focusin

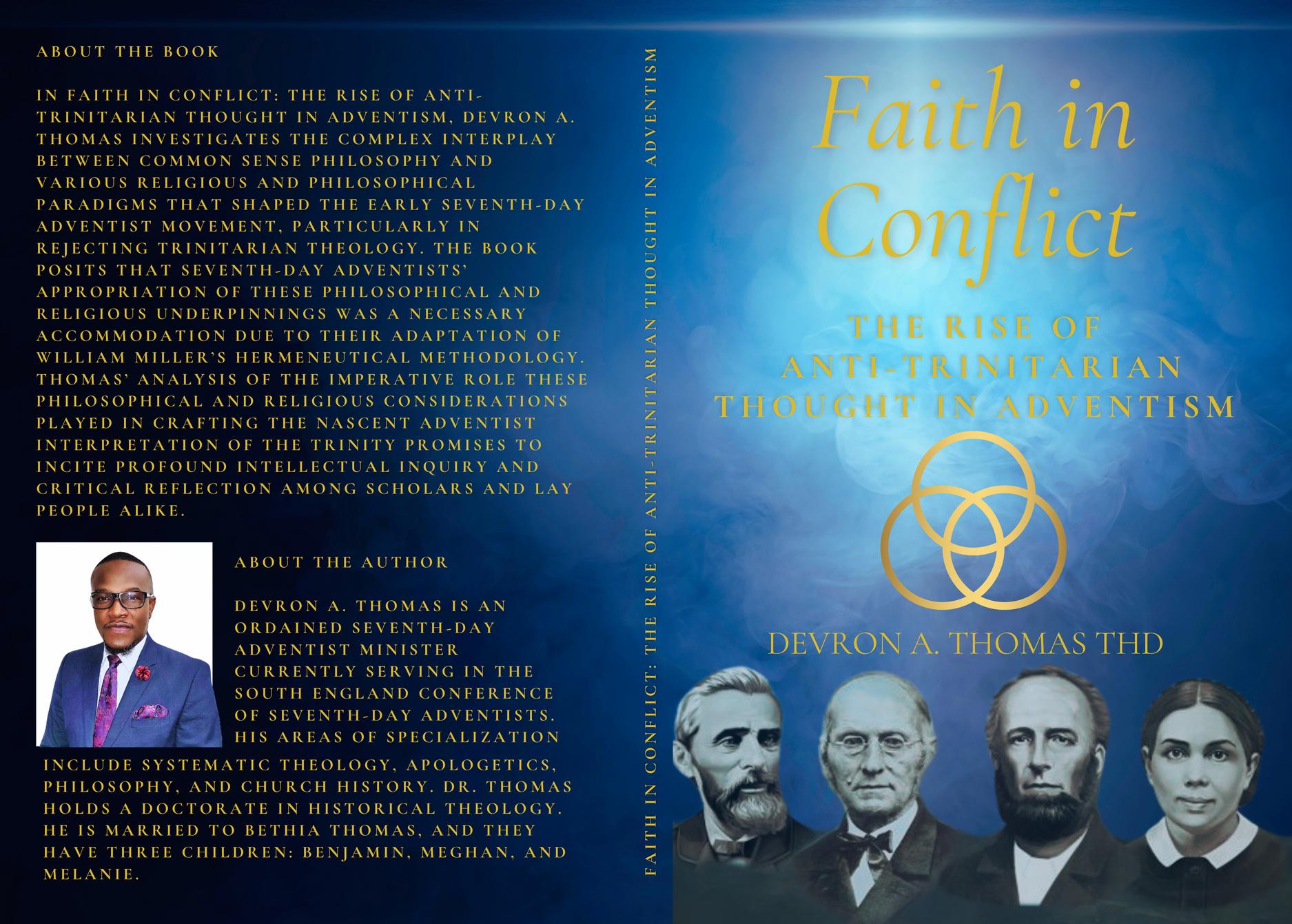

Reasons why early Seventh-Day Adventists

RE JECTED THE TRINITY

Dr. Devron A. Thomas Chief Editor Pastor Apologist

REASONS

By Dr. Devron A. Thomas

The reasons attributed to the rejection of the Trinity can be described as follows. First, some pioneers rejected the classical Christian view of the Trinity as a pagan belief, a later forgery, due to a faulty or inaccurate view of what the doctrine espouses. Second, they perceived a lack of evidence from Scripture to validate such a concept. Third, the perceived origins of the doctrine of the Trinity as a Roman Catholic phenomenon further fueled their antiTrinitarianism. Fourth, the doctrine of the Trinity distorted their concept of the atonement. Fifth, a denominational predisposition to anti-Trinitarianism influenced their views. Sixth, the doctrine of the Trinity had creedal overtones that some pioneers found objectionable. Seventh, their appropriation of common sense philosophy to understand the Trinity created misunderstandings. Lastly, Ellen White’s ambivalent statements before the 1880s indirectly influenced other leaders to reject the Trinity.

Reason Number One: A Faulty Comprehension of the Trinity

The early Seventh-day Adventists needed an accurate and comprehensive grasp of the intricate tenets of the doctrine of the Trinity. According to Fortin, the early pioneers’ “view of the Trinity does not correspond with the traditional orthodox understanding of the Triune God; it nonetheless highlights that in early Adventism, the doctrine was not accurately understood to start with.”1 Fortin’s

observation aptly highlighted the epistemic inaccuracy of the early Seventh-day Adventists concerning the Trinitarian theological tenets from the inception.

Some early Adventists believed the doctrine espoused that three beings make up the Godhead, thus three gods. For example, in 1861, Loughborough wrote, “If Father, Son, and Holy Ghost are each God, it would be three Gods.”2 Loughborough postulated that the attribution of divinity to each of the three persons, Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, would have necessitated the existence of a triad of deities, thereby contradicting the fundamental tenet of monotheism in Christianity. Loughborough erroneously believed that the doctrine of the Trinity espoused tritheism - a heretical belief that posited the existence of three separate gods, as opposed to the classical teaching of one God in three distinct persons.3 Others thought the doctrine of the Trinity taught that the Father and the Son were the same being.4 This view was called modalism or Sabellianism: one person in the Godhead manifests himself in three modes.5 Cottrell believed the Trinity doctrine taught “that one person is three persons, and that three persons are only one person.”6 Cottrell’s belief was based on his understanding of the Trinity doctrine, which he perceived as teaching that one person was three beings and that three beings were also one person.

James White believed that the Trinity taught that Jesus was identical to the Father. He stated, “But to say that Jesus Christ is the very and eternal God, makes him his own son, and his own father, and that he came from himself, and went to himself.”7 White postulated that the notion of Jesus as the ‘eternal God’ engendered a logical inconsistency, mainly because Jesus would be both the progenitor and the offspring of himself, having originated from and returned

1 Denis Fortin, “God, the Trinity, and Adventism: An Introduction to the Issues,” Journal of the Adventist Theological Society, 17/1 (Spring 2006): 4.

2 J. N. Loughborough, “Questions for Bro. Loughborough,” Review and Herald (November 5, 1861), 184.

3 Augustine wrote, “In this Trinity there is nothing greater and nothing less, no separation of works, no dissimilarity of substance. The Father is one God, the Son is one God, the Holy Spirit is one God. However, the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit are not three gods, but one God; so that he who is the Son is not the Father, nor he who is the Father the Son, nor he who is the Holy Spirit either the Father or the Son. But the Father is the Father of the Son; and the Son is the Son of the Father, and the Holy Spirit is the Spirit of Hie Father and of the Son; and each of these is one God, and the Trinity itself is one God. Let this faith saturate your hearts and direct your confession. Hearing this, believe so that you might understand, so that in making progress you might understand what you believe [reference to Isa 7.9].” Quoted in John P. Hoskins, The Unity of The Spirit: The Trinity, the Church and Love in Saint Augustine of Hippo (Durham theses, Durham University, 2006), 32.

4 Bates stated that, “respecting the trinity, I concluded that it was impossible for me to believe that the Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of the Father, was also the Almighty God, the Father, one and the same being.” (Joseph Bates, The Autobiography of Elder Joseph Bates (Battle Creek, MI: SDA Publishing, 1868), 205. Smith also stated about the Holy Spirit, that “the Bible uses expressions which cannot be harmonized with the idea that it is a person like the Father and the Son. Rather it is shown to be a divine influence from them both, the medium which represents their presence…...” Uriah Smith, “In the Question Chair,” Review and Herald (March 23,1897),188.

5 G. T. Stokes, “Sabellianism,” in A Dictionary of Christian Biography, Literature, Sects and Doctrines, eds. William Smith and Henry Wace (London: John Murray, 1877), 567.

6 Cottrell, “The Trinity,” Review and Herald (July 6, 1869), 10.

7 James White, “Mutual Obligation,” Review and Herald (June 6, 1871), 197.

to himself. According to White, the ascription of the title ‘eternal God’ was reserved solely for the Father, and thus, to apply it to Jesus would make him identical to the Father.

Mark Driscoll and Gerry Breshears observed that “the three main heresies that contradict the doctrine of the Trinity are Modalism (the persons are ways God expresses himself, as in Oneness theology), Arianism (the Son is a creature and not divine, as with Jehovah’s Witnesses), and Tritheism (there are three distinct gods, as in Mormonism and Hinduism).”8 Early Seventh-day Adventists believed in the “distinct personality of the Father and Son, rejecting as absurd that feature of Trinitarianism which insists that God, Christ, and the Holy Spirit are three persons, and yet but one person.”9

Given that early Adventists misunderstood the concept of the Trinity, it is pertinent to provide a clear definition and analysis of the Christian perspective on the doctrine of the Trinity. Trinitarian theology postulates that there are three persons, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, who deserve to be called God, and yet there is but one God, not three.10 The Father is not the Son or the Holy Spirit; the Son is not the Father or the Holy Spirit; and the Holy Spirit is not the Father or the Son. Despite this distinction, they are one God, a mystery complex for the human mind to comprehend fully. James R. White posited that “within the one Being that is God, there exist eternally three coequal and coeternal persons, namely, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.”11 Bruce Ware provided a succinct yet comprehensive definition of the Trinity:

The Christian faith affirms that there is one and only one God, eternally existing and fully expressed in three Persons: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Each member of the Godhead is equally God, eternally God, and fully God—not three gods but three Persons of the one Godhead. Each

person is equal in essence as each possesses fully the identically same, eternal divine nature, yet each is also an eternal and distinct personal expression of the one undivided divine nature. 12

In other words, the Christian doctrine of the Trinity affirms that God is one, yet exists in three Persons: the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Each member of the Godhead - Father, Son, and Holy Spirit - is equally God, eternally God, and fully God. This means that the divine nature of each Person was identical and that there was no hierarchy or subordination among them. Moreover, the three persons are not construed as three separate deities but as distinct yet indivisible entities of the same divine essence. Trinitarianism utilized specific theological terminology that early Seventh-day Adventists did not fully comprehend. Among these phrases were “one being consisting of three persons” and “same substance.” These terms created theological complications when interpreted through a materialistic lens as referring to a singular body. It seems that the early Adventist community struggled with using these expressions. This notion of the oneness of God was so central to ancient Israel that it could not have been missed, given that they lived in a pagan/ polytheistic culture. John MacArthur commented on the importance of God’s oneness, “That truth was central to Israel’s religious convictions. Because they lived in the midst of polytheistic societies, it was vital that they give their allegiance to the one true God.”13

The theological concept of the Trinity has a rich and intricate history spanning many centuries. The Council of Nicaea in AD 325 was a pivotal assembly that sought to define God’s essence and elucidate the interrelationships between the Father and the Son. The council ultimately formulated the Nicene Creed, which validated the belief in the Trinity and condemned the heretical teachings of Arius, who contested the full divinity of Christ.14

8 Mark Driscoll and Gerry Breshears, Doctrine: What Christians Should Believe (Wheaton: Crossway, 2010), 71.

9 W. H. Littlejohn, “Scripture Questions. 96 - Christ Not a Created Being,” Review and Herald (April 17, 1883), 250.

10

“There is only one God (Deut. 6:4), however, Father, Son and Holy Spirit are all called God (Matthew 27:46, John 20:28: Acts 5:3-4). Consequently, we do not worship three Gods, but one God who reveals Himself in and consists of three “persons”. The three persons share one indivisible nature. Each person of the Godhead is by nature and essence God, and the fullness of the deity dwells in each of them. On the other hand, each person of the godhead is inseparably connected to the other two.” Ekkehardt Mueller, “Biblical Research Institute,” Reflections Newsletter, July 2008, 8.

11 James R. White, The Forgotten Trinity: Recovering the Heart of Christian Belief (Bloomington, Minnesota: Bethany House Publishers, 1998), 25.

12 Bruce A. Ware, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit: Relationships, Roles and Relevance (Wheaton: Crossway Books. 2005), 121-122.

13 John MacArthur Jr., God: Coming Face to Face with his Majesty (Victor: Wheaton, 1993), 18. 14 H. M. Gwatkin, The Arian Controversy, (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1898), 20 and Mark A. Noll, Turning Points: Decisive Moments in the History of Christianity (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic,

Over time, various challenges and heterodoxies arose, necessitating subsequent councils and gatherings to clarify and consolidate the doctrine of the Trinity. One such council was the Council of Constantinople in AD 381, which reasserted the Nicene Creed and expounded further on the nature of the Holy Spirit, affirming the orthodox belief in the Trinity as three co-equal and co-eternal persons in one Godhead.15

For Seventh-day Adventists, a fundamental component of Trinitarian theology is the co-equality and co-eternality of each person of the Godhead.16 The logical implication is that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are all equal in their ontology; none is derived from the other. The Father, Son, and Holy Spirit have no beginning and have always existed as the One God.

Adventist theologian Fernando Canale believes that the “Bible simultaneously affirms both the oneness and the plurality of God.”17 He notes:

The Old Testament notion regarding divine oneness distinguishes Jehovah from the general polytheism of the times. However, Old Testament revelation does not conceive God’s oneness as a monad or single, simple, indivisible entity. Its writers do not limit their understanding of God to the simplicity of one divine entity. By using language that implies a duality of divine entities, the Old Testament opens a beyond-oneness complexity in the reality of God.18

According to Canale, the Old Testament does not view God as a singular entity but rather as a complex reality that defied simple categorization. This complexity is hinted at through language that implies the existence of more than one divine entity. Canale believes the Old Testament reveals God as one and a plurality simultaneously; the New Testament is more explicit in its declaration of the Trinity. He views Jesus as the person who unveiled the concept of the Trinity. He posits:

Jesus Christ personally revealed the Trinity. 2000), 48.

Through His ministry, His less-than-obvious divine nature shone through humanity in deeds and words. As a divine entity, Christ is directly and personally related to God in heaven. God in heaven was His “Father,” a second intelligent, active, powerful, eternal divine entity standing side by side with Christ. Finally, when the time of Jesus’ death and resurrection was drawing near, Christ presented His successor, the divine person of the Holy Spirit. Thus, through the Trinity Christ revealed that the plurality implicitly present in the Old Testament included three full divine entities, God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit. Christ revealed the doctrine of the Trinity because it is the necessary presupposition for the possibility and proper understanding of both the incarnation and the cross as divine acts.19

Canale asserts that Jesus Christ revealed the Trinity during his ministry on earth, and it is necessary to understand the incarnation and the cross as divine acts. Canale emphasizes that each person of the Trinity is a complete divine entity and that Christ relates directly and personally to God the Father in heaven. In Canale’s view, the Old and New Testaments affirm the oneness and threeness of God. God is one essence, but three persons or entities, as he calls it.

Although Seventh-day Adventists are officially Trinitarians, they maintain, “in no way could human minds achieve what the classic doctrine about the Trinity claims to perceive, namely, the description of the inner structure of God’s being. Together with the entire creation, we must accept God’s oneness by faith (James 2:19).”20

Given that some early Seventh-day Adventists lacked a nuanced comprehension of the Trinitarian doctrine, disavowing a concept that eluded their grasp would be fallacious. Substantive research and dialectical engagement with knowledgeable interlocutors are pivotal in pursuing a comprehensive understanding of theological concepts. Moreover, it is critical to recognize that an initial lack of comprehension, as in the case of the Trinitarian doctrine, does

15 Justo L. Gonzalez, The Story of Christianity: Volume 1: The Early Church to the Dawn of the Reformation (HarperCollins 2014), 298.

16 “There is one God: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, a unity of three co-eternal Persons. God is immortal, all-powerful, all-knowing, above all, and ever present. He is infinite and beyond human comprehension, yet known through His self-revelation. He is forever worthy of worship, adoration, and service by the whole creation.” Seventh-day Adventists Believe (Nampa, Idaho: Pacific Press Pub. Assn., 2005), 16.

17 Fernando L. Canale, Basic Elements of Christian Theology: Scripture Replacing Tradition (Berrien Spring, MI: Andrews University Lithotech, 2005), 78.

18 Ibid., 82.

19 Ibid., 83.

20 Fernando Canale, “Doctrine of God,” in Handbook of Seventh-Day Adventist Theology, ed. Raoul Dederen, (Hagerstown, MD: Review and Herald, 2000), 150.

not necessarily render it spurious or erroneous. Aiming for a robust apprehension of the concept in question is necessary before levying any judicious determination regarding its validity.

Reason Number Two: Perceived Lack of Biblical Evidence

The pioneers and early Seventh-day Adventists saw no evidence in Scripture supporting the Trinity. Their theological understanding was deeply rooted in a literal and straightforward interpretation of the Scriptures and a desire to return to what they believed were the pure teachings of the early Christian church. Their quest for a return to the teachings of the early Christian church fostered a deep commitment to the purity of biblical doctrine. Consequently, they refrained from subscribing to theological tenets not explicitly articulated in Scripture.

According to Loughborough, the Trinity “is contrary to Scripture.”21 James White called the concept of the Trinity “the old unscriptural”22 doctrine. To many early Seventh-day Adventists, Trinitarian theology involved complex theological jargon and concepts that took centuries to develop and articulate through creeds and councils. They further argued, “the word Trinity nowhere occurs in the Scriptures.”23 This strict biblicism was characteristic of Miller’s approach, which the early Seventh-day Adventists adopted. Biblicism is the “method [in which] one asks a question or makes a propositional statement and then cites one or more Scripture passages, in the first instance to answer the question, and in the second to support the proposition.”24 According to the 1857 Review and Herald:

God may be perfect, thoroughly furnished unto all good works.” 2Tim. 3:16,17.25

The statement accentuated the Bible’s indispensability as the exclusive fount of veracity and direction. It encouraged us to scrutinize and apprehend the Scriptures, as they comprised the testimony of Jesus and furnished readers with eternal life. The text acknowledged that certain mysteries might be exclusive to God, but the revelations contained in Scripture were crucial for its readers. Moreover, the quotation underscored that readers should consider the Scriptures’ totality as their guide, not just a fragment. All the Scriptures were divinely inspired and were advantageous for teaching, rebuking, correcting, and training in righteousness. Through adherence to the Scriptures, readers could be perfected and thoroughly equipped for all good works.

Cottrell postulated, “The Trinity, or the Triune God, is unknown to the Bible; and I have entertained the idea that doctrines which require words coined in the human mind to express them, are coined doctrines.”26 Canright also wrote, “The Bible says nothing about the Trinity. God never mentions it, Jesus never named it, the apostles never did. Now men dare to call God, Trinity, Triune, etc.” 27 Cottrell and Canright expressed their skepticism about the Trinity as it was commonly understood in Christian theology. According to Cottrell, the Trinity was not mentioned in the Bible, and he believed that doctrines that require newly coined words to express them were not valid. Canright also argued that the Bible did not refer to the Trinity and was not named by God, Jesus, or the Apostles. Instead, he suggested that the terms “Trinity” and “Triune” were invented by men.

The bible, and the bible alone. It is our duty to search the Scriptures. “Search the Scriptures; for in them ye think ye have eternal life; and they are they that testify of me.” John 5:39; Isa. 8: 20. The Scriptures may be understood. “The secret things belong unto the Lord our God; but those things which are revealed, belong unto us and to our children for ever.” Deut. 29: 29. The whole, and not a part only, of the Scriptures our Guide. “All scripture is given by inspiration of God, and is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in righteousness, that the man of 21 J. N. Loughborough, “Questions for Bro. Loughborough,” Review and Herald (November 5, 1861), 184.

22 White, Day-Star, 25.

To the early Seventh-day Adventists, the Scriptures emphasized God’s oneness and unity. For them, the absence of explicit endorsement for the Trinity in Scripture provided a basis for alternative perspectives that propelled rejection of the traditional doctrine of the Trinity. In their view, Scripture did not endorse the personhood and deity of the Holy Spirit. Consequently, they saw deep entrenched incompatibilities with the doctrine of the Trinity and biblical revelation. However, the Bible speaks about the plurality within the Godhead in several places. A case in point is Genesis 1:26, “Let us make man in our image, according to our likeness.” Commenting on this text, Millard Erickson argued,

23 Loughborough, “Questions for Bro. Loughborough,” 184.

24 Francis D. Nichols, “What’s Wrong With the Proof-Text Method?,” Review and Herald, (March 11, 1976), 10.

25 “The Bible and the Bible Alone,” Review and Herald (May 19, 1857), 155.

26 R. F. Cottrell, “The Doctrine of the Trinity,” Review and Herald (June 1, 1869), 180.

27 D. M. Canright, “The Personality of God,” Review and Herald (August 29, 1878), 73.

“Here the plural occurs both in the verb, ‘let us make’ and in the possessive suffix ‘our.’ What is significant from the standpoint of logical analysis is the shift from singular to plural. God is quoted as using a plural verb with reference to himself.”28 In his commentary of Genesis 1:26, Erickson highlighted God’s use of the plural form while declaring, ‘Let us make man in our image, according to our likeness.’ This usage of the plural indicated an intriguing dimension of the doctrine of the Trinity, which asserts the unity of God’s essence while acknowledging His existence as a tripersonal being. Erickson’s interpretation of this verse as a testimony to the Trinity posited that God was addressing other members of the Godhead, thus indicating that He was a coequal community of persons in perfect relational unity.

Deuteronomy 6:4, generally cited by antiTrinitarians to support their position, is often misinterpreted. The word translated “one” in Deuteronomy 6:4 is the Hebrew word אֶחָֽד-echad. This word אֶחָֽד-echad is frequently used in the Old Testament to mean compound plurality, “for a unity that is not a simple singularity.”29 It is the kind of united plural one, as in “one nation under God,” or the idea behind “bunch,” as in “a bunch of grapes.” The usage of the term in other places in the Old Testament will surely help put into perspective in what way is God ‘one.’ Genesis 1:9 (“Let the waters under the heavens be gathered into one place”); Genesis 2:24 (“Therefore a man shall leave his father and his mother and hold fast to his wife, and they shall become one flesh”). The consistent idea behind אֶחָֽד-echad, then, is one made up of others or “a united one.”30

The New Testament also confirms the “three-ness” of God. Matthew 28:19, “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit.” In the scripture text above, “name” is used in the singular to denote the one nature of God. Erickson observed, “So name is singular, but there are three persons included in that name.”31 Wayne Grudem also expressed similar thoughts when he wrote:

Once we understand God the Father and God the Son to be fully God, then Trinitarian expressions in verses like Matthew 28:19 (“baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit”) assume significance for the doctrine of the Holy Spirit, because they show that the Holy Spirit is classified on an equal level with the Father and the Son.32

According to Grudem, the Father and Son to be fully God is crucial because it establishes the Holy Spirit’s classification on an equal level with the Father and the Son.

Ellen White provided commentary on the baptismal formula, “There are three living persons of the heavenly trio; in the name of these three great powers, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, those who receive Christ by living faith are baptized, and these powers will cooperate with the obedient subjects of heaven in their efforts to live the new life in Christ.”33 She mentioned three living persons in the heavenly trio: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. She further emphasized that those who receive Christ by living faith were baptized in the name of these three great powers and that these powers would cooperate with the obedient subjects of heaven in their efforts to live the new life in Christ. This quote reflected the Christian belief in the Trinity and the importance of baptism to receive salvation and live a new life in Christ.

Anti-Trinitarians often cite John 14:28, where Jesus states, “My Father is greater than I.” This, they claim, showed Jesus’s subordination to the Father, thus disqualifying Jesus to be God (possessing divine immortality before the incarnation). Jesus is indeed subordinate to the Father, but it does not describe His essence or substance but His operations as a human being. Bruce Metzger argued, “Equal to the Father, as touching His Godhead: and inferior to the Father, as touching His manhood.”34 French Reformer John Calvin commented on this text: “Christ does not here compare the divinity of the Father with his own, nor his own human nature with the divine essence of the Father; but

28 Millard J. Erickson, Introducing Christian Doctrine, 2nd ed. (Baker: Grand Rapids, 2001), 110.

29 W.A. Pratney, The Nature and Character of God: The Magnificent Doctrine of God in Understandable Language (Minneapolis: Bethany House Publishers, 1988), 291.

30 James Strong, The New Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible, Hebrew and Aramaic Dictionary of the Old Testament (Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1995), 5.

31 Millard J. Erickson, Introducing Christian Doctrine , 110.

32 Wayne Grudem, Bible Doctrine: Essential Teachings of the Christian Faith (Zondervan: Grand Rapids, 1999), 109.

33 Ellen G. White, Evangelism (Washington DC: Review and Herald, 1946), 615. See also, Special Testimonies, Series B, No. 7, 62, 63.

34 Bruce M. Metzger, “The Jehovah’s Witnesses and Jesus Christ: A Biblical and Theological Appraisal,” Theology Today (April 1953): 81.

rather his present condition with the celestial glory to which he would be presently received.”35

Jesus was not simply human but Divine-human. John 1:1 says, “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” The Word is expressed as God himself and is not an impersonal idea. “Word” in the text is not “a personification but a Person, and that Person is divine. The Word is nothing less than God.”36 The Greek preposition πρὸς- pros is generally used (in this instance) to describe relationships of a personal nature. It further distinguishes the Father and the Word, making the Father God, the Word (Jesus) God, but distinct persons having one essence and substance. Furthermore, in John 20:28, Thomas refers to Jesus as “My Lord and my God.” To think that Jesus would rebuke Thomas, instead, He accepts and commends Thomas’s statement of faith. Metzger thus concluded, “As has often been pointed out, Jesus’ statement is either true or false. If it is true, then he is God. If it is false, he either knew it to be false, or he did not know it to be false. If while claiming to be God he knew this claim to be false, he was a liar. If while claiming to be God he did not know this claim to be false, he was demented. There is no other alternative.”37

According to 1 John 4:16, “God is love.” C. S. Lewis reasoned that “God is love has no meaning unless God contains at least two persons. Love is something that one person has for another person. If God was a single person, then before the world was made, he was not love.”38 This is a potent observation on the part of Lewis. If God is love, then He cannot be one solitary person. God must be understood as a family of persons who have always related to each other in eternity. The interplay of love between two individuals may still be perceived as self-centered due to the exclusive nature of their bond, which allows them to monopolize each other’s attention without the need for external involvement. However, introducing a third party necessitates a redistribution of attention, thereby requiring each individual to relinquish their self-interest to facilitate the interaction between the other two parties. Consequently, it can be inferred that the minimum number of individuals needed for unselfish love is not two but rather three. Robert Letham expressed those same sentiments but in a reverse

manner when he wrote, “Islam’s doctrine of God leaves room neither for diversity, diversity in unity, nor a personal grounding of creation, for Allah is a solitary monad with unity only. The Islamic doctrine of God is centered on power and will. There is virtually no room for love.”39 This relational attribute, love within the Godhead, gives credence to the distinctness of personhood that Trinitarians confirm. MacArthur thus contended, “God is one, yet exists not as two but three distinct persons. That is a mystery unparalleled in our experience.”40 Simply put, the Father is God, the Son is God, and the Holy Spirit is God. The Father is not the Son, the Son is not the Holy Spirit, and the Son is not the Father. The publication of Questions on Doctrine by the Seventh-day Adventist Church in 1957 was a response to inquiries made by Evangelical Christians regarding the beliefs and practices of the Adventist Church. The book’s primary objective was to elucidate Adventist doctrines and foster harmonious interactions between Adventists and other Christian denominations.

According to the authors of Questions on Doctrine:

As to Christ’s place in the Godhead, we believe Him to be the second person of the heavenly Trinity, comprised of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, who are united not only in the Godhead but in the provisions of redemption. . . .Christ is one with the Eternal Father, one in nature, equal in power and authority, God in the highest sense, eternal and selfexistent, with life original, unborrowed, underived; and that Christ existed from all eternity, distinct from, but united with, the Father, possessing the same glory, and all the divine attributes.41

The statement asserted that the three persons of the Godhead are united in nature and the provisions of redemption. It further affirmed that Christ was one with the Eternal Father, equal in power and authority, and God in the highest sense. Christ was eternal and self-existent, possessing original, unborrowed, and underived life. Jesus’ co-equality and coeternity with the Father were expressed unambiguously, having the same glory and all the divine attributes.

For Seventh-day Adventists today, “Scripture

35 John Calvin, Commentary on the Gospel According to John, II (Edinburgh: Calvin Translation Society, 1847), 103.

36 Joseph Barclay, Alice Lucas, and S. L. MacGregor Mathers, Hebrew Literature: Comprising Talmudic Treatises, Hebrew Melodies and the Kabbalah Unveiled (New York: The Colonial Press, 1901), 109.

37 Metzger, “The Jehovah’s Witnesses and Jesus Christ: A Biblical and Theological Appraisal,” 74.

38 C.S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (New York: Harper Collins, 2001), 174.

39 Robert Letham, The Holy Trinity (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 2004), 442.

40 John MacArthur Jr., God: Coming Face to Face with his Majesty, 19.

41 Seventh-day Adventists Answer Questions on Doctrine (Washington: Review and Herald, 1957), 30, 31, 36.

presents God as a relational Trinity, in which the three Persons of the Godhead experience an eternal, divine, reciprocal love among themselves, which necessitates a temporal experience in the give-and-take exchange in their nature as a God of love.”42

In explaining early Seventh-day Adventist theological discourse, it is evident that several terms, such as investigative judgment, pre-advent judgment, and millennium, were employed. These terms were not explicitly expressed in biblical texts, but proponents of this theological paradigm contended that their underlying concepts could be adduced from Scripture. Nonetheless, the same hermeneutic principle could be applied to the notion of the Trinity, which could be considered a biblical concept despite a conspicuous absence of explicit biblical references. Thus, the salient criterion for theological analysis should not explicitly mention a term in the Bible but rather identify its underlying concept. In this regard, according to its adherents, Trinitarianism can be deemed a biblical concept.

Reason Number Three: Preconceived Origins of the Trinity

Another reason for the rejection of the doctrine of the Trinity was its preconceived origins. Several pioneers believed that Trinitarian theology was an invention of Roman Catholicism.43 In 1854, James White wrote:

As fundamental errors, we might class with this counterfeit sabbath other errors which Protestants have brought away from the Catholic church, such as sprinkling for baptism, the Trinity, the consciousness of the dead and eternal life in misery. The mass who have held these fundamental errors, have doubtless done it ignorantly; but can it be supposed that the church of Christ will carry along with her these errors till the judgment scenes burst upon the world? We think not.”44

White argued that specific errors, such as the belief in sprinkling for baptism, the Trinity, the consciousness of the dead, and eternal life in misery, are not compatible with the teachings of the church of Christ. He suggested that those who keep the commandments of God and have faith in Jesus will not hold such fundamental errors and will reject the traditions of men. The perceived Roman Catholic association

was sufficient to reduce Trinitarianism to paganism, a concept adopted by apostate Christianity. Consequently, any idea or language associated with Trinitarian theology was viewed with heightened skepticism. In 1909, Robert Hare made the following statement:

In the fourth and fifth centuries, many absurd views were set forth respecting the Trinity, views that stood at variance with reason, logic, and Scripture. The enemy gladly leads to what appears to be a more rational, though not less erroneous idea that there is no trinity, and that Christ is merely a created being. But God’s great plan is clear and logical. There is a Trinity, and in it there are three personalities [or three individuals]… We have the Father described in Dan. 7:9, 10 … a personality surely … In Rev. 1:13-18 we have the Son described. He is also a personality. The Holy Spirit is spoken of throughout Scripture as a personality. These divine persons are associated in the work of God. But this union is not one in which individuality is lost. There is indeed a divine trio, but the Christ of that Trinity is not a created being as the angels, He was the “only begotten” of the Father.45

In his discourse, Hare expounded on the doctrine of the Trinity, which posits the existence of three distinct divine persons - the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit - within the Godhead. While conceding the prevalence of erroneous views in the past, which contradicted the tenets of logic, reason, and Scripture, Hare contended that the notion of the Trinity was unequivocal and coherent and enjoyed substantial biblical validation. The Father, Son, and Holy Spirit were depicted as distinct personages united in the divine enterprise. Notwithstanding this union, Hare underscored that individuality was not subsumed within it, and each person within the Trinity retained their unique identity while endeavoring towards a shared objective. Hare further addressed the notion that Christ was a created being and refuted it by invoking the term “only begotten” of the Father. This phraseology denoted that Christ was not a created being akin to the angels but one who existed perpetually and was an inseparable constituent of the Trinity.

42 Norman R. Gulley, Systematic Theology: God as Trinity, vol. 1 (Berrien Springs, MI: Andrews University Press, 2011), 3.

43 James White stated that “the greatest fault we can find in the Reformation is, the Reformers stopped reforming. Had they gone on, and onward, till they had left the last vestige of Papacy behind, such as natural immortality, sprinkling, the trinity, and Sunday-keeping, the church would now be free from her unscriptural errors.” James White, “The Word,” Review and Herald (February 7, 1856), 149.

44 James White, “The Position of The Remnant, Their Duties and Trials Considered,” Review and Herald (September 12, 1854), 36.

45 Robert Hare, Australasian Union Conference Record, July 19, 1909.

In essence, the statement attempted to elucidate the doctrine of the Trinity and repudiate any spurious beliefs that may have arisen in the past. The author underscored that the concept of the Trinity was rational and logical, buttressed by numerous biblical references.

Because the doctrine of the Trinity, based on mainstream Protestantism and Roman Catholicism,46 taught that “there is but one living and true God, everlasting, without body or parts,”47 early Adventists vehemently opposed such a view, perceiving this doctrine as perverting God’s personality. To the pioneers, this view of the Trinity “spiritualizes the existence of the Father and the Son as two distinct persons, literal and tangible.”48 For the pioneers, this view of God was incompatible with what the Bible revealed about God’s nature. Thus, they saw the Bible depicting God in a material way, which appeared contrary to saying that God has no body or body parts.

Notwithstanding the strong repugnance harbored by the early Adventists towards many Roman Catholic doctrines, their comprehension and articulation of the relationship between the Father and the Son exhibited a semblance to the Roman Catholic perspective. Although not identical, the terminology employed to designate the correlation between the Father and Jesus bore a resemblance. Many pioneers and early Seventh-day Adventists espoused the belief that the Father’s act of begetting the Son took place in a temporal reality that is so far removed that it is beyond the complete comprehension of the human intellect. Despite this, this event was undoubtedly firmly situated within the context of time. They emphatically asserted that Jesus was not a created being but rather begotten of the Father and that this event transpired so remotely in the depths of eternity that it transcends human comprehension. For example, C.W. Stone stated:

The Word then is Christ… He is the only begotten of the Father. Just how he came into existence the Bible does not inform us any more definitely; but we may believe that Christ came into existence in a manner different from that in which other beings first appeared; That he sprang from the Father’s being in a way not necessary for us to understand.49

Stone acknowledged that the Word, Christ, was the Father’s only begotten Son. He believed that Christ’s origin differed

from that of other beings, and the Bible did not provide a clear explanation of Christ’s origin but asserted that Christ came into existence in a way that is beyond our understanding. Observe Stone’s choice of words, Jesus “sprang from the Father,” Jesus, “the only begotten of the Father.” Interestingly, this language utilized by Stone resembles the terminology employed in the Nicene Creed. The Son’s begottenness took place so far into eternity that the mind cannot understand it. Uriah Smith once believed that Jesus was a created being but changed his view some years later, adopting the position that the Son was begotten. According to Smith, “The Scriptures nowhere speak of Christ as a created being, but plainly state that he was begotten of the Father.”50 He further stated:

God alone is without beginning. At the earliest epoch when a beginning could be, a period so remote that to finite minds it is essentially eternity, appeared the Word. “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” John 1:1. This uncreated Word was the Being, who, in the fulness of time, was made flesh, and dwelt among us. His beginning was not like that of any other being in the universe. It is set forth in the mysterious expressions, “his [God’s] only begotten Son” (John 3:16; 1 John 4:9), “the only begotten of the Father” (John 1:14), and, “I proceeded forth and came from God.” John 8:42.51

Smith believed that God was the only one without a beginning and that the Word (referring to Jesus Christ) was with God from the earliest epoch when a beginning could be discerned. According to Smith, the Word was not created like any other being in the universe but was the only begotten Son of God, who proceeded forth and came from God.

Speaking about Jesus’ past existence, J. N. Andrews posited, “And as to the Son of God, he would be excluded also, for he had God for his Father, and did, some point at the eternity of the past, have beginning of days.”52 According to Andrews, the Son of God had a beginning of days in the past, implying that the Son of God was not intrinsically eternal but had a finite existence at some point. The Son, he believed, was begotten in time but in the eternity past. According to the Catholic Catechism, “the onlybegotten Son of God, eternally begotten of the Father, light

46 “The mystery of the Trinity is the central doctrine of Catholic faith. Upon it are based all the other teachings of the Church……” Handbook for Today’s Catholic, 1977. 12.

47 Doctrines and Discipline of the Methodist Episcopal Church (New York: Carlton and Porter, 1856), 15.

48 James White, “Letter from Bro. White,” The Day-Star (January 24, 1846), 25.

49 C. W. Stone, The Captain of our Salvation (Chicago: Moody Press, 1972), 17.

50 Smith, Thoughts, Critical and Practical, on the Book of Revelation, 430.

51 Smith, Looking Unto Jesus, 10.

52 John N. Andrews, “Melchisedec” Review and Herald (September 7, 1869), 84.

from light, true God from true God, begotten not made, consubstantial with the Father.”53 The statement emphasizes that Jesus Christ was begotten and not made, which meant He was not created but begotten of the Father in an eternal and unchanging relationship. Catholics believe that the Son is eternally generated by/from the Father in eternity in a timeless manner. The Son proceeds from the Father; the Father has no origination, so He has no procession. The Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son. This procession takes place in a timeless manner in eternity.

It is worth noting that the perspective mentioned above resembles the theological stance of the early pioneers concerning the Son’s relationship with the Father. However, our analysis has revealed that some of these pioneers did not recognize the Holy Spirit as a distinct person but as a manifestation of the Father and the Son. This position bears some semblance to the doctrine of the procession of the Holy Spirit as explicated by the Catholic Church, which posits that the Spirit proceeds from both the Father and the Son. The only discernable difference is that the pioneers did not accord personhood to the Holy Spirit but perceived it as an influential presence emanating from both the Father and the Son. According to the Catholic Church, “the eternal order of the divine persons in their consubstantial communion implies that the Father, as ‘the principle without principle,’ is the first origin of the Spirit, but also that, as Father of the only Son, He is, with the Son, the single principle from which the Holy Spirit proceeds.”54 According to Catholicism, the Father is the first origin of the Holy Spirit, and as the Father of the only Son, He is also the single principle from which the Holy Spirit proceeds. This reflects the idea that the Father is the source and origin of both the Son and the Holy Spirit and that there is an eternal order and relationship among the members of the Trinity.

Modern-day Seventh-day Adventist anti-Trinitarians who think that the pioneers’ view of the “begotten of the Son” or that the Son “sprang from the Father” was an original idea that the pioneers extrapolated from Scripture would be astonished to discover that the Cappadocian Fathers taught a similar concept.

The Cappadocian Fathers were Basil (c. 330- 379), bishop of Caesarea, and his brother Gregory of Nyssa (c. 335- 394), together with a friend, Gregory of Nazianzus (c. 329- 389). The Western and Eastern Churches highly revere and celebrate the Cappadocian Fathers. Basil is honored as a Doctor in the West, while Basil and Gregory of Nazianzus are hailed as the “Great Hierarch” in Eastern traditions. According to Gregory of Nazianzus, “The Father is the begetter and the emitter; without passion of course, and without reference to time, and not in a corporeal manner. The Son is begotten, and the Holy Ghost is the emission.”55 Gregory of Nazianzus believed the Father was the source of the Son and the Holy Ghost. He was the begetter and emitter, but not in a physical sense. The Son was begotten by the Father, which meant that he was of the same essence as the Father but was not identical to him. The Holy Ghost was the emission of the Father, which meant that he proceeded from the Father but was also of the same essence as the Father and the Son.56

The Cappadocian Fathers taught that the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit were distinct persons within the Godhead, co-equal and co-eternal. They also believed in the eternal generation of the Son and the procession of the Holy Spirit from the Father. In their view, the Son was begotten from the Father before all ages, not created, and the Holy Spirit proceeded from the Father, not created either. This view became the orthodox doctrine of the Trinity after it was ratified at the Council of Constantinople in 381 AD.57

Before the Cappadocian Fathers, Origen (c.185c.253 AD) taught a similar concept about the eternal generation of the Son. The language the pioneers and early Seventh-day Adventists used was similar to that of Origen’s description of how the Son relates to the Father. This will be explained below.

Origen has been classified as the first Christian systematic theologian,58 a prolific author dubbed “the greatest genius the early church ever produced.”59 Origen’s Trinitarian model is predicated upon reflecting a person’s spiritual journey toward God combined with Platonic and Greek ideologies. He affirmed the oneness of God when

53 Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2nd Edition, part 1, sec. 2, 242. Date of Access: 9/26/2023 http:// www.scborromeo.org/ccc/p1s2c1p7.htm

54 Ibid., part 1, sec. 2, 248.

55 Gregory of Nazianzus, “The Third Theological Oration - On the Son,” op. cit.,161.

56 John McGuckin, “Gregory of Nazianzus,” in The Cambridge History of Philosophy in Late Antiquity, Part 1 (ed., Lloyd Gerson; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 491.

57 Robert Letham, “The Three Cappadocians,” in Shapers of Christian Orthodoxy: Engaging with Early and Medieval Theologians, ed., Bradley G. Green (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 2010).

58 C. Kannengiesser, “Divine Trinity and the Structure of Peri Archon,” in Origen of Alexandria: His World and His Legacy, eds. C. Kannengiesser and W. L. Petersen (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1988), 238-241.

59 John A. McGuckin, “The Life of Origen (ca. 186–255),” in The Westminster Handbook to Origen: The Westminster Handbooks to Christian Theology, ed. John A. McGuckin (Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press, 2004), 25.

he wrote, “We Christians, however, who are devoted to the worship of the only God, who created these things, feel grateful for them to Him who made them.”60 He also affirmed the threeness of the Godhead:

As, then, after those first discussions which, according to the requirements of the case, we held at the beginning regarding the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, it seemed right that we should retrace our steps, and show that the same God was the creator and founder of the world, and the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, i.e., that the God of the law and of the prophets and of the Gospel was one and the same; and that, in the next place, it ought to be shown, with respect to Christ, in what manner He who had formerly been demonstrated to be the Word and Wisdom of God became man; it remains that we now return with all possible brevity to the subject of the Holy Spirit. It is time, then, that we say a few words to the best of our ability regarding the Holy Spirit, whom our Lord and Savior in the Gospel according to John has named the Paraclete. For as it is the same God Himself, and the same Christ, so also is it the same Holy Spirit who was in the prophets and apostles, i.e., either in those who believed in God before the advent of Christ, or in those who by means of Christ have sought refuge in God.61

Though distinct from the Father, the Son is God, eternally begotten by the Father but consubstantial with Him. For Origen, the Father is the source of all existence beyond being, while the Son is generated from the Father. This eternal generation in Origen’s mind did not have a starting point or an end but was best understood as light generates its splendor continuously. Thus, the Son is God in essence, but not by participation because the Father begets Him in eternity, while the Father is not begotten.

It is necessary at this juncture to juxtapose the Cappadocian Fathers and Origen’s theology of the Son’s relationship with the Father with a statement from E. J. Waggoner:

As to when He was begotten, it is not for us

to inquire, nor could our minds grasp it if we were told. The prophet Micah tells us all that we can know about it in these words, “But thou, Bethlehem Ephratah, though thou be little among the thousands of Judah, yet out of thee shall Hepaper come forth unto Me that is to be ruler in Israel; whose goings forth have been from of old, from the days of eternity.” Micah 5:2. There was a time when Christ proceeded forth and came from God, from the bosom of the Father (John 8:42; 1:18), but that time was so far back in the days of eternity that to finite comprehension it is practically without beginning.62

Waggoner postulated that the cognitive capacity of the human psyche was insufficient to comprehend the enigma surrounding the origin of Christ. He substantiated his claim by alluding to Micah 5:2, emphasizing that the advent of Jesus was predestined from eternity and that He emanated from God. The statement underscored that at one point, Christ emanated and proceeded from God, that is, from the Father’s bosom. Waggoner espoused the notion that the Father procreated the Son, albeit in a distant past, so profound that the human mind could not comprehend this intricate enigma. It is worth noting that this idea was not exclusive to Waggoner or the early Seventh-day Adventists. According to Origen, “the God and Father, who holds the universe together, is superior to every being that exists, for he imparts to each one from his own existence that which each one is; the Son, being less than the Father, is superior to rational creatures alone (for he is second to the Father).”63 Origen advanced an ontological inferiority in the Son because the Son is less than the Father. For Origen, the Holy Spirit derives His substance (ousia) from the Son and the Father.64 Thus, the Holy Spirit is also ontologically subordinate to the Father and the Son. Just as the Son is ontologically subordinate to the Father, so is the Holy Spirit subordinate to the Son. The Holy Spirit, he writes, “is the most honored of all things which came to be through the ‘Word’ and is the first in rank ‘of all the things which came to existence by the Father through Christ.”65

Both the Cappadocian Fathers and Origen held to

60 Origen, “Ante-Nicene Fathers Vol. IV,” Against Celsus (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2013), 531.

61 Origen, “Ante-Nicene Fathers Vol. IV,” in Origen De Principiis, trans. Frederick Crombie (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2013), 284.

62 Waggoner, Christ and His Righteousness, 21, 22.

63 Origen, On First Principles, trans. G. W. Butterworth (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1973), 33, 34.

64 “For if … the Son is distinct from the Father in essence and in underlying reality (kat’ ousian kai hypokeimenon), then we should pray to the Son and not to the Father, or to them both, or to the Father alone.” Origen, “On Prayer,” in Tertullian, Cyprian, and Origen, On the Lord’s Prayer, trans. and annotated by Alistair Stewart-Sykes (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2004), 147.

65 Origen, Commentary on the Gospel according to John, Books 1–10, trans. R. Heine, Fathers of the Church, 80 (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 1989), 114.

the doctrine of the eternal generation of the Son and the procession of the Holy Spirit from the Father while also affirming the unity of God and the trinity of the Godhead. However, certain distinctions exist in their respective perspectives.

For the Cappadocian Fathers, the Son was begotten from the Father before all ages, not created, and the Holy Spirit proceeded from the Father, not created either. They posited that the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit constituted distinct persons within the Godhead who were co-equal and co-eternal. On the other hand, Origen maintained that the Father is the source of all existence beyond being, while the Son is generated from the Father. This eternal generation was without a starting point or an end and was best understood as the continuous generation of light and its splendor. In this manner, the Son is God in essence but not by participation since the Father begets Him in eternity, while the Father is not begotten.

Furthermore, the language employed by the pioneers and early Seventh-day Adventists was similar to Origen’s depiction of how the Son relates to the Father. They held that the Son was begotten of the Father, which indicated that He was of the same essence as the Father but not identical to Him. They believed that the Son was begotten so far back in the past that the human mind could not comprehend it.

They diverged from the Cappadocian Fathers and Origen in that they believed the begottenness of the Son occurred in time. In contrast, the Cappadocian Fathers and Origen thought it took place in a timeless manner in eternity.

During the Middle Ages, Thomas Aquinas, on whose views much of Roman Catholic theology is built, had a unique view of how the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit relate to each other. The pioneers’ view bears a striking resemblance to his perspective as well. Aquinas amplified Augustine’s66 notion that the persons of the Trinity were identified or defined by their relations. His idea of relation was predicated upon Aristotelian metaphysics:

According to the Philosopher, in Metaphysics, every relation is founded either on quantity (for example, double and half); or on action and passion (for example, that which does something and the thing which it produces, or father and son, or master and servant). And there is no quantity in God: he is ‘great without quantity’, as Augustine says. It follows that a real relation in God can only be founded on action.67

Aquinas claimed that for relations to be real, there must be action, and actions presuppose both an acting subject and that which is being acted upon. This notion implied a double relation of giving and taking, proceeding and being responsible for the procession of another. According to Christopher Hughes, for Aquinas, “relations both constitute and distinguish the divine persons: insofar as relations are the divine essence (secundum res) [i.e., they are the same thing], they constitute those persons, and insofar as they are relations with converses, they distinguish those persons.”68 Relations were the divine essence, constituting and distinguishing the divine persons. This meant that relations were not just properties or attributes of the persons but were the same thing as the persons themselves. However, relations also had converses, which meant that they were not identical but distinguished the persons from one another. In other words, relations both unified and differentiated the divine persons, and they were essential to understanding the nature of the Trinity. Aquinas understood ‘person’ primarily as an ontological reality. We refer to God as three persons for him, but this must be construed analogously. Thus, any acceptable definition of person, in which we express how we understand persons, cannot be applied as such to God. Aquinas’s position was that the term ‘person’ signified a relationship in a certain way and that, therefore, the term was especially suited to be used for the relational ‘three’ in God.69 Relations in God can exist without any composition

66 “As Augustine affirmed, the distinction of Persons is constituted precisely by the differing relations among them, in part manifested by the inherent authority of the Father and inherent submission of the Son.” Bruce A. Ware, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit: Roles, Relationships, and Relevance (Wheaton: Crossway, 2005), 79–80.

67 Aquinas in Gilles Emery, The Trinitarian Theology of Saint Thomas Aquinas, trans. Francesca Aran Murphy (Oxford University Press, 2007), 54.

68 Christopher Hughes, On a Complex Theory of a Simple God: An Investigation in Aquinas’ Philosophical Theology (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1989), 217.

69 Rudi A. Te Velde (lecturer in philosophy and professor in the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas at the School of Catholic Theology of Tilburg University) posits: “When Christian doctrine speaks of the Trinity as consisting of three ‘persons’, person does not have quite the same meaning as that intended by our current use of the term. The specifically theological use of ‘person’ may rather impress us as quite abstract and even ‘impersonal’ in so far as we usually perceive the meaning of ‘person’ from the perspective of the ability to share in the human symbolic framework of communication and mutual recognition.” He further notes: “The relational aspect, Aquinas argues, is part of the meaning of person as applied to God. The term ‘person’, therefore, can be legitimately used of God personaliter, and this in virtue of its proper meaning. However, initially the term ‘person’ was used of

due to their nature, “compared to the divine essence in which they subsist, the divine relations differ from the essence in a merely rational way (to be exact, Aquinas says that in this way, the relation “is only a ratio”).”70

For Aquinas, divine persons were subsistent relations (relation ut subsistens), and these relations came from processions, and “in each of the processions, all of the divine attributes are brought into play ‘concomitantly’. All divine attributes concur in the begetting of the Son, and all concur in the breathing forth of the Spirit. In begetting as in spiration, one must recognize the fullness of God, by the mode of the speaking of the Word and the procession of Love.”71 These divine processions were not external but an internal reality in which these relations were real.72 Aquinas’ perspective on the Trinity “remains the classical explanation for the Trinity to the present day,” 73 at least among Roman Catholic theologians.

Canale rejects the notion of the eternal procession of the Son from the Father and the Holy Spirit from the Son and the Father because he believes that the idea of divine processions inevitably leads to subordinationism. He contends:

relation of dependence on the entity of the Father. And so we see that the orthodox view of the Trinity departs from Scripture both by assuming that divine entities are timeless, and by implicitly subordinating the entity of the Son to that of the Father. Because they view divine eternity as timeless, the “eternal generation” of the Son is not a divine movement but an immutable “relation” of dependence. The unavoidable result is that the divinity of the Son becomes less divine than the divinity of the Father who eternally generates Him.74

Canale’s theological position on the concept of ontological subordination is a nuanced one. While he rejects the notion of subordinationism in a strict sense, he acknowledges a certain subordination of roles among the persons of the Trinity, as expressed in the language of Scripture. This subordination, however, is understood by Canale in a temporal and salvific sense and must be interpreted in light of the divine processions. Specifically, Canale argues that the Father sent the Son and that within the context of the incarnation, the Son sent the Spirit as the Comforter, who was responsible for the governance of the Church in this present dispensation.75

This view places the entity of the Son in an eternal God in such a way that the indirectly signified aspect of relationship was not yet perceived clearly. Only later, as a consequence of heresies, Catholic theologians began to emphasize the relational dimension of the meaning of ‘person’ as applied to God. This emphasis on the relational aspect of ‘person’ must not be understood merely as a linguistic accommodation of the use of ‘person’ in order to deal politically with the heresy resulting from the fact that the term ‘person’ has an absolute signification; on the contrary, Aquinas claims that the term lent itself, in virtue of what it properly signifies, to express relationship. It was, thus, a matter of making explicit what was already implicitly present in the meaning of ‘person’.” Rudi A. Te Velde, “The Divine Person(s): Trinity, Person, and Analogous Naming,” in The Oxford Handbook of the Trinity, ed. Gilles Emery and Matthew Levering (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 360, 365.

70 Russell L. Friedman, Medieval Trinitarian Thought from Aquinas to Ockham (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 13.

71 Emery, The Trinitarian Theology of Saint Thomas Aquinas,70. Gilles Emery observed, “The doctrine of the persons and of their relationships (including those in the economy: the divine missions) constitute quite clearly for Aquinas the summit to which Trinitarian thinking leads us.” Gilles Emery, O.P., Trinity in Aquinas (Naples, FL: Sapientia Press of Ave Maria University, 2006), 71.

72 “(a) The relation of the Father to the Son. This is paternity or fatherhood, (b) The relation of the Son to the Father. This is filiation or sonship. (c) The relation consequent upon the proceeding in which Father and Son are the principle whence proceeds the Holy Ghost. This is the spiration or breathing forth of the Holy Ghost. (d) The relation consequent upon the same proceeding as considered from the standpoint of the Person spirited. This is the procession of the Holy Ghost.” Paul J. Glenn, A Tour of the Summa (Charlotte, NC: TAN Books, 1978), 45.

73 McGinn, “Theologians as Trinitarian Iconographers,” in The Mind’s Eye: Art and Theological Argument in the Middle Ages, eds. Jeffrey F. Hamburger and Anne-Marie Bouché (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006), 187:

74 Canale, Basic Elements of Christian Theology: Scripture Replacing Tradition, 87.

75 According to Canale, “Jesus’ promise of the coming Counselor is not stated in the context of Greek ontology regarding divine eternal entities. Instead, Jesus is talking about the mission which the Holy Spirit will fulfill in the historical flow of created space and time to achieve the goals of the Trinity’s plan of salvation. In this context, Christ, “sends” the Holy Spirit as His representative. The

The pioneers and early Seventh-day Adventists utilized language and expressions about the relationship between Jesus and the Father that appeared to be more in line with the Roman Catholic and early Church Fathers’ understanding of the Trinity rather than the official Trinitarian language used by the Seventh-day Adventist church today. These expressions were characterized by a focus on the notion of the Father begetting the Son, the generation of the Son from the Father, the procession of the Holy Spirit from the Father and the Son, and the Son’s subordination to the Father.

The Roman Catholic and mainstream Protestant understanding of the Trinity is predicated upon a timeless view of God. The notion of God’s timelessness has its roots in Greek philosophy. Greek philosopher Plato (423-348 BC) advocated a dualistic cosmology that posited the existence of two distinct ontological domains: the world of forms and appearances.76 The world of forms was characterized as the realm of absolute reality, where eternal, unchanging, and perfect forms exist. These forms are regarded as the ultimate reality and the source of all knowledge and truth.77 On the other hand, the world of appearances was identified as the physical reality, where imperfect, changing, and transient objects exist. According to Plato, the world of forms was timeless and eternal, whereas the world of appearances was temporal and subject to change. Therefore, divine timelessness was rooted in this dualistic ontological framework, positing a clear distinction between the temporal world of human experience and the eternal world of divine reality.78

Plato believed that the world of forms was the ultimate reality, and the world of appearances was merely an imperfect copy or imitation of the Forms. He argued that the physical world was constantly changing; therefore, having proper knowledge of it was impossible. The only way to

achieve actual knowledge was to access the world of forms through reason and contemplation. He further surmised that these spheres of reality are mutually exclusive, and there was no point of intersection between the two.79

Aristotle (384–322 BC) developed Plato’s ideas into a dualistic ontology. For Aristotle, there were two spheres in which beings exist. One was the ultimate reality, the sphere of forms. In this sphere, nothing changed; nothing moved; it was pure existence.80 The other sphere of existence was that which was movable and mutable. This was the sphere of the tangible, which humans were a part of. These two spheres were mutually exclusive.81 Aristotle proposed a dualistic ontology that divided reality into two categories: the material and the immaterial. The material world was composed of physical substances that change, while the immaterial world consisted of non-physical substances that did not change.82 A central component of timelessness is the exclusion of past, present, and future events, which transcends chronological time. God exists, lives, and acts outside the future-present-past sequence of time. Wolterstorff writes, “I am persuaded that ... the most important factor accounting for the tradition of God eternal (i.e., His being above time) within Christian theology was the influence of classical Greek philosophers on the early theologians.”83 As taught by the Greeks, this view of God was introduced into the Church by Augustine (c. 354- 430) and later by Thomas Aquinas (1225 -1274).

Augustine, one of the most influential theologians in the Western tradition, drew on the writings of Plato and Aristotle to explain the concept of God’s timelessness. Augustine posited, “Since time did not exist, God did not have time to do anything....in the Eternal nothing passeth, but the whole is present; whereas no time is all at once present: and that all time past, is driven on by time to come, and all to come followeth upon the past; and all past and to come, is

Holy Spirit, sent by Christ to testify about Him, comes or proceeds from the Father. Thus, this is not a statement about God’s reality but about God’s life and mission.” Basic Elements of Christian Theology, 90.

76 Douglas R. Campbell, “Located in Space: Plato’s Theory of Psychic Motion”, Ancient Philosophy 42, no. 2 (2022): 419-442; John M. Cooper, ed., Plato: Complete Works (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1997).

77 Russell Dancy, Plato’s Introduction of Forms (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

78 David Ebrey and Richard Kraut, eds., The Cambridge Companion to Plato (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022).

79 Gabriela R. Carone, Plato’s Cosmology and its Ethical Dimensions (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

80 Jonathan Beere, “Activity, actuality, and analogy: Comments on Aryeh Kosman, The Activity of Being: An Essay on Aristotle’s Ontology,” European Journal of Philosophy 26 (2018): 872–880.

81 Rogers Albritton, “Forms of Particular Substances in Aristotle’s Metaphysics,” Journal of Philosophy 54 (1957): 699-707.

82 Jonathan Beere, Doing and Being: An Interpretation of Aristotle’s Metaphysics Theta (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 7.

83 Nicholas Wolterstorff, in God and the Good. Essays in Honor of Henry, eds. Stob Clifton Orlebeke and Lewis Smedes (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1975), 182, 181.

created, and flows out of that which is ever present... see how eternity is ever still-standing, neither past nor to come.”84 According to Augustin, there was a qualitative difference between eternity and time, where the latter was seen as a constantly flowing stream of past, present, and future. At the same time, the former was in a constant state of being without any fluctuations.

For Augustine, God existed in timeless eternity before he created the world. God was in a timeless state, seated, contemplating Himself. This view taught that God’s knowledge of all past, present, and future events is complete and unchanging. According to Augustine, God’s knowledge of the future did not interfere with human free will; instead, he knew what we would choose to do. For centuries, this view of God’s relationship to time has influenced Christian theology and philosophy. Augustine’s ideas about God’s timelessness were also influenced by his belief in divine simplicity, which asserts that God is not composed of any parts and is, therefore, not subject to change. Augustin perceived time as a four-dimensional block in which one entered and exited. He surmised that God was outside the block; thus, He existed timelessly in an eternal now.85

Like Augustine, Thomas Aquinas postulated that “there is no before and after in Him: He does not have being after non-being, nor-nonbeing after being, nor can any succession be found in His Being. For none of these characteristics can be understood without time.”86 Aquinas made a distinction between eternity and endless time. For him, eternity was now forever; time, on the other hand, included past, present, and future, now and then. The now of time was movable. The now of eternity was not movable in any way. The eternal now was unchanging, but the now of time was ever-changing. This meant that God was not affected by the past, present, or future but existed beyond them. This view of God had significant implications for understanding His relationship to the world and human beings. This implied that God existed outside of time and that the universe was a temporal creation that flowed out of the eternal present. It also suggested that time was a linear construct, with the past driving the future and the present ever fleeting. This view had significant implications for how

we understood the nature of reality and our place within it. These ideas are also seen in the writings of later Protestant scholars. For example, Charles Hodge argued, “God does not exist during one period of duration more than another. With Him, there is no distinction between the present, past, and future, but all things are equally and always present to Him. With Him, duration is an eternal now. This is the popular and the scriptural view of God’s eternity.”87 Hodge posited the notion of God’s ubiquitous and perpetual existence throughout all temporal phases, without any differentiation between the past, present, and future. He further contended that for God, the concept of duration was an everlasting present. Nonetheless, the idea that God existed beyond time raised questions about how the eternal God could become a temporal being, such as Jesus Christ. If God was outside of time, then how could God enter into time and take on human form? Some scholars argue that the traditional doctrine of the incarnation, which asserts that Jesus was fully God and fully man, was incompatible with the notion of God’s timelessness.

For instance, Canale critiques the traditional Christian interpretation of the term “only begotten” about Jesus as the Son of God. He argues that the conventional view of the term as indicating an eternal, ontological relationship between the Father and the Son was based on an incorrect reading of the biblical texts. For Canale, the term “only begotten” should be understood in its historical context rather than in a timeless, abstract context. He challenges the traditional view of the Trinity, which holds that the Father generates the Son in a timeless, spaceless reality. To Canale, this view is problematic because it posits the existence of divine entities that are beyond human comprehension.88 The notion of a timeless God directly relates to hermeneutics and God’s ontology. How we read and interpret Scripture is contingent upon how we interpret God’s ontology. Hermeneutics is a three-dimensional paradigm: Macro, meso, and micro. Micro-hermeneutics approaches the interpretation of texts and proceeds within the realm of biblical exegesis.89 Meso-hermeneutics deals with the interpretation of theological issues and, therefore, belongs appropriately to the area of systematic theology.90

84 Augustine, Confessions, book 11, chap. 13, Section 16. .262.

85 Ettiene Gilson, The Christian Philosophy of St. Augustine, trans. L.E.M. Lynch (London: Victor Gollancz Ltd., 1961), 191-196; Richard Sorabji, Time, Creation, and the Continuum (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1983).

86 Thomas Aquinas, Summa Contra Gentiles, trans. Vernon J. Bourke (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1956), 153.

87 Hodge, Systematic Theology, 385.

88 See Fernando L. Canale, “Doctrine of God,” in Handbook of Seventh-day Adventist Theology (Hagerstown, MD: Review and Heralds Publishing Association, 2000), 179-183.

89 See Fernando L. Canale, “From Vision to System: Finishing the Task of Adventist Biblical and Systematic Theologies—Part II,” Journal of the Adventist Theological Society 16/1-2 (2005): 129-133.

90 See Fernando L. Canale “From Vision to System: Finishing the Task of Adventist Theology Part III

Macro-hermeneutics interprets the first principles from which doctrinal and textual interpretations derive. Macrohermeneutics is related to the study and clarification of philosophical issues directly or indirectly related to the criticism and formulation of concrete principles of interpretation.91 This macro-hermeneutic, rooted in God’s timelessness, gave rise to the traditional concept of the Trinity in Roman Catholicism and Protestantism.92

Early Adventists refrained from using philosophical and technical theological terms when discussing the relationship between the Father and the Son. This is not to suggest that they were ignorant of such terms as substance (ousia), person (hypostasis), and face (prosopon). However, there is no evidence in their writings where it can be shown that they utilized these categories when expressing views about the Father or Jesus. They described the unity in God in simple Scriptural language, as in the Father and Son are one in mind, purpose, and unity. Thus, early Adventists shunned the philosophical abstractions about the Godhead.

of God’s being, as described by the classic doctrine of the Trinity. Instead, Canale suggests that faith was required to accept God’s oneness, as the Bible stated. This implies that the Trinity is ultimately a mystery that may only be grasped through faith rather than rational understanding alone.

The belief in the “eternal begotten Son of God” and the idea that “the Son sprang forth” from the Father, as taught by early Seventh-day Adventists, resembles certain aspects of the traditional expressions of the Roman Catholic understanding of the Trinity. Although they did not use philosophical terms to express their perspective, some similarities can be seen.

Reason Number Four: The Trinity Destroyed the Concept of the Atonement

As per the initial Seventh-day Adventist perspective on the Atonement, the notion of the Trinity was deemed pernicious. This stance was premised on their interpretation of the Atonement, which accentuated that only Christ could mediate between the divine and human realms. Early Adventists held a divergent view from Trinitarianism due to the latter’s postulation that Jesus Christ possessed two distinct natures, divine and human. Subsequently, only the human nature died, while the divine nature remained unscathed. This perspective was perceived as inherently

Canale states, “In no way could human minds achieve what the classic doctrine about the Trinity claims to perceive, namely, the description of the inner structure of God’s being. Together with the entire creation, we must accept God’s oneness by faith (James 2:19).”93 Canale argues that the human mind cannot fully comprehend the inner structure Sanctuary and Hermeneutics,” Journal of the Adventist Theological Society, 17/2 (Autumn 2006): 36–80.

91 For a detail analysis see Fernando L. Canale, A Criticism of Theological Reason: Time and Timelessness as Primordial Presuppositions, vol. 10, Andrews University Seminary Doctoral Dissertation Series, (Berrien Springs: Andrews UP, 1983).