12 minute read

Kevin Tuohy

Kevin Tuohy (l.) during lens fitting

The success of Kevin Tuohy

Advertisement

History of the first corneal lenses

The history of contact lenses begins in the late Middle Ages when the first attempts were made to compensate for malformations of the eye using water-filled glass bowls. The breakthrough came towards the end of the 19th century when the German ophthalmologist Adolf Eugen Fick, the French ophthalmologist Eugène Kalt and the German doctoral student August Müller developed the first scleral shells made of mineral glass that could be worn on the eye. Around 1888 they experimented independently with small shells that rested on the cornea and parts of the sclera. A decisive contribution to today’s contact lenses was made in the first half of the 20th century by the American optician Kevin Tuohy. By Hans-Walter Roth Fig. 1: Blown glass scleral lens,1924.

The first scleral shells made of glass at the end of the 19th century served exclusively to compensate for malformations of the cornea, evening out irregularities of the anterior surface of the eye by applying gentle pressure to the cornea. These anomalies were the consequences of a variety of symptoms such as corneal staphyloma, the historical term for keratoconus or cicatricial astigmatism as a result of malformation, inflammation or injury. In such cases, it was not possible to achieve satisfactory compensation with spectacle lenses. Early attempts at contact optics often failed because the glass available was difficult to mold and the original two-curve design still required a lens diameter of over 20 mm which, due to its poor gas permeability, significantly impaired corneal metabolism (Fig. 1). Frequent lens breakage also made the lenses difficult to wear for a long time.

THE BREAKTHROUGH: PLASTIC LENSES

The breakthrough in contact optics only came with the successful synthesis of a transparent plastic: polymethyl methacrylate. Its easy formability when heated, the ease with which it could be reworked and lastly its high breaking strength made it the plastic of choice in contact optics for many years. However, the disadvantage remained that large scleral lenses could still only be worn for a limited amount of time each day. Impairment of the corneal metabolism due to lack of oxygen permeability of the material and restricted tear convection under the scleral lens made it impossible to wear such lenses for longer periods. In the long run, smaller lens diameters had to be achieved. This would become possible thanks to the American optician Kevin Tuohy (1919-1968) (Fig. 2) who was the first to patent a much smaller corneal lens in 1948. He called it corneal lens (Fig. 3), a term that was confusing at the time. The reason for this was that some inventors before him also referred to their lenses as corneal lenses. Although these lenses also covered the cornea, with their wide rim they were seated on the sclera; thus they were better termed scleral shells or scleral lenses.

AS CHANCE WOULD HAVE IT

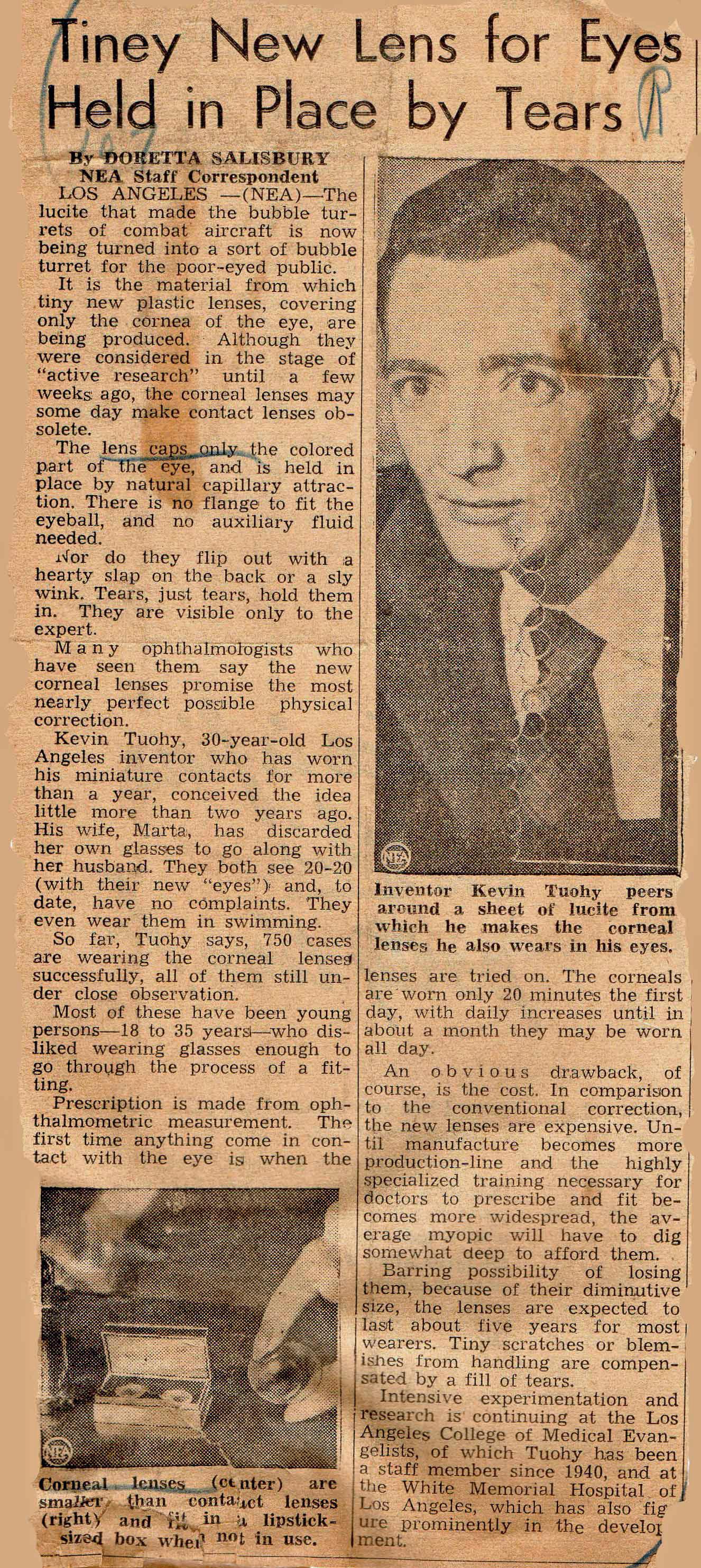

Like many great inventions, the discovery of the corneal lens was ultimately due to an accident. While measuring the diameter of a scleral lens on the lathe, its haptic part – i.e. the part located on the sclera – accidentally split off; all that remained was its central part, i.e. its optical zone. The lens was Fig. 2: First report on the new lens with picture of Kevin Tuohy, 1948.

Fig. 3: Press report about the invisible vision aid from 1948.

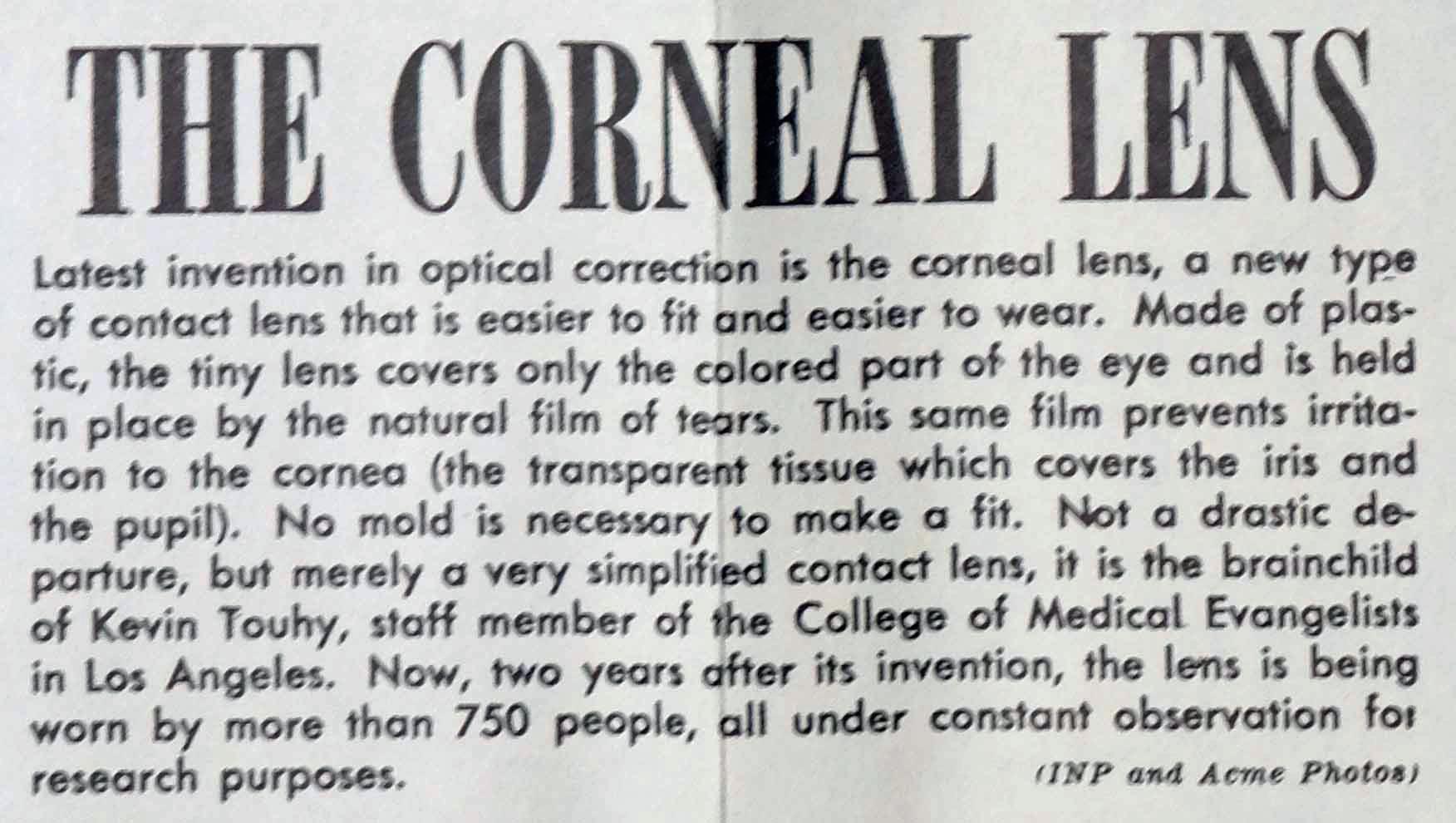

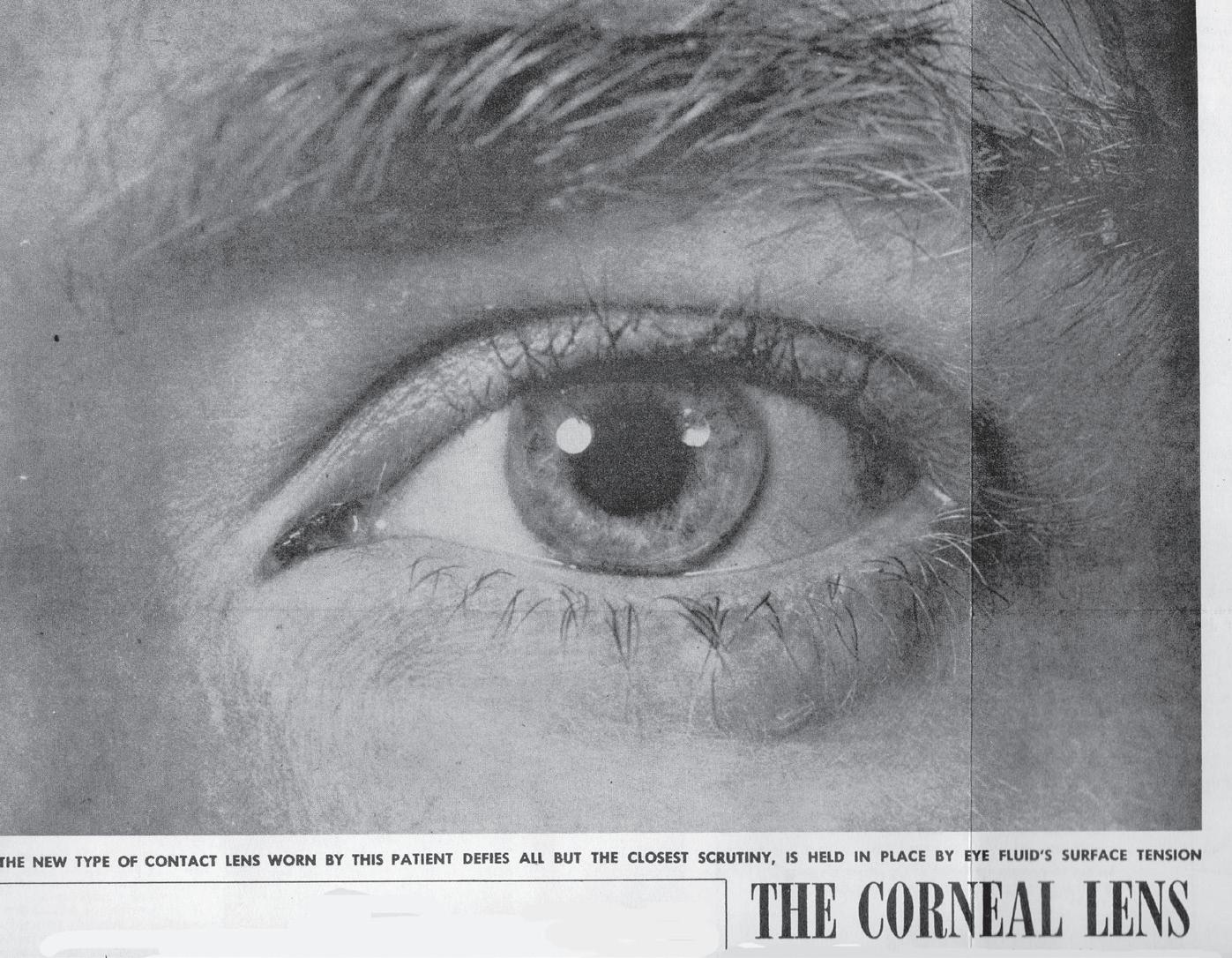

Fig. 4: DIn 1949, the headline read "The Corneal Lens".

Fig. 5: Early large-diameter corneal lenses from Solex.

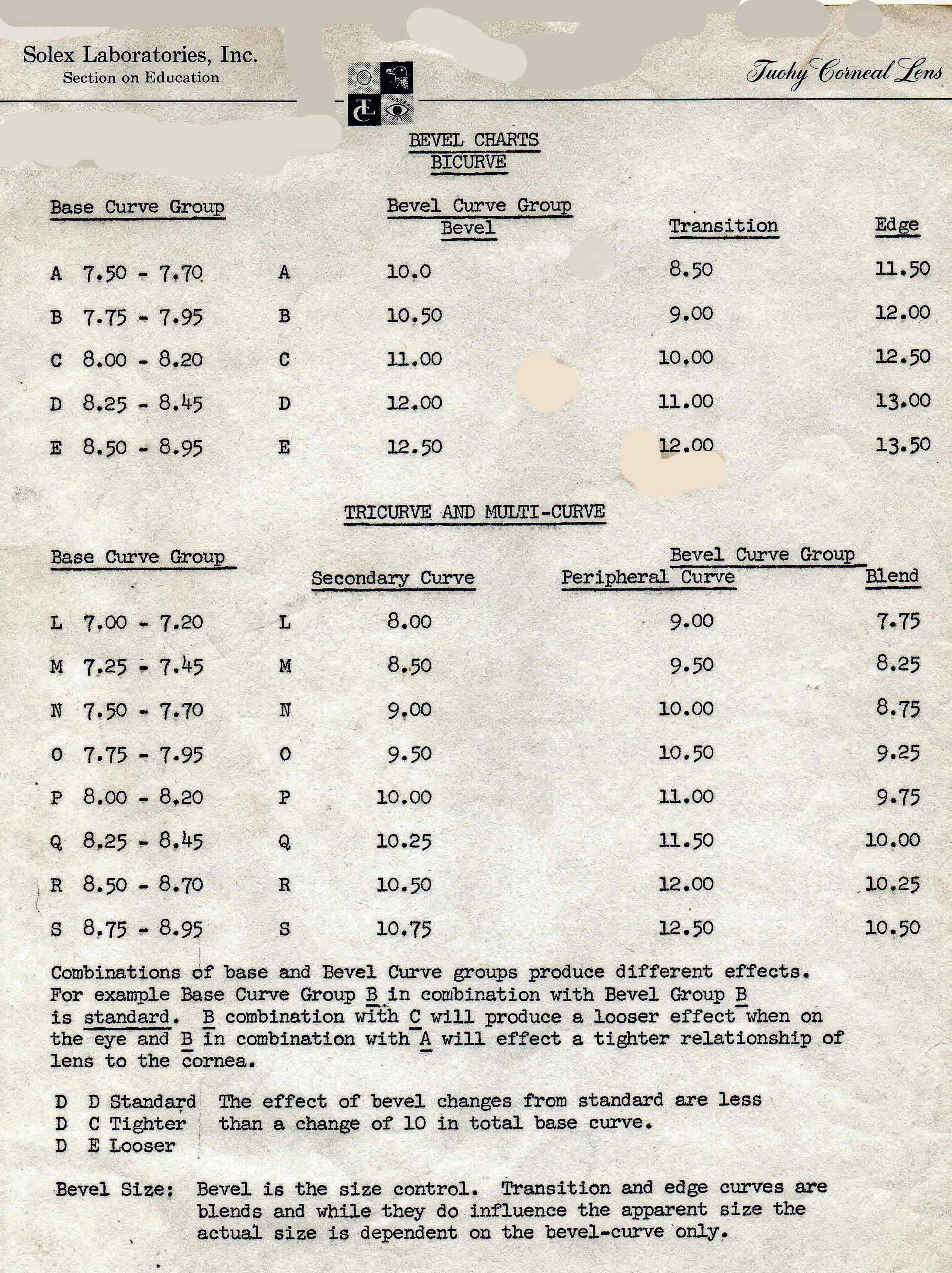

Fig. 7: Lens values available and tolerance range of the first Solex corneal lenses . Fig. 6: List of fitting parameters for the first corneal lenses.

Like many great inventions, the corneal lens was ultimately discovered by chance.

going to be discarded but somehow Tuohy came up with the idea of trying out this fragment which only covered the cornea on himself, or as other reports say on his wife. Contrary to expectations, this middle part of the scleral lens positioned itself spontaneously directly in front of the cornea. The foreign body feeling also seemed to be acceptable. The development of a corneal lens which could be worn for longer periods of time had begun. In 1948 Kevin Tuohy was granted the first patent in the USA for a contact lens made of PMMA, now known as a corneal or mini-lens (Fig. 5). As noted in the patent specification, his lens still had a diameter of 11.0 mm and a central thickness of 0.3 mm (Fig. 4). At the time, Tuohy was working for Solex, who immediately skillfully brought this new kind of "corneal mini-lens" to the attention of the public. However, before they could go to market, it was still necessary to introduce standardization of the lens parameters, in contrast to the scleral lenses previously produced from thermoplastic impressions of the eye or on a lathe. The purpose of this standardization was to make it easy for as many opticians as possible to fit them, as well as to be able to manufacture them in large quantities. In order to achieve an optimal fit, the inner radii had to be curved in such a way that ultimately the lens could only move up and down in front of the cornea through a capillary gap filled with tear fluid when the eye blinked or was closed. Initially, the inner curvature of the lens was calculated based on the central radii of curvature of the front surface of the cornea, from which pre-defined parameters for the fitting sets could then be derived (Fig. 6).

MODERN MEASUREMENT DATA COMES INTO PLAY

It was soon realized that the lens fit was only optimal when multispherical inner curves were used. Now the use of Gullstrand's ophthalmometer for determining the central radii of curvature of the cornea and their use for selecting the base curve of the corneal lens took on a particular importance. Indeed, this measurement data is still the basis of all contact lens fitting today.

Fig. 8: Graphic representation of the lens design for myopia.

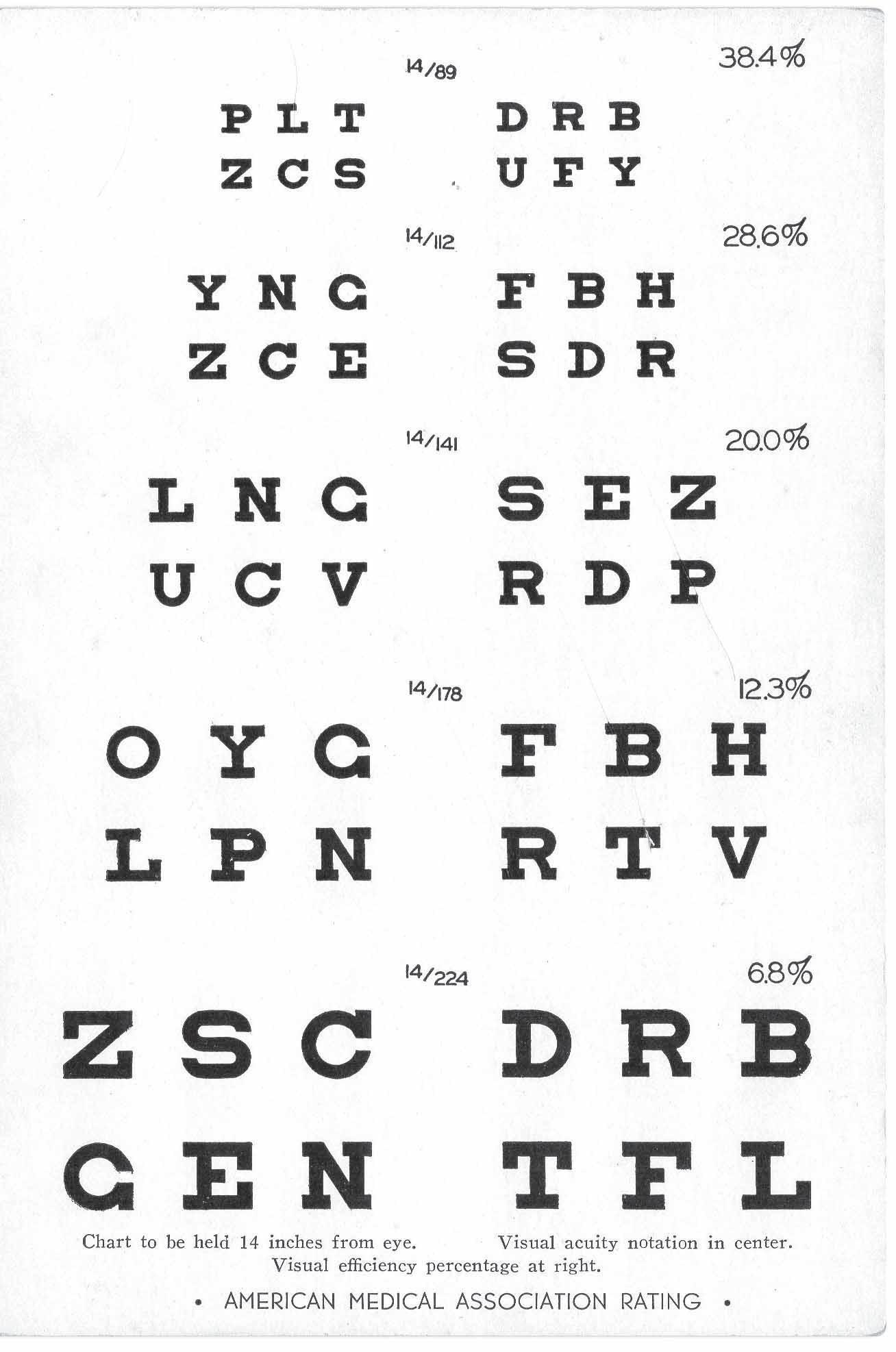

Fig. 9: Distance vision test charts from the Solex contact lens studio.

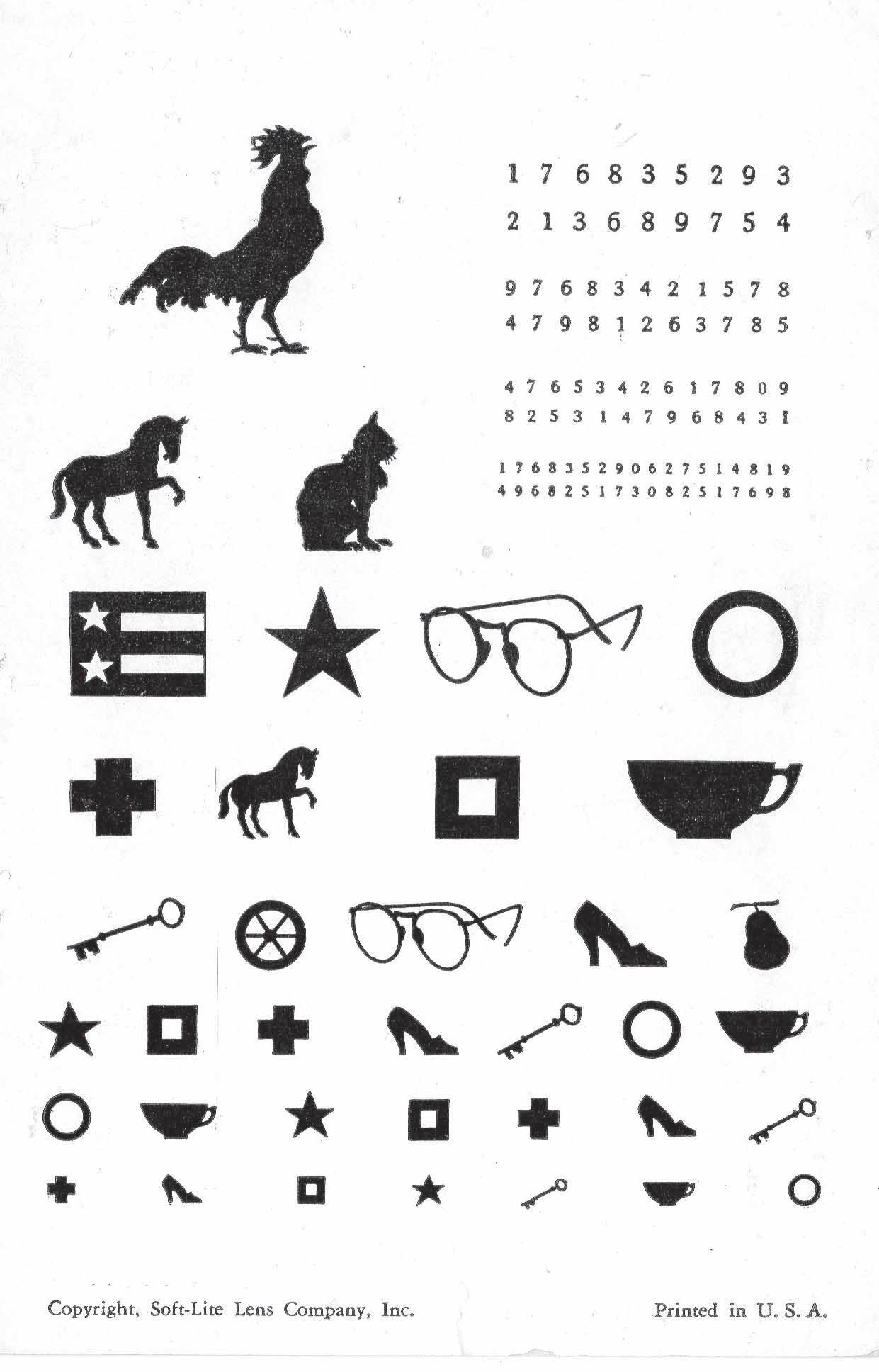

Fig. 10: Test chart for children.

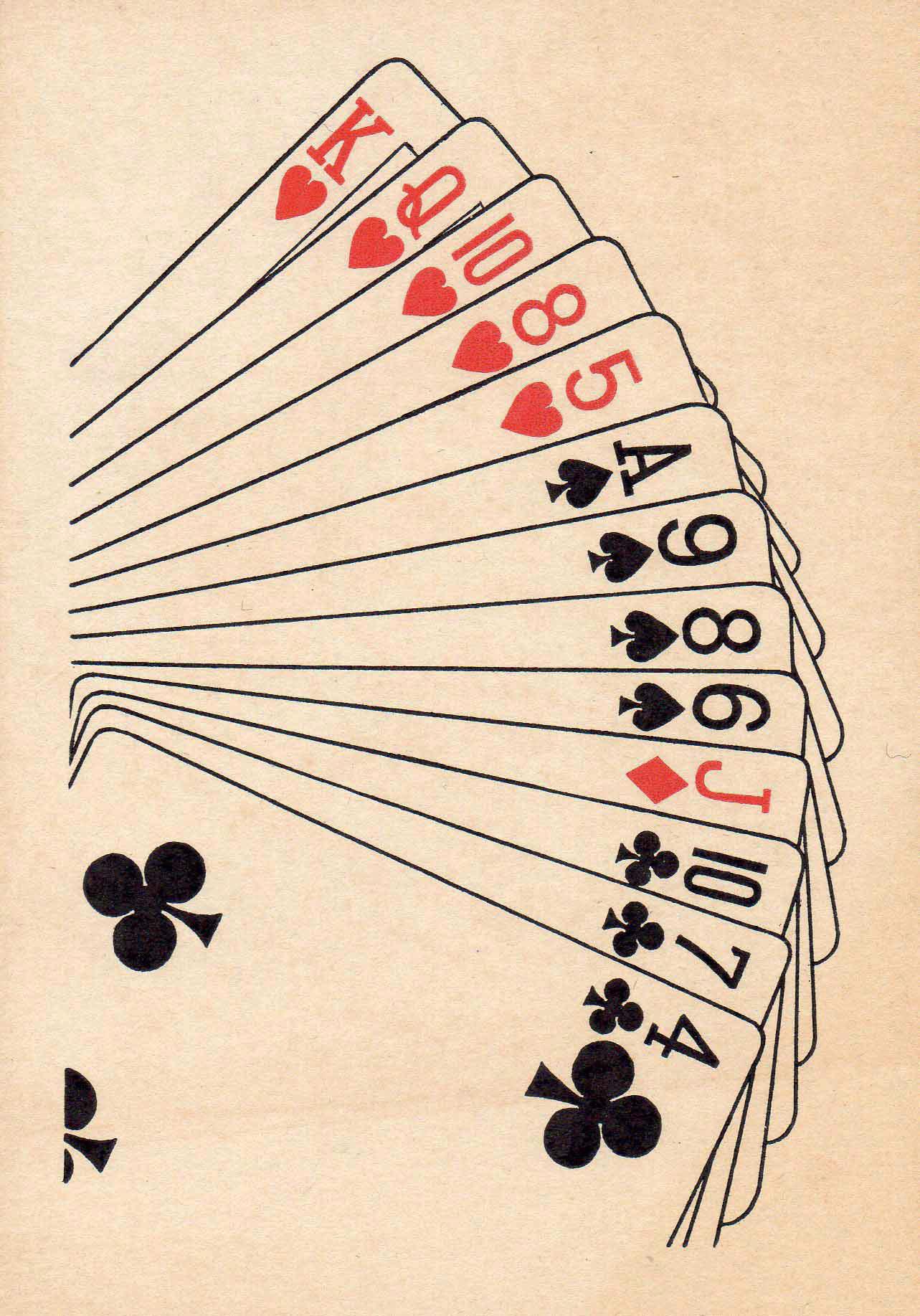

Fig. 11: Test chart for near vision, card game.

Once it had been proven that contact lenses with the diameter of the cornea could be worn comfortably on the eye, Tuohy continued with his experiments. He recognized that the design of the edge of the lens was largely responsible for the fit on the eye, the loss rate and ultimately for the wearing comfort. While the back surface of the corneal lens – also known as the inner or base curve – was primarily responsible for the seat of the lens on the eye, an optical zone had to be incorporated into its front surface. Its values were based on the respective refraction values of the eye. The first corneal lenses were still over 10 mm in diameter with rounded edges. After measuring the central radius of curvature as a basic value, the optimal lens design had to be determined by trial and error. The Solex product range (Fig. 7) contains the lens parameters available for the first fitting set of Tuohy’s corneal lenses. Some of the equipment from Tuohy's workplace is still on display. It can be seen in the Contact Lens Museum at Forest Grove, Oregon, USA on the Atlantic coast. Not only is there equipment from his workshop on display but also some of his drawings (Fig. 8), graphs and the first fitting sets of his corneal lenses. Even the test charts from his studio at Solex are still to be seen (Figs. 9, 10 & 11).

THE RIGHT MARKETING

Tuohy knew better than anyone else how to advertise his "Tiny Lenses" as he called his contact lenses in the media. (Fig. 12). With catchy advertising slogans, he knew how to get people’s attention. "The new window for your eyes" was the headline of the New York Times in 1949, going on to explain that his lenses were "held on the eye by tears alone". “The new mini-lenses do not irritate the eye,” wrote the London Observer in 1951. To demonstrate the quality of PMMA as a lens material, the article mentions that it was the same plastic material as used for the cockpits of US Air Force bombers.

Fig. 12: "Tiny Lenses" made of plastic material from aircraft panes.

Fig. 13: Advertisement for Tuohy's invisible vision aid, 1952.

Fig. 14: Eye casts for molding contact lenses .

Almost all the media at the time reported on his invention and its wearers, and he constantly encouraged prominent artists, actors and athletes to wear the lenses. At the time, however, not all lens wearers were as enthusiastic about the "invisible lens for everyone" (Fig. 13). Corneal lenses were still often accompanied by a strong foreign body feeling in the eye, and it often took several weeks to get used to them. There was no advice on lens cleaning or care, and artificial tear drops for rewetting the lenses had not yet been introduced. Even one US president is reputed to have worn the lenses, and Marilyn Monroe is also said to have been one of his customers. While the eye casts in a museum in Ulm, Germany, made for the production of contact lenses (Fig. 14) could possibly be ascribed to her, this cannot be proven beyond doubt because the relevant prescription data is missing. All that is known for certain is that the casts came from Tuohy's workshop. Kevin Tuohy was not the only person who worked on the development of hard contact lenses in the post World War II years, countless others contributed to improving the wearing comfort of contact lenses through their own developments. Both before and after him, opticians, optometrists and ophthalmologists were constantly searching for new, better-tolerated plastics and lens designs, in order to extend daily wearing times and reduce foreign body irritation. For example, Heinrich Wöhlk, a scientist from Kiel in Germany who developed a contact lens made of Plexiglas in 1946, should undoubtedly be considered one of the pioneers of the corneal lens. He certainly made a mistake in not applying to patent his lens in 1947, ahead of Kevin Tuohy. As a result, Tuohy took precedence and the credit for having developed the scleral lens into the corneal lens, thus making it suitable for almost everyone with ametropia to wear.

Dr. Hans-Walter Roth

Institut für Wissenschaftliche Kontaktoptik Ulm, Germany. E-mail: institut.roth.ulm@t-online.de

Larsen Equipment

In 2004, Keith Parker and I opened Advanced Vision Technologies (AVT). At that time, the economy was going through a very bad recession and as a result, it was impossible for a new business starting up to get a loan. We immediately reached out to Erik and Pam at Larsen Equipment to get refurbished equipment to use in our Laboratory. As AVT’s business grew, we invested in many different pieces of new equipment from Larsen Equipment and this helped us grow into one of the Premiere Labs in the United States. Our success is due in part to Erik and his Team with their state-of-the-art equipment and maintenance of their products. AVT is forever grateful for Larsen Equipment’s support of AVT. It is great to know AVT is working with Industry leaders with the Larsen Equipment and their Team! Janine Bungo, Vice President

QUALITY MANAGER: RANDY MINGOY

I have known Erik Larsen since 1992. Since then I have used just about every piece of equipment his company has built. My experience with Erik and the Larsen team has been one of great appreciation as they have always helped me in my needs of fully understanding equipment used to manufacture quality contact lenses. Erik has also been able to engineer any part needed for me even it was a custom part. Erik (Larsen equipment) has been and still is a pioneer in the contact lens and optical industry, and I am thankful to him for his support over the years.

Randy Mingoy

Quality Manager Advanced Vision Technologies

DIRECTOR OF OPERATIONS: JORDAN GOBEL

There can be a lot of moving parts when it comes to managing operations, so it is key to have reliable precision equipment that assists in overall efficiency. Larsen Equipment delivers just that! I have been utilizing Larsen manufacturing equipment for over 15+ years and have yet to run in to an issue they could not resolve. I am a satisfied owner of bladder polishers, edge roller’s and auto-blockers etc. Each one of these units greatly assist in the reduction of rejects and manufacturing waste. Their ability to customize and retrofit specific tools certainly sets them apart from the competition. Larsen stands behind their equipment with a knowledgeable staff that provides exceptional service. Simply put, we are a better laboratory because of our relationship with the folks at Larsen.

Jordan Gobel

Director of Operations/Consultant Advanced Vision Technologies PRESIDENT: KEITH PARKER

I have had the pleasure of working Erik since the beginning of Larsen Equipment. The first piece of equipment, a 6 spindle horizontal arm polisher revolutionized our production of GP contact lenses. Through the years, I watched his business grow as he and his team listened to our Industry needs and developed now numerous products not only simplifying many tasks of manufacturing but improving the consistency of quality in our finished products. Innovation has been an ongoing experience of our Company only made possible through the innovation of necessary equipment developed and made available by the Larsen team. Larsen Equipment is a family owned business hosting a team of willing Staff all having the attitude of serving their Customer’s needs. As a Customer, we are made to feel like we have a friend in the business helping us develop a more efficient process allowing our Company to deliver better products for our Customers. Our success of AVT simply could not have been possible without the help, assistance and dedication of Larsen Equipment. I will be forever grateful for my opportunity to work with Erik and his very capable Staff.

Keith Parker

President

969 S. Kipling Parkway, Lakewood, CO 80226 Phone: 303-384-1111 888-393-5374 Fax: 303-384-1124 www.AVTLENS.com