OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF AIFST

Extrusion - a food engineering powerhouse

Hygienic design in allergen risk management Food

Cultivated meat - future predictions

OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF AIFST

Extrusion - a food engineering powerhouse

Hygienic design in allergen risk management Food

Cultivated meat - future predictions

In the highly regulated and competitive food and beverage industry, maintaining a clean and controlled production environment is critical. Contaminants—whether microbial, chemical, or allergenic— not only endanger consumer health, but also put brand reputation and financial performance in jeopardy.

An effective Environmental Monitoring Program (EMP) is a fundamental pillar of modern food safety, contributing to both proactive risk management and operational excellence.

In practice, environmental monitoring programs typically involve a variety of tests—including ATP, indicator organisms, pathogens, spoilage microbes, and allergens—performed on diverse samples collected across different areas of a facility, at multiple time points, and with varying frequencies.

A well-structured EMP can identify trends and potential problem areas early, allowing for timely corrective actions that reduce the risk of product recalls, foodborne illness outbreaks, and regulatory issues.

Many manufacturers now recognise that robust environmental monitoring can also drive operational efficiency. Modern EMPs go beyond detection— they generate data that can help optimise cleaning schedules, reallocate labour more effectively, and improve production.

For example, consistent monitoring could reveal hard-to-clean problem areas. Addressing these issues through design improvements or modifying workflows not only enhances food safety, but also enables longer production runs and reduces downtime, leading to more

efficient, cost-effective operations. Additionally, the integration of digital systems and advanced data analytics enables predictive maintenance and long-term process improvements, transforming food safety from a reactive task to a strategic advantage.

As a global leader in food safety solutions, Neogen offers a comprehensive suite of tools to support effective EMPs. From rapid ATP hygiene monitoring systems and allergen test kits to indicator testing and a cloud-based analytics platform, Neogen provides robust and reliable options tailored to the needs of food and beverage manufacturers of all sizes.

Neogen also leads in education and training. Our extensive library of ondemand training videos empowers QA teams to stay informed about the latest practices, technologies, and regulatory expectations. And the recently released second edition of the Neogen Environmental Monitoring Handbook offers a complete, modern, and flexible framework for environmental monitoring—combining theoretical background with practical, real-world application.

Developed in collaboration with experts from Cornell University and more than 20 global food safety professionals, this updated guide introduces new chapters that provide deeper insight into validating sanitation controls, investigating contamination events, and turning monitoring data into actionable insights for continuous improvement.

As companies like yours navigate growing demands for safety, transparency, and operational efficiency, environmental monitoring plays a vital role in managing risk and ensuring quality. Neogen’s team of experts is here to support you in enhancing your environmental monitoring programs—helping you protect consumers, build stronger, more resilient operations, and improve overall productivity.

To learn more about our environmental monitoring solutions, visit neogenaustralasia.com.au email FoodSafetyAU@neogen.com or call us on 07 3736 2134

12 Internationalisation of food science curriculum

Preparing students to work in an increasingly global context

14 The hard-to-cook phenomenon in Australian-grown faba and adzuki beans

Understanding why the cooking quality of beans can deteriorates during storage

22 Navigating the food additives landscape

An overview of the latest trends in food additives and future opportunities

26 Food system resilience: unlocking the power of Australian food manufacturing

A systems thinking perspective will help unlock synergies and opportunities in the sector

31 Building a safer tomorrow: the role of hygienic design in allergen risk mitigation

A proactive tool for ensuring food safety

34 Will cultivated meat meet the market’s expectations?

A look at the predictions for cultivated meat

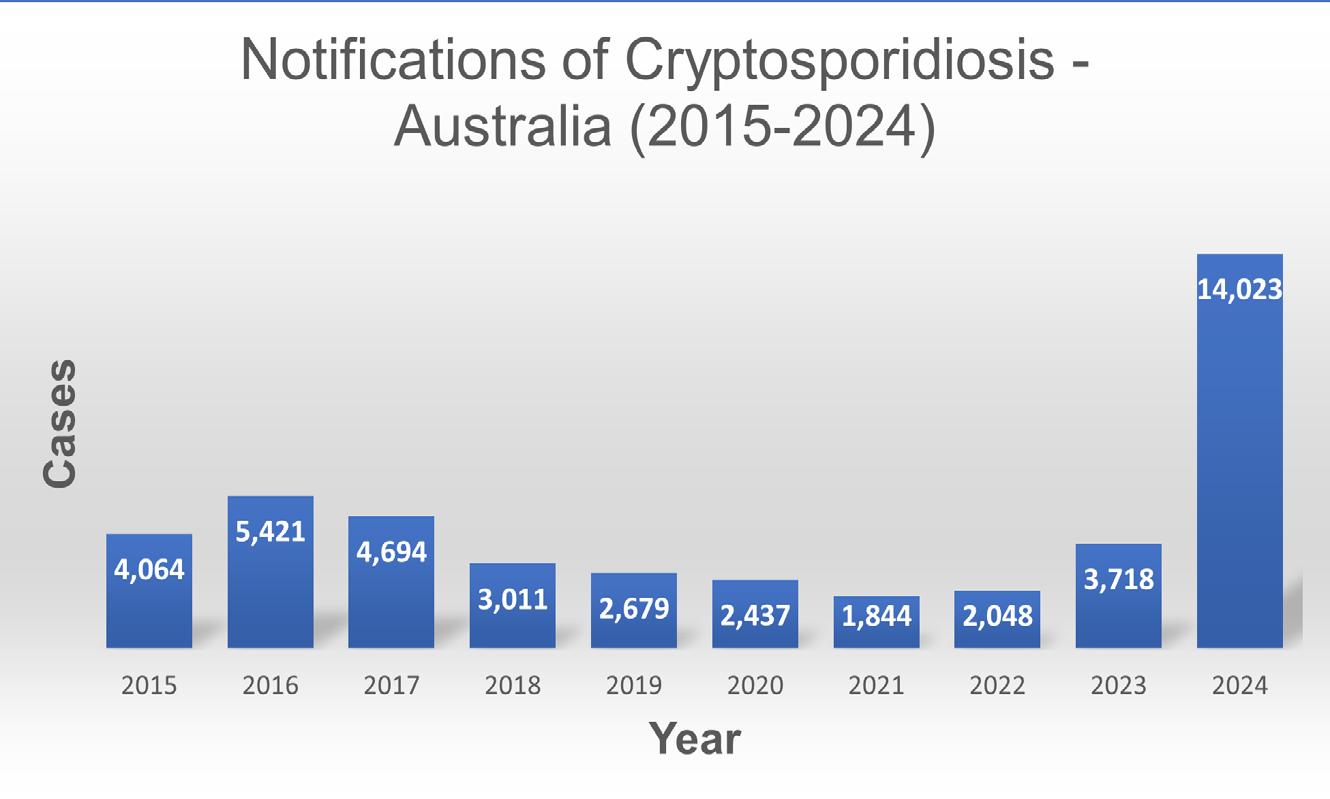

38 Foodborne parasites in Australia: a primer

An under-recognised food safety concern

41 Extrusion’s evolution to a multidisciplinary food engineering powerhouse

This long-established technology has developed into a sustainable and versatile method for meeting emerging market demands

44 Knowledge commercialisation and transfer

Technology transfer in Australia’s agrifood sector

47 What does a career in food policy look like?

Insight into the role of food policy across the agrifood sector

Obligation or Opportunity?

Published by The Australian Institute of Food Science and Technology Limited.

Editorial Coordination

Melinda Stewart | aifst@aifst.com.au

Contributors

Dr Ingrid Appelqvist, Karin Blacow, Dr Andrew Costanzo, Dr Duncan Craig, Dr Sushil Dhital, Dr Dan Dias, Dr Peter Halley, Dr Gregory Harper, Alice Joubran, Dr Pablo Juliano, Dr Djin Gie Liem, Deon Mahoney, Laura Mumford, Dr Dilini Perera, Dr C Senaka Ranadheera, Dr Samira Siyamak, Dr Jason R Stokes, Dr Mahya Tavan, Dr Paul Wood.

Advertising Manager

Clive Russell | aifst@aifst.com.au

Subscriptions

AIFST | aifst@aifst.com.au

Production Bite Communications

2025 Subscription Rates ($AU)

Australia $152.50 (incl. GST)

Overseas (airmail) $236.50

Single Copies (Australia) $38.50 (incl. GST) Overseas $59.50.

food australia is the official journal of the Australian Institute of Food Science and Technology Limited (AIFST). Statements and opinions presented in the publication do not necessarily reflect the policies of AIFST nor does AIFST accept responsibility for the accuracy of such statement and opinion.

Editorial Contributions

Guidelines are available at https://www.aifst.asn.au/food-australia-Journal.

Original material published in food australia is the property of the publisher who holds the copyright and may only be published provided consent is obtained from the AIFST. Copyright © 2018 ISSN 1032-5298

AIFST Board

Co-Chair: Marc Barnes

Co-Chair: Dr Gregory Harper

Non-executive directors: Dr Angeline Achariya, Dr Anna Barlow, Mr Antony Cull, Dr Heather Haines, Ms Melissa Packham.

AIFST National Office

PO Box 780

Cherrybrook NSW 2126

Tel: +61 447 066 324

Email: aifst@aifst.com.au

Web: www.aifst.asn.au

As global challenges around sustainability, nutrition, and food security intensify, the role of food scientists and technologists has never been more vital. This was the central message of the inaugural webinar for Australian Food Science and Technology Week held in June. The webinar ‘Why Food Scientists Matter More Than Ever’, featured a panel of experts from leading institutions and organisations and aimed to raise awareness of the critical role food scientists and technologists play in global food systems and real-world challenges, such as food safety, sustainability, and nutrition.

A recurring theme from the panel was the broad and evolving scope of food science and technology careers. The panel emphasised food scientists’ multidisciplinary roles across product development, food safety, engineering, nutrition, and regulation. They are also integral in tackling critical global challenges, including climate change, food waste, health and sustainable protein supply.

Panellists stressed the importance of communication skills, agility and systems thinking in the next generation of food science and technology professionals. They advocated for food science as a platform for varied career paths and highlighted the value of curiosity and collaboration across industry, government and academia to strengthen the resilience of the agrifood system.

Engaging students early was identified as key to inspiring future food scientists and technologists. Initiatives such as school outreach, STEM integration, storytelling, mentorship and career visibility were recommended. Programs like AIFST and FaBA’s Engage 2025 and the newly launched Knowledge Hub were promoted as valuable resources.

As Australia works to build a more sustainable and resilient food future, the role of food scientists and technologists has never been more important—and the industry is rising to meet that need. Awareness is growing, collaboration is strengthening, and a new generation is discovering the impact and opportunity offered by food science and technology careers.

Food science and technology is not just about what’s on your plate. It’s about the science underpinning how food is made, and critical aspects of safety, nutrition and impacts on both people and the planet.

AIFST is proud to champion the people and the science behind every bite—and to support the many faces of food science and technology –our heroes!

Fiona Fleming B. App Sc (Food Tech); MNutr Mgt; FAIFST Chief Executive Officer fiona.fleming@aifst.com.au

Going out to dinner is a simple pleasure for many, but for the more than 1.5 million Australians with food allergy, it can be frustrating, stressful and potentially life-threatening.

A recent survey by Allergy & Anaphylaxis Australia (A&AA) found that 98% of people with food allergy experience anxiety when eating out. The survey revealed people are often reluctant to disclose their allergy for fear of not being taken seriously, being a burden to others and feeling embarrassed. Concerningly, less than half of teenagers said they would always tell wait staff about their allergy.

Although Australia is considered the allergy capital of the world, there is no mandatory training for the food service industry, making it hard for people with allergy to eat out with ease. Research by the National Allergy Council found that 50% of food service staff didn’t feel confident answering questions about allergens on the menu, and only a third always asked customers about allergies.

At A&AA, the message is simple: always ask, always tell. It’s imperative for wait staff to ask customers if they have a food allergy, and for those living with allergies to feel confident disclosing them.

The National Allergy Council provides free online training courses for those in the food service industry. It’s time for all food service providers to commit to best practice food allergen management and ensure their staff complete the training as a requirement of their position, just as they would for the responsible service of alcohol.

Australians have a food allergy, one of the highest rates in the world.

84% of people with food allergy have avoided a social gathering because of their allergy. 30% reported that they avoid most or all social gatherings because of their allergy.

86% of adults with food allergy would like more food service staff training about food allergy management.

98% of people with food allergy felt anxious and stressed when eating out.

73% of adults don’t always tell those preparing food about their allergy because they don’t want to be a burden.

Only 41% of teenagers said they always tell the people preparing their food about their allergy.

Visit foodallergytraining.org.au to find out more about The National Allergy Council’s online training, and allergyfacts.org.au for A&AA’s consumer resources on eating out with food allergy.

AIFST is pleased to welcome a new Non-Executive Director to the Board. Mr Antony Cull was appointed for a three-year term at the 2025 AGM, held on 29th May 2025. The Board is responsible for steering the strategic direction of the Institute, ensuring sound governance, and providing the necessary expertise relevant to the dynamics of our not-for-profit Institute, while supporting agrifood science professionals in the science of feeding our future. For more information on the role of the Board, please visit the AIFST website: https://www.aifst.asn.au/AIFST-Governance-board.

Dr Angeline Achariya, Non-Executive Director

Marc Barnes, Non-Executive Director, Co-Chair

Dr Gregory Harper, Non-Executive Director, Co-Chair

Dr Anna Barlow, Non-Executive Director

Dr Heather Haines, Non-Executive Director

Melissa Packham, Non-Executive Director

AIFST thanks our outgoing Non-Executive Director, Dr Michael Depalo, for his three years of support and wise counsel, including as Board Chair and President.

Antony is an accomplished NonExecutive Director and Chair with over 25 years board-level experience within multinational corporations, large cooperatives, Cooperative Research Centres, and familyowned businesses operating in Australia, SE Asia and East Asia across highly competitive industries. Tony has demonstrated success as a board member (currently at Kalyx Australia Pty Ltd, Mondo Doro Pty Ltd, Chorus Australia Limited, Future Foods Systems Cooperative Research Centre). His roles span the manufacturing, agriculture, FMCG, retail, wholesale, distribution, export, health care, scientific research and not-for-profit sectors, both in Australia and internationally Tony has proven expertise in designing long-term business sustainability solutions in highly complex and competitive industries, achieved by developing business capabilities to adapt to dramatic structural and industry changes and aligning business design to commercial, market and consumer realities. This has been developed within industries subject to intense volatility and market risk resulting from dynamic international commodity markets, the entrance of global competitors and industry deregulation. He has a deep understanding of leadership, people and engagement, particularly in leveraging these to drive productivity.

Tony holds a Bachelor of Business and an MBA from Curtin University, is a Member of CPA Australia and a Graduate of the Australian Institute of Company Directors. f

Unlock the power of nature with ROHA’s NATRACOL CERISE – a premium RED BEET concentrate that delivers vibrant red-to-pink hues with exceptional heat stability. A natural alternative to synthetic colors, it ensures your creations –from dairy to confectionery to bakery – are as eye-catching as they are natural.

Our Offerings Are: Vegan/Vegetarian-Friendly | Halal & Kosher Certified

Words by Fiona Fleming

The Australian Institute of Food Science and Technology (AIFST) launched the inaugural Australian Food Science & Technology Week in June 2025. This strategic initiative is designed to raise national awareness of food science and technology and its essential role in the agrifood system.

The week was established in response to consumer research commissioned by AIFST in 2024, which found that 36% of Australians had never heard of the job title “food scientist” or “food technologist.”

Despite the breadth and depth of these disciplines, which span food safety and quality, microbiology, engineering, chemistry, nutrition, sensory science, and food policy and regulation, there remains limited public understanding of their contributions to food safety, nutrition, innovation and sustainability across the agrifood system.

As the peak body representing food scientists and technologists in Australia, AIFST identified the need for a dedicated platform to inform, engage, and advocate - not only for the profession but also for the science underpinning Australia’s agrifood sector.

Throughout the week, AIFST facilitated a range of publicly

accessible activities designed to deepen understanding of the field and highlight its relevance across the agrifood system.

Three free webinars formed the backbone of the engagement program:

• Why Food Scientists and Technologists Matter More Than Ever, featuring a multi-disciplinary panel on the profession’s critical role in addressing emerging agrifood system challenges

• An Essential Ingredient: The Food Supply Chain Workforce presented in collaboration with Jobs and Skills Australia,

examining current and future workforce needs

• Food Safety: Science in Action, aligning with World Food Safety Day, spotlighting innovations and practices that underpin the integrity of our food supply. More than 1000 participants registered for the live sessions, with ongoing access to recordings extending reach well beyond the initial broadcasts. These sessions provided a timely opportunity to showcase the diverse career pathways within the sector, the scientific rigour that underpins professional practice, and the

collaborative effort required to sustain a resilient and safe agrifood system.

The week also marked the release of key AIFST resources designed to put a spotlight on food science and technology as a career option, as well as support educators and those working in the sector :

• The AIFST Knowledge Hub, a curated platform offering accessible, science-based resources to support ongoing learning and development

• The first edition of the AIFST Food Science & Technology Dictionary, designed to clarify terminology and strengthen understanding across disciplines

• A social content toolkit for the broader community to engage with and share across their networks.

These resources were developed to support greater visibility and understanding of food science and technology across both professional and educational contexts.

AIFST members played an integral role in the success of the week. Members across industry, research, academia and government shared personal reflections, experience and insights, and helped amplify campaign messages through their networks. The week’s campaign also encouraged participation from non-members, inviting those from across the agrifood sector to connect with AIFST’s mission and contribute to its advocacy efforts. A key theme emerging from the week was the need to reposition food science and technology as a recognised scientific discipline within school-level STEM education. Currently, it is often conflated with home economics or hospitality – a perception that constrains its potential to

attract emerging talent. By clearly distinguishing food science and technology as a critical branch of applied science, with relevance to food safety, nutrition, sustainability, regulation, and innovation, the sector can better align with national STEM priorities and support future workforce development.

Australian Food Science & Technology Week represents more than a celebration – it marks the establishment of a national platform to advocate for the profession, highlight its societal value, and build stronger connections across the

agrifood system. By anchoring the week within the annual calendar, AIFST is creating a focal point for sustained communication, collaboration and policy engagement. Food science and technology play a crucial role in ensuring that Australia’s agrifood system is safe, sustainable, nutritious and responsive to global challenges. Through this initiative, AIFST is reinforcing its commitment to elevating the profession, growing recognition of its impact, and supporting the next generation of scientific leaders across the agrifood sector.

Fiona Fleming is CEO of AIFST. f

AZ_R+K 2025_RZ_FA_118x162_Junior_Page.qxp_Layout 1 22.04.25 09:15 Seite 1

Words by Tas Westcott (FAIFST) and Bob Cracknell

Di Westcott (also known professionally as Di Miskelly) sadly passed away in early May after a prolonged illness.

Di completed her tertiary studies part time while working for the Bread Research Institute. After graduating BSc from UNSW she became a fulltime employee.

Di started her distinguished career in noodle research, working with John Moss. Together they led the way in identifying the unique flour quality features that defined “Asian noodle quality.”

Di was also a member of the team that helped to develop specialised wheat varieties that placed Australia at the cutting edge of wheat exports into the Asian region.

Di was the author or co-author of more than 100 published papers, 10 book chapters and two books and an examiner of many PhD and MSc theses.

The publication of the book Steamed Breads – Ingredients, Processing and Quality co-authored with Sidi Huang was and remains a seminal work on this subject.

Whilst a very talented person, she was never one to seek the limelight, preferring to work behind the scenes.

She was a great mentor for many young emerging scientists, particularly young women, a great promoter of the importance of a sound education and encouraged many young scientists to achieve their highest potential.

She was a Fellow of the Royal Australian Chemical Institute (RACI), a Member of the Australian Institute of Food Science and Technology and a Fellow of the Australasian Grain Science Association.

She was the recipient of the RACI Cereal Chemistry Division Guthrie Award and the RACI Cereal Chemistry Division Service (Megazyme) Award and received a Jack Kefford Award from the AIFST.

Di volunteered for many years as part of the team transcribing Sydney

shipping records which are published on the State Library of NSW website “Mariners and Ships in Australian Waters”.

Di had a love of the great outdoors and was an avid bushwalker, Himalayan trekker and cyclist.

Her international travel exploits were often work-related, taking her to many of Australia’s major wheat markets. In doing so Di built a wealth of knowledge of the food products being consumed in those countries and the wheat and flour quality characteristics required to produce them. As a result, Di played a long and influential role in the direction and prioritisation of Australian wheat research, the refinement of the wheat classification process to improve wheat marketability and as a member of the Wheat Classification Panel, the classification of new Australian wheat varieties.

Di was well known and respected both in Australia and internationally for her extensive knowledge of the testing of wheat and flour, flour milling as well as end product manufacture and assessment.

Di was a kind and gentle person with an engaging personality and a great sense of humour who always had a positive outlook on life.

Dr Lisa Szabo (FAIFST) has been appointed as Executive Director of Biosecurity and Food Safety in the NSW Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development (DPIRD). Best known by many as CEO of the NSW Food Authority, an organisation she worked with for nearly 20 years. Lisa has led strategic food safety initiatives and compliance operations while providing expert advice to the government on emerging threats and incident management. In her new role with NSW DPIRD, Lisa is responsible for leading the development and implementation of NSW’s biosecurity and food safety strategies to protect the state’s people, environment, economy and lifestyle from emerging biosecurity and food safety threats. She also collaborates with other jurisdictions and stakeholders to create robust, evidence-based biosecurity and food safety systems that are prepared for future incidents, outbreaks and emergencies, enabling a collaborative response and promoting a shared responsibility.

Lisa holds a PhD in Microbiology and has had a career spanning scientific research, operational leadership and regulatory policy. She is highly respected in her field and has a deep understanding of risk management, legislative reform, and biosecurity and food safety frameworks at both state and national levels

Lisa’s outstanding contributions to the field of food science and technology were recognised through the AIFST President’s Award in 2020.

For accuracy and professionalism

Your one stop shop for Food and Feed laboratory supplies and equipment. Contact Rowe Scientific Pty Ltd today, for a complete solution for all your Food and Feed laboratory requirements.

• Containers • jars • tubes • measuring vessels • plates and dishes • blender bags • spoons • spatulas and scoops

• crushers • blenders • homogenisers

• stirrers, • shakers • hot plates

• centrifuges • digesters • water baths

• balances • extractors.

2. CHEMISTRY

• Wet chemistry

• chromatography

• filtration and electrochemistry

• buffers • acids • solvents

• volumetric solutions standards • indicators

• allergens • quantitative and qualitative analysis • general microbiology

• pathogenic organism analysis.

3. MICROBIOLOGY

• Dehydrated media / pre-poured plates • enzymatic kits • colony counters • microscopes

• spectrophotometers • Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) tests.

New South Wales & ACT Ph: (02) 9603 1205 rowensw@rowe.com.au

Western Australia Ph: (08) 9302 1911 rowewa@rowe.com.au www.rowe.com.au

Queensland Ph: (07) 3376 9411 roweqld@rowe.com.au

Victoria & Tasmania Ph: (03) 9701 7077 rowevic@rowe.com.au

South Australia & NT Ph: (08) 8186 0523 rowesa@rowe.com.au

Words by Dr C Senaka Ranadheera

Food science is considered one of the most universal professional fields as the principles and procedures in the production and processing of safe, nutritious and healthy foods are applicable worldwide. Although university food science curricula usually have an international focus due to their inherently global focus and common technological applications, further strengthening the internationalisation of food science curricula is a timely step. It will prepare the next generation of food science professionals to better address the evolving challenges of the global food industry, from the increased complexities of global food systems to environmental and climate issues, and cultural and regional perspectives.

The internationalisation of the curriculum goes far beyond recruiting international students into degree programs. It is an initiative to incorporate international and intercultural dimensions into curricula, and also into teaching and learning programs, through various approaches including the use of relevant international case studies and examples, the incorporation of guest lectures from international speakers, integrating diverse cultural perspectives in class activities and enhancing student engagement by encouraging them to share their diverse experiences and views in the classroom so that the exposure to different perspectives, beliefs or backgrounds is possible.1 To some extent, simple changes to curricula can achieve this without the need to incorporate more complex changes.

Internationalised food science

curricula can better prepare students to work within an increasingly global context. Benefits of internationalisation of the curriculum for university students can be categorised into five major areas: (1) development of cognitive skills including critical thinking and problem solving, (2) preparedness for the diverse workplace, (3) improvement of cross-cultural skills and competencies, (4) positive changes in student’s attitudes and worldviews and, (5) promotion of civic engagement and attitudes.2

Phan-Thien and Turner3 have previously outlined the list of core competencies for undergraduate food science programs as developed by the US Institute of Food Technologists (IFT), which includes five main areas: (1) food chemistry and analysis, (2) food safety and microbiology, (3) food processing and engineering, (4) applied food science, and (5) success skills.3

The internationalisation of food science curriculum has benefits across all five core competency areas. For example, in-class discussions of international case studies, such as the 2011 German E. coli O104:H4 outbreak,4 not only enhance students’ food safety and microbiological knowledge, but also foster critical thinking, develop diverse perspectives, and build cross-cultural competencies aligned with academic and professional success. Hence internationalised food science curricula helps students to become well informed, skilled and engaged global citizens upon graduation. International content can be co-delivered with the help of industry specialists and experts from professional bodies such as AIFST. Enhanced industryacademia collaborations in teaching and learning have also been

demonstrated to improve educational outcomes for students.5

There are challenges associated with successfully internationalising the curricula. For students, factors such as class size, student year level, past experience with intercultural learning, cultural background, and whether they are enrolled as an international or local student, can all affect the benefits achieved from an internationalised curriculum. For educators, challenges include the time and effort required to make changes to the curriculum and contextualise the intercultural learning into programs of study, as well as assessing the outcomes appropriately.3 Despite these challenges, and thanks to technological advancements across many fields, becoming global without leaving home or investing significant amounts of time and effort is now possible, providing opportunities for both students and educators to enhance their international perspectives. In addition, factors such as the increasing number of students attending overseas universities, possibilities for student exchange, and international partnerships and collaborations can strengthen the opportunities for an internationalised curriculum.

Depending on the teaching context, discipline and learning objectives, the inclusion of international and intercultural content in curricula can be as simple as making small changes to subject learning activities, such as inviting a guest lecturer with international experience, or more complex in nature, including larger changes in program offerings,6 for

example, redesigning a Master of Food Science program to include global relevance at all levels.

The University of Melbourne categorised common strategies of internationalisation of curriculum into four key approaches: (1) incorporating international and/ or intercultural perspectives, (2) facilitating interaction between diverse student groups, (3) designing subjects with an international or intercultural focus, and (4) providing experiential learning experiences either locally, nationally or internationally.1

In the context of food science, one example for incorporating international and/or intercultural perspectives could be analysing a case study to explore the flavour comparison of natural cheeses manufactured in different countries using international publications and resources.7 Various practices can be incorporated into a curriculum to facilitate interactions among diverse student groups. For example, students can be placed in small groups of three to five to complete a food microbiology project, such as a case study with an international component. Each group can intentionally be made up of students from diverse backgrounds to encourage intercultural collaboration.8

Designing subjects with an international or intercultural focus, such as Global Food Safety and Current Trends in Food Science and Technology, could be included in new or existing food science programs. Additional strategies, such as a site visit to a food processing facility or assigning work-integrated learning tasks that involve interactions, such as interviews with local food industry partners, can provide valuable experiential learning opportunities.

Establishing a clear structure and setting expectations from the outset is essential to ensure the smooth implementation of internationalisation in the curriculum. Ensuring the

availability of sufficient facilities and resources to support delivery is also crucial. Ongoing professional learning, including engagement with diversity and global issues, and regularly enriching the curriculum can help maintain its relevance. Both existing and new collaborations and partnerships could be helpful to initiate and continue with timely and meaningful updates to curriculum design. Starting with some simple, manageable changes is often more feasible, as complex higher level changes could be challenging and time consuming, and may require additional resources and funding. It is also important to foster a safe and inclusive learning environment where students can contribute their perspectives openly and honestly.

Internationalisation of the curriculum, particularly when implementing complex changes, can be challenging and demands significant time, effort and resources. Regardless, even modest steps towards the internationalising of the food science curriculum offer substantial benefits for students. Such initiatives foster innovation and equip graduates with the knowledge and skills needed to address the increasing number of global food-related issues.

1. The University of Melbourne, Centre for the Study of Higher Education, Internationalisation of Curriculum - Strategies https://melbournecshe.unimelb.edu.au/ioc/strategies

2. Cai, J and Marangell, S. (2022), The benefits of intercultural learning and teaching at university: A concise review, The University of Melbourne, Centre for Study of Higher Education https://melbourne-cshe.unimelb.edu.au/__ data/assets/pdf_file/0006/4193745/Thebenefits-of-intercultural-learning-and-teachingat-university.pdf

3. Phan-Thien, K. Y., and Turner, M. (2019). Training next-gen food scientists. food australia, 71(1), 32-36.

4. Mack, A., Hutton, R., Olsen, L., Relman, D. A., & Choffnes, E. R. (Eds.). (2012). Improving food safety through a one health approach: workshop summary. National Academies Press.

5. Male, S. A., & King, R. (2019). Enhancing learning outcomes from industry engagement in Australian engineering education. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability, 10(1), 101-117.

6. The University of Melbourne, Centre for the Study of Higher Education, Internationalisation of the Curriculum, (https://melbourne-cshe. unimelb.edu.au/)

7. Koppel, K., & Chambers, D. H. (2012). Flavor comparison of natural cheeses manufactured in different countries. Journal of Food Science 77(5), S177-S187.

8. Zhang, Y., & Ranadheera, C. S. (2023). Redevelopment of undergraduate food microbiology capstone projects for unprecedented emergency remote teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic: then and now. Microbiology Australia, 44(3), 140-143.

Associate Professor Senaka Ranadheera is a teaching and research academic in Food Science at The University of Melbourne and a recipient of the University Learning and Teaching Initiative GrantInternationalisation of the Curriculum. f

Words by Dr Sushil Dhital and Dilini Perera

Australia is one of the largest exporters of faba beans, primarily exporting to Middle Eastern countries such as Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Over the past five years, Australia has produced an average of 500,000 tonnes of faba beans a year, exporting approximately 300,000 tonnes and contributing around USD$150 million to the Australian economy.1,2 Faba beans are generally consumed as whole beans or as value-added products in canned, split or flour-based forms. In recent years, they have also gained popularity as a key ingredient in plant-based protein isolations.3,4,5 Despite their growing demand, the domestic utilisation of faba beans remains limited. A major barrier is the challenge of maintaining bean quality during storage, which can negatively affect protein functionality, canning efficiency and overall product quality. The cooking quality of beans deteriorates significantly during prolonged storage under improper conditions. Exposure to high temperatures (>30 °C) and humidity (>60% RH) leads to structural and functional modifications in key macromolecules, particularly starch and protein, which together account for more than 70% of the bean composition.6 These biochemical changes, along with cell wall modifications, result in the development of the hard-tocook (HTC) defect, which limits the processing, preparation and consumption of beans. HTC beans show significantly reduced water absorption during soaking and cooking, increased lag phase time,

decreased equilibrium moisture content (EMC), slower hydration rates and extended cooking times.7 Additionally, hydration of HTC beans leads to increased leaching of total solids and oligosaccharides, while the leaching of total phenols and anthocyanins decreases, indicating structural changes and complex formation that compromise both consistency and nutritional quality. These changes are particularly relevant to the canning industry as canned beans processed from HTC beans exhibit longer cooking times, greater hardness and more phytochemical loss into the processing water compared to freshly harvested beans. This not only degrades sensory qualities such as texture and flavour but also results in both nutritional and economic losses.

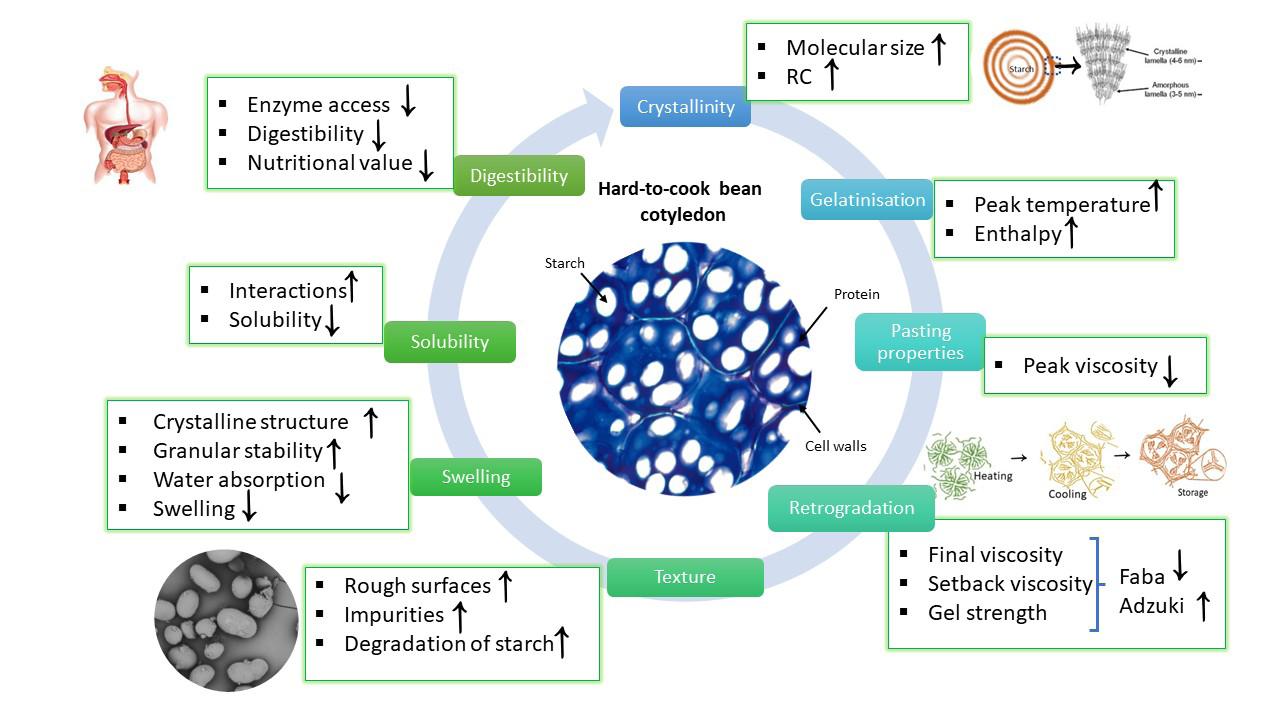

1. Changes in starch Starch and proteins are the main components in bean composition, accounting for approximately 40–45% and 25–30%, respectively.8 Prolonged storage of beans under high-temperature and high-humidity conditions leads to structural and compositional changes that contribute to the development of the hard-to-cook phenomenon. These conditions significantly alter

the crystalline structure of starch by increasing the molecular size of amylose and amylopectin and enhancing the relative crystallinity of starch.9 Such changes negatively impact starch gelatinisation during cooking, increasing both peak temperature and enthalpy, and making the beans harder to cook. The resulting more crystalline and compact starch structure reduces starch solubility and swelling power, thereby affecting functional properties such as gel viscosity.10 In HTC beans, peak viscosity typically decreases due to reduced solubility and swelling. The final viscosity may either increase or decrease depending on the bean type. For instance, a soup mix made from freshly harvested beans may exhibit different viscosity behaviour compared to one made from HTC beans. Differences in starch retrogradation also influence gel strength, suggesting that HTC bean starch may have varying potential for use in specific product applications. Moreover, these changes negatively affect starch digestibility by limiting enzyme accessibility, ultimately reducing the nutritional value of legumes.9 Figure 1 summarises the overall changes in starch structure and composition during hightemperature and high-humidity storage.

1: Schematic diagram showing the changes in structural and functional properties of starch during HTC development at high temperature and humidity storage.9

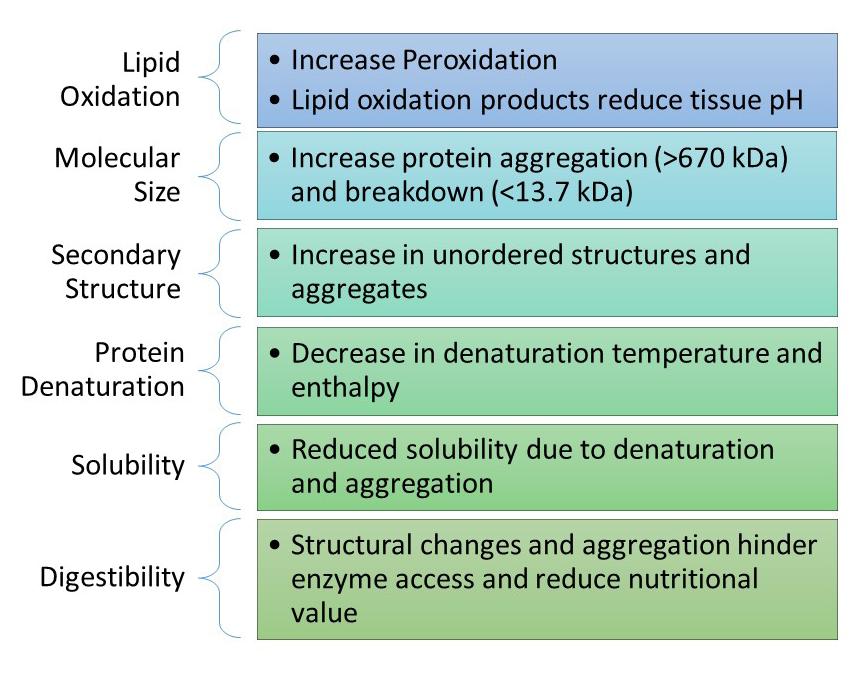

2. Changes in proteins and lipids

In addition to starch, the structure and composition of proteins are significantly altered by high storage temperatures and humidity levels (40°C, 80% RH and 60%).6 These modifications in proteins are primarily associated with the development of the HTC phenomenon and further affect protein functionality. Most importantly, protein extraction is negatively impacted, resulting in variations in both the yield and quality of the extracted proteins.

Although legumes contain relatively small amounts of lipids, these lipids are susceptible to oxidation and polymerisation during storage, which can lead to the development of offflavours and odours.11 The oxidation of medium-chain fatty acids (MCFAs) and long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs) generates aldehydes, ketones and organic acids, which lower the pH of the tissue.12 These acidic conditions within the cotyledon cells of legumes contribute to changes in both legumin-rich and vicilin-rich protein structures.

Faba beans are particularly rich in legumin-type globulin, a hexameric protein (~360 kDa) with disulfide

bonds (Figure 2). On the other hand, adzuki beans are rich in vicilin-type globulin, a trimer (~150 kDa) linked through hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonds.13 During storage, the solubility of vicilin proteins decreases, indicating that these proteins are more susceptible to structural changes. Storage conditions induce both aggregation and partial degradation of proteins, resulting in a decrease in the corresponding vicilin and legumin fractions in the molecular size distribution.14 Analysis of the secondary structures reveals an increase in the relative percentage of unordered structures and protein aggregates. Furthermore, the denaturation temperature and

enthalpy of both vicilin and legumin fractions decrease under hightemperature and high-humidity storage, suggesting reduced protein stability.

As a consequence, these changes in lipid composition and protein structure increase resistance to water absorption during soaking and cooking, which further contributes to the HTC phenomenon. Figure 3 summarises the changes in lipids and proteins in relation to HTC development in beans. These modifications in proteins are primarily linked to alterations in functional properties, especially those relevant to protein-based product development, while changes in lipids

are associated with the development of off-flavours and odours.

High-temperature and high-humidity storage significantly change the cell wall structure and composition. During cooking, the middle lamella of cotyledon cells breaks down, allowing cell separation and tissue softening.6 Storage reduces cell wall pectin solubility, as loosely bound (water-soluble) pectin converts into more tightly bound forms via calcium bridges (chelator soluble) and covalent ester bonds (Na2CO3soluble).16 This can be evidenced by

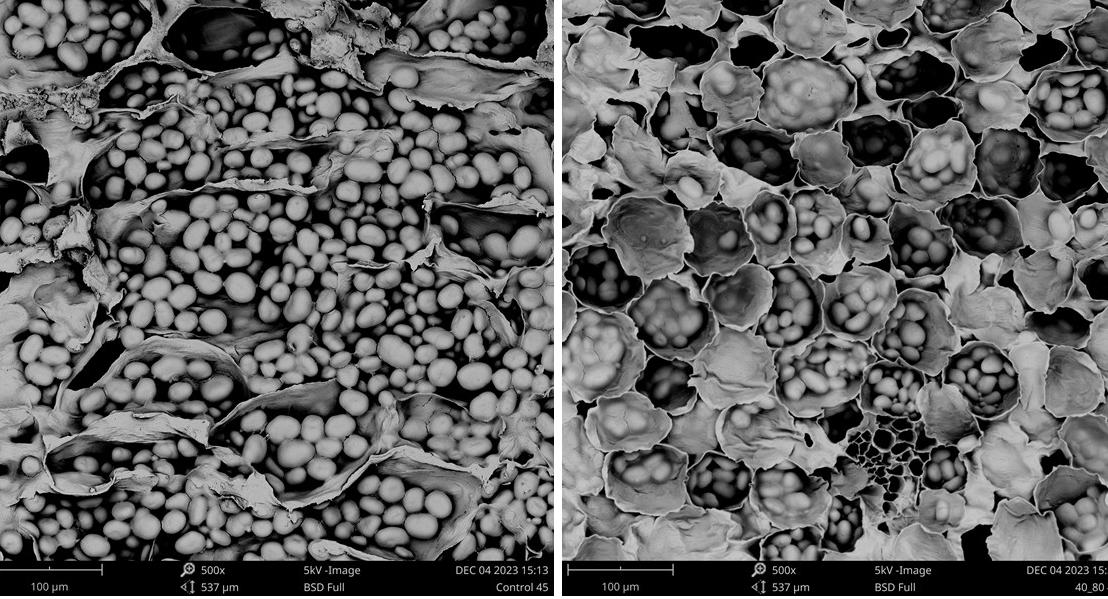

microstructural images, which exhibit a more compact cotyledon cell arrangement with fewer intercellular spaces and distinct tri-cellular junctions (Figure 4).

Additionally, phytic acid degradation releases Ca, Mg and phosphate ions that bind with pectins, forming insoluble pectates that limit water absorption.17

Furthermore, the free phenolic acids decrease while bound phenolics increase, forming complexes that migrate to the seed coat, increasing hydrophobicity and reducing water uptake. These structural changes, coupled with altered enzyme activity (eg. phytase) and polyphenol

interactions, collectively contribute to the HTC phenomenon.

The combined effect of these molecular changes, primarily in starch and proteins, along with cell wall alterations, creates a synergistic impact that drives the development of the HTC phenomenon, significantly affecting the beans’ cooking properties and limiting their suitability for various product applications.

Since the HTC phenomenon is irreversible, beans affected by this condition cannot be restored to their original cooking properties. Therefore, the proposed strategies primarily focus on reducing cooking time through various pre-treatments and thermal or non-thermal processing techniques. The following recommendations aim to mitigate the HTC phenomenon and promote sustainable utilisation of HTC beans.

1. Optimising storage conditions to prevent the development of hard-tocook phenomenon

Storage temperature and humidity are critical factors in preventing the HTC phenomenon in legumes. To minimise biochemical changes, storage temperature should be maintained below 20°C, while the relative humidity level should be controlled between 50-60%. Implementing proper ventilation and aeration systems – using fans, refrigerated air if necessary, dehumidifiers, and sensors to regulate heat, moisture content and CO2 in silos can help to prevent the development of HTC.18 Additionally, drying grains to an optimal moisture level (10-12%) and periodically turning stored legumes to prevent moisture accumulation further support maintaining their quality.

2. Improve the cooking quality of HTC beans by soaking in salt solutions

Soaking beans before cooking significantly reduces cooking time. In the case of HTC beans, soaking in solutions containing sodium chloride, sodium carbonate, sodium

bicarbonate, sodium phosphate, or ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) enhances cooking quality by increasing the water solubility of pectin, compared to soaking in pure water.6

3. Enhancing hydration of HTC beans with novel technologies

Bean hydration can be accelerated using various non-thermal techniques such as ultrasound, high hydrostatic pressure (HHP), and pulsed electric field (PEF). These methods can also be applied to HTC beans to reduce the cooking time by increasing the hydration rate. Ultrasound induces structural changes through sonic cavitation, causing cell and tissue disruptions.19 These microstructural changes may enhance water movement in HTC legumes. Similarly, HHP treatment improves water absorption into the cotyledon by forcing water into capillaries and intercellular spaces under high pressure, followed by a rapid transition of the seed coat from a glassy to a rubbery state.20 Since the thick seed coat is the primary barrier to water uptake in beans, PEF treatment helps by creating tiny pores in the seed coat, increasing water permeability.21 However, further research is needed to fully understand the effects of ultrasound, HHP and PEF treatments on the hydration of stored legumes.

4. Utilisation of HTC beans for new product development

HTC beans exhibit unique pasting and gelling properties due to modifications in their starch and protein structures, making them suitable for the development of new food products with distinct sensory attributes. In particular, HTC beans are well-suited for extruded products such as precooked flours, infant foods and expanded snacks. During extrusion, hydrogen and disulfide bonds in the secondary and tertiary structures of proteins are broken, increasing their exposure to enzymatic activity and thereby improving digestibility.22 Additionally, thermal processing during extrusion

reduces anti-nutritional factors such as phytic acid, tannins, polyphenols and enzyme inhibitors (eg. α-amylase and trypsin inhibitors). The extrusion process also enhances starch gelatinisation and in vitro starch digestibility. Furthermore, fibre degradation during extrusion increases its solubility, altering its physiological effects.23,24 These structural and nutritional changes make extrusion an attractive approach for utilising HTC beans. Extruded products offer advantages in both sensory characteristics (texture, flavour, aroma and colour) and nutritional properties, including increased protein content and a more balanced amino acid profile.

5. Genetic and breeding approaches for faster cooking beans

Cooking is an oligogenic trait influenced by various factors,

including planting time, cultivation practices, environmental conditions (such as temperature and humidity), and harvest timing. Marker-assisted breeding offers a potential strategy for developing fast-cooking bean varieties. However, its application is challenging due to the complex genetic nature of the HTC defect, which may be controlled by multiple genes.25 Identifying candidate genes associated with cooking time and implementing targeted breeding approaches to develop HTC-resistant or fast-cooking bean varieties will enhance consumer acceptance and improve industrial processing efficiency.

References:

1. https://mecardo.com.au/pulse-plantings-onthe-rise/ 2. https://www.graincentral.com/ 3. https://approteins.com.au/ 4. https://www.essantis.com.au/products/pulseproteins/ 5. https://integrafoods.au/

6. Perera et al., (2023), Hard-to-cook phenomenon in common legumes: chemistry, mechanisms and utilisation, Food Chemistry, 415, 135743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. foodchem.2023.135743

7. Perera et al., (2024), Crucial role of storage conditions on faba (Vicia faba) and adzuki beans (Vigna angularis) with an emphasis on the Hard-to-Cook phenomenon, Food Bioscience, 62, 105270. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.fbio.2024.105270

8. Dhull et al., (2022), A review of nutritional profile and processing of faba bean (Vicia faba L.), Legume Science, 4(3), e129. https://doi. org/10.1002/leg3.129

9. Perera et al., (2025), High temperature and humidity storage alter starch properties of faba (Vicia faba) and adzuki beans (Vigna angularis) associated with hard-to-cook quality, Carbohydrate Polymers, 351, 123119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2024.123119

10. Ferreira et al., (2017), Characteristics of starch isolated from black beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) stored for 12 months at different moisture contents and temperatures, Starch‐Starke, 69(5-6), 1600229. https://doi. org/10.1002/star.201600229

11. Sofi et al., (2022), What makes the beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) soft: insights into the delayed cooking and hard to cook trait. Proceedings of the Indian National Science Academy, 88 (2), 142–159. https://doi. org/10.1007/s43538-022-00075-4

12. Yousif et al., (2007), Effect of Storage on the Biochemical Structure and Processing Quality of Adzuki Bean (Vigna angularis), Food Reviews International, 23(1), 1-33. https://doi. org/10.1080/87559120600865172

13. Martineau-Cote et al., (2022), Faba Bean: An Untapped Source of Quality Plant Proteins and Bioactives, Nutrients, 14(8), 1541. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14081541

14. Yousif et al., (2003), Effect of storage of adzuki bean (Vigna angularis) on starch and protein properties, LWT - Food Science and Technology, 36(6), 601-607. https://doi.org/10.1016/S00236438(03)00078-1

15. Shrestha et al., (2023), Lentil and Mungbean protein isolates: Processing, functional properties, and potential food applications, Food Hydrocolloids, 135. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2022.108142

16. Njoroge et al., (2014), Extraction and characterization of pectic polysaccharides from easy- and hard-to-cook common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris), Food Research International, 64, 314-322. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.foodres.2014.06.044

17. Chen et al., (2023), Novel insights into the role of the pectin-cationphytate mechanism in ageing induced cooking texture changes of Red haricot beans through a texture-based classification and in situ cell wall associated mineral quantification, Food Research International, 163, 112216. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.foodres.2022.112216

18. https://grdc.com.au/

19. Kumar et al., (2023), Innovations in legume processing: Ultrasoundbased strategies for enhanced legume hydration and processing, Trends in Food Science & Technology, 139, 104122. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.tifs.2023.104122

20. Belmiro et al., (2018), Impact of high pressure processing in hydration and drying curves of common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.), Innovative

Food Science & Emerging Technologies 47, 279-285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ifset.2018.03.013

21. Alpos et al., (2022), Influence of pulsed electric fields (PEF) with calcium addition on the texture profile of cooked black beans (Phaseolus vulgaris) and their particle breakdown during in vivo oral processing, Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies, 75, 102892.https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ifset.2021.102892

22. Camire, (2000), Chemical and nutritional changes in food during extrusion, In Extruders in Food Applications, CRC Press, pp.127-147.

23. Jombo et al., (2025), Proximate, functional and sensory characteristics of blended yellow maize and hard-to-cook cowpea extruded snacks, Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 105(1), 483-488. https://doi. org/10.1002/jsfa.13846

24. Ruiz-Ruiz et al.,( 2008), Extrusion of a hard-tocook bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) and quality protein maize (Zea mays L.) flour blend, LWTFood Science and Technology, 41(10), 17991807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2008.01.005

25. Toili, (2022), Insights into the molecular mechanism of the hard-to-cook defect towards genetic improvement of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) through CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing optimization, PhD thesis, Vrije Universiteit Brussel. https:// researchportal.vub.be/en/publications/ insights-into-the-molecular-mechanism-ofthe-hard-to-cook-defect-

Dilini Perera is a PhD candidate at Monash University working under the supervision of Associate Professor Sushil Dhital. Dr Dhital’s research group focuses on the structure–function–health relationships of food systems, with particular emphasis on food waste valorisation, plant-based proteins and legume functionality. Dr Dhital can be contacted at: sushil.dhital@monash.edu f

Dr Djin Gie Liem, Dr Andrew Costanzo and Dr Dan Dias

The rise of online surveys has revolutionised the way researchers gather data, offering a convenient and cost-effective method to reach a wide audience. However, this digital transformation comes with a significant downside: the infestation of bot responses. A recent paper in the journal Appetite stresses the importance of bot mitigating strategies. This awareness is important for authors and reviewers as well as readers of studies which applied online questionnaires and the like. Bots are automated programs which can flood surveys with fake answers, leading to biased and unreliable results, and posing a serious threat to the integrity of scientific research. Since the early 2000s, the number of online surveys published in social science and psychology journals has increased exponentially. The COVID-19 pandemic further accelerated this trend, with over 10,000 papers published in 2023 alone. While online surveys provide an efficient solution to traditional low response rates, they also attract bots—sophisticated AI programs designed to mimic human behaviour and generate fraudulent responses. Recent studies suggest that bot responses can comprise anywhere from 30% to over 90% of the total

size in online surveys. These bots can skew results, impacting public opinion, health policies, and scientific trust. For example, bots often ‘prefer’ undesirable behaviours in surveys on risky activities, which can distort findings and influence public health decisions.

To combat this growing threat, researchers must employ a multilayered defence strategy (for a more comprehensive list, see Liem 2025):

Prevention: The first line of defence involves making surveys less attractive to bots. This can be achieved by removing financial incentives and using unique codes for participants, making it harder for bots to infiltrate.

Detection at entry: Tools such as CAPTCHA and reCAPTCHA serve as gatekeepers, filtering out bots before they can access the survey. These methods require respondents to complete puzzles that are easier for humans than bots, or obtain a digital fingerprint of the respondents’ digital behaviour (eg. mouse behaviour, browser history, cookies and screen settings).

Detection during surveys: Various strategies help identify and eliminate bot responses that manage to bypass initial defences. These include monitoring response times, theory of mind questions and checking for patterns in IP addresses and completion times.

Despite these efforts, the battle against bots is far from over. It is important to realise that there is no way to fully guarantee that bots will not enter online surveys. Similarly, there is no guarantee that no fraudulent human respondent will ever participate in a face-to-face research. Advanced AI bots continue to evolve, finding new ways to bypass detection systems. Researchers, reviewers and editors must remain vigilant, continuously adapting their methods to safeguard the integrity of online research. The researchers conclude that whilst online research offers numerous advantages, it requires robust bot mitigation strategies to ensure data quality. By combining prevention, detection at entry, and detection during surveys, the scientific community can better protect against bot attacks and maintain the credibility of their findings. As AI technology advances, the cat-andmouse game between researchers and bot developers will continue, but with vigilance and innovation, the integrity of online research can be preserved.

Source: Liem DG, (2025) The future of online or web-based research. Have you been BOTTED?, Appetite, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. appet.2025.108058.

Bitterness is one of the main reasons consumers reject foods,

yet it is a defining characteristic of dark chocolate. A new study from researchers at Penn State University explores how aroma affects the perception of flavour in chocolate. Aromas in food, which are volatile chemicals perceived by the nose, can have perceptual interactions with tastants, which are non-volatile chemicals perceived by the tongue, to create unique interactions that affect the overall sensory experience of foods. The study assessed the effect of roasting and cocoa mass on consumer acceptance and sensory attributes of chocolate in participants with and without the ability to smell (via nose clips).

Two experiments were conducted. In the first, 100% cocoa chocolates that had been roasted at different temperatures (64°C to 171°C) and durations (11 to 80 minutes) were evaluated by consumers with and without the ability to smell. In the second, participants tasted commercial white, 40%, and 100% cocoa mass chocolates under similar conditions. Participants evaluated the chocolates on chocolate flavour, bitterness, sweetness, sourness, dryness, grittiness and overall liking. The results revealed that the ability to smell impacted the taste experience. In chocolates roasted at lower temperatures, aroma significantly increased the perceived bitterness, sourness, and astringency. However, for samples roasted at higher temperatures, these effects were less pronounced. Similarly, for the commercial chocolates, the ability to smell amplified the intensity of bitterness and chocolate flavour, particularly in the 100% cocoa chocolate.

Interestingly, the influence of smell was not reflected in overall liking. Apart from the unroasted and lightly roasted chocolates, which were liked less when smell was allowed, most samples were rated similarly regardless of whether participants could smell them. This suggests that texture and other mouthfeel properties may play a larger role in consumer enjoyment of chocolate than aroma.

This study has important implications for chocolate manufacturers. It demonstrates that not only the chemical composition but also the overall sensory experience of chocolate is highly dependent on aroma and how it’s processed –especially roasting temperature. Understanding these interactions can help guide product development to balance bitter compounds with the right aroma profile and create more appealing chocolates, even with high cocoa content.

Source: Loi C, McClure A, Hayes JE, Hopfer H. (2025) Olfaction modulates taste attributes in different types of chocolate. Food Quality and Preference https://doi.org/10.1016/j. foodqual.2025.105584

The sweet science: how sugar cane extracts are revolutionising reducedsugar beverages

Reducing added sugars in food and beverages has emerged as a global health priority, largely due to the increasing prevalence of obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease. These metabolic conditions are escalating at an alarming rate worldwide. Although their causes are multifaceted, extensive research has consistently identified high sugar intake as a significant contributor. In particular, added sugars in beverages have been strongly linked to the growing incidence of type 2 diabetes, obesity, heart disease and other metabolic disorders. Beyond its impact on public health, this trend places a substantial strain on healthcare systems worldwide. In response, the World Health Organization (WHO) issued guidelines in 2015 recommending that free sugars account for no more than 10% of daily caloric intake, with an additional suggestion to reduce this further to 5% (roughly 25 grams per day).

Governments have begun to tackle the issue through a range of strategies, such as taxing sugarsweetened beverages, introducing front-of-pack nutrition labeling and setting voluntary reformulation targets to lower sugar content in products. While these initiatives aim

to curb sugar consumption, they also highlight the urgent need for viable alternatives that provide the desired sweetness without adverse health effects. As a result, food and beverage companies are under increasing pressure to create low- or no-sugar products that still satisfy consumer taste expectations. However, reducing sugar content without sacrificing taste remains a significant hurdle for food and beverage manufacturers. Vidal and co-authors examine the potential of sugar cane extracts –specifically Modulex™ – as natural taste modulators that can enhance sweetness, suppress bitterness and improve mouthfeel in lowsugar formulations. Sourced from Saccharum officinarum, these extracts comprise a complex blend of sugars, polyphenols, amino acids and minerals that interact with multiple sensory pathways, including sweet (T1R2/T1R3) and bitter (TAS2R) taste receptors. Sensory studies have shown that sugarcane extracts can markedly enhance the flavour profile and overall acceptability of beverages sweetened with both natural and artificial low-calorie sweeteners. The authors explore the biochemical mechanisms underlying these effects, examine their regulatory status, and consider their relevance for product innovation in-line with clean-label trends and public health objectives. Sugarcane extracts emerge as a compelling ingredient for nextgeneration sugar reduction strategies that aim to harmonise health benefits, taste quality and consumer appeal.

Source: Vidal TML, MacNab G, Mitchell S and Flavel M (2025) Sugar cane extracts as natural taste modulators: potential for sugar reduction in beverages and beyond, Frontiers in Nutrition 12:1603101, https://doi.org/10.3389/ fnut.2025.1603101.

Dr Djin Gie Liem is Associate Professor and Dr Andrew Costanzo is Senior Lecturer at CASS Food Research Centre, School of Exercise and Nutrition Science, Deakin University. Dr Dan Dias is Senior Lecturer at CASS Food Research Centre and Academic Investigator at the ARC Training Centre for Hyphenated Analytical Separation Technologies (HyTECH). f

Words by Alice Joubran

Food additives are defined by The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) as ’any substance not normally consumed as a food in itself and not normally used as a characteristic ingredient of food, whether or not it has nutritive value, the intentional addition of which to food for a technological purpose in the manufacture, processing, preparation, treatment, packaging, transport or storage of such food results, or may be reasonably expected to result, in it or its by-products becoming directly or indirectly a component of such foods’. Regulation (EC) No 1333/20081 details the various functional classes of food additives e.g. antioxidants, a list of approved food additives, levels of use, labelling requirements and other key considerations. In addition, manufacturers need to comply

with Commission Regulation (EU) No 231/2012,2 which provides specifications for all authorised food additives, whether the additives are for sale or being used by the manufacturer within his products. The United Kingdom (UK) assimilated this European regulation.

In the UK as well as in the European Union (EU), any food additive not included in the approved list requires it to complete an authorisation procedure prior to it being used in food products. Authorisation requests must be submitted to the relevant regulatory body: Food Standards Agency (FSA) and Food Standards Scotland (FSS) in Great Britain; EFSA in the EU and Northern Ireland. Following the thorough review, it will be decided if the additive is safe to use and consume with additional information on maximum levels, any associated restrictions and exemptions.

It may seem surprising since many people think of food additives as a more recent ‘invention’, however throughout history, food additives have been used in different food products and cuisines. The first deliberate use of a food additive was likely salt for the preservation of foods such as fish and meat. Other examples with a long history of consumption are sulphites in wine, or the preservatives nitrates and nitrites in cured meat such as bacon, which prevent the growth of the pathogenic bacteria Clostridium botulinum and its toxin production.3

During the Industrial Revolution (~1760-1840), the use of food additives increased dramatically due to the need to prolong shelflife, whereas beforehand food was prepared freshly at home and consumed immediately. While many

food additives traditionally used existed in nature such as ascorbic acid (vitamin C), technological advancements enabled the development of other additives to support specific functions, such as the antioxidant butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA). Regulatory bodies were later formed to control the different aspects of food production, including the use of food additives.

Within Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008,1 which is an assimilated regulation in the UK, EFSA classified the categories food additives are used for. These include, among others: preservatives, antioxidants, emulsifiers, foaming agents, gelling agents, sweeteners and thickeners.

Techno-functionality and compatibility with key ingredients

Some of the food additive categories mentioned relate to technofunctionalities that are vital in food formulation, food processing, structure formation and consumer acceptance. ‘Emulsifiers are substances which make it possible to form or maintain a homogenous mixture of two or more immiscible phases such as oil and water in a foodstuff’.1 This functionality will be relevant in food products like flavoured milk drinks, mayonnaise, or salad dressings. Another example is foaming agents utilised in the production of ice cream and whipped dairy cream, since they ‘make it possible to form a homogenous dispersion of a gaseous phase in a liquid or solid foodstuff’.1

During the different steps of product development, from kitchen prototypes to scale-up, it is important to evaluate the techno-functional properties. In-depth scientific understanding of the structurefunction-processing interplay is driving innovation in this space as well as reformulation efforts. Another key aspect to consider is the compatibility with other key ingredients, such as proteins, carbohydrates, fats and oils, which could possess functional attributes

themselves. In fact, hydrocolloids like the polysaccharides carrageenan and xanthan gum are increasingly used for their stabilising, emulsifying, gelling and thickening properties.

Analytical measurements can guide and accelerate the development of new food products. While functionality can be assessed by simple methods which don’t require costly analytical equipment, further characterisation is beneficial to benchmark performance against other food additives or ingredients. This can be useful, for example, to measure viscosity easily and accurately under different shear rates and/or temperatures which are relevant to the process. In addition, the high-throughput nature of the instruments allows for the analysis of more samples or prototypes. State-of-the-art techniques like 3D modelling could provide valuable insights, including the localisation of

the various components in a food matrix. These insights could be used for improving texture, mouthfeel, flavour release or control, and even help address issues like separation or undesirable consumer perception.

Analytical methods are also important to quantify the food additive in the food product, most of them rely on chromatography.4 Due to the complexity of the food matrix and potentially low levels of food additives, it can be quite challenging to detect and quantify these components. Based on our experience, we can develop an optimal sample preparation and extraction, where needed, and ensure the analytical method is fit for purpose.

Recent years saw numerous supply chain strains, driven by the COVID-19 pandemic, geopolitical and climate events. The example of lecithin,

which is widely used as an emulsifier, often comes to mind. The war in Ukraine significantly impacted the food industry, since ~70% of the global sunflower lecithin is produced in Ukraine and Russia,5 further highlighting how fragile the global food supply chain really is.

In addition, regulations in the UK relating to food and drink high in fat, salt and sugar (HFSS) were introduced, and consumer and retailer demand for ‘clean label’ products is increasing.

Consequently, the food and drink industry is constantly looking for novel additives and new sources of food additives, alongside novel processing technologies to support reformulation, improve functionality and/or extend shelf-life.

While some ‘natural’ food additives are already approved, e.g. stevia and tartaric acid, other food-derived ingredients are being explored as potential food additives. One of the trends we’ve observed is that instead of isolating compounds like pectin, manufacturers are utilising fractions that contain several constituents, such as apple pomace. This approach adds complexity from the analytical perspective, for example, but is more cost-effective and could also be coupled with circular economy principles when valorising sidestreams or by-products. However, it is important to highlight that even

’natural’ alternatives may still need to undergo authorisation before use if they fall under the above definition of a food additive and do not meet any of the exemptions listed in the legislation. Furthermore, the selective extraction (ie. by physical/chemical extraction) of constituents like pigments, even if prepared from foods and other natural source materials, are considered additives. Therefore, they are in scope of the legislation and will require authorisation. Even if the ‘food additive’ legislation does not apply, there may be novel food implications6 for the ingredient or product which need to be considered. We understand the ins and outs of legislation may be confusing, and since regulation is dynamic, it is important to keep up to date. Therefore, working closely with regulatory professionals is key when considering a new food additive.

One of the latest innovative food products is plant-based meat alternatives or analogues. Using plant-based proteins in these products proved as a challenge, and numerous additives are required to compensate for their functional limitations. Methylcellulose (E461) is commonly utilised in plant-based meat alternatives as a binder due to its thickening and emulsifying properties. However, consumer perception of ‘E-numbers’ and

demand for ‘clean label’ products resulted in replacements such as sugar beet pectin.7 Another area we’ve seen growth in are various food additives produced by precision fermentation, in which an end product is produced by a microbial host. This is proving challenging for regulators where equivalency data may be required.

Overall, food additives have been used historically for various functions, including preservation, thickening, antioxidant activity etc. It is important to ensure the food additives you are selling or using comply with the legislation and that you consider the interplay of structure-function-processing when choosing the right food additive. It will be exciting to see what new food additives are coming next and how the recent advancements in the food industry, including cultivated meat, plant-based meat analogues and precision fermentations, drive innovation further.

1. Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 on food additives http://data.europa.eu/ eli/reg/2008/1333/oj

2. Commission Regulation (EU) No 231/2012 of 9 March 2012 laying down specifications for food additives listed in Annexes II and III to Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/

3. Food additives, Food Standards Agency https://www.food.gov.uk/safety-hygiene/ food-additives

4. Wu, L. et al. (2022). Food Additives: From Functions to Analytical Methods. https://doi.or g/10.1080/10408398.2021.1929823

5. Missing Emulsifiers: Brands reformulate in face of sunflower lecithin shortage, https:// www.foodingredientsfirst.com/news/missingemulsifiers-brands-reformulate-in-face-ofsunflower-lecithin-shortage.html

6. Novel Foods & Regulatory Submission, https://www.rssl.com/food-consumer-goods/ regulatory-submissions-and-novel-foods/

7. Jang, J. and Dong-Woo Lee. (2024). Advancements in plant based meat analogs enhancing sensory and nutritional attributes https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-024-00292-9

Alice Joubran is Protein Specialist and Novel Foods Project Manager, Food Sciences at Reading Scientific Services Ltd. (RSSL) Contact details: Alice.joubran@rssl.com and foodsales@rssl.com. https://www.rssl.com/

*This article is reproduced here with permission from IFST. f

Words by Dr Pablo Juliano and Dr Ingrid Appelqvist

Domestic food manufacturing has played an important role in Australia’s economy and society, contributing to employment, domestic consumption, export revenue, and overall prosperity. The sector is challenged by the long-standing perception that Australia’s high labour costs limit local manufacturing, and rising costs of goods threaten its ability to supply to niche markets. Bringing innovative technologies and business models can boost local manufacturing profitably. These models can minimise the reliance on imported food towards a more resilient and autonomous food system, enabling 100% Australian-made food to reach domestic and export markets. Given the interconnection between manufacturing and other parts of the Australian food system, a holistic systems approach is useful for further examining the challenges and opportunities, particularly identifying the barriers and

feedback mechanisms required for manufacturing facilities to improve the sustainability of the food system.

Food manufacturing is Australia’s largest employer in the manufacturing sector, accounting for nearly 30% of jobs,1 with over 40% of these jobs in regional areas. In 2023, the gross value of food product manufacturing was $125 billion.1 However, 98% of food manufacturing businesses are classified as small to medium enterprises, and reporting and policy frameworks are not set up to support them or their business models.2,3 While 89% of domestic food and beverages are manufactured locally, many rely on imported ingredients, making Australia heavily dependent on countries such as China, the United States and a number of European nations for essential inputs.4,5

Australia’s food manufacturing industry faces several challenges,

including high input costs, which have impeded the growth of domestic food manufacturing and supported a continuing focus on agricultural commodity exports.6 Another challenge is the limited access to R&D and innovation expertise, as well as pilot innovation facilities across the country for scale-up and market testing.7 This indicates that exports of agricultural output are likely to remain an important aspect for agriculture in the long-term future. Policies to support value-adding of agricultural commodities are fragmented across the system,8 while agricultural policy strongly promotes commodity exports. In addition to high input costs, other challenges include market dynamics and size, labour shortages, infrastructure constraints, logistics of distance, energy use and compliance with environmental sustainability rules. However, new process innovations and business models, and advancements in food manufacturing

science and technology are emerging opportunities. New business models, such as cooperative innovation and manufacturing hubs (bringing processing infrastructure close to the raw materials), have the potential to lower start-up costs. This will improve the indivisibility of labour and capital costs, enabling small to medium enterprises to thrive. Similarly, new food manufacturing technologies such as precision fermentation can reduce reliance on access to land and labour required for production of, for example, new types of food such as complementary protein ingredients. Adopting new technologies, digitalisation and Artificial Intelligence (AI) will enable the industry to manage their production costs and become more cost competitive.

Taking a systems perspective to food manufacturing in Australia allows us to identify the complexity and interconnectivity across the value chain, helping to meet multiple and sometimes conflicting objectives, including productivity, profitability, environmental sustainability and public health. By thinking holistically, we can better understand how actions in one area may create synergies or trade-offs in other areas across the supply chain. This supports the notion of a national food processing network that identifies processing facilities and maps them to where raw materials are grown and can be value-added and upcycled (Figure 1). It will also help us prioritise research needs and coordinate and co-design policy actions. This has the potential to expand opportunities to grow the food industry and improve access to affordable, locally manufactured ingredients and food in regional and remote areas.

Australia’s food system is currently fragmented and siloed among key actors across the value chain (eg. grain growers may not consider

the requirements of grain millers to improve efficiency), resulting in limited integration across the value chain, exacerbating industry reliance on imported ingredients and reducing the opportunity for local manufacturing.9 It is also the case that different food sectors have varying value-added capabilities through processing. For instance, the dairy industry significantly enhances the value of its products through processing. Approximately 72% of domestically produced milk is used to make cheese and other value-added products such as butter, milk powder, and yoghurt, with 45% of these manufactured products exported.10 In contrast, processing in horticulture accounts for only 27% of Australian fruit and vegetable production.11