FLUX

Anchored in Community

Finding solace in trying times

For over 54 years, The Fishermen’s Wives of Newport, Oregon, have rallied together to support one another during hard times. They were photographed by Geoffrey Kerrigan. To read about the Fishermen’s Wives, turn to page 24.

The story of the Fishermen’s Wives encompasses the thread that follows all our stories— community. Co-Art Directors Elizabeth Sgro, Sam Butler and Romie Avivi Stuhl ensured the cover and each design embodies this theme and the standards FLUX strives to reach. Read more stories on our website, fluxoregon.com

OM MU YNIT C

At FLUX, we focus on what glues the Pacific Northwest together: the people that populate this landscape; the connection we all share; and, most of all, the community we find in those around us.

Bigfoot Seekers

The mystery of Sasquatch continues through the dedicated members who keep searching.

From Mine to Scrapyard

20

As lithium demand grows, the process of recycling isn’t keeping pace.

Anchored in Community

Women of Newport understand the importance of community through a social club turned non-profit.

Liberating Heritage

A new generation of artists are working to help decolonize Oregon museums.

A Fight for Change

Jimmy Jennett has used his challenging life experiences to positively impact his community through MMA. 42

It Comes in Waves

Grief and loss can feel isolating, but there are people out there to help.

Where Red & Blue Intermix

Oregon House District 52 is a microcosm of modern American politics.

Home on the Road

Van lifers speak on the highs and lows of living in their vehicles.

54Returning to Nature

A new approach to death care curbs the environmental impact of traditional practices. 60

Preserving the Past

How Eugene’s rail lines and millrace fostered the community’s growth.

64

Critical Conditions

Nurses keep moving forward despite the harsh working conditions they face every day.

This Must be the Place

Two nature lovers find solace from grief and stress in the fraternity that is the Northwestern wilderness.

74 Peace is More Difficult Than War Violence is the simpleton’s answer to conflict. Dialogue and discussion are more difficult — the editor’s thoughts on the world today.

ED OIT

Tis edition of FLUX will always hold a special place in my life. A major reason for that is the team that surrounded me.

Ainsley Maddalena was this magazine’s backbone. She kept us all grounded. Not one story in this edition went untouched by her vision. She has a talent for editing and I leaned on her so hard to ensure each story met the FLUX standards. Ainsley’s spirit and vision guided this group. She always helped pull my ideas from theoretical to practical. Tis magazine wouldn’t be what it became without her. I was fortunate to catch a ride on the wave of excitement that she created.

Carlie Weigel, one of the most talented writers and reporters I’ve ever been around, used those talents not just on an incredible story of her own but also in shaping the framework of our other stories, like “Anchored in Community.” She always looked for more to take on to challenge herself but also to push FLUX to a higher level.

Anna Ward’s enthusiasm was contagious. In times when the rest of us might have less energy, Anna would light our meetings up and keep us motivated. Te focus and determination she brought to each of the stories was unmatched. Her dedication helped bring to life the vision of “Critical Conditions.” Her writing skills are phenomenal.

Sammy Pierotti brings us all unparalleled optimism. Any challenge we faced, Sammy was always there with a smile and a willingness to face it. Sammy channeled their auspicious energy towards each of the goals we envisioned for FLUX. “Home on the Road” benefted by having Sammy’s spirit help awaken it. Hearing “Yeah, dude!” in our meetings became a sort of rallying cry for me.

Evan Susswood remained level-headed no matter what came our way. His eye for what pictures spoke to the truth of the stories was key in helping this edition of FLUX sing. Trough reshoots, story changes, and all the other unpredictability that comes with a magazine, Evan kept his eye true.

Te half-year we spent helping shape this edition of the renowned FLUX Magazine are memories I’ll hold tight for decades to come. Te stories and the photos are all aspects that I’m immensely proud of, however, what I’ll cherish most though is the comrad-

ery forged while working to bring out the best of each story.

FLUX embodies what it means to be in the School of Journalism and Communication. Community, friendship, creativity, collaboration and belonging.

As I refect now, those are the attributes that I feared would escape me as a student here. As a non-traditional student with no journalism background prior to college, fear almost held me back from challenging myself. Fear of being diferent, of being an outsider, of lacking the skills needed to be equal with my peers. Instead, I used those fears to push myself forward toward my goals.

Each of the stories featured this year also highlights those attributes. Tey are the pillars that hold this edition together.

I speak for each of the incredible students who put their efort and talents into FLUX when I say, we hope you enjoy this edition. Our goal, from day one, was to deliver a magazine that resonated with its readers. I believe we’ve achieved that and so much more.

Lastly, I want to give a special thanks to three amazing people, without whom I wouldn’t be where I am today.

My loving wife, Stephanie. Her endless support is incalculable. I wouldn’t be me without you. You are, without a doubt, my better half.

My daughter, Artemis. She’s my inspiration to continue pushing myself. She flls my heart with infnite love. Being her dad is the most precious role I hold in life and one I never take for granted.

My big brother, Tim. Writing was a talent he held. Each time I put words on a page, I feel your love surround me. You’re with me in all I do and I miss you dearly. Without your guidance growing up, I wouldn’t be the man I am today.

RI could fll this entire magazine with people who helped me get to where I am today. Instead, let me just say thank you.

I’m so grateful to have had this opportunity and to have been a part of something so special. And, as always,

Johnny Media

Editors

Editor-in-Chief: Johnny Media

Executive Editor: Ainsley Maddalena

Managing Editor: Carlie Weigel

Senior Editor: Sammy Pierotti

Senior Editor: Anna Ward

Photo Editor: Evan Susswood

Writers

Pierce Baugh

Bart Brewer

Sylvia Davidow

Malya Fass

Ellie Graham

Ethan Harmon

Sydne Long

Lily Lum

Armando Ramirez

Researchers

Tatum Staurt

Akila Wickramaratna

Photographers

Eliott Coda

Sophie Craft

TJ Jenkins

Geoffrey Kerrigan

Danielle Lichtenstein

Harper Mahood

Social Media Editors

Jessica Hodges

Brooklyn Stern

Designers

Art Director: Romie Avivi Stuhl

Art Director: Sam Butler

Art Director: Elizabeth Sgro

Gillian Blaufus

Jack DeKoker

Aidan Gratton

Olivia Greer

Skyler Kenan

Kevin McAndrews

Illustrators

Gillian Blaufus

Sam Butler

Madeline Dunlap

Brooke Hatchman

Kevin McAndrews

Advisors

Editorial: Charlie Deitz

Design: Steven Asbury

Photography: Chris Pietsch

FLUX is printed annually by the University of Oregon School of Journalism and Communication. The staff would like to thank Charlie Butler and Maya Lazaro for proofing, Juan-Carlos Molleda and Deb Morrison for their advocacy and QSL Print Communication, without whom, FLUX would not be possible.

F SA F T

Copyright 2024

2024

flux

Best Ouseplants or College he

These low-maintenance plants are perfect for college students or people on the go. They don’t require much upkeep and are very forgiving.

Jade plants are easy to grow and can live for a long time. They require little water but need lots of bright sunlight. Jade Plant

Spider Plant

Spider plants are one of the most adaptable houseplants and is known for their air-purifying qualities.

Golden Pothos

Pothos thrive in bright, indirect light, but risk burning up if placed in direct light. It should be watered every 1-2 weeks.

Vriesea

Vriesea should be in a well-lit spot, but not in direct sunlight. They only need to be watered once every 2 weeks.

WORDS of the year

Disinformation (dis·in·fr·may·shn)

noun: the world’s biggest game of telephone — gossip’s evil twin whispers made-up stories in everyone’s ears just to cause chaos

Eclipse (uh·klips)

noun: when the sun and moon play hide-and-seek, but the earth is awlays the seeker

Inflation (in·fay·shn)

noun: the supervillain of the economy — it makes your wallet cry for mercy

Metaverse (meh·tuh·vrs)

noun: digital playground where dragons give coding lessons and gravity only works when it feels like it

Sustainability

adjective: like throwing a never-ending party where the decorations are made of recycled confetti that magically turns into compost by morning

BIG SMALL HABITS IMPACT

Start the day with a gratitude practicethat reflects three things you’re thankful for.

Take a short walk outside during your lunch break to clear your mind.

Dedicate five minutes each day to deep breathing or meditation to promote relaxation.

Compliment yourself or someone else each day to foster positivity.

Write one thing you accomplished (even tiny things) that day, to celebrate your achievements.

SSustainable

waps

Go Thrifting

If you’re looking to refresh your wardrobe as the weather gets warmer, consider visiting some of the thrift stores around your community.

Take the Train

Plane rides can add up financially and environmentally. Decrease your carbon footprint by taking the train instead.

Use a Bicycle

Biking alleviates traffic congestion and provides an enjoyable way to experience the surroundings.

Road Trip PNW

Open Spotify on your cellphone and scan me for our FLUX roadtrip playlist.

Orcas Island

The setting for the 2017 video game, “What Remains of Edith Finch,” Orcas Island is the largest of the San Juan Islands. Take the ferry across the Salish Sea and enjoy picturesque views, natural wildlife and striking whale watching vantages.

Bellevue Botanical

Explore the 53 acres of cultivated gardens, restored woodlands and natural wetlands, highlighting the natural beauty of the Pacific Northwest’s bewitching plants. A short nature trail through Bellevue includes a 150-foot suspension bridge spanning a deep ravine.

Manzanita

Set out early for a coastal exploration on the Oregon Coast. Head to Manzanita Beach, stopping to admire stunning ocean views and spot some whales.

Oregon Dunes

Decide if you’re on Arrakis or the Oregon Coast while hiking through the sandy trails of Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area. These sandy mountains were the inspiration for Frank Herbert’s novel “Dune.”

Tamolitch Falls

Take a short hike along the McKenzie River Trail to reach this mesmerizing natural pool fed by underground springs. The vibrant blue color of the pool is truly captivating.

ADVICE FROM FUTURE THE

STORY BY JESSICA HODGES

As graduation approaches, young adults stand at the brink of a thrilling yet daunting transition. It can feel like a crossroads with too many choices, or a cliff dropping off into the unseeable future, the precipice of the unknown. It’s a time filled with excitement for the possibilities ahead, but also tinged with uncertainty about the “right” path forward.

Scan me with your cellphone to read the full story on our website.

Where graduates are living today

STORY BY BROOKLYN STERN

Diego Saranda Bickle

San

Saranda Bickle moved to San Diego after graduating in 2022. Despite not having a job lined up, she was enticed by warm weather and beaches. Bickle said, “It’s got to be one of the best places to live in the country. So I decided to give it a shot.” She enjoys the abundance of yoga studios, the city’s walkability and Mexican food. After months of searching, Bickle eventually secured a remote internship.

Reflecting on her move, she was “maybe overly confident,” Bickle said. “Graduating felt scary. It was like, ‘Hey, you did all this work, here’s a diploma, now go figure it out.’”

“Money is not the most important thing, but it does give you a feeling of security and some freedom, and when you don’t have it’s incredibly stressful.”

-Hollie Roman

“There are prices you pay for a career, and your family does suffer.”

- Charmaine Foltz

Naomi Meyer

Austin

Naomi Meyer, UO class of 2022, took a leap of faith moving to Austin. “I didn’t want to move back to Portland right after graduation,” Meyer said, “I knew if I did, I would get stuck.”

Meyer made the move after LinkedIn named Austin the No. 1 city for graduates to land entrylevel jobs in 2022. She began working at a jewelry boutique but wanted to use her degree. She continued job-searching and attended several coffee dates hoping to open a door. After an eight-month search, Meyer secured a job with a tech PR firm. Meyer has played pickleball, attended live music shows and stumbled upon a dog drag show in Austin. Despite adjusting to humid summers, Meyer is confident about calling Austin home.

$2295 Median rent for a 1 bed, 1 bath 47.3 Economic Score 40.7 Desirability Score

“Take your time picking out a career because you’re going to be doing it a long time.”

- Diane Blake

Olson is known for her work in “It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia.” In an article from “Around the O,” she reflected on her memories from the University of Oregon, including having her fake ID confiscated at Rennie’s Landing

AnnCurry

Curry is a journalist known for her anchor work on the “TODAY show.” Her broadcasting career began as an intern at the NBC affiliate KTVL in Medford, Oregon. She was the station’s first female reporter.

H a r ry Glickman

Glickman paused his journalism education to serve in WWII. When he didn’t land a newsroom job after graduation, he moved into the world of sports promotion, eventually founding the Portland Trailblazers.

Explore the vibrant tapestry of Pacific Northwest cinema through its diverse and dynamic film festival scene.

OMSI’s sci-fi Film Festival

The Oregon Museum of Science and Industry will host a sci-fi Film Festival showcasing over 40 of science fiction’s most memorable films. Classics such as “2001: A Space Odyssey” and recent favorites like “Everything Everywhere All at Once” will be shown on the Empirical Theater’s four-story screen.

Seattle Asian American Film Festival

The Seattle Asian American Film Festival is in its 12th year. Showcasing Asian and Asian American independent cinema, the festival offers every type of film, from shorts to animation to documentaries. The goal is to promote diversity and cultural understanding through film.

Seattle International Film Festival

The Seattle International Film Festival began in 1976 and has expanded into a cultural arts organization. Their mission is to “create experiences that bring people together to discover extraordinary films from around the world,” according to their website.

Famous filming locations in Oregon THEBEHINDSCENES

THE GOONIES

1985, Astoria, Oregon

Mikey (Sean Astin) and Data (Ke Huy Quan) ride their bikes from Mikey’s house in “The Goonies,” released in 1985. Most on-location filming took place in Astoria, including the famous “Goonies House,” Clatsop County Jail and the Captain George Flavel House Museum.

“The Goonies” was largely popular, placing among the top 10 highest-grossing films in 1985, earning $63.9 million in North America.

Picks Staff

Directed

By:

Darren Aronofsky

“I love finding movies with smart writing paired with brilliant acting.”

Directed By: Wes Anderson

“I love this movie because it’s a good mix of art and cinematography.”

Black Swan

Isle of Dogs

Picked by Ainsley Maddalena

Picked by Jack DeKoker

Astoria, OR

STORY AND PHOTOS BY SOPHIE CRAFT

STAND BY ME

1985, Brownsville, Oregon

Chris (River Phoenix) and Gordie (Wil Wheaton) are shocked when the gun Chris stole from his brother goes off behind the Blue Point Diner.

“Stand By Me” is the movie adaptation of Stephen King’s “The Body.” Brownsville was chosen as the setting for the fictional town of Castle Rock, Oregon, for its 1950s small-town ambiance.

Brownsville, OR

FREE WILLY

1993, Warrenton, Oregon

Willy jumps over Jesse (Jesse James Richter) to freedom from Hammond Bay. “Free Willy” was filmed along the northern Oregon Coast from May to August 1992. The film was popular upon release grossing $153.7 million at the box office. The movie also picked up a few accolades, including the Environmental Media Award for a feature film in 1994.

OR

TWILIGHT

2008, St. Helens, Oregon

OR

Directed

By:

Gus Van Sant

“It’s

Bella Swan (Kristen Stewart) arrives at her new home, the town Forks. The fantasyromance movie, based on Stephenie Meyer’s novel, was primarily filmed in northern Portland in 2008. “Twilight” grossed $35.7 million on its opening day — the highestgrossing film directed by a woman.

Peter Pan Live Action

Directed

By:

P. J. Hogan

The Devil Wears Prada

Directed

By:

David Frankel

“It’s

Picked by Olivia Greer

Picked by Eliott Coda

Picked by Gillian Blaufus

St. Helens,

Warrenton,

THE INVESTIGATORS WHO KEEP BIGFOOT ON HIS TOES.

Story by Lily Lum and Sammy Pierotti

Photos by Evan Susswood

Thom Powell claims he had his first Bigfoot encounter here, on the back trail of his expansive property along the Columbia River.

Thom Powell was strolling through his overgrown backyard in Clackamas County, the Columbia River roaring in the distance, mossy pine trees around him reaching toward the starry sky. Suddenly, everything went black. He heard the footsteps of bipedal creatures approaching him on either side. He frantically clung to a nearby tree. Sandwiched between the two creatures, Powell felt a jolt of fear run up his spine. Ten, ever so softly, one of the creatures brushed his ear with its hairy fngertips before retreating into the forest.

As Powell entered his log cabin he heard an indescribable sound. He couldn’t shake the feeling that the ‘Saskies’ were laughing at him from between the pines.

Some Bigfooters share similar experiences with Powell, while others have never gotten close to having a visual encounter. Powell, an avid Bigfoot researcher, aligns himself with the supernatural side of the community. Dubbed the “woo,” these Sasquatchers believe that Bigfoot is an alien. Other researchers, nicknamed “apers,” hypothesize that Bigfoot is a hominid that lives in the woods.

Native tribes in the Pacifc Northwest have shared knowledge of Sasquatch for generations.

Te Kwakwaka’wakw tribe of British Columbia tells stories of a hairy woman who carries misbehaving children into the mountains. Te frst ofcial documentation of a Bigfoot encounter in Oregon was in 1904 when Oregonians reported seeing a wild, ‘hairy man’ by the Sixes River area, and sightings have been reported regularly ever since.

“Interest in the existence of the creature is at an all-time high,” said paleontologist Darren Naish to Smithsonian Magazine in 2018. He added, “ Tere’s nothing even close to compelling as goes the evidence.” But the Sasquatch-seeking community continues to grow, despite a lack of support from academia.

“ Te mystery is what keeps us coming back,” Powell said. “You’re always left to wonder and debate theories.”

Te North American Bigfoot Center wants to answer that mystery. Clif Barackman, the center’s owner, is an enthusiastic Bigfoot researcher. He

started doing feldwork and research about Bigfoot in 1994 while working toward his music degree at California State University, Long Beach. During a two-hour class break, Barackman would hole up in the library and bumble through the stacks, reading scientifc journals about Sasquatch sightings.

“I started reading about the actual evidence associated with Sasquatches, and that’s what got me on this path,” Barackman said. He frst started going out Sasquatching in Northern California on weekends, hiking through the Sierra Nevada mountain range, and searching for a sight of the hominid.

Barackman worked as an elementary school teacher for 14 years until he got a call from the Discovery Channel asking if he wanted to head the TV Show, “Finding Bigfoot.” He was running a successful Bigfoot blog called North American Bigfoot and was excited to continue his passion on screen. “Finding Bigfoot” ran for nine years, taking him to 48 states and fve continents.

“I met my wife on the show, in fact, I met my dog on the show,” he said. “So it really turned my life around in a lot of ways, and put me in a position where I could continue my Bigfoot research.”

Life on the road wasn’t glamorous. Barackman flmed six days a week and spent his day of doing laundry and trying to fnd a beer. He saved his money while flming “Finding Bigfoot” and, when the show ended, he started the North American Bigfoot Center.

Tucked away behind a Chevron gas station of Highway 26 near Boring, Oregon, the North American Bigfoot Center is a hub for all things Bigfoot — casts, memorabilia, footage and even a reconstructed Sasquatch nest. Te door frame that separates the gift shop from the display section of the museum is lovingly signed by Bigfooters who have visited the museum from around the country.

“Other Bigfoot nerds like me,” Barackman said, gesturing to the signatures. Barackman fnds himself as a focal point of the Bigfoot community. People regularly contact him with stories, research and questions.

He feels like the sensational side of journalism accentuates the ridiculous and paranormal parts of the Bigfoot community to get clicks. “We’re often portrayed as naive, gullible fools that are chasing lights in the woods,” Barackman said. He’s also frustrated by the “woo”, who Barackman thinks

Powell holds up a concrete cast of a Bigfoot hand. The creature, according to Powell, is not only known to have big feet.

discredit more factual and scientifc aspects of the Bigfoot community as supernatural extremists. “People love to laugh at us because I guess that makes them feel better about themselves,” he said. “We’re easy targets because we believe in the unbelievable.”

Powell’s garage is a home for the unbelievable. Rows and rows of concrete Bigfoot casts line the tables inside. Powell’s research desk sits in the corner, piled with a bottle of maple syrup, a heavily- used notepad, a magnifying glass and a bottle of cherry bitters.

Powell was a science teacher before he started searching for Bigfoot. A model of the solar system hangs above a framed and signed Coach Powell basketball jersey, remnants of his past life. Before he was a part of the Bigfoot community Powell made fun of Bigfooters, laughing at them because of their faith in so-called pseudoscience.

But his mind changed as he did more research. When Internet forums became accessible in the ‘90s, Bigfooters could document sightings and connect over shared

Powell stands in his garage surrounded by his collection of Bigfoot casts.

experiences. Powell became active in the community, going to hot spots like Sunriver, Oregon.

Powell believes that Bigfoot is an extraterrestrial being tasked with protecting the human race that lives beneath the Earth’s crust with other aliens. He’s aware that his views might seem extreme but doesn’t mind if others don’t agree with him.

“ Tere’s nothing I could say or do to change the mind of a skeptic,” Powell said, “and these things are too complicated for some people to understand…” He looks of for a moment, lost in thought.

“Sasquatches are the guardians of humans, they’re running the show, the lords of the planet,” Powell said. “People like Clif don’t want to hear about the supernatural, they call themselves researchers, but flter out what they don’t want to hear.” Powell believes that when researching a new feld, like Bigfoot, one can’t pick and choose what evidence they see.

It might be hard to imagine Barackman and Powell in a room together. “We’re like the ugly ducklings in a way,” Barackman said. “We tend to be rather pigheaded and stubborn individuals who don’t ft in anywhere else.” But at Squatchfest, Bigfoot researchers and enthusiasts of all mindsets gather, shaking hands and trading stories. Harsh overhead lights il-

luminate the events hall, creating an artifcial glare of of the cover of Tim and Dina Halloran’s book, “ Te Bigfoot Infuencers.”

“We’re like the ugly ducklings in a way. We tend to be rather pigheaded and stubborn individuals who don’t fit in anywhere else.”

- Cliff Barackman

Te Hallorans are well-known fgures in the Bigfoot community because of their unique approach to the subject. Tey want to spread the work of Bigfoot researchers and connect

them with people interested in the subject. Te couple’s book surveys 30 diferent Sasquatch investigators and serves as an “encyclopedia of Bigfoot.” Unlike Powell and Barackman, the Hallorans don’t adhere to an “aper” or “woo” philosophy. Tey simply want to share Bigfoot research with the world and help expand the community.

“We’re not judging,” Tim said. “We’re just laying it out there for people so they can pick and choose what they want to listen to and what they want to read.”

But spaces like Squatchfest don’t appeal to all Bigfoot investigators. As a member of the Kwakwaka’wakw and Cree tribes from North Vancouver Island, Tomas Sewid is tired of white people shoving their ideology down his throat, whether it’s Christianity or their theories on Sasquatch.

Sewid drafted a set of guidelines that explain the principles of chance encounters with Sasquatch or Sasquatch investigation. It mandates that no one will hunt or kill the hairy man, and stresses that Native knowledge of Sasquatch is honored. Sewid won’t

At the North American Bigfoot Center in Boring, Oregon, Barackman displays his life’s research on the elusive creature.

tolerate the erasure of Indigenous people’s culture and contributions to continue in the pursuit of Sasquatch. In his guidelines, Sewid stipulates that when people wish to investigate Sasquatch they must ask for permission and protocols of tribes because “they’re the ones that need to be respected.”

Sewid is a self-proclaimed bushman, spending extensive periods out in the wilderness and living of the land. He mocks outdoor enthusiasts who spend money on what he deems fancy equipment — expensive hiking shoes or camoufage print — as it’s unnecessary to be covert and thrive in the woods.

Unlike many other seekers, Sewid has had multiple encounters with the hairy man because of his extensive knowledge and con-

pens with the Sasquatch in our traditional territories that we’ve shared with them since the dawn of our creations,” he said. “ Tey’re just the other tribe anyway. Tey’re just bigger humans.”

As the weather warms, Bigfoot hot spots become more accessible to Barackman. He just made one of his frst casts of the year in the muddy April grass near a section of the Clackamas River.

Barackman feels most at home when he’s out walking in the woods, and if he happens to fnd evidence of Sasquatches, it makes his day. If not, that’s okay too. He’s doing what he loves and encourages others to do the same.

nection to the wilderness. He goes out in his cheap Walmart shoes and cargo shorts, able to blend in with the environment around him seamlessly. He even shared how he snuck up on a young Sasquatch near his cabin once. Sewid regularly shares his experiences on podcasts like “Monster X” and “Sasquatch Odyssey” and even takes tourists out on Sasquatch expeditions.

“[Sasquatches are] the perfect human,” Sewid said. “So when you look at a Sasquatch, you don’t ever think of them being inferior to you. Te Sasquatch has forgotten more about the bush environment than you will ever know in your lifetimes.”

While he sees Sasquatches with a lens of respect, Sewid is sometimes disappointed in his own species. “We as a species have lost our way,” he said of the human race, referring to people who are cut of from nature living in big cities, including Natives whom he refers to as concrete Indians.

“We’re Indians. We control what hap-

Barackman poses for a portrait at the front desk of the North American Bigfoot Center. On the door to his left, he’s amassed a collection of signatures from other important people in the Bigfoot community.

SCRAPYARD FROM TO

Lithium has become a prominent resource in our everyday lives through phones and computers, but where does it come from? And where does it end up?

Story by TJ Jenkins and Armando Ramirez

panning 28 miles from north to south, McDermitt Caldera looks like a wasteland. It’s fat, flled with scrubby, low-lying plants. But what appears to be a desolate landscape is actually rich with resources. Tacker Pass, located at the southernmost tip of the caldera, at the Oregon-Nevada border, holds one of the largest lithium deposits in the world. Being the primary component in most rechargeable batteries, lithium powers most devices — cell phones, laptops and tablets — that people use daily. However, many don’t know what happens to their devices, or the lithium batteries, when people are done with them.

“Lithium is an element that generally gets enriched in the [Earth’s] crust, similar to alkalis, sodium, potassium and so on,” said Philipp Ruprecht, a volcanologist and professor at the University of Nevada, Reno. Ruprecht has been analyzing the lithium development in McDermitt Caldera.

McDermitt formed following a volcanic eruption that occurred millions of years ago. According to Ruprecht, most of the minerals from the eruption settled at the bottom of the caldera. Over roughly 100 million years, water collected in the caldera creating a lake, encasing those minerals in a clay-like deposit.

“ Tat’s 50 million years ago, roughly speaking. Tat lake eventually dried up, and you have these clay deposits that are the base of the lake that were enriched from the volcanic deposit, now they’re at the surface,” said Ruprecht. Succeeding lead-acid batteries, lithium-based batteries were frst de-

Photos by TJ Jenkins

Illustrations by Kevin McAndrews

veloped 45 years ago. Te emergence of 21st-century technology and new devices powered by lithium batteries have created an especially high demand for the product.

Te Tacker Pass lithium deposit is believed to have around 80,000 tons of lithium.

“Once we build phase one and phase two, we’ll produce enough for 1.6 million electric vehicles every year,” said Tim Crowley, Lithium Americas’ Vice President of Government and External Afairs. Lithium Americas, the company with mining rights at Tacker Pass, aims to harvest the lithium at Tacker Pass in two phases over 40 years.

“ Te big cost is on the front end, it’s building the facility. It’s gonna cost us $3 billion,” said Crowley.

“We can reuse them, and we can recycle them,” said Jessica Ahrenholtz, Executive Director of NextStep. She sits at her ofce desk at the newly renovated NextStep Donation Center. Te wall behind her is adorned with posters and mementos. “We do have a way to do it, but there’s a lot to it.”

Lithium batteries leaving the NextStep warehouse must be taped and labeled with stickers designating the type of battery and declaring the contents hazardous waste.

“ Te lithium can be a little crazy,” said Ahrenholtz, “I try to be really on top of it because we don’t want to have any fres.” To minimize fre hazards, NextStep goes through its tub of lithium batteries daily to inspect for any swollen batteries in danger of catching fre.

Te Department of Energy recently loaned Lithium Americas $2.26 billion to develop the facility. General Motors, who owns rights to the entire frst phase of the operation, which aims to harvest 40,000 tons of lithium, also contributed $650 million to the development.

- Jessica Ahrenholtz

While lithium mining at Tacker Pass will occur over the next 40 years, Crowley is optimistic that lithium mines at some point in the future will be obsolete.

“Lithium can be recycled over and over and over again,” said Crowley. “Recycling will play a big role, and you probably can project a time when we won’t have to mine for lithium anymore.”

Te process of recycling lithium is not always simple.

Te United States Environmental Protection Agency considers most lithium batteries a hazardous waste to be handled with care. NextStep Recycling in Eugene, Oregon, provides an opportunity for people to dispose of old electronics containing lithium batteries safely.

Lithium batteries are a cost item for NextStep, meaning they are often too expensive to dispose of in bulk. Ahrenholtz said that consumers can drop of batteries in smaller quantities at home improvement stores, “but as a business, I can’t take large quantities to them.”

Te Hazardous Waste Department of Lane County Waste Management is equipped to handle larger quantities of lithium batteries. Tey require a cap on the donatable amount, less than 35 gallons of materials from any household.

Ahrenholtz said she was thankful to have places to refer people to when they bring donations that NextStep isn’t equipped for.

“I have a lot of referrals and can send people to the correct places,” she said. “So then we’re only having to deal with what we’re on the list for electronics battery recycling.”

Lithium batteries in laptops and computers make up only a small portion of the electronic waste NextStep works with. At their donation warehouse in Eugene, NextStep accepts most elec-

tronics ranging from hard drives to stereos to microwaves.

“We take it whether they’re in working condition or not,” said Ahrenholtz. Te work is sorely needed, as the U.S. EPA categorized electronic waste [e-waste] as the fastest-growing waste stream in 2021.

Since 2002, NextStep has kept over 30 million pounds of electronics out of landflls. “Reuse is always our top priority,” said Ahrenholtz, “but if we can’t reuse it then we can recycle it properly.”

While one part of NextStep’s mission focuses on protecting the environment from hazardous waste, the other is providing the community with access to technology.

“A lot of people don’t realize how much we give back to the community,” said Ahrenholtz. “ Tey just think of us as a place to take their old junk.”

While small nonprofts like NextStep can defer to waste management services when needed, global e-waste is still on the rise. However, these small nonprofts remain essential to lithium recycling, and with their help, a future without lithium mining, as Crowley mentioned, is entirely possible. K

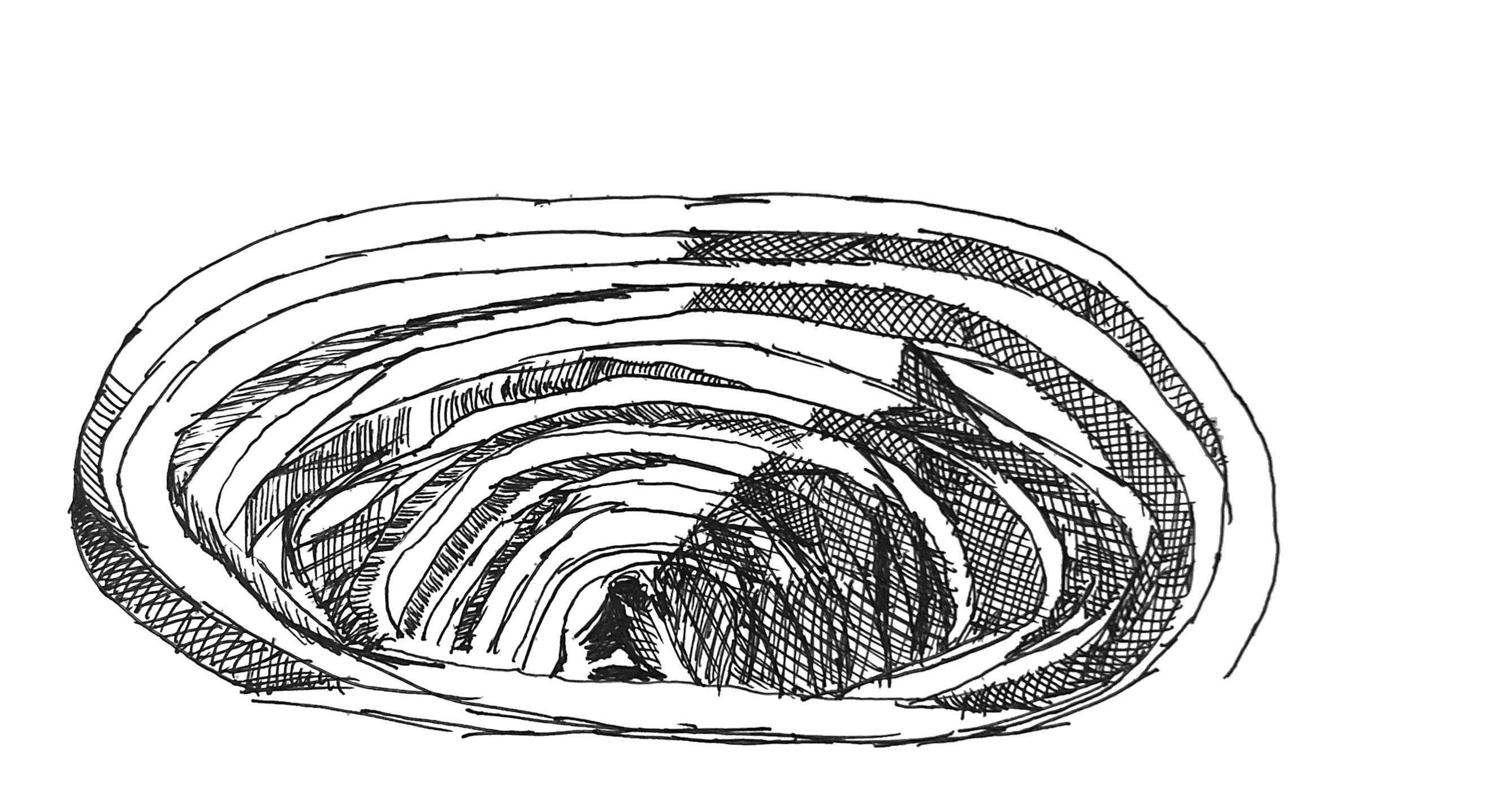

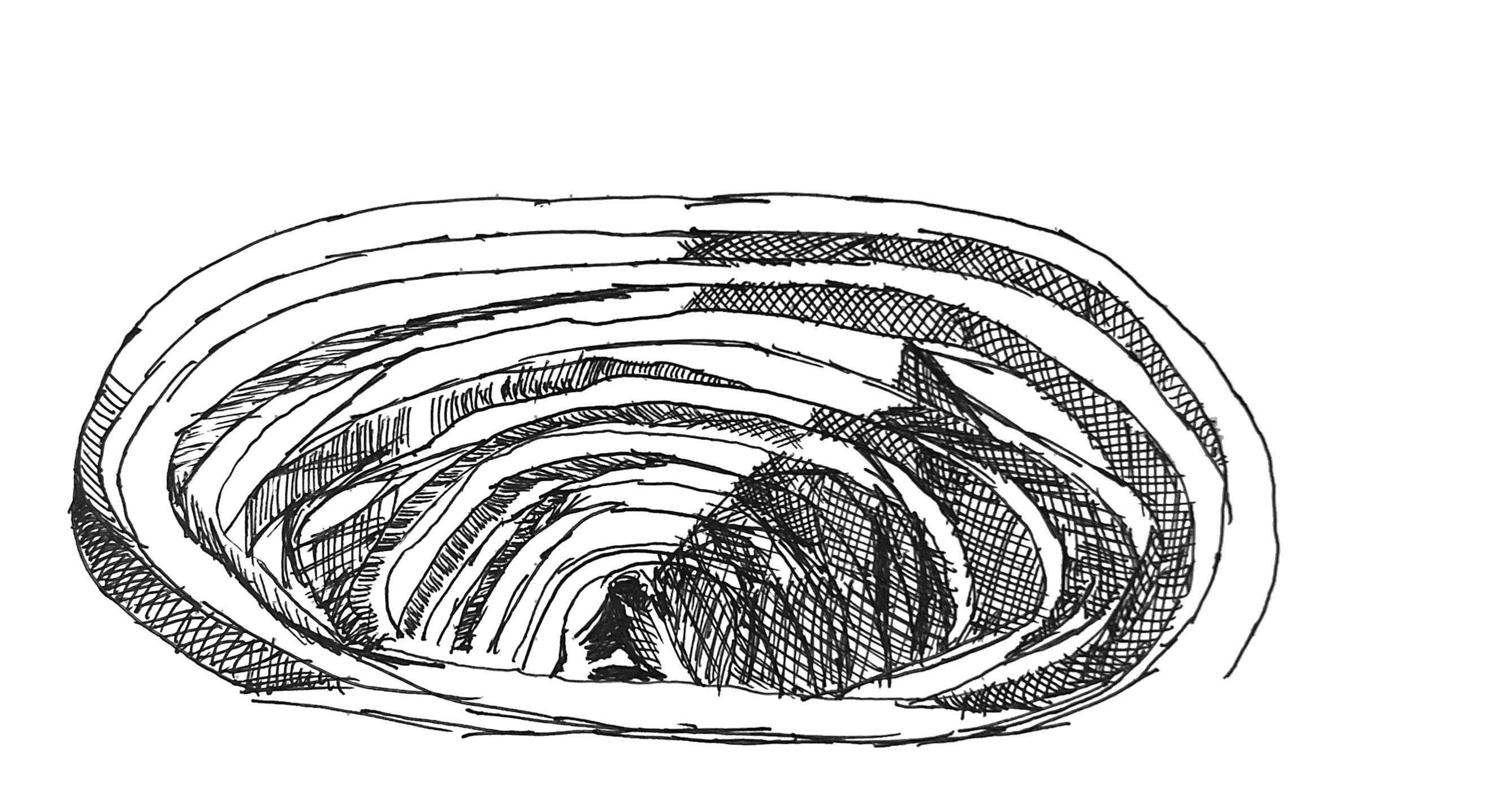

To extract lithium, that liquid is pumped from the earth and then placed in pools where the water can evaporate, leaving behind lithium and other elements.

shallow open-pit will have an average depth of 300 feet and will be mined in blocks in order to be actively reclaimed.

The

Newport Fishermen’s Wives board

members Taunette Dixon and daughter

Kalli Flatt look out on the harbor at the Port of Newport.

ANCHORED IN COMMUNITY

A social club turned nonprofit provides support and life-long friendships for women of Newport during times of loneliness and grief.

Story by Malya Fass and Sydne Long

Photos by Geoffrey Kerrigan

O“One day I’m going to die at sea,” Josh Porter said as he walked into his living room to greet his wife, Denise. He was fresh of the crabbing boat, the fshy, salty smell permeating his clothes. “You need to be a part of the Fishermen’s Wives,” he said. “ Tey’re the ones that are going to be there for you.”

A year and a half later, on Jan 8, 2019, the crabbing boat Mary B II capsized, pulling Josh, two other crew members and its captain down with it.

Josh made the last minute decision to join the crew aboard the boat. Members of the town warned him of the captain’s history with substance abuse and disregard for harsh weather conditions. He believed he could help the man and accepted the job.

When Josh passed away, it was only his second trip on the crabbing boat, and a day before he was slated to join a diferent crew. According to toxicology reports, the captain of the ship had alcohol and methamphetamine in his system when the boat overturned.

the vice president of the Newport Fishermen’s Wives. Te group has helped her navigate life after losing Josh.

“I became a part of something,” Denise said. “Before I was a part of fshing, I was part of Josh. Now I’m a part of a community.”

Fishing communities all share one thing in common: their town’s dynamics shift when fshermen leave for months at a time. In Oregon, nearly 1,000 fshing vessels depart from the state each year. Over 300 of those boats touch base in Yaquina Bay, the port of Newport, Oregon, where many of those left on shore must endure the unpredictability of the fshing industry. One group supports the unique needs of Newport’s community, their fshermen and their families.

Te Newport Fishermen’s Wives was frst established in 1970. It’s the only nonproft of its kind on the West Coast. What was frst a social club has become the backbone of the town in the last 54 years.

Denise displays a maritime tattoo at the Newport Fishermen’s Memorial, located at Yaquina Bay State Recreation Site. She has several tattoos in remembrance of her late husband Josh.

Five years after her husband’s death, Denise stands at the Newport Fishermen’s Memorial on a bluf overlooking the sea that took his life. She visits every other week. Pictures of lost loved ones, candles, birthday cards and bouquets of vibrant dafodils and hydrangeas adorn the memorial. Engraved on its side are the names of approximately 150 Lincoln County fshermen who have died at sea since 1900.

“I became a part of something.”

-Denise Porter

Co-president Taunette Dixon was raised within the fshing community of Newport and inherited the responsibilities of the generations before her. Growing up, Taunette spent her fair share of time on a fshing boat.

A photo of Josh sits atop the memorial just above the engraved names. Denise reaches out to lovingly dust the dark wooden frame. She is now

“When I graduated high school, I was shipped of with my grandfather to go fshing for eight months,” said Taunette. “ Tere are so many life lessons you learn when you’re out at sea and there’s no one there to rescue you. If you’re in a fshing family, you usually just kind of have it in your blood.”

When Taunette and her husband decided to have children, her life on land expanded to motherhood. She had two children, Kalli and Kaino.

After Taunette lost her 28-year-old son, Kaino, to a car accident in August 2022, her world turned upside down. She credits the Fishermen’s Wives for helping her through. Tey surrounded her with love, planned her son’s memorial and left meals at her door for months on end.

“After I lost my son, I thought I really needed to take a break,” Taunette said.

Taunette didn’t take a break. In fact, her role as a community resource only grew. After losing someone, she knows what grieving families need.

Her home pottery studio doubles as a therapy ofce of sorts. Inside, sunlight beams through the windows, illuminating shelves stacked carefully with clay vases and mugs. Every surface is covered in clay dust. In the back of the room sits two throwing wheels accompanied by a pair of wooden stools. Denise and Taunette often sit together, not only to sculpt but to discuss their losses.

“It made me so calm when we talked about our tragedy there,” Denise said. “She can cry. I can cry, and I think there’s so much freedom in crying in front of somebody that isn’t judging you.”

Taunette values having a space she can share

Fishermen’s Wives Vice President Denise visits the Newport Fishermen’s Memorial every other week. The colorful photograph beside Denise depicts her late husband Josh who perished while working on a crabbing boat which capsized in January 2019.

Fishermen’s Wives board member Ashlie and her daughter Aurora near the docks at Newport, Oregon. In the background is a mural dedicated to a late local fisherman, Clement “Pogo” Grochowski.

with the community. She invites the wives and their children into her studio to create Christmas ornaments every year. It’s an opportunity for the group to be together, outside the heavy work they do.

One of the newest members of the organization, Ashlie Freeman, knew nothing about fshing three years ago. Ten she fell in love with a fsherman after moving from Las Vegas to the Oregon Coast. She cares for her toddler, Aurora, alone while her husband, George, is away for six months at a time fshing in Alaska.

One day, Ashlie met Denise and expressed her difculty fnding friends, more specifcally women, who understood what she was going through.

“ Tere’s a lot of people out there that are like, ‘I don’t know how you do it, having your husband gone for that long,’” Ashlie said. “I’m like, ‘Well, soldiers do it all the time.’ It’s nice to be a part of something where we’re also taking care of our fshermen husbands as well. Tey’re not just taking care of us.”

Without hesitation, Denise invited Ashlie to meet the Newport Fishermen’s Wives who welcomed her with open arms. She is involved with various volunteer groups, such as the Red Cross, Salvation Army and the Newport Food Pantry, but she has never experienced a sense of belonging the way she has with the wives.

Now, Ashlie is the volunteer coordinator for the Fishermen’s Wives. She helps to organize annual events such as the Fishermen’s Appreciation Day dinner and the Blessing of the Fleet, which takes place at the Fishermen’s Memorial Sanctuary gazebo.

Te space not only serves as a meeting place for community events, but a personal place for Denise.

Sitting at one of the 12 benches facing the pedestal, she recalled the moment a few years prior, when she sat in the same gazebo in a daze. It was packed with people paying their respects to her husband, just days after his death.

Te Fishermen’s Wives organized the memorial service for Josh, and Denise didn’t have to lift a fnger. Te town showed up for her and gathered around this tragedy. It was the largest turn out for a memorial service they had ever seen.

“I think I’d probably go into a depression if I didn’t have this group of women.”

- Ashlie Freeman

Over the past year, the treasurer of Newport Fishermen’s Wives, Carrie Brandberg, has become one of Ashlie’s closest friends. Since she does not have her driver’s license, Brandberg drives her around to run errands, make appointments and attend meetings. Tis is something Ashlie’s husband does when he is home.

“I think I’d probably go into a depression if I didn’t have this group of women,” Ashlie said. “I feel like the more I’m around them, as confdent as they are, I want to be that way.”

“At the memorial, I remember one fsherman that came in,” Denise said. “He had fshed with Josh on another boat.”

Denise’s face lit up as she remembered the scene.

“He smelled like crap,” she said. “I just remember, he gave me a hug. He had just come running up from the docks and he said, ‘I just got of the boat. I’m sorry.’ I just said, ‘Oh my God, I miss that smell already.’ It’s comforting, because those are my smells.”

Te Fishermen’s Wives taught Denise how to thrive within a tight-knit fshing community. She thought about moving back to her hometown in Washington after her husband passed away but eventually decided she had no reason to. Newport is her home now, and despite all she has lost, the wives have given back to her.

“Josh, he was my protector,” Denise said. “He was the person that walked through everything with me, and that’s what they’ve been. Tey’ve been my Josh.” R

Ashlie and her 2-year-old daughter visit the docks in Newport, Oregon.

Oregon has been plagued with a history of racism and anti–indigenous policy. Today, a new generation of artists are using their voices to fight for change.

LIBER HERI

TTe sun reaches through the trees, casting rays onto Stephanie Craig. Her blue eyes dashed with green catch the light refecting years of wisdom and talent. Te wind rustles through the bushes. Craig sits under an awning at a wooden picnic table. Hand-woven decoy ducks, baskets and baby rattles are strewn across a green and yellow tribal-patterned blanket. Craig acquired this blanket at a recent powwow at the University of Oregon. It’s just before 9 o’clock in the morning.

Less than two hours north of Eugene, Or-

egon sits Amity, Oregon. Te hospitable town with a population less than 2,000 is encompassed by trees and scattered with mom-andpop shops. Tucked away behind conventional homes is Amity City Park.

“I’ve been weaving over 25 years, and I’ve had three hand surgeries, and I have severe arthritis in both hands,” said Craig. “So I will take all the good prayers.”

Atop both her wrists are dotted tattoos. “I fgured it wouldn’t hurt to have them put on,” she said. Traditionally done at the puberty

Story by Ainsley Maddalena

Illustrations by Madeline Dunlap

Photos by Harper Mahood

ATING I

TAGE

ceremony, this tattoo means that the person who wears it will have strong hands for the rest of their life. Tey are a symbol of strength as Craig’s arthritis has worsened over the years.

Beneath the pine trees in Oregon, Craig said that all things she creates come from living things. Whether a plant or an animal, it gave its life to create something new. Tere is an energy exchange, Craig said, and when you hunt, fsh, or gather, your energy must be positive so as not to negatively afect what you are making.

Above the cream and green felt blanket, bas-

kets woven with willow root and hazel represent the her determination in spite of her condition. Tough she knows she cannot continue weaving forever, she is teaching her children, and others, traditions from decades before. Along with her traditions come stories of ancestors and their history, good and bad. Craig is just one voice who is creating change.

Native art in Oregon museums serves as a powerful intersection of culture, history and artistic expression. It is a reminder of the colonization that occurred across Oregon and its dark past

with racism and colonialism. Some museums, such as the Museum of Natural and Cultural History in Eugene are a part of this rethinking.

Tese paintings and weavings embody the diverse traditions, beliefs and creativity of Indigenous peoples. Tey ofer insight into Native identities and experiences.

However, the presence of such art in museums also raises complex questions. Representation, ownership, or colonial legacies, are at the forefront of the movement. Alongside sits a complicated dialogue between preservation and cultural revitalization. As traditionally white institutions strive to engage with Indigenous communities respectfully and authentically, the meaning of holding Native artifacts has transformed across America and the world.

In recent years, Te British Museum in London has come under fre for owning Native American artifacts, many of which are labeled incorrectly or are not being cared for the way they were intended.

Bull, — a member of the Nez Perce tribe — is still adjusting to his new ofce. Native American artwork lines the walls and shelves. Dinosaur knickknacks sit along the window sill. Since December 2023, Bull has been juggling work at the university, while working as a jounrlaist for the local NPR affliate, KLCC.

“I think that there is a growing movement and awareness that Native Americans and Indigenous people would like to have better inventory of where their cultural items are,” said Bull when asked about his OPB article detailing Oregon being the frst US state to share survey fndings on tribal items.

“I think if governments are sincere about wanting to work with tribes, and respect the tribes, that they will do something very similar with us,” Bull said.

“Because there are a lot of state agencies, public institutions, museums, galleries, archives that have a lot of Native American pieces in them.”

Todd Braje has spent the last fve months with the Museum of Natural and Cultural History settling into the role of executive director. Tere he has been engaging Native makers and activists to incrementally make progress on inclusion and representation.

Before the museum, Braje got his Ph.D. in archaeology where he then went on to be a professor at Humboldt State and San Diego State University. After his 11 years as a professor, Braje decided to switch career paths and look beyond the classroom.

“Museums are one of the places that do that really efectively,” Braje said.

Braje likes that museums have become a place for important conversations to happen.

It is museums and places where we can tell these stories that bring people together, not divide them, and find ways to talk about them

-Todd Braje “ “

While the MNCH at the University of Oregon is progressive, not all museums in Oregon are as forward-thinking. In the past, the MNCH has invited Craig to host basket weaving demonstrations, and currently has a long-term installation with work from Steph Littlebird. “Start of in hiring Native

Above: Steph Littlebird displays her hand tattoos which spell out “Chinook,” a tribe which she is a descendant of.

Left: Craig uses a variety of native plants in her basket weaving. These include spruce root, willow root, cedar root, sandbar willow, hazel, willow sticks, sugar pine root, western red cedar and yellow cedar.

Craig, a member of the Confederate Tribes of Grand Ronde, displays her basket weavings in Amity City Park, a small park in Amity, Oregon. Craig has been basket weaving for over 25 years and comes from seven generations of basket weavers.

consultants that are active in creating and making things,” said Craig. “Have them come in and correctly identify what is in museums and tie them back to a tribe, tie them back to their communities.”

For Craig, community is something she knows all too well. Craig is enrolled in the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde but comes from Kalapuya, Cow Creek, Umpqua, Tacoma Rogue River, Clackamas Chinook, and Lower Chinook.

Littlebird, also a member of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, comes from various backgrounds — Chinook and Kalapuya. She channels her background into children’s books, watercolor paintings and digital drawings.

Littlebird’s jet black hair drapes gracefully down her shoulders, dancing across an ornate foral tattoo on her neck, deep, brown eyes, a smile and that invites new friends.

Te painter-turned-digital-artist creates work across a multitude of mediums. Most recently, some of her work has been on exhibit at the MNCH. Whether the pieces are on loan, or have been purchased from her Etsy shop by the museum, Littlebird just wants people to access her art.

“I really do try to manage my price points to make them accessible to my community,” said Littlebird. “Because a lot of us are coming from poverty or, you know, have emerged from poverty.”

No matter how busy, the Las Vegas-based artist

fnds time to visit her home state of Oregon.

“It’s such an amazing opportunity to get to share this stuf through [the MNCH], and have them be so supportive of my work,” Littlebird said. “And then also just hearing from educators in Oregon who are going to visit the exhibition and how the museum has done such a great job of explaining my work, because some of it is political and can generate some negative responses sometimes.”

Braje has not only been able to appreciate how the work has been able to reach diferent communities but also how the work has been able to reach the students. With the museum’s rotating exhibitions, there is something diferent to see that reaches a larger community of people in order for important conversations to happen.

With the work Braje is doing and his own experience as a professor, he wants to be able to connect with students and enhance their education.

As the morning air drifts through Craig’s hair, she refects on the progress made not only in museums, but in schools. Tough slow, a change is being made. More importantly, Indigenous people are being acknowledged. “I see a change and and I question museums, we have every right to ask,” said Craig. “Because if you’re not putting action behind it, don’t even say it.”

C A GE N HFIGHT FOR

Photo story by Evan Susswood

Research

by Akila Wickramaratna

At 6’7” and 295 pounds, heavyweight fighter Jimmy “Jungle” Jennett is a force to be reckoned with. After more than a decade in MMA and a lifetime of fighting personal battles, Jennett has stepped back from the ring and is teaching the next generation of fighters a better way to channel their aggression.

Sitting along Main Street in Springfield, Oregon, Checkered Past MMA opened in 2019 as a place for outreach and discipline-building, offering a home for anyone who walks through the door. At-risk youth, recovering addicts and veterans train alongside moms and their children. Jennett, who comes from a background of addiction and violence, advocates a message of sobriety and personal accountability. Inside Checkered Past, fighters’ belts hang alongside posters promoting staying clean and news clippings from Jennett’s career. Classes for different age groups and skill levels are held Monday to Saturday, led by Jennett and his team of instructors.

Fighters from Checkered Past compete up and down the West Coast. Jennett works closely with the tight-knit team, whose specific disciplines range from jiu-jitsu to kickboxing. Andrew Thomas (right) trains with Jennett before his first official match in Vancouver, Washington.

“If you can move, if you can tie your shoes, if you can hike a mountain, if you can kick a soccer ball, you could do what we’re doing here. That’s what it’s all about. We like to say training can be for anyone.”

- Jimmy Jennett

Growing up in a household of addicts in Sacramento, California, Jennett stayed away from drugs until his teenage years. During a period of athletic success, as the star basketball player on his high school team, Jennett started using marijuana, and shortly after, methamphetamine. Meth shaped much of his adolescence and early adulthood, leading him to deal drugs alongside using them. Eventually, this lifestyle caught up to Jennett. It was in a cell, at 26, in Folsom State Prison that he realized he needed to make a change. The name of his gym, “Checkered Past,” was born during this time. Writing letters from prison, he would use the phrase as his signature. Upon his release, Jennett got the moniker tattooed across his back.

The way he helps the community, preaching his clean and sober life to the kids and how he’s always there to help people. He’s the type of guy who would give the shirt off his back.

- Melissa Hisel

Above: After his release from prison, Jennett moved between various construction jobs, including on oil rigs where he worked with guys “tougher than anybody I’d ever met in prison or the streets.” Now, he works a day job as a union laborer, which allows him to support both Checkered Past and his five children. Sometimes, his daughter, Rosalyn Jennett, watches in on evening classes before Jennett takes her home to the rest of the family.

Left: When he moved to Eugene in 2010, Jennett found a mentor in Jason Georgina, the owner of Art of War gym. “He was a very big, physically athletic, gifted guy,” Georgina said. “He didn’t have a lot of formal martial arts training at that time. I watched his progression. The more experienced he got, the more mentally calm and centered he got.” Now, Jennett can rely on his own team of instructors, like Melissa Hisel (right), to help run the gym.

The 21 fights of Jennett’s career are tattooed in tally marks across his chest. After developing a heart condition, he won’t be adding any more marks to the list. Instead, Jennett has turned his energy entirely into the message of Checkered Past: “Clean + Sober = Winning.” Since hanging up his gloves, Jennett has worked with schools around Central Oregon, speaking about his experience with addiction and how MMA can be used as an outlet. Now nine years sober, he has become a shoulder to lean on in his community and hopes to continue bringing awareness to the youth in it. “I have to keep it humble,” Jennett said. “I have to keep it in perspective and I can’t let down people, but the fact of the matter is, I’m still a human and I’m still a recovering addict.” E