The fall semester is full of excitement— bringing feelings of hope and anticipation for a new year, a flurry of anxiety over internship applications, and the idea of reviving a part of yourself as soon as you walk onto campus.

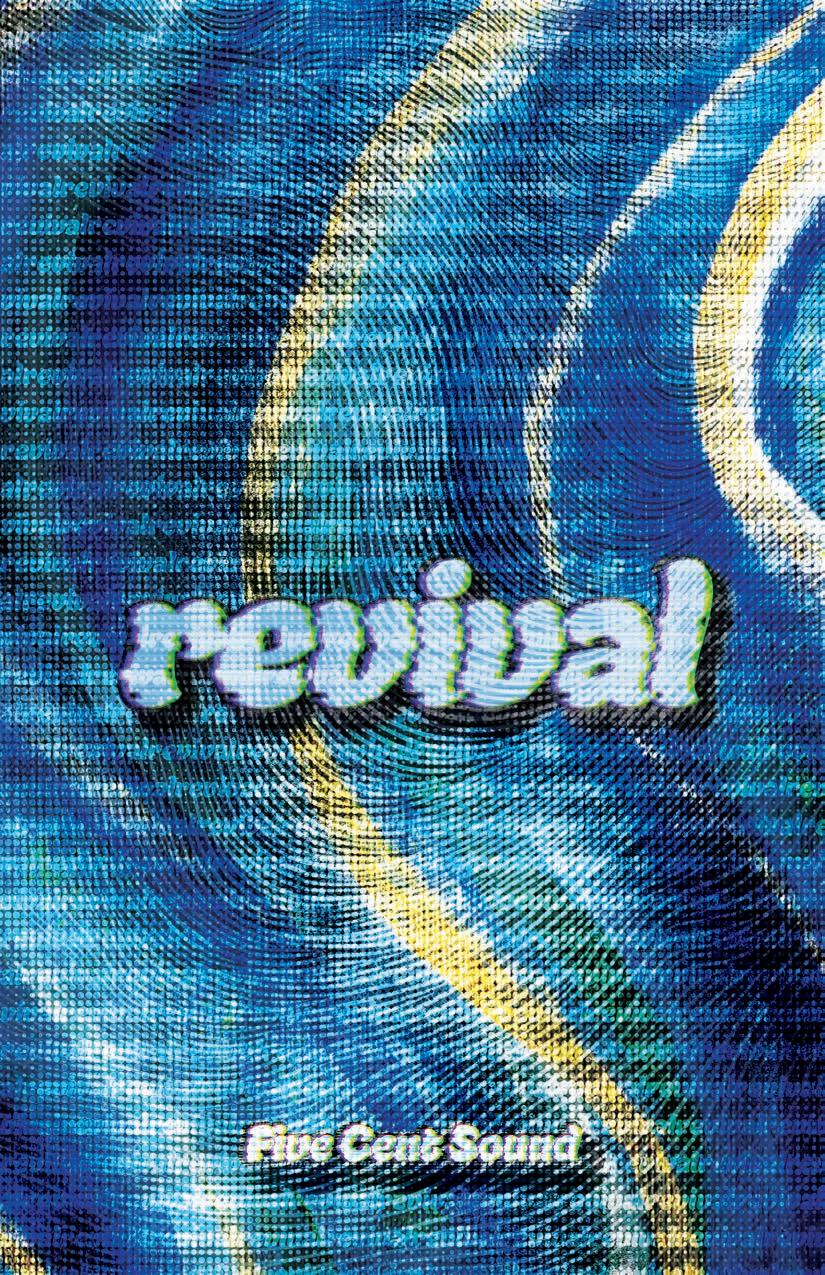

Emma and I started this semester with lots of dreams and ambitions and while some have been accomplished and others never came into fruition, Revival is by all means a success story. We spent many hours sending paragraphs long Slack messages and emails to pull these thirteen pieces together alongside many beautiful images from our excellent creative team and are incredibly overjoyed to share it all with you.

Thank you to our wonderful editorial team who worked tirelessly over multiple weeks to ensure our pieces were the best they could be. Thank you to our writers who put their heart and soul on the page for us to read and enjoy. Thank you to our wonderful E-Board members who stepped up to help ease some of the weight off of the shoulders of our editorial team! Thank you to our wonderful visuals and creative team who have made the magazine look gorgeous and something for all of us to be proud of! I’m entirely grateful for all of you and we may have been a small team this semester, but we were mighty.

Thank you. Thank you. Thank you to Emma, my Co-Editor in Chief and all your hard work putting this team together and helping create a finished product. Thank you for all the hours spent hiring, emailing, and being at every event I couldn’t. It’s been an interesting

semester, but I wouldn’t want anyone else to learn the ropes with together.

Each year we all partake in a sense of “revival,” whether it’s reinventing study habits, trying new trends, or putting on those fall tracks we all know and love. This semester our theme of “revival” is meant to represent that comeback-like change in music from the runway to the CD’s in your parents’ cars and push us towards a revival of our own!

Much

love,

Olivia Lindquist

The first thing I can see is our signature collage style visuals. A mod podge of magazine cut-outs that look different every time despite the same artistic format. And that’s what every print issue of Five Cent Sound is. We pick a theme and worry that the pitches will be too similar, too obvious, and every time we’re surprised by the ideas and perspectives our writers bring us and our visual artists accentuate.

Revival, in particular, is an issue with a variety of writing styles, strong opinions, and interpretations of the theme that I never would have thought of myself. These articles range from personal essays to features, that all revolve around music that has come back either into the mainstream or as corny as it sounds, into our hearts.

I’ve loved writing for the print magazine every semester since joining Five Cent Sound and was initially sad to step back from writing and step into a more administrative role. But experiencing firsthand the time, effort, and creativity that goes into making a magazine has brought me a newfound appreciation not only for our past EIC’s but for everyone that worked on Revival.

Without my Co-Editor in Chief Olivia, the magazine you are holding would not exist. She’s the reason we met our deadlines and the reason I didn’t go crazy when we didn’t. We were in constant communication throughout the

semester and as the cliche goes, I couldn’t have done it without her.

Working with Olivia and the executive board was one of my favorite parts of running Five Cent Sound. I can’t imagine how different the experience would’ve been if I hadn’t been working with people I’m so happy to call my friends. To be able to rely on them to lead essential parts of making Five Cent Sound happen was expected and more than appreciated but the way that they went above and beyond their duties is something I can’t thank them enough for. Marianna, Chloe, Milan, and Olivia stepped outside of their positions to put together four stunning visuals for this issue that stand next to the respective articles perfectly.

The same has to be said for the rest of the graphics in this magazine, which bring me back to Five Cent Sound’s eccentric style. No two of these graphics look the same and that’s what makes Five Cent Sound so special. And of course, the writers, who met short, strict deadlines and met them with words that make you think, sometimes make your heart melt, and oftentimes make you want to keep reading more. I hope you will as you flip through the pages of Revival.

All the best, Emma

Executive

Co-Editor-in-Chief - Emma O’Keefe

Co-Editor-in-Chief - Olivia Lindquist

Head Designer - Lauren Mallett

Managing Editor - Marianna Orozco

Head Online Director - Sydney Johnson

Assistant Online Editor - Emie McAthie

Photo Coordinator - Ari Mei-Dan

Creative Director - Rocio Sola Pardo

Assistant Creative Director - Lila Williams

Playlist Coordinator - Norah Lesperance

Social Media Manager - Mia Rodriguez

Marketing Manager - Chloe Morehouse

Assistant Marketing Manager - Milan Glass

Editorial

General Editors

Jasper Chen

Shannon Cullen

Tess Gleason

Abby Hoyt

Emie McAthie

Emma Samuels

Alison Sincebaugh

DEI Editors

Norah Lesperance

Ari Mei-Dan

Mia Rodriguez

Kalyn Thompson

Copyeditors

Shannon Cullen

Tess Hennedy

Liv Mazzola

Emie McAthie

Donna Neghabat

Emma Samuels

Alison Sincebaugh

Creative

Visual Artists

Liam Alexe

Milan Glass

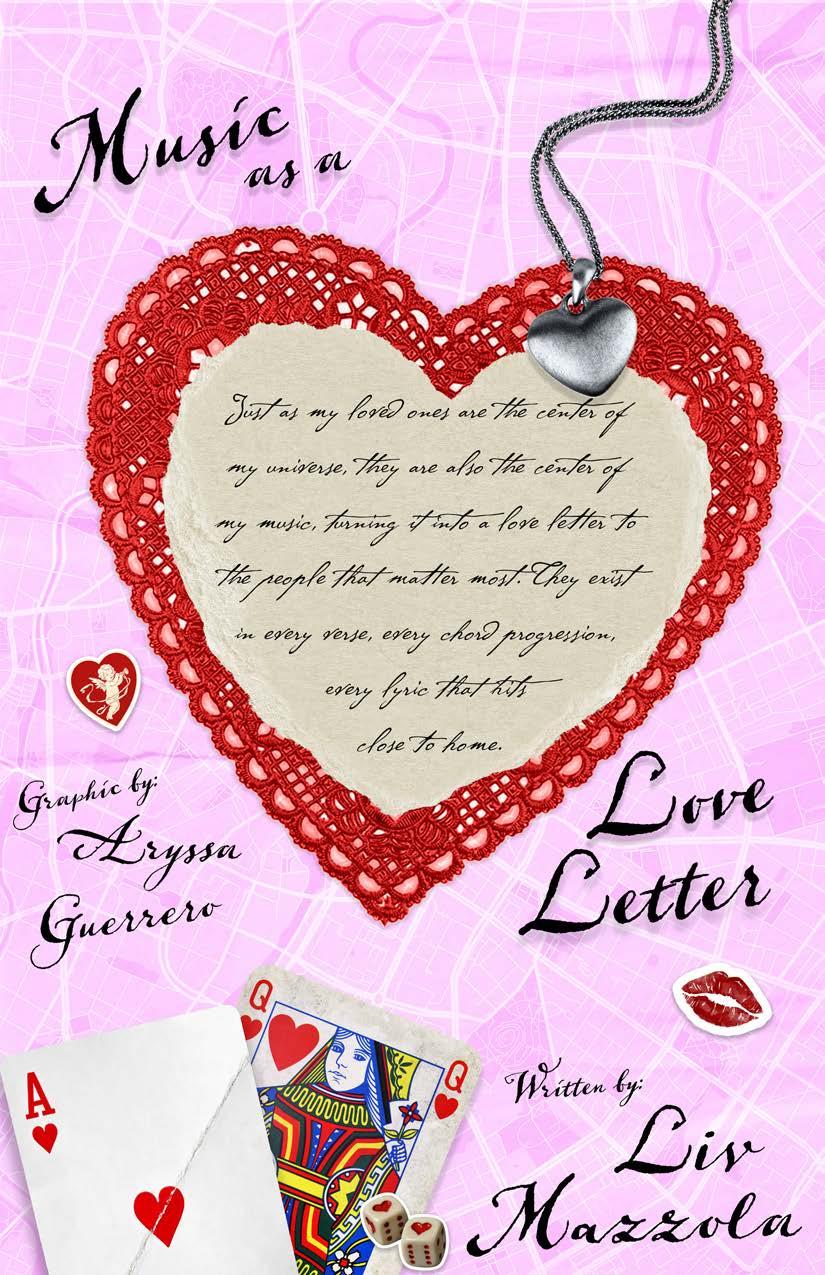

Aryssa Guerrero

Olivia Lindquist

Lauren Mallett

Ari Mei-Dan

Chloe Morehouse

Marianna Orozco

Rocio Sola Pardo

Lila Williams

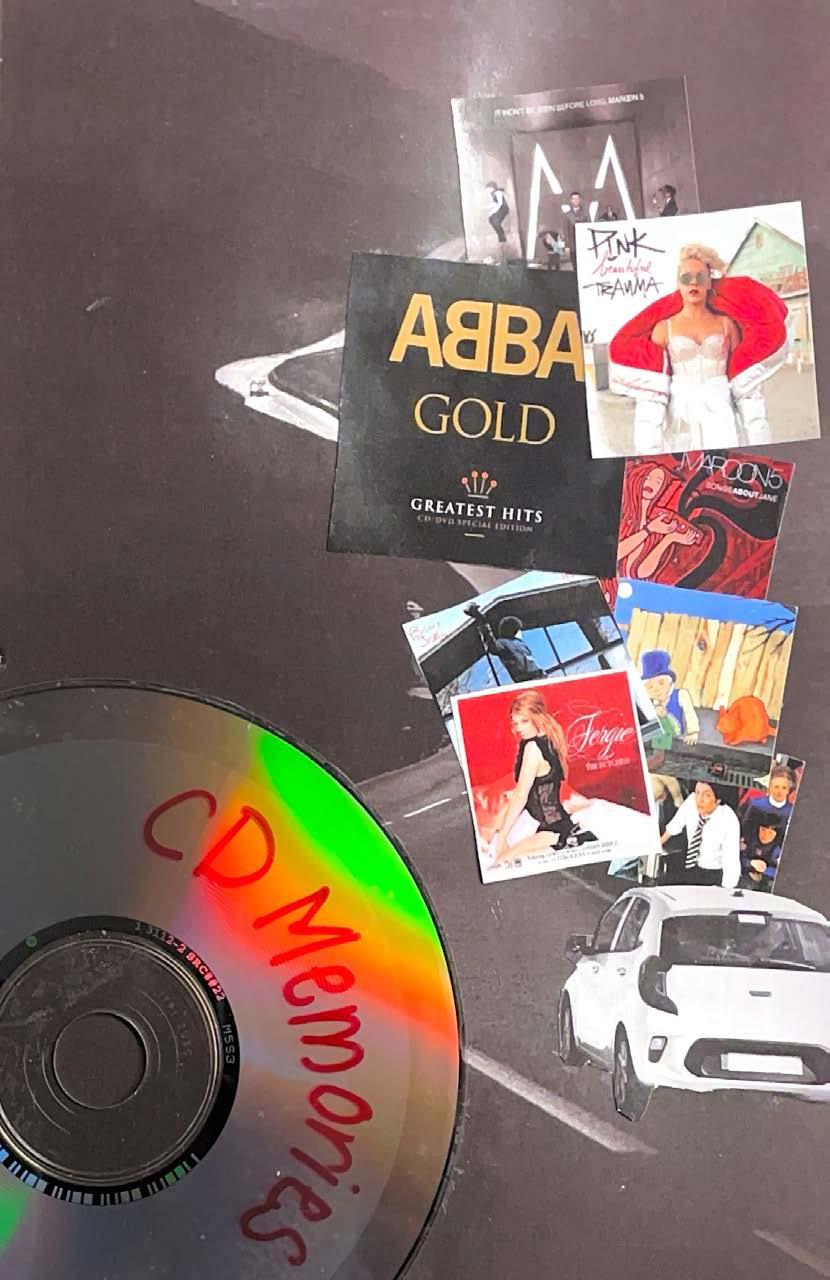

CD Memories by Matt Provler // 8

The Rebirth of Alt-Country by Jack Silver // 14

Lost in Translation by Sachi Andrade // 18

Runway Reignited: Can Sound Save Style by Jagger van Vliet // 24

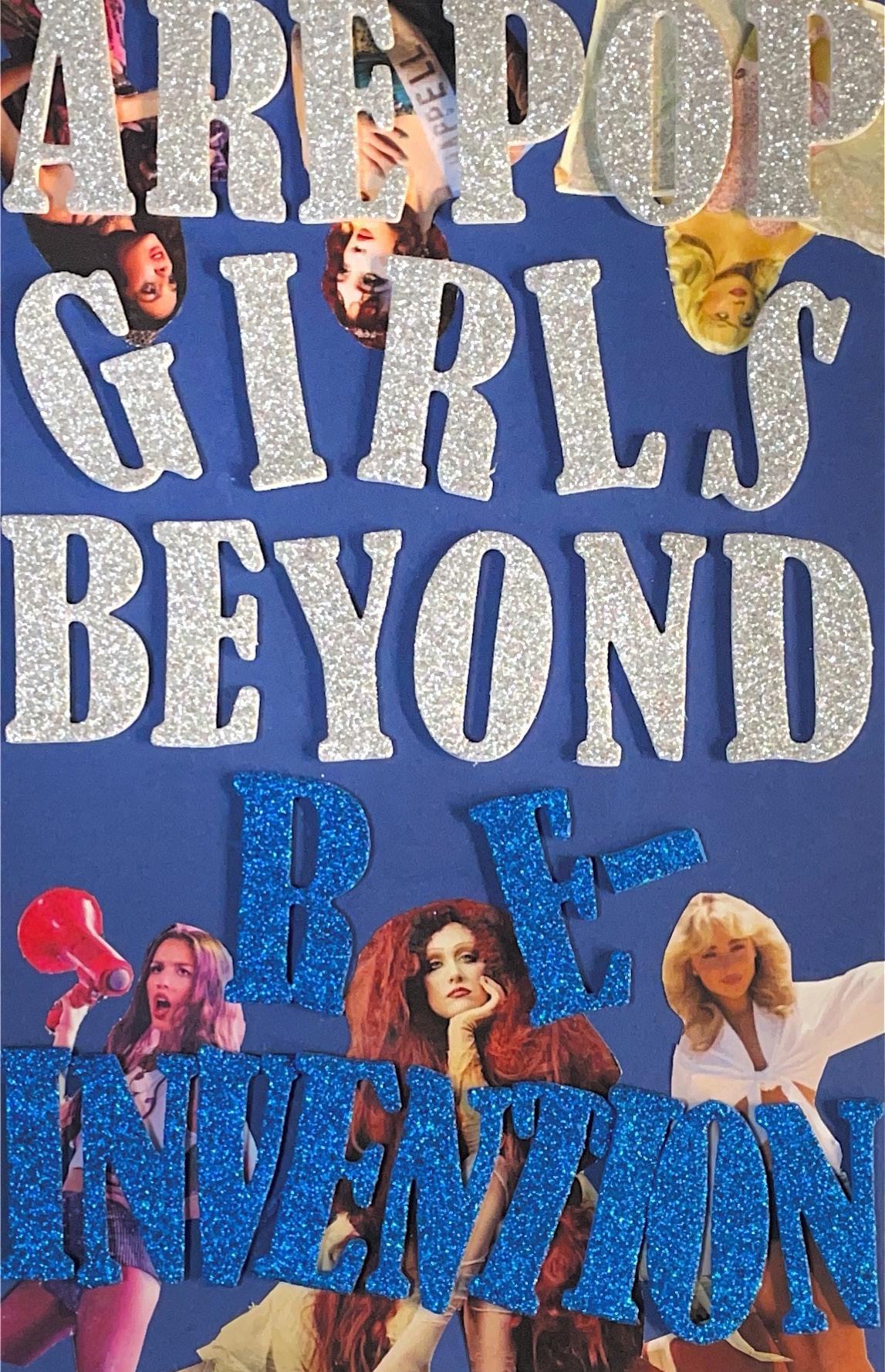

Are Pop Girls Past Reinvention? by Grace Chandler // 30

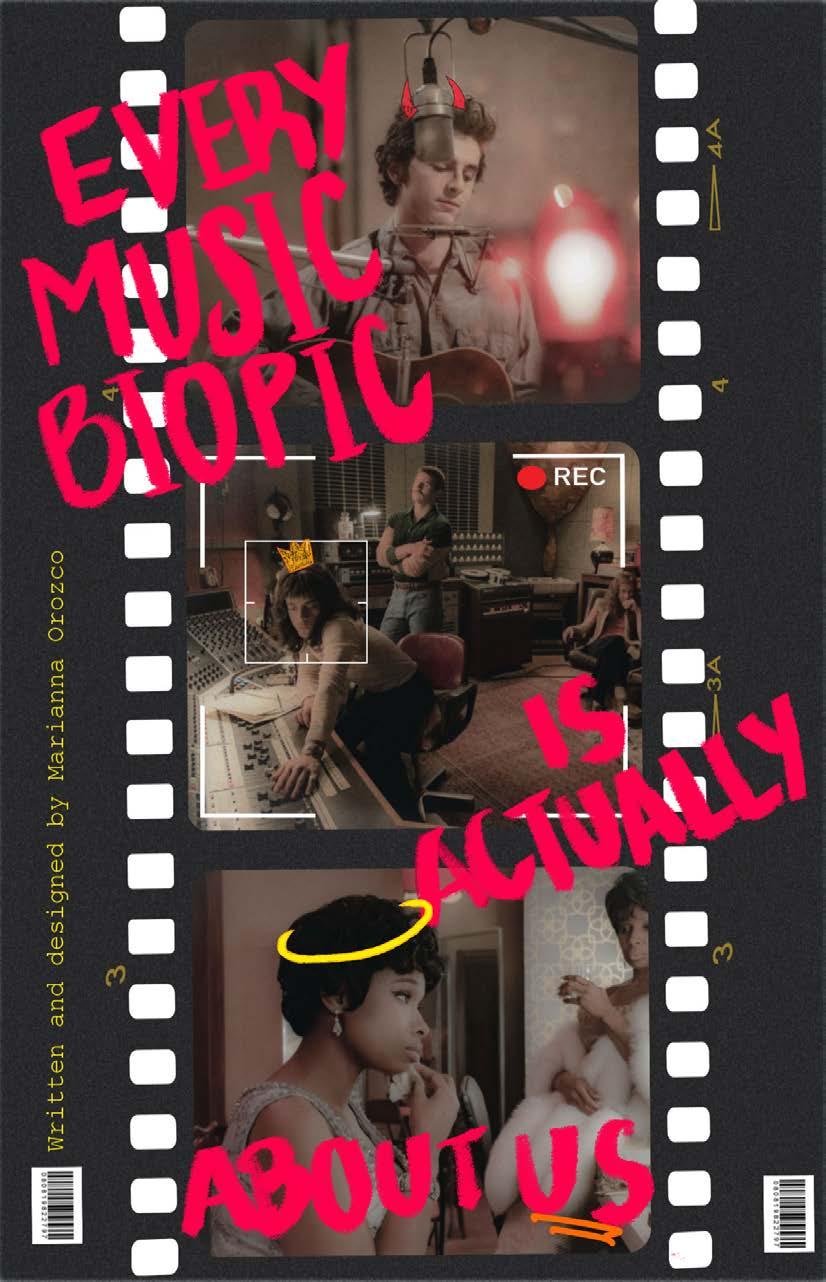

Biopics aren’t just reviving musicians, they’re canonizing them by Marianna Orozco // 36

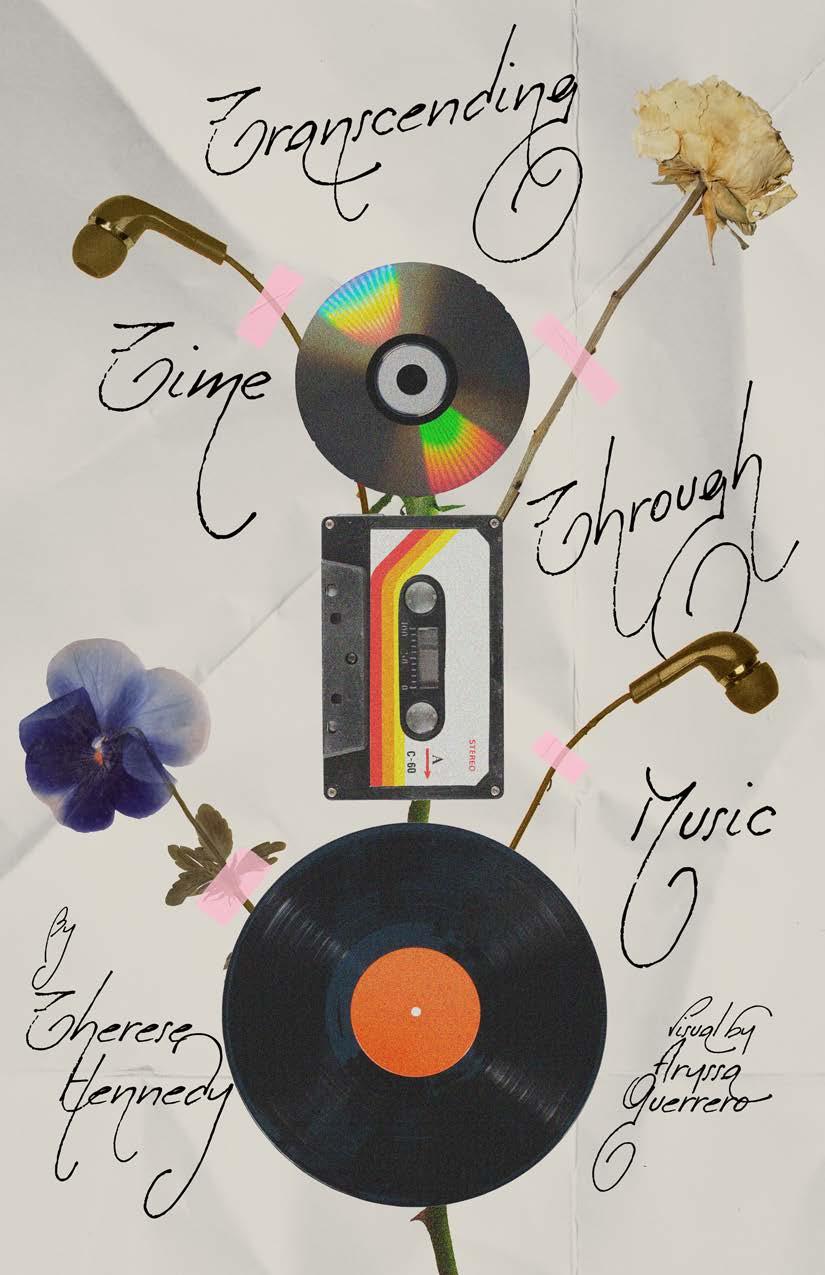

Transcending Time through Music by Tess Hennedy // 42

Getting the Band Back Together: The Art of the Reunion Album by Jasper Chen // 48

Borinquen: The Global Stage by Rocio Sola Pardo // 56

Tribute Bands: Why Are They Important? by Julia Velez // 62

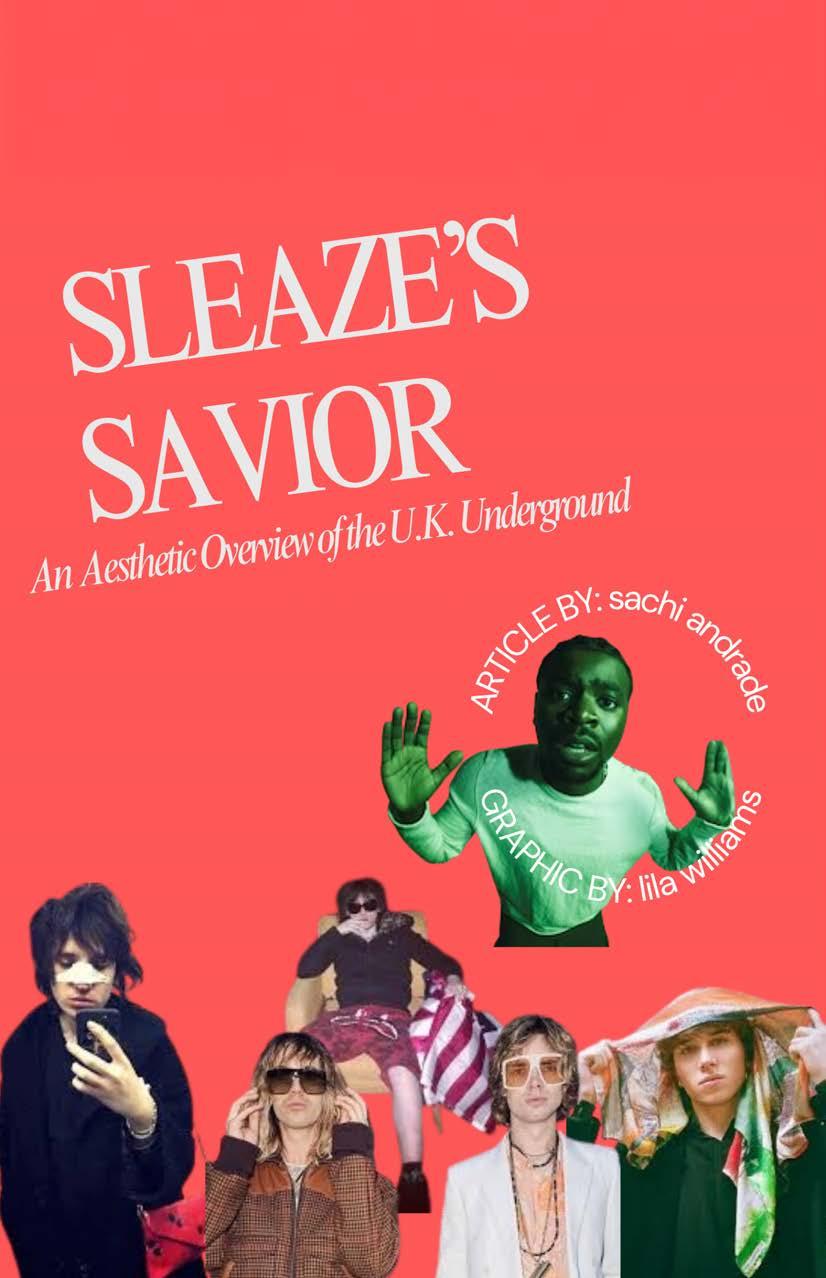

Sleaze’s Saviour: An Aesthetic Overview of the U.K. Underground by Sachi Andrade // 70

Folk is Back and Your Socks Aren’t Safe by Ella Sutherland // 76

Music as a Love Letter by Liz Mazzola // 84

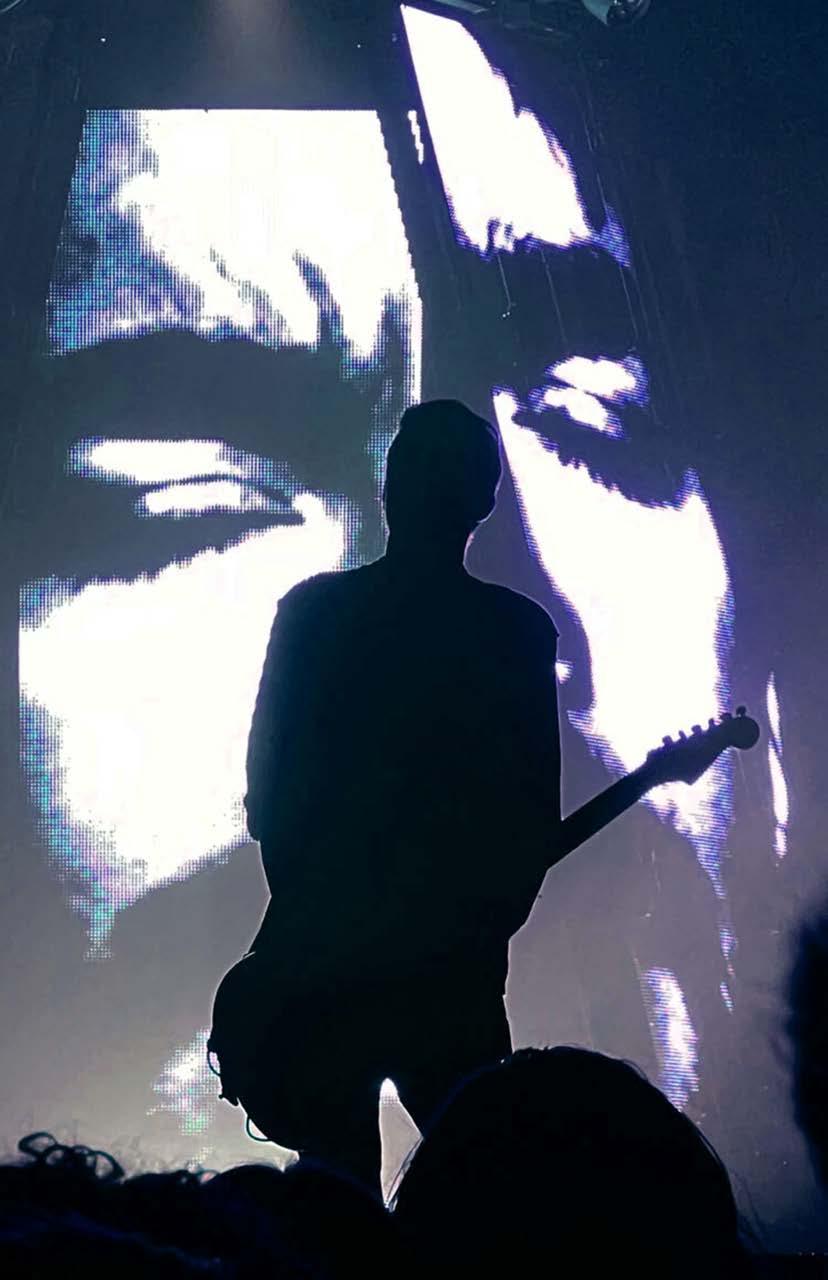

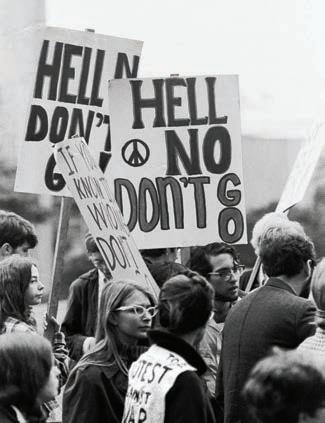

V i sual b y L i a m A l e ex

The slow, shriveling, cascading shower of warmth that arrives each fall, alongside the sudden yet welcome chilly air carrying the scent of changing seasons, always reminds me of particularly lengthy car rides back in middle school: my mom at the wheel, and I the sole passenger. We’d make our way to one of the dozens of different high schools across Long Island, traversing endless stretches of cracked highway to sit on icy cold steel bleachers as my brother and sister’s trumpets echoed across the turf-ladden football field— just another marching band performance. I heard the same performance, like a skipping CD, every Saturday afternoon during “marching band season,” which equates to all of autumn, before it tapers off into the dead of winter, no more pattering of line drums nor low hum of trombones filling the now solemn air.

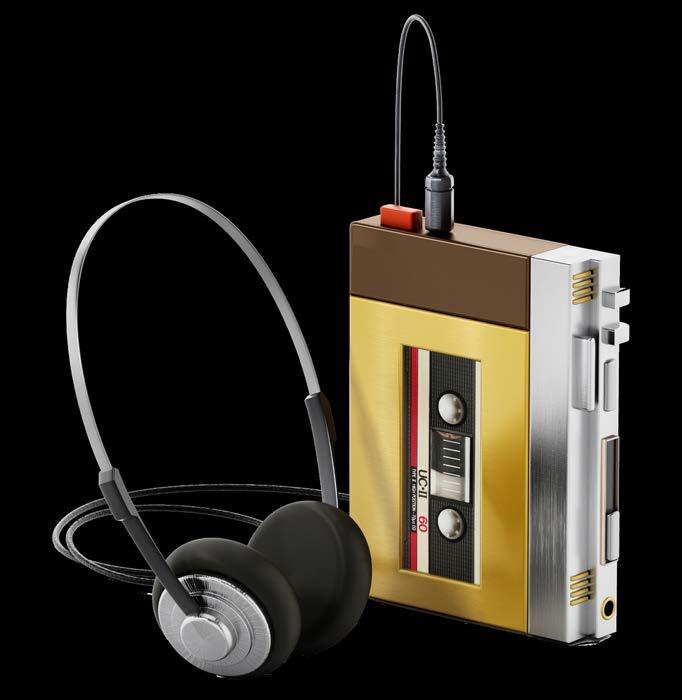

During our rides in my mom’s 2003 Volkswagen, the air filled with melodies held within the grooves of her collection of CDs. Thanks to a faulty radio antenna, CDs were our only option to play music in the car. She would always play the various CDs tucked away on the shelf attached to the driver-side door: P!nk was a recurring favorite, with Beautiful Trauma particularly driving itself into my ears after dozens of listens; compilation CDs of Chicago and Neil Diamond (gifts from my siblings) wove in between the P!nk albums as palate cleansers. My mom would also pick up CDs from our local library; I learned of “Dreams” by Fleetwood Mac by her playing Rumours until the CD was past due.

Soon, my siblings and I would bring our own CDs to play in the car, my additions of ABBA’s ABBA Gold beloved and beloathed. As a Long Island resident, I was obligatorily introduced to the sounds of Billy Joel that played ad nauseum at the request of my brother. I flipped between exhaustion from

listening to Glass Houses for the fifth time in a row to personally requesting Turnstiles instead of my own overplayed ABBA album. Nowadays, when I play Beautiful Trauma out of a nostalgic whim, I’m cast back to drives along the Meadowbrook parkway, on our way to the Walt Whitman High School for my brother and sister’s annual State Championship competition, the early afternoon sky glazed with an autumnal haze stretching beyond the moderate Long Island traffic into the obscured horizon.

My first semester at Emerson, tucked away in a triple dorm room where the sun barely shined, left me uncharacteristically nostalgic, even homesick, for Long Island. I opened Apple Music on my phone, and pressed play on—of all albums—Turnstiles by Billy Joel; the warm, cozy autumnal energy flowed through my barren, icy dorm room.

My experience, however, is no fluke—many others have similar stories to mine, riding in the car while listening to the same CDs over and over. My friend and suitemate, Maria-Renee Herman, described specific memories tied to the CDs played in her family’s car. Her Dad, acting as the dual role of driver and DJ, would play “anything” as he drove her and her brothers to school, to go grocery shopping, or to visit her grandmother. Additionally, her family regularly took trips from San Diego, her hometown, to visit relatives in Mexicali, where she recalled that Fergie’s Duchess played most often during the car ride there. Her 7-year old self imagined quite inaccurate music videos of Fergie’s songs: she innocently thought of Daphne from Scooby-Doo in Hawaiian-styled flora, performing a soft hula dance to Fergie’s “Clumsy.” Alongside Fergie, other albums were in frequent rotation during car rides: Teaser and the Fire Cat by Cat Stevens was one of her dad’s favorites, with Black Sabbath and Iron Maiden played at her younger self’s detestment. At her admission, she’s since

grown to enjoy the metal of the aforementioned artists, like how I myself grew closer to Billy Joel’s songs—once it wasn’t forced upon me in the confines of the car.

As time has gone on, Herman stated how she will revisit albums and songs on Spotify, while using some as a jumping off point to find new artists and songs similar to them. CDs of her childhood—such as the first 3 (and only three, according to Herman) studio albums by Maroon 5—still stand strong in her own music choices, but now mix in alongside newer choices such as K-Pop group Dreamcatcher. Still, the memories of the iconic Scooby-Doo character Daphne hula-ing softly to a song with sensual lyrics like “Clumsy” are forever embedded in her mind, even as her music taste evolves and transforms from beyond its humble origins.

As for CDs themselves, Herman has mixed feelings about their utility nowadays, amidst the commonality of smartphones. However, if not inconvenient, she would always want to play CDs instead of relying on digital services like Spotify; she expressed how physical media like CDs help her stay grounded and focused, their coziness unmatched by the cold insincerity of digital media formats. Even in her newer interests, Herman explained to me that in K-Pop circles, CDs are huge releases: bundled with posters, photocards and other collectable paraphernalia alongside the album, CDs are a staple to the K-Pop genre and the culture of its worldwide fanbase.

Speaking on the topic of the current state of music streaming, Herman demonstrated to me, an Apple Music user, the current “Tiktokification” of Spotify: endless scrolling, sudden podcasts by unknown individuals playing immediately after the app is opened, and with a never ending stream of music inundating the average user.

Originally meant to simplify the end user’s

listening experience, music streaming services are becoming impossible-to-navigate digital landscapes turned wastelands for listeners to sift through its rubble. This phenomenon, coined “enshittification” by Cory Doctorow, is leading listeners away from these decaying platforms and back to where it all began—physical media, baby.

Vinyl collecting, albeit cozy and cultivating a certain indie aestheticism, is incredibly and increasingly costly. A common, well-regarded “beginner” record player starts at approximately $200—not including external speakers, costing in the $100s range for quality, entry-level sets. On top of its hefty barrier-to-entry, vinyl collecting requires exceptional funds and space to keep your collection: new vinyls range from the lower end of $20 per album, to nearly triple digits if a multiset or exclusive pressing made in purposefully scant quantities. Left with vinyls, the most efficient storage results in large square sleeves taking up most of the shelf space of a common entertainment center—or delegated to a plastic bin beside the shelving. All that is to say, vinyl is neither a cheap hobby nor a wise investment—I say this as a proud owner of an entry-level record player and eighteen vinyl albums, most of which I bought from bargain boxes at a local record store— almost all of which are Barbra Streisand vinyls no one else wanted.

As of late, a new wave of physical music media collecting has begun as acquaintances and others around me express their desire to turn to physical media—but this time, many are opting for the cheaper, more portable, highest-quality format of CDs. I call all those wishing for a more intimate, smoother listening experience to opt for CDs as a way to collect your favorite albums, and even introduce yourself to choice artists. The barrierto-entry costs of purchasing an individual CD

often comes to half that of a new vinyl, a little more than $10.

I think back to the Volkswagen, the matte gray stereo trimmed with glossy walnut-hued wood grain spinning its current resident as its laser rapidly reads each miniscule node and notch in the delicately thin CD of The Very Best of Chicago: Only the Beginning. The CDs were merely a necessity thanks to the non-functional radio. And yet, if not for the broken radio, my mom and I would’ve never shared these particular moments together: Chicago was one her parents’ favorite bands, and now she shares it with myself and my siblings. These flimsy jewel cases and disintegrating paper sleeves held not only the foundations of my music taste, but a bridge to cast memories across—from the tired yet supportive mom to the overthinking, awkward middle school boy twiddling his thumbs in the seat beside her. And so, we both soaked in the music, the memories they held made palpable through its melodies, with new memories made alongside them— without a word exchanged between us.

Music critics love to beat dead horses. They love to make grand statements like “music is dead.” They love to wax poetic about how this band, this magnificent new band, is better than every other band who ever dared to touch an instrument. They love to write entire essays about subgenres like alt-country, which most people have never heard of.

So the question is: what is there left to say? Even talking about talking about indie music has been played out for at least twenty years; at least since James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem released “Losing My Edge”, featuring lyrics such as, “I hear that you and your band have sold your guitars and bought turntables/I hear that you and your band have sold your turntables and bought guitars/I hear everybody that you know is more relevant than everybody that I know.” The horse has been beaten and resuscitated and beaten again for the past six decades, and even the people who got a kick out of the beatings have grown tired. What is there left to say? It seems to be the ultimate question not only for critics, but for new musicians themselves. Country music continues to top the charts, and rock music is certainly not forgotten, but these genres are excessively commercialized to the point of suffocating creativity.

Often, people say that what these genres lack most today is authenticity, but authenticity is an elusive word thrown around far too often in music discourse. There is no guaranteed way for an artist to appear genuine, and searching for authenticity is paradoxically inauthentic. Everyone likes to think their favorite artist became popular solely on their own merits, that they dragged themselves up from the bottom with no one to rely on. It’s a nice story, but one that doesn’t apply to every successful artist today. Does that mean every single musician on the planet is a morally bankrupt

industry plant without an ounce of originality? Of course not—only most of them. The truth is that the music industry thrives on inauthenticity; it thrives on easily replicated trends, lyrics made for social media soundbites, and melodies made to torture H&M workers. But there is always a light at the end of the hellish corporate tunnel.

The answer lies in the rebirth of alt-country. It’s a genre that originated in the 1990s, and later captured the hearts of a new generation with its eclectic blend of folk, Americana, and alternative rock. Alt-country is defined by its messy, heartfelt guitar parts, personal lyrics, and less-than-polished voices. It’s a subgenre that invites its listeners down an old path, a path that dates back to the very beginnings of rock and country. The artists shepherding the altcountry resurgence aren’t exclusively concerned with mainstream popularity or social media trends. They know that sometimes the only way forward is to fall blindly backward—to trust the principles of good songwriting that have always guided great artists.

The alt-country revival is spearheaded by Waxahatchee, MJ Lenderman, Frog, and Friendship, among many others. Their music is rooted in the foundations of country, rock, and indie music, which gives their songs a timeless and familiar feel. The sound is reminiscent of artists like Wilco, Lucinda Williams, Silver Jews, and Songs: Ohia, but these new artists are not merely carbon copies. On Waxahatchee’s latest album Tigers Blood, the songs are meticulously crafted and full of vulnerable, earnest lyrics. A standout is “Right Back to It”, which features backup vocals from MJ Lenderman. The two join together, singing, “I’ve been yours for so long/We come right back to it/I let my mind run wild/Don’t know why I do it/ But you just settle in/Like a song with no end/

If I can keep up/We’ll get right back to it.” It’s undoubtedly a catchy sing-along, but at no point does it feel made for the sake of a radio hit.

At its best, alt-country mixes the gritty, downto-earth sound of country with the peculiarities and experimentation of indie rock. On Frog’s 2023 album Grog, the band fuses all their influences into a carnivalesque masterpiece. When the chorus arrives on their song “Goes w/o Saying,” the instruments are deceptively simple, pulling you into a trance-like state in seconds. Even the lyrics are simple but irresistibly hypnotic: “Hey boys, I’m walking on water/Somebody’s daughter made me feel rotten/I forgot her name/And the bells of the father rang over the water/Oh, God, I want her/It goes without saying.” The songs are often filled with desperate lyrics like this, but contrasted with soaring, beautiful instrumentals. It’s authentic in every sense of the word, and it’s enough to melt the hearts of even the most cynical of music critics.

Pioneer DJ’s DDJ-FLX4 is everywhere, and it’s nearly inescapable. The two-deck DJ controller with orange accents is responsible for most of the DJ content you see outside of Boiler Room sets. It’s the small controller they’ll often have at a dorm, frat, or even a chill dinner party. It feels like everyone wants to be a DJ now. Or at least, everyone wants their piece of the “niche pie” as electronic dance music makes its return to the mainstream. It’s seen in 2hollis’s recent surge in popularity, the unearthing of older Charli xcx tracks, and even in long-standing artists reentering virality, like Aphex Twin’s “Xtal” and the phantasmagoric music video for “Korg Funk 5,” directed by Nadia Lee Cohen. Online, quick tutorials on Reels, homemade mashups uploaded daily, accommodate new DJs, and thus usher in a growing wave of bedroom DJs. Unlike the past decade, the affordability of a two-channel controller has also created an exponential growth within the culture. The hype behind the FLX4 is warranted; it’s one of the best beginner controllers—easy to use and supported by major industry-standard software such as Rekordbox and Serato. The barrier to entry has been broken down, causing the rejuvenation of electronic music for both new listeners and emerging producers.

Artists who represent this new era for house music include UK-based artist PinkPantheress, who has reignited interest in jungle and drum ‘n’ bass, as well as other producers like Gaskin and JACK MARLOW, who are the bigger names in the genre

of house. House music now has a different look and reputation, more pristine and exclusive—or so some netizens believe. Perhaps, it prompts one to go on a trip to Ibiza, or maybe “on a yacht party in Greece wearing all linen and Margielas” (@dylan. santorini on TikTok) listening to Cody Wong’s “What Does It Take.” Even if you aren’t on a yacht on the Mediterranean, you might go to a rave that costs $35 just to get in because you didn’t purchase the “Early Bird” tickets for $10 two days ago. You just saw the ad for the rave today, sandwiched between two people’s stories on Instagram.

Rave culture may be the hip, new thing to bandwagon; arguably, it is more mainstream than ever before. Of course (and as always), the internet will turn anything into a game of “performative or not,” with a minute-long thinkpiece. The current discourse that follows this sudden uptick in rave culture is concerned with the authenticity of those who bolster a newfound love of electronic music genres and raving. Are people pretending to like house music just for the sake of fabricating an interesting persona or is it genuine interest? Frankly, it’s difficult to tell, especially as it’s a rather harsh generalization of novice listeners.

Another concern throughout the history of house and other electronic music genres, whitewashing, which has been a persistent issue. Calvin Harris, one of the most prominent names of contemporary electronic music, had an odd source of inspiration in crafting his pseudonym. His goal was to make his musical persona racially ambiguous; in other

words, if he was assumed to be a Black man, he believed that it would benefit his musical career. It’s a half-baked concept; cognizant of the origin of the genre he produces, Harris is willing to actively capitalize on Blackness while erasing the history simultaneously.

Other major genres, such as jungle and drum ‘n’ bass, are the product of marginalized, workingclass people. It’s for the people, by the people.

The name ‘house’ originates from its birthplace: The Warehouse, a queer, underground, and inviteonly nightclub in Chicago, established in 1977 by Robert “Robbie” Williams. Resident DJ, Frankie Knuckles, helmed the sound of the Warehouse from 1977 to 1982. Hailing from New York City, Knuckles—dubbed the Godfather of House—melded disco, funk, and other early electronic genres to create house music. House music then grew in popularity throughout the Midwest and New York City. The popularization was also partly due to the teenagers who would sneak in, the spread of the 12” record, and airplay on the radio. The global influence has created numerous genres, spanning from dubstep to Eurodance. These producers were still primarily normal people with extraordinary forms of expressing their experiences, lives, and more.

Therefore, to argue, there is weight and importance of the limited invitation—these exclusive spaces are created to counter the grossly discriminatory practices many clubs at the time incorporated, such as barring Black patrons,

and this still occurs today in very covert ways through “dress codes.” The invitation acts as a safeguard against the close-minded, and it protects its typically diverse crowds from the dangers of racism, homophobia, transphobia, and other forms of bigotry. After all, the ultimate foundation of rave culture is its code of conduct: PLUR, or Peace, Love, Unity, and Respect. Yet, with the recent popularization of raves, one could even argue that PLUR is dead. The rave has become so heavily commodified to the point it has become an oversaturated market..

The selective “if you know, you know” culture created to maintain these sanctuaries has shifted to a money grab. That’s why your supposedly “exclusive” ticket rose from $10 to $35 in just two days.. Or the “rave-themed” frat party with the pashmina dress-code, converting a symbol of harm reduction, comfort and safety, and community into an accessory of little to no value. The meaning chips away, the symbolism and language of electronic music, developed over the years, now dissolve into nothing. Just vague signifiers that “kinda-sorta” mean rave.. The core of this music and community, based on liberation and respect, will never truly die. It’s just becoming lost in translation.

On June 24, Pharrell Williams debuted his Spring/Summer 2026 Louis Vuitton collection to scores of mixed reviews. Some publications offered automatic praise, and other unconvinced netizens traduced it as “something AI would come up with.” It’s no secret that Williams’ recent collections at Louis Vuitton have routinely fallen short of the mark, but where the multi-platinum designer, artist extraordinaire never falters is music. On a runway inspired by the Indian children’s game Snakes and Ladders, models strutted to the sounds of Virginia-based gospel choir, Voices of Fire. The choir performed a soaring score, co-written by The-Dream, and accompanied by l’Orchestre du Pont Neuf. As it would happen, it’s actually incredibly easy to overlook Williams’ stale monograms when a 75-person gospel choir is performing a certified trap-soul banger. Maybe that was Williams’ plan all along. In an era of fashion where major houses are wrestling with how to get the public interested in luxury, maybe Williams knows what we don’t—good music is rarely a bad bet.

For as long as models have been stalking runways, the fashion and music industries have remained closely intertwined. Spectacle is nearly always the name of the game, with some of the most memorable shows in past eras incorporating vivid set-dressing, unorthodox venues, and yes, even star-studded musical performances. The iconic conclusion of Mugler’s 1995 Fall/Winter show featured the late legend James Brown screaming over house beats. In the Fall 1991 Versace show, supermodels Linda Evangelista, Cindy Crawford, Naomi Campbell, and Christy Turlington walked out, arm-in-arm, lip-synching George Michael’s hit “Freedom! ’90.” Even earlier than the 90s, Vivienne Westwood’s infamous partnership with the Sex Pistols, and Studio 54’s nightlife—turned art

space, turned runway—were already blurring the lines between live music and living style. The rich history of music and fashion highlights a perfect nexus point between performance and presentation.

Yet, moving into the late 90s and early 2000s, fashion shows routinely began to implement curated soundtracks and DJ sets over live performances. This was likely a joint response to rampant club culture and the irresistible allure of music that could be timed to the minute—perfectly synced with the runway with no room for error. Sound curators and music supervisors were increasingly employed by the largest houses to ensure a creative director’s vision could be captured not just visually, but sonically. For Ben Brunnemer, a go-to curator for Thom Browne, this process entails extensive conversations with the designer in order to best understand the conceptual vibe of the show. Michel Gaubert, who has overseen music direction at Chanel, Dior, Loewe, and Fendi, collects sounds from a seemingly infinite amount of musical references (2,022 days’ worth of music sits in his iTunes). In many ways, the ultimate endgame of fashion DJs and sound curation came in the form of Virgil Abloh, whose previous work as a DJ and producer ensured his groundbreaking collections acted as veritable cultural mixtapes.

Smash cut to the present, where familiar strategies just aren’t working for high fashion. The luxury world is already suffering at the hands of tariffs and worldwide economic instability, which has prompted a full-scale identity crisis within the industry. Many houses have resorted to knee-jerk firings and subsequent hirings of new creative directors, in hopes that this will get audiences interested again. We’ve still yet to see whether this method will pan out, but what Pharrell and others have come to suspect is that in the 21st-century media sphere, the

production of a show should be at the forefront of any designer’s mind. Speaking about these changing tides, fashion critic Tim Blanks explained, “It’s no longer enough to stage a show of sellable looks set to a soundtrack that matches the designer’s particular vibe that season because fashion is no longer a ten-minute-plus spectacle for a fabled few on invite lists.” Nowadays, fashion shows are disseminated throughout the internet, available not just to the exclusive readers of Vogue, but to anyone with even a casual understanding of Instagram.

The fashion world is also still very much reeling from the COVID-19 pandemic, which rendered live runway shows and glitzy guest lists unfeasible. Designers grappled with these challenges in a myriad of ways. Jaquemus, for one, presented their SS21 show in a bucolic wheat field, with guests spread 6 feet apart. Other shows were played out in empty venues, streamed to thousands of online viewers.

In-person fashion shows have returned, but the impacts of post-pandemic declining sales have encouraged many major houses to scale back their shows. Even B2B trade shows have declined in attendance since 2019, despite there never being more of an online demand for glamorous showcases. Retail tech expert Jessica Couch reports, “Buyers and exhibitors are coming back where value is unmistakable—especially when organizers redesign around curated matchmaking, hands-on demos, and community moments that feel real rather than manufactured.”

Pharrell’s Louis Vuitton extravaganza certainly checks the box of “Community moments.” Backstage videos circulated on social media showing models clad in LV, dancing and bumping their heads along to the music. Before Williams released official versions of the soundtrack, Soundcloud users had

even uploaded pirated copies. All of this generates the exact kind of buzz that luxury houses are desperately craving.

If Williams offers a vision of large-scale musical accompaniment, Jil Sanders’ FW24 show provided a more intimate, albeit still effective approach. Attempting to capture a surreal atmosphere, creative directors Lucie and Luke Meier invited the elusive musician, Mk.gee to perform a medley of distortion-heavy hits. Though the show itself was set-dressed with a number of blue funnel-shaped sculptures, Mk.gee himself stayed shrouded in back, tucked behind innumerable amps and pedals. This was well before Mk.gee would come to work with the likes of Justin Bieber, and at the time, Jil Sanders’ choice to feature his music was a nod to a relatively niche audience. Even in a scaleddown way, the Jil Sanders show underscored live music’s role in reviving intrigue in fashion.

Even as the major houses continue to grapple with decreasing sales, interest in fashion among young people has never been higher. Social media has allowed more people than ever to observe and comment on fashion runways, and according to Statista, “Platforms like TikTok have also influenced young consumers’ shopping habits, creating a shorter lifespan for trends.” In such a rapidly changing milieu, a runway can be a prime opportunity to hold attention. Whether Williams’ SS26 collection was or wasn’t “The male equivalent of Dior by Maria Grazia” hardly mattered when Voices of Fire’s recently created Spotify page has already amassed 750,000 listeners.

Pop girls may not be “reinventing the wheel” in the genre at large, but they certainly have to reinvent themselves every era. They may bedazzle the wheel, or beat it to the point of no return, but they have to sell the wheel, don’t they? An autoshop would have no problem selling the same old wheel many times. A pop princess, however, would.

As Taylor Swift said in the 2020 documentary Miss Americana, reinvention is a necessity. “The female artists I know of, they’ve reinvented themselves 20 times more than the male artists. They have to or they’re out of a job.” Reinvention, to her, equals relevance. While this certainly has applications in past decades, we’ve reached a strange time in which reinvention may no longer be necessary for success. Can we expect this to stay true in the future? And what does it mean for the music industry?

There’s no example, of course, as obvious as Swift herself. Her eras warrant their own article. From the albums with an old-fashioned country twang, to the pop Bible 1989, to the folksy records of the COVID-19 pandemic, Swift is proof that “reinvention=relevance.” Every new era finds her more successful than the last, and for an artist with twenty years under her belt, that’s impressive.

But Swift is not alone in reinventing herself. The examples are endless. Beyoncé went country; Lorde’s gone from teenage angst to beach classic; Charli XCX has gone from britpop to brat. Billie Eilish and Gracie Abrams have left so-called “whisper singing” and now showcase their excellent vocals. Artists like Ariana Grande, Doja Cat, Halsey, Selena Gomez, and Lady Gaga have had countless eras of their own. In a newer instance, global girl group KATSEYE has seen success in their two thematically contrasting EPs: the first being SIS (Soft is Strong), and the second being

As is implied by Swift’s quote, men do not face the same pressure. Their success doesn’t hinge on transformation. If a woman spent twelve years releasing albums titled after mathematical symbols like Ed Sheeran, she’d certainly need to have a hell of a lot else going for her. There’s nothing wrong with Sheeran or his music, but using the same concept for twelve years is something only a man is capable of. Similarly, when men reinvent themselves, it’s not as often a necessity—it’s pure personal enjoyment.

Some female artists have reached a level of success where they have the freedom to do the same. Swift has spoken with nothing but excitement about her newly released album The Life of a Showgirl. It’s not a bad thing for Swift to create an album that’s different, and there’s no saying the motivation behind her thematic rebranding. There’s a thin line between reinvention for reinvention’s sake and reinvention to stay relevant in the public eye. Both can be applicable at once. We’ve seen this with the new class of pop girls, but it seems as if many of them are leaning away from concept. While Sabrina Carpenter is certainly not new to the pop scene, her relevance has increased with her 2024 album Short n’ Sweet. It was followed by Man’s Best Friend in 2025. The latter pop album sees some country influence, but really, they aren’t too different. Carpenter’s brand is strong, sexy, and saccharine. While this hasn’t been the case with every one of her seven albums, it’s how she’s defining herself now, and it’s this definition that’s found her the most successful.

Similarly, Chappell Roan and Olivia Rodrigo are consistent with how they’ve labeled themselves so far. We’ll see what Roan’s eventual second album brings, but Rodrigo’s matured from Sour to GUTS and stays true to the spunky Y2K and light “riot

grrrl” image.

Carpenter, Roan, and Rodrigo create music that builds community in spaces that have long been ignored. Of course, they have their role models— female artists who paved the way for hypersexuality (Madonna), queer culture (Lady Gaga), and the brutal nature of being a teenage girl (Avril Lavigne) to be represented in music. But they’ve found their niche, and they’ve found commercial success in it. Additionally, they’ve contributed to defining the sound of the 2020s, launching their genre of music into a new stratosphere of popularity.

“Be new to us, be young to us, but only in a new way and only in the way we want,” Swift continues in her documentary. “And reinvent yourself, but only in a way that we find to be equally comforting but also a challenge for you.”

For decades, women have carved out space for themselves in the male-dominated music industry. Then, when the space starts to be filled, or simply isn’t interesting to mass consumers anymore, they’ve carved out new spaces. They’ve pushed themselves further and further; they’ve pushed the boundaries of pop music. Now, on equal footing, it’s almost like taking a deep breath and wondering what’s next.

The music industry is heading in a direction where female artists can pursue the music they want to make. With the widespread use of social media, there’s an audience for everything. Reinvention is no longer essential for success. At the same time, if a female artist wants to reinvent herself, she has the choice to do so.

With this movement, though, there’s also the danger of society trapping new artists in a box. If reinvention is no longer the expectation for female artists, we might find that stagnation is. If Sabrina Carpenter wants to play the femme fatale for the rest of her career, it should be her choice

to do so, not a niche that she’s pushed into.

Hopefully, we’ll continue in the direction of women experiencing creative freedom and control of their own work. The pop music scene has been built on the backs of thousands of unique musicians, and every female artist mentioned in this article has played a part in shaping the space into what it is today. There’s still room for them, and there’s room for new artists to break through as well. It’s the listener’s duty to show respect to these artists and to give them space to be who they want to be.

In the fall of 2018, actor Rami Malek was adorned with giant prosthetic teeth, a protruding, crooked set of faux enamel that, when paired with an effete English accent, elegant posture, and an emblematic broken microphone stand, revived rock legend and Queen frontman Freddie Mercury. Malek went on to win the most distinguished awards for an actor, sweeping Hollywood ceremonies at the behest of his peers. But Bohemian Rhapsody’s most impressive feat was its ability to reinvigorate the fanaticism around Queen, which had dwindled in the decades following Mercury’s death.

This is the power of the musician-biopic, a sub-sub-genre that follows the life and career of musical icons, displaying moments of grandeur and struggle in a three-act structure, which Bohemian Rhapsody perfected. Since its release seven years ago, biopics have been on the rise, rallying the masses to obsess over the pivotal yet mysterious figures of pop culture.

A year after the release of Bohemian Rhapsody, another biopic about a 1970s queer British rockstar who wore tight, sparkly outfits hit theaters in what seemed to be an echo of the preceding film’s success. Rocketman, starring Taron Egerton as pop legend Elton John, is a fantastical journey through the lens of a larger-than-life artist struggling with identity and addiction throughout his rise to fame. The two films represent the majesty and tragedy of these artists’ lives, drawing ‘normals’ in with the fuss and feathers, and gripping our hearts with emotional narratives, leaving us moved and enraptured with these mythical figures.

After Bohemian Rhapsody and Rocketman, artists like Aretha Franklin, Elvis Presley, Bob Dylan, and even “Weird” Al Yankovic got the biopic treatment, their legacies and careers re-examined by a changed — practically unrecognizable — world from the one that first heard their music. The

modern mainstream, driven by a digital world of algorithms, sensationalism, and the fickle interests of young people, creates an oversaturated, fastmoving attention market that consumes art just as quickly as it spits them out.

Biopics reflect reality, albeit one construed, written, and aestheticized by Hollywood elites for the sake of entertainment and box office success. It’s difficult to discern mercenary intent from genuine, impassioned storytelling — exploitation from artistic exploration. Passion is not lacking from performers. Austin Butler, having famously gone full method in the role of Elvis and allegedly permanently maintaining the baritone of the late musician, certainly doesn’t lack it. Neither does Timothe Chalamet, who, to promote the film A Complete Unknown, traveled across America spreading the gospel of Bob Dylan’s life and discography.

But there is something to say about how the film industry perceives the appeal of biopics. With built-in audiences ranging from older, nostalgic crowds of classic rock enthusiasts to younger generations who think retro is trendy or find the actors oh-so dreamy, millions of viewers are willing to see musicians revived on the big screen.

And in a post-COVID world of empty movie theaters and a hundred billion-dollar streaming industry, studios need the cash — and nostalgia is a very profitable investment.

Over the past seven years, these films have revived both the careers of mid-century musicians and the biopic genre itself. Streaming of Queen’s music catalog more than tripled after the film’s release in November of 2018, which means the band’s revenue tripled as well. In 2022, Elvis Presley’s monthly listeners on Spotify increased by three million, and his estate value doubled from $500 million to almost $1 billion.

Driving numbers in tandem with nostalgia is

modern celebrity culture, a force that has stolen society’s attention with the glamour of high-profile individuals and gives us new, old celebrities to obsess over. But at times, captivation gives way to idolatry. Biopics are the perfect recipe to create mass obsession around a revived, mythical figure, their fall from grace only adding to their mystery and appeal. Using a combination of pointed writing, dramatic music, and visceral cinematography, the evocative nature of filmmaking becomes centered around a single person, whether alive or dead.

Following the release of A Complete Unknown, a 2024 biopic about a young Bob Dylan, younger generations were enraptured with the folk singer’s Midwestern accent and laid-back and pretentious, yet mysteriously attractive persona. Folk songs released as early as 1960 were suddenly circulating throughout groups of young people, but this time they weren’t sung by a Minnesota legend, but rather a beloved actor with a large and dedicated fanbase. The resulting surge of Dylan-themed media raises questions about whether audiences’ reception of the film truly revived the musician’s career or co-opted his music and Chalamet’s performance in order to create another trend.

A Complete Unknown is an example of the potential danger in attempting to revive a musician’s persona and artistry. The film was successful in making people listen to Dylan’s music, his weekly streams growing by around 150% after its release, but it also altered his life and legacy. Dylan’s stance as a purveyor of change in music, society, and culture, as well as a prominent activist and poet, isn’t taken seriously or acknowledged by the mass culture. Instead, we see “Bob Dylancore” TikToks of young men hunching over in oversized jackets to Dylan’s crooning voice in “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright.” But even as ridiculous, albeit amusing, as these reactions

may seem, it’s the same way Gen Z reacts to any prolific figure that we become enraptured by. When a prominent contemporary artist, like Taylor Swift, Beyoncé, or Bad Bunny, releases an album, the first reactions on social media are young people dancing to, singing along with, or attempting to embody the music in a carefree manner. Dylan’s music, which many adolescents listened to for the first time in December 2024, is not excluded from this phenomenon.

However, social media isn’t strictly to blame for misinterpretations: Studios are often at fault as well. Movies are a 120-minute, at times less, momentary glance into a complex person’s life, and while they create buzz around older artists, they risk misrepresenting motives and personhood. Even in the most successful biopic of all time, Bohemian Rhapsody, integral aspects of Mercury’s life, including his sexuality, are glazed over and diluted as a third-string storyline. In Elvis, in an effort to evangelize the late artist, many of his misdeeds are also overshadowed by the villainous nature of his manager, Tom Parker, played by Tom Hanks, whose portrayal is overwhelmingly dramatized to the point of absurdity. There are also instances, as in the Amy Winehouse biopic Back in Black, where artists are demonized more than deified. In Back in Black, Winehouse’s life is oversimplified to focus on sensationalizing her addiction and dysfunctional relationships, and neglecting her artistry and mental health struggles. No matter how much criticism is thrown in the way of studios, there is still damage done. By the time this article is printed, another

huge biopic project, Deliver Me From Nowhere, will have hit theaters and likely revive the career of American singer-songwriter Bruce Springsteen. Hollywood will have gotten their check, Jeremy Allen White’s portrayal will have generated an Americana-themed trend, and Springsteen himself will likely receive some new praise and attention past his political statements. In the next few years, Sam Mendes’ Beatles project, starring some of the U.K. ‘s most eligible bachelors, will be released and recreate 60s Beatle-fever. Michael, the upcoming 2026 Michael Jackson biopic, is basically a sure thing in terms of success and cultural relevance, with his nephew Jafaar Jackson playing the late King of Pop. Fred Astaire, the Bee Gees, and the Grateful Dead will also be getting their own career-reviving biopics, which is likely a sign that Hollywood is beginning to run out of artists.

Still, musician biopics aren’t dying down any time soon. With the state of celebrity culture and affinity for nostalgia, these films endear themselves to the masses in a perfect recipe of drama, passion, and legendary music. But until we as a collective society attempt to cohesively inspect, rather than just quickly consume the personhood of artists, we may miss out on real lessons and cultural reality in favor of mythology. Until then, we’ll continue to consume, listen, and watch in unabashed fascination, perhaps because we want to be a part of the enduring legacy they created, or to satiate our desires to see the rich and famous struggle — just like we do.

Speeding down I-84 at 80 mph in the carpool lane, the car is silent until a soft nasal voice warbles through the speakers, closely followed by our voices matching the tone and pitch exactly. My mom and I sing along: “Day after day/I will walk and I will play/but the day after today/I will stop and I will start.” Bam! The instruments break through with a crash, the bass guitar bouncing around the car, vibrating off the windows. We bob our heads furiously to the beat. I look at my mom and smile. I feel completely connected to her at this moment. Nothing comes between us but the music flowing through the air.

The song we were singing along to was the Violent Femmes’ 1983 track “Add It Up” from their self-titled debut album, a monumental record that inspired the angsty, high-energy, genre-mixing style of 1990s alternative rock. I discovered this band through my mom when she first showed them to me on one of our many car rides together a couple of years prior, and it has become a staple of ours ever since.

Much of the foundation of my music taste comes from the albums my mom would show me as I entered my teenage years. Every few months, we would take a two-hour road trip out to Canton, Connecticut, to visit her cousin, who she grew up with. On the car ride there and back, I would listen intently as she divulged stories from her past, her music playing in the background. As a teenager, she used to pick up her cousins from Canton on the weekends and drive back into Hartford, where she lived, to dance all night at 18+ dance clubs. I can imagine them, hair full of hairspray, bright shades of eye shadow covering their eyes, wearing their best outfits, complete with fishnet tights and black lace blouses. They danced until they could no longer stand, exposed to all different types of music for the first time: Depeche Mode, The Cure, The

Clash, Public Enemy, INXS, Madonna, New Order, the list goes on. These stories filled me with joy and nostalgia for a time I was never even a part of. I wish so badly I could go back and dance in those clubs with them, experiencing the rush those songs brought them. But at least I can listen to the music to get an inkling of how my mom must have felt hearing the same sounds all those years ago.

Music is one of the most fundamental ways we connect as humans. When we are born, we are often sung to in order to soothe us to sleep. For many, music is deeply ingrained in early education, with nursery rhymes and other memorized tunes. We each grow up listening to different kinds of music from all around us, whether it’s on the radio, what our parents play for us, or what we happen to find online. Every one of us has had different songs that we’ve played over and over until we couldn’t bear to hear them anymore. The songs we listen to as we grow up are more than just music; they become a part of us—our life, our identity, our history. When we share that music with others, we keep that history alive.

I remember when I started to really take my mom’s music recommendations seriously, not just listening to them with her in the car, but also taking the time to explore her music on my own. When I listened to The Lion and the Cobra by Sinead O’Connor for the first time and heard Sinead’s voice build to the impassioned shouts on “Just Like U Said It Would B,” I was overcome with emotion I didn’t know music could evoke. Her desperate pleas, “Will you be my lover?/Will you be my mama?/ Will you be my lover?/Will you be my babe?” before breaking into her shrieking repetitions of the title of the song, filled me with a feeling of satisfaction that I have been chasing in the music I listen to ever since. The raw power of her voice blew me away, and I couldn’t wait to talk to my mom

about the genius behind her music. I not only felt connected personally to what I was listening to, but I felt a stronger connection to my mom than ever before, all from listening to a song in my headphones. Just knowing that my mom had listened to the same music during the same formative years of her life made me feel like I knew her on a deeper level.

I was in high school when we first got a record player, not long after we began our trips to Canton. I took a whole afternoon going through the tightly-packed crate of records my mom kept hidden away in the basement. One by one, I placed each vinyl on the machine and was disappointed each time when the sound would come out all warped. The thin cardboard sleeves didn’t do much to protect the records from the New England moisture they’d been exposed to for decades. But just holding these family artifacts in my hands, I felt privileged to have this evidence of my history. Some of the oldest records, like the Beatles and Elvis, even came from my grandmother. My grandmother passed away when I was just a toddler, so I don’t have many physical things to remember her by, but I always feel close to her when I play the music that she passed down to my mom and me. It doesn’t matter whether I’m listening to the original records or not; the music is the same either way. That’s the beauty of music. It’s timeless. As long as we keep sharing and preserving it, the music will live on forever.

When I moved away to college for the first time, one of my brothers had the idea to create a shared playlist for the whole family, with the intention that each of us would add one song to it every week. At first, I didn’t think anyone would stick with it, or that we wouldn’t want to listen to each other’s songs, but soon enough, we had a considerably lengthy playlist that blended each of

our music tastes together seamlessly. From song to song, I was able to track the influences our parents passed on to us. My dad contributed his 80s alternative rock: Throwing Muses, Pop Will Eat Itself, and the Talking Heads. My mom added her favorites, both old and new: Cage the Elephant, Foo Fighters, and Siouxsie and the Banshees. Then my brothers and I brought in the music we’d acquired over the years: Green Day, Mac Miller, TV Girl, the Pixies, and Fiona Apple, to name a few. This range of artists might seem vast, but they can all be traced back, in one way or another, to the music we heard growing up. Each artist charts not only our musical history, but also our family history. You can see how our music tastes branch out from the same influences, overlapping and winding into different directions. In the same way, our family has branched out into all different directions as we’ve grown into adulthood, while always staying grounded in the roots that make us who we are.

I can’t wait to continue rediscovering the music of the generation before me and those before them. It is through these rediscovered roots that we stay connected to one another and keep our collective history from being forgotten. Without this exchange of culture, we lose the richness of the full picture of musical influences that can be seen in every single artist releasing music today. I hope to one day pass down the music that inspires me to the next generation as well, continuing the feeling of overwhelming connection and community that I experience when listening to music in the car with my mom.

Ialways find it miraculous that more bands don’t break up. A band, to me, seems like an inherently volatile unit: a group of highly creative individuals falling into each other’s lives in a desperate attempt to make good music, get famous, or just get paid (your motives may vary). Add in the unbelievable amount of time bandmates spend together, and you’re guaranteed at least some conflict. Enter: the equal parts exciting and heartbreaking phenomenon of a band breaking up.

Breakups are dramatic, but what’s really interesting is what happens afterwards. Does the band fall into cold silence, never speaking to or about each other again? Do individual members produce increasingly bad solo work? Does one member launch a new and successful career while the rest bitterly look on? Or maybe, just maybe, do they get back together?

A reunion album is a fascinating piece of art. They are created within the context of the band’s previous breakup. They are a prime opportunity to address conflicts in musical form. They can be innovative and brilliant, or they can be soulless cash grabs rolling out the greatest hits in the hopes of maintaining an audience. Above all, reunion albums showcase the unique magic created by these specific musicians under this specific name, a magic we recognize all the more for its previous absence. This is my attempt at reviewing reunion albums that fascinate me.

After cycling through several lineups in their early history, Fleetwood Mac settled into a fivemember configuration by the 1970s: Mick Fleetwood, Stevie Nicks, Lindsey Buckingham, Christine McVie, and John McVie. Together, they created the classic album Rumours (1977), a fantastic record created as

the band was barely avoiding total collapse. Nicks and Buckingham were in the midst of ending their years-long romantic relationship; Christine and John McVie were struggling through a divorce; most of the band was addicted to cocaine. Fleetwood Mac made it through several more albums before falling apart, as personal conflict and creative differences proved overwhelming. None other than Bill Clinton helped end the breakup: he requested that the Rumours lineup reunite for his 1993 inauguration. They obliged, didn’t kill each other, and four years later reunited fully with The Dance.

The Dance is a live album. It’s almost simplistic; for the most part, it’s a set of Fleetwood Mac’s greatest hits, a retreading of old songs.

On the other hand, they’re very good songs. There’s a reason the Rumours lineup churned out so many hits. The magic is in Nicks’ otherworldly voice; Buckingham’s guitar skills; the steady rhythm section of Fleetwood and John McVie; and the perfect harmonies between Nicks, Buckingham, and Christine McVie. Classics like “The Chain,” “Dreams,” “Everywhere,” and “Landslide” are as great as ever.

There are some innovative moments. A few songs are arranged differently. “Sweet Girl”, “Temporary One”, “Bleed to Love Her”, and “My Little Demon” are new material.

Then there’s “Silver Springs”. The song is Stevie Nicks’ pure fury over the end of her relationship with Buckingham. “I know I could have loved you / but you would not let me…” she sings. “You’ll never get away from the sound / Of the woman that loves you.” In a 1997 interview with Arizona Republic, Nicks explained the song like this: “You will listen to me on the radio for the rest of your life, and it will bug you. I hope it bugs you.” During the live performance, Nicks and Buckingham turn and stare each other down while playing

through the final minutes of the song.

This is the most notable moment in The Dance that goes beyond reliving already famous songs; “Silver Springs” was an obscure B-side before it made it onto the reunion album. The performance is somewhat self-conscious, aware that it is part of a reunion that has been years in the making and will draw significant attention. It is venomous enough that you have to ask yourself: Is this a dramatic representation of past emotions, or is this how the members feel towards each other now? The performance breaks from The Dance’s main purpose as a safe retread of greatest hits to reference the conflict that originally destroyed the band. It is the one part of The Dance that leaves you uncomfortably aware that the drama isn’t over yet, not by a long shot.

Bruce Springsteen described his relationship with his longtime backing band best: “Though I would have never gotten where I am without the E Street Band, it is ultimately my stage.” Springsteen is not part of a band. He’s a performer who often plays with one.

Still, the E Street Band was an indelible part of Springsteen’s image as he rose to fame. Their guitars, drums, saxophones, and organs worked their way into many of his most iconic albums, including 1984’s unbelievably successful Born In The U.S.A. It was not just a musical partnership; Springsteen was close friends with many members of the band.

But Springsteen’s star eclipsed that of his band, and as he started to record projects without them (like 1982’s Nebraska), small conflicts arose. Born In The U.S.A. would be the last album they recorded together until 2002’s The Rising, released a full

18 years later.

In 1999, Springsteen and the E Street Band began a successful reunion tour. They decided to record new music, but thought the material sounded flat and dull.

The Rising emerged out of a national tragedy. Springsteen wrote most of it in response to September 11th, often directly referencing the event. “The sky was falling and streaked with blood,” he sings in “Into the Fire”. “I heard you calling me, then you disappeared into the dust.”

It’s perhaps fitting that Springsteen chose this record to reunite with the E Street Band. When confronted with unimaginable grief, who else would Springsteen go to but his faithful backing band? In the midst of a national rebirth, Springsteen staged a personal one. The E Street Band propels The Rising forward and imbues it with a stronger sound. Springsteen, meanwhile, touches on familiar and fitting themes of faith, destruction, and revival.

The Rising is a reunion album that succeeds because it feels so little like a reunion album. It does not call back to the immensely popular albums Springsteen previously released with the E Street Band. It contains no anxious references to the personal troubles that lingered within the group before their reunion. If The Rising failed to produce as many standout songs as some of Springsteen and the E Street Band’s previous work, it remains a perfect example of what the group does best: responds to American tragedy with a touching combination of grief and hope. It never feels like a nostalgic album; rather the start of another chapter in Springsteen and the E Street Band’s long story.

Bratmobile - Ladies, Women, and Girls (2000) Bratmobile was started in the 90s by Allison

Wolfe and Molly Neuman, then classmates at the University of Oregon. Intrigued by the emerging riot grrrl scene in Olympia, the pair launched a fanzine interviewing other bands, and then formed one of their own. Bratmobile released one album— 1993’s Pottymouth—before breaking up as the scene grew increasingly complicated.

Like other renowned albums broadly grouped into the riot grrrl genre, Pottymouth focuses on matters of misogyny, sexuality, and the commodification of punk rock. The band’s anger at the place of girls in society is palpable, and their songs are driven by sharp and sarcastic lyricism. Their musical strategy, as described by writer Sara Marcus in her book “Girls to the Front”, was “profane ridicule”.

A standout track off Pottymouth is “Stab”, which confronts violence and rape with simplistic yet intense lyrics and an almost muted tone. These elements serve only to heighten the uneasy feeling that such brutality is so normalized, we barely pause to notice it anymore.

Bratmobile was relatively quiet after their breakup. They reunited with the 2000s Ladies, Women, and Girls.

Unlike Fleetwood Mac or Bruce Springsteen, Bratmobile didn’t have a massive back catalog to return to. Their only major output was Pottymouth. This is why, perhaps, it is difficult to listen to Ladies, Women, and Girls without comparing it to Pottymouth.

Ladies, Women, and Girls begins with more complex and fantastical lyrics in the opening tracks “Eating Toothpaste” and “Gimme Brains”. “We’re eating toothpaste and blue Play-Doh / We’ve got a dress up box with no place to go.” There are other great moments in the album, as with the prophetic line: “They say the Silicon Valley boys are lonely, and so are you / But I don’t care, ‘cause no one cares about girls who are lonely too.”

The album grows more repetitive towards the back half. Compared to Pottymouth, it often sounds like more of the same. Unlike Fleetwood Mac’s reflective reunion, Ladies, Women, and Girls focuses on external rather than internal issues and boasts a slate of fresh songs. But unlike Springsteen’s rebirth, Bratmobile’s return feels like the continuation of a golden age, rather than the invention of a new one.

On the other hand, is that a problem? A band’s breakup stings because we know we are losing a unique sound, something that once was and is no longer. A reunion is magical because we get to return to that sound. Bratmobile’s angry, lovesick, and witty tone was cathartic to listen to, so why not revive that tone? Why not revive that band?

Maybe that’s the real miracle: not that bands stay together, but rather that they can fall apart and still sound like themselves when they reunite. And even after all these years, they ring with familiar brilliance as they stage a miraculous return from the dead. We’re lucky to witness it.

Last summer, Bad Bunny turned the humble, tropical island of Puerto Rico into a global stage. Following the release of his sixth solo studio album DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS, the recordbreaking artist announced a three-month residency in Puerto Rico’s coliseum. Leveraging his global superstar status, Bad Bunny used the residency to promote Puerto Rican tourism during the island’s low season. Also, with the increased political tension in the mainland U.S. and a negative bias against immigrants due to Trump’s targeted policy changes, Bad Bunny hosted the residency in Puerto Rico due to fear of ICE agents being at his shows. The theme No Me Quiero Ir de Aquí (“I Don’t Want to Leave”) carried a powerful message: instead of capitalizing on his album’s success with a world tour, he stayed home, celebrating the culture that shaped him while giving back to his community.

In a surprising move, he reserved half of the 30 shows for Puerto Rican residents—ensuring his community would be first in line. In the days before ticket sales opened, makeshift camps popped up outside the box office. Tents, coolers, beach chairs, umbrellas, and speakers blasting reggaeton transformed sidewalks into a communal space where residents took shifts holding spots. It wasn’t just a ticket line—it was a celebration of culture.

A mountain-like forest lined with tropical flora transformed the coliseum into a nostalgic Puerto Rican countryside. Concertgoers would expect preshow outdoor events such as fashion pop-ups, food vendors, and even makeshift “clubs” filled with dance music. Discover Puerto Rico, the island’s largest tourism company, estimated that the residency would bring in $200 million in revenue.

The residency also attracted international fame. Inside the coliseum, a makeshift “casita” (a full-sized house replicating rural architecture) was built in the middle of the stage, serving

as a microstage where guests joined him in singing “Acho PR es otra cosa” as a kickstart to one of the most popular songs in the album. Celebrities such as Penélope Cruz, Javier Bardem, Austin Butler, LeBron James, and Kylian Mbappé all made appearances. Alongside them were Puerto Rican icons. Wisin & Yandel performed classic reggaeton hits; Marc Anthony joined Bad Bunny for a show-stopping collaboration; and artists like Ricky Martin, Eladio Carrión, Rauw Alejandro, and Residente partied inside La Casita. Bad Bunny also extended his commitment to honoring national figures like boxing legend Félix “Tito” Trinidad, Oscar-nominated Puerto Rican filmmaker Jacobo Morales, and local plena and salsa orchestras such as Los Pleneros de la Cresta.

The concert was divided into three acts, each paying homage to an essential Puerto Rican musical tradition. The first act opened with “ALAMBRE PúA,” an original folkloric song inspired by the “jíbaro” or rural working class, featuring Bomba and Plena performances in traditional Puerto Rican dress. In the second act, Bad Bunny shifted the spotlight to La Casita, an energetic “party de marquesina” (“garage party”), where surprise guests—from Hollywood actors to urban music superstars—joined him for a set of his reggaeton hits. The third and final act debuted Bad Bunny’s last outfit of the night: a classic salsa suit paired with a “pava” hat. Together, these elements symbolized Puerto Rico’s musical evolution—from its humble agrarian roots to the global rise of salsa, popularized by legends such as Héctor Lavoe and Willie Colón in the mid-twentieth century. Performing alongside a large ensemble orchestra, the superstar performed his record-breaking hit “BAILE INoLVIDABLE,” closing the night by taking a picture of the audience–a visual homage to the album’s theme and to the community that embraces him.

The residency also sparked an unexpected trend that stretched beyond the borders of the coliseum: a revival of Puerto Rican folkloric culture. Because of the concert’s theme of paying homage to the island, concertgoers celebrated Puerto Rican pride through creative outfits and accessories that highlighted different aspects of the island’s culture.

Local businesses quickly caught on. Joanne Pardo, a local business owner, highlighted how the trend raised her revenue during the months of the residency.

“When I worked in local [thrift] markets during the weekends, suddenly every vendor had a ‘Bad Bunny Residency’ section. They sold clothes in the colors of the Puerto Rican flag, artisanal accessories like domino earrings and pava hats, t-shirts with graphics of famous Puerto Rican artists, and coquí stickers. As soon as I put a dozen amapola flower hair clips in one of my markets—the most popular accessory among women— they sold out immediately,” Pardo shared.

Major brands joined in as well. Local fashion labels like FRSH CO and Arrecife released residencyinspired merchandise. Hotels, clubs, and bars promoted pre-games and after-parties to extend the concert experience. Even Discover Puerto Rico produced guides connecting visitors to small local businesses in areas that usually don’t benefit from increased tourism.

The residency ended up boosting the local economy and attracting global attention. Out of 600,000 attendees across 30 shows, 48,000 were international tourists from Spain, Mexico, the Dominican Republic, and Colombia, while the vast majority—93%—came from the United States. The success of Bad Bunny’s residency serves as a valuable case study in responsible tourism, cultural preservation, and creative approaches to

strengthening local economies. At a time when political, economic, and social pressures drove many Puerto Ricans out of the island in search of opportunities abroad, the residency pulled people back home, reignited national pride, and demonstrated the island’s potential for prosperity.

His multifaceted impact is clear: Bad Bunny didn’t just stage concerts, he staged a cultural movement. By staying rooted in Puerto Rico, he amplified its heritage, boosted its economy, and demonstrated the power of music in spreading cultural identity beyond geographic borders.

Written by Julia Velez

It’s no secret that the aesthetics of the late 20th century have made their return. In fashion, there’s lacey bohemian styles of the ’70s, ’90s slip dresses, and early 2000s low rise denim and cargo. Television shows set in past decades like Daisy Jones and The Six or Stranger Things have risen in popularity. There’s also been a resurgence of vinyl sales and music sampling old tracks and synthesizers. Often these old trends become fused with new styles and technology to create a more modern version of an old product, ensuring further advancement into the future. There are some instances, however, where this cultural mix of past and future is not always necessary for advancement.

The tribute band industry profits by reselling an old product in unaltered condition. They adopt the techniques of a particular retro group and perform their music as it had been originally performed. Once tributes became popularized, the distinction between them and cover bands was more widely understood. While they do cover songs, tributes focus on one specific group. This means perfecting performances until they sound very close to original recordings or original performances. Tributes must practice the same instrumentation and style as the original performers, use the same amount of instruments on stage as is in original recordings (sometimes using vintage instruments and equipment to resemble that of the original artist), dress similarly to the original group (which could even mean dressing specifically like the respective member of the group that they are “portraying”), and hold a similar stage presence to the original performers (which includes facial expressions, movements, and interaction with audience).

Since their popularization in the 1980s, the talent, worthiness, and necessity of tribute bands

has been questioned by critics, but they have proved to be more successful than new rock groups in regard to revenue and search volume.

Before tribute bands were the large scale productions they are today, they were mere impersonations. In the late ’50s, after Elvis Presley’s rise to fame, performers began covering his songs with similar mannerisms and vocal techniques. These performances remained singleperson acts until the 1960s when The Beatles were popularized.

While bands covered Beatles songs, it wasn’t until a Broadway-produced “rockumentary” in the late ’70s called Beatlemania that tribute bands gained recognition. During this show, groups of four musicians were cast in rotation to perform exactly like the original band. The show lasted two years and songs were performed chronologically from the dates of their release. As a result, multiple Beatles tribute bands formed around the country. Beatlemania was eventually sued for copyright infringement after using Beatles trademarks, also beginning the long controversy behind tribute bands.

With the emergence of other rock bands like Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, and The Who, large live concerts, concept albums, and controversial lifestyles marked the rock and roll scene as unique and, with increasing popularity, encouraged more tribute bands. As groups began disbanding, tribute bands became necessary to maintaining a band’s legacy. They allowed audience members to relive their younger years and musicians to live out the lives of their idols. After iconic performances like Woodstock, Monterey Rock Festival, and Bath Festival, tributes were further influenced to replicate big productions, beginning to sell concerts instead of small venues. Starting in the ’80s, the rise of MTV granted exposure to a

multitude of rock groups which skyrocketed demand for concert tickets. Tributes, gaining greater attention, offered the experience of classic rock groups to newer generations who would never have the chance to see the real group live. Even if the group was still together, tributes toured smaller cities and venues that the real bands didn’t play, and had cheaper ticket prices, making them more accessible to a larger audience. This popularization was both for better and worse, because while it generated a steady income and recognition, it also, once again, raised questions as to the legal limits of the bands. Like with Beatlemania, tributes can infringe upon the rights of the original artists if they utilize the same logos or branding, or if venues don’t obtain licenses for the music being performed. Additionally, taking an artist’s “likeness,” as in tributes promoting themselves as if they are the original artists, can cause further issues.

Entering the 1990s, tribute bands began forming for newer artists and angered critics who claimed the tributes took attention and sales away from the actual bands. There were instances, however, when tribute bands led to greater opportunities. For example, Tim Owens was lead vocalist to a Judas Priest tribute band called British Steel. When the lead of Judas Priest (Rob Halford) left the original group in 1992 the band took a brief hiatus, after which they recruited Owens as their new lead. Similarly, Tommy Thayer performed in a Kiss tribute band called Cold Gin in the early 90s, and was later recruited to take the place of lead guitarist in the original band.

Today tribute bands generate larger audiences than ever before. Get the Led Out is a modern Led Zeppelin inspired tribute based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. GTLO is composed of six accomplished musicians who have all had careers in various bands

and as solo artists, but come together to perform in honor of musicians who inspire them. While endeavoring in other projects, GTLO has played about 130 large-scale shows per year for the past six years, including a 50-city tour in 2024. Tommy Zamp, electric and acoustic guitarist as well as vocalist for the band, began his career in 2006, first in the band Fixer, then beginning his own band Circus Life, and more recently releasing his first solo record. To gain further insight into the world of tribute bands, I’ve asked Zamp a number of questions.

Julia: How did you get into music?

Tommy Zamp: I got a guitar when I was eight or nine years old … I played it for two months and then it sat in a corner for two years, I never touched it. And then my step father showed me how to play the riff to a song called “Plush” by Stone Temple Pilots, and I don’t know why but all of a sudden a light switch went on in my head and everything made sense. Then I learned all the songs on that record and who those guys were influenced by. I was eleven and that summer, over three months, I learned everything from every band I heard on the radio.

J: What were your biggest inspirations when you were starting out?

T: Rock guitar guys. Joe Perry, Slash … Axel Rose, Steven Tyler, Mick Jagger, Keith Richards. The guitar player is just always more what I was drawn to.

J: When did you join GTLO? Why did you join?

T: I got a phone call—actually I remember it was May 4th of 2021. I was sitting in my house, it was right in the middle of the pandemic. I’d been friends with Paul Hammond [guitarist and one of the founders of the band] for probably four or five years at that point. It was right in the middle

of the pandemic … so when everything stopped I didn’t know what I was going to do because all of my gigs dried up. Nobody was hiring anyone. Paul Hammond called me and he was like “Hey listen, this thing came up. Would you be interested in auditioning for Get the Led Out?” I was like “Of course, absolutely, tell me when you want me to show up and let’s just get moving.” I think it was like four or five days later I did an audition with them…Paul Sinclair [lead vocalist, other founder of the band] called me and said, “Hey listen, we’ve got some gigs coming up we’d like to have you come on to see how you do. If it all works out then we’ll talk about making you a permanent guy.” They were kind of in a bind, and I’m just so grateful it all worked out the way it did. I mean, this is probably one of the greatest gigs you can land as a musician. The music is amazing, you’re playing iconic venues all over the country, the guys in the band are great. Everyone pushes you to be a better musician which is always fun.

J: Was there any difficulty when you joined or did you have instant chemistry with the other members?

T: I thought it gelled really well, especially considering we did one audition and then we did a three day dress rehearsal at a place called Rock Lititz in Pennsylvania. We have never stopped.

J: Is there a bigger emphasis on making performances sound like the recordings or do you more so try to make them similar to Zeppelin concerts (with improvisation)?