The Impact of Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine on Migration

Volume 69, Issue 6

page 40

SAVE THE DATE ANNUAL MEETING & CONVENTION SEPTEMBER 21-23, 2023 The Peabody Memphis • Memphis, TN www.fedbar.org/event/fbacon23 For available sponsorship opportunities contact sponsor@fedbar.org.

EDITORIAL BOARD

Editor in Chief Andrew Doyle andrew.doyle@usdoj.gov Associate Editor

James W. Satola jsatola@roadrunner.com

Managing Editor

Lynne G. Agoston (240) 404-6488 social@fedbar.org

Elizabeth Kelley

Peter M. Mansfield

Judicial Profile Editors

Hope Forsyth Hon. Karoline Mehalchick

Articles Editors

Kristine Adams-Urbinati

Anna Archer

Sara L. Gold

Niles Illich

Jon Jay Lieberman

Bruce A. McKenna

Jeffrie Boysen Lewis

Amanda Thom

Stewart Michael Young

Columns Editor

Ira Cohen

Senior Proof Editor

Ellen M. Denum

Proof Editors

Melanie L. Alsworth

Tamar Rebecca Birckhead

John Black

Leonid Feller

Reid Jones

Michelle Quist

Kirsten Samantha Ronholt

Benjamin R. Syroka

The Federal Lawyer (ISSN: 1080-675X) is published bimonthly six times per year by the Federal Bar Association, 1220 N. Fillmore St., Ste. 444, Arlington, VA, 22201 Tel, (571) 481-9126, Fax (571) 481-9090, Email: social@fedbar.org.

Subscription Rates: $14 of each member’s dues is applied toward a subscription. Nonmember domestic subscriptions are $50 each per year; foreign subscriptions are $60 each per year. All subscription prices include postage. Single copies are $5. “Periodical postage paid at Arlington, VA., and at additional mailing offices.” “POSTMASTER, send address changes to: The Federal Lawyer, The Federal Bar Association, 1220 N. Fillmore St., Ste. 444, Arlington, VA 22201.”

©2022 Federal Bar Association. All rights reserved. PRINTED IN U.S.A.

Editorial Policy: The views published in The Federal Lawyer do not necessarily imply approval by the FBA or any agency or firm with which the authors are associated. All copyrights held by the FBA unless otherwise noted by the author. The appearance of advertisements and new product or service information in The Federal Lawyer does not constitute endorsement of such products or services by the FBA. Manuscripts: The Federal Lawyer accepts unsolicited manuscripts, which, if accepted for publication, are subject to editing. Manuscripts must be original and should appeal to a diverse audience. Visit www.fedbar.org/ tflwritersguidelines for writers guidelines.

November/December 2022: Immigration Law

By Lauren Anselowitz

By Dr. Alicia Triche

By Francesca Braga

By Dr. Gavin Clarkson and Eric Smith

By Julie A. Werner-Simon

By Kyle R. Kroll and Alexander M. Johnson

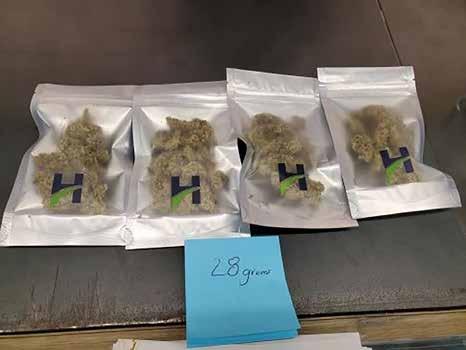

32 Through The Looking Glass: An Examination of Current Case Law as It Relates to Controlled Substances Offenses

40 The Impact of Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine on Migration

46 Fiduciary Imprudence: The Evolving Dynamics of the ERISA Battlefield

52 Four Ways to Mitigate Current Legal Risks in Pointof-Sale Financing So That “Buy Now, Pay Later” Doesn’t Lead to “Get Sued”

58 A Tale of Two Cases: Two Intrepid Women in the Sixth Circuit Move the Lever on Domestic-Violence-Based Asylum Law

64 Marijuana and the Noncitizen: Warning! The Same Rules Do Not Apply to You

Also in This Issue 76 Annual Meeting & Convention Recap 90 Meet Your Board Volume 69, Issue 6

Book Review Editors

November/December 2022 • THE FEDERAL LAWYER • 1

COLUMNS

3 President’s Message Making Progress

By Matthew Moschella

5 Beltway Bulletin Remarks on the Daniel Anderl Bill

PROFILES

28 Hon. Debra Ann Livingston Chief Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit By Phil Schatz

1220 N. Fillmore St., Ste. 444 Arlington, VA 22201

Ph: (571) 481-9100 • F: (571) 481-9090 fba@fedbar.org • www.fedbar.org

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

President • Matthew C. Moschella mcmoschella@sherin.com

President-Elect • Jonathan O. Hafen jhafen@parrbrown.com

Treasurer • Glen R. McMurry gmcmurry@taftlaw.com Hon. Alison S. Bachus bachusa@superiorcourt.maricopa.gov

Third Circuit

Christian T. Haugsby

Fourth Circuit

Kacy L. Hunt Fifth Circuit

Mark L. Barbre

Paul D. Barkhurst

Sixth Circuit Jade K. Smarda

Seventh Circuit Melissa Schoenbein Eighth Circuit

By

Hon. Bruce H.

Hendricks 8 At Sidebar Deep in the Heart of Texas: How Three Immigration Attorneys in Texas Are Making a Difference

BOOK REVIEWS

Ernest T. Bartol etbartol@bartollaw.com

Bonnie S. Greenberg bonnie_baltimore@yahoo.com

Anna W. Howard anna.howard@uga.edu

Joseph S. Leventhal joseph.leventhal@dinsmore.com

Adine S. Momoh adine.momoh@stinson.com

David A. Goodwin Ninth Circuit

Jody A. Corrales

Darrel J. Gardner

Tenth Circuit Kristen R. Angelos

Kate Simpson

Eleventh Circuit Lauren L. Millcarek

Oliver A. Ruiz III

By

Jeffrie B.

Lewis

and

Soledad Valenciano 13 Diversity & Inclusion It Takes a Village: The Promise of the Southern District of Florida’s Judicial Intern Academy to Inspire Mentorship and Leadership Through Service

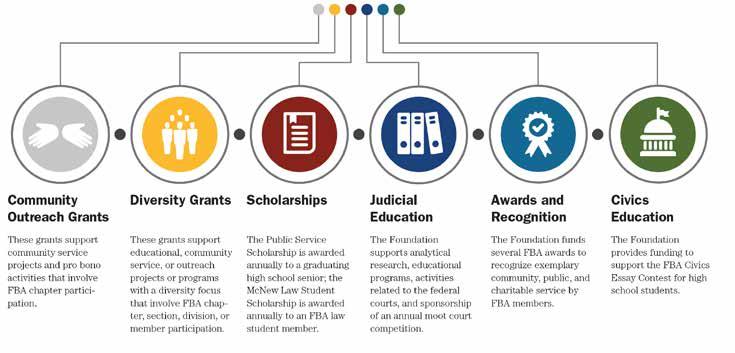

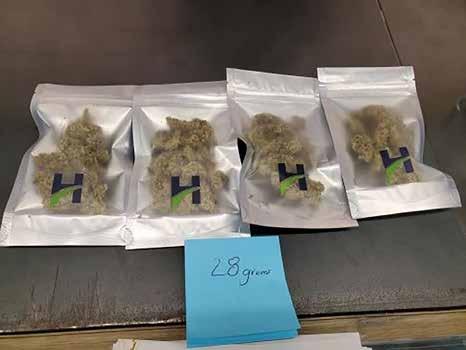

By Jonathan Osborne 16 From the Foundation It’s Not Your Grandfather’s Buick Anymore!

By Aaron Bulloff 18 Immigration Law Update Help! We Need a Doctor: How an Antiquated and Dysfunctional Immigration System Jeopardizes U.S. Healthcare By Tina R. Goel

In-House Insight Litigation in the Attention Economy: Developing Defenses to Social Media Addiction Claims

By Kyle W. Cunningham

By Kathleen Gasparian

Nancy Morisseau nancy.morisseau@nationalgrid.com

Michelle M. Pettit michelle.pettit@usdoj.gov

Rachel V. Rose rvrose@rvrose.com

Kelly T. Scalise ktscalise@liskow.com

Michael S. Vitale mvitale@bakerlaw.com

Ex Officio Members

Amy E. Boyle aboyle@mjsbjustice.com

Anh Le Kremer akremer@nystromcounseling.com

Scott P. Lopez splopez@lawson-weitzen.com Hon. Karoline Mehalchick karoline_mehalchick@pamd.uscourts.gov

Nathan A. Olin nate@oliplaw.com

NATIONAL STAFF

Executive Director Stacy King sking@fedbar.org Deputy Director R. Yvonne Cockram ycockram@fedbar.org

Director of Membership and Chapters Dominick Alcid dalcid@fedbar.org Managing Editor Lynne G. Agoston social@fedbar.org

Outreach and Foundation Manager Cathy Barrie cbarrie@fedbar.org

Program Coordinator, Membership & Events Marisa Beam mbeam@fedbar.org

Membership Coordinator Clarise Diggs cdiggs@fedbar.org Program Coordinator Daniel Hamilton dhamilton@fedbar.org

Director of Sections and Divisions Mike McCarthy mmccarthy@fedbar.org

Marketing Director Jennifer Olivares social@fedbar.org

Senior Conference Manager Caitlin Rider crider@fedbar.org

Leadership Support & Board Specialist

Shaniece Rigans srigans@fedbar.org

Program Coordinator, Conference & Webinars Nikki Toledo mtoledo@fedbar.org

Administrative Coordinator Kim Wonson kwonson@fedbar.org

Database & Technology Administrator

Miles Woolever mwoolever@fedbar.org

VICE PRESIDENTS FOR THE CIRCUITS

First Circuit Scott P. Lopez

Second Circuit Olivera Medenica Dina T. Miller

D.C. Circuit Patricia D. Ryan

SECTION AND DIVISION CHAIRS

Chair, Sections and Divisions Council

Nathan A. Olin

Admiralty Law Michelle Otero Valdes

Alternative Dispute Resolution James N. Downey

Antitrust and Trade Regulations Robert E. Hauberg Jr. Banking Law John Court

Bankruptcy Law Angela Sheffler Abreu Civil Rights Law Kyle J. Kaiser

Corporate and Association Counsel Lawson E. Fite Criminal Law Madison Bader

Environment, Energy & Natural Resources

Vacant

Federal Career Service Dina T. Miller

Federal Litigation Andrea L. Marconi

Government Contracts Vacant Health Law

Thomas S. Schneidau

Immigration Law

Kate Melloy Goettel

Indian Law Helen B. Padilla

Intellectual Property Law Oliver Alan Ruiz

International Law Bijan Kasraie

Judiciary Hon. Karoline Mehalchick

Labor and Employment Law Mary Augusta Smith Law Student

Jenifer Tomchak

LGBTQ+ Law

Mario Choi

Qui Tam Megan Mocho Securities Law

Vacant Senior Lawyers Albert Lionel Jacobs Jr.

Social Security Law Jerrold A. Sulcove

State and Local Government Relations Vacant

Taxation

Daniel Strickland

Transportation and Transportation Security Law Sarah Bell Nural

Veterans and Military Law Frank J. McGovern

Younger Lawyers

Amy E. Boyle

Federal Bar Association

22

26 Commentary 100 Years of Love in the Time of COVID

78 Real to Reel: Truth and Trickery in Courtroom Movies Reviewed by Henry Cohn 79 Retail Gangster: The Insane, Real-Life Story of Crazy Eddie Reviewed by Christopher Faille

90

96

98

99

100

105

DEPARTMENT 82 Supreme Court Previews FBA MEMBER NEWS

Meet Your Board

Chapter Exchange

Sections and Divisions

Hon. Constance Baker Motley Essay Competition

Member Spotlight

Calendar of Events

2 • THE FEDERAL LAWYER • November/December 2022

Making Progress

By Matthew Moschella

Matthew C. Moschella is chair of the Litigation Department at Sherin and Lodgen and a partner in the firm’s Litigation and Employment Departments. He represents companies and individuals in a wide variety of civil matters in state and federal courts across the country as well as in arbitration proceedings. Moschella also represents employers concerning complaints filed against them with state and federal administrative agencies. In addition to representing clients in various types of civil litigation, he counsels clients in a wide variety of industries on employment risk management issues. Moschella is also an adjunct professor at New England Law Boston, where he teaches contract drafting. Following law school, he was a law clerk to Hon. Judith Gail Dein, U.S. magistrate judge, U.S. District Court for the District of Massachusetts.

I am writing this installment during the first week of November (although you are likely reading it long after that) and reflecting on the super-productive first month of the FBA year, which was due to the excellent work of numerous FBA leaders and members across the country. Anyone who was at the annual meeting in Charleston, S.C., may remember that we talked about focusing on three areas this year: (1) being the dominating bar association presence at law schools across the country; (2) recognizing, supporting, and appreciating the broader court community; and (3) strategic membership placement by having current knowledgeable FBA leaders identify other potential leaders and members, connect them with the FBA, and get them placed in leadership roles that will maximize their interests and skillsets.

We are off to a great start on these areas. Regarding law schools, in October, the National Board of Directors voted to set the dues for law student membership at $0 for the duration of a joining member’s time in law school and—to facilitate the transition from law student member to the Younger Lawyers Division and professional member—for the year immediately following their graduation from law school (provided that they joined the FBA while in law school). This step will greatly facilitate the FBA’s ability to attract new law student members. In addition, there is a newly formed working group of national leaders holding key positions that meets regularly to collaborate and discuss steps for implementing a methodical outreach effort and plan to law schools across the country. This approach is already yielding helpful information and results.

The FBA has also continued to make great progress in recognizing, supporting, and appreciating the broader court community. The Clerk’s Committee of the Judiciary Division developed a new national award called the FBA Unsung Hero Award, which was created to honor a person whose work exemplifies the many individuals who ensure the safety and efficient operation of the federal judiciary. The Award will be presented annually to a member of the court community who, while serving in a nonlawyer or nonjudicial role at the local, state, or federal level, has—in service of the federal judiciary—demonstrated career contributions or exceptional heroics that have maintained and

improved the safety and functioning of the courts and the community at large. The National Board approved the award in October, and eligibility and nomination criteria will be announced soon. The FBA also took the lead in organizing a group of bar and judicial organizations to collectively support the Daniel Anderl Judicial Security and Privacy Act (which would prohibit federal agencies and private businesses from publicly posting certain personal information (e.g., home addresses) of federal judges and their immediate family members and also (1) requires information to be removed upon written request from the federal judge concerned, (2) prohibits data brokers from purchasing or selling such information, and (3) establishes programs to protect such information at the state and local level and to enhance security for judges). The collective efforts led to these organizations sending two jointly signed letters to members of Congressional leadership supporting the Act and advocating for its approval.

Getting to the other focus area—strategic membership placement—the question often comes up of what we should be telling prospective members about the benefits of the FBA and reasons to join. To assist us all in formulating responses to this frequently asked question, I asked a group of FBA past presidents—who know this organization inside and out—how the FBA has most benefited them in a specific and concrete way. They responded as follows:

• “As a judge for over two decades, the FBA has during this time served as a forum to exchange ideas with federal practitioners from across the nation as to how bench and bar can continuously support and improve our justice system.” (Hon. Gustavo Gelpi, Circuit Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit)

• “I cannot emphasize how important the FBA has been to my career. Simply put, I wouldn’t be a federal judge without all of my years of service in the FBA. I’ve been afforded leadership opportunities that I never otherwise would’ve had; I’ve made good friends from throughout the United States; and the FBA allowed me to have a civics platform, on a national basis, to work with young people to explain the important role of federal

President’s Message

November/December 2022 • THE FEDERAL LAWYER • 3

judges throughout the United States. I am forever grateful.” (Hon. Michael Newman, U.S. District Judge, Southern District of Ohio)

• “FBA membership—and particularly leadership at chapter, circuit, and national levels—permitted me to expand my professional experience and enjoyment beyond imaginable scope of what otherwise would have been available. There can be no substitute for opportunities such as personally meeting and having informal conversations with judges and other judicial officers, helping develop and promote legislative and regulatory improvements, and meeting and developing new and genuine friendships with colleagues all over the country.” (Robert Mueller)

• “Thanks to the FBA and the network it provides, I have access to top attorneys in other states who did exactly what I needed them to do—for example, closed a difficult and contentious real estate transaction, provided skilled co-counsel for defending a class action, provided a lovely conference room for a deposition and an arbitration, and took good care of referrals which resulted in very grateful clients.” (Joyce Kitchens)

• “Even though the FBA is a national organization, I found opportunity abounds for participation and leadership, for all.” (Juanita Sales Lee)

• “As Chairman of the Indian Law Section my name and position as an attorney for the civil rights division (USDOJ) was announced to the 750 attendees of our annual Indian Law conference three times a day which brought referrals to me of American Indian victims of civil rights violations; at my retirement the AAG for Civil Rights said I’d filed more cases on behalf of American Indians than any other attorney in the history of the Division, a direct result of being an FBA member.” (Lawrence Baca)

• “The FBA strengthened my personal and professional relationships with our local federal judges, before whom I still continue to practice. When I was president of the FBA in 2003, the organization jointly presented a white paper at the U.S. Supreme Court with the ABA to then-Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist, who was accompanied by Associate Justices Breyer, Kennedy, and Souter, concerning the pressing issue of federal judicial pay. The conference was undoubtedly a career highlight for me, but more importantly it allowed the FBA and the Chief Justice to speak as a

collective voice about an important issue that never ceases to resonate. Several judges in Dallas, and Justice Souter with a follow-up note, kindly thanked me afterwards for the work we do with the FBA, and it was only because of the opportunity the FBA offered me, particularly at a national level, that I was able to enhance my relationships with the federal bench and those fine people who work to support and sustain our court system.” (Kent Hofmeister)

• “The Federal Bar Association it’s a steal because it offers local chapters, substantive law sections, and a national organization at the lowest cost of any Bar Association in America.” (Robert De Sousa) “Membership in the FBA led to an invitation to speak at an annual, prestigious conference. Through that annual conference, I was fortunate to meet a long-term, repeat client. Membership in the FBA helped me to better serve a Fortune 150 client by having relationships with trustworthy and effective local litigation counsel in cities throughout the United States.” (Maria Vathis)

• “Being involved in the Federal Bar Association over my career has given me the opportunity to build lifetime friendships with those serving within our national legal community, from America’s Judicial, Legislative, and Executive Branches of government to its law schools, private corporations, legal organizations, and non-profit organizations that seek to improve our system of justice and increase understanding of our U.S. Constitution. One could not hope for better friends.” (West Allen)

• “As in-house counsel, I have relied on my FBA network to assist me with legal matters throughout the United States. I’ve hired counsel for employment and litigation matters through my FBA connections and importantly, have also had the ability to pick up the phone informally and run things by attorneys who know the local laws and landscape better than I do, which has helped me provide better guidance to my company. It’s been a big “value add” for me.” (Anh Le Kremer)

Hopefully these responses and insights can assist us all in approaching and recruiting new members to involve them in the FBA, and in working with existing members to get them placed in key leadership positions to best maximize their interests and skill sets.

Get Published in The Federal Lawyer The Federal Lawyer strives for diverse coverage of the federal legal profession, and your contribution is encouraged to maintain this diversity. Writer’s guidelines are available online at www.fedbar.org/tflwritersguidelines. Contact social@fedbar.org or (240) 404-6488 with topic suggestions or questions. 4 • THE FEDERAL LAWYER • November/December 2022

Remarks on the Daniel Anderl Bill

By Hon. Bruce H. Hendricks

Guest columnist Hon. Bruce H. Hendricks is a U.S. district judge for the District of South Carolina and former U.S. magistrate judge of the same court. Judge Hendricks served as an assistant U.S. attorney for 11 years before her appointment as magistrate judge in 2002. As magistrate judge, she presided over the first drug court program in the District of South Carolina, which Attorney General Eric Holder praised as “a national model.” Nominated for a seat on the U.S. District Court for the District of South Carolina by President Obama in 2013, Judge Hendricks was confirmed by a vote of 95-0, a tally not often seen in judicial confirmations these days. She is the first woman from Charleston to serve on the federal bench.

Note: At the FBA’s Annual Meeting in Charleston, S.C., Judge Bruce Hendricks delivered the following inspiring remarks, not only urging support for the Daniel Anderl Judicial Privacy and Security Act, but also calling on each of us, as members of the bar, to address the root of the increase in attacks on our judiciary: pervasive mistrust in our institutions of government. As Judge Hendricks eloquently explains, “[w]e are curators of the public trust and the rule of law,” and we must “practice in such a way that people accept justice even when they don’t prefer it.”

It’s an honor to address you all on this account.

Of course, I did invite myself.

I looked around at our Board of Directors for the South Carolina Chapter, which is apparently literally every member of our chapter, … and, I didn’t see anyone who could stop me. Certainly not Beattie Ashmore. Now our national president, Ms. Kremer, maybe. But she has no jurisdiction here. This is still South Carolina.

And, even Trey and Bakari, who are certainly rockstars, have long since abandoned any real power in Article I or General Assembly authority. So, it was pretty much an unimpeded waltz to the dais today to say whatever it was that I preferred.

I would sincerely like to thank the federal bar and our local chapter. For this event every year. For your undying support of the federal judiciary. Our chapter is relentless in offering service however they can. For mentoring programs. For CLEs. For our federal drug court program. For our practitioners and court personnel. And, I would especially like to thank them for giving me some time today to discuss something that has become increasingly personal for me.

As you know, the Daniel Anderl Judicial Security and Privacy Act is pending in the Senate. The Bill is named after U.S. District Judge Esther Salas’s late son, Daniel Anderl, who was shot at their home in New Jersey. The assailant was disgruntled over one of her honor’s rulings. The Act proposes to shield the personal information of jurists in order to better protect against such attacks. It restricts the ability of public and private entities’ ability to publish the personal information of federal jurists. It is a kind of anti-doxing bill. The bill has been hung up in some of the typical

machinations of our legislative process. I wanted to share briefly about it with you today. I think it is important on a few fronts.

I’d like to first express my desperate condolences to Judge Salas and her husband—who was also shot in the incident—for their unspeakable loss. As a mother and grandmother, I cannot imagine. I have gotten to know her some recently as a colleague and friend, in her grief, and this shared and sacred duty to do justice. It is a tragedy for them that has touched me deeply. Unfortunately, the Salas’s story is not aberrational. There have been other high profile and lesser known attacks on, or inappropriate contacts with, judicial officers, court personnel, and their families, federal and state. And, indeed the rate of such incidents have spiked in just 7 short years from only 768 in 2014 to 4500 in 2021. A rubicon has certainly been crossed.

But, it feels a little self-serving to ruminate on judicial security, as a judicial officer. We take these jobs for their tremendous privilege—but unequivocally knowing their tremendous personal risk. Accepting, the presidential nomination is caveat emptor so to speak. We can’t say that we didn’t know.

And, we also cannot say that our safety is not already a national priority. Our benches are bullet proof. Entry into our courthouses is well managed. There is an entire federal agency tasked with protecting us around the clock. Court security dutifully escorts us wherever we fancy, whenever we like. Marshalls are at our door the moment a threat materializes. I have an adventure dog, Henry, who is with me at all times, and I work out with nine personal trainers, give or take. I’m not asking for trouble, but I grew up fist fighting boys and my brothers, and I am no damsel in distress.

And, so these remarks are not an appeal about physical protection, necessarily. Although, the lives that might be saved are worth every bit of ink in the bill, on their own accord. And, I only wish that Daniel could be returned to his grieving parents.

But, truthfully, my concerns are not about personal threats. They are about democratic, indeed constitutional, ones. I am not a sociologist. And, this is not a Netflix docuseries on the evils of social media or the conspiracy hives occupying the deepest parts of the web. But, you don’t have to be a culture expert to know we are at a moment of pervasive mistrust.

Beltway Bulletin

November/December 2022 • THE FEDERAL LAWYER • 5

Mistrust in information. Mistrust in others. Mistrust in institutions and government. Mistrust in the court system. We can’t even be sure that the video or audio we see and hear is authentic or whether it’s a deep fake cooked up by your middle schooler on Tik Tok. It’s a kind of collective information vertigo. And, it’s driving us mad.

Jon Jay said in some enumerated Federalist Paper, “Distrust naturally creates distrust, and by nothing is good will and kind conduct more speedily changed.” Our pervasive distrust is a direct threat to civilized society and the constitutional institutions and procedures upon which it operates.

All my family are lawyers. Almost anyone else would probably be ashamed to confess it. But, it’s my every personal pride. Some of the most prominent litigators in this State’s history are my forebears. It’s all I ever wanted to do. Skipping class to run down to the courthouse and watch my dad in closing argument through courtroom door window. I was raised to believe we were the good guys.

We wax romantic about our profession and those more convivial and philosophical days. But, I still genuinely believe it about us. We are curators of public trust and the rule of law. We occupy authority and power in every quadrant of society and business and government. We are front-line ambassadors to the world on essentially every issue that matters. So how we behave, and the accuracy of our speech, matters. There is no system. We are the system.

And, so, we are stereotypically and historically perceived as part of the problem. And, indeed institutions, including our own profession, offend. Communities of color. Historically marginalized groups. Their distrust has been regrettably hard earned. It’s not based on some collective delusion or dizziness algorithmed by Twitter or YouTube. That kind of distrust is justified.

But, I know we, as lawyers, are well suited to be a part of the solution – for both justifiable and unjustifiable mistrust. We have to renew a commitment to conduct and language which resurrects trust in our institutions and each other.

Let our consultations be earnest. Don’t treat clients like a “mark,” I’ve heard Frank Eppes say.

Let our arguments be authentic. Don’t treat the court like a fool. Let our prosecutions be proportionate. Don’t treat defendants like numbers.

Let our orders be human. Don’t treat the public like a transaction. Let us practice in such a way that people accept justice even when they don’t prefer it, which is essentially every single time

There are so many simple and everyday ways for us to help restore order and some sense of stability.

Our chapter of the Federal Bar has an amazing civics program. Its aim is to help reraise the lost collective IQ in how federalism and a democratic republic works. FDR summarized this need well, “Democracy cannot succeed unless those who express their choice are prepared to choose wisely. The real safeguard of democracy, therefore, is education.”

Ironically and sadly, it was a lawyer disgruntled with one of Judge Salas’s rulings who shot Daniel. Among probably other things, he suffered the vertigo. He couldn’t figure out which end was up.

It is very frustrating being a lawyer. You are at our mercy. The mercy of our rulings. The mercy of our power. The mercy of our sometimes, maybe often, ignorance. I really get it. Your practice feels

like a swirling cauldron of irrationality. But, your training is specifically in sense making. You know how to bring order to intellectual chaos. To reduce complexity to usable paradigm, like a—I don’t know—a McDonald Douglas burden shifting scheme, for example. It’s what you do. The insanity of a right or left wing extremist podcast is no match for the unique musings of a pro se 1983 filing.

The point being—your skills in reason and sense making have never been more needed. Let us turn it back again on each other and the world. To restore hope to those offended and order to those who think there is simply none left.

The Daniel Anderl bill is definitely about human safety. As tough as I think I am, unlike the bench I sit behind, I am unequivocally not bullet proof. The special and important lives of Daniel and so many others might have been spared for the protections it would now propose.

And, we can lead by supporting it. I’d simply ask today that you educate yourself about the Bill and then encourage others, in power and elsewhere, to do the same.

But, you know this. The very worst use of your legal practice is you. The personal gain and the prestige, it’s not our calling. We will do Daniel and ultimately free society, the most justice, if we practice and work in a way that begins to slowly unwind this public distrust which is so much the real source of all kinds personal and physical risk in our country - from the courthouse to the schoolhouse. When we set our sense making loose on the world again, we will safeguard democracy and hopefully protect many lives in the process.

Thank you again to the Federal Bar and for your kind attention and time today.

Editorial Policy

The Federal Lawyer is the magazine of the Federal Bar Association. It serves the needs of the association and its members, as well as those of the legal profession as a whole and the public.

The Federal Lawyer is edited by members of its Editorial Board, who are all members of the Federal Bar Association. Editorial and publication decisions are based on the board’s judgment.

The views expressed in The Federal Lawyer are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the association or of the Editorial Board. Articles and letters to the editor in response are welcome.

6 • THE FEDERAL LAWYER • November/December 2022

HYBRID QUI TAM CONFERENCE FEBRUARY 16-17, 2023

New Frontiers:

Redefining

the Landscape of the FCA

Join the Qui Tam Section for its Annual Qui Tam Conference on Thursday, February 16 – Friday, February 17. This year’s hybrid program offers in-person or online viewing options for registered attendees.

This annual event, dubbed “the Oscars for False Claims Act nerds” by a 2020 panelist, provides timely perspectives from all sides of the FCA ecosystem: prosecutors, relator-side attorneys, defense counsel, inspectors general, federal judges, and in-house counsel. Register

Today at https://www.fedbar.org/event/quitam23 Rates Increase after Friday, January 20!

Deep in the Heart of Texas: How Three Immigration Attorneys in Texas Are Making a Difference

By Jeffrie B. Lewis and Soledad Valenciano

One can hardly turn on the news without hearing something about the immigration crisis in America. How one defines crisis, however, is a matter of perspective. Texas is undoubtedly one of the key southern border states affected by the social and economic effects of immigration. For example, one in six Texas residents is an immigrant, while another one in six residents is a native-born U.S. citizen with at least one immigrant parent.1 At least 1.4 million U.S. citizens in Texas live with at least one undocumented family member.2 And, Texas is home to over 107,000 Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) recipients.3 Economically, immigrants in Texas have contributed tens of billions of dollars in taxes, and as consumers, add over $100 billion to Texas’s economy.4 According to the Brookings Institution, immigrants are essential to the U.S. workforce, and without them, the aging workforce cannot meet the U.S. economy’s capacity.5 Yet, the influx of people crossing into the United States through Texas border towns has been linked to property damage, an increase in crime, and a sense of danger.6 With immigration being such a hot-button issue, and immigration law practiced within the Department of Justice regime, it is no wonder that the good work—no, the great work—of our fellow practitioners and the reforms they seek go relatively unseen and unheard.

Jeffrie B. Lewis is assistant general counsel at Zachry Group in San Antonio. Soledad Valenciano practices commercial and real estate litigation with Spivey Valenciano, PLLC, in San Antonio. ©2022 Hon. Jeffrie B. Lewis and Soledad Valenciano. All rights reserved.

U.S. immigration law is based on the following principles: the reunification of families, admitting immigrants with skills that are valuable to the U.S. economy, protecting refugees, and promoting diversity.7 In line with these principles, the “transactional” side of immigration law is made up of the family-based immigration system, the employment-based immigration system, refugee/asylee protection, and diversity.

As an initial matter, once a person obtains an immigrant visa and comes to the United States, they become a lawful permanent resident (LPR). In some circumstances, noncitizens already in the United States can obtain LPR status through a process known as “adjustment of status.” LPRs are eligible to apply for nearly all jobs and can remain permanently in the United States even if they are unemployed. After residing in the United States for the required period, LPRs may apply for U.S. citizenship. The family-based immigration system allows U.S. citizens and LPRs to bring certain family members to the United States. Prospective immigrants and the relative(s) in question in the family preference system must meet standard eligibility criteria, and petitioners must meet certain age and financial requirements.

Immigrants with valuable skills may enter the United States on either a permanent or temporary basis under a program known as employment-based immigration. This process allows employers to hire and petition for foreign nationals for specific jobs for limited periods. There are numerical caps and strict requirements to follow.

Refugees are admitted to the United States based on an inability to return to their home countries because of a “well-founded fear of persecution” due to their race, membership in a particular social group, political opinion, religion, or national origin. The admission of refugees depends on numerous factors, such as the degree of risk they face, membership in a group that is of special concern to the United States, and whether they have family members in the United States. Asylum is available to individuals already in the United States who are seeking protection based on the same five protected grounds upon which refugees rely. Refugees and asylees are eligible to become LPRs under certain circumstances.

Although not currently used as often, the Diversity Immigrant Visa Program was created by the Immigration Act of 1990 as a dedicated channel for immigrants from countries with low rates of immigration to the United States. Applicants from qualifying countries must have a high-school education (or its equivalent) or have, within the past five years, a minimum of two years working in a profession requiring at least two years of training or experience. There are other forms of relief, including temporary protected status, which is granted to people who are in the United States but cannot return to their home country because of “natural disaster,”

At Sidebar

8 • THE FEDERAL LAWYER • November/December 2022

“extraordinary temporary conditions,” or “ongoing armed conflict.” Another program, deferred enforced departure, protects individuals from deportation when the home country is unstable. DACA and humanitarian parole are other options for immigrants who wish to remain in the United States.

In contrast to the systematic methods of entry into the United States described above, there is the body of immigration law that involves noncitizens who have been charged by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) with violating immigration law.8 When DHS does not have the authority to administratively deport an individual, it brings the matter to the immigration court and asks an immigration judge to issue a removal order authorizing DHS to deport that individual. Immigration court is an administrative court within the Department of Justice responsible for adjudicating immigration cases, where immigration judges resolve issues such as:

• Whether an individual should be allowed to remain in the United States.

• Whether an individual’s application for relief from deportation (removal) should be granted.

• Whether a detained individual should be allowed to post bond or whether the bond amount should be changed.

Unlike defendants in criminal courts, immigrants—even unaccompanied children—have no legal right to an attorney in cases of indigency. Cases generally begin when Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officials or Customs and Border Protection agents issue a “Notice to Appear” to an individual and then file the notice with the immigration court. Appeals of immigration judge decisions can be made to the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA). Some BIA decisions can be appealed by immigrants further to the federal courts. Both the immigration court and the BIA are part of the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) within the DOJ, while criminal and civil courts are part of the United States judicial branch.9 The immigration court system employs approximately 600 trial immigration judges and 23 immigration appeals judges.10 There are over 60 U.S. immigration courts, with 13 in Texas alone.11 Approximately 1.7 million cases are now pending before approximately 600 immigration judges nationwide, which is an average of over 2,800 pending cases per judge.12

Whether one practices immigration law on the “transactional” or the “litigation” side of the law, the technical, political, and emotional complexity of this bursting-at-the-seams practice area is shocking.13 Wanting to learn more about this practice area, we interviewed three immigration attorneys located in South Texas to get their perspective on their practices, their clients, and the immigration system in general. What we heard from these attorneys was informative, heartbreaking, and inspiring, all at the same time. Each attorney is a female solo practitioner whose practice focuses primarily if not exclusively in immigration law. Their backgrounds varied, but their motivations were similar.

For Analisa Nazareno, once a journalist for the Miami Herald and the Philadelphia Inquirer, this is a second career.14 Nazareno immi-

grated from the Philippines as a child and grew up in the immigrant suburbs of Los Angeles. Nazareno’s practice focuses on affirmative family-based applications and naturalization and humanitarian relief, including asylum and Violence Against Women Applications. Her main docket currently includes assisting Afghan asylum seekers following the evacuation of Afghanistan.

Jacqueline Sandoval15 has offices in deep South Texas in the area known as “the Valley,” where she primarily handles family-based applications and assists clients seeking immigration relief for family members or based on marriage, with some asylum cases.

Ofelia Delgado,16 whose studies have taken her to Wisconsin, California, New Orleans, and now Texas, handles naturalizations; adjustments of status; DACA proceedings; and waivers for criminal convictions, bars to reentry, and unlawful presence charges. Delgado’s practice is primarily transactional work centered around the Department of State and U.S. Citizen and Immigration Services (USCIS) where she assists her clients in adjusting their status outside of immigration court.

Immigration law is extremely complex and circumstance driven. Several bodies of law determine what relief, if any, can be sought. Generally, the overarching law discussed above is found in the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA),17 which the practitioners we interviewed referred to as the “bread and butter” of immigration law. However, immigration law practitioners must stay abreast of frequent changes from other directions (e.g., the availability or unavailability of certain relief that changes from presidential administration to administration, internal political pressure, other orders that change the priority of applications). The law on asylum applications, for instance, is primarily found outside the INA. Moreover, the federal court system issues rulings affecting the types of relief that can be sought. For example, a recent Fifth Circuit opinion regarding DACA has the potential to change the entire existence of the program.18 One of the lawyers we interviewed noted that, at a minimum, something “significant” changes every quarter.

As far as processing and granting or denying relief, two avenues exist there as well. The USCIS is granted the governmental authority to process immigration applications.19 It is largely transactional and it processes the forms, sometimes with large backlogs depending on the type of relief sought. For example, according to the data maintained by USCIS, the time for processing a petition for an alien relative in Texas who is an unmarried child 21 years or older is 32 months.20 The other avenue is the immigration court system.21 Each of the immigration practitioners we interviewed expressed a general feeling that immigration court is not where a lawyer would want their client to be. In fact, at least one of their practices (Delgado’s)

November/December 2022 • THE FEDERAL LAWYER • 9

Jaqueline Sandoval (left), Analisa Nazareno (middle), and Ofelia Delgado (right).

is specifically focused on moving clients out of immigration court to seek relief through the USCIS transactional process.

Even if you do not specifically practice immigration law, immigration influences are bound to impact matters. For example, we discussed the overlap of immigration and criminal law, or “crimmigation” law as our immigration practitioners referred to it. The effect of a conviction for even a relatively minor misdemeanor charge can have devastating consequences on a client seeking adjustment of immigration status. In some cases, even the charge of criminal activity can have a consequence. Our practitioners described scenarios for their clients in which they are arrested on minimal criminal charges and are checked and cross referenced with ICE to determine status, where previously there was no question about their legal status. They described scenarios where family members pay a bond to get them out of county jail, only to have them immediately released from custody to ICE, which has a second detainer bond placed on them, unbeknownst to the family that paid the initial bond to have them released. The result is that they are picked up by ICE; taken to the nearest detention facility, wherever that may be (sometimes hundreds of miles away); and held there indefinitely while the detained family member awaits an immigration court date, thereby missing their court date on the underlying criminal offense and leading to convictions that all but destroy the ability to seek certain immigration relief. We all know that a basic tenet of the U.S. criminal justice system is the presumption of innocence. But how does that tenet stand when intermixed with immigration considerations?

With immigration law constantly changing and evident in different bodies of law, what is a practitioner to do who may find themselves occasionally handling matters that overlap with immigration law? First, the attorneys we interviewed suggested a USCIS listserv that will send an email update any time there is a decision affecting any application.22 They suggested that criminal law attorneys be familiar with orders and priorities issued by presidential administrations. They stressed the importance of Padilla letters based on the 2010 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Padilla v. Kentucky23 where the Court held there is a right to know the immigration consequences of entering a guilty plea to a criminal charge. A criminal defense attorney can ask their clients to obtain a Padilla letter from an immigration attorney and advise the client of the consequences of a criminal conviction on their future ability to seek immigration relief.

What cannot be understated is the emotional toll taken on attorneys specializing in immigration law. We know too well the statistics of mental health of the legal profession in general.24 In her practice assisting asylum seekers, Nazareno recounted watching her clients cry when recalling how they witnessed others being killed, including members of their own family. The process for relief for these clients often relies heavily on evidence to demonstrate they are entitled to the relief sought. Her clients are repeatedly forced to relive the most painful, traumatic events they have ever experienced, in excruciating detail. Then, they must reduce it to writing in a declaration and study it in preparation for the hearing, where they are scrutinized in order to establish the requirements needed for a waiver or for asylum.25

Delgado recounted her assignment to a children’s detention center that housed child gang members. She explained how these children, hailing from countries like Honduras and El Salvador, were stolen away from their families and forced to join gangs and commit awful atrocities to avoid their own deaths or the deaths of their families at the hand of the gang members who abducted them. Reliving

these memories with her clients brought on terrible nightmares for which she sought counseling to process.

But each of these attorneys expressed their love for their job. Nazareno stated that as a second career, it was important for her to be happy. She did some research before embarking on her second career and found that amongst lawyers, immigration lawyers are the happiest. She reflects that her clients are good and humble people who need advocacy, and that it feels good to help people in need. Delgado shared a story where she assisted a survivor of domestic abuse from an ex-boyfriend and was able to get her a green card and, afterwards, the same relief for her now-husband and father of her children based on her status. After finally receiving her green card, Delgado’s client was able to go back to Mexico to see her mother after 20 years, and her mother was able to meet her grandchildren for the first time.

Sandoval states that immigration was a place where her heart laid, noting she herself is from a border town and her grandparents were migrants. It is important for her to speak up for those who do not know the language or the laws and to be the voice that her family needed for a very long time. Sandoval shared a story about assisting a Liberian client with his application under the Liberian Refugee Immigration Fairness Act (LRIF).26 Under the LRIF, if you are Liberian and have lived a certain number of years in the United States, you are eligible for a green card if you meet certain qualifications. She tells us this particular client had suffered unspeakable violence in his home country, witnessing his sister raped and butchered in front of him, his brother beheaded, and the rest of his family tortured and killed. Thereafter, he was taken as a slave until he escaped and was able to flee the country, eventually arriving in the United States. Putting together this client’s application required him to recount and relive all the atrocities he had witnessed. An affidavit from his wife about the effects these experiences had on him was required. After the application was submitted, all that was left to do was wait. Sandoval recalls sometime later, while on vacation, she began receiving multiple calls. Immediately thinking something was wrong, she was overjoyed to find out her client’s application had been granted. She spoke with her client, who was crying uncontrollably, and he told her he was able to save his babies and his family by being permitted to stay in the United States and was so grateful. Our interviewees recognize that their work is at times emotionally daunting and taxing, but at the same time, they all reflected that keeping families together and seeing the joy and relief they bring to their clients makes it all worth it.

What do these immigration attorneys want to see changed for their practice or their clients? Sandoval noted that the remote options COVID-19 brought to the legal profession have greatly improved her practice and her ability to assist clients in ways she could not before. Client meetings and audiences with a judge have been made easier with platforms such as WebEx and Zoom. Both Delgado and Nazareno mentioned the uncertain course of DACA and the desire for clarification as well as updates to the asylum laws.27 All three practitioners expressed frustration with the sometimes draconian nature of some immigration laws. Delgado spoke to us about the heartbreaking time she had to inform a young client that she would be ineligible for relief. The client, who sought Delgado’s assistance in adjusting her status, was a legal permanent resident who had lived in the United States since she was an infant. She spoke little Spanish and attended elementary, middle, and high school in Texas. One day, the high school she attended hosted a program to encourage students of age to vote. The client, having grown up in the

10 • THE FEDERAL LAWYER • November/December 2022

United States and mistakenly believing she was a U.S. citizen, signed up to vote. Unfortunately, a law bars individuals from naturalization if they have ever told anyone they are a U.S. citizen when they are in fact not. There is no exception for a mistake. Delgado had to explain to her young client that due to an innocent mistake she made in high school, she was not entitled to the relief she was seeking.

More generally, all three lawyers struggle with the misunderstandings, misconceptions, and misinformation surrounding immigrants and immigration law. With no signs of immigration efforts slowing down and the constantly evolving nature of immigration law, we need to be aware of the effect of immigration on our fellow practitioners, our profession, our communities, our country, and the individuals seeking entry into the United States. While the world is made better by practitioners such as Nazareno, Sandoval, and Delgado, their devotion and stamina should not be taken for granted. It takes heart to do what they do each day. So, if economic studies prove correct, the national economy could benefit from a targeted immigration reform policy while simultaneously improving the delivery of just legal services to an important population.

Endnotes

1Immigrants in Texas, Am. Immigr. Council. (Aug. 6, 2020), https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/sites/default/files/ research/immigrants_in_texas.pdf

2Id.

3Id

4Id

5The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit public policy organization based in Washington, D.C., whose mission is to conduct in-depth research that leads to new ideas for solving problems facing society at the local, national, and global level. According to the May 2022 data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, there were over 11.2 million job openings, with significant gaps in construction, retail trade, accommodation, and the food services industry. It is believed that immigration reform that facilitates an immigrant workforce will help the U.S. economy. See Dany Bahar & Pedro Casas-Alatriste, Who are the 1 million missing workers that could solve America’s labor shortages?, Brookings Inst. (July 14, 2022), https://www.brookings.edu/blog/ up-front/2022/07/14/who-are-the-1-million-missing-workers-thatcould-solve-americas-labor-shortages/.

6James Barragán, Republican county officials in South Texas want Gov. Greg Abbott to deport migrants. Only the federal government can do that, Texas Trib. (July 5, 2022, updated July 6, 2022), https://www. texastribune.org/2022/07/05/texas-migrants-deportation/.

7How the United States Immigration System Works, Am. Immigr. Council. (Sept. 14, 2021), https://www. americanimmigrationcouncil.org/sites/default/files/research/how_ the_united_states_immigration_system_works_0.pdf

8Immigration Court Primer, TRAC Immigr., Syracus Uni., https:// trac.syr.edu/immigration/quickfacts/about_ eoir.html (last visited Oct. 22, 2022).

9An Article 1 Immigration Court-Why Now is the Time to Act, A Summary of Salient Facts and Arguments, Nat’l Assoc. of Immigr. Judges (Feb. 20, 2021), https://www.naij-usa. org/images/uploads/ newsroom/Article_1_-_NAIJ_summary-of-salient-facts-andarguments_2.20.2021.pdf.

10Board of Immigration Appeals, U.S. Dep’t of Just., https://www. justice.gov/eoir/board-of-immigration-appeals-bios (last visited

Oct. 24, 2022) (including biographical information for immigration appeals judges); Office of the Chief Immigration Judge, U.S. Dep’t of Just., https://www.justice.gov/eoir/office-of-the-chiefimmigration-judge-bios (last visited Oct. 24, 2022) [parenthetical].

11EOIR Immigration Court Listing, U.S. Dep’t of Just., https:// www.justice.gov/eoir/eoir-immigration-court-listing (last visited Oct. 24, 2022).

12Executive Office for Immigration Review Adjudication Statistics, U.S. Dept. of Justice, https://www.justice.gov/eoir/page/ file/1242166/download (last visited Oct. 24, 2022) (listing 1,699,636 cases pending at the end of the fiscal year as of the third quarter of 2022 based on data generated July 15, 2022).

13In Feb. 2022, the FBA announced its support of legislation introduced by Rep. Zoe Lofgren, D-Calif., chair of the House Immigration and Citizenship Subcommittee, that seeks to establish independent immigration courts under Article I of the Constitution. See FBA Statement on Rep. Zoe Lofgren’s (D-CA) Independent Immigration Courts Legislation, Fed. Bar Assoc. (Feb. 2, 2022), https://www.fedbar.org/government-relations/policy-priorities/ article-i-immigration-court/

14Nazareno graduated cum laude from St. Mary’s University School of Law in San Antonio, where she gained practical experience in the Immigration and Human Rights Clinic, served as an editor and writer for the St. Mary’s Law Journal, founded the Immigration Law Students Association, and earned the Women in Law Leadership Award and Pro Bono and Public Service certificate. Nazareno interned at the Executive Office of Immigration Review, serving as a clerk in the Pearsall Immigration Court, Texas’s Fourth Court of Appeals, the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, and American Gateways, doing asylum rights workshops for women in immigration detention facilities in South Texas.

15Sandoval graduated cum laude from the University of Texas Pan American in 2014, only two years after graduating with honors from Johnny G. Economides High School. She went on to work at the Texas State Capitol during the 2015 legislative session and subsequently attended St. Mary’s University School of Law in San Antonio. Sandoval was a student attorney at the St. Mary’s Center for Legal and Social Justice Immigration Clinic, where she completed over 140 pro bono service hours, earning the Pro Bono and Public Service Certificate. 16Delgado graduated from the University of Wisconsin (Madison) with a B.S. in sociology, behavioral science, and law. While at the University of Wisconsin, Delgado founded La Semana Chicana Conference and the Tiahui Mentorship Program. She earned her M.A. in sociology from the University of California (Santa Barbara), where she was the recipient of the Center for Chicano Studies Graduate Research Award and the Sociology Graduate Fellowship Award. Delgado earned her J.D. from Loyola University New Orleans College of Law. Prior to opening a solo practice, Delgado worked for the Refugee and Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services, a 501(c) (3) nonprofit agency that provides free and low-cost legal services to underserved immigrant children, families, and refugees.

17The Immigration and Nationality Act, 8 U.S.C. §§ 1101-1537.

18Texas v. U.S., No. 21-40680, 2022 U.S. App. LEXIS 27845, __ F.4th __ (5th Cir., Oct. 5, 2021).

19On Mar. 1, 2003, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) officially assumed responsibility for the immigration service functions of the federal government. The USCIS was formed to enhance the security and improve the efficiency of national

November/December 2022 • THE FEDERAL LAWYER • 11

immigration services by exclusively focusing on the administration of benefit applications. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and Customs and Border Protection, components within DHS, handle immigration enforcement and border security functions. See U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Fed. Reg., https://www. federalregister.gov/agencies/u-s-citizenship-and-immigrationservices (last visited Oct. 24, 2022).

20Check Case Processing Times, https://egov.uscis.gov/processingtimes/ (last visited Oct. 24, 2022).

21How the United States Immigration System Works, Am. Immigr . Council (Sept. 14, 2021), https://www. americanimmigrationcouncil.org/sites/default/files/research/ how_the_united_states_immigration_system_works_0.pdf; see also Immigration Court Primer, TRAC Immigr., Syracus Uni., https:// trac.syr.edu/immigration/quickfacts/about_ eoir.html (last visited Oct. 22, 2022).

22You can sign up for email alerts on the USCIS.gov website at https://www.uscis.gov/news/alerts.

23Padilla v. Kentucky, 559 U.S. 356 (2010).

24See, e.g., Anh Kremer, President’s Message – COVID and Beyond, Fed. Bar Assoc. (Feb. 7, 2022), https://www.fedbar.org/blog/ covid-and-beyond/ (president of the FBA Anh Kremer’s message noting that an ALM Mental Health and Substance Abuse Survey in 2021 found that 31.2% of 3,800 respondents feel depressed, 64% feel they have anxiety, and 10.1% feel they have an alcohol problem).

25Asylum in the United States, Am. Immigr. Council., https://www. americanimmigrationcouncil.org/sites/default/files/research/

asylum_in_the_united_states_0.pdf (providing an overview of the asylum system in the United States, including how asylum is defined, eligibility requirements, and the application process), (last modified Aug. 16, 2022).

26For more information on LRIF see Liberian Refugee Immigration Fairness, https://www.uscis.gov/green-card/green-card-eligibility/ liberian-refugee-immigration-fairness (last visited Oct. 24, 2022).

27For more commentary on the recent Fifth Circuit DACA decision see Uriel J. García, DACA remains intact as appeals court sends case challenging its legality back to lower court in Texas, Texas Trib. (Oct. 5, 2022), https://www.texastribune.org/2022/10/05/texas-dacaappeals-court-ruling/.

AL | CO | D.C. | GA | LA | MA | MS | NC | NM | NY | PA | SC | TN | TX | VA | UK | SG YOU CAN STAY IN YOUR LANE. OR YOU CAN SET THE PACE. We’re law. Elevated. See the difference at BUTLERSNOW.COM At Butler Snow, our attorneys have the specialized knowledge and depth of experience to predict trends and anticipate challenges before they become obstacles. 12 • THE FEDERAL LAWYER • November/December 2022

It Takes a Village: The Promise of the Southern District of Florida’s Judicial Intern Academy to Inspire Mentorship and Leadership Through Service

By Jonathan K. Osborne

Jonathan K. Osborne is a shareholder and co-chair of the White-Collar Defense & Internal Investigations Practice Group at Gunster law firm. Previously, he served as a Criminal Division assistant U.S. attorney in the Southern District of Florida.

Osborne serves in the FBA’s Broward County Chapter as the chapter’s national delegate. ©2022 Jonathan K. Osborne. All rights reserved.

There are many inspiring quotes about the virtues of service. Martin Luther King Jr. said, “Life’s most persistent and urgent question is, ‘What are you doing for others?’” and “Everybody can be great … because everybody can serve.” Mother Teresa said, “Never worry about numbers. Help one person at a time, and always start with the person nearest you.” Anne Frank said, “How wonderful it is that nobody need wait a single moment before starting to improve the world.”

And on leadership, John C. Maxwell has explained that “A leader is great not because of his or her power, but because of his or her ability to empower others” and that “leadership is influence.” There is a U.S. district judge in Miami who personifies these principles and, through her service and leadership, is multiplying leaders while inspiring future generations of attorneys. That judge is Hon. Beth Bloom.

A graduate of Broward Community College, Judge Bloom received her undergraduate education at the University of Florida and attended the University of Miami School of Law. Judge Bloom’s judicial career began at the state level in 1995 and, on Feb. 6, 2014, President Barack Obama nominated her to serve as a U.S. district judge for the Southern District of Florida. She received her judicial commission on June 25, 2014, and, in the ensuing years, has presided over numerous significant cases.

The focus of this article, however, is what she has done for our bench and bar—and the students and aspiring lawyers of our community—and how her example can galvanize generational progress in federal jurisdictions around the country with respect to mentorship and leadership.

The Key Roles of Federal Law Day and Civil Discourse and Decisions in Fostering Mentorship in the Southern District of Florida

For many years, U.S. courts have participated in Law Day, which was established by President Dwight D. Ei-

senhower in 1958 to celebrate the role of law in American society. Federal courts, including in the Southern District of Florida, have also participated in Civil Discourse and Difficult Decisions (CD3), a national initiative of the federal judiciary, which brings high school and college students into federal courthouses to tackle legal issues youth face. Both Law Day and CD3 facilitate student interactions with judges, court personnel, private attorneys, and representatives from U.S. Attorney’s and Federal Public Defender’s offices. In our district, Judge Bloom spearheads Law Day and works with federal judicial colleagues in Broward and Palm Beach counties to deliver the CD3 program, with help from local FBA chapters. These programs teach about the role of law in society and introduce students from various communities—across a wide range of backgrounds—to the court.

Law Day and CD3 are also inspirational. These programs have inspired me to be grateful for the mentors

Diversity & Inclusion

November/December 2022 • THE FEDERAL LAWYER • 13

who have enriched my life and career and to become a leader who, like Judge Bloom, serves with humility, commitment to excellence, a team mentality, and vision.

Feedback from the 2021 Law Day program, which was held via Zoom due to the pandemic, illustrated the impact of the program on students. Last year, through the leadership of the court and Stephanie Turk, a shareholder at Stearns Weaver Miller, Law Day touched nearly 1,000 students across Miami-Dade, Broward, and Palm Beach counties. In providing feedback, students indicated they learned, among other things, that with hard work and dedication, you can achieve your goals and aspirations. Another student remarked that Law Day was a “once in lifetime opportunity.” A teacher from a participating school remarked that she appreciated that Law Day offered students “an opportunity to hear from attorneys that looked like them and had different backgrounds that [her] students could relate to and be inspired by.” These examples demonstrate the value of our court’s outreach to high school students, many of whom aspire to careers in law enforcement, law, and other forms of public service. Moreover, Judge Bloom’s latest project, the Judicial Intern Academy, holds great promise for the development of our youth and federal bar.

The Judicial Intern Academy Motivates Service at Every Level of the South Florida Federal Legal Community Research on the value of mentorship shows that “[m]entoring relationships are critical to launch successful careers in law and, at a minimum, necessary to adequate career development in law.”1 It is also widely understood that, in the law firm context,

A good mentor acts as an advisor, teacher, exemplar, and career advocate. A good mentor can also acquaint a new associate with firm culture and client relations, and can help groom the associate for partnership. The road to success is often paved by a good mentor.2

More broadly, quality mentorship offers strategies for managing job demands, provides advice on how to balance work and family demands, models ethical behavior, communicates values of the legal profession, and “lend[s] meaning to work through demonstration of its broader social worth.”3

Judge Bloom’s Judicial Intern Academy—which launched in summer 2022 in its pilot stage—demonstrates the power of the federal judiciary to advance mentorship and teach leadership through creativity and inclusion. Designed to offer the benefits of a federal judicial internship to rising 2Ls who are unable to devote their summer to a full-time unpaid judicial internship, the inaugural Academy paired each of its 18 participants with a former federal law clerk. The former clerks, who now work in state and federal government agencies and an array of law firms, served as law clerk advisors (LCAs), volunteering their time to supervise the interns. As far as workload, the Academy asked each student to draft a proposed order and argue an issue at a mock hearing, with the goal of developing recommendations for the court and producing a writing sample. In addition to the tremendous value generated by these assignments and relationships with the LCAs, the Academy leveraged the court’s ties to our legal community to expose the interns to the litany of career options available and invited judges, court personnel, and federal practitioners from varied backgrounds to the mentorship table.

To that end, a highlight of the program included an initial session about the work of the court, ethics, and wellness. Over the course of the ensuing eight weeks, interns attended federal civil, criminal, and bankruptcy proceedings as well as a naturalization ceremony, and at the state level, they attended civil, criminal, juvenile, and family proceedings. Among the summer’s invaluable experiences, the Academy convened “Conversations with the Court” and “Meet and Greets” with more than 20 federal circuit, district, magistrate, bankruptcy, and immigration judges as well as state judges. Each week also featured “Learning from the Legends” sessions with renowned and emerging leaders of the federal bar who discussed their careers and offered advice to the interns. Through sessions on practical topics like preparing for on-campus interviews and maximizing law school, the Academy also provided practical tools for success. Impressively, Judge Bloom and her team accomplished all this while she maintained her active docket and hosted full-time interns in chambers.

The Promise of the Judicial Intern Academy Judge Bloom herself said it best:

Creating the Judicial Intern Academy allows the Court to provide intern opportunities for a greater number of law students and to reach out to more law schools. Many students are unable to devote their entire summer to an internship because of financial or other personal reasons but still want to learn and grow.¼The Academy will allow more law students to learn about our judicial system, meet dedicated members of our court family, and hopefully become inspired about their futures.

And in a profession that continues to confront how to foster a diverse and inclusive legal community, resources like the Academy illustrate the capacity for federal courts to leverage their role in society and legal communities to inspire, equip, and mentor future lawyers while multiplying leaders across the bench and bar by inviting us to serve.

Endnotes

1Fiona M. Kay, John Hagan, & Patricia Parker, Principals in Practice: The Importance of Mentorship in Early Stages of Career Development, 31 L. &Pol. 69 (2009).

2Elizabeth K. McManus, Intimidation and the Culture of Avoidance: Gender Issues and Mentoring in Law Firm Practice, 33 Fordham Urb. L.J. 217, 219 (2005).

3Fiona M. Kay, John Hagan, & Patricia Parker, Principals in Practice: The Importance of Mentorship in Early Stages of Career Development, 31 L. &Pol. 69, 74 (2009).

14 • THE FEDERAL LAWYER • November/December 2022

Register Today! LABOR & EMPLOYMENT LAW CONFERENCE FEBRUARY 23–24, 2023 San Juan Marriott Resort & Stellaris Casino San

Rico www.fedbar.org/event/labor23 The Labor and Employment

biennial

labor

employment

REGISTRATION Standard Rates apply after Friday, January 27. $405 Sustaining Member $425 FBA Member $345 FBA Section Member $525 Nonmember $375 Government/Academic $120 Law Student

Juan, Puerto

Law Section’s

conference returns to San Juan, Puerto Rico! During this one and a half-day conference, leaders in

and

matters will address compelling and timely topics of interest to practitioners. In addition to ample networking opportunities, this conference will provide educational insight on current hot topics in the field.

It’s Not Your Grandfather’s Buick Anymore!

By Aaron Bulloff

Without law, civilization perishes.

—Talmud

As of Oct. 1, I became president of the Foundation of the FBA board of directors, and it is my intention to write about the Foundation in each edition of The Federal Lawyer while holding the position.

Aaron Bulloff is a long-tenured FBA and National Council Member who has held numerous chapter and national positions. He is a Charter Life Member of the Foundation’s Fellows and in 2015 received the Earl Kintner Award.

The FBA has had a Foundation since 1954. While its assets have changed dramatically over the last several years, its mission has not wavered:

• Promote and support legal research and education.

• Advance the science of jurisprudence.

• Facilitate the administration of justice.

• Foster improvements in the practice of federal law.

The Foundation is a congressionally chartered 501(c)(3) organization. Title 36, United States Code, Section 70502 (2) states its purpose:

To apply its income, and if the corporation so decides, all or any part of its principal, exclusively to the following educational, charitable, scientific, or literary purposes, or any of them: (a) To advance the science of jurisprudence; (b) To uphold high standards for the Federal judiciary and for attorneys representing the Government of the United States; (c) To promote and improve the administration of justice, including the study of means for the improved handling of the legal business of the several Federal departments and establishments; (d)

To facilitate the cultivation and diffusion of knowledge and understanding of the law and the promotion of the study of the law and the science of jurisprudence and research therein, through the maintenance of a law library, the establishment of seminars, lectures, and studies devoted to the law, and the publications of addresses, essays, treatises, reports and other literary works by students, practitioners, and teachers of the law.

For many years, however, the Foundation could not advance its mission or further its purposes very well. It simply did not have assets to do so; they primarily consisted of some plaster busts of eminent jurists and old law books. And then, at a watershed time, former national FBA president Bob McNew took it upon himself to raise funds for the Foundation. His persistent, relentless, arm-twisting efforts coupled with a favorable investment climate and the astute guidance of the Foundation’s investment managers culminated in the successful realization of a corpus goal of $1 million. We were on the map, and we could start properly funding worthy programing and scholarships. Then, within the last two years, through the incredible largesse of the Federal Bar Building Corp. (FBBC), distributions from the FBBC’s investment portfolio to the Foundation have helped us more than double our corpus.

The stewardship of these funds has been overseen by the Foundation’s board, but I wish to give a special shout out to the two long-tenured board members whose terms ended Sept. 30: Sharon O’Grady and Henry Quillian. Some of you may not know them, but for several years they helped raise, invest, and distribute Foundation funds in such impactful ways. We technically lose incredible institutional knowledge, but I am asking them to continue to assist the board as we move forward. I also wish to acknowledge Judge Pamela Mathy’s completion of her board presidency on Sept. 30. I am space-limited to give her all the kudos to which she is entitled for her calm, quiet leadership that always found consensus among any disagreement. For small feet, she has amazingly large shoe steps to follow.

It is now my great pleasure to introduce the four individuals whom the National Council elected to new board membership at the 2022 Annual Meeting and Convention. They are Bruce Moyer, who just finished an open term and now succeeds himself to a full term; David Guerry; Erin Brown; and Cal Chipchase. They arrive at an incredible time for the Foundation and the association. With the pending sale of the business condominium that has housed the FBA’s headquarters, further distributions by the FBBC may be forth-

From the Foundation

16 • THE FEDERAL LAWYER • November/December 2022

coming. We are working with a strategic planner to help us chart a proper, even more impactful course through a post-pandemic legal world. What a time for them to come on board!

Everyone knows Bruce. He retired last year as the FBA’s government relations counsel after 25 years of service. Here is what he says regarding his election:

I became a member of the Federal Bar Association in 1975 and have served as a leader, volunteer, and donor to the Foundation ever since. Back in the 1990s I served on the board of the Foundation and was privileged to be part of then President Bob McNew’s working group that led to the creation the Fellows of the Foundation. Now, three decades later, it’s an exciting time to return to the board. The Foundation’s greatest challenge is making relevant its mission to promote a wider understanding of the administration of justice and the rule of law.

If you don’t know David Guerry, it’s because you haven’t spent enough time at host hotels’ “evening business venue” at national meetings. He writes:

I am delighted to have the opportunity to serve on the board of the Foundation again. The Foundation serves an important purpose within the Federal Bar—it accomplishes the charitable giving so many of us desire to pursue and does so within the federal practice areas we all embrace. The Foundation has great opportunities for growth, and I am excited to have the opportunity to assist in both raising that corpus and growing the Fellows.

Erin Brown is a younger superstar immigration attorney in northeast Ohio who will bring fresh ideas to the board. She writes:

I am honored and excited to serve on the Foundation Board of Directors. As the new kid on the board, I am looking forward to learning about the history and workings of the Foundation and applying that knowledge towards awarding scholarships and grants on behalf of the FBA that promote civics, diversity, and community outreach. The oversight of these investments is a significant responsibility and ensures that quality lawyering and judgeships are not only maintained but also cultivated and promoted. The quality of our profession isn’t limited to what we do today, but also reflected in what we are willing to invest into tomorrow. The Foundation’s willingness to continue to devote its collective energy to ensuring that

the profession of lawyering remains vibrant is an important priority for me.

Cal Chipchase is a partner at Cades Schutte in Honolulu, so just by virtue of distance, his service and attendance at national meetings as a National Council member and as the prior general counsel of the FBA has been all the more meaningful. He writes:

I’m glad to be on the board. It’s super exciting! Having met great lawyers and friends from around the country and having improved my practice through many FBA programs, I look forward to continuing my FBA service on the Foundation board. I will look for opportunities to improve the practice of law in the federal courts, including greater support for the hardworking judges and staff of the federal bench.

There is much additional to tell, but as one wise man said, “Leave them wanting more.”1 Future columns will, inter alia, discuss the Fellows program, detail specific programs and distributions undertaken by the Foundation, and update you on strategic planning efforts and our investment strategies. But, as I hope you can see, it’s not your “grandfather’s” Foundation anymore. Those days have passed. We are now and will continue to be light years ahead from what our efforts could be and were even just a few years ago. We are looking at the good fortune of assets to foster our mission and purposes in ways in which we could only dream.

So, in this new day, keep in mind that this is now your Foundation and not that of the ancients. Now that you have been introduced to our new board members, inundate them (and the rest of us on the board) with your ideas and requests for resources. As Linus Pauling said, “The best way to have a good idea is to have lots of ideas.”