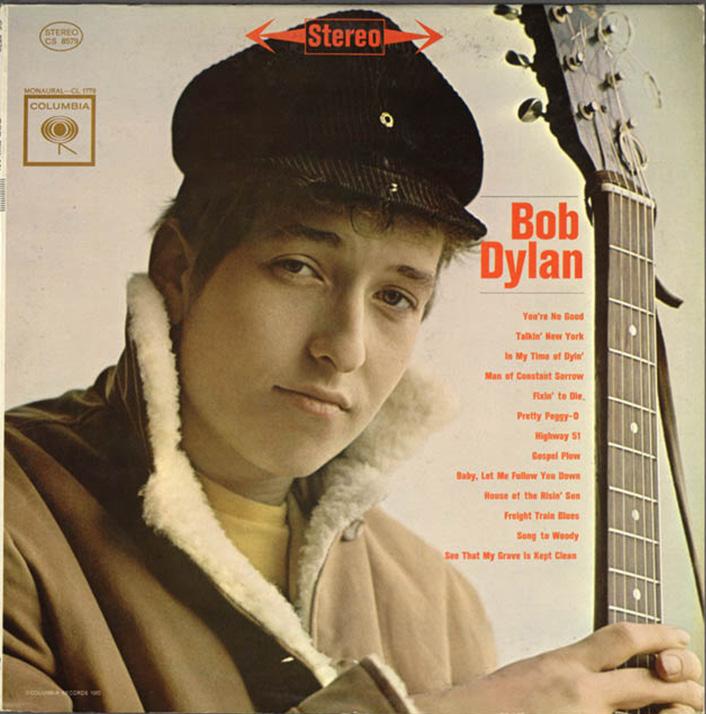

“Did you ever hear that to conquer your enemy, you must repent first, fall down on your knees and beg for mercy?” –Bob Dylan

“I considered all the oppressions that are done under the sun: and behold the tears of such as were oppressed, and they had no comforter, and on the side of the oppressors there was power; but they had no comforter.”

—Ecclesiasties 4:1

“Ah but I may as well try to catch the wind.”

—Donovan

Chris Murray told me “Victor, you have soul.” With that benediction, here is my editorial.

August 30, 1995 . I’m starting with the date because today is the day it became overwhelmingly obvious that I must not read the newspapers anymore. When I pass a newsstand, I’m going to have to turn away. I’ll bring computer magazines to the deli. I’ll learn how to launch a web page. I’ll bring a pad and scribble my own thoughts. Just keep the newspaper away.

I can barely fathom that almost forty years have gone by since I was allowed to walk to the corner of 57th Street and First Avenue with a quarter to buy the Daily News, the Daily Mirror and three packs of Topps baseball cards. I didn’t stop with the sports section, either. In those days, the centerfolds of the NY tabloids were rife with action photos — derailing trolley cars, natural disasters, car crashes. There was Jimmy Cannon and Walter Winchel; the Inquiring Photographer, Leonard Lewin and Earl Wilson and later on, Pete Hamill

and Jimmy Breslin. Yet, between Mark Fuhrer’s sick and sickening revelations and the sadness of the constant reminders of man’s inhumanity to man...I’m going to break this habit. Oh, I’ll be uninformed. I won’t know Winona Ryder is dating some grunge star, or that Monica Seles is back on the courts after two plus years of therapy, or that her attacker was let off twice by the German courts, or that a child in Sarajevo is calling out to her mother, after a bomb blast, that she cannot find her little hand. Or that an eighty-five year old gentleman who went fishing in Brooklyn every other day for decades was murdered by two thugs for whatever pocket change such a person would carry along with his rod, reel and bait bucket. No, I’ll not be aware that a one year old in a hospital in Kampala has no food or water. The reality is, Fine Art should be the Daily News — we should be coming out every day cheering on all that is good and beautiful in creation. There should be no 85 year-old fishermen murdered; there should be no autistic five year-old repeating the only word she knows—“Mom-mom”—for hours on end because her mother was run down by a truck in the act of saving the child’s life; there should be no screams knifing down hospital corridors from the shattered , burned and bloodied victims of plane crashes, jealous lovers, guided missiles or suicide bombers. You sons of bitches out there who, in the name of whatever you deem holy—be it your god, your country or

the Almighty Dollar—stop! In the name of purity, in the name of peace, in the name of the one supreme being who created us all: STOP. There is abundance on this planet beyond your comprehension. There is room for many millions more of us. There are resources available — right before our eyes — that you, in your frothing hatred and lust cannot see. From fishing out the waters to deforesting the land to piercing the very ozone that keeps us safe — this mass of arrogance and stupidity is carrying the human race out with the tide, careening from crisis to crisis on a one-way path to oblivion. Even in this country, that was once hailed as a melting pot for the opporessed peoples of the world, in which immigrants with barely the clothes on their back could at least think they would be afforded, upon arrival, an opportunity—our own citizens are killing each other and not only in the ghettoes. The threat is not solely from outside our borders. Militias, cults and government agencies are in constant preparation for war. Wake up people.What is it going to take for us to turn this around?

2 • Fine Art Magazine • Spring 2022

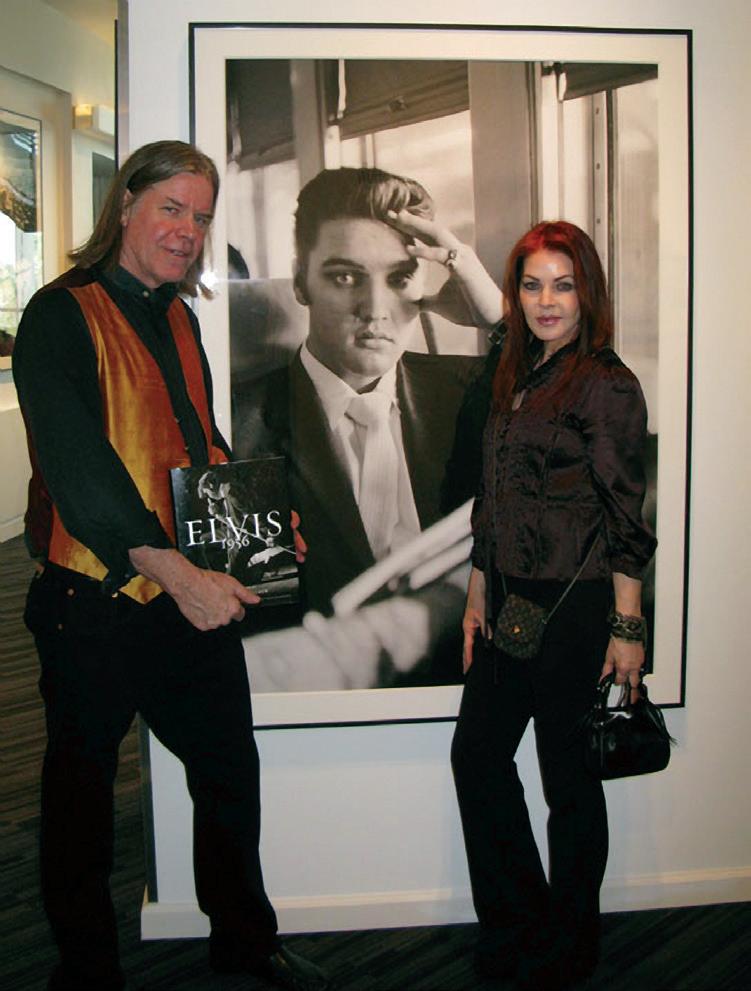

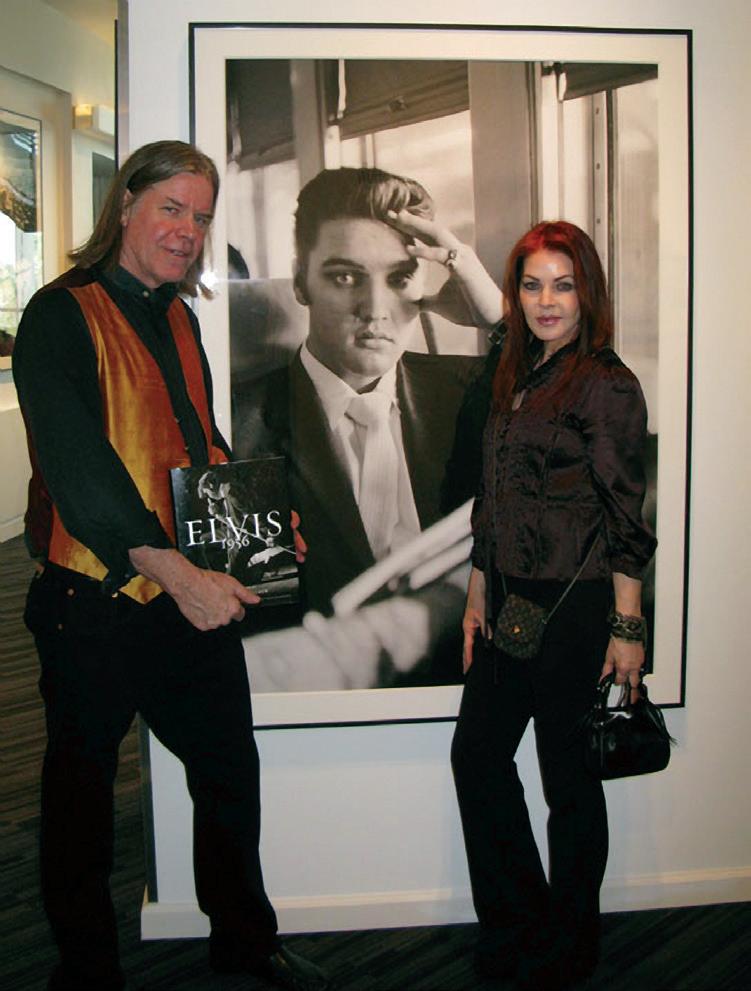

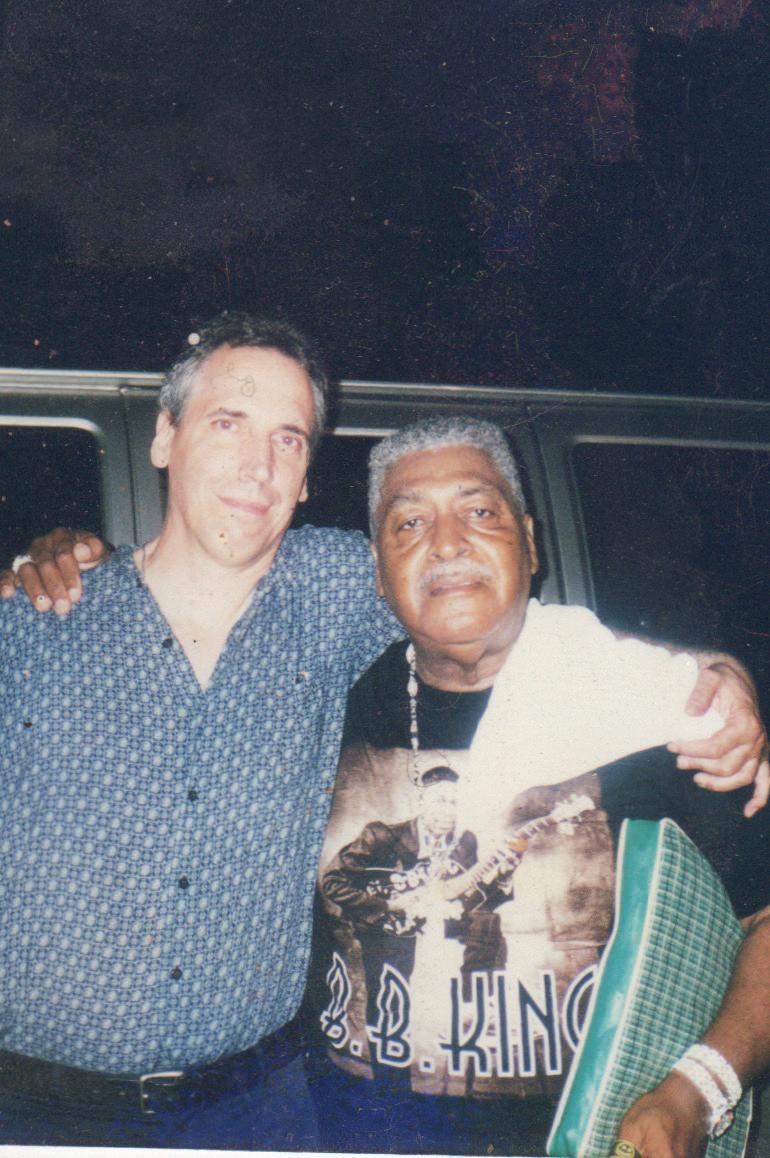

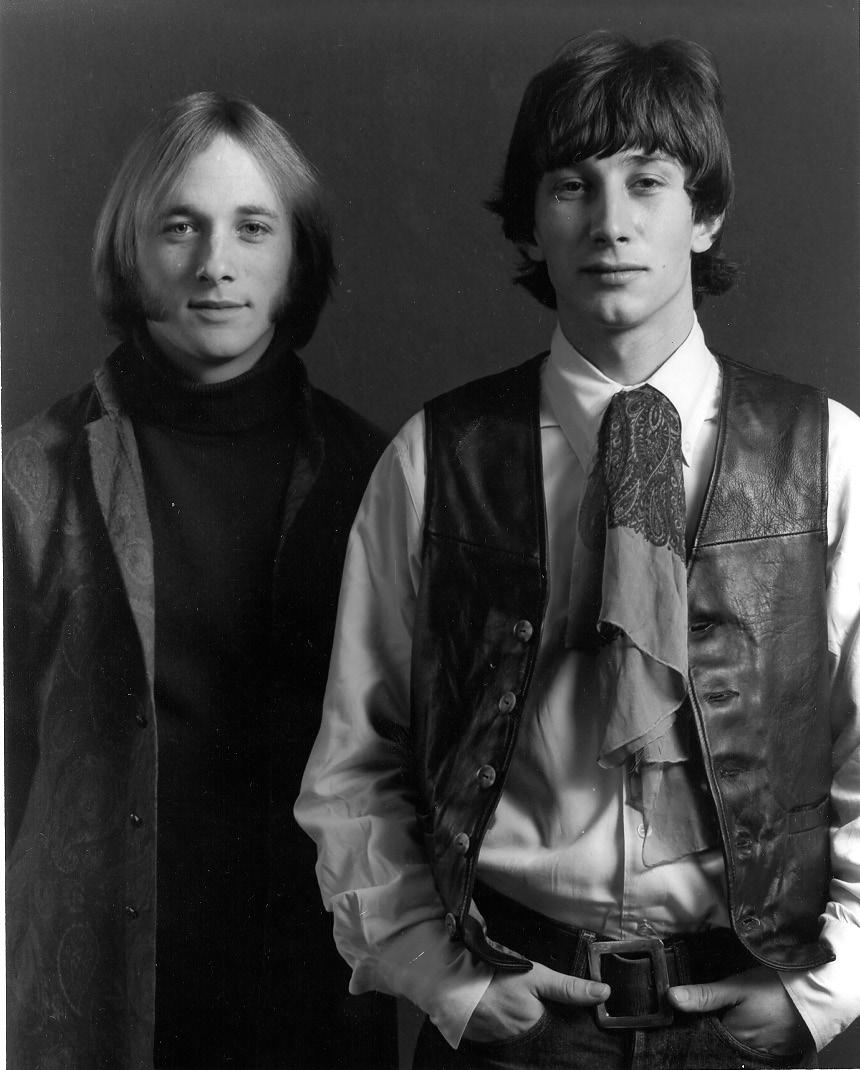

Gallerist, author, publisher and long-time Aide-de Camp to Donovan, Chris Murray, pictured above with Priscilla Presley, played a major role in putting this issue together.

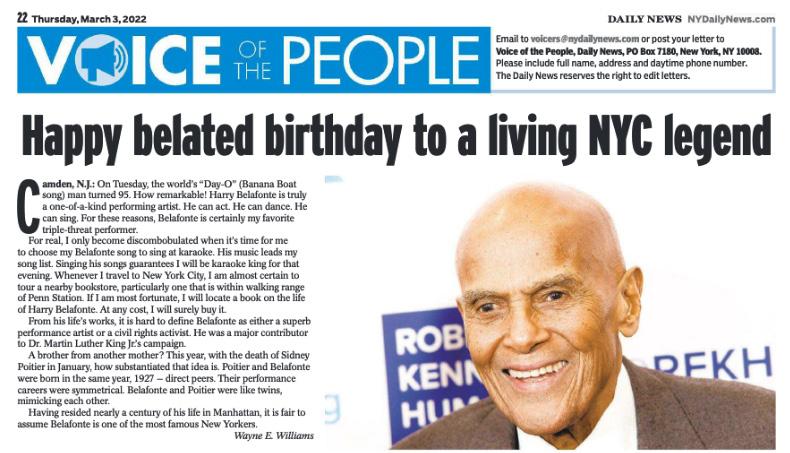

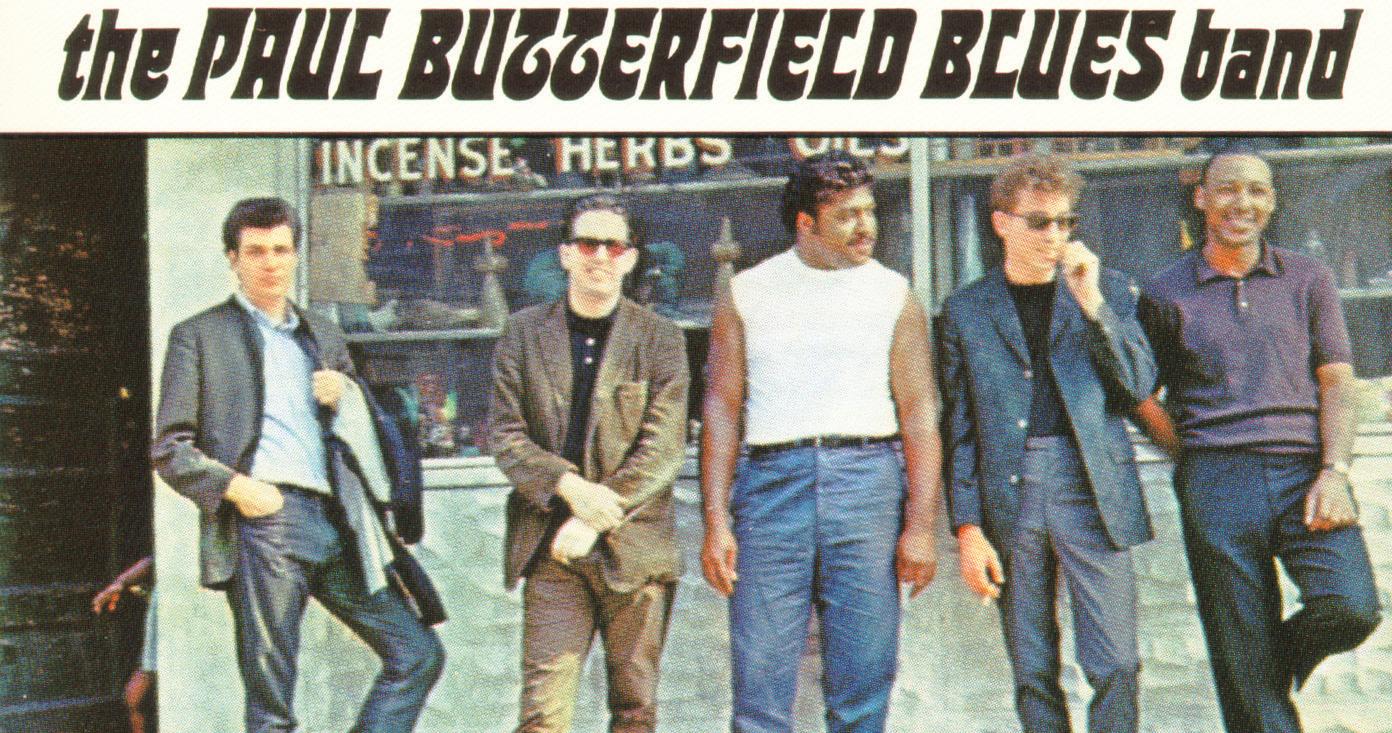

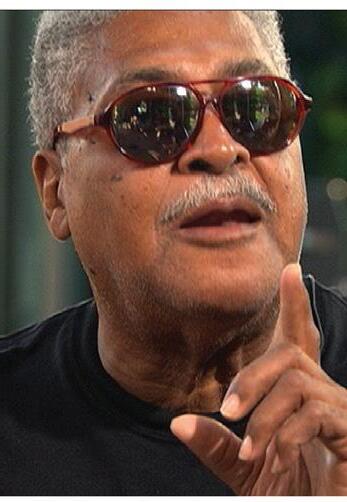

Harry Belafonte, newly ensconced in Rock and Roll Hall of Fame at age 95. Page 3

Steven & Dion hit Broadway. Page 18

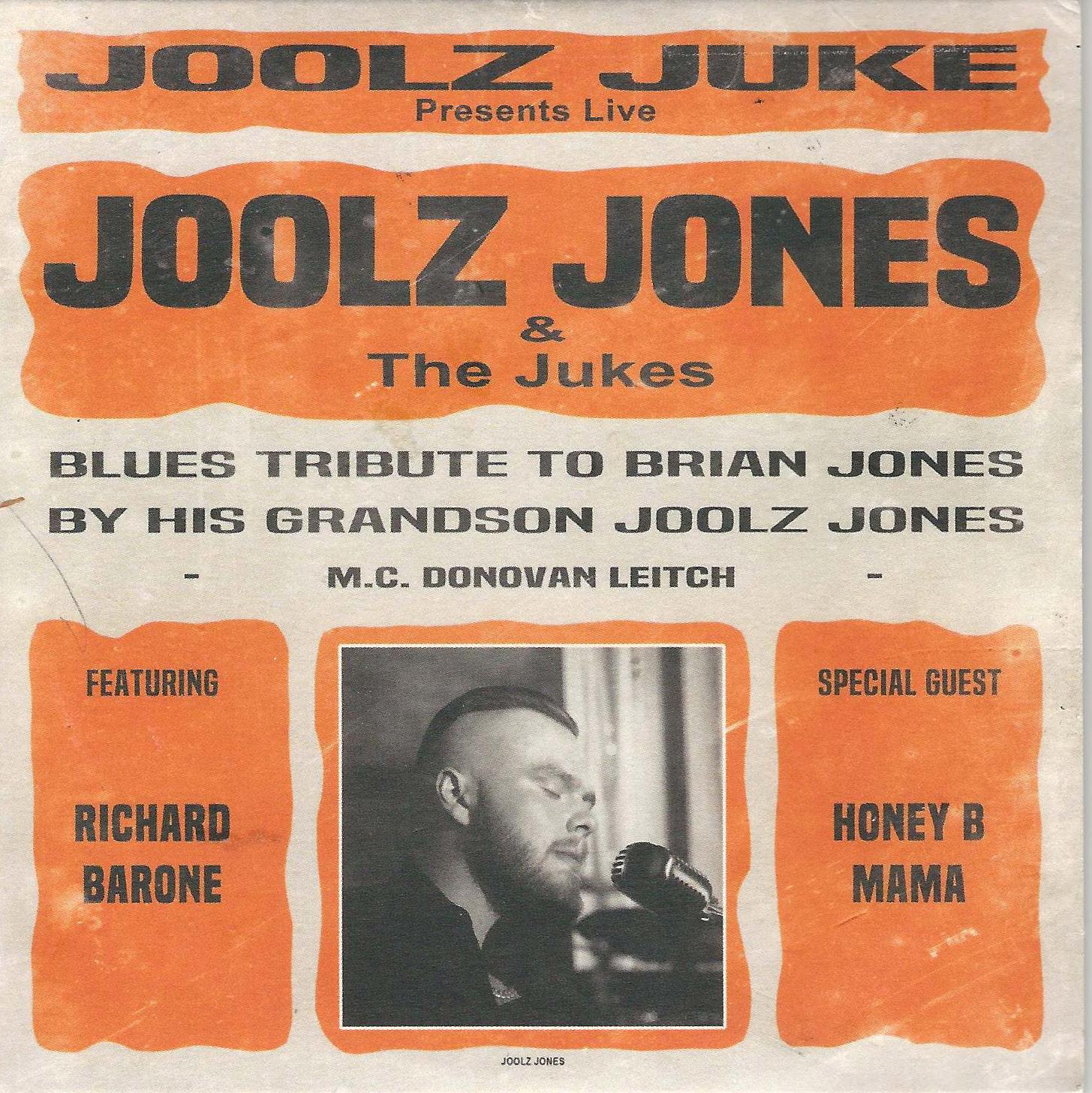

Joolz Jones & the spirit of the Stones. Page

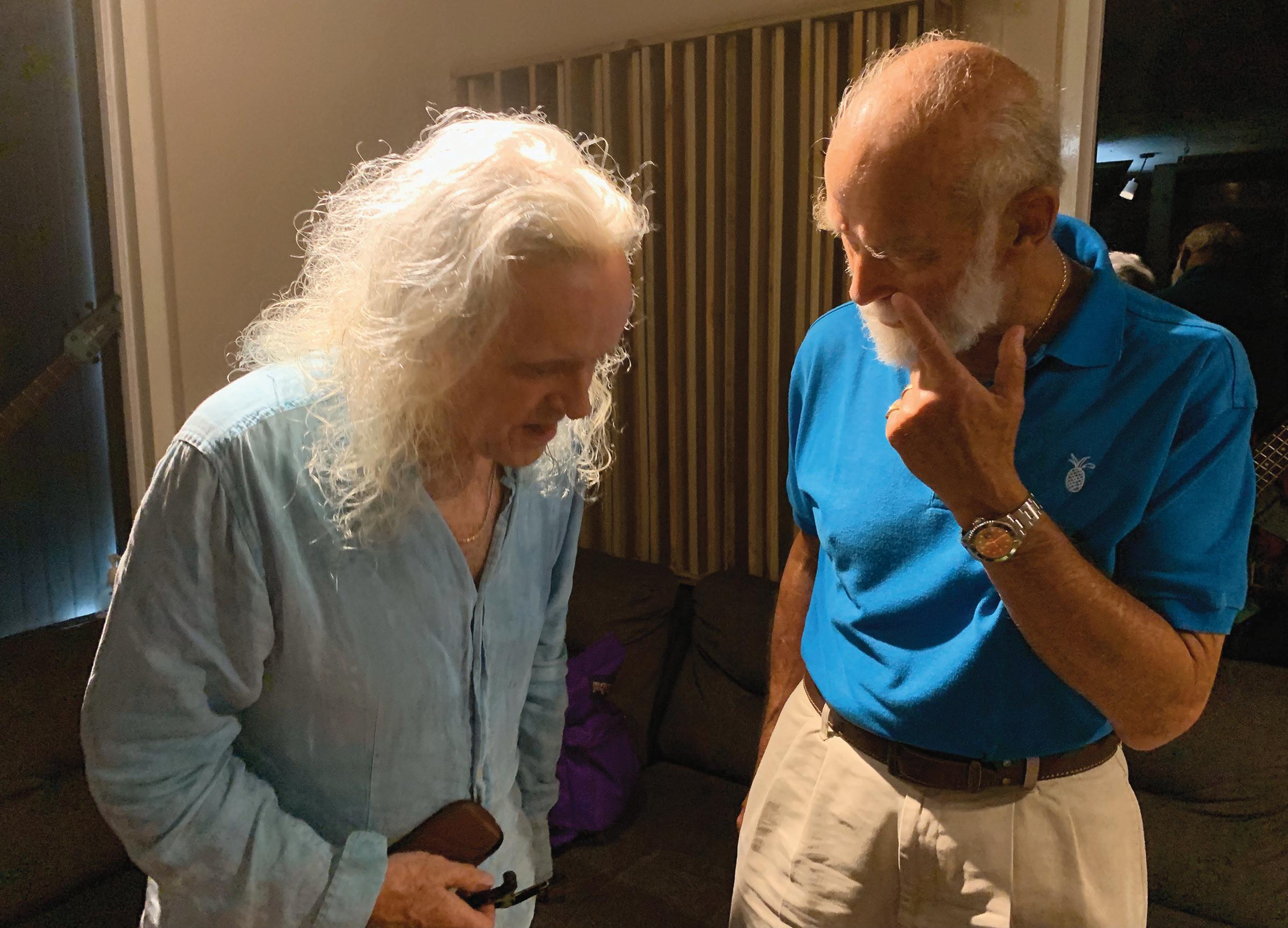

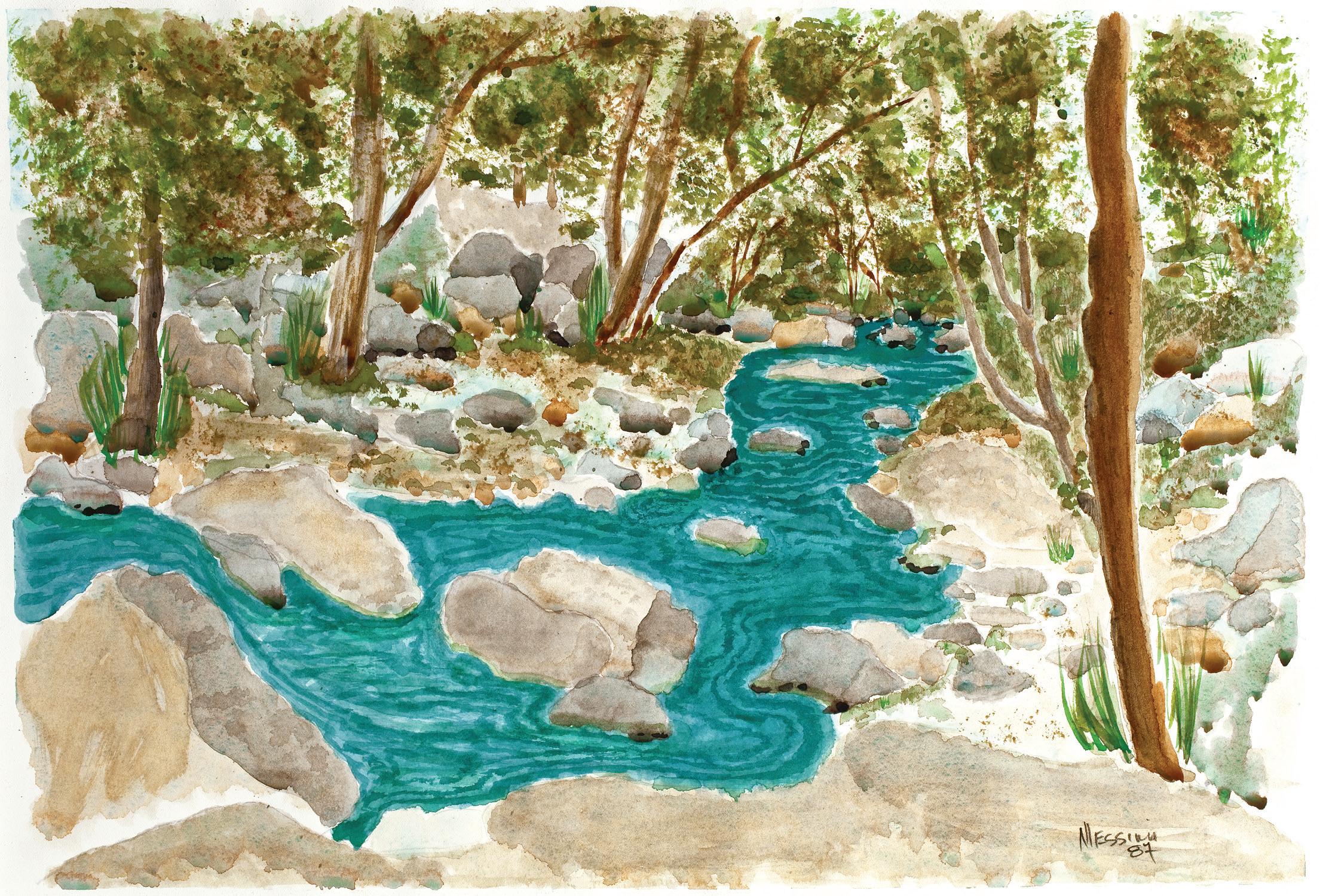

Patrick Francis Kirmer Obituary

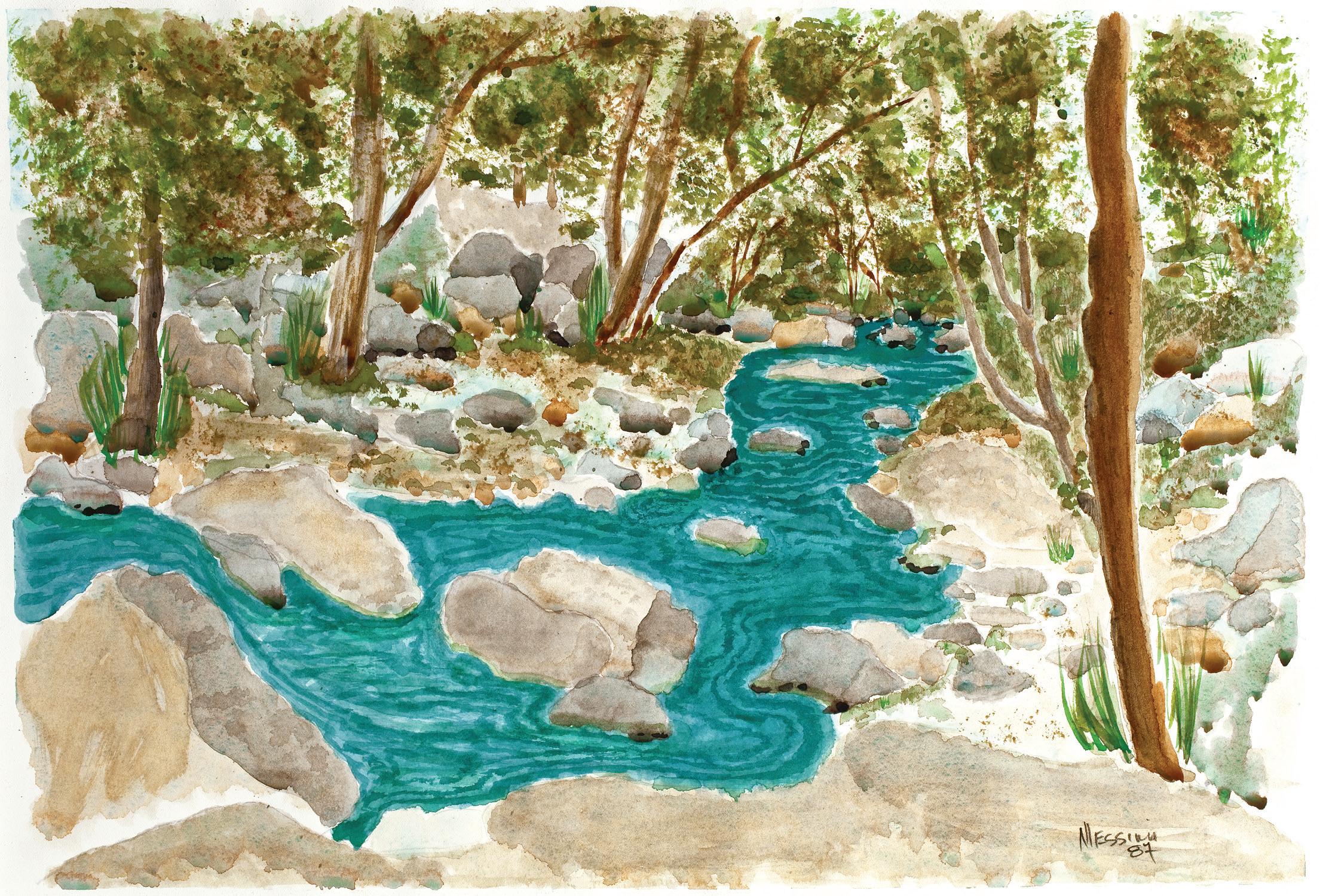

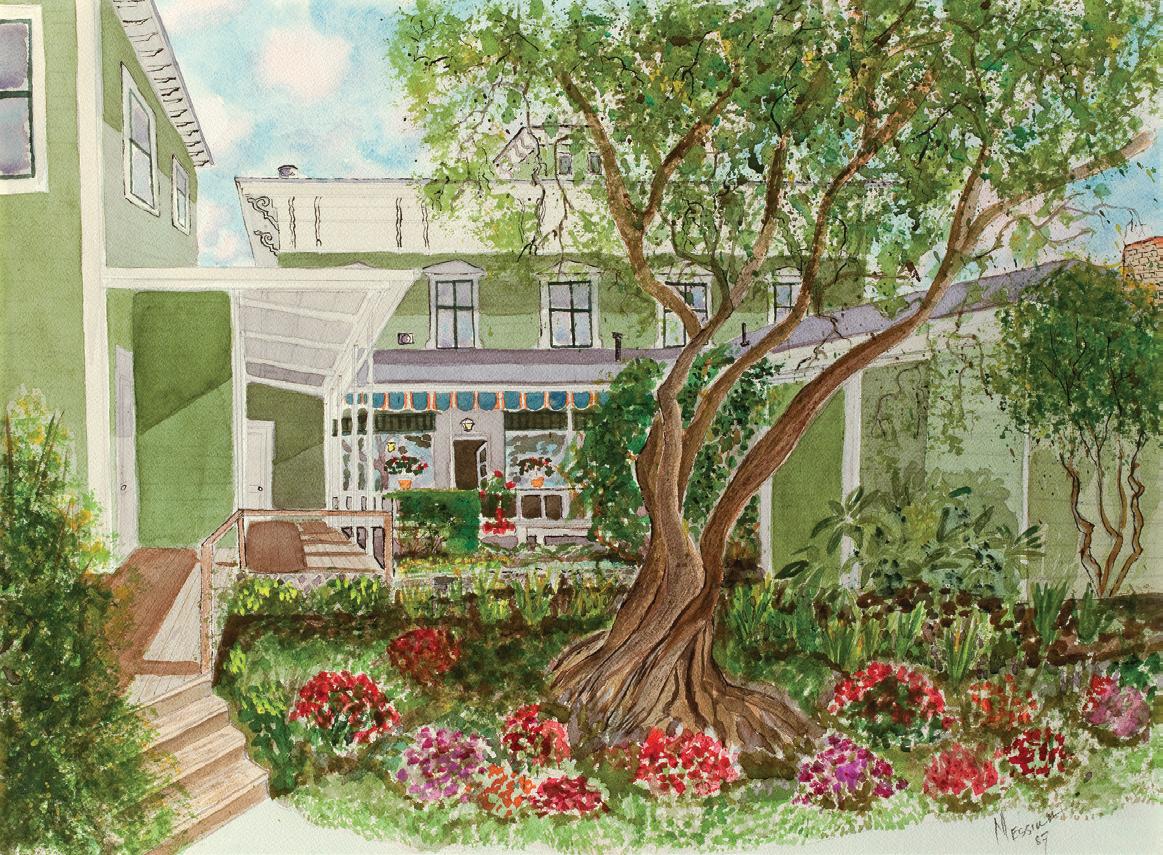

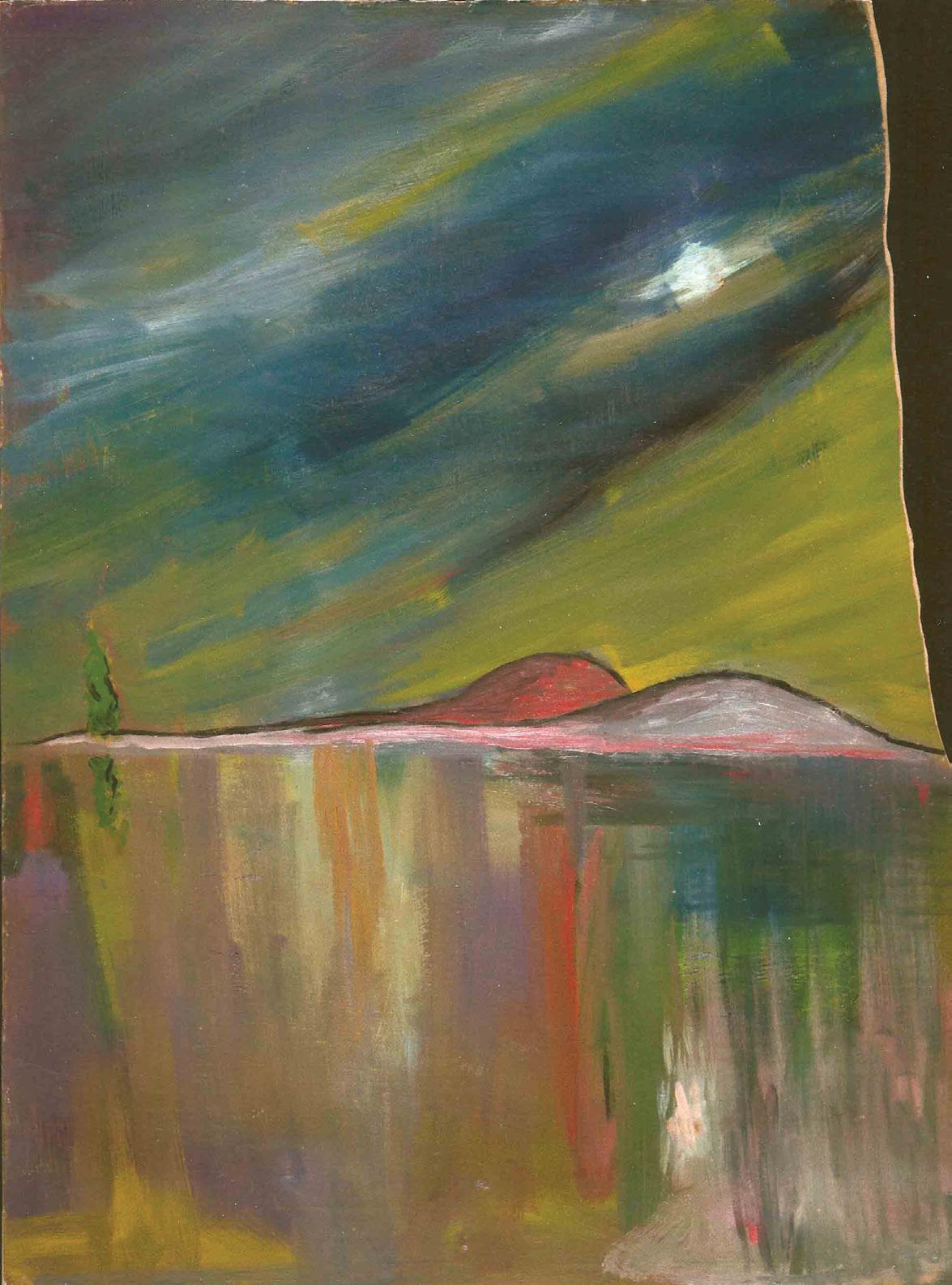

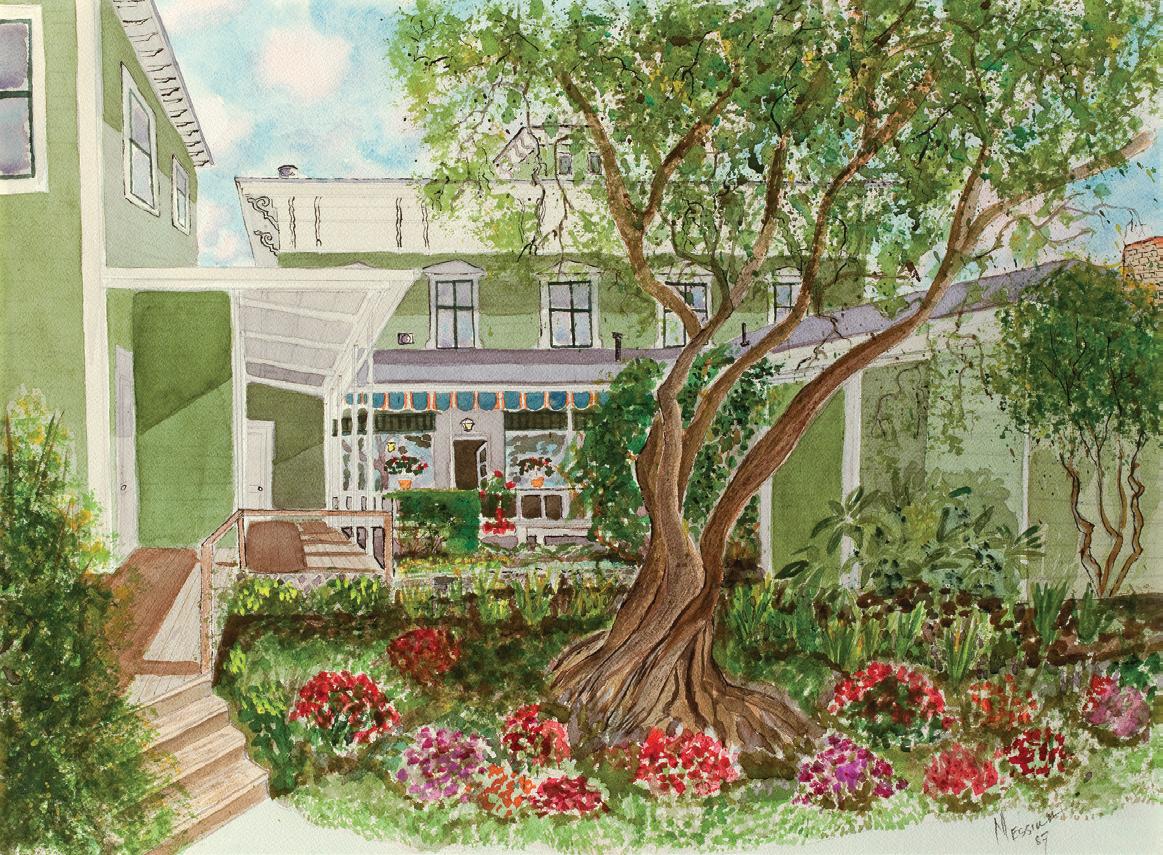

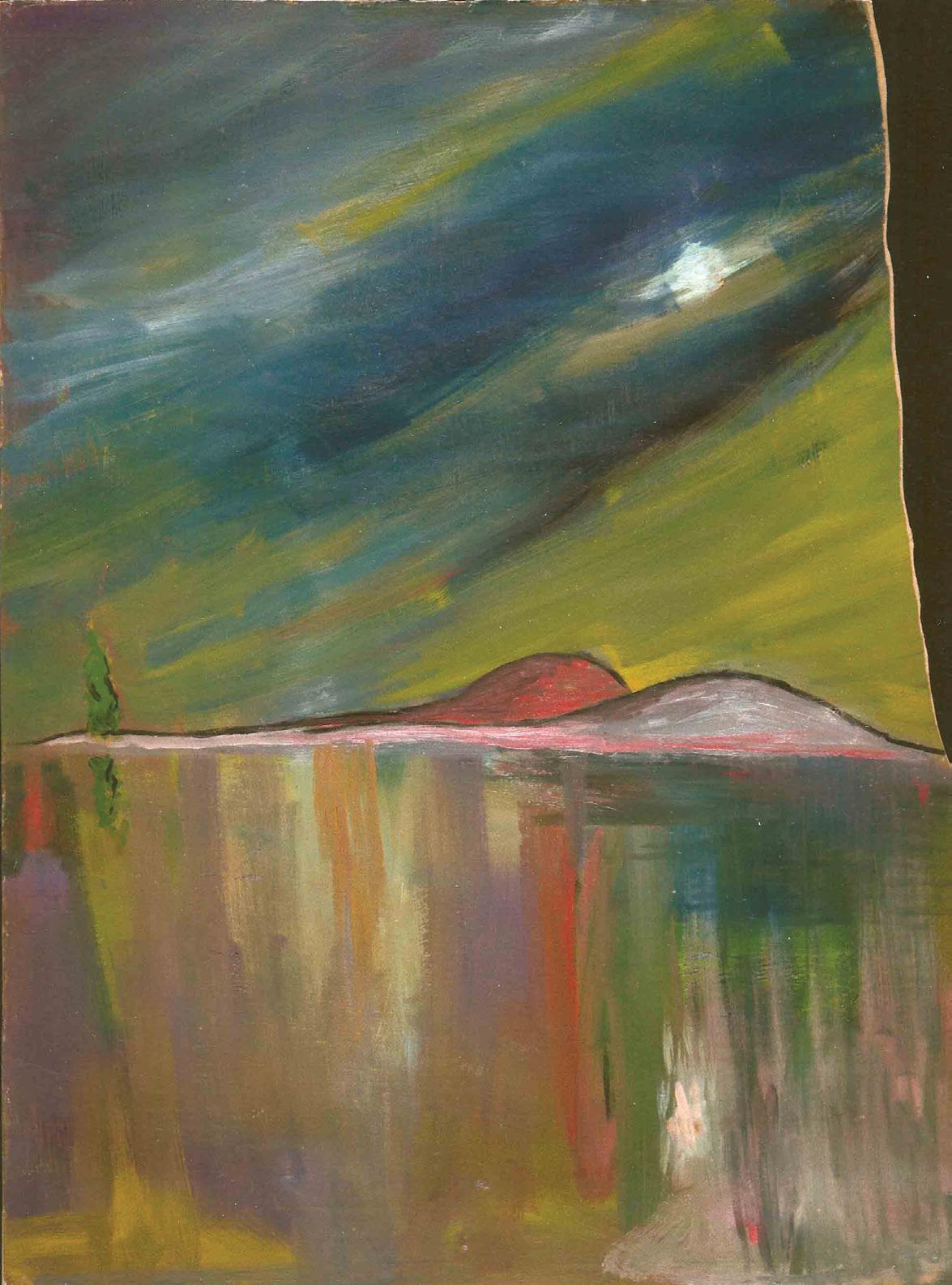

Patrick was born to John and Johannah Kirmer in Hollywood, California on May 1, 1929. Pat was one of six children, four boys and two girls. During his early years he worked with his father, John, in the family butcher shop. He enlisted in the Army during the Korean War, and served stateside for three years. After leaving the service, Pat completed his college education at the California College of Arts and Crafts in northern California. He moved to New York, where he received a Scholarship to the Brooklyn Museum to pursue his studies in art. Upon completing his education, he went to work at the Baldwin School in Manhattan. He taught art there for 30 years, and retired in 1988. During his career at the Baldwin School, he worked at the Baldwin School Camp in Keene Valley, New York. This was his introduction to the Adirondacks and his beloved Johns Brook.

Upon retiring, Pat and his wife Therese, moved to Keene Valley and eventually purchased a home on Market Street. Johns Brook became Pat’s muse and he devoted the vast majority of his time painting the brook. Pat was very engaged with the community and volunteered at the Keene Valley Fire Department selling raffle tickets for their Annual Field Day. He was very engaged with the Keene Central School and he worked tirelessly on sets for many school plays. He was also known as the “apple man”, because of his yearly custom of passing out apples to trick or treaters on Halloween.

Over the past several months, Pat had been living at the Essex Center nursing facility. He took his last “brush stroke” on the evening of May 3rd. Pat and Therese had no children and he was predeceased by two sisters, and two brothers. He is survived by his brother Michael Kirmer and his wife Sandy, who live in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Pat established an annual Johns Brook Scholarship Fund to support a deserving graduating student from Keene Central School who plans to major in music, art, or theater. Memorial donations may be made to the Adirondack Foundation, PO Box 288, Lake Placid, NY 12916 or visit https://www.adirondackfoundation.org/funds/johns-brook-art-and-music-scholarship-fund. All gifts will be added to the John’s Brook Scholarship Fund. An open house celebration of Pat’s life at the Keene Valley Congregational Church was held at the Van Santvoord room on November 16 where many people came to share stories about Pat.

Fine Art Magazine • Spring 2022 • 3

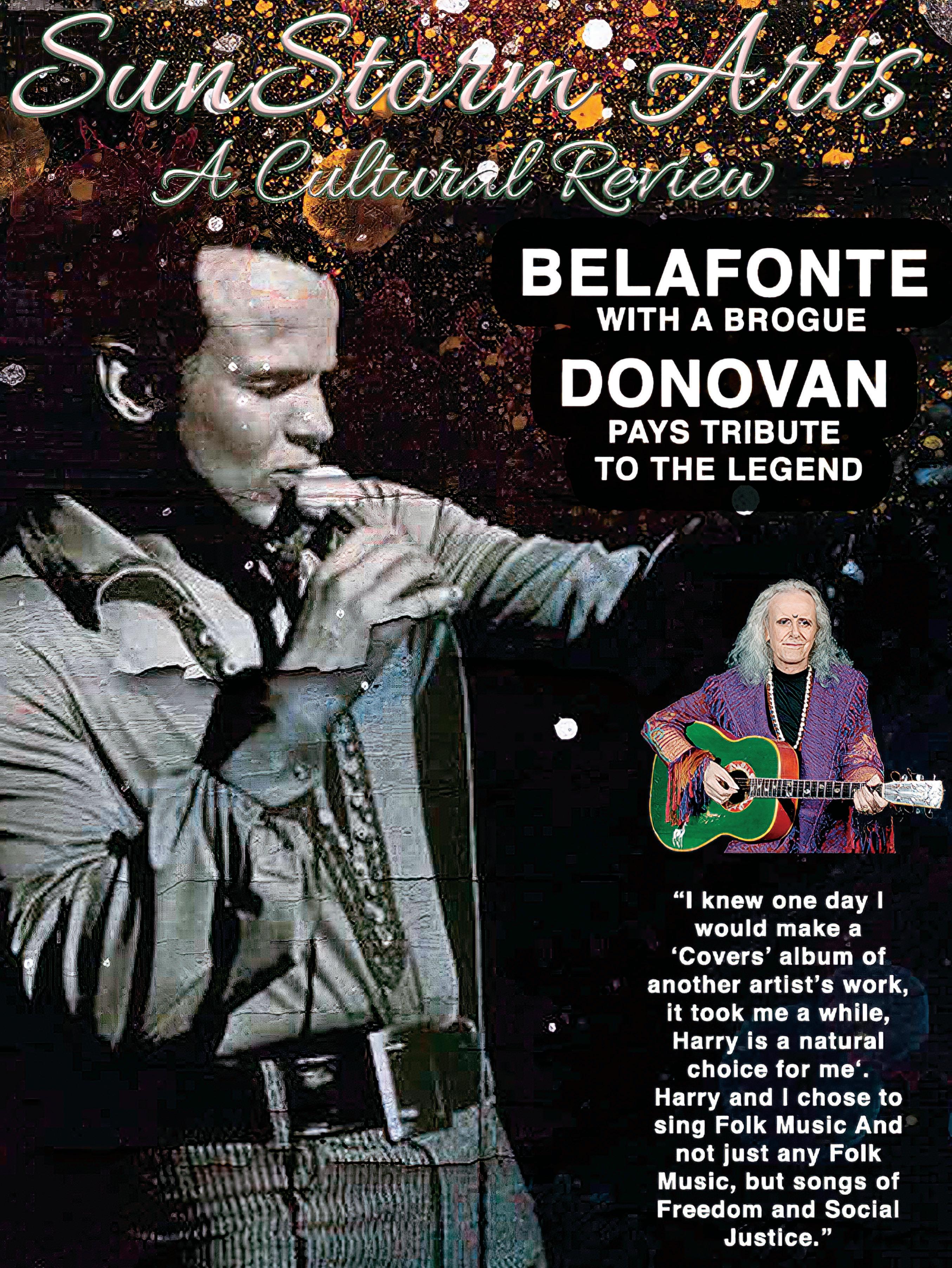

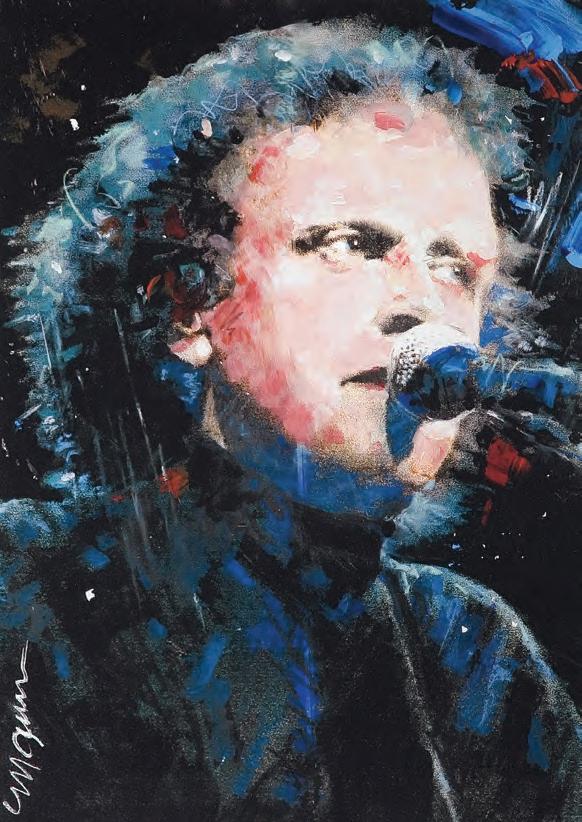

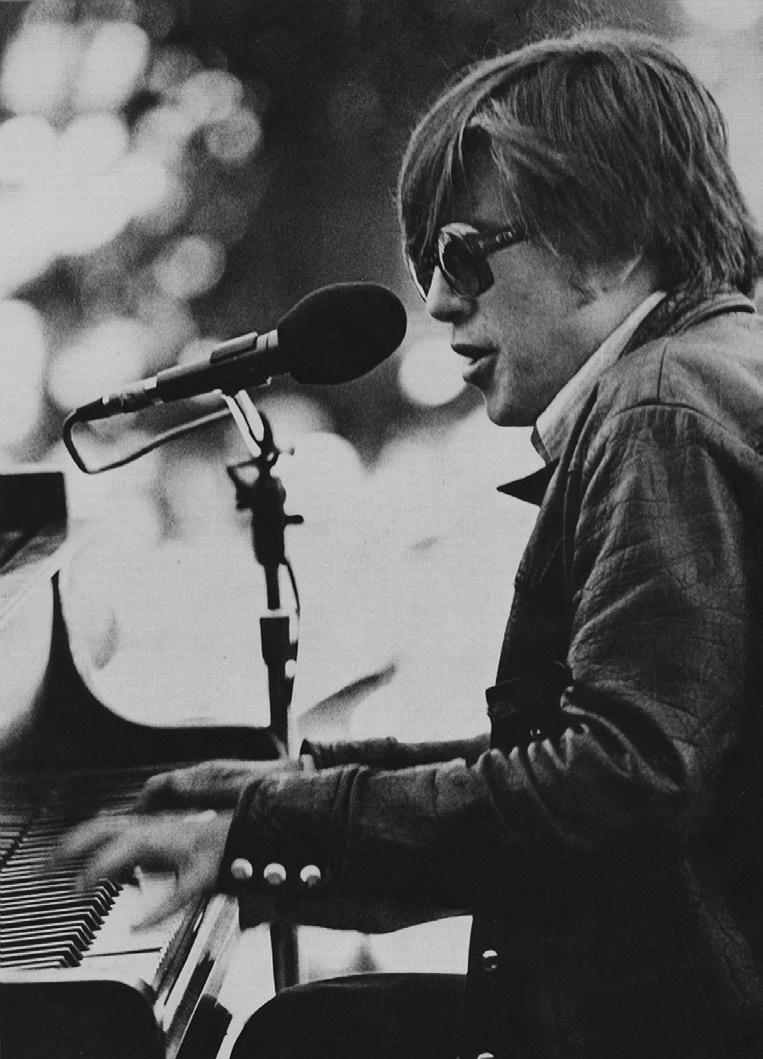

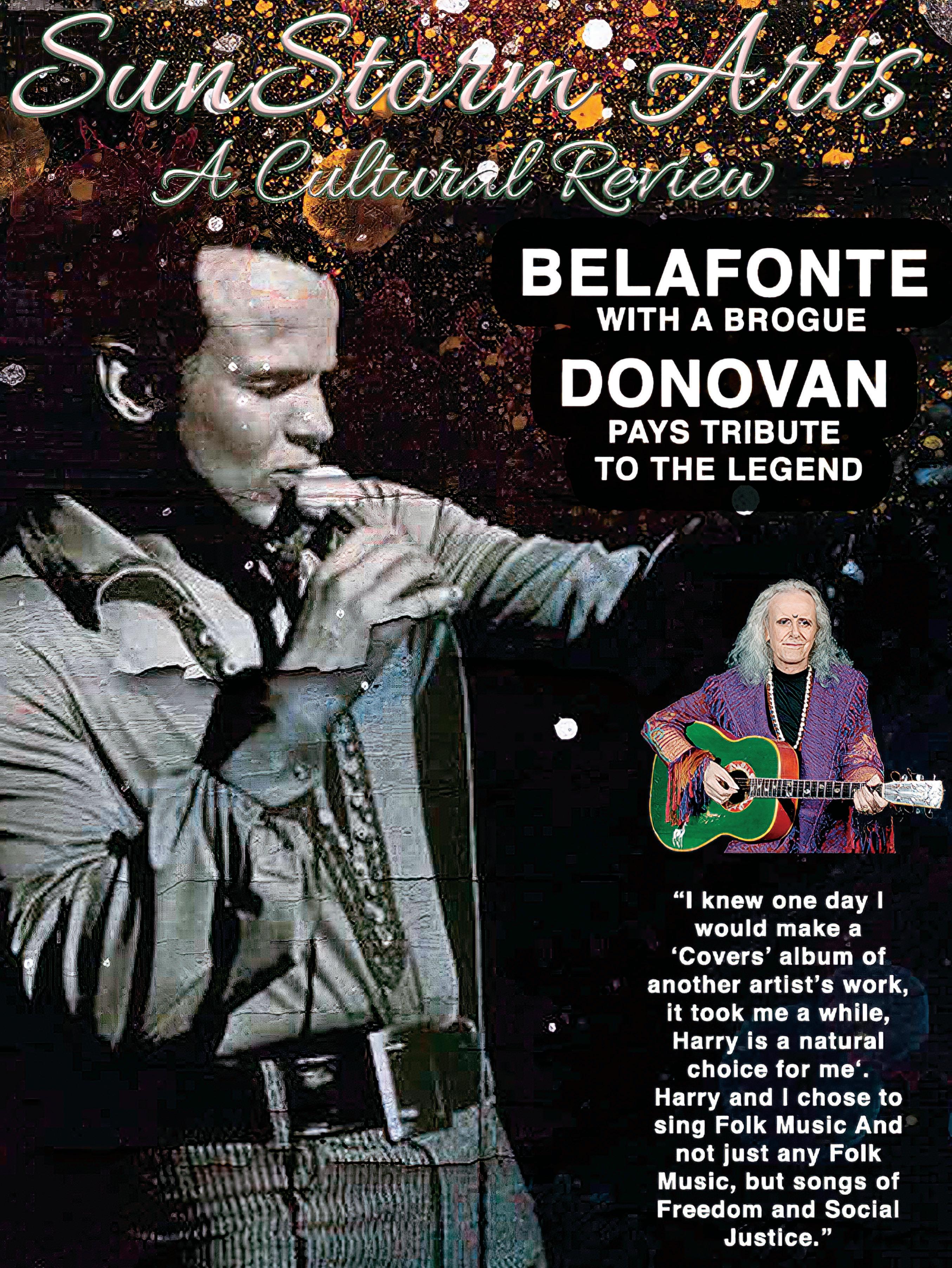

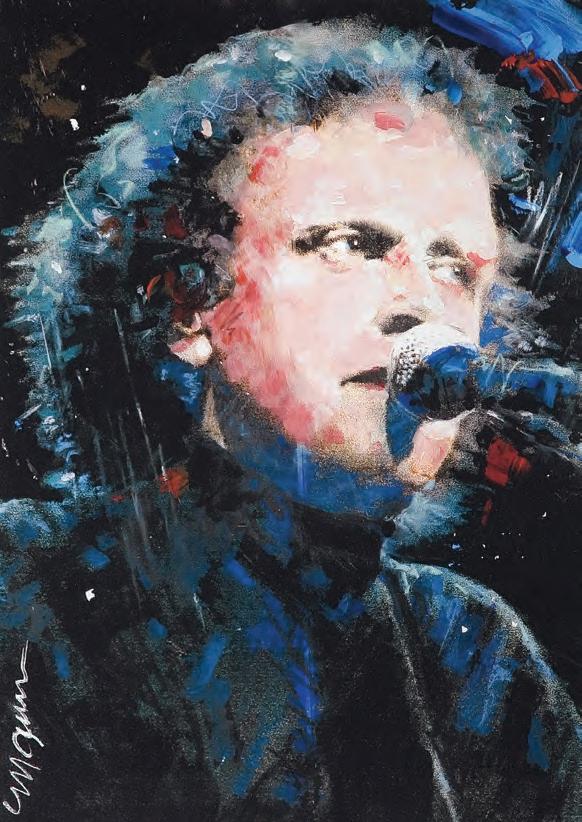

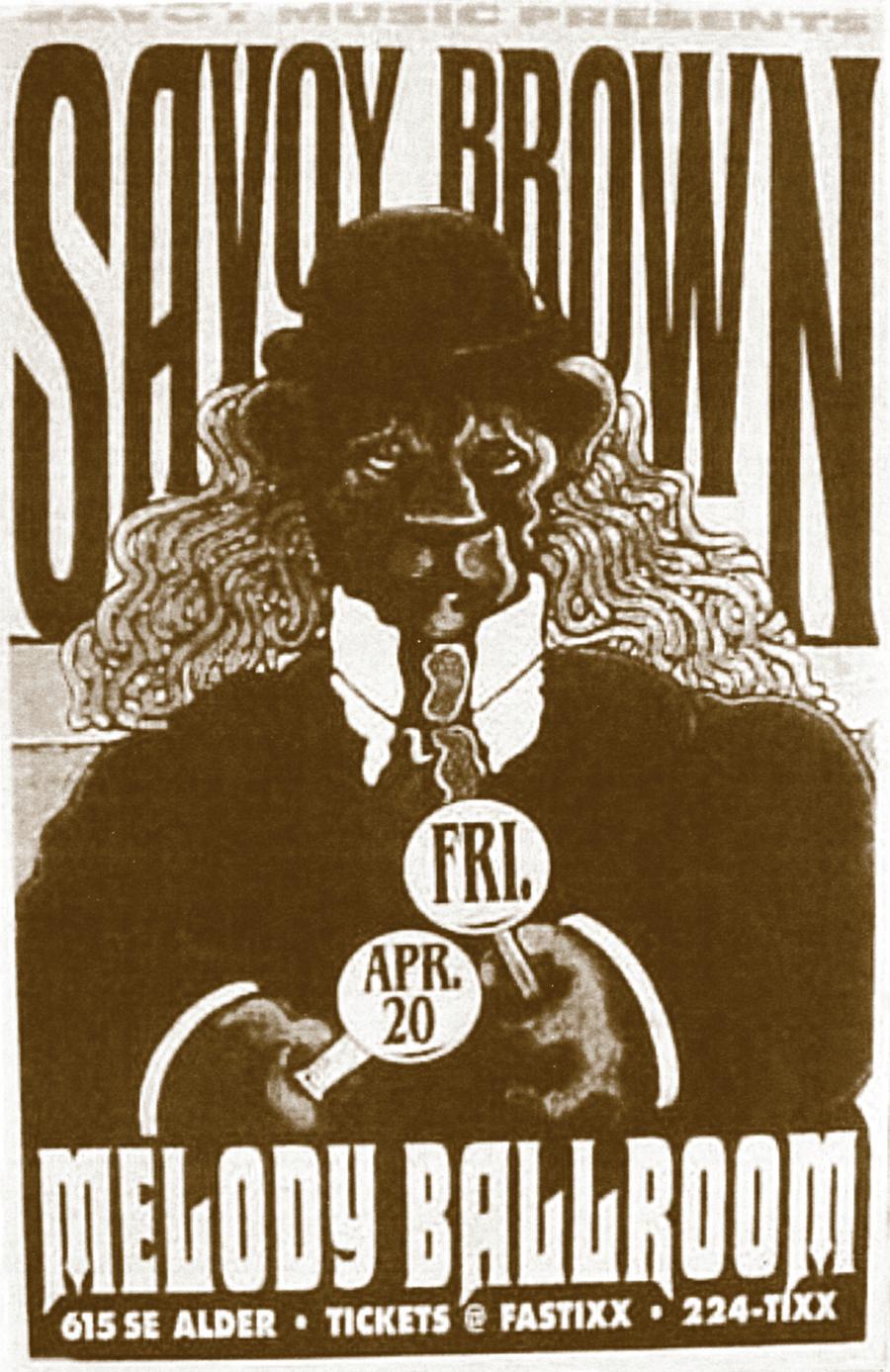

PUBLISHED BY SUNSTORM ARTS PUBLISHING CO., INC. JAMIE ELLIN FORBES, Publisher jamie@fineartmagazine.com POB 404, CENTER MORICHES NY • 631-827-7424 VICTOR BENNETT FORBES, Editor victor@fineartmagazine.com POB 481, KEENE VALLEY, NY 12943 • 518.593.6470 Donovan is without question a poet laureate, a bard, a minstrel and songwriter of tremendous importance. In the Flower Power era, he was the leader of the pack. Yet, when it comes to giants of an era, no one was more gigantic than Harry Belafonte DONOVAN PERFORMING AT THE NEW YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY SET ONE ACOUSTIC< SET TWO WITH FULL BAND SHOW WAS NOTHING SHORT OF SPECTACULAR - TWO HOURS OF HIT AFTER HITOriginal Material © 2022 SunStorm Arts publishing Co., Inc. Artwork © by the artists ESTABLISHED IN 1975

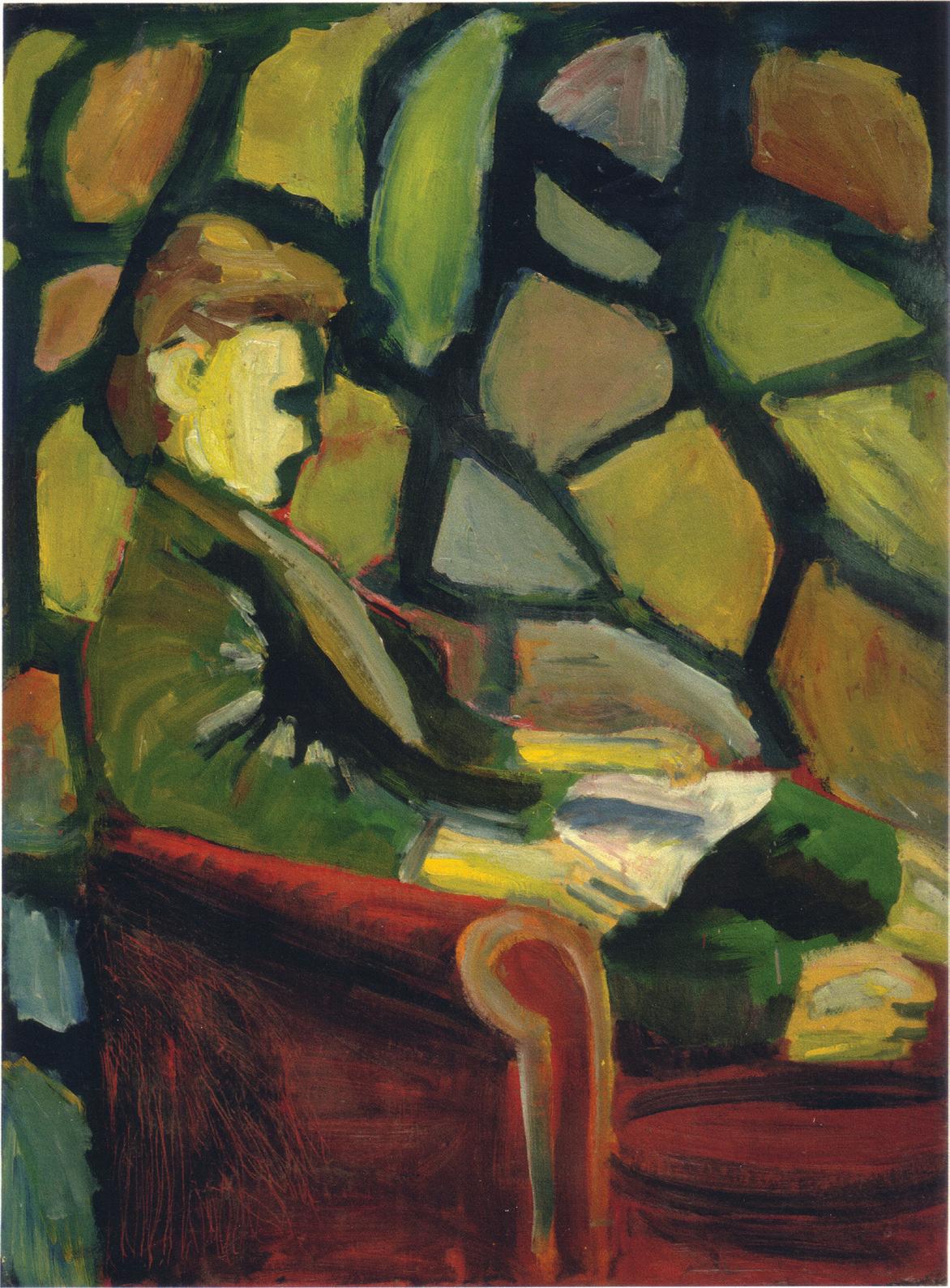

Pat Kirmer portrait by Paul Matthews

CALYPSO PAVES THE REGGAE ROAD

The Harder They Come, Jimmy Cliff, Mango 9202, Released: 1972, Chart Peak: #140; #119 on Rolling Stones top 200 albums of all time; Rolling Stone ROCK MOVIE OF THE YEAR 1973

Reggae is one form of Jamaican music that is gaining attention around the pop music world. This soundtrack LP is a good collage of reggae done authentically. The tunes show the smooth flow of the percussion instruments and the excitement inherent in the voices, individually and collectively. Shades of calypso and Belafonte. This is modern Jamaica, and Cliff is assisted by several local groups like the Melodians, Maytals, Slickers and Desmond Dekker himself, the top reggae name. - Billboard, 1975.

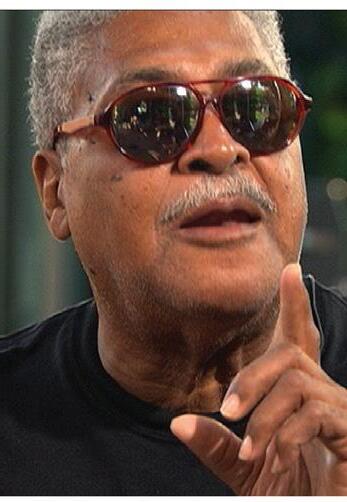

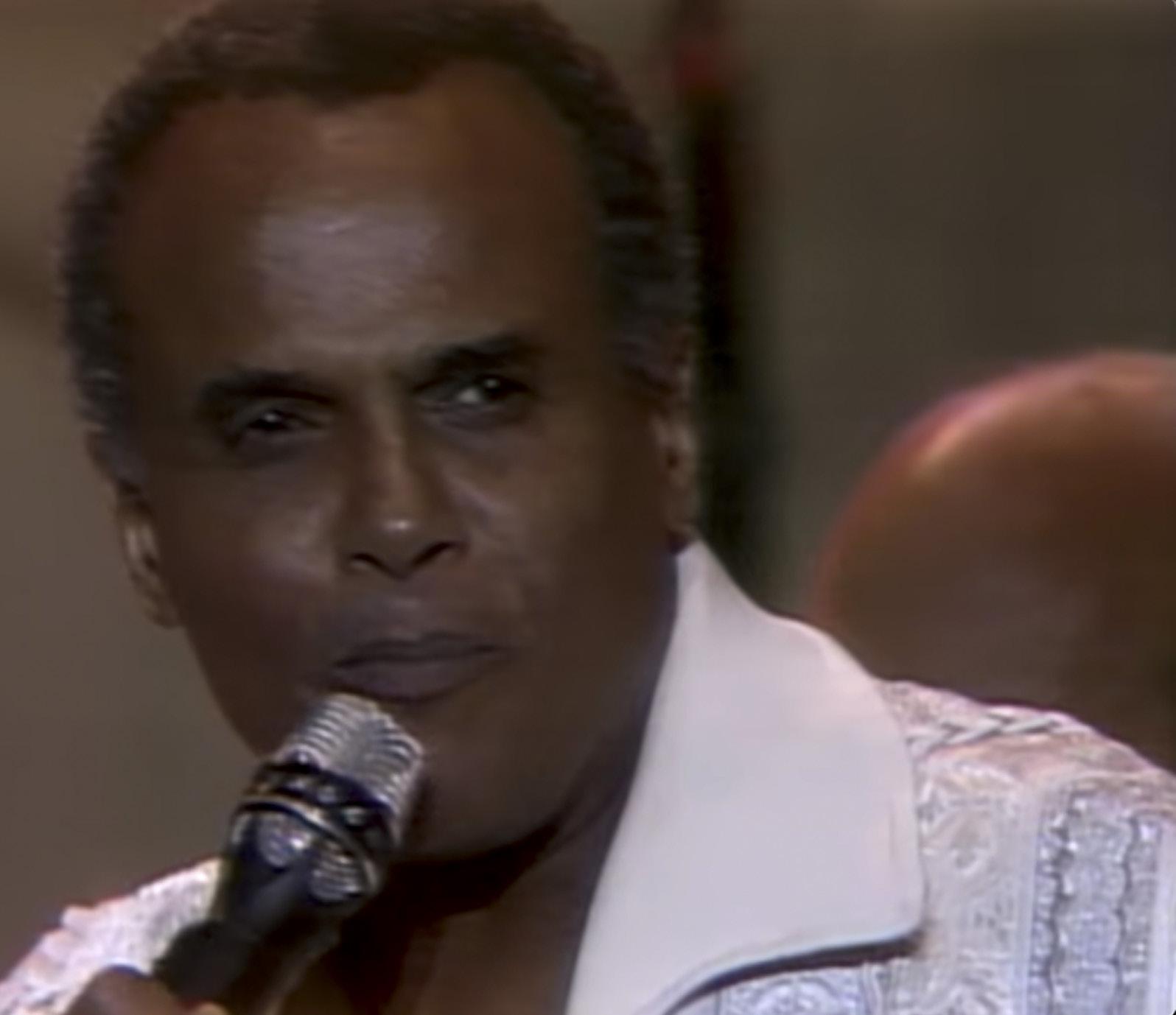

MAY 4, 2022 – Formally and finally recognized to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as an “Early Influence”, in his latter days, at 95, Harry Belafonte is having quite the career resurgence. A serious activist from the dawn of the Civil Rights Movement, the first singer to sell a million albums and receive the first Billboard Gold Album, Belafonte is no stranger to controversy or the controversial Hall. In 1996, he was there to induct Pete Seeger. In 2013, he and Spike Lee inducted Public Enemy. Now the question is, “Who will induct Harry?” Would it be Dylan who backed him on harmonica on a 1961 release, or Jimmy Cliff, the lead living proponent of classic reggae, or his good friend Donovan whose tribute album sheds a

whole new light on the power and influence of Calypso. Esther Anderson, acclaimed photo-journalist, filmaker and author, who was Miss Jamaica and starred in A Warm December with Sidney Poitier, says of Belafonte, “A Singer, Actor, Producer and Humanitarian, he was at the forefront of Live Aid American contribution to the famine in Ethiopia..A Jamaican of mixed heritage born in Harlem grew up in Jamaica suffered racism but overcame all his obstacles to become one of the leading Artists — who’ve contributed to popular cultureas much as Bob Marley

Esther Anderson guest on John Hearne “In Town,” Jamaican Broadcasting Corporation, 1973.

Day-O, Day-O-OO-O. These lines ring out in stadiums across America and around the world with few these days understanding the meaning behind the melody. Described as a “catchy Calypso tune,” it is much more than that: A blues, a Lament, an Incantation, a rebellion against oppression. Yet, a ballplayer comes to the plate or is announced over the PA and thousands of fans full of enthusiasm but loaded with ignorance cheer their heroes. Do they know that…

“A beautiful bunch of ripe banana

Hide the deadly black tarantula?

(Daylight come and we want go home)…”

Well, now they know. Then one may remember the famous phrase from the advertising world: “What Becomes A Legend Most?” The proverbial question, straight out of a Mad Men’s real-life episode, can be answered this way: “Another Legend.”

1 • Fine Art Magazine • Spring 2022

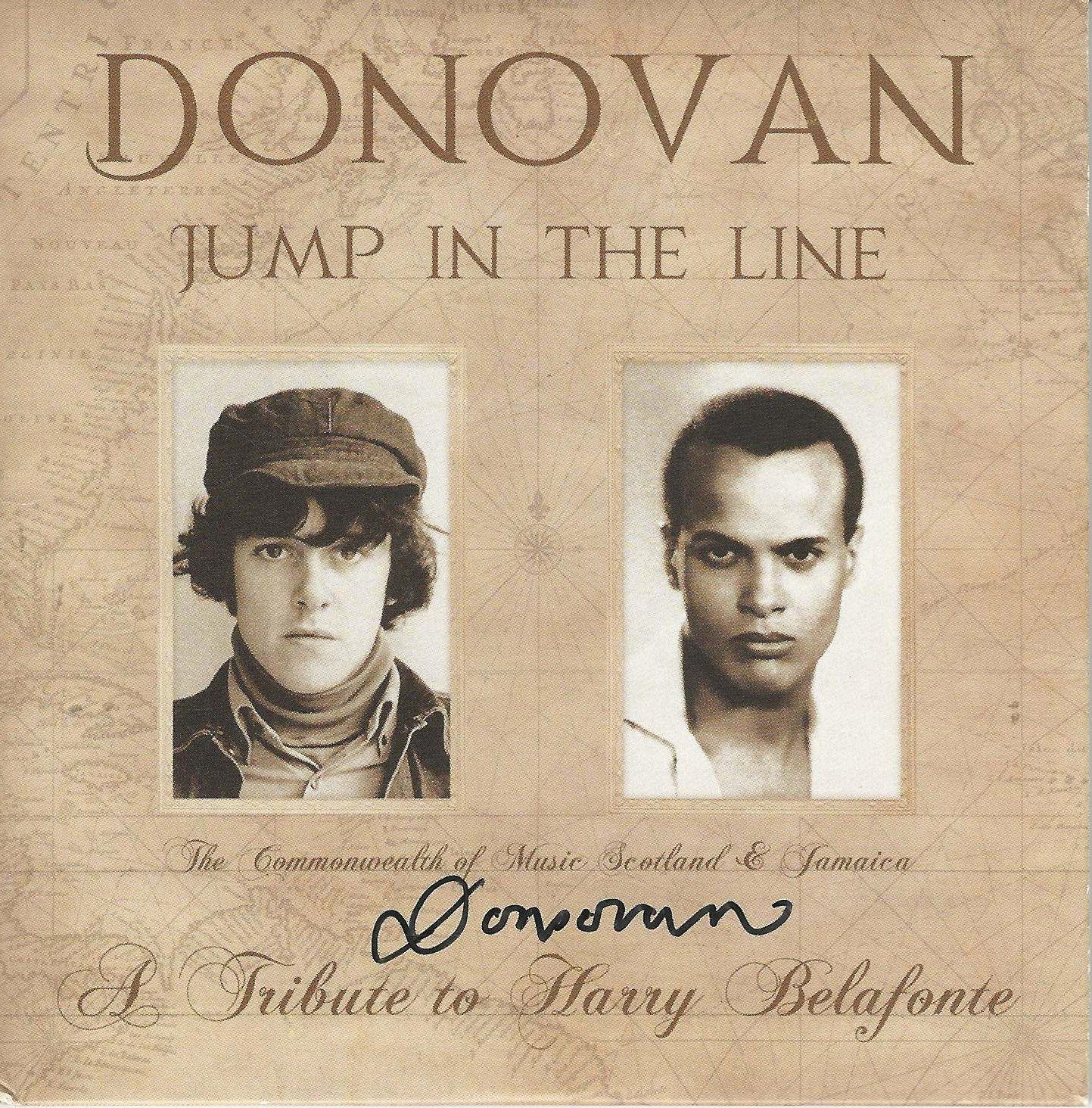

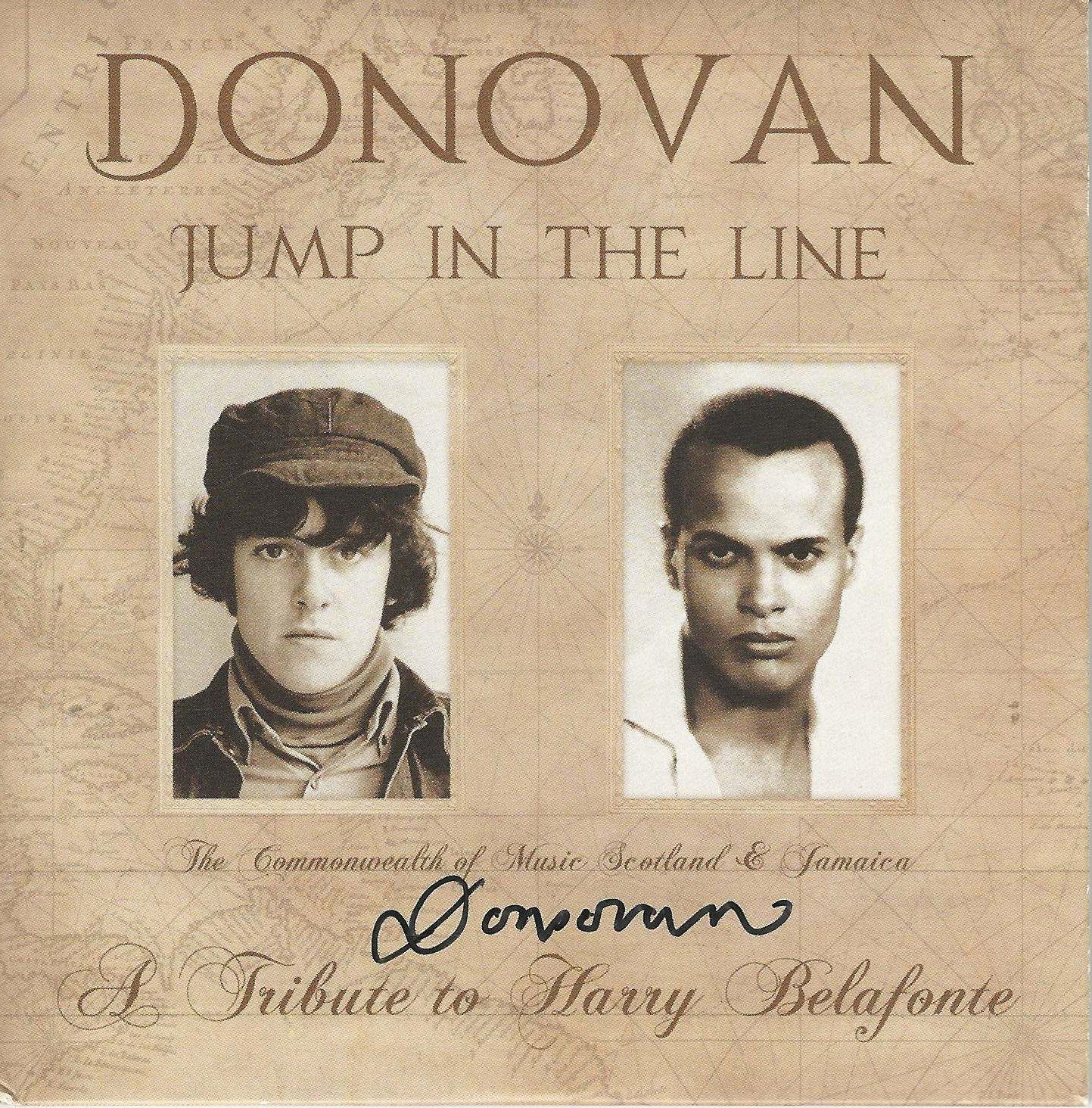

A Tribute To Harry Belafonte

In this case, it is Legend-on-Legend in which Greatness begets Greatness as evinced in this stunning, spectacular, riveting and very danceable collection of music produced by a Legend in tribute to his Hero. States Donovan in the liner notes credits,“It took me a while but I knew one day I would make a ‘Covers’ album of another artist’s work. Harry is a natural choice for me. There is a simple connection of Roots Folk Music, and after a young fascination with Jazz when we first began, Harry and I chose to sing Folk Music And not just any Folk Music, but songs of Freedom and Social Justice. I saw in Harry and I a natural and committed understanding of how an artist can dive deep into Roots Music of Jazz and Folk, and change the content of the Pop Music World with important lyrics and Social Commentary.”

At the age of 95, Belafonte has epitomized the life of a world citizen, living by a single truth: “Get them to sing your song, and they will want to know who you are, and if they’ve made that first step, we can find a solution to hate.”

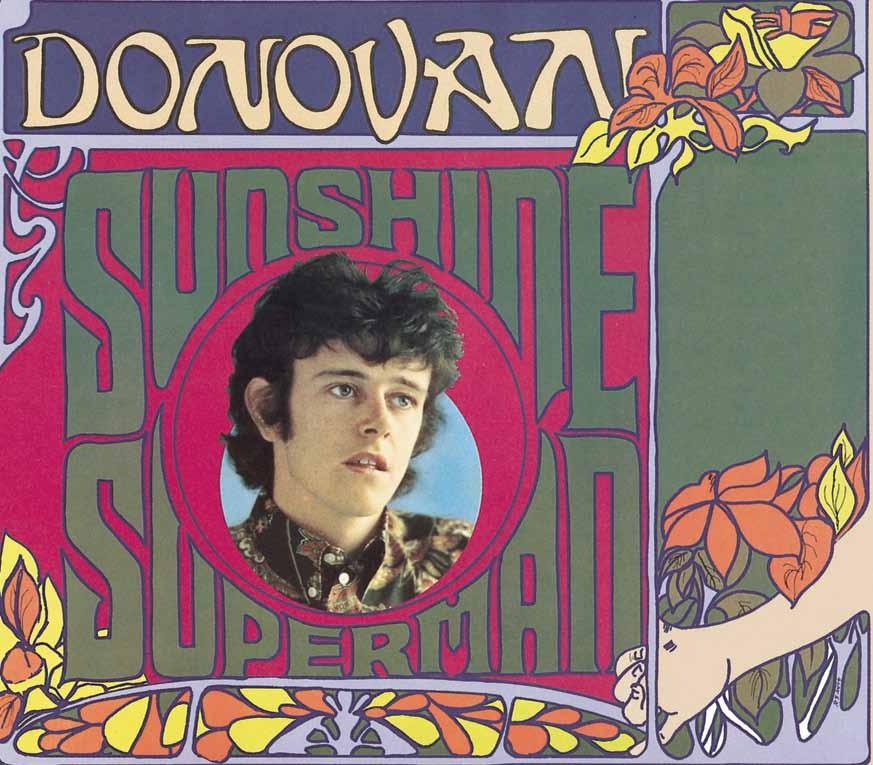

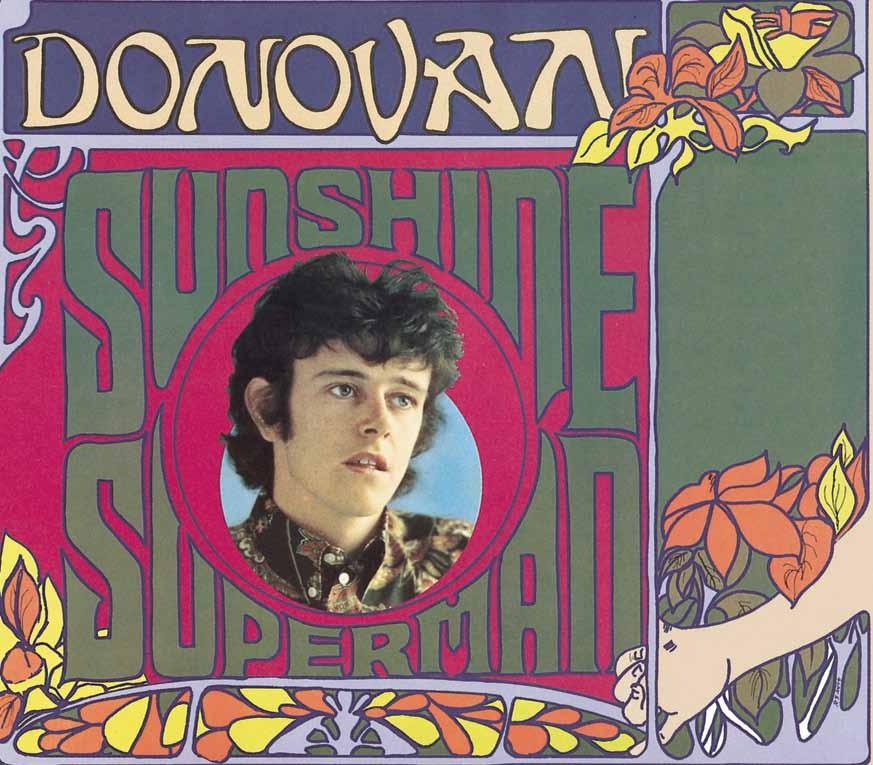

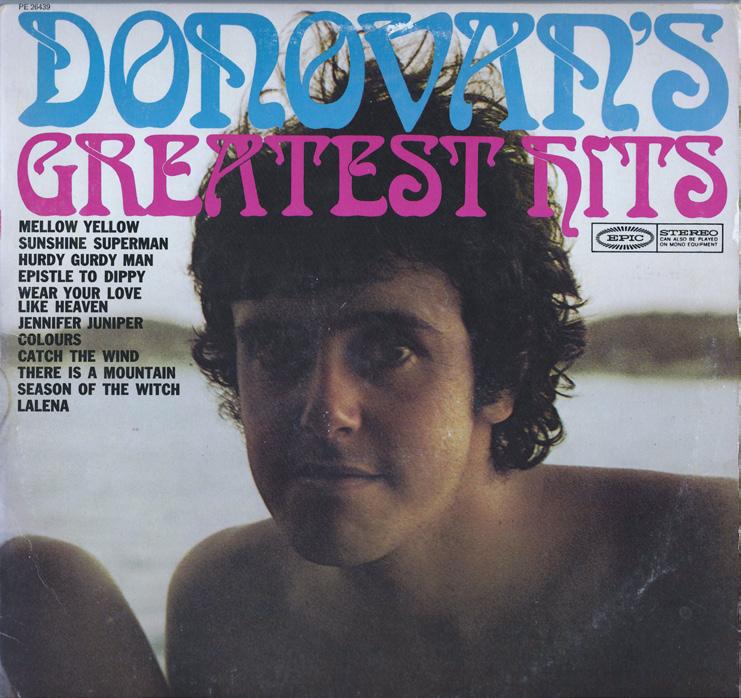

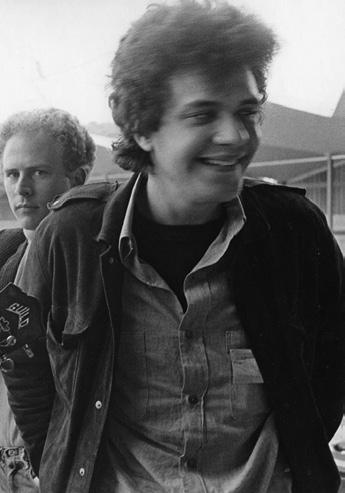

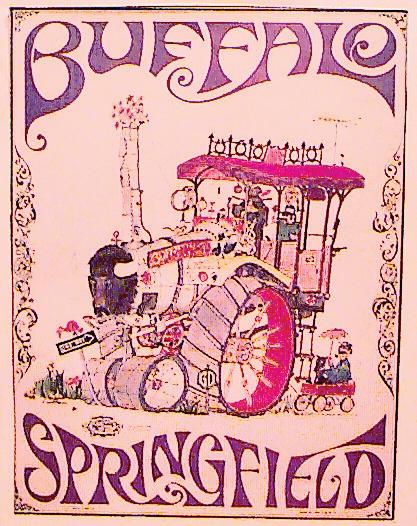

At the age of 16, Donovan set his artist vision — to return Poetry to Popular Culture — and he has done so on a worldwide scale. He was four years younger than The Beatles, Dylan and The Rolling Stones when he achieved all this. Widely regarded as one of the most influential songwriters and recording artists working today, at his induction into the R & R Hall of Fame in 2012 it was stated, “Donovan singlehandedly initiated the Psychedelic Revolution with Sunshine Superman.”

Drawing from many musical traditions and Belafonte’s lyrical baritone and emotive singing, Donovan’s new album has eight Belafonte classics plus two new songs. One written by Donovan titled No Hunger which is a direct UNICEF appeal for donations. Donovan says: ‘Harry was a UNICEF Ambassador and my tribute cover album to Harry is to remind new generations of artists to include in your work Social and Ecological Issues to help save our Planet for the future children of the world.” The other new song is Jamaica Time, written by Wayne Jobson (Co-Producer of seven

tracks on this album) which highlights Jamaica’s positive music influence on the world. Jobson, an expert on Jamaican Music History, states: “Donovan was first in the 1960s to bring into his recordings Jamaican influences. On his breakthrough Mento Music Hit Record, There Is A Mountain (1967), Jamaican Jazz Flautist Harold ‘Little G‘ McNair was featured. Donovan also recorded the first Reggae Fusion track Riki Tiki Tavi (1970) where he anticipated the Reggae Music explosion into Pop music.”

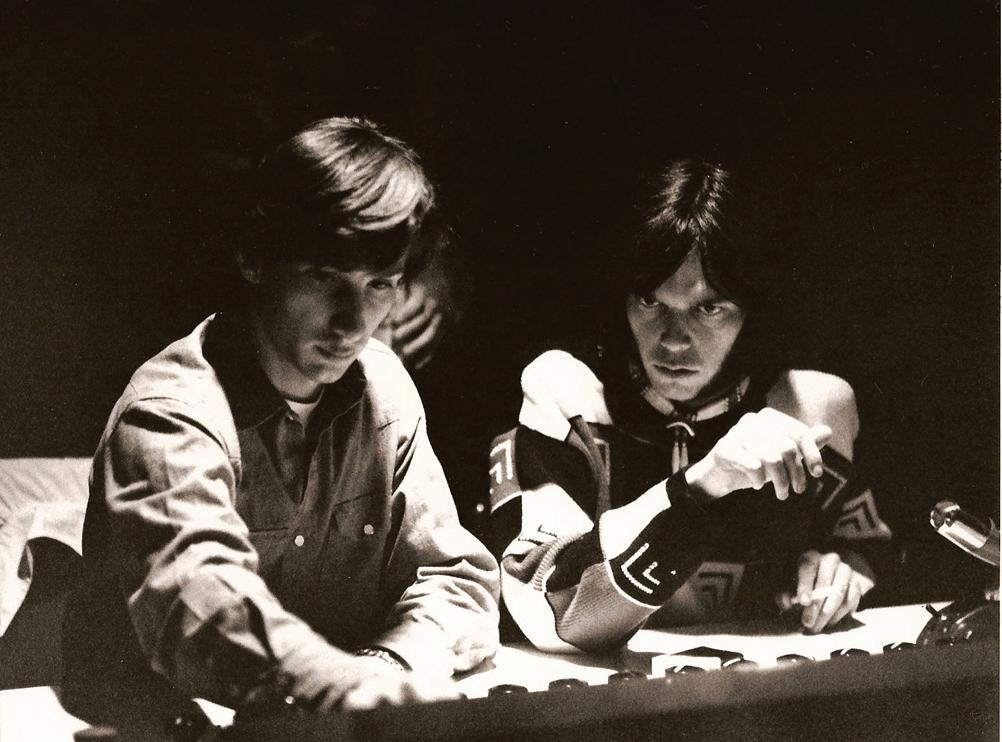

Hailed in the 1960s as Britain’s Bob Dylan, Donovan became one of the most influential songwriters of his generation. His early backup bands were the Jeff Beck Group and a pre-Led Zeppelin band, minus Robert Plant. That’s Jimmy Page’s guitar solo on Sunshine Superman

Donovan caught the wind with his very first single in which he amplified the words of King Solomon. Catch The Wind, came out when he was living on a beach, a park bench for his bed. It skyrocketed him to fame winning the very prestigious Ivor Novello Award. Paul Wales wrote that Donovan is “a musician that never became a hypocrite and whose music stands the test of time, trust me, a rare thing. His songs have a rare beauty.”

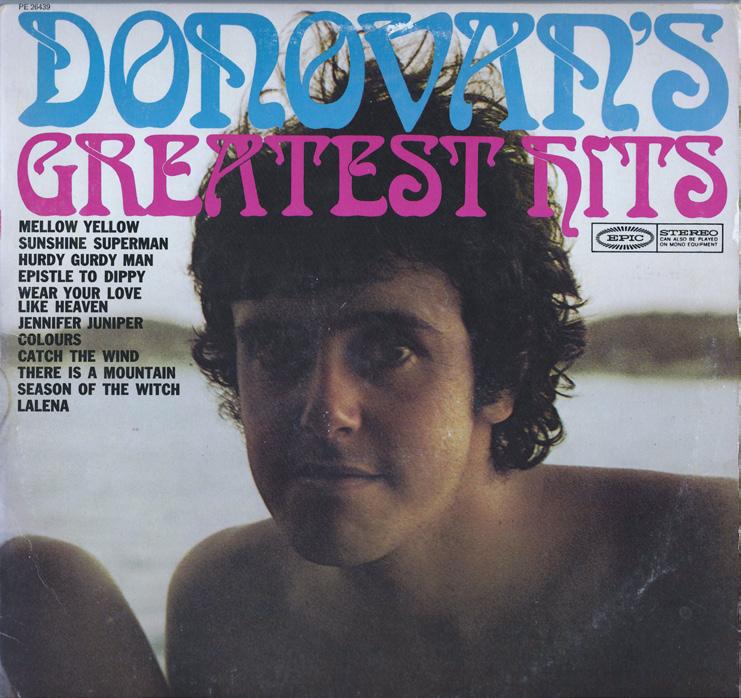

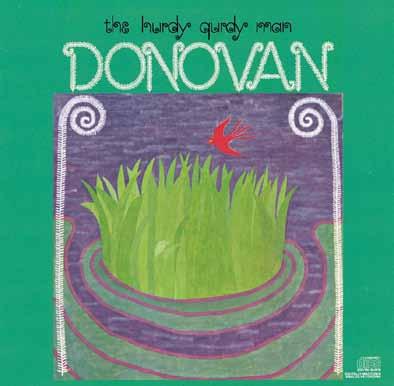

He emerged onto the scene in 1965 with three UK hit singles: Catch the Wind , Colours and Universal Soldier , the last written by Buffy Sainte-Marie. In September 1966, Sunshine Superman topped America’s Billboard Hot 100 chart for one week, followed by Mellow Yellow in December 1966, then 1968’s Hurdy Gurdy Man and Atlantis in 1969.

He counts the BMI Ikon Award,The Mojo Maverick Award, LifeTime BBC Folk Award among many additional international awards. 2014 saw Donovan inducted into The Songwriters Hall of Fame. He is also Doctor of Letters for Ecology, Hertfordshire University and Officer of the Order of Arts & Letters of The French Republic.

This masterwork album he created late 1965 at 19 years of age, one year before his friends The Beatles, influencing their album Sgt.

Fine Art Magazine • Spring 2022 • 2 DONOVAN’S “JUMP IN THE LINE” ALBUM

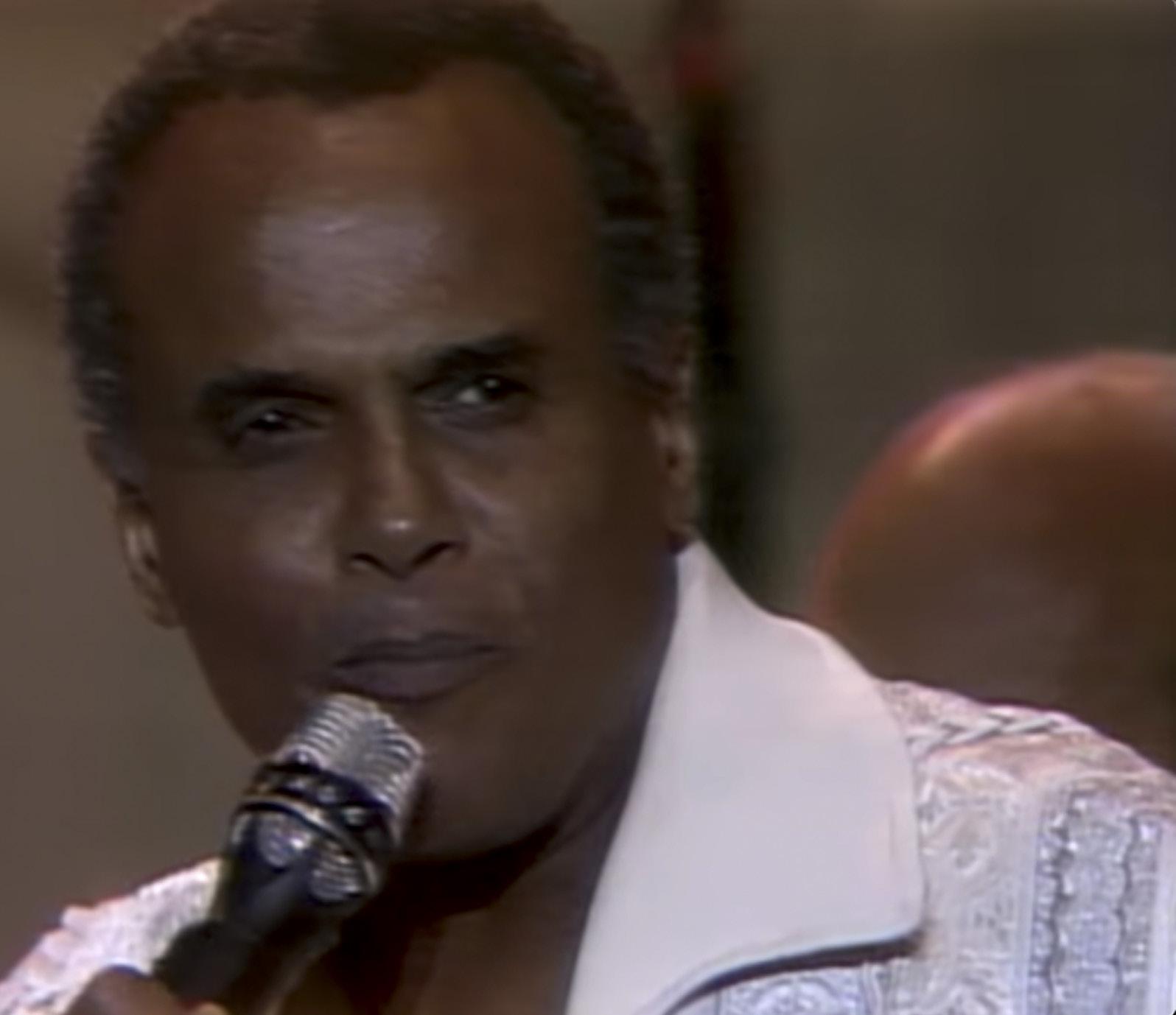

Belafonte was handed the mic by Lionel Richie to be the first soloist in the USA For Africa - We Are The World (Live Aid 1985)

DONOVAN STOOD ALONE AMONG HIS SONGWRITING PEERS IN THE SIXTIES, JUST AS YOUNG GRETA THUNBERG

STOOD ALONE IN STOCKHOLM 50 YEARS AFTER.

Pepper’s Lonely heart’s Club Band, and leading the way for many other artists. Can’t argue with that and while Donovan is an international superstar, rising to mercurial heights in the Flower Power era as not just a poet, bard, prophet, historian and proponent of all that is good and beautiful, it is now history that Donovan became the tutor of The Beatles on the famous trip to India. He was a genuine guitar hero, teaching both Lennon and McCartney finger style techniques that would later show up in such Beatles classics as Julia and Dear Prudence by Lennon, Paul’s Blackbird and George’s While My Guitar Gently Weeps. “Donovan was all over the White Album,”noted Harrison in the 1995 documentary The Beatles Anthology. Donovan encouraged and nurtured Harrisons’ songwriting, in particular teaching him secret descending chord patterns that he did not share with John or Paul, patterns which resulted in George writing the hugely successful Something from the Abbey Road record covered by everyone from Sinatra to Billie Eillish.

And yet Donovan is much more than the creator of the first Psychedelic Album — Sunshine Superman announced Flower Power for the first time and presented to the world the first World Music fusions of Folk, Classical, Jazz, Indian, Gaelic, Arabic and Caribbean. As highly influential and successful as the Sunshine Superman album was, Donovan had already scored four Top 20 singles, E.P.’s and albums in his so-called ‘Folk Period’ of early 1965 in which the seeds of what was to come were sown. This was evident on his Classical – Jazz fusion track on his Fairytale album of that year, Sunny Goodge Street. The lyric was first to describe the coming Bohemian invasion of popular culture, the return of Gaelic Mythology and True Meditation as the door to The Source. Donovan was oddly compared to Bob Dylan when it was Ramblin’Jack Elliot that both Donovan and Dylan emulated in their initial works. But Dylan never sang “that would” as “t’would.” The true similarity between them is that they are Poets of the highest Order. Donovan is chiefly responsible for introducing meditation and Eastern Philosophy into modern lifestyle and songwriting and also known for pioneering new production recording techniques in the studio, influencing many.

Donovan in his “Songs of Innocence,” has been compared to William Blake; his metaphysical songs to Donne and Herbert, his Gaelic-Celtic songs to Yeats, his children’s songs to Stevenson, his Nonsense songs to Carroll and Lear, his Yoga songs to the Vedic Hymns, his Jazz Classical compositions to Ellington and Lewis, his poetic public appeal to Auden. It cannot be overstated that Donovan has displayed the widest variety of songwriting skill, surpassing any songwriter one can name today. The sheer range of his accomplishment is Bardic, empowering our human journey through all stages of life and, most importantly, he displays a Poets’ true vocation, reuniting us with The Source.

Donovan’s most lasting achievement to date is that he was first to have created songs to save the earth from ecological disaster. He began this in the sixties and went on to compose 21 songs concerning what we now call ‘climate change’ highlighting the threat to the Ecosystem of our Planet Earth. Thus returna Donovan to be once again a poet of current events and a champion of climate change youth It is clear there is no such composer/artist like Donovan. Listening to his versions of Bleafonte classics on the tribute album, one also realizes there are few in the music world who have the breadth and scope, as well as heart, to bring back to life such well-known materaial as in his terpretation of the classic genius of Belafonte as in his sweet yet mournful version of Day-O

BELAFONTE STOOD ALONE AMONG HIS PEERS IN THE FIFTIES. THE FIRST SINGER TO SELL A MILLION ALBUMS AND THE FIRST BLACK MAN TO SWIM IN LAS VEGAS.

According to historydaily.org post by Barbara Harris, “The Banana Boat Song (a traditional work song), most likely originated around the turn of the twentieth century when banana trade in Jamaica increased. It was sung by workers who loaded shipping vessels with bananas down at the docks. The dockworkers typically worked at night to avoid the harsh heat of the day. When daylight arrived, they knew the boss would come to tally up the loads so they could go home. The tune had a ‘response’ chorus, meaning the workers were supposed to chime in with a response to the singer’s statements. Like most work songs, the lyrics of The Banana Boat Song often changed or were altered to fit the situation.”

Belafonte was born in Harlem in 1927 to multiethnic parents from the Caribbean. As a child, he moved to his mother’s native Kingston, Jamaica – “an environment that sang” – where he was exposed to the captivating music of calypso as well as prejudice based on his skin tone. Back in New York, Belafonte began acting classes at the New School’s Dramatic Workshop in 1945, where he befriended actor-singer-activist Paul Robeson, the inspiration for Belafonte’s social activism. Swept up in the New York folk scene in 1950, Belafonte created a new repertoire of folk songs, work songs, and calypsos, providing an authentic and dignified look at Black life and earning him a contract with RCA Victor in 1953.

In 1955, Belafonte met Irving Burgie (aka Lord Burgess), whose songwriting on Belafonte’s debut album would forever change Belafonte’s career. The first album to sell over a million copies in a year, Calypso (1956) introduced Caribbean folk music to American audiences, who dubbed Belafonte the “King of Calypso.” This early sound made a lasting impact on American music – Gotye, Lil’ Wayne, and Jason Derulo have all sampled “Day-O (The Banana Boat Song)” in recent years, while Jump in the Line (Shake, Senora) was featured in the 1988 film Beetlejuice and its 2019 Broadway musical production.

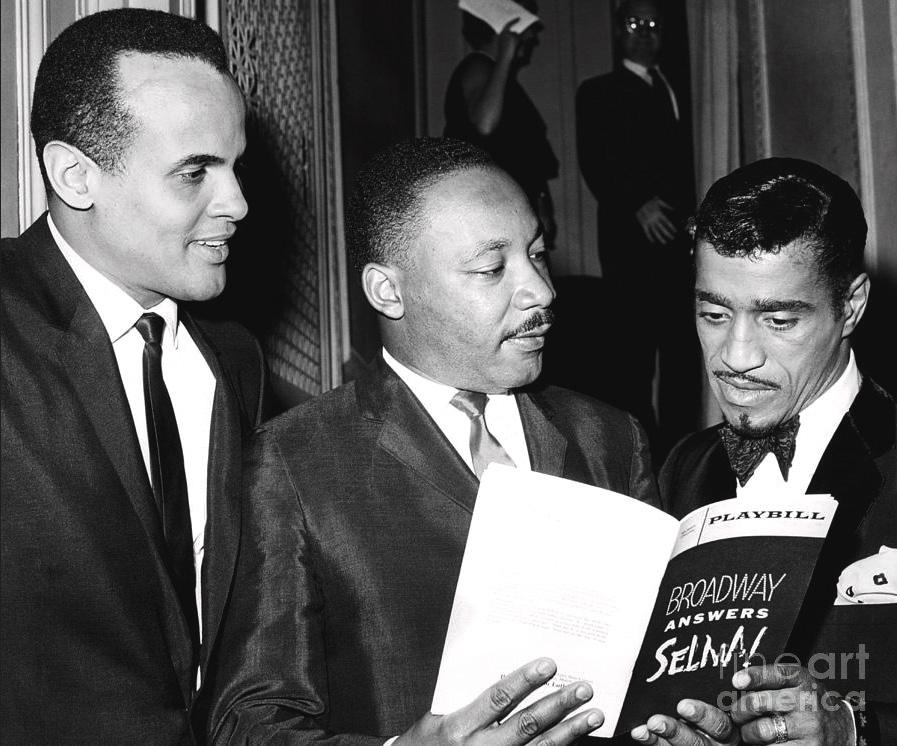

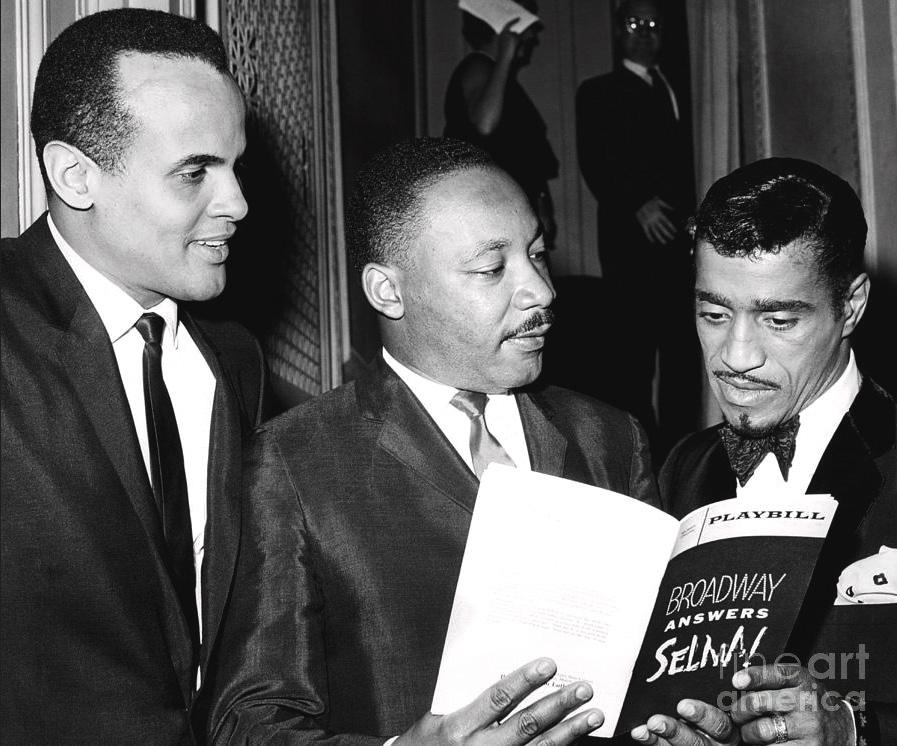

In the 1960s, Belafonte returned to his musical roots in American folk, jazz, and standards, while also emerging as a strong voice for the civil rights movement. Belafonte was a close confidante, friend, and supporter of Martin Luther King, Jr. He helped organize “We Are the World” and has been a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador since 1987. He was a Grand Marshal for the 2013 New York City Pride Parade and advised on the 2017 Women’s March on Washington.

He also, almost single-handedly, integrated Las Vegas. According to Rosemary Pearce’s post Segregation and Celebrity on the Strip, “The top black artists could earn between $25,000 and $50,000 per week in a residency at one of the big Vegas hotels. ‘Residency’ is a perhaps a misnomer, however: black entertainers were frequently banned from staying in the hotels they performed at. Las Vegas was so strict in its segregation policies that it was known as the “Mississippi of the West.” It was, after all, a town built on tourism and to allow blacks in was to affront white tourists from strictly segregated regions.”

For example, Belafonte recalls his first Las Vegas engagement in 1952 at the Thunderbird. Forbidden to stay at the hotel, Belafonte was told to leave by the back door and stay in a black motel room that smelt of dog urine (singer Pearl Bailey’s dog had been staying there previously). When he attempted to cancel or buy out the contract, he was told the only way he could leave Vegas without fulfilling his obligations was “in a box.” Belafonte managed to turn the situation around and was welcomed back to the hotel to stay, although this was through a family mob connection he had back in New York.

3 • Fine Art Magazine • Spring 2022

Singer, actor, producer, activist and ally, Belafonte used the arts as a mechanism to effect social change on a global scale.

Belafonte took revenge on the Thunderbird by plunging into their swimming pool, the first black person to do so. His swim was a bold move in consideration of the prevailing stigma around African Americans being “unclean”; in 1953 the Hotel Last Frontier drained their pool when actress Dorothy Dandridge dared to dip her foot in. This was at a time when Dandridge was a movie star who became the first African American to receive an Academy Award nomination for best actress for her role Carmen Jones (1954), a well-mounted modernizing of the Georges Bizet opera, set in the U.S. South with an all-black cast that featured Pearl Bailey and Harry Belafonte.

Belafonte’s next role was in Island In The Sun, Otto Preminger’s film about race relations and interracial romance set in the fictitious island of Santa Marta. As a result of playing interracial love scenes with Belafonte, Joan Fontaine received poison pen mail, including some purported threats from the Ku Klux Klan. Fontaine turned the letters over to the FBI.

Belafonte’s refusal to accept the discriminatory hotel policies foreshadows the intensity with which he later became involved in the Civil Rights Movement during the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Though Belafonte describes the incident as a personal affront, his later Civil Rights work shows clearly that he was not a man who wanted to be an exception to the rules, but used his influence and wealth to further the civil rights cause

In his autobiography, My Song, Belafonte compares his attitude toward the policies to that of another black performer in Vegas at that time: Sammy Davis Jr. Part of the famous ‘Rat Pack,’ Davis Jr. hung around hotel suites with Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin while in town performing his song and dance routines at the Frontier. Belafonte reflects that he did not fit in with the Pack, perhaps being too serious or proud, but observed that Davis Jr. “oozed deference and accommodation” in the way he clowned about for the others’ entertainment. Despite being paid more than Belafonte, Davis Jr. did not even have a suite of his own, having agreed to stay in a black motel at the edge of town. The hotel management also barred him from the casino and restaurants, and Davis Jr. omplied.

“You have to be twice as good to get half a chance,” Earl Woods often said to his son, Tiger.

Fine Art Magazine • Spring 2022 • 4

Harry Belafonte, Martin Luter King, Jr., King, Sammy Davis, Jr. at the Broadway production of Selma.

“Calypso”—Harry Belafonte (1956)

Added to the National Registry: 2017

Essay by Judith E. Smith

Harry Belafonte, the Harlem-born son of poor undocumented Jamaican immigrants, an untrained singer whose heart was set on becoming an actor, made music history with “Harry Belafonte: Calypso.” This record was the very first by a solo performer to sell a million copies, holding the top spot on “Billboard’s” pop album charts for an unprecedented 31 weeks (in addition, 58 weeks in the top ten, 99 weeks among the top 100). The higher-ups at RCA had doubted the commercial potential of a thematically unified recording of “island and Calypso songs,” but the “Calypso” record, released at the end of May 1956, quickly soared in sales, knocking Elvis Presley’s first album out of the way to take over the top spot within a few weeks. The “Calypso” album also reached the top of music charts in most of Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean, and was “covered” via native language recordings in many countries.

Belafonte often joked that it took him 30 years to become an “overnight success.” He had dropped out of high school after one semester and joined the World War II Navy at age 17. His experience in the military included political education from college-educated soldiers about how the Jim Crow racial status quo would have to be challenged as part of a national system. From this moment on, Belafonte committed himself to “help make things different.” Through the American Negro Theatre, acting classes at the New School’s Dramatic Workshop, and a friendship with Paul Robeson, he found the postwar black and interracial left dedicated to keep fighting to end Jim Crow. But he couldn’t find paid work in the theater. A jazz club he frequented invited him to sing jazz standards; although his voice was untrained, he projected something powerful and compelling on stage. His performing life had begun.

Participating at left-wing political events in 1950 and 1951, Belafonte experimented beyond the jazz standards he was paid to sing, trying out songs associated with Robeson, such as “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child” and “John Henry”; Dizzy Gillespie’s “Cubano Be Cubano Bop” and the Calypsonian King Radio’s 1946 calypso song “Brown-Skinned Girl.” When he quit singing jazz in clubs in December 1950, and reintroduced himself as a folk singer at New York’s famed Village Vanguard in October 1951, he drew on this experimentation for his new repertoire of “folk songs, work songs, [and] calypsos.” Belafonte felt these songs signaled to an audience: “here’s Negro life with as much dignity as I can give it.” Singing with guitar accompaniment freed Belafonte to draw on his dramatic training to use his hands, his face, and his body to inhabit and convey the world invoked by a song. His musical style, appeal and charisma were inseparable from his uncompromising political stance, personal beauty, and emotional expressiveness. Reviewers described him as the “total package”: “his baritone, his facial expressions, and bodily movements become part of the words and music, and the result is a rich dramatic portrayal.”

With this repertoire of “folk songs, work songs, and calypsos,” Belafonte was not seeking to embody one particular cultural tradition, but instead to present himself as a Black world citizen who drew from and respected multiple traditions. Rejecting the segregation of musical genres was one of the ways Belafonte chose to protest racialized boundaries and to resist white supremacy. He did not have the vocal resonance or concert presence of Robeson. He did not convey the experiential authority or musical ingenuity of southern born blues performers like Lead Belly, and he didn’t possess the facility with wordplay of the Trinidadian calypsonians. But his

juxtaposition of folk songs, work songs, and calypsos renewed each form. His clearly articulated calypsos, absent the island costumes, enabled him to represent calypso as part of other forms of black and non-elite culture, repositioning the music away from colonial associations with “native” inferiority or tourist-driven exoticism.

Belafonte’s intensity, his dramatic authority, his phrasing and his vocal emphasis made his audiences feel they were hearing the music for the first time, engaging directly with a world that came alive through his performance.

The collection of songs that constituted the “Calypso” album resulted from several fortuitous events. By August 1955, Belafonte was a full-fledged celebrity as a result of nightclub and stadium appearances across the country, performance on Broadway, and his starring role in the hit film production of “Carmen Jones.” This gave him the clout to bargain successfully for an extended time slot on television, and more control over the musical selections, as his conditions for an appearance on the television show “Colgate Comedy Hour.” Belafonte’s good friend, the left-wing writer William Attaway, then working for NBC, was assigned to write the show. Attaway introduced Belafonte to his friend, left-wing singer, composer and folklorist Irving Burgie, who was then collecting and performing Caribbean folk music. Burgie explored black diasporic musical borrowings, including meringues from Santo Domingo and mentos from Jamaica.

With five of Burgie’s songs as thematic core, Attaway and Belafonte went to work on a Caribbean script, introducing ordinary working people and Caribbean culture on the island. In advance publicity for the TV show, Belafonte promised “authentic West Indian work songs and love ballads, something no one has ever done on TV before.” He argued that the well-known Calypsos “covered” by American singer Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Jordan’s well-known “Stone Cold Dead in the Market” and the Andrews Sisters’s “Rum and Cocoa Cola,” were no more representative of West Indian culture than Patti Page’s novelty pop song “How Much is That Doggie in the Window” was of American culture. Burgie’s songs included two that would become indelibly attached to Belafonte’s persona: the Jamaican work song “Day-O (Banana Boat Song),” dramatized

5 • Fine Art Magazine • Spring 2022

with a capella opening and a call-and-response chorus, and the sweet love song “Jamaica Farewell.” The television show itself was limited by its “Caribbean as tourist haven” framework, but the integration of songs and theme, and the appeal of the music generated great excitement. Within two weeks of the broadcast, the recording process for the album began.

For the recording sessions in October 1955, Belafonte gathered his close friend, the jazz clarinetist Tony Scott and members of Scott’s orchestra (Belafonte wanted to inject “a jazz feeling” where it seemed to fit) and other talented musicians, including Burgie’s colleague, Jamaican pianist and penny-whistle player Herb Levy, and Haitian guitarist Franz Casseus. The powerhouse chorus of singers was led by actor/singer Brock Peters. Burgie played guitar and sang harmony on the chorus of four of the songs, and Attaway wrote the liner notes. The album included eight songs written by Burgie, one written by Attaway and Belafonte, and two songs that were King Radio calypsos Belafonte had been singing for several years, “Brown Skinned Girl,” and “Man Smart (Woman Smarter).”

The album’s rich and varied orchestration, Belafonte’s articulation, and the versions of new and older songs made this album a departure from Belafonte’s previous recordings and from other calypso recordings. Attaway’s liner notes signaled this when he wrote that the collection was “not just another presentation of island songs…. Here are songs ranging in mood from brassy gaiety to wistful sadness, from tender love to heroic largeness. And through it all runs the irrepressible rhythms of a people who have not lost the ability to laugh at themselves.”

The “Calyso” album’s extraordinarily enthusiastic reception had many sources. It drew from the synergy and cross-promotion of Belafonte’s multiple sources of celebrity from the nightclub stage to radio, television, and film. Recording for national sales through RCA, his repertoire of folk songs, work songs and calypsos was well suited to the new long-playing album format, purchased primarily by record buyers with more discretionary income. Belafonte’s recordings became increasingly commercially successful in the cross-over pop market, offering diverse audiences of black and white steelworkers, grandmothers, symphony patrons, bobby soxers and school children a Black alternative to rock and roll. His first long-playing folk album “Mark Twain,” composed of songs he had sung on Broadway and on television, had been released in 1954, but rose to third place on the “Billboard” charts in January 1956; the folk album “Belafonte” released in 1955, rose to first place on the charts in February 1956, holding the top spot for six weeks. After release in May 1956, “Calypso’s” rise on the charts was immediate and long-lasting.

The unprecedented national and international success of the Caribbean folk songs, the occasional calypso, and songs composed in the folk song mode, written by Burgie and performed by Belafonte performed on “Calypso,” attached Belafonte’s celebrity to calypsostyled music, and generated a commercial “calypso craze.” Music fan magazines tagged Belafonte as “King of Calypso,” a title normally reserved for the winner of Trinidad’s annual carnival competition. The success of this recording accelerated an already well-established process of calypso reinvention, which West Indian literary critic Gordon Rohlehr described as traveling in the 1930s from Trinidad into the United States, the United Kingdom, Jamaica, the Bahamas, Surinam, Venezuela, Ghana and Sierra Leone, all places where singers began to refer to themselves as “calypsonians.” In the US, the success of the “Calypso” album encouraged Latin artists Candido, Tito Puente, and Perez Prado, jazz singers Sarah Vaughan and Dinah Washington, pop singers Rosemary Clooney and Pat Boone, and even actor Robert Mitchum to record calypso songs. Rohlehr noted that, after Belafonte, distinctly different folk singers from throughout the Caribbean would call themselves “calypsonians” or “calypso singers,” as long as it was profitable to do so.

In interviews, Belafonte tried to distance himself from the

“calypsomania” spurred by the album’s success. In one interview published early in 1957, he described himself as a “singer of folk material…from every section of the world” and described the hit singles “Jamaica Farewell” as a West Indian folk ballad and “Day-O” as a “West Indian work song.” He praised the topicality of “True calypso” as a “kind of living newspaper,” and promised to keeping singing “true calypso as I see it [and]…every other kind of music that carries truth in it.”

The timing of Belafonte’s celebrity, and his chosen political commitments connected him with the new stage of civil rights protest, with growing conflicts between challengers and defenders of racial segregation and backlash following the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education school desegregation decision. Belafonte’s rise coincided with new demands for racial equality, which he thoughtfully shaped his performance to embody. Buying and playing his records may have provided audiences with a tangible connection to the combination of Black and multi-racial and international cultures he and his music represented. A survey of New York area male and female high school and college students reported in Billboard in December 1956, found that although more students ranked white performers Elvis Presley, Frank Sinatra, Teresa Brewer and Doris Day as their favorite singers, Belafonte had “the highest percentage of record buyers.” Perhaps when students at Marquette, a Jesuit university in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, petitioned to replace Presley with Belafonte in the student union jukebox, they wanted to associate themselves with the civil rights promise Belafonte represented.

When in March 1956, the young minister from Montgomery, Martin Luther King, Jr., approached Belafonte to ask for his support for the bus boycott underway, Belafonte’s second record was at the top of the music charts, and the “Calypso” album had been recorded but not yet been released. Belafonte answered the call, and from then on, he drew on his star power to lead demonstrations and raise money for the civil rights movement. The Black press enthusiastically covered Belafonte’s stunning accomplishment and his commitments to the struggle for racial equality. White audiences may have wanted to embrace Belafonte as a token of racial progress. But Belafonte consciously used all his interviews and superstar media attention in white spaces to open doors for other performers, to challenge racial exclusions and discrimination, and to associate his name and his music with the freedom struggle.

The enormous popularity of the Calypso album gave Belafonte’s stunning performance of Burgie’s songs an outsized impact on defining “calypso” music for American audiences, and around the world. The long life of Day-O offers one trace of the music first introduced here. The Nashville sit-in students would sing Day-O when in jail in 1960; the Freedom Rider protesters wrote new words, singing “Freedom’s Coming and It Won’t Be Long” in their cells in Mississippi’s Parchman Penitentiary in 1961. In the 1980s, new generations encountered its memorable presence in Tim Burton’s 1988 film Beetlejuice; New York Yankee fans have heard the song reverberating throughout the stadium; it has been sampled in recent releases by rap artist Lil Wayne and popular singer Jason Derulo. The work song of the Caribbean labor gang still “carries truth in it.”

Judith E. Smith is Professor of American Studies at University of Massachusetts Boston where she teaches courses on media history, film history, and US culture since 1945. She has published essays on postwar film, radio, and television, and is the author of “Visions of Belonging: Family Stories, Popular Culture, and Postwar Democracy, 19401960” (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004) and “Becoming Belafonte: Black Artist, Public Radical” (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2014).

* The views expressed in this essay are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Library of Congress.

Fine Art Magazine • Spring 2022 • 6

The Ocho Rios Sessions

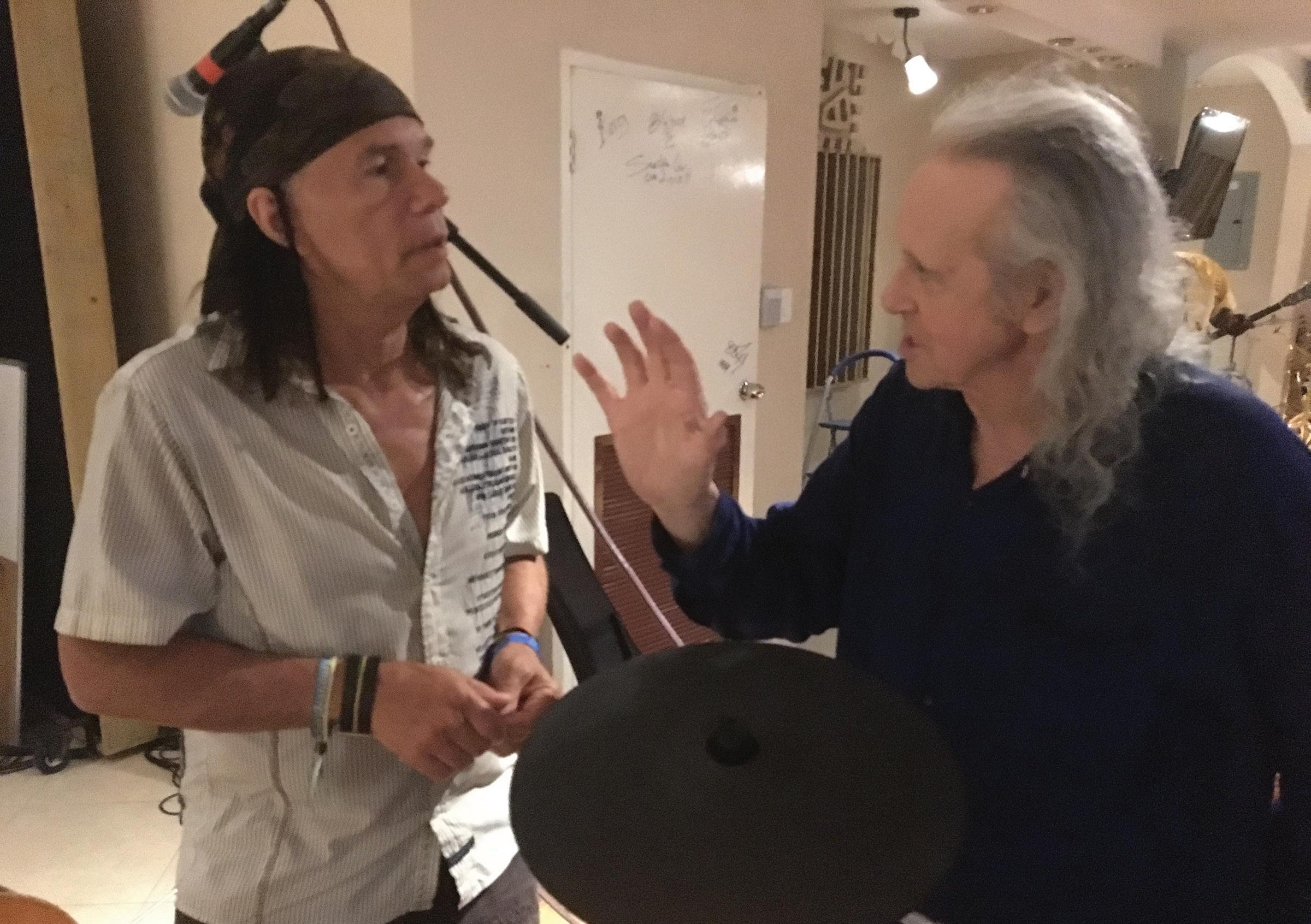

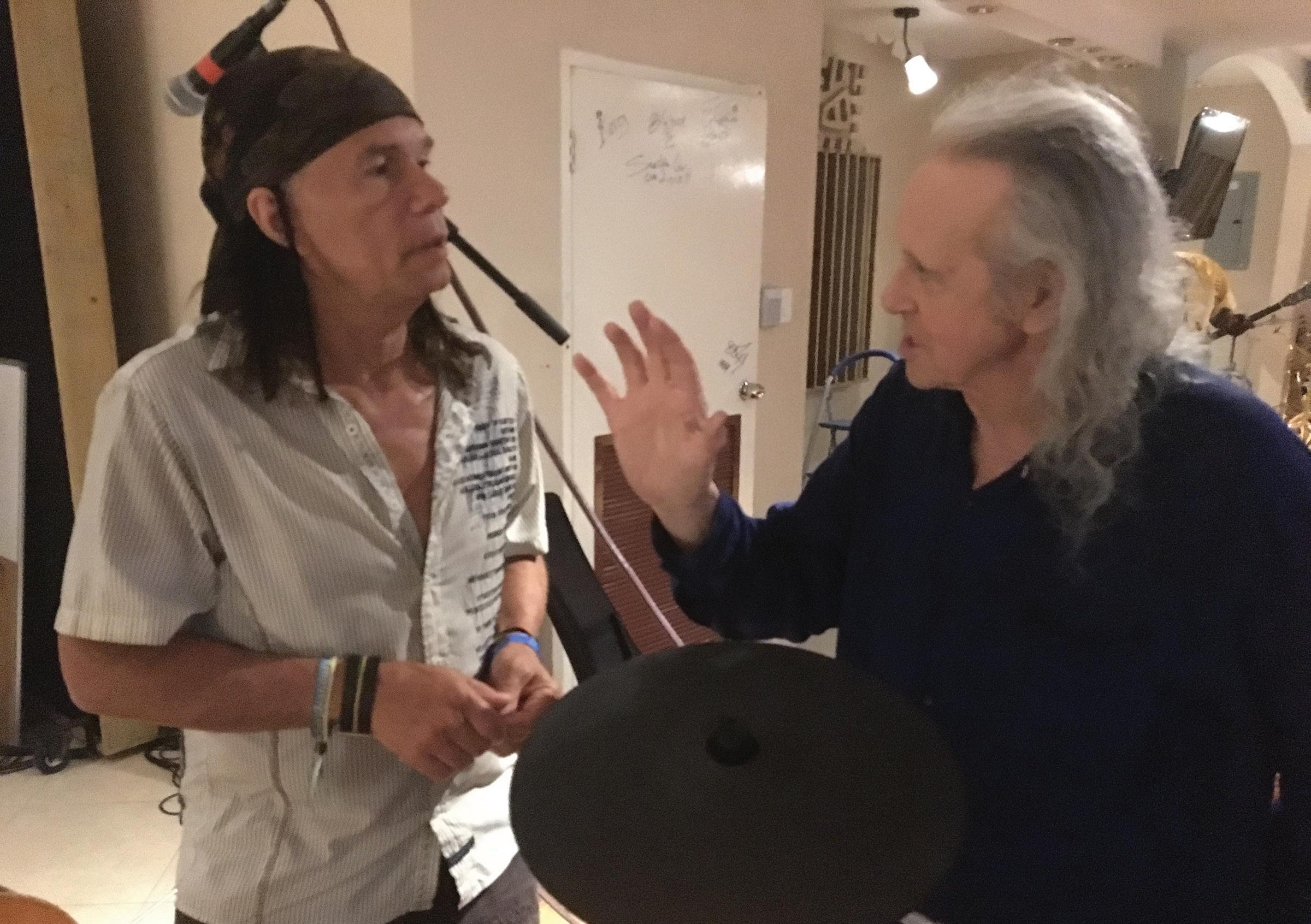

PHOTOS BY CARLOTTA HESTER/GOVINDA GALLERY

Leave it to Donovan to produce and record a tribute to one of the all time greats, Harry Belafonte. Jump In The Line is not just a brilliant tip of the hat musically speaking. It is also Donovan's shout out to Harry as a great champion of social justice, an actor and everything else that we all love about Belafonte. After all, both Donovan and Belafonte are ‘folk artists’. Donovan made sure Belafonte was the first to hear the album and when he did, he told Donovan how pleased he was. Donovan’s album was now part of Belafonte’s legacy. Donovan’s take on Calypso is timelessly enchanting. Everything he sings is pure heaven — beautiful, haunting and evocative. Yet, even beyond this, it is an emotional and poetic work of art. I hope he never stops singing. His message is iconic, encapsulating the sixties and bringing it home to today. Who doesn’t love Donovan?

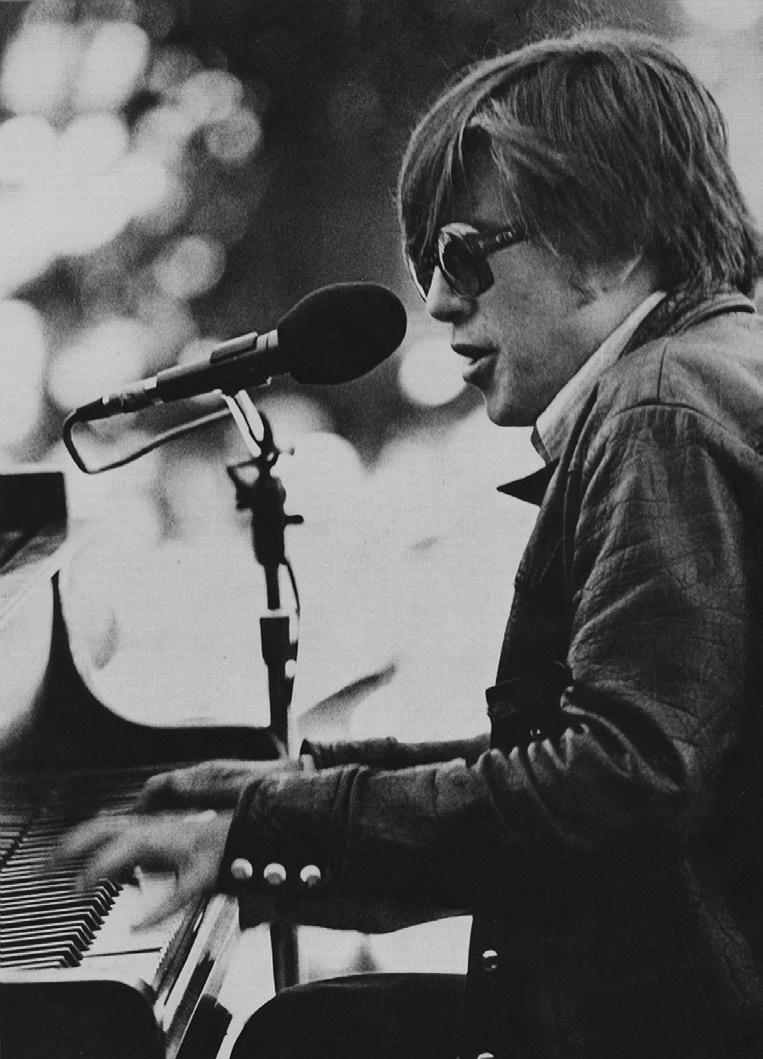

Chris Murray: “I was delighted that Donovan asked me to come with him and assist in Jahmaica during the recording of Jump In The Line at Zak Starkey’s studio. It was an amazing two weeks. Donovan’s muse and wife Linda and his grandson Joolz were also on hand for inspiration and good times. Recording with all Jamaican musicians, Donovan was assisted by our mutual friend Wayne Jobson as coproducer. Wayne lives in Ocho Rios and is a remarkable talent. I had assisted Donovan during his producing and recording of his album Shadows of Blue in Nashville in 2013, which featured the cream of the crop of the Nashville session cats. John Sebastian also came to Nashville to play harmonica on that beautiful album for his life

long friend Donovan. Both Jump In The Line and Shadows of Blue are remarkable and demonstrate yet again the genius of Donovan. It was a thrill to be with Donovan for both of those endeavors.”

Beginning with Devon Ferguson’s rough and tumble banjo, and with his Wooden Flute featured on the fills and solo, Jump In The Line rocks one’s body in time. It is happy music with brilliant lyrics and enough background chatter to bring to mind the similar effect used in Mellow Yellow. Donovan gives an acoustic guitar reggae strum to Where Have All The Flowers Gone? No effects are needed - the tremolo in Donovan’s voice carries us where we need to go. “Gone to graveyards everyone…when will they ever learn?”

A beautiful choir featuring Jeffrey Starr (arranger), Earl Smith, Paul Lymie Murray and Matthew Christie brings it home. Shenandoah is equally touching and The Banana Boat song becomes a poetic call and answer with the choir adding more than a touch of power, grief and anger to what is definitely not a pop ditty. Clarity of production is the keynote to this recording and producers Wayne Jobson & Donovan get the most out of the studio. and features the percussion of Prince Michael. “Sounds of laughter everywhere and the dancing girls sway to and fro” lighten the mood even though it is Jamaica Farewell. Throughout all the cuts, Donovan’s acoustic guitar comes through soft, loud and clear. “Ackee, rice and fish are nice,” you know that’s why the singer’s heart is down and his head is turning around.” because he has to leave his little girl in Kingston Town.

7 • Fine Art Magazine • Spring 2022

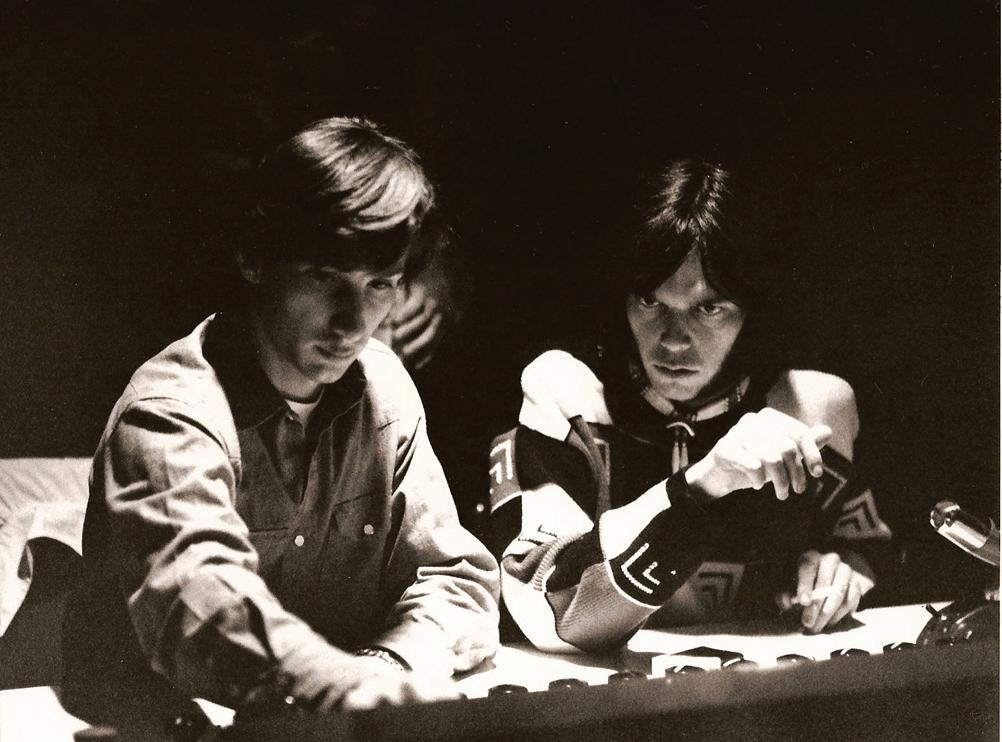

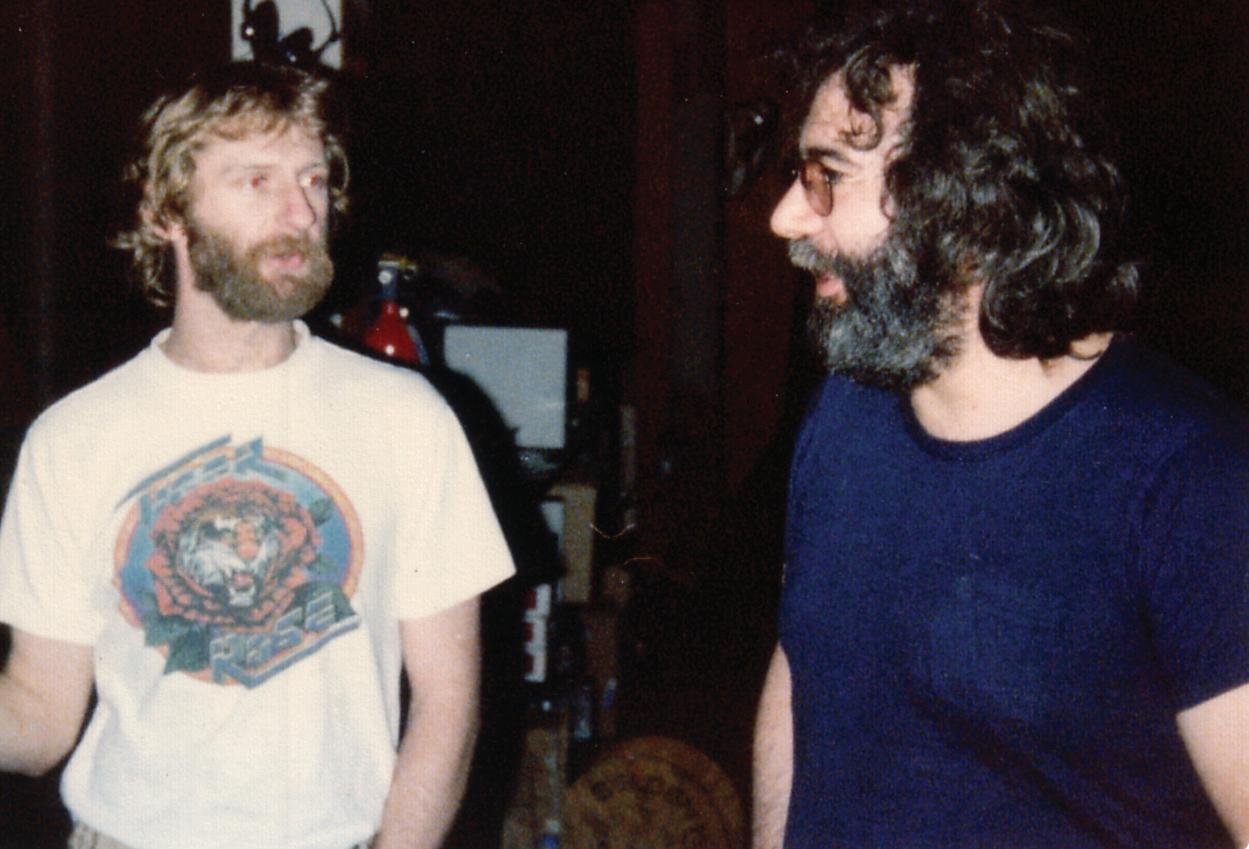

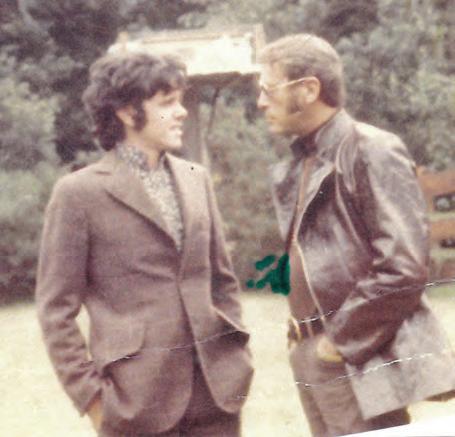

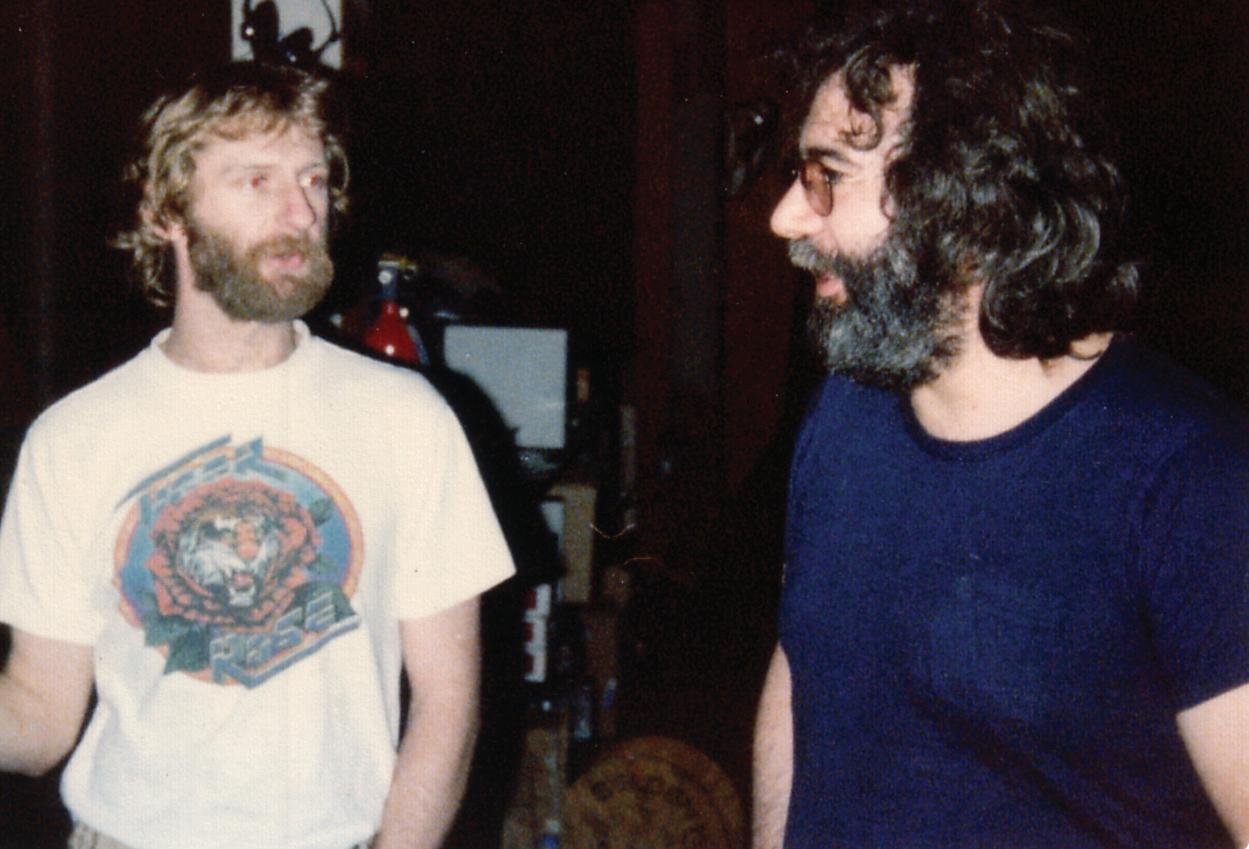

Co-producer Native Wayne Jobson with Donovan, Trojan Records Studio, Ocho Rios, Jamaica.

Light up your spliff/ Light up your chalice

Make we burn it in a Buk In Hamm Palace

—Peter Tosh, “Mystic Man”

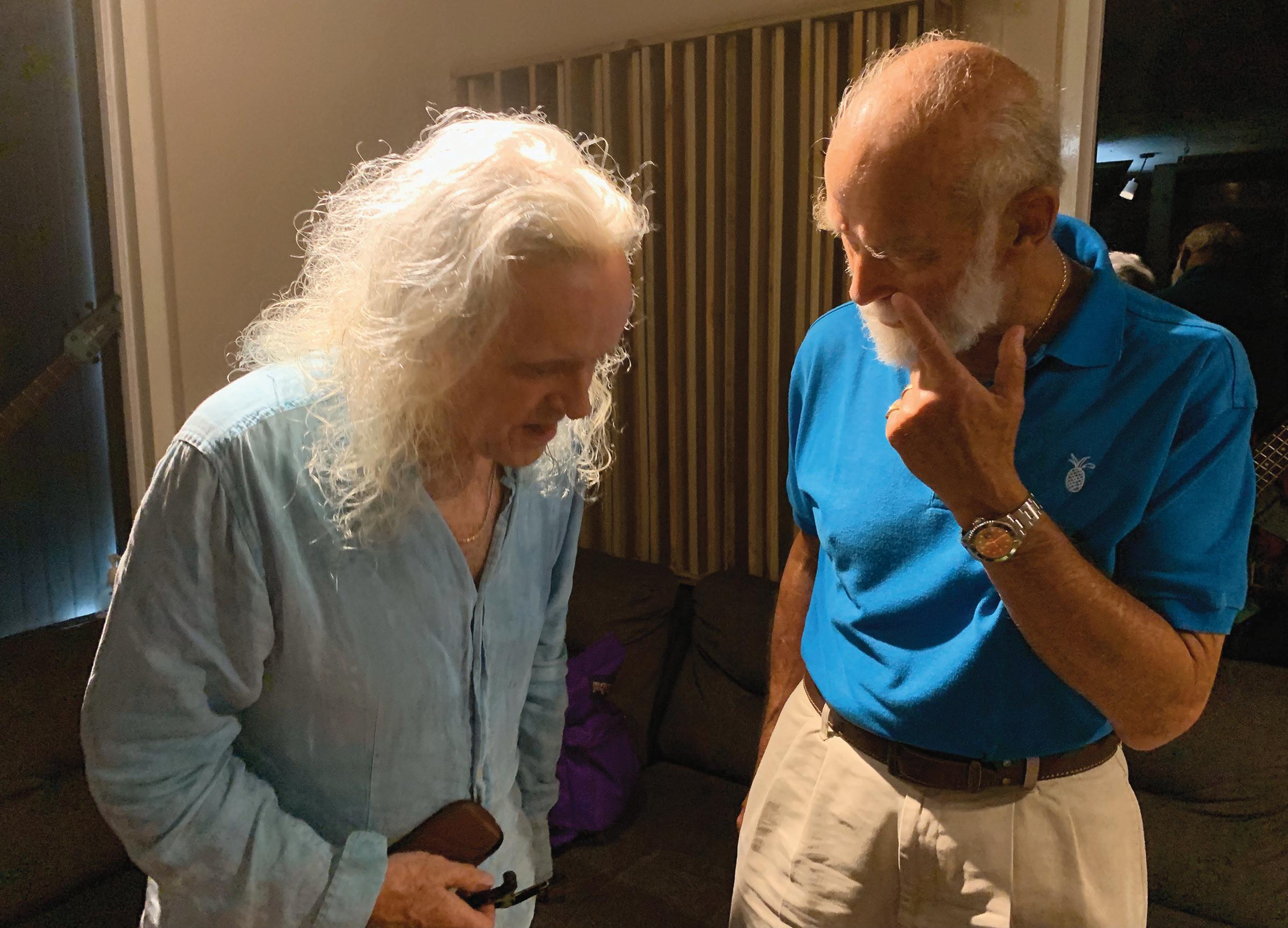

One evening Wayne Jobson arranged for Donovan and Linda along with myself and my wife Carlotta who was visiting for three days, to visit the Golden Eye resort built by Chris Blackwell, who was also in Ocho Rios. I knew Chris as I launched the illustrated book about his label “Keep on Running: The Story of Island Records” at Govinda Gallery in Washington, and Chris was at the launch signing books. We had dinner together after, and Chris is good company. Donovan and Linda rested after long day recording, but I went with Carlotta and “Native Wayne”. At Golden Eye was Prince Michael of Kent, and the beautiful Caroline St.George, and we all had a great chat together. Though the sessions were ‘closed’, I did invite Prince Michael and Caroline to stop by and meet Donovan and Linda. The next morning when the day’s recording began all was running smoothly and I exited the studio and went out front. There was Prince Michael and Caroline just then arriving. I was so glad to see them both, and welcomed them and brought them into the studio and the session. When Donovan took a break, he came over to Prince Michael and I introduced them. It turns out Prince Michael is a big fan of Harry Belafonte and he and Donovan talked about the music. The next thing you know Prince Michael is playing percussion in the session! He is credited on the album, but you will have to listen to the album to hear on which track. It was great day for all. I sent Prince Michael the album on its release. He wrote back a lovely letter with words to the effect that “Jump In The Line” was being heard in the hallways of Buckingham Palace.

Fine Art Magazine • Spring 2022 • 8

Donovan and Prince Michael of Kent talking about Harry Belafonte and his music at Trojan Records Recording Studio, Ocho Rios, Jamaica.

ZAK STARKEY (SON OF RINGO AND LONG-TIME DRUMMER WITH THE WHO) OPENED HIS STUDIO IN JAMAICA IN 2018.

“I first got into reggae music through my mother who had a copy of Toots & The Maytals “Funky Kingston” and then I got into punk and “White Man (In Hammersmith Palais)” name checks a bunch of artists like Dillinger and I started checking them out. Then when I was about 12, my dad gave me a copy of “Man in the Hills”. He’s a big Burning Spear fan so basically my first exposure to Reggae came through my parents and The Clash, which is a bit weird.”

9 • Fine Art Magazine • Spring 2022

Donovan talking with recording engineers Barry O’Hare and Bravo, with Wayne Jobson and Chris Murray, at Trojan Records Studios

Donovan with backup singers Jeffrey Starr, Matthew Christie, Earl Smith and Paul Lymie Murraya.

“Tripppin’ down the rhythm of time to the Fountain of Youth / Escaping to another world to discover the truth – I’m on Jamaican time.” — Donovan, “Jamaican Time”

CHRIS MURRAY

Aide de Camp For The Ages

Aide-de-camp It’s a term you don’t hear with regularirty these days, but in the last couple of weeks, I came upon it twice, both times used by the heroic folk poet balladeer Donovan Leitch, simply known as Donovan. Like Dion and Dylan, Madonna and Elvis, one name more than suffices for this living icon. In the first instance, chronologiclly, The Bard referenced longtime tour manager Gypsy Dave (David John Mills). Most recently, I found it in the liner notes to Donovan’s great new Harry Belafonte tribute album Thanks to : Aide-d-Camp : Chris Murray. is French expression meaning literally “helper in the [military] camp”) is a personal assistant or secretary to a person of high rank, usually a senior military, police or government officer, or to a member of a royal family or a head of state a subordinate military or naval officer acting as a confidential assistant to a superior, usually to a general officer or admiral.

Oh - you mean like Silvio in The Sopranos?

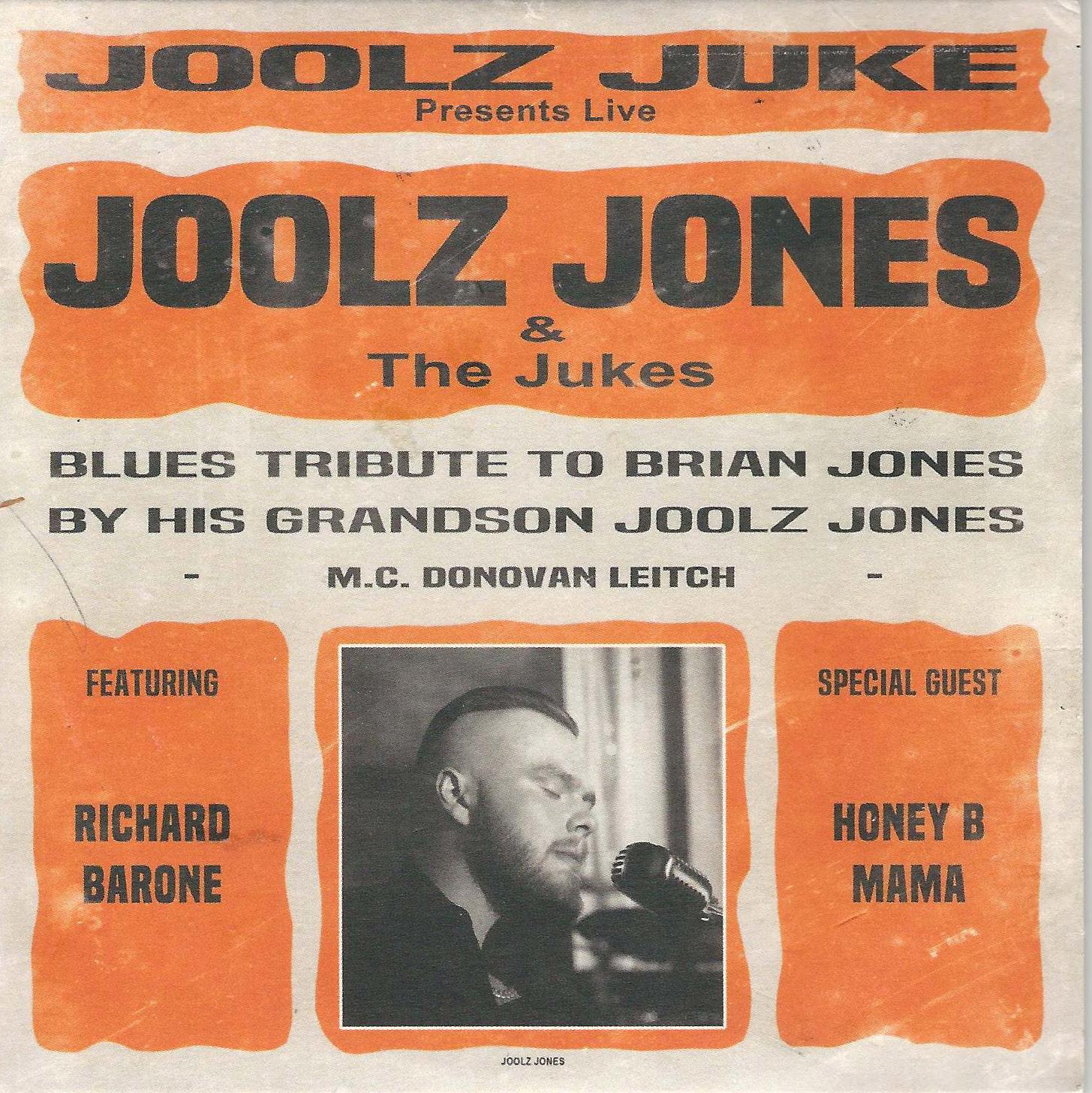

addition to the Donovan/Belafonte CD came the JOOLZ JONES & The Jukes “BLUES TRIBUTE TO BRIAN JONES BY HIS GRANDSON JOOLZ JONES - M.C. DONOVAN LEITCH. That’s a long title but a must have for any collection. Brian never sung a note on a Stones album and listening to Joolz, makes you wonder what Brian might have sounded like.

One of the cool things about knowing the A-d-C is that sometimes you get stuff along with information. In this case, in

Getting back to the Aid-de-Camp, Chris, owner of the heralded Govinda Gallery in Washington D.C., as well as publisher of books by an awesome collection of writers, artists and photographers has been everywhere lately — NYC for Andy Warhol’s 35th Anniversary Memorial Service; the launch of Christopher Makos’ just published book Andy Warhol Modeling Portfolio (G Editions) at the legendary Strand Bookstore also in Manhattan; the major Dylan art show in Miami followed by the openeing May 4th of the Dylan Center in Tulsa. Chris’s blog is an on-going travelogue of cultural happenings not to be missed. You can find it easily on line and take the trip here.

Fine Art Magazine • Spring 2022 • 10

Donovan with his wife and muse, Linda Lawrence, and aide-de-camp, Chris Murray, Ocho Rios, Jamaica.

Speaking of Silvio, here he is with Victor Forbes, Capitol Theater for the Rascals Once Upon a Dream Show, 2012

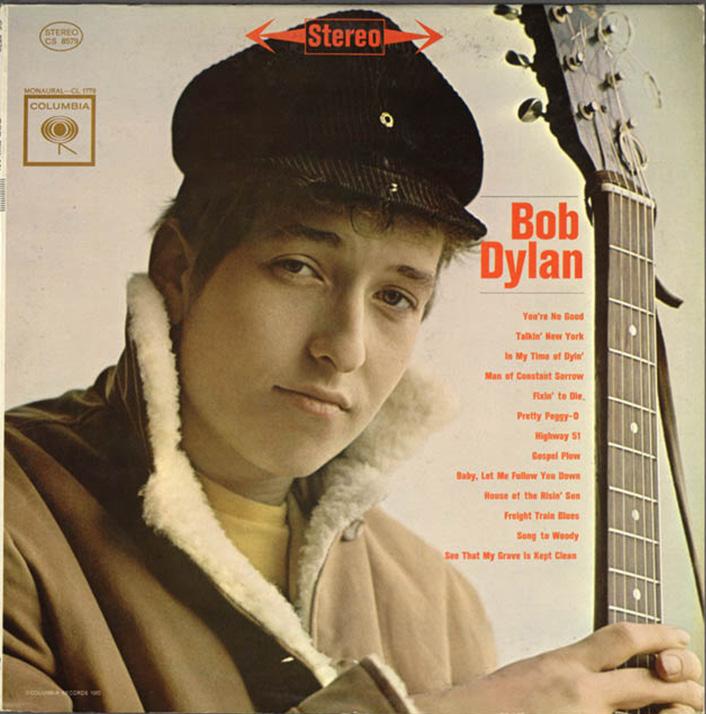

The Amazing Bob Dylan Retrospectrum Exhibition

I believe that the key to the future is in the remnants of the past. That you have to master the idioms of your own time before you can have any identity in the present tense. Your past begins the day you were born and to disregard it is cheating yourself of who you really are.”

— Bob Dylan, The Beaten Path, 2016

11 • Fine Art Magazine • Spring 2022

Chris Murray: “I went to see the extraordinary exhibition of Bob Dylan’s pantings, drawings, and iron works at the Frost Museum in Miami. I was blown away by Dylan’s art.”

Dylan or Donovan? Fortunately, we have both

(I) Don’t think Donovan gets enough props. He started that whole singing in a posh English accent thing copied by Syd Barrett, Mark Bolan, David Bowie, Peter Gabriel, Nick Drake, Al Stewart etc.. His psychedelic stuff with strings is ace too. People just thought he ripped off Dylan but he gives a good account of himself here “The one who really taught us to play and learn all the traditional songs was Martin Carthy – who incidentally was contacted by Dylan when Bob first came to the UK. Bob was influenced, as all American folk artists are, by the Celtic music of Ireland, Scotland and England. But in 1962 we folk Brits were also being influenced by some folk Blues and the American folk-exponents of our Celtic Heritage ... Dylan appeared after Woody [Guthrie], Pete [Seeger] and Joanie [Baez] had conquered our hearts, and he sounded like a cowboy at first but I knew where he got his stuff – it was Woody at first, then it was Jack Kerouac and the stream-of-consciousness poetry which moved him along. But when I heard Blowin’ in the Wind it was the clarion call to the new generation – and we artists were encouraged to be as brave in writing our thoughts in music ... We were not captured by his influence, we were encouraged to mimic him – and remember every British band from the Stones to the Beatles were copying note for note, lick for lick, all the American pop and blues artists – this is the way young artists learn. There’s no shame in mimicking a hero or two – it flexes the creative muscles and tones the quality of our composition and technique. It was not only Dylan who influenced us – for me he was a spearhead into protest, and we all had a go at his style. I sounded like him for five minutes – others made a career of his sound. Like troubadours, Bob and I can write about any facet of the human condition. To be compared was natural, but I am not a copyist.” – From a post on a youtube comment by Roddy Fraser.

“Season of the Witch, Catch The Wind, Sunshine Superman, Hurdy Gurdy Man, Mellow Yellow, Atlantis, Wear Your Love Like Heaven, Riki Tiki Tavi, Lalena, To Susan On The West Coast Waiting. And those are just the songs that were on the radio. The further we get away from the original, the worse it gets.” – John MellancaMp

Fine Art Magazine • Spring 2022 • 12

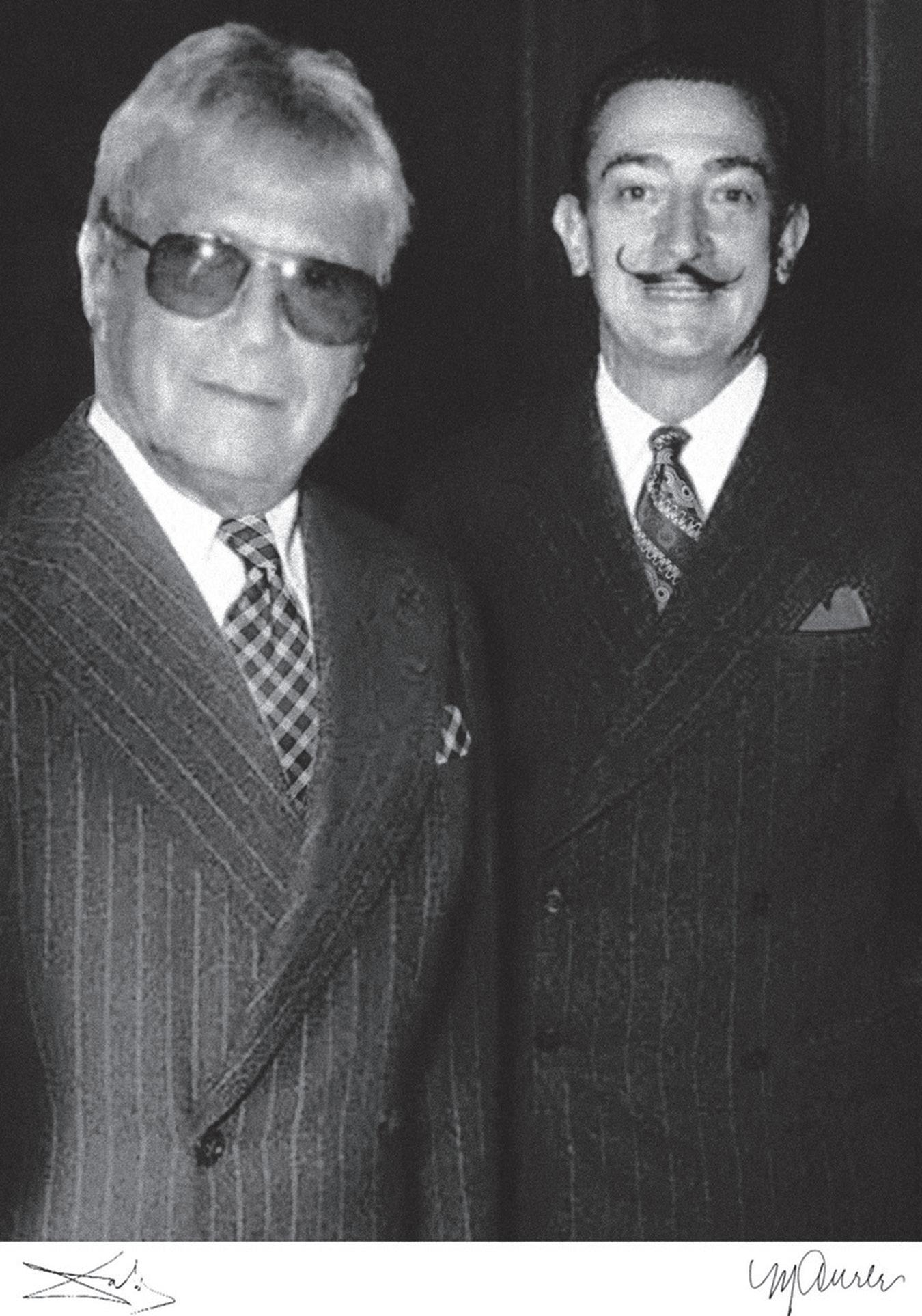

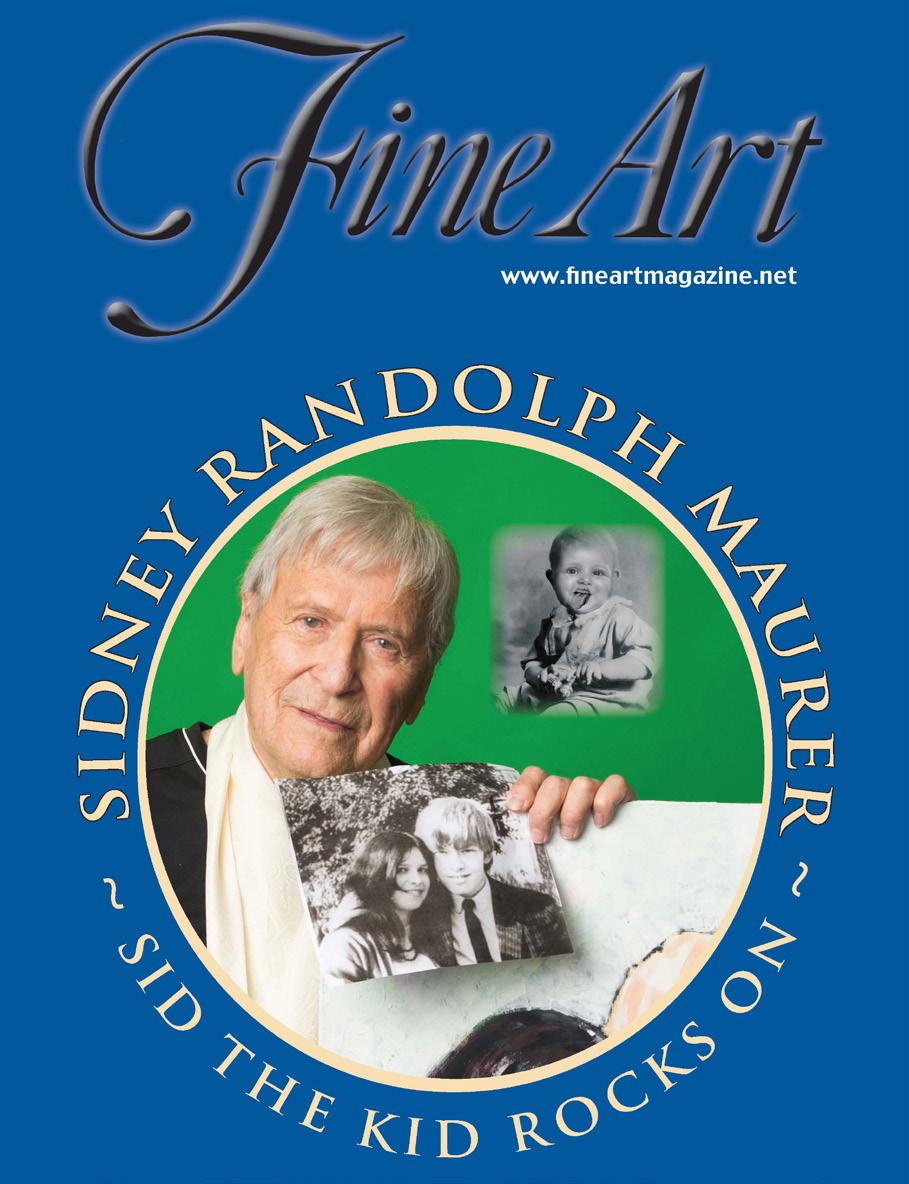

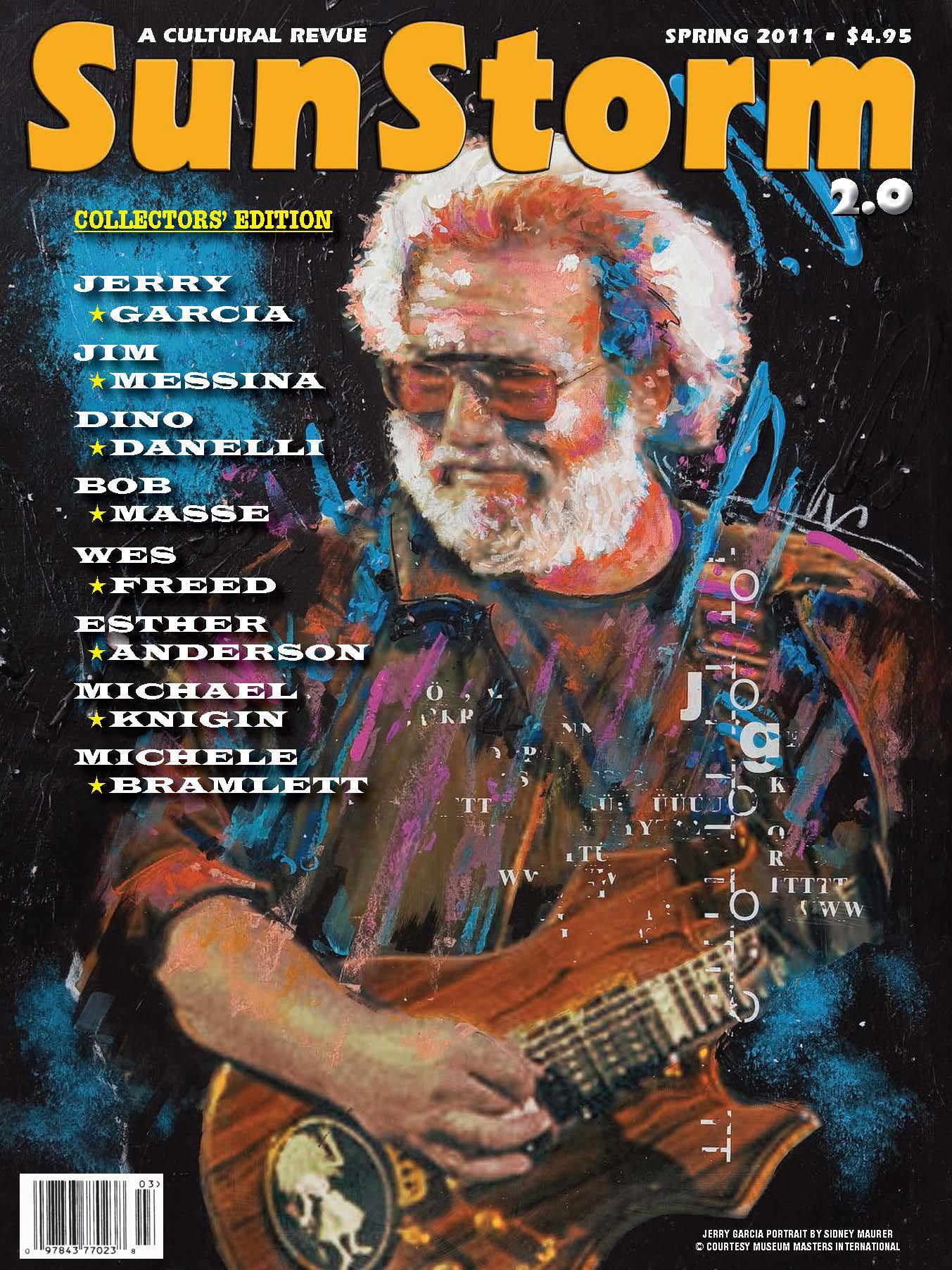

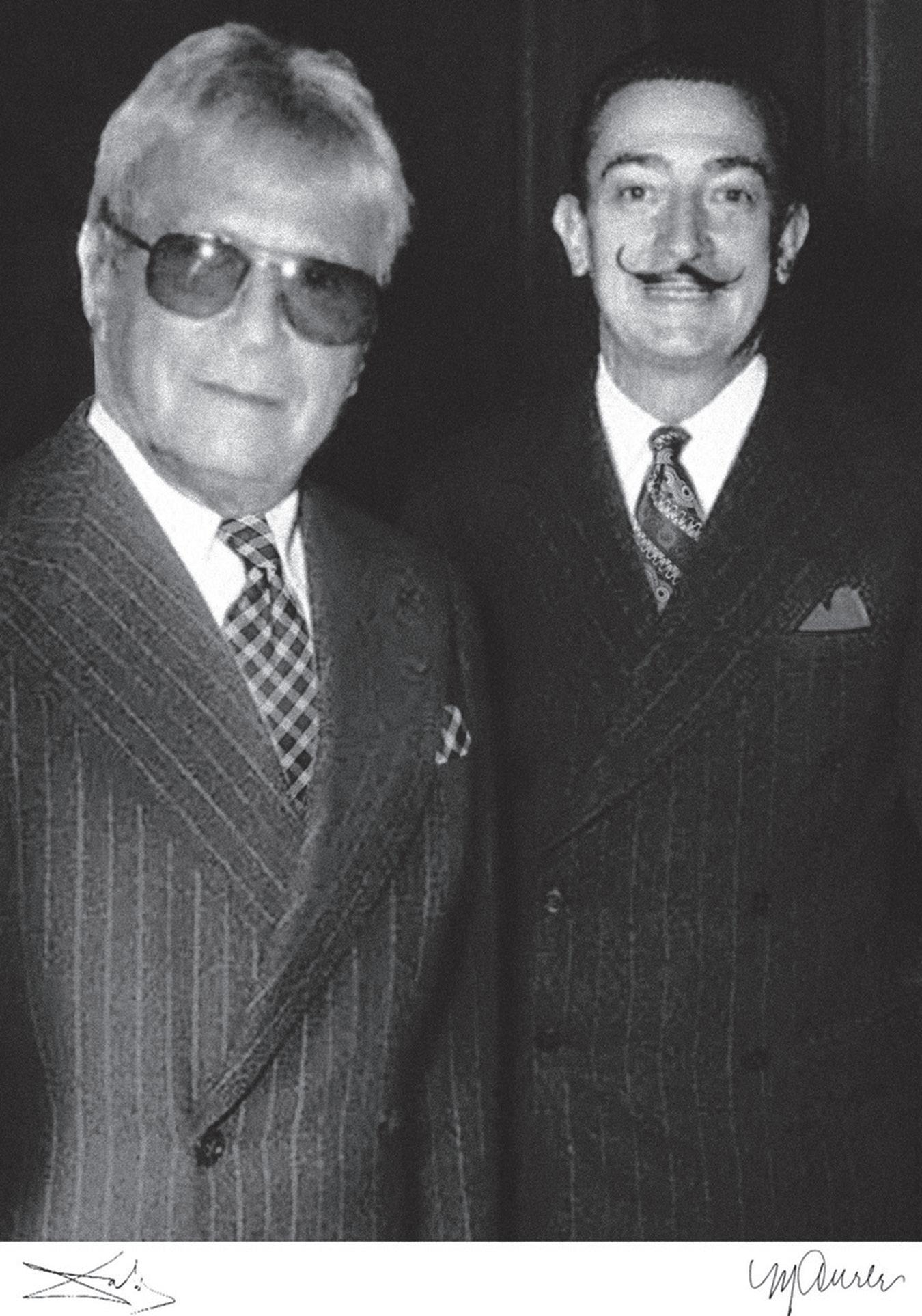

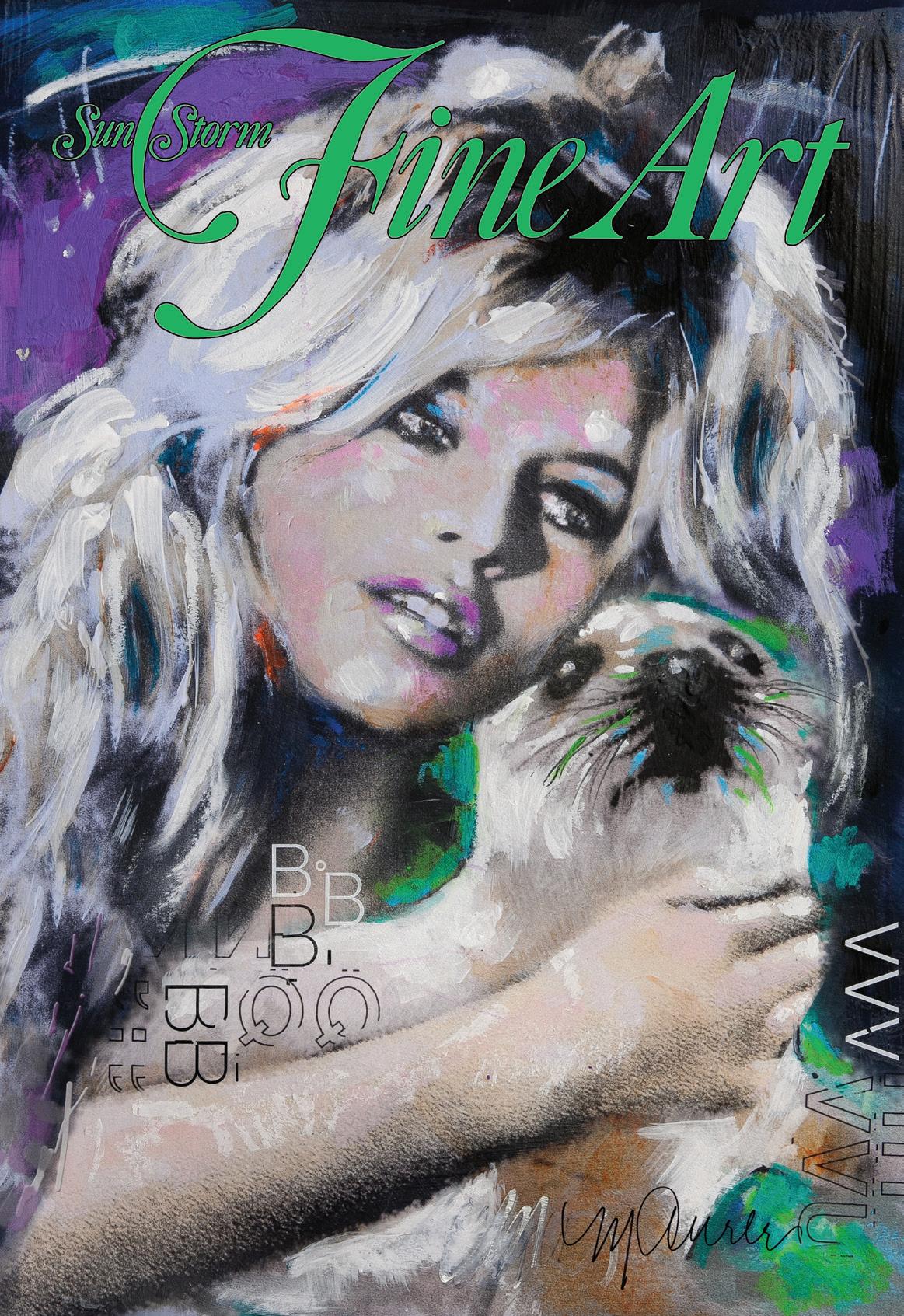

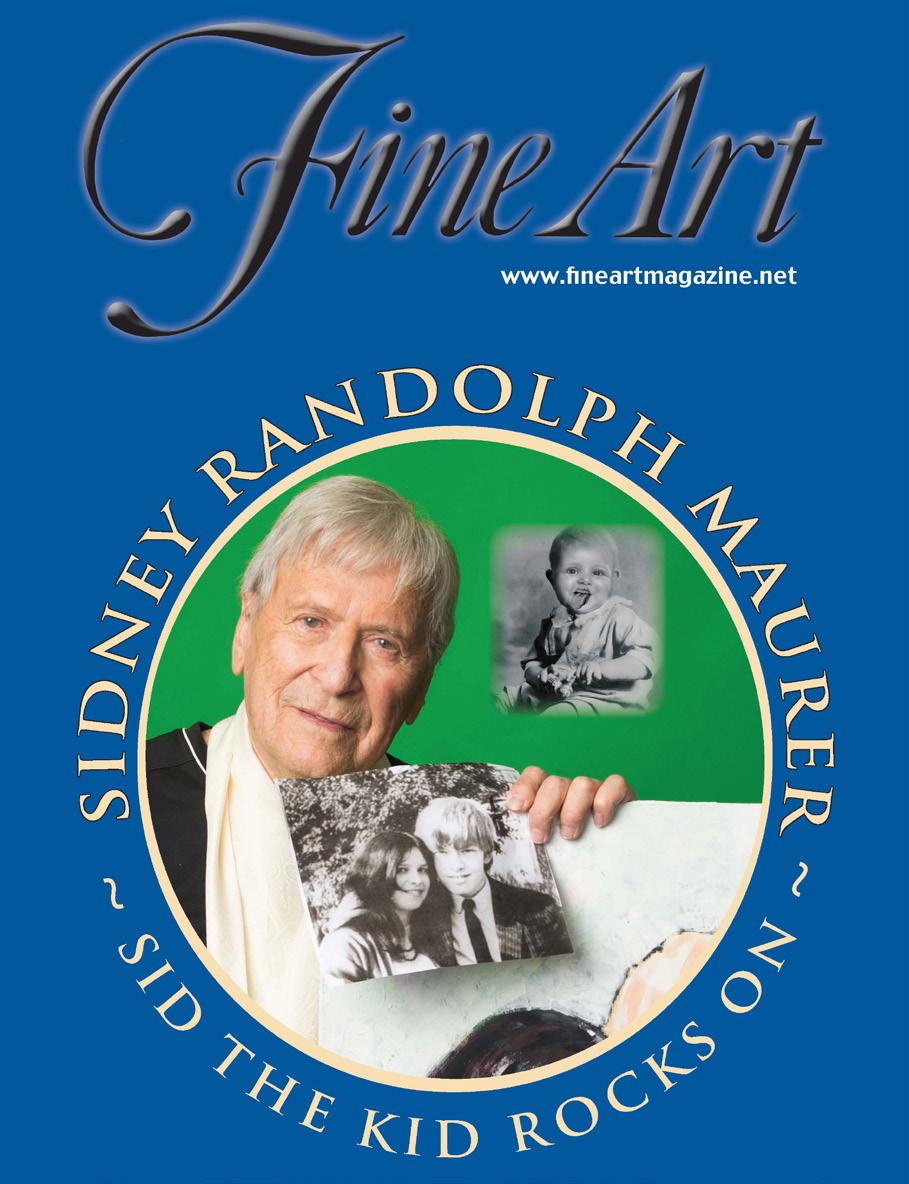

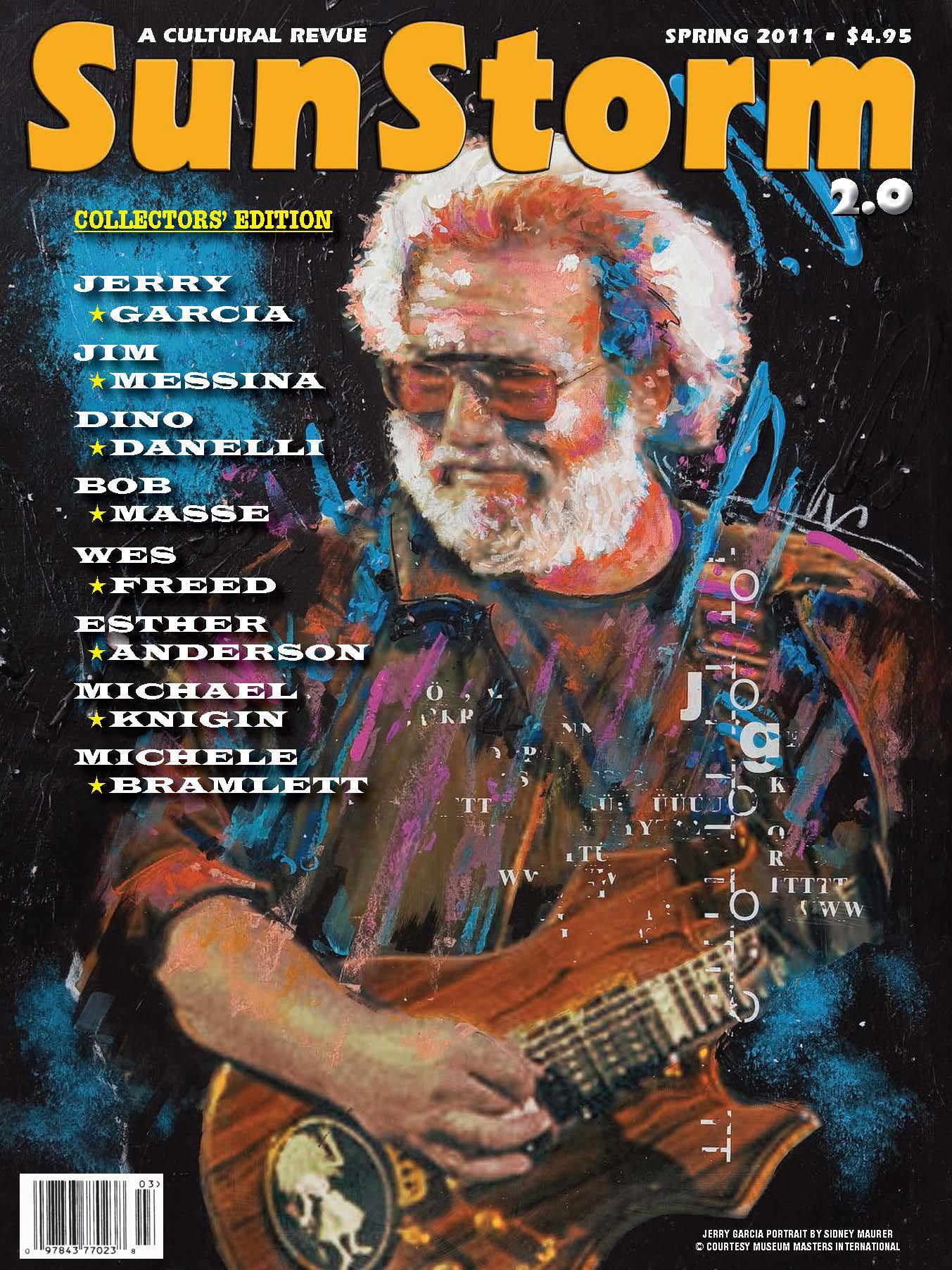

SID “THE KID” MAURER

Donovan’s Art Director, Collaborator and Friend

Sid Maurer is a man of great and many stories now compiling the soon to be published book of his life and times globally in the music industry. His long career in the world of Art and Music began at seventeen when he was hired as assistant art director at Columbia Records in New York City, where he spent weekends playing trumpet in Jazz clubs. As the music business exploded, Maurer worked designing album covers and promotional material for popular artists most of whom live beyond their years, today in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.His friendship with and ground-breaking work with Donovan is described in depth in the following pages.Thanks to Marilyn Goldberg of Museum Masters International for our introduction to this great artist and man —VBF

13 • Fine Art Magazine • Spring 2022

Marilyn Goldberg, Pres. Museum Masters International, builds on Sid’s legacy with future exhibitions

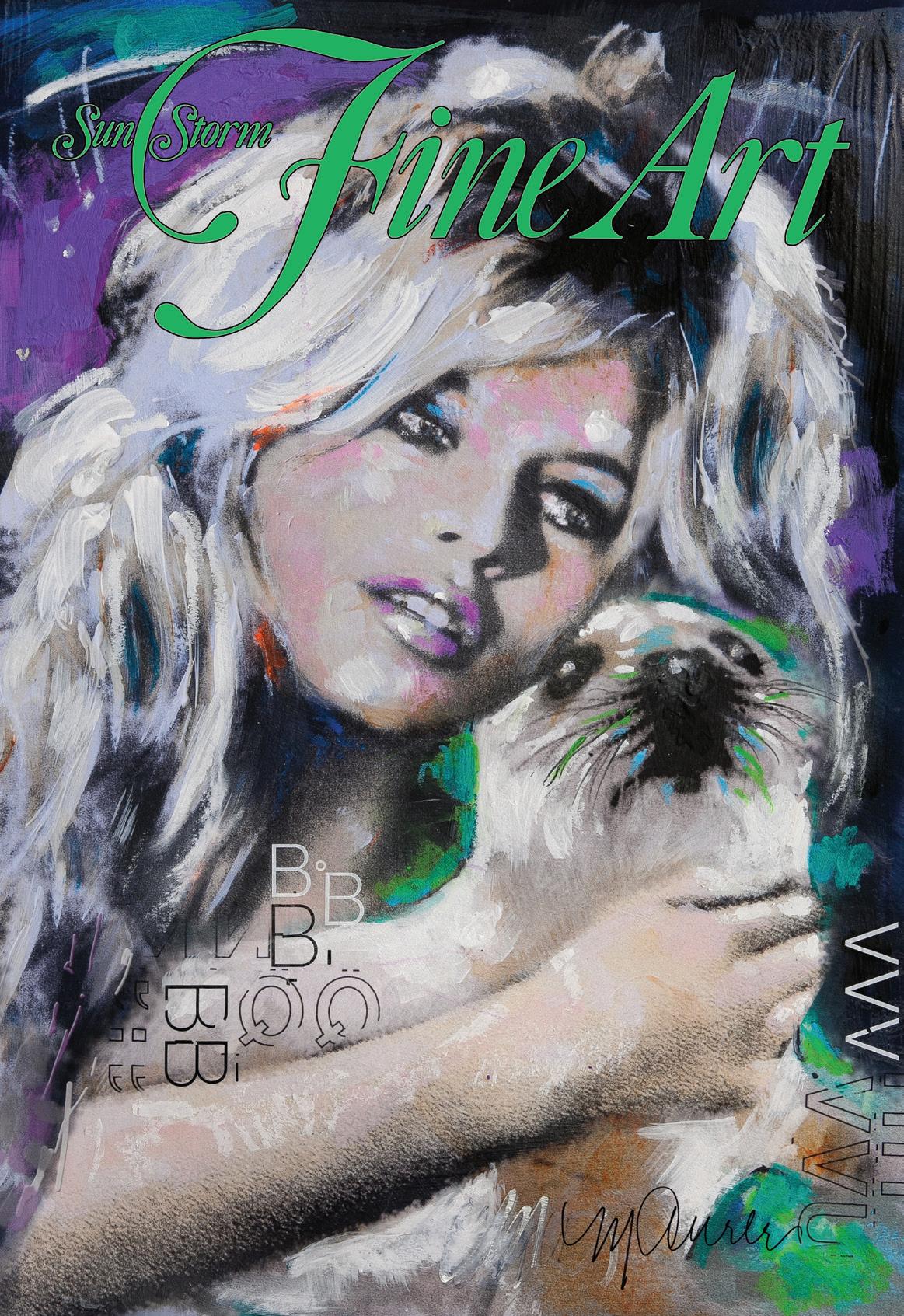

Sid & Sal

Sid Maurer’s Brigitte Bardot graced the cover of Fine Art Magazine

®

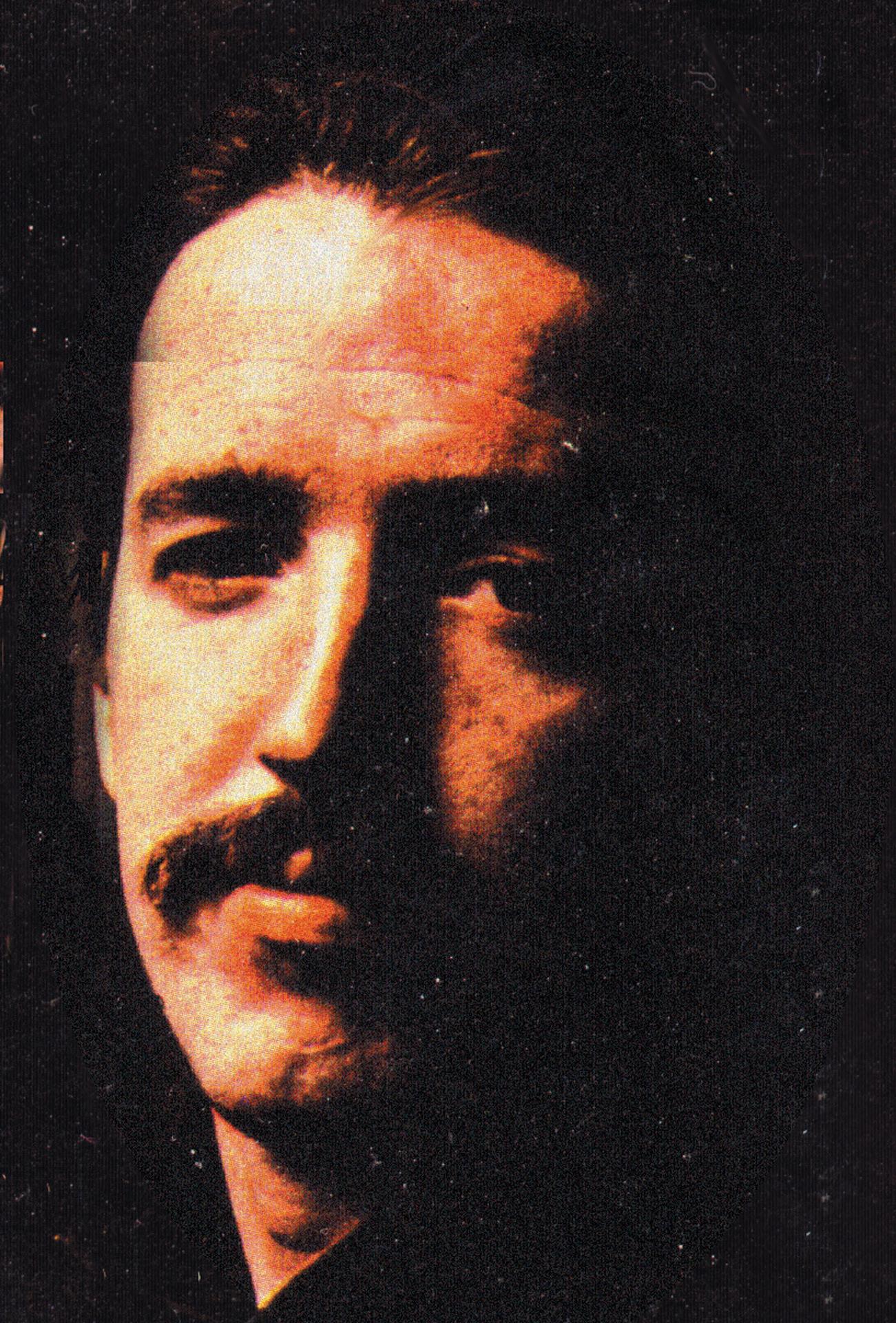

He was so shy....So quiet...And overwhelmed by his success. He went from sleeping on the beach and park benches to stardom literally overnight.

Somewhere between Their Satanic Majesties Request album and the recording of Sympathy For The Devil, Brian Jones, went to the dark side. Unceremoniously canned from the band he started, Jones, arguably the heart and soul of the Rolling Stones, was found (still-breathing some say) at the bottom of his swimming pool at English countryside home, Cotchford Farm. In one of those yet-to-be-solved legendary rock and roll deaths, the mystery remains. Yet the facts of his life are indisputable. “He formed the band. He chose the members. He named the band. He chose the music we played. He got us gigs…he was very influential, very important, and then slowly lost it,” said Stones bassist Bill Wyman. None other than Bo Diddley called him “a fantastic cat who handled the group beautifully.”

Enter Sid Maurer, a major league New York City art director/artist who helmed an agency that produced album covers at the rate of one a day for a few years in the psychedelic era. It was during this period that Maurer’s work gained major recognition with best-selling records and sales of his paintings in galleries from Manhattan to London to where he regularly commuted to visit his best friend, the legendary troubadour/teen idol/rock star who still goes by the single name of Donovan. They met on his maiden voyage to America when “Don” was freaking out over the excessive enthusiasm of secretaries-turned-groupies and the business persona of label president Clive Davis at the Columbia/Epic offices. At the time, Sid was under contract with Epic to produce all their album art and was called in by Davis to meet his newest star. Barefoot and

in what Sid could only describe as a Turkish wedding gown, the Sunshine Superman took Sid up on his offer to take a short walk back to his studio, located around the corner. “We hung out, smoked a couple of joints, talked about all kinds of nice stuff and he invited me to his sold-out Carnegie Hall show and that’s how our friendship started.” Donovan, belatedly elected in 2013 to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, readily states, “Sidney did all my album jackets and design in the ’60s He’s the best there is. His artworks are to be treasured and we are friends to this day.”

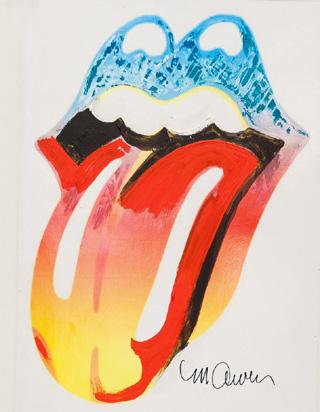

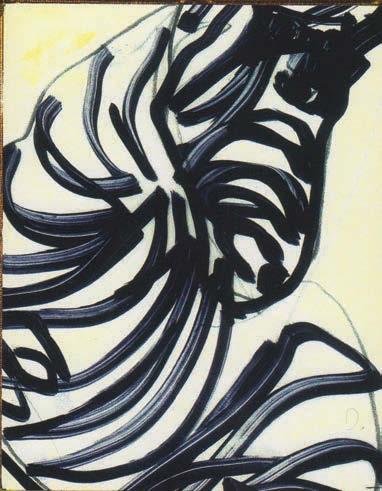

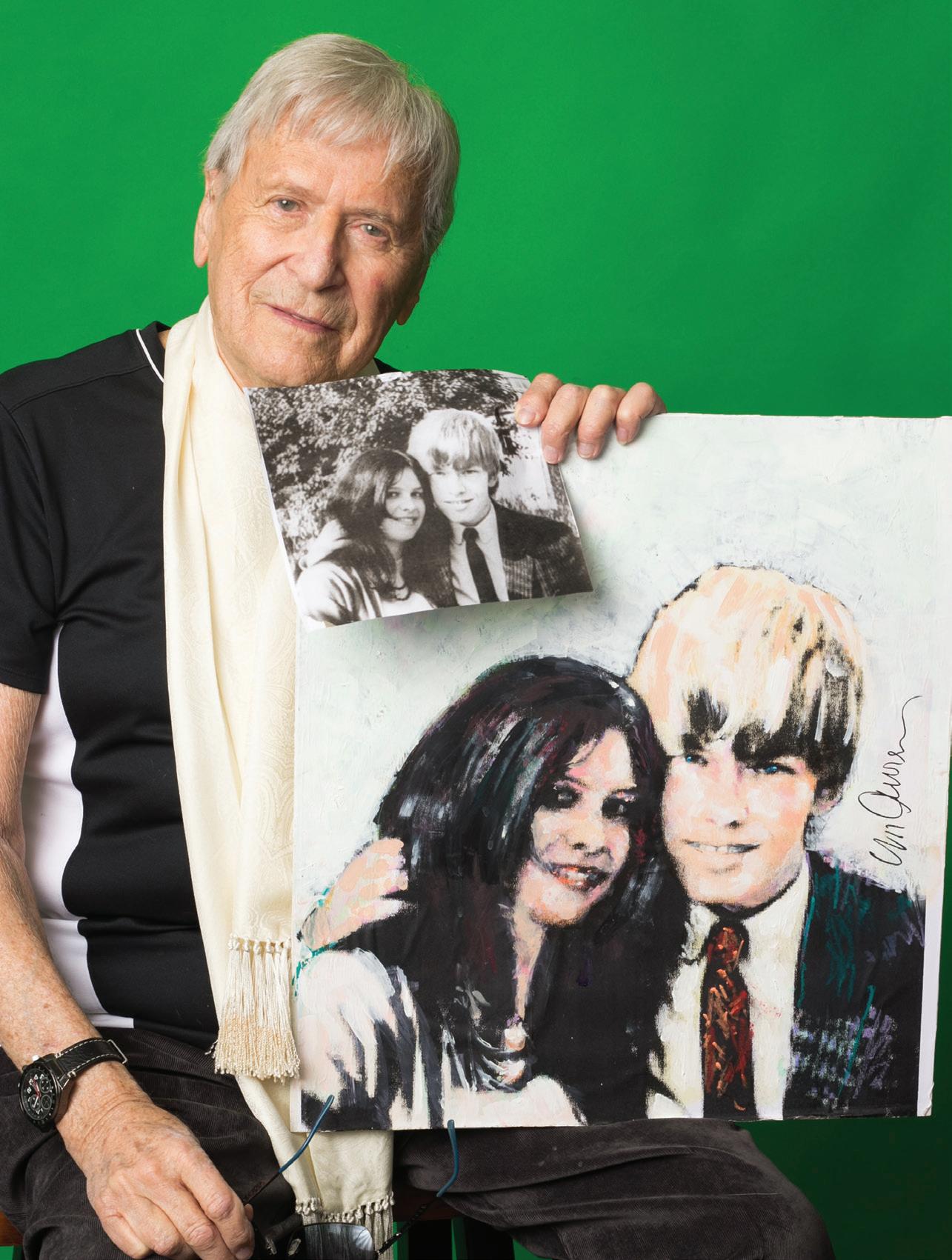

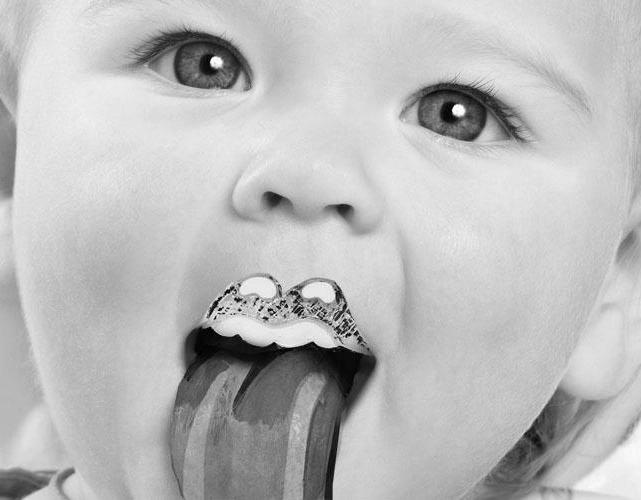

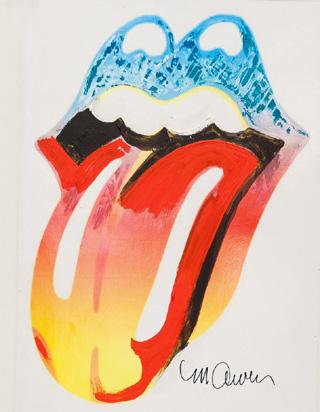

(l) Sid’s original concept; Brian Jones bought Sid’s painting (c) for $1500. (r) John Pasche’s version sold at auction for $92,500 to Victoria Albert Museum. Another artist, Ruby Mazur also claims he did work on the logo and was paid $10,000 for its use. According to Novagraaf/Musidor.com “The Rolling Stones are one of the longest running acts in the history of rock music, having remained wildly popular and prodigiously productive over their 50-year career. They are also well known for the lips and tongue logo, one of the world’s most instantly recognizable symbols of rock and roll. (Ed. note: with a value of $100 million USD). The global music rights of the Rolling Stones are being handled by Musidor BV in Amsterdam, The Netherlands in Partnership with Novagraaf and hold Intellectual Property rights of the trademark The Rolling Stones, including the iconic logo.

In those halcyon times, “Don would phone me from England,” recalled the artist in recent interview from his Atlanta studio “and say, ‘What are you doing this weekend?’ and I would hop on a plane and we’d have a visit. He had a beautiful cottage in Hartforsdhire with a very colorful large bird painted on the roof. In those days, we’d simply hang out, which one could do back then.” Visitors might include George Harrison or one of the other Beatles as Donovan had just returned from a trip to India to visit the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi with the band to study with the founder of Transcendental Meditation, etc. It was there that Donovan taught John and Paul his unique guitar style of which Lennon’s Julia is the most famous example.

During one of many parties Sid attended in London, he met Andrew Loog Oldham, manager of the Rolling Stones, who went on to dedicate a chapter to Sid in his book 2Stoned. Sid recalls one gala with Princess Margaret and Sean Connery in

Fine Art Magazine • Spring 2022 • 14 Fine Art Magazine • 2014 • 27

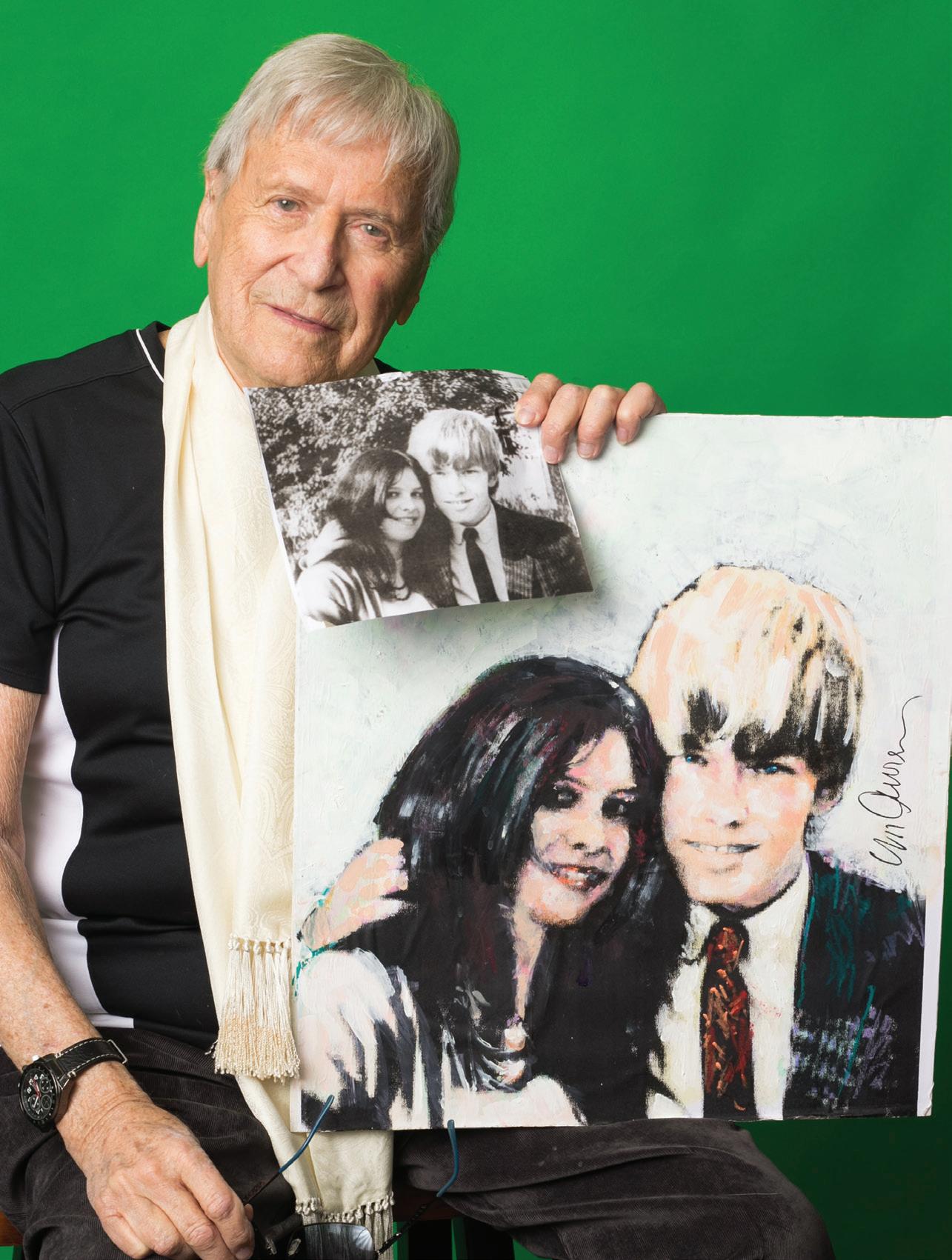

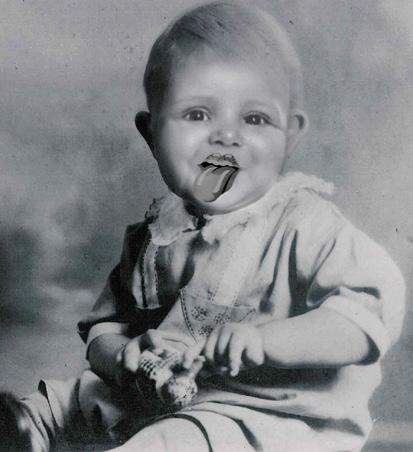

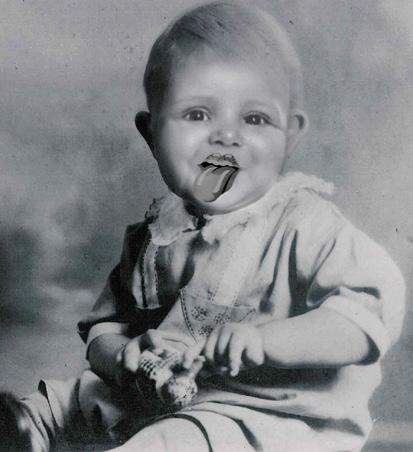

Sid Maurer with portrait of Brian Jones and Linda from a photo he took of them in 1967. Below, left, is Sid’s graphic rendition on a baby picture (inset above is Sid’s from 1927) showing details of what would become the famous tongue logo. Below center is the painting by Sid bought by Jones in 1968 which eventually morphed into the logo ultimately executed by a British design student John Pasche after a meeting with Mick Jagger.

attendance where Oldham and Sid bonded over a warning to not touch the punch. “‘It’s loaded with LSD,’ he told me. That’s how it was back then. You had to be careful. Our ’60s conversations were mostly, ‘Take a hit. Far out. Have another hit. Too much. What’s your sign?’”

AThrough Oldham, Sid met the doomed Brian Jones who commissioned him to paint a portrait of himself with his girlfriend Linda Lawrence, mother of his son Julian. Sid recalls, “Brian loved collecting. He had tidbits here and there, and many photographs. He loved my baby picture from 1927! Unfortunately, the photo was old and not in great shape so I found an alternate (not of me) and embellished it with a little graphic concept with a tongue and lips penciled in, basically to reflect the Stones as they were: the bad boys of the era sticking their tongues out at authority, as opposed to the Beatles, who were considered more safe. He liked that image a lot and asked me to make a color drawing, which, unknown to me at the time, morphed somehow into the famous Rolling Stones tongue logo, which originated from my baby picture, of all things. I first offered the drawing to their record label, Decca, who were willing to give me a few hundred dollars for it but Brian liked it enough to pay me 500 British Sterling pounds, which was about $1500 back then. I thought nothing of it until years later. In 2013 I was commissioned to make shirts and other items in France featuring my original tongue painting. Shortly after they were placed on display in a Paris department store, they were seized by Musidor and taken off the shelves for ‘trademark infringement.’ Without Brian around to tell the real story, the manufacturer had no choice but to comply.”

The next thing Sid created for Brian was a portrait of the Stone and Linda. The photo Sid is holding (preceding page) became the basis for the initial small painting. “This shows how beautiful a guy he was,” said the artist. “I painted that picture somewhere along the line and tucked it away. After Brian died, Linda married my best friend, Donovan, and they became a family.”

In 2013, by Linda’s request to honor the 50th anniversary of the Rolling Stones, Sid was commissioned to re-create the portrait on canvas from his initial painting done all those years ago. The final painting is exactly the same but on canvas. The new version now resides in Ireland with Linda.

“I traveled all over with Donovan, and even accompanied he and Linda on their honeymoon. After one of his concerts at the Hollywood Bowl, Tommy Smothers threw a party for him. Hendrix, Janis, Morrison, Mama Cass, and a new kid on the block who didn’t even have a record out — Elton John — were all there. Many of the people I met became casualties, but Don did not. He was always very careful where he hung out and didn’t do drugs. After he made some money, he asked me to invest it for him so I put it in a bank in the Bahamas that I found out was ready to go under a year later. Somehow, I managed to salvage the dough and we bought a boat and took it to Greece with a crew of 12 and three hippies — me, Don and a friend. We landed at the Island of Hydras, to visit Leonard Cohen, who had a house up on a hill, accessible only by donkey.”

long way from The Bronx, where Sid was born and raised when “the streets were black from horseshit, not asphalt. I was going to attend Taft (high school) but somewhere along the line a typographer friend of my family saw some of my work and suggested that I would be more suited to attend The School of Industrial Art on Jones Street in the Village. There were two teachers there, one for art, the other for academics and it was great, kind of like being an apprentice in the Renaissance. In the morning, we’d find our teacher on the stoop recovering from the night before and the first who arrived was designated to get him coffee. One of my classmates was Anthony Benedetto, better known as Tony Bennett, singer and artist. Anthony Benedetto is the name the signs his paintings with. I wrote the class theme song and conducted our band. After graduation, I worked for Columbia Records in the art department. Their office was then in Bridgeport, Connecticut and I made the commute every day via the elevated Jerome Ave. line, bus crosstown to Grand Central and then a train ride. I was drafted, injured and sent home. After the war and I was OK, I started knocking on doors of record companies and was hired by Decca.”

During the late ’50s and early ’60s, Sid frequented the fabled Cedar Tavern where he met artists such as Rauschenberg, Johns, and Larry Rivers in their salad days and witnessed the zaniness of that particular scene. “Every night they would knock each other to the floor, fueled by alcohol. This was just before grass became mainstream in the mid ’60s and in those days I would run into Dylan, Joni Mitchell and many others in small clubs in Greenwich Village. That’s where I became especially close to music. My whole life as an artist has been fueled by my love of music.”

Sid’s career in the art and music field flourished in New York City where among his friends were Alan Klein (the businessman who helped form Apple Records for the Beatles and managed the Rolling Stones) and Bob Guccione. “He came to my exhibit at the Beilin Gallery on Madison Avenue, liked my stuff and asked me to show him a few things. I also met him in London. He was a slick guy, loved the girls and very handsome. I painted his portrait and helped him style the girls for photo shoots. He had his own penthouse, the girls were there and that was his life. We hung out,” Sid continued, “and I began to write chapters — not a book — about El Sid The Kid.”

15 • Fine Art Magazine • Spring 2022 28 • Fine Art Magazine

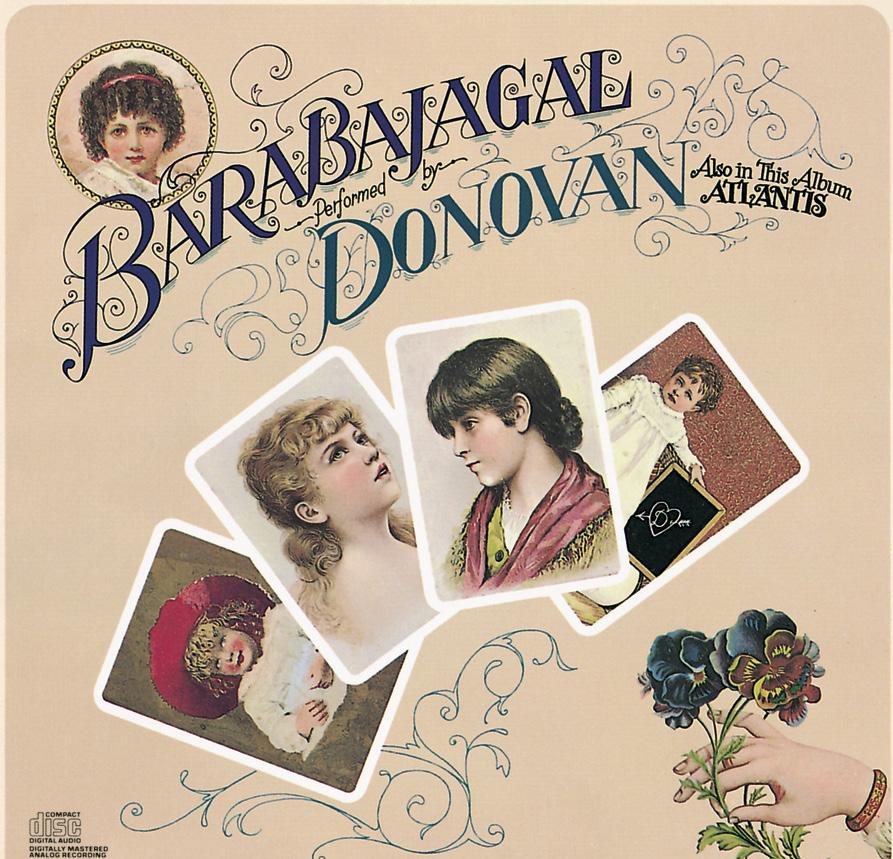

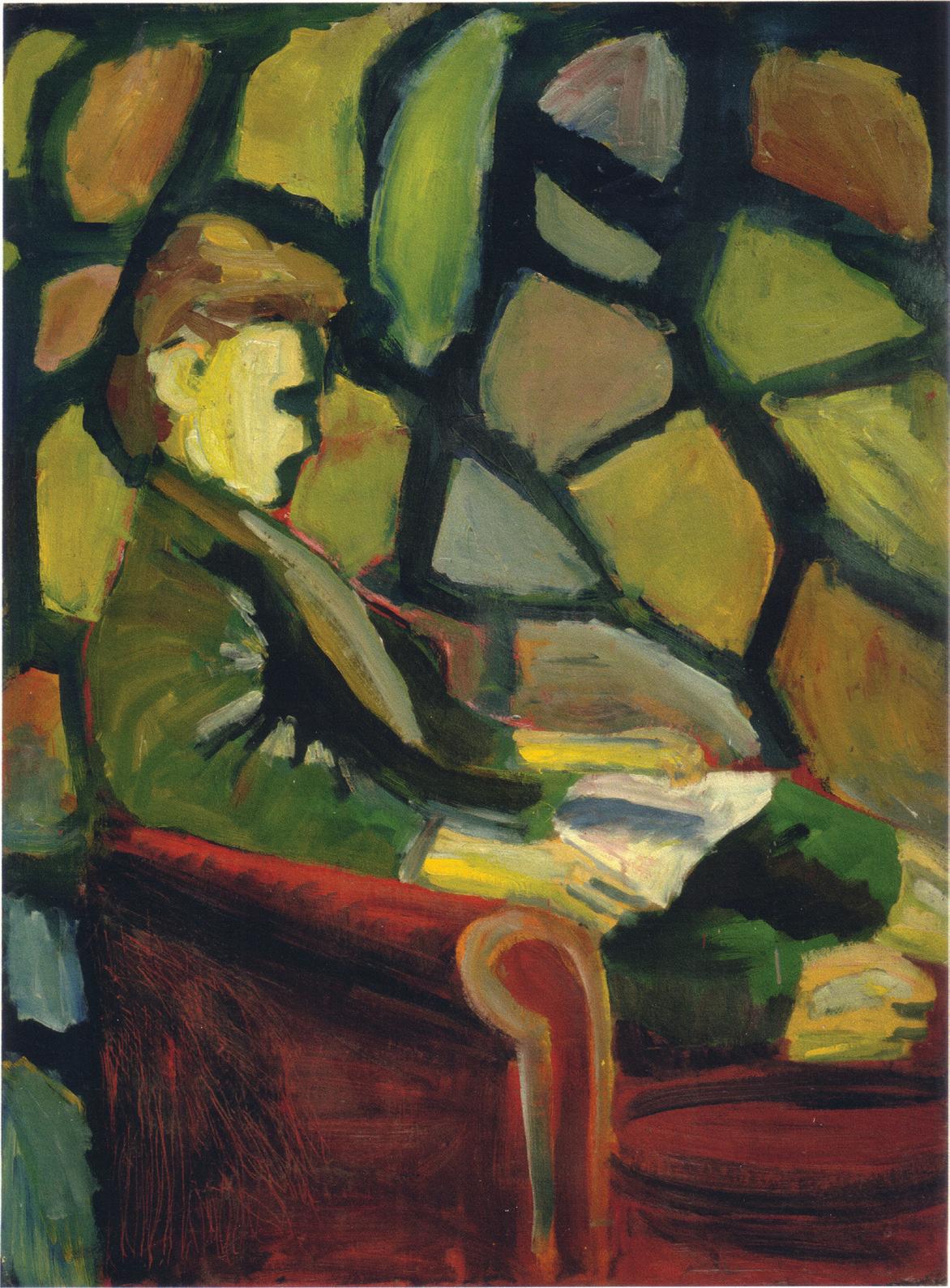

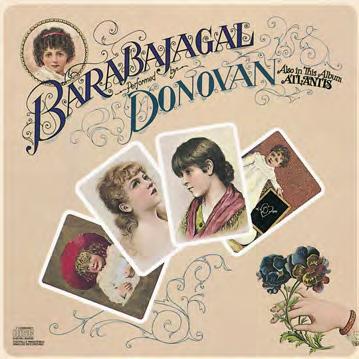

Sidney Maurer album design for Donovan’s Barabajagal

Sid on the boat with Donovan, Greece, 1968

By JAMIE ELLIN FORBES

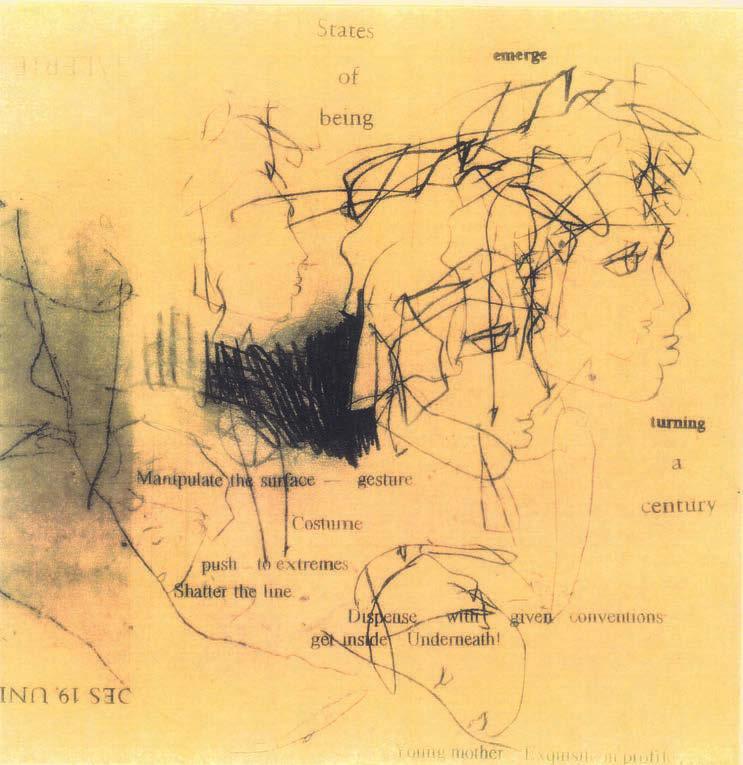

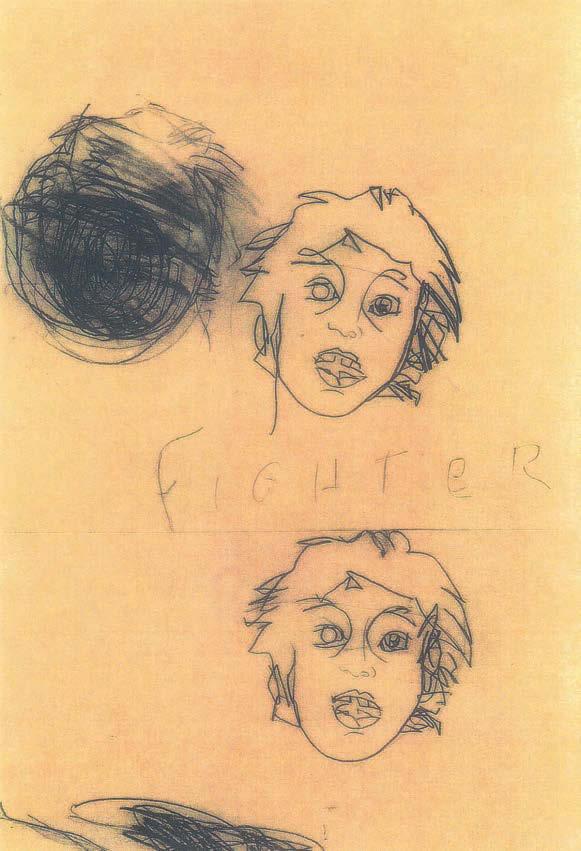

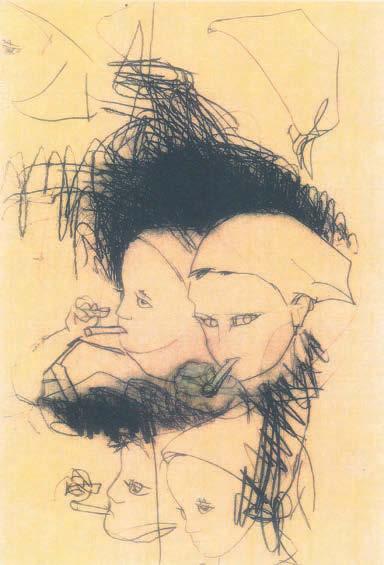

DONOVAN . I am a fan. I lived the 60s. Freedom of imagination ruled. Season of the Witch was my favorite song as well as his. The resurgence of popular style in music, clothing and artas-graphic from the era is not nostalgic for me, rather a comfortable place to be. As if I were visiting where the Season of the Witch lives. A good fit. Donovan was and is the seminal leader of innovation, a clear and channeled voice for this mid to late 20th century generational art renaissance movement beyond Pop. It is easy to understand why the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame will be inducting him into the ranks of cultural rock trailblazers this spring, as a poet/artist/musician who inspired the icons of his era. Donovan the troubadour bard formed the vision and the artistic framework implemented in the 60’s as style, drawn upon from his art school years. “We singer songwriters from Britain who are very prolific…you can see colors and landscapes in songs full of images when we put down paint brushes and picked up the guitar… Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds - One of my first songs was called Colors. In Wear Your Love Like Heaven - Sid saw that right away here comes a singer/songwriter who wants true art on his covers.

people know it but Lennon and McCartney are Irish names from Liverpool and I became aware I was from that tradition of the troubadour sound. I dressed up the songs in different costumes at times.

“We come from a tradition,” continues Donovan, “not many

Like many of his era from England, including Ronnie Wood (who is also being inducted as a member of The Small Faces), Donovan cites his art background as the impetus for the visual quality of story-telling in his poetry and music. The team of Donovan and Sidney Maurer used graphic art, classical art and even Kirilian Photography to expand the possibilities of the 11” x 11” album cover. Visuals as stories that would change 60’s art forever, words used as pictures; metaphors long alive with meaning are infused with an electric jolt when brought to new life by Donovan.

Fine Art Magazine spoke with Donovan and Sid from Maurer’s home in Atlanta. Friends since meeting in Clive Davis’ office at CBS in 1966, they completed each others sentences, lending insight as to how deep and easy the artistic rapport is between them. The cascading ribbon of ideas flashed as they spoke. For an instant as I listened I saw the evolution of their art as process; how it manifested in the album packaging as a visual concept unfolding allowing the route—the continuance of the

Fine Art Magazine • Spring 2022 • 16 33 • Fine Art Magazine • Spring 2012

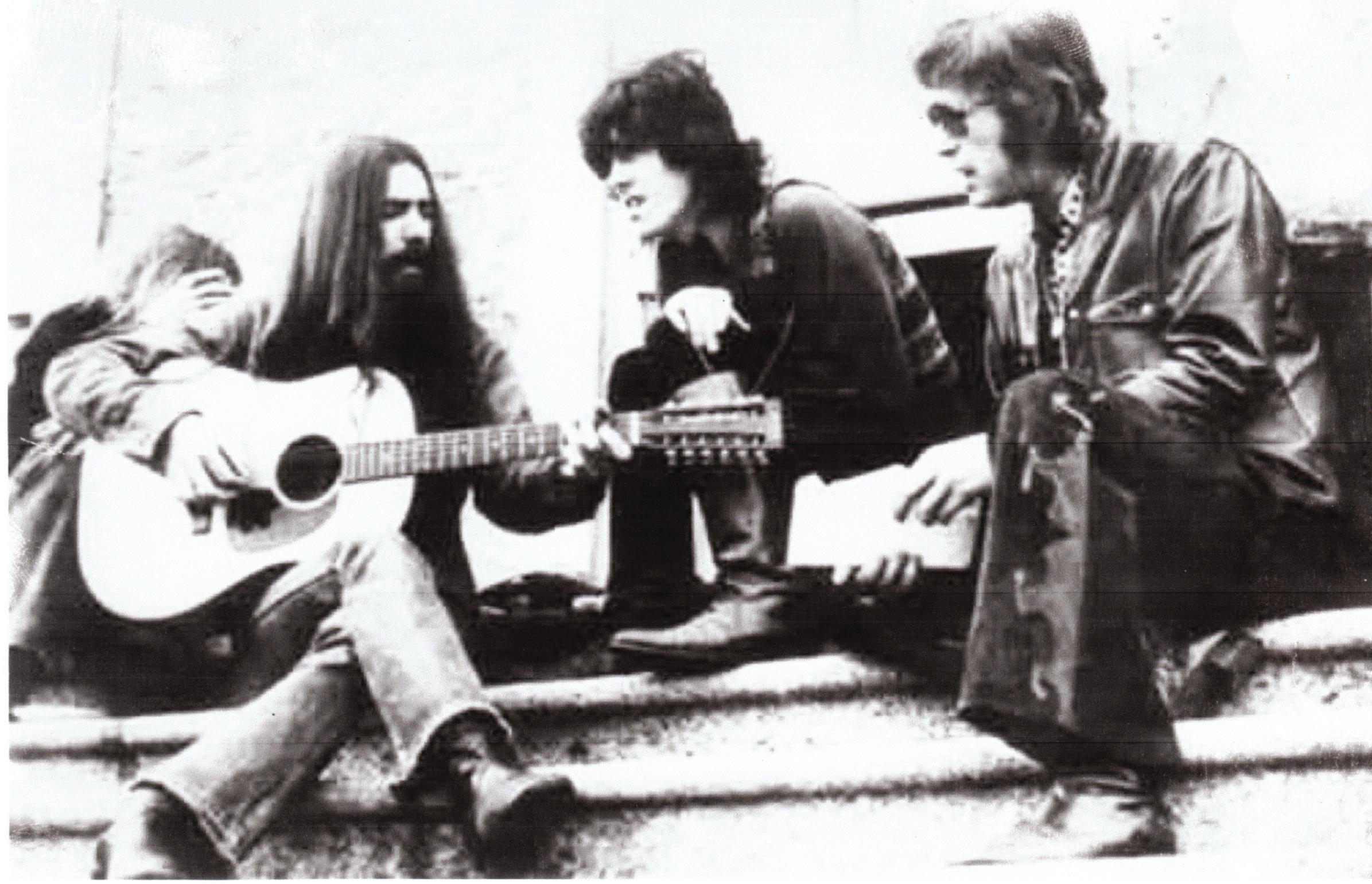

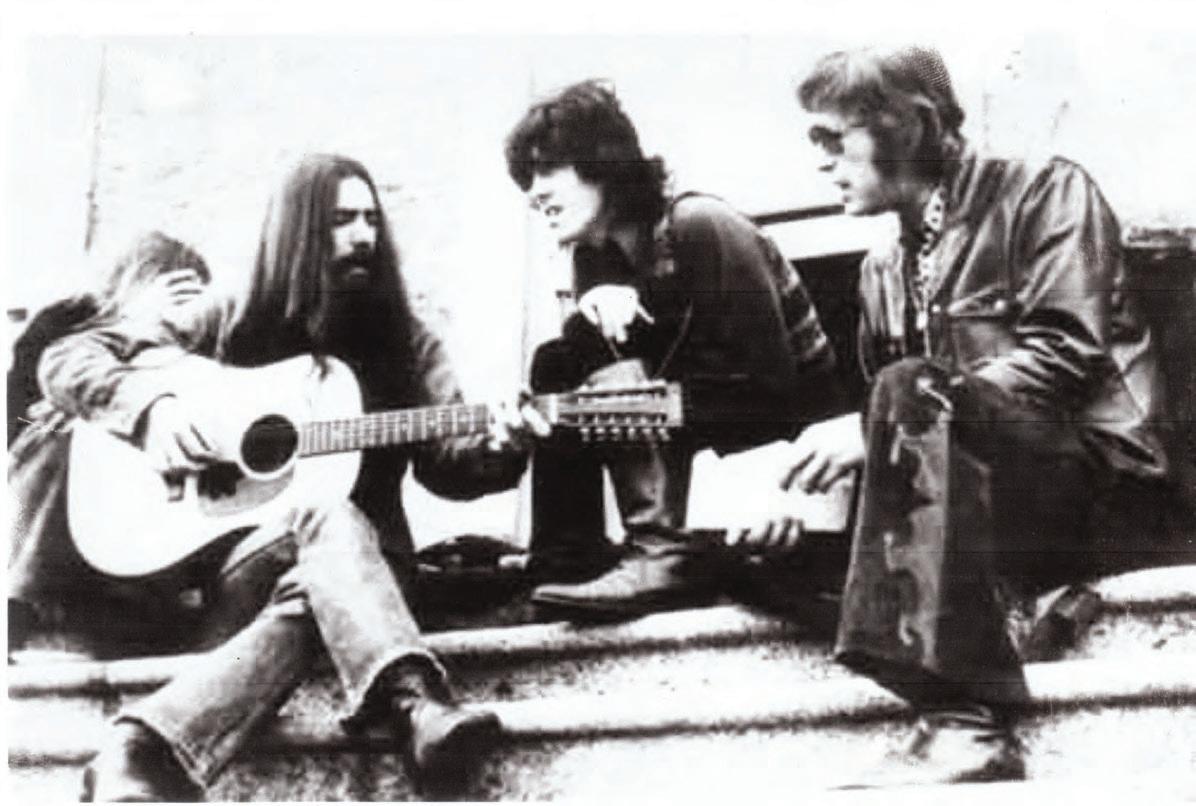

George Harrison on the twelve string with Donovan and the artist Sid Maurer at Donovan’s castle in Ireland; wonder what tune they’re singing?

Donovan and Sid Maurer, 1968

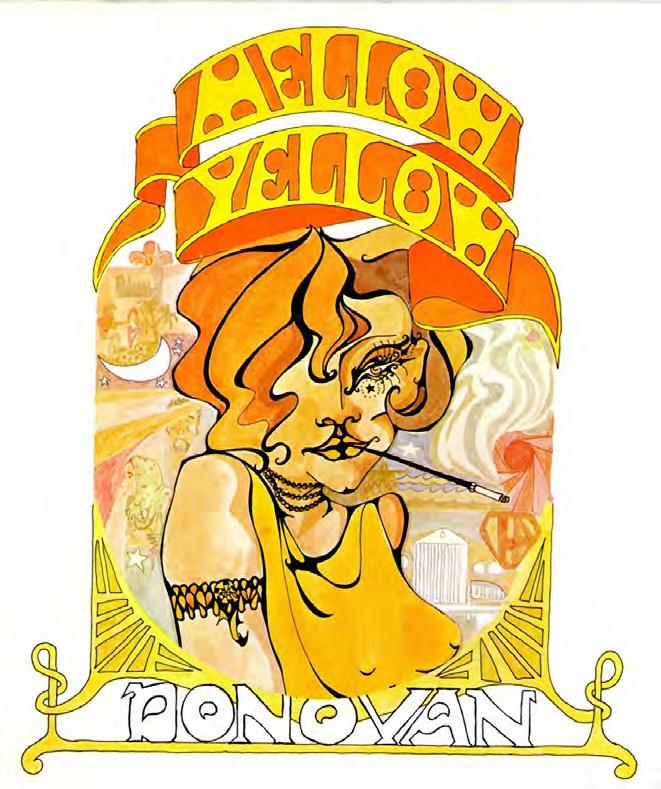

story telling—to be seen. Each described how they collaborated on the albums that showcased both of their formidable gifts: Sunshine Superman, Mellow Yellow, Hurdy Gurdy Man and Barabajagal provided a vehicle for the multi-dimensional impressions that Donovan envisioned and with the help and encouragement of Maurer was able to convey.

“I was under contract to CBS/Epic to create all their album covers when they signed a young man named Donovan to the label,” said Sidney. “They invited me to come up and say hello. They called him Mr. Donovan and it was just the beginning of long hair. He was wearing a white Hungarian wedding gown down to the floor. I thought I was talking to Jesus…no shoes, just barefoot in a robe in Black Rock and all the girls in the offices were gaga. It was quite a thing. He and I struck up a friendship when I said, ‘Let’s get out of here and go over to my studio.’ I rolled a couple so we could relax and we spent the next few days working on the first of his album covers for Epic - Sunshine Superman.”

Here Donovan picks up the story. “I am an artist myself and I wanted my covers to be visual just as I was making my appearance on stage visual to illustrate my lyrics. I was a bit ahead of the scene. Nobody really cared or had done this before. At most there was a photo of the band or the artist and ‘Let’s get that album out as soon as possible.’ I wanted Sunshine Superman to be Art Nouveau, Pre-Raphaelite because my songs were so romantic. Sid said to Clive ‘This boy’s right, you’ve got to do it.’ Clive went along and Sid became my champion.

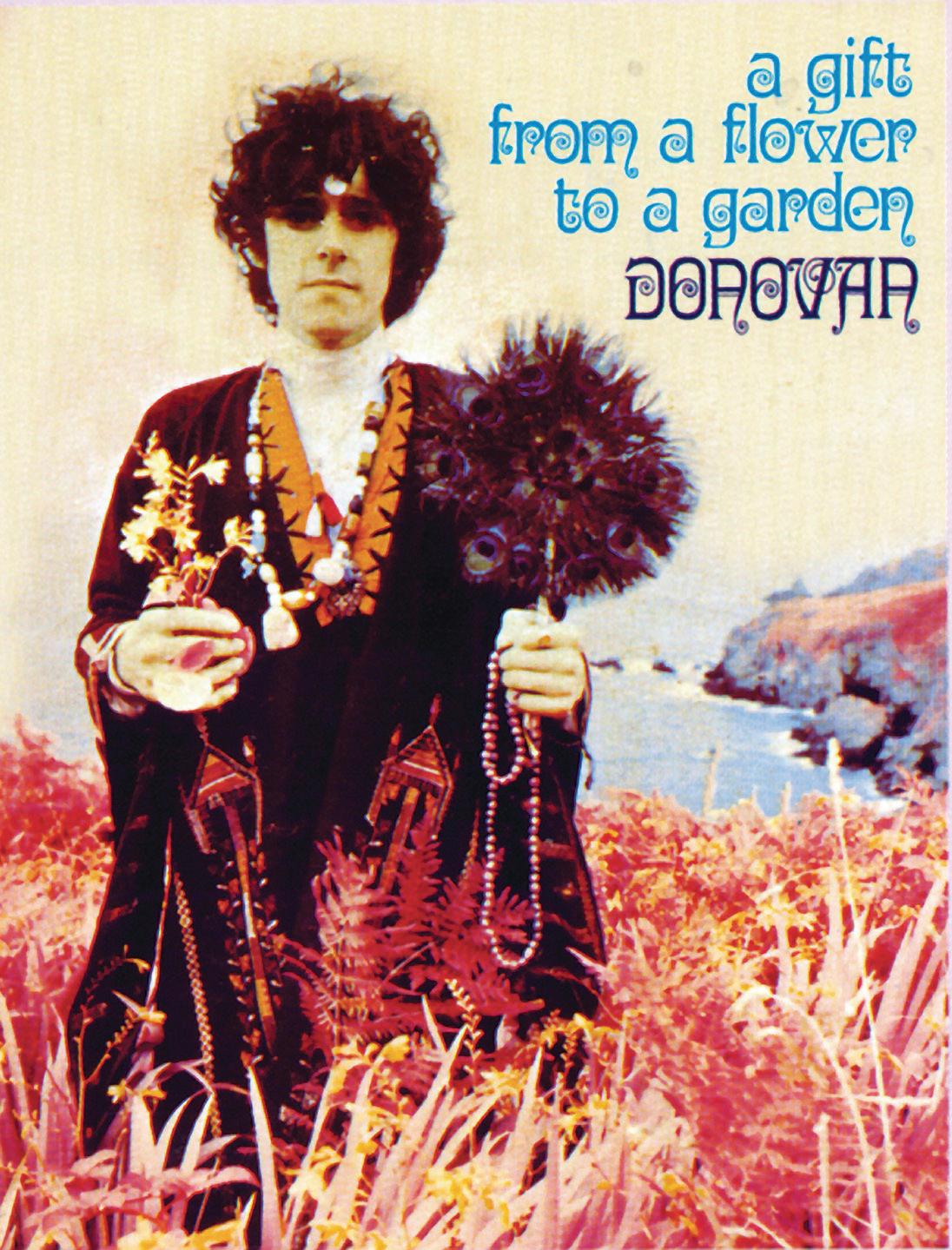

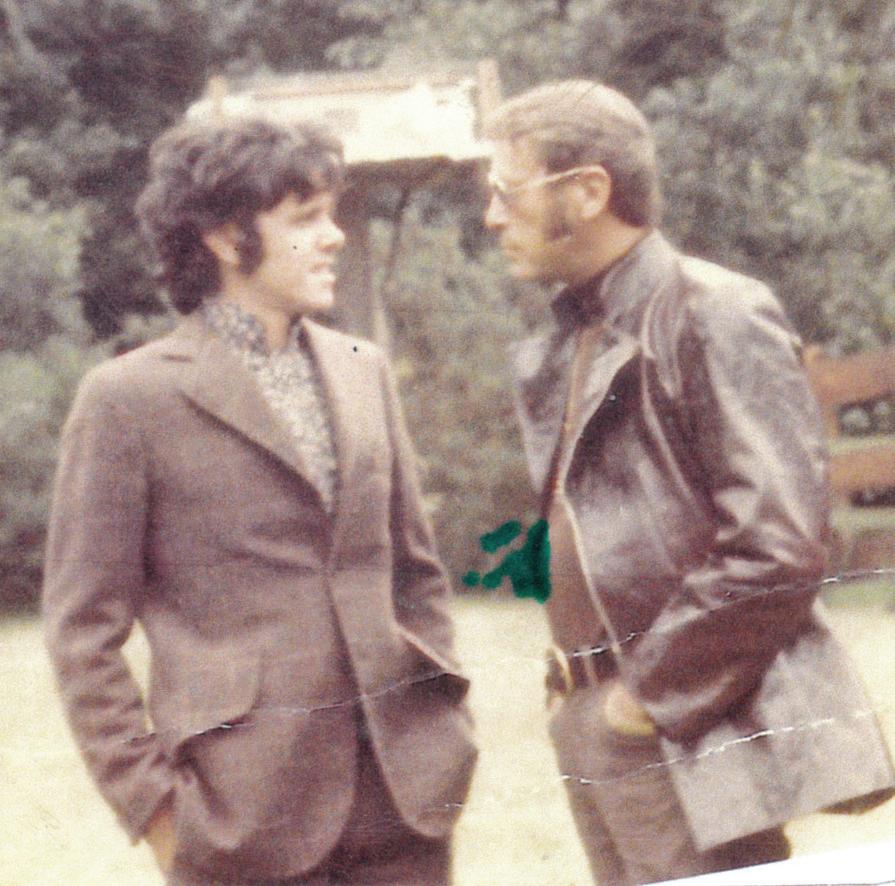

“The first album was really why I was nominated. That’s the one that initiated the psychedelic revolution.” Sid continues: “A year later, I’m sitting in the office and get a call from England. ‘What are you doing? Why don’t you come over this weekend? We’ll do a few things.’ Donovan had a cottage in a small suburb of London. It was painted all lavender in the woods and on the roof was a large white dove. This is where Don lived. He and I spent the entire weekend working on a project that became kind of history: the first boxed set that was ever done in rock and roll: A Gift From A Flower To A Garden.”

Back in New York, Davis was reluctant. Donovan recalls the conversation. “A box? This is impossible we can’t do this. This is gonna cost a lot of money. It’s fine art paper, individual sheets, in a box! No pop singer gets a box! They are for classical and jazz.’ I said, I want one. I actually had to pay out of my royalties or it would never have been done. Clive said ‘we’ll release the two albums on their own

17 • Fine Art Magazine • Spring 2022 34 • Fine Art Magazine • Spring 2012 Copyright © 2012 Donovan Disc Archive & Barabajagal LLC. www.barabajagal.com www.donovan.ie

On Donovan’s yacht, Greece, 1971

One of Donovan’s Sapphongraphs, with Sid Maurer

Special edition of Fine Art Magazine features Sid Maurer

before Christmas and after Christmas we’ll release it as the box.’” Sid recalled, “Either of them didn’t reach #100 on the charts and the box set went gold almost instantly I said, Clive - you should have got that box set out before Christmas. I knew what I was doing with marketing from art school.”

The upshoot is that Donovan owns all the original art and is now making it available worldwide through Museum Masters International which also has a history in music. “In 1996,” said Museum Masters President Marilyn Goldberg, “ We did Elvis/ Warhol Hall of Fame anniversary products and editions with the Elvis Estate and Andy Warhol Foundation. Now we will be licensing the Donovan/Sid Maurer collection honoring Donovan’s Hall of Fame induction.”

These artful album covers ushered in an era of big ideas and changing cultural attitudes expanding the nuance of the message, fueling the cultural revolution. Donovan credits Maurer for opening the doorway for him as a musician to use the art studio as a colleague. Sidney’s expertise, vast professional background and generous explanation of how the machinations of printing and art prep worked made the magic happen, changing art and style through innovation. Maurer noted that the cover art played a major role in focusing attention on sales as well as conveying a musical vision

Fine Art Magazine • Spring 2022 • 18

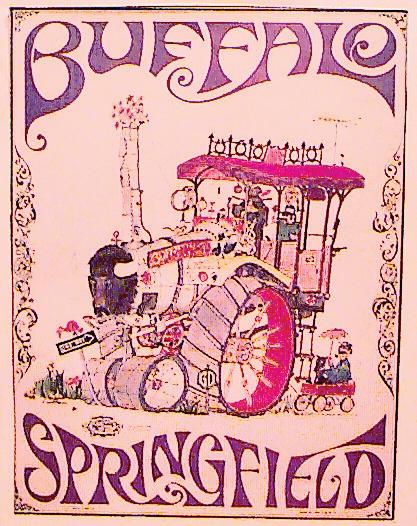

“BEATNIKS OUT TO MAKE IT RICH”

The first British folk troubadour who truly captured the imaginations of early Beatles-era fans on both sides of the Atlantic, Donovan Leitch made the transition from a scruffy blue-jeaned busker into a brocaded hippie traveler on Trans Love Airways. As a folkie on the road with Gypsy Dave, Donovan became a Dylan-esque visual presence on the BBC’s Ready Steady Go! starting in 1964, and released several classics: “Catch The Wind,” “Colours,”

Buffy Ste.-Marie’s “Universal Soldier,” “To Try For The Sun” and more. That changed in 1966, as he came under the production arm of UK hitmaker Mickie Most, and was signed by Clive Davis to Epic Records in the states. Donovan ignited the psychedelic revolution virtually single-handedly when the iconic single “Sunshine Superman” was released that summer of ’66 (and the LP of the same name, with “Season Of The Witch”). His heady fusion of folk, blues and jazz expanded to include Indian music and the TM (transcendental meditation) movement. Donovan was at the center of the Beatles’ fabled pilgrimage to the Maharishi’s ashram in early ’68 (where, it is said, he taught guitar finger-picking techniques to John Lennon and Paul McCartney). Donovan’s final Top 40 hit with Most was “Goo Goo Barabajagal (Love Is Hot)” in the summer ’69, backed by the Jeff Beck Group. In the ’70s and ’80s, Donovan continued to record and tour sporadically, including songs for Franco Zeffirelli’s Brother Sun, Sister Moon (finally issued in 2004). During the 1990s, Rick Rubin (after working with Johnny Cash) produced Donovan’s Sutras. The 2008 documentary film, Sunshine Superman: The Journey Of Donovan is an essential overview of his career. –ROCK AND ROLL HALL OF FAME

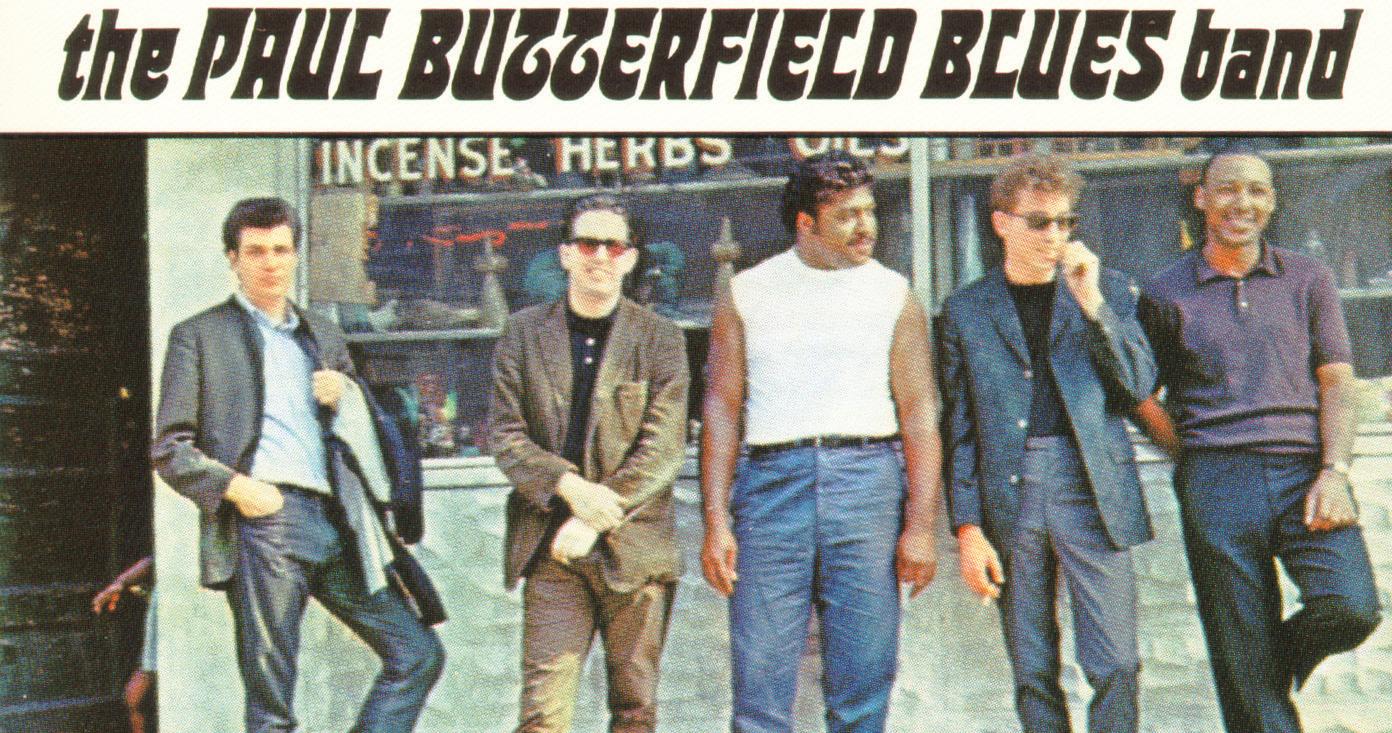

“MUST BE THE SEASON OF THE WITCH”

The day of the scheduled Donovan interview, in true Steve Jobs “iTunes is prophetic” mode, what comes on shuffle but the Al Kooper Birthday concert at BB King’s with Jimmy Vivino, John Simon and even Harvey Brooks from SuperSession for a live rendition of Season of the Witch. I cued up all the versions of that cut in my library and let them run and run. Here’s Harvey doing his bass solo live, the one he did on Mike Bloomfield’s sole career gold record (SuperSession), on which he only played on one side before cutting out. Steve Stills was called in by producer Kooper in a rush to occupy the expensive studio time and they came up with the wah-wah/Hammond B3-driven eleven minute classic version of Season of the Witch with some powerful Eddie Hoh drumming along with the aforementioned Brooks. Of this, the critics wrote “Stills showed the wah-wah pedal was more than a war toy.”

Donovan loved the Julie Driscoll/Brian Auger version best, but for posterity we have the “Live From the Filmore East Lost Concert” with Mike doing a classic guitar part on his only recorded version of the song as Kooper references Terry Reid. It’s a two chord vamp but people have made careers of it. That, in fact, is what Donovan said the Allman Brothers did with their extended versions of Mountain Jam which often, when coupled with Whippin’ Post, lasted the better part of an hour and featured some of

Duane’s most inspired guitar work. That Donovan’s songs would bring out the best in these high level musicians and the many others who have covered and accompanied him speaks volumes.

“We had some good old times, took some trips, not all psychedelic The whole process of creating art for the album covers I learned from Sid. He had a studio that was fully working and he was so proficient. I was able to talk his language after the first album. We didn’t just do it once, we went through two, three, four, five different things that he sent me by post.” A former art student, Donovan was fascinated with Sid Maurer’s tools of the trade in pre-computer, pre-fax, pre-Pantone and even pre-Fed Ex days. Things were slow and you needed very specific skills to get a complex color album jacket from color separations to rubylith masking ready for press. “Sid knew how to make sure that the yellow is really the right yellow. The wonder of albums was that you could actually see and touch them and put them on the wall as art. It’s great to celebrate the coming around of records again.”

“You carry life as a force in your music,” said Sid to his good friend. “You didn’t just write songs and sing them, you created a body of work and the excitement remains.”

19 • Fine Art Magazine • Spring 2022

Donovan portrait by Sidney Maurer, courtesy © 2012 Sid Maurer / Museum Masters International www.MuseumMasters.com

—VICTOR FORBES SunStorm • Spring 2012 • 33

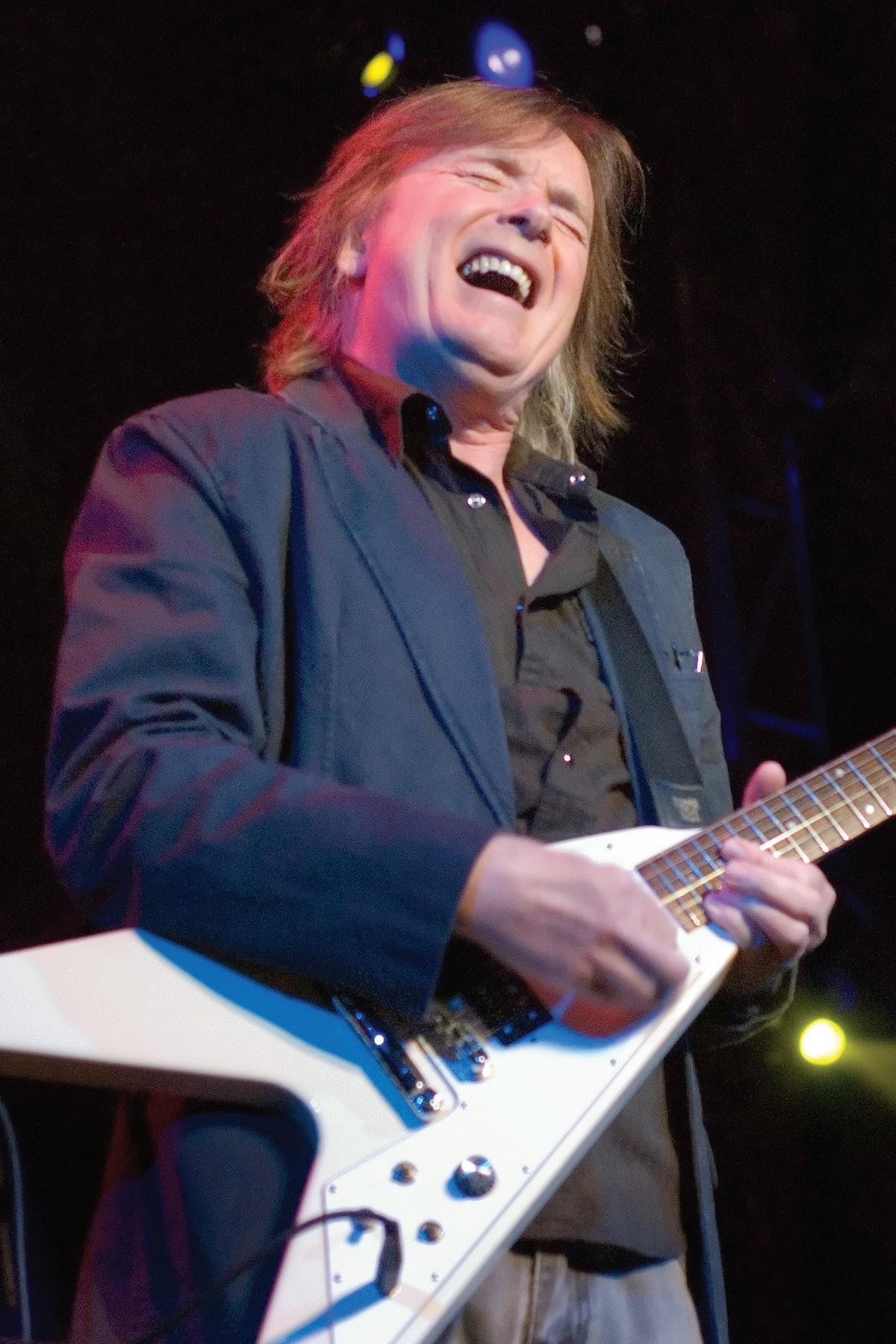

By proclamation of the governor of Texas, Ann Richards, September 3, 1993, was declared Freddie King Day, an honor reserved for Texas legends, such as Bob Wills and Buddy Holly. He was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2012, and placed 15th in Rolling Stone magazine’s list of the 100 greatest guitarists of all time.

By their own account, the late, great Freddie King influenced Eric Clapton, Duane Allman, Jeff Beck, Keith Richards and Stevie Ray Vaughan, among others. King was among many pioneering African-American blues musicians to embrace the British blues scene and tour its club circuit in the late 1960s. Robert Christgau credited King’s embrace of Britain with creating his renown as a pioneer of electric blues guitar. In Gary Graff’s Music Hound Rock (1996), the entry on King states: “Although his reputation rests with his guitar, King also sang with an underrated, powerful style. His lasting influence has insured Freddie King’s recognition as

“He is the psychedelic guru of folk poetry”

one of the great postwar blues masters.”

A ’super group’ was formed to perform in Freddie King’s honor, which included Derek Trucks, Billy Gibbons, Dusty Hill, and Joe Bonamassa. King was being inducted into the Hall of Fame just before Donovan, and the band for King shared the backstage dressing room with Donovan, his wife Linda, and myself. Derek and Billy truly enjoyed meeting Donovan and a good time was had by all.

This is John Mellancamp’s Donovan induction speech:

“I got my first Donovan record in 1965. I was in the 7th grade and back then, we waited for every record and I waited for every album to come out so that I could learn to play those songs. I wasn’t just listening to Donovan, I was living Donovan. I was stealing all the s--- from Donovan. Other artists, and you know who you guys are, call that being inspired. But I was inspired by his beautiful melodies, his lyrical content, his arrangements

Fine Art Magazine • Spring 2022 • 20

Linda Leitch, ZZ TOPS’ Billy Gibbons, Donovan, backstage at Donovan’s Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction, 2012. Photos by Chris Murrau

was

and the overall presentation of his material.

I am going to now read from the liner notes of this album: Less than a year ago, the British Recording Industry reached a sort of floating period between the wild rampage of Liverpool and the sound shifting gears into a new trend. It was one of those indecisive moments when the followers and the opportunists -- and you know who you are -- tumbled all over each other as record buyers and began to look around for something new. They looked all about and soon they were attracted to a young lad with a sensitive face, jeans, a denim jacket, a miner’s cap and a touch of northern dialect from Scotland in his speech, tempered by roamings throughout the British Isles. This lad was Donovan, an 18-year-old singer from Glasgow, who brought a new kind of music that was almost old as the hills. Donovan was the simple, direct, sincere music of a folk artist. He blew his harmonica and preached his poetic words to all that would listen.

Man’, ‘Mellow Yellow’, ‘Atlantis’, ‘Wear Your Love Like Heaven’, ‘Riki Tiki Tavi’, ‘Lalena’, ‘To Susan On The West Coast Waiting’. And those are just the songs that were on the radio. Think of all the undiscovered songs that are on these albums that nobody has ever heard or paid attention to. Beautiful songwriting like nobody else.

So really, I guess what it all boils down to in the long run is that you can do whatever you want and look however you want, but if you don’t have the songs, it don’t matter.

Let me see if I can think of a couple of songs that Donovan might have written. I think I could come up with a couple: ‘Season of the Witch’, ‘Catch The Wind’, ‘Sunshine Superman’, ‘Hurdy Gurdy

I think it’s only fair that we mention that this was all done by one kid from Scotland, right? One guy wrote all these songs. He was also part of one of the greatest collaborations maybe in music history and that was the marriage of Donovan to Mickie Most. Together, those guys created a folk-rock sound that invaded the world’s radio. In 1965 and 1966, every kid that was sitting in their bedroom heard that sound and they style that this guy brought to the music industry and to the youth along with the Rolling Stones, leading the way for the youth culture (...crowd noise...) the world had not seen anything like it before and haven’t seen anything like it since.