Creative Industries in the Great South West:

FROM THE EDGE

DRIVING INNOVATION, SKILLS AND BUSINESS GROWTH

Preface

This report reviews and analyses evidence to describe the characteristics of the creative industries in the Great South West (GSW) region of England. The Great South West is a pan-regional partnership that covers an area of the south west of England stretching from Bournemouth to the Isles of Scilly. With a population of 3.2 million, it includes all of Devon, Cornwall, and Dorset, and most of Somerset, and the urban areas of Exeter, Plymouth and Bournemouth – but excludes Bristol and Bath. The GSW is comprised of 15 local authority districts (LADs): Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole; Dorset, Somerset; East Devon; Exeter; Mid Devon; North Devon; Torridge; Teignbridge; Torbay; South Hams; West Devon; Plymouth; Cornwall; and Isles of Scilly.

Our analysis uses the Department for Culture, Media & Sport (DCMS) classification of the creative industries, which encompasses nine subsectors: IT, software and computer services; film, TV, video, radio and photography; advertising and marketing; publishing; music, performing and visual arts; architecture; design and designer fashion; museums, galleries and libraries; and crafts. Focusing on commercial subsectors and creative businesses, rather than publicly-funded culture organisations, our report draws data from sources including Companies House, Data City, ONS, DCMS and six universities in the GSW to make the economic case for investment in the creative industries sector.

We compare the growth of the creative industries in the GSW with the UK overall and with the North East, another region with an emerging creative industries sector. We also compare the creative industries with other sectors in the GSW and explore how spillover effects from the activity of creative companies drive growth elsewhere in the economy. Finally, we recommend a number of interventions to support the future growth of the creative industries in the region.

This report was produced by creative industries specialist Joanne Evans and data journalist Miriam Quick on behalf of the Great South West University Alliance, with assistance from Fiona Waters of Waters Economics.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Bigger than you think

The creative industries, taken as a whole, are one of the UK’s eight priority sectors, identified as those with the highest growth opportunity for the economy and business –sectors the ‘UK excels in today and will excel in tomorrow’.1 They generate an enormous amount of wealth for the UK. In 2022, they contributed £124.6 billion to the UK economy, or 5.7 percent of UK GVA 2 – almost as much as the entire construction sector (£139.1 billion). 3 And they are growing fast. Between 2010 and 2022, real GVA growth in the creative industries (50.3 percent) was more than double the UK economy as a whole (21.5 percent).

In 2019-2023, the creative industries generated a 15.1 percent increase in jobs compared with only 1.4 percent across all UK industries.4 They employed 2.4 million people in the UK in 2023. That’s 7.1 percent of all UK jobs.

A force for innovation

The development of technologies in the creative industries’ largest subsector – IT, software and computer services – drives innovation in other sectors, from energy and the environment to security, health to education, manufacturing to agriculture. And the creative thinking that underpins all creative industries subsectors generates spillover effects elsewhere. Creative jobs attract highly qualified people: 69 percent of those working in the UK creative industries had a degree or equivalent in 2023, compared to 44 percent of workers across all UK sectors. 5 The innovative mindset of those working in the creative industries ripples out across the wider economy: evidence shows businesses more closely connected to the creative industries, or with more employees from the sector, are more likely to produce novel product innovations.6

Creative growth in the GSW

The Great South West (GSW) is emerging as a serious creative contender. Office for National Statistics (ONS) data shows that while the GSW had only 2.4 percent of creative industry jobs in 2022, it had the joint fastest jobs growth in this sector of any British region over the 2019-22 period (4.1 percent CAGR), tying with the East Midlands. Over the longer term (20152022), the GSW’s creative industries jobs growth rate (2.8 percent CAGR) approached that of London (3.5 percent CAGR), which dominates the UK creative industries with 40 percent of sectoral employment. Within the GSW, creative industries jobs grew faster in 2019-22 than in every other major sector except arts and entertainment, with which the creative industries substantially overlap.

Our new analysis reveals at least 15,870 companies in the creative industries are registered in the GSW and active as of 1 July 2024. Around 70 percent are located within 22 geographical clusters, with significant clusters in Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole, Exeter and Exmouth, Plymouth and Falmouth. Collectively, these companies employ at least 34,600 people. In addition, around 40,000 freelancers work in the GSW creative industries. Nearly 49,900 people, including freelancers, worked in creative jobs in other sectors in 2023, ONS data shows – an increase of 60 percent since 2014 that has helped to drive creative thinking across industries.7 Our data suggests the creative industries turnover at least £2.3 billion per year and generate £2.7 billion of GVA in the GSW.

01. Government green paper: Invest 2035: The UK’s modern industrial strategy Published 14 October 2024.

02. Department for Culture, Media & Sport: DCMS Sectors Economic Estimates Gross Value Added 2022 Released 15 February 2024. 2022 data is provisional.

03. ONS: Regional gross value added (balanced) by industry: all ITL regions Published 24 April 2024.

04. DCMS: Economic Estimates: Employment in the DCMS sectors, January 2023 to December 2023. Updated 18 July 2024.

05. DCMS: Economic Estimates: Employment and APS earnings in DCMS sectors, January 2023 to December 2023. Published 13 June 2024. Updated 18 July 2024. Percentages calculated from raw estimates.

06. Frontier Economics (2023): Creative Spillovers: Do the Creative Industries Benefit Firms in the Wider Economy? (PDF link) Report co-commissioned by DCMS and the Creative Industries PEC.

07. ONS Local: Overview of creative jobs and creative industries for the Great South West over the years 2014 to 2023 using Annual Population Survey and Business Counts Survey. Custom data request reference 2381, released 27 September 2024.

Leading from the Edge Leading from the Edge

From coastal edge to cutting edge

The GSW has unique advantages when it comes to the creative industries, including three specialist creative industries universities (Falmouth University, Arts University Plymouth and Arts University Bournemouth) and three other universities (Bournemouth, Plymouth and Exeter) with strong specialisms in creative industries subjects. Together, these six universities produced over 6,700 highly skilled graduates in creative and createch disciplines in 2023-24, 8 and drew in £33.6 million of research grant funding over the 2021-24 period,9 while supporting the creative sector – as well as emerging crosssectors such as agritech and health tech – with R&D, incubation programmes and state-of-the-art facilities.

The GSW had faster jobs growth over 2019-22 than the British average in advertising and marketing; architecture; and (the largest subsector) IT, software and computer services, as well as the creative industries as a whole. Our analysis shows that music, performing and visual arts contributes a higher share of the GSW’s GVA (15.6 percent) than the UK 2022 average (9.1 percent), hinting at the huge potential of this subsector.10 Indeed, the GSW is home to the world’s largest greenfield music festival, Glastonbury, and accounts for a substantial share of the two million music tourists who visited the South West region as a whole in 2023, ranking it second behind London for music tourism spend and employment.11

Overcoming barriers

Despite these advantages, significant barriers exist to investment and growth of the sector in the GSW. They include low regional and national awareness of the creative industries’ importance in the GSW, lack of a GSW-wide strategy, and the small number of large anchor companies based in the region. On top of this, creative industries growth is hampered by factors affecting all GSW industries, including a shortage of affordable housing and poor transport infrastructure.

And yet the potential of the GSW as a creative region has recently begun to be recognised. In the last two years, the Department for Culture, Media & Sport (DCMS) has designated Cornwall and Devon as a Create Growth region as part of its Create Growth Programme, a

£28.4-million mentoring and access to finance programme run in several English regions outside London.12 While it is too early to measure the direct impact of the Create Growth Programme, other evidence suggests that the GSW’s creative industries are becoming more innovative and better able to take advantage of R&D funding. GSW creative industries companies captured £1.7 million of Innovate UK grant funding in 2022-23, an amount that has surged since 2020.13 Forty-one percent of this – almost £700,000 – went to 10 organisations based in Cornwall, where Cornwall Council’s industrial strategy has targeted interventions at creative companies for a number of years.

Potential for future growth

The creative industries bring enormous economic benefits, including higher productivity, skilled jobs and spillover effects to other industries. They also benefit regions through urban regeneration, improved health and wellbeing, and net-zero behaviour change.14 And they will continue to grow. The UK government plans to expand the creative industries’ GVA by £50 billion a year and add a million extra jobs by 2030 and is investing £50 million in a new round of the Creative Industries Clusters Programme.15 As we have seen, the creative industries in the GSW are growing faster than in the rest of Great Britain. The GSW must develop its creative industries strategy to ensure that this message is heard regionally and nationally to compete with other regions for its share of national investment. Maximising the GSW’s potential as a creative industries region will roll out the benefits of a thriving regional creative economy across industry sectors.

08. Figure excludes IT and tech graduates for the non-creative industries universities

09. Data provided by universities listed

10. GSW source: our analysis for mid-2024. UK source: DCMS: DCMS Sectors Economic Estimates Gross Value Added 2022 (provisional) Published 15 February 2024.

11. UK Music press release 26 July 2024.

12. The Create Growth Programme was launched in 2022 by DCMS and Innovate UK, which is part of the UK Research and Innovation Organisation (UKRI). It was originally launched at £17.5 million then extended by £10.9 million

13. UK Research and Innovation (UKRI): Innovate UK funded projects since 2004 Last updated 13 August 2024.

14. See for example UKRI: Evaluation of the Creative Industries Clusters Programme, published 1 July 2024.

15. DCMS: Creative Industries Sector Vision. Published 14 June 2023. Last updated 20 June 2023.

SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS

Develop a GSW-wide strategy and sell our story

The GSW can take some immediate steps to create the right environment and campaign for more national investment by empowering the University Alliance to continue to be the strategic lead for the GSW creative sector. They should develop an economic strategy focused on growing the commercial creative industries and sell the region nationally as a rapid-growth rural and coastal cluster.

Match fund a Creative Clusters Programme bid

Local authorities will need to offer financial support for a GSW University Alliance bid for the new round of the Creative Clusters Programme. Universities will also be required to put in 20 percent match fundinng proportionate to the size of their institutions and activity. This investment will increase the region’s chance of successfully capturing the £7-8 million of UKRI funding and, with it, the potential to leverage private sector match funding.

Target interventions at growth subsectors and spillover with priority sectors

To generate the best returns, we recommend interventions are focused on subsectors that are large in the UK and growing fast in the GSW including:

⦁ IT, software and computer services because it underpins the development of technology for the creative industries and other sectors

⦁ Advertising and marketing because it is one of the UK’s and the GSW’s largest, fastest-growing and most productive subsectors

⦁ Music, performing and visual arts because it is one of the UK’s largest and most valuable subsectors and the GSW has unique and distinctive strengths here

⦁ Film, TV, video, radio and photography because key agencies now in place have shown the GSW has significant growth potential in this high-value sector

⦁ Architecture because it is vital to the green economy and energy security priorities in the region

Improve access to finance

Create a clearer funding roadmap that bridges the gap between UKRI grants and large equity raises to build a pipeline of companies ambitious to scale up. This will create the large companies the region needs as anchors for micro businesses. A dedicated digital and creative equity and loan fund for companies located in the GSW would also attract companies into the region.

Designate Culture and Creative Zones and develop infrastructure

Culture and Creative Zones (CCZs) can target areas for regeneration and make creative industries more visible. Create and name CCZs dedicated to the creative industries. They should be within the GSW’s 22 clusters, could be at town, city, village, or district level, and could reflect particular subsectoral strengths in particular areas. Investment in mid-scale infrastructure is needed to address a significant lack of production facilities compared to other regions.

Invest in skills for people living in the region

Degree apprenticeships can help regions retain skills, as students are likely to be resident within their geographical area of study. However, micro businesses’ work is often projectbased and they are unable to take on apprentices on long-term contracts. To tackle this, the GSW should create a new flexi-job apprenticeship agency, or work with an existing one.

Support companies to reach wider markets

Micro businesses need support to connect with national markets and supply chains, while more established businesses may need conference and travel bursaries to reach international markets. Both would benefit from additional support.

OVERVIEW

The creative industries in the GSW

THE UK CREATIVE INDUSTRIES

The creative industries are, collectively, one of the eight UK sectors with the highest growth opportunity for the economy and business.16 The Department for Culture, Media & Sport (DCMS) defines the creative industries as ‘those industries which have their origin in individual creativity, skill and talent and which have a potential for wealth and job creation through the generation and exploitation of intellectual property’.17 DCMS also has a precise, statistical definition of the creative industries, using the concept of “creative intensity” – the proportion of occupations in an industry (at four-digit SIC code level) that are considered creative. DCMS groups the list of creative industries into nine subsectors, from architecture to publishing. (See Annex 1.1 for more information on how the creative industries and subsectors are defined.)

The creative industries are a UK economic powerhouse. In 2022, they contributed 5.7 percent of all UK GVA, at £124.6 billion.18 This is a lot: it approaches the £139.1 billion GVA contributed by the UK construction industry in 2022, for example – see Figure 1 for a comparison of the creative industries with a selection of other UK industrial sectors.19 The creative industries are growing fast. Between 2010 and 2022, their real GVA growth (50.3 percent) far outstripped that of the UK economy as a whole (21.5 percent). And the

Exports from the UK creative industries are substantial – in 2021, they generated a £2.1 billion trade surplus (in current prices), helping to reduce the UK’s trade deficit. The value of creative industries goods exports, driven by the music, performing and visual arts subsector, was £9.8 billion, equivalent to 2.7 percent of all UK goods exports. Across all DCMS sectors (with the creative industries accounting for the lion’s share), the USA bought the most goods, followed by Switzerland, France, Hong Kong and Germany.

Creative industries service exports were driven by IT, software and computer services and generated a trade surplus of £18.7 billion in 2021. USA, Germany, Ireland, Netherlands and France were the biggest customers for services across all DCMS sectors; again, the creative industries accounted for the majority. 21 Creative jobs attract highly qualified people: across the UK, 69 percent of those working in the creative industries had a degree or equivalent in 2023, compared to 44 percent of workers across all UK sectors. 22 And a larger share of workers in the creative industries are in jobs requiring degree-level skills than in other sectors. In 2023, 40 percent of those in the creative industries had a skill level of four –the highest – compared to 34 percent in other industries. While it’s true that the average UK worker is becoming more skilled over time, the share of those with level four skills is increasing faster in the creative industries than elsewhere, swelling by 11 percentage points in the last decade (see Figure 3). 23

The creative industries, which include the IT, software and computer services subsector, are increasingly collaborating with other industries, including the GSW’s priority sectors, creating hybrid sectors that can be highly innovative and disruptive. Examples include the application of AI and robotics to agriculture, collaborations between defence specialists and tech developers to create virtual training systems, and immersive health applications that combine the skills of content creators with those of health practitioners. Spillover effects from the creative industries produce considerable benefits for other sectors, as well as local communities. Work undertaken for a group of European agencies, including Arts Council England, in 201524 defined three types of spillovers:

Tom

(PDF)

Cultural

⦁ Knowledge spillovers: new ideas, innovations and processes developed by creative businesses spill over into the wider economy and society, including via skill transfer and training.

⦁ Industry spillovers: successful creative enterprises affect business culture and entrepreneurship; property markets; private and foreign investment; productivity, profitability and competitiveness; and innovation and digital technology.

⦁ Network spillovers: a high density of creative industries in a particular area leads to clustering and agglomeration effects, increasing regional attractiveness and boosting economic growth.

These spillovers can have a direct impact on employment in other industries. While our analysis cannot quantify the amount of spillover activity from the creative industries in other industries in the GSW, we know that creative jobs have a strong multiplier effect. For example, Creative PEC research reveals that, on average, each creative job in a locality generates 1.9 new jobs in other sectors, like leisure and retail, because creative company employees spend their money locally. 25

AMUTRI

Amutri (amutri.com) is a Penryn-based software company supported by Falmouth University’s flagship venture programme, Launchpad (falmouth.ac.uk/launchpad). Amutri has launched a first-of-its-kind product that offers fast, cloud-hosted 3D visualisation for designers, engineers and architects. The technology also supports the UK Government’s strategic goal of reducing reliance on fossil fuels for energy production by supporting alternative energy companies, like Rolls-Royce SMR, in planning, constructing, and securing stakeholder approval for alternative energy plants.

With Amutri, users can create and access 3D experiences through the web, simplifying the adoption of 3D visualisation technology. The platform is designed to be automated, costeffective, and user-friendly, lowering the barriers to entry and providing a straightforward solution for integrating 3D visualisation into sales and stakeholder engagement activities.

After participating in Launchpad, the company secured and successfully delivered a £500,000 UKRI-funded project. They raised £600,000 in equity funding at the pre-seed stage to refine their technology and expand their team to 12 employees.

Rolls-Royce Small Modular Reactors (SMR), which makes nuclear reactors, is among the early pilot adopters of Amutri’s technology from the energy sector. “3D experiences can help de-risk activities by prototyping digitally” says Greg Wilkinson, their research and technology manager. “Photorealism gives confidence to stakeholders building the plant.”

“3D experiences can help de-risk activities by prototyping digitally ]...[ Photorealism gives confidence to stakeholders building the plant.”

Greg Wilkinson, Research and technology manager

THE GSW CREATIVE INDUSTRIES

Business landscape

Is the GSW fully sharing in the benefits the creative industries can bring? To find out, we conducted original research into the current state of the creative industries in this region of 3.2 million people. 26 First, we took the list of companies registered by Companies House as active as of 1 July 2024, and filtered it to companies with a first-listed SIC code within the DCMS definition of the creative industries and with a registered address located within the GSW. We then matched our list to company-level economic data from Data City, a commercial data provider. (See Annex 1. Methodology for a full description of our methodology.) Our analysis uncovered 15,870 GSW-registered companies within the creative industries active in July 2024.

Only 14 companies are large (listed in Table S49 in Annex), and 58 are medium-sized, based on employee counts. Sixty-two percent are micro-sized enterprises of one to nine employees. Indeed, micro businesses characterise the creative industries nationally, with 93.4 percent of UK creative industries businesses falling into the micro band in 2023, slightly higher than 89.1 percent of all UK registered businesses. 27 A further 36 percent of our companies register no employees or turnover data, so their size cannot be determined. The apparently lower share of micro businesses in our GSW dataset compared to the UK picture is likely because we lack company size information for such a high proportion of businesses. These businesses of unknown size are likely to be mostly micro-sized businesses in reality, and will probably include many businesses of one person. Our company size breakdown should therefore not be compared to the UK-wide data.

Looking at the local authority district (LAD) of a company’s registered business address, Dorset has the largest number of companies in the creative industries (23 percent), followed by Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole (BCP, 19 percent). Divided by county, 42 percent of GSW creative industries businesses are in Dorset (including BCP), 28 percent in Devon (including Exeter, Plymouth and so on), 16 percent are in Somerset and 14 percent in Cornwall and Isles of Scilly. 28 However, the company counts for Dorset and BCP should be treated with caution, owing to the large number of companies in these LADs registered to single addresses, mainly of accountancy firms. Some of these companies, while registered in the GSW, are likely to be mainly active outside the region – see Annex 1.3.1 for a discussion.

Economic impact

Our analysis reveals that companies in the creative industries contribute at least £2.7 billion in GVA to the GSW and turn over at least £2.3 billion per year. 29 However, the creative industries make up a smaller share of GSW GVA (3.3 percent) than across the UK (5.7 percent) as Figure 5 shows. The GSW’s 14 large companies by employee count account for the biggest share of turnover, at 33 percent, or £764 million – almost £55 million per company. The nearly 10,000 micro-sized companies combined account for a slightly smaller share: 30 percent, or £700 million of annual turnover.

By local authority, BCP, Dorset and Cornwall lead creative industries GVA, reflecting both their healthy company counts (bearing in mind the caveat listed in the Business landscape section above) and their strengths in high-value subsectors like film and TV. North Devon has a high GVA figure from large companies largely because of the Mission Group – an AIMlisted group of 19 advertising agencies all registered in Filleigh, near Barnstaple – which accounts for 47 percent of North Devon’s total creative industries GVA.

Each creative industries employee contributes an average of £76,700 to the GSW economy per year, calculated as total creative industries GVA divided by the number of employees. This compares favourably with the ONS figure for GVA per filled job of £61,700 across all UK sectors in 2022, 30 although these figures should be compared with caution. Their different data years and underlying methodologies should be noted, along with the fact the company-level Data City GVA data upon which our figures rest is provisional. These caveats aside, it is still likely that creative industries jobs contribute far more to the GSW economy than the average job.

Employment

Our analysis shows at least 34,597 people were employed in companies in the creative industries in the GSW in mid-2024. 31 This is close to the ONS figure of 36,015 people in 2022, including company directors, which implies our data is robust. 32 (Note that these figures are not directly comparable and do not demonstrate a fall in employment between 2022 and 2024.) Based on our analysis, 69 percent of the almost 34,600 creative industries employees work in small or micro-sized businesses, with 16 percent in medium and 15 percent in large companies. By local authority district, BCP dominates, with 25 percent of GSW creative industries employees, followed by Dorset (16 percent) and Cornwall (14 percent).

The GSW is a high-growth region for creative industries employment. ONS data shows that while the GSW had only 2.4 percent of creative industry jobs in 2022, it had the joint fastest jobs growth in this sector of any British region, at 4.1 percent CAGR over the 2019-22 period, tying for first place with the East Midlands. 33 Looking at this data as a shift-share chart (Figure 7) shows that, while London and the South East dominate creative industries jobs, as you would expect, they are growing faster in the GSW than any other region over 2019 to 2022. Indeed, over the longer term (2015-2022), the GSW’s creative industries jobs growth rate (2.8 percent CAGR) approached that of London (3.5 percent CAGR), which dominates the UK creative industries with 40 percent of sectoral employment. 34

Within the GSW, this 4.1 percent year-on-year growth means creative industries jobs are growing faster than in every other major sector except arts and entertainment (4.7 percent CAGR over 2019-22), with which the creative industries substantially overlap. The shift share analysis represented in Figure 8 shows that, while the creative industries make up a relatively smaller share of employment in the GSW relative to other sectors –for example the bedrock sector of agriculture, forestry and fishing –creative industries employment grew faster in the GSW over 2019-22 than you would expect, relative to the national growth rates.

As well as people employed by creative industries companies, many people work in creative jobs in non-creative industries. An ONS custom data request we submitted reveals there were 49,863 people working in creative jobs in other sectors in 2023, an increase of 60 percent since 2014.

35 Such overlaps are productive: the innovative mindset of these people who work in creative jobs for companies outside the creative industries generates spillover effects to other industrial sectors. Evidence shows businesses that are more connected to the creative industries, or with more employees from the sector, are more likely to produce novel product innovations.

36

These new ONS figures total 75,749 people working in the creative industries in 2023. This is substantially higher than our estimate of 34,597, and the ONS BRES figure of 36,015 in 2022, because it also includes freelancers. While this report focuses on limited companies with employees, which have the strongest potential to drive growth, freelancers make up a substantial share of the national creative industries workforce – around a third (or a ratio of one freelancer per two employees).

37 The ONS data suggests that somewhere in the region of 40,000 creative freelancers may work in the GSW, a ratio of roughly one freelancer per employee.

38 This would indicate that many freelancers may be resident in the region and working elsewhere, often remotely.

Universities

One of the GSW’s unique strengths is that it is home to three creative industries universities – Falmouth University, Arts University Bournemouth and Arts University Plymouth – plus the universities of Exeter, Plymouth and Bournemouth, which have also achieved national and international recognition for their creative industries disciplines. These include digital media, art and technology at University of Plymouth, communications, drama and film at University of Exeter and creative technology and special effects at Bournemouth University, which is also home to the National Centre for Computer Animation. These six GSW universities produce world-class research: 31 percent of their research was rated world-leading (4*) and 45 percent was rated internationally excellent (3*) in Units of Assessment relevant to the creative industries in REF 2021. 39

They are also home to state-of-the-art facilities for students, academic researchers and business collaborators. These include studios and labs supporting digital and immersive technologies: the Centre for Blended Realities at Falmouth,40 i-DAT Open Research Lab for creative technology at Plymouth,41 VSimulator at Exeter,42 and Immersive Technology Lab at Bournemouth. The Fablab at Arts University Plymouth43 and the Innovation Studio at Arts University Bournemouth44 provide companies from across sectors access to equipment and expertise to support the development of new products and processes.

The universities support early-stage businesses in the creative industries with a number of programmes including Launchpad Futures at Falmouth,45 which develops research partnerships with organisations to increase R&D and economic activity in Cornwall.

The six universities produced at least 6,727 graduates in creative disciplines in 2023-24.46 Creative graduates are valuable. As a recent report from GuildHE and UKADIA points out, they typically have flexible skill sets including originality, critical thinking, initiative, risktaking, teamwork and problem-solving, in addition to their subject-specific skills.47 They are agile in how they harness these skills and – because many creative graduates go into self-employment – often also possess strong business and enterprise abilities. To support students and recent graduates to set up their own companies, universities, local authorities and business advisory services deliver entrepreneur programmes such as Ignite in BCP.48

But while the GSW is producing thousands of these valuable graduates in creative fields each year, it is not hanging on to them. Graduate retention rates are low: only 20 percent of graduates stay in the South West, across all occupations.49

39. Results of Research Excellence Framework (REF) 2021 Average of data for five universities (Arts University Plymouth did not participate in REF 2021) across the following Units of Assessment: Architecture, Built Environment and Planning (Plymouth only); Art and Design (four universities); Communication, Cultural and Media Studies, Library and Information Management (Bournemouth only); English Language and Literature (three universities); Music, Drama, Dance, Performing Arts, Film and Screen Studies (three universities).

40. Falmouth University Centre for Blended Realities

41. University of Plymouth i-DAT Open Research Lab

42. University of Exeter VSimulator

46. Data provided by all six universities. This figure excludes some postgraduates, who had not graduated by the time we conducted our research, so the true figure will be higher. Further, defining a ‘creative’ graduate can be difficult. For the three creative industries universities –Falmouth, AUB and AUB – it includes graduates across all disciplines. For Plymouth, Exeter and Bournemouth, the subjects included do not match exactly across institutions. In addition, they do not include graduates and IT and technology subjects for the three non-creative industries universities.

47. GuildHE and UKADIA: The Value of Creative Graduates. Research report 2024

48. Ignite is funded by BCP Council and delivered by Evolve, a local business advisory company.

49. Based on graduate survey data from five universities (Bournemouth, Falmouth, AUB, AUP and Exeter). Graduate retention data is collected as part of the Graduate Outcomes Survey, run by HESA. Graduates complete the survey 15 months after graduation. The responding universities also took data from different time periods, for example, AUP used a 3-year average whereas Exeter is last 10 years, so are not strictly comparable.

CASE STUDY: OUTPOST VFX

Outpost VFX (outpost-vfx.com/en) is a high-end visual effects company with a diverse portfolio across film, broadcast, advertising and VR. It is one of the largest creative industries companies in the GSW. Outpost VFX has studios in London, Montreal and Mumbai, but its headquarters is in Bournemouth, where it has state-of-art facilities across 10,000 square feet. Founder and CEO Duncan McWilliam chose to base the Outpost VFX studio in Bournemouth because the company works closely with Bournemouth University (particularly its visual effects programme) and mentors and employs its graduates, helping the company counter the global shortage of people with visual effects skills with a local skilled labour pool. A base outside London also enables them to be more competitive on overheads. Outpost’s stunning work can be seen in critically-acclaimed films and series including Napoleon, Pachinko series 2 and House of the Dragon.

CLUSTERS

Where do GSW creative companies gather?

Clusters have long been recognised by researchers and the UK government as the engines of growth for the creative industries. When creative businesses cluster, companies and individuals can more easily share ideas, form supply chains and bring together the collaborative skills they need to innovate.

SUPERCLUSTERS, MICROCLUSTERS AND CREATIVE CORRIDORS

The UK’s international-scale creative industries ‘supercluster’ is London and the South East, which was responsible for 57 percent of UK creative industries jobs in 2022. 50 In a bid to compete with this supercluster, cities outside London with a large number of creative industries companies are coming together to develop strategies and ‘creative corridors’. One such creative corridor is One Creative North, which stretches from Liverpool to Newcastle via Manchester, Sheffield and Leeds and is closely associated with the Northern Powerhouse. 51 Launched in February 2024, One Creative North has been widely promoted by the North’s metro mayors. It is a strategy that seems to have produced early dividends as Beyond (the UK’s annual creative industries R&D conference, part-funded by UKRI) moves north to Salford in the heart of the corridor in November 2024.

During the pandemic, focus shifted from the role played by clusters at a large city level to the characteristics of more distributed microclusters, and the significant contribution they make to UK regions. In 2020, research from the AHRC-funded Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre (PEC) defined these microclusters as areas in which at least 50 creative industries businesses and organisations gather together. 52 It found 709 distinct creative industry microclusters spread across the UK, including several in the GSW. Earlier work by the PEC team from back in 2016 had identified Bournemouth, Exeter and Penzance as three distinct creative industry clusters among 47 in the UK. 53

A 2022 Frontier Economics paper for the DCMS identified Bournemouth as one of 55 creative industries clusters, the DCMS-55, and grouped it with 11 other ‘creative districts’, including Brighton and Harrogate. 55 Creative districts are characterised by Frontier Economics as having “many micro-businesses and stable firms from a wide range of creative sectors, and a smaller share of high-growth businesses”. Creative districts also “score well on most counts [based on the indicators measured by Frontier Economics], the main exception being access to talent. The proportion of firms reporting that access to skills is a hindrance and that vacancies are hard to fill is higher in creative districts than the UK average. Average graduate retention is also lower [...] than in other creative clusters.”

55.

Clusters outside established clusters

MAPPING THE GSW’S CREATIVE CLUSTERS

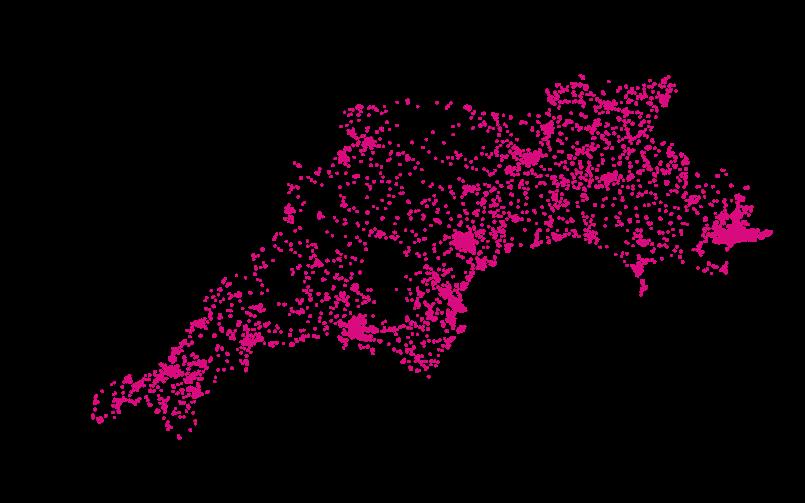

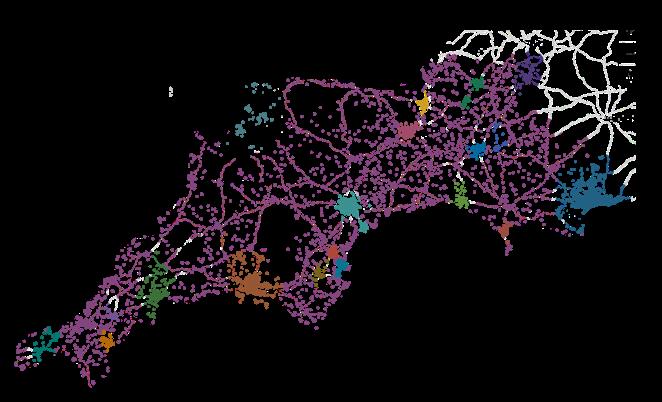

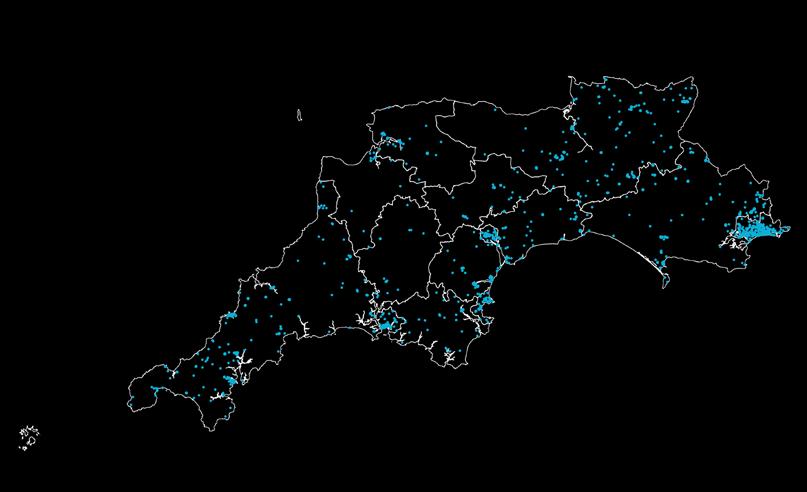

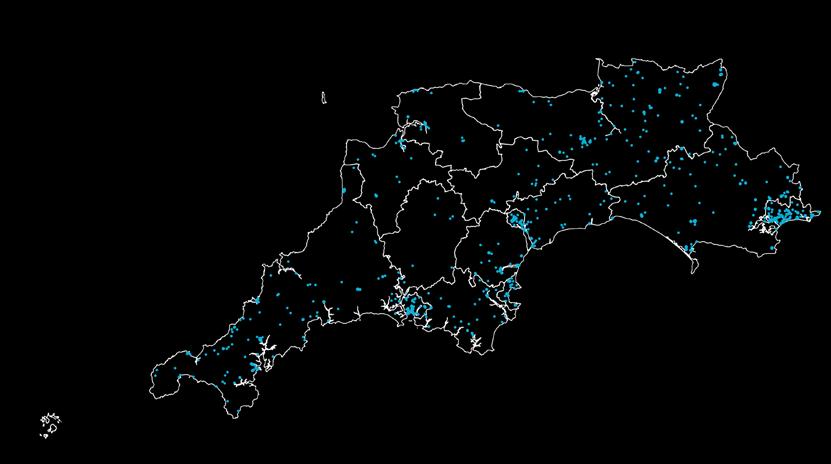

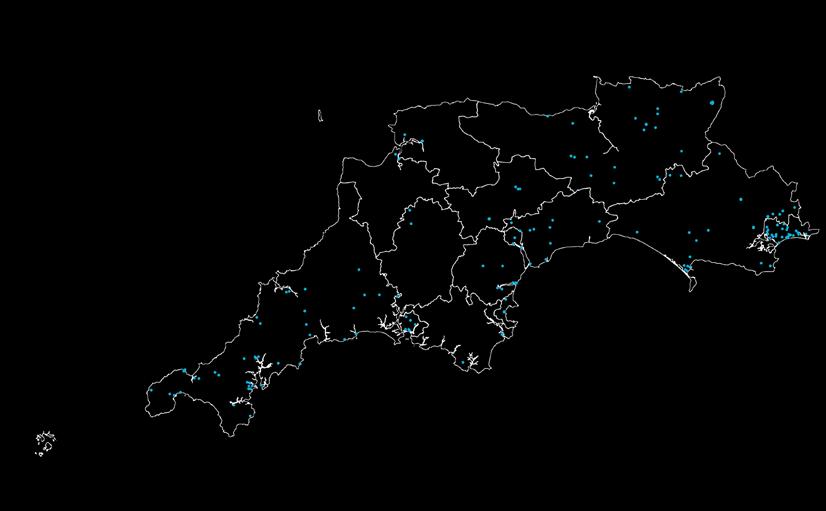

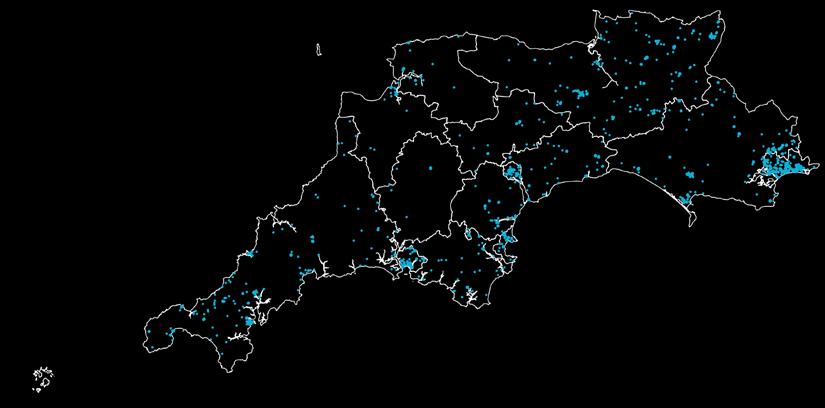

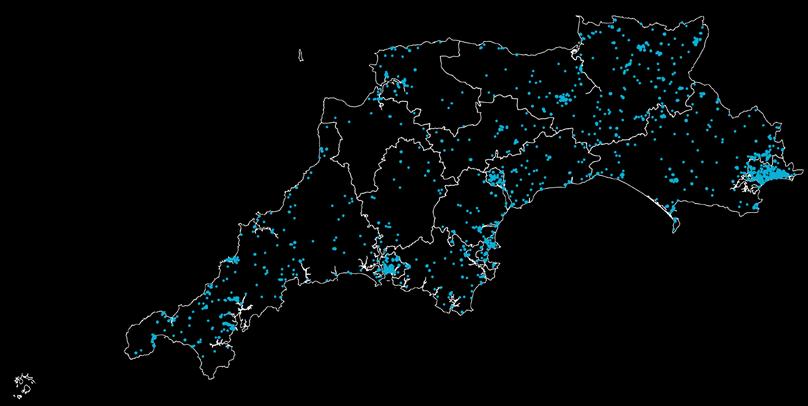

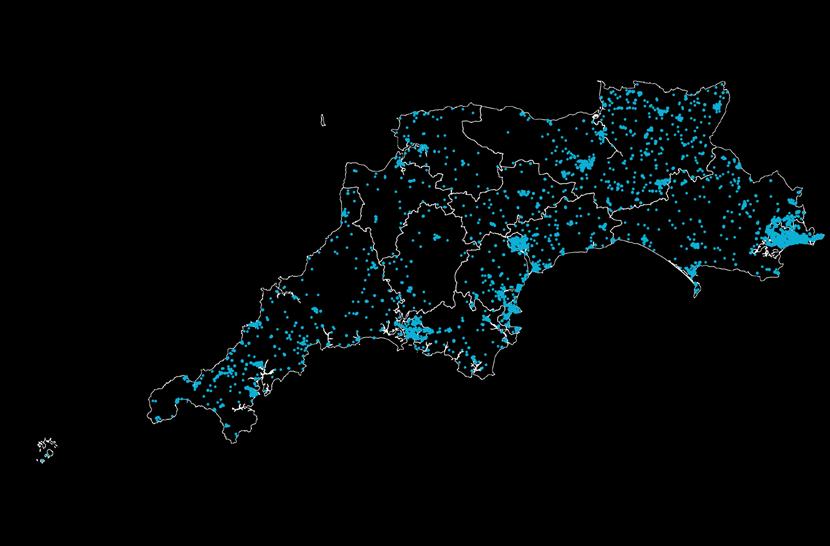

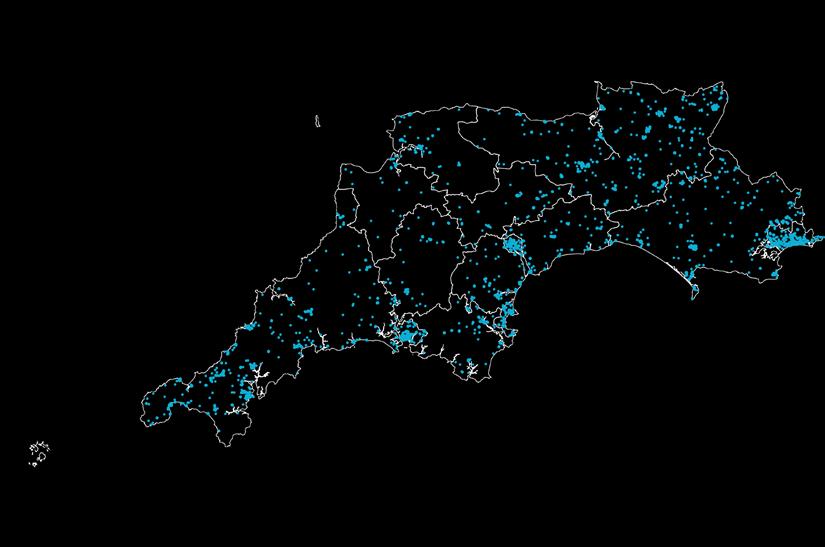

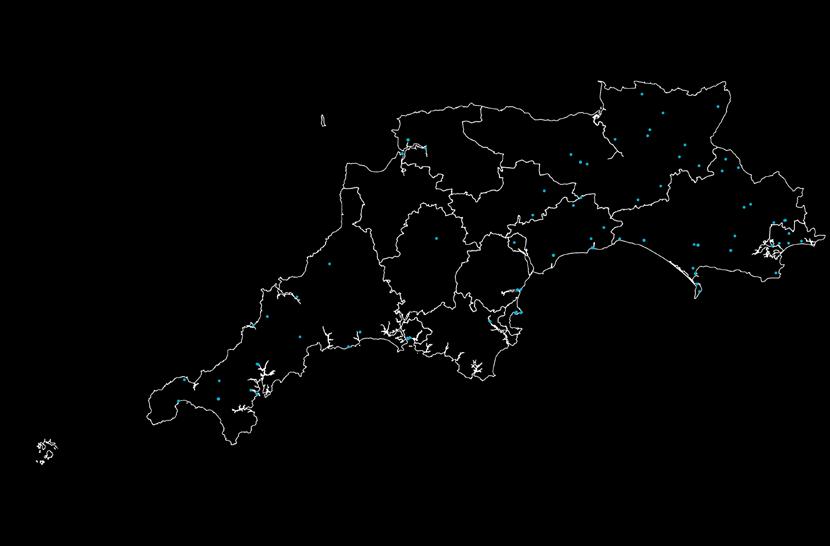

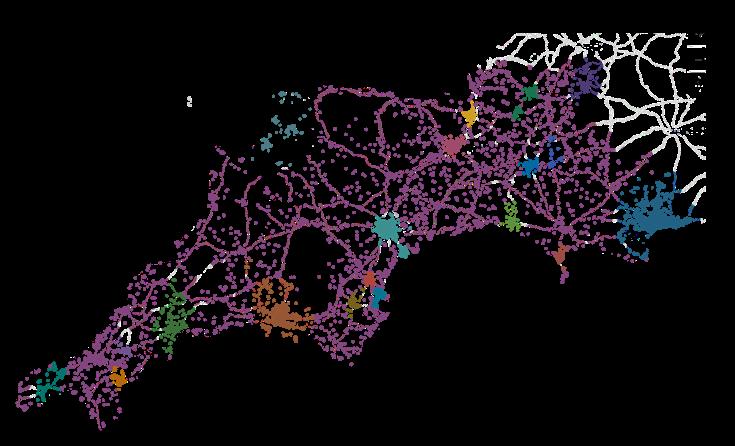

In our analysis for this report, we mapped the registered company locations of all 15,870 creative industries businesses in the GSW. We then clustered their latitudes and longitudes using the HDBSCAN clustering algorithm, with a minimum number of companies per cluster of 100. This clustering was based purely on geographical proximity and not, for example, on travel time. (See Annex 1.4.3 for a more detailed description of our cluster analysis.)

Our analysis revealed 22 distinct creative industries clusters in the GSW of at least 100 companies each. In total, 71 percent of companies fall into a cluster and 29 percent do not. Clusters are centred around towns and cities but also include many businesses in surrounding rural areas. The largest clusters by number of companies are Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole (5,451 companies, 34 percent), Exeter and Exmouth (913 companies, 5.8 percent) and Plymouth (847 companies, 5.3 percent), but sizeable clusters can also be found in places as wide-ranging as Falmouth, North Devon, Taunton, Torquay, and Frome. Others, such as Glastonbury with 101 companies, might be better termed microclusters.

Being in a microcluster makes a big difference to companies outside the established creative clusters, research from the Creative Industries PEC has found. 56 Companies in microclusters are more likely to want to grow than those not in a microcluster, and more likely to behave like companies in bigger, established creative clusters, benefitting from a proximity to skills, customers and knowledge. In later research into rural microclusters, they found the drivers behind clustering in rural areas are the same as those in towns and cities, meaning policy interventions for the creative industries can have a significant positive impact in rural as well as urban locations. 57 Being close to a university, further education college and/or cultural anchor institution (including a museum or gallery, archive or heritage site), can also support rural as well as urban clustering, the research found.

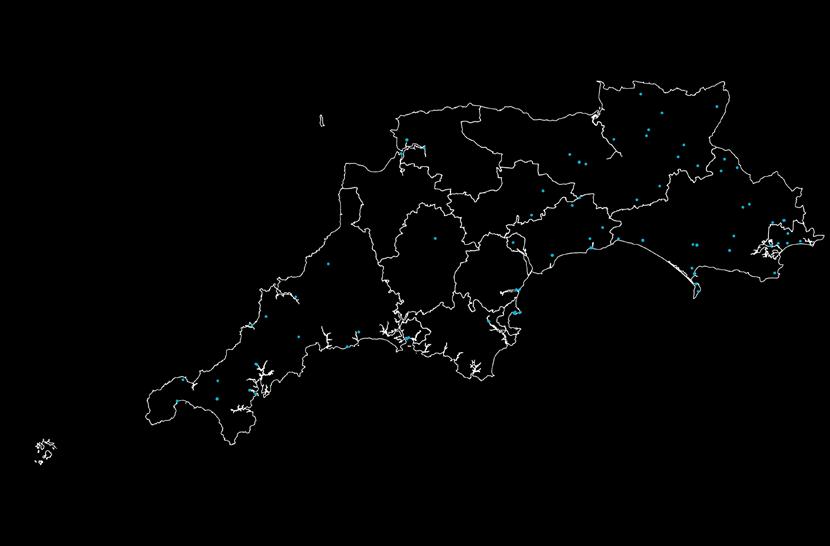

We then mapped the locations of key creative infrastructure, meaning infrastructure that could attract creative industries businesses in the GSW and incentivise them to cluster. We categorised these as:

⦁ Universities and further education (FE) colleges with significant digital and creative industries courses

⦁ Cultural and heritage organisations. In this case those designated by A rts Council England as National Portfolio Organisations (NPO)58

⦁ Immersive facilities such as Falmouth University’s Centre for Blended Realities 59

⦁ Fab labs,60 digital innovation labs and production spaces (marked ‘Space’ on Figure 12)

⦁ Major work hubs

Unsurprisingly, GSW creative industries infrastructure including culture and heritage organisations and creative industries companies tend to cluster in approximately the same areas, including BCP, Plymouth, Exeter, Taunton, Torbay, North Devon and Cornwall.

The wealth of an area may also be important when it comes to the location of creative industries businesses. The phenomenon whereby creative industries companies move into areas with cheap rent and drive the prices up (‘gentrification’) is a staple of the popular imagination, but research on the creative industries’ real influence on gentrification paints a mixed picture. Velez Ospina et al (2023), cited in the Creative Industries PEC research, found that UK creative microclusters are less likely to occur in areas with higher levels of unemployment.61 However, when they looked at the Index of Multiple Deprivation (a measure that combines various measures of deprivation), they found microclusters are slightly more likely to occur in more deprived urban areas. In rural areas, the researchers found microclusters are more likely to be affluent. This suggests the attraction of cheaper areas for creative industries companies is likely to be an urban phenomenon, whereas, in rural areas, higher incomes and the presence of cultural assets may provide a more reliable customer base for creative industries businesses and organisations.

SUBSECTORS

What are the GSW’s strengths?

Business landscape

The Department for Culture, Media & Sport (DCMS) groups the creative industries into nine subsectors, from architecture to publishing. (See Annex 1.1.2 for more information on how the creative industries and subsectors are defined.) We calculated company and employee counts, GVA and turnover by subsector based on our dataset of 15,870 companies. One limitation of our dataset is that data availability differs substantially by subsector, from just 46 percent for crafts employees to 82 percent for architecture turnover.

Our analysis shows that the IT, software and computer services subsector accounts for the largest share of creative industries companies in the GSW (6,754 companies, or 43 percent), followed by music, performing and visual arts (2,489, 16 percent) and film, TV, video, radio, and photography (2,092, 13 percent). These are also the three largest creative industries subsectors across the whole UK, based on DCMS company counts.62 Indeed, the breakdown of GSW businesses by subsector is close to the UK-wide proportion (see Figure S44 in Annex 2.2).

Breaking down the GSW company counts by both subsector and International Territorial Level 3 (ITL3) region63 reveals a significant number of IT and software companies in Dorset and BCP. While this could indicate the potential presence of a subsectoral cluster there, it could also be a result of the large number of companies registered to single-address accountancy firms there (see Annex 1.3.1).

Economic impact

By turnover, the top three creative industries subsectors in the GSW are IT, software and computer services at £957 million (42 percent), advertising and marketing at £529 million (23 percent), and film, TV, video, radio and photography at £278 million (12 percent), as Figure 15 shows. The list is the same for GVA, with IT at £933 million (35 percent), advertising at £475 million (18 percent), and film at £454 million (17 percent). This mirrors the picture across the UK, where IT is the largest creative industries subsector by GVA. It contributed £53.4 billion to the national economy in 2022, according to provisional data –more than twice as much as the next largest subsector (film, at £20.8 billion).64

IT is clearly a significant subsector in the GSW. However, it is relatively less well represented regionally than nationally, as evidenced by its lower share of creative industries GVA (35 percent) than in the whole UK (43 percent), as Figure 16 shows. The large number of IT companies registered to single-address accountancy firms in Dorset and BCP, but potentially operating outside the region, will also be a factor here (see Annex 1.3.1 for discussion), meaning the true size and value of the IT subsector may be smaller than these figures suggest. By contrast, music, performing and visual arts is strong in the GSW: it contributes 15.6 percent of GSW creative industries GVA, based on our analysis –considerably higher than its 9.1 percent share nationally. Advertising and marketing is a little stronger regionally (17.9 percent) than nationally (15.2 percent) while publishing is relatively weaker. Other subsectors are similar to the national picture.65

Across the UK, the creative industries are growing faster than the economy as a whole (see 1. Overview), but some subsectors are growing faster than others. Topping the list is music, performing and visual arts, which grew 32 percent between January 2019 and June 2024, based on monthly GVA data from DCMS.66 Film, TV, radio and photography only grew 1 percent over the same period, affected not only by the pandemic, but also by strikes by two major film unions in the USA which slowed production for US studios in the UK67 . Publishing actually declined by 1 percent. Growth in the creative industries is not distributed evenly across subsectors and is volatile over time, as Figure 17 shows.

Our GSW analysis is a snapshot and cannot measure GVA growth over time in the same way as this national data. Nonetheless, our productivity figures reveal interesting current differences between subsectors. While the average GVA per employee (as of July 2024) is £76,700, this varies greatly by subsector, from only £23,300 for museums, galleries and libraries, up to £98,500 for film, TV, video, radio and photography companies (see Figure 18). Advertising and marketing and publishing also generate more than £90,000 per employee, according to our research. This is in keeping with UK-wide figures from DCMS, which also show the film and advertising subsectors with the highest output per hour worked of all creative industries sectors, at £47 and £46 respectively.68

Museums, galleries and libraries generated just £8 per hour, although it’s worth noting that many are likely to be registered charities, rather than the commercial businesses that are within the scope of this report. Further, DCMS observes that economic benefits from this subsector can be hard to quantify.69 Nonetheless, this huge disparity in output between subsectors does suggest that investment to grow the size of the GSW creative industries in easily measurable ways would do well to focus on the highest-value, like advertising and marketing, film and TV. This is not always the case currently. For example, the crafts subsector is small, although it is larger in the GSW (0.6 percent of GVA) than across the UK (0.4 percent).

70 However, the crafts subsector is not growing nationally – in fact it shrank by 11 percent between 2010 and 2022, which suggests there may be a ceiling on its growth in the GSW, too.

71

66. DCMS: DCMS Economic

Monthly GVA (to June 2024)

on DCMS’s monthly GVA series, measured in 2022 prices, which is more timely but less accurate than the annual series. It can be used as a leading indicator.

67. British Film Institute (BFI): Official BFI 2023 statistics

68. DCMS: DCMS and digital sector productivity 2022 (provisional).

GVA cannot capture wider cultural and societal benefits associated with these sectors (which may also include indirect effects on UK GVA). Hence, these productivity measures cannot fully account for output in these sectors.” Quoted from DCMS: DCMS and digital sector productivity 2022 (provisional). Published 28 March 2024.

70. UK figure from DCMS: DCMS and digital sector GVA 2022 (provisional). Based on 2022 data. Published 15 February 2024. Updated 3 September 2024. GSW figure from our analysis. 71. DCMS: DCMS and digital sector GVA 2022 (provisional).

Employment

Looking at creative industries employee counts, the top three subsectors are again IT, software and computer services with 13,619 employees (39 percent), advertising and marketing with 5,070 (15 percent), and music, performing and visual arts with 4,726 (14 percent). In the top four subsectors for jobs, a substantial share of employees work in large or medium-sized companies, as Figure 19 shows.

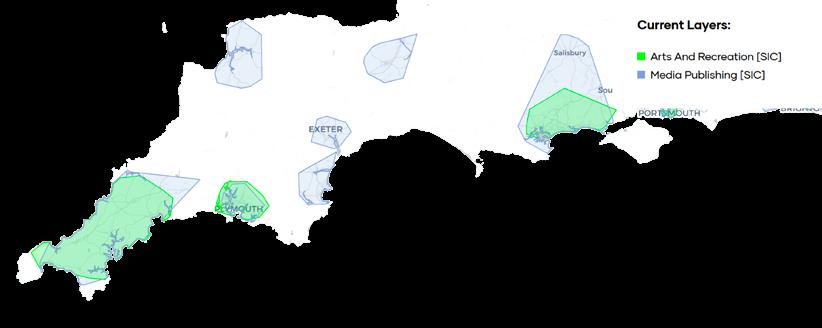

Breaking down the employee counts by subsector and ITL3 region reveals concentrations of IT employees in BCP, Dorset and Devon, with an above-average share of advertising and marketing employees in Devon. Cornwall and Isles of Scilly punches above its weight in film, TV, video, radio and photography, as well as music, performing arts and visual arts, with the second largest number of employees in both these subsectors by ITL3 region.

ONS data – complementary to ours but not directly comparable with it – shows the GSW had faster jobs growth over 2019-22 than the British average in numerous creative industries subsectors (see Figure 21). Crafts and museums, galleries and libraries show the fastest relative employment growth (local share effect on Figure 21) and are also largest relative to the national average (location quotient), though they remain small, as does design and designer fashion. Encouragingly, however, several larger subsectors also have local share effects above zero, indicating they are growing faster than the national average. These are: advertising and marketing; architecture; and (the largest subsector) IT, software and computer services, as well as the creative industries as a whole.

CASE STUDY: BRAY LEINO

Bray Leino (brayleino.co.uk) is an integrated marketing communication agency based in Filleigh, North Devon, with offices in Bristol, London, North America and Asia. It provides an end-to-end service for B2B and B2C clients across sectors including food and drink, industrial and healthcare. It is one of the top five UK B2B marketing agencies and the only agency to have held this position for over 10 years, according to a B2B Benchmarking Report.72 In 2005, it was one of the first acquisitions for the Mission Group, an AIM-listed group of 19 agencies all registered in Filleigh, North Devon. The Mission group is the largest company in our dataset, with 1,084 employees, turnover of £196 million and GVA of £111 million. Bray Leino, which is listed separately, employs 206 people, has turnover of £56.7 million, and contributes £21.2 million in GVA. As well as global brands, Bray Leino has a strong track record of helping regional businesses grow into national and international brands, including some of the GSW’s most recognisable food manufacturing companies, Rodda’s and Burts.

SECTOR PROFILES

The GSW has differing levels of strength among the nine DCMS creative industries subsectors. Here we profile these in detail.

ADVERTISING AND MARKETING

GSW COMPANY COUNT:

1,250 GVA: £479.7 MILLION (data available for 56 percent of companies) TURNOVER: £528.8 MILLION (57 percent) EMPLOYEES: 5,070 (56 percent)

EMPLOYMENT LOCATION QUOTIENT (ONS 2022):73 0.60

EMPLOYMENT GROWTH (ONS): 11.7 PERCENT CAGR 2019-22

KEY LOCAL AUTHORITY DISTRICTS FOR EMPLOYMENT (ONS 2022):74 BCP (LQ 1.16)

Advertising and marketing is a strong candidate for strategic focus as one of the largest and fastest-growing creative industries subsectors in the GSW. It is the second largest by turnover, GVA and employees. The subsector contributes a larger share of creative industries GVA in the region than nationally and is growing faster. It also has at least one large company to act as a potential subsector anchor: Bray Leino. This North Devon-based creative agency, part of the Mission Group of agencies but recorded separately in our data, is one of the ten largest creative industries companies in the GSW in terms of turnover and GVA.

ARCHITECTURE

GSW COMPANY COUNT:

784 GVA: £97.9 MILLION (data available for 81 percent of companies)

TURNOVER: £88.9 MILLION (82 percent)

EMPLOYMENT LOCATION QUOTIENT: 0.90

EMPLOYEES: 2,204 (81 percent)

EMPLOYMENT GROWTH (ONS): 3.2 PERCENT CAGR 2019-22

KEY LOCAL AUTHORITY DISTRICTS FOR EMPLOYMENT (ONS 2022): DEVON (LQ 1.09)

Architecture is another candidate for a strategic focus in the GSW. While the subsector is dominated by London, as all creative industries subsectors are, the GSW almost reaches the national architecture job share (LQ 0.9), while Devon exceeds it (LQ 1.09).

The architecture subsector, which includes construction engineering and planning businesses, is vital to the green economy and energy security priority in the region.

For example, Tor & Co (torandco.com) is a planning, design and environmental consultancy based in Bournemouth, with offices in London and Birmingham. It has advised 36 schemes across the wind, solar and biomass sectors, including on the geothermal energy plant at the Eden Project.

GSW

COUNT: 166 GVA: £15.0 MILLION (data available for 46 percent of companies)75 TURNOVER: £4.3 MILLION (46 percent) EMPLOYEES: 241 (46 percent)

EMPLOYMENT LOCATION QUOTIENT: 1.79

EMPLOYMENT GROWTH (ONS): 15.9 PERCENT CAGR 2019-22

KEY LOCAL AUTHORITY DISTRICTS FOR EMPLOYMENT (ONS 2022):

PLYMOUTH (LQ 2.69)

DEVON (LQ 2.4)

CORNWALL (LQ 2.15).

DESIGN: PRODUCT, GRAPHIC AND FASHION DESIGN

GSW COMPANY COUNT:

6,754 GVA: £932.6 MILLION (data available for 66 percent of companies)

TURNOVER: £956.6 MILLION (66 percent) EMPLOYEES: 13,619 (59 percent)

EMPLOYMENT LOCATION QUOTIENT: 0.68

EMPLOYMENT GROWTH (ONS): 8.6 PERCENT CAGR 2019-22

KEY LOCAL AUTHORITY DISTRICTS FOR EMPLOYMENT (ONS 2022): CORNWALL, DORSET, ALTHOUGH BOTH HAVE LQS BELOW 1 (0.84)

When it comes to the green economy, design is a core subsector. Practical design skills are needed to reduce or reuse resources in products and buildings, and to drive behaviour change by ensuring sustainable products, services and places are an attractive choice for everyone. Designers are already designing for environmental impact: 66 percent of designers surveyed by the Design Council in 2024 said they had done so in the previous 12 months.76 The most common issues addressed were carbon emissions and the net zero transition, awareness and sustainable behaviour change (26 percent) and climate change adaptation (24 percent).

Although our data suggests design is a relatively small subsector in the GSW, it is growing faster than average. Note that fashion designers that are also fashion manufacturers and retailers, such as Cornish sustainable surfwear company Finisterre (finisterre.com) are not included in the data as they are registered under SIC codes for clothes manufacture rather than the creative industries.

FILM, TV, VIDEO, RADIO AND PHOTOGRAPHY

GSW COMPANY COUNT:

2,092 GVA: £454.5 MILLION (data available for 61 percent of companies)

TURNOVER: £278.2 MILLION (63 percent)

EMPLOYMENT LOCATION QUOTIENT: 0.38

EMPLOYEES: 4,612 (61 percent)

EMPLOYMENT GROWTH (ONS): -2.5 PERCENT CAGR 2019-22

KEY LOCAL AUTHORITY DISTRICTS FOR EMPLOYMENT (ONS 2022): CORNWALL (LQ 0.78)

Film and TV is a hugely important subsector nationally because of its GVA, productivity, and exports that contribute to the UK’s soft power.77 In the GSW, there are fewer jobs in this subsector than the national average, but recent strategic developments that replicate successful interventions in other regions are already boosting growth. The GSW has had organisations anchoring film and TV businesses for many years, including the Exeter Phoenix, which manages small grants for resident filmmakers. Most local authorities or cities have film offices, usually hosted and funded by councils and the GSW is home to some outstanding VFX (visual effects) companies, including Outpost VFX, one of the largest creative industries companies in the region. However, the GSW has been relatively slow to put in place the scale of support and incentives, skills and infrastructure that film and TV production companies need to attract them to film in the region. There are no large studios west of The Bottle Yard Studios in Bristol,78 so companies that use GSW for on-location filming go outside the region for studio filming. Large studio complexes have been proposed for locations within the GSW, but they are capital-intensive to develop and need a commitment to fill them for several years to be commercially viable. Other regions have done better in this respect: Yorkshire, for example (see 5. Comparisons) has had a Screen Agency since 2002, with a remit to attract incoming productions and develop homegrown filmmaking.

That is changing, however. Screen Cornwall (screencornwall.com), a screen agency for Cornwall, was launched in 2019 and has already scored major strategic successes for film and TV in Cornwall. This can be seen in the relatively higher than average number of film and TV jobs in Cornwall. Successes include the recognition of Kernewek (Cornish) as a minority language in the 2023 Media Bill,79 which presents a unique opportunity for Cornish production companies, and the facilitation of £16.2 million of production spend in Cornwall in 2023-2024.80 Other screen agencies as well as additional film offices are also forming across the region to lead on screen industries strategies in their areas.

IT, SOFTWARE AND COMPUTER SERVICES

GSW COMPANY COUNT:

6,754 GVA: £932.6 MILLION (data available for 66 percent of companies)

TURNOVER: £956.6 MILLION (66 percent)

EMPLOYMENT LOCATION QUOTIENT: 0.45

EMPLOYEES: 13,619 (66 percent)

EMPLOYMENT GROWTH (ONS): 4.3 PERCENT CAGR 2019-22

KEY LOCAL AUTHORITY DISTRICTS FOR EMPLOYMENT (ONS 2022): BCP

(although job counts may be overinflated owing to the high number of IT firms registered at accountancy firm addresses in BCP)

Although it is the largest creative industries subsector in the GSW, IT, software and computer services has a lower jobs share compared with Great Britain (albeit with faster growth) and a lower GVA share than the UK average. Although 43 percent of creative companies in the GSW are in the IT, software and computer services subsector, they only contribute 35 percent of GSW creative industries GVA. This is partly because GSW IT businesses are generally smaller than those in other subsectors. IT has the highest share of companies with just one employee: 39 percent, compared to 31 percent for non-IT companies.81 Many of these will be registered to accountancy firms in Dorset and BCP, and not truly resident within the GSW. But there is some indication in our dataset that GSW IT companies may be underperforming economically too: they contribute only £68,479 in GVA per employee, much lower than the most productive sectors (£90,000+) and only slightly higher than crafts at £62,095. Nonetheless, large IT companies are also among the largest creative industries companies in the GSW. They include Bournemouth-based Visor Commerce, which has raised 49.5 million investment into its rapidly growing OnBuy online marketplace.82 IT, software and computer services companies must be a strategic focus as they underpin activity and innovation across all sectors.83 Software companies such as Amutri in Penryn (see case study) and Invidar in Poole (invidar.com), together with film and TV companies and supported by universities, are building a convergent screen sector in the region. This produces visualisations, immersive and augmented reality (AR), and real-time simulations for diverse sectors including energy, defence and health. Devonport in Plymouth is home to the largest immersive dome in the UK,84 which is poised to develop collaborations with the blue and defence sectors.

MUSEUMS, GALLERIES AND LIBRARIES

(data

EMPLOYMENT LOCATION QUOTIENT: 1.28

EMPLOYMENT GROWTH (ONS): 20.5 PERCENT CAGR 2019-22

KEY LOCAL AUTHORITY DISTRICTS FOR EMPLOYMENT (ONS 2022): CORNWALL, DORSET, SOMERSET

MUSIC, PERFORMING AND VISUAL ARTS

GSW COMPANY COUNT:

2,489 GVA: £415.1 MILLION (data available for 52 percent of companies)86

TURNOVER: £212.6 MILLION (59 percent)

EMPLOYMENT LOCATION QUOTIENT: 0.68

EMPLOYEES: 4,726 (52 percent)

EMPLOYMENT GROWTH (ONS): -1.3 PERCENT CAGR 2019-22

KEY LOCAL AUTHORITY DISTRICTS FOR EMPLOYMENT (ONS 2022): PLYMOUTH (LQ 1.01)

Note that the GVA and employee estimates for this subsector are based on a substantially smaller number of companies and so are not comparable to turnover.

The GSW should develop its unique strengths in music, performing and visual arts. It is already a strong subsector in the GSW by GVA share (see Economic impact above), though employment location quotients are lower than they should be. The exception is Plymouth, which is home to Theatre Royal Plymouth, one of the ten largest creative industries businesses in the GSW. The GSW is home to the 210,000-capacity Glastonbury Festival, the largest greenfield music and performing arts festival in the world. Other major festivals include Boardmasters (capacity 58,000), Sidmouth Folk and Sidmouth International Jazz and Blues festivals, and Summer Sessions on Plymouth Hoe. The region is also home to the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, which is receiving its largest annual Arts Council England grant in 2023-26 (see 4. Investment).

The South West region (including Bristol and Bath) is ranked second behind London for music tourism spend and employment, and third for the number of tourists attending live music events (behind London and the North West). Moreover, the South West accounts for 10 percent of all UK gig, concert and festival visits, 11 percent of music tourism spend and 14 percent of employment. The number of music tourists coming to the South West increased 86 percent between 2022 and 2023, from 1.1 million to 2 million. 87

In theatre, the GSW is home to some very distinctive venues and producers. Theatre Royal Plymouth (TRP) is not only one of the UK’s largest regional producing theatres, but also builds sets for other national and international productions at its TR2 Production and Learning Centre on the waterfront in Cattedown. In Ilfracombe, North Devon, the doubleconed Landmark Theatre became an NPO for the first time in 2023 to support its work with communities. In Cornwall, a long tradition of site-specific theatre, exemplified by theatre companies including Wildworks, is also symbolised by the spectacular open-air Minack Theatre in Porthcurno. Home to the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, Poole’s Lighthouse multi-arts venue is one of the largest in the South West.

PUBLISHING

GSW COMPANY COUNT:

1,118 GVA: £160.2 MILLION (data available for 55 percent of companies)88

TURNOVER: £75.9 MILLION (60 percent)

EMPLOYMENT LOCATION QUOTIENT: 0.56

EMPLOYEES: 1,741 (55 percent)

EMPLOYMENT GROWTH (ONS): -5.3 PERCENT CAGR 2019-22

KEY LOCAL AUTHORITY DISTRICTS FOR EMPLOYMENT (ONS 2022): DEVON, DORSET (BUT BOTH LQS BELOW 1, AT 0.76 AND 0.75)

Note that the GVA and employee estimates for this subsector are based on a substantially smaller number of companies and so are not comparable to turnover.

Publishing in the GSW reflects the state of publishing nationally, which is experiencing a decline in jobs as the subsector continues to pivot to digital and adopt new business models. One of the largest creative industries businesses in the GSW is equity-backed Kortext (kortext.com), based in Bournemouth. Kortext is a leading online learning platform and supplies digital textbooks to students globally. Exeter is one of five UNESCO Cities of Literature in the UK, 89 which reflects the GSW’s international contribution to literature. Torbay-born Agatha Christie is still regarded as the bestselling author of all time90 and many other writers of world standing from Thomas Hardy, to Michael Morpurgo to Hilary Mantel have made the GSW their home. These four writers have in common extensive adaptation of their work in other media. Extensive literary archives and expertise in IP (intellectual property) exploitation, make the universities well placed to support the region’s publishing industry to explore cross-media exploitation of content and establish successful new business models.

INVESTMENT

Creative industries companies in film and television, music, software and games can yield substantial investment returns through recurring and multiple revenue streams, while digital media can be highly lucrative due to the scalability of digital products. Venture capital (VC) funding in UK createch businesses exceeded a forecast of £1.12bn to reach £1.14bn in 2021, according to data from Tech Nation.91 UK creative industries have generated several unicorns (companies valued at over US$1 billion), including games companies Playdemic 92 and Improbable.93

While there are publicly-funded equity funds, most public sector programmes are aimed at enabling markets to work effectively and reducing barriers to growth, rather than directly investing in companies. In this way, public investment underpins the creative industries and public ‘returns on investment’ are seen through the positive contribution of the creative sector to the UK economy, in terms of the number of jobs, GVA, and growth compared to the economy as a whole.

The case for investment in the creative industries was neatly summarised in the Council of Science and Technology’s recent advice to the Government.94 It describes the creative industries as an economic and cultural success story, quoting that the creative industries delivered more economic value than the life sciences, aerospace and automotive sectors combined. Further evidence of the health and potential of the creative industries is noted in its:

⦁ High level of R&D: creative industries spend 3.2 percent of the sector’s GVA on R&D, higher than the UK average (2.3 percent).

⦁ High spillover potential: The report notes that R&D in the creative industries has produced spillover benefits in sectors as diverse as defence, agriculture, healthcare and education. It also recognises the creative industries as important generators of new ideas and knowledge with significant growth potential in subsectors that combine science and technology with arts and humanities.

Further, the multiplier impacts of the creative industries are considered to be relatively high. In considering the overall economic impact of the creative industries, Oxford Economics95 note that the contribution of the creative industries is larger than its direct employment and GVA contribution through procurement and supply chain impacts. Their report states that for every 10 jobs in creative industries, a further seven are supported in other sectors. For every £1 contributed in GVA, a further £0.5 is generated in other sectors.

The largest channel for public investment in the creative industries is Creative Industries Tax Relief. There are plans to merge them into one, but the UK government currently has eight separate tax relief programmes to support creative industries businesses: Film Tax Relief (FTR)

⦁ Film Tax Relief (FTR)

⦁ High-end Television (HETV) Tax Relief

⦁ Animation Tax Relief (ATR)

⦁ Video Games Tax Relief (VGTR)

⦁ Children’s Television (CTV) Tax Relief

⦁ Theatre Tax Relief (TTR)

⦁ Orchestra Tax Relief (OTR)

⦁ Museums and Galleries Exhibition Tax Relief (MGETR)

In the financial year 2022-23, £2.2 billion was paid out in these tax relief schemes across all creative industries companies nationally, up from £1.9 billion in 2021-22.96 High-end TV includes large-budget productions for international streamers such as Netflix, Amazon, Disney and Apple. It dwarfs the other schemes in terms of payouts. In 2021-22, it took over from film as the scheme rewarded the most tax relief. No regional breakdown of creative industries tax relief data is available, but the heavy weighting towards high-end TV, film and video games shows regions with many companies in screen industries will benefit the most from tax relief schemes.

MEASURING RETURN ON INVESTMENT

The DCMS and others have attempted to measure the outcomes and impacts of specific programmes and investments. However, given the very different investment and sector types, broad industry-wide return on investment (ROI) figures, in terms of GVA or jobs, are difficult to ascertain. It is easy to appreciate that the ROI in crafts would be different to that in gaming for example, with very different risks. What we can do is to point to broad indicators, and pinpoint examples.

Probably the best overarching measure of expectation of investment return lies in the amount of private capital that is attracted to public sector investment. Private sector co-investment in public programmes clearly demonstrates that the private sector can see the benefits of the activity and believes the investment will benefit them, directly or indirectly. At an industry level, the value of co-investment is probably the best broad indicator of potential return.

Creative Industries Clusters Programme

The most significant UK public programme to support clusters that has attracted coinvestment has been the Creative Industries Clusters Programme from the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and UKRI.97 The first wave ran from 2018 to 2023, with a public investment of £61 million, including £55 million to universities. Its goal was to anchor nine regional creative industries clusters by delivering interventions at a local level. This included R&D support and devolved grant funding to SMEs.98 Most of the nine clusters had a subsectoral as well as regional focus – for example in video games, film and TV, or fashion. All had strong underpinnings from IT, software and computer services. The Clusters Programme was designed to build links between research in universities and the creative industries and deliver regional economic benefits associated with R&D cluster development, including building the capacity of creative businesses to exploit technology and data-driven innovation.

An analysis of Clusters Programme data suggests businesses were able to leverage £57 million of co-investment, follow-on funding, or investment from public and private sources over the course of the programme, a ratio of 1:1,99 with public and private coinvestment at a ratio of 1:4.6.100 Information self-reported by businesses engaged in the clusters suggests there were 107 spin-outs, start-ups and scale-ups and 3,413 jobs were created or safeguarded. The Clusters Programme has also helped to identify the types of partnerships that are critical for developing clusters, namely local authorities, cultural organisations, creative businesses including large companies and micro businesses, and higher and further education institutions.

A second AHRC R&D investment programme is Convergent Screen technologies and Performance in Realtime (CoSTAR).101 It supports immersive R&D facilities over 2023 to 2029 and recently attracted similar amounts of private sector investment. Public investment of £75.6 million attracted co-investment of £68 million, a ratio of 1:0.9. (This excludes any follow-on investment.)

In 2023, DCMS published its Creative Industries Sector Vision with a target to grow the creative industries by £50 billion and an additional one million jobs by 2030.102 This committed the government to investing £50 million in a new round of the Clusters Programme. A pre-announcement since the election has confirmed there will be a call for regional bids led by universities in spring 2025.103

PUBLIC AND PRIVATE FUNDING OF THE GSW CREATIVE INDUSTRIES

Creative businesses and cultural organisations across the GSW have benefitted from devolved funding, including Shared Prosperity Funds and Town Deals. They also receive funding directly from national government bodies, including UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) R&D grants, Arts Council England core funding and project grants, and HMRC creative industries tax relief schemes. Regional interventions targeted at creative industries companies can help them capture external funding. In this section, we outline the main sources of additive funding and investment for GSW creative industries (not Shared Prosperity Funding) and describe some recent successful interventions in the creative industries in the region.

Create Growth Programme

The Create Growth Programme (CGP) was designed to help address barriers to accessing finance in the creative industries (see Section 6 Barriers to growth) outside London. It supports management development, R&D grant applications and investment. Launched in 2022 by DCMS in partnership with Innovate UK, the CGP provided six regions with £1.275 million each. Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly received CGP funding in 2023 as part of a ‘West of England’ region that also included Bristol, Bath and North East Somerset, North Somerset and South Gloucestershire.104 In 2024, the programme was extended to six more geographical areas, with an additional £10.9 million of funding provided. Devon joined the CGP in March 2024 and DCMS has recently announced that 13 businesses in Devon successfully won £30,000 each in funding from the Create Growth competition in 2024 (although this was an open competition, and not all these businesses were on the GCP).105 Participating businesses also have the opportunity to access part of a finance growth support fund totalling £9 million in the financial year 2024-25.106 The programme is scheduled to finish in March 2025.

Innovate UK

Innovate UK, part of UKRI, is the UK’s ‘innovation agency’.107 It awarded £54.6 million of R&D grants to organisations with an address in the GSW (including universities) between 200405 and 2022-23. Almost £5.2 million of this (9.5 percent) went direct to companies in the creative industries, almost all of them SMEs, across 99 grants (we excluded grants direct to universities from this list).108 In 2022-23, 24 GSW-based creative industry SMEs captured £1.7 million of Innovate UK grant funding. Almost £700,000 of this – or 41 percent – went to 10 companies based in Cornwall, where Cornwall Council’s industrial strategy has targeted interventions at creative businesses for a number of years.109

The Innovate UK funding received by GSW creative industries companies has surged each year since 2020 (Figure 24). Over the last few years, UKRI has launched national competitions with small grants targeted at creative industries SMEs, including a Creative Catalyst110 fund and the Create Growth111 fund, as well as Women in Innovation112 and Young Innovators113 competitions, which have been won by creative industries entrepreneurs in the GSW, suggesting an increased capacity for innovation. However, there were no Innovate UK grants awarded to GSW creative industries companies in 2018-19 and 2019-20. These years coincided with the launch of the Creative Industries Clusters Programme, also funded by UKRI, which suggests that UKRI may have diverted its funding for creative industries SMEs to the nine flagship cluster regions of the Clusters Programme. As the GSW was not among the nine selected, not only did the GSW creative industries fail to gain around £7 million in Clusters Programme funding, they also may have lost more than £1 million in Innovate UK money.

104.

Arts Council England

Arts Council England (ACE, artscouncil.org.uk) is one of the most important sources of funding for non-commercial organisations. Non-commercial organisations include museums, galleries and cultural centres. They help to anchor commercial creative industries clusters and develop a skilled workforce that moves between non-commercial and commercial subsectors. Every three years, ACE provides grant funding to selected organisations – designated as National Portfolio Organisations (NPOs) or Investment Principles Support Organisations (IPSO) – to be allocated to core funding. In February 2022, the Government instructed the Arts Council to redistribute more of its National Portfolio funding from London to other parts of England from London, starting from 2023.114

In the 2023 round of NPO selections, the Arts Council committed investment of £445 million a year over the 2023-26 period to 985 organisations across England. Just 3.3 percent of this, or £14.5 million a year, has been awarded to 42 organisations in the GSW. Twentyfour percent of this (£3.5 million a year) is going to eight theatre organisations, with 18 percent (£2.6 million) to one music organisation – The Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra – and the same amount to 14 organisations working in combined arts (Figure 25).

Figure 26 shows that, by local authority district, 28 percent of GSW total Arts Council funding, or £4.1 million a year, is going to organisations based in Plymouth, with BCP close behind on 27 percent (£3.9 million). The Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra accounts for two thirds of the BCP total: its £2.6 million grant is the single largest awarded to a GSW organisation. The Arts Council has a target to distribute a larger share of funding to English locations designated as Levelling Up for Culture Places. In the GSW, these are North Devon, Torridge, Torbay and Somerset. In total, organisations in these local authorities have been awarded £2.1 million per year for 2023-26. This is up sharply from £0.5 million a year in 2018-22, thanks mainly to new grants of £1 million to Landmark Theatres in North Devon and £0.25 million to Octagon Theatre in Somerset.

University research income

The six GSW universities received £33.6 million of research grant funding in the three years 2021-22 to 2023-24.115 These universities committed £9.4 million of match funding alongside these grants, with an additional £2.1 million coming from third-party businesses and organisations, bringing the total match over three years to £10.7 million.116

Equity and loan funding

Limited data is available for angel and private equity investment and retail bank loans for the creative industries in GSW. However, publicly funded equity and loan funds have been available in the GSW since 2018.

CLOSIF