by Michael Edwards

Michael Edwards

Perfume is my passion and profession. I am a taxonomist. I classify information. Specifically, perfumes. During the past forty years, my team and I have matched more than fifty thousand perfumes and made online fragrance finders possible.

Modern perfume history has always fascinated me but there was very little information about how the iconic fragrances were actually created. Until this century, perfumers were invisible, rarely acknowledged.

While checking my classifications, I would ask perfumers about their newest creations. To my surprise, most were more than willing to talk.

One insight led to another and in 1996, Perfume Legends : French Feminine Fragrances was published. For the first time, perfumers spoke about their work and the sources of their inspiration.

“There is no book like it,” stated Edmond Roudnitska (Eau Sauvage 1966), the most influential perfumer of the 20th century.

I always intended to follow Perfume Legends, with American Legends. One of my first interviews, for example, was with perfumer Joséphine Catapano. I spoke to her about her creation of Fidji (1966) but took the opportunity to talk also about her creation of Youth-Dew (1953) and Norell (1968).

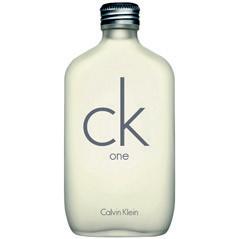

All the fragrances in both Perfume Legends and American Legends have been very carefully selected. Each legend introduced either a new note, a new accord so innovative – Chanel No 5 (1921), cK one (1994) – that hordes of competitors flocked to copy it, or made such an impact that it created a new trend (Opium (1977), Giorgio (1981).

Some inclusions may surprise: Antonia’s Flowers, for example, has disappeared, but it deserves a listing because it pioneered headspace technology.

I am often asked why American Legends took so long to complete. The answer is that my team and I were overwhelmed by the avalanche of new fragrances; in the thirty years from 1995 to 2024, we matched some forty-seven thousand new fragrances.

My sources and the people I interviewed are detailed by fragrance, in chronological order, at the back of this book, My interviews were mostly face-to-face, conducted over a period of twenty-seven years.

American Legends is the result and the first book to document the richness, the sheer originality of American fragrances.

It is living history.

Michael Edwards Paris and Sydney

I happen to love perfume!

I’m not alone. Millions are drawn to its magnetic, wonderfully evocative qualities. As alluring as fragrance is on a personal level, it’s also big business.

In American Legends, Michael Edwards delivers a living history, decade by decade, of fragrance in America. From historical, cultural, industrial and creative perspectives to the personalities behind the world’s favorite perfumes, the book in your hands captures it all.

It is a story of American ingenuity, creativity and business growth; but, ultimately, it is a love story.

The creation of perfume is a passionate endeavor, a search to find the elusive blend of ingredients that will turn heads.

Fragrance creation is truly both art and science, akin to a high wire performing act. Once the blend is perfected, the design of bottles and packaging must accentuate its characteristics and speak to its heart. Behind the scenes, perfumers, bottle designers and creative directors work together in graceful collaboration, making the magic happen.

The history of perfume in America is a fascinating one.

By the 1950s, the French were renowned as perfumers, while Americans were newcomers. Early fragrance entrepreneurs had to take enormous risks; among them was my mother, Estée Lauder.

I mention my mother because her story very much illustrates the genesis of the American fragrance business. In 1953, she introduced Youth-Dew, a bath oil that doubled as a skin perfume.

Youth-Dew wasn’t subtle. It was bold, a scent that demanded attention and lasted all day long. Notably, it was a fragrance that was marketed to women to buy for themselves. It wasn’t a delicate glass vial that sat on a dressing table, only to be dabbed on for special occasions. Women loved it! I believe that men did, as well.

In the competitive world of fragrance, many competitors were eager to dismiss Youth-Dew. However, my mother understood American consumers, and Youth-Dew wasn’t just hugely popular; it helped set the stage for a new style of perfumery in America, the success of which soared throughout the world.

In the end, the perfume industry in the United States came to reflect American ingenuity and creativity at its best.

After all, what better way to break into the market—and break through!—than to break the rules and take chances?

The goal was to win the hearts of Americans.

It is in this book that you will find the stories of creative women and men who did just that and more.

Our author is not only a wonderful storyteller, but I happen to know he spent decades researching the material for American Legends. The fragrance industry owes huge gratitude to Michael for his decades of dedication to the topic.

There is so much to say about American Legends, but I’ll close with this: Read it! Give it to every business student, entrepreneur and marketer you know. Give it to the historians in your circle. Most importantly, share it with people who are passionate about perfume and all who appreciate beauty.

As I said from the start, it’s a love story. Like a wonderful perfume, who can resist?

Leonard A. Lauder

New York

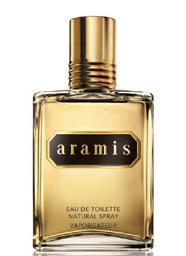

Newsweek dubbed it the ‘Scent of the Century’: Giorgio was sexy, glitzy, bold and brash. It shifted the perfume focus from Paris to Beverly Hills and turned the fragrance industry upside down.

Norell’s (1968) success had inspired upscale American department stores to feature perfumes as star products, but it took Giorgio’s powerful performance in Bloomingdale’s New York to convince managements that fragrance was a core business. For retailers, the key criteria are always turnover per square foot and the ability to bring customers through the doors. Giorgio delivered both in spades.

For many visitors to New York, the Giorgio carts at Bloomingdale’s were high on the list of must-see tourist attractions, right up there with the Empire State Building and the Statue of Liberty. Never had a fragrance caused such a sensation, or such a backlash. In restaurants, signs read ‘No dogs, no Giorgio’.

Giorgio, the store, was opened in 1961 by George Grant and his partner, Jack Axelrod. Back then, Rodeo Drive was no more than an ordinary thoroughfare in Beverly Hills.

Fred Hayman, who at the time headed the

banqueting department of the Beverly Hilton hotel, invested $30,000 in the venture. Hayman was famous for his sales skills – and his impressive business network. When in 1962 the store faltered, Hayman bought out his two partners. But it wasn’t until 1966 that he and his wife Gale moved to run the boutique full-time.

Hayman became the architect of luxury in Los Angeles, “bringing high fashion, a social shopping atmosphere, and white glove service to what was still a sleepy main street,” wrote the Los Angeles Times.

“Most of the stores in Beverly Hills, such as I. Magnin and Saks, carried the same things,” Denise Hale, Vincent Minnelli’s ex-wife, told Steve Ginsburg, author of Reeking Havoc: The Unauthorized Story of Giorgio. “When Fred came into Giorgio, he said, ‘Come in, my lady. Have a little drink’. I thought it was original and relaxing to come in, sit down, talk with the proprietor, and have a few laughs. When I went to Giorgio, I had the feeling I was going to Paris or Milan to buy something. It was the beginning of the resurrection of Beverly Hills.” 1 To enhance its relaxed atmosphere, the chic boutique featured a fireplace, bookshelves and a pool table. Cappuccino, tea, wine and liquor were

served. A 1952 Rolls-Royce delivered customers’ purchases.

“Fred Hayman brought to retail a sense of showmanship and focus on service, both of which he learned while working at hotels and restaurants, and created a store whose fame extended far beyond Rodeo Drive,” wrote Lorna Koski in Women’s Wear Daily. 2 The shop was the model for ‘Scruples’ in the best-selling novel of that name by Judith Krantz

After years of selling luxury fashion and accessories, fragrance seemed the next logical step. “I was convinced that our fragrance would be very different, because it would be created by a retailer, not a designer,” says Gale Hayman. “Designers have always done fragrances, retailers haven’t.”

In 1973, Giorgio introduced a signature fragrance for the boutique, a twist on Joy (1930) created by IFF’s head perfumer, Bernard Chant. It was not a success.

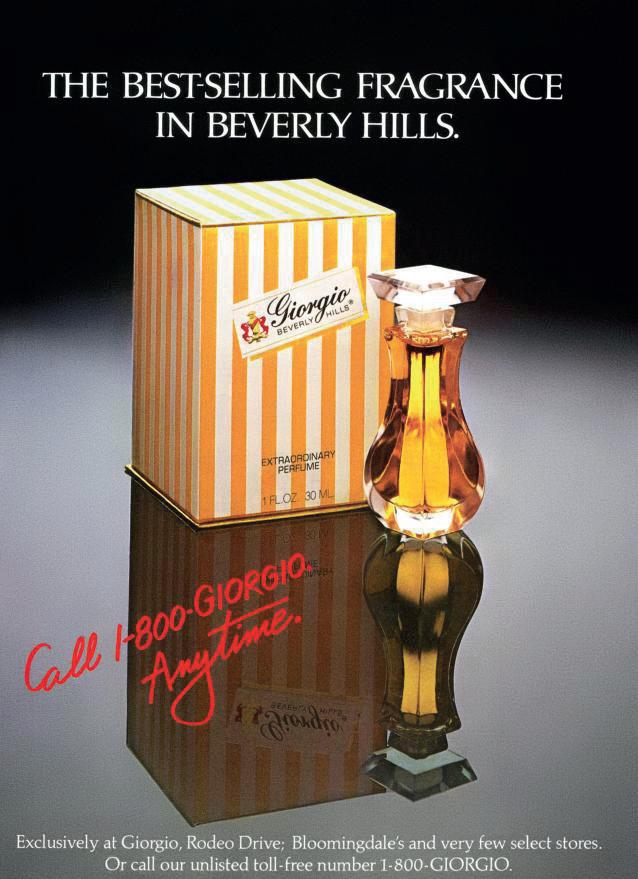

“We didn’t know much then about the fragrance business,” Gale Hayman remembers. “We purchased a square stock bottle. Everything I did had our signature yellow and white stripes – even the stationery, the cocktail napkins, everything – so the fragrance’s packaging had the stripes too. It was controversial, because it wasn’t acceptable in the perfume business to have yellow and white stripes. We called it Giorgio with the tag line ‘The Beverly Hills Fragrance’.”

Four years later, Hayman returned to the idea: “I wanted a fragrance that was happy, upbeat, positive, strong – no, not just strong, powerful! That old saying of less is more. Not true. More is more. I wanted it to be so diffusive that everyone could smell it. A powerful and potent and sensual and warm fragrance. A sexy fragrance. That’s the word I always used when I was asked to put my feelings in one word. Giorgio had to be ‘sexy’.” 3

This time, she approached Roure Bertrand Dupont. Their collaboration proved difficult. “Gale initially wanted a heavy, sexy fragrance, but then changed her mind and asked for a floral,” says Tom Virtue, then Roure’s senior vice president of sales. “Again, and again, we tried to interpret what she was looking for. She obviously had a feeling for what she wanted but it didn’t translate for us.”

It frustrated Hayman. “I don’t think I made a lot of sense to them. I knew only what my customers

wanted, a socko fragrance. Powerful, commercial obviously, but assertive.”

She decided to work again with IFF. “The words I used were oriental, Chloé (1975), sexy, musky, violet, glamorous, and some sandalwood and sweetness.”

Twenty-two submissions and seventeen months later, nothing pleased Hayman

Hayman reached out to other oil houses but liked none of their submissions.

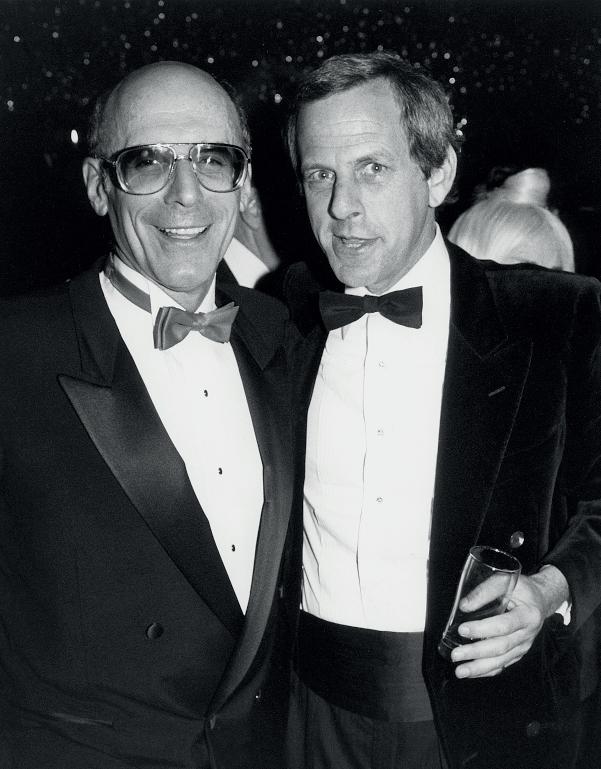

A chance encounter in the street with Jim Roth, whom Fred Hayman had known for many years, would give the couple the help they desperately needed with the development. After leaving Max Factor, Roth had started a fragrance and cosmetics consultancy in partnership with David Horner

Roth was a veteran of the cosmetics industry, while Horner had played key roles at Revlon and Max Factor. The two proposed to finance and develop Giorgio’s new fragrance.

Despite their frantic efforts, they were unable to raise the money to launch Giorgio. Rather than abandon the project, Roth and Horner presented a revised plan to Fred Hayman. In return for his investing $200,000 upfront, they would guarantee to launch Giorgio in forty department stores and develop a mail-order business.

Hayman liked the idea but refused to go ahead without a fragrance. “He had planned to launch it at a big party to celebrate Giorgio’s upcoming twentieth anniversary,” said Horner. “Fred said, ‘I’ll give you ninety days to help Gale find a fragrance. If you find it, I’ll put you on retainer’.”

Frustrated by the lack of progress with IFF, Roth called Frank Buchwalter, an old friend from his days at Revlon and Max Factor. “He had retired and set up a consultancy. We called him to ask him to provide some inside track to some of the oil houses that we didn’t know. Frank called up Jack Friedman, the president of Florasynth, with whom he was very friendly.”

“We came into the project very late,” says Ken Rugg, then Florasynth’s executive vice president. “The first time we met Gale was in New York. I remember it as if it were yesterday. Gale left a message for Jack, who asked me to call back. By way of putting her off, I said that if we did accept the brief, we would ask her to come to New York to

sit down with our perfumers on a one-to-one basis. Jack figured that we’d never hear from her again but Gale, quick as a flash, said ‘I’ll be in New York next week’.

“‘I really don’t know that much about perfumery’, were her first words to us. ‘Why don’t you just explain to the perfumers in your words what you would like this perfume to be or smell like or whatever’, I suggested. ‘I want this fragrance to be very, very strong’, she told the group of four or five perfumers. ‘If I were a hooker walking down 42nd Street, I’d want everyone to smell me. I want a powerhouse’.”

Gale Hayman

Friedman was skeptical, but asked his son, Freddy, to send a submission to Buchwalter, for forwarding to Roth and Horner. “We received a number of submissions, but none of them excited Gale,” said Horner.

When Friedman failed to provide Buchwalter with anything that interested Gale, Horner called him direct. “I knew him well from my Revlon days. I used to see him at Charles Revson’s house. ‘I’m in trouble here’, I said. ‘We’re desperate for a fragrance. If we don’t have one within a month, we are going to have to call the project off’. Jack said, ‘I have something, and I want to tell you right now that it’s great. It’s something I’ve had on my shelf, but

I’m not going to mess with it for a little store on Rodeo Drive. Take it or leave it’.

“Jack sent it to us in May 1981. Oh God! It was just so powerful. My secretary spritzed herself with it. When we got into the office elevator, four guys said, ‘What are you wearing?’ I said, ‘Give me back the fragrance!’.”

That fateful sample –Cinq Fleurs – had a checkered history. “Jack Friedman and our perfumers, Francis Camail and Harry Cutler, created it to be a floralized Youth-Dew (1953), a very, very lovely floral as strong and as powerful as Youth-Dew, but without the heaviness of an oriental. Jack intended it for Estée Lauder. He showed it to Leonard Lauder, who sadly turned it down,” says Rugg

Friedman never gave up. He submitted Cinq Fleurs to Germain Monteil and Helena Rubinstein Both declined. A twist was offered to Revlon for Scoundrel (1980). It too was rejected. Cinq Fleurs was among the fragrances that Yves Saint Laurent considered for Paris (1983).

After each rejection, Cinq Fleurs was slightly modified. Friedman never gave up on it. He believed in it with an enduring passion.

At Giorgio, Cinq Fleurs found its home.

Created by Francis Camail Florasynth, now incorporated into Symrise

Perfumer Vincent Marcello, who translated Giorgio’s formula into an extrait de parfum interpretation, explains the evolution of Giorgio: “Cinq Fleurs (1926) was an old French fragrance, made by Forvil. It was named that because it was composed of five white floral accords: lily of the valley, jasmine, tuberose, rose and gardenia. Forvil stopped making it, but Jack acquired a formula for

Cinq Fleurs, which the company produced exclusively for his wife who had worn it for years. Giorgio is a reinterpretation of Cinq Fleurs, adding in modern ingredients like Iso E Super.”

Perfumer Guy Robert elaborated: “One can take an old formula like Cinq Fleurs, for instance, and by replacing an old base with a modern one, with different tones and colors, one

creates something as structured and strong, but different. For me, that’s the story of Giorgio. It might easily have been created in two minutes by someone who took the old formula and changed the main product.”

Perfumer Francis Camail confirms that Giorgio originated with a Cinq Fleurs type of fragrance. “I wrote the original formula and worked on it with Jack Friedman. The idea was very simple. I was in New York, and American women back then were very flashy – big hair, a lot of make-up, a Gucci or Vuitton bag. That’s the way we made Giorgio We thought, if they look flashy, they should smell flashy too.”

IFF perfumer Sophia Grojsman also picks up nuances of Private Collection (1973) in Giorgio. “Of course, if you smell one next to the other, there are differences. But you have the same green and orange blossom notes, which are so characteristic of both fragrances.”

Camail agrees that he found inspiration in Private Collection, according to Marcello. “Francis told me he was working on a fragrance at Florasynth, and he asked me, ‘What are some of the ingredients you used in Private Collection?’ I said, ‘Go duplicate it and you’ll see for yourself’. ‘No, no, I don’t have time for that’, he said. So I revealed four ingredients that he could have found had he tried to duplicate it. Lo and behold, these four ingredients, in the same proportions, happened to be in Giorgio sometime later. And there are even more similarities if you look closely enough. So, I guess that, indirectly, I had something to do with Giorgio’s creation.”

In Marcello’s opinion, Florasynth’s president Jack Friedman contributed directly to Giorgio’s composition. “I’m certain that Jack Friedman had a hand in creating Giorgio. I worked with him on a number of fragrances. Whenever he would smell my trials, he would start making suggestions, saying ‘Put in some of this or some of that’. I was shocked! These were the exact same ingredients that were in Giorgio. I thought, how does the president of the company know the formula so well?’ It’s really unusual. I believe Friedman worked on the formula with Francis Camail, saying ‘Add more of this. Add more of that’. He’d done the same thing for Charlie (1973). Friedman wasn’t a perfumer, but he certainly made

important suggestions.”

“It possibly developed from several fragrances that they were working on,” says Bob Aliano, who, as a designer, competed for Giorgio’s packaging before directing the reformulation of the fragrance in 1986. “When you expand the formula, it’s got neither rhyme nor reason. It was either the most painstakingly constructed thing you could ever imagine, or it was a mad combination that just happened to work. It’s as if the perfumer liked one fragrance, and then another, and added them together and, by chance, it worked, so he said, ‘Well, okay! Let’s keep it as it is’. When you break down Giorgio’s formula, there are 450 ingredients, including 47 naturals, an overdose of methyl anthranilate, three rose accords, three jasmine accords, two lilies of the valley, tuberose, gardenia, with woody, musky, iris and green notes.

“The accord of methyl anthranilate and the fresh, watery notes of Helional (IFF) are crucial to Giorgio’s powerful trail. There’s also Iso E Super, which was just beginning to be used at the time, after Halston (1975). The thing is that all these materials work so well together. If there’s one word I would pick to describe Giorgio, I’d say ‘radiance’. It just blows off your skin. It has a real signature and identity. It’s so beautiful and compelling that, when the wearer leaves, she’s missed.”

The secret of Giorgio was the discovery of an accord that could stand up to a monstrously powerful tuberose while extending it in interesting directions, “Two heroically strong aroma chemicals were drafted: one being allyl amyl glycolate, an intense fruity-peppery ester reminiscent of pineapple, and the second a mysterious Schiff base made between Helional (a fresh, almondy, marine material) and methyl anthranilate (the Concord grape smell),” explains technical expert Luca Turin 4

This Schiff base, called Helioforte, was a formidable specialty developed by Florasynth. “Jack Friedman always told me that Giorgio’s exceptionality was due to Helioforte,” recalled Horner. “It gave the perfume its powerful staying power.” Helioforte was combined with the more traditional Schiff base of methyl anthranilate and the lily of the valley-like hydroxycitronellal. Their fruity-floral

character complimented the fruity note of gammadecalactone, at about a 0.5 percent, as also used in Charlie. Maturation and maceration were key to Giorgio’s power. Quite simply, the older it gets, the better it smells.”

Schiff bases had been used in the past “but the emergence of Helioforte, a proprietary material from Florasynth, gave birth to this classic,” says perfumer Steven Claisse “Helioforte was in a solid, powder form due to the process used by Florasynth, quite different to other Schiff bases which were not as yellow and more of a liquid than a powder. Its intense yellow color made it somewhat difficult to use in fragrance compositions, particularly at the level used in Giorgio. Its unique characteristics and intensity made it difficult to disguise, too, giving way to ‘it smells like Giorgio’ any time it was used in a fragrance.”

“Inevitably, Gale wanted to boost the fragrance even further,” said Horner. “At her instruction, we putzed around a bit with the juice. We fine-tuned and increased the concentration, but in reality the formula barely changed.”

“The Haymans made almost no modification to Giorgio,” confirms Camail. “The perfume was essentially finished when we first presented it.”

Still Hayman hesitated. Horner continued, “Jim and I were convinced that the fragrance was ready and wanted to test it, but Gale was just not receptive. We went to Fred. ‘If we get decent results, would he intercede on our behalf?’ He agreed, so we went to work. We falsified questionnaires by the hundreds. We got as many people as we could find with different kinds of writing to fill them out. Even my kids signed some. That’s how desperate we were to get the fragrance out in time for the launch.”

Gale Hayman conceded. Frustrating as the development had been, it was her stubborn persistence that forced Roth, Horner and Florasynth to push the concentration of Giorgio above and beyond what any of them would have considered feasible. That proved the key to Giorgio’s success.

Giorgio was launched in November 1981 at a black-tie party for 1,200 guests in a huge yellow-andwhite striped tent in the parking lot across from the Giorgio boutique.

‘A provocative alchemy of heady flowers, musky woods and sensuous fruits’

Chamomile, geranium, orange blossom, patchouli, rose, tuberose, yang-ylang, vetiver

Amber notes, cedarwood, iris, musk, sandalwood, vanilla

From an idea by Jim Roth and David Horner (below) interpreted by Allan Johnson of Emerson/Johnson/Mackay Inc.

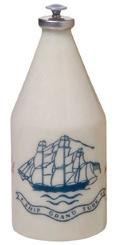

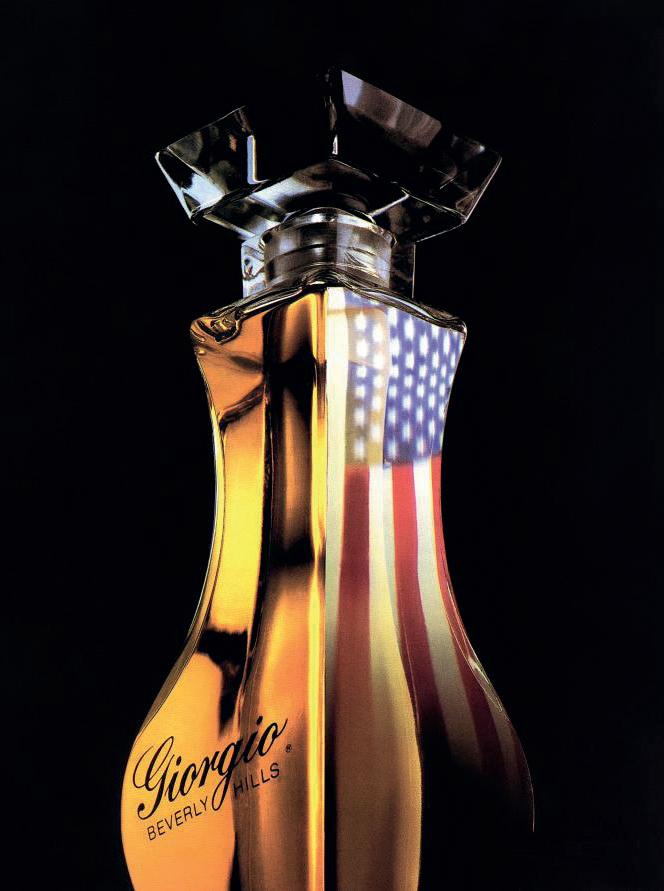

A Baccarat bud vase spotted at Tiffany provided the model for Giorgio’s bottle. “We researched its shape at the Beverly Hills library and found that it had both Phoenician and Ming antecedents, so it could not be copyrighted,” said Horner Allan Johnson at EmersonJohnson-MacKay transformed the vase into a perfume bottle, adding a cap, for a mere $1,500. “Fred and Gale fell in love with it, said Horner “If you have no money, it’s amazing what you can do. That’s the genius of poverty!”

For the outer packaging, Fred insisted on having yellow and white stripes on the box matching the Giorgio awnings.

Giorgio appeared in the Giorgio boutique in October 1981. “The fragrance sold very nicely,” said Horner. “We wanted to roll it out into department stores, but Fred was adamant that no department store was ever going to carry another retailer’s fragrance. We tried to convince him otherwise, but he wouldn’t hear of it. So, we came up with the idea to try mail orders.”

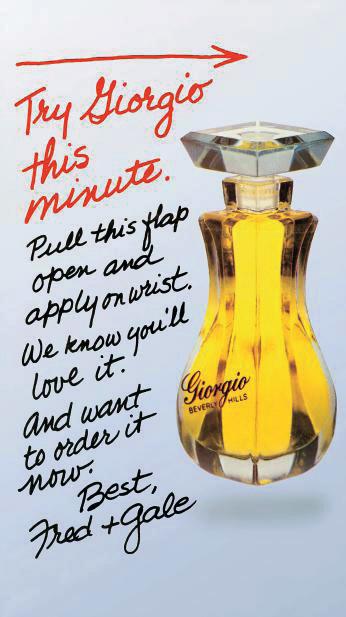

Initially, Giorgio employed scented cards, sealed in small mylar envelopes, and blown into magazines. It proved effective until the US Postal Service added a hefty premium for any unbound inserts.

Since the mylar envelops could not be bound into magazines, Horner and Roth searched for an alternative. ScentStrip samplers, a descendant of the scratch-andsniff fragrance strips, provided the solution.

“Like so many of mankind’s truly pioneering inventions, the ability to make magazine pages redolent was an accidental byproduct of a search for something else,” explains Andrew Malcolm, in an article for The New York Times Magazine. “Back in the 1940’s Barrett Green, a research chemist for the NCR Corporation, was trying to find a way to prevent purple fingers, the

stains that remained after changing his company’s cash register tapes. His new process, which produced tiny capsules of ink safely sealed in chemical bubbles, eventually led to carbonless paper.

About 25 years ago 3M and NCR, working independently, developed a new microencapsulation process that inspired scratch-and-sniff strips and, ultimately, fragrance strips. This time around, the microscopic pimples contained not ink but scent.” 5

In 1979, Hermès’ Calèche was the first perfume to use the new sampler. A few other fragrances trialed it, but it was not until 1982 that the first ScentStrip sampler was inserted into a magazine, for Halston Night (1980) in Chicago magazine.

“The ScentStrip insert was sensationally true to life,” says Gale. “Since we got an unheard-of 80 percent response, the business grew amazingly fast. Those ScentStrips sold the perfume, and sold it, and sold it – beyond my wildest dreams.”

Giorgio’s ScentStrip samplers would change the face of fragrance marketing. The company negotiated a three-year exclusivity with Arcade and year by year, unleashed more and more ScentStrip samplers: One million, five million, ten million and more. Once, in a single year, the numbers topped 100 million.

In 1982, Giorgio debuted at Bloomingdale’s flagship store in New York, part of their Italian promotion.

“Although Fred was convinced that no retailer would ever carry a fragrance created by another retailer, he was finally persuaded to try,” said Roth

Robin Burns, Bloomingdale’s cosmetics division merchandise manager, positioned Giorgio at the fringe of the fragrance department, atop a four-footsquare cube painted yellow and white, with a couple of small topiary trees around it. Despite the out-of-the-way location, the

fragrance rang up over $1,800 during the first two days. Giorgio continued to sell at a rate far above the meagre space and location allotted to it. “Not wanting to infuriate the manufacturers of Opium (1977), Oscar (1977), or Lauren (1978), the store’s top-volume scents, Burns conjured a way of getting Giorgio more space without displacing the others. She asked the display department to create a yellow-and-white striped wooden cart that could be wheeled through the store as a sort of mobile fragrance outpost. When the two models pushing the cart passed through an area, they would blast Giorgio,” says Ginzburg.

The original ScentStrip magazine sampler

Giorgio’s sales exploded. “In the history of fragrance in America there is no success story like Giorgio,” said Lester Gribetz, Bloomingdale’s former executive vice president.” Cautiously, Horner and Roth permitted other upscale stores to carry the fragrance. Hayman’s son, Robert, was sent to London to oversee Giorgio’s European expansion. Market by market, spectacular success followed.

Behind the scenes, though, trouble was brewing. Fred and Gale Hayman had divorced in 1983. Their relationship deteriorated further as Giorgio soared. “The couple jointly ran the company … but the Hayman’s recent court battles have made it clear that

this situation could not continue,” reported The New York Times 6 Giorgio, Inc. was put up for sale. In 1987, Avon Products outbid Shiseido to acquire the company for $185 million.

Six years later, in 1993, Avon resold its Giorgio unit for $150 million to the Procter & Gamble Company. “For P&G, the household and personal-care conglomerate, the acquisition will bring its worldwide fragrance business to about $500 million, including $330 million in prestige fragrances,” reported The New York Times. “Avon, the world’s largest direct seller of beauty products, with $4 billion in annual revenues, has been trying to sell Giorgio since 1989 – two years after acquiring it – to streamline operations around cosmetics.” 7

In 2007, Giorgio was among the fragrances sold to Elizabeth Arden as P&G slimmed down its fragrance portfolio.

With each move, Giorgio’s luster faded. It deserved better. From a single boutique, Giorgio conquered the world. It was the ultimate niche fragrance. It brought people into stores like no other fragrance. Its stock turn was phenomenal. It pioneered ScentStrip samples.

In the history of fragrance, there is only one Giorgio.

“In American Legends, Michael Edwards delivers a living history, decade by decade, of fragrance in America. From historical, cultural, industrial and creative perspectives to the personalities behind the world’s favorite perfumes, the book in your hands captures it all. ■ It is a story of American ingenuity, creativity and business growth; but, ultimately, it is a love story. ■ Read it! Give it to every business student, entrepreneur and marketer you know. Give it to the historians in your circle. Most importantly, share it with people who are passionate about perfume and all who appreciate beauty.”

Leonard A. Lauder

ISBN 978-0-6454839-0-1

9 780645 483901 >