Palmetto

Point Washington State Forest

by Tom Greene

Point Washington State Forest Overview

Total Acreage: 15,399

Location: Walton County, Florida

Description: 10 natural communities can be found throughout the forest. The majority of the area consists of sandhill, basin swamps and titi drains, wet flatwoods, wet prairie and cypress swamps.

The Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Forestry has lead management responsibility, and uses an ecosystem management approach that provides for multiple uses of forest resources including timber management, wildlife management, outdoor recreation and ecological restoration.

Source: www.fl-dof.com/state_forests/point_washington.html

Field Review

In August of 2010, the FNPS Land Management Review Team participated in a land review at Point Washington State Forest, in southern Walton County. The forest features a variety of natural communities including sandhill, wet flatwoods and cypress swamps, and has several areas of old-growth longleaf pine (Pinus palustris). Populations of gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus), flatwoods salamander ( Ambystoma cingulatum), Curtiss’ sandgrass (Calamovilfa curtissii), whitetop pitcher plant (Sarracenia leucophylla), Gulf coast lupine (Lupinus westianus) and 6 additional listed plants live in Point Washington’s longleaf pine habitat.

The forest’s whitetop pitcher plants occur in nitrogen poor, acidic soils that are seasonally flooded. Typical habitats include bogs, savannas, seepage slopes and hydric pine flatwoods. Interestingly, the pitcher plant’s hollow leaves are modified to serve as passive traps, allowing the plant to supplement its intake of nutrients with an insect diet.

The forest contains the largest population of Curtiss’ sandgrass in the State. Listed as threatened by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, this rare grass species is restricted to two disjunct regions – populations in Florida’s Panhandle occur in wet flatwoods and adjacent to wet cypress forests, while populations on the Atlantic coast occur in interdunal swales.

Some surveys for Calamovilfa curtissii have been made at Point Washington State Forest, but it is not certain whether complete rare plant surveys have been done for any of the plants on the tract. The forest supervisor invited us to provide volunteer surveys – these would be helpful in assisting staff responsible for managing sites containing rare plants.

Uplands in Point Washington State Forest consist largely of sandhill and flatwood pineland in moderate to good condition. Extensive areas of floodplain, basin and dome swamps in the forest are also in good condition, although their upland boundaries are dominated by shrubs due to past fire suppression. The number of acres treated with prescribed fire have been significantly increased in the past two

Continued on page 13

The purpose of the Florida Native Plant Society is to preserve, conserve, and restore the native plants and native plant communities of Florida. Official definition of native plant: For most purposes, the phrase Florida native plant refers to those species occurring within the state boundaries prior to European contact, according to the best available scientific and historical documentation. More specifically, it includes those species understood as indigenous, occurring in natural associations in habitats that existed prior to significant human impacts and alterations of the landscape. Organization: Members are organized into regional chapters throughout Florida. Each chapter elects a Chapter Representative who serves as a voting member of the Board of Directors and is responsible for advocating the chapter’s needs and objectives. See www.fnps.org

Palmetto

Features

4 Protecting Endangered Plant Species in Panhandle State Parks

Florida’s Panhandle is well known for its botanical and ecological wonders, including some 242 sensitive plant taxa that occur west of the Suwannee River.

Gil Nelson and Tova Spector examine endangered plant species and their protection in the panhandle’s State Parks.

8 Native or Not? Carica papaya

How did Papaya come to Florida, and when did it arrive? Was it carried here by ocean currents, or by Homo sapiens who savored its edible fruit?

Dr. Dan Ward investigates these and other questions that determine Papaya’s status as a native or non-native member of Florida’s flora.

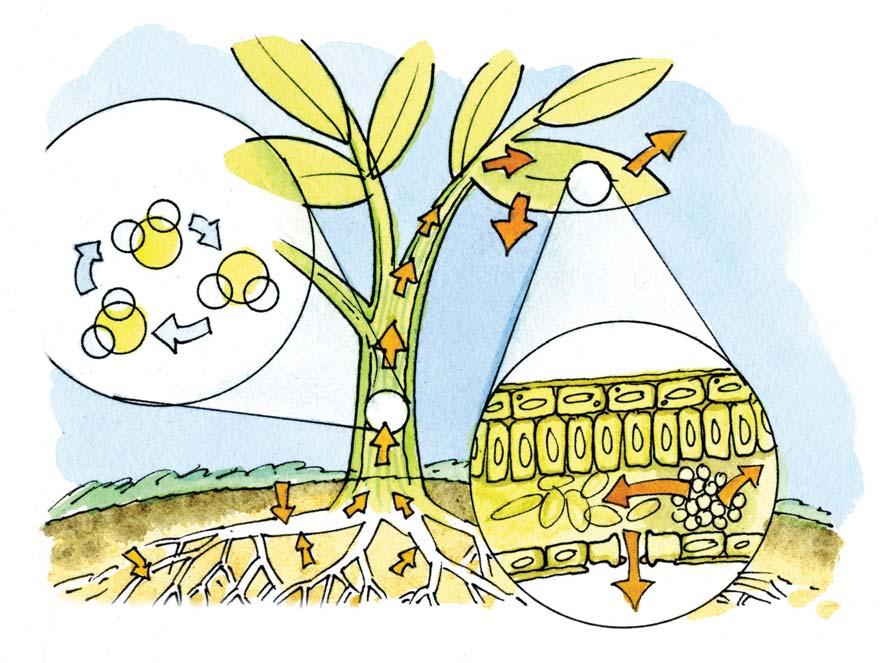

12 Water Science & Plants

Knowing how plants take advantage of water’s unique chemistry makes us better caretakers of both wild and cultivated landscapes. Ginny Stibolt discusses how we can use this knowledge to get the most out of a precious and limited resource.

ON THE COVER:

plant)

Palmetto seeks articles on native plant species and related conservation topics, as well as high-quality botanical illustrations and photographs. Contact the editor for guidelines, deadlines and other information at pucpuggy@bellsouth.net, or visit www.fnps.org and follow the links to Publications/Palmetto.

Make a difference with FNPS

Your membership supports the preservation and restoration of wildlife habitats and biological diversity through the conservation of native plants. It also funds awards for leaders in native plant education, preservation and research.

● Individual $35

● Family or household $50

● Contributing $75 (with $25 going to the Endowment)

● Not-for-profit organization $50

● Business or corporate $125

● Supporting $100

● Donor $250

● Lifetime $1,000

● Full time student $15

Please consider upgrading your membership level when you renew.

The Palmetto (ISSN 0276-4164) Copyright 2011, Florida Native Plant Society, all rights reserved. No part of the contents of this magazine may be reproduced by any means without written consent of the editor. The Palmetto is published four times a year by the Florida Native Plant Society (FNPS) as a benefit to members. The observations and opinions expressed in attributed columns and articles are those of the respective authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official views of the Florida Native Plant Society or the editor, except where otherwise stated.

Editorial Content: We have a continuing interest in articles on specific native plant species and related conservation topics, as well as high-quality botanical illustrations and photographs. Contact the editor for submittal guidelines, deadlines and other information. Editor: Marjorie Shropshire, Visual Key Creative, Inc. ● pucpuggy@bellsouth.net ● (772) 692-2251 ● 1876 NW Fork Road, Stuart, FL 34994

Protecting Endangered Plant Species

To date, a total of 117 listed taxa have been recorded in 26 panhandle parks, making these parks a key resource for the protection of endangered plant species.

in Panhandle State Parks

by Gil Nelson and Tova Spector

The Florida Panhandle is well known for its natural endowments, chief among which are its botanical and ecological diversity. Approximately 242 sensitive plant taxa occur in the 21 counties west of the Suwannee River. These include 15 taxa listed as endangered or threatened by the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), 212 listed as endangered or threatened by the State of Florida, 191 tracked by the Florida Natural Areas Inventory, 52 candidates for federal listing, and 7 categorized by the state as commercially exploited.

Since the conservation of threatened and endangered plant species depends largely on effective management of protected populations, the occurrence of such plants on publicly or privately owned conservation lands, coupled with institutional knowledge of their location and extent is essential. District 1 of the Florida Park Service manages 33 state parks encompassing approximately 53,877 acres in the 18 counties from Jefferson County and the southwestern portion of Taylor County westward. While not all of the Panhandle’s sensitive plants occur within the confines of these parks, many do, including several known to occur on conservation lands only within state park boundaries. Federally listed species of particular interest to park personnel include: Conradina glabra, Spigelia gentianoides, Taxus floridana, and Torreya taxifolia. An herbarium voucher of the federally listed Silene polypetala was collected in 1843 from Torreya State Park, but no recent observations within the park are known. To date, a total of 117 listed taxa have been recorded in 26 panhandle parks, making these parks a key resource for the protection of endangered plant species.

In early 2008 we began a joint effort to catalog all endangered plant species that occur in District 1 parks, a project that is ongoing. The second author, as part of her continuing professional role, had previously developed lists, localities, and management plans for endangered species in panhandle parks using a combination of personal knowledge, historical reports, and numerous field surveys throughout the district. The goal of our project was to augment this ongoing work by seeking new avenues for cataloging and locating endangered plant species and providing additional field resources to support survey efforts.

Our proposed project included three phases. Phase I (completed in 2008) consisted of searching all regional herbaria and cataloging any specimen collected within (or in a few cases, very close to) known state park boundaries. Phase II (ongoing) includes ground truthing herbarium records and verifying and/or finding sensitive

sites based on previous collections. Phase III (ongoing) includes pinpointing state parks that are under-represented in our data, or that currently lack or significantly lack records of endangered species. Parks so identified are then surveyed for listed taxa.

Cataloging Herbarium Collections

The first phase of our project was to catalog all herbarium specimens collected from regional herbaria. This included visiting (electronically and/or physically) several important herbaria (Table 1) and examining all specimens of endangered species known or suspected to occur in the panhandle. Specimen locality data were

Table 1: Regional Herbaria

Herbarium Acronym Records Visitation Type

Angus K. Gholson AKG 135 Physical (personal herbarium, now at FLAS)

Florida State University FSU 272 Physical/Electronic (Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium)

Tall Timbers Research Station TTRS 53 Physical/Electronic (Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium)

University of Florida Herbarium FLAS 126 Physical/Electronic (Museum of Florida History)

University of South Florida USF 57 Electronic

University of West Florida UWFP 39 Physical (M. I. Cousens Herbarium)

Total

682

Protecting Endangered Plant Species in Panhandle State Parks

compared to a multi-layer GIS-based map of current park boundaries. In many cases, label data included notation of the park in which the collection was made. In other cases, labels lacked such data, or the collections were made prior to the establishment or expansion of park boundaries. This resulted in a number of records for plants that were not located within state park boundaries when originally collected, but that are located within state park boundaries today. Phase I also included reviewing records from the database of the Florida Natural Areas Inventory, which includes references to numerous vouchered records. We recorded 682 specimens from six herbaria included in our study.

We established a secure, password protected online database for our records, hosted through www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora, which facilitates remote access and allows for customized searching, data analysis, and downloads in various formats. To date, our herbarium reviews and ongoing field surveys reveal that 26 District 1 parks include at least one listed species (Table 2). This constitutes 79% of all parks managed by District 1, and 87 % of those parks with significant natural areas (30 parks). A total of 117 listed and special interest taxa have been recorded district wide (Table 3), meaning that approximately 48% of the threatened or endangered plant taxa that occur in the panhandle are protected in at least one state park. This effort recorded sensitive plant taxa for 5 parks in District 1 that were previously not known to harbor listed species.

Phase 2 of the project includes ground truthing records to determine species presence and location on state parks. Based on information found in herbaria, some of the rarer plants were targeted for field surveys. In several cases targeted plant species were not found. For example, a herbarium record of Asplenium verecundum occurring at a recently acquired part of Torreya State Park was selected for ground truthing. Despite survey

Table 2: District 1 State Parks in which Listed or Special Interest Plant Species have been Documented

Park Number of Species

Bald Point State Park 2

Big Lagoon State Park 1

Blackwater River State Park 4

Camp Helen State Park 2

Deer Lake State Park 7

Econfina River State Park 1

Falling Waters State Park 5

Florida Caverns State Park 37

Grayton Beach State Park 5

Henderson Beach State Park 3

Lake Talquin State Park 6

Maclay Gardens State Park 4

Ochlockonee River State Park 3

Perdido Key State Park 2

efforts, A. verecundum has not yet been re-discovered. Instead, surveys helped to verify the presence and extent of a new exotic invader, Deparia petersenii (Japanese False Spleenwort) at the park in the areas where we were also looking for A. verecundum Failure to find historically recorded species could mean that the species is no longer on site, the species is on site but has not been found despite searching, or that the species was never on site and was misidentified or the purported location of the species was poorly described in the record.

Disappearance of species can be puzzling but can also help land managers recognize when or if different management practices are needed. A restoration of a small area of upland pine natural community is being conducted at Florida Caverns State Park in response to the disappearance of two occurrences of Brickellia cordifolia. Restoration planning and efforts were only undertaken after failure to find B. cordifolia in historically known locations. Hopefully, B. cordifolia will respond to these efforts.

Phase 3 of the project, plant surveys, has also yielded surprises. No listed plant species had been previously vouchered for T.H. Stone St. Joseph Peninsula State Park prior to this project. Since the majority of the park is a designated wilderness preserve with little development, famously high intact dunes, and multiple listed wildlife species, the lack of listed plant species was unexpected. Many listed coastal dune plant species in the panhandle occur in similar natural communities in nearby coastal parks. A limited plant survey of the park yielded one listed plant species thus far, Chrysopsis godfreyi. Similar plant surveys may yield discovery of listed plant species on other parks where they were previously unknown.

Sweetwater Ravines

Park Number of Species

Ponce de Leon Springs State Park 2

Rocky Bayou State Park 10

San Marcos de Apalachee

Historic State Park 2

St. Andrews State Park 1

St. George Island State Park 1

St. Joseph Peninsula State Park 1

Tarkiln Bayou State Park 4

Three Rivers State Park 13

Topsail Hill Preserve State Park 6

Torreya State Park 65

Wakulla Springs State Park 2

Yellow River Marsh Preserve

State Park 1

In 2009, the Florida Native Plant Society joined with District 1 through a $2,500 FNPS conservation grant for the purpose of conducting additional rare plant surveys in the Sweetwater Ravines tract of Torreya State Park. District 1 provided a partial match to the grant through in-kind contributions.

Torreya State Park is located approximately 7 miles north of Bristol. Conservation purchases over approximately the last decade have expanded the park dramatically from about 3,000 acres in the year 2000 to more than 13,200 acres today. These acquisitions include essentially all of the biologically rich Big Sweetwater Creek drainage on the southeastern side of the park as well as the Aspalaga and Flat Creek landings tracts north of the main park.

The Sweetwater tract, acquired from St. Joe Paper Co. within the last decade, encompasses approximately 2,000 acres of steep-sided ravines, steepheads, and steephead streams surrounded by approximately 4,000 acres of degraded longleaf pinelands, now planted mostly in sand pine but in the process of being restored to longleaf pine–wiregrass upland.

Table 3: Listed and Special Interest Plant Taxa Recorded in State Parks of the Florida Panhandle

Actaea pachypoda

Agrimonia incisa

Anemone americana

Aquilegia canadensis

Aristolochia tomentosa

Arnoglossum diversifolium

Asarum arifolium

Asplenium monanthes

Asplenium resiliens

Asplenium verecundum

Asplenium x heteroresiliens

Athyrium filix-femina

subsp. asplenioides

Baptisia calycosa var. villosa

Baptisia megacarpa

Brickellia cordifolia

Calamintha dentata

Calamovilfa curtissii

Callirhoe papaver

Calopogon multiflorus

Calycanthus floridus

Calystegia catesbeiana

Carex baltzellii

Carex tenax

Chrysopsis godfreyi

Chrysopsis gossypina subsp. cruiseana

Conradina glabra

Corallorhiza wisteriana

Croomia pauciflora

Cryptotaenia canadensis

Cynoglossum virginianum

Desmodium ochroleucum

Dirca palustris

Drosera intermedia

Echinacea purpurea

Eleocharis rostellata

Enemion biternatum

Epidendrum conopseum

Epigaea repens

Erythronium umbilicatum

Euonymus atropurpureus

Euphorbia commutata

Forestiera godfreyi

Gentiana pennelliana

Goodyera pubescens

Hexalectris spicata

Hydrangea arborescens

Hymenocallis godfreyi

Illicium floridanum

Kalmia latifolia

Leitneria floridana

Liatris gholsonii

Liatris provincialis

Lilium catesbaei

Lilium iridollae

Lilium michauxii

Lindera benzoin

Listera australis

Litsea aestivalis

Lobelia cardinalis

Lupinus westianus

Lycopodiella cernua

Lythrum curtissii

Magnolia ashei

Magnolia pyramidata

Malaxis unifolia

Malus angustifolia

Marshallia obovata

Matelea alabamensis

Matelea baldwyniana

Matelea flavidula

Matelea floridana

Matelea gonocarpos

Myriophyllum laxum

Najas filifolia

Nuphar advena subsp. ulvacea

Osmunda cinnamomea

Osmunda regalis var. spectabilis

Pachysandra procumbens

Physocarpus opulifolius

Pinckneya bracteata

Platanthera flava

Podophyllum peltatum

Polygonella macrophylla

Polymnia laevigata

Quercus arkansana

Rhapidophyllum hystrix

Rhexia salicifolia

Rhododendron austrinum

Rhododendron canescens

Rudbeckia triloba

Salvia urticifolia

Sarracenia leucophylla

Sarracenia psittacina

Sarracenia rosea

Sarracenia rubra

Schisandra glabra

Sideroxylon lycioides

Silene polypetala

Sium suave

Spigelia gentianoides

Spiranthes laciniata

Spiranthes tuberosa

Staphylea trifolia

Stewartia malacodendron

Symphyotrichum racemosum

Taxus floridana

Tephrosia mohrii

Thalictrum thalictroides

Tipularia discolor

Torreya taxifolia

Trillium lancifolium

Uvularia floridana

Veratrum woodii

Woodsia obtusa

Yucca gloriosa

Zanthoxylum americanum

Zephyranthes atamasca

Papaya Carica papaya (Caricaceae)

by Daniel B. Ward

The Papaya (Carica papaya L.) is a small unbranched tree sparingly cultivated in southern Florida and found rather commonly in wild situations throughout the Keys, on islands of the Everglades, and sometimes on aboriginal shell middens as far north as the Ten Thousand Islands of Collier County on the west and Turtle Mound, Volusia County, on the east. It has been unqualifiedly considered a native by some authors (West & Arnold, 1946) and equally firmly marked as non-native and stated to be “escaped from cultivation” by others (Wunderlin, 1998).

The determination of whether Carica papaya is native to Florida, or a recent introduction from cultivated sources, is important. If believed to be non-native, the little tree may be perceived by land managers as an unwelcome invader in the Florida flora and will be subject to eradication from protected natural areas throughout the state. If considered a part of our native flora, that status will give it protection and its presence on state lands will add interest as a link with the earliest human inhabitants of the Florida peninsula.

Papaya is a distinctive plant, with its spindly trunk topped by a crown of large, palmately-lobed leaves, below which are small cymes of yellow flowers or a few broadly elliptic, longitudinally-ridged fruits borne close to the stem. The fruits – sliced crosswise at maturity, seeds scooped from the center, leaving the delicately fragrant, smooth textured, sweet pulp – are a culinary delight. Thus it is most unlikely that early explorers with descriptions in their books, even if unfam iliar with the plant from personal experience, would confuse it with any other.

Bartram

The first Florida venturer to mention the Papaya was the Philadelphia naturalist, William Bartram. His father, John Bartram, who in 1765 traveled with his son “Billy” along the St. John’s River and elsewhere in Florida, made no mention of Papaya or Carica in his detailed diary (Harper, 1942). But nine years later,

William returned, and traversed much of the same Florida wilderness. In the spring, and again in the late summer of 1774, he boated up the St. Johns River, camping on the shores either alone or with a companion, and experiencing the adventures with bellowing alligators, schooling fish, and clouds of birds that made his later Travels (1791) such a literary and natural-history classic.

“And now appeared in sight a tree that claimed my whole attention: it was the Carica papaya, both male and female, which were in flower, and the latter both in flower and fruit, some of which were ripe, as large, and of the form of a pear, and of a most charming appearance. This admirable tree is certainly the most beautiful of any vegetable production that I know of; the towering Laurel Magnolia and exalted Palm indeed exceed it in grandeur and magnificence, but not in elegance, delicacy and gracefulness; it rises erect with a perfectly strait tapering stem, to the height of fifteen or twenty feet, which is smooth and polished, of a bright ash colour, resembling leaf silver, curiously inscribed with the footsteps of the fallen leaves, and these vestiges are placed in a very regular uniform imbricated order, which has a fine effect, as if the little column were elegantly carved all over. Its perfectly spherical top is formed of very large lobe-sinuate leaves, supported on very long footstalks....The ripe and green fruit are placed round about the stem or trunk....The tree very seldom branches or divides into limbs, I believe never unless the top is by accident broke off when very young....” (Travels, 1791:131-132).

Bartram apparently also kept a journal, now lost, from which he prepared a series of reports to Dr. John Fothergill, London, who had financially supported his journey. His reports to Fothergill have survived, and have been published (Harper, 1943). They are less lyric and more detailed than Travels, but often permit a reader to gain better understanding of the epic journey into the Florida wilderness.

The financial stimulus from Dr. Fothergill, is, of course, not referred to in the Travels, and is consequentially little known. It is detailed in a letter written 23 October 1772 by Fothergill to Dr. Lionel Chalmers of Charleston (Harper, 1943:126). “Another person...claims a little of my assistance.... He is the son of that eminent naturalist John Bartram of Philadelphia, bound to merchandize but not fitted to it by inclination....He knows plants and draws prettily. I received a letter from him this summer from Charleston, offering his services to me in a Botanical journey to the Floridas....Lend him any assistance that may seem expedient at my expense.... I was thinking to give him Ten guineas, to fit him out with some necessarys....and to allow him any sum not exceeding 50 [pounds] pr Ann for two years....In consideration of this sum, he should be obliged to collect and send to me all the curious plants and seeds and other natural productions that might occur to him....I would wish to encourage [him], not to injure him by proposing a provision that may make him idle.”

In his report to Fothergill, Bartram spoke only briefly of Papaya. Once, in a listing of useful plants, he noted, “The Floridians eat this fruite when ripe.” Elsewhere he observed “Indian Papaya, profusely adorn’d with garlands of joyfull airey Climbers.”

Presumably the observations detailed in his Travels and the brief comments in the Fothergill report are of the same location. His descriptions of natural landmarks both before and after the Papaya sighting permits us to be confident that he encountered the tree somewhere along the upper St. Johns River, along the eastern border of Lake County, between the present town of Astor (then a trading post) and Lake Beresford.

Much of the St. Johns waterway is bordered by extensive marshes, where Carica would not thrive. But immediately before his mention of the Papaya in the Travels he noted, “The banks of the river on each side began to rise and present shelly bluffs.” “Shelly” indicates Bartram’s site may have been an aboriginal midden, which in turn suggests the Papaya had reached that location via human transport. [The inhabitants, until destroyed by the invading Creeks (our Seminoles), were the Timucua, who had also planted many acres of sweet and sour oranges received from their masters, the Spanish of St. Augustine.]

Michaux

In 1788 the French botanist, Andre Michaux, with guidance following a visit to Bartram in Philadelphia, retraced much of the earlier explorer’s route. He too found Carica, though his description was disappointingly brief. On March 12 he and his party (his son, his black servant, and two oarsmen) left

St. Augustine by canoe, proceeding south along the Matanzas River. By March 22 they had reached the Halifax River and Ponce de Leon Inlet (then called Mosquito Inlet), Volusia County. The camped “on dry ground at 4 Miles distant from the mouth of Spruce Creek” (Taylor & Norman, 2002:70, in trans.), apparently a short distance south of the Inlet. Michaux’s diary simply noted, “There I found Carica papaya.”

[The longstanding puzzlement of why a central Florida stream would bear the name “Spruce Creek.” when no Picea is known south of North Carolina, is hereby resolved. A 1769 map (Taylor & Norman, 2002:44) shows it as “Spruce Pine Creek.” “Spruce Pine” was long given to Pinus clausa until persnickety botanists reserved that common name for the more northern Pinus glabra, assigning “Sand Pine” to the abundant peninsular conifer.]

Present Distribution

It is apparent that Bartram’s observation on the St. Johns River in 1774 and Michaux’s comment along the Ha lifax River in 1788 could not have been of the same location. They were

Native or Not: Studies of problematic species

on different waterways, separated by perhaps 30 miles across almost the entire width of Volusia County. One may speculate that the tree was then sufficiently common as not to merit mention, for Bartram boated past Ponce De Leon Inlet with his father in 1765 and again in 1774, and Michaux in May 1788 traveled much of the same St. Johns waterway as had Bartram, yet neither mentioned Carica at the place it had been seen by the other.

For the last century Papaya has been gone from both Bartram’s St. Johns River location and the site on the Ha lifax River where seen by Michaux. However several small trees are present today, atop nearby Turtle Mound, a large Timucuan midden 9 miles south of New Smyrna, Volusia County. When Michaux visited Turtle Mound – which he knew of as Mount Tucker – five days after leaving the Papaya location near Ponce De Leon Inlet, he noted that he collected there “several shrubs and plants of the Tropics,” but made no mention of Papaya. Turtle Mound was not again visited by a botanist until J.K. Small (1923:203) reported that in 1921 “Papaya (Carica) was there in its wild state, evidently brought up the coast by migratory birds.” When E.M. Norman (1976) inventoried plants of the midden in the early 1970s, she recorded Papaya as “rare.”

On the southwest coast of peninsular Florida, Carica papaya is also present atop the steep-sided shell middens of the Ten Thousand Islands just south of Everglades City, Collier County (as seen in January 1996). The trees are few, overtopped by the thick tropical vegetation that now covers the aboriginal sites, and give the impression of marginal survival.

Papaya has been reported from the southwest coast since its discovery by A.W. Chapman, a physician and amateur botanist of Apalachicola. In the mid-19th century Chapman traveled at least twice to southern Florida to add tropical species to his herbarium. About 1876 (the date is uncertain, though it probably could be determined from his collections at the New York Botanical Garden) he visited what is now Collier County, and published a lengthy listing of his discoveries (Chapman, 1878). He perhaps saw the tree on or near Marco Island (he noted Caximbas Bay for several collections probably obtained on the same trip), 25 miles northwest of the Ten Thousand Islands area. Regrettably, he limited his report to a botanical description, merely noting the tree was from “South Florida.”

Southwest coastal Florida was the ancestral home of a quite distinct aboriginal culture, that of the Calusa. Unlike the Timucua, the Calusa were consistently hostile to the Spanish and had less opportunity to obtain plants from that source. It is quite possible the Calusa had obtained their Papaya directly from trade sources in the Caribbean. But here, too, the date of that transport is not made clear from the mere

existence of plants surviving on their shell middens. Papaya is also present throughout the Everglades and Florida Keys, always in hammocks, never in the open prairies. It was infrequent, occasionally encountered but never in appreciable numbers, until Hurricane Andrew swept over the area in August 1992, crushing and removing the trees and shrubs from many hammocks. The following season Carica seedlings appeared in great numbers throughout the area, indicating the seeds had lain dormant in the soil for many years (W. S. Judd, pers. obs., Sept 2003). One speculation, that they perhaps represented Indian campsites, was discounted by the widespread and diffuse distribution of the seedlings.

The Everglades Papayas, as they matured and bore fruit, displayed a characteristic that reflects on their origin. The fruits were small, the size of golf balls or eggs, much smaller than those of modern cultivated strains.

Carica papaya is known in the state far more widely than these records indicate. Herbarium records are available for 13 South Florida counties (R.P. Wunderlin, pers. comm., 1996). Yet many of these additional records are of plants recently escaped from cultivation – most have large, commercial-sized fruits – and give us no information as to the origin of plants on the aboriginal sites.

Origin of Papaya

Papaya is a member of a smallish (perhaps 40 species) genus native to tropical and subtropical America. Carica papaya itself has never been found wild, but is believed to have originated in southern Mexico and Costa Rica where close relatives occur. Most strains are dioecious (male and female flowers on different trees). The tree is an important tropical fruit, but travels poorly, so is little known far from its origin. (See Purseglove, 1974; Rehm & Espig, 1991.)

How did Papaya come to be in Florida? The first possibility, that it was carried here by ocean currents, is improbable. The fruits do float, though there is no data on seed survival with exposure to seawater. Ocean transport has the further burden of explaining how the battered seeds would reach the more upland, mesic soils necessary for their growth. Further, the dioecious sexual structure reduces the odds even more, for a single surviving plant would be ineffective, the male naturally sterile and the female unpollinated and thus infertile.

The second possibility, human transport, thus becomes a near certainty. But concluding that Homo sapiens was the vector tells us little. It is also essential to determine the date of transport – either pre-European contact, and thus native, or post-European contact, and thus introduced. That distinction has been discussed in the first number of this series (Ward, 2003). Thus the objective

of this essay is to determine whether Papaya was brought to Florida by the early aboriginal peoples at some indeterminate time in the past, or given to them by the Spanish in the early years of their colonization of the peninsula.

It is clear the Papaya was available for transport and cultivation by the aboriginals – the Timucua in the St. Johns River area, and the Calusa in the Southwest. But did they bring the fruits and viable seeds from a Caribbean source closer to the tree’s area of origin? Or did they perhaps obtain it from the Spanish of St. Augustine, and move it together with oranges into areas far outside Spanish settlement and direct influence?

Solid Evidence

At last evidence is in hand. For some years a series of excavations has been underway on Pine Island, just inland from Sanibel Island, Lee County. The Pineland Site Complex is acknowledged as a remarkable deposit of early settlement and is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Before protection was attained, parts of the mounds on the site were removed and low areas filled, thus limiting the scope of modern excavation. Even so, a wealth of artifacts has been recovered, as well as abundant animal and plant remains.

Radiocarbon dating of materials from Pineland show cultural periods from A.D. 50 to A.D. 1750. The waterlogged deposits in which most plant materials were found were early in this series, from the first through the third centuries A.D. Fragments were recovered of fleshy fruits, as well as species of wetland, woodland, and hammock taxa (Marquardt & Walker, 2001). Among these materials were nearly 3,000 seeds of various species.

Only 8 seeds of Carica were found among the many recovered seeds. Yet their presence and form answers much. In size, texture of seed coat, and overall morphology, these seeds were somewhat different from Papaya seed from elsewhere, suggesting that there had been some selection by the Pineland residents (L.A. Newsom, pers. comm., Aug 2003). But they were indubitably Papaya. There can now be no question that this species was introduced to Florida by the early inhabitants, probably the Calusa, no later than 300 A.D., vastly predating European influence. The Papaya (Carica papaya) is thus confirmed to be a native member of the Florida flora.

I wish to thank Walter Judd for his acute observations of Papaya in the Everglades and realization of the significance of their distribution and fruit size, to Lee Newsom for her generosity in providing information on her Pineland discoveries in advance of her own publication, to Karen Walker and Bill Marquardt for their recent Pineland data, and to Richard Workman for his constant interest and significant help in the search for a definitive answer to Papaya’s nativity.

References Cited

Bartram, W. 1791. Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida. James and Johnson, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. 522 pp.

Chapman, A.W. 1878. An enumeration of some plants – chiefly from the semi-tropical regions of Florida – which are either new, or which have not hitherto been recorded as belonging to the flora of the southern states. Bot. Gaz. 3:2-6, 9-12, 17-21.

Harper, F. 1942. John Bartram, “Diary of a journey through the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida.” Trans. Amer. Philos. Soc. 33:1-120.

Harper, F. 1943. William Bartram, “Travels in Georgia and Florida, 1773-74: a report to Dr. John Fothergill.” Trans. Amer. Philos. Soc. 33:121-242.

Harper, F. (ed.). 1958. The Travels of William Bartram: Naturalists Edition. Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut. 727 pp.

Little, E.L. 1979. Checklist of United States Trees. U.S. Dept. Agric. handb. 541. 375 pp.

Marquardt, W. H. & K.J. Walker. 2001. Pineland: A coastal wet site in southwest Florida. From: B.A. Purdy (ed.), Enduring Records: The Environmental and Cultural Heritage of Wetlands. Oxbow Books, Oakville, Connecticut. Michaux, A. 1803. Flora Boreali-Americana. Paris.

Norman, E. M. 1976. An analysis of the vegetation at Turtle Mound. Florida Sci. 39:19-31.

Purseglove, J.W. 1974. Tropical Crops – Dicotyledons. John Wiley, New York. 719 pp.

Rehm, S. & G. Espic. 1991. The Cultivated Plants of the Tropics and Subtropics. Univ. of Gottingen. 552 pp.

Small, J.K. 1923. Green deserts and dead gardens. J. New York Bot. Gard. 24:193-247.

Taylor, W. K. & E.M. Norman. 2002. Andre Michaux in Florida: an eighteenthcentury botanical journey. University Press of Florida, Gainesville. 246 pp.

Ward, D.B. 2003. Native or Not: Studies of problematic species. No. 1: Introduction. Palmetto 22(2): 7-9.

West, E. & L.E. Arnold. 1946. The Native Trees of Florida. Univ. of Florida Press, Gainesville. 218 pp.

Wunderlin, R. P. 1998. Guide to the vascular plants of Florida. Univ. Presses of Florida, Gainesville. 806 pp.

About the Author

Dr. Dan Ward is Professor Emeritus at the University of Florida.

Water Science & Plants

by Ginny Stibolt

Without water, life as we know it would not exist. Plants and animals contain high percentages of water and depend upon its unique properties to survive. Humans are attracted to bodies of water for both their beauty and their usefulness for many aspects of our lives.

Water’s unique properties

Water is made up of two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom giving it the familiar chemical formula of H20. The hydrogen atoms attach themselves to one side of the oxygen, covering about 1/3 of a circle, and so that the molecules look very much like Mickey Mouse ears (Figure 1). The side of the molecule with the hydrogen atoms has a slight positive charge and the oxygen side is slightly negative. Water molecules act like little magnets and are attracted to each other and form weak bonds, called hydrogen bonds. You notice this self-attraction, called cohesion, when water beads up into droplets on leaves or flower petals (Figure 2).

Water’s polarity makes it a good solvent that can break apart, absorb, and carry organic materials such as sugars, other carbohydrates, and nutrients.

Water is highly unusual as well, because it can exist simultaneously as a gas (water vapor), liquid, and a solid (ice). The solid form is unique because it is less

dense than the liquid due to its crystalline structure and floats on the liquid. Water readily evaporates into the atmosphere and gathers as mist or clouds. Knowing how plants deal with and take advantage of water’s unique chemistry makes us better caretakers for both wild and cultivated landscapes.

Osmosis and root hairs

Starting at the bottom, near the tip of the roots, there are thousands of single-cell extensions on the root’s surface called root hairs that absorb water from the soil. Root-hair cells have a semi-permeable cell membrane that allows water and some materials that are dissolved in water, such as nutrients, to flow into the cell. Everything else is blocked from entry into the plant.

Water will equalize over an area and when there is less water within the root hair cells than in the surrounding soil, then the water flows across the cell membrane to equalize that pressure. Once water fills the root hair cells, it moves into neighboring cells and builds up pressure that pushes water up into the plant; this is called root pressure. Then the process of transpiration, as discussed below, carries the water farther up the plant.

Root hairs usually last just a few weeks before they are reabsorbed into the root tissue – a root must be growing in order to develop new root hairs. We need to keep this in mind when irrigating plants; water needs to be applied to the region where new roots are growing. Roots of established trees and shrubs

More than 90% of the water that enters a plant runs straight through it and evaporates into the air. A full-grown oak tree could transpire more than 400 gallons of water on a summer day.

might be growing yards away from the trunks or stems.

When a plant is transplanted, most of its delicate root hairs are rubbed off as soil falls away from roots, so these plants need a lot of water in the planting hole and frequent irrigation until new root growth begins and the plant regains its network of root hairs. The larger the plant, the longer the time period when additional irrigation is necessary for the establishment of that plant. This close attention and adequate irrigation during its establishment period vastly increases the chances of a plant’s survival. A drought-tolerant native plant needs the same care after transplanting as other plants. It only becomes truly drought tolerant after it is fully established in its new location.

Before we leave water’s interaction with roots and soil, let’s kill an old gardeners’ tale. For years we’ve been advised to lay a thick layer of gravel or potshards in the bottom of our pots and containers to aid drainage. It was shown 100 years ago that this is false, but even today, so-called gardening experts and master gardeners continue to pass this myth on as if it were fact. Because of water’s tendency to hang together, it will be reluctant to jump gaps created by a coarse medium such as gravel. It won’t move away from the fine medium of soil until it’s completely saturated. In order to create the best drainage in your container gardens, use taller pots and use all soil with just a screen or leaves covering the drainage holes. You can test for the effectiveness of the taller pots with a simple cellulose kitchen sponge: Completely saturate the sponge and hold it in the horizontal position over the sink until it stops dripping. Then turn it so that it is vertical and after a short delay the sponge will give up more of its water. So if you wish to grow a large pot of prickly pears, make it a tall one. On the other hand, if you wish to grow some hooded pitcher plants and other native bog plants use a shallow pot so the soil retains the moisture more efficiently.

Transpiration

After water enters the root tissues, there is pressure that begins to push the water higher in the plant. But it would not go very far up the tubular, water-carrying cells in plants, called xylem, without the suction effect of evaporation through the pores in the leaves and stems called stomata (Figure 3). For many years it was thought that capillary action (movement of a liquid up a narrow tube) accounted for much of this movement, but more advanced measuring techniques show that capillary action is not a major factor in water movement through the xylem.

More than 90% of the water that enters a plant runs straight through it and evaporates into the air. A full-grown oak tree could transpire more than 400 gallons of water on a summer day. The larger the plant’s biomass, the higher the volume of transpiration. The area near large plants

Point Washington State Forest

Continued from page 2

years. Although management at Point Washington State Forest seems to be on the right track, the forest’s management plan was revised in 2002 and season of burn was eliminated from its goals and measurements. As a result, no prescribed burns have been done during the growing season in the last five years and none are expected by staff for the next five years.

Other deterrents include extensive development on the beach along the southern boundary of the tract, increasing development along its northern boundary, and the presence of a four-lane highway (U.S. 98). Additional factors include unpredictable winds, unfamiliarity with growing season fire, and the need for staff to respond to wildfires elsewhere in Florida.

The land management review team recommended increased burning during the growing season. In addition, we will continue our conversation with forest staff about the importance of season of burn and managing listed species.

Tom Greene is a member of the Magnolia Chapter (Leon County) and an FNPS Land Management Review volunteer.

Water Science & Plants

is cooled by the transpiration process and on a hot day, the temperatures may be up to 20 degrees cooler than nearby spaces without large plants.

The transpiration rate is also an important factor in planting rain gardens. Rain gardens are designed to collect rainwater in swales. The water will be both absorbed by the plants and also percolate into the soil to refresh our aquifers. A rain garden should not have standing water for more than three days –the more biomass in the rain garden plants, the higher the transpiration rate and the faster water is sucked from the soil.

The remaining 10% of the water that is absorbed into the plant’s cells serves several purposes: it carries nutrients, it keeps the cells turgid and it will also be used by the plant for photosynthesis during the daylight. When the soil is dry, this whole process slows down. The guard cells around each stomate are highly sensitive to water supply and when they become flaccid, the stomata close up, and the evaporation of water is slowed to protect against severe wilting. We need to pay attention to the wilting of plants – especially seedlings – and irrigate before permanent damage is done to the plant’s tissue.

Guttation

When the temperature lowers at night, less water evaporates into the air. Nighttime temperatures put the brakes on the transpiration rate, but in many types of plants, the root pressure is not immediately reduced, so there is a flow of water from the leaves at night to relieve the pressure. This is called guttation.

The water is excreted as liquid through specialized pores called hydathodes at the ends of veins (Figure 4). If the plant is a salt tolerant plant, you can often see a build up of salt crystals near these pores.

This excreted water is often confused with dew, but the source of the water is not the same. The water from guttation comes through the plant, while dew is formed when water vapor in the air condenses on plant surfaces in the cool night air. Dewdrops form randomly on plants and will not form

About the Author

neat droplets at the ends of veins or at the tips of narrow blade-like leaves. Some of the water – both from dew and guttation – on plant surfaces may be absorbed through the plant’s stomata the next morning when the temperature rises again, but most of it will either drop to the ground or evaporate into the air.

Most people recommend that we irrigate, if needed, in the morning so plants have all day to cycle the water, because dry plant surfaces at night are less vulnerable to fungus attacks, and so less water is lost to evaporation during irrigation. Perhaps the most compelling reason is, if you water at night much of the water may be out of reach of the roots by the time the plant is ready to restart the transpiration cycle.

Water drops act like little magnifying lenses or prisms and if you look closely you can often see rainbows in the drops. They are beautiful, and contrary to the old gardeners’ tale, the water drops on leaves in the full sun will not burn the leaf tissue. So you may irrigate without fear in the middle of the day if your plants – again particularly seedlings – are wilting in the Florida heat.

Photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is the process wherein green plants combine carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H 2O) with energy from sunlight to form sugar (C 6H12O 6) and oxygen gas (O 2). For most vascular plants, the water is supplied by transpiration flow and the carbon dioxide is available from the air through the open stomata. (Respiration is the equal and opposite chemical reaction, and all organisms respire as they gain energy for living.)

When it gets too hot and plants close up their stomata to preserve water, most plants cannot continue photosynthesizing because they don’t have ready access to water and carbon dioxide. Some heat-loving plants have adapted to make better use of the sunlight in the heat.

Water: it’s a limited resource

Before we knew better we wasted much of our water and used up or spoiled many water resources. Water, especially usable fresh water, is a limited resource. As landscape managers we can do our part and create water-wise landscapes planted with native plants that have adapted to survive in Florida’s climate and its seven-month dry season.

Ginny Stibolt is a lifelong gardener who earned an M.S. in Botany from the University of Maryland. She blogs for The Florida Native Plant Society at http://fnpsblog.blogspot.com, The Lawn Reform Coalition at http://www.lawnreform.org, and writes on Florida gardening for The Florida Times Union, (Jacksonville). Ginny is the author of Sustainable Gardening for Florida, (ISBN 13: 978-0-8130-3392-1) published by The University Press of Florida. This article, originally published as part of the blog action day on water, http://blogactionday.change.org/ has been modified for The Palmetto.

Protecting Endangered Plant Species in Panhandle State Parks

Big Sweetwater Creek, the centerpiece of this tract, lies at the center of distribution of some of Florida’s richest examples of slope forest habitat. It is bordered on the south by the Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve, a Nature Conservancy (TNC) holding well known for its botanical richness. This region is valued for its large number of rare, endangered, and special interest plant species. Figure 1 shows the dendritic pattern of the Big Sweetwater Creek drainage.

During summer and fall 2009 and spring 2010, we made several field trips into the ravines; additional field trips have continued following the close of the one-year FNPS grant. In addition to the authors, several knowledgeable naturalists and field botanists volunteered on one or more of these surveys. To this end, we acknowledge the assistance of Bill Anderson, Pam Anderson, Wilson Baker, and Mark Ludlow. Based on these surveys and those conducted following the FNPS project year, our Sweetwater database includes a total of 177 points for 17 listed or otherwise special interest species (Table 4). These numbers do not include known locations for mountain laurel

(Kalmia latifolia), sweetshrub (Calycanthus floridus), and torreya (Torreya taxifolia). Approximately 50 records of Torreya taxifolia from the Sweetwater region are maintained in an offline database as part of an ongoing range-wide study of the status and health of this species. It should also be noted that the single occurrence for Liatris gholsonii was recorded to ensure this species’ inclusion on the list. Liatris gholsonii is common and widespread along the upper 25% of the slope along many if not most of the drainages in the Sweetwater region.

Use of the data generated from our herbarium review and continuing surveys will enhance management of endangered species in District 1 parks, facilitate a centralized districtwide database of important park resources, and provide for the smooth flow of information to new park managers and staff.

About the Authors

Gil Nelson holds a Beadel Fellowship in Botany at Tall Timbers

Station, 13093 Henry Beadel Drive, Tallahassee, FL 32312; gnelson@ttrs.org

Tova Spector is an Environmental Specialist, District 1, Florida Park Service, 4620 State Park Lane, Panama City, FL 32408; Tova.Spector@dep.state.fl.us

The Florida Native Plant Society PO Box 278 Melbourne FL 32902-0278

FNPS Chapters and Representatives

1. Callicarpa .............................Kim Nusbaum ....................kimnusbaum@mchi.com

2. Citrus ...................................Bob Schweikert .................bschjr@gmail.com

3. Coccoloba ............................Dick Workman ...................wworkmandick@aol.com

4. Cocoplum .............................Anne Cox ...........................anne.cox@bellsouth.net

5. Conradina .............................Vince Lamb .......................vince@advanta-tech.com

6. Coontie .................................Kirk Scott ..........................kirkel1@yahoo.com

7. Cuplet Fern ............................Deborah Green ..................watermediaservices@mac.com

8. Dade ....................................Lynka Woodbury ................lwoodbury@fairchildgarden.org

9. Eugenia ................................Judy Avril...........................jfavril1@comcast.net

10. Heartland .............................Sharon Olson .....................olsoncheek@msn.com

11. Hernando .............................Brooke Martin ....................brooke_martin@mac.com

12. Ixia .......................................Linda Schneider.................lrs409@comcast.net

13. Lake Beautyberry .................Jon Pospisil .......................jsp@isp.com

14. Lakelas Mint .........................Ann Marie Loveridge ..........loveridges@comcast.net

15. Longleaf Pine .......................Amy Hines .........................amy@sidestreamsports.com ........................................Cheryl Jones......................wjonesmd@yahoo.com

16. Lyonia ...................................Jim McCuen ......................jimmccuen@yahoo.com

17. Magnolia ..............................Scott Davis ........................torreyatrekker@gmail.com

18. Mangrove .............................Al Squires .........................ahsquires@embarqmail.com

19. Marion ..................................Jim Coulliard ....................jrc-rla@cox.net

20. Naples ..................................Ron Echols ........................preservecaptains@aol.com

21. Nature Coast ........................Marilyn Smullen.................(727) 868-8151

22. Palm Beach ..........................Lynn Sweetay ....................lynnsweetay@hotmail.com

23. Pawpaw ...............................Elizabeth Flynn ..................eliflynn@cfl.rr.com

24. Paynes Prairie ......................Sandi Saurers ....................sandisaurers@yahoo.com

25. Pine Lily ...............................Jenny Welch ......................mwelch@cfl.rr.com

26. Pinellas ................................Debbie Chayet ...................dchayet@verizon.net

27. Pineywoods ...........................Rick Dalton ........................rickinfl@comcast.net

28. Sarracenia ............................Jeannie Brodhead ..............jeannieb9345@gmail.com

29. Sea Oats ..............................Martha Delaney-Hotz .........marthadhotz@gmail.com

30. Sea Rocket ..........................Paul Schmalzer ..................paul.a.schmalzer@nasa.gov

31. Serenoa ................................Dave Feagles .....................feaglesd@msn.com

32. South Ridge ..........................VOLUNTEER NEEDED .........executivedirector@fnps.org

33. Sparkleberry..........................Carol Sullivan ....................csullivan12@alltel.net

34. Sumter .................................Vickie Sheppard.................vsheppa@cox.net

35. Suncoast .............................Troy Springer .....................president@suncoastNPS.org

36. Sweetbay ............................Ina Crawford ......................ina.crawford@tyndall.af.mil

37. Tarflower ..............................Jackie Rolly .......................j.y.rolly@att.net

38. University of Central Florida ...Christy Bitzer-Jaffe ............christy270@knights.ucf.edu

39. University of Florida ...............Mia Requesens ..................miareq87@ufl.edu

Volunteer opportunity: volunteer needed for Okaloosa/Walton County area.

Visit www.fnps.org to ● Find more information on Chapters and meeting locations. Use the Chapters drop down box. ● Join or renew your membership online. Click Join/Renew