Neocolonial Aspects of Cannabis Legalization in Africa

Neocolonial Aspects of Cannabis Legalization in Africa

Interviewwith Chris S. Duvall

Cannabis as a crop has a long and varied history on the African continent, with its present distribution, use, and legal status largely influenced by colonial structures. Current legalization efforts in many countries around the world have also touched African countries. Chris S. Duvall, Professor and Chair, Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque (USA) has observed neocolonial aspects in the process of cannabis legalization on the continent. In an interview with CannaVision, he explained the origins of these factors and their impact on local citizens.

By Rebekka NurkanovicHow did you come to study the agricultural history of cannabis in Africa?

I am a geographer and mostly study people/plant interactions. While doing research on plant use in the African diaspora with regard to other plants, I found a rich body of literature on cannabis history in Africa and particularly how enslaved Africans used cannabis around the South Atlantic. For me, looking at cannabis in the present began as a way to understand how historical patterns persisted in virtually all cases through 1925, when cannabis entered into international controls.

In the late 1800s, there was official commercial trade in cannabis and marijuana coming out of Angola, where the term marijuana originated. From there it traveled across the Atlantic and into Brazil. Yet looking at conditions in Angola today there is no interest or movement towards legalization. Similar things are evident in other parts of the continent where historical trade and value on cannabis has been lost.

There have been significant changes to the legal control of cannabis in some places like South Africa and I am trying to understand how that connects to the past. Interestingly, I have found that for the most part, it does not connect with the past except for the fact that there is familiarity with the plant, but the actual le-

galization processes are divorced from the history and from the resources that potentially could be brought to bear on the development of this new economy.

In your article ‘A brief agricultural history of cannabis in Africa, from prehistory to canna-colony’1, you have analyzed cannabis history in Africa to identify the foundations and trajectory of cannabis-centered economies in Africa. What role does cannabis play as a crop in Africa?

Cannabis has at minimum two economies on a very basic level, the illegal and the authorized economy. Prior to the period of global reform of marijuana control laws, starting about 20 years ago, there were estimates that Africa produced about a quarter of the world‘s cannabis crop. This is most certainly underestimated because the statistic was just based on captures by drug control authorities.

People have used cannabis and grown it as a crop, and have had multiple uses for it in different parts of the continent, for instance the Swahili coast down to Madagascar in Eastern Africa, where it first arrived on the continent from South Asia a thousand years ago or more. The plant has been very important in many societies, comparable to tobacco during some periods. In other parts of Africa, like most parts of West Africa, it has only been in use the last 200 years.

Cannabis is not as important as food crops but it has always had a vibrant trade and monetary economy. Following the period in the first decades of the 20th century when it became illegal under the colonial governments in many, if not most parts of Africa, this vibrant economy remained – it just went illegal. Many people made money off it similar to drug economies elsewhere. The people, who take the risks of growing it, do not make much money in general. The most money is made by the transporters and sellers, who generally are fairly well connected and protected within systems of power, whether these are organized crime groups or – in many cases –military or government officials. This illegal economy is productive and supports many people.

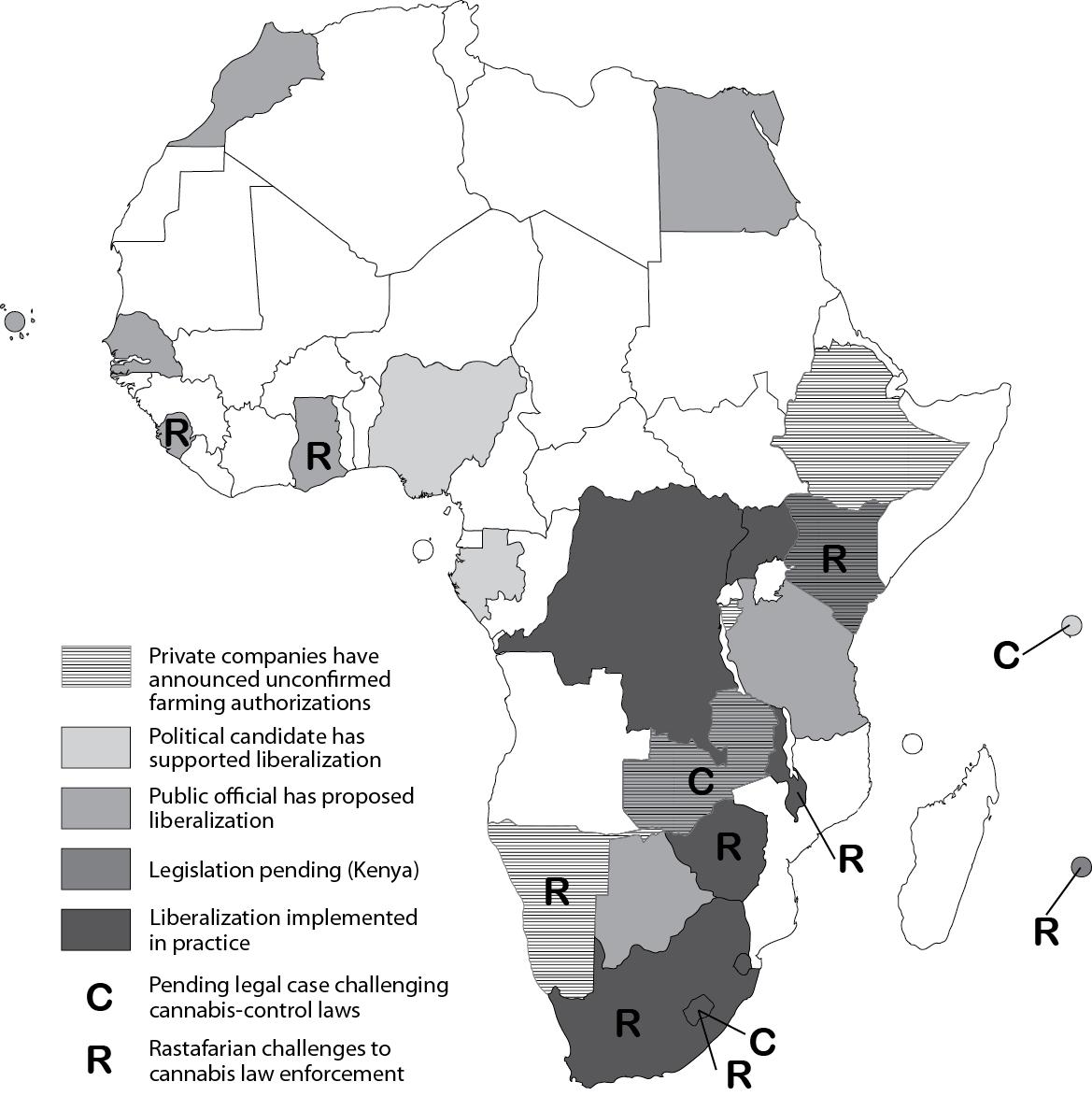

Where does cannabis legalization stand in Africa?

Legalization is a difficult term with regard to cannabis in Africa but an authorized economy is starting to emerge. Authorized means legal in many cases, because most of the drug control laws that I could locate and understand – usually drawn in the early 20th century under colonial powers – had an exemption clause meant for pharmacists. In the early 20th century, many of the laws were concerned with pharmacy practice, mirroring the colonialist’s attitude towards what they saw as pseudo pharmacy or witch doctors. Within all those laws, it has always been technically possible to grow, produce and sell cannabis legally for pharmaceutical uses; it was just never authorized. Therefore, it is a little simplistic to talk about legal and illegal in African countries.

Authorized cannabis economies have developed in Central and Southern Africa, with varying success. Lesotho made global news in 2017 by authorizing a Canadian company to begin production for export, and a number of other countries have followed – Malawi, Eswatini, Zimbabwe, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Other countries have considered it. Authorization has not proven highly lucrative, because the terms of authorization mostly benefit the outside companies. South Africa is a different case, because their constitutional court ruled in 2018 that South Africans have a legal right to grow, posses, and use cannabis; there is a domestic medical market there, but they have not pursued commercialization as the neighboring countries. Given South Africa‘s economic strength in the region, there are illegal imports from nearby countries, and they have had success in producing paraphernalia. In many of the countries in Africa, high-CBD and high-THC material is grown for export, and some countries, notably Malawi, are looking at hemp fiber production.

There are distinct political economic dynamics in each of the different countries. As far as I know, Ghana and Morocco have moved strongest towards legalization since I wrote that paper in 2019. The Ghanaian case was a little different from others because they moved formally towards legalization, but they did not make it there. In 2020, the Parliament passed a new drug control law that authorized licensed medical production but it was never enacted because it was legally challenged and their supreme court overturned the law last fall.

In Morocco production and controlled sales was legalized but they have not figured out a way to implement it for a complex set of reasons. The growers in the important production zone of the Rif Mountains, who could benefit from legalization, just do not trust the government. Therefore, they are not participating in the legal economy, but staying involved in the illegal economy. I am sure this kind of distrust is very widespread, but in Morocco, it has a very long history that goes back through colonial times, and into the pre-colonial period. Historically, Morocco has profited from illegal exports to Europe, but that is declining because legalized production has increased in Europe itself.

Legalization is a difficult term with regard to cannabis in Africa but an authorized economy is starting to emerge.Chris D uvall 1 Duvall, Chris. (2019). A brief agricultural history of cannabis in Africa, from prehistory to canna-colony. EchoGéo. article 4. 10.4000/echogeo.17599.

What are the neocolonial power structures in the process of cannabis legalization that you have observed?

It is hard as an outsider to understand the social dynamics in African countries, but the disparities that exist in broad social terms, and specifically within the cannabis industry, are remarkable. In the United States, there is a lot of interest in equity in the emerging markets and attempts are made to allow a broad diversity of people access to these industries. As far as I know, this does not exist anywhere in sub-Saharan Africa. “Neocolonial” means that a foreign company pays a government to change its laws or policies to the company’s benefit. In all cases, except for South Africa, “legalization” has happened only because a non-African company or a businessperson went to a government and asked how much it would cost to obtain a license to grow under existing narcotics control laws. The licensing costs have been astronomically high for most Africans, but pretty small for the outside businesses relative to the cannabis economies in places like Canada, the United States, or Western Europe. For instance, in Zimbabwe, in the mid-2010s, a Canadian business was able to negotiate with the government for a license for around $75,000, an amount that would be impossible to pay for most Zimbabweans. It made international headlines that Zimbabwe “legalized” cannabis but they did not really change anything, they just sold a license under existing laws. Similar things have happened with Canadian companies in most of the other countries, notably Lesotho and Eswatini. There are many instances of public officials, whether elected or non-elected, who sign off on licensing for companies to produce and export cannabis, who have explicitly said that the traditional uses of cannabis in their countries are absolutely not included in their policies because the indigenous uses and plants are portrayed as something completely different and unacceptable. That is a very strong contrast in terms of equity considerations. Of course, in many countries, those laws are not meaningfully enforced unless they become convenient, but the principle is still there.

What is the impact of those structures on African economies?

People who are not in the legal, internationally connected economy are unlikely to grow low CBD material because African cannabis has always been a high THC material. Within the authorized economies, the plants that are being grown are all grown from seeds or clones that are brought in from breeders in Europe, primarily the Netherlands, and the means of production is highly technical. The expertise that Africans have about indigenous cannabis agriculture – plant breeds, production, and processing – is not valued or incorporated into the system. In fact, most Africans are excluded from the legal economies because they do not have the expertise necessary to produce plants in the highly technical ways. With very few exceptions, they are not offered training and those very few exceptions are the small number of people who are employed by the foreign companies.

These structures are not allowing the development of equitable wealth and power within these countries and they enable foreign businesses to extract the resources. Generally, it is like any colonial structure. In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DR), for instance, the government announced that it had licensed production and leased huge amounts of land to international companies

for 99 years. They did this before there was any announcement that this was actually legal in terms of Congolese law and what the licensing rules were. Only a year and a half after leasing the land, they said, “by the way, we decided we can do this”. It is my understanding that only a very narrow segment of those in power, whether in government positions or military positions, knew of the legal opportunity to produce cannabis. While the outside companies received an opening, there was still active law enforcement going against regular Congolese people for cannabis. This is conceptually identical to the oil industries and places like the Niger Delta in Nigeria, albeit on a very different scale and with different politics. With regard to cannabis, the problem lies in the legal liabilities or vulnerabilities for people who are trying to feed themselves by growing and selling cannabis, or to pursue their interests by using it, but are not getting any support from their governments to do these things.

It is also relevant to bring up the condition of Rasta. Cannabis is a sacrament in Rastafarianism, and Rastas have been targeted for their use of cannabis throughout Africa. There have been a handful of times where Rastas have brought legal cases against governments for restricting religious freedom, but in no case did they succeed and in most, they were dismissed out of hand.

Where do you see African cannabis economy headed at the moment?

There are politicians in some countries, notably in Nigeria and in Tanzania, who say outright that they would legalize cannabis if they were elected for the reasons that I’ve suggested – social equity, economic development, and national sovereignty.

As far as I know, there is not a lot of activism about cannabis legalization in Africa, but there are news reports where people on the ground are interviewed who say that it is not fair that legalization only benefits export to Europe or North America and demand that they should be able to grow without fear as well.

At the same time, there are cases where prominent people maintain twentieth-century prohibitionist rhetoric against cannabis. In 2019, Uganda’s First Lady called the authorization of cannabis production a “satanic” act, after an Israeli company was licensed to grow THC-rich plants. As in all societies globally, there are many Africans who disapprove of cannabis, and there are many places where anti-cannabis laws are strongly enforced. It‘s up to each country to determine what they want. I can say something about cannabis history in many African countries, and note that the current meaning of cannabis is an outcome of real and meaningful histories. For instance, Sierra Leone has had a well-documented cannabis economy since the mid-1800s. Cannabis spread from there to Senegal, Ghana, and elsewhere in West Africa. Yet today, cannabis is a hundred percent illegal there. One factor to consider is that in Sierra Leone and in Liberia, cannabis along with other drugs was used by fighters during their civil wars in the 1980s to 2000s. Therefore, it carries a lot of baggage that from their perspective might mean that cannabis needs to stay illegal.

As an outsider, I wonder if cannabis is staying illegal because of the power of the international drug control regime. African countries are mostly poor and do not have leverage to ignore international laws, as more powerful and wealthy countries do by legalizing

within their borders. Or are the controls still in place because of a genuine conviction that cannabis has to stay controlled? In many places, it is clear that people want to legalize it because they see personal and potential economic benefits, but it is a slow process.

How would African cannabis policy need to be designed to benefit African citizens?

It is important to recognize that African cannabis has highly valued sativa strains, which are famous worldwide, e.g. Durban Poison and Malawi Gold. Professional breeders, mostly from the Netherlands, go on expeditions to different parts of Africa to find landraces with genetics that are not represented in commercial strains. They incorporate these into high-end breeding programs that produce seeds that are sold back to commercial producers worldwide. People in an African grow facility might buy seeds from Amsterdam that were derived from seeds that were collected in the same country where they are growing now. This shows why more protection on intellectual property and genetic resources is needed. For example, I think Durban Poison, Malawi Gold, or Angola Red should be claimed. If you are involved in the industry, you know those are valued names, and the concerned countries should protect them, just as many European countries have protected certain providence designations for food items, like Parmesan or Champagne. As far as I know, Jamaica is the only country that has taken steps towards protecting provenance on a cannabis strain, Jamaican Ganja.

With regard to the individuals in Africa, there should be licenses that are affordable enough to allow people to participate in legal industries. A broader change that would positively affect people is to remove most legal controls, so that a person whose ancestors have grown cannabis for decades or centuries can grow in their backyard without fear of prosecution.

With regard to the international context, the overall international drug control regime does not match todays’ needs and African countries have a role in making the process of change go forward. African countries have little leverage but they could look at the policies that have been introduced in places like the United States, Canada, different parts of Europe, and Uruguay, and understand how those countries justify bypassing international rules. They could then do the same and argue that the same rules should apply to all.

It would be especially relevant to look at Uruguay, where the government did a cost benefit analysis: what costs and benefits are there to enforce these laws and what costs and benefits might it have to reject these laws? The international drug control regime saw what Uruguay did and was horrified but it really did not have any impact on the country, despite its relatively low power position in the global context. Every country has different sets of political and economic dynamics but I think Uruguay is an interesting example that many countries in the global south should look at and understand what they can learn from it.

Is it currently at all possible for a cannabis company from the global north to do non-exploitative business with African cannabis farmers?

There are certainly opportunities but each country is different. Many of these countries are only allowing outside operators to

come in if they pay a very large fee. One way could be to pay that large fee, but then establish means of production that are inclusive, built on using local expertise and labor, thereby generating jobs for a number of people instead of just a handful of technicians. Paying fairly for using the resources is another way, be it through fair wages or making investment opportunities available to people. I‘m not a cannabis business person and do not know the actual financial analysis that go into decisions like this, but if you look at the value of the markets in the global north, in Africa, and other parts of the global south, there‘s clearly a lot of profit being made somewhere. Divert some of that profit to people in the countries, and not just the government representatives who are already in power. Figure out ways to promote real and meaningful local engagement. Some companies have claimed to do that simply by appointing an African to some executive position, but in all cases that I have been able to get enough information on from news sources it appears that those are just titleholders without any actual role.

Establishing a company to produce and process, while having a clear plan of ownership transfer over time might be feasible, too. Anyway, acknowledging that there are resources being extracted that Africans cannot extract themselves is an important first step in the right direction and following best corporate practices and consulting experts on creating equity within industries and on working in particular countries is always helpful.

Some of the big players who sponsor production could influence countries by lobbying or negotiating for lower licensing costs for citizens, so that people in the country can afford a license. While this would also be an example of neocolonial control, it could at least use unequal power in a way that could reduce inequity in the long run. But I’m an outsider – I can’t speak for any of the countries or companies that might be involved.

Thank you for the interview. ↙