SEPTEMBER 2O23

An Evoke Contemporary publication

SEPTEMBER 2O23

An Evoke Contemporary publication

After a particularly warm summer, we applaud the cooler days of fall and a raft of new shows featuring popular artists who never disappoint. West Virginia artist Lynn Boggess has produced luscious and tactile new paintings for his new show, Nature’s Go-Between; in this issue of Evokation we interview him about how he got started painting. In her Restoring Earth’s Canvas: Lordsburg Project, Esha Chiocchio presents stunning photographs of the landscape around Lordsburg, New Mexico, and the heroic efforts by a dedicated group of individuals and agencies to reclaim these grasslands from the desert.

Thomas Vigil shows a new body of work, Lost Prophets, based on his graffiti-inspired art, which continues to push boundaries—his own and others’. In his own new show, Retablos, Patrick McGrath Muñiz uses that traditional genre to pay homage to the archetypal imagery of the tarot, always with piercing visual commentary on issues of social justice. Aron Weisenfeld’s ethereal and provocative paintings find magic and enchantment in modern settings, as his exhibition, Past Lives, reveals. In this issue we also introduce you to two good friends of Evoke, gallerists Frank Rose and Jared Antonio-Justo Trujillo, who are creating spaces for new voices while making art accessible and exciting for new audiences.

Finally, we are delighted to welcome our new Railyard neighbor, the Vladem Contemporary, the new branch of the New Mexico Museum of Art. In this issue we profile Christian Waguespack, curator for both the Vladem and the Museum. With its much-anticipated opening slated for the weekend of September 23, the Vladem cements the Railyard as a nexus for contemporary art in Santa Fe.

Kathrine Erickson + Elan Varshay Owners and Publishers

Our January issue will ring in the New Year with a special profile and new works of art by each of Evoke’s artists!

Michael Abatemarco is a freelance writer and amateur photographer with a passion for New Mexico’s culture and history. He lives in Santa Fe.

Mara Christian Harris is a marketing and communications professional. She has been associated with Evoke since its inception.

Kelly Koepke is a freelance arts, culture and food writer who loves talking to smart people about what they are smart about.

Richard Lehnert is a poet, music critic, and freelance copyeditor who for 40 years has edited arts copy for many New Mexico publications. After 30 years in Santa Fe, he now lives in Ashland, Oregon.

Kate Nelson , based in Placitas, NM, has been managing editor of New Mexico Magazine and The Albuquerque Tribune, and wrote the artist biography Helen Hardin: A Straight Line Curved.

© EVOKE Contemporary. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. On the cover: Patrick McGrath Muñiz, Santa de Copa y Espada (detail), oil and gold leaf on triptych panel 19.5"

All events take place at Evoke Contemporary, 550 S. Guadalupe Street, Santa Fe, NM 87501. Visit evokecontemporary.com to sign up for special previews and for further information.

Aug 25 LynnBoggess | An exhibition of the artist’s ongoing tribute to our majestic wooded landscapes with an indepth look into this artist’s process.

On display through September 23, 2023.

Oct 27 Autumn Glow | A group exhibition highlighting sumptuously rich colors and aura of the fall season.

On display through November 18, 2023.

Aug 25

RestoringEarth’sCanvas | Esha Chiocchio uses her photography to document grassland restoration in Southwestern New Mexico.

On display through September 23, 2023.

Sep 29 LostProphets | Thomas Vigil explores the idea that every individual, well-recognized or not, has a powerful voice within them in this solo exhibition.

On display through October 21, 2023.

Sep 30 ArtistSpotlight | David T. Alexander’s remarkably bold and confident landscapes are featured in Evoke’s Northwest Gallery.

On display through October 21, 2023.

Nov 24 Retablos | Patrick McGrath Muñiz’ solo exhibition using traditional Spanish retablos as the platform for his contemporary reflection on social and environmental injustice and indifference.

On display through January 20, 2024.

Nov 24 Past Lives | Aron Wiesenfeld’s solo exhibition of his narrative paintings and etchings illustrating the freedom and loneliness of youth.

On display through January 20, 2024.

Evoke Contemporary sat down with West Virginia artist Lynn Boggess to chat about nature, his art, and using all that paint.

Evoke Contemporary: How did painting become a significant part of your life?

Lynn Boggess: I grew up in a rural farming community in the Ohio Valley, exploring the streams and woodlands for hours on end. At the same time, I drew constantly—not from nature, at first, but from stories of adventurers and explorers.

I was introduced to Andrew Wyeth’s paintings in early adolescence; at the same time I began working with acrylic paints—both of which I connected with immediately. Summer art camps on college campuses with college instructors helped tremendously throughout my high school years.

Wyeth’s realism followed me to college, but was soon replaced by extensive exposure to the modernist traditions—especially abstract expressionism and color-field painting. In graduate school, I further explored the current theories of conceptual and installation art. At the same time, through all this, I continued to paint small studies from nature.

EC: You taught for years—what was your approach as a teacher?

LB: When I was invited to teach at my former undergraduate college, I thought it was crucial that students balance their explorations with disciplined skills in rendering from life— still lifes, the posed human figure, and, on location, from nature. I wasn’t an instructor who would lecture and hover over students. I worked alongside them on assignments, doing endless demonstrations. I was my own best student, and my skills developed rapidly. After my promotion to Professor an opportunity came for a sabbatical, and that allowed me to sort out what direction I needed to go in painting.

EC: Was the sabbatical productive?

LB: Yes and no. I set up a studio and worked tirelessly on large, complicated, postmodern forms of layered imagery, with numerous processes of applying paint. And yes, the paintings won awards and acceptance in a museum, but it purged from me the idea of making art solely in a studio. The work was introspective and dark in content—something I couldn’t imagine devoting my life to doing.

In the months that followed, I painted exclusively out of doors, and that has continued to be an obsession for decades now. Walls contain things—the vastness of outdoor space brings a timelessness and grandeur that make you feel insignificant. I find significant form outside. I look for contrasts—water near rock, a tree against the wind. It’s very consoling and addictive.

EC: Where

LB: We built a remote studio in the woods and a house in town, so we can Ping-Pong between the extremes of solitude and community. We pack up and drive into the mountains (a blessing during the recent hot summer!) until we miss people again—at which time we head home to Shepherdstown, a picturesque small town with a tree-lined main street and plenty of friends. I think mankind is a nomadic creature, and it’s natural for us to live between nature and urban environments.

LB: I have favorite spots, and where I paint is often about access. A place I love to look at looks different at different times, different light, different seasons. It doesn’t take a lot to find a difference in the same scene. Sometimes I build a platform to give me that different vantage point on a familiar scene.

LB: Plein air pushes you—three to four hours to complete a painting instead of three or four days in the studio. I don’t use brushes, I use trowels—they really lay paint on the canvas! Paint is thick, it absorbs movement. Oil paint is meant to be thick and layered, and thinning it down makes it something it’s not.

EC: Your paintings are full of movement and emotion. Talk a little about that.

LB: For me, painting is more about a negotiation with my feelings, thoughts, ideas, and emotions. I like to balance the emotions I’m feeling with the realism I’m seeing. I’m keenly aware of styles of art—there is a difference between naturalism and realism. Within realism, there’s a spectrum—high realism is not just what things look like. Realism to me is injecting not just the external but also the internal dialog.

It’s like a melodrama for me—taking the clutter and confusion of a scene and making sense of it all. To me, it creates clarity. It’s comforting, and makes me make sense of the world around me.

—Mara Christian Harris

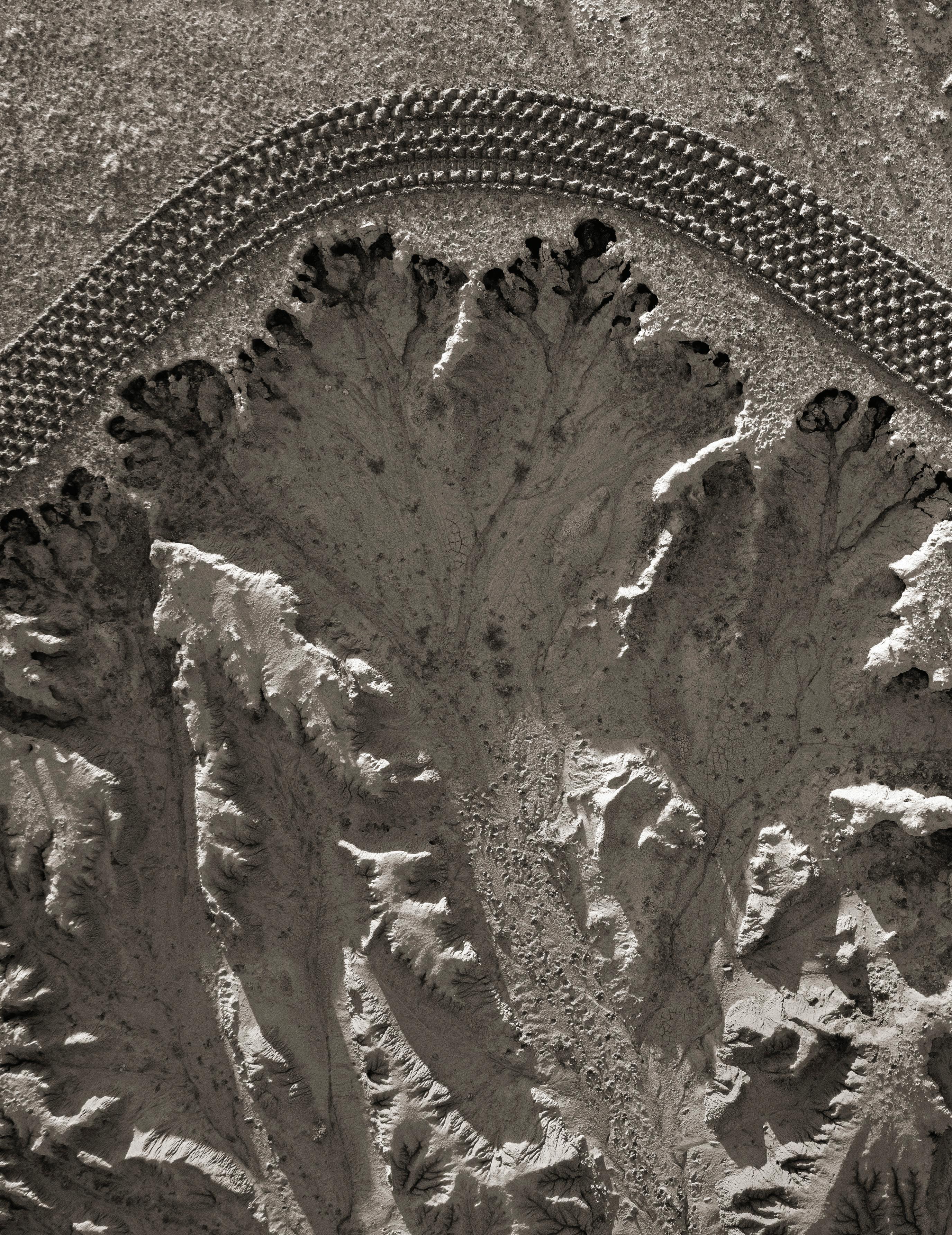

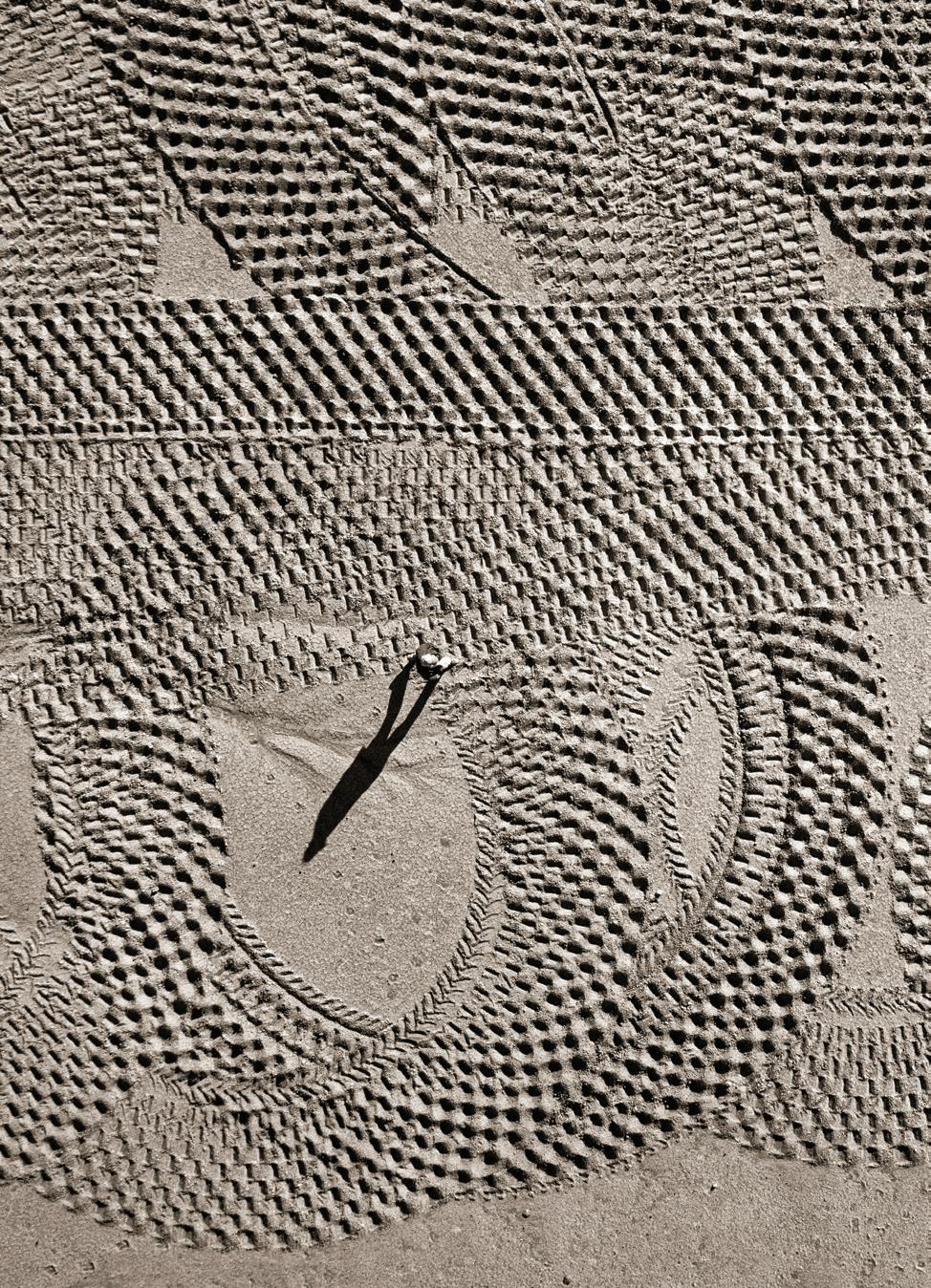

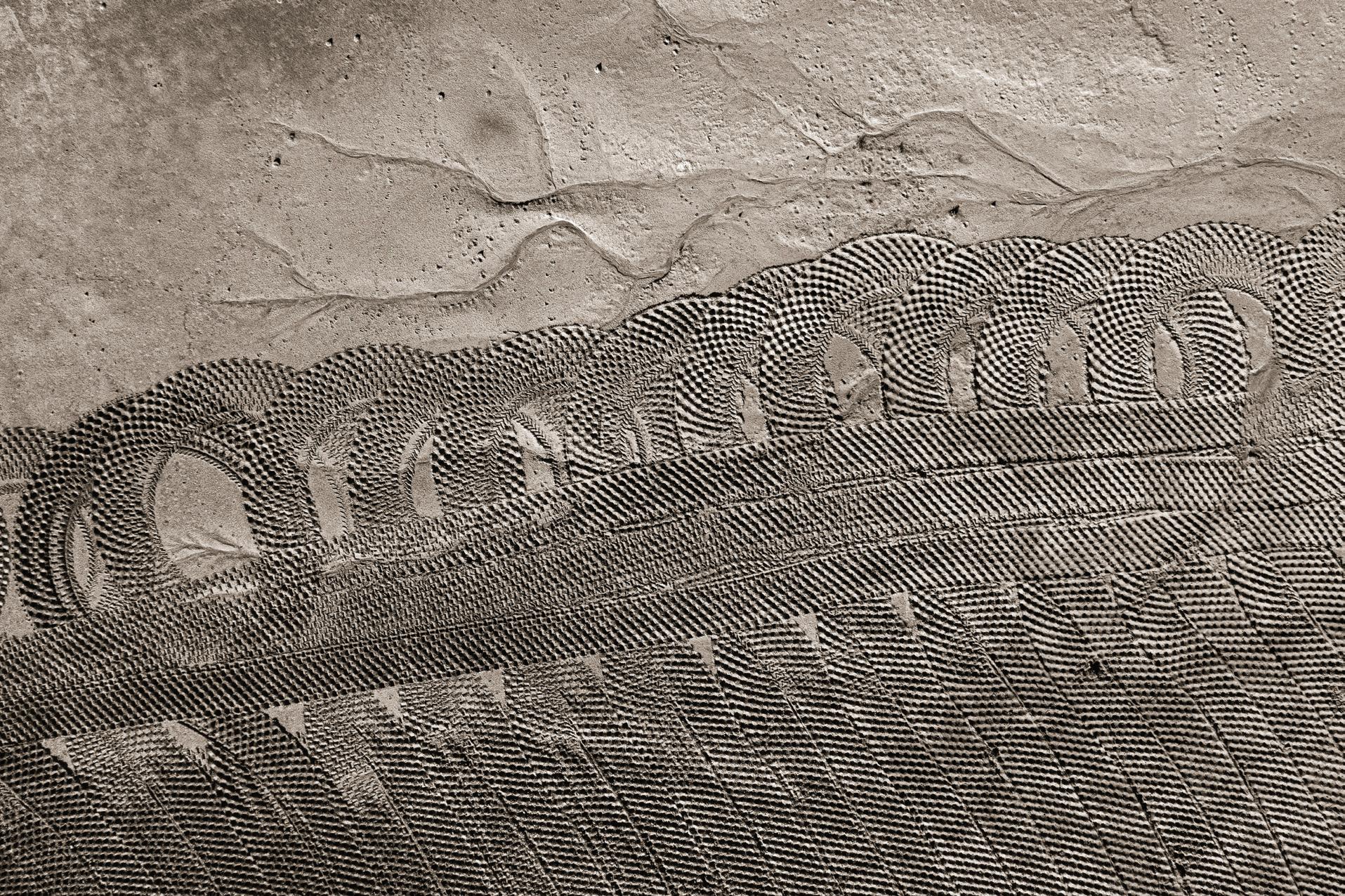

Swirls of broken black lines twist on themselves in geometric abstractions that could represent ocean waves or storm clouds. But look closely at one small section and terra firma appears, indicated by the silhouette of a person in mid-stride. Except that the silhouette is not a person. It’s the looming shadow of Gordon Tooley, himself a mere dot in this vast landscape captured by photographer Esha Chiocchio.

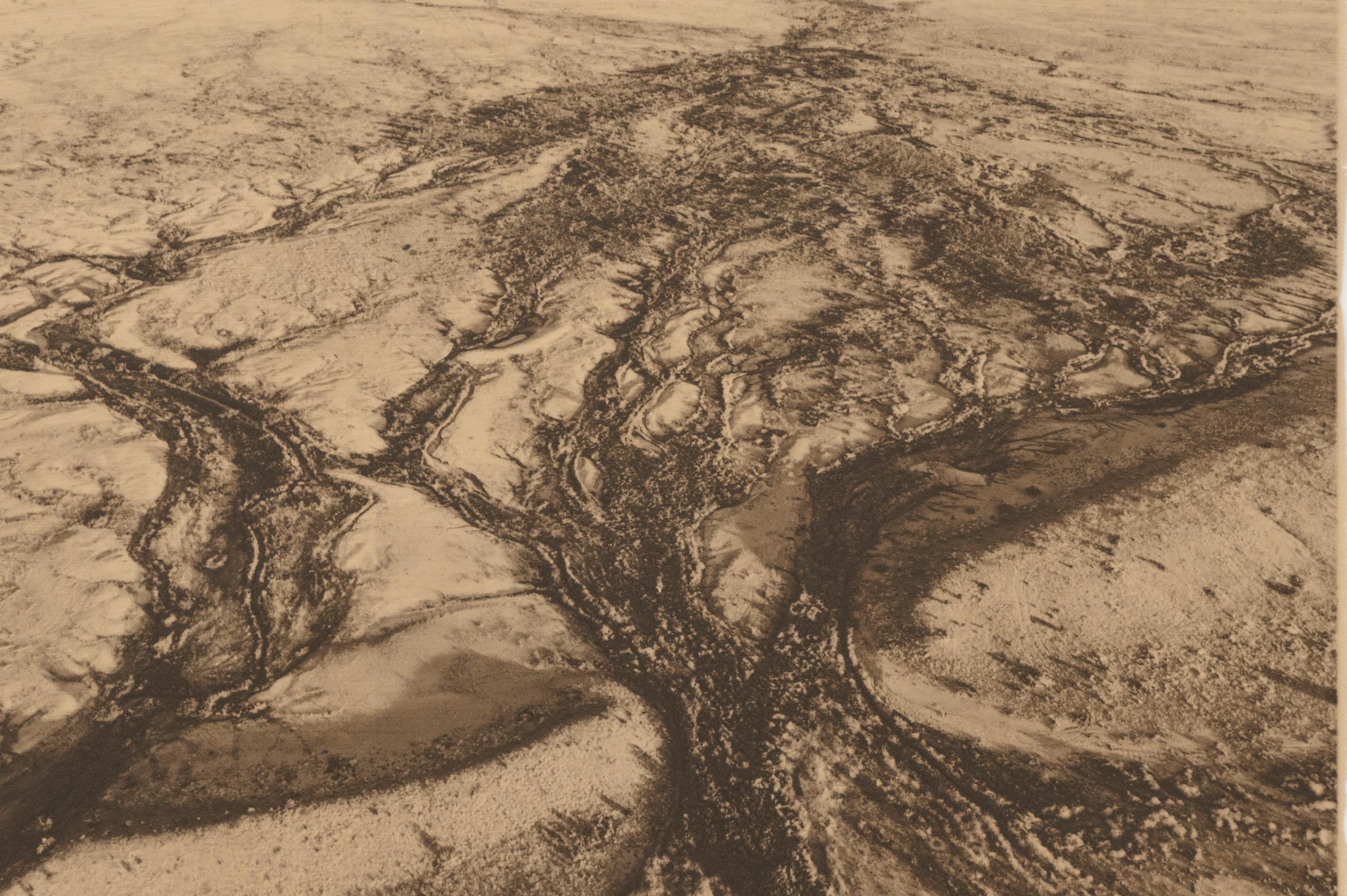

Taken with a camera borne aloft by Chiocchio’s drone, the image encapsulates a valiant effort by a handful of people and a rare coalition of government agencies. Together, they aim to temper the disastrous effects of climate change and overgrazing in the far southwestern corner of New Mexico. The exhibition Restoring Earth’s Canvas, held from August 25 through September 23 at Evoke Contemporary, is Chiocchio’s beautifully realized ode to land art grounded in a life-and-death reality: Can a 60-mile-long dry lakebed learn again to accept water, grow native plants, and tame deadly dust storms?

“The whole watershed is broken,” says Chiocchio of the Pleistocene-era Lordsburg Playa, which runs north to south between the city of Lordsburg and the Arizona state line to the west, and is bisected by the heavily traveled Interstate 10. Chiocchio learned about the Playa from Tooley, a wellknown orchardist in northern New Mexico, while developing her Good Earth multimedia project, which features agrarians devoted to healing the land. In 2020, Tooley took her to the Playa’s remote northern edge, which is anchored by a campsite lovingly dubbed the “Town of Dust” by its three regular denizens, the “Dustafarians” (see sidebar, starting on page 11.).

“I camped out in my little tent, the temperature below freezing,” Chiocchio says. “But when I saw the land, I thought, Wow, this is drone territory.”

Seen from above, the northern part of the Playa blooms in a cauliflower shape. Descriptions of its appearance in Chiocchio’s images can range from sensuous beauty to cancerous growth. It is, in fact, beautiful and awful.

The remote Lordsburg Playa might look like a wasteland. Photographer Esha Chiocchio conjures it into art that carries a serious message— and a measure of hope.Opposite: Esha Chiocchio, First Tracks (detail), archival pigment print, 26.7” x 40”. Above: Esha Chiocchio, Tooley in Circles (detail), archival pigment print, 20” x 30”.

The Peloncillo Mountains rise to the west, Big Hatchet Peak and the Little Hatchet Mountains to the east. Far from city lights, the Playa gleams under a canopy of stars. Rain still occasionally fills the lakebed, turning it into a birdwatching hotspot—images that Chiocchio renders from ground level with a dreamy touch.

But pounding rain can also sluice across it. Howling winds whip it with tornadic force. Cattle continue to graze on the few grasses that survive. A casual observer can easily write off the Lordsburg Playa as an expendable wasteland.

Chiocchio, however, saw art.

“The patterns are amazing,” she says. “Parts of it look like the veins in a human body. Water moves through us just as it moves through the land. What we do to the land affects us all. It affects the planet. We’re all connected.

“For me, this project is mostly about hope—the hope of taking a place that has been desertified like many places around the globe and restoring it to health. This is an

inflection point for turning it around.”

Shooting with her Sony DSLR for ground-based photography and a DJI drone for aerials, Chiocchio has amassed a collection of images that marry natural beauty to a social conscience and an environmental message. Grama grasses pause in perpetuity as a breeze blurs some of the feathery seed heads. Cattle describe an arabesque atop the weatherworked landscape. The Playa secures the base of the image as a towering thunderstorm muscles toward the viewer.

Evoke owner Kathrine Erickson says that while it was the alluring imagery of Chiocchio’s work that first captured her eye, once she heard the backstory she was completely taken. “Even when I’m looking at the erosion of the land, how Esha captures it is beautiful,” she says. “And she’s spreading the word of the hard work of these pioneers bringing the land back to the way it once was. Our collectors are drawn to much more than beauty; they appreciate the stories that artists tell. And this is a time and a story that is critically important. It’s urgent.”

A Florida native who attended high school and college in Colorado, Esha Chiocchio began honing her artist’s eye and environmentalist’s soul as a Peace Corps volunteer in Mali. To learn more about photography, she enrolled in courses at Santa Fe Workshops, where she ended up working for several years, all of which led her to fall in love with the City Different’s commitment to a wide variety of arts.

She and her husband, photographer Jamey Stillings, raised two children in the Santa Fe Commons on the Alameda, a cohousing community where residents cooperatively tend the luscious gardens connecting their homes and gather twice weekly for dinners of organically grown foods— activities that fit her ideal of living lightly on the land.

On the walls of their home, which includes a spacious studio, are hung images that Chiocchio made on return trips to Africa, including of the traditional remudding of the massive Great Mosque of Djenné for a 2001 National Geographic article, and a health clinic in Lamu, Kenya, supported by Santa Fe’s Jambo Café.

Meet the three-man clean-up crew of the Lordsburg Playa.

Esha Chiocchio’s exhibit includes portraits of those who have endured freezing winters and grueling summers to repair patches of the Lordsburg Playa. These self-styled “Dustafarians” come from different places and possess different types of expertise. From long days in the field to quiet nights around a campfire, they’ve grown into a gottabelieve squad that knows their efforts might not bear fruit for years to come. They also agree that everyone can play a role in building a better tomorrow, one drop of water at a time.

After successfully rescuing diverse species of desert-hardy fruit trees in New Mexico, Gordon Tooley got to the root of the problem. “The landscape below ground is much, much larger than what we view as terrain,” he says. “We’ve fragmented our grasslands and forests with developments, roads, culverts. It changes how water behaves, and our landscape is drying.”

The solution, he determined, required a deep focus on what lies beneath. With his keyline plow—a contraption developed in Australia in the 1950s—Tooley re-contours land with long, thin shanks that oxygenate the soil without turning it over. A seeder follows, and then an imprinter, pockmarking soil to further slow rainfall and use nature’s biology to heal itself.

Most of Chiocchio’s photography falls into an editorial framework, some of it funded by the New Mexico Department of Agriculture and National Geographic Explorer grants, of which the Lordsburg project is a recipient. She began moving into fine-art photography this July with Circular Solutions, an exhibit of her Good Earth images at the Turchin Center, in Boone, North Carolina.

For her Evoke show, Chiocchio is creating limited editions of large black-and-white prints, medium-size color images, and a selection of smaller prints that play off the historic orotone (gold-tone) photographic process made famous by Edward S. Curtis, with a haunting digital twist. “I’m using a modern printer and printing on Mylar paper, then using gold-leaf on the back,” she says. The effort imparts a feeling that these contemporary activities belong to the distant past, a dislocation of time that hints at the potential of the Lordsburg reclamation project’s long-term impact. “The thought behind the gold leaf is that soil is our most precious resource, it’s our black gold, our bank account. We have been

abusing it and therefore depleting our reserves. It’s time to regenerate the land and rebuild our resilience.”

With all of her images, Chiocchio seeks to beguile viewers with an impressionistic quality of the area, and encourage them to learn more about holistic ways of mending our impact on the Earth.

“I didn’t want to just take pictures of the land,” she says. “I want to tell stories of the land.”

When in the Lordsburg Playa, Gordon Tooley uses a keyline plow to which he’s added a number of tools. The plow’s long shanks dig slices in the soil without turning it, to recontour the Playa’s upper edge. Next comes a seeder, its hopper loaded with grasses, forbs, and shrubs chosen by native plant expert Mike Gaglio (see sidebar). Finally, an imprinter with a lineup of offset points pushes the seeds into foot-deep divots, each capable of holding a gallon of water. Complementing those efforts, waterflow expert Van Clothier

(see sidebar) marshals rocks and soil to divert rainfall, slowing its passage across the land so that it can nurture plants that hold the soil in place.

So far, only a small part of the Playa has received this treatment—some 700 acres, with another 950 acres planned for this fall and winter. Tooley calls their work quixotic, but the consequences of doing nothing are dire. The nation’s worst dust storms regularly close I-10 and lead to crashes that have claimed dozens of lives over the last 50 years—in 2014, seven deaths in single incident. They also disrupt interstate commerce, deplete the resources of law-enforcement agencies, and divert truck traffic onto two-lane roads built for much lighter vehicles, which shortens the life spans of those roads.

“I view all landscapes as tattered, worn out,” he says. “It’s our job to be weavers and repair them. If we had millions of people thinking like drops of water, we could get land to retain that water and keep it as high on the landscape as possible.”

This past summer, his Lordsburg days began at dawn. He’d work until the temperature climbed above 100°, take a few hours off in his air-conditioned trailer, then return in late afternoon to drag more plow lines across the troubled Playa. He endured the high-summer brutalities because that’s when these seeds can best respond to their natural cycles.

“This is what we’re supposed to be doing,” he says. “It’s our stewardship: to take care of ourselves, our neighbors, and the soil. We’re the same thing as plants.”

None of his previous projects come close to the size of the Lordsburg Playa, Mike Gaglio says—and those projects include installing rainwater-harvesting systems, building wetlands along the Río Grande, and revegetating Chihuahuan Desert lands just beyond the urban reach of El Paso.

“For me, the Lordsburg project allows me to be a biologist, a restoration practitioner, a heavy-equipment operator, and to tinker and experiment,” he says. “It allows me to do it all.”

Gaglio chose a variety of grama grasses for the project, along with alkali sacaton, fourwing saltbush, and len-scale saltbush. “They’re drought- and flood-tolerant,” he says. “They’re good species to experiment with in an ephemeral dry lake with really salty soils.”

In 2020, during a campfire chat, Gordon Tooley had mentioned a photographer friend he wanted to invite down.

The 2014 accidents drew action from New Mexico’s Department of Transportation, an agency more used to laying pavement, installing culverts, and building bridges than working with a plucky crew of Whole Earth Catalog adherents. Besides installing new warning signs, wider highway shoulders, and a network of weather-detection stations, NMDOT looked well beyond its right-of-way to the sources of the dust. That required partnerships with the federal Bureau of Land Management and the State Land Office, each of which oversees a checkerboard of parcels across the Playa.

NMDOT obtained federal funds—so far about $3.5 million—to experiment with reclamation. Anecdotally, the work has improved conditions, especially at an earlier and smaller test site south of I-10. “The eyes don’t lie,” says Trent Botkin, Acting Manager of NMDOT’s Environmental Bureau. “There’s grass. And where there’s grass, the soil is being held down.”

That much was expected. But no one predicted someone like Chiocchio creating gallery-worthy art.

“It’s amazing she came to us,” Botkin says. “It’s hard to get people excited about something that happens in the middle of nowhere. It’s hard to get the federal government excited. It’s great she saw the dream borne out on the land.”

In a summer of record-breaking heat, disastrous floods, and capricious tornadoes, Chiocchio’s images could galvanize even more action against climate change. “There’s so much more to do,” she says. “This is just a drop in the bucket.”

—Kate Nelson“Sure,” Gaglio said, and soon found himself enthralled by Esha Chiocchio’s images.

“This is a tough site to be on,” he says. “It takes a special person to see the beauty. It takes work. Esha’s pictures are so deep. There’s such a soul to them.”

As a California surfer kid, Van Clothier loved studying the power of moving water. That he ended up doing so in the desert Southwest speaks to his commitment to improving how water interacts with land. As the founder of Stream Dynamics, he helps repair damaged watersheds, sometimes by simply moving rocks into the way of rainfall to slow its pace. And with Bill Zeedyk, he wrote the seminal book Let the Water Do the Work: Induced Meandering, an Evolving Method for Restoring Incised Channels, which has inspired farmers, municipalities, and backyard gardeners. Clothier began visiting the Lordsburg Playa years ago.

“It’s beautiful in its own way,” he says. “It’s an interesting landform. We’ve camped there. A friend who’s a pilot landed his plane there. It’s almost like you’re on top of a mountain, with 360° views.”

The Playa restoration project introduced him to Tooley and Gaglio, who’ve since become fast friends. “We work seamlessly together,” he says. “We work, we camp, we have yummy food. We have beautiful sunrises and sunsets. We’ve watched rains and storms, seen the tremendous success of the project—and we’re having the time of our lives out there.”

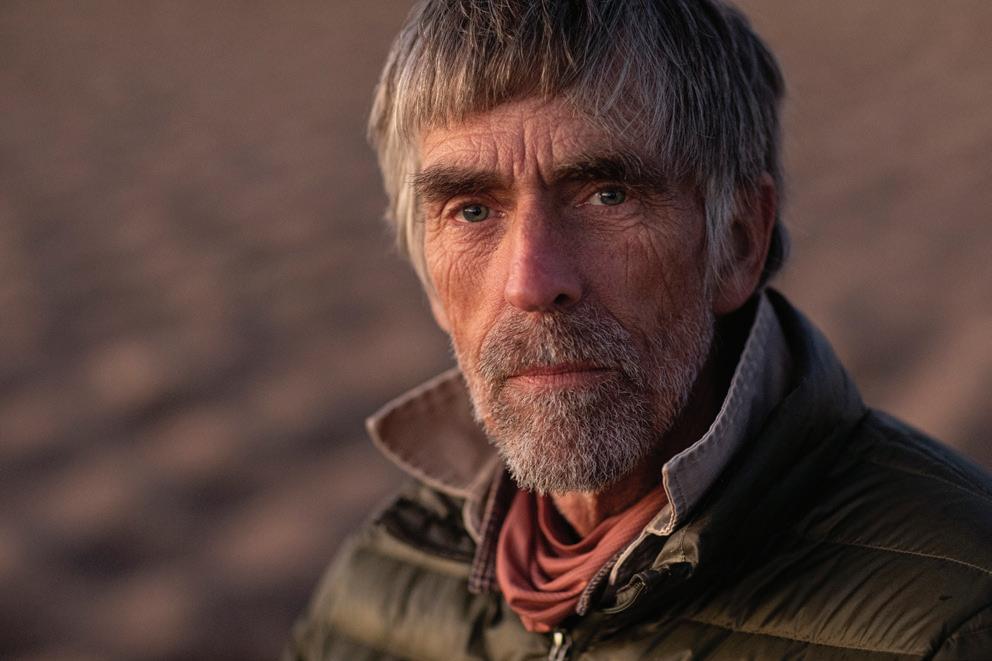

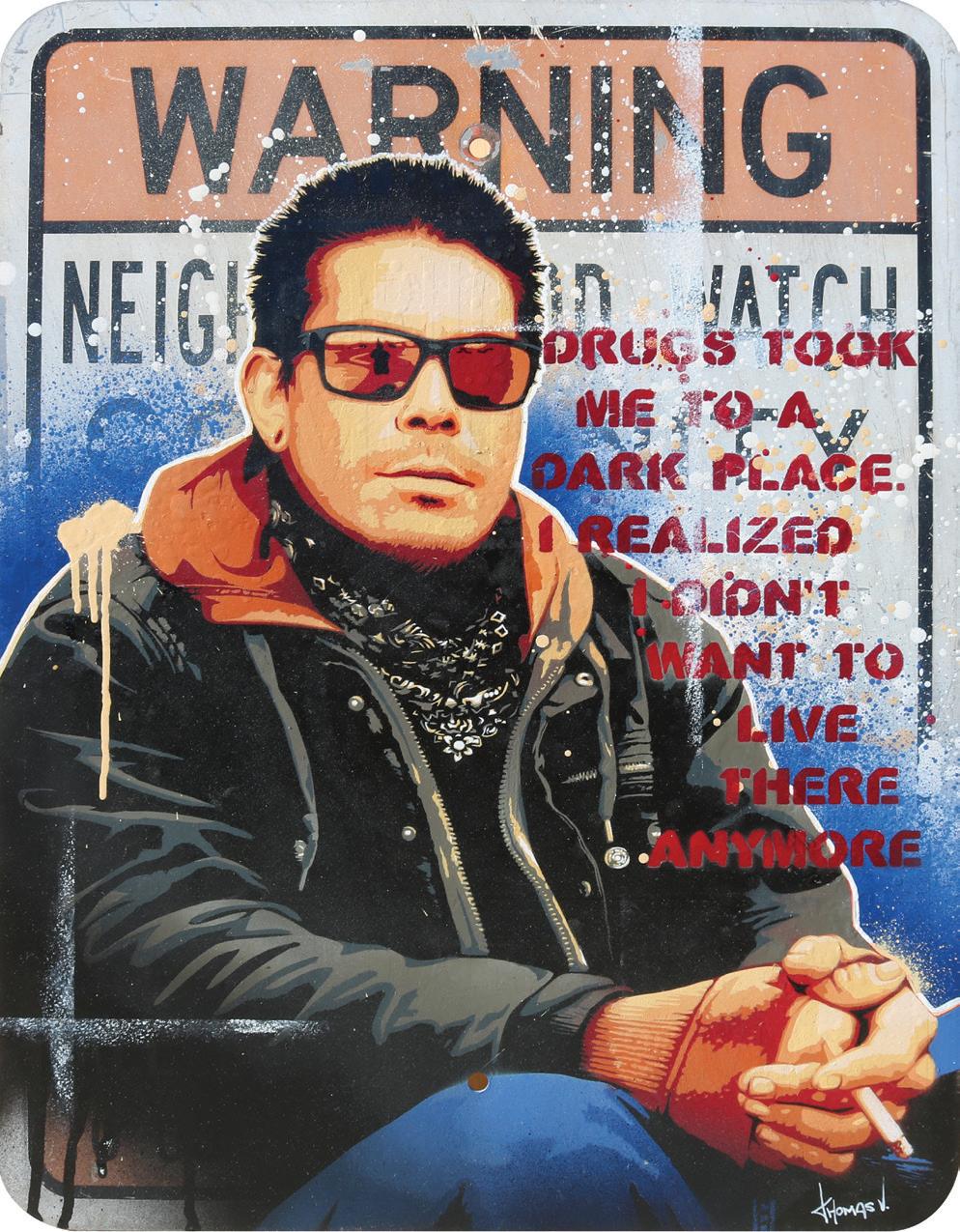

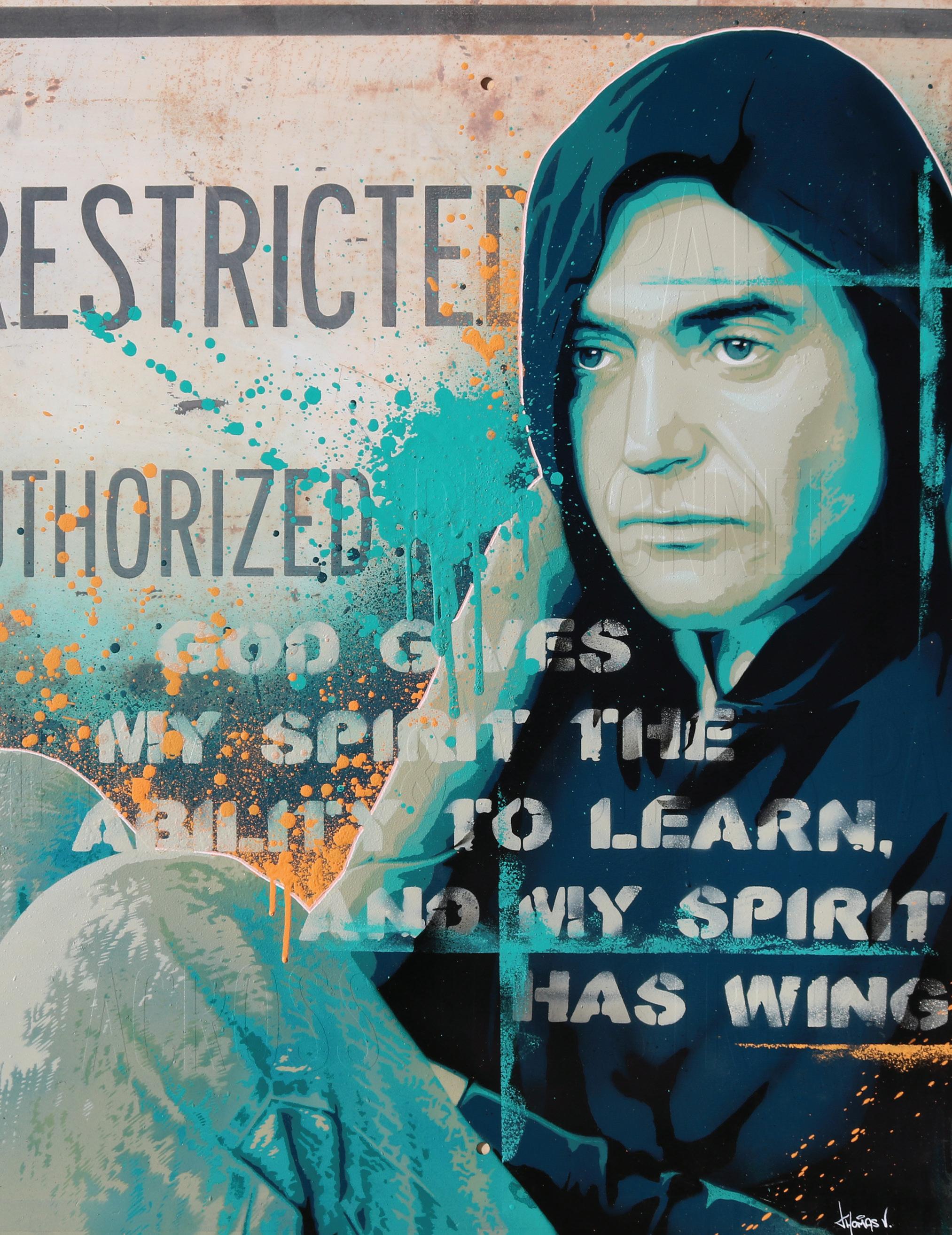

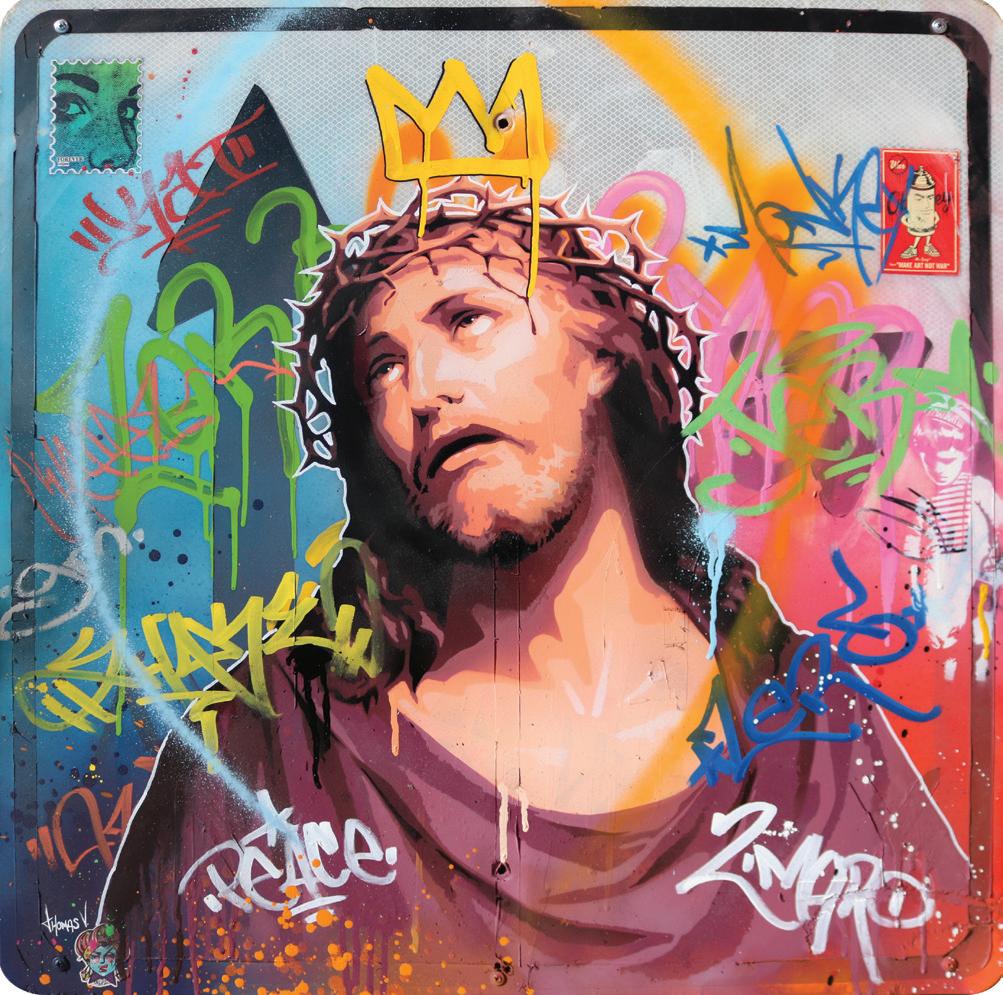

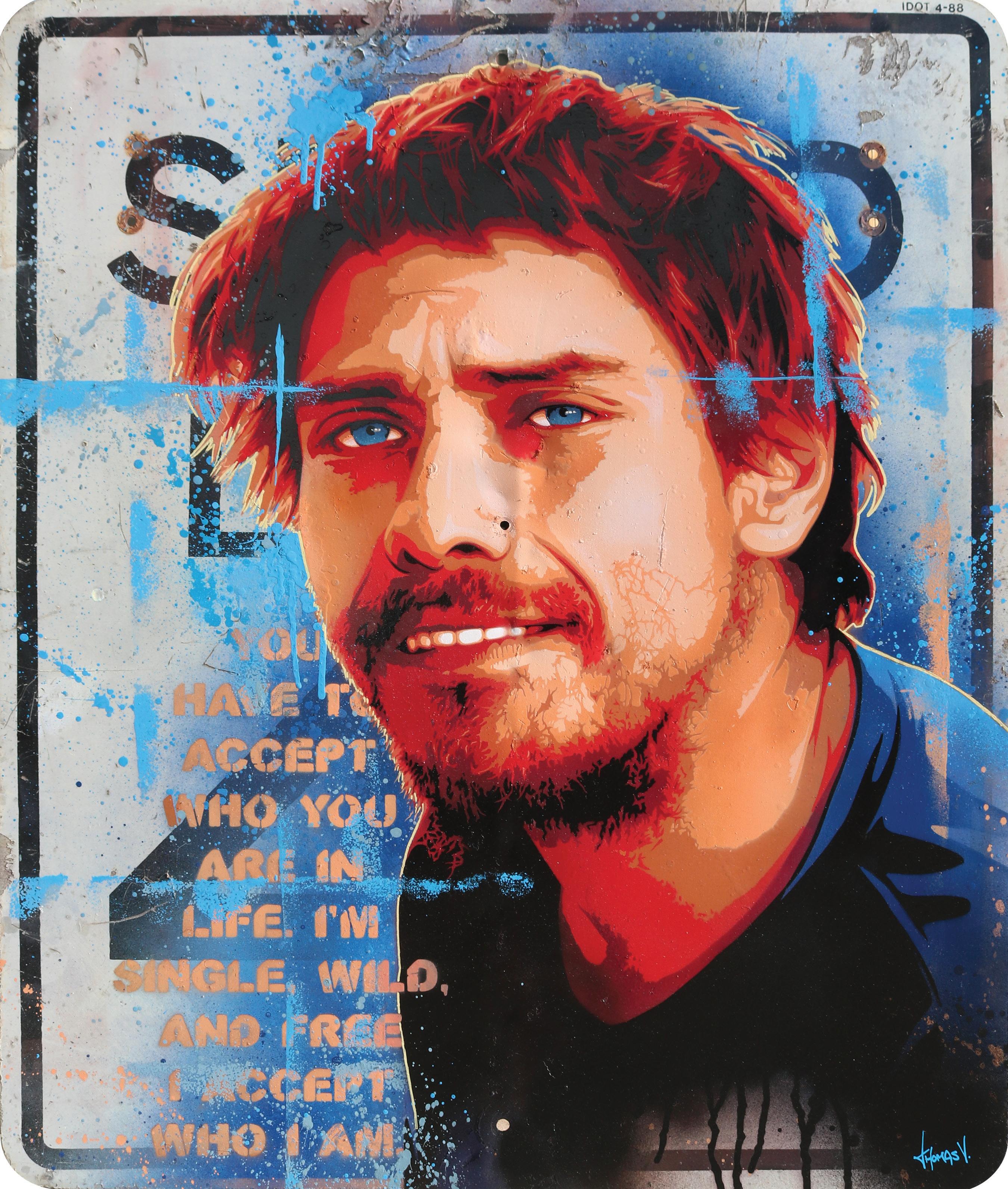

—Kate NelsonIn his solo exhibition Lost Prophets, Española native Vigil explores the idea that within every individual, well known or not, is a powerful voice. “The idea behind this show was that I was going to photograph local people from my hometown and place them in a setting where they look like religious icons,” he says. “In my head, I saw images of everyday people that might mean something—a great deal to me, but maybe nothing to anybody else. I pictured saints, and how those saints are depicted, and thought I could do the same thing with local people, but maybe with a halo or something that makes them feel more iconic, even though they’re everyday figures. Because I’m big on the fact that nobody’s above anybody else in this world. I don’t care if you’re the CEO of a company—that doesn’t give you the right to belittle other people.”

Of the dozen portraits in the exhibition, some are of recognizable celebrities, such as musicians Kurt Cobain and Chris Cornell. Others are friends, family, or otherwise anonymous or overlooked individuals Vigil has photographed on the streets. Most have faced or are facing challenges with homelessness, mental health, and addiction.

ThomasVigil’s studio in La Mesilla, about 40 minutes north of Santa Fe, is a study in contrasts. From an ordinary backyard shed comes extraordinary art that marries traditional imagery to decidedly modern tools and techniques in an innovative graphic style.

A small table holds an orderly array of spray paints arranged for Vigil’s current work in progress. The walls and a few tables are piled with objects of inspiration—posters, photographs, stickers. One wall has clearly been used as a test canvas for designs and color schemes. Hung in a corner are award ribbons from art fairs and markets, including Contemporary Spanish Market. On the floor sits a stack of stencil cutouts ready to be used to create as many as twelve painted layers on the scavenged road and construction signs that are Vigil’s preferred backgrounds.

“For example, I saw Benny at a gas station picking off pieces of lint from a brimmed hat very meticulously. Benny is originally from Belén—he worked in construction and as a bouncer in Florida. He ended up hurting his back and got addicted to opioids. After that, he started dealing prescription drugs because he needed a way to pay for his addiction. One of his customers shot him a bunch of times and shattered his leg, so he had to come home. When I spoke with him, he said that he had been off opioids for, like, three months or something, and he was trying to wean himself off alcohol as well. That’s where the quote came from on the piece: ‘Drugs took me to a dark place. I realized I didn’t want to live there anymore.’ ”

Vigil combines a penetrating photographic image with the subject’s provocative words into an archetypal painted vignette. “By using an iconic image and putting words behind it, it gets people to question their assumptions and beliefs,” he says. “I try to use my images to get people to question what they’re looking at. And I don’t care if it pisses you off or excites you. The whole concept is provoking something and an emotional reaction, period. I’ve always been rebellious that way, because I was raised so strict. I push the limits, because what’s important to me is being different and

questioning things. You can’t believe everything your teachers tell you, or what the news is saying, or what political figures say.”

Using and adapting religious and iconic imagery is not new to Vigil’s work. He credits his childhood growing up in the Spanish Colonial and Roman Catholic culture of northern New Mexico for the focus, in his early paintings, on landscapes and saints. “I am drawn to those images. They hold power.”

Interested in sketching, painting, and design at an early age, Vigil attended Northern New Mexico College, in Española, studying graphic design and art history, and earning an associate degree in applied science in visual communications. Though he then thought what people wanted were paintings of religious images, churches, and local landscapes, he says today that those genres were never true to his artistry or his rebellious nature. “I didn’t want to be like everybody else, to just get by. I was trying to express myself, be my own person, be my own artist. I realized right away that I was forcing myself to create things I was not enjoying.”

In his teens, a visit with his older brother in California had exposed Vigil to a street-art culture that has since bubbled to the surface of his creativity. “I started incorporating spray paint because graffiti was the artwork that I really loved and enjoyed. I said, ‘Okay, no more landscapes, no more acrylics, no more paintbrushes. I’m going to do things my way.’ That’s when things took off. My artwork improved, because people saw that I was showing more of myself, and they related to that.”

Vigil’s paintings include stickers, stencils, and wheat-paste illustrations, graffiti elements that also speak to his desire for originality and nonconformity. On top of this he then builds an image, all of it layered over the splashed, graffitiesque background.

Graffiti’s fragility, impermanence, and, ultimately, freshness also appeal to Vigil. “I can argue that graffiti artists are pure artists because they create for the sake of creating, because they have to create. Somebody takes the time to create something that they know will disappear in a week. And they know that this is a means to an end and that this thing’s going to disappear. But they still have to make it.”

His hybrid style and technique make Vigil’s paintings

relatable in a way that much traditional religious or religiousinfluenced work is not—it’s chaotic, messy, and visceral. He credits such graphic artists as Shepard Fairey and Banksy in shaping both his methods and the media he uses, in addition to the graffiti artists he met in California and those he follows on social media. Vigil has incorporated Fairey’s use of iconic figures to spread his own message and philosophy and to draw people in by use of familiar images.

“I’ve grown dramatically over the last 10 years, and my message has changed as well,” he comments. “I feel like what we [artists] do matters. It’s about evoking that response—it’s about being original and doing what I want to do the way I want to do it, without the influence of outside people. I love being a part of the artist community, but at the same time, I’m not going to conform anymore. That is definitely growth—not caring anymore what people think about the way I express myself. It’s a huge step.”

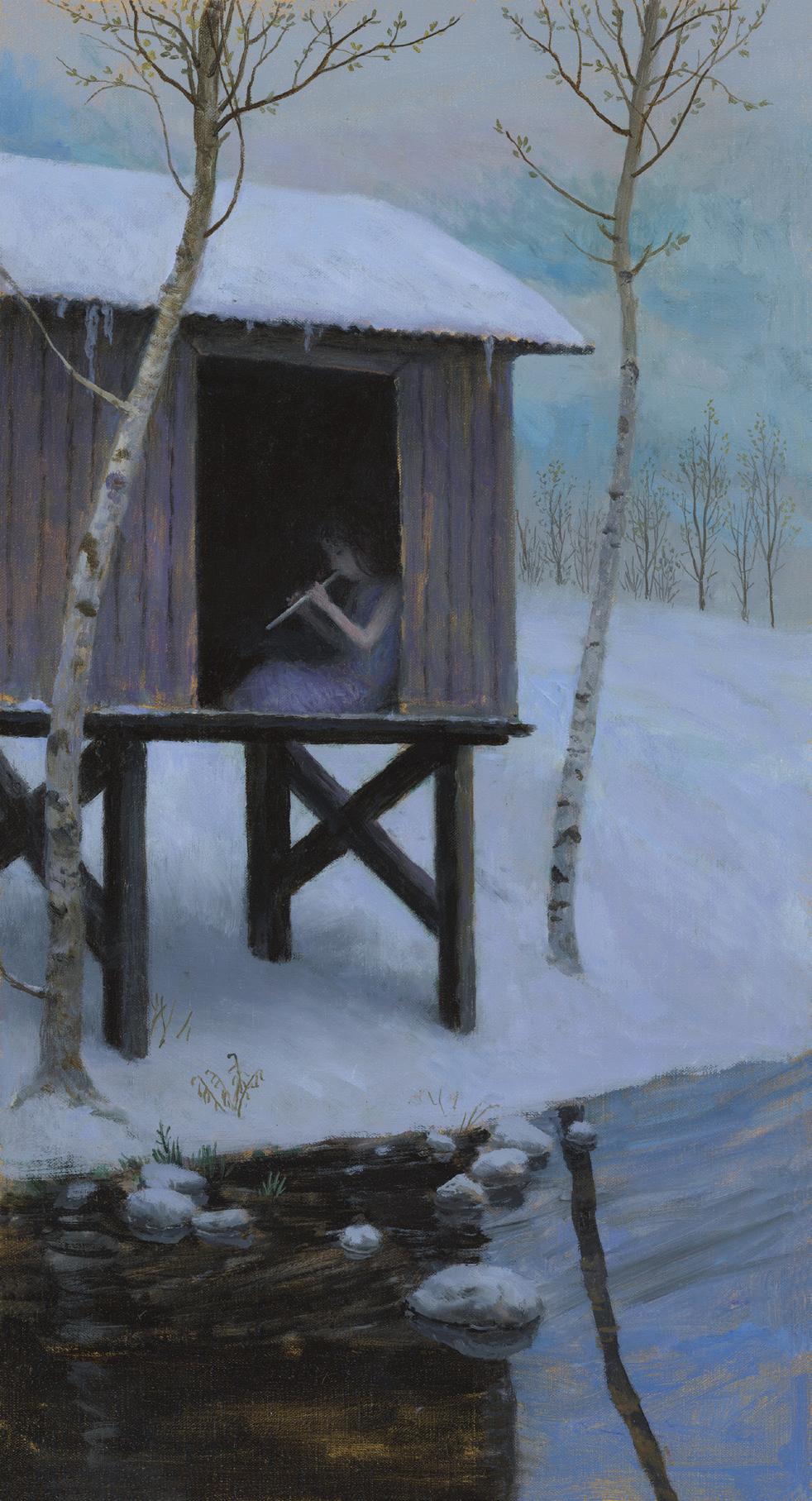

Ayoungwoman sits barefoot on brick steps and cradles a young swan, apparently overcome by melancholy. Is it time to set the bird free? She holds the swan gently but close, at about the level of her solar plexus, as if it were her spirit stretching its neck toward freedom.

In this painting, Sheltered, by artist Aron Wiesenfeld, the steps are set below ground level, providing a womb or place of emergence for these young souls. The image evokes the loss of innocence and childhood as the day, as if in sympathy, casts a gray pall over the scene. Weeds sprout joyless from a brick plaza stretching to the horizon. Soon a life emerges in full from the young woman surrounded by bleak walls—a life that can fly. The painting’s somber tones are balanced by the soft, two-tone pinks of her sweater and skirt, and the red of the

swan’s eye draws the viewer’s eyes like a magnet. That spot, the painting’s brightest, belongs to the untainted new life emerging, not yet browbeaten by the uninspired dullness of life, its adoptive mother driven to the outskirts to protect it.

Isolation, solitude, loneliness, aloneness, and retreat are depicted frequently in the works of this California-based artist. In them, a figure’s solitary engagement with the environment sometimes happens purposefully, as an escape to the safety of woods and trees.

“The act of painting should be a way for an artist to find magic in the mundane, in my view,” Wiesenfeld says. “As Western society has become more materialist in its philosophy, one of the biggest challenges artists have faced is finding ways of making painting evoke the spiritual.”

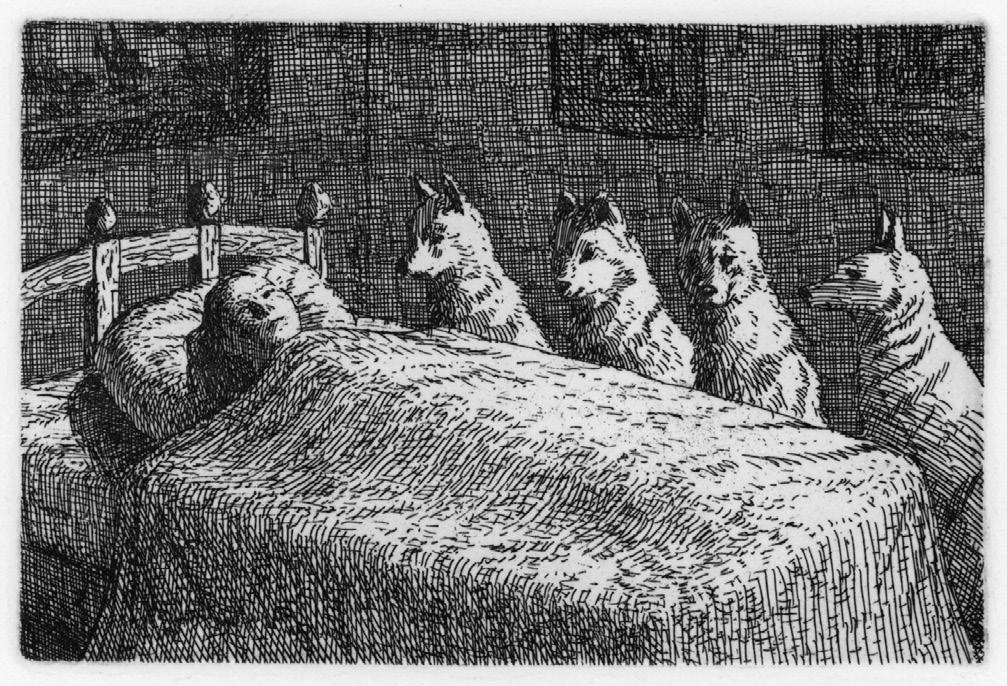

Wiesenfeld is a narrative painter. Many of his compositions remind the viewer of fairy and folk tales, recalling stories of enchantment told at bedtime but played out in modern settings. One can easily see his recent etching Siesta as an illustration for such a story. A young woman, tucked into her bed is watched over by four dogs or wolves, but its mood is not threatening. Perhaps the beasts are spirits who have come to her in a dream.

The near-monochrome of many of Wiesenfeld’s works lends itself readily to his etchings, but his paintings are enlivened by colorful swaths and flourishes that take on metaphorical meanings. The works of this figure and landscape painter belong—and don’t belong—to the traditions of mannerism, German romanticism, and magical realism.

In fact, Wiesenfeld’s work is a heady witch’s brew. A draught of it clears the eyes to wonders of the past that reach like ghosts into the present. Empathy with his protagonists is an inevitable consequence of the predicaments they are presented in, which are equivocal—caught at the edge of a dark forest, say, just as evening casts an ominous pall over the scene, but with no immediate threat emerging.

“Setting a figure within a landscape lends itself to telling stories more than portraiture, generally speaking,” says Wiesenfeld, who is 51. “It’s most effective if you can invite the viewer in and let them identify with the central character on some level.” He cites as a classic example the painting Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, by Caspar David Friedrich.

“Since the figure is seen from behind, and Friedrich gives the viewer virtually no information about him, we naturally find ourselves in his place, looking down on those mountains. That desire to let the viewer enter the painting is part of the reason I treat my own figures the way I do, sort of like cartoons. If the figures were more photo-realistic it would be counter to my aims. I think this idea was best stated by Scott McCloud in his book Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. The combination of an iconic, cartoony character within a very realistic background ‘allows readers to mask themselves in a character and safely enter a sensually stimulating world,’ leading to greater audience involvement in the story.”

Aron Wiesenfeld was born in 1972, in Washington, DC, and raised in Santa Cruz, California. He was educated at The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, in New York City, and at the ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena, California.

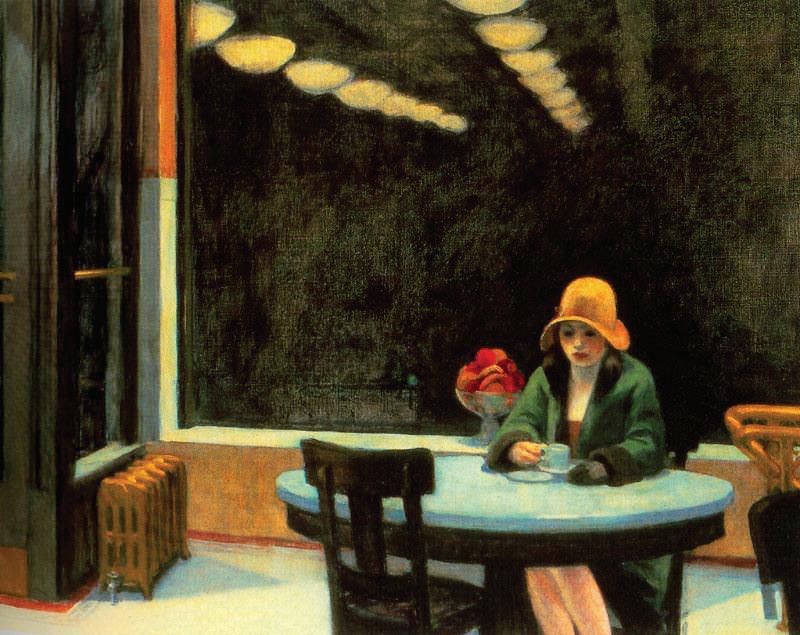

He has a precursor in Edward Hopper (1882–1967), whose works also could find some resonance with earlier Romanticism. Hopper was another artist whose figures, even when painted together in a scene, seem each locked into a place within themselves. But as the reader of any good novel knows, the inner realm is a sovereign domain. In visual art, that dimension, which can veil the spiritual, is evoked through a combination of mood, tone, and image.

“I think of Edward Hopper as someone who did that so well,” Wiesenfeld says. “Just to pick one of his paintings, Automat is a mundane scene of a woman at a table with coffee. The window behind her, which takes up most of the composition, shows nothing, just reflected ceiling lights receding into the darkness. That darkness feels like it’s alive, looking in, like a second character in the painting. Hopper was profoundly in touch with a sense of mystery, the unknown, the uncanny, all those things that religious imagery used to do for viewers.”

Wiesenfeld laments the lack of a spiritual sense of mystery in the art of our times. But it’s there in his art, as it is in Hopper’s. The figures are less realistically described by his brush, and the reflection of his subjects’ moods in their immediate environments are more emphatic, but often in a lilting manner that brings moments of grace—as in his painting The Cabin. The lilac tones of a young flutist’s dress are mirrored in the stream, which flows like the music of her instrument.

Instead of using a dramatic tone that could be described as cinematic (as in Hopper’s work), Wiesenfeld draws his imagery from storybooks and dreams. And rather than overtly make his work autobiographical, he instead concentrates on the potential for empathy. He might feel his subjects’ pain, love, fear, or awe—but he’s also interested in getting the viewer to see and feel them. This viewer finds that easy to do, because Wiesenfeld’s paintings reflect who we are.

“If I were to list the difficulties of my past, they would sound pedestrian and not very interesting,” he says. “Inasmuch as those personal trials inspired the images, they were merely a jumping-off point. I’m much more interested in what painting can do in terms of kindling wonder, potential, emotion, beauty, and stories in myself and viewers.”

—Michael Abatemarco

Accordingto the scholarly mystic and prolific author A.E. Waite (1857–1942), The Fool, one of the Major Arcana cards of the popular 78-card divination system known as the tarot, represents the human spirit in search of experience. Of the 22 cards that comprise the Major Arcana, only The Fool has no number. Most tarot readers position him between numbers 21 (The World) and 1 (The Magician). The Fool is thus the alpha and the omega, and so a reflection of God.

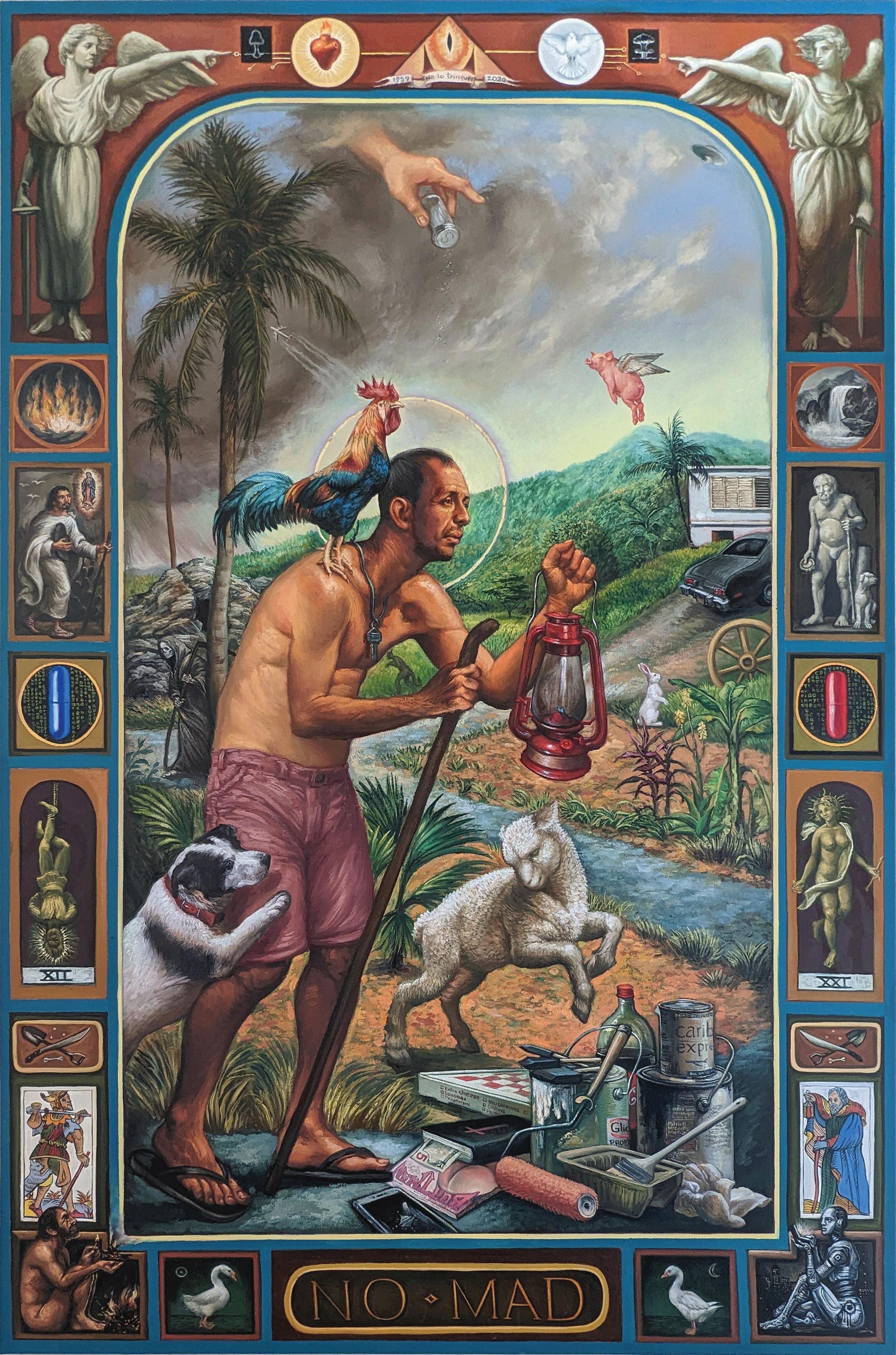

Puerto Rico–born artist Patrick McGrath Muñiz pays homage to the tarot and its archetypal imagery, drawing, as cartomancy has for hundreds of years, from the contemporary world as well as from the world’s long past. His No Mad, painted in the tradition of retablos, or devotional paintings on wood, is The Fool (El Loco) reimagined as an immigrant, and contains allusions to the crossing of borders and to the lowwage jobs that exploit immigrants’ manual labor.

In No Mad, the apparition of death haunts a nearby river like

Charon on the River Styx. A dog nips at the central figure’s heels, as in typical images of The Fool. Muñiz combines the imagery of this, the tarot deck’s “zero” card, with that of The Hermit (El Ermitaño), the seeker within, as well as with other tarot images, allusions to the quest for spiritual enlightenment, and references to contemporary life and pop culture, such as the red and blue pills from the Matrix films.

“I’m not saying this is good or this is bad, or this is right or wrong,” says Muñiz, whose oeuvre is a reflection on the impact of humankind on our present Anthropocene (i.e., the age of humans), “I am interested in how the past informs the present and the present reflects the past.”

Muñiz, whose exhibit Retablos opens at Evoke Contemporary on Friday, November 24, sees more in the past 500 years of history than the stories told by the victors. He also looks beyond more obscure narratives salvaged from the histories of peoples trampled by European conquest.

The artist received his BFA from the Escuela de Artes Plásticas, in San Juan, in 2003, and his MFA the Savannah College of Art and Design, in Georgia, in 2006. His painting style recalls the work of well-known Puerto Rican artist José Campeche (1751–1809), who learned in turn from the Spanish court painter Luis Paret y Alcázar (1746–1799), who lived in exile on the island. But the retablo tradition in North America is mainly associated with 17th- and 18th-century New Mexican santeros, or saint makers, a tradition that continues today. Early on, painters of the Spanish Colonial period painted and carved in a style derived from the Spanish baroque and rococo. Following suit, Muñiz, an astute student of classical

painting traditions, brings a stately poise to his figures, but often adds satirical elements that provide humor and invite afterthought.

For instance, La Emperatriz (The Empress), the third figure encountered on a journey through the tarot, holds her icecream cone aloft, offering the milk of the domesticated cow in place of the fecundity of the Earth, as in more traditional cards—at least, that’s one suggested meaning. Much of Muñiz’s work counters the absurdities of the consumer age with the sound of a spiritual hammer banging on a door.

The rectangular format of retablo portraits seems ideally suited to the tarot, and Muñiz was captivated enough to already have begun designing his own entire tarot deck of 78 cards—the Major and Minor Arcanas, and the Court Cards— when Hurricane Maria tore through Puerto Rico in 2017, destroying his childhood home. Whether by chance or design, precious little was salvaged—except a deck of tarot cards.

Muñiz’s deck, the Tarot Neocolonial de las Américas, was published by U.S. Games System, publisher of some of the best-known decks in the English-speaking world, including the famous Rider-Waite-Smith deck, designed by A.E. Waite and artist Pamela Colman Smith. But while the Tarot Neocolonial owes more to the simpler images of the centuries-old Tarot de Marseilles than to the Rider-WaiteSmith deck, the images in Retablos are different again. The inspiration of the tarot remains, but the archetypes change clothes and names; Pater, for instance, alludes to the tarot’s The Emperor (El Emprador).

Clad in the robes of a saint from Roman Catholic iconography, the figure of the father (Pater) holds an infant already indoctrinated in the ways of the dominant culture: he wears a Baby Yoda hat, and his hands hold a selfie stick and camera and a McDonald’s Happy Meal. The father, in a tie, beams with pride. In the background, protestors knock down an obelisk like the 1867–1868 Soldiers’ Monument toppled on the Santa Fe Plaza in 2020. It is a reference to the protests that swept the country during the pandemic against historic figures of the Americas whose actions led to the deaths of many, or whose views no longer align with the values of the nation.

The topical themes explored in Retablos serve also as reminders that contemporary issues often inform art, and that the past informs the present. Muñiz looks for the hidden meanings between the correspondences, recognizing patterns that are repeated throughout history. The past holds lessons unlearned. Rather than a didactic treatise on what’s wrong with the world, he lends it a certain noble prestige. The drama of the human story unfolds, comedy and tragedy its recurrent themes. Through the imagery, art, and history, Patrick McGrath Muñiz unveils a portrait of humanity with a shadow aspect gnawing at its soul.

—Michael AbatemarcoIts galleries and museums are high on the list of things Santa Fe is best known for. While some of the city’s historic museums focusing on New Mexico’s past engage that history in dialogue with the contemporary moment, few collecting institutions make contemporary art their first priority.

Which is why the Vladem Contemporary was built, in response to the New Mexico Museum of Art’s growing need to expand its mission to include contemporary art. The new museum’s doors are scheduled to open to the public on Saturday, September 23—but it was a long time coming. Plans for the new museum were seriously considered under three previous museum Directors—Mary Kershaw, Marsha Bol, and Stuart Ashman—and now it has been completed under the auspices of the NMMA’s current Executive Director, Mark White. The Vladem Contemporary is located in Santa Fe’s historic Railyard District and designed by local architect Devendra Narayan Contractor (of DNCA Architects) and Albuquerque-based Studio GP.

Then came the coronavirus pandemic, which brought construction to a halt. “Because of the pandemic, there were supply-chain issues that contributed greatly to the delayed timeline,” Mark White says. “A lot of people

have experienced those, but it’s particularly acute in the construction field right now.”

The Vladem’s troubles were still not over. Part of the new museum occupies the former state-owned Halpin Building, at the corner of Guadalupe Street and Montezuma Avenue. Built in 1936 by the Charles Ilfeld Company as a mercantile warehouse, this structure served for decades as a repository for state archives before its eventual rebirth as a contemporary art space. Plans for the Vladem were delayed by a legal battle, now settled, involving Gilberto Guzman, lead artist of the Halpin Building’s street-facing mural, MultiCultural (1980). The new construction threatened the mural, which ultimately couldn’t be saved. In 2021, Guzman agreed to a create a 24-foot replica of it for the Vladem’s lobby to be viewed free of charge.

“DNCA wanted to preserve as much of the [Halpin] building as possible and some of its original, somewhat industrial character.” White says. “Leaving the box of that original warehouse, they created a bridge-like structure that runs over the top of the original space.” This bridge adds an educational classroom, a museum store, and a gallery. “It also sort of follows the design of the city. The original warehouse was

oriented along the railroad tracks. The bridge-like structure over the top follows Guadalupe Street.”

The Vladem includes a collections study room for research, and an overall storage capacity increase for the Museum of Art of more than 80 percent. But the new museum’s primary reason for being isn’t to revamp a crumbling old structure, or even to add more storage space, however badly needed. It’s to display the work of the contemporary artists who are shaping history now.

“We wanted to continue the museum’s original mission, which is to show the art of our time,” White says. “That was getting increasingly difficult in the Plaza building, because it wasn’t built for a lot of post-1960s contemporary art, which is often larger, [and] often has more complicated media than what they were used to in 1917. We’ve tried to expand a couple of times here, and it did not work out.”

The NMMA was founded more than a century ago as New Mexico’s first dedicated art museum, with an open-door policy that provided local artists with public exposure. But examining the full scope of the region’s media practices and artistic legacy, which remain parts of its mandate, requires an engagement between present and past. To that end, the two spaces will work together and share resources.

“We’re not siloing people, and we’re not siloing projects,” says Christian Waguespack, Head of Curatorial Affairs and Curator of 20th-Century Art (see “Curators We Love,” page 30.).

The new space is named after Robert and Ellen Vladem, major contributors to the project’s $12.5 million capital campaign. Its addition of 4100 square feet of storage space enables the NMMA to add more contemporary works to its permanent collection. Public spaces include the unveiling of the Windowbox Project, an installation by renowned New Mexico artists Cristina González, Leo Villareal, and Oswaldo Maciá, and available for viewing by passersby.

The inaugural exhibition, Shadow and Light (through May 28, 2024), draws its theme from New Mexico’s light, which remains a source of inspiration for artists and photographers. Shadow and Light includes works by regional New Mexico modernists Emil Bisttram and Florence Miller Pierce, land artist Nancy Holt, contemporary artists Erika Wanenmacher, Judy Chicago, August Muth, and many others. The show expands on the deeper meanings behind these artists’

appreciation for New Mexico’s natural beauty, and traces the trajectory from modernists such as Bisttram and the Transcendental Painting Group members into the 21st century. It also explores how light and shadow are treated in representational works, as media in their own right, and as conceptual ideas.

Admission to the Vladem is free to the public the weekend of the opening, Saturday and Sunday, September 23-24. Food, refreshments, music, and art-related activities will be offered, and volunteer docents will be available to answer questions about specific works in the exhibition. Guided tours will be available on Sunday. White expects capacity crowds.

“The space will be devoted primarily to contemporary art, largely from 1980 and later, although that’s not really a hard line,” he says. “In fact, the inaugural exhibition will go back to the 1950s. We want to keep our options open in terms of what we show, but the focus will be the last 40 or 50 years.”

The Vladem Contemporary has no immediate plans for a permanent exhibition, but expects to use as much of the present collection as possible. “About 60 percent of Shadow and Light draws from the permanent collection, and about 40 percent takes the form of loans,” White says. The exhibition Off-Center: 1970–2000, slated to open at the Vladem sometime next year, will incorporate even more of the permanent collection, he says.

In the meantime, this vibrant new space in the Railyard promises to be a home for living artists’ work far into the future.

—Michael AbatemarcoWiththe long-awaited addition, this September, of Vladem Contemporary to the New Mexico Museum of Art’s Santa Fe footprint, Christian Waguespack (wag’-us-pack) finds himself wearing two hats: those of Head of Curatorial Affairs and of Curator of 20th-Century Art.

“The Curator of 20th-Century Art part of me will be focused here on the 20th-century downtown building and keeping up the kind of programs I’ve been doing there,” says the 35-yearold Waguespack, who for the last six years has been Curator of 20th-Century Art at the NMMA’s historic building, just off the Plaza. “The Head of Curatorial Affairs part of me will be engaged in collaborating in exhibitions across the two spaces.”

One of the things Waguespack most loves about this dual role is the fluidity it demands, which manifests in the collaborative nature of the projects in both spaces and as opportunities for individual expression.

His windowless downtown office, walled in old brick, occupies a sort of liminal space between the museum’s public areas and collection storage. He usually sits instead in the museum’s courtyard, in the sunshine, amid sculpture, murals, poppies, and hollyhocks.

“I focus primarily on what we consider to be the museum’s

core collection,” he says, going on to mention prominent groups who shaped and influenced New Mexico’s 20th-century art scene: the New Mexican Modernists and the Transcendental Painting Group, as well as specific artists whose legacies are tied to the museum and to regional art in a broader sense, among them Robert Henri, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Gene Kloss.

Although Waguespack’s focus ostensibly extends up to the 1980s, where art historians mark the beginning of the contemporary period, there are still opportunities for a curator who works in a historic era to include works being made today, as well as work that might belongs other curators’ areas of expertise.

“There’s a lot of artwork in our collection that might fall into another curator’s purview—for instance, photography,” he says. “But I always want to include photography in telling the story of 20th-century New Mexico art. Then there are other contemporary pieces that just speak so strongly to the stories that we tell here that they need to be included in those narratives. A lot of times, when we’re putting these exhibitions together, there are contemporary pieces that are the natural continuation of those stories.”

Waguespack recalls a phenomenon among curators who were, like him, apparently born to the role, and characterize oddities of their behavior as children that now make more sense to them in their professional roles. “One time, we had a hurricane come through,” he says of his boyhood in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. “That happened pretty regularly. The electricity was out, and kids had to occupy themselves. What I did was make reports on all the artwork in the house. I recorded what it was, who I thought it was by, what I thought the title was, and what I thought it was worth. A few years ago, my grandma called me because she found the paper, done in crayon. She said, ‘Look, you’ve been doing your job since you were a little kid.’ ”

Along with his curatorial instincts, Waguespack has a penchant for the dark. Although singularly good-natured, he’s had a lifelong love of horror films, and gothic literature and art. As a curator, that interest occasionally surfaces in his narratives of New Mexico’s darker histories, which artists have addressed for as long as they’ve been celebrating the state’s natural beauty and diverse cultures.

“There are ways a curator brings their own point of view to something,” he says. “For instance, with Cady Wells, I tend to talk a lot about the more gothic aspects of his work, the way that I think they’re rooted in German Romanticism—and how some of his dark, Cubist constructions of New Mexico remind me of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari [a 1920 German Expressionist film directed by Robert Wiene]. So, it shows up.”

Waguespack, however, remains aware of his audience. “We’ve got to do the exhibitions that are right for the community, but I’m very thankful that I’ve had a lot of freedom to bring some of myself to the shows here.”

Some of the NMMA exhibitions he’s recently curated include the past exhibits Storytellers: Narrative Art and the West and A Fiery Light: Will Shuster’s New Mexico. He curated the current exhibit With the Grain (through September 4), a survey of Patrociño Barela and the regional woodcarving tradition. He is also involved in planning the Vladem’s inaugural exhibition, Shadow and Light (September 23–May 28, 2024).

“The inaugural show was, of course, curated by Merry Scully, and it is, for the most part, going to be true to her vision.” Scully, the former Head of Curatorial Affairs at NMMA, left in 2022 to take a top position at the Robert and Frances Fullerton Museum of Art, at California State University–San Bernardino. Waguespack took over her position in March and is already developing future Vladem exhibits. Although these have yet to be announced, among them is a collaboration among the museum’s curatorial team: a yearlong survey, in three stages, of New Mexico art from the 1970s through the 1990s.

“We’re going to be pulling primarily from the [NMMA] collection, with a few key loans. Each iteration is going to explore the same group of work from a different curator’s perspective, based on their primary interest. So it’s another instance where the curator can bring their own flavor to something.”

Waguespack says that much of his work is rooted in the sense of place, in terms of both geography and of physical institutions and the role they’ve played in New Mexico art. His stage of the future exhibit will reflect this interest, he says; the other curators will focus on the aspects of spectacle and identity in the contemporary period.

“So much of my understanding of the collection comes through the lens of how artists, over time, have engaged with this place,” he says. “My work, too, has changed to reflect the place where I am.”

—Michael AbatemarcoDon’t miss the Recycle Santa Fe Art Festival, one of our favorite events of the year. One person’s trash is another’s treasure, and that adage is amply demonstrated by artists who transform discarded materials—tin cans, buttons, bits of wood, scrap metal, textiles, paper, plastic, etc.—into highly creative works of art: jewelry, wearable art, sculpture, paintings, decorative objects, and much more. With more than 100 artists from New Mexico and surrounding states, the Festival is the nation’s largest and oldest market for recycled art. Be sure to attend the first night, Friday, for the Fashion Show featuring eye-opening approaches to apparel—and, in the lobby, the charming and inspirational Student Art Exhibition, with projects from area elementary schools.

Festival

November 10–12, 2023

Santa Fe Community Convention Center

201 W. Marcy Street

recyclesantafe.org

This two-acre urban farm operates ten interrelated programs around food and sustainability. Reunity’s food-waste collection turns commercial and private food scraps into compost; their Soil Yard provides rich, nutrient-dense soil, compost, and mulch; the Farm Stand offers fresh organic produce grown on-site; the Santa Fe Community Fridge and pantry is a mutual-aid foodsupport system available to anyone, no questions asked—and those are only some of their programs. Grab a coffee and burrito at the resident food truck and browse for fresh produce, or bring a lawn chair and blanket to one of the occasional concerts offered on the grass under large elms. Reunity Resources, a nonprofit, is committed to supporting regenerative agriculture and community collaborations, to build a future in which everyone is part of a resilient, nourishing food system.

Baked & Brew serves breakfast and lunch in a former used-car shop, itself a former gas station. Breads, pastries, and cookies are baked on-site by the owners, professionally trained pastry chefs. Customize your breakfast or lunch sandwich (pick your bread! pick your filling!), then round out your meal with house-made soups, salads, and local coffees and teas. B&B also create holiday and seasonal treats, and custom cakes.

1310 Cerrillos Road

sfbakedandbrew.com

1829

A coffee shop in a tire store? A bakery in an auto showroom? A slew of new cafés and bakeries have adapted old buildings into eateries new and refreshing, literally and figuratively.

Housed in a former Discount Tire store, this third location of local favorite Iconik Coffee Roasters has abolished all signs of the building’s rubbery roots. This Iconik is called Red; the others are Lupe (at 314 S. Guadalupe Street) and Lena Street (1600 Lena Street). Each has a hip vibe and well-made coffees and teas, along with a varied breakfast and lunch menu.

1366 Cerrillos Road

iconikcoffee.com

San Ysidro Crossing reunityresources.comMeet the gallerists who are bringing new energy to the Santa Fe art scene. Committed to making art accessible and unintimidating, these curators are providing forums for new voices and are helping change how we perceive art and galleries in Santa Fe.

In February 2019, Frank Rose opened a tiny gallery, Hecho a Mano (Made by Hand), near the top of Canyon Road. There he mostly focused on printmaking, with an emphasis on Mexican and New Mexican artists. “Affordably priced prints are a great way to get into collecting art or add to a collection,” says Rose. “The artists I represent, whether printmakers, ceramicists, or jewelers, are at the intersection of innovation and tradition.” After he began mounting shows with painters and sculptors, Rose began to look for a space to create a different environment, and in April 2022 opened Hecho Gallery, on W. Palace Avenue. The latter shows primarily New Mexican artists who are creating genre-defying art.

“I want my spaces, and the work that’s in them, to be relative to each other,” Rose says. “My desire is for people to see the art in dialogue with the space, and to involve the space with the work. The spaces share color, media, and visual qualities. So whether it’s the small space on Canyon Road or the larger space on Palace, I would

like to provide a variety of points of entry for visitors. But the main thing both galleries share is an attitude of accessibility. More than anything, I want art to be accessible and not intimidating.

“I would really like to see people stop seeing ‘Southwestern art’ as a narrow genre, and instead have a broader definition of styles and voices,” he continues. “My wish is to change the narrative of art in Santa Fe to be more inclusive and experiential.”

Rose is creating a community through frequent and popular events: gallery openings with DJs, and quarterly quickdraw events in which artists produce small works live in front of gallery attendees. “Art is the shared inheritance of humanity,” he concludes—“everyone can have access to it, buy it, do it.”

Hecho a Mano

830 Canyon Road

hechoamano.org

Hecho Gallery

129 W. Palace Avenue https://hecho.gallery

of Indigenous, Hispanic, outsider, and New Contemporary/pop surrealist art, this gallery is a vibrant space in which to experience unique, edgy work—he has always been interested in finding new talent. After he earned his BFA from the former College of Santa Fe he operated pop-up gallery shows and a small gallery on Water Street. Trujillo is himself an artist; he cites his first solo show at Evoke Contemporary, in 2010, as a watershed moment in his career as an artist.

Keep Contemporary represents 85 artists from all over the world—Chile, Iceland, Scotland, the Philippines, Mexico, and elsewhere—as well as established and up-and-coming local artists. Trujillo looks for new techniques, and wants to see artists with unique voices whose work is at the forefront of prevailing trends. “I want people to not be intimidated by the art experience. We have all price ranges, and hope visitors find it both exciting and comfortable. Art should be for everybody, not just a certain demographic.

“My main purpose is to give a voice to artists who don’t have representation in the more traditional Santa Fe art market,” says Jared Trujillo, owner of Keep Contemporary. With a plethora

“I hope we’re changing the way we look at art in Santa Fe,” Trujillo continues. “I’m taking a long-term perspective—20 or 30 years from now, I want people to look back and see that we had an influence on the market It’s important to understand the history of art in Santa Fe—the long and deep Indigenous art and history and culture. It’s also good to remember that Santa Fe is a huge art market, and we’re doing our part to keep it refreshing and sophisticated.”

Keep Contemporary

142 Lincoln Avenue

keepcontemporary.com

New Mexico Museum of Art expands to the Santa Fe Railyard District, creating new avenues to make art available to everyone.