by Kit Brash

Gilbert Shelton taught himself to read and draw from comics… and never stopped drawing.

Born in Dallas, Texas in 1940, he grew up immersed in cartooning, and developed an eye for craft almost immediately. In a time when most comic books were unsigned, Shelton took to John Stanley’s take on Little Lulu vs. creator “Marge” in the newspaper and could predict a Donald Duck story would be funny if he spotted Carl Barks’ lettering. He would copy faces from the newspaper strips: the simplicity of Nancy by Ernie Bushmiller, and the ultra-stylized grotesques of his favorite, Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy.

Young Gilbert never took art in high school, instead going straight to hitting deadlines for public assessment. Each week, the members of a cartoonist club would post their best work on a bulletin board at the school. A new color comic also made a major impact on his cohort.

“When Mad came along in ’52, that was a really revolutionary thing. At recess time in junior high school, dozens of us would gather around if someone had brought a new Mad comic to school, and read it until the bell rang.”

The anti-authoritarian Mad’s combination of cultural satire, slapstick, wordplay, and intricate, gag-filled illustration had a seismic effect on American culture, and on the developing sensibilities of this burgeoning artist. Shelton even took to defacing billboards with his own anti-advertising character. “I kept this up until the billboard companies were no longer able to sell advertising space, and they all fell blank… so then I just had a much larger canvas.”

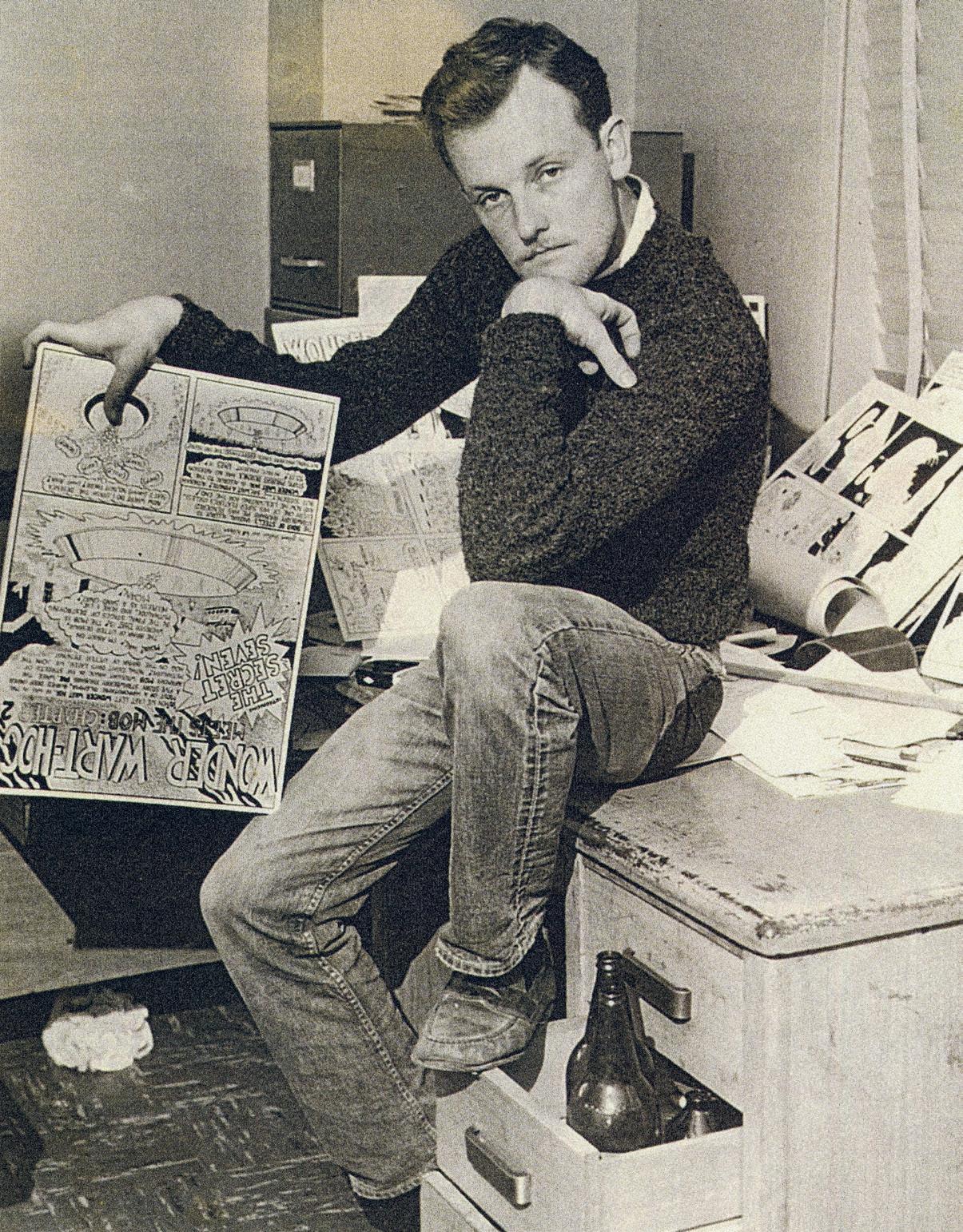

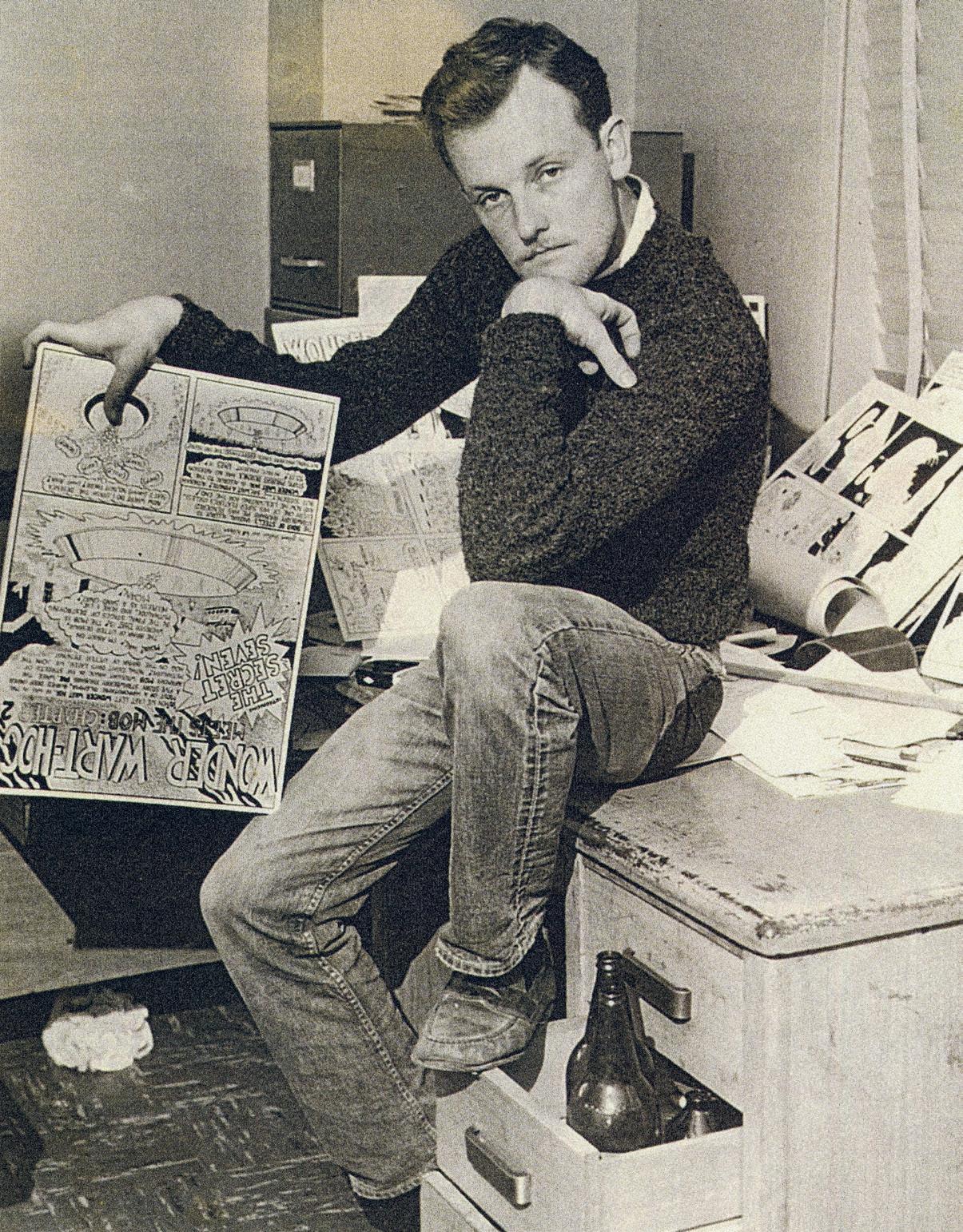

When the nervous 18-year-old cartoonist first walked into the offices of the monthly humor magazine Texas Ranger at the University of Texas in Austin, editor Frank Stack thought his Mad-inspired samples “Somewhat derivative of Don Martin, but different, a bit less zany, better controlled, funnier. Naturally we ran them, several in every issue, giving him a double page spread in the February 1959 issue.”

Shy at first, after six months’ stifling transfer to a smaller college, in a town with no artistic scene, Shelton threw himself into the creative and social aspects of the magazine on return. Across the educational years ’59–’60 and ‘60–’61, he submitted as many cartoons as they could take, and hit it off with art director Tony Bell giving him even more chances to fill corners with his gags, and stretch his writing with humorous essays. Fellow Rangers would go on to collaborate with him through the 1960s and ’70s, including Lieuen Adkins, Bell, and Joe E. Brown.