CRACKING THE KUBE

SOLVING THE MYSTERIES OF STANLEY KUBRICK THROUGH ARCHIVAL RESEARCH

First edition: December 2024

Revised: September 2025

Copyright © 2024 Filippo Ulivieri

Typeset and layout: Filippo Ulivieri

Cover design: Gianni Denaro

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews.

6. THE JEALOUSY MOVIE

At the heart of this chapter lies a seemingly simple question—which, in truth, is not simple at all: why was Kubrick so attached to Arthur Schnitzler’s Traumnovelle, the literary source of Eyes Wide Shut?

This essay exemplifies the hybrid approach discussed in Chapter 1, combining archival research with textual analysis. It uses documents, eyewitness reports, and historical facts to sustain the interpretative work. Beyond methodology, I invite you to think of this chapter as a psychoanalytic session with Kubrick, where we journey back in time to bring to the surface what lies beneath his work on Eyes Wide Shut.

“INFIDELITY TROUBLED HIM DEEPLY.”

A JOURNEY TO THE ROOT OF EYES WIDE SHUT

Among the mixed reviews earned by Eyes Wide Shut, those that spotlighted the film’s personal nature stood out. Jack Kroll noted, “The film clearly meant a great deal to Kubrick,” while Amy Taubin remarked, “What’s most fascinating is how openly personal it is.” Philip French observed that “Kubrick had a strong personal commitment” to the film’s theme, and Michael Wilmington added, “You can sense an intimate connection between director and subject.” Jonathan Rosenbaum described it as “personal filmmaking,” and Angie Errigo noted the film was “imbued with Kubrick’s uncomfortable personal vision.” Bob Graham summed it up as the director’s “most heartfelt film.” However, none of these critics 1 elaborated on their opinion.

Jack Kroll, “Dreaming with Eyes Wide Shut”, Newsweek, 18 Jul 1999, https://bit.ly/3TC 1tupw; Amy Taubin, “Imperfect love”, Film Comment 35.5, Sep/Oct 1999, p. 33; Philip French, “Keep your shirt on…”, The Observer Review, 12 Jul 1999, p. 7, https://bit.ly/ 3TC7DOU; Michael Wilmington, “The sexy, scary, stylish Eyes Wide Shut is Stanley Kubrick’s final masterpiece”, Chicago Tribune, 16 Jul 1999, https://bit.ly/3zsPbRN; Jonathan Rosenbaum, “In dreams begin responsibilities”, Chicago Reader, 23 Jul 1999, https://bit.ly/3U0GUvJ; Angie Errigo, “New films: Eyes Wide Shut’, Empire #123, Sep 1999, p. 13; Bob Graham, “An eyeful: Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut is an absorbing tale of jealousy and obsessiveness in a marriage”, San Francisco Chronicle, 16 Jul 1999, https:// bit.ly/4gBdH3S.

Kubrick’s family members shared the sentiment. “It’s a very personal film,” said Jan Harlan, Kubrick’s executive producer and brother-inlaw; “It’s Stanley’s film and every word in it is his.” Kubrick “felt very 2 strongly about this subject and theme,” emphasized his daughter Anya: Eyes Wide Shut is “a very personal statement from my father.”3

Okay—there’s a consensus that Eyes Wide Shut is Kubrick’s “most personal” film, even though no real clue was given to understand why 4 it is so. But what does that even mean, exactly?

Is Eyes Wide Shut more personal in the sense that it is a much-cherished project? A film in which Kubrick put his heart and soul, as his daughter Anya seemed to suggest? Or, is it personal because it is more revealing, as if it were an autobiographical film in disguise? A few anecdotes from the production seem to support this view: for example, Kubrick’s wife Christiane once revealed that the Harfords’ apartment in the film is a replica of their Central Park West property from the early 1960s. May 5be, as Philip French proposed, “because Eyes Wide Shut completes the Kubrick cycle, it has a special importance.” Coming after a series of films that investigate past, present and future states of existence, Kubrick told a contemporary, intimist story with Eyes Wide Shut: “In what is truly the riskiest film of his career,” wrote Janet Maslin, “the man who could create a whole new universe with each undertaking chose the bedroom as the last frontier.” Kroll seemed to agree when he explained 6 that the film is personal because it “deals with the most personal of subjects, sex.”7

Critics sometimes share an often-misguided tendency to consider the last work as the culmination of an artist’s career, revealing his or her preoccupations more clearly. I believe that all works of art are the product of the artist’s sensibility, personality, and experiences, regardless of when in their life span they were produced. In other words, all works are personal to serious artists. Likewise, it is easy, perhaps obvious, to say that a marital story must draw from an artist’s personal backJosh Young, “An eye-opener for everyone concerned”, The Sunday Telegraph, 10 Jul 1999.

2 Richard Schickel, “All eyes on them”, Time #154.1, 5 Jul 1999, pp. 65-70.

3 Kroll, op.cit.

4 Andrew Biswell, “No longer Eyes Wide Shut”, The Scotsman, 5 Oct 2002, p. 3.

5 Janet Maslin, “‘Eyes Wide Shut’: Danger and desire in a haunting bedroom odyssey”,

7

6 The New York Times, 16 Jul 1999, https://bit.ly/3zvgWt5. French, op.cit.; Kroll, op.cit

6. Eyes Wide Shut ground. This may even be truer for a film with a psychoanalytical subtext, derived from a literary work imbued with the burgeoning analysis of the unconscious mind. Indeed, there is hardly anything original in Kubrick’s selection of subject matter, which has been widely treated in all arts throughout human history. Frederic Raphael, co-screenwriter of Eyes Wide Shut, concurs: “Whether or not adultery was a particularly interesting topic to him is really not very interesting, or surprising. It’s been a topic of western fiction since… forever. I don’t believe that Kubrick was much more, or less, obsessed with infidelity than a host of writers who have dwelt on the theme. See Tony Tanner’s Adultery in the Novel.”8

Yes and no. I do see something special in Kubrick’s selection of Arthur Schnitzler’s Traumnovelle as material for a film, if only because this particular story occupied Kubrick’s imagination for the longest time, developing an obsessional quality that was unprecedented even by Kubrick’s standards. Eyes Wide Shut is in fact the outcome of a very long process that involved several radically diflerent attempts at adapting the novella.

To begin with, the film’s laborious gestation aflected its materialization. Distributed in July 1999, Eyes Wide Shut entered pre-production five years before, in the summer of 1994. Shooting the film took a notoriously long time—I calculated 294 days, spread over 579 calendar days, including 19 for re-shooting with a diflerent actress. It is slightly over one year and seven months, the longest for any Kubrick film. Post-production lasted an additional nine months, brought to a halt only by Kubrick’s death. Nor was the adaptation a straightforward job: Raphael was the writer whose input convinced Kubrick Traumnovelle could indeed become a film, and the two worked on the screenplay from November 1994 to June 1996. But this didn’t stop Kubrick from considering other options. He did so with Sara Maitland at the end of 1995 and Michael Herr in mid-1996, both unsuccessfully. Before hiring Raphael, Ku-

Author’s interview with Frederic Raphael, 4 May 2020.

ONE: Kubrick Unknown

brick had also worked on Traumnovelle with Candia McWilliam for a few weeks in July 1994.9

But if we take a look at the director’s career, as illustrated in Chapter 2, we can see how Traumnovelle pervaded the entirety of his working life: it is the one story to which Kubrick immediately returned every time he finished another film. Looking back, we can see how Traumnovelle was always there, on his mind.

Eyes Wide Shut can itself be regarded as a return to Schnitzler after the failures of the three main projects under development in the early ‘90s: All the King’s Men, A.I., and Aryan Papers

A decade earlier, when actor and consultant Lee Ermey had a car accident, causing a hiatus in the shooting of Full Metal Jacket, interest in Traumnovelle promptly rose again. In April 1986, Kubrick contacted Clockwork Orange author Anthony Burgess to help him crack the mysteries of Schnitzler’s ending, but the writer did not reply. Undaunted, 10 when Full Metal Jacket was completed, Kubrick solicited opinions on Traumnovelle from several readers he had hired to write reports on books that seemed promising source material. This survey didn’t produce any idea that unblocked Kubrick, though. He also tried to include a political, conspiratorial subtext in the adaptation, again in vain.11

During and after the making of The Shining, between 1977 and 1983, Kubrick discussed Traumnovelle with writers Diane Johnson and Michael Herr, considered comedy playwright Neil Simon as a possible writing partner, questioned John le Carré about how to approach the story, wrote to Arthur Schnitzler’s grandson Peter, asked his assistant Anthony Frewin to draft a scene, and had satirical writer Terry Sou-

Frederic Raphael, Eyes Wide Open: A memoir of Stanley Kubrick, New York: Ballantine 9 Books, 1999; author’s interview with Sara Maitland, 23 Aug 2008; Michael Herr, Kubrick, New York: Grove Press, 2000, pp. 17-18; author’s interview with Candia McWilliam, 21 Nov 2007.

Kubrick, letter to Anthony Burgess, 23 Apr 1986, SK/17/11/7, Stanley Kubrick Archive, 10 University Archives and Special Collections Centre, London College of Communication, University of the Arts London, UK (SKA).

James Fenwick, Stanley Kubrick Produces, New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 11 2020, p. 195.

6. Eyes Wide Shut thern send a few tentative dialogue sequences. In these years, Kubrick 12 oscillated between a comic take on the story and an erotic thriller, but neither approach seemed to work.13

In 1976, following the release of Barry Lyndon, Kubrick asked Gaby Blau, his lawyer’s daughter, to write a concept for the story; despite appreciating her eflort, Kubrick didn’t use it. He then sent the book to 14 Anthony Burgess and started a written conversation, only to interrupt it without getting the needed closure. Kubrick also brieffy contemplated 15 an art-house approach to the story, with Woody Allen playing the lead.16

Before that, after A Clockwork Orange, he committed to the project for the first time, with an announcement from Warner Bros. in April 1971.17 This attempt failed because Kubrick had problems with the last third of the narrative.18

And before that, in May 1968, a month after the release of 2001: A Space Odyssey, Kubrick enquired about buying the rights to the story, with the help of journalist and future screenwriter Jay Cocks. This marks the first documented evidence of the material being selected for a film.19

Although this recurrence is shared by other unrealized projects— most notably Napoleon which was set in motion in July 1967 and still considered in 1987, and a film about Nazi Germany which occupied Kubrick repeatedly from the early 1970s—Traumnovelle is indeed special in the sense that it is the longest-running and most constantly active project in Kubrick’s career. Despite all his uncertainties about tone, subtexts and structure, Traumnovelle was the single literary property for

Author’s interview with Diane Johnson, 12 May 2017; Kubrick, “Shining SK editing

12 notes to Jack + Lloyd book 1”, 17 Jul 1979, SK/15/4/1, SKA; author’s interview with John le Carré, 3 Sep 2008; Anthony Frewin, letter to Stanley Kubrick, 29 Oct 1981, uncatalogued, SKA; Terry Southern, letter to Stanley, 1 Jul 1983, SK/17/6/7, SKA. Fenwick, op.cit. pp. 194-5.

14

13 Ibid., p. 194.

15 Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin, USA. Author’s interview with Jan Harlan, 16 Sep 2016.

Kubrick, letter to Anthony Burgess, 15 Oct 1976, Anthony Burgess Papers, 83.1, Harry

16 Anon., “Kubrick will make WB’s ‘Traumnovelle’”, Daily Variety, 20 Apr 1971, p. 1.

17 Michel Ciment, Kubrick: The definitive edition, London: Faber and Faber, 2001, p. 269.

18 Kubrick, filing card, in Alison Castle (ed.), The Stanley Kubrick Archives, Cologne: Ta

19schen, 2005, p. 482.

ONE: Kubrick Unknown which Kubrick never ceased to renew his option and which he proposed to virtually every writer he contacted.20

In actuality, Kubrick’s attraction to it predates 1968. While we still can’t pinpoint when exactly he first read Traumnovelle, we do know that the book was amongst his belongings in 1963, and that he was appa 21rently made aware of it in 1959, when Kirk Douglas’s psychiatrist recommended it to him. In any case, Kubrick’s interest in Austrian litera 22ture, and specifically in Schnitzler, around the late 1950s is confirmed by three facts: in January 1959, Kubrick wrote to cartoonist Jules Feifler and asked him to develop “a modern love story … much in the same mood and feeling as some of Arthur Schnitzler’s works.” A few months later, 23 he met with Schnitzler’s nephew during the filming of Spartacus. Fi 24nally, Kubrick’s then producing partner, James B. Harris, told me that they considered adapting another story by Schnitzler, “The Death of a Bachelor,” in 1956, around the time they developed an adaptation of Stefan Zweig’s Burning Secret 25

My study of Kubrick’s unmade films reveals another intriguing point. In addition to “The Death of a Bachelor” and Burning Secret, several other projects that Kubrick developed deal with love, marriage and sexual relationships; however, once Kubrick decided on Traumnovelle in 1968, he stopped considering alternatives. Traumnovelle apparently was for him the best story to explore everything that occurs between men and women, or at least his favorite.

In fact, Traumnovelle must have been so crucial to Kubrick’s understanding of male-female dynamics that he used it as a blueprint during the scriptwriting phase in diflerent projects. For example, a certain Schnitzlerian air permeated the Napoleon script, where Kubrick had Napoleon watch an orgy from a distance without feeling brave

Cf. Filippo Ulivieri, “Waiting for a miracle: a survey of Stanley Kubrick’s unrealized

20 projects”, Cinergie: Il cinema e le altre arti #12 , Dec 2017, pp. 95-115, https://bit.ly/4ehlQsY.

21

“London - miscellaneous”, SK/11/9/77, SKA.

22 2012, p. 195.

Kirk Douglas, I am Spartacus! Making a film, breaking the blacklist, New York: Open Road,

Kubrick, letter to Jules Feiffer, 2 Jan 1959, General Correspondence, 1951-1993, Box 8,

23 Jules Feiffer Papers, Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Washington, DC, USA.

24

Peter A. Schnitzler, letter to Kubrick, 27 May 1959, SK/9/4/1/2, SKA.

Author’s interview with James B. Harris, 4 May 2010. 25

6. Eyes Wide Shut

enough to participate, much like Fridolin, the main character in Traumnovelle . Additionally, it can be argued that the romantic relationships between Napoleon and Josephine, and between Josephine and Barras, have a certain Reigen ffavor to them. Kubrick also stated in 26 an interview that Napoleon’s “sex life was worthy of Arthur Schnitzler” and marked a passage in J. Christopher Harold’s The Mind 27 of Napoleon, deeming an encounter between Napoleon and an unknown woman to be “very Schnitzler.”28

Traumnovelle was also discussed with Diane Johnson as an inspiration to shape the marital relationship between Jack and Wendy Torrance in The Shining. The script that Johnson originally wrote portrayed 29 Wendy as a more rounded character, “so that the kind of deteriorating relationship between the married couple was pretty much explicit and acted out.” Johnson said to me that Traumnovelle was a source of inspiration for such deterioration: “It was all happening kind of at the same time: the script [of The Shining] was being written, Traumnovelle was being read, and we talked about aspects of it too. [Schnitzler’s story was used] as a kind of subtext.” At a certain point, the script even featured 30 an orgy in the Overlook Hotel ballroom, blending Traumnovelle and “The Masque of the Red Death” by Edgar Allan Poe, a source that is quoted in Stephen King’s novel.31

It appears that an adaptation of this Schnitzler story was not only constantly on the verge of happening but also so fundamental that it pollinated the projects which took priority. There does seem to be something special about Traumnovelle, and hence about Eyes Wide Shut. But what is it? And why was Kubrick so fond of it?

Answering this is not easy. In fact, virtually all the writers Kubrick approached for the adaptation wondered the same thing, not really li-

26 The greatest movie never made, Cologne: Taschen, 2011.

Kubrick, “Napoleon. A screenplay”, in Alison Castle (ed.), Stanley Kubrick’s Napoleon:

28

27 Castle (ed.), Napoleon, cit. p. 54.

Joseph Gelmis, The Film Director as Superstar, New York: Doubleday & Co., 1970, p. 387.

29 Peter Krämer, Richard Daniels (eds.), Stanley Kubrick New Perspectives, London: Black Dog Publishing, 2015, p. 285.

Catriona McAvoy, “Creating The Shining: Looking beyond the myths”, in Tatjana Ljujić,

30

Author’s interview with Johnson, cit.

Catriona McAvoy, “The uncanny, the gothic and the loner: Intertextuality in the adapta

31tion process of The Shining”, Adaptation #8.3, Dec 2015.

Kubrick Unknown

king Traumnovelle themselves. Frederic Raphael thought it was “kinda maddening … it’s good, but it’s not that good [and] very dated.” John le Carré saw it as “an incomplete erotic novel” that worked as a mysterious piece on paper but “did not withstand the naturalistic treatment” of cinema. Sara Maitland bluntly told Kubrick that she found it “really boring.” Diane Johnson expressed a similar opinion: the story didn’t grab her; she “thought it was clumsily Freudian” and, when she talked about it with Michael Herr, she remembers they both “did not get it, [they] both wondered what the appeal of this story was for Kubrick.”32

The exception is Candia McWilliam, who had no problem with Kubrick’s choice of material and understood its potential immediately: “Of course, because it was all about the unknowability of those we love. … The story at that point was very clearly about the mutual manipulation of jealousy. Which is torture, it’s what we can do to one another, in the most intimately painful way. … Who hasn’t felt atrocious jealousy, and atrocious remorse, and who hasn’t in the end felt that fidelity is absolutely crucial, especially after it’s too late and one’s broken it. And it’s heartbreaking.” When I spoke to her, McWilliam admitted that she, too, felt that there was something special about the project: “A very great deal about that film was personal, and I never wanted to be so impertinent as to ask why.”33

A clue to understanding why Traumnovelle resonated so deeply with Kubrick comes from the film’s press release: it is a single sentence, and the only statement Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman were allowed to make before its premiere—Eyes Wide Shut was marketed as “a story of jealousy and sexual obsession.”

McWilliam’s insight underscores jealousy as pivotal here. One reason Traumnovelle held such enduring appeal for Kubrick was that it finally oflered him the opportunity to make a ‘jealousy movie.’

Kubrick’s fascination with the theme is illuminated by Albert Brooks, who received an unexpected call from Kubrick after his film Modern Romance’s release in 1981. “How did you make this movie?” Kubrick asked Brooks; “This is a brilliant movie, the movie I’ve always

Raphael, Eyes, cit. pp. 23-5; author’s interviews with le Carrè, Maitland, Johnson, cit.

32 Author’s interview with McWilliam, cit.; Paul Joyce, The Last Movie: Stanley Kubrick and 33 “Eyes Wide Shut”, Lucida Productions, 1999.

6. Eyes Wide Shut wanted to make about jealousy.” Modern Romance, a wordy, neurotic 34 comedy of self-deprecating humor, alerted Kubrick at a time when he contemplated a comic adaptation of Traumnovelle. Brooks’s film touches exactly on jealousy and sexual obsession, echoing elements found in Eyes Wide Shut, such as the protagonist’s introspective soliloquy in a car and his nighttime encounters with couples happily in love.

Albert Brooks wasn’t the only director Kubrick had his eye on. Eyes Wide Shut is replete with references to films by directors who eflectively tackled the ‘jealousy movie’ challenge before Kubrick.

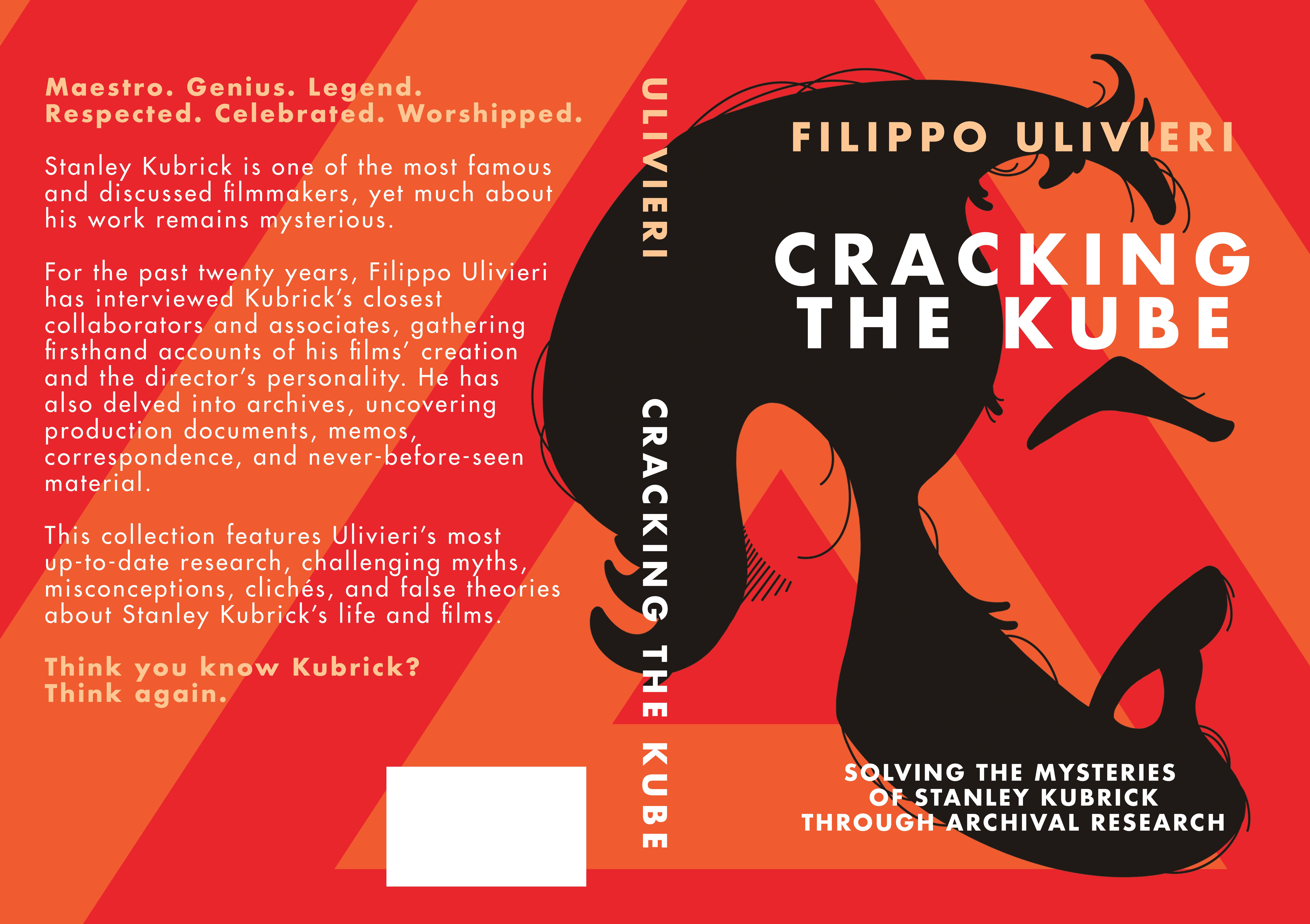

A clear example is Eric Rohmer’s 1972 film Love in the Afternoon, which essentially shares the same storyline as Eyes Wide Shut: a man tempted with infidelity ultimately returns to his wife. Kubrick drew inspiration from several scenes in it. The film begins with the main character gathering his personal items and turning ofl the lights before leaving his apartment—a sequence closely mirrored in Eyes Wide Shut, and which is absent from Raphael’s scripts. Additionally, both films’ opening scenes include casual glimpses of bathroom intimacy among married couples, followed by scenes of the husbands lost in thought inside taxi cabs. Notably, Love in the Afternoon concludes with a reconciliation of sorts, where the wife explicitly invites her husband to make love to her, a scene reminiscent of the dénouement of Eyes Wide Shut—which was again not authored by Raphael. It’s worth mentioning that the couples in both films are played by real-life married actors.

First frame: looking for something before going out. Mitchell Fink, “Battling Leroys look to reheat the romance”, Daily News, 12 Aug 1999, p. 34 17.

Who is she, really?

ONE: Kubrick Unknown

Watching his daughter in her bedroom.

Lost in thoughts in a taxi cab.

Last frame: reconciliation takes place in the bedroom.

Several films referenced in Eyes Wide Shut were directed by individuals whom Kubrick knew personally.

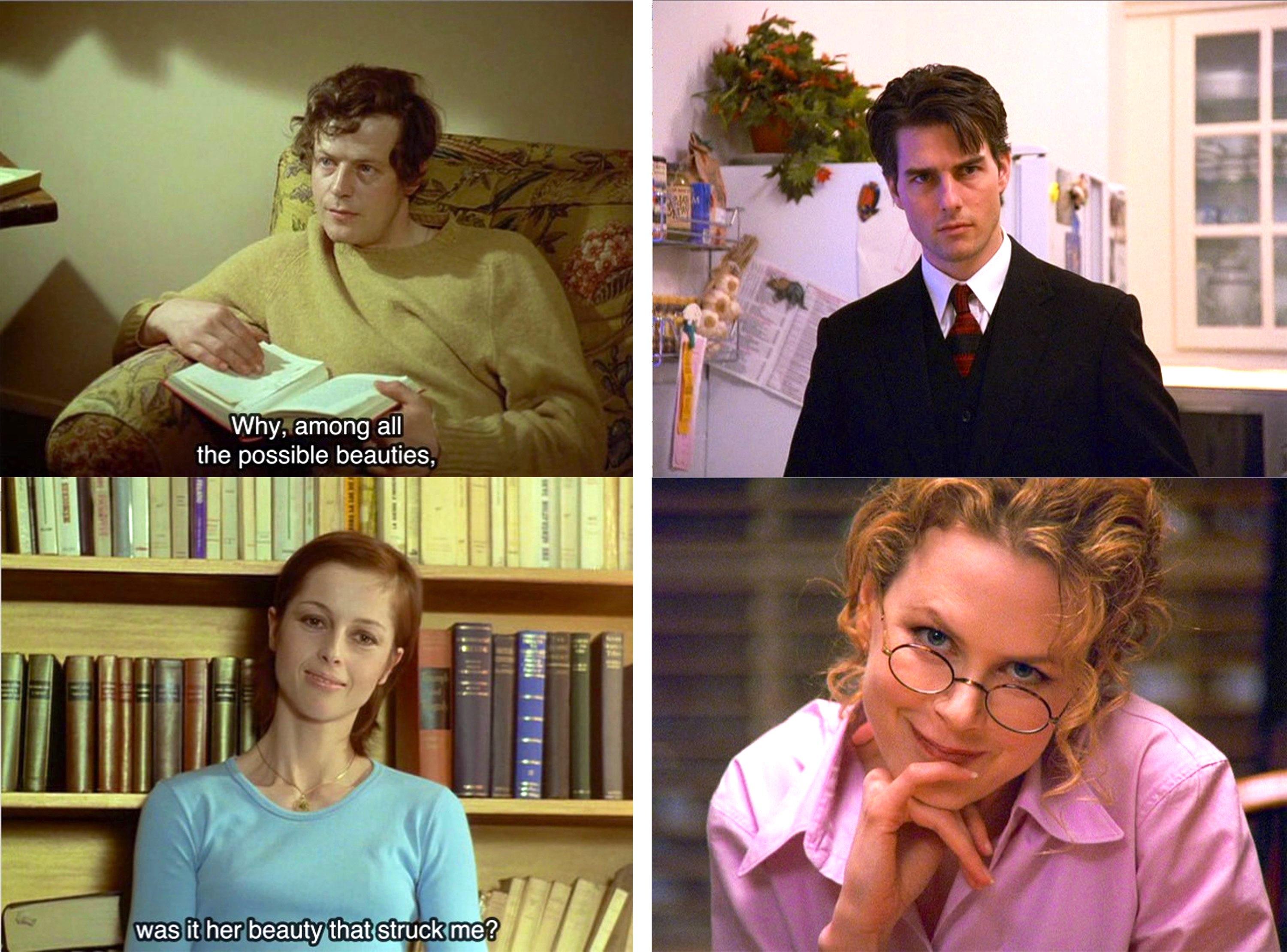

It has been observed previously that the scene featuring the old charmer includes two lines of dialogue seemingly borrowed from James Cameron’s True Lies: “Do you like the period?” asks Juno (Tia Carrere); “I adore it” replies Harry (Arnold Schwarzenegger).

Records in possession of Kubrick’s assistant Emilio D’Alessandro show that Kubrick rented a 35mm print of True Lies on 5 August 1994, coinciding with the beginning of Eyes Wide Shut’s pre-production. D’Alessandro recalls Kubrick summoning Cameron to discuss the film and keeping a copy of True Lies’ screenplay in his oflice. While 35 speculation surrounds any inffuence on the film’s title—True Lies and Eyes Wide Shut both embody oxymorons—documents in the Archive con fi rm that Kubrick altered the dialogue during rehearsal to incorporate this exchange. After all, what is True Lies if not the James 36 Cameron take on the ‘jealousy movie’?

35 International Pictures, 5 Aug 1994, Emilio D’Alessandro’s belongings. “Script 1996”, SK/17/1/8, SKA. 36

Author’s interview with Emilio D’Alessandro, 21 Nov 2006; receipt for True Lies, United

6. Eyes Wide Shut

Seduction through art.

Another scene that Kubrick altered to nod toward a director friend is Alice’s phone call to Bill. Initially set in the bedroom, it was reshot nine months later and relocated to the kitchen, where Alice is depicted watching Paul Mazursky’s 1973 film Blume in Love on TV. Mazursky’s film, 37 promoted with the tag line “A love story for guys who cheat on their wives,” proves to be a clever choice for the scene, considering that cheating on his wife is exactly what Bill is about to do on the other end of the line. Like Modern Romance, Blume in Love is a variation on the onagain-ofl-again type of relationship and an exploration on the theme of jealousy—all its subplots revolve around it. Ultimately it is, like Eyes Wide Shut, a statement on true love, something that both Mazursky and Kubrick seem to say is only attainable within the confines of marriage.

Mazursky wasn’t a random choice for Kubrick; they were friends during Kubrick’s Greenwich Village years, and Mazursky even played Pvt. Sidney in Fear and Desire. Indeed, another of Mazursky’s films proved an even more direct inffuence on Eyes Wide Shut Next Stop, Greenwich Village, an autobiographical work from 1976 in which Mazursky gave dramatic form to his experiences as an aspiring actor in the 1950s. Essential to the narrative is the protagonist’s love story with a girl and her betrayal with one of his friends. While there are several visual connections between the two films, what stands out is the moment

“Slate by Slate Frame Clips”, SK/17/4/3/4, SKA.

6. Eyes Wide Shut

when the couple attempts to reconcile after her confession. Kubrick instructed Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman to emulate the position and gestures of the couple in Mazursky’s film. The visual homage is particularly poignant, linking two couples grappling with betrayal—whether real or imagined—and seeking resolution.

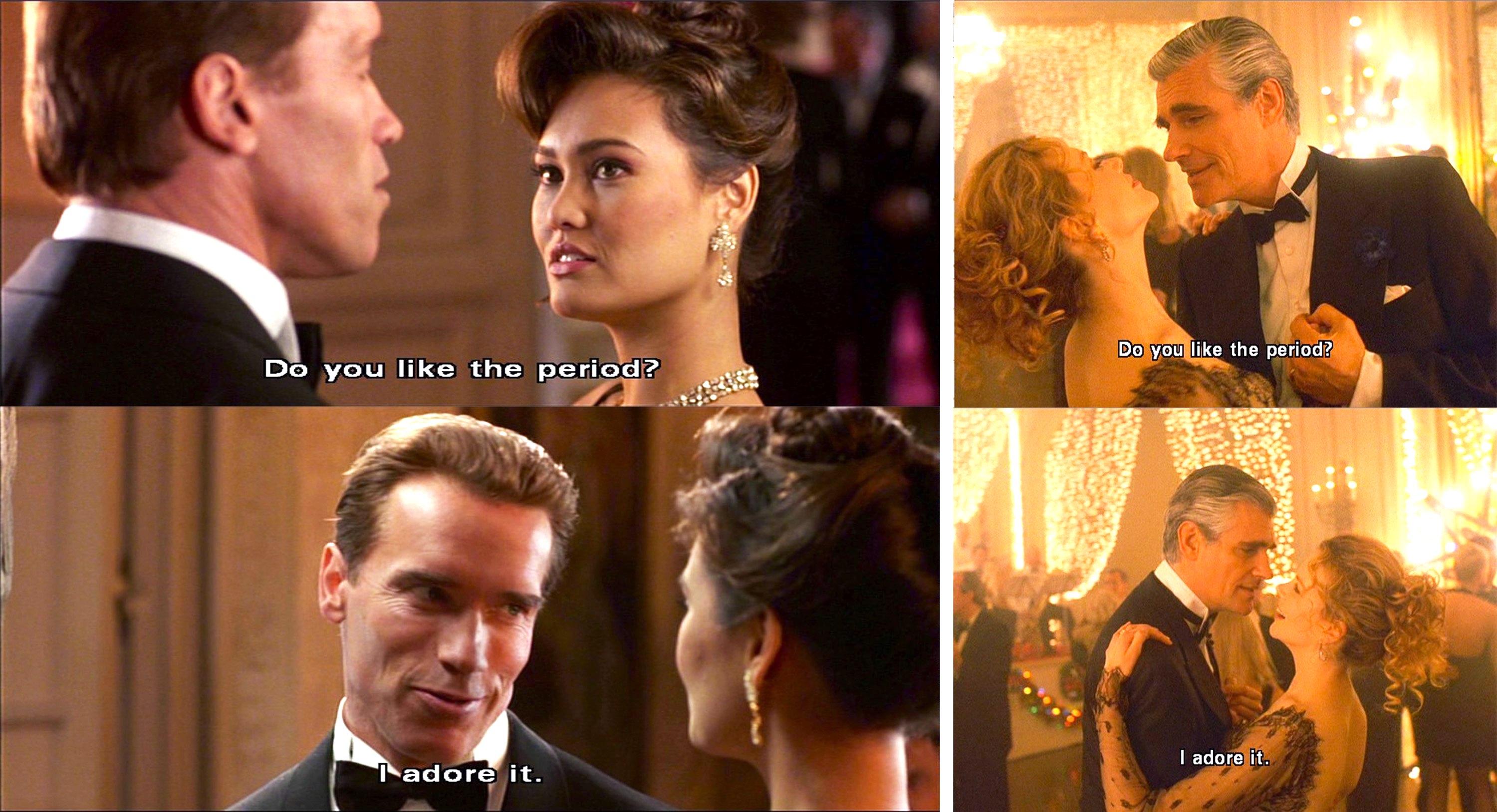

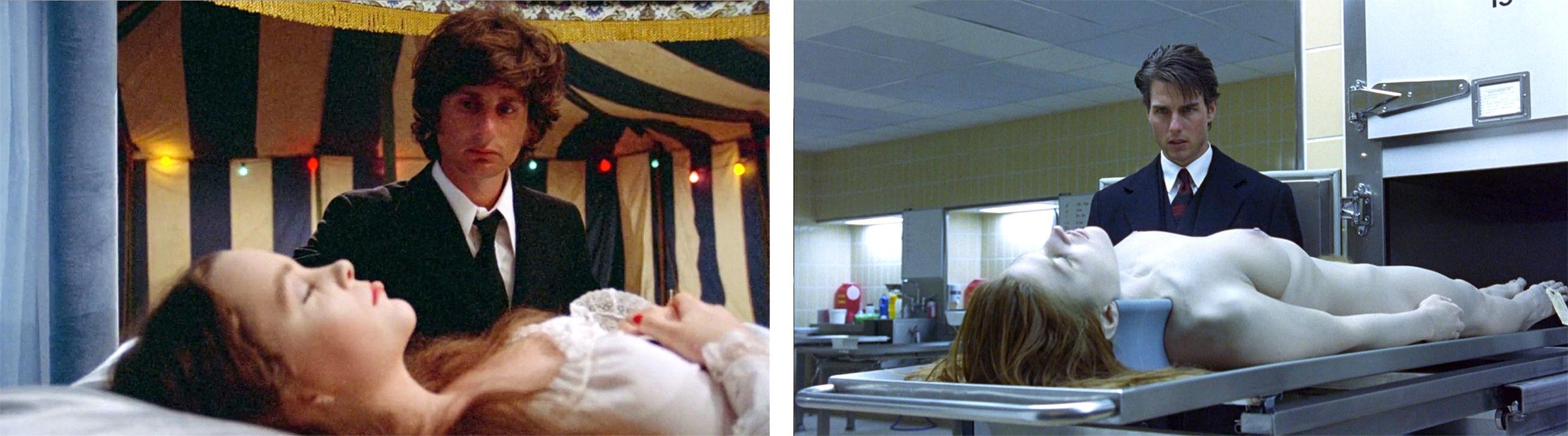

Naturally, Kubrick’s best friend and former business partner, James B. Harris, holds a place of honor with Some Call it Loving, a film Harris wrote, directed, and produced in 1973 by adapting a short story by John Collier. A personal film to Harris as much as Eyes Wide Shut is to Kubrick—“You don’t often get a chance, in a lifetime, to make a film that personal,” he once commented Some Call it Loving is an exploration 38 of sexual fantasies and erotic role-playing, telling the story of a man who awakens a sleeping beauty yet finds no happiness.

Kubrick directly referenced Some Call it Loving in the Sonata Café scene in Eyes Wide Shut. The staging, blocking, and camera movements closely mirror those of the jazz club scene in Harris’s film. Earlier in Eyes Wide Shut , during the Christmas party scene, the music band leader announces: “The band’s gonna take a short break now, and we’ll be back in ten minutes.” This line, again added during rehearsals,39 echoes a closing line from Some Call it Loving: “We’re going to take a short break; we’ll be right back.” One might also argue that the warm, glowing cinematography of Harris’s film inffuenced Kubrick and his cinematographer, as did the dream castle setting which served as a model for an equally oneiric location in Eyes Wide Shut. Even some costume choices appear to have been borrowed from Harris’s film.

39

38 “Script 1996”, cit.

Anon., “Cable column: a conversation with James B. Harris”, Galaxy, Mar 1982, p. 43.

Heartbroken embraces.

Some call it Eyes Wide Shut.

ONE: Kubrick Unknown Jazz sessions.

6. Eyes Wide Shut

We’ll discuss Some Call it Loving some more in a moment. For now, I think it’s clear that Traumnovelle was the story that enabled Kubrick to make his own jealousy movie.

However, jealousy is not merely a focal point in Eyes Wide Shut but an undercurrent that reoccurs throughout Kubrick’s career, with Bill Harford representing its most overt manifestation. In Barry Lyndon, Redmond Barry experiences jealousy toward his cousin Nora when she ffirts with Captain Quinn, while Lady Lyndon becomes jealous of Barry’s infidelities later on. In Lolita, Charlotte Haze is jealous of Humbert Humbert, who is in turn madly jealous of Lolita. The theme of jealousy also surfaces in The Killing, where George Peatty is suspicious of his wife Sherry. Finally, in Killer’s Kiss, Vincent Rapallo is perhaps the most jealous character in Kubrick’s filmography, to the point of becoming a violent criminal. Even in The Shining, Kubrick contemplated injecting jealousy into the narrative, considering scenes where Wendy admits ffeeting thoughts of infidelity, and Jack harbors jealous fantasies. “Could a scene start like this and turn into something horrible?”—he wrote in one of his notebooks. There is virtually no film in which the 40 topic of jealousy has not been touched in some way or another. This theme extends to the Napoleon script, where Napoleon and Josephine grapple with mutual jealousy. Kubrick’s exploration of anthropology for 2001: A Space Odyssey revealed to him the primal fear of discovering oflspring not biologically his own—the origin of jealousy in the animal kingdom. Jealousy appears in less obvious places too, like in A.I. 41 where the little robot-boy David feels envious of Monica’s love for her biological son.

The closer we get to Kubrick’s early projects, the more jealousy becomes prominent and connected with marital infidelity. Adultery is central to the plot of both Burning Secret and “The Death of a Bachelor,” which is essentially a psychological study of how three husbands react to the news that their wives all cheated on them with the same man. Moreover, several plot and character sketches that Kubrick jotted down

McAvoy, “The uncanny”, cit.; McAvoy, “An interview with Diane Johnson”, in Danel

40 Olson (ed.), The Shining: Studies in the horror film, Lakewood: Centipede Press, 2015, p. 548.

41 Positif #464, Oct 1999, p. 43, author’s translation.

Yann Tobin, Laurent Vachaud, “Brève rencontre: Christiane Kubrick et Jan Harlan”,

Kubrick Unknown

when he was young deal precisely with dysfunctional marriage, jealousy, and adultery. For example, a treatment titled Jealousy portrays a wealthy New York business manager who suspects his wife is having an aflair. With a growing sense of paranoia, he begins to have visions of his wife’s infidelity and contemplates revenge by sleeping with a stranger, an act he ultimately cannot execute. Another archived folder, titled The Perfect Marriage, contains a document with a series of philosophical musings on the ‘marriage story,’ as Kubrick termed it, which is inevitably entwined with cheating, echoing Schnitzler’s insights into the intricate psychology of men and women. It is revealing that various recurring 42 narrative and visual motifs in these writings—such as a wife’s confession, sexy dreams, haunting fantasies of betrayal, and so on—are closely reminiscent of Schnitzler’s own plot devices and imagery.

An incomplete screenplay, titled The Married Man, following an unfaithful husband who cannot stand his wife any longer and plots against her with an unsuspecting friend, helps us bring into focus another aspect of jealousy. An excerpt shows it as something that the husband would like his wife to feel about him: marriage is “like drowning in a sea of feathers,” Kubrick wrote, “Sinking deeper and deeper into the soft, suflocating depths of habit and familiarity. If she’d only fight back. Get mad or jealous, even just once.” Fifty years later, Kubrick would 43 have this very feeling uttered by a woman character: “And why haven’t you ever been jealous about me?” Alice cries out in front of her husband in Eyes Wide Shut.

Why was Kubrick so taken by stories about jealousy and betrayal? Or, to put it diflerently, how personal is indeed the story told in Eyes Wide Shut?

Much speculation has already been made on the topic, but I aim to take a diflerent approach. As is my practice, I seek primary sources. In this case, I interviewed the composer Gerald Fried, one of Kubrick’s closest friends during his formative years in Greenwich Village. His insights into Kubrick’s perspectives on romantic relationships turned out to be quite significant. Here’s what he shared with me: “I have a memory of him being amazed and even appalled at the infidelities of

Fenwick, op.cit. pp. 75-76.

Dalya Alberge, “Newly found Stanley Kubrick script ideas focus on marital strife”, The

Guardian, 12 Jul 2019, https://bit.ly/3XQtOTV.

6. Eyes Wide Shut

the people we knew around us, and the fact that so many people, for sexual advantage, would make up lies and stories. I think he was appalled and fascinated by the length people would go to, perhaps especially men, to achieve some sexual advantage at the risk of truth, and honesty, and even decency. I think that he was a little nervous about the facility with which people can betray one another, or betray a marriage, for the sake of a little… biological action or aggrandizement. I think that— there’s no doubt about it—that was a preoccupation of Stanley’s: how we could deal with people knowing that there are sub-currents they won’t speak about, but that they are present in most people. It’s a little scary to know that people we see every day, and trust, and love, are capable of this kind of psychological bifurcation.”44

This is exactly what Tom Cruise said during the promotional interviews for Eyes Wide Shut: “Stanley had understood and was very clear on this: people often have a split personality, just as they passed from darkness to light, and vice versa, permanently.” This aligns with 45 Candia McWilliam’s observation that the film she began to write for Kubrick had to explore the unknowability of those we love.

Fried elaborated further: “It was as if Stanley was appalled by the concept of someone looking you right in the eye, without blinking, and lying about a sexual aflair. That, to him, was a horror story.”

A Kubrickian horror story.

ONE: Kubrick Unknown

“And it troubled him deeply, infidelity. Like, it could happen to him, too.”

Indeed, it appears it did.

During those years, Kubrick was married to Ruth Sobotka, a Viennese-born ballerina he met in late 1946. They began living together around 1952 or 1953 and married in January 1955. Sobotka was erudite, multi 46lingual, passionate about the performing arts and part of the New York avant-garde. She contributed significantly to Kubrick’s education. Some scholars even speculate she introduced him to Austrian literature, including Traumnovelle. Their marriage faced challenges stemming from confficting careers ambitions and, according to some sources, Kubrick’s own feelings of jealousy toward her.47

The breaking point came in the summer of 1956 when Kubrick received a letter from an anonymous person alleging that Sobotka was being unfaithful while she was touring Europe with the New York City Ballet. Fried informed me that Sobotka denied the letter’s validity, a 48 sentiment echoed by many mutual friends. Fried attempted reconciliation, but Kubrick refused to listen and ended the marriage. According to Fried, Kubrick had been deeply anxious about Sobotka’s global tours, haunted by the possibility of her betrayal. “I think Stanley found out all about infidelity, and the difliculties, and the requirements of marriage, and then, when he understood that he too was subject to those kinds of feelings, I think he was very troubled and didn’t like it.”

Numerous commentators have discussed Sobotka’s role in the genesis of Eyes Wide Shut and Kubrick’s jealousy toward her—quite often in wild and salacious ways. I only want to emphasize that, much like 49 how scholars draw parallels between Arthur Schnitzler’s unrestrained sexuality and his stories of jealousy and promiscuity, I think it is possi-

46 and film, Bristol: Intellect, 2013, p. 184; Vincent LoBrutto, Stanley Kubrick: A biography, New York: Donald I. Fine, 1997, p. 101.

Philippe Mather, Stanley Kubrick at Look Magazine: Authorship and genre in photojournalism

Dalia Karpel, “The real Stanley Kubrick”, Haaretz, 3 Nov 2015, https://bit.ly/4dib30f;

47 Sharon Churcher, Peter Sheridan, “Did Kubrick drive his second wife to suicide and is that why he made this haunting film of sexual obsession?”, The Mail on Sunday, 18 Jul 1999, p. 64.

John Baxter, Stanley Kubrick: A biography, New York: Carroll & Graf, 1997, p. 91; Chur

48cher, Sheridan, op.cit.; Cf. author’s interviews with Fried, cit. Cf. Baxter, op.cit., p. 91; Churcher, Sheridan, op.cit 49

6. Eyes Wide Shut ble to interpret events in Kubrick’s life as inffuencing his aflinity for those narratives. At the very least, it should be noted that, by looking at the chronology of Kubrick’s projects, it is evident how the stories about jealousy and marital strife cluster around 1956, the year in which Kubrick’s marriage with Sobotka began to unravel. Whether driven by personal or artistic motivations, or a blend of both, undoubtedly there is something about Schnitzler that captivated Kubrick’s imagination.

Because Kubrick passed away before giving any interviews for Eyes Wide Shut, quotes from him regarding Schnitzler are scarce. However, his enduring interest in Schnitzler’s stories prompted occasional discussions about him in preceding years. In 1960, for instance, he said: “It’s diflicult to find any writer who understood the human soul more truly and who had a more profound insight into the way people think, act, and really are.” Perhaps the most insightful quote capturing Kubrick’s 50 perspective on Schnitzler came in 1972, when he commented on Traumnovelle: “The theme of the story is that people have a desire for stability, security, habit and order in their lives, and at the same time they would like to escape, to seek adventures, to be destructive.” This is precisely 51 what he was trying to express in those three early unfinished scripts. All those protagonists live the unending conffict between stability and adventure: some engage in multiple aflairs while yearning for a stable future, while others feel trapped in monogamous family life and seek thrills outside their relationship.

Given the importance of this duality to Kubrick’s worldview, I queried Gerry Fried about it. Among those within the Greenwich Village circle, Howard Sackler, the co-writer of Fear and Desire and Killer’s Kiss most epitomized the ‘adventure’ part of the equation. According to Fried, Sackler seemed primarily concerned with “getting kicks out of life,” often at the expense of friends. As a matter of fact, the fictional betrayal in Next Stop: Greenwich Village was inspired by Mazursky’s reallife experience, when his then-girlfriend betrayed him with Sackler. In the film, a fictional version of Sackler is portrayed by Christopher Walken. Fried explained: “I think there was an element, maybe in me as

50 16-22.

Robert Emmett Ginna, “The odyssey begins”, Entertainment Weekly, 9 Apr 1999, pp.

51 1972, p. 29, author’s translation.

Michel Ciment, “Entretien avec Stanley Kubrick sur ‘A Clockwork Orange’”, Positif, Jun

Kubrick Unknown

well as in Stanley, of kind of admiration that Howard Sackler would lead this kind of life and take pleasure in destroying marriages, to show his masculine power… And I remember we were talking about it, and I got this feeling that it was not 100% disapproval of Howard Sackler’s behavior. It was disgusting and we felt like punching him out, but there may have been an element of, My gosh, this fellow has a power that we don’t have.” There is a documented anecdote that supports Gerry’s recollections. According to Mazursky, Kubrick too made advances toward Mazursky’s future bride during his marriage to Toba Metz, his first wife.52

Anya Kubrick, when stating that Eyes Wide Shut reffects her father’s moral philosophy, added that the film’s central idea is that “we are all both good and evil, and if you think you have no evil in you, you’re not looking hard enough.” Through Eyes Wide Shut, Kubrick explored the 53 male psyche with the honesty and insight of someone who acknowledges he is not exempt from the themes he examines.

The pursuit for adventures aligns with other anecdotes from Kubrick’s life, such as his admiration for Kirk Douglas’s reputed sexual prowess and voracity during the shooting of Paths of Glory and Spartacus, where Douglas purportedly had an assistant arrange liaisons with women two or three times daily. Frederic Raphael perceptively noted, “Like Schnitzler’s hero, Kubrick was fascinated and appalled by things he witnessed but could not quite bring himself to do.” These situations 54 are quintessentially Schnitzlerian, testing the tension between yearning for a life filled with adventures and the inability to find the audacity to act; between recoiling from the callous behavior of those who betray their partners and yet being fascinated by the freedom and power associated with such actions.

It really is no surprise that Schnitzler’s stories struck a powerful chord in Kubrick. In a sense, it is almost beside the point to ponder why he chose Traumnovelle. One might argue it encapsulates the themes more profoundly than other stories or possesses a dreamlike quality that naturally appealed to Kubrick. Yet, as he once remarked, it would be “a bit like trying to explain why you fell in love with your wife: she’s

52 Schickel, op.cit 53 Raphael, op.cit., pp. 48, 111.

Paul Mazursky, Show Me the Magic, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1999, p. 19.

6. Eyes Wide Shut

intelligent, has brown eyes, a good figure. Have you really said anything?” Traumnovelle had something that appealed to Kubrick, to the 55 extent that it became the story he wished to live with for the rest of his life.

However, for those compelled to delve into the rationale behind selecting Traumnovelle, one might revisit Some Call it Loving, particularly a pivotal scene midway through the film where the awakened girl tells about what happens to her during her sleep. Her monologue unfolds as follows:

I don’t remember when I fell asleep, but it couldn’t have been too long after when I had a dream. It was more like a nightmare: a man, someone I’ve never seen before, was kissing me, I don’t know how he got there or anything, but he was kissing me and I couldn’t seem to do anything to stop him. Then he would stop and go away, and there’d be nothing, for a long time there’d be nothing. Then it would start again. Only in this dream lots of strange men would kiss me and touch me and I couldn’t stop them.

The resemblance to Alice Harford’s description of her own dream is striking:

He was kissing me. And then, then we were making love. Then there were these other people around us… hundreds of them, everywhere. Everyone was fucking. And then I… I was fucking other men. So many… I don’t know how many I was with.

Harris told me that he hadn’t read Traumnovelle at the time, so he couldn’t have drawn from Schnitzler to write this monologue. Nevertheless, in adapting Collier’s story Sleeping Beauty, Harris discarded everything but the core idea. In his hands, the story evolved from a satirical take on the romantic view of love intended by Colliers to be a study about the impossibility of reconciling sexual dreams with real life. In particular, Harris introduced a dream element to the film that is completely absent in the original story but central in Austrian literature. Under Harris’s direction, Sleeping Beauty became a Schnitzlerian type of story. Given their close professional and personal relationship, it’s not

Ciment, Kubrick, cit., p. 167. 55

Kubrick Unknown

surprising that Harris and Kubrick both viewed sex, love and relationships through the lens of Austrian intellectuals. Schnitzler, Zweig, and Freud educated them both on the inner workings of the psyche, our fantasies and fears.

Another rare quote by Kubrick on Traumnovelle proves insightful. He said the novelette “tries to equate the importance of sexual dreams and might-have-beens with reality.” The same can be said about Harris’s 56 film. In this regard, Eyes Wide Shut and Some Call it Loving are sibling works.

They are sibling works for another reason, I think. Harris gave shape to his own tendencies and fears in Some Call it Loving. The film was a way for him to acknowledge his inability to have a solid, faithful relationship because he indulged in his sexual fantasies: “I wanted to make the point that, if the girl is everything you wanted her to be and you still have a problem, the problem must rest within yourself. You can’t blame the girl for that, which John Collier did. If you have multiple relation 57ships in your life, if you keep moving on from one girl to another, as I had… Could there be something wrong with all the girls? It had to be something within myself that was causing these abortive relationships.”58 Even though Some Call it Loving is not autobiographical, the film’s hero can be seen as an oblique persona for Harris. Equally, it would be too much of a stretch to identify Bill Harford as an alter ego for Kubrick; nonetheless, Eyes Wide Shut is the film in which Kubrick expressed his own personal views on love and marriage.

If Harris unleashed the hunger for ‘adventures’ in Some Call it Loving—his protagonist’s story ends without any reconciliation—Kubrick focused on the ‘stability’ side of the equation in Eyes Wide Shut—Bill returns to his wife, and they both strive to make their marriage work. “The fact that he’s been married three times, I’d say pretty much says he’s marriage material,” Harris told me with a laugh; “Stanley was a man who believed in the sanctity of marriage.”59

56

Ibid., p. 156.

Author’s interview with Harris, 27 Jun 2014.

57 Nick Pinkerton, “Interview: James B. Harris (part one)”, Film Comment, 2 Apr 2015,

58 https://bit.ly/3ZwZC1e.

59

Author’s interview with Harris, 27 Jun 2014.

6. Eyes Wide Shut

Among all the stories by Schnitzler, Traumnovelle is one about a marriage that holds despite internal and external forces. Fridolin, and Bill Harford in Eyes Wide Shut, is a character caught between dreams and reality, navigating the opposite forces of order and disorder until he ultimately chooses to return to his wife, remain faithful, and restore stability, habit, security. In contrast, the hero in Harris’s film is similarly caught between dreams and reality, but opts to awaken the girl, and perpetually indulge in his fantasies.

The choice of source material and how they were adapted reffect Harris’s and Kubrick’s respective personalities and life experiences.

Marital infidelity was a deeply felt subject for Kubrick, one that he tried to bring to the screen throughout his entire life. The fear of what might lie beneath the surface of marriage is another taboo subject he explored in his films, each tackling an unspeakable, suppressed issue: the Jungian ‘Shadow’ and the allure of war in Full Metal Jacket, the vanity and transience of all human endeavors in Barry Lyndon, the horror within the family, and more. Like any artist, what he observed and experienced during his youth forged his sensibility. The same holds true for Mazursky and Harris, and the other filmmakers who made personal films.

When Kubrick encountered Arthur Schnitzler and his stories of inner conffict, he immediately recognized their caliber. Perhaps he even saw reffections of himself in those tales. As Diane Johnson told me, “Definitely I think that Fridolin spoke to Stanley in a powerful way, in a way that caused Stanley to stick with him for all those decades.” Screenwriter Jay Cocks, who assisted Kubrick in acquiring the rights to Traumno-

The two heroes in the face of temptation.

Kubrick Unknown

velle in 1968, may have been the most perceptive of all: “I think he found a soulmate there, in Schnitzler’s approach.”60

While testing a draft of this essay in its YouTube incarnation during one of the Meet-Up meetings of The Stanley Kubrick Appreciation Society, the chairman, Mark Lentz, said something that I believe is worth mentioning: “What really rang true to me is, if there’s one thing that we know about Kubrick is that he was obsessed with control. We can therefore assume he feared the loss of control the most. I think there’s nothing like jealousy to make you feel like you’re losing control. I feel like he felt that, with Ruth Sobotka.”

Frederic Raphael has a different opinion: “There was a dread of the female in [Kubrick], was there not? I don’t think [the film] has to do with his resentment of his supposedly adulterous second wife, or his wish for it. I think that the fear of women runs through the entirety of his work. I think that Kubrick’s horror of what women might mean, or might do, or might be doing, is what is expressed in Traumnovelle and what he made of it.” However, Raphael does believe—like Diane Johnson, Jay Cocks, and, well, myself—that Kubrick saw something of himself in Fridolin: “I suppose so. I mean, he would have to, to some extent, otherwise it just wouldn’t be interesting, would it?”61

On the topic of artists and their most personal films, I am reminded of something Sergio Leone said while presenting his film Once Upon a Time in America to the Italian press: “I say to everybody that it is my best film, and perhaps it is. Surely, I do think it is. But what I really mean to say by that is that Once Upon a Time in America is me.” According 62 to his family, Kubrick too believed Eyes Wide Shut was his best film, or, as he apparently said, “his greatest contribution to the art of cinema.” He could have said “Eyes Wide Shut is me” just as easily.

63

61

60 Author’s interview with Raphael, cit.

62

Author’s interview with Johnson, cit.; author’s interview with Jay Cocks, 29 Mar 2017.

Piero Negri Scaglione, Che Hai Fatto in Tutti Questi Anni. Sergio Leone e l’avventura di

C’Era Una Volta In America, Torino: Einaudi 2021, author’s translation. Nick Wrigley, “The right-hand man: Jan Harlan on Stanley Kubrick”, British Film Insti

63tute website, 24 Jul 2013, https://bit.ly/3XBrfDJ.

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS CHAPTER GET THE BOOK ON AMAZON

Eyes Wide Shut