“

It is a world of unceasing conflict and often of dangerous tensions. At the heart of the human condition is an unending struggle for power, sometimes benign and sometimes ruthless. The great danger is that the stakes of conflict in our time have grown far above the threshold of tolerance. The issue is not the primacy of power. The issue is whether we shall permit the destruction of life – all of life – in our small and vulnerable planet.”

– Carlos P. Romulo Retirement speech, 1984

Born within the walled city of Intramuros, Manila—a bastion of Spanish authority—Romulo had always dreamed of a world where people no longer sought to conquer other lands. On January 14, 1898, at the twilight of the Spanish colonial regime and the dawning of the American era, he dreamed of freedom not only for his countrymen but for Indonesians, Indians, and all people oppressed, exploited, and bound by imperialism.

With the atrocities of the Second World War still fresh in his mind, he wished for an organization like the United Nations—one that would spare humanity from more killing. He envisioned “a world in which the conditions of peace and the conditions of life would be understood and upheld.”

Romulo grew up in the town of Camiling in the province of Tarlac in northern Philippines, the third child of a revolutionary. His father, Gregorio, fought for Philippine independence against Spain and, until surrender, America. The bitterness of the conflicts filled young Carlos with animosity toward the United States, but this did not stop him from forming close relationships with certain American military personnel, and these friendships taught him an important lesson—that people were basically good even if, sometimes, their cause was not.

This nugget of understanding would serve as a guiding principle in forging friendships between nations during his long and distinguished career—one that spanned more than fifty years, including seventeen years as secretary of foreign affairs and ten years as the Philippines’ ambassador to the United States.

Doña Juana Besacruz Romulo, his paternal grandmother whom he affectionately called “Bae,” taught him the ABCs in Spanish, and was his first teacher. He started attending school at the age of five.

The Romulo family transferred to Manila when he was in his third year of high school. The enthusiastic teenager took Manila by storm pursuing several different interests with boundless energy.

At the Manila High School he played the role of Agesimos in the Greek play Pygmalion and Galatea on December 10, 1915.

He took on his first job, while still in high school, as a cub reporter for The Manila Times, assigned to the Senate.

He served as president of the Cryptia Debating Club in 1916, and was also editor-in-chief of his high school’s annual.

After high school he entered the University of the Philippines, joining the UP Dramatic Club and founding a theater group together with Jorge Bocobo and Vidal Tan.

The Real Leader, in which he acted, was the first recorded drama performance in the history of the university. This photo is a scene from Schools for Scandals (ca. 1917).

He became editor-in-chief of the UP student paper, College Folio, reviving it as Varsity News.

He graduated from UP with a bachelor’s degree in 1918. By this time he was already working as an assistant editor on the staff of Senator Manuel Quezon’s newspaper.

On the morning of July 23, 1919, he boarded the Japanese ship S.S. Suwa Maru as a government-sponsored pensionado on his way to attend Columbia University. From the ship he wrote to his older sister Lourdes and her husband:

You cannot fathom how difficult it is to leave one’s motherland. I have had the experience this morning, and I have never suffered like this in my life. I spilled tears, but more than tears my heart felt like it was being pierced by a lance. And more profound was the pain of not being with Mama, Papa, Henry, Pepita, and Gilbert, both of you, and Choleng, to whom I was not able to give kisses of departure.1

The forty-five-day journey took him to several places, including Hong Kong, China, Japan, Seattle, and Chicago. When at last he arrived in New York City in September, he marveled at the skyscrapers and sights in a letter to his grandfather:

The street called Broadway that is in the middle of the city is as wide as the plaza of Camiling, and as long as the highway of Camiling to Bayambang, more or less.2

After earning his master’s degree in philosophy in the spring of 1921, he returned to the Philippines in November, leaving behind a young American – a student at Columbia’s college for women -- with whom he had fallen in love. To add to his anguish, his father died from a ruptured pancreas a few days after he arrived home.

On December 24, 1921, he wrote to his mother:

Tonight is the birth of Our Lord. Tonight is the night of the nativity. It is the first Christmas that I am experiencing in the Philippines after many years of absence.

I am in my office at the Herald tonight because at work is oblivion and I want to forget the sadness that corrodes my soul and my heart. My first Christmas in my country - and alone, alone I am, more alone than when I am abroad, and thinking of someone who has gone so as not to return.

And I write you, my dear mother, because you are the only one that I have now, and the only one who can understand the beats of one heart pierced by pain. I write you because I need to vent, why I am sad, so sad, and to write you is a relief.

I know that you suffer and as in the unity of sadness there is comfort, I, too, participate in. My mother, in your pain, and in this unity, I hope that you will find comfort, conformity, and resignation.3

The following month he became assistant editor of The Philippines Herald, the first Philippine daily printed in English, with Conrado Benitez as his boss. He was also assistant professor in the English Department of UP; and, for a third job, Senate President Manuel L. Quezon appointed him as his private secretary around the same period.

Romulo’s admiration of Quezon was nothing short of hero-worship. When young Rommy was still a student, in 1917, he worked as a beat reporter assigned to the newly formed Philippine Senate. That’s when he first set eyes on Quezon.

Quezon was a natural idol especially for young boys such as myself. He was proud. He was brave. He was elegant.4

When Quezon took notice of Rommy and invited him to work for The Citizen, the future Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist jumped at the chance.

He knew he was my hero. He was the hero of all Filipino youth. Quezon was an idealist, but he was a pragmatist as well, and the needs of the Philippines were his all-in-all. If any talent of mine could serve those needs in the smallest way then I would be grist for his mill.5

A couple of months later, in February, he met sixteen-year-old Virginia Serapia Vidal Llamas of Pagsanjan. She was one of the contestants of the Manila Carnival of 1922—a much awaited and much publicized annual event that involved multiple balls and social gatherings. He was assigned to be her official escort, and at the end of nine-day event she was crowned Queen of the carnival.

Almost immediately he fell hopelessly under her spell. “She had a fragile doll-like beauty,” he recalled in his memoirs.

Duty called on April 30, 1922, interrupting their love story. Senate President Manuel Quezon had included Romulo in the delegation that was to appeal to President Harding for Philippine autonomy. With Quezon and twenty-seven others, Romulo sailed to Washington, DC, on the Philippine Independence Mission. His role was “publicity agent.”

“There are three things that we want made plain,” Quezon laid out. “First, we want full independence; second, we are entirely capable of running our own government; third, we appreciate what the United States has done for us and will always want her friendship.”

After spending three months traveling and working closely with him on the Mission, Romulo’s admiration for Quezon only grew. He felt inspired and invigorated.

How much at ease he was in Washington, and how well thought of by the Americans on Capitol Hill. I was proud of him, proud to be seen with him, proud of the small victories won.

Our return home was a triumph. Once I had watched Quezon make such an entry into Manila from my perch with other students on the old Spanish wall. Now I was part of his entourage. Part of the glory of his return rubbed off on me.6

Once back in the Philippines, Romulo pursued Miss Llamas in earnest, traveling six hours from Manila to Pagsanjan, and then back again, just to catch a glimpse of her or to exchange a few words. The courtship progressed very slowly, but, finally, after more than two years they married on July 1, 1924, in Pagsanjan.

They had their first son, Carlos, Jr., on July 30, 1925. Their second, born on January 3, 1927, they named after both their fathers, Gregorio and Vicente. “No laurels can equal those moments when the newly born is placed in one’s arms to cherish for life, if God wills,” Romulo wrote several years later.

As manager of the UP Debate Team, which went around the world in 1928, Romulo began to win fame abroad. “Everywhere we went we were royally entertained and warmly welcomed, and we won every debate.” 7

At home he was promoted to editor of the Manila Tribune in 1927. Then, in 1930, Don Alejandro Roces appointed him editor-in-chief of the TVT Newspapers: The Tribune (English), La Vanguardia (Spanish), and the Taliba (Tagalog).

In 1933—the same month his third son, Ricardo Jose, was born—Romulo traveled to Washington, DC, as part of another Philippine Independence Mission. While in DC he wrote a series of articles on the mission’s progress, becoming the chief publicist and spokesman of the Philippine independence movement.

Though it heralded our long-awaited freedom from America, the Philippine commonwealth era (1934–1944) was a tumultuous time. The Great Depression, which started in 1929, had plunged the world into a decade-long economic and financial crisis, leading to years of mass unemployment and misery. Many in the US Congress thus held the view that keeping the P.I. as a territory was an unnecessary liability, giving some the worrying impression that they might get rid of us in a “surgical rather than therapeutic manner.”8

It was at this significant juncture that Quezon organized another mission to secure independence, and successfully got the Tydings-McDuffie Act passed in Congress in March 1934, which provided for self-government of the Philippines and for independence after a period of ten years.

Quezon then became the first president of the Philippine Commonwealth, elected through a national election, and was inaugurated in November 1935. Designed as a transitional administration in preparation for full Philippine independence, the Commonwealth replaced the Insular Government of the Philippine Islands.

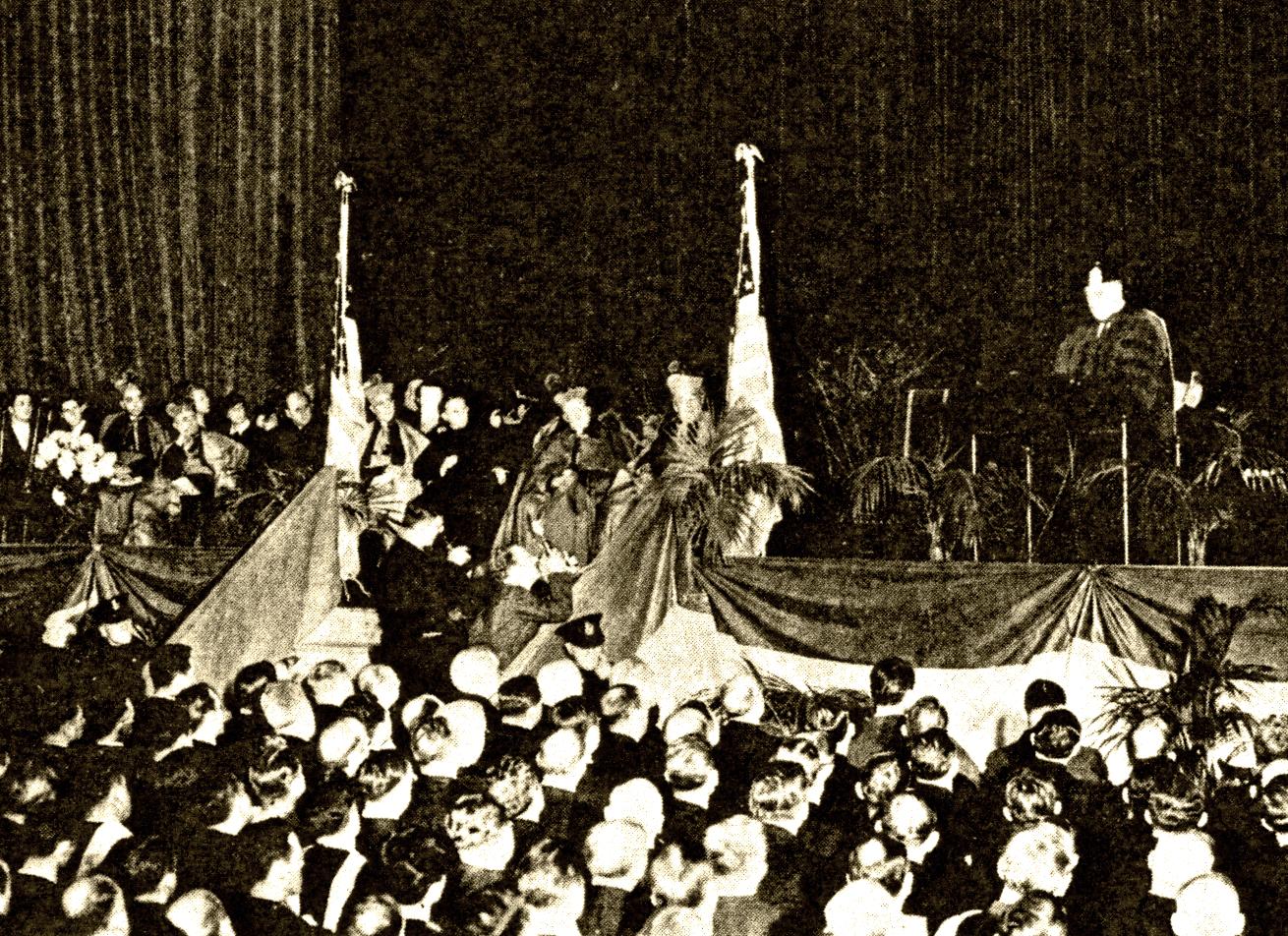

A month later, Romulo – the newly appointed publisher and editor of Vicente Madrigal’s D-M-H-M newspapers -- represented his people at a ceremony commemorating the establishment of the Commonwealth of the Philippines. After he addressed seven thousand people at Notre Dame University on December 9, 1935, Reverend John F. O’Hara, the president of the university, presented him with his first honorary degree.

We have requested independence. The American people have granted it. So let it be, and may it prove a blessing for both and a pledge for friendship through the years that are to come. We shall go forward bulwarked with abiding faith in God; confident of the particular good-will of the United States and the amity of our Far Eastern neighbors, and we shall take our place glorying in our freedom, with restrained courage, ambitious of peace, with malice toward none and with charity toward all.

We thank you, Mr. President, Prelates, the Faculty of Notre Dame, for the honor you have, this day, conferred upon us and we bring to each and all the expression of high regard and cordial esteem from the Honorable Manuel Quezon, President of the Philippine Commonwealth.9

In his brief remarks, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who also received an honorary degree, said: “We are here to welcome the commonwealth. I consider it one of the happiest events of my office as President of the United States to have signed in the name of the United States the instrument which will give national freedom to the Philippine people.”

Many years later Romulo recalled how he felt:

Sitting on that platform by the president, receiving, with him, the highest honor conferrable by a great university, and seeing around us the leaders of America’s governmental hierarchy, I felt proud, as any man would be. President Roosevelt represented the world’s greatest nation; in a humbler way I represented the Philippines.10

Two years later, on his fortieth birthday, Romulo, now publisher of The Philippines Herald, sat down privately with Roosevelt in the White House for an unplanned 40-minute conversation. This was remarkable not only because Romulo was a brown-skinned Filipino but also because the US president had only once before shared his views privately with a journalist.

Political observers described the conference “as one of the most significant honors ever paid to a private Filipino individual.” A news editorial declared it “one of those things that never happen” that “will be remembered in the journalistic annals of the executive mansion.”11

Romulo reported in The Herald the very next day, on January 15, 1938:

The President greeted me, recalling how we met at Notre Dame in December 1935. He asked me to be seated.

He was dressed in a dark grey suit with faint white stripes. Dynamic and full of energy, his is the personality that radiates strength and vigor.

As I write this dispatch two hours after leaving the White House, there are certain definite impressions that are uppermost in my mind and which I would like to convey to the Filipino people.

My first impression is that President Roosevelt is a true friend of the Philippines. His interest in us is that of the American people—to see it that America’s colonial adventure in the Far East should be a success. He knows it is a cooperative effort by Americans and Filipinos and that it can succeed only if that cooperation continues between the two peoples.

There is nothing selfish in his desire to see Filipinos succeed in the experiment. He is aware of the clamor of certain groups in America to “get rid” of the Philippines for obvious reasons. But it is my impression that he looks at the Philippine question from a moral standpoint—that America, having voluntarily assumed the obligation of helping the Filipinos, should do so wholeheartedly and finish the job properly.12

He was elected Third Vice President on the board of Rotary International in 1937. It was considered a tremendous honor to have been elected to the position, as he was the first and only Rotarian to sit on the international board of directors without having served as district governor. He was also the first Filipino to do so.

On December 9, 1938, his youngest son, Roberto Rey, was born.

Romulo’s I Am a Filipino, the most recited literary work in the history of Philippine literature, appeared in the editorial section of The Philippines Herald in August 1941.

He traveled to Hong Kong in September, on assignment for The Herald, where he wrote the first of a series of articles that won him the Pulitzer Prize. From there he traveled on, chronicling his observations in China, Burma, Thailand, Singapore, French Indochina, and the Dutch West Indies. He returned home to Manila in November 1941.

“I Am A Filipino”, reconstructed from the original newspaper publication using a microfilm image

On December 8 the Japanese dropped bombs on Manila, Davao, Aparri, Baguio, Clark Field, and the Iba Landing Field, having attacked Pearl Harbor just hours before. General Douglas MacArthur called Romulo to active duty, and he took his oath as a Major in the Philippine Army Reserve, commissioned to the US Army. By December 17 General MacArthur had appointed Romulo as his Executive Press Relations Officer. Romulo left for Corregidor, where he joined General MacArthur and President Quezon. He said his good-byes to his wife and four sons at their Vermont Street house in Malate on January 1, 1942. Within days he was broadcasting over the Voice of Freedom. By March Filipino and American forces on Bataan and Corregidor were plagued by disease and short of ammunition and supplies. President Roosevelt ordered General MacArthur to leave Corregidor for Australia. Before his departure on March 11, he promoted Romulo to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel and awarded him the Purple Heart. (He was later decorated with the Silver Star as well.)

I believe above all that a man should be true to himself. I believe a man should be prepared at all times to sacrifice everything for his convictions. Twice during my life I have been called upon to make this kind of sacrifice. After Pearl Harbor, the Philippines was invaded by Japan. I had never been a soldier. I was a journalist. But something impelled me to enlist.

I was attached to General MacArthur’s staff and went with him first to Bataan and later to Corregidor. In Corregidor, I was placed in charge of the broadcast called the Voice of Freedom. The Japanese reacted violently to the broadcast. I learned that a prize had been put on my head, and worse that they had gone after my wife and four sons who had been left behind in the occupied territory. I suffered indescribable torment, worrying about my loved ones. I wanted to go back to Manila at whatever cost. But I was ordered to proceed to Australia on the eve of the fall of Bataan.

From Australia, I was sent on to the United States, where I continued to make the Voice of Freedom heard, regardless of the consequences to my family. I did not see them again until after the liberation of my country by the American forces under General MacArthur, aided by the Filipino guerillas who had carried on a vigorous resistance during the more than three years of enemy occupation.13

Bataan fell on April 9, 1942, with Filipino and American forces surrendering to the Japanese. Romulo managed to escape at 1:18 am on a small plane that just barely got off the ground. He then sailed a Navy J2F4 to Melbourne to join MacArthur, who appointed him as his aide-de-camp.

Together they flew to San Francisco, where Romulo began a twenty-four-month lecture tour, determined to make Americans pay attention to the war going on in the Pacific. He traversed 143,000 kilometers and visited American 466 cities, often giving multiple lectures in a single day.

In 1943, just weeks before his death from tuberculosis, President Manuel Quezon appointed Romulo as Secretary of Information and Public Relations. Sergio Osmeña then took over as President, appointing Romulo as Resident Commissioner to the United States and Acting Secretary of Public Instruction.

That same year his wartime memoirs were published as I Saw the Fall of the Philippines. Other titles he wrote and published around this time included The United (1951), Mother America (1943), and I See the Philippines Rise (1946).

On October 20, 1944, Romulo returned to the Philippines, now as a Brigadier General, with President Osmeña and General MacArthur in the historic landing at Leyte. It was reported that the American general waded ashore in waist-deep water. Reporter Walter Winchell immediately wired asking how Romulo could have waded in that depth without drowning.

After three and a half years of separation, the Romulo family was reunited in March 1945. Carlos, Jr., who served with the guerrillas, assisted in the rescue mission.

Naval dispatches between Romulo onbard the USS John Land and MacArthur on the USS Nashville, right before landing.

Naval dispatches between Romulo onbard the USS John Land and MacArthur on the USS Nashville, right before landing.

October 20, 1944, Romulo (middle) returns triumphantly to the Philippines, with President Osmeña (first on left) and General MacArthur in the historic landing at Leyte

October 20, 1944, Romulo (middle) returns triumphantly to the Philippines, with President Osmeña (first on left) and General MacArthur in the historic landing at Leyte

Romulo—whose lifelong dream was to help build a body such as the United Nations—resolved to make the Philippines the voice of small nations. He launched himself fully into the world of international diplomacy, standing his ground against the big powers and committing himself to the causes of fledging nations.

In 1945, 282 delegates from 50 nations made the trek to San Francisco to draft a Charter for the United Nations. I headed a delegation from my country, the Philippines, which was not yet even independent. It was one of 45 other delegations from weak and disadvantaged nations, some of them still colonies of the great powers.

It was a time of exaltation and high hopes, but there were also many fears among us. The war still raged. The world still manifested much evidence of the old order.

But there was promise in the invitation to join the conclave in San Francisco: We were to participate in the shaping of the peace that was expected soon. The Conference was to be the first sign of the onset of a new order.

All of us knew that it was the unflagging determination of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, ably assisted by his Secretary of State

Romulo addressing the United Nations in San Francisco (ca 1945).

Romulo addressing the United Nations in San Francisco (ca 1945).

Cordell Hull, that made the Conference possible. It was the United States President who summoned the statesmen of the five great powers who were allies to Dumbarton Oaks to forge the guidelines for the Organization.14

The colonial powers proposed that the United Nations Charter should read that non-self-governing nations should aspire to “self-government.” But Romulo and the Philippine delegation felt this choice of words would render the Charter and the UN organization a farce because it essentially allowed imperialism to continue.

The word “independence” is paramount because that only can be the goal of all peoples. If we are drafting a charter for the whole world, it is essential that “independence” should be included in the general policy. 15

In the end, the phrase “or independence” was included in the Charter.

I come from a small country, one of the humblest in this sprout gathering of States. We know our place, we the little peoples, who must sit quietly here while the giants “hurl their barbaric yawps over the rooftops of the world.” We know our

place, it is a humble place, but it is not a place of shame. There may be places in the world where the mighty have gagged the humble or reduced them to the pitiful condition of a claque, but the General Assembly is not such a place. Therefore, we the small ones, we the little Davids of the world, will stay in our places, with slings for weapons, taking the utmost care not to be trampled underfoot by the great hulking and blustering Goliaths. We shall not be terrified of the big bullies, but shall try to reason with them, yes, in a loud voice if necessary, and ask them to sit down with us and learn to be civil. Occasionally, whenever the spirit moves us, and the occasion presents itself, we shall be hurling truth at them like stones between the eyes, where it will hurt most and yet also do the most good…16

That summer of 1945, San Francisco, Romuvlo signed the charter of the United Nations on behalf of the Philippines. We were, at that time, a US territory on the verge of becoming a sovereign nation, after having been for centuries a colonial people.

I came to San Francisco starryeyed, believing that we were going to form an organization that was the culmination of all my dreams.17

Romulo served as chairman of the Philippine delegation to the first session of the United Nations General Assembly in London, January 1946. He also represented the Philippines in the new Far Eastern Commission, and chaired the London Conference on Devastated Areas.

The day after President Manuel L. Roxas was sworn in as the first president of the Philippine Republic, Romulo was appointed as the country’s permanent delegate to the United Nations with the rank of Ambassador. Around this time the Commission on Human Rights was established by the United Nations, with Eleanor Roosevelt as its chairperson. Romulo joined the committee to help draft a declaration of human rights.

By October 1946 the Romulo family settled into what would be their home for the next fourteen years, at 3422 Garfield Street, Washington, DC.

In the fall of 1947 Romulo attended the second session of the United Nations General Assembly in Flushing Meadows, New York, as chief of the Philippine delegation.

In the spring of 1948, he chaired the monthlong Conference on the Freedom of Information in Geneva, Switzerland.

By August he was heading back to Europe, this time with his wife and youngest son, Bobby, aboard the RMS Queen Mary, to attend the Third Regular Session of the UN General Assembly, which was held at the Palais de Challiot in Paris. He was elected chairman of the Ad Hoc Political and Security Committee and was named

as one of the four candidates for the UN presidency.

At the end of 1948 the General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which Romulo, Roosevelt, and other committee members had arduously worked on and argued over for nearly two years.

Back home Vice President Elpidio Quirino had assumed the presidency in April 1948 after Roxas died suddenly of a heart attack. A month later Romulo’s mother passed away in Camiling.

On September 20, 1949, Romulo won the election for UN President. It was an honor unprecedented in at least three ways: he was elected by an overwhelming majority of 53-6, he was Asian, and he was the first UN President with the rank of ambassador, predecessors having been either premiers or prime ministers.

Confronted with a heavy agenda, his first words were to say that he wished the session would become known as the “peace assembly” by accomplishing further progress away from the tensions building toward World War III.

The most pressing need was still to lay the groundwork for dealing with the regulation of atomic weapons and disarmament. It had been three years since the General Assembly established the Atomic Energy Commission under Resolution 1(I), and after many meetings and clarifications made by the delegates of the General Assembly and the Security Council, still no progress had been made. A deadlock persisted.

Frustrated, Romulo made an emotional appeal to the General Assembly on November 14, 1949.

It is a common error to distrust a solution merely because it seems too audaciously simple. The many learned men who have applied themselves to this problem have been either atomic scientists or political thinkers who know all the physical and political equations involved in this problem. Yet I dare say that none of them, having the innate modesty of greatness, will deny a hearing for any proposal which attempts to inject the human factor into the mechanical equations that seem, so far, to be leading us nowhere…

In certain respects, we seem to be developing a tendency to disregard the substance of problems and to consider them merely as incidents in a

continuing polemic. Whatever may be said of less pressing problems, atomic energy is too serious to be treated as an incidental phase in the battle of propaganda. This is one problem before which all mankind stands equally interested and equally defenseless.

If the horrors of atomic war should ever be visited upon this planet, the pitiful survivors of blasted and ruined cities will take little consolation in the thought that the representatives at the U.N. made brilliant and witty speechews about atomic energy. They will ask just one question: why did you not stop this before it happened?

If I may presume to interpret the resolution which you have just adopted, it can be summed up in one sentence: Save humanity while there is still time.18

When panned by Russia as a puppet of the United States, Romulo characteristically quipped with amusement: “If I am anybody’s puppet, I am the puppet of the 59 nations which elected me. They are my boss.”19

He later recalled having to be “perched atop three thick New York City telephone books” just to see and be seen by all the delegates below the podium.

In 1950 President Quirino was in office, as Romulo continued serving as ambassador to the US as well as head of the Philippine

Mission to the UN. Romulo also represented the nation at other key meetings, such as the conference of Southeast Asiatic and Western Pacific nations, known also as the Bandung Conference.

Only a month after Romulo took on the top diplomatic position as Philippine Foreign Minister, appointed by Quirino, North Korea attacked South Korea, igniting the Korean War. June 25, 1950 Cold War assumptions governed the immediate reaction of US leaders, who instantly concluded that Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin had ordered the invasion as the first step in his plan for world conquest. “Communism,” President Harry S. Truman argued later in his memoirs, “was acting in Korea just as [Adolf] Hitler, [Benito] Mussolini, and the Japanese had acted ten, fifteen, and twenty years earlier.” If North Korea’s aggression went “unchallenged, the world was certain to be plunged into another world war.”20

In 1951 he represented the Philippines at the fifty-one-nation Japan Peace Treaty conference in San Francisco. While he felt the treaty was not wholly acceptable to the Philippines, he also felt (as a citizen of Asia) that it was important to not stand in the way of peace.

You, Japan, have done us a grievous injury…but fate has decreed that we must live as neighbors, and as neighbors in peace…

In December 1951 Romulo’s term as Secretary of Foreign Affairs ended, and in February 1952 he presented his credentials as ambassador to US President Truman in Washington, DC.

Norwegian Trygve Lie resigned as UN secretary-general by the end of that year, largely because of the Soviet Union’s resentment of his support of UN military intervention in the Korean War.21 The United States backed Romulo as Lie’s successor; while Russia put her support behind Madame Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit from India.

In the end Dag Hammarskjöld from Sweden got the job, and he took office in April 1953 just as Romulo was contemplating running for the Philippine presidency.

By May Romulo was headed back to Manila, having decided he would run with Fernando Lopez as his vice-president; however, they withdrew their candidacy three months later in favor of Ramon Magsaysay.

I had never been a politician, but having become convinced that I should do everything I could to help effect a change of government in my country, I resigned as Ambassador to the United States and permanent representative to the United Nations in order to enter the field against the incumbent president. I founded a third party, the Democratic Party, and accepted the nomination for president. I started a vigorous campaign to awaken the Filipino people to the need for a change in administration.

Midway in the campaign, it became apparent that the two opposition parties might lose the election

if they remained divided but had an excellent chance to win if they would present a united front. I made the painful decision to withdraw my candidacy. After withdrawing my own candidacy, I was the campaign manager of Mr. Ramón Magsaysay and campaigned up and down the land for him. I could not have worked harder if I had been the candidate myself.

Magsaysay won by a landslide. The temptation was strong for all those who had worked for him to share in the rewards of victory. I was convinced, however, that the first duty of everyone who had helped to bring about a change of government was to give the new president a completely free hand in making appointments to keep positions in his administration. Immediately after the elections, I left for the United States.22

President Ramon Magsaysay appointed Romulo in 1954 as Special and Personal Envoy of the President of the Philippines to the United States without portfolio. Later that year he gave him the Golden Heart Presidential Award.

Throughout his lifetime Romulo received well over a hundred awards and decorations internationally. Ripley’s Believe It or Not featured him as the most decorated human being on the planet.

Romulo served as chairman of the Philippine delegation to the Afro-Asian Conference in Bandung, Indonesia in 1955. In The Meaning of Bandung, published in 1956, he expressed the senti-

ments and aspirations of the peoples of Asia and Africa, especially those who had just emerged as independent nations.

In 1957 he served twice as president of the UN Security Council (the body primarily charged with maintaining international peace and security), a position he would hold again in 1980 and in 1981.

That same year Romulo’s personal life hit an all-time low when his eldest son died in a plane crash south of Manila on October 11, 1957. With two toddlers and young wife, Carlos Jr was just 31 years old.

Remembering his grief, Romulo later wrote, “How much did I know of this boy I so deeply loved?”23

Just ten years before, Romulo witnessed Carlos Jr graduate from Georgetown University, the first of his four sons to do so. The family had developed close ties to the university since moving to DC in 1945, and Georgetown invited Romulo as a guest speaker from time to time. He was famous for his speaking prowess and touched scores of people through speeches so impactful, they had the power to change lives.

A student at Georgetown pursued a career in diplomacy after hearing him speak in 1958. Romulo had given the year’s first lecture in the Gaston series, delivering an urgent and vivid examination of America’s security interests in Asia in the global fight against communism.

When Lenin laid down the basic strategy for Soviet Russia to achieve its objective of world conquest, he wrote for all eyes and for all ages. “The road to London and Paris is through Peking and Calcutta.”24

Meaning, for Soviet Russia to conquer the world, Soviet Russia must first conquer Asia; and in strict conformance with that basic strategy as laid down by Lenin. While all your statesmanship and all your leadership and all your national attention was concentrated on Europe, Soviet Russia took the first big grab in Asia by conquering China. Hence, the subject of my talk tonight: “America’s Stake in Asia.” What is it? Nothing more nor less than your national security, the safety of your lives and of your dear ones, the survival of the American way of life. That is America’s stake in Asia. Nothing more, nothing less. Why do I say that? I don’t say that. It’s your Congress that says it. It’s your Pentagon. It’s your White House. It’s your State Department. For years you had been appropriating billions of your American dollars, taxpayers’ money, for the establishment and maintenance of your air, naval, and military installations in what is known in military language as your American perimeter of defense.

The newspapers sometimes call it your Pacific chain of defense, which extends from the Aleutians way up north through Japan, Okinawa,

Korea, Formosa, Guam, and the Philippines. And unless and until your intercontinental ballistic missile is operational, which according to your experts will take from at least five to 10 years, unless and until your intercontinental ballistic missile is operational, that American perimeter of defense in Asia -- there is anchored your national security. Because that chain can only be as strong as its weakest link. If any of the links in that chain falls under communism, that whole chain can snap.

And if that chain snaps, the whole of Asia will fall under Soviet Russia. And if the whole of Asia falls under Soviet Russia, good night for democracy. And curtains for the American way of life. Do you realize that?

This is one of the truths that I’ve come to tell you tonight. That is why President Eisenhower, after securing the prior sanction of Congress, announced to the world that America will defend Formosa to the last ditch, because you cannot allow Formosa to fall under communism, because that’s an important link in the chain.25

The hourlong lecture stressed the need for alliances to counter the communist threat and was a resounding success. A masterful introduction to geopolitics, Romulo’s talk underscored the high stakes for democracy if Asia should fall.

Inspired perhaps by a sense of patriotic duty, the student later became a US ambassador and had a distinguished career serving in Latin America and in Southeast Asia.26

Even Eleanor Roosevelt was moved to tears when she first met him in 1945: General Romulo made a most moving speech -perhaps one of the most interesting speeches on race relations that I have ever heard… Several times, as he spoke, I looked across the table and saw the mistiness in the eyes of the women opposite, and I knew they could see the same in mine…I went from there with a curious sense of having heard a sermon and seen a very extraordinary human being.27

Romulo continued serving the country under President Carlos Garcia as Philippine Ambassador to the US, and in 1959 he also took on the designation of Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to Cuba and Brazil, with residence in Washington, DC.

During the 1960 graduation ceremonies of Georgetown University, Romulo served as commencement speaker and was conferred with an honorary degree. (In his lifetime Romulo received 73 honorary degrees from universities all over the world.) His youngest son, Bobby, was part of the graduating class, receiving his Bachelor of Arts degree.

Before the end of 1961, President Diosdado Macapagal appointed Romulo as the president of the University of the Philippines effective upon the retirement of Vicente Sinco in 1962. At the same time, Macapagal gave him the position of Secretary of Education.

After ten years as our ambassador to the United States, Romulo announced that he was going home.

I am going home, America—farewell. For seventeen years I have enjoyed your hospitality, visited every one of your 50 states. I can say I know you well. I admire and love America. It is my second home. What I have to say now in parting is both a tribute and a warning: never forget, Americans, that yours is a spiritual country. Yes, I know that you are a practical people. Like others, I have marveled at your factories, your skyscrapers, your arsenals. But underlying everything else is the fact that America began as a God-loving, God-fearing, Godworshipping people, know that there is a spark of the Divine in each one of us. It is this respect for the dignity of the human spirit which makes America invincible. May it always endure. And so I say again in parting, thank you, America, and farewell. May God keep you always; may you always love God.28

Wrote Leonard Lyons of The New York Post: “No diplomat ever left Washington with as much acclaim as did Romulo… [who] received tributes from all three branches of government, and keys to cities all across the nation. Even New York’s tough, cynical citizens gave him a standing ovation.…”29

In a farewell letter to him, United States President John F. Kennedy wrote, “You are identified with great moments in the history of my nation – with the emergence of the Philippines as a free and democratic republic, with the resistance to aggression during the Second World War, with the formative years of the United Nations. You leave behind not only good friends but imperishable memories.”30

Kennedy also received Romulo in the Oval Office: “Not since Lafayette left has anyone received such acclaim,” said Kennedy, referring to the French military officer who fought in the American Revolutionary War.

Romulo quipped, “Maybe they’re just eager to get rid of me.”31

His autobiography I Walked with Heroes came out in 1961, quickly becoming a best-seller in the Philippines and the United States. He authored several other titles during this period, as well, such as Contemporary Nationalism and the World Order (1964), Evasions and Response: Lectures on the American Novel (1966), and Filipino Nationalism: Jose Rizal Its High Priest and Chief (1963).

Virginia Llamas Romulo, who in Romulo’s words was his “shrewd and loving adviser” and an “artist in homemaking and in social living,” died on January 22, 1968, at the age of sixty-two.

Secretary-General U Thant at a banquet at the UN Headquarters on September 24, 1969, gave Romulo the moniker “Mr. United Nations” for his significant contributions in advancing the cause of the United Nations and as its dedicated and devoted advocate.32

In the middle of 1968, Romulo filed his retirement as university president and Secretary of Education. At the end of the year President Marcos made him Secretary of Foreign Affairs, a position he would stay in from 1969 to 1984.

After a serious collision with a cargo truck in March 1972 that left him unconscious for sixteen days, with broken bones, and needing massive surgical repair on various organs, Romulo amazed everyone with

a miraculous recovery. Already seventy-four, no one expected that he would be able to attend the 7th ASPAC ministerial conference in June, but in fact he not only traveled to Seoul for it; he headed up the Philippine delegation.

By fall Romulo was in New York for the 27th Session of the UN General Assembly, when martial law was declared by President Marcos. He was starting to become known as the only surviving signatory to the United Nations Charter.

On September 8, 1978, Romulo married Beth Day in a secret ceremony at the Pasay City home of Chick and Katsy Parsons. When asked how he won over such a lovely American lady, he quipped, “Why don’t you ask how she managed to marry such a distinguished Filipino?”

In 1979 he chaired the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, hosted by the Philippines, and he co-chaired the Philippine delegation to the UN’s fall assembly.

“We now have a strong voice in the international community,” he said of the Philippines in January 1981, just after serving as chairman of the UN Security Council for the third time. “With its membership in the UN Security Council, its chairmanship of the ASEAN Standing Committee, its status as observer in the Non-Aligned Movement, as well as its close association with the Arab, African, and Latin American groups, the Philippine position in world affairs has been clearly established and defined.”

In September 1981 UN Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim awarded him with the United Nations Peace Medal. “General Romulo needs no tribute from me,” he said. “[This medal] is a modest token of our grati-

tude to a world statesman to whom the world owes so much.”

In 1982 he was named a National Artist for Literature, having authored eighteen books, four plays, and several poems.

In recognition of his lifetime contributions to world peace, President Ronald Reagan conferred upon him in 1984 the highest civilian award of the United States, the Presidential Medal of Freedom -- the same honor that would later be given to Mother Teresa, Pope John Paul II, and Nelson Mandela.

Presented in Manila by US Ambassador Michael Armacost, the text of the award reads as follows:

“As parliamentarian, soldier, educator, U.N. Charter signatory, diplomat, and foreign minister, Carlos P. Romulo’s statesmanship and promotion of international accord add up to a remarkable record of achievement. His more than fifty years of public service embody the warm relationship between the United States and the Philippines from the colonial period through the Commonwealth, wartime, and independence to the present. In tribute to his long and close association with the United States, this medal is gratefully conferred.”33

By the time he died on December 15, 1985, he was a major general in the Philippine Army, and had served on the boards of a number of prestigious Philippine corporations.

Extolled by three United Nations Secretary-Generals (U Thant, Waldheim, and Javier Perez de Cuellar) as “Mr. United Nations” for his dedication to freedom, world peace, human rights, and decolonization, Romulo acknowledged the goodness, the godliness, of every human being. This, which he learned early in life, was to him the very basis of peace.

“There is a spark of the divine in every human being no matter how bad he may be thought to be. All it takes is for his spark of the divine to strike the spark of the divine in the other fellow and the result is mutual understanding. Perhaps harmony.”

– Carlos P. Romulo

Endnotes

1 Letter

2 Letter

3

4 I Walked With Heroes

5 I Walked With Heroes

6 I Walked With Heroes

7 I Walked With Heroes

8 Julius C. Edelstein, “Significance of Interview in Picture of P.I.–U.S. Relations Pointed Out,” United Press, January 16, 1938.

9 “The Mind of a New Commonwealth,” December 9, 1935.

10 Mother America

11 Julius C. Edelstein, “Significance of Interview in Picture of P.I.–U.S. Relations Pointed Out,” United Press, January 16, 1938.

12 Carlos P. Romulo, “A Realistic Re-examination of the Philippine Question,” DMHM Newspapers, January 14,1938.

13 This I believe - San Antonio Express and News (Texas), July 25, 1954, p. 66

14 Carlos P. Romulo, “The Genesis and Progress of the UN,” The Diplomatic World Bulletin, Vol. 8 No. 17, October 23, 1978.

15 SOURCE?

16 Illustration by Malang Santos. This Week (Sunday Magazine of The Manila Chronicle), Nov. 28, 1948, p. 36

17 I Walked With Heroes

18 Francis W. Carpenter (1950) United Nations Atomic Energy News, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 6:1, 18-20, DOI: 10.1080/00963402.1950.11461193

19 “Romulo: U.N. General Assembly President,” The Philippines Herald, Sep. 1949.

20 https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/the-korean-war-101-causes-courseand-conclusion-of-the-conflict/#:~:text=North%20Korea%20attacked%20South%20 Korea,Communism%2C%E2%80%9D%20President%20Harry%20S.

21 Google

22 This I Believe, Tufts University Digital Collections and Archives. Medford, MA. Catalog no: tufts:MS025.006.016.00008.00002. Permanent URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10427/76138/. San Antonio Express and News (Texas), July 25, 1954, p. 66

23 I Walked With Heroes?

24 Who said it first?

25 Gaston

26 Erwin Tiongson’s talk at Georgetown

27 Eleanore Roosevelt, My Day, 1945?

28 “Something to Remember.” This Week Magazine, 10 June 1962, p. 2.

29 Lyons

30 Quote from the letter of US President John F. Kennedy to Romulo upon his retirement as Ambassador to the US, January 15, 1962

31 SOURCE?

32

33 https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/speech/announcement-conferral-presidential-medalfreedom-carlos-p-romulo-foreign-minister