Filip Nyborg

Filip Nyborg

A case for ornament in an economy with no space for craftsmen

Introduction

My process and work during this project has been split between three broad categories; the aesthetical, the practical and the technical The aesthetic category contains my research and work with design, the dialog with the artist Astrid Specht Seeberg, the theoretical philosophy as well as architectural theory, and practicing aesthetic judgement as a tool for informing my approach.

The practical component takes into account historical and current building practices, sustainability, economical feasibility, and the economical and logistical quirks of the construction industry today. I’ve spent countless hours dwelling on the practical application of my research, and used this as a constraint in both design and production.

The technical part of my thesis is the actual problem-solving that went into the code in CAD, CAM and Robots, and also the technical knowhow I had to get familiar with when working with clay – the properties of the material when shaping and drying, the surprisingly chemical process of working with glazing as for the esoteric science of firing ceramics.

All three categories played a major role during the whole process from the theoretical discussion, designing and fabricating the architectural system in the end. One informs the other, and none of the categories could be removed.

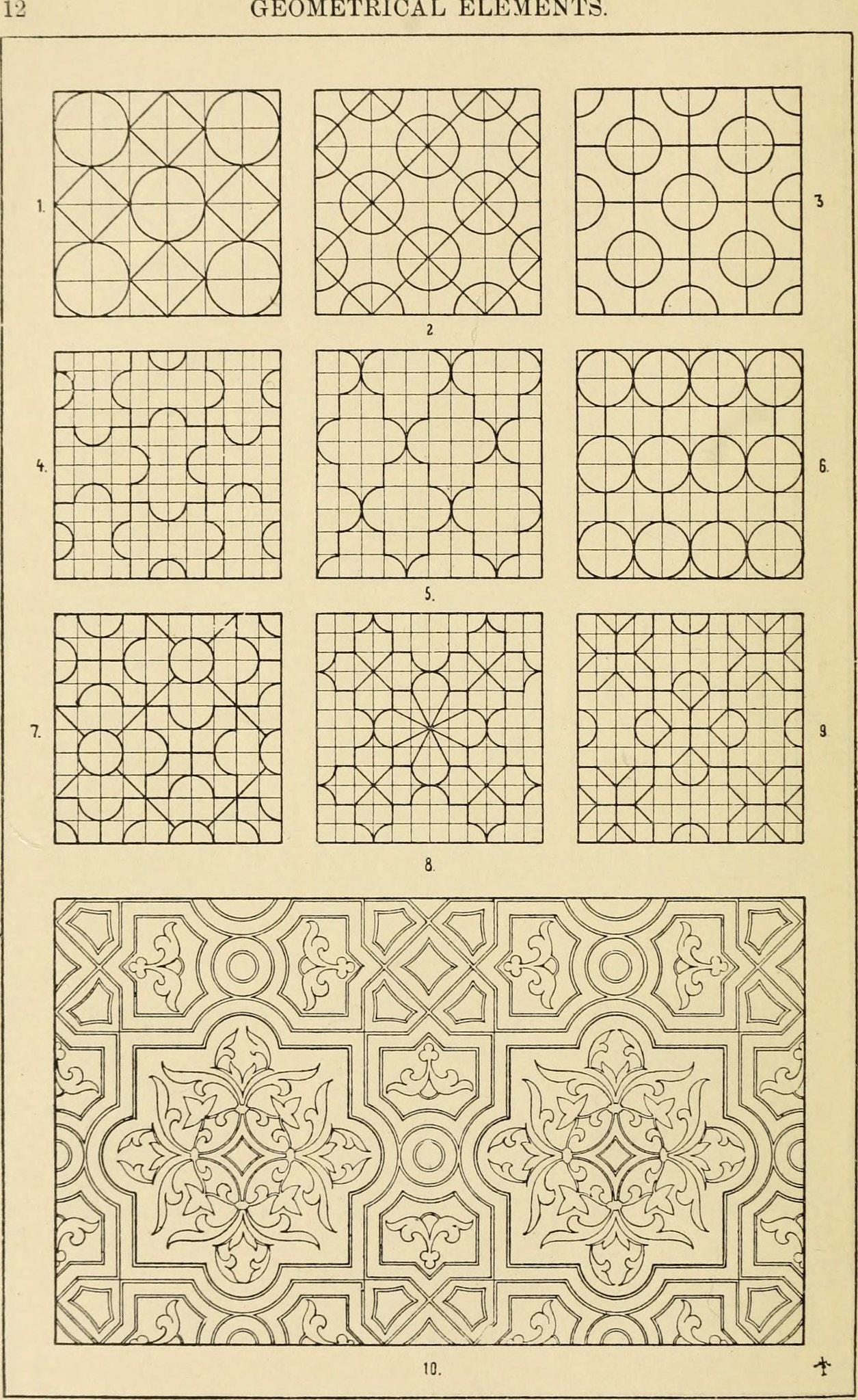

In my previous research as a student of architecture, Emanuel Kants work on aesthetics has been a source of interest. According to Kant, beauty possesses a form of «finality», that it seems to be designed with a purpose even without any practical use-cases. Beauty is that which pleases universally, without a concept. Kant’s view that beauty cannot be deducted in a rational sense is a dogma I would like to use for reflection in my research. In a practical sense, ornament or embellishments would be the most useless parts of the built environment. This lack of practical qualities makes the ornament difficult to discuss and it is often left out of the conversation. Still architects has to deal with the issue of decoration at some point in the design process and it should be more than an afterthought.

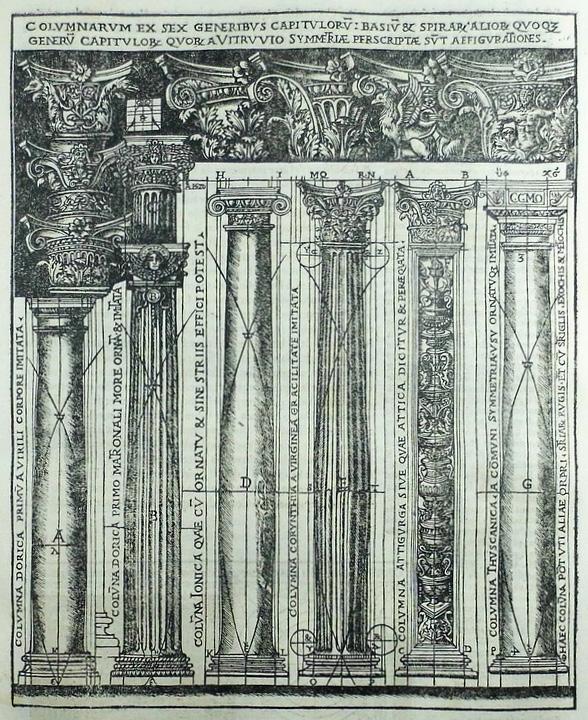

The roman architect and military engineer Marcus Vitruvius Pollio wrote his treatise on architecture dedicated to emperor Augustus, De Architectura. The treatise was a pragmatic guide on conducting a broad spectrum of building projects ranging from aqueducts to bathhouses. In De Architectura, Vitruvius states that all buildings should have three attributes; firmitas, utilitas, and venustas. Which roughly translates to durability, utility and beauty. Vitruvius explains that a building is beautiful if its appearance is pleasing and of good taste.

Is it possible to explain good taste? The British philosopher Roger Scruton, a self proclaimed Kantian, denies this. According to him, a judgement of taste is not a conclusion derived from logical reason, and there is no deductive relation between premises and conclusion when the conclusion is a judgement of taste. We judge taste to be good or bad in the same alley as virtue and vice. Bad taste is to us a negative trait of the character who holds it.

“I will rather assume that these rules of the critics are false… For it is to be a judgement of Taste and not of Understanding or Reason.”

Another British philosopher, John Ruskin, has written extensively about the craft of ornament in architecture. In his work The 7 lamps of architecture, where he lays the philosophical groundwork for the arts and crafts movement, Ruskin views the art of architecture as separated from the engineering of building. According to him the architecture starts where the useless and unnecessary begins. In the section of the book: The lamp of truth, Ruskin comments on the dishonesty by mass-producing ornament. A machine could effortlessly churn out identical copies of something that originally was a labour intensive craft. For Ruskin there is a morality attached to the craft, and a machine should never be used to make ornament, as it is inherently deceitful. Something that may seem like a bagatelle, can jeopardize the integrity of the whole. If the outermost appearance of a structure is dishonest, what other lies are hidden?

Ruskin’s work is strongly tied up to the time it was written and his christian faith, and may not be directly applicable to our current society without some translation. Although many of his thoughts hold universal value if you look at them through a sympathetic lense. His view on the tasks of an architect as a sacrifice to God does not need to be taken literally, while the idea that aesthetic tasks could simply be ethical tasks, is not reserved for any time period in particular.

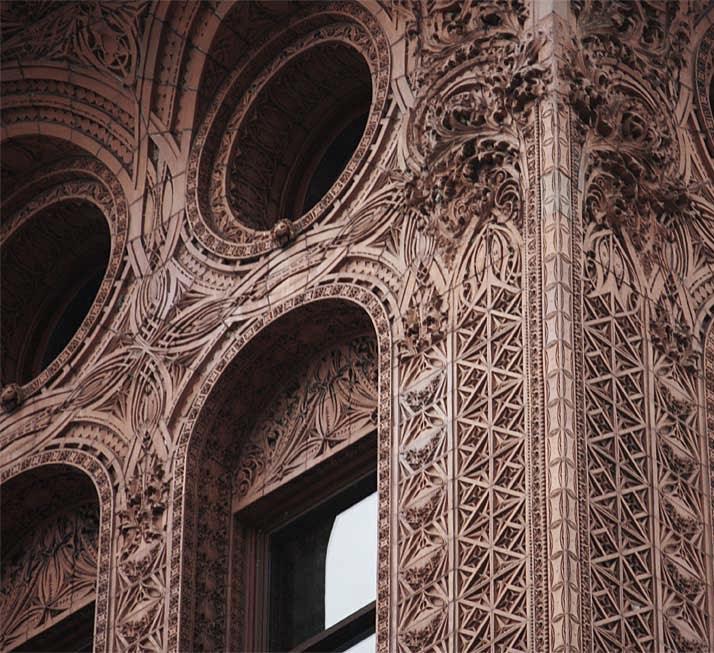

The modernist Louis Sullivan also observed issues with the ornament around him and was troubled by its stagnation and failure to adapt along with the technology. He proposed that one solution was to remove it all together, until it could come back organically, this time more fitting to the times. To Sullivan a building without any ornament was as unthinkable as a summer tree without any leaves.

“It is not the material, but the absence of the human labour, which makes the thing worthless; and a piece of terra cotta, or of plaster of Paris, which has been wrought by the human hand, is worth all the stone in Carrara, cut by machinery...nobody wants ornaments in this world, but every body wants integrity.” (Ruskin, 1849)

“I believe the right question to ask, respecting all ornament, is simply this: Was it done with enjoyment - was the carver happy while he was about it?”

(Ruskin, 1849)

Is there a way to incorporate machinery as tool to produce real craft, and end up with something beautiful? With our current economic climate and construction culture it is a mere pipe-dream to wish for the return of the original craftsman. My interests is to explore the possibilities of reintroducing the craft to architecture in the modern building culture.

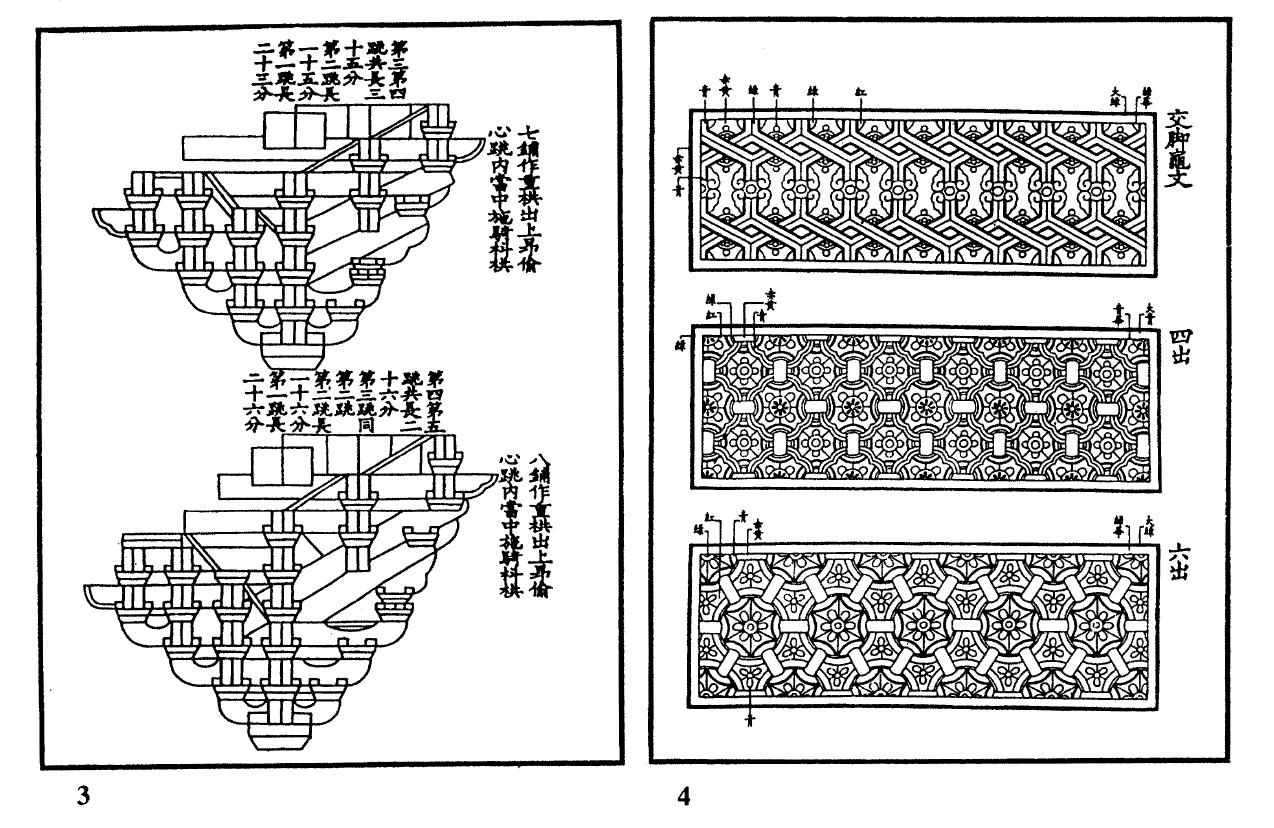

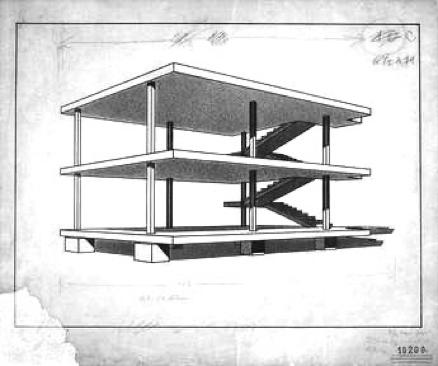

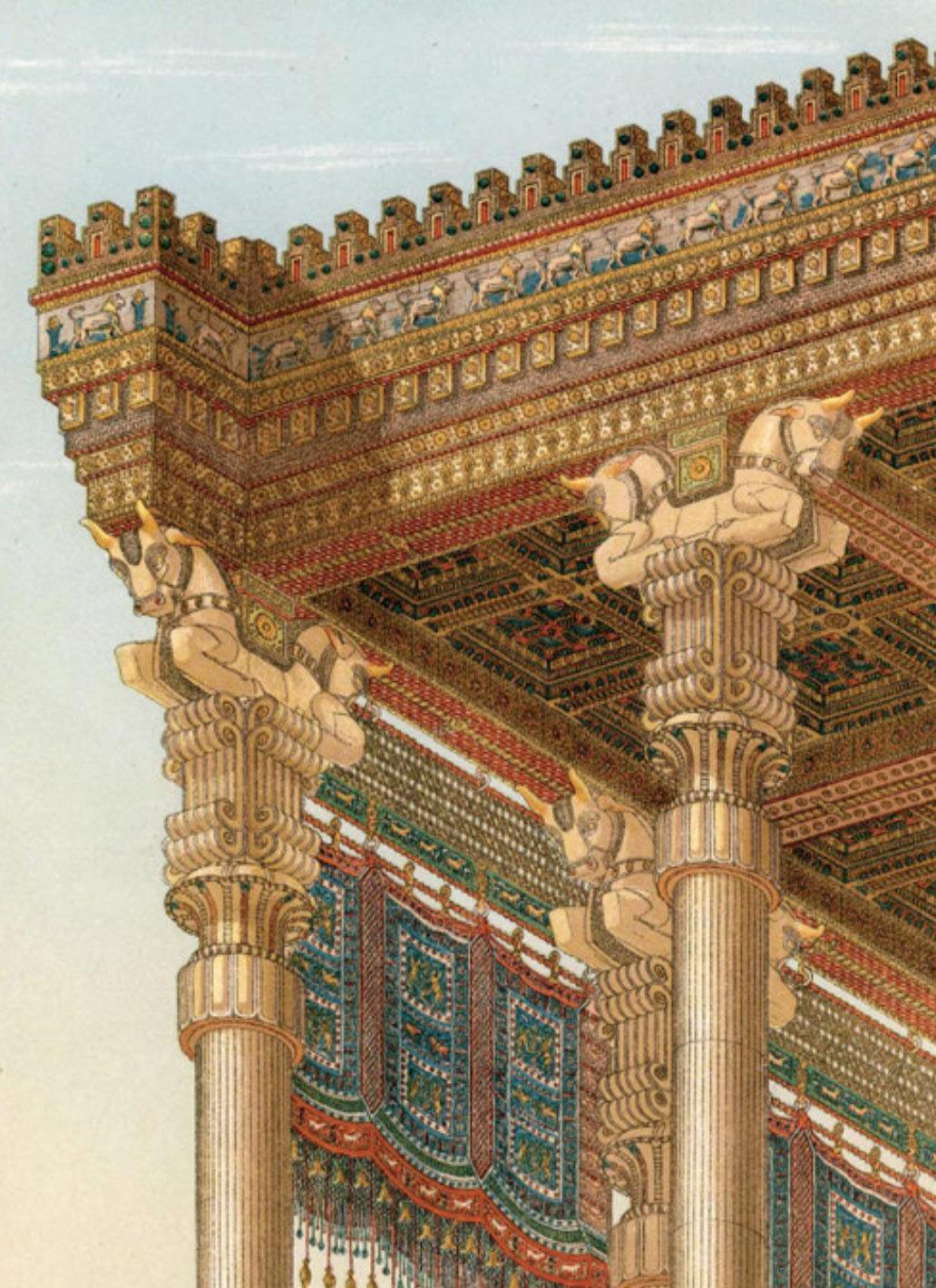

In many cases, the ornament of a culture has strong ties to its vernacular building practice. It makes sense for a danish bricklayer to be the one to adorn a facade with the same stones they would lay anyways, as for the Chinese artisan to decorate the complex bracketing units that only his family guild had the expertise to make. Looking at our current vernacular the question arises, who should decorate the Maison Dom-Ino?

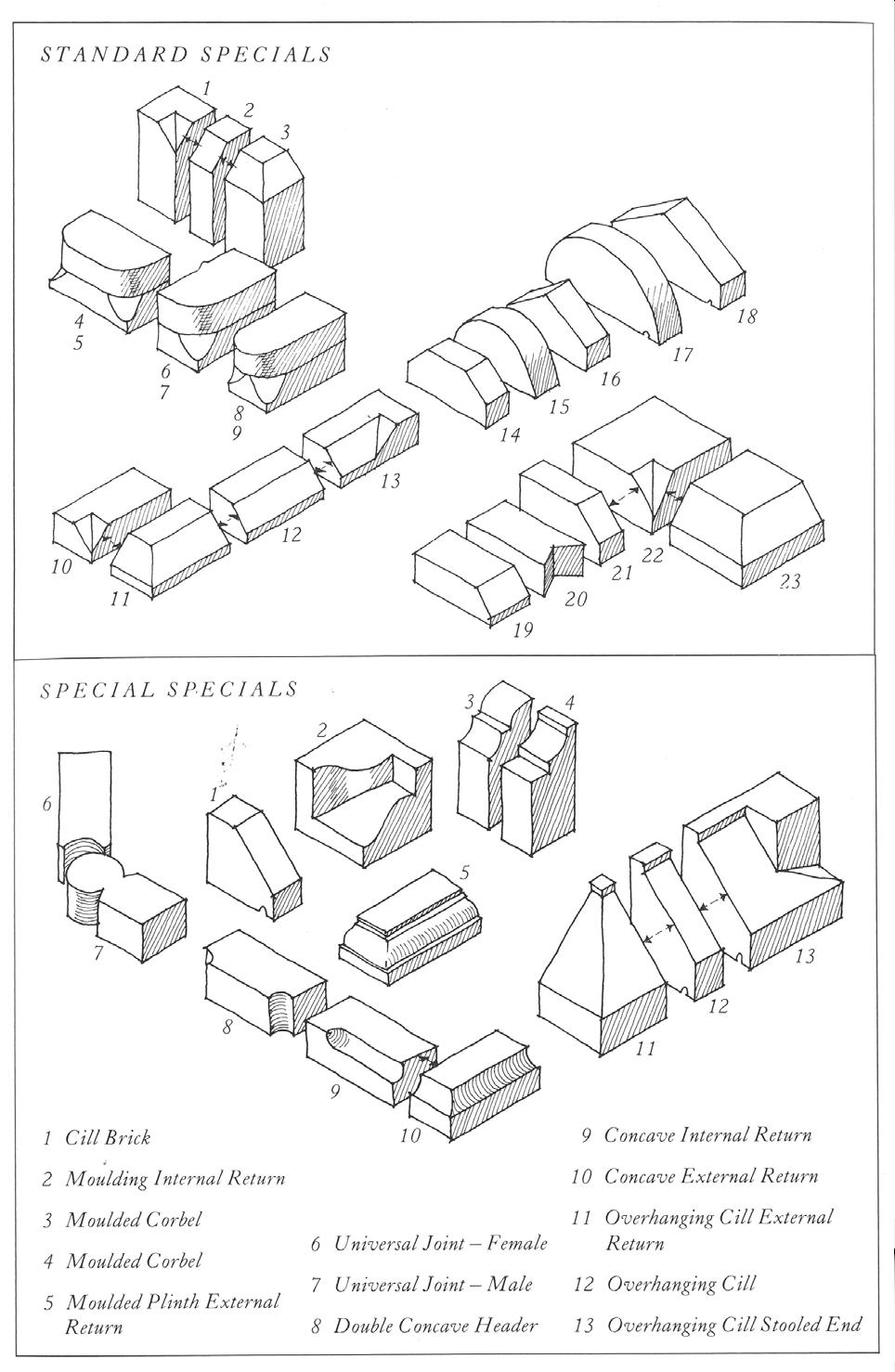

Depending on budget and how ambitous the project, the danish bricklayer would lay down a mix of standard elements and custom made profiles and shapes. It is the standard that sets the dimensions of the whole system. The specials solves what the standards can not. In this case it’s the common brick, sized to be lifted with one hand. An efficient design makes use of as few specials as possible and with as few unique moulds as possible. These elements can be called standard specials. Because a third category, special specials, can be introduced, an element sized to the system but designed to a specific niche, where can gift a detail to the building placed where it can be appreciated the most. I think the idea of the special specials are interesting.

These unique elements can be a valuable tool in an efficient system mostly existing of standard elements. Solving special quirks and creating specificity to the architecture, while still fitting to the underlaying system.

Even when a project doesn’t allow for elaborate bespoke ornament, the bricklayer can still arrange the standard bricks in patterns and ribbons on the facade without introducing too many new moulds or bespoke elements. This is a type of agility that the material and construction principe allows. When architecture is made in a system such as this, even low budget projects can afford to be adorned.

Brickwork, architecture and design, andrew plumridge and wim Meulenkamp

Method

The thesis will be done in a parallell iterative workflow. I will use research and case studies to inform a fabrication process, while also documenting it. At the end of each round of tests, I will gather the documentation and reflect on the experience, producing a catalogue and inform the next iteration. The thesis will not necessarily reach a natural conclusion other than the ornament mockups and the fabrication catalogues.

To limit the scope of the thesis, I will start the research focusing on a single material. This is done to be able to get a deeper understanding of one material, and not scratch the surface of many. I have chosen to focus on terra-cotta. Translated directly from latin terra-cotta means baked earth, and is a clay based ceramic. Before terra-cotta is fired, it is just clay. Clay has an incredibly rich history in architecture, as a glazed or unglazed architectural ornament, but its most famous use is the fired brick. Around one-half and two-thirds of the worlds population lives in buildings made with clay. Since clay is a very common substance, it is economical, sustainable and easily available.

Terra-cotta and clay has desirable qualities for my research. Clay is easily malleable by hand or with a variety of tools. Using a low hydration, the clay is suitable for carving and a wet mix can be extruded. This adaptability of terra-cotta is probably the reason for its ubiquitousness. It is both a practical and cultural relevant choice for investigation.

Our current building culture is still heavily dictated by available materials and techniques, these issues are not very different from vernacular building practices. Instead of the more intuitive availability of materials, the global economy and government regulations are the biggest factors for how and what we build with today. Building code, cost of land, human labour and raw materials has changed dramatically in the last century, and this in-turn has changed what are the most efficient and available materials, and what construction methods are used. Another huge factor is that we have gone from an economy where material is expensive and labour is cheap to the opposite. Time, logistics and human labour takes a major slice of the construction budget.

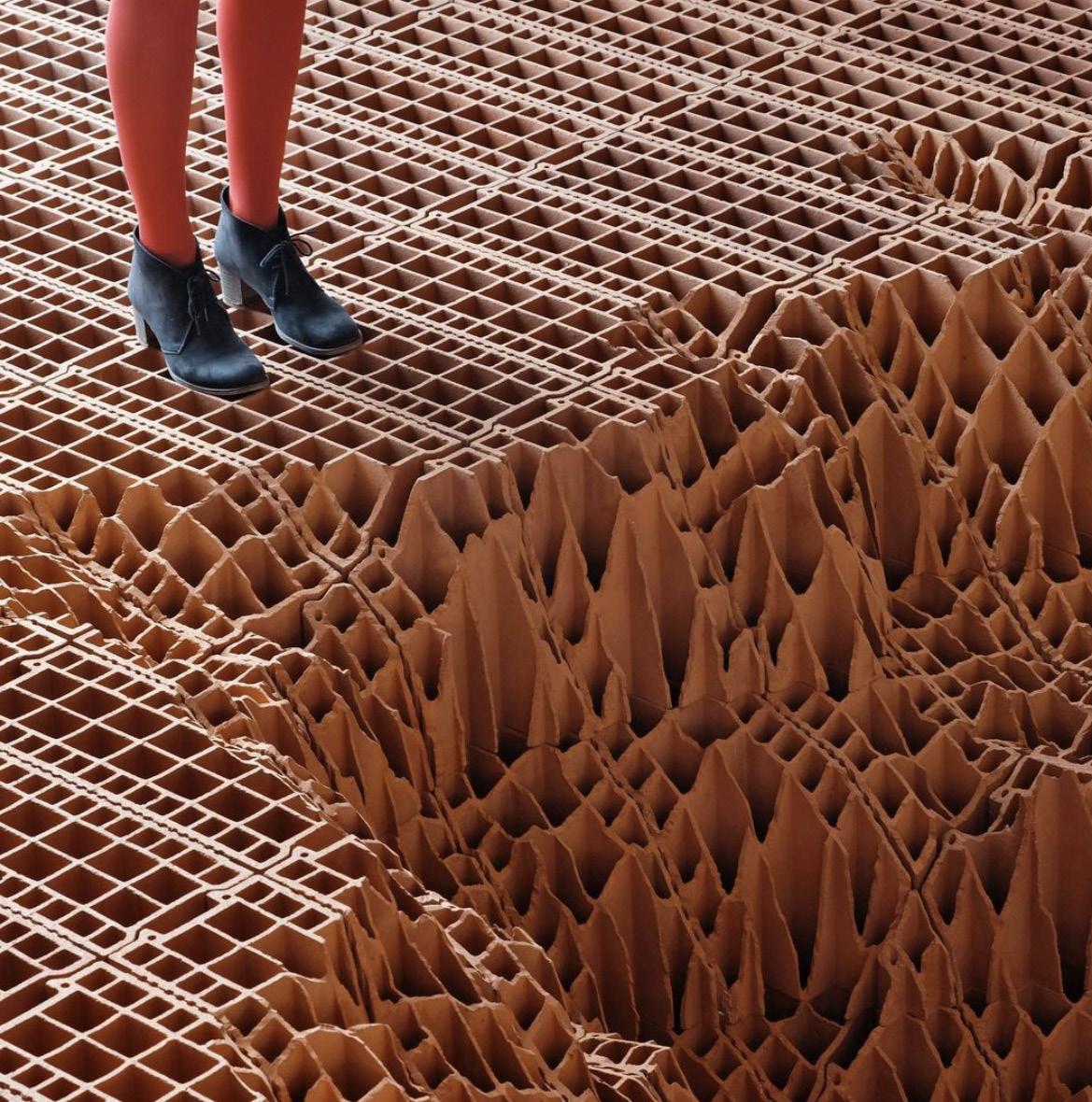

The most prominent construction practice today is the concrete slab and column system, popularized by Le Corbusier as the Maison Dom-Ino. For energy efficiency these are mostly clad with a non structural skin with a type of insulation between outer and inner wall. After the consulting with the school engineer, I found that the most economical and sustainable method to do this, is with a rain-screen facade cladding system. The skin “hangs” on the structural elements with a gap of air between the skin and the insulations, allowing the outer skin to be ventilated and dry out moisture. It also works as an extra layer of insulation since the skin is only in contact with the building at the mounting brackets. Even if it doesn’t help combat the ambient air temperature, it does work as a radiation heat insulator.

The rainscreen is hung on the construction as a skin for protection against the elements. Rain-driven rain is kept away, and the gaps between the panels allows for air circulation.

Today, the most widely used construction material is concrete. As a small speculation on what could be a new standard, I imagine a timber construction as a more sustainable and humane successor to the concrete Maison Dom-Ino.

The screen-screen-facade system has the same benefits for a timber construction. It also has an extra benefit in fire-safety, as timber constructions has stricter codes regarding this.

Looking at two of the large scale producers of brick and clay products for the building industry in Denmark today, Pedersen Tegl and Randers Tegl, the size of their orders are in the millions. If just 1% of the bricks in an order of this magnitude is bespoke designed, it would be 40 000 handcrafted pieces. It is very hard to imagine that it exist enough teams of specialist artisans for this to be feasible logistically for entrepeneurs to even consider.

Artisans and craftspeople has a wide range of experience and expertise that makes it hard to concretize the speed and pay for the labour, as it differs with too many factors to take into account. This is another reason why current entrepreneurs are hesitant to work with skilled specialists in this manner.

Lavish materials, priced highly solely because of their looks, are still used today. This should mean that the budget for purely aesthetic purposes exists in the market. In my belief its not necessarily too expensive to implement crafts in todays architecture.

The largest obstacle i have observed is uncertainty. When entrepeneurs can go bankrupt from a 5% over-expenditure they tend too chose the safer options. This can be producers of specific products that has a set price and delivery time and a product line the entrepenuers know their contractors are familiar with.

My research for this thesis sprung out of the belief that there has to exist ways to circumvent these ob-

stacles and get more art and craftmansship into archi tecture.

From unfired clay spread onto straw, to the fired brick and complex facade systems of extruded terracotta panels, clay as a building material has followed the architecture and technology from the beginning. An observation on how clay is being used in Denmark today, where clay bricks are hung on concrete facades ignited a curiosity. The thought «what should the role of clay be in the future of architecture» has been a driver for my later research.

terra-cotta (pronounced [ˌtɛrraˈkɔtta];[2] Italian: "baked earth"

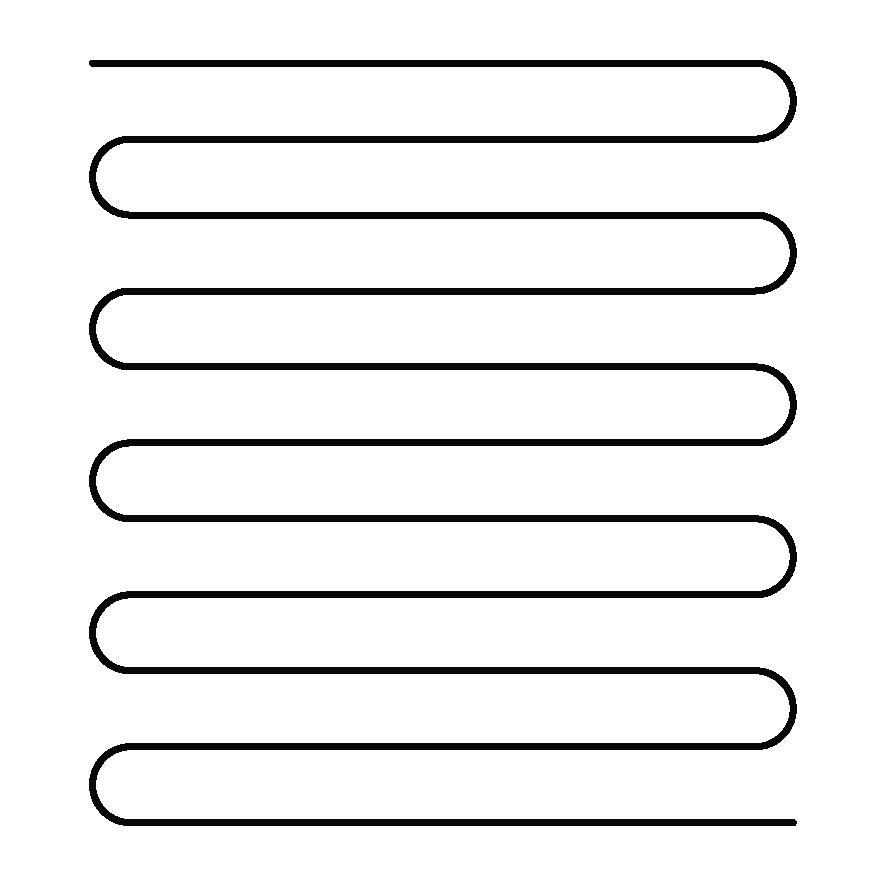

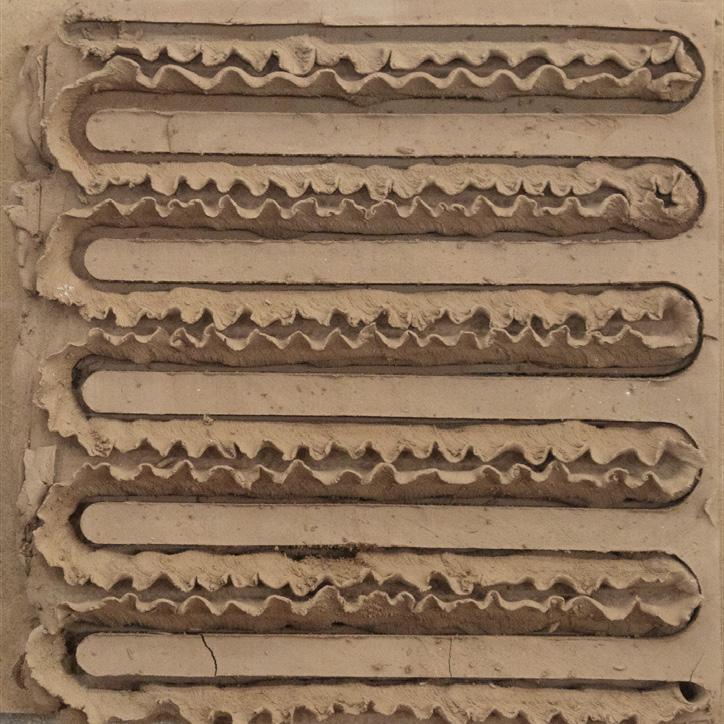

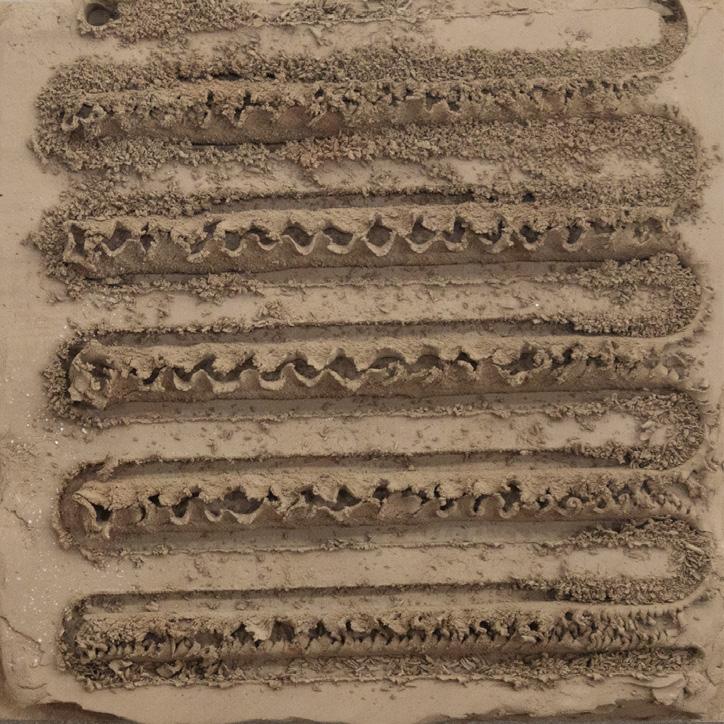

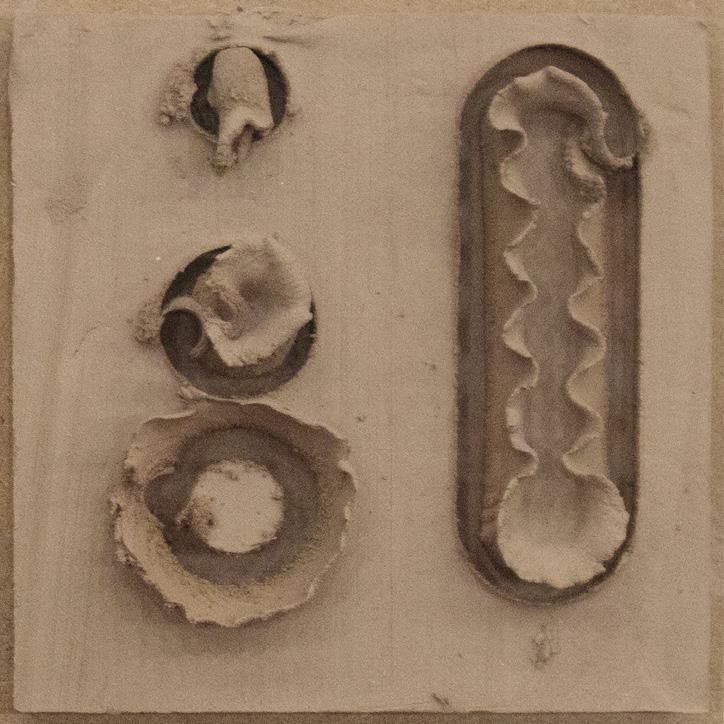

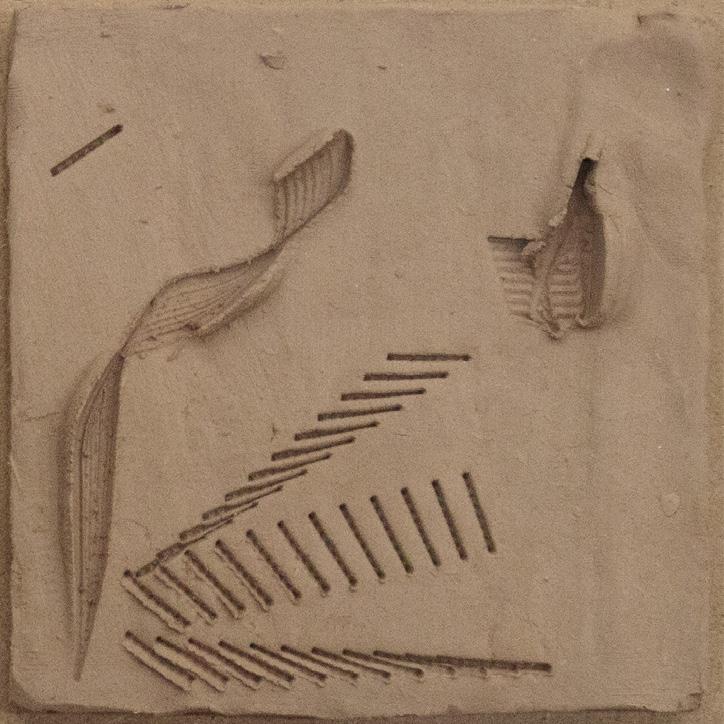

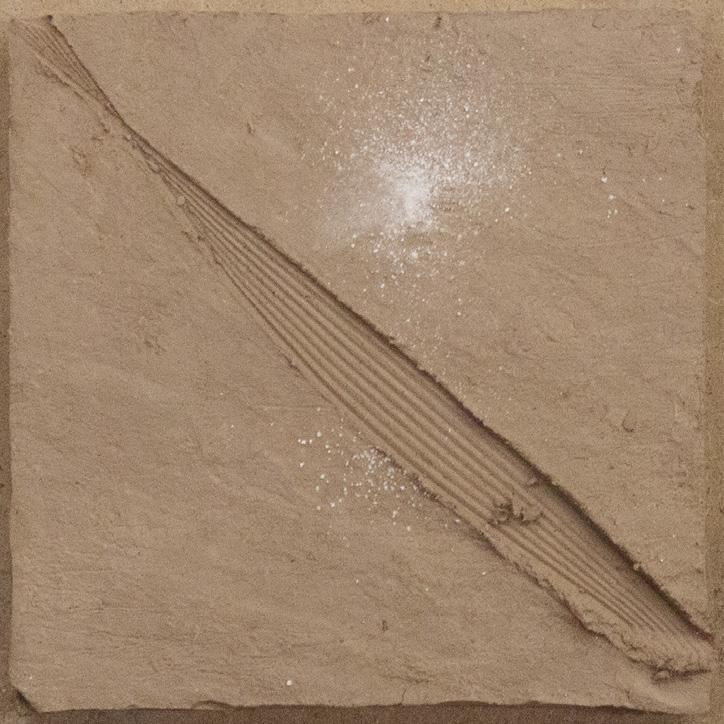

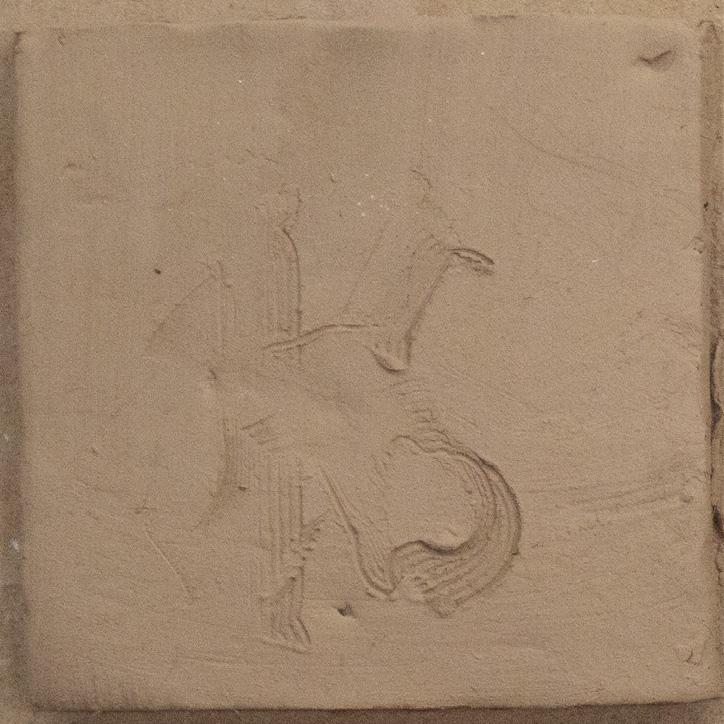

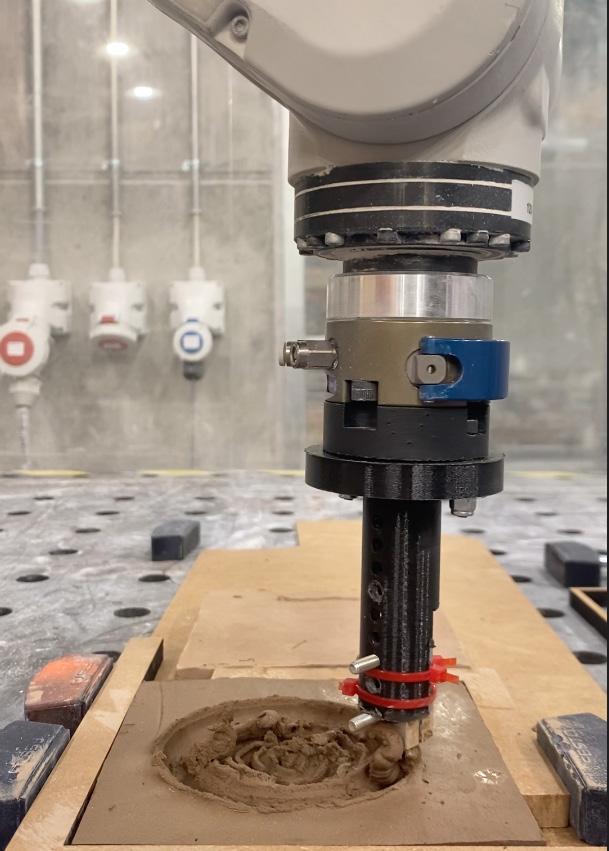

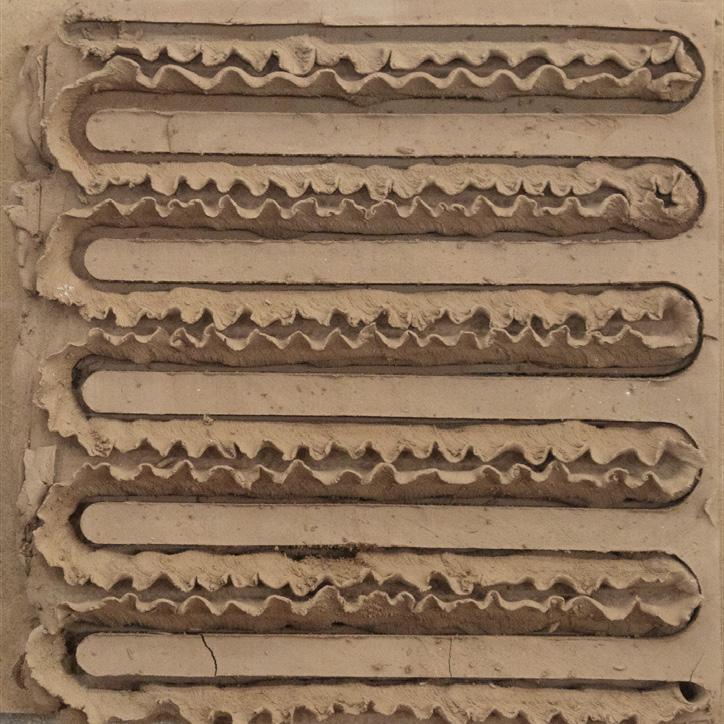

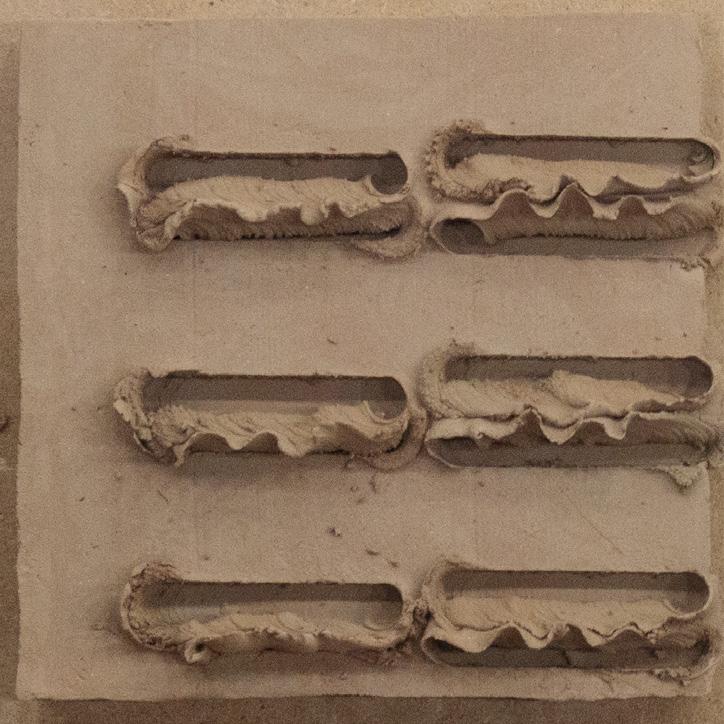

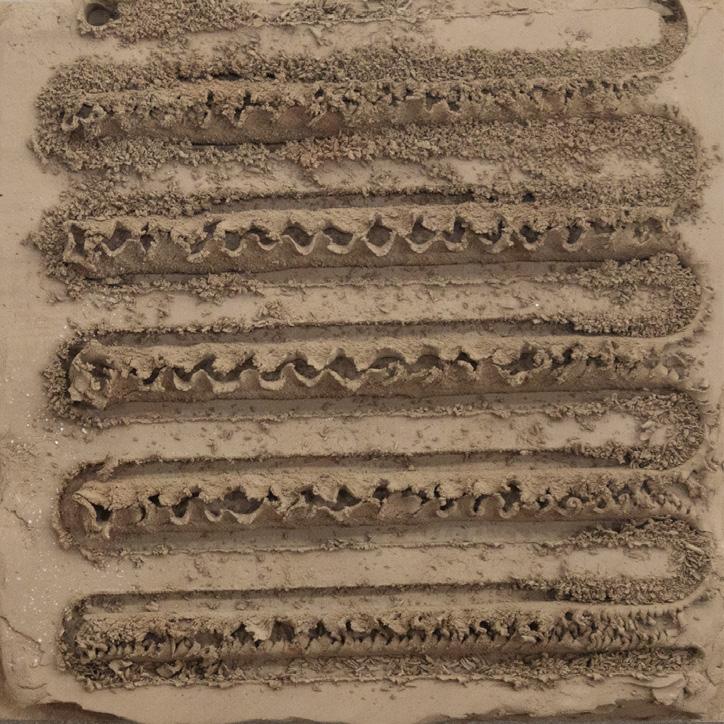

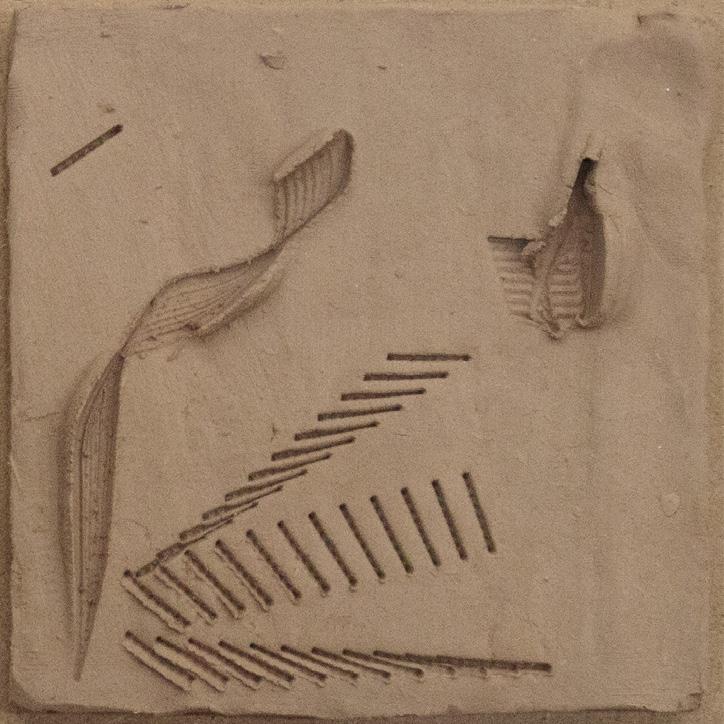

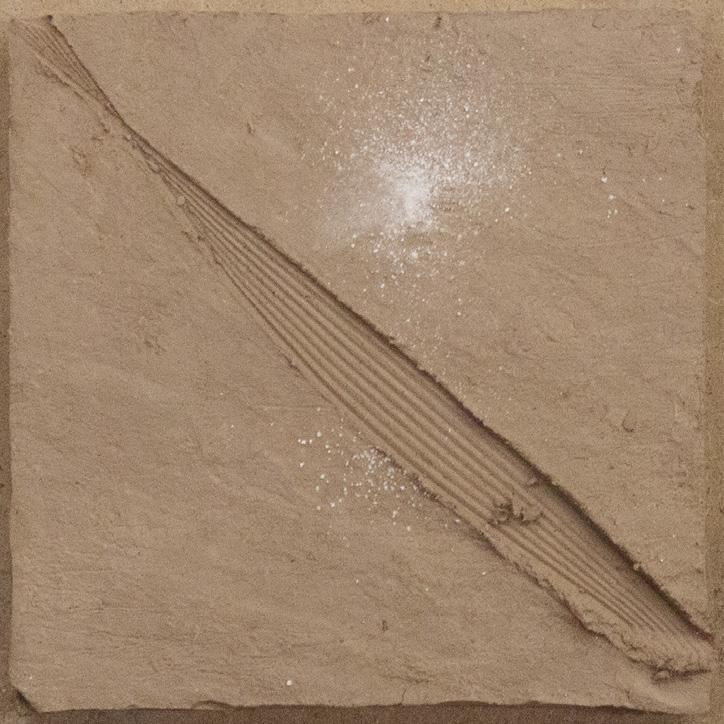

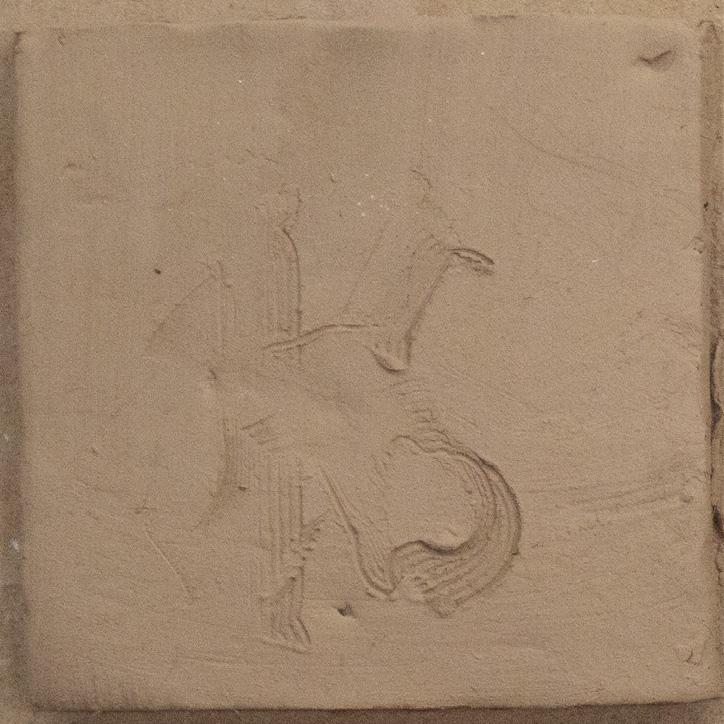

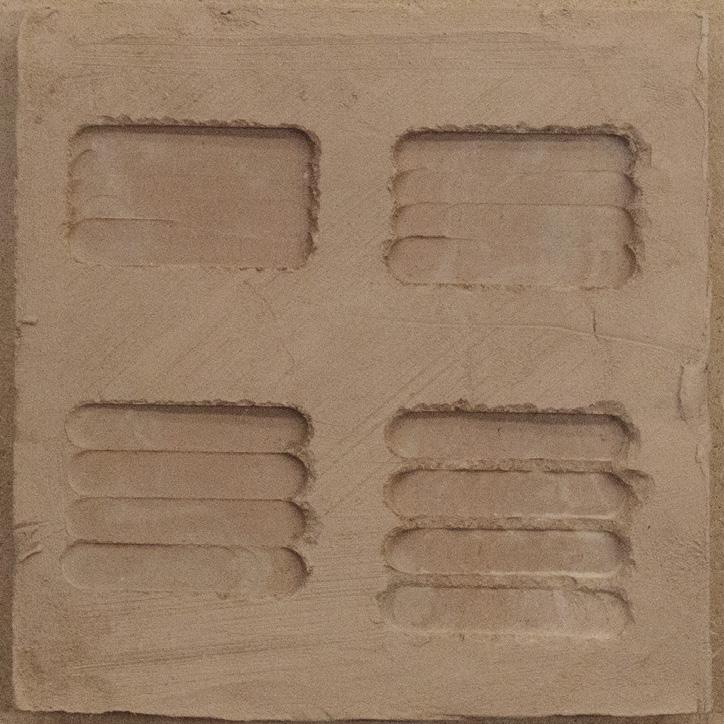

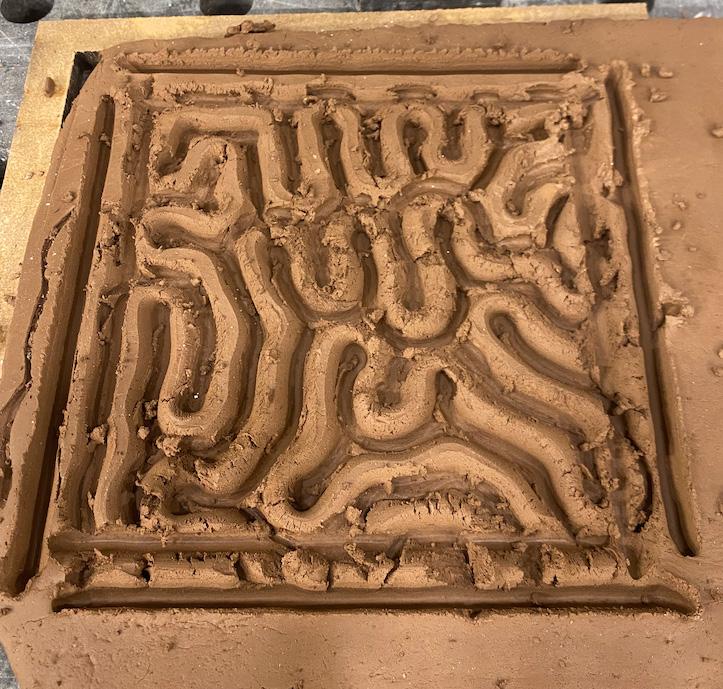

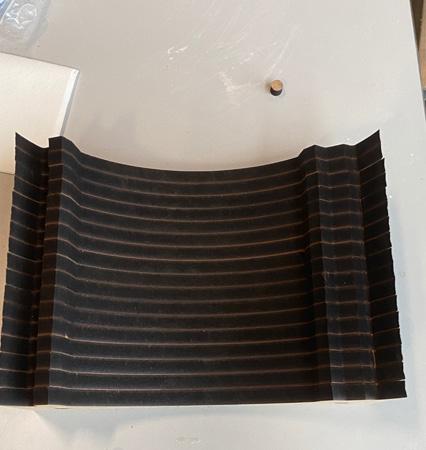

The first test was done with red clay still in its plastic, malleable state. Something I wanted to test, was milling in the clay, so I used a spindle on the robot with a wood router-bit attached. The tool-path was made to observe how the test would behave with straight and curved lines, directionality, repetitiveness and spacing.

The resulting geometry caught me off-guard, the organic but uniform shape had a quality that I wanted to explore further. I did a test and noted the parameters: the tool used, drying time, tool-path, depth and speed. When I did the same test the day after, with a clay blank that I allowed to dry overnight, the result was completely different. The clay behaved very differently depending on dryness. In the ceramic field these dryness stages are called: plastic, leather dry and bisque dry.

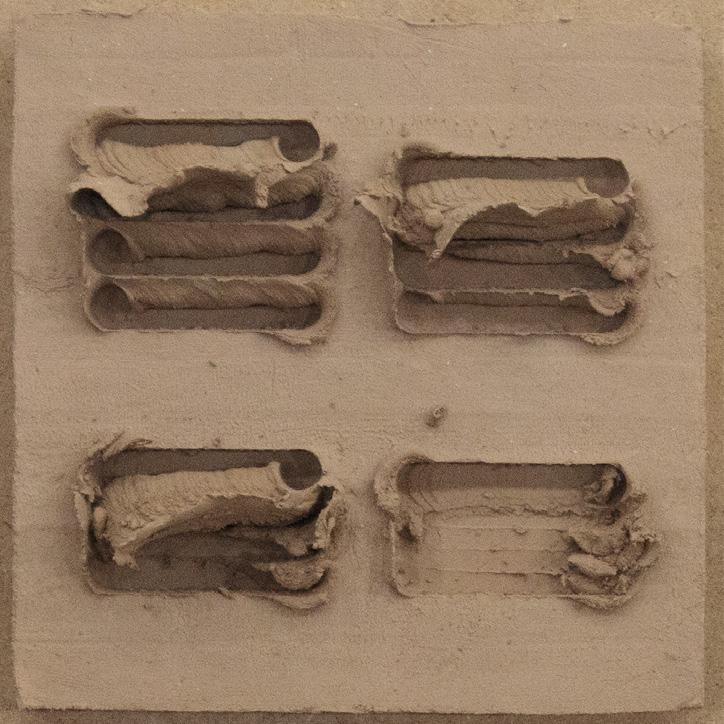

Making a standard tile

To gain control over some variables in testing, I made a standard template for the tiles, a 10mm thick square with 125 mm sides. I rolled it out in the same manner and tried to keep the drying process similar. Even when using the same rack in the same room with the same amount of plastic covering, the drying of the

blanks was hard to control. It was dependent on the initial clay, how warm and humid the room was when rolling it out, and other factors such as the placement on the rack and how much air circulation it was underneath the plastic.

minmal surface ridge

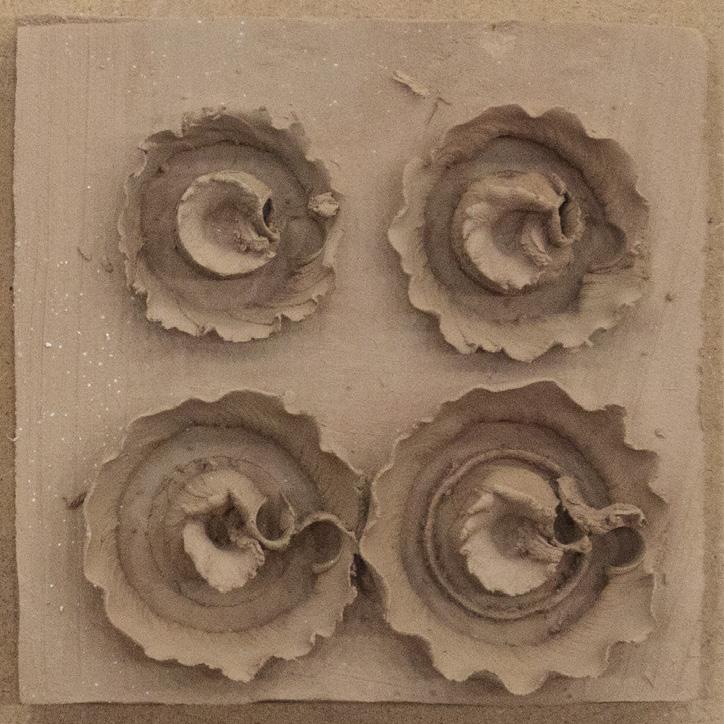

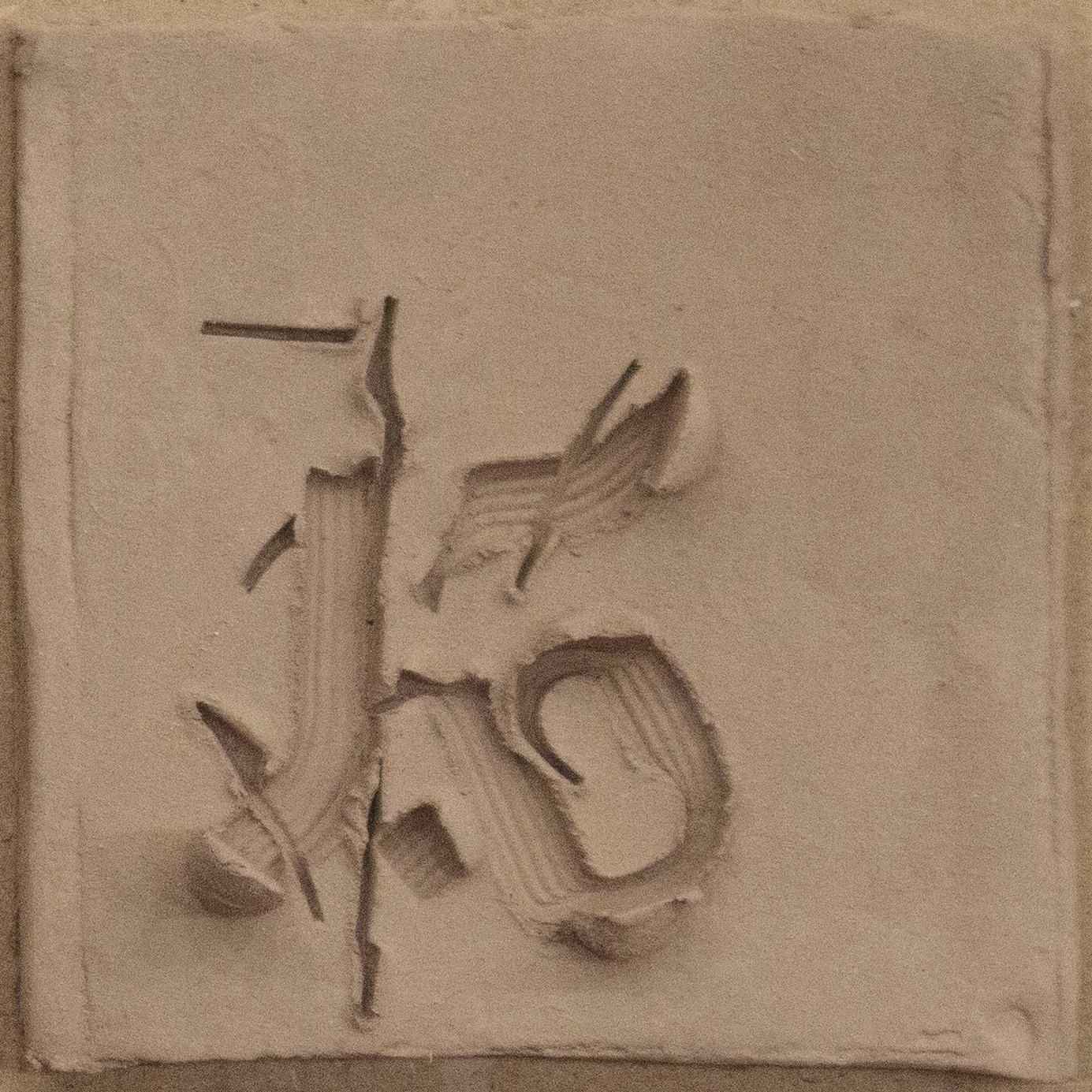

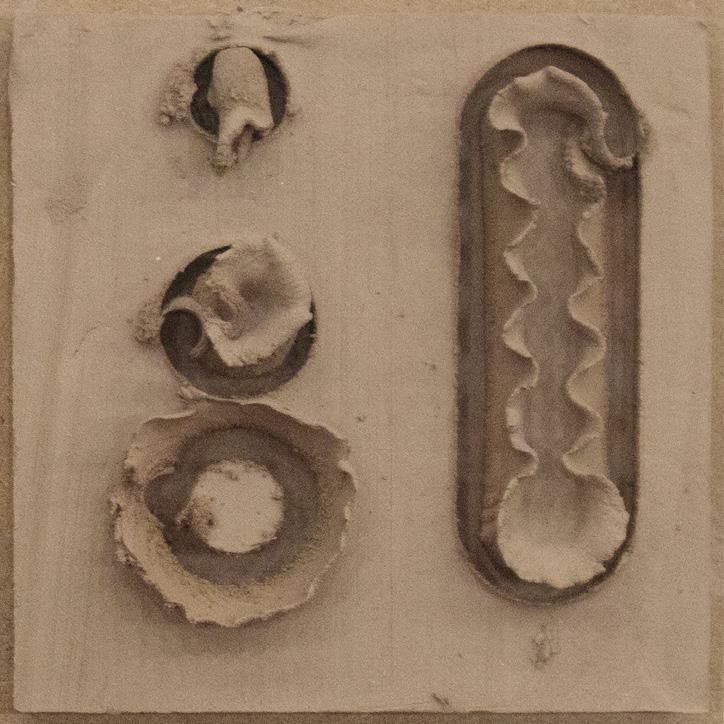

The second iteration was a test to explore the replicability of the effect observed in the first test T01. The test were made on the new standard tile with roughly the same dryness. New tool-paths were made to explore edge-cases and tolerances. T03 proved that the ridge could both be replicated and also that changing to a counterclockwise tool-path could control the side the ridge appeared.

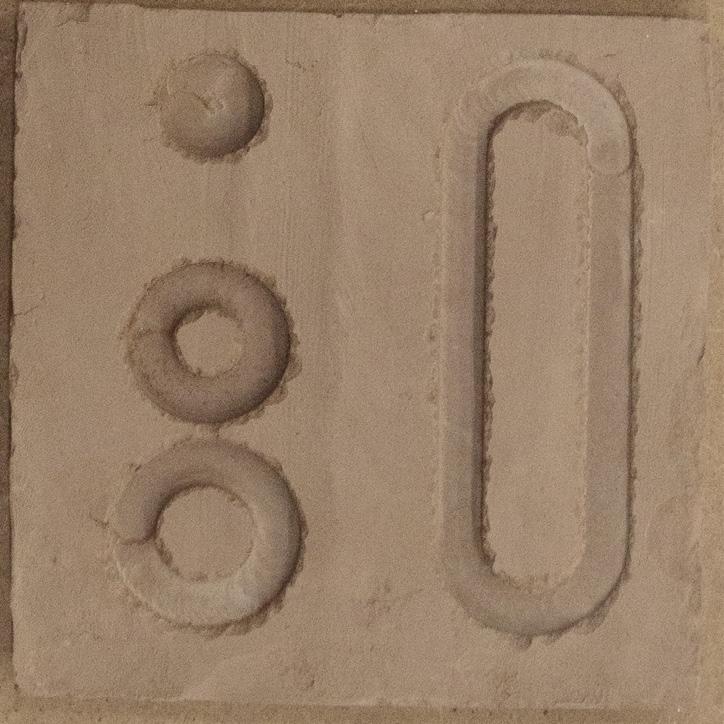

Testing closed crv, different diameters and directionality effect.

Intersection tests

Double layered circles with oposite directionality. Outerring cut clockwise and innerring counterclockwise.

Double lines with opposite directionality. Upperpath is rightfacing and bottom path is leftfacing.

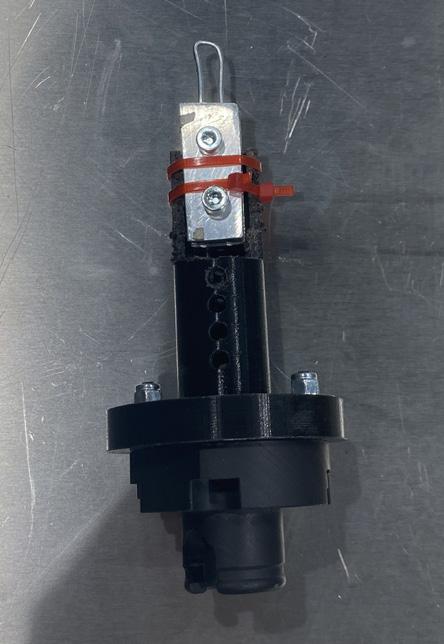

T09 Claypen trial

WORKPIECE:

dried < 1 hour(s)

TOOL: Claypen

Flat 15mm

TOOLPATH: A1

depth 0.5mm

1

Custom

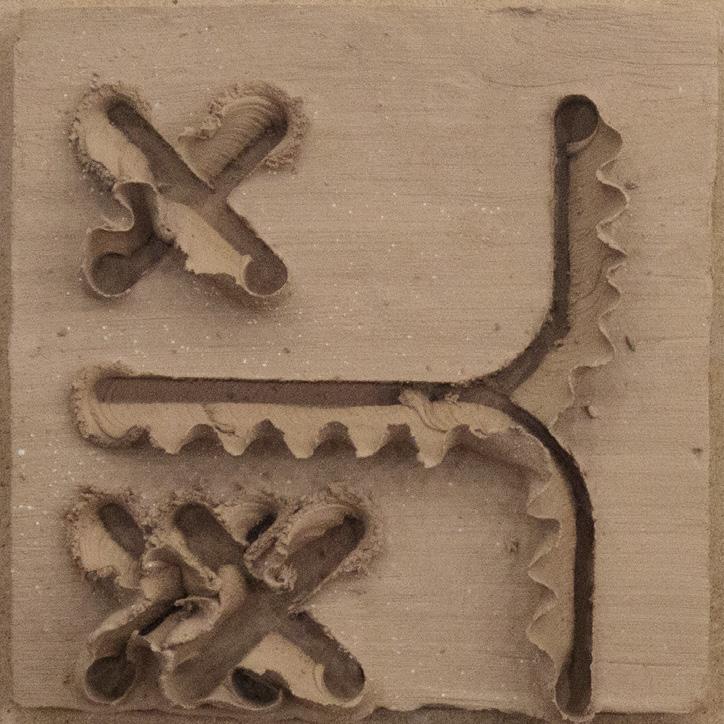

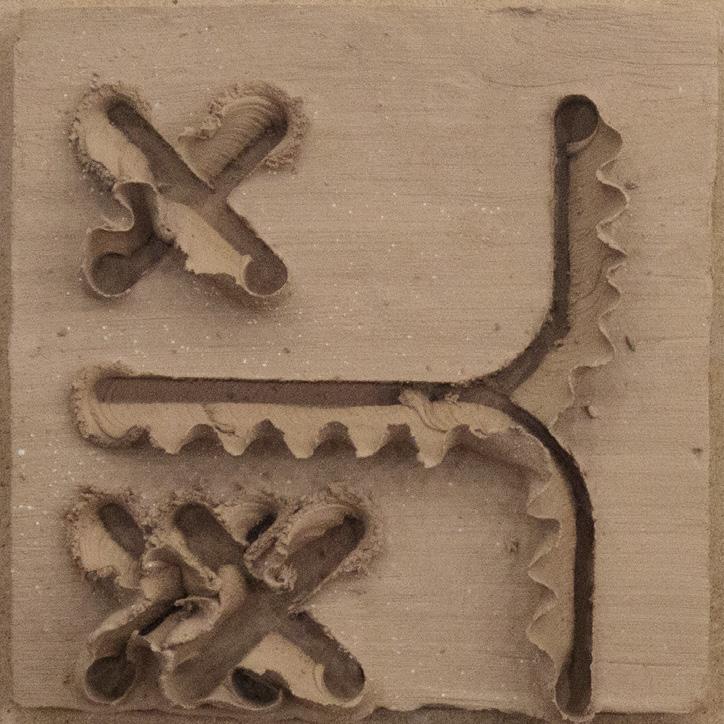

Trying to develop some new techniques for working with wet clay, I attached a 3D-printed carving insert on the robot. This experiment was done to explore a more intuitive approach. The rotation/direction of the toolhead dictaded how thick or thin the carved line ended up. This could be changed in the code for the

WORKPIECE:

TOOL: Claypen

TOOLPATH: A1

1

robot and gave some interesting results and a better control over the output. Working within the code to translate such a simple idea of how to operate a pen on paper to the robot has a lot of potential.

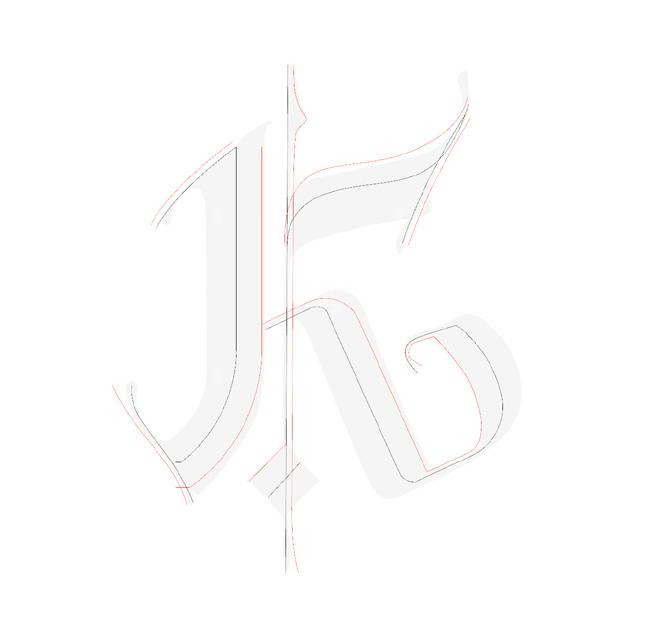

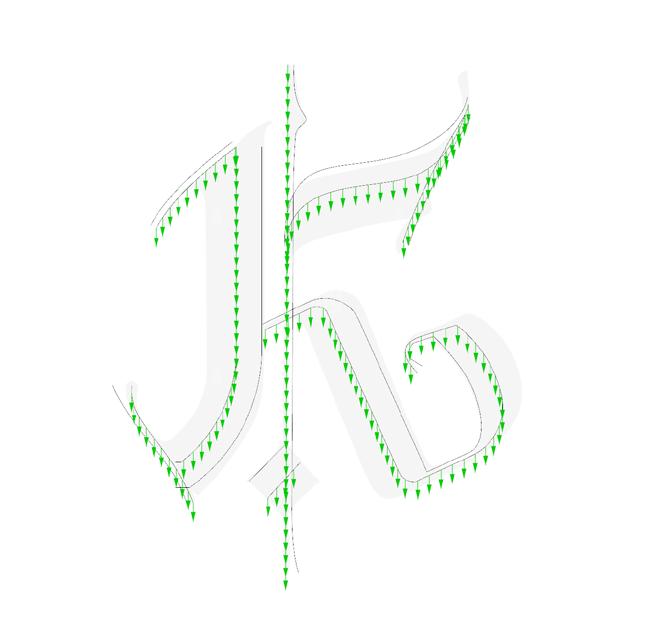

Iteration 3

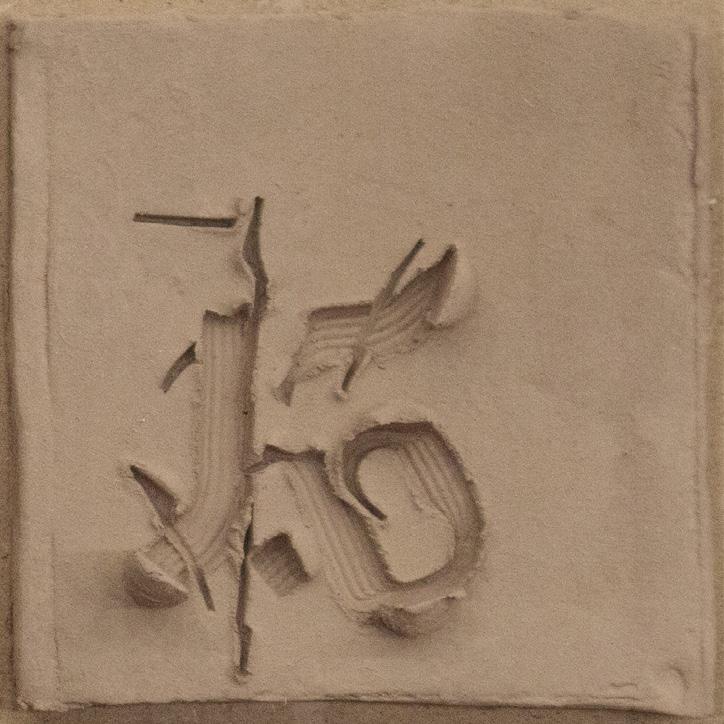

Calligraphy

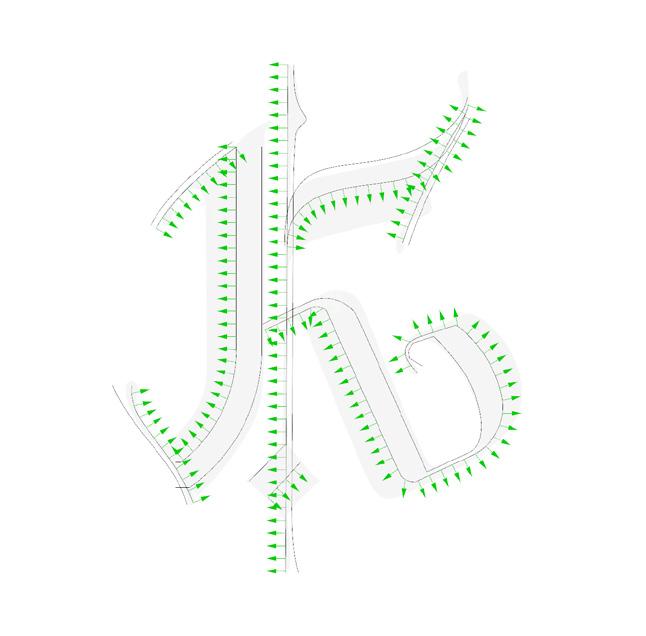

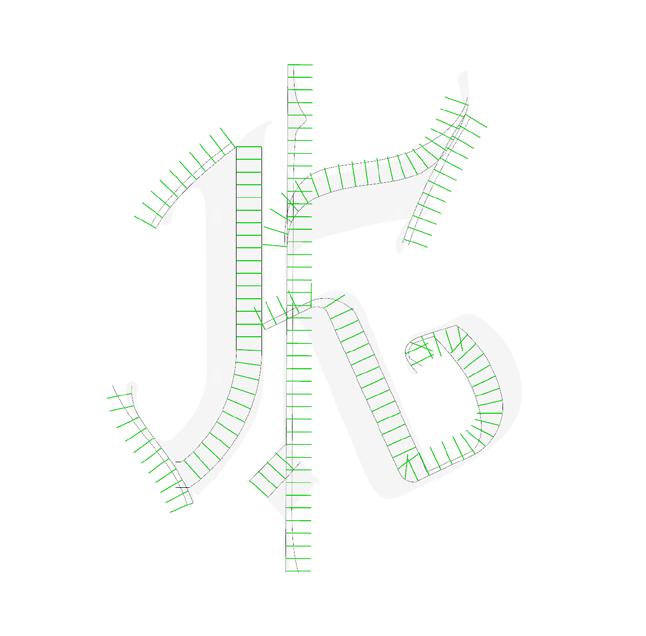

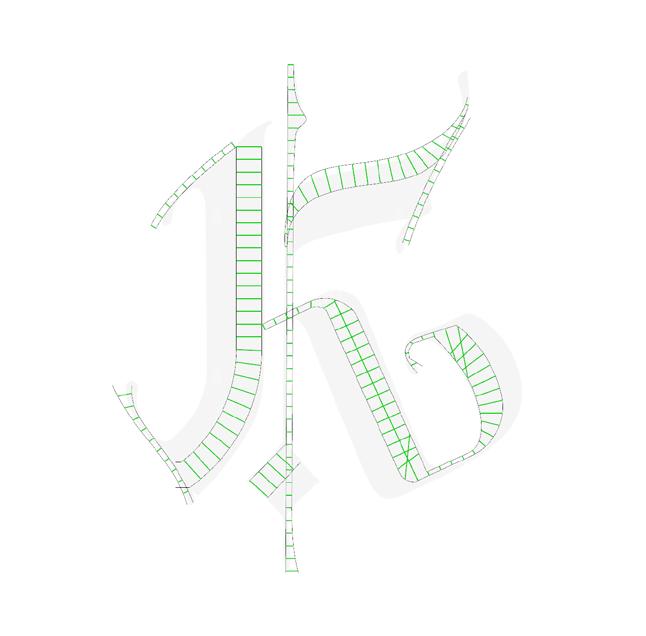

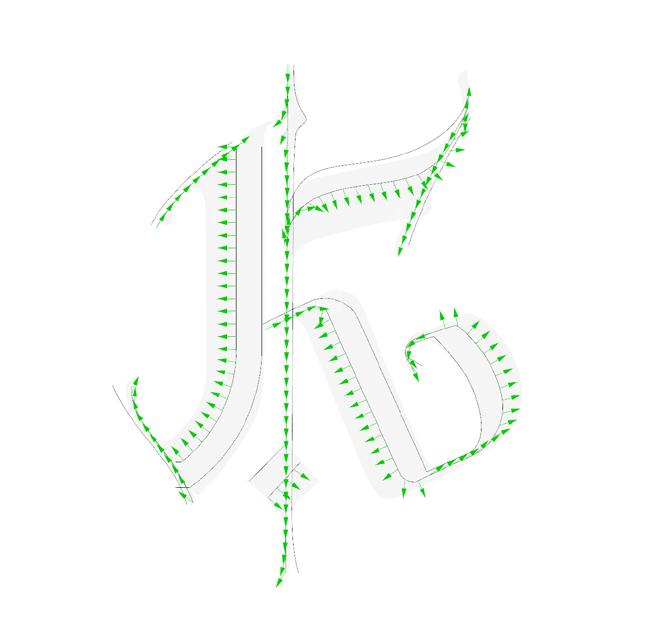

I looked into controlling the factor of toolhead rotation as a way to write the letter K in a calligraphy typeface. K1 shows the two input curves in the code.

This direction is projected and used to check for intersection with the red line from K1.

The initial rotation of the tool shown in K2, would grant a line with random thickness depending on the curvature of the input-curve.

Taking this intersection the length of the new curve is used to maptoolhead rotation, the rotation is gradually going from 0 degrees at full length to 90 degrees for the lowest values.

Mapping the direction of the curve and translating that to the rotation of the toolhead. If K3 was carved the resulting line would be at maximum thickness throughout the entire path.

This is the resulting toolpath, the tool goes from a thin to thick line as the input curves dictated.

Calligraphy

The first testing of a new tool or technique is repetetive small tasks like adjusting depth settings, changing the tool insert and small changes to the tool-paths and work surface.

Iteration 4

Carving

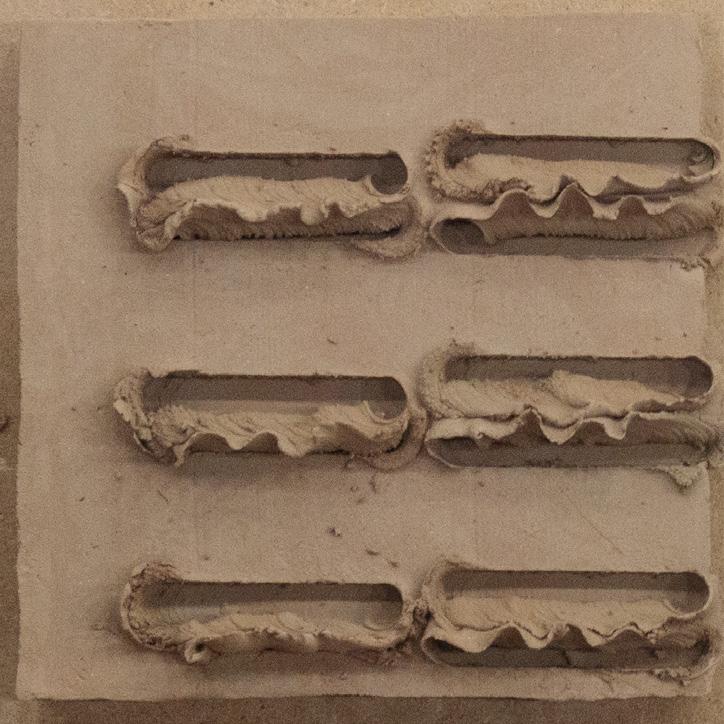

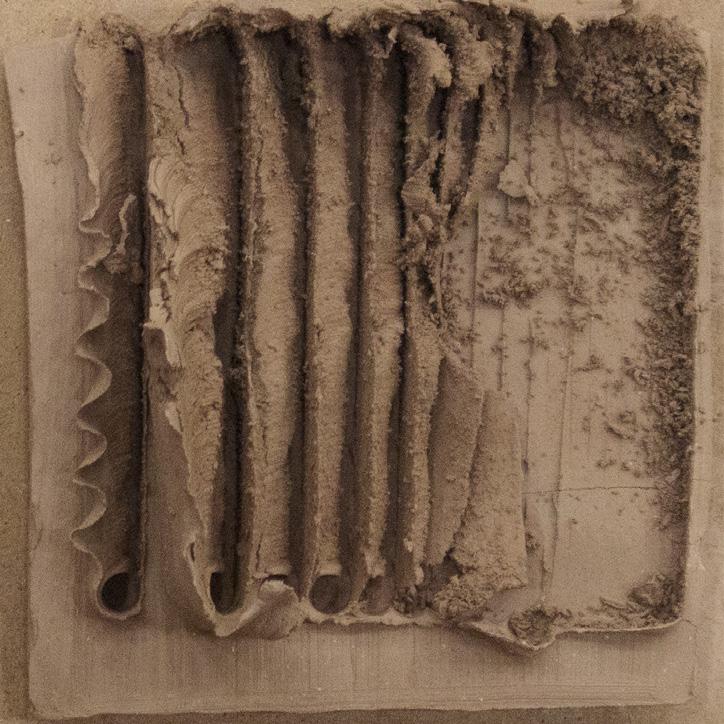

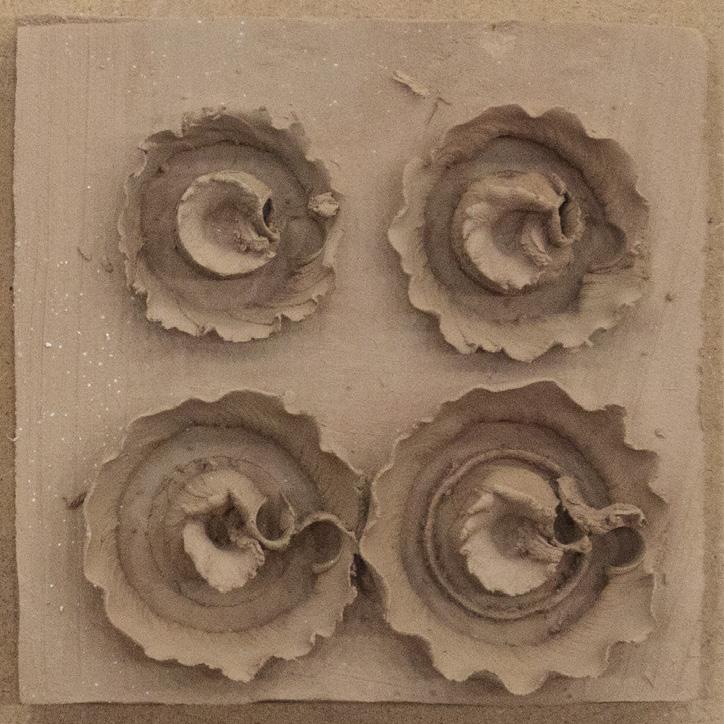

A prototype was made to test a new type of tool, the wire cutter. Made to resemble standard clay tools found in every ceramic artists studios. The first protype was tested and the issues observed was then reworked for the new version, longer wire to prevent clay piling on the tool.

WORKPIECE:

TOOL:

TOOLPATH:

Case studies

of ornament

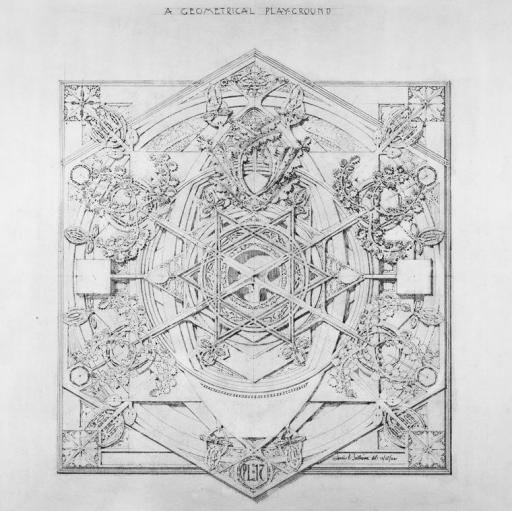

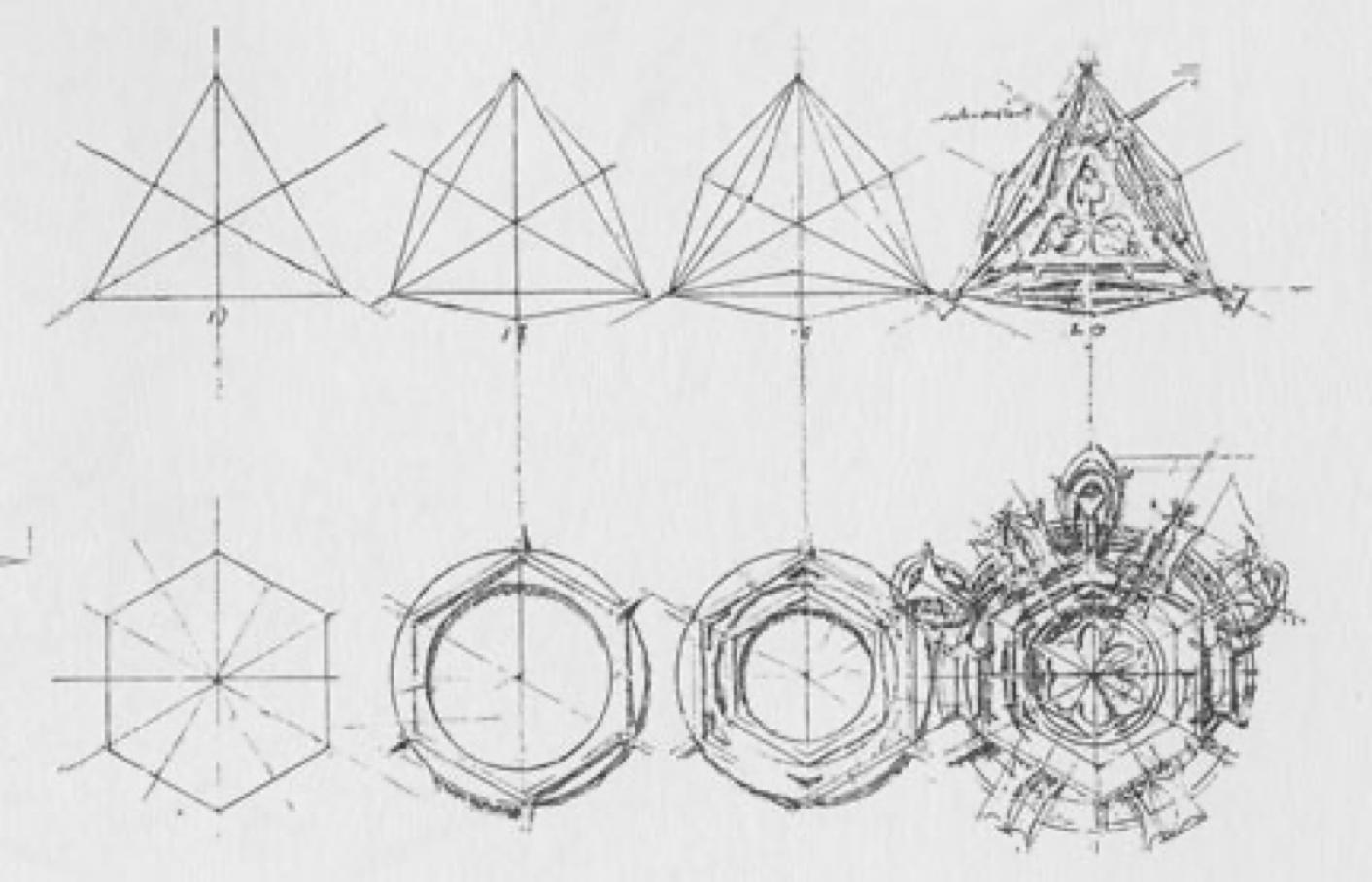

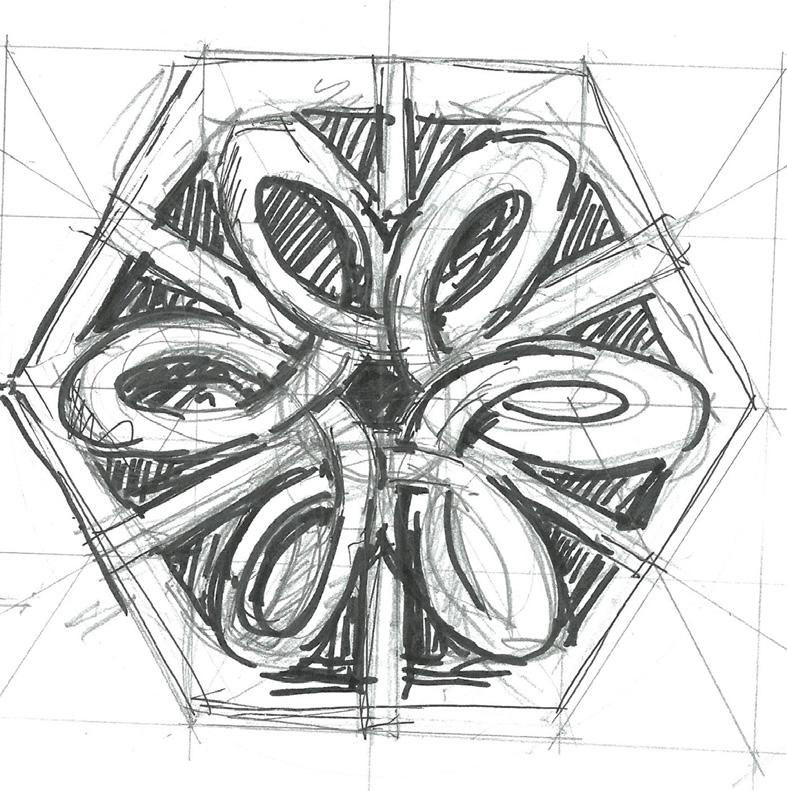

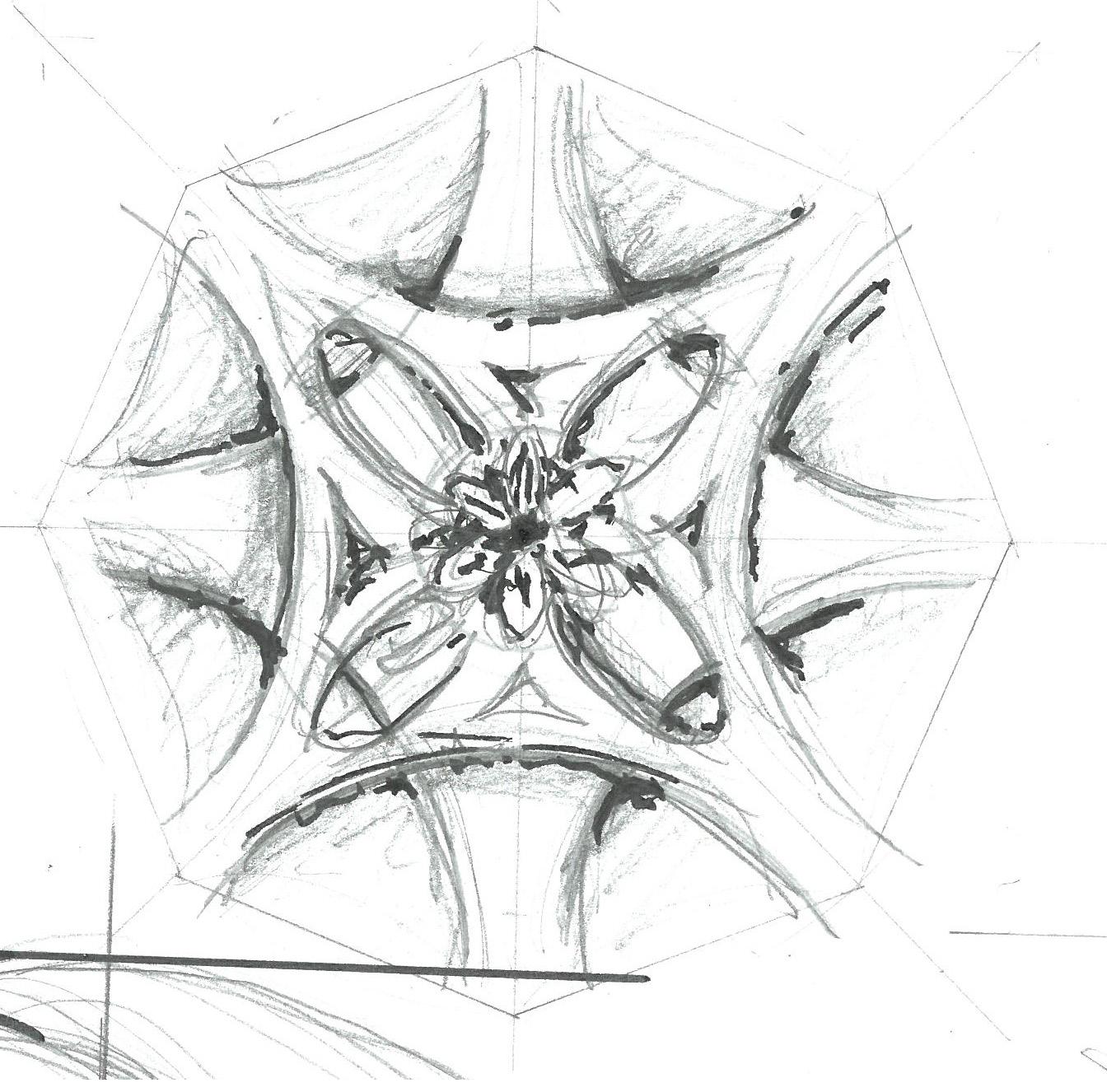

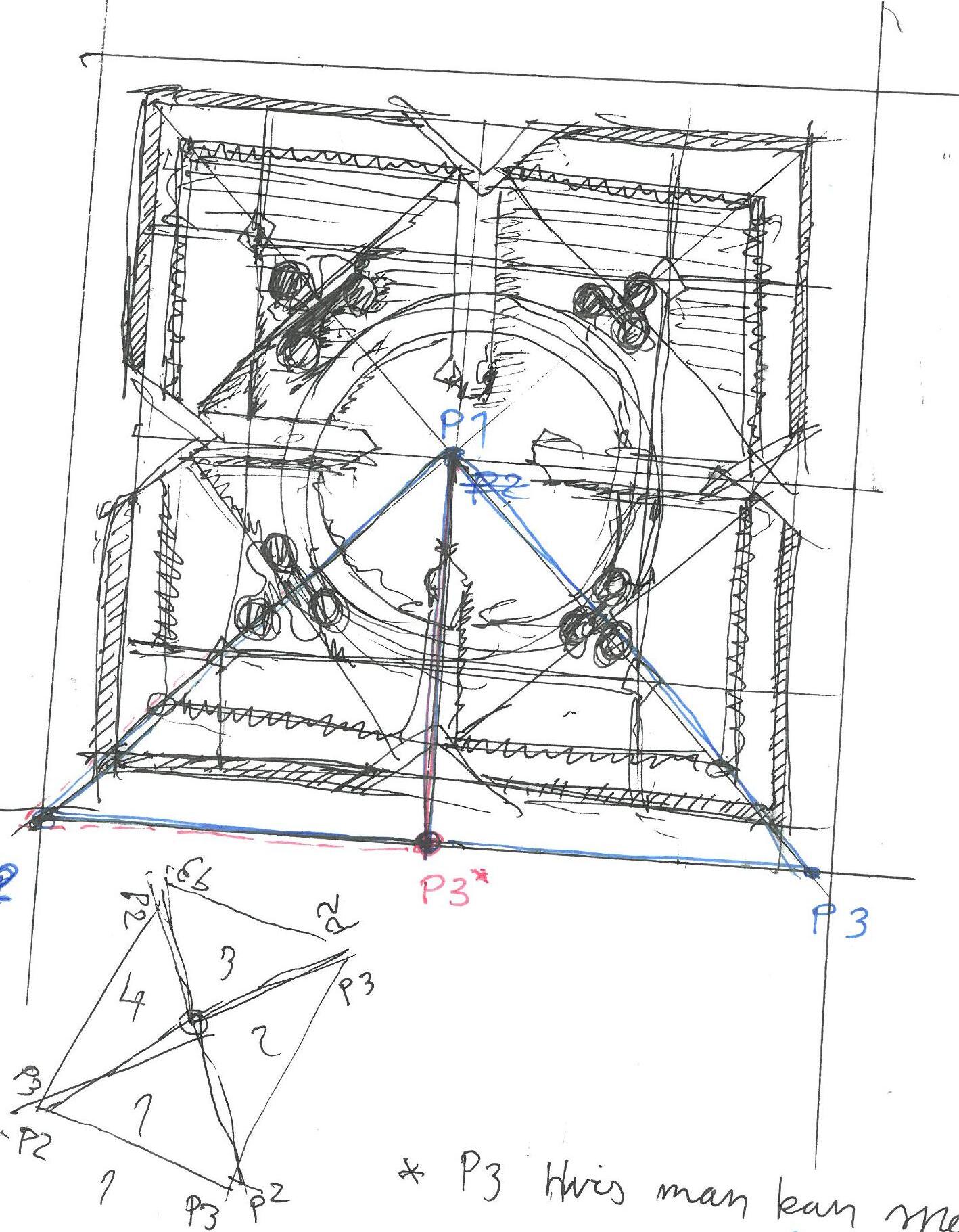

A system of architectural ornament

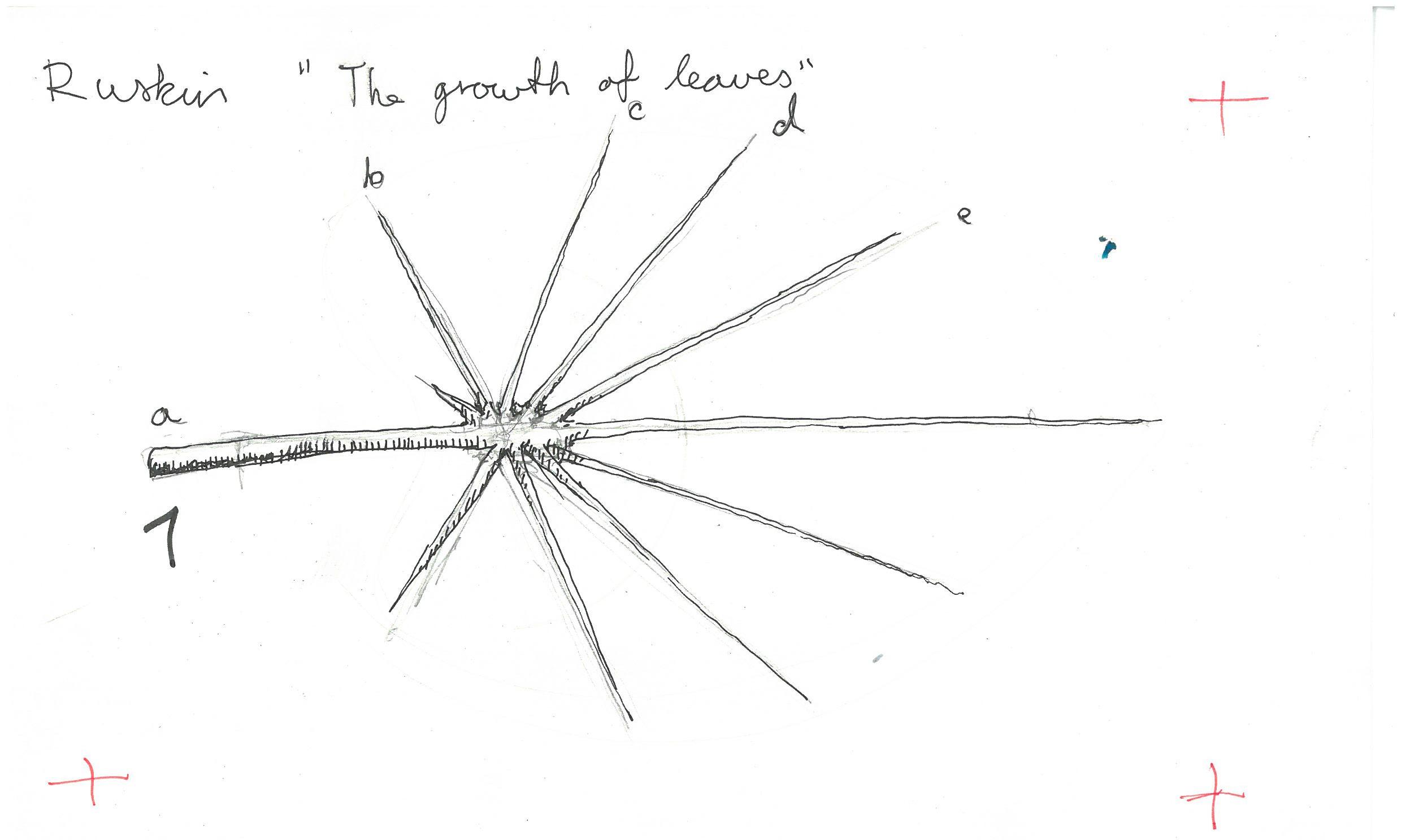

Sketches studying Sullivan and Ruskin

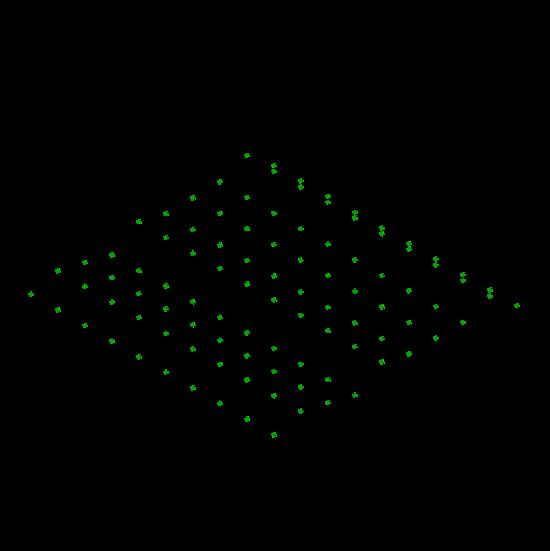

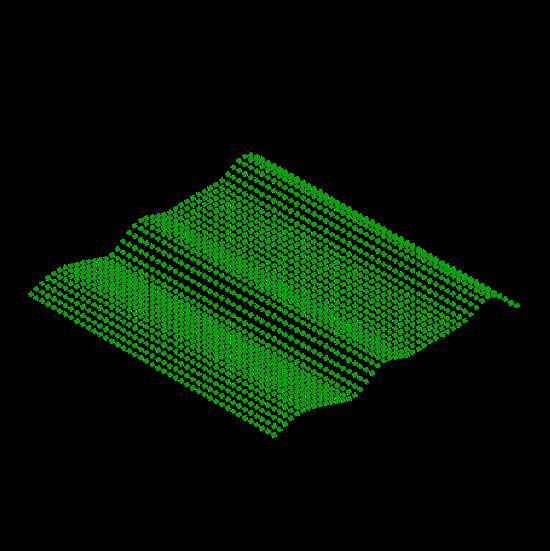

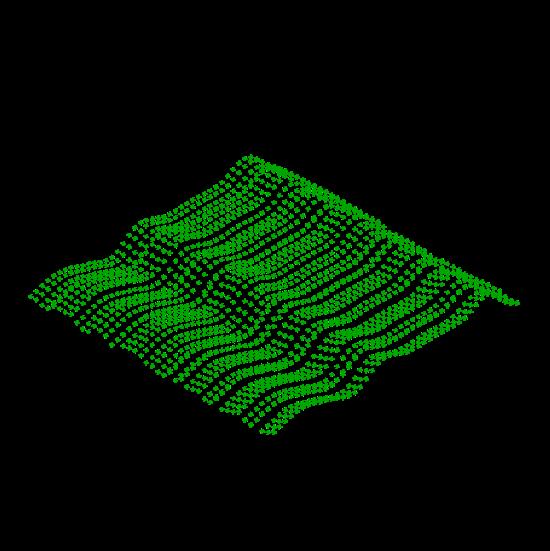

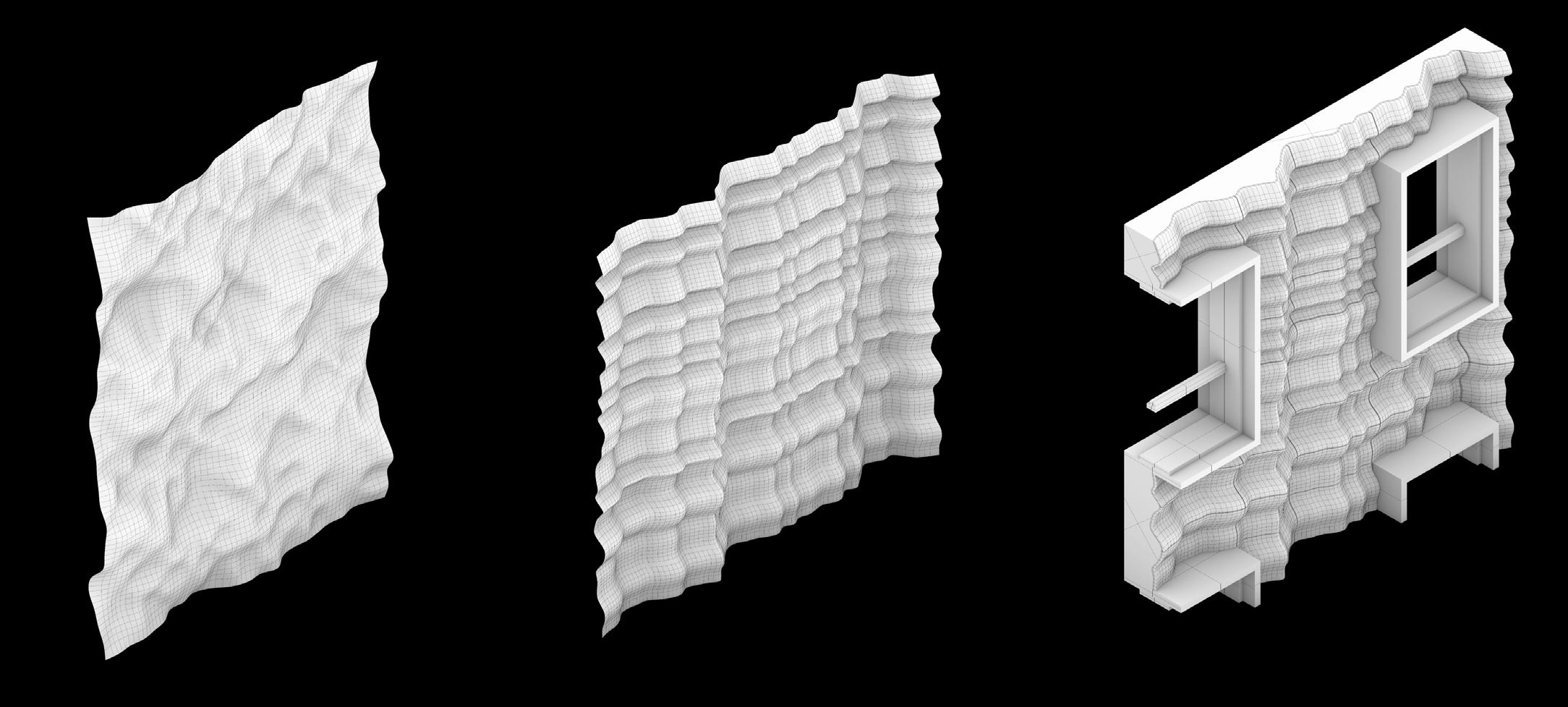

Perlin noise and controlled randomness

Move x rows random in z direction

Points with interpolated z values fill the spaces

Move y rows with random z value in a smaller range

Same for x rows

Self organization with rulebased simulation

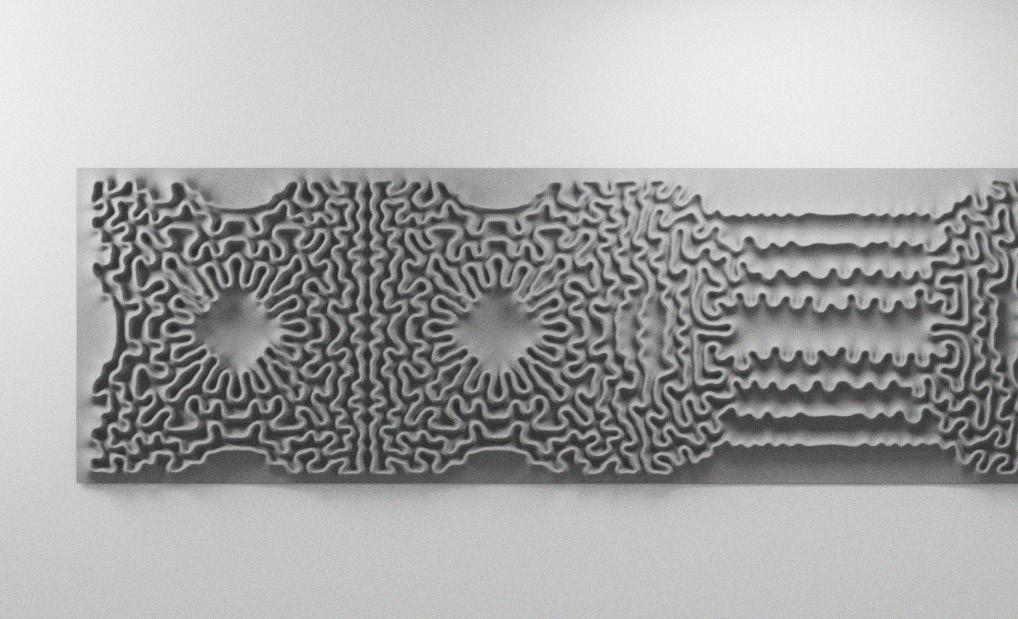

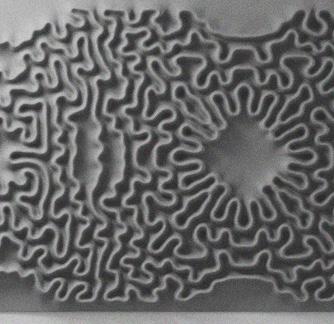

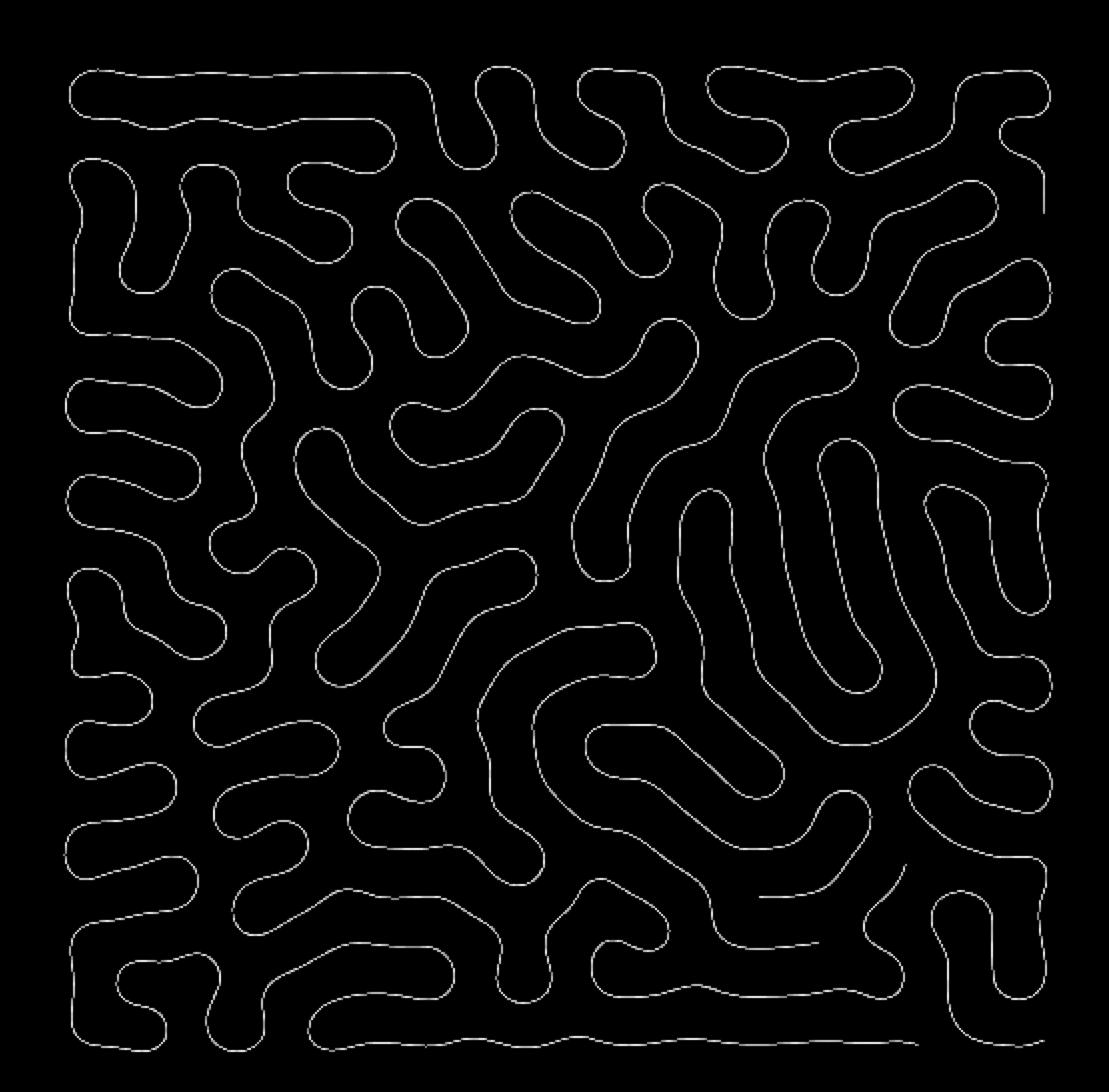

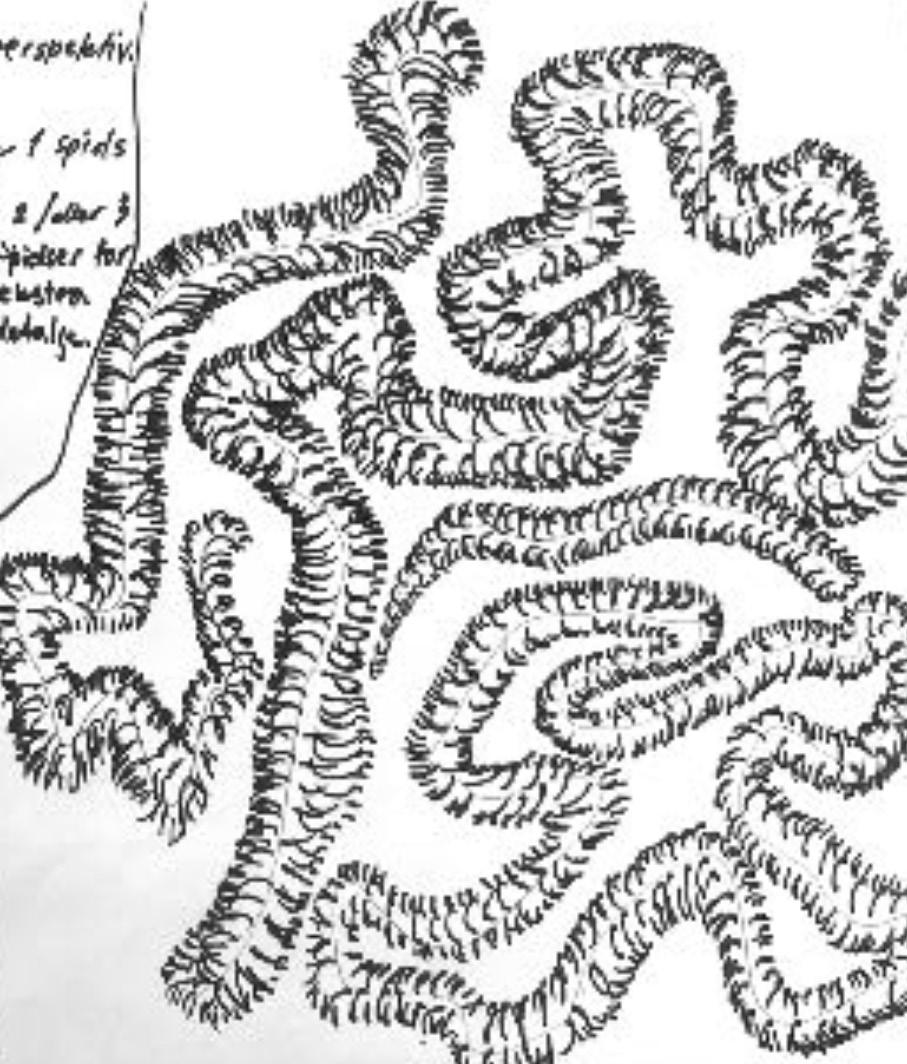

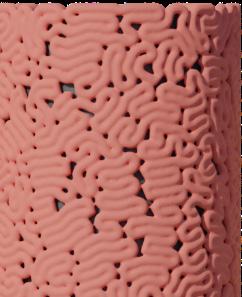

The next few pages is captured from the process of evolving a script for self organizining system. , I wished to explore an aesthetic inspired by nature. A complex, almost chaotic behaviour but guided by rule-set.

The curves will try to maximize their area and compete for space, resulting in a self organized pattern. The paramters can controll how far the curves could be apart before colliding or how many points each were divided into.

The same system of self organization can be found many places in nature, this specific script is inspired by the phenomena called reaction diffusion theorized by allen turing.

start posisjon

Astrid Specht Seeberg

Codeveloping a design with ceramic artist

Astrid Specht Seeberg is a young artist from the Copenhagen underground with a medium in ceramics.

She is self-taught with a degree from the Danish Design and Craft Continuation School in 2015/16. Her artistic career has gained momentum over the past year, and she has exhibited in the up-comming section of Kunst For Alle in Lokomotivværkstedet Curated by Connie Boe Boss, solo exhibition Galleri Symbol, and most recently had a major duo exhibition with Hanne Schmidt in Copenhagen’s well-known gallery Kbh Kunst.

Co-designing tools and toolpaths, artist working hands on as a creative director

Simulating toolpath to fit artist specification

Knife with designs-pecific profile

Knife with designs-pecific profile

First iteration, clay too wet and stuck to the tool. The tool also needed to be sharpened.

Second iteration with a more satisfactory result, in a third, adjusting the cutting could solve issue with breaking the cut geomtry.

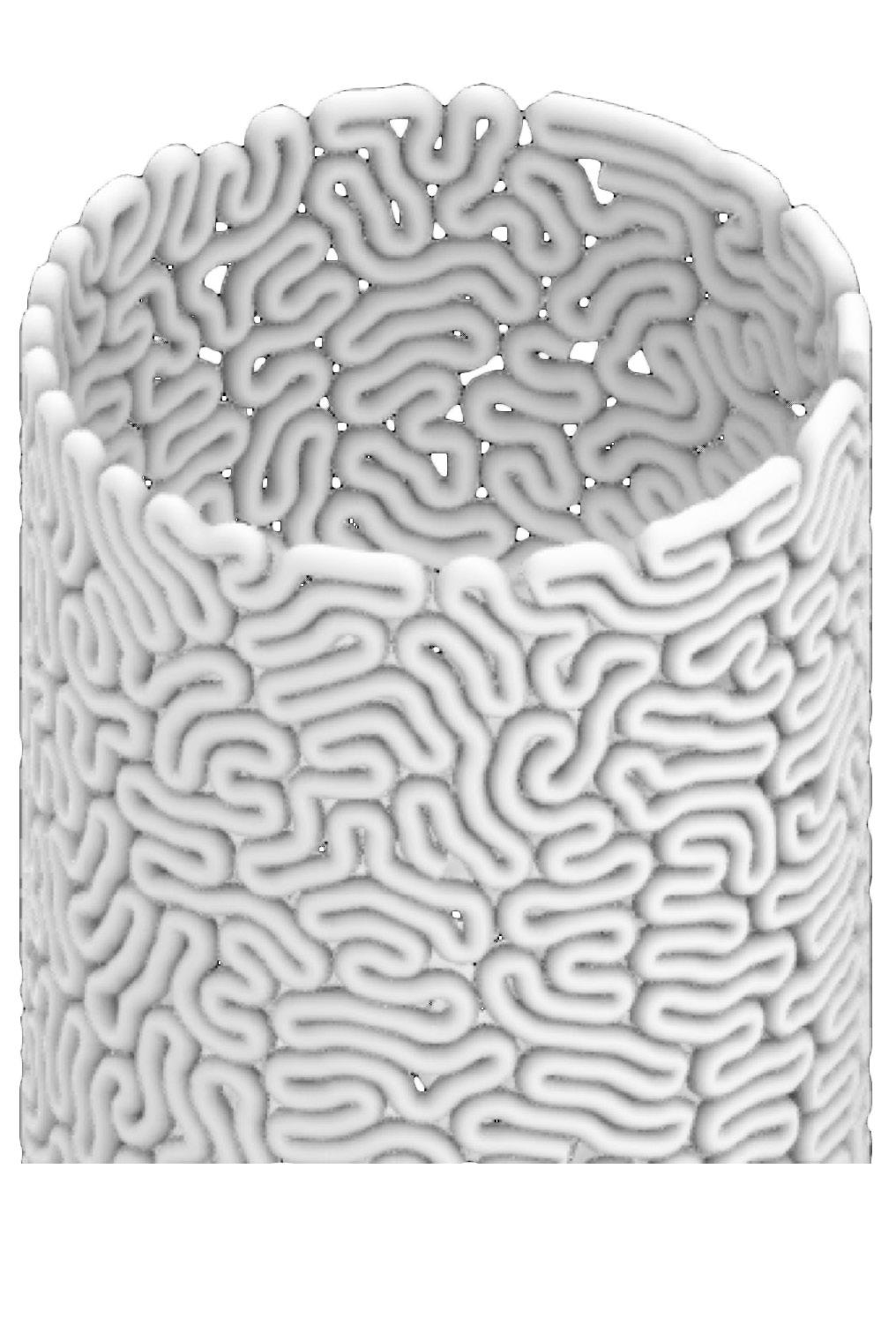

I made the decision to fabricate a full scale mockup of a column. All of my experiments so far had been done on flat tiles in a small scale, and as I saw it the best proof of concept for my system was a column. The column would challenge design, fabrication and assembly.

Translating concept to production

start posisjon

First iteration

Working together with Astrid to create the column, I made changes to the self organizing script i had made earlier to wrap around a column seamlessly.

start posisjon

Second iteration after Astrids feedback

Translating concept to production

We tried to get as close as possible to Astrids initial idea and aesthetic vision, making changes to the script after discussing the outcome -- often using 3D renderings of the tool-path to convey the progress.

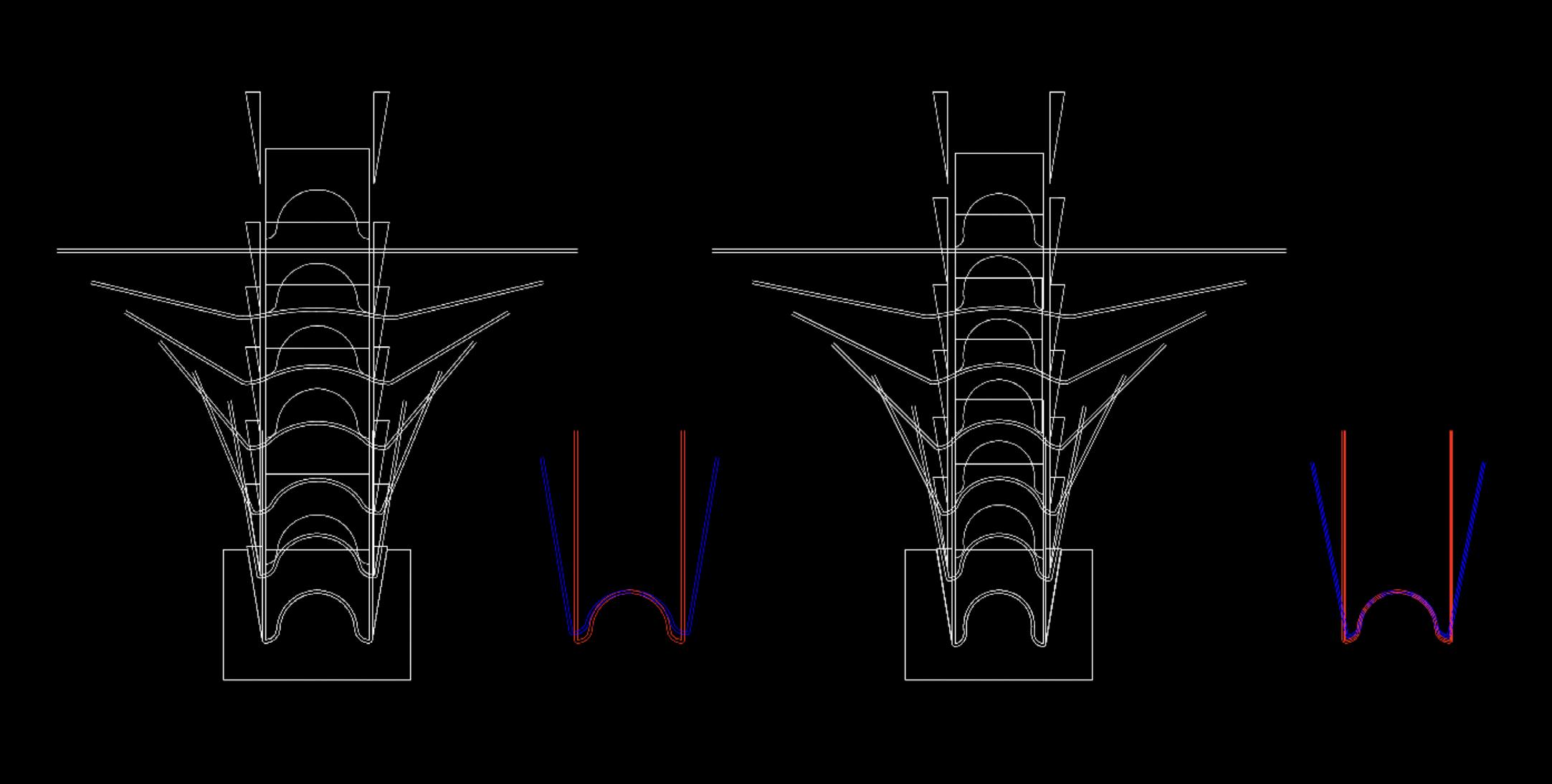

Dimensioning modules for production

To plan how to construct the modules of the column, some restraints had to be taken into account. The weight of each module, the appearance of the joined pieces, the size of the kiln, the reach of the robot, fastening methods etc.

Since the modules would be mounted on an inner column, at least two pieces is needed to make a cylinder, I made a study on elements that divided a cylinder into 2, 3 and 4 pieces.

I got to the conclusion that 3 pieces would work best with the constraints at hand. With 2 pieces the geometry would be fragile while drying and drastically limit the reach of the robot, as the normal direction at the extremes is horisontal.

Dividing into 2,3 and 4 pieces to test possibilites

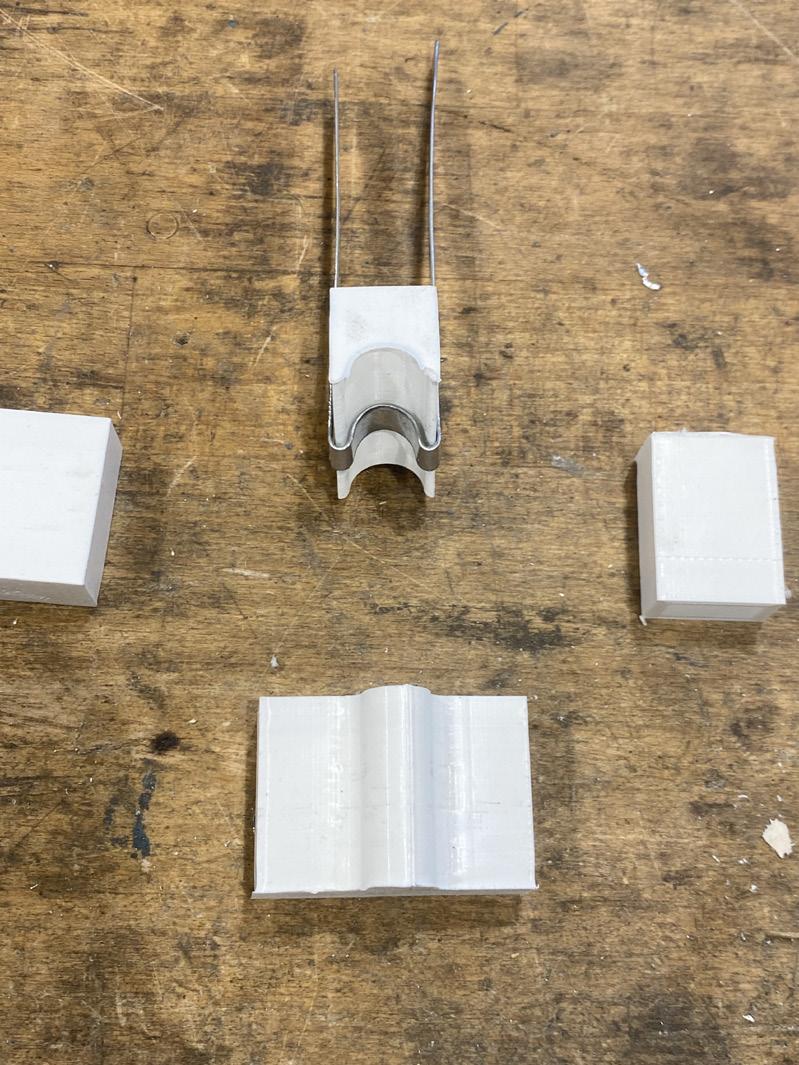

Plaster mould design

The original geometry would not be able to release from a plaster mould, to solve this the geometry of the flanges was changed.

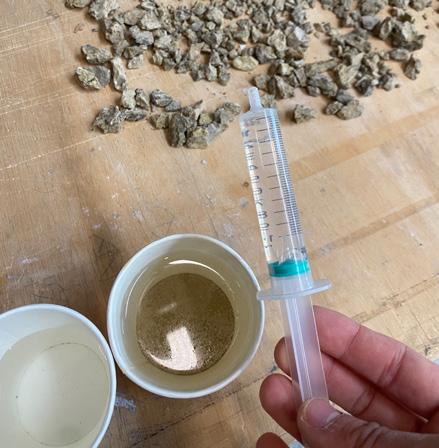

The optimal way to fabricate the modules is a clay extruder with a machined profile/die. The geometry is therefor designed with this constraint in mind as well. I dont have access to an extruder at this scale so instead i designed a mould to make in plaster.

The module can be released from the mould with the function and apperance intact

Dimensioning modules for production

Assembly diagram

Blank module from start to finish

Fabrication glazing

The Column Visualzation

Construction drawings

Pillar section

1:5