I have always tried to laugh more, especially as we spend so much of our working lives being so serious.

The news that Emily in Paris star Lily Collins is at the centre of a love triangle between European political powers, French President Emmanuel Macron and Rome’s Mayor Roberto Gualtieri, over the show’s relocation for its fifth season, cracked me right up.

Macron vowed that he would “fight hard” to keep the show in Paris. “We will ask them to remain in Paris! Emily in Paris in Rome does not make sense,” he said before an unexpected political twist ensued during Collins’s appearance on NBC’s The Tonight Show. She told Jimmy Fallon that Kyriakos Mitsotakis, the Greek Prime Minister, had revealed that it is his favourite too. Mitsotakis said his wife loves Emily in Paris, and that after a long day, he too enjoys unwinding by watching the programme.

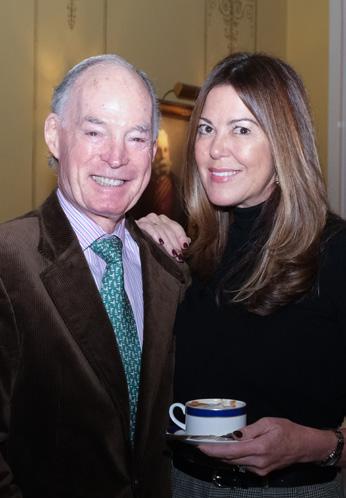

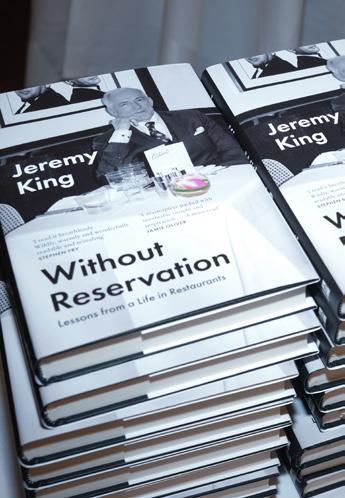

I took a significant risk when hosting the latest in our series of business breakfasts with Jeremy King, restaurateur extraordinaire. When he had finished addressing eighty of our guests before his book signing, I mentioned that waiting patiently outside was a candidate seeking an opportunity to work at Simpsons in the Strand, one of London's most historic restaurants, which he is refurbishing. As I opened

the door in burst Manuel from Fawlty Towers carrying a silver tray, stumbling, and murmuring in character. He brought the house down and it turned out to be one of the funniest moments.

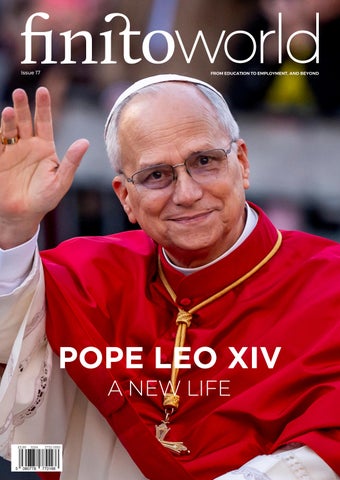

Robert Francis Prevost is the first clergyman from the United States to lead the Roman Catholic church, taking the name Pope Leo XIV. He has made care for immigrants and the poor key themes of his early papacy. We celebrate his vision for the future.

As a child, I remember gathering with my family around the television, watching Dave Allen, the Irish comedian, satirist, and actor. His TV shows, full of elaborate sketches, poked gentle fun at life and at Catholicism in particular. The formula of chatting to the audience from his high stool, with breaks for sketches involving other actors, was phenomenally successful. But his jokes about religion were a frequent source of controversy. A sketch in the 1970s, in which the Pope did a striptease, brought protests from many quarters, and resulted in a de facto ban on his shows by RTE, the Irish state broadcaster. Allen sketch-dressed as a priest. His satire on religion stemmed from his education. He once said: "The institution you never laughed at in Irish society as a kid was the church, whether it be the Catholic Church or the Church of Ireland. "It was alright to snigger at the Church of Ireland, but certainly not to laugh at the Church of Rome."

He will always be remembered when closing his show for saying: "Goodnight, good luck, and may your God go with you."

ABI INTERIORS ALEXANDER LAMONT + MILES ALTFIELD

ALTON-BROOKE AND OBJECTS ANDREW MARTIN ARTE

ARTERIORS AUGUST + CO BAKER LIFESTYLE BELLA FIGURA

BOX GALLERIES BRUNSCHWIG & FILS C & C MILANO

CA’ PIETRA CASAMANCE CECCOTTI COLLEZIONI CHASE ERWIN

CHRISTOPHER HYDE LIGHTING COLE & SON COLEFAX AND FOWLER COLONY BY CASA LUIZA DAVID HUNT LIGHTING

DAVID SEYFRIED LTD DE LE CUONA DEDAR THE DESIGN COLLECTIVE EMPORIUM DESIGNMIXER DONGHIA AT GP & J BAKER ECCOTRADING DESIGN LONDON EDELMAN

EGGERSMANN DESIGN ELITIS ESPRESSO DESIGN EVITAVONNI

FABRICUT LONDON FLEXFORM FORBES & LOMAX FOX LINTON

FRATO GALLOTTI&RADICE GASTÓN Y DANIELA GEORGE

SPENCER DESIGNS GLADEE LIGHTING GP & J BAKER HAMILTON

HARLEQUIN HEATHFIELD & CO HECTOR FINCH HOLLAND & SHERRY HOULÈS HOUSE OF ROHL IKSEL DECORATIVE ARTS

INTERDESIGN UK JACARANDA CARPETS & RUGS JAIPUR

RUGS JASON D’SOUZA JEAN MONRO JENNIFER MANNERS

DESIGN JENSEN BEDS JULIAN CHICHESTER KINGCOME

KRAVET LEE JOFA LELIÈVRE PARIS LEWIS & WOOD LINCRUSTA

LIZZO LONDON BASIN COMPANY LONDONART WALLPAPER

LOOM FURNITURE MARVIC TEXTILES MCKINNON AND HARRIS

MINDTHEGAP MODERN BRITISH KITCHENS MORRIS & CO.

MULBERRY HOME THE NANZ COMPANY NOBILIS OBEETEE OFICINA INGLESA FURNITURE ORIGINAL BTC OSBORNE & LITTLE

PAOLO MOSCHINO LTD PERENNIALS SUTHERLAND STUDIO

PHILIPPE HUREL PHILLIP JEFFRIES PIERRE FREY PORADA PORTA ROMANA QUOTE & CURATE RALPH LAUREN HOME RESTED ROBERT LANGFORD ROMO RUBELLI THE RUG COMPANY

SACCO CARPET SAMUEL & SONS SAMUEL HEATH SANDERSON

SAVOIR BEDS SCHUMACHER SHEPEL’ SIMPSONS SOURCE AT PERSONAL SHOPPING THE SPECIFIED STARK CARPET STUDIO BASED UPON STUDIO FRANCHI STUDIOTEX SUMMIT

FURNITURE THG PARIS TILLYS INTERIORS THREADS AT GP & J BAKER TIM PAGE CARPETS TISSUS D’HÉLÈNE TOLLGARD

TOM RAFFIELD TOPFLOOR BY ESTI TUFENKIAN ARTISAN CARPETS

TURNELL & GIGON TURNSTYLE DESIGNS TURRI VAUGHAN

VIA ARKADIA (TILES) VISPRING VISUAL COMFORT & CO. WATTS 1874 WEST ONE BATHROOMS WIRED CUSTOM LIGHTING WOOL CLASSICS ZIMMER + ROHDE ZOFFANY ZUBER THE WORLD’S LEADING DESIGN DESTINATION

Design Centre, Chelsea Harbour, London SW10 0XE +44 (0)20 7225 9166 www.dcch.co.uk

Elon Musk’s latest forecast – that within two decades, work will become “optional” – is the kind of statement only the world’s richest man can make without irony. Speaking at the US-Saudi Investment Forum, Musk sketched a vision of the future where employment is reduced to a hobby – as optional and pleasant as growing vegetables or playing sport. Powered by exponential advances in robotics and AI, his vision is utopian. He even went so far as to say money itself may become irrelevant. There are many who will dismiss this as a privileged tech-fantasy, a Silicon Valley mirage untethered from the stubborn realities of ordinary life. And yet, Musk’s pronouncements are rarely as far-fetched as they seem at first glance. When the man who brought electric cars into the mainstream, launched a private space company, and is now at the centre of the AI arms race speaks about the future, it is wise to at least listen.

Musk’s prediction is, at its heart, about productivity. He believes that the only path to universal wealth lies not in redistribution, nor in political reform, but in scaling machines capable of doing human work better, faster and more cheaply. This is not a wholly new idea. The industrial revolutions of the past were powered by similar promises. But unlike steam or electricity, artificial intelligence has the capacity to replace not just labour, but judgement, creativity and even care. The implications for employability are profound.

At Finito World, we are grounded in the belief that work is not simply a

means to income, but a fundamental pillar of personal development, purpose and dignity. For all Musk’s talk of optional work, what he describes is a future where work becomes the preserve of the curious and the passionate, while the rest are relegated to passive recipients of abundance.

This is not a future to be welcomed uncritically. If work becomes optional, who chooses to opt in – and who gets left behind? If currency becomes irrelevant, what replaces the economic relationships that bind us, motivate us, and allow us to contribute? Musk implies that robots will do the work, and humans will be free. But free to do what – and in what kind of society?

In fact, many of the seeds of this future are already being sown. The rise of generative AI is beginning to touch sectors previously thought immune to automation: design, law, journalism, even teaching. At the same time, labour markets are fracturing. More young people are entering insecure or freelance work, while mid-career professionals face growing pressure to reskill or risk obsolescence.

Yet, the solution cannot be to drift passively toward a post-work society. Nor should it be to declare war on technology. Instead, we must urgently begin to build the scaffolding that will allow human potential to flourish in an AI-enabled world. That means rethinking how we educate, how we train, how we value non-economic contribution, and – crucially – how we define success.

Musk is right in one sense: we are at the threshold of an extraordinary

technological transformation. But his version of a work-free future risks leaving out the very thing that makes us human – our drive to contribute, to build, and to grow through effort. Work is not just toil. It is structure, selfworth, and community. The idea that it could one day become obsolete should alarm us as much as it excites us.

There are also real dangers in the assumption that technology will lift all boats. The history of automation has always been uneven. The benefits flow to capital and to those with the skills to leverage it, while the dislocated are often left navigating bureaucratic welfare systems or casualised labour markets. As ever, Musk’s remarks glide over the political and social consequences of rapid change.

The question, then, is not just whether work will become optional. It is whether society will survive the transition intact – and whether we are willing to put in the hard policy work now to ensure that the post-work world, if it comes, is a better one.

Finito World exists because we believe in the transformational power of work. We believe that human beings need purpose, and that work – real, meaningful, rewarding work – is one of the surest routes to it. That won’t change in twenty years, no matter how clever the robots get.

Let the machines take the strain. But let us not lose sight of the fact that employability is not just about surviving in the economy. It is about thriving in our humanity. And no algorithm, however advanced, can replace that.

Plans to scrap jury trials for all but the most serious criminal cases—murder, rape, manslaughter— represent not reform but retreat. Justice Secretary David Lammy is reportedly backing the creation of a new tier of jury-less courts for offences carrying sentences of up to five years. In doing so, he risks dismantling one of the most enduring foundations of British democracy. It is true that the courts are in crisis. With more than 78,000 cases pending in the Crown Court and that number forecast to rise to over 100,000, delays are stretching into years. Victims are left waiting for justice; defendants are left in limbo. But to suggest the solution lies in removing juries is to mistake cause for consequence.

The backlog in our courts is not due to the presence of juries but to long-term government neglect: years of funding cuts, chronic shortages of barristers

and judges, court closures, and broken infrastructure. Rather than investing to repair a weakened system, the proposed reforms shift the burden onto democratic rights. It is an attempt to manage the decline of a vital institution by quietly undermining one of its core principles.

Juries are not just a procedural choice— they are the public’s voice in the justice system. They represent a civic contract: ordinary citizens taking responsibility for serious decisions about guilt and innocence. To strip them from all but the gravest of cases would be to sever the bond between community and justice.

The proposal also threatens to deepen the inequality already present in the justice system. Under a two-tier model, only the most sensational cases will be considered worthy of a jury. Other serious offences—fraud, assault, coercive behaviour—would be

downgraded, with fewer safeguards. In a time of eroding trust in institutions, this move risks alienating the public further.

Let us be clear: there is no constitutional right to a jury trial in all cases. But there is a long-standing principle that trial by one’s peers is a hallmark of a free society. Convenience must not trump that principle.

If the government truly wants to resolve the court backlog, the path is clear: invest in the system. Fund legal aid, hire more judges, modernise courtrooms, improve digital infrastructure. But do not dismantle the very values we should be protecting.

We must resist this false choice between timely justice and democratic justice. A system without juries may be faster—but it will not be fairer.

At a Finito event on 1 December — sponsored by Claire Cummings and the Centre for Digital Assets and Democracy — Lord Toby Young delivered a characteristically forthright defence of free expression, reminding attendees why he has become one of the most persistent voices resisting the creep of censorship in Britain. Speaking to a packed room, he traced the rapid growth of the Free Speech Union, the organisation he founded in 2020, and set out with forensic clarity the case for renewed vigilance.

Young offered a stark diagnosis of the national drift. Citing the more

than 12,000 arrests for online speech offences in a single recent year and the extraordinary rise in cases involving women punished for expressing mainstream views, he showed how the policing of opinion increasingly takes place far from the criminal courts — in workplaces, universities, and even schools. His warning about the proposed curtailment of jury trials struck a particular chord, as he argued that ordinary citizens, not officials, have proven far more reliable judges of what constitutes criminal speech. “Free speech has to be constantly defended — each generation has to fight the battle anew,” he reminded the room,

capturing the spirit of the afternoon.

Yet for all the gravity of his subject, Young’s tone was neither bleak nor partisan. He emphasised that free speech has historically been the ally of the marginalised, not an indulgence of the powerful, and that its defence must be universal if it is to be meaningful. The event underscored why his work matters: in an era of growing digital oversight and shrinking tolerance, Lord Young continues to insist that open debate is not a luxury but the foundation of a healthy democracy.

Alan

Naomi

Nigel

David

Sarah

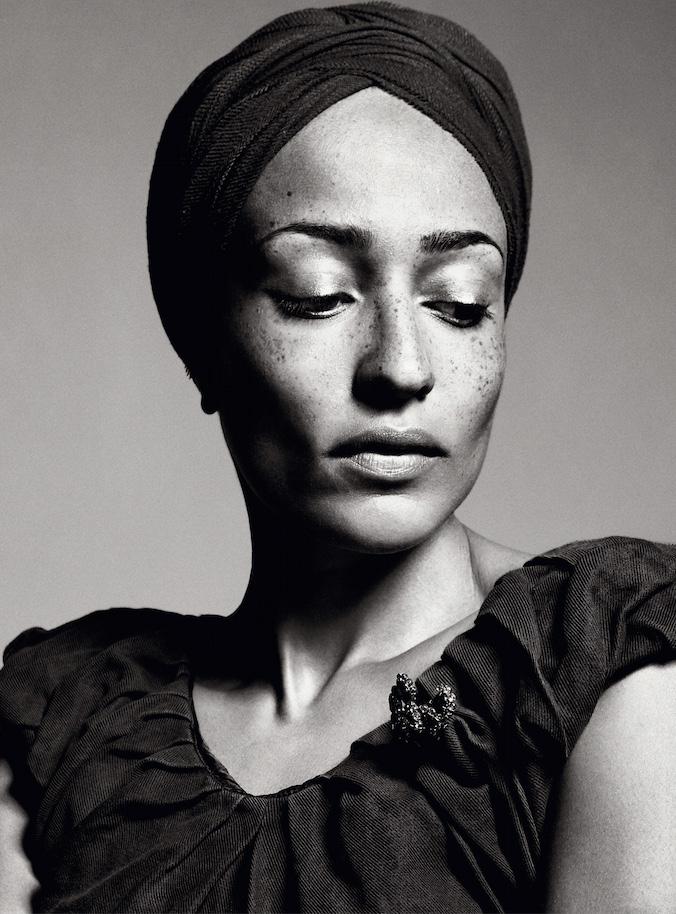

Zadie

Stephen

Lydia

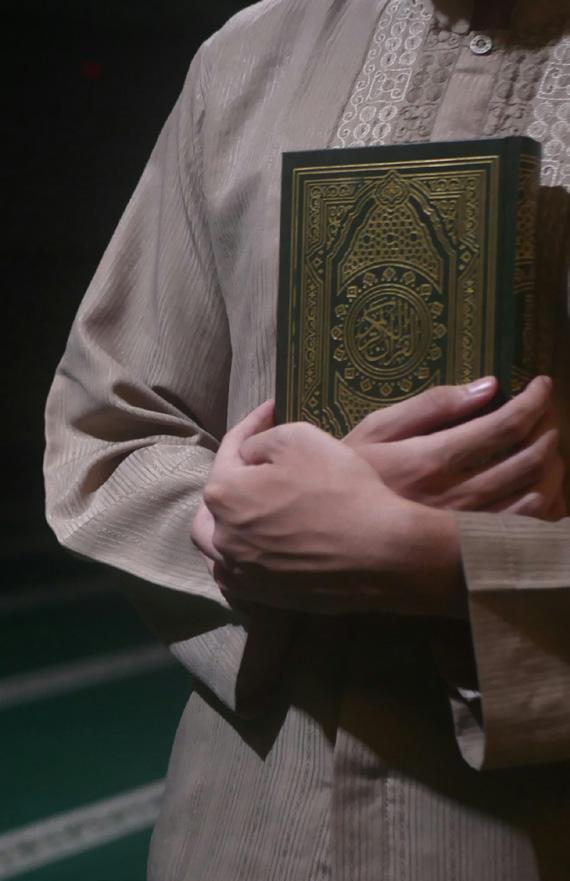

58 COVER STORY

How Pope Leo XIV found his voice 72 RELIGIOUS INSTRUCTION

What do the world’s scriptures say about work?

78 AN INDELIBLE MARK: SIR TOM STOPPARD

Our tribute to the great playwright

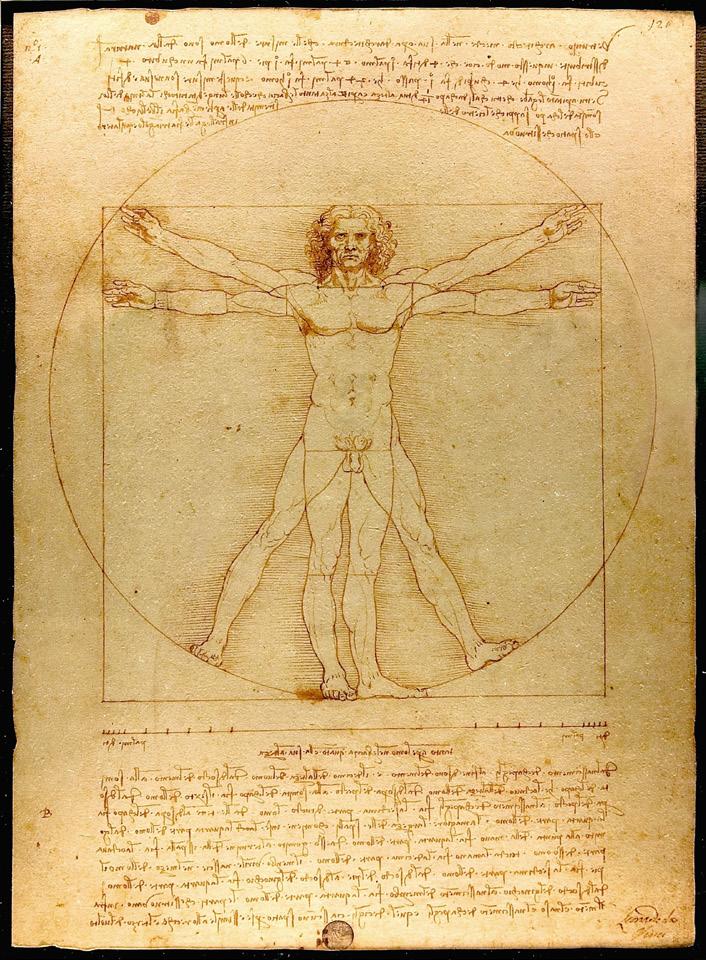

82 THE FUTURE OF THE MEANING OF WORK

What are our deepest reasons for our careers?

UK PLC

How do you know the state of an economy?

98 HIDDEN DISABILITY ISSUES IN THE WORKPLACE

Tamsin Aston and Aarifah Karim

100 BURSARY UPDATE

The latest on Yassen Ahmed

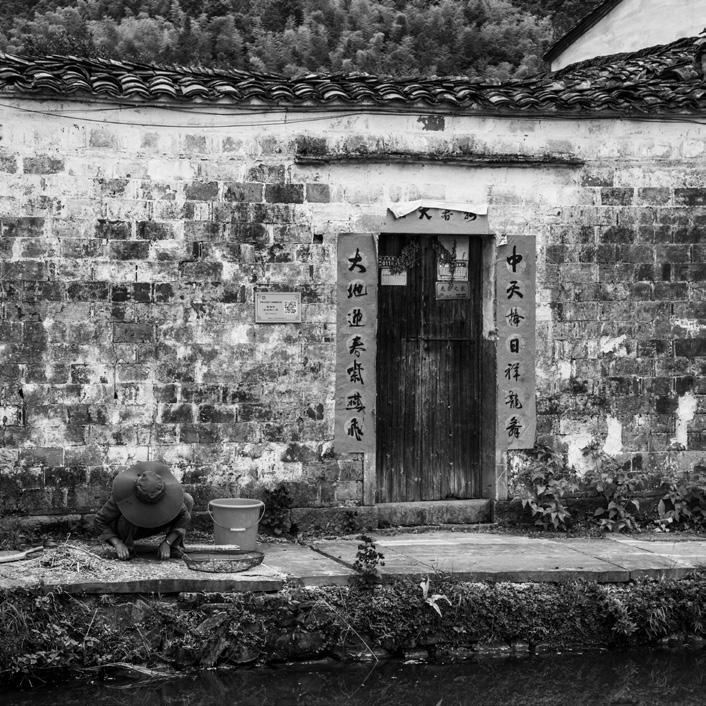

104 LETTER FROM CHINA

Sarah Tucker on work and life in today’s China

108 LETTER FROM JAIPUR

Nishad Sanzagiri writes from Rajasthan

Louise

Ilaria

Jeremy

114 WITH CONSTABULARY DUTIES TO BE DONE…

John Constable at 250

118 VANBRUGH AT 300

With Charles Saumarez Smith

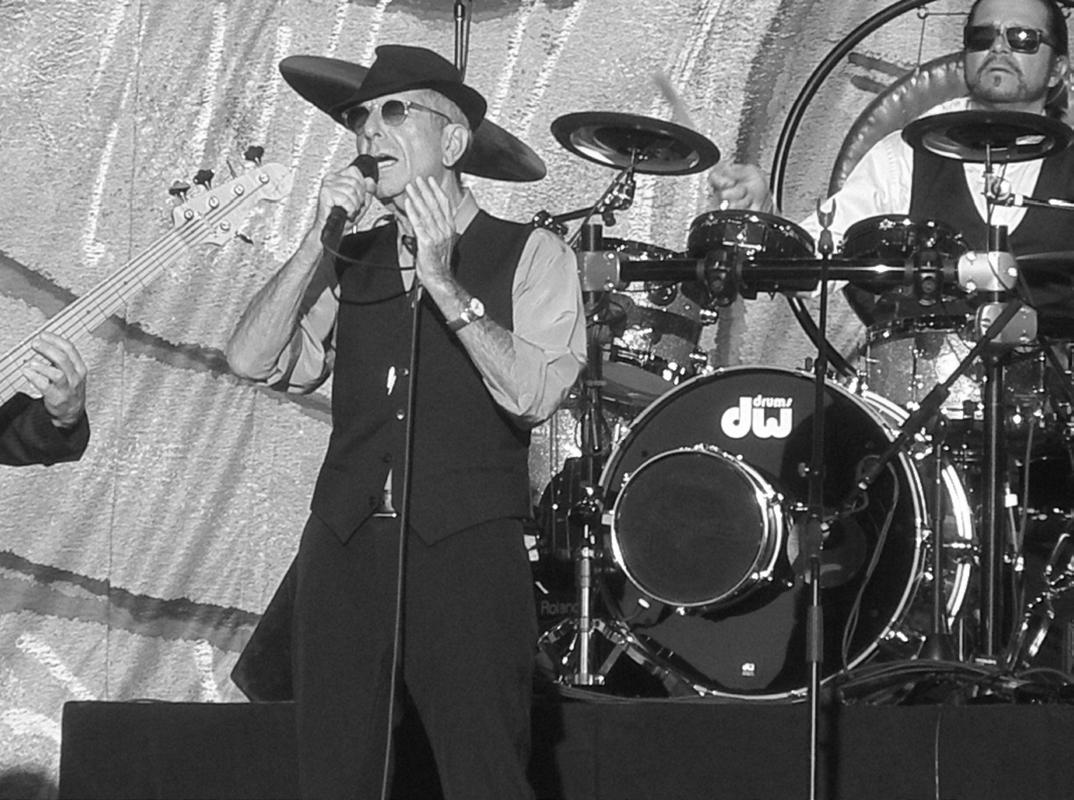

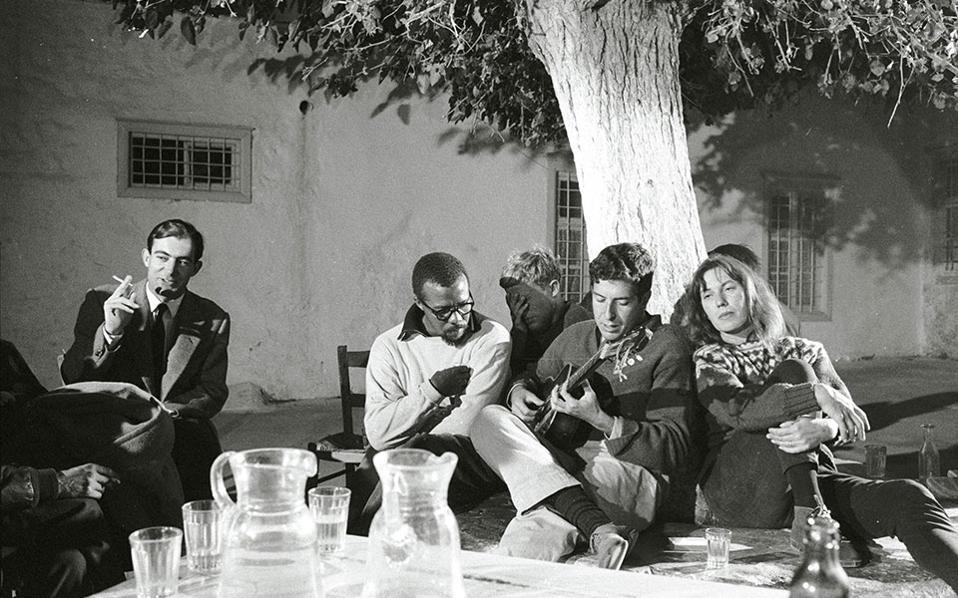

124 LEONARD COHEN AT TEN YEARS GONE

Reflections on the poet-singer

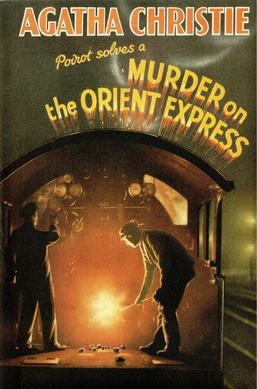

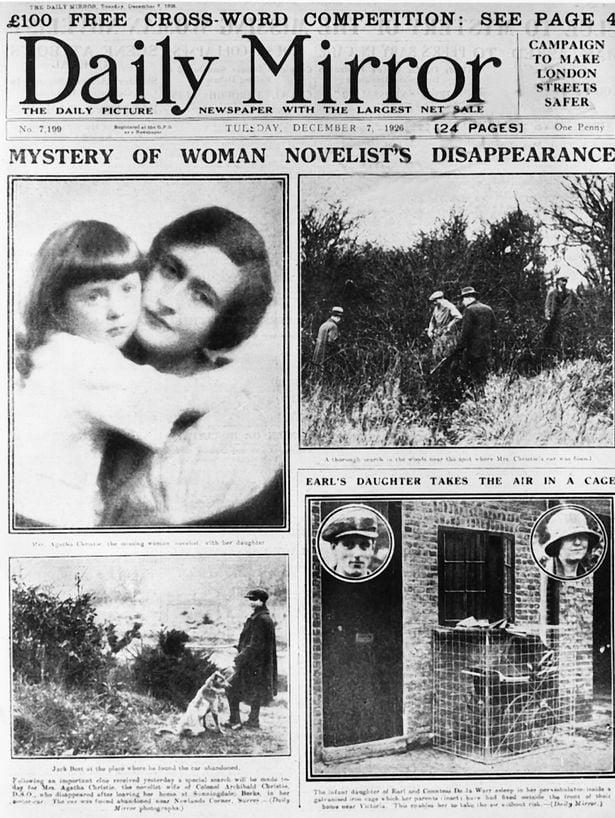

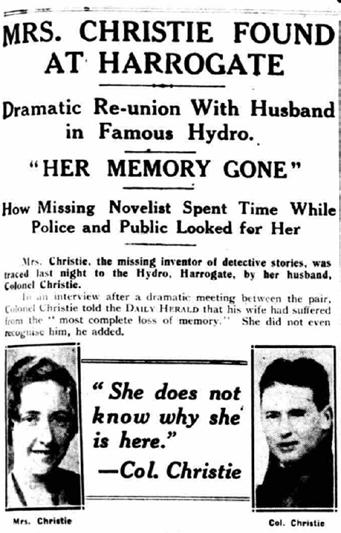

128 MURDER SHE WROTE

Agatha Christie and her heirs

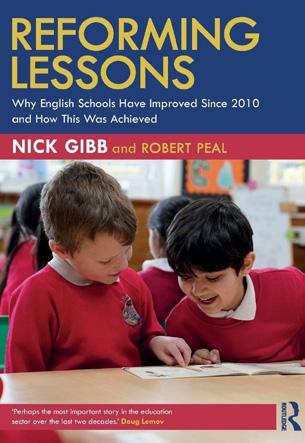

134 BOOK PAGES

Tim Clark on Nick Gibb

136 SIX NATIONS

Lessons from a life-long rugby fan

140 ALL BEEFED UP

The effects of Trump’s tariffs

144 CLASS DISMISSED

Dame Esther Rantzen

SCAN BELOW TO SUBSCRIBE TO FINITO WORLD

Ilike setting up businesses that solve very specific problems. I co-founded Flynn & Giovani Art Provenance

Reach with Dr Tom Flynn in 2017 to fill a gap in the art market. I then setup the Art Market Academy to make provenance and due diligence training available to everyone. It remains the only digital resource of its kind, offering pre-recorded lessons translated into more than a dozen languages. In the two years since its foundation we have had hundreds of course completions from all continents.

The main issue we seem to constantly face is access, which is a rather ridiculous issue to have in 2026. On an everyday basis, researchers across disciplines struggle to access archival material around the world. It turns out that everything is not online, and Google is limited. Over the past few months alone, I have needed access to resources that exist only in physical form in Chile, St Petersburg and Cyprus. I am still waiting on this information.

Certain research cases have been on my desk for much longer. Twelve years ago I embarked on solving the mysterious case of a couple dozen modern British paintings sent to France on a travelling exhibition in 1940 which were never to return. Some progress has been made but the mystery has not been solved yet. And as I persist more mysteries have followed. Where has the body of work produced by British artist Christopher Bledowsky been scattered and what does this market look like? How did a lost masterpiece by Francois Gerard survive

the Russian Revolution to end up in a glitzy department store in Argentina? Happy to say, this last mystery has since been solved!

Much of the world’s knowledge still lives on shelves. Libraries, archives and private collections hold material that will never be digitised in full, nor should they be expected to. Digitisation is expensive, selective and slow. In the meantime, research continues. Claims need evidence. Students need sources. Facts need verification. The assumption that information is universally accessible has simply not caught up with reality. So how do we solve an information access problem in the era of supercomputers?

The obvious answer would be to outsource it to artificial intelligence. That answer does not work. AI is useful for pattern recognition, summarisation and prediction, but it does not replace access to primary material. It cannot retrieve a page from a book that has never been scanned. It cannot verify an archive it has never seen. And it is frequently confident about information that is simply wrong.

So in a way we had no option but to create Source. Source addresses access as a logistical problem rather than a technological fantasy. The premise is straightforward. If information exists somewhere, then someone can physically access it. Source connects people who need access to specific materials with people who can retrieve it. Requests are matched only with users who are able to fulfil them. This avoids noise and

focuses on execution. All providers get paid for their time, and all requesters get factual information.

London is the best place from which to launch a startup while juggling existing businesses and motherhood because it offers density without isolation. Being able to fit research appointments, fundraising meetings and museum visits before doing the school run is a gift. We are spoiled for options when it comes to choosing museum exhibits and shows.

From the latest rendition of The importance of being Earnest at the Noel Coward theatre featuring the inimitable Stephen Fry in the role of Lady Bracknell to the Cecil Beaton Fashionable World exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, the opportunities to cleanse the palette are as accessible as they are essential.

We meet one of our leading mentors, and quiz him about his stellar career – and advice for mentees

With a 35-year career spanning NatWest, global FX, payments brokers, and now consultancy, how have you navigated transitions across such varied environments — and what motivated those shifts?

My career at NatWest Bank proved hugely beneficial and instrumental as I navigated the transition into other sectors due to excellent bank training, the scale of the bank, and pivotally, learning about customer service and satisfaction. Both the broking firm and, language services companies I was employed at had an innate need to attract and retain customers. My experience and commercial acumen were paramount throughout my transition into language services, having no previous knowledge of this industry. Interestingly, it was at this point in my career that Ronel Lehmann and I first connected before I became a mentor at Finito Education.

My 35 years at NatWest ended after working in the City of London, Manchester, and Leeds. However, I continued my professional services career working with global language services providers whilst I established a consultancy business.

At NatWest, you rose through trading desks to senior FCA-regulated roles and even served on a sub-Board committee. What were the key milestones or mindsets that helped you get there?

The key moment was in 1992 when I was working on the world’s largest

trading room just before the Pound Sterling exited the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) and “Black Wednesday” occurred, and I first encountered financial derivatives. I was fascinated how these instruments, when used appropriately, could significantly assist a UK corporate manage a financial risk that it was unable to de-risk itself during the course of its ordinary business. Following this, my career remained derivative and corporate focussed which meant that I had to be authorised and regulated by the FCA. Subsequently, towards the end of my time at NatWest I represented my unit on a sub-Board committee specifically for my expertise in how the bank should package and disseminate derivatives to corporates and how the bank itself should manage the credit risk of such products.

Leading and revitalising underperforming sales teams to award-winning performance requires both strategy and empathy. What leadership lessons from that experience resonate most with you today?

As mentioned previously, my time at NatWest provided me with a catalogue of leadership, sales, and human insight training. The leadership lessons that still resonate today are to ask an underperforming team unambiguous, non-accusatorial questions such as what is going badly and why. Furthermore, ask them for their suggestions as to how they would fix and improve matters. Finally, I would

ask what could be achieved if we made the improvements. In summary, demonstrating that I listened to them and created a strategy to improve with a self-chosen commitment from the team to succeed. This lesson still resonates as a key part of my thinking on leadership today.

In your role as a Banking Consultant, you support businesses with funding, corporate governance, debtrefinancing and FX risk. What is one complex client challenge you helped resolve, and what was your approach?

I will condense my answer as much as possible without diluting the relevance of the example. I was asked to help a UK, medium size organisation that needed to purchase USD, EUR, and CHF over an initial 12-month period with a manageable hedging strategy. My approach suggested a strategy combining a mixture of forward contracts for those orders with certainty of cashflow and a percentage left un-

hedged (whilst monitoring prevailing rates). I used two providers to ensure competitive pricing with the following three steps that formed the basis of my approach. The initial task was to establish a robust, risk management policy that defined goals that stabilised cash flow and protected profit margins from adverse currency movements. It also determined the risk appetite, and who was responsible for managing the strategy, with the board agreeing a policy mandate of hedging 75% of all known currency exposures and 25% of projected exposures left un-hedged.

The next task was to help the procurement and accounting teams to forecast USD, EUR, and CHF purchase volumes for the next 12 months, breaking this down by month to align with the purchase cycle. This also meant analysing each currency pair and identify timing and amount mismatches where cash inflows and outflows in a particular currency do not align in time and amount. This helped determine the exposure to be hedged.

The final task of the initial phase was to select the foreign exchange (FX) providers, which included both banks and specialist FX platforms. This meant clear communication of hedging requirements to each provider, including forecast transaction volumes, maturities, and specific needs for USD, EUR, and CHF. It was imperative that each provider established timely and transparent reporting cadence, including trade confirmations, markto-market valuations, and performance reports.

Given the current regulatory landscape, especially around foreign exchange exposures, what are the top three pieces of advice you’d give to a small business exploring export/ import opportunities?

It is broadly the same advice I would have offered many years ago, however, with advancement in technology now significantly assisting all parties, I would recommend that an importer or an exporter uses a provider that offers not only a customer portal that facilitates complete on-line audit trail and reporting but also human intellect to support the technology with sensible, knowledgeable market commentary. The first piece of advice would be to undertake thorough research based on the business's GBP pricing in different currencies, whether it is financially beneficial and then establish a strategy with a provider of foreign exchange services that also embeds cross border payments into its customer eco-system.

The second piece of advice would be to choose a strategy based on the need for certainty. If there that need, it would follow to use foreign exchange forward contracts to manage the exposure over a period. Of course, each business has different exposures and price points that could allow a degree of flexibility in the strategy. The final piece of advice would be to re-evaluate the chosen strategy on a regular basis and monitor foreign exchange rates as they can move very quickly, often wiping out anticipated sales margin on nonmanaged requirements.

Dissertation Supervisor at the University of Salford, how do you integrate your real-world experience into your teaching? How does it resonate with students?

It is a privilege to be at the University of Salford, Salford Business School supporting and guiding young people through their relevant journey leading to, one hopes, a career in financial services. I integrate real-world experience into my teaching. For

example, helping my Masters students, completing their dissertations, to consider real world events such as Black Wednesday or the 2007/8 Global Financial Crisis and discuss the events leading up to the crisis, during the crisis, and post crisis. To add relevant and real-world experience we debate the causes and the lessons learned in relation to the particular module or question being analysed.

Many aspiring professionals struggle to translate academic knowledge into workplace success. What practical tips do you offer students to bridge that gap?

I agree it is a challenge for aspiring professionals to apply their academic knowledge into the workplace. I would, however, suggest these practical tips to both students and aspiring professionals. The first tip is to learn about the current issues, challenges, and latest developments (legal, regulatory, economic and environment) the target industry or a specific company in question faces and crucially keep up to date with events. This is essential when preparing for an interview or, if already in the workplace, being relevant in conversations with co-workers and more senior colleagues. The second tip would be to use as many existing support network opportunities as possible. Universities will have useful programmes to tap into and young professionals should use LinkedIn to broaden their professional network. The third tip would be to consider taking professional qualifications to enhance learning. Moreover, this is an excellent route to enhance credibility and may be a key factor for future career progression.

After decades in banking, you moved into language service providers— helping firms with multilingual

communication. What inspired that shift, and how do your banking skills apply in that new domain?

When I left the banking sector, I considered how best my banking experience, skills and commercial acumen could be used. It soon became apparent that my career was built upon many years of working alongside hundreds of customers and providing solutions to their problems. I soon realised that I could apply my financial, banking, and professional knowledge to a new industry, helping customers with different challenges. Furthermore, I wanted to maintain customer connectivity and centricity. This added to the excitement of having to quickly learn and understand a completely new dictionary of terms and to grapple with different technology.

My banking skills applied in this new domain, primarily due to many years managing customer relationships and experience of gaining and retaining new customers with integrity, trust and professionalism.

Navigating two very different industries—finance and language services—what skills do you see as truly transferable, and what new ones did you develop?

I would consider many skills truly transferable, however, for a customer facing role these key skills would apply in any industry; firstly, asking the customer the right questions with answers that illuminate their issue or problem. Secondly, sharing the solution with the customer and what impact it will have on them. Finally, ensuring services and products are delivered in a professional, competent manner. The skills I had to develop were two-fold. One was learning and understanding the format and process of undertaking a language translation project and the

other was this industry already had developed significantly new machine learning skills and artificial intelligence which were far ahead of traditional banking sector.

You’ve mentored newcomers in FX and derivatives markets. What are the most common misconceptions mentees have, and how do you help them overcome those?

I would say the most common misconception mentees have is an urgency to progress without fully understanding the products they are selling and why they are appropriate to the customer. I helped them to overcome this misconception by highlighting the consequences of an inappropriate proposal to a customer and the potential financial and reputational risks incurred by such an action. Another misconception that often features is failing to appreciate the need for accuracy and accountability where details on the customer journey and key due diligence when recording the transaction on the bank’s records are missing. To help overcome this misconception I explained that by not documenting each step and process it could cause inaccurate credit reporting, poor audit outcomes and worst of all, an incomplete picture of the customers’ banking profile.

What characteristics or habits do you find set apart successful mentees in your experience?

Successful mentees are those who listen intently, ask pertinent questions, and then take action to move forward. I would also add persistence and pragmatism in the current employment marketplace as being beneficial traits.

You’ve maintained a long and successful career alongside family

life—your daughters are pursuing distinct and exciting paths. How have you balanced professional growth with family commitments over the years?

Thank you. It was not easy to balance a career that meant navigating long hours and the occasional weekend away, with my priority of family commitments. I had a clear approach to managing my time which meant I had to be present, completely focussed, and in the moment, whether spending time with my family or in my commitment to serving employers and customers. There were times when I had to compromise, but whilst working alongside my wife, her work commitments, and family commitments, I was able to build my career maintaining the stance of proud husband and father.

If you could speak to your younger self, just starting in banking, what advice or reassurance would you offer?

My advice would be this; have the confidence to ask questions of more experienced colleagues about their role, what they do, for whom?, and why it is important to the bank. I would also advise seeking out a mentor to help steer and guide me through my early career progression. As for any reassurance I would simply say banking in its purest form will remain as the lifeblood of an economy facilitating the movement of capital and money. However, when I started my banking career in 1982, processes where archaic and labour intensive but with the rapid advancement in financial technology, the incredible opportunity artificial intelligence offers banking customers, and new entrants offering new and interesting services, banking remains an exciting and fulfilling career; it’s just a different landscape to navigate.

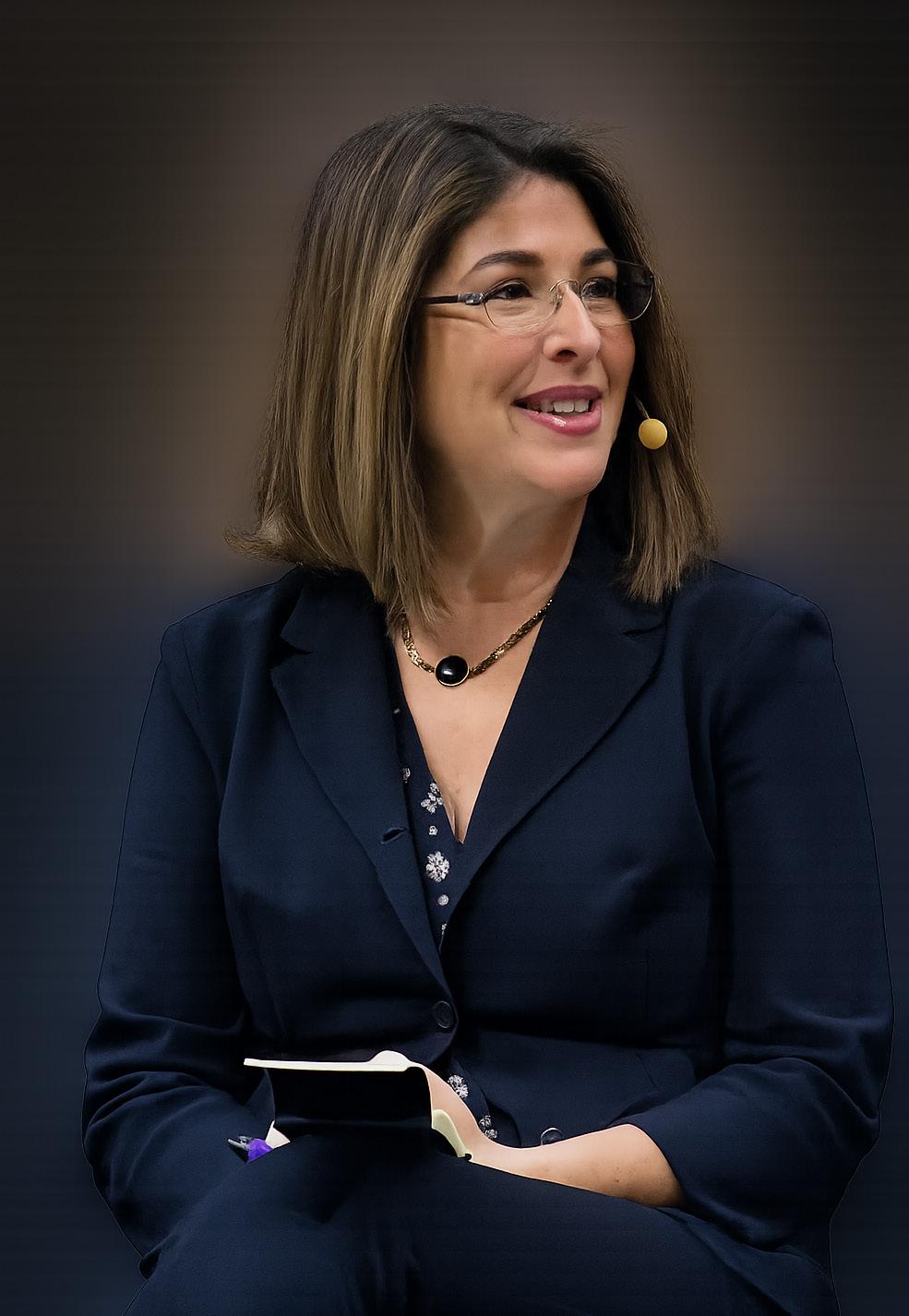

MRS DOPPELGANGER

Klein on AI

PEARL OF A GUY

David Pearl on his property career

VANISHING COMMONS

Zadie Smith on the shrinking public square

The author of Doppelganger and No Logo on the frightening advances of AI

We are living amid an explosion of doubles—digital replicas, curated avatars, shadows we polish and present as ourselves. When I first began writing about these phenomena, I touched only lightly on artificial intelligence; ChatGPT had not yet been released, and our anxieties were still primarily about deepfakes. What I could not yet see was how quickly we would find ourselves inside an entirely new mimetic landscape, one in which the mechanisation of speech and the smoothing of expression render us more replaceable by machines precisely because we begin to behave like them. The more formulaic art becomes, the easier it is for algorithms to pass for its creators.

We are now on the cusp of a mirror world expanding with stunning speed, entering spaces we once relied on as alternatives to precisely this kind of enclosure. Universities, for instance, have moved with breathtaking swiftness from anxiety about students using AI to write their essays to actively urging professors to use the same tools to teach in their place. This rush towards the synthetic is not just cultural or intellectual—it is profoundly material and vampiric.

AI feeds on the creative labour of artists whose work has been scraped without permission, leaving them to compete not only with the endless stream of influencers recycling their styles, but with machine replicas of themselves. And it feeds, too, on the physical lifeblood of our world: the water evaporating to cool data centres,

the fossil fuels powering computational infrastructures whose scale is almost impossible to fathom. To build this mirror world, we quite literally sacrifice the animate one—and we are told not to worry, because AI will solve climate change for us.

Before his death, Pope Francis was turning his attention sharply to this

contradiction. In 2015, when I was at the Vatican for the launch of Laudato Si’, I watched a profound theological struggle unfold. Some framed the encyclical as a continuation of the Church’s longstanding environmental work; others saw it as a rupture. In my reporting, I quoted Father Sean McDonagh, who spoke with striking candour about being raised in a Church

that taught its followers to hate this world. He reminded us of a Latin prayer once recited after communion: teach us to despise the things of the earth and to love the things of heaven. If we are to defend this earth, he argued, we must finally confront and overturn that worldview.

“The more formulaic art becomes, the easier it is for algorithms to pass for its creators.”

In many ways, Laudato Si’ was an invitation to re-enchant the world—to find the sacred here, not elsewhere. And Francis, whose namesake ministered to plants and animals as kin, extended the notion of fraternity beyond the human realm to all living beings. This, of course, was controversial in some quarters. I remember a headline in The Federalist appearing around the encyclical’s release: Pope Francis: The Earth Is Not My Sister. The panic was telling; re-enchantment threatens entrenched hierarchies.

For me, re-enchantment is not an abstraction. I live in British Columbia, a place where sacredness was never fully extinguished, though settler colonialism tried. Eighty percent of the province remains unceded Indigenous land, with no treaty and nothing but papal bulls—repeatedly petitioned for rescission—to justify its appropriation. The sacred is present everywhere: in Coast Salish art, in the land itself, in the potlatch ceremonies that were once criminalised, in the masks that were stolen and circulated through the Western art world.

While researching a piece for Pankaj Mishra’s forthcoming journal, I found myself tracing the surrealists exiled during the Second World War who stumbled upon these Northwest Coast masks in New York secondhand shops. They recognised their power immediately. André Breton believed he had found the original surrealists in those objects. In Indigenous cosmologies, those masks are portals between worlds—yet they were portals violently taken. There has been a long, ongoing struggle to repatriate them. When the Breton family returned the mask they held, they joined a ceremony bringing it home, acknowledging the rupture and helping to mend it.

Re-enchantment, then, is often less about invention than unearthing: listening to what was always here, to knowledge systems that survived despite sustained efforts to silence them. And it is, I believe, inseparable from feminism—from the work of restoring what patriarchal and colonial systems deemed inferior, irrational, or disposable.

As we confront the loneliness of the mirror world and the seduction of its synthetic infinities, the task before us is not to invent meaning anew

but to defend the animate world—to stay connected to the living, tangible presences that have always grounded human purpose. The enchantment never truly vanished; it was suppressed, marginalised, mocked. But in every place on earth, someone held on to it.

“To build this mirror world, we quite literally sacrifice the animate one—and we are told not to worry, because AI will solve climate change for us.”

To resist the vampiric pull of AI’s extractive logic, we cannot retreat into nostalgia or technophobia. We need instead a politics—and a spirituality— capable of honouring this world as sacred, not as raw material for another. The mirror world will keep expanding. But we can still choose which world we nourish.

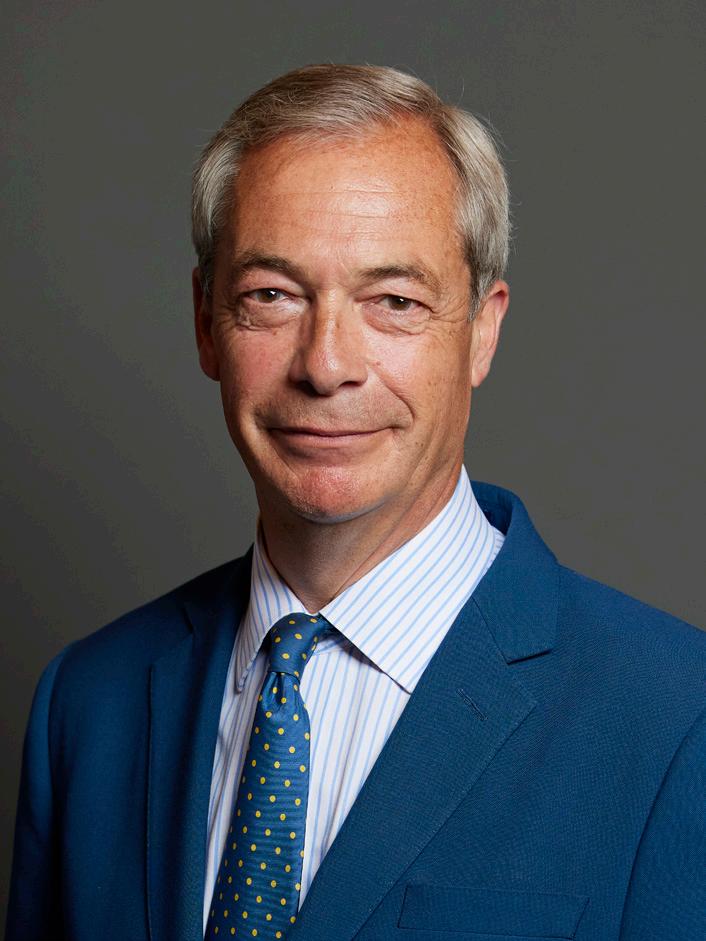

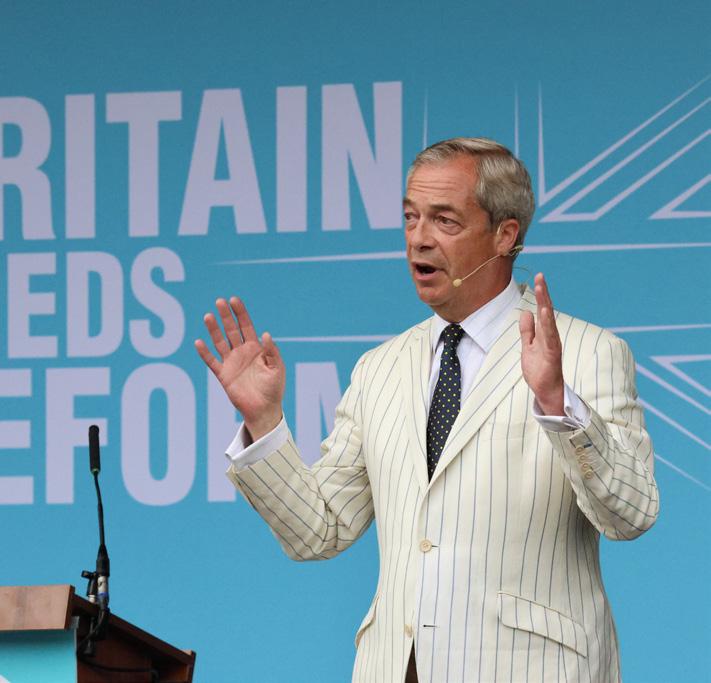

The Reform leader isn’t going away any time soon. Here he outlines why Britain needs a major shift

We have to change. Not because it’s trendy. But because it’s necessary for survival. And let’s not pretend this is just about economics. It’s moral, too. When free speech is punished with prison sentences, when the justice system bends to political pressure, when we have two-tier policing that targets some while ignoring others –the very idea of British fairness dies.

I’ve always said we need to stand up for what makes this country special. Common law. Free speech. Individual responsibility. It’s not about pandering to one group or another. It’s about building a society in which everyone is equal before the law –regardless of race, religion, gender or sexuality. No one gets a pass. And no one gets scapegoated.

“We have to change - not because it’s trendy, but because it’s necessary for survival.”

That’s why I’ve spoken up on issues others would rather avoid. When Jewish families in North London are afraid to let their children out, when we see cars parading antisemitic slogans through our streets and the police do nothing – that’s a failure not just of policing, but of principle. It’s a sad irony. Eighty years after the landings in Normandy, we’re now in a Europe where Jewish families

can’t live safely in Paris, Brussels, or Strasbourg unless they’re under armed guard. I saw it as an MEP. I saw the silence and cowardice of those who prefer not to notice. We must never go down that road here.

Can we turn things around? Of course we can. We’ve done it before. Anyone who lived through the threeday week, the power cuts, the 30%

inflation of the 1970s knows how bad things can get – and how quickly they can be turned around with the right leadership.

But it takes honesty. And bravery. And the will to say: enough.

We need to tell young people the truth – that hard work leads to success. That being proud of your country is not a sin. That being

ambitious is not shameful. That family, stability and tradition are not relics of the past, but essential ingredients for a healthy future.

“When free speech is punished, justice bends to politics, and policing becomes two-tier, the very idea of British fairness dies.”

I’m not in this to please everyone. I never have been. If I wanted an easier life, I’d be on the after-dinner circuit talking about Brussels bureaucracy over fillet of beef. But I came back because I believe Britain can be better – and that someone has to say so. You can believe in me, or not. That’s your call. But know this: I’m not going away. Because the stakes are too

high. Because the values that made this country great are worth fighting for. And because if we don’t stand up for them – no one else will.

What pushed me back into public life wasn’t nostalgia or ego — it was witnessing, with my own eyes, a country losing its nerve. I saw it during my years in Brussels, where Jewish families in Paris, Brussels and Strasbourg were already living behind armed guards. That was nearly a decade ago, and nothing has improved. In fact, it’s got worse. Today, friends of mine in North London tell me there are evenings when they’re frightened to let their children out. We saw cars driving through London shouting antisemitic abuse on an industrial scale — and the police simply looked the other way. If that isn’t two-tier policing, what is?

And let’s be blunt: the political establishment is terrified of confronting the ideology behind

it. Ministers tiptoe around radical Islam because they’re frightened of the backlash. Well, leadership means saying what everyone else is whispering. Seventy-five percent of those who come to Britain adopt our way of life and contribute just as previous generations did — but a significant minority do not, and pretending otherwise won’t make the problem disappear.

“Leadership means saying what everyone else is whispering - pretending the problem doesn’t exist won’t make it disappear.”

It’s the same cowardice we see everywhere. Take the economy. Every small business owner in the country can tell you what soaring employers’ National Insurance has done to hiring. Add the minimum wage hikes, the rates burden, the avalanche of regulations designed for multinationals but dumped onto corner shops — and you have a recipe for decline. I’ve lived it. I’ve run a business. I know what it’s like to pay staff more than you pay yourself, and to wonder if you’ll make payroll. The people writing the rules today have never done a real day’s business in their lives.

Government can’t create wealth — it can only clear the path for those who do. Hong Kong did it in the 1960s: low taxes, light regulation, and the freedom for people to succeed. Within a generation it was transformed. We could do the same, if only we had leaders who believed in aspiration instead of resenting it.

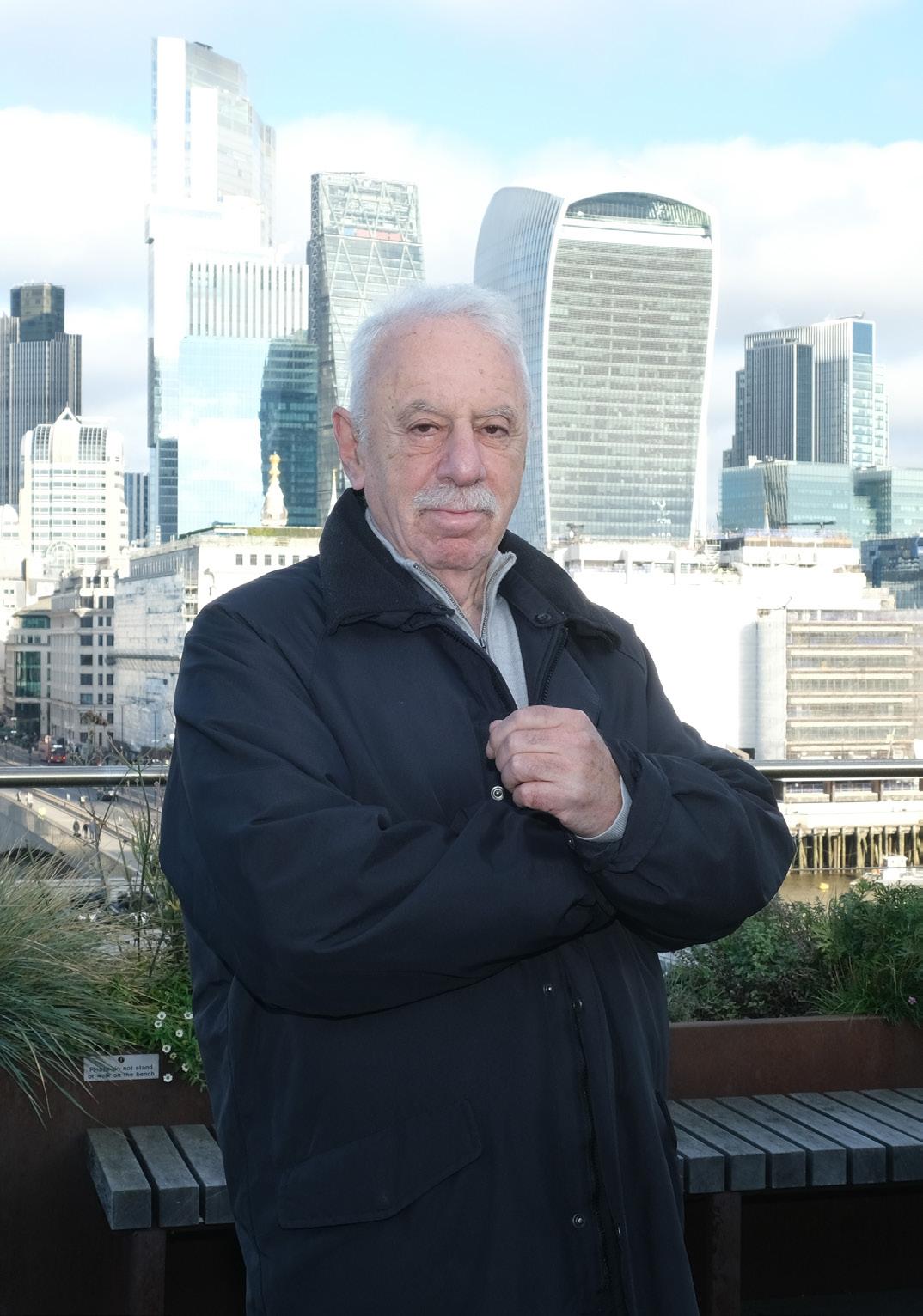

The great property investor on how he made his way in the world

People often assume that if you end up owning hundreds of buildings and running a sizeable property company, you must have started life with a map — a plan, a mentor, a lucky break, something. I can tell you now: I started with nothing of the sort. I left school at fifteen with no qualifications and no job. In those days, no one asked what you wanted to do. You were told. Tea taster. Apprentice chef. Garment trade. I tried each, lasted a few days, and found myself back at square one. I wasn’t gifted, and I wasn’t guided. I was just trying to survive.

“I left school at fifteen with no qualifications and no job.”

The turning point was almost laughably ordinary. A friend said he wanted to open an estate agency in Hackney and asked if I fancied joining him. I was eighteen. I said yes. And that was it. No divine revelation. No great ambition. Just a door that opened and a decision to walk through it. Hackney back then wasn’t the fashionable postcode journalists write about today. Mortgages were almost impossible to get. Many houses were in multiple occupation. Whole areas were dismissed as undesirable. But that was my training ground — not in any formal sense, but in learning to see value where others saw bother.

Back then, people wanted quick money. Buy cheap, sell fast, head to Marbella for two weeks. I couldn’t understand it. Why part with something that would

appreciate? Why sell and hand half the profit to tax? I learned early about regearing — letting the bank lend against the rising value. No tax, no drama, just the ability to go again. That became my rhythm: buy, hold, borrow, buy again. Patience in bricks and mortar pays. It’s amazing how few people realised it. Some of the buildings I bought for six or seven thousand pounds are now worth a million or more. And yes, I still own a good number of them fifty years on.

What I did have, even then, was an instinctive love of buildings. That may sound sentimental coming from someone in property, but it’s true. Other people fell in love with fast profits; I fell in love with structures. I’d look at a house and think: *I’m never selling you*. They didn’t love me back, of course, but that didn’t matter. You have to believe in something. For me, it was London’s stock of solid, characterful buildings. Move with them long enough and they reward you.

“We’re a business, yes, but also a family. We celebrate birthdays with cakes. We tease each other.”

Partnerships shaped me too. Norman Silver and I started together. Four years later he wanted pastures new, and we did a deal that was good for both of us. I learned then that property isn’t just about bricks — it’s about people. You need honesty. You need to be someone people like dealing with. If you’re a rogue, word

gets around. If people enjoy working with you, they’ll bring you opportunities. I’m proud of the fact that if you ask anyone in this business about me, they’ll say I’m a decent bloke. That has mattered more than any qualification I never had.

Today the business is enormous. Around 800 buildings. Roughly 3,000 tenants. Staff who don’t leave — literally. Some have been here forty years; many over twenty. My PA has survived 5 years with me, which must qualify her for sainthood. We’re a business, yes, but also a family. We celebrate birthdays with cakes. We tease each other. We talk about food endlessly. I walk the office every day — not to monitor, but because I genuinely want to say hello. If someone’s got family trouble, they go home immediately. And every staff member knows I mean it when I say “family first.” People stay because they’re looked after, and because the work is varied. As Chris, who came to work for me forty years ago, says: no two days are the same.

And I’m hands-on — by choice, not necessity. I still look at every letting in a little black book. Every week. I go out visiting properties. Knock on tenants’ doors. Chat. See things with my own eyes. One moment I’m negotiating a banking facility worth hundreds of millions; the next I’m talking about a broken door lock. That mix keeps me alive. A CEO who hides from the details shouldn’t be a CEO. People ask if I worry about tax, legislation, or what Westminster might do next. The answer is: not really. If I obsessed over every rumour, I’d be suicidal. Ignorance is bliss — truly. They talk about inheritance

tax, capital gains, National Insurance on lettings. Fine. Let them talk. When you’ve been in this business fifty years, you know that some proposals happen and many don’t. And even when they hurt, they create opportunities. Always.

Take the Rent Act in 1965. It sent values through the floor. But it also let people buy incredibly cheaply — and decades later, when the regulated tenancies ended, the properties became goldmines. That’s property: cycles, distortions, corrections, chances. The trick is to stay calm.

“People are fleeing Britain in fear of taxation — Marbella, Dubai, Portugal, Israel. I’m not going anywhere. I live in Highgate and I adore London.”

People are fleeing Britain in fear of taxation — Marbella, Dubai, Portugal, Israel. I’m not going anywhere. I live in Highgate and I adore London. I love its history. I love its oddities. I’m deeply involved in the English Heritage Blue Plaques scheme, which I think is one of the great quiet joys of this city. You see a plaque for Captain Bligh or for Jimi Hendrix next to Handel, and suddenly time collapses. You feel connected to something bigger. In London every street has a story. That’s magic. And it’s why I’ll never leave.

Young people often ask for advice about entering the property world — residential or commercial. I tell them the same thing: learn the graft. Read the legislation. Understand tenancy law. Don’t chase quick money; it won’t last. And don’t imagine you know everything — you don’t. Listen to those who’ve done it. Put the work in. Residential is highly legislated and requires a cool head. Commercial is different, but the principles are the same: honesty, consistency, graft.

If you’re decent and you work hard, you’ll go far.

What’s next for us? Two major developments — one next to Bloomberg in the City, and one in Hatton Garden. Big projects. Complex ones. But exciting. At the same time, the day-to-day never ends: compliance, maintenance, tenant relationships. It’s not glamorous, but it’s real. And that’s what matters.

Looking back, if there’s a theme that runs through my life, it’s that problems can become opportunities. I’ve seen crashes, booms, reforms, disasters. I’ve seen managers panic and landlords bolt. And I’ve stayed put. You don’t plan every detail. You adapt. You look after your people. You trust your instincts. And you keep walking through doors when they open.

Fifty years on, I still love it. I love the buildings. I love London. I love the people I work with. And I love that, somehow, through luck, graft, and a lot of patience, this strange journey has worked out. I wouldn’t change a thing.

The writer and Edward de Bono biographer on why entrepreneurs must reclaim play, perception and the power of simplicity

In 1992, Edward de Bono published Simplicity , a book that should have changed the way industry, academia and politics think - but didn’t, largely because these sectors tend to read only things that confirm they were right all along. De Bono’s thesis was disarmingly straightforward: simplicity is not childish. Simplicity is power. It is the sharp tool that cuts through the armour plating of jargon, ego, bureaucracy and overthinking that “serious” adults construct around themselves like an emotional MOT test.

Instead, we treat simplicity as though it belongs in infant school - something charming, but not quite to be trusted, like glitter glue or show-and-tell. The grown-up world rewards complication. Academics write as though clarity is a dreadful social failing. Politicians speak in sentences so long and syntaxheavy that they should be sold with a safety warning. A business leader recently described a new policy as “the recalibration of multi-layered operational efficiencies in the context of cross-departmental interface alignment”—a phrase that could have been replaced entirely with: we’re trying to work better together. You could almost hear the relief in the room when someone translated.

We swim in condensed soup - dense, salty, impenetrable. Meanwhile, entrepreneurs starve for clean water and, occasionally, a spoon.

Yet when something genuinely worldchanging emerges, it is almost always simple. Steve Jobs held up an iPhone and said only, “It just works.” Jeff Bezos built Amazon around one sentence: “The customer is always delighted.” Warren Buffett famously said, “If you can’t explain it to a ten-year-old, don’t invest in it” - which also describes most of the FTSE 100’s annual reports. Elon Musk framed the Mars mission as: “We must become a multiplanetary species,” a line so simple it sounds like a tagline for a Netflix series. Greta Thunberg’s entire message is six words: Listen to the scientists and act. None of these required a glossary.

Simplicity isn’t childish.

Simplicity is leadership - just without the unnecessary PowerPoints.

This truth runs through Will Hayler, founder of the Blue Earth Summit, who seems constitutionally allergic to waffle. When Hayler describes the moment Blue Earth became real - a surfer sitting in the Atlantic, realising Twitter-scale outrage wasn’t producing Web Summit–scale solutionswhat he’s describing is the moment perception becomes truth long before logic finishes its coffee.

Blue Earth is built on one principle: well-being for everyone forever. Not “wellbeing within the context of multisectoral pathways aligned to the Paris Accord at 1.5°C,” which is how an academic might put it while everyone else quietly loses the will to live.

De Bono would have approved. Hayler talks about adventure, uncertainty, eating the elephant bite by bite, and the wonderfully disobedient idea that optimism is not a weakness but a fuel source. He describes solution-finding, not problem-polishing. Water logic, not rock logic. His language is so clear that at times one wonders whether he has been banned from government communications departments for lack of opacity.

Ask him why Blue Earth unites activists, artists, athletes, scientists, investors, policymakers and founders, and he avoids the usual jargon about “cross-pollination of ecosystem stakeholders.” Instead, he says, “Everyone has a voice - and everyone has a role to play.”

This is the gift of simplicity: it lets people actually speak to one another, rather than nodding politely while mentally Googling acronyms.

Simplicity outperforms complexity everywhere:

1. Negotiations: The most effective negotiators use short sentences like: “This is what I need. What do you need?”—instead of “circling back to align on deliverables.”

2. Pitching: Investors prefer sentences, not epics.

3. Health: “Sleep. Move. Don’t eat beige food” works far better than a 900-page wellness protocol.

4. Technology: Google: one box. Enough said.

5. Diplomacy: The Good Friday Agreement did not attempt interpretive dance to make its point.

6. Teaching: The best teachers use metaphors, not migraine triggers.

7. Branding: “Just Do It” has outperformed every corporate mission paragraph ever written.

8. Policy: “Free at the point of delivery” remains unmatched.

9. Climate action: “Use less, restore more.” No need for a white paper.

10. Entrepreneurship: If you need a flowchart to describe your startup, it’s not ready.

Hayler sees simplicity not as a communication tactic but as an operating system. Young founders often agonise over balancing purpose and profit, as though they are trying to negotiate peace between warring nations. His answer is charmingly plain: Blue Earth must be commercially robust - tickets cost money, partnerships cost money, staging a festival costs approximately the GDP of a small island - but the mission does not drift because it is simple enough to survive contact with reality.

Even partnerships are simplicitydriven. Hayler is clear: no fossil fuel

sponsors. Not because of ideology, but because “they are too committed to profit above everything else.” Also, one imagines, because “Fossil Fuel–Powered Regeneration Pavilion” would look terrible on the brochure.

Instead, Blue Earth partners bring solutions. The test is simple: Do you move the boat faster? (Preferably in the right direction.) If not, the kayak is full.

Hayler’s embrace of regeneration - a word currently in its identity crisis era - is again rooted in clarity. Regenerative systems give more than they take. They don’t require you to become a monk or sell your car or memorise carbon budgets before breakfast. They simply ask: Does this restore? Does this renew? Does this make the world more alive? Entrepreneurs understand this intuitively. It is the opposite of the “less, less, less” messaging that makes everyone miserable.

And then there is optimism - a topic treated in grown-up circles the way one treats a wasp: gingerly, with suspicion. Hayler rejects this entirely. “Optimism is absolutely everything.” Without it, entrepreneurs would never begin, investors would never invest, and movements would never move. “Media kills hope,” he says. “Young entrepreneurs start full of optimism until the world stereotypes them into cynicism.” One imagines de Bono nodding vigorously from the afterlife.

Blue Earth channels climate anxiety into agency because anxiety, when simplified, becomes focus. “If you don’t like the way the world works, invent something better.” The kind of line that makes you wonder whether it should be tattooed on the wrist of every young founder who has been told to wait their turn.

But the deepest simplicity of all is play.

Adults forget that every great invention began in play: the Wright brothers tinkering with bicycles, early programmers fiddling with circuits, Einstein imagining riding a beam of light like a child trying out a new scooter. We spend years teaching children curiosity and humour, then spend the rest of their lives stamping it out. Hayler refuses this. His festival invites surprise. People don’t know what to wear, which means they arrive as themselves - possibly for the first time that week. Bankers sit with activists, find shared ground, then go home wondering why it took a festival to realise they were both human. This is not climate as scolding. It is climate as community.

In a culture so addicted to complication it practically needs a 12-step programme, perhaps the most radical thing a young entrepreneur can do is simplify. Strip an idea down to what is true. Speak plainly. Act before permission is granted. Bring hope into rooms that haven’t felt hope since 1997. Build regenerative systems that give more than they take. Laugh at the absurdity of overcomplication, then proceed without it.

Simplicity is not the opposite of intelligence.

It is intelligence delivered without the nonsense.

Will Hayler knows this. Edward de Bono knew it.

And deep down, young entrepreneurs know it too.

The world does not need more complicated adults. It needs braver simplifiers.

The great writer on the vanishing commons and the novelistic imagination

The novelistic approach to the human subject begins with the premise that power is not an identity. It moves. It shifts. To imagine otherwise—to imagine fixed categories of victim and oppressor, static and eternal—is to misunderstand the political world entirely. We see this most vividly in the present moment: if your model of history presumes permanent victims, then you are wholly unprepared when those victims become aggressors. Novelistic imagination, at its best, makes such moral and psychological movement conceivable.

Over the past fifteen years, so much public discourse has insisted on permanent identities—on citizens who are forever this or forever that—that entire realities become unintelligible. I saw this in my classroom during the height of Black Lives Matter. When police violence in Nigeria erupted, my students could not comprehend it. Their mental model was fixed: white police, Black victims. Nigeria did not fit the script; therefore, for them, it could not happen. That rigidity is profoundly apolitical. Politics demands a capacity to imagine power relocating itself, inhabiting new bodies, expressing itself in new forms.

“For more than two decades I have lived without a mobile phone.”

But as I listened to this conversation about imagination, another worry

Zadie Smith Photographed by Sebastian Kim

arose: where will the readers of such imaginative work come from? What is happening to the people capable of reading? For more than two decades I have lived without a mobile phone— an accidental experiment whose results are painful. The loneliness of existing outside the dominant mediation system is overwhelming. Every train carriage, every bus, every queue: 100%

captured. People submerged entirely elsewhere. I understand the impulse; I, too, was once a reader avoiding reality on public transport. But the question now is not why we escape, but who is mediating the escape. Personally, I prefer to be mediated by Tolstoy rather than Musk.

What strikes me most, however, is the

disappearance of the commons. There has always been a space—physical, public—where human beings shared a more or less unified reality, a place of noise and irritation and ordinary life. That commons no longer exists anywhere. The most heartbreaking evidence comes from children. A British subway carriage in my youth was full of noise: arguments, jokes, mischief, children pointing at strangers and whispering outrageous things. Now there is silence. Absolute silence. Every child on every bus, every train, every street—absorbed, solitary.

If you still walk in the commons, as I do—since I live spiritually in 1992—you see the desolation clearly. It feels like Mars. I have travelled to tiny villages in The Gambia and found the same silent absorption. The same small, glowing rectangles replacing the unpredictable chaos of public life.

“A British subway carriage in my youth was full of noise: arguments, jokes, mischief, children pointing at strangers and whispering outrageous things. Now there is silence.”

visited thirty years ago—homes full of Somali families, once cacophonous with voices, siblings shouting, parents debating. Now those houses are silent too. Entire childhoods, lived in mute isolation.

“Anyone raising children will recognize the pattern: a child may read passionately until about age twelve; then the phone arrives, and the reading life vanishes.”

From such conditions, what kind of interiority can emerge?

Still, the novel must remain new; novelty is built into the form. And every so often a book appears that meets the moment. Recently, David Szalay’s Flesh struck me for this reason. Its protagonist is one of these denuded figures—a young Eastern European man with no nineteenthcentury soul, no cultivated interior life, no capacity for reflection. He might be the man at the door of a club, the supermarket cashier, the gym devotee with the thick neck and blank expression. His consciousness is stark. Time barely passes for him. He lives inside his phone. And then, through a sexual misadventure, he drifts into marriage with an extraordinarily wealthy woman. The revelation of her world comes casually: her son takes a helicopter to school.

This denuded commons does not produce readers. Anyone raising children will recognise the pattern: a child may read passionately until about age twelve; then the phone arrives, and the reading life vanishes. If you are lucky, and wealthy, and middle class, you might coax it back at fifteen or sixteen. Everyone else is lost. My mother, a social worker, describes visiting the same crowded flats she Wikipedia.org

The book’s style is equally stripped. No Tolstoyan largesse. No Carveresque transcendence. Yet it worked. When

I finished it and walked through my neighbourhood, I saw that man everywhere—at the corner shop, outside the club, driving my cab. I saw him for the first time. That is the empathetic miracle the novel can still perform, even in a world whose readers have razor-thin bandwidth. As Szalay himself said, you must work with the bandwidth you have. The modern reader cannot process indulgent expansiveness; the writer must find a new form, a new clarity, a new mode of communicating consciousness.

“The modern reader cannot process indulgent expansiveness; the writer must find a new form. ”

The commons is vanishing. Attention is collapsing. But the novelistic imagination remains one of the few tools we have left—one that insists upon the mutability of human beings, the possibility of seeing one another anew, even across the silent gulf of our mediated age.

Have you observed that your children’s pride in their community and history is eroded in the media or at school? Have you seen the reduced interest among the young in family life and in helping society progress, replaced by zombie-like addiction to social media and victimhood? Are you worried you will lose your children to current mainstream education, turning them barren in all ways? Are you worried your children will learn how to function in a decaying system, unprepared for the harsh realities when that system crashes?

We are. We – academics, consultants, educators, and policy advisers from LSE, Yale, the World Health Organisation, Washington, the EU organisations, and so forth – have seen it getting worse for decades. We were deeply moved by what we saw happening to our own children and the students we taught at universities –even the top UK universities. We saw bright-eyed, hopeful young students become fearful to speak their minds in a matter of months after starting their studies, taught to be ashamed of whom they were and cowed into becoming bureaucratic followers, not confident leaders. They became increasingly lonely, shallow, alienated from their family, and self-obsessed, not proud builders of their own lives and of new communities. Lockdowns made it all much worse.

Not merely did our students start to believe they were a burden to the planet rather than a blessing, but

they were also lacking vital work skills. They lacked critical thinking and realism about how the sectors of our society actually worked. They came out of universities thinking that government is purely top-down: that leaders could simply choose a bit more GDP, ‘nature’, ‘equity’, or ‘health’ when they felt like it. The ‘how’ and its costs were out of sight. Real leadership is a combination of the coal face – where the question is what is workable – and of what one values.

“We saw bright- eyed, hopeful young students become fearful to speak their minds… taught to be ashamed of whom they were and cowed into becoming bureaucratic followers, not confident leaders.”

Our students were not taught what is workable in government, the health sector, the education sector, finance, or any other sector – let alone how to reform them. They were simply educated to fit in, either as a minion doing some office job, or as a ‘leader’ versed in virtue-signalling. That is not a problem whilst the system keeps going as before, but leaves them stranded when the system radically changes. We are hence not surprised at the fear many university graduates now have that they don’t know anything that AI does not also know.

In a way, they are right: many don’t know more than AI. They are stranded, unprepared to think on their feet, view things from different perspectives, and adjust. Businesses calls for critical thinking skills and creativity that current education no longer produces. Indeed, IQ levels have dropped dramatically in the UK since the 1990s, particularly at the top end.

What did we do? We decided to build an alternative, calling it Academia Libera Mentis – the academy of the free mind.

Among the initial group of a dozen academics and thinkers, Paul and Erika were willing to take the lead. They were born in the Netherlands around 1970 and met early in their studies, building a life together. Three children, a successful academic career, and stints in four continents later, they took the plunge in setting up this new academy, backed up by Gigi, Tjeerd, Michael, Willem, Andrew, Dolf, Esther, Benno, and many others who also wanted to do more with their life than pay the mortgage and go on holidays.

Academia Libera Mentis and the castle

So, in March 2024 Paul and Erika bought a 260-year old castle in the middle of the Ardennes: Chateau de Hodbomont, once the ancestral home of an entrepreneurial Portuguese sheep-herding family, with a proud history of having sheltered Jews in the Second World War and once serving as an eye-injury sanatorium. The region has as its official motto ‘Pays de Liberte’ (‘lands of freedom’) and displays a strong streak of independence from Brussels. The stars seemed aligned: a place of refuge, of helping people see again, in a region dedicated to freedom.

Of course – given the limited funds a bunch of academics can cough up –the castle was what they call a ‘fixerupper’. Not so much Hogwarts as Stone Henge: great to look at, but just wait till you have to live there. Half the place was a ruin and the other half barely liveable. The large castle grounds had beautiful ponds and fruit trees, but it was also overgrowing with ivy and had an insatiable need to be mowed and weeded. Large spaces and many rooms also meant many things to fix. As soon as one has overcome one problem, such as a leaking roof, another is discovered, such as mouldy walls and missing insulation. Yet, since March 2024 it has become a home, full of life and beauty brought by those who came to be part of the journey. With each new group of students, the place has not only become more liveable, but also richer in traditions and emoluments.

Help came from many enthusiastic academics and professionals, each pitching in their own expertise, adding to the endeavour. For instance, whilst we are not a religious academy, we do openly value the accomplishments of

the West and the place of the church therein. Theo, a retired Catholic priest, thus found us, joined us, and renovated the chapel of the castle, which was consecrated by a bishop on September 21st. Mass can now be given at our academy for those of the faith.

Similarly, top artists and scientists added new elements to the project, ranging from the school-song ‘Minds that dare’, to a world-class curriculum, to new paintings that adorn the halls.

Gradually both the castle and the organisation became populated and connected. Professor Gigi Foster, educated at Yale and now working in Sydney. Professor Ulrike Guerot, working in Bonn and a former supporter of the EU. Dr Delsing the architect and libertarian entrepreneur. Jeffrey Tucker, director and founder of the Brownstone Institute. Dr Piers Robinson and Dr David Bell, experts in propaganda and former leaders of world health institutions. Lodewijk Regout, artist, peace activist, and theatre director. Liberals, conservatives, Marxists, Christians, libertarians, and influencers. Many sharp minds working towards a common cause: a brighter, more informed future, fuller of the various joys offered by the human experience.

Since April 2024, over 100 students from all over the world have come and joined for (parts of) the programme. This programme is intense with freeflowing discussions on economics, health, neuroscience, statistics, leadership, and the future. It combines the Socratic method of 2,000 years ago with the latest AI – as a tool that adds, not a crutch that replaces. Teachers work together to harmonise their language and arrive at an integrated curriculum, something unique in this world as atomisation among academics is the rule. Yet, our teachers want to find common ground and enjoy learning new things themselves, not just debating to dominate.

Students learn about appearances and reality. We point out this distinction in everything and help students understand both. For instance, in statistics we teach the usual (statistical tests and hypotheses), but also the less talked about art of preparing data for analysis (‘cleaning it up’, ‘weeding out inconsistencies’) and the reality of gathering data (inevitable ‘framing effects’ everywhere). Similarly, we

depict organisations dragged down by corruption not in terms of ‘evil people taking over’, but rather the way in which most organisations meet their end: as the virility and pride in the organisation fails, workers and leaders in an organisation stop cooperating to improve the organisation and instead become parasitical on the resources of the organisation. We do not moralise such parasitism but pose the deeper question of how to reform organisations to keep them virile and internally cooperative.

The typical weekday has intense academic sessions in the morning, connected over the weeks and months by leading questions, like

‘Suppose you are the lead architect of a new constitution for the country of Albiona.

How would you set up its institutions, its media, its health system, its education system, its legal system, its economic underpinnings, and so forth?

How would family life function and the relation between communities and

larger overarching institutions? How would you transition from where it is now? Who would be your allies and your enemies?’

“The typical weekday has intense academic sessions in the morning… leading questions encourage students to re-imagine their own countries and their own lives.”

These leading questions encourage students to re-imagine their own countries and their own lives. Their answers very quickly become quite intricate, with detailed transition plans on how to get from where we are to where we should be. There is steel in the classroom discussions as the students realise that the job of reforming their societies may fall on them and therefore necessitates a realistic understanding of how the world works.

In the 12-month programme, students are individually mentored and set themselves to particular tasks, like thinking of radical reforms to the legal system in their country, or reforming the property market or media sector. They learn the skills one sees in top public servants, consultants, or the founders of start-ups. They can read data and board rooms. They spot the difference between well-oiled new businesses and decaying departments overtaken by parasitism.

Whilst the mornings are led by academics, the afternoon is for student-lead activities, primarily arts and sports. This grows their emotional and social resilience and fosters a greater appreciation for aesthetic movement, creativity and beauty. A core community activity is communal eating, with cooking done in rotating teams so that everyone learns how to cook for others. To help coordination and prevent conflicts, there are sessions on attentive listening, and

group lessons where the students work through modern social challenges (atomisation, gender relations), which they then implement in their student community. We have noticed in our students that few of their generation have ever experienced true community and find the experience intensely exhilarating once they realise that – as Csenge, one of our Hungarian students put it – “community can make us stronger, freer, and more human.”

“Students become much more realistic about how organisations and sectors of the economy work, making them capable of seeing both systemic decay and opportunities for systemic reform.”

Alumni help the next group learn the ropes, but as with the academic programme, the students start as followers looking for instruction and gradually morph into leaders who take the community by the hand in their endeavours. Students organise trips to towns nearby like Aachen, the birthplace of Charlemagne. They garden together and protect each other. There is a lot of experimentation on campus: students practise leading initiatives by designing and implementing new projects and endeavours, ranging from making a list of the medicinal plants found in our forest to mapping the perimeter with a drone.

How are we preparing our students for the world of work? For one, of course, they become part of an international network of rather free-thinking but well-connected teachers and students.

That network also gives them a community to help them understand what is really going on in their society and to give them the belief that better is possible: the ALM community steadies and motivates our alumni to look for opportunities to grow and co-create, both professionally and privately. Most of all, they become much more realistic about how organisations and sectors of the economy work, making them capable of seeing both systemic decay and opportunities for systemic reform. The journey is far from over. Our first alumni are now trying to make their way in the world (with the first ones finding jobs and marriages through each other!) and our community is slowly expanding. A cat guards the stairs (and the pantry). Our aim

remains to be a place of hope and regrowth, spawning similar endeavours throughout the West. Students who want to join the journey and teachers who hope to set up their own new academies in their own countries are welcome.

What about ourselves – has it been worth walking away from a full-time ‘normal career’ that was going well and is now on the back-burner via emeritus appointments and such? We know what we have given up. We now travel less, spend less time in fourstar hotels, and eat less caviar. Life is more raw and more stressful. But the company is better and our joy in teaching is more genuine. It feels like we are doing what we were meant to.

The legendary parliamentarian on what drove him in his political career – and beyond

Italk a lot and try to listen even more, but I never really talk about what drives me; my hunger, my passion to succeed and achieve so I can help others. At heart - I am a lad from Liverpool, although I left almost 25 years ago, it has never left me and I am home (I still call it home) every other week. Home is where my family is and they have been the driving force in my life. Not one of those families that need you to overachieve, as they would be proud of me whatever I did, and they are – furiously proud. They are proud I am The Right Honourable Stephen McPartland, but they call me “our Ste” and some other familial names – my mum, dad, brother and sisters (the twins) – I am the middle child and keep trying to persuade my mum she should give me more attention, but she is having none of it. I am clearly the favourite and keep explaining that to my siblings, but they are having none of it either. What we do all agree on is that family has to be fun, being there for each other and laughing at the best and worst of times.

This is not going to be a rags to riches story, I never had rags and I was always rich in terms of love and laughter, rather than money. Another insight into what makes me the person I am – wealth is defined in terms of love, laughter, happiness, kindness and joy not money or material items. Family really is where my heart is and it has been the cause of great joy and sadness over the years, especially the last 12 months.

“This is not a rags to riches story — I was always rich in terms of love and laughter rather than money. Wealth is defined by love, happiness, kindness and joy, not material things.”