in diverse locations. And, remarkably, in 2012 he succeeded in convincing the directorate of the Nieuw-West district to donate a number of play elements from condemned playgrounds to the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum. The gift was kindly accepted by curator Harm Stevens who incorporated Van Eyck’s play elements into his collection of twentieth-century art. Through this act, these elements were de facto recognised as works of art.

At that time, Anna van Lingen and Denisa Kollarová were embarking on their investigation of the playgrounds. They too were upset by the state of a airs: the careless and destructive way of dealing with a unique urban heritage, the nonchalant replacement of the original with phony kitsch. So, they decided to contribute to the awakening of the public consciousness by composing a small and handy guide. It became a nice booklet in which they presented a dozen reasonably-preserved playgrounds, outlining their qualities. At the same time, they denounced the general state of neglect of most of the playgrounds, pleading for them to be rehabilitated and protected. In this new edition, they widen their scope with some additional playgrounds, pictures, and stories, among which are two significant testimonies, by Paul Lappia and Harm Stevens respectively.

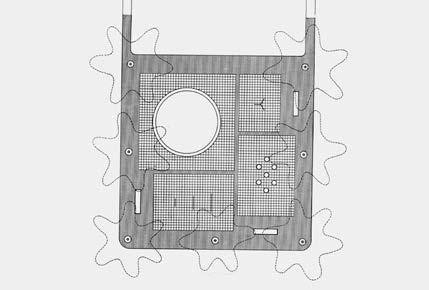

Yet the authors consciously limit their attention to playgrounds which still exist, meaning that nowhere do they mention or discuss the most beautiful and telling examples such as Zaanhof, Mariniersplein, Antillenstraat, Zeedijk, or Mendes da Costahof. These have all disappeared. In order to experience again the iconic qualities of Van Eyck’s elementary early compositions we should consider reconstructing some of them, whether at their original locations or in a museum park. The Zaanhof playground in particular seems a suitable candidate for reconstruction. It measures only 20 × 20 m and o ers a striking example of Van Eyck’s view of ‘harmony in motion’. Four di erent play situations are related to one another through the centrifugal movement they evoke.

A fence has been placed around the playground. The play tables and the climbing arch that were once located inside the sandpit have disappeared, and a catalogue play element has been added. Large metal flowerpots have been incorporated in this location.

Museum

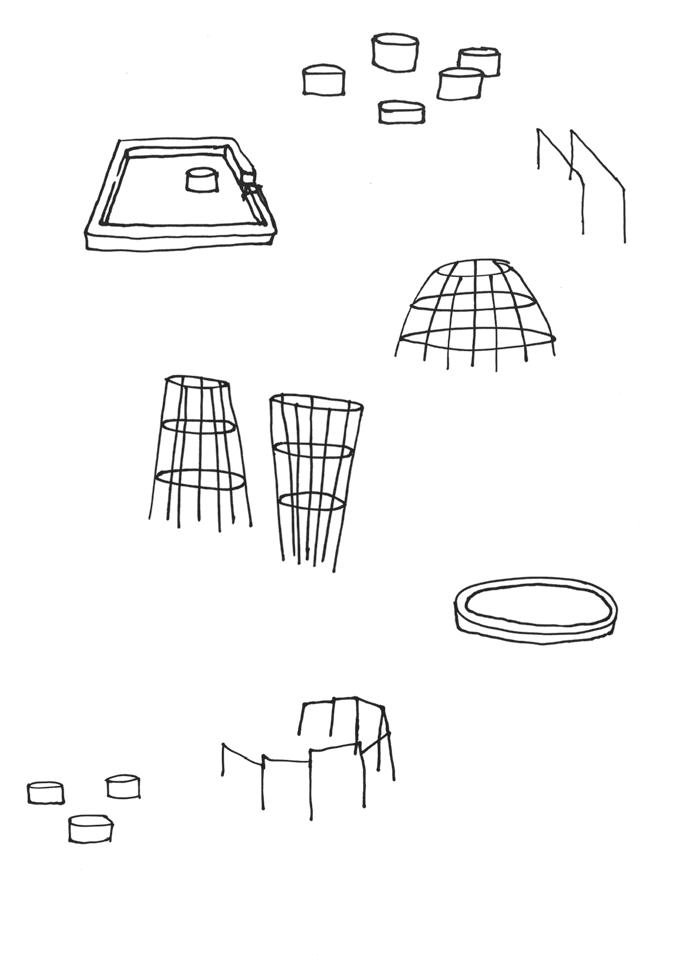

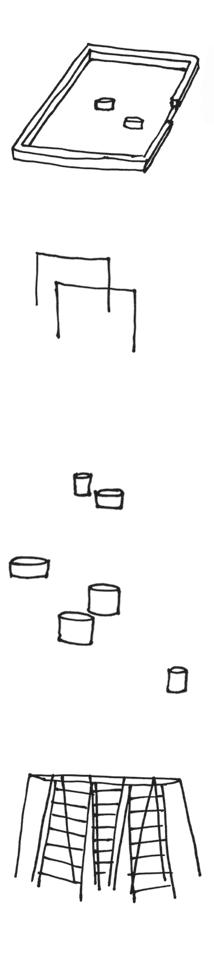

In 2013, the Rijksmuseum incorporated two climbing funnels, one of the famous climbing domes, and a couple of somersault frames into the design of its new garden. These play elements come from different plagrounds in Amsterdam Nieuw-West and were donated to the collection of the Rijksmuseum by the city of Amsterdam in 2012.

A small climbing arch, included in the donation, was placed in the museum’s depot (object no. NG-2012-73-3). It later became accompanied by a hexagonal climbing frame (object no. NG -2013-19) which was added to the collection by a private donation in 2013.

Thanks to the dedicated involvement of district o cial Paul Lappia.

The play elements are not solely presented as artworks for visitors to look at, but actually invite visitors to use them. The playground is open to anyone during the museum’s opening hours. Accompanying the play elements, a small sign tells the history of Van Eyck’s designs for children, with a reference to the playground at the Witte Klok in Nieuw-West, the last playground in the district still to exist in its original form.

A typical example of how a traditional square was designated as a play location. Though now sharing its space with catalogue play equipment, the sandpit and benches and somersault frames remain intact. The somersault frames have been removed.

5. The Locations

The Urban Development Department wanted each neighbourhood in Amsterdam to have its own public playground and gave the Site Preparation section of the Town Planning Department the task of designating the terrains that could be used to realise this plan. Locations were found throughout the various parks of Amsterdam and on the traditional squares between housing blocks in the older parts of the city centre, such as here at the Herenmarkt. Sometimes space for playgrounds was created by broadening the pavement or even by creating a square where traffic intersections used to be.

What is truly remarkable is the fact that the playgrounds were often placed on derelict sites previously used as rubbish dumps or were hidden behind a fence, surrounded by old walls and ramshackle buildings. Van Eyck transformed these overlooked spaces into intimate places , urban living rooms, where social interaction could take place, and by doing so changed the cities’ urban and social landscape.

In contrast to the authoritarian top-down town planning of the Urban Development Department, Aldo van Eyck ’s designs were inspired by the potential of the existing urban contex t. adjusted his design to the already existing urban layout. By focusing on the public playgrounds, he didn’t have to participate in the development of Van Eesteren’s town planning – something he didn’t fully agree with.

While at first he built his web of playgrounds by filling up spaces in the city centre, they later became an integral part of the design for the new post-war areas outlined in Amsterdam’s General Expansion Plan.

A large climbing frame, with an incorporated water fountain, surrounded by three clusters of jumping stones.

by Luca Carboni, Oreri—Iniziativa Editoriale

I learned about Denisa Kollarová and Anna van Lingen’s research in 2013 when a weird metal object in the shape of a crooked dome appeared in the backyard of the Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam. As a second-year student in the Graphic Design department, at first I thought of it as yet another oddity making its appearance on the academy premises. But once I had learned what it was, and why it was there, many corners of the city that I had never really noticed started speaking to me. I was fascinated by the thought that most of the youth that had animated Amsterdam’s Provo movement in the late 60s and 70s (the subject of a popular exhibition by Experimental Jetset a few years earlier) must have climbed those structures and jumped between those stones in their childhood years – was it a mere coincidence that the most disruptive, rebellious generation of the post-war era had developed their relationship with their city in the playgrounds designed by Aldo van Eyck? Could a person’s drive to transform an environment perceived as oppressive stem from the freedom they had experienced as a child?

An old friend from Amsterdam, who is of that generation, once told me: ‘When we rebelled against that world, in the 1960s, we felt it was the most oppressive system that could ever be. But now it is much worse, we had a lot more freedom!’

When Andrea Garcés and I first approached Denisa Kollarová, we wanted to share the findings of her and Anna van Lingen’s research with our audience to spur conversations on how to create engagement, responsibility, and a sense of joy and freedom in public space; we never expected to have the pleasure of printing and publishing a second edition of this book in collaboration with the Faculty of Fine Arts at Brno University of Technology. At a time when the excessive regulation of public space increasingly restricts collective action and the collective imagination, we hope that Van Eyck’s legacy – and Kollarová and Van Lingen’s reading of the spaces he created – contribute to starting those long-overdue conversations and help us invent new ways of playing and being together.

Concept, text, design, and photography:

Anna van Lingen and Denisa Kollarová

Other contributors: Francis Strauven, Tobias Krasenberg, Paul Lappia, Joná š Vere š pej, Tess van Eyck, Harm Stevens

Editing: Eve Richens and Rowan Coupland Translations: Remus Thijssen

Peer Review: Markus Miessen

Fonts: Arizona Text by Dinamo, Univers

Artists Referenced: page 65 – Céline Condorelli page 69 – Simon and Tom Bloor page 73 – Leon de Bruijne page 81 – Miquel Hervás Gómez

Co-published by:

Oreri—Iniziativa Editoriale

Piazza Dettori 3, 09124 Cagliari, Italy www.oreri.ooo

ISBN 979-12-80674-20 -3

Photography Credits:

page 5 – Francis Strauven

pages 26–27 – Tobias Krasenberg pages 29–36 – Paul and Josephine Lappia

pages 38–41 – Joná š Vere š pej

pages 62–63, 125 – Courtesy of the Aldo+Hannie van Eyck Foundation

page 85 – Konstantin Guz

pages 88–97 – Harm Stevens page 97 (top) – Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Brno University of Technology, Faculty of Fine Arts

Údolní 244/53, 602 00 Brno, Czech Republic favu.vut.cz

ISBN 978-80 -214- 6284-7 © 2024, Anna van Lingen, Denisa Kollarová, Francis Strauven, Tobias Krasenberg, Paul Lappia, Joná š Vere š pej, Tess van Eyck, Harm Stevens, Oreri—Initiativa Editoriale, Brno University of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission of the publishers.

Information on the project Seventeen Playgrounds can be found at www.seventeenplaygrounds.com

Printed in November 2024 by Oreri—Iniziativa Editoriale Piazza Dettori 3, 09124 Cagliari, Italy.

Learning how to play means learning how to share, how to negotiate, how to pause. In times of increasing screen time, social media, online shopping, and – therefore – the hollowing out of inner cities, the most radical act is to face one another physically, in di erent and changing locales, cutting across a multitude of communities, local habits, and territorial claims.

Aldo van Eyck’s project for the city of Amsterdam presented a milestone regarding the notion of the decentralised project – one that does not simply distribute its physical reality over a larger (than usual) territory, but one that decentralises the core notion of what it means to design a project itself: it distributes authority. Rather than placing artefacts, Van Eyck’s landscape of urban islands is feeding the user with a set of open gestures, suggestions, and unfinished ideas – producing a geography of a ective learning, a framework for a yet-unknown action by a yet-unknown urban user.

What we are witnessing here constitutes the design of gatherings, agonistic assemblies for an intergenerational audience. As a design, it is deeply aware that, in reality, planning is a myth. Such an approach, as well as this book which summarises it, is a great reminder that planning can and indeed should be understood as an unfinished practice, one that leaves space for uncertainty: thinking about design not as a formal commodity, but as enablers in a social setting with a particular scale.

What we are witnessing here is the design of a ect. A ect not only towards the city itself but directed at every one of us.

MARKUS MIESSEN is an architect, writer, and Professor of Urban Regeneration at the University of Luxembourg, where he holds the Chair of the City of Esch.