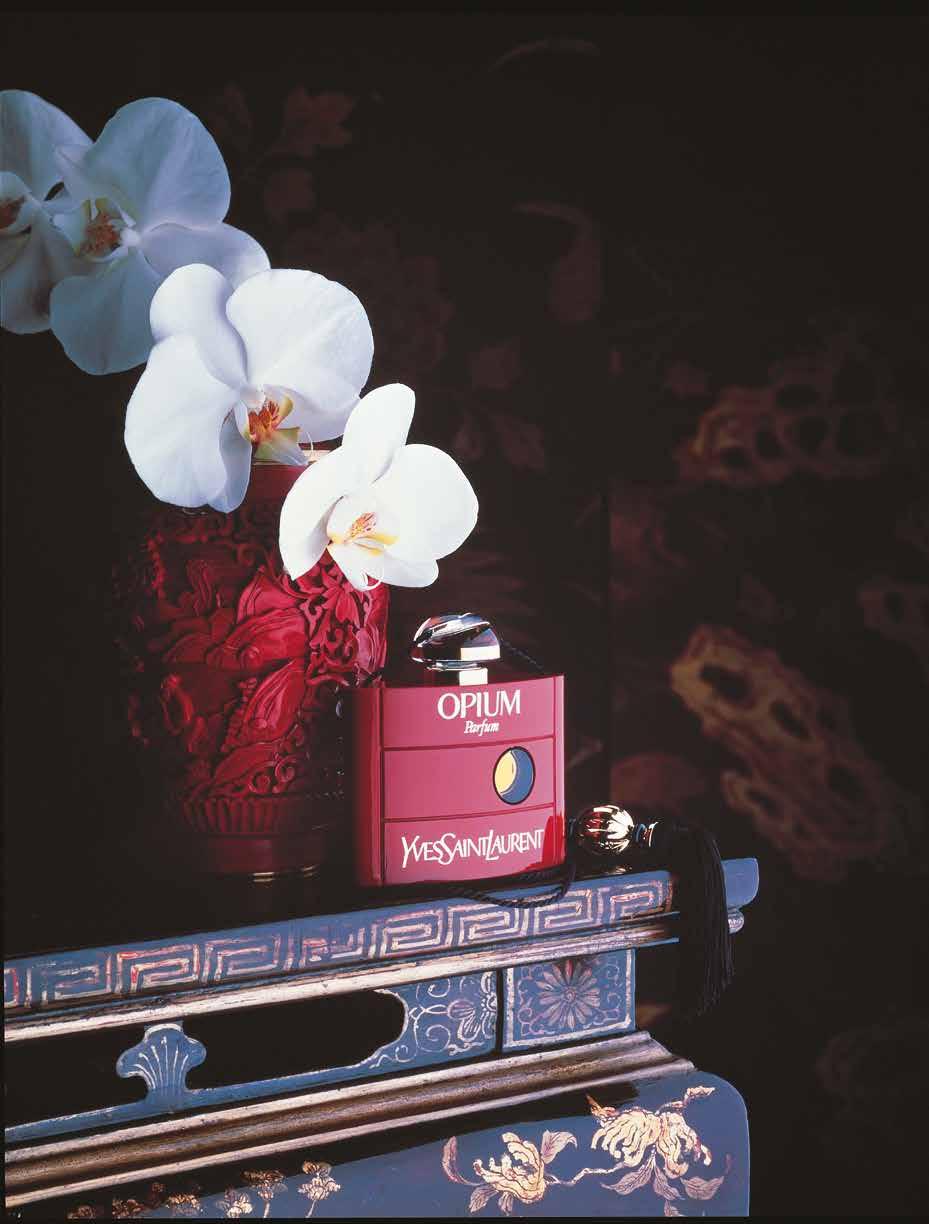

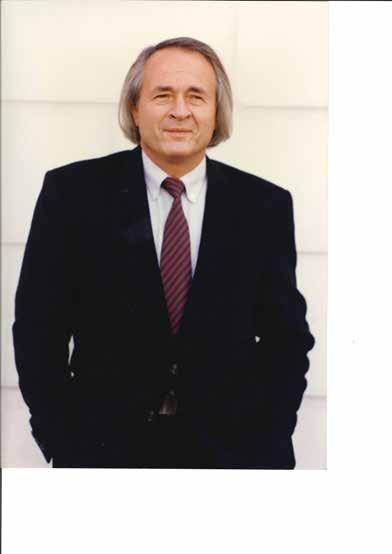

Designed by Pierre Dinand (below)

The selection of the fragrance proceeded more smoothly than the development of the packaging. “Everything was running late,” recalls Roos. “Originally, the inro bottle was to be made of wood with the bottle inside, but we were concerned that the wood gave it too rustic an appearance. M. Saint Laurent agreed. ‘Why not lacquer it?’ he suggested. He gave me a tiny antique Chinese drawer, which had the exact feel and colour he wanted. Not realis ing that it was so old and valu able, I cut it up and gave a little piece to everybody to match the colour and the texture. Lacquer would have cost a fortune so we replicated it with a beautiful ny lon plastic.”

Saint Laurent was unavail able at that critical point. “In his absence, Bergé approved Pierre Dinand’s inro bottle,” says Miller, “and we ordered the moulds. Months later, after Laurent’s health improved, the

first production samples of the bottles arrived. Yves was so upset by what he saw, he told us that he didn’t want to go ahead with the project and that we could not use his name on the fragrance. Although the contract gave us the right to package the fragrance any way we chose, clearly, we had to find a way around the problem. All kinds of threats and recriminations were flying back and forth. When things got to the point of Bergé telling us, ‘If you launch it, Yves is going to denounce it!’, we took a very strong stand. We made it clear that we would never have developed a perfume named Opium on our own, that we had gone forward out of respect for Saint Laurent’s genius, despite the misgivings of our parent company, Squibb Corp., that we had invested substantially in the project, and that if the project did not proceed, we would hold Saint Laurent accountable for any losses we sustained.

“Earlier, I had decided to re-

tain Dinand to prepare detailed engineering drawings and defuse the issue with Bergé, who was then very unhappy with the U.S. company, which he felt was incapable of executing Saint Laurent’s ideas. That was another reason why I reacted so strongly to Yves’ threat to denounce the project. We had accommodated him in every way possible, and the problems he subsequently found with the packaging were due to his absence at a critical stage in the project’s development, not to our failure to perform as he desired. His reaction was not due to any mean spiritedness, but reflected the evolutionary progress of his creative genius. Having been separated from the project for months, he was looking at the packaging with a totally different eye, demonstrating clearly that creativity is never stagnant. As a businessman, my challenge was to balance the desires of the artist to make late changes in the packaging with the financial consequences of those changes.”

Miller flew to Paris to review the production samples with Saint Laurent and Bergé: “Yves was still very upset. ‘This is not the bottle I wanted,’ he said. ‘It’s not the right colour. The plastic is too thick. The cap is too small. The carton is not right and the logo is not good.’ Although Bergé eventually agreed that what we had produced was what had been approved, Yves remained adamant. ‘I’m not going to allow it. It’s not me. It’s not right,’ he said. My attitude was simple: ‘Let’s try and find a solution.’

“By that stage, Yves was even uncertain as to whether or not he wanted plastic to cover the inro bottle. Unfortunately, we already owned some two million dollars’ worth of plastic material, so I told him we couldn’t do anything about that. Yves accepted the reality of the situation and turned his thoughts elsewhere. At the time, the perfume bottle was finished with a cord, knotted through a wooden ball, like a real inro. ‘It looks wrong,’ said Yves. ‘It needs something else.’ He walked out of the room, and re-

turned a few minutes later with a box of black tassels he had used that season for some of his couture clothes. One by one, he took them out of the box and placed them against the bottle. ‘What do you think about this?’ he asked me. It was an extraordinary experience. Here I was being asked for my opinion by the greatest designer in the world! Finally, he found the tassel he liked.

“Next, he told me to change the lettering of the Opium logo. The O was too slim for his taste. Then he looked at the cap of the perfume bottle. ‘It’s too small,’ he said. Not only was he right, but he also came up with a brilliant solution to create the right size impression. He replaced the cap of the 1/2 oz bottle with the cap designed for the 1 oz bottle. Then, of course, the neck finish looked too small so he came up with the idea of putting the gold band around it.”

The changes Saint Laurent wanted were not easily accommodated. “The inner package could be changed quickly, but we had no idea how to attach the tassels and beads,” says Roos. “Here we were in June, just three months before the launch date ... but if we had to do it, we had to do it! We could not change the ‘O’ of Opium for the first production run, but we managed the beads and tassel. It cost a fortune, because we bought them from a shop in the centre of Paris. Imagine the time it took the staff in the factory to thread each bead by hand. Imagine the costs! Later, the process was automated and less expensive suppliers were found.”

Miller and Roos then met together with Saint Laurent and Bergé. “By then, we had settled our differences,” says Miller. “We showed Yves new designs for the logo to allow him to pick one that he liked, and the new packaging. He was not an unreasonable person, and he accepted that there were some things which could not be done. There was not enough time, for example, to put the gold band around the neck of the bottles in the first production run, but we agreed

they would be added as soon as possible. Yves questioned us on the Chinese lacquer colour used in the plastic, and it was only when Chantal showed him the antique piece he had given her that he realised how very close we had come to his requirements. Once again, the project was on stream.”

A few weeks later, Miller and Amic showed the final fragrance to Saint Laurent. The designer’s initial reaction was hesitant. Although he had kept a close watch over the perfume’s development, something bothered him. “There’s something missing,” Miller recalls him saying. “It isn’t quite right. It’s got to remind me of the Empress of China.”

Miller’s comments give no indication of the consternation those words must have caused. “After re-

viewing Yves’ comments,” he says diplomatically, “we returned a few days later and showed him four different concentrations. We held our collective breaths, Yves smelt them all ... and selected one. Opium was born.”

Miller’s colleagues at Squibb still remained cautious. “They made a cop-out decision, and told Miller to launch Opium only in Europe,” says Appel. “They reasoned that perceptions of morality were different over there, and that there was not the sensitivity to promoting drugs as there was in the States. It was a case of ‘out of sight, out of mind’. The unspoken consensus was that it would probably just fizzle away.”

In October 1977, Opium was launched in France, and then rolled out through Europe. The reaction was extraordinary. Opium was an event. “It sold like mad,” says Delteil. “When there was no eau de toilette, people would buy the parfum no matter the price. Bottles of perfume disappeared from the counters. Whole delivery trucks were stolen. It sold so well that we cancelled all the advertising planned for 1978.”

Opium was introduced at a time of crisis for French designer fragrances. Courrèges’ Empreinte (1971), Carven’s Variations (1971), Balenciaga’s Cialenga (1973), Nina Ricci’s Farouche (1974) and Ted Lapidus’ Vu (1975) were all poor performers. Some were near-disasters. The costly failure of DiorDior (1976) represented a stunning setback for the leading House of the decade, while Bourjois-Chanel withdrew Ungaro (1977) within a year of its launch, for fear that its lack of success would damage the reputation of the couturier.

Opium’s success was even more remarkable in the light of its premium pricing. “Prior to its introduction, the highest priced fragrances were Joy

(1930) and Bal à Versailles (1962),” says Miller. “They sold at the equivalent of sixty-five to seventy-five dollars throughout Europe. When we were deciding on Opium’s price points, there was much discussion as to whether we should enter that ‘stratosphere’ and be satisfied with selling limited quantities, or whether we should make the price more accessible to achieve greater volume. In the end, I made the decision to introduce it at the seventy-dollar range, anticipating that within three to five years we could still achieve a profitable ten million dollars in sales, which reinforced Saint Laurent’s ‘exclusive’ image in the fragrance category. My reasoning was sound, but my vision as a financial prognosticator was not. We achieved my three to five-year estimate in the first full year. And when Opium was introduced in the United States the following year, there was no hesitation to price the one ounce parfum at one hundred dollars.”

Opium’s runaway success in Europe galvanised the decision to launch in the U.S. “Ironically, it was a decision made by the U.S. marketing group under pressure from Dick Furlaud,” says Miller. “Squibb’s

attitude begun to change when they saw the completed package and advertising, even before Opium’s French launch. Bloomingdale’s, New York’s avant-garde department store, was so determined to be the first to carry Opium in the United States that it began to buy supplies in Europe. It was only after some arm-twisting and a commitment to buy back the supplies already purchased abroad that Bloomingdale’s relented and agreed to wait for the formal introduction of Opium to the United States.”

Opium’s first advertisment featured model Jerry Hall, and was photographed in Yves Saint Laurent’s tiny Chinese study at his Parisian apartment

In September 1978, Opium reached America. Kristina Wrba, who by then had replaced Appel, Marina Schiano, Saint Laurent’s representative, and Cathy Spellman Cash orchestrated a spectacular party. “Yves Saint Laurent sails into Manhattan with a hot cargo - Opium at $100 an ounce,” read the headline in People magazine. “It’s Youth-Dew with a tassel,” retorted Estée Lauder.

“Yves Saint Laurent was certainly the host with the most with a bash to launch his new perfume, Opium,” reported New York’s City Daily News. “The setting: the sailing ship Peking, anchored in South Street Seaport. Fresh rose petals strewn on the gangways, sequins on the dance deck. Purple and crimson silk banners flying from the masks. Thousands of white orchids fastened to bamboo poles. One deck, turned into a carpeted ‘opium den’, was presided over by a thousand-pound bronze Buddha. Chinese lanterns, Japanese parasols, and several hundred down-filled pillows were everywhere for the guests to flop on. Rivers of Bollinger champagne; endless oysters, clams and mussels; canapés and crudités, disco music, Oriental dancers and a troupe of Chinese acrobats who were last seen wandering around the pier in the dark.”

Huge controversy surrounded the U.S. launch. “Activists wrote letters to us, people protested outside our offices,” says Richard Furlaud. “At one point, 57th Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenue in New York was blocked off by a demonstration of people who viewed Opium as an insult to the Chinese people. The impact of their protest was somewhat diluted by the fact that Opium had been very well received

in the People’s Republic of China. Others accused us of staging the whole Chinese protest as a publicity stunt. Little by little, the protests died down. They probably helped sales, but that was not our intention.

“In retrospect, I believe that it was right that Opium was launched first in France. Its great success there, and in Europe generally, greatly lessened the drug perception problem when we introduced it in the United States. Yves Saint Laurent understood this issue perfectly. At one point, in order to help explain why Opium represented an orientalist vision of romance, glamour and fashion but not a drug, he wrote a poem which I felt was right out of Baudelaire and Rimbaud. It was Yves’ extraordinary vision that was at the heart of the triumph of the fragrance.”

What made Opium succeed? Every one has an opinion. “Opium breaks all the taboos associated with escapism and drug use,” says perfumer JeanClaude Elléna. “Woman becomes a being apart, her perfume something mysterious, magical, sacred - to possess it is to gain access to a higher spiritual plane in quest of the absolute.”

Delteil attributes its success to the fact that “we understood the spirit of the times. Women wanted to have a ball. We created Opium to let people escape from their ordinary lives. Opium was an addictive product, but not a drug, so we put the emphasis on richness, opulence and innovation. It was a mad success in the media.”

“What makes Opium unique is that it had all the elements that make a perfume successful,” says Miller. “Its name, its parentage, its packaging and its advertising communicated the promise of mystery and sensuality, and its fragrance delivered that promise.”

The final word belonged to Yves Saint Laurent: “I think the great success of Opium comes not only from the quality of its perfume but from its scandalous mystery. It is mysterious. What other word can flatter itself as proudly for releasing so many evocative flows and uninterrupted cascades of poetical images?”

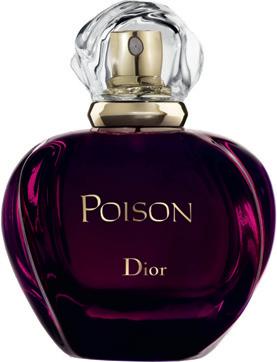

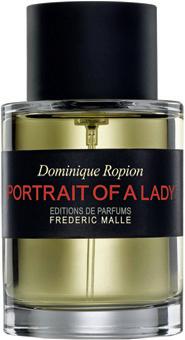

Perfume Legends (1996) revolutionised perfumery. For the first time ever, perfumers spoke openly about their work and the sources of their inspiration. ■ Today, perfumers are celebrities and Perfume Legends has acquired cult status. ■ Now the saga is updated in Perfume Legends II with new research, stunning images and eight new legends. The result is a fascinating journey through the evolution of French perfumery, through the stories of fifty-two perfumes from Aimé Guerlain’s Jicky (1889) to Fréderic Malle and Dominique Ropion’s Portrait of a Lady (2010).

«…there is no other book like it,» wrote Edmond Roudnitska, perfumery’s most influential perfumer.