“

Museums, galleries, and exhibition spaces present artworks; Fountainhead introduces you to the artists who create them. ”

Museums, galleries, and exhibition spaces present artworks; Fountainhead introduces you to the artists who create them. ”

Based in Miami, FL, Fountainhead is an artist residency and career empowerment program serving artists across the global arts ecosystem. Founded in 2008 by collectors and passionate art appreciators Kathryn and Dan Mikesell, the Mikesells created Fountainhead to positively impact the lives and careers of artists, and nurture and grow their local arts community. Establishing a residency program for visiting national and international artists and a local artist studios complex that same year, Fountainhead has since welcomed over 580 artists from 49 countries and served nearly 1,000 local artists through its county-wide open studios event series, Artists Open.

With a mission to elevate the voices, visibility, and value of artists in our society and make their work accessible in a

welcoming and inclusive environment, Fountainhead focuses on encouraging public engagement with artists and their work. This approach empowers artists by making connections that lead to growth in their work and careers, providing time and space to experiment and challenge their practice, and mentorship and business skills to help them lead thriving careers.

In its 17-year history, Fountainhead has become a pioneering force in the arts and culture landscape, developing innovative artist and community engagement programs and cultivating key relationships with leading art institutions in South Florida and beyond.

Harnessing the power of our collective diversity, Fountainhead is building a global family of artists and appreciators, one personal connection at a time.

AForeword by Kathryn Mikesell

ChasingWonder:HowResidencyArtistsResurrectMyth asaBlueprintforModernLife by Nicole Martinez

January

Merik Goma, Pacifico Silano, Samuel Levi Jones

February

Nardeen Srouji, Reniel Del Rosario, Zoe Walsh

March

Ana Silva, Kevork Mourad, Liz Cohen

April

Ato Ribeiro, Ho Jae Kim, Sagarika Sundaram

May

Claudia Joskowicz, Nadía Hernández, Natia Lemay

June

Andrea Ferrero, Daniela Gomez Paz, Jessica Taylor Bellamy

July

Estelle Maisonett, José Villalobos, Victoria Martinez

August

Anastasia Komar, Catalina Ouyang, Yongqi Tang

September

Emiliana Henriquez, Octavio Abundez, Sarah Zapata

October

Adam Amram, Adam Beris, Tyler Christopher Brown

November

Christiane Peschek, dach&zephir, Leo Marz

LookingBackat2024

Kathryn Mikesell

2024, our sweet 16, was a tumultuous and magical year. It was a year where personally dug deep through experiences and conversations, reading, and internal exploration. learned that I am exactly where need to be in life, doing what was put on this Earth to do: uplifting and connecting beautiful humans.

Artists are our heroes, teachers, and seers. They are the bravest people I know. Through their work, they guide us down unexpected paths, challenge our beliefs and biases, amplify the beauty surrounding us, enliven our curiosity, and inspire hope. Having the

opportunity to meet artists and be able to learn about their motivation and work is truly a gift. Each and every artist has taught me something new and left an indelible mark on my conscience and in my heart. believe everyone who had a chance to meet artists while they were with us feels the same.

Thank you to the artists for trusting us, sharing your stories, and opening your hearts.

As write this, there is a smile on my face.

I’m thinking about all the interactions I witnessed, friendships that have been made, conversations I’ve had and heard, and hugs that were shared. I’m thankful and proud of the community we have built together. We are one in this world, and feel you experience that at Fountainhead. Fountainhead is a family affair. want to thank our kids, Galt and Skye, who continue to share their short periods at home with artists. This year’s Thanksgiving at our home was uniquely special with 12 countries represented around the table. The love, effort, and time you put into preparing the feast with me, meant the world to me. My husband Dan, co-founder of Fountainhead, remains my rock and continues to inspire me daily. He cares deeply about artists successfully navigating the entrepreneurship of art and treasures his one-on-one time with artists talking business and life during their residency and beyond.

Everything is made possible through the love, talent, and commitment of our team, board, donors, and community that surrounds us.

I’m blessed with THE dream team. Each of us complements the other, and we lead with respect, trust, and appreciation. Nicole began working with Fountainhead by writing our stories in 2018. Now as associate director, her thought leadership and vast experience led to the book you have in your hands; the launch of FHTV, featuring mini-documentaries about artists-in-residence; a partnership with PBS; our branding and communications which are captivating and informative; and so much more. When we were looking to grow the team, our wish list was long. We assumed we would have to compromise but, not only did that not happen, Nicole and I found our

soulmate. Francesca joined the team three short years ago with an energy that has lit the way ever since. She is the sunshine that welcomes and guides the artist’s experience, the engine that keeps the team efficient, and this last year and going forward, the secret sauce to our membership program’s experiences and travels.

Attendees of our open houses are always greeted at the bar with a warm smile from Rory Feinberg. Thanks to our wonderful sponsors Marjanne Kalf of Estrella Damm, Todd White and Cameron Carani, and Evan Marcus of Liquid Death, who keep us hydrated and happy during our events. Estela Ribiero helps keep the place in order with love and efficiency. Natalie Galindo, who joined us near the end of the year as an intern, is already taking initiative and inviting artists to speak to her MFA class at UM. Marcos Cherlo is our quiet genius repairing the beauty of experimentation to ready the home for each cohort, along with Marcela Reis who makes sure the home is looking its best to welcome its new guests.

We could not do this work without our incredible board of directors. Continuing to steer the ship and guide us forward are Don Savelson (President), Teresa Enriquez (Vice President), David Ross (Treasurer), Lois Whitman Hess (Secretary), Nicole Blackburn, Spring McManus, Ian Krawiecki Gazes, Jumaane N’Namdi, Carole Server, Leslie Weissman, Ben Wolkov, Ibett Yanez, and Henry Zarb. Thank you to Alexa Wolman for your years of dedicated service and friendship. know speak for the whole of the organization when say we look forward to welcoming Sabrina Beraja, Emilly Campbell, Jimena Guijarro, and Donahue Peebles III as new board members in 2025.

So much of what we do creates a dialogue between visiting artists and local artists, and I’m so proud to see the fruits of that come alive in this book. Thank you to the photographers and writers who contributed their time and creativity to us this year. While you’ll have to head online to see them, want to thank Alexa Caravia and Juancy Matos for the brilliant films they created for each artist. Check out

FHTV to see films about artists who have joined us since 2022.

Artists were selected to join Fountainhead by an esteemed jury; our 2024 artists were thoughtfully chosen by artist alum Lauren Kelley; curator and co-founder of Art in Common Zoe Lukov; curator and experiential designer Ché Morales; and Perez Art Museum Miami chief curator Gilbert Vicario. They were as generous in reviewing the applications as were their 2023 predecessors, Allison Glenn, Melissa Wallen, Rodrigo Valenzuela, and Susanna Temkin. While the number of artists we’re able to bring is limited, the evaluation process led each of them to discover new artists, several of which they’ve gone on to include in exhibitions and projects. We can’t thank them enough for their time, and continued support of Fountainhead and the arts ecosystem in which they play such a valuable role.

This year’s book is dedicated to two extraordinary women, Rosa de la Cruz and Linda Schejola. They were dear friends and mentors who I admired greatly. Rosa was a visionary in the arts. She was always open to share her knowledge, loved welcoming people into her collection and believed deeply in supporting young artists as they were starting their professional journey. She would muster every bit of energy so as to not miss visiting Fountainhead artists-in-residence. Linda was a uniquely beautiful human who loved fully and freely and championed women and girls globally. She led by example with warmth and grace, supported family and friends, and gave generously to causes she cared about. She loved meeting artists, hearing their stories, and sharing the experience with her friends.

Connection is at the forefront of everything we do. The ripple effects that start from just one meeting can flow for years to come. Each month curators and arts professionals donate their time and share their knowledge with artists-in-residence. Thank you sincerely to Amanda Morgan, Ana Clara Silva, Anelys Alvarez-Munoz, Gladys Garrote, Heike Dempster, Jennifer Inacio, Laura Novoa, Melissa Wallen,

Mindy Solomon, Neil Ramsey, and Patti Garcia-Velez Hanna. Mera and Don Rubell, thank you for taking Sunday afternoons to visit Fountainhead, imparting your 50+ years of collecting wisdom and always leaving the artists with something to ponder. Beth Rudin DeWoody, Maynard Monrow, and Laura Migdon Dvorkin, thank you for taking us on the most informative tours of the Bunker and breaking bread after.

Fountainhead would not be able to reach its ambitious goals without the generosity and support of donors. The people behind family foundations and individual donors are not only our supporters, they are our partners, mentors, and friends. want to thank Victoria Rogers and Jennifer Farah and John S. and James L. Knight Foundation; Jorge and Darlene Pérez and Belissa Alvarez and the Jorge M. Pérez Family Foundation; and Lindsey Linzer and The Miami Foundation who have supported Fountainhead since it transitioned to a nonprofit in 2018. Thank you to the government entities that invest in the arts and their communities, like National Endowments for the Arts, The State of Florida, and Miami-Dade County Division of Cultural Affairs.

I want to say a very personal thank you to Britta Jacobson and Philip Berlinski and Goldman Sachs Gives; Linda Schejola, Lisa Schejola Akin and Jeff Akin and the Carlo and Micol Schejola Foundation; Debby Bussel and the Shepard Broad Foundation; Harriet, Leslie, and Michael Weissman and the Paul & Harriet Weissman Family Foundation; Sarah Arison and Arison Arts; Francie Bishop Good and David Horvitz; Lois Whitman Hess and Eliot Hess; Hesty Leibtag and Terry Verk; Adriana and Ricardo Malfitano; Julie Mercier and A. David Mikesell; Jane Wesman and Don Savelson; Anne and Rolf Coppenrath; Jane Marcus; Mary McIntosh and Dan Abele; and Ann and Melvin Schaffer. For the past several years we’ve had the honor of commissioning artists for Windstar Cruises thanks to the brilliant direction of Stijn Creupelandt, Chris Prelog, and Jessica Payne. While I’d love to personally thank all our generous Fountainhead

Experience Members, the list is long. hope they all feel the love and appreciation each time they step inside Fountainhead or attend one of our events and trips.

This year we partnered with several outstanding organizations, each working diligently to highlight artists in their own unique way. The Human Rights Foundation, led by Celine AssafBoustani, Holly Baxter, Issa Sarikamis and Michelle Gulino, fights tirelessly to bring rights and dignity to people living under authoritarian regimes and supports artists whose works provide a voice and visual to create change. Our partnership with YoungArts, led by Clive Chang with support from Joey Butler and Lauren Sloane, identifies leading artists from high schools throughout the country, provides priceless education and experiences, and nurtures them throughout their careers— including with a Fountainhead Residency for one prior YoungArts award winner per year. Atlantic Arthouse, led by Lisa Howie and Vanessa Selk, bring much-needed awareness to artists working throughout the Caribbean, elevating their representation in the art world and creating opportunities for them globally. Untitled Art Miami Beach, led by Omar LópezChahoud and Clara Andrade Pereira, focuses on curatorial balance and integrity across all disciplines in contemporary art. Zona Maco, led by Direlia Lazo and taking place in Mexico City, is the leading art fair bringing worldwide attention to artists working throughout Latin America.

For me, and believe many, life is purposeful, rewarding, and flows seamlessly when you surround yourself with people you admire, who push you to be the best version of yourself and share in your curiosity. While there are many names written here and on the pages to follow, can give you an example for how each of them has impacted my life. I am immensely grateful for the family of Fountainhead, for helping what began as a passion project in 2008 to grow and flourish 16 years and 580 artists later.

With hugs and gratitude, Kathryn

by Nicole Martinez

As a child, I had a fascination with mythology. I’d check out scores of volumes from the library, bewildering my parents and teachers, who struggled to understand why a sevenyear-old was so interested in the existential crossroads and crises portrayed in the myths of the ancient Greeks and Romans. From the parables of Narcissus and Sisyphus to the sins of Orpheus and Eurydice, found the exploits of gods and mortals alike to be riveting. Lately, find myself reflecting on the lessons gleaned from the myths that filled my childhood with a sense of wonder. know am not alone in feeling disillusioned with the current state of culture in our modern society. An endless stream of notifications, news alerts, and hot takes construed as fact has made it challenging to hold true to one’s values and belief systems without secondguessing whether those principles even make sense anymore. Is it realistic to within a world mired with so much chaos?

Serendipitously, recently our board member Dave Ross gifted me The Power of Myth, a transcript of an infamous 1988 six-part documentary series featuring hourslong interviews with Joseph Campbell, an American author and teacher best known for his work in comparative mythology, and journalist Bill Moyers. In the book, Campbell explains the universality of myth—what he refers to as “mankind’s one great story”—by pointing out that myths occur throughout the history of humanity, emerging from many different cultures, epochs, and societies, as the same stories over and over again. The reappareance of key themes, whether among

the Greeks and Romans, the Chinese and the Aztecs, the Jews or the Judeo-Christians, or Western film and literature, reveal universal and eternal truths about ourselves. They also provide a roadmap for living authentically through the ups and downs of life.

Campbell made it a point to discuss how the concept of myth—and the ability to access the spiritual consciousness it instills upon us—was largely absent in American life in the late 1980s, and that’s even more true today.

But there was one passage that immediately drew my attention toward something that does light up our ability to go deeper into our understanding of our selves.

“[Myths],” he writes, “are the world’s archetypal dreams, and they deal with great human problems. Original experience has not been interpreted for you, and you’ve got to work out life for yourself. The courage to… bring a whole new body of possibilities into the field of interpreted experience for other

people to experience—that is the hero’s deed.”

I saw then that the mythological heroes that sparked the awe I felt in youth are now the artists whose work am fortunate enough to sit with, muddle through, and gawk at in my daily life. Artists are the heroes that draw our focus toward something we previously did not see or could not comprehend on our own. They dispel our preconceived biases and reframe how we view culture and history. If you look closely, you realize myth is at the root of so many of the objects and frameworks within which artists work. They are the modern-day alchemists churning magic into our everyday.

This investigation into myth and artmaking is driven by the artists who honored Fountainhead with their presence this year. Within their works, see the familiar allegories of our mythologies, the original interpretations they’ve assigned to form and material, and a distillation of the natural order governing our environment and our societies. Symbols, stories, and identities abound in their practices, shaping our collective consciousness to a higher plane. Whether hailing from China, Peru, Ghana, Europe, or the United States, their stories are universally identifiable.

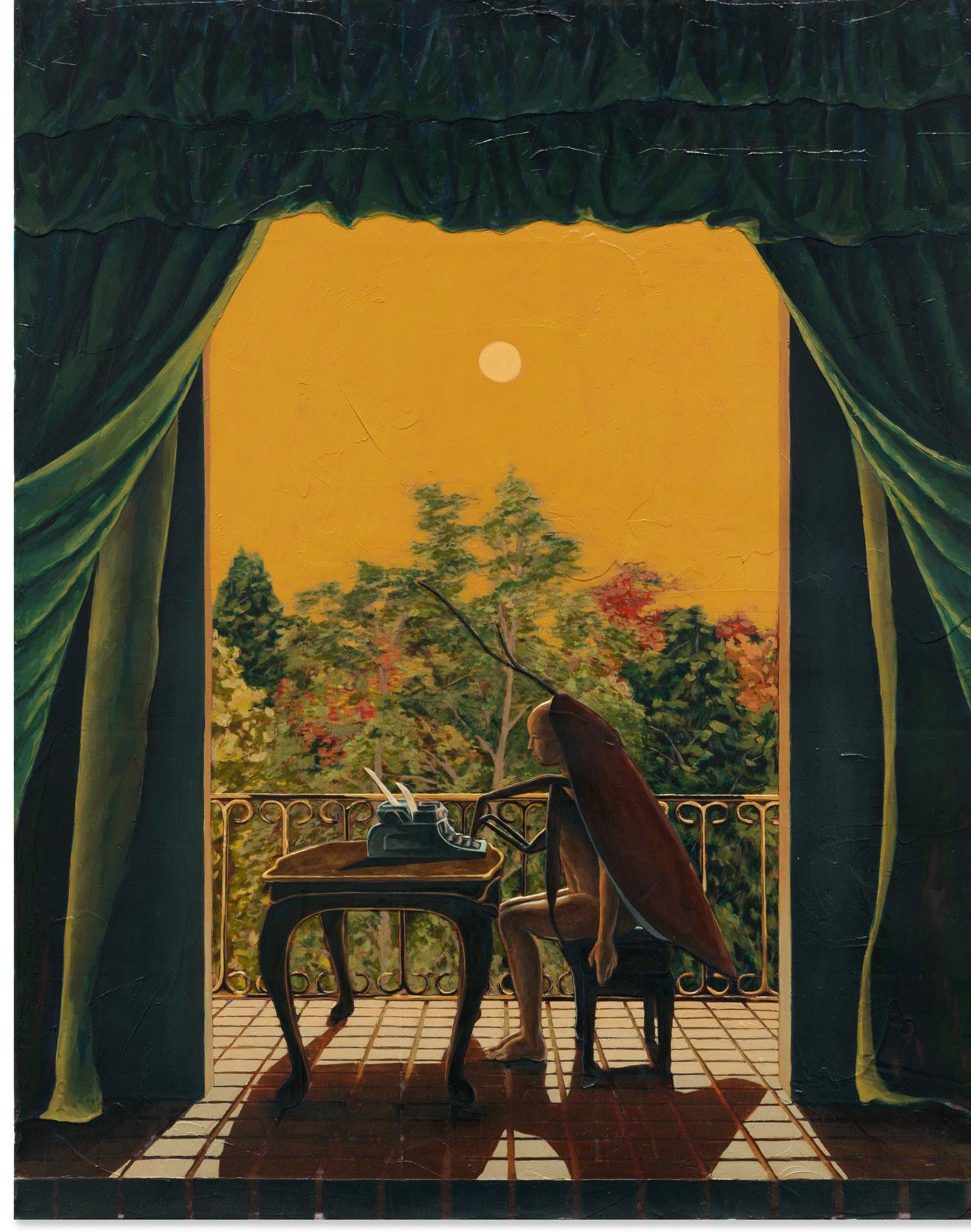

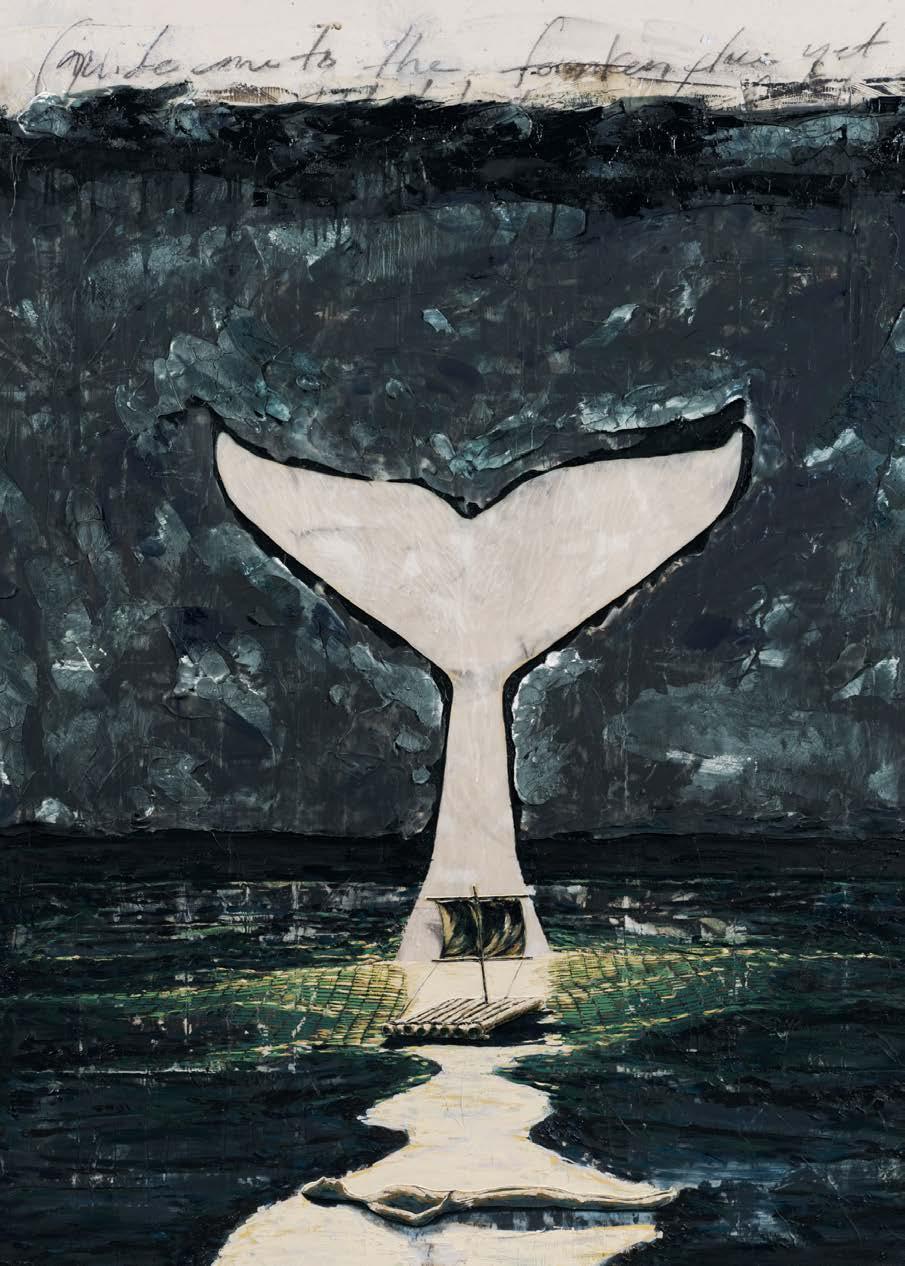

Some artists build upon the myths that govern humanity more literally within their work, while others pull from personal narrative and experience and unwittingly underscore tales as old as time. Born in Peru and currently based in Mexico City, Andrea Ferrero is inspired

by the classical Greek and Roman motifs (those that, through decorative elements and design, visually represent mythological stories and concepts) that appear in colonial architecture in the the two cities she has inhabited. Living between the Mexican and Peruvian capitals “got [me] more interested in fictionalities and possible futures, and the destruction of symbols,” she says. Coinciding

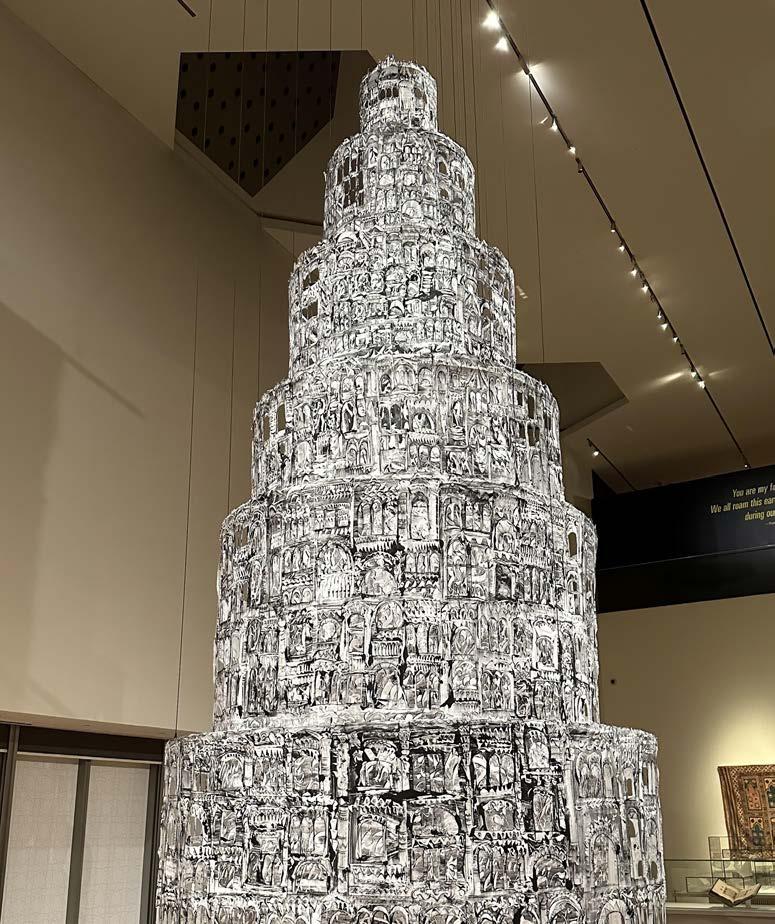

with her research into the classical styles imported by colonizers into these new lands, Ferrero began investigating how goods like sugar and chocolate were used as symbols of power and control by the ruling class, who had sole access to foods cultivated and farmed by slaves and indentured laborers. Ferrero creates silicone molds of architectural motifs and symbols, like columns and reliefs or the heads of gods and beasts, then pours in white chocolate she often colors and marbles with dyes and gold leaf. Ranging from smaller to large-scale, and often installed in hierarchical patterns, viewers are encouraged not only to break a piece off but to eat it, as well. In that way, Ferrero meditates on the destruction of the symbol through the process of digestion and ultimately excrement—a cheeky ‘eat the rich’ gesture that feels as current as it does humorous.

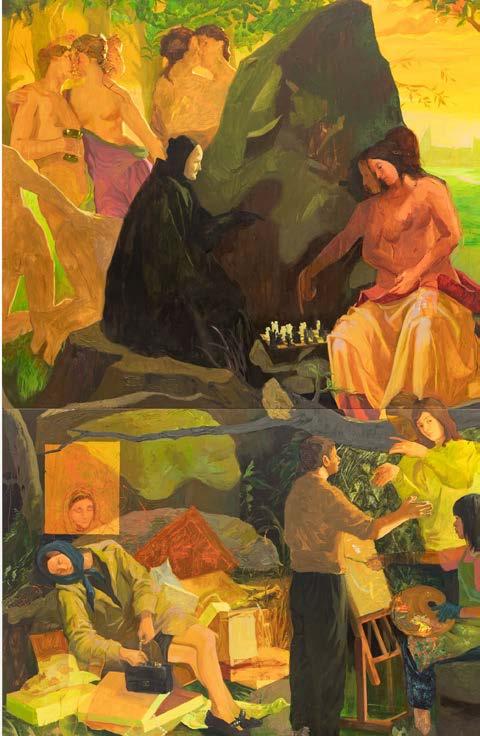

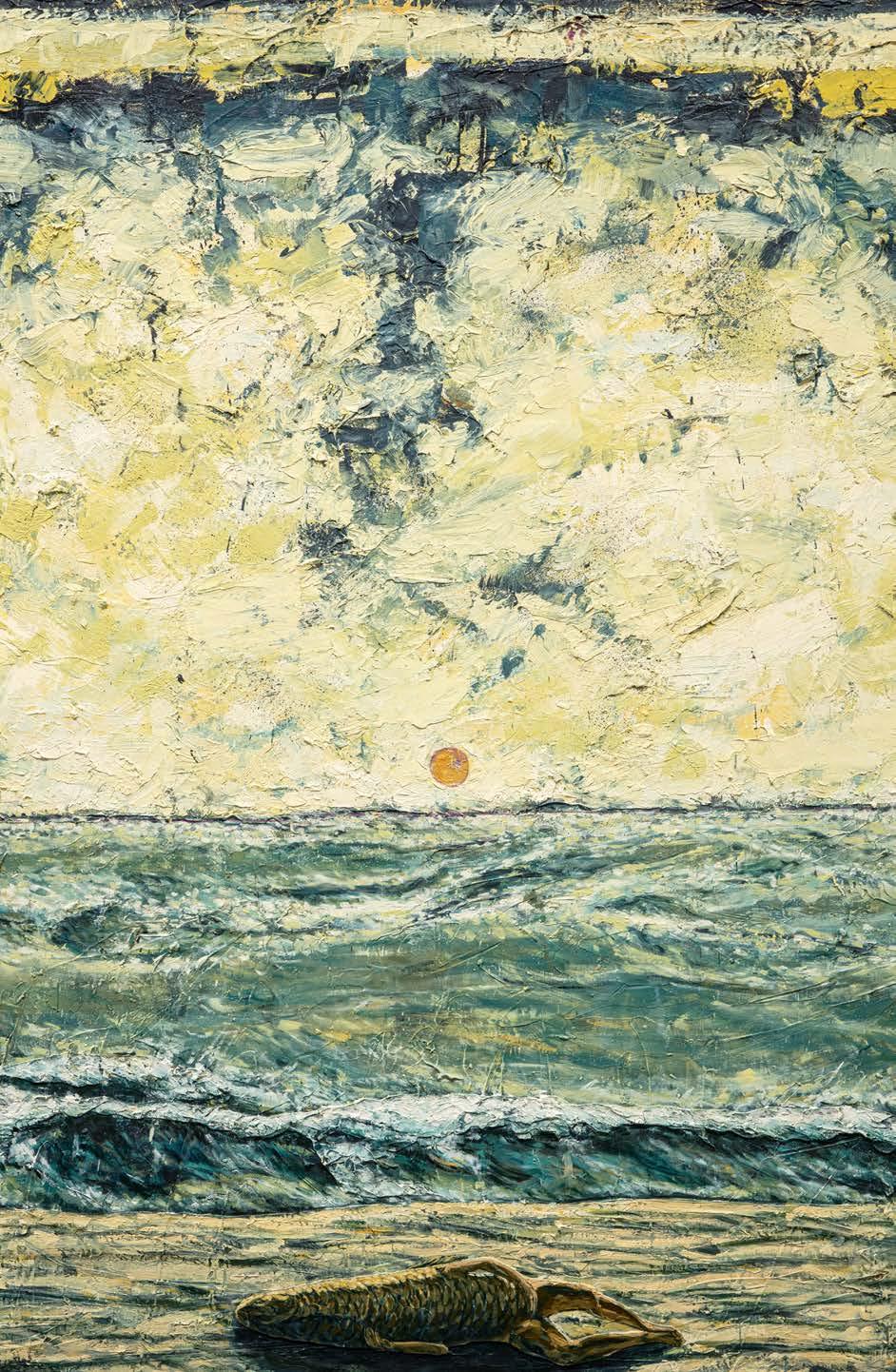

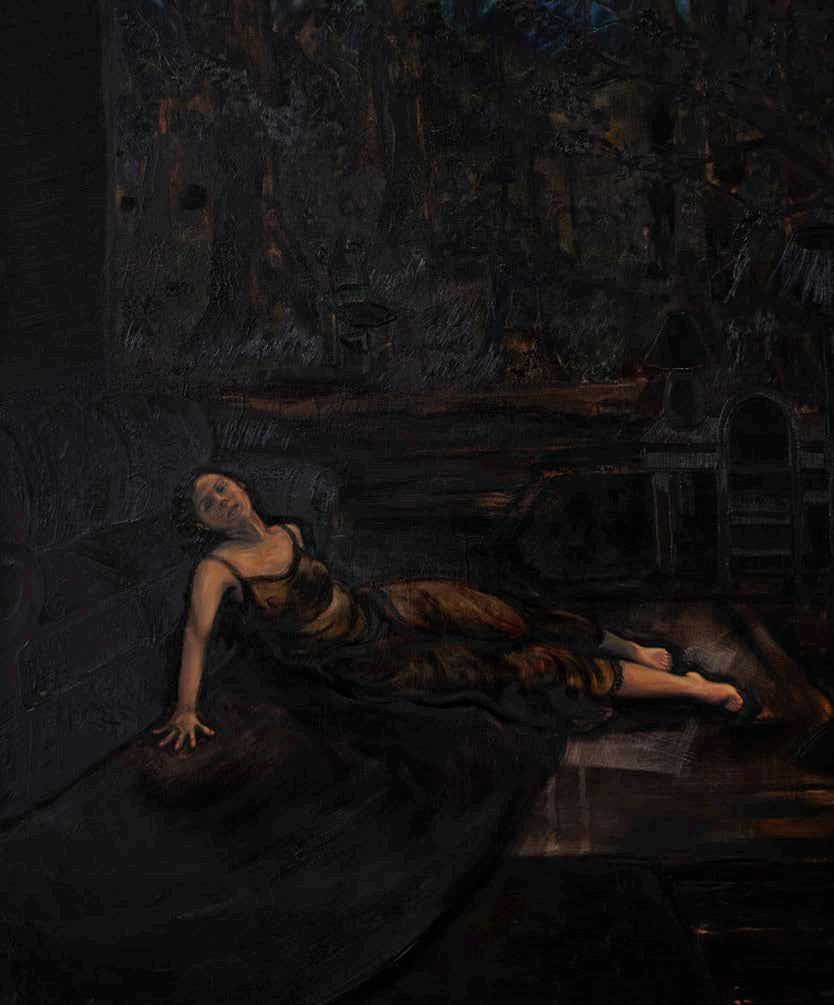

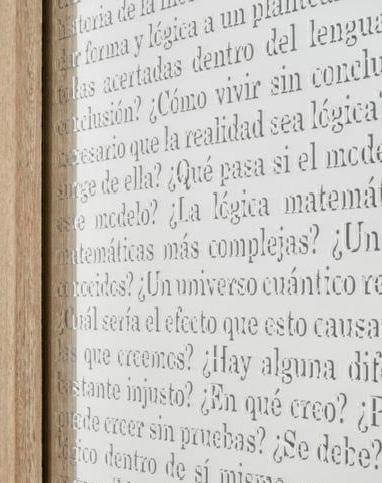

Tang references visual and literary religion and mythology narratives to form the stories within her work. She is most interested in the existential pursuit of questioning whether “there is any external value in our contemporary society,” as she puts it. Tang studied psychology before she turned to a creative practice, and her work intertwines the philosophical and mythological underpinnings present within psychological theory. Her paintings are infused with Chinese lore, but they also reference Italian Renaissance and Baroque painting to create chimerical compositions of a mythic quality. In one of her works, titled Eros/Thanatos(2023), Tang references Freud’s ‘death drive’ theory, in which Freud uses the myth of Eros, the god of sexual and life instincts, finding himself at odds with Thanatos, the god of death. “When I’m painting, it gives me the urgency to think about what these questions mean for me.”

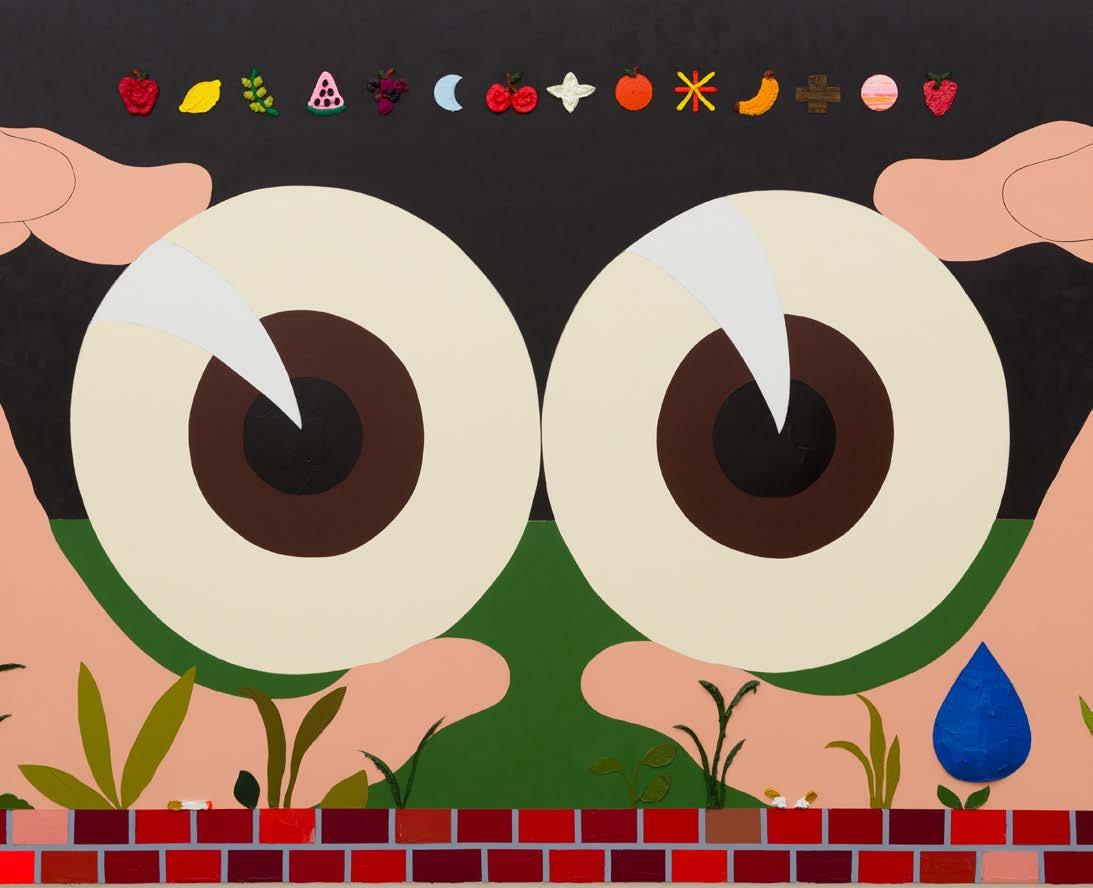

Ho Jae Kim follows a similar pattern, in that the South Korean-born artist is interested in illuminating aspects of the human condition

through religious or mythological parable. Kim’s highly methodical process—paintings come alive by creating a 3D rendering, then printed on inkjet, slathered in glue and tape, carved into and painted over to create different layers and textures—are inspired by the exacting process of Italian Renaissance painter and mathematician Piero della Francesca. Kim draws like inspiration from Dante’s Inferno, in which Dante journeys through the nine circles of hell with the Roman poet Virgil. Kim draws an allegory between the liminality of human existence—the endless waiting and recalculating that defines how we move through the world. “There’s a moment in life when adults become displaced from their own dreams,” he says. “The idea that anyone can relate to these moments in transit is a universal human experience. I wanted to capture the mundanity of life, but find the beauty in it.”

Layers upon layers of symbolism, history, and personal identity make up the fabric of Sarah Zapata’s textile works, which often reflect on how biblical and colonial narratives wind up informing modern-day oppressive systems like prisons or queer prejudice. Born and raised in Texas to a white Christian mother and Peruvian father, Zapata researches evangelical scripture, queer theory, and the Paracas and Nazca cultures of Peru to inform the process, patterns, and color stories within her work. She works on a large loom in her Brooklyn studio, designing patterned textile fragments she then builds into largescale sculpture. Her practice lately has evolved into world building, like in Upon the

Divide of the Vermillion (2024), which was on view in the UBS Art Studio during Art Basel Miami Beach. Zapata’s ruins—large plinths blocked together and draped in her handloomed textiles—and patchwork columns were installed against a backdrop of stripes. The work nods to how biblical lore about the untrustworthiness of ‘cloth made of two’ is

a queer prejudice that informs the design of the flag, the jail stripe, and other symbols of oppression in contemporary life.

While these artists specifically address ancient or pre-colonial histories, others address how myth has been reinterpreted through popular culture and media to bring ancient tropes and rituals into the present day. Within this framework, I’m drawn to the moving images of Claudia Joskowicz, who reflects on the myths created out of historical events once they’ve been mediated through technology. Growing up Jewish in Bolivia during a time of upheaval across the Latin American region, Joscowicz mines Bolivian and Latin American history for content, and uses structuralist cinematic language to tell stories “that aren’t traditionally told within a structuralist framework,” she says. The legend of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kids, and the assasination of Che Guevara and subsequent funeral, are just some of the events Joskowicz parses through as she creates a reenactment of how the event was portrayed in media, versus how it happened in real life. In these works, Joskowicz meditates on life, death, and resurrecton—familiar scenes within the greatest mythologies on earth.

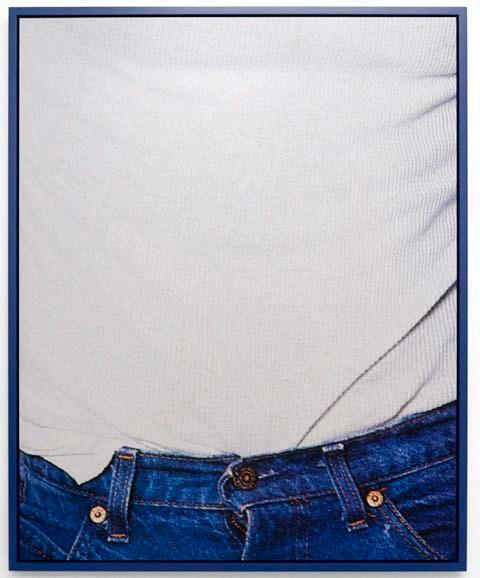

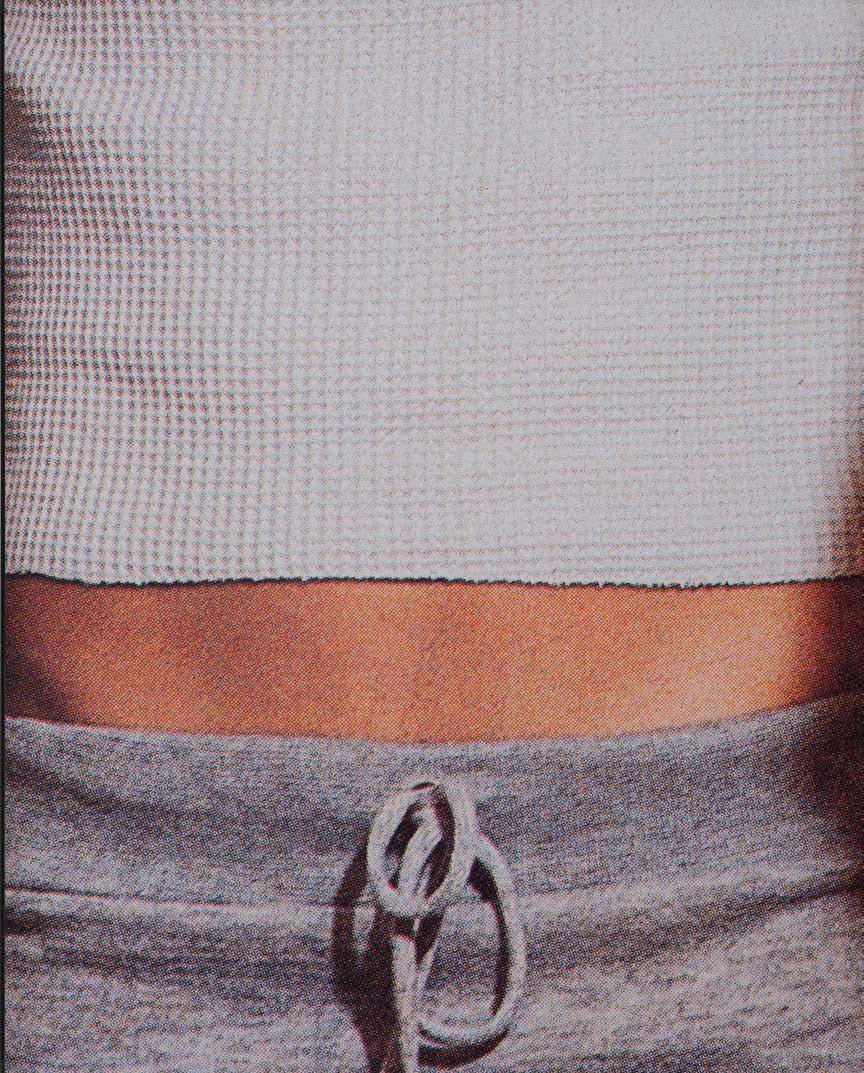

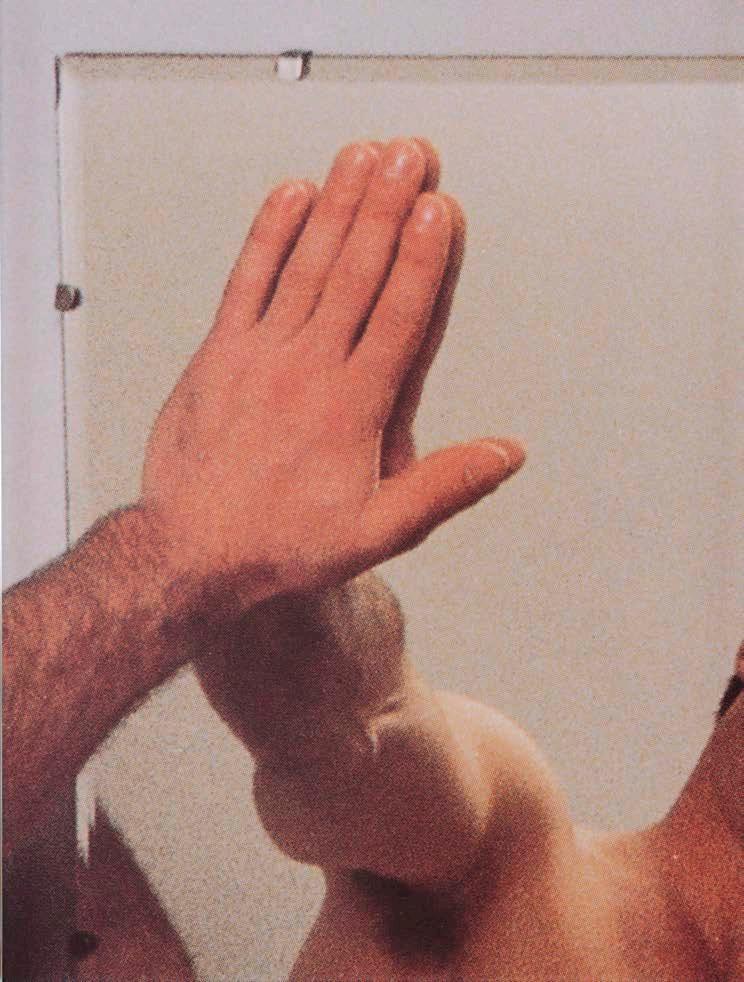

New York-born and based Pacifico Silano employs the mythology of the Trojan Horse implicitly within his process, utilizing content derived from midcentury homoerotic magazines. Silano collects images from gay pornography, keeping an archive of images in his studio. Sifting through these images in an

intuitive way, he’ll hone in on one aspect of the image and blow it up large scale, completely altering the image’s context and subtly introducing queer culture into the hegemonic contemporary art world. “I love finding the ‘Trojan Horses’ by presenting images that are slippery and can go either way in terms of what they could be trying to say,” he says.

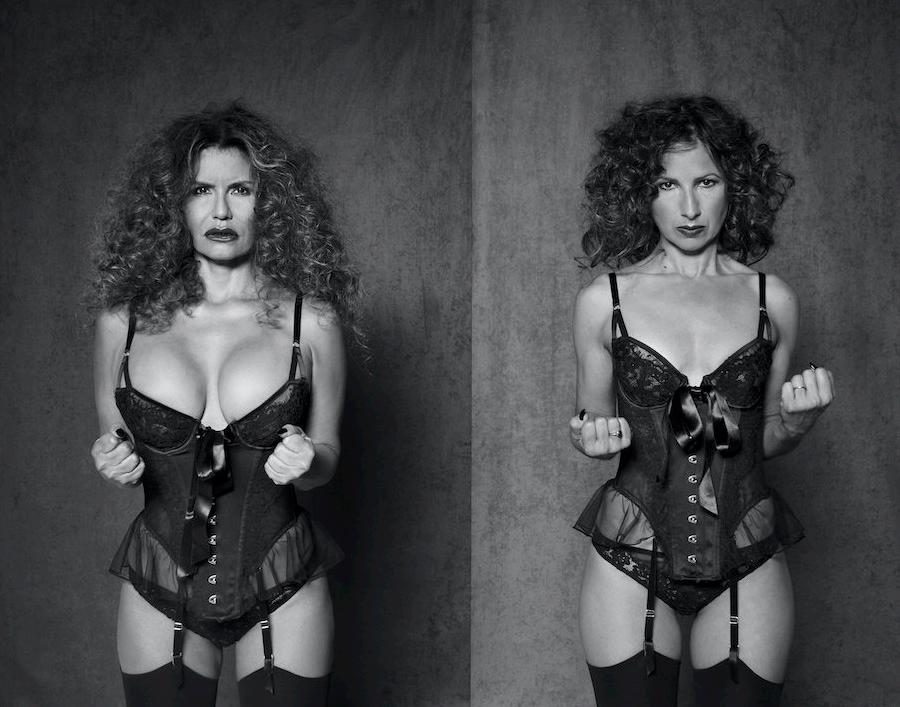

Austrian artist Christiane Peschek is working through a new mythology exploring the blurring of boundaries between humans, machines, and nature. Inspired by Donna Haraway’s seminal essay, The Cyborg Manifesto—in which the author posits that the cyborg is a creature defying gender, race, and sexuality that disrupts patriarchal structures—Peschek mediates femininity in the age of social media. She is interested in how we alter our bodies through filtering tools widely available on the internet, blurring the lines of reality within the virtual context. Scouring the internet for images of people who have clearly altered the original photo, Pescheck uses sublimation dying to imprint the image on polar fleece, then alters it by painting over it. “I’m often thinking about immortality, and how we deal with the potential for new life,” Peschek says.

In recapping the artists working at Fountainhead in 2024, thought about Dean Kissick’s viral essay assessing the state of culture in 2024. His screed suggests a dull artistic landscape in which identity politics has taken center stage, rendering the thrill of art making and criticism obsolete. Much of his argument rested on major art events like

the Venice and Whitney Biennials as signs that artists are no longer original; he claims they’re just regurgitating old historical and cultural methods of making and viewing the world. But if not them, than whom will remind us to look for the beauty and rapture of the world around us? Who will unlock the journey into a higher consciousness, as Campbell suggests? Going into a new year, where tumult and uncertainty will certainly abound, I am hopeful that I’ll manage to stay above the fray, and find purpose, tranquility and awe in the tiny moments. For that, you’ll find me walking in the path of the artists.

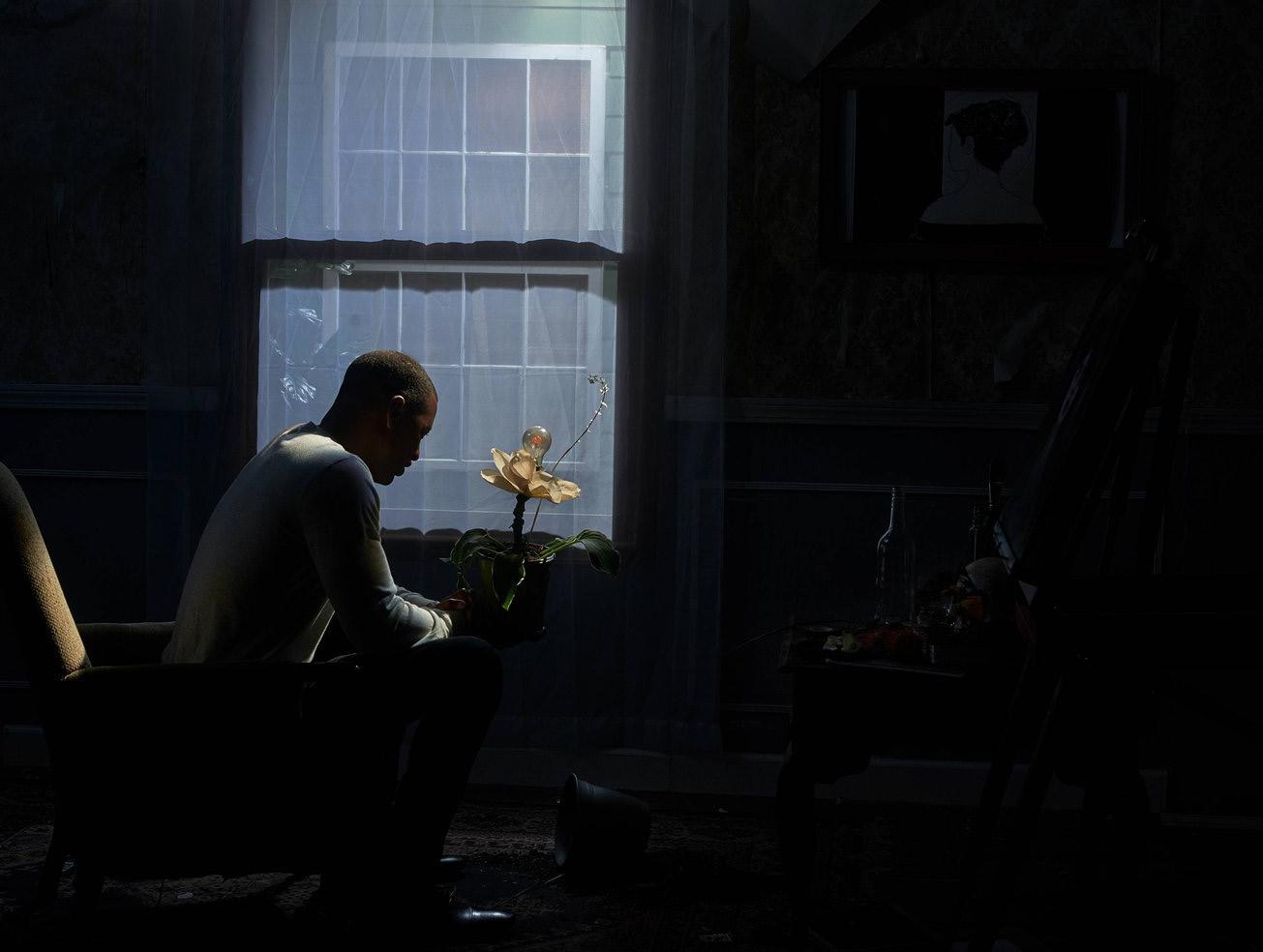

On the shelf towards the front of Merik Goma’s New Haven studio are monographs he has collected. There’s Lorna Simpson, Erwin Olaf, Miles Aldridge—artists who, like Goma, have a penchant for highly staged photographs. In the middle of his studio, Goma has constructed a theatrical set for one such photograph, the latest in his series Night Was Fraught With Blue Devils, titled after a line from one of his poems. On my studio visit in February 2024, lingered over details of the set—a wooden radio console, nicotine stains on the dressedup wainscotted wall, the wall with a door and a window built-in. Goma told me he imagined this scene looking at photographs of people dancing at home in the 1950s and 60s. His photograph, when it’s finished, will show a couple embracing in the evening, mid-sway, dancing slowly. Their dance together may be their ritual, how they softly reset as day turns to night.

In his practice, Goma is set builder, prop shop, director of photography, and one-man costume, lighting, and concept department. He did a lot of reading and writing during his residency at Fountainhead in Miami, expanding the worlds around his photographs. His interest in interiority kept him thinking in the realm of Kevin Quashie’s 2012 book In The Sovereignty of Quiet: Beyond Resistance in Black Culture, which argues for nurturing an understanding of quiet, of expansive inner life for Black people as individuals full of stillness, longing, vulnerability, beauty, and sometimes disarray.

“Quiet is like the moon,” Quashie writes, “rarely showing its full wondrous sphere and instead offering slivers of its potent, tideshifting self.” What is at stake for Quashie and Goma are lives that are full, fluctuating, inward, undisclosed, and–Quashie asserts–largely unfamiliar in mainstream thinking. Blackness shouldn’t only be about lives in public, societal ills, resistance, and social change.

Goma talks to the actors he hires while he photographs them, giving them cues.

“Imagine you’re waiting for someone and realize they’re not coming,” he might say. A photograph from Goma’s recent series Your Absence Is My Monument shows a woman sitting in a kitchen. There is smoke in the air. There are dishes in the sink, a phone receiver off the hook, and an agitated jumble of foliage on the table. The woman holds a photograph in her hand and looks at it. It appears to be a picture of a boy. She is quiet. Her gaze is serious. We don’t know, but she could be mournful, wistful, disapproving, mustering courage, about to formulate a plan, wanting to stay and sit in silence, all of the above, or more.

– Words by Marcus Civin

Goma’sresidencywasgenerouslysponsored inpartbyLoisWhitman-HessandEliotHess.

Cops. Cowboys. A construction worker. Leather. Tank tops. Muscles. Bare chests. Wanting. Waiting. Sly. Available. These men are playing. They’re subversive. They’re enacting dominance in a world that reserves that for straight men. Maybe these men will be sweet and the right kind of rough. But what if they’re not? What if they’re not respectful? What if they’re just like the other men? What if they cross the line?

In an influential 1985 essay in the journal October, the film theorist Christian Metz explored photography’s relationship to the fetish or the fetishistic nature of male desire stoked by fear of castration as expounded by Sigmund Freud and Jacques Lacan. In her writing, the art historian Amelia Jones explains Metz’s essay, in part, as an argument that photography castrates the real. Because photography can stop time, preserve, capture, selectively point to the past, isolate, and crop, figuratively and by extension, we might even say it can kill.

In rephotographing vintage gay male porn—all the tough cops, cattlemen, and leather daddies— Pacifico Silano enters a doubly dangerous space of potentially violent psychologically and culturally informed play within an arguably violent medium.

At Fountainhead, Silano had the time and space to

edit and flesh out the elements of Psychosexual Thriller his March 2024 exhibition at Island, a gallery on the Bowery in New York. “It’s very fleshy,” he explains,“There’s a lot of skin. No [full] nudity. There are a lot of tightly cropped photographs that are blown up very large, so you see the printing matrix dots… The residency was like a test launch for the show.”

When we got together after the residency but before the show, Silano and discussed power. “To me, there’s this fascinating push-pull,” he said “an image can be both empowering and oppressive at the same time. Some people will be empowered by my work and some people will be seduced by it and also uncomfortable. I’m asking questions about what [we have] been told is desirable, which is power.”

“I believe in self-criticality,” he adds. “I believe in stepping back and taking a look at the bigger picture. love photographic clichés, but we play into them.”

– Words by Marcus Civin

Silano’sresidencywasgenerouslysponsored inpartbyLoisWhitman-HessandEliotHess.

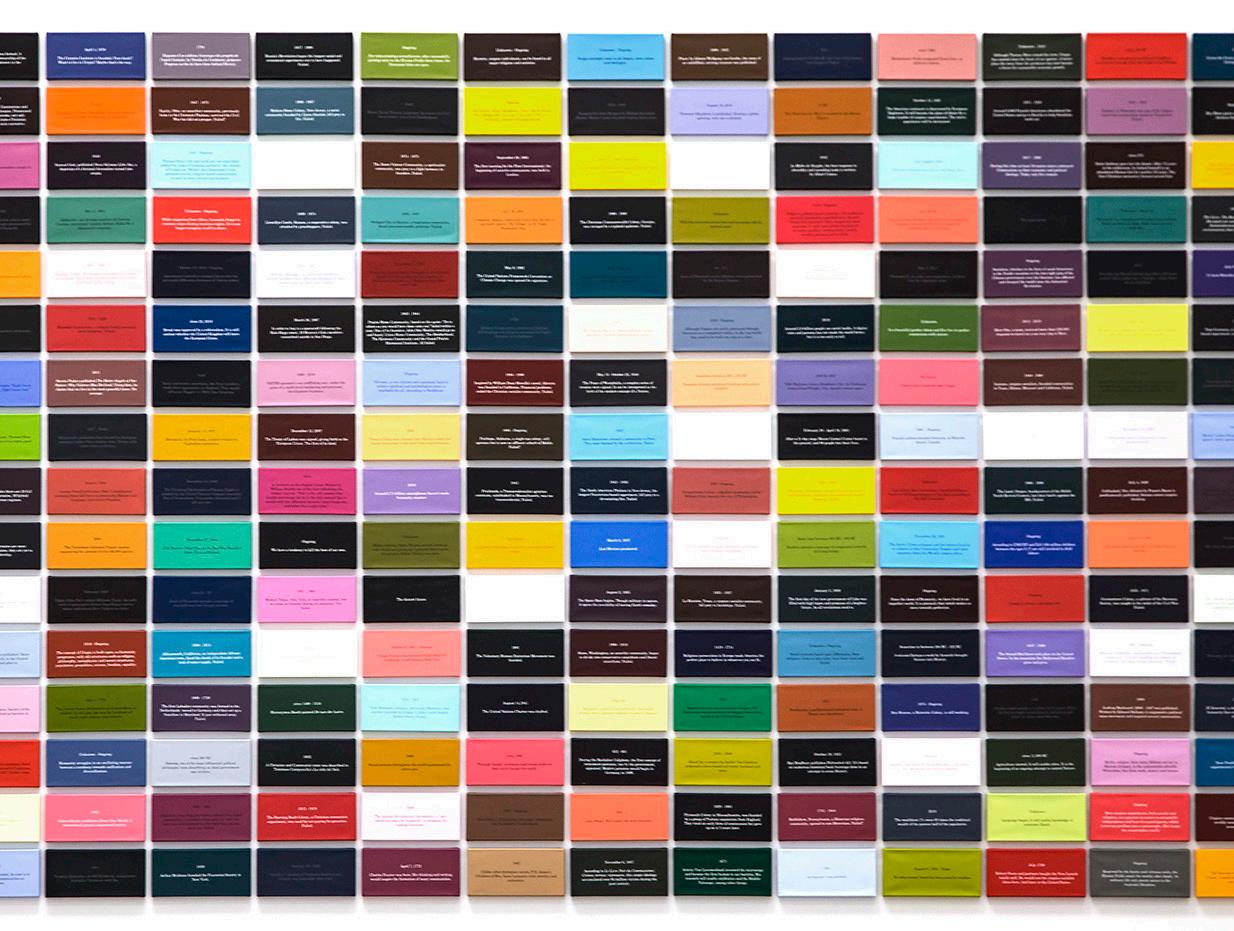

Since about 2013, Samuel Levi Jones has created palimpsests of history and calls for reconsideration and reconstruction. He takes apart or pulps books, often encyclopedias or school texts, producing quilt-like compositions of interlocking rectangles made of ripped-away book covers, book spines, and mashed-up paper. Jones gives these works titles such as Holding Space,HappinessWithin,BurningAllIllusion, Statutes, Promises and Pleasure from Pain. The remnants stand in for what was included or excluded between these and similar covers—all the possibilities, joyful diversions, marginalia, and sadly woeful categorizations, that stained patchwork of printed history.

These days, Jones is moving from project to project, continuing to create book-related works for exhibitions and also developing his first-ever public piece, a monument and a garden in collaboration with the design studio LAA Office and Sam Van Aken, an artist who, among other things, cultivates antique and heirloom fruit varieties. Jones was sharing both bodies of work with the Miami community when he was at Fountainhead.

Born in Marion, Indiana, Jones is the great nephew of Abraham Smith, the nineteen-yearold a white mob lynched in Marion in 1930. (Thomas Shipp, eighteen, was also lynched. James Cameron, sixteen, was beaten but survived.) Abel Meeropol wrote the iconic song StrangeFruit after seeing a photograph of the two lynchings. Billie Holliday recorded the song before the end of the decade. (“Here is a fruit for the crows to pluck/ For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck/ For the sun to rot, for

the tree to drop/ Here is a strange and bitter crop.”) As of early 2024, Jones was planning to cultivate a garden with a tree whose main purpose would be to contribute to life rather than death. A perimeter metal wall he was conceiving would be perforated and backlit. He was working with the community and wanting to offer a space where local Black people can sit, reflect, and interact.

Speaking with Jones on a video call, shared my observation that many monuments and books function similarly in preserving just one view, one version of the past. Jones’s artworks and his monument-in-development go after more. They propose that neither the material that makes up the monument nor the physical form of the book is what lasts. Monuments are not only bronze and stone. At best, they’re imperfect ideas in time. And, as much as love paper, type, and binding, great books—or truly great ideas in great books—are ultimately revelatory, elastic, durable, demanding, and generous. Maybe someday the same will be true of more monuments. “There are times where people don’t want to engage with my work,” Jones shares with me. “The thing about my work, and hopefully this project, is that it’s an icebreaker. I hope people will come in and take on difficult conversations.”

Jones’sresidencywasgenerously sponsoredinpartbyLoisWhitmanHess and Eliot Hess.

Nardeen Srouji is always attempting to understand herself in relation to different spaces. “I’m in a gap in between,” she says. “And my work is really influenced by that gap.” A Palestinian artist from Israel, Srouji creates sculptures and installations that investigate the sites in which they appear; the hidden histories all spaces contain.

In 2022, Srouji created site-specific installations for a show at Haifa Museum of Art. Through interviews and archival research, she learned there was a window in one of the galleries. It was walled over and hadn’t been opened for forty years. For Landscape Layers I (2022) Srouji removed the wall and opened the window to the world outside. She took photos of the neighborhood view, then placed window-sized prints of the view flipbook-style on the windowsill. “It’s really complicated to live here, have to think about things ten times to find solutions,” Srouji says. “This is why keep looking at spaces that nobody looks at. I need to understand all the layers and how it makes sense for me to exist in a specific place.”

At Fountainhead, the outer wall of Srouji’s studio space was in an area of the yard where no one really goes. The wall has a sculptural relief, the kind you find on many Miami dwellings. Srouji created two braids made from wool and installed them on the outside of the wall, right where her head would be.

“Braids in Palestinian culture were very rooted—women used to do two braids most of the time,” Srouji says. “It was the traditional way of doing your hair.” Now, these braids are mostly a symbol of childhood, or still worn by older Palestinian women. An affirmation of identity, yet also obscured, the installation is a subtle, powerful acknowledgement of Srouji’s tenuous position. “It’s in a very hidden place,” Srouji says. “I think I did it for me. Not for the viewer at all.”

– Words by Rob Goyanes

Srouji’s residency was generously sponsored in part by Leslie and Michael Weissman.

During Reniel Del Rosario’s month-long residency, he says he made “fifteen plates, one hundred flowers, two hundred cigarettes. Like ten eggs. A basket. Twenty-four cups.”

For Del Rosario, this is actually a modest number. A ceramicist exploring the notion of overproduction, Del Rosario renders everyday objects into ceramic sculptures, usually numbering in the few hundred to several thousand. “It’s about the overwhelmingness of the products, a critique on mass production and mass consumption,” he says. Rather than slick refinement, Del Rosario is seeking an almost amateurish quality in the work. He makes all the sculptures without the help of assistants—“I can make a hamburger in, like, two minutes” — and sells them for the same price as the consumer goods they represent.

Del Rosario was born in Iba, a fishing town on the northern west coast of the Philippines, and studied ceramics at UC Berkeley. This was not a lifelong dream. He went to a tech middle school and high school, studied robotics and computer science, and at Berkeley he took a ceramics class because it was the only class with space left. The tactility of ceramics drew

him in. “It changed everything,” he says. “I was like, ‘This is what I want to do.’”

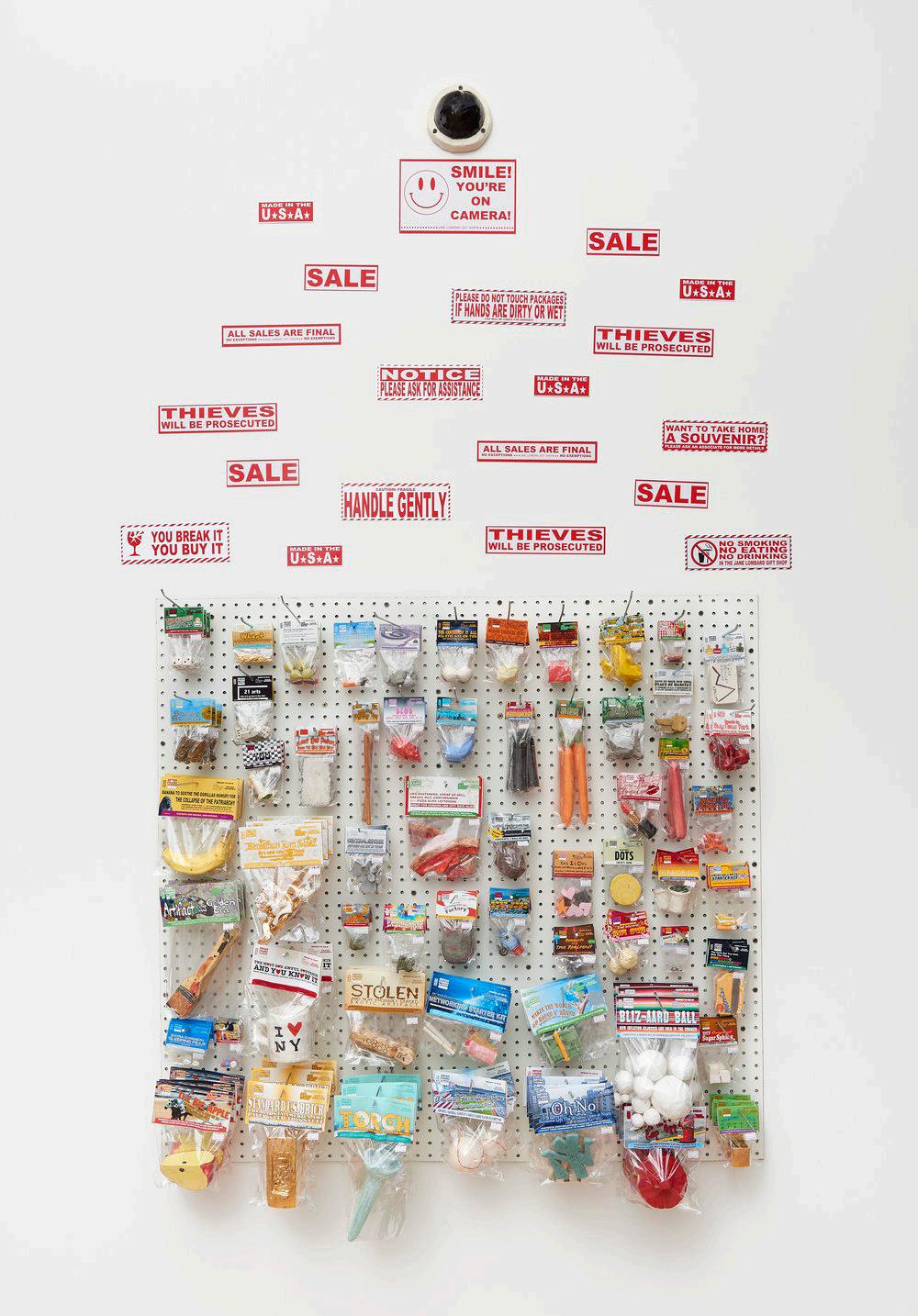

His abundant ceramics are presented in public installations that recreate retail environments. For TheAmericanDream/Renny’sDelicatessen (2018), he made loads of pastries, burgers, and macarons. Del Rosario also performs as purveyor of these spaces. He acted like a midcentury delicatessen worker for The American Dream, and as a sleazy museum director for another project. At Fountainhead, he made Florida gift shop merchandise and ad hoc signage for guns and psychic tarot readings. “Those are the kinds of things that I really, really want to get into,” he says of future work. “This kind of dichotomy between the ‘high end’ and ‘low end,’ and how those affect each other in our actual consumer decisions.”

– Words by Rob Goyanes

DelRosario’sresidencywasgenerously sponsoredinpartbyLeslieandMichael Weissman.

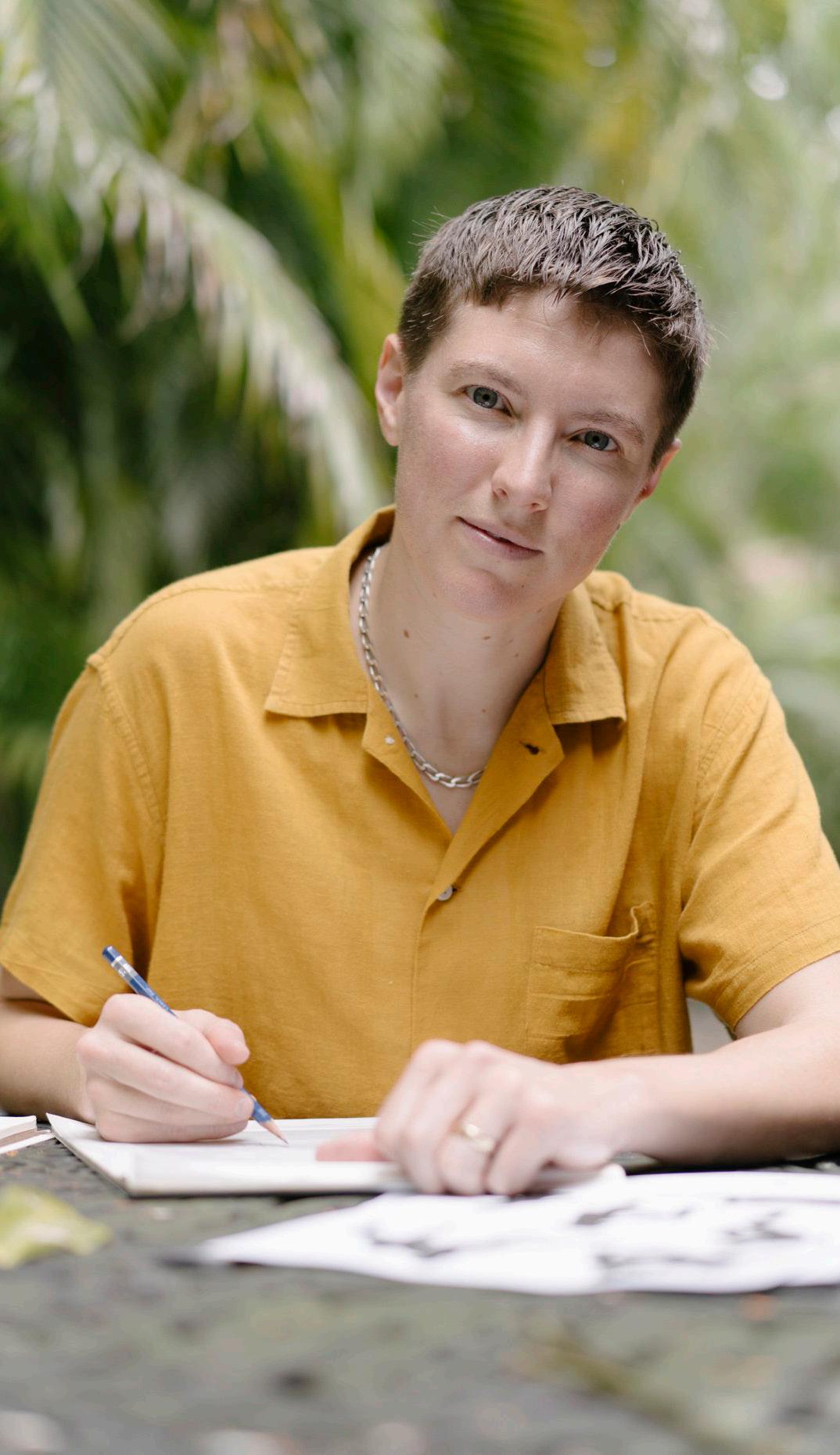

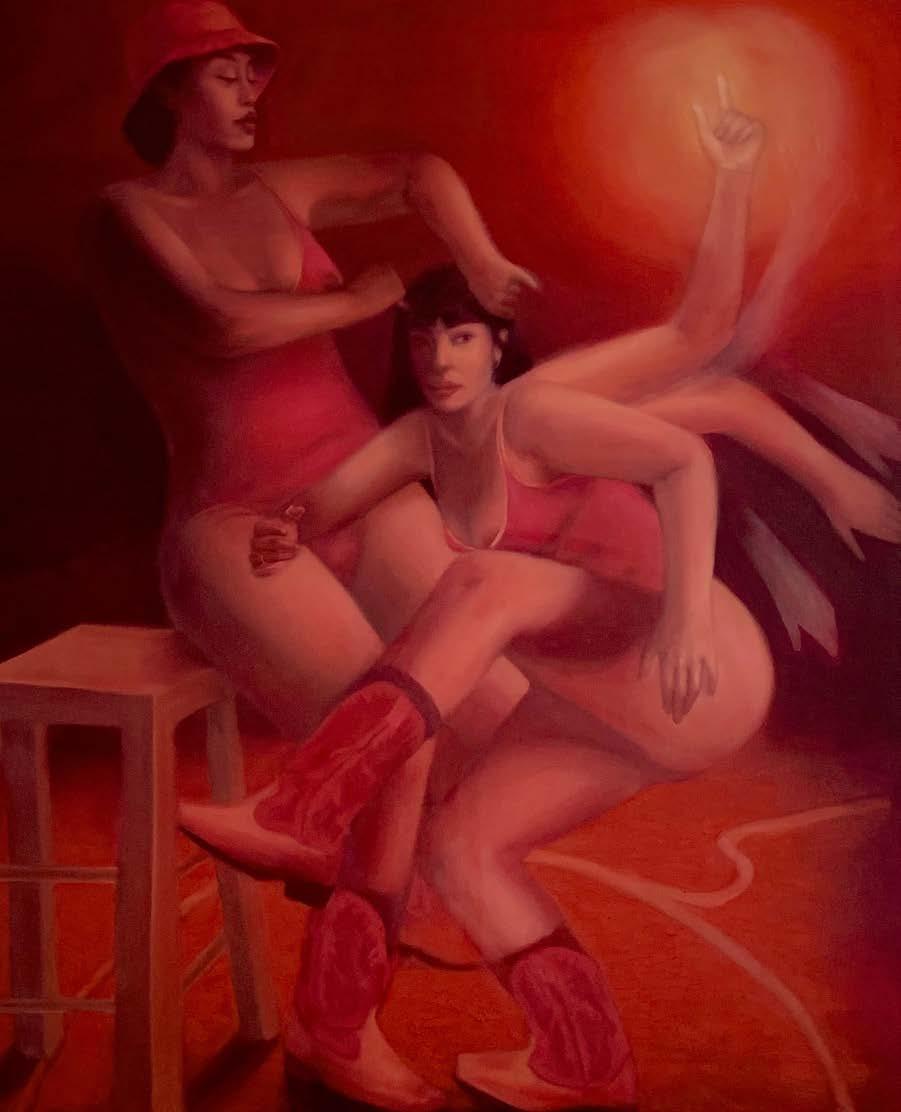

Zoe Walsh’s residency was focused mostly on the pre-production phase. They spent their time reading CAConrad’s ECODEVIANCE.

A series of rituals and poems—such as pollinating flowers for security cameras— the poems are “about disrupting the factory within oneself,” Walsh says. Pulling elements from archival photographs and staging their own, Walsh creates radiant and monumental works containing silhouetted figures amongst polychromatic landscapes. The paintings are models of what Walsh calls trans-visual pleasure. “I wanted to make paintings that have a type of optimism in them,” Walsh says.

One of their sources is Pat Rocco, a filmmaker and activist who lived in Los Angeles and documented the first Pride Parade. Rocco also shot erotic films in public spaces throughout the city, where Walsh is based. Rendering the figures from these films as silhouettes, and photographing their friends as well, Walsh is interested in gender expressions that move beyond the body. “It’s a way to get out of having to talk about gender through body parts, which is a demand that was placed heavily on my work

in grad school,” Walsh says. “It’s getting away from this idea that you can understand something about people based on their appearance.”

The works themselves are labor intensive. “The first layers of the paintings are screen printed with acrylic paint, then they’re stenciled, then use squeegees and spatulas to pull these thick gels of acrylic across,” Walsh says. The larger paintings can include fifty prints, and the results are psychedelically flavored, a mix of representational and abstract. “One of the places my work comes from is the experience of going to see a movie as a kid and identifying with a character on-screen,” they say. “That fantasy space, that imaginary space, can give you an alternative lens to understand yourself and to feel yourself.”

–

Words by Rob Goyanes

Walsh’sresidencywasgenerouslysponsored inpartbyLeslieandMichaelWeissman.

The morning after she arrived in Miami, Ana Silva began painting. It was her first time in the United States, but she felt at home with the weather, foliage, and local Latino community, almost as if she were back in Angola. Building upon a canvas she had begun creating in Angola out of lace and embroidered elements, she began to portray a woman who stands tall and faces the viewer, surrounded by animals and plants.

“The woman, mother nature, goddess of fertility, sets herself up as the protector of this nature that is tending to disappear,” Silva says. Female figures and nature have always been present in the artist’s work, reflecting her memories of growing up on a farm, witnessing life and local ecologies upended by rebel groups and civil war, and navigating intergenerational traumas as a woman simultaneously burdened with expected societal roles—as provider and caregiver.

The painting, part of an ongoing series titled Source, was above all a way for Silva to explore a new technique. Using lace as a kind of

stencil, she applied paint and glitters through the intricate patterns—in effect imitating the intricacies of embroidery. “In Miami, I found a new kind of painting,” she says. She felt encouraged by studio visits with other artists and curators, who she felt were more approachable and constructive in their feedback than curators in Europe.

“The discussions are more direct and we talk very quickly about the works without going into side conversation,” she says. “And rarely in such a short space of time have come across such a concentration of collectors and institutions.” That month, she was also preparing to exhibit at Frieze New York, so finding a balance between meeting deadlines and honoring her creative vision was critical. “This experience really gave me some courage to continue this work and be sure that what I’m doing is important,” she says. “It really gave me the energy I needed at the time.”

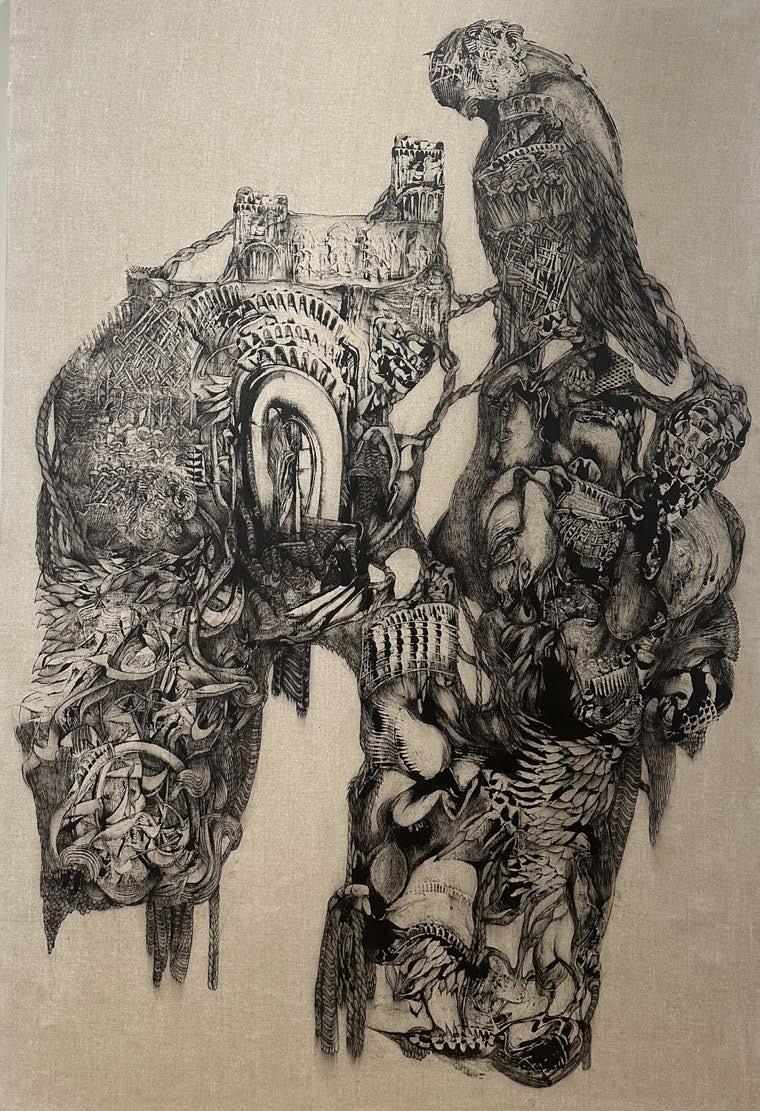

– Words by Claire Voon

Looking at Kevork Mourad’s works is like slipping into a dream. Monochrome drawings of figures and architecture meld into swirling panoramas on canvas, which Mourad often cuts and layers into intricate portals that beckon close inspection. These dense worlds showcase the beauty and tragedies on land that has witnessed waves of love, war, regrowth—histories of civilization tearing apart and reattending to itself. For Mourad, a descendant of Armenian refugees who fled to Syria during the Ottoman-perpetrated genocide, what’s past still haunts the present, and necessitates wrestling with. “I’m always addressing the idea of urgency, destruction —how so many ancient places have been demolished or erased,” he says. “The idea of layers is related to time; I’ve been exploring how I can take the concept of time, put it in something still.”

A month in residence yielded what felt to him like almost a year’s work: Every day, after running, he’d enter the studio ready—“eyes, mind, and spirit so high from the light and surrounding beauty,” as he put it—to create deep into night. In a new environment, the trained printmaker experimented with dimensionality, keeping his canvas loose rather than stretching it, and by fraying the fabric. He also added

color—specifically, a deep red inspired by the Armenian cochineal worm, historically used to produce vibrant dyes.

“It gives a trace of violence,” he says. His focus was a large-scale tableau whose subjects tuck into themselves, like a peony’s folded petals: women lost in their own worlds amid ancient architecture. “It’s trying to capture this nostalgia,” Mourad says. “When you see what’s happening in the world now — the war and killings — why are we destroying ourselves? I’m trying to create a sense of urgency for people to rethink how to address each other, to find more beauty instead of seeing the ugliness.” It’s an ethos he carried as he met people in Miami, such as Jaime Odabashian,a fellow Armenian who owns a rugmaking company. For Odabashian’s studio visit, Mourad, a skilled baker, quickly mixed his guest some dough with olive oil and cheese, and together, they broke bread.

–

Words by Claire Voon

Mourad’sresidencywascarriedout inpartnershipwiththeHumanRights Foundation’sArtinProtestcampaign.

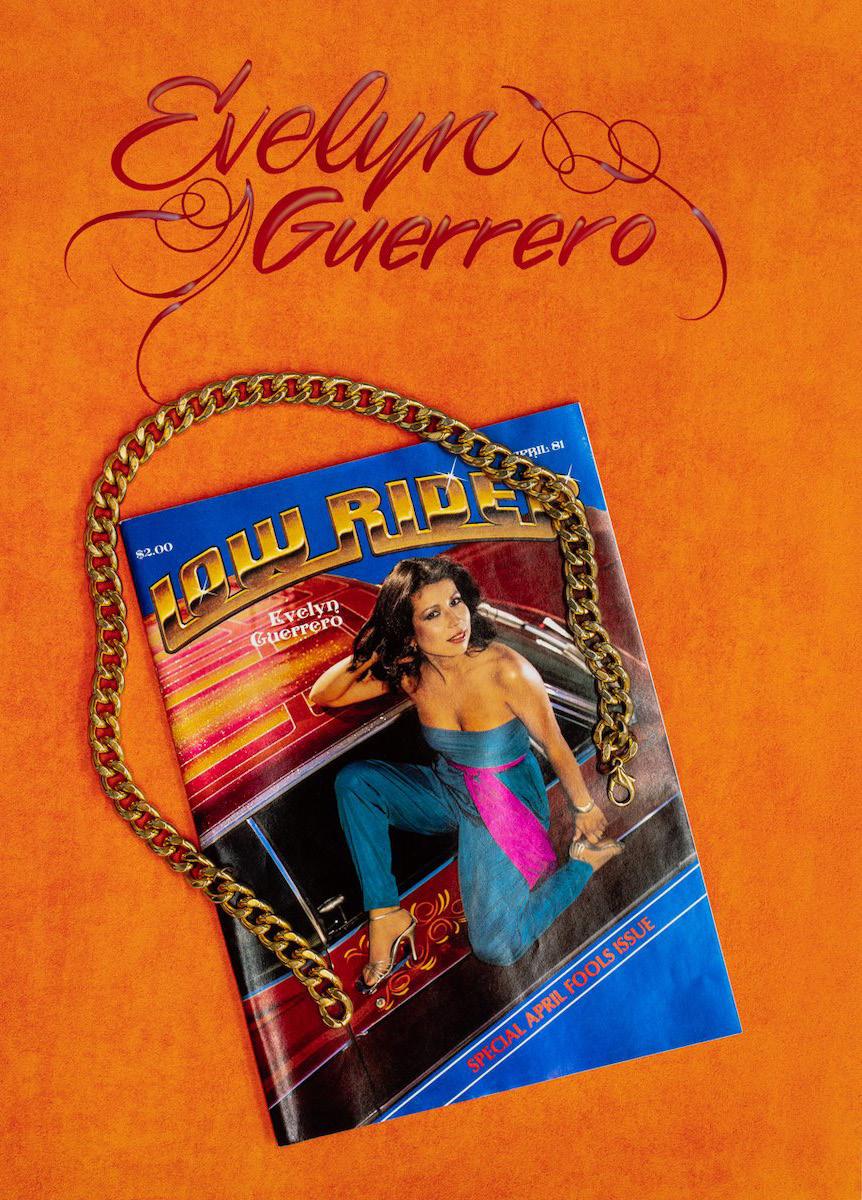

Liz Cohen works deeply and slowly. She creates extensive bodies of work whose layers of historical and cultural investigation unfold over many years to reflect generative inquiries into labor, gender roles, and migration networks. Perhaps best known for her project BODYWORK—in which she custom-built a hybrid sedan-lowrider and adopted new identities to probe notions of in-betweenness—Cohen has been researching the history of coffee production and its effects on the Global South, particularly during the Cold War in Colombia, where her family is from. The ongoing GAZ COFFEE presents an interactive coffee station operating out of a Soviet utility truck that traces the flow of labor and capital from extractive industries.

“I often have a central object that functions like the sun, and then there are all these satellites around it that are just spinning off of it,” Cohen says. “It’s this anchoring force where get to spiral out into all these tangential stories, but they all come back and relate to this central thing.”

In Miami, she extended the GAZ COFFEE universe, working on a large textile piece she

had started years ago but hadn’t had time to finish.

Sewn with automotive-upholstery threads, the applique work depicts the Soviet military jeep at the project’s heart—a GAZ-69A— coffee plant branches, and a machete. It is in essence a picnic blanket meant to go inside the car—thus imagining the jeep’s use within the realms of leisure and pleasure. “The works are part of this elaborate way of creating parameters for experience,” Cohen says. “I produce objects and images to create an atmosphere for something to happen.”

This was her first residency in more than two decades, and it gave her space to clear her mind, with mornings spent swimming in the ocean before diving into sewing.

“It’s great to shake up your daily routine,” Cohen says. “It made me realize ways to lean into aspects of my process, given the structure of my life—how can I stitch for 10 minutes, if that’s all I have. Leaving for a month was really healthy for me, in terms of focusing and having clarity.”

– Words by Claire Voon

Wood is Ato Ribeiro’s primary medium, but he first arrived at the material through his training in printmaking, a trajectory that’s easy to trace once you realize he’s an artist for whom “everything informs the next thing.”

In West African strip weaving traditions, Ribeiro intuited new ways of seeing. He was fascinated by the way such vivid and intricate textiles, namely Ghanaian Kente cloths, seemed to encode language. He brings all this to bear on his assemblage creations, in which he combines spare scrap wood to create monumental works of interlocked forms. These works offer a means of thinking with and through the complexities of the Black diaspora on both the collective and personal scales.

Ribeiro spent part of his childhood in Accra, Ghana, and much of his work aims to reconcile the fact—the vertiginous experience—of belonging to two cultures. An autobiographical current runs through his work, though it hardly makes recourse to familiar methods of representation. You won’t glimpse figuration here. Rather, Ribeiro’s art revels in the possibilities of abstraction. He roots himself within and draws upon the vast spiritual resource of the lineage of Black practitioners who preceded him and whose labor is often invisibilized, absorbing the textures and rhythms of their forms, the fluency and flash of their patterns. Flash: a word which invariably quickens the legacy of

the late Robert Farris Thompson, the historian of African art who took as his great theme the affinities that animate the aesthetic traditions of the Black diaspora. Those affinities compel Ribeiro’s art, which might be understood in part as a gesture of prostration before them.

For the duration of his residency in Miami, Ribeiro was concerned less with production per se than with rest, with being as “present as possible,” and with carving out and cultivating a discipline that stands apart from the rigors—the capitalist demands—of the contemporary art market. He knows well that any attempt at making must begin with living, which is a kind of art unto itself, an art that exceeds the habits of the studio. He makes room in his practice for his body, which is to say, he considers how best to nurture his physical and mental reserves. For Ribeiro, care, of the self and of the collective, is a liberatory endeavor, a portal to the pleasure, imagination, and beauty that the eye and mind encounter everywhere in his work.

Ribeiro’sresidencywassponsoredinpartby ShepardBroadFoundation, andJaneWesmanandDonSavelson.

The in-between: not a place one can pin on the map, but rather a state of mind, one that the Korean-born artist Ho Jae Kim restlessly surveys. All preoccupations originate somewhere; many of Kim’s derive at least partly from his own life. Born in Seoul, Korea, he immigrated with his family to Los Angeles when he was ten or so. He was immediately slung between the language and culture of his adopted hometown and the one he’d left behind—of age “to have absorbed enough Korean culture to embody it, but still malleable enough to absorb a lot of new things,” he says.

His early intimacy with deracination, displacement, fracture, and loss perhaps accounts for his inclination toward “quieter scenes” from the history of art; for instance, the symbol-laden compositions of de Chirico or Magritte, from which he gleaned models for how to transmit the surfeit of human experience in meticulously constructed worlds ruled by metaphor and allegory. Kim has often called his enigmatic worlds, brimming with figures whose gazes we rarely meet and looming thresholds that beckon plangently, purgatory, and has drawn inspiration from the text of Dante’s Inferno He aims to “paint the reality live in,” and by doing so he helps us see and contemplate the complexities we inhabit,

In Miami, where the sun brightens the senses, Kim found time for leisure, for healthy moments of rest he’d seldom allowed himself in the past. His residency was rejuvenating. During his time he devoted himself to an upcoming body of work that will debut at a pair of shows in New York City and Seoul. His recent paintings retain the force of his abiding fixations, but they mark in some ways a departure from his method. His work to date demonstrates his great facility as a draftsman, but lately he’s sought to wed this technical finesse to a burgeoning fascination with the potencies of color. His surfaces have changed, too. Thick swirls of impasto accrete in the newer works, the result of an impulse to “let paint be paint.” This process of discovery and experiment has yielded great pleasure, and even fun, a perhaps unexpected reward for an artist who contends so valiantly, so consistently, with the unknown.

– Words by Ade Omotosho

Kim’sresidencywassponsoredinpartby ShepardBroadFoundation, and Jane Wesman and Don Savelson.

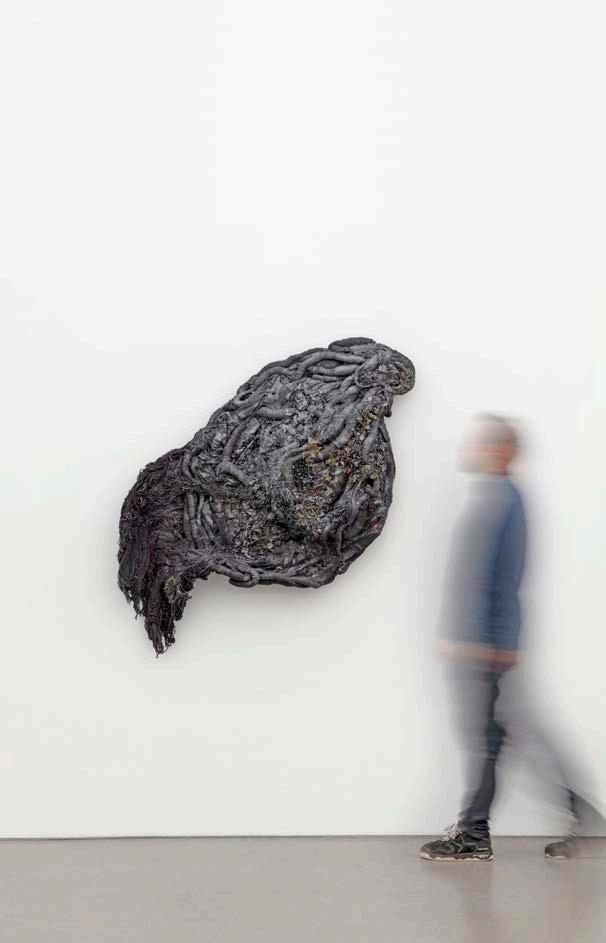

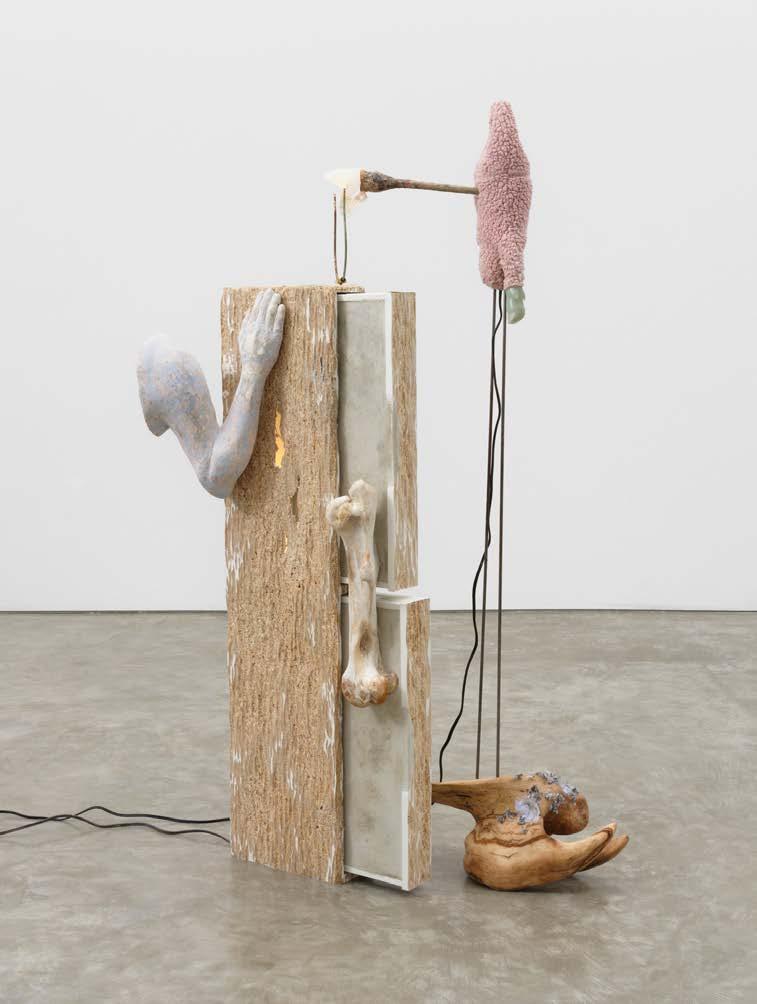

In 2020, the textile artist Sagarika Sundaram made her first large-scale work, Oracle. It is an impressive creation of hand-dyed felted wool bursting with rich red, blue, and yellow hues. Every textile work coaxes the hand into a deep and sensual intimacy, but the tactility involved in creating Oracle was altogether overwhelming. After mounting the work, she took a moment to “sit with it” to “talk to it” and in turn to “let it talk to me.” Sundaram was moved by her communion with the work. Here was validation that she is indeed an artist.

Born in Kolkata, India, Sundaram is an inheritor of vast and extensive South Asian textile traditions. Her work continues to weave the threads of a lineage that reaches across time and geographies while expanding its aesthetic variety. Felt is one of the world’s oldest textile traditions—thousands and thousands of years old—but Sundaram isn’t burdened by this history. Instead it galvanizes her into testing and experimenting with felt’s various properties, working the textile in new forms and arrangements and imbuing it with newer and bolder colors.

Words by Ade Omotosho

Sundaram’sresidencywassponsoredby ShepardBroadFoundation, and Jane Wesman and Don Savelson.

In the years since making Oracle Sundaram has continued to construct large-scale works that evoke the forms and textures of the natural world, ranging from sea creatures to rich, pendulous vegetation. She’s acutely aware of how her work is bound up with and dependent upon nature, whether it’s raw sheep’s wool or natural dyes, and this knowledge shapes her approach to sourcing materials from locales as varied as the Himalayas and the Hudson River Valley.

imagine Sundaram’s time in Miami was especially congenial to her sensibility given her penchant for natural phenomena and imagery. Waves and rain and palm fronds and wildlife: all these stir the humid atmosphere of South Florida, giving it its distinctive character. These elements surely delighted Sundaram’s eye, and it will be interesting to see how the region’s lush landscape might manifest in her work as it evolves.

Where does history end and a myth begin? This question, this temporal dichotomy, is central to the work of media artist Claudia Joskowicz.

Joskowicz is a Bolivian artist, currently splitting her time between Bolivia and New York, while also holding a teaching position at Wellesley College in Massachusetts. With over 20 years of experience developing a practice in the pioneering era of video and technology-based art forms, she creates portals into complex narratives rooted in history and memory.

Joskowicz’s artistic practice is primarily centered around film, video, installation, and digital media. With an academic background in architecture and photography, her work integrates structural and visual elements that force viewers to meditate on how a sense of place and time influence our perceptions of the past. She employs long, slow video footage and often oscillates between film and photography, with her early works incorporating minimalist reenactments. Today, we see her reimagining cinematic staging of landscapes, both urban and natural, where nuanced political dramas unfold in real-time and are restructured with her single-shot and tracking techniques.

Her work builds upon the visionaries of the medium who not only inspired but also mentored her. Learning from the work of

people like Bill Viola and studying directly under Peter Campus, she incorporated video and film studies into the foundations of her artmaking. Blending photography and video to unearth these hidden and distorted historical narratives, she takes a structuralist film aesthetic and combines it with her own conceptual framework based on landscape and memory.

At the core of her work is the idea of the falsity of collective memory. Whether it be the manipulation of the media, the omissions in our historiography, or the nature of a place being imbued with its own history, she asks us to rethink our contemporary social realities. Witnessing her own family’s romanticization and relationships to the events of the past, specifically Bolivia’s role in the Cuban Revolution and the international intervention that ensued, the narratives of power unravel. Claudia Joskowicz’s work becomes a liminal space between cultural myth and reality that may forever remain unknown.

– Words by Charles Moore

Joskowicz’s residency was sponsored in part byHestyLeibtagandTerryVerk.

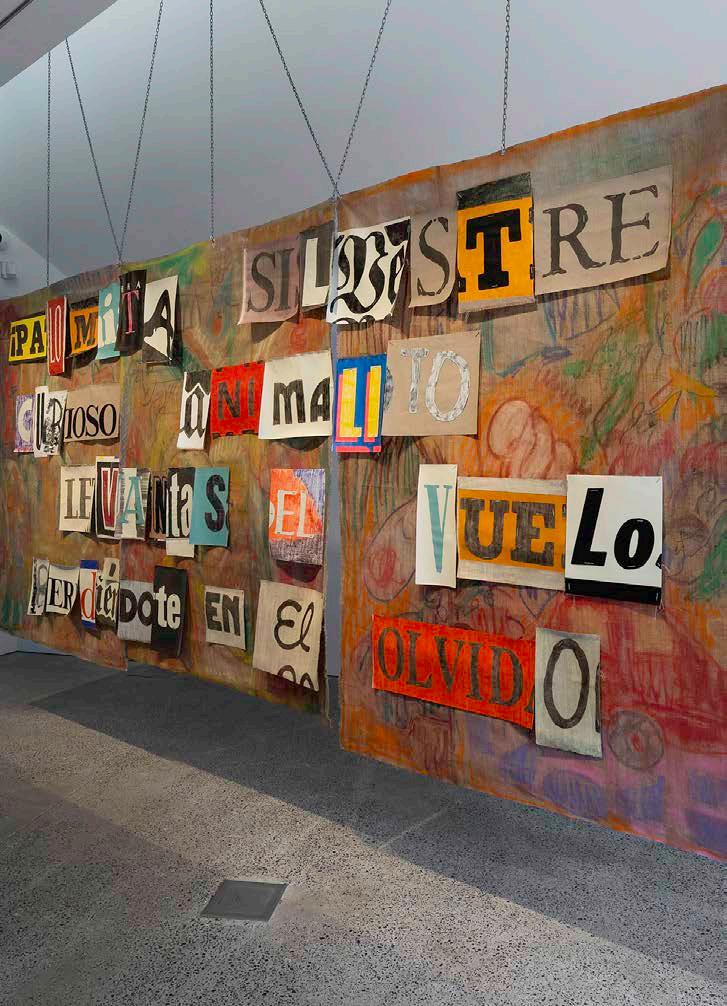

Born in Mérida, Venezuela, artist Nadía Hernández spent her youth in Tucson, in the United States, and has since made a home for her creative practice in the Wurundjeri Country of Melbourne, Australia. While Hernández studied design and fashion, there was an undeniable pull to the realm of fine art. Her work transcends a single medium, often embracing collaboration and activation as she illuminates the multitude of parallel histories that shape a sense of identity, culture, and heritage in our modern world.

Hernández’s studio is a testament to her eclectic approach to art-making. Here, she experiments with painting, mixed media, textiles, sculptures, and installations. Whether it be sourcing secondhand materials to become visual allusions, taking from her own familial archive, or creating her own aesthetic language through text and abstract forms waiting to be deciphered, she manipulates the viewer on multiple sensory levels. Her control of her palettes set the tone, evoking an idealistic wanderlust or even a militarist presence. The ambiguity she plays with carries over into her installations. Embracing relational aesthetics, she allows the actions, artistry, and performative actions of her audience and collaborators to help her works evolve and react to their environments and time.

The influences that shape her artwork are as diverse as her techniques. In her early years, she found inspiration from folk and pop art, rethinking what it meant to view the everyday. Her style now incorporates a diverse set of influences, from the bold color and form of Abstract Expressionism to the intricate absurd layering of Surrealism, and the socially charged yet humor-imbued practices of the Dadaists; however, she views these monumental shifts in art through the lens of Latin

American modernism. Thinking about artists like Jesus Soto, Carlos Cruz-Diez, and Gego alongside major non-European styles like the Tropicalia movement in Brazil, she embraces yet critiques their contributions. Her work channels their innovation with her own contemporary flare, which leaves us questioning the alternate, additional, and suppressed histories in our midst.

Hernández’s art is a profound exploration of identity, heritage, and protest, deeply rooted in her experience as a Venezuelan living in the diaspora. As personal and political narratives intersect, her perspective of existing in a liminal space between the different cultures of her upbringing reveals larger questions of truth in identity and history. The themes of her art are steeped in the rich history and culture of Venezuela, the complexities of geopolitical contexts, and the powerful role of art in pushing and fighting political agendas. Through the writings, notes, reflections, and poetry that she creates to accompany each body of work, Hernández delves into the daily exchanges that teach us about blending cultures and languages across borders. Her art critically examines the past and present, offering speculative futures that speak to the nuanced and often dark idealization of a lost homeland. Hernández’s work is the act of coming together to claim culture and unity over polarizing forces as we examine the complexities of identity and belonging that exist today.

Hernández’s residency was carried out in partnership with Human Rights Foundation’s Art inProtestcampaign.

Dedondenoseveelhorizonteylavistachocacontralamontaña/from whereyoucan’tseethehorizonandsightcollideswiththemountain(2020), installation with oil, acrylic, flashe, linen, wool, cotton, ribbon, grommets

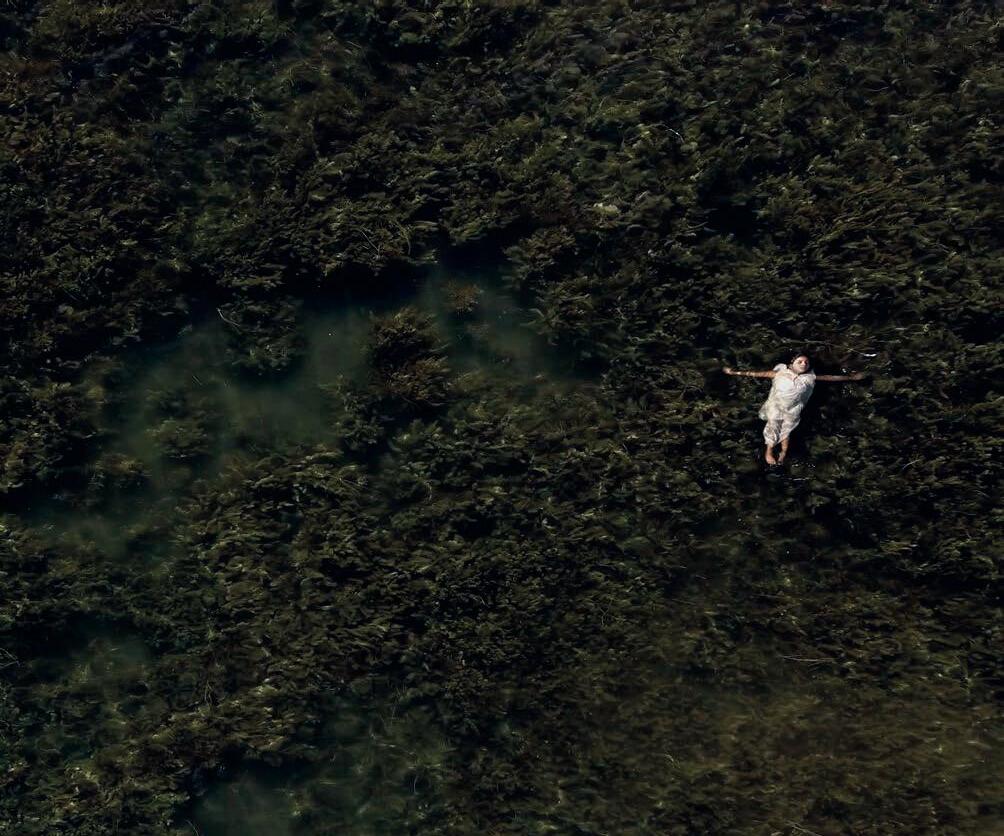

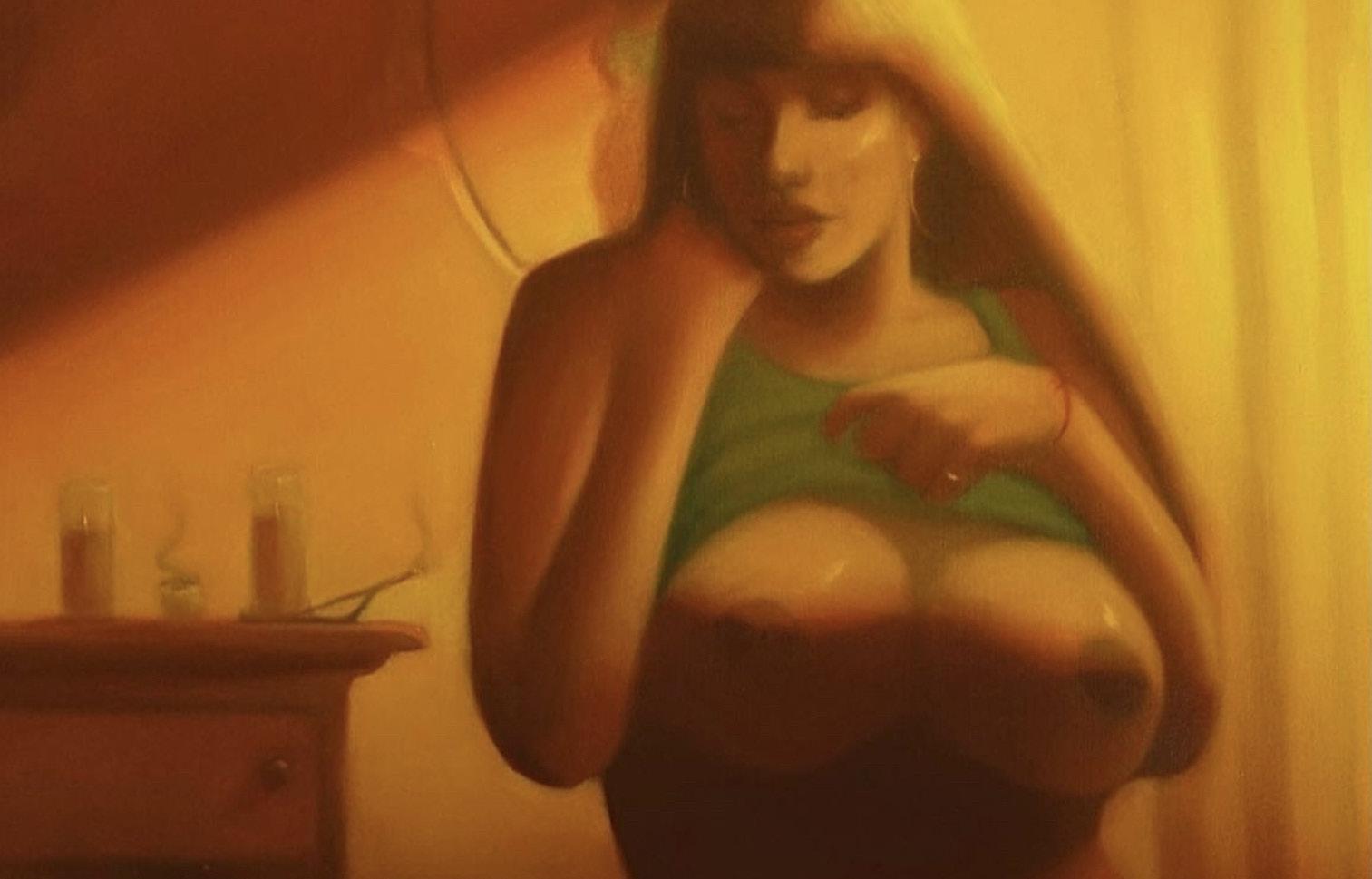

Natia Lemay works instinctively, exploring themes of identity, race, and personal history in her figurative paintings. Her works are characterized by their fluidity, jet-black backgrounds, and the expressive body language of her subjects, which reflect her own emotional experiences. It makes sense, in this way, that Lemay has turned to artmaking as a form of meditation. Though she didn’t pick up a paintbrush until age 32, the mixedrace, Afro-indigenous artist—who earned her MFA from Yale School of Art in 2023—was long driven by a pull to heal. Using dollarstore paints and cheap canvases, she found serenity in the act of bringing her subjects to life.

As Lemay began to sift through her adolescent and early adult wounds, her work became more intuitive, allowing her to explore a wider range of emotions through her Black female subjects. Today Lemay works quickly and vulnerably, painting wet-on-wet to capture the frenetic nature of her generational trauma, leveraging a method that requires her to complete pieces fast, usually within a day or two, ensuring her brushstrokes are set and

left alone once the paint dries. This approach— a form of meditation—complements the improvisational nature of her practice, which is less about careful planning and more focused on capturing her subjects’ inner worlds. To this end, the figures she depicts represent a blend of personal and collective identity, examining how societal structures and individual histories shape one’s sense of self. Influenced by conceptual artists such as Adrian Piper and Glenn Ligon, Lemay creates immersive environments: soft, domestic scenes featuring Black female subjects at rest, gently beckoning, inviting the viewer to become part of the work. Her paintings challenge audiences to reconsider notions of race and identity, prompting introspection and dialogue on the complexities of the human experience.

–

Words by Charles Moore

Lemay’sresidencywassponsoredinpartby HestyLeibtagandTerryVerk.

You’llgetabetterlookattheworld(2023), oil on canvas.

Andrea Ferrero’s signature sculptures are as transient as they are touchable, edible, and interactive. From afar, her works look like ancient archeological ruins and appear to be made of long-lasting materials: light pink Marmol, solid porcelain, and white stone that looks rusted by time. Yet the works acquire deeper meanings as we approach them, interact with them, and find that each piece is made of delicate white chocolate, melted and cast by the artist. Ferrero, who lives and works between Lima and Mexico City, explores power structures such as colonialism and conquest, the symbolic meanings of ancient architecture, and how these power structures and meanings play out in urban public spaces. The temporal aspect of her materials is central to the meaning of her work.

Ferrero’s 2023 exhibit, “all my life i’ve been afraid of power,” at Swivel Gallery, Brooklyn, includes white chocolate sculptures shaped of ancient Roman ruins, some large-scaled, spread between the gallery space. Each piece re-appropriates and re-signifies aspects of power as it confronts colonial ideology. “I allow the audience to eat my sculptures, at my studio and at the gallery, with the idea that they will slowly destroy themselves through consumption,” she said. During her Miami residency, Ferrero incorporated small hand-sculpted silver-appearing fruit flies, which she placed on top of her sculptures to speak to excess consumption and wasteful behaviors of the wealthy.

Working with the 18th-century European notion of banquets and opulence reserved only for the mega-rich, Ferrero, who started experimenting with chocolate after starting her own vintage dessert shop during the pandemic, plays with the famous “let them eat cake” response from Marie-Antoinette to the peasants. Reversing the power dynamic and adding some irony, her audiences can eat her aesthetically beautiful, sweet sculptures, touch them, and take them home. “I found that chocolate has so many symbolic and conceptual elements,” Ferrero explains. Once a sacred ingredient of Mesoamerican culture, chocolate became a commodity of European conquest and luxury consumption. The Aztecs and Incas from the regions of what is now Mexico and Peru, who used chocolate as a sacred ritual, served it bitter and pure. Later, through European colonization, ingredients such as sugar and milk were added and assimilated into the cacao, which became a sweet good only accessible to the rich.

The history of chocolate accompanied the narrative of conquest. In all their delicacy, Ferrero’s pieces also function as smaller acts of subversion to power structures. Be sure to try one.

Ferrero’sresidencywassponsoredby theCarloandMicolSchejolaFoundation.

ALL MY LIFE I’VE

Can a story be embodied in a work of art?

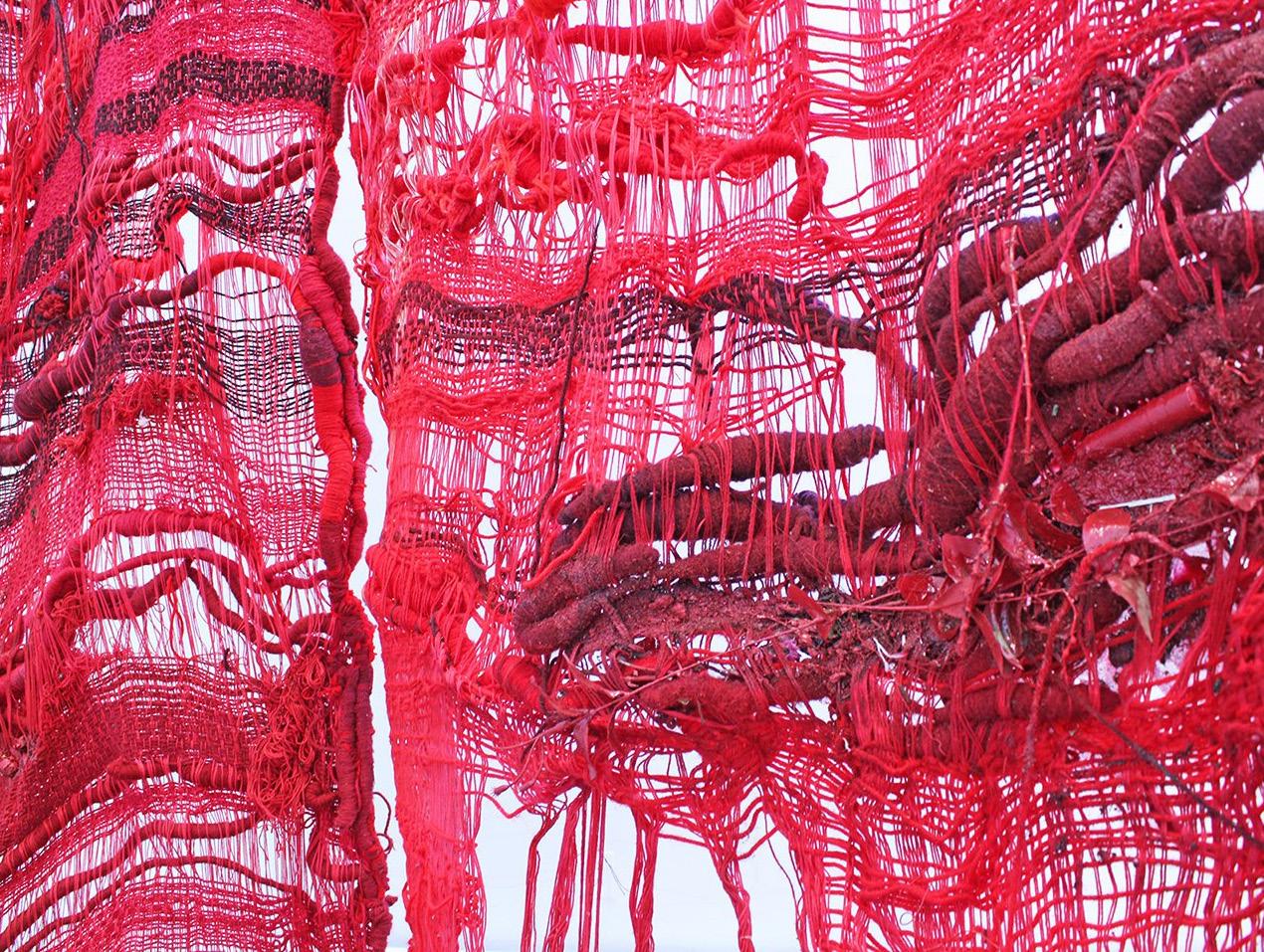

Daniela Gomez Paz is a threader of layered, intimate narratives. Her nest-to-human-scaled pieces, which she calls entanglements between sculpture, painting, and embroidery, play with the logical and the poetic, memory, and biology.

Born in Cali, Colombia, Gomez Paz immigrated to Queens, New York, when she was eight. “Weaving is a thinking framework and feel it as a map or as an intricate diagram unraveling existence,” she says. The Argentine poet Alejandra Pizarnik wrote, “el cuerpo se acuerda de un amor, como encender la lampara.” (the body remembers love/ a lover like lighting up a lamp). Gomez Paz’s entangled sculptures are also layered with different stories of home, questions about femininity, and migration that seem to light up, like a lamp, as the viewer approaches them.

The works created for her recent exhibition, Corrientesenmarañadas/Streamsofentanglements (2024, NOON Projects) are fleshy and vivid, tender like open wounds, synthetic and organic, each layer disclosing a history of the body as a home for remembrances.

“I work in different ways and all these processes connect by informing one another, consisting of coiled forms, soil, found objects, and fibrous components,” she says. Her medium-scaled, square-shaped piece, Grietas en su Apoyo/ Light in the Dark (2023), appears like a skin biopsy sample open to the viewer. Tangled layers of cloth reveal different elements: dried sunflowers, vintage handkerchiefs, a basket, a small mold of the artist’s hand made of plaster and beeswax, and a used soft sweater. Here, Gomez Paz questions the categorical identity of femininity.

“How can femininity be felt and communicated through color, motion, and tactility? How does the

psyche construct its meaning within private and public terrains?” she asks. Another work displayed at Mindy Solomon Gallery in Miami, a bloodred large-scale dynamic installation Tesando Agujeros (2023), hangs from the ceiling and is is in a twisting position alluding to a DNA molecule.

“Tesar means to tighten in Spanish,” Gomez Paz explains, and is indicative of how she crafted the work, coiling different red forms to mimic “blood clots, fiber, skin and muscle tissue, and the flowing of menstruation blood,” she adds, while also giving up control of its final form, and letting each thread pull and depend on the other.

Her June residency in Miami allowed the artist to focus on reflection rather than production. She experimented with materials and pondered on topics such as light, weight, and gravity. But Florida will only let you get away if you don’t consider what is happening to its climate. After one of the many summer storms had passed, flooding part of her studio garage, Gomez Paz thought about the permeability of color across different reflective surfaces, including water. “I had this textile work in process and its color reflected on the water with all the debris and other objects that flooded my studio floor. It was a crucial reminder of the climate conditions we live in. The water also felt like a mirror, a moment of looking into nature as also a way of looking into ourselves,” she adds.

– Words by Carolina Drake

Paz’sresidencywasgenerouslysponsoredbythe CarloandMicolSchejolaFoundation.

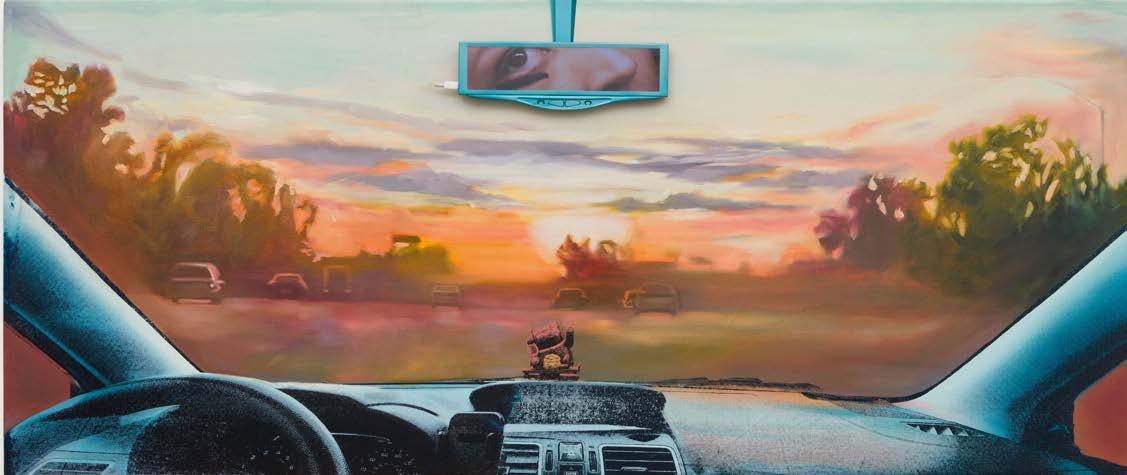

Jessica Taylor Bellamy cut out and collected weather maps from the local LA Times newspaper for three years. Through time, those archives displayed clear evidence of global warming. They also allowed her to discover the moon cycles, the changes in tides, and the exact times when the sun rose and set in her region, “like a rainbow palette, the maps are so beautiful,” Bellamy says. Born in a multi-generational Los Angeles home with an Ashkenazi Jewish mother and an Afro-Cuban Jamaican father, Bellamy, who studied political science and wanted to be a lawyer, worked in public media until art made its calling. Her works and video sculptures, at times, capture the dimming light of a daunting, sometimes weary sunset, which she has chased endlessly, sometimes obsessively. Her process involves capturing those UV rays, those “blades of light,” as she calls them, in her paintings and silk screens.

Bellamy mixes fantasy and reality to address notions of home, homeland, and landscape. “A lot of my work comes from wanting to collect what’s around me,” she expressed. “This includes figures, data, sunsets, and how information is presented in a newspaper.”

However, the newspaper is only a door, a way to frame her broader ideas. Bellamy’s ability to manipulate realities by adding dystopian and paradisiacal motifs or replacing elements to create her own visions is at the center of her creative strength. Her technique includes both journalistic and artistic skills. The pieces for her 2023 show VanitiesCometoDust:FromHavanatoLosAngeles with Love at the Roski Graduate Gallery in LA were

created after she visited Cuba in 2022. In those works, she captured the nostalgia of a Caribbean immigrant’s memories of home.

In Cuba, it was almost impossible for Bellamy to find newspapers, although she included fragments of some in her paintings. Some of her pieces include pop culture elements or an airline ticket blown up over paintings of sunsets and beaches near empty roads. The dire realities shown in the news are blurred under soft colors and dreamy images of fantasy settings that evoke the escapism of a vacation island trip. Her vision of “rose-colored glasses” contributes to the artwork’s aura.

During her residency at Fountainhead, Bellamy found Miami, a city so close to Cuba, to be the most inspiring and “strangely felt like home.” She witnessed, photographed, and reflected on how climate change continues to affect the built and natural environment of the city. “The gates and the architecture look like they have been through a lot. The way the vegetation grows so fast here .”

“Is this storm normal?” she asked as the water entered her studio. She has gathered enough material for new artworks, and yes, in Miami, she concluded that this sort of flooding, this waiting for the rain to stop, was indeed normal.

Bellamy’sresidencywassponsoredby theCarloandMicolSchejolaFoundation.

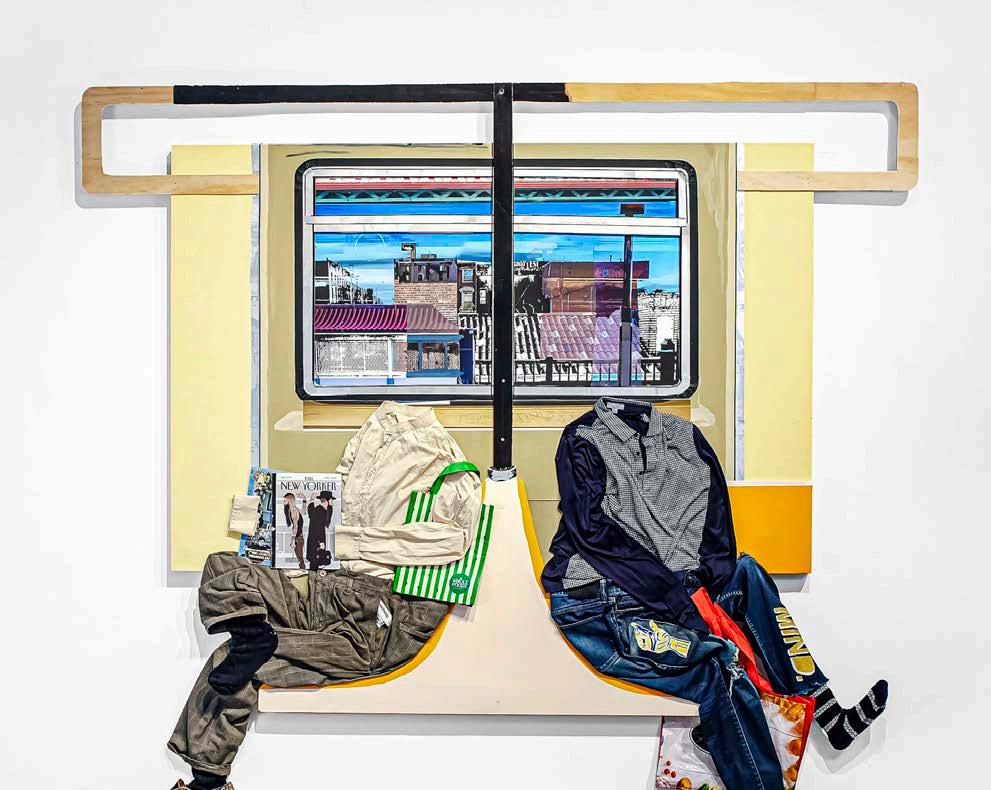

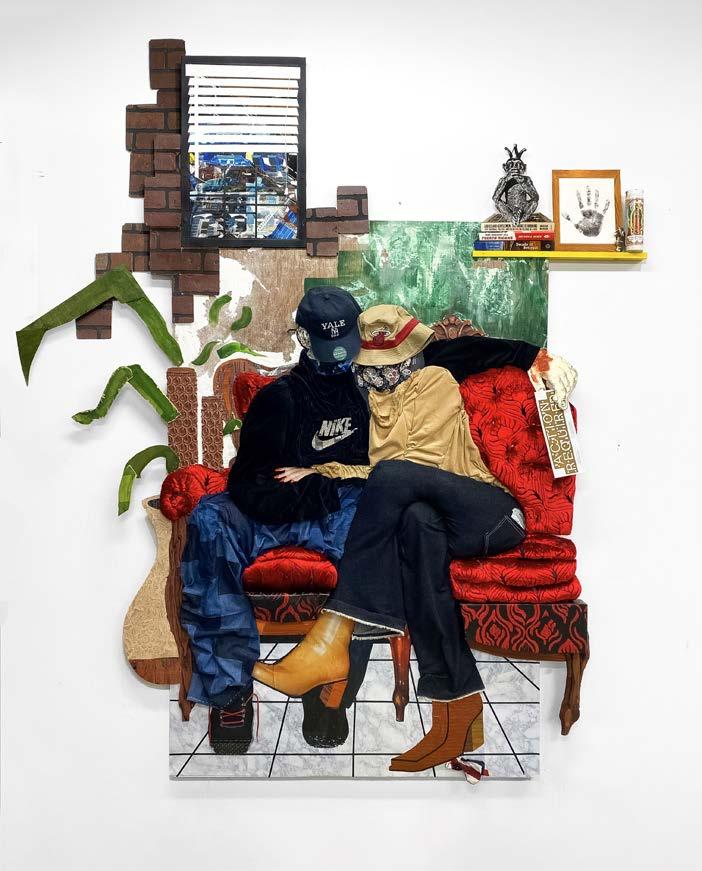

Multimedia artist Estelle Maisonett has long been drawn to the overlooked remnants of everyday life. Since 2012, she has collected found objects—discarded items encountered around her home in the Bronx—that serve as evidence of a population, a culture, and a specific moment in time. These objects, combined with her prints and photographs, form the foundation of her life-size collages, which pay homage to her experiences in New York and her family’s history in Puerto Rico and Mexico. “Building homes in my work serves as a conduit for exploring themes of cultural preservation, identity, and displacement,” she explains.

One such work, Tracing Roots (2022), encapsulates this theme by depicting her parents embracing on a crushed velvet sofa. Every detail speaks to the artist’s heritage and New York upbringing. Her father wears a “Yale Dad” hat, with the Y cleverly transformed into the Yankees logo, while the background features faux brick, a familiar, cost-effective upgrade in rented apartments. A photograph of her mother’s hand, emerging from a golden sweatshirt, gently clasps her father’s arm. Though her parents’ figures are abstracted and the room is simply sketched, Maisonett’s trompel’oeiltechnique suggests the presence of fully realized individuals and a well-loved home beyond the panel. “I think about drawing a lot,” she says of her object paintings. “Drawing

creates a two-dimensional, flattened space— similar to photography—yet it retains a sense of realism. I use this flatness to explore the condensation of layered histories embedded in personal and cultural artifacts.”

Maisonett’s artistic exploration extends beyond collage into sculptural work, particularly in response to her time at the Fountainhead Residency in Miami. There, she found herself captivated by the interplay of light, shadow, and reflection. “This obsession with light as a record of time, led me to working with mirrors,” she says. Her hand-cut mirrors feature image transfers of important figures in her life, including her grandmother and Puerto Rican intellectual Pedro Albizu Campos. Suspended from thick metal chains sourced from Fountainhead’s backyard, these delicate mirror portraits drape across the wall like shimmering lockets or dog tags, evoking themes of memory, identity, and personal history. They function as both personal keepsakes and broader commentaries on historical memory, their reflective surfaces engaging viewers in an interplay between past and present. In her collages and new sculptural work, Maisonett builds intimate, familiar spaces that belie the layers of complex, difficult history existing just beneath the surface.

– Words by Meg Burns

José Villalobos uses sculpture, photography, installation, and performance to interrogate and unsettle normative understandings of masculinity and Mexican American culture. The instruments and iconography of Norteño culture play a prominent role in Villalobos’s work, either as found objects or sources of language, designs, and actions within his performances. Recent eight-foot sculptures like AngieandEli (2024)(named for Villalobos’ siblings) twist and arc in patterns amplified from the intricate saddle-stitching found on cowboy boots like those made by Villalobos’s stepfather. Other designs are drawn from the embroidered shirts his father wore as a Norteño musician.

In Miami, Villalobos faced unexpected challenges of scale, shifting his focus from massive sculptural objects to more intimate experimentations that could take place in Fountainhead’s garage studios. “I took the opportunity while was there to experiment with materiality,” he says. During his residency, Villalobos made large castings of leather-tooled belts in metal and resin,

shaping and curling the cast belts by hand before they fully hardened. He also envisioned new lives for older objects in his collection, like a pair of white cowboy boots that he adorned with tangled, stringy rope fibers for the work DeeplyRootedinMachismo (2022).

When asked about a typical studio day, Villalobos said that wherever he is, he asks himself, “If I am here, what does the landscape look like with my body in it?” At his childhood home in the border town of El Paso, Texas, Villalobos reckons with his queer identity in the context of his family and community’s conservative religious and cultural values. In Miami, Villalobos found an entirely new cultural dynamic amidst vibrant Cuban, Dominican, and Puerto Rican communities. “There are very different costumbres [between Latinx communities],” Villalobos described, ”[...]but the machismo is there for sure.”

– Words by Meg Burns

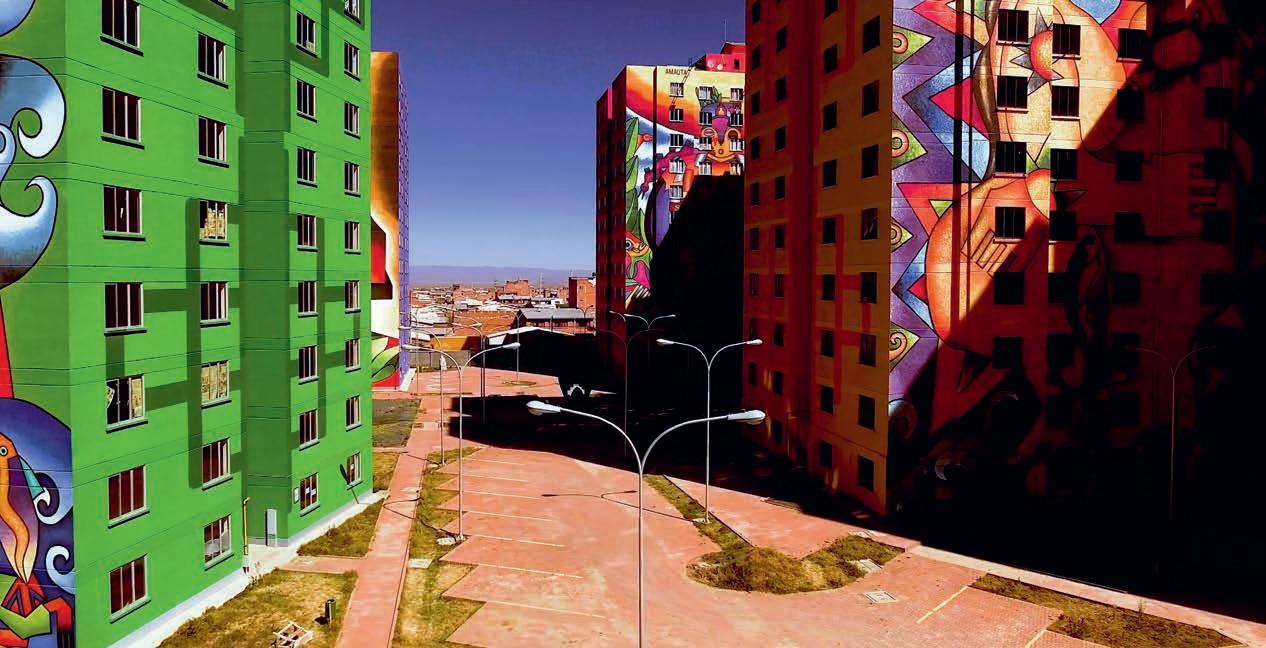

For Victoria Martinez, inspiration is often born from interactions with architecture or the landscape: “It’s first and foremost what see,” she says. “From there, the spark of energy inspires me to work with textiles and color.” Martinez utilizes painting, sculpture, installation, and fiber art to enter into a dialogue with the physical materials comprising urban spaces and the histories embedded within them.

Although abstract in nature, Martinez’s work is intimately tied to the human body and its unavoidable messiness. The artist often paints with squeeze bottles to capture the sensations of seeping fluids. Stretched across jagged bricks in small sculptures, her chosen fabrics of nylon and silk distend, twist, and tear like skin. In Miami at the height of summer, sweat preoccupied Martinez: “The sweat. You can’t control it. You’re just continuously drenched,” she laughs. Back in the studio, she experimented with rubber and various pigments to try and recreate the perspiration generated by a fast-paced residency in a tropical climate.

Martinez was particularly drawn to the unique architecture of Miami, elements of which made

their way onto the canvas. A brick window covered by Modernist breeze blocks, for example, was translated into vibrantly hued abstract forms on diaphanous silk in Miami Window (2024). In a departure from her typical focus on the built environment, Martinez found unexpected inspiration in the lush vegetation encountered at Fountainhead and in trips to the Everglades.

“There were so many trees I hadn’t seen before that were so beautiful and exotic,” Martinez recounts. “They’re unique and they have a life of their own. am very inspired and want to create a painting echoing the shapes experienced.” Ripened fruit from public markets, painted houses, and bright foliage all made their way onto Martinez’s palette –sometimes literally, like the deep pink dye she created from local hibiscus flowers. “I come with a public art background in color,” Martinez says. “In Miami, there’s a ton of color; it’s a very seductive city.”

– Words by Meg Burns

Systemsthatliveforever.OurDNAiscomposed of relics. Of what life once was. These are the handwritten phrases found in Anastasia Komar’s studio while in residence at Fountainhead. Taped adjacent to intimate graphite sketches and work on display, the makeshift studio feels like a mass lab of the artist’s brain on view. In speaking with Komar, learn of how she dedicates one hour in her morning routine to sketching and drawing what she finds in her computer research, and how these phrases come from the articles and podcasts she reads and listens to across the Internet. Sourcing from synthetic biology and bioengineering, her interest centers on the digestibility of science through the storytelling of her layered compositions. Electroplated glass polymer weaves its way around the acrylic on board works in odes to the subjects that she pulls from her research—everything from flowers to the vertebrae of sea creatures.

There is no pressure to understand the science on view as Komar interprets what is witnessed in the online photographs and studies of contemporary scientific fields. Waves of electromagnetic fields are painted with delicate movement, appearing abstract in presentation. In combining the board of her works with the hand-manipulated elements, a dialogue begins about what inherently exists in the natural world and what is controlled by human touch. Nature is inherently violent, a reality that Komar acknowledges in the scientific subjects that she dissects visually. In addressing the aesthetic beauty of what science uncovers, there’s the tangible pain and growth development of how life plays out that needs to occur in these discoveries. As she talks about preventative cancer medicine and disputes between researchers, Komar returns to this idea of hope at the core of it all, investigating our own limitations and individual mortality through her practice.

Komar’s residency was sponsored in part by FrancieBishopGoodandDavidHorvitz.